The Project Gutenberg eBook of Arctic exploration, by Douglas Hoare

Title: Arctic exploration

Author: Douglas Hoare

Release Date: March 21, 2023 [eBook #70329]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, Brian Coe and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by the Library of Congress)

SAILING THE ARCTIC SEAS

ARCTIC

EXPLORATION

BY

J. DOUGLAS HOARE

WITH EIGHTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS AND FOUR MAPS

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & CO.

1906

[Pg v]

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Early Voyages | 1 |

| II. | From Hudson to Phipps and Nelson | 17 |

| III. | The Voyage of Buchan and Franklin | 30 |

| IV. | Ross’s Failures and Parry’s Successes | 35 |

| V. | Franklin’s First Overland Journey | 45 |

| VI. | Parry’s Last North-West Voyages | 64 |

| VII. | Franklin’s Second Land Journey | 70 |

| VIII. | Parry’s North-Polar Voyage | 79 |

| IX. | Ross’s Adventures in the “Victory” | 86 |

| X. | Back’s Two Journeys | 95 |

| XI. | The Discoveries of Dease and Simpson | 102 |

| XII. | Franklin’s Last Voyage | 116 |

| XIII. | Rae and the Boothia Peninsula | 122 |

| XIV. | The Franklin Search begun | 129 |

| XV. | The Voyages of Collinson and M’Clure | 137 |

| XVI. | Belcher and the Franklin Search | 150 |

| XVII. | Rae’s Journeys of 1851-53 | 159 |

| XVIII. | M’Clintock and the “Fox” | 168 |

| XIX. | The Voyages of Kane and Hayes | 182 |

| XX. | Hall and the “Polaris” | 192 |

| XXI. | The “Germania” and the “Hansa” | 200 |

| XXII.[Pg vi] | The Voyage of the “Tegetthoff” | 207 |

| XXIII. | Nares and Smith Sound | 215 |

| XXIV. | The Greely Tragedy | 223 |

| XXV. | Nordenskiöld and his Work | 235 |

| XXVI. | The Story of the “Jeannette” | 244 |

| XXVII. | Leigh Smith and the “Eira” | 252 |

| XXVIII. | Greenland and the Earlier Journeys of Nansen and Peary | 257 |

| XXIX. | The Jackson-Harmsworth Expedition | 270 |

| XXX. | Nansen and the “Fram” | 278 |

| XXXI. | Conway and Andrée | 287 |

| XXXII. | The Later Voyages of Sverdrup and Peary | 293 |

| XXXIII. | Other Recent Expeditions—Abruzzi, Wellmann, and Toll | 301 |

| Index | 309 |

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | ||

| Sailing the Arctic Seas | Frontispiece | |

| From an old print | ||

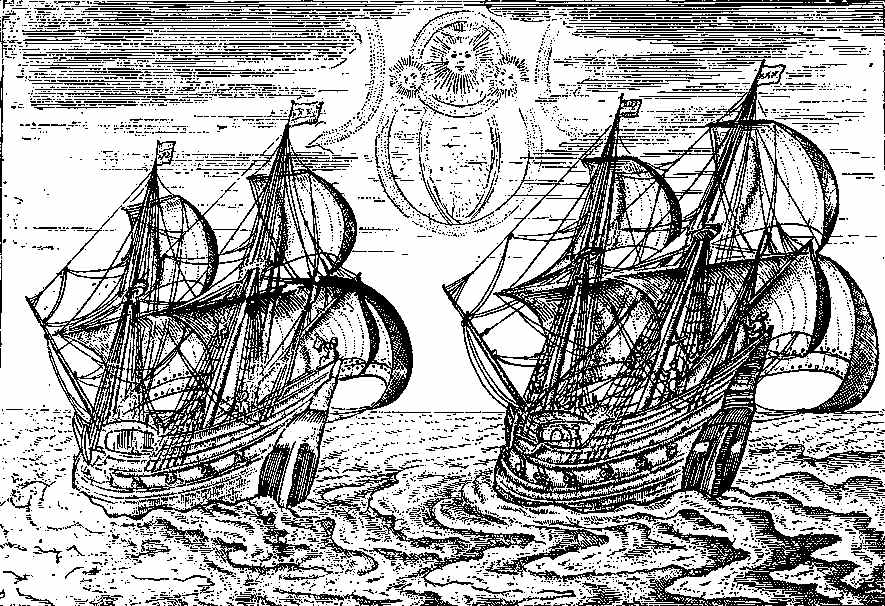

| An Old Map of the Polar Regions | 1 | |

| From “Narborough’s Voyages,” 1694 | ||

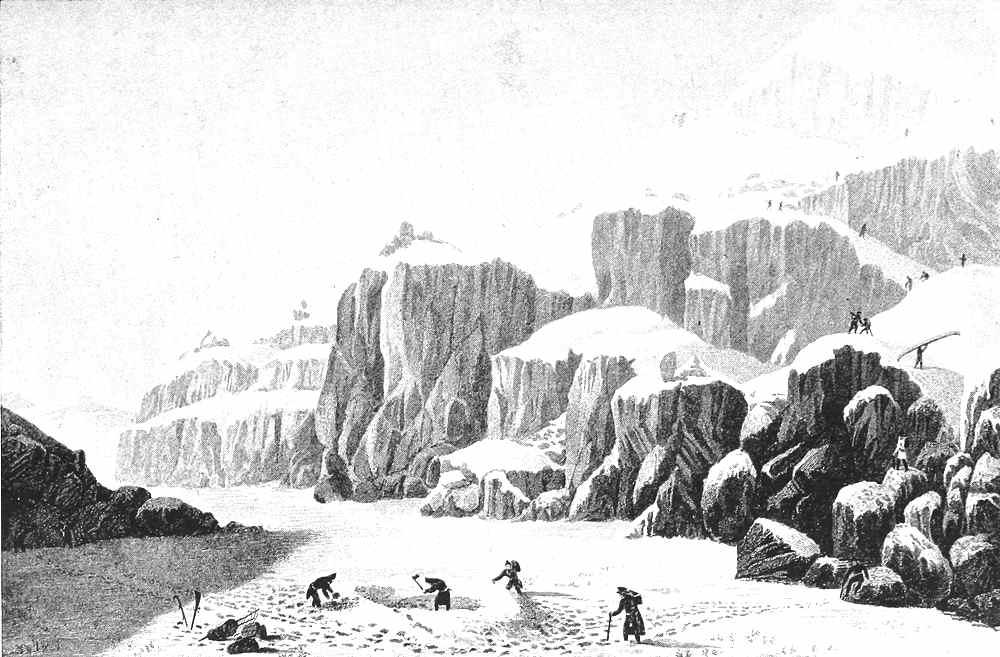

| Stranded on Nova Zembla | 13 | |

| From an old print | ||

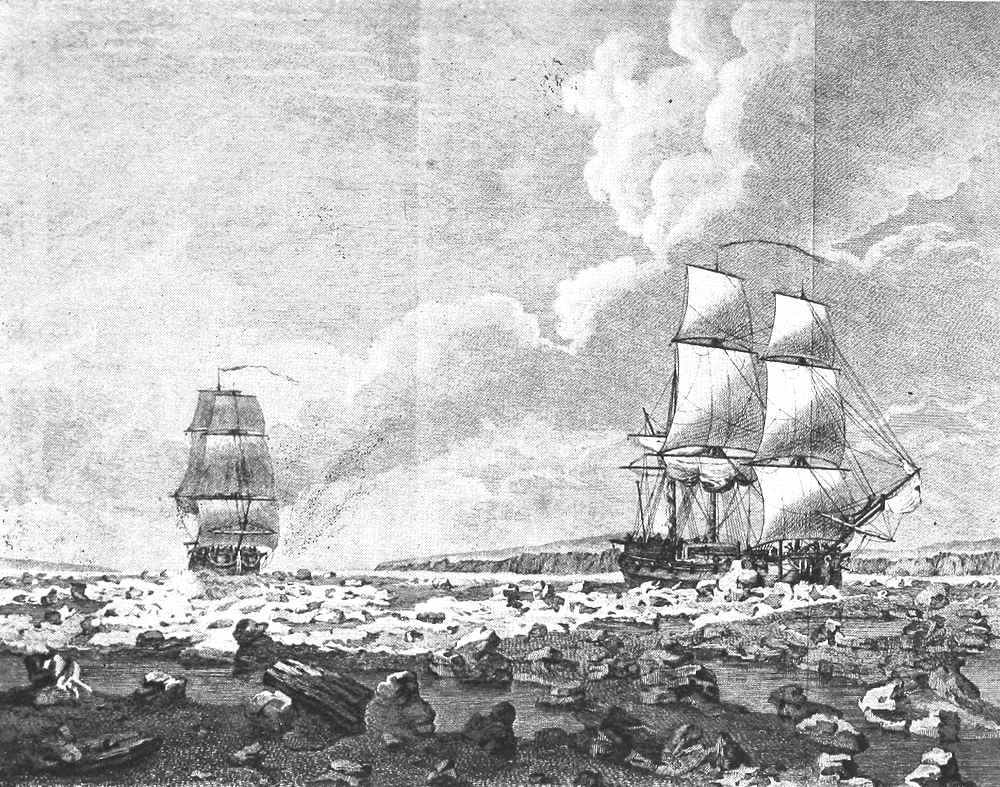

| The “Racehorse” and the “Carcase” in the Ice | 28 | |

| From a picture by J. Clively | ||

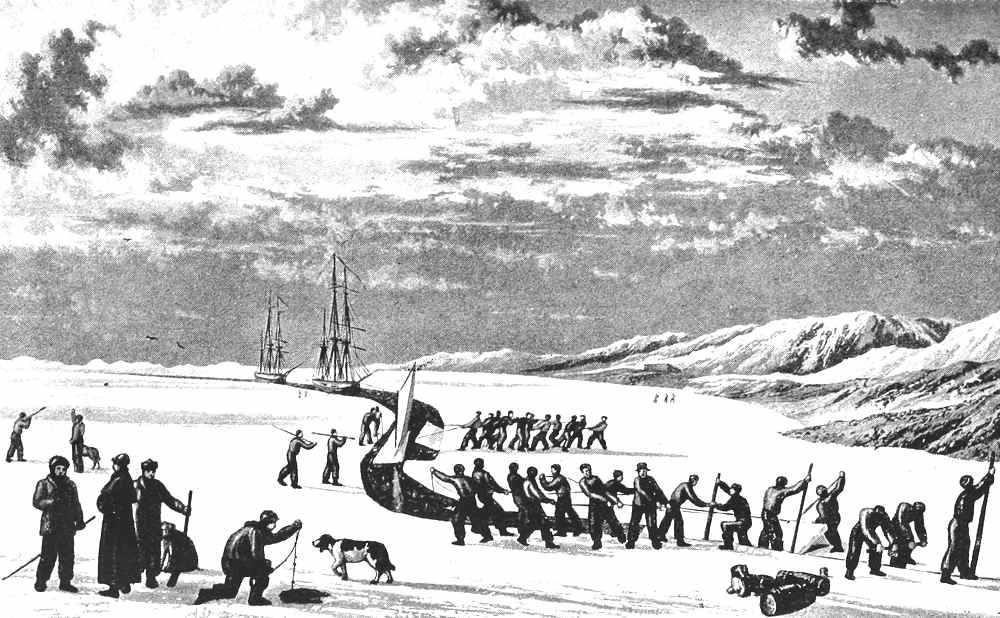

| Cutting a Passage into Winter Harbour | 42 | |

| From a sketch by Lieut. Beechey | ||

| Crossing the Barren Grounds | 56 | |

| From a drawing by Capt. Back | ||

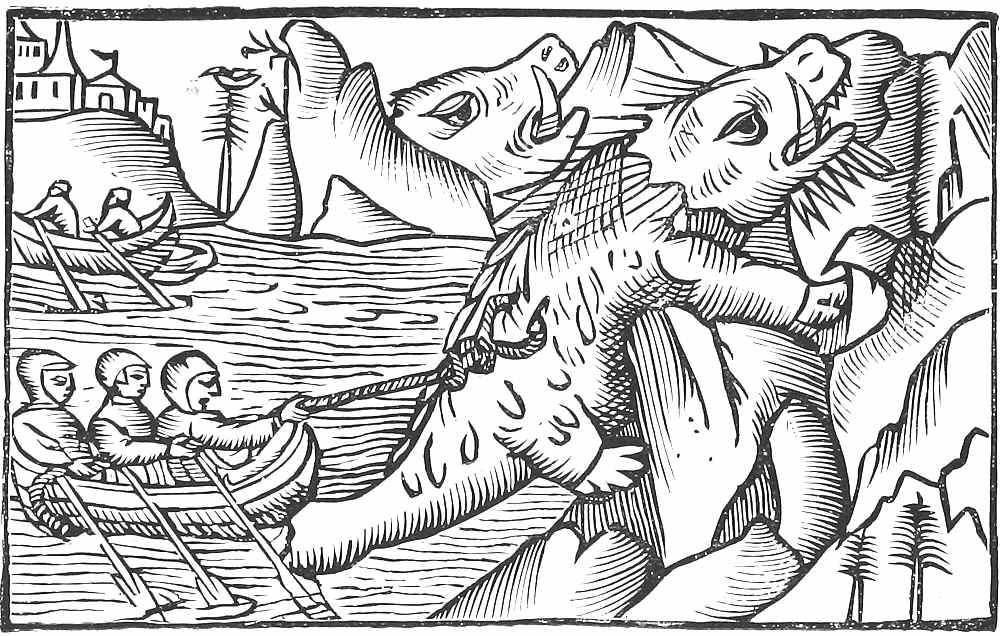

| The Walrus as seen by Olaus Magnus | 68 | |

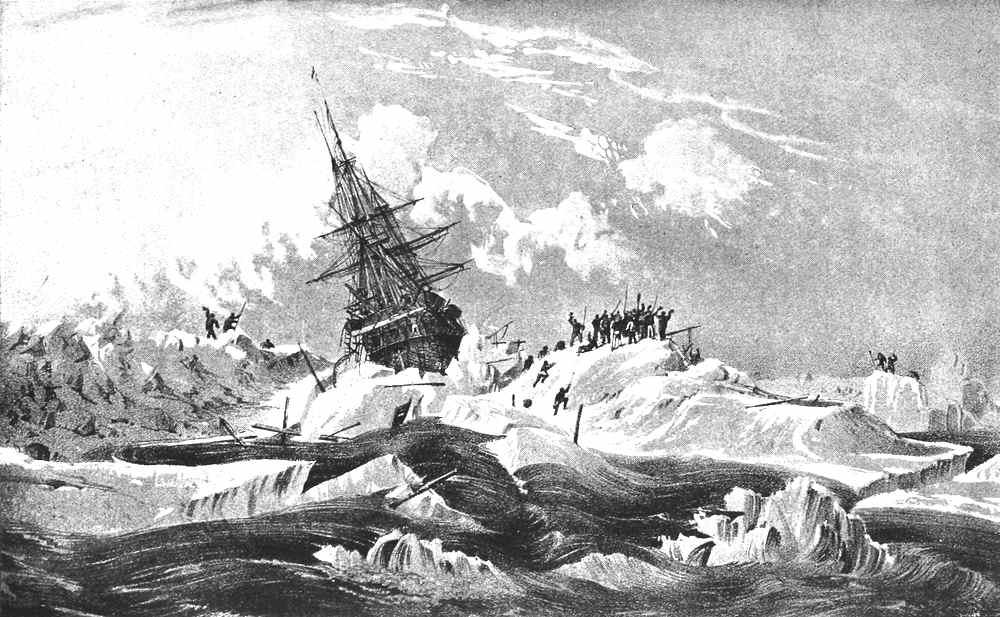

| The Disruption of the Ice round the “Terror” | 100 | |

| From a drawing by Capt. Smyth | ||

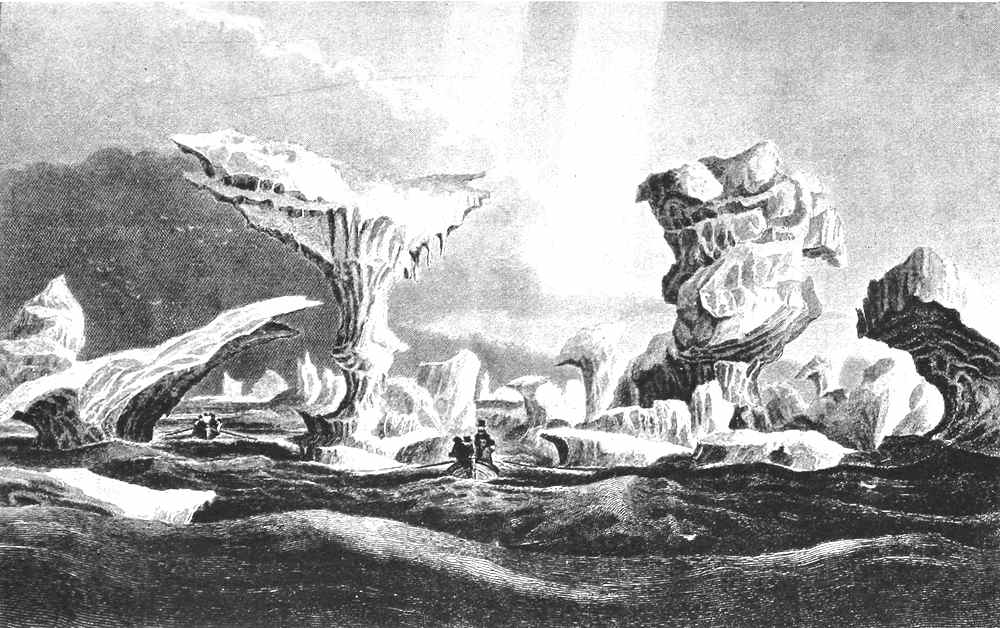

| Boats among the Ice | 134 | |

| From a drawing by Capt. Back | ||

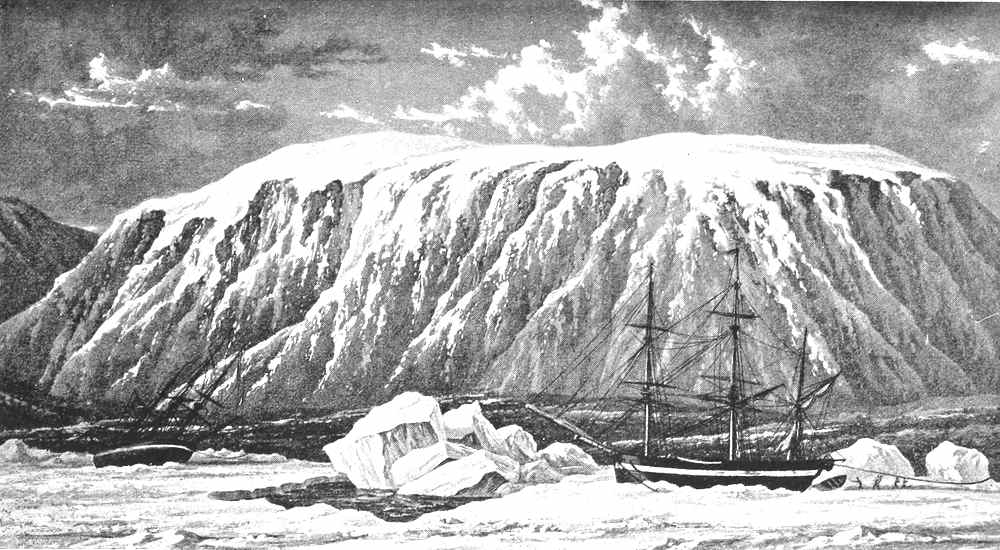

| Fast in the Ice | 154 | |

| From a sketch by Lieut. Beechey | ||

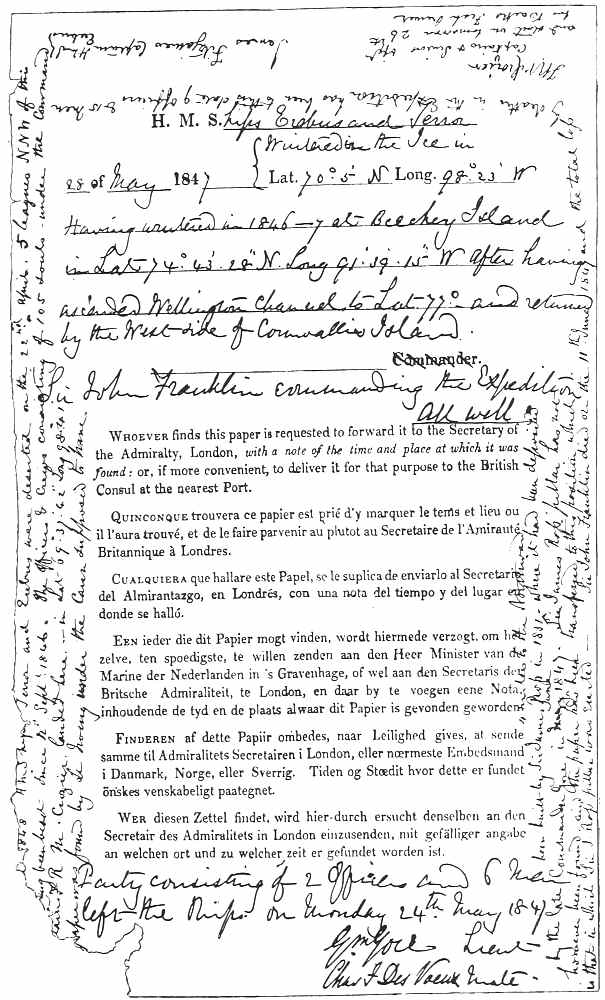

| The Franklin Record | 174 | |

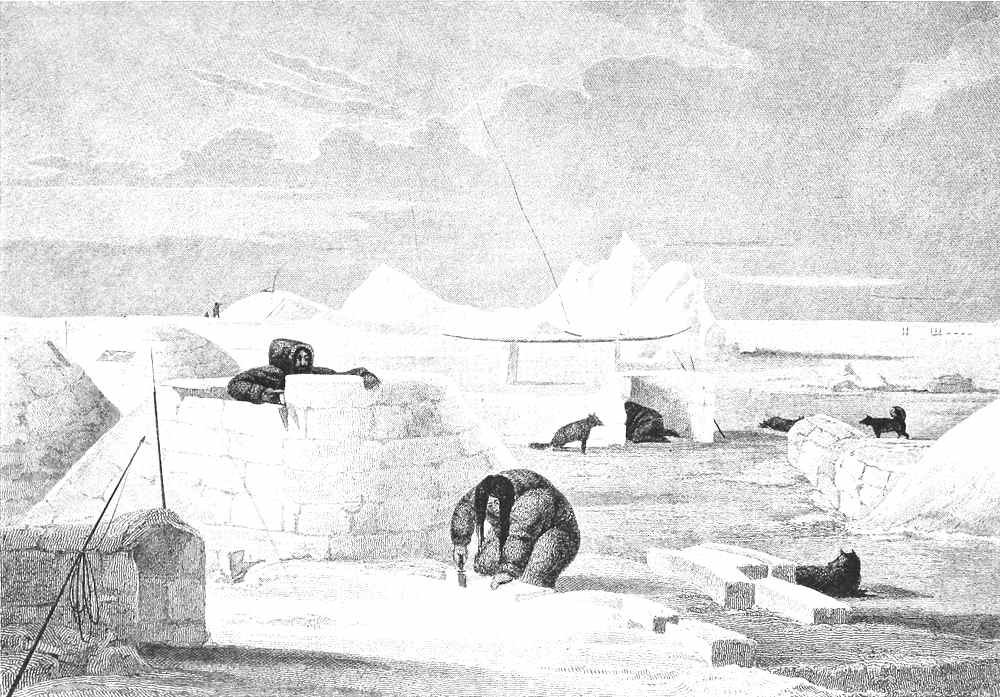

| Eskimo Architects | 192[Pg viii] | |

| From a drawing by Capt. Lyon | ||

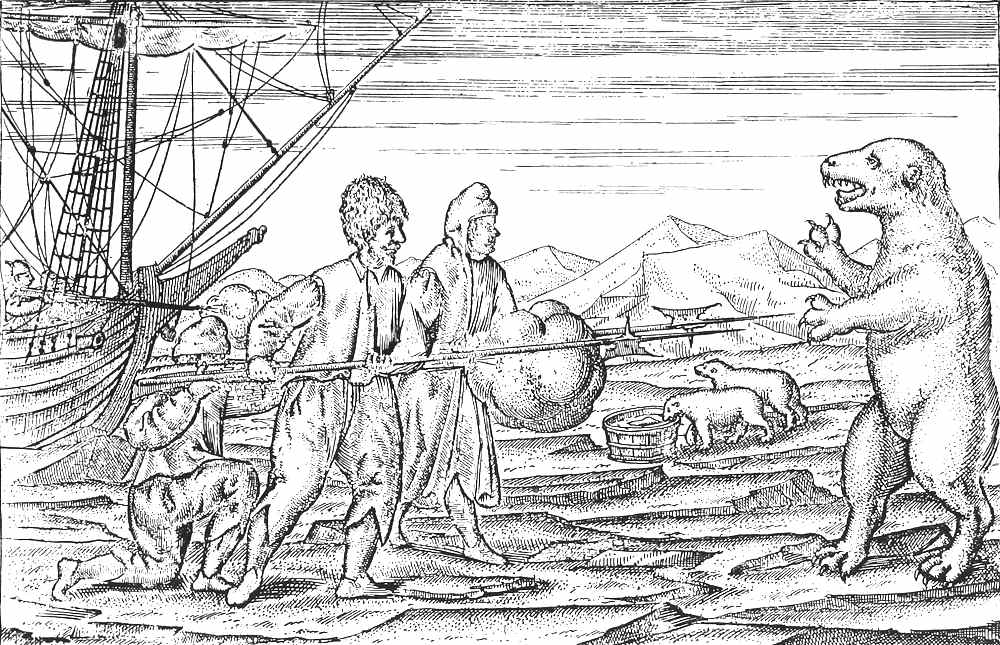

| A Bear Hunt | 212 | |

| From an old print | ||

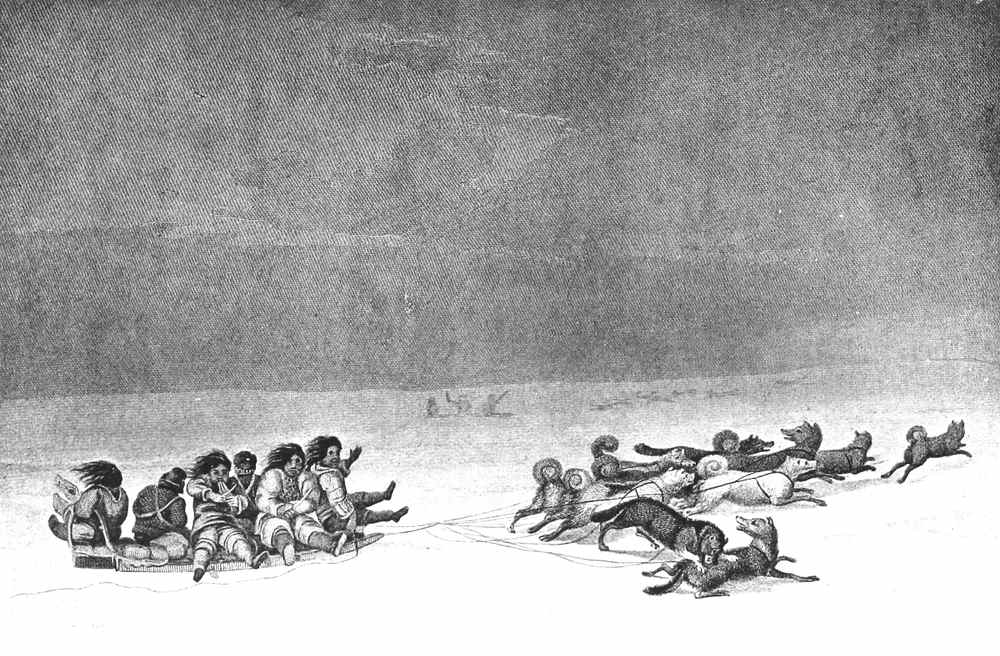

| Eskimos Sledging | 248 | |

| From a drawing by Capt. Lyon | ||

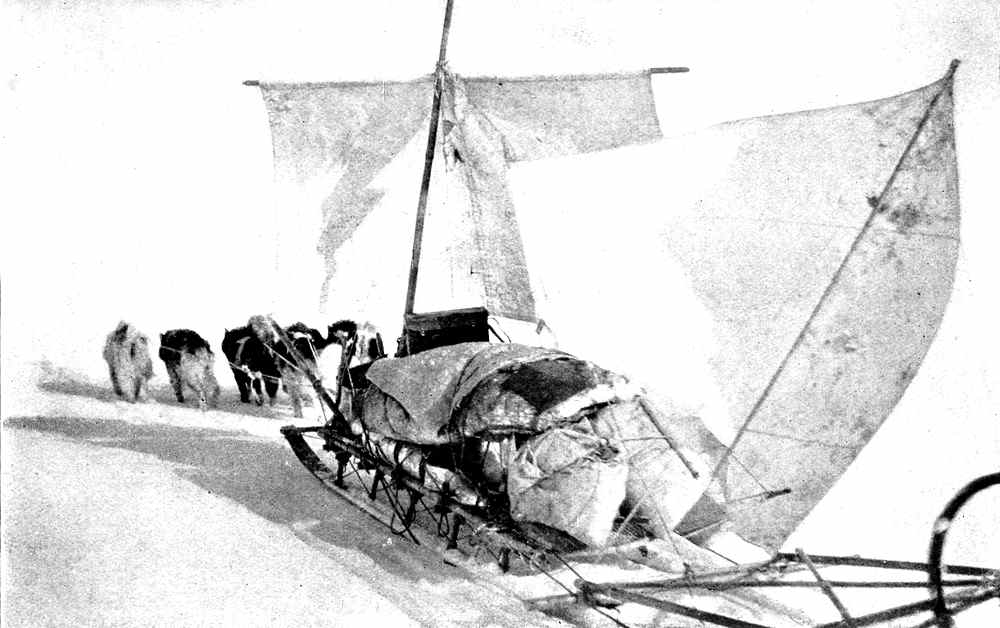

| Peary’s Travelling Equipment | 266 | |

| By kind permission of Messrs F. A. Stokes Co. | ||

| The Meeting between Jackson and Nansen | 274 | |

| By kind permission of Capt. Jackson and Messrs Harper Bros. | ||

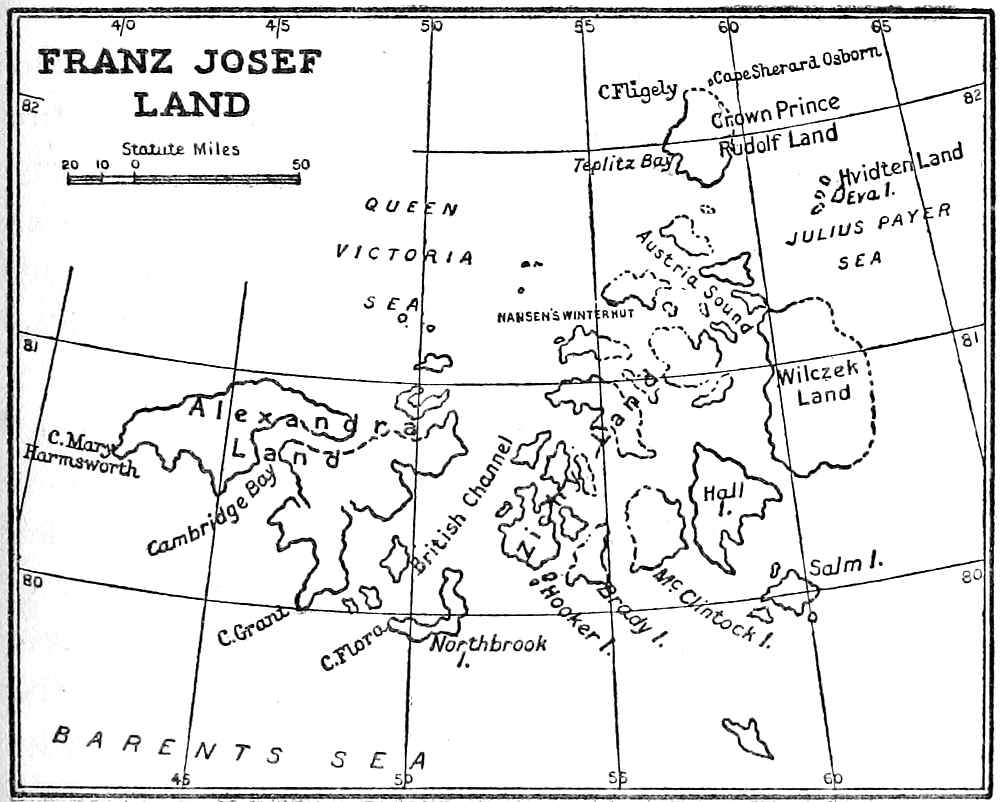

| Map of Franz Josef Land | 277 | |

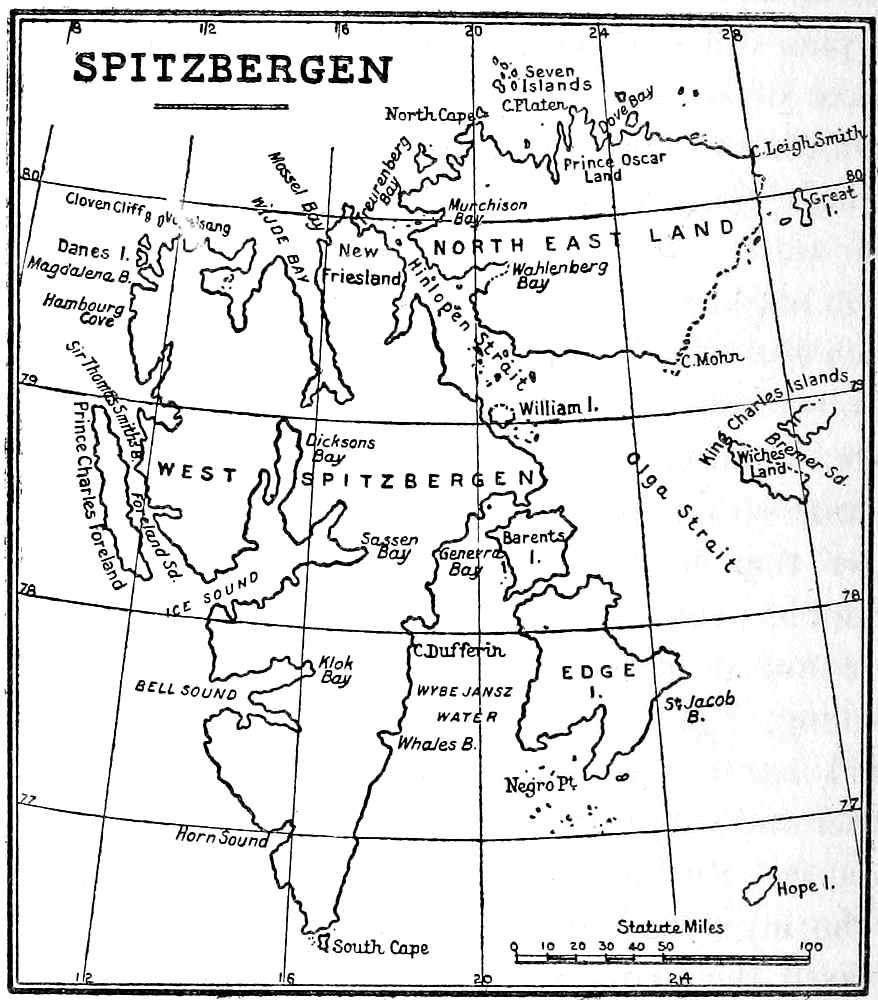

| Map of Spitzbergen | 286 | |

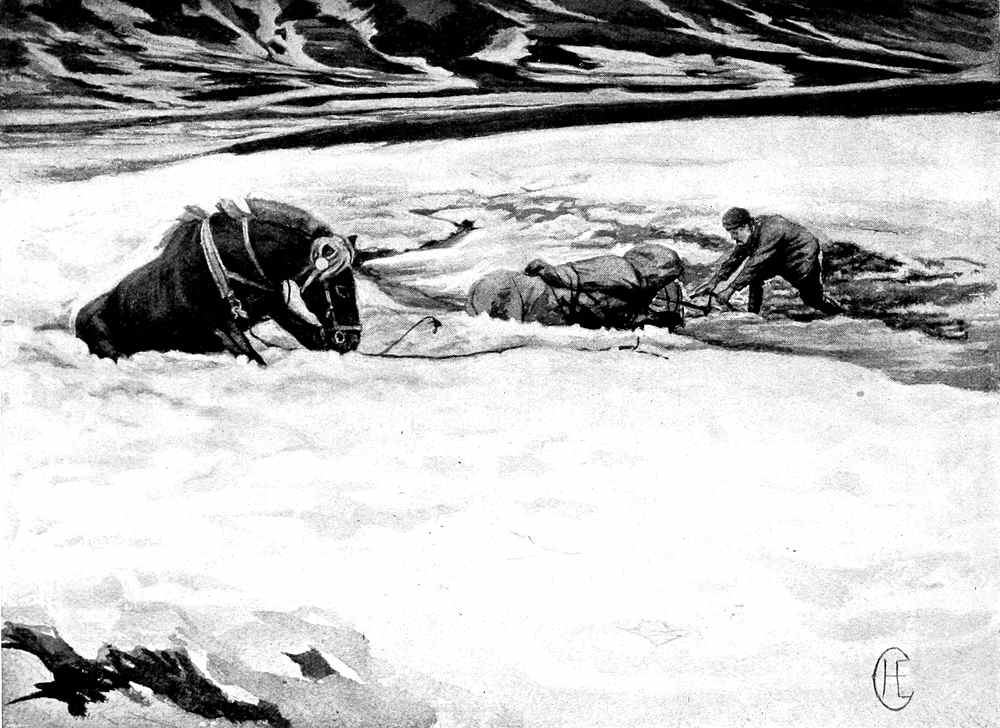

| In the Slush | 288 | |

| By kind permission of Sir Martin Conway and Messrs J. M. Dent & Co. | ||

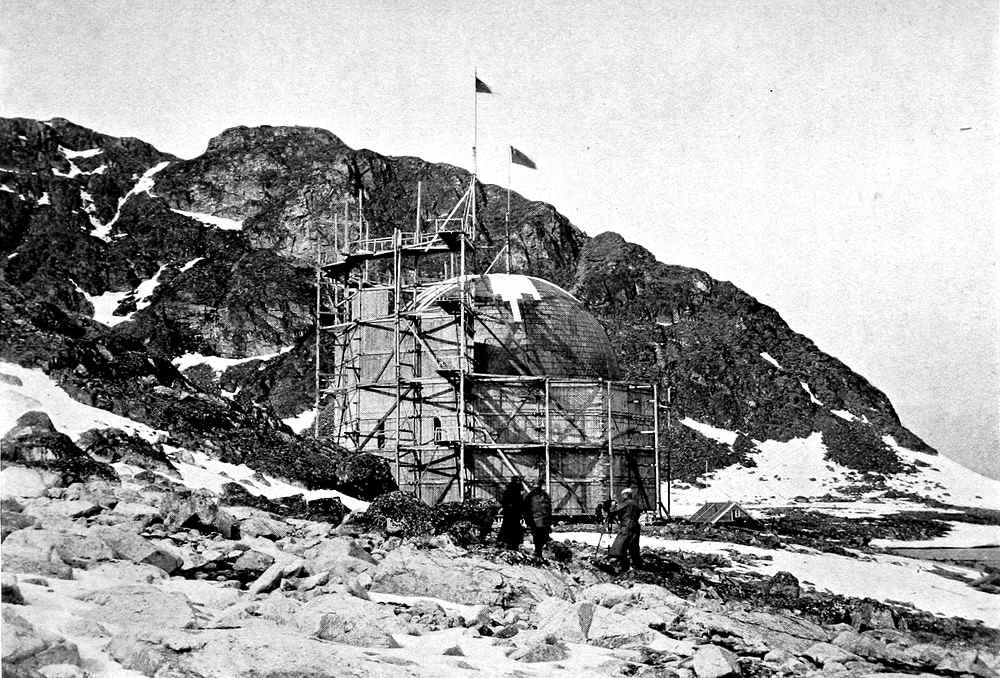

| Andrée’s Balloon in its Shed | 292 | |

| From a photograph | ||

| The “Polar Star” under Ice Pressure | 304 | |

| By kind permission of Messrs Hutchinson & Co. | ||

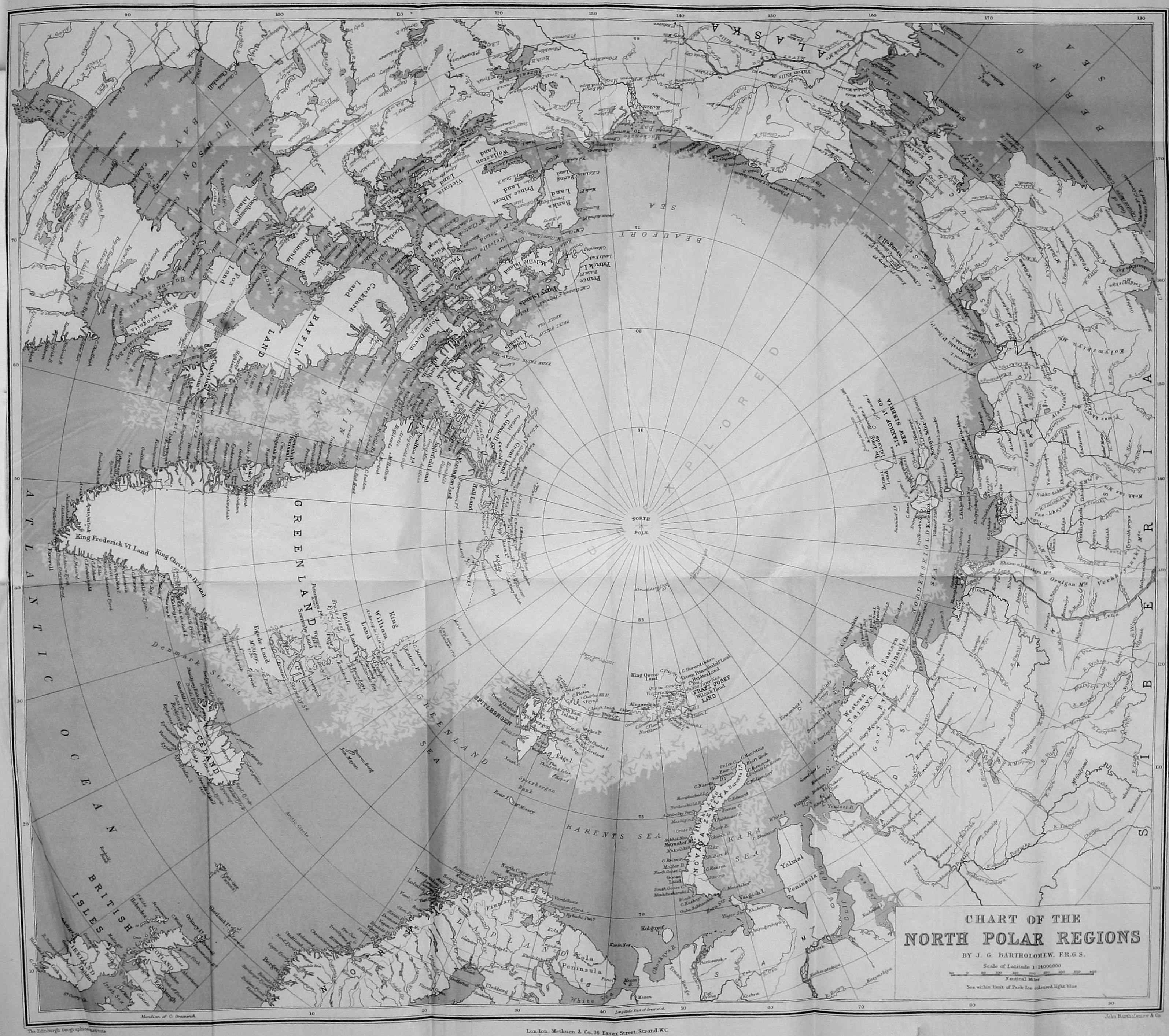

| Chart of the North Polar Regions | Attend | |

[Pg 1]

ARCTIC EXPLORATION

The story of the first few centuries of Arctic exploration can, of course, never be written. The early Norsemen, to whom must go the credit for most of the first discoveries, were a piratical race, and their many voyages were conducted, for the most part, in a strictly business-like spirit. Occasionally one of them would happen on a new country by accident, just as Naddod the Viking happened upon Iceland in 861 by being driven there by a gale while on his way to the Faroe Islands. Occasionally a curious adventurer would follow in the footsteps of one of these early discoverers, but no serious attempt was made to widen the field of knowledge thus opened up, unless the Norsemen saw their way to entering upon commercial relations with the natives, to the great disadvantage of the latter.

AN OLD MAP OF THE POLAR REGIONS

FROM NARBOROUGH’S “VOYAGES” (1694)

The erroneous intersection of Greenland by Frobisher’s Strait should be especially noted

Rumours of the existence of Iceland, or Thule as it was then called, were first brought home by Pytheas, while Irish monks are known to have stayed there early in the ninth century, but probably the first attempt to colonise it was made by Thorold about a hundred years after Naddod’s visit. This worthy Viking, feeling it advisable to leave his native land [Pg 2]after a quarrel with a relative, during the course of which the latter had been killed, set his course for Iceland, and made himself a new home there. Shortly afterwards his son Erik, who seems to have inherited his father’s taste for murder, followed him to his new abode, and later on, when on a voyage of adventure, set foot upon Greenland. Erik’s son, Leif, who was also of a roving disposition, sailed far westward in 100 A.D., and landed either on Newfoundland or at the mouth of the St Lawrence, thus anticipating the discovery of America by Columbus by nearly five hundred years.

It was not until the end of the fifteenth century that the first serious attempts at Arctic exploration were made by John Cabot and his son Sebastian. John Cabot was a Venetian, who settled at Bristol probably about the year 1474, and to him belongs the honour of being the first to suggest the possibility of finding a north-west passage to India. In 1496 he received a commission from Henry VII. to sail out for the discovery of countries and islands unknown to Christian peoples, and though the real object of his voyage, discreetly veiled beneath these purposely vague terms, was not attained, he immortalised his name by the discovery of Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island. The history of the earlier Cabot voyages is sadly obscure, and was rendered more so by Sebastian himself, who in his later years seems to have claimed discoveries which properly belonged to his father. Sebastian is unquestionably the hero of his own account of the expedition of 1496, which is given by Hakluyt:—

“When news were brought that Don Christoval[Pg 3] Colon (i.e. Christopher Columbus), the Genoese, had discovered the coasts of India, whereof was great talke in all the court of King Henry VII., who then reigned, insomuch that all men with great admiration affirmed it to be a thing more divine than humane to saile by the West into the East where spices growe, by a way that was never knowen before, by this fame and report there increased in my heart a great flame of desire to attempt some notable thing. And understanding by reason of the Sphere (i.e. globe) that if I should saile by way of the North-west I should by a shorter tract come into India, I thereupon caused the king to be advertised of my devise, who immediately commanded two Carvels to be furnished with all things appertayning to the voyage, which was as farre as I remember in the year 1496, in the beginning of Sommer. I began therefore to sail toward the North-west, not thinking to find any other land than that of Cathay and from thence to turn toward India; but after certaine days, I found that the land ranne towards the North, which was to me a great displeasure. Nevertheless, sayling along by the coast to see if I could finde any gulfe that turned, I found the lande still continent to the 58th degree under our Pole. And seeing that the coast turned toward the East, despairing to finde the passage, I turned backe againe, and sailed downe by the coast of that land toward the Equinoctiall (ever with intent to finde the saide passage to India) and came to that part of this firme lande which is nowe called Florida, where my victuals failing, I departed from thence and returned into England, where I found great tumults among the people, and preparation for warres[Pg 4] in Scotland, by reason whereof there was no more consideration had to this voyage.”

John Cabot made a second expedition in 1498, and probably died soon after. Sebastian, who had accompanied his father on both his American voyages, finding the English Government little inclined to spend money on further exploration, transferred his services to the King of Spain, for whom he did excellent work by examining the coast of South America. In 1548, however, he returned to England, and Edward VI. did him the honour that was his just due, by settling on him the sum of 500 marks (£166, 13s. 4d.) a year for life, and, according to Hakluyt, creating him Grand Pilot. Never did a man deserve his honours more, for, by founding the company of Merchant Adventurers, of which he was the first governor, he did much to extend the foreign commerce of the nation, and, by fostering a spirit of enterprise, he paved the way for that immense success won by our sailors and merchants during the next century.

The first purely British expedition was that of Robert Thorne, of Bristol, at whose instigation, say Hall and Grafton, “King Henry VIII. sent out two fair ships, well manned and victualled, having in them divers cunning men to seek strange regions, and so they set forth out of the Thames, on the 20th day of May, in the nineteenth yere of his raigne, which was the yere of our Lord 1527.” The “fair ships” had as their objective no less a place than the North Pole, but the men do not seem to have been sufficiently “cunning” to make much headway against the difficulties that beset their path, and the chronicles[Pg 5] of the time are singularly reticent concerning their doings.

The voyage of the Trinitie and Minion, which sailed in 1536, is one of the most disastrous on record. The expedition was sent out with a view to exploring North-West America, and it reached the coast of Newfoundland in safety. It seems, however, to have been hopelessly under-provisioned, and the men, having little to eat on board and finding themselves unable to supplement their scanty store on land, took to cannibalism, and would all have perished but for the timely arrival of a French ship, which they promptly set upon and misappropriated. We are not told what happened to the unfortunate Frenchmen, but Henry VIII. is reported to have compensated such as survived.

Hitherto the energies of our sailors had been principally devoted to discovering a north-west passage to India, Cathay, and the Indies. When, however, Cabot returned from Spain and was made “Governour of the mysterie and companie of the marchants adventurers for the discovery of regions, dominions, islands and places unknown,” he promptly showed how well fitted he was for that honourable post by suggesting that, as the voyages towards the north-west had not been attended by much success, it would not be amiss to try a change of tactics and to attempt to find a way to Cathay by the north-east. The idea was taken up enthusiastically, and, as this was the first extended maritime venture made by us in distant seas, the utmost care was exercised over the preparations. Three ships were specially built for the enterprise,[Pg 6] and were fitted out in the most substantial manner possible. The admiral of the fleet, the Bona Esperanza, 120 tons, was placed under the command of Sir Hugh Willoughby, and carried thirty-five persons, who included six merchants. The Edward Bonaventure, 160 tons, was commanded by Captain Richard Chancellor, her company consisting of fifty, including two merchants; and the Bona Confidentia, 90 tons, was commanded by Cornelius Durfourth, and carried twenty-eight souls, also including two merchants. These three ships sailed from Ratcliffe on May 20, and, after tracing the coast of Norway, rounded the North Cape in company. Here a storm separated the Bonaventure from her sister ships, and, fortunately for her and her company, drove her to Vardö, in Norway. Willoughby and his two ships succeeded in making the coast of Lapland, and spent the winter on the desolate coast of the Kola Peninsula. In those days, unfortunately, but little was known of the art and science of wintering in the Arctic regions, and every member of the company perished miserably of scurvy.

Chancellor, after waiting awhile at Vardö in the hope that the rest of the fleet would join him there, determined to push on on his own account, and he eventually succeeded in reaching the north coast of Russia. The intelligence of his arrival was conveyed to the Czar, Ivan Vasilovich, who was so much interested in what he heard that he invited him to Moscow. There Chancellor spent the winter, and with such ardour did he forward the interests of his country, that he laid the foundations of that great trade between England and Russia which has flourished[Pg 7] ever since. It is worthy of note that his first landing place is now marked by the great seaport of Archangel.

Chancellor’s second expedition was less fortunate, for the gallant sailor lost his life in his attempt to continue his work. He reached Russia in safety, and once more repaired to Moscow, where he continued the negotiations which he had previously begun. While returning home, however, his ship was wrecked in Pitsligo Bay on the east coast of Scotland and he was drowned.

The expedition of Chancellor and Willoughby had, of course, been primarily sent out with a view to finding a north-east passage to China, and these negotiations with Russia were a side issue not originally contemplated by its promoters. Consequently, while Chancellor was away on his second voyage, the Company of Merchants Adventurers equipped a second expedition for the discovery of the North-East Passage, which they placed under the command of Stephen Burrough. The Searchthrift, as the ship was named, set sail on April 23, 1556, but it was stopped by fog and ice, and Burrough was obliged to return to England without accomplishing his mission, though he succeeded in discovering Nova Zembla.

The next English mariner to win fame for himself by his adventures in the Arctic seas was Martin Frobisher, who, under the auspices of Queen Elizabeth, the Earl of Warwick, a well-known merchant named Lok and others, fitted out a fleet of three cockle-shells, the united burden of which was only 73 tons, and set sail in 1576, with intent to discover the North-West[Pg 8] Passage. The chief result of Frobisher’s voyage was a vast mass of very misleading information. On reaching Davis Strait he came to the conclusion that it bisected Greenland, an error which retained its place in the maps for some three centuries. In the middle of the strait he discovered an island which did not exist, while he brought home with him the interesting information that large deposits of gold existed on the shores which he had visited. On the strength of this all sorts of plans for working these deposits were taken up, which only ended in the financial loss and bitter disappointment of their promoters. Frobisher undertook the command of two subsequent expeditions, but neither of them resulted in any discoveries of much value. His name, however, will always be kept alive by the discovery of Frobisher and Hudson Straits, both of which he entered on his first journey.

We now come to by far the most important of these early voyages, namely that made by John Davis, of Sandridge, in 1585. Davis was a splendid old sea-dog of the finest type—shrewd, patient, and of absolutely indomitable courage. So high was his reputation, that when a number of merchants, headed by William Saunderson, determined to fit out a new expedition for the discovery of the North-West Passage, they offered him the command, and their offer was promptly accepted. The expedition, which consisted of two ships, the Sunshine, of 50 tons, and carrying twenty-three men, and the Moonshine, 35 tons, and carrying nineteen men, started on June 7, and by July 19 it was off the south-east coast of Greenland, where Davis heard for the first time the grinding together of the great icepacks.[Pg 9] The shore looked so barren and forbidding—“lothsome” is the epithet which Davis applied to it—that he named it “Desolation.” Rounding the southern point of Greenland and bearing northward, he soon reached lat. 64°, where he moored his ships among some “green and pleasant isles,” inhabited by natives who were very friendly disposed and quite ready to trade with him. From these he learnt that there was a great sea towards the north and west, so he set sail and shaped his course W.N.W., expecting to get to China. Crossing the strait which now bears his name, he sighted land in 66° 40′ and anchored in Exeter Sound. The hill above them they named Mount Raleigh; the foreland to the north, Cape Dyer; and that to the south, Cape Walsingham—names which they still bear. The season was too far advanced for him to attempt to explore the sound, but he discovered the wealth of those regions in whales, seals, and deerskins—a discovery which, it need hardly be said, was very highly valued by the merchants who had equipped the expedition.

As was only natural, both Davis and his patrons were anxious to continue the discoveries thus auspiciously begun, and May 7, 1586, saw him starting on his second expedition, his fleet strengthened by the addition of the Merimade, a ship of 120 tons. She did not prove of very much service, however, for she deserted in lat. 66°, and Davis went on his way without her. He did not succeed in adding anything of value to his discoveries of the previous year, merely coasting southward along Labrador, without observing the entrance to Hudson Strait.

Davis’s third expedition left on May 19, 1587, and[Pg 10] consisted of three ships, the Elizabeth, the Sunshine, and the Ellen. On reaching lat. 67° 40′ he left two of his ships to prosecute fishing, and sailed on by himself on a voyage of discovery. He came, as he tells us himself, “to the lat. of 75°, in a great sea, free from ice, coasting the western shore of Desolation.... Then I departed from that coast, thinking to discover the north parts of America. And after I had sailed toward the west near forty leagues, I fell upon a great bank of ice. The wind being north, and blew much, I was constrained to coast towards the south, not seeing any shore west from me. Neither was there any ice towards the north, but a great sea, free, large, very salt and blue, and of an unsearchable depth. So coasting towards the south, I came to the place where I left the ships to fish, but found them not. Thus being forsaken and left in this distress, referring myself to the merciful providence of God, I shaped my course for England, and unhoped for of any, God alone relieving me, I arrived at Dartmouth. By this last discovery it seemed most manifest that the passage was free and without impediment toward the north; but by reason of the Spanish fleet, and unfortunate time of Master Secretary’s death, the voyage was omitted, and never since attempted.” So ended the Arctic voyages of John Davis. “The discoveries which he made ...,” says Sir John Ross, “proved of great commercial importance; since to him, more than to any preceding or subsequent navigator, has the whale fishery been indebted.”

In the meantime interest in the North-East Passage had by no means subsided; indeed, it had actually[Pg 11] been quickened by Philip II.’s accession to the throne of Portugal and by the consequent fact that Spain and Portugal, not content with already holding the monopoly of the route to the East, attempted to make their influence felt upon the trade operations of the nations of Northern Europe. It was in 1580 that Arthur Pet, in the George, and Charles Jackson, in the William, sailed from England under the auspices of the Muscovy Company, with instructions to push as far east as they possibly could. The expedition was singularly ill-found, for the burden of the George was only 40 tons, her crew consisting of nine men and a boy, while the William was but half the size of her sister ship, and carried a crew of five men and a boy. The adventurers, however, made light of the difficulties that beset them, and, after making Nova Zembla in the neighbourhood of the South Goose Cape, they turned south and, coasting along Waigat Island, entered the mouth of the Pechora. Thence they pushed their way into the Kara Sea, being the first sailors from Western Europe who ever achieved such a feat.

The Muscovy Company does not seem to have considered it worth its while to proceed with the exploration of these unattractive regions, but the Dutch, who were no less anxious than the English to find a North-East Passage, sent out in 1594 an expedition which consisted of three ships, commanded by Willem Barents, Nay, and Tetgales. Barents attempted to find a passage round the north of Nova Zembla, while his companions turned south and made their way into the Kara Sea. The reports which these pioneers brought home with them so encouraged their fellow-countrymen,[Pg 12] that they were sent off with a fleet of seven ships in the following year to continue their discoveries. This expedition penetrated a little further along the coast, but it by no means succeeded in fulfilling its mission, and the States-General became rather chary of spending any more money upon the venture. Accordingly they contented themselves with offering a large reward to any person or persons who could find a practicable passage to China, and left it to private enterprise to do the rest. The result of this step was that a company of merchants fitted out two ships of discovery in 1596, and gave the command of one of them to John Cornelius Ryp and of the other to Heemskeerck, appointing Barents chief pilot to the latter. On June 9 they discovered an island which they called Bear Island, in memory of a terrific encounter that they had with a polar bear there. They now found that their progress eastwards was checked by ice, and they accordingly stood north, with the result that it fell to their lot to be the discoverers of Spitzbergen. They spent two days in a bay which appears to have been that known as Fair Haven, and then, after an ineffectual attempt to push further north, they returned to Bear Island, where, owing to a difference of opinion as to the best course to pursue, they parted company, Ryp revisiting the coast of Spitzbergen, while Barents set his course for Nova Zembla. We may mention parenthetically that Heemskeerck was not himself a sailor, and that, in consequence, the lion’s share of the honours which this expedition earned has always been given to Barents, on whom the navigation of the ship necessarily devolved.

STRANDED IN NOVA ZEMBLA

[Pg 13]

The rest of the story of this unfortunate voyage is one of terrible trials borne with heroic fortitude. While coasting along the shore of Nova Zembla, Barents suddenly found himself in the midst of heavy ice, and time after time his ship only just escaped destruction by the squeezing together of the floes. His duty to his employers always being uppermost in his mind, he bravely attempted to push on to the east, but he soon found that that was impossible, and that all his efforts must be directed towards getting his ship home. As he drew near the shore, however, in the hope of finding a little open water there, the ice bore down upon it, crushed his boats to pieces and almost annihilated his ship. To add to his misfortunes, a northerly gale arose, which placed him in an even more dangerous position than before. He now found himself to the east of the island in an inlet which he named Ice Haven, but which is now called Barents Bay, with his retreat cut off both to the north and to the south. There was nothing for him to do, therefore, but to make the most of an exceedingly bad business and spend the winter where he was. Now it must be remembered that no traveller had ever yet passed a winter in the Arctic regions, and that Barents and his men were totally unprepared for such an emergency. They had little food, less fuel, no proper clothes and, last but by no means least, their ship was not suited for a winter abode. In the midst of their misfortunes, however, they kept up their hearts, and instantly set about building a hut wherein they could spend the long, dark months.

Fortunately for them there was an abundance of[Pg 14] driftwood on the island “driven upon the shoare, either from Tartaria, Muscovia, or elsewhere, for there was none growing upon that land, wherewith, as if God had purposely sent them to us, we were much comforted.” This driftwood lay at a distance of some eight miles from the site of this house, and the labour of fetching it was enhanced by the darkness which was now setting in, and by the ferocity of the bears which haunted the neighbourhood and were a constant source of danger to the party. The Dutchmen, however, worked with a will, and by October 24 they had moved into their new abode, one of the features of which was a wine cask, with a square opening cut in its side, which was set up in a corner and used as a bath.

The bears afforded them some fresh meat up till November 3, when they and the sun disappeared at one and the same time. After this they occasionally succeeded in trapping foxes, but the cold was so intense that they were often unable to venture out of the house for days together. “It blew so hard and snowed so fast,” writes Gerrit de Veer, the chronicler of the expedition, “that we should have smothered if we had gone out into the air; and to speake truth, it had not been possible for any man to have gone one ship’s length, though his life had laine thereon; for it was not possible for us to go out of the house. One of our men made a hole open at one of our doores ... but found it so hard wether that he stayed not long, and told us that it had snowed so much that the snow lay higher than our house.” Again, “It frose so hard that as we put a nayle into our mouths[Pg 15] (as when men worke carpenter’s worke they use to doe), there would ice hang thereon when we tooke it out againe, and made the blood follow.” Or, “It was so extreme cold that the fire almost caste no heate; for as we put our feete to the fire, we burnt our stockings before we could feele the heate.... And, which is more, if we had not sooner smelt than felt them, we should have burnt them quite away ere we had knowne it.” De Veer also tells us that the clothes on the backs even of those who sat near the fire were frequently covered with hoar-frost, and that the beer and all the spirits were frozen solid. Yet in the midst of all this he was able to make the following entry in his journal: “We alwaies trusted in God that hee would deliver us from thence towards sommer time either one way or another.... We comforted each other giving God thanks that the hardest time of the winter was passed, being in good hope that we should live to talke of those things at home in our owne country.” It was in this spirit of patient resignation that the brave Dutchmen met all their troubles.

Even when the sun returned it brought them but little relief from their sufferings, for the intensity of the cold seemed to increase, and there was no hope that the ice in their harbour would break up early. The ship was so badly damaged that she could not survive the voyage home, so they set about repairing the boats as best they could, with a view to crossing in them the thousand miles of sea that lay between them and Lapland. At last the time came for them to make their departure, but Barents was now so ill that he had to be taken to the boat on a sledge. His courage, however,[Pg 16] was still indomitable, as this passage in De Veer’s account shows: “Being at the Ice Point the maister called to William Barents to know how he did, and William Barents made answer and said, Quite well, mate. I still hope to be able to run before we get to Wardhuus. Then he spak to me and said: Gerrit, if we are near the Ice Point, just lift me up again. I must see that point once more.” His courage, however, was greater than his strength, and on June 20, six days after the start, the end came. We quote our chronicler once more: “William Barents looked at my little chart, which I had made of our voyage, and we had some discussion about it; at last he laid away the card and spak unto me saying, Gerrit, give me something to drink and he had no sooner drunke but he was taken with so sodain a qualme, that he turned his eies in his head and died presently. The death of William Barents put us in no small discomfort, as being the chiefe guide and onely pilot on whom we reposed ourselves next under God; but we could not strive against God, and therefore we must be content.”

The sufferings of the party of fifteen on their terrible voyage over the stormy and ice-laden sea were scarcely less terrible than those which they had endured on the island. Such was their courage and determination, however, that they at last reached Lapland in safety, where they had the satisfaction of finding Cornelius Ryp, on whose vessel they were conveyed back to Holland.

[Pg 17]

With the voyages of Weymouth, Knight, and Hall, which occupied the first few years of the seventeenth century, we need not concern ourselves at all, for they resulted in no discoveries of any importance. In the year 1607, however, Henry Hudson started off on the first of that series of travels by which his name became famous, and during the course of which he succeeded in carrying the British flag to places that had never before been trodden by the foot of civilised man.

As has already been seen, the north-west and north-east passages to the Indies had been tried and found wanting. British merchants, however, were by no means disposed to let Spain and Portugal retain their lucrative monopoly without making a struggle to wrest it from them, so they determined to send out a fresh expedition which should attempt to force its way to the land of gems and spices over the North Pole itself. The command of this expedition was entrusted to Henry Hudson, a seaman of such daring and skill that he was well able to accomplish the work if it lay within the power of a human being to do so. Hudson started off from the Thames on May 1, 1607, in a small barque which was manned by ten men and a boy, and made[Pg 18] direct for the east coast of Greenland. By June 22 he had reached lat. 72° 38′, where he discovered the land which still bears his name, the chief promontory of which he named Cape Hold-with-Hope. He then set his course for Spitzbergen, which, as we have seen, had been first sighted by Barents eleven years earlier, and there he reached the high latitude of 80° 23′. His provisions being now nearly exhausted, he was obliged to return home.

On his second voyage he attempted to discover a north-east passage round Nova Zembla, but was so hampered by ice that he was unable to proceed far on his way, while the only geographic result of his third voyage was the discovery of the Hudson River. These early expeditions, however, though they achieved little in the way of discovery, proved of great commercial value, for they gave rise to the great Spitzbergen whale fishery.

Hudson’s fourth and last voyage, that of 1610, was organised by Sir John Wolstenholm and Sir Dudley Digges, who were convinced of the existence of the North-West Passage, and felt that Hudson was the man to find it. Accordingly, Hudson sailed on April 17 in the Discovery, a ship of 55 tons, which was provisioned for six months. By June 9 he had reached Frobisher Strait, and here a contrary wind arose which compelled him to ply westward into Hudson’s Bay. Several British seamen had already visited the mouth of the strait, and it is believed that Portuguese fishermen had actually entered the bay; but the terrible circumstances which attended Hudson’s voyage to it made it only natural that it should be[Pg 19] named after him in commemoration of his achievements and his fate.

The Discovery had penetrated the bay to a distance of over three hundred miles further than ever an English ship had penetrated it before when she was beset by ice, and all chance of retreat was cut off. As we have already seen, she was only provisioned for six months, and the unfortunate crew found themselves, in consequence, with starvation staring them in the face. Hudson, fortunately, was a man of resource, and he lost no time in organising hunting and fishing parties which provided his party with sufficient provisions to tide over the winter. Had his crew remained faithful to him all might have been well, but disaffection broke out early in the winter, which, gathering force as the store of provisions grew more and more scanty, broke out into open mutiny in the spring. The ringleaders were the former mate and boatswain, whom Hudson had been obliged to displace for using improper language, and a young man named Greene, a protégé of Hudson, who repaid his benefactor’s kindness by deserting him when he most needed friends. These men, seeing that when the ship broke out of winter quarters in June there were barely fourteen days’ provisions left for the whole crew, determined to place Hudson and eight other men in a boat, and, leaving them to shift for themselves, to sail home for England. This heartless plan was promptly carried into execution. Hudson was seized and bound when he came out of his cabin, and with five sick men, John Hudson and John King, the carpenter, who bravely refused to join the mutineers, was thrown into a boat and[Pg 20] deserted. Of the unfortunate castaways nothing more was ever heard, and the most careful search of Sir Thomas Button, who examined the whole of the western shore of the bay, failed to discover any clue to their fate. Of the mutineers, Greene and four others were killed in a fight with the natives, while the rest only just succeeded in reaching England.

The voyages of Hall in 1612 and Gibbons in 1614 did not result in much, but in 1615 William Baffin started out on the first of his two expeditions which were destined to add so much to the world’s store of knowledge of the Arctic seas. Baffin, who was described by Sherard Osborn as “the ablest, the prince of Arctic navigators,” was in 1615 appointed by the Merchants Adventurers pilot and associate to Richard Bylot, of the Discovery, which was now to make her fourth voyage in search of the North-West Passage. Making first for Hudson Strait, they soon discovered that they were being led into a blind alley. As the conditions, however, did not permit them to extend their voyage much that season, they were obliged to return home. In the following year, however, they were sent out once more by the Merchants Adventurers, and on this occasion they determined to push on north along the coast of Greenland. On May 30 they reached Sanderson’s Hope, Davis’s farthest point, and there they entered upon an entirely new field of discovery. With such energy did they apply themselves to the work that they had crossed Melville Bay by the beginning of June, and were sailing merrily on their way past Cape York, Cape Dudley Digges, and Whale Sound. At last, when they had exceeded[Pg 21] Davis’s farthest north by over three hundred miles, their triumphant career was stopped at the entrance to Smith Sound, within sight of Cape Alexander. This latitude, 77° 45′, remained unequalled for over two centuries.

Unable to proceed any further to the north, Baffin and Bylot determined to sail south-west, and to see if they could not add to their growing list of discoveries on their homeward journey. Their hopes were amply fulfilled, for on July 12 they found themselves off the entrance to Lancaster Sound, which was the gate, as it afterwards proved, to the North-West Passage. The ice, unfortunately, did not permit them to enter the Sound, so they made for the coast of Greenland, where they rested their men prior to their return to England.

For the next hundred years or so very little was done in the way of Arctic discovery. A Dane of the name of Jens Munk started out to seek for the North-West Passage, and succeeded in making a few discoveries in Hudson’s Bay. In 1631, again, Captain Luke, alias “North-West,” Fox sallied forth on the same mission, bearing with him an epistle from the King of England to the Emperor of Japan, which, however, remained undelivered. The work which he did was not of much value, but he made up for this deficiency by writing a very humorous account of his experiences. Captain James, who went exploring in the same year, seems to have been dogged by ill-luck from the beginning to the end of his voyage, and Barrow describes his narrative of it as “a book of lamentation and weeping and great mourning.”

[Pg 22]

Though, however, very little was done in the way of exploration during the second half of the seventeenth century, great strides were made in the development of the country already explored by the formation of the famous Hudson Bay Company, which for two hundred years did a tremendous trade in Northern Canada. The inception of this Company was mostly due to a certain French Canadian of the name of Grosseliez, who, after an ineffectual attempt to induce the French Government to consider his schemes for founding a great industry, came to England, where he obtained the ear of Prince Rupert. The Prince sailed for Hudson Bay with Grosseliez, saw the possibilities of the country, and obtained from King Charles a charter, dated 1669, which conferred on him and his associates, exclusively, all the trade, land, and territories in Hudson’s Bay. The charter further ordained that they should use their best endeavours to find a passage to the South Sea, but the Company soon became so rich from its trade that it seems to have conveniently forgotten this clause.

Occasionally, it is true, it attempted to do something in the way of exploration, but these efforts were for the most part only half-hearted, and resulted in little. In 1719, for example, James Knight, allured by reports of mines of pure copper by a great river to the north, gave the Company to understand that he would call upon the authorities to examine their charter unless they arranged an expedition and appointed him its leader.

Very reluctantly they consented to do as he wished, and equipped two ships for the purpose of surveying[Pg 23] the northern coast of their territories. Not a single member of the expedition returned, and nothing was known of their fate until, forty years later, a quantity of wreckage was found on Marble Island.

With the exception of Middleton’s expedition of 1741, during the course of which Wager Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Frozen Strait were discovered, nothing much more was done in the way of Arctic exploration for the next fifty years. In 1769, however, the Company determined to make another effort to find the mines of copper of which the natives brought so glowing an account, and with this end in view they sent out an overland expedition under the command of Samuel Hearne. This expedition, which started out in November, was a complete failure, because it began its work too late in the year, while the second expedition, which left in February, failed because the preparations were inadequate. Warned by these two experiences, Hearne sallied forth once more in December 1670, and on this occasion he claimed to have found the mouth of the Coppermine River. His observations, however, were rather hazy, and it is doubtful whether he really reached the Polar Sea. The end of his journey was marred by an unfortunate collision between his Indian guides and a tribe of Eskimos, during the course of which all the unfortunate natives were massacred. The effects of this incident were to be felt later on, when Franklin, visiting those inhospitable shores with his gallant companions, was regarded with such suspicion by the Eskimos that he could hardly obtain that assistance which he so sorely needed.

One other early attempt to reach the Polar Sea[Pg 24] by the land route deserves to be recorded: that of Alexander—afterwards Sir Alexander—Mackenzie, the discoverer of the river which bears his name. Having been led to believe by the accounts of Indians that the sea could be reached by a large river issuing from the Great Slave Lake, he determined to test the story himself, and set out on June 3, 1789. The difficulties in his way were innumerable, for not only was the river broken up by dangerous rapids, but it was only after infinite trouble that he could induce any guides to accompany him, for the natives believed the river to be peopled by monsters, who were ready to devour the unwary traveller without the least provocation. However, he succeeded in reaching the sea near Whale Island, and had the satisfaction of knowing that the tales of the Indians were true, though he was unable to use his knowledge for any practical purpose.

Meanwhile, Russia was busily opening up the north-east coast of Siberia, partly with a view to getting some control over the unmanageable Chukches, the only Siberian tribe who succeeded in resisting their somewhat rough and ready methods, and partly with a view to developing trade in that direction and to discovering whether or not the Asiatic and American continents were united. Many expeditions set out with these ends in view, among them being those of Ignatieff, Deshneff, Alexieff, and Ankudinoff, but of these it is impossible to give a detailed account here, and we need not take up the story of exploration in these regions until 1725, when the Great Northern Expedition, conceived by Peter the Great and carried into execution by the Empress Anne, set forth under[Pg 25] the command of Vitus Bering, a Dane in the Russian service.

Immense difficulties had to be overcome before the expedition could start at all. Long overland journeys had to be made across Siberia, supplies had to be accumulated at Okhotsk and a vessel had to be built there, with the result that it was not until the end of June, 1727, that Spanberg, Bering’s assistant, was able to sail for Bolsheretsk in the Fortuna. Here more supplies had to be accumulated and a second ship built, which involved a delay of yet another year. At last, however, on July 24, 1728, Bering sailed gaily down the Kamchatka River, in the Gabriel, on his voyage of exploration. The preparations had extended over more than three years, and the voyage occupied about seven weeks, during which no discoveries whatever were made, so that the game seems to have been hardly worth the rather expensive candle. During the following summer he sallied out of his harbour once more, but he does not seem to have prosecuted his work with very much ardour, for he returned at the end of three days, during which he had sailed about a hundred miles. He then made his way to St Petersburg.

The Empress Anne seems to have been easily pleased, for although Bering had been away for five years and had accomplished nothing whatever, she gave orders that a second and even larger expedition should be placed under his command. The preparations for this voyage occupied some seven years, but at last, in September 1740, Bering was ready to start, and before winter closed in upon him he succeeded[Pg 26] in rounding Kamchatka and reaching Avatcha, now known as Petropaulovsk; not a very remarkable voyage, perhaps, but a step in the right direction. There he spent the winter, and in June of the following year he started out in the St Peter, accompanied by the St Paul, under the command of Tschirikoff. Even now, however, he could not succeed in overcoming his passion for dawdling, and much valuable time was wasted in searching for the land of Gama, which, in point of fact, did not exist. At last, however, the two ships set their course north-east, and a few days later they parted company during a heavy fog. Both of them succeeded in making America, a feat, however, which had already been accomplished by Gwosdef during Bering’s absence at St Petersburg. Tschirikoff made the American coast on July 26, and after some exciting experiences, during which two parties who were sent ashore to explore were completely lost, he returned in safety to Petropaulovsk. Bering, who reached America three days later than his companion, was less fortunate. Caught by contrary winds and heavy gales, his vessel was ultimately stranded on Bering Island, where she broke up. Her commander, utterly disheartened, refused to eat or drink or to take shelter in the hut which had been constructed of driftwood, with the result that he died on December 19. The command of the party now devolved on Lieutenant Waxell, who, ably assisted by a brilliant young naturalist, named Steller, succeeded in bringing the party safely out of its quandary. Their stay on the island, though it was miserable in the extreme, had its compensations, for they found that the place[Pg 27] abounded in the rare blue fox and the no less valuable sea-otter, of the skins of which the men secured such quantities that they took twenty thousand pounds’ worth home to Russia.

Bering did not succeed in discovering either the sea or the strait which have been named after him, but he mapped out a large tract of the Asiatic coast with some accuracy and opened up a trade which proved to be of immense value.

Up to the middle of the second half of the eighteenth century the efforts of navigators had, for the most part, been directed to finding a passage to the Indies either by the north-western or by the north-eastern route. Robert Thorne, it is true, had come forward with a bold plan for attempting to sail across the North Pole, but he had not succeeded in getting very far on his way, and the idea had been allowed to lapse. In 1773, however, the Earl of Sandwich, then First Lord of the Admiralty, having been approached upon the subject by the Royal Society, suggested to George III. that an expedition should be sent out to discover how far it was possible to sail in the direction of the Pole. The King was pleased with the idea, and preparations for the venture were at once set on foot. The Racehorse and the Carcase, two of the strongest ships of the day, were selected as being best suited for the purpose, and were fitted out as the ideas of the time dictated. The command was entrusted to Captain Constantine John Phipps, afterwards the second Lord Mulgrave, Captain Skiffington Lutwidge was appointed second in command, two masters of Greenland ships were attached to the expedition as pilots, and an astronomer, with all[Pg 28] the latest instruments, was recommended by the Board of Longitude.

So far as actual achievements were concerned, there is nothing much to be recorded. Phipps was unfortunate in his year, and north of Spitzbergen he found a solid wall of ice which it was quite impossible for him to penetrate. He had the satisfaction, however, of reaching lat. 80° 48 N., a higher point than any of his predecessors. One episode deserves to be noticed as it came near causing the death of Nelson, who was serving in the humble capacity of captain’s coxswain. “One night,” says Southey, “during the mid-watch, he stole from the ship with one of his comrades, taking advantage of a rising fog, and set out over the ice in pursuit of a bear. It was not long before they were missed. The fog thickened, and Captain Lutwidge and his officers became exceedingly alarmed for his safety. Between three and four in the morning the weather cleared, and the two adventurers were seen, at a considerable distance from the ship, attacking a huge bear. The signal for them to return was immediately made; Nelson’s comrade called upon him to obey it, but in vain. His musket had flashed in the pan, their ammunition was expended, and a chasm in the ice, which divided him from the bear, probably preserved his life. ‘Never mind,’ he cried, ‘do but let me get a blow at the devil with the butt-end of my musket, and we shall have him.’ Captain Lutwidge, however, seeing his danger, fired a gun, which had the desired effect of frightening the beast; and the boy then returned, somewhat afraid of the consequences of his trespass. The captain reprimanded him sternly [Pg 29]for conduct so unworthy of the office which he filled, and desired to know what motive he could have for hunting a bear. ‘Sir,’ said he, pouting his lip, as he was wont to do when agitated, ‘I wished to kill the bear that I might carry the skin to my father.’”

THE “RACEHORSE” AND THE “CARCASE” IN THE ICE

FROM A PICTURE BY J. CLIVELY

It was three years after the return of the Racehorse and Carcase that Captain Cook made his only expedition into the Arctic seas. His success in the Antarctic had led his friends in England to hope great things of his voyage through the Bering Strait, but, unfortunately, his two ships, the Resolution and the Discovery, proved but ill-adapted for service in the Arctic, and though he succeeded in charting a good deal of the unknown American coast, he made no approach to finding that North-West Passage for the discovery of which he had been set out. He had intended to return to the Arctic again with a view to prosecuting his discoveries there, but his death at Hawaii in 1779 prevented him from fulfilling his purpose, and his second in command, Captain Clerke, on whom the leadership of the expedition devolved, died of consumption at Petropaulovsk.

[Pg 30]

What with the American War and the Napoleonic Wars, our sailors had their hands so full at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centuries, that they had no time to spare for unnecessary exploration, and there is, in consequence, a hiatus of forty years in the story of Arctic discovery. In 1817, however, Captain William Scoresby, junior, one of the most famous of Scotch whalers, reported to Sir Joseph Banks that he had found nearly 2000 square leagues of the Spitzbergen Sea free from ice, and that he had, in consequence, been able to sight the eastern coast of Greenland, at a meridian usually considered inaccessible, adding that it would be greatly to the advantage of our whale fishery if expeditions were sent out to continue the work of exploration which had remained in abeyance for so long. Both Sir Joseph Banks and Sir John Barrow, then Secretary to the Admiralty, were much impressed by this report and it was through their representations that the Government decided to send out two expeditions in 1818, one of which was to make an effort to reach the Pole, while the other was to search for the elusive North-West Passage. The list of the officers of these two expeditions included six names which were destined[Pg 31] to become famous all over the world for their Arctic work—those of Back, Beechey, Franklin, Parry, John Ross, and James C. Ross.

The ships detailed for the first of these two expeditions were the Dorothea (370 tons) and the Trent (250 tons), two stout whalers which were specially strengthened for work in the ice with all the extra wood and iron that they could carry. They were provisioned for two years, and the leadership of the expedition was entrusted to Captain Buchan, who sailed on the Dorothea, while Franklin commanded the Trent, with Beechey as his lieutenant. The object of the mission was scientific as well as geographical, and it was hoped that many useful investigations would be made into the atmospheric, meteorological, and magnetic phenomena of the unknown region which it was to traverse.

The expedition sailed on April 25, the Arctic circle was crossed on May 18, and Bear Island sighted on the 24th. Standing north for the south cape of Spitzbergen, the ships met with their first serious opposition from the ice. They succeeded in making their way through the belt, however, and they were soon lying in Magdalena Bay. Further progress north was summarily checked by a vast field of ice through which it was impossible to penetrate, for the moment at any rate. Accordingly, Buchan decided to spend some time in exploring Magdalena Bay, in the hope that the conditions would change, and that he would be able to pass through it. His second venture, however, met with no better success. Indeed, disaster very nearly cut short the career of the two ships, for, while they were coasting along the pack, the breeze suddenly[Pg 32] dropped, and they were driven by the swell into the midst of the innumerable floes which were constantly being dashed by the rollers against the main sheet of ice. So fierce was the impact of these floes that they were crumbled to pieces, and for miles around the sea was covered with a thick pasty substance, known as brash ice, which often extended to a depth of five feet.

Fortunately, however, a breeze arose which carried them out of their dangerous predicament, and they were able to proceed on their way. Continuing their reconnaisance to the west, they found but little change in the condition of the pack, and they decided to desist for the present from their attempts to find a way through it. Accordingly they put about and made for Spitzbergen, where they found that the pack, though still impenetrable, had shifted a little, leaving a passage between it and the land. Rather unwisely, perhaps, Buchan attempted to make his way along this channel, and he had only just passed Red Cliff when the ice closed in upon him on every side, making it impossible for him either to advance or to retreat.

Here they remained for thirteen days with little to do except to observe the habits of the animals which appeared on all sides, and to indulge in a little hunting when the opportunity offered. In this connection Beechey tells a rather interesting story illustrating the ingenuity of the Polar bear. “Bears, when hungry,” he writes, “seem always on the watch for animals sleeping on the ice, and endeavour by stratagem to approach them unobserved: for, on the smallest disturbance, the animals dart through holes in the ice, which they always take care to be near, and thus evade pursuit. One[Pg 33] sunshiny day a walrus, of nine or ten feet in length, rose in a pool of water not very far from us, and after looking round, drew his greasy carcase upon the ice, where he rolled about for a time, and at length laid himself down to sleep. A bear which had probably been observing his movements, crawled carefully upon the ice at the opposite side of the pool, and began to roll about also, but apparently more with design than amusement, as he progressively lessened the distance that intervened between him and his prey. The walrus, suspicious of his advances, drew himself up, preparatory to a precipitate retreat into the water, in case of a nearer acquaintance with his playful but treacherous visitor; on which the bear was instantly motionless as if in the act of sleep, but after a time began to lick his paws and clean himself, and occasionally to encroach a little more on his intended prey. But even this artifice did not succeed; the wary walrus was far too cunning to allow himself to be entrapped, and suddenly plunged in the pool.” The bears, however, were not always so unlucky in their hunting, for in the stomach of one that they killed they found a Greenlander’s garter.

Walrus hunting also afforded them a little sport, and on one occasion the crew were so unwise as to attack a herd in the ordinary ship’s boats. Immediately the walruses rose on all sides, and it was no easy matter to prevent them from staving in the sides of the boats with their tusks, or dragging them under water. “It was the opinion of our people,” says Beechey, “that in this assault the walruses were led by one animal in particular, a much larger and more formidable beast than any of the others; and they directed their efforts[Pg 34] more particularly towards him, but he withstood all the blows of their tomahawks without flinching, and his tough hide resisted the entry of the whale lances, which were, unfortunately, not very sharp, and soon bent double. The herd were so numerous, and their attacks so incessant, that there was not time to load a musket, which, indeed, was the only mode of seriously injuring them. The purser fortunately had his gun loaded, and the whole crew being now nearly exhausted with chopping and sticking at their assailants, he snatched it up, and thrusting the muzzle down the throat of the leader, fired into his body. The wound proved mortal, and the animal fell back amongst his companions, who immediately desisted from the attack, assembled round him, and in a moment quitted the boat, swimming away as hard as they could with their leader, whom they actually bore up with their tusks, and assiduously prevented from sinking.”

The release which they had been praying for came at last, but it brought little improvement to their position, for a terrific gale arose which drove both the ships into the pack, with the result that half the timbers of the Trent were strained, while the Dorothea was reduced to something little better than a wreck. To attempt any further exploration was hopeless, so they made for Spitzbergen, where they found a safe anchorage in South Gat. Here the vessels were put into a state of repair, the officers in the meantime exploring the part of the island on which they found themselves, and making observations. On August 30 they put to sea once more, and arrived safely in England on October 22.

[Pg 35]

While Buchan and Franklin were in difficulties in the ice off Spitzbergen, Ross and Parry with the Isabella (385 tons) and the Alexander (252 tons) were searching the shores of Baffin’s Bay for the North-West Passage. They had set sail from Lerwick on May 3, and by the end of June they were past Disco Island. Here, through the medium of John Sackheuse, their invaluable interpreter, they opened up very friendly relations with the natives, in whose honour they gave a ball, which afforded immense entertainment to all concerned. After this, progress became slower, for the sea was cumbered with ice, and the crew were compelled to adopt the tedious expedient of “tracking” the ship through it, that is to say, of going ashore with a rope and dragging her through the obstruction. At the end of July, however, Ross succeeded in reaching Melville Bay, which proved to be one of the most important discoveries of the voyage, for the sea was full of whales, and has proved a lucrative hunting-ground for whalers ever since.

As they were nearing the northern shores of the Bay the voyage of the Isabella and the Alexander came near to being summarily ended by a terrific gale which drove the ice upon them in such quantities that they[Pg 36] were almost overwhelmed by it. Fortunately they both survived, and shortly after the storm had subsided, a number of natives with dog-sleighs were seen in the distance. All attempts at enticing them nearer by means of presents proved vain, but eventually the interpreter, Sackheuse, succeeded in getting into communication with them. At first they were inclined to distrust the strangers, imagining that the ships were some kind of weird animals with wings which had come either from the sun or the moon, they could not be sure which, with the express object of doing them an injury. The misunderstanding, however, was eventually cleared up, and they were induced to visit the ships, where everything that they saw was a source of infinite interest to them, with the exception of the ship’s biscuit and salted meat, for which they expressed supreme disdain.

Pressing on north, the explorers found the sea fairly clear of ice, and they soon passed Cape Dudley Digges, Wolstenholme Island and Whale Sound, none of which had been visited since Baffin’s day, and which cartographers had thought fit to erase from the maps, believing that Baffin had been the victim of hallucinations.

It was just after he had passed the Canary Islands that Ross made his first great mistake. It must be remembered in his extenuation that he was totally inexperienced in Arctic travel, and that he was unused to the strange atmospheric phenomena and illusions which meet the voyager in these regions at every turn. Even in the short period of his stay in the Polar seas, however, he ought to have learnt enough to prevent him[Pg 37] from being beguiled into the belief that Smith’s Sound was nothing but a bay headed by a huge range of impenetrable mountains. That, however, was the conclusion to which he came, and he made no effort to push further north than the entrance to the Sound. Had he done so he would, of course, have found that his mountains were nothing but weather-gleam.

He now put about and pushed south, taking very accurate bearings of the various headlands which he passed. In the course of his voyage he came upon the entrances to Jones and Lancaster Sounds, both of which he was deterred from exploring by more ranges of impenetrable mountains, through which, however, his own lieutenant, Parry, sailed with perfect ease in the following year.

He reached Grimsby on November 14, meeting with no adventures worth recording on the way home. His voyage had two great results. It opened up an enormous and most lucrative whale fishery in and around Melville Bay, and it vindicated Baffin’s position as an explorer. Otherwise it was a little disappointing, for if he had not been so obsessed with the idea that mountains hemmed him in on every side, he might have accomplished much more than he actually achieved.

In the narrative of his voyage, which he published after his return, Ross distinctly implies that his opinion as to the impossibility of finding a passage through any one of these three sounds was shared by the rest of his officers. This, however, appears to have been very far from the truth, as Parry’s journals and letters attest. At the time when the two vessels were cruising[Pg 38] about in the mouth of Lancaster Sound they were some three miles apart, the Isabella being in advance. When the Isabella put about, the crew of the Alexander were positively amazed, for so far as they could discern, there was no land anywhere in sight.

The Admiralty seems to have had some inkling of the truth, for shortly after their return, Parry and Franklin were summoned into the presence of Lord Melville, and they gathered from the words that he let fall that he was of opinion that Lancaster Sound was a passage leading into some sea to the westward, an opinion which they heartily endorsed. The result was that, when it was decided to send out another expedition in the following spring, Parry was offered the command. This expedition was to consist of two ships, the Hecla, a bomb of 375 tons, and the Griper, a gunboat of 180 tons. Both of these ships were selected by Parry before he knew that he was to be placed in command, and it was under his supervision that they were put in thorough repair, and specially strengthened for work in the Arctic regions. Parry himself was to command the Hecla, while the Griper was to be entrusted to Lieutenant Liddon. The full complement of both ships was ninety-four, and the Admiralty had no difficulty in finding excellent seamen, for they offered double pay to all those who took part in the expedition. Captain Sabine, whose name subsequently became famous for his excellent scientific work, was appointed naturalist and astronomer, and among the officers were Lieutenants Beechey and Hoppner. The object of the mission, as stated in the Admiralty instructions, was to seek out a north-west passage from[Pg 39] the Atlantic to the Pacific either through Lancaster, Jones or Smith Sounds.

The ships weighed anchor on May 5, 1819, and at first progress was slow, for the Griper proved such a bad sailor that the Hecla had to take her in tow. On the 23rd they sighted the ice of Davis Strait, and for a while they were obliged to bear to the eastward of it owing to its thickness. On July 21, however, Parry was able to set his course westwards, and eight days later they sighted the mountains at the southern entrance of Lancaster Sound.

Parry unquestionably had excellent luck at this part of his voyage. A good easterly breeze sprang up and the ships bowled merrily along under all the sail that they could carry. The sea was practically open, no land could be seen ahead, and the shores of the sound were thirteen leagues apart. The one and only drawback was the poor sailing powers of the Griper.

At midnight on August 4 the sun being then, of course, as bright as at midday, they reached long. 90, and here they were pulled up by a barrier of ice that stretched from shore to shore. The part of the sound in which he now found himself Parry named Barrow Strait, while to two islands which lay ahead of him he gave the names of Leopold Islands, after Prince Leopold of Saxe-Coburg. To the westward of the islands he perceived a bright light in the sky which is known to Arctic sailors as “ice-blink” and which told him that there was no chance of a passage in that direction; to the south of him, however, there was a broad open space and over it was a dark water-sky, so he determined that,[Pg 40] as he could not push forward for the present, he would set his course southward.

The wind was favourable and the ships soon found themselves bowling along down an inlet at least ten leagues broad at the mouth, to which Parry subsequently gave the name of Prince Regent’s Inlet. He explored this inlet for about 120 miles in the hope that he might find a passage leading westward but in this he was disappointed, and perceiving presently that icebergs covered the whole of the westerly horizon, he put about, and on the 13th was once more off Leopold Islands. The sea was still covered with ice, but in a few days this obstruction had cleared away completely and he was able to make his way along the coast of North Devon.

The question of the continuity of land to the north had for some time been worrying Parry, for there was a possibility that it might take a turn to the south and join the coast of America. Presently, however, his eyes were gladdened by the sight of a broad passage leading to the north through which he hoped that he would be able to sail if it proved impossible for him to make his way further westward, and to which he gave the name of Wellington Channel. There was no necessity, however, to explore it yet, for their way was still open before them, and they sailed merrily along passing and naming, of course, at the same time, Cornwallis, Griffith and Bathurst Islands. Towards the end of August, however, the sea began to fill with ice, and Parry saw that it was high time for him to begin to look for winter quarters. These he eventually found in Hecla and Griper Bay, on the coast of Melville Island,[Pg 41] and here the ships were made snug for the winter, though not until after the expedition had had the satisfaction of crossing the meridian 110° W., thus earning the reward of £5000 offered by the Government to the first British subject who should penetrate so far within the Arctic circle. They found that they were none too soon, for the bay, when they reached it, was already covered with a coating of ice, through which they had to carve a way for the ship with saws.

The work of putting the ships in order for the winter was instantly begun. The upper masts were dismantled, the lower yards were lashed fore and aft amidships and a roofing erected over the deck in order that the men might have a fairly warm house in which to take exercise when the rigours of the winter made it impossible for them to venture ashore. The question of how to provide his crew with that rational amusement which was absolutely necessary for them if they were to remain in good health next occupied Parry’s attention. He was himself an excellent amateur actor, and as there were a couple of books of plays on board, he promptly founded the Royal Arctic Theatre. The scene-painting and rehearsals kept officers and men occupied for weeks, and on November 5, the theatrical season opened with a brilliant performance of “Miss in her ’teens,” with Parry as Fribble, and Beechey as Miss Biddy.

At the same time, Sabine founded a weekly paper entitled the North Georgia Gazette and Winter Chronicle, to which most of the officers became regular contributors. Parry suddenly displayed poetic gifts of which he had never before been suspected, Sabine showed a perfect[Pg 42] genius for dramatic criticism, while humorists galore sprang into being.

One or two extracts from the Gazette may here be quoted. In the issue of November 29, for example, we find an advertisement for “a middle-aged woman, not above thirty, of good character, to assist in DRESSING the LADIES at the THEATRE. Her salary will be handsome and she will be allowed tea and small beer into the bargain.” This drew forth a reply from Mrs Abigail Handicraft, who wrote as follows: “I am a widow, twenty-six years of age, and can produce undeniable testimonials of my character and qualifications; but before I undertake the business of dressing the ladies at the theatre, I wish to be informed whether it is customary for them to keep on their breeches; also if I may be allowed two or three of the stoutest able-seamen or marines, to lace their stays.” From the following issue we learn that Mrs Handicraft was duly engaged and that she was granted her two assistants who were to be equipped with “marline-spikes, levers, and white-line” for the reduction of Beechey’s waist to more reasonable proportions.

The theatricals, though they provided great amusement for the crew, were often conducted under great difficulties, for the temperature on the stage sometimes sank below zero, and on one occasion Captain Lyon, when playing in “The Heir-at-Law” had to go through the last act with two of his fingers frost-bitten.

CUTTING A PASSAGE INTO WINTER HARBOUR

FROM A SKETCH BY LIEUT. BEECHEY

At the beginning of February the sun returned once more, but it brought with it very little improvement in the temperature, and the thermometer sometimes sank as low as 55° below zero. Several of the men [Pg 43]were badly frost-bitten, notably Smith, Sabine’s servant, who, in his anxiety to save the dipping needle from a fire which broke out in the observatory, ran out without putting on his gloves. As soon as he returned to the ship, the surgeon plunged his hands into a basin of icy water, the surface of which was immediately frozen by the cold thus communicated to it.

During the latter part of the winter some exceedingly beautiful atmospheric phenomena were seen. On March 4, for example, a halo appeared round the sun, consisting of a circle which glowed with prismatic colours. “Three parhelia, or mock suns, were distinctly seen upon this circle; the first being directly over the sun and one on each side of it, at its own altitude. The prismatic tints were much more brilliant in the parhelia than in any other part of the circle; but red, yellow and blue were the only colours which could be traced, the first of these being invariably next the sun in all the phenomena of this kind observed. From the sun itself, several rays of white light, continuous but not very brilliant, extended in various directions beyond the halo, and these rays were more bright after passing through the circle than within it. This singular phenomenon remained visible nearly two hours.”

On March 19 the theatrical season came to an end with performances of “The Citizen” and “The Mayor of Garratt,” in which Parry took the parts of old Philpot and Matthew Mug. The severest part of the winter was now over, but the ice showed as yet no signs of breaking up. Indeed, though a great deal of the snow melted during April and May, there seemed to be no[Pg 44] chance either of continuing the voyage or of returning to England. June passed, and brought no prospect of release, and Parry began to fear that he was doomed to spend another winter in the ice, an eventuality for which he was but ill prepared. Towards the end of July, however, the thaw began to have its effect upon the ice of the harbour, and on August 1 the two ships were able to weigh anchor and sail out of the bay.

They were not destined, however, to achieve much more. For several weeks they were checked by contrary winds and battered by the ice, till at last, on August 23, Parry decided that, as the season for navigation would be coming to an end in a fortnight, he had better return to England. This he accordingly proceeded to do, and the two ships reached Peterhead in safety on October 29.

[Pg 45]

It is now necessary to return to Parry’s friend and fellow explorer, John Franklin, who, it will be remembered, was summoned into Lord Melville’s presence with Parry on November 18, 1818. The results of this interview were that while Parry was appointed to the command of the Hecla and Griper, Franklin was commissioned to undertake the no less important overland expedition to explore the shores of the North American continent from the mouth of the Coppermine River eastward.

The members of this expedition were five in number, and consisted of Franklin himself, Dr John Richardson, a surgeon in the navy, George Back, who had sailed as mate in the Trent with Franklin in 1818, Robert Hood, a midshipman, and John Hepburn, a sailor who was to act as servant. The object was to survey the coast carefully, to place conspicuous marks at the points at which ships might enter, and to deposit such information as to the nature of the coast as might be of service to Parry if he should actually succeed in finding a north-west passage. Franklin was also to conduct a series of scientific observations, making careful notes of the changes in the temperature, the state of the wind and weather, the dip and variation of the magnetic needle, and the intensity of the magnetic[Pg 46] force. In order that his chance of success might be as great as possible, he was provided with letters of recommendation from the Governors of the two great fur-trading companies of British North America—the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North-West Company—in which the agents were ordered to do their utmost, by every means and in every way, to forward the interests of the expedition.

Franklin’s first care on reaching Hudson’s Bay was to proceed to York Factory, where he consulted a number of officials, among them being Mr Williams, the Governor of the Factory, as to the best way of reaching the mouth of the Coppermine, where, of course, the serious work of his expedition was to begin. They were decidedly of opinion that he should proceed to Cumberland House, and thence travel northwards along the chain of the Company’s posts to the Great Slave Lake.

This route is practically a water-way, though the portages separating the various streams and lakes of which it is composed are almost numberless. Mr Williams, therefore, offered to provide the expedition with one of the Company’s best boats, together with a large store of provisions and the other things necessary for the journey, an offer which, needless to say, was promptly accepted. Unfortunately, when these stores were brought down to the beach they were found to be of too great a bulk to be accommodated in the boat, so that a large portion of them, including the bacon and part of the rice, flour, ammunition, and tobacco, had to be left behind, the Governor promising to send them on during the next season.

[Pg 47]

They set out on September 9, and they found that, though their journey took them through very beautiful scenery, it was of the most arduous description. The rivers were narrow, winding, and full of rapids, while the current was frequently so swift that the use of sails or oars was out of the question, and the boat had to be towed, a method of progression which would have been pleasant enough had not the shores been lofty and rocky and intersected by ravines and tributary streams. In addition to this, there were the innumerable portages to be reckoned with, and their progress was in consequence slow in the extreme.

At last they reached Rock House, one of the posts of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and there they were informed that still worse rapids lay before them, and that the boat must be lightened if they were to reach Cumberland House before the winter set in. Franklin was therefore obliged to leave still more of his cargo there, with orders for it to be forwarded by the Athabasca canoes as early in the following season as possible.

Proceeding on their way, they reached Cumberland House on October 23, and here they found the ice already forming on the lake, and learnt that it would be impossible for them to travel any further that season. Accordingly, when Governor Williams arrived a few days later and suggested that they should all winter at Cumberland House, they gladly fell in with the idea. On talking matters over, however, with the officers of the two great Companies, both of which had posts on the lake, Franklin came to the conclusion that by far his best plan would be to push on overland[Pg 48] during the winter into the Athabasca Department, where alone he could obtain the guides, hunters, and interpreters necessary for the success of his expedition. Accordingly, he requested Mr Williams to provide him with dogs, sledges, and drivers for the conveyance of himself and his two companions, Back and Hepburn. They started on January 18, 1820, and after a most unpleasant journey of 857 miles, in cold so intense that newly-made tea used to freeze in the tin pots before they had time to drink it, they reached Fort Chepewyan, on Athabasca Lake, on March 26. There Franklin spent several months, picking up such information as he could concerning the course of the Coppermine River and the coast about its mouth from the Indians and interpreters of the two Companies. The results of his investigations were fairly satisfactory, and he decided to send messages to the Companies’ representatives on the Great Slave Lake, asking them to provide him with any knowledge that they could collect, and to engage a number of Copper Indians as guides and hunters.

On May 10 mosquitoes, these early harbingers of spring, put in an appearance, and Franklin realised that the time was approaching for him to make a move onwards. It was no easy matter, however, to obtain the stores and men that he needed. The provisions collected at the Fort were not much in excess of the actual needs of the inhabitants, while the employées of the Company were very unwilling to engage with his expedition except at an extortionate remuneration.