THE ANCIENT WORLD

The Project Gutenberg eBook of A history of commerce, by Olive Day

Title: A history of commerce

Author: Olive Day

Release Date: March 30, 2023 [eBook #70410]

Language: English

Produced by: Turgut Dincer, Brian Wilcox and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BY

CLIVE DAY, Ph.D.

KNOX PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL ECONOMY IN YALE UNIVERSITY

REVISED AND ENLARGED

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

55 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

TORONTO, BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS

1925

Copyright, 1907, by

Longmans, Green, and Co.

Copyright, 1914, by

Longmans, Green, and Co.

Copyright, 1922, by

Longmans, Green, and Co.

First Edition, May, 1907

Reprinted, April, 1908; June, 1909; August, 1910

August, 1912

New Edition, June, 1914

Reprinted, February, 1916; April, 1917

August, 1919

September, 1920

August, 1921

New Edition thoroughly revised, September, 1922

Reprinted, February, 1923; January, 1924,

May, 1925

MADE IN THE UNITED STATES

To

E. L. D.

The year 1914 marks one of the great turning points in history. I have accordingly revised the part of this book covering the recent period to close the narrative at that date, and have added another part, covering the history of commerce in the war and in the two or three years of peace immediately following. The commerce of the great nations of the world has departed since 1914 far from its accustomed paths and forms. In my attempt to make intelligible the commercial changes of the time I have had to take account of matters in public finance, currency and foreign exchange which are usually treated apart from the history of international trade. I have thought it better, by touching on these outside subjects, to show the reasons for the course which commerce has followed, rather than to omit the reasons because they are hard for the student of the history of commerce to understand.

Clive Day

v

| PART I | ||

|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT COMMERCE | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | General Conditions | 1 |

| II. | Oriental Period | 9 |

| III. | Greek Period | 17 |

| IV. | Roman Period | 26 |

| PART II | ||

| MEDIEVAL COMMERCE | ||

| V. | Conditions about the Year 1000 | 31 |

| VI. | Town Trade | 41 |

| VII. | Land Trade | 54 |

| VIII. | Fairs | 63 |

| IX. | Sea Trade | 70 |

| X. | The Levant Trade | 79 |

| XI. | Commerce of Southern Europe | 90 |

| XII. | Commerce of Northern Europe | 102 |

| XIII. | Development of the Medieval Organization of Commerce | 113 |

| XIV. | Commerce and Politics in the Later Middle Ages | 123 |

| PART III | ||

| MODERN COMMERCE | ||

| XV. | Exploration and Discovery | 128 |

| XVI. | Development of the Economic Organization | 139 |

| XVII. | Credit and Crises | 150 |

| XVIII. | The Modern State and the Mercantile System | 161 |

| XIX. | Spain and Portugal | 174 |

| XX. | The Netherlands | 190vi |

| XXI. | England: Survey of Commercial Development | 199 |

| XXII. | England: Exports | 209 |

| XXIII. | England: Imports; Shipping; Policy | 219 |

| XXIV. | France: Survey of Commercial Development | 229 |

| XXV. | France: Policy | 242 |

| XXVI. | The German States | 250 |

| XXVII. | Italy and Minor States | 263 |

| PART IV | ||

| RECENT COMMERCE | ||

| XXVIII. | Commerce and Coal | 270 |

| XXIX. | Machinery and Manufactures | 280 |

| XXX. | Roads and Railroads | 290 |

| XXXI. | Means of Navigation and Communication | 302 |

| XXXII. | The Wares of Commerce | 317 |

| XXXIII. | The Modern Organization | 329 |

| XXXIV. | Commercial Policy | 345 |

| XXXV. | England: Commercial Development, 1800-1850 | 357 |

| XXXVI. | England: Reform of Commercial Policy | 368 |

| XXXVII. | England: Commercial Development, 1850-1914 | 376 |

| XXXVIII. | England: Pre-War Problems | 386 |

| XXXIX. | German States | 400 |

| XL. | Germany Under the Empire | 408 |

| XLI. | France | 422 |

| XLII. | Minor States of Central and Northern Europe | 431 |

| XLIII. | States of Southern Europe | 442 |

| XLIV. | Eastern Europe | 454 |

| PART V | ||

| UNITED STATES | ||

| XLV. | Organization of Production, 1789 | 469 |

| XLVI. | Internal Trade and Foreign Commerce, 1789 | 485 |

| XLVII. | Commerce and Policy, 1789-1815 | 498 |

| XLVIII. | National Expansion, 1815-1860 | 511 |

| XLIX. | Exports, 1815-1860 | 530 |

| L. | Imports, Policy, Direction of Commerce, 1815-1860 | 540 |

| LI. | National Development, 1860-1914 | 552 |

| LII. | Exports, 1860-1914 | 566 |

| LIII. | Imports, Policy, Direction of Commerce, 1860-1914 | 578 |

| PART VIvii | ||

| WORLD WAR | ||

| LIV. | Commerce and the World War, 1914-1918 | 593 |

| LV. | United Kingdom, 1914-1920 | 607 |

| LVI. | France and the Problem of Reparations | 622 |

| LVII. | Central and Eastern Europe, 1914-1920 | 634 |

| LVIII. | United States, 1914-1920 | 648 |

| Index | 671 | |

ix

| LIST OF MAPS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NO. | PAGE | ||

| 1. | The Ancient World (colored) |

Facing | 9 |

| 2. | Roman Roads in Southern Britain |

28 | |

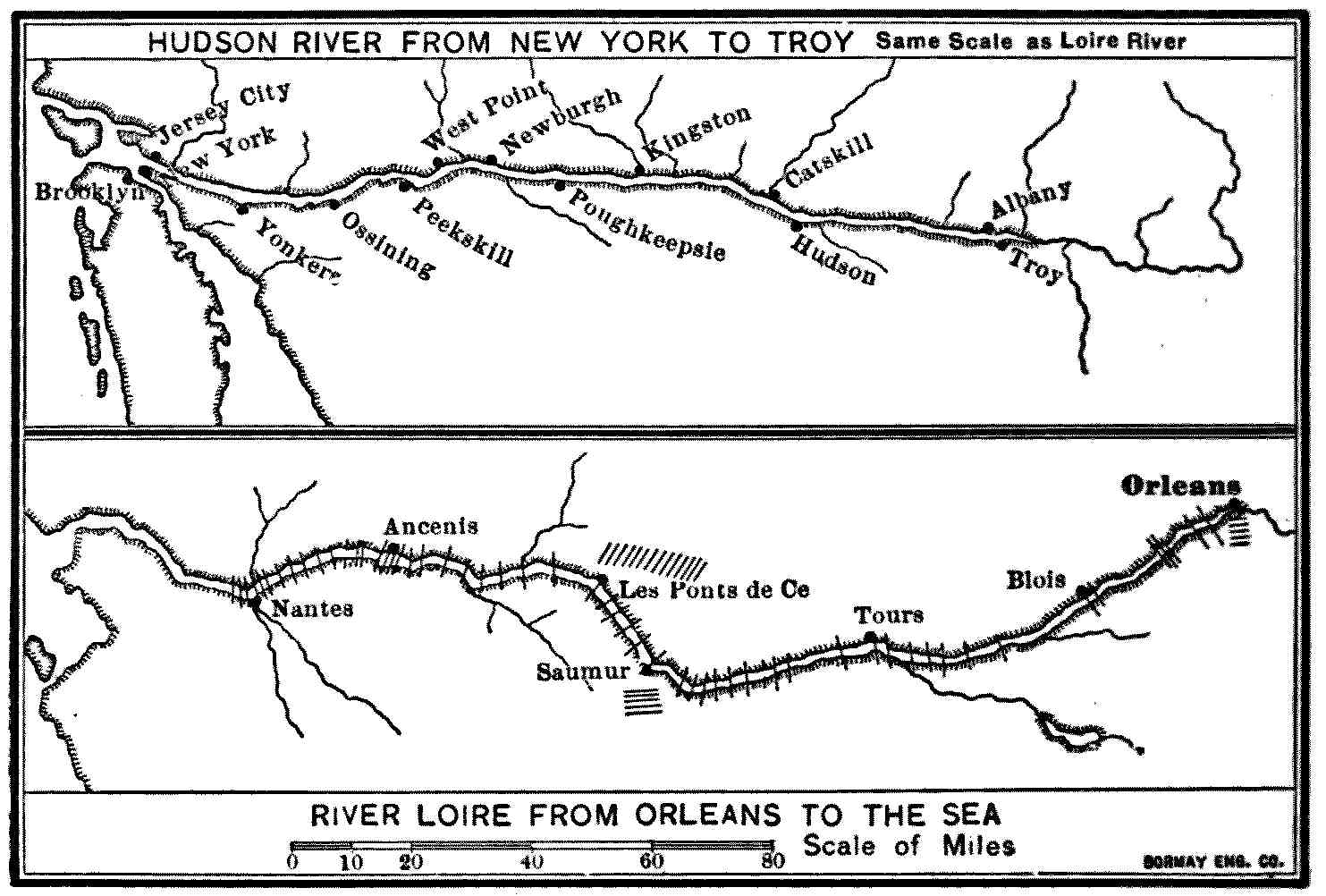

| 3. | Tolls on the River Loire |

58 | |

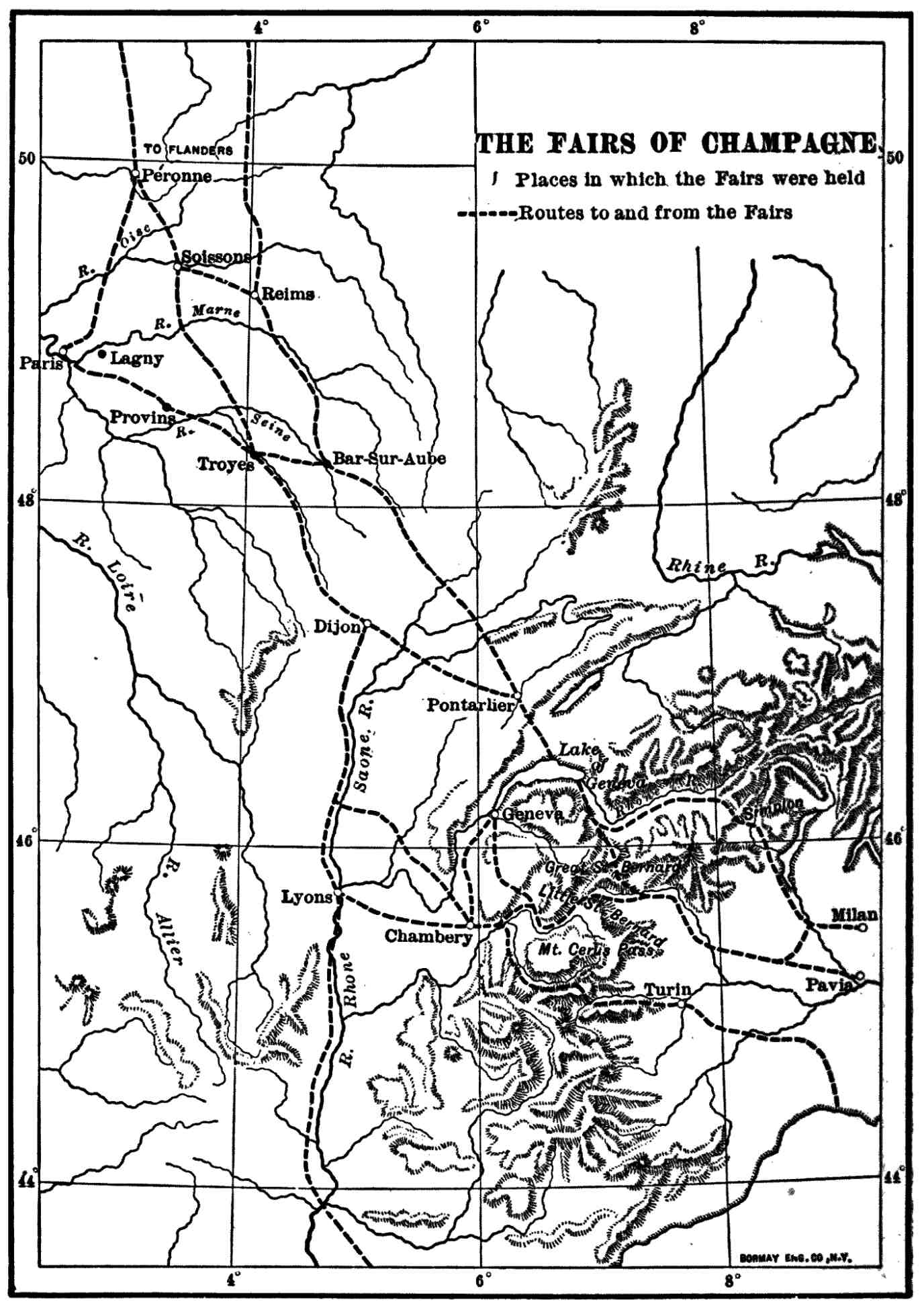

| 4. | The Fairs of Champagne |

66 | |

| 5. | Trade Routes between Asia and Europe |

85 | |

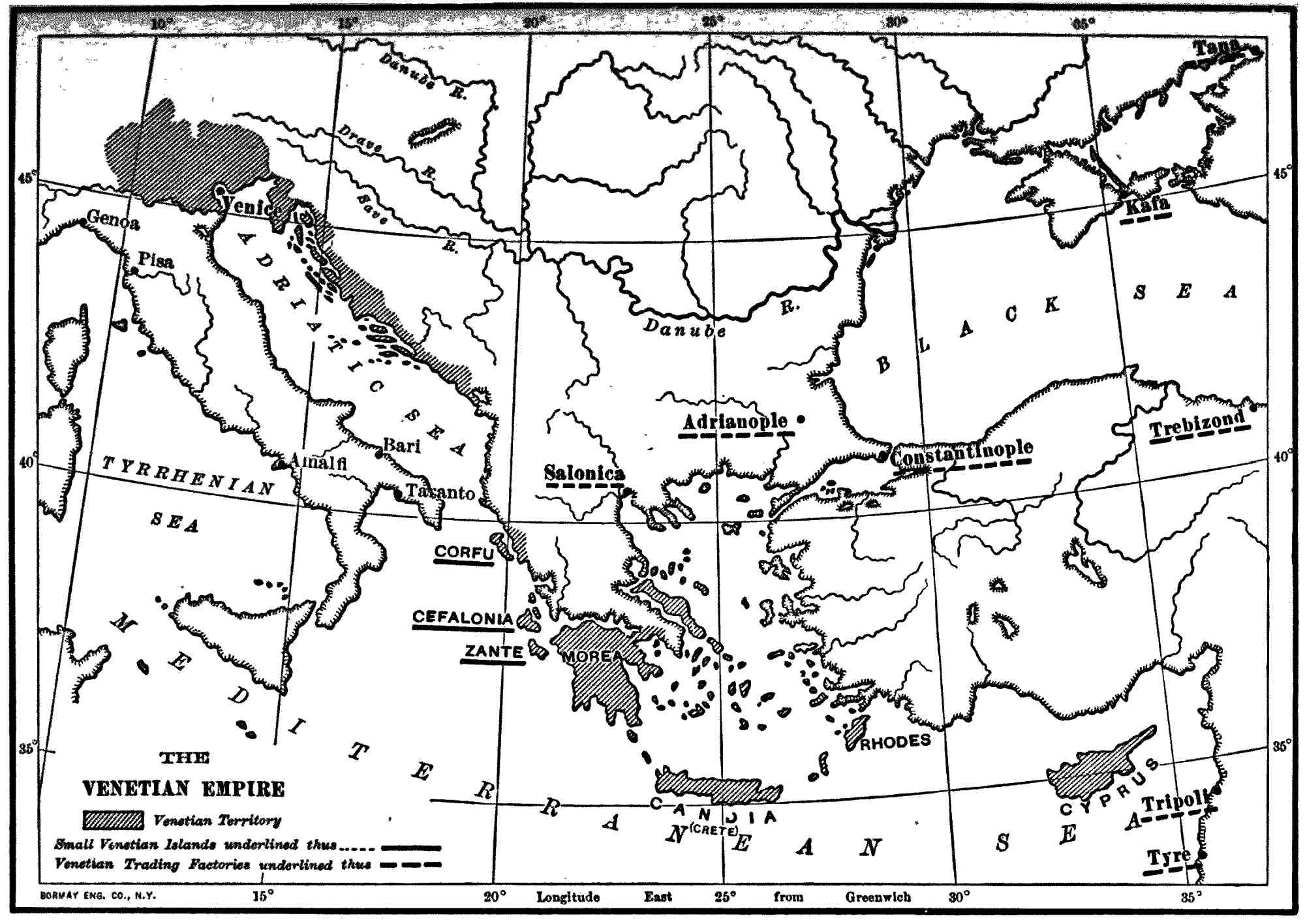

| 6. | The Venetian Empire |

91 | |

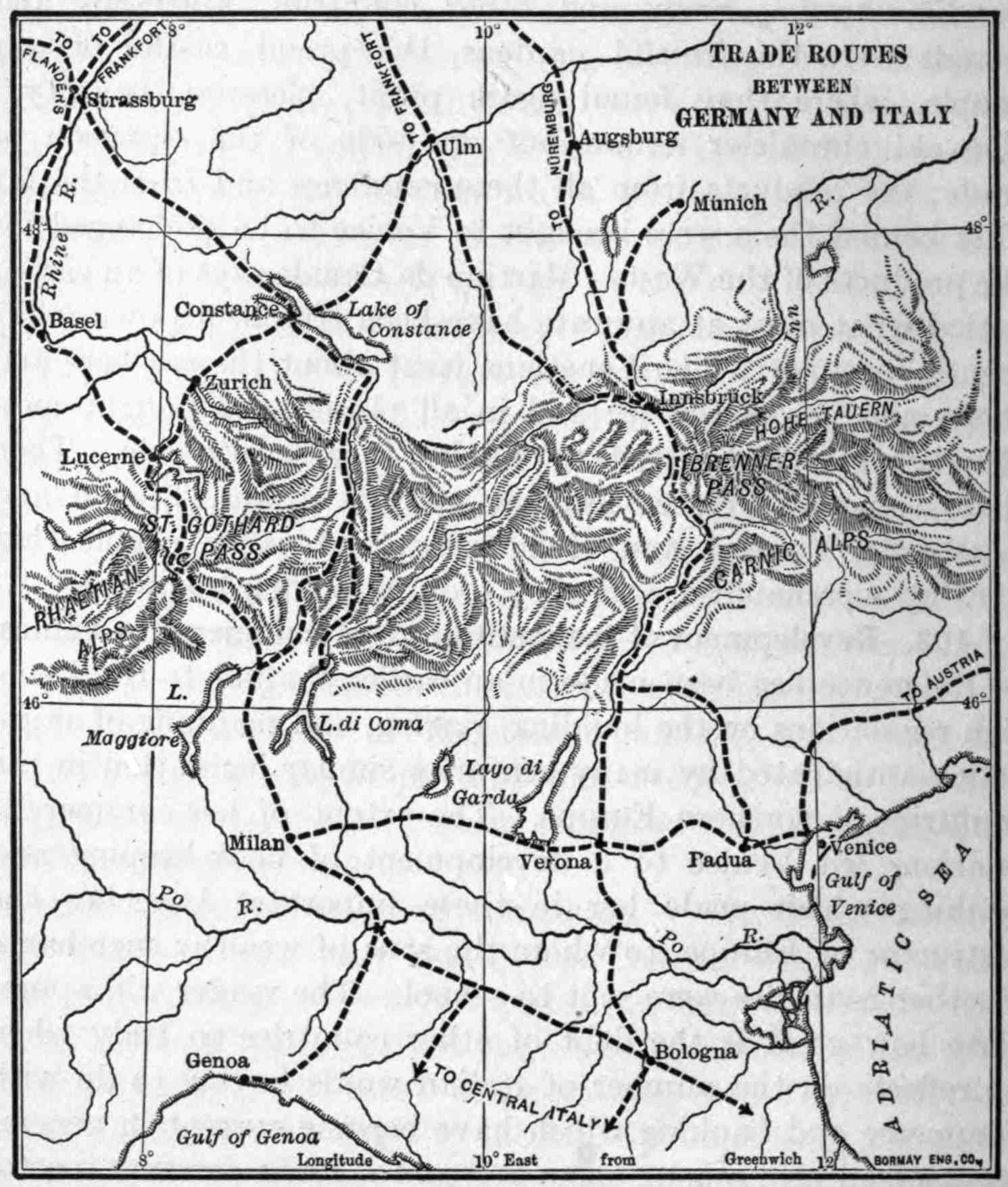

| 7. | Trade Routes between Germany and Italy |

94 | |

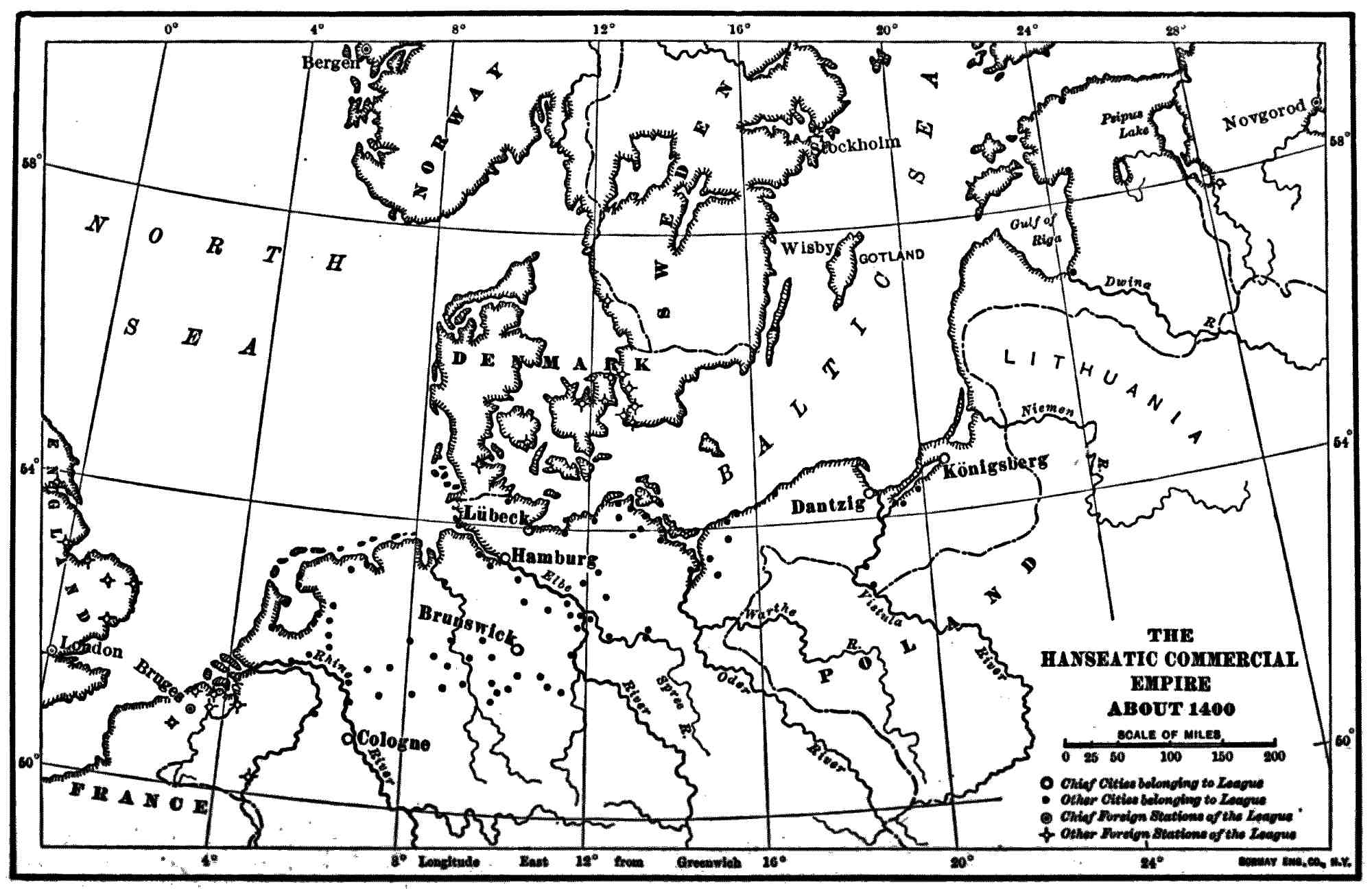

| 8. | The Hanseatic Commercial Empire about 1400 |

106 | |

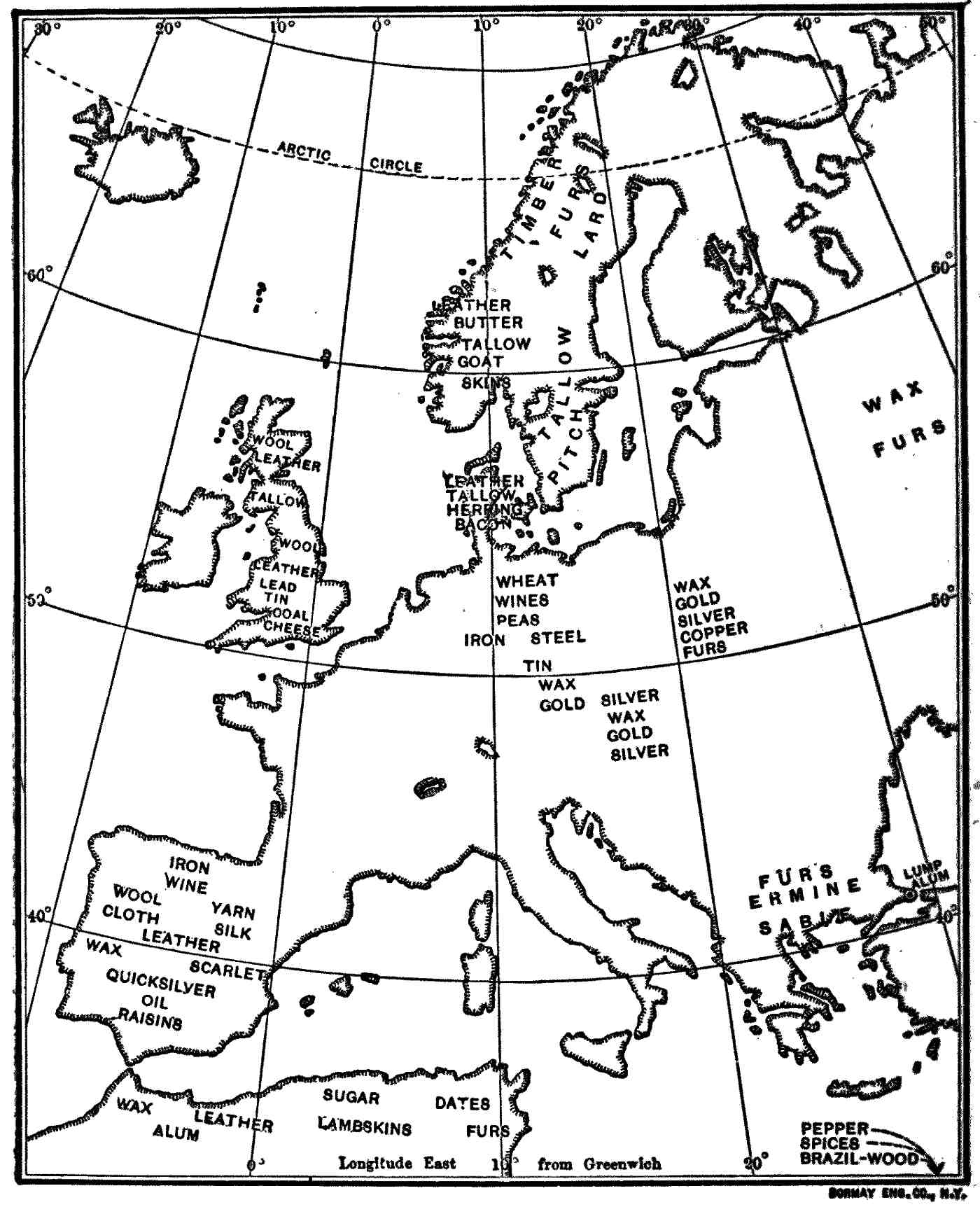

| 9. | Commercial Geography of Europe about 1250 |

108 | |

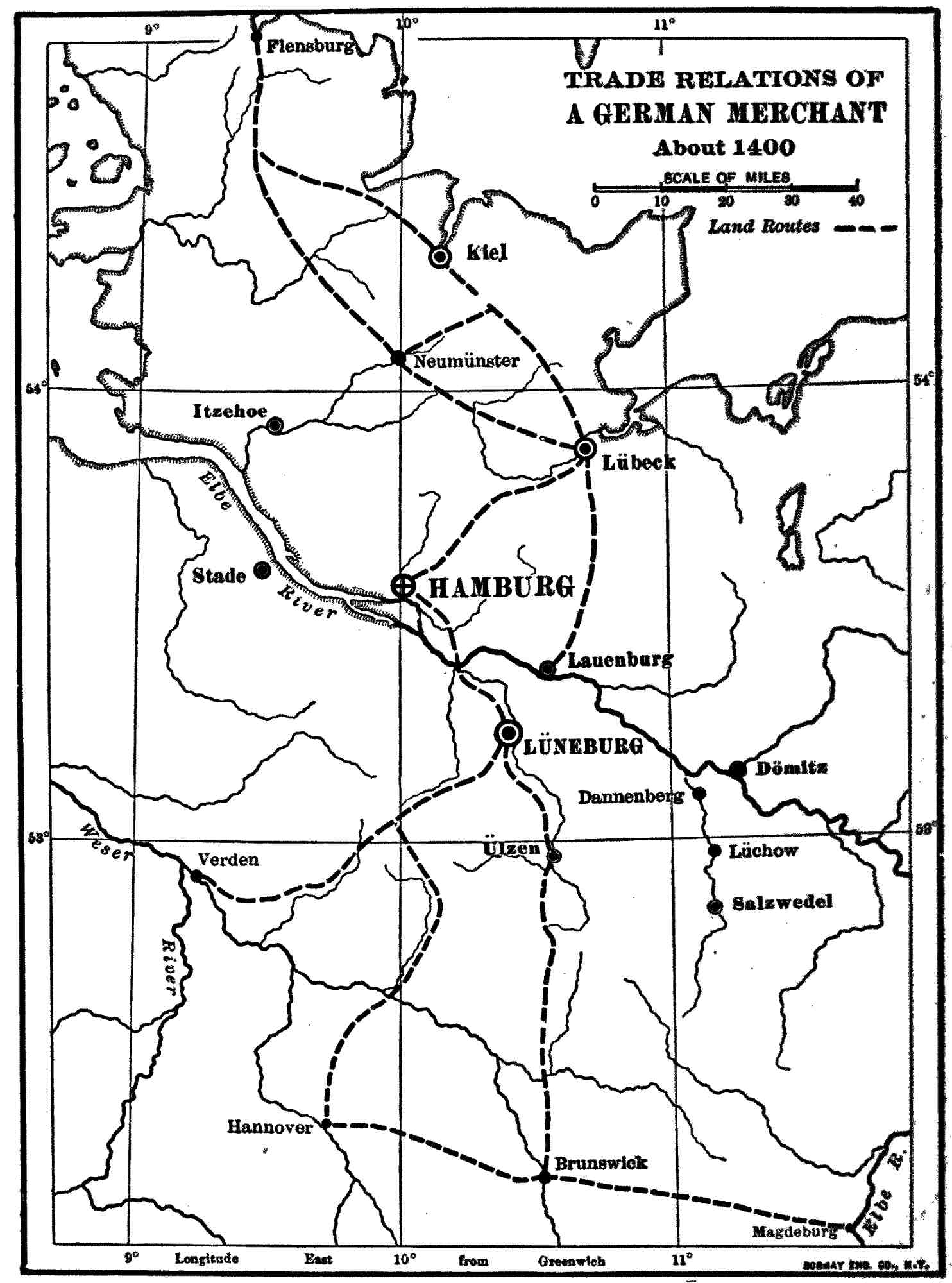

| 10. | Trade Relations of a German Merchant about 1400 |

114 | |

| 11. | A Medieval Map of the World The Laurentian Portolano of 1351. Reproduced by permission from Beazley’s “Prince Henry, the Navigator,” (Putnams). |

Facing | 129 |

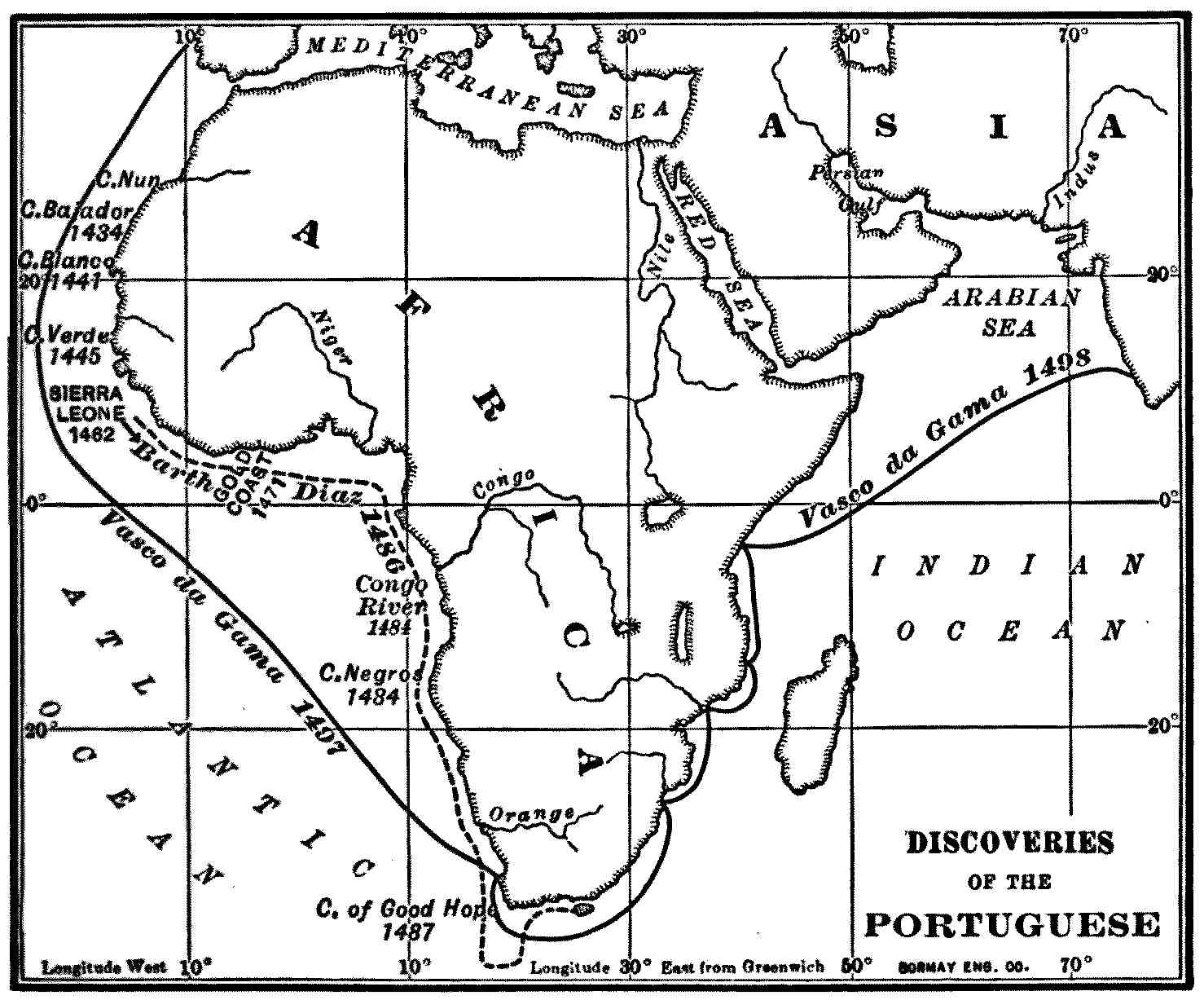

| 12. | Discoveries of the Portuguese |

131 | |

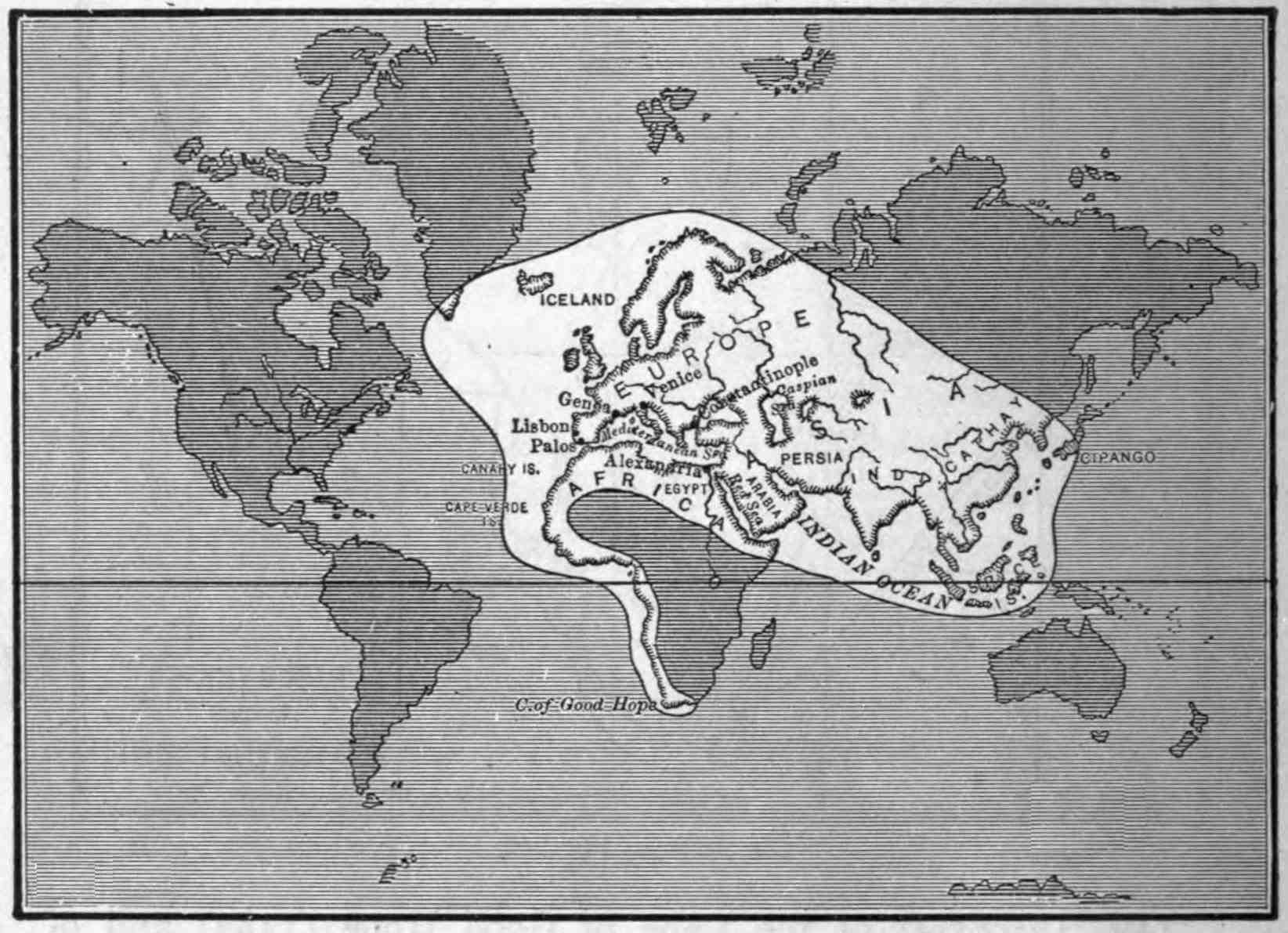

| 13. | Map of the Known World in the Time of Columbus |

132 | |

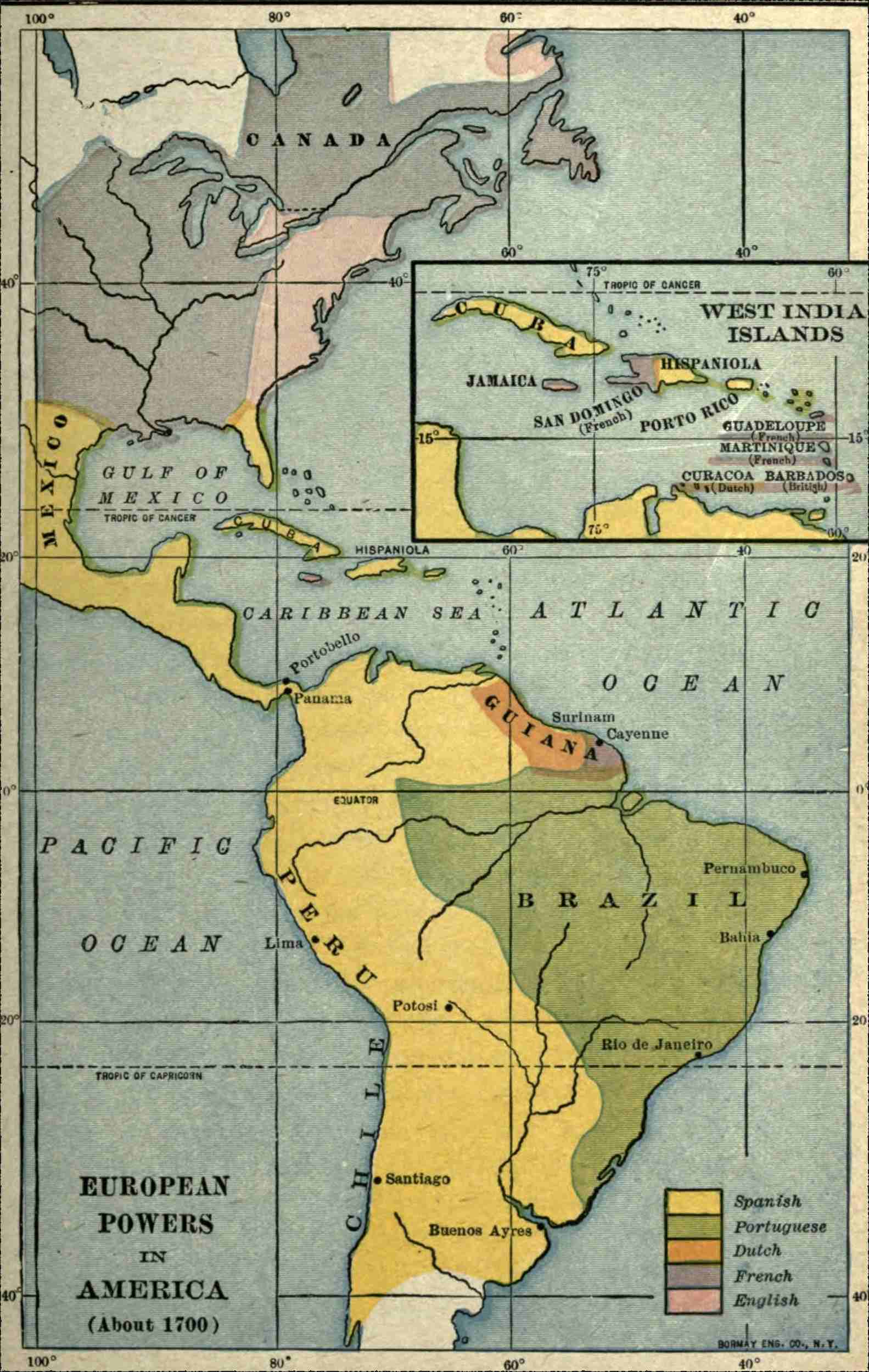

| 14. | European Powers in America (colored) |

Facing | 166 |

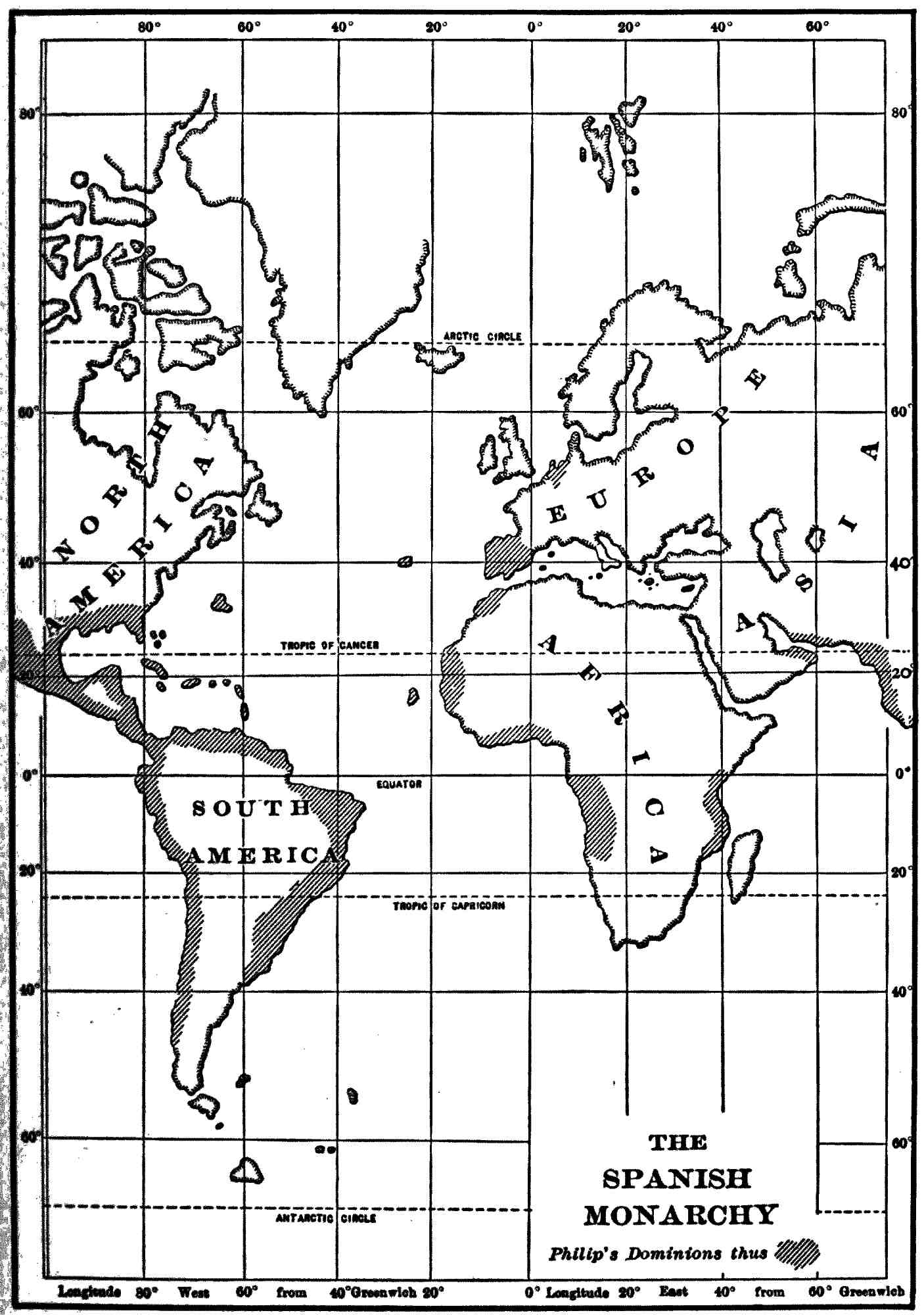

| 15. | The Spanish Monarchy |

175 | |

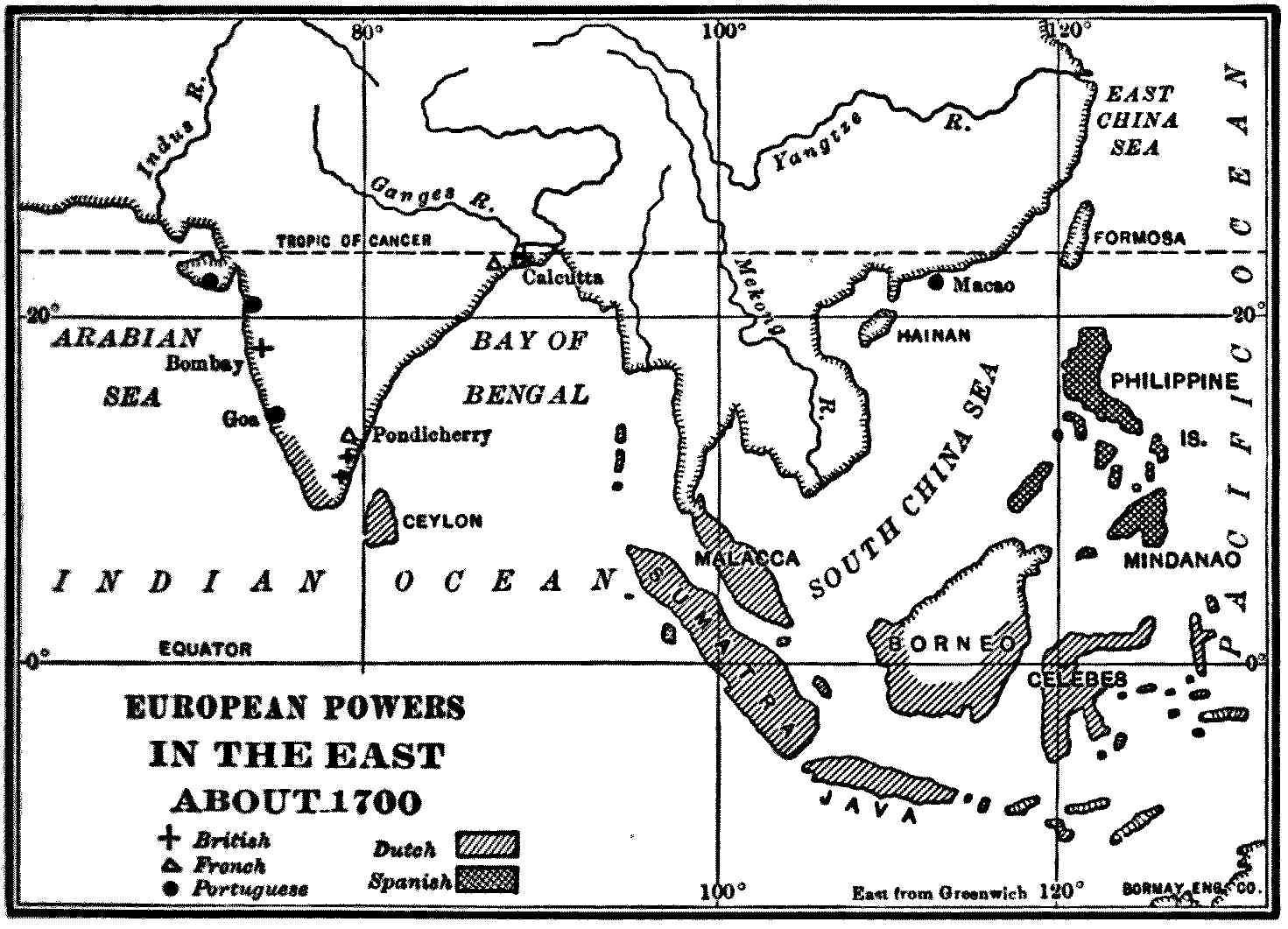

| 16. | European Powers in the East about 1700 |

193 | |

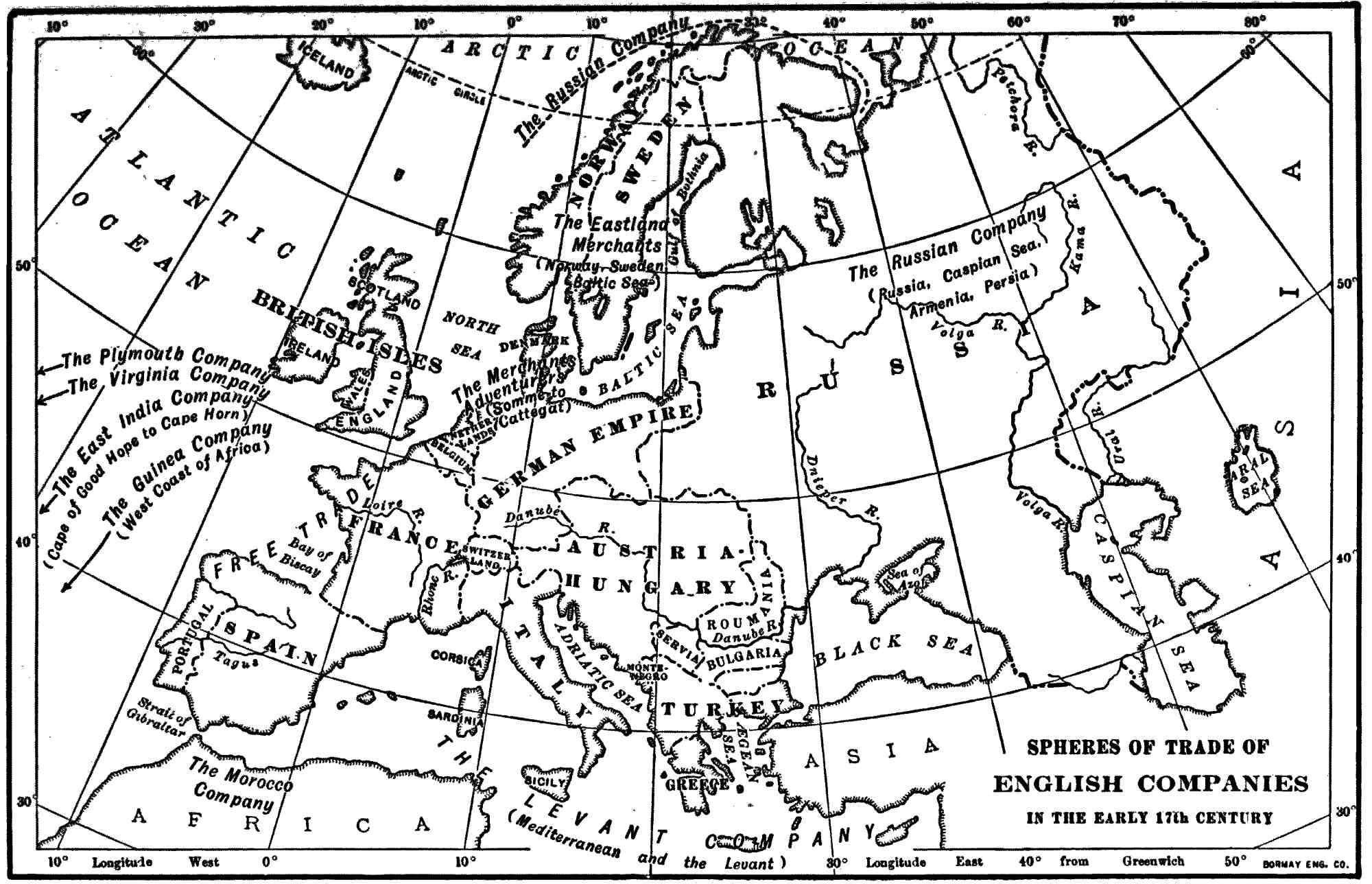

| 17. | Spheres of Trade of English Companies in the Early Seventeenth Century |

203 | |

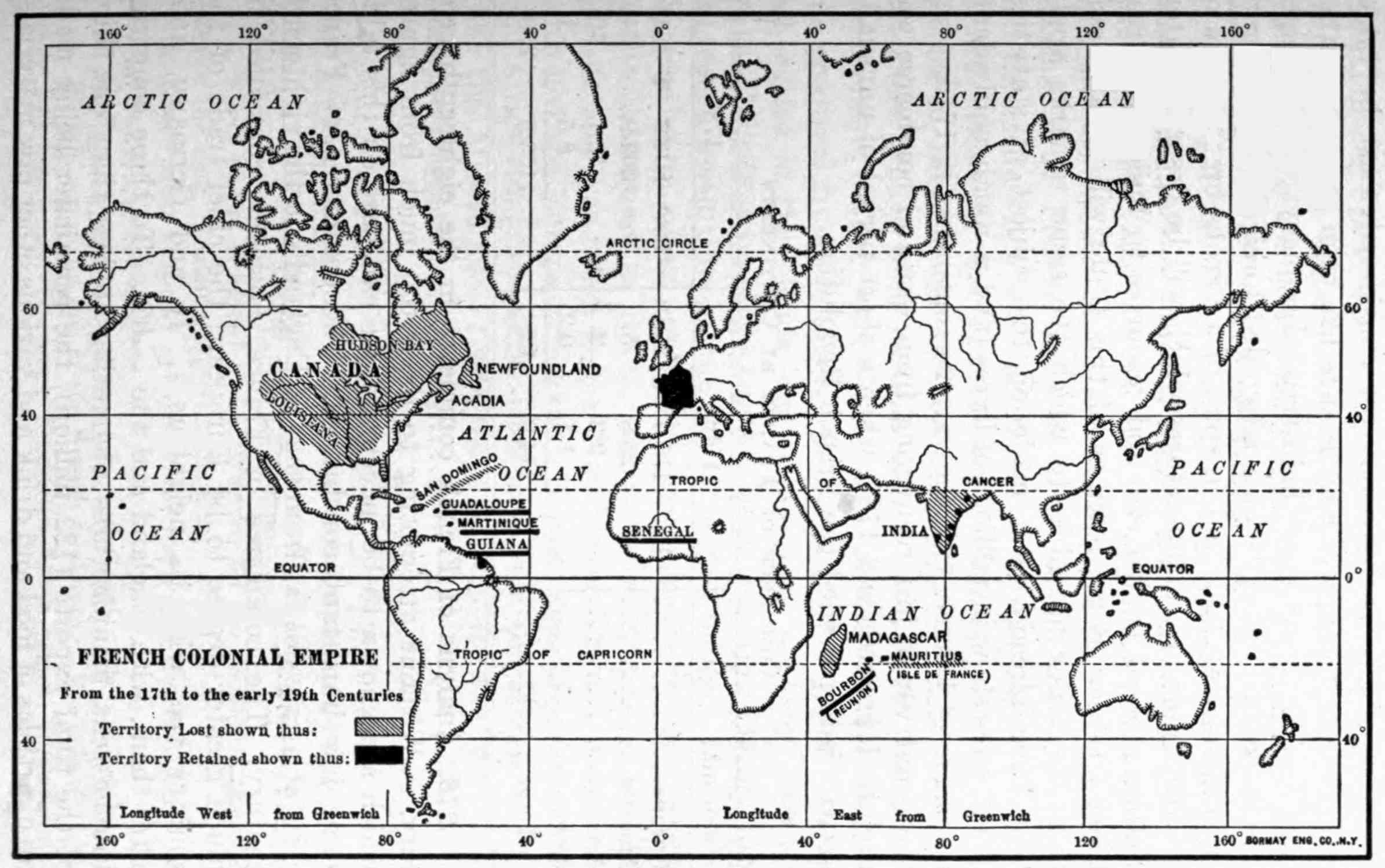

| 18. | The French Colonial Empire |

237 | |

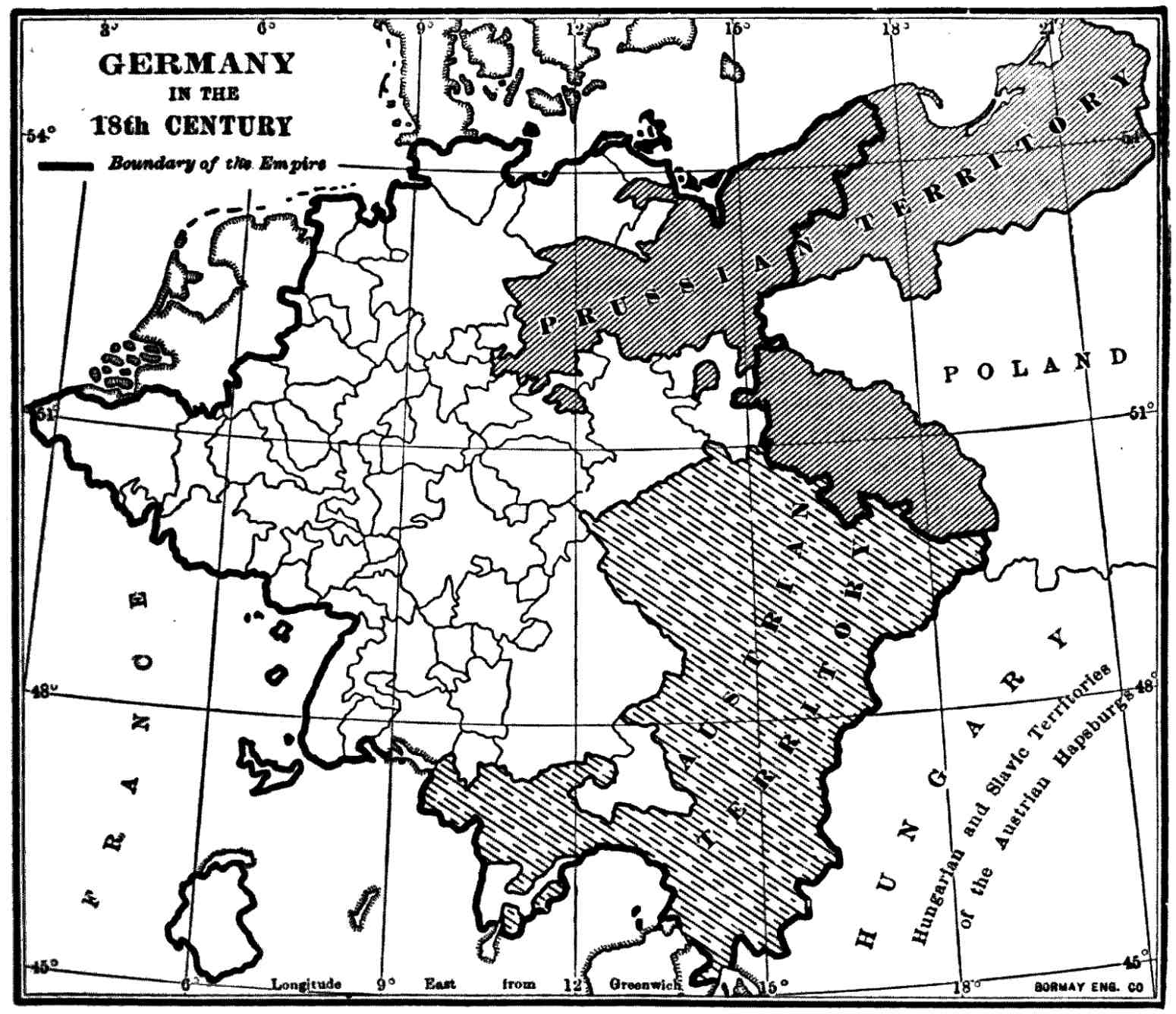

| 19. | Germany in the Eighteenth Century |

251 | |

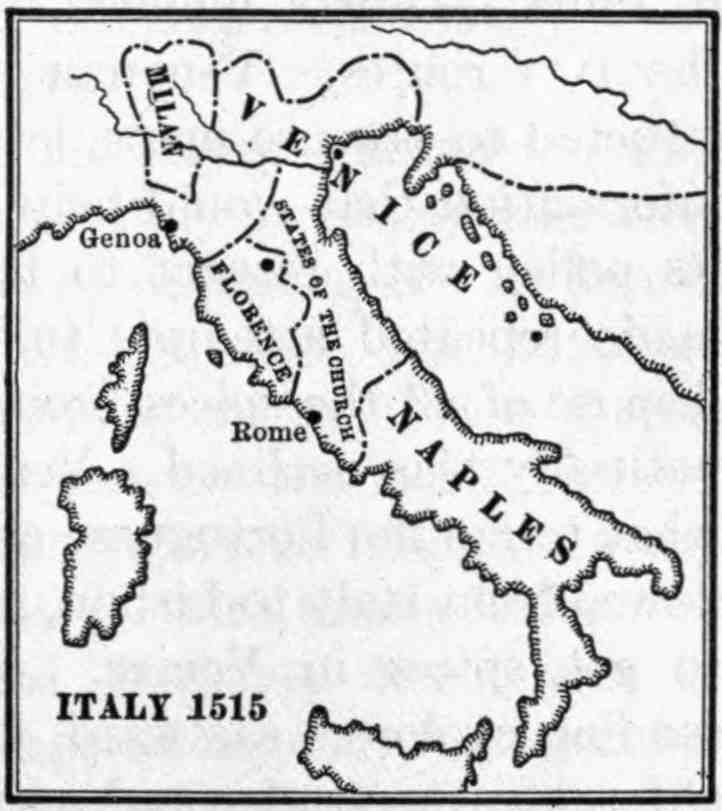

| 20. | Italy, 1515 |

263 | |

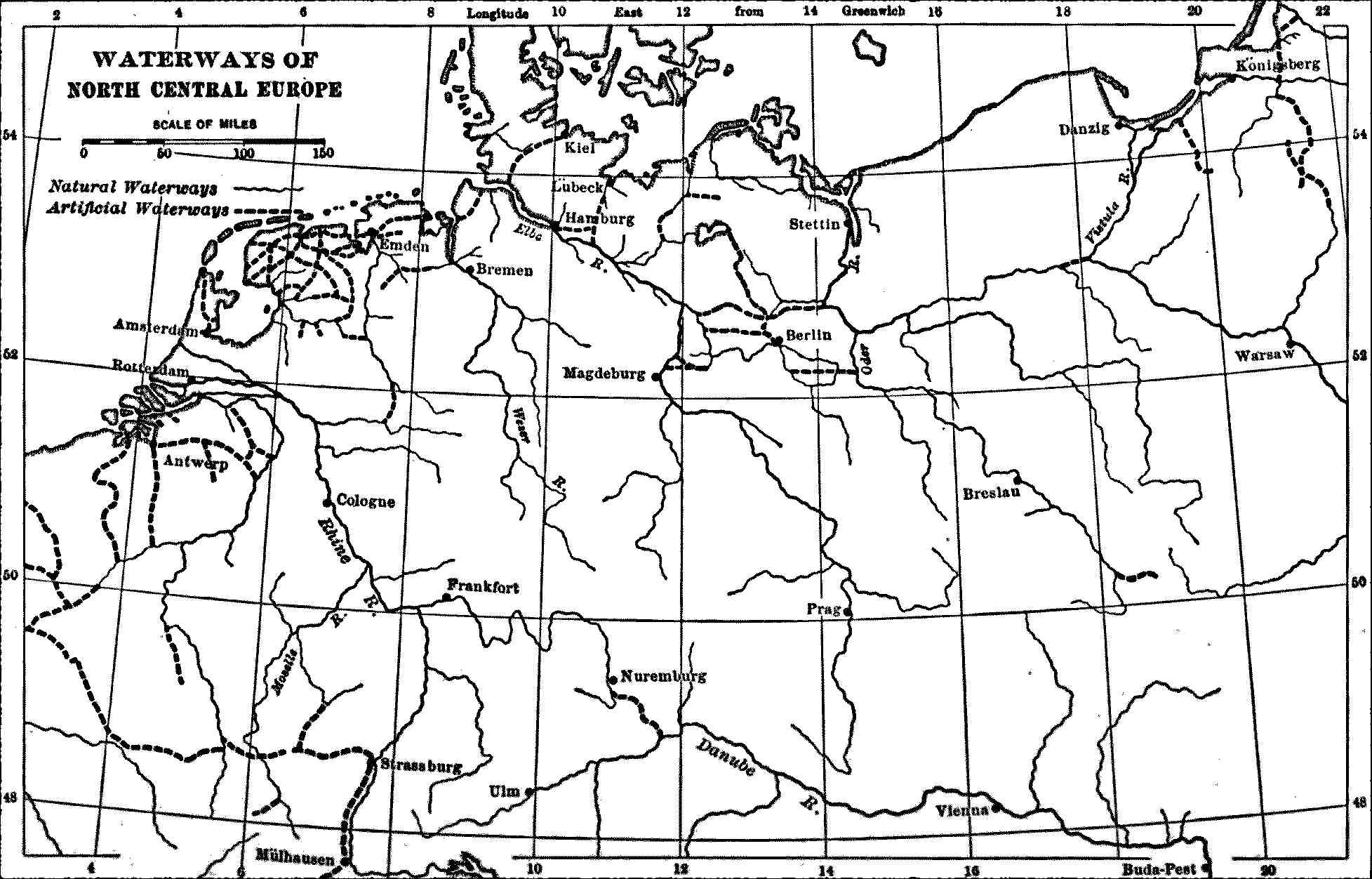

| 21. | Waterways of North Central Europe |

294 | |

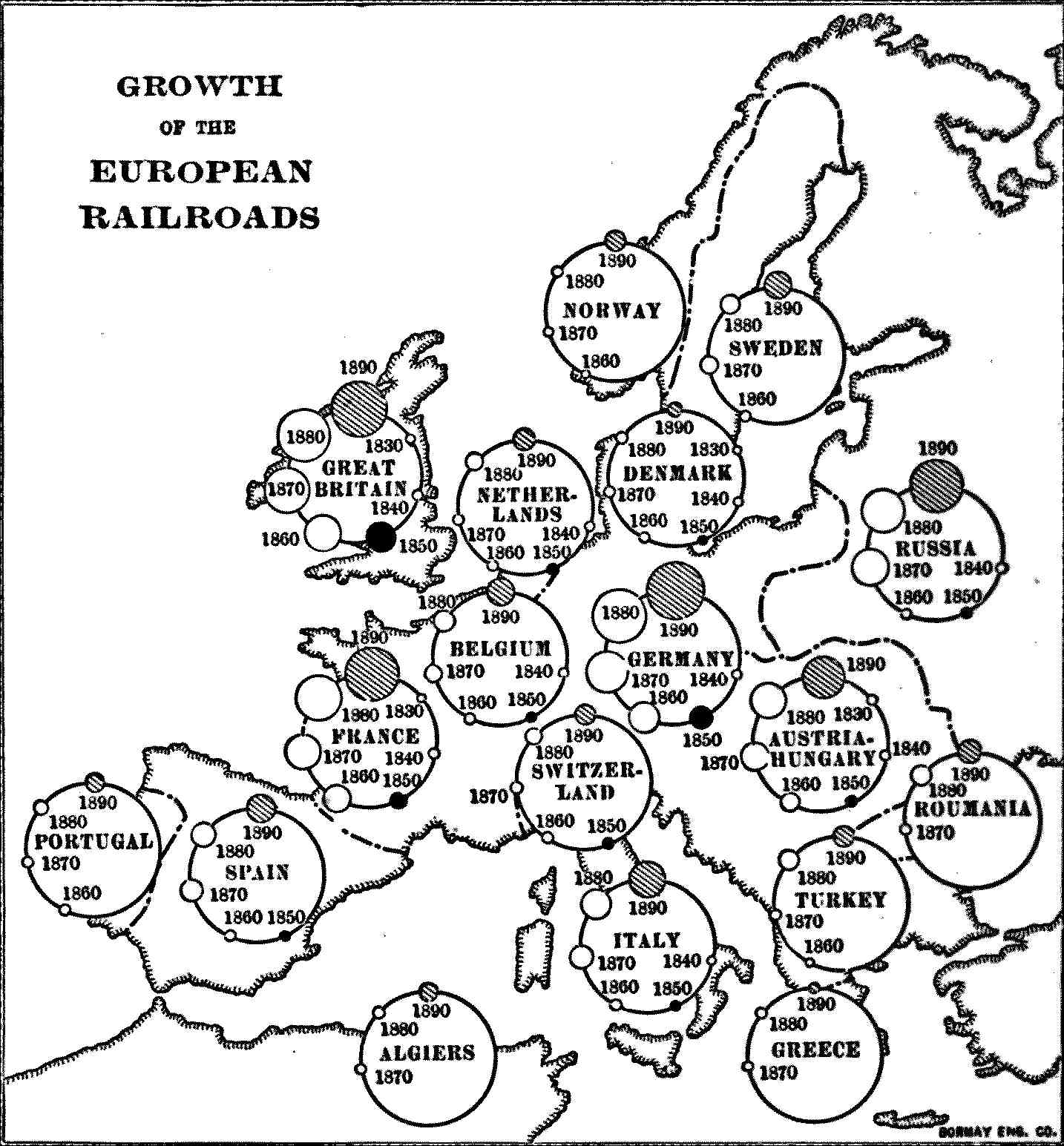

| 22. | Growth of the European Railroads |

298 | |

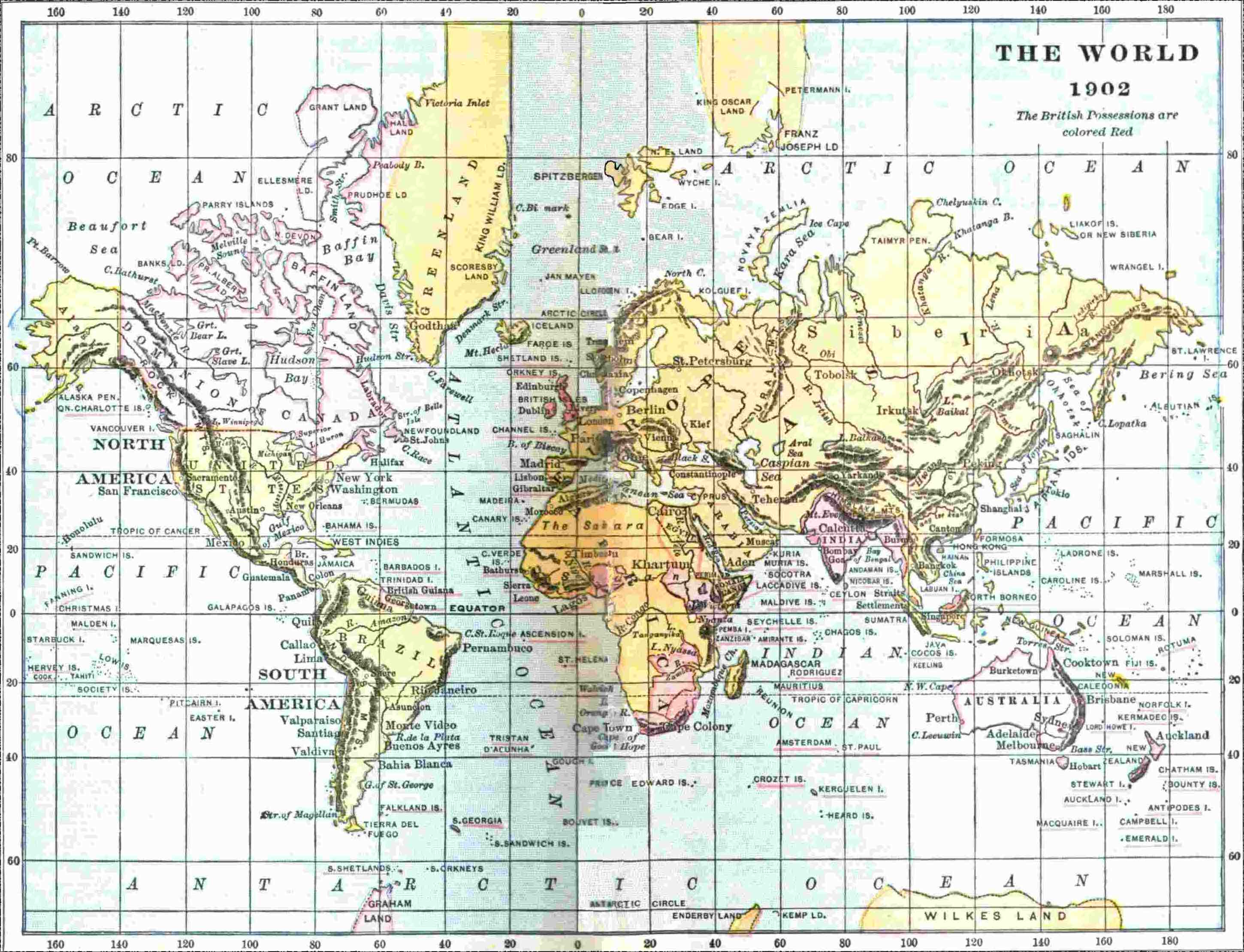

| 23. | The British Empire, 1902 (colored) x |

Facing | 362 |

| 24. | Development of the German Zollverein |

403 | |

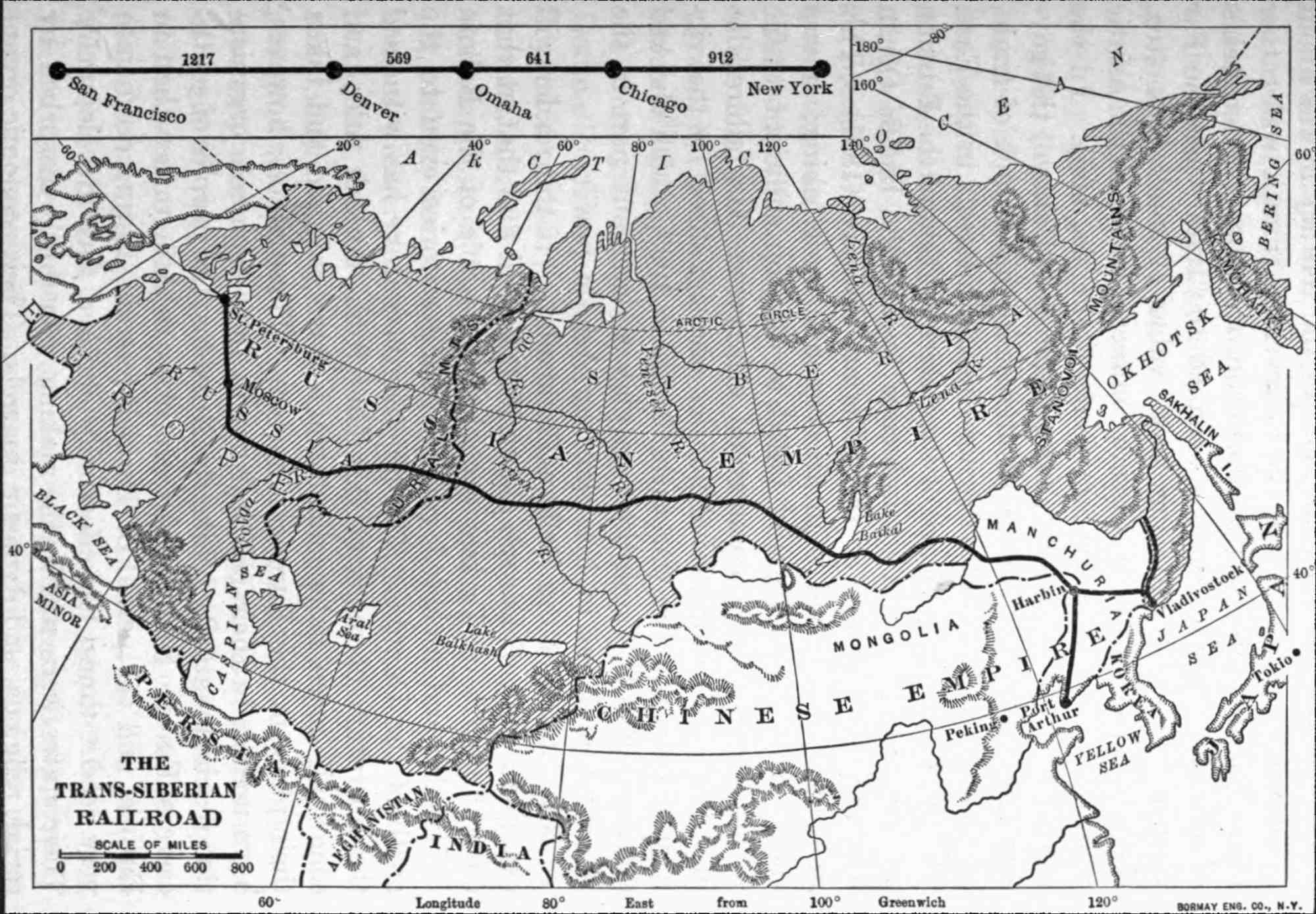

| 25. | The Trans-Siberian Railroad |

463 | |

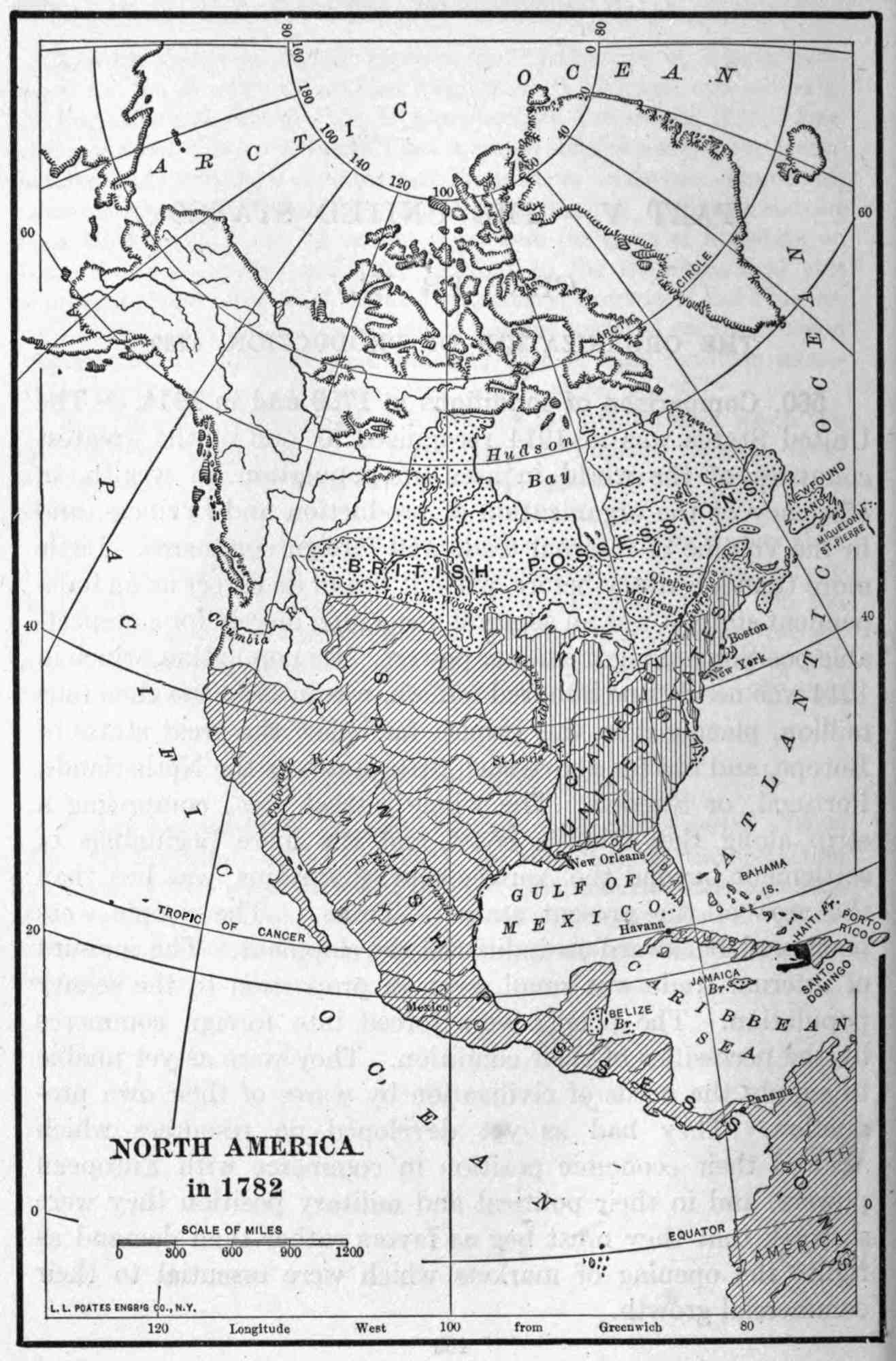

| 26. | North America in 1782 |

470 | |

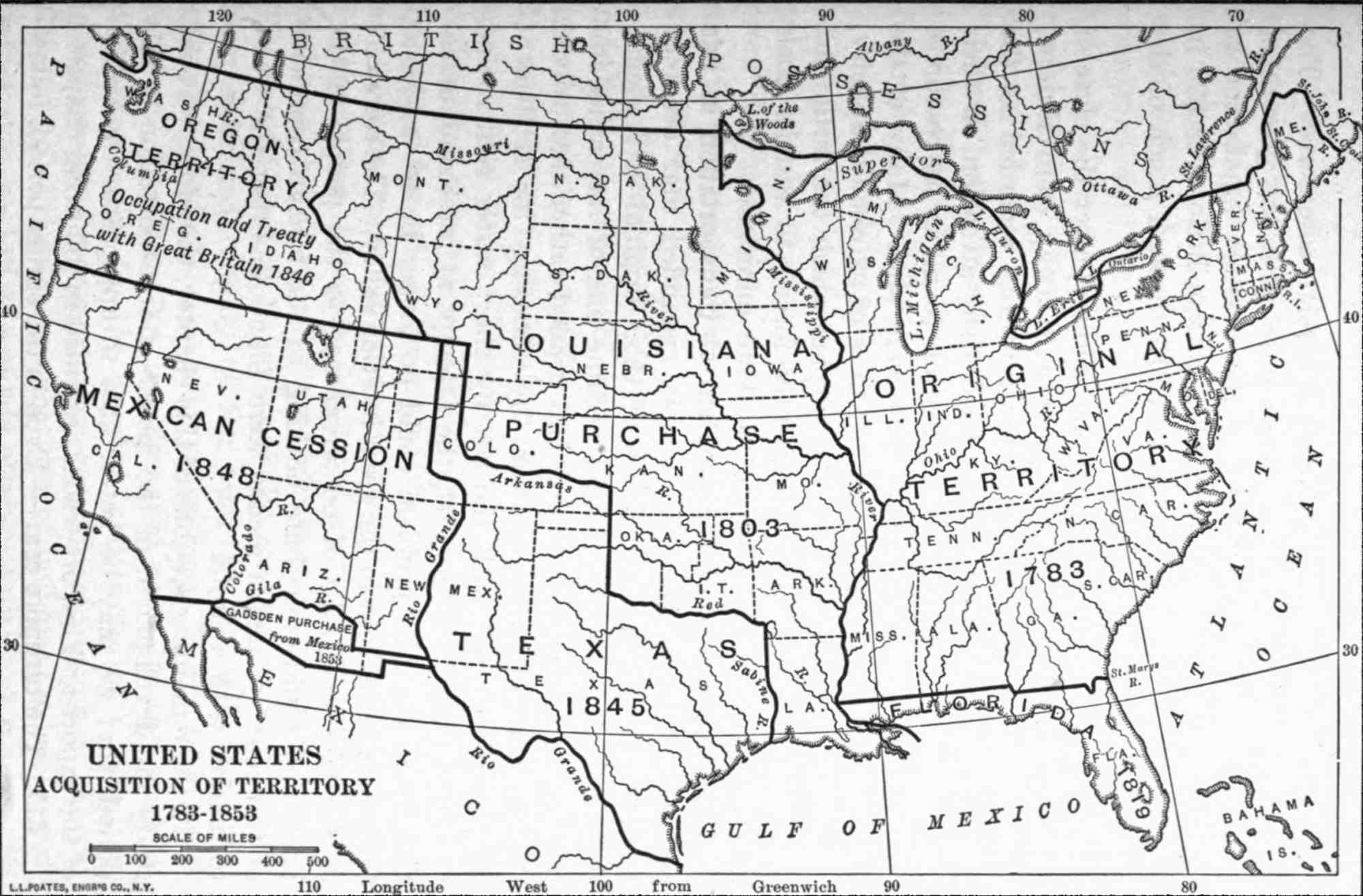

| 27. | United States, Acquisition of Territory, 1783-1853 |

513 | |

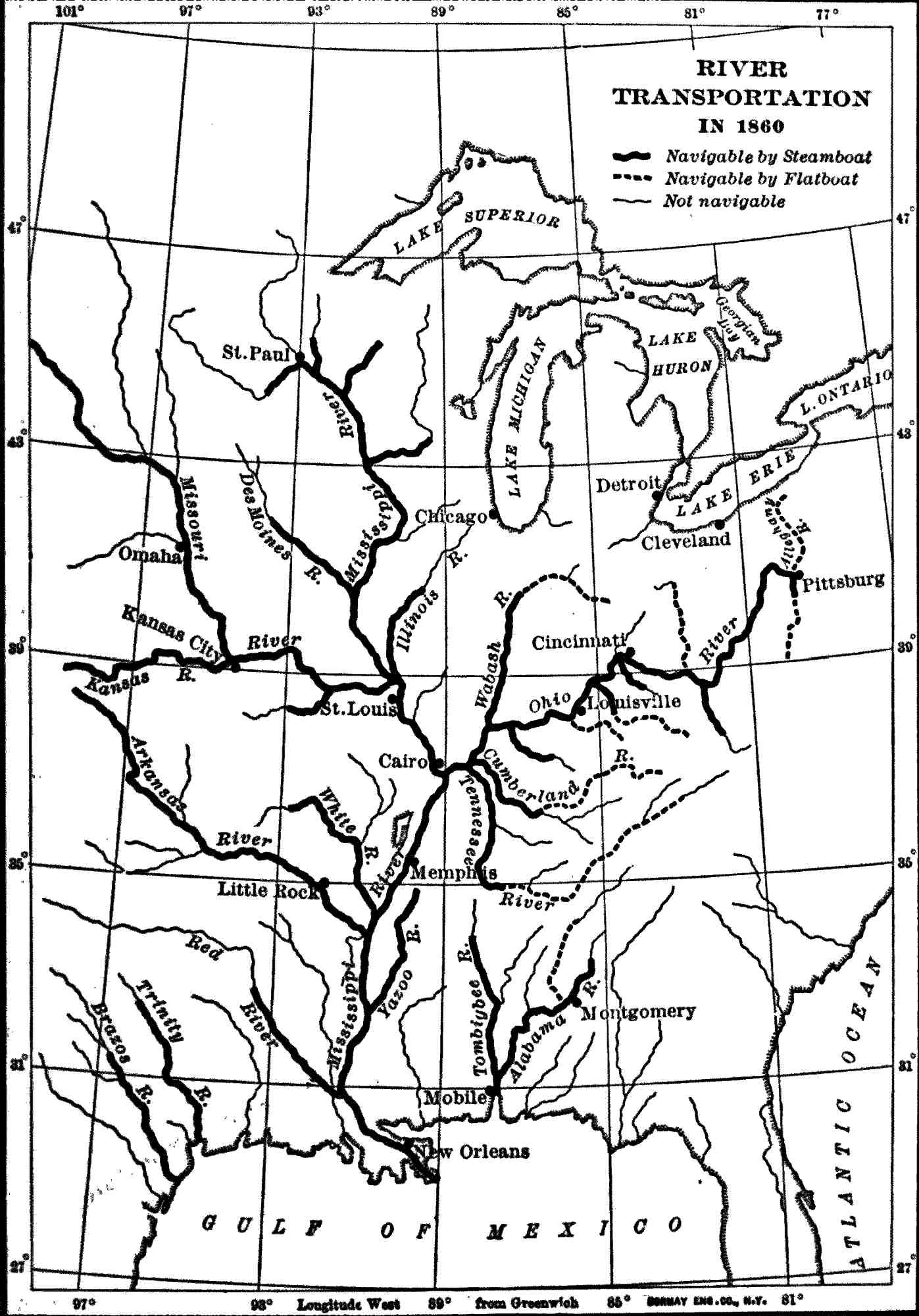

| 28. | River Transportation in 1860 |

517 | |

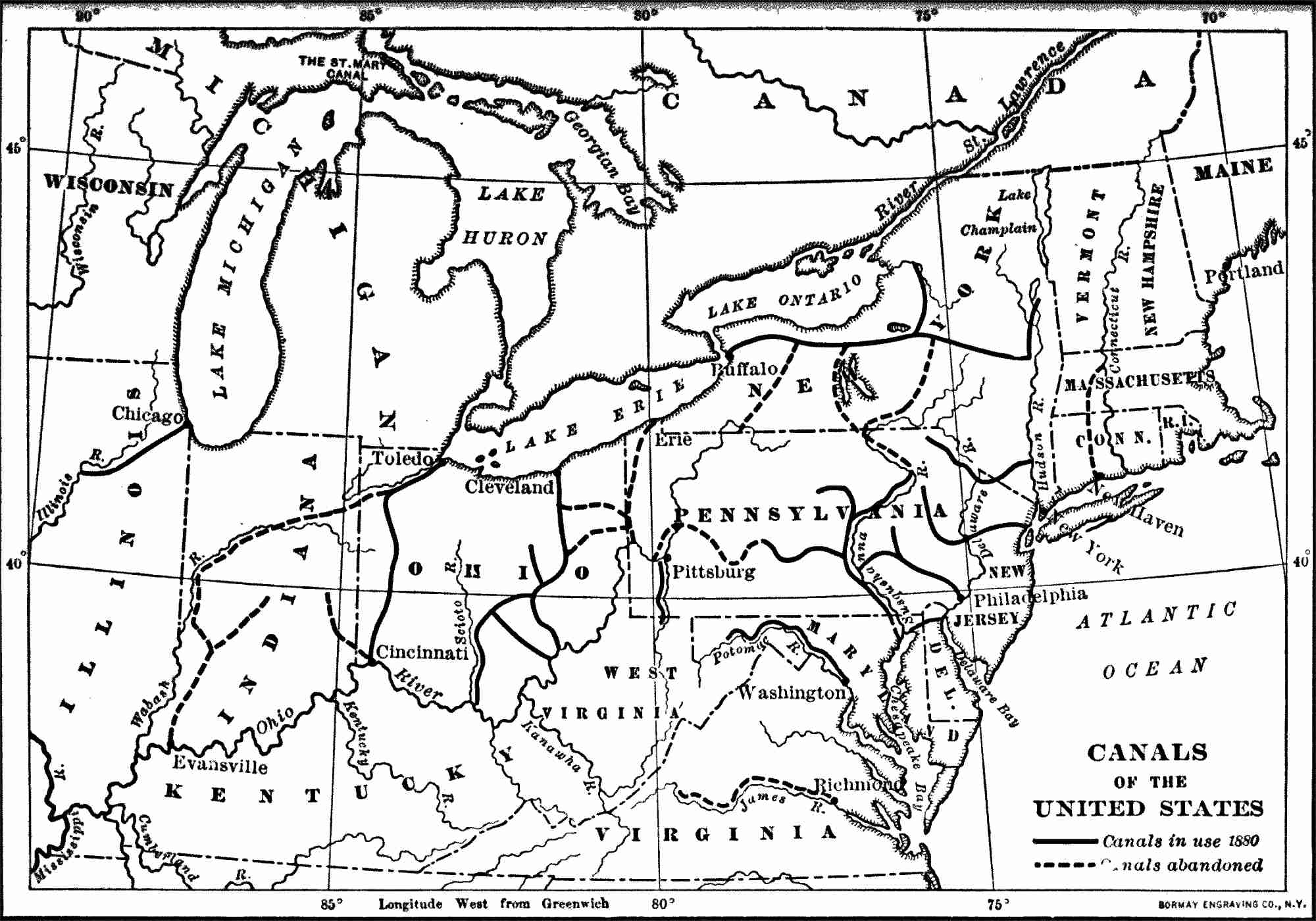

| 29. | Canals of the United States |

Facing | 520 |

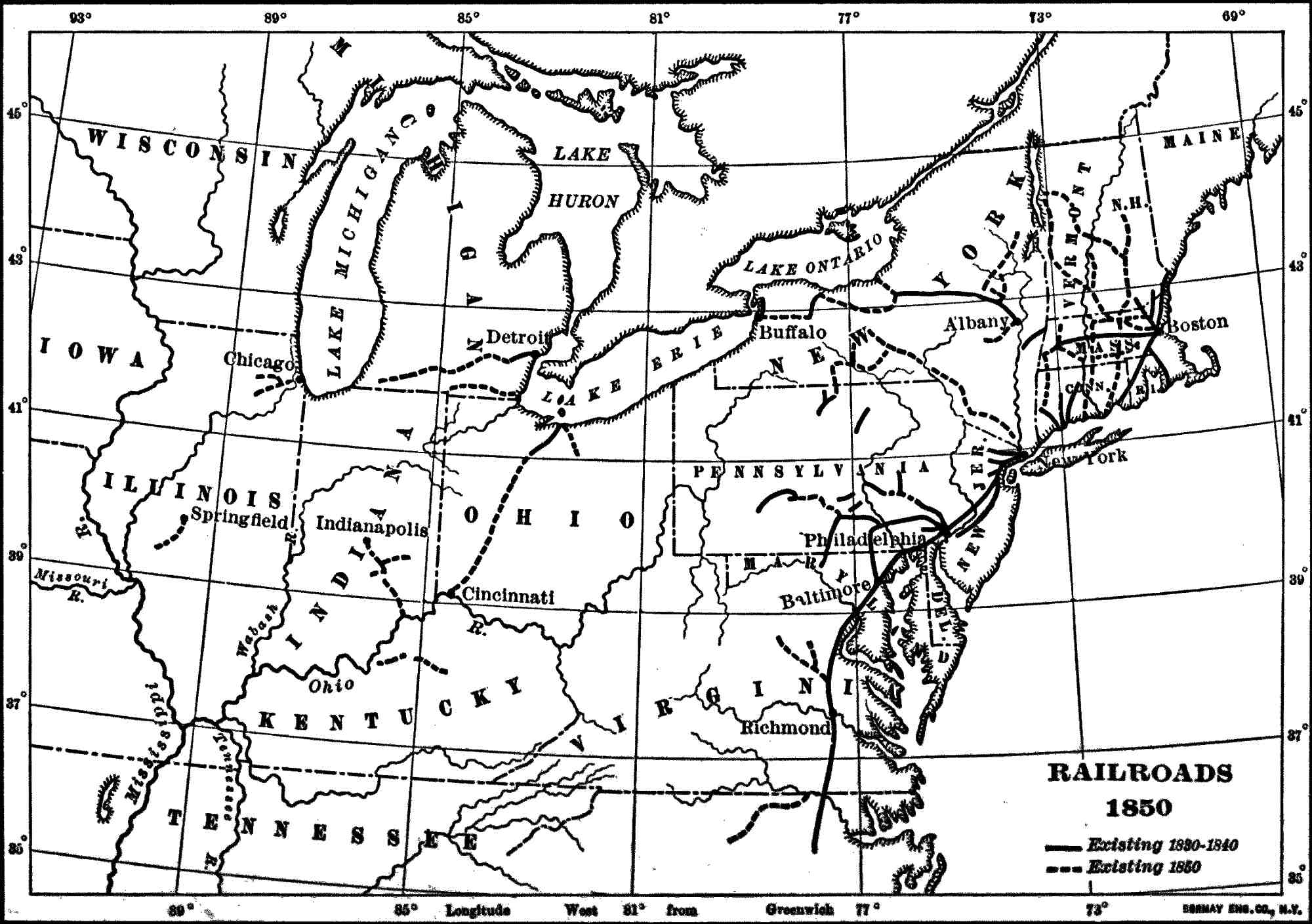

| 30. | Railroads, 1830-1850 |

524 | |

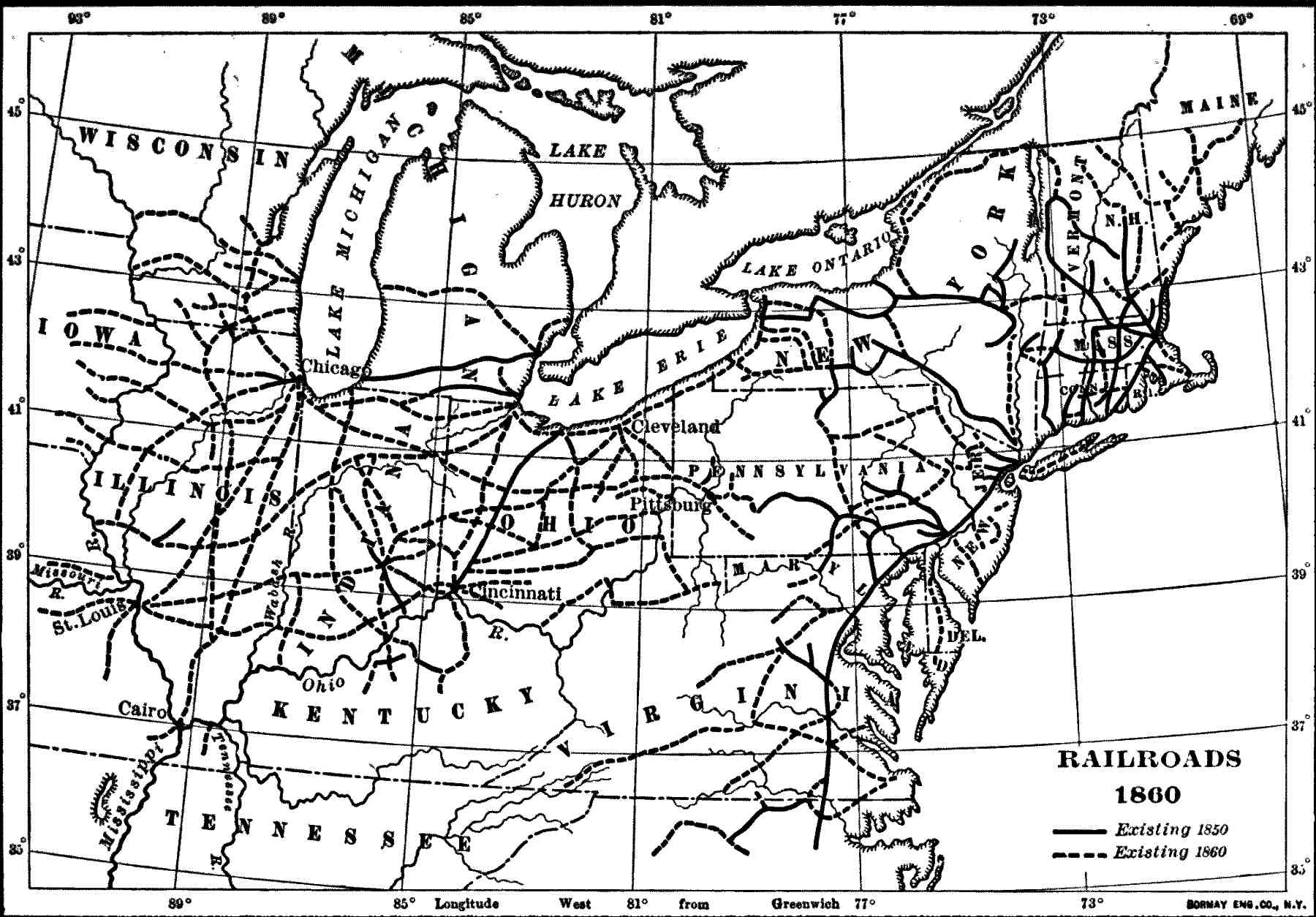

| 31. | Railroads, 1850-1860 |

525 | |

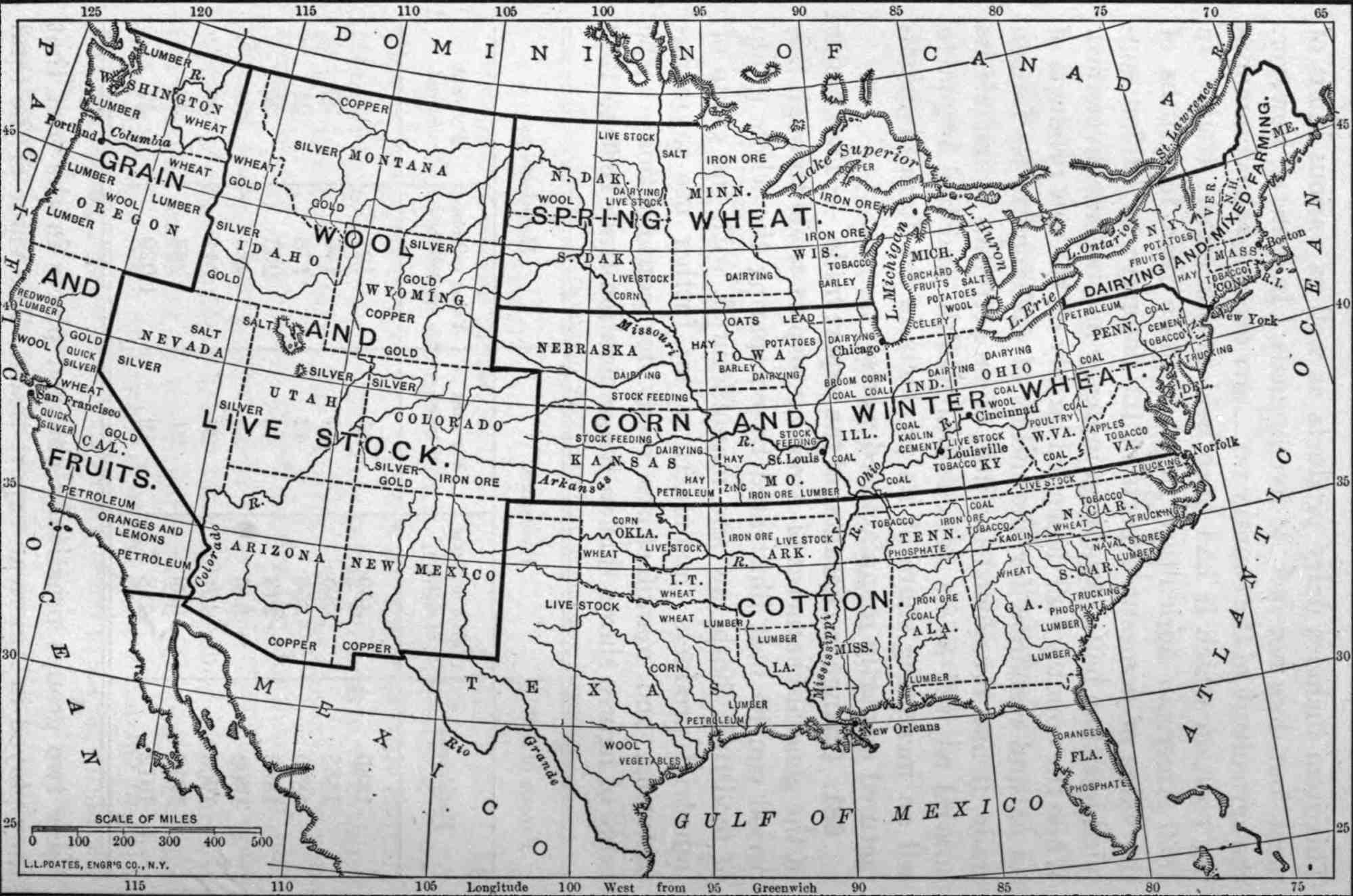

| 32. | Products of the United States |

568 | |

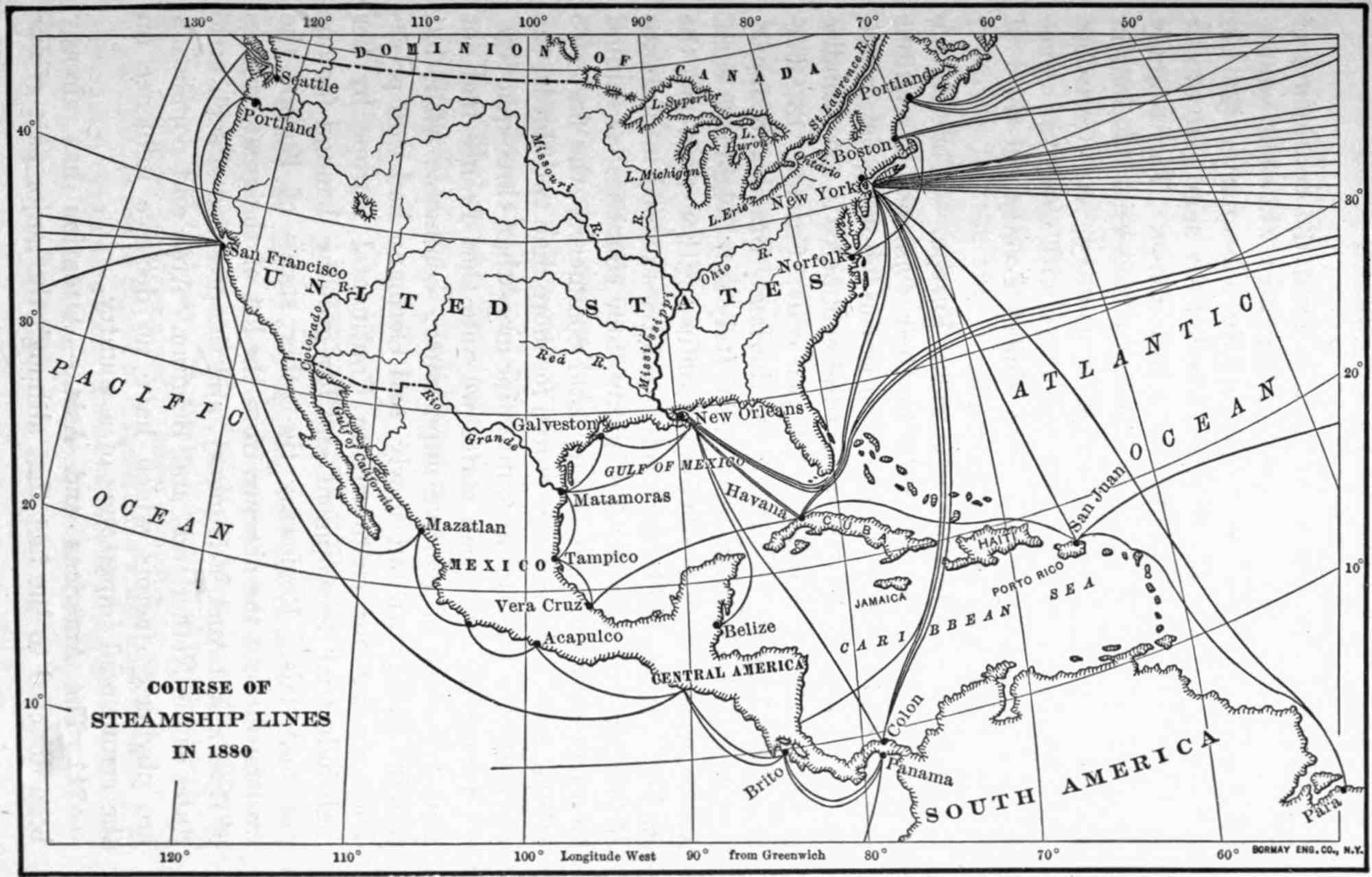

| 33. | Course of Steamship Lines in 1880 |

587 | |

1

1. The purposes of commerce.—The reader will follow more intelligently the history of commerce if he will stop a moment at the start to consider the purposes of commerce and the difficulties which must be overcome if it is to be successfully carried on.

As to the purposes we may be brief. The largest part of the time and energy of the ordinary man is consumed in getting the material things which furnish him with the means of subsistence and of culture. We are accustomed to think of the farmer and the manufacturer as charged especially with supplying our material wants, but a little reflection will show that the work of these classes, without the aid of another class, would be of little use to us. The food and clothing and tools and other desirable articles which they produce are valuable only when they are put into the hands of a man who wants them and can use them. Articles which we all should pronounce desirable, the ripe fruit of the farmer and the finished product of the manufacturer, have still only the possibility of good in them; and this possibility is realized only when they are put in the place where they are wanted at the time when they are wanted. It is the business of the merchant to attend to the proper distribution of wares, in place and time. He does not change the form of things, like the farmer or the manufacturer, but he is as truly a producer as they are.

2

Ice may be manufactured in summer by the ammonia process, or it may be saved from the preceding winter, or it may be brought in summer from Greenland. To the consumer it makes no difference which one of these methods is employed; he wants his ice in summer, and the trader who satisfies his wants by saving or transporting the ice is as useful a member of society as the manufacturer who makes the ice.

2. Obstacles to the development of commerce. (1) Personal.—Great as are the advantages of commerce, ages of progress were required to give it the position which it holds in the modern world. It has had to make its way against innumerable obstacles; and to some of these obstacles the reader is asked now to give his attention.

There is, first of all, the difficulty which we may term personal. A man now accepts trade as a matter of course. He devotes himself to some special line of production, the growing of wheat or the making of shoes, feeling sure that he can exchange his surplus for whatever else he wants, and making his exchanges without hesitation. An uncivilized man, however, is accustomed to satisfy his wants in only two ways, by his own labor in production or by robbing another man. He is suspicious of any offer to exchange wares, and is unwilling to apply himself to any special line of production that would make him dependent on trade. The ignorance and suspicions of men were in early times the greatest hindrances to the rise of commerce, as they are still in backward portions of the world; it has required generations of experience to teach men wants for things which they did not themselves produce, and to teach them to satisfy these wants by exchange. Commerce took on definite proportions and became of considerable importance only when a special class of traders and merchants arose, who made it their business to study wants, to inspire new ones, and to provide the means of satisfying them.

3. (2) Physical obstacles.—Another difficulty in the pursuit of commerce, which we may term physical, appears in3 the exchange of articles which are produced at some distance from each other, so that they need to be transported by land or sea. A farmer who sets out for the city with a load of grain will have to count carefully the cost of getting it to market. Assume that he feeds himself and his horses from his wagon-load; evidently, if the road is long, or so bad that progress is slow and many horses are necessary, he may find all the wheat consumed on the journey before he has secured a purchaser. In this aspect the facilities for transportation, whether by land or water, by pack-animal, cart, canal boat or steamer, are of great importance. It has been estimated that a human burden bearer would require more than a day and a half to move a ton of goods a mile; a strong pack-horse can carry three hundredweight a considerable number of miles in a day; while on first-rate level roads a horse can drag a ton even further. Another factor in this question is the character of the ware. A farmer who could not afford to bring wheat to market might still find it profitable to bring butter, which has much greater value in the same bulk, so that the profits on a wagon-load might pay the expenses of the journey. Gold can be exported from the interior of Alaska under difficulties which would make the transportation of any other product impossible.

4. (3) Risk of loss at the hand of public enemies or robbers.—The carrier of merchandise has to face not only physical difficulties, but also dangers from another source. From time to time we read in the modern newspaper of high rates charged for war insurance, when ship or cargo may be captured and confiscated by an enemy on the sea. The merchant must count his insurance charges before he can figure out his profits. This illustration will make clear the character of one of the obstacles to commerce, which we may term military, by some stretching of the current meaning of the word. It gives, however, no idea of the extent of this danger in earlier times, when not only were wars far more common, but when even in times of peace the state was so weak that the merchant, in4 every mile of his progress, was exposed to attack by highwaymen on land and by pirates at sea. Either the merchant must bear his own risks, or pay somebody to protect him against them. In either case the result would be the same, the necessity of charging higher prices for the wares, and so making sales less attractive and less common.

5. (4) Political restrictions.—Still another element can be distinguished in history, which seems often to be an obstacle to the development of commerce. This element may be termed the political. A man is not only a producer and consumer; he is also, whether he is conscious of it or not, a member of the state, and subject to some kind of political organization which restrains and directs him in his economic life. His efforts to further his own interests are restricted by laws meant to protect the interests of the people as a whole against the selfishness of individuals. A merchant in the United States who proposes to import some ware from another country will find that he must pay not only the natural transportation and insurance charges, but possibly also a customs duty in addition, that would make the exchange unprofitable. If he proposed to import a foreign ship for use in the American coasting trade he would find that he is absolutely prohibited from doing this, no matter how much he might be willing to pay as duty.

These restraints are imposed nowadays, not because the government assumes that individuals cannot take care of themselves and is afraid that they may lose money by making purchases abroad, but because it thinks that they may hurt the interests of producers in the home market, whom it proposes to protect. We shall find that governments in earlier times restrained the flow of commerce to protect not only producers but also consumers and even the merchants themselves; and that regulations were imposed, of such variety and such strictness, that they made a very important element in the commercial life of peoples. The church as well as the state interfered with the course of exchange in the Middle Ages, and5 thought it necessary to safeguard public morals by many restrictions which have since disappeared.

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

1. Consider some articles of your clothing; try to ascertain from what different sources the materials were gathered by the merchant for the manufacturer, and how the finished product reached you. Do the like for a common implement, a lead-pencil or pocket knife, or an article of furniture. What countries were drawn upon to supply the food and setting of your breakfast table? [Compare The cost of a dinner, Outlook, March 13, 1897, quoted in Clow’s Introduction to the Study of Commerce, Silver, Burdett & Co., 193-194.]

2. What articles would you have to do without if your supply were limited to the things produced within a radius of 10 miles of your home? Within a radius of 100? Within a radius of 1,000?

3. Ice was given as an example of a ware which varies greatly at different times. Are all wares subject to such variation? [If you find what seems to be an exception, verify it by the wholesale prices quoted in newspapers.]

4. What is the use of grain elevators and wheat speculators?

5. Can you detect any difference between city people and country people in making a bargain?

6. What has been the attitude of the North American Indians to trade? With what wares have traders had to tempt them?

7. Arrange the following articles in the degree of their transportability, i.e., according to the distance which they may be carried with profit: raw cotton, coal, potatoes, silver, building stone, gold, wheat, cotton cloth, diamonds, hay, coffee, salt, silk ribbons, copper. [The price per pound of many of these wares is given in the newspaper.]

8. Give an instance of articles wasting, unused for lack of good wagon-roads; for lack of railroads.

9. In what regions has piracy persisted to recent times? [Read some description of Borneo or of the Philippine Islands, or a description of Chinese junk trading and Chinese river life.]

10. What effect did the Civil War have on American commerce? [See reference in chap. 51.]

11. In what regions of the world is land trade still unsafe?

12. To what restrictions, if any, does an American merchant have to submit who desires to trade in one of the following wares: cigars, gunpowder, whisky, lottery tickets, imported iron, cigarettes, improper literature?

13. Government restrictions now are due usually to one of three6 objects: (1) collection of revenue, (2) protection of other producers, (3) protection of the consumer and the public. Classify the wares above according to the object of the legislation.

14. Read Bourne, Romance of trade, 96-137, on the close relations of politics and commerce.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The reader will find at the end of most of the following chapters titles of books suggested for further reading and study; titles of books that are warmly recommended are marked by an asterisk, titles that are particularly noteworthy are marked by two asterisks. In all cases the references are restricted to books available in English. The prices given are in most cases those at which the book was sold before the war, and are retained as giving some indication of the relative expense involved in the purchase of the books; prices have changed so much during and after the war that an attempt to list current prices appears impracticable.

Bibliography.—The best available bibliography of English books on the history of commerce is Sonnenschein’s Bibliography of social and political economy, London, 1897, reprinted from The Best Books and The Reader’s Guide. Useful bibliographical information will be found also in Palgrave’s Dictionary, and in the Subject Index of the British Museum Library, which has been published at brief intervals since 1902, and which lists all the new books added to the Library. The American Economic Review, established in 1911, is a quarterly publication which has devoted particular attention to the bibliography of economic subjects, and which should be consulted for the announcement of new books, the summary of articles in periodicals, and the appreciation of important works in book reviews. The American Library Association Catalogue, which has appeared in various editions, gives full bibliographical information about popular books which are on sale in the American market.

In default of a general bibliography the student must refer to books describing conditions in England. The most complete and scholarly bibliography is that given by Cunningham, in appendixes to his Growth, etc. References which to most students will be more useful are given in Traill’s Social England. Both these sources cover the whole period, into the nineteenth century. For the medieval period the general student has a bibliography approaching near to perfection by Charles Gross, Sources and literature of English history, London and N. Y., 1900, and the student of the history of commerce will find many references in the Select bibliography of English mediaeval economic history, edited by Hubert Hall, London, 1914. A revision of C. K. Adams, Manual of historical literature, which has been undertaken by the American Historical Association will be of great value when completed.

7

Manuals.—Cheesman A. Herrick, **History of Commerce and industry, N. Y., 1917, resembles in plan the present book. Bibliographies are appended to the different chapters. Two English manuals on the history of commerce, H. de B. Gibbins, *History of commerce in Europe, London, Macmillan, 1891, and J. R. V. Marchant, Commercial history, London, Pitman [about 1901], suffer from the attempt to compress an immense number of facts into a small compass. William C. Webster, *General history of commerce, Boston, Ginn, 1903, $1.40, marks a decided advance in the selection and presentation of material, but is lacking in scholarship; the present writer discusses this book in detail in Yale Review, Feb., 1904, vol. 12, p. 436 ff. It has scattered bibliographies, unclassified. George W. Sanford, *Outlines of the history of commerce, Chicago, Powers & Lyons, 1902, occupies a place by itself, and should be of decided value in supplementing any manual. It gives topical outlines of the different chapters in the history of commerce, suggestions and references for reading, and skeleton maps for the student to fill in. It seeks to give no information directly.

General Works.—Of the general works on the history of commerce most are old and out of print. Of these only one need be noted here, Lindsay’s *History, of which the first volume covers ancient and medieval times. This will be of value to any school library, if it can be procured. John Yeats, Growth and vicissitudes of commerce, Boston, Boyle, covers the whole subject, from ancient to recent times, in a volume of about 400 pages; it was compiled about 1870, from other compilations, and is not to be trusted entirely, but is about the only book of its kind now in the market. Bourne’s *Romance of trade and Oxley’s *Romance of commerce answer well to the description Bourne gives of his book, “an interesting gossip-book about commerce”; both books contain readable discussions of various topics in the history of commerce, and references will be given to them hereafter. Morris, History of colonization, 2 vols., N. Y. Macmillan, 1900, would be a valuable book to the teacher if it were well done, as it covers the history of colonization and commerce from earliest times to the present. It is, however, so badly constructed and so unreliable that it cannot be recommended. See the reviews in The Nation, Yale Review, American Historical Review. A far better book on the subject is A. G. Keller, **Colonization, N. Y. 1908.

The book which I recommend most strongly to teachers who are restricted in their choice is Cunningham’s **Growth; it will enable the teacher to dispense with many other books, and no other book could be substituted for it. Ashley’s *Economic history, always desirable, is less necessary for the purposes in view here. Ashley’s **Economic Organization of England, London, 1914, is an admirable survey of English economic history and is well suited to serve as collateral reading, but has little on8 the history of commerce proper. If Cunningham’s large work is provided, the teacher and student can afford to neglect the smaller manuals on English economic history by Cunningham and MacArthur, Warner, Price, Cheyney (revised edition, 1920), Usher, and others. Frederic A. Ogg *Economic development of modern Europe, N. Y., 1917, deserves separate mention since it embraces not only England, but also the more important countries on the Continent; it covers the earlier periods briefly, but treats the nineteenth century fully, and has extensive bibliographies.

Many of the general histories of Europe and England can be used to advantage by the teacher or student of the history of commerce. The only work, however, which can receive special mention here is Traill’s *Social England; chapters contributed by various writers cover the history of commerce from earliest times to 1885.

Maps.—The student must look to the general historical atlas for help in studying the history of commerce. He will find that the more elaborate atlases are hardly worth the extra expense for his purposes.

William R. Shepherd, **Historical Atlas, N. Y., Holt, revised ed. 1921, includes considerable economic material, is provided with a full index of places, and will serve all ordinary needs.

The outline maps of the McKinley Publishing Company (Philadelphia), and the Rand McNally Co., will be found valuable for the use both of teacher and class.

In many cases a modern atlas is more desirable than a historical atlas. Longmans’ **School atlas, N. Y., 1901, is an admirable work, which should be in the hands of every student, and the Century **Atlas is indispensable for reference purposes.

THE ANCIENT WORLD

9

6. Prehistoric commerce. Ancient Egypt.—The origins of commerce are lost in obscurity. Before people are sufficiently civilized to leave written records of their doings they engage in trade; we can observe this among savage tribes at the present day, and we know that it held true of the past, from finding among the traces of primitive man ornaments and weapons far from the places where they were made. Such evidences, interesting as they are, belong to the prehistoric period, and this sketch of early commerce must begin with the peoples who had acquired the art of writing and have left us records from which we can gain some idea of their history.

First among these peoples, in point of time, were the Egyptians. Three thousand years before Christ, at the time when the great pyramids were built, this people had already attained a developed civilization, which, in the opinion of modern scholars, can be traced back even thousands of years more. The Egyptians, however, were not a commercial people. Their main resource was agriculture, and though they developed some of the industrial arts to great efficiency they used the products for direct consumption rather than for trade. Their country, a strip of the Nile valley over five hundred miles long, and but a few miles wide, was so much alike in its different parts that it offered little inducement to internal exchange over great distances; while its isolation by deserts was a bar to the growth of foreign commerce. The sea, in this early period, was a hindrance, rather than a help, to communication.

7. Rise of Egyptian commerce; characteristic wares.—Egypt10 never became a commercial country so long as it remained under its native rulers. With the period known as the New Empire, however, beginning about 1600 B.C., commerce at least became more important than it had been before. Regular communication was established with Asia, and caravans brought to the country the products of Phœnicia, Syria, and the Red Sea district. Before the eyes of Joseph and his brethren “behold, a company of Ishmaelites came from Gilead with their camels bearing spicery and balm and myrrh, going to carry it down to Egypt”; to this caravan Joseph was sold as a slave. The wares named here were characteristic imports of Egypt; among others were precious woods, ivory, gold, wine, and oil. Among the exports of the country were grain, linen, and manufactured wares like weapons, rings, and chains. Even to a late period trade was carried on by barter, the use of coins being rare, and many of the imports came as tribute, for which the Egyptians needed to make no return.

8. Development of Egyptian commerce in a later period.—Only in the last period of Egyptian independence, a few centuries before the country was conquered by Alexander, did commerce bind it closely to other portions of the ancient world. The government, which formerly had discouraged trade, now permitted and encouraged it; Greek merchants came in considerable numbers to Egypt; and an active commerce sprang up. It is said that Necho, the king who ruled about 600 B.C., sent out Phœnician sailors to attempt the circumnavigation of Africa; and the same king took up the work of cutting a canal across the isthmus of Suez which was completed shortly afterward. The canal was allowed to fill up with sand, but was reopened later, and its course may be distinctly traced, it is said, along the route of the modern canal.

9. Rise of commerce in the Mesopotamian Valley.—The district northwest of the Persian Gulf, centering in the river valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates, offered opportunities for the rise of civilization which led to the establishment of settled11 governments while Egypt was still living secluded from the rest of the world. This district was rich in agricultural products, but lacked the metals, some of the building materials, and other of the raw materials of industry. Though it was bordered in part by deserts, communication with other districts was far easier than in the case of Egypt; and commerce with other countries early acquired an importance here which Egyptian commerce attained only in the last period of the country’s history. Ancient Babylon, which rose to importance some time after 3000 B.C., under a Semitic people (with a language akin to that of the Jews), was a market-place for wares brought not only from the South (Arabia) and West (Syria), but also from the East (Iran, the later Persia). Clay tablets, used like modern paper for the preservation of records, have been discovered and deciphered in modern times, and show an active trade in the precious metals, grain, wool, building materials, etc.

10. Development of commerce under the Assyrian and Persian empires.—Military expeditions extended the commercial relations of the people of this district; and the conquests of an Assyrian, who founded a great empire about 745 B.C., were guided in part by commercial considerations. Babylon, Armenia, Syria, and parts of Iran and Palestine, were brought under one rule; peoples on the frontiers were held in check, and order was fairly well maintained within; so that merchants could traverse the different parts of the empire, and meet at its capital, Nineveh, to exchange their wares. The Assyrian empire was made by the sword, and it fell by the sword after a brief duration; but its place was taken by succeeding states, and commerce continued to grow. The Persian empire, which enjoyed its full power for about two hundred years, until its destruction by Alexander in 330 B.C., included an area more than half that of modern Europe; it stretched from the Mediterranean on the West to the Indus on the East, from the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf to the Black and Caspian seas. Within these boundaries12 lay some of the richest regions of the ancient world, the products of which could now be exchanged without passing from under the protection of the Great King.

11. Relative insignificance of the commerce of the ancient empires. The Jews. The Phœnicians.—In the Oriental states which we have hitherto considered, commerce never grew to a position of decisive importance in the national life, however great it may seem when we compare it with its meager beginnings. It served mainly the needs of luxury, and left untouched the economic position of the mass of the people. If we seek in the ancient Orient a people whose very existence depended on trade we must look further. We do not find the Jews to have been such a people, though we are accustomed nowadays to think of them as devoted largely to the pursuit of trade. The descriptions of the Bible show that they lived mainly a pastoral and agricultural life; and down to the time of the Roman Empire they counted for little in the world of commerce. A truly commercial people we do find, however, in near neighbors of the Jews, the Phœnicians, who inhabited a strip of land on the coast of Syria and Palestine, scarcely ten miles wide in most places and little over a hundred miles long. They could gain a scanty food supply from the level ground, and had timber in abundance on the mountains that separated them from the interior, but had to look to trade with other peoples for the means of growth which their home denied them.

12. Commerce of the Phœnicians. Beginnings of sea-trade.—From raw materials which were in many cases procured from other countries they manufactured products which found a market throughout the ancient world. Their cloths and glass were celebrated; they exported large amounts of metal ware; and they had a monopoly of the purple dye extracted from a species of shell-fish, which was highly prized throughout this period. These wares were but a few of those in which they regularly traded; the reader who would have a more detailed account of the wares of Phœnician commerce,13 especially the imports, is advised to study the description in the Bible. They maintained an active exchange with peoples to the South, East, and North of them by caravan routes, while they were the first people of antiquity to secure such mastery over the sea that it could be made the medium of regular and extensive transportation. The beginning of these sea voyages is lost in the obscurity of the past. We know that they were highly developed by 1500 B.C., when Sidon was the leading Phœnician city, and that they did not cease to extend when the primacy of the Phœnician cities passed to Tyre. The Phœnicians taught the art of navigation to the ancient world. Their ships were long the accepted models of construction, and the Greeks learned from them to direct their course at night by the North, or, as the Greeks called it, the Phœnician star.

13. Development of sea-trade; wares of Phœnician commerce.—Beginning, presumably, with fishing and short coasting trips, and reluctant always to venture out in the stormy season, they had reached the islands of Cyprus and Rhodes, and had established regular commerce with Greece in the heroic age of Greek history, say before 1000 B.C. From this point their progress was rapid, and soon they had traversed the whole Mediterranean, and passed outside it into the Atlantic. The means of cheap transportation which they controlled gave them an immense economic advantage. We may accept as a product of the imagination the story that on their arrival in Spain they found silver so plentiful that they not only filled their ships but made their utensils, even their anchors, from it; still the story shadows forth a truth. They found wares in some districts cheap and begging a market because of their abundance, which were rare and highly prized elsewhere; and they could make great profits by exchanging wares so as to put each where it was most wanted. From the island which we now call England they procured tin, which is a very rare metal in Europe, and which was especially desired as a component of the important alloy bronze. They14 got copper in Cyprus and Spain, also silver and iron in Spain, and gold and ivory in Africa. They carried westward the wares of the Orient (cf. our words cinnamon, cassia, hyssop, cumin, manna, all from Hebrew forms), and manufactures, which not only gratified the momentary needs of Europeans but served also as models for imitation.

14. Establishment of colonies by the Phœnicians. Carthage.—The Phœnicians are noteworthy not only as the greatest merchants and the first navigators of the ancient world; they were the leaders also in the founding of colonies. At points important for commercial or naval reasons they established stations which enabled them to trade in security with the natives and to control the sea. Gades, for instance (the modern Cadiz), near the straits of Gibraltar, was a rallying-point from which the Carthaginians extended their voyages to the tin islands in the North, and far down the Atlantic coast of Africa on the South. Similar stations were established on many of the Mediterranean islands (Malta, Sicily, Sardinia, Balearics); and one founded on the north coast of Africa, Carthage (near the site of modern Tunis), grew to especial importance. The power of the Phœnicians declined, a few centuries after 1000 B.C., partly by reason of internal dissensions and the attacks of land-powers like Assyria, partly by reason of the commercial rivalry of the Greeks, who had risen to an independent position and cut the lines of communication between East and West. In this period Carthage fell heir to the Phœnician establishments in the western Mediterranean, and maintained its power and policy on substantially similar lines until it received its great defeats at the hands of Rome.

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

1. What evidences of prehistoric commerce are given by Indian arrow-heads, wampum, Indian ornaments, or the relics of the mound-builders?

2. What modern countries have the strip-form of Egypt? [See a map of South America.]

3. Are there any modern countries like Egypt in the uniformity of15 their conditions and products, diminishing the stimulus to internal trade? [Study, for example, conditions in Alaska, Nevada, or Australia.]

4. Are any of the exports of ancient Egypt still characteristic wares of the country? [See the Statesman’s Year-Book, index under words Egypt, commerce.]

5. What can you infer as to the security of trade from the fact that it was carried on by caravans, bands of merchants?

6. What physical barriers obstructed Egyptian commerce? [See map 33 of Longmans’ School atlas, noting the deserts and the cataracts of the Nile.]

7. Write an essay on the economic conditions of Egypt, from references to that country in the Bible.

8. What countries of the modern world fill the space occupied by the ancient empires of the East? What commerce do they carry on? [See Statesman’s Year-Book.]

9. Can you suggest any reasons why the commerce of these regions seems now much less important than in ancient times?

10. Write an essay on the economic conditions of later Babylon, from descriptions in the Bible. [See Babylon, in the subject-index of the Oxford Bible.]

11. Write an essay on the economic life of the Jews from the descriptions of the Bible.

12. Write a similar essay on the Phœnicians. [See Sidon and Tyre in the subject-index.]

13. Show the similarity of conditions in Phœnicia and in Norway, forcing the inhabitants of both countries to the sea. [Study the physical characteristics of Norway in a geography, and note the history of the Vikings, and the importance of commerce and navigation in modern Norway.]

14. Write a report, from information to be got from the Encyclopædia Britannica, on one of the following subjects:—

(a) The commerce and manufactures of the Phœnicians. [See the index in the last volume of the ninth edition, under Phœnicians.]

(b) The manufacture and trade in glass in the ancient world. [See vol. 10, p. 647.]

(c) The Phœnician purple. [See the references under the word Purple, vol. 20, p. 116, and the index.]

(d) Early navigation. [See the index.]

15. Wares of Phœnician commerce. [Bible, Ezekiel, chap. 27.]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ancient Commerce.—The best available survey of the economic development of the ancient world is Cunningham’s **Western civilization16 in its economic aspects, vol. 1, Ancient times, Cambridge (N. Y.) Macmillan, 1898; this may be used for parallel reading throughout. On Egypt, Adolf Erman, Life in ancient Egypt, London, 1894, is interesting and reliable. Readers of English are fortunate also in having a translation of Holm’s *History of Greece, N. Y., Macmillan, 1894, 4 vols.; it may be made to serve as a history of commerce in the Mediterranean down to the second century. The popular books on Alexander’s conquests and their results, by Wheeler and Mahaffy, give, unfortunately, little attention to economic affairs. P. V. N. Myers, *History of Greece, Boston, Ginn, 1895, is a convenient manual for general reading. Alfred E. Zimmern, **The Greek Commonwealth, revised ed., Oxford, 1915, is an interesting account of the economic and political factors in Athens of the fifth century.

On economic development in the Roman world the student has now available a good manual by Tenney Frank, **An economic history of Rome, Baltimore, 1920. A detailed account of conditions in the provinces is provided by Mommsen’s *Provinces of the Roman Empire, N. Y., Scribner, 1887, 2 vols., $6. The current Roman histories give a distorted idea of Roman commerce by viewing it from the capital.

Maps.—In default of an atlas of the history of commerce students must seek the maps scattered through special works, or rely upon an ordinary historical atlas. Justus Perthes’ *Atlas antiquus (about $.75) can be recommended for use in ancient history; it is admirably executed, and is provided with an index.

17

15. Greece, physical character and products.—The mention of the Greeks at the close of the last chapter introduces us to a people who were, for a time, the leading merchants of the Mediterranean. The peninsular part of Greece has an area less than that of the State of Maine, little more than half that of the State of New York. It is, however, most richly diversified geographically, and no country in the world of an equal area, it is said, presents so many islands, bays, peninsulas, and harbors. The coast line of this little country is longer than that of Spain. No point is more than a few miles from the coast, and there are few points on the coast from which an observer does not see an island. In the Greek sea, moreover, every island is in plain sight either of the mainland or of another island, and in the good season the winds are very regular. Favoring conditions such as these are of vast importance in the early days of navigation, when sailors faced real perils due to their inexperience, and perils of the imagination which were even greater. At home the Greeks inhabited a country which was not rich enough to support them without exertion, but was, on the other hand, not so poor as to force them to use all their ingenuity in finding the means of subsistence. They could easily produce a surplus of oil and wine, but found a deficiency of other products, especially grain and, in the early period, manufactured wares.

16. Rise of Greek commerce. Colonies.—Though it would be hard to conceive a better nursery for the growth of commerce than existed under the conditions here described, the Greeks, when we first get knowledge of them, about 1000 B.C.,18 were not yet ready to take advantage of their opportunities. There was some commerce, it is true, but it lay entirely in the hands of the Phœnicians, who brought utensils and cloth and took away timber and metals. Little by little the Greeks rose to commercial prominence, and gained the place formerly held by the Phœnicians. A striking feature of this revolution was the Greek colonial movement, which covered some five hundred years, and ended about 600 B.C. Greek emigrants settled throughout the Ægean Sea and established themselves as a fringe on the coast of Asia Minor and about the Black Sea; in the West they chose by preference the shores of southern Italy and Sicily, but founded colonies as far as Malaga in modern Spain, and created a great commercial center on the site of modern Marseilles. The colonies kept up an active intercourse with the mother country, and Greek sailors and merchants ousted the Phœnicians from their commanding position. The Greeks at home began to produce wares for export, seeking customers not only among the colonists but in other markets also; they emancipated themselves from their former dependence on Oriental manufactures, and developed the clay, bronze, and woolen industries to a point not dreamed of before.

17. Rapid development in the fifth century, B.C.—In this, which may be termed the preparatory period of Greek commerce, the leadership rested with the Greek colonies in Asia; Miletos was the first of the Greek cities in commercial importance. The advance of the Persian kings about 500 broke the power of the Greek colonies in the East; at the same time the western colonies, especially Syracuse, grew rapidly in importance, and forced Carthage to recognize their supremacy in the northern Mediterranean. The mother country itself was, however, that part of the Greek world which showed the most striking gains. The successful resistance to the Persians was followed by a remarkable development not only in politics but in industry and commerce as well, and Greece now took for two centuries the position which England occupies in the19 modern world. The little island of Ægina (near Athens), rocky and sterile, supporting to-day but 6,000 inhabitants, became for a time the most important market of the Greek world; it amassed fabulous riches by a commerce penetrating all seas, aided by an artificial harbor and a strong war navy. Another great commercial city, destined to a longer career, was Corinth; this city was the natural medium of trade with the western colonies, not only because it offered an opportunity to reach them without rounding the dreaded promontory of the southern tip of Greece, but also because some of the leading colonies of the West were Corinthian or closely allied to the Corinthians.

18. Rise of Athens to leadership. Exports.—The city of Athens, which had developed rapidly in the century preceding the Persian wars, rose to the first place among the Greek cities in the century in which they occurred (500-400 B.C.). The Athenians broke the power of Ægina in armed conflict, and appropriated its commerce; the Athenian sea-port, the Piræus, became the leading commercial port of the Greek world, and remained so until the Macedonian period (about 300). Readers must be referred to one of the narrative histories of Greece for an account of the way in which Athens built up its empire in the Ægean Sea, and for the story of the varied fortunes of its political power. Even in times of defeat, when its war-navy was scattered and its leagues and alliances broken up, it was still able to control a large part of the trade of the Ægean and Black seas, and maintained an important commerce with the South and West. The favorable situation of the city, and the ability and energy of its navigators and business men, enabled it to conduct a large carrying trade for other peoples, and many of the exports were foreign wares which were merely transshipped in the Piræus. Of native wares it exported silver and coin, from the mines near the city, some natural products (oil, figs, honey, wool, marble) of comparatively slight importance, and especially manufactured wares, of which pottery was the chief.

20

19. Athenian imports and policy.—The chief import was wheat, on which Athens was then as dependent as England is now; the city had grown so great by trade that the surrounding country was unable to support it. The great granary of Athens was the level country north of the Black Sea, and the Athenians made extraordinary efforts to control the narrow entrance to the Black Sea, that they might assure their food supply. They were not entirely dependent on this source, however, and imported wheat also from Sicily, Egypt, Syria, and the mainland to the North. Among the other imports were ship-building materials, salt fish, slaves, raw materials for the Athenian manufacturers, and articles of luxury. The breadth of the Athenian trade is pictured in the statement of a contemporary: “What delicacies there are in Sicily, or Lower Italy, or Cyprus, or Egypt, or Lydia, or on the Pontus, or in Peloponnesus, or anywhere else, they all are brought to Athens by her control of the sea.”

The commercial policy of the Athenians was framed with an eye especially to the interests of the consumer. What duties were levied were low, and had no leaning to “protection” in the modern sense. The export of articles especially desired (wheat, ship-building materials) was restricted in the hope of keeping up the home supply, and commercial advantages were granted or withheld with the idea of exercising political pressure on other states; but nothing like modern protectionism can be found in the commercial policy of this period.

20. Contrast of the ancient and modern world; effect of Macedonian and Roman conquests.—In the course of our narrative we are now approaching a point when a great change came over the ancient world. The isolation of the earlier states of antiquity is their most striking feature. Each one lives only unto itself. It rises in civilization and then declines, without sharing its gains and losses with other states. It may conquer and hold them for a time, it is true, but it rules them as foreign territory, with alien interests; and the great empires crumble as readily as they are made. This21 characteristic of ancient history is one of its main difficulties to the student, for it deprives him of any bond of connection between the peoples, and forces him to pass from one to another of them, until he feels lost in the complexity of the narrative.

The modern world, with its common fund of culture and its community of interests uniting different peoples, could arise from these conditions only after long centuries of struggle. The unity of the Christian faith was needed to confirm the union of peoples in a common civilization. The process of union begins, however, at the point which we have reached; the great conquests of Alexander of Macedon, and those of Rome, did much to break down the barriers between peoples, and to prepare them for the acceptance of a common civilization and a common religion. It is to be hoped that the student knows already something of the narrative of those conquests. We shall have to confine ourselves to the results as they appear in the history of commerce. Here the reader can merely be reminded that Alexander united the eastern world into an empire extending from Greece to India, a little before 300 B.C., and that the Romans began about 200 B.C. to extend their authority outside the Italian peninsula, and before the birth of Christ had subjected to it practically all the peoples whose history we have been studying.

21. Effect of Alexander’s conquests on commerce; decline of Greece.—In appearance the empire of Alexander outlived its founder but a few years, and then dissolved. Alexander, however, was a civilizer as well as a conqueror; he endowed the East with a common fund of Greek culture; and however distinct or hostile the states might seem thereafter the peoples were united as they had never been before. Commerce took on a new aspect. Greece, which before had been at the center of the great commercial movements, was now left on the western edge. Greek merchants could for a time use their former commanding position to share in the great commercial development, but in the long run their struggle was hopeless. The most energetic Greeks left their home to settle in eastern22 countries which were richer, more populous, and closer to the great currents of trade. Corinth was the only city which managed to maintain and extend its trade. Athens declined rapidly in commercial importance; and grass grew and cows were pastured in the streets of other towns which had once been important markets.

22. Rise of great cities.—Some indication of the development of commerce, and of the rearrangement of its important centers, can be got from a study of the great cities of the ancient world. Before the time of Alexander there were only three cities of the Mediterranean with a population of over 100,000, Syracuse, Athens, Carthage; none of these had a population far above that figure. About 200 B.C., scarcely more than a century afterward, there were four cities with a population over 200,000, Alexandria, Seleukia, Antioch, Carthage; one city with a population far above 100,000, Syracuse; and of cities with a population about 100,000 there were Corinth, Rome, Rhodes, Ephesos, and possibly others. The names of some of these cities are already familiar to us. Carthage was enjoying its last century of commercial greatness, before Rome robbed it of its influence in the northern Mediterranean. Syracuse was the chief Greek colony of the West, destined also to fall under the Roman power just before 200. Other names, however, are entirely new to history, or first became of great importance at this time, and the best idea of the commerce of the period can be got by considering the reasons for their greatness.

23. Alexandria, Seleukia, Antioch.—Alexandria, as its name suggests, was founded by the Macedonian conqueror. It was situated on a tongue of land between a lagoon and the sea, near the most western of the mouths of the Nile. It had a double harbor, formed by the island Pharos, which has given the name for lighthouse in some of the modern languages (French, phare, Italian, fáro), as the most celebrated lighthouse of antiquity was erected there. Alexandria furnished the only good harbor for large vessels on the coast of Egypt; it had access to the Nile, tapping one of the great granaries of23 antiquity, and connected with the Red Sea through the canal that ran from the Nile to the Bitter Lakes. It was at the point where the sea-route from the far East reached the Mediterranean, and it became by right the greatest market and the largest city that the world had known.

Next to it in size and importance came two other cities, Seleukia and Antioch, which were founded even later than Alexandria. Seleukia, on the Tigris, took the place of the earlier Babylon and the later Bagdad; it was situated in a rich plain at the points where the routes from the Persian Gulf and the Persian highlands met on their way westward. Antioch was at the focus of the routes by which the trade with inner Asia was carried on. Situated at a point where the Euphrates approaches to within a few days’ march of the coast, and where the valley of the Orontes offers the best means of reaching the sea from the interior, it had the full benefit of the revival of eastern commerce which followed the conquests of Alexander and the enlightened rule of his successors.

24. Rhodes.—Only one other city, Rhodes, deserves especial attention, and this not because of its size alone but also because it was so specifically a commercial city. The little island could offer but scanty products to commerce, but it enjoyed an exceptionally favorable position, where navigators from Egypt and Syria, avoiding the dangers of the open sea, would put in for shelter and to trade. Rhodes followed a far-sighted foreign policy, guided by the idea of securing the greatest freedom of trade; it policed the seas and repressed piracy with vigor; and established a code of mercantile law which was celebrated as a model and which invited dealings in its market. The Rhodians were skilful navigators, and developed the principles of commercial association to a point of high efficiency. It is little cause for wonder, therefore, that commerce flowed hither from all parts of the eastern Mediterranean and even from the Black Sea; that foreign merchants sent their sons there to learn the conduct of commerce; and that great riches were accumulated, of which one24 evidence was furnished by the many colossi, gigantic statues, about the city.

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

1. Prove the statement in the text, regarding the Greek islands. Take a good map, measure off on the scale 25 miles, the distance at which hills of about 125 feet are visible (the Greek islands are mountainous and the air very clear), and show by what stepping-stones timid sailors could advance.

2. Study in detail the influence of the physical characteristics of Greece on the people and their history. [See Myers, chap. 1; Holm, vol. 1, chap. 2.]

3. Write a report on the evidences of early civilization and trade. [Holm, vol. 1, chap. 8.]

4. Write a report on the early commerce carried on by Phœnicians. [Holm, vol. 1, chap. 9.]

5. Make a careful study of the Greek colonial movement, noting, (a) the motives to colonization, (b) the extent of Greek colonies, (c) the relations with the mother-country, (d) the mode of life in the colonies, (e) the influence on the commercial development of the different parts of Greece. [Myers, chap. 5; Holm, vol. 1, chaps. 12, 13, 14, 21, 25.]

6. Write a report on the history of the Greek colonies of the West, especially Syracuse and its contest with Carthage. [Holm, vol. 1, chap. 25; vol. 2, chap. 6, 29; Freeman, Story of Sicily, N. Y., Putnam, 1892, $1.50.] ·

7. Study the growth of the sea-power and empire of Athens, indicating on a map the allied or subject cities. [Myers, chaps. 15, 16; Holm, vol. 2, esp. chap. 17.]

8. Contrast Athenian exports of this period with the exports of modern Greece. [Statesman’s Year-Book.]

9. What is the leading port of modern Greece? [Same.]

10. Write an essay comparing the Athenian and the British empires, noting, (a) advantages of geographical position, (b) products of the home country, exports and imports, (c) naval power and naval stations, (d) policy to members of the empire, (e) commercial policy of the home country. [See Myers or Holm, and the chapters in this book on England; compare E. A. Freeman, Greater Greece and Greater Britain, London, 1886.]

11. Compare the imports of ancient and of modern Greece. [Statesman’s Year-Book.]

12. Make a chart, naming on a horizontal line the leading states of antiquity, from Egypt to Rome, placing dates (3000, 1500, 1000, etc.) in a column at the left, and indicating changes in the history of each state in the appropriate place in its column.

25

13. Draw a map showing the extent of Alexander’s conquests, and comparing the empire with earlier Oriental empires. [See the maps in Myers, and if no good historical atlas is available consult the maps in the Oxford Bible, teacher’s edition.]

14. Study the influence of the Macedonian conquests on civilization and commerce. [Myers, chaps. 25, 26, 27; Holm, vol. 3, esp. chap. 27.]

15. Write a report on the economic decline of Greece after the Macedonian conquest. [Holm, vol. 4.]

16. Is England exposed to such a change in the currents of trade as furthered the decline of Greece?

17. Why do great cities rarely grow up without the aid of commerce? [The answer to this question is suggested in a later chapter, but the student should be able to work it out himself.]

18. Are there any exceptions? What is the commerce of Washington, D. C.? Is there any one of the cities named in this section which may have owed its size to something beside commerce?

19. Has there been any later period in which great cities have risen suddenly, as in this period after Alexander?

20. Write a commercial history of Carthage from the information to be got in a Roman history, or in the Encyclopædia Britannica. Write a commercial history of Syracuse in the Roman period, from the same sources.

21. Write a report on the commerce and civilization of one of the cities, using Holm, vol. 4, and the encyclopedia.

22. Endeavor to trace the later history of one of these cities, and to discover its population now, using the encyclopedia and a geographical gazetteer.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

See chapter ii.

26

25. The Roman state; Rome not a commercial city.—In entering on the period of Roman domination we need spend no time over the earlier history of the city which came to rule the world. The Romans were not a commercial people. Even in the last two centuries B.C., when Rome extended her sway over the eastern countries which have already been noticed, and subjected a large part of the West as well, Rome did not become a commercial center. The city grew to unparalleled size, it is true, and required immense imports of food to support the population. These imports came, however, as taxes and tribute to the conquerors. Rome supplied no exports of considerable amount, and built up no great carrying and forwarding trade such as would have made the city the center for the exchanges of other people. The service which the Romans gave to the world of their time, and for which they received such rich reward, was not economic but political in character; they were the greatest organizers and administrators of antiquity, and by their skill in the arts of war and government succeeded in living on the labor of subject peoples. They were not mere parasites. They earned all that they received by one great contribution, “pax Romana,” Roman peace, which continued almost unbroken for centuries, and which furnished an opportunity for commercial development before unknown.

26. Development of commerce in the Roman East.—The study of commerce in the Roman period resolves itself, as suggested above, into a study of commerce in the different regions of which the great Roman state was composed. In27 the East commerce developed on the lines which have already been described; Alexandria and Antioch continued to be great markets for Oriental wares, coming now even from India and China; and Carthage remained an important outlet for the African trade. Asia Minor, northern Africa, and southeastern Europe reached the very pinnacle of their historical development in the Roman period; these countries have never since attained to anything like the prosperity they then enjoyed. We shall not have the time hereafter to notice the commerce of these regions in detail; the reader may take it for granted that merchants struggled strenuously to keep the place they had reached, and that decline came slowly, when it did come later.

Our attention must be directed hereafter mainly to the West. It was there that the most important states of modern Europe arose, and there that commerce grew up in its modern form. Our chief interest must be to know what progress the peoples of the West made under Roman rule, and how far commerce had developed among them.

27. Backward condition of the people of the West.—The peoples of the West were far behind those of the East in civilization. They have sometimes been compared to the American Indians, and though the comparison is inexact in detail and may easily mislead, it gives still a rough indication of their backwardness. They lived more from the products of their flocks and herds than from agriculture, when the Romans came in contact with them; they had practically no towns, and no considerable trade.

The five hundred years (roughly) of Roman rule made some striking changes in the Roman provinces of the West (modern Spain, France, England; not Germany or countries farther east). It kept the people in order, and gave them an opportunity to acquire the elements of a higher civilization. The fact that modern Spanish and French are based on Latin remains always a striking testimony to the Roman influence on the provincials.

28

28. Limited influence of Rome on the commercial development of the West.—It is easy, however, to overestimate the results of this influence, especially so far as regards economic progress. Rome gave her subject peoples of the West a chance at commercial development, but none had sought it and few were ready to profit by it. The Roman government constructed a system of military roads, models of their kind, which enabled troops and messengers to reach speedily the different provinces. Romans settled in the provinces as officials or private gentlemen, and Roman culture was acquired by the wealthy provincials; cities and large landed estates formed centers of industry and exchanged manufactured products for the raw materials of the surrounding districts.

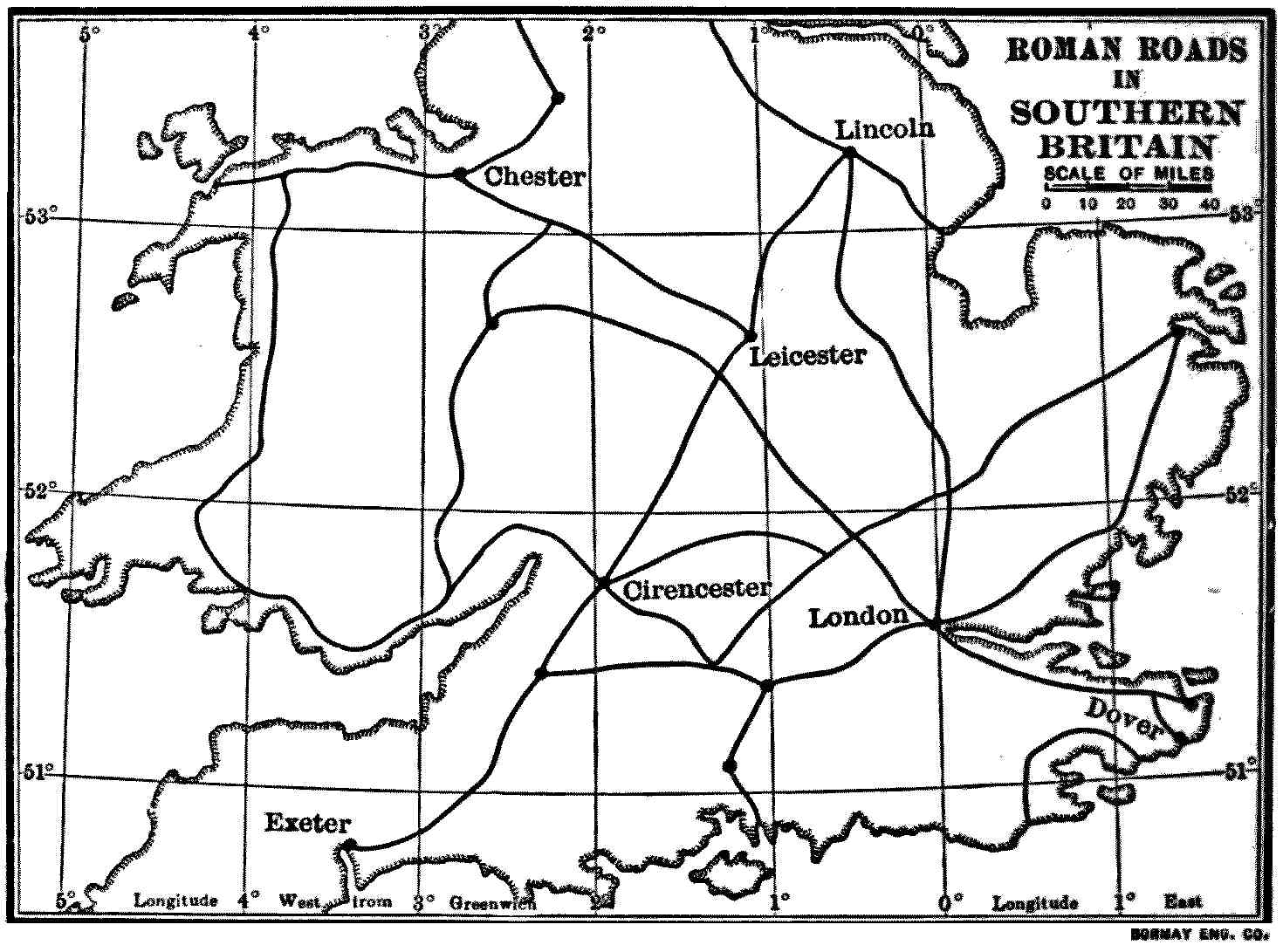

ROMAN ROADS IN SOUTHERN BRITAIN

The course of some of the roads is uncertain, and the number would be increased or diminished according to the authority followed. The map gives, however, a fair picture of the Roman road system; it was, evidently, not so extensive as our modern railroad system.

The roads, however, seem to have served mainly Roman purposes, and the cities and culture depended mainly on29 Roman influence for their support. The mass of the people remained passive, and advanced slowly. Most of them lived by agriculture in the country districts, producing the things necessary for their own subsistence and a small surplus for the Roman tax-gatherer; they received for their surplus no wares which would have formed the basis of commerce. However much Rome did to efface the differences of race, language, and national tradition, such differences remained to hinder commerce; and peoples were still separated by great distances and by serious physical barriers. The commercial development of the West, though it may seem great in comparison with conditions in the following period of disorder, was very limited even at the height of Roman power.

29. Decline of Roman power and of commerce in the West.—The time came soon when the provincials could no longer look to Rome for protection and stimulus. In the third century, A.D., the Roman government began to go to pieces. It lacked the force to repress internal revolts in the provinces, and to repel the inroads of barbarians on the frontiers. The process of decline had already proceeded far before the “Fall of Rome” (476), when even the shadow of authority passed from the Roman Emperor of the West. The remnants of Roman rule centered henceforth about the eastern capital, Constantinople. In the West barbarian chieftains established government of a kind on the fragments of the Roman state, but endeavored in vain to follow the models which the Romans had set them. The motives to commerce grew weaker as Roman culture disappeared, and the obstacles to commerce increased rapidly with the decline in public order. Brigandage and piracy became more profitable than honest industry; roads and bridges deteriorated; the course of rivers was obstructed. Even a great ruler like Charlemagne, who had himself crowned Emperor in 800, could do little to stay the process of decline, and weaker successors could do still less. The last remnants of the Roman organization seemed to have passed away, and the European world passed into the “Dark Ages.”

30

QUESTIONS AND TOPICS

1. Endeavor to verify the statements in the text by studying the descriptions of Roman commerce in the current Roman histories. Ask the following questions of them. What wares, beside manuscript books and a few other items of no great importance, did the people of Rome produce for export? What wares beside food for the people and luxuries for the rich did they import?

2. Show how the taxes and tribute from conquered provinces can be regarded as war-insurance.

3. Write a report on the civilization and commerce of one of the provinces of the Roman Empire. [See Mommsen, Provinces, esp. vol. 1, chap. 7, Greek Europe; chap. 8, Asia Minor; vol. 2, chap. 12, Egypt; chap. 13, the African Provinces.]

4. Write a similar report on one of the provinces of the West. [Vol. 1, chap. 2, Spain; chap. 3, Gaul; chap. 4, Germany; chap. 5, Britain.]

5. Study the civilization of Roman Britain, distinguishing carefully the life of the upper (Roman) classes, and the life of the common people. What effect would this contrast of classes have on the extent and character of commerce in the Roman period? [Consult manuals of English history.]

6. Study the economic and political factors in the fall of Rome. [Cunningham, West. civ., vol. 1, p. 170 ff.; Adams, Civ., chap. 4.]

7. Compare the fall of Rome with the growth of political corruption in some modern cities, as affecting the prosperity of commerce.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

See chapter ii.

31

30. Political conditions affecting commerce; the modern system of government.—The reader who studies the history of commerce in the medieval period faces a system of government entirely different from that of modern times, which he must understand before he can appreciate the peculiar conditions of commerce then. We can illustrate the modern method of government by taking a country, say France, for an example. We wish to understand the relations of the capital, Paris, to other parts of the country, say the district around Bordeaux, in the southwest corner. An observer of this country will find that Paris and Bordeaux are united by different means of communication and transportation, telegraphs and posts, railroads, highways and canals, which are constantly employed in the service of government. On the path from the province to the capital go the reports of the officials who are in charge of the government of Bordeaux; and, if they fail in their duties, petitions and complaints from private citizens, asking relief, will take the same path. By this path, also, the taxes collected at Bordeaux will stream to the treasury at Paris, to be employed in maintaining the government. Part of these taxes will be expended at Paris, to support the officials who live in the capital, the central army, etc. Part, however, must be used to fulfil the local needs of Bordeaux; and on the road from the capital to the province we shall find money and wares, going as salaries to officials, appropriations for public works and the like. On this road, furthermore, we shall find a stream of messages, sent by the central government to its local subordinates,32 directing them in their work; these messages will answer the reports of officials and the petitions and complaints of subjects.

31. Impossibility of applying modern methods of government in the period after the fall of Rome.—The system of government, thus roughly outlined, was the system used in the period when Rome was still strong. But when the power of Rome declined it became constantly more difficult to maintain a system of the kind; every obstacle to the free passage of men and wares weakened the hold of the government on its provinces. The roads grew worse, and while they were still passable the danger of traversing them increased, so that the expense of maintaining this government became prohibitive. The reports from officials and the petitions from subjects were delayed or lost; only a small part of the local taxes reached the treasury at the center. The central government, on its side, found that it had no longer the means to pay the bills for salaries and public works in the provinces, and found that its commands were not received there, or were not obeyed, because the government could no longer send officials and troops to force obedience.

32. The feudal system; rise and character.—The time came, finally, when the government had to recognize publicly the change in conditions, and to adopt a system of quite a different kind, known as the feudal system. In substance it told the man who before had been a salaried official that it could no longer pay salaries, and that he must support himself henceforth from the revenues of land which would formerly have gone to it as taxes. It maintained still a nominal superiority, and exacted from the feudal lords who now assumed the responsibility of government certain payments for general public service, occasionally a sum of money and more frequently personal service of a military or judicial kind. Practically, however, the state had split into little pieces; the central government had lost the right even to nominate the successor of an official, and each was succeeded in the duties and profits of government by his son, as though he had been33 a petty king. It is impossible to state accurately the number of little governments of this kind that existed in the different countries of Europe; in France, in the tenth century, it is supposed to have exceeded 10,000. The character of government varied greatly, of course, according to local conditions, not only in different countries but in different parts of the same country, but it was everywhere extremely low when measured by modern standards. This will be apparent as we survey the conditions under which commerce was carried on in the period known as the Dark Ages.

33. Difficulties and dangers of transportation.—Attempt was made to maintain the roads, which of course are essential to trade by sea as well as by land, by making the proprietors through whose land they ran responsible for their repair. Many of the proprietors managed to escape contribution, and what work was done was largely wasted, through ignorance and lack of proper superintendence. We shall see that even in later periods the roads were bad; in this early time they were so bad that they seem to have been mere tracks, of service to passengers on foot or on horseback, but of little use for wagon traffic.

The merchant suffered even more, however, from bad men than from bad roads. Government was so weak that robbery was common; people were so ignorant of everything outside the narrow sphere of local interests that they suspected every stranger, and too often with reason. There is a whole series of English laws, beginning about 700 and continuing for centuries, of which this is an early example; “If a man come from afar, or a stranger, go out of the highway, and he then neither shout nor blow a horn; he is to be accounted a thief, either to be slain or to be redeemed.”

34. Restrictions imposed to insure security. The market.—The dangers of travel required a merchant to go in company with others, and the danger that a merchant would himself turn robber made it necessary for him to subject himself constantly to public supervision, and to get residents who34 would act as sureties for his good behavior. In England, even in the eleventh century, the central government thought it necessary to pass a law “that every man above twelve years of age make oath that he will neither be a thief nor cognizant of theft.” Such a general statute would surely be of little use.

Many other statutes of a more specific nature were passed, which may have helped to repress robbery, but which must have hampered trade at the same time. The idea in general was to force a man to make his purchases in public, so that if he appeared at home with new wares he could get witnesses to prove that he came honestly by them. Cattle formed a large part of the personal property in early times, and as these could readily be stolen, many laws were passed restricting the trade in cattle. Other things were included in the restriction, however, as the need of protecting commerce became more apparent. In England, in the tenth century, a man was not allowed to buy or sell any goods above the value of twenty pence, unless he did it within a town where a public official and witnesses could legitimate the bargain. In this practice is found the origin of the market, a medieval institution of which more will be said later. A market was a place appointed by the government, where bargains could properly be made; and only small exchanges of household produce could be made outside it, in the open country. Beginning in the need that was felt to prevent thieving it developed as a public institution, which the people found it profitable to extend as a means of collecting tolls and of regulating internal trade.

35. Society organized to exist with the minimum of commerce; the medieval village.—The striking and important feature in the life of European peoples at this period was not the large amount of commerce carried on, but the small amount. The people were organized on a system which enabled them to support life with the least commerce possible. Instead of being concentrated in towns, they were isolated in little groups, often called manors, one of which would be composed often35 of less than 100 people, who got their living from the square mile or so of land surrounding them. It is not necessary here to discuss the social and political life of these little groups, though it is proper to remark that often some of the inhabitants were slaves, and many more were only half-free, like the Russian serfs of the nineteenth century.

36. Self-sufficiency of the villages; low stage of the arts of production.—The economic life of these village groups is the side in which we are interested, and the chief point in that was the self-sufficiency of each group. A village tried to produce everything that it wanted, to be free from the uncertainty and expense of trade. We find, then, that almost all the people in a village were agriculturists, and these raised the necessary food supply by methods which were always crude, and were often very cumbersome and wasteful. The stock was of such a poor breed that a grown ox seems to have been little larger than a calf of the present day, and the fleece of a sheep weighed often less than two ounces. Many of the stock had to be killed before winter, as there was no proper fodder to keep them, and those that survived were often so weak in the spring that they had to be dragged to pasture on a sledge. Insufficient stock meant insufficient manure, and though the fields were allowed to lie fallow every third year they were exhausted by constant crops of cereals, and gave a yield of only about six bushels of wheat an acre, of which two had to be retained for seed.

Not only the food but nearly everything else had to be raised where it was to be consumed. Houses were constructed of materials from the forest, clothes were made out of flax and wool from the village fields, furniture and implements were made at home. Nearly every village had a mill, usually run by water, to grind its meal or flour; some villages had a smith or carpenter; few special artisans beside those suggested were to be found in the ordinary manor.

37. Evils resulting from the lack of commerce.—Before we proceed to describe the growth of European commerce from36 such origins it will be well to stop and consider the results of a system which was based on the lack of commerce. With regard to the main product, food staples, the result was an alternation of waste and want. A good year brought a surplus for which there was no market outside the village, and which could not be worked up inside for lack of manufacturing skill and implements. A bad harvest, on the other hand, meant serious suffering, because there was no opportunity to buy food supplies outside the manor and bring them to it. Nearly every year was marked by a famine in one part or another of a country, and famine was often followed by pestilence. Diseases now almost unknown in the civilized world, like leprosy and ergotism or St. Anthony’s fire, were not infrequent. The food at best was coarse and monotonous; the houses were mere hovels of boughs and mud; the clothes were a few garments of rude stuff. Nothing better could be procured so long as everything had to be produced on the spot and made ready for use by the people themselves. Finally, these people were coarse and ignorant, with little regard for personal cleanliness or for moral laws, and with practically no interests outside the narrow bounds of the little village in which they lived.