The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Anzac Book, by Various

Title: The Anzac Book

Author: Various

Release Date: April 2, 2023 [eBook #70441]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

“The Australian and New Zealand

troops have indeed

proved themselves worthy sons of the Empire.”

GEORGE R.I.

The

Anzac Book

Written and Illustrated in Gallipoli by

The Men of Anzac

For the benefit of Patriotic Funds

connected with the

A. & N. Z. A. C.

Cassell and Company, Ltd

London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne

1916

The Copyright in all

the Contributions, both

pictures and writings,

contained in The

Anzac Book is

strictly reserved to the

Contributors.

[Pg v]

| PAGE | ||

| INTRODUCTION. By Lieut.-Gen. Sir W. R. Birdwood | ix | |

| EDITOR’S NOTE | xiii | |

| THE LANDING. By A Man of the Tenth (A. R. Perry, 10th Batt. A.I.F.) | 1 | |

| THE REMINISCENCE OF A WRECK. By Lieut. A. L. Pemberton (R.G.A.) | 7 | |

| AN AUSTRALIAN HOME IN 1930. By “Soldieroo” (2nd Field Co., Aust. Engrs.) | 9 | |

| NON NOBIS. By C. E. W. B. | 11 | |

| THE ÆGEAN WIND. By H. B. K. | 14 | |

| OUR FATHERS. By Capt. James Sprent, A.M.C. (3rd Field Amb.) | 14 | |

| GLIMPSES OF ANZAC. By Hector Dinning (Aust. A.S.C.) | 17 | |

| PARABLES OF ANZAC. | 23 | |

| THE YARNS THAT ABDUL TELLS. By A. P. M. | 24 | |

| THE GRAVES OF GALLIPOLI. By L. L. | 25 | |

| TO A LYRE-BIRD. By H. J. A. (8th Batt. 2nd Infantry Brigade) | 26 | |

| THE NEVER-ENDING CHASE. By Am. Park | 30 | |

| ANZAC DIALOGUES. By N. Ash | 31 | |

| FROM QUINN’S POST. By Pte. V. N. Hopkins, A.M.C. | 32 | |

| THE HAPPY WARRIOR. By M. R. | 33 | |

| HOW I SHALL DIE. By Pte. Charles Lowry (9th Aust. Batt.) | 34 | |

| BEACHY. By Ted Colles (3rd L.H. Field Amb.) | 35 | |

| THE ANZAC HOME—AND A CONTRAST. By E. Cadogan (1/1 Suffolk Yeomanry) | 41 | |

| FLIES AND FLEAS. By A. Carruthers (3rd Aust. Field Amb.) | 44 | |

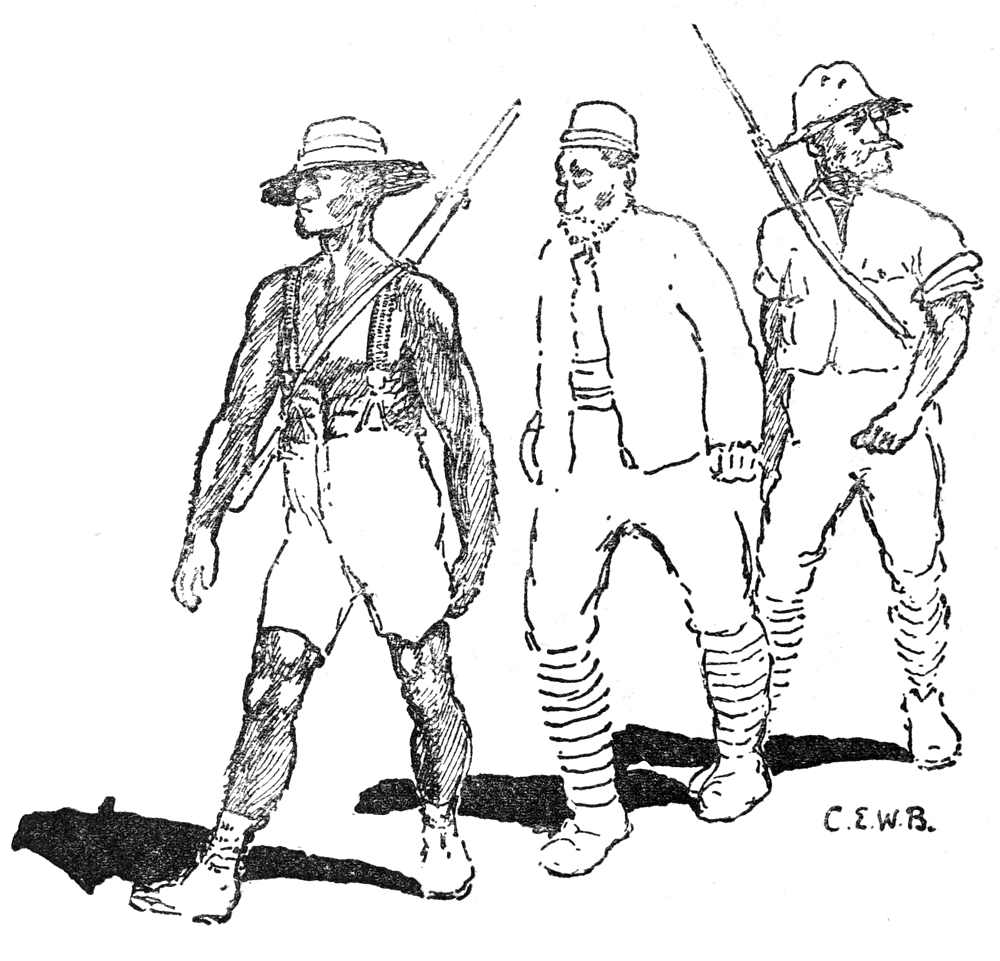

| ANZAC TYPES:— | ||

| 1. Wallaby Joe. By W. R. C. (8th Aust. L.H.) | 45 | |

| 2. The Dag. By E. A. M. W. | 47 | |

| 3. Bobbie of the New Army. By “Tentmate” (11th London Regt.) | 49 | |

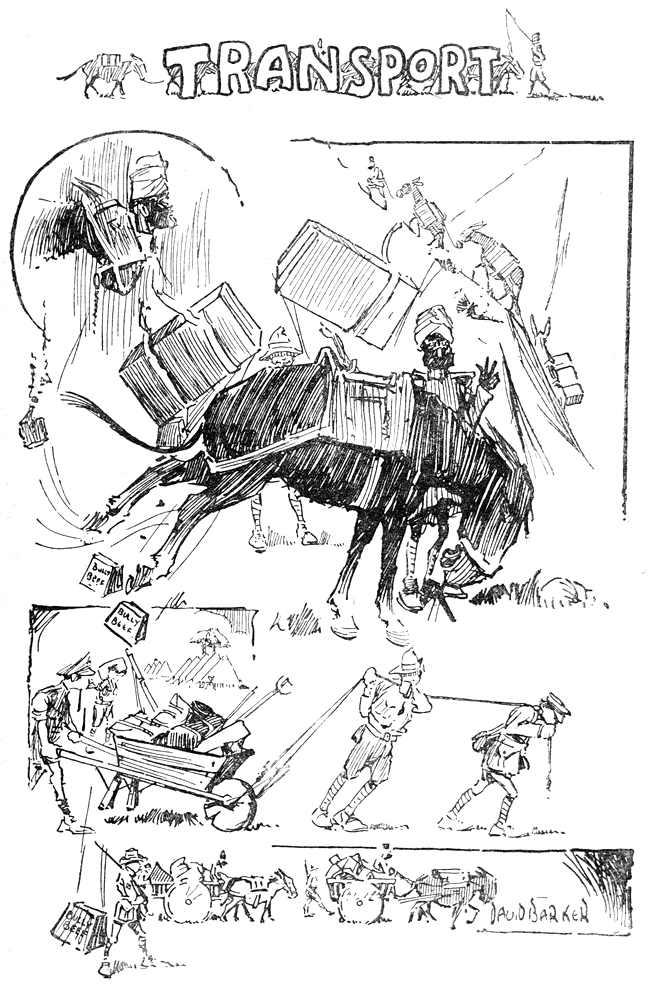

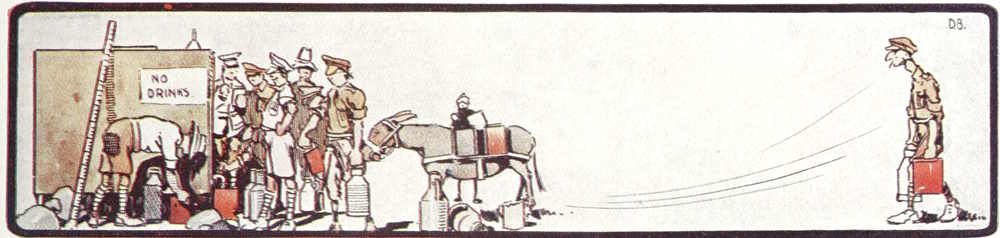

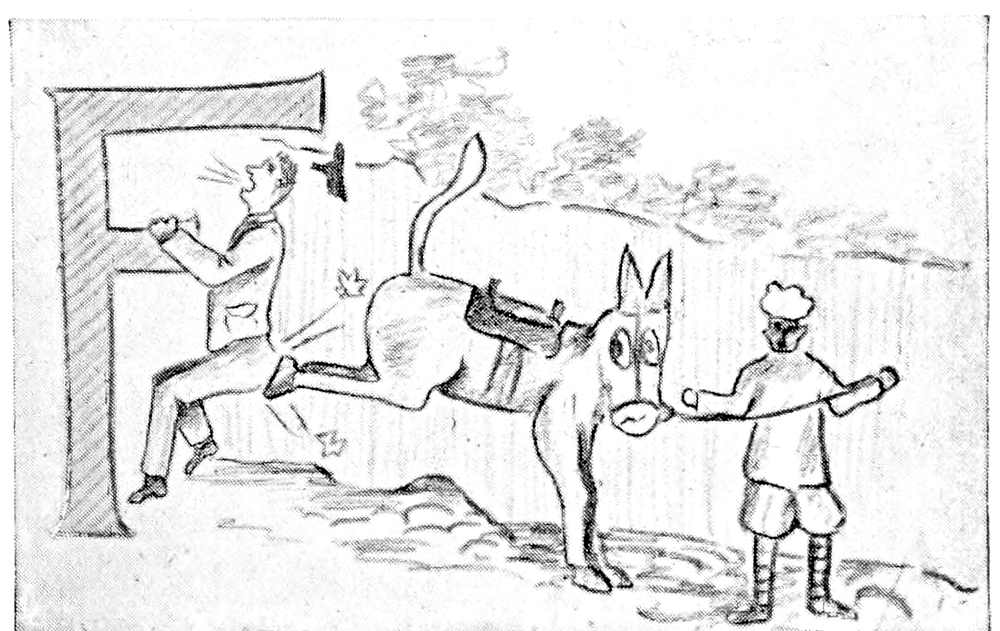

| THE INDIAN MULE CORPS. By B. R. | 50 | |

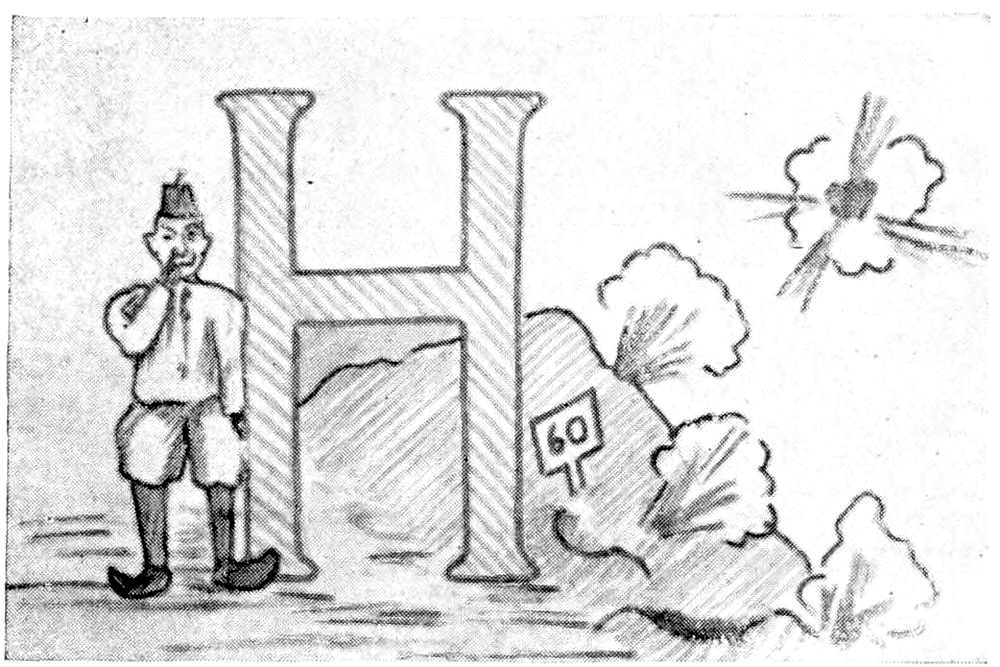

| HILL 60. By C. J. N. | 50 | |

| JENNY. By Lance-Corp. F. C. Dunstan (B Depot, 6th A.A.S.C.) | 53 | |

| MARCHING SONG. By C. J. N. | 54[Pg vi] | |

| FURPHY. By Q. E. D. | 56 | |

| FROM MY TRENCH. By Corp. Comus (2nd Batt. A.I.F.) | 57 | |

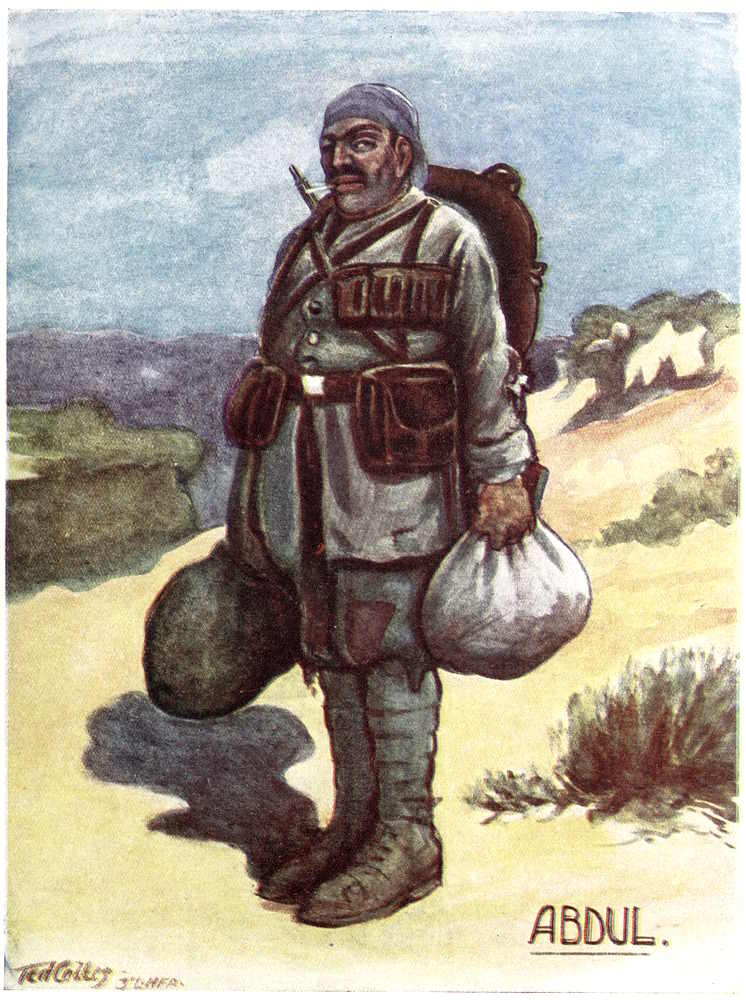

| ABDUL. By C. E. W. B. | 58 | |

| A CONFESSION OF FAITH. By Capt. James Sprent (A.M.C.) | 59 | |

| OUR FRIEND THE ENEMY. By H. E. W. | 60 | |

| ARMY BISCUITS. By O. E. Burton, N.Z.M.C. | 61 | |

| THE LOST POEM. By R. A. L. (1st Aust. Stat. Hosp.) | 65 | |

| A LITTLE SPRIG OF WATTLE. By A. H. Scott (4th Battery, A.F.A.) | 67 | |

| THE TRUE STORY OF SAPPHO’S DEATH. By M. R. | 68 | |

| THE EVERLASTING ARGUMENT. By C. D. Mc., R.S.D. (11th Aust. A.S.C.). | 68 | |

| THE UNBURIED. By M. R. (N.Z. Headquarters) | 69 | |

| THE STORY OF ANZAC. (Sir Ian Hamilton’s Dispatches) | 71 | |

| ANZACS. By Edgar Wallace | 95 | |

| TO MY BATH. By H. H. U. (Northamptonshire Regt.) | 96 | |

| ANZAC LIMERICKS. By C. D. Mc. | 96 | |

| HOW I WON THE V.C. By “Crosscut” (16th Batt. A.I.F.) | 98 | |

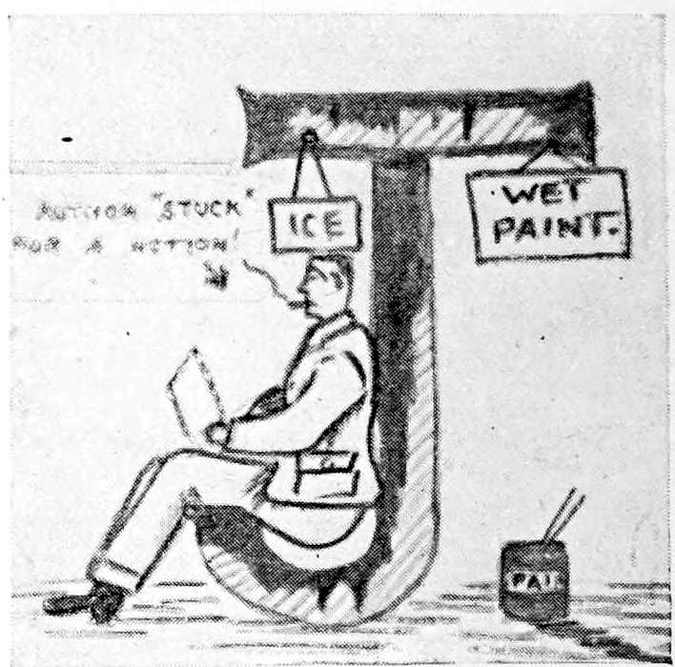

| ICY. By E. A. M. W. | 102 | |

| THE TROJAN WAR, 1915. By J. Wareham (1st Aust. Field Amb.) | 104 | |

| THE PRICE. By Corp. Comus (2nd Batt. A.I.F.) | 104 | |

| KILLED IN ACTION. By Harry McCann (Headquarters, 4th Aust. Light Horse) | 105 | |

| A GREY DAY IN GALLIPOLI. By N. Ash (11th A.A.S.C.) | 106 | |

| MY ANZAC HOME. By Corp. George L. Smith (24th Sanitary Sect., R.A.M.C.T.) | 107 | |

| WHAT FRANK THOUGHT. By A. J. Boyd (A.N.Z.A.C.) | 108 | |

| ARCADIA. By Bombardier H. E. Shell (7th Battery, A.F.A.) | 110 | |

| THE CAVEMAN. By J. M. Collins (9th Batt.) | 113 | |

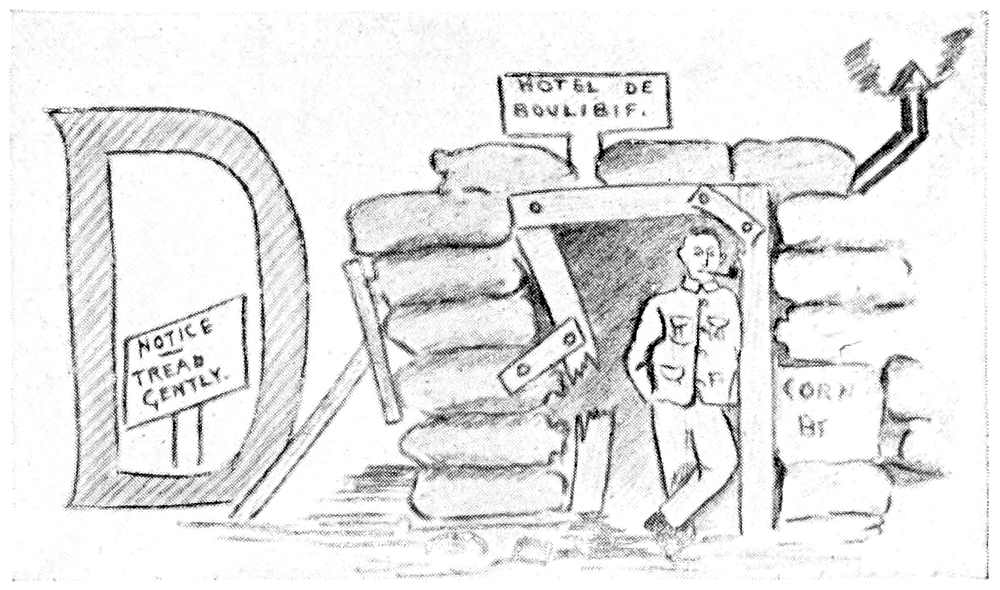

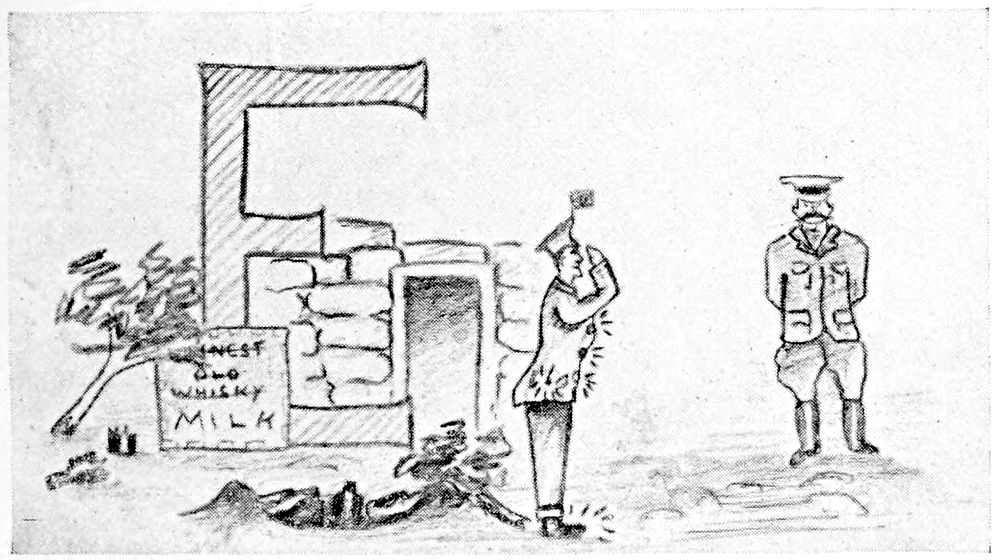

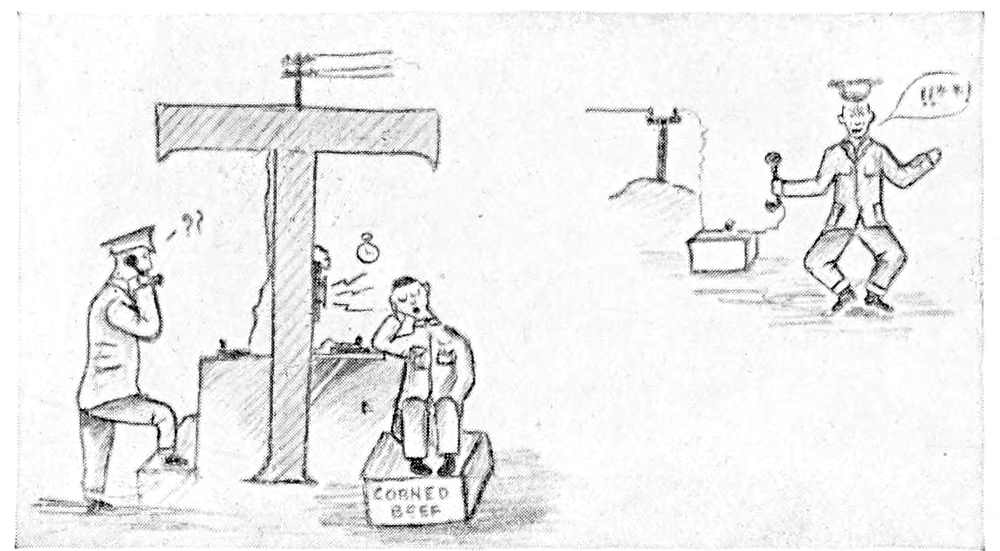

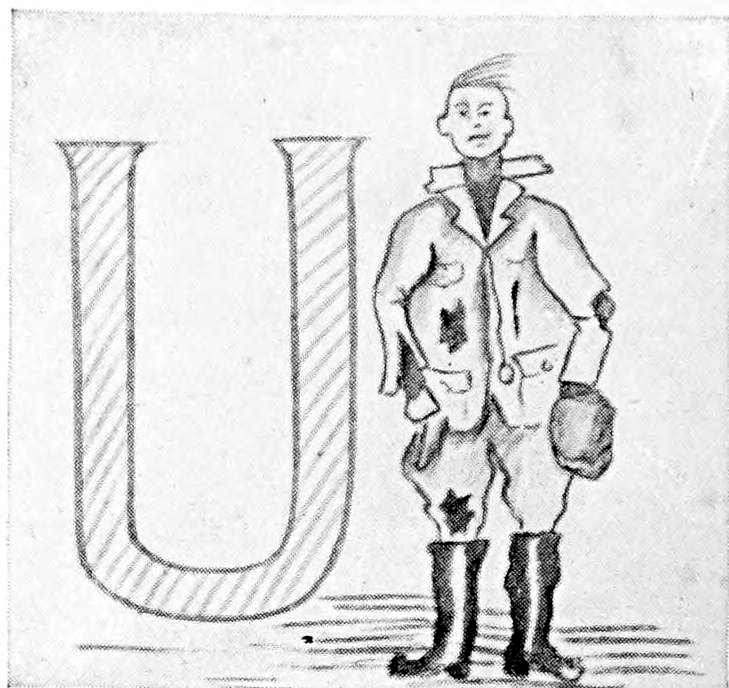

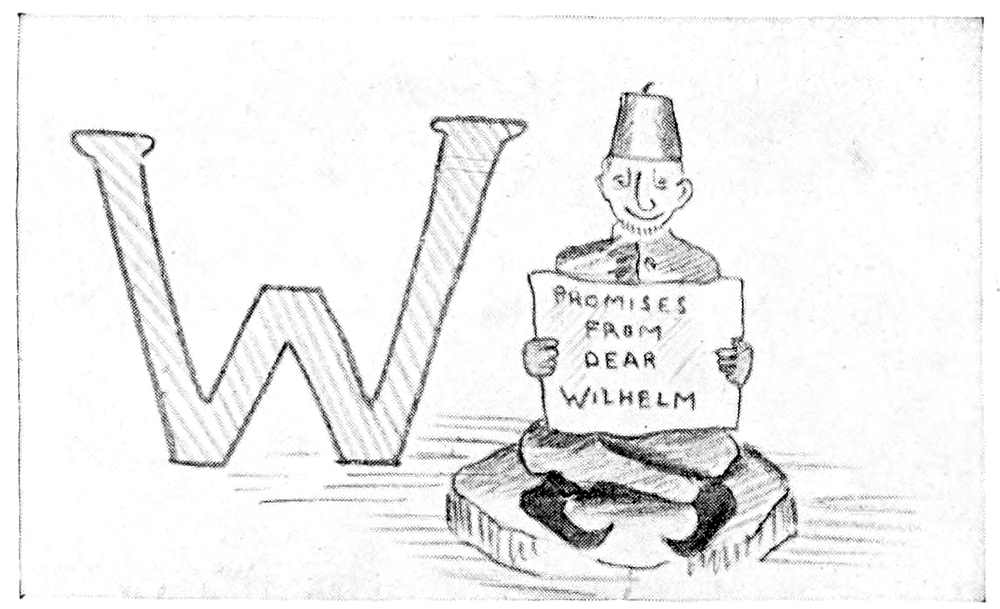

| AN ANZAC ALPHABET. By J. W. S. Henderson (R.G.A.) | 115 | |

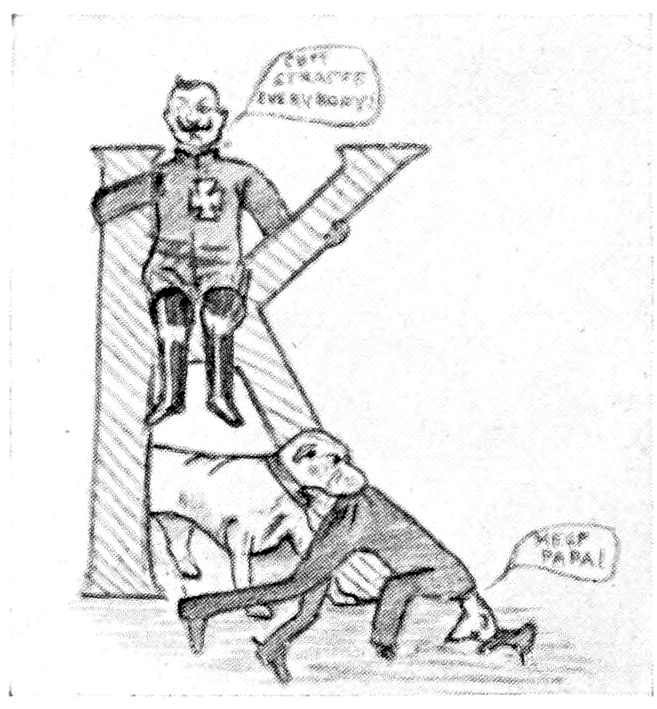

| THE KAISER TO HIS SECRETARY. By H. B. C. | 119 | |

| THE ANZAC THUNDERSTORM—FROM THE TRENCHES. By I. A. Saxon (21st Aust. Batt.) | 122 | |

| SENSE OR ——? By C. D. Mc. (Sergt.) | 123 | |

| OUR SAILORS—THE AMPHIBIOUS MAN. By Lieut. A. L. Pemberton | 124 | |

| POSSIES. By “Ben Telbow” | 125 | |

| MR. AEROPLANE. By H. G. Garland (16th Aust. Batt.) | 126 | |

| ANZAC IN EGYPT:— | ||

| 1. Mahomed—and Australia. By C. | 127 | |

| 2. Anzac in Alex. By L. J. Ivory (4th Howitzer Battery, N.Z.F.A.) | 128[Pg vii] | |

| GREY SMOKE. By R. G. N. (11th Aust. A.S.C.) | 131 | |

| A WAIL FROM ORDNANCE. By Lieut. Kininmonth (A.O.C.) | 132 | |

| “DINKUM OIL” | 134 | |

| THE BOOK OF ANZAC CHRONICLES:— | ||

| 1. The Flood. By “Genesis Gallipoli” | 135 | |

| 2. The Book of Jobs. By W. R. Wishart (No. 1 Aust. Stat. Hosp., Anzac) | 136 | |

| 3. The Perfectly True Parable of the Seven Egyptians. By Capt. A. Alcorn (No. 1 Aust. Stat. Hosp.) | 138 | |

| THE SILENCE. By Pte. R. J. Godfrey (7th Aust. Field Amb.) | 141 | |

| THE GROWL. By E. M. Smith (27th Batt.) | 142 | |

| MY LADY NICOTINE. By H. G. Garland | 142 | |

| THE RAID ON LONDON. By “Private Pat Riot” | 143 | |

| SING! | 145 | |

| ANOTHER ATTEMPT AT AN ANZAC ALPHABET. By “Ubique” (21st Indian Mtn. Battery) | 146 | |

| TO SARI BAIR. By “Ben Telbow” (10th Aust. Batt.) | 148 | |

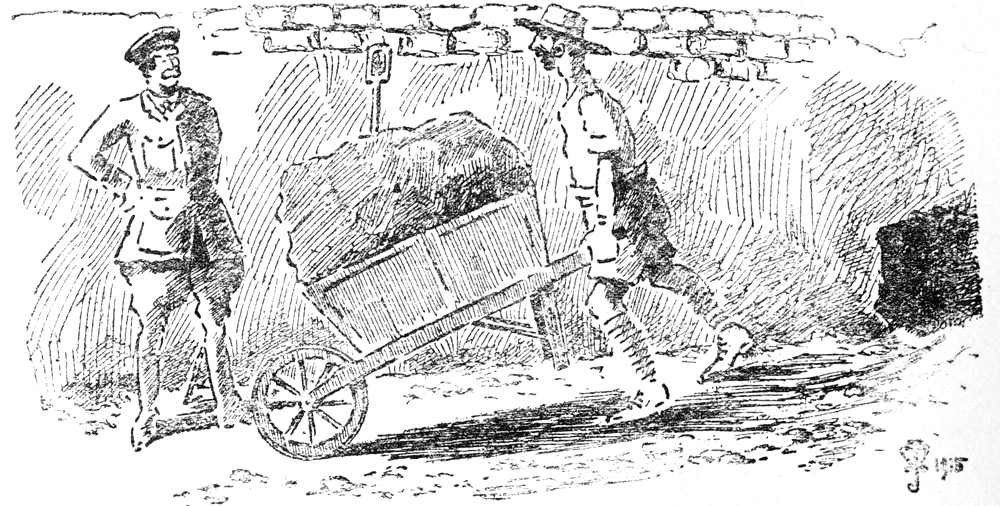

| ON WATER FATIGUE. By Trooper George H. Smith (7th Light Horse) | 148 | |

| WHEN IT’S ALL OVER.... By Harry McCann (4th A.L.H) | 151 | |

| SPECIAL A. & N. Z. A. C. ORDERS:— | ||

| 1. The Landing | 152 | |

| 2. The Battles of August | 152 | |

| 3. Arrival of 2nd Australian Division, and Sinking of the “Southland” | 153 | |

| 4. Lord Kitchener’s Message | 153 | |

| 5. Gen. Birdwood Relinquishes Command of A. & N.Z. Army Corps | 154 | |

| 6. The Evacuation of Anzac | 154 | |

| 7. Telegrams | 156 | |

| FOUR DESIGNS FOR “THE ANZAC MAGAZINE” COVER | 159 | |

| CORRESPONDENCE | 161 | |

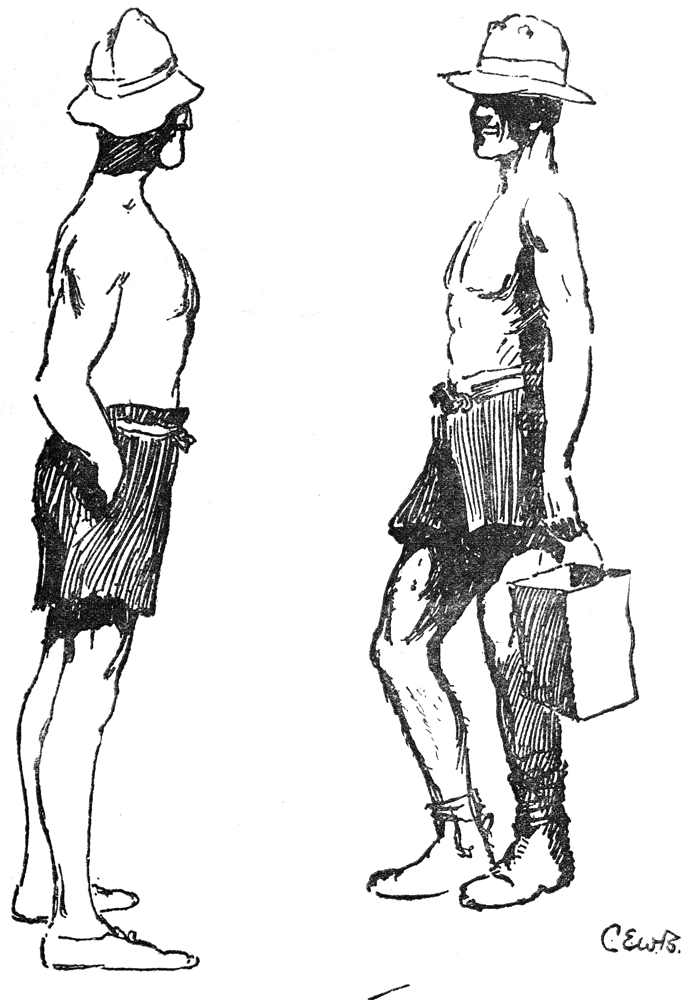

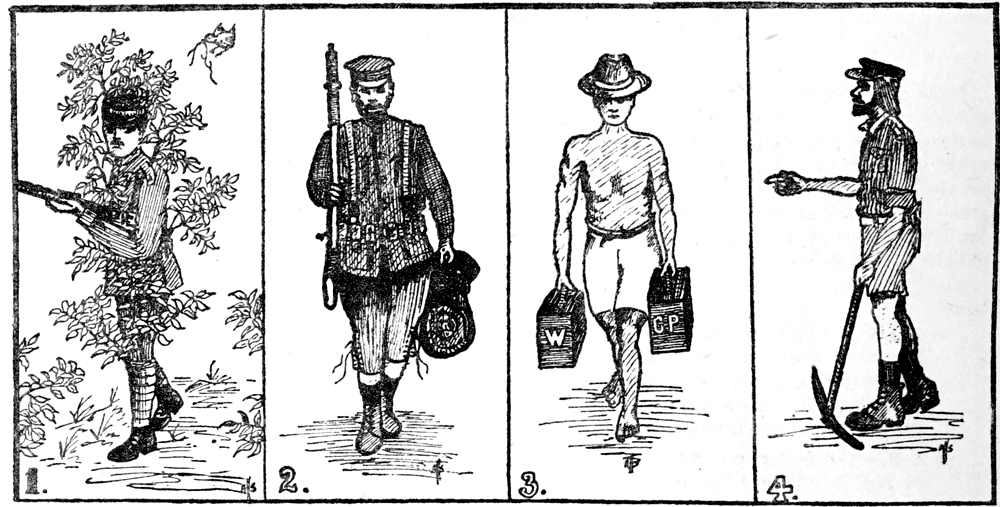

| ANZAC FASHIONS: SUMMER | 162 | |

| ” ” WINTER | 163 | |

| ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS | 164 | |

| ADVERTISEMENTS | 165 | |

[Pg viii]

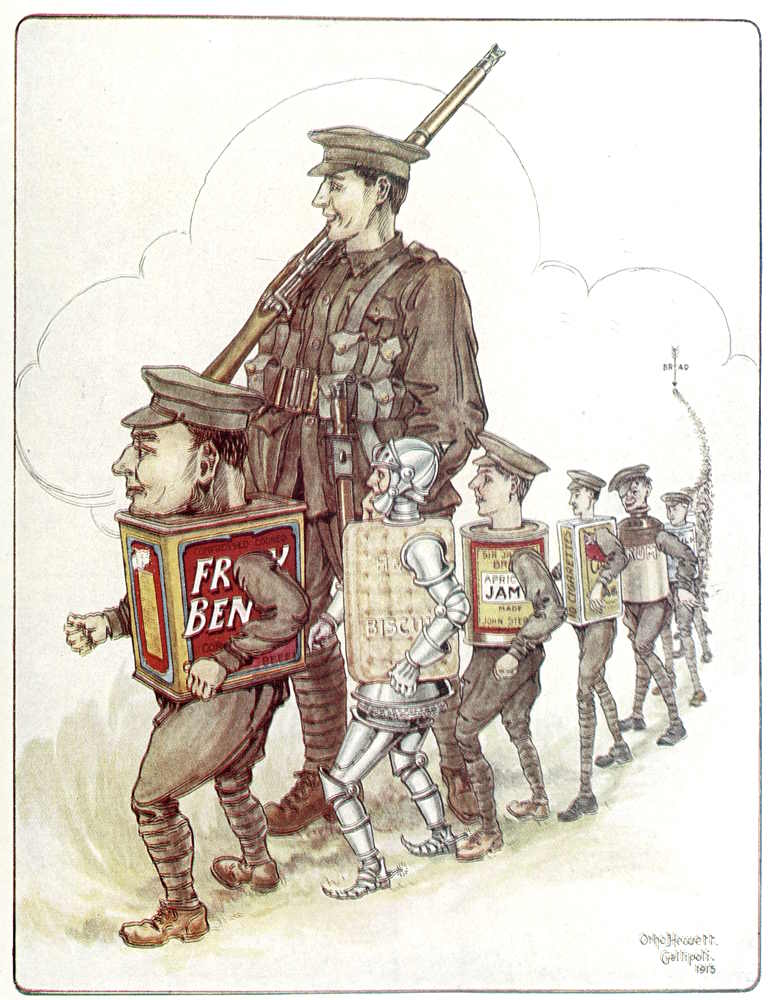

| A.N.Z.A.C. By W. Otho Hewett. (Colour) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| LIEUT.-GEN. SIR W. R. BIRDWOOD | x |

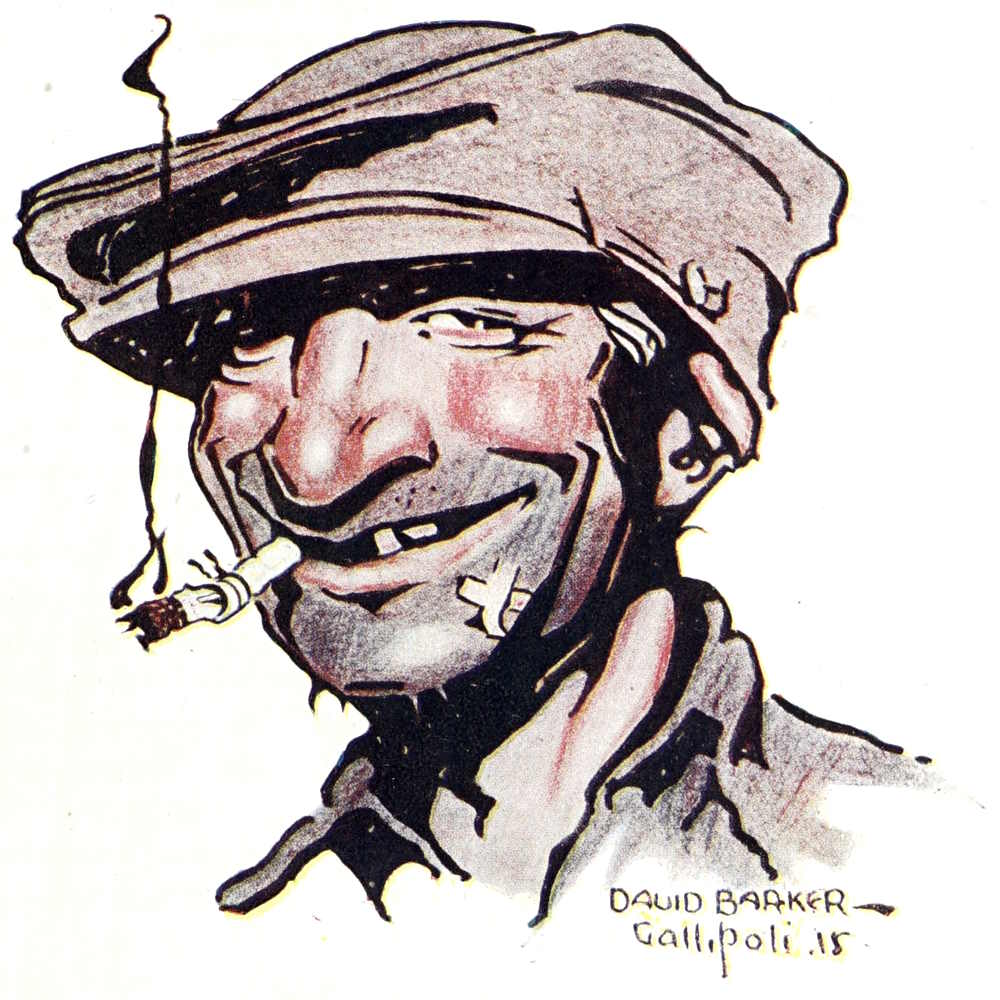

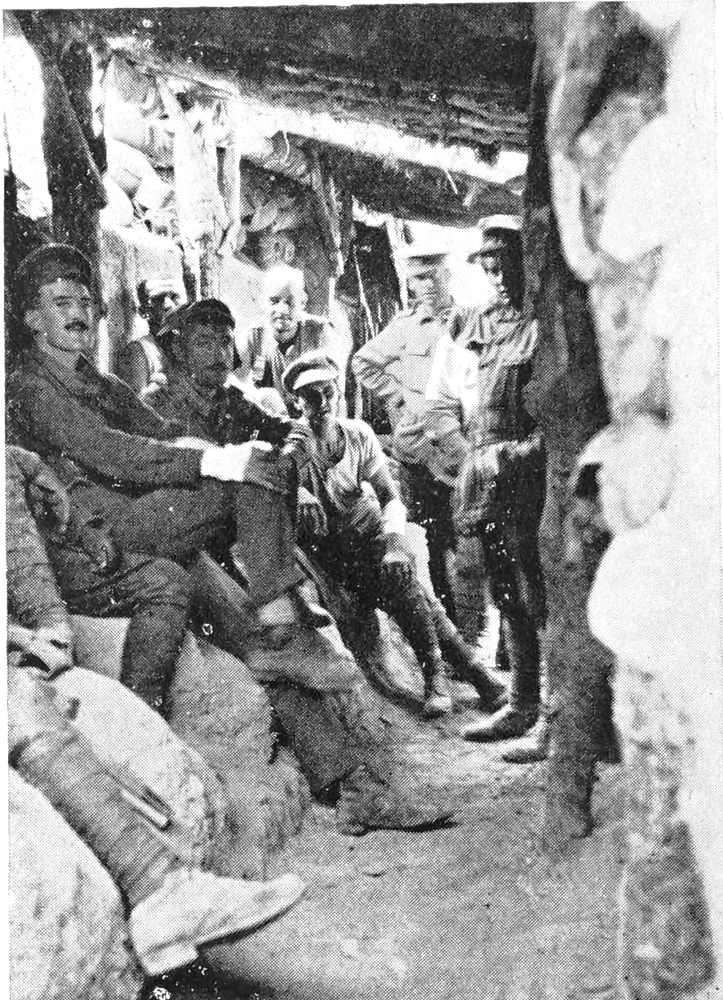

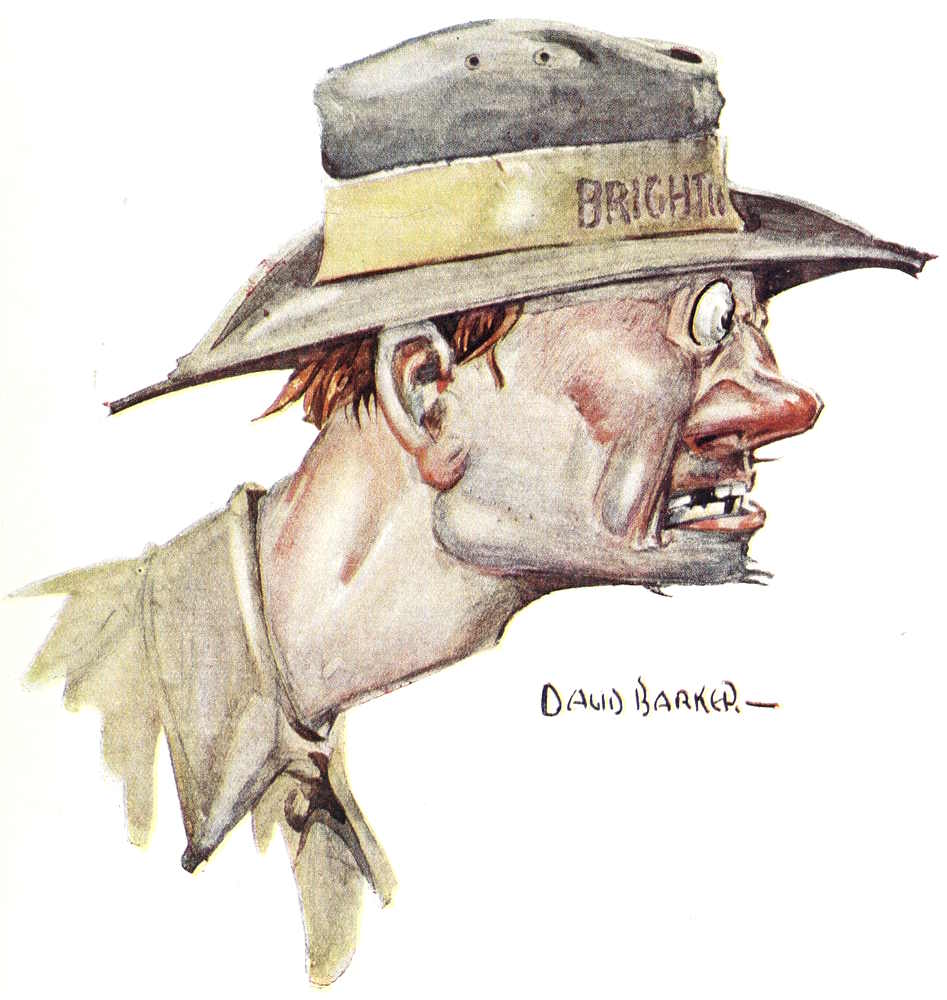

| “AT THE LANDING AND HERE EVER SINCE.” By David Barker. (Colour) | 22 |

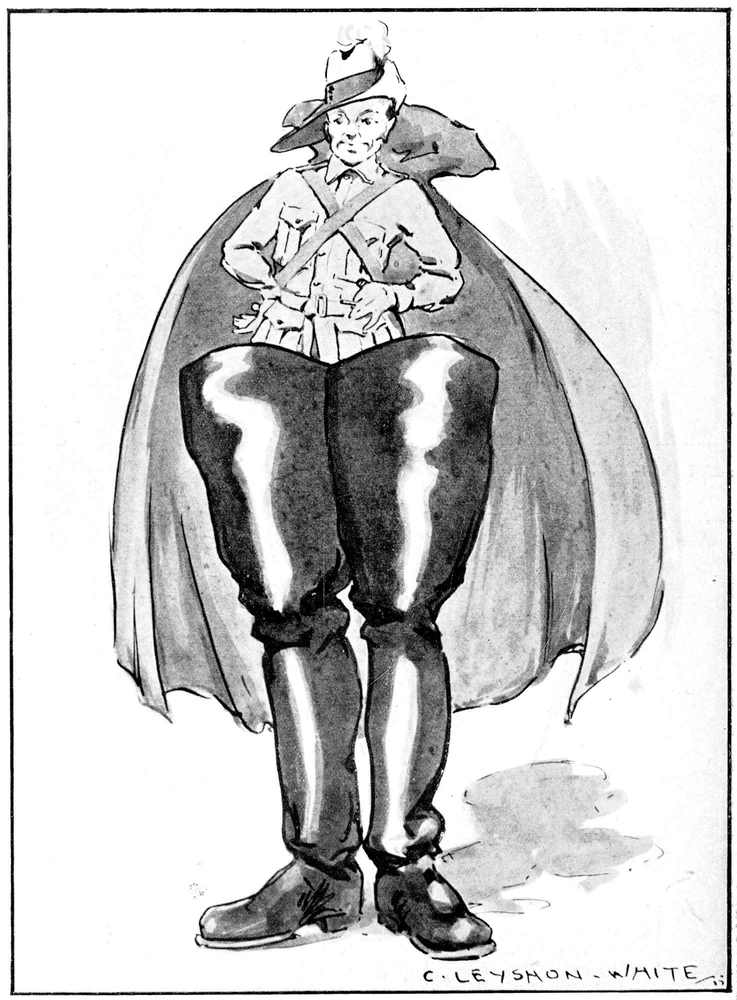

| “KITCH.” By C. Leyshon-White. (Colour) | 32 |

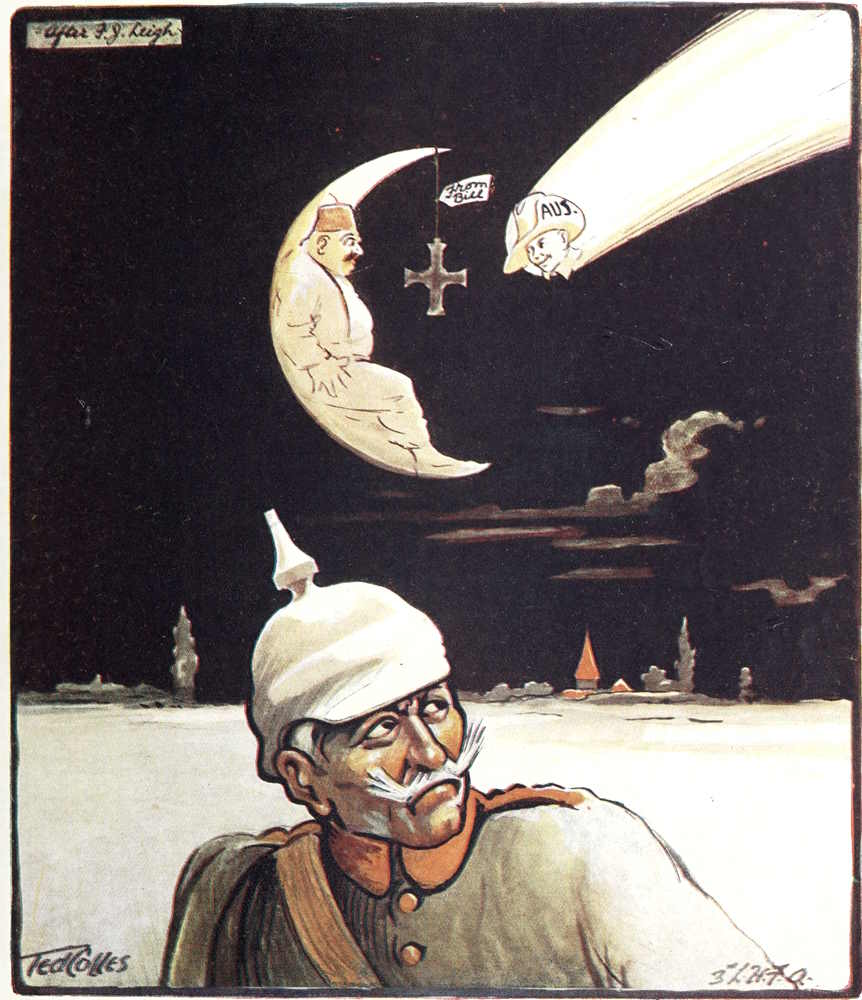

| ABDUL. By Ted Colles. (Colour) | 58 |

| ANZAC SKETCHES. By David Barker. (Colour) | 66 |

| SOMETHING TO REMEMBER US BY. By Ted Colles. (Colour) | 70 |

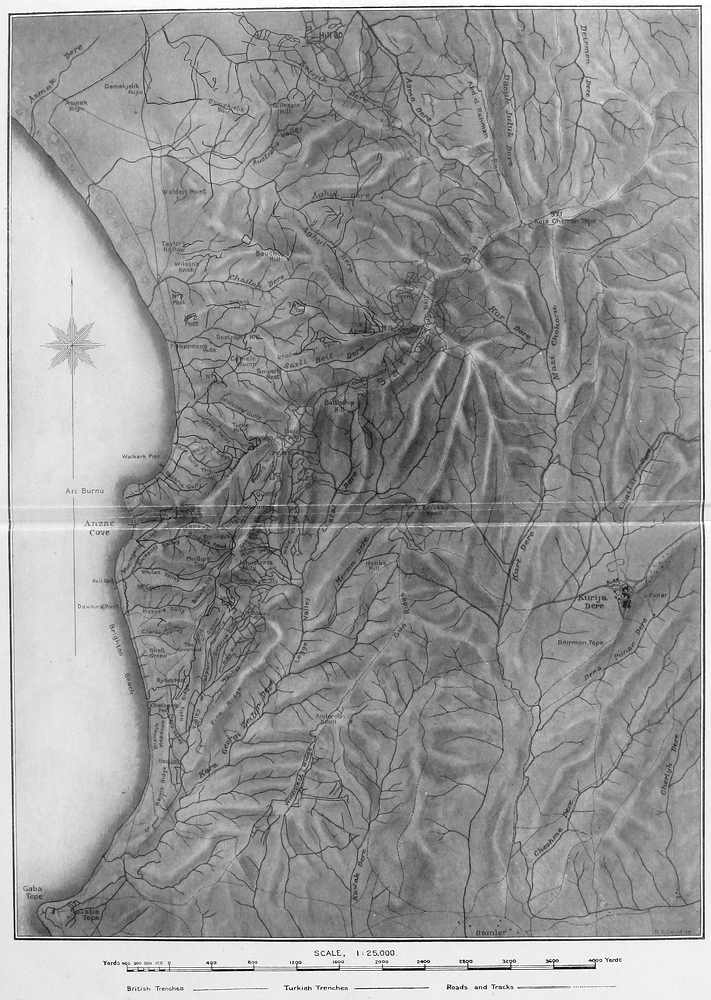

| MAP OF ANZAC. Drawn by Private R. T. Goulding (N.Z. Inf.) | 90 |

| THE NEW STAR. By Ted Colles, after F. J. Leigh. (Colour) | 96 |

| THE SILVER LINING. By C. E. W. Bean. (Colour) | 122 |

| OUR REPTILE CONTEMPORARY. By David Barker. (Colour) | 134 |

| “APRICOT AGAIN!” By David Barker. (Colour) | 142 |

| EACH ONE DOING HIS BIT. By W. Otho Hewett. (Colour) | 164 |

[Pg ix]

It is my privilege to have been asked to write an Introduction for The Anzac Book, and to convey the cordial thanks of all the inhabitants of our little township here to those who have so kindly given us the free use of their brains and hands in writing and illustrating this book in a way which does as much credit to them as the fighting here has done to the Force. We all hope that readers of our book will agree in this, while those who are more critical will perhaps remember the circumstances under which the contributions have been prepared, in small dug-outs, with shells and bullets frequently whistling overhead.

It may be of interest to readers to hear the origin of the word “Anzac.”

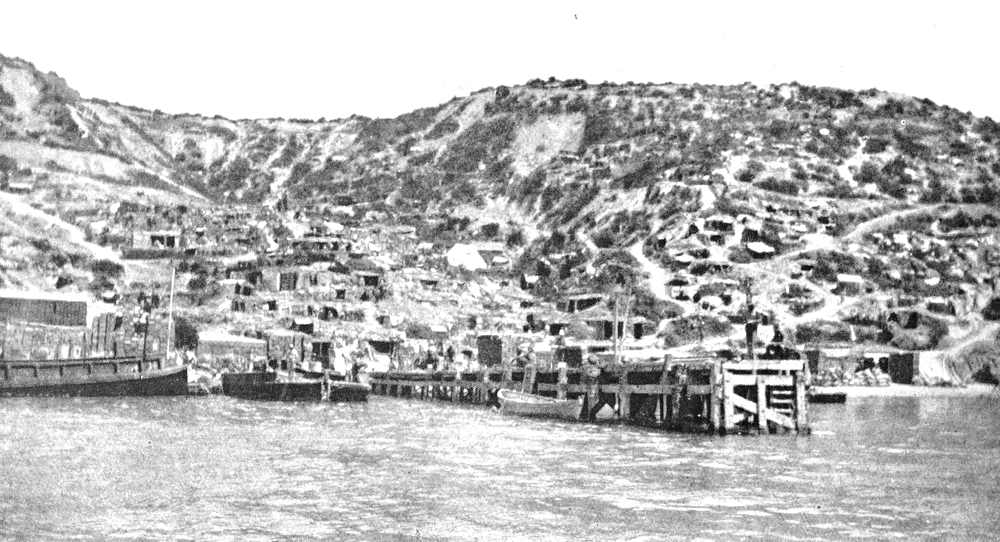

When I took over the command of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps in Egypt a year ago, I was asked to select a telegraphic code address for my Army Corps, and then adopted the word “Anzac.” Later on, when we had effected our landing here in April last, I was asked by General Headquarters to suggest a name for the beach where we had made good our first precarious footing, and then asked that this might be recorded as “Anzac Cove”—a name which the bravery of our men has now made historical, while it will remain a geographical landmark for all time.

Our eight months at “Anzac” cannot help stamping on the memory of every one of us days of trial and anxiety, hopes, and perhaps occasional fears, rejoicings at success, and sorrow—very deep and sincere—for many a good comrade whom we can never see again.

I firmly believe, though, it has made better men of every one of us, for we have all had to look death straight in the face so often, that the greater realities of life must have been impressed on all of us in a way which has never before been possible. Bitter as has been my experience in losing many a good friend, I, personally, shall always look back on our days together at “Anzac” as a time never to be forgotten, for during it I hope I have made many fast friends in all ranks, whose friendship is all the more valuable because it has been acquired in circumstances of stress and often danger, when a man’s real self is shown.

In days to come I hope that this book will call to the minds of most of us incidents which, though they may then seem small, probably loomed very large before us at the time, and the thought of which will bring to mind many a good comrade—not only on land, but on the sea. From the day we were put ashore[Pg x] by Rear-Admiral Thursby’s squadron up till now we have had the vigilant ships of His Majesty’s Navy watching night and day, in all weathers, for any opportunity to help us. We will all of us look back in years to come on Queen Elizabeth, Prince of Wales, London, Triumph, Bacchante, Grafton, Endymion, as well as such sleuth-hounds of the ocean as Colne, Chelmer, Pincher, Rattlesnake, Mosquito, and many others, as our best of friends, and will think of them, their officers and ship’s company, as the truest of comrades, with whom it has been a privilege to serve, and as the best of representatives of the Great Fleet and Service which carries with honour and ensures respect for the British flag to the uttermost parts of the earth.

Boys! Hats off to the British Navy.

It may be that, in thinking of old “Anzac” days, the words of the Harrow school-song will spring to one’s mind:

But it has indeed helped us all to have been with strong men at “Anzac,” and whatever the future may have in store, I, personally, shall always regard the time I have been privileged to be a comrade of the brave and strong men from Australia and New Zealand, who have served alongside of me, as one of the greatest privileges that could be conferred on any man, and of which I shall be prouder to the end of my days than any honour which can be given me.

No words of mine could ever convey to readers at their firesides in Australia, New Zealand and the Old Country, one-half of what all their boys have been through, nor is my poor pen capable of telling them of the never-failing courage, determination and cheerfulness of those who have so willingly fought and given their lives for their King and country’s sake. Their deeds are known to the Empire, and can never be forgotten, while if any copy of this little book should happen to survive to fall into the hands of our children, or our children’s children, it will serve to show them to some extent what their fathers have done for the Empire, and indeed for civilisation, in days gone by.

I sincerely hope that every one of my old comrades may meet with all the good fortune his work here has deserved, and live to a ripe old age, with happiness, and be occasionally reminded of old times by a glance at The Anzac Book.

W R Birdwood (signature)

Anzac,

December 19, 1915.

[Pg xi]

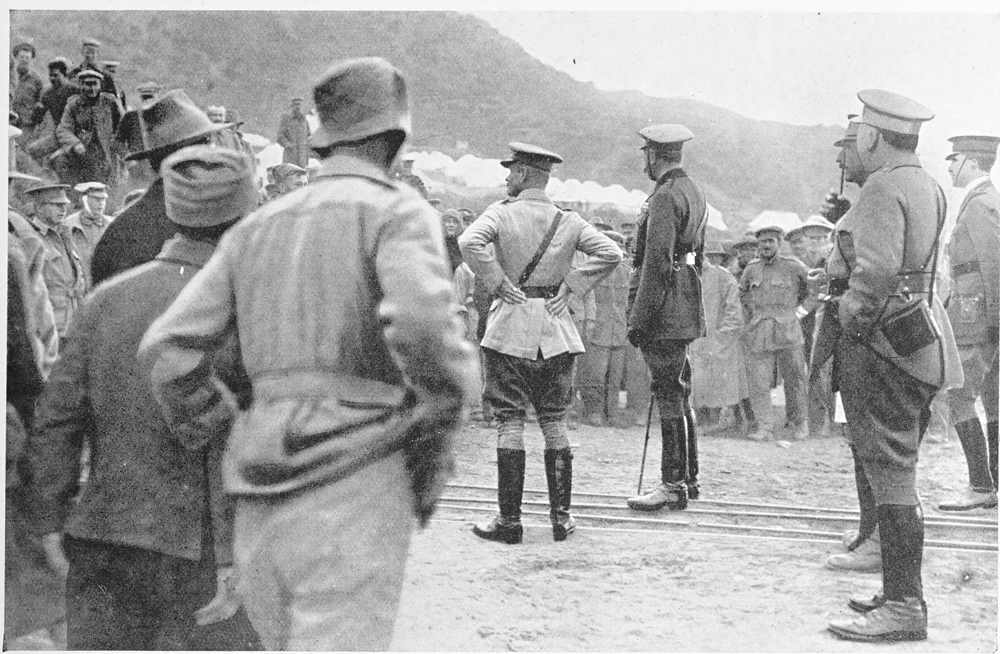

“LIEUTENANT-GENERAL SIR W. R. BIRDWOOD

Has been the soul of Anzac. Not for one single day has he ever quitted his post. Cheery and full of human sympathy, he has spent many hours of each twenty-four inspiring the defenders of the front trenches, and if he does not know every soldier in his force, at least every soldier in the force believes he is known to his chief.”

Sir Ian Hamilton’s dispatch.

[Pg xii]

[Pg xiii]

This book of Anzac was produced in the lines at Anzac on Gallipoli in the closing weeks of 1915. Practically every word in it was written and every line drawn beneath the shelter of a waterproof sheet or of a roof of sandbags—either in the trenches or, at most, well within the range of the oldest Turkish rifle, and under daily visitations from the smallest Turkish field-piece. Day and night, during the whole process of its composition, the crack of the Mauser bullets overhead never ceased. At least one good soldier that we know of, who was preparing a contribution for these pages, met his death while the work was still unfinished.

The Anzac Book was to have been a New Year Magazine to help this little British Australasian fraternity in Turkey to while away the long winter in the trenches. The idea originated with Major S. S. Butler, of the A.N.Z.A.C. Staff. On his initiative and that of Lieutenant H. E. Woods a small committee was formed to father the magazine. A notice was circulated on November 14th calling for contributions from the whole population of Anzac. Any profit was to go to patriotic funds for the benefit of the Army Corps.

Between November 15th and December 8th, when the time for the sending in of contributions closed, The Anzac Book was produced. As drawings and paintings began to come in, disclosing the whereabouts of some of the talent which existed in Anzac, a small staff of artists was collected in order to produce head- and tail-pieces and a few illustrations; and a dug-out overlooking Anzac Cove became the office of the only book ever likely to be produced in Gallipoli.

It was after the contributions had been finally sent in, and when the work of editing was in full swing, that there came upon most of us from the sky the news that Anzac was to be evacuated. Such finishing touches as remained to be added after December 19th were given to the work in Imbros. The date for the publication was necessarily delayed. And it was realised by everyone that this production, which was to have been a mere pastime, had now become a hundred times more precious as a souvenir. Certainly no book has ever been produced under these conditions before.

Except for this modification in the scheme of its production, The Anzac Book remains to-day exactly the same as when it was planned for the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps still clinging to the familiar holly-clothed sides of Sari Bair.

[Pg xiv]

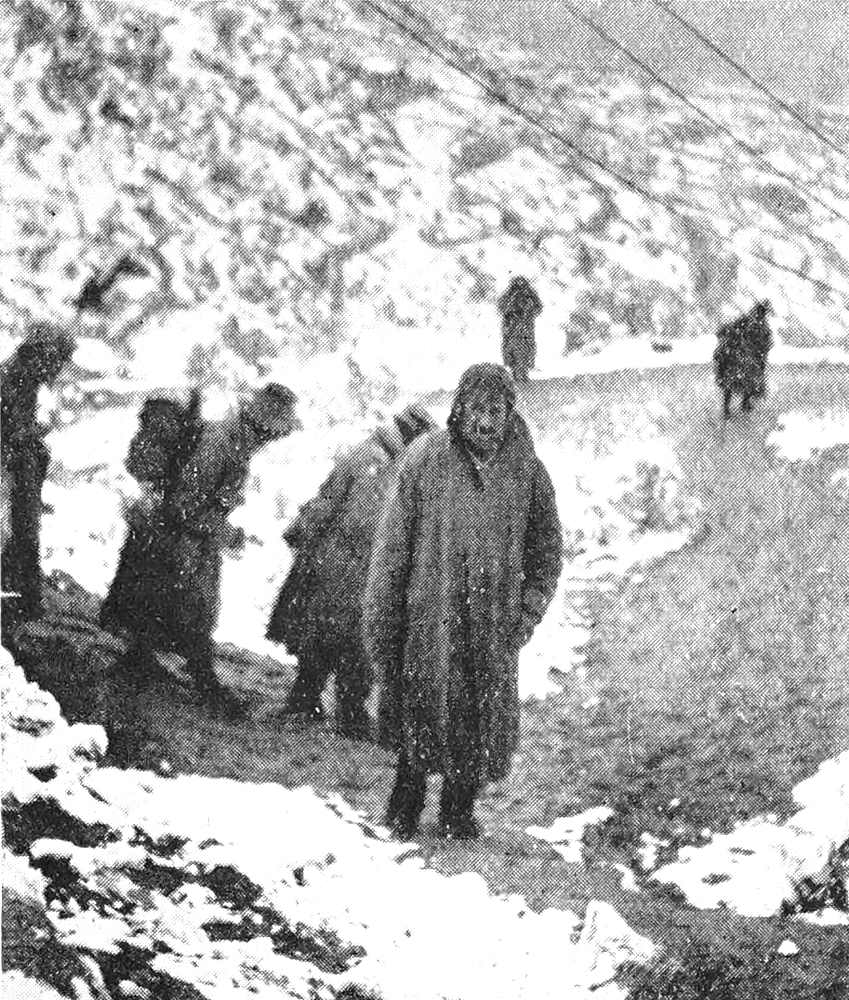

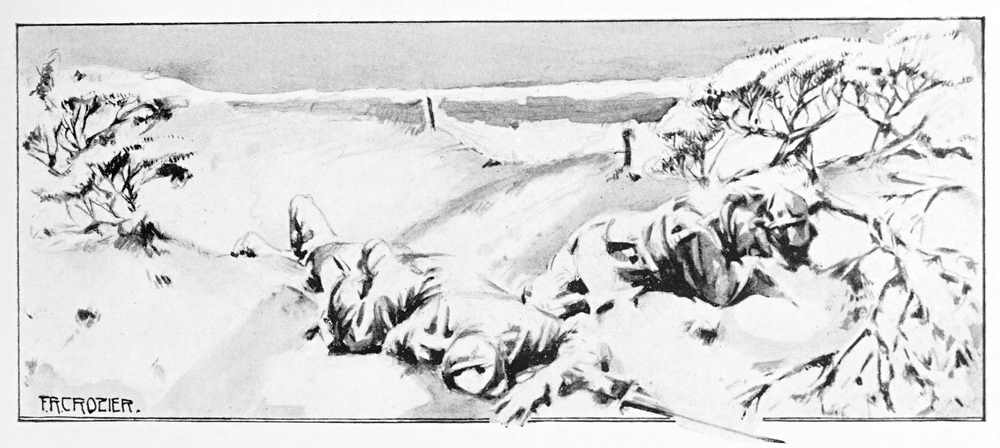

The three weeks during which this book was being produced will be remembered by the men of Anzac as being the period during which we were visited by the two fiercest storms which descended upon the Peninsula. During the afternoon of November 17th the wind from the south-west gradually increased to more than half a gale, and brought with it, after dark, a most torrential thunderstorm. A day or two later this subsided, leaving a dishevelled Anzac. But the wind swung slowly round to the north, and by November 27th it was blowing a northerly blizzard; and the next day five out of every six Australians, for the first time in their lives, woke to find a white countryside and the snow falling. How deeply that snow impressed them can be seen in these pages—for dust, heat and flies were much more typical of Gallipoli.

The book was composed from first to last in the full prospect of Christmas at Anzac, and it remains a record, perhaps, all the more interesting on that account. The Printing Section of the Royal Engineers, especially Lieutenant Tuck and Corporal Ashwin, and Lieutenant G. L. Thomson, R.N.A.S., and certain Naval Officers helped us with some drawing-paper, ink and paints, and the Photographic Section with some excellent panoramas; but for the rest, the contributors had to work with such materials as Anzac contained: iodine brushes, red and blue pencils, and such approach to white paper as could be produced from each battalion’s stationery.

The response to the committee’s request for contributions was enormous, and in consequence the editors have been able to use only portions, even if they be a half or a quarter, of the longer articles and stories submitted to them—but they have done this without hesitation, rather than reject the articles altogether. The competitions for certain contributions resulted as follows: Cover—Private D. Barker, 5th Australian Field Ambulance; Drawing—Trooper W. O. Hewett, 9th Australian Light Horse; Drawing (Comic)—Private C. Leyshon-White, 6th Australian Field Ambulance; Prose Sketch—H. Dinning, 9th Co., Australian A.S.C.; Prose (Humorous)—Second-Lieutenant J. E. G. Stevenson, 2nd Field Co., Australian Engineers; Verses—Captain James Sprent, 3rd Australian Field Ambulance; Verses (Humorous)—T. H. Wilson, A Co., 16th Battalion A.I.F. The greater number of the contributors were private soldiers in the Army Corps. The sole “outside” contribution is Mr. Edgar Wallace’s poetic tribute to the Australian and New Zealand Force, which is included in these pages with the consent of the author.

The thanks of those particularly concerned in the production are especially due to General Birdwood, for his close and constant interest; to Brigadier-General C. B. B. White, who, though at the time burdened with most anxious duties, never failed to give some of his few spare moments to the solving of difficulties incidental to this publication; to the Commonwealth authorities and the Publicity Department in London; and particularly to Mr. H. C. Smart,[Pg xv] for his untiring assistance, invaluable advice, and for the help of his outstanding ingenuity in organisation, and of the splendid business system and abundant facilities which he has created in the Australian Military Office in London; to the War Office and the Admiralty, and the Central News for permission to use valuable photographs; and to many others, both in the A. and N.Z. Army Corps and outside it, who have given their best help to make this book a success. For the Staff—C. E. W. Bean, editor; Privates F. Crozier, T. Colles, D. Barker, W. O. Hewett, C. Leyshon-White, artists; A. W. Bazley, clerk—the work has been a labour of love for which only they realise how little thanks they deserve.

The Anzac Book Staff.

Ægean Sea,

December 29, 1915.

The Ideal

And the Real.

[Pg xvi]

C. LEYSHON-WHITE

1915

COMPLAINTS of the SEASON

[Pg 1]

The Anzac Book

Come on, lads, have a good, hot supper—there’s business doing.” So spoke No. 10 Platoon Sergeant of the 10th Australian Battalion to his men, lying about in all sorts of odd corners aboard the battleship Prince of Wales, in the first hour of the morning of April 25th, 1915. The ship, or her company, had provided a hot stew of bully beef, and the lads set to and took what proved, alas to many, their last real meal together. They laugh and joke as though picnicking. Then a voice: “Fall in!” comes ringing down the ladderway from the deck above. The boys swing on their heavy equipment, grasp their rifles, silently make their way on deck, and stand in grim black masses. All lights are out, and only harsh, low commands break the silence. “This way No. 9—No. 10—C Company.” Almost blindly we grope our way to the ladder leading to the huge barge below, which is already half full of silent, grim men, who seem to realise that at last, after eight months of hard, solid training in Australia, Egypt and Lemnos Island, they are now to be called upon to carry out the object of it all.

“Full up, sir,” whispers the midshipman in the barge.

“Cast off and drift astern,” says the ship’s officer in charge of the embarkation. Slowly we drift astern, until the boat stops with a jerk, and twang goes the hawser that couples the boats and barges together. Silently the boats are filled with men, and silently drop astern of the big ship, until, all being filled, the order is given to the small steamboats: “Full steam ahead.” Away we go, racing and bounding, dipping and rolling, now in a straight line, now in a half-circle, on through the night.

The moon has just about sunk below the horizon. Looking back, we can see the battleships coming on slowly in our rear, ready to cover our attack. All at once our pinnace gives a great start forward, and away we go for land just discernible one hundred yards away on our left.

[Pg 2]

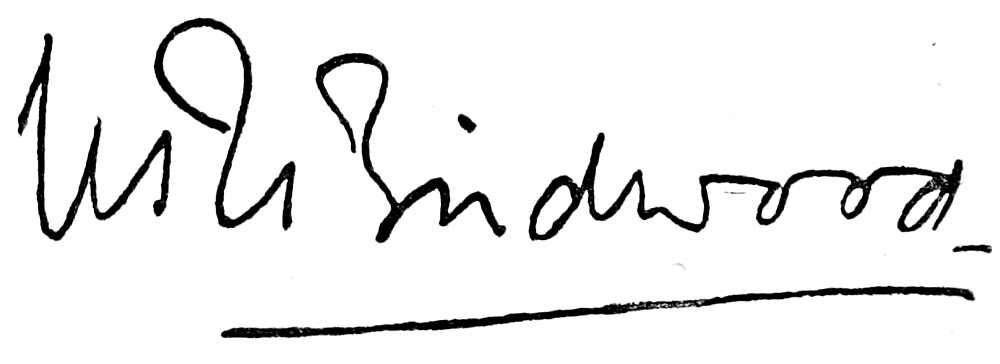

—North flank—

Suvla from Anzac.

Then—crack-crack! ping-ping! zip-zip! Trenches full of rifles upon the shore and surrounding hills open on us, and machine-guns, hidden in gullies or redoubts, increase the murderous hail. Oars are splintered, boats are perforated. A sharp moan, a low gurgling cry, tells of a comrade hit. Boats ground in four or five feet of water owing to the human weight contained in them. We scramble out, struggle to the shore, and, rushing across the beach, take cover under a low sandbank.

“Here, take off my pack, and I’ll take off yours.” We help one another to lift the heavy, water-soaked packs off. “Hurry up, there,” says our sergeant. “Fix bayonets.” Click! and the bayonets are fixed. “Forward!” And away we scramble up the hills in our front. Up, up we go, stumbling in holes and ruts. With a ringing cheer we charge the steep hill, pulling ourselves up by roots and branches of trees; at times digging our bayonets into the ground, and pushing ourselves up to a foothold, until, topping the hill, we found the enemy had made themselves very scarce. What had caused them to fly from a position from which they should have driven us back into the sea every time? A few scattered Turks showing in the distance we instantly fired on. Some fell to rise no more; others fell wounded and, crawling into the low bushes, sniped our lads as they went past. There were snipers in plenty, cunningly hidden in the hearts of low green shrubs. They accounted for a lot of our boys in the first few days, but gradually were rooted out. Over the hill we dashed, and down into what is now called “Shrapnel Gully,” and up the other hillside, until, on reaching the top, we found that some of the lads of the 3rd Brigade had commenced to dig in. We skirted round to the plateau at the head of the gully, and took up our line of defence.

As soon as it was light enough to see, the guns on Gaba Tepe, on our right, and two batteries away on our[Pg 3] left opened up a murderous hail of shrapnel on our landing parties. The battleships and cruisers were continuously covering the landing of troops, broadsides going into the batteries situated in tunnels in the distant hillside. All this while the seamen from the different ships were gallantly rowing and managing the boats carrying the landing parties. Not one man that is left of the original brigade will hear a word against our gallant seamen. England may well be proud of them, and all true Australians are proud to call them comrades.

South Flank—

Gaba Tepe from Anzac.

Se-ee-e-e ... bang ... swish! The front firing line was now being baptised by its first shrapnel. Zir-zir ... zip-zip! Machine-guns, situated on each front, flank and centre, opened on our front line. Thousands of bullets began to fly round and over us, sometimes barely missing. Now and then one heard a low gurgling moan, and, turning, one saw near at hand some chum, who only a few seconds before had been laughing and joking, now lying gasping, with his life blood soaking down into the red clay and sand. “Five rounds rapid at the scrub in front,” comes the command of our subaltern. Then an order down the line: “Fix bayonets!” Fatal order—was it not, perhaps, some officer of the enemy who shouted it? (for they say such things were done). Out flash a thousand bayonets, scintillating in the sunlight like a thousand mirrors, signalling our position to the batteries away on our left and front. We put in another five rounds rapid at the scrub in front. Then, bang-swish! bang-swish! bang-swish! and over our line, and front, and rear, such a hellish fire of lyddite and shrapnel that one wonders how anyone could live amidst such a hail of death-dealing lead and shell. “Ah, got me!” says one lad on my left, and he shakes his arms. A bullet had passed through the biceps of his left arm, missed his chest by an inch, passed through the right forearm, and finally struck the lad between him and me a bruising blow on the wrist. The[Pg 4] man next him—a man from the 9th Battalion—started to bind up his wounds, as he was bleeding freely. All the time shrapnel was hailing down on us. “Oh-h!” comes from directly behind me, and, looking around, I see poor little Lieutenant B——, of C Company, has been badly wounded. From both hips to his ankles blood is oozing through pants and puttees, and he painfully drags himself to the rear. With every pull he moans cruelly. I raise him to his feet, and at a very slow pace start to help him to shelter. But, alas! I have only got him about fifty yards from the firing line when again, bang-swish! and we were both peppered by shrapnel and shell. My rifle-butt was broken off to the trigger-guard, and I received a smashing blow that laid my cheek on my shoulder. The last I remembered was poor Lieutenant B—— groaning again as we both sank to the ground.

When I came to I found myself in Shrapnel Gully, with an A.M.C. man holding me down. I was still clasping my half-rifle. Dozens of men and officers, both Australians and New Zealanders (who had landed a little later in the day), were coming down wounded, some slightly, some badly, with arms in slings or shot through the leg, and using their rifles for crutches. Shrapnel Gully was still under shrapnel and snipers’ fire. Two or three platoon mates and myself slowly moved down to the beach, where we found the Australian Army Service Corps busily engaged landing stores and water amid shrapnel fire from Gaba Tepe. As soon as a load of stores was landed, the wounded were carried aboard the empty barges, and taken to hospital ships and troopships standing out offshore. After going to ten different boats, we came at last to the troopship Seang Choon, which had the 14th Australian Battalion aboard. They were to disembark the next morning, but owing to so many of us being wounded, they had to land straightaway.

And so, after twelve hours’ hard fighting, I was aboard a troopship again—wounded. But I would not have missed it for all the money in the world.

A. R. Perry,

10th Battalion A.I.F.

One for Chanak.

[Pg 5]

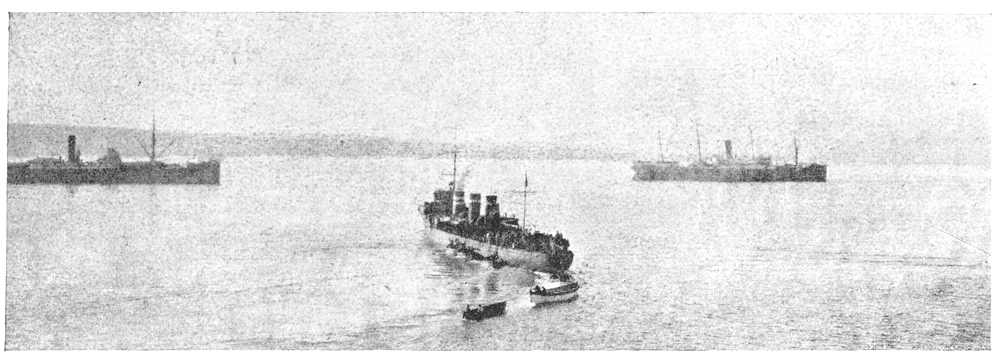

Photograph by C. E. W. BEAN

THE SUNRISE OF APRIL 15, 1915

The small boats taking troops to the shore can be seen beside the transports and close to the land

[Pg 7]

[It may be necessary to explain that wood—for the roof-beams of dug-outs and the shoring up of trenches in wet weather—was priceless in Gallipoli. But whilst this book was being compiled Providence sent a storm. In the morning the beach was littered with portions of a wrecked schooner, stranded lighters, pieces of pier—all strictly the property of H.M. Government as represented by the officer commanding the Royal Engineers. “A gift from Heaven,” one Australian was heard to remark as he looked at the desolate scene next morning. Nor were his British brethren less grateful.—Eds.]

The storm had ceased, the sea was calm, the wind a trifle raw,

And miles and miles of wreckage lay upon the sandy shore;

And every time the waves came up they brought a little more.

The Sergeant and the Junior Sub. in contemplation stood.

They wept like anything to see such quantities of wood—

And then they smiled a furtive smile which boded little good.

The wood lay round in lovely heaps and smiled invitingly.

“Do you suppose,” the Sergeant said, “that this is meant for me?”

“I doubt it,” said the Junior Sub. “Here comes the C.R.E.[1]

“If fifty kings and fifty queens and fifty C.-in-C.’s

Presented fifty indents and bowed low upon their knees,

I hardly think that they would get more than a few of these.”

The Sergeant and the Junior Sub. walked on a mile or so,

Until they found a shelving bank conveniently low;

And there they waited sadly for the C.R.E. to go.

“Oh, timbers,” quoth the Junior Sub., who spoke with honeyed speech,

“I hardly think it safe for you to lie upon the beach.”

And as he spoke he stroked the backs of those within his reach.

[Pg 8]

The timbers leapt beneath his touch and hurried plank by plank;

They crowded round to hear him speak, and lined up rank on rank—

But one old timber wagged his head and hid behind a bank.

“The time has come,” the Sergeant said, “to talk of many things—

Of bully beef and dug-outs, of Kaisers and of Kings,

And why the rain comes through the roof, and whether shrapnel stings.

“Some good stout planks,” the Sergeant cried, “are what we chiefly need,

And four by fours and spars besides are very good indeed—

So if you’re ready, sir, I think we may as well proceed.”

“Oh, C.R.E.!” remarked the Sub., “I deeply sympathise.”

With sobs and tears they sorted out those of the largest size,

While happy thoughts of days to come loomed large before their eyes.

Next morning came the C.R.E. to see what could be done;

But when he came to count the planks he found that there was none—

And this was hardly odd, because they’d collared every one.

Lieut. A. L. Pemberton,

R.G.A.

Taylor’s Hollow,

8.12.15.

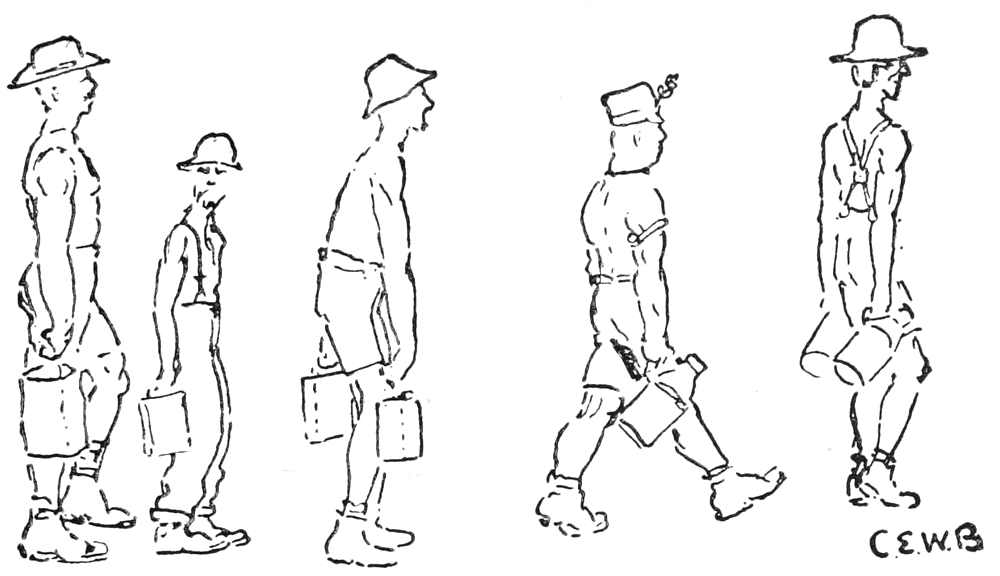

C. E. W. B.

Study of a battalion in Repose.

[Pg 9]

[1] C.R.E.—Officer commanding Royal Engineers.

When you come to an old spotted gum right on the saddle of Sandstone Ridge, after an eighteen-mile ride from Timpanundi, you’re very close to Freddy Prince’s war selection. There’s a well-made gate in the road fence on your left, and it bears the legend, “Prince’s Jolly.” Through that the track will lead you gently uphill into a wide and gradually deepening sap, until you think you’ve made some mistake. Then look to your left, and behold the front entrance to Freddie’s dug-out.

An old shell-case hangs near by, and when you strike it you’ll hear an echo of children’s voices, and a small platoon of youngsters charge you at the double. First time I blew in it was just on teatime, and my first glance in at the well-lit gallery and the smell of the welcome food are worth the recollection. Fred came out and led my cuddy round to the stable sap, where he was given what had been on his mind for some hours past. I didn’t lose much time in settling down to tea—it was already too dark to look around outside. Besides, as Fred explained, there was nothing to see of the homestead bar the inside, and by the third year of excavation most of that had been dumped into the gully and pretty well all washed away.

The meal finished, we played games with the kids. Fred seldom read the papers—he said he didn’t want to strain the one eye that was left to him—so Mrs. Prince retired to absorb the news I had brought in their mail-bag, and to prepare herself to issue it to her husband later.

Long after the children went to burrow, he and I smoked and pitched away about the past. He told me how he and many others had come to adopt the underground home. It had been the case of making a penny do the work of a pound, and Fred himself had done the work of a company. It had been a hard struggle, but the missus was a treasure, and never growled except when things were going well—as some people will do. It was just a case of dig in, dig up, and dig down. Anything in the way of iron or steel was prohibitive. Timber was too expensive, and in any case the timber that stood on the selection he had been forced to sell in order to stock the farm. It had been a problem of years, but he had made a job of it; and when he showed me round the house I didn’t grudge him his little bit of pride.

The main gallery opened to the surface[Pg 10] at the front and back, and was about forty-five paces long. It was driven through hard ground, and was well arched so that it required no timber. On one side there was a branch to the pantries and the galley, and on the other side the dining-room and the bedrooms, which were really one big chamber with solid pillars of earth left at intervals, forming a group of rooms each with a dome roof and canvas partitions. A borehole had been put through to the surface at the centre of every room for ventilation and light, a device of reflectors enabling one to bring the sunlight in at all hours of the day.

Once, as we sat and smoked, a subdued chattering came from the adjoining room. I looked up and saw the top of a periscope over the partition. Instantly it disappeared with a noise like the scattering of furniture. Then a voice: “Oh, daddy, do you know what?”

“What’s happened, Kit?” replied the father.

“Two of your biscuit photo-frames are smashed.”

“Oh, never mind, old girl,” said Fred; “it’s time they began to break up after fifteen years. Go to sleep, both of you.”

As I lay awake next morning I overheard some homely details. How the baldy steer had hopped over O’Dwyer’s parapet into his lucerne patch; and Jimmy ought to have widened the trench last week when he was told to; and the milking sap hadn’t been cleaned out the previous day because Georgie had forgotten he was pioneer; and Jerry O’Dwyer had shot two crows from the new sniper’s pozzy[2] down at the creek—and so on.

When we sat down to breakfast Mrs. Prince was primed with news. “I told Fred,” she said, “I didn’t believe we’d taken Lake Achi Baba; the latest cable says it’s still occupied by the German submarines.” Fred nodded as if he didn’t care much.

“Achi Baba used to be a hill once, wasn’t it, daddy?” chipped in one of the youngsters.

“Yes, it used to be one time,” replied his father, looking into the blue puffs that drifted away from his pipe and out past the waterproof sheet of the dug-out door. In those blue mists of the past what he saw was the bald pate of the great hill, with the howitzers tearing earth out of the crest of it by the hundredweight, while the Turkish miners ever heaped the outside of it with the spoil from their tunnels. “Yes, it was a hill once.”

Thus Freddy and his wife and family live their life as happily as if there were no war.

“Soldieroo,”

2nd Field Co., Aust. Engrs.

[Pg 11]

[2] Pozzy or Possie—Australian warrior’s short for “position,” or lair.

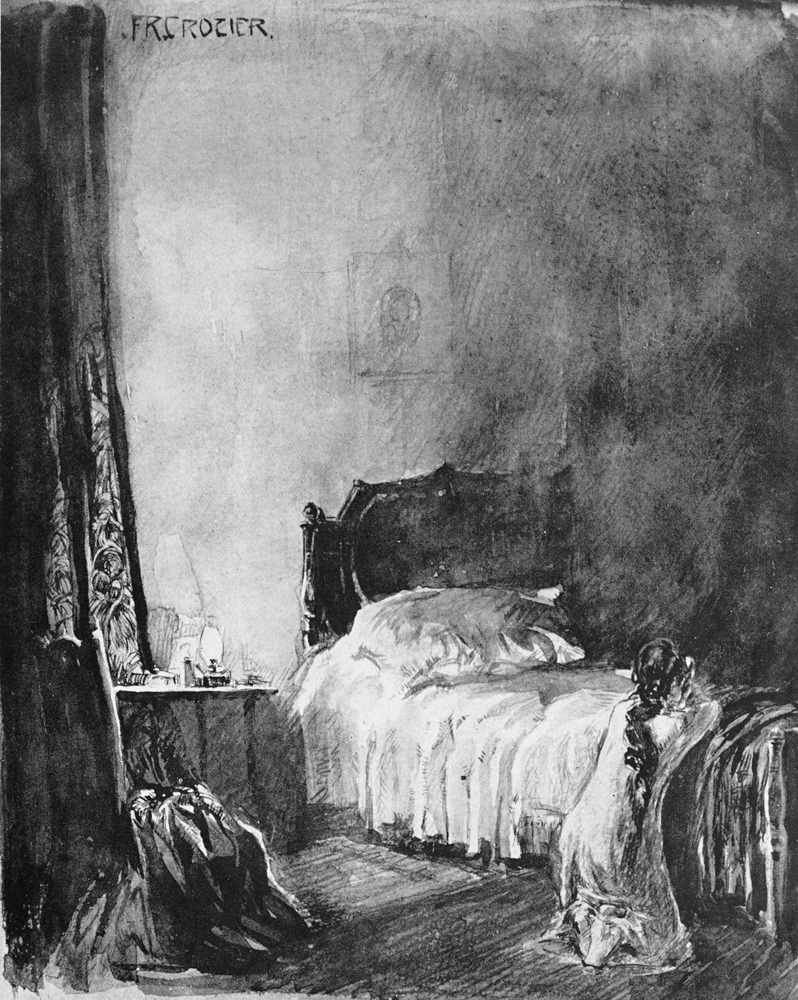

F. R. CROZIER

[Pg 12]

TED COLLES

FROM

SKETCH

BY

C. McCRAE

New Arrival (as something hums past the parapet): “’Strewth! Wot’s that?”

Officer: “Only a ricochet.”

N.A.: “An’ d’we use ’em, too, sir?”

[Pg 13]

THE DESTROYER ON THE FLANK

Drawn by GILBERT T. M. ROACH

[Pg 14]

OUR FATHERS

Wandering spirits, seeking lands unknown,

Such were our fathers, stout hearts unafraid.

Have we been faithless, leaving homes they made,

With their life’s blood cementing every stone?

Nay, when the beast-like War God did intone

His horrid chant, was our first reckoning paid

For years of ease. Their restless spirits bade

Us fight with those whose Homeland was their own.

Rest easy in your graves, the spirit lives

That brought you forth to claim of earth the best.

Ours it is now, and ours it shall remain;

Mere jealous greed no honest birthright gives.

Shades of our fathers, hear our faith confessed,

We shall defend your Empire or be slain.

Capt. James Sprent,

A.M.C. (3rd Field Amb.).

[Pg 15]

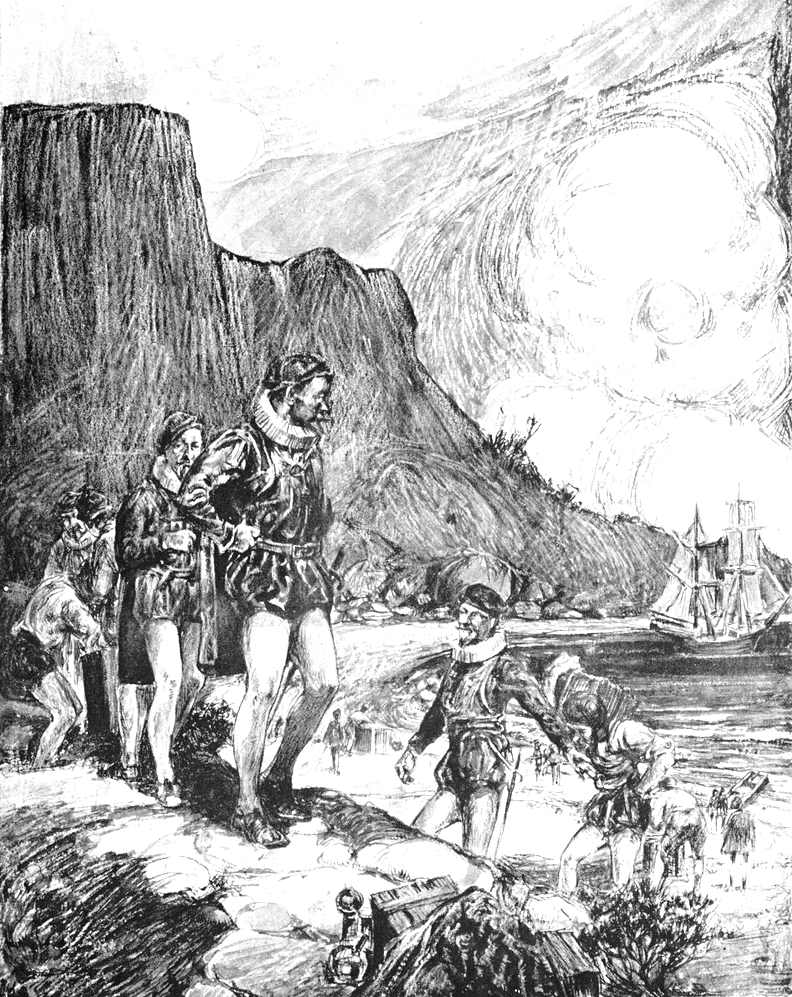

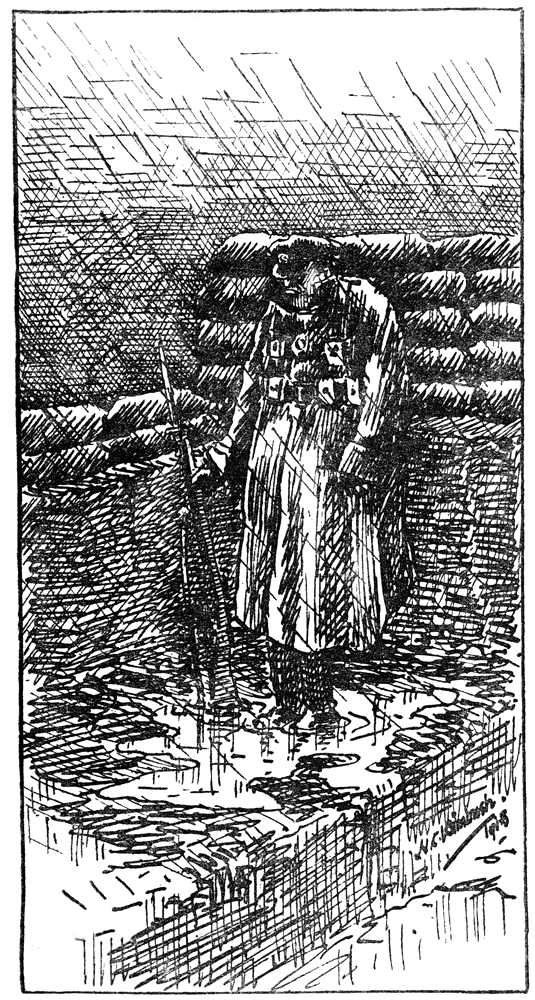

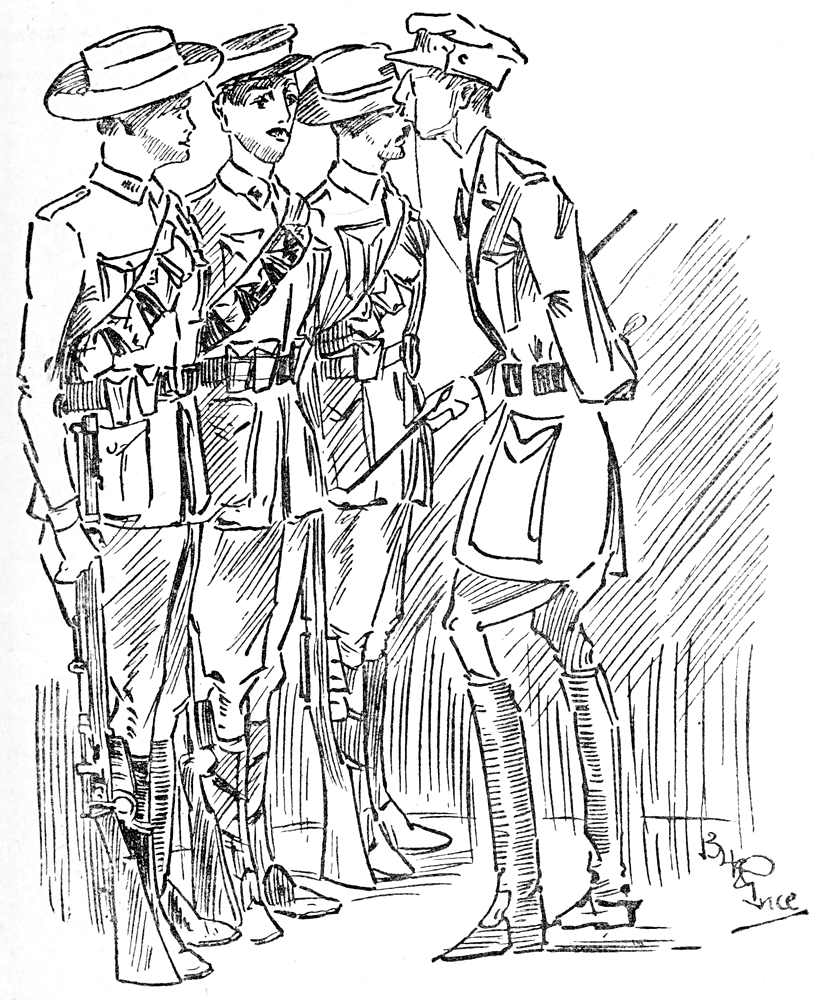

Drawn by F. R. CROZIER

“Wandering spirits, seeking lands unknown,

Such were our fathers, stout hearts unafraid.”

[Pg 17]

C. E. W. B.

·Picture of a battalion Resting·

It’s the monotony we revile, not—to a like degree—hard work or hard fare. To look out on the same stretch of beach or the same patch of trench wall and the same terraces of hostile black and grey sandbags day after day is to be wearied. There is the same sitting in the same trench, shelled by the same guns, manned, perhaps (though that we endeavour to avert), by the same Turks. Unhappily it is not the same men of ours that they maim and kill daily.

And if one’s dug-out lies on a seaward slope there is, every morning, the same stretch of the lovely Ægean, with the same two islands standing over in the west.

Yet neither the islands nor the sea are the same any two successive days. The temper of the Ægean at this time changes more suddenly and frequently than ever does that of the Pacific. Every morning the islands of the west take on fresh colour, and are trailed by fresh shapes of mist.

To-day Imbros stands right over against you; you see the detail of the fleet in the harbour, and the striated heights of rocky Samothrace reveal the small ravines. To-morrow, in the early morning light, Imbros lies mysteriously afar off like an Isle of the Blest, a delicate vapour-shape reposing on the placid sea.

Nor is there monotony in either weather or temperature. This is the late autumn. Yet it is a halting and irregular advance the late autumn is making. Fierce, biting, raw days alternate with the comfortableness of the mild late summer. This morning, to bathe is as much as your life is worth (shrapnel disregarded); to-morrow, in the gentle air, you may splash and gloat an hour and desire more. And you prolong the joy by washing many garments.

Here in Anzac we have suffered the tail-end of one or two autumn storms, and have had two fierce and downright gales blow up. The wind came in the night, with a suddenness that found us most unprepared. In half an hour many of us were homeless, crouching about with our bundled bedclothes, trespassing tyrannically upon the confined space of the stouter dug-outs of our friends—a sore tax upon true friendship. They lay on their backs and held down their roofs by mere weight of body until overpowered. Spectral figures in the driving atmosphere collided and wrangled and swore and blasphemed. The sea roared over the shingle with a violence that made even revilings inaudible.

The morning showed a sorry beach. There were—there had been—three piers. One stood intact; the landward half of the second was clean gone; of the third there was no trace, except in a few splintered spars ashore. A collective dogged grin overlooked the beach that morning at the time of rising. The remedying began forthwith; so did the bursting of shrapnel over the workmen. This stroke of Allah upon the unfaithful was not to go unassisted.

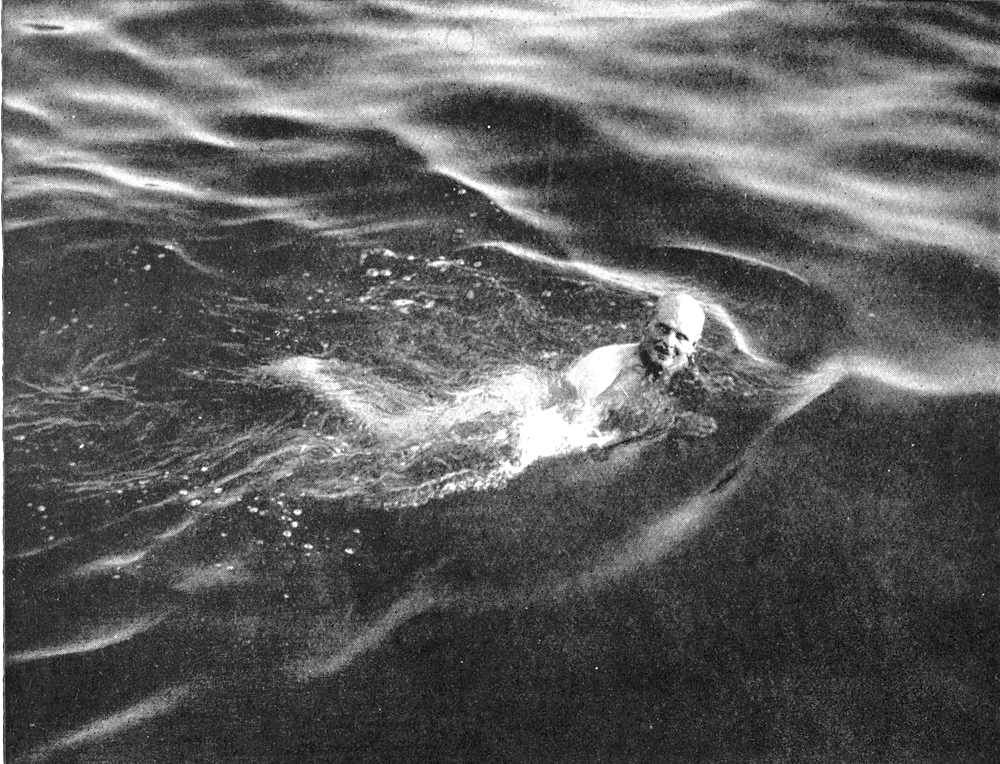

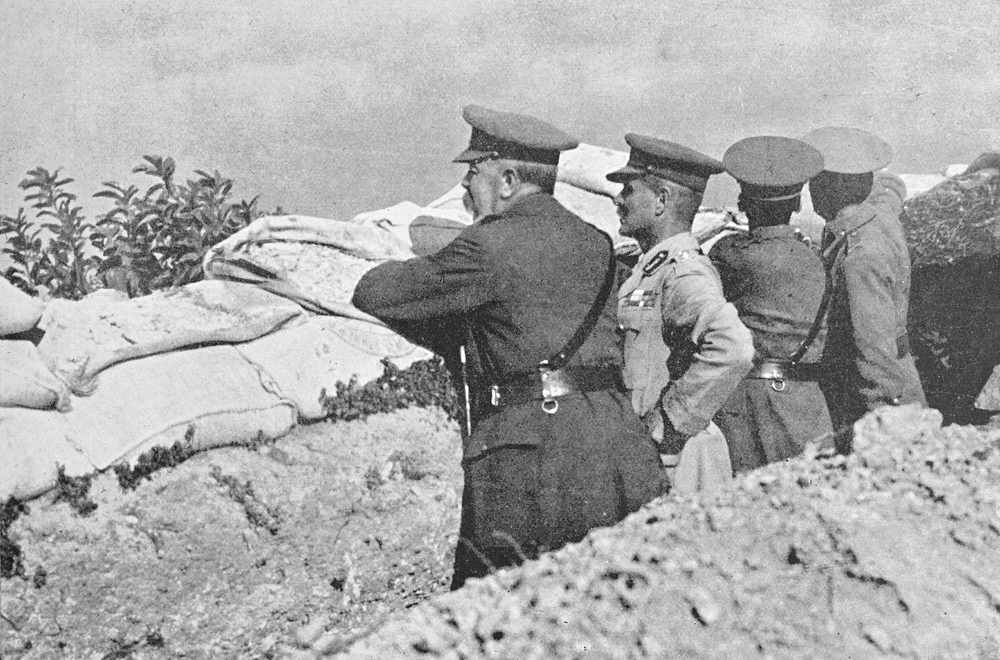

With misgiving we foresee the winter robbing us of the boon of daily bathing. This is a serious matter. The morning splash has come to be indispensable. Daily at six-thirty you have been used to see the head of General Birdwood bobbing beyond the sunken barge inshore; and a host of nudes lined the beach. The host is diminishing to a few isolated fellows, who either are fanatics or are come[Pg 18] down from the trenches and must clear up a vermin-and-dust-infested skin at all costs.

Not infrequently “Beachy Bill” catches a mid-morning bathing squad. There is ducking and splashing shorewards, and scurrying by men clad only in the garment Nature gave them. Shrapnel bursting above the water in which you are disporting raises chiefly the question: “Will it ever stop?” By this you mean: “Will the pellets ever cease to whip the water?” The interval between the murderous lightning flash aloft and the last pellet-swish seems, to the potential victim, everlasting.

The work of enemy shell behind the actual trenches is peculiarly horrible. Men are struck down suddenly and unmercifully where there is no heat of battle. A man dies more easily in the charge. Here he is wounded mortally unloading a cart, drawing water for his unit, directing a mule convoy. He may lose a limb or his life when off duty—merely returning from a bathe or washing a shirt.

One of our number is struck by shrapnel retiring to his dug-out to read his just delivered mail. He is off duty—is, in fact, far up on the ridges overlooking the sea. The wound gapes in his back. There is no staunching it. Every thump of the aorta pumps out his life. Practically he is a dead man when struck; he lives but a few minutes—with his pipe still steaming, clenched in his teeth. They lay him aside in the hospital.

That night we stand about the grave in which he lies beneath his groundsheet. Over that wind-swept headland the moon shines fitfully through driving cloud. A monitor bombards off[Pg 19] shore. Under her friendly screaming shell and the singing bullets of the Turks the worn, big-hearted padre intones the beautiful Catholic intercession for the soul of the dead in his cracked voice.

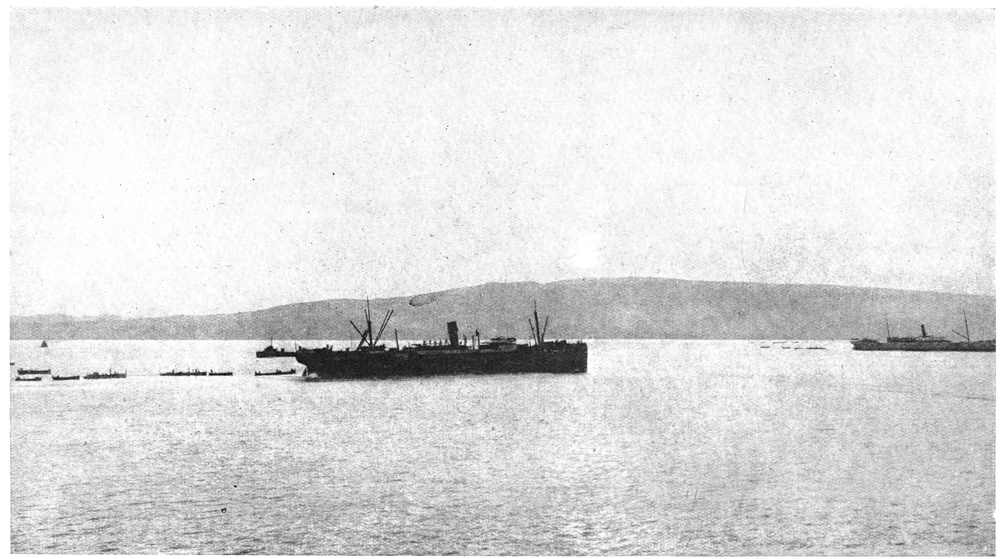

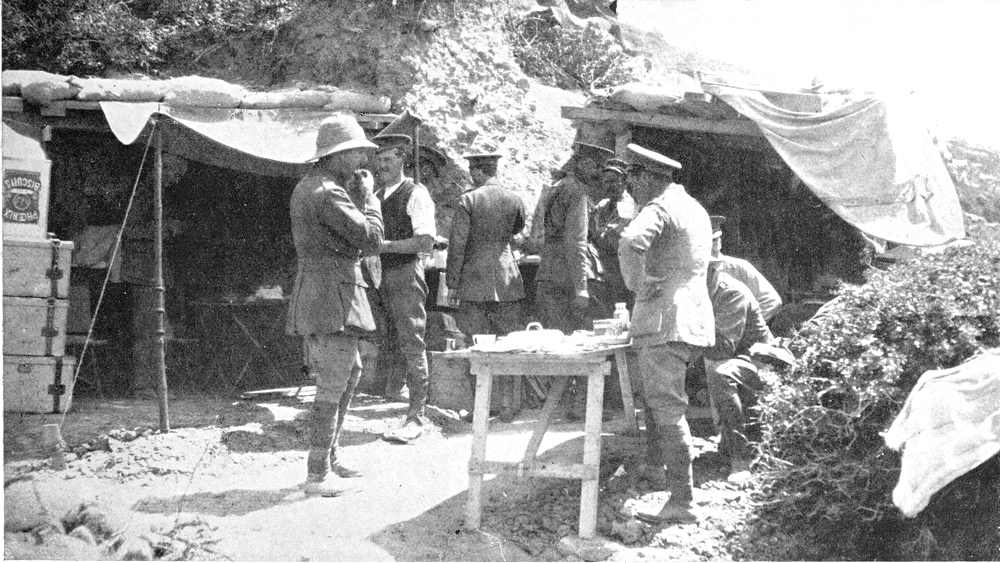

THE STORMS OF NOVEMBER

Transport in Trouble, November 17

After the Blizzard of November 29

Anzac Pier in the Storm of November 17

Photographs by C. E. W. BEAN

[Pg 20]

Photograph by Central News

General Birdwood taking a Dip

Photograph by C. E. W. BEAN

Shrapnel over Anzac Beach

The shrapnel cloud can be seen, and also the water off the beach whipped up by the pellets from the shells

[Pg 21]

At the burial of Sir John Moore was heard the distant and random gun. Here the shells sometimes burst in the midst of the burial party. Bearers are laid low. A running for cover. The grave is hastily filled in by a couple of shovel-men; the service is over; and fresh graves are to be dug forthwith for stricken members of the party. To die violently and be laid in this shell-swept area is to die lonely indeed. The day is far off (but it will come) when splendid mausolea will be raised over these heroic dead. And one foresees the time when steamers will bear up the Ægean pilgrims come to do honour at the resting places of friends and kindred, and to move over the charred battlegrounds of Turkey.

Informal parades for Divine Service are held on Sabbath afternoons for such men as are off duty. Attendances are scanty. The late afternoons are becoming bleak; men relieved from labour seek the warmth of their dug-outs.

The chaplain stands where he can find a level area and awaits a congregation. When two or three are gathered together he announces a hymn. The voices go up in feeble unison, punctuated by the roar of artillery and the crackle of rifle fire. The prayers are offered. The address is short and shorn of cant. This is no place for canting formula. Reality is very grim all round. There is a furtive under-watchfulness against shrapnel. One almost has forgotten what it is to sit in security and listen placidly to a sermon at church.

The chaplains have come out to do their work simply and laboriously. They are direct-minded, purposeful men. One is a neighbour in a Light Horse regiment—a colonel. He flaunts it in no sandbagged palace. His dug-out is indistinguishable from those of the privates between whom he is sandwiched—mere waterproof sheet aloft and bed laid on the Turkish clay; a couple of biscuit boxes with his oddments—jam, and milk, and bread: writing materials and toilet requisites. A string line beneath the roof holds his towel and lately washed garments. He is a simple parson, hard-worked by day and night in and about the trenches, careful for such comforts as can be got for his men in this benighted land; lying down at nights listening to the forceful lingo of his neighbours, and confessedly admiring its graphic if well-garnished eloquence. He sees his duty with a direct gaze—a faithful Churchman at work in the throes of war.

In a land of necessarily hard fare a regimental canteen in Imbros does much to compensate. Unit representatives proceed thence weekly by trawler for stores. One feels almost in the land of the living when so near lie tinned fruit, butter, cocoa, coffee, sausages, sauces, chutneys, pipes, tobacco, and chocolate. Such a repertoire, combined with a monthly visit from the paymaster, removes one far from the commissariat hardships of the Crimea.

The visualising of unstinted civilian meals is a prevalent pastime. Men sit at the mouths of their dug-outs and relate the minutiæ of the first dinner at home. Some men excel in this. They do it with a carnal power of graphic description which makes one fairly pine. One has heard a colonel-chaplain talk for two hours of nothing but grub, and at the end convincingly exempt himself from any charge of carnal-mindedness. Truly we are a people whose god is their belly. But that we never admitted until this period of enforced deprivation.

Those comforts embraced by the use of good tobacco and deliverance from vermin at night are the most desired; both hard to procure. There is somehow a great gulf fixed between the civilian quality of any tobacco and the make-up of the same brand for the Army. Once in six months a friend in Australia dispatches a parcel of cigars. Therein lies the entrance to a fleeting paradise—fleeting indeed when one’s comrades have sniffed or ferreted out the key. After all, the pipe, given reasonably good tobacco, gives the entrée to the paradise farthest removed from that of the fool.

Of the plague of nocturnal vermin little need be said explicitly. The locomotion of the day almost dissipates the evil. But it makes night hideous.

The tendency is to retire late and thus abridge the period of persecution. One’s friends drop in for a yarn or a smoke after tea, and the dreaded hour of turning-in is postponed by reminiscent chit-chat and the late preparation of supper. One renews, here, a surprising bulk of old acquaintance. Old college chums are dug out, and one talks back and lives a couple of hours in the glory of days that have passed. Believe it not that there is no deliverance possible from the hardness of active service. The retrospect, and the prospect, and the ever-present faculty of visualisation are ministering angels sent to minister.

Mails, too, are an anodyne. Their arrival eclipses considerations of life and death—of fighting and the landing of rations. The mail-barge coming in somehow looms larger than a barge of supplies. Mails have been arriving weekly for six months, yet no one is callous to them.

Of incoming mail, letters stand inevitably first. They put a man at home for an hour.

But so does the local newspaper. Perusing that, he is back at the old matutinal habit of picking at the news over his eggs and coffee, racing against the suburban business train. Intimate associations hang about the reading of the local sheet—domestic and parochial associations almost as powerful as are brought by letters.

And what shall be said of parcels from home? The boarding-school home-hamper is at last superseded. No son, away at Grammar School, ever pursued his voyage of discovery through tarts, cakes and preserves, sweets, pies and fruit with the intensity of gloating expectation in which a man on Gallipoli discloses the contents of his “parcel.”

“AT THE LANDING, AND HERE EVER SINCE”

Drawn in Blue and Red Pencil by DAVID BARKER

“’Struth! a noo pipe, Bill!—an’ some er the ole terbaccer. Blimey! Cigars, too!—’ave one, before the mob smells ’em.... D——d if there ain’t choclut! Look ’ere.... An’ ’ere’s some er the dinkum[3] coc’nut-ice the tart uster make.... Hallo! more socks! Nev’ mind: winter’s comin’. ’Ere, ’ow er yer orf fer socks, cobber?... Take these—bonzer ’and-knitted. Sling them issue-things inter the sea. [Pg 23]... I’m d——d!—soap for the voy’ge ’ome.... ’Angkerch’fs!—orl right w’en the —— blizzards come, an’ a chap’s snifflin’ fer a —— week on end.... Writin’ paper!—well, that’s the straight —— tip, and no errer! The beggars er bin puttin’ it in me letters lately too. Well, I’ll write ter-night on the stren’th of it. Gawd! ’ere’s a shavin’ stick!—’andy, that! I wuz clean run out—usin’ carbolic soap, —— it!... Aw, that’s a dinkum —— parcel, that is!”

Hector Dinning,

Aust. A.S.C.

[3] Dinkum—Australian for “true.”

From a Correspondent in Australian Field Artillery, “Sea View,” Boltons Knoll, near Shell Green.

I was looking out from the entrance of my dug-out, thinking how peaceful everything was, when Johnny Turk opened on our trenches. Shells were bursting, and fragments scattered all about Shell Green. Just at this time some new reinforcements were eagerly collecting spent fuses and shells as mementoes. While this fusillade was on, men were walking about the Green just as usual, when one was hit by a falling fuse. Out rushed one of the reinforcement chaps, and when he saw that the man was not hurt he asked: “Want the fuse, mate?”

The other looked at him calmly.

“What do you think I stopped it for?” he asked.

The same Correspondent writes:

I am sure that wherever the old 5th Light Horsemen, who put in such a warm spell at “Chatham’s”[4] some time ago, congregate after this war the following incident will be told and retold:

Bill Blankson was a real hard case, happy-go-lucky, regardless of danger. Bill was put on sapping for over a fortnight, and at the end of that time had a growth of stubble that would have brought a flush of pride to his dirty face if he had seen it. But he hadn’t seen it—one does not carry a looking-glass when sapping.

At the end of the fortnight he was taken off sapping and put on observing.

[Pg 24]

Anyone who has used a periscope knows that unless the periscope is held well up before the eyes, instead of the landscape, one sees only one’s own visage reflected in the lower glass.

Bill did not hold the periscope up far enough, and what he saw in it was a dark, dirty face with a wild growth of black stubble glaring straight back at him. He dropped the periscope, grabbed his rifle, and scrambled up the parapet, fully intending to finish the Turk who had dared to look down the other end of his periscope.

He had mistaken his own reflection for a Turk’s.

[4] Chatham’s Post at the southern end of the line was attacked by the Turks for several days in November.

One of the chief pastimes of the Turks who live behind the black and white sandbags opposite (writes an officer who knows them intimately) is that of listening to stories told by the storytellers in the cafés of the Asia Minor villages. The hero of these stories is very often a certain Nastradi Hodja (who really existed at one time, and made a reputation by his wit as well as through his stupidity). Here is an example of the sort of story about Nastradi which especially pleases the Turk:

Nastradi Hodja’s wife woke up one night through hearing a noise. She got up, and going out on to the landing on the upper floor, outside her bedroom, called out:

“Nastradi, what was that noise?”

Nastradi’s voice came up from below. “Don’t pay any attention to it,” he said. “It was only my shirt that tumbled down the stairs.”

“Does a shirt make such a noise?” she asked.

“No,” was the reply; “but I was in it.”

A. P. M.

[Pg 25]

[Pg 27]

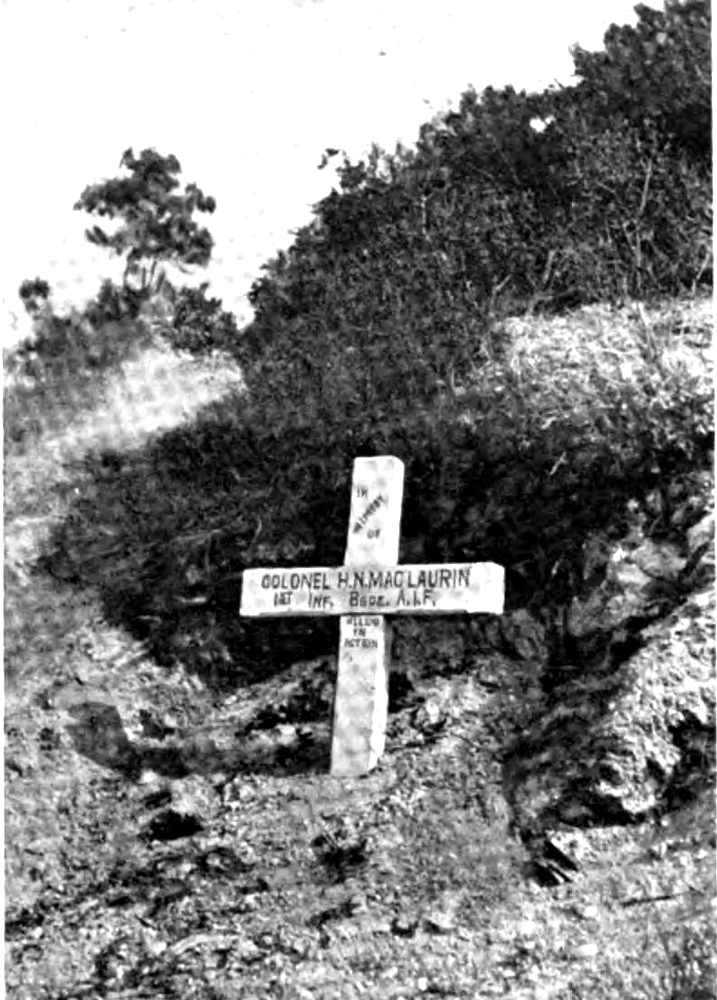

The Cemetery in Shrapnel Valley

The Grave of a Brigadier—Col. H. N. Maclaurin, killed April 27, 1915

A Cemetery by the Beach

Photographs by C. E. W. BEAN

[Pg 29]

DAVID BARKER

Gallipoli, 15.

“STANDING TO!”—4.30 a.m.

[Pg 30]

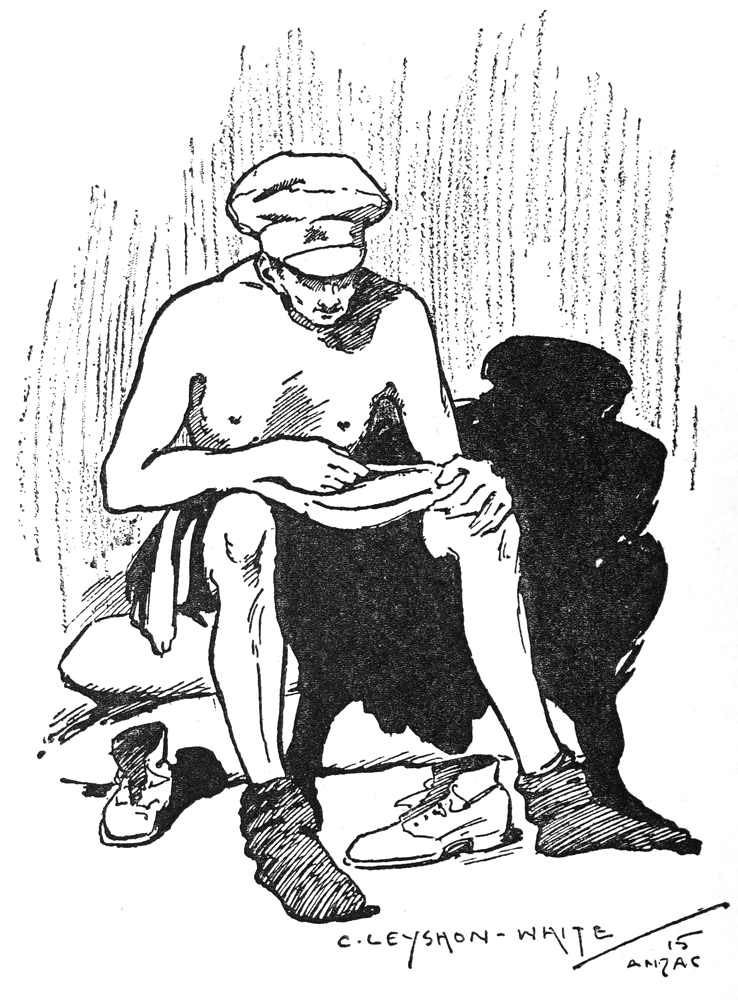

C. LEYSHON-WHITE

15

ANZAC

[Pg 31]

It was a fine day, and they were standing by waiting for instructions from the warrant officer to commence unloading and loading; and in the general murmur of voices one noted the broad tones of the British Tommy and the harsher ones of Tommy Kangaroo, the latter less careful of his grammar than the other; also the loud-voiced directions of the Indian Tommy, or rather Johnny, who condescended now and then to break into pidgin-English (with a smile).

Presently from amongst a group sitting in the shelter of a stack of bully beef came the request: “Give us a light, mate,” in the blunt style which belongs to Tommy Kangaroo.

“Aw, yes,” replies Tommy Atkins, or “Kitch,” as he is beginning to be called. “Aw, yes.” And while the other is pulling at his fag: “Have you got any baadges, choom?”

“No, I gave mine to a little nipper who used to sing on the stage at the El Dorado in Cairo.”

“Did you now! She must have a fine stack of baadges now, that ’un. You’re about the fifteenth lad that I know has given his baadges to ’er. Aw, thanks”—taking back his cigarette. “I see you’re from Austra-alia. What State did you live in?”

“Vic,” is the reply.

“I wonder if you knew my brother? He went to Victoria a couple of years ago. Got a job on the ra-ailways, he did, and wanted me to come out too. I’ll go when this is over; but ’ee’s married now, ’e is, and got a couple of pet lambs that ’e said was given to ’im by a chap named Drover; ’is name is Dobbs.”

“Never met him, matey, but he is all right, you bet. A Pommy[5] can’t go wrong out there if he isn’t too lazy to work.”

“Ah, yes, he tells me they called ’im Pommy, but that they was good lads. I could not understand them slinging off at ’im and ’im thinking they were treatin’ ’im like as ’e was one of themselves.”

“Oh, well, yer see, mate, we don’t call the like of ’im ‘Pommies’ because we dislike ’em, but just as a matter of description. Of course, sometimes one of ’em gets ’is back up and calls us sons of convicts in return for us chuckin’ off at ’im, and then he’s told lots of things—sometimes true and very often untrue; but Australia’s all right, mate. You need not be ashamed to be called a ‘Pommy’ out there.”

“Blime, there’s old ‘Beachy’[6] at it again,” breaks in another. “’Ee’s a fair cow, ’e is. Made me spill two buckets er water this mornin’, and our flamin’ cook told me I was too lazy to go down for it. I’ll give ’im ‘Beachy’[Pg 32] after this job is over if ’e don’t look out. Hallo, Johnny, Beachy catch-em mule, eh?”

“Beachy no good—mule good,” replies the tall spare Indian, with a smile, as he tries to bring his pair of mules under the shelter of the stack. “Mule very good,” he says, as he squats in front of his pair.

“’Ow long yer been ’ere, choom?” asks Kitch of Kangaroo.

“Nearly six munce now. Blime, I could do with a spell now, too. I’m beginnin’ to get a ’ump like a camel from carryin’ these flamin’ boxes.”

“Aw, yes, but it’s better than bein’ in the trenches, ain’t it?” asks Kitch.

“Blime, no,” is the reply. “A man’s got a chance to hit back there, but down ’ere it’s up to putty. It’s bad enough to be eatin’ bully beef, but carryin’ it as well is rotten. I couldn’t look a decent bullock in the face now for what I’ve said about ’im when ’e’s tinned.”

“Did yer ’ear wot was doin’ up at Narks Post larst night, Bill?”

“Yes; some d——d gobblers thought they would catch our mob nappin’ but missed the bus, and some of ’em are still runnin’ yellin’ to Aller to stick to ’em. Blast ’em! I’ll give ’em Aller when I get a chance. Keepin’ a man stuck on ’ere when ’e might be havin’ a good time somewhere else. I’ll bet——”

“Come on, Bill, ’ere comes the W.O.,”[7] says his mate.

“D—— ’im—see yer later, matey; and I’ll try to get a badge for yer.”

“Don’t forget, choom. Ah want it to send to my married sister’s little lass. She thinks youm lads be prime boys.”

“Prime boys,” mutters Bill, as he grabs his case of bully. “Yes, prime boys jugglin’ Best Prime Bully Beef.”

“D—— it—shut up, Bill,” says his mate. “You’re always growlin’—you’ll want flowers on your grave next.”

N. Ash.

[5] Pommy—short for pomegranate, and used as a nickname for immigrants.

[6] “Beachy”—a battery of Turkish guns, well known on Anzac Beach.

[7] W.O.—Warrant Officer.

C. LEYSHON-WHITE

15

“KITCH”

Drawn With an Iodine Brush by C. LEYSHON-WHITE

[Pg 33]

(A SOLILOQUY) SOMEWHERE IN THE ANZAC ZONE

[Pg 35]

Outside was a cold, dark, windy and cheerless night, and the world seemed cowering under the black, threatening rain-pall above, which could be felt rather than seen. Inside my host’s diggings we were lounging back in the warmth and light, smoking and yarning of other times and places, while the partner of his home brewed the warm, fragrant, comforting decoction which seemed to contribute so much to the mood and proper appreciation of such friendly comfort in the midst of the audible turmoil of unfriendly outer circumstances.

Once again from outside there came a whir and rattle past the door, and I smiled significantly and glanced in that direction.

“Oh, don’t go until after the next one,” urged my host’s companion, seeing my attention diverted to things outside of our present cheery circle.

With this my friend seemed to concur, and drew himself closer to the fire. “Yes, there’s plenty of time yet,” he said. “There’ll be a lot more of ’em. So you might as well sit tight in, safely and comfy, and try another cup.”

I didn’t need much coaxing, and thrusting the thought of the long, unpleasant journey home out of my mind, I settled down to further cheery chat and the enjoyment of stimulating internal comforts.

The conversation seemed to have progressed but a little further when above the wind outside could be heard again the warning roar and rumble, fading away and terminating in a muffled clang and clatter in the distance. “That settles it, Billo, old chap,” I said, half rising. “Pass over my coat. If I hurry off now I’ll be just in time.”

But my friend didn’t move to oblige. “Now, what’s the use of hurrying?” he urged once more. “They’ll be passing every minute now for a long time yet. So why not settle down and enjoy yourself a bit longer? ’Taint very often you come this way.”

By the time I had finished my reply to his persuasions I found, again, that my chance had gone—and I would have to wait now, anyhow.

And so the time passed. We talked and talked, while a useful youth who lived near by, and had attached himself to my friend Billo, made three reappearances with hot water for the cups that cheered as the night went on.

“I wonder where ‘Razzy’ is?”[Pg 36] presently remarked my host; “the jug wants refilling.”

Just then the disturbing rumble passed the door again, and I rose to my feet. “Don’t bother to disturb him,” I said. “I suppose he’s retired to his digs. Besides, now’s my chance to scoot too; I’ve a long way to walk. Throw me that coat.”

Finding that all protestations were useless, my friends reluctantly allowed me to go, but not without wilily expressed forebodings as to what unpleasantness might await me outside now that I had refused to enjoy their society and comforts any longer.

They accompanied me to the door, and a cold blast of wind met us. There were ominous thunder rumbles in the murky distance.

“A boshter[8] night for a walk,” I remarked, buttoning my coat about me.

“Yes,” grinned my friend, peering out into the darkness. “And they’re running to a peculiar sort of time-table to-night—passing about every seven minutes. You’d better get a wriggle on. There’s a short cut that way,” he added, pointing to the right, “just past the corner of the cemetery. That’s where they stop. So for God’s sake shake it up; if you don’t, they won’t see you home at all. It’s an unhealthy night to be out.”

I asked them to say good night to the youth “Razzy” for me, and to thank him for his comforting ministration, then bade them farewell and moved off.

I blundered along the sloppy, unpaved footway, peering tensely into the uncanny blackness about me, and hurried uneasily in the direction of a patch of faint pale blotches that I hoped and took to be the monuments in the little burying-ground down beyond. I found that my direction was right, and presently I was hurrying past it as fast as I could manage in the wind and darkness. From somewhere behind me—it sounded miles and miles away through the noise of the wind—a faint low moaning sound reached my ear. I stepped forward uneasily, but before I had advanced a yard it had become more prolonged, and growing ever louder and closer until I seemed to feel it coming—coming with tremendous and ever-increasing speed: a horrible, nerve-shattering, deafening, wailing shriek. I stood dazed and paralysed—rooted to the spot. With a scream of hellish intensity—it was all within a second, really—it was on me. There was a flash of blinding light, then everything ended so far as I was concerned.

My next interest in life was a feeling that I had just been hurled up at the moon, over it, and had descended slowly, ever so slowly, like a feather, to earth again. In fact, I wasn’t quite sure that I was not a feather; and I opened my eyes carefully and tried to feel myself. “’Ssh-sh-sh! Don’t disturb yourself—remain quiet and comfy,” said a persuasive voice beside me. I looked around as far as I could move, and knew that I was in a hospital, but where or of what kind I could not think for the moment. I lay awhile gazing blankly and unthinkingly at a low white ceiling above me. Presently I fell to wondering.

[Pg 37]

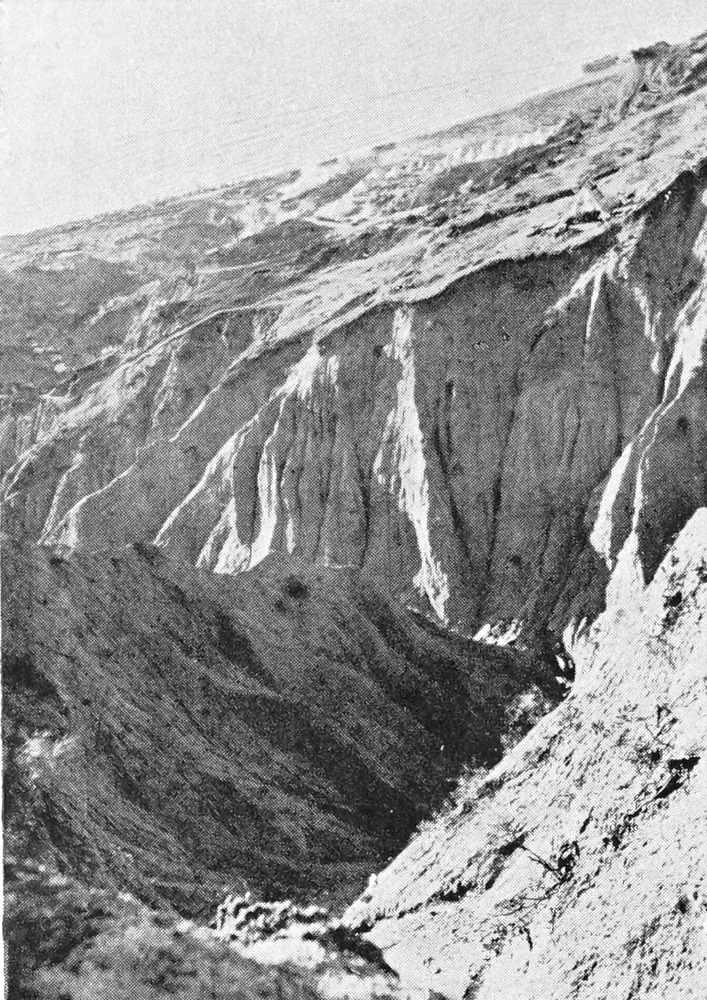

ACHI BABA, SEEN FROM ANZAC

(The dug-outs and paths of Anzac are seen in the foreground. Above them on the sky line is the massive Kilid Bahr plateau, the near promontory in the centre is Gaba Tepe, and above is the peak of Achi Baba. The British position at Helles comprised the distant coast up to a point a little astern of the destroyer.)

Drawn by G. T. M. ROACH

[Pg 38]

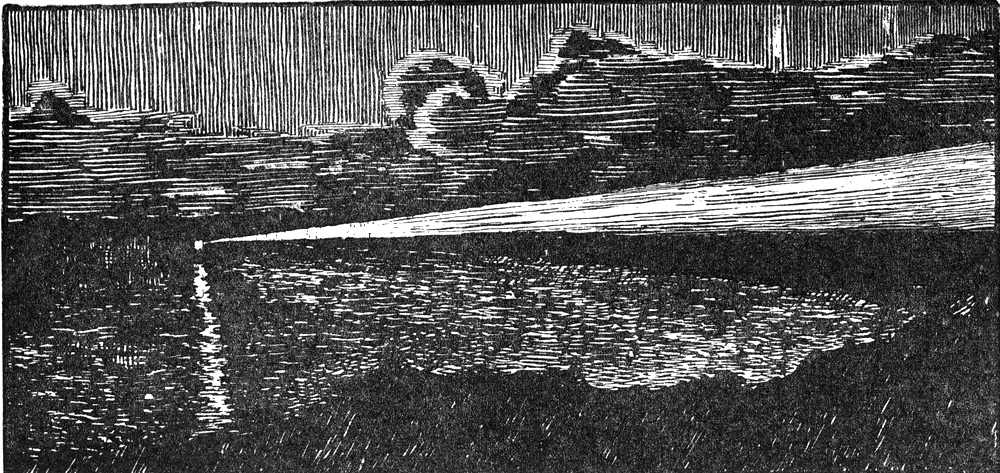

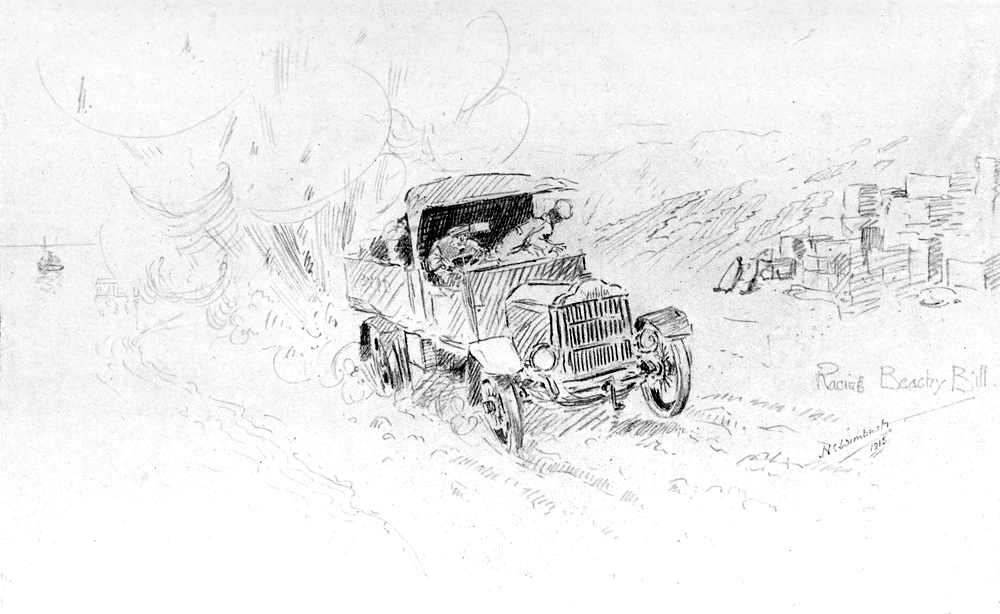

RACING BEACHY BILL

Drawn by H. C. WIMBUSH

[Pg 39]

In what suburb, in what town (it seemed to have been hundreds of years ago that it had happened), and what part of Australasia could it be that a peaceful citizen, walking a darkened street, homeward bound, could be violently assailed, near the resting-place of its harmless sleeping dead, by an awful uncanny horror descending from the black unknown? Was I cursed, haunted, bewitched—or what? Then there came to me the vague memory of a friend, one whom I familiarly knew as “Billo,” and in some way associated with my terrible, mysterious experience. But somehow it didn’t seem to fit in with the slowly gathering evidence of my returning senses, for it seemed to me that “Billo” had long before quitted suburban civilisation for some great adventure—perhaps—yes, it was a war somewhere—in which I, too, had later resolved to follow his example and do my share. Then how came it that this terrible experience had befallen me in the midst of the enjoyment and comforts of civilisation?

I had a positive though hazy memory of a comfortable, warm room, pleasant drinks, cheery conversation; “Billo” and his companion, the latter a rough, kindly sort of being—no, it could not have been a woman; besides, “Billo” was a bachelor. I remembered that distinctly.

Suddenly it became clear to me, and I remembered a silent, rugged man facetiously dubbed “’Enery” by my friend—a kindly chap, of very few words, with whom I had not been long acquainted. Where had “Billo” picked him up? There also came before me the memory of a small, dilapidated man or youth, dark complexioned; somehow also attached to “Billo.” His name was—yes, that was it.... Who the deuce was “Razzy”? My mind here became dazed, and speculation drifted off into a confusion of reflections: that “Razzy” was a foreigner of some sort, living with us under the same conditions, yet in some way very different and in a degree inferior; that the hour at which I left my friend “Billo’s” home and his inexplicable associates was quite early in the night—perhaps only nine-thirty. This latter fact seemed to linger in my mind, for presently—with a hazy conviction that there were sure to be other pedestrians abroad on a suburban street at that hour—I heard my own voice asking no one in particular: “Was there anyone else there?”

It came as no surprise to hear a man’s rough voice reply:

“Only a Maltese—at least, we think he was. He was blown to smithereens. But don’t let ’em see you talking too much, mate.”

The room seemed to rock. I opened my eyes, and with difficulty caught sight of the speaker. He was in khaki and wore an A.M.C. badge on his arm. I was on a hospital ship.

“Then that must have been poor ‘Razzy,’” I muttered at last. Before my mind’s eye there seemed to unfold a dissolving scene. The cosy rooms of my friend “Billo” became a dug-out in a hillside, lit by a slush lamp made from bacon fat. “Billo” and his rugged, silent companion were wearing the familiar time-tattered uniform that I knew so well ages and ages ago (actually it was five days back); the door through which I had passed into the unpleasant night was an oilsheet tied down to keep the weather out; and the frequent rumbling roar was not that of a passing suburban train which I was timing myself to catch. On the[Pg 40] contrary, it was the intervals between that sound which interested me. For each of those rushes past the door of my friend’s dug-out was a hurtling Turkish shell, and I wanted to make my escape at a reasonably safe moment. Also, the place where “they” chiefly lobbed was the cemetery at the foot of the rugged track (I had dreamed of it as the unpaved footpath of a new suburb), where rest a score or more game Australian lads who had taken part in the landing on Gallipoli. The unfortunate “Razzy,” by the way, was but one of a gang of Maltese labourers brought by the authorities, at a later and safer period, to help in the landing of stores from the transports in the bay at Anzac. He had become friendly with my luxury-loving friend “Billo,” and, in gratitude for various kindly considerations, was willing to provide the hot water to make our hot-rum drinks on that memorable night at “Billo’s” station on our right wing. (I was quartered miles away on the extreme left.)

So it was near the cemetery that the unexpected shell got me; and apparently “Razzy” also, who was returning to his camp a hundred yards away. There seemed something so droll about the whole strange illusion that, although in a state of dazed depression, I might have laughed but for an indescribable pain in my left side. I saw that my left arm was supported on something and lay above the bedclothes and seemed very heavy.

“Feel comfortable?” said the A.M.C. man.

“Yes, except for the pain in my left hand,” I answered.

He looked down, and I followed his gaze.

“You haven’t got no left hand,” he said quietly.

I saw that he was right, and this new illusion struck me as being about the last straw.

With a dazed sort of conviction I muttered: “Well, it’s a rummy world”—and promptly lay back and drifted out of it for the time being.

Ted Colles,

3rd L.H. Field Ambulance.

C.E.W.B.

Portrait of an

Australian

soldier returning

from the field of

glory at Helles.

May 11th 1915

[Pg 41]

[8] Bosker, boshter, bonzer—Australian slang for splendid.

I am sitting, at the moment of writing, in a dug-out, one of those dismal, dark, damp holes cut into the clay of the Dardanelles, serving us as a haven of refuge by day and by night from the ubiquitous Turkish bullet.

The proportions of this extemporised dwelling resemble those of an exceedingly small family tomb—one which might belong to a family too proud not to possess a family tomb at all, but too poor to possess one of adequate size and comfort (if one can speak of comfort in such a connection). Its dimensions should be about ten feet by four, but I am not enthusiastic enough at the moment to ascertain them precisely. Its three walls are of crumbling clay. Where the fourth wall strictly should be is an exit which lets in the draught. Over my head are stretched waterproof sheets which let in the water. On the floor, in fine weather, is an inch of dust, and in bad weather a proportionate amount of slimy mud. A few sandbags ranged round the parapet threaten to tumble in and annihilate my existence. I am sitting on a roll of bedding. My haversack, water-bottle, field-glasses, webbing, pistol, gas helmet, and india-rubber basin are arranged round my feet like so many pet dogs begging for biscuit; and in such an entourage I think of my room at home—and that is where this matter of contrast comes in.

It was the same at dinner. We—that is to say, my brother officers and I—sat in another variety of dug-out; this time an open one—open to all that blows and falls. Our repast consisted of an exceedingly stringy rabbit, extracted from a tin of an ominous purple hue—an evil-looking dish eked out with somebody or other’s baked beans, which are all very well in their way, but when used as an unvarying vegetable at all meals begin to pall; bread, with the crust like a cinder, to which fondly cling bits of sacking and mules’ whisker; the corpse of a cheese; and the whole washed down with tea made in the stew dixie, and tasting more of dixie and stew than of tea.

As I lean back against the clay wall of my dug-out, and innumerable particles of dust cascade down my neck, a soft reverie steals over my senses. It seems to me to be about six or seven o’clock on a murky November afternoon in London. I have splashed home from my work in the wind- and rain-swept streets—the motor-buses have covered me with black mud—my umbrella has afforded me the most inadequate shelter. But these things seem of little account to me here in Gallipoli. I see myself reaching my home in the best of spirits, entering[Pg 42] the hall, and shutting off the outer darkness. My sense of contrast gives me a lively notion of dry clothes, of a comfortable room, of a genial fire, and of an absorbing book. In future I shall be grateful for the rain and the mud and the murky streets for making these good things seem by contrast so much more valuable.

Think of it! To sink into a great arm-chair in front of my library fire, after a hard and anxious day’s work, and contemplate the near approach of an excellent evening meal. How comfortable and warm and hospitable my room appears as I lean back and listen to the rather depressing, smothered rumble of the traffic in the street below. Thick curtains hide away the melancholy November London atmosphere. Sweet-smelling logs crackle cheerily on the hearth; a reading-lamp by my side sheds subdued lustre on the immediate vicinity of my chair. My servant glides into the room noiselessly over the soft carpet, and places the evening paper by my side. I choose a cigar from my case, light it, and then I am perfectly content—and my contentment is due to contrast between my content with the existing situation and my past discontent with other situations at other times and in other places.

After a refreshing siesta I go upstairs, exchange my workaday clothes for a smoking-suit. Two or three bachelor friends are due to dine with me, and by the time I have dressed and descended again to the sitting-room they are there ready for my greeting.

And what a pleasant evening it is with their company. We talk of old times, old acquaintances, and old places. We talk of our big-game shoots, of our campaigns, and of our travels, the recollection of which seem so delightful now that distance lends enchantment to the view. Dinner is over; a glass of brandy and old port, some smokes, and we are just adjourning to the next room——

“Wake up, old chap—three o’clock. Your turn for the trenches. It is snowing hard and the Turks are very active.”

Contrasts indeed!

E. Cadogan,

1/1 Suffolk Yeomanry.

its not what

you were.—

but what

you are

to-day—

[Pg 43]

DAVID BARKER 15.

AFTER

B. HARTMAN

The Ass: “Are you wounded, mate?”

The Victim: “D’yer think I’m doing this fer fun?”

[Pg 44]

Regarding these two particular pests, my attitude in the past has been characterised by the utmost forbearance; I tolerated them and looked upon them as harmless and possibly of some usefulness to the community. The Gallipoli specimens, however, have changed my state of “benevolent neutrality” into one of most deadly warfare. No “Hymn of Hate” has yet been composed which would give expression to the hatred which has possessed me.

Do you but go into the trenches in the endeavour to perform your duty to your country, and the flies immediately try to dissuade you by getting into your eyes, ears, nose and mouth. Nothing will drive them away; they delight in this; they are entirely without pity. Retire to your dug-out in the hope of escaping their attentions, and they are sure to follow you. Smoke till you all but asphyxiate yourself, and you find them as active as ever. Nothing that human ingenuity can devise will cause them to retreat; they defy our puny efforts. You may imitate the Kaiser and “strafe” them for all you are worth, but it is only waste of breath; they glory in this and come back all the more.

What we frequently distrust in the way of tucker holds no terrors for the Gallipoli flies; they delight in taking risks if only to impress us with their fearlessness. Stepping boldly on the edge of a syrup-covered biscuit, they immediately get their feet entangled; but they will not retreat—that would be against all their traditions. Instead, they will struggle their way towards the centre, where they gladly give up the contest and die.

They are born conquerors. I doff my hat to them in spite of my hate.

With the setting sun the flies retire, but operations are simply handed over to their allies, the fleas; and no worthier ally could be found than those pilgrims of the night. You may feel beat to the world, but there is no rest for you; as soon as you lie down to enjoy a well-earned rest the attack commences. Advancing in open or close formation, according to circumstances, the enemy attacks on every flank with fixed bayonets, in the handling of which his units are experts. If driven off, they come again in still greater numbers; they appear to have unlimited reserves of reinforcements which can be mobilised on the shortest notice. Their organisation is perfect. Counter-attacks in the dark are all in the favour of the enemy, and morning finds that they have withdrawn their forces to advantageous cover in the blankets, from which it is impossible to dislodge them. Keating’s Powder is of no avail against the Gallipoli fleas; it requires a still higher explosive to have any effect.

The honours have so far fallen to the enemy. Personally, I would be inclined to discuss terms of peace, but I doubt not he is too depraved to accept my advances.

A. Carruthers,

3rd Australian Field Ambulance.

[Pg 45]

C LEYSHON-WHITE ’15

His real name matters little; suffice it that he was known among his comrades as “Wallaby Joe.”

He came to Gallipoli via Egypt with the Light Horse. Incidentally, he had ridden nearly a thousand miles over sun-scorched, drought-stricken plains to join them.

Age about 38. In appearance the typical bushman. Tall and lean, but strong as a piece of hickory. A horseman from head to toe, and a dead shot. He possessed the usual bushy beard of the lonely prospector of the extreme backblocks. Out of deference to a delicate hint from his squadron commander he shaved it off, but resolved to let it grow again when the exigencies of active service should discount such finicking niceties.

His conversation was laconic in the extreme. When the occasion demanded it he could swear profusely, and in a most picturesque vein. When a bursting shell from a “75” on one occasion blew away a chunk of prime Berkshire which he was cooking for breakfast, his remarks were intensely original and illuminative.

He could also drink beer for indefinite periods, but seldom committed the vulgar error of becoming “tanked.” Not even that locality “east of Suez,” where, as the song tells us, “There ain’t no Ten Commandments and a man can raise a thirst,” could make his steps erratic.

He was very shy in the presence of the softer sex. On one occasion his unwary footsteps caused him some embarrassment. Feeling thirsty he turned[Pg 46] into one of those establishments, fairly common in Cairo, where the southern proprietors try to hide the villainous quality of their beer by bribing sundry young ladies of various nationalities and colours to give more high-class vaudeville turns. The aforementioned young ladies are aided and abetted by a coloured orchestra, one member of which manipulates the bagpipes.

A portly damsel had just concluded, amidst uproarious applause, the haunting strains of “Ta-ra-ra boom-de-ay.” She sidled up to Joe with a large-sized grin on her olive features.

“Gib it kiss,” she murmured, trying to look ravishing.

But Joe had fled.

Henceforth during his stay in Egypt he took his beer in a little Russian bar, the proprietor of which could speak English, and had been through the Russo-Japanese War.

When the Light Horse were ordered at last to the front, Joe took a sad farewell of his old bay mare. He was, as a rule, about as sentimental as a steamroller, but “leaving the old nag behind hurt some.”

On the Peninsula and under fire his sterling qualities were not long in coming to the surface. Living all his life in an environment in which the pick and shovel plays an important part he proved himself an adept at sapping and mining. At this game he was worth four ordinary men. No matter how circuitous the maze of trenches, he could find his way with ease. He could turn out all sorts of dishes from his daily rations of flour, bacon, jam, and of course the inevitable “bully” and biscuits. An endless amount of initiative showed itself in everything he did. His mates learned quite a lot of things just by watching him potter about the trenches and bivouacs. His training at the military camps of Australia and, later, in Egypt, combined with the knowledge he had been imbibing from Nature all his life, made him an ideal soldier.

He was used extensively by his officers as a scout. As the Turkish trenches were often not more than twenty yards from our own, needless to say the scouting was done at night, the Turks’ favourite time to attack being just before dawn. Often during these nocturnal excursions a slight rustle in the thick scrub would cause his mate to grasp his rifle with fixed bayonet and peer into the darkness, with strained eyes and ears and quickened pulse.

“A hare,” Joe would whisper, and probably advise him to take things easy while he himself watched.