The Project Gutenberg eBook of The life savers of Cape Cod, by J. W. Dalton

Title: The life savers of Cape Cod

Author: J. W. Dalton

Release Date: March 29, 2023 [eBook #70407]

Language: English

Produced by: Steve Mattern, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

Transcriber’s Note

This book has no Table of Contents, no List of Illustrations, and no Index.

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

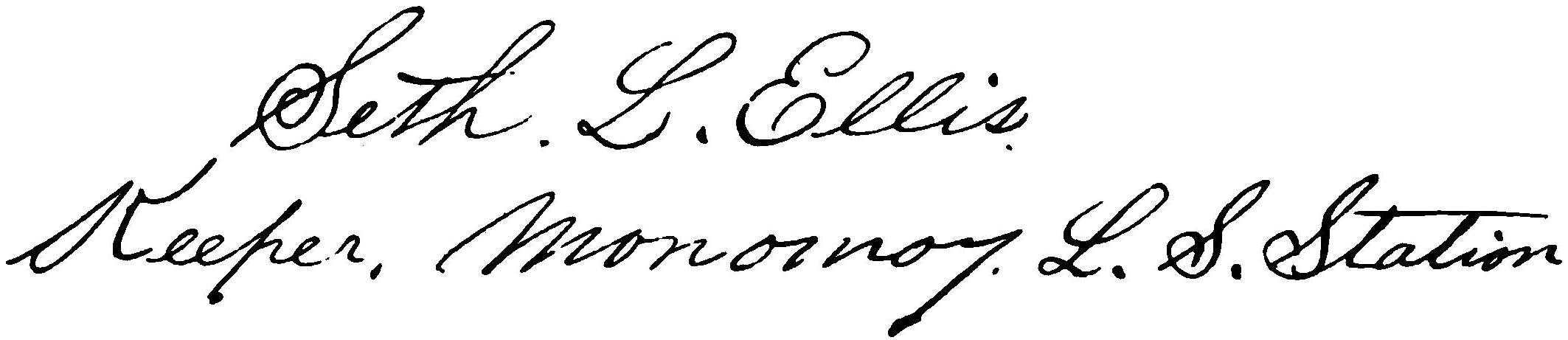

BY

J. W. DALTON

Sandwich, Massachusetts

Copyright, 1902, by J. W. Dalton

The Barta Press, Printers

Boston, Mass.

5

Cape Cod’s life savers are known the world over for their intrepid, enduring bravery, gallant deeds, and the success in rescuing life that they have achieved in their hazardous duties along the most dangerous winter coast of the world.

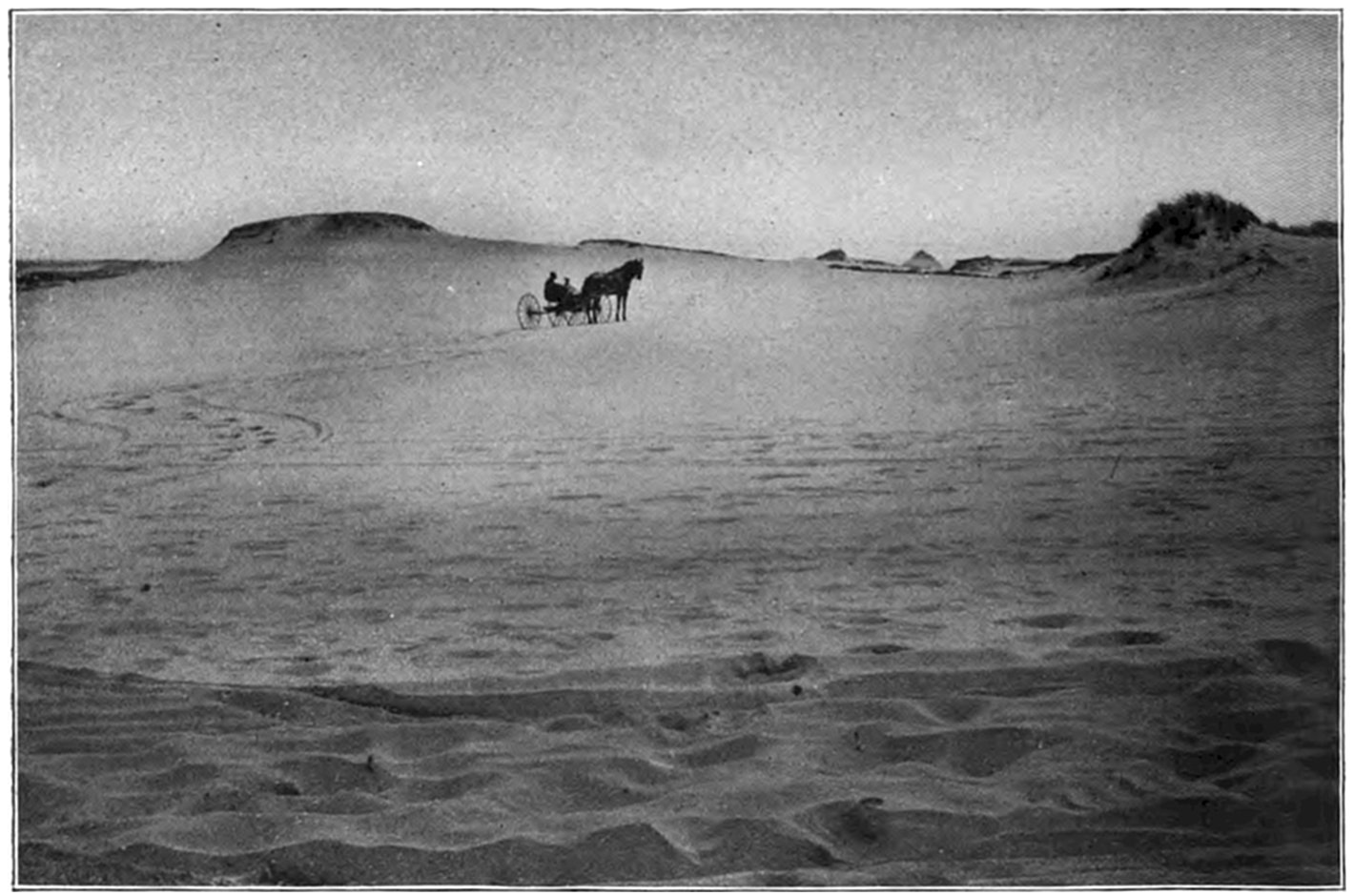

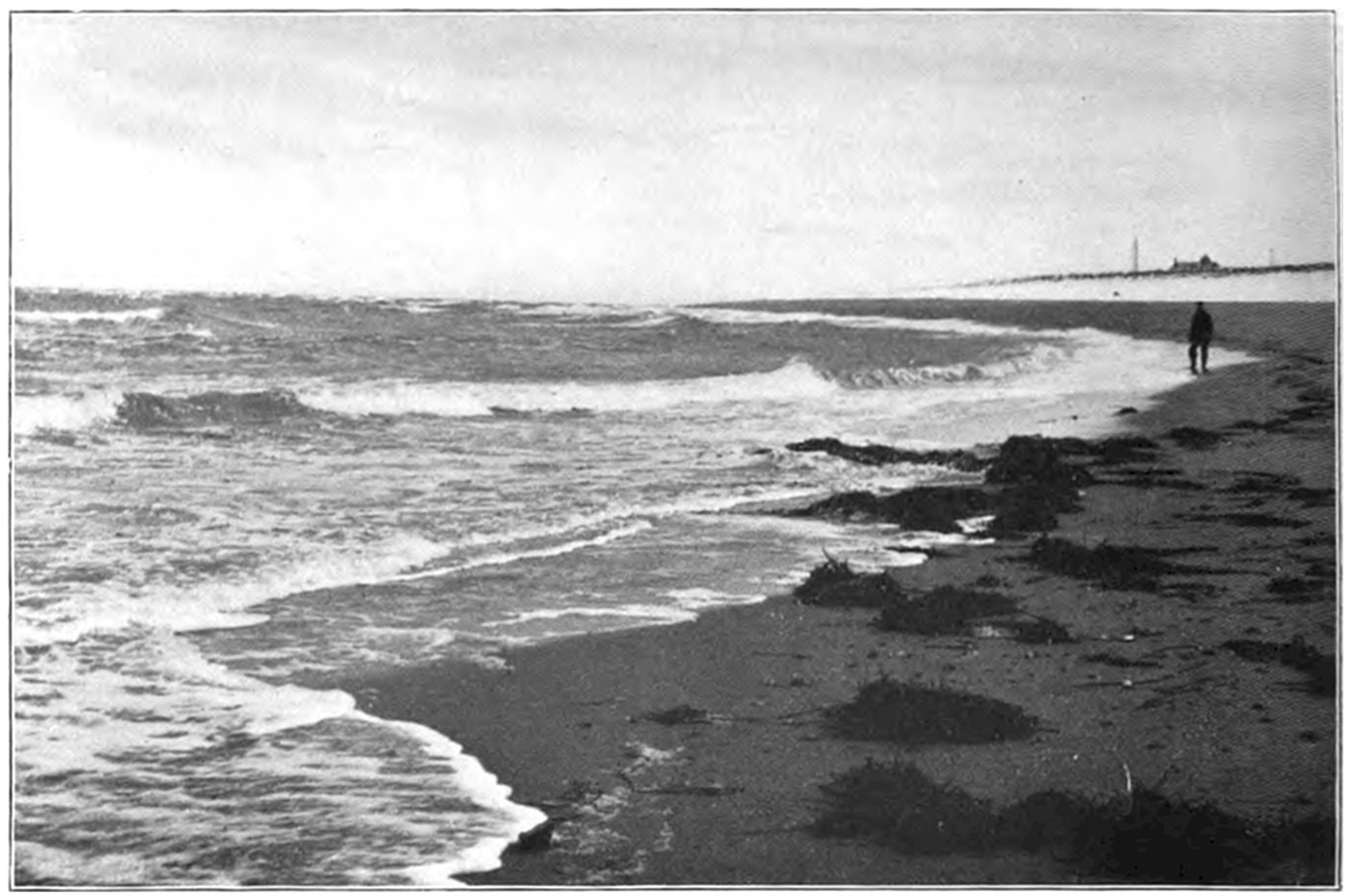

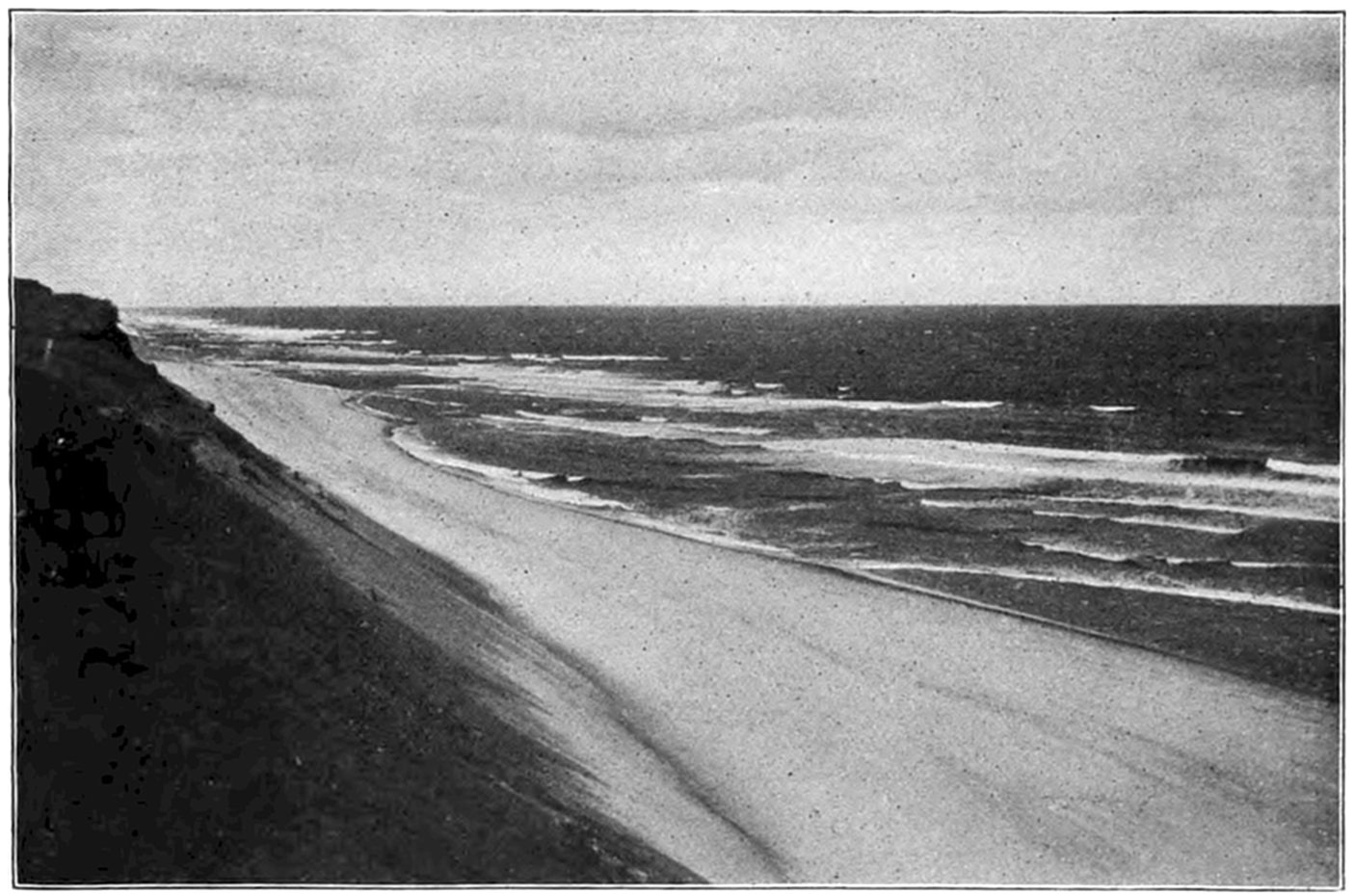

Every night, along the shores of Cape Cod, from Wood End at Provincetown to Monomoy at Chatham, in moonlight, starlight, thick darkness, driving tempest, wind, rain, snow or hail, an endless line of life savers steadily march along the exposed beaches on the outlook for endangered vessels.

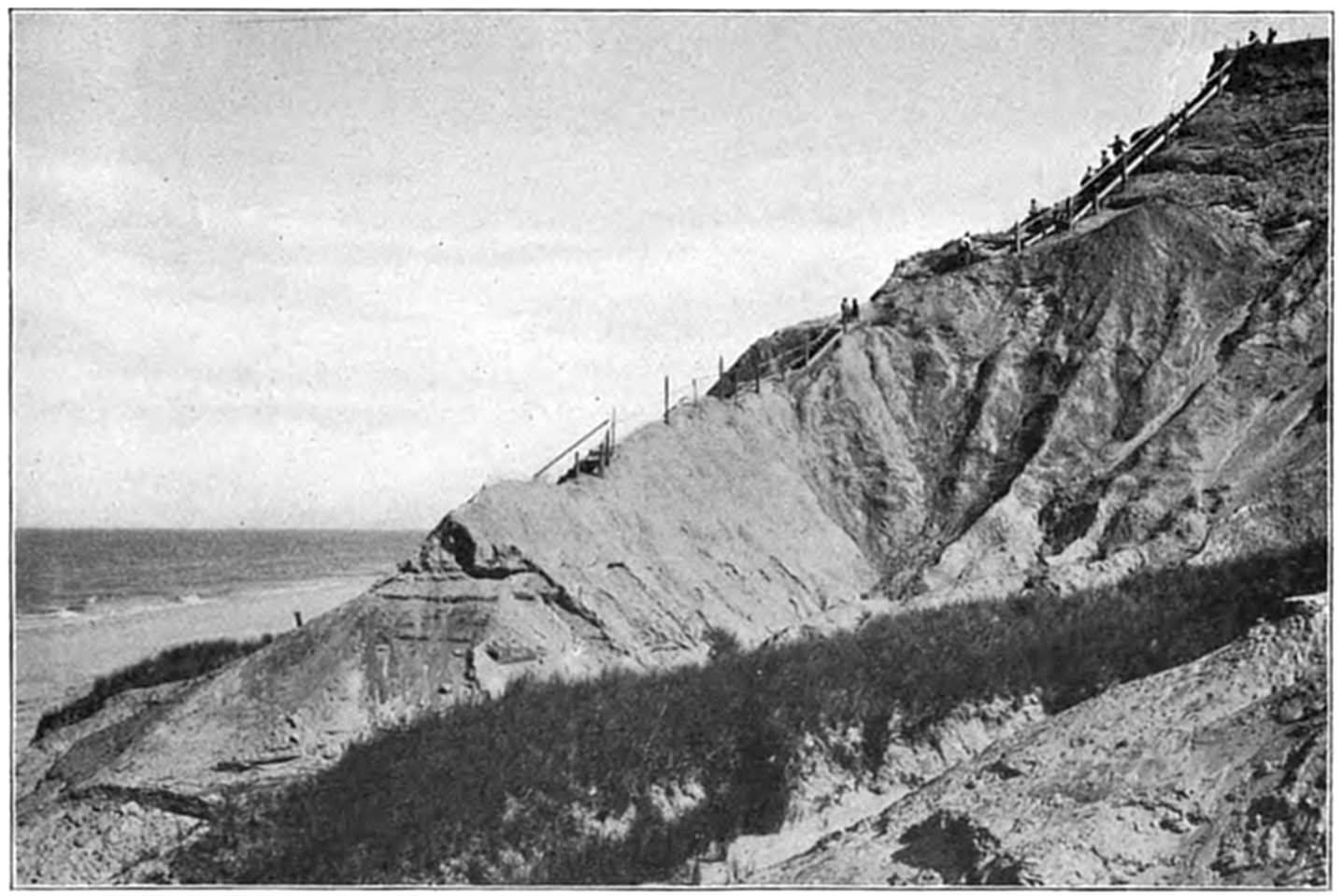

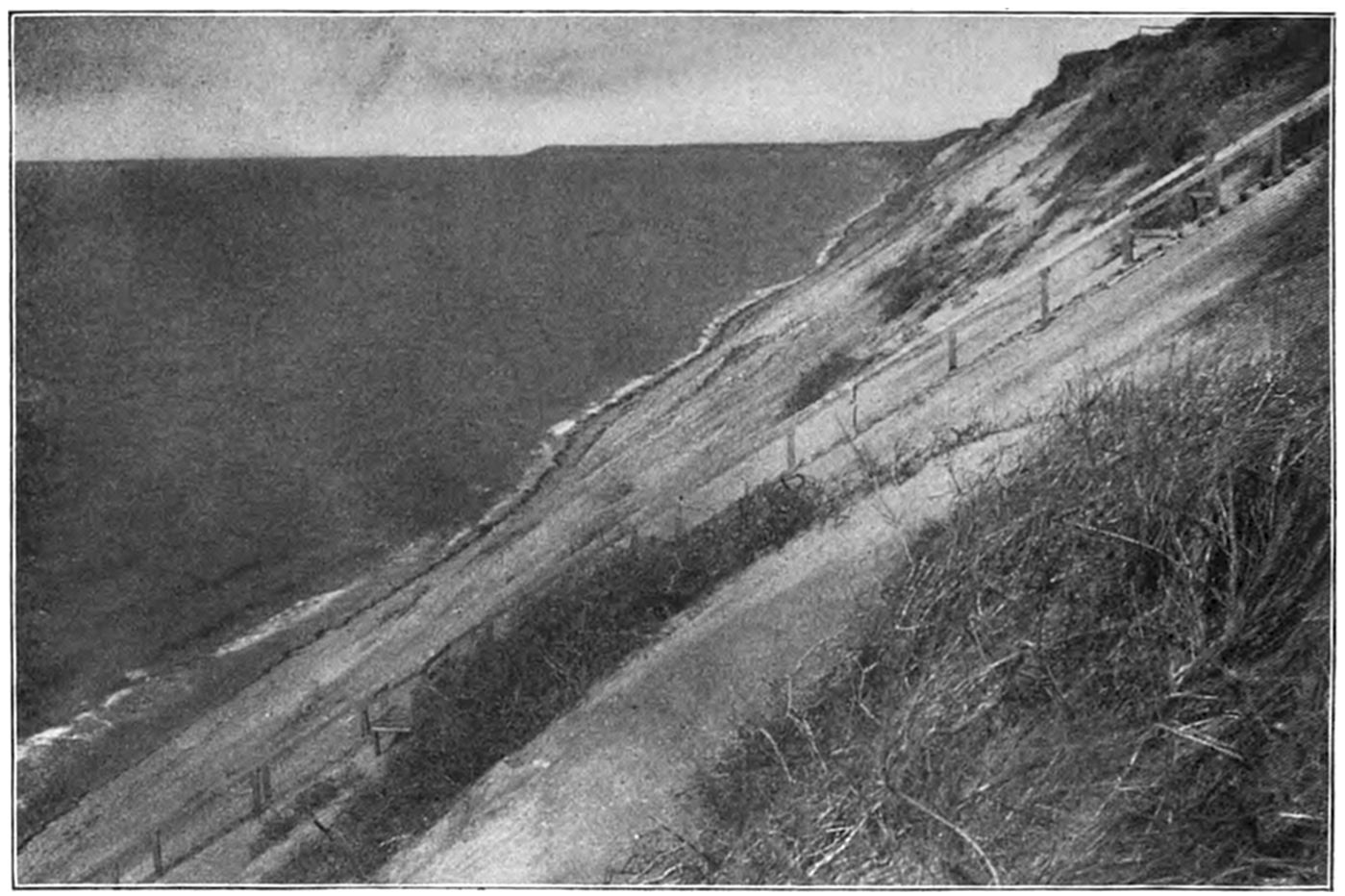

The life saver’s work is always arduous, often terrible. Quicksands, the blinding snow and cutting sand storms, the fearful blasts of winter gales, are more often than not to be encountered on their journeys; storm tides, flooding the beaches, drive them to the tops or back of the sand dunes, where they plod along their solitary patrol with great peril.

When a ship is in distress, whatever way the crew is rescued by the life savers, the task involves great hazard of their lives, hours of racking labor, protracted exposure to the roughest weather conditions, and a mental and bodily strain under the spur of exigency and the curb of discipline that exhaust even these hardy fearless coast guardians. In cases of boat service tremendous additional peril and hardships are added.

Death has often claimed the life saver at his work. Or as a result of his gallant, unselfish toil for the safety of others in the rigors of6 winter, one life saver after another is compelled to retire from the service on account of shattered health.

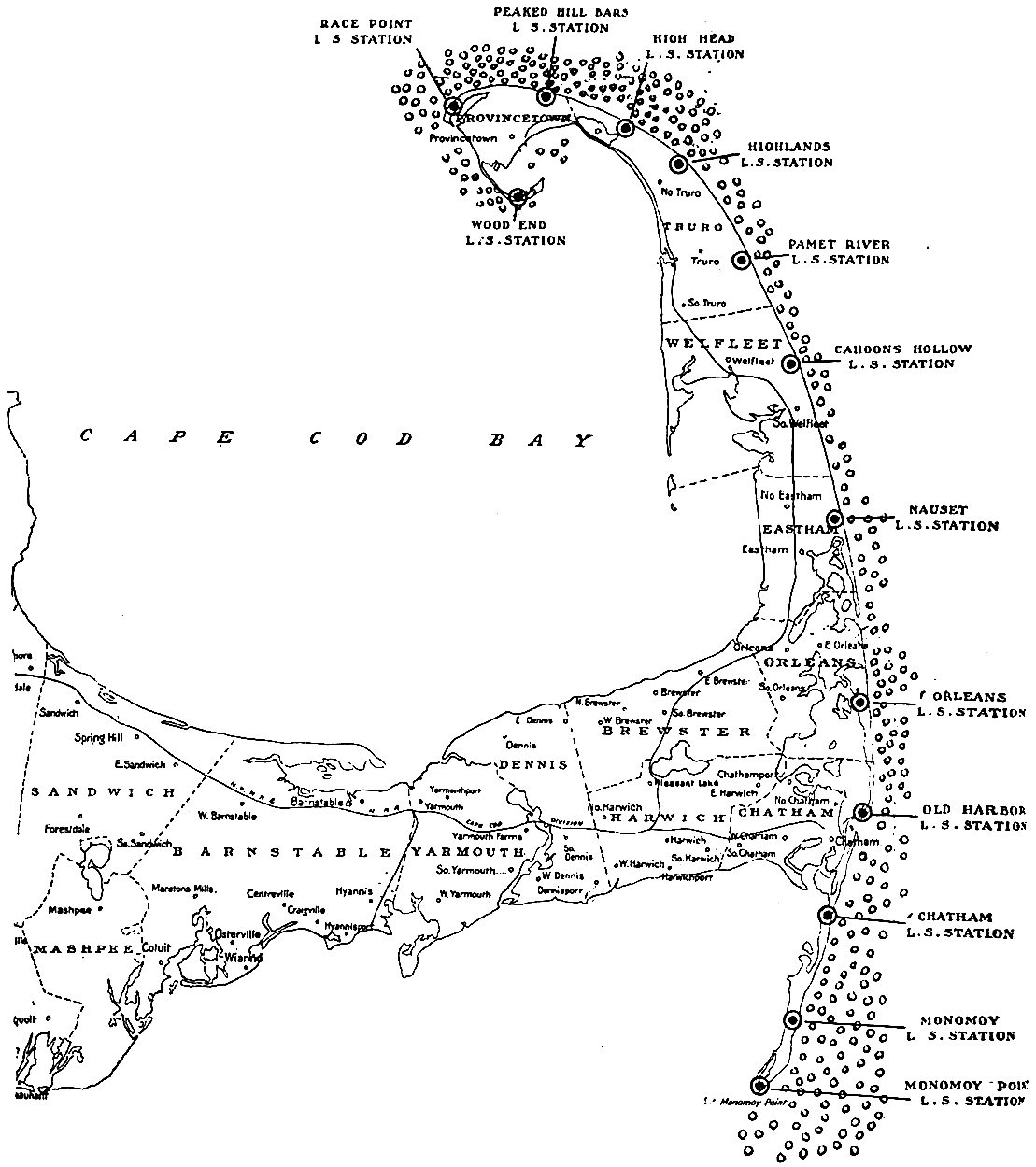

MAP OF CAPE COD, SHOWING LOCATION OF U. S. L. S. STATIONS.

Small circles show where principal wrecks have taken place within past fifty years.

Beyond their wages of sixty-five dollars per month the surfmen receive no allowances or emoluments of any kind except the quarters and fuel provided at the stations.

No person belonging to the service is allowed to hold an interest in or to be connected with any wrecking company, nor is he entitled7 to salvage upon any property he may save or assist to save. A surfman cannot be discharged from the service without good and sufficient reason. For well proven neglect of patrol duty or for disobedience or insubordination at a wreck the keeper may instantly discharge him; in all other cases special authority must be first obtained from the general superintendent.

The keeper lives at his station throughout the year, thus being on hand during the two summer months to summon the crew and volunteers in case of shipwreck or accident.

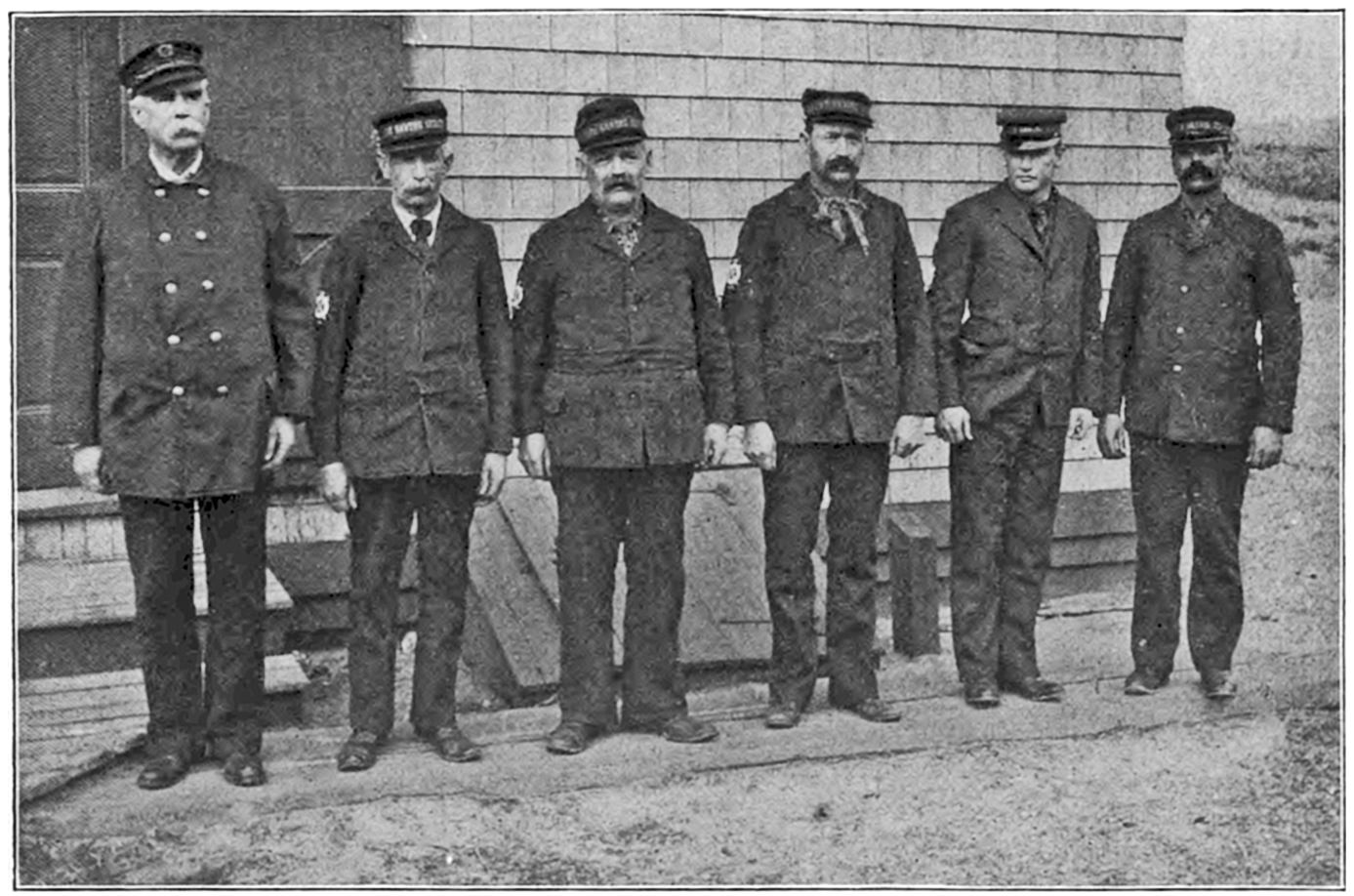

In “The Life Savers of Cape Cod” it has been the aim of the author to pen-picture some of the heroic deeds performed by these guardians of the “ocean graveyard,” as the shores of Cape Cod are known, the terrible hardships they are called upon to endure, and the peril they constantly face in the work of saving life and property, together with illustrations of the life-saving stations on Cape Cod, the boats, beach apparatus, breeches-buoy, etc., used in saving lives, photographs of the crews of the different stations, a historical sketch of the life-saving service, and stories of historic disasters, with biographies of the life savers of Cape Cod, their duties, manner of living, and their achievements.

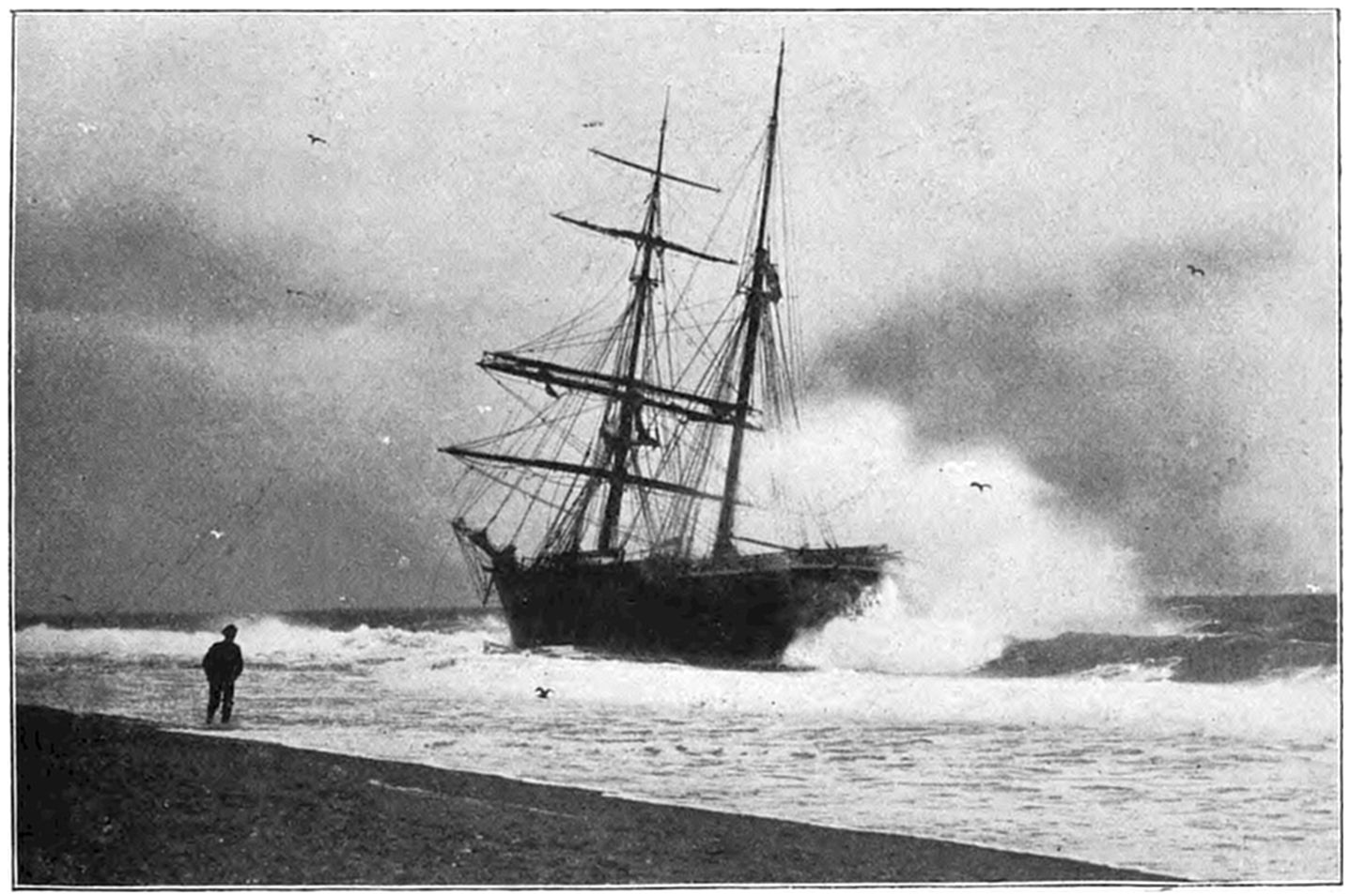

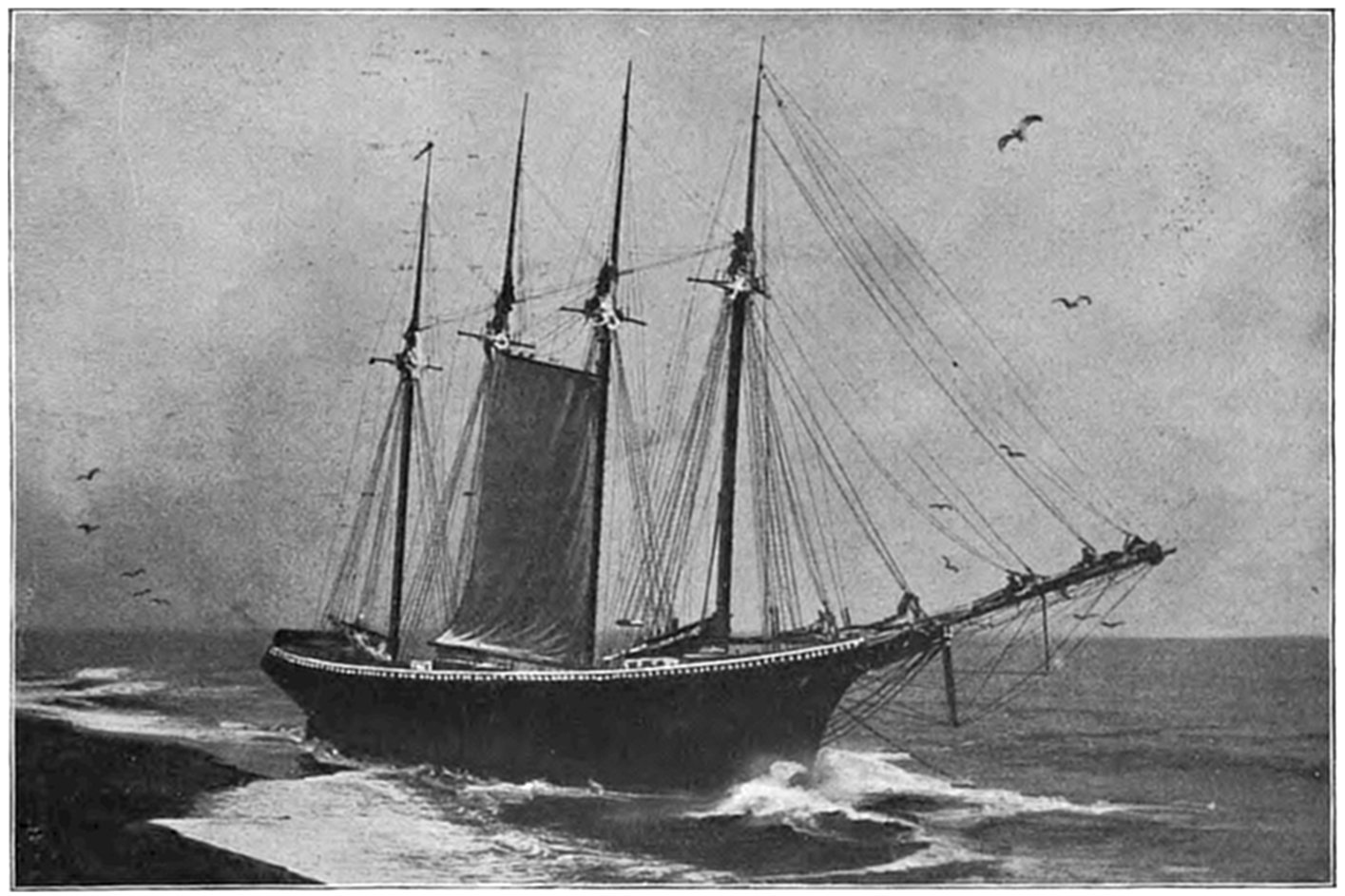

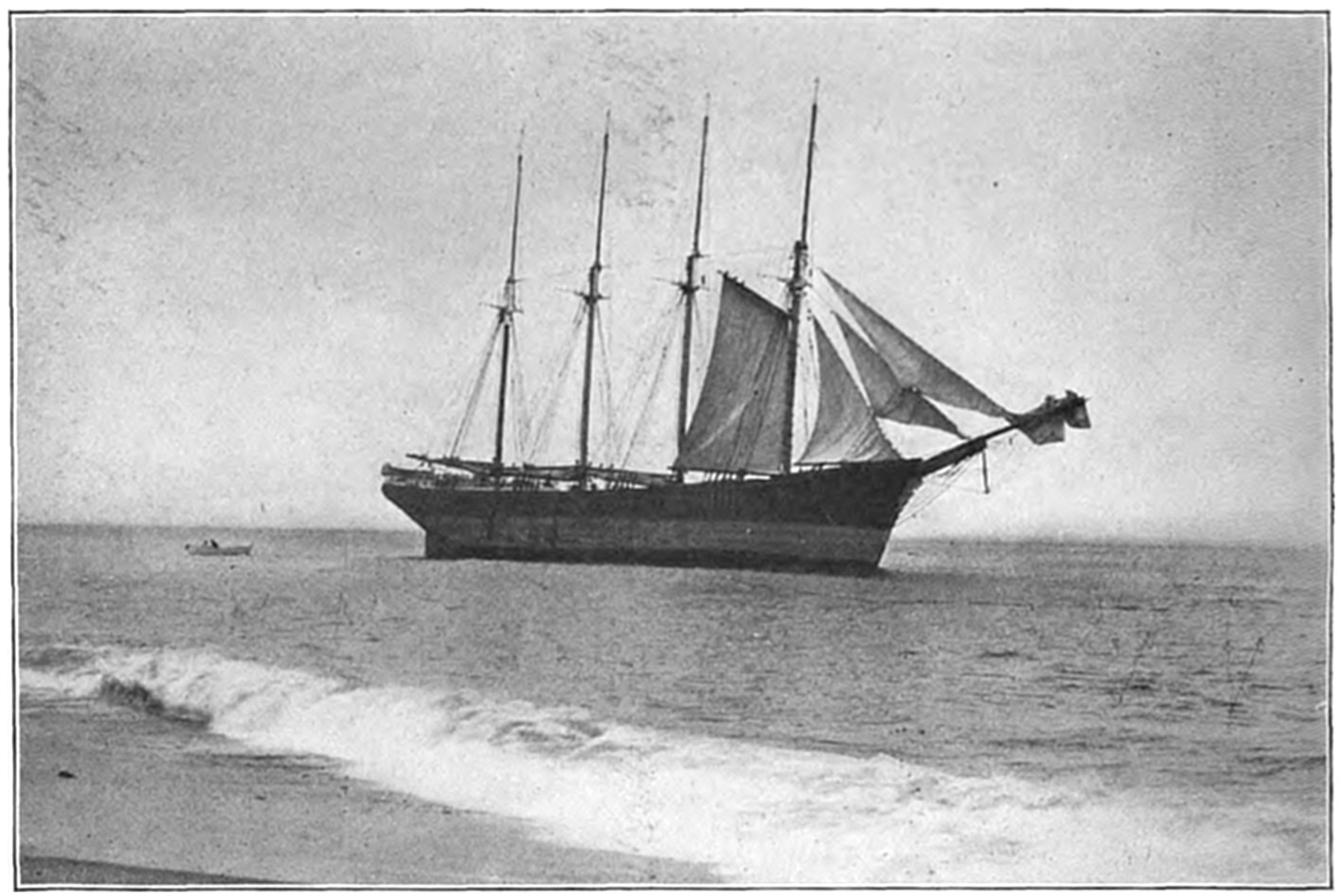

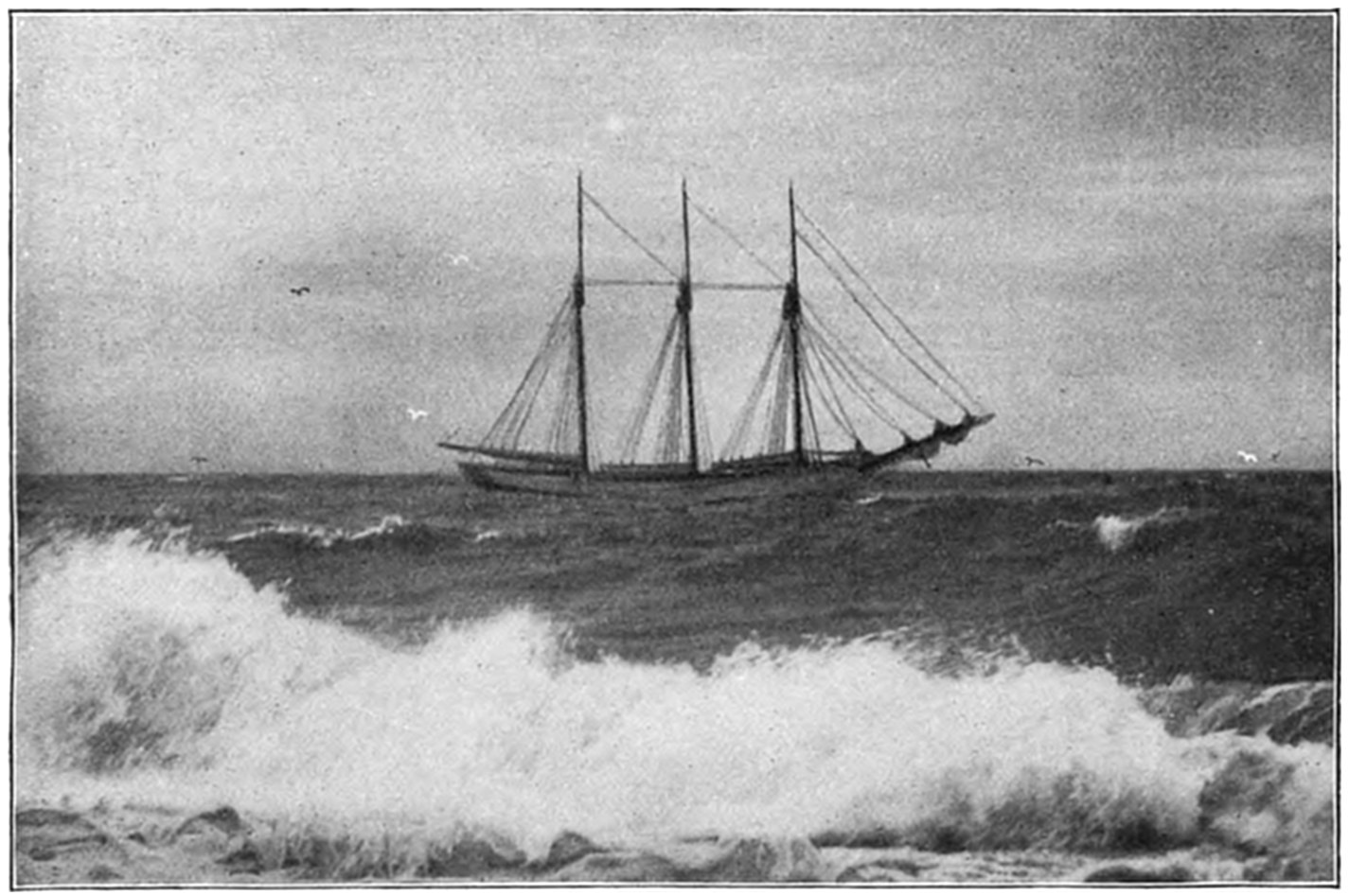

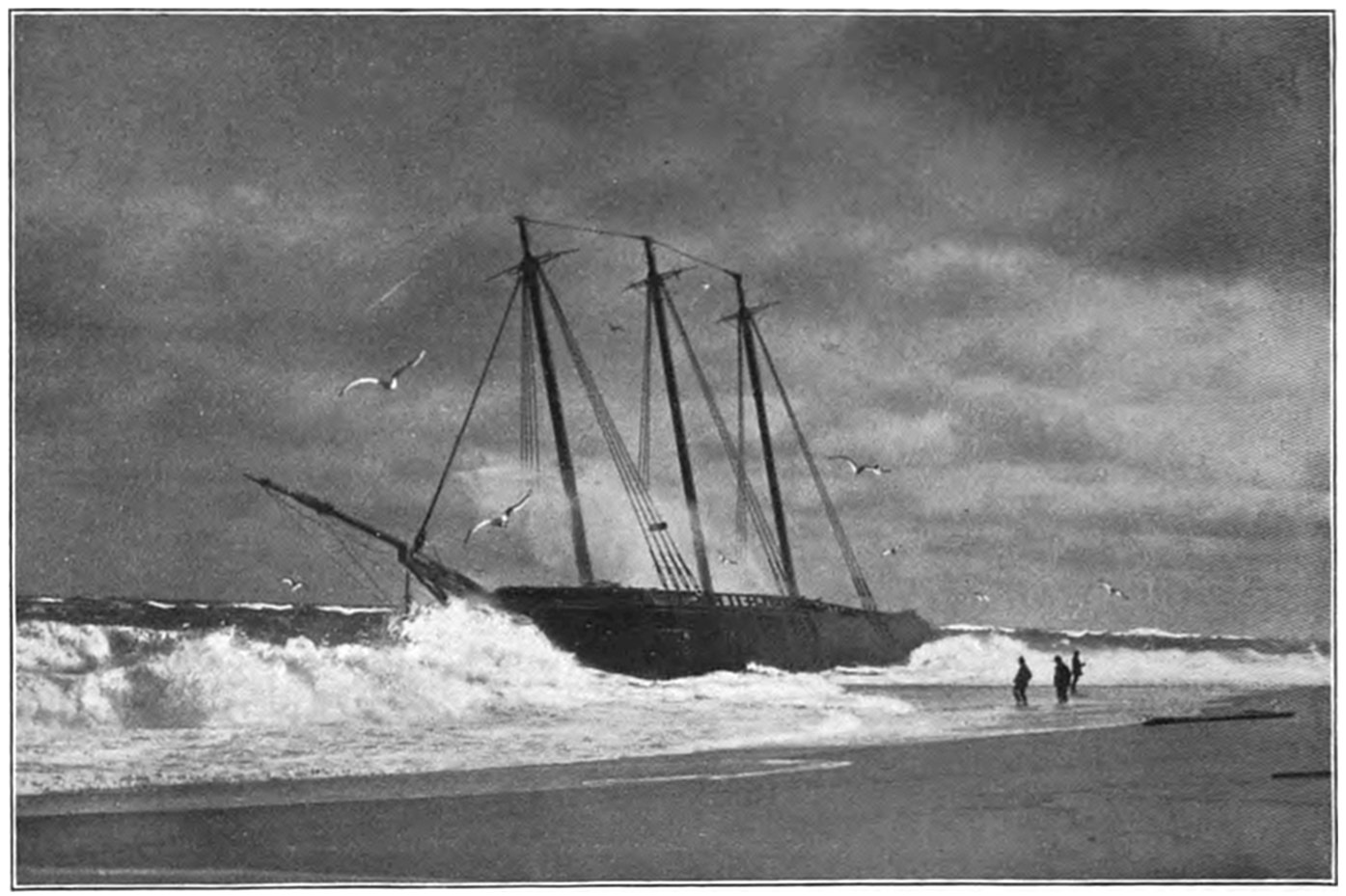

Cape Cod extends directly out into the Atlantic, like a gigantic arm with clutched hand, bidding defiance to the mighty ocean, for a distance of forty miles. Shifting sand bars parallel its eastern shores, which are an unbroken line of sandy beaches from Monomoy Point at Chatham to Wood End at Provincetown, a distance of about fifty miles. Myriads of shoals lie along the coast, and unnumbered vessels have met their doom along its shores, which rightly bear the name “Ocean Graveyard.”

The shores of Cape Cod from Monomoy to Wood End are literally strewn with the bones of once staunch crafts, while unmarked graves in the burial-places in the villages along the coast mutely relate the sad tale of the sacrifice of human life.

Scenes of awful terror and heroic rescues have taken place at the time of shipwreck along these shifting sand bars, and here, too, the life savers have given up their lives in devotion to their duty.

Thousands of lives have been lost in the wrecks that have taken place along the shores of Cape Cod since the Mayflower cast anchor in the harbor at Provincetown in 1620. There is no record of the disasters previous to the establishment of the United States Life-Saving Service in 1872, other than mention in town records and histories of the dates and circumstances of the most memorable, or those attended by great loss of life.

8

The first shipwreck on Cape Cod, of which there is any record, occurred in 1626, when the historic ship Sparrowhawk, Captain Johnson, from England, with colonists bound for Virginia, stranded on the shoals near Orleans, and became a total loss. The story of the wreck is told by Governor Bradford in his diary of the Plymouth Colony. The ship’s bones were discovered in a mud bank in 1863, the washing away of the shore line disclosing them to view.

Another historic wreck was that of the British frigate Somerset, which stranded on Peaked Hill Bars, Nov. 2 or 3, 1778. The Somerset was one of the fleet of British men-of-war, whose guns had stormed the heights of Bunker Hill, and terrorized the commerce of9 the colonies. She was at anchor in Boston Harbor the night that Paul Revere made his famous ride. When she met with disaster she was in pursuit of a fleet of French ships, which were reported to be in Boston Harbor. The Somerset had been at anchor in Provincetown harbor for some time, leaving there a few days before she was lost, to go in search of the French ships. She struck Peaked Hill Bars during a northeast gale, while trying to round the Cape, and enter the harbor at Provincetown. She had a complement of four hundred and eighty men, and is supposed to have carried sixty guns, thirty-two, twenty-four, and twelve pounders. She struck on the bars with terrific force, and instantly the seas began to pound her to pieces. She was finally thrown up on the beach by the tumultuous walls of water, and Captain Aurey and the few of the crew who had not perished reached the shore.

The residents of Provincetown viewed the wreck from High Pole Hill, and summoned Capt. Enoch Hallett, of Yarmouth, and Colonel Doane, of Wellfleet, who, with a detachment of militia, made Captain Aurey and the survivors prisoners.

Captain Hallett took charge of the prisoners, marching them up the Cape to Barnstable, and later to Boston, Colonel Doane being left to look after the wrecked craft. There was much jubilation on Cape Cod and in Boston over the disaster. The bones of the Somerset remained buried for a century, when the shifting sands exposed them10 to view. Relic hunters soon carried away nearly all of the wreckage that could be obtained, and the shifting sands have again entombed what remains of the famous old frigate.

Another historic wreck was that of the pirate ship Widdah, which was lost near the site of the Cahoon’s Hollow Life-Saving Station in 1718. The ship was commanded by Captain Bellamy, and carried twenty-three guns and a crew of one hundred and thirty men. Captain Bellamy had captured seven vessels off the shores of Cape Cod, and on one of them had placed seven of his crew. The captain of the captured ship ran his vessel close to the shore, and the seven pirates were taken prisoners. Later six of them were executed in Boston. The Widdah soon after was driven ashore during a gale, and all hands, save an Englishman and an Indian, were lost.

A scene of awful terror occurred when the Josephus, a British ship, was wrecked on Peaked Hill Bars in the year 1842. She had a cargo of iron rails. Her crew had been driven to the rigging as soon as the vessel struck, and one after another they were seen to fall into the raging sea. Those who had gathered on the shore could hear the despairing cries of the imperiled crew, but were powerless to aid them. At last two of the spectators, Daniel Cassidy and Jonathan Collins, procured a dory, and against the earnest pleadings of their friends, and in the almost certain assurance that they were going to their death, pushed off from the beach, saying as a last farewell, “We11 can’t stand this any longer; we are going to try and rescue those poor fellows if it cost us our lives.” Half-way out to the wreck the two heroes successfully battled with the sea, then a giant comber, catching their frail boat, carried it along and buried it under tons of tumbling water. The gallant men were seen to rise and struggle desperately to reach the overturned boat, but perished in the attempt. The men remaining in the rigging of the Josephus were soon after swept to death by the monstrous waves that tore the ship to pieces.

In 1848 the brig Cactus was lost on the bars along the back of the Cape.

Along the shore near the Cahoon’s Hollow Station the immigrant ship Franklin was deliberately run ashore in 1849, and many of her poor, helpless passengers perished in the disaster. This was one of12 the most appalling disasters that ever occurred on Cape Cod. Speedy retribution came to the officers of the ship for their terrible crime, the captain and nearly all the others losing their own lives in the wreck. The late Capt. Benjamin S. Rich, afterwards of the United States Life-Saving Service, was the first to discover the wreck, and also found a box containing some papers that subsequently proved that the disaster was intentional.

The year 1853 was a memorable one in the history of Cape Cod, there being twenty-three appalling disasters along its shore during that period. Among the vessels lost were many ships and brigs well known in shipping circles in Boston and on Cape Cod. The weather was bitter cold and violent storms swept the coast when most of the vessels were lost, so that nothing could be done to assist the imperiled crews, and those who did reach the shore perished from exposure on the desolate uplands and beaches.

In 1866 the White Squall, built for a blockade runner, while on her way home from China, struck on the bars along the back of the Cape and became a total loss.

The wreck of the Aurora is known to Cape Codders as the “Palm Oil Wreck.” The vessel was loaded with palm oil from the west coast of Africa. She struck on the bars off the back of the Cape, and was a total loss.

Another terrible disaster was the wreck of the schooner Clara Belle,13 coal laden, which stranded on the bars off High Head Station, on the night of March 6, 1872, at the height of a fearful blizzard. Captain Amesbury and crew of six men attempted to reach the shore in their boat. The craft had gone but a few yards when she was overturned, throwing the men into the sea. John Silva was the only member of the crew that reached the shore. He found himself alone on a frozen beach with the mercury below zero. He wandered about during the night trying to find some place of shelter, and was found the next morning by a farmer standing dazed, barefooted, and helpless in the highway three miles from the scene of the wreck. His feet and hands were frozen, and it was a long time before he recovered from the effects. The schooner was driven high and dry on the beach, and when boarded the next day a warm fire was found in the cabin. The haste of the crew to leave the vessel had cost them their lives.

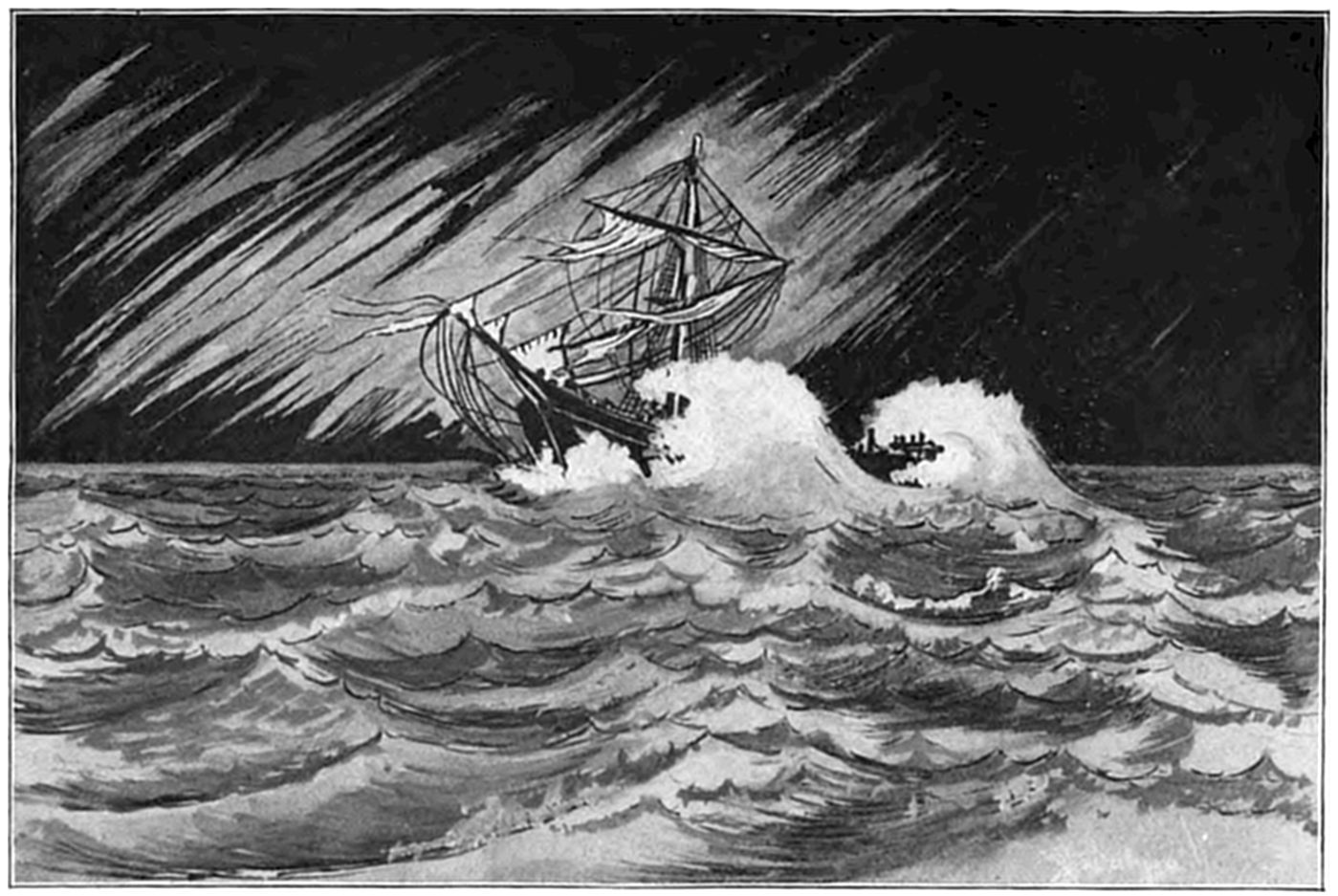

The first fearful disaster after the life-saving service reorganization, took place on Peaked Hill Bars, March 4, 1875, when the Italian bark Giovanni became a total loss and her crew of fourteen perished. The bark stranded too far from the beach to be reached by the wreck ordnance used in those days, and the surf was pounding on the shore with such fury that a boat could not be launched, much less live, in the sea. No assistance could be rendered the poor sailors, and one by one they dropped into the sea and were lost.

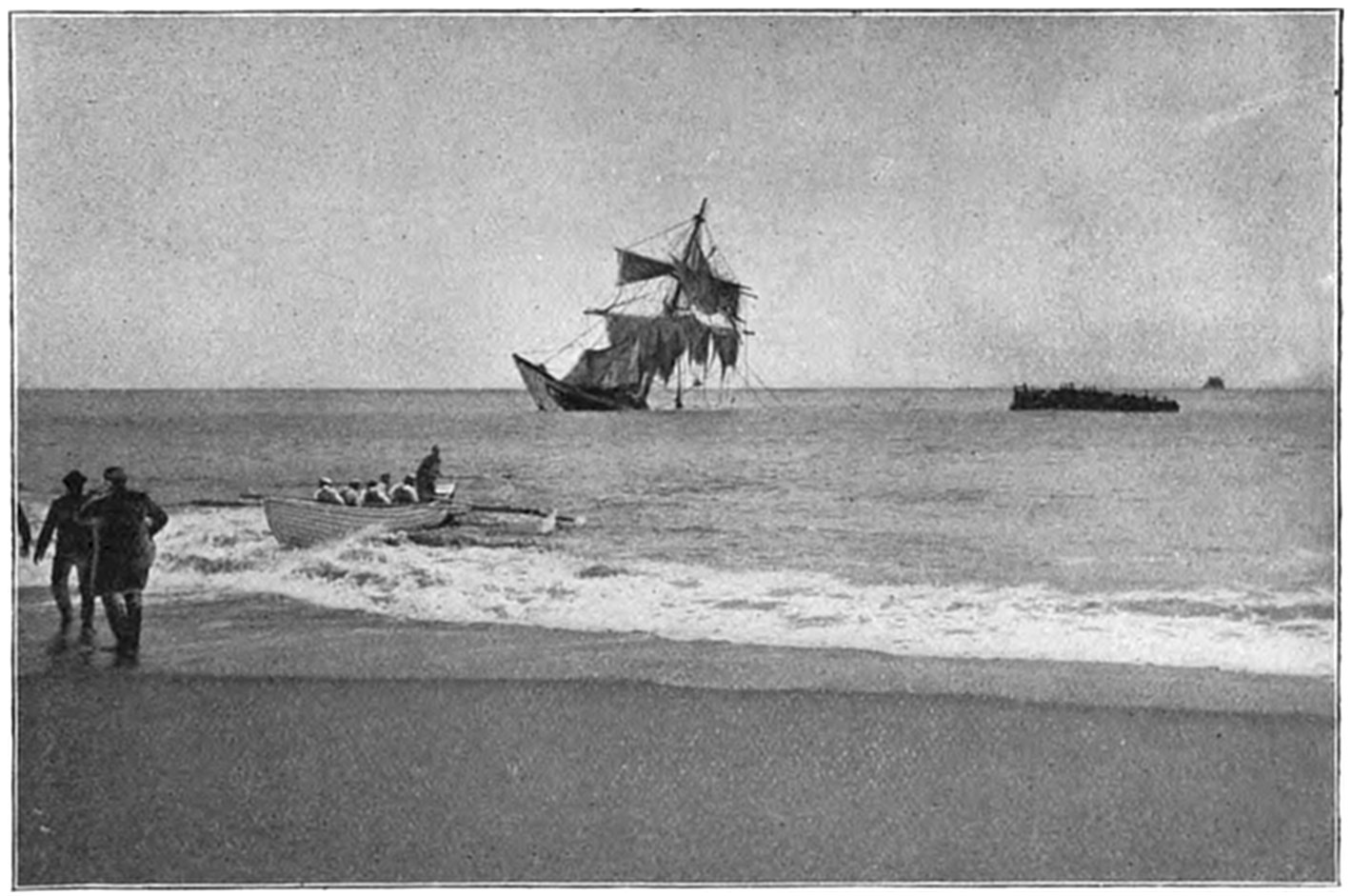

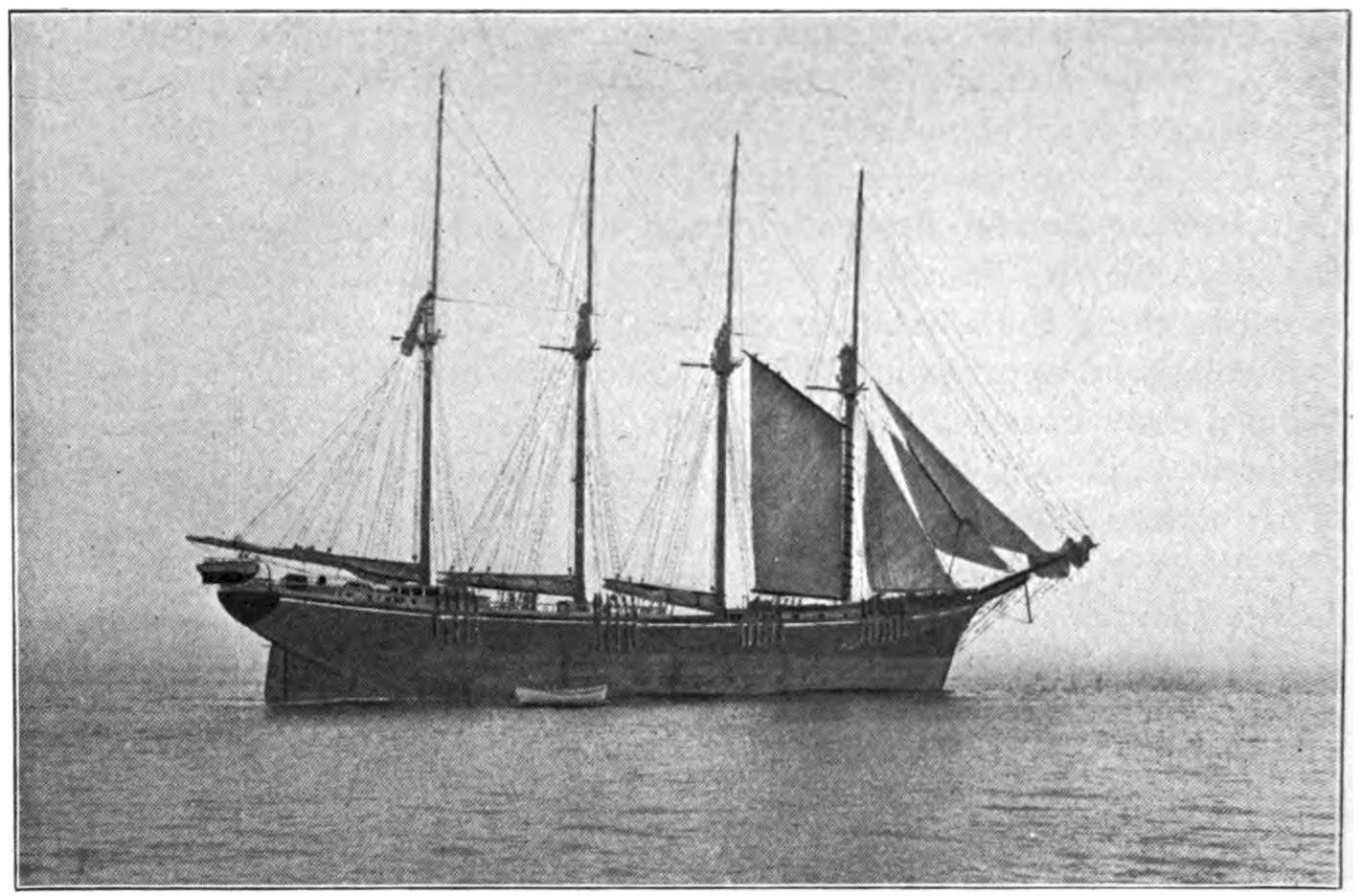

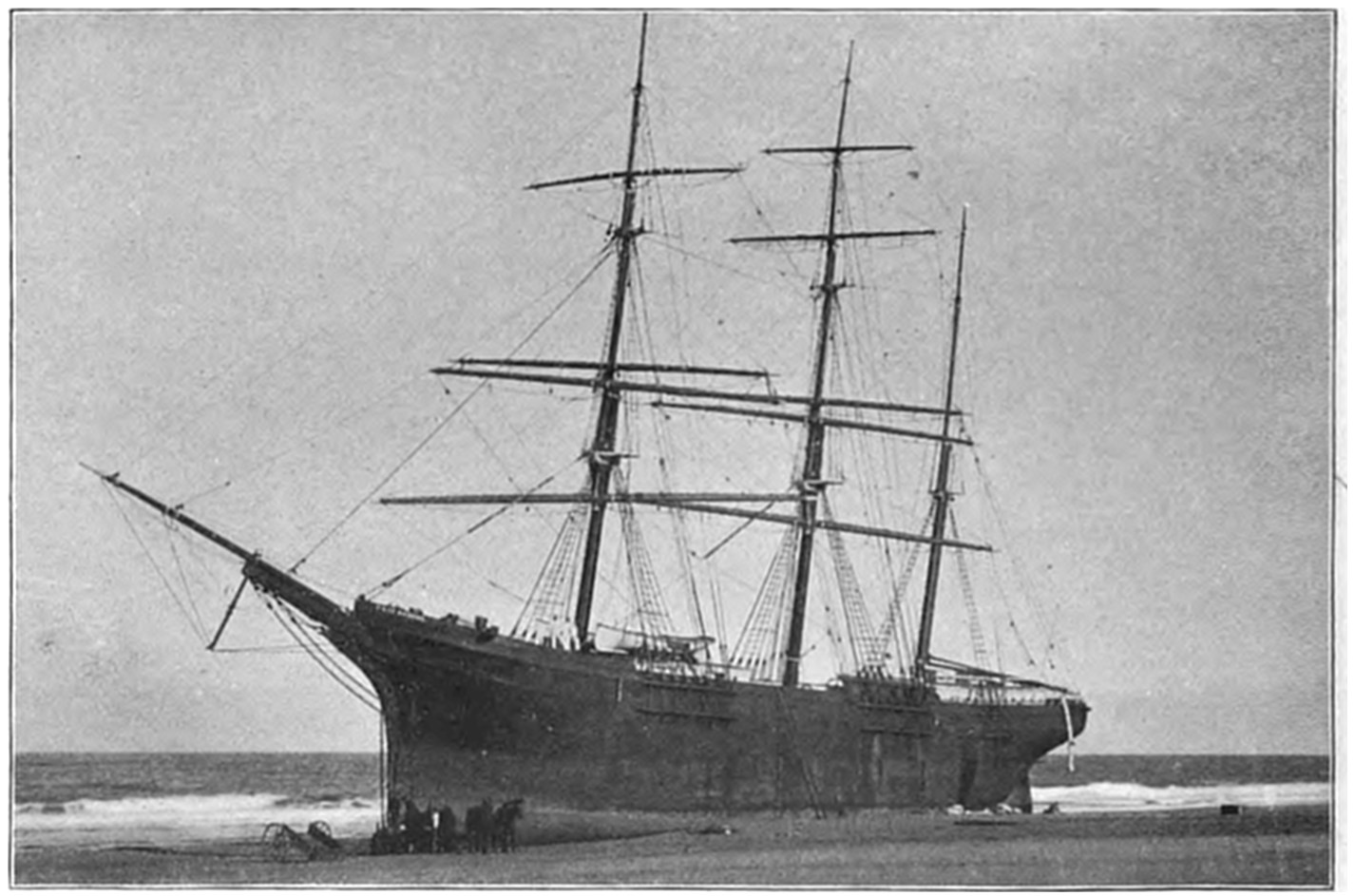

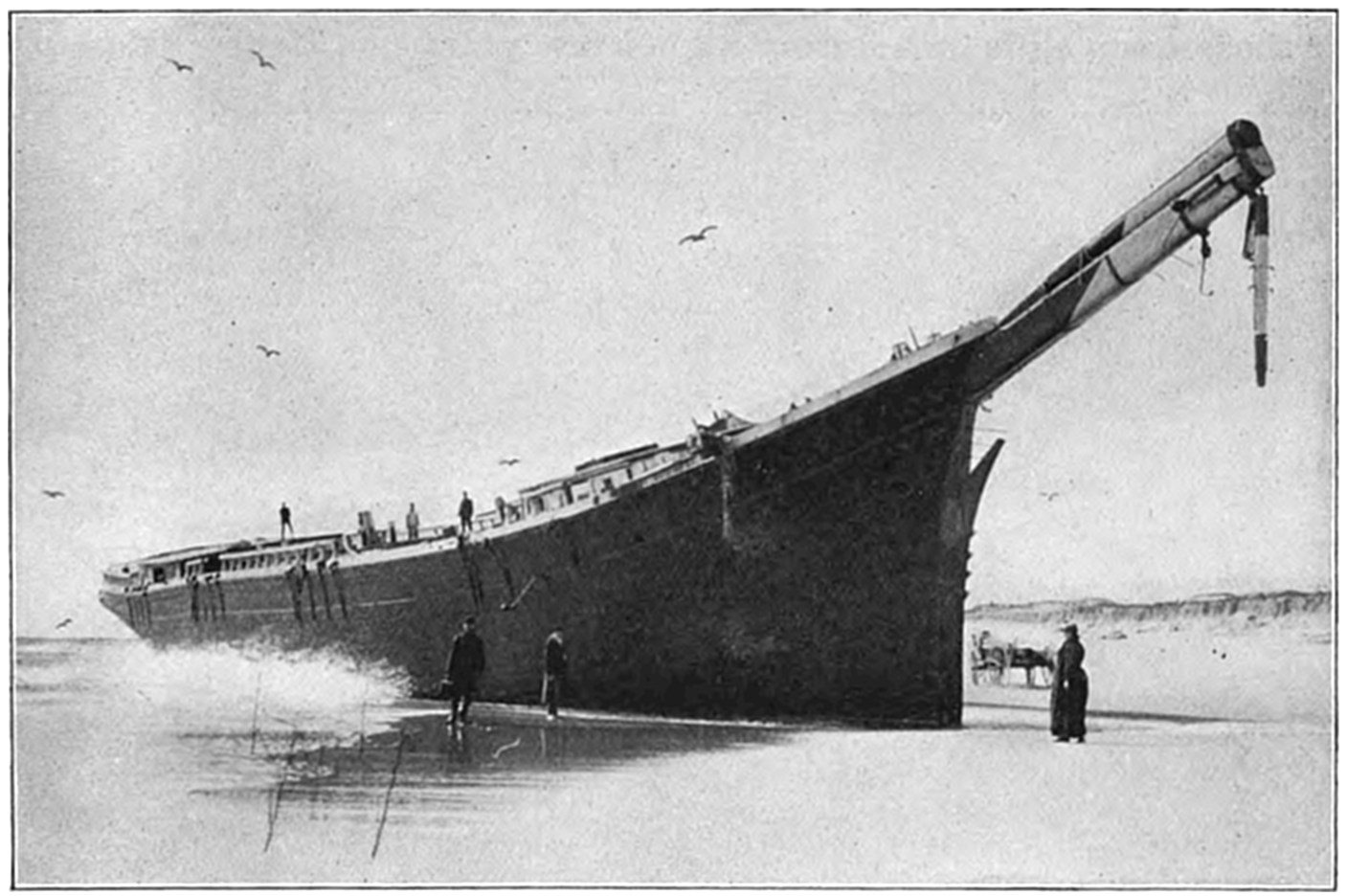

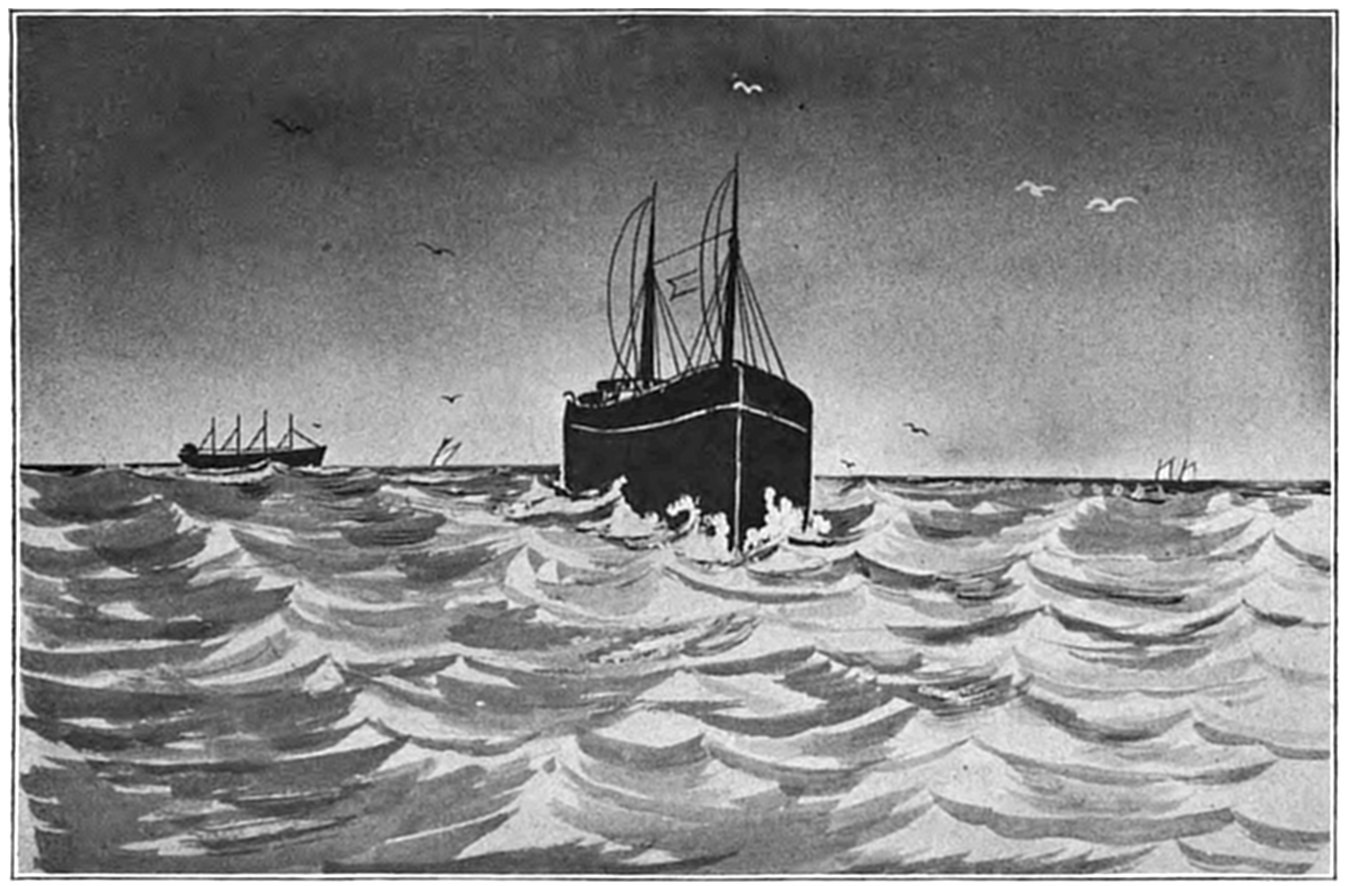

The most appalling disaster in the history of the life-saving service14 on Cape Cod was the wreck of the iron ship Jason, on the bars at Pamet River, Dec. 5, 1893. Twenty-four lives were lost. The ship was bound from Calcutta, India, for Boston, with a cargo of jute. Captain McMillan, who was in charge of the ship, had a crew of twenty-four men, including an apprentice, Samuel J. Evans, of Raglan, England. Thick weather prevailed off the coast for several days preceding the disaster, and Captain McMillan, not being in possession of reliable information as to his position, obtained it from a New York pilot boat.

When about one hundred miles off the coast he unfortunately shaped his course to the westward for the purpose of raising some landmark. When the Jason approached the Cape, the wind was blowing a gale from the northeast, and the atmosphere was thick with rain, which soon turned to sleet and snow.

The life savers along the shore at Nauset first saw the Jason, and word that a ship was in dangerous proximity to the shore was sent along the Cape to all the stations. The Jason was last seen just before five o’clock by the day patrol of the Nauset Station. The life savers, knowing that she could hardly weather the Cape, kept a sharp lookout for her, and at all the stations the horses were hitched into the beach carts and every preparation made to go to the assistance of the ship without a moment’s delay. It was a fearful night along the shores of Cape Cod, the coast guardians having all they could do to go over their patrol. Nothing was seen or heard of the doomed ship15 up to seven o’clock in the evening, and the life savers hoped that she had managed to work offshore or around the Cape. At half-past seven, however, Surfman Honey, of the Pamet River Station, burst into the station, and shouted, “Hopkins (the north patrol) has just burned his signal.” A moment later Hopkins rushed into the station and reported that the Jason had struck on the bars about a half mile north of the station. Keeper Rich and his crew were ready for the emergency, and, with the beach cart, rushed to the scene. The shore was then piled with wreckage, and the slatting of the sails of the wrecked ship sounded above the roar and din of the storm. A careful lookout for the shipwrecked seafarers was kept by the life savers as they hurried to the scene, and Evans, the sole survivor of the disaster, was found clinging to a bale of jute. He was clad only in his underclothes, and was almost totally helpless.

The wrecked vessel was sighted through the storm and a shot promptly fired over the craft, but the crew had perished almost as soon as the ship struck, and the efforts of the life savers were of no avail. The ship (it was afterwards learned from young Evans) broke in two almost as soon as she struck, and the members of the crew perished shortly after. Evans told the author that as soon as the ship struck he put on a life-preserver and took to the rigging. The captain ordered the boats launched, but they were smashed as soon as they struck the water. While clinging to the rigging, considering16 what was best to do, Evans says that he must have been hit by a big wave or wall of water, as the next that he knew he was on the beach and the life savers were taking him to the station. The bodies of twenty of the crew were found and buried in the cemetery at Wellfleet. Evans soon recovered from the effects of the buffeting he received by the seas, and returned to his home in England. Part of the ship is now visible at low tide, and is an object of much interest to visitors to Cape Cod.

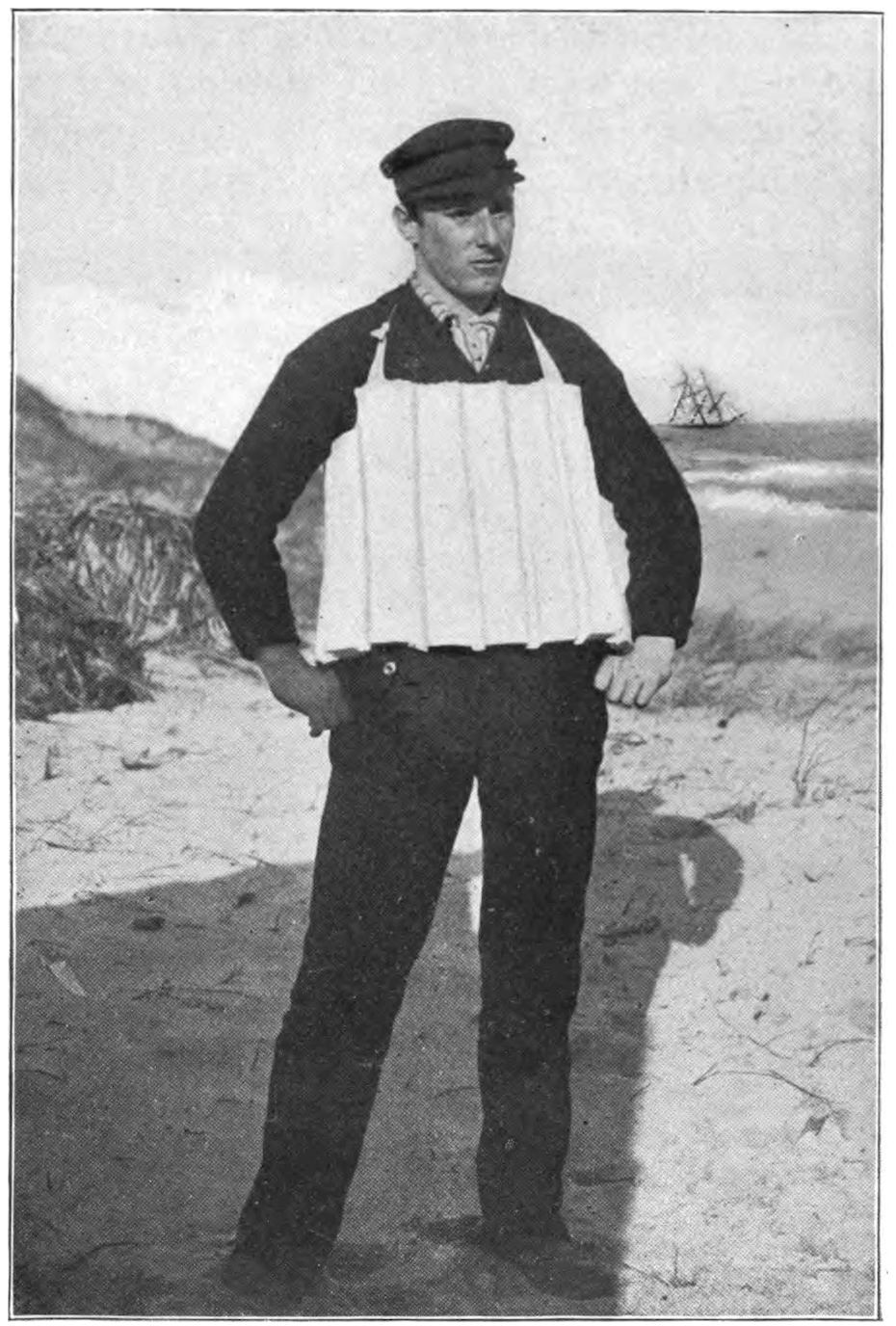

SAMUEL J. EVANS, SOLE SURVIVOR OF WRECKED SHIP JASON,

With life preserver which he wore when cast ashore.

The wreck of the ship Asia, in which twenty lives were lost, occurred on Nantucket shoals, near the Great Round Shoal Lightship in February, 1898. The ship was on her way from Manila for Boston, and was commanded by Captain Dakin. Besides the crew of twenty-three men Captain Dakin’s wife and little daughter were aboard.

17

The ship struck on the shoals during a furious northeast gale and snowstorm on Sunday afternoon, but did not begin to break up until the next day.

When the ship commenced to pound to pieces, the mate and the few members of the crew who had not been swept overboard did all in their power to assist Captain Dakin in shielding his wife and daughter from being swept away by the seas which were breaking over the craft. Before the ship broke up, the mate lashed the captain’s daughter and himself to a big piece of wreckage, hoping in that way to reach the shore. Captain Dakin and his wife were swept to death before they could fasten themselves to any of the wreckage. Of the whole number aboard the ill-fated craft but three were saved. These were sailors, who clung to a piece of the ship, and after drifting about in Vineyard Sound for several days, were picked up nearly dead and placed aboard one of the lightships. The bodies of the mate, with his arms locked about the captain’s daughter, and both securely lashed to a piece of wreckage, were picked up a few days later in Vineyard Sound. Both had been frozen to death. But few of the bodies of the other members of the crew were found. The ship became a total loss, and the following day there was not a vestige of her left to mark the spot where the tragedy took place.

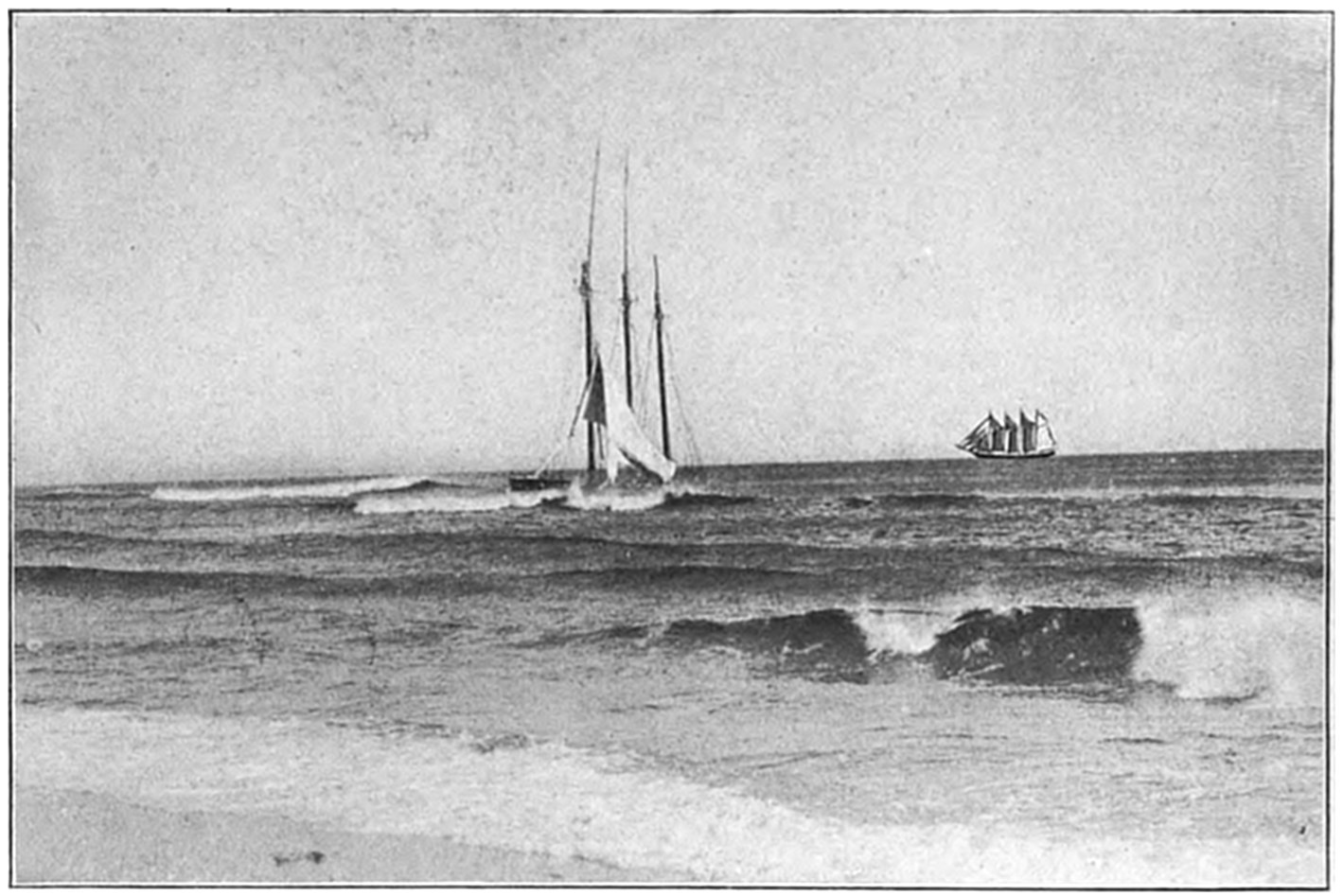

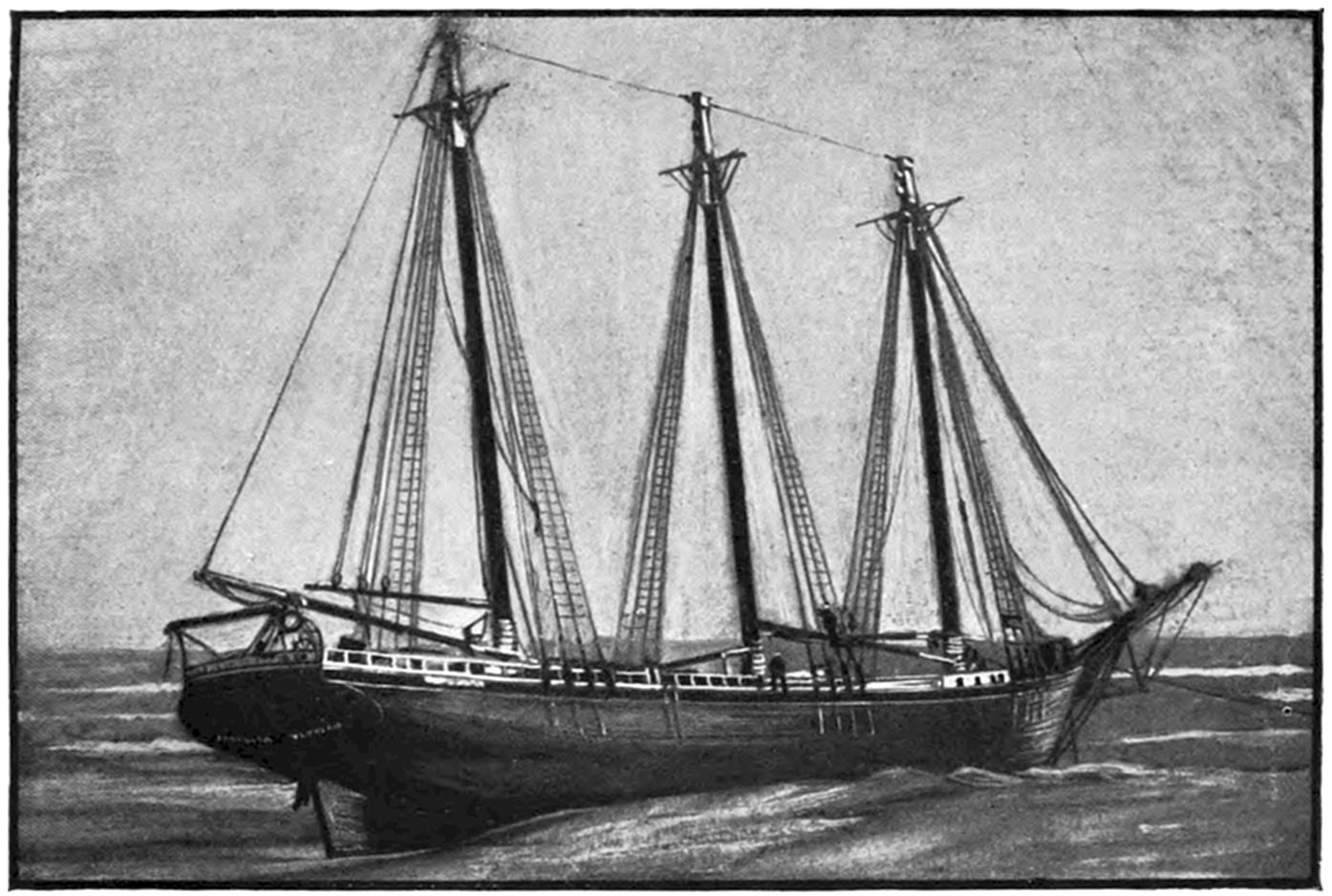

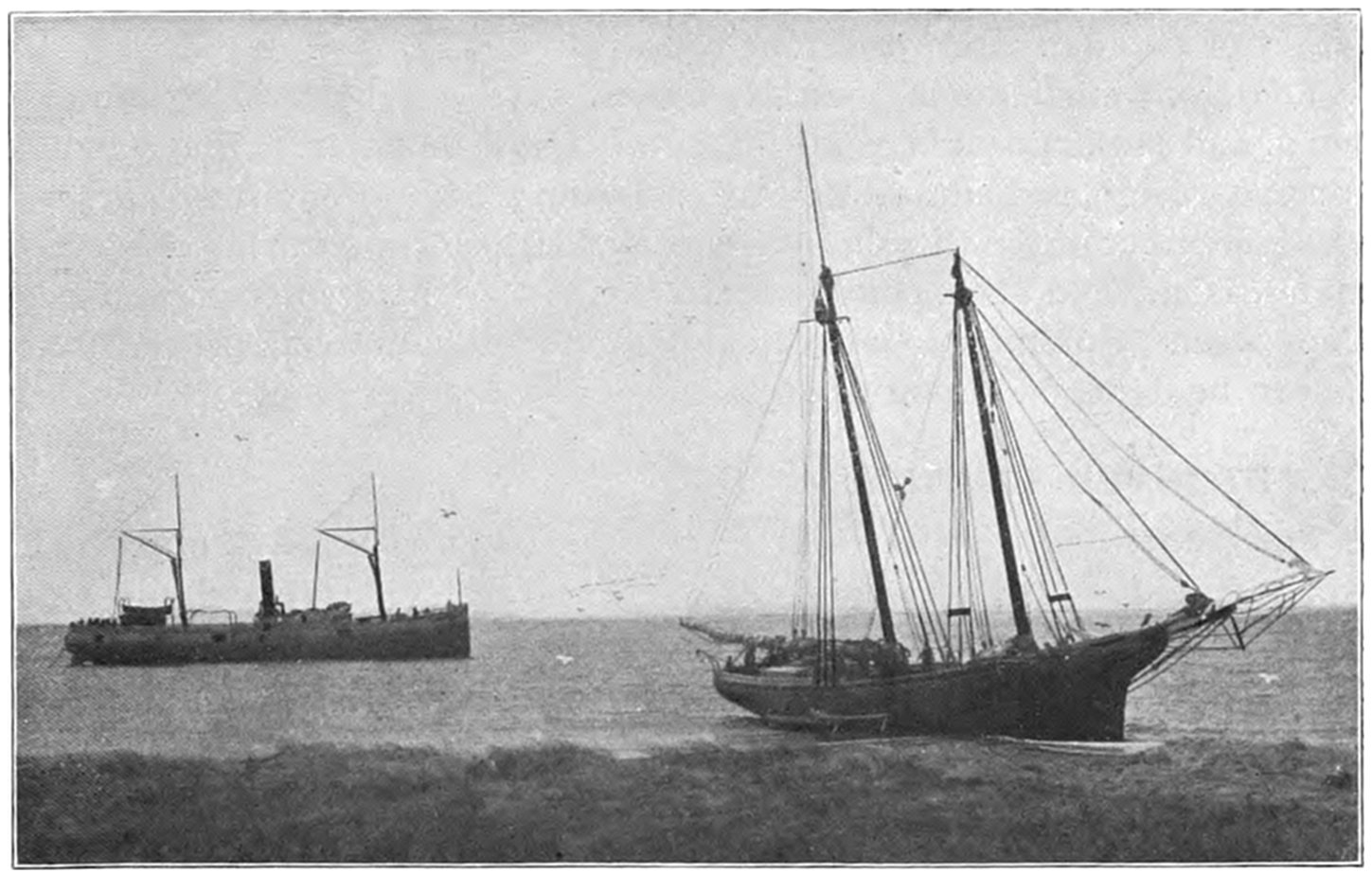

The schooner Job H. Jackson was another terrible wreck that occurred on Peaked Hill Bars. The schooner struck on Jan. 5, 1895,18 during bitter cold weather, and the crew were driven into the rigging. A fearful sea was pounding on the shore, and it required the combined herculean efforts of the Peaked Hill Bars, Race Point, and High Head life-saving crews, with their life-boats, to rescue the imperiled seafarers, who were badly frost-bitten and helpless when taken from the wrecked vessel.

The schooner Daniel B. Fearing, which became a total loss on the bars off Cahoon’s Hollow Station, struck there during a fog on May 6, 1896. The life savers put off to the wreck in their surf-boat, and brought the crew ashore. A gale sprung up with great suddenness as the crew were leaving the doomed vessel, and as the last man jumped into the life-boat the masts of the big schooner fell with a crash, and the sea soon completed the work of total destruction.

On Sept. 14, 1896, the Italian bark Monte Tabor struck on Peaked Hill Bars during a furious northeast gale. The disaster was attended with the loss of five men, whose deaths were involved in circumstances of mysterious and almost romantic interest. Three were suicides, while the manner in which the other two perished could not be certainly explained. The bark hailed from Genoa, and carried a crew of twelve persons, including the officers and two boys. She had a cargo of salt from Trapani, Island of Sicily, for Boston. The craft had been struck by a hurricane on September 9, and when off Cape Cod on the night of the 13th, in endeavoring to make the harbor at Provincetown,19 she struck the dreaded Peaked Hill Bars. She was discovered by Patrolman Silvey, of the Peaked Hill Bars Station. The night was pitch dark, the surf extremely high, and the bark was soon pounded to pieces. As the life-saving crews could not locate the wreck, there was20 nothing to shoot at and nothing to pull to, even if a boat could have been launched. It is believed that the captain was so humiliated by the loss of his vessel, that he fell into a frenzy of despair, and resolved to take his own life, and it would appear that others of his crew followed his example of self-destruction.

Six of the crew managed to reach the shore on the top of the cabin, and were pulled out of the surf by the life savers. Another, a boy, said that he swam ashore. An investigation, conducted by the Italian counsel, disclosed that the captain committed suicide.

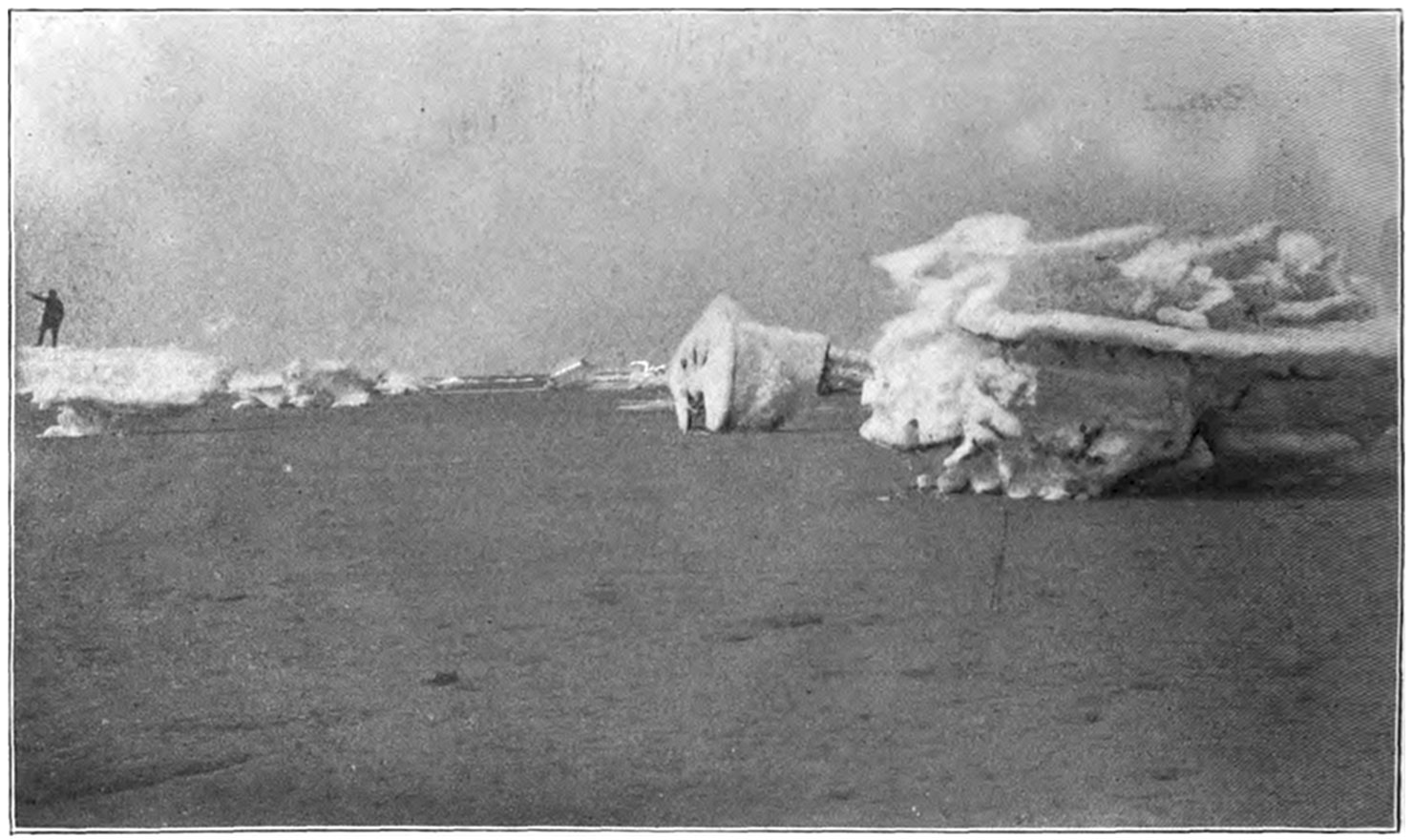

The first evidence that the steamer Portland had met with disaster during the memorable gale of November, 1898, was found by John Johnson, a surfman of the Race Point Station, who picked up a life-preserver from the ill-fated craft.

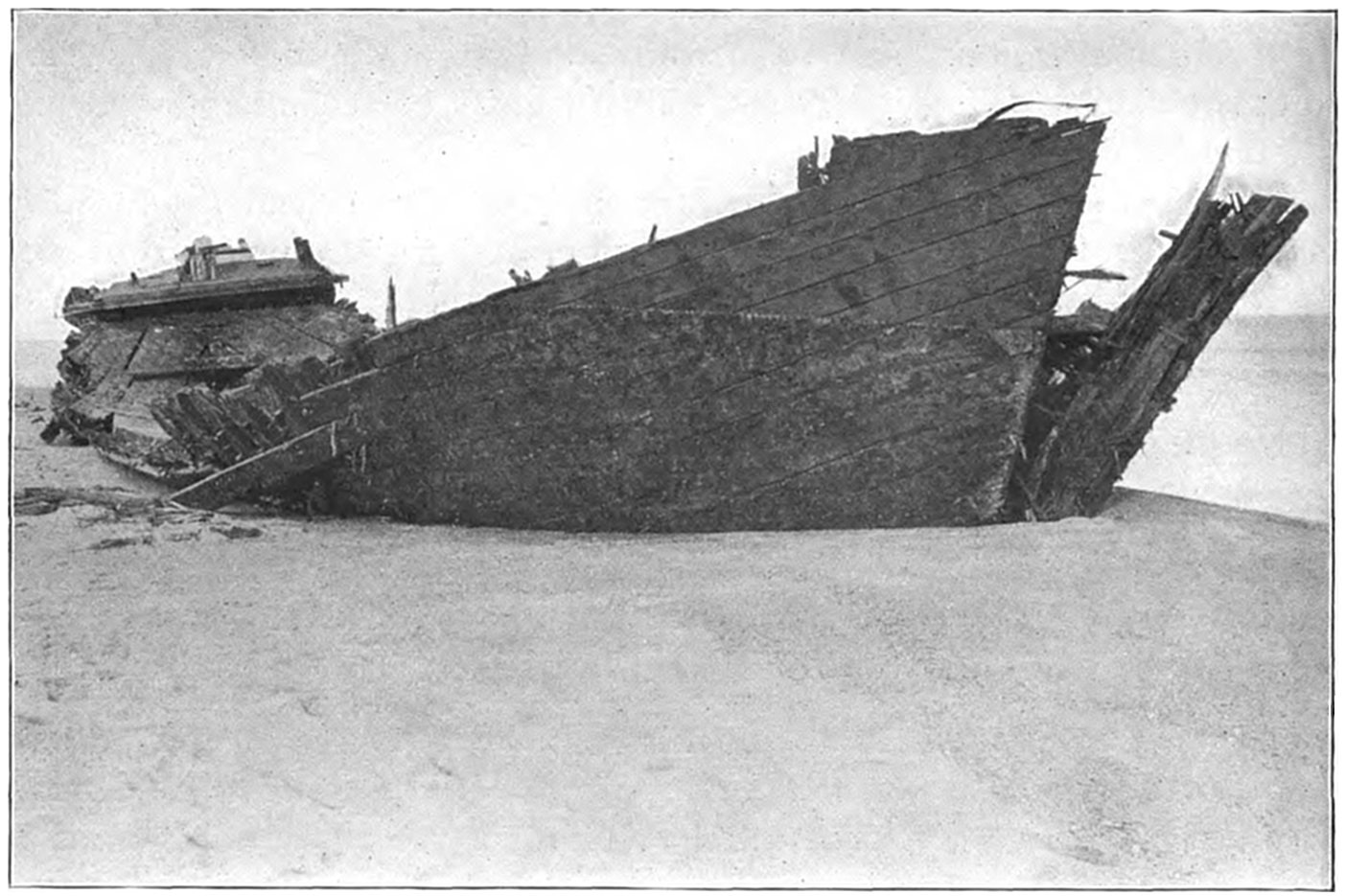

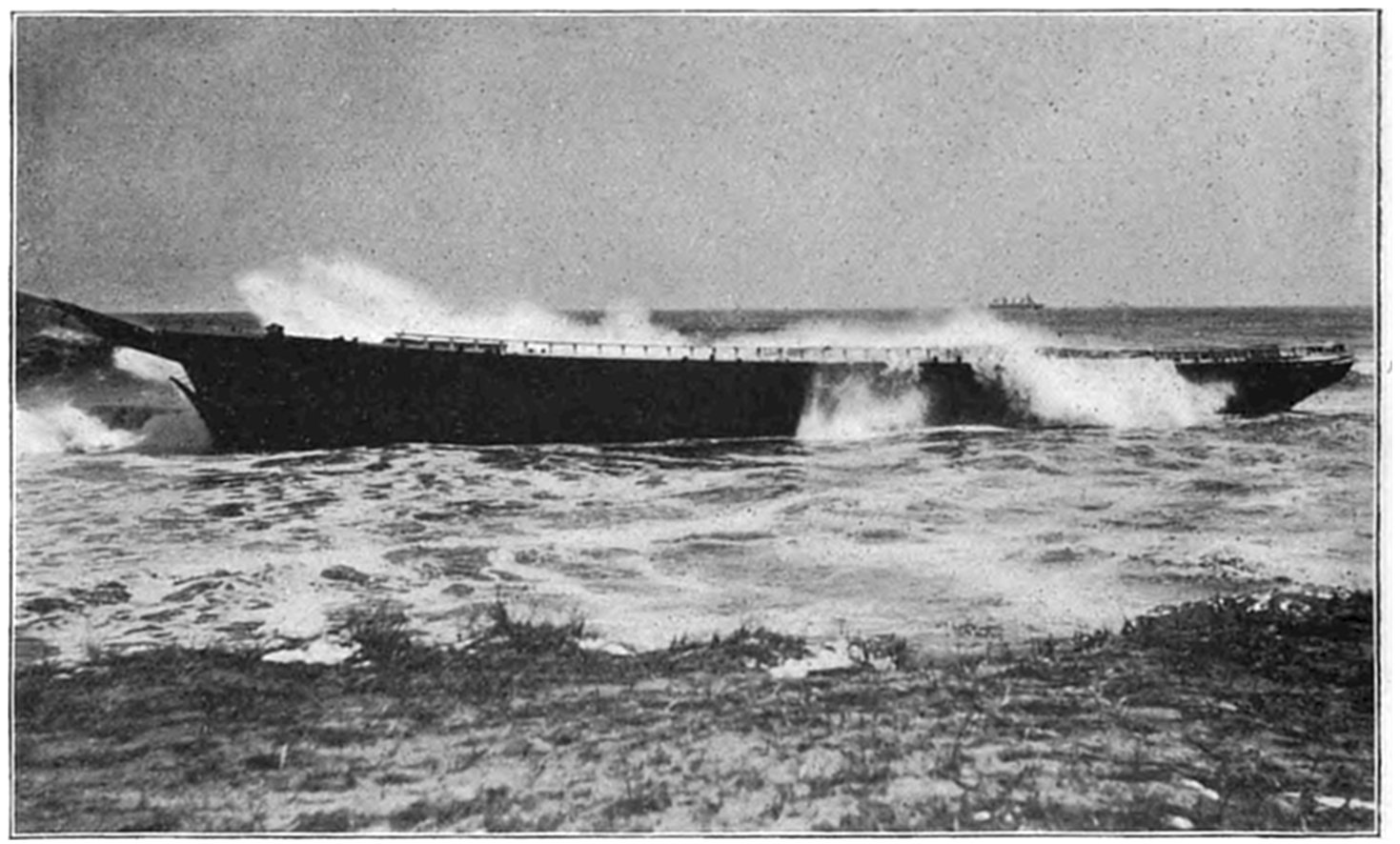

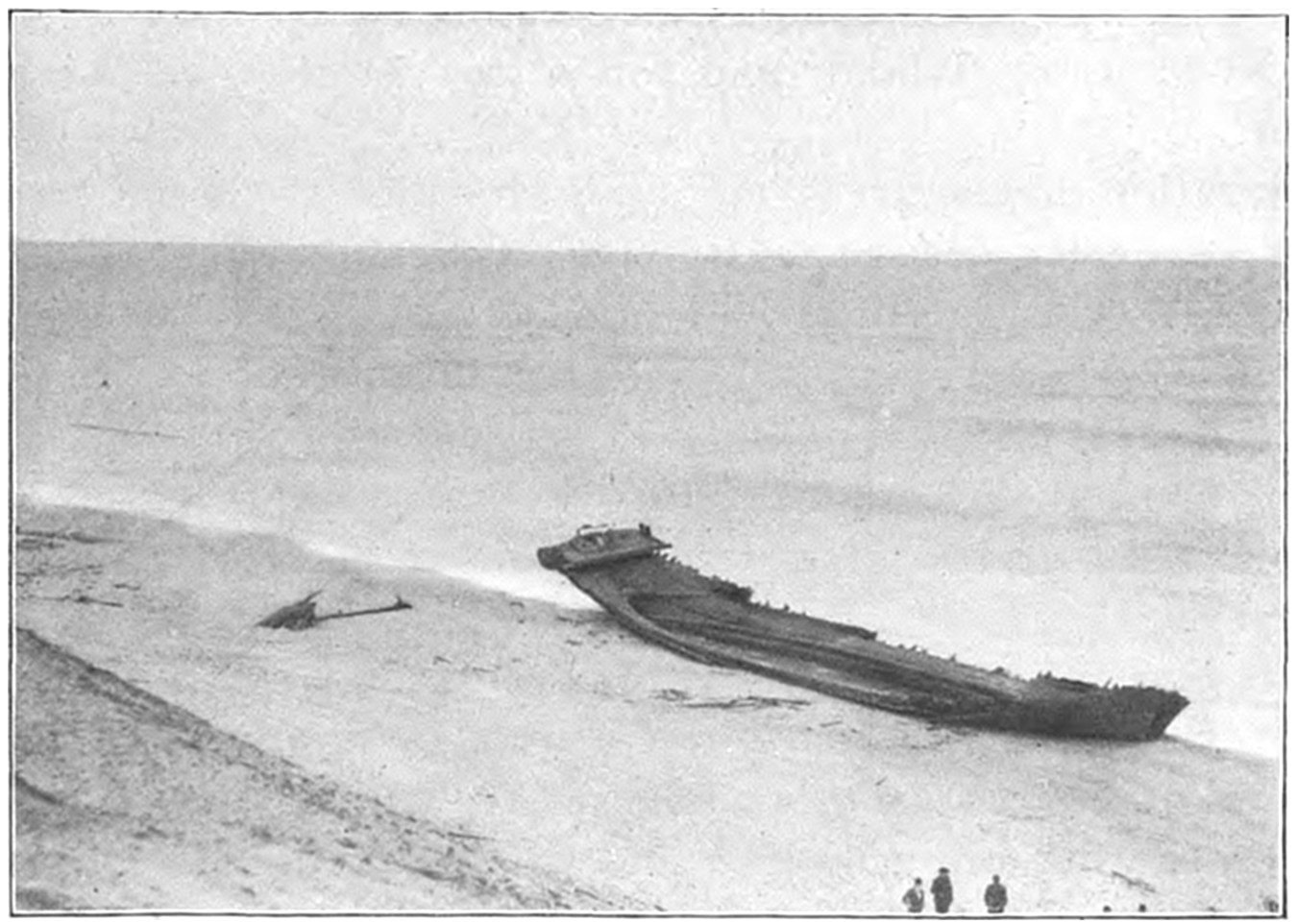

WRECKAGE WHICH CAME ASHORE AFTER THE STEAMER PORTLAND WAS LOST AND LIFE PRESERVER FROM THE ILL-FATED CRAFT.

Life preserver in right foreground.

Soon after Johnson found the life-preserver, wreckage from the steamer was seen in the surf along the shore, and within a short time the beach for miles was strewn with it. All the life savers suffered great hardship during that gale, which was the worst in the history of the life-saving service.

Twice since the establishment of the United States Life-Saving Service on Cape Cod, the life savers in the life-boats have met with disaster, and members of the crews perished in the catastrophe.

21

Keeper David H. Atkins and Surfman Frank Mayo and Elisha Taylor of the Peaked Hill Bars Station perished by their boat being wrecked during a second trip to the stone-loaded sloop, C. E. Trumbull,22 on the morning of Nov. 30, 1880, to take off two sailors who refused to go ashore the first time.

Surfman S. O. Fisher, now keeper of the Race Point Station, C. P. Kelley, now keeper at High Head Station, and Isaiah Young, who has not since seen a well day, lived to tell the story after a life or death struggle with icy seas and currents and being swept for miles along the shore before they crawled up on the beach.

But the Monomoy disaster of March 17, 1902 was the most appalling and attended with the greatest loss of life, twelve men, seven of them life savers, perishing.

The conduct of the Monomoy crew on this occasion affords a noteworthy example of unflinching fidelity to duty. By long experience they were fully aware of the perils that must be encountered in going to the wrecked vessels, but it was a summons which the brave and conscientious life savers could not disregard.

The story of this disaster is still fresh in the public mind.

The establishment of the United States Life-Saving Service on Cape Cod dates back but thirty years, which time also marks the reorganization, extension, and beginning of its efficiency in the United States. While as early as 1797 the town of Truro sold to the United States23 Government a tract of land upon which to erect the first lighthouse on Cape Cod,—Highland Light, so called,—it was not until half a century later that the government began to provide means for the relief of mariners wrecked upon its coasts, and seventy-five years afterwards that the first United States Life-Saving Station was erected on the shores of Cape Cod.

The Massachusetts Humane Society, originally formed in 1786, and incorporated for general purposes of benevolence a few years later, was the first to attempt organized relief for shipwrecked seafarers in the United States as well as upon Cape Cod.

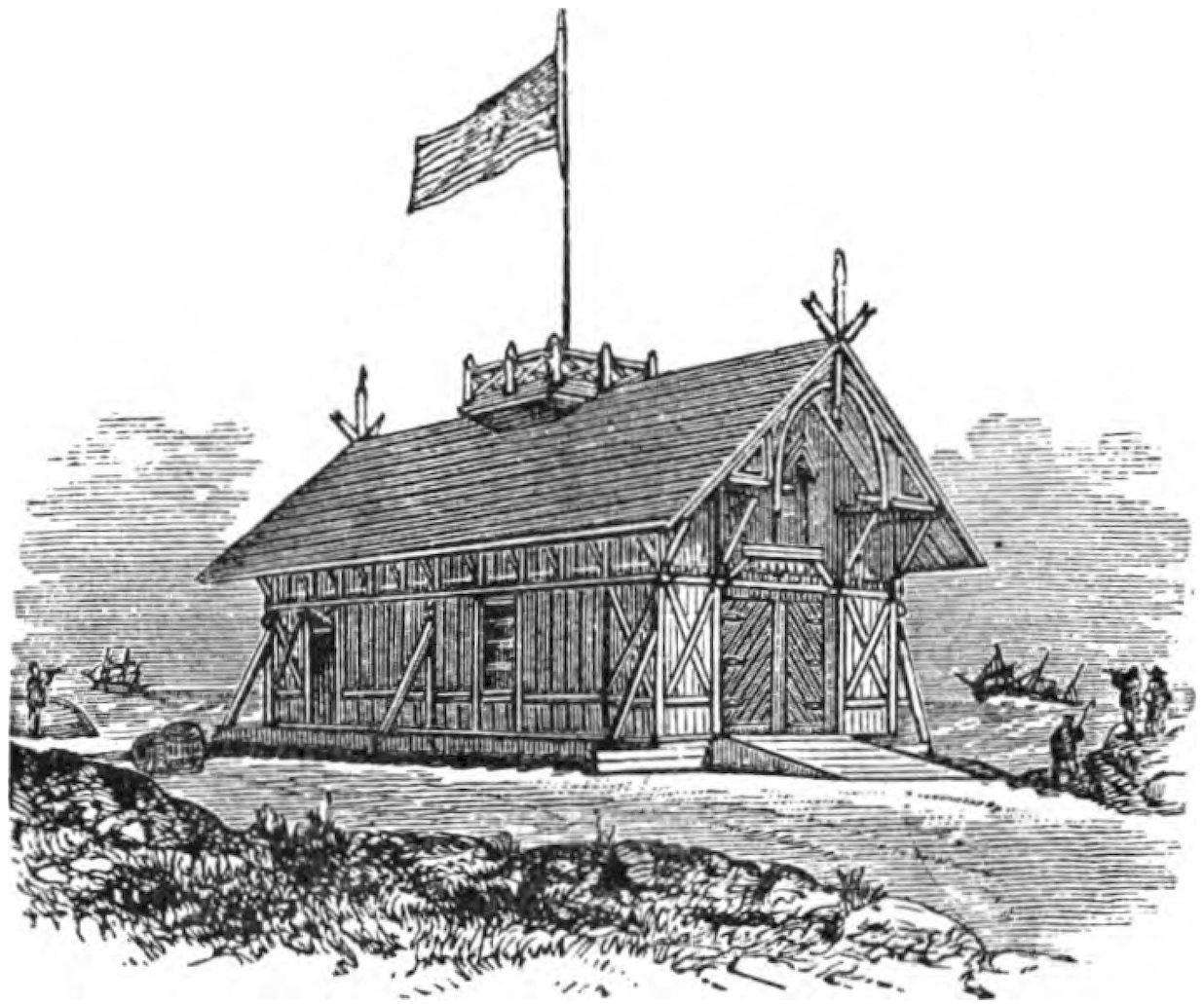

The Society first began its work of rendering assistance to shipwrecked mariners by building huts on many of the desolate sections of the coast. These huts were for the shelter of shipwrecked persons who might reach the shore. The first building of this kind was erected on Lovell’s Island in Boston Harbor in 1807. Later, the Society established the first life-boat station at Cohasset, subsequently erecting others along the coast, and extending its good work to the shores of Cape Cod.

While the Society relied solely upon volunteer crews to man these life-boats in times of disaster, its efforts in saving life and property were of great value, and both the state and general government tendered it pecuniary aid at various times. When the government extended the life-saving service to Cape Cod, the Society was relieved of24 its burden of protecting that dangerous coast, thus enabling it to better provide for other sections of the coast of Massachusetts.

The Massachusetts Humane Society may be considered the parent of the United States Life-Saving Service. The Society is one of the oldest in the world. It originated its coast service more than thirty-six years before the English did, while the French service dates its birth much later.

In 1845, a few years before Congress took steps for providing means for rendering assistance to wrecked vessels along the coasts of the United States, the Society had eighteen stations on the Massachusetts coast, with boats and mortars for throwing life lines to stranded vessels, in addition to numerous huts of refuge.

With the exception of the Life-Saving Benevolent Association of New York, chartered by the Legislature of that State in 1849, no other successful organized efforts outside of those of the government were made up to this time to lessen the distress incident to shipwreck.

The first appropriation made by Congress for rendering assistance to the shipwrecked from shore was March 3, 1847. For nearly a half century prior to this time the efforts of the government for the protection of mariners upon the coasts of the United States were mainly in establishing the coast survey and extending the lighthouse system.

In 1848 the attention of Congress was called to the immediate needs of providing further means for rendering assistance to wrecked vessels25 along the Atlantic coast, and a second appropriation of $10,000 was made. The first appropriation of $5,000 remained in the treasury as an unexpended balance.

Later, this money was placed in the hands of the Collector of Customs at Boston for the benefit of the Massachusetts Humane Society, for use in the work of building and equipping new life stations along the Massachusetts coast.

The second appropriation of $10,000 was for expenditure upon the New Jersey coast. With this appropriation eight boat-houses were erected and supplied with appliances for saving life and property. This marks the beginning of the life-saving service of the United States.

In 1849 Congress appropriated $20,000 for life-saving purposes. With this sum eight life-saving stations were built on the Long Island coast and six additional stations erected on the shores of New Jersey. While these newly established life-saving stations were not manned by regular drilled crews of surfmen, as at present, they often proved of great value at times of disaster, and in 1850 Congress made another appropriation of $20,000 for life-saving purposes.

Of this sum half was expended in erecting additional stations along the shores of Long Island, and for a new station at Watch Hill, R. I.

The attention of Congress having been called to the needs of some means of rendering assistance to wrecked vessels along the coasts of North and South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, and Texas, the remaining $10,000 of this appropriation was expended in placing life-boats at the most exposed points on these coasts.

In 1853 and 1854 Congress made liberal appropriations for life-saving purposes, and fourteen new stations were built on the coast of New Jersey.

The service was at this time extended to the Great Lakes, twenty-three life-boats being stationed at different points on Lake Michigan, and several others on the other lake shores and on the Atlantic coast. In 1854 there were one hundred and thirty-seven life-boats stationed along the coasts of the United States. Of this number fifty-five were at stations on the New York and New Jersey coasts.

26

The absence of drilled and disciplined crews at these stations, however,—together with irresponsible custodians and the lack of proper equipments, the result of pillage or decay,—contributed to great loss of life and heartrending scenes of disaster along the Atlantic coast. The inefficiency of the life-saving service, as it then existed, was apparent to all. Public sentiment had now become excited, and Congress27 was appealed to for immediate relief from the existing conditions.

In 1853 a bill which provided for the increase and repair of the stations and the guardianship of the life-boats passed the Senate; but, unfortunately, failed to reach the House before adjournment. An appalling disaster, the wreck of the Powhatan, on the coast of New Jersey, in which three hundred lives were lost, caused the bill to be promptly and favorably acted upon at the next session of Congress. Under the provisions of this bill a superintendent at a salary of $1,500 per annum was appointed for the Atlantic and Lake coasts, keepers were placed in charge of the stations at a salary of $200, bonded custodians secured for the life-boats and other apparatus, and the stations and equipments speedily put in order.

The service was somewhat improved as a result of this, but there were still many defects in it, which were brought to light as disaster followed disaster along the seaboard. Up to this time the life-saving crews were not regularly employed.

A bill providing for the employment of regular crews of surfmen was presented to Congress in 1869. Strange though it may seem, in view of the terrible disasters and loss of life which had so recently taken place along the Atlantic coast, the bill suffered defeat. A substitute bill, however, which provided for the employment of crews of surfmen, though only at alternate stations, was passed. This marks28 the beginning of the employment of crews of surfmen at the United States life-saving stations, and was the first step in the direction of their employment at all stations for regular periods.

During the winter of 1870–71 a number of appalling, fatal disasters occurred along the Atlantic coast. These disasters not only revealed the fact that the coast was not properly guarded, but also that the service was inefficient and needed a more complete organization. In 1871 Congress again appropriated $200,000 and authorized the Secretary of the Treasury to employ crews of surfmen at such stations and for such periods as he might deem necessary.

Mr. Sumner I. Kimball, the present general superintendent of the United States Life-Saving Service, was at that time in charge of the Revenue Marine Service, and the life-saving stations being then under the charge of that bureau, he at once took steps to ascertain the conditions of the service.

An officer of the Revenue Marine Service was at once detailed to visit the life-saving stations and to make a report of their condition and requirements.

The report made by the officer was a startling revelation. Absolutely no discipline was found among the crews, no care had been taken of the apparatus, some of the stations were in ruins, others lacked such articles as powder, rockets, and shot lines, every portable article had been stolen from many stations, and the money that Congress had appropriated had been practically wasted.

29

From the report it was plainly evident that the reorganization of the service must be speedily brought about, and in accordance with an act of Congress in 1872, the organization of the present system of life-saving districts with superintendents took place.

The inefficient keepers were at once removed and the most skilled boatmen obtainable were placed in charge of the stations.

The stations were also manned by the most expert surfmen to be found along the coast, and the patrol of the coast at night and during thick weather by day was inaugurated. It was soon found that the life-saving stations, however, were too far apart for the crews to be of assistance to one another in the event of a wreck, and measures were adopted to place them within distances of from three to five miles of one another. To bring about this result, twelve new stations were built on the New Jersey coast, six on Long Island, while the location of some of the existing stations were changed.

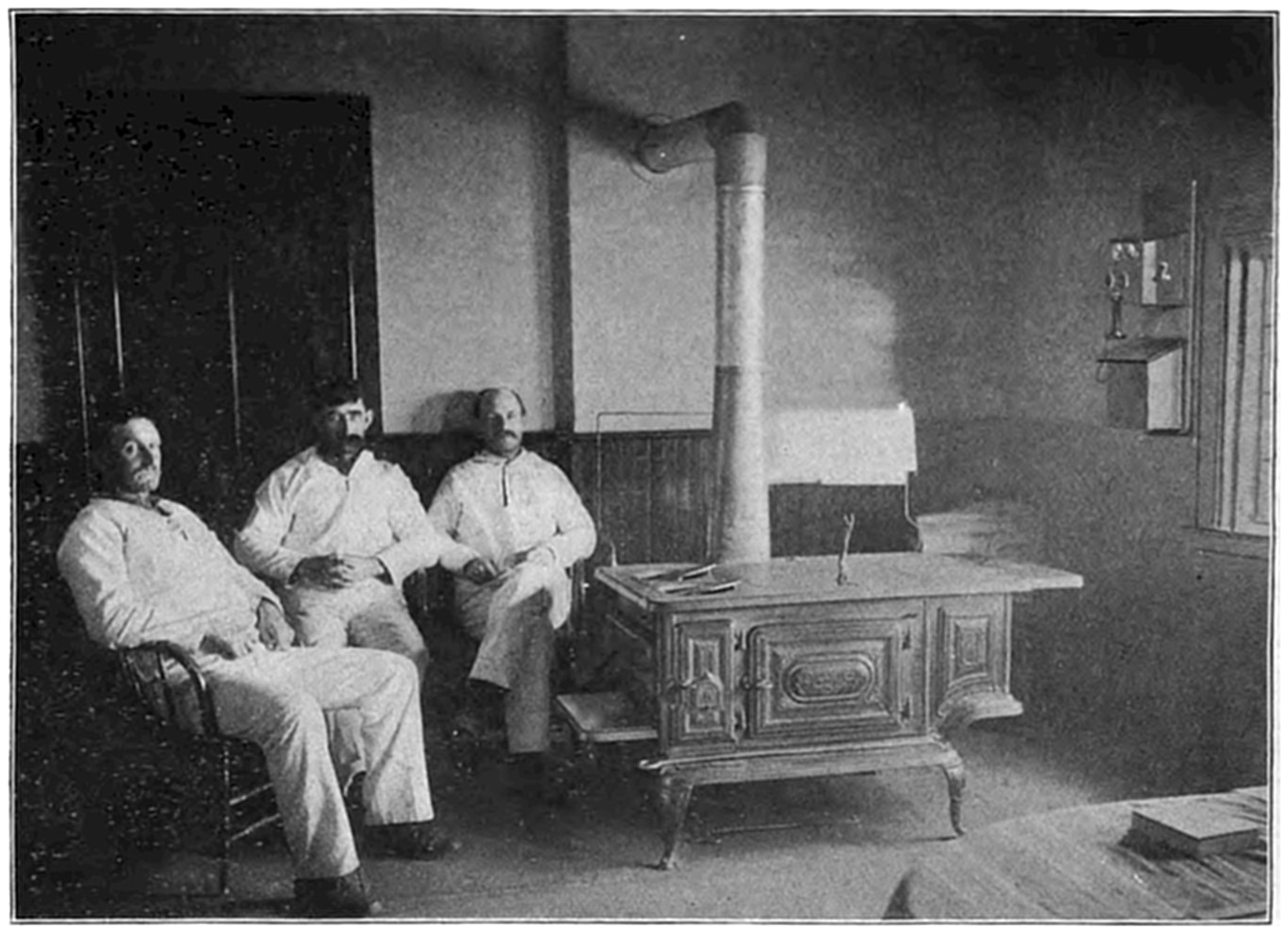

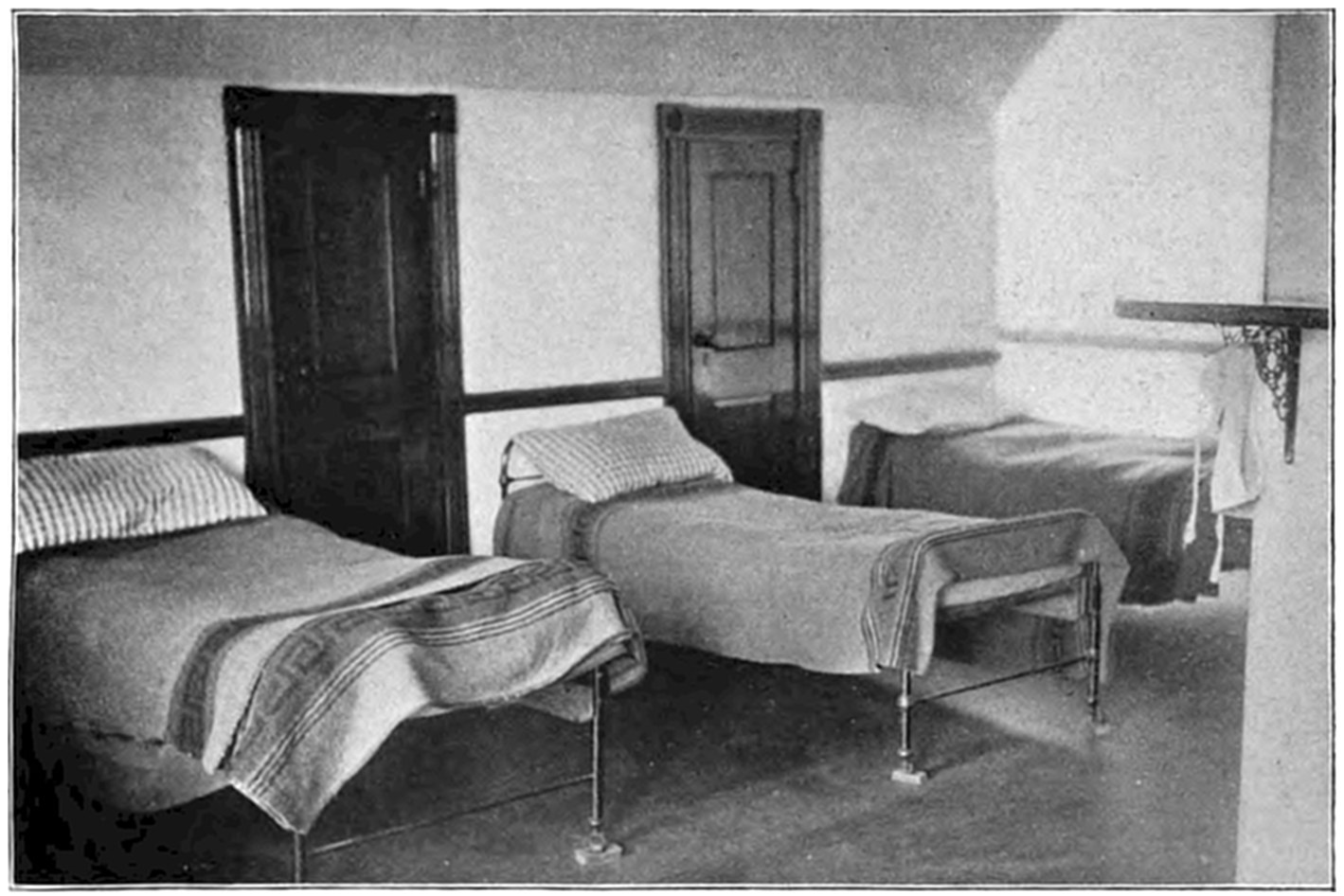

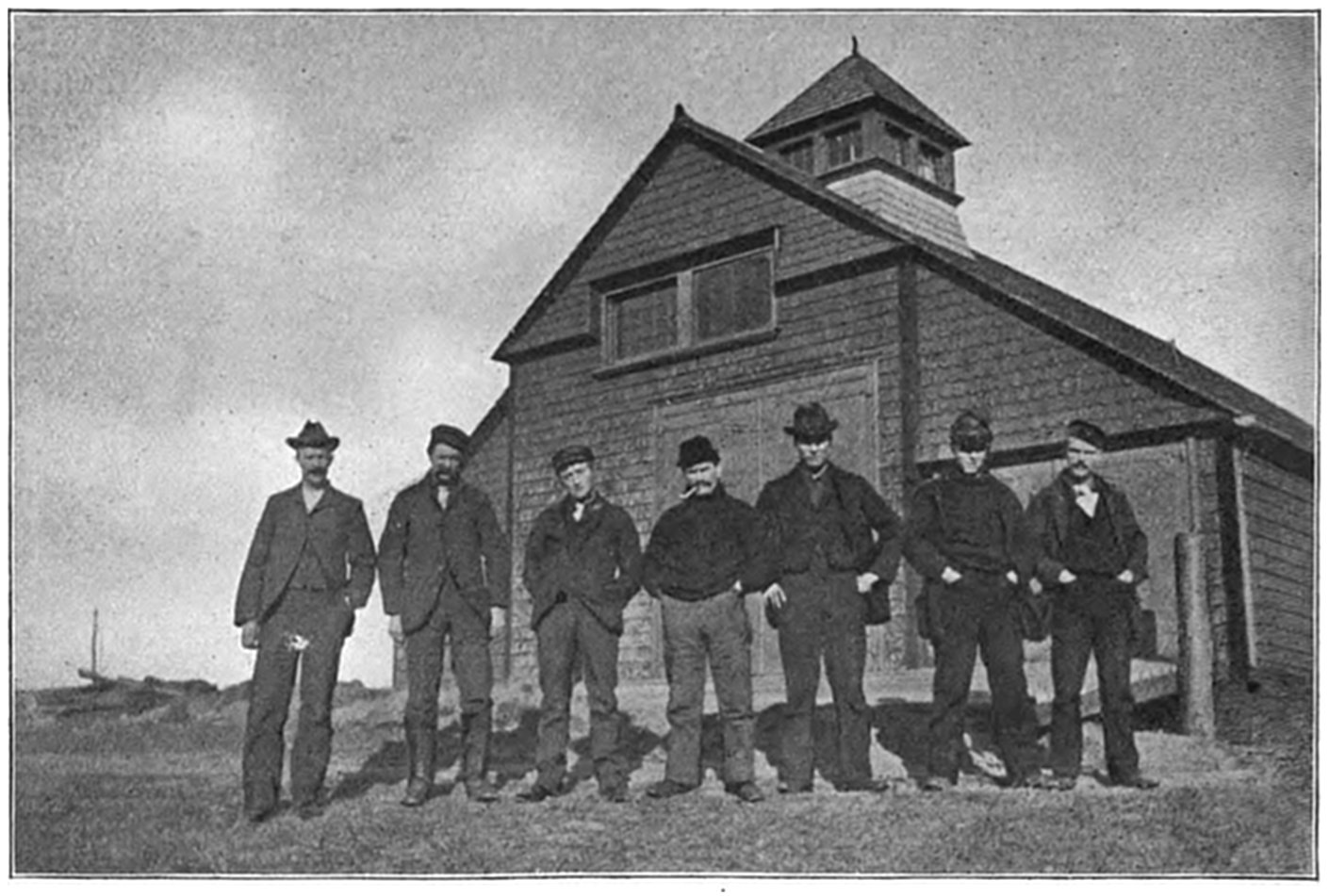

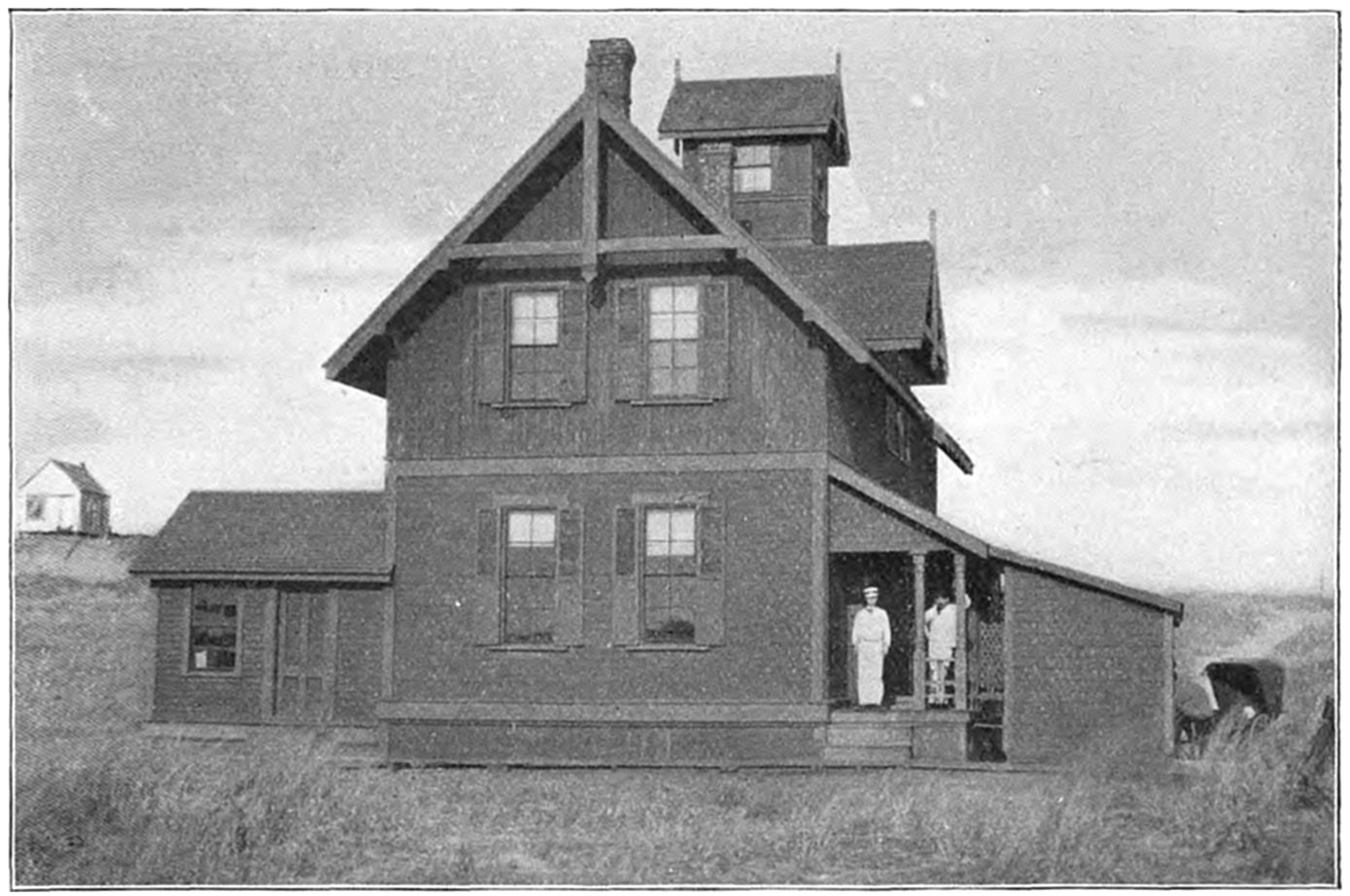

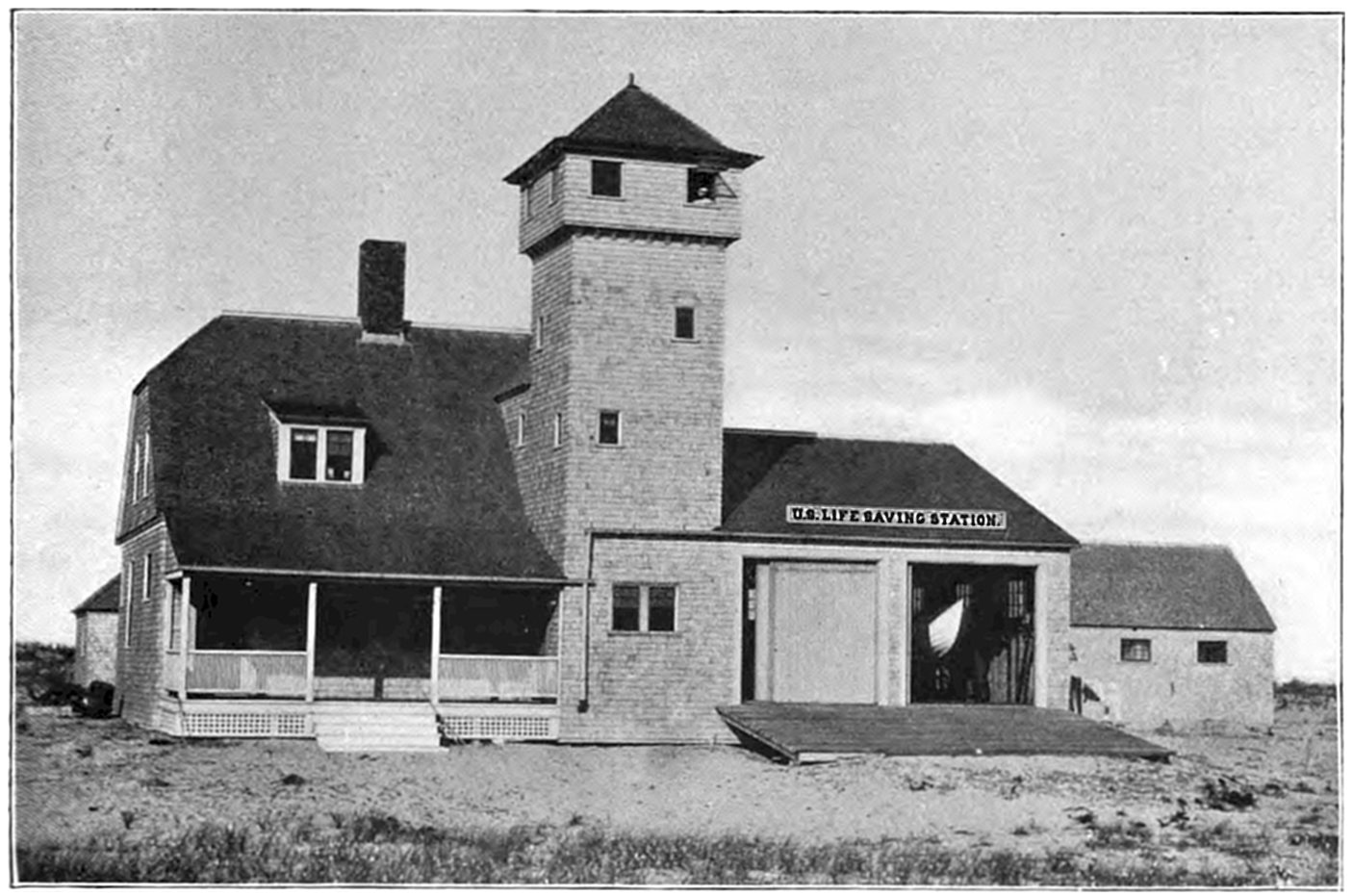

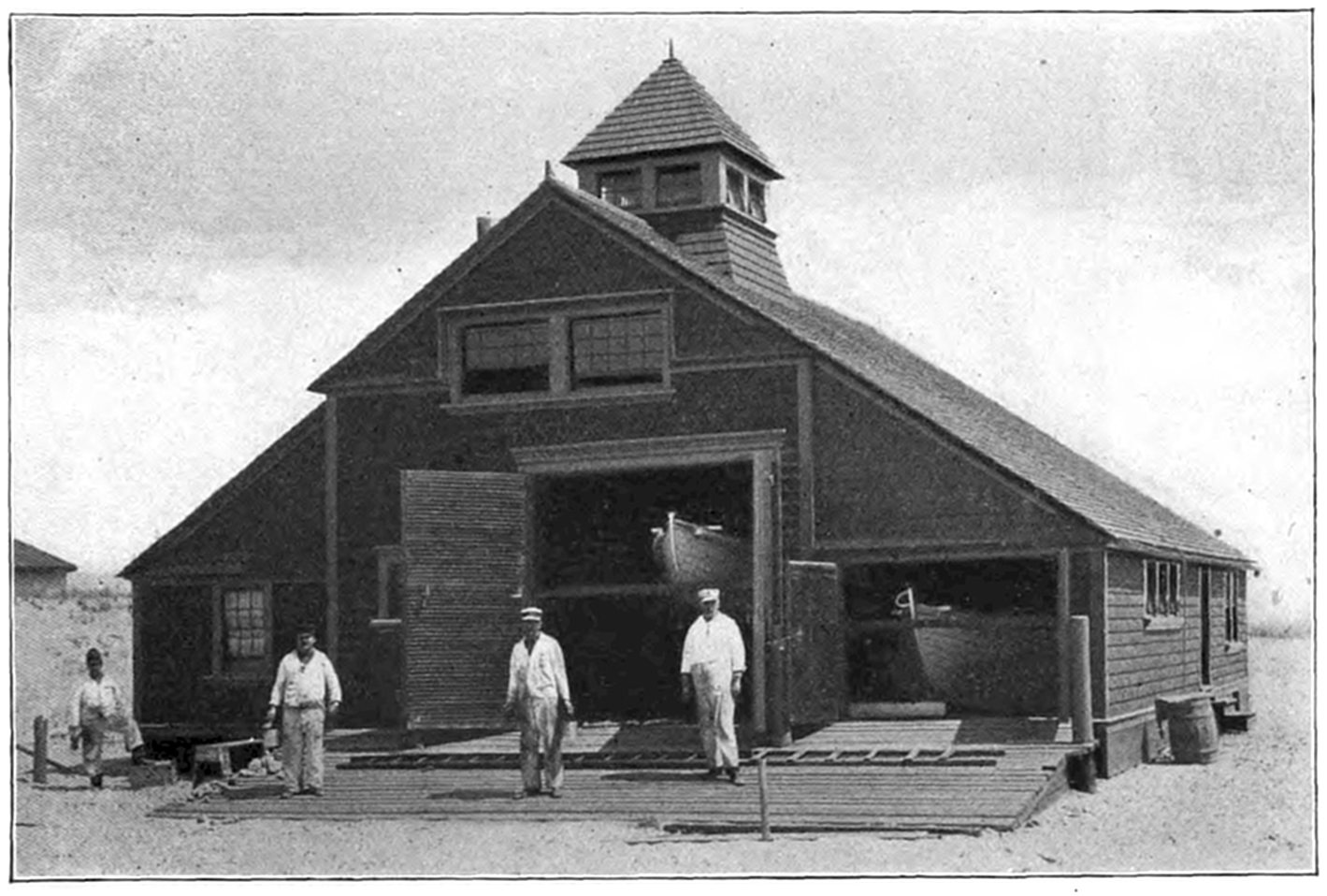

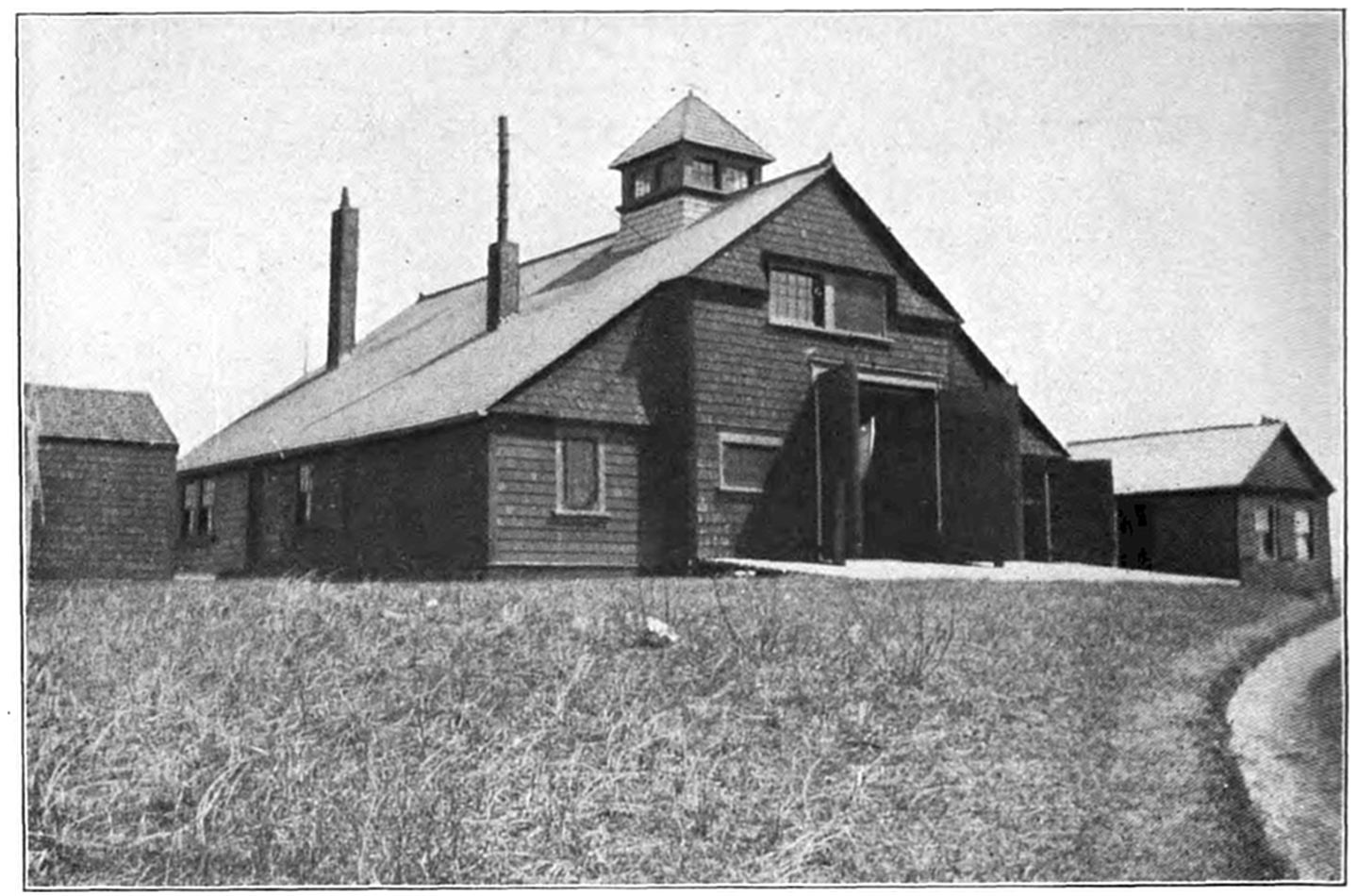

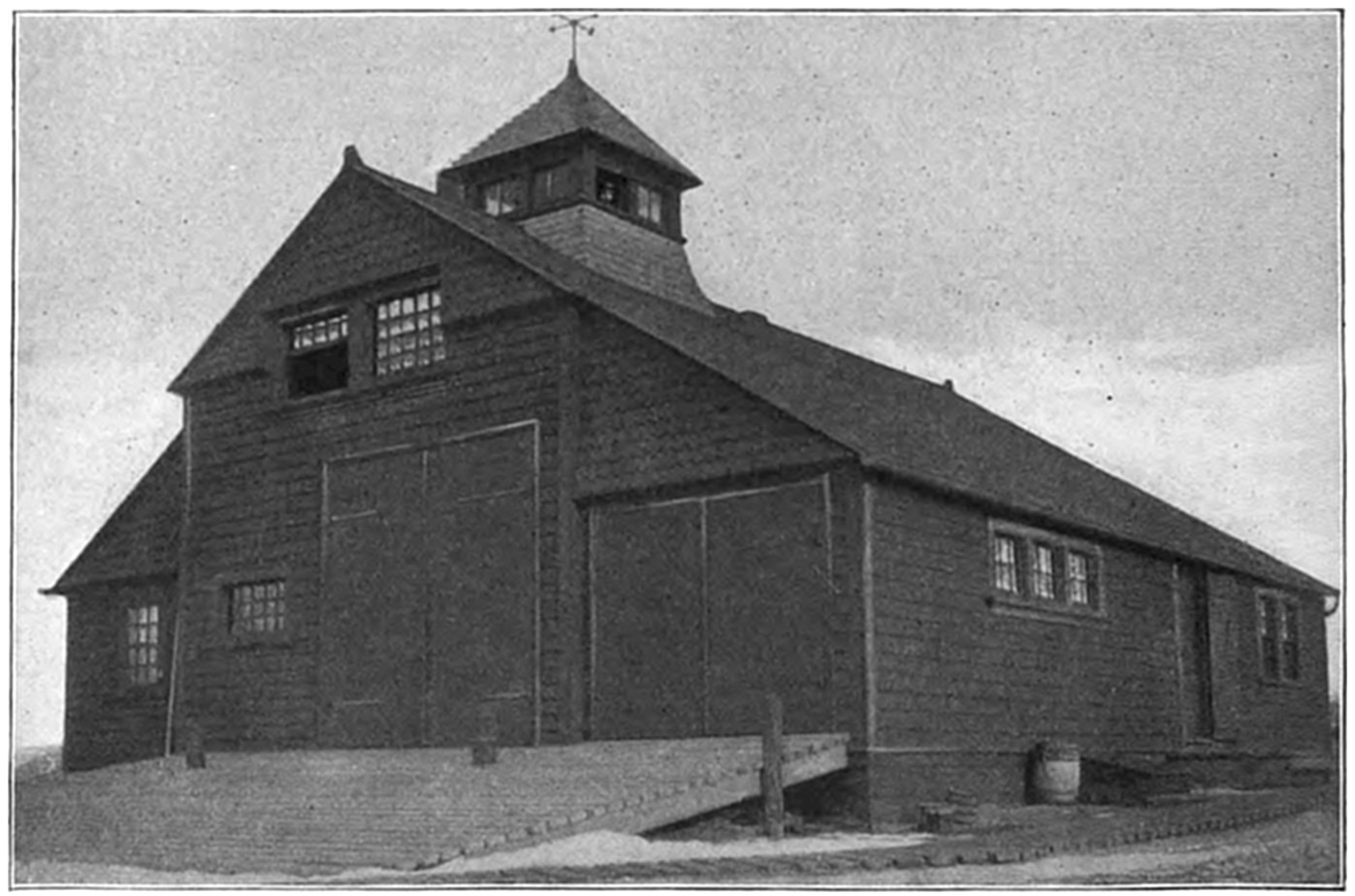

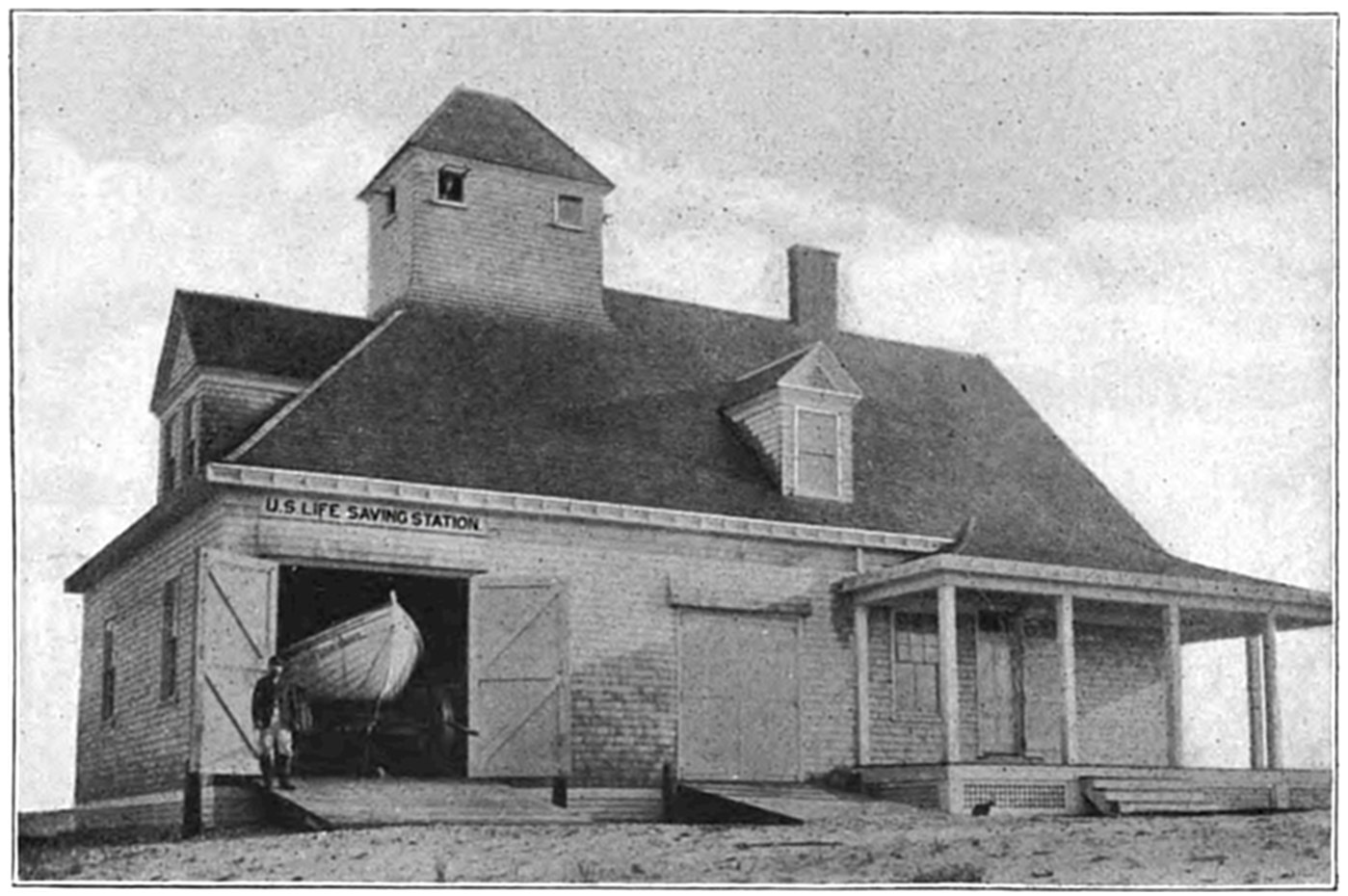

The stations were plain houses forty-two feet long and eighteen wide, of two stories and four rooms. One room below was used by the crew as mess-room, the other room contained the boats and other apparatus used at wrecks. One of the upper rooms was used as a sleeping room for the crew, the other room was used as a storeroom.

As a result of the reorganization of the service, the record for the first season shows that not a life was lost in the disasters that occurred on either the Lake shores or the Atlantic coast.

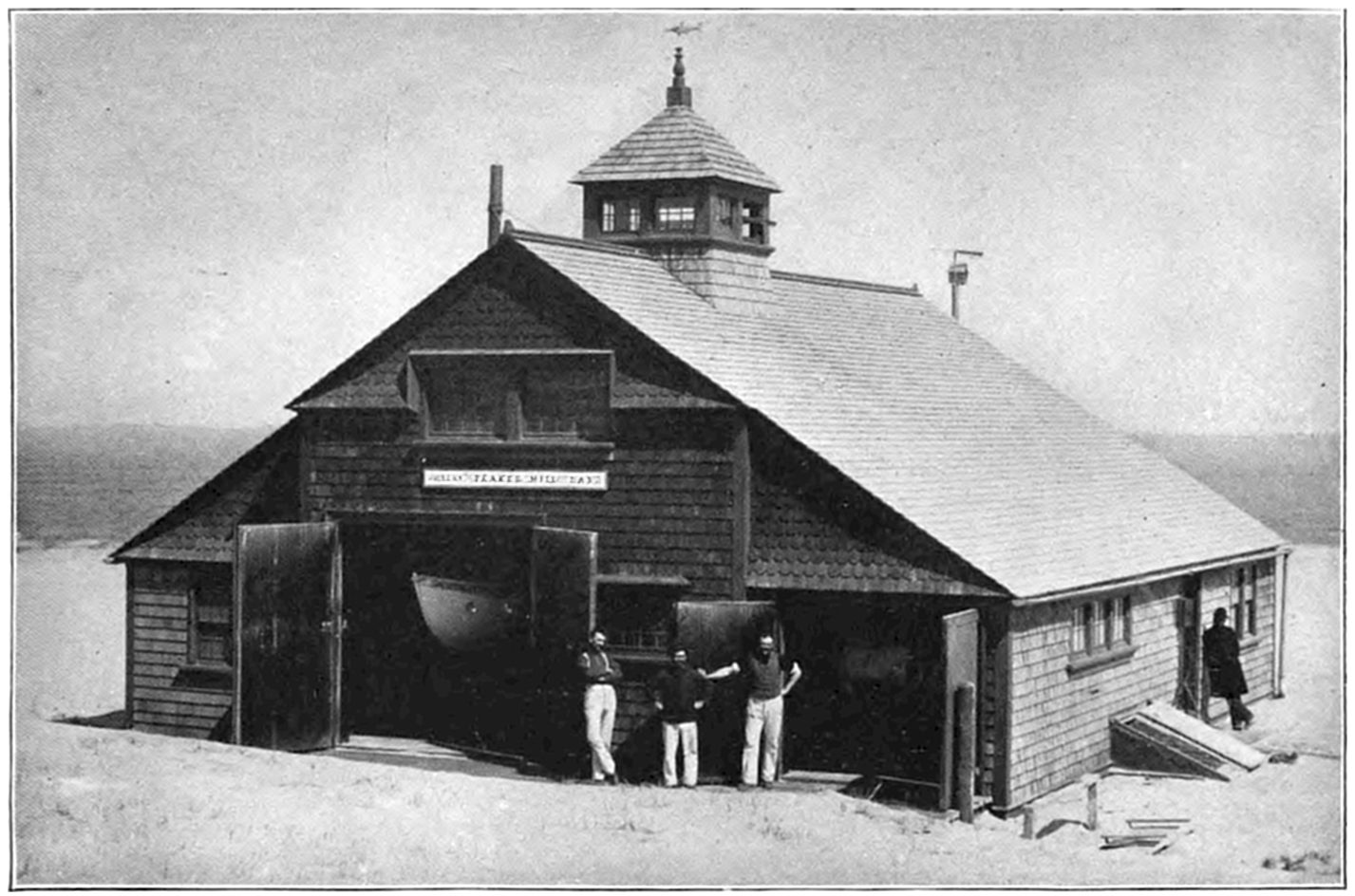

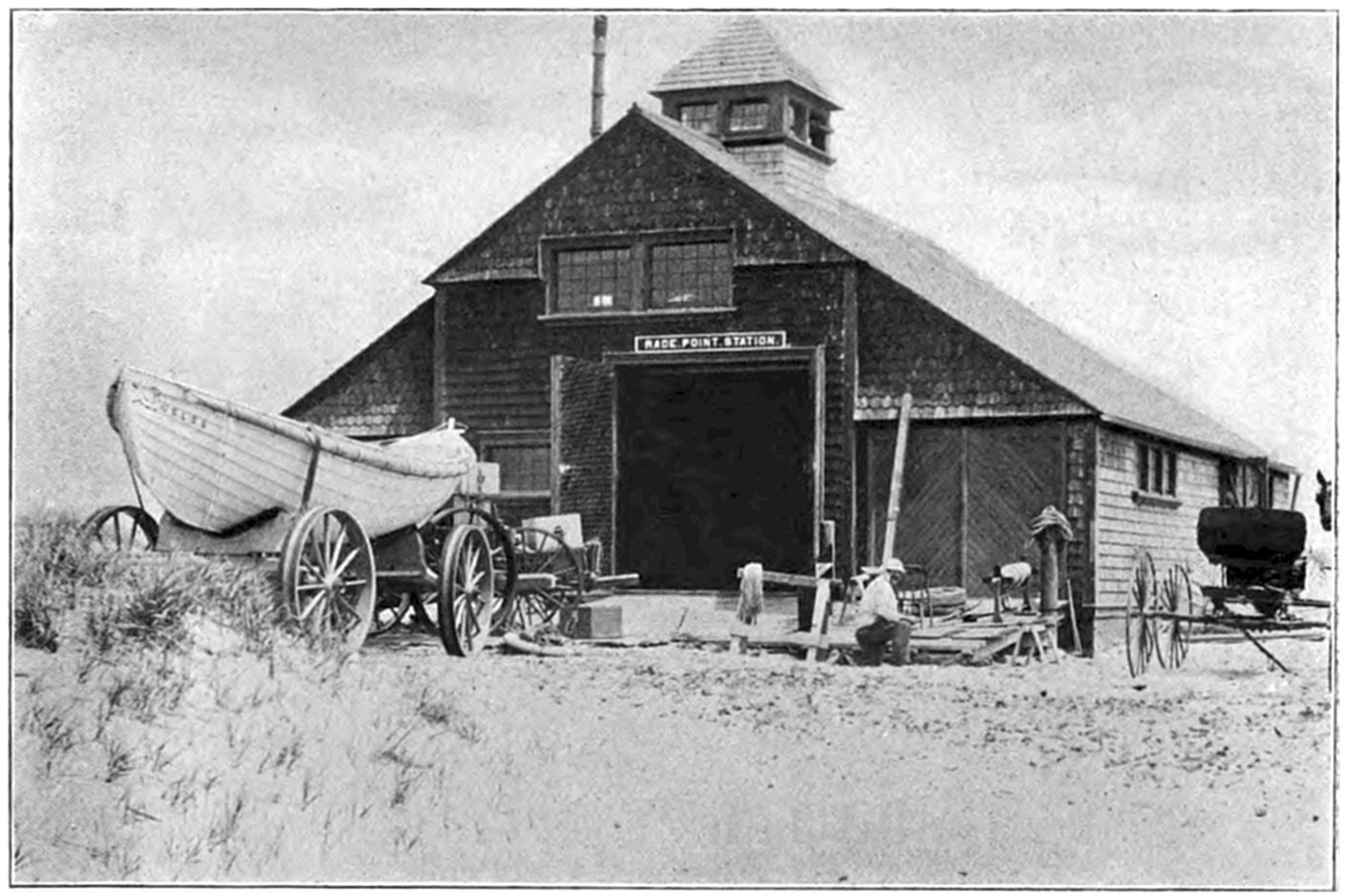

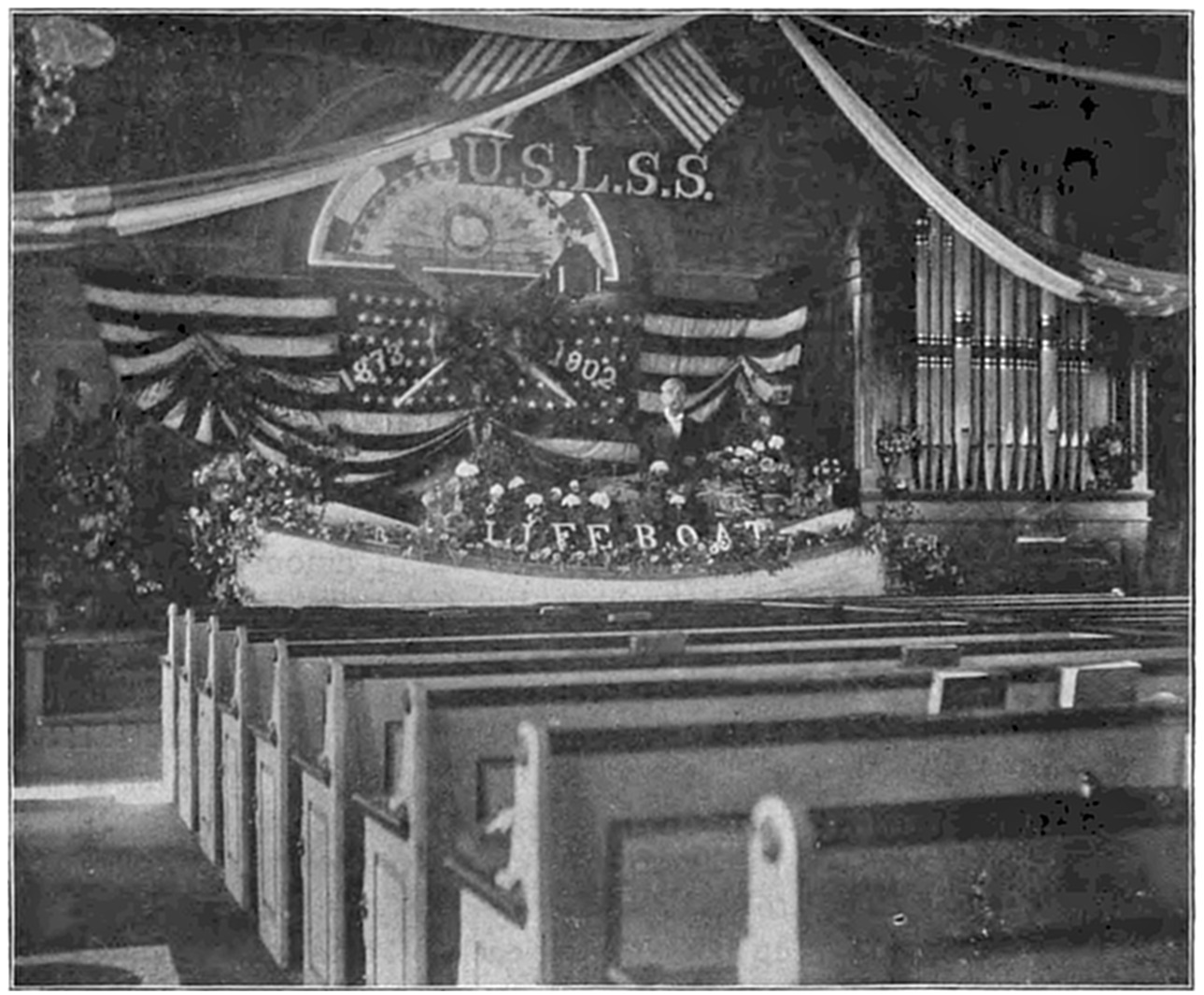

Interest in the success of the life-saving service under the new30 system was now keyed up to a high pitch. Congress had authorized a new station for the coast of Rhode Island in 1871, and in June, 1872, one more was ordered for that coast, and nine for the coast of Cape Cod. These stations were built and manned in the winter of 1872. The nine that were erected on Cape Cod were located as follows: Race Point and Peaked Hill Bars, at Provincetown; Highlands, at North Truro; Pamet River, at Truro; Cahoon’s Hollow, at Wellfleet; Nauset, at North Eastham; Orleans, at Orleans; Chatham, at Chatham; and Monomoy, on Monomoy Island. Since that time four new stations have been established, the Wood End, High Head, Old Harbor, and Monomoy Point.

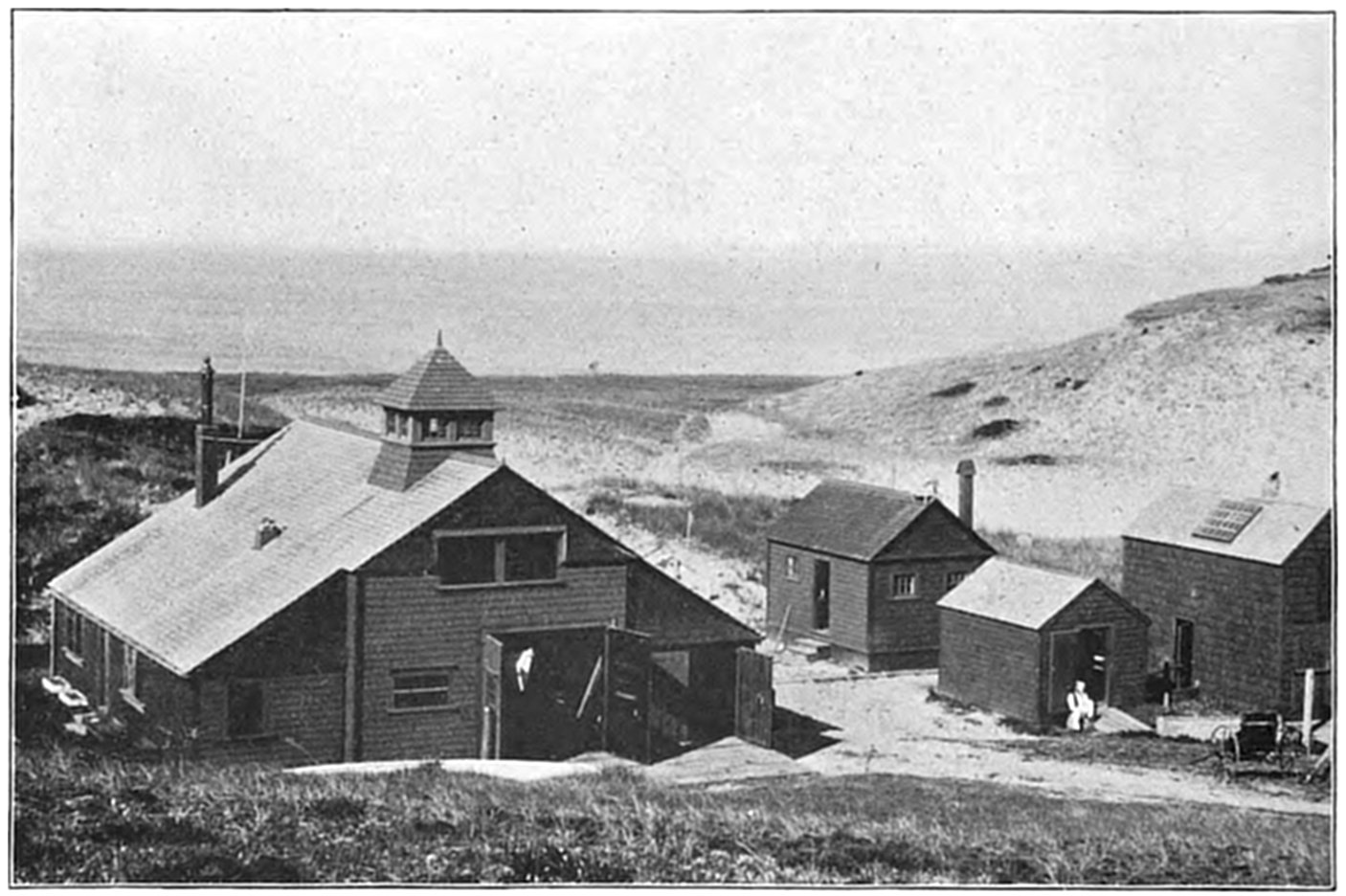

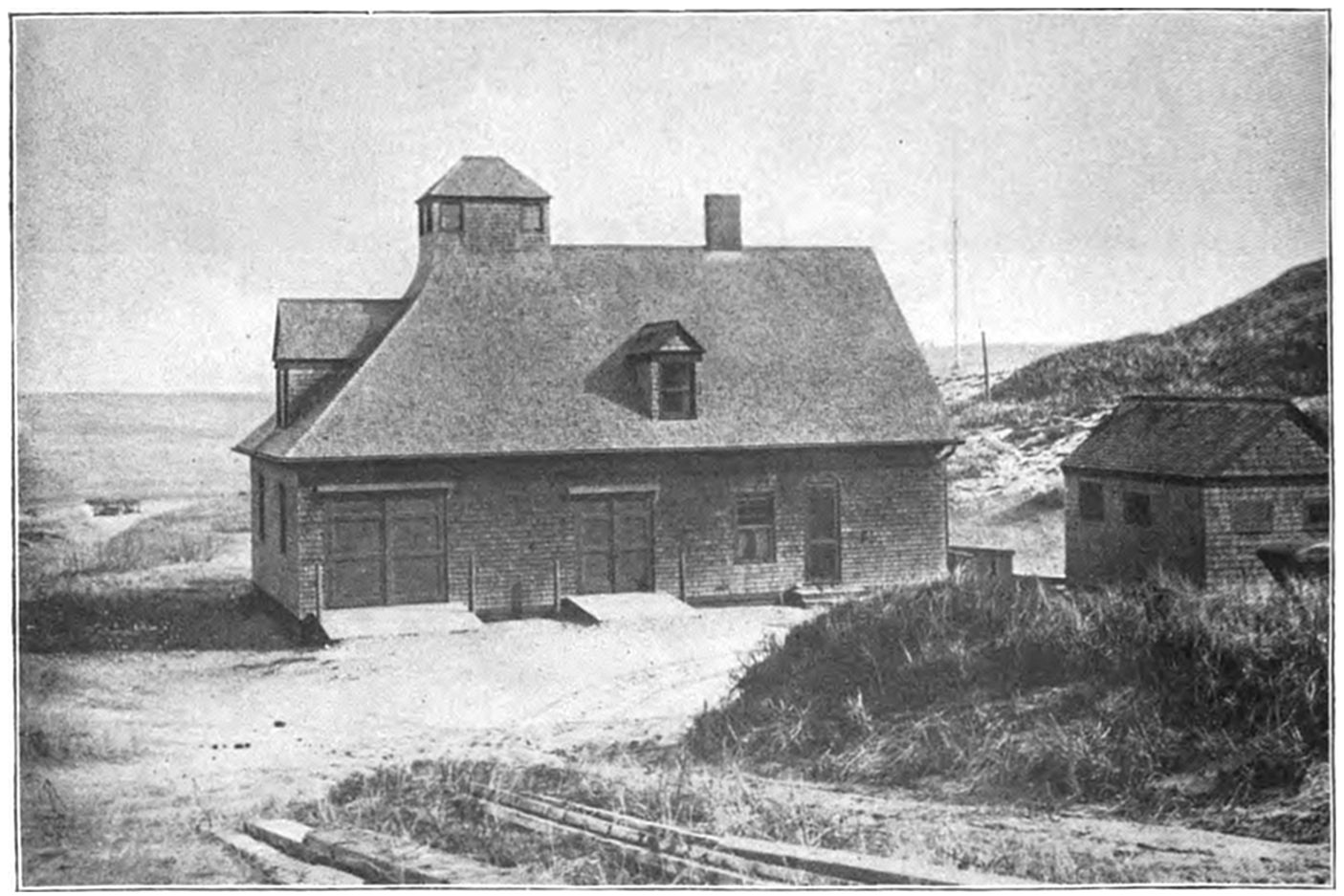

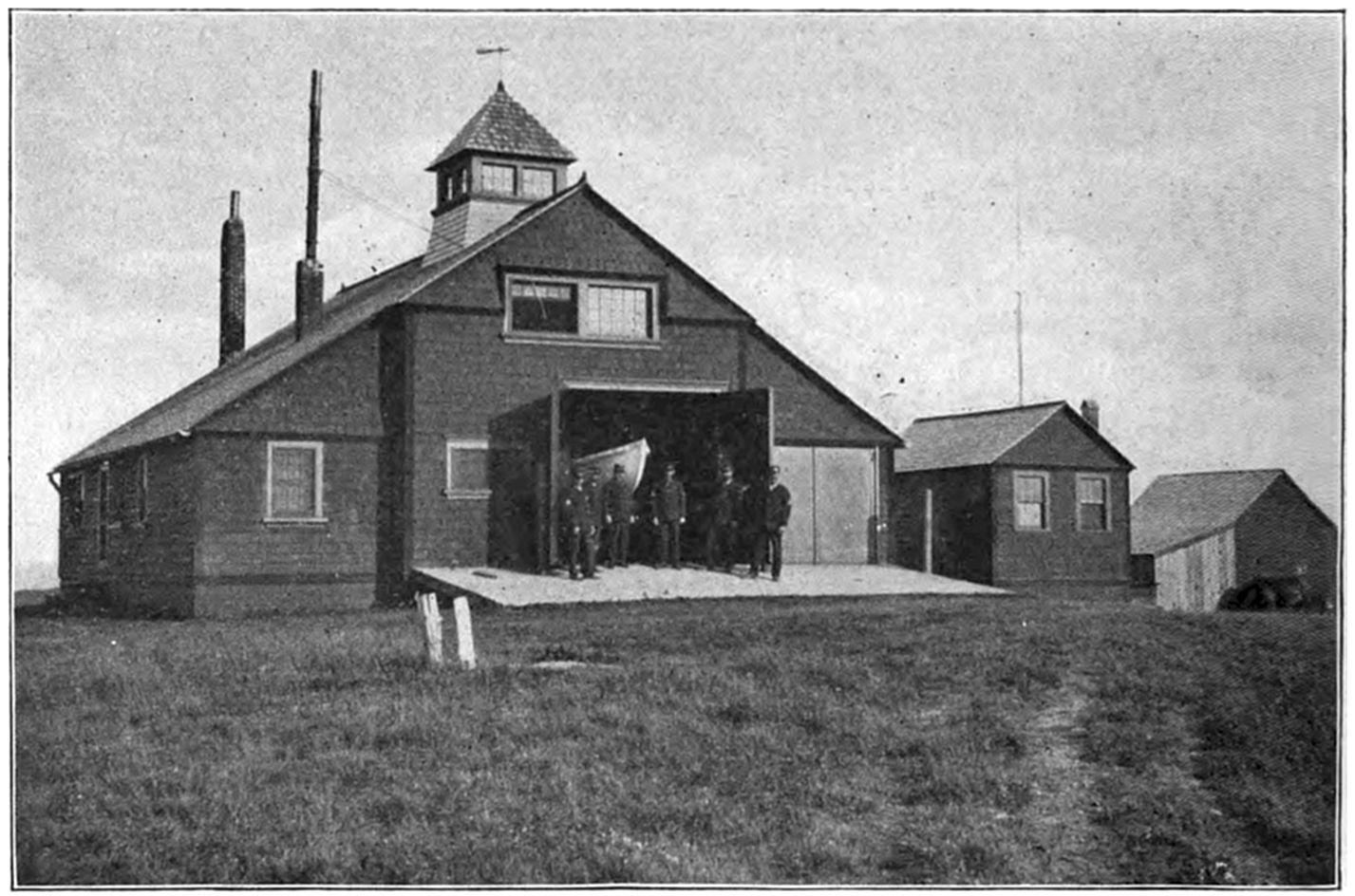

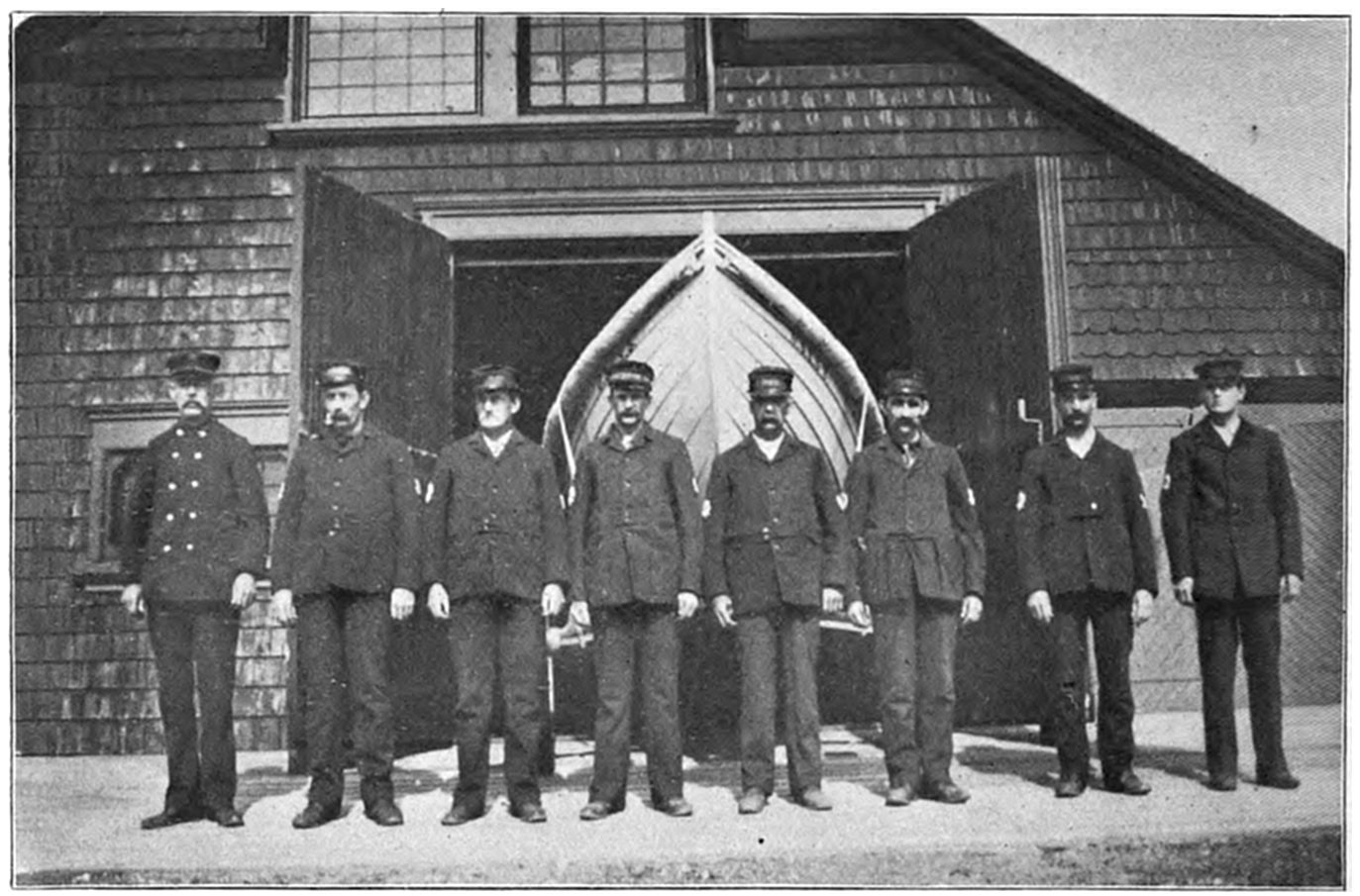

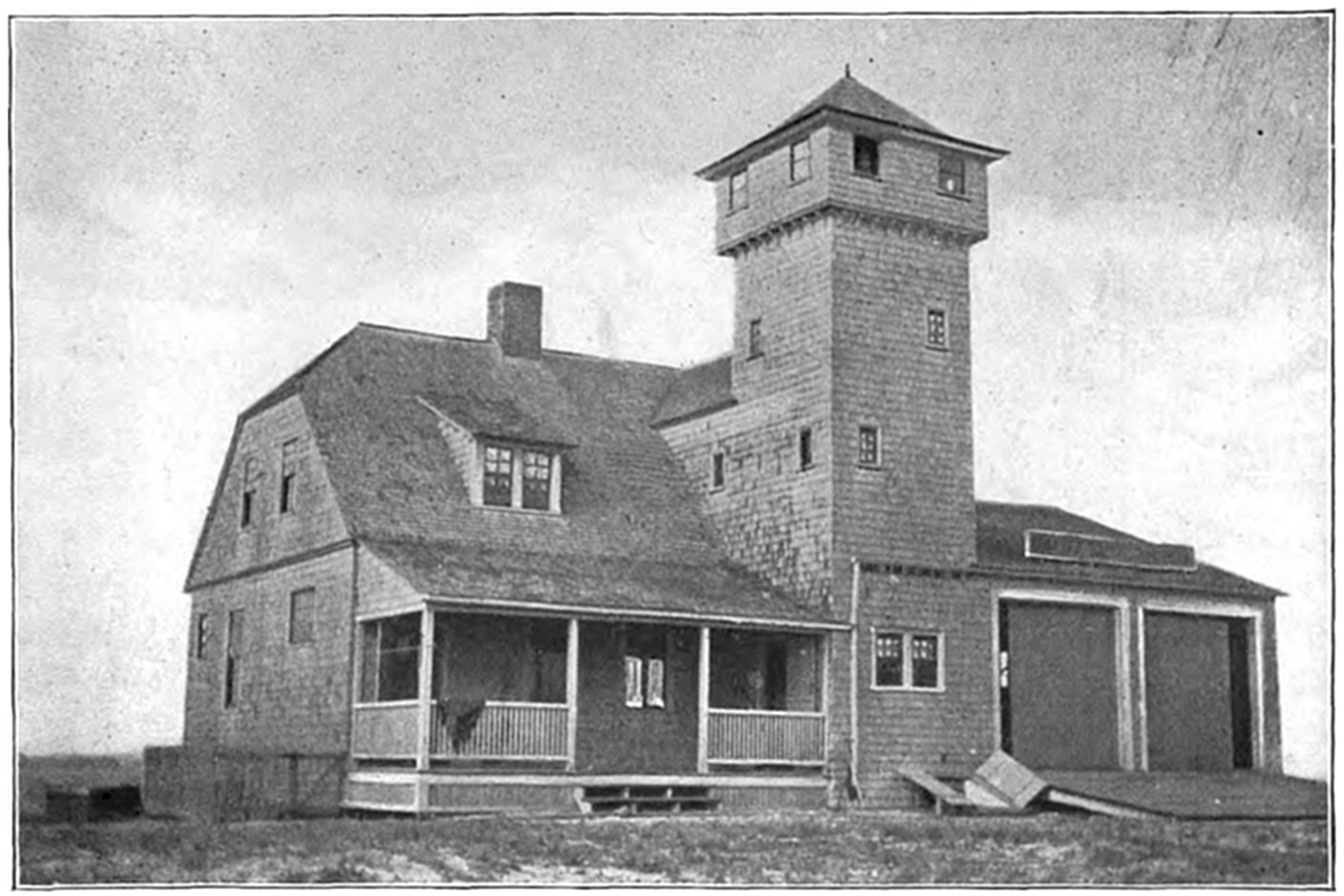

The life-saving stations on Cape Cod are situated among the sand hills common to the eastern shores of the Cape, at distances back from the high-water mark as to insure their safety. In most instances they are plain structures, designed to serve as a home for the crew and to afford storage for the boats and other apparatus. In most of the stations on Cape Cod the lower floor is divided into five rooms—a mess room, which also serves for a sitting room for the crew, a kitchen, a keeper’s room, a boat and beach apparatus room. Wide double-leafed doors with a sloping platform permit the quick and easy running out of the surf-boat and other apparatus from the station.

31

The second story contains two rooms: one the sleeping room for the crew; the other has spare cots for rescued persons, and is also used as a storeroom.

On every station there is a lookout or observatory, from which the life savers, during the day when the weather is fair, keep a careful watch of all shipping along the coast. In order that the life-saving stations may be distinguished from a long distance at sea, they are usually painted dark red, and as a further aid to shipping, they are marked by a flagstaff about sixty feet high erected close by them. This flagstaff is also used to signal passing vessels by the International code. These stations are manned from the 1st of August until June 1st following, the keeper remaining on duty throughout the year. The stations are generally furnished with two surf-boats (supplied with oars, life preservers, life-boat compass, drag, boat-hooks, hatchet, heaving line, knife, bucket, and other outfits), boat carriages, two sets of breeches-buoy apparatus (including guns and accessories), carts for the transportation of the apparatus, a life-car, cork-jackets (life preservers), Coston signals, signal rockets, signal flags of the International and General signal code, medicine chests with contents, patrol lanterns, barometer, thermometer, patrol clocks, the requisite furniture for housekeeping by the crew and for the succor of rescued persons, fuel, oil, tools for the repair of the boats and apparatus, and minor repairs to the buildings, and the necessary books and stationery.

32

With the International and General code of signals, shipping, when miles at sea, can, by this means, open communication with the stations, be reported, obtain latitude and longitude, or, if disabled, can thus send for assistance.

All the life-saving stations on Cape Cod are connected by telephone with lines running to central stations in Provincetown and Chatham. Close watch of the movements of all shipping is in this way easily maintained, and in time of disaster help is quickly summoned and obtained from one station to another.

In the life-saving service the week begins on Sunday night at midnight, and the days are each set apart for some particular kind of employment.

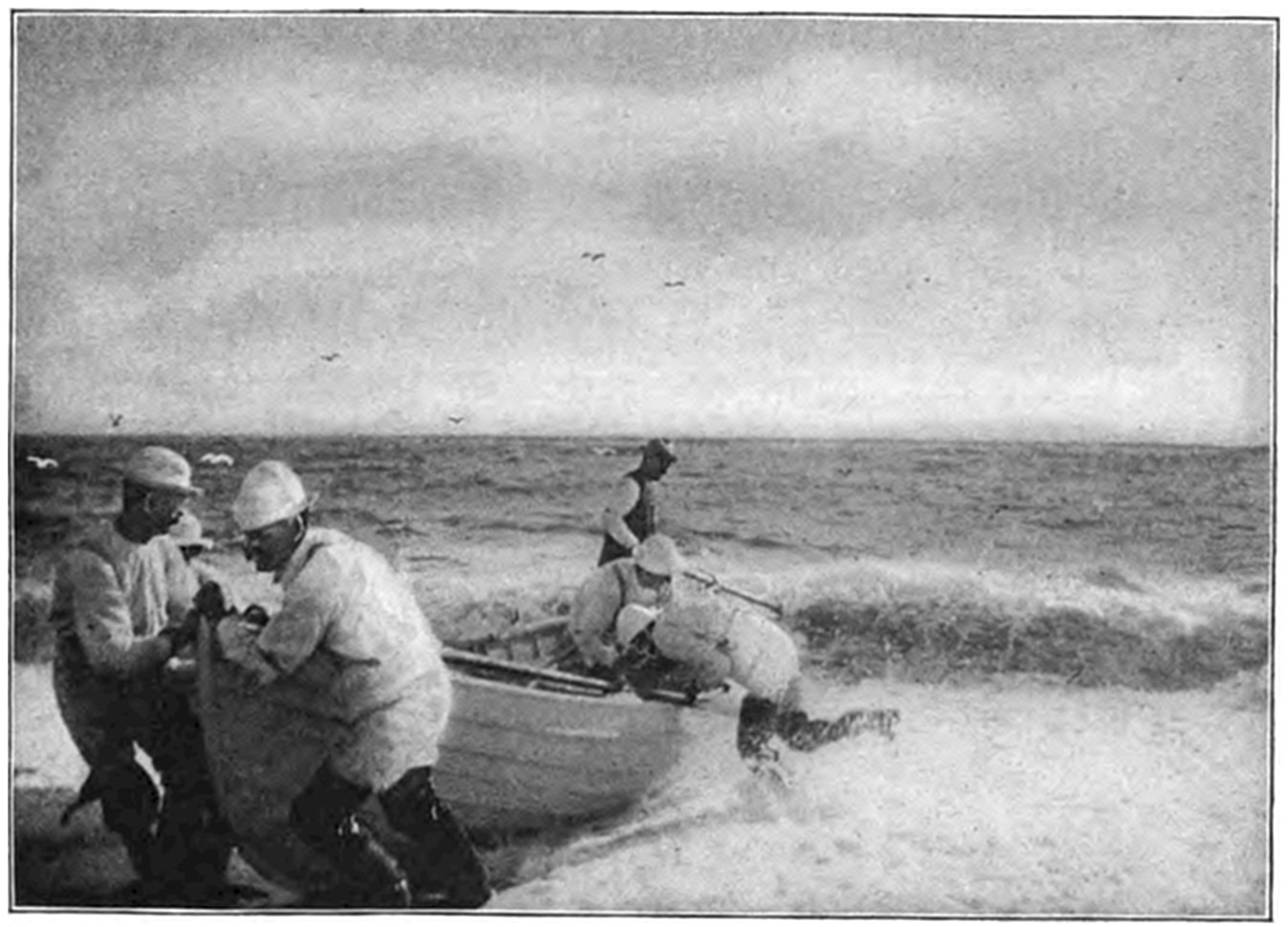

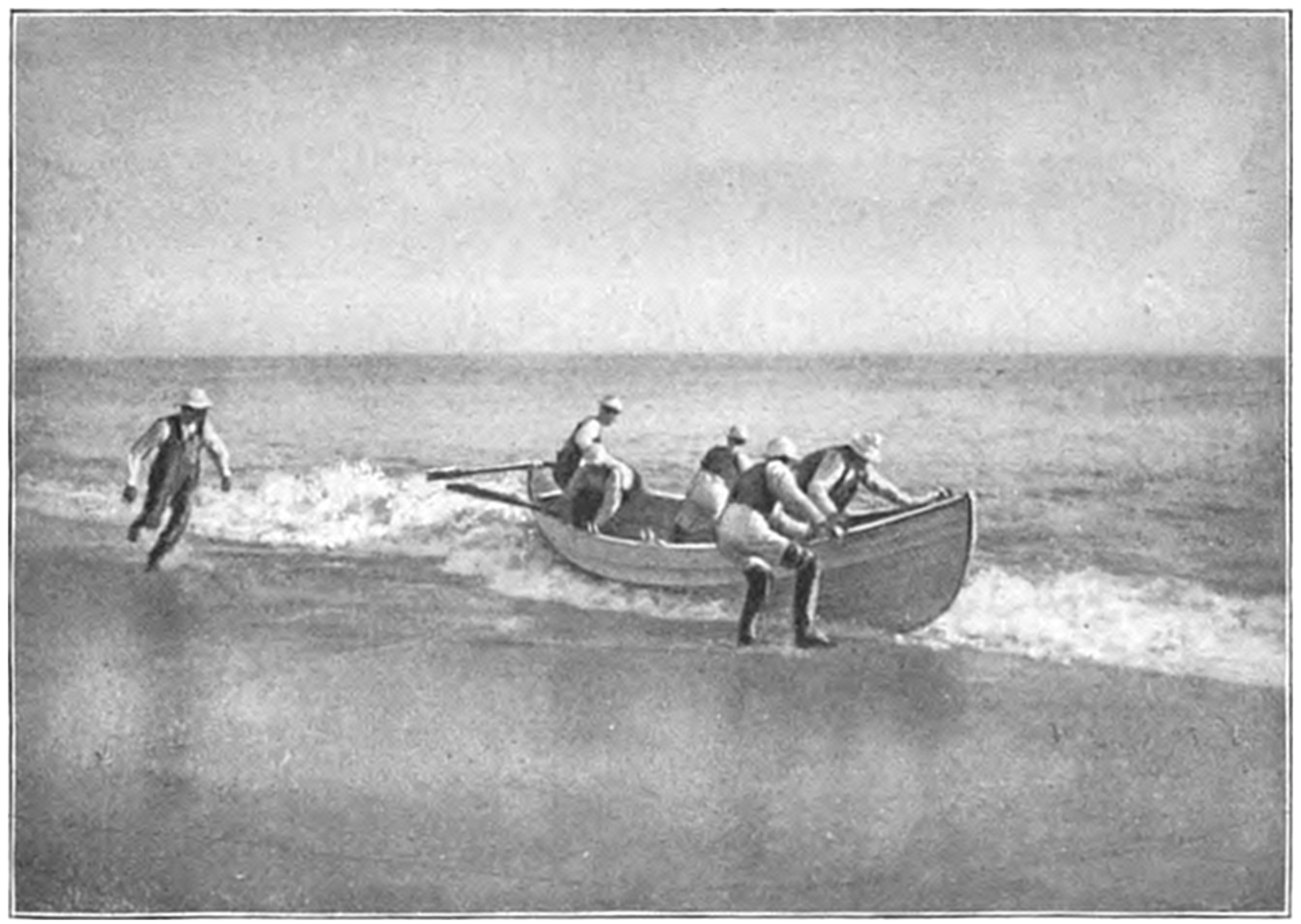

On Monday the members of the crew are employed putting the station in order. On Tuesday, weather permitting, the crew are drilled in launching and landing in the life-boat through the surf.

On Wednesday the men are drilled in the International and General code of signals.

Thursday, the crew drill with the beach apparatus and breeches-buoy.

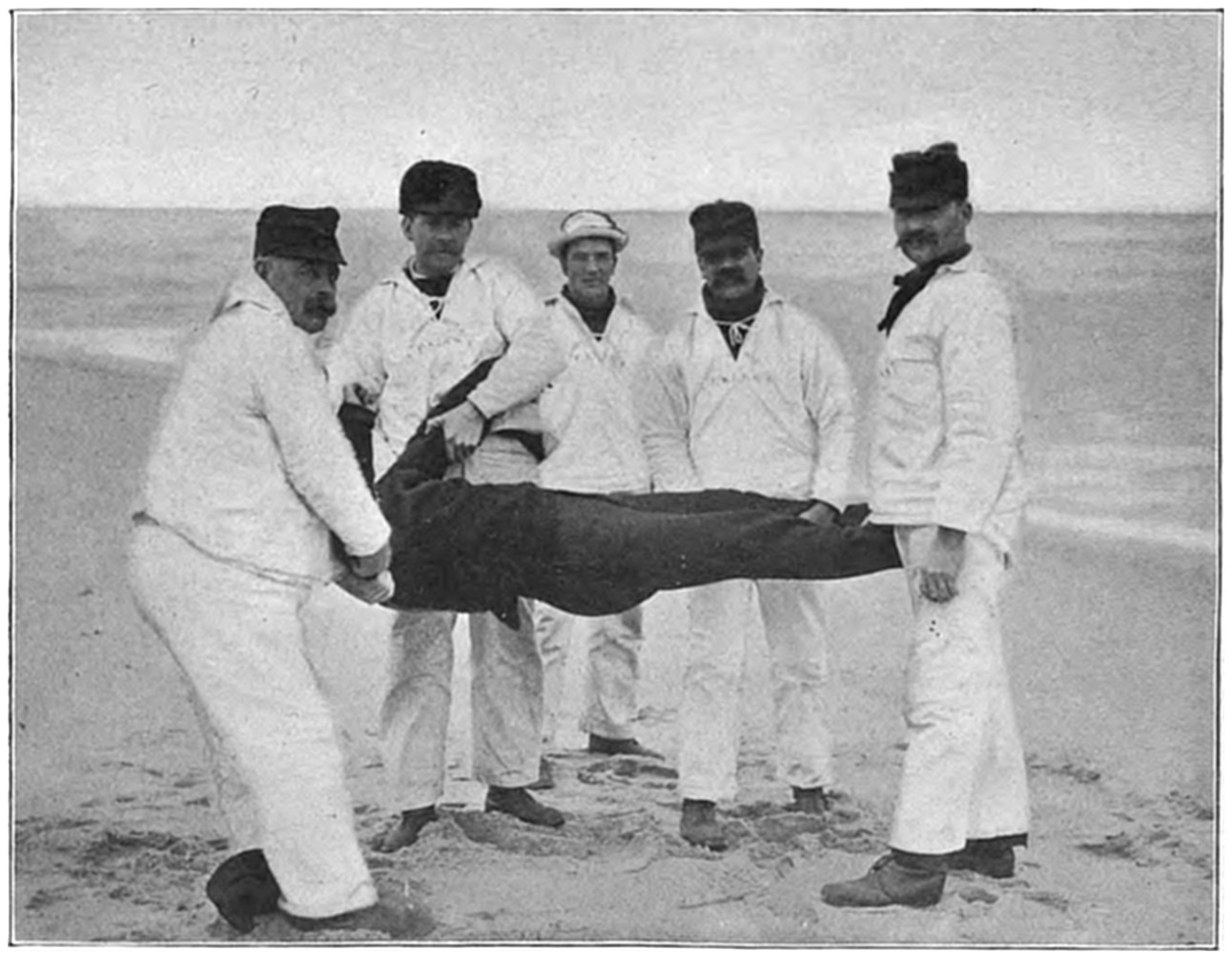

Friday, the crew practice the resuscitation drill for restoring the apparently drowned.

Saturday is wash-day.

Sunday is devoted to religious practices.

33

The keepers of the life-saving stations receive $900 per year for their services, and the surfmen $65 per month.

In the early history of the life-saving service the keepers received but $200 per year, later their salary was increased to $400, then to $700, and, finally, to the present figure.

The surfmen in the early days of the service received but $40 per month, later it was increased to $45, then to $60, and, finally, to the present sum.

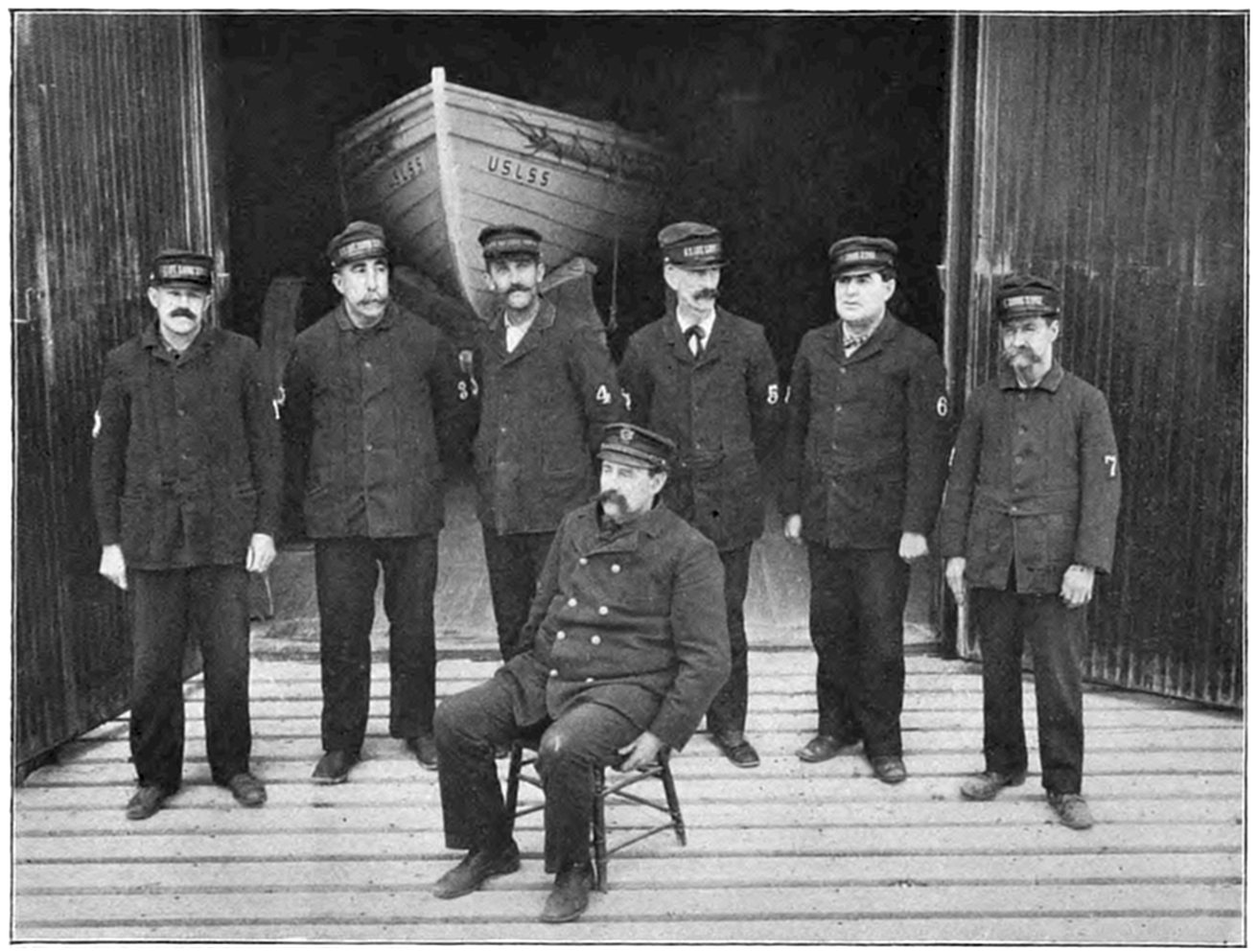

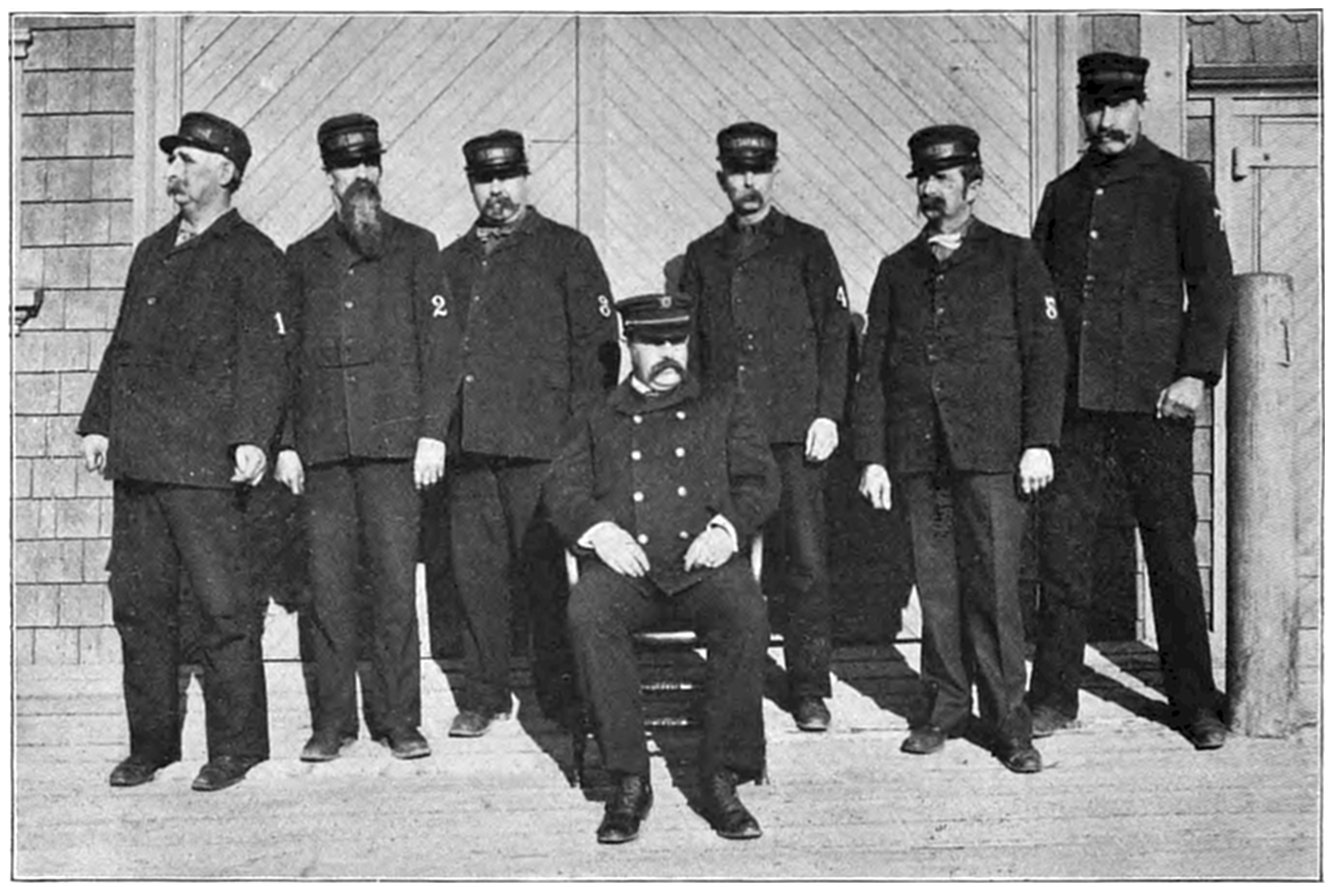

At the opening of the “active season,” August 1 of each year, the men assemble at their respective stations and establish themselves for a residence of ten months, being allowed one day in seven to visit their homes between sunrise and sunset. They arrange for their housekeeping, usually forming a mess, each man taking turns by the week in cooking. The crew is organized by the keeper arranging and numbering them in their supposed order of merit, the most competent and trustworthy being designated as No. 1, the next No. 2, and so on. These numbers are changed by promotion as vacancies occur, or by such rearrangement from time to time as proficiency in drill and performance of duty may dictate. Whenever the keeper is absent, the No. 1 surfman assumes command and exercises the keeper’s functions. When the rank of the crew has been fixed, the keeper assigns to each his position and prepares station bills for the day34 watch, night patrol, boat and apparatus drill, care of the station, etc. Then all is ready for the active work and the watch of the sea and shore that never ceases, day or night, until the close of the active season ten months later.

The patrol of the beaches each night, and during thick weather by day, by which stranded vessels are promptly discovered and the rescue of the imperiled crews made the object of effort by the life saver, distinguishes the United States Life-Saving Service from all others in the world, and in a great measure accounts for its unparalleled triumphs in rescuing shipwrecked seafarers.

If the surfman sights a vessel in distress or running into danger during the night, he fires a brilliant red Coston signal which he always carries. This is a signal to the shipwrecked crew that they have been seen and assistance has been summoned, and to the crew of a vessel which is approaching the danger line along the coast that it is time to haul offshore.

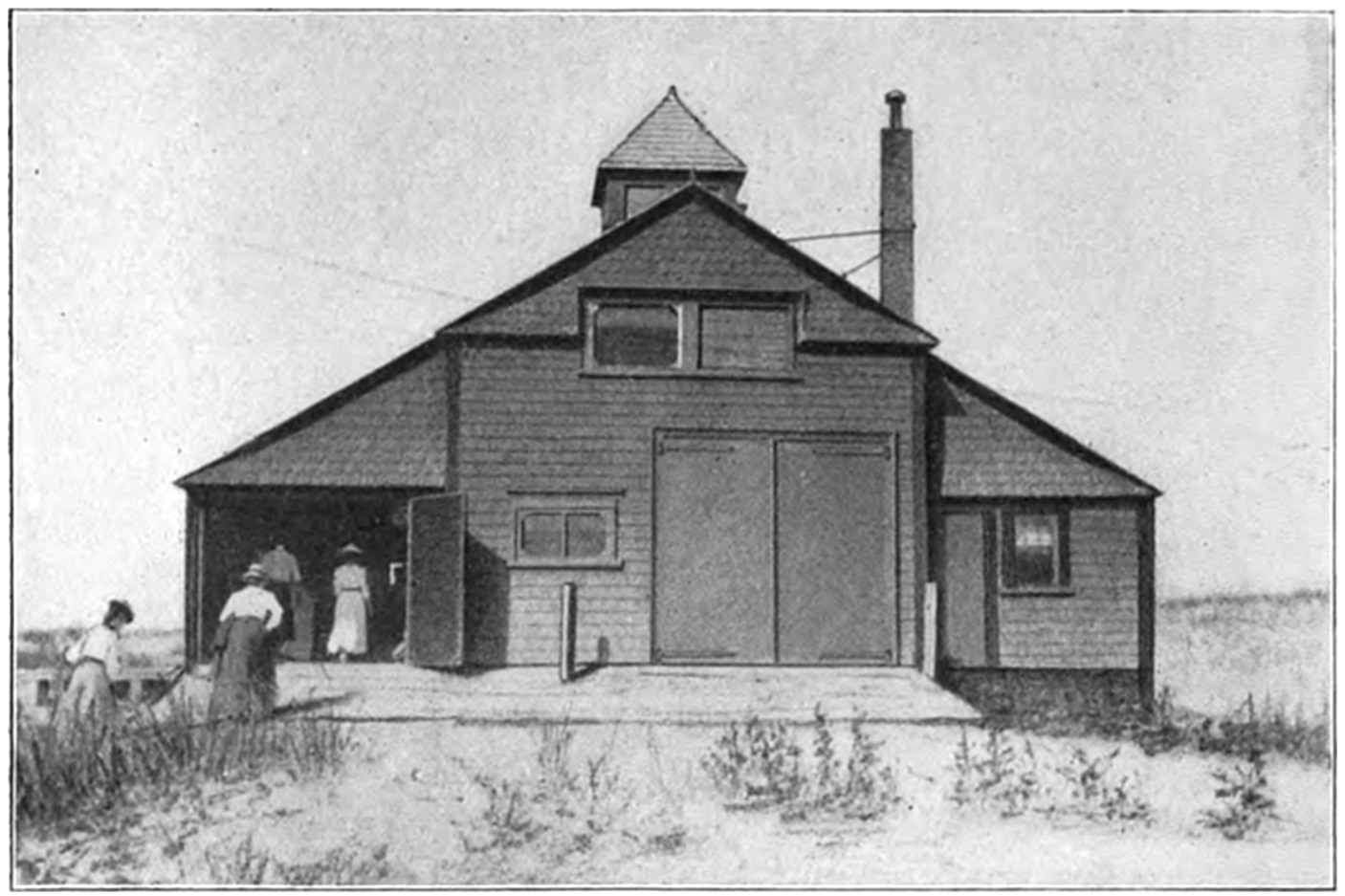

During the daylight on clear days the watch is kept from a lookout on the station, or by observation from points where the entire beach and sea limits of the station’s district can be clearly seen. Foggy days, and during thick weather, and every night, fair or foul, the watch is by the patrol of every foot of the water front of each district. The stations are located about five miles apart, and the district patrol beats of each are thus about two and one-half miles on either side of the station. The boundaries of each district are marked by a little hut in some protected spot on the beach called “The half-way house,” except at the Wood End Station. The night patrol is divided into four watches, one from sunset to 8 o’clock (the dog watch), one from 8 to 12, one from 12 to 4, and one from 4 to sunrise. Two surfmen are designated for each watch.

When the time for their patrol arrives, the surfmen set out from the station, in opposite directions, keeping well down on the beach as near the surf as possible until they reach the half-way house. Here they get warmed, and the surfmen from the adjoining station are met and checks exchanged. If a patrolman fails to meet the patrolman from the adjoining station at the half-way house, he, after waiting for a reasonable time, continues his journey until he either meets the patrolman or reaches the other station and ascertains the cause of failure. He thus patrols the neglected shore and is at hand to assist in case of disaster detaining the other patrolman. At the stations where the patrolmen carry watchmen’s time-clocks the key is35 secured to a post at the end of the beat, and the patrolman is required to reach it, wind the clock, and must bring back the dial in his clock properly recorded.

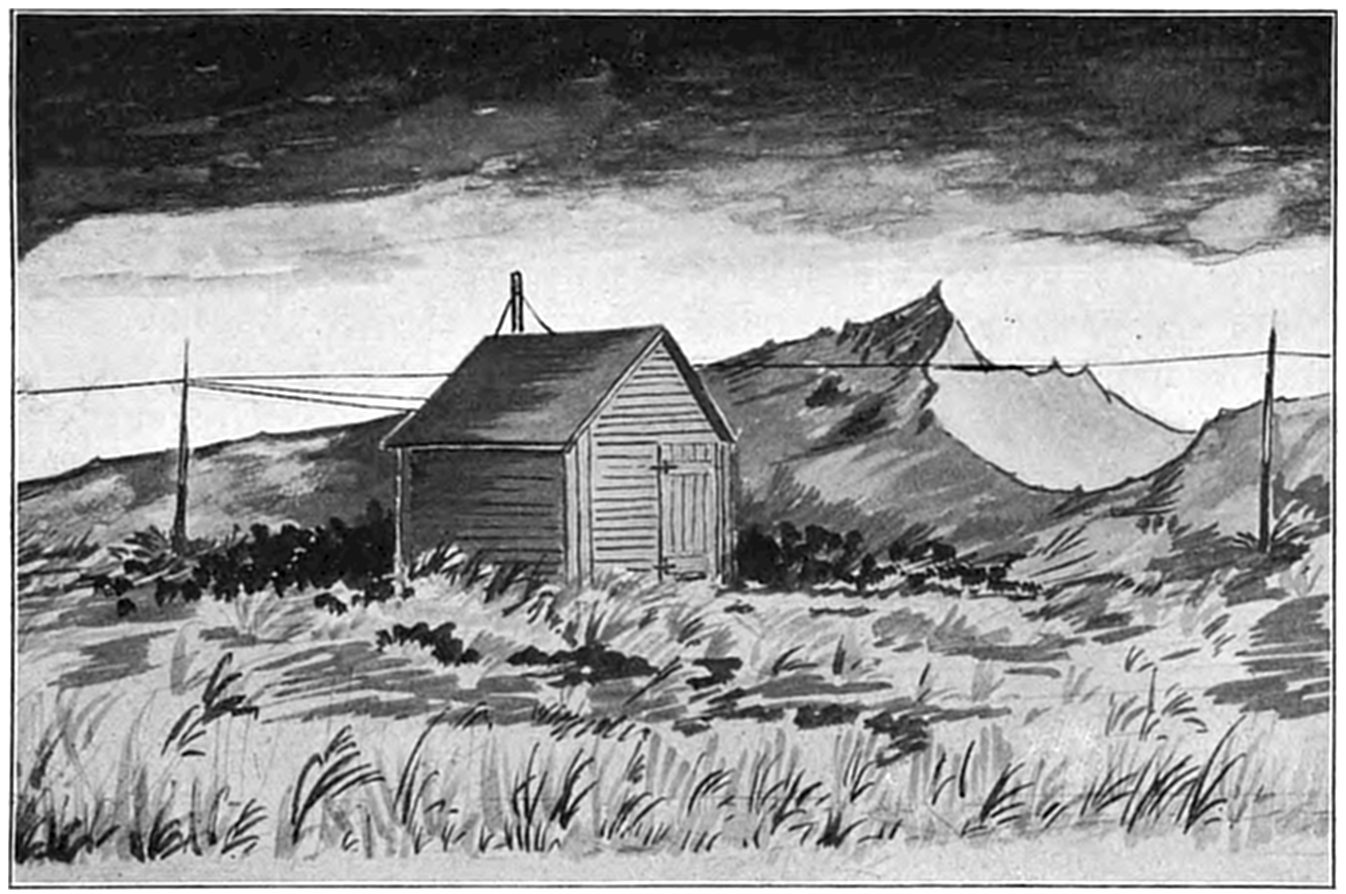

HALF-WAY HOUSE, WHERE SURFMEN FROM ADJOINING STATIONS MEET AND EXCHANGE CHECKS.

These houses are connected with the stations by telephone, and often from here the keepers are notified of disaster, and the crew summoned to a wreck.

The means employed at the life-saving stations for rescuing persons from wrecked vessels is everywhere essentially the same, either a life-boat is sent out through the surf or the breeches-buoy, or life-car used. The rescues by boat are the most thrilling and hazardous. The method of establishing communication with stranded vessels is over a century old, successful experiments with this method having been made as early as 1791 by Lieutenant Bell of the Royal Artillery. He demonstrated the practicability of the method by means of a mortar, which carried a heavy shot four hundred yards from a vessel to the shore. Lieutenant Bell also observed that a line might be carried from the shore over a stranded vessel by the means of his mortar, but the credit for the actual execution of this method of establishing communication is given to Capt. G. W. Manby, according to a report of a committee of the House of Commons, dated March 10, 1810. A London coach-maker first conceived the idea of a life-boat. The present type is the product of a century’s devoted study and experiment.

36

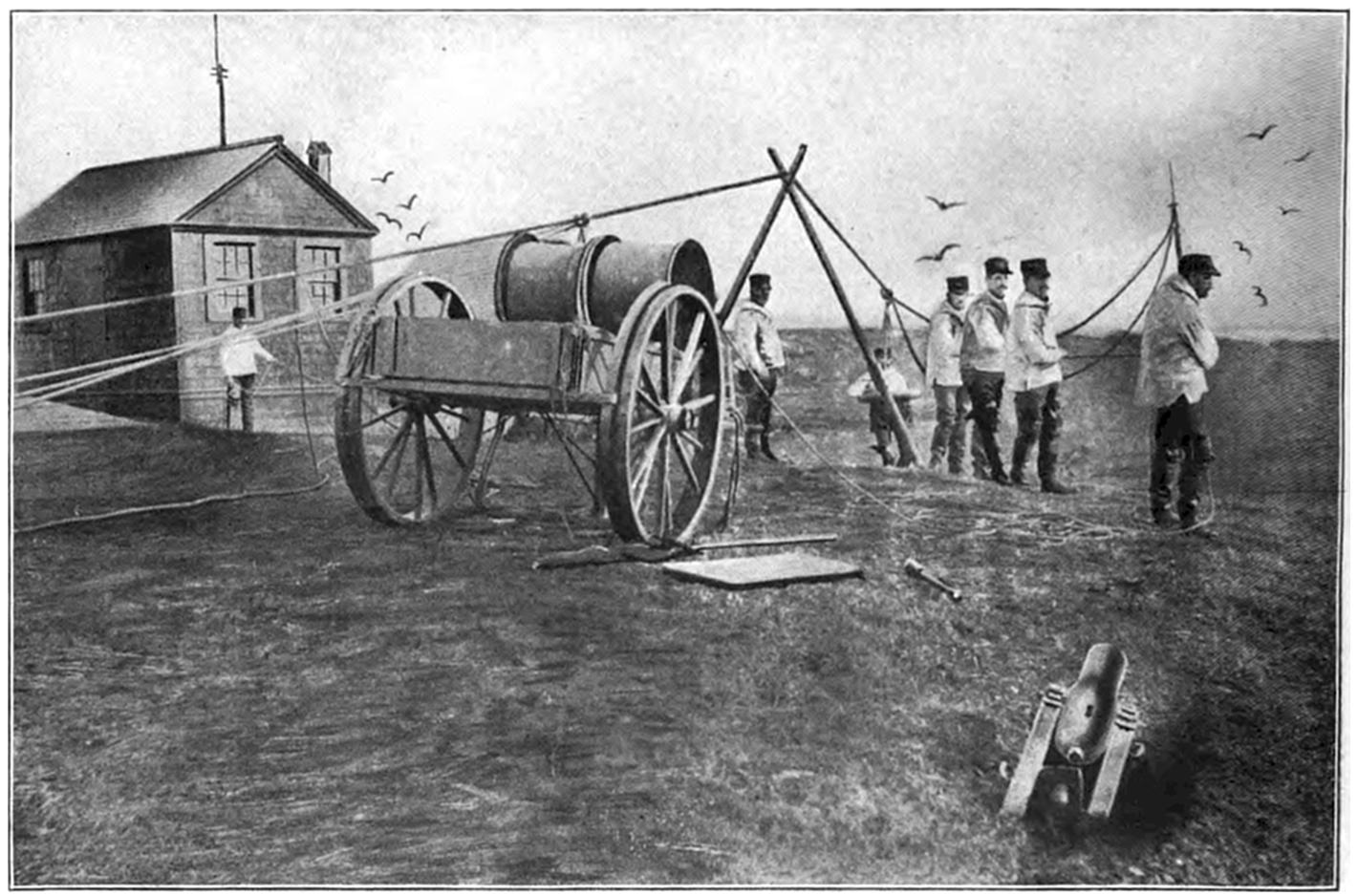

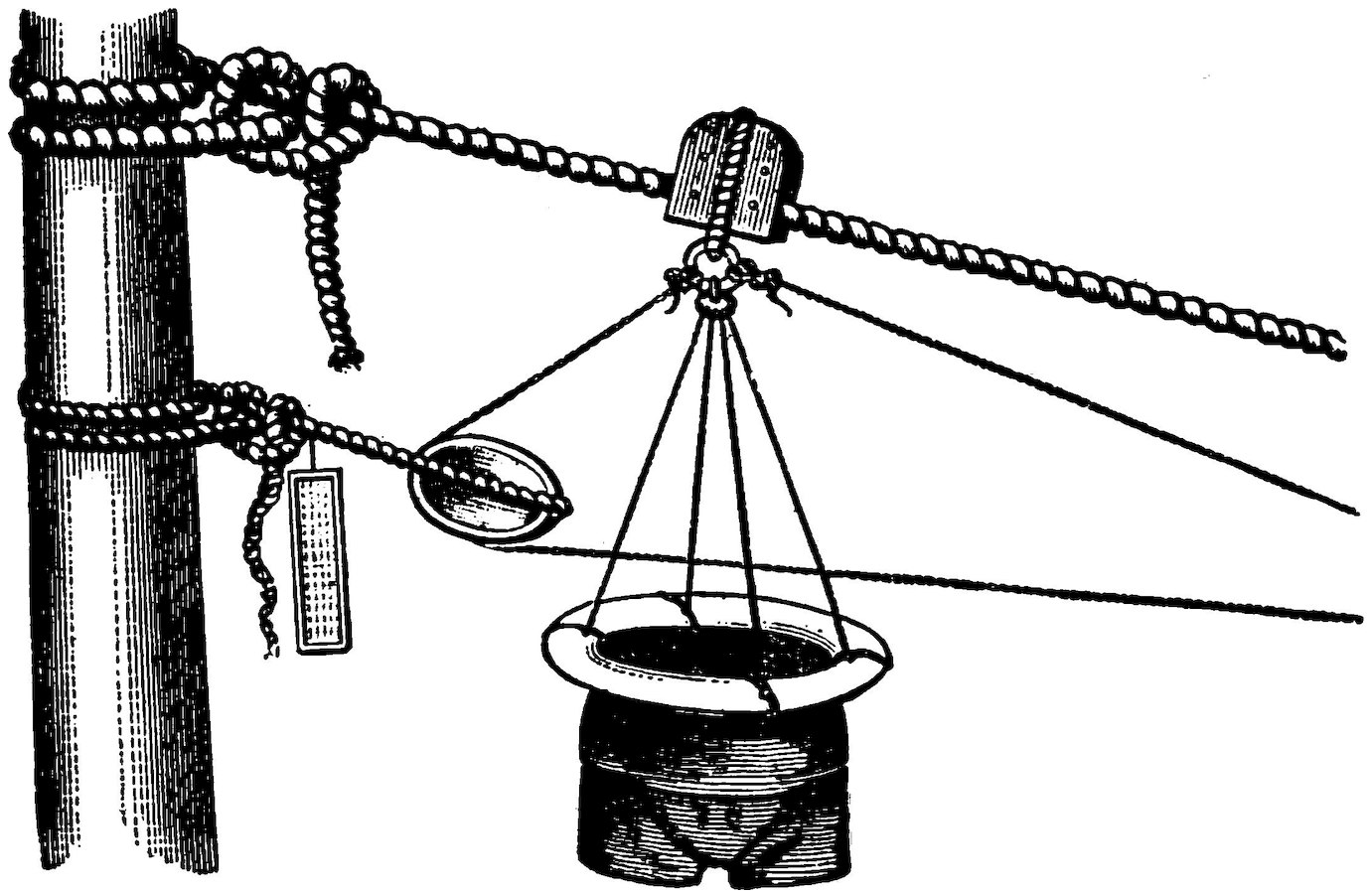

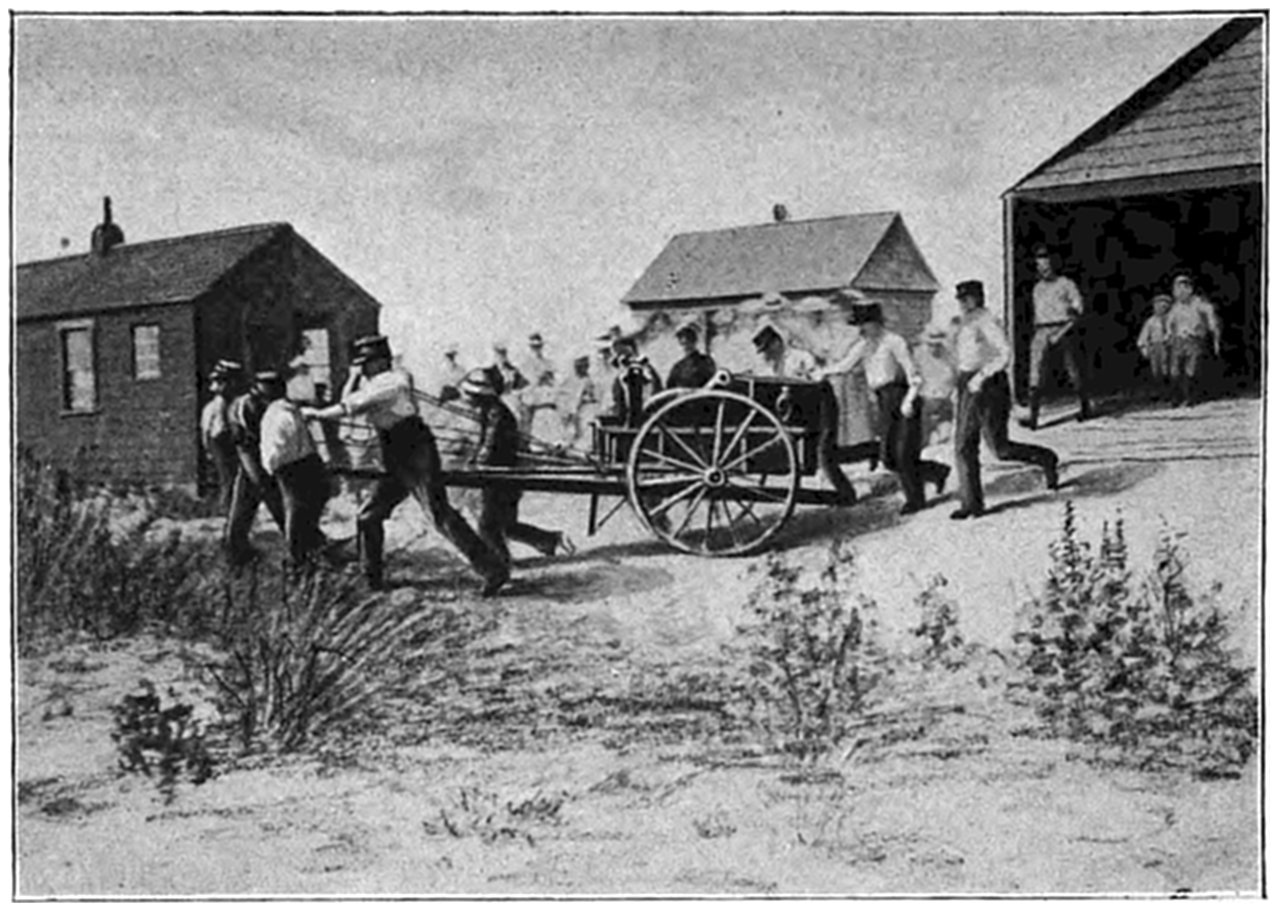

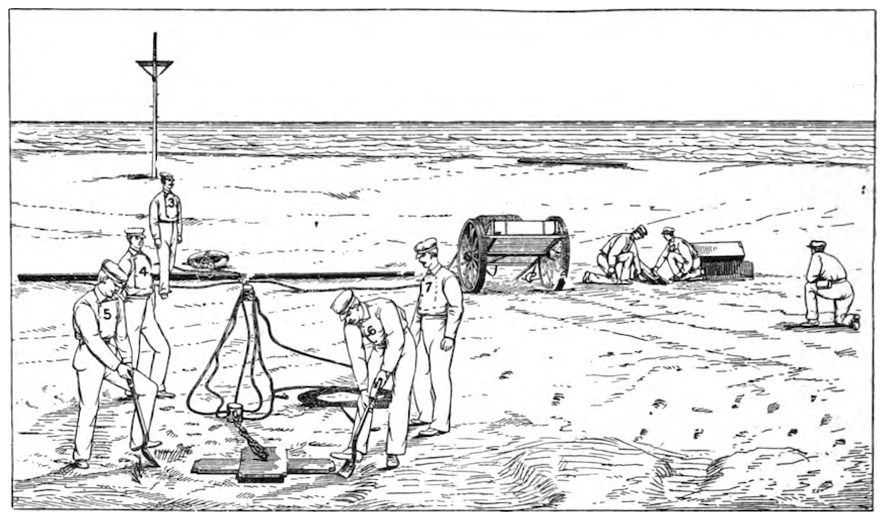

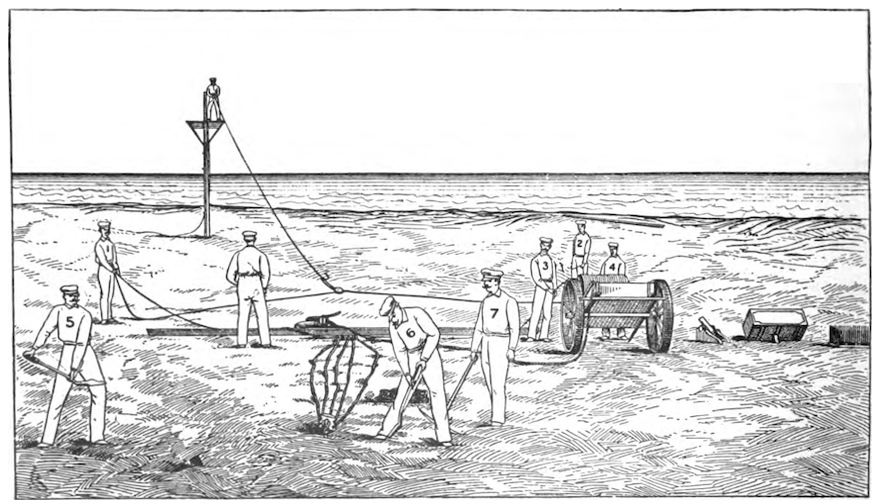

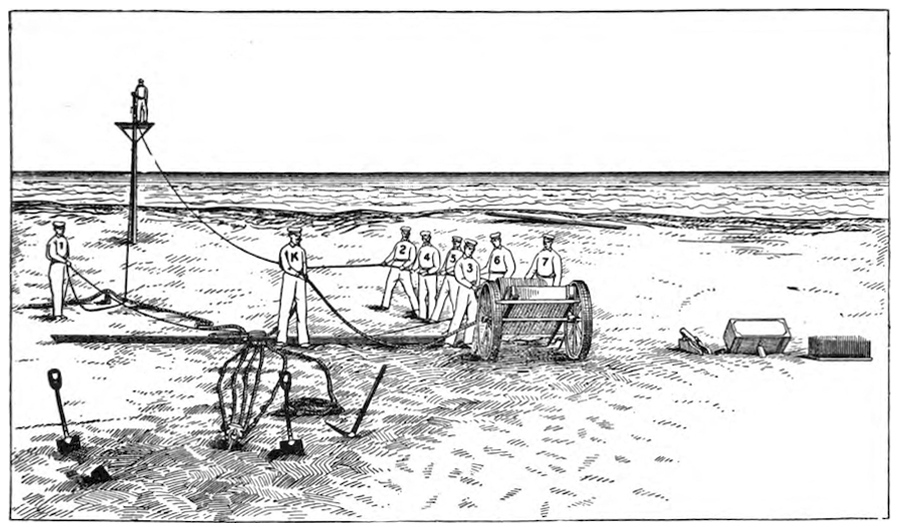

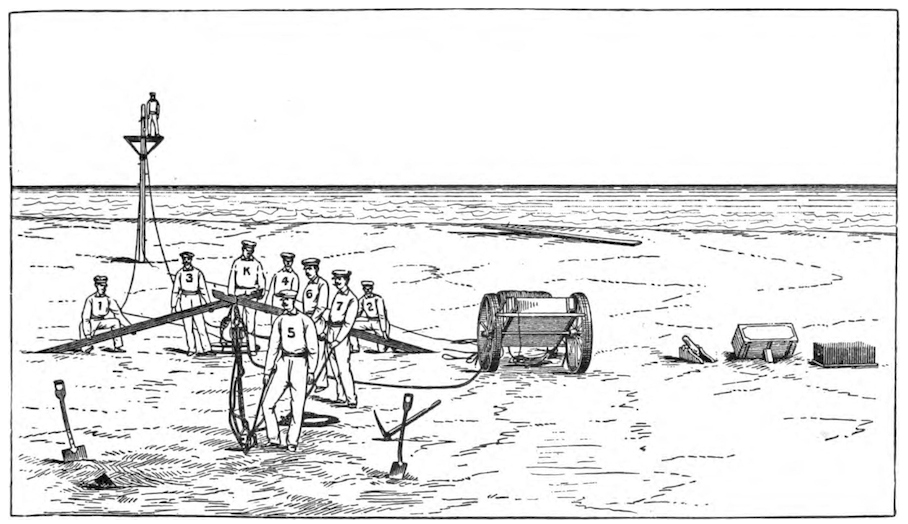

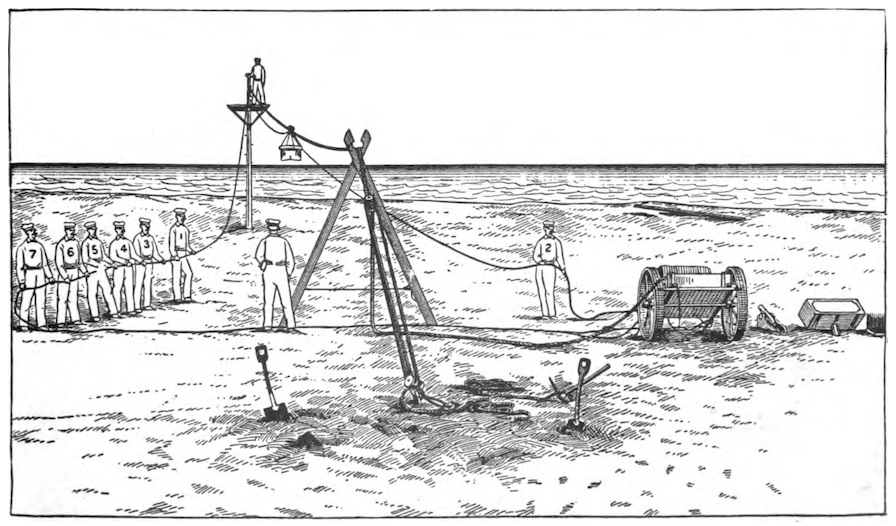

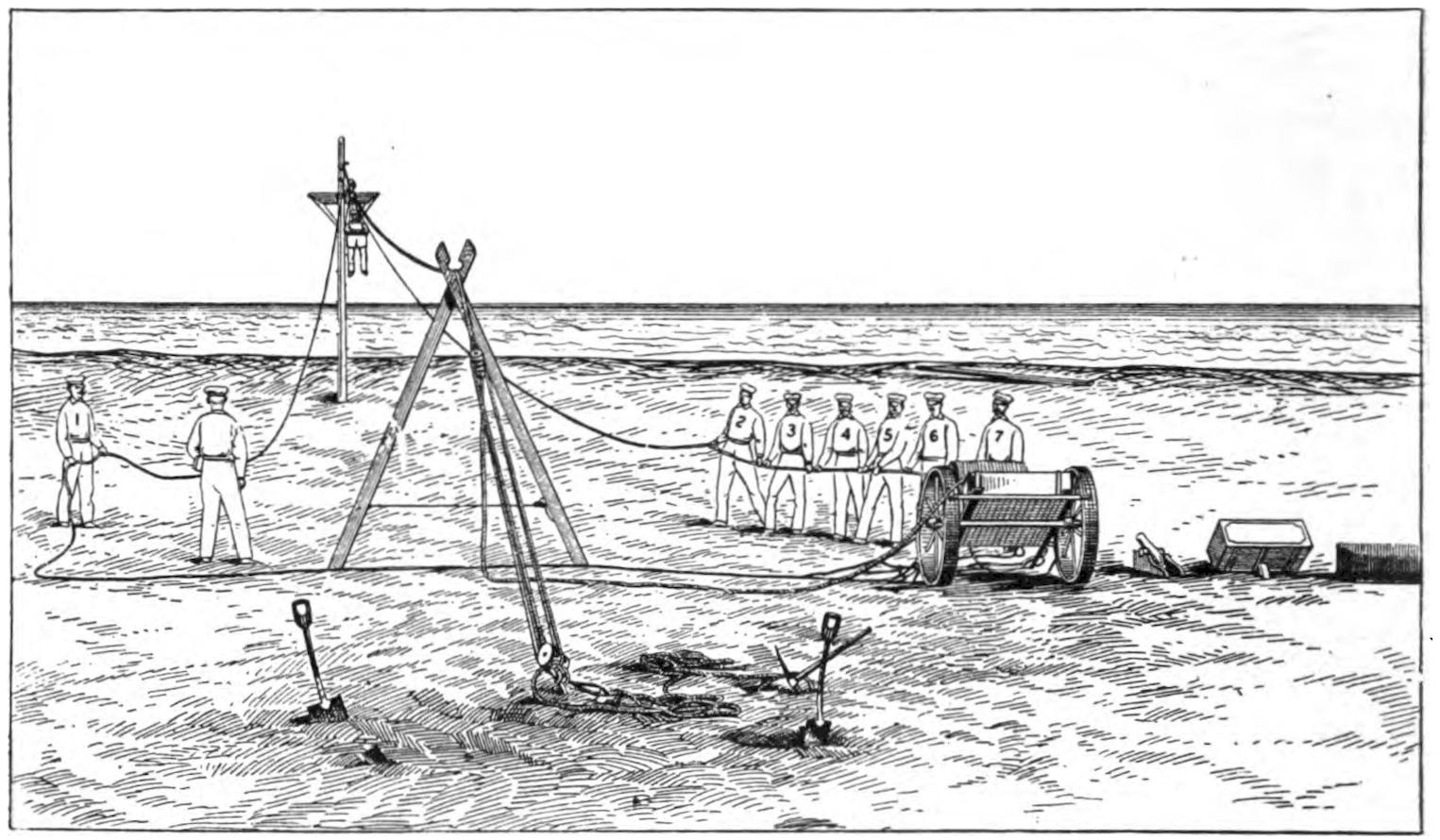

Practice drills in the use of the breeches-buoy and surf-boats are carried on constantly at each station, until so proficient are the crews that practice rescues are often made in less than three minutes. The practice is carried on under conditions as near active work in a disaster as are possible, and a description of a drill will give the best idea of actual work at a wreck.

For the practice with the beach apparatus, the breeches-buoy, each station has a drill ground prepared by erecting a spar, called a wreck pole, to represent the mast of a stranded vessel seventy-five yards distant. This is over the water, if possible, from the place where the men operate, which represents the shore.

Each man knows in detail every act he is to perform in the exercise from constant practice, and as prescribed in the Service Manual. At the word of command they drag the apparatus to the drill ground, where they effect a mimic rescue by rigging the gear and taking a man ashore from the wreck pole in the breeches-buoy. If one month after the opening of the active season a crew cannot accomplish the rescue within five minutes, it is considered that they have been remiss in drilling.

No such celerity, however, is expected of the life savers in effecting rescues from shipwrecks, when storm, surf, currents, and motion of the stranded crafts conspire to obstruct. The hastening of the work of mimic rescue, however, gives the life-savers the utmost familiarity37 with the apparatus and prepares them for working speedily and successfully in utter darkness and under the most trying weather conditions.

The boat practice consists in launching and landing through the surf, capsizing and righting the boat, and practice in handling the oars. Drill signaling is interrogating each surfman as to the meaning of the various flags, the use of the code book, and actual conversation carried on by means of sets of miniature signals provided for each station.

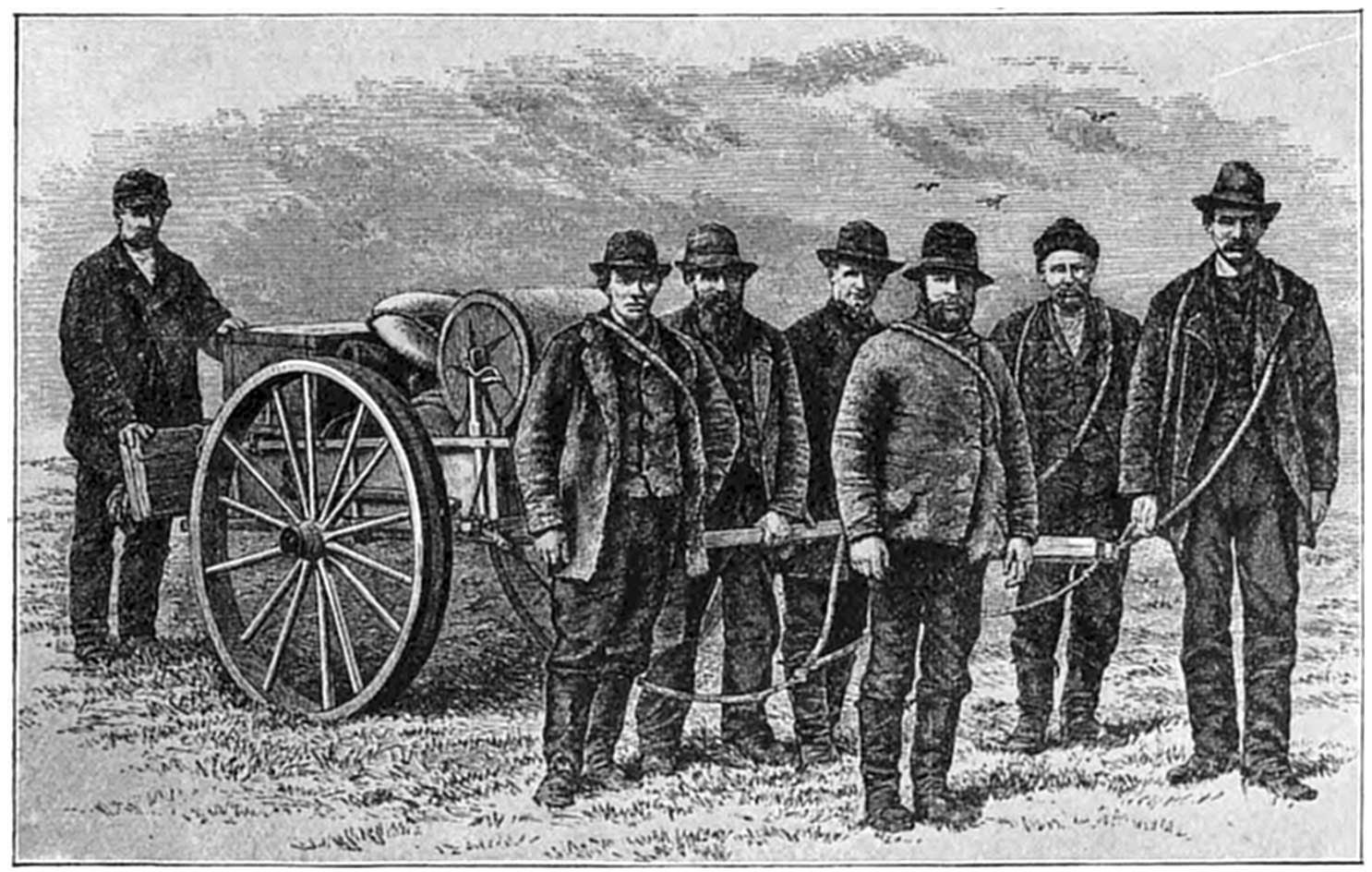

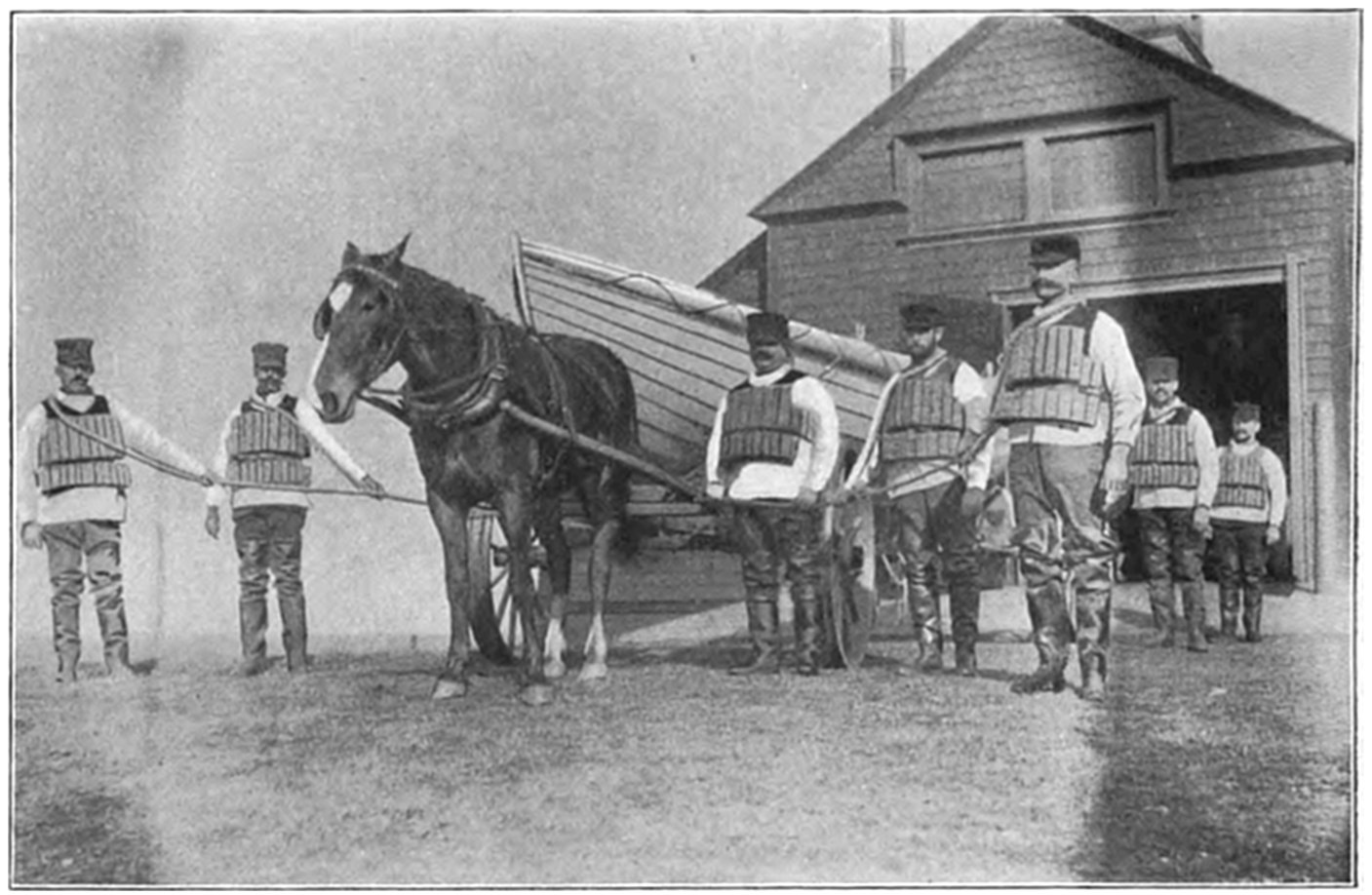

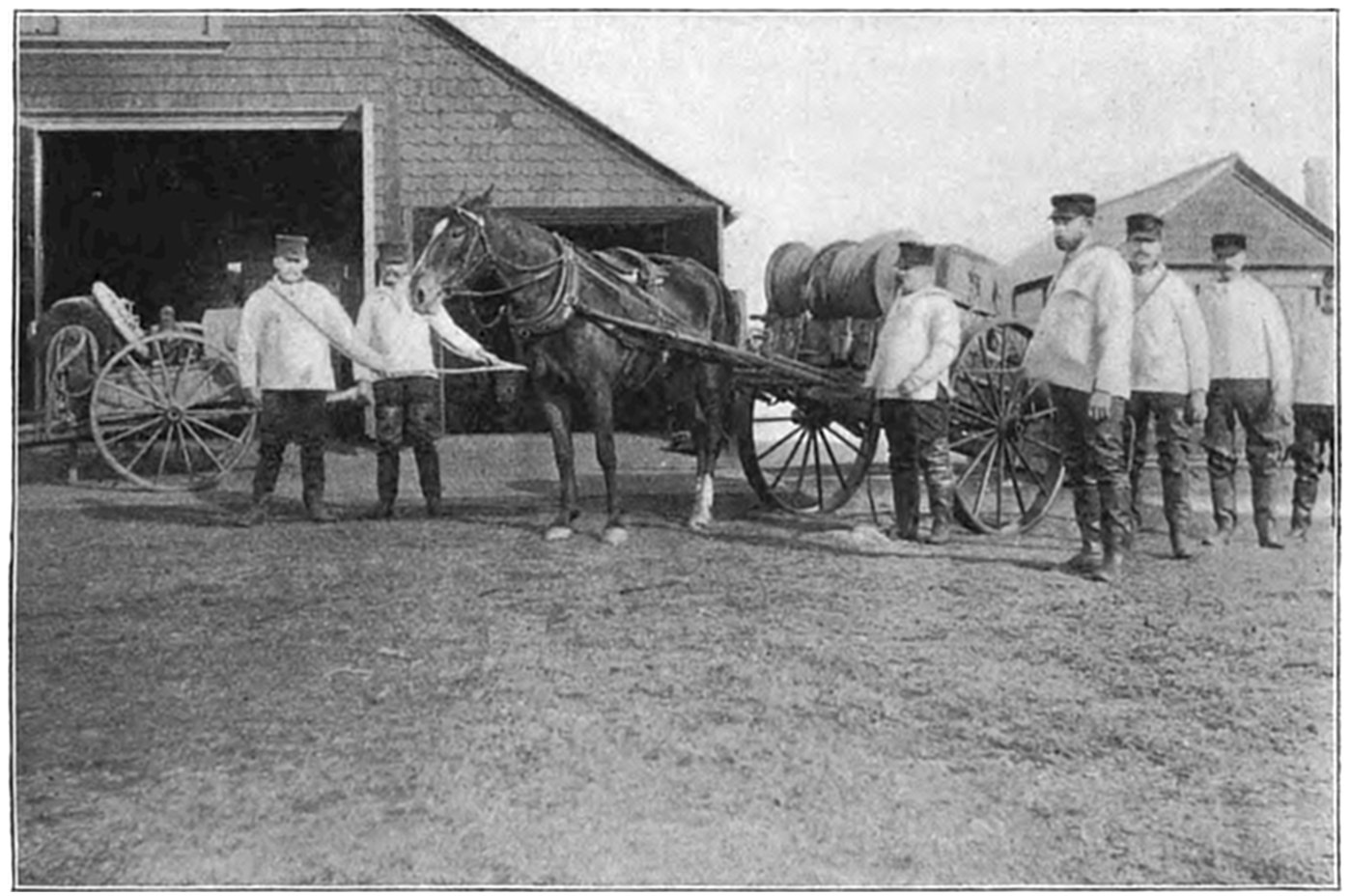

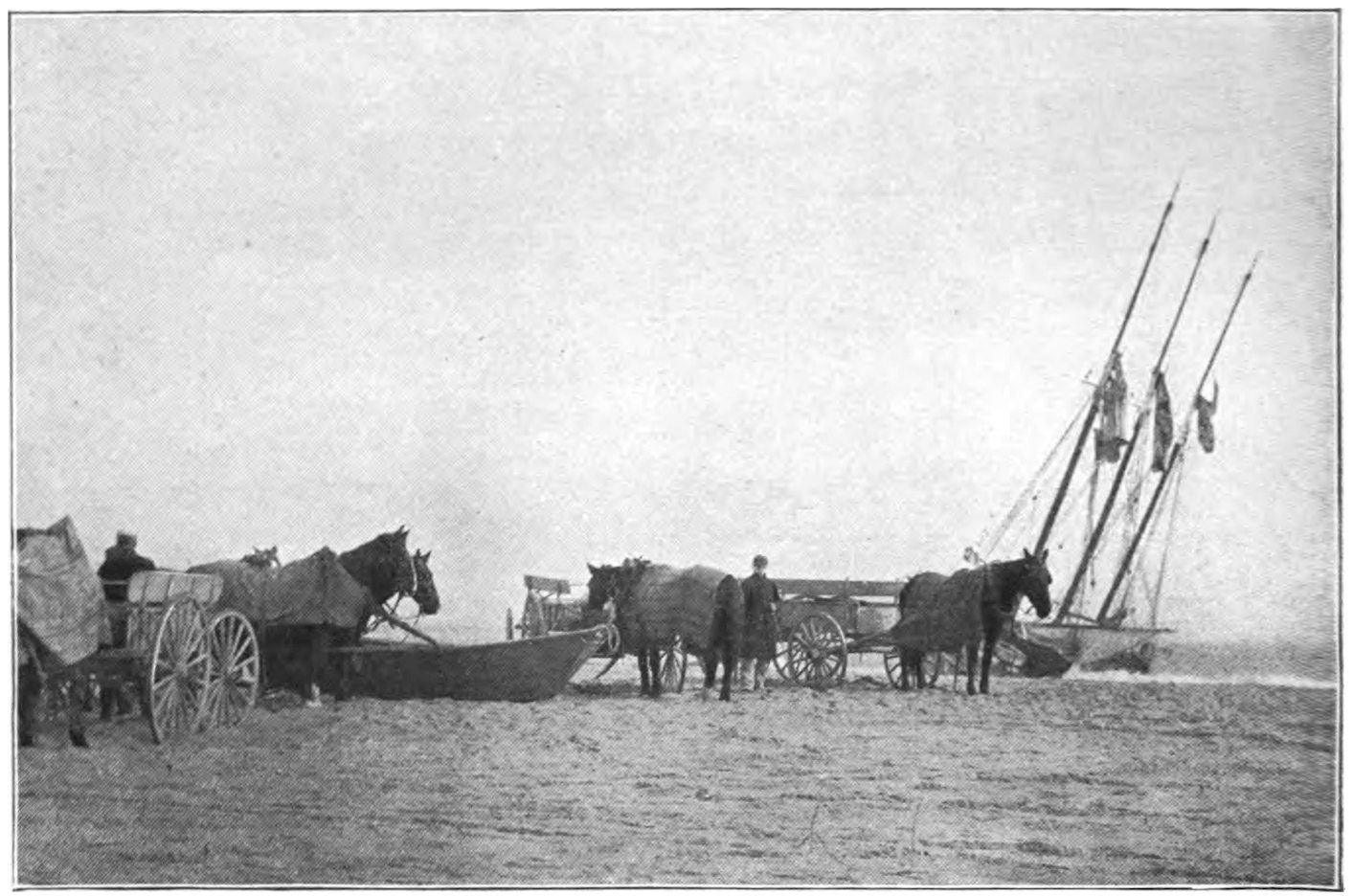

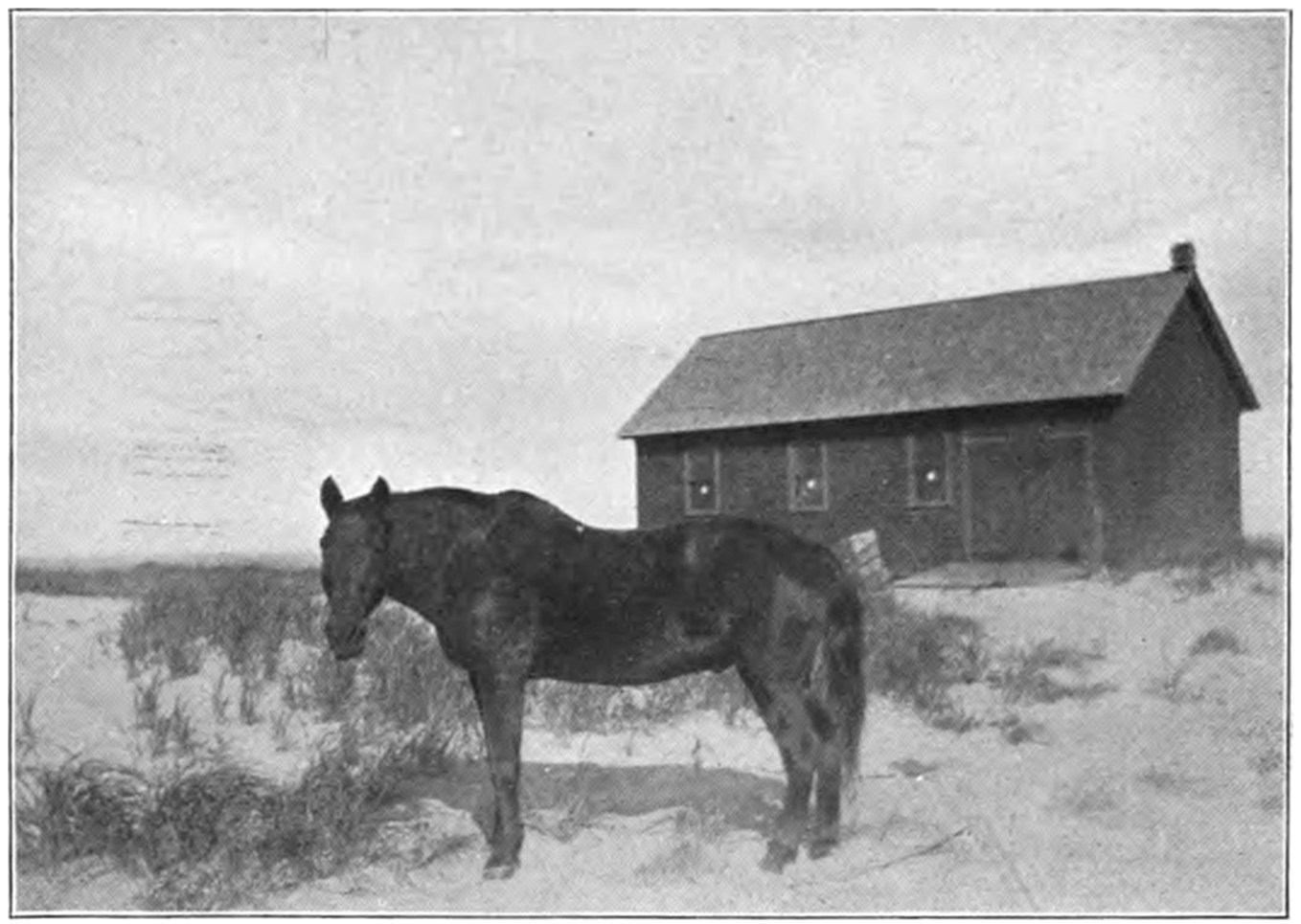

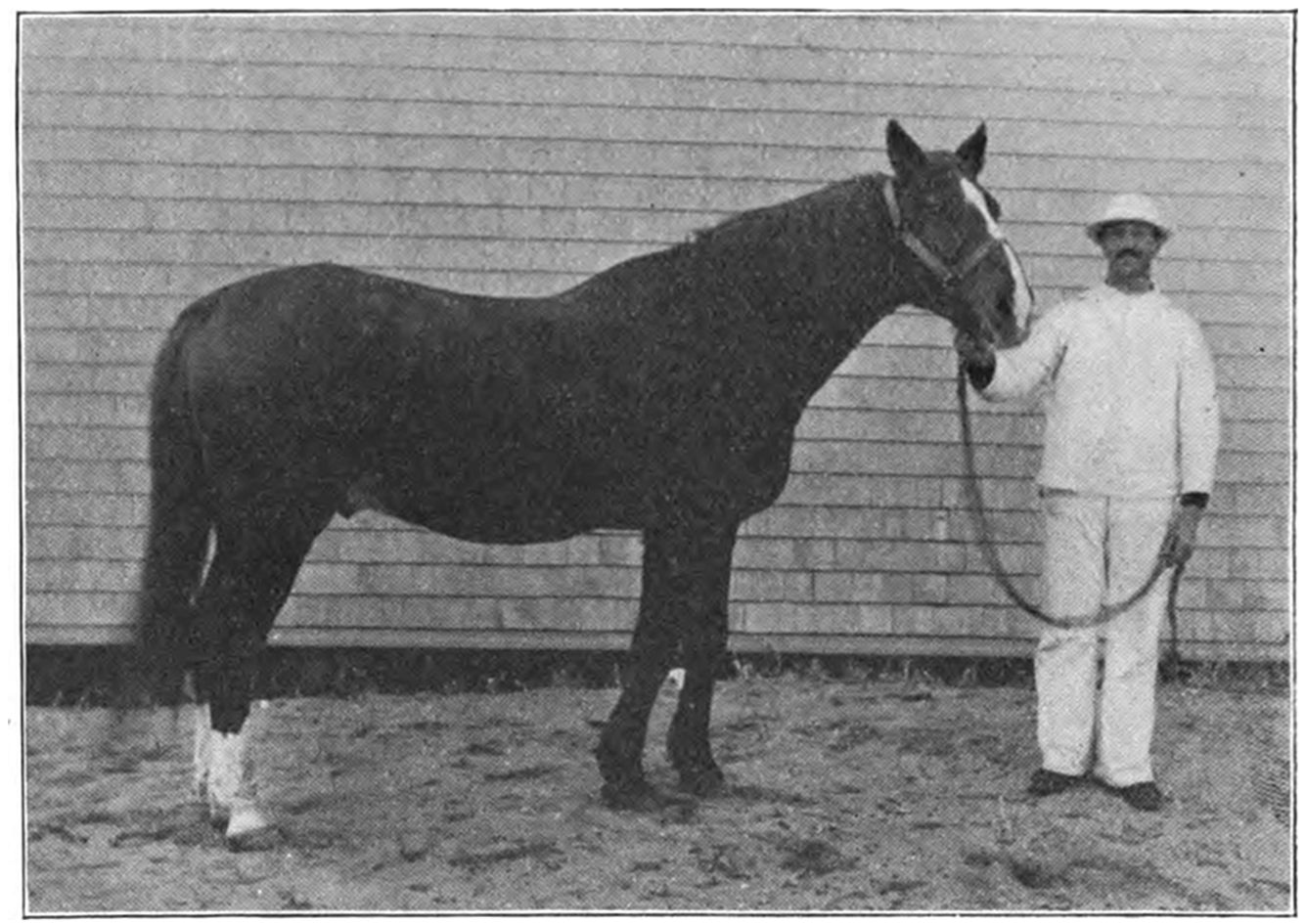

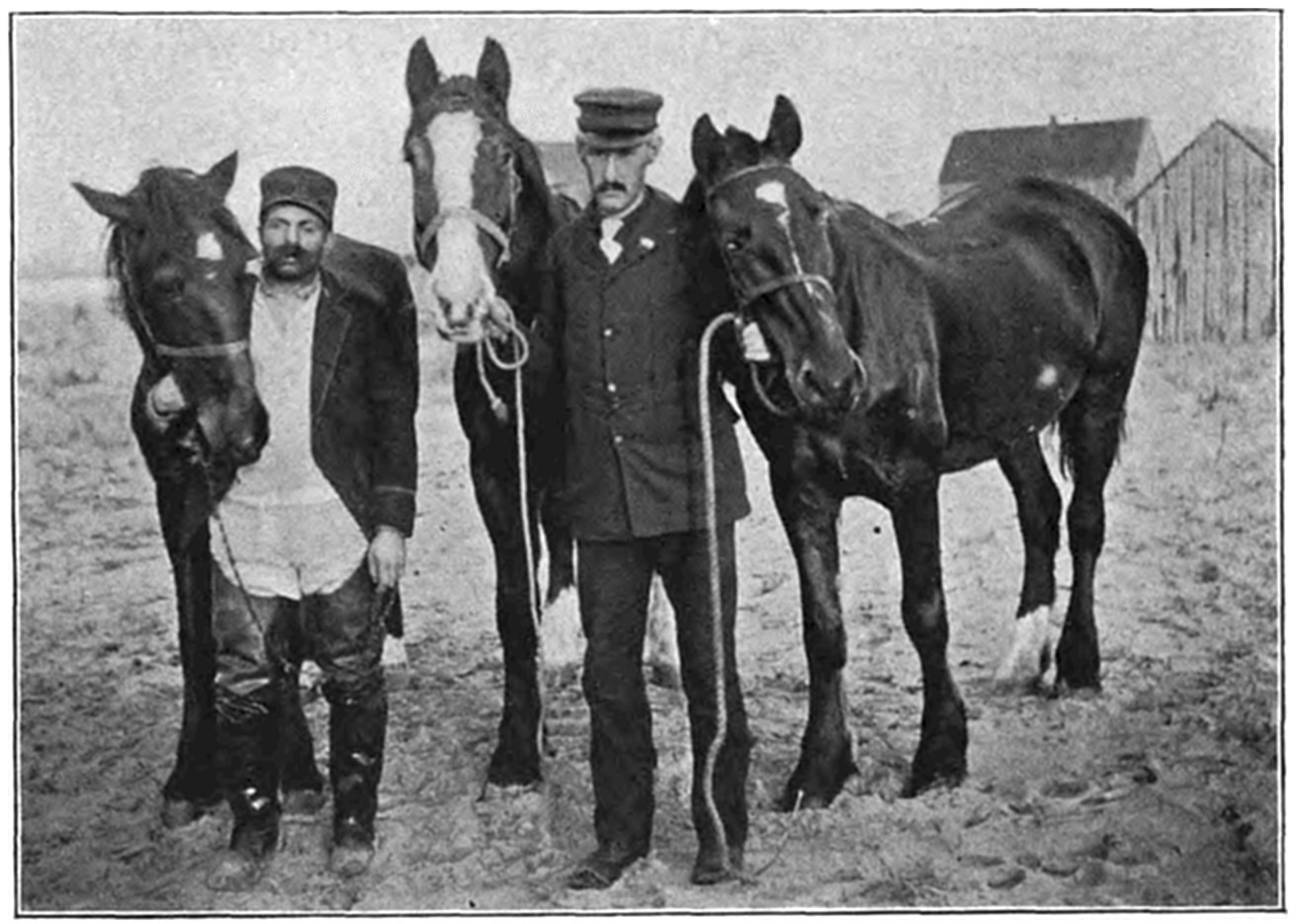

The beach apparatus, the breeches-buoy, is used to effect the rescue of shipwrecked seafarers when vessels have stranded near the shore and the conditions make it inexpedient to use the surf-boats. At such times the apparatus is hauled to the scene in the beach cart; horses, kept at all the stations for the purpose, assisting the life savers in the work.

Frequently the storms which sweep the beaches are so violent that the horses refuse to pull the cart, and the life savers are then obliged to cover the head of the animals before they can be induced to face the fury of the elements. The life savers when on such journeys are usually driven to the back of the beaches by the tides, and the task of dragging the apparatus over the sand dunes is extremely difficult and hazardous.

The “cut throughs” in the beaches, places where during storms38 the seas rush through to the lowlands, further contribute to the dangers that confront the life savers as they rush along with the apparatus.

These “cut throughs” are also the dreaded menace of the surfmen on patrol, during stormy weather and high tides, the seas, as they sweep through them, often entrapping the life savers, throwing them down, burying them in the rushing waters, and jeopardizing their lives.

As soon as the life savers reach the scene of disaster, the Lyle gun is quickly taken from the cart, loaded, sighted, and fired, the captain, who sights and fires the gun, taking good care that he has sent the shot flying through the storm well to the windward of the wrecked vessel, so that if the shot should fail to go across the vessel, yet beyond it, the line will be carried to the wreck by the force of the gale.

The work of burying the sand anchor, getting the crotch, whip line, hawser, and breeches-buoy ready is speedily accomplished. Torches are kept burning by the life savers to tell those on the wrecked vessel that assistance is at hand and the life savers are at work, and even if the imperiled crew do not hear the report of the gun, which has fired a shot to the vessel, they at once begin a search for the shot-line which is invariably found somewhere in the rigging.

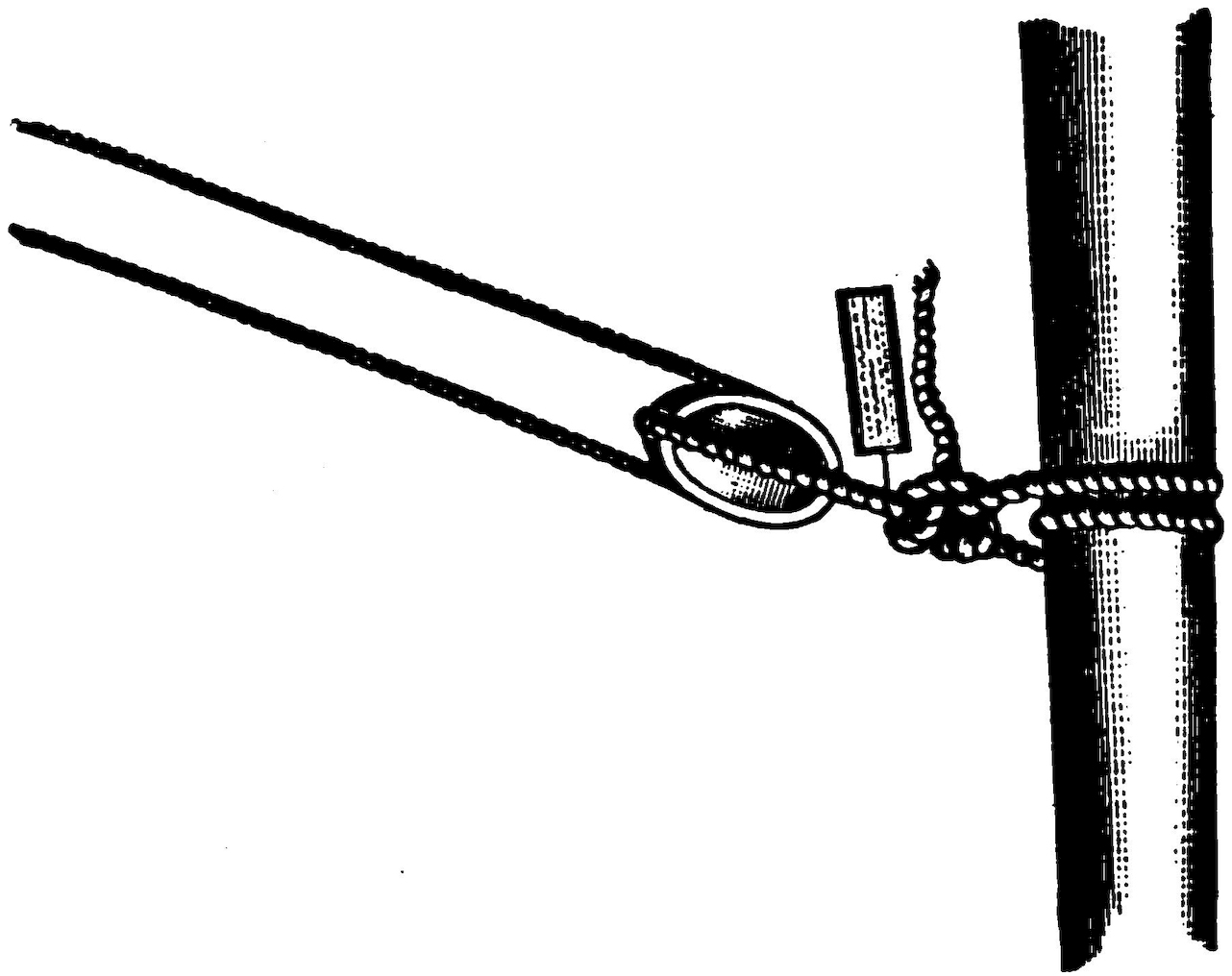

The captain, with the shore end of the shot-line in his hand, waits for a signal from the ship that the line has passed over the vessel, and39 that the crew have found it and are ready to proceed with the work of rescue. A tail-block with a whip, an endless line rove through it, is made fast to the shot-line, and the wrecked seafarers haul it aboard their vessel as speedily as possible. Attached to the tail-block is a tally board with the following directions in English and French printed on it:—

“Make the tail of the block fast to lower mast well up. If the masts are gone, then to the best place you can find. Cast off shot-line, see that rope in the block runs free, and show signal to shore.”

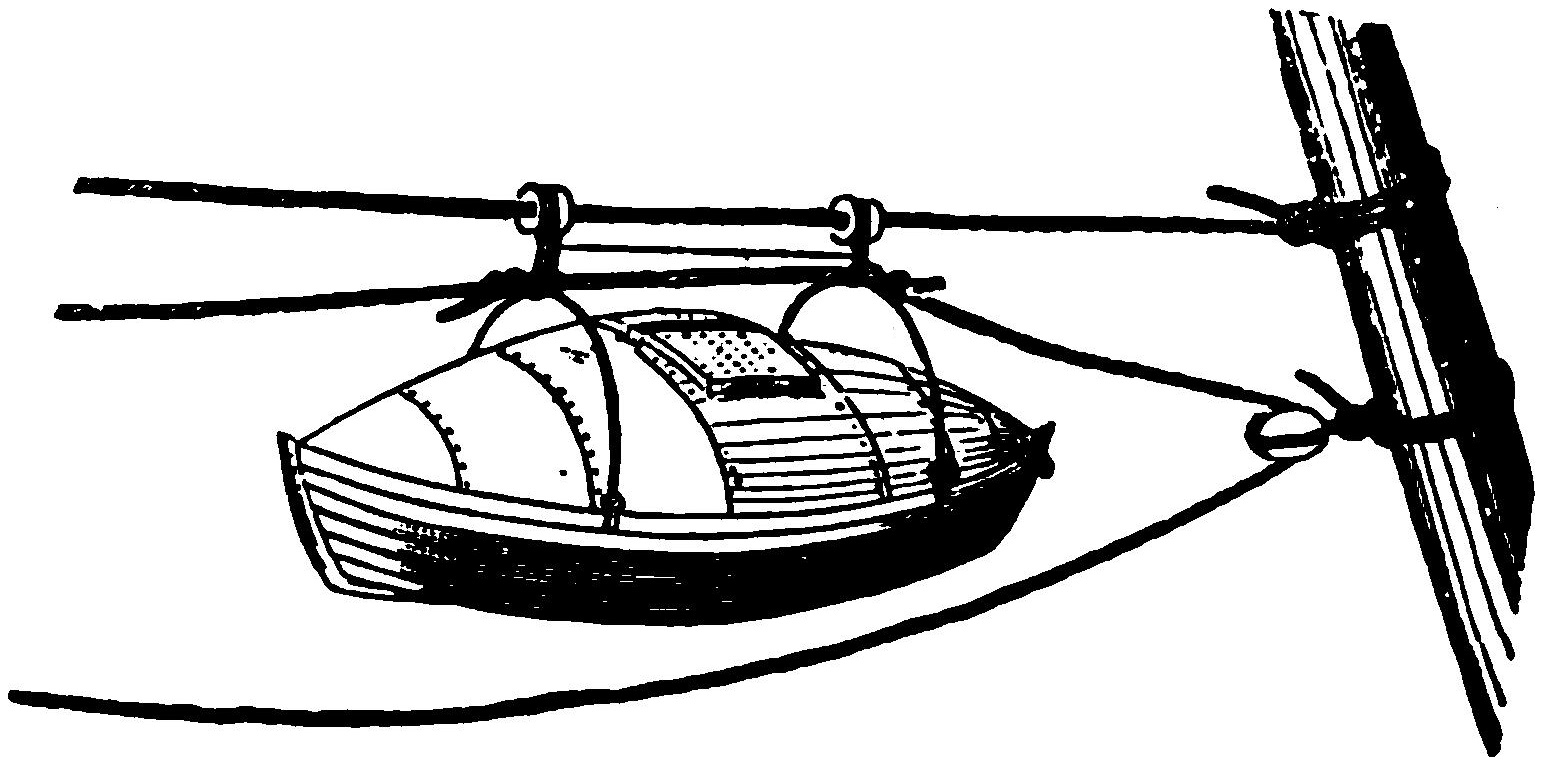

The foregoing instructions having been complied with, the result will be as shown in Figure 1.

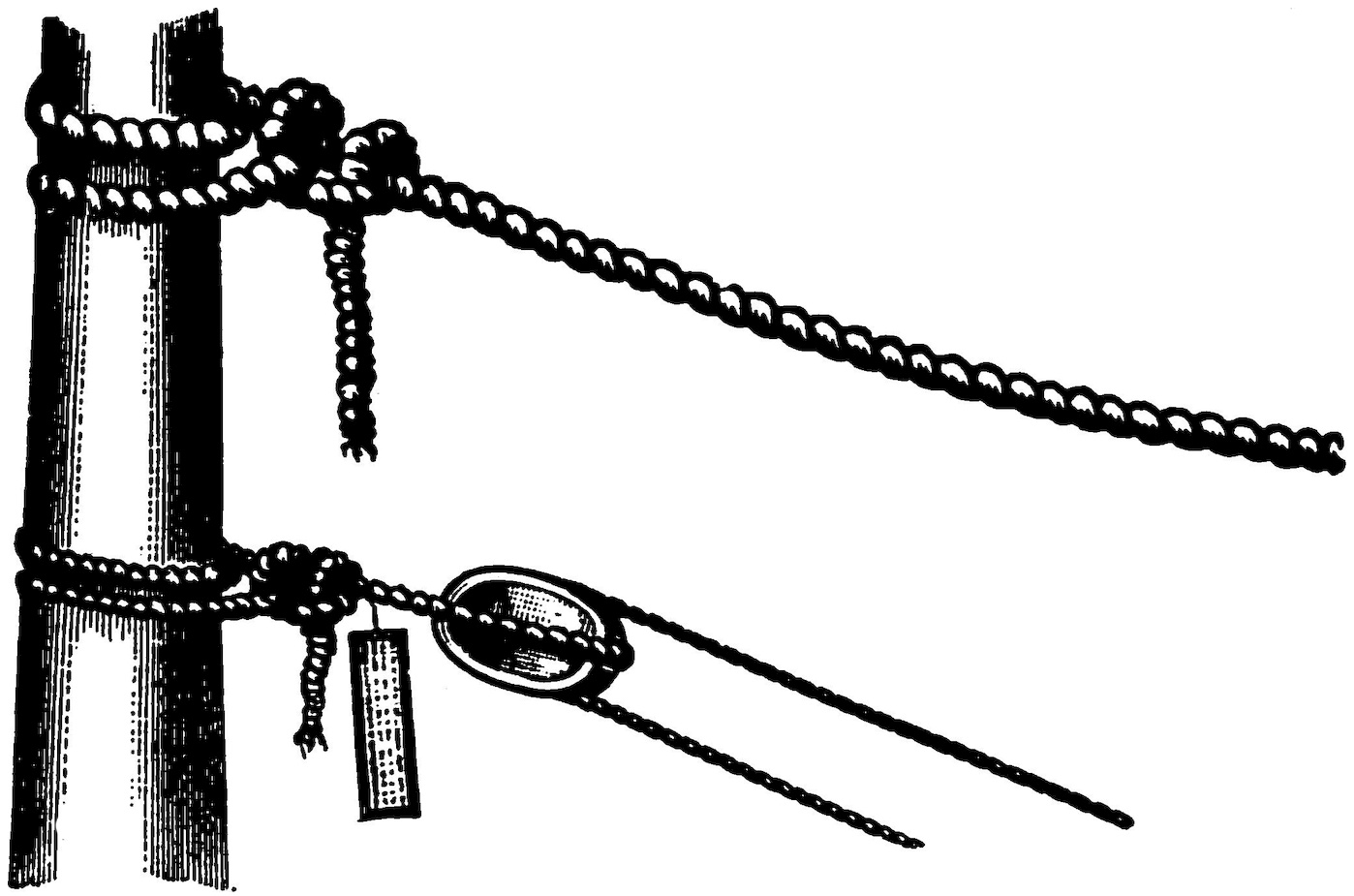

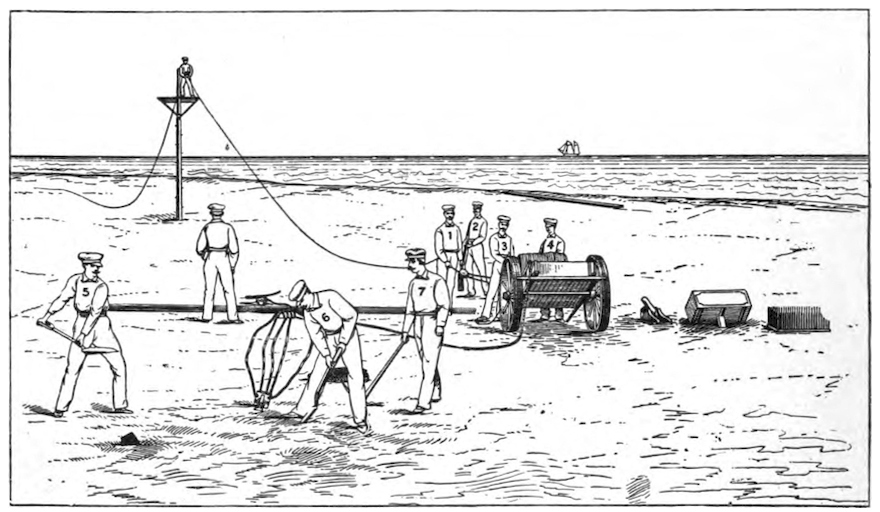

As soon as the life savers get a signal from the vessel that the tail-block has been made fast, they “tie”40 bend on a three-inch hawser to the whip, the endless line, and by it haul the hawser off to the vessel. Occasionally circumstances permit wrecked crews to assist in this part of the work, but usually the life savers are compelled to do it alone. To the end of the hawser, which has been bent on to the whip, the endless line, is also attached a tally board with the following directions in English and French:—

“Make the hawser fast about two feet above the tail-block; see all clear, and that the rope in the block runs free; show signal to the shore.”

These instructions being obeyed, the result will be shown as in Figure 2.

Particular care must be taken that there are no turns of the whip, the endless line, around the hawser; to prevent this the end of the hawser is taken up between the parts of the whip, the endless line,41 before making it fast. When the hawser is made fast to the wrecked vessel, the whip, the endless line, is cast off from the hawser, and the life savers, having been signaled to this effect, make the shore end of the hawser fast to the strap of the sand anchor. The crotch is then placed under the hawser and raised, and the latter drawn as taut as possible, thus making a slender bridge of rope between the vessel and shore. The traveler block, from which is suspended the breeches-buoy, is then put on the hawser, the whip, the endless line, made fast to breeches-buoy, and thus hauled to and from the vessel, as shown in Figure 3, which represent the apparatus rigged with the breeches-buoy hauled out to the vessel.

The life savers always carry a good supply of shot and lines with them, and if the first shot fails to carry the line to the vessel, which seldom occurs, owing to the skill of those who have charge of this important branch of the work, a second one is promptly fired. The work of hauling the breeches-buoy to and from a wrecked vessel is an arduous task. The whip, the endless line, after passing through the seas, becomes coated with ice and sand, which cuts the mittens and lacerates the hands of the surfmen in a fearful manner at times.

The captain and one of the life savers rush into the surf and take the rescued persons out of the breeches-buoy as soon as it reaches the beach, while the other members of the crew stand ready to again send the breeches-buoy off to the wreck as soon as one rescue has been accomplished. In this way one after another of shipwrecked crews are brought ashore.

Women and children and helpless persons are landed first from wrecked vessels. Children when brought ashore in this way are held in the arms of some elder person or securely lashed to the breeches-buoy. The instructions to mariners are to remain by the wreck until assistance arrives, unless the vessel shows signs of immediately breaking up. If not discovered immediately by the patrol, the crews of wrecked vessels are instructed to burn rockets, flare up, or other lights, and if the weather is foggy to fire guns.

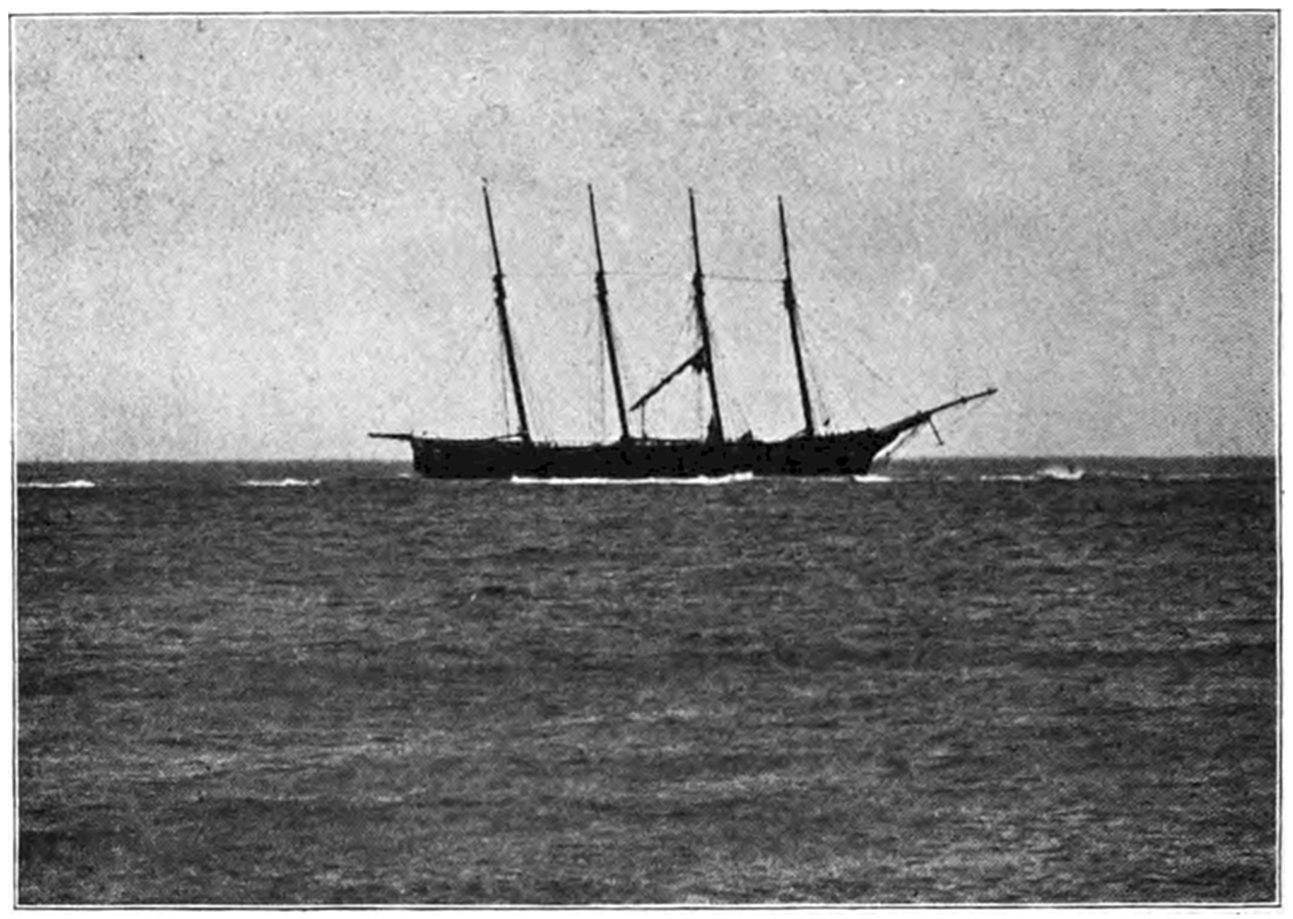

Under no circumstances should the crew of wrecked vessels attempt42 to land through the surf in their own boats, until the last hope of assistance from shore has vanished. Often when comparatively smooth at sea, a dangerous surf is running alongshore, which is not perceptible three or four hundred yards offshore, and the surf when viewed from a vessel never appears so dangerous as it is. Many lives have been unnecessarily lost by crews of stranded vessels being thus deceived and attempting to land in the ship’s boats.

After a crew has been rescued the work of recovering the apparatus is quickly accomplished, and every part of it except the shot is invariably recovered, and often even the shot is also saved. This is done by a hawser cutter, which is pulled off to the wreck on the hawser the same as the breeches-buoy, cutting the hawser off close to where it is attached to the wrecked vessel. The life savers then haul the apparatus through the sea to the shore.

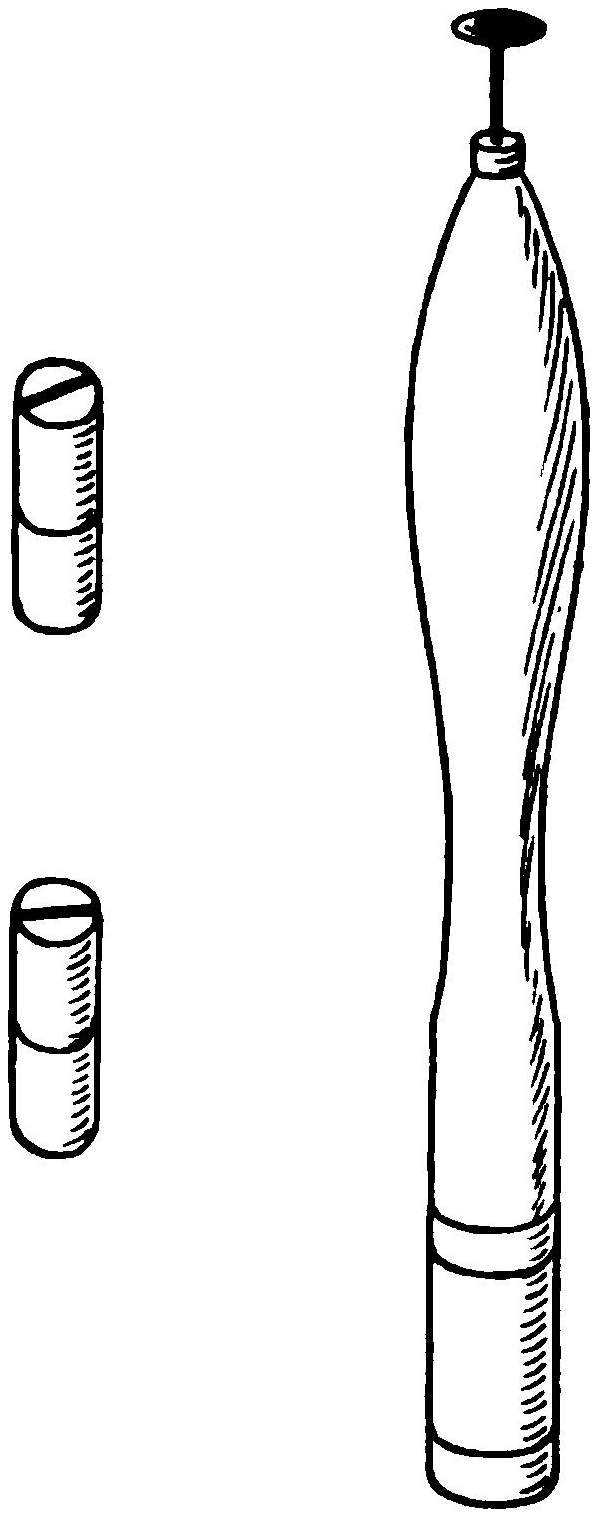

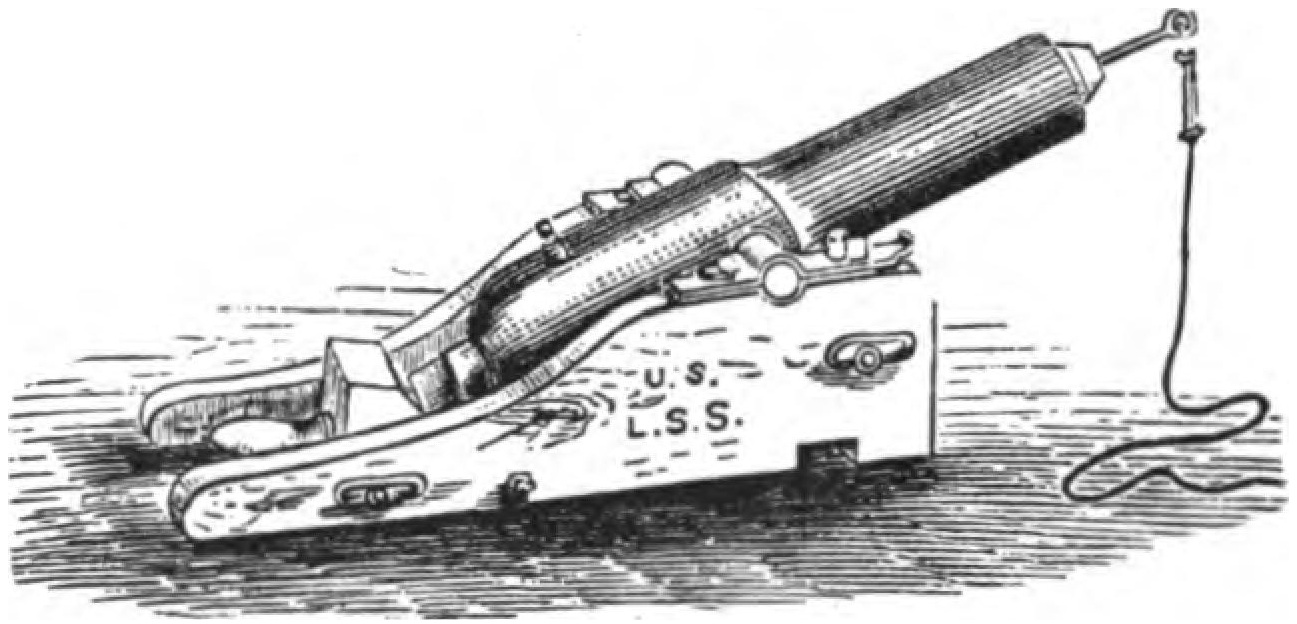

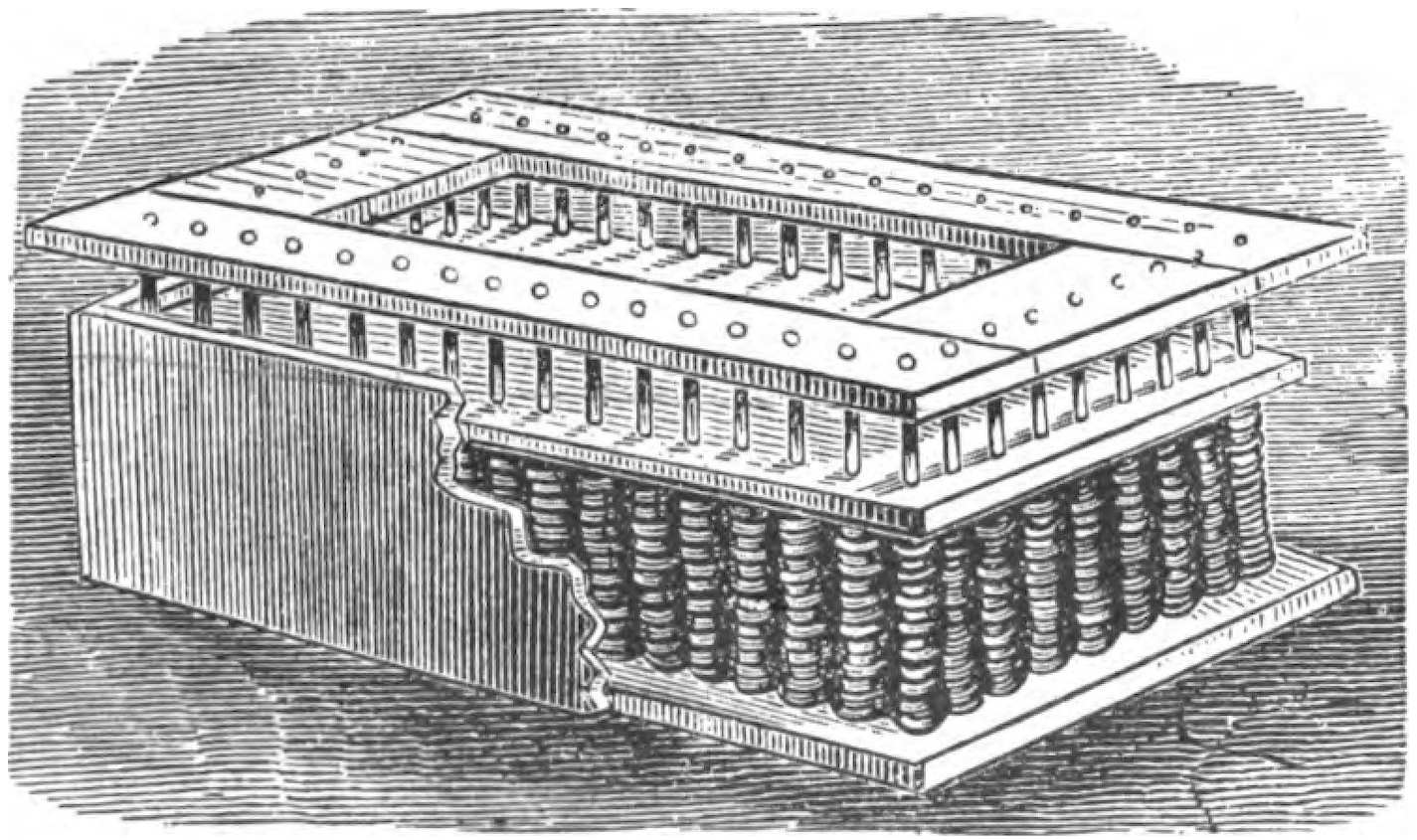

The first gun used for throwing a line to stranded ships was of cast iron, and weighed two hundred and eighty-eight pounds, and threw a shot weighing twenty-four pounds, with an extreme range of four hundred and twenty-one yards. This soon gave place to an improved gun, which was of cast iron, with steel lining, mounted on a wooden carriage. This gun weighed two hundred and sixty-six pounds, and carried a twenty-four pound shot four hundred and seventy-three yards. The Lyle gun, which is now used by the life savers of Cape Cod, is a bronze smooth bore gun, weighing but one hundred and eighty-five pounds, and fires a cylindrical line, carrying shot, weighing about eighteen pounds, some six hundred and ninety-five yards. This projectile has a shank protruding from the muzzle of the gun to an eye in which the line is tied—a device which prevents, to a degree, the line from being burned off by the ignited gases in firing. As further protection against this happening, the life savers wet that part of the line liable to become burned. When the gun is fired the weight and inertia of the line cause the projectile to reverse. The shot-line is made of unbleached linen thread very closely and smoothly braided, is waterproof, and has great elasticity, which tends to insure it against breaking. The lines in use vary in thickness according to circumstances. They are of three sizes, designated as number 4, 7, and 9, being respectively 4/32, 7/32, or 9/32 of an inch in diameter. Any charge of powder can be used up to the maximum six ounces.

The Lyle gunshot line is43 carried in a faking box, so called, a wooden box with handles for convenience for carrying. The line is coiled on wooden pins, layer above layer. When brought into use the pins are withdrawn, and the line lies disposed in layers ready to pay out freely and fly to the wreck without entanglement. While six hundred and ninety-five yards is the greatest range to be obtained by a Lyle gun, about two hundred yards is considered the working limit. The line sags so, at more than two hundred yards, and the currents are usually so swift, that the crew of a stranded vessel could not haul the whip aboard their craft at a much greater distance, and in addition any one being pulled ashore in the breeches-buoy further than that would most likely perish from the cold and buffeting of the seas before they could be rescued.

The crotch is made of two pieces of wood, three by two inches thick, and ten feet long, securely bolted together, and crossed near the top so as to form a sort of X. The sand anchor is two pieces of hard wood, six feet long, eight inches wide and two inches thick, crossed at their centers, bolted together, and furnished at the center with a stout iron ring. It is laid obliquely in a trench behind the crotch. An iron hook, from which runs a strap of rope, having at its other end an iron ring called bull’s-eye, is fastened into the ring of the sand anchor. This strap connects with a double pulley-block at the end of the hawser behind the crotch, by which the hawser is drawn and kept taut. The trench is solidly filled in, and the imbedded sand anchor, held by the lateral strain against the side of the trench, sustains the slender bridge of rope constituted by the hawser between the stranded vessel and the shore.

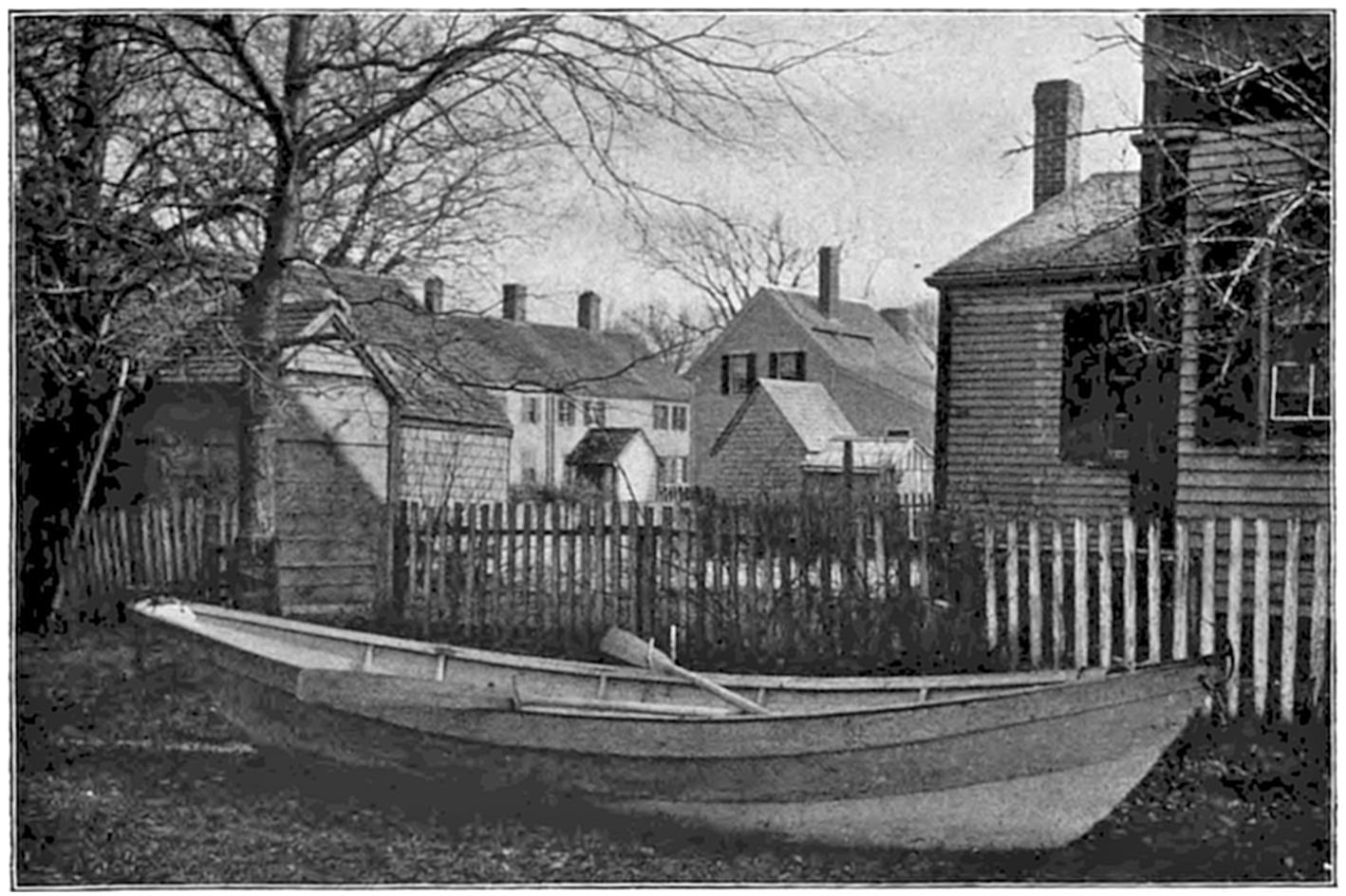

The large majority of vessels now stranded on the shores of the Cape being coasters, with crews from six to ten men, the breeches-buoy is invariably used in preference to the life-car. It weighs but twenty-one pounds. It consists of a common life-preserver of cork, seven and one-half feet in circumference, to which short canvas breeches are attached. Four rope lanyards, fastened to the circle of this cork, meet above an iron ring, which is attached to a block, called a traveler. The hawser passes through this block, and the suspended breeches-buoy is drawn between ship and shore by a whip, an endless line. At each trip it receives but one person, who gets into it with their legs down through the canvas breeches legs, holding to the lanyards, sustained in a sitting position by the canvas saddle, or seat of44 the breeches, with his legs dangling below. When there is imminent danger of the vessel breaking up and great haste is required, two persons get into the breeches-buoy at once, and to further expedite the work of rescue, the hawser is dispensed with, part of the hauling line being used for the breeches-buoy to travel on to and from the wreck.

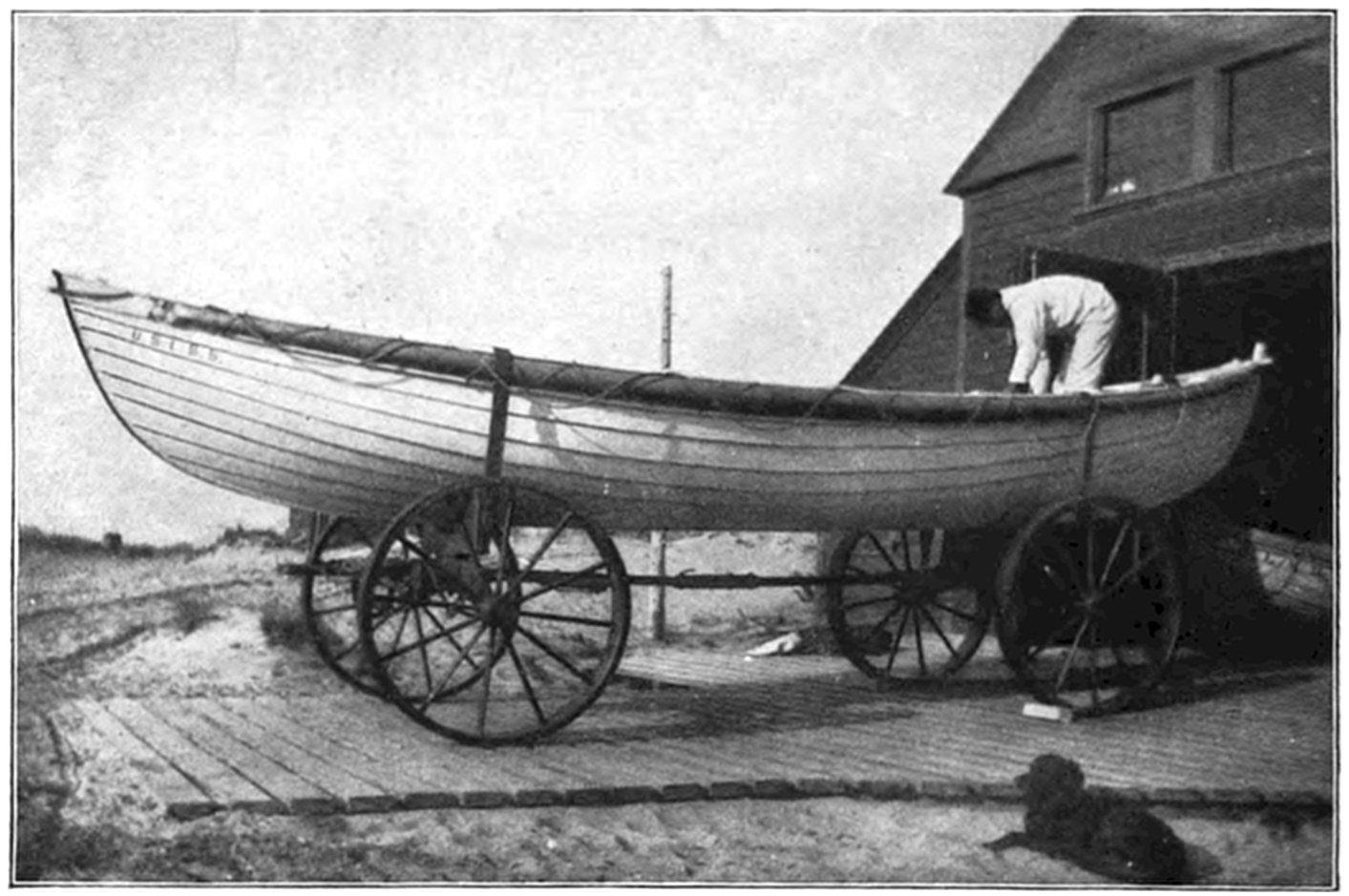

There are many kinds of life-boats, and various devices for effecting communication by line with stranded vessels. The type of boats in use on Cape Cod are the Monomoy and Race Point models. All these boats are distinctly known as surf-boats. They are constructed of cedar with white oak frames, and are from twenty-two to twenty-four feet in length. The surf-boats have air chambers at the ends, and are fitted with cork fenders along the outer side to protect them against collisions with hulls or wreckage, and to further aid in keeping them afloat, and righting lines by which they can be righted if capsized in the surf. They weigh from seven hundred to one thousand pounds. In the hands of the skilled surfmen of Cape Cod they are capable of marvelous action, and few sights are more impressive than the surf-boat plowing its way through the breakers, at times riding on top of the surge, at others held in suspension before the roaring tumultuous wall of water, or darting forth as the comber breaks and crumbles, obedient to the oars of the impassive life savers. All these boats are so light that they can be readily transported along45 the sandy shores of the Cape under normal weather conditions, and launched in very shallow water.

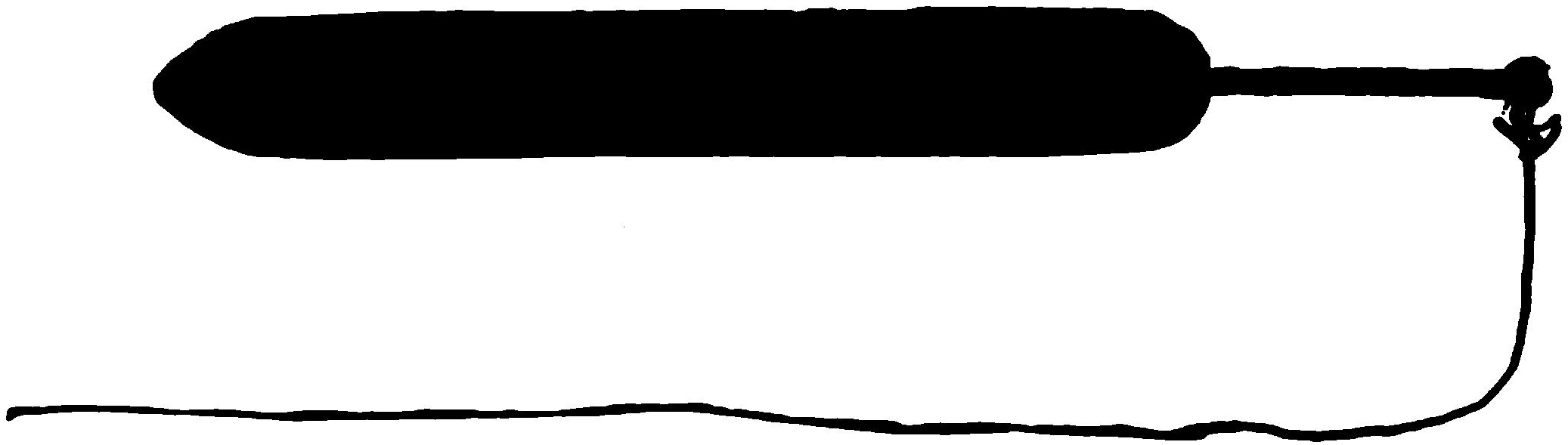

HEAVING STICK.

A small line is attached to this, and the life savers find it a very valuable means of getting a line to a vessel or piece of wreckage. It can be used advantageously at about fifty yards.

The type of boat that is best suited for one locality, however, may be ill adapted for another, and a boat that would be serviceable at one time might be worse than useless at another. On the coast of Cape Cod the boat service at wrecks is generally not very far off from shore, and the chief and greatest danger lurks in the lines of surf which must be crossed, and in the breakers on the outlying shoals.

The self-righting and bailing boat is more unwieldy, not so quickly responsive to the tactics of the steersman, and not so well adapted to the general work on Cape Cod. Where long excursions are apt to be undertaken, and the service is especially hazardous, the men feel safer in a self-righting and bailing boat, one of which has been introduced at the new Monomoy Point Station.

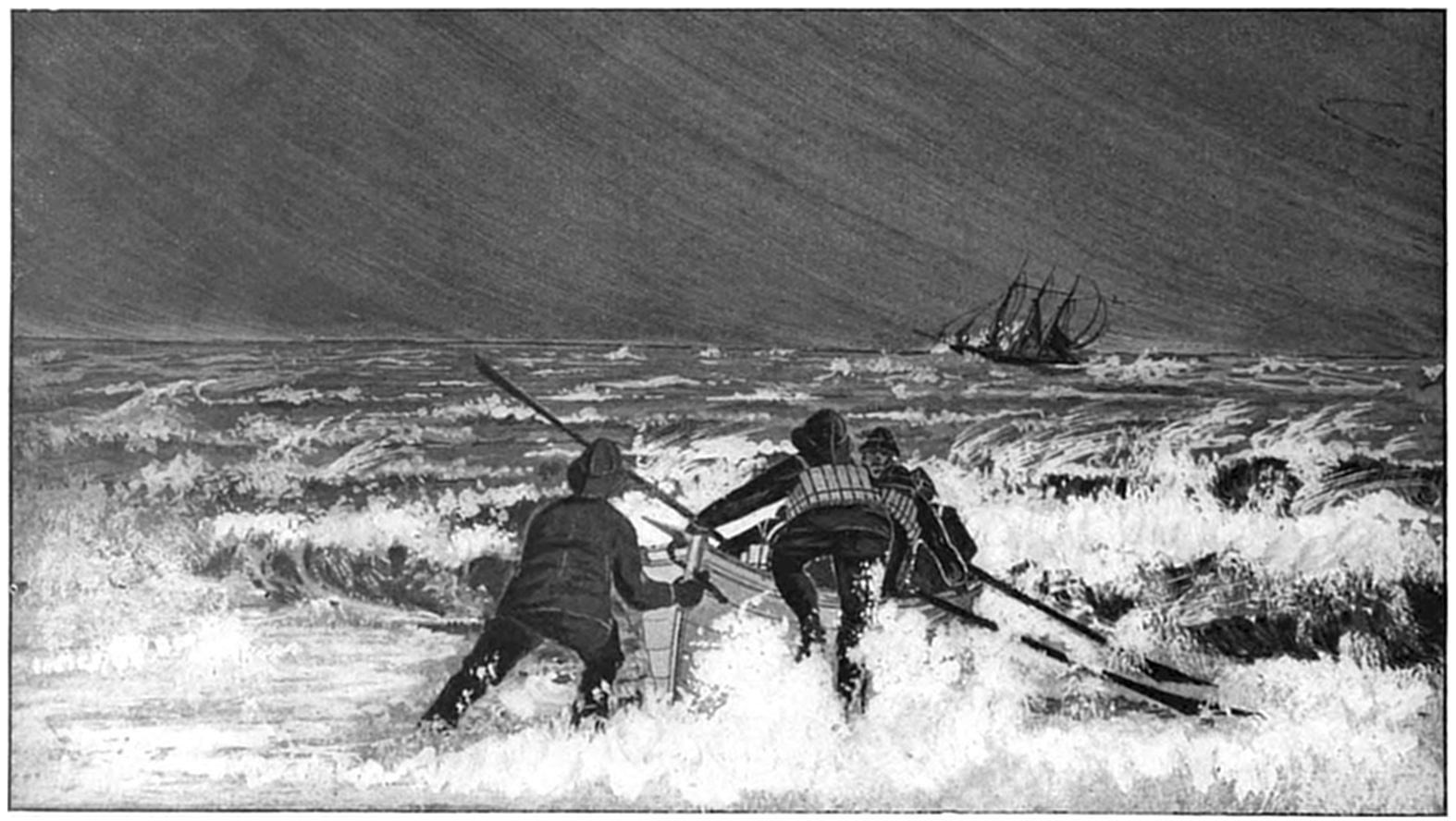

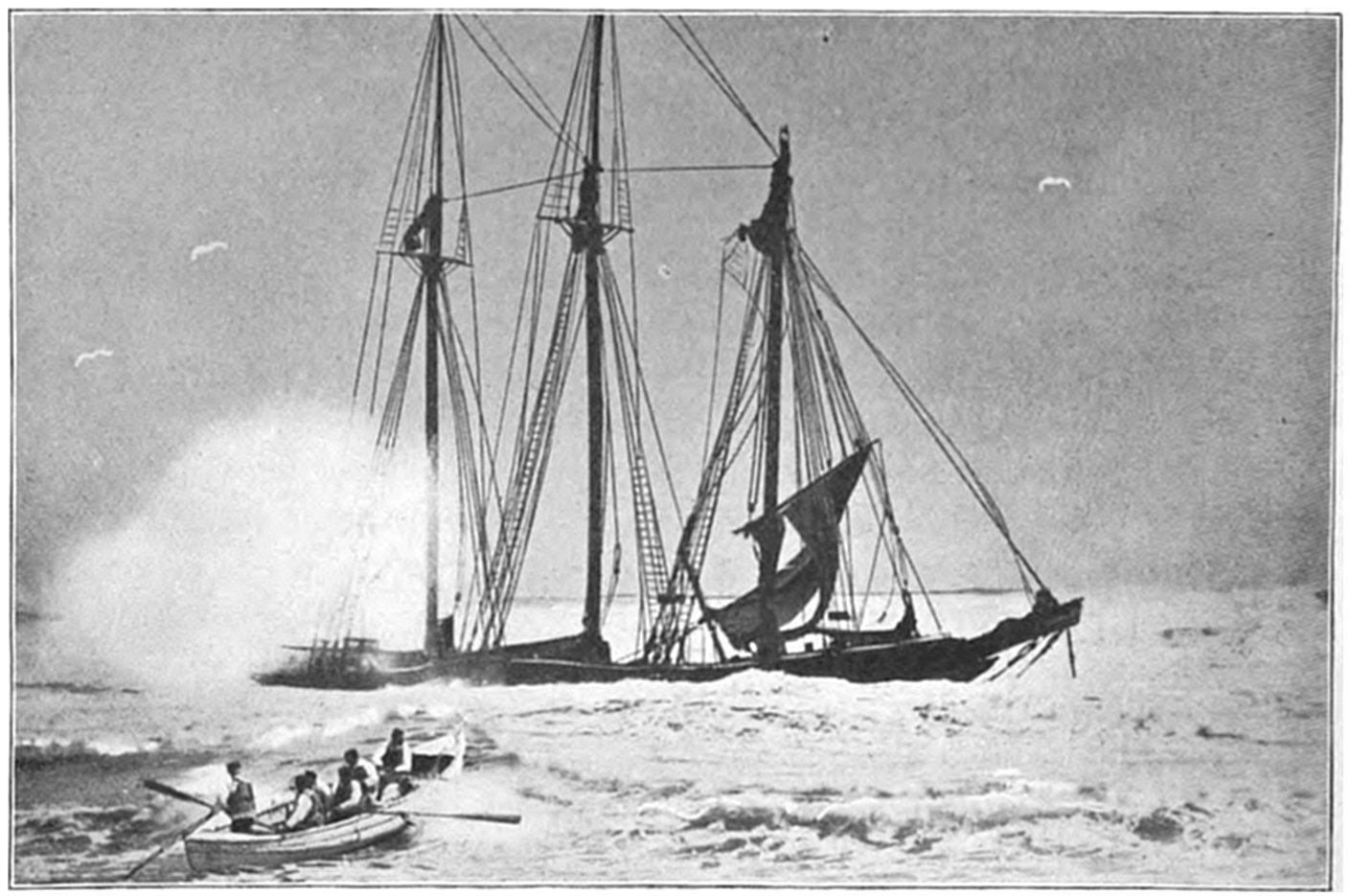

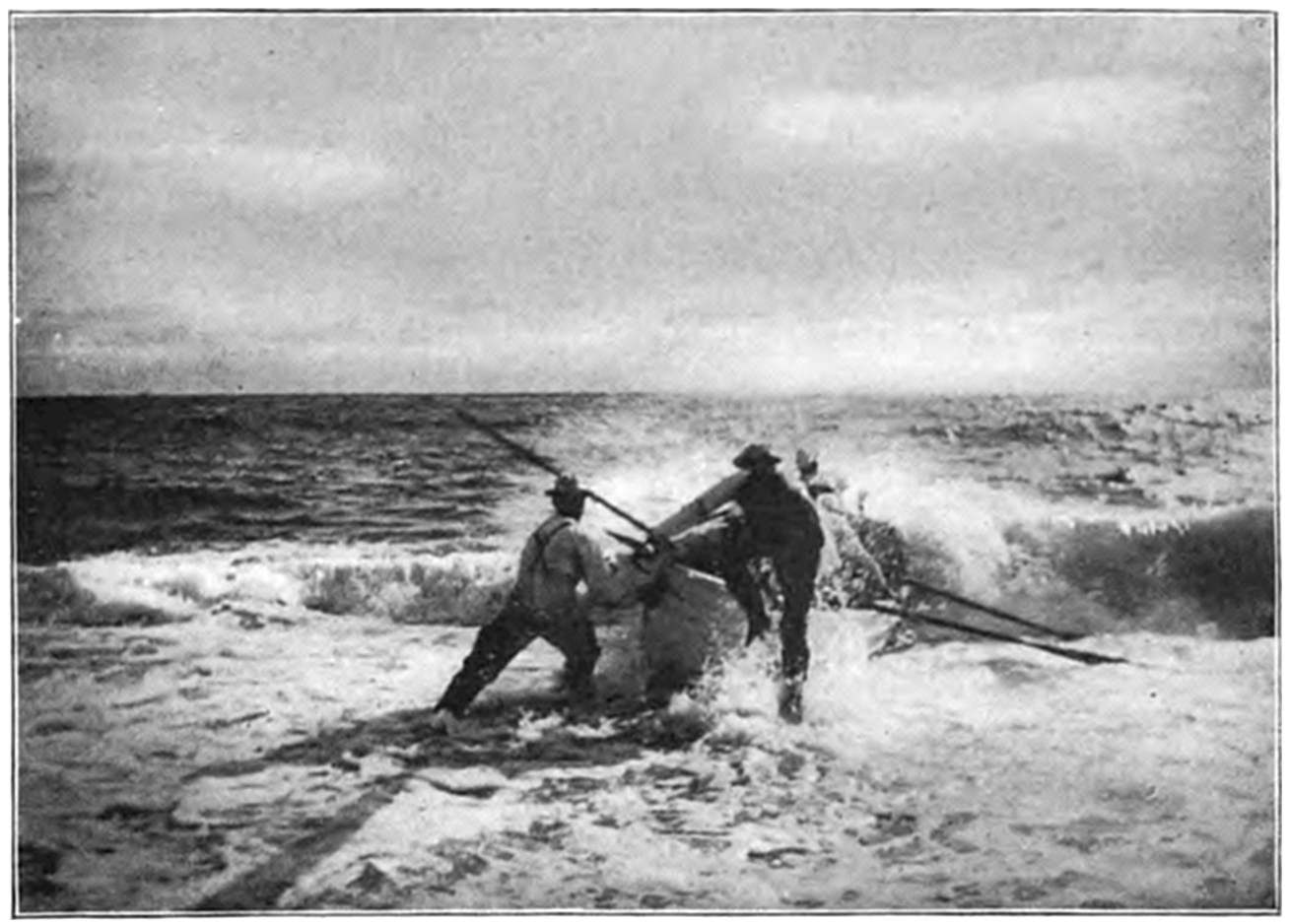

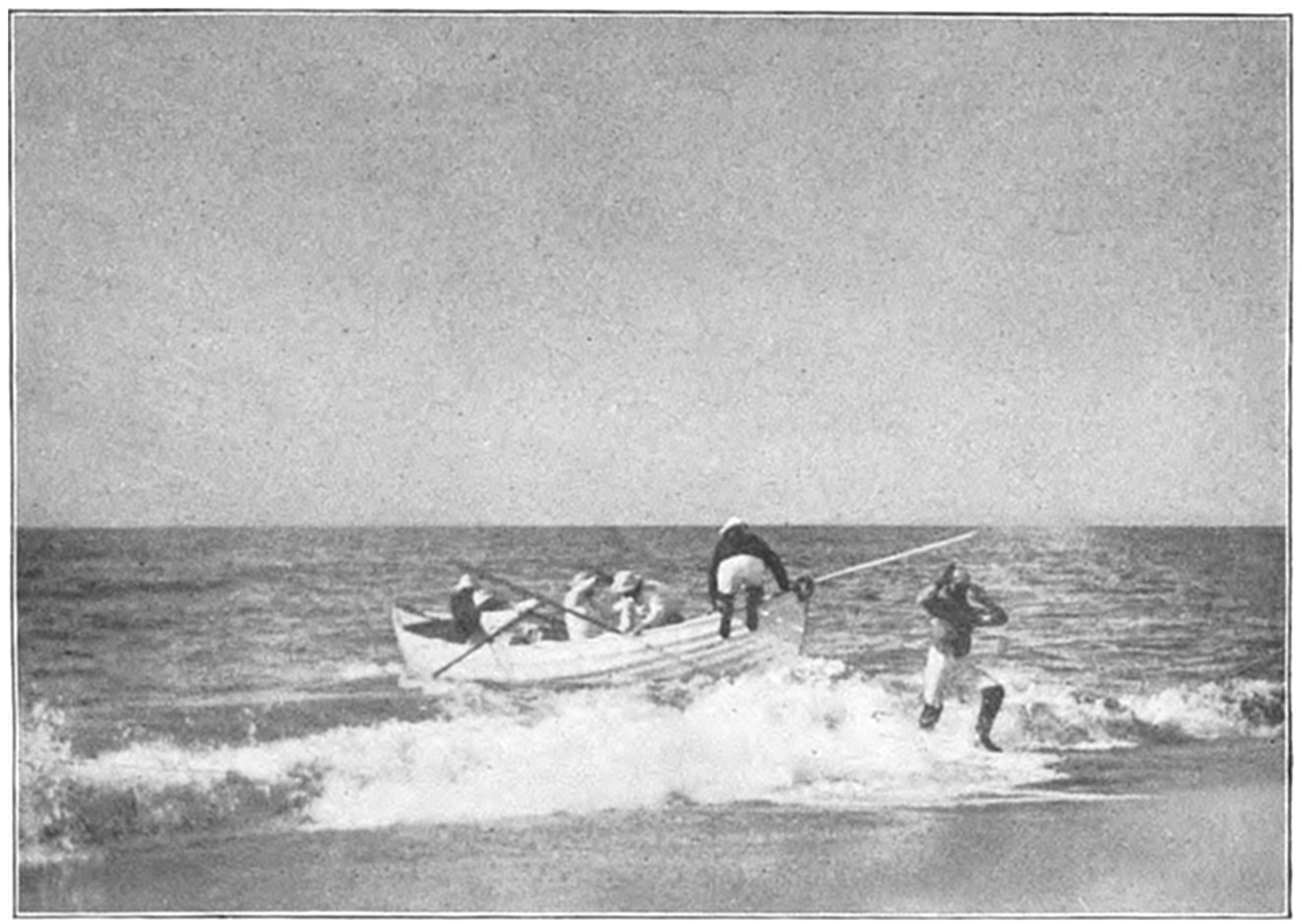

When the surf-boat is used to effect rescue it is taken along the46 beach to a point as near the wreck as possible, unloaded from the cart, and at a favorable time run into the raging waters. The keeper is the last man to get aboard the surf-boat, climbing in over the stern as she is run into the sea. The life savers who remain ashore to assist in getting the boat off run waist deep into the sea, helping to guide the boat, and to prevent her, if possible, from being capsized in the surf. The keeper steers with a long oar, and with the aid of his trained surfmen, intent upon his every look and command, guides the buoyant craft through the surf with masterly skill. He is usually47 able to avoid a direct encounter with the heaviest breakers, but if he is obliged to let them strike him, he meets them directly “head on.”

Although sometimes hurled back upon the beach and broken in desperate and unavailing attempts at a launch against a resistless sea, this boat, which might easily be upset, has rarely been capsized in going through the surf. While there is always great peril in launching these boats in times of shipwreck, the greatest danger lies in landing through the surf. The gigantic walls of water speeding to the shore cannot then be met head on as when the boat is passing out,48 and when one of these tumultuous combers break over the stern of the boat, which, fortunately, has rarely occurred on Cape Cod, the lives of those aboard the craft are placed in great peril.

In landing the life savers jump into the surf as the boat is about to touch the beach, and with the assistance of those of the crew who remained ashore to select a good landing place, the craft is quickly run up on the beach far out of the reach of the dangerous undertow.

This work is also attended with great danger, the surfmen sometimes receiving injuries by being struck by the boat, which incapacitates them from further duty in the service. The keepers and crews place their faith in the surf-boats which they use, and they are ever ready to face any sea in which a boat will live.

When a distressed vessel is reached, the orders of the keeper, the captain of the crew of life savers, who always steers and commands, must be implicitly obeyed.

There must be no headlong rushing or crowding, and the captain of the ship must remain on board to preserve order until every other person has left. Women, children, and helpless persons are taken into the boat first. Goods or baggage will not be taken into the boat49 under any circumstances until all persons are landed. If any be passed in against the keeper’s remonstrance he throws it overboard.

It often happens, however, that some of the crew, and even captains of wrecked vessels, attempt to get their baggage into the surf-boats. At a wreck which Captain Cole and his crew went to in the night a few years ago the captain of the craft insisted that the life savers should wait until he could get his baggage ready to take ashore. Captain Cole, in a voice that could be heard above the roar and din of the storm, commanded the bow oarsmen, who was holding the painter that kept the surf-boat alongside the wreck, to cut the painter. The captain of the stranded craft no sooner heard this command than he jumped into the boat, leaving his effects behind, and was safely taken ashore.

Persons rescued from shipwreck are taken to the nearest life-saving station, the weak, sick, and the disabled are treated with remedies from the medicine chest, supplied under the direction of the Surgeon-General of the Marine Hospital Service. Those who have escaped from shipwreck and are wet, hungry, and cold are provided with dry clothing, warmed, fed, lodged, and cared for until they are able to leave.

The method adopted for restoring the apparently drowned is formulated into rules which each member of the crew commits to memory. In drill he is required to repeat these and afterwards illustrate them by manipulations upon one of his comrades. The medicine chest is also opened, and he is examined as to the use of its contents.

The dry clothing is taken from the supply constantly kept on hand at the different stations by the Women’s National Relief Association, an organization established to afford relief to sufferers from disasters of every kind. The libraries at the stations are from the donations of the Seamen’s Friend Society and sundry benevolent persons. The food is prepared by the keepers or the station mess, who are reimbursed by the recipients if they have the means, or by the government.

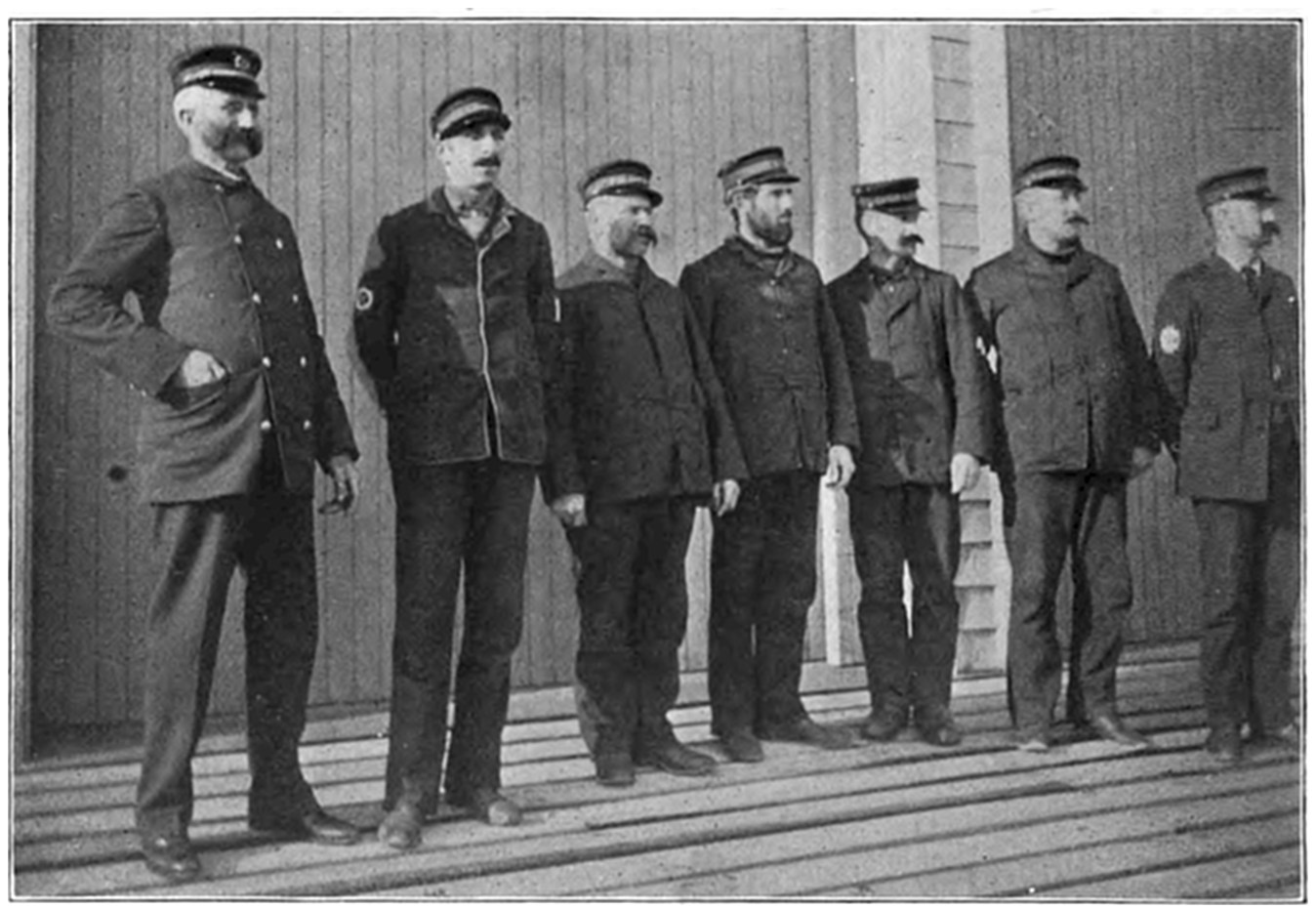

The life-saving service is attached to the treasury department. The sea and lake coasts of the United States have an extent of more than ten thousand miles, and are divided into thirteen life-saving districts, each under the immediate supervision of a district superintendent. The chief officer of the service is the general superintendent, who has general charge of it and of all administrative matters connected with it. An inspector from the Revenue Marine Service visits each station monthly during the “active season,” which is ten months, from August 1 to June 1, and examines and practices the crews in50 their duties. On his first visit, after the opening of the stations each year, if any are found not up to the standard, they are promptly dropped from the service. The district superintendents are promoted from the corps of keepers, and must be residents of the respective districts for which they are chosen, and are rigidly examined as to their professional familiarity with the line of coast embraced within the district and the use of life-boats and all other life-saving apparatus.

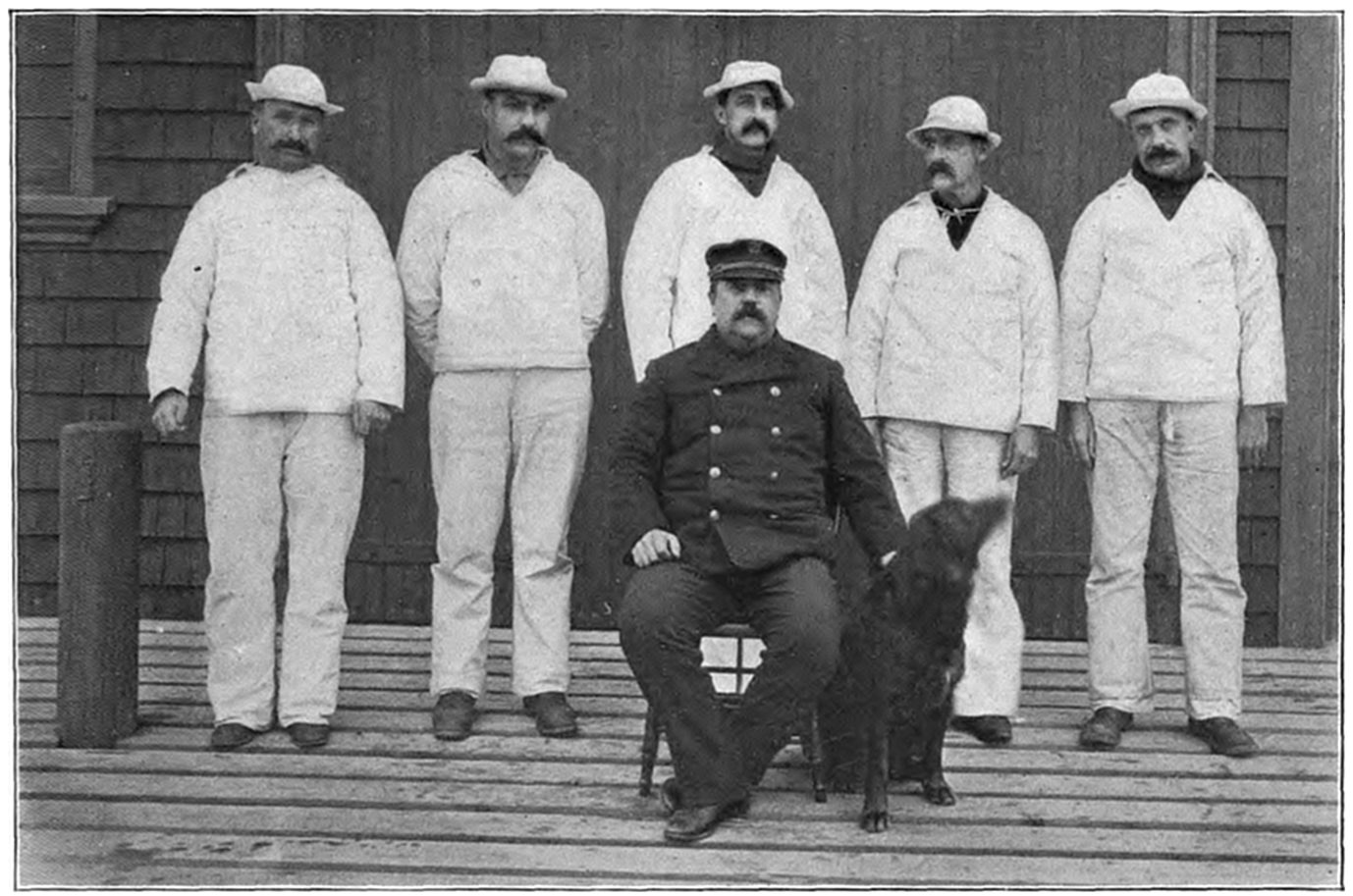

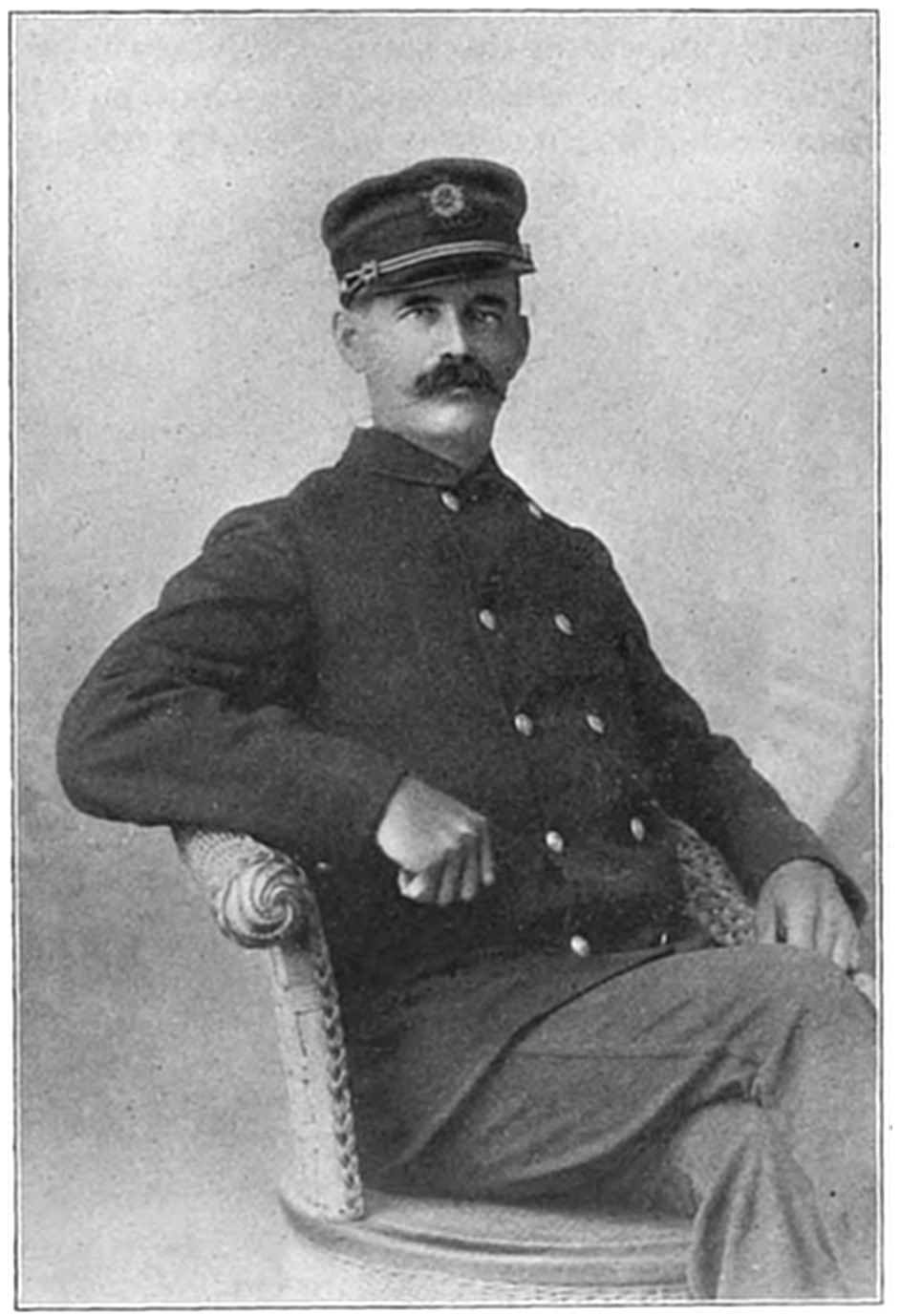

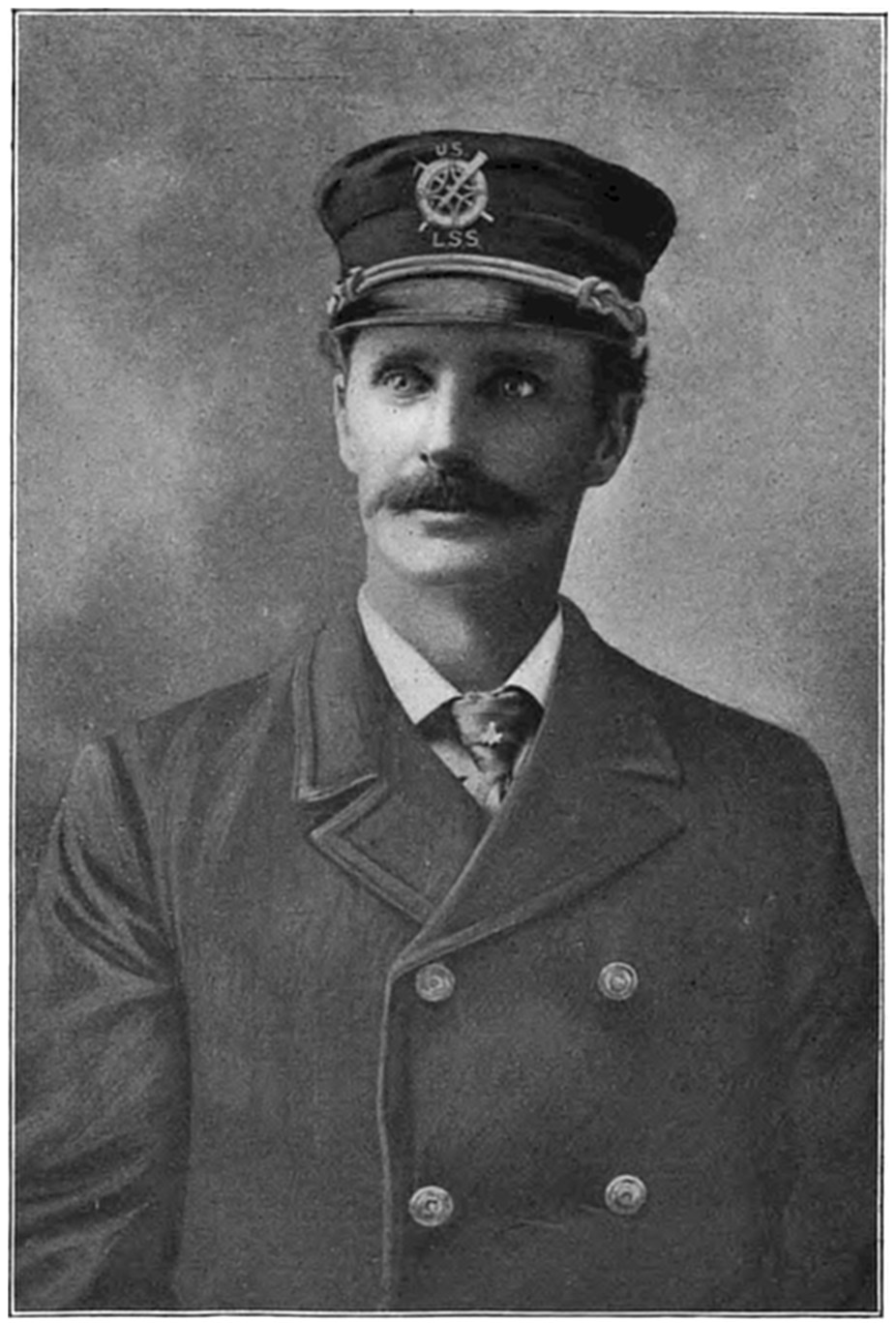

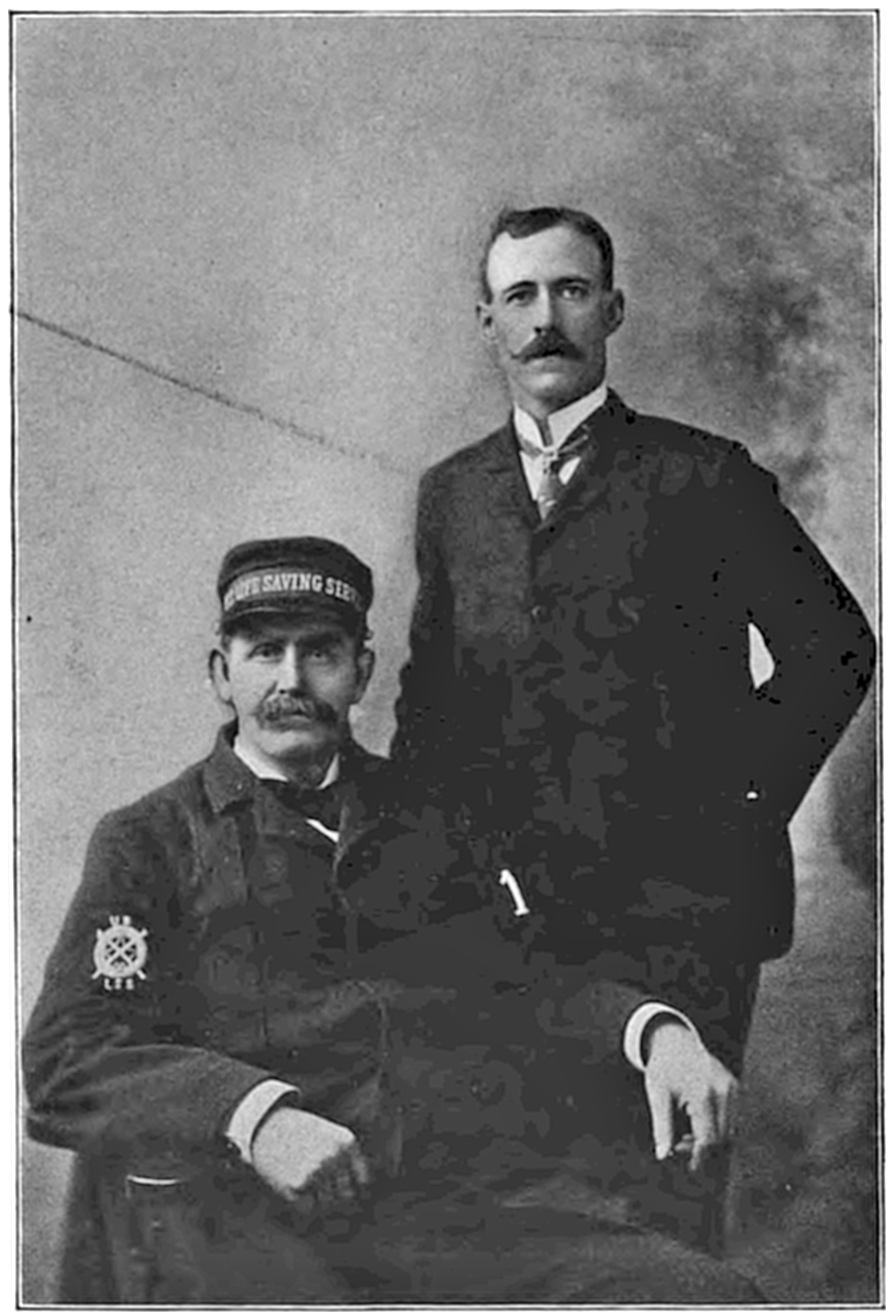

The keeper of each station has direct control of all its affairs, and as his position is one of the most important of the service, the selection is made with the greatest care.

The indispensable qualifications are that he shall be a man of good character and habits, not less than twenty-one and not over forty-five years of age, with sufficient education to be able to transact the business connected with the station, be able bodied, physically sound, and a master of boatcraft and surfing.

No difficulty is found in filling vacancies that occur among the keepers, as they must be promoted from the ranks of the surfmen, and the merits of all the surfmen, having been ascertained by inspection, drill, and active service, are on record. The keepers are required to reside at their stations all the year round, and are entrusted with the care, custody, and government of the station and property. They are captains of their crews, exercise absolute control in matters of discipline, lead the men, and share their perils on all occasions of rescue, always taking the steering oar when the boats are used, and directing all operations with the other apparatus.

51

52

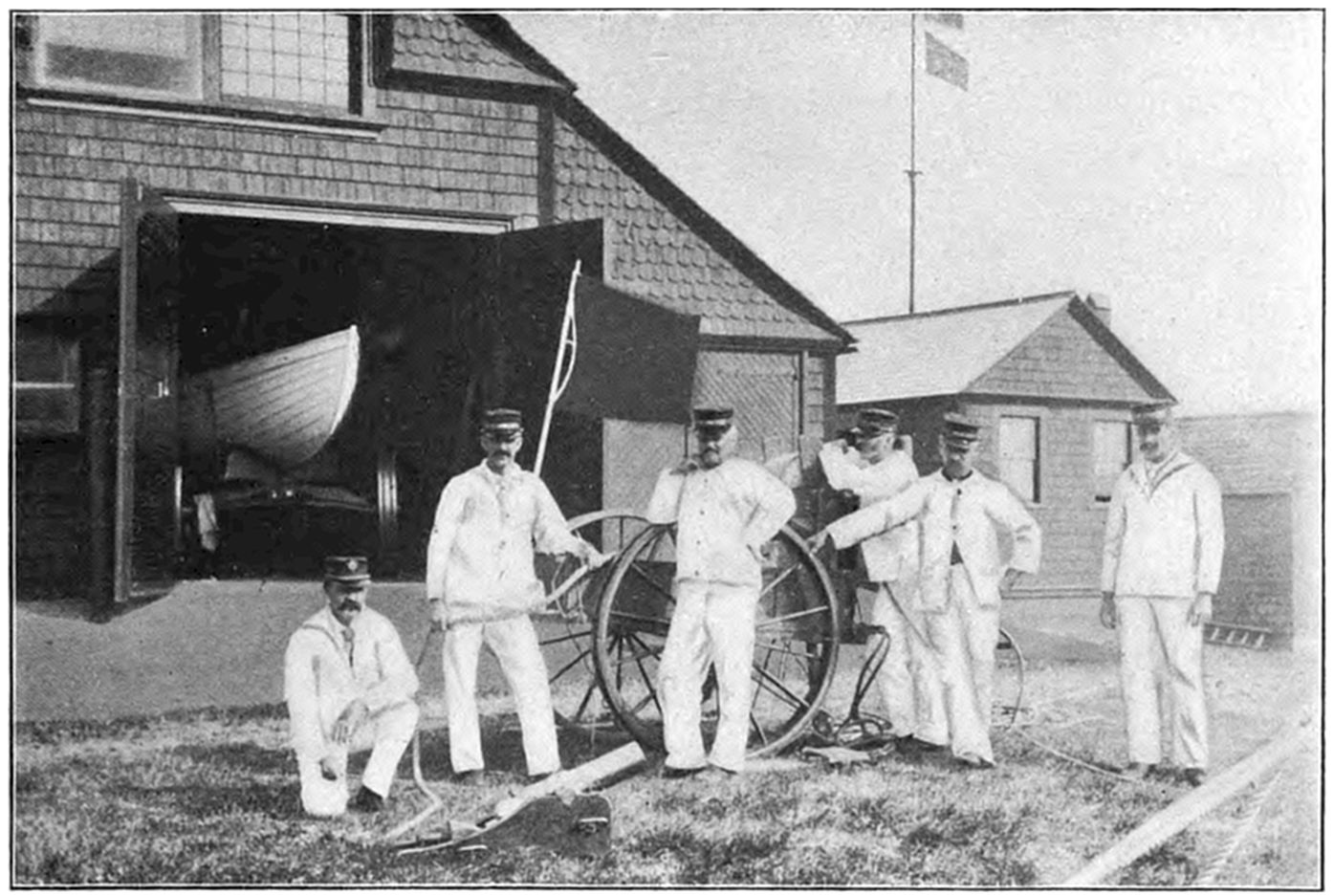

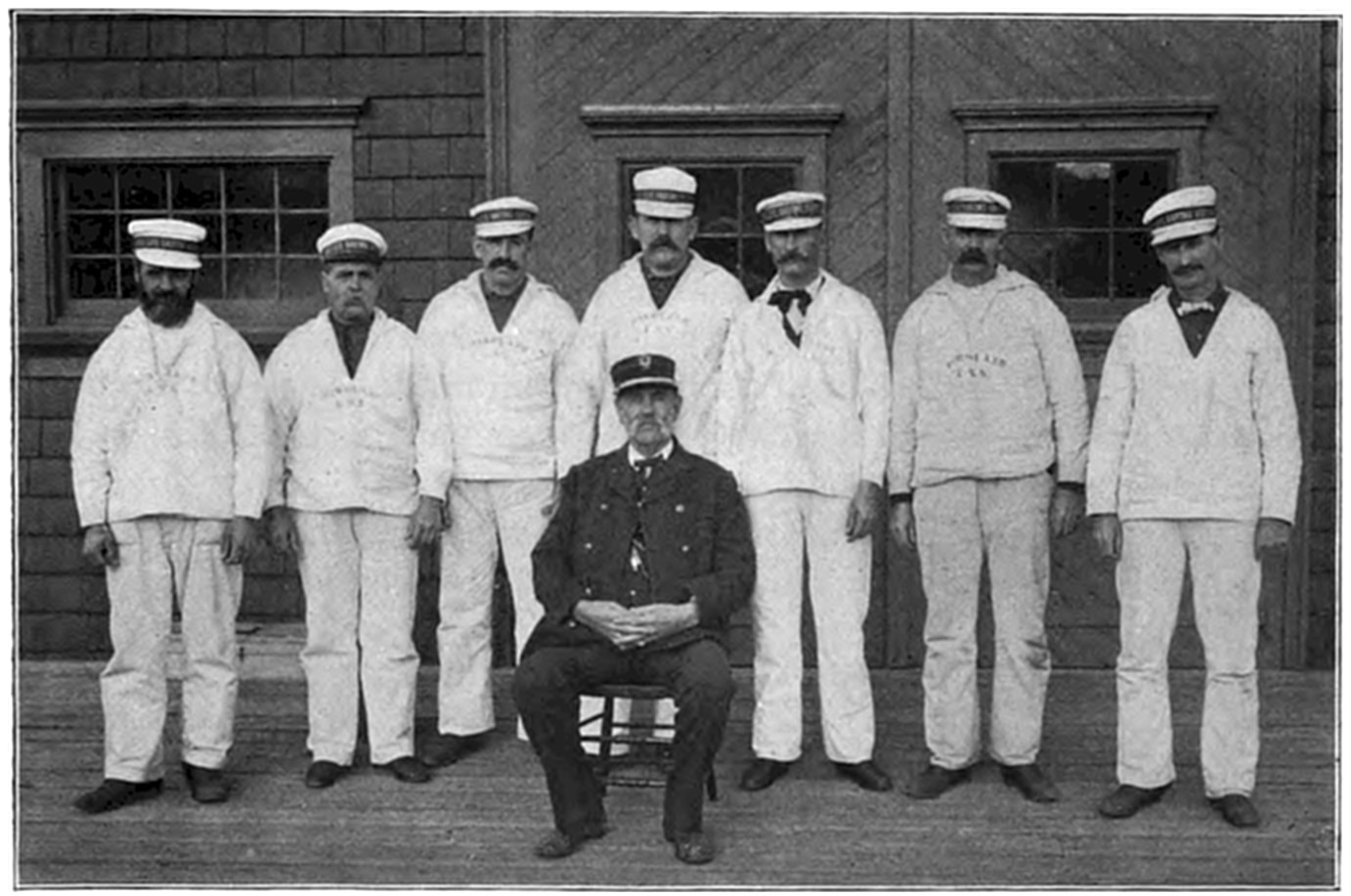

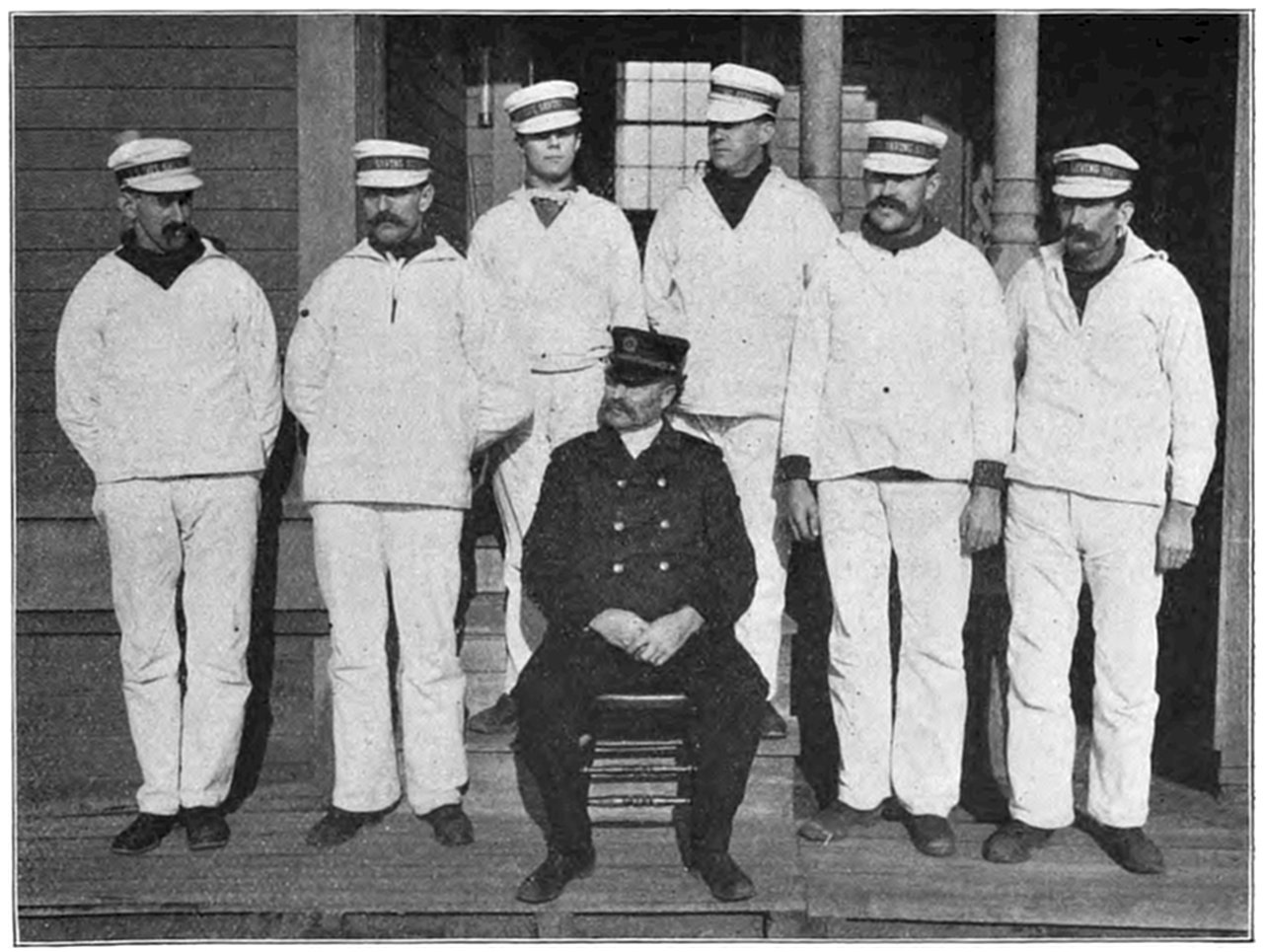

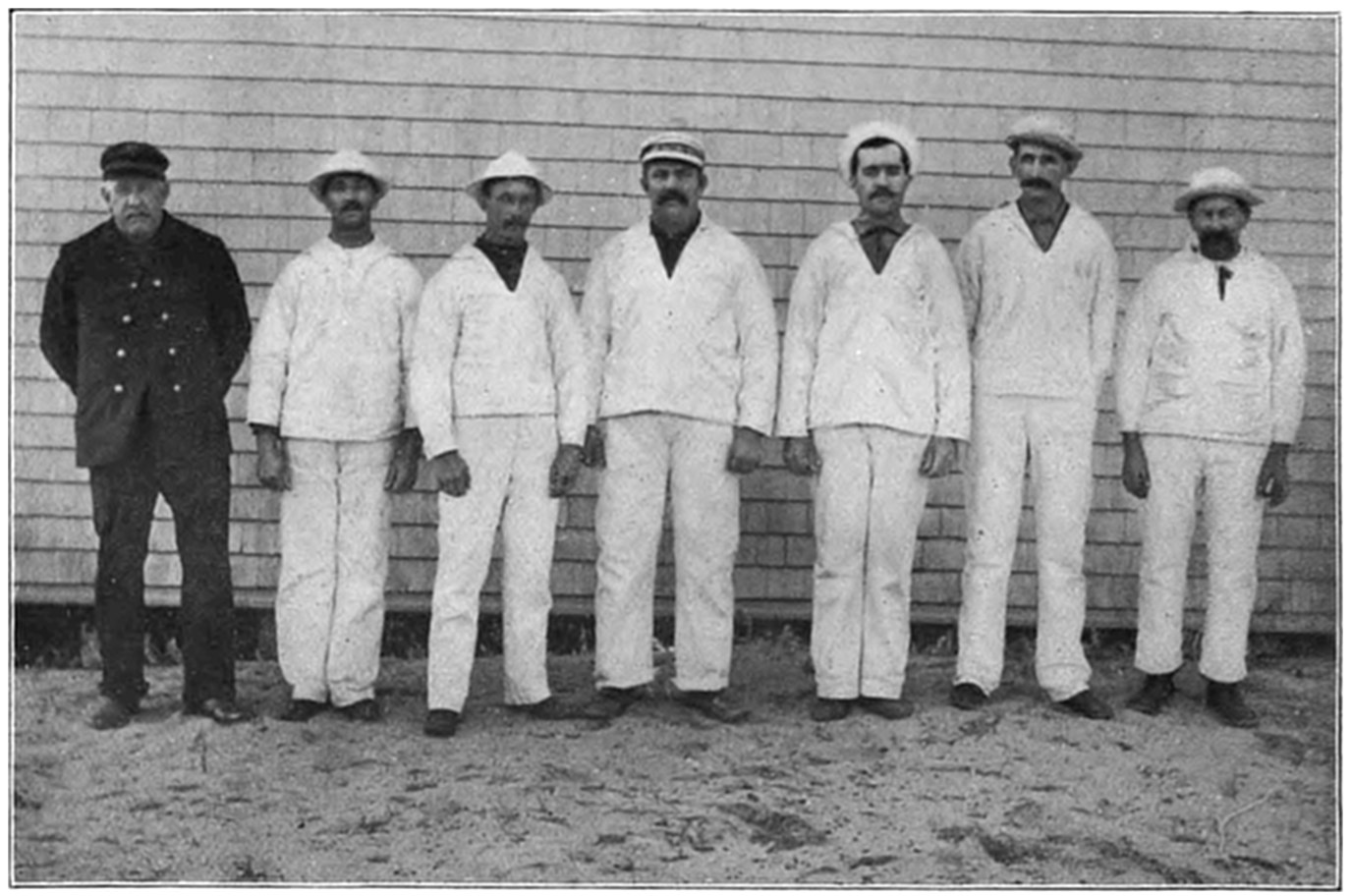

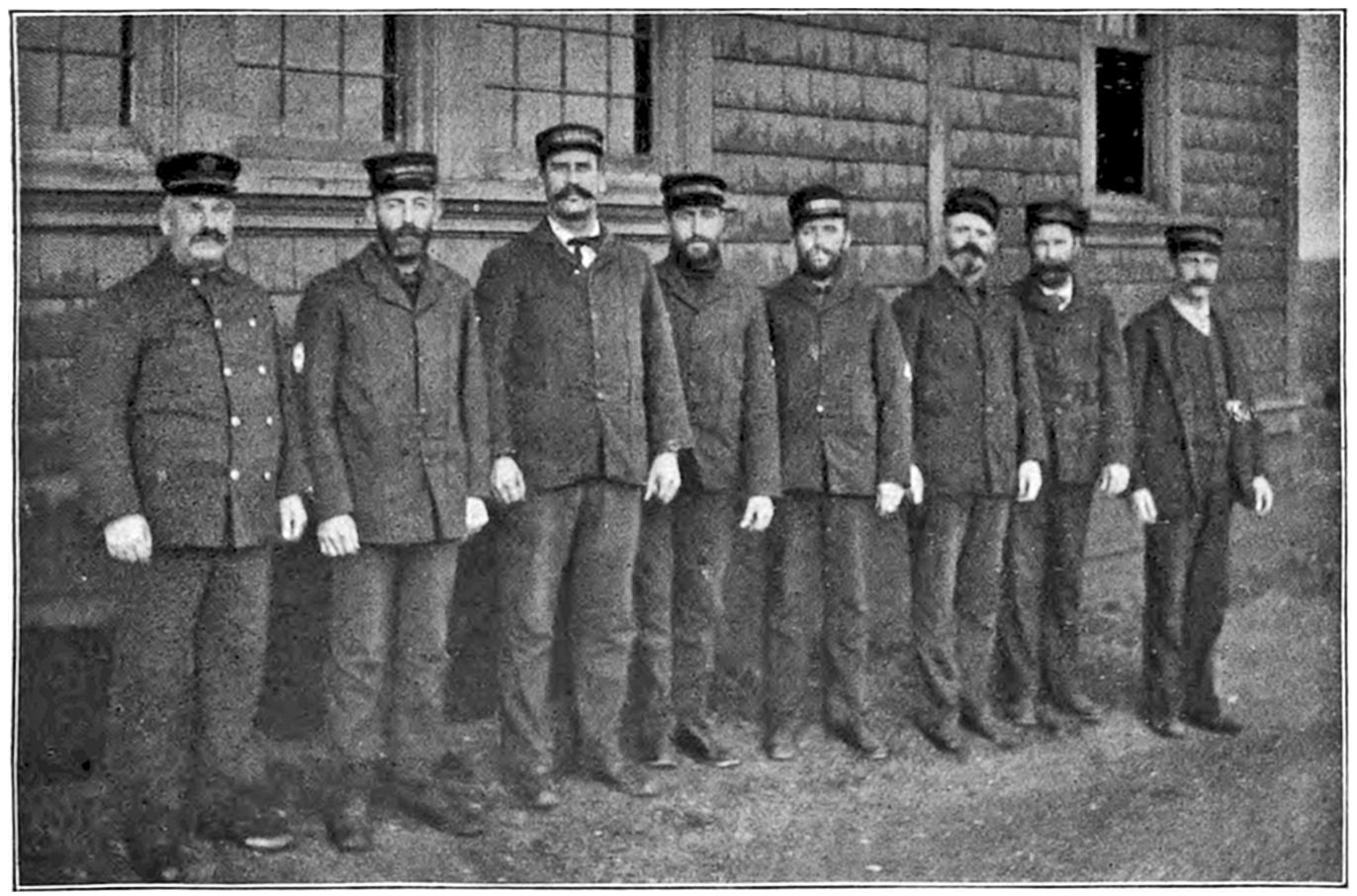

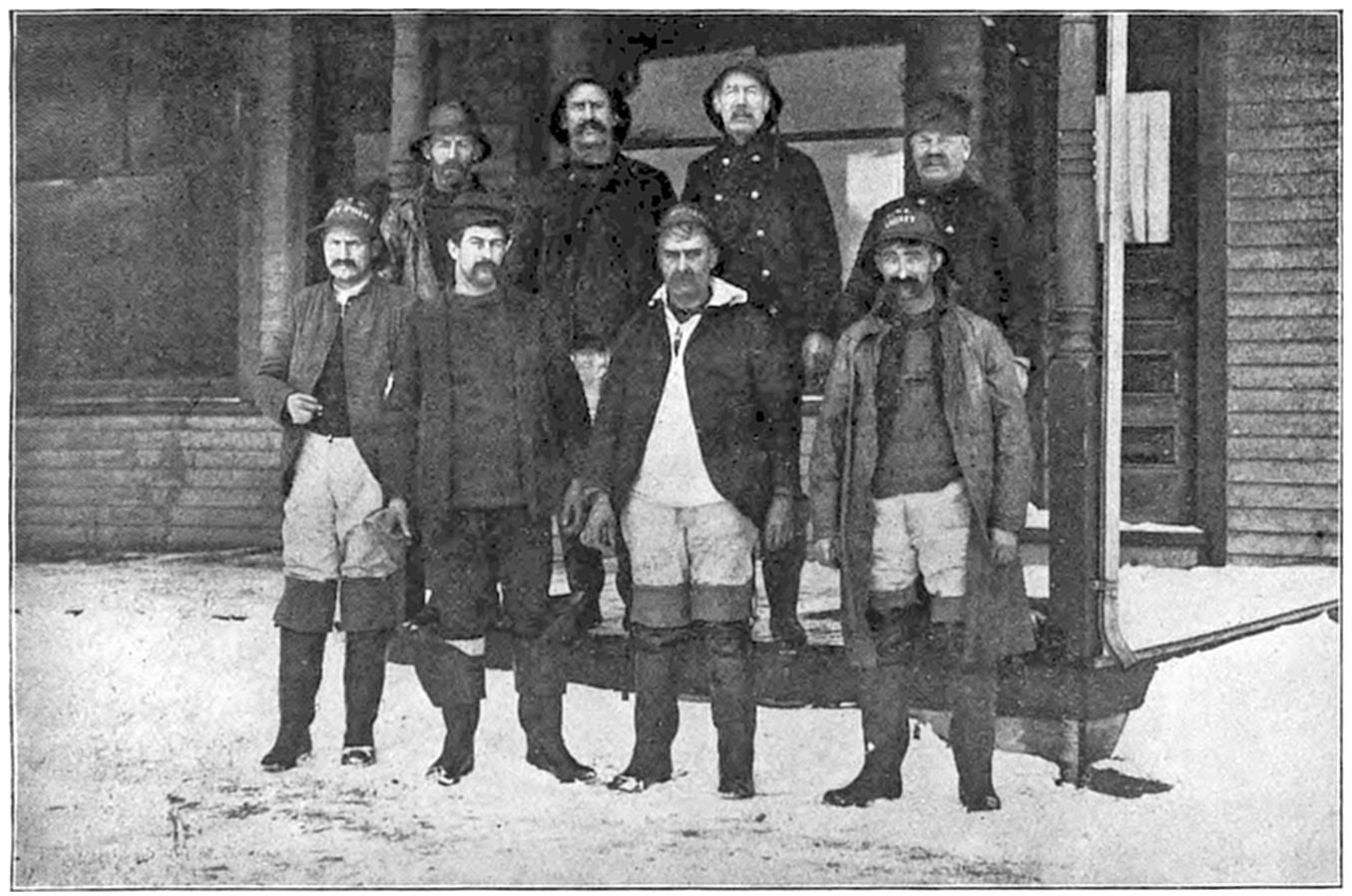

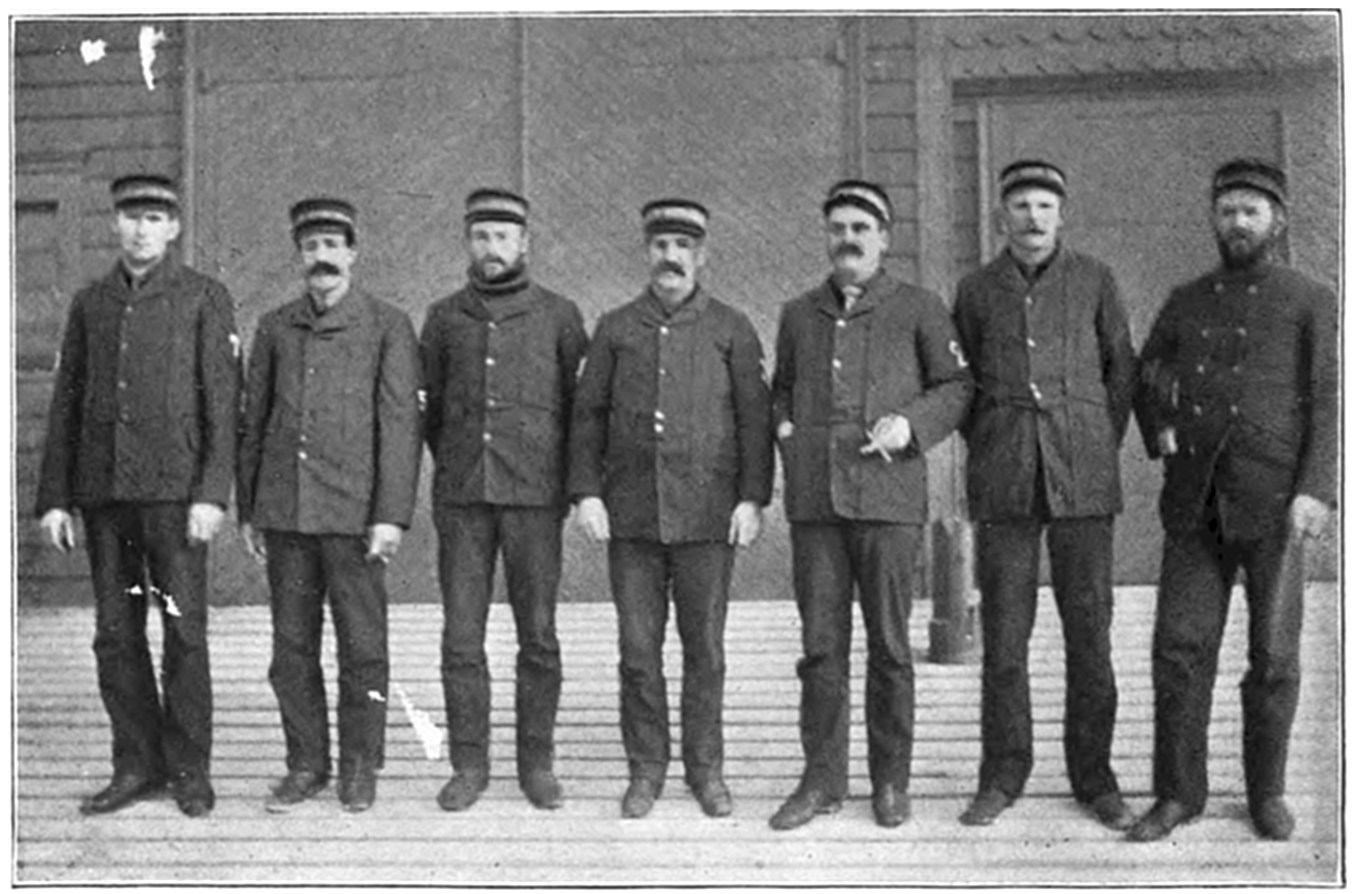

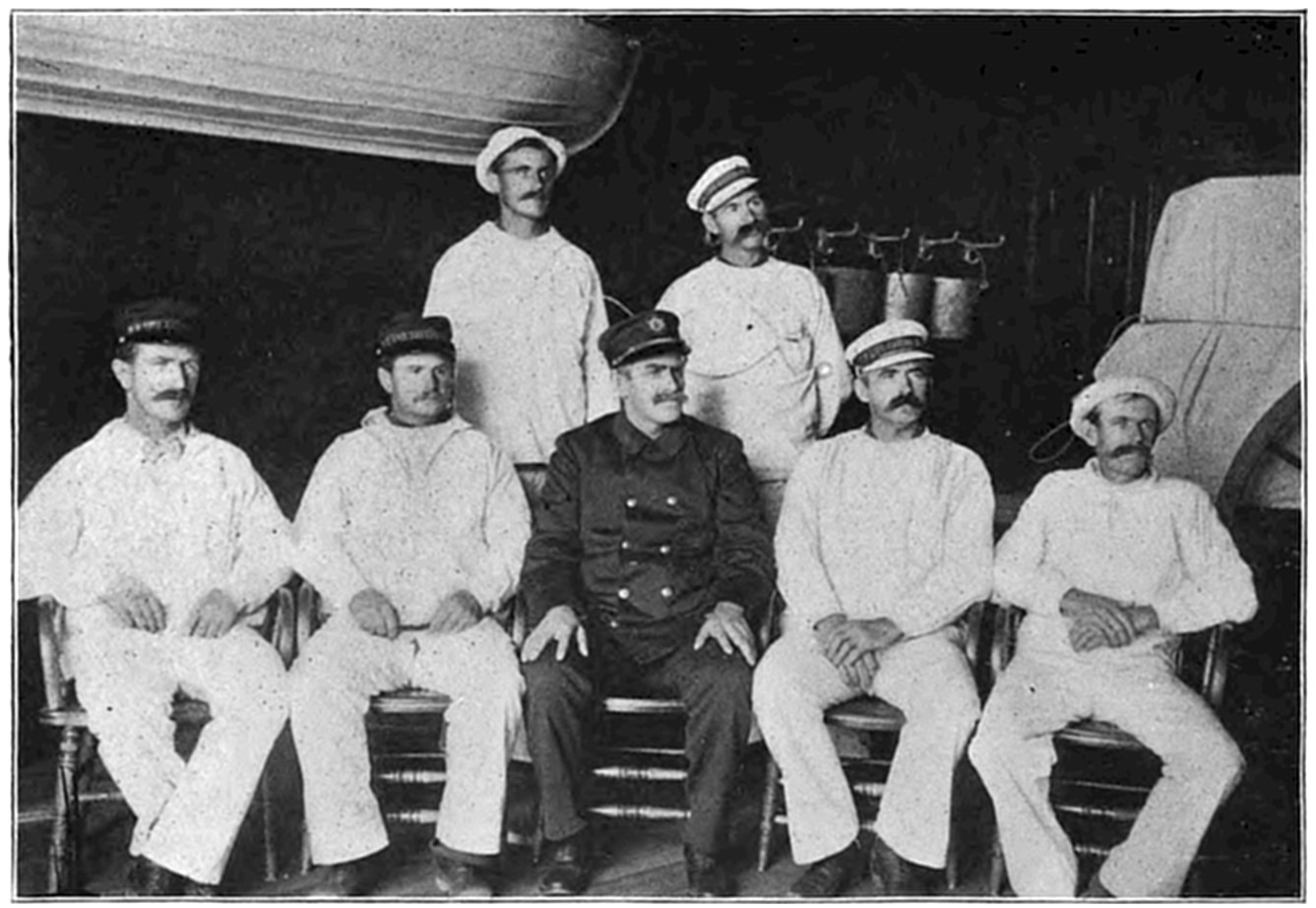

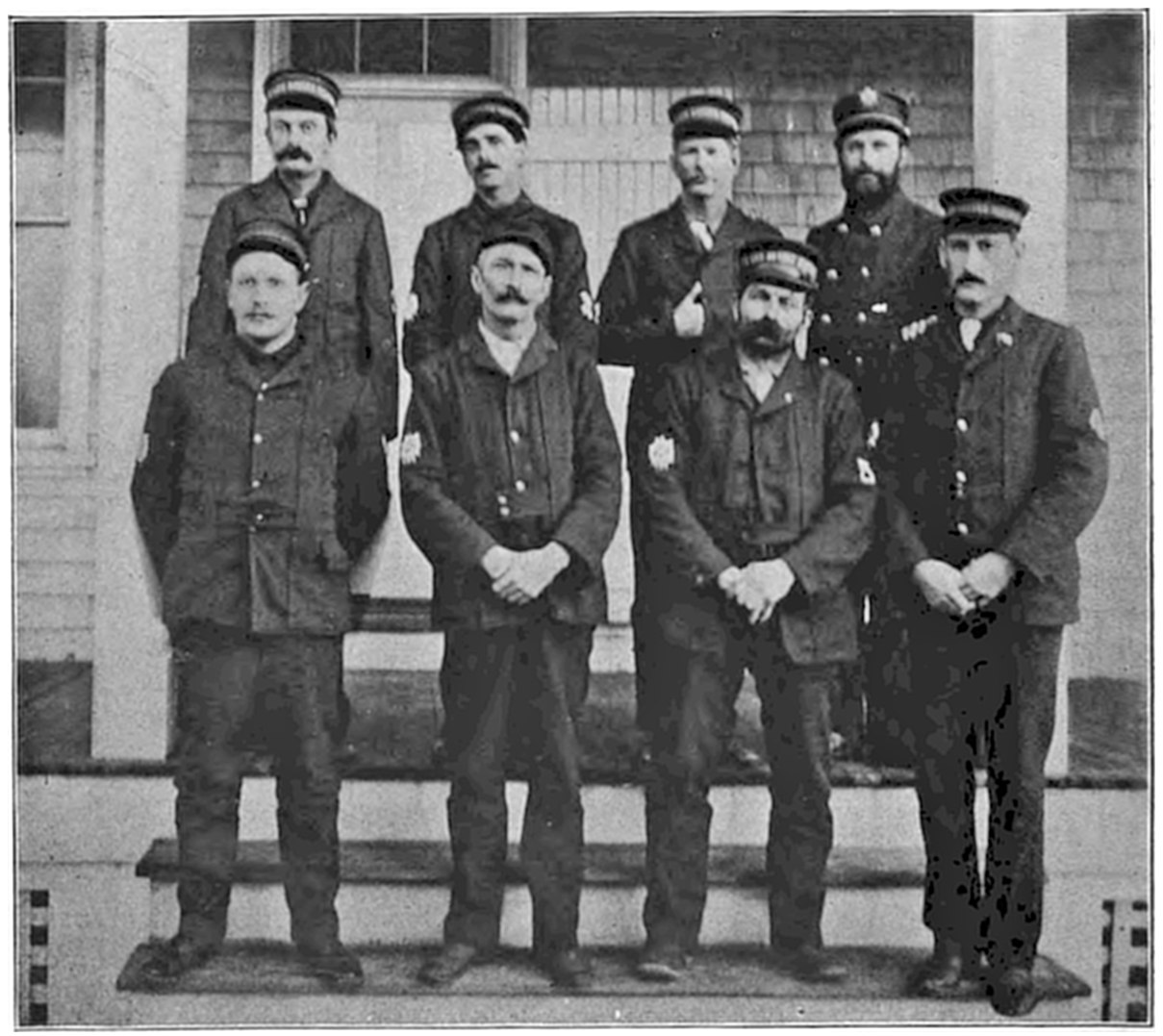

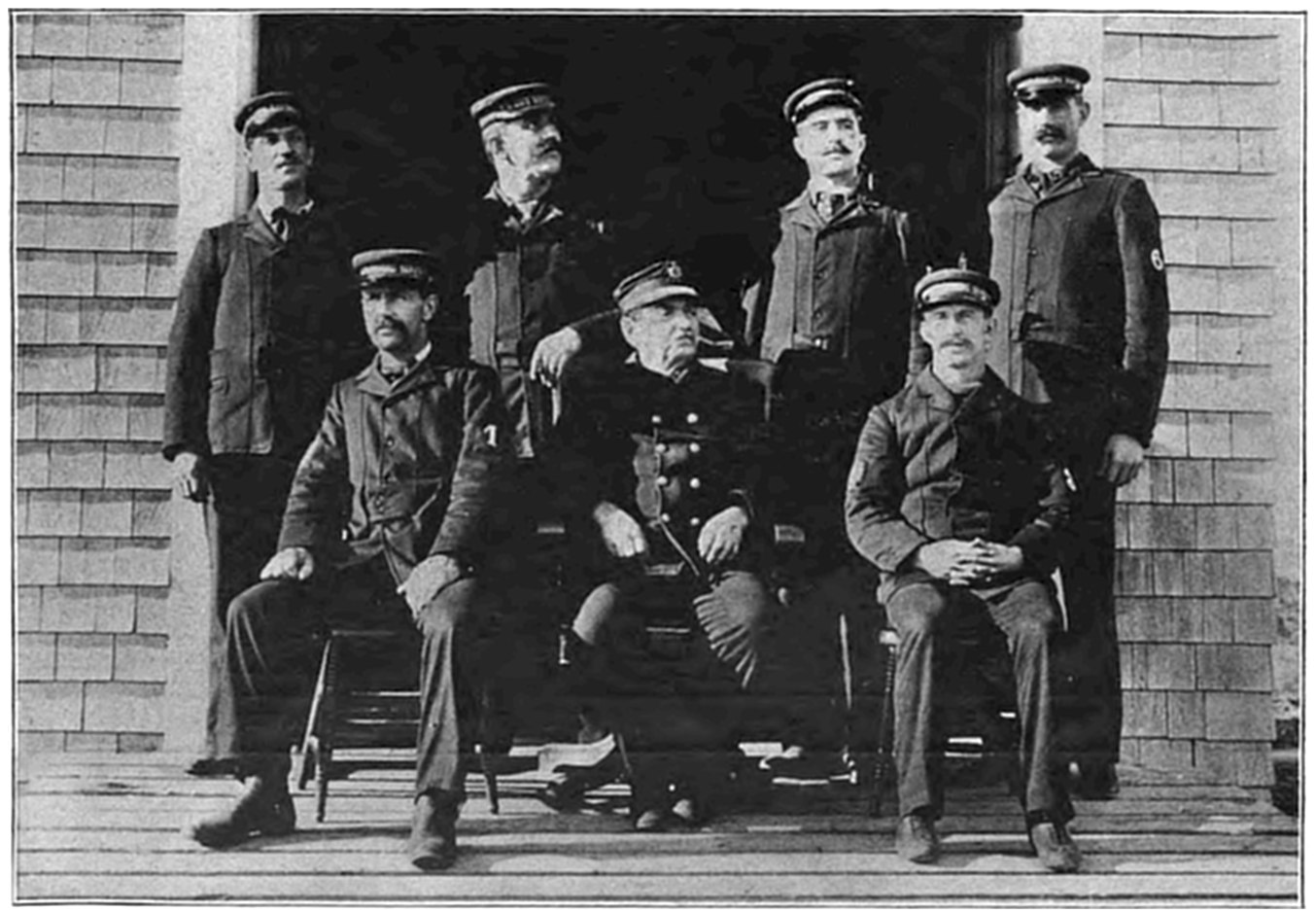

The keeper and six men constitute the regular crew at each of the stations on Cape Cod, except at the Monomoy Station, where the regular crew is seven men. An additional man called “the winter man” is added to all stations on December 1 of each year, so that during the most rigorous part of the season one man, at least, may be left ashore to assist in launching and beaching of the surf-boat, and to have charge of the station and perform the extra work that winter weather necessitates.

The life-saving crews are selected from able-bodied and experienced surfmen after the rigid examination required by the department.

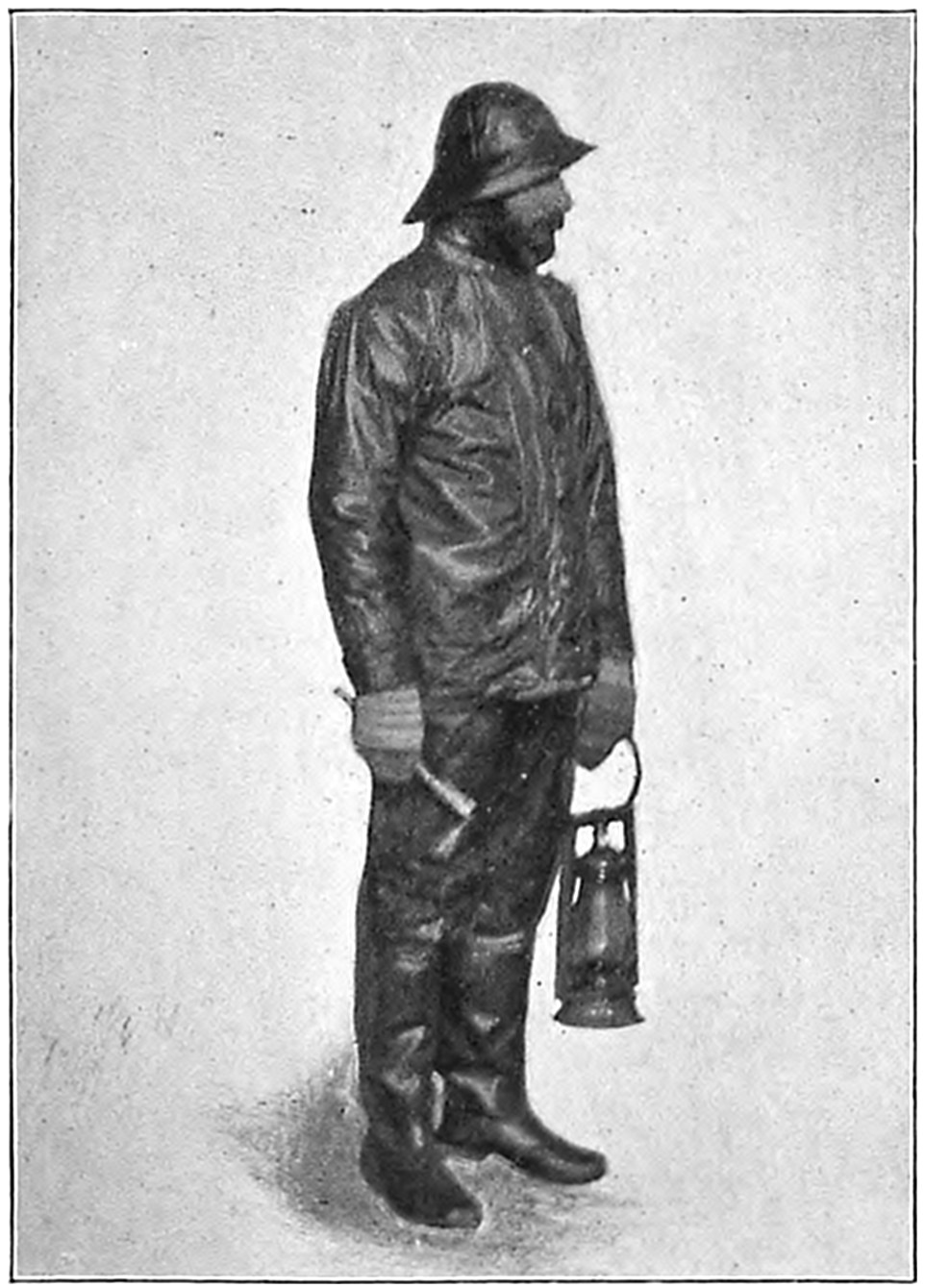

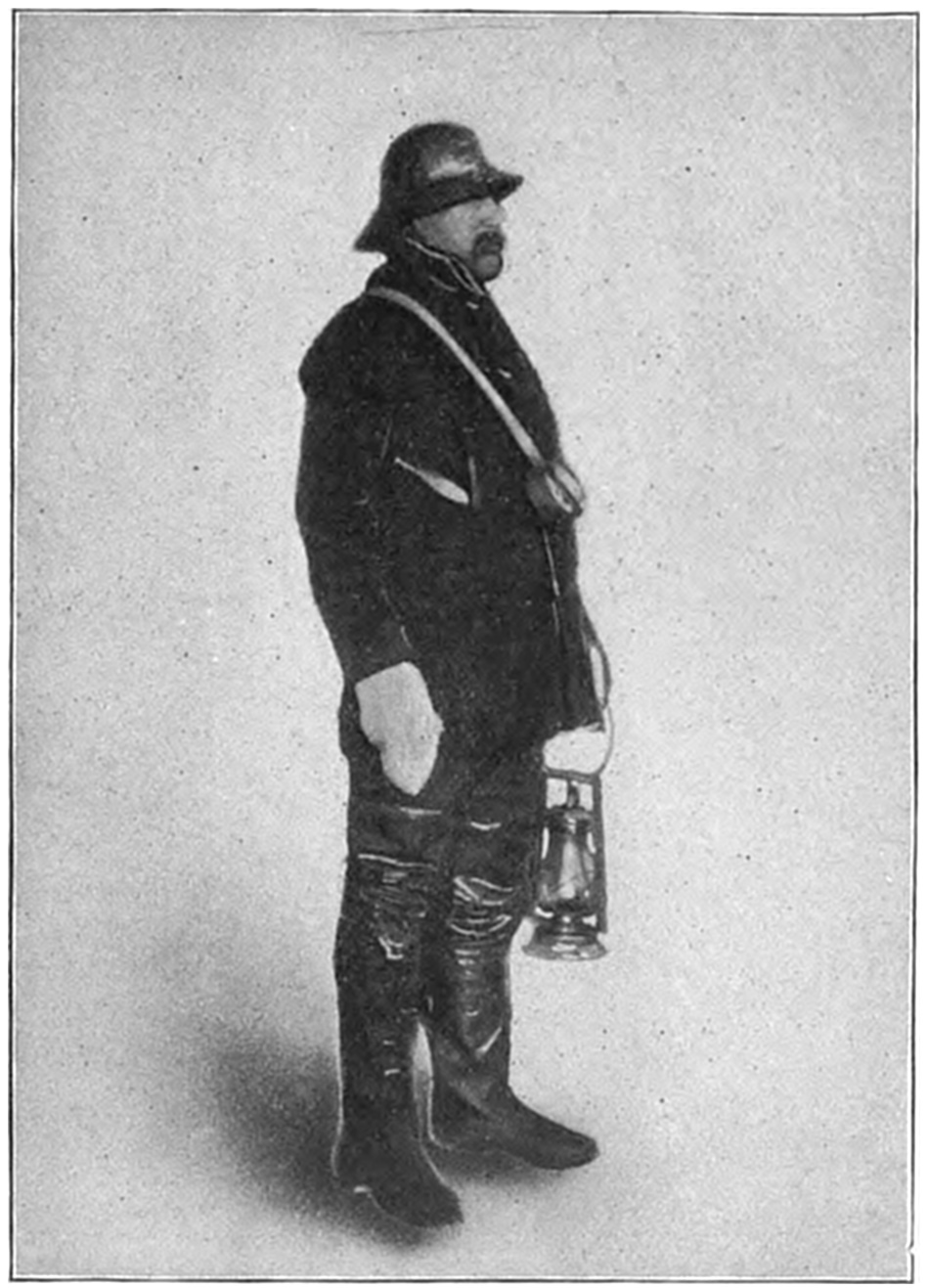

SURFMAN GAGE, ORLEANS STATION,

Dressed for cold night, with time clock, beach lantern, and coston signal.

The surfmen, in addition to being obliged to pass a rigid physical examination before they can enter the service, must also pass a similar examination yearly before the opening of the active season. No matter how long they may have been in the service, the hardships they have suffered, the perils they have faced, or the great deeds of heroism they have performed, if they are found not to be physically sound they are dropped from the service, ruined in health, without the slightest compensation for the years of faithful service.

The profession of a surfman is entirely different from that of a sailor, being only acquired by coast fishermen and wreckers after years of experience in passing in and out through the surf. The method of selecting the life-saving crews has resulted in securing the most skilful and fearless surfmen, whose gallant deeds of heroism have made them famous throughout the land. Upon original entry into the service a surfman must be a citizen of the United States, not over forty-five years of age.

He is examined as to his expertness in the management of boats53 and the use of other life-saving apparatus, and matters of that character. He signs articles by which he agrees to reside at the station continuously during the active season, to perform such duties as may be required of him by the regulations and by his superior officers, and also to hold himself in readiness for service during the inactive season if called upon. For this he receives sixty-five dollars per month. For each occasion he is called upon, during the two months’ inactive season, he receives three dollars.

The district superintendents, inspectors, keepers, and crews, the law says, are to be selected “solely with reference to their fitness and without reference to their political or party affiliations.”

Every time a wreck occurs the keepers are required to make out and forward to the department a wreck report, containing answers to a great number of pertinent questions.

If a life is lost the law requires that a thorough investigation be instituted with a view of ascertaining the circumstances, and whether the fatality was due to any neglect or misconduct on the part of the service. Any misconduct or incompetency at other times is likewise subject to rigid investigation. The results of the investigations into the circumstances of loss of life are fully set out in the annual reports of the service, which the general superintendent is required to make.

Life savers, disabled in the line of duty, are retained upon the payrolls during the continuance of their disability, not to exceed one54 year, though in certain cases the period may be extended upon recommendation for a greater period, but not more than two years. In case of their death from service or from disease contracted in the line of duty, their widows and children under sixteen years of age are entitled to be paid during a period of two years the same amount that the husband or father would have received.

In addition to saving the lives of the imperiled, an important part of the duty of the life savers is that of saving property. The amount of property saved annually by these guardians of the coast largely exceeds the cost of maintenance of the service. The keepers are authorized and required by law to take charge of and protect all such property until claimed by those legally entitled to receive it, or until otherwise directed by the department as to its disposition. The keepers have the powers of the inspectors of customs and faithfully guard the interests of the government in all dutiable wrecked property.

Doubtless the United States Life-Saving Service system appears to be an expensive and elaborate one, but it must be remembered that, putting aside entirely the consideration of the value of human life, which is beyond computation, it saves many times its cost in property alone, and that it fulfils the functions usually allotted to several different agencies. It rescues the shipwrecked by both the principal methods which humane ingenuity has devised for that55 purpose, and which, in some countries, are practiced separately by two distinct organizations; it furnishes them the subsequent succor which elsewhere would be afforded by shipwrecked mariners’ societies; it guards the lives of persons in peril or of drowning by falling into the water from piers and wharves in the harbors of populous cities, an office usually performed by humane societies; it nightly patrols the dangerous coast for the early discovery of wrecks and the hastening of relief, thus increasing the chances of rescue, and shortening by hours intense physical suffering and the terrible agony of suspense; it places over peculiarly dangerous points upon the rivers and lakes a sentry prepared to send instant relief to those who incautiously or recklessly incur the hazard of capsizing in boats; it conducts to places of safety those imperiled in their homes by the torrents of flood, and conveys food to those imprisoned in their homes by inundation and threatened by famine; it annually saves, unaided, hundreds of stranded vessels, with their cargoes, from total or partial destruction, and assists in saving scores of others; it protects wrecked property after landing from the ravage of the elements and the rapine of plunderers; it extricates vessels unwarily caught in perilous positions; it averts numerous disasters by its flashing signals of warning to vessels standing in danger; it assists the custom service in collecting the revenues of the government; it pickets the coast with a guard, which prevents smuggling, and, in time of war, surprise by hostile56 forces, which makes the service unlike all other organizations established for similar purposes.

The distinction of having founded and created the United States Life-Saving Service having been the subject of much discussion in recent years, General Superintendent Kimball, in his report to the Secretary of the Treasury as to the claims of W. A. Newell, as the originator of the system of the Life-Saving Service of the United States, in conclusion states as follows:—

“The fact is, the credit of originating and developing the United States Life-Saving Service cannot truthfully be awarded to any single individual.

“In Congress and out of Congress many men have contributed, some in a great and some in a less degree to the success of its fortunes. To even write down the names of the legislators in both houses of Congress, who have been its advocates and champions, and to refer ever so briefly to their valuable assistance, would occupy much space and require considerable research, but there occurred to me at once as conspicuous among the host of its promoters, Senators Hannibal H. Hamlin, O. D. Conger, W. E. Kenna, W. J. Sewell, and William P. Frye, and Representatives S. S. Cox, Charles B. Roberts, John Lynch, James W. Cobert, and Jesse J. Yeates. Presidents of the United States and various Secretaries of the Treasury have promoted its welfare. Many officers of the life-saving service also, as well as officers57 detailed to it from the Revenue Cutter Service, have, from time to time, suggested and assisted to carry into effect important improvements.

“The life-saving service was not designed and laid out at one stroke, in a single comprehensive plan, as an architect designs a building, or a military genius, perhaps, devised a scheme of army organization, but its system and development have been accomplished step by step, day teaching unto day the necessity and wisdom of each successive measure of progress.”

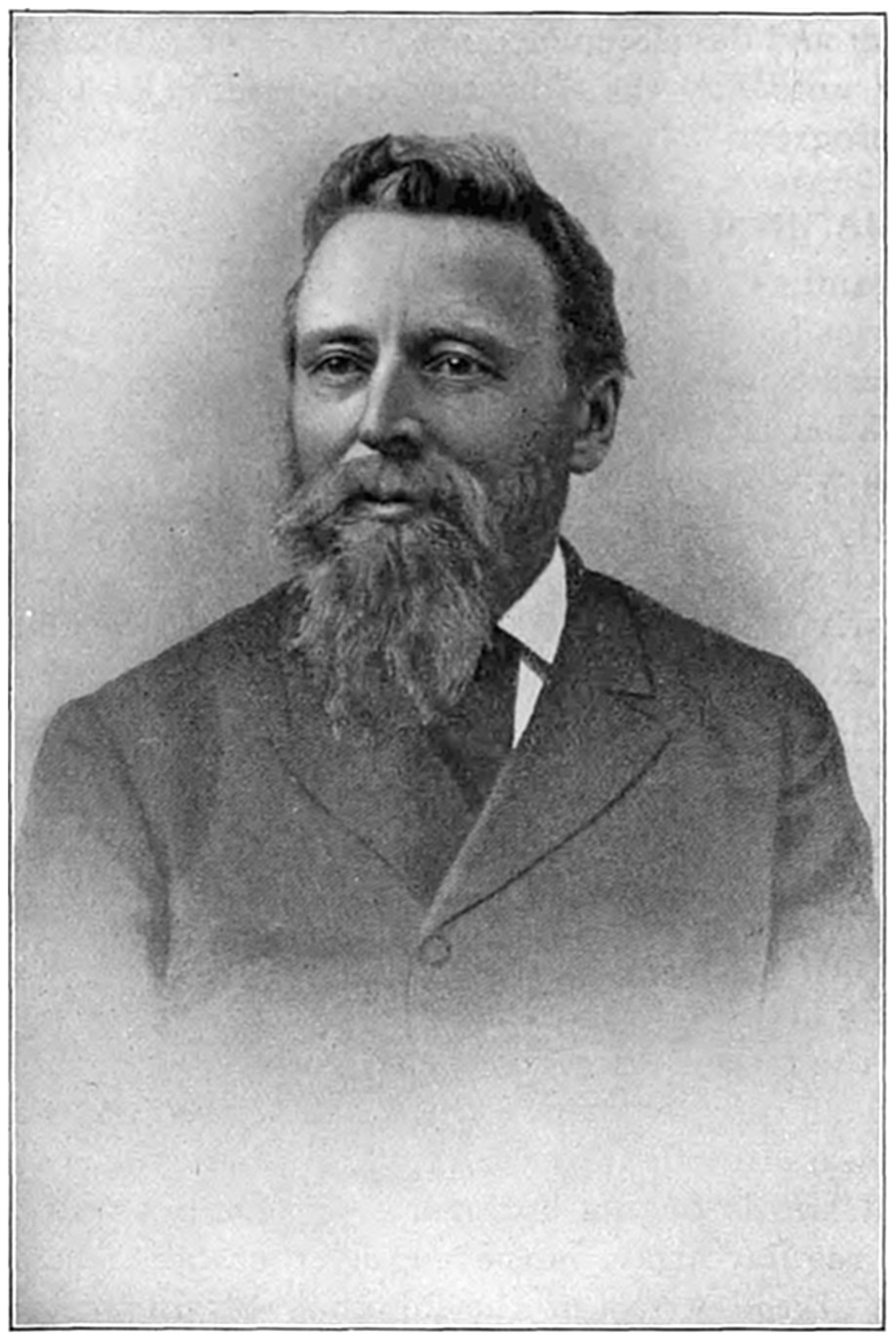

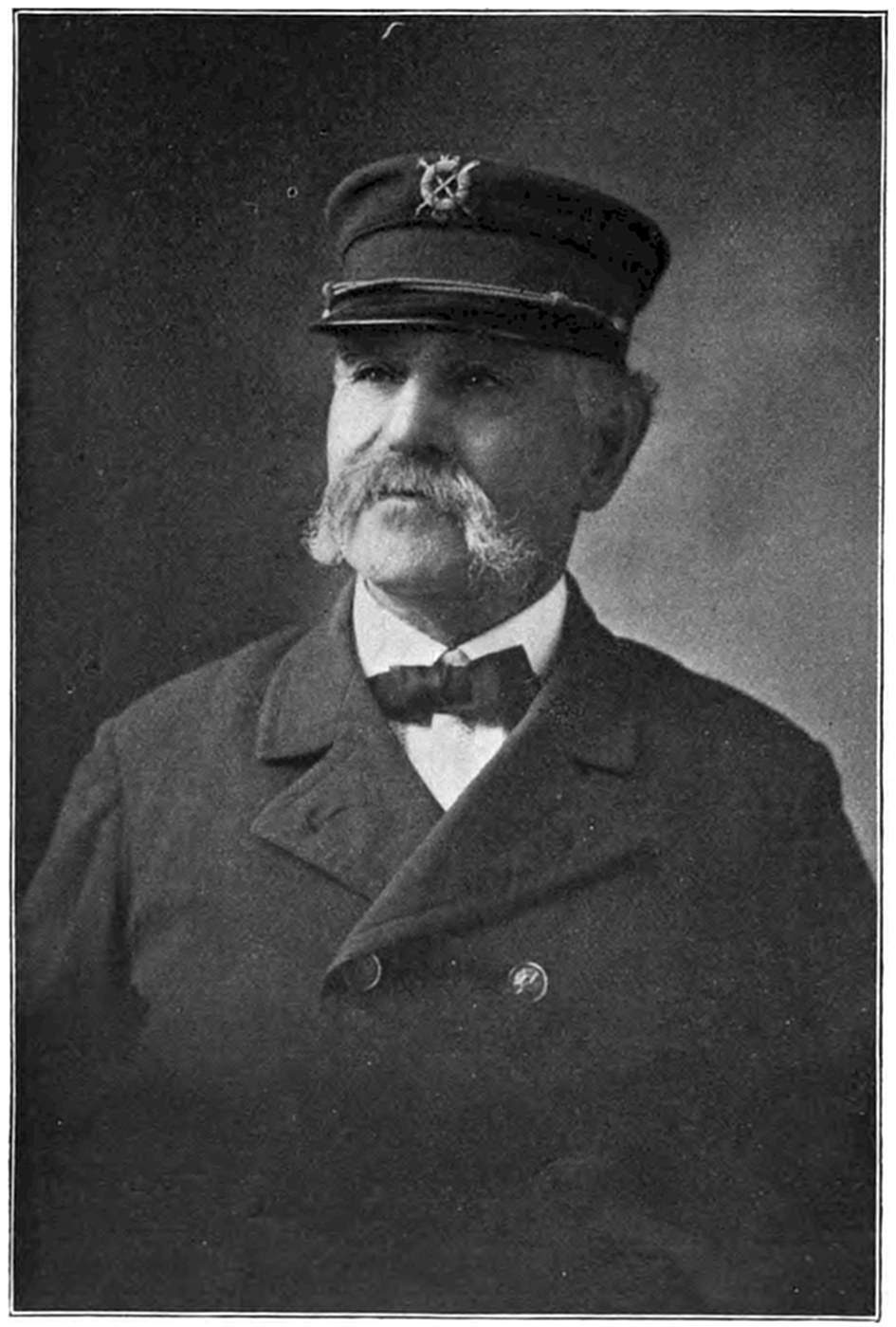

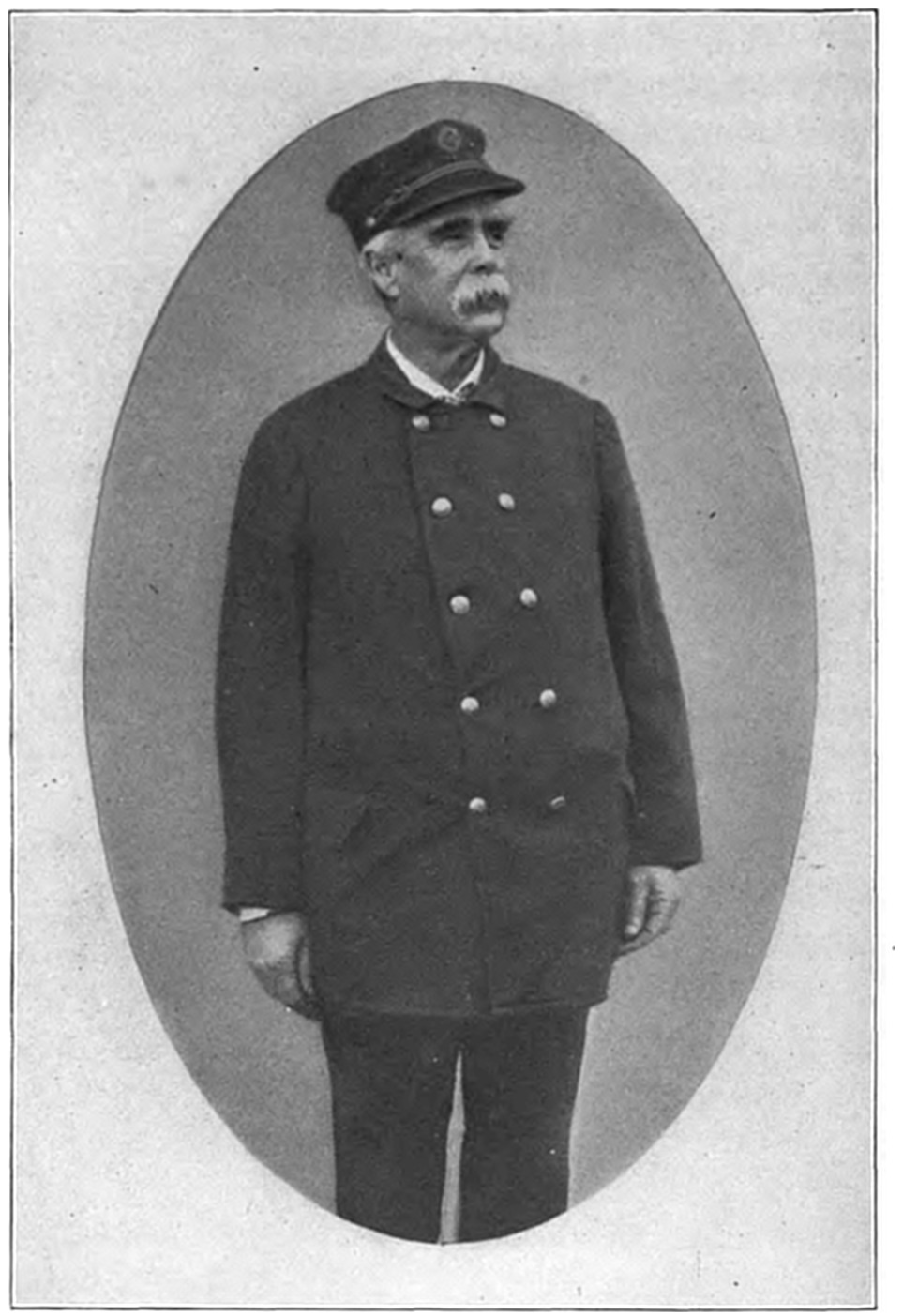

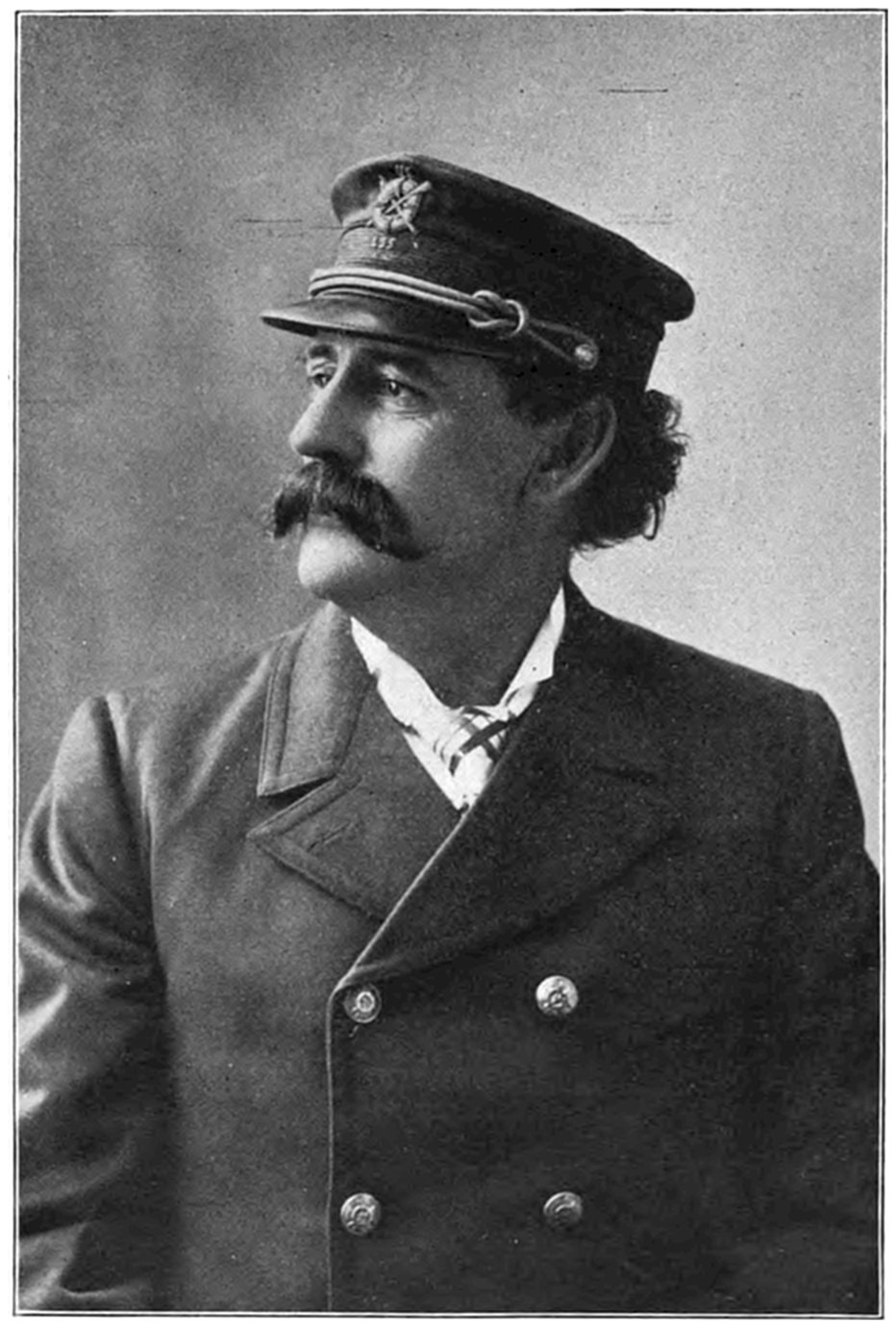

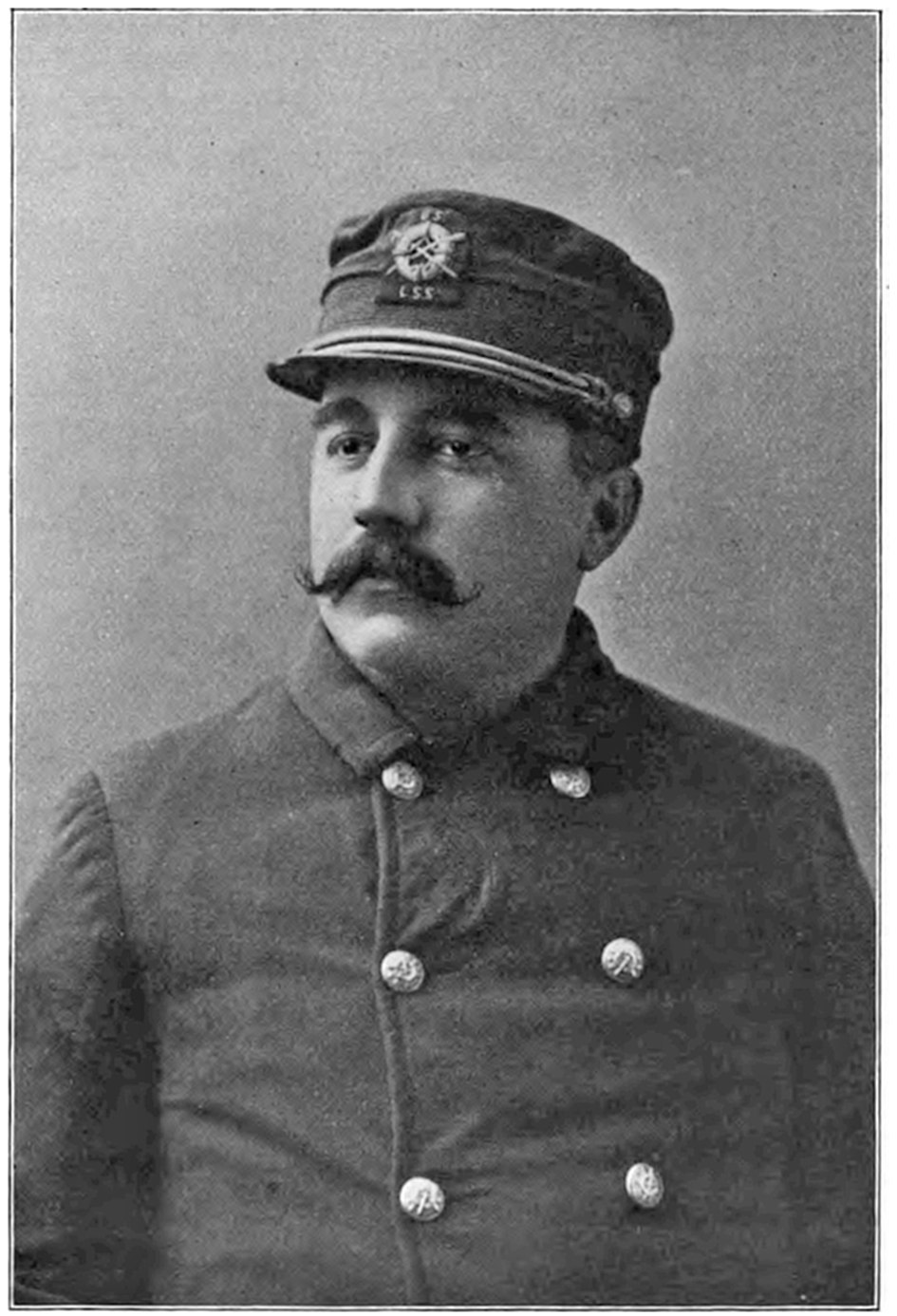

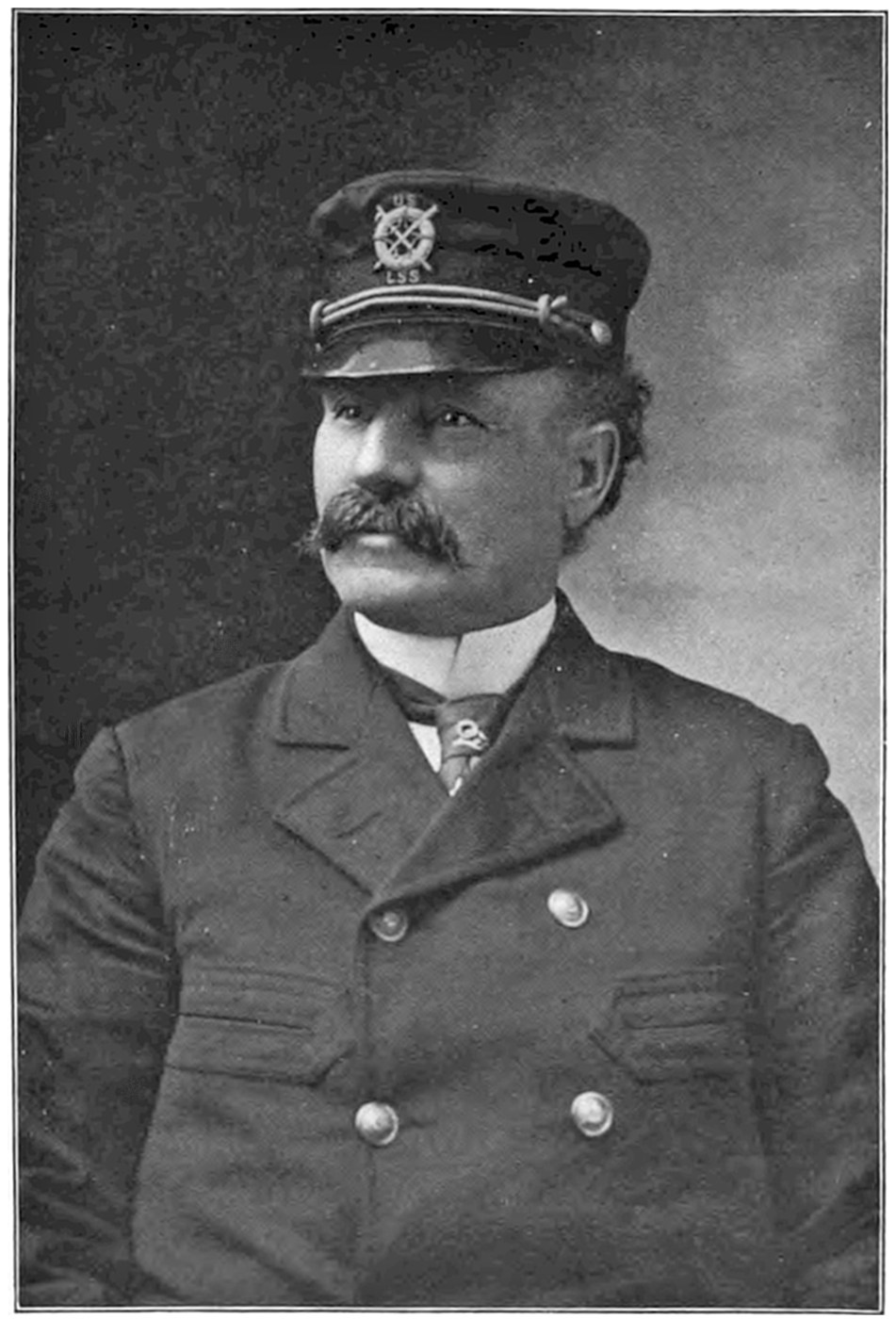

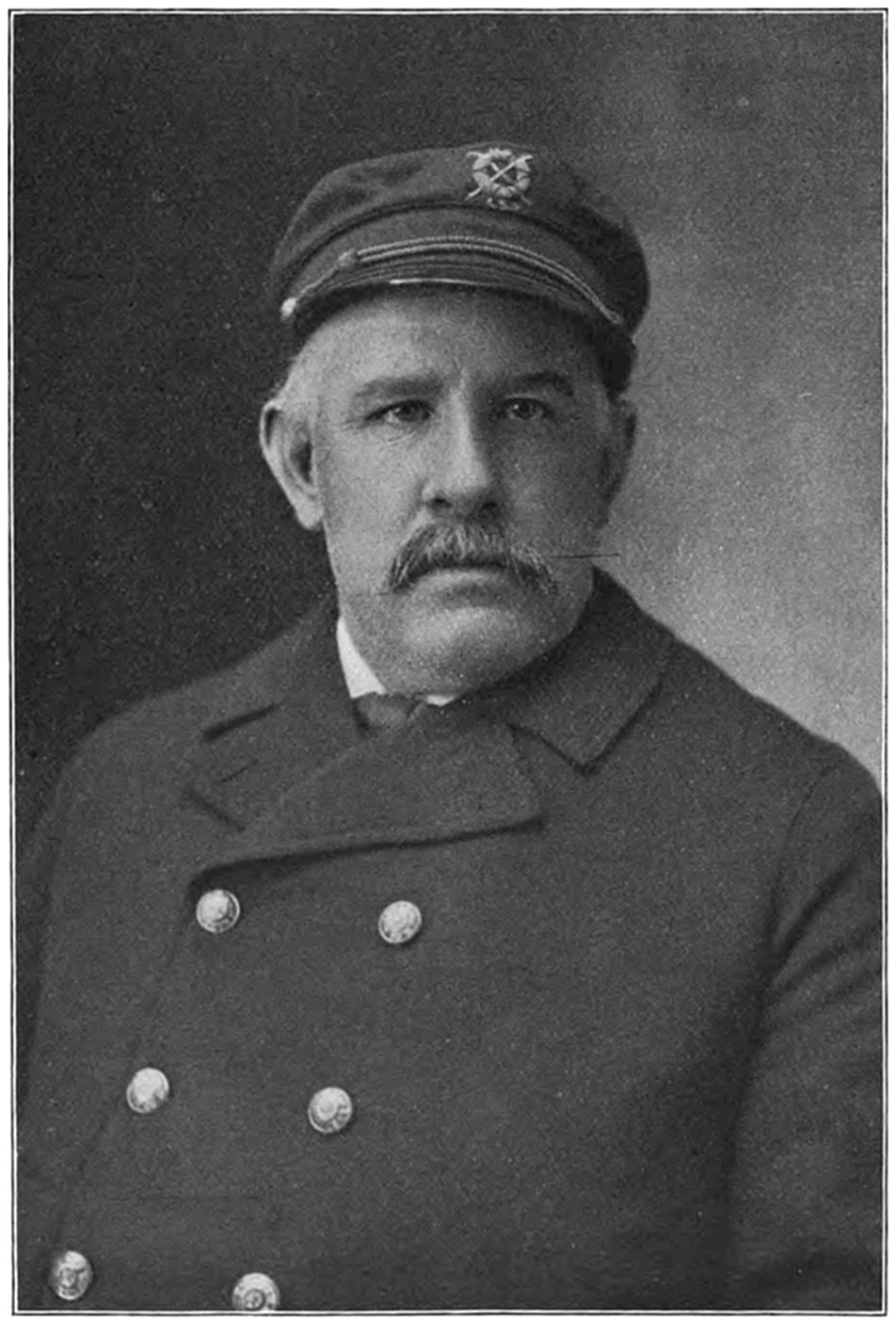

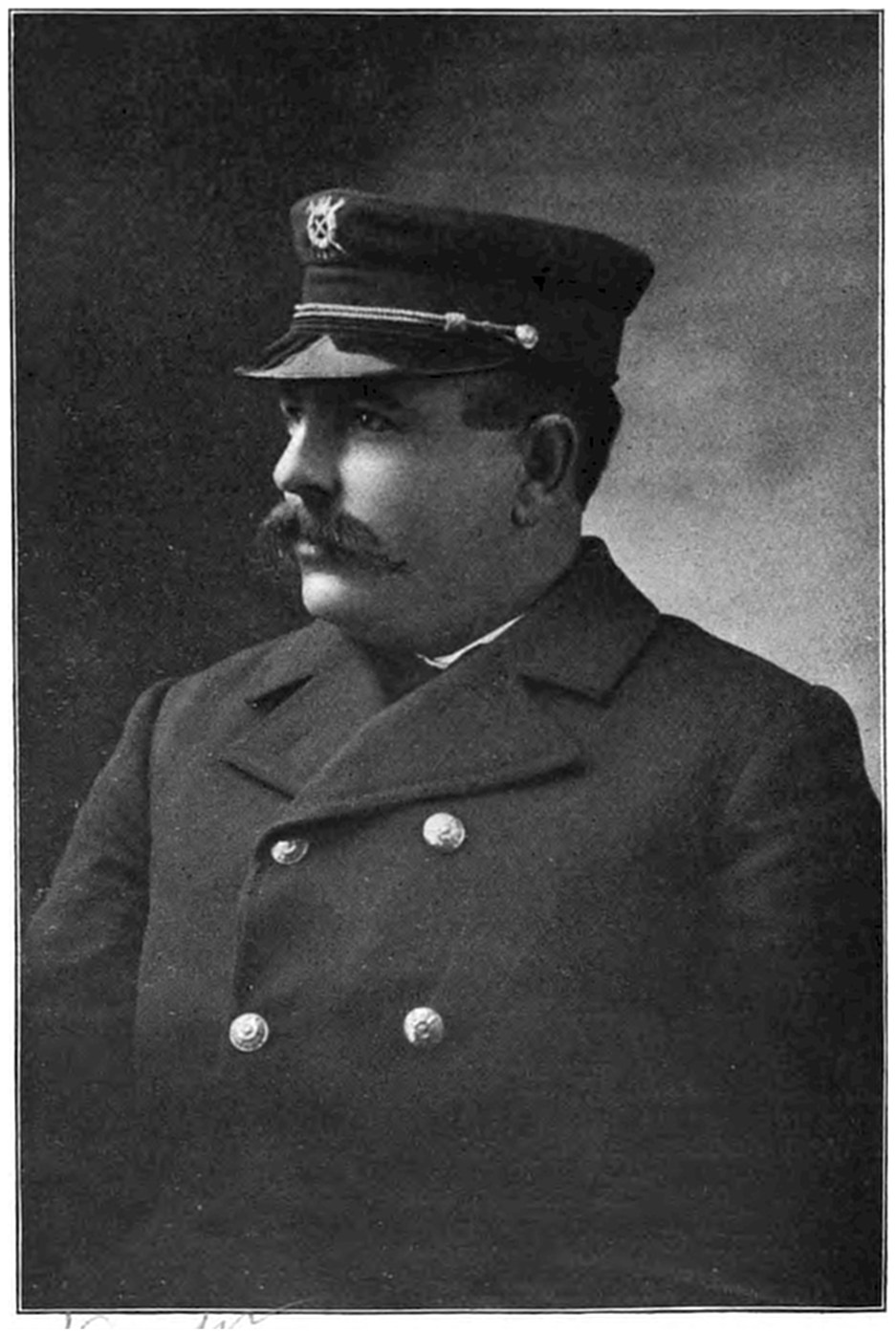

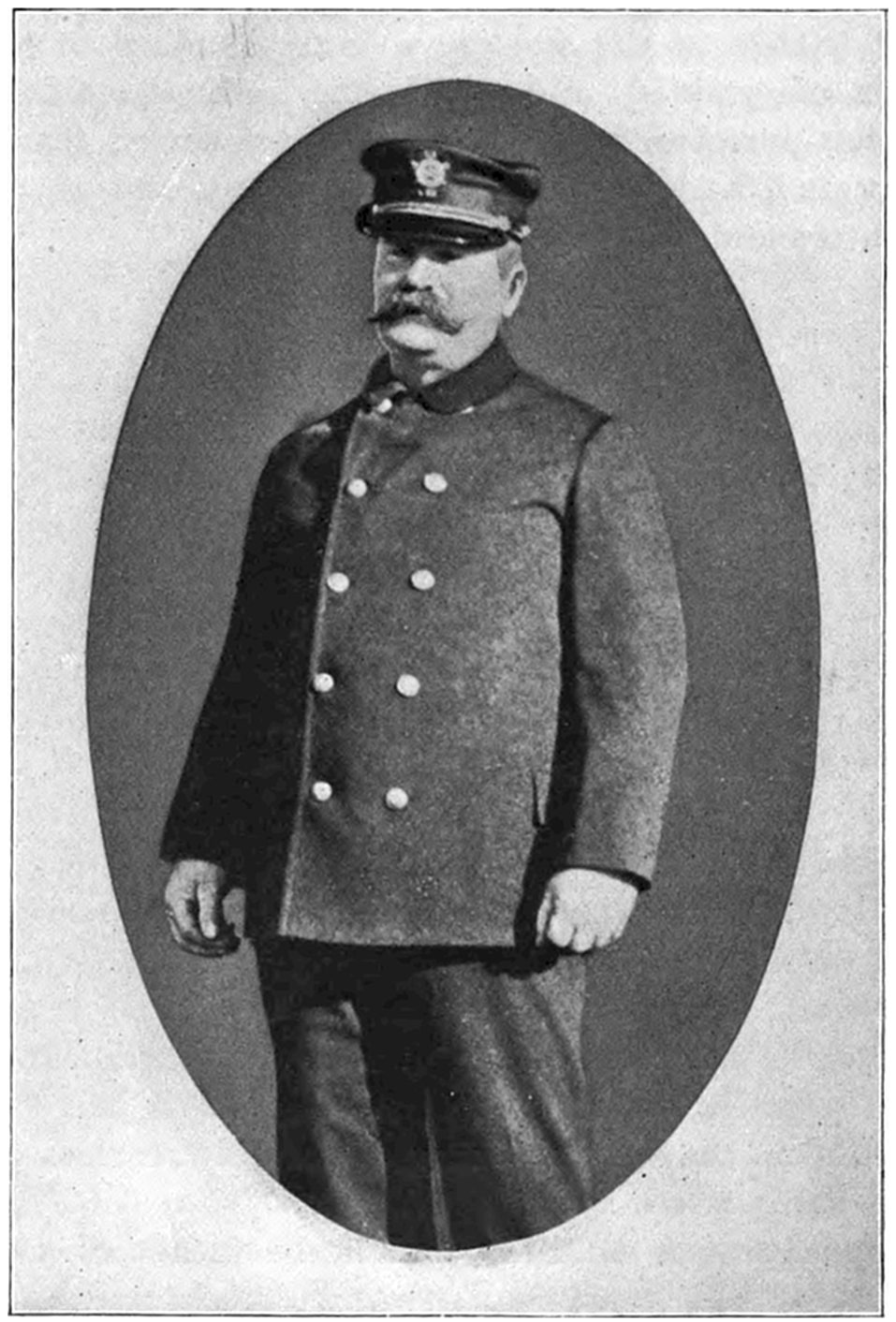

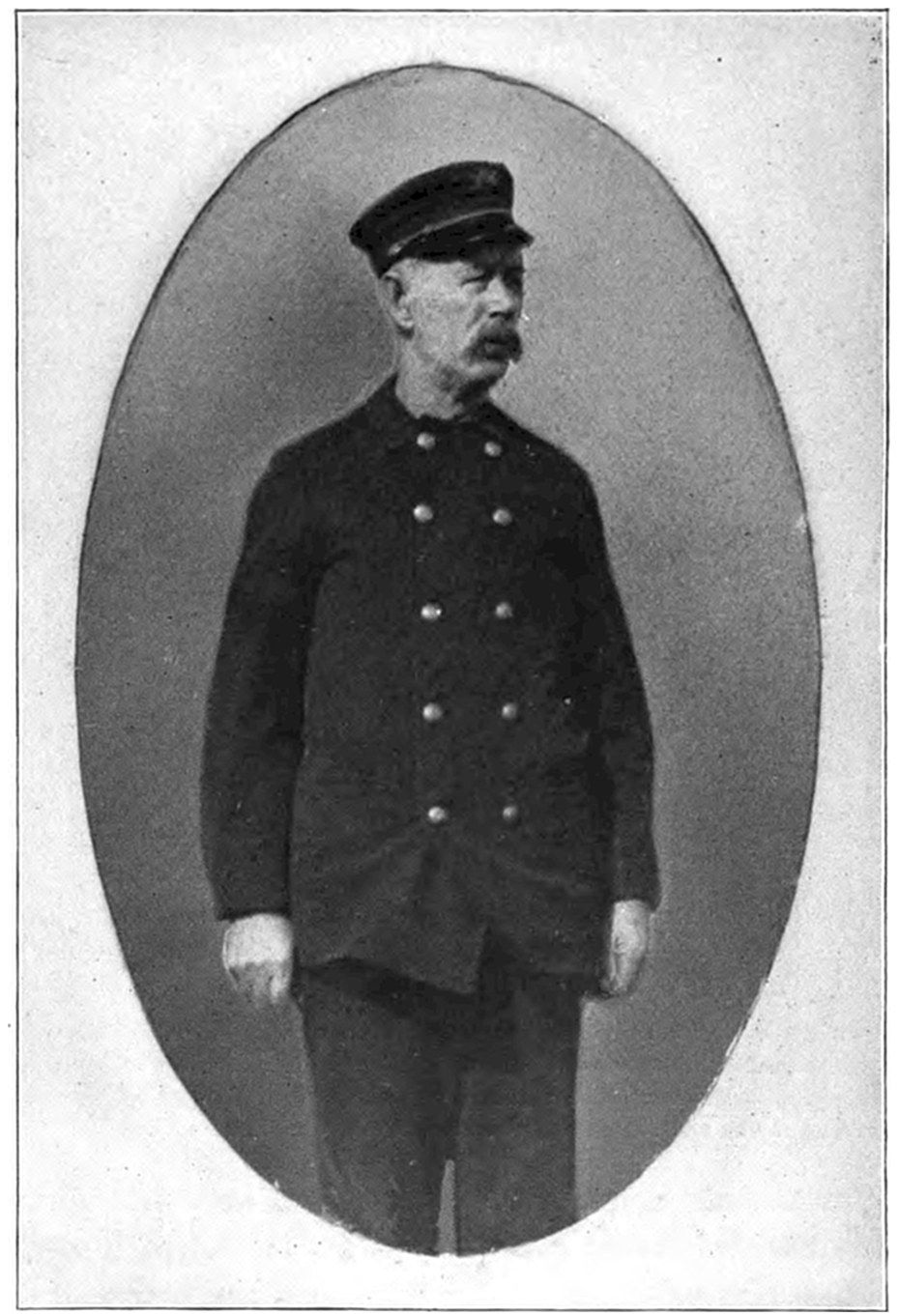

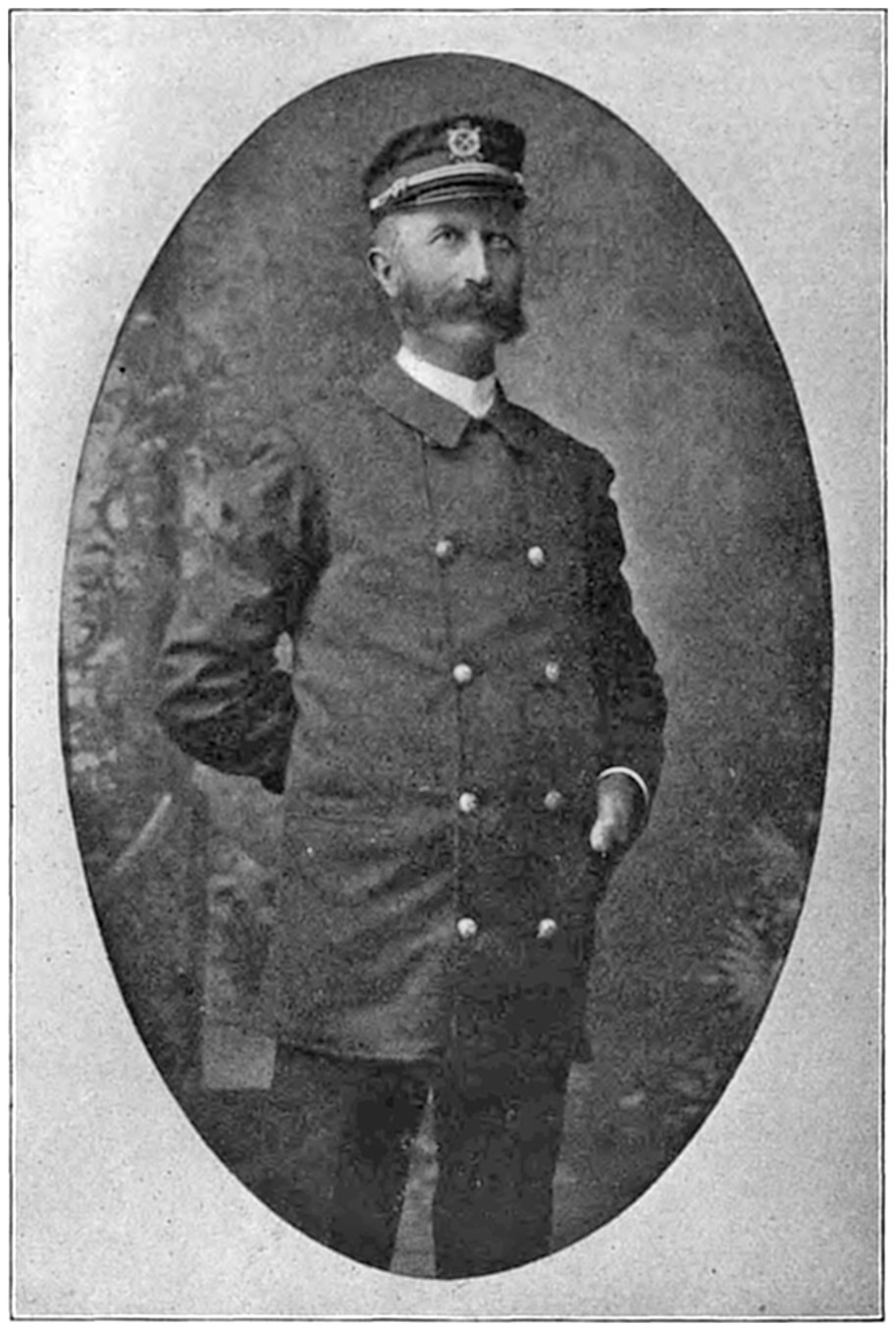

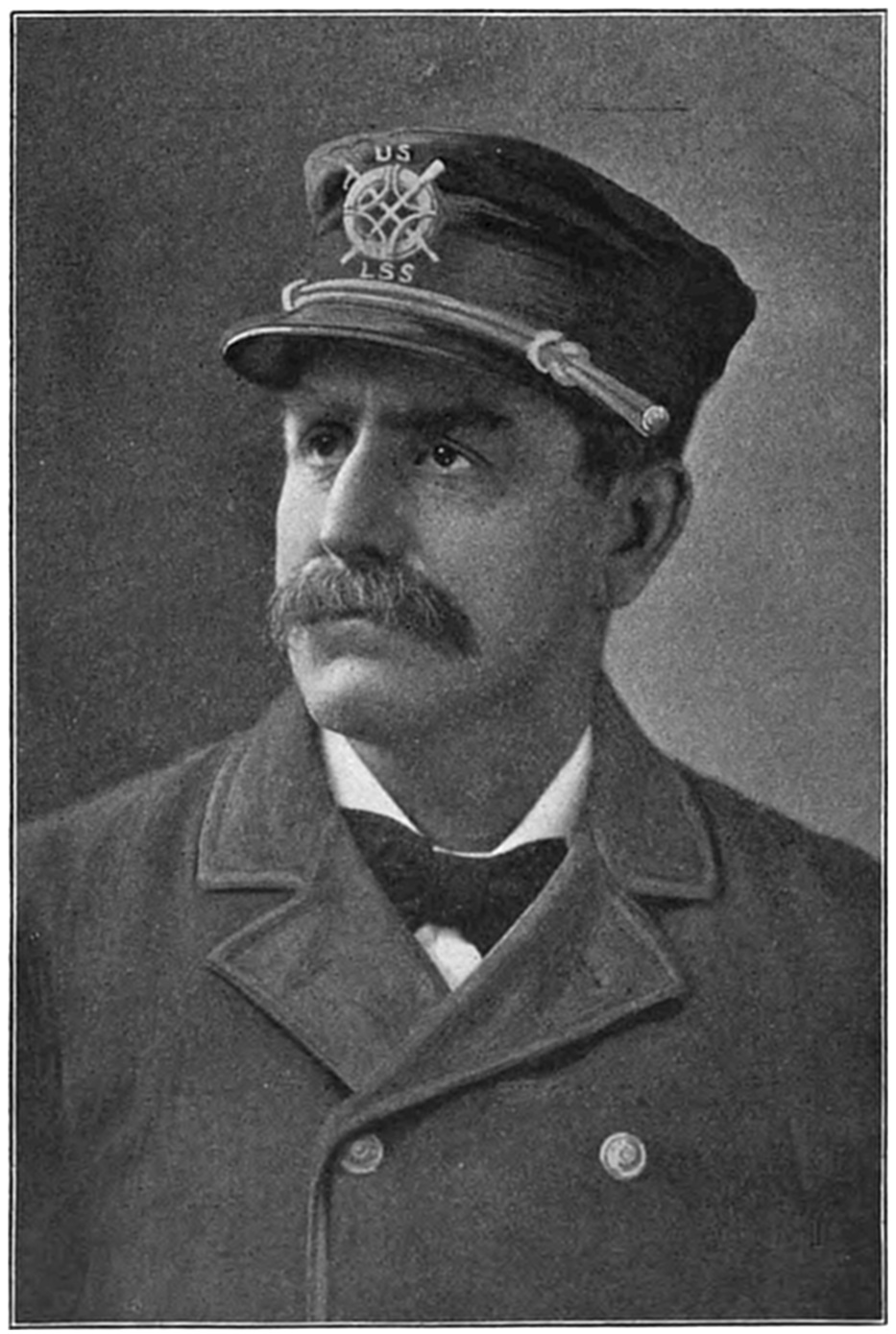

Capt. Benjamin C. Sparrow, superintendent of the second life-saving district, was born in Orleans, Oct. 9, 1839. He is a lineal descendant of Richard Sparrow, who came over in the ship Ann, landing at Plymouth. When a boy he always accompanied his father, a well-known life saver and wrecker, to the shipwrecks that occurred along the coast, and at an early age became familiar with the scenes of disaster from which the shores of Cape Cod have become noted.

In those early days, long before the establishment of United States life-saving stations on Cape Cod, volunteer crews responded to the calls for assistance when there was a wreck along the coast. There were others who engaged in the work of saving lives and of wrecking, or assisting distressed vessels, and they were known as “beach combers.”

Captain Sparrow was a “beach comber” for many years, and relates thrilling and interesting incidents that occurred during his experience. After finishing his education in the public schools of his native town, he taught in the public schools in the adjoining town of Eastham.

He entered Phillips Academy to prepare himself for the legal profession, and was a student there at the outbreak of the Civil War. The war had hardly begun, however, before he left college, and enlisted in the regular army, in the engineer battalion attached to the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, serving in this capacity until 1864. During his term of service he endured much hardship, being a prisoner at Belle Isle in the summer of 1862.

At the close of the war he returned to his home in East Orleans, where he has since resided. On Dec. 25, 1866, he married Miss Eunice S. Felton, of Shutesbury, Mass.

He has been connected with the United States Life-Saving Service for thirty years, or since the time of its reorganization, his appointment as district superintendent being a part of the plan adopted by the government to stamp out the evils which existed in the service at the time.

Captain Sparrow in the thirty years in which he has been superintendent58 of the second district has been actively engaged in the arduous duties of his calling, and to his efforts is due the success in securing the discipline and efficiency in this hazardous service in the district under his charge.

His home is connected by telephone with all the stations along the shores of the Cape, and the moment a wreck is reported to him he is away to the scene.

Ofttimes he has been obliged to travel many miles on foot in the teeth of a raging gale and driving storm to reach the scene of a disaster, yet he has attended nearly every wreck that has taken place along the shores of Cape Cod during the past thirty years.

The veteran captain has often shared the hardships and braved the perils with the life savers in their work along the beaches, and the59 hardships of thirty years have left their deep imprint upon him. The night that the schooner Calvin B. Orcutt was wrecked on Chatham bars, Captain Sparrow suffered such hardship going to the scene that his eyesight has since been seriously impaired.

The life-saving department recognized Captain Sparrow’s ability from the first by appointing him on the board of experts to examine new appliances and methods proposed for use by the department.

This position he has filled with great credit to himself and to the betterment of the department to the present.

Captain Sparrow has always taken an active interest in the affairs of his town, and his fellow-citizens have honored him from time to time with public offices within their gift. To the life savers of Cape Cod Captain Sparrow has ever been a staunch friend.

This station derives its name from the Highlands of Cape Cod which are in the immediate vicinity, and is one of the original nine stations built on Cape Cod in 1872. It is seven-eighths of a mile west of Cape Cod Highland Light, and about one and one-half miles from the North Truro village.