The Project Gutenberg eBook of The feather symbol in ancient Hopi designs, by J. Walter Fewkes

Title: The feather symbol in ancient Hopi designs

Author: J. Walter Fewkes

Release Date: April 15, 2023 [eBook #70555]

Language: English

Produced by: Robert Tonsing and The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Although the prehistoric Indians of Tusayan have left no written records in the forms of books, documents, or codices, there survives from their time a most elaborate paleography which has been preserved on imperishable material in the dry soil of Arizona for several centuries. This paleography is a picture writing, often highly symbolic and complicated, but from it the student can obtain an idea of Hopi thought and its expression at that remote time. It reveals phases of ancient life which have been modified or lost in the subsequent development of the race.

The most abundant of all objects found in the ruins scattered over the Southwest are fragments of pottery, and if the cemeteries of these ancient habitations are excavated large collections of decorated bowls, vases, and jars may be had from any ruin of considerable size. The majority of these fragments of pottery from Tusayan are richly decorated with designs, some of which are very complicated. The figures represented in this ornamentation are often realistic, but many are highly symbolic and conventionalized. It is an object of the present article to discuss one symbol of the latter group, and for this purpose I have chosen the feather, which, through its metamorphosis in form, is one of the more difficult to recognize.

Before passing to a consideration of the feather in ancient Hopi symbolism, it may be interesting to note that very few of the figures with which pottery from pueblo ruins is decorated have been interpreted, and we may say that the study is as yet in its infancy. The ancient Tusayan ware bears several designs of a simple, geometric shape, which are widely distributed over the2 whole Pueblo area of the Southwest. So far, however, as my knowledge of ancient Pueblo paleography goes, the symbols of the feather as here indicated are confined to ruins of villages which are purely Hopi in origin, although they may later be found elsewhere in Arizona or New Mexico.

I have shown in several previous publications on the ceremonials of the Hopi ritual the significant part which the figure of the feather plays in the decoration of altars and ceremonial paraphernalia, but I am unaware that any one has yet called attention to the very important use of the feather symbols in the decoration of ancient Hopi ceramics. A pottery ornamentation has a religious intent, and, since from its presence as a decorative element there is every reason to believe that the feather in ancient times held much the same position in the ritual as at present, it is instructive to trace its many variations as a symbol.

While what is here written is drawn more especially from the paleography of Sikyatki,[1] it is true, likewise, of that represented in all the Tusayan ruins where yellow ware is abundant. I might instance examples from old Cuñopavi, Kisakobi or Old Walpi, and Old Micoñinovi. It does not, however, hold in all particulars when we study the red ware characteristic of the ruins along the Little Colorado river, where the feather takes another symbolic form not fully discussed in the present article. It applies to representations of the feather as depicted on altars now in use in Tusayan, symbols of feathers on dolls and ceremonial paraphernalia used by people who are lineal descendants of the inhabitants of the ruined pueblos mentioned above. The ruins of Sikyatki lie about three miles east of Walpi, and the pueblo of which they are the remains was destroyed previously to the middle of the sixteenth century.

I have grouped all the striking modifications in bird and feather symbols in close approximation in an installation of the more instructive pieces of pottery from Sikyatki in the National Museum, at Washington, and the reader may there find a larger series illustrating ancient Hopi paleography than has ever before been displayed. A forthcoming report[2] of the Bureau of American3 Ethnology, under the auspices of which institution these objects were collected, will describe these variations in detail, and as this report is elaborately illustrated, the reader will soon have abundant published material from which to study modifications of the feather symbol in ancient Tusayan.

We have no difficulty in recognizing among the many figures of animals which the ancient Hopi potter depicted on her wares the great group to which any one belongs. Four-legged animals of two kinds, frogs and lizards, are readily separated from mammals; apodal reptiles or snakes are easily distinguished from both, and there is no difficulty in separating the moth or butterfly from the spider or dragon-fly. The great group to which the animal depicted belongs is not difficult to discover, and from a large series of related designs one may trace quite readily the changes in form which have resulted in highly conventionalized modifications.

The most constant group of animals chosen for realistic or symbolic representation on ancient Tusayan ceramic ware is that of birds. More than two-thirds of all the pictographs on ancient pottery where animals are intended represent avian forms. The modifications which these figures pass through as they become conventionalized likewise exceed in number and variety those of any other animals, and a comprehensive study of the different symbols representing birds would be a most interesting and instructive one. This study is important as a ground-work for the following conclusions, for in no other way can we identify as feathers some of the highly modified symbols which are here considered. An adequate discussion of different forms of birds in ancient designs would necessitate more pages of text and illustrations than could here be devoted to it. If my conclusions seem hasty, I must ask the reader not to reject them without examining collateral evidences which I have elsewhere presented.

The ancient Hopi decorator not only represented birds in many more different shapes than she did other animals, but even decorated other animals with feathers in accordance with ancient traditions. Nor did she stop with animals; symbolic figures of the sun or the lightning or the rainbow have symbols of feathers attached to them, and this, to us incongruous, association is often essential to indicate the symbol. This predominance in the number of pictures of feathered gods is a faithful4 reproduction of denizens of their ancient Pantheon. The majority of the gods were avian in character, even when anthropomorphic.[3] Several animals, as mythic lizards, snakes, and even mammalian forms, are represented in ancient pictography, furnished with crests of feathers on their heads. These are drawn in this way in conformance with ancient legends, and, with traditions to guide us, we have little difficulty in determining some of the symbolic forms which the feather takes in pictography. This method is used by me as corroboratory evidence in determining the prescribed symbols of feathers which have been previously identified by their relative positions on the bodies of birds.

It is plain, I think, that having determined from an avian figure the form of the organs and appendages of the bird in their different modifications, due to conventionalism, we are able to recognize the symbolic forms adopted by ancient artists to represent the feathers of wing, tail, or body. If figures of feathers were so well drawn that we could identify them as such, we would have no difficulty in recognizing a feather when drawn on a fragment of pottery, where no other part of a bird was represented. An accurately drawn feather in such cases would be easily recognized; but the feathers made by the ancient Hopi decorators of pottery were not accurate representations—they were symbolic. The only way we can identify them is by association. Having determined the head, body, legs, tail, and wings of an animal which must be a bird, we examine the separate components which form the tail and conclude what part represents a tail feather. We use, in other words, the morphological method of determining the homologies of organs and appendages which we borrow from naturalists and apply to pictographs.

Having thus determined the symbol of a tail or wing feather from their positions in representations of birds and fixing in the mind its form, we are able to recognize it where it reappears, isolated, or in new combinations. While this way of determining the feather symbol was the method adopted, there was brought to its aid likewise the testimony of living priests, among whom knowledge of some of the ancient symbols still survives. This latter aid to a comprehension of the symbols of ancient paleography5 is valuable, so far as it goes, but it does not take one long to discover that it is limited in its application. Many ancient designs are incomprehensible to living Hopi priests, and their interpretations are in some cases simply conjectural. The decay in knowledge of the meanings of old symbols is due to the fact that most of the ancient symbolism has been replaced by the modern.

In their drawings of animals the ancient Hopi artists were often far from realistic. They violated many fundamental rules in perspective. This is well illustrated in profile figures. It often happens, for instance, in delineating the head of an animal, as seen from one side, that both eyes are represented. The feathers of a bird's tail, normally on a horizontal plane, are brought into a vertical. Internal organs which are hidden from sight are sometimes represented—a characteristic of modern Pueblo art, where, as in pictures of antelopes, it is not uncommon to find the heart and œsophagus, or even the intestinal tract, drawn as if the animal were transparent. In a figure of a bird shown on plate LIX in my preliminary account of Sikyatki, where the artist apparently had no available space in which to represent the extremity of the tail, it is bent upward, and the tips of three feathers conventionalized into three triangles, one of the symbols of wing feathers, as elsewhere shown.

In their simplest forms figures of birds are crudely represented, consisting of a head with curved beak and elongated body, which is continued backward into three or four parallel lines, representing tail feathers.

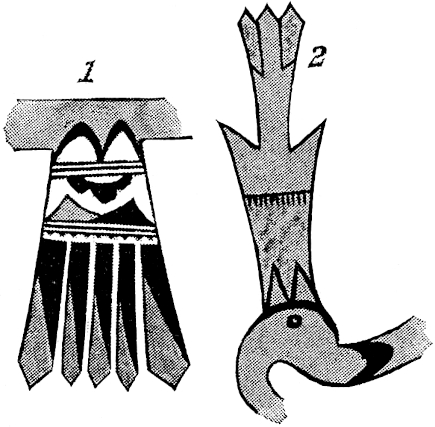

It is an instructive fact that three[4] seems to be the predominating number of tail feathers in pictures of birds, as seen in the clusters of symbolic feathers, f, in the richly decorated vase a part of which is depicted in figure 5. This number, however, is not universal, for there are many well-drawn figures of birds with more than three tail-feathers, and in some of the simpler forms there are but two. Certain jars in the form of birds have the wing and tail feathers represented by parallel lines, and the same bands are often employed on the bodies of dolls to represent a feathered garment which some mythological personages are reputed to have worn.

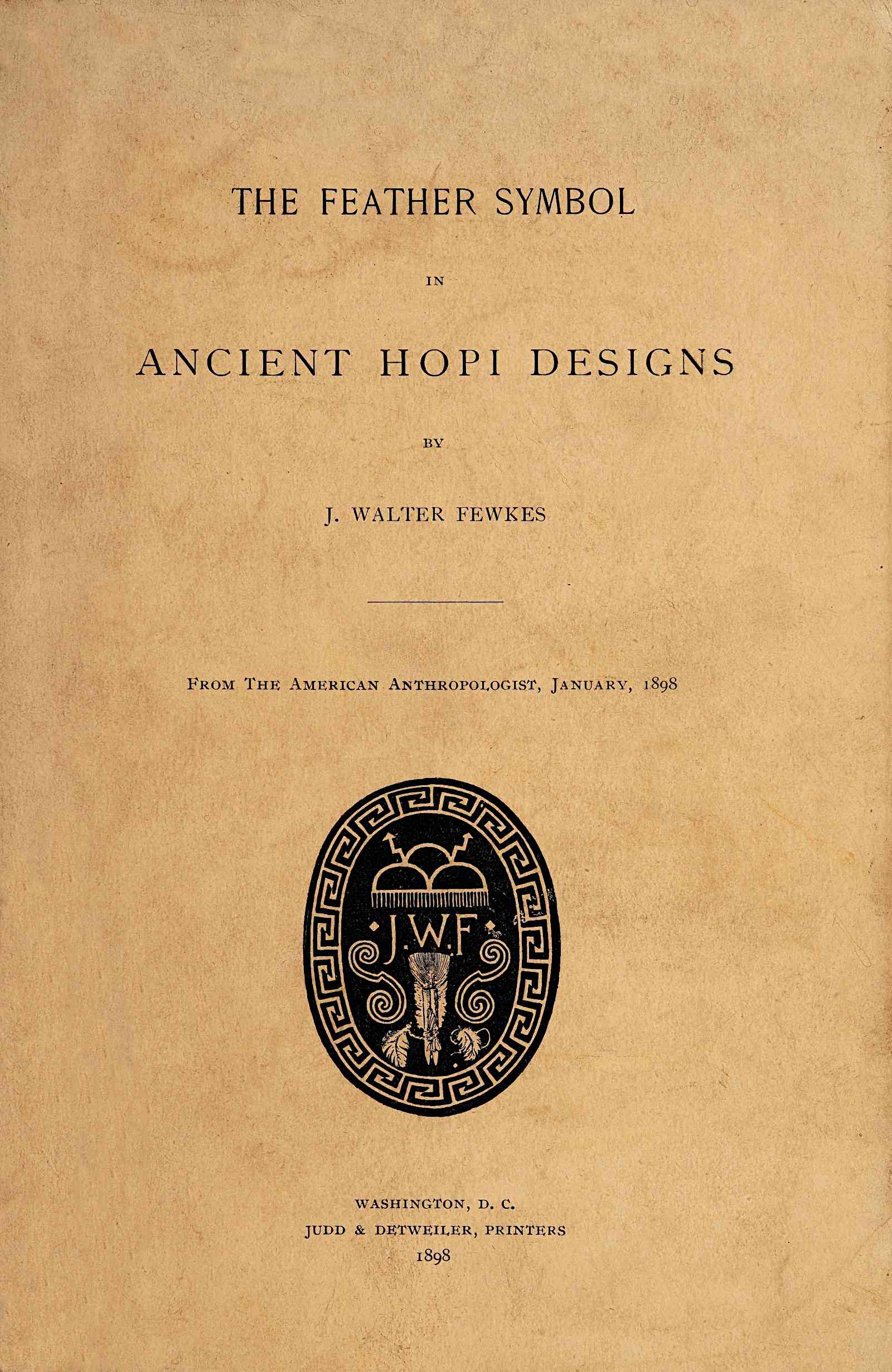

One of the common forms of the feather symbol is shown in 6figure 1, which represents the tail of a bird as pictured on a beautiful food basin from Sikyatki. In this figure five feathers are represented, and the characteristic marking of each feather is a division into a black and red zone by a diagonal line. The upper part of the figure represents the body and the two lateral appendages the wings, which in the original figure are well represented. A figure of feathers with the same outline, but destitute of the characteristic markings of figure 1, may be seen in figure 2, where three feather symbols are represented.

Figure 2[5] represents a crest composed of three feathers copied from a design on the head of a reptilian figure depicted on the interior of a food basin from Sikyatki. There are other figures of animals which bear this symbolic form of feather on the head, and its occurrence as a decorative design on the exterior of food basins, where there is no other suggestion of a bird, is common.

The same form of the feather symbol appears in figure 3, where we have the triangular tips differently marked from any of the previous symbols. There are in the Sikyatki collection designs representing birds where the feathers of the tail are identical in shape and markings with these, and it is reasonable to suppose that in this figure they represent the same parts as when attached to a picture of a bird.

The fragment shown in figure 3 represents a portion of the upper surface of a vase, of which the dotted line is the border of the orifice.

Having determined from its position on a bird that the main design in figure 3 is a conventionalized feather, let us see if there is corroborative evidence from other sources telling the same story.

In modern Hopi ceremonials the priests use a small gourd receptacle for sacred water, specimens of which have been figured elsewhere.[6] It sometimes happens that an earthen vase is used 7for the same purpose. This water gourd is covered by a cotton net, and feathers are tied to that part of the net which surrounds the orifice. When an earthen vase is used a cotton string is tied around the neck of the vase, and to this string feathers are attached. Apparently we have a deep-seated and significant connection between the ancient vase and the modern ceremonial counterpart with appended feathers. The ancient form had symbols of feathers painted on the upper surface about the orifice, the modern has the feather itself tied in the same position.

In the design represented in figure 3 we have, therefore, symbols of feathers represented as tied around the neck of an ancient Sikyatki vase. The figure represents only a portion of the top of this vessel, but gives enough to show the general character of this form of feather symbol. If we compare this symbol with those on the head of the picture of Tuñwup[7] on the upright slats of the Katcina altars of modern times we will find an exact correspondence. They are also the same in shape and markings as the painted wooden sticks representing feathers on the heads of several dolls.[8]

The symbolic picture of the feather has still other modifications in its markings from the preceding, although preserving the same shape.

One of the most highly conventionalized symbolic figures of the feather is a triangle in which there are two parallel lines on one side. This form of the feather symbol is said to be the feather of the wild turkey, and the double marking recalls that of a tail feather.

We find this symbol on the angles of the lightning snakes of the sand-picture of the Antelope altar at Cuñopavi,[9] on wooden slats of the Flute altars,[10] and elsewhere. I have ceramic objects from the ruins of Homolobi and Chevlon which bear this form of feather symbol, and it appears to have been used as far south as Pinedale, on the northern edge of the Apache reservation.

8

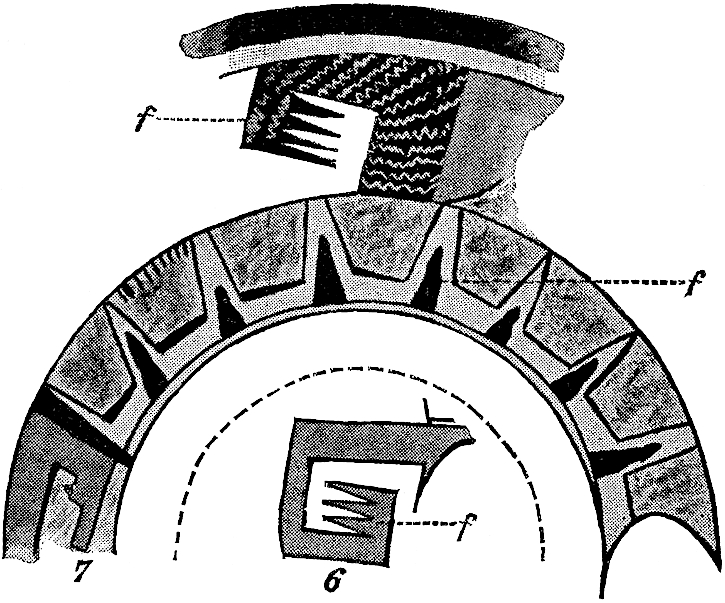

One of the most beautiful vessels from the cemetery of Sikyatki is the "butterfly vase," the complicated design on which I have figured in plate LX of the Smithsonian Report for 1895. I have represented a sector of this design in figure 5 in order to point out the feather decorations which form an important element in the ornamentation. The other sectors closely resemble that figured, with the exception that the butterflies in alternating sections have different markings on their heads, indicative of the sex. The butterfly here represented is female, and it is interesting to note the fact that the symbol of the female was the same when this vase was made as that now used in Hopi ceremonials.[11] There are three clusters of feathers (f) in this section, and each cluster is composed of three members. One of these clusters corresponds with those from the head of the reptile, figure 2.

9

The three feathers shown in the cut below the butterfly, and peripherally placed on the surface of the vase, are likewise feather symbols, but as they have different markings from the others are probably from a different genera of birds. This form of feather symbol is a common one on ancient Sikyatki ware. One of the best illustrations may be seen in the wing of the bird which is figured on plate LX of my preliminary report on Sikyatki (op. cit.). That portion of the wing which reproduces the wing feathers is shown in figure 4, and its resemblance to the feathers on figure 5 will, I think, be evident at a glance.[12]

On several of the food basins from Sikyatki we find two or more feathers of this kind represented as hanging from a ring-shape or crescentic figure. One of the former is represented in plate LXI of the Smithsonian Report for 1895. The latter symbol has come down to modern times, and the figure painted on a shield of the Soyaluña ceremony, represented in color on plate CIV of my article on Tusayan Katcinas,[13] is almost an exact reproduction of the design on a Sikyatki food basin. This is one of several symbols on modern ceremonial paraphernalia which we can trace back over three hundred years by the aid of archaeology.

The feather may lose all semblance to the preceding forms and become a simple triangle. This is the case in figures 6 and 7 from a vase and food basin from Sikyatki. If the whole design, of which figure 6 is one wing, were represented we should have no hesitancy in regarding it a figure of a bird. From their position on this figure, then, we conclude that their triangular designs are wing feathers. If we seek to apply the conclusion that the triangular figure represents a feather to the jar, a portion10 of which is shown in figure 7, we find that the seven triangular designs in this figure bear the same relation to the orifice of the jar as the symbols of feathers in figure 3. This relationship, as will readily be seen, is confirmatory of the conclusion that the feather symbol is sometimes reduced to a simple triangle, or, looking for corroborative evidence, we approach the subject in another way.

The conception of a serpent with a plumed head is common in modern Tusayan, and we find several serpents represented on ancient food basins from Sikyatki. Two of these figures have triangular appendages on top of the head, and, as there are no other designs on that organ that can be referred to feathers, we conclude that the triangular symbols represent the feathered crest of the Great Plumed Serpent. Evidently not all triangular figures represent feathers, for some may be simply ornamental geometric designs; but that many figures of this shape are symbols of feathers there can hardly be a reasonable doubt, from the evidence adduced above.

From our studies of the triangle as a wing feather we are able to interpret many designs, where all semblance to the feather or wing is lost. Thus in the upper part of figure 7 we have one of the most common designs on ancient Hopi ceramics. There is nothing in it to suggest a bird's wing, but if we compare it with the wing on the undoubted figure of a bird (figure 6) we find a perfect homology.

The presence of eagle feathers on ancient Hopi disks, symbolic of the sun, is frequent, and feathers are still inserted in a cornhusk border on the margin of hoops covered with painted buckskin representing the sun in modern Tusayan ceremonies.[14] In the old forms of sun pictographs the disk is represented by a circle, and the symbolic feathers are arranged in four clusters on the margin. In some instances each of these clusters of feathers is accompanied by a curved horn similar to that near the right-hand cluster of feathers in figure 5. The significance of this curved addition is unknown to me, but there are a large number of specimens in which a similar design is associated with two or more feathers.

11

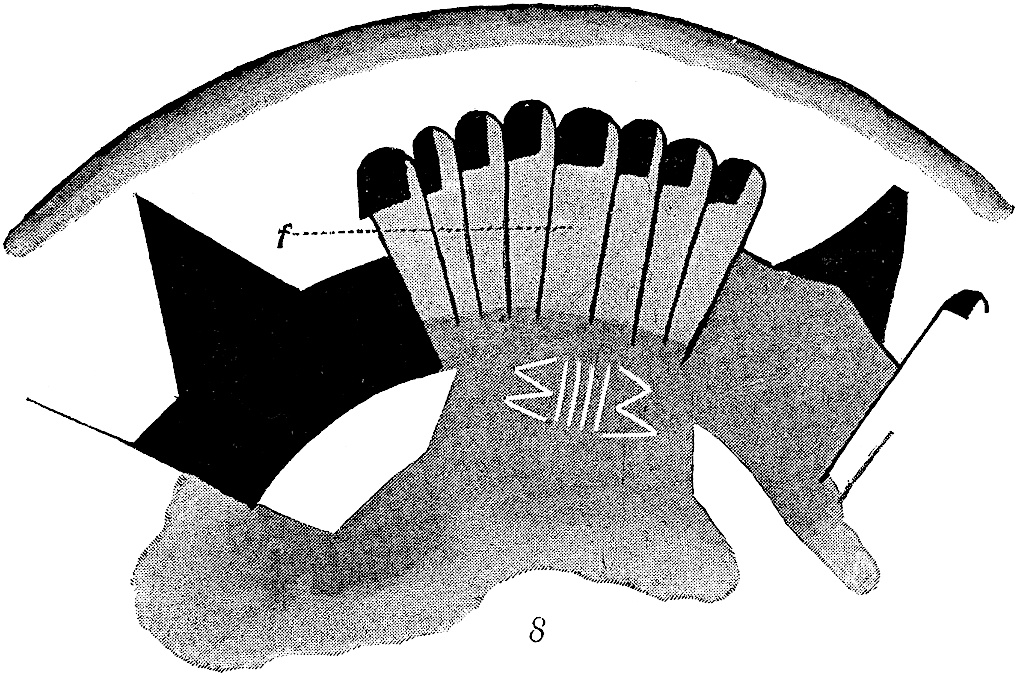

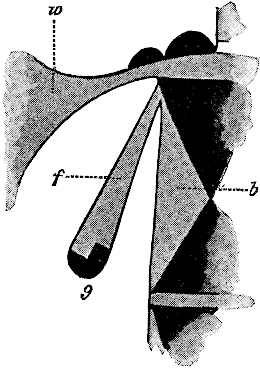

In figure 9 we have a symbolic form of feather which is very common in ancient Hopi decorations. The whole design from which this was taken represents a bird in which the part lettered w is the wing and b the body. It will be noticed that this feather is attached to the body directly under the wing, and as feathers found on the breast of birds are at present given an especial signification in ceremonials, it is supposed that the symbol in this design has a similar meaning. This symbol is therefore identified as the breast feather.

In looking over the variety of designs in which this form of the feather symbol occurs, one of the most instructive is shown in figure 8, from a food basin obtained at Sikyatki by Dr Miller, of Prescott, Arizona, after my excavations at that ruin were abandoned. The complete design on this bowl represents a figure with five triangular peripheral extensions from a circular band, and alternating with these are five bundles[15] of feathers of the symbolic form shown in figure 9. This design is probably a sun emblem, although in figures of the sun tail-feathers in four clusters are more common.

The symbol of the feather shown in figure 9 likewise occurs on the head of a snake and that of a bird which is figured on the inside of a ladle found at Sikyatki. It is also represented on the upper surface of several vases in the same relative position to the orifice as those already described and illustrated (figure 3).

12

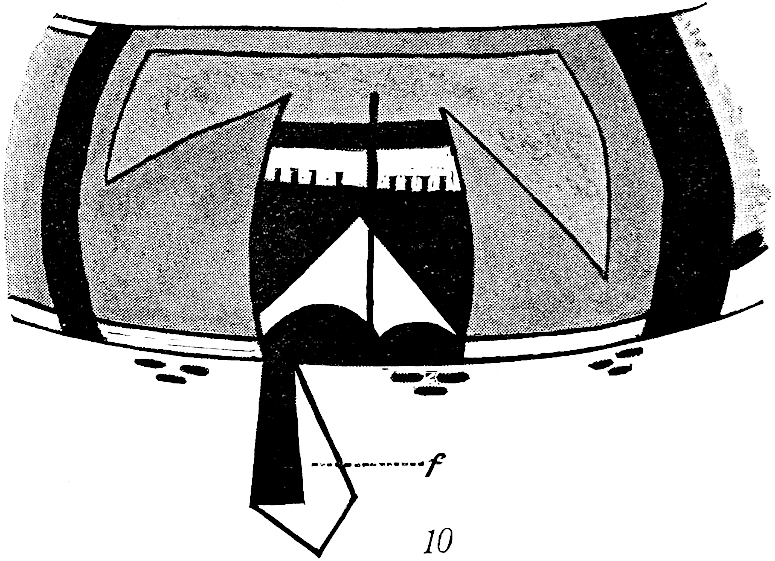

The symbol of a feather with the markings shown in figure 10 is likewise a common one in the decoration of ancient Hopi ceramics. The design here reproduced (figure 10) is a section of a small, beautiful vase, with the decoration confined to the equatorial region. From this zone hang symbols of feathers, one of which is plainly indicated. These zones are repeated at intervals around the vase. They may be comparable with the feathers tied about modern ceremonial vessels to which I have elsewhere referred.[16]

I have attempted in the preceding pages to show the symbolic forms assumed by one letter, the feather, in the alphabet of design on ancient Hopi ceramics. These designs, or some simple modifications of them, occur in almost three-fourths of all the decorated ancient vessels of Tusayan. With a little practice the student can readily recognize them, thus rendering comprehensible a most important element in ancient Hopi symbolism. There are two or three other known letters in this alphabet, representing two or three other types which can be identified with the same ease, but limited space prevents a consideration of them in this article.

As would naturally be the case with an element of decoration so constantly duplicated as the feather, there are numerous instances where it has become so changed that while a figure was 13 probably intended for a feather symbol, it is difficult to prove that it was such. These doubtful cases are not, therefore, discussed from the uncertainty which hangs about their identification.

I believe enough has been written above to show that the feather was regarded by ancient Hopi potters as an important decorative motive, and that its symbolism had significant differentiations, so that even different kinds of feathers were indicated by different markings on those symbols.

Considering also how strong a hold the feather has on the modern Hopi mind in ceremonial usages, I am led to the belief that its influence on the ancient mind was of the same general character. Thus we come back to a belief, taught by other reasoning, that ornamentation of ancient pottery was something higher than simple effort to beautify ceramic wares. The ruling motive in decorating these ancient vessels was a religious one, for in their system everything was under the same sway. Esthetic and religious feelings were not differentiated, the one implied the other, and to elaborately decorate a vessel without introducing a religious symbol was to the ancient potter an impossibility. This union is weaker in the mind of the modern Hopi, yet still potent; but as the new conception of beauty has crowded out the religious element, the character of the pottery and its decoration have deteriorated. Many patterns which once had a religious symbolism are mechanically followed, through conservatism, and pottery of fair character is still made, but every Pueblo shows a marked decadence in the potter's art. As time goes by and the Hopi are more modified by their new environment—contact with civilization—the white crockery of the traders will replace the aboriginal wares. This will lead to a still greater degeneracy of native ceramics, and, if they survive at all, it will be more as a commercial product than a medium of religious expression. It can readily be seen that the decorations on pottery made "for the trade" will no longer be a spontaneous expression of aboriginal art, but imitative of types of beauty which please the purchaser. Into that condition much of the pottery made in pueblos along the railroad has already drifted, and Hopi potters are not behind their neighbors in recognizing those decorative designs which please the buyer and those which are most often rejected. Quite in line with what is said above is the feeling which leads14 some of the best potters of the East Mesa to imitate ancient forms of decorations. These copies are adorned with old patterns because ethnologists ask for ancient ware and purchase vessels with imitations of ancient symbols more eagerly than modern. Trade cannot revive the old religious feeling which expressed itself on ancient Hopi ceramics or resuscitate the defunct intimate union of esthetic and religious inspiration.

Finally, and this is embraced in the primary reason why I am interested in the archeology of the Southwest or any other region, a study of the religious decorative symbols of ancient pottery is an investigation not alone of the peculiarities of one cluster of men and women in ancient Arizona, but of religion in a characteristic environment.[17] A psychologist devises experiments in which he places individual men or animals under conditions to observe how they are thereby affected. Nature has performed a psychological experiment on a grand scale for the ethnologist in the semi-deserts of Arizona, and has set tribes of men in a special environment for our study. The problem of the ethnologist is to consider the effect on religion as shown in the products or expression of the same. The most important ethnic characteristic of man is his religion. It distinguishes him from other animals and embraces all other mental characteristics, sociology, language, and arts.

Man can transmit his religious feelings to posterity by legends and by paleographic records. The former, if not recorded, may suffer changes in transmission, may be colored by successive generations, which have heard them from their elders and passed them along to their children. Paleography does not change. The ancient pictures are the same as when buried in the ancient graves. We may not be able to fully interpret them, but we are sure they have not been materially changed in the years which separate our time from that in which they were drawn. Imperfect as this picture-writing is as a means of transmitting to us the religion of prehistoric Tusayan when compared with written documents, it will in connection with legends yield a rich harvest to the student of the history of the Pueblo beliefs. The investigator who neglects this element in them misses the soul of the study.

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.