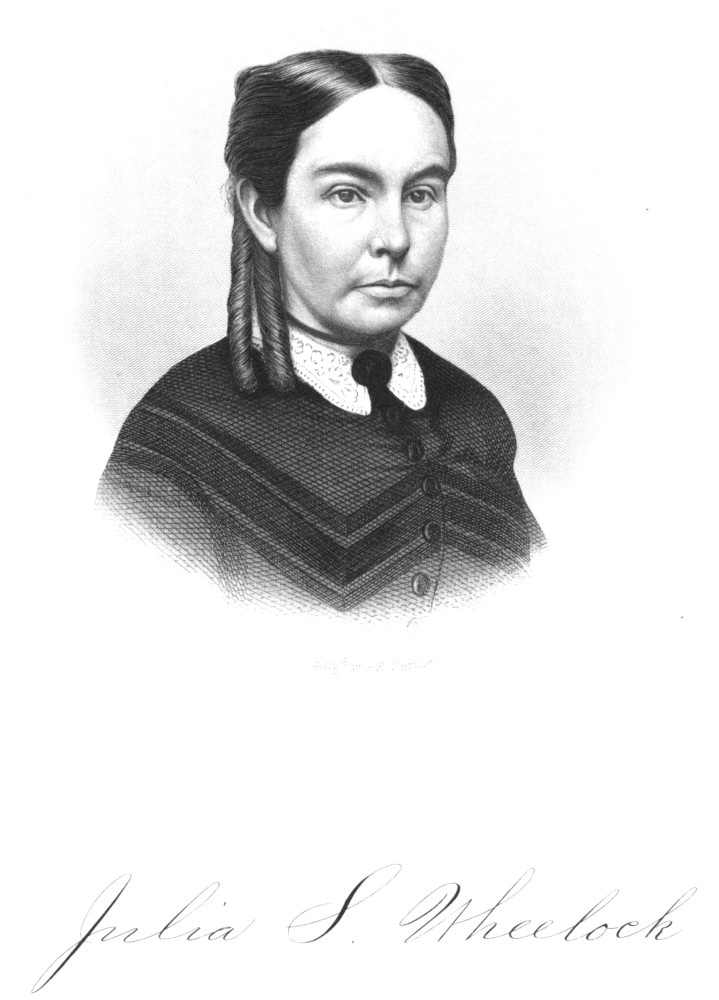

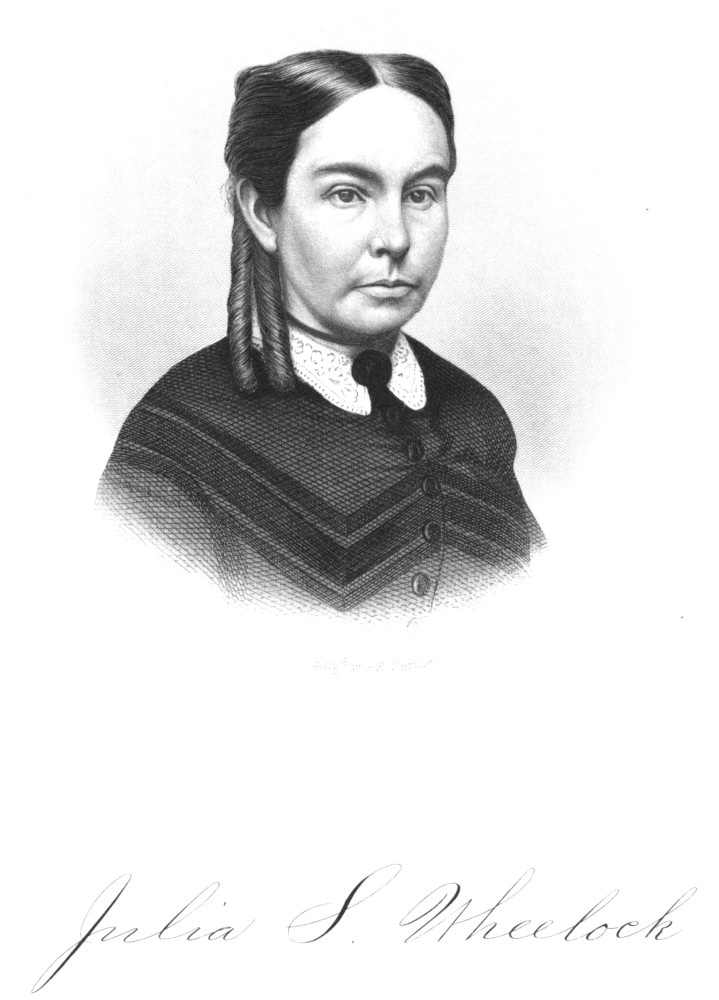

Julia S. Wheelock

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The boys in white, by Julia S. Wheelock

Title: The boys in white

The experience of a hospital agent in and around Washington

Author: Julia S. Wheelock

Release Date: April 3, 2023 [eBook #70450]

Language: English

Produced by: Steve Mattern and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Julia S. Wheelock

THE BOYS IN WHITE;

THE

EXPERIENCE

OF

A HOSPITAL AGENT

IN AND AROUND WASHINGTON.

BY JULIA S. WHEELOCK.

NEW YORK:

PRINTED BY LANGE & HILLMAN,

STEAM BOOK AND JOB PRINTERS, 207 PEARL ST.,

NEAR MAIDEN LANE.

1870.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1870, by

JULIA S. WHEELOCK,

In the Clerk’s Office of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia.

Printed by Lange & Hillman,

207 Pearl Street,

Near Malden Lane, N.Y.

[Pg v]

From September, 1862, to July, 1865, I was in the hospitals in and around Washington. I kept a journal of my experience, portions of which appear in this volume. The journal was kept for my personal benefit, and not for publication. Much of it was written late at night when so wearied by excessive labor, anxiety, and excitement, that I would not unfrequently fall asleep with the pen in my hand. I often sat upon a box or some rude bench, and held my book on my lap as I wrote, and now this journal, condensed, is thrown into the lap of the public and of my friends, who have earnestly requested that “The Boys in White” may be embalmed, as well as the “Boys in Blue.” My object in going South was to help care for a wounded brother. When I left home I expected to remain only until he became able to travel; but, upon arriving in Alexandria, we found that death had already done its work. A little mound of earth in the soldier’s cemetery marked the spot where that dear, almost idolized brother slept, and[Pg vi] thus our bright hopes and fond anticipations were suddenly and forever blighted. I resolved to remain and endeavor, God being my helper, to do for others as I fain would have done for my dear brother. A field of labor soon presented itself which I most gladly entered. Justice to our noble soldiers demands that I should here state that, during my hospital and army experience of nearly three years, I was uniformly treated with the utmost courtesy and respect. I know it was thought and even said by some, that a lady could not be associated with the army without losing her standard of moral excellence. I pity those who have such a low estimate of the moral worth and true nobility of the soldier.

I have sometimes been asked if I did not feel afraid when in the midst of so many soldiers. I can truthfully say that I never knew what fear was when in the army, for I felt that every noble boy in blue was my brother and protector. What cause had one to fear, when brave, heroic hearts and strong arms were ever ready to defend?

Any one, during war’s dark hours, whose mission was to do good, was almost an object of worship by those so wholly excluded from home influences. For, if there ever was a time when the better angel of their nature guarded the citadel of their hearts, it was in the presence of woman—when she was a true representative of what that sacred word implies.

I take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to the officers of the “Michigan Relief Association,”[Pg vii] with which I was connected, for their kindness and forbearance; to our military State agents, Dr. J. Tunnecliff and Rev. D. E. Willard, to whom I never appealed in vain for aid or counsel; also to military agents of other States, and to the officers and agents of various “State Reliefs.” We were greatly indebted to the Christian Commission for large supplies which we frequently drew from their stores, and for occasional drafts on the Sanitary Commission. Officers of the Government, and hospital officials, as a rule, were kind and obliging. Our thanks are also due to our Congressmen and other Michigan gentlemen residing in Washington, who were ever ready to assist us in our work.

That this little volume may be the means of renewing the acquaintance and of strengthening the friendship of those who labored together in this blessed work, as well as of the soldiers themselves, is the earnest desire of my heart. If this shall be the result, I shall feel that I have not written in vain.

[Pg viii]

I take the liberty of publishing the following private letter from Grace Greenwood:

Washington, May 10th, 1869.

My Dear Miss Wheelock:

I am pleased to hear that you propose to make a book of your varied and interesting reminiscences of the war, and of the touching records of our brave soldiers which you have treasured up.

I well remember seeing you at your post of duty with the army, at the camp of a portion of the Second Corps, on the Rapidan, in that critical time of the great struggle, the winter of 1864, just before the grand move of the army under General Grant, which resulted in the fall of Richmond.

I saw you at your lonely and sad, but most noble and womanly work, and felt gratified that the poor, sick soldiers had such a friend in their darkest hours.

[Pg ix]

Truly those past heroic days should be kept in remembrance, and every faithful record of them should be welcome to us. So I hope your little literary enterprise may be successful.

Truly yours,

GRACE GREENWOOD.

[Pg 9]

THE BOYS IN WHITE.

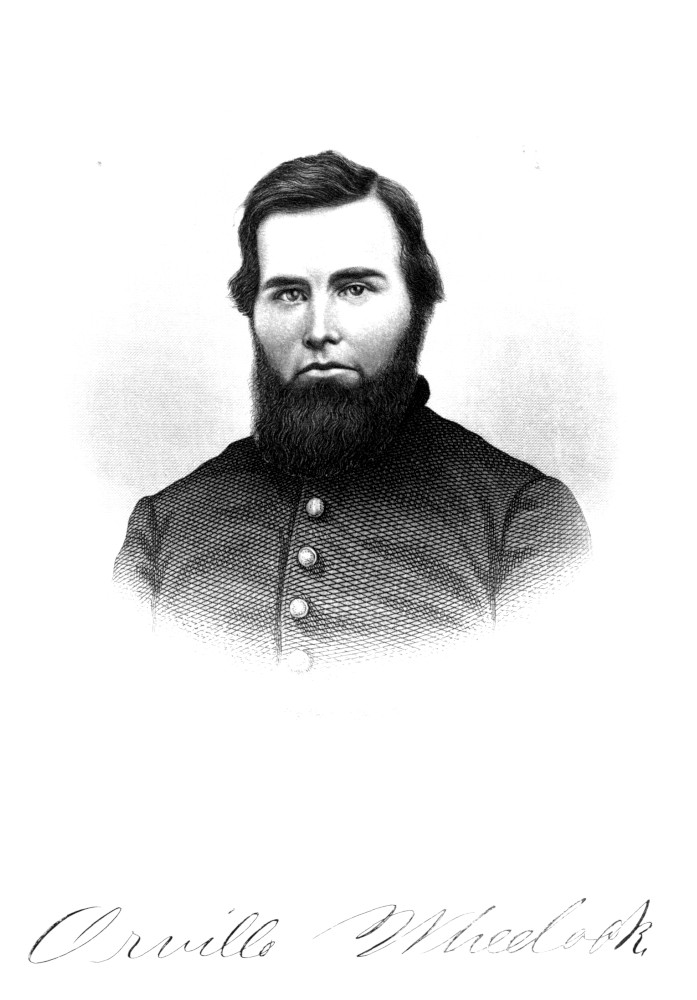

RETROSPECT—HOME-LEAVING—LAKE ERIE—ALLEGHANIES—ACCIDENT—WASHINGTON—PROVOST MARSHAL—THE PRESENTIMENT—BLIGHTED HOPES—ORVILLE WHEELOCK—MY BROTHER’S GRAVE.

Alexandria, Va., Oct. 1, 1862.

Well, here I am, strange as it seems, in the rebellious city of Alexandria! Alone, among strangers, hundreds of miles from home and kindred, surrounded by scenes new and strange; scenes of sadness, of suffering, of death.

As I look over the past, it does not seem possible that only three weeks have elapsed since leaving home. Oh! what a lifetime one may live in a very short period, when it is measured by heart-throbs instead of years. While retrospecting, memory goes back to the morning of the 10th of the month just closed. Its dawn is calm and beautiful. Nine[Pg 10] o’clock finds me in the old red school-house in the township of Ionia, Michigan, where are assembled the rural children and youth for instruction. All are joyous and happy. Three days more and the term will close. This day promises to end as it began, full of joy and gladness—yet, knowing that the fearful battles of Bull Run and Chantilly had recently been fought, we were anxiously waiting for tidings from the loved one who had gone to battle for the “dear old flag,” and, if need be, die to maintain its honor. But the interval that had elapsed since the occurrence of those bloody conflicts gave us reason to hope that our soldier brother was safe. Nor voice, nor spirit, nor sighing wind, nor playful breeze, told of the future. But time on rapid wing approached with tidings the most heart-crushing. A child is made the bearer of the sad message.

About three o’clock, while engaged in hearing a recitation, there is a gentle tap at the door—a little girl steps upon the threshold; her eyes are red with weeping, and, in great agitation, she says: “Orville is wounded; his limb is amputated. He has sent for Anna, and she starts for Washington to-morrow!” My womanly heart said, that “Orville Wheelock, my brother, must not suffer alone. I will accompany Anna to Washington.”

The dawn of the morning of the 11th was calm[Pg 11] and peaceful, but to us every breeze seemed laden with sighs from some stricken heart. Little Minnie gathered a bouquet of flowers to send to “dear papa,” and every blossom was a wish that he might come home. At nine o’clock sister and I bade adieu to friends, and in Ionia village we were joined by Mrs. Peck, the sister of my brother’s wife, who was starting to Washington to care for her wounded husband. Off at two o’clock. Soon the enterprising little town of Ionia is lost in the distance. Familiar objects fade from our view, and all becomes new and strange—as this is my first ride over the Detroit and Milwaukee Railroad. The scenery is rather monotonous along the line of the road—the country most of the way being new—though every few miles we pass thriving little villages which have sprung up within a few years as if by magic, and which northern industry and enterprise will soon convert into fine cities, and those dismal swamps and marshes into beautiful meadow lands. At Detroit we take the steamer “May Queen,” bound for Cleveland. The evening is delightful. The stars one by one shine forth from the blue canopy above, and their gentle light is reflected from the blue expanse below; and while we gaze, the full-orbed moon emerges from the waters, and, “blending her silvery light with that of her sister stars,” adds new lustre to the scene.

[Pg 12]

At eight o’clock we leave the shores of Michigan, and are soon plowing our way through the blue waters of Lake Erie. How pleasantly and quickly would have passed the hours of that long night, were it not for the sad mission upon which we were going. The battle-field with its thousands of mangled forms, the dead and the dying, and all the horrors connected with such scenes of carnage, are spread out before us. These, with the conflicting hopes and fears, which alternately take possession of our hearts, banish “tired nature’s sweet restorer, balmy sleep.”

We land in Cleveland at 5 A. M., purchase tickets for Washington via Philadelphia. After four weary hours of waiting, we find ourselves comfortably seated in the cars, and are hurried on toward our destination. We arrive at Pittsburg at 2 P. M., where we change cars, and hasten away, leaving the dingy, smoke-wreathed city in the distance.

As we approach the Alleghanies, the scenery becomes picturesque and grand, often approaching the sublime. Those mountain ranges with their lofty peaks towering heavenward, those rocky cliffs and deep gorges, those long tunnels through which we pass, where in a moment midnight darkness succeeds to the brightness of noon, producing feelings—one might imagine—akin to a sudden exchange of worlds.[Pg 13] While passing through these tunnels an almost breathless silence prevails—scarce a whisper is heard until we again emerge into the light. Next we describe a semi-circle around a sharp curve; then we pass through some deep cut; across valleys, where now and then we catch a glimpse of some little town with its long rows of white-washed buildings, nestled cosily at the foot of the mountains. New objects appear for a moment and are gone, until at length the day wears away, and night drops her sable curtain o’er the scene.

We pass Harrisburg in the night, so we have not even a glimpse of the capital of the old Keystone State. All is hushed and still; we have just composed ourselves for a little sleep, when suddenly there is a crashing and jarring which throws many from their seats; but in a few moments all is explained—the cars are off the track. The first thought is, that some villainous “Reb” had placed obstructions on the track, but the truth is soon known: an innocent horse is the cause of the accident, and “Johnny Reb” is for once wrongfully accused.

No one seriously hurt; only a few moments’ delay; the passengers are crowded into the few remaining cars, and we are soon on our way again, leaving the poor horse on both sides of the track. We arrive in Philadelphia at four A. M., where we wait for the[Pg 14] eleven o’clock train to Baltimore. We saw but little of the city. Being very tired, and having our minds constantly occupied with anxious thoughts and fearful forebodings, we felt no desire for sight-seeing.

The seven long hours we have to wait at length wear away, and once more we find ourselves hurrying on toward the monumental city, where we arrive about three P. M. The bloody scene which transpired in the streets of this great and beautiful city, the 19th of April, 1861, came fresh to memory. It was here the loyal blood of Massachusetts’ patriot sons was first shed—not, however, by a manly foe, but by a furious, disgraceful mob, which mad riot incited to deeds of violence and blood. But, oh! what thousands since then have fallen, and still the sword is unsheathed! We would adopt the language of the Psalmist: “How long, O Lord, how long shall the wicked triumph?”

After a short delay, once more the shrill whistle is heard, and again we are moving on toward the nation’s capital, where we arrive in good time. The first object that attracts our attention is that magnificent building—the Capitol. But, as it is getting late, we engage a hack, and go directly to Columbian Hospital in search of Mr. Peck, having learned that he was there; but to the great disappointment of us all, and especially of his poor wife, we found that he had[Pg 15] been sent only the day before to Point Lookout, and, it being impossible for her to procure transportation to that place, the hope of seeing him had to be abandoned. Oh, how trying, after travelling three weary days with a babe in her arms, to be just one day too late. Too late! How significant and full of meaning those little words! How many have been one day too late, and no hope of a re-union on earth! It now being too late to go to Alexandria—the boats having already stopped running—the fond hope of seeing the dear husband and brother that day had to be given up. Oh, how could we remain even for one night with only the Potomac between us and the dear object of our search! What if this should be his last night on earth? What if his released spirit should take its everlasting flight ere the dawn of another day? How could we say, “Thy will be done”? But there is no alternative. We must wait.

On our way to Columbian Hospital we passed thousands of our soldiers, some of them apparently having recently arrived—judging from their clean uniforms—while others had evidently seen hard service, looking worn and tired, and well-nigh discouraged. We concluded that they belonged to Pope’s grand army, which had so recently retreated from the disastrous battle-field of Bull Run. We wondered how such numbers could have been defeated. To us, having[Pg 16] never before seen more than a single regiment at a time, it was a vast army. We began to realize that we had a mighty foe to contend with, and as we looked upon those war-scarred heroes—heroes, notwithstanding the retreat—we could not help repeating to ourselves: “Poor boys, how little you or we know what lies before us; there may be many battles to be fought, and, perhaps, some more inglorious retreats. Many of you will see home and friends no more; your final resting-place will be upon Southern soil.”

Early next morning we hastened to the Provost Marshal’s office to obtain passes for Alexandria. Arriving at the office, hope almost dies within us, for we see this notice: “No passes granted on Sunday.” What is to be done, now? Shall we retrace our steps, and wait another twenty-four hours in such terrible suspense? No, we resolved not to leave until an effort had been made, and the last argument exhausted in setting forth the justice of our claim. We entered the office, found it already filled with applicants, saw one after another as they applied and were refused. Tremblingly we crowd our way to the Marshal’s chair, and with the greatest respect, and more deference than is meet should be paid to mortals, request passes to Alexandria. He straightens himself up, and with the cold dignity of a prince, replies: “Don’t you know we don’t give passes on Sunday? Why do[Pg 17] you ask us to violate orders?” Still acting as spokesman, I inquired: “Will no circumstances justify you in granting a pass to-day?” “Well, what are the circumstances,” said he, in the same stern manner. Our story was briefly told, after which, with some hesitation, and watching us closely to see whether we were deceiving him, he directed them to be made out. Oh, what a load was that moment lifted from our hearts! Those little strips of paper, how precious! With tears of gratitude we left the office, and immediately started for the boat landing, and were soon on the steamer “James Guy,” and off for Alexandria, eight miles down the river. How delightful, had we been on a pleasure excursion! Scenes and scenery so entirely new! The forts along the river, with those iron-throated monsters looking defiantly upon us, almost causing one to shrink back with terror, were a great curiosity. The beautiful residence of Gen. Robert E. Lee, now his no longer—having been forfeited by treason—on Arlington heights, half hidden amid stately forest trees and luxuriant evergreens, was pointed out to us; also the Washington Navy Yard, the Arsenal and the Insane Asylum. But what attracts our attention more than all else, are the multitudes of soldiers with their snowy tents skirting the banks on either side of the river, and extending back as far as the eye can reach, covering every hill-side and every valley,[Pg 18] which, with the desolate appearance of the country, remind us that we are in the presence of WAR.

Soon the ancient city of Alexandria—ancient in American history—heaves in sight. It presents a gloomy, dingy, dilapidated appearance. As we set foot upon the “sacred soil,” we experience quickened heart-beatings, for we know that this terrible suspense will soon give place to, it may be, a dreadful reality. As we pass up King street we pause a moment to look at the building where the brave young Ellsworth fell, drop a tear to his memory, and hasten on. Turning from King into Washington street, we notice a soldier in full uniform with a shouldered musket, pacing to and fro in front of what appeared to be a church. We are told by the guard that it is the Southern M. E. Church, but now used for a hospital. We enter the building, make known the object of our visit, but find he is not there. My poor sister could go no farther; she seemed to have a presentiment that her worst fears were about to be realized. “Oh!” she says, “his wound is fatal, for he came to me in my dreams only a few nights since, looking worn and pale and haggard, having lost a limb in battle, and seemed to say, ‘My work is done, I’m weary and must rest.’” She felt that his work was done, and if so, well done, having “fought the good fight and kept the faith,” and that he had gone to receive the crown.[Pg 19] And yet, amid these consoling reflections, thoughts of her own desolation and the great loss she would sustain if her fears were realized, would rush upon her with an overwhelming force, crushing out life’s bright hopes, while the language of her heart was, “Who will care for the fatherless now?”—forgetting for the time the promise of God, “Leave thy fatherless children with me and I will preserve them alive.” We tried to comfort her, saying we should soon have him with us; that one so strong, physically, would certainly survive the amputation of a limb; and, bidding her be of good cheer, Mrs. Peck and I hastened to the next hospital—the Lyceum Hall—but to our anxious inquiry met with the same reply as before. We cross the street to the Baptist church, which is also used for a hospital, our fears every moment increasing. Happening to look back before entering this hospital, to the one we had just left, we saw some one beckoning to us to return. Hope began to revive; we hurried back and were told he was there, and doing well, though still very weak. Our informant asked us if we would see him? “No,” we replied, “not until we have informed his wife,” requesting him in the meantime to try and prepare his mind to see her, cautioning him to break the news very carefully, fearing that the excitement might prove injurious to one so weak. Having given these instructions, I left Mrs. P., and[Pg 20] hurried back with a light heart and a quick step to the hospital where my sister was waiting in such agony of suspense. She heard my voice before reaching the hospital, exclaiming at almost every step: “I’ve found him! I’ve found him! Oh, Anna, come quickly!” I did not realize that I was in the streets of a city, attracting the notice of passers-by, nor did I much care, for a deep anxiety and long days of suspense had given place to joyful hopes and sweet anticipations.

She rose to accompany me, hesitated a moment, and then sank back upon her seat, and with a look almost of despair, says: “Julia, are you sure, have you seen him?” I assured her, that though I had not seen him, there could be no mistake, for they certainly would not have said he was there, had he not been. Thus reassured she rose the second time, took my arm, and we started. We had gone but a few steps when our ears were saluted with the sad and mournful tones of the fife and muffled drum, and on looking back we saw a soldier’s funeral procession approaching—a scene I had never before witnessed, but one with which I was destined to become familiar. How unlike a funeral at home! No train of weeping friends follow his bier; yet one of our country’s heroes, one of the “boys in white,” lies in that plain coffin. He is escorted to his final resting-place by perhaps a[Pg 21] dozen comrades, who go with unfixed bayonets, and arms reversed, keeping time with their slow tread to the solemn notes of the “Dead March,” plaintively executed by some of their number.

The tear of sympathy unbidden starts at the sight of the “unknown,” and for the bereaved friends who weep in far off homes. In a few minutes we are at the Lyceum Hospital where, instead of the realization of our hopes, heart-rending tidings await us. He who, but a few moments before, was the bearer of such good news, again makes his appearance; but why is his countenance so sad? His own words will tell. “I was mistaken, he is not here;” but something either in his tone or manner indicated that he had been there, and at the same moment we all inquired: “Oh, where is he?” “He is dead!” was the reply. Oh, that terrible word—“dead!” How suddenly it blighted our fond hopes, and turned our anticipated joy into the deepest grief.

From the hospital we were conducted to the Rev. Mr. Reid’s, my poor sister being carried in an almost senseless condition, where we spent a sleepless night[Pg 22] brooding over our sorrow and shedding the unavailing tear. Oh! that never-to-be-forgotten day! A day not only of bright, but blighted hopes, a day of mourning, of sadness and bereavement, a day that revealed to an anxious wife that she was a widow and her children fatherless; a day that said to my sad heart, “Thy brother has fallen.” He died like thousands of others, far from home and friends, with no loved kindred near. But God had sent an angel of mercy in human form—that noble girl, Miss Clara F. Jones, of Philadelphia—to watch over and administer to his wants. She watched him day by day as he grew weaker, she stood beside him in his dying moments, held his icy hand in hers, wiped the death dew from his brow, received his last message for his wife and child, and, when life had fled, prepared him as far as she could for his burial. Such are her daily duties. May God reward her with the rich blessing of his love.

My brother was one of those with whom religion was a vital principle. He heeded the injunction of the Saviour, “Go work in my vineyard.” And when the tocsin of war was sounded, and there was a call for volunteers, he committed all to God, and cheerfully responded to that call and hastened to the rescue of his imperilled country, and, while battling for freedom and humanity, he felt that he was fighting for God, and that he was still in his Master’s service.

[Pg 23]

The night of his death Mr. Reid spent the evening with him, speaking words of comfort and Christian consolation. But to the dying saint death had no terror, for “his anchor was cast within the veil,” and “that anchor holds.” He could adopt the sweet words of the poet:

The morning of the 15th, sister Anna and I, accompanied by Rev. Mr. Reid and wife, Miss Jones and Chaplain Gage, visited brother’s grave. Oh! how could we realize, as we stood by that little, narrow, turfless mound, that dear Orville lay there? His poor heart-broken widow threw herself upon his grave and gave vent to her deep grief in sobs and bitter tears. Nearly three hundred brave “boys in white” lay side by side in the same enclosure, with not even a stone to mark the place where they were sleeping, nor a spear of grass growing upon their graves, simply buried out of sight; but each little mound is cherished, oh, how sacredly by some one!

We returned to Mr. R.’s, feeling that the grave was a poor place to go for consolation in times of affliction; but there is comfort in the promise, “Thy brother shall rise again.” If you ask where my brother shall rise, I reply: “The scene of his death and burial is to be the scene of his resurrection.” “How beautiful the thought, that, when the trumpet sounds, the dead shall come forth from the spot whereon they fell. The sailor who found a watery grave will emerge from his long deep resting-place; the warrior who fell upon the battle-field will rise side by side with him who was slain by his hand, their feuds all ended.”

“Whole families will stand together on some green[Pg 25] spot which they have adorned with care; brother and sister will rise side by side, and long parted friends will re-unite.”

“They will rise to enjoy all that angels feel of the celestial love and peace, to swell the anthem of the redeemed, which, beginning upon the outer ranks of the hosts of God, rolls inward, growing deeper and louder until it gathers and breaks in one full deep symphony of praise around the throne.” “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive honor, and power, and glory, and dominion for ever and ever!”

Viewed in this light, what a glorious idea the resurrection is! How does it destroy the fear of death, and take away the dark appearance of the grave!

[Pg 26]

MR. REID—LOYAL FRIENDS—VISIT TO THE LYCEUM—HOSPITAL—MISS JONES—LIEUTENANT STEVENSON—THE DECISION—FRIENDS—RETURN—THE FIRST WOUNDED—APPOINTMENT AS AGENT—FAIRFAX SEMINARY—HOSPITAL OF THE FIRST MICHIGAN CAVALRY—NEW SCENES—FIRST HOSPITAL WORK.

Our kind host and his excellent lady were untiring in their efforts to give consolation. We found them to be the most devoted friends of the soldiers, and the purest patriots of which our country can boast. They had been driven from their home in Martinsburg, Va., where Mr. Reid was preaching, and were refugees for several months, Mr. R. barely escaping with his life. They know full well what it costs to be loyal to the flag of their country in these perilous times, having sacrificed everything but life itself in its defence. When treason became so bold and threatening that he no longer dare pray, as had been his wont, for the President of the United States and his advisers, he would pray for those in authority, “and the Lord knew,” he says, “I did not mean Jeff. Davis.” Their sacrifice and sufferings[Pg 27] have only made the fires of loyalty burn with an intenser heat upon the altar of their hearts.

The second day after our arrival, Chaplain Anderson, of the Third Michigan Volunteers, called to see us; also, some of the good loyal ladies of the city—of whom I am sorry to learn there are so few—and extended their kind sympathy. We felt very grateful to those dear friends: we did not expect to find so much true sympathy among strangers. But, oh! they could not heal the wound that death had made.

Sept. 16th.

To-day we visited the Lyceum Hospital, where so recently dear Orville took his leave of earth. Only a few days ago he was among the sufferers there; now he is forever at rest. The hospital is full of the wounded from the late battles, suffering, oh, so much, and yet so patiently! There are many others upon whom Death has already set his seal, and whose places will soon be vacant, or occupied by others. Oh, how I long to stay and go to work for them! Perhaps I might be the means of saving somebody’s husband or brother.

This hospital was in a most wretched condition until the advent of Miss Jones, under whose wise management and untiring efforts it has greatly improved.[Pg 28] Everything that woman can do will be done by her for her “boys,” as she calls them. She is indeed an angel of mercy to those poor sufferers. Mrs. May, wife of Chaplain May, of the Second Michigan, called on us this afternoon. She is one of those who has a heart to sympathize with the afflicted everywhere.

During the day we have had some business to attend to concerning my deceased brother’s effects and back pay. But now, as the shades of another night draw around us, and all is hushed and still, what thronging memories come! How keen, how intense the agony of mind under God’s afflictive dispensations, and how hard at such times, without large supplies of grace, to say from the heart, “Even so, Father, for so it seemed good in thy sight!”

Sept. 17th.

This morning we took leave of our kind host and lady, the dear Miss Jones, and other friends, and, with one long, lingering look at that hospital, around which, to us, a sacred solemnity still lingers, hastened to the wharf and took the first boat to Washington. We had scarcely landed, when a fine-looking officer approached us, and extended his hand to my sister, inquiring at the same time, “Did you find your husband?” She could make[Pg 29] no reply; there was no need of words, he understood it all. We soon recognized the countenance of Lieutenant Stevenson, of the Second Michigan Volunteers, with whom we fell in company on our way to Washington. In a moment he is gone, and we see him no more; but the earnest solicitude of the stranger to know whether our fond hopes were realized, and his kind sympathy in our affliction, will long be cherished as one of the pleasant remembrances of this sad journey. And we will pray God to watch over and protect him and return him in safety to his dear family. But should he fall amid the din of battle, or become a victim to disease, may kind hands administer to his wants, and loving, sympathizing friends comfort the bereaved widow and orphans. We engage a room for the night at Mr. Treadway’s, a family formerly from Detroit, now residing at No. 541 H Street (which has since become noted as the place where that dark assassination plot was concocted which robbed the nation of its chosen leader), and then call to see Hon. J. M. Edmunds, President of the Michigan Soldiers’ Relief Association, to learn what was necessary to be done in order to secure a pension for my sister. He received us kindly, and gave us the desired information.

My mind is at length made up to remain, and[Pg 30] engage in the work of caring for the sick and wounded, as my desire to do so has increased with every day and almost every hour since our arrival. I am also encouraged to do so by Mrs. Brainard, an agent of the Michigan Association, boarding at this place.

Sept. 18th.

Sister Anna and Mrs. Peck started for Michigan this morning. One week ago to-day, we left home for this city. Oh! what bitter experiences, what anxious fears, what terrible suspense, what dreadful realities have been ours in this one short week! As I bade my sister “good-by” at the cars, she exclaimed, “Oh, Julia! How can I return to my children without their father? Their injunction, ‘Be sure and bring papa home with you,’ still rings in my ears.” My heart was too heavily burdened to reply; the train moved on; I retraced my steps, and have spent the remainder of the day in my room lonely and sad, reflecting upon the past and trying to penetrate the future.

A few days after my sister’s arrival home, instead of joy and gladness, the friends meet with bowed heads and stricken hearts to observe the solemn services of a soldier’s funeral. Rev. Isaac Errett officiated. His sermon being extemporaneous,[Pg 31] not even a synopsis of it was preserved. The following appropriate hymn was sung:

I remained at Mr. Treadway’s until the 31st, and, while awaiting an opening for work, visited hospitals with Mrs. Brainard. The 25th, I saw for the first time the wounded as they came from the battle-field—the bloody field of Antietam. They were taken to the Patent Office Hospital. Oh! those bloody, mangled forms will long be fresh in memory.[Pg 32] Some were able, with the help of a comrade, to crawl up the stairs, while others were carried up on stretchers. A few moans were heard, but no complaining, and no loud groaning, as I expected to hear. Mrs. B. had a basket filled with cakes and crackers, which we handed them as they were carried past us. How eagerly they were caught by those who had an arm to raise.

The sight was too much for me; I was completely unnerved, and found it impossible to conceal the emotions so deeply stirred in my inmost soul. I returned to my room to weep over the sufferings I was powerless to alleviate. Oh, cruel, cruel war!

Sept. 29th.

This morning I received an appointment from Judge Edmunds, as visiting agent for the society of which he is the President. Alexandria is to be my field of labor for the present—the very place I had wished and prayed for, since there the object of my hopes, only two weeks ago so bright, lies buried. How rejoiced I am in the prospect of work. I trust I shall be enabled to do some little good—to alleviate some poor sufferer, and to encourage the desponding.

During my short stay in Washington I have seen but little—speaking of the city itself—to attract[Pg 33] notice. The public buildings are very fine, the Capitol magnificent; remove these, and Washington is shorn of its beauty.

Sept. 30th.

I came over to Alexandria this morning, in company with Mrs. Brainard, Mrs. Colonel Fenton, and Miss Moor. I have engaged board at Mrs. May’s, at five dollars per week. Soon after arriving, an ambulance, which Mrs. M. had ordered, reported, and we all went out to Fairfax Seminary Hospital, a distance of about three miles from the city. This is a large hospital, and will accommodate several hundred patients. It is situated in a delightful place, standing on a high eminence, and commanding a fine view of the country for miles around. It was formerly a theological seminary; hence Seminary Hospital. The patients appeared comfortable, and, as a general thing, cheerful. The hospital wore an air of neatness, which made it seem quite home-like. On our way back we called at the hospital of the First Michigan Cavalry, which we found much more comfortable than I expected; in fact, I think those large airy tents are much better for hospital purposes than close rooms. The country, before the war, must have been beautiful; but now, so desolate! Fences gone, buildings in ruins, shrubbery destroyed, fields uncultivated—all showing the sad effects of[Pg 34] desolating war—while in every direction may be seen the “canvas home” of the soldier. Frequently we passed squads of men under drill—recruits, I suppose—their glistening bayonets and gleaming swords sparkling and flashing in the sunlight, innocent of the destructive work they will soon aid in executing. Every now and then we caught sight of the stars and stripes proudly floating from some strongly-fortified place, with its big guns bidding defiance to the enemy. At almost every step I was reminded of that dear brother, who only three weeks ago closed his eyes in death, and now lies buried in yonder cemetery. He no more rallies at the bugle’s call, or starts at the tap of the drum, but he sleeps with his comrades in arms, in the sacred soil “of historic old Virginia” where, through the branches of the tall cedars over his head, the sighing winds of autumn sing his requiem, and the placid waters of the Potomac murmur at his feet.

[Pg 35]

Oct. 1st.

To-day, the date at which my journal begins, I have spent nearly all my time in the hospitals; in fact this has been my first hospital work, though having been to them before, but simply as a visitor. Now I have something to do, and I am happy in the hope of being able to do some good. The experience of this day teaches me that no one—especially a lady—who is in sympathy with our cause can visit these hospitals without doing good. Her very presence is cheering to the soldier. A kind, cheerful look, a smile of recognition, one word of encouragement, enables him to bear his sufferings more bravely.

I am now, where I have earnestly prayed to be ever since the war began, among the sick and wounded, that I might in some degree supply personal wants and relieve present necessities; yet I have never seen an opening before. But that mysterious Providence “whose ways are past finding out” has appointed me a field of labor, the path hereto passing through the deep waters of affliction. I sometimes feel like exclaiming,

[Pg 36]

MICHIGAN RELIEF ASSOCIATION—ALEXANDRIA HOSPITALS—CONVALESCENT CAMP—FORT LYON—GENERAL BERRY’S BRIGADE—SOLDIER’S BURIAL—REBEL WOMEN—EVENING WORK—DEATH OF MICHIGAN SOLDIERS.

Perhaps I ought here to give a brief account of the Society with which I was connected. This Association was organized in the autumn of 1861, but was not, according to the report of one of its officers, called into full activity until the spring of 1862. “This was the first organization of the kind upon the Atlantic slope, and the last to leave it.” Its officers at the time I became a member were: Hon. J. M. Edmunds, of Detroit, President; S. York Atlee, of Kalamazoo, and Mr. F. Myers, Vice-Presidents; Dr. H. J. Alvord, of Detroit, Secretary; and Z. Moses, of Grand Rapids, Treasurer.

Mrs. Brainard and myself were at this time the only regularly employed visiting agents, and were the only agents who remained with the Association year after year. Others were employed for a few weeks or months, as the exigencies of the times demanded.[Pg 37] Our time and labor were gratuitously bestowed, as were also the services of the officers; hence it will be seen that it cost comparatively little to keep the “institution” running—a large proportion of all the funds received going to the direct relief of our needy soldiers. The above-named officers, with the exception of one of the Vice-Presidents and the Secretary, remained with the Association during the entire period of its existence, and were earnest and efficient laborers. I will now give a condensed report of my work for the month of October, 1862:

This was my initiation month. I spent my time in preparing and distributing supplies to the hospitals in the city—of which there were fourteen, including some twenty different buildings—and the surrounding camps. These hospitals would accommodate from two to fifteen hundred patients each. All of the largest and finest private residences, the churches—with two exceptions—school buildings, and hotels, were converted into hospitals. The largest of these was the “Mansion House,” formerly known as the old “Braddock House,” in one of the rooms of which—at this time used for an office—General George Washington held his Councils of War. The same old furniture was still in use.

Our Michigan soldiers were scattered through all these hospitals, and to find out and visit every one[Pg 38] was no small task, it being almost a day’s work to go through one of the largest. After having gone the rounds once, and obtained a list of the names of those I was to visit, the number of their ward, and what each one needed, the work of supplying these wants would have been comparatively light, were it not for the changes which were constantly taking place by death, discharges, transfers, furloughs, new arrivals, and returns to duty, which were of almost daily occurrence.

In my visits to these hospitals I seldom went empty-handed; sometimes taking cooked tomatoes or stewed fruit, at others, chicken broth, pickles, butter, cheese, jelly, tea hot from the stove, and, in addition to these, I would frequently buy oranges, lemons, and fresh fruit, according as the appetite seemed to crave. Besides, I gave out clothing to those most in need—such as shirts, drawers, socks, slippers, dressing-gowns, towels and handkerchiefs, also stationery and reading-matter. During this month I received a nice box of goods from Ionia. Could the donors have known how much good that one box did, they would have felt amply repaid for all they ever did for the soldiers, and encouraged to renewed efforts in the good work.

I made several visits to old “Camp Convalescent”—very properly called “Camp Misery”—which was[Pg 39] about a mile and a half from the city. Pen would fail to describe one-half its wretchedness. Here were from ten to fifteen thousand soldiers—not simply the convalescent, but the sick and dying—many of them destitute, with not even a blanket or an overcoat, having little or no wood, their rations consisting of salt pork and “hard tack,” whatever else might have been issued they had no fire with which to do the cooking, consequently much of the time they were obliged to eat their pork raw. Oh! how many times my heart was wrung with pity, and indignation too, on seeing those shivering forms with their thin, pale faces, cold and hunger-pinched, sitting upon the sunny side of their tents, eating their scanty meal.

While our hearts were justly filled with indignation toward the rebel government for its inhuman treatment of their prisoners, should they not also have been toward our own, for thus shamefully neglecting those within its reach? I do not pretend to say that this camp equalled Southern prison-pens in degradation and wretchedness; but they were beyond our control, while over this floated the flag of our country. Think of men sick with fever, pneumonia, or chronic diarrhœa, eating raw pork and lying upon the cold, damp ground, with only one blanket, and, it may be, none, and the wonder will be, not that they died, but that any recovered. I[Pg 40] would not be understood to say that all in this camp were thus feeble and destitute, but there were many such; while, at the same time, there were others, who, had they possessed a spirit of true manliness and patriotism, would have been ashamed to have been seen hanging around the Convalescents’ Camp, but would have been found at the front, at their posts of duty.

There were, at this time, some two hundred Michigan men in this camp. Their tents were pitched on a side-hill, so that, when it rained, the water would run through them like a river, in spite of the little trench surrounding each one. I was frequently told that when there was a drenching rain they were obliged to stand up all night to keep their clothing from being completely saturated, and, wrapping their blankets around them, they like true soldiers submitted to their fate.

During the cold, chilly nights, those not fortunate enough to possess a blanket were compelled to walk to and fro the entire night to keep warm, thus pacing off the long, weary hours while waiting for the dawn, and, when the sun was up, lie down and sleep beneath his cheering rays, and so prepare themselves for another night’s tramp. Methinks there will be a fearful account for some one to settle when the “final statements” are forwarded to the Court of Heaven.

[Pg 41]

In going to “Camp Misery” I always filled my ambulance—when I had one—with quilts, under-clothing, towels, handkerchiefs, pies, stewed fruits, and whatever else I happened to have on hand. Mrs. May and daughters usually accompanied me, and assisted in distributing the goods. This was always a pleasant task; pleasant, because some hearts were made happier, and a few shivering forms more comfortable. And yet there was sadness mingled with all the pleasure experienced in this blessed work. To have so many cups presented as the last spoonful of sauce was dished out, and after the supply of clothing had been exhausted, to hear the appeals—“Say, got any more socks there?” “Drawers all gone?” “Can’t you let me have a flannel shirt?” “I’ve the rheumatis awful.” “Haven’t another of those quilts, have you?” “Pretty cold nights,”—and not satisfied until they had taken a peep into the ambulance to be sure there was not something held in reserve for some one more highly favored than themselves, would produce a sadness of heart which could be relieved only by a continued distribution of the articles needed. We could only tell them to keep up good courage—that we would come again soon, and leave them, a little comforted, with the hope of being served the next time.

I have sometimes been told that soldiers were not[Pg 42] half as destitute as they often pretended to be, and that we were frequently imposed upon. Be that as it may, the fact that imposition was practised upon us by unprincipled men rendered the needy no less deserving, and would not have justified us in ceasing our efforts in their behalf. The soldier had my confidence. I looked upon him as good and true, consequently I might not have detected frauds as readily as some; neither do I believe I was imposed upon as frequently as I would have been had I always doubted his word and suspected he was trying to deceive me.

Then there was the camp of paroled prisoners, where some fifteen hundred were waiting to be exchanged, who demanded not only our sympathy but our supplies; yet they were not as destitute as many at Camp Convalescent, as clothing was issued by the Government soon after their arrival. Neither were they as reduced and emaciated as many who were returned to us from Southern prisons during the latter part of the war. The troops stationed at Fort Lyons were also greatly in need. Upon one of my visits to this fort, among other things wanted, one of the sick—a young, delicate-looking boy—wished to know if I couldn’t bring him a feather-bed; but the nearest I could come to it was a good soft pillow. There was so much needed and so many to be supplied,[Pg 43] that the little I could do with the limited means at my disposal seemed like a drop of the ocean.

After one of my visits to these depots of misery, I went out in company with Mrs. May and daughters to General Berry’s Brigade, encamped near Munson’s Hill, a few miles from Alexandria. I found several of my former friends and school-mates, while others, alas! were missing. Where were “Eldred,” and “Birge,” and “Woodward?” Had they, too, gone to swell the ranks of the “Boys in White?” Ah! yes; young Birge, the Christian boy, was sleeping at Fair Oaks; Woodward, only a few weeks before, closed his eyes in death at Fairfax Seminary; and Eldred—the gifted, the pride of his class—at Georgetown. They left their books and college halls for the camp, the bivouac, the battle-field, and a soldier’s grave.

One Lord’s Day, while visiting my brother’s grave, I witnessed, for the first time, a soldier’s burial; and a more solemn scene my eyes had never beheld. The lone ambulance, the plain coffin, the sad strains of music, the slow tread of the escort, the salute fired[Pg 44] over the grave, the absence of all mourning friends, rendered the scene peculiarly solemn and impressive!

Who would believe that the human heart could ever become so lost to all feelings of humanity as to rejoice and exult over the sufferings and death of even an enemy? And yet I was told by the Rev. Mr. Reid that he had seen those calling themselves ladies dance to the tune of the “Dead March,” and clap their hands and exclaim, “Good, good! there goes another Yankee!” on seeing a soldier’s funeral procession passing slowly to the city of the dead. This seems almost incredible, but Mr. R.’s word is unimpeachable. Rebel women there were exceedingly bitter toward the North—that “Hydra-headed monster,” Secession, being the great object of their worship. All the finer feelings and tender sympathies of woman’s nature seem to have given place to malignant hate and fiend-like cruelty.

I devoted my time evenings to cooking and preparing things for distribution at the hospitals next day. The 24th inst. I went to Camp Convalescent with forty-two pies and several gallons of sauce. The boys seemed to think a piece of dried-apple-pie, however plain, one of the greatest luxuries they ever enjoyed. The moment it was known there were pies in camp our ambulance would be surrounded, and we, the occupants, literally taken[Pg 45] prisoners; some begging for themselves, others for a sick comrade who was unable to leave the quarters. At such times how earnestly I have wished that the miracle of the “loaves and fishes” might be repeated.

The last three or four days of the month I spent in going the rounds of the hospitals attending to special cases; and ere its close many a noble heart ceased to beat, many a manly form was cold in death, and many a newly-made grave might have been seen in the Soldier’s Cemetery; yet comparatively few of the Michigan soldiers in the hospitals I visited died—only four, I believe—two of the Eighth, one of the Sixteenth Infantry, and poor William Eaton, of the First Cavalry, who lingered beyond all expectation. He was the first Michigan soldier that died to whom my attention was particularly called, and for whom I had felt a special interest, and his death seemed like taking another from our already broken circle.

[Pg 46]

MOUNT VERNON—JOHN DOWNEY—CHAPLAIN HOPKINS—MRS. MUNSELL—COLD WEATHER—NEW ARRIVALS—GEN. BERRY AND DR. BONINE—DEATH OF MASSACHUSETTS SOLDIERS—THANKSGIVING—RED TAPE—KIDNAPPING.

November 4th.

As a party, consisting of Dr. Bonine and wife, Mrs. May and daughters, and Mrs. Johnson, wife of Adjutant Johnson, of the Second Michigan volunteers, were going to Mount Vernon this forenoon, they insisted upon my going with them, and as I had never been there, and fearing that another opportunity might not present itself during my stay here, I consented to do so, provided they would call at Camp Convalescent on their way, as I had a few quilts to dispose of. My request being granted, we are soon on our way; arriving at camp, we distribute our quilts, and head our horses for Mount Vernon, seven miles from Alexandria. It is nearly noon when we arrive, and a few minutes after we are within the same walls where once had lived and died the “Father of his country.” The mansion is a two-story frame building, made in[Pg 47] imitation of marble, with a colonnade fronting the river. We are conducted through the house—that is, the portion of it open to the public—by the gentleman in charge of the estate, whom, I am sorry to learn, is a secessionist. There are but few articles of furniture left—an old harpsichord, table, sofa, a large blue platter, and a bedstead—is about all. The bedstead, said to be a fac-simile of the one on which that great and good man died, stands in the room which witnessed the closing scene of his life—a pleasant room on the second floor, commanding a fine view of the Potomac. As I stood and looked out upon the lovely landscape before me, I could not help thinking how many times Washington had looked from the same window, upon the same scenery—the same pleasant grove, the same sweet flowers, the same grand old Potomac. But now he sleeps peacefully amid all these beauties—he heeds not the tread of the stranger—the sound of the war-drum disturbs not his slumbers.

In one of the rooms is Washington’s knapsack, holsters, and medicine-chest. In the hall hangs the large iron key of the ancient Bastile of France, presented to General Washington by General La Fayette. The ceilings are stuccoed and contain many curious devices, such as flowers, human figures, implements of husbandry, etc.

Having finished our visit here, we repair to the[Pg 48] flower-garden, through which we are conducted by a colored man, who claims to have been a slave of General Washington. “I’ve lived here right smart; heap o’ years afore mass’ and missis died,” he tells us. This garden is beautiful, but sadly neglected. The greenhouse[1] contains many choice plants. A variety of evergreens and stately forest trees, including a large and beautiful magnolia—which we are told Washington brought from Florida and planted with his own hands—constitute a fine grove in front of the mansion. We gathered a few stray leaves, which had fallen to the ground, as precious mementoes of the place. But the most sacred spot is yet to be visited—the vault—where are deposited the remains of that noble couple, George and Martha Washington. We approach the sleeping dead with slow and cautious step, for it seems that we are treading upon holy ground. Oh, what memories cluster around this venerated tomb! The past and the present are strangely linked together. The principle of universal liberty, for which he fought, is that for which we are now contending. In the outer apartment of the vault are two large sarcophagi, which can plainly be seen through the iron grating; but the remains are deposited in the inner apartment. On either side of the tomb are monuments erected to the memory of different members[Pg 49] of the family. We gather a few pebbles from the vault as sacred relics from a consecrated tomb, and leave the sainted dead to their silent slumbers.

[1] Since burned.

We next direct our steps to the spring-house, which is situated far down the bank; we drink of the crystal waters of the spring, take a peep into the house, and clamber back up the steep hill, return to the mansion, rest for a few moments, drink once more of the sparkling water from the “old oaken bucket that hangs in the well,” bid farewell to Mount Vernon, and are soon safely at home again; and, though tired and hungry, we feel that the trip has not been a lost opportunity. We saw nothing more of the rebel officer whom we met on our way down, when we all so much regretted that none of our party was armed, in which case he would have been halted; for the idea of returning from a pleasure excursion with a captured prisoner was not only romantic, but pleasing, especially as our party consisted—with one exception—entirely of ladies. Mount Vernon has not, like most places of the South, been visited with the ravages of war, it being neutral ground, and held sacred by both armies.

LINES SUGGESTED ON LEAVING THE TOMB OF WASHINGTON.

November 5th.

Having heard that there was a young man in one of the hospitals at Georgetown, who was with my dear brother while he lay on the battle-field, after he had received his fatal wound, I resolved to see him and learn, if possible, the particulars of those long weary days and nights of suffering, preceding his removal to the hospital. I went, therefore, this morning, and, after searching through five hospitals, found him, and learned from him more of the care my brother received than I had ever known before.

This soldier, John Downey, belonged to the same company with my brother—Co. K, Eighth Michigan Infantry—and though himself wounded, he refused to leave his friend until he saw him removed from the field, each day managing to furnish a little something for him to eat, and a cup of hot coffee, and suffering himself to be taken prisoner rather than forsake his comrade. He tried to get a surgeon to dress[Pg 51] his wounds, but could not until it was too late, as each had to wait his turn where there were so many to be cared for.

Brother was wounded late in the afternoon of September 1, and lay on the field until the evening of the 5th, arrived at Alexandria on the morning of the 6th, and died on the 9th. Before leaving the battle-field he seemed to realize that he could not live, and committed to the keeping of young Downey photographs of his family which he had carried with him since first entering the service, saying, “Should I not recover, please send these to my wife.” The request has been granted. He saw him as he was put into the ambulance, after the amputation of his limb, for that painful ride to Alexandria, a distance of twenty miles or more. Noble boy! I shall ever hold him in grateful remembrance for his kindness to my dying brother.

Hundreds of others were brought in that night in the same way. Oh, what untold suffering those long weary miles witnessed! During that tedious journey, at all hours of the night, whenever the train halted for a few moments’ rest, two ministering spirits might have been seen going from ambulance to ambulance with canteens of water, bathing inflamed wounds, adjusting the little cushions under bleeding “stumps,” administering some gentle stimulant to those weak[Pg 52] and exhausted from the loss of blood, speaking words of encouragement to the desponding, and commending the dying to the Saviour. These were the Rev. Mr. Hopkins, chaplain of the Mansion House Hospital, and Mrs. Munsell, a lady whose soul seems absorbed in her work for the soldiers—a Southern lady, a native of South Carolina, but loyal and true. They were returning from the battle-field, where they had been working night and day among the wounded and dying.

As the cold weather set in unusually early, and continued for some time, the number of sick increased very rapidly.

The 18th inst., Dr. Cleveland, of the Second Michigan, came in from the front with two hundred sick, one of whom died on the way. Large accessions were also made to our hospitals from the surrounding camps, especially the old Convalescent; and new arrivals always implied increased labor. Of the sick thus brought in, death kindly relieved many of their sufferings; yet I remember but two from Michigan who died that month. These were Henry T. Gilmore of the Eighth, and Daniel Morrell of the Fifth Volunteers. The last named I saw many times. Poor boy! he lingered days after it became apparent that he must die. It was my privilege frequently to administer[Pg 53] to his wants, though I met with some opposition from the surgeon-in-charge. He told me his patients were sometimes injured by persons coming in and distributing food indiscriminately to them; and what he would be glad for one patient to have, would be injurious to another. But I still insisted upon taking nourishment to Daniel, as he couldn’t relish anything cooked in the hospital. I finally obtained the doctor’s consent, provided I would bring only such and such articles. Having previously learned from the nurses what he was allowed to eat, I complied with the surgeon’s wishes. I always made it a rule to do so, believing that their judgment was superior to mine, or at least ought to be, though I sometimes saw those whom I thought knew less.

Toward evening of the 10th, after visiting hospitals all day, I called at the Lyceum Hall, where I found Sergeant Colburn, a noble Massachusetts soldier, dying. He had suffered long months from the effects of three fearful wounds, yet he had always appeared hopeful; but those ghastly wounds had made too great a drain upon his system. Nature yielded to the stern mandate of the “king of terrors.” I sat by his bedside some two hours bathing his parched lips and heated brow, and watching the flickering taper of life, slowly yet surely burning out; but as there was a prospect of his lingering some hours longer, and having[Pg 54] other duties to attend to, I rose to go, promising to call again in the morning. He extended his cold, bony hand, and bade me “good-by,” while he gave me a look that said, “You will not see me in the morning.” And sure enough, the next morning all that remained of Sergeant Colburn was the clay tenement robed in white. The brother whom he had so anxiously hoped to see ere his departure arrived soon after his death, and returned with the remains of this once noble form to the stricken band at home. And thus one after another sealed his devotion to his country with his life-blood, “all warm from his heart.”

November 27th.

Thanksgiving day, Miss Jones came on from Philadelphia with a sumptuous dinner for her boys in Lyceum Hospital. She had eight barrels and five boxes filled with good things, consisting of vegetables of all kinds, fruits, roast turkey, nice home-made bread, butter, cheese, pickles, jellies, tea, coffee, sugar, celery, etc. It was a complete surprise, and, as may be imagined, a joyful one. It was my happy privilege to assist in preparing and distributing this beautiful[Pg 55] Thanksgiving dinner. After all had eaten until they could eat no more, there still remained several barrels unopened, which Miss Jones took to Camp Convalescent and distributed among the poor, half-fed soldiers belonging to her own State. What a luxury, roast turkey at this camp! When she retires this night, how happy she will be in the thought of having made so many hearts rejoice—while many a “God bless you” will follow her to her home. Truly, it is more blessed to give than to receive.

In all of our hospitals they have had an extra dinner, and, in some, pleasant gatherings in the evening of all who are able to leave their rooms, at which speeches were made, toasts given, and a general good time enjoyed.

Towards the latter part of November, I learned from bitter experience the meaning of the phrase “red tape,” so commonly made use of in the army.

I also fell in with a practice which I had always greatly abhorred, that of kidnapping—not black men however, but white men—soldiers. But in this business I never had—as many kidnappers must have—any remorse of conscience. Perhaps it was because I stole with the free will and consent of the stolen, but somehow I felt that I was bidden “God-speed.” I know I had the benediction of the soldiers and their[Pg 56] friends, and God’s approval; what more could I ask? My kidnapping consisted in bringing sick men from Camp Convalescent without permission. My reason for this course will be seen at length. At one of my visits to this—as the boys called it—“confounded old camp,” I found several Michigan soldiers very ill, lying upon the cold damp ground, with no fire, no medical attendance, little or nothing they could eat, with such care only as their comrades, under the circumstances, could give. I resolved to get them admitted, if possible, into some hospital before I slept. So going to the commanding officer—Col. Belknap—I told him there were several sick men in camp whom I wished to take with me to Alexandria. He very politely refers me to Dr. Jacobs, the surgeon-in-charge, who will give permission to remove them. On calling at his office, I found that he had left for Alexandria only a few moments before. Hurrying back to Alexandria, I find the doctor and make my wishes known, and receive the reply, “I will gladly do so, but you must first get a written statement from the surgeon of the hospital where you wish to take them, certifying that he will admit them; then come to me and I will give you a written permit to remove as many as you like.” We drove over to Fairfax street Hospital in full faith that the required certificate would be obtained; but imagine my disappointment on hearing[Pg 57] Dr. Robertson—who, by the way, was one of the kindest and best surgeons it was my good fortune to meet while in the army—say, “I wish I had the authority to give you such a statement—you will have to see Dr. Summers.” (I will here state that these hospitals were divided into the First, Second and Third Divisions. Dr. R.’s hospital was in the first division, of which Dr. S. had charge, and, consequently, subject to his orders.) My heart almost failed me as I turned away, for I had but little hope of success left, and was not much disappointed to hear Dr. S. sternly say, “I have no authority to give you any such permission. You will have to go to Washington and see the Medical Director.” It was now dark, and Saturday at that, consequently I could not see the Medical Director before Monday. I returned home well-nigh discouraged, but made up my mind that, if I lived to see another day, I would go on my own responsibility and bring them away. So early the next morning, “it being the first day of the week,” I sent for my ambulance and started for camp, having first been assured by Dr. Robertson that he would assume the responsibility of admitting the boys into the hospital, in case I should succeed in getting them out of camp. An hour later I had the pleasure of seeing six of them safely quartered in Dr. R.’s comfortable hospital, where they were kindly cared for. One, however—Edward[Pg 58] Furnam, sick with pneumonia—needed care only a short time. He lingered a few days, and then went to join the army composed of the “boys in white.” Of all the soldiers to whose comfort it was my privilege to administer, there is none whom I remembered with feelings more peculiarly sad. His imploring look for help as I saw him that Saturday evening in his tent—his expressions of gratitude after his removal to the hospital, the feeling experienced upon seeing, so soon, so unexpectedly, his vacant bed, have left an indelible impress on my mind. The others recovered, one of whom I was joyfully surprised to meet at Portland, Michigan, last winter; and who still claims that his timely removal from camp was the means of robbing Death of his prey.

Orville Wheelock

[Pg 59]

A CRUEL EXPERIMENT—THE QUARREL—MY BROTHER’S LAST LETTER—THE APOLOGY—SPECIAL CASES OF INTEREST—A HAPPY MEETING—BATTLE OF FREDERICKSBURG—MCVEY HOSPITAL—REV. J. A. B. STONE—CHRISTMAS—RUMORS—CLOSE OF THE YEAR.

December 1st.

Quite a change in the weather. Though the first day of winter, it is warm and pleasant. Have been to three hospitals with various articles, both of food and clothing. At the Baptist Church I saw a noble-looking man cold in death, who might have been living still but for the wicked experiment of a surgeon in probing his wound, and then injecting a substance which so irritated the nervous system that it produced convulsions, followed by lockjaw; and death, in a few hours, was the result. He was able to be about the ward at the time the probing was done, but from that moment he suffered the most excruciating pain, till death came to his relief. He leaves a wife and two children to mourn his untimely death. For the truth of this statement, I refer to Dr. Hammond—surgeon-in-charge—in[Pg 60] whose absence the operation was performed, and from whom I learned the above facts.

In St. Paul’s Hospital, among the many serious cases, there is one whose pale face and patient endurance of suffering have enlisted all my sympathy. This is a New York soldier, a beautiful young man of perhaps twenty-two summers. He has received a mortal wound in the body; life is slowly ebbing away, and he expects soon to receive a “starry crown, and robe of white.”

December 3d.

Among the hospitals visited to-day was St. Paul’s, where I had a quarrel with a surgeon. As I entered the hospital I met the doctor in one of the aisles. I saw at once there was something wrong, but not for a moment thinking that I was the “rock of offence,” when in an authoritative manner he demanded to know what I had in that bowl. “Tea, doctor,” was my reply. “Who is it for?” “That New York man over there; he can’t drink the tea made here, so I bring him some occasionally—any objections, doctor?” “I’ve no objections to the tea, but I don’t want you to bring any more here.” Before I had time to reply, he had left the ward. As the poor fellow drank the tea, and returned the bowl—being weak and childish—he burst into tears and begged me to “come again,” while[Pg 61] others expressed their regrets, saying, “The doctor is real mean to act so.” “Never you mind, boys,” said I; “I shall surely come again; the doctor and I will have a settlement, and we will find out what all this means.” I left the hospital, feeling deeply grieved at the rude treatment I had received; having given, to my knowledge, no provocation whatever.

The evening after this unpleasant experience, I received a letter from my widowed sister, enclosing my brother’s photograph; also, a letter he had written a short time before he was wounded—the last ever traced by his dear hand for me. It was sealed and directed, but not mailed, having been found after his death in his diary and sent to his wife, who forwarded to me. The following is the letter, written only twelve days before the battle of Chantilly, where he received that fatal wound:

“Camp near Cedar Mountain, Va.,

August 18th, 1862.

“Very Dear Sister—After so long a delay, I attempt to answer your very kind letter, dated, I think, about the first of July. I have not your letter with me now, as I send all the letters I get to Anna. It was about a month in tracing me out, which accounts for your not receiving an answer sooner; and, since receiving it, we have been constantly on[Pg 62] the move, and, as I am still acting Orderly Sergeant, I have my hands full, as you may well imagine. I, as well as the rest of our regiment, have seen some hard times since leaving home last Spring. I have seen the time more than once that it would have been a luxury to have lain down in the road, or most any place. Had any one told me that I could have endured what I have, I certainly should not have believed him; yet I am still in good health. I wrote Anna yesterday. I told her you would have to wait until we get settled before I wrote you, expecting to be on the move again to-day. But this morning things looked as though we were going to stay here a day or two, and I thought I would write you a good long letter and give you a description of the country and of our different marches, thinking perhaps it would interest you; but I had scarcely began when the order came for ‘three days’ rations in our haversacks;’ so, you see, we shall soon be on the march again. We are at present some four or five miles from Culpepper Court House, and about two from the late battle-ground. Jackson has retreated across the Rapidan, and I presume we shall cross over in pursuit of him. He must be overcome, cost what it may. Do not forget to pray for me. Do what you can to comfort and cheer Anna. Tell her all will yet be well. Our regiment is in the 9th[Pg 63] corps, which is attached to ‘Pope’s Grand Army of the Potomac.’ You must watch the papers and keep track of our brigade. Colonel Crist is in command; look for his brigade to learn the fate of the Michigan 8th. I have much to write, but must close. Remember me at the Throne of Grace.

“Your brother,

Orville Wheelock.

“P. S.—Direct to Co. K, 8th Mich. Vols., 9th Corps, Washington, D. C.”

December 6th.

Cold and unpleasant. Have been to St. Paul’s again—the hospital where I had the quarrel a few days since—with some more tea and raspberry-sauce for the sick. The doctor happened to be in, making his “grand round.” Now is my time, thought I; so, setting down my dishes, I approached him and asked an explanation of his strange conduct toward me a[Pg 64] few days before. He replied, in anything but a pleasant tone: “You are a nurse in Wolfe Street Hospital, and have no business to interfere with mine; and I don’t want you to come here any more.” “You are mistaken, doctor. I do not belong to Wolfe Street, or any other hospital,” was my somewhat indignant reply. “Well, where do you belong? and what is your business?” On showing my appointment from Judge Edmunds, I noticed a sudden change in his appearance, and I never saw any one more profuse with apologies. “I acknowledge my rudeness. I know I was hasty; but I felt vexed to think a nurse from another hospital should trouble herself about my affairs. But it’s all right now; I do not intend to cease to act the part of a gentleman. I hope you will continue your visits to my hospital. Come whenever it suits your convenience best, and bring in for the boys any thing you see fit. You need never trouble yourself to ask me; I will trust to your judgment.” Of course I couldn’t help forgiving the doctor; but, after all, I can’t see why I should be entitled to more consideration, or my judgment considered superior to what it would have been had I been a nurse in some particular hospital. How much better it would be to treat every one with true politeness, which costs nothing, and thereby save ourselves much deep mortification.

[Pg 65]

December 11th.

This morning I went to Camp Convalescent with an ambulance filled with quilts, flannel shirts, socks, towels, handkerchiefs, sixteen pies—which I made last evening—and two large pails of stewed fruit, which I distributed among our needy soldiers. I found three quite sick, for one of whom I procured admittance to the “Examining Board” for discharge, and took the other two to Fairfax Street Hospital, in Alexandria. Came home, wrote two letters, and then went with some delicacies to St. Paul’s.

Poor Clark—the young man previously referred to as being so seriously wounded in the body—was, to all human appearance, dying. His grief-stricken mother is with him. I remained two or three hours: he still lingered. As it was getting late, and being very tired, I came home, when Mrs. May went over and stayed until a late hour with them.

December 12th.

Cold and windy. This morning went again to St. Paul’s. To my surprise I found young Clark still living, but another poor sufferer had passed away before him; he had just breathed his last. His mother, who was with him when he died, was then making preparations to take the body of the poor boy to her home. As I could render no assistance, I left[Pg 66] these scenes of mourning and grief, and went to other hospitals. In visiting five, I found a large number whose names were added to my list. This cold weather is causing much sickness. Another of our boys—Henry Tenyck, of the 5th, for whom I have felt a deep solicitude—is no more. In one of the hospitals I saw a man who had been accidentally shot through the lungs, for whose recovery, his physician says, “there is no hope.” Sad sights are an everyday experience. Death is at work, as the lone ambulance on its way to the “silent city” too plainly tells. Soon after returning home from a tour through the hospitals, a gentleman called, who was in search of a sick son, and wanted to know if I could give him any information in regard to him. As soon as the name—Frank Rowley—was mentioned, I recognized it as the name of one of the boys whom I had “stolen” a few days before from old “Camp Misery,” and, donning my hat and shawl, I accompanied the anxious father to the hospital where his son was. That joyful meeting of father and son I shall never forget. As the young man caught a glimpse of his father on his entering the room, he sprang up in bed, and, with extended arms, exclaimed, “Oh, my father! my father!” while the tears chased each other in quick succession down his pale cheeks. In a moment they were clasped in each other’s arms, and both[Pg 67] weeping for joy. I left them to enjoy their visit without interruption. The evening has been devoted to letter-writing for soldiers.

December 15th.

A terrible battle has been raging all day at Fredericksburg, but no particulars have been received. We can only hope and pray that the God of battles may speed the right.

Have visited four hospitals: took clothing, wine, and fruit. I first went to Prince Street Hospital, with some clothes for Monroe, of the Sixteenth, another of our noble, patient boys, who is as brave under sufferings as amid the dangers of battle. For months he has lain upon his narrow cot, much of the time suffering intensely from a severe wound in the thighs, yet never uttering a word of complaint. We hope the crisis is passed, as he seems to be convalescing, though yet very low.

My next visit was to the Methodist Episcopal Church, with a bottle of wine for one very sick with pneumonia, who has failed very rapidly during the past few days. From here I went to the McVey House, a hospital recently established as a branch of Camp Convalescent. While there, two more brave soldiers closed their eyes in death—one from Michigan, and the other from Maine. They came from far-distant[Pg 68] homes, but died together. In the same hospital, with their cots only a few feet apart, they laid their lives a sacrifice upon their country’s altar at the same time.

Dr. Holmes, of Lansing, is here to take the body of young Morehouse home to his weeping relatives and friends; while the Maine soldier will soon sleep with his comrades in yonder cemetery.

My last visit was at Washington Hall, where I found several new arrivals, some of whom are very sick. Oh, how much there is to be done! The entire evening has been devoted to making pies and stewing fruit, to take to the hospitals to-morrow, though I have felt more like folding my hands and weeping over the sad experiences of the day.

December 16th.

After visiting Fairfax Hospital, I went again to Camp Convalescent with pies, stewed fruit, and under-clothing. Mrs. May and Mrs. Bonine accompanied me, and assisted in giving out my supplies to those who seemed most in need, though that was rather a[Pg 69] hard matter to decide. We succeeded in getting four, who were wholly unfit for service, admitted to the “Examining Board” for discharge, and two others who were very sick were brought by us to Alexandria, and admitted into Fairfax Street Hospital. Cousin George Jennings, whom I found here about the middle of last month, is still at the old camp; having taken “French leave,” he is now with us, and will remain until to-morrow. He is still quite lame from the effects of a wound received on the 15th of last April, at the battle of Wilmington Island, and there is no prospect of his ever being fit for duty again; yet he is kept, like multitudes of others, who ought to be discharged and sent home to their friends. What a comfort to himself and family, could he have been with them when his only son, a dear little boy of fifteen months, was buried a few weeks ago. But no, he must follow the intricate windings of “red tape” a little longer.

Though the wounded from Fredericksburg are daily expected, as yet none have arrived. Burnside’s army has been forced to fall back and recross the Rappahannock. Our loss is estimated at ten thousand—another great slaughter and nothing gained. Oh! when will these scenes of carnage cease? Echo answers, “when!”

[Pg 70]

December 18th.