[Pg 3]

BY-PATHS

IN HEBRAIC BOOKLAND

BY

ISRAEL ABRAHAMS, D. D., M. A.

Author of “Jewish Life in the Middle Ages,” “Chapters on

Jewish Literature,” etc.

Philadelphia

The Jewish Publication Society of America

1920

The Project Gutenberg eBook of By-paths in Hebraic bookland, by Israel Abrahams

Title: By-paths in Hebraic bookland

Author: Israel Abrahams

Release Date: March 29, 2023 [eBook #70401]

Language: English

Produced by: Sharon Joiner, Jeff G. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg 1]

[Pg 2]

[Pg 3]

BY-PATHS

IN HEBRAIC BOOKLAND

BY

ISRAEL ABRAHAMS, D. D., M. A.

Author of “Jewish Life in the Middle Ages,” “Chapters on

Jewish Literature,” etc.

Philadelphia

The Jewish Publication Society of America

1920

[Pg 4]

Copyright, 1920,

by

The Jewish Publication Society of America

[Pg 5]

Wayfarers sometimes use by-paths because the highways are closed. In the days of Jael, so the author of Deborah’s Song tells us, circuitous side-tracks were the only accessible routes. In the unsettled condition of Israel those who journeyed were forced to seek their goal by roundabout ways.

But, at other times, though the open road is clear, and there is no obstacle on the way of common trade, the traveller may of choice turn to the by-ways and hedges. Not that he hates the wider track, but he may also love the less frequented, narrower paths, which carry him into nooks and glades, whence, after shorter or longer detours, he reaches the highway again. Not only has he been refreshed, but he has won, by forsaking the main road, a fuller appreciation of its worth.

Originally written in 1913 for serial publication, the papers collected in this volume were designed with some unity of plan. Branching off the main line of Hebraic development, there are many by-paths of the kind referred to above—by-paths leading to pleasant places, where it is a delight to linger[Pg 6] for a while. Some of the lesser expressions of the Jewish spirit disport themselves in those out-of-the-way places. Though oft neglected, they do not deserve to be treated as negligible.

None can surely guide another to these places. But the first qualification of a guide, a qualification which may atone for serious defects, is that he himself enjoys the adventure. In the present instance this qualification may be claimed. For the writer has turned his attention chiefly to his own favorites, choosing books or parts of books which appealed to him in a long course of reading, and which came back to him with fragrant memories as he set about reviewing some of the former intimates of his leisure hours. The review is not formal; the method is that of the causerie, not of the essay. Some of the books are of minor value, curiosities rather than masterpieces; in others the Jewish interest is but slight. Yet in all cases the object has been to avoid details, except in so far as details help even the superficial observer to get to the author’s heart, to place him in the history of literature or culture. Not quite all the authors noted in this volume were Jews—the past tense is used because it was felt best to include no writers living when the volume was compiled. It seemed,[Pg 7] however, right that certain types of non-Jewish workers in the Hebraic field ought to find a place, partly from a sense of gratitude, partly because, without laboring the point, the writer conceives that as all cultures have many points in common, so it is well to bear in mind that many cultures have contributed their share to produce that complex entity—the Jewish spirit. Complex yet harmonious, influenced from without yet dominated by a strong inner and original power, the Jewish spirit reveals itself in these by-paths as clearly as on the main line.

But, though some such general idea runs through the volume, it was the author’s intention to interest rather than instruct, to suggest the importance of certain authors and books, perhaps to rouse the reader to probe deeper than the writer himself has done into subjects of which here the mere surface is touched. The writer could have added indefinitely to these papers, but this selection is long enough to argue against extending it, at all events for the present.

Having decided to stray into the by-paths, it sometimes became necessary to resist the temptation to turn to the main road. This necessity accounts for another fact. Fewer books are treated[Pg 8] of the older period. For the older period is dominated by Bible and Talmud, and these were ex hypothesi outside the range. So, too, the scholastic masterpieces and the greater products of mysticism and law are passed over. Yet, though the writer did not consciously start with such a design, it will be seen that accidentally a great fact or two betray themselves. One is that, in the Jewish variety, technical learning can never be wholly dissociated from what we more commonly name literature. Some books which, at first sight, are merely the expression of scholarly specialism are seen, on investigation, to belong to culture in the æsthetic no less than in the rational or legal sense. Again, there becomes apparent the vital truth that Jewish thought, dependent as it always has been on environment, is also independent. For we see how Jews in the midst of Hellenistic absolutism remained pragmatical, how under the medieval devotion to a stock-taking of the past Jews were to a certain extent creative, and how the modernist tendency to disintegration was resisted by an impulse towards constructiveness.

But, to repeat what has already been indicated, the author had no such grave intentions as these. Many of the papers appeared in a popular weekly,[Pg 9] the London Jewish World, the editor of which kindly conceded to the writer the privilege of collecting them into a book. Some, however, were specially written for this volume. All have been considerably revised, in the effort to make them more worthy of the reader’s attention. The writer feels that this effort, despite the valuable help rendered by Dr. Halper while the proofs were under correction, has been imperfectly successful. The papers can have little in them to deserve attention. Nevertheless there is this to be urged. Some of the topics raised are apt to be ignored. Yet it is not only from the outstanding masterpieces of literature that we may learn wisdom and derive pleasure. “A small talent,” said Joubert, “if it keeps within its limits and rightly fulfils its task, may reach the goal just as well as a greater one.” This remark may be applied to what may seem to many the minor products of genius or talent. Hence, be they termed minor or major, the books discussed in this volume were worthy of consideration. Beyond doubt most of them belong to the category of the significant and some of them even attain the rank of the epoch-making. And so, without further preface, these papers are offered to those familiar as well as to those unfamiliar with the[Pg 10] works themselves. For to both classes may be applied the Latin poet’s invocation: “Now learn ye to love that loved never; and ye that have loved, love anew.”

[Pg 11]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Preface | 5 |

| PART I | |

| The Story of Ahikar | 17 |

| Philo on the “Contemplative Life” | 24 |

| Josephus Against Apion | 32 |

| Caecilius on the Sublime | 39 |

| The Phoenix of Ezekielos | 46 |

| The Letter of Sherira | 53 |

| Nathan of Rome’s Dictionary | 60 |

| The Sorrows of Tatnu | 67 |

| PART II | |

| Ibn Gebirol’s “Royal Crown” | 77 |

| Bar Hisdai’s “Prince and Dervish” | 84 |

| The Sarajevo Haggadah | 91 |

| A Piyyut by Bar Abun | 97 |

| Isaac’s Lamp and Jacob’s Well | 102 |

| “Letters of Obscure Men” | 108 |

| De Rossi’s “Light of the Eyes” | 116 |

| Guarini and Luzzatto | 122 |

| Hahn’s Note Book | 129 |

| Leon Modena’s “Rites” | 136 |

| PART III | |

| Menasseh and Rembrandt | 147 |

| Lancelot Addison of the Barbary Jews | 153 |

| The Bodenschatz Pictures | 160[Pg 12] |

| Lessing’s First Jewish Play | 166 |

| Isaac Pinto’s Prayer-Book | 171 |

| Mendelssohn’s “Jerusalem” | 178 |

| Herder’s Anthology | 184 |

| Walker’s “Theodore Cyphon” | 191 |

| Horace Smith of the “Rejected Addresses” | 199 |

| PART IV | |

| Byron’s “Hebrew Melodies” | 207 |

| Coleridge’s “Table Talk” | 214 |

| Blanco White’s Sonnet | 220 |

| Disraeli’s “Alroy” | 226 |

| Robert Grant’s “Sacred Poems” | 233 |

| Gutzkow’s “Uriel Acosta” | 240 |

| Grace Aguilar’s “Spirit of Judaism” | 247 |

| Isaac Leeser’s Bible | 254 |

| Landor’s “Alfieri and Salomon” | 260 |

| PART V | |

| Browning’s “Ben Karshook” | 269 |

| K. E. Franzos’ “Jews of Barnow” | 276 |

| Herzberg’s “Family Papers” | 283 |

| Longfellow’s “Judas Maccabæus” | 290 |

| Artom’s Sermons | 297 |

| Salkinson’s “Othello” | 303 |

| “Life Thoughts” of Michael Henry | 311 |

| The Poems of Emma Lazarus | 319 |

| Conder’s “Tent Work in Palestine” | 325[Pg 13] |

| Kalisch’s “Path and Goal” | 333 |

| Franz Delitzsch’s “Iris” | 340 |

| “The Pronaos” of I. M. Wise | 347 |

| A Baedeker Litany | 353 |

| Imber’s Song | 359 |

| Index | 365 |

[Pg 14]

| FACING PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Menasseh Ben Israel | 148 |

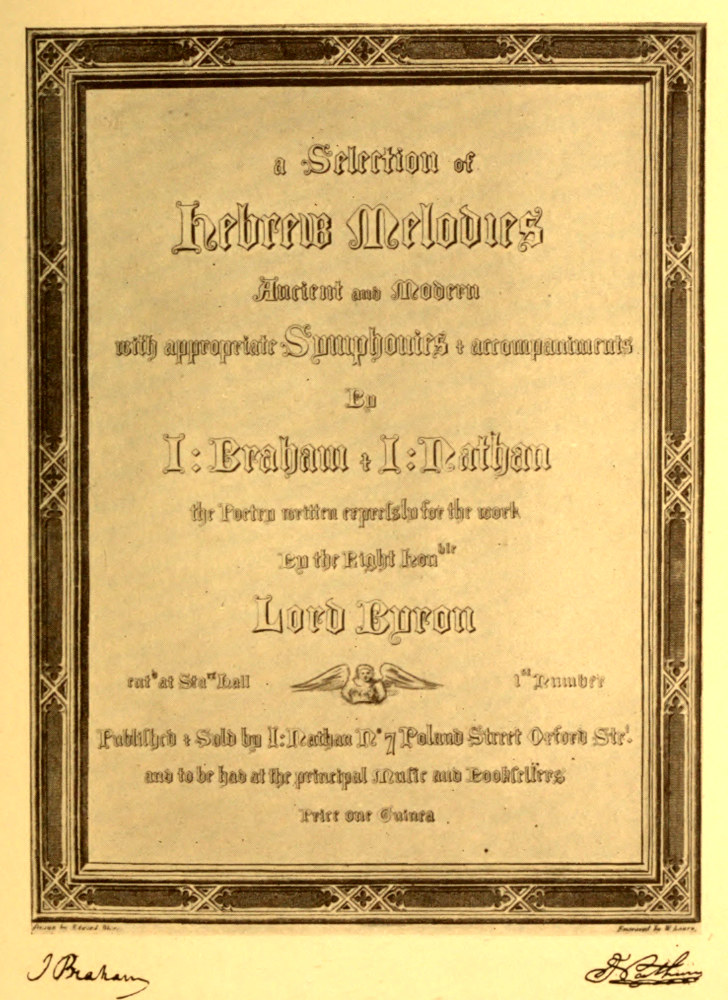

| Title-Page of the First Edition of Byron’s “Hebrew Melodies” | 208 |

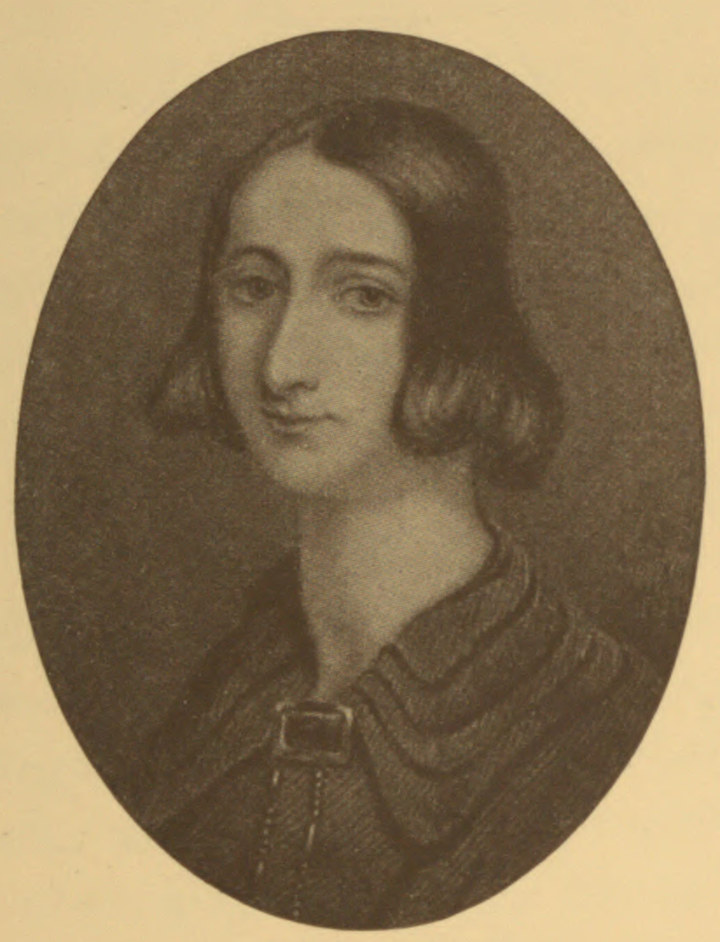

| Grace Aguilar | 248 |

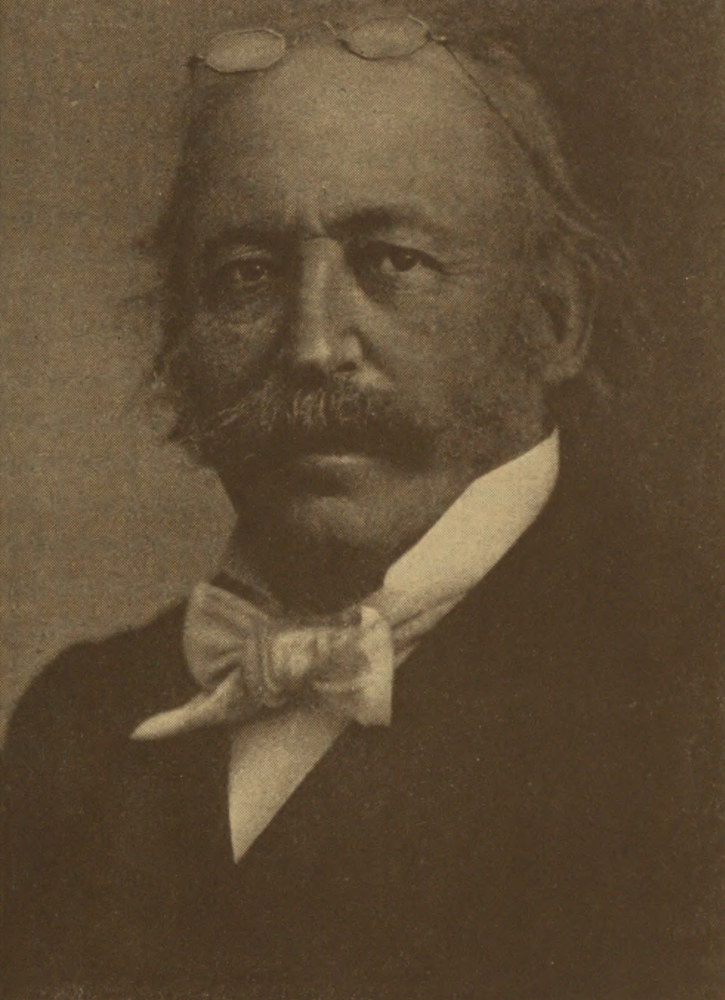

| Isaac Leeser | 254 |

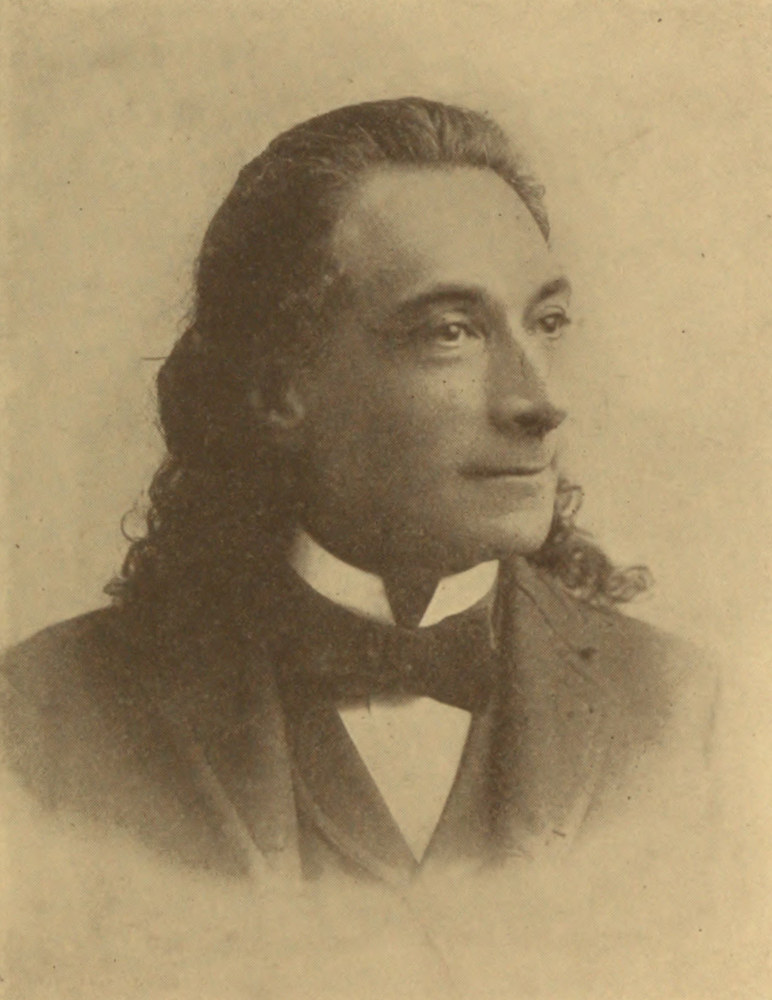

| Emma Lazarus | 320 |

| Isaac Mayer Wise | 348 |

| Naphtali Herz Imber | 360 |

[Pg 15]

[Pg 17]

PART I

We are happily passing out of the critical obsession, under which it was a sign of ignorance to attribute a venerable age to the records of the past. All the old books were written yesterday, or at earliest the day before! Facts, however, are stubborn; and facts, as they come to light, justify and re-affirm our fathers’ faith in the antiquity of the world’s literature. The story of Ahikar is a good illustration.

In the course of the Book of Tobit more than once Achiachar or Ahikar is mentioned. These allusions are verbal only, but in one scene the reference is more precise. The pious Tobit on his death-bed bids his son “consider what Nadab (Nadan) did to Achiachar, who brought him up” (14. 10).

What did Nadan do, and who was Ahikar? It is only within recent years that a complete answer has become possible to these questions. The older commentators on the Apocrypha were much worried by the allusion, and had to be content with the[Pg 18] blindest guesses. Some versions of Tobit had, in place of the words quoted above, the following: “Consider how Aman treated Achiachar, who brought him up.” Hence the suggestion arose that the reference was to Haman and Mordecai. But the Book of Esther does not hint that Mordecai had “brought up” Haman, and was then repaid by the latter’s ingratitude.

But in 1880, G. Hoffmann discovered the clue. He recognized that Tobit’s references were paralleled in a story found in Æsop’s Fables and in the Arabian Nights, but much more fully recorded in the Story of Ahikar preserved in several versions, such as Syriac, Arabic, and Armenian. The story, briefly told in those fuller records, is as follows:

The hero is Ahikar. The name probably means something like My Brother is Precious, or A Brother of Preciousness, or possibly (as Dr. Halper suggests) A Man of Honor. He was grand vizier of Sennacherib, the king of Assyria. Noted for wisdom as for statesmanship, he rose to a position of the highest dignity and wealth. But he had no son. He, accordingly, adopted his infant nephew Nadan, and reared him with loving care. He furnished him with eight nurses, fed him on honey, clothed him in fine linen and silk, and[Pg 19] made him lie on choice carpets. The boy grew big, and shot up like a cedar; whereupon Ahikar started to teach him book-lore and wisdom. Nadan was introduced to the king, who readily agreed to regard the youth as his minister’s son, and made promise of future favors to one in whom his faithful vizier was so much interested. The narrative then breaks off to give in detail the wise maxims which Ahikar sought to instil into Nadan; maxims which have parallels in many literatures, including the rabbinic. Now, Ahikar was grievously mistaken in the character of his nephew. Nadan seemed to listen to his uncle’s wisdom, but all the while considered his monitor a dotard and a bore. The young man began to reveal his true disposition; his cruelties to man and beast were such that Ahikar protested, and offended Nadan by preferring a brother of the latter. Nadan, in revenge, plotted Ahikar’s downfall. By means of forged letters, the old vizier was condemned for treachery, though the executioner, mindful of a similar act of mercy previously shown to himself, secretly spared Ahikar’s life. Nor was the day distant when Sennacherib bewailed the loss of Ahikar’s services. Menacing messages came from Egypt of a kind which it needed an Ahikar to deal with. To the[Pg 20] king’s joy, Ahikar was brought out from his hiding-place; he was again taken to court, and despatched to Egypt.

Here, once more, the narrative is interrupted to tell the details of these Egyptian experiences; how Ahikar satisfied the Pharaoh’s plan of “raising a castle betwixt heaven and earth” by placing boys on the backs of eaglets, and how he countered the puzzling questions of the Egyptian sages. Thus, bidden to weave a rope out of sand, he bored five holes in the eastern wall of the palace, and when the sun entered the holes he sprinkled sand in them, and “the sun’s furrow (path) began to appear as if the sand were twined in the holes.” Then, again, the king of Egypt ordered that a broken upper millstone should be brought in. “Ahikar,” said the king, “sew up for us this broken millstone.” Ahikar, who throughout tells his story in the first person, was not daunted. “I went and brought a nether millstone, and cast it down before the king, and said to him: My lord the king, since I am a stranger here, and have not the tools of my craft with me, bid the cobblers cut me strips from this lower millstone which is the fellow of the upper millstone; and forthwith I will sew it together.” The king laughed. Ahikar scored all[Pg 21] round, and returned home to Assyria laden with the revenues of Egypt.

The third part of the story relates how Nadan was given over to Ahikar. His uncle bound him with iron chains, and “struck him a thousand blows on the shoulders and a thousand and one on his loins”; and while Nadan was thus imprisoned in the porch of the palace door, living on “bread by weight and water by measure,” being compelled willy-nilly to listen, Ahikar proceeded with further lessons in wisdom. “My son,” he says, “he who does not hear with his ears, they make him to hear with the scruff of his neck.” Then there follow many wonderful parables, which (as with the maxims) are similar to those in many literatures. “Thereat,” ends the tale, “Nadan swelled up like a bag, and died. And to him that doeth good, what is good shall be recompensed; and to him that doeth evil, what is evil shall be rewarded. But he that diggeth a pit for his neighbor, filleth it with his own stature. And to God be glory, and His mercy be upon us. Amen.”

What was the original of this story? Nothing in the romance of its incidents, or in the marvel of the spread of it and its maxims and its incorporated fables throughout the folk-lore of humanity, exceeds[Pg 22] the dramatic fact that a large fragment of the tale, in Aramaic, has been found in Egypt among other Jewish papyri of the fifth century before the Christian era! The discovery proves many things, among them two being most significant. First, the Ahikar story is far older than people used to think, and thus the theory that the story of Ahikar was invented to explain the reference in Tobit is once for all disproved. Second, it is at least tenable that the original language was Aramaic and the story Jewish. Here, at all events, we have unquestionable evidence that there must have been among the Jews, nearly 2,400 years ago, an impulse towards that species of popular tale which so deeply affected the literature and poetry of the world. Ahikar, it has even been suggested, is the ultimate source of at least one of the New Testament parables. But, more generally, now that we know that the story of Ahikar was at so early a date current among Jews, we shall be more plausibly able to justify the belief, long ago held by some, that Aesop and other similar collections of fables do truly come from Jewish originals. At any rate, ancient Jewish parallels must have been in circulation.

[Pg 23]

So much for the main results of the discovery. Small details of interest abound. Tobit bade his son: “Pour out thy bread and thy wine on the graves of the righteous (4. 17).” All sorts of changes have been suggested in the text. But the saying is found in the versions of Ahikar, and may be accepted as genuine. It is not necessarily a pagan rite; it has analogy with the funeral meal which long prevailed (and still prevails) as a Jewish custom. Even more interesting seems another detail (of the Syriac Version), which the writers on the books of Ahikar and Tobit have overlooked. When Tobit’s son starts on his quest, his dog goes with him. This is a remarkable touch. Nowhere else in ancient Jewish literature does the dog appear as man’s companion. Nowhere else? Yes, in one other place—in the story of Ahikar. “My son,” says the vizier to Nadan, “strike with stones the dog that has left his own master and followed after thee.” Here we see the dog regarded as a comrade, to be forcibly discouraged if he show signs of infidelity. There must have been a period, therefore, when the olden Jews considered the dog in a light quite other than that which afterwards became usual.

[Pg 24]

Much depends on the mood of the hour. Maimonides, in his Eight Chapters and in the opening section of his Code, acutely remarks that though excess in any moral direction is vicious, nevertheless it may be necessary for a man to practise an extreme in order to bring himself back from the other extreme into the middle path of virtue. Or, to use another phrase of the same philosopher, it is with the soul as with the body. To adjust the equilibrium it is proper to apply force on the side opposite to that which is over-balanced.

Hence it is not surprising to find Philo speaking, as it were, with two voices on the subject of the ascetic life. In the Alexandria of his day there was at one time prevalent a cult of self-renunciation. This cult had special attraction for the young and fashionable. They joined ascetic societies, and, in the name of religion, abandoned all participation in worldly affairs. Philo denounced these boyish millionaire recluses in fine style.[Pg 25] Wealth was not to be abused, true; it was, however, to be used. “Shun not the world, but live well in it,” he cried. Do not avoid the festive board, but behave like gentlemen over your wine. It is all beautifully said, though I have modernized Philo’s terms somewhat. “Be drunk with sobriety” is, however, one of Philo’s very own phrases.

But there is this other side to consider. Alexandria was the very hotbed of luxury and extravagance. People speak about the inequalities of modern civilization, and seem to imagine that it is a new thing for a slum and a palace to exist side by side. But this was exactly the condition in Alexandria at about the beginning of the Christian era. Its busy and gorgeous bazaars, as Mr. F. C. Conybeare has said, blazed with products and wares imported and designed to tickle the palates and adorn the persons of the aristocracy. The same marts had another aspect, narrow and noisy, foul with misery and disease. Wealth and vice rubbed shoulders. Passing through such scenes, Philo might well be driven to see the superiority of asceticism over indulgence. Religion after all is renunciation. Idolatry, said Philo, dwarfs a man’s soul, Judaism enlarges it. Idolatry may be compatible with “strong wine and dainty dishes,” Judaism[Pg 26] prefers a meal of bread and hyssop. In speaking thus, Philo reminds us of the Pharisaic saying: “A morsel with salt shalt thou eat, and water drink by measure, thou shalt sleep upon the ground, and live a life of painfulness, the while thou toilest in the Torah” (Pirke Abot 6. 4.). The association of “plain living” with “high thinking” could not be more emphatically expressed.

Few scholars nowadays doubt the Philonean authorship of the treatise “On the Contemplative Life.” Conybeare, Cohn and Wendland have convinced us all, or nearly all, that the work is really Philo’s. At first sight, no doubt, it was easier to suppose that the book was not his. It seems too cordial in its praise of seclusion, and comes too near the monastic spirit. But the Essenes were Jewish enough, and Philo’s Therapeutae are essentially like the Essenes. “Therapeutae” is a Greek word which literally means “Servants,” and was used to denote “Worshippers of God.” The community of Therapeutae, according to Philo’s description, was settled upon a low hill overlooking Lake Mareotis, not far from Alexandria. We need not go into details. These people adopted a severely simple life, each dwelling alone, spending the day in his private “holy room,” passing the hours[Pg 27] without food, but occupied with the Law, the Prophets, and the Psalms. On the Sabbath, however, they abandoned their isolation, and met in common assembly, to listen to discourses. The “common sanctuary” was a double enclosure, divided by a wall of three or four cubits, so as to separate the women from the men. Women formed part of the audience, “having the same zeal and following the same mode of life,” all practising celibacy. Men and women alike, or at least the most zealous of them, well-nigh fasted throughout the week, “having accustomed themselves, as they say the grasshoppers do, to live upon air; for the song of these, I suppose, assuages the feeling of want.” Their Sabbath meal was held in common, for they regarded “the seventh day as in a manner all holy and festal,” and, therefore, “deem it worthy of peculiar dignity.” The diet, however, “comprises nothing expensive, but only cheap bread; and its relish is salt, which the dainty among them prepare with hyssop; and for drink they have water from the spring.” For, continues Philo, “they propitiate the mistresses Hunger and Thirst, which nature has set over mortal creatures, offering nothing that can flatter them, but merely such useful food as life cannot be supported without. For this[Pg 28] reason they eat only so as not to be hungry, and drink only so as not to thirst, avoiding all surfeit as dangerous and inimical to body and soul.” There is only one relaxation of this severity. No wine is brought to table, but such of the more aged as are “of a delicate habit of life” are permitted to drink their water hot.

Of course, the main tendency of Judaism has been in another direction. Fascinating though Philo’s picture of the community of Therapeutae is, yet it cannot be felt to be a model for ordinary men and women. From time to time, indeed, Jews (like the disciples of Isaac Luria) followed much the same course of life. But most have been unwilling or unable to accept such an ideal as worthy of imitation. It is not at all certain that Philo meant it to be a model; anyhow, as we have seen, he was not always in the same mood. Judah ha-Levi opens the third part of his Khazari with just this distinction between the ideal circumstances, under which the ascetic life may be admirable, and the normal conditions, under which it is culpable. “When the Divine Presence was still in the Holy Land among the people capable of prophecy, some few persons lived an ascetic life in deserts” with good results. But nowadays, continues Judah[Pg 29] ha-Levi, “he who in our time and place and people, ‘whilst no open vision exists’ (I Samuel 3. 1), the desire for study being small, and persons with a natural talent for it absent, would like to retire into ascetic solitude, only courts distress and sickness for soul and body.” The real pietist, he concludes, is not the man who ignores his senses, but the man who rules over them. And this was really the view of Philo also, as we find it in his other works. “The bad man,” he says, “treats pleasure as the summum bonum, the good man as a necessity, for without pleasure nothing happens among mortals.” And so he counsels men to follow the avocations of ordinary life, and not to disdain ambition. “In fine, it is necessary that they who would concern themselves with things divine should, first of all, have discharged the duties of man. It is a great folly to think we can reach a comprehension of the greater when we are unable to overcome the less. Be first known by your excellence in things human, in order that you may apply yourselves to excellence in things divine.” (I take these quotations from C. G. Montefiore’s brilliant Florilegium Philonis, which he ought to reprint.) Philo undoubtedly thought more highly of the contemplative than of the practical life. But in this last[Pg 30] passage he gets very near the truth when he treats the former as only noble when it is based on the latter. It is another aspect of the rabbinic truth that “not study but conduct” is the end of virtue. Philo does not contradict this truth; he offers to our inspection the reverse side of the same shield.

One other point remains. The reader of Philo’s eulogy of the Contemplative Life must be struck by the gaiety of these ascetics. Again and again Philo speaks of their joyousness. They “compose songs and hymns to God in divers strains and measures.” There is nothing morose about them. They build up the edifice of virtue on a foundation of continence, but it is a cheerful devotion after all. Above all is the music, the singing. They have “many melodies” to which they sing old songs or newly written poems. One sings in solo, and then they all “give out their voices in unison, all the men and all the women together” joining in “the catches and refrains,” and “a full and harmonious symphony results.” Philo grows ecstatic. “Noble are the thoughts, and noble the words of their hymn, yea, and noble the choristers. But the end and aim of thought and words and choristers alike is holiness.” And this summary ought to be applicable to every form of Jewish life, to those phases[Pg 31] particularly which reject the excesses of asceticism. “Serve the Lord with joy,” says the hundredth Psalm. True we must have the joy; but we must also not omit the service.

[Pg 32]

“Buffon, the great French naturalist,” as Matthew Arnold reminds us, “imposed on himself the rule of steadily abstaining from all answer to attacks made upon him.” This attitude of dignified silence has often been commended. In one of his wisest counsels, Epictetus recommended his friends not to defend themselves when attacked. If a man speaks ill of you, said the Stoic, you should only reply: “Good sir, you must be ignorant of many others of my faults, or you would not have mentioned only these.” An older than Epictetus gave similar advice. Sennacherib’s emissary, the Rabshakeh, had insolently assailed Hezekiah; “but the people held their peace, for the king’s commandment was: Answer him not” (II Kings 18. 36). On this last text a fine homily may be found in a printed volume of the late Simeon Singer’s Sermons. Mr. Singer illustrated his counsel of restraint by a reference to Josephus. Apion more than 1,800 years ago had traduced the Jews, and Josephus demolished his slanders in “as powerful a piece of controversial literature as is to be found.” “But,” continued the preacher, “note[Pg 33] the irony of the situation. But for Josephus’ reply, Apion would long have been forgotten”; not his name, but certainly the details of his typical anti-Semitism.

This fact, however, does not carry with it the conclusion that Josephus rendered his people an ill-service. There are two orders of Apologetics—the destructive and the constructive. Apologia was originally a legal term which denoted the speech of the defendant against the plaintiff’s charges. As we know abundantly well from the forensic giants of the classical oratory—such as Demosthenes and Cicero—these defences were largely made up of abuse of the other side. Josephus was an apt pupil of these masters. His abuse of Apion leaves nothing to the imagination; everything is formulated, and with scathing particularity. Josephus, it is true, does not seem to have been unjust. Rarely, if ever, has an out-and-out anti-Semite possessed a pleasing personality. Apion was a grammarian of note, but there is much evidence as to his unamiable characteristics. The emperor Tiberius, who knew a braggart when he saw one, called Apion “cymbalum mundi”—a world-drum, making the universe ring with his ostentatious garrulity. Aulus Gellius records his vanity; Pliny accuses[Pg 34] him of falsehood and charlatanism. Josephus was, therefore, not going beyond the facts when he describes him as a scurrilous mountebank. It cannot be denied, moreover, that Josephus scores heavily against his opponent, in solid argument as well as in verbal invective. If the Jewish historian made Apion immortal, it was a deathless infamy that he secured for him.

Certainly, too, Josephus successfully rebuts Apion’s specific libels: the most silly of them, however, antedated Apion and survived him. Tacitus, indeed, seems to have gathered his own weapons out of Apion’s armory, and the Roman repeats the Alexandrian’s libel that in Jerusalem an ass was adored. Those who are interested in this legend of ass-worship may turn to a learned article by Dr. S. Krauss in the Jewish Encyclopedia (vol. ii, p. 222). It has been suggested that the charge arose from a confusion between the Jews and certain Egyptian or Dionysian sects. Others believe that at bottom there lies a misunderstanding of the “foundation-stone,” which, according to talmudic tradition, was placed in the ark during the second temple. The upper millstone was called by the Greeks “the ass,” for its tedious turning resembled an ass’s burdensome activity. But, be the explanation[Pg 35] what it may, the ignorance of a professed expert such as Apion was inexcusable. Yet, most grimly amusing of all Apion’s charges is his repetition of the ever-recurrent libel that the Jews were haters of their fellow-men. Never was there a more perfect illustration of Æsop’s fable of the wolf and the lamb: the hated transformed into the haters! Apion was a fine type of lover. Off to Rome went he, leading the Alexandrian deputation against the Jews (who were championed by Philo), denouncing them to the Cæsar, and using every artifice to incite the imperial animosity. With a heart bitter with hostility, Apion would be a fitting assailant of the “haters of mankind.” It is one of the curiosities of fate that, apart from what Josephus has told of him, Apion is best remembered as the author or transmitter of the story of Androcles and the lion. Apion was neither the first nor the last to have a kindlier feeling for a wild beast than for a fellow-man.

To all the points adduced by Apion Josephus makes a triumphant answer. But his book, termed rather inaptly Against Apion, would not deserve its repute merely because it demolished a particularly malignant opponent. The book really belongs to Apologetic of the second of the two orders[Pg 36] distinguished above. Higher far than the destructive Apologetic is the constructive, which rebuts a falsehood, not by denouncing the liar, but by presenting the truth. “Great is truth, and it will prevail,” is the maxim of an ancient Jewish book (I Esdras 4. 41), a maxim well known in substance to Josephus himself (Antiquities, xi. 3). “Who ever knew truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?” asks Milton. If we once give up confidence in the unconquerable power of truth to win in the end, we have already made an end of human hope. Apologetic, then, of the better type attaches itself to this belief in the inherent virtue of truth. It meets the enemy not with weapons similar to his own, but with a shield impervious to all weapons.

Josephus can sustain this test. Judged by the constructive standard, the treatise Against Apion is a masterpiece. That the Jews were an ancient people with an age-long record of honor, and not a race of recent and disreputable upstarts, Josephus proves by citations from older writers who, but for these citations, would be even less known than they now are. It is not, however, on such arguments that Josephus chiefly rests his case. The external history of the Jews, their glorious participation in the world’s affairs—these are much.[Pg 37] But there is something which is far more. “As for ourselves, we neither inhabit a maritime country, nor delight in commerce, nor in such intercourse with other men as arises from it; but the cities we dwell in are remote from the sea, and as we have a fruitful country to dwell in, we take pains in cultivating it. But our principal care of all is to educate our children well, and to observe the laws, and we think it to be the most necessary business of our whole life to keep that religion that has been handed down to us” (i. 12). This passage is famous both for its denial of the supposed natural bent of Jews to commerce and for its assertion that education is the principal purpose of Jewish endeavor. Josephus, especially in the second book of his Apology, expounds Judaism as life and creed in glowing terms. This exposition is one of our main sources of information for the Judaism of the first century of the Christian era. His picture of life under the Jewish law is a panegyric, but praise is not always partiality. Is it an exaggerated claim that Josephus makes on behalf of Judaism? Surely not. “I make bold to say,” exclaims Josephus in his peroration, “that we are become the teachers of other men in the greatest number of things, and those the most excellent. For what is more excellent[Pg 38] than unshakable piety? What is more just than obedience to the laws? And what is more advantageous than mutual love and concord, and neither to be divided by calamities, nor to become injurious and seditious in prosperity, but to despise death when we are in war, and to apply ourselves in peace to arts and agriculture, while we are persuaded that God surveys and directs everything everywhere? If these precepts had either been written before by others, or more exactly observed, we should have owed them thanks as their disciples, but if it is plain that we have made more use of them than other men, and if we have proved that the original invention of them is our own, let the Apions and Molos, and all others who delight in lies and abuse, stand confuted.”

There were grounds on which contemporary Jews had just cause for complaint against Josephus. He lacked patriotism. But only in the political sense. When Judea was invaded, he did not stand firm in resistance to Rome. But when Judaism was calumniated, he was a true patriot. He stands high in the honorable list of those who championed the Jewish cause without thought of self. Or, rather, such self-consciousness as he displays is communal, not personal. When he pleads his people’s cause, his pettinesses vanish, he is every inch a Jew.

[Pg 39]

Favorable remarks on Hebrew literature are very rare in the Greek writers. One of the most significant is contained in the ninth section of Longinus’ famous treatise on the Sublime.

This Greek author—it will soon be seen why the name Caecilius and not Longinus appears in the title of this article—analyses sublimity of style into five sources: 1) grandeur of thought; 2) spirited treatment of the passions; 3) figures of thought and speech; 4) dignified expression; 5) majesty of structure. Longinus points out that the first two conditions of sublimity depend mainly on natural endowments, whereas the last three derive assistance from art.

It is when illustrating the first of the five elements that our author refers to the Bible. The most important of all conditions of the Sublime is “a certain lofty cast of mind.” Such sublimity is “the image of greatness of soul.” As he beautifully says: “It is only natural that their words should be full of sublimity, whose thoughts are full of majesty.” Longinus, accordingly, refuses to[Pg 40] praise without reserve Homer’s picture of the “Battle of the Gods”:

A trumpet sound

Rang through the air, and shook the Olympian height,

Then terror seized the monarch of the dead,

And, springing from his throne, he cried aloud

With fearful voice, lest the earth, rent asunder

By Neptune’s mighty arm, forthwith reveal

To mortal and immortal eyes those halls

So drear and dank, which e’en the gods abhor.

An impious medley, Longinus terms this, a perfect hurly-burly, terrible in its forcefulness, but overstepping the bounds of decency. (I take these and other phrases from Mr. H. L. Havell’s fine translation). Far to be preferred are those Homeric passages which “exhibit the divine nature in its true light as something spotless, great, and pure.” He instances the lines in the Iliad on Poseidon, though there does not seem much to choose between them and the passage condemned above. But then follows the remarkable paragraph which is the reason why I have chosen Longinus for a place in this gallery: “And thus also the lawgiver of the Jews, no ordinary man, having formed an adequate conception of the Supreme Being, gave it adequate expression in the[Pg 41] opening words of his Laws: God said: Let there be light, and there was light; let there be earth, and there was earth.”

Few will dispute that this passage in Genesis belongs to the sublimest order of literature. It is of the utmost interest that Longinus (whoever he was) should have recognized this fact. Whoever he was—whether the true Longinus, or an unknown rhetorician of the first century. Whether it belongs to the age of Augustus or Aurelian, it is equally noteworthy that the Greek writer should have admitted that the sublime might be exhibited by Moses as well as by Homer. It is quite clear, however, that Longinus did not take his quotation from the Hebrew Bible itself or from the Greek translation. Had he known the Bible, he must have made much fuller use of it. Read his analysis of the sublime quoted above. He could, and would, have illustrated every one of his five conditions from the Bible, had he been acquainted with it. Moreover, the quotation from Genesis is inexact. There is no text: God said: Let there be earth, and there was earth. Obviously, as Théodore Reinach points out, the reference is taken from the sense, not the words, of Genesis 1. 9 and 10. Longinus, therefore, either knew it from hearsay,[Pg 42] or he had found the quotation in the course of his reading.

This latter suggestion was made as long ago as 1711 by Schurzfleisch—how Matthew Arnold would have jibed at a man with such a name commenting on the Sublime! Longinus quotes a previous treatise on the Sublime by a certain Caecilius. His predecessor, says Longinus, wasted his efforts “in a thousand illustrations of the nature of the Sublime,” while he failed to define the subject. Be that as it may, Longinus quotes Caecilius several times, especially for these very illustrations. It is by no means improbable, then, that Longinus’ reference to Genesis was derived from Caecilius, who may have paraphrased from memory rather than have quoted with the Bible before him. Now, Suidas informs us that Caecilius was reported to be a Jew. Reinach (Revue des Études Juives, vol. xxvi, pp. 36-46) has provided full ground for accepting the information of Suidas, which is now generally adopted as true.

Caecilius belonged to the first century of the current era, and, born in Sicily, the offspring of a slave, he betook himself as a freedman to Rome, where he won considerable note as a writer on rhetoric. The Characters of the Ten Orators was[Pg 43] one of his most important books; several histories are ascribed to him; and, as we have seen, he wrote a formal treatise on the Sublime, which gave rise to the better-known work attributed to Longinus. It is not clear whether Caecilius was a born Jew or a proselyte. Probably the theory that best fits the facts is that of Schürer. We may suppose that the rhetorician’s father was brought to Rome as a Jewish slave by Pompey, and was then sold to a Sicilian. In Sicily, the son, who bore the name Archagathos, received a Greek education, and was freed by a Roman of the Caecilius clan. The freedman would drop his own name, and adopt the family name of his benefactor, according to common practice. Schürer offers a very acute, and I think conclusive, argument against the view that Caecilius was a convert to Judaism. A proselyte would have exhibited much more zeal for his new faith. In the works of Caecilius, I may add, his Judaism seems more a reminiscence than a vital factor. It is, on the whole, more likely that he came of Jewish ancestry than that he was himself a new-made Jew. Reinach contends that because he was a proselyte, Caecilius knew the Bible only superficially, and hence arose his misquotation of Genesis. Is that a probable view to take? If we[Pg 44] conceive, with Schürer, that the father of Caecilius, a born Jew, had passed through such vicissitudes, being carried a slave from Syria to Rome, transferred into an alien environment in Sicily, we can well understand that the son would possess but a superficial memory of the Bible. On the other hand, a proselyte would have become a devotee to the Scriptures, the beauties of which had burst upon his mind for the first time. He would not misquote. The chief Jewish translators of the Bible into Greek (apart, of course, from the oldest Alexandrian version) were, curiously enough, proselytes to Judaism. Perhaps it would be too far-fetched to suggest that Caecilius had a particular reason to remember the first chapter of Genesis. His original name, Archagathos, is not a bad translation of the Hebrew “very good” (tob meod) which occurs prominently in the story of the Creation.

Unfortunately, none of the works of Caecilius is preserved. We know him only by a few fragments. Plutarch described him as “eminent in all things,” yet neither Schürer in his earlier editions, nor Graetz in any edition, placed him where he ought to be—to use Reinach’s phraseology—in the phalanx of the great Jewish Hellenists, with Aristobulus, Philo, and Josephus. Caecilius was the[Pg 45] restorer of Atticism in literature, a piquant rôle for a Jew to play. Yet it is a part the Jew has often filled. An instructive essay could be written on the services rendered by Hebrews to the spread of Hellenism, not merely in the ancient world, but also in the medieval and modern civilizations.

[Pg 46]

“The plumage,” writes Herodotus (ii. 73), “is partly red, partly golden, while the general form and size are almost exactly like the eagle.” The Greek historian was describing the phoenix, the fabled bird which lived for five hundred years. According to another version, she then consumed herself in fire, and from the ashes emerged again in youthful freshness. Herodotus likens the phoenix to the eagle, and the reader of some of the Jewish commentaries on the last verse of Isaiah 40 and the fifth verse of Psalm 103 will find references to similar ideas. In particular to be noted is Kimhi’s citation of Sa’adya’s reference to the belief that the eagle acquired new wings every twelve years, and lived a full century. Such fancies easily attached themselves to Isaiah’s phrase and to the psalmist’s words: “Thy youth is renewed like the eagle.” The biblical metaphors, in sober fact, merely allude to the fullness of life, high flight, and vigor of the eagle; there is nothing whatever that is mythical about them.

[Pg 47]

What passes for one of the most famous descriptions of the phoenix is contained in the well-known Greek drama of the Exodus (or rather Exagogê) written by the Jewish poet, Ezekielos. This writer probably flourished rather more than a century before the Christian era. It is commonly supposed that he lived in the capital of the Ptolemies, in Alexandria; but it has been suggested by Kuiper that his home was not in Egypt, but in Palestine, in Samaria. If that be so, it is a remarkable phenomenon. We should not wonder that a Jew in Alexandria composed Greek dramas on biblical themes, with the twofold object of presenting the history of Israel in attractive form and of providing a substitute for the heathen plays which monopolized the ancient theatre. But that such dramas should be produced soon after the Maccabean age in Palestine would imply an unexpected continuity of the influences of Greek manners in the homeland of the Jews. Ere we could accept the theory of a Palestinian origin for Ezekielos, we should need far stronger arguments than Kuiper adduces (Revue des Études Juives, vol. xlvi, p. 48, seq.).

The drama of the Exodus—which was apparently written to be performed—follows the biblical[Pg 48] story with some closeness. We are now, however, interested in a single episode, preserved for us among the fragments of Ezekielos as quoted by Eusebius (Prep. Evangel., ix. 30). A beautiful picture of the twelve springs of Elim and of its seventy palms is followed by a description of the extraordinary bird that appeared there. I take the passage from Gifford’s Eusebius (iii, p. 475). A character of the play, after the Greek manner, is reporting to Moses:

Another living thing we saw, more strange

And marvellous than man e’er saw before,

The noblest eagle scarce was half as large;

His outspread wings with varying colors shone;

The breast was bright with purple, and the legs

With crimson glowed, and on the shapely neck

The golden plumage shone in graceful curves;

The head was like a gentle nestling’s formed;

Bright shone the yellow circlet of the eye

On all around, and wondrous sweet the voice.

The king he seemed of all the winged tribe,

As soon was proved; for birds of every kind

Hovered in fear behind his stately form;

While like a bull, proud leader of the herd,

Foremost he marched with swift and haughty step.

Gifford has no hesitation in accepting the common identification of this bird with the phoenix. Obviously, however, Ezekielos says nothing of the[Pg 49] mythical properties of the bird; he merely presents to us a super-eagle of gorgeous plumage and splendid stature, unnatural but not supernatural. Even the magnificence of the superb bird pictured by Ezekielos is less bizarre than we find it in other authors. Ezekielos’ figures sink into insignificance beside those of Lactantius, who tells us that the bird’s monstrous eyes resembled twin hyacinths, from the midst of which flashed and quivered a bright flame. If Ezekielos really refers to the phoenix, how does it come into the drama at all? Gifford has this note: “There is no mention in Exodus of the phoenix or any such bird, but the twelve palm-trees (phoenix) at Elim may have suggested the story of the phoenix to the poet, just as in the poem of Lactantius. Phoenix 70, the tree is said to have been named from the bird.” The word phoenix has, I may add, a romantic history. It means, literally, Phoenician. Now, certain of the Phoenician race were the reputed discoverers and first users of purple-red or crimson dyes. Hence these colors were named after them, Phoenix or Phoenician. The Greek translation, in Isaiah 1. 18, renders “scarlet” by Phoenician. The epithet was applied equally to red cattle, to the bay horse, to the date-palm and its fruit. It[Pg 50] was also used of the fabulous bird because of its colorings. Gifford supposes, then, that Ezekielos knowing of the palms reached at Elim in the early wanderings of Israel, introduced the bird into his drama. The palms at Elim are indeed described by this very word (Phoenician) in the Greek translation of the Bible which Ezekielos used (Exodus 15. 27). The lulab is also termed phoenix in the Greek of Leviticus 23. 40.

The explanation seems at first sight as plausible as it is clever. But it involves a serious difficulty. For Ezekielos in a previous passage has already described the Phoenician palm-trees at considerable length. The passage has been partly noted above, but it is musical enough to be worth citing as a whole:

See, my Lord Moses, what a spot is found,

Fanned by sweet airs from yonder shady grove;

For as thyself mayest see, there lies the stream,

And thence at night the fiery pillar shed

Its welcome guiding light. A meadow there

Beside the stream in grateful shadow lies,

And a deep glen in rich abundance pours

From out a single rock twelve sparkling springs.

There, tall and strong, and laden all with fruit,

Stand palms threescore and ten; and plenteous grass,

Well watered, gives sweet pasture to our flocks.

[Pg 51]

It seems incredible that the poet who thus describes the palms could then have proceeded to confuse the palms with a bird. Ezekielos does not use the epithet Phoenician in his account of the latter. Thus the theory breaks down. How then is the passage to be explained? As it seems to me, in another and simpler way.

“There is no mention in Exodus of the phoenix or any such bird,” says Gifford. He is right as to the phoenix, but is he right as to “any such bird”? My readers will at once remember the forceful metaphor in the nineteenth chapter of Exodus: “And Moses went up unto God, and the Lord called unto him out of the mountain, saying: ‘Thus shalt thou say to the house of Jacob, and tell the children of Israel: Ye have seen what I did unto the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings, and brought you unto Myself.’” The Mekilta interprets the words to refer to the rapidity with which Israel was assembled for the departure from Egypt, and to the powerful protection which it afterwards enjoyed. But we may also find in the same words the clue to the poet’s fancy. “I bore you on eagles’ wings,” says the Pentateuch. No doubt the phrases of Herodotus, as well as those of Hesiod, were familiar to Ezekielos. With these[Pg 52] in mind, he introduced a super-eagle, figuratively mentioned in the book of Exodus, and gave to it substance and life. He personified the metaphor. It would be a perfectly legitimate exercise of poetical license. The description is bizarre. But it is not mythological, and it has little to do with the phoenix of fable.

[Pg 53]

Though all Israelites are brothers, they do not admit that they are all members of the same family. “Of good genealogy” is the proudest boast of the modern, as it was of the talmudic, Jew. It is, accordingly, not wonderful that we find our notabilities from Hillel to Abarbanel claiming, or having assigned to them, descent from the Davidic line. Of Sherira the same was said. He ruled over the academy in Pumbeditha during the last third of the tenth century. A scion of the royal house of Judah, he was rightful heir to the exilarchy, yet preferred the socially lower, but academically higher, office of Gaon. The Gaon’s sway was religious and scholastic; the exilarch’s secular and political. Sherira’s ancestry might have given him the latter post, but for the former it was intrinsic, personal worth which qualified him and his famous son Hai. Who shall deny that he made a worthy choice?

Sherira’s fame rests less on his general activities as Gaon than on the Letter which he wrote about[Pg 54] the year 980, in response to questions formulated by Jacob ben Nissim, of Kairuwan. One of these questions retains, and will ever retain, its fascination, although the answer has now no vital interest. Historically the Letter has other claims to continued study. To quote Dr. L. Ginzberg (Geonica, i, p. 169): “The lasting value of his epistle for us lies in the information Rabbi Sherira gives about the post-Talmudic scholars. On this period he is practically the only source we have.” Without Sherira, the course of the traditional development would be a blank for a long interval after the close of the Talmud. “But,” continues Dr. Ginzberg, “we shall be doing Rabbi Sherira injustice if we thought of him merely as a chronologist.” And this same competent scholar launches out into the following eulogy of the Gaon: “The theories which he unfolds ... regarding the origin of the Mishnah ... and many other points important in the history of the Talmud and its problems, stamp Rabbi Sherira as one of the most distinguished historians, in fact, it is not an exaggeration to say, the most distinguished historian of literature among the Jews, not only of antiquity, but also in the middle ages, and during a large part of modern times.”

[Pg 55]

This must suffice for the general estimate of Sherira’s work. What is of more striking interest is just the one question, the answer to which does not much matter. As Dr. Neubauer formulated the question put to Sherira, it ran thus: “Was the Mishnah transmitted orally to the doctors of the Mishnah, or was it written down by the compiler himself?” Judah the Prince, we know, compiled the Mishnah, but did he leave it in an oral or a documentary form? Was it memorized or set down in script? The answer does not much matter, as I have said, for sooner or later the Mishnah was written out, and it is not of great consequence whether it was later or sooner. And it is as well that Sherira’s answer matters little, for we do not know for certain what Sherira’s answer was! Most authorities nowadays believe that the Gaon pronounced in favor of the written compilation; but this was not always the case. For Sherira’s Letter was current in two versions which recorded opposite opinions. In the French form the oral alternative was accepted, but the Spanish text adopted the written theory. Which was the genuine view of Sherira? There are many reasons for preferring the Spanish version. As Dr. Neubauer points out, “books, letters, and responsa coming from the[Pg 56] East, reached Spain and Italy before they came to France and Germany.” Hence the Spanish text is more likely to be primitive; while, when the Letter was carried further, it might easily have been altered so as to fall in with the talmudic prohibition against putting the traditional laws into writing. It will, again, come as a surprise to some to note another argument used by Dr. Neubauer in favor of the Spanish text. “From the greater consistency of the Aramaic dialect in the Spanish text, a dialect which, as we know from the Responsa of the Geonim, they used in their writings, it may be concluded that this (the Spanish) composition is the genuine one.” The Gaonate was able to maintain a pretty thorough Jewish spirit without insisting on the use of Hebrew as the only medium of salvation. Actually Dr. Neubauer saw in the more consistent Aramaic of the Spanish text an indication of its superior authenticity over what may be called the French text!

But all these points are secondary. The real interest lies in this whole conception of an oral book. Tradition necessarily must be largely oral; ideas, maxims, and even defined rules of conduct not only can be, they must be, transmitted by word of mouth. But is there any possibility that a whole,[Pg 57] elaborate book, or rather series of six books, should be put together and then trusted to memory? A new turn to the discussion was given by Prof. Gilbert Murray’s Harvard Lectures on “The Rise of the Greek Epic.” To him the Iliad of Homer appears in the guise of a “traditional book.” No doubt the Mishnah belongs to a period separated from Homer by well-nigh a millennium. But the phrase holds. A book can be the outcome of tradition, can be carried on by it, expanded and elaborated, just as much as an oral code or history or poem. When, then, we speak of a traditional book, it does not necessarily mean that the book was not written down. The written words become precious, and the fact that they are written does not of itself spell finality or stagnation. There never was any danger of such an evil result until the age of printing and stereotyping. Nor can we conceive of a traditional book as the work of one mind. Judah the Prince neither began nor ended the chain of tradition because he wrote the Mishnah. There had been Mishnahs before him, just as there were developments of law after him.

Yet, on the other hand, it is not incredible that Judah the Prince’s traditional book remained an unwritten book. It is improbable, but not at all[Pg 58] impossible. A modern lawyer of the first rank must hold in his mind quite as many decisions and principles as are contained in the Mishnah. Macaulay could repeat by heart the whole of the Paradise Lost and much else. Many a Talmudist of the present day must remember vast masses of the traditional Halakah. Before the age of printing, before copies of books became common and easily accessible, scholars must have been compelled to trust to their memory for many things for which we can turn to our reference libraries. When Maimonides compiled his great Code, he must have done a good deal of it from memory. Not that men’s memories are worse now than they were. But we are now able to spare ourselves. It is not a good thing to use the memory unnecessarily. It should be reserved for essentials. What we can always get from books we need not keep in mind. Besides, in olden times men remembered better not because they had better memories, but because they had less to remember.

On the whole, however, it is safer to conclude that Judah the Prince made a contribution to written literature, that he set down at a particular moment (about 200 C.E.) the traditional book which had been writing itself for many decades,[Pg 59] partly by the minds of the Rabbis, partly by their pens. He started the book on a new career of humane activity. Sherira and the Geonim were what they were because Judah the Prince was what he was. This is the essential fact about tradition. The more we give of our best to our age, the more chance is there for all future ages to transmit of their best to posterity.

[Pg 60]

A dictionary may seem an intruder in this gallery. The present series of cursory studies clearly is not concerned with works of technical scholarship. But the dictionary by Nathan, son of Jehiel, earns inclusion for two reasons. First, because when one surveys the expressions of the Jewish spirit, it is impossible to draw a line between learning and literature. Secondly, quite apart from this intimate general connection between the scholar and the man of letters, the dictionary of Nathan belongs specially to the course of culture. Among the Christian Humanists who, at the period of the Reformation, promoted the enlightenment of Europe, were not lacking appreciators of the services rendered to enlightenment by Nathan’s Aruk (to give it its Hebrew title).

Nathan (born about 1035 and died in 1106) was an itinerant vendor of linen wares in his youth. He belonged to the family Degli Mansi, an Italian rendering of the Hebrew Anaw or Meek. The latter is still a rare but familiar Jewish surname. Legend has it that the founder of the Degli Mansi[Pg 61] house was one of the original settlers introduced into Rome by Titus. At all events, the family had a long record of literary fame. Like many another merchant-traveller of the Middle Ages, Nathan made use of his earlier wanderings (as he did of his later journeys), to sit at the feet of all the Gamaliels of his age. Many and various were his teachers. He abandoned business when he returned to Rome after his father’s death. He tells us how he made the arrangements for the interment, and here straightway we perceive that his Aruk is no ordinary dictionary. For in the poem, which he appends as a kind of retrospective preface, he records how sternly he had ever disapproved of the expenses incurred at Jewish funerals in his time. Protests were vain, but example was more fruitful. In place of the double cerements in common use, he laid his father in his tomb with a single shroud. This, he records, became the model for others to imitate. Death was a frequent visitor in his abode. Of his four sons, none survived the eighth year, one not even his eighth day. Grief did not crush him. “I found sorrow and trouble, then I called on the name of the Lord,” he quotes. He proceeded to erect a house of another kind. Not of flesh and blood, but vital with the spirit of[Pg 62] Judaism, his Aruk is a monument more lasting than ten children.

In what, then, does the importance of the dictionary consist? It is, of course, primarily, what Graetz terms it, “a key to the Talmud.” No doubt there were earlier compilations of a similar nature, but Nathan’s book was the most renowned of its own age, and became the basis of every subsequent lexicon to the Talmud. Gentile and Jew, from Buxtorf to Dalman and from Musafia to Jastrow, employed it as the ground-work of their own lexicographical research. Moreover, it was again and again edited and enlarged; but we are not dealing here with bibliographical details. Suffice it to mention the final edition by Alexander Kohut. Kohut began his Aruch Completum while a European Rabbi in 1878, and finished it in New York in 1892. It is remarkable that two of the best modern lexicons to the Talmud (Kohut’s in Hebrew and Jastrow’s in English) both emanate from America.

Besides its value for understanding the text of the Talmud, Nathan’s Aruk has earned other claims to fame. Nathan’s dictionary marks an epoch, says Vogelstein. Consider the situation. The centre of Jewish authority was leaving Babylon. The last[Pg 63] of the great literary Geonim—or Excellencies, as the heads of the Babylonian schools were called—died in the year 1038. Europe was replacing Asia as the scene of Jewish life. Was the old tradition to die? At the very moment of the crisis, three men arose to prevent the chain snapping. They were almost contemporaries, and their works supplemented each other. There was the Frenchman Rashi—the commentator; the Spaniard al-Fasi—the codifier; and the Italian Nathan—the lexicographer. Between them they re-established in Europe the tradition of the Gaonate. The Babylonian schools might come and go; they might for a time enjoy hegemony, and then fall into decay; but the Torah must go on forever!

The manner in which this dictionary carried on the tradition is easily told. Much of the lore it contains, explanations of words and of things, must have been orally acquired in direct conversations with those who were personally linked with the older régime. It is again full of quotations of the decisions and customary lore of the Babylonian schools. If on this side the Aruk has almost played out its part for us, it is not because those decisions and customs are less interesting to us than they were to our fathers. But we are now in possession of very[Pg 64] many of the gaonic writings in their original. We have recovered several of the sources from which Nathan drew. The Egyptian Genizah—that wonderfully preserved mass of the relics of Hebrew literature—has yielded its richest harvest just in this field. We are getting to know more about the thought and manner of life of the eighth to the eleventh centuries than we know about our own time. But for a long interval men’s knowledge of those centuries was largely derived from the Aruk. As a source of information it is not even now superseded. There still remain authors whose names and works would be lost but for Rabbi Nathan’s quotations.

Another aspect of the book which makes it so valuable for the history of culture among the Jews is the number of languages which Nathan uses. What an array it is! Kohut enumerates (besides Hebrew and Aramaic) Latin, Greek, Arabic, Slavonic dialects, Persian, and Italian and allied speeches. Nathan cannot have known all these languages well. He certainly had little Latin and less Greek, but he repeated what he had heard from others or read in their books. It is remarkable, indeed, how well the sense of Greek words was transmitted by Jewish writers who were ignorant[Pg 65] of Greek. They often are not even aware that the words are Greek at all; they suggest the most impossible Semitic derivations; but they very rarely give the meanings incorrectly. This applies less to the Italian than to the German Jewish scholars. I mean that the former had, on the whole, a more intimate acquaintance with the classical idioms. In the case of Nathan’s Aruk the languages cited do imply a wide and varied culture. Most interesting is Nathan’s free use of Italian. Just as we learn from the glosses in Rashi’s commentaries that the Jews of northern France spoke French, so we gather from Nathan’s dictionary that the Jews of Rome must have used Italian as the medium of ordinary intercourse.

Nathan’s Aruk, while, as we have seen, it was a link between the past and his present, was also part of the chain binding his present to the future. Nathan records the tradition as he received it, but he also points forward. Take one of his remarks, which is quoted by Güdemann. There is much in the Talmud on the subject of magic, and Nathan duly explains the terms employed. But he says: “All these statements about magic and amulets, I know neither their meaning nor their origin.” Does the reader appreciate the extraordinary significance[Pg 66] of the statement? Nathan, the bearer of tradition, yet sees that the newer order of things also has its claims. Tradition does not consist in the denial of science. And so, though a Gaon like Hai had a pretty considerable belief in demonology, Nathan cautiously expresses his scepticism. Even more emphatically, a little later, Ibn Ezra frankly asserted that he had no belief in demons. It may be questioned whether this enfranchisement from demonological conceptions could be matched in non-Jewish thought of so early a date. The Aruk assuredly points forwards as well as backwards.

And all this we derive from a dictionary! The Aruk obviously belongs to culture as well as to philology—if the two things really can be separated. The study of words is often the study of civilization. Max Müller maintained that if you could only tell the real history of words you would thereby be telling the real history of men. He carried the idea absurdly far; but Nathan’s Aruk is a striking instance of at least the partial truth of the great Sanskrit scholar’s contention.

[Pg 67]

Tatnu has a weird sound. But it is not the title of a fetich; it is not a personal name; it is not even a word at all. It is, indeed, a figure; but the figure it stands for is numerical. The letters which compose the Hebrew combination Tatnu amount to 856 (taw = 400; taw = 400; nun = 50; waw = 6). It represents a date. To transpose it from the era anno mundi to the current era, it is necessary to add 240. This brings us to 1096, the year of the First Crusade.

If Tatnu is no person, neither do its sorrows form a book. They constitute rather a library of narratives, small in size but great in substance. They are hardly literary, yet they belong to the masterpieces of literature. Their story is recorded with few ornaments of style, but their simple, poignant directness is more effective than rhetoric. Martyrdom needs no tricks of the word-artist; it tells its own tale.

The Historical Commission for the History of the Jews in Germany had but a brief career, though it has revived under the newer title of the Gesamtarchiv.[Pg 68] The Commission aimed at two ends: to introduce to Jewish notice information about the Jews scattered in Christian sources, and to make accessible to Christians facts about themselves contained in Jewish authorities. From 1887 to 1898, the Commission was actively at work, and among the books it published were two valuable volumes dealing with the martyrologies of the Jews. For the first time, these narratives were adequately edited. The pathetic records of sufferings endured in the Rhine-lands and elsewhere stand, for all time, ready to the hand of the historian.

The first moral to be extracted from these records is the certainty that war is an evil. No one can dispute the noble motives of the crusaders. The unquenchable enthusiasm which led high and low to forsake their homes and engage in eastern adventures, the unflinching courage with which the dangers of battle and the hardships and privations of wearisome campaigns were borne, the transparent singleness of purpose which animated many a soldier of the cross—all these factors tend to cover the sordid truth with a glamor of idealism and chivalry. But the wars of the Crusades were tainted with savagery, and if so what wars can be clean? The barbarities inflicted in Europe on the[Pg 69] Jews color with a red and gruesome haze the heroisms performed against Mohammedans in Asia. War, it is said, brings to the fore some of the finest qualities of human nature. Exactly, but the war of man against nature calls for the exercise of the same qualities. The heroism of the coal-mine is as great from every point of view as the heroism of the battlefield. And the battlefield from first to last is the scene of human nature at its lowest as well as at its highest. Nor is the battlefield the whole of war. Those who persuade themselves that war, though an evil, is not an unmixed evil, will find in the Sorrows of Tatnu and allied books a rather useful corrective to their complacency.

When in 1913 I re-read Neubauer and Stern’s volume (1892) and Dr. Salfeld’s magnificent edition of the Nuremberg Martyrology (1898)—it was not long before the outbreak of the European war—I was so moved that I sent a donation to the Peace Society. Quite a nice thing to do, some will urge, but is it worth while, for such an end, to rake up these miserable tales? The whole of this class of literature was long neglected because of a similar feeling. Stobbe, who rendered such conspicuous service to the Jewish cause, was actuated by the identical sentiment, when he wrote that it would be[Pg 70] “a grim and a thankless task” to enter fully into the sufferings of the Jews in the medieval period. But the Commission above referred to took another view; it printed the texts and circulated them in the completest detail. Now it depends entirely on the purpose with which such remorseless crimes are as remorselessly dragged to the light of day. If the desire is to revive bitterness, then it is a foul desire which ought to be crushed. And not only if this be the desire, if it prove to be the consequence, if as a result of such re-publication animosity is rekindled, then the re-publication is to be condemned. But in the case of the Sorrows of Tatnu, neither the motive nor the consequence is of this character. Salfeld gave us his edition of these monuments of the Jewish tribulations, “den Toten zur Ehre, den Lebenden zur Lehre”; to honor the dead, to inspire the living. Neither he nor any other Jewish writer wishes to play the part of Virgil’s Misenus, who was skilled in “setting Mars alight with his song” (Martem accendere cantu). The heroism of the sufferers, not the brutality of the aggressors, is the theme of the Jewish historian who deals with the Sorrows of Tatnu and of many another year; not the lurid glow of the bloodshed, but the white light of the martyrdom; not the pain, but the triumph[Pg 71] over it; not the infliction, but the endurance unto and beyond death. These aspects of the story ought, indeed, to be told and retold “to honor the dead, to inspire the living.”

Closely connected with this thought is another. The Commission, be it remembered, was a Jewish body, appointed by the Deutsch-Israelitische Gemeindebund in 1885. But Graetz was not appointed a member. (Comp. the Memoir in the Index Volume of Graetz’s History of the Jews, Philadelphia, 1898, p. 78). Why did the leaders of Berlin Jewry ignore Graetz, the man who, above all others, had stirred the conscience of Europe by his vivid pictures of the medieval persecution so poignantly illustrated in the Sorrows of Tatnu? That was the very ground for excluding Graetz. There is no doubt but that Graetz’s method of writing Jewish history was somewhat roughly handled at about the period named. This assault came from two sides. Treitschke, the German and Christian, attacked Graetz as anti-Christian and anti-German, and used citations from Graetz to support his propaganda of academic anti-Semitism. Certain Jews, on the other hand, felt that, though Treitschke was wrong, Graetz was too inclined to regard the world’s history from a partisan and[Pg 72] sectarian point of view. Whether or not this was the reason for the exclusion of Graetz from the Commission, what is interesting to note is the fact that the Commission, when it came to grips with the records, produced quite as emphatic an exposure of the medieval persecution as Graetz himself. It is, in brief, impossible for any student of the records to do otherwise.

The Commission included among its members some (conspicuously L. Geiger) who subsequently proved to be the strongest anti-Zionists. The duty and the desire to honor the dead for the inspiration of the living are not restricted to any one section of our community. There is nothing nationalistic or anti-nationalistic in our common sympathy with the Sorrows of Tatnu, in our common impulse to turn those sorrows to vital account in the present. In a soft age it is well to be reminded that Judaism is above all synonymous with hardihood. Thus these memories are cherished because “the blood of the martyr is the seed of the church.” This magnificent thought originated with Tertullian, though the precise phrase is not his. The idea conveyed by these oft-quoted words must be carefully weighed, lest we make of it a half-truth instead of a truth. No institution is founded on its dead, it is[Pg 73] its living upholders who alone can support it. We tell these stories of the dead, because, in their day, they, living, recognized that to save themselves men must sometimes sacrifice themselves. To pay, as the price of life, the very thing that makes life worth living is an ignoble and futile bargain. The Sorrows of Tatnu, regarded as the expression of this conviction, are converted from an elegy into a pæan. But the song is discordant unless we, who sing it, are also prepared to act it, in our own way and in our own different circumstances. Den Toten zur Ehre, den Lebenden zur Lehre.

[Pg 75]

[Pg 77]

PART II

Authors are not invariably the best critics of their own work. Was Solomon Ibn Gebirol, who was born in Andalusia, perhaps in Malaga, in the earlier part of the eleventh century, just when he regarded as the crown of all his writings the long poem which he called the “Royal Crown” (Keter Malkut)? Some will always doubt his judgment. Plausibly enough, preference may be felt for several of his shorter poems, particularly “At Dawn I Seek Thee” (which Mrs. R. N. Salaman translated for the Routledge Mahzor) or “Happy the Eye that Saw these Things” (paraphrased by Mrs. Lucas in her Jewish Year).

Ibn Gebirol was, however, sound in his opinion. One line in the “Royal Crown” is the finest that he, or any other neo-Hebraic poet, ever wrote. Should God make visitation as to iniquity, cries Ibn Gebirol, then “from Thee I will flee to Thee.” Nieto interpreted: “I will fly from Thy justice to Thy clemency.” But the line needs no interpretation. In his Confessions (4. 9) Augustine says:[Pg 78] “Thee no man loses, but he that lets Thee go. And he that lets Thee go, whither goes he, or whither runs he, but from Thee well pleased back to Thee offended?” A great passage, but Ibn Gebirol’s is greater. It is a sublime thought, and its author was inspired. He must have felt this when he named his poem. For the title comes from the Book of Esther, and the Midrash has it that, when the queen is described as donning the robes of royalty, the Scripture means to tell us that the holy spirit rested on her.

It has been said (among others, by Sachs and Steinschneider) that the “Royal Crown” is substantially a versification of Aristotle’s short treatise “On the World.” This is in a sense true enough. The “Royal Crown” is largely physical, and to modern readers is marred by its long paragraphs of obsolete astronomical conceptions, which go back, through the Ptolemaic system, to Aristotle. Moreover, Aristotle, in his treatise cited above, anticipated Ibn Gebirol in the motive with which he directed his ancient readers’ attention to the elements and the planets. “What the pilot is in a ship, the driver in a chariot, the coryphæus in a choir, the general in an army, the lawgiver in a city—that is God in the world” (De Mundo, 6).[Pg 79] This saying of Aristotle is indeed Ibn Gebirol’s text. But the Hebrew poet owes nothing else than the skeleton to his Greek exemplar. The style—with its superb application of biblical phrases, a method which in al-Harizi is used to raise a laugh, but in Ibn Gebirol at every turn rouses reverence—is as un-Greek as are the spiritual intensity of thought and the moral optimism of outlook.

Our Sephardic brethren were wiser than the Ashkenazim in their selections for the liturgy. Why the Ashkenazim have neglected Ibn Gebirol and ha-Levi in favor of Kalir will always remain a mystery. The Sephardim did not include all that they might have done from the Spanish poets, but the Ashkenazic Mahzor has suffered by the loss of such masterpieces as Judah ha-Levi’s “Lord! unto Thee are ever manifest my inmost heart’s desires, though unexpressed in spoken words.” But most of all is our loss apparent in the omission of the “Royal Crown” from the Kol Nidre service. In Germany, the Ashkenazim have been better advised. The Rödelheim Mahzor and the Michael Sachs edition both include the poem in their volumes for the Atonement Eve. Sachs (unlike de Sola) omits the astronomical sections in his fine German rendering, and wisely, for the “Royal Crown”[Pg 80] notably illustrates the Greek epigram: “part may be greater than the whole.” On the other hand, in his famous Religiöse Poesie der Juden in Spanien, Sachs includes the omitted cosmology. There is a difference between our attitudes to a poem as a work of literature and to the same poem as an invocation or prayer. Sachs the scholar refused to mutilate the “Royal Crown,” but as a liturgist (though he printed all the Hebrew) he took liberties with it.