The Project Gutenberg eBook of Docas, by Genevra Sisson Snedden

Title: Docas

The Indian boy of Santa Clara

Author: Genevra Sisson Snedden

Release Date: April 4, 2023 [eBook #70460]

Language: English

Produced by: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

DOCAS

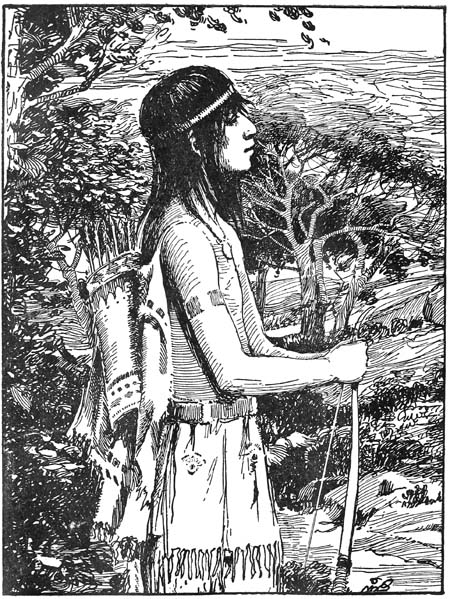

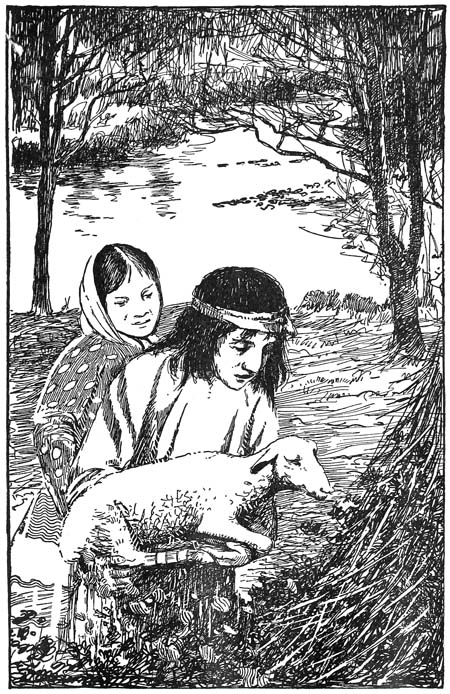

Frontispiece

HEATH SUPPLEMENTARY READERS

By

GENEVRA SISSON SNEDDEN

D. C. HEATH AND COMPANY

BOSTON NEW YORK CHICAGO ATLANTA

DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO LONDON

Copyright, 1899,

By D. C. Heath and Company

Copyright Renewed, 1927,

By Genevra Sisson Snedden

3 K 6

No part of this book may be reproduced in any

form without written permission of the publisher

Printed in U.S.A.

My dear Children:—

What sort of people do you like best to read about—white people or Indians?

I think you will say Indians, because all the children of whom I have ever asked this question have said that they liked best to read about Indians. Indians do everything so differently from the way we do that they are always interesting.

This book which we are now going to read is about Indians,—the Indians who lived near the Pacific Ocean before our grandfathers were born, and before we Americans came west and settled the country.

Do you like best to read about grown-up people or about children? I think I can hear you say, “What a question! Children, of course!” Yes, children can have such fun, running and playing and finding out about all kinds of things for which grown people never have time, that it is much pleasanter to read about them. So[vi] this whole book is about children. The first part tells about the little Indian boy, Docas; farther on, when Docas grows to be a man, the book tells about his children and grandchildren.

Last of all, the stories tell about things that actually happened to Indian children long ago in California, so they are what you call “truly stories,” not “made-up ones.”

These are some of the reasons why the children for whom the stories were first written liked them and learned from them, and for these same reasons I think many of you will care to read about Docas, the Indian boy of Santa Clara.

THE AUTHOR

NOTE

These stories were originally written to serve as reading material for the children in the University School connected with the Department of Education at the Leland Stanford Junior University. The never-failing delight with which those children welcomed each new instalment was the first impetus toward putting the stories in a form where they would have a larger audience.

The work was done as a thesis in history under the direction of Mary Sheldon Barnes. To her careful supervision and many suggestions the book owes much of whatever merit it may possess.

| PART I | |

|---|---|

| WHEN DOCAS LIVED AT THE INDIAN VILLAGE | |

| PAGE | |

| Building the Fire | 3 |

| Docas at Breakfast | 5 |

| How Docas went Fishing | 7 |

| Massea’s Storehouse | 10 |

| How Docas caught the Grasshoppers | 15 |

| The Grass-seed Basket | 17 |

| Docas’s New Skirt | 21 |

| The Sweat House | 24 |

| The Feast of the Eagles | 27 |

| The Invitation to the Dance | 30 |

| The Acorn Dance | 31 |

| Docas playing “Teekel” | 36 |

| Making the Mountains | 40 |

| The Measuring-worm Rock | 42 |

| The First White Man | 44 |

| Docas goes to the Red Hill | 49 |

| Docas in a Fight | 52 |

| PART II | |

| WHEN DOCAS LIVED AT THE MISSION | |

| Docas goes to live at the Mission | 57 |

| Breakfast at the Mission | 59 |

| The Mission School | 63 |

| Raising Corn | 65[viii] |

| Threshing the Grain | 69 |

| Getting ready to make Bricks | 72 |

| Getting the Timbers | 79 |

| Building the Church | 80 |

| Visit of Father Serra | 85 |

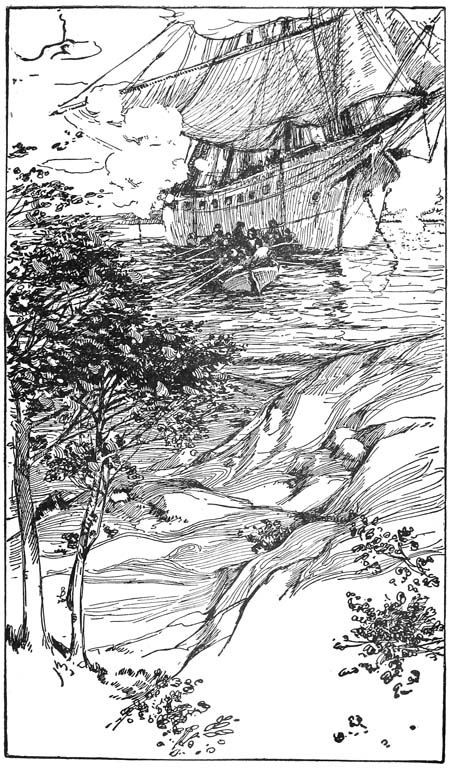

| Visit of Captain Vancouver | 88 |

| Preparing Hides and Tallow | 93 |

| Making the Ox-cart | 98 |

| Shipping the Hides and Tallow | 102 |

| Trading on the Ship | 108 |

| Leaving the Mission | 111 |

| PART III | |

| WHEN DOCAS LIVED WITH DON SECUNDINI ROBLES | |

| Wash-day | 117 |

| The Cascarone Ball | 122 |

| The Sheep-shearing | 128 |

| The Barbecue | 133 |

| Horseback-riding | 138 |

| The Rodeo | 142 |

| Bibliography | 148 |

| Pronunciation of Names | 151 |

A little Indian boy poked his head out of a brush house.

PART I

WHEN DOCAS LIVED AT THE INDIAN VILLAGE

“OH, mother!” cried a little Indian boy, “I am hungry.”

“Then go and start the fire so that I can cook breakfast,” answered his mother.

It was about a hundred years ago that this little boy, whose name was Docas, poked his head out of a brush house. Ama, his mother, was sitting on the ground just outside, grinding acorns in a stone bowl.

Docas went to the middle of the hut, where the blazing fire of wood had been the night before. Just before Ama had gone to sleep she had covered with ashes the glowing coals that were left from the fire.

Docas raked off the ashes and began to blow on the blackened coals that were left. There was not much life in them, but they began to redden a little.

He put some dry leaves against them and blew[4] harder. The leaves smoked, but would not light, no matter how hard he blew. And all the time the coals were getting blacker and blacker.

At last he called, “I cannot light it, mother.”

Ama came over where he was and began to blow, too; but even she could not start it, for the fire had died out.

“I must get some new fire,” said Ama at last.

She picked up two dry willow sticks and two flints. She rubbed the willow sticks together very hard for a while.

“Do you see the little dust that is gathering?” she asked. “Now I will strike the flints together until they send a spark down into that dry dust.”

In a few minutes a spark fell into the dust, the dust flared up, and Docas exclaimed, “There! now we have a fire.” He dropped some dry leaves on the burning dust, then he put some little twigs on the leaves. After that he called to his younger brother:—

“Wake up, Heema! Come and get some big sticks for the fire.”

Heema rolled off the mat of tule reeds on which he had been sleeping, rubbed his eyes, and said, “I’m ready, Docas.”

Heema did not have to spend time dressing. All the Indian children ever wore was a little skirt made of rabbit-skin or deer-skin.

[5]In a minute more Heema had piled some large sticks on the fire. Then it blazed up brightly.

“It’s foggy, and I’m cold,” said Docas. “Sit down by the fire with me and get warm.”

Docas and Heema were California Indians. They lived in an Indian rancheria, or village, near San Francisco Bay. Their father, whose name was Massea, was chief of the rancheria.

Docas was seven years old, while Heema was six. Alachu, one of their sisters, was three. Umwa was the other sister. She was so tiny that she had to be carried in a basket on her mother’s back.

“PUT the stones into the fire, boys, so that they will be hot when the acorns are ground,” said Ama.

Docas pulled toward the fire five large stones that were lying near.

“I’ll throw them in,” said Heema, tossing them into the middle of the hottest blaze.

Then Docas said, “Let’s surprise father by shooting a rabbit for breakfast.”

“Here are your bow and arrows,” answered Heema.

In a moment more they ran off. Docas hunted among the brush and trees near by for a rabbit,[6] but he could not find one, so he ran back toward the rancheria.

“I’ve found something that’s better than rabbits,” Docas heard Heema say suddenly.

“Where are you, Heema?” asked Docas.

“Here among the bushes, eating thimble-berries,” answered Heema, peeping out from among the large green leaves.

Docas laughed and began eating berries, too. The berries were so good that they forgot all about breakfast, until suddenly they heard their mother’s voice calling:—

“Boys, where are you? The acorns are ready to cook.”

The boys took one last mouthful of thimble-berries and then bounded toward the rancheria.

Ama put a basketful of cold water down by the fire as they came up.

“Heema, pour the acorn meal into the water. Docas, rake out the hot stones and put them into the water to cook the mush,” said Ama.

“I hope this mush will not be bitter,” said Docas, as he dropped a red-hot stone into the water.

“No; this will be good, for I soaked the acorns a long time and then dried them in the sun before I ground them,” answered Ama.

In a few minutes the mush was cooked; then Ama called Massea, and the whole family sat[7] around the basket. They all ate out of it at once, using sticks hollowed out at the end instead of spoons.

ONE day Massea came up to Docas.

“To-day we will go fishing,” he said.

Then Docas ran away to find his playmates.

“We are going fishing! We are going fishing!” he cried.

Then all the children began to dance and jump.

“We are going fishing! We are going fishing!” they screamed. For the children were glad when the fishing days came.

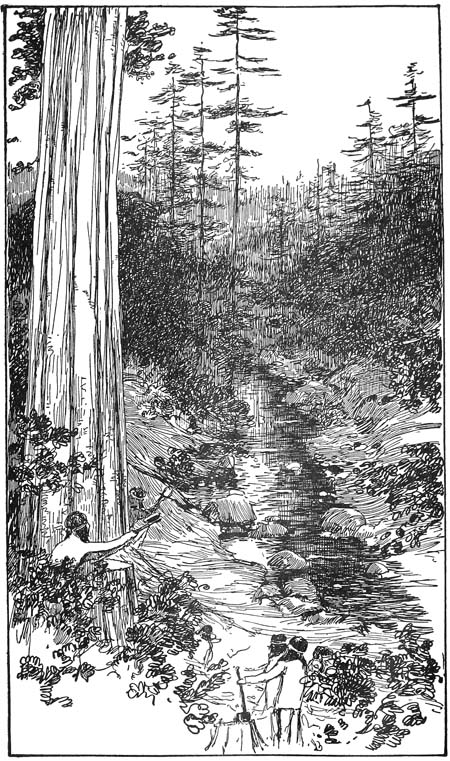

But first Massea must drive stakes across the bed of the creek just below the boys’ swimming hole.

And he must drive them very close together, for he wants to keep the fish from swimming through.

After Massea had made the fence, Docas called to Heema, “I’ll race you up the creek.”

“You will have to hurry or I shall beat you,” answered Heema.

Then they both started to run along the bank of the creek.

[8]“Come, Alachu. You may go, too,” said Ama.

All the women and children in the rancheria went also. They walked along the bank of the creek for about a quarter of a mile, then Alachu cried, “I see Docas. I see Heema.”

Docas was standing on the bank. “Watch me!” he called to Alachu.

He dived off the bank and disappeared in a large hole.

“Mother! mother! Docas is drowned!” cried Alachu.

Ama smiled and answered, “Wait and see.”

In a minute more Docas’s head popped suddenly out of the water.

Then the women and children walked out into the middle of the creek and began to wade down it.

Alachu heard a shout and saw Heema getting ready to jump.

“Be careful; I am afraid you will jump on top of me,” she cried.

There was a big splash, and Alachu gave a scream as the water splashed over her. Heema was standing in the water a few feet away.

“A water fight! We’ll have a water fight!” cried the children.

[9]

“Then we will spear them.”

They jumped about in the water. They splashed it all over each other. They laughed and shouted and made all the noise they could.[10] As they stopped for a moment to take breath, Docas said, “See the fish swim down the creek. They are scared.”

The battle lasted until the rancheria was in sight, and by that time all the fish were in the swimming hole. Then Massea said, “Now we must build a fence above them.”

When the fence was built, Docas said, “Now the fish cannot swim away, for there is a fence below them and a fence above them.”

That night Massea said, “We will build fires on the bank of the creek. The fish will come near to look at the light; then we will spear them.”

And so it happened. The men speared enough fish that night to give them something to eat for several days.

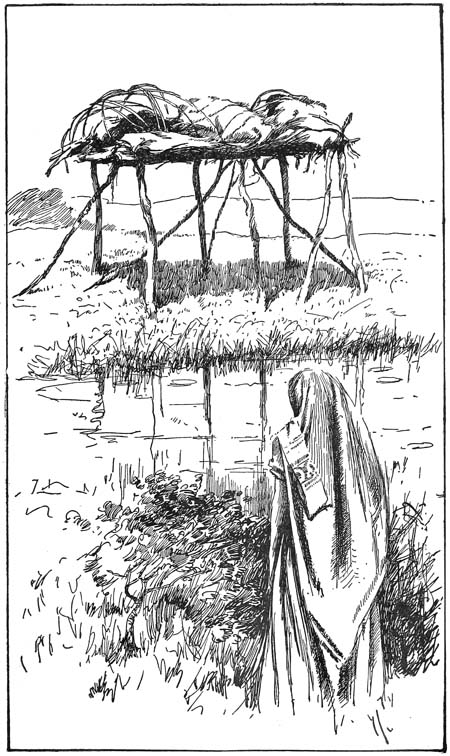

ONE day in October, Massea said to Docas, “Come, Docas, you must help me make a storehouse to-day, so that we shall have something to eat by and by.”

Massea and Docas went out into the woods. They hunted until they found an oak tree with two branches growing straight out at about the same height from the ground.

[11]Massea said, “Climb the tree, Docas;” so Docas scrambled up.

Massea then handed him some straight sticks. Docas put these sticks across from branch to branch, and tied the ends fast to the two branches of the tree with deerskin strings. After this his father brought up some twigs that bent easily. They wove these back and forth among the sticks until they had a good floor for their storehouse. In the same way they made the sides and the top, leaving a hole near the trunk of the tree for a door.

After the storehouse was made, Docas said to some of the other little Indian children, “Let’s go off and get some acorns to put in the storehouse.”

They took their baskets and went off toward the hills. Soon they came to some big oak trees.

One of the little boys called out, “Look! the ground is covered with acorns under that tree.”

Sure enough, the acorns had dropped down from the tree until they were so thick on the ground that the children could scrape them up. Before night they had filled their baskets.

Docas put the acorns he had gathered into the storehouse which he and his father had made. Every day the children went out to gather acorns; every night they poured them into the storehouse, and soon it was full.

[12]The day they finished filling it, Docas saw a little squirrel run up the trunk of the tree and go into the storehouse. Docas stood very still and watched. In a few minutes he saw the squirrel come back with his cheeks sticking out. He was carrying off the acorns.

Docas ran over to where his father was lying in the shade of a large tree, and said, “Oh, father, we shall not have any acorns left in a few days. The squirrels have begun to carry them off.”

Massea went over to the tree in which the storehouse was built. He smeared a broad band of pitch clear around the trunk.

“This will stop them,” he said.

The Indians had no more trouble after that; for if anything tried to climb the tree, it was caught in the band of sticky pitch.

While Massea was smearing the pitch around the trunk, Docas saw a bird at work in a tree near by.

“There is the woodpecker,” cried Docas, pointing to a woodpecker busily putting acorns away in his storehouse.

The woodpecker’s storehouse was not like Massea’s. Every summer the woodpecker pecks a great many holes just the size of an acorn in the bark of a tree. When fall comes, and the acorns are ripe, he puts the best ones in his holes. He hammers them in so tight that they do not often fall out.

[13]

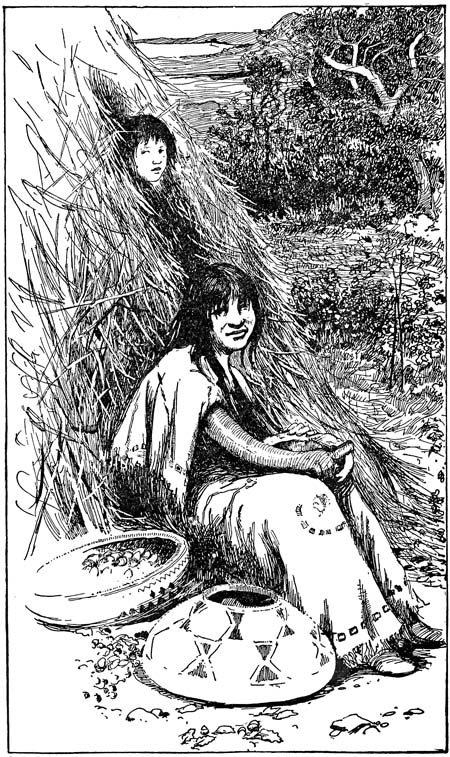

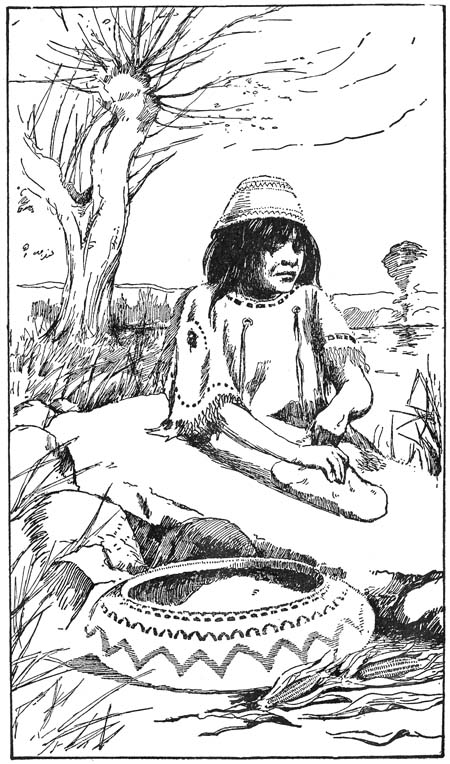

After the storehouse was made.

[14]“I hope we shall not have to take the woodpecker’s acorns this winter,” said Massea.

As long as their acorns lasted, Massea and the other Indians did not touch the acorns that the woodpecker had gathered. But one day all the Indians at the rancheria went off fishing. While they were gone their campfire spread and burned the tree in which they had made their storehouse.

Docas was skipping along ahead as they came home. He saw what had happened. He ran back to Massea and Ama, crying out, “The storehouse is burnt! The storehouse is burnt!”

Massea looked very sad at supper that night, and said, “I am afraid we shall have to take the woodpecker’s acorns.”

The Indians did not like to take the acorns, so they waited three days. By that time they were so hungry that they could wait no longer.

Docas built a fire near the woodpecker’s tree. The smoke that went up from it told the woodpecker that he would have to go. After a little he did not care to stay, for the smoke spoiled the acorns for him. So he flew away.

Docas then climbed the tree and pulled off the bark. That let the acorns fall out and then the Indians gathered them up and put them into a new storehouse, ready for future use.

ONE day in September, Docas and the rest of the family were all seated round a large basket. They were eating their acorn mush. Just as Docas put his stick in to get some, he heard something go “click” behind him.

He thought to himself, “The grasshoppers are getting thicker.”

He lifted his stick, and there in the mush on the end of it was a grasshopper.

“Look!” said Docas to Heema.

“Let me get him out,” said Heema, laughing and picking up a stick from the ground. Heema lifted the grasshopper out of the mush.

Then Docas said, “Let’s catch grasshoppers to-morrow.”

Heema said, “Yes.”

All day they heard the “Click, click,” of jumping grasshoppers.

That evening, when the children began playing, Docas ran up to them and said, “Help me dig a hole to catch the grasshoppers in.”

The children began digging a little way out from the rancheria, and before dark they had made a big hole.

Next morning, while the grasshoppers were still cold and stiff, Docas said to the children,[16] “Let’s make a big ring around the hole before the sun warms the grasshoppers.”

And they did so.

“Now we will walk slowly toward the hole,” said the children.

Little by little the children came nearer. Little by little the ring grew smaller. Little by little the grasshoppers inside the ring grew frightened.

“They’re jumping down into the hole now,” said Docas.

Soon the children were close to the edge of the hole.

“I am going to jump into the hole,” said Docas. “I can soon catch them down there. They cannot jump out so easily as they jumped in.”

So Docas caught all the grasshoppers that were in the hole. He longed to eat them, but he waited until they were cooked. Ama baked the grasshoppers in the fire until they were quite dry; then she ground them in the stone bowl just as she did the acorns.

After that the Indians ate them.

ONE morning in spring, Ama said to Docas, “Stir up the fire. I must get breakfast.”

“I shall have to get some sticks,” answered Docas, running off to the woods.

Baby Umwa was playing near. “Baby will make a big fire for mother,” she thought.

She began picking up dry leaves and throwing them on the fire. “Here are some good sticks,” she said to herself.

Docas had dropped his bow and arrows on the ground. She picked them up and threw them on the blazing leaves; then she picked up a basket and threw it on also.

“Hurry, Docas! See baby’s big fire!”

Docas rushed forward and seized the blazing basket, but it was so badly burned that it could not be used.

“Umwa! Umwa!” he cried. “You silly little baby! Mother will have to work for weeks to make her basket for grass-seed again.”

Ama felt very sorry when she saw the burnt basket.

“You must go to-day and get some more roots with which to make some new baskets,” she said.

After breakfast Docas and Heema went down to the edge of the bay.

[18]“How are you going to dig up the roots?” asked Heema.

“With my toes,” answered Docas.

The long round roots ran along just under the ground in the mud. Docas stuck his bare toes into the mud, wriggling them along under a root. He loosened it a little at each wriggle, and by and by he pulled up a long straight root.

Heema helped also, and that evening they carried home a big bundle of roots.

The next day they went up in the hills and gathered a large number of maidenhair ferns. They came back by the San Francisquito creek and broke off a great many willow branches.

As they trudged home, Heema asked, “Do you think mother will put feathers or shells on these new baskets?”

“I don’t know,” answered Docas, “but she will make a pretty pattern with the dark fern stems or the willow bark.”

Next morning Ama began making the new basket. She made this basket flat.

By the time the basket was finished, the grass-seed was ripe in the fields around them.

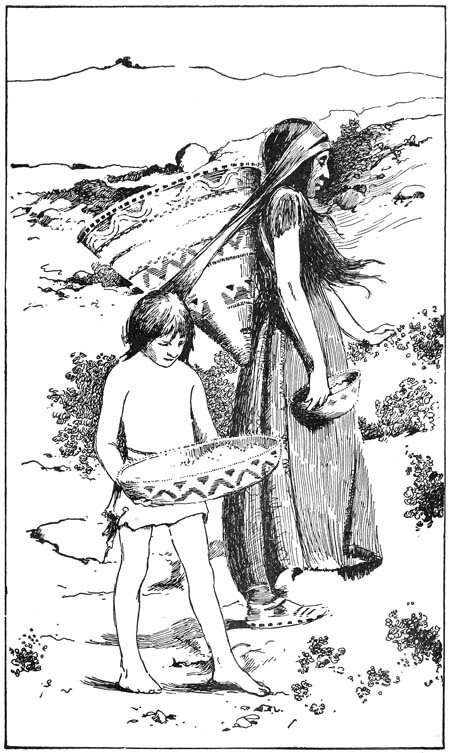

One morning Ama got up very early. Docas saw her pick up the new flat basket and a deep basket with a handle.

“I’m going to see what she does with the new basket,” thought Docas, creeping out very softly.

[19]

“I can carry the new basket,” said Docas.

[20]He trotted along behind Ama as she walked out to the field of grass. The grass was so tall that Docas was almost hidden, and his mother did not see him.

Docas watched Ama brush the tops of the grass with the flat basket. Every few minutes there would come a little rattle as Ama knocked the seeds down into the deep basket. “Just hear the grass-seed rattle down into the deep basket,” said Docas to himself.

The poppies were still asleep. Docas tried to poke some of them open, but they closed tightly again. He pulled some of the little green caps off the buds, but the little golden buds refused to open.

“They want the sun to drive away the mist before they wake up. Everything is sleepy this morning except mother. I think I’m sleepy myself.” With that he fell asleep among the poppies, with the tall grasses nodding over him. After a little Ama came over that way, brushing the grass tops as she came. Suddenly she stumbled and looked down.

“Why! There’s a child! It’s my own little Docas!” she exclaimed.

Docas rubbed his eyes and looked at her. Then he rolled out of her way and jumped up.

By that time the basket was full of seeds, so they started back to the rancheria. Ama slung[21] the deep basket on her back, carrying it by a strap across her forehead.

“I can carry the new basket,” said Docas.

After they came to the rancheria, Ama made the grass-seed into bread for breakfast.

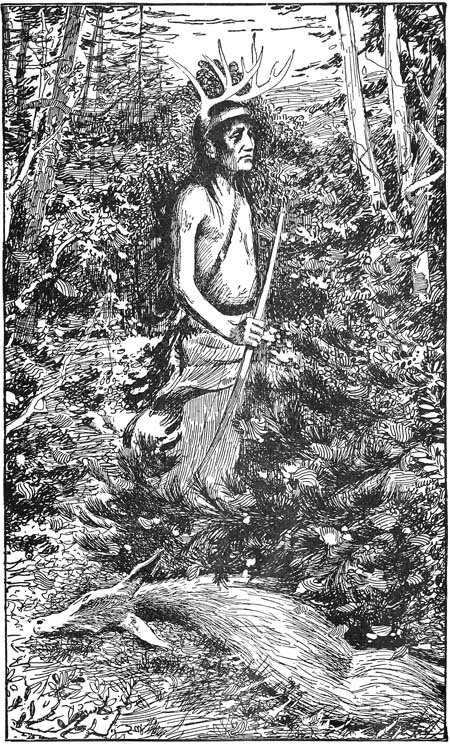

MASSEA and some of the other Indian men went out to hunt deer. Docas ran to meet them as they came home.

“How many did you get? One, two, three, four, five, six,” he said, counting the deer.

Then he ran to his mother and said, “Oh, mother, may I not have a new skirt? I want one of deer-skin instead of rabbit-skin this time.”

“Yes, you shall have it as soon as I can make it for you,” answered his mother.

After the deer were skinned, Ama took up a skin and said to Docas, “Put it into a still pool in the creek and let it stay there.”

“How long must it stay?” asked Docas.

“Until the hair is loose,” answered Ama.

So every morning Docas went out to the skin to see if the hair was loose. One morning he came running to his mother, crying, “Look, mother, I pulled this bunch of hair out so easily this morning!”

[22]Then Ama took the skin out of the water.

“You may pull all the hair out,” she said to Docas. “After that I will scrape it with a sharp stone.”

When both sides were scraped clean, Ama and Docas went out into the woods.

“We must find two trees so close together that we can stretch the skin between them,” said Ama.

By and by they found them, stretched the skin, and went back to camp. Every little while Docas went running out to the skin to see how fast it was drying.

“It just seems as if I couldn’t wait for my new skirt,” he said.

When it was half dry, Ama warmed some deer’s brains at the fire.

“Now, Docas, get the deerskin,” she said. “You may rub some brains of a deer on the skin.”

Docas rubbed and rubbed for a long time.

“Haven’t I rubbed enough?” he asked after a while.

“No, you must get the skin very soft,” she answered.

Docas’s arms grew tired after a little, so Ama said, “Go out where the ground is wet and dig a hole. I will finish rubbing the skin.”

[23]

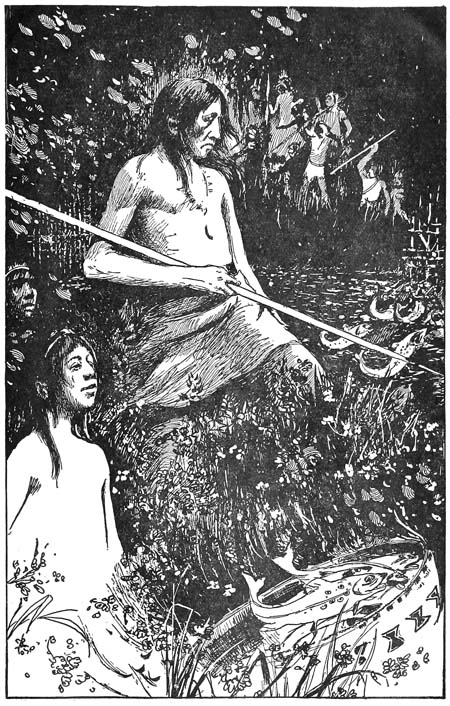

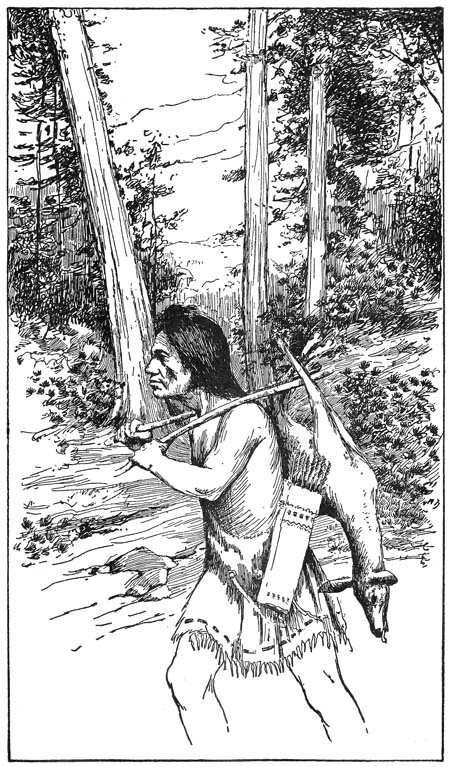

Massea bringing home a deer.

By the time the hole was ready the skin was[24] soft. Ama brought it to the hole and said, “Now we will bury the skin for four or five weeks.”

“Bury it!” exclaimed Docas. “I thought it was ready to make into my skirt, now.”

“Not yet,” answered Ama.

For several days Docas kept asking Ama if the skin was not almost ready, but after a while he grew tired of asking and forgot all about it.

When the time was up, Ama went out to the hole one evening after Docas was asleep. She dug up the skin, cleaned it, and made it into a skirt. She put a fringe on the bottom of the skirt to finish it off. After the skirt was done she laid it by Docas’s side, where he would see it the first thing in the morning.

Such a happy boy as he was when he found his new skirt!

MASSEA and the other Indian men were not feeling well one day. They said, “We ate too much deer. We must go to the sweat house.”

The Indians had dug a large hole in the ground and made a rude cave. They had covered this with brush, leaving only one little hole for a door. They called this place the sweat house.

[25]

“Look at them! There they go!” cried Docas to Heema.

[26]As the Indians went into the sweat house, Massea said to Docas:—

“Build a fire in the doorway so that we cannot get out.”

The sweat house was almost full of Indians, and after the fire was built they began to dance. They danced as hard as they could.

“I should not like to be in there,” said Docas to Heema. “Just think how hot it must be!”

“Hear them grunt!” exclaimed Heema.

It grew hotter and hotter in the sweat house, but the men kept on dancing.

Soon the sweat began to pour off them until the ground was wet. Massea went around with a scraper and scraped the other Indians.

By and by the fire went down, and Docas went off to play. By that time the Indians were tired out.

“Look at them! There they go!” cried Docas to Heema. Massea and the other men had jumped over the fire at the door and were running down to the river.

Heema and Alachu came running.

“Now father’s in the water!” cried Docas. A moment later he added, “See, he has come up out of the river. They are going to lie down in the sun to get warm and dry again. Let’s go down and play in the sun near them.”

IN the mountains near the camp was a gorge where the eagles built their nests. One day, Massea said to the other men:—

“To-morrow we will get the eagles.”

Next morning early they started.

“We shall not be back until evening,” said Massea to Docas. “The eagles build their nests so high among the rocks that it is hard to reach them.”

It was so late before the men came back that Docas was asleep, but he waked when he heard the voices. He looked out of the hut; then he shook Heema, saying, “Wake up, Heema; father has brought home two little eagles.”

“Let me take them to their huts,” said Docas to his father.

Docas took the little eagles and put them into two brush huts that had been built for them.

Little Umwa had died a few weeks before, so every day Massea, Ama, and the children went to see the eagles. Docas always took them something to eat.

“Tell Umwa we love her still,” said Docas to the eagles.

“Tell Umwa I’ll take good care of her if she will come back,” said Heema.

[28]“Tell Umwa ’Lachu want to play,” said little Alachu.

The father and mother also, told the eagles many things to tell their baby, for the Indians thought that the eagles would see Umwa, and could talk to her after they were killed.

The men built a very large brush hut, large enough to hold all the Indians in the village. At the end of two weeks, Massea said, “Now we will build a fire in the big hut.”

As the sun set they began dancing around the fire, and danced all night until almost sunrise. Each carried in his hands a bunch of owl feathers tied to a stick, with rattles from a rattlesnake in among the feathers. Whenever the bunch was shaken it made a rattling noise.

Several times during the night Massea threw baskets on the fire. Sometimes the baskets rolled off without burning. Massea put those baskets into the laps of women who were sitting near the fire, saying to them, “Give these baskets to the poor people.”

This went on till sunrise, and then the fire was made to burn very brightly. The eagles were killed and their bodies were laid on the fire. As the bodies burned, Massea danced more wildly than ever, shaking the rattle even more rapidly. And all the time he kept calling, “Don’t forget to tell Umwa.”

[29]

“Tell Umwa we love her still.”

ONE day Docas and his little brother Heema were playing near their brush hut, when Docas heard a slight noise near by. He looked up and saw another Indian boy about twelve years old. The boy held in his hand some strings of deerskin.

“It’s Apa, whose father is chief of the camp nearest us,” Docas said.

The boy Apa came forward. “Where’s your father?” he asked.

“In the sweat house,” answered Docas.

“Give him this string when he comes out,” said Apa, taking one of the strings from the little bunch. “Good-by. I have more camps to visit to-day,” and he started off on the run.

Docas and Heema looked the string over as soon as Apa had gone. They found five knots tied in it, each a little way apart from the others.

“I wonder what the knots are for,” said Heema. “Do they mean that they wish to fight us?”

“No, for Apa’s father is our friend. Here comes father. We will ask him,” answered Docas.

Docas and Heema ran toward Massea and gave him the string. As they passed Ama she saw the string and smiled. When they gave it to Massea, he smiled, too, and said, “It is well.”

[31]“What does it mean, father?” asked Heema. “Why do you and mother smile when you see it?”

“It means that Chief Yeeta sends to Chief Massea an invitation for everybody in our rancheria to come to a dance at his rancheria,” answered Massea.

“All right. Let’s go this morning,” said Heema, starting toward the hut to get the new rabbit-skin skirt his mother had just made for him.

“Wait,” said Massea. “The five knots mean that we are not to come for five days.”

“Oh, that’s so long to wait,” said Heema.

“You can watch the time for us,” said Massea. “Every morning you may untie one of the knots for us, and when the last but one is reached, we will start.”

So every morning, as soon as it was light, the two boys crept out of the hut and untied a knot.

“THERE’S only one knot left. Can’t we start now?” shouted Heema, as he untied the next to the last knot.

“Not until afternoon; but you may go to the marsh with me to gather reeds to blow on at the dance,” answered Massea.

Just before lunch, Heema burst into the hut[32] where Ama was busy putting food into their baskets.

“I got all these reeds myself and I tied them together myself,” he cried. He held up a bunch of reeds tied together with a deerskin string and almost as big as he was.

“Such fun as we shall have at the acorn dance!” he exclaimed, pulling a reed out of the bunch, and cutting it in such a manner that it made a rude flute. He began to jump around the hut, blowing on the reed meanwhile. As he gave an extra big jump, he lit on the edge of one of the baskets, tipped it over, and spilled the clams in it all over the ground.

“I wish you would be more quiet, like Docas,” said Ama.

“Never mind, I’ll pick up the clams,” said Heema, hurrying to get the clams back into the basket again. “Docas wants to be a man. You can’t have much fun with him these days,” he said.

Just as he put the last clam back, Docas and Massea came in sight, and Heema ran to meet them.

By the middle of the afternoon, everything was ready, and they started with their reeds for the village of Chief Yeeta. They carried a great many clams and much grass-seed bread, for they were to be gone several days. Yeeta’s village was about eight miles away, by the side of a little brook.

[33]

The Red Deer

[34]Docas walked quietly along by Massea’s side, but Heema ran around so much, chasing squirrels, that he began to grow tired.

Suddenly Docas said, “There’s Apa.”

“He has come to meet us. We must be almost there,” said Heema, forgetting that he was tired, and running forward.

From the top of the next hill Heema could look down on the village where Apa lived. In a minute he came running back to Docas.

“Oh, there are so many people there! And they are making a big circle by sticking green boughs in the ground out in an open place,” exclaimed Heema. “Please hurry up, Docas, you are so slow.”

Docas laughed and said, “Not when I get started, Heema,” and he began running toward Apa. Docas could run fast, so he reached Apa long before Heema did.

“Why are the people putting grass down in a circle?” asked Heema, as the three boys walked into the village.

“That’s where they dance, and they want it to be soft so that they can lie down when they get tired,” answered Docas.

It was dark before all the invited people had come, so they all had supper and went to bed.

[35]Next morning the dancing began. Massea stood on one side and stamped on a hollow log, while the women and the other men made one big circle, and swayed back and forth, singing as they danced. They kept time with their singing and dancing to Massea’s stamping.

By and by they grew tired and stopped dancing.

Heema had gone down to the brook, for he was tired of watching the dance.

“Come, Heema,” called Docas. “We must take around the acorn porridge now. The people are hungry.”

After the porridge had been served, the men stepped out again into the circle, while the women sat on the ground outside and looked on. Yeeta had a big rattle in his hand, and each of the other men had a reed.

Yeeta stood in the centre and shook his rattle. The other men blew on their reeds, and began jumping toward the right. The dance went on for a little while, and then suddenly Yeeta stopped shaking the rattle. The men, who were watching him, stopped dancing and blowing their reeds at the same time.

“Good,” said Docas, who was standing near. “No one got caught that time.”

Yeeta again began shaking his rattle, and the dance went on once more. This time he had[36] been shaking the rattle for a long while, when suddenly he stopped a second time.

“Look at them! Look at them! Half the men were not looking at him, and they are still dancing,” shouted Docas, and he laughed and pointed his finger at the dancers who were caught. The other boys laughed too, and the careless men looked foolish.

And so the dance went on for days, until they had eaten all the food they had with them. As they went home, Docas said to Heema, “I wish next autumn were here so that the acorns would be ripe again, and it would be time for another acorn dance.”

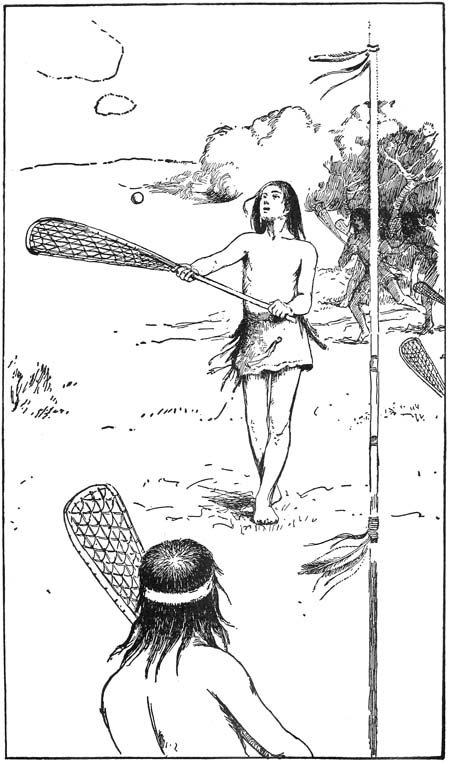

“OH, Docas, I am so tired of working! Let’s play something,” said Heema one evening.

“Help me get the boys together and we will play teekel. Father and the other men played it last night,” answered Docas.

Docas and Heema ran through the rancheria shouting, “Come play teekel! Come play teekel!” as loud as they could.

Before five minutes had passed, a crowd of boys were gathered in an open space at one side of the rancheria. Each boy brought with him a long, slender stick about as tall as himself.

[37]“I will get the ball, if you will make the lines,” shouted Docas, running toward the hut.

In a minute Docas came back carrying the ball, which was made of deerskin and looked like a small dumb-bell. While he was gone, the boys had scratched two long lines in the ground about ten feet apart. The lines were in the middle of the open space.

“You haven’t made the hole for the ball yet,” said Docas. He dug out a little hole midway between the two lines and laid the ball in it.

“We’ll give you first hit, and then we’ll get the ball back over your goal,” said Heema, tossing the ball up into the air for Docas to strike at with his stick.

But Docas hit the ball and sent it flying toward Heema’s goal.

“After it, boys!” shouted Heema.

In an instant the whole mass of boys were rushing toward the ball. Then such a running to and fro as there was! Back and forth went the ball, first toward one goal, then toward the other.

Such wild blows as were aimed at the ball! Sometimes they hit it, but more often the sticks beat the air wildly, or else fell on some boy’s head or shoulders. Not a boy cried even if the blows did hurt, because, they thought, “Our fathers did not cry when they played last night, and we must[38] not be less brave.” But they shouted and laughed so much that Massea came out to see what was going on.

“Run, Docas, run!” shouted Massea, as one of the boys on Docas’s side sent the ball flying far over the heads of the other boys, and down toward where Docas was standing near his goal.

And Docas did run. He knew that the boys on the other side were coming as fast as they could. He knew that he was the only boy on his side who was near the ball, and that unless he reached it first they would send it back over to their goal. He knew that Massea and the other men were watching him.

On came the crowd of boys. Now they were so near that their sticks were raised to strike the ball back. But Docas slipped in just ahead, hit the ball and sent it flying over his goal. Docas had fallen, but the other boys could not stop. They tumbled over Docas, and then in an instant there was a mixture of boys and sticks in a heap on the ground, with Docas at the bottom.

In a minute more, however, they were on their feet. Docas got up and laughed, although he had a big lump on his forehead. He was happy, for he had won the game. And more than that, Massea’s hand lay on his head for an instant, as he said, “My oldest son. He will be a man like his father some day.”

[39]

And sent it flying over his goal.

ONE summer Massea went across the mountains east of the rancheria to the big valley beyond. He went to make a visit and to get some good wood from which to make bows, for the best wood for bows grew only on the mountains which were farther to the east.

When he came back, all the Indians were lying around the campfire after supper.

“Tell us what you saw, father,” said Docas.

“I saw great mountains beyond the big valley.”

“Bigger mountains than ours?” asked Docas.

“Yes, mountains so high that it is always winter on their tops,” answered Massea.

“I don’t see how the mountains ever came to be so big,” said Heema.

“Shall I tell you a story about how the mountains were made? I heard one over there,” said Massea.

“Yes! Yes!” cried the children.

“Once upon a time there was nothing in the world but water. Where Tulare Lake now is, there was a pole standing up out of the water, and on it sat a hawk and a crow. First one of them would sit on it awhile, then the other would take his turn. Thus they sat on the pole above the water for a long, long time.”

[41]“How long?” asked Docas.

“A great many times as long as you are years old,” answered Massea. “At last they grew tired of living all alone, so they made some birds. They made the birds that live on fish, such as the kingfisher, the duck, and the eagle. Among them was a very small duck. This duck dived down to the bottom of the water and came up with its beak full of mud. When it came to the top it died; then it lay floating on the water.

“The hawk and the crow then gathered the mud from the duck’s mouth.”

“What did they do with it?” asked Alachu.

“Keep still, Alachu, and let father tell the story,” said Docas.

“They began to make the mountains. They began away south. We call the place Tehachapi Pass now. The hawk made the eastern range, and the crow made the western. Little by little, as they dropped in bit after bit of the earth, the mountains grew. By and by they rose above the water. Finally the hawk and the crow met in the north at Mount Shasta. When they compared their mountains, the eastern range was much smaller than the western.

“Then the hawk said to the crow, ‘You have played a joke on me. You have taken some of the earth out of my bill. That is why your mountains are larger.’

[42]“It was so, and the crow laughed in his claws. The hawk did not know what to do, but at last he got an Indian weed and chewed it. This weed made him very wise, so he took hold of the mountains and slipped them round in a circle. He put the range he had made in place of the other. That is why the mountains east of the big valley are now larger than our Coast Range.”

WHEN Massea had finished his story, Docas said, “Tell us another, father!”

“Yes, tell us another!” cried all the children.

By this time every child in the rancheria had come to listen.

“Very well,” said Massea. “When I was over in the great mountains, I saw a valley, the Yosemite, with one rocky wall going up out of it a mile high. The Indians over there told me a story about that rock. There were once two little boys living in a valley. These boys went down to the river to swim, and after they had paddled about awhile, one said, ‘I am going on shore to take a sleep.’

“‘I am going with you. We will lie down in the sun on that rock,’ said the second boy.

“They both lay down on the rock and fell fast asleep. They slept so long that winter came and[43] then the next summer. Another summer and winter came, and still they slept on. Summer after summer went by, and still the children did not wake.

“Meanwhile the rock on which they lay was rising slowly into the air. Day after day, and night after night, it rose higher and higher, until soon they were up beyond the reach of their friends. Far up, far up they went until their faces scraped the moon, and still the children slept.

“At length all the animals came together, for they intended to get the boys down in some way.

“‘Suppose we all make a spring up the wall. Some of us will be sure to reach the top,’ said the lion.

“‘Agreed,’ said the others.

“One by one they began to jump. The little mouse jumped up a hand-breadth. The rat jumped two hand-breadths. The raccoon jumped a little higher; and so on.

“All the smaller animals had failed when the grizzly bear came to take his turn.

“‘I shall jump far higher than any of you. I shall get to the top,’ said the bear.

“He gave a tremendous leap, but he, too, failed.

“Last of all came the lion. ‘It is not strange that you have all failed. You are not lions. But I am the king of beasts. I shall bring the little boys down,’ said he.

[44]“He stepped back from the wall, then he ran and jumped with all his might. He jumped higher than any of the others, but the top of the rock was still far above him, so he fell back and tumbled flat on his back.

“Without saying anything, a tiny little measuring-worm began to creep up the rock. It was so tiny that none of the animals noticed it. Little by little, it crept slowly upward. Presently it was above the bear’s jump, then it was far above the lion’s jump, then it was out of sight.”

“Please hurry up, father,” said Alachu. “I can scarcely wait to see if it got the little boys.”

Massea only smiled and went on. “So it crawled up, and up, and up, through many winters, and at last it reached the top.”

“Goody!” cried Alachu, clapping her hands. “Then what did it do?”

“Then the measuring-worm took the little boys and brought them down the way it went up.”

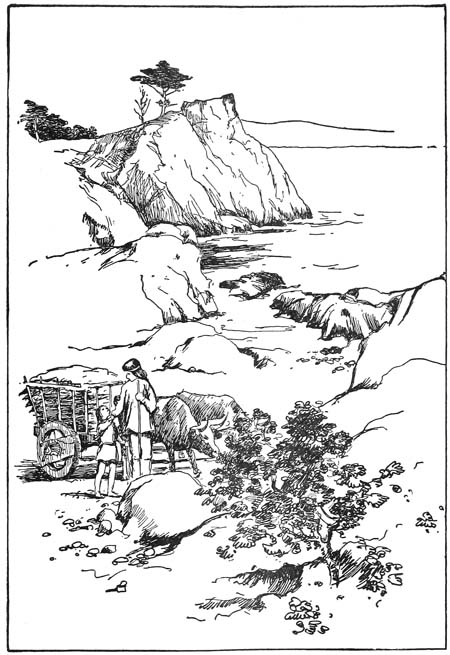

ONE morning Massea said, “I am going out to hunt deer to-day.”

Docas went to a corner of the cave and got a deer’s head with the horns on it, and gave it to Massea. Massea took the head, picked up his[45] bow and arrows, and went away. He carried it until he had walked nearly to the top of the mountains, then he tied the deer’s head on top of his own head.

After that he looked as if he were a deer himself as he walked along through the bushes. He did this so that he would not frighten any deer which might see him coming.

By and by he saw some deer not very far off. He bent down so that only his horns showed above the bushes; then he walked toward the deer. They looked up when they heard the noise, and saw the deer’s head coming toward them. “It’s nothing but another deer,” they thought.

Massea kept walking closer and closer to them, until he was so near that he was sure he could hit them. Then he raised his bow, put the arrow into its place, pulled the string, and took good aim. He let go the string, and the arrow flew. In a minute more a large deer was lying dead, and the others were running away.

Massea went up to the dead deer. When he saw how large it was he said to himself, “That will give Ama and Docas something to eat for a long time.” He threw the deer over his shoulder and started to carry it home.

After a while he became tired, so he lay down to rest under a big redwood tree. By and by he[46] heard a noise and looked up, and there, a little way off, were three deer. He picked up his bow and arrows to shoot, but saw something that surprised him so much that he stopped.

He saw two men with white skins. They did not see Massea, because they too were looking at the deer. One of them raised something long and black which he had in his hand. There was a loud noise, and one of the deer fell dead.

Massea was frightened, for he had never seen white men before. He hid himself so that they could not see him. He was afraid they might kill him in the same way that they had killed the deer, without even using a bow and arrow.

They picked up their deer and went off toward the ocean. Massea followed a little way behind until he saw that they were going down the mountains. Then he came back to where he had left his deer, and carried it down to the Indian rancheria. You can imagine how surprised the Indians were when he told them what he had seen.

A few days later, Docas and some of the other Indian boys were playing at the edge of the camp, when Docas heard a noise and looked up.

“Look! What’s that queer animal coming toward us?” he said.

“It has two heads!” exclaimed Heema.

[47]

“That will give Ama and Docas something to eat for a long time.”

The children were so surprised that they did[48] not think of running. They just sat still and looked at this thing as it came nearer.

“There are three more of them,” cried Docas. “They are coming toward us, too.”

“Now the first one is stopping! Now it’s breaking in two!” exclaimed Heema.

In a moment more, however, the children found that it was not one creature. It was a white man riding on a queer little animal with long ears that wagged backward and forward.

They walked toward Docas, and Docas called his father. Massea did not run away, but came up to where they were. The white men told Massea by signs that they were trying to find out how far the great bay extended to the south.

Massea showed them as well as he could. The white men made the Indians understand that they were going round the bay, and that there were more white men camped on a creek a few miles back.

After they had gone on, a great many of the Indians went up to the camp to see the white men. They took them some acorn meal to eat.

At the camp they found the white chief, Governor Portola. The white men had more of the strange animals at the camp. They let Docas and his little brother Heema look at them as long as they liked. Heema said to Docas, “Oh,[49] Docas, do you think they would let me ride one of the queer animals a little way?”

Docas said, “I don’t know, but I will ask and find out.”

The white men smiled and nodded when they understood what Docas wanted. Docas went to Heema and said, “They do not care.”

In a moment Heema was seated on the mule’s back. As the mule began to walk, Heema held very tightly to the saddle.

“Riding a mule is easy,” said Heema.

“Let me try,” said Docas.

Docas led the mule to a rock, and Heema jumped down. Docas rode around until Massea said, “It is time to go home.”

After a day or two, the men who had gone south around the bay came back, then the whole party went away over the mountains to the ocean again. That was the last that Docas saw of the white men for eight years.

ONE day Massea said, “Docas, we have used the last of our red earth. We must go to the red hill and get some more.” They wanted the red earth to paint their bodies.

Next morning they started very early, while it was still cold. They went to the creek near by[50] and took some mud from the bank. This they smeared all over their bodies to keep them warm. After they were covered with mud the cold wind did not strike the bare skin, so they were warmer.

Then they walked south across the valley toward what we now call the New Almaden Mine. Docas was old enough and strong enough to walk almost as far as his father.

A little after noon they came to the hill where the red earth was. They filled some baskets with it and sat down to rest. They soon saw five more Indians coming with empty baskets.

When they came nearer Massea spoke to them, and asked them from what place they came. They said they lived over on the coast on the southern part of the big bay. They told Massea that they had gone to live at what was called the Carmel Mission. Massea had never heard of a mission before, so he asked them to tell him what it was.

One of the strange Indians said, “Some white men came and settled near our rancheria.”

Docas had been sitting by his father’s side all this time, listening. When he heard this, he said to Massea, “Oh, father, perhaps it is some of the white men who came past our rancheria when I was a little boy.”

Massea said, “Perhaps.”

Then he asked the strange Indian if they were[51] the white men who had come across the mountains about eight summers ago.

The Indian said, “No; but they were friends.”

He then said to Massea and Docas, “We call the white men ‘father.’ They are very good to us. They showed us how to make a very large house. It is not made of brush, but is made of clay, and we call this house the church.”

“How big is it?” asked Docas.

“It is so large that many oak trees could stand inside it. On the walls are things that, when you come in front of them, show your face clearer than the quietest spring of water. Then there are long white sticks that make a soft light when they are lit. But the most beautiful things in the church are the pictures.”

“What are pictures?” asked Massea.

“Flat things that hang on the wall and look like people,” the stranger answered.

He stopped for a while after he had told all this. Massea and Docas did not say anything. By and by he said, “The fathers have been kind to us, so I have gone to live with them. I am a Mission Indian now.” After this Massea and Docas asked him many questions about how they lived.

Before he went away, Massea said to him, “I think I should like to be a Mission Indian. Are not any of the fathers coming over across the mountains?”

[52]The strange Indian from Monterey said, “Yes, a little while ago a new father, called Father Pena, came to our Mission. He soon started over the mountains to begin a new Mission. He must be out in the valley somewhere now.”

After a while, Massea and Docas took up their baskets and started off. All the way home they kept talking about the Mission and what the Indian from Monterey had told them.

That night, as they sat around the campfire, Massea told the other Indians all they had heard that day. Some of the Indians laughed at the story, but Massea said, “If one of the fathers comes over here, I am going to know more about him. Perhaps I shall go to live with him.”

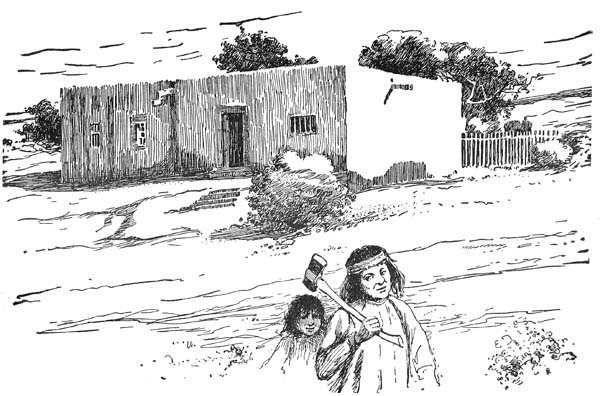

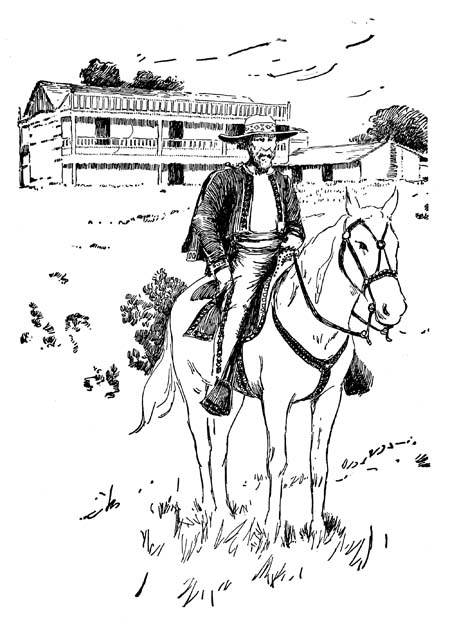

A FEW days after this visit to the red hill, Massea and his family saw some white men coming into the rancheria. Three of them were riding on animals very much like those ridden by Portola’s men; but these were not mules—they were horses.

Each man wore a cloak of padded deerskin. Arrows could not go through these cloaks, so the white men always wore them. Sometimes the Indians shot arrows at them, but when they came to this rancheria the Indians did not try to hurt[53] them. They gave the white men some acorn mush to eat.

While they were eating, Docas crept up to his father and said, “Do you think that man with the long dark dress is the father the Indian from the coast told about?”

Massea said, “I think so, but we will see after dinner.”

The white men had an Indian with them who could talk both Indian and Spanish. After they had eaten, they began to talk to the Indians.

Docas was right. One of the men was Father Pena, who had come into their valley to start a new mission.

He went about ten miles farther south. There he started the new mission, and called it Santa Clara, after a very good and beautiful woman.

One day, a few weeks later, Massea got into a quarrel with some Indians from another rancheria, about some deer they had trapped. That night Docas heard something go “thud” by the side of his head while he was asleep. He put out his hand and felt an arrow sticking in the ground beside the tule mat on which he was sleeping.

“Some one is shooting at us,” he shouted.

Massea jumped up and got his own bow and arrows. He came over and felt of the arrow that had been shot into the hut, to see from what direction it came.

[54]Massea gave a long call to tell the Indians of their rancheria that there was danger and that they must help. Then he and Docas crept out of the house and hid behind two trees that stood near the front of the hut. In a moment more they saw some dark figures moving about in the direction from which the arrow had come.

They raised their bows and were just going to shoot, when they heard a rustle behind them. They turned quickly, but before they could help themselves, their arms were seized and tied behind their backs.

“Now we have you,” said the strange Indians.

Some of the strange Indians hurried into the hut and brought out Ama, Heema, and Alachu and took them off. The others stayed to fight.

Next day they took Massea and his family out to the middle of their rancheria. The Indians who had captured them were going to torture them.

Suddenly a man in a long gray gown stood among them. It was Father Pena, and he was holding up a cross.

He said, “My children, what are you doing? Do you know that it is wrong for you to torture your neighbors? Let them go.”

These Indians loved Father Pena already and wanted to do as he told them, so they let Massea go, and all his family with him.

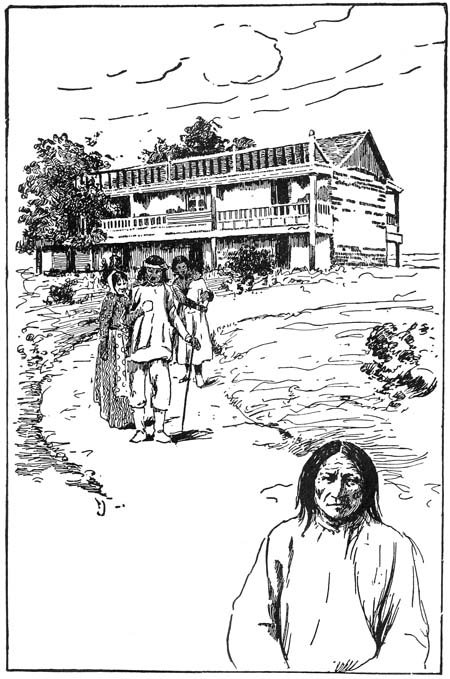

He decided to go to the Mission to live.

PART II

WHEN DOCAS LIVED AT THE MISSION

AFTER Father Pena had saved Massea from being tortured, Massea liked him very much,—so much that he decided to go to the Mission to live.

Therefore after a few days they gathered together their baskets, their bows and arrows, and some seeds. Then they were ready to start, for they had nothing more to take with them. Docas walked with Heema, his little brother. Massea walked at the side of Ama, who was carrying Keoka, Docas’s baby sister. Alachu trotted behind.

When they came to the Mission they found that some of the Indians who were already there had helped Father Pena to build a very large brush house. This the Father called a church. Near it was the Father’s hut, and off at one side were the huts of the Indians. These huts were built in rows, but they were of brush just as they had always been.

[58]As soon as they arrived, Docas and Massea went off a little way to the creek, where there were many willow trees growing. They broke off the leafy branches and carried them up to the Mission to make their own hut. When they had a large pile of branches they began to build it.

First they stuck one end of a branch into the ground. They did that with all the branches until they had a circle, putting the branches so close together that Docas could hardly look between them.

When the circle was finished, they bent all the tops of the branches together and tied them; then they covered the house with dry grass.

The Father tried to get Massea to build a better kind of house; he said he would show him how to do it, for the brush house was too cold. But Massea said, “No; we like this kind of house. When it gets too dirty, we will burn it down and build another.”

They left a little hole for a door. They left it open all the time because they had nothing with which to close it.

After the house was finished and the baskets were put away in it, they all went to help their friends build their houses. One of the Indians who was already living at the Mission brought them a bundle of straw, which Massea put across[59] the hole in front of their house. That meant to any Indian who might come to see them, “We are away from home, and shall be gone some time.”

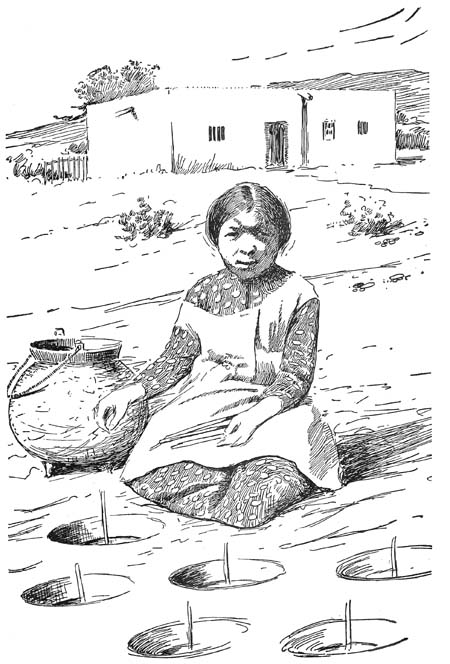

NEXT morning Ama got up very early. She went down to the creek bed and hunted about until she found two stones that she liked. One was large and flat on top; the other was small and long, with one end that had been worn smooth by the water. She wanted to make a new mortar and pestle, for the old ones were so heavy that she had not brought them with her.

Ama carried her corn down to the creek, put it on the big stone, and tried to pound it with the little one; but the corn flew all over the ground, for there was no hole worn yet in the top of the flat rock.

She poured some more corn on the top of the flat stone, but this time she did not pound it so hard. Even then she could not grind it very well, but by and by it was fine enough so that she could make mush of it.

She started to go to the hut to tell Docas to make a fire. Just as she climbed up the bank the sun came over the top of the mountain. It shone on the queer, shiny thing that looked something like a basket upside down. This thing[60] hung between two posts by the church, and it was shining so brightly now that Ama could hardly look at it.

At the same moment that the sun rose, she heard something go, “Clang, clang, clang!” The sound seemed to come from this same shiny thing.

It waked Massea and Docas, and they came running out of the hut to see what was the matter. In a few minutes all the other people in the village came out of their huts, too.

Everybody seemed to be going toward the shiny thing that made the noise. So Ama snatched up little Keoka, and they all followed after the other people to see what was the matter.

They found that all the Indians were going into the big brush house, and they followed. As the people went in they knelt down. Massea said, “I am going to do as other people do,” so he knelt down, too. Then he took Ama and the children and went to a corner of the house to see what was going to happen.

Up in the front of the house some of the long white sticks were burning that the Indian from Monterey had told about. In a few minutes more Docas heard the sweetest sound! Heema began to talk to him just then, but Docas said, “Stop! I want to listen.”

In a few minutes some more boys came in, all[61] singing. Docas could not understand anything they said, but he liked the sound.

Then Father Pena came out and said something, but Docas could not understand that either. After the little boys had sung, everybody got up and went out of the house. Massea and his family followed, and they all went back to their homes.

Ama asked Docas to build the fire. He found some dry sticks and soon had a fire roaring. Just then a strange little Mission boy with a red skirt on came up. “What are you building that fire for?” he said.

“For my mother to cook breakfast,” answered Docas.

“We don’t do that here at the Mission,” said the strange Indian boy.

“Don’t have any breakfast?” asked Docas. Docas was almost ready to wish he were back at the old rancheria, if he could not have any breakfast.

“Oh, no!” said the boy. “I meant that each family does not get its own breakfast.”

“Then who does get it?” asked Docas.

“Well, you see my mother and some of the other women stayed home and got breakfast ready for all of us while we were at mass,” said the boy. Then he asked, “Where is your mother?”

[62]“She is down at the creek trying to grind some more corn while I build the fire,” answered Docas.

“Let’s surprise her,” said the boy. “Have you some baskets? Get one, and we will go and get the breakfast while she is gone.”

Docas went into the hut and brought out one of the flat baskets. The boy looked at it; then he said, “Haven’t you any deeper basket? They give you so much to eat here.” Docas went back, and this time he brought out one of the deep baskets in which Ama used to carry the grass-seed. Then they went off.

Soon Ama came back. She looked all round, but could not find any fire. “I wonder what has become of Docas,” she said.

Docas had not put any big wood on the fire, but only some small sticks, so by the time Ama came up from the creek it was all burned out.

In a little while Ama saw Docas coming toward them, carrying a basket very carefully in his hands. The other Indian boy was with him.

“I wonder where he has been and what he is carrying in that basket. I should think he would be hungry himself, and build the fire, instead of running off to play before breakfast,” thought Ama.

In a minute more Docas set the basket down at her feet. She looked into it, then she said,[63] “Why, it is filled with mush. Where did you get it?”

Docas then told Ama about the big boilers full of mush, and how every family sent and got its breakfast from them.

The strange little boy, whose name was Yisoo, said, “Good-by; I will be back after breakfast, but I must hurry now and take our breakfast home.”

AFTER a little while Yisoo came back. “Come now; it is time to go to school,” said he.

“What is school? What do you do there?” asked Docas.

“Why, it’s a place where all the Indian boys go every day. They just say over things that the Father tells them.”

“Is that all? I don’t think that’s any fun,” said Docas.

“No, it isn’t,” said the boy; “but I tell you what is fun,” he added. “If you have a good voice, the Father will teach you to sing and maybe he will teach you to play on a violin.”

Docas was glad to hear that perhaps he could learn to sing, for he loved music. As they walked along Yisoo told Docas about what he must do at school.

[64]As they came out of the school, Yisoo said to Docas, “I can beat you home.” They both started off on a run, but Docas came out a little ahead. Yisoo looked at his bare legs and said, “You know how to run.”

Docas said, “Yes; but you see I haven’t so many clothes on as you.”

“I must take you after dinner to get some clothes like mine,” said Yisoo.

They hurried to get their baskets and go for the dinner. For dinner they had some meat as well as mush. Father Pena told the women who were giving out the dinner that both Docas and Yisoo had studied very hard that morning, and if there were any scraps of dinner left they should have them. So Docas and Yisoo had a big dinner that day, for when they came back, the women gave them each an extra piece of meat and a little cake made of corn.

After dinner, Yisoo said, “Now we will go for your clothes.”

They went to the house where the Indian clothes were kept. Father Pena went with them and gave Docas a suit of clothes just like Yisoo’s. Docas liked them very much, for the jacket was white and the shirt was scarlet.

After Docas was dressed, Father Pena said, “Haven’t you a brother and a sister?”

“Yes, Father,” said Docas.

[65]“Then take them each a suit of clothes, too. All the children here wear the same kind of clothes,” said Father Pena.

THE place the Fathers first selected for the Mission was very low, and before they had lived there many winters, a great rain made the creek overflow its banks and flood the Mission.

“This place is too low; we must move farther away from the creek,” said the Fathers, as they watched the muddy water swirling about among their houses.

So before long the entire Mission was moved three miles away to a safe place.

Father Joseph was the name of the younger of the two Fathers. He had charge of the Mission gardens, and one day in May he walked out among the gardens that had been planted. Massea was at work pulling weeds. As Father Joseph came near, he said, “Massea, our garden needs more water.”

Massea said, “Yes, it is too dry; but there will be no rain for three or four months yet.”

“What can we do to bring some water to the garden?” said Father Joseph. “I wonder if we[66] could not make a long ditch from the Guadalupe Creek around our garden and then back to the creek again.”

“It would bring the water, but it would be much work, Father,” said Massea.

“We have many Indians who could work,” said Father Joseph. “I will ask Father Pena what he thinks about it.”

Father Pena thought the idea was a good one. So in a few days, after they had marked out the course of the ditch, there were two hundred Indian men at work digging. Even Docas worked after school was done. They worked so hard that in a few weeks the ditch was made, and part of the water of the creek was flowing through it. After that the gardens were never dry any more.

The children liked the ditch too, for it was such a fine place to go wading in. Heema made tiny boats out of tules[1] as nearly like Massea’s big boat as he could. Even Docas liked to watch his little brother and sister sail their boats on the water in the ditch.

By the side of the irrigating ditch grew many rows of corn. When it was ripe, Massea went to his house and got a very large, deep basket.

Docas said, “Where are you going, father?”

[67]

Massea gathering corn.

[68]“Father Joseph told me to get this basket and cut the corn,” said Massea.

“May I go with you, father?” asked Alachu.

“Yes, if you will not get in the way,” said Massea.

So Massea carried his basket to the cornfield, and Alachu trotted along by his side. He went down each row of corn, cutting off the heads and putting them into his basket. Sometimes he happened to drop a head, but when he did that, Alachu picked it up for him, and he put it into his basket.

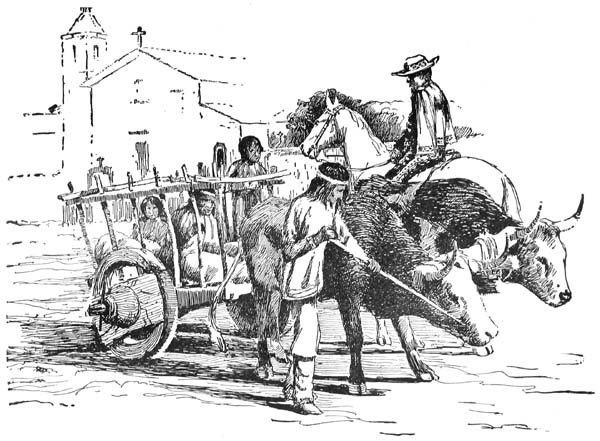

When the basket was full, he carried it to the end of the field where Docas was waiting with a cart drawn by oxen. Massea emptied the baskets into the cart until it was full; then Docas drove the cart to a storehouse.

One rainy day in winter when they could not work outside, Father Joseph said to a number of the Indian men, “I want you to go to the storehouse to-day to husk corn.”

After school Docas went to the storehouse, too, and found Massea sitting on the floor with the other men. Massea tied a few empty husks together; then he took the ears that Docas had husked. He rubbed a full ear against the husks until all the grains of corn had dropped down into the basket on the floor.

Then it was ready to be roasted.

[1] Tu’le, a large bulrush growing abundantly on overflowed land in California and elsewhere.

ONE morning Massea took the rough wooden plough and went out to a smooth piece of ground near the Mission. He began to plough the ground in a circle, not ploughing very deep, but only loosening the top.

Heema and Alachu were wading in the irrigating ditch.

Alachu said, “See! father is making a garden.”

“That’s a queer place to make a garden,” said Heema.

They did not pay any more attention, but went on wading.

That afternoon Docas and some other boys and men went out with Massea to make a tight fence around the circle Massea had ploughed. Docas tied the fence together with rawhide strings so that it could not come apart.

After the fence was built, Massea poured water over the top of the ground. Then the men drove a band of wild horses into the circle and closed up the gate so that they could not get out.

When the children saw the horses going into the circle, they all ran to see what was going to happen. Docas peeped through a hole in the fence. He could see the horses standing around inside, so he called Yisoo to come and peep through, too.

[70]One horse was standing near the hole in the fence. When he heard Docas call, he pricked up his ears, ducked his head, kicked up his heels, and started off on a run. As soon as one horse began to run all the other horses began to run, too. The children clapped their hands, and the men yelled, so the horses kept on running round and round.

By the time Father Joseph told Massea to let them out, the ground was tramped as smooth and hard as cement.

Then Massea and Docas began hauling wheat from the fields in the big ox-carts, and piling it up in the middle of the circle on the hard ground. Heema had to go to school most of the time, but Alachu rode out with Docas in the empty cart, and came back on the top of the load.

One day Docas piled the cart very full. When he was ready to go, he gave Alachu a toss up on the load, but he tossed her so hard that, instead of staying on top, she slipped clear off on the other side. Docas saw her slide off and heard a thud on the ground. He ran around the back of the cart, but he could not see Alachu. He could see only a pile of grain on the ground.

“Alachu!” he called. In a moment the grain on the ground began to shake, and Alachu’s head came up out of the middle of it. A big bunch had slid off with her and covered her up.[71] Docas was afraid she was hurt, but when she began to laugh, he picked her up, and this time he set her very carefully on top of the hay in the cart.

By and by there was a big stack of grain in the centre of the circle. Massea spread some of the grain out on the open space between the stack and the fence, and the men turned the horses in again. Again the horses ran round and round until they had tramped all the wheat out of the grain.

Massea said to Docas, “Run, Docas. Go and get the pitchforks.”

Docas ran to a house near the Father’s and brought back four big, wooden pitchforks. Docas gave Massea a pitchfork. He also gave Yisoo’s father one; then he gave one to Yisoo, and kept one for himself.

They went inside the circle and tossed the straw over the fence. Of course the pitchforks would not lift the wheat, so it stayed on the ground. They kept on putting down new layers of grain and letting the wild horses run over it and trample the wheat out, until there was no longer any stack in the middle.

Yisoo had the wooden shovels ready, and they shovelled all the wheat into a pile in the centre of the circle. Some of it they swept into the pile with brush brooms.

[72]“What dirty wheat! I don’t want to eat any mush made of that wheat. It’s all full of little pieces of chaff,” said Alachu. She shivered as she spoke, for a cold wind was blowing.

“Don’t you want to come inside the fence? It is warmer inside,” said Docas. Alachu went inside and ran over to Docas, but he said, “No, you must not stay here. Go across to the other side of the circle, close to the fence.”

In a moment more she saw why Docas made her go over to the other side of the circle. Docas threw a big shovelful of the grain and chaff up into the air.

The chaff was light, and the wind blew it away, but the grain fell back to the ground. The air was so full of the bits of flying chaff that Alachu could hardly see the fence where she had been standing at first.

ONE morning, Father Pena came to Massea.

“I received a letter yesterday saying that a ship has come to San Francisco,” he said. “It has brought some pictures for the church at our Mission. I want you to go to San Francisco with an ox-cart and bring the pictures back.”

Father Pena gave Massea charge of many things. Massea had been a chief at his Indian rancheria, and so Father Pena sent him for the pictures.

[73]

Threshing the grain.

[74]Docas went with Massea. As they rode along they passed their old rancheria, which was deserted now.

“Where have the Indians gone?” asked Docas.

“They went away across the mountains toward the rising sun,” answered Massea. “They live now in the big valley down by Tulare Lake.”

The next day they came to San Francisco. Docas was much interested in the big, new church that the Indians had just finished building. It was made of adobe bricks instead of brush.

They loaded the pictures into the cart and started home. As they went slowly along, Docas said, “Why don’t we have a big, new church like the one here at the Mission Dolores? I hate to put these new pictures in the old brush house.”

“We are going to build one very soon. Father Pena told me so just before we started,” said Massea.

The day after Massea and Docas came home from San Francisco, Father Pena came to Docas and said, “Docas, where is the best clay bank?”

Docas thought a moment. Then he answered, “At the back of Yisoo’s house. Every time we try to walk across it after a rain we get stuck.”

[75]“Let’s go and take a look at it,” said Father Pena.

When they got there, they found Heema and Alachu making little clay mortars and pestles out of the adobe mud.

“They play here every day,” said Docas.

Father Pena picked up a dry mortar that Alachu had made a few days before. It had dried very smoothly, with no cracks in it. Father Pena nodded his head. “I think this adobe will do,” he said.

On the next day Father Joseph and a number of the other men came out to the adobe bank.

“Dig up a patch of adobe,” said Father Joseph to Massea.

The children all stood around and watched while Massea dug.

“Now pour some water on the adobe and mix it up,” said Father Joseph.

In a few minutes Massea said, “It doesn’t mix easily. The adobe is in such large lumps.”

“Jump in, children, and dance around in the adobe. That will break up the lumps and make the adobe into a smooth paste,” said Father Joseph.

Docas, Yisoo, and a number of the other boys jumped in.

“Take hold of hands and make a ring,” said Docas. “Now we will play we are having an eagle dance.”

[76]“It’s great fun!” said Yisoo.

“I’m stuck!” cried Docas. Yisoo and the other boys ran to him and pulled him loose from the big sticky lump in which his feet had stuck.

They jumped faster and faster. “You’re jumping on my toes,” cried Yisoo to Docas.

Then they both laughed, for Yisoo was not hurt.

They jumped about so fast that very soon they had crushed every lump.

While the children were jumping, Massea was sitting on the ground near by, chopping tules. He carried the chopped tules to where the children were jumping.

“Stop jumping a minute while I throw these in. Then you can mix them with the adobe,” said Massea.

“What are the broken tules for?” asked Docas.

“To make the bricks stick together better,” answered Massea.

While the children were mixing the tules into the adobe paste, the men were busy, carrying piles of wooden moulds out from the Father’s house.

When the adobe was smooth, Father Joseph said, “Now watch me make the first brick.” He filled a mould with the mixture of adobe, tule, and water. “Now help me carry the mould to a smooth piece of ground,” said Father Joseph to Docas.

[77]

And there was another brick.

[78]The mould had a bottom that slid out. Father Pena pulled the bottom out from under it after they set it down. Then he raised the sides of the mould, and the brick was left flat on the ground.

“What a nice brick!” said Alachu. She ran forward, and before any one could stop her, she put her hand down and tried to lift the brick. It was still soft, and her fingers made marks on it.

Father Joseph said, “You will have to wait until it dries.”

Docas had watched very closely. He went back to the hole and filled a mould; then he and Heema brought it out to the smooth piece of ground. They put it down near the first brick, pulled out the bottom and raised the sides just as they had seen Father Joseph do. And there was another brick.

Soon a great many Indians were at work making the bricks, and after a little while there were rows and rows of bricks drying in the sun. They were left lying flat until they were about two-thirds dry; then Docas went around and turned them up on their edges.

ONE day Heema jumped into the hut where Ama was sitting. “Where’s Docas?” he asked.

“Out making bricks. What do you want of him?” answered Ama.

“We are going up into the mountains to get a big tree. Father Joseph wants him to come and help drag it down.” Before Ama could answer him he was off to find Docas.

Soon Father Joseph, Docas, Heema, and a great many other Indian men and boys started off for the mountains where the redwood trees grow. They took several oxen and several chains with them. The day before, Massea and two other men had gone up to the hills to fell the trees.

About noon the party came to the place where Massea was. He had two trees cut down, ready for them. They rested and ate some dried deer meat. After that they fastened the oxen to one of the trees that Massea had cut down; then they drove back to the Mission. The log dragged along behind the oxen until it reached the Mission.

Massea had cut down two trees. There were no oxen left to drag the second tree to the Mission, so Docas helped fasten some long chains to[80] the log. Then all the Indian men and boys took hold of the chains and dragged the log down to the Mission themselves. It was not very hard work, for there were almost a hundred Indians pulling.

Early the next day they began to chop at one of the logs with their axes to make it square. When Massea saw that one side of it was flat he said, “Stop.” Massea and the other men tried to roll the log over on the other side, but it did not move at first.

“It is heavy,” said one of the men.

“Yes, but we must roll it over so that we can smooth the other side,” said Massea.

They gave another big pull all together, and the log rolled over.

At last, instead of a rough log with bark on it, it was a smooth, square piece of timber ready to use in building the church.

AFTER they had made many bricks, Father Joseph came to Massea and Docas and said, “We can begin to build the church now.”

Alachu had been playing with some of the broken bricks. That night she said to Docas, “I think you can’t build a very big church.”

“Why not?” asked Docas.

[81]

The day before, Massea and two men had gone to the hills to fell the trees.

“It will tumble down,” said Alachu. “I built[82] up a brick wall that was not any higher than I am, and it fell over while I went to get some more bricks.”

“Oh, but we are going to make ours thick. Father Joseph told father to-day that we should make the walls three feet thick. Besides, we shall fasten the bricks together with mortar.”

“What’s mortar?” asked Alachu.

“Sticky stuff to keep the bricks together,” answered Docas.

Next morning they began to build the Mission church. Day after day they worked. Massea and some of the men spread the mortar and laid the bricks, while Docas and other men and boys made more bricks.

It took so many, many bricks!