The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Survey, volume 30, number 7, May 17, 1913, by Paul U. Kellogg

Title: The Survey, volume 30, number 7, May 17, 1913

Editor: Paul U. Kellogg

Release Date: April 12, 2023 [eBook #70514]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg 237]

Pittsburgh school affairs are under a cloud but the outside world should understand certain facts, notably that the cloud itself is stirred up, to some extent at least, by interests using it as a cloak for their operations. These interests are two-fold: the first, political, embracing the faction opposed to Senator Oliver; the second, partly political and partly personal, embracing the men from whose hands the school affairs of Pittsburgh were wrested by the Legislature two years ago. Under the old system school buildings and maintenance were in control of petty ward boards; in some districts the schools were excellent but in others waste, mismanagement and graft were rampant. Under the new system many of the old directors secured election as ward school visitors and, shorn of their spoils, have been bitterly opposed to the control of the small, centralized executive board appointed by the judges of the Allegheny county courts.

Charges brought against Supt. S. L. Heeter by a housemaid gave politicians and ousted directors their chance to start an agitation for a return to conditions under which they throve. These charges were given publicity by Coronor Jamison, president of the old central board. Superintendent Heeter demanded a court trial and was acquitted. Afterward a committee of citizens, including the president of the chamber of commerce and two clergymen, was appointed to investigate the superintendent’s fitness to remain in office. This committee has not yet reported.

Whether Superintendent Heeter is retained in office or not is aside from the main issue—the revolution in the conduct of the Pittsburgh schools in the past year and a half. The new board has been obliged to spend $150,000 in transforming indescribably dirty old fire-traps, with poor light, worse ventilation and unspeakable toilets, into schools that could be used with decency.

The great mass of Pittsburgh’s good citizens refuse to get excited. Not all the scare heads of the interested newspapers, the Leader and the Press, or mass-meetings and parades of children arranged by still more interested individuals, have befogged the recognition by Pittsburgh people of the improvement in school affairs since 1911. The exaggeration of the children’s strike in the press of the country, however, has been broadcast. Collier’s Weekly, for example, that usually accurate publication, prints a picture with the explanation that “a strike of 50,000 school pupils paralyzed the Pittsburgh school system.” There was marching of children; but when an effort was made to discover the identity of the men who the children reported were urging them on, the agitators quickly dropped out of sight. For a few days attendance dropped off in certain sections, but many parents had kept their children at home for fear of their becoming involved.

The situation has been tense, but social workers in Pittsburgh do not anticipate that the Legislature will respond to the manufactured agitation and put the schools back in the hands of the ward boards whose long regime left conditions that can not be remedied in years. A bill introduced this week would make the central board elective. Theoretically there are arguments in support of the election-at-large of members of the centralized board, but the appointive board was regarded as a necessary measure if the schools were to be freed from the domination of the old boards.

Efficiency has been the new board’s watch-word. Janitors and teachers are not appointed on the basis of political “pull.” Already the high school attendance has increased over 60 per cent. Manual training, cooking and sewing classes are now found not only in wealthy districts, but also in sections where boys and girls need such training most.

The one point in which the new board has been weak was the failure to establish sympathetic relations with the public in the reforms it is putting forward and to utilize publicity as a constructive force in the securing of them. This indifference to public opinion, although only apparent, has been mistaken in many quarters as contempt, especially because of the autocratic personalties of two members of the board. It is perhaps unfortunate that the board’s president, David Oliver, is a brother of Senator Oliver, thus giving a decided political turn to newspaper discussion. He was the logical man for the place, a leading member of the state school commission which drafted the new code. As president of the old board in Allegheny, now the north side, he had helped to make the schools of that section far superior to those of the old city; this, in spite of the fact that civic conditions in Allegheny were even worse than in Pittsburgh.

The unfortunate Heeter affair is in fact but an incident in the forward movement toward responsible municipal rule in Pittsburgh.

[Pg 238]

Judge John E. Owens of the Cook County Court, Chicago, has the distinction of having inaugurated the service of social investigators, of having extended the court’s supervision over thirty-three child-helping agencies and of having promoted their close co-operation with the court and with each other.

Although Judge Owens has a contingent fund for the employment of other judges to assist him in passing upon cases of insane and dependent persons, he prefers to do all the work himself and use the money for four social investigators. They report upon the conditions involved in each case, and, aided by this information, the judge enters his decision.

Hitherto the board of visitors, which the judge of the County Court appoints to report upon the care of children committed to child-helping institutions and agencies, has ordinarily attempted little more than a perfunctory service. The present board with Wilfred S. Reynolds as its secretary, however, had the services of experienced social workers.

The first report of the board of visitors to the county judge tells of co-operation and fellowship which has come into being, and of the standardization thus brought about in buildings, equipment, methods and service.

Among the recommendations of the report are the following:

A full record of all facts concerning the child and its previous environment which are in the possession of the court should accompany all commitments to institutions;

Regular and definite reports should be required by the court from all institutions and organizations concerning all children under guardianship;

Money which the court orders parents or guardians to pay for the support of children should be paid to the clerk of the court and turned in to the county treasury;

The submission of plans for new buildings or improvements should be required of all institutions, so as to secure suggestions and approval from a board of competent ability;

A diet should be established upon a scientific analysis of food properties;

Assignment of routine work to be done by the children should be strictly upon the basis of the child’s training, not service to the institution;

Classes in industrial and special training should be organized, and supplemented by routine work about the institution;

Record systems must be complete of the child’s history, its institutional life and the after disposition;

Visits to placed-out children should be made as often as once in six months;

Adoption should not be consented to until six months after placing;

Placements should be kept within the state; and

Personal investigations of all applying for children should be made.

To estimate fully the importance of the achievements recorded in this report requires some knowledge of the acute disturbance[1] within the field of child-care in Chicago during the year or so preceding the work of this board of visitors. To it is attributed the credit of having brought harmony and efficiency out of the chaos produced by the disruption and antagonism which marked the recently repudiated county administration.

The Missouri Legislature of 1911 passed a law which provided for the gradual abolition of the convict leasing system. Under this law contracts employing 1,700 prisoners were due to expire December 31, 1913. Before the convening of the next Legislature, January, 1913, many had decided that the law of 1911 by no means solved for Missouri the problem of convict labor. It was discovered that it was most difficult to employ convicts to the satisfaction of all.

A number of bills were introduced to solve the problem. One representative went into the penitentiary to explain to the convicts his bill to repeal the 1911 law. He was hissed by the convicts who showed in this way their disapproval of the system of leasing out their labor to contractors. When, however, the representative explained that his bill provided that the state would get thirty cents a day for each man and that thirty cents would go to their nearest relative the convicts became calmer. Another bill provided that the contract system be maintained, but set $1 a day as the smallest wage that might be paid. Of this amount thirty cents a day was to be given to the convict.

Finally a resolution was passed appointing three senators to investigate and recommend to the Legislature then in session the best means of handling the situation.

The gist of the report follows:

Prisoners in penitentiary, 2403; employed under contract system, 1600; 1650 prisoners let at $.70 per day each, forty-six cripples at $.50 and forty-four females at $.50. The earning capacity of the prison for the biennial period 1911-1912 was $710,000. This excludes 400 prisoners employed by the state. The committee further reports that about 1000 of the prisoners are confirmed criminals and could not under any circumstances be employed outside of the prison walls. About 300 white men and a like number of Negroes could be worked upon the public highways.

The committee states that at this time the state[Pg 239] cannot afford to purchase the machinery and manage the industries now in the prison. This it is estimated would cost about $1,000,000 for two years and such an expenditure would cramp badly all other state institutions.

The report finally advises the Legislature to extend by enactment the time of the prevailing contract system to a period beyond the convening of the next Legislature, because it would be inhuman and dangerous in many ways to allow the men to be idle.

Before the Legislature adjourned a bill was passed following in the main the suggestions of this report. The abolition of the leasing system is suspended till December 31, 1915. The services of the major portion of the prisoners may be contracted at 75 cents a day for each (an increase of 5 cents). A number not to exceed one-quarter of all the prisoners are to be tried out on public road work and in the manufacture of school furniture. The state binding twine factory is to be continued.

The post-office appropriation bill for the year beginning July, 1913, which was passed in the last days of the Sixty-second Congress, provided for 2,400 additional clerks as well as an increased number of carriers. It raised the minimum pay for clerks and carriers from $600 to $800 a year and set the minimum for substitutes at forty instead of thirty cents an hour. Large appropriations were made for auxiliary clerk and carrier hire, a special sum being set aside to prevent overwork of the regular employes during the summer vacation period. The minimum pay for laborers and watchmen in the department was raised from $650 to $720.

The raising of minimum salaries and the provision of extra service to prevent overwork and insure the effectiveness of the eight-hour day worked within ten consecutive hours, which was passed last year, rounds out the legislation of the Sixty-second Congress affecting the postal employes. This Congress, in the words of the Union Postal Clerk, in the two years of its existence, “enacted more legislation providing for the betterment of the condition of the postal employes and the improvement of the service than has ever been enacted since the establishment of the civil service among postal employes.”

The conditions which prevailed at the opening of this Congress were described in The Survey of August 6, 1911. Last year’s improvements, which were summarized in The Survey of July 13 and September 14, include the abolition of the gag rule; the enactment of an eight-hour day for clerks: and a Sunday-closing provision, with compensatory time off for the group of employes who are not affected by this provision; the raising of pay in the mail service; the providing of safer construction for mail cars, and the provision that 75 per cent of clerks and carriers in the second highest grades of pay should be automatically raised each year to the highest grade.

The post-office is not as yet, however, in the opinion of those who have studied its labor problem, a model employer. The substitutes are not on an entirely satisfactory basis, as no provision is made guaranteeing them a minimum number of hours a week, or setting a limit to the number of years they serve before they are received into the regular service. By the terms of the bill, whatever may have been done by administrative readjustments, no provision is made to relieve the overstrain on certain sections of the railway mail service. In spite of many years of vigorous agitation no retirement or pension bill for the service has as yet been passed.

Over a hundred strong and representing over three-fourths of the states and Canada, the American Commission for the Study of the Application of the Co-operative System to Agricultural Production, Distribution and Finance in European Countries sailed from New York on April 26. This commission is to visit certain European countries under the direction of the Southern Commercial Congress. According to the officers of the Congress it will take special note of

| 1st. | The parts played, respectively, in the promotion of agriculture by the governments and by voluntary organizations of the agricultural classes. |

| 2nd. | The application of the co-operative system to agricultural production, distribution and finance. |

| 3rd. | The effect of co-operative organization upon social conditions in rural communities. |

| 4th. | The relation of the cost of living to the business organization of the food-producing classes. |

The work of the commission was given standing by the joint resolution of the Senate and the House of Representatives authorizing the secretary of state to bespeak for the commission the diplomatic courtesies of the various European governments. It was further strengthened by the appointment by President Wilson of a commission composed of seven persons to accompany and co-operate with the American commission, and through the appropriation by Congress of $25,000 for the expenses of this federal commission. Senator Duncan Fletcher, of Florida, president of the Southern Commercial Congress is chairman of the federal commission. The other members are: Senator Gore, of Oklahoma;[Pg 240] Congressman Moss, of Indiana; Clarence J. Owens, of Maryland, managing director of the Southern Commercial Congress; Kenyon L. Butterfield, of Massachusetts, president of Amherst College; John Lee Coulter, of Minnesota, the government’s expert on agricultural statistics; and Colonel Harvie Jordan, of Georgia, president of the Southern Cotton Growers’ Association. Sevellon Brown accompanies the federal commission as a representative of the State Department.

The American commission will return to New York on July 25. The federal commission will as soon as possible thereafter render its report to Congress. A committee of nine governors appointed at the last conference of governors is awaiting the report of the American commission in order to draft appropriate state legislation in regard to farmers’ credit and co-operative organizations. Few commissions have gone abroad with the backing and the enthusiasm that accompanies this one. Representative of national and state public authorities, business men, and farmers, its report promises to hasten practical measures for the relief of the financial burden of the American farmer.

Louisville, Ky., is at last making progress in the task of securing better housing for the people. Three years ago a law which set much higher standards than those previously prevailing was secured. The act simply gave the city permission to employ a housing inspector instead of commanding it to do so. As a result, Louisville’s housing legislation remained until last summer a matter of purely academic interest despite all the efforts of the housing committee.

During the vacation season four medical school inspectors were assigned to housing work. There were hopes that these men would accomplish something but when the schools opened again in the fall and the result of their efforts was summed up the total, according to the housing committee, was disappointingly small.

Meanwhile some amendments had been made to the law which included a mandatory provision for an inspector. This inspector was to be appointed by the health officer, Dr. W. E. Grant, who is in sympathy with those who are working for better housing for Louisville. The city administration pleaded that it was too poor to pay an additional salary but the offer of the Charity Organization Society to provide the money was not accepted. At last, however, a policeman was detailed to the task and though he was without training he proved to have tact and persistence. As a result one hundred violations of the law were corrected within two months.

At almost the very close of the session of the New York Legislature, the bills introduced at the instigation of the New York Milk Committee by Assemblyman Carroll to give to the state more complete control over milk production and milk handling through the State Departments of Agriculture and Health were defeated, although one came within half a dozen votes of passing. These bills were drawn in accordance with the resolutions adopted by the governors’ delegates from eastern and middle states at a conference last February.

The bills were drawn to supplement each other and provided that the State Department of Agriculture should have charge of dairy inspection and the State Department of Health of medical inspection of the dairy employes and laboratory tests of milk. According to the first of these bills, veterinarians now in the employ of the State Department of Agriculture were to be employed as dairy inspectors. It is the opinion of the committee that only competent veterinarians can perform the examination of dairy cattle and that the training which competent veterinarians receive equips them to make sanitary inspections of the buildings in which dairy cattle are housed and the surroundings of these buildings. The companion bill to amend the public health laws gave to the local medical representatives of the State Department of Health power not only to make medical examinations of dairy employes but to test the water supply on dairy farms and the milk delivered by farmers to creamery and milk stations.

After the Carroll bill was defeated Senator Wagner introduced a bill providing for a commission to investigate the methods of production, distribution and sale of milk and cream. The state commissioner of agriculture, the Senate and Assembly chairmen of the Committees on Agriculture, the master of the grange, the secretary of the New York Sanitary Milk Dealers’ Association and the president of the National Housewives’ League were named in the bill as the members of the commission. This substitute was attacked by the New York Milk Committee as merely a measure for delay and on the ground that it contains but one actual representative of the consuming public, the president of the National Housewives’ League. The secretary of the Milk Committee pointed out that the commission contained no health expert, no sanitarian, no bacteriologist and no veterinarian. In the closing moments of the Legislature an attempt was made to have at least the state health commissioner added as a member of the commission. This effort proved to be unnecessary for the bill was only passed by the Senate.

[Pg 241]

“Hunting a job” in social work presents almost as many terrors as confront the unemployed casual laborer. The New York Charities Directory lists 3500 organizations, a large part of which employ paid workers. This is but a local index of the number of societies that need trained workers. Yet the individual who is looking for a position in social work, soon learns that the task of finding the right opening is not easy. He secures interviews with busy executives only to find that the positions he had heard of are already filled. Executive officers, on the other hand, are forced to spend much time looking up references and writing to possible applicants, and then often fail to find the right candidate. As a result the right person and the right place frequently fail to make connections.

This difficulty it has been felt was only partially overcome by the existing employment agencies and employment departments of colleges and schools of philanthropy. In an effort to meet the needs more completely the Intercollegiate Bureau of Occupations, with the co-operation of the New York School of Philanthropy and of the Russell Sage Foundation, has established a separate department to serve as a clearing-house for workers and positions in social work. This bureau was organized by the New York alumnae societies of nine eastern colleges for women to help solve the problem of employment for college graduates and other trained women in occupations other than teaching. Since its opening on October 1, 1911, the bureau has filled 158 positions in the field of social work and 271 in other lines of activity.

The new Department for Social Workers will follow in its special field the methods which have proved successful in the general work of the bureau. It will accept for registration both women and men, and will be national in scope. It is governed by an Executive Committee of eight, which includes three representatives from the Board of Directors of the bureau, Mary Vida Clark, Mary Van Kleeck and Margaret F. Byington. The other members of the committee are Edward T. Devine, of the New York School of Philanthropy; John M. Glenn, of the Russell Sage Foundation; R. H. Edwards, of the International Committee of the Young Men’s Christian Association; Elizabeth W. Dodge; and James S. Cushman. An Advisory Committee composed of persons actively interested in social and civic work of national scope will assist in increasing its usefulness to social organization.

At the outset it has been decided to limit the services of the department to those who have had some training or experience. A year in social work, or in a school of philanthropy or a college degree, is required of applicants. A registration fee of one dollar is charged, and a small commission for positions secured through the bureau. No fee is charged to employers. Sigrid Wynbladh, formerly with the New York School of Philanthropy, has been appointed assistant manager, in charge of the Department for Social Workers, under the supervision of Frances Cummings, manager of the bureau. The office is located for the present in connection with the main office of the bureau, at 38 West 32nd Street, New York, but it is hoped that space may be secured later in the United Charities Building. The new department opened March 1. Already 182 well qualified applicants are registered and 107 calls have been received for responsible workers.

The United States Department of Agriculture which, together with the various state agricultural agencies, has hitherto given primary attention to the problems of production is now aiming to bring about a better organization of rural life. One of the first things the department will attempt is to look into existing organizations, enterprises and activities in order to determine just how they are working and just what their effect is on rural communities. Next, it expects to take steps to encourage and bring into active co-operation organizations that will be helpful in advancing rural life.

The Department of Agriculture and some of the states have already developed work in this field and it will be the object of the Rural Organization Service, operating through the department, to secure the co-operation of all these agencies. The Department of Agriculture is now charged specifically with the problem of studying the marketing of farm produce. Congress at its last session appropriated $50,000 to enable the secretary of agriculture “to acquire and to diffuse among the people of the United States useful information on subjects connected with the marketing and distributing of farm products.”

Marketing, however, is only one aspect of the problem of rural organization. The General Education Board, which for several years has co-operated with the Department of Agriculture in the support of its farm demonstration work, has expressed a willingness to extend its co-operation with the department in this problem of Rural Organization Service. This offer of further co-operation has been accepted. The secretary of agriculture has sought and secured the services of Dr. T. N. Carver, professor of economics in Harvard University, as director of this work, and the president of Harvard University[Pg 242] has granted Dr. Carver indefinite leave of absence.

It is expected that the work of investigation, experiment and demonstration now conducted by the Department of Agriculture and by many of the state colleges and experiment stations will fit into the new scheme. The Rural Organization Service plans to co-ordinate and crystalize these results and apply them in community effort for the advancement of agriculture.

A conference on Rural Industrial Schools for Colored People in the South was held in New York April 17-18. The conference was called by six colored principals: Leslie Pinckney Hill, of Manassas, Va.; William E. Benson, of Kowaliga, Ala.; W. J. Edwards, of Snow Hill, Ala.; W. A. Hunt, of Fort Valley. Ga.; W. D. Holtzclaw, of Utica, Miss., and Emma Wilson of Mayesville, S. C. Between one and two hundred people attended the various sessions, and nearly every southern state was represented.

There are about 200 schools for Negroes in the South which are supported by private philanthropy. Some of these schools are supported by such bodies as the American Missionary Association but a larger number have been organized by the initiative of their principals and have no backing save that of their individual boards.

Mr. Hill, in his opening address, pleaded for co-operation among the principals and the boards of Negro schools. Under the present system he said each school works for itself, determines its own educational standard, buys its supplies and unaided raises its money. He recommended co-operation in the raising of funds, in the standardizing of studies, in the standardizing of accounts and in the buying of supplies.

These four suggestions were the central themes of the conference.

The problem of how to raise money received the most attention. At present the members of the board of the school and the principal appeal to any person of means who can be approached. As the number of schools increases the same people are solicited again and again, and the raising of money becomes increasingly difficult. The colored principal jeopardizes his school by his continued absences, and he often grows despondent as he knocks, frequently in vain, at the door of office or home.

Clarence H. Kelsey, president of the Title Guarantee and Trust Company of New York declared that the present system of money-raising is breaking down. Many of the smaller schools, he said, would in the future find it impossible to continue unless they could enlarge their plans for self-support.

Oswald Garrison Villard, editor of the New York Evening Post and chairman of the board of directors of the Association for the Advancement of Colored People, suggested that the field be divided and one section of the country assigned to one school, another section to another. Instead for instance of twenty-five schools trying to get support from a city like Rochester, two or three should use this territory.

The city would then feel responsible he argued for a definite amount of support, and would take a keener interest in doing a good deal for a few schools than in doing a little for a score or two. The conference came to no decision on this matter.

The discussion on co-operation in the raising of funds incidentally indicated the need for carrying out Mr. Hill’s next two suggestions, the standardizing of the curriculum, and the standardizing of accounts. The curriculum in the Negro schools is left to the principal and his board. While recognizing the different conditions in different southern states, it was agreed that some uniformity in courses of study should be secured. The need of good academic training was strongly emphasized by the conference. It was argued that in his zeal for industrial work, the principal must not forget the foundation of all school work, the ability to read and write well, to use numbers, and to reason clearly and intelligently.

Standardizing studies it was recognized would facilitate the standardizing of accounts. A suggestive paper was read on this subject by Charles E. Mitchell, certified public accountant of the West Virginia Colored Institute.

The fourth suggestion that the schools might save by co-operative buying was a new idea to most of the people present, and was felt to be worth looking into carefully. Mr. Hill pointed to the co-operative movement in Germany, where the farmers, each insignificant as a unit, as a co-operative body can command a credit of 200,000,000 marks.

“Why,” he said, “should not the schools buy their flour from the same mill, their coal from the same mine? Such an arrangement would save them tens of thousands of dollars each year.”

While the conference was concerned with the smaller secondary schools of the South, delegates were present from Hampton and Tuskegee.

The conference closed with the formation of a temporary organization consisting of W. D. Holtzclaw, president; Emma Wilson, vice-president, Leslie Pinckney Hill, secretary and treasurer, and four other board members W. A. Hunt, W. J. Edwards, W. T. B. Williams and O. L. Coleman. These officers are to hold a meeting in Atlanta on June 17, and will submit their conclusions to the larger body of school principals in November. It was the hope of the meeting that a practical plan of co-operation might be presented.

[Pg 243]

THE RURAL CHURCH

FRED EASTMAN

Secretary Matinecock Neighborhood Association,

Locust Valley, N. Y.

Farmer Smith needs help. He needs it here and now. He is trying to keep his family supplied with food and clothes. He is struggling to give his children an education and at the same time to pay off the mortgage on the farm and to save enough to keep his wife and himself from want in their old age. All around him are those who are waging the same battle, but they give him little help. Each one fights alone, as his father did before him.

Twelve years ago Farmer Smith had a $5,000 farm. It yielded him an income of about $500. That was a return of 10 per cent. Today, because of the general rise in land values, that farm is worth $10,000. It yields him about $700. It is now only a 7 per cent investment. His profits have decreased. Moreover, his land is poorer than it was twelve years ago. Smith never learned how to farm intensively. He knows only the crude methods used by his father in the days of virgin soil. The years ahead give him no promise that he will be able to make even as much from his farm as he is making now.

The economic pinch has left its marks upon his social life. Many of his old neighbors have sold their farms and moved away. Some have left their farms in the hands of tenants who are robbing the land of its fertility. Community spirit has vanished. The old forms of recreation have lapsed with the passing of the settled population. No new forms have taken their place except in the towns, and these are usually of a character that would not be tolerated in the country. Smith’s boy is waiting his first opportunity to get off the farm. His has been a life of all work and no play, and while it has not exactly made him a dull boy, it has made him hate farming. Smith’s wife is leading the life of a drudge, and she swears her daughters are not going to live on the farm if she can help it. With the stagnation in social life has come stagnation in moral and religious life, for morals do not flourish in a stagnant community.

Yes, Smith needs help. He needs to know how to farm more scientifically. He needs a better income. He needs to know how to organize with his fellow farmers to protect themselves against the inroads of the middlemen and the tenants. He needs better markets for his crops and better transportation facilities to those markets. He needs a school for his children that will give them as good an education as they would get in any city school, a school that will instill in them a love of the country, a knowledge of farming and an appreciation of its economic significance. He needs more recreation facilities for the whole family. He needs a handier kitchen for his wife and daughter and many more opportunities for them to broaden their lives and enrich their minds in literary and social activities.

The question is, Should the church give it? Should it go to Farmer Smith and say:

“Smith, I am a bit ashamed of myself; I have not been doing for you what I ought. I have been preaching about Elysian fields and allowing the riches of bluegrass, corn and wheat fields to be squandered with prodigal hand; I have been trying to pave your road to Glory Land, but I have paid no attention to your road to the nearest market; I have talked about mansions in the skies and cared little about the buildings in which you and your family must spend your lives here and now; I have been teaching your children God’s word in the Bible, but I have left his word in the rivers and the hills, in the grass and the trees, without prophet, witness, or defender.

“Forgive me, Smith; I am not going to do it any more. I am going to take an interest in your every day affairs—your crops, your stock, your markets, your school, your lodge and your recreations. I am going to see if I can help you in your effort to get your boy started on a farm[Pg 244] of his own. I’ve preached a long time against Sunday baseball; now I’m going to try to give your children so much recreation through the week that they won’t care for it on Sunday. I am going to take as one of the articles of my creed, ‘I believe in better roads for Smith, and I propose to have them.’ I am going to try to save you and your family not only for Paradise, but for America and American farms.”

Should the country church take its place shoulder to shoulder with Smith in the line in which he is battling for existence? Should it take up the task of encouraging agricultural organizations that will work for more scientific farming, better roads and better markets? Should it throw open its doors, not three hours a week but three hours a day, to Smith’s sons and daughters that they may have a place to meet and to play and to mingle with each other in literary, athletic and social activities? Should the church forget all about itself and its creedal and polemic differences? Should it forget its own salvation in its effort to save Smith? Should it lose itself in his service, even if some churches have to die in the attempt, as long ago their Master died?

Should it?

JOHN R. HOWARD, Jr.

General Secretary Thomas Thompson Trust

The rural leader, whether his interest is primarily in the church, the school, good roads, health, wholesome recreation or the care of the neglected, must, if he would get anywhere, be interested, also, in better farming. For one reason, there is no better way to obtain the interest of the farmer. Then, too, a normal standard of health, intelligence or morals depends, in the country as in the city, upon a normal standard of living. Finally, the socialized church, the vocationalized school, good roads, sanitation, community play places, experienced advisers for family problems all cost money, and the majority of our rural townships are taxed already to the limit of endurance.

The “county man” is the man the United States Department of Agriculture is sending into the counties of the North, not only to make two blades of grass grow where one grew before, but to help the farmer earn two dollars where he earned one before—quite a different proposition. This entails not only scientific choice and treatment of crops, but co-operative buying of fertilizers and feed and co-operative marketing of products. Further, this “county man,” who is helping the farmer to double his dollars, has a rare opportunity to work out with him the problem of spending them and will prove to be a vital factor in the promotion of any of the ends of community betterment.

That the government requires the formation of a county organization to direct the work and to finance it, beyond the $100 a month allowed by the government toward the agent’s salary, establishes at the outset a co-operative county agency through which other work may be taken up. It is the intention of the government to encourage all purposes looking to a better country life.

There are 127 of these men now in the field. They are serving in twenty-three different states. The unfulfilled applications number 276. In January the number was but sixteen although fifty-nine more had been promised. This shows how eager counties throughout the country have been to take advantage of this important new service. Rural leaders should urge the establishment of this service in their counties, encourage it when started, and, whether the initial organization be an agricultural association or an improvement league, be ready to make use of it for the social and educational as well as the agricultural needs of the county.

PHILIP WELTNER

The second Southern Sociological Congress came to a close on the night of April 29. Its four days were given over to solid criticism and constructive suggestion. Eight hundred delegates gathered together from all over the Southland to learn from the ninety-six specialists the congress brought to Atlanta. Most of the ninety-six were men and women of the South.

One fact the Congress made plain enough, and that was that the South knew its problems and was busy about their solution. Those present seemed to realize that they were the empire builders of a new South. While the questions coming before the several conferences were the same as those that confront the North and West, they were treated from the standpoint of the peculiar needs of the South. But this was done without the slightest sectional consciousness. The South was taking counsel of itself that the entire nation might profit by its advance. Although the field of the congress was sectional, its outlook was national.

The plan of organization followed was much the same as that of the National Conference of Charities and Correction. There were seven special conferences gathered under the name of the Southern Sociological Congress. Each was separately organized and met with the other divisions only in the general night session. The seven divisions were: organized charities, courts and prisons, public health, child welfare, travelers’ aid, race problems and the church and social service.

The latter was an innovation with the Southern Sociological Congress. It served to emphasize the fact that “the church is the fellowship of those who love in the service of those who suffer.”[Pg 245] The discussions in this conference all served to bring out in sharp relief the new spirit beginning to dominate the old church. It was agreed that the social worker who can satisfy only the bare material needs of life is poorly equipped for his task, that religion must lend its strength to every effort towards individual or social reconstruction, and that the call of the church is a call to service.

The individual conference that enjoyed the greatest popularity was the one on race problems. Throughout its four days of almost continuous session there were in attendance about 400 persons, half white and half colored. Some of the Negro delegates, fearing an unjust discrimination against those of their race in the conference sessions, had prepared, while on the way to Atlanta, resolutions of protest. These were never tendered. No reason was intruded for their presentation. One of the Negro delegates expressed the situation most aptly. He said:

“The old order of whites understood the old black man. But it has remained for this Congress to demonstrate the possibility of the young white men of the new order sympathizing in and appreciating the hopes and aspirations of the Negro of today.”

Too great a significance can not be attached to this simple statement of fact. Its optimism is the culture-soil out of which we may expect to see develop that happy adaptation of the two races, which after all is the solution of the race problem.

This incident, and what it goes to show, would alone justify the existence of a southern congress separate and distinct from the National Conference of Charities and Correction. The peculiar problems that faced the conference on courts and prisons make this separate treatment even more desirable. In the South there are not many of those great central, highly organized penal institutions known as penitentiaries. For the most part we have county chain-gang camps engaged in road work. A distinct contribution was made to southern penology by Hooper Alexander, of Georgia, when he showed the absolute identity of the convict lease in Georgia with the system once known as the institution of slavery.

The conference discussion made clear the fact that the county convict road camp, prosecuted without a scintilla of effort at training or character building, is not less immoral than the old lease system; that the wrong of public exploitation is as great as exploitation at the hands of a private lessee.

The congress made a tremendous impression on Atlanta and the whole state of Georgia. Its influence will spread over the entire South. It served to quicken the civic consciousness of our people and to make them better acquainted with their common problems. It took the mask off sociology and unfrocked it of scholastic appearance. In pointing out our needs, the congress unified our aims and at the same time broadened our vision.

(In downtown New York)

JEREMIAH W. JENKS

Director of the Division of Public Affairs, School of Commerce, Accounts and Finance, New York University

New York University has added a chapter to the history of “town and gown” by opening a University Forum in lower New York. This has been held throughout the winter in the Judson Memorial Building in Washington Square, and its purpose has been to put the university at the service of people in New York interested in a thoroughly impartial discussion of questions of the day.

The purposes of the forum as announced last fall are to make the university a greater force in training students to perform the duties of citizenship, in helping citizens to understand the problems of government, and in making thinking men act and active men think. Public officials, business leaders, social workers, eminent authorities were asked to present important questions of government and industry and discuss vital problems of civic and commercial life.

The methods employed were somewhat different from those usually followed in public discussions. In order that the academic atmosphere of thoroughness, sincerity and impartiality might so far as possible be conserved without sacrificing at the same time the interest that comes from having questions presented by experts and from the stimulus of controversy, it was decided that each question discussed should cover three sessions. At the first session an able authority has presented one side of the question. If there were time, as has usually been the case in the hour and a half, the audience has questioned the speaker in order to bring out more fully the points made.

At the second session, a week later, the opposite side has been presented with similar questioning.

At the third meeting the director of the forum has enumerated briefly the most essential points made on both sides, giving his own judgment regarding their validity and the relation of the question under discussion to the public interest. In some instances where it has seemed desirable, he has supplemented the arguments presented in the discussion by points of his own in order to make the discussion as complete as possible. In this summary an effort has been made to present the questions as impartially as possible from the viewpoint of the public interest.

[Pg 246]

In addition to this, representative citizens from the audience have given in brief talks of not more than ten minutes each their own views. Sometimes these voluntary speakers have been students, sometimes citizens. So far as possible the names were learned in advance in order that the discussion might proceed in the nature of a debate with the two sides presented alternately. In these third meetings especially, the interest has chiefly centered. In two or three instances, notably perhaps in the consideration of woman’s suffrage and the closed shop, the discussion was most animated, not to say excited, but nevertheless the temper of university study and the desire, however heated the feelings, to reach the truth and a fair judgment was not lost.

The list of topics and speakers included:

The Control of Vice and Crime—

William J. Gaynor, mayor of New York; Arthur Woods, former deputy commissioner of police, in special charge of the investigation of Italian criminals and the white slave traffic.

The Relation of Government to Corporations—

Martin W. Littleton, member of the Congressional Committee on Investigation of Industrial Monopolies; Herbert Knox Smith, late United States commissioner of corporations in charge of the Investigations of the Standard Oil Company, the American Tobacco Company, the Meat Packers, the International Harvester Company, and many other of the great corporations.

Socialism—

Victor L. Berger, the first Socialist to be elected to Congress; Bird S. Coler, former comptroller of the City of New York.

Woman Suffrage—

Anna Howard Shaw, president National American Woman Suffrage Association; Mrs. A. J. George, organization secretary of the Massachusetts Association Opposed to Woman’s Suffrage.

The Open Shop versus the Unionized Shop—

John Kirby, president National Association of Manufacturers, and Joseph W. Bryce, president of the Trades and Workers’ Association of America; James O’Connell, president Metal Trades Department and vice-president American Federation of Labor, and C. G. Norman, ex-chairman Board of Governors of the Building Trades Employers’ Association.

The meetings seem to have reached the results sought in more than one way. They have been well attended both by students and public, although comparatively few students have registered and done the reading required and passed the examination in order to secure university credit. For those students, however, who entered upon the work seriously the course has been as severe both in the quantity of reading required, in the reports upon that reading and in the examination as the regular university courses, and students have expressed their appreciation of the interest as well as the value of the course. Similar expressions have come from citizens in numerous instances. There have been regular attendants from Manhattan, Brooklyn, the Bronx, Yonkers and also from New Jersey. Requests have been made for an extension of the forum to other boroughs and the matter is under consideration for the coming year. Inquiries have come from as far west as Kansas and Calgary in western Canada regarding the methods employed; and numerous requests for printed reports of the addresses and discussions have been received.[3]

The audiences in one respect at any rate seem to have lacked somewhat the university spirit of inquiry, having retained rather the normal human spirit of liking to hear views that agree with one’s own. It was noticeable, for example, that the people who came to hear the Socialist speaker were the Socialists coming to be flattered, and not the anti-Socialists coming to learn. Likewise, the anti-Socialist speaker was not listened to by so many Socialists as by those of his own opinion. Perhaps equally noticeable was this tendency to listen to speakers of their own side in the case of the discussion on woman’s suffrage. Surely it is to be hoped that in another year the academic spirit will have increased sufficiently so that each group will be equally anxious to hear their opponents, because it is, after all, primarily from those who differ from us that we learn, rather than from those with whom we agree.

CHARLES E. BEALS

Secretary Chicago Peace Society

The biennial gathering of the pacifist clans in the Fourth American Peace Congress at St. Louis, May 1-3, enabled those who attended the previous congresses (at New York in 1907, at Chicago in 1909 and at Baltimore in 1911) to gauge the direction and speed of the movement.

Like its predecessors, the St. Louis congress was initiated by the American Peace Society, which has been the national peace organization in the United States since 1828. Unlike any of its predecessors, the Fourth American Peace Congress was financed entirely by the local commercial association. The New York Congress had Mr. Carnegie for its god-father. The Chicago congress received material assistance from the Chicago Association of Commerce. The St. Louis congress was the first one the expenses of which were entirely underwritten by business men through a business men’s organization. This precedent will render easier the organization of future congresses.

In one respect the St. Louis congress was unique—in the official participation of Latin-American governments. This is not saying that this was the first congress in which ambassadors have taken part. Earl Grey, then governor general of Canada, Ambassador Bryce and the Mexican ambassador were notable figures at New York. Count von Bernstorff, the German ambassador, and diplomatic representatives of other nations were present at Chicago, and Minister[Pg 247] Wu Ting Fang was the most picturesque and popular visitor at the latter congress. Indeed the international session of the Chicago Congress may perhaps be reckoned as the most thoroughly international of the four congresses. At Baltimore a French senator and a Belgian senator were conspicuous figures. But the St. Louis congress was the first in which the ambassadors and ministers of the Latin-American nations sat as official delegates representing their respective governments. And the frank, honest, kindly message delivered by the Peruvian minister was welcomed by all lovers of truth and international justice. In fact the congress insisted that he should repeat his address at another session.

The two addresses most warmly applauded were those of Dr. Thomas E. Green and Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones, both of Chicago. Dr. Green, a wide traveler and popular Chautauqua lecturer, spoke in place of Secretary of State Bryan, and his address was a piece of oratory of the sort seldom heard in this scientific age.

Rev. Jenkin Lloyd Jones discussed the psychology of heroism. The writer recalls riding with Mr. Jones in Washington in 1909, when we were corralling speakers for the Chicago congress. Mr. Jones burst out: “I want some one to discuss the psychology of war. There will be plenty of discussion of international law and of the economic, moral and educational aspects of the peace problem.” Then and there the subject of Armaments as Irritants was assigned to the veteran social worker and militant pulpiteer. And his presentation of this subject before the Chicago congress (using the homely barnyard figure of de-horning cattle) was one of the most delightful and valuable contributions to that congress. At St. Louis he followed up this psychological investigation with his survey of heroisms. So human, so true to life, so morally prophetic, so shot through and through with first hand information gained in four years of service in the Civil War, so illumined with poetry and ripe literary culture was this address, that again and again the speaker was forced to bow in response to the prolonged applause.

There were not lacking men who “spoke by the book,” men who had participated in the Hague Conferences, senators and representatives, authors of books on international problems—men like former Vice-President Fairbanks, Dr. James Brown Scott, Senator Burton (president of the American Peace Society), Congressman Bartholdt (president of the congress), Congressman Ainey, Dr. Benjamin F. Trueblood (for over a score of years secretary of the American Peace Society), Prof. Paul S. Reinsch, Prof. W. I. Hull, Dean W. P. Rogers; the United States commissioner of education, Dr. Claxton; college presidents like David Starr Jordan, C. F. Thwing, S. C. Mitchell, A. Ross Hill, Laura Drake Gill, Frank L. McVey, Booker T. Washington, and others; business men like Andrew Carnegie, Leroy A. Goddard, J. G. Schmidlapp and Eugene Levering; the secretaries and directors of various peace offices from Bunker Hill to the Golden Gate; the official head of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, Mrs. Pennypacker, and her predecessor, Mrs. Phillip N. Moore, under whose administration was created the peace department of the women’s clubs. British America was represented by such distinguished men as Hon. Benjamin Russell, justice of the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, and John Lewis, editor of the Toronto Star.

In connection with the congress inter-collegiate oratorical contests were conducted, the coming Hundred Years of Peace Celebration described, special church services held, and social courtesies bestowed through receptions and dinners.

Should one ask what is the most characteristic feature of the peace movement in 1913, perhaps it might truly be said that pacifism more and more is being formulated into a science. The organized peace movement began ninety-eight years ago purely as a moral reform. It is no less a moral reform today. But it has accumulated a vast amount of historic, economic, juridical, biological and general sociological data.

When one considers the movement of the human animal from the day of the man whose bones recently were dug up from the Sussex gravels; when one measures the progress of human beings from cave-dwelling to Universal Postal Unions and Hague Conferences and Courts; when one notes the marked decrease in the number of wars, the total abolition of private war, the almost revolutionary mitigation of war practices (so that today one finds it comparatively comfortable to “get his living by being killed”); when one remembers that the world is beginning to think in economic terms; when one examines the beginning already made towards the substitution of judicial procedure for fist law; when one counts up the half hundred things actually being done officially by governments acting internationally; when one perceives that the man animal is specializing in two things—rational thinking and morality—then one can easily believe that, having so progressed from jungleism towards internationalism, the race probably will not stop now and here.

Direction and distance are prophetic. Only by some unforeseen and catastrophic and utter extinction of the human species can man escape his blessed and inevitable and rapidly approaching terrestrial destiny of organized pacifism and world-wide scientific and industrial co-operation. The tiny mountain rill of pacifism has become an ocean-seeking river, on whose mighty current the war-afflicted human race is being borne on towards the ocean of a real civilization.

[Pg 248]

[1] See The Survey for March 30, 1912.

[2] See The Survey for May 10, page 212.

[3] It would be desirable if a sufficient number of persons interested would contribute so that it would be practicable to print in full the discussions, properly edited with bibliographies and notes, so as to make a really authoritative booklet on the questions under discussion.

By H. G. Wells. B. W. Huebsch. 61 pp. Price $.60;

by mail of The Survey $.65.

This is a small book, sixty-one pages of large type, containing an address delivered at the Royal Institution in England. But the value of the publication is out of proportion to its size. Here is the abundant Wells literature of the last two decades in a compact and highly concentrated extract form. And this means, as every lover of this English author will know at once, a wealth of suggestive speculation and stimulating idealism.

The thesis of the book is that we now have the materials in hand for a systematic and accurate “exploration of the future.” There is no reason why we should not be able to forecast the future development of society, by a critical study of operative causes, as definitely as we now reconstruct the past conditions of the race by a critical study of the geological and archeological record. What the scientist now does in the fields of physics or astronomy, we ought to be able to do just as easily in the field of social life. “Suppose,” says Wells, “that the laws of social and political development were given as many brains, were given as much attention, criticism and discussion, as we have given to the laws of chemical combination, and what might we not expect?” Here, evidently, is the philosophical justification of The War of the Worlds, Anticipations, The Future in America, New Worlds for Old, and many another fascinating volumes from Wells’ pen which might be mentioned.

This thesis, however, constitutes only a part of the book’s abundant material. A keen psychological discussion of the two divergent types of mind, the forward-looking and the backward-looking, into which all men may be divided; a passing glance at the pragmatic standard of “it works”; a survey of the great-man theory versus the economic theory of social determinism; an incisive critique of positivism; a bold and eloquent prophecy of the future destiny of man upon this planet—here are only a few of the “extras” which are contained in this distillation of the Wells philosophy. About as good an example of multum in parvo as I have ever seen!

John Haynes Holmes.

By Hugh H. Lusk. Sturges & Walton Co. 287 pp.

Price $1.50; by mail of The Survey $1.62.

Looking back as an old man upon the record he himself has helped to shape, Hugh H. Lusk, in his Social Welfare in New Zealand, points out the significance, particularly for the United States, of that method of government which he calls State Socialism. Nothing so annoys New Zealanders as the ever-recurring criticism that their experiments have been carried out upon too small a scale and under conditions too unusual to be of value to the great remote countries whose single cities contain more people than the whole dominion of New Zealand. Yet doubters still will question, and standpatters will refuse to be moved, by this account of actual accomplishments. He who is not blind, however, to the evils which have followed private profit in public utilities, and who has seen governments conferring special privileges upon the few at the expense of the many, as he turns here again to New Zealand may well find inspiring faith in the ability of a whole people to legislate toward the common good.

Mr. Lusk shows how in New Zealand, government-built railroads became a necessity in a sparsely settled country where private capital would not venture, and how an extensive scheme of legislation for the benefit of settlers on the land was forced upon a people whose appetite for mutual help grew with what it fed upon. Each piece of legislation had in view no more than the meeting of a definite difficulty as it arose. Yet step by step New Zealanders went on in the same direction, until they had reached the point where, somewhat to their own surprise, they found themselves famous and envied in the world at large. Some of that surprise is due to the fact that politics, even as we know them here, are there recognized to have played an important part in shaping the destinies of those islands. “Dick” Seddon and his followers appreciated to its full, the vote-getting value of land reform, progressive taxation and public improvements. Mr. Lusk makes too little of this significant lesson from New Zealand.

And by one who understands the “States” so well, and who is writing for our encouragement and warning, it is surprising that more emphasis is not placed upon methods of administration. To me, as I came to appreciate the New Zealand civil servant, his integrity, his ability, the esteem with which he is held, it always seemed that in him more than anywhere else was to be found the secret of such success as New Zealand has attained. Turn the present corps out and put in such incompetents and grafters as we have in many of our state departments in America, and the whole New Zealand structure would come tumbling down immediately. Not until law and public opinion make it possible, can we have here such administration of labor laws, for instance, as Edward Tregear has given these many years to New Zealand, and not until then will new labor laws be of much more avail to us than old ones are now.

Mr. Lusk’s moral is, “Go thou and do likewise.” By law prevent the accumulation of inordinate riches and provide for the general diffusion[Pg 249] of the sum total of prosperity. But when we find that, putting the best construction upon available data, the definition of a man or woman not in receipt of an income of more than $975, “in New Zealand, practically includes all classes and persons engaged in laboring or mechanical pursuits as well as junior clerks or school teachers,” we wonder, after all, whether New Zealand’s road is the one for others to follow. There is many and many a man and woman in that country to whom $975 a year is undreamed of comfort. If this is all that reform can do under the best of circumstances, is this particular game worth the candle? The New Zealand worker just now is saying rather vociferously that it is not. There lies the real hope for reform, that it does not stop, even though it falters. The final lesson from New Zealand is beyond what we are here told. Surely it is that those who will may preach reform and State Socialism to their hearts’ content, but that the workers of other countries must not imitate the mistakes of their New Zealand brothers, neglecting political and industrial organization and leaving it to others to decide what is the public welfare.

Paul Kennaday.

By Edward F. Croker. Dodd. Mead & Co. 354 pp.

Price $1.50; by mail of The Survey $1.

Fire Prevention, by Edward F. Croker, formerly chief of the New York Fire Department for almost twelve years, is a presentation of the principal safeguards against loss by fire. In it ex-Chief Croker tells in a readable way what, from his long experience as a fire fighter, he considers the most effective ways to extinguish fires.

Most of all he emphasizes the necessity of preventing fires. “If I had my way about it,” he says, “I would not permit a piece of wood as big as a man’s finger to be used in the construction of any building in the United States which had a ground area larger than twenty-five by fifty feet and was more than three stories in height.” He calls attention also, to a point which has been emphasized many times when he declares that “it is not so much the buildings which should receive added protection but the contents and the inmates of them. We must add to the term ‘fire-proof,’ the terms ‘death-proof’ and ‘conflagration proof.’”

Perhaps to a lay reader to whom some of the intricacies of steel construction, high pressure, and fire-fighting apparatus are not plain, the most interesting chapters are those which deal with housekeeping whether in the home, store or workshop.

In his chapter on Prevention of Fire in the Dwelling, Mr. Croker gives a number of simple suggestions which would prevent most of the thousands and thousands of fires in the 11,000,000 wooden buildings in this country and save a financial loss which in two years equals the cost of the Panama Canal. Concerning these suggestions there can be little disagreement, although those which he makes for additional laws may not win as unanimous support.

James P. Heaton.

By Ernest K. Coulter. McBride, Nast & Co. 277 pp.

Price $1.50; by mail of The Survey $1.62.

By Elizabeth McCracken. Houghton Mifflin, Riverside

Press. 191 pp. Price $1.25; by mail of The Survey

$1.35.

To gain the sympathetic and accurate knowledge of children shown in his book, Mr. Coulter stood on the reviewing stand for ten years. His was the eye to see and the heart to feel from the first, but as clerk of the Children’s Court in Manhattan for ten years he had the unique opportunity of looking into the faces of a procession of 100,000 dependent, neglected and delinquent children as they filed by the judge and told their stories.

These stories he often verified in alley, street, tenement, station house, reformatory and prison. He shows how crowded streets, lack of play space, poverty, sickness, insanitary houses, criminal companions and parental neglect provide a fruitful soil in which to breed neglected and delinquent boys and girls. These conditions he charges to the greed of individuals and to the careless, neglectful indifference of society.

As a means of helping individual boys who need the personal touch of a friend right now, Mr. Coulter started the Big Brother Movement, which is spreading all over the country. His permanent remedy for the woes of children, however, requires not only the love of Big Brothers, parents and friends, but also sanitary houses, good food, playgrounds, fresh air and sky. Mr. Coulter’s pen pictures of Children in the Shadow challenge us all not to rest until all such children are brought out into the sunlight.

Miss McCracken’s book is a reprint of articles which originally appeared in the Outlook, and deals with actual children and parents of rather exceptional intelligence in both city and country. What these exceptional American parents do for their children in home, play, school, library and church is told in such a way as to appeal to and educate parents who are not exceptional.

What children do for their parents is also set forth. The real message of the book is that the reciprocal relation of children and parents can be and should be one of the most beautiful and helpful that this old world knows. The title might have been True Stories of Parents Who Knew How to Live with Their Children.

Henry W. Thurston.

By James Ford. Introduction by Francis G. Peabody.

Russell Sage Foundation Publication, Survey Associates,

Inc. 300 pp. Price $1.50, postpaid.

Individualism is generally assigned as the primary cause of the failure of co-operation to gain a more extensive foothold on American soil. But to the student of the subject this off-hand explanation is far from conclusive. For not only have Americans been the leading exponents of political, social and religious co-operation, but they have likewise shown marked aptitude for economic co-operation. Our very[Pg 250] national life is purely co-operative. Our big business is, though not in a strict sense, in a large sense co-operative. Furthermore, were the traditional American individualism the sole or even the main cause, why has co-operation in this country met with no wider acceptance or greater success among the immigrants coming from countries where co-operation is practiced to a very high degree? We must therefore look for other reasons to account for the bankruptcy of co-operative effort in this country. These are set forth by Dr. James Ford in his book Co-operation in New England.

The first co-operative movement in the New England States, the New England Protective Union stores, began in 1845 and ended in 1857. The second movement, the Sovereigns of industry, which was launched in 1874, had an equally brief history. The first had at one time as many as 700 stores, of which but two remain; while five are left of the 280 of which the latter movement once boasted. At the present time urban co-operation is practically confined to immigrants, largely non-English speaking. Their efforts have not met with much greater success than those of New England’s native sons. All told, there are about sixty co-operative stores throughout New England. Most of them are too young, too small, and too isolated to be dignified as a movement.

The meagre results of distributive co-operation are only exceeded by those of co-operation in manufacture. All effort in that direction has been abortive, and “true co-operative production does not exist in New England.”

The author finds greater cause for encouragement in rural co-operation. “The farmers’ movement,” he says, “which is much more influential in the industrial world, not only penetrates, by means of co-operative creameries, almost every township of western New England, but through association for co-operative sale extends to many other large territories.” Co-operation among farmers consists of co-operative buying of supplies, co-operative marketing of products, and co-operative production in the way of butter and cheese making. He estimates the number of more or less co-operative creameries throughout New England at 125, although probably not more than twenty-five of these are purely co-operative. “There are many indications today,” continues the author, “that rural New England has reached a point not only desirable but increasingly practicable.” With a large American commission now abroad for the special purpose of studying agricultural co-operation, it is to be hoped that this movement will be accelerated.

The really important part of Dr. Ford’s hook is his discussion of general co-operative principles. The economic conditions for successful co-operation are wanting in this country. People will co-operate either because they are driven to it by necessity, as is the case in Europe, or because they see in it special inducement to make it worth their while. Unfortunately, or rather fortunately, these conditions do not exist in the United States so far. In a country where every workingman carries the baton of a captain of industry in his dinner pail, it is not surprising that he will not set aside the opportunities of individual effort in favor of the uncertain, remote, and, at best, meagre returns of co-operative endeavor. All other reasons, such as the mobility of our population, our improvidence, and our lack of co-operative spirit must give way before this one fundamental reason.

The conditions that are responsible for the heavy mortality of co-operative enterprises in this country are rapidly changing. The obstacles in the way of co-operative success are gradually disappearing. Once the point is reached in New England as it has been abroad, at which societies of like interest federate for educational and trade advantage, these smaller federations “will in turn unite in a general co-operative union with common funds to sustain societies that are weak, and promote development on lines of common importance, an immense force will be set at work for the moralization of trade, the reduction of the cost of living, and the socialization of the people.”

As the title indicates, the book deals only with co-operation in the New England states. The author further limits his research to “associations for the production and distribution of the immediate necessities of life.” Notwithstanding this limiting of the inquiry both in scope and extent the book should prove of value to the student of co-operation in this country. The facts have been painstakingly collected. The author’s insight is keen and penetrating, his deductions are clear and logical, and his hopeful tone is most invigorating.

Leonard G. Robinson.

By A. Conan Doyle. George H. Doran Co. 103pp.

Price $.50; by mail of The Survey $.57.

The case of Oscar Slater, sentenced in the High Court of Edinburgh to life imprisonment for the murder of an old lady in Glasgow, was some time ago brought to the attention of the famous writer of detective stories, together with certain circumstances which cast doubt on Slater’s guilt. With a sincere desire to clear the man, the creator of Sherlock Holmes set to work to examine the evidence and testimony presented at the trial, and to analyze the conduct of the case and the decision of judge and jury.

The result is a convincing argument for the man’s innocence of the offence for which he was convicted and an arraignment of the ineffective methods of the police who were engaged in the investigation, both in Scotland and in this country.

The undeniably bad character of the suspect created so strong a presumption of guilt that even the total refutation of the strongest piece of evidence and an obviously false accusation by the judge in his final charge, secured only a commutation of the death sentence to life imprisonment when an appeal was made.

It will be interesting to know whether the detective knight’s efforts toward securing justice meet with success.

May Langdon White.

[Pg 251]

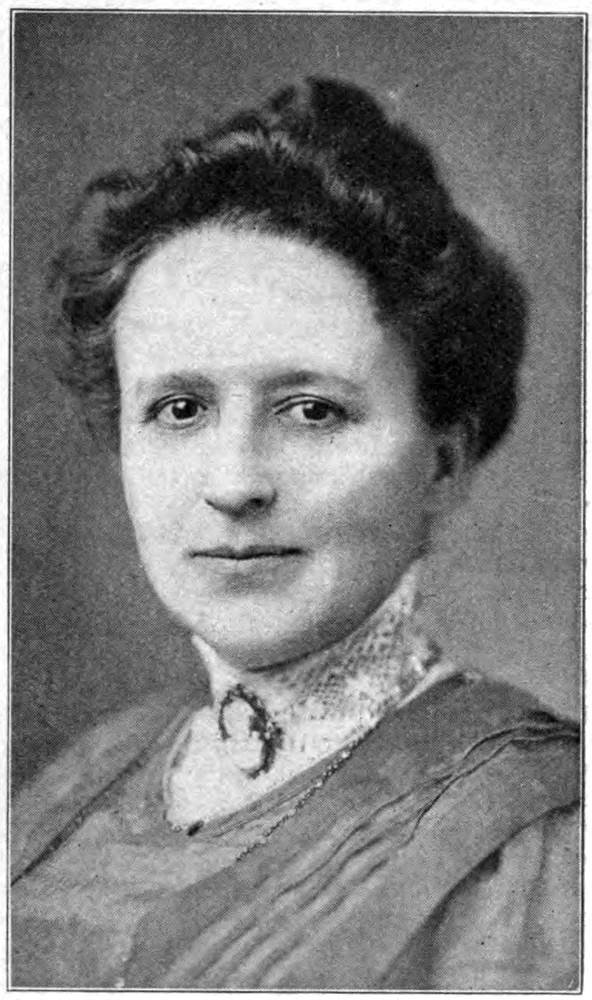

The first woman judge of delinquent girls sits on the bench in the Chicago Juvenile Court. She is Mary M. Bartelme, a Chicago lawyer. Previous to her present connection she was for eighteen years public guardian of Cook County, acting in this office, in the words of the Continent, as “official mother to hundreds, perhaps thousands, of children” who had no other parents and whose persons or estates were in the care of the court. Guardianship of their persons meant actual custody and education, and this for a period of many years; it meant also in many cases interest and love for the child and always, in the tangled relations of life, an understanding of human nature, as well as a thorough knowledge of the institutions best fitted for special cases. All this experience has thus been excellent preparation for Miss Bartelme’s present delicate task of reconstructing the lives and characters of delinquent girls.

MARY M. BARTELME

Up to the time of her appointment cases of delinquent girls were heard, like those of boys, in open court. The effect is thus described by Judge Pinckney of the Chicago Court, whose assistant Miss Bartelme is:

“The delinquent girl, unlike the delinquent boy, is generally brought to court for some sexual irregularity. This means that the story of her shame and downfall is told openly, publicly. There are often present at such times curiosity seekers, sensation hunters, and now and then among the latter, I am sorry to say, are newspaper reporters looking for a story. Frequently the name of the girl, the names of her parents, of her brothers and sisters, and her home address appear in the newspapers, with all the harrowing details of her trouble. She is fortunate if her picture is not surreptitiously taken for publication.

“After such an exploitation of her trouble, you tell the unfortunate child that you want to do something for her—you want to help her. Is it any wonder that she does not readily respond to the proffered aid? Her feelings shocked, her sensibilities blunted, her sense of justice outraged, she is more apt to refuse than accept your suggestions for her future welfare. To my mind this procedure is unnecessary, is wrong, is barbarous. Even under the most favorable conditions possible to a public hearing, it is difficult to get into sympathetic touch with the child so that she will be in a receptive mood and willingly amenable to helpful suggestion and treatment.

“The plan proposed is to have the case of each delinquent girl heard by a woman, who shall act as the representative and assistant of the presiding judge. To this woman assistant, in the presence of the girl’s father and mother, the witnesses will tell the girl’s story. Every consideration will be shown the girl and her family. In so far as it is possible to do so, this darkened page in their lives will be guarded from the public gaze.

“It is believed that these delinquent girls will the more readily unburden their souls to one of their own sex, and especially if allowed to so do out of hearing of the public and surrounded by father and mother and those in sympathy with her and them.

“This is the all-important work for delinquent girls which Mary M. Bartelme is expected to do—will do. She is the unanimous choice of the judges of the Circuit Court for the position of assistant to the judge of the Juvenile Court.”

At the recent annual meeting of the Society of Sanitary and Moral Prophylaxis, Dr. Edward L. Keyes, Jr., was elected president, to succeed Dr. Prince A. Morrow, founder, and until his death the head of the society.

Dr. Keyes is a charter member of the society and was for many years its secretary. He has also been a member of the Executive Committee, and worked in close touch with Dr. Morrow. Dr. Keyes is a professor at the Cornell Medical School and president of the American Association of Genito-Urinary Surgeons.

Professor Maurice A. Bigelow of Teachers’ College, Columbia University, and Dr. Rosalie Slaughter Morton were elected to fill the vacancies in the Executive Committee. Mr. Marshall C. Allaben of the Presbyterian Board of Home Missions was chosen chairman of the Executive Committee.

[Pg 252]

The Italian Club of New York is an interesting center. In the low-ceilinged basement opera singers, art importers, physicians, orchestra leaders and the like rub elbows at the club tables.