The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Burlington magazine, by Various

Title: The Burlington magazine

for connoisseurs. vol. II--June to August

Contributor: Various

Release Date: March 25, 2023 [eBook #70374]

Language: English

Produced by: Jane Robins and Reiner Ruf (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive.)

THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE

FOR CONNOISSEURS

VOL. II

Illustrated & Published Monthly

Volume II—June to August

LONDON

THE SAVILE PUBLISHING COMPANY, LIMITED

14 NEW BURLINGTON STREET, W.

PARIS: LIBRAIRIE H. FLOURY, 1 BOULEVARD DES

CAPUCINES

BRUSSELS: SPINEUX & CIE., 62 MONTAGNE DE LA COUR

LEIPZIG: KARL W. HIERSEMANN, 3 KÖNIGSSTRASSE

VIENNA: ARTARIA & CO., I., KOHLMARKT 9

AMSTERDAM: J. G. ROBBERS, N. Z. VOORBURGWAL 64

FLORENCE: B. SEEBER, 20 VIA TORNABUONI

NEW YORK: SAMUEL BUCKLEY & CO., 100 WILLIAM STREET

1903

[Pg v]

|

PAGE

|

|

|

I.—Clifford’s Inn and the Protection of Ancient

Buildings

|

|

|

II.—The Publication of Works of Art belonging to

Dealers

|

|

|

The Finest Hunting Manuscript extant. Written by W. A.

Baillie-Grohman

|

|

|

A newly-discovered ‘Libro di Ricordi’ of Alesso

Baldovinetti. Written by Herbert P. Horne:

|

|

|

Part I.

|

|

|

Part II (conclusion)

|

|

|

Appendix—Documents referred to in Articles

|

|

|

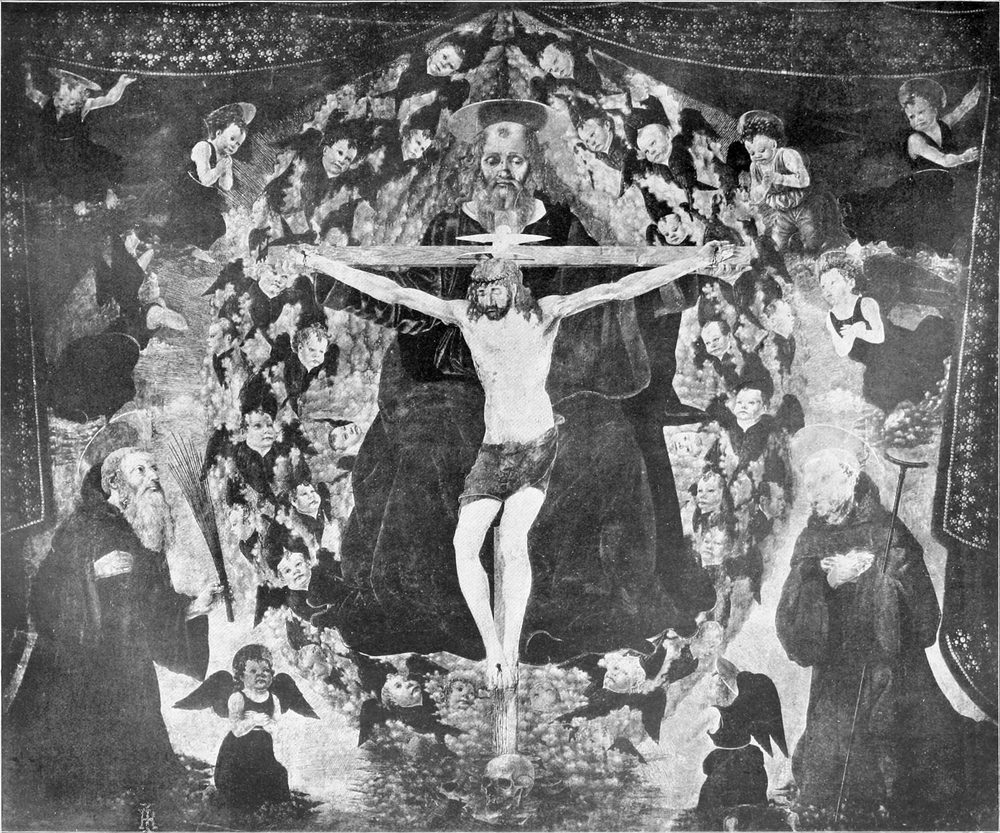

The Early Painters of the Netherlands as Illustrated by

the Bruges Exhibition of 1902. Written by W. H. James Weale:

|

|

|

Article IV

|

|

|

Article V

|

|

|

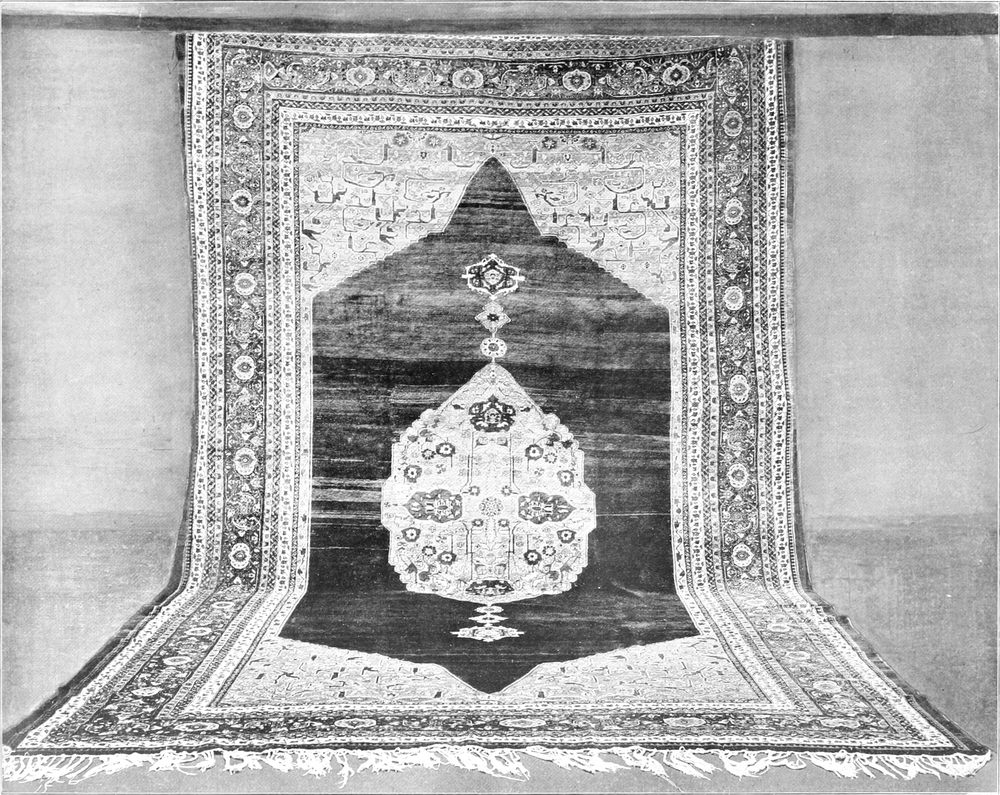

On Oriental Carpets:

|

|

|

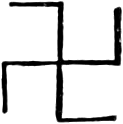

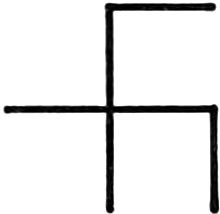

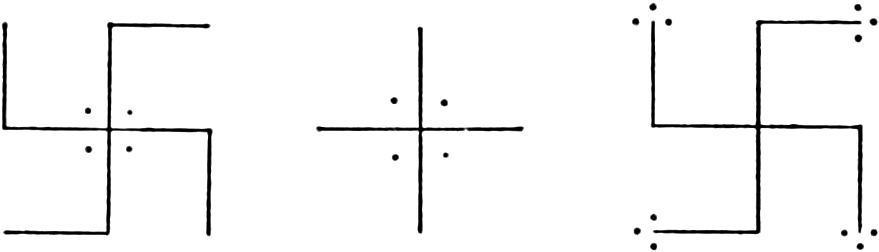

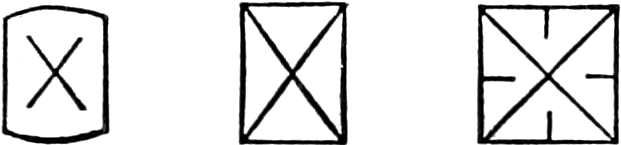

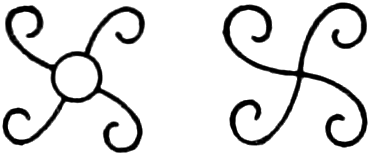

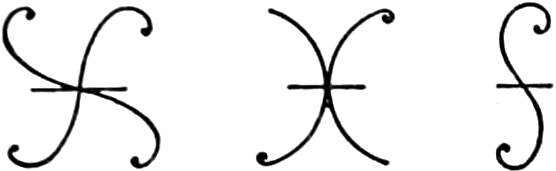

Article III.—The Svastika

|

|

|

Article IV.—The Lotus and the Tree of Life

|

|

|

The Dutch Exhibition at the Guildhall:

|

|

|

Article I.—The Old Masters

|

|

|

Article II.—The Modern Painters

|

|

|

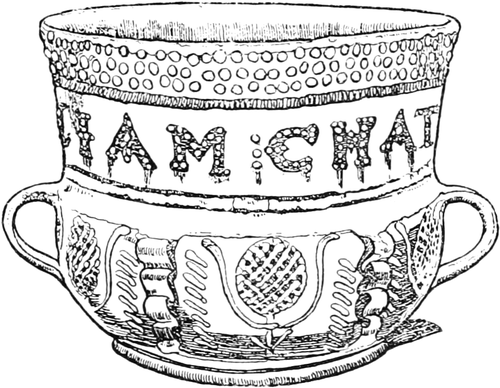

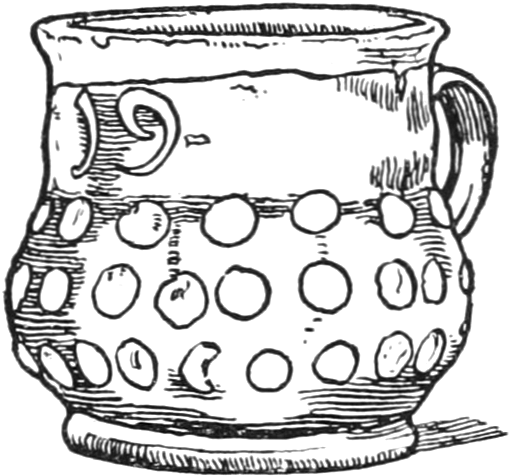

Early Staffordshire Wares Illustrated by Pieces in the

British Museum. Article I. Written by R. L. Hobson

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two alleged ‘Giorgiones’

|

|

|

Two Italian Bas-reliefs in the Louvre

|

|

|

Two Pictures in the Possession of Messrs.

Dowdeswell

|

|

|

A Marble Statue by Germain Pilon

|

|

|

Lace in the Collection of Mrs. Alfred

Morrison at Fonthill

|

|

|

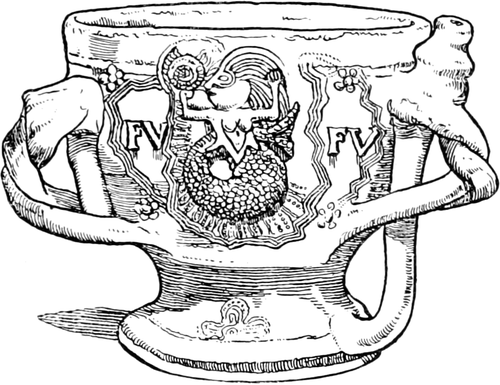

The Sorö Chalice

|

|

|

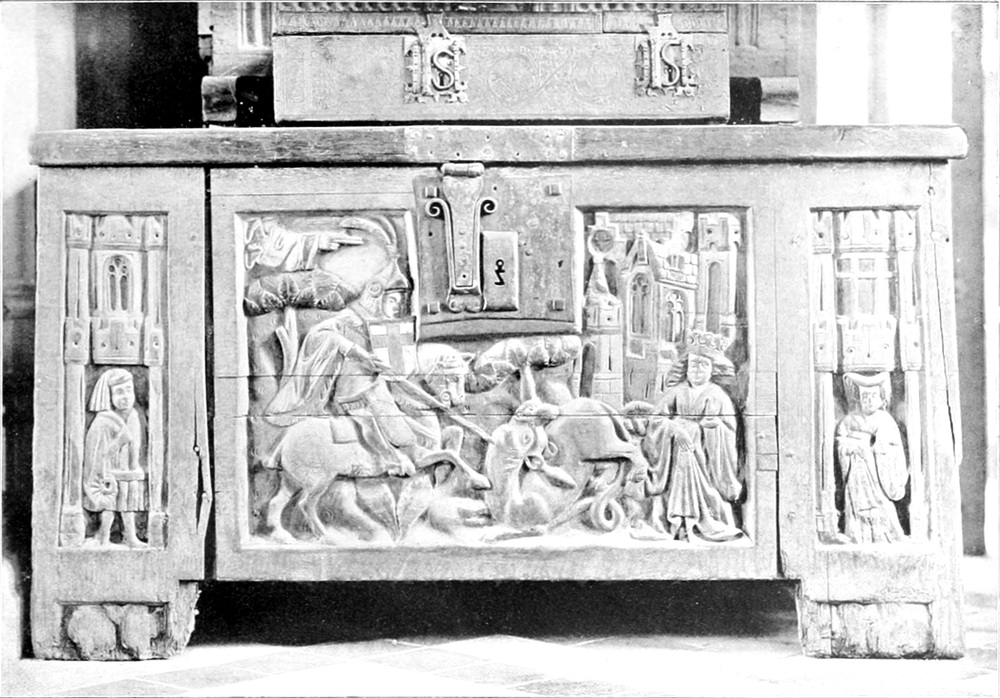

The Oaken Chest at Ypres

|

|

|

A Burgundian Chest

|

|

|

A New Fount of Greek Type

|

|

|

Portrait of a Lady by Rembrandt

|

|

| [Pg vi]

Pictures in the Collection of Sir Hubert Parry, at

Highnam Court, near Gloucester. Article I.—Italian Pictures of the

Fourteenth Century. Written by Roger Fry

|

|

|

Mussulman Manuscripts and Miniatures as Illustrated in

the Recent Exhibition at Paris. Part I. Written by E. Blochet

|

|

|

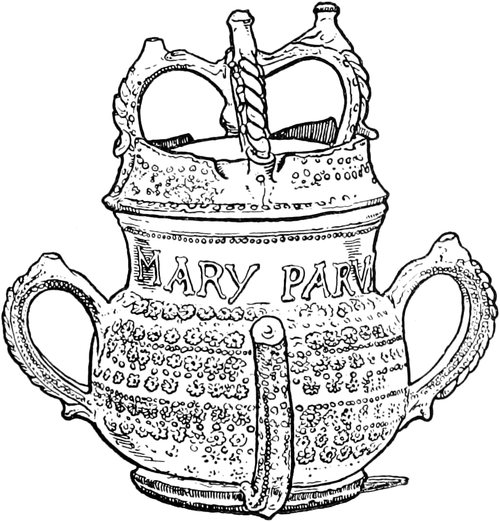

The Plate of Winchester College. Written by Percy

Macquoid, R.I.

|

|

|

The Seals of the Brussels Gilds. Written by R.

Petrucci

|

|

|

Note on the Life of Bernard van Orley

|

|

|

The Collection of Pictures of the Earl of Normanton, at

Somerley, Hampshire. Article I.—Pictures by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Written

by Max Roldit

|

|

|

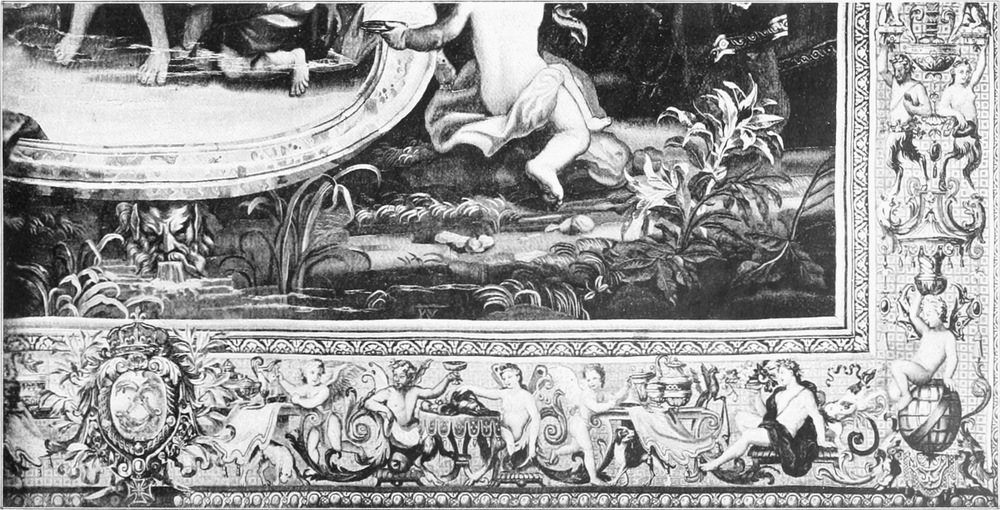

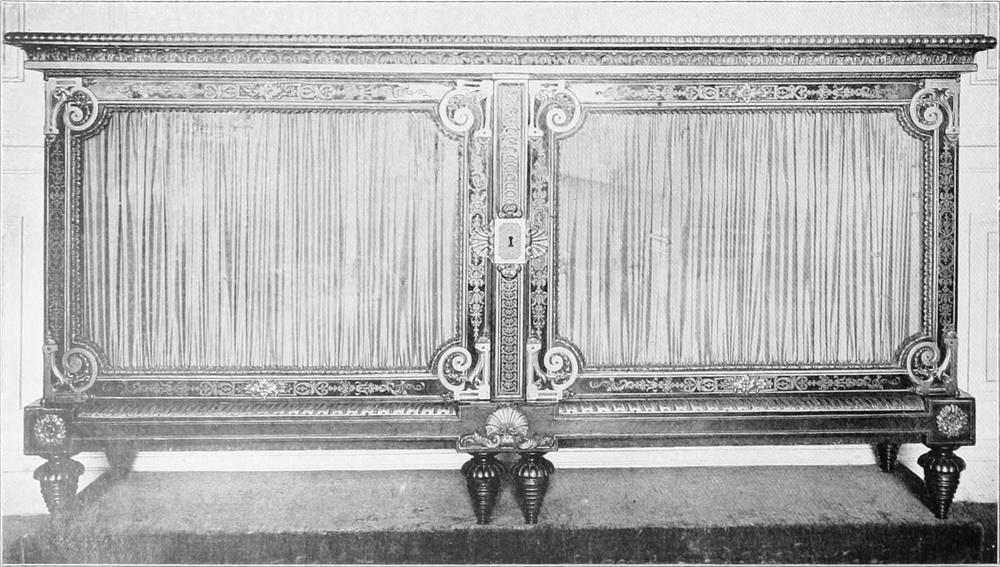

French Furniture of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth

Centuries. Article II.—The Louis XIV Style (cont.)—The Gobelins.

Written by Emile Molinier

|

|

|

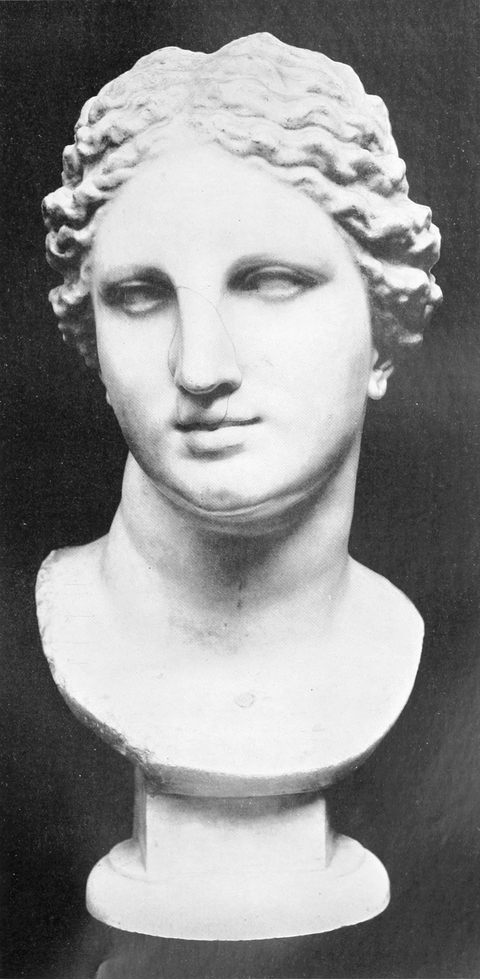

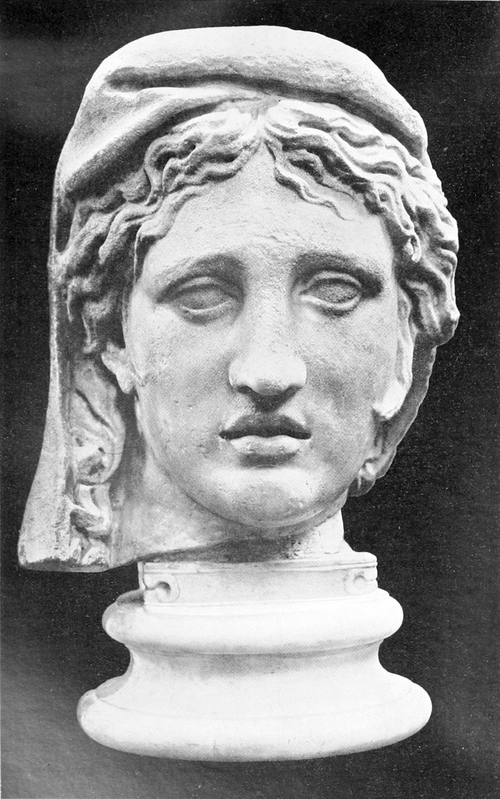

The Exhibition of Greek Art at the Burlington Fine Arts

Club. Written by Cecil Smith

|

|

|

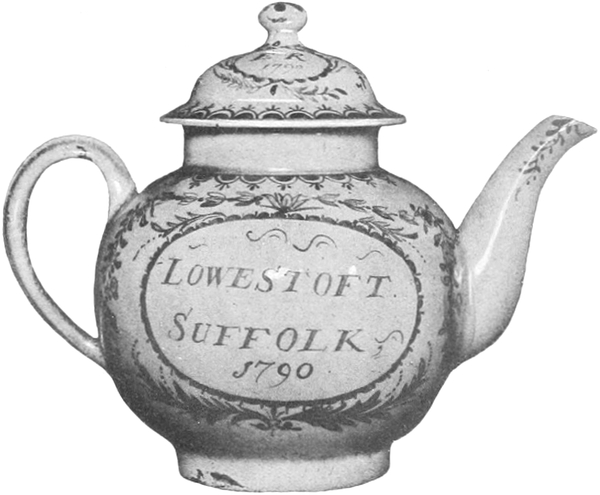

The Lowestoft Porcelain Factory, and the Chinese

Porcelain made for the European Market during the Eighteenth Century.

Written by L. Solon

|

|

|

Titian’s Portrait of the Empress Isabella. Written by

Georg Gronau

|

|

|

A newly-discovered Portrait Drawing by Dürer. Written by

Campbell Dodgson

|

|

|

Later Nineteenth-Century Book Illustrations. Article I.

Written by Joseph Pennell

|

|

|

Andrea Vanni. By L. Mason Perkins

|

|

|

The Geographical Distribution of the First Folio

Shakespeare. Written by Frank Rinder

|

|

|

Recent Acquisitions at the Louvre

|

|

|

New Acquisitions at the National Museums

|

|

|

Bibliography

|

|

|

Correspondence

|

|

|

Foreign Correspondence

|

[Pg vii]

|

|

PAGE

|

|

Frontispiece—The Judgement of Cambyses—Gerard David

|

|

|

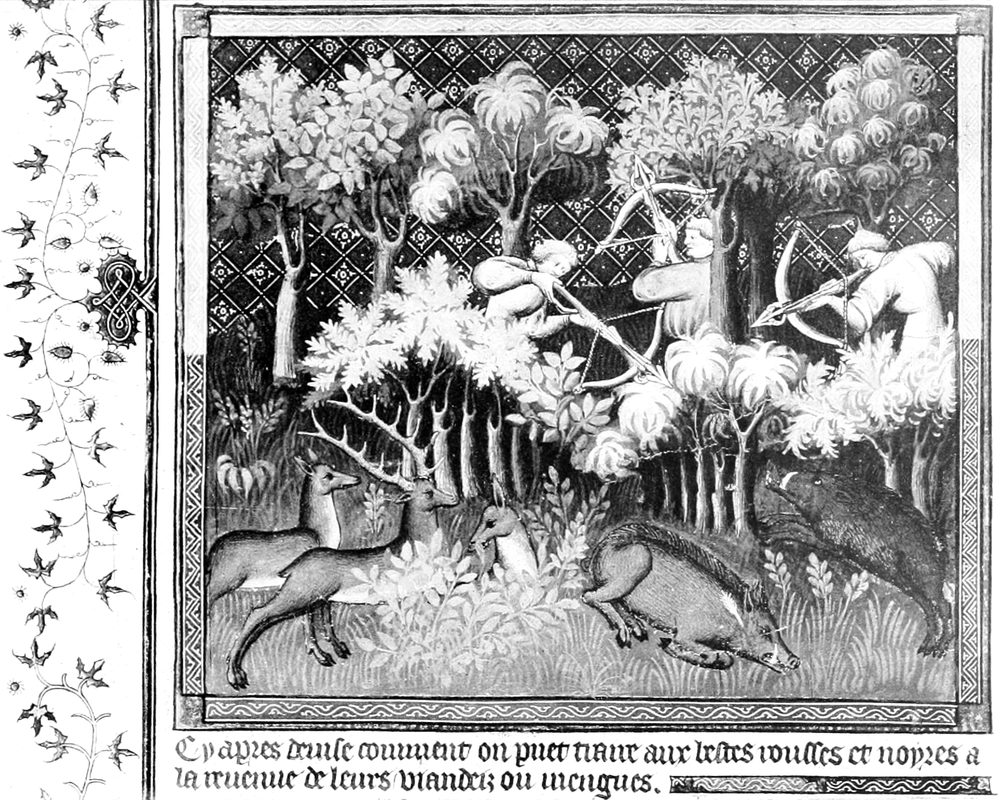

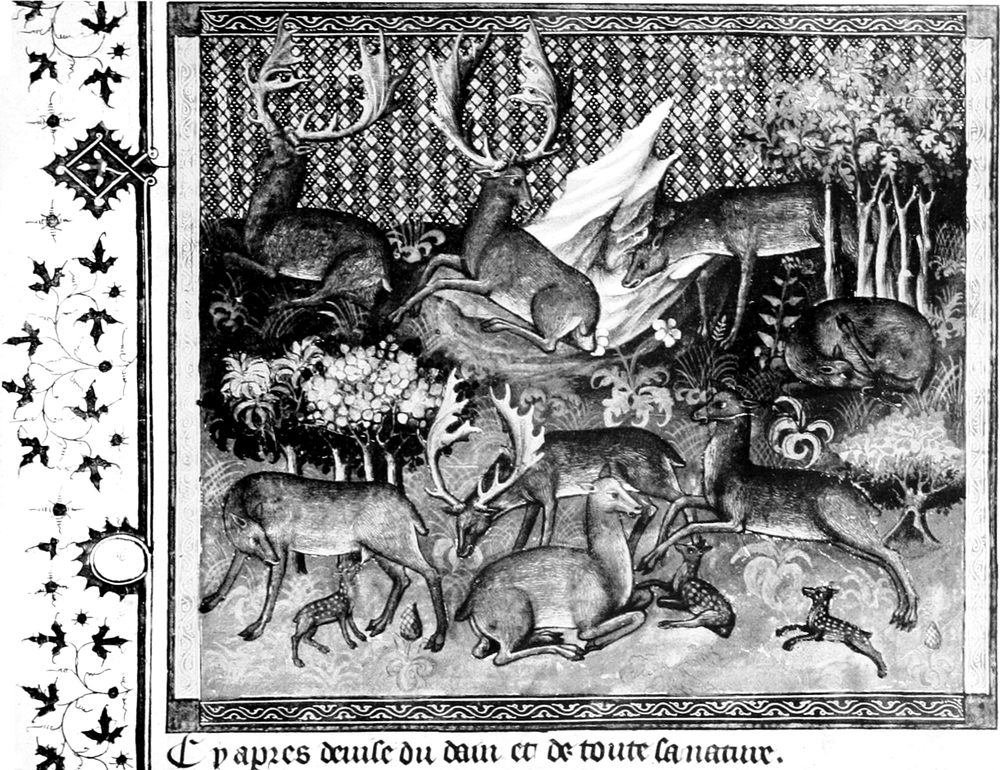

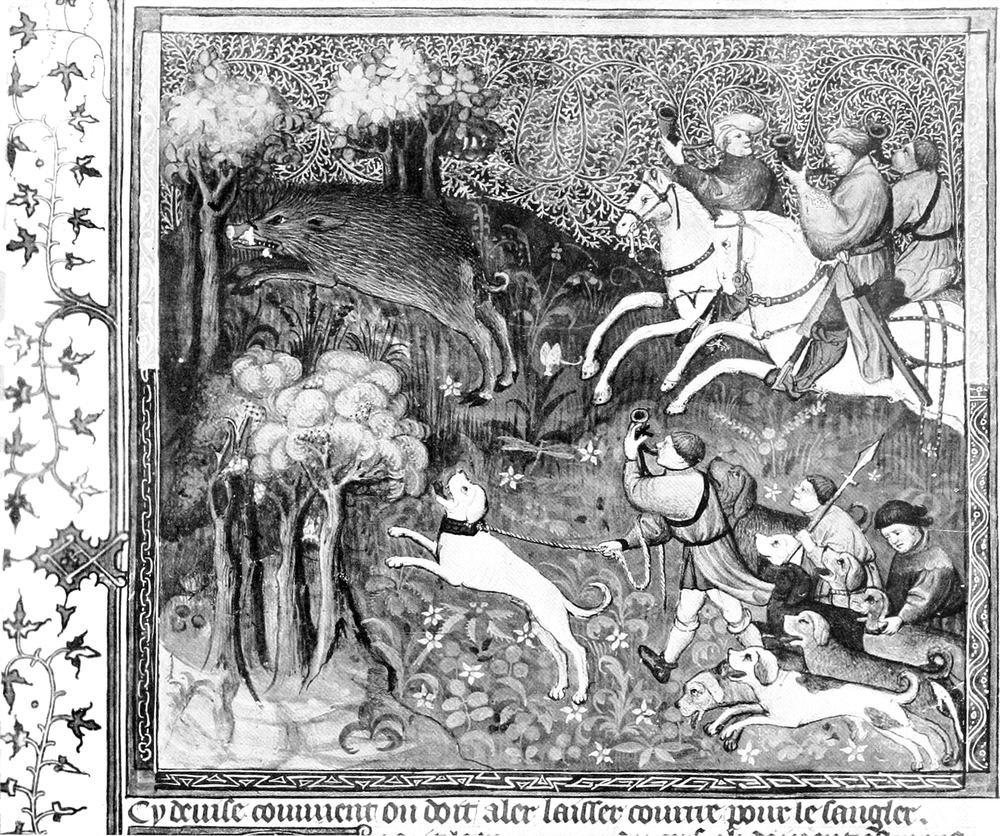

The Finest Hunting Manuscript Extant:—

|

|

|

Stripping the Boar

|

|

|

Hunting the Fallow Buck

|

|

|

Pages from Gaston Phoebus MS.

|

|

|

Page from Gaston Phoebus MS.

|

|

|

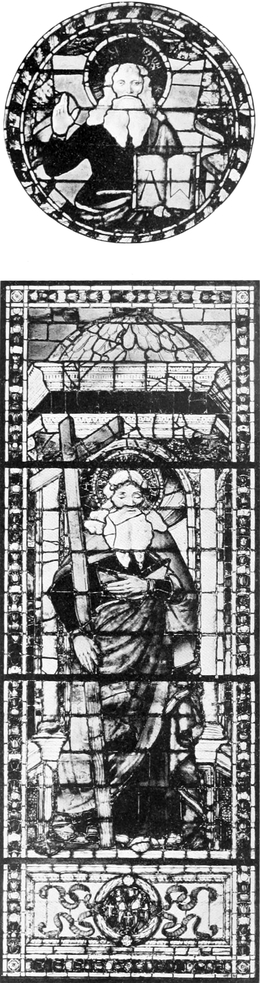

Painted-glass Window in the Cloister of Santa

Croce, Florence—Alesso Baldovinetti

|

|

|

Altar-piece, in the Florentine Academy—Alesso

Baldovinetti

|

|

|

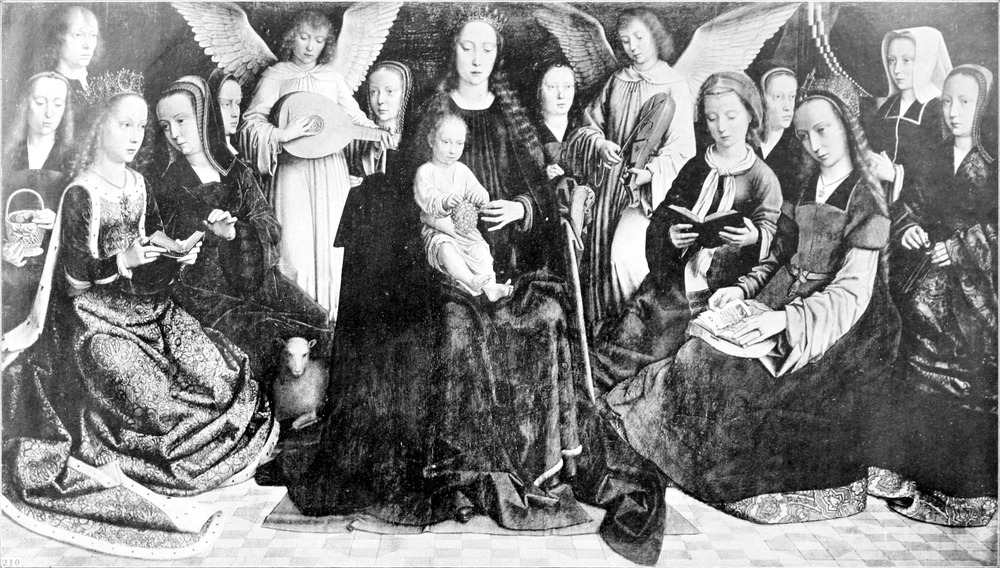

The Blessed Virgin and Child, with Angels,

surrounded by Virgin Saints—Gerard David

|

|

|

The Blessed Virgin and Child, St. Catherine,

and St. Barbara—Cornelia Cnoop

|

|

|

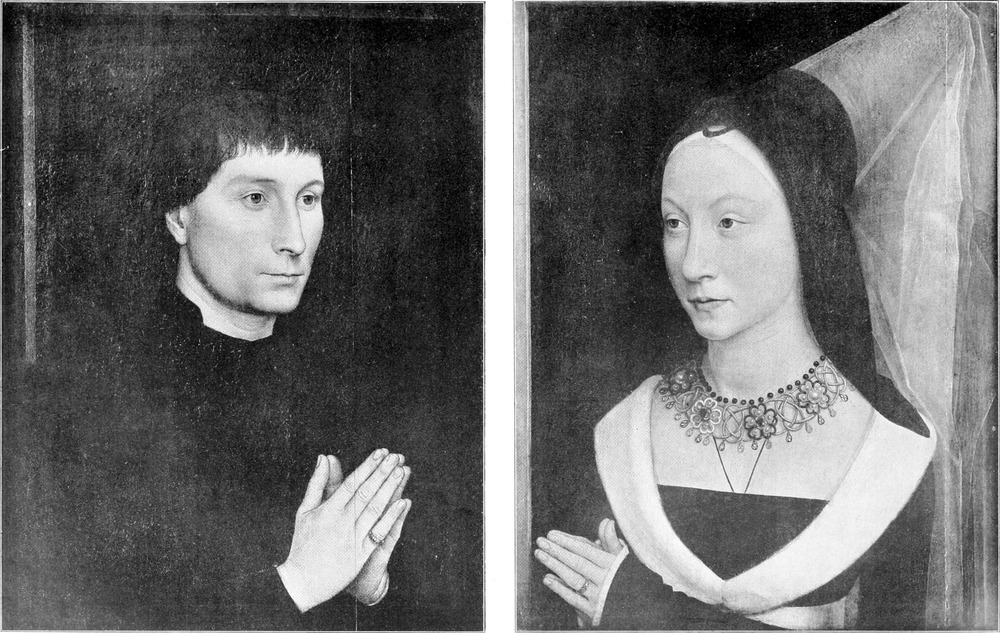

Portraits of Thomas Portunari and his Wife—Attributed

to Hans Memlinc

|

|

|

Section of Oriental Carpet, showing the Svastika

|

|

|

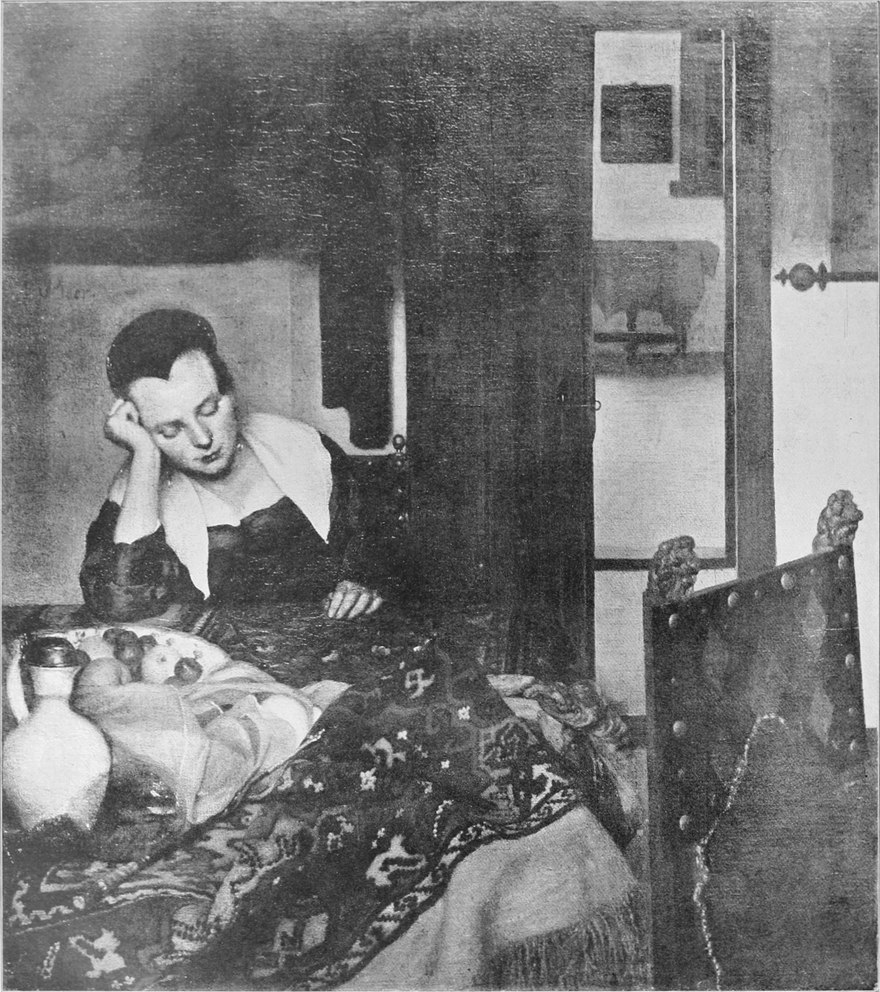

The Cook Asleep—Jan Vermeer of Delft

|

|

|

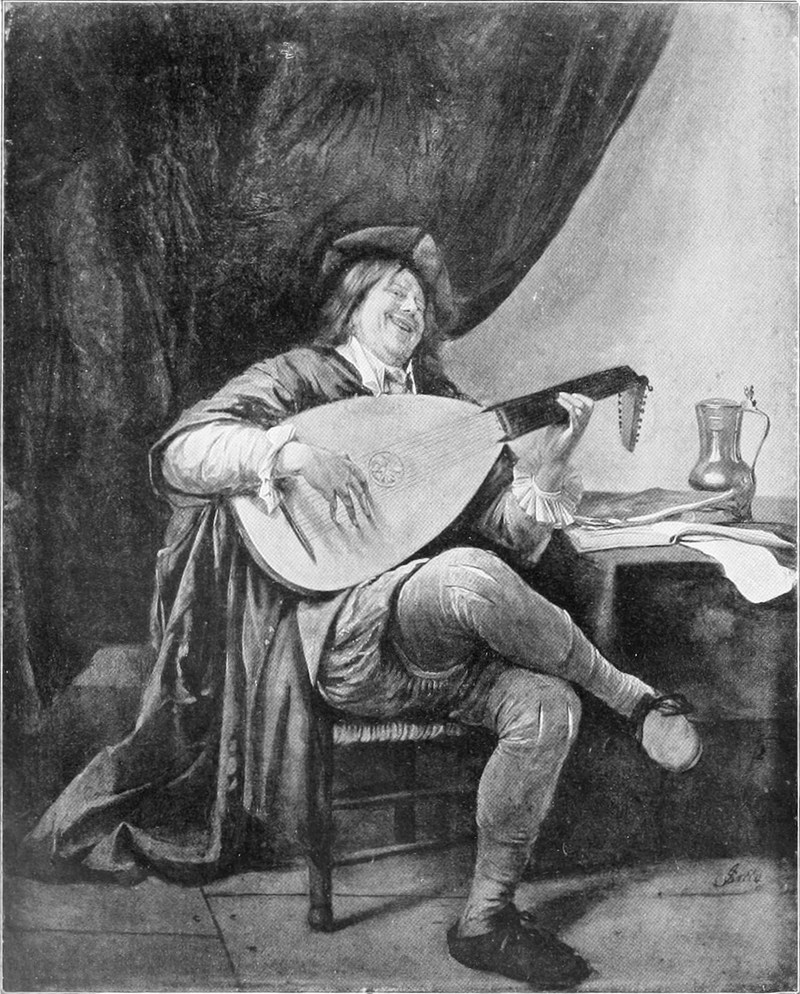

Portrait of Himself—Jan Steen

|

|

|

Portrait of the Wife of Thomas Wijck—Jan Verspronck

|

|

|

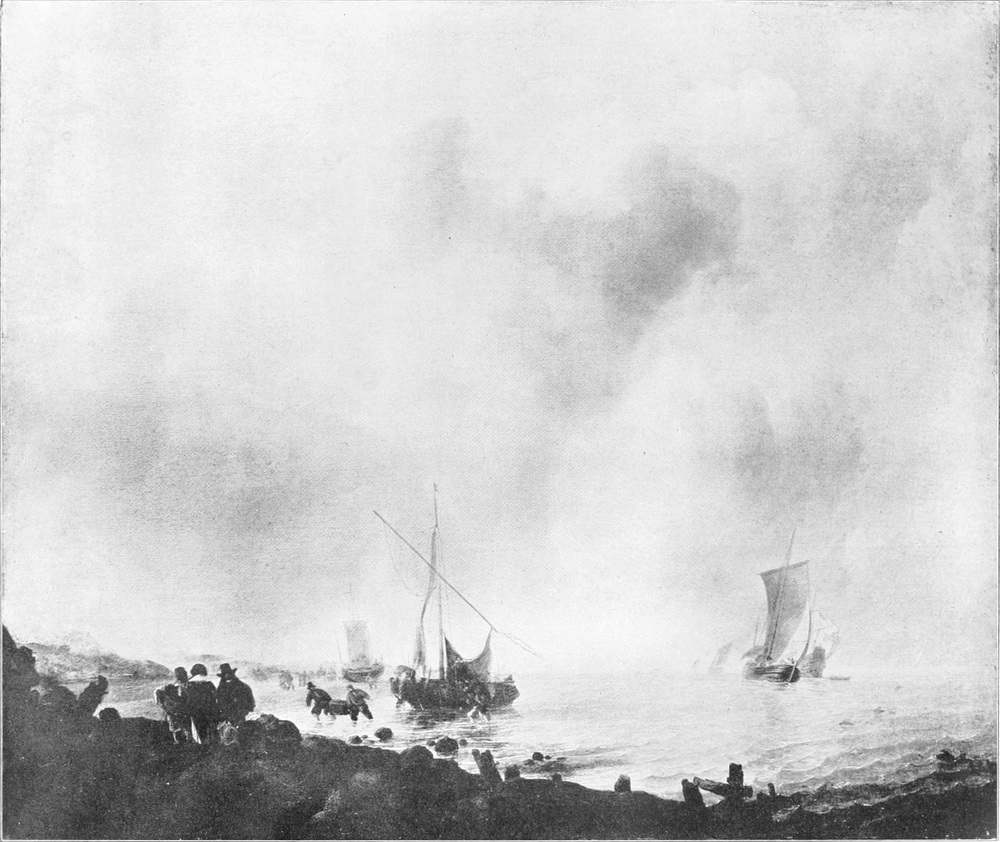

Off Scheveningen—Jan van de Capelle

|

|

|

Le Commencement d’Orage

|

|

|

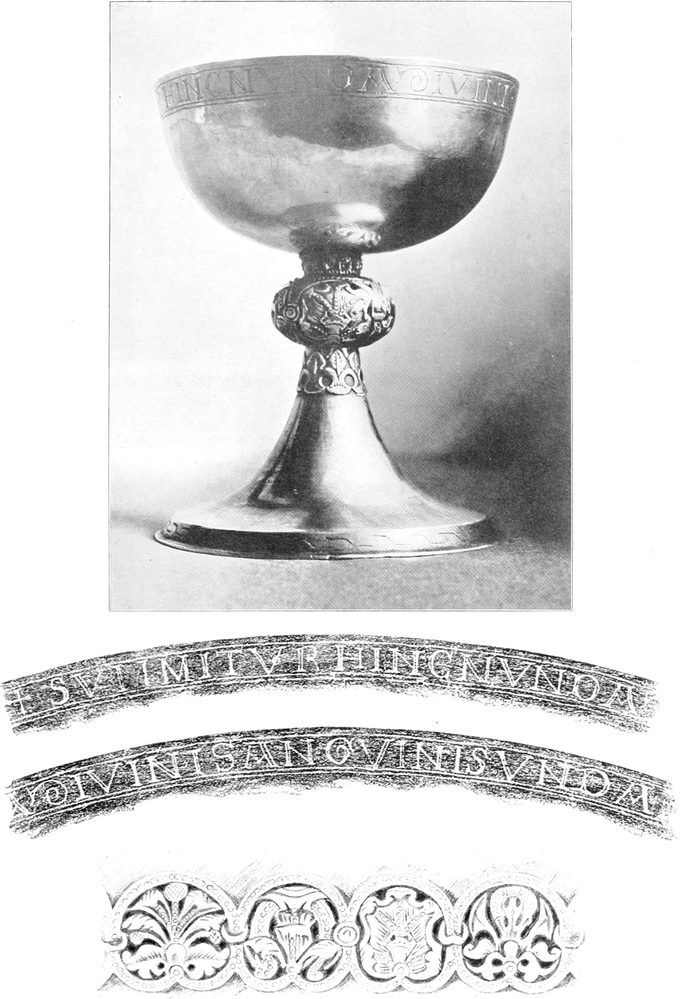

A Scandinavian Chalice, with details

|

|

|

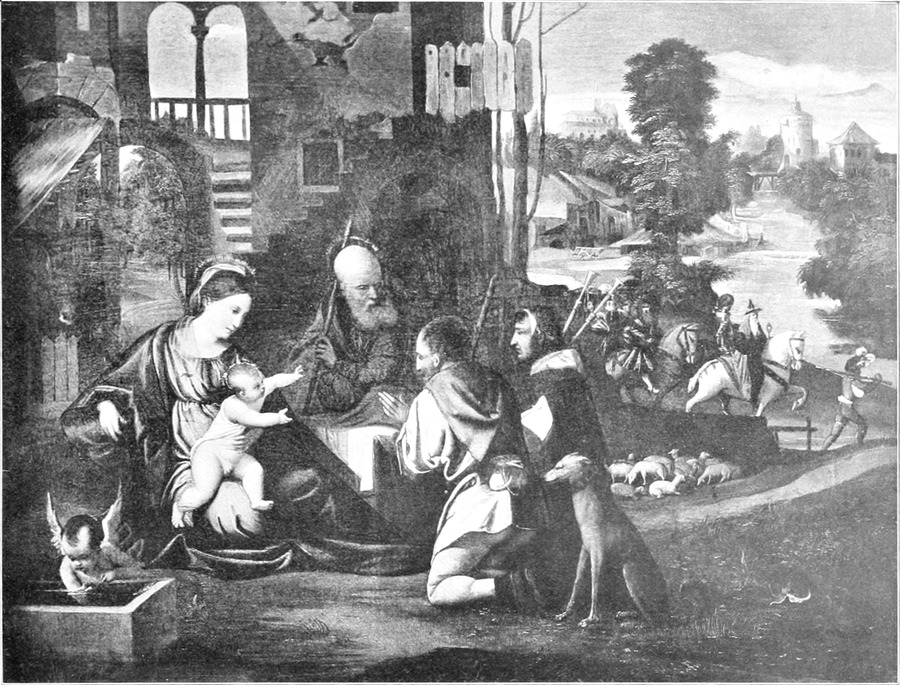

Madonna and Child—Cariani

|

|

|

The Sempstress Madonna—Cariani

|

|

|

Adoration of the Shepherds—Venetian School

(Two Pictures)

|

|

|

Bas-relief—School of Leonardo da Vinci

|

|

|

Bas-relief—Agostino di Duccio

|

|

|

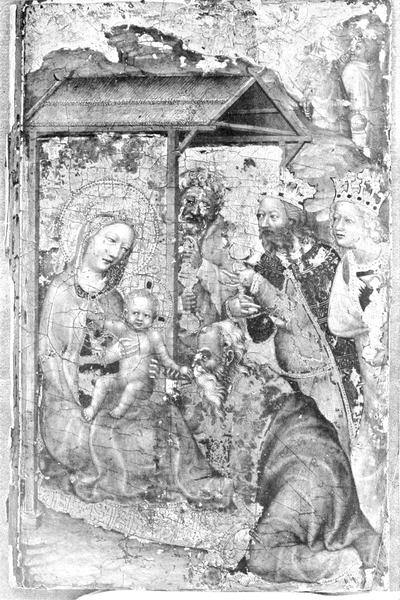

Adoration of the Magi, and Dormition of the

Blessed Virgin—French fourteenth century

|

|

|

La Charité—Germain Pilon

|

|

|

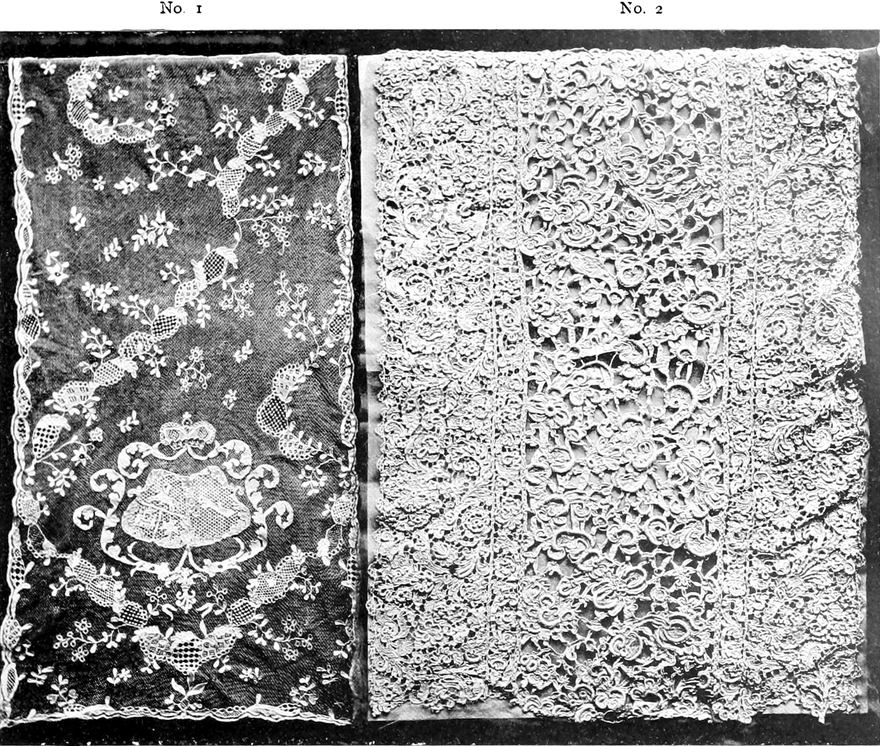

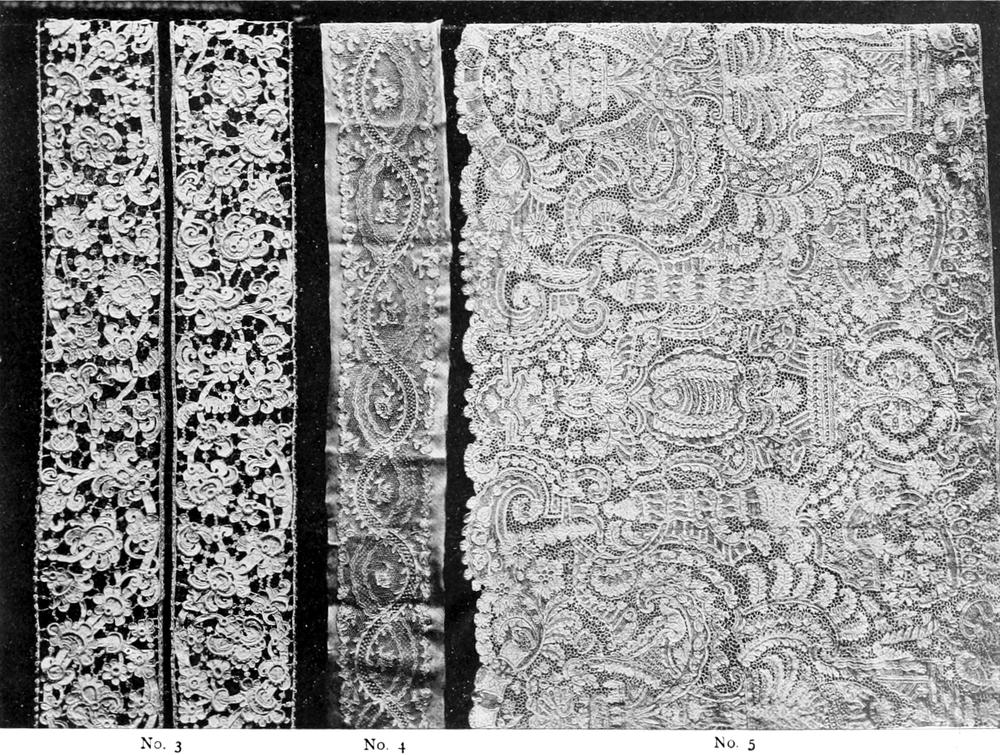

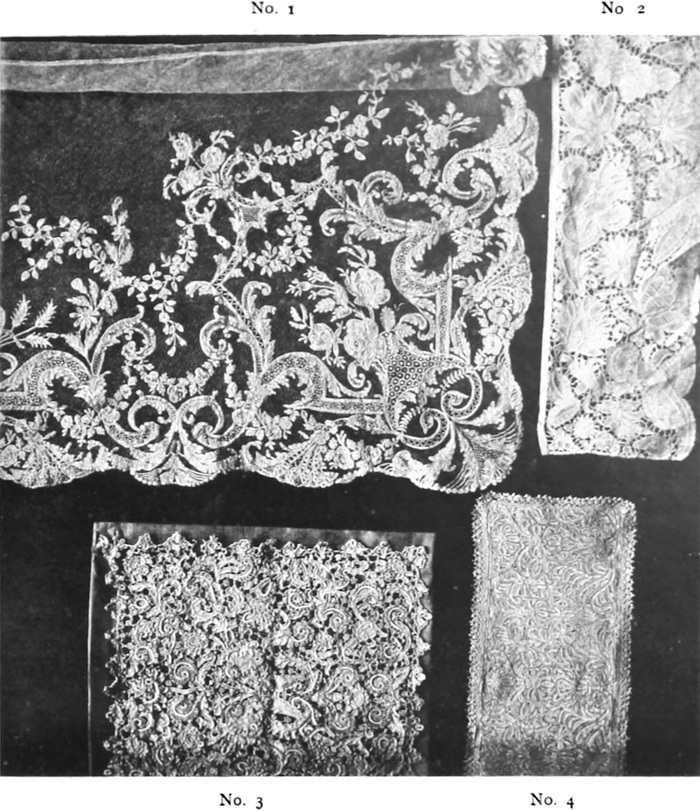

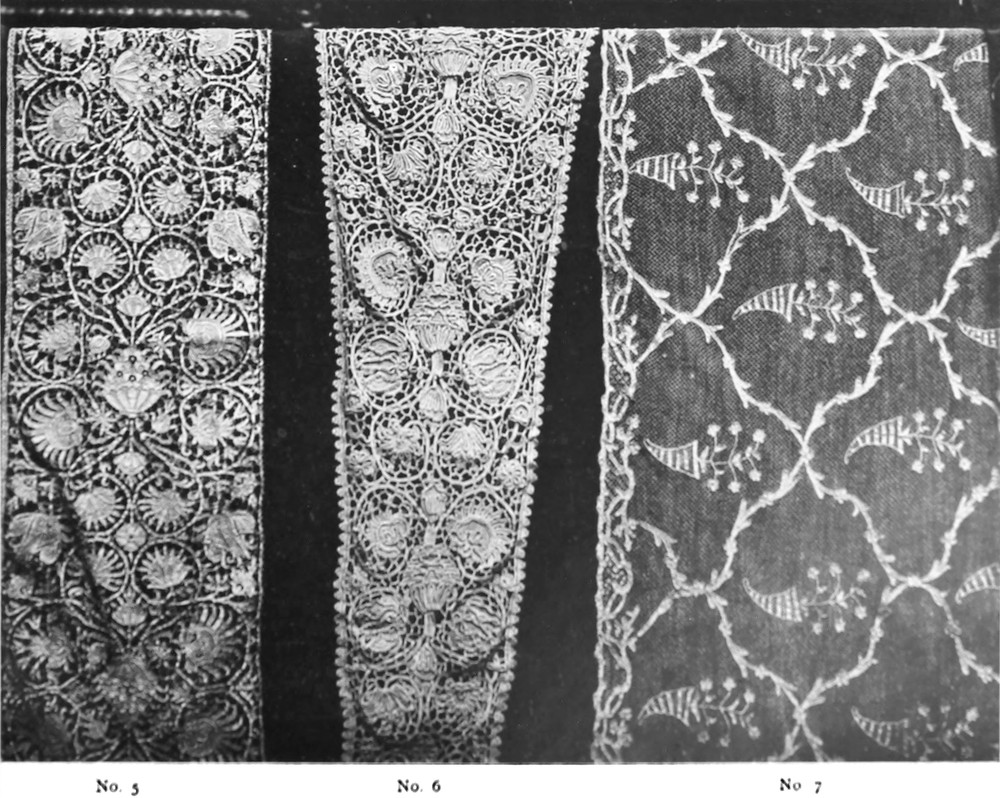

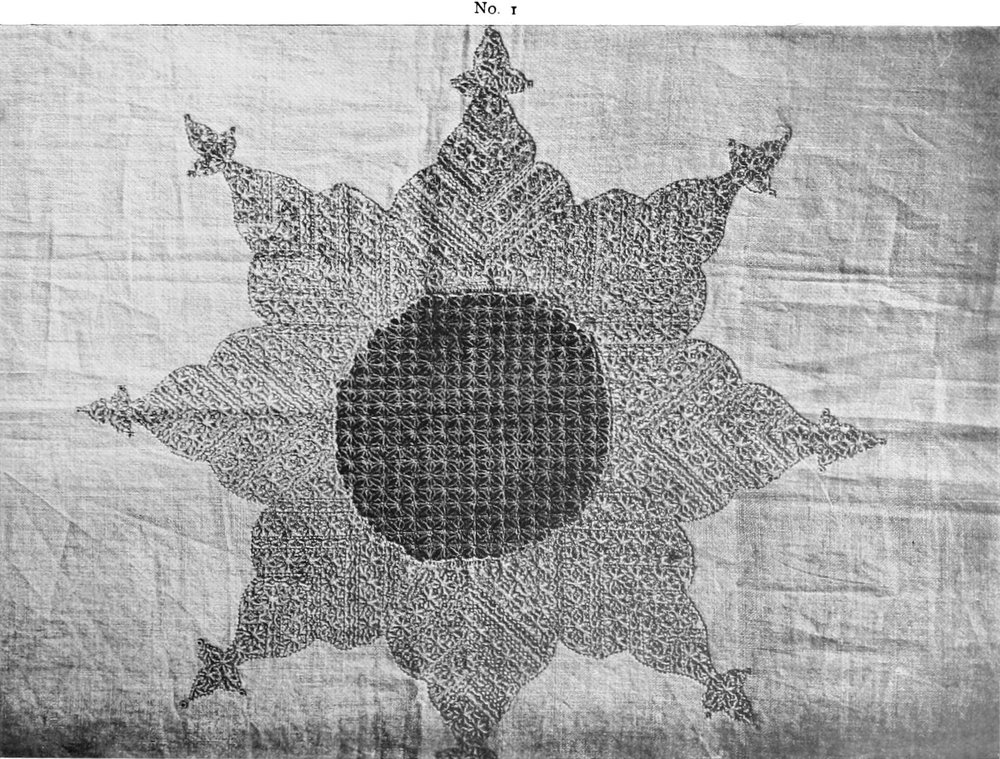

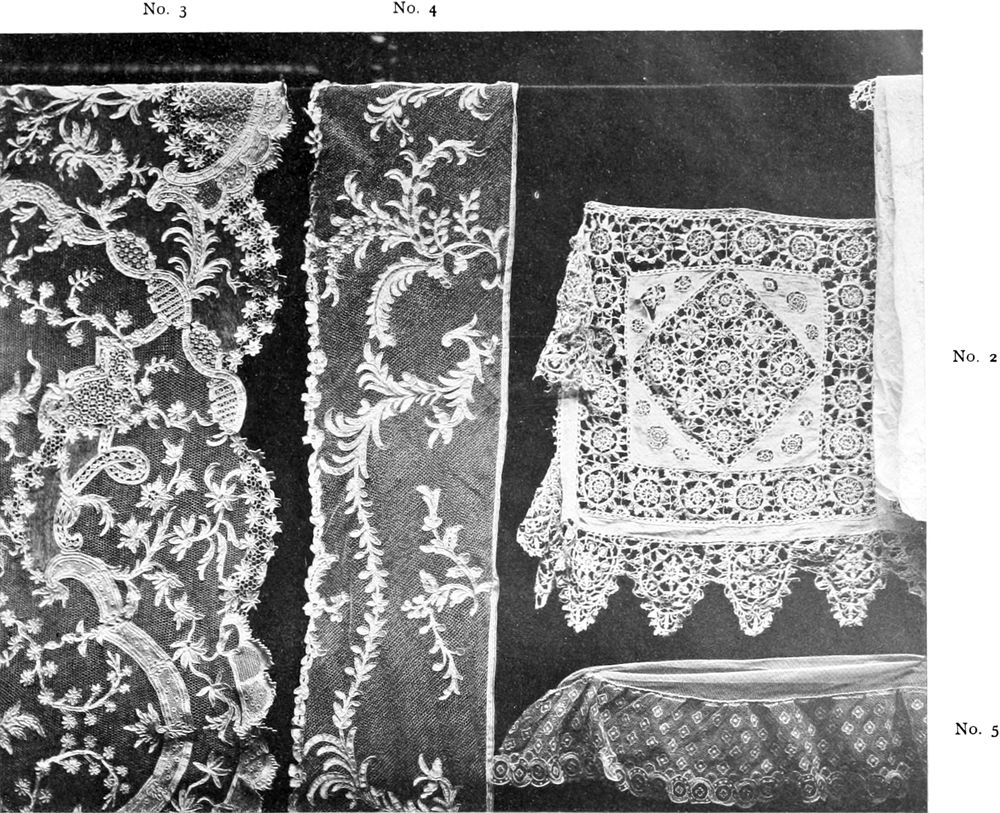

Specimens of Lace:—

|

|

|

Plate I

|

|

|

Plate II

|

|

|

Plate III

|

|

|

Lady Betty Hamilton—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

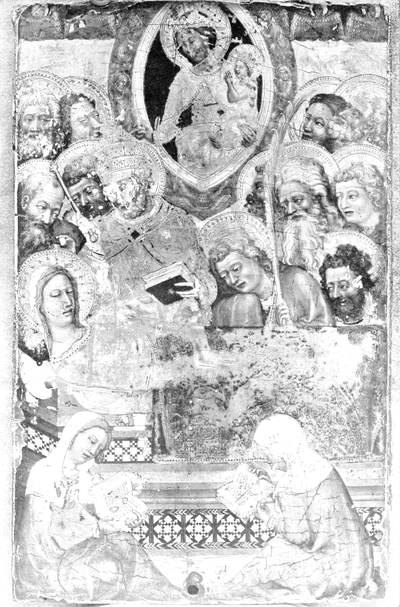

Nativity and Adoration—School of Cimabue

|

|

|

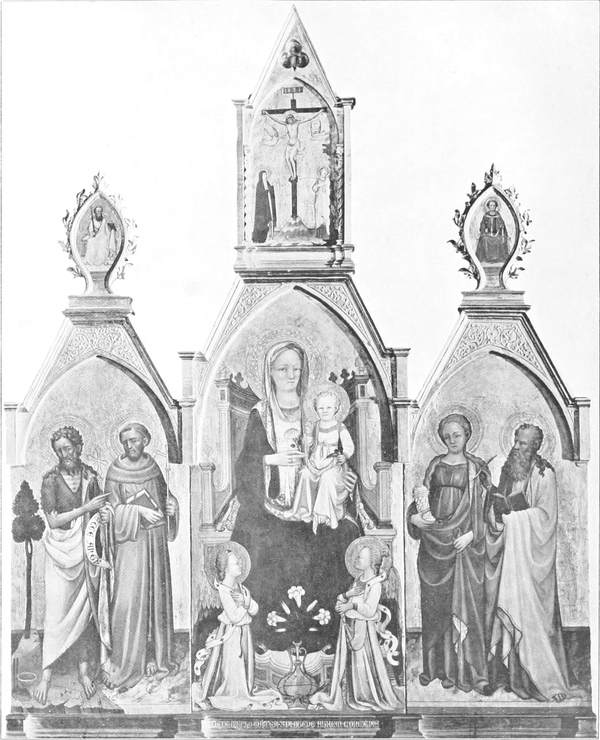

Altar-piece—Bernardo Daddi

|

|

|

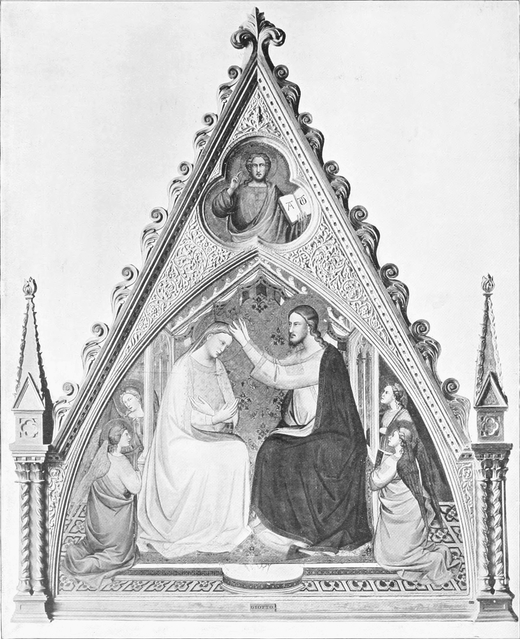

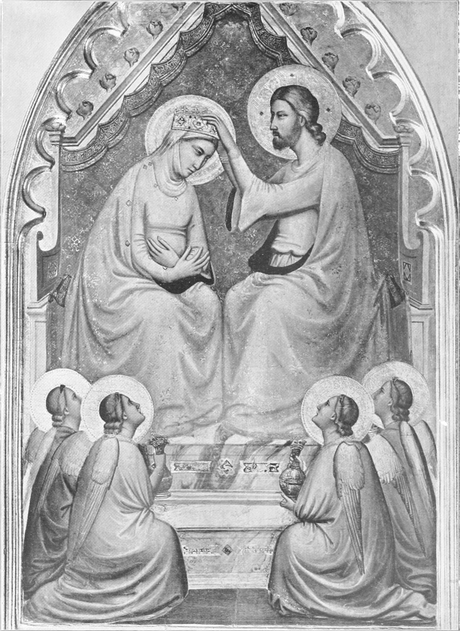

Coronation of our Lady (Two Subjects: 1, by

Agnolo Gaddi; 2, by Taddeo Gaddi)

|

|

|

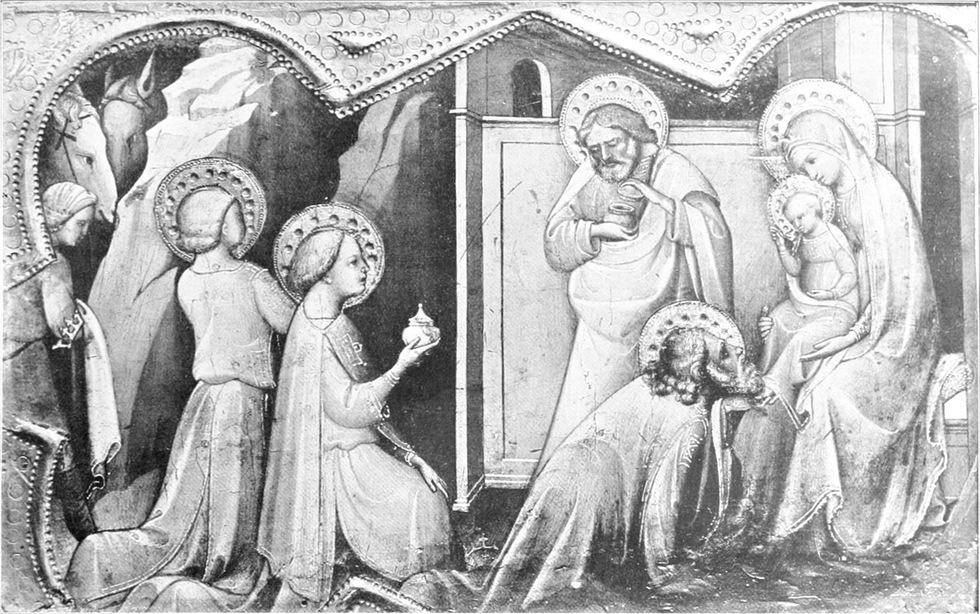

Adoration of the Magi—Lorenzo Monaco

|

|

|

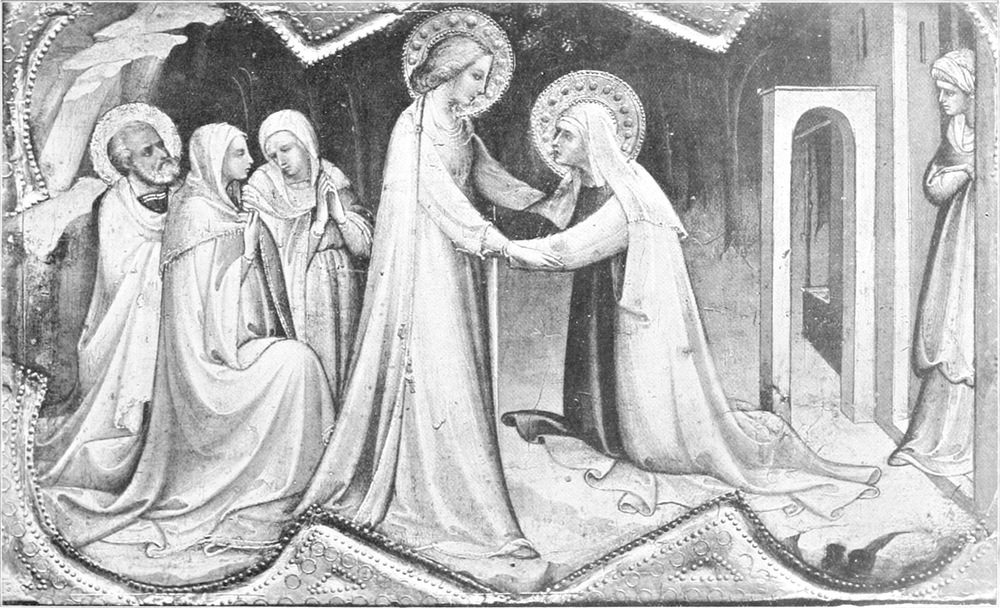

The Visitation—Lorenzo Monaco

|

|

|

Madonna and Child, with Angels—Florentine of

the early fifteenth century

|

|

|

Triptych, by the same painter

|

|

|

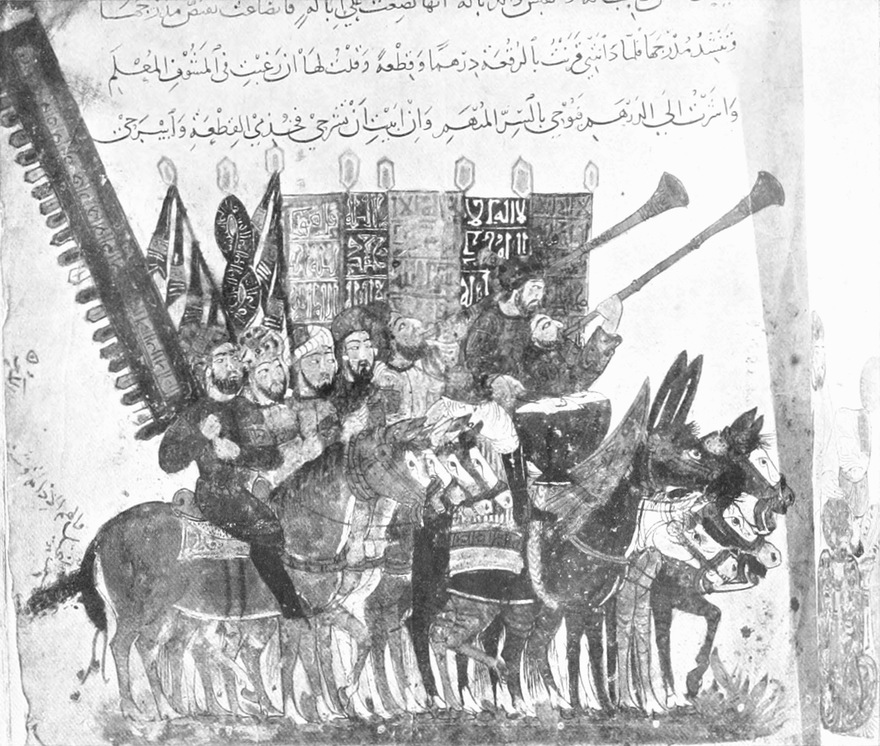

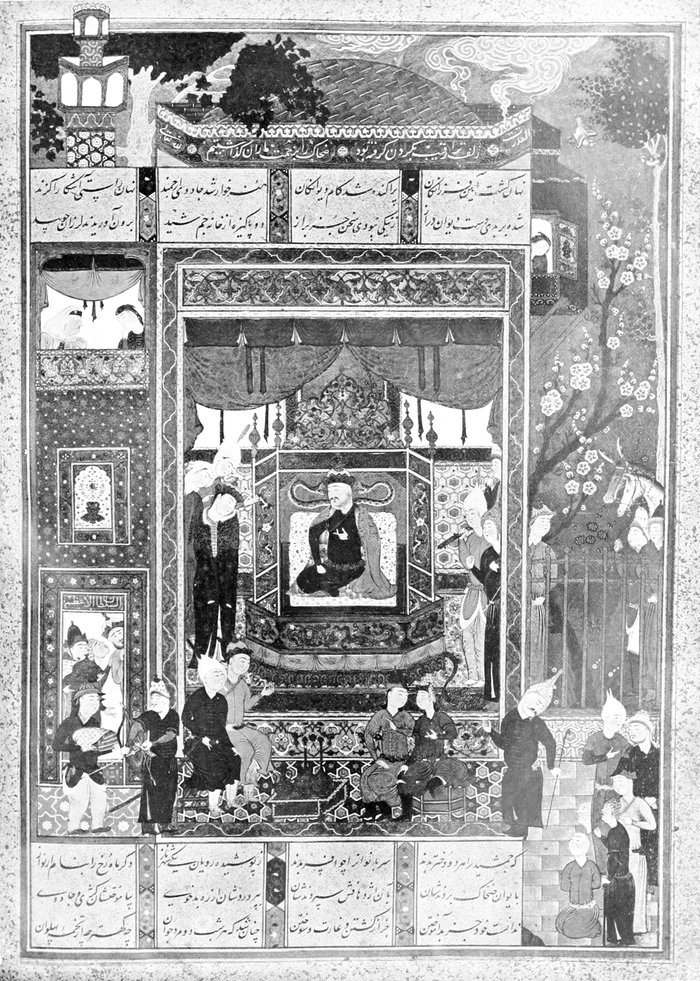

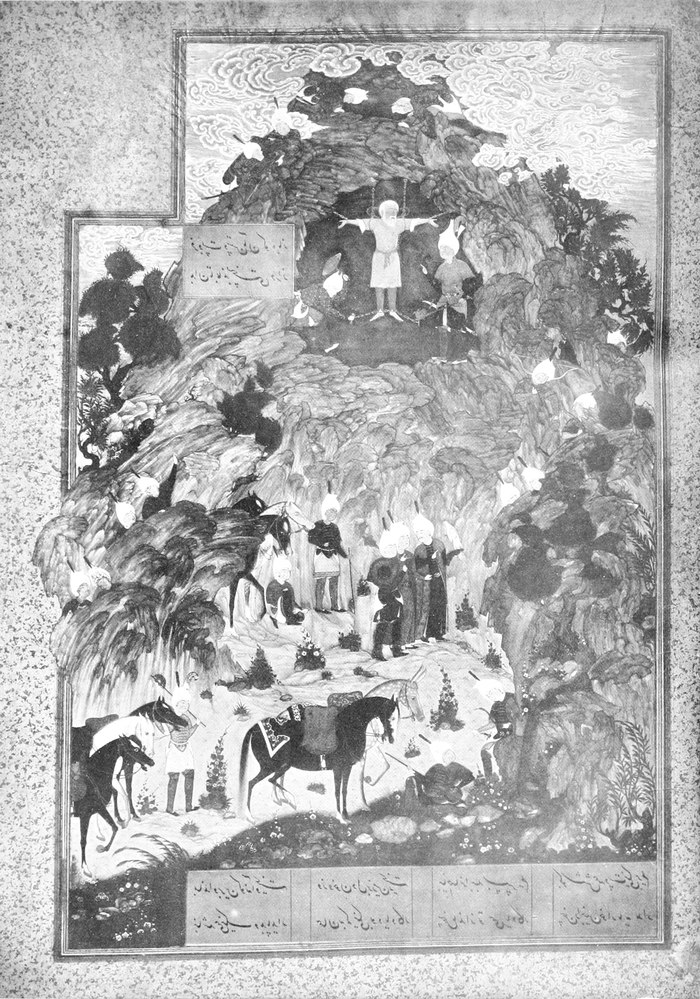

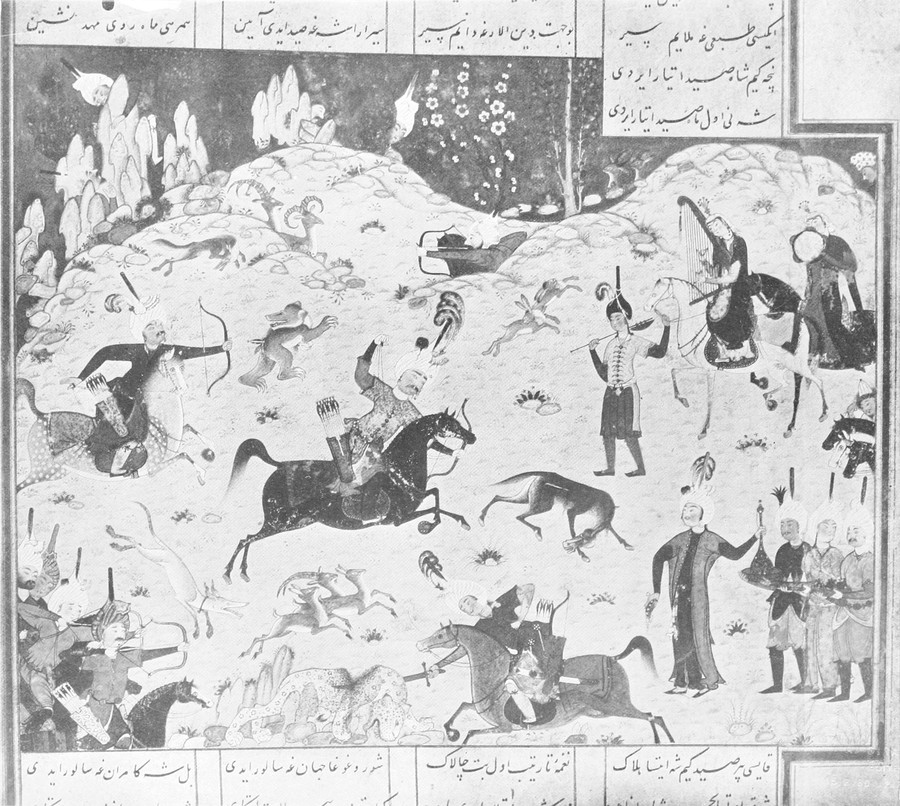

Mussulman Miniatures:—

|

|

|

Plate I—From the Makamat of Hariri—From

MS. of the Astronomical Treatise of Abd-er-Rahman-el-Sufi

|

|

|

Plate II—From the Book of Kings

|

|

|

Plate III—From the Book of Kings

|

|

|

Plate IV—A Hunting Scene

|

|

|

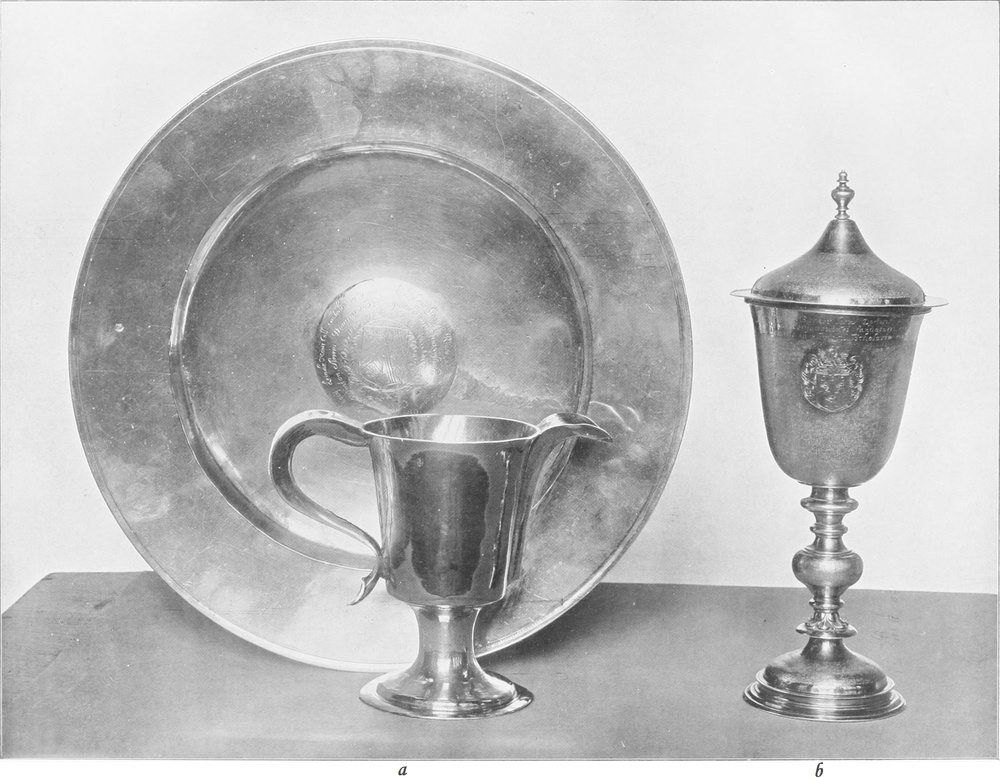

Plate of Winchester College:—

|

|

|

The Election Cup

|

|

|

Parcel Gilt Rose-water Dish and Ewer

|

|

|

Sweetmeat Dish and Gilt Standing-Salt

|

|

|

Gilt Cup with Cover

|

|

|

Rose-water Dish and Ewer, and small Gilt

Standing Cup and Cover

|

|

|

Two Tankards and Standing Salt

|

|

|

Steeple-cup and Hanap

|

|

|

Ecclesiastical Plate

|

|

|

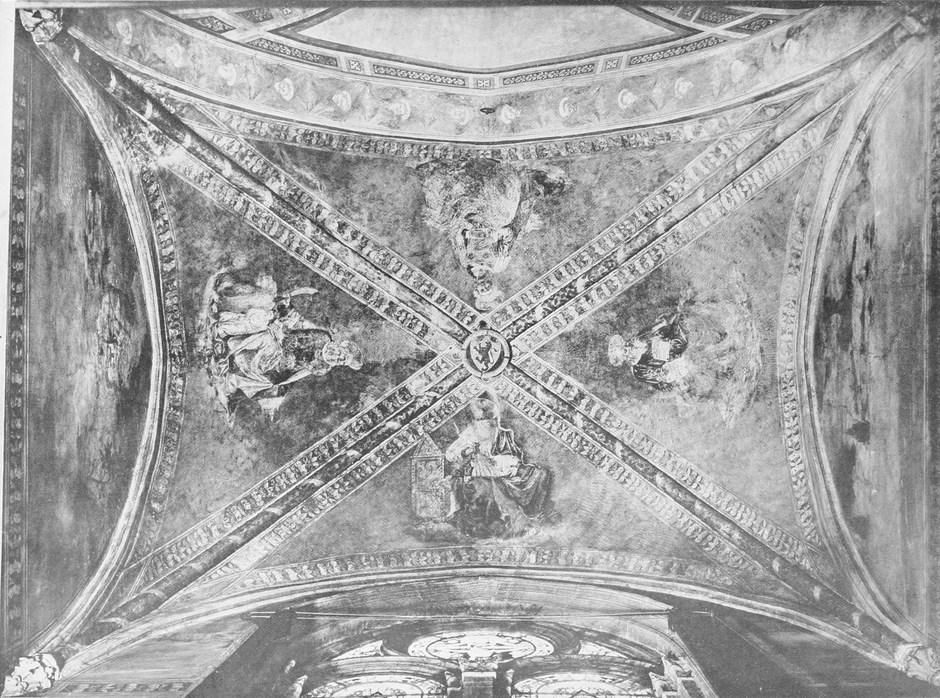

Paintings on a vaulted roof at S. Trinita,

Florence—Alesso Baldovinetti

|

|

|

A Group of Three—Jan Miense Molenaer

|

|

|

The Archives at Veere—Jan Bosboom

|

|

|

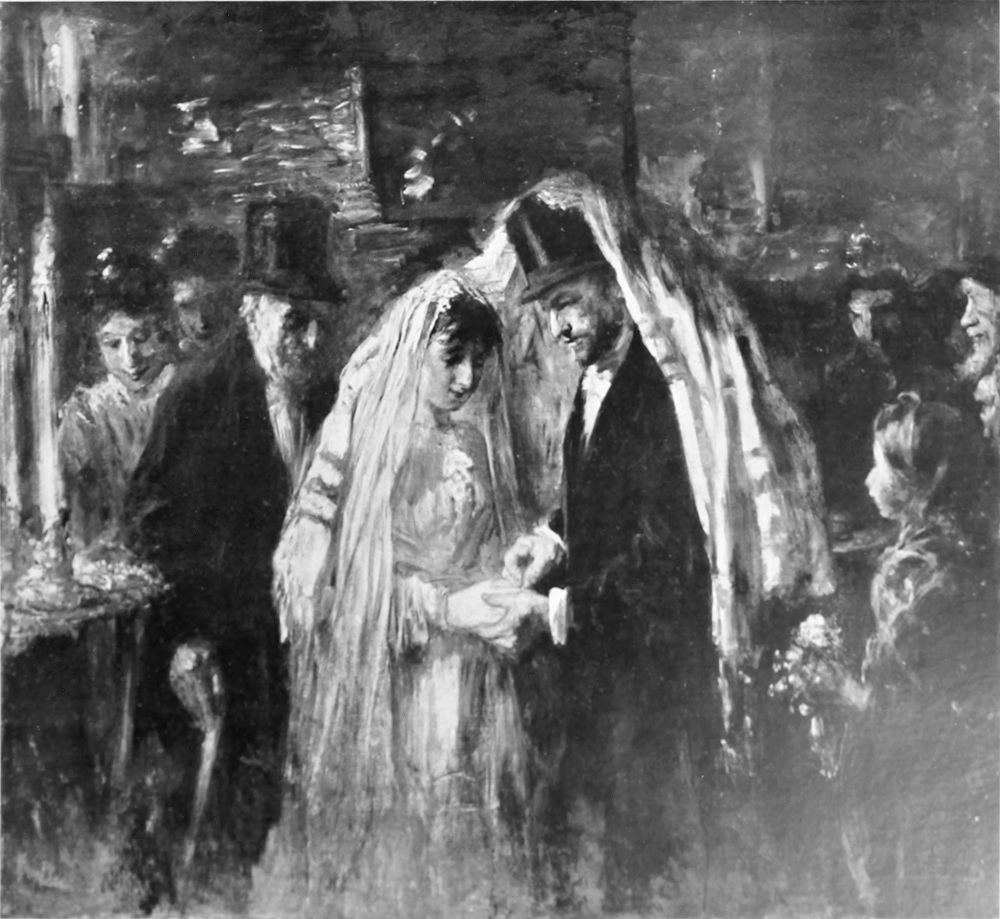

A Jewish Wedding—Joseph Israels

|

|

|

A Fantasy—Matthew Maris

|

|

|

The New Flower—Joseph Israels

|

|

|

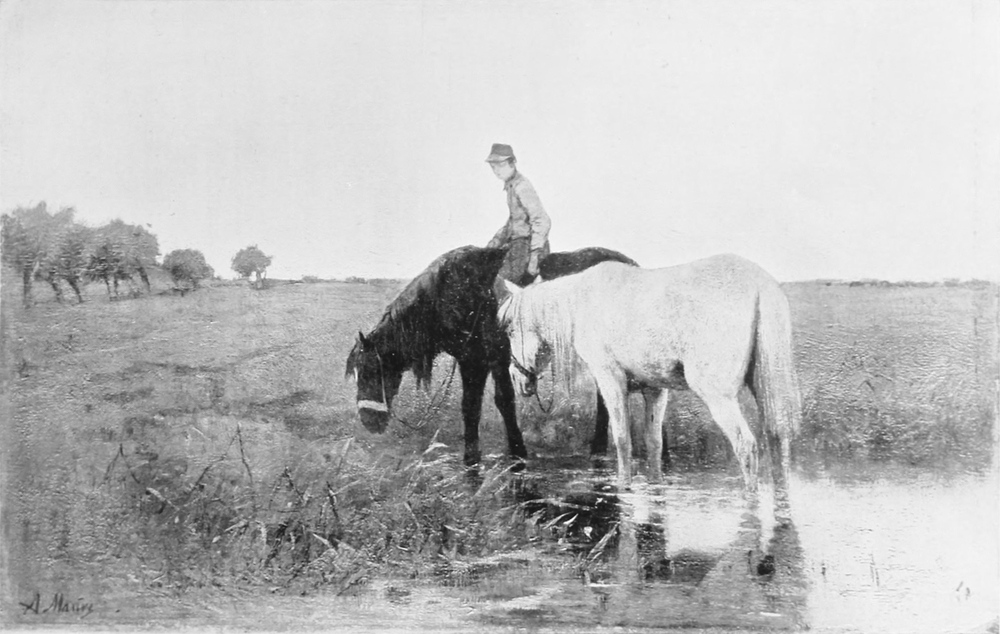

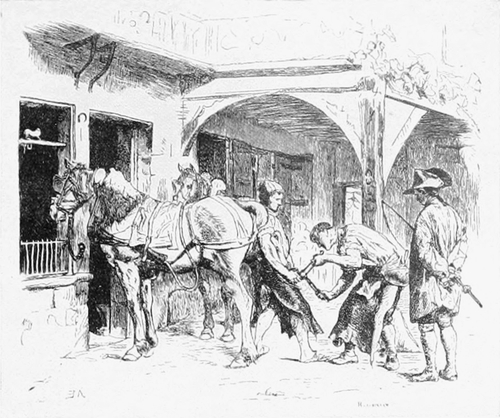

Watering Horses—Anton Mauve

|

|

|

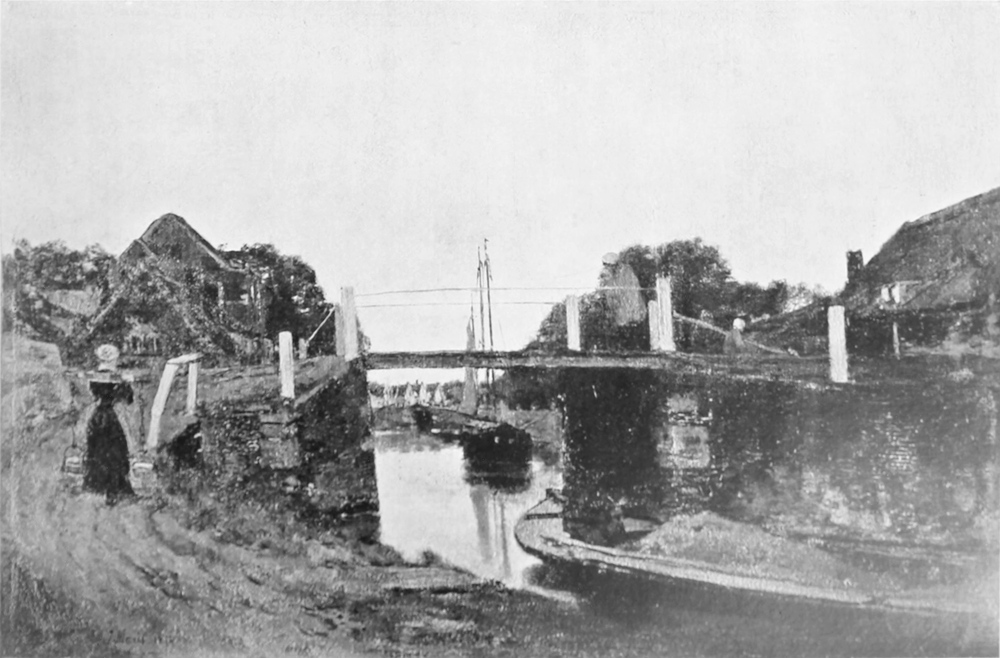

The Canal Bridge—Jacob Maris

|

|

|

A Windmill, Moonlight—Jacob Maris

|

|

|

The Butterflies—Matthew Maris

|

|

|

Engravings at S. Kensington:—

|

|

|

Queen Elizabeth—William Rogers

|

|

|

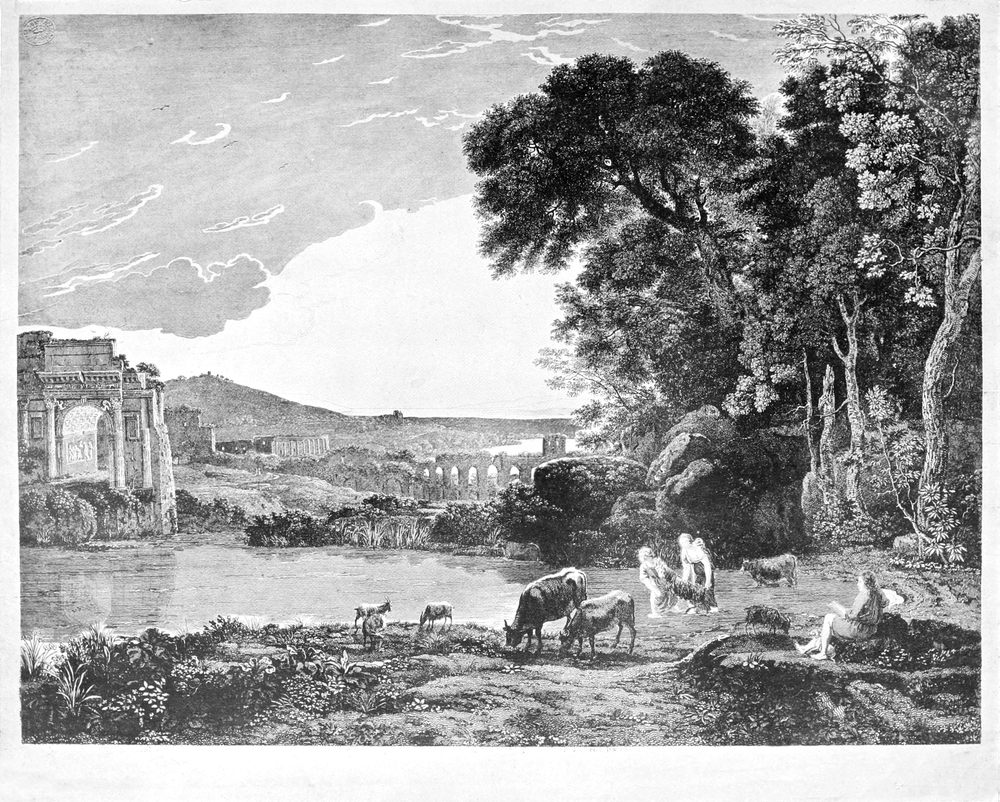

Roman Edifices in Ruins—Thomas Hearne

and William Woollett

|

|

|

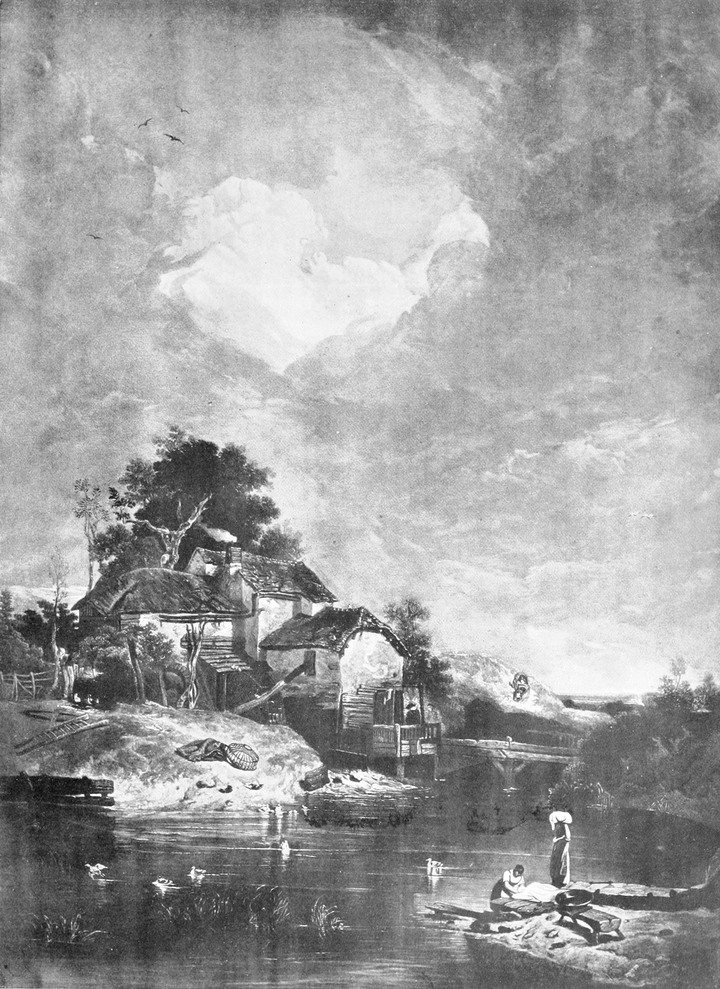

The Water Mill—C. Turner

|

|

|

The Hôtel de Ville at Louvain—J. C. Stadler

|

|

|

Miss Murray of Kirkcudbright—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

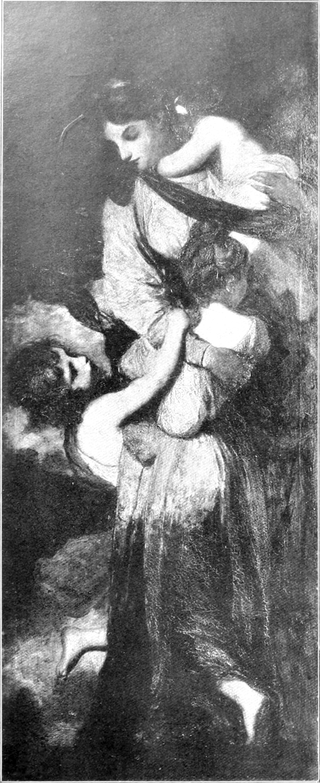

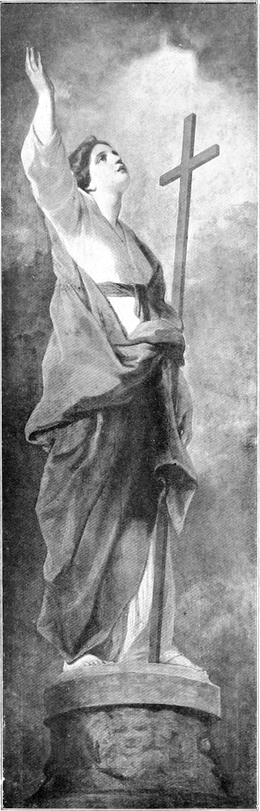

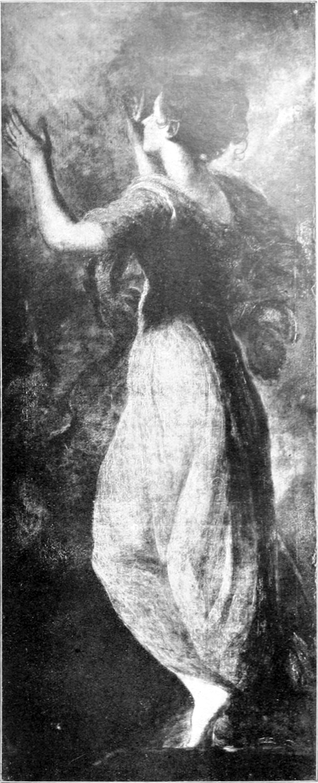

Charity, Faith, Hope—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

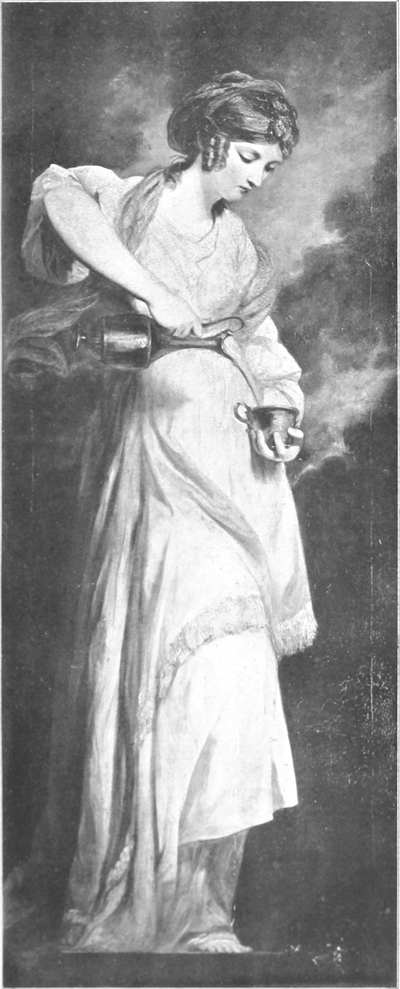

Temperance and Prudence—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

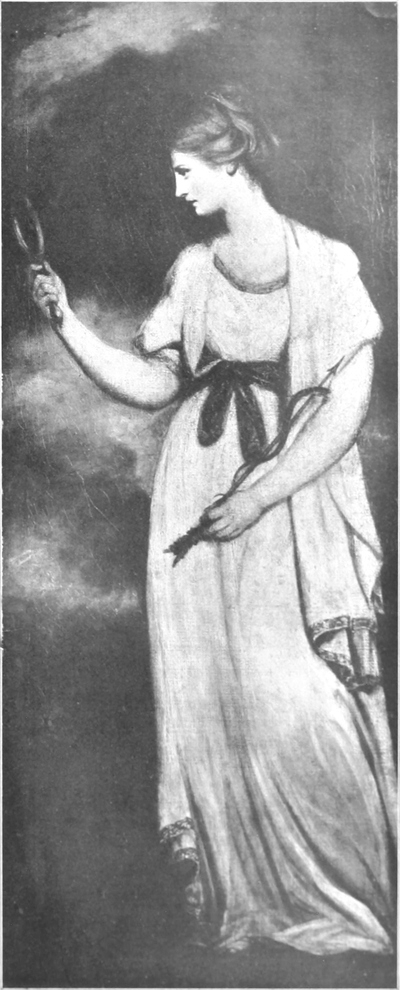

Justice and Fortitude—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

The Little Gardener—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

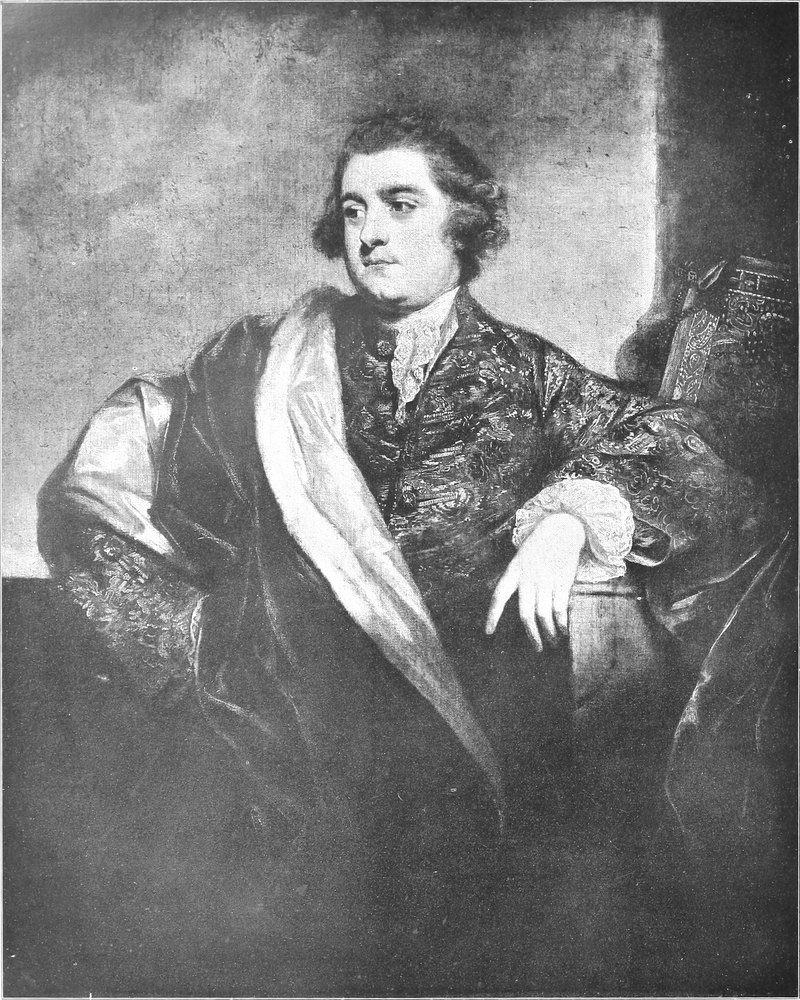

George, third Duke of Marlborough—Sir J.

Reynolds

|

|

|

Study of a Little Girl—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

The Misses Horneck—Sir J. Reynolds

|

|

|

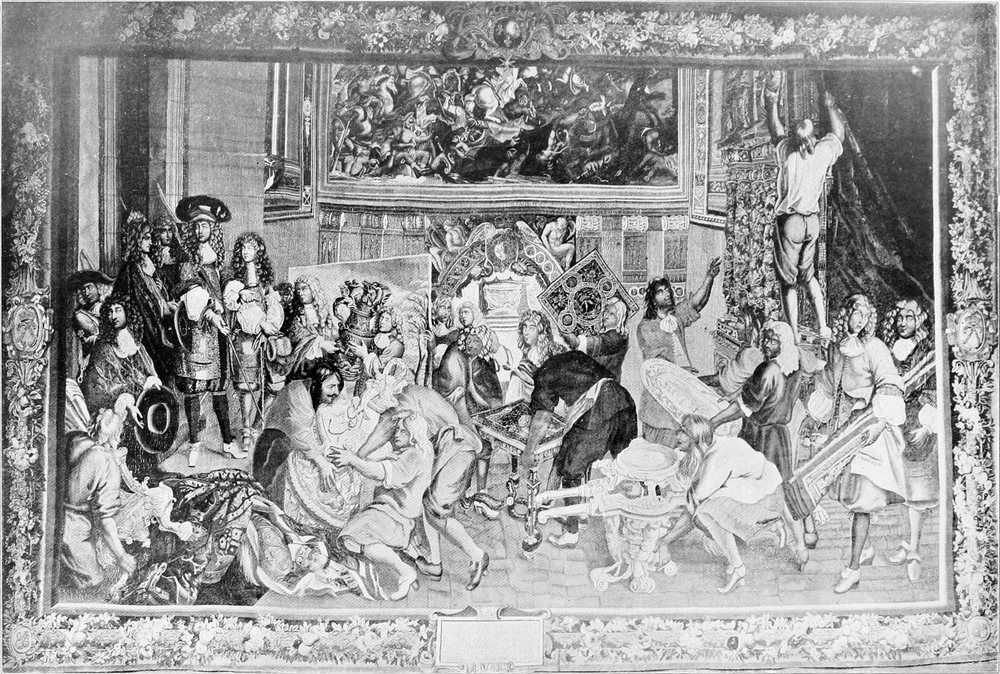

High Warp Tapestry, Louis XIV—After

Charles Le Brun

|

|

|

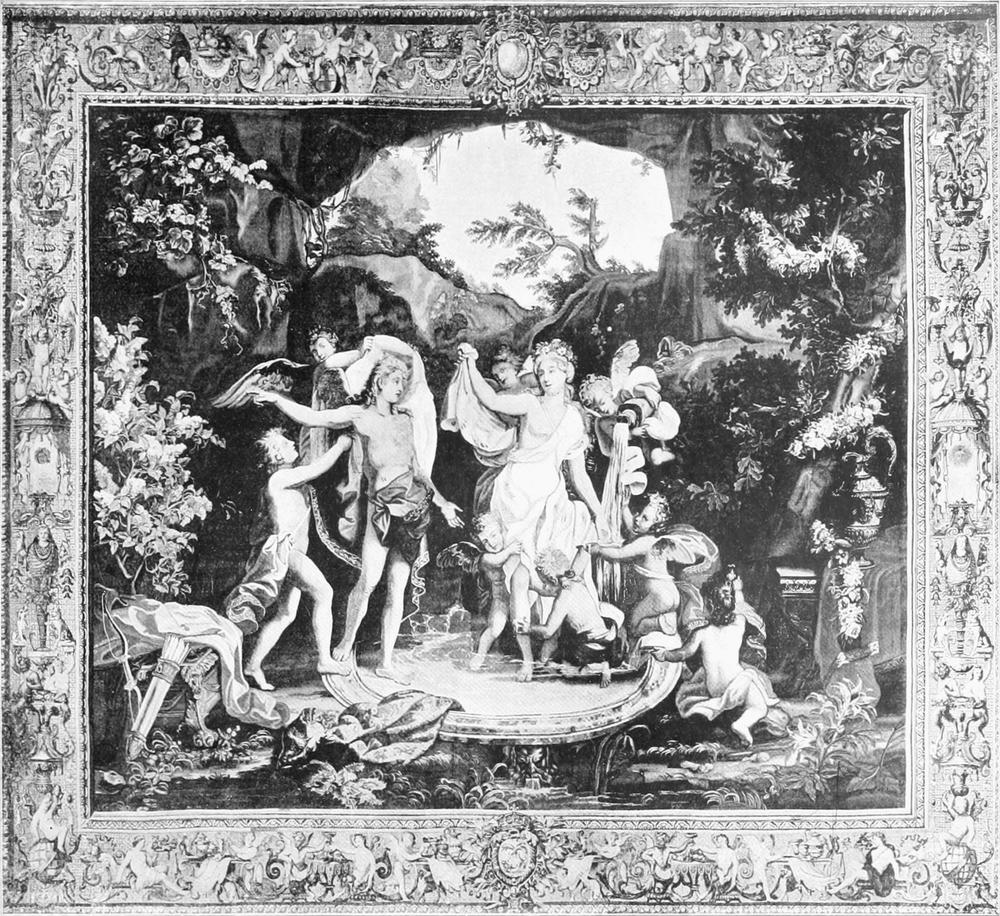

Gobelin Tapestry

|

|

| [Pg viii]

A Marquetry Bureau—André Charles Boule

|

|

|

A Bookcase—André Charles Boule

|

|

|

Fragment of the Frieze of the Parthenon

|

|

|

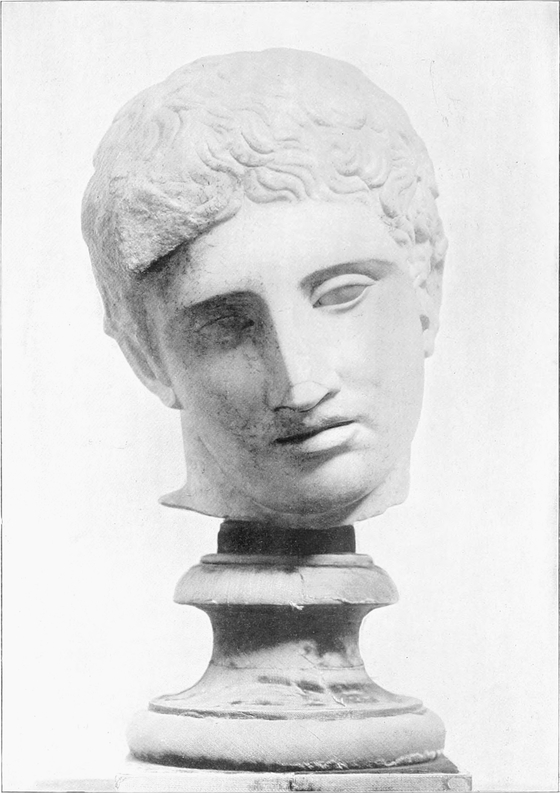

Bust of Aphrodite—Probably by Praxiteles

|

|

|

Head of a Mourning Woman

|

|

|

Head of a Youth

|

|

|

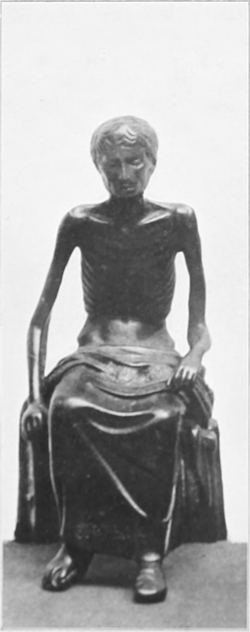

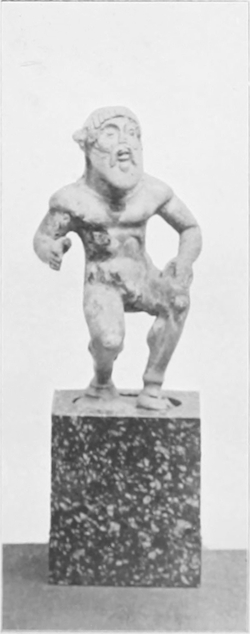

Group of Bronzes

|

|

|

Repoussé Mirror-Cover

|

|

|

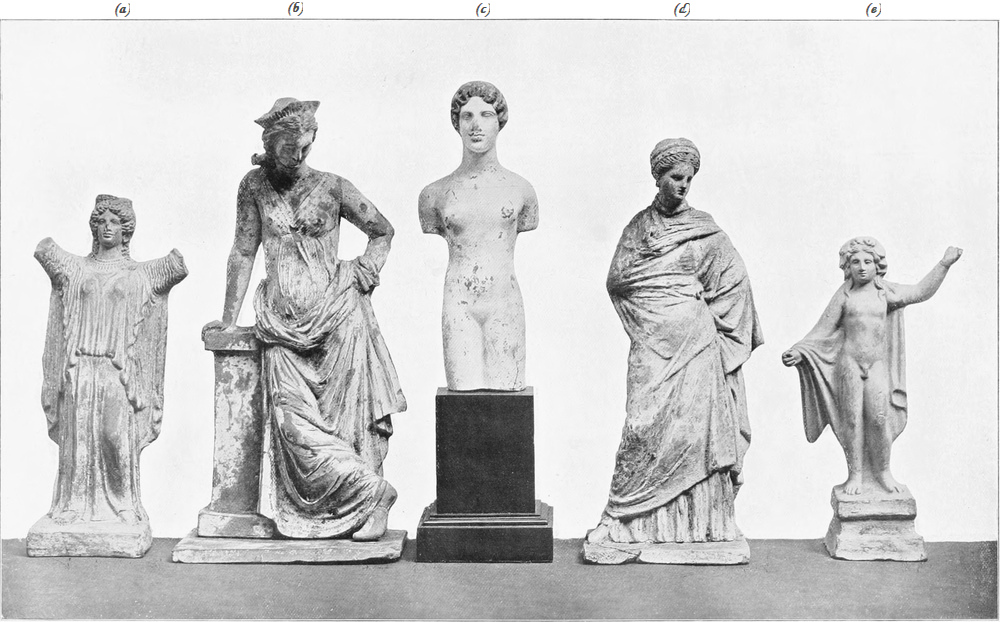

Terracottas

|

|

|

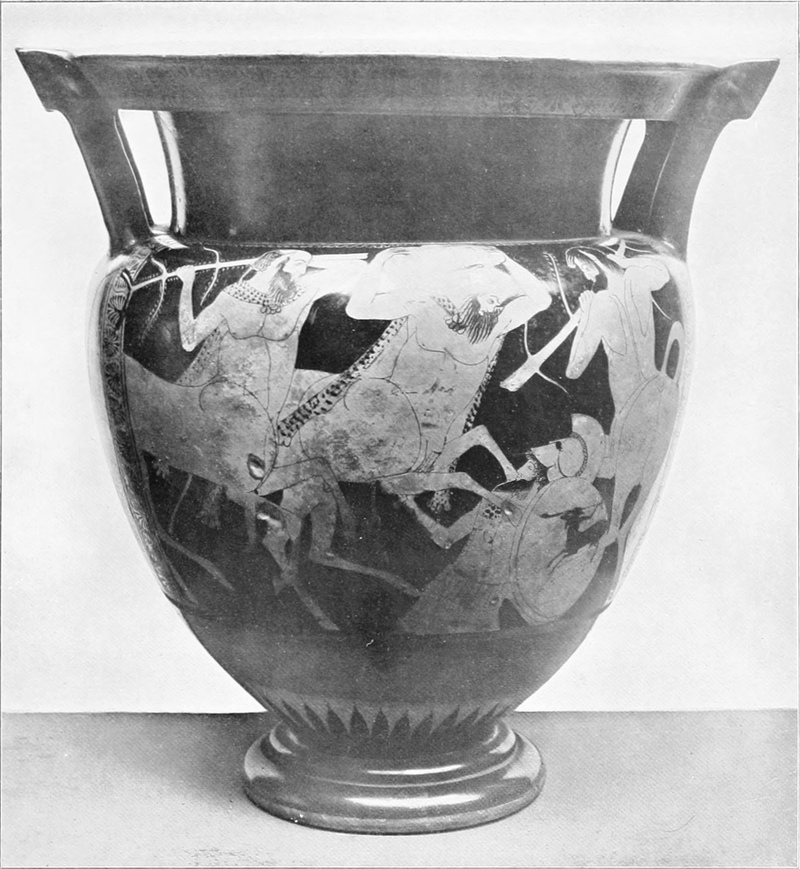

Krater, belonging to Harrow School

|

|

|

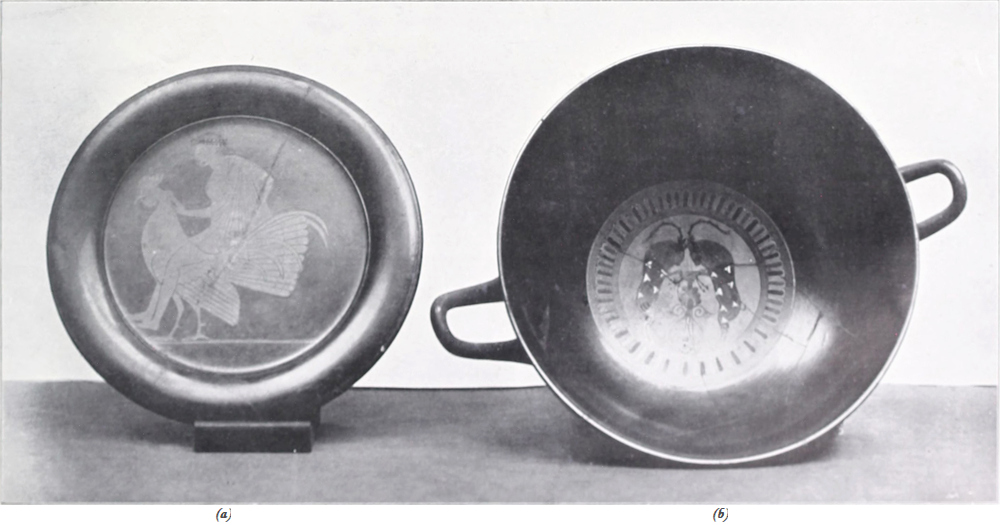

Kylix, and plate

|

|

|

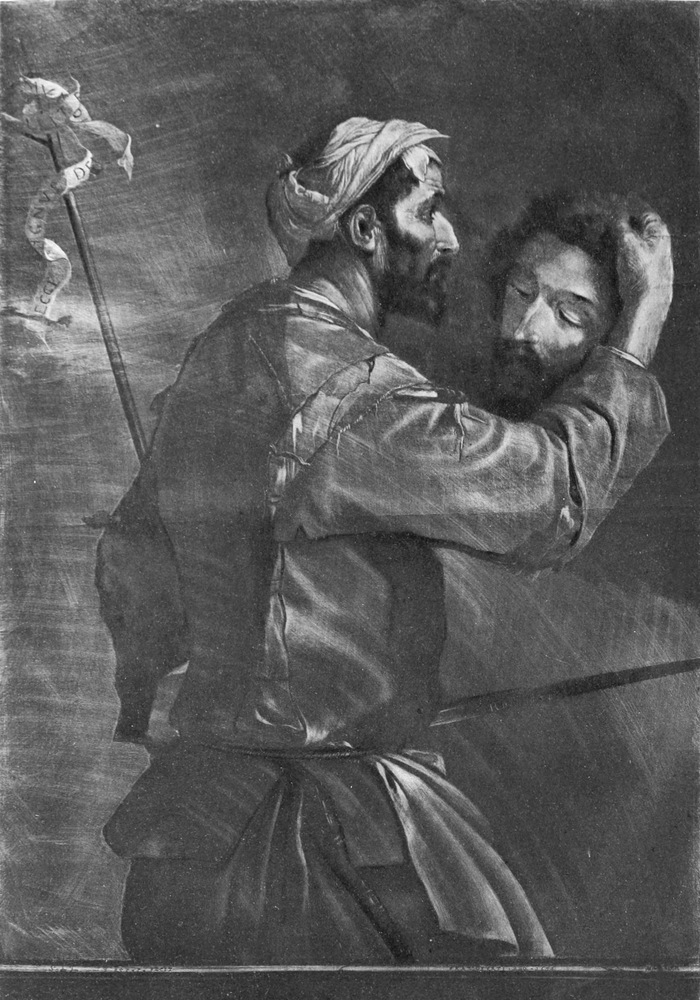

The Great Executioner

|

|

|

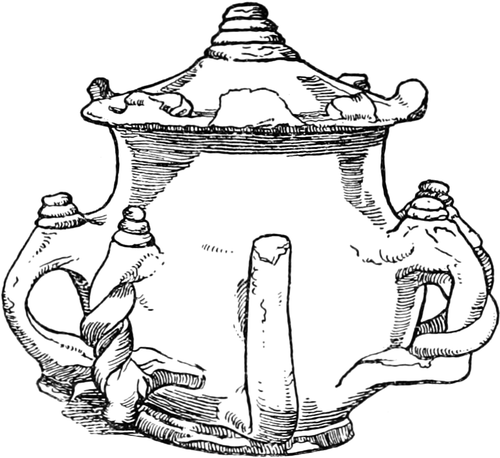

Lowestoft Porcelain Teapot of Soft Paste

|

|

|

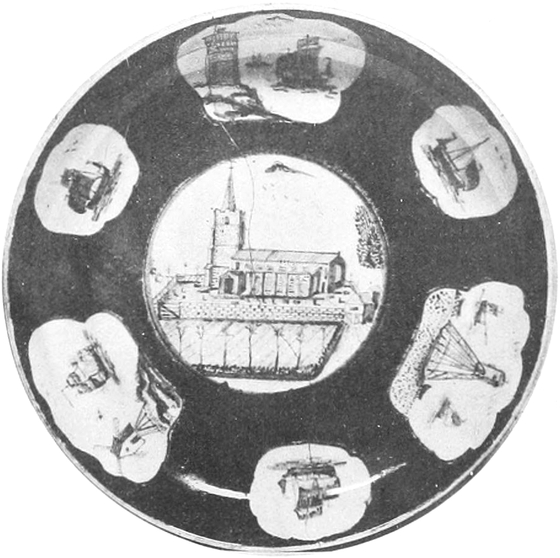

Small Plate painted in Underglaze Blue, with a

View of Lowestoft Church

|

|

|

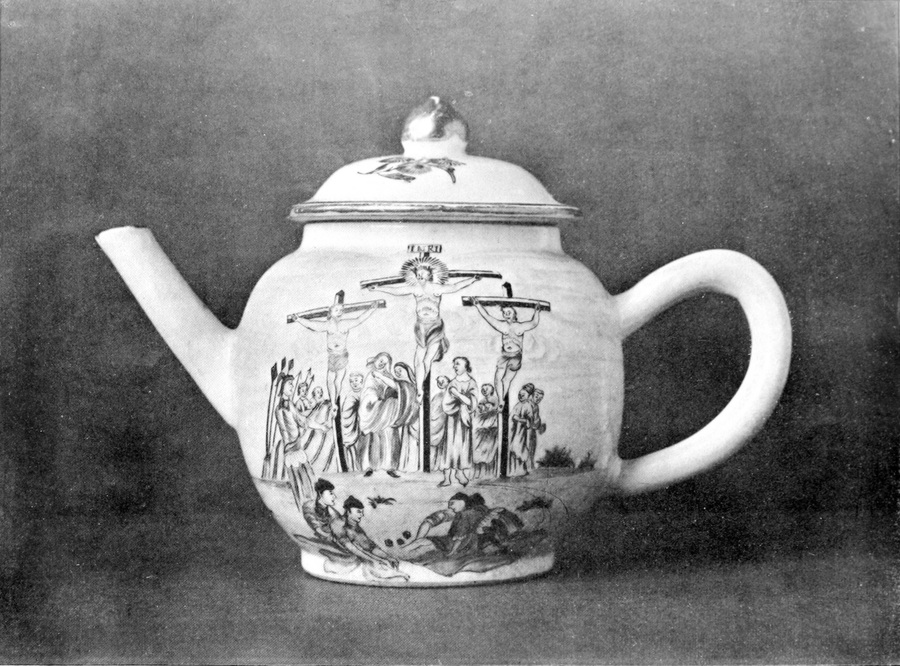

Hard Porcelain Teapot, marked ‘Allen,

Lowestoft’

|

|

|

Portrait of the Empress Isabella—Titian

|

|

|

Copy of the Portrait of the Empress Isabella from

which Titian painted the above Portrait

|

|

|

Portrait of a Lady—Albrecht Dürer

|

|

|

Portrait of a Lady—Albrecht Dürer

|

|

|

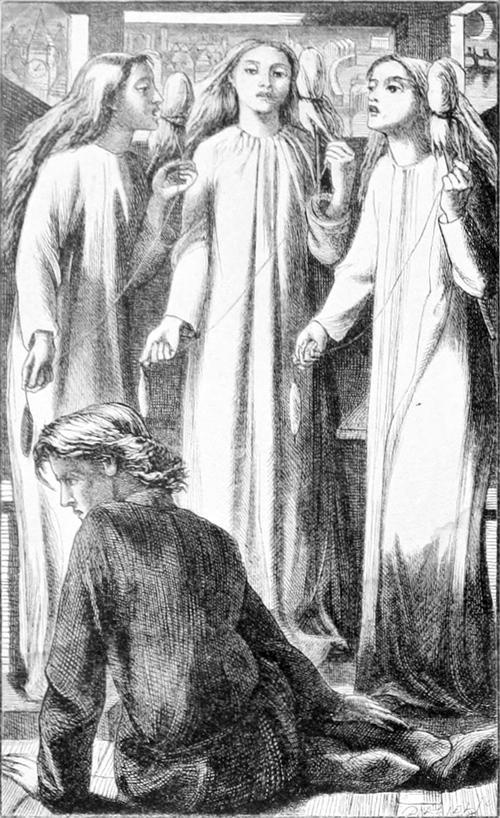

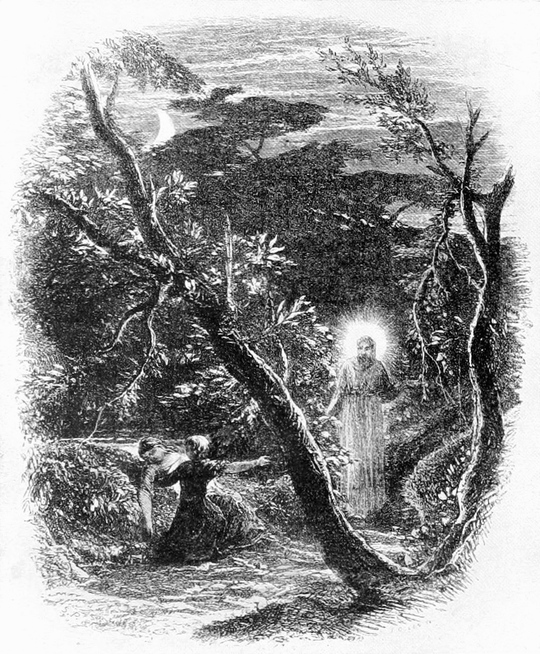

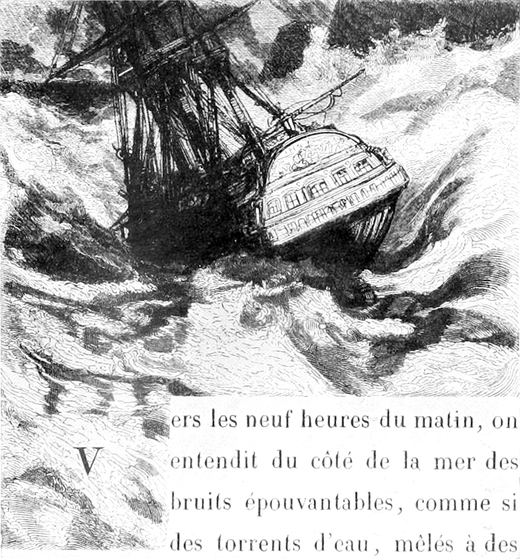

Later Nineteenth-Century Book Illustrations:—

|

|

|

Plate I

|

|

|

Plate II

|

|

|

Plate III

|

|

|

Plate IV

|

|

|

Plate V

|

|

|

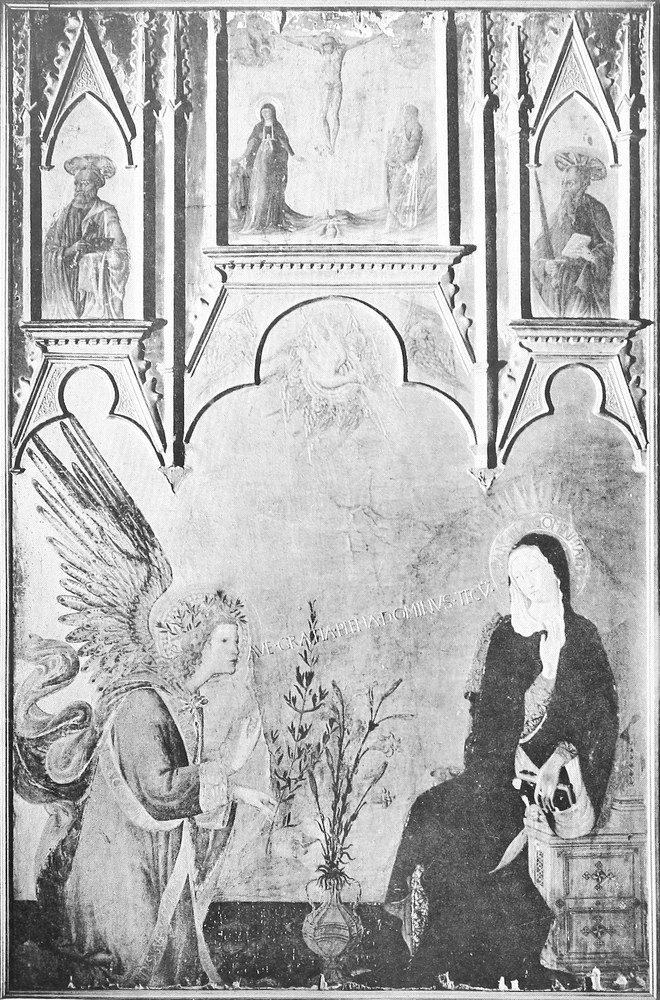

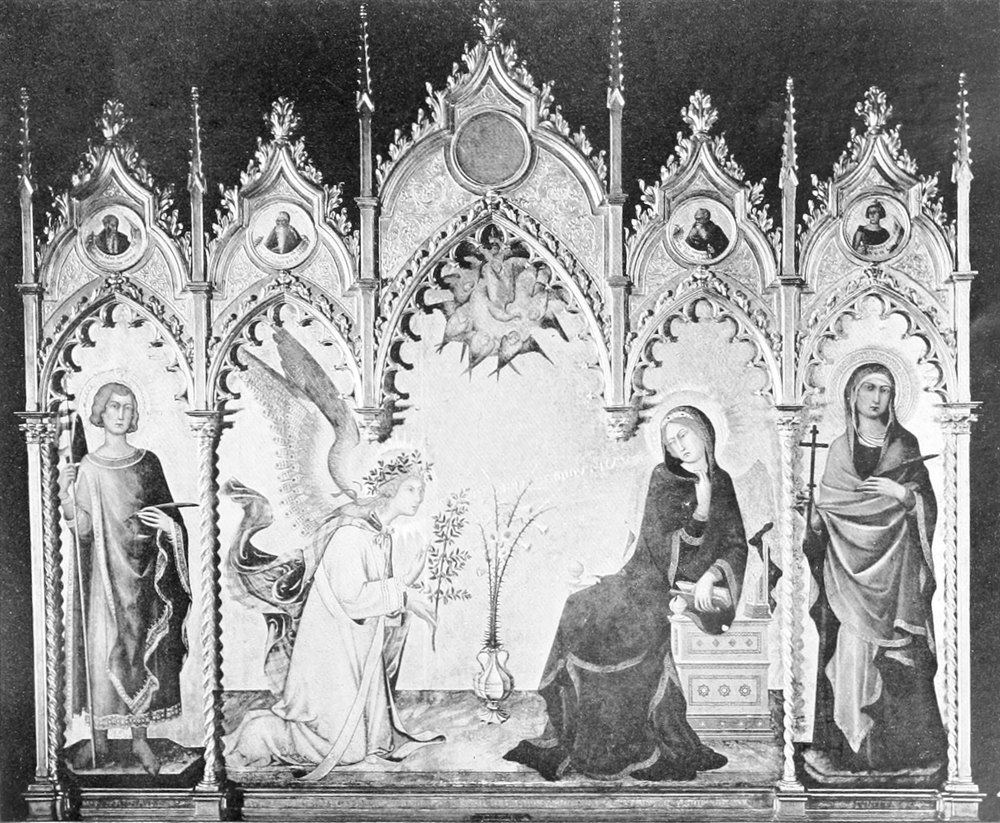

Polyptych in the Church of S. Stefano, Siena—Andrea

Vanni

|

|

|

Annunciation, in S. Pietro Ovile, Siena—Andrea

Vanni

|

|

|

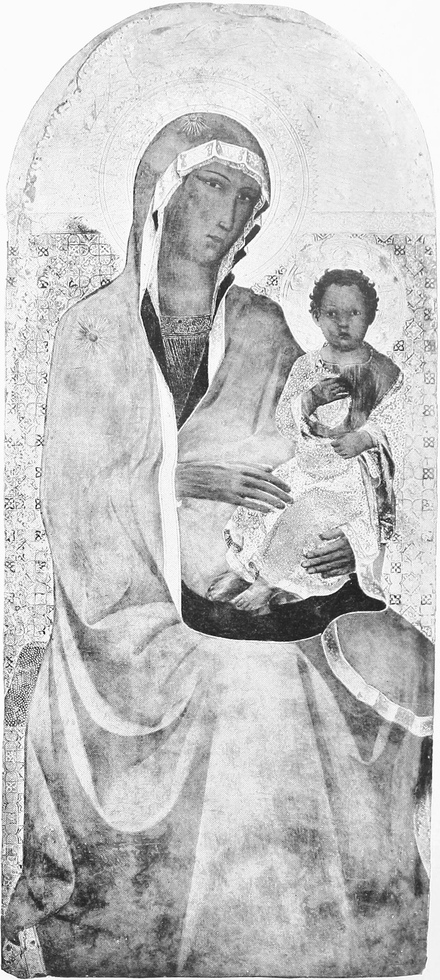

Virgin and Child, from the Altar-piece in S. Francesco,

Siena—Andrea Vanni

|

|

|

Madonna and Child—Andrea Vanni

|

|

|

Details of the Annunciation in S. Pietro Ovile,

Siena—Andrea Vanni

|

|

|

Annunciation, in the Collection of Count Fabio

Chigi, Siena—Andrea Vanni

|

|

|

Annunciation, in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence—Simone

Martini

|

|

|

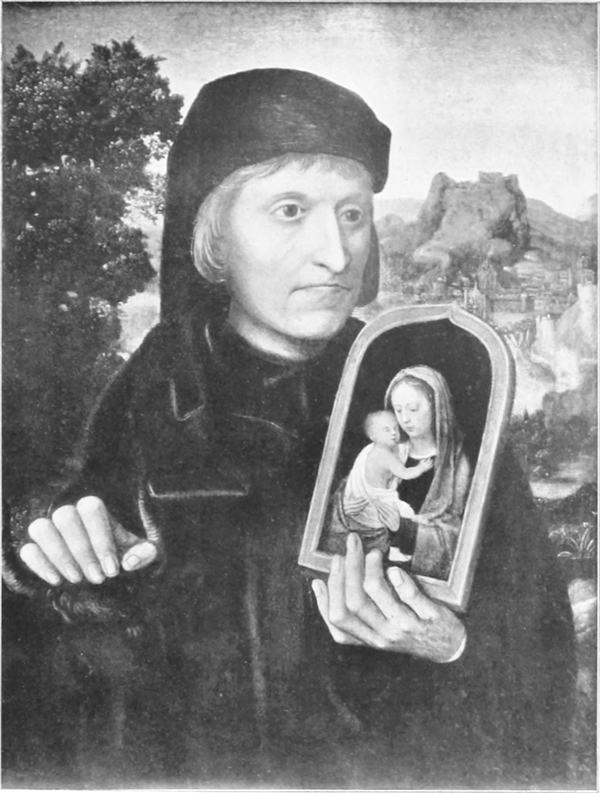

St. Luke—Adrian Isenbrant

|

|

|

Triptych: The Blessed Virgin and Child with

Two Angels—Adrian Isenbrant

|

|

|

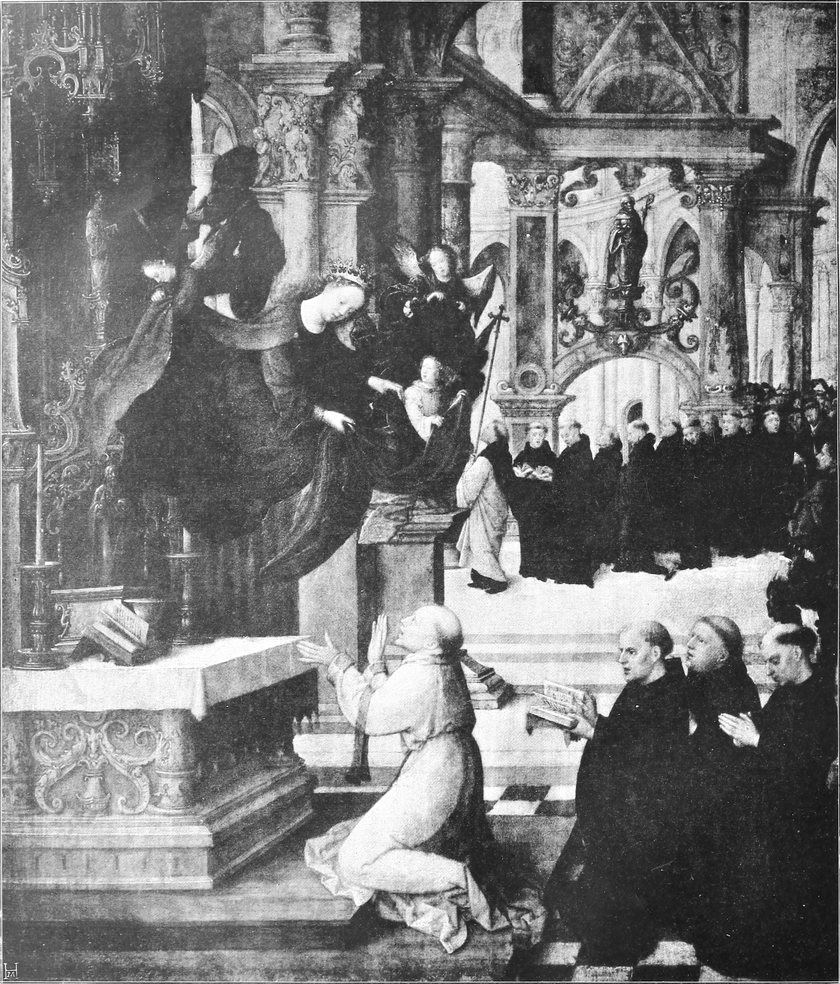

The Vision of Saint Ildephonsus—Adrian Isenbrant

|

|

|

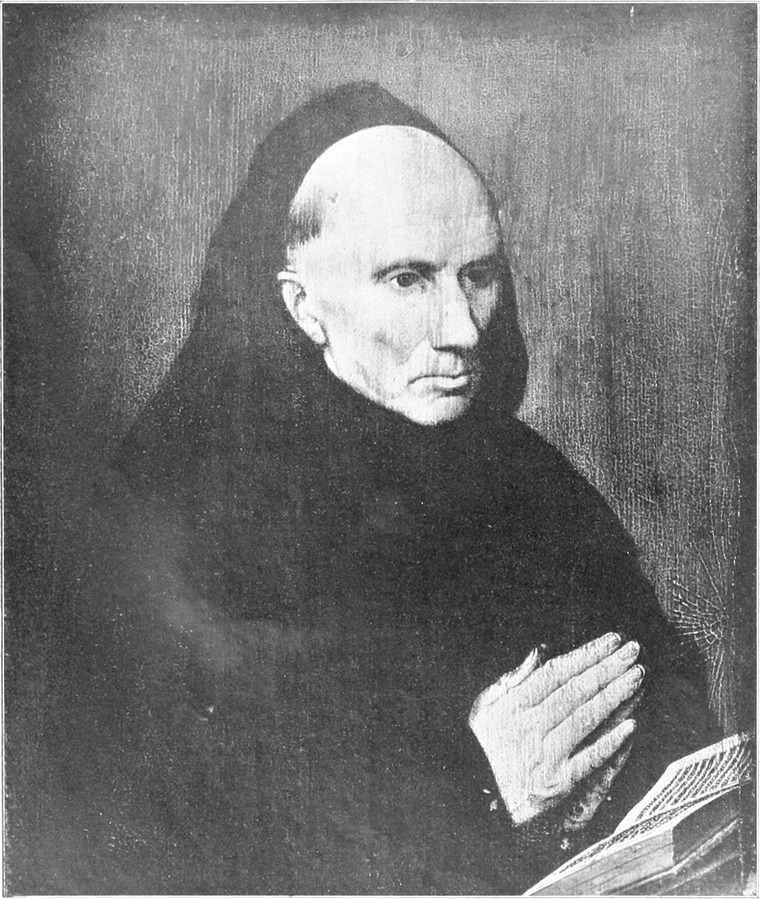

Portrait of Roger de Jonghe, Austin Friar

|

|

|

Episodes in the Life of St. Bernard—John van

Eecke

|

|

|

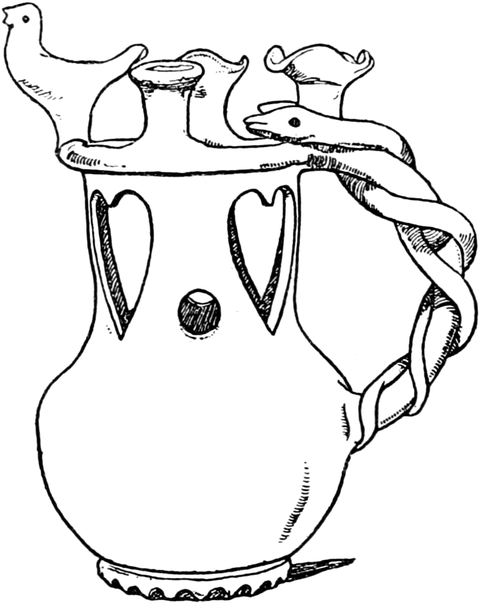

Three Italian Albarelli of the fourteenth century

|

|

|

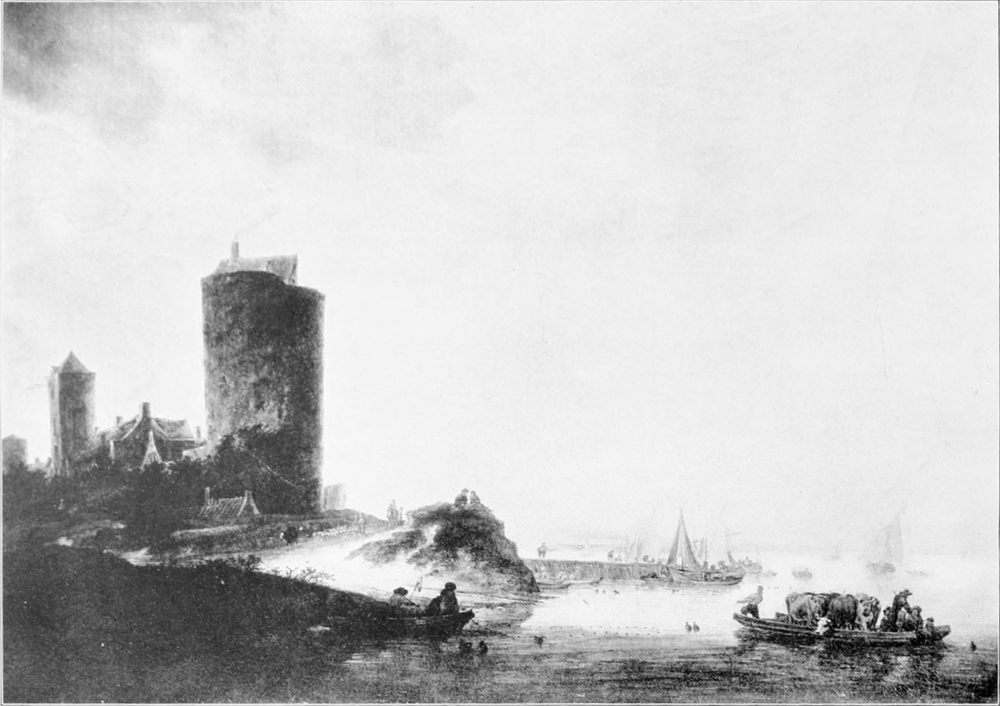

Landscapes—Solomon Ruysdael

|

|

|

Portrait of Dame Danger—Louis Tocqué

|

|

|

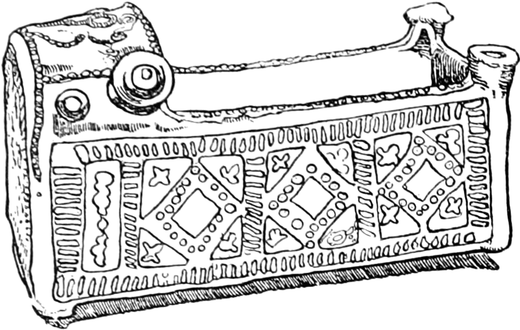

Lid of an Arabic Koursi of the fourteenth

century

|

|

|

Tabriz Carpet

|

|

|

The Sorö Chalice

|

|

|

Polychrome Chest belonging to the Office of

Archives at Ypres

|

|

|

A Burgundian Chest of the fifteenth century

belonging to the Hospices Civiles at Aalst

|

|

|

Portrait by Rembrandt van Rijn

|

|

|

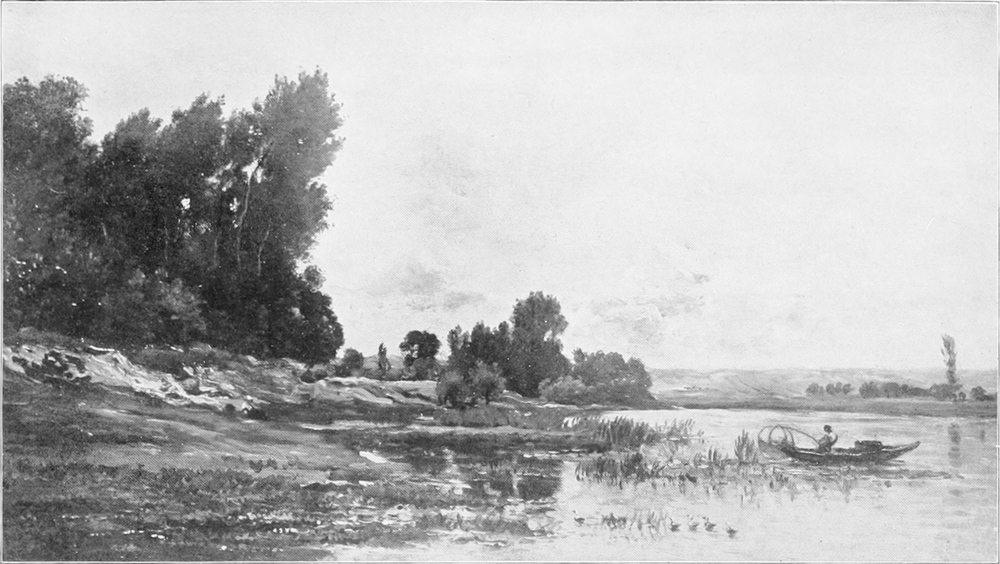

On the Seine—Charles François Daubigny

|

|

|

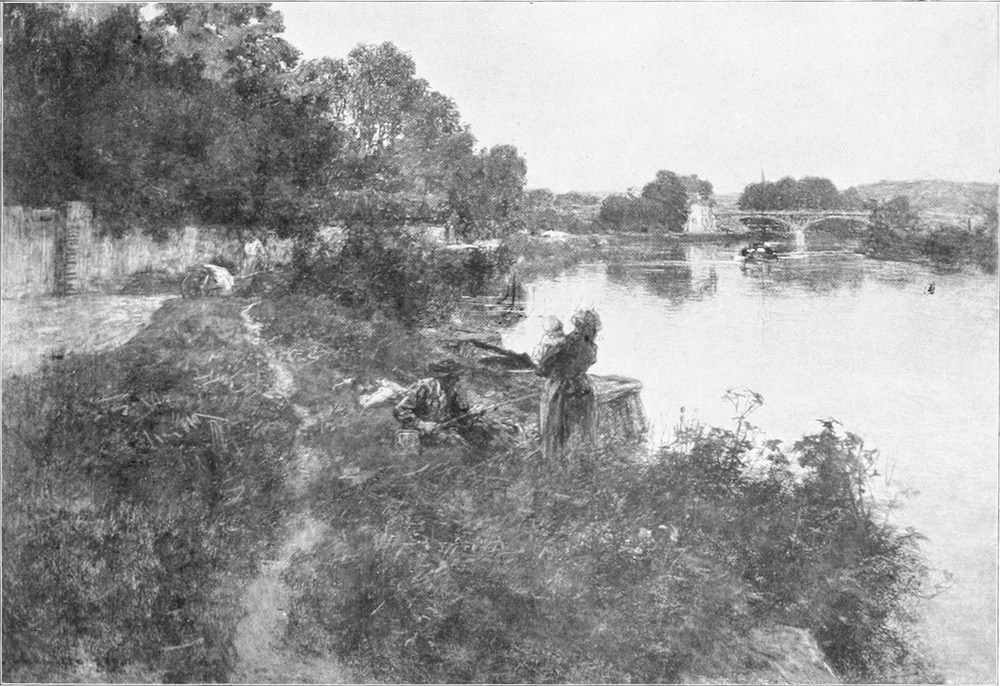

Le Pêcheur—Léon Lhermitte

|

[Pg 3]

E must confess that when we published Mr. Philip Norman’s appeal to the Government to save Clifford’s Inn, we had little hope that the appeal would be listened to; it is too much to expect an English Government to take any interest in a question of an artistic nature; in agreeing to ignore such questions the unanimity of political parties is wonderful. Nor does the English public really care about such matters. The appeal received considerable support in the press, but it was a support given by men who, whatever they themselves think, know well enough that an agitation for the preservation of an ancient building would only bore most of their readers. ¶ So Clifford’s Inn has been sold, and sold at a ridiculously low price. It is some satisfaction to know that legal education, which condemned it to destruction, will profit little if at all by its sale, for the income derived from the purchase money can be no larger than could have been derived from the rents of the Inn under proper management. The end, however, is not yet, for the gentleman who now owns Clifford’s Inn is happily not without appreciation of its artistic and historical interest; for the present, at any rate, he will leave matters in statu quo, and all the tenants have been informed that they need not fear early ejection. Moreover we have every reason to believe that, if there were any movement to preserve the Inn, the present owner would be willing to part with his property at a very moderate premium on the sum of £100,000 that he paid for it. ¶ The London County Council—the only public authority in London that cares about such matters—has had its eye on Clifford’s Inn, and a committee of the Council only refrained from recommending its purchase from fear of the ratepayers. We would, however, appeal to the County Council to cast aside fear of the Philistines and reconsider the matter. Expert opinion in such matters holds that Clifford’s Inn could be made, as it stands, to return £3,000 a year; its purchase, therefore, at a little more than £100,000 would involve little or no loss to the ratepayers. The County Council has done and is doing admirable work for the preservation of ancient buildings; it might well add to its laurels by acquiring Clifford’s Inn for the citizens of London. ¶ The case of Clifford’s Inn raises the larger question of the preservation of ancient buildings generally. We in England pretend to be an artistic nation; we talk and write very much about art, and we all collect more or less works of art or imitations thereof; most of us try to paint pictures, and the world will soon be unable to contain the pictures that are painted. But there is one fact that brands us as hypocrites, the fact that Great Britain shares with Russia and Turkey the odious peculiarity of being without legislation of any kind for the protection of ancient buildings and other works of art such as is possessed to some degree by every other country in Europe, and by almost every State of the American Union. We have calmly looked on while amiable clergymen, restoring architects, and legal peers with a mania for bricks and mortar and more money than taste, have hacked, hewn, scraped and pulled to pieces the greatest architectural works of our forefathers; too many modern architects, when they are not engaged in copying the work of their predecessors, are engaged in destroying it. Though the legend of ‘Cromwell’s soldiers’ still on the lips of the intelligent[Pg 4] pew-opener accounts for the havoc wrought in many an ancient church, the historian and the antiquary know that to the sixteenth and not the seventeenth century must that havoc be in the first place attributed, and the observer of recent history knows that the mischief worked by the iconoclast of the sixteenth century has been far exceeded by that worked by the restorer and the Gothic revivalist of the nineteenth. And if this has been done by persons who imagined themselves to be artistic and were actuated by the best possible motives, what has been the destruction wrought by those who made no profession of any motive but that of commercial advantage? Within the memory of the youngest among us, buildings of great artistic and historical interest have been ruthlessly swept away in London and in every other town in the kingdom, and the few that have been left are rapidly disappearing. ¶ There is no way of saving the remnant of our heritage but that of legislation; but we cannot honestly recommend the advocacy of such legislation to a minister or a party in need of an electioneering cry, and we are not sanguine as to the prospects of anything being done. Still, it may be interesting to some to learn what the despised foreigner has done in this respect; we take the information from a Parliamentary paper presented to the House of Commons on July 30, 1897.[1] ¶ We will briefly summarize the facts given in this paper, referring those of our readers who wish for further information to the paper itself. In Austria there has existed for many years a permanent ‘Imperial and Royal Commission for the investigation and preservation of artistic and historical monuments.’ This Commission had, in 1897, direct rights only over monuments belonging to the State (in which churches are included); but it acted in concert with municipalities and learned societies, and promoted the formation of local societies to carry out its objects. No ancient monument coming within its scope can be touched without the sanction of the Commission. Since 1897 its powers have, we believe, been extended. Not only buildings, but objects of art and handicraft of every kind as well as manuscripts and archives, of any date up to the end of the eighteenth century, come within the scope of activity of the Commission, which is a consultative body advising the Minister of Public Worship and Education, who is the executive authority for these purposes. ¶ In Bavaria, alterations to all monuments or buildings of historical or artistic importance (including churches) belonging to the State, municipality, or any endowed institution, have, since 1872, required the sanction of the Sovereign, who is advised by the Royal Commissioners of Public Buildings. The ecclesiastical authorities and even religious communities are prohibited from altering a church or dealing with its furniture without the consent of the Commissioners. ¶ In Denmark there has been a Royal Commission with similar objects since 1807; ancient monuments are scheduled, and since 1873 the Royal Commission has had power to acquire them compulsorily if their owners will not take proper measures for their preservation. ¶ In France the Minister of Public Instruction and Fine Arts, who is advised by a Commission of Historical Monuments, has as drastic powers as the Danish Royal Commission; some 1,700 churches, castles, and other buildings (including buildings in private ownership) have been scheduled and classified, and cannot be destroyed, restored, repaired, or altered except with the approval of the Minister, who has power to expropriate private owners under certain circumstances. ¶ Belgium has statutory provisions of a similar character; there a Royal Commission on Monuments was constituted so long ago as 1835, so that Belgium is second only to Denmark in this matter. The Commission[Pg 5] may schedule any building or ancient monument, and the scheduled building cannot be touched without the consent of the Commission, even if it is in private ownership. In Belgium, as in France and Denmark, grants of public money are given for the purchase and preservation of ancient monuments, and the Belgian municipalities are very zealous in the same direction. In Bruges, we understand, the façades of all the houses belong to the municipality, so that their preservation is secured, and also congruity in the case of new buildings. No object of art may legally be alienated or removed from a Belgian church; this law, however, is unfortunately still evaded to some extent. ¶ In Italy several laws have been passed, beginning with an edict of Cardinal Pacca for the old Papal States in 1820. The Minister of Public Instruction may, by a decree, declare any building a national monument, and the municipalities have large powers; works of art, as is well known, cannot legally be taken out of Italy, but this law is often evaded. ¶ In Greece the powers of the State are perhaps more drastic than anywhere else. Even antique works of art in private collections are considered as national property in a sense and their owner can be punished for injuring them; if the owner of an ancient building attempts to demolish it or refuses to keep it in repair, the State may expropriate him. ¶ Holland, Prussia, Saxony, Spain, Sweden and Norway, Switzerland, and many American States have provisions of a more or less stringent character with the same purpose. But we need not now go further into details; the whole of the facts will be found in the Parliamentary paper, and we have given enough of them to show how far behind every other civilized country England is in this matter. The protection of monuments of the past which Denmark has had for nearly a century and Belgium for nearly seventy years we have not yet thought of. Surely the time has come to wipe out this reproach; until it is wiped out let us have done with the hypocritical claim that we are an artistic people.

N the April number of THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE we stated that it was our intention not to exclude from the Magazine works of art likely to be of interest to the student and collector because they happened to be in the hands of dealers. The policy of including objects belonging to dealers has been adversely criticized by friends who have the interests of the Magazine at heart; we therefore think it well to refer again to the matter, although the purpose of our decision was, as it seems to us, clearly enough stated in the April number. Suggestions have, it seems, been made in certain quarters that some corrupt or at least commercial arrangement with the dealers concerned is accountable for the publication in the Magazine of objects belonging to them. Such suggestions we may pass over, for they are not and will not be credited by anyone whose opinion need concern us. But we owe it to the friendly critics who are concerned for the welfare of the Magazine, and anxious that it should not be affected even by a breath of suspicion, to state our position quite frankly. ¶ In the first place we may say that we entirely sympathize with their point of view, and we recognize as fully as they do the harm that has been done to artistic enterprises—literary and otherwise—by commercial entanglements, and, in the case of periodicals, by a too intimate relation[Pg 6] between the advertisement and editorial pages. So much has this been the case that we are not surprised at the alarm which is felt by some of our friends lest even a suspicion of a similar tendency should attach to a periodical in the success of which they are, we are glad to know, keenly interested. But we would point out that in such cases as those to which we have referred far more subtle methods are resorted to than that of frankly publishing a work of art that may happen to be for the time in the hands of a dealer; a little reflection will convince anyone that an Editor of a periodical ostensibly devoted to art, if he wishes—to put it quite plainly—to puff the goods of this or that individual, does not set about it in so palpable a way as that of publishing without subterfuge objects which are frankly stated to be in the possession of the individual or individuals whom it is desired to advertise. It is the very purity of our motives that has enabled us to take a course the boldness of which we do not for a moment deny. Nor must it be supposed that the publication of works of art in their possession is necessarily desired by the dealers themselves; on the contrary, as is well known to every one with experience in these matters, the idiosyncrasies of collectors are such that in many cases a dealer who has a fine work of art in his possession does not wish it to be generally known. We have in some cases had considerable difficulty in inducing dealers to allow their property to be reproduced, and we will go so far as to say that, strange as it may seem to the purist in these matters, we believe that some of them are really actuated by a desire to assist the study of art. It would be false modesty on our part to affect to believe that publication of a work of art in THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE is injurious to the owner, whether dealer or collector; we are willing to admit that such publication may, on the contrary, be advantageous to the owner of the work of art published. But, surely, that is not the question to be considered; the only question, it seems to us, is whether the work of art is likely to be of interest to readers of THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE and of value to students. This is, at any rate, the only question that we have taken into consideration; and we have felt that if any particular work of art is of interest to our readers, and particularly to those who make a special study of the branch of art concerned, we ought not to hesitate to publish it merely because it happens to be in the hands of a dealer. ¶ Is there not after all just a suspicion of cant in this squeamishness about the publication of pictures or other objects belonging to dealers? Even private collectors have, we believe, been known to sell objects out of their collections, and, so far as our information goes, they do not invariably sell them at a loss; indeed, when one comes to define the boundary between collecting and dealing one finds a considerable difficulty in doing so with exactitude; the border country between the two is very wide in extent and very hazy. We have heard of cases in which private collectors, who would not for the world be considered to be dealers, have written anonymously in a periodical about objects in their own possession and then put them up to auction with a quotation from their own article in the catalogue. Any such practice as that we shall certainly discourage or rather repress; these are difficulties which beset the path of an editor of an art periodical. But if we are to be deterred by such difficulties it will end in our being afraid to publish any work of art in case we haply enhance its value, and thus indirectly do a service to its owner. ¶ Let us restate more fully the case which we have already stated shortly in the April number of this Magazine. At any given time there are in the hands of London dealers not a few pictures which are of profound interest to all students of art, and which may indeed throw light on vexed problems and assist in their solution.[Pg 7] Are we to deprive the readers of THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE of the opportunities which the publication of such pictures may give them? Doubtless in a normal state of things such pictures would ultimately find their way either into the National Gallery or at least into the possession of some English collector. But as things are they are far more likely to find a home either, let us say, in the Berlin, Amsterdam, or Munich Museum, or in a private collection on the other side of the Atlantic; and it may be very difficult to trace them if the opportunity is lost of publishing them while they are in London. Were the National Gallery still a buyer of pictures, it might not be necessary for a periodical to take such a course as we have taken. But it is notorious that the National Gallery is no longer a buyer of pictures; not merely is the money allotted by the Government absurdly inadequate, but it is also the case that, inadequate as it is, it is not made the best use of. Only last month Mr. Weale pointed out in this Magazine that the Berlin Gallery had recently bought for £1,000 a charming picture by a rare Flemish master, which was sold at Christie’s eight years ago for £3 10s., and this is merely one example of the almost innumerable opportunities that escape those who at present direct the National Gallery. Although we are told that present prices in England are prohibitive so far as public collections are concerned, it is nevertheless the fact that museums such as those of Berlin, Boston, Munich, and Amsterdam find it worth while to buy largely in London, and we do not suppose that they always pay exorbitant prices, although of course a large and wealthy country like Bavaria can afford to spend more on art than a country like England. In former years a London dealer who had a particularly fine picture in his possession would have offered it to the National Gallery; now that is the last thing that he thinks of doing; he knows too well that the authorities of the National Gallery would probably not take the trouble even to look at it, and that some of those who would have a voice in deciding whether it should be purchased have not the necessary qualifications for making such a decision. The evil has been increased by the insane rule now in force, that the trustees of the National Gallery must be unanimous before any picture is purchased—a rule which, as anyone with sense would have foreseen, has led to an absolute deadlock. Within the last few weeks, for instance, the chance of purchasing a superb work of Frans Hals at a very moderate price has been lost to the nation, simply because one of the trustees of the National Gallery refuses to agree to any purchase that does not suit his own preference for art of what may be called the glorified chocolate-box type. ¶ But we need not now enlarge upon this subject, with which we hope to deal at some future time; we have said enough perhaps to support our contention that it is hopeless to expect that fine pictures which have passed into the hands of London dealers will find their way into that collection which has been made by former directors one of the most representative in the world of the best European art. This being so, we feel very strongly that we ought to risk something in order to give the readers of THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE the opportunity of seeing, at least, reproductions of works of art which they may otherwise never have the opportunity of seeing. At the same time we cannot lightly reject the objections which have been raised by those who, as we know, have only the best interests of THE BURLINGTON MAGAZINE at heart; and, while we do not at present feel disposed to alter our policy in this respect, we are nevertheless open to argument, and if the considerations which we have put forward can be shown to be unsound or inadequate we are prepared to be convinced. We invite from our readers expressions of opinion on the subject.

[Pg 8]

❧ WRITTEN BY W. A. BAILLIE-GROHMAN ❧

HEN the burly Landsknechte stormed the walls of the deer park and therewith won the hard-fought battle of Pavia, one of the treasures they captured in Francis’s sumptuous gold-laden tents was a vellum Codex of folio size, almost every leaf of which bore beautifully illuminated pictures of hunting scenes. We know from other evidence that this precious volume was one of the favourite books of the luxury-loving French king, and the fact that he took it with him to the Italian wars in preference to a printed copy, infinitely more portable, such as had been turned out in three different editions by the hand-presses of Antoine Verard, Trepperel, and Philippe le Noir, is a further proof that Francis’s love for finely illuminated manuscript was a ruling passion with him. It is this very MS. which forms the subject of these lines, and the facsimile reproductions, which the writer obtained permission to have executed by competent hands, show the rare skill of the fifteenth-century miniaturist of whose identity we unfortunately know but little. ¶The history of this Codex is an extremely interesting one and well worth the research expended upon it by Gaucheraud, Joseph Lavallée, Werth, and others. The eighty-five chapters are written in a wonderfully regular and perfect hand, and the ink is today as black and clean of outline as it was four and a half centuries ago. The author of what is unquestionably the most beautiful hunting manuscript extant was Count Gaston de Foix, the oft-cited patron of Froissart. This great noble and hunter began the book on May Day 1387, and we know that it was completed when a fit of apoplexy, after a bear hunt, cut short his remarkable career four years later, when he was in his sixty-first year. Of the forty, or possibly forty-one, ancient copies of this hunting book that have come down to us, one or two were written it is almost certain during the author’s lifetime, though the original itself, which was dedicated by Gaston to ‘Phelippes de France, duc de Bourgoigne,’ disappeared in a mysterious manner from the Escurial during the eventful year of 1809, and has not turned up since. None of the other contemporary copies have illuminations at all comparable to those in our MS., for the simple reason that it was not until some decades later that art had reached, even in France, the brilliancy that our illuminations show. For although Argote de Molina—who in his ‘Libro de la Monteria,’ published in Seville in 1582, describes the lost original—says ‘el qual se vee illuminado de excelente mano,’ it is safe to say that, could we place the original side by side with the MS. of which we are speaking, its illuminations would be found to be far inferior to those in the MS. owned by Francis I. ¶ Very likely the lost original MS. was written by one or the other of the four secretaries Froissart tells us were constantly employed by Count de Foix. These he did not call John, or Gautier, or William, but nicknamed them ‘Bad-me-serve,’ or ‘Good-for-nothings.’ The illuminations were probably the work of some wandering master-illuminator attracted to the splendid court at Orthéz by the Count’s well-known prodigal liberality. ¶ Gaston de Foix, to interrupt for a brief spell our tale, was the lord of Foix and Béarn; buffer countships at the foot of the Pyrenees—the castle of Pau was one of Foix’s strongholds. He succeeded, as Gaston III, at the age of twelve to his principalities. Two years later he was serving against the English, and shortly afterwards was made ‘Lieutenant de Roi’ in [Pg 11] Languedoc and Gascony, and at the age of eighteen he married Agnes daughter of Philip III King of Navarre. His person was so handsome, his bodily strength so great, his hair of such sunny golden hue, that he acquired the name of Le Roi Phoebus or Gaston Phoebus, by which latter both he and his hunting book have gone down to posterity.

The oldest copy that is extant is preserved in the same treasure-house that contains our MS. and some fourteen other copies of it, namely the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. It bears the number 619 (anc. 7,098), while our MS. is numbered f.fr. 616 (anc. 7,097), and if P. Paris MSS. Franc. V 217 is right, it was Gaston’s working copy. The pictures in this MS. are shaded black-and-white drawings, and are not illuminations. That its origin was the south of France is proved, as M. Joseph Lavallée says, by the spelling of certain words: car being spelt guar, baigner as bainher, montagne as montainhe, a manner peculiar in the fourteenth century to the langue d’Oc. The fact that in the MS. 616 these words are spelt in the more modern fashion supports the theory, according to the last-mentioned authority, that it was written at a later date, i.e. in the first half of the fifteenth century, thus confirming the impression already produced by the far superior illuminations in MS. 616. These latter, as we see by a glance at the two full-page reproductions, somewhat reduced in size though they necessarily had to be to find space in this place, evince the unmistakable signs of having been created during a period of transition in the miniaturist’s art. For while the one has the characteristic diapered background, the other has a more realistic horizon, which betokens a later origin than the beginning of the fifteenth century. Of the eighty-seven illuminations in our MS. 616, only four have a natural horizon as background, the rest are diapered in the conventional older manner, in the invention of which the miniaturists of the fourteenth century developed a perfectly wonderful ingenuity, and of which this exquisite Codex is one of the most remarkable examples. ¶ In the opinion of some experts the illuminations in MS. 616 are by the hand of the famous Jean Foucquet, born about 1415, who was made painter and valet-de-chambre to Charles VII. Amongst the choicest works of this artist rank, it is perhaps hardly necessary to mention, the Book of Hours that he executed for Estienne Chevalier, Charles VII’s Treasurer, another Hours which he made for the Duchess Marie of Cleves, and most famous of all the ninety miniatures of the Boccaccio of Estienne Chevalier which is one of the principal treasures of the Royal Library in Munich. Those who are acquainted with Count Bastard’s monumental work will probably discover a distinct resemblance between one of his reproductions, especially in the foliage and scroll work, and the two full-page pictures now before the reader. On the other hand, the opinion of such a painstaking critic as is Levallée deserves attention. According to him—and nobody expended more time and trouble in Gaston Phoebus researches—the illuminations are not by Foucquet’s hand, but possibly by an artist of his school. If they are Foucquet’s, they cannot have been executed before 1440, or at the earliest 1435. ¶ And now to return to the romantic history of our Codex. On one of the front leaves is painted a large coat-of-arms. It is that of the Saint-Vallier family, and two events connected with the then possessors of this precious manuscript throw a telling sidelight upon French social conditions at the period to which the opening scene on Pavia’s bloody field has introduced us. A generation before that event, namely in 1477, Jacques de Brézé, a rich noble of well-known sporting proclivities, returning suddenly home found his wife in a compromising position with a young noble. Swords flashed on slighter provocation than this one in those days, and the angry husband killed both the lover and his wife without further[Pg 12] ado. Unhappily for him, the latter was no less a personage than Charlotte of France, natural daughter of Charles VII, and it cost the stern husband a fine of 100,000 ducats, a huge sum in those days, and a couple of years’ confinement in a castle to save his life. The eldest of the six children who were made motherless by this event subsequently married Diane of Poitiers, who not long afterwards became the all-powerful mistress of Francis I, and later on of Henry II, his son. Now Diane de Poitiers was the daughter of Jean de Poitiers, Sieur of Saint-Vallier, on whom his King (Louis IX) had bestowed the hand of his natural daughter Marie. The Codex whose reproductions we have before us had been given, probably as part of the King’s dower, to Jean de Poitiers’s wife, hence the armorial bearings. If we want to become acquainted with the circumstances that probably were the cause of its presence in King Francis’s tents on the eventful day of Pavia, we have to turn to another tragic event which occurred two years before Pavia. In 1523 Jean de Poitiers involved himself in the Connétable de Bourbon’s conspiracy, and the discovery by the King’s minions, among Jean’s secret papers, of the code treacherously used by the Connétable in his correspondence with Charles V of Germany, sent Jean speedily to the scaffold. He was in the act of kneeling down to receive the deathblow when the pardon obtained by his daughter from her royal lover, the King, saved his life. But all his goods and chattels were confiscated by Francis I, and amongst them was most probably our Codex, and thus it came to form part of the vast booty captured by Emperor Charles’s rough-handed Landsknechte. ¶ These formidable soldiers, who, under their giant leader, Georg von Frundsberg, had performed in the Italian campaigns deeds of great prowess—they were really the first trained infantry—were recruited almost exclusively in Tyrol, and for this reason it is not surprising that the next authentic news we have of our Codex is from that country. Bishop Bernard of Trent purchased it evidently from some returning booty-laden Landsknecht, and, recognising its great value, he presented it about the year 1530 to Archduke Ferdinand, Duke of Tyrol, one of the greatest collectors of his time, whose museum and library at his castle Ambras, near Innsbruck, was the wonder of the day. ¶ It remained in the possession of the Hapsburgs for about 130 years, when victory returned it once more to the country from whence defeat had removed it. During Turenne’s campaign in the Netherlands, General the Marquis of Vigneau became possessed of the volume—how remains unfortunately a mystery—and on his return to Paris presented it, July 22, 1661, to his King, Louis XIV. Bishop Bernard’s and General Vigneau’s dedications to the respective royalties are inscribed on the fly leaves, the former, in the shape of a long-winded Latin ‘humblest offering,’ taking up a good deal of space, though, unlike the Frenchman’s dedication, it fails to indicate the year when the presentation was made. ¶ Louis XIV deposited it in the Royal Library, where it received its librarian’s birthmark, the number 7,097, which it retained down to recent days, when it was rechristened, to be known henceforth, as already stated, as MS. 616. It never should have left those sacred halls, but Louis XIV was no venerator of his own law when it suited him to break it. Regretting his gift to the Library, a few years afterwards he demanded the volume back, and back again he got it, his son, the Count of Toulouse, becoming the next owner of it. From him it passed to Orleans princes until, in the fateful year 1848, it formed part of the private library of Louis Philippe at Neuilly, when that royal residence was plundered and fired by the populace.

By a wonder it escaped complete destruction on that occasion, and though the covers were badly damaged and blood-bespattered, the inside of the book was left intact. Although a new cover of somewhat gaudy modernity has been supplied to it in[Pg 15] consequence of the fiery ordeal through which it had passed, the student visiting the great Paris library, where this unique Codex is exhibited in what is known as the Reserve, will find its vellum leaves in very much the same perfect condition as they were when Diane de Poitiers and Francis I turned them over with the care that is bestowed upon a work one loves. ¶ Another fine copy of Gaston Phoebus is preserved in the late Duc d’Aumale’s magnificent library at Chantilly, now the property of the French nation. When recently making some researches there the writer came across a pathetic little note in the late Duke’s catalogue respecting our Codex, which, as we have heard, belonged to the House of Orleans for upwards of a century. It occurs where the Duc d’Aumale speaks of the MS. 616, and it runs: ‘Saved from the conflagration of 1848, it was taken to the Bibliothèque Nationale, but our appeals for a return of the volume addressed to the Conservateurs of the Library were rejected, however well founded we considered our claim!’ The miniatures in the Chantilly copy are finely drawn, but evince in some instances a grotesqueness which is absent from those adorning MS. 616. Thus the much suffering reindeer comes in for some exceedingly quaint limning, with antlers of perfectly ludicrous proportions and a coat like an Angora goat’s. ¶ One curious fact obtrudes itself upon our notice as we examine the illumination in almost all the Gaston Phoebus copies that are adorned with illuminations (the majority of the existing forty MSS. are not illuminated, or at best only with very inferior pictures). It is the bright colours of the huntsmen’s dress in the fifteenth century. With the exception of the wild-boar hunters, who are generally garbed in grey costumes, mounted and unmounted hunters engaged in the pursuit of the stag, buck, bear, otter, fox, wild cat, wolf, hare, and badger, wear with curious promiscuousness blue, scarlet, mauve, white, and yellow costume quite as often as they appear in the more orthodox green-coloured dress. It may possibly have been merely an instance of artistic licence on the part of the miniaturists, for according to the text grey and green were the only colours of venery known to the good veneur. ¶ To come to the contents of our MS. we can introduce it by the broad statement that Gaston Phoebus is the first mediaeval hunting-book in prose that does not deal with the subject in the catechism-like form of question and answer. The few previous prose works that have come down to us take the form of questions asked by the keen young apprentice and answered by his instructor, an experienced veneur, explaining to him the A B C of venery. Some bits in Gaston’s Livre de Chasse are borrowed from Roy Modus, written about sixty years earlier, some from Gace de la Buigne (or Vigne), King John’s first chaplain, written less than thirty years earlier, and a few from La Chace dou Serf, a poetic effusion of the second half of the thirteenth century. But taking it as a whole Gaston Phoebus is unquestionably as original as could be any work upon such a popular subject as hunting then was. ¶ To those who know their Froissart, Count Gaston de Foix’s personality will be very familiar; but, considering that the chronicler’s visit occurred in 1388, the year after the commencement of the Livre de Chasse, it is somewhat strange, in view of his long stay and intimate intercourse at the Count’s court, that he does not mention the opus upon which his host was then engaged. ¶ The prologue mirrors in a characteristic manner the spirit of the age, as does also the last miniature in MS. 616, which represents the noble sportsman in an attitude of beatitude kneeling in a chapel. That Gaston was a pious lord we can see by the score or so of Latin prayers said to have been composed by him in the dire hour of mortal distress after the tragic death of his only son by his—the father’s—hand. ‘By the Grace of God’ Count Gaston speaks wisely and well of the good qualities that a hunter should have, and how hunting[Pg 16] causeth a man to eschew the seven deadly sins, concluding his homily with a sentiment that appeals to the sportsman of the twentieth century as much as it did to him of the fourteenth. ‘And also, say I, that there is no man who loves hunting that has not many good qualities in him, for they come from the nobleness and gentleness of his heart of whatsoever estate he be, great lord or little, poor or rich.’ ¶ The prologue once finished, Gaston starts with zest on his task, beginning with the stag, or, to be quite correct, with the ‘nature’ of what was considered in all Continental hunting the most important beast of venery. The next thirteen chapters deal respectively in a similar way with the natural history of the reindeer, the fallow deer, the ‘bouc,’ under which the ibex and the chamois were included, the roe-deer, the hare, the rabbit, the bear, the wild boar, the wolf, the fox, the badger, the wild cat, and the otter. ¶ Following these fourteen chapters, we get ten very interesting ones on the various kinds of sporting hounds, their training, treatment when ill, the construction and management of the kennel, and other details relating to the subject. In Gaston’s time there were five kinds; the first is the Alaunt, which he subdivides into the Alaunt gentle and the Alaunt veautres; the second is the levrier or greyhound; the third the chien courant or running hound; the fourth the bird dog or espainholz, from which the modern spaniel has sprung; and the fifth the mastin or mastiff. Then come two chapters on how to make nets, and how to blow and trumpet, followed by eighteen chapters on how to track the stag and the wild boar, and how to judge of their presence, size, age, etc., by the various signs known to the veneur, who made a very exact science of what we would call woodcraft. The next fifteen chapters relate to the chase proper of the fourteen beasts named at first, with a double chapter on the chase of the wild boar. The concluding twenty-six chapters deal with the various manners of netting, snaring, trapping, and poisoning of wild beasts of prey and other less noxious animals. They are mostly short chapters, and in more than one place the author displays his unwillingness to deal with matter that a good sportsman need have no ken of, except in so far as was necessary to keep down vermin and destroy ‘marauders of the woods’ for the benefit of his legitimate quarry. ¶ Certain historians have called Gaston Phoebus a ‘cruel voluptuary,’ and no doubt some of his repressive measures sound unnecessarily harsh, not to say merciless, in these soft times; but the spirit in which he wrote his famous book is unquestionably that of a really good sportsman who abhors all underhand advantages that curtail the hunted beast’s chances, and who takes his bear or wild boar single-handed, and pursues his stag to a finish, be the forest a trackless maze, and the river to which the hunted deer finally takes a swift flowing stream, into which to plunge is but a minor incident of an exciting sport. ¶ Of the forty or forty-one ancient MS. copies of Gaston Phoebus that are known to exist in Europe to-day, twenty-one are in France, fifteen keeping our MS. 616 company on the shelves of the Bibliothèque Nationale. Five form part of the Vatican Library, and six adorn the principal libraries of Continental capitals. Of the eight copies that are or were in England one is in the British Museum, and two form part of the well-known collection formed in the first half of the last century by the late Sir Thomas Phillipps, Bt., a bibliophile as wealthy as he was discerning. Of these two MSS., No. 11,592 is an incomplete late copy of little value; but the other MS., 10,298, is on the other hand a treasure of great value. Of all the Continental and English copies that the writer has examined this one contains, next to those in MS. 616, the finest miniatures. It is less carefully written, and there are some variations, but nothing of importance so far as is known, [Pg 21] though it has never been carefully collated with the best French copies.

The British Museum copy of Gaston Phoebus, catalogued as Addit. MS. 27,699, is on vellum, quarto, written in the first half of the fifteenth century. The miniatures are by an indifferent hand, and have been left in an unfinished state, the miniaturist having apparently expended most of his time, and nearly all his bright colours and shining gold, upon the diapering of the backgrounds. It was bought at the Yemeniz Sale in Paris, in May 1867, for something less than £400. The Ashburnham Library contained two copies, both early ones, and of these MS. App. 179 is interesting on account of an hitherto unknown treatise on hawking and birds being added at the end of the hunting book, which is incomplete, and the spaces at the head of each chapter for the usual miniatures are left blank. It was bought at the fourth Ashburnham Sale in May 1899 by the writer. ¶ Of the copy which Werth and Lavallée quote as being in the possession of a Cambridge Library, it is regrettable that no information could be obtained by them or by myself. As a rule the lot of the student making researches of this sort in English libraries, always excepting, of course, the British Museum and the Bodleian, is not a happy one. Not only is study in the libraries discouraged, and letters of inquiry are left unanswered, but valuable MSS. seem to get mislaid, lost, or stolen, rather more frequently than should be. The two remaining copies of Gaston Phoebus in this country, one being in a public museum, the other in a well-known ducal library, have shared this fate, and their whereabouts are unknown. The latter copy must have been a very beautiful MS., for it is described in Dibdin’s Decameron, Vol. III, p. 478, and was bought in 1815 for £161, then a large sum, by Loché; and according to Werth (Altfranzösische Jagdlehrbücher, 1889, p. 70) it was, when he wrote, in the Duke of Devonshire’s library, from which, however, it seems to have disappeared, for no trace of it can be found. Curiously enough, this fate is shared by yet another valuable hunting MS., which for the English student has even greater interest, namely, one of the few existing copies (nineteen all told) of the Duke of York’s translation of Gaston Phoebus, which has disappeared from a well-known nobleman’s library. ¶ In conclusion, it is necessary to say a few words respecting the subject matter of the MS. just mentioned, for many erroneous impressions regarding it are abroad. Gaston Phoebus deals with some animals that were not found in England in Plantagenet times, e.g. the reindeer, the ibex and chamois, and the bear. Hence when Edward, second Duke of York, who filled the position of Master of Game at the court of his cousin, Henry IV, made a translation of his famous contemporary’s hunting book, he took only those parts of it which related to game and dogs found in England, and added five original chapters, calling the whole ‘The Master of Game.’ This book is the oldest hunting book in English, but has never been published. The writer’s reproduction of it, illustrated by photogravure copies of the illuminations in the Paris Codex MS. 616, some of which are reproduced in the present article, is now going through the press.[2] It will, it is hoped, fill a gap in English hunting literature, and remove numerous misconceptions concerning this subject.

[Pg 22]

❧ WRITTEN BY HERBERT P. HORNE ❧

MONG the books of the Spedale di San Paolo, at Florence, is a volume marked on the cover ‘Testimenti,’ and lettered ‘B.’ It contains a record of all wills between the years 1399 and 1526 under which the hospital in any way benefited; and on fol. 16 recto is the following entry: ‘Alexo di Baldovinecto Baldovinetti has this day, the 23rd of March, 1499, made a donation to our hospital of all his goods, personal and real, after his death, with obligation that the hospital support Mea, his servant, so long as she live: [the deed was] engrossed by Ser Piero di Leonardo da Vinci, notary of Florence, on the day aforesaid.’ ‘Alexo died on the last day of August, 1499; and was buried in his tomb in San Lorenzo; and the hospital remained the heirs of his goods. May God pardon him his sins!’[3] ¶ Milanese, who quotes this ‘ricordo’ textually, though not without some slight errors, in his notes to Vasari, states that the volume in which it occurs is preserved in the Archivio di Stato at Florence; whereas the archives of the hospital are now in the ‘Archivio’ of Santa Maria Nuova, San Paolo having been united to the latter hospital by the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo, c. 1783.[4] ¶ At first sight, this ‘ricordo’ would not seem to bear out the story which Vasari tells of Alesso and his dealings with the authorities of San Paolo. It states only that Alesso made a donation to the hospital of all his worldly goods after his death, upon the condition that his faithful servant, Mea, was to be lodged, clad, and fed, during her life; whereas Vasari, on the contrary, states that the painter himself became an inmate of San Paolo. ‘Alesso,’ he says, ‘lived eighty years; and when he began to grow old, desirous of being able to attend to the studies of his profession with a quiet mind, he, as many men often do, entered the Hospital of San Paolo: and in order, perhaps, that he might be received the more willingly, and be better treated (though it might, indeed, have happened by chance), he caused a great chest to be brought into his rooms, in the hospital; acting as if a goodly sum of money were therein: whereupon the master and the other ministrants of the hospital, believing that this was so, bestowed on him the greatest kindness in the world; since they knew that he had made a donation to the hospital, of whatever was found in his possession at his death. But when Alesso died, only drawings, cartoons, and a little book which set forth how to make the tesserae for mosaic, together with the stucco and the method of working them, were found therein.’[5] ¶ The apparent discrepancy between the ‘ricordo’ in the books of San Paolo and Vasari’s account led me to search, and not without success, for the deed by which Alesso’s property passed to the hospital. I found that both the name of the notary and the date of the execution of the instrument were incorrectly given in the ‘ricordo’ cited above. The instrument was engrossed by Ser Piero di Antonio di Ser Piero da Vinci, the father of Leonardo da Vinci, and executed on March 16, 1497–8. By this deed Alesso, ex titulo et causa donationis, ‘irrevocably gave and bequeathed during his life-time, to the Hospital of the Pinzocheri of the third order of St. Francis, otherwise called the Hospital of San Pagholo, and to the poor of Christ living in the said hospital for the time being,’ etc., ‘all his goods, real and personal, present and future, wherever situate or existent,’ etc., reserving to himself[Pg 23] ‘the use and usufruct of the said goods,’ etc., ‘for the term of his natural life.’ The ‘rogiti’ of Ser Piero da Vinci for the year 1498 have not been preserved among the ‘protocols’ of that notary now in the Archivio di Stato at Florence; and so it is no longer possible to say under what conditions, if any, the donation was made: but it is to be presumed upon the evidence of the ‘ricordo’ cited above, that it entailed the obligation on the part of the hospital, to maintain Mea, his servant, during her life. ¶ On October 17, 1498, Alesso executed what was technically known as a ‘renuntiatio,’ which was likewise engrossed by Ser Piero da Vinci. This second instrument, which begins by reciting the former deed of donation in the terms quoted above, sets forth how, on that day, Alesso, ‘by reason of lawful and reasonable causes of motion influencing, as they assert, his mind, and by his mere, free, and proper will,’ etc., ‘renounced the said use and usufruct, expressly reserved to himself in the aforesaid donation, and freely remitted and released the said use and usufruct to the said hospital, and to the poor of Christ dwelling in the said hospital,’ etc. The text of this document, which is preserved in the Archivio di Stato at Florence, is printed at length at the end of this article.[6] It allows us to draw but one conclusion; namely, that when the painter executed the deed of donation on March 16, 1497–8, he had been left without wife or children; and that he anticipated but two contingencies against which he would provide after his death—the health of his soul and the maintenance of his faithful servant, Mea. ¶ Alesso had married late in life. It appears from the ‘Portata al Catasto,’ returned by him in 1470, that he was still unmarried at that time, and that he was possessed of no real property, but rented a house in the ‘popolo’ of San Lorenzo, in Florence, described in his later ‘Denunzie,’ as being in the Via dell’ Ariento, at the Canto de’ Gori.[7] In another ‘Denunzia’ returned in 1480, Alesso thus describes his family:—‘Alesso Baldovinetti, aforesaid, aged 60, painter; Monna Daria, his wife, aged 45; Mea, his maid-servant, aged 13.’ As a matter of fact, Alesso was 63 years of age, having been born on October 14, 1427, Milanesi, by the way, in his notes to Vasari, gives the name of his, Alesso’s wife, as Diana, in error for Daria.[8] According to the same ‘Denunzia,’ the painter was at that time possessed of a parcel of land of twelve staiora, situate in the ‘popolo’ of Santa Maria a Quinto, and another parcel of seven staiora, in the same ‘popolo,’ the latter having been bought in 1479, with a part of his wife’s dowry. It is, therefore, probable that he had not long been married at that time.[9] It appears from a yet later ‘Denunzia’ on which the ‘Decima’ of 1498 was assessed, though the return itself was probably drawn up in 1495, that he possessed, in addition to the two parcels of land in the ‘popolo’ of Santa Maria a Quinto, a third parcel of over eleven staiora, in the adjoining ‘popolo’ of San Martino a Sesto, on the road to Prato. He was still living at that time in the same house at the Canto de’ Gori; and he also enjoyed the rents of two shops, with dwellinghouses above, which had been made over to him for the term of his natural life, by the Consuls of the Arte dei Mercanti, on February 26, 1483–4, in payment of his ‘magistero e esercitio et trafficho,’ in having restored the mosaics of the Baptistery of San Giovanni.[10] ¶ The Spedale di San Paolo, of which the beautiful loggia, with its ornaments by Andrea della Robbia, still remains on the Piazza of Santa Maria Novella, was originally a hospital for the care of the sick; and as such it is mentioned in a document of 1208.[11] From the time that St. Francis himself is said to have lodged at San Paolo, the hospital appears to have been administered by Franciscans,[Pg 24] called in the records ‘Fratres tertii Ordinis de Penitentia S. Pauli.’ During the fourteenth century, the house underwent certain reforms; and in 1398 it was decreed by the Signoria, ‘that the place was to be no longer a hospital, but a house of Frati Pinzocheri of the third order.’[12] Notwithstanding, the members of the community continued to devote themselves to the care of the sick; and a papal brief of 1452 directs that the revenues of the house were to be set apart for the infirm.[13] At an early period in the history of San Paolo, mention occurs of Pinzochere, that is to say, women attached to the community, no doubt for the service of the hospital; but unlike the men of the house, who are invariably called Frati Pinzocheri, they were not dignified by the title of ‘Monache’: from this Stefano Rosselli infers that they originally had no share in its government.[14] Owing, however, to some cause which is not very clear, the Frati Pinzocheri appear to have died out towards the latter part of the fifteenth century, leaving the women in possession of the hospital. From evidence that Rosselli and Richa adduce, it seems that in 1497 San Paolo was controlled and administered entirely by Pinzochere; and in the document of 1499, cited below, it is called ‘lo spedale di pizichora del terzo ordjne dj san franchesco.’[15] From this we must conclude that, when Alesso renounced the use and enjoyment of his property on October 17, 1498, he entered the hospital of San Paolo, not as a member of the community, but as a sick man who sought nothing more on earth than to be tended during the brief span of life that was left to him. He died ten months later, on August 29, 1499, and was buried in his own tomb in San Lorenzo.[16] The hospital of San Paolo probably inherited, along with Alesso’s other property, all his cartoons and drawings, as Vasari asserts: they, certainly, came into the possession of his books and papers, as we know. The little treatise on the art of Mosaic has long been lost; but Milanesi has stated in a well-known passage in his Vasari, that the autograph manuscript of certain ‘Ricordi’ of Alesso Baldovinetti still existed in his time, in the Archivio of Santa Maria Nuova, among the books of the hospital of San Paolo. He adds that these ‘Ricordi were published at Lucca in 1868, by Dr. Giovanni Pierotti, per le nozze Bongi e Ranalli.’[17] Few of those innumerable, little pamphlets with which Italians, learned and unlearned, delight to celebrate the marriages of their patrons, friends, or relatives, are more difficult to find than the little brochure of ten leaves, in a green paper wrapper, to which Milanesi alludes. The title page runs thus: ‘Ricordi di Alesso Baldovinetti, pittore fiorentino del secolo xv. Lucca. Tipografia Landi. 1868.’ Unfortunately only a portion of Baldovinetti’s manuscript is given in this pamphlet. The extracts, which fill less than a half of its twenty pages, are partly given in the text, and partly in an abstract, of the original. The rest of the pamphlet is filled with the introductory preface and notes of Dr. Pierotti. ¶ It is now some years ago since I first made an attempt to find the original manuscript of these ‘Ricordi,’ in the Archivio of Santa Maria Nuova, only to discover that I was not the first student of Florentine painting to search in vain for the volume. Whether it had been borrowed by Pierotti, or merely mislaid, or in what way it had disappeared, no one could tell me. Not long after this attempt, however, I chanced upon what proved to be a clue to its history. While searching among the ‘Carte Milanesi,’ the voluminous manuscript collections which the famous commentator of Vasari left to the Communal Library of Siena, I came across a series of extracts from the ‘Ricordi’ of Baldovinetti, in the handwriting of Milanesi, with the title: ‘Estratto del libro dei Ricordi di Alesso Baldovinetti autografo [Pg 27]essitente nell’ Archivio dello Spedale di Santa Maria Nuova di Firenze.—Libri dello Spedale di San Paolo, 12 Febbo. 1850.’ On comparing these extracts with Pierotti’s pamphlet, I found that the two copies agreed word for word with one another. It was evident that Pierotti had made use of Milanesi’s manuscript (indeed, he owns as much in his concluding note), and that he may never have seen the original manuscript. ¶ Last autumn, having occasion to make some researches in the Archivio of Santa Maria Nuova, with my friend Sir Domenic Colnaghi, for his ‘Dictionary of Florentine Painters,’ I took the opportunity of renewing my search for the missing volume. On the top shelf of one of the presses which contain the books and papers of the hospital of San Paolo, I came across a ‘filza’ labelled ‘Libri Diversi,’ and filled with miscellaneous account-books of the hospital, chiefly of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Among these was a small, upright book of forty-seven leaves, bound in a parchment cover which was inscribed:—

RICHORDI[18]

·Ḅ̇·

On the recto of the first leaf was written: ‘1470. In this book I will keep a record of all the expenses that I shall incur in the chapel of the High Altar of Santa Trinita, namely of gold, blue, green, lake, with all other colours and expenses that shall be incurred on behalf of the said chapel; and so we may remain in agreement [I and] Messer Bongiani Gianfigliazi, the commissioner of the work, and the patron of the said chapel, as appears by a writing which I hold, subscribed by his own hand.’ ¶ Fol. 2 tergo, and fol. 3 recto, were filled with entries relating to the purchase of colours and other materials for the work of the chapel, and fol. 3 tergo contained two further entries in the same hand; after which was written, in a different hand: ‘Here follow the records of the hospital of the Pinzochere of the third order of St. Francis, written by Giovanni di Ser Antonio Vianizzi.’ The remainder of the book was filled with entries relating to the hospital of San Paolo, the first of which recorded a payment of twenty-three lire, made by the hospital on October 19, 1499, to Luca d’Alesso Baldovinetti. On comparing the ‘Ricordi’ relating to Santa Trinita, with the ‘Portata al Catasto,’ returned by Alesso in 1471, it was clearly evident that both documents were in the handwriting of the painter. Of the ‘Portata al Catasto,’ returned by Alesso in 1480, two copies exist in the same hand; but they do not appear to have been written by the painter himself, although Milanesi has reproduced a portion of one of them, in his ‘Scrittura di Artisti Italiani,’ Florence, 1876, Vol. 1, No. 74, as a specimen of his handwriting. ¶ What is more, this manuscript, which I may call ‘Libro B,’ throws a light upon the nature of the missing volume, ‘Libro A.’ In the case of ‘Libro B,’ what undoubtedly happened was, that the good Pinzochere, on looking over Alesso’s property after his death, found an account-book of which only the first three leaves had been used. With a proper spirit of economy, they determined to make use of the rest of the book for the accounts of their hospital: but instead of tearing out the leaves containing Alesso’s ‘Ricordi,’ they fortunately allowed them to stand; their procurator adding the note I have cited above. The same thing probably happened in the case of ‘Libro A.’ From the extracts that Milanesi made, it appears that Alesso’s ‘Ricordi’ only filled some sixteen pages of a volume, that cannot well have contained fewer leaves than ‘Libro B.’ With this clue to its discovery, I leave my friends and rivals in Florence to continue the search for a volume, whose loss every genuine student of Italian painting must regret. ¶ The history of the Cappella Maggiore of Santa Trinita affords a curious instance of the tardy process by which many of the Florentine churches and their chapels were brought[Pg 28] to completion. The present church of Santa Trinita was begun c. 1250, but many of the lateral chapels remained unfinished until the fifteenth century, and among them the Cappella Maggiore. On November 1, 1371, the abbot of Santa Trinita, inter missarum solepnia, made an appeal to many of the chief parishioners, who had assembled for mass, to contribute to the expenses necessary for the erection of the Cappella Maggiore.[19] The work appears to have proceeded very slowly, since it is on record that the chapel was but half built in the year 1463. In order to bring it to completion, the abbot, having assembled the parishioners in the church, gave notice that since money was wanting to finish the work, licence to do so would be granted to the family that was able and willing to undertake the expense; and accordingly on February 4 of the same year, the patronage of the chapel was granted by acclamation of the parishioners, to Messer Bongianni Gianfigliazzi and his descendants.[20] ¶ The Gianfigliazzi were an ancient Florentine family, of no little repute in the conduct of affairs and arms during the last two centuries of the republic. Ugolino Verino celebrates them in his Latin poem, ‘De Illustratione Urbis Florentiae’:—

According to Piero Monaldi, the Gianfigliazzi were descended and took their name from one ‘Ioannes filius Acci,’ who is named in a treaty concluded between the Sienese and Florentines in the year 1201.[22] Besides knights of Malta and Santo Spirito, this family boasted of ten gonfaloniers of the republic, and thirty priors; the first of whom held office in 1345. Gherardo Gianfigliazzi was gonfalonier in 1462; and Messer Bongianni, his brother, in 1467, and again in 1470. The latter, ‘magnificus miles’ as he is styled in documents, was a ‘cavalier spron d’oro,’ and famous in his day as a leader of the Florentine forces. He was several times created ambassador of the Florentine republic, and one of the Dieci di Balia. In 1471 he was one of the six ‘orators’ sent to felicitate Sixtus IV on his election to the papacy; and in 1483 he was appointed ‘commessario’ in the war against the Genoese, which ended in the capture of Sarzana. Alesso was not the only famous artist which this family patronized. Their shield of arms, carved with a lion rampant, by Desiderio da Settignano, is still to be seen on the front of their palace on the Lung’ arno Corsini, at Florence.[23] ¶ Giuseppe Richa states that the deed granting the patronage of the Cappella Maggiore of Santa Trinita to the Gianfigliazzi, was engrossed by Ser Pierozzo Cerbini on February 13, 1463–4, which we may well believe;[24] but he adds that the ‘ius patronale’ was vested in the persons of Messer Bongianni and Messer Gherardo.[25] The latter statement, however, would seem to be incorrect, for Gherardo was already dead at that time, as we learn from the inscription on the sepulchral slab (one of the most beautiful of its kind in Florence), which is still to be seen on the floor of the chapel, but now partly covered by a choir-organ:

GHERARDO . IANFILIATIO . DE . SE .

FAMILIA . ET . PATRIA . BE[? NE-

MERITO BONIOANNES] . FRATRI .

PIENTISSIMO . SIBI ..... IDVS . SEP .

AN . SAL . MCCCCLXIII