The Project Gutenberg eBook of An Egyptian oasis, by H. J. Llewellyn Beadnell

Title: An Egyptian oasis

An account of the oasis of Kharga in the Libyan desert, with special reference to its history, physical geography, and water-supply

Author: H. J. Llewellyn Beadnell

Release Date: April 4, 2023 [eBook #70461]

Language: English

Produced by: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive and the HathiTrust Digital Library)

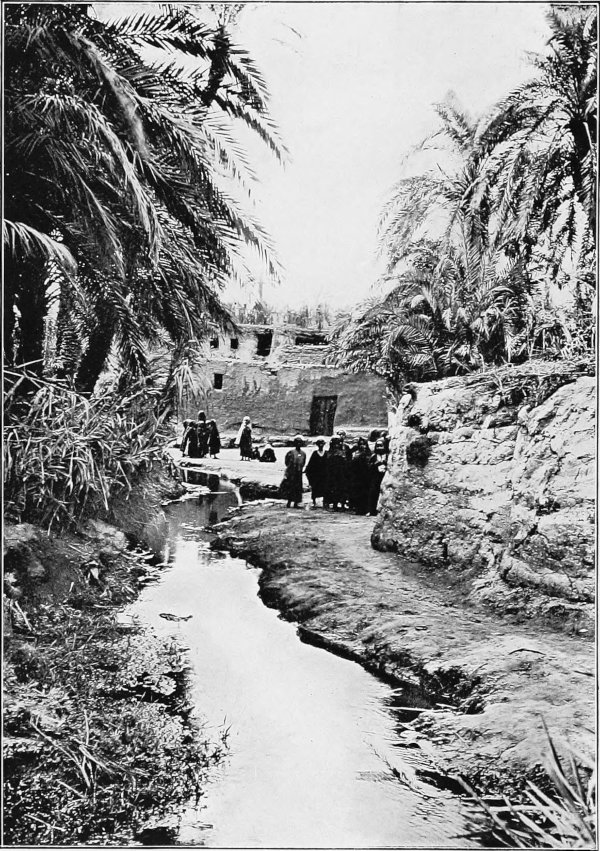

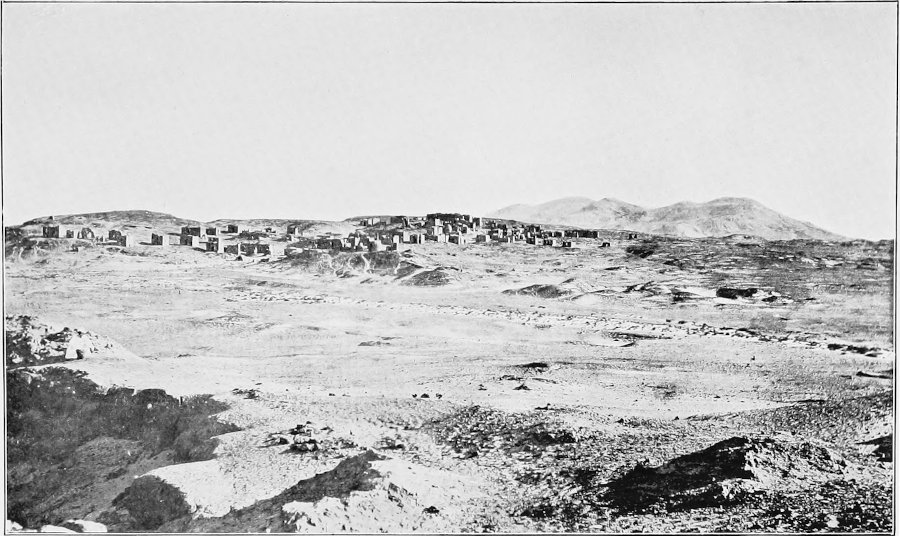

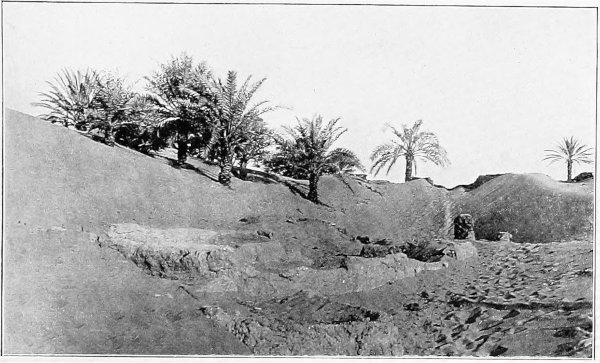

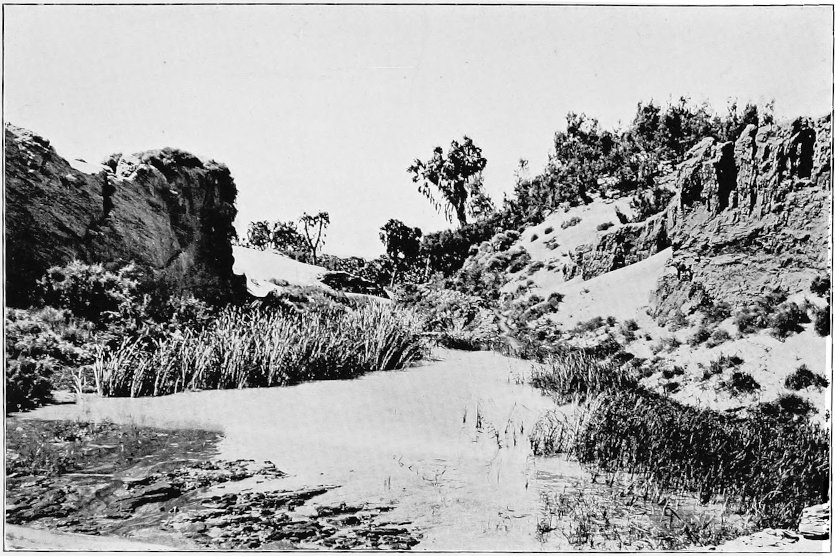

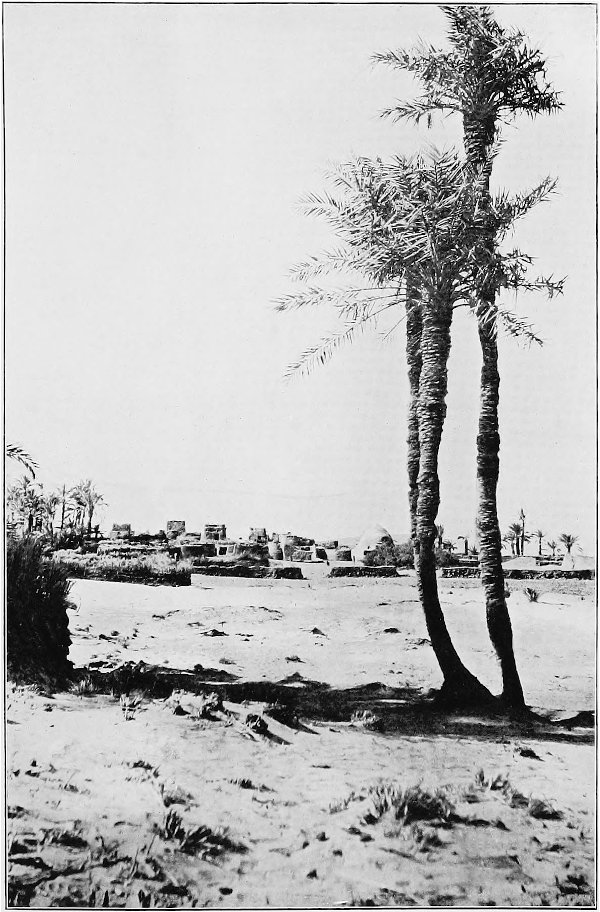

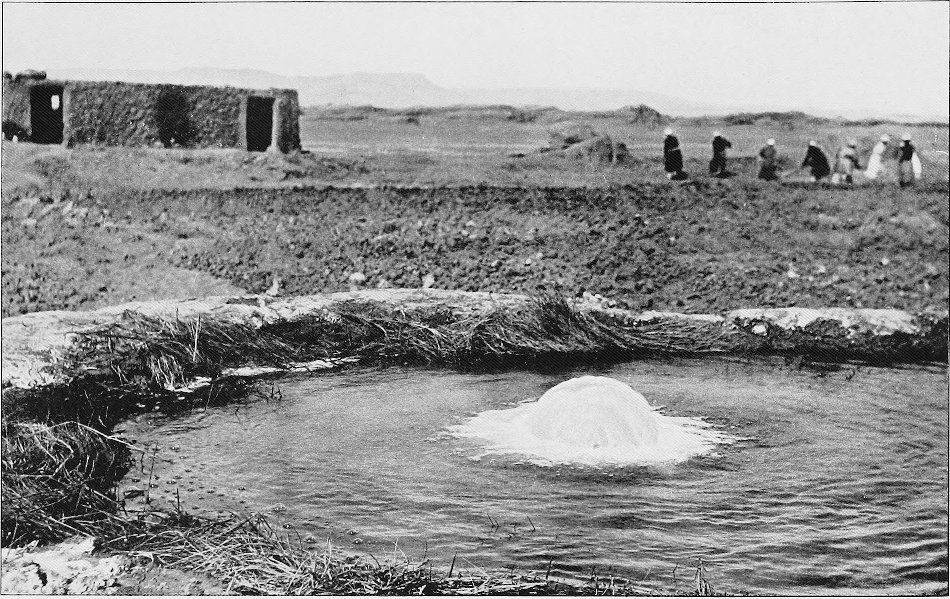

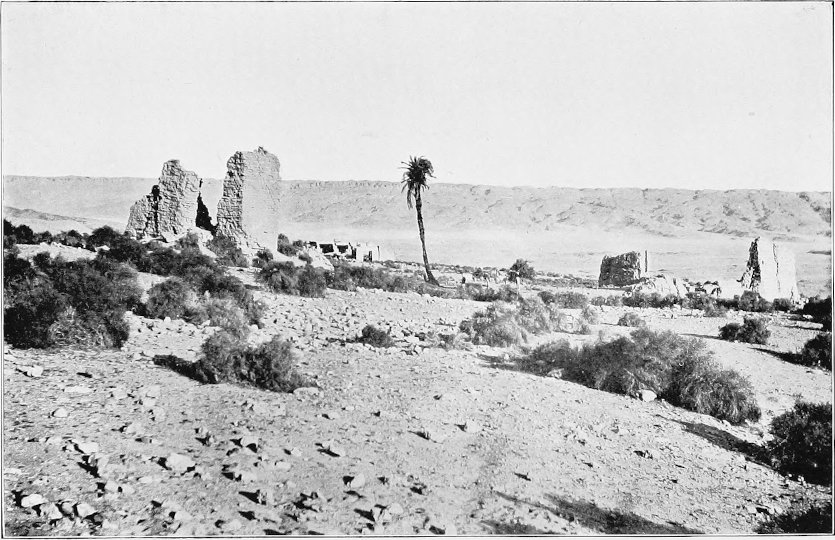

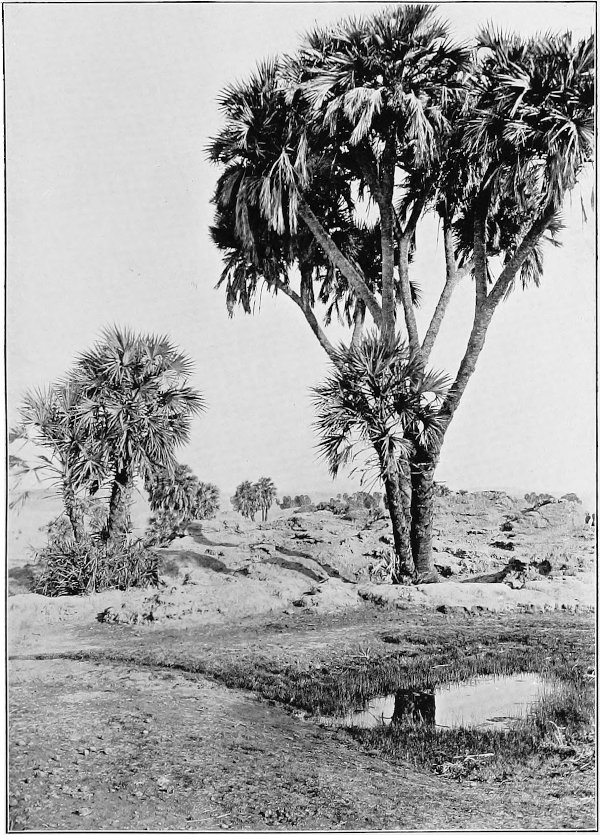

AIN ESTAKHERAB, GENNAH

AN

ACCOUNT OF THE OASIS OF KHARGA

IN THE LIBYAN DESERT, WITH

SPECIAL

REFERENCE TO ITS HISTORY,

PHYSICAL

GEOGRAPHY, AND WATER-SUPPLY

BY H. J.

LLEWELLYN BEADNELL

F.G.S., F.R.G.S., Assoc.Inst.M.M.

FORMERLY OF THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF

EGYPT

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY,

ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1909

TO THE

MEMORY OF A FRIEND AND FELLOW-GEOLOGIST,

THOMAS BARRON,

WHO LOST HIS LIFE IN THE SUDAN

IN FEBRUARY, 1906

[vii]

The inhabited depressions of the Libyan Desert, called by Herodotus the ‘Islands of the Blest,’ are interesting alike to the archæologist, to the geographer and geologist, and to the tourist who wishes to wander from the well-beaten tracks, and perhaps none more so than the Oasis of Kharga, lying 130 miles west of Luxor—the site of ancient Thebes—and recently connected by railway with the Nile Valley.

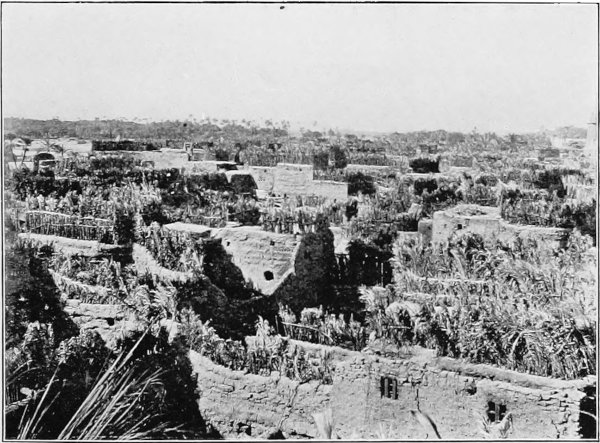

Descended from the ancient Libyans, the inhabitants of the Egyptian oases (numbering over 30,000 souls) are quite distinct from the Fellahin and Bedawin of the Nile Valley. Isolated by arid and desolate wastes, these communities occupy quaint walled-in towns and villages, tucked away among groves of palms, interspersed with smiling gardens and fields of corn. Rain is almost unknown, and rivers are non-existent, the trees and crops being irrigated by bubbling wells, deriving their waters from deep-seated sources.

Kharga—the subject of the present memoir—[viii]formed part of the Great Oasis of ancient days, and was governed in turn by the Pharaohs, the Persian Monarchs, and the Roman Emperors. Through it the ill-fated army of Cambyses is recorded to have marched, and in it is to be seen the most important Persian monument in Egypt, the temple of Hibis. But most interesting of all is the wonderfully preserved Early Christian necropolis, dating from the time of Bishop Nestorius, who was banished to Kharga in A.D. 434. Juvenal, Athanasius, and other celebrities likewise appear to have made unwilling acquaintance with this portion of the Roman Empire.

The character of the people at the present day—a curious mixture of stupidity, apathy, and shrewdness—seems to reflect in great measure their past history, as well as the peculiar conditions under which they still live. A history of the inhabitants since the withdrawal of the Roman garrisons would resolve itself into an account of an endless combat with Nature, which, with sand and wind as its chief agents, has never abated its efforts to recover those tracts which the Ancients, by the exercise of much skill and industry, wrested from the desert.

As a member of the Geological Survey of Egypt from 1896 to 1905, I spent nearly nine years in survey and exploration work in the Egyptian deserts, and for the past three years I have been in charge of extensive boring and land-reclamation[ix] operations in the particular oasis with which this book deals, so that I have had exceptional opportunities of studying at first hand a region of peculiar interest. Among other questions dealt with are the vast systems of subterranean aqueducts constructed by the Romans; the extensive lakes which occupied the floor of the oasis-depression well into historic times; the rate and mode of movement of desert sand-dunes; the formation and gradual elevation of the cultivated terraces by the constant accumulation of wind-borne material; and the deep-seated water-supplies, a subject which, in view of recent discussions as to the origin of the artesian waters of arid regions, is of more than local interest.

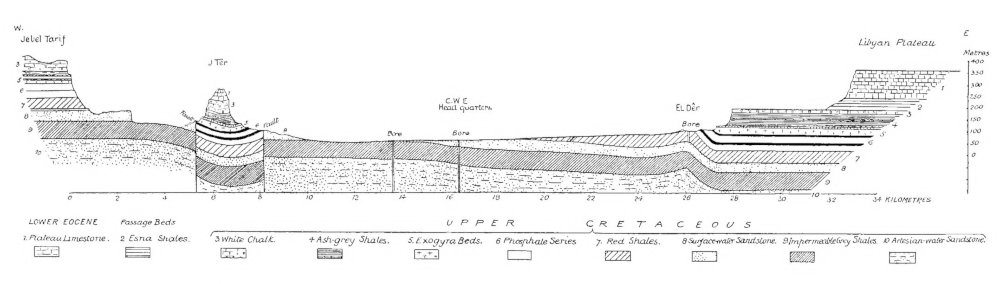

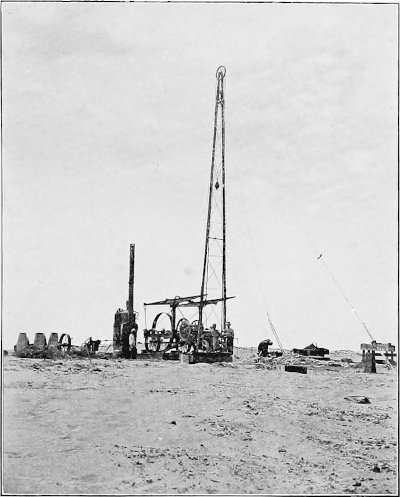

Some portions of the book, more especially those dealing with geology and water-supply, have already been published in somewhat different form in the Geological Magazine, and I am indebted to Dr. Henry Woodward, F.R.S., for permission to reproduce them, as well as the plate showing Bore No. 39 and the geological section across the oasis.

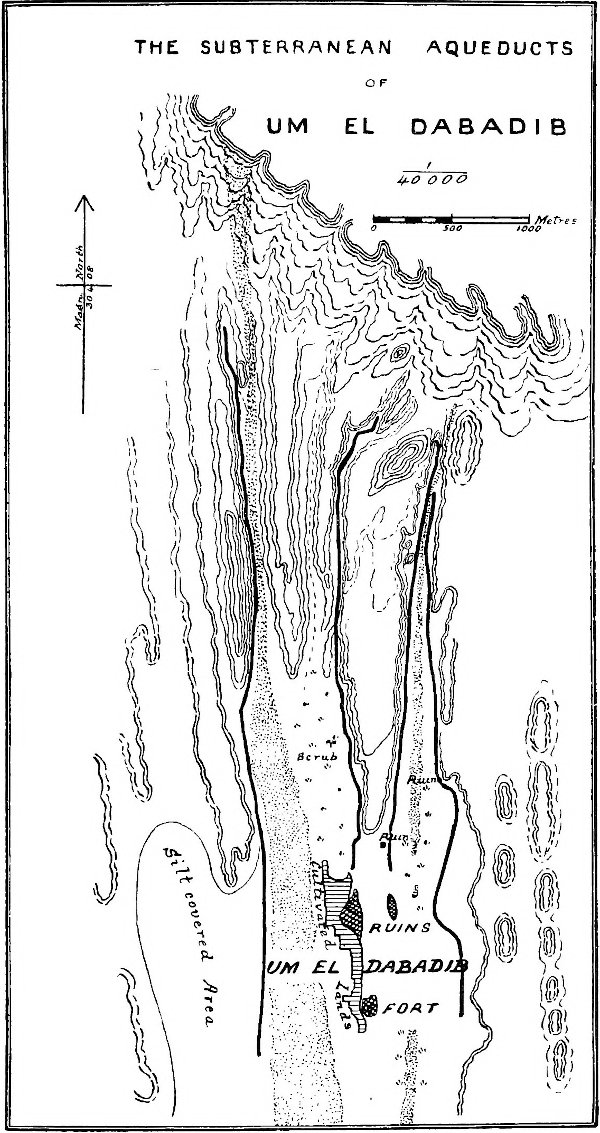

The illustrations are reproduced from photographs taken by me at different times during the last few years. The maps, showing the relative positions of the oasis and the Nile Valley, the caravan roads, and the geology, have been compiled from all available published material, chiefly the work of Dr. John Ball and myself. Some portions of these, as well as the plan showing[x] the subterranean aqueducts of Um El Dabâdib, are now published for the first time. The caravan routes, while shown with sufficient accuracy for all practical purposes, have not been surveyed with the same degree of exactness as the other details shown on the maps.

H. J. LLEWELLYN BEADNELL.

London,

March, 1909.

[xi]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE LIBYAN DESERT AND ITS OASES | 1 |

| II. | EARLY RECORDS | 12 |

| III. | THE ROADS LEADING TO THE OASIS | 25 |

| IV. | TOPOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY | 45 |

| V. | THE NORTHERN VILLAGES | 61 |

| VI. | THE SOUTHERN VILLAGES | 75 |

| VII. | THE OASIS UNDER PERSIAN AND ROMAN RULE | 86 |

| VIII. | THE EXTINCT LAKES OF THE OASIS | 110 |

| IX. | THE UNDERGROUND WATER-SUPPLY | 123 |

| X. | FLOWING WELLS: SOME EXPERIMENTS AND OBSERVATIONS | 139 |

| XI. | THE ORIGIN OF THE ARTESIAN WATERS | 154 |

| XII. | THE ANCIENT SUBTERRANEAN AQUEDUCTS | 167 |

| XIII. | BORING METHODS: ANCIENT AND MODERN | 186 |

| XIV. | THE CONTEST BETWEEN MAN AND WIND- BORNE SAND | 198 |

| XV. | SOME ECONOMICAL ASPECTS OF THE OASIS | 212 |

| XVI. | SOME NOTES ON SPORT AND NATURAL HISTORY | 224 |

| APPENDIX: LITERATURE ON THE OASIS OF KHARGA | 234 | |

| INDEX | 237 |

[xiii]

| 1. | AIN ESTAKHERAB, GENNAH | Frontispiece | ||

| FACING PAGE | ||||

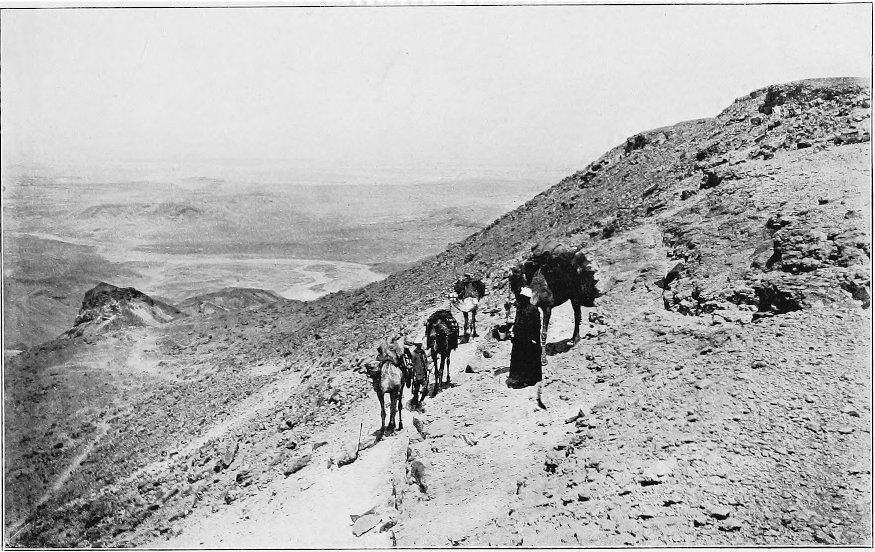

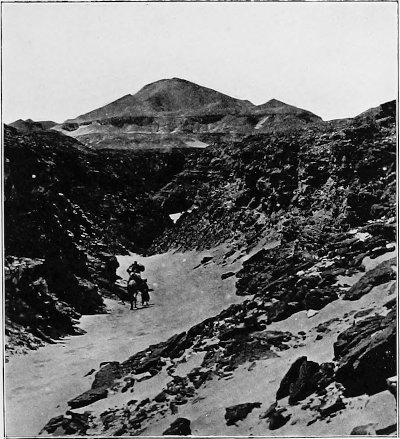

| 2. | A PASS INTO THE OASIS | 16 | ||

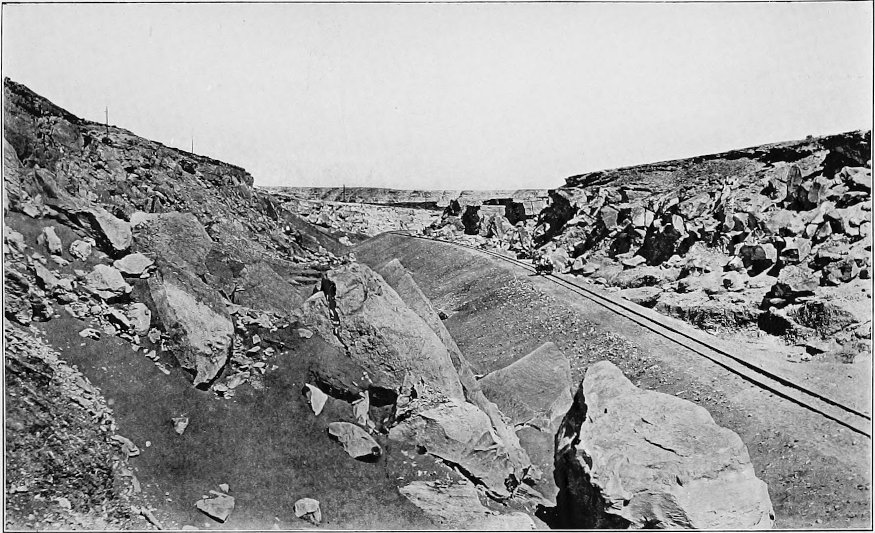

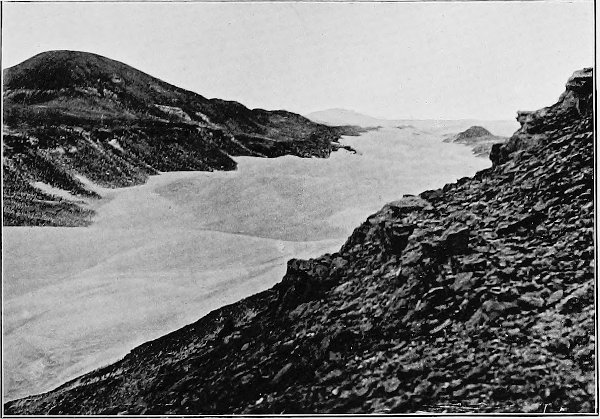

| 3. | THE RAILWAY DESCENDING INTO THE OASIS THROUGH THE CHALK FORMATION | 38 | ||

| 4. | THE CHRISTIAN NECROPOLIS AND JEBEL TER | 46 | ||

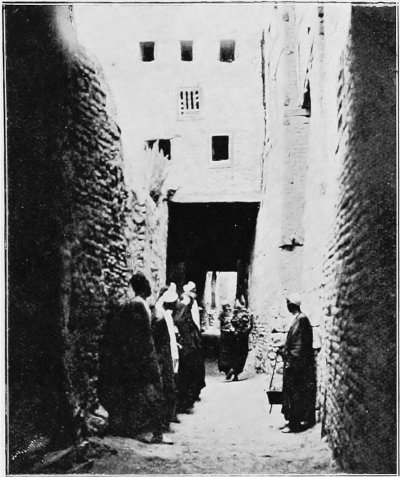

| 5. | ⎰ ⎱ |

A STREET IN KHARGA | ⎱ ⎰ |

66 |

| KHARGA VILLAGE | ||||

| 6. | ENCROACHMENT OF SAND-DUNES AT MEHERIQ | 70 | ||

| 7. | ⎰ ⎱ |

A PTOLEMAIC TEMPLE (QASR EL GHUATA) | ⎱ ⎰ |

73 |

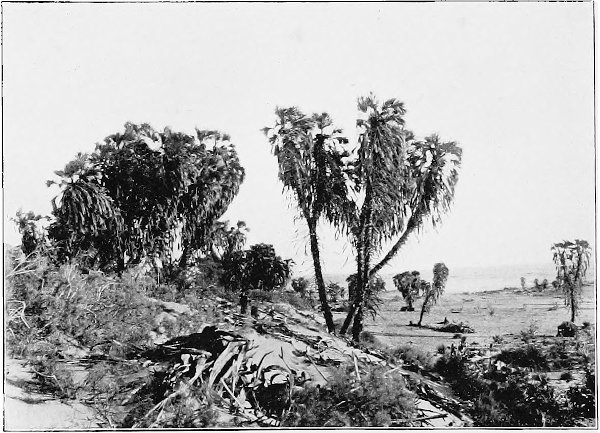

| DOUM-PALMS NEAR QASR EL GHUATA | ||||

| 8. | AIN DAKHAKHIN | 78 | ||

| 9. | DUSH VILLAGE | 84 | ||

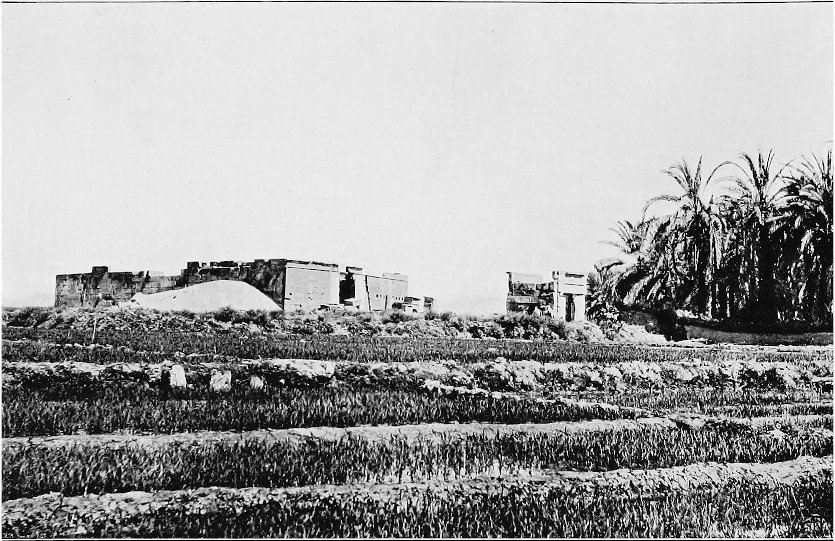

| 10. | THE TEMPLE OF HIBIS, FROM THE SOUTH-EAST | 92 | ||

| 11. | THE TEMPLE OF HIBIS (INTERIOR) | 96 | ||

| 12. | THE CHRISTIAN NECROPOLIS | 103 | ||

| 13. | BIBLICAL SCENES IN A TOMB OF THE NECROPOLIS | 104 | ||

| 14. | LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS AT EL GALA, NEAR BULAQ | 110 | ||

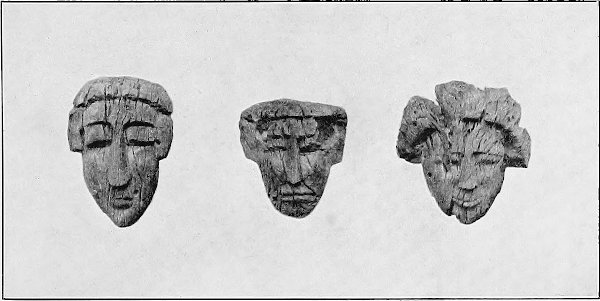

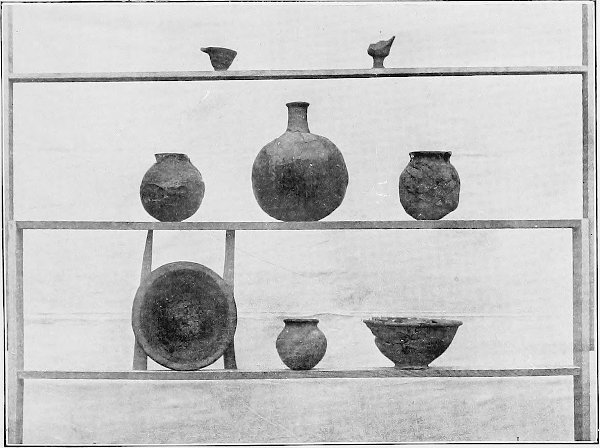

| 15. | ⎰ ⎱ |

COFFIN MASKS FROM BELLAIDA | ⎱ ⎰ |

116 |

| ANCIENT POTTERY FROM THE LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS | ||||

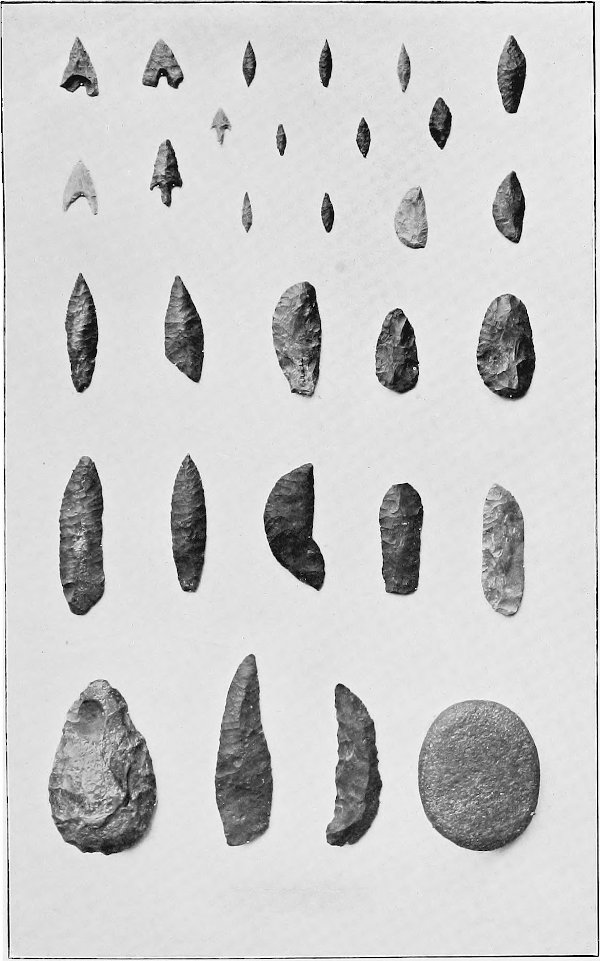

| 16. | FLINT IMPLEMENTS | 120 | ||

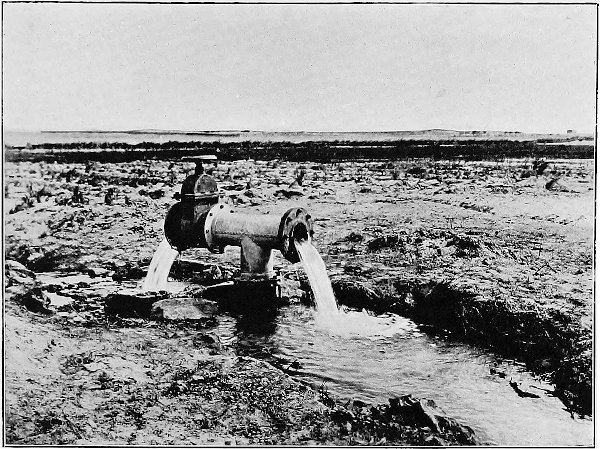

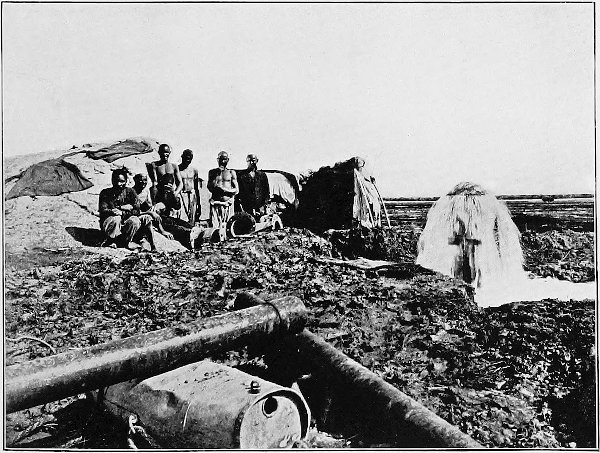

| 17. | AN ARTESIAN WELL (BORE NO. 39) | 124 | ||

| 18. | ⎰ ⎱ |

BORE NO. 5 | ⎱ ⎰ |

142 |

| BORE NO. 14 | ||||

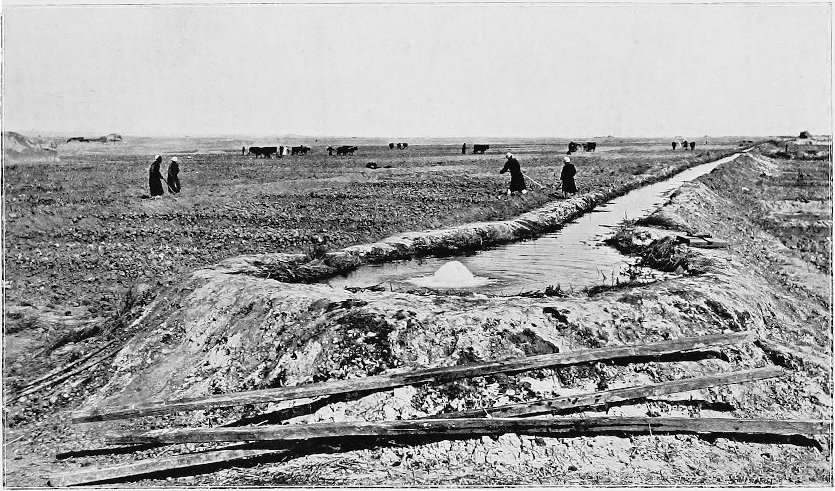

| 19. | LANDS UNDER RECLAMATION AT BORE NO. 39 | 156 | ||

| 20. | AIN AMUR, ON THE UPPER DAKHLA ROAD | 165 | ||

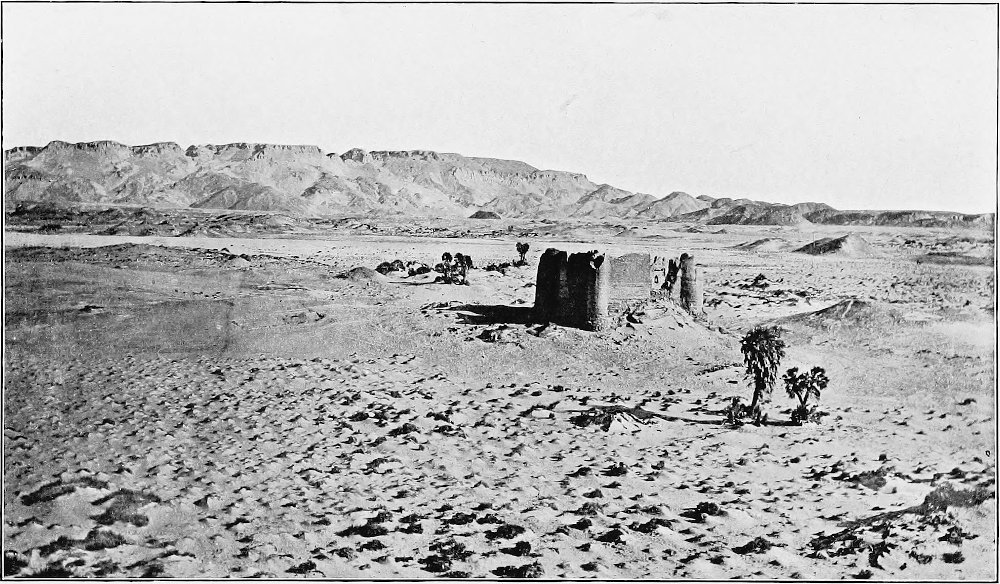

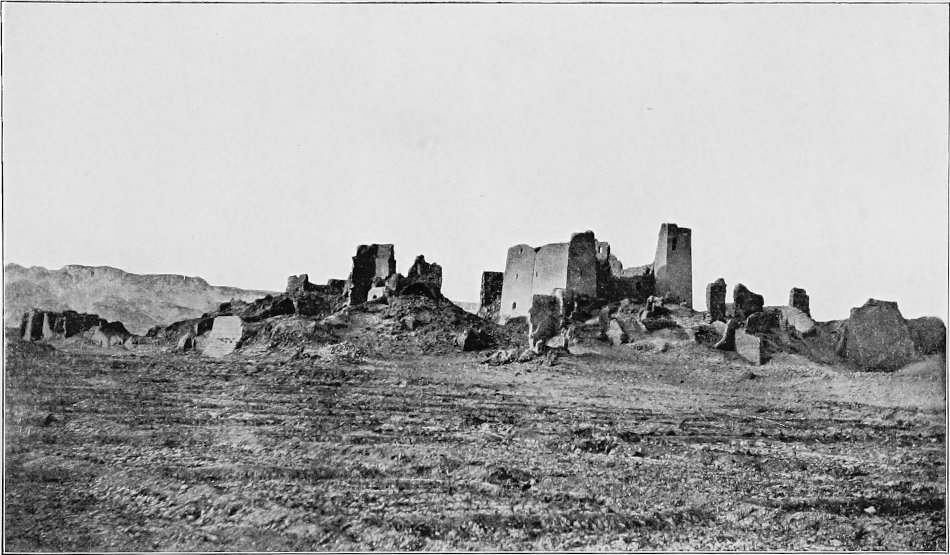

| 21. | QASR LEBEKHA AND THE NORTHERN ESCARPMENT OF THE OASIS | 169 | ||

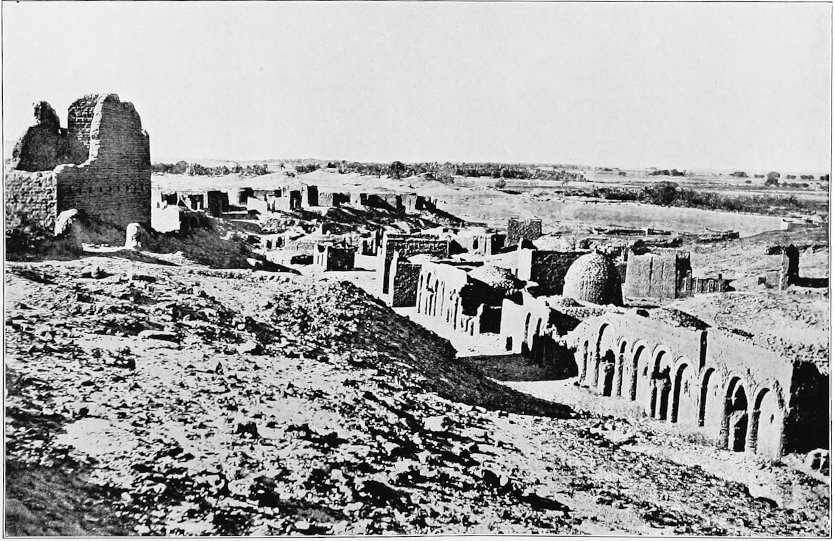

| 22. | RUINS AT UM EL DABADIB | 172 | ||

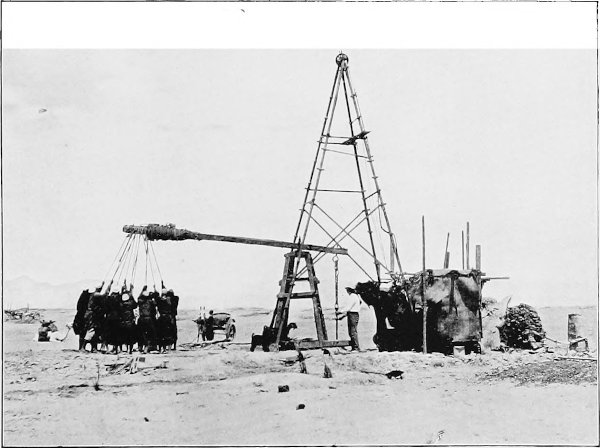

| 23. | ⎰ ⎱ |

[xiv]A STEAM BORING RIG | ⎱ ⎰ |

196 |

| A HAND BORING RIG | ||||

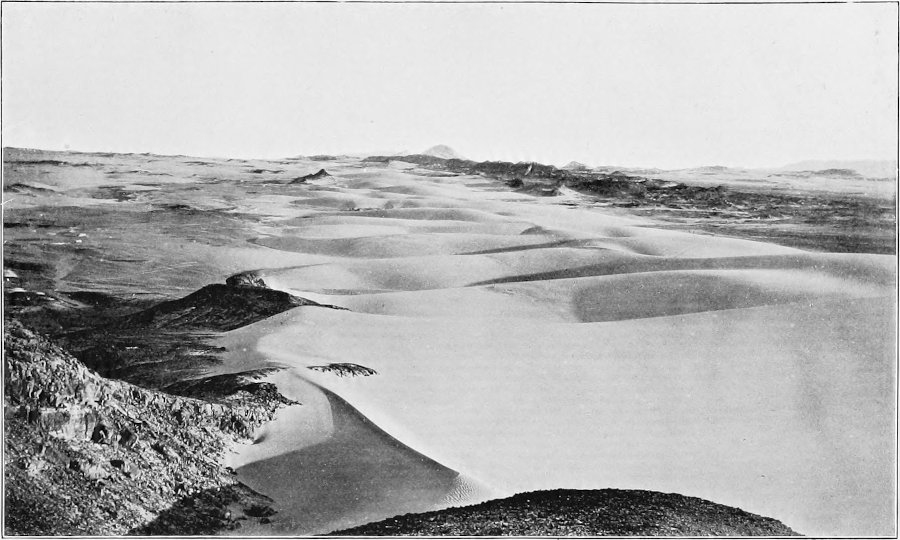

| 24. | A BELT OF DUNES NEAR QASR LEBEKHA | 200 | ||

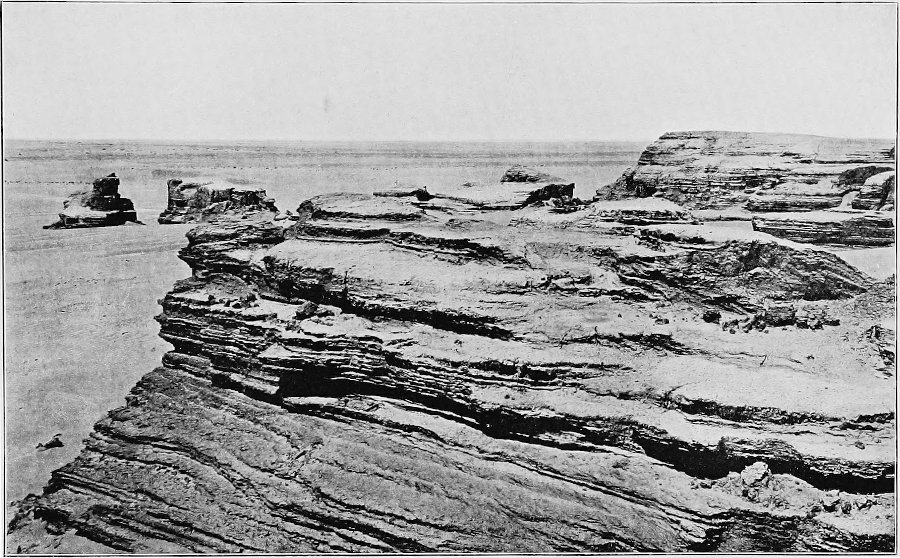

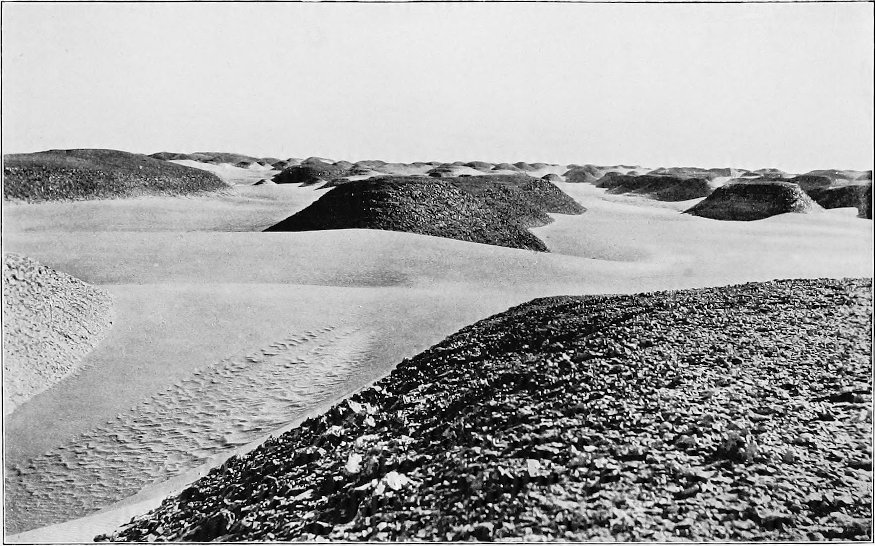

| 25. | SAND EROSION ON SUMMIT OF JEBEL TARIF | 206 | ||

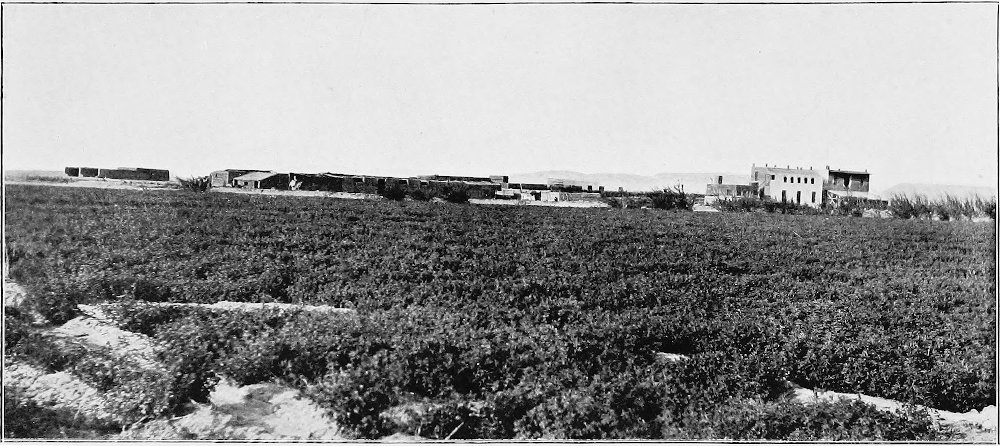

| 26. | THE CORPORATION’S HOMESTEAD (HEADQUARTERS) | 208 | ||

| 27. | DOUM-PALMS AT AIN GIRM MESHIM | 218 | ||

| 28. | ⎰ ⎱ |

A WADI IN JEBEL TARIF | ⎱ ⎰ |

222 |

| A RIVER OF SAND NEAR UM EL DABADIB | ||||

| MAPS AND SECTIONS | ||||

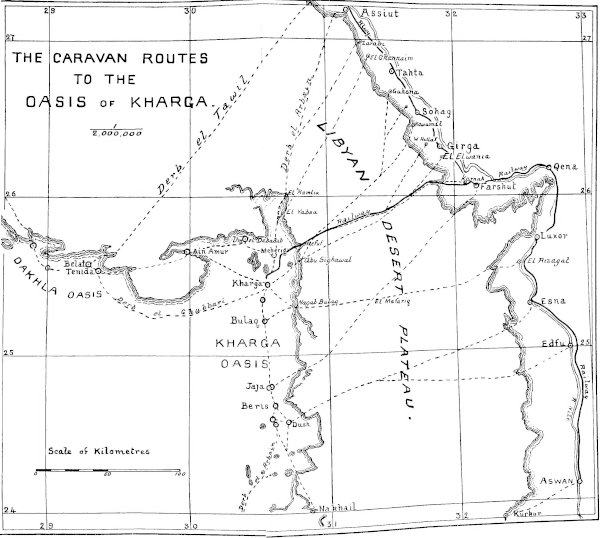

| I. | THE CARAVAN ROUTES TO THE OASIS OF KHARGA | 26 | ||

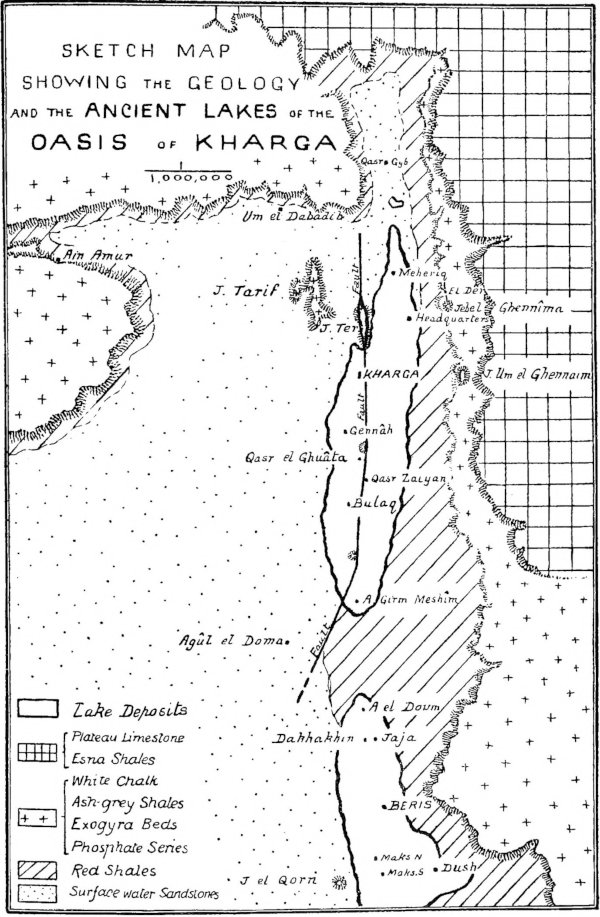

| II. | SKETCH-MAP SHOWING THE GEOLOGY AND THE ANCIENT LAKES OF THE OASIS OF KHARGA | 50 | ||

| III. | GEOLOGICAL SECTION ACROSS THE OASIS, FROM JEBEL TARIF TO THE EASTERN ESCARPMENT | 56 | ||

| IV. | THE SUBTERRANEAN AQUEDUCTS OF UM EL DABADIB | 176 | ||

[1]

AN EGYPTIAN OASIS

Contrast of Libyan Desert and Nile Valley — Area and Geographical Position — Barrenness — Dunes and Sand-submerged Areas — Underlying Water-charged Sandstones — Early History of Oases — Condition in Prehistoric Times — Cultivated Lands and Wells.

No more striking contrast can be imagined than that between the intensely cultivated Valley of the Nile and the barren deserts on either side. There are arid wastes in many parts of the world—in Australia, in the Western States of America, in Asia—but in point of desolateness, in the absence of animal and vegetable life, there is probably nothing to rival the greater portion of the Libyan Desert, on the west side of the Nile. Its barrenness is aggressive; it is not necessary to travel far to make its acquaintance; so sharp is the junction that, in a single step, one may pass from the richly cultivated alluvial soil of the Nile to the bare sandy plains which skirt the more rocky interior of the desert. Along the borders of the[2] Egyptian wastes one generally looks in vain for the Persian poet’s

Geographically the Libyan Desert is the eastern and most inhospitable portion of the Sahara, or Great Desert of Africa. On the north and east its boundaries are clearly defined by the Mediterranean Sea and the Valley of the Nile; on the south it is bounded by the Darfur and Kordofan regions of the Egyptian Sudan; to the south-west its limits may be regarded as coterminous with the elevated districts of Tibesti; while on the west it stretches to the outlying oases of Fezzan and Tripoli. Its area is about 850,000 square miles, or approximately seven times that of the British Isles.

With the exception of a narrow belt fringing the Mediterranean, the region is, to all intents and purposes, rainless, the occasional thunderstorms being extremely local, and seldom breaking over the same district in two consecutive years. In the more elevated deserts on the eastern side of the Nile rains appear to be of sufficiently frequent occurrence to maintain a water-supply in the isolated water-holes and valley-springs, and to allow of the growth of a fairly permanent though scanty herbage in the more favoured areas. The Eastern desert does, therefore, to some extent, support a migratory Arab population. On the other hand, the greater portion of the Libyan[3] Desert is quite devoid of vegetation and water-holes, and is, in consequence, uninhabited even by nomad tribes. At the same time, the extreme barrenness of the region as a whole is in great measure counterbalanced by a number of isolated fertile oases, in which there is a permanent resident population, deriving its water-supplies entirely from underground sources.

The term ‘oasis,’ an ancient Egyptian word signifying a resting-place, in its strict sense means a fertile spot in a desert, but in Egypt has usually been applied to a depression as a whole, each individual cultivated area being known by the name of the well from which its water is derived. The chief groups of oases in the Libyan Desert are the Siwan on the north, that of Kufra on the west, and the Egyptian, including the four large oases of Baharia, Farafra, Dakhla, and Kharga, on the east. The present volume deals more especially with the last of these.

The Libyan Desert is primarily divisible into two entirely different parts, distinguished by the presence or absence of surface accumulations of blown sand. Extensive dunes are confined to the western portion, where areas of hundreds of square miles are literally buried under deep seas of sand, blown into more or less parallel dunes of great height, lying N.N.W. and S.S.E., in the direction of the prevailing winds. In this country it is almost impossible to travel in a latitudinal direction, so that the sand-covered area forms an[4] effective barrier between the Egyptian oases and Kufra, one of the strongholds and, at any rate until recently, the headquarters of the powerful Senussi sect. It is probable that, within the last century, the area of this sand has extended considerably to the south, as an old caravan road trending westwards, and believed to have originally connected the oases of Dakhla and Kufra, is now lost in the dunes. As long ago as 1874 some of the members of the Rohlfs expedition made an attempt to penetrate westwards from Dakhla, but on reaching the edge of the great sand-region, about 170 kilometres W.S.W. of Qasr Dakhl, were compelled to turn northwards and travel in a direction parallel to the lines of dunes, from which they emerged, after a long and wearisome journey of 400 kilometres, in the neighbourhood of the oasis of Siwa. Outlying portions of this sand invade the Egyptian oases; for instance, the depression of El Daila, lying to the west of Farafra, is to a great extent filled with blown sand, while an extensive area in the south of Farafra itself is buried under dunes.

On the eastern portion the sand is for the most part confined to isolated lines of dunes, the most remarkable being that known as the Abu Mohariq. This commences in latitude 29° 45′ north, at Arûs el Buqar, some 50 kilometres south-west of the Mogara swamp, in the low country to the south of the great east and west Miocene escarpment. From Arûs el Buqar the Abu Mohariq sand-belt[5] runs in an almost straight and unbroken line across the Libyan plateau to the oasis of Kharga, through which it continues into the desert to the south. The average breadth of this line of dunes is only some 6 or 7 kilometres, whereas its length cannot be less than 650. Less extensive accumulations of blown sand are found in the oases themselves, in the depressions of Gharaq and Muailla to the south of the Fayûm, and encroaching on the cultivated lands of the Nile Valley between Bahnessa and Mellawi.

The eastern part of the Libyan Desert, in which are situated the Egyptian oases, is itself divisible into three areas having essentially different characters, the northern being an undulating rolling country of sandstones, grits, and gravels; the central consisting of bare elevated limestone plateaux; the southern a lower-lying expanse of rugged sandstone, broken only occasionally by ridges and bosses of granite and other crystalline rocks.

The Egyptian oases are deep and broad hollows or depressions in the Libyan Desert plateau. In position they appear to coincide with areas where rocks of comparative softness became exposed at the surface during the gradual lowering of the country by denudation. At such points the general rate of weathering must have become greatly accelerated, with the result that those vast depressions, which form such conspicuous features in the configuration of the country at the present day, were eventually cut out.

[6]

Underlying the greater part of the Libyan Desert are porous sandstones, and these, when pierced by deep borings put down from the lower-lying parts of the floors of the depressions, yield abundant supplies of water of remarkable purity. As these sandstones, as well as the shales with which they are associated, have a general dip or inclination from south to north, we are led to infer that they outcrop or come to the surface to the south, so that in all probability the water with which they are so highly charged has its origin in that direction. Whether the water obtains access to the sandstones by direct infiltration of the rains of Abyssinia or the Sudan, from the swamps of the sudd region of the Upper Nile, or from the Nile itself in the Nubian reaches, has not yet been decided with certainty. Recent observations, however, show that far more water is lost in some reaches of the Nile than can be accounted for by irrigation and evaporation, and it seems probable, therefore, that the excess disappears by infiltration into these sandstones.

Little is known of the early history of the oases, though the remains of ancient towns and cemeteries are abundant, and only await systematic excavation by Egyptologists to bring our knowledge of this part of Egypt into line with that of the Nile Valley. That the oases were inhabited in prehistoric times is evident from the occurrence of flint implements of Palæolithic types, both on the margins of the surrounding plateaux and within the depressions, though there is not at present sufficient evidence to[7] enable us to affirm that the makers and users of these flints were contemporaneous with Palæolithic man in Europe. Implements of Neolithic type, often of finished workmanship, are, moreover, common in places on the floors of the depressions, but it is probable that these were in use well into the historic period.

In historic times the oases, according to Sayce, were governed by Egyptian Kings in the eighteenth dynasty (1545-1350 B.C.), and the oldest monuments as yet found in the oases-depressions date from this period. The most important of the earlier remains belong, however, to the Persian epoch, notably the temple of Hibis near the modern village of Kharga, which was built by Darius. Ptolemaic remains are also known in Kharga, but the greater number of the historical monuments date from the time of Roman occupation, when the oases appear to have attained a considerable degree of prosperity, which continued to Coptic times. Since the Mohammedan conquest of Egypt they have fallen into a state of neglect, and with the consequent diminution of the water-supply the population has decreased, and large areas of formerly fertile country have been absorbed by the surrounding desert.

It is interesting to speculate on the conditions which obtained in Kharga before the first borings were made, as at the present day we cannot point, so far as I am aware, to a single natural efflux of water on the floor of the depression. Surface-water,[8] of quite a different character from the deep-seated water, is met with at comparatively shallow depths in various localities, and may either represent drainage water from the flowing wells and cultivated tracts, or be water which has escaped from the underground sandstones and found its way to the surface through fissures. Probably it is derived from both sources. In prehistoric times natural springs fed through fissures may have existed here and there within the depressions; and in any case it is probable that prehistoric man obtained sufficient supplies by sinking wells into the upper sandstones, which in some parts of the oasis occur at or near the surface, and contain large quantities of sub-surface or sub-artesian water. Nothing is known as to when flowing wells were first obtained, or by whom the original deep borings were made, and no traces of the implements used have been discovered. Many of these ancient wells, frequently over 120 metres in depth, continue to flow at the present day, although in most cases with a greatly diminished output; a few, however, are still running day and night at the rate of several hundred gallons a minute.

In some parts of the oases water-bearing sandstones occur at or near the surface, and from these beds the Romans obtained additional supplies by the excavation of underground collecting tunnels. Subterranean works of this description are found in all the oases, the most remarkable being in Baharia and at Um el Dabâdib and Jebel Lebekha in[9] Kharga. They are frequently of great length, cut throughout in solid rock, and connected with the surface above by numerous vertical air-shafts. Many of the latter measure from 30 to 50 metres in depth, so that the construction of these and the horizontal carrying channels must have involved an immense amount of labour.

In Roman times water-stations appear to have been maintained at frequent intervals on the desert roads between the oases and the Nile Valley, and a great development of the water-supply took place. After the Arab invasion, however, no attention seems to have been given to irrigation works, the wells, owing to silting, becoming gradually choked up. As the result of this neglect the water-supply diminished to such an extent that a large portion of the population was compelled to emigrate to the Nile Valley, and even the remaining inhabitants were scarce able to raise sufficient supplies for their maintenance. Within the last fifty years a considerable number of new wells have been made by means of simple hand-boring appliances sent out by the Egyptian Government; most of the new bores have been very successful, but latterly, through want of effective supervision, a great deal of harm has been done by promiscuous boring. Moreover, a very large amount of water is wasted owing to the wells not being fitted with regulating and closing appliances; the water, when not required for irrigation, continues to run, finding its way to the low-lying lands, and forming swamps which[10] furnish ideal breeding-grounds for fever-carrying mosquitoes.

Within the last year or two this part of Egypt has received renewed attention; extensive boring operations and land reclamation works have been commenced, and the oasis of Kharga has been brought into railway communication with the rest of Egypt.

The floor-level of the oases varies considerably, but in general the cultivated lands lie between 30 and 120 metres above sea-level. The exact area under cultivation is only known very approximately, but it is certain that with an increased water-supply it could be very much augmented. The existing water-supply is totally insufficient to irrigate the available lands, and such portions of the latter as are tilled are generally left fallow in alternate years, and in many cases are only under crops once every four or five years. Now that an attempt is being made to restore the oases to their former prosperity, the question of ownership of land has become of the greatest importance, and it is one bristling with difficulties. As a general rule the wells are owned collectively, the different proprietors having the right to utilize the flow for periods corresponding to the extent of their holdings in the well. Individual shares may amount to as much as one-third or one-half of the well, or be only the merest fraction; in the latter case the small holders combine so as to obtain control of the flow for an appreciable period. Frequently the[11] whole of the land irrigated by a well is cultivated collectively, the crop on reaping being divided among the owners in portions corresponding to their shares of the water. The question of ownerships is further complicated by there being persons who own water but no land, and by others who claim land but own no water.

[12]

Travellers’ Names inscribed on the Monuments — Poncet passes through Kharga en route for Ethiopia — Browne — Cailliaud’s Extensive Researches — Drovetti — Sir Archibald Edmonstone, Bart., discovers Dakhla Oasis — Hoskins — Exaggerated Opinions of Ancients regarding the Oases — Names of Explorers on the Walls of Hibis — Rohlfs’ Expedition — Zittel’s Geological Work — The words ‘Oasis,’ ‘Wah,’ ‘Otu,’ and ‘Set-ament’ — A Theban Myth — Dr. Schweinfurth — Brugsch Bey — Captain H. G. Lyons — Government Survey of the Oases — Dr. John Ball.

Inscribed on the walls of the ancient monuments in the oasis one frequently comes across the names of travellers who visited the same scenes fifty, a hundred, or even two hundred years ago. Many of these explorers wrote descriptions of their travels and experiences, and such early records are naturally of the greatest interest and importance; unfortunately they are now out of print and somewhat difficult to procure, so that I make no apology for briefly referring to those which I have been able to examine. Most of these early records are extremely quaint, and although they are chiefly descriptive of the personal experiences and impressions of the writers, in some cases numerous observations are[13] recorded in a sufficiently exact manner to be of permanent scientific value.

A French physician, Monsieur Poncet, who passed through Kharga in 1698, en route for Abyssinia, appears to have been the only traveller who left any written records of the Great Oasis between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. A translation of the account of his travels was published in English in 1709 (‘A Voyage to Æthiopia’). Accompanied by one Hagi Ali, an officer of the Abyssinian Emperor, and by a Jesuit missionary, Father Charles Francis Xaverius de Brevedent, Poncet set out from the town of Manfalut in the Nile Valley, and travelled along the Derb el Arbaîn, the well-known caravan route to the south. His description of this portion of the journey is as follows:

“We set forward on the 2d of October early in the Morning, and from that very Day we enter’d a frightful Desart. These Desarts are extremely dangerous, because the Sands being moving are rais’d by the least Wind which darken the Air, and falling afterwards in Clouds, Passingers are often buried in them, or at least lose the Route, which they ought to keep.”

Poncet refers to the oasis as ‘Helaoue,’ but although his caravan rested there four days, before proceeding to Dongola, via Shebb and Selîma, he makes no reference to the antiquities; in fact, his remarks on this region are extremely meagre. To quote his own words: “We Arriv’d on the 6th of[14] October at Helaoue; ’Tis a pretty large Borough, and the last that is under the Grand Signior’ Jurisdiction. There is a Garrison in it of 500 Janisaries and 300 Spahi’s under the Command of an Officer whom in that Country they call Kachif. Helaoue is very pleasant, and answers fully its Name, which signifies a Country of Sweetness. Here are to be seen a great Number of Gardens water’d with Brooks, and a World of Palm-trees, which preserve a continual Verdure, Coloquintida is to be found there, and all the Fields are fill’d with Senna, which grows upon a Shrub, about three Foot High. This Drug which is so esteem’d in Europe, is of no use in the Country hereabouts. The Inhabitants of Helaoue in their Illnesses, make only Use of the Root of Ezula, which for a whole Night they infuse in Milk, and take the day after, having first Strain’d it thro’ a Sieve. This Medicine is very Violent, but ’tis what they like and commend very much. The Ezula is a thick Tree, the Blossom of which is blue; it grows into a sort of Ball, of an Oval Figure, full of Cotton, of which the People of that Country make pretty fine Cloth.”

Referring to the deserts which surround the oases, Poncet remarks: “Those vast Wildernesses, where there is neither to be found Bird, nor wild Beast, nor Herbs, no nor so much as a little Fly, and where nothing is to be seen but Mountains of Sand, and the Carcasses, and Bones of Camels, Imprint a certain horrour in the Mind, which makes this Voyage very tedious and disagreeable.[15] It wou’d be a hard matter, to Cross those frightful Desarts without the Assistance of Camels. These Animals will continue six or seven Days, without either eating or drinking, which I cou’d never have believ’d, if I had not observ’d it very particularly.” Poncet further relates that he was assured by a venerable old gentleman of his caravan that camels had been known to cover a desert journey of forty days and nights without either food or water. Although it is to be feared that the ‘ship of the desert’ at the present day is scarcely so abstemious as formerly, we must admit that Poncet’s description of the sterility of the Libyan Desert is little, if at all, exaggerated. One may, indeed, travel for hours without seeing bird, beast, or herb; and even ‘the little fly,’ which seldom fails to make known its presence for some time after leaving the inhabited districts, generally forsakes one before the caravan has proceeded far into the depths of the desert.

W. G. Browne traversed the same route nearly a hundred years later, passing through the oasis in June, 1793. He relates how he entered the depression at the northern extremity, at the pass known as El Ramlia, and camped at Ain Dizé (probably in the neighbourhood of the modern Ain el Qasr), eight hours’ march from Kharga. Browne passed through the depression from north to south, visiting Kharga, Bulaq, Beris, and Maks, whence he followed the usual route to Shebb and Selîma. Like his predecessor, he makes no mention of the antiquities.

[16]

Cailliaud, a young French mineralogist, explored Kharga in 1818, and to him we owe the earliest published detailed descriptions and illustrations of the chief antiquities of the oasis. As the existence of important monuments in the oasis was at that time quite unsuspected, Cailliaud’s work attracted considerable attention, and his drawings and descriptions were purchased and published by the French Government and dedicated to the King. Cailliaud set out from Esna in the Nile Valley and crossed the Libyan plateau to the village of Jaja. After visiting the most southerly villages of Dush and Beris, he journeyed northwards to Kharga, then, as now, the chief village, whence, on the completion of his researches, he returned to Farshut on the Nile, via Dêr el Ghennîma and the Wadi Samhûd. Cailliaud’s observations are almost entirely confined to the archæology of the oasis, and his writings yield little information regarding the villages, wells, and cultivated lands.

The Chevalier Drovetti, French Consul-General in Egypt, visited Kharga the same year as Monsieur Cailliaud. He started from Beniâdi, following the Derb el Arbaîn caravan route southwards, and entered the depression at the northern extremity. Drovetti traversed the oasis from north to south, and proceeded thence to Dongola. Later, on his return journey, he crossed the depression in the opposite direction, eventually returning to the Nile Valley by way of the oasis of Dakhla and the Derb el Tawîl.

A PASS INTO THE OASIS.

[17]

In 1820 Cailliaud again passed through Kharga. He had explored the oasis of Siwa the previous year, whence he travelled, via Baharia and Farafra, to Dakhla, and thence past Ain Amûr to Kharga village. On this occasion no further researches were undertaken in the depression.

Sir Archibald Edmonstone, Bart., accompanied by two friends, visited Dakhla and Kharga in 1819, and constructed a rough but fairly accurate map, showing the relative position of the two oases, with their bounding escarpments and principal villages. Their situation in the Libyan Desert, with regard to the Nile Valley, is, however, greatly in error, being shown fully a degree too far west and nearly half a degree too far north. Edmonstone followed the Derb el Tawîl route from Beniâdi in the Nile Valley to the village of Belat in Dakhla, returning by the Ain Amûr road to Kharga, and thence to Farshut. The major portion of the account of his travels refers to Dakhla, of which oasis he must, indeed, be regarded as the modern discoverer.

Hoskins explored Kharga in 1835, and published a most valuable and engaging account of his travels a couple of years later. This work, entitled ‘Visit to the Great Oasis of the Libyan Desert,’ contains a number of illustrations depicting the scenery, the chief monuments and their hieroglyphics, etc., made from original drawings and paper casts. Many of the inscriptions are given in full, both in the original and translated into English, and the work of all previous writers and explorers is carefully[18] summarized. In some cases I have verified the accuracy of Hoskins’ drawings by comparing them with photographs taken from the same points, and have been much struck with the insignificant amount of decay which some of the buildings have undergone during the course of over seventy years.

Rizagat, near Thebes, was Hoskins’ starting-point, and he entered the depression by the Bulaq pass, crossing the oasis-floor to the eminence known as El Gorn el Gennâh. Surveying the oasis from this point of vantage, Hoskins remarks that the attractions of the cultivated portions of the depression, those

are apt to be exaggerated, owing to their great contrast to the surrounding deserts. “The fair appearance then of this oasis is in a great measure fictitious; and has chiefly its origin in the relief afforded to the mind, wearied by the monotony and dreariness of the surrounding wastes. It seems to me therefore, that the only rational way of accounting for the exaggerated epithets which the ancient writers and some modern travellers have applied to this district, is to attribute them to their surprise, at finding in such a fearful region any verdure, any habitable spot, and to the exhilarating effect on the spirits of this agreeable contrast to the dreary deserts which they have just crossed. But comfortless as was my journey through the wilderness, and beautiful as the woods[19] of palm-trees, doums, and acacias in the Oasis certainly are, still the vivid recollection of the superior loveliness of the banks of the Nile, prevents my consenting to call these regions ‘the Gardens of the Hesperides’; and sadly must the oasis have diminished in beauty, if it ever merited the praise which Herodotus bestowed upon the place, in calling it ‘the Island of the Blessed.’”

Hoskins, who was accompanied by two other Englishmen, made splendid use of the fortnight spent in the oasis, although unfortunately, just before the termination of his visit, he sustained a violent attack of fever. Their departure is thus described: “After ascending the mountain which bounds the Oasis, we lingered some time at the summit, to take, I may certainly say, our last view of the place; for having, as the Arabs say, got all its antiquities on paper, and having providentially once escaped its pestilential atmosphere, we shall never, I think, by any possibility, have the slightest inclination to revisit such a baneful region.”

Most of these early explorers found time to cut their names on the walls of the temple of Hibis, and Cailliaud must have spent hours in this occupation, as he has left a long and neatly executed inscription recording himself as the original and genuine discoverer of that noble edifice. The names of these explorers, who in some cases suffered considerable hardships in visiting the oases, are, however, quite overshadowed by the numberless scrawls made in recent years by a host of otherwise unknown[20] petty officials of the Government, who have had to take their turn of duty and banishment in the greatly dreaded desert. The dated names cut in the walls of the temple are of some value, as an examination of them frequently yields reliable evidence of the rate of weathering of the stone since the time at which they were inscribed.

It was not until after the winter of 1873-74, when the great German expedition, under the leadership of Rohlfs, with Zittel, Jordan, and Ascherson as geologist, topographer, and botanist respectively, visited all the chief oases of the eastern portion of the Libyan Desert, that any connected scientific observations of importance, other than those dealing with archæology, were published. The Rohlfs expedition astronomically determined the positions of selected points in each oasis, and produced a map on which the principal villages and the approximate limits of the depressions were correctly shown. Zittel at the same time worked out the general relations of the different geological formations found in the country, described their main divisions, and indicated approximately the areas occupied by them. So thoroughly, indeed, did this expedition accomplish its mission that its results have formed a sound basis for all later scientific work in this part of Egypt.

As the voluminous memoirs recording the observations of the members of the Rohlfs expedition are easily obtainable at the present day, it is unnecessary here to do more than briefly[21] refer to a few of their more general remarks on the oasis of Kharga. In his ‘Three Months in the Libyan Desert,’ Gerhard Rohlfs states that he and his companions travelled from Dakhla Oasis by the Ain Amûr road, and were greeted at Kharga village by Schweinfurth, who was for the time being residing in a disused alum factory. Rohlfs spent only two or three days in the neighbourhood of Kharga, and remarks that the expedition did not undertake detailed work on the antiquities, as the latter had already been so competently described by Hoskins and other previous explorers; a few corrections and amendments of published accounts of the temple were, however, made. The splendid preservation of the Christian necropolis, with its mausolea of unburnt brick, is remarked upon, and Rohlfs adds that, in beauty and ingenious arrangement, this burial-ground can only be excelled by the necropolis of Cyrene.

Rohlfs describes Kharga village as being pretty from a distance, but remarks that the narrow dirty alleys are the pictures of laziness and poverty; the streets are covered in for protection against the rays of the sun, a common practice throughout the Sahara.

The word ‘oasis’ is old Egyptian, as also is the Arabic ‘wah,’ the latter word being also found in Coptic, and signifying an inhabited place; nevertheless, the word ‘wah’ was never used by the ancient Egyptians to designate the oases. These they called ‘otu,’ which means a place where[22] bodies are embalmed. ‘Otu’ has its origin in the Theban myth, according to which Seth, the murderer of Osiris, was pursued by Horus to Koptos, where he was captured and thrown into a dungeon. His corpse was afterwards found by his friends, and taken to the oases for burial.[1] The inscriptions on the temple of Hibis in Kharga refer to the oases under the comprehensive name ‘Set-ament,’ the ‘Western Lands.’

About the same time Dr. Schweinfurth, whose services to Egypt in so many branches of science stand pre-eminent, published important contributions on some of the archæological remains. Two or three years later Brugsch Bey brought out an account of the antiquities of the oasis, with translations of a number of the inscriptions on the temples of Nadûra and Hibis. The antiquities will be briefly referred to in my account of the history of the oasis under the Persians and the Romans, and for fuller details the reader is referred to the publications of Cailliaud, Hoskins, Schweinfurth, Brugsch, and some still later writers.

In 1893-94 Captain H. G. Lyons, R.E., in the course of a military patrol, undertaken in order to ascertain the measures necessary to protect the inhabitants of the oasis from possible Dervish raids, made valuable geological observations on the Eocene and Cretaceous systems, especially in relation to the connection of folding and water-supply.[23] These he discussed in a paper read before the Geological Society of London in 1894, and it was mainly due to the interest it aroused, and to his initiative in pointing out to the Egyptian authorities the importance of having a comprehensive examination of the country carried out, that the Geological Survey of Egypt was established in 1896.

The detailed survey of the Libyan Desert was taken up in October, 1897, and completed in June of the following year, the four oases being mapped on the scale of 1 to 50,000 by plane-table triangulation, checked and adjusted by numerous astronomical observations. Direct measurements by measuring-wheel were also employed to a considerable extent. Baharia Oasis was the first to be taken in hand, Mr. Leonard Gorringe and I taking the western side, and my colleagues, Messrs. Ball and Vuta, the eastern. This plan of splitting up an oasis-depression between two surveying parties was not, however, found satisfactory, and on the completion of Baharia it was decided that Ball should take up the oasis of Kharga, while Farafra and Dakhla fell to my lot. The results of this survey are published in the Memoirs of the Geological Survey of Egypt.

During the last three years I have been fortunate in having had opportunities of studying in some detail the topography, geology, and water-supply of the oasis of Kharga. This detailed examination has enabled me to revise and amplify pioneer work, and has, in certain instances, forced me to differ[24] from the opinions expressed by my predecessors in the same field, views which, in the light of the evidence available at the time, were doubtless well justified. In the same way may future research necessitate the modification or alteration of the conclusions herein expressed, and for many years to come the region of the oases will offer a vast field for further scientific work.

Before concluding this brief account of the literature on the oasis of Kharga, I should like to take the opportunity of expressing my high appreciation of the energy and purpose of my former colleague, Dr. John Ball, who, in spite of the many hardships and difficulties inseparable from scientific work in the Libyan Desert, in such a short time accomplished so much.

[25]

Lines of Communication between the Nile Valley, Kharga, and Dakhla Oasis — Principal Passes out of the Oasis — Ascent to Plateau with Caravans — Main Roads to Assiut, Sohag, Karnak, Esna, and Edfu — Nature of intervening Plateau — Ghubbâri Road to Dakhla — The Upper or Ain Amûr Road — The Railway between the Nile Valley and the Oasis — Nature of Desert Roads — The Bedawin Arabs — Cross-Country Traverses as the Crow flies — Traverse from Farafra to Assiut — Rate of Travelling with Camels.

The oasis of Kharga is in communication with Dakhla to the west, and with the Nile Valley to the east, by a number of caravan routes, the most frequented of which connect directly with the two villages Kharga and Beris, in the north and south of the depression respectively. Formerly, everyone bound for the oasis was compelled to undertake a four or five days’ journey along one or other of these routes, and although nowadays most persons will elect to cross the plateau by train, a description of the oasis would be incomplete without some reference to the desert roads.[2]

[26]

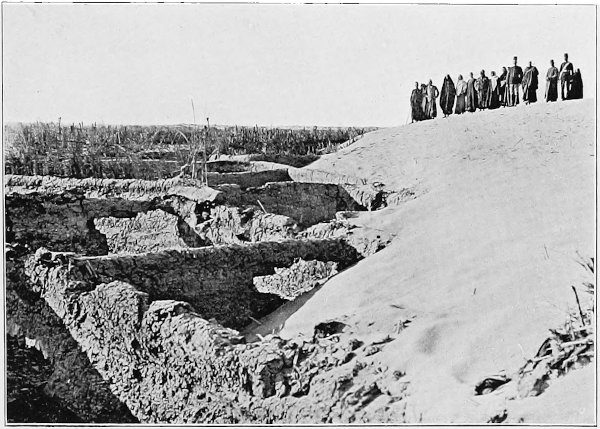

The depression is for the most part bounded by steep and lofty escarpments, quite inaccessible to camels, except at a few points where the gradients are less severe, and the loose blocks of rock and other cliff débris have been removed. The principal passes up the eastern scarp of the oasis are seven in number, the most northerly, known as El Ramlia, being in the extreme north-east corner of the depression. Thirteen kilometres south of this is El Yabsa pass. The next is the Refûf, at the head of the gully 45 kilometres north-east of Kharga village. A little farther south, east of the old Roman fort near the foot of Jebel Ghennîma, one of the two prominent outliers of the eastern plateau, is the pass of Abu Sighawâl, and 35 kilometres to the south is the Nagab Bulaq, N.N.E. of the village of Bulaq. In the south end of the oasis there are passes to the north-east of Jaja, and N.N.E. of Dush. These seven passes are the main exits from the depression on the east side, though there are several other little-used routes, up which lightly laden camels can be taken, for instance, near Jebel Um el Ghennaim. The illustration showing the descent to the depression was, in fact, taken at one of the latter.

Although the roads ascend the escarpments at the best available points, in some cases taking advantage of the easier gradients of the extensive cake-like masses of calcareous tufa, which in places have been deposited over the face of the original cliffs, their ascent with heavily laden camels may at[27] times become somewhat of an undertaking. The paths are frequently rough, and the difference in height between the foot of the scarp and the plateau is usually between 200 and 300 metres. The pack-saddles should always be carefully adjusted and secured by ropes passing round the base of the neck or below the butt of the tail, according to whether the caravan is making the ascent or descent; otherwise the loads are likely to slip off, and the restricted limits of a steep path, in the middle of a train of camels, is not an ideal place for their readjustment. In hot weather the ascent to the plateau, though perhaps occupying only one or one and a half hours, will take as much out of the pack-animals as a whole day’s march. I experienced no little trouble on one occasion when returning to the valley after some months’ survey work in Dakhla Oasis. After halting one day at Kharga village, we proceeded on our way to Esna by the Bulaq pass. It was hot weather, towards the end of May, and the ascent of the pass tired our camels, naturally not in the pink of condition, to such an extent that Gorringe and I had some difficulty in getting them across the plateau to the valley. In summer-time it is always advisable to negotiate this part of the journey in the early morning or late in the evening, unless the heavier portion of the baggage can be sent in advance to the top of the scarp, and the animals taken back and watered at the nearest well.

THE CARAVAN ROUTES

TO THE

OASIS OF KHARGA

The main roads from the oasis run to Assiut, Kawâmil near Sohag, Waled Hallaf near Girga,[28] Karnak near Farshut, and to Rizagat, Esna, and Edfu, and their disposition may be seen on the accompanying plan.

The Assiut road, after leaving Kharga village, passes the hamlet of Meheriq and follows the line of wells to Ain el Ghazâl, which is the last place at which water-skins and tanks can be filled. From Ain el Ghazâl the most direct route ascends to the plateau by the Ramlia pass in the extreme corner of the depression, but the Yabsa exit is recommended as easier and very little longer. After crossing a tract of country with an abominably rough surface, the two tracks unite a few kilometres north of the depression, and about a day’s march farther on the Zarâbi road takes off on the right. The main road proceeds direct to Assiut, descending the scarp about 8 kilometres before the town is reached, a by-path to the little village of Dronka having branched off beforehand.

From the summit of El Yabsa a separate road proceeds direct to El Ghennaim, a village on the edge of the desert to the north-west of Tahta. By these roads the distances from Kharga village to Assiut, Zarâbi, and El Ghennaim, are 210, 200, and 180 kilometres respectively.

El Refûf, the pass by which the Sohag (Kawâmil) road leaves the depression, is situated at the head of a gully, and offers an easy ascent to the plateau. A few kilometres beyond, the road passes to the north of El Shugera, a prominent detached block perched on end at the foot of the southern slope of[29] a small limestone range. The road runs in a fairly steady direction 40 degrees north of east, striking the Nile Valley scarp 15 kilometres before Kawâmil, on the edge of the cultivated lands, is reached. About 33 kilometres before reaching the scarp a branch takes off and runs nearly due north to Guhêna, south of Tahta; this branch is, in fact, usually referred to as the Tahta road.

If the traveller, after leaving the Refûf pass, keeps to the south of El Shugera, he will find a branch road leading to El Tundaba, a deep shaft in the centre of the plateau, at kilometre No. 92 on the railway; a little farther east this track strikes the main road from the Abu Sighawâl pass. The shaft is sunk through a thick deposit of silt, which has filled a local depression in the plateau to some depth. The silt must be regarded as rain-wash from the surrounding country, possibly deposited in the time of prehistoric man. Flint implements are to be found scattered about, and from the presence of pottery and graves it would seem that the place had been inhabited in comparatively modern times. The pit was evidently sunk for water, although at the present time it is quite dry; given, however, a heavy thunderstorm within the catchment-basin, drainage-water would in all probability find its way to the bottom of the deposit, where it would be held up by the limestone, and might form a supply lasting possibly for many years.

The road leaving the depression by the Abu Sighawâl pass, and leading to villages in the neighbourhood[30] of Girga and Farshut, is reckoned the best and shortest route between Kharga and the Nile Valley, and, by making a very short détour, caravans have the advantage of being able to water at the old Roman fort at the base of Jebel Ghennîma, 27 kilometres after leaving the village. The ascent of the pass was formerly very rough going, but a good road with an easy gradient has recently been cut for the transport of heavy boring machinery into the oasis. From the top of the Abu Sighawâl pass a well-marked track crosses to El Refûf and connects with the Sohag road, and care has to be taken by travellers for Waled Hallaf, El Elwania and Karnak not to make the initial mistake of getting on to this track.

For the first few kilometres the main road from Abu Sighawâl runs very straight over a level plain, on which fossil sea-urchins are so abundant as to attract the attention of the most casual observer; it then ascends a low escarpment, the Nagab el Jellab. The somewhat rough limestone country beyond is known as the Mishâbit, and then El Botîkh, with its countless millions of spherical chert concretions, is crossed. Beyond El Botîkh the road passes an isolated limestone hill called El Mograbi, where tradition has it that a Mograbi Arab from the west and his stolen oasis bride were overtaken and decapitated by the Kharga people. A little farther to the east there is a bifurcation, but the branches soon rejoin, and after passing El Masaâd the plain is fairly level, though covered[31] with very angular blocks of crystalline limestone and cherty concretions. Farther on are the rocks of El Buraig, where large quantities of broken pottery indicate the site of one of the many water-stations maintained by the Romans along this road. Garat el Melh is so called from the occurrence of salt in the limestones of this locality. A few kilometres to the east of Garat el Melh the road passes El Suâga, an artificial heap of stones to which every self-respecting Bedawi is careful to contribute; and a couple of hours beyond, a fairly conspicuous limestone hill, called Garat Radwan, is reached.

Shortly after passing Garat Radwan the most prominent landmarks met with on this road, in the form of two solitary crescent-shape sand-dunes, loom into sight; these are called El Ghart by the Arabs and are distant 55 kilometres from Abu Sighawâl. They form part of a belt of single isolated dunes which crosses this part of the desert in a N.N.W. and S.S.E. direction. The same line of dunes is passed by the railway at kilometre No. 100, and I have observed its continuation still farther north on the Sohag road, at a point 45 kilometres from the Refûf pass. These dunes mark the entrance to an area of very rough hummocky crystalline limestone known as El Zizagat, through which the track is not easily followed. On emerging from El Zizagat the road bears slightly to the north, and is here only a few kilometres south of El Tundaba. At this point it bifurcates,[32] the northern branch proceeding direct to Waled Hallaf near Girga, the southern continuing over the easy level plains of El Ishab to the rocks of El Baglûli, and thence past those of Dilail el Kelb to the twin hillocks of Dubîya. Beyond El Dubîya the road crosses the shallow drainage-line of Rod el Ghanam, near the head of the Wadi Samhûd, down which it passes, and thence over the Nile Valley plains past El Hamera and Hagar Hawara to Karnak and Farshut.

It should be mentioned that at Rod el Ghanam, shortly before reaching the head of the Wadi Samhûd, a branch road takes off on the left-hand side and descends by a separate pass to El Elwania; and here again care has to be exercised to avoid taking the wrong branch, as the tracks cover a broad area, and the actual junction may be easily missed.

The Kharga-Waled Hallaf road, via the Abu Sighawâl pass, is the shortest route from the oasis to the Nile Valley, the distance being only 160 kilometres; that to Karnak, by the Wadi Samhûd, is somewhat longer, being approximately 174 kilometres.

The next pass of importance to the south lies east of the village of Bulaq, whence it takes its name. From the summit a road runs nearly due east, meeting a second, starting from Beris and gaining the plateau by the Jaja pass, after one and a half days’ march. From the cross-roads, ‘El Mafâriq,’ routes run direct to Farshut and Rizagat.[33] From Beris to Farshut, by the Jaja pass, the distance is approximately 224 kilometres; from Kharga, by the Bulaq pass, the roads to Farshut and Rizagat measure about 203 and 198 kilometres respectively. Another road from Beris leaves the depression by a pass to the east of the village of Dush; this bifurcates about two days’ march from the latter, the left-hand track leading to Esna, the right to Edfu. Other roads lead from the south end of the oasis, via Nakhail, to Kurkur and Dungun, while the Derb el Arbaîn runs southwards to Selîma and thence on to the Sudan.

The road between the oasis and Assiut is best known as being the last and worst portion of the Derb el Arbaîn, or forty days’ road, which, starting from Darfur, was originally one of the main lines of communication between Egypt and the Sudan. It was along this desert route that great numbers of slaves and large quantities of merchandise, such as ivory, gum, and other products of the Sudan, were imported into Egypt from the south. After passing the last spring in the oasis, caravans had still a little over 200 kilometres to cover before reaching the Nile Valley, with a steep ascent to the plateau at the outset, and thence for a considerable distance over the very worst surface imaginable—loose sand full of sharp angular blocks and fragments of flint and cherty limestone. Little wonder that, overladen and fatigued by the long distance already covered, the camels died in great numbers on this last stretch of road. Along most[34] desert routes the dried bones of camels are of fairly frequent occurrence, but on the Derb el Arbaîn, between Kharga and Assiut, the skeletons of these poor beasts are met with in groups of tens and twenties, and must number hundreds and thousands. In many instances the skeleton still lies undisturbed, in the position assumed by the luckless animal in its death agony, the long neck curved back by muscular contraction so that the skull lies in contact with the spine. When one sees these remains, half buried in the sand, the bones bleached snow-white by a pitiless sun, with still adhering fragments of skin and muscle dried hard as adamant, one cannot but feel pity for those patient ‘ships of the desert,’ wrecked almost within sight of port.

Cailliaud, in 1817, observed the arrival at Assiut of a large caravan from Darfur, consisting of 16,000 individuals. It included 6,000 slaves—men, women, and children. He remarks: “They had been two months travelling in the deserts, in the most intense heat of the year; meagre, exhausted, and the aspect of death on their countenances, the spectacle strongly excited compassion.”

The actual width of the plateau varies from 120 kilometres between Abu Sighawâl and the scarp above Waled Hallaf, to 200 kilometres between Beris and Esna. The maximum elevation above sea-level is about 550 metres on the latitude of Esna, and on the whole the plateau has a fairly general slope to the north. As already mentioned, several distinct types of country, depending on the[35] nature of the rocks constituting the surface strata, are met with. Smooth, hard, level plains, formed of a superficial layer of weathered limestone covered by a brown veneer of insoluble flint and cherty fragments, alternate with bare rugged rock desert of hummocky limestone. The sombre level or gently undulating flint-covered plains, frequently spoken of as ‘serir’ by the Arabs, have ideal surfaces for travelling; the light-coloured hummocky country, often called ‘kharafish,’ is in its most developed form made up of innumerable elongated hillocks, every portion of the exposed rock-surfaces being deeply scored; the furrows are separated by upstanding edges, often so sharp and knife-like as to be capable of injuring the feet of man and beast. The hillocks are separated by deep troughs half buried in drift-sand, all lying parallel, in the direction of the prevailing winds, so that progress in a latitudinal direction through this type of desert is a slow and tedious undertaking. Both types of country are equally desolate and barren, scrub of any description being of the rarest occurrence, except after local thunderstorms. Another type of country, to which we have already briefly alluded, is the curious desert-surface called El Botîkh (the water-melons), which results from the weathering of certain bands of the Lower Eocene formation containing numbers of large globular concretions; these, it may be mentioned, often lie so thickly strewn on the surface as to actually obstruct the passing caravan.

[36]

Kharga is connected with the oasis of Dakhla to the west by two roads, the lower and more southerly, known as the Derb el Ghubbâri, being the one most frequently used. This road, by taking a wide sweep to the south, avoids the intervening plateau altogether, so that the fatiguing ascent and descent are avoided. After leaving Kharga village the route leads past a group of wells, known as Ain Khenâfish, distant some 6 kilometres; thence it lies over wide-stretching plains of sandstone, leading up to the more broken country formed by the foot-hills of the towering plateau, which is always plainly visible on the north side of the road. The distance to Tenîda, the most easterly of the Dakhla villages, is 143 kilometres by the Derb el Ghubbâri.

The alternative route by way of Ain Amûr is appreciably shorter, though, owing to the extra time involved in negotiating the steep passes to and from the plateau, there is little saving in time when travelling with a heavily-laden caravan. Compared with the lower road, however, this route is much more interesting and picturesque, and the presence of water at Ain Amûr, about half-way between the two oases, is a distinct advantage. The road from Kharga village lies over a broad plain, whose only features are occasional conical hills of dark ferruginous sandstone. It follows a W.N.W. direction, heading for the great indentation to the west of the Jebel Tarif range. After getting well into the recess, but when still some[37] 15 kilometres from its head, the road turns abruptly to the south, and winds its way up an escarpment littered with huge blocks of tufaceous limestone. Perched near the summit of the cliffs stands the solitary palm which marks the site of the water-hole, in the immediate neighbourhood of which grows a fair amount of prickly scrub. The remains of mud-brick buildings and a stone temple show that this place was formerly inhabited, and of some importance.

The ascent to the plateau from Ain Amûr needs care with laden camels. The road proceeds up a narrow defile, the actual track being very rough, and so confined that in places the packs are liable to be dragged off by the rocks on either side. Once on the plateau the going becomes first rate, the freedom of the surface from blown sand being very noticeable. This is due to the isolation of this portion of the plateau-massif, which is cut off from the main mass to the north by the deep recess, and is bounded by a low-lying plain to the south. After a distance of 33 kilometres has been traversed the road descends into a narrow valley opening on to the low country to the south, and proceeds in a westerly direction to Tenîda. The distance from Kharga to Tenîda by this route is 128 kilometres.

It is possible on leaving Ain Amûr to cross to the top of the indentation, and thence to proceed across the plateau almost due west, striking the road from Assiut, known as the Derb el Tawîl, at the top of the pass 25 kilometres from the village[38] of Belat. There is, however, no track, and the surface is covered with parallel north and south ridges of rock, the crossing of which is extremely wearisome. Both near the head of the Ain Amûr recess and in the extreme north-west corner of the oasis very old tracks trending in westerly and northwesterly directions are observable, and although unused at the present day, these may mark the positions of formerly frequented routes leading to the oasis of Farafra. At the present time that oasis is not in direct communication with Kharga, the routes used being from Manfalut in the Nile Valley, from Qasr Dakhl in the oasis of Dakhla, and from Ain el Hais in Baharia.

Before leaving the subject of roads we must briefly refer to the route taken by the railway. The line, which has a gauge of 75 centimetres, was built by the Corporation of Western Egypt, Limited, to develop their concessions in the oasis. It commences at Mouaslet el Kharga, a new station on the Egyptian State Railway near Farshut, and crosses to the border of the desert, a few kilometres distant, by way of one of the embankments separating two of the great irrigation basins of Upper Egypt. At the edge of the desert is the station of El Qara, the point of departure for the oasis. After skirting the margin of the Nile Valley cultivation for a short distance it heads straight for the Wadi Samhûd, by means of which the plateau is gained without encountering any very heavy gradients. From the top of the Wadi Samhûd[39] the line follows the Abu Sighawâl road for about 40 kilometres, after which it diverges a few degrees and proceeds to El Tundaba, the shaft already described, 92 kilometres from Mouaslet el Kharga. From El Tundaba the railway follows more or less closely the cross-track, sometimes called the Derb el Refûf, which joins the Sohag road at El Shugera, and, entering the depression by the Refûf pass, follows down the gully, and thence across the plain to the station of Meheriq. From Meheriq it proceeds nearly due south to the Corporation’s headquarters, and thence on to its present terminus a few kilometres from Kharga village.

THE RAILWAY DESCENDING INTO THE OASIS.

My friend Ball lays great stress on the tortuous nature of the roads between the oasis and the valley, and recommends the scientific traveller to steer an independent course. But after traversing the majority of the main caravan roads, and with a fairly intimate knowledge of the characters of the intervening areas, I must say that, in my opinion, it would be difficult to better them. These roads were not laid out yesterday, but result from the accumulated experience of centuries. The original tracks may have been tortuous enough, but they have become straightened out by the cutting off of corners here and there, until at the present day the roads fulfil the three most important objects in view—the ascent and descent to and from the plateau at the points offering the easiest gradients, and the crossing of the plateau itself as directly as[40] possible over the smoothest and most level ground available. The roads give a wide berth to the outcrops of rough limestone, and anyone who has done much cross-country travelling in the Libyan Desert will appreciate their doing so.

Nor can I concur with the same author in his opinion that the Bedawin of this side of the Nile have a poor knowledge of their beloved desert. It is certainly true that the Arab does, for very good reasons, prefer to travel on the beaten tracks rather than undertake exploratory missions as the crow flies, his main object being to get to his destination as rapidly and easily as possible. If by chance, however, rain should fall on any portion of the desert, the Arab will very shortly be found there, taking full advantage of what Allah has provided in the way of free grazing for his herds. My own experience has been that the Arabs have among them a fair proportion of men with an extensive knowledge of the western desert, and I have frequently been struck by their wonderful knowledge of the roads and the facility with which many of them can follow the tracks on the blackest of nights, as even in broad daylight the landmarks which a European could recognize on second acquaintance are few and far between. The average Bedawi cannot be said to have exceptionally long sight, but he is frequently possessed of a wonderful sense of direction.

Travellers in the Egyptian deserts are apt to underrate the intelligence of the Bedawin, owing to the fact that they unconsciously form their impressions[41] from the miserable specimens of humanity so frequently sent out by the actual owners of the camels to act as drivers and attendants to a hired caravan. In such caravans there is seldom more than one man who knows the particular roads to be followed; the rest are wretched underfed creatures, generally half-breeds, who for a mere pittance tramp day after day, uncomplainingly and shoeless, alongside the caravan. They are much to be pitied, and it would be as unreasonable to expect them to have any special knowledge of the desert as it would be to look for information regarding, say, the mountains of Wales among the poorer classes of a Welsh town.

I do not wish to minimize the value of cross-country traverses carried out with special scientific objects; they are, indeed, often necessary for topographical and geological purposes. I would, however, warn the enthusiastic tyro that, in the Libyan Desert, travelling as the crow flies is not always so simple and glorious an affair as it may seem when planning expeditions from a comfortable arm-chair; and if his object is to get a short cut he will probably have reason to bitterly regret the moment he left the beaten track. I have in mind more than one instance where mistakes of this kind have been made, mistakes which might easily have led to disastrous consequences. In long cross-country traverses an error in steering of only two or three degrees will in a few marches throw a caravan many kilometres out of its course, and guiding camels[42] over rough country by compass is by no means an easy undertaking. Moreover, easily distinguishable landmarks are rare, and the desert plains over wide areas maintain remarkably persistent characteristics. Quite recently I recollect an Englishman, whose Arab attendant had become suddenly incapacitated by an attack of fever or sunstroke, getting hopelessly astray between the edge of the plateau overlooking the oasis and rail-head, which was then only 20 or 30 kilometres distant, in consequence of his missing the bifurcation of the road at El Shugera, and proceeding, owing to this mistake, along the route leading to Sohag.

Along the caravan roads the sharp fragments of rock have been stamped underground or kicked to one side, but elsewhere they usually litter the surface, and are very trying to camels, whose pads, though soft and yielding, are easily worn by much travelling over rough country. This has more than once been painfully impressed upon me by the antics of my own riding camel, whose mode of progression at such times resembled more the dance of a fanatic on red-hot coals than the ordinary gait of a well-bred ‘hegîn.’ Over some areas, however, one can travel in a straight line without let or hindrance, and in such cases it is only necessary to lay out the course correctly in the first instance, and to have the courage of one’s opinion to stick to that course until the destination is reached. One must not heed the remonstrances of the less sporting members of the expedition, who will lose no opportunity[43] of predicting disaster, and in this respect the new chum fresh out from home is generally the greatest offender.

One of the longest cross-country traverses I myself have undertaken in the Libyan Desert was from Farafra Oasis to Assiut. The only road between that oasis and the Nile Valley strikes the latter near El Qusîya, midway between the towns Manfalut and Derut, so that travellers who wish to make Assiut have an additional day’s march southwards alongside the margin of the cultivated lands. On gaining the summit of the pass above Bir Murr, on the east side of the Farafra depression, I abandoned the road and set a course direct for Assiut, steering and plotting my route by compass and plane-table, the distance being reckoned by measuring-wheel. The most satisfactory method of procedure on desert traverses is to lay out a line, representing the correct bearing of the destination, along the centre of the longer axis of the plane-table, and then to steer to any well-marked object lying on either side, but within reasonable distance, of the proper course. At every station the exact position reached is plotted, and steps are taken, when selecting the next point on which to march, to converge towards the correct course marked down the centre of the table.

On this particular traverse I was unaccompanied by Europeans or Bedawin, my camel drivers being fellahin from the Nile Valley. The surface proved excellent going, and the Abu Mohariq belt of dunes,[44] 190 kilometres from Qasr Farafra, was crossed without trouble. Eight days after leaving Farafra village we struck the escarpment of the Nile Valley, having covered nearly 300 kilometres, and found we were marching on a point only very little to one side of the town of Assiut. From this traverse it was possible to calculate the longitude of Farafra with fair accuracy.

The normal rate of travelling of camels carrying ordinary loads weighing from three to four hundred-weight is 4 kilometres, or about 2½ miles, an hour, ten hours being the usual day’s march of caravans when accompanied by Europeans. The native caravans, carrying dates and other heavy merchandise, usually traverse the plateau in three days and nights, doing stages of 60 to 70 kilometres at a stretch. By travelling very light with trotting camels I have, on more than one occasion, crossed from the oasis to the valley in between thirty and thirty-five hours, doing from 180 to 190 kilometres in two stages of about twelve hours each, with one stop only of nine or ten hours.

[45]

Dimensions of the Oasis-Depression — Jebel Têr, Jebel Tarif, and other Hills within the Depression — Aspect of the Oasis from the surrounding Escarpments — Geological Sequence — Nature and Thickness of the Strata — Geological History of the Oasis — Formation of the Depression — Difference of Level of Strata on either side of the Depression — The Great Longitudinal Flexure — Height of the Floor compared with Sea-Level — Altitudes.

Kharga, the eastern of the two southern oases, is a depression lying with its longer axis north and south, mostly bounded by steep and lofty escarpments, but open to the south and south-west, on which sides the country rises gradually from the floor of the oasis. The extreme length of the depression, from the northern wall to Jebel Abu Bayan, which for convenience may be regarded as the southern limit of the oasis proper, is 185 kilometres, or 115 miles. The general trend of the eastern escarpment is nearly due north and south, but that on the west is very irregular, while to the south and south-west there is no definite boundary. The breadth of the depression may therefore be said to vary from 20 to 80 kilometres.

[46]

The ranges of Jebel Têr and Jebel Tarif form isolated hill-massifs in the centre of the northern part of the depression, while Jebel Ghennîma and Jebel Um el Ghennaim are conspicuous outliers of the plateau on the east side. With the exception of these, the floor is destitute of anything beyond comparatively insignificant eminences, unless we include the small range of hills known as the Gorn el Gennâh, to the south-east of the village of Gennâh, which is noticeable more on account of its sharply-defined peaks than of its general elevation above the surrounding country. Referring to the two conspicuous peaks, Ghennîma and Um el Ghennaim—Jimmy and Jemima, as I have heard them dubbed—reminds me that on the Survey and on some of the older maps the names are reversed. I have questioned a number of natives regarding the names of these hills, and have invariably been informed that Ghennîma is the more northerly of the two.

The villages, wells, and cultivated lands lie within a north and south band, occupying the lowest portion of the floor, and following the general trend of the depression. They are, however, broken up by a broad area of barren desert into two distinct north and south groups, of which Kharga and Beris villages are the chief centres respectively. A description of these is reserved for a later chapter.

When a traveller, after crossing the broad monotonous plateau, at length reaches the scarp or wall of the oasis, and sees spread out before him a vast[47] depression, stretching in some directions as far as the eye can reach, in others to the opposite bounding walls dimly discernible on the far horizon, he can hardly refrain from speculating as to the causes which have given rise to such huge hollows in the plateau. When he descends to the cultivated portions of the floor of the depression, and sees those numerous bubbling springs, which alone make life possible in the midst of this otherwise deadly wilderness, his second inquiry is as to whence comes such abundance of water in one of the most arid regions in the world. These questions are worth asking, and, so far as the present state of our knowledge permits, it will be my endeavour to answer them. I propose, therefore, to briefly place on record such information and data as I have been able to gain, but as both topography and water-supply are intimately connected with the geology of the district, it will be necessary at the outset to devote a few pages to a consideration of the latter.

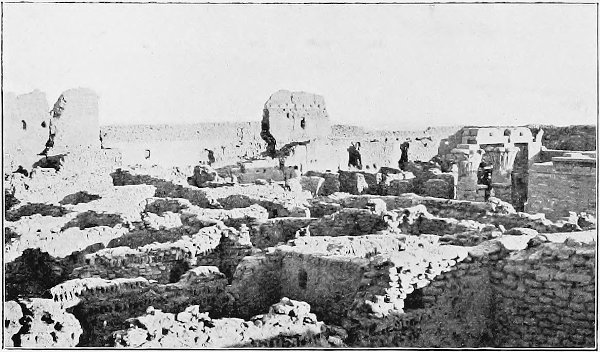

THE CHRISTIAN NECROPOLIS AND JEBEL TER.

The geological deposits found in the oasis of Kharga are tabulated on the following page, commencing with those most recently formed. The succession, as shown in the table, is that which obtains in the northern part of the depression, but as far as is known the same stages occur throughout the oasis, and do not vary either in thickness or in lithological characters to any great extent. Over large areas the lower-lying parts of the oasis-floor are formed of those beds which we have designated the Surface-water Sandstone, though in

[48]

| Geological System. | Stage. | Thickness in Metres. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recent and Pleistocene | } | ⎧ ⎪ ⎨ ⎪ ⎩ |

Sand-Dunes | ⎫ ⎪ ⎬ ⎪ ⎭ |

Very variable | |

| Spring Deposits (modern) | ||||||

| Lacustrine Sands and Clays | ||||||

| Calcareous Tufa | ||||||

| Lower Eocene | Lower Libyan | Plateau Limestone | 115 | |||

| Passage Beds | Esna Shales and Marls | 55 | ||||

| Upper Cretaceous | Danian | ⎧ ⎨ ⎩ |

White Chalk | ⎱ ⎰ |

70 | |

| ⎧ ⎪ ⎪ ⎨ ⎪ ⎪ ⎩ |

Ash-grey Shales | |||||

| Exogyra Beds | 30 | |||||

| Campanian (Nubian Series) | ⎧ ⎪ ⎨ ⎪ ⎩ |

Phosphate Beds | 70 | |||

| Purple Shales | 50 | |||||

| Surface-water Sandstone | 45 | |||||

| Impermeable Grey Shales | 75 | |||||

| Artesian-water Sandstone | 120 | |||||

| Total | 630 | |||||

places the still older underlying grey shales are exposed. The purple or red shales generally form the rising ground towards the escarpments, at the base of which are usually found the phosphatic beds, with hard, pronounced bands made up of fish-remains and phosphatic nodules. Above come the Exogyra Beds, with thick bands of limestone almost entirely composed of large oyster-shells. Rising up above these is the generally well-marked cliff of grey shales, capped by a snow-white chalk of much the same age geologically as the well-known chalk of the South of England. The summit of the chalk frequently forms a separate plateau, subsidiary to the high desert tableland, and separated from it by the cliffs formed of the massive Eocene limestones.

The total thickness of the exposed strata is about 435 metres, a figure obtained by actual measurement.[49] Numerous borings show the thickness of the unexposed underlying Impermeable Grey Shales to be 75 metres, and the deepest borings yet made have pierced the still lower Artesian-water Sandstone to a depth of 120 metres, making a grand total of known deposits of 630 metres, or 2,067 feet. The depth to which the water-bearing sandstone extends is at present a matter of speculation; the point is of great importance in connection with the water-supply, though up to the present no borings of sufficient depth have been made to determine its thickness, nature, and relation to the underlying igneous rocks.

With the exception of a few isolated bosses of eruptive rock in the desert to the south of the oasis—indications of the granitic foundation which probably underlies the entire area—the geological deposits of the oasis-depression, and of the surrounding escarpments and plateaux, are entirely of sedimentary origin, that is to say, they were laid down on the shores and beds of pre-existing seas and inland lakes. The sand-dunes are, of course, an exception, having been deposited by the wind on the surface of the land. Although, geologically speaking, the oldest group of sediments with which we have to deal belongs to the later chapters of the earth’s history, many hundreds of thousands of years have elapsed since the sandstones and shales, now forming and underlying the floor of the oasis, were accumulated on the bed of a vast inland lake. This sheet of comparatively fresh water was then[50] invaded by the sea, which held sway in the region while the whole of the series of sediments, now exposed in the cliffs of the oasis and some 350 metres in thickness, were being laid down. In Middle Eocene times the sea commenced to retreat to the north, and the area under description became dry land with a continually receding shore-line. Since that time the forces of denudation have constantly been at work lowering the general surface of the plateau and excavating those depressions in which alone at the present day man is able to exist.