The Project Gutenberg eBook of The trial of John Jasper for the murder of Edwin Drood, by Gilbert Keith Chesterton

Title: The trial of John Jasper for the murder of Edwin Drood

Author: Gilbert Keith Chesterton

Contributor: J. W. T. Ley

Release Date: May 3, 2023 [eBook #70690]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRIAL

OF JOHN JASPER

Lay Precentor of Cloisterham Cathedral in the County

of Kent, for the

MURDER

OF EDWIN DROOD

Engineer.

Heard by

MR. JUSTICE GILBERT KEITH CHESTERTON

sitting with a Special Jury, in the King’s Hall, Covent Garden,

W.C., on Wednesday, the 7th January, 1914.

Verbatim Report of the proceedings from the Shorthand Notes of

J. W. T. Ley.

LONDON

CHAPMAN & HALL, LTD.

1914

Printed by The Westminster Press (Gerrards Ltd.), 411a Harrow Road, London, W.

KING’S HALL, COVENT GARDEN

JANUARY 7th, 1914.

The Trial of John Jasper for The Murder of Edwin Drood

Under the Auspices of The Dickens Fellowship (London Branch)

Frank S. Johnson, Hon. Sec.

| Judge | Mr. G. K. Chesterton |

| Counsel for the Prosecution | Mr. J. Cuming Walters |

| and | |

| Mr. B. W. Matz | |

| Counsel for the Defence | Mr. Cecil Chesterton |

| and | |

| Mr. W. Walter Crotch | |

| John Jasper | Mr. Frederick T. Harry |

| (Lay Precentor at Cloisterham Cathedral) | |

| Anthony Durdles | Mr. Bransby Williams |

| (The Cloisterham Stonemason) | |

| The Revd. Septimus Crisparkle | Mr. Arthur Waugh |

| (Minor Canon at Cloisterham Cathedral) | |

| Miss Helena Landless | Mrs. Laurence Clay |

| (Ward of Mr. Honeythunder) | |

| “’Er Royal Higness Princess Puffer” | Miss J. K. Prothero |

| (The Opium Woman) | |

| [Thomas] Bazzard | Mr. C. Sheridan Jones |

| (Clerk to Mr. Grewgious) | |

| The Clerk of Arraigns | Mr. Walter Dexter |

| The Usher | Mr. A. E. Brookes Cross |

| Police Officers | Mr. H. H. Pearce |

| and | |

| Mr. C. H. Green |

The Jury will be chosen from among the following:

| Mr. George Bernard Shaw (foreman) | Mr. Coulson Kernahan |

| Sir Francis C. Burnand | Mr. Edwin Pugh |

| Sir Edward Russell | Mr. William de Morgan |

| Dr. W. L. Courtney | Mr. Arthur Morrison |

| Mr. W. W. Jacobs | Mr. Raymond Paton |

| Mr. Pett Ridge | Mr. Francesco Berger |

| Mr. Hilaire Belloc | Mr. Ridgwell Cullum |

| Mr. Tom Gallon | Mr. Justin Huntly McCarthy |

| Mr. Max Pemberton | Mr. Oscar Browning |

| Mr. G. S. Street | Mr. Wm. Archer |

Barristers, Reporters and Spectators.

Lay Precentor of Cloisterham Cathedral, in the County of Kent,

for the

MURDER

of

EDWIN DROOD, Engineer.

TRIAL

Holden at the ASSIZES at WESTMINSTER,

on the 7th January, 1914.

| ASSIZE COURT | } | To wit: |

| KING’S HALL, COVENT GARDEN | ||

| County of LONDON |

The Jurors for this trial upon their oath[1] present, that JOHN JASPER on the 24th day of December in the year of our Lord One thousand eight hundred and sixty in the Parish of Cloisterham and within the jurisdiction of the said Court, feloniously, wilfully, and of his malice aforethought did kill and murder one EDWIN DROOD against the peace of every true Dickensian.

[1] Or, if one of the Grand Jurors be a Quaker or other person entitled to affirm instead of taking an oath, say instead: “The jurors of Our Lord the King upon their oath and affirmation present, &c.”

[Pg 8]

WHEREAS, in support of the above Indictment, divers allegations are set forth, as follows, that is to say:—

The accused, JOHN JASPER, aged 26, is Choirmaster at Cloisterham Cathedral, otherwise known as “lay precentor.” He lodges over the Gateway of the Cathedral. For some years he admits he has been in the habit of taking opium, and has resorted to an Opium Den in the East End of London kept by an elderly woman known as “Princess Puffer.”

The man of whose murder he stands accused was his nephew, EDWIN DROOD, in his 21st year, and by profession an Engineer. The Prisoner, who was likewise Trustee and Guardian of the said Edwin Drood, professed the greatest affection for him, and on the occasion of his visits to Cloisterham manifested every appearance of joy and satisfaction.

The said Edwin Drood was betrothed to one Rosa Bud, this being in fulfillment of a contract made by their respective parents (now deceased). Certain formalities in connection with the confirmation of this engagement, notably the handing of a ring by Mr. Grewgious, solicitor, Staple Inn, legal adviser to Edwin Drood, were witnessed by Mr. Grewgious’s clerk, Bazzard. There is evidence to show that they had grown weary of each other, and wished the Contract to be annulled. On the other hand, Jasper, the Accused, was admittedly in love with Rosa Bud, and it is alleged was secretly jealous of his nephew. Miss Bud, on her part, deposes that she not only disliked but “feared” Jasper and avoided his attentions as much as possible. Eventually the engagement between Edwin Drood and Rosa Bud was rescinded by mutual consent; but the said John Jasper, for sufficient reasons, was not at the time warned of this fact. The circumstance, however, was revealed to Mr. Grewgious.

WITNESSES will be called to prove that in the early part of the year, the Accused, Jasper, accompanied a stonemason named Durdles to the Cathedral and made particular enquiry into the destructive qualities of quicklime. It is also alleged that Jasper applied a drug to this same Durdles, causing sleep, and that he then appropriated his keys, and therefrom made a close investigation of the vaults, especially of the Sapsea vault, which was partly hollow.

There were also residing in Cloisterham an orphan brother and sister, twins, by name Neville and Helena Landless. They came from Ceylon, where they had been subjected to personal ill-treatment, and after staying with Mr. Honeythunder, their guardian, Neville was lodged with Canon Crisparkle, and Helena was sent to Miss[Pg 9] Twinkleton’s school. Neville Landless is described as “fierce” and hot-blooded, Helena Landless is “almost of the gipsy type.” Between her and her brother is a strong bond of affection. In her girlhood she had escaped at times from her cruel step-father by disguising herself as a boy. She is a woman of much daring.

Soon after their arrival in Cloisterham, they met Drood, Jasper and Miss Bud at a party. It will be given in evidence that there was a contention between Drood and Neville, and that Jasper afterwards fomented the ill-feeling and charged Neville Landless with being “murderous.” At the same time, Miss Landless was seized with an instinctive hostility towards Jasper, who, she thought, was unduly menacing Rosa Bud. Matters between the two young men were smoothed over to some extent, and on the following Christmas Eve, John Jasper decided to bring them together at a convivial gathering in his own house.

On December 23rd Jasper visited the Opium Den in London. Next day he returned to Cloisterham, and was followed thither by the Opium Woman, who had heard him use threatening language in his sleep towards someone called “Ned” (Jasper’s nickname for Edwin Drood).

At night (Christmas Eve) the three men met and dined. It was a night of wild storm. The next morning Jasper hastened to Canon Crisparkle’s house shouting excitedly that his dear nephew had disappeared, and that he was convinced he had been murdered.

He plainly indicated that he believed the murderer was Neville Landless, in whose company Drood had left Jasper’s house at midnight; and Neville Landless was apprehended, but subsequently released for want of evidence.

On December 26th Mr. Grewgious visited Jasper and informed him that the engagement between Drood and Miss Bud had been broken off. It is in evidence that on hearing this news for the first time, Jasper “gasped, tore his hair, shrieked” and finally swooned away.

Shortly afterwards Canon Crisparkle visiting the Weir on the river, discovered Edwin Drood’s watch and chain, which had been placed in the timbers; and in a pool below he found Drood’s scarf-pin.

It is in evidence that the accused, Jasper, after a short interval, renewed his attentions to Miss Rosa Bud, and exercised so great a terror upon her that she deemed it advisable to take refuge in London under the supervision of Mr. Grewgious and her friend Miss Twinkleton. Neville Landless also removed to London, where he was visited by his sister Helena.

Meanwhile, a careful watch was kept upon John Jasper by a “stranger,” known as Dick Datchery. This person took lodgings opposite Jasper’s house and had him under close observation. “Datchery” (which is admittedly an assumed name) interviewed[Pg 10] several persons, including Durdles and “Princess Puffer,” and kept a private record in chalk marks of all facts thus ascertained. In consequence of the suspicions excited by these circumstances, a warrant was applied for and John Jasper was arrested on a charge of Wilful Murder.

To this he pleads “NOT GUILTY,” and this is the issue to be tried.

The following WITNESSES will be called:

| ANTHONY DURDLES | } | By Counsel for the Prosecution. |

| CANON CRISPARKLE | ||

| HELENA LANDLESS | ||

| “PRINCESS PUFFER” | } | By Counsel for the Defence. |

| [THOMAS] BAZZARD |

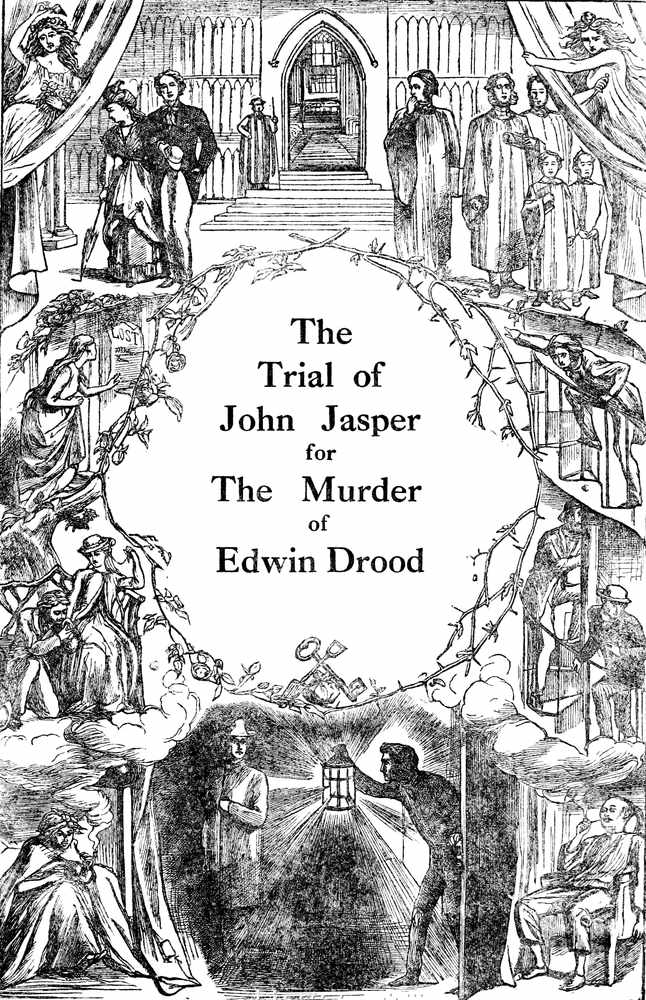

NOTE

The design on the front page of this Indictment is a reproduction of that on the wrapper of the monthly parts of “The Mystery of Edwin Drood” as originally issued in 1870. It was drawn by Charles Allston Collins, and has been the cause of much controversy and speculation.

[Pg 11]

The three formal witnesses (that is to say, Crisparkle and Durdles for the Prosecution and the Opium Woman for the Defence) shall not in their evidence-in-chief go beyond the book or make any statements not expressly made therein, but in cross-examination they may, in response to specific questions, give explanations not expressly contained in the book.

The two chief witnesses (that is to say, Helena Landless for the Prosecution and Bazzard for the Defence) shall be free both in examination-in-chief and in cross-examination to make statements not made in the book, provided that they are not contradicted therein.

All statements made in the book shall be taken to be true and admitted by both sides, and any statement by a witness contradicting such statements shall be considered thereby proved to be false.

The said two chief witnesses (and no others) shall be allowed to give hear-say evidence.

The Defence having agreed not to call Edwin Drood, the Prosecution agree not to comment upon his absence from the witness-box either in speech or cross-examination, but the Prosecution reserve the right to comment upon the silence of Edwin Drood subsequent to the murder.

Both sides having agreed not to call Grewgious, it is agreed that neither side shall comment upon the fact that the other has not called him.

The Defence agree that the legal point that no conviction can take place since no body has been found, shall be raised only after the retirement of the jury, but the Defence reserves the right to comment upon the absence of a body as part of the general absence of direct evidence of the commission of a murder.

[Pg 13]

His Lordship having taken his seat, the Prisoner was immediately put into the dock, and addressed by the Clerk of Arraigns in the following terms:

John Jasper, the charge against you is that you did feloniously, wilfully, and with malice aforethought, kill your nephew, Edwin Drood, in the City of Cloisterham, on the night of the 24th of December, 1860. Are you guilty, or not guilty?

The Prisoner: Not guilty.

The Clerk of Arraigns: Will the gentlemen of the Jury please rise, and sit down as I call their names? Mr. George Bernard Shaw, Sir Edward Russell, Dr. W. L. Courtney, Mr. W. W. Jacobs, Mr. Pett Ridge, Mr. Tom Gallon, Mr. Max Pemberton, Mr. Coulson Kernahan, Mr. Edwin Pugh, Mr. William de Morgan, Mr. Arthur Morrison, Mr. Francesco Berger, Mr. Ridgwell Cullum, Mr. Justin Huntly McCarthy, Mr. William Archer, Mr. Thomas Seccombe—you shall well and truly try the Prisoner at the Bar, John Jasper, for the murder of Edwin Drood, and a true verdict give according to the evidence.

Mr. George Bernard Shaw was elected Foreman.

Mr. Walters: I appear for the prosecution, my Lord.

Judge: Mr. Cuming Walters, I think, for the prosecution. Is there anyone with you?

Mr. Matz: I am with him, my Lord.

Mr. Cecil Chesterton: I appear for the defence, my Lord.

Judge: Mr. Chesterton, I think, for the defence. One s, I think. Is anyone with you?

Mr. Crotch: I am, my Lord.

[The Case for the Prosecution.]

Mr. Matz then proceeded to open the case for the prosecution in the following speech:

My Lord and Gentlemen of the Jury—

The case to be tried is one of murder—murder which we shall contend was premeditated, pre-arranged and carried out in a methodical and determined manner.

The Prisoner is John Jasper, Lay Precentor at Cloisterham Cathedral. The Prosecution will set itself to prove that on the night of the 24th December he murdered in that city his nephew Edwin Drood, an Engineer.

The said Edwin Drood was 21 years of age, and for some years was betrothed to Miss Rosa Bud in fulfilment of a dying wish of their respective parents (now deceased).

To this young lady the Prisoner acted as music master, and admittedly was enamoured of her, although he kept this fact secret from Edwin Drood.

On the evening in question—the 24th December—Edwin Drood and Neville Landless—a pupil of the Revd. Septimus Crisparkle—dined together with the Prisoner in his rooms in the Gate House adjoining the Cathedral.

The night was a terribly stormy one. After leaving the Prisoner, some time about midnight, the two young men took a walk to the river to see the effect of the storm on[Pg 14] the water, and returned to the house of the Revd. Septimus Crisparkle in Minor Canon Corner. Here Edwin Drood left his companion, intending to return to his Uncle’s lodgings.

Nothing has been heard or seen of him since.

Gentlemen, it is our painful duty to produce evidence to prove that Edwin Drood was murdered by his Uncle, the Prisoner. We contend that Jasper divested him of his watch and chain and his scarf pin, articles the Prisoner had, on another occasion, explained to the local jeweller he knew Drood to possess. The words he used were that he had “an inventory of them in his mind.”

We contend that Jasper then cast the body of his victim into a vault in the Cathedral precincts, the key of which, or a duplicate, he had previously become possessed of. There had also been placed in the vicinity a quantity of quicklime, and we submit that Jasper, having made some inquiries into its properties, used this for the purpose of removing all traces of the body in the shortest period of time. We submit that he got rid of the watch and chain and scarf pin in the river, either in the hope of disposing of material which the quicklime would not destroy, or to give the impression, should they be found, that the young man was drowned.

We shall in evidence show that the Prisoner had motive for his crime, that he made elaborate preparations for its enactment, and that he succeeded in his terrible deed.

The evidence may be circumstantial only. But circumstantial evidence, I submit, may be extremely strong—as strong indeed as any direct evidence.

We shall show you that all the acts of John Jasper for some time previous to the committal of his atrocious crime were self-incriminatory. Not merely that, but they exhibit his mind working out the very means by which that crime was to be committed. After his terrible deed was accomplished, his actions, to those who observed him closely, also indicated clearly his guilt.

The Prisoner, having made up his mind that, for his own selfish ends Edwin Drood must be killed, first chose the spot best suited to his purpose, and laid methodical plans to secure access to that spot. He paid visits to it in the company of one, Durdles, the Cloisterham stonemason, whom he drugged with doctored wine whilst there, in order that he might acquire secretly the key to a certain vault. He knew where quicklime could be procured without loss of time. He interviewed other persons, and timed the hour and everything else so thoroughly that nothing essential for his purpose was overlooked.

Now, gentlemen, it is necessary to refer briefly to some further facts bearing upon the history of this crime.

Neville Landless, upon whom Jasper cast suspicion of being the murderer, and his sister Helena, were both students in Cloisterham: the brother, a pupil of the Revd. Septimus Crisparkle, and the sister a pupil at Miss Twinkleton’s Academy in the city. They came from Ceylon, where they had been severely ill-treated, and had made several attempts to escape. On each occasion of the flight Helena “dressed as a boy and showed the daring of a man.” Neville, a highly strung and emotional youth, took immediate objection to Drood because of his “air of proprietorship” over Rosa; whilst Helena instinctively disliked Jasper because she saw that he loved Rosa and that Rosa feared him. It is worth noting as a significant fact that at the earliest stage Rosa appealed to Helena for aid and every assistance was promised to her.

A slight quarrel between Edwin Drood and Neville Landless took place in Jasper’s rooms, and undoubtedly Jasper goaded them on by his taunts. On this occasion Jasper gave them some mulled wine which had taken him a long time to mix and compound.[Pg 15] They drank to the toast proposed by Jasper and their speech quickly became thick and indistinct, indicating that there was a sinister design in the mixing and compounding. Drood became boastful, and Neville Landless resented his tone, and at the height of the dispute, flung the dregs of his wine at Edwin Drood. Although posing as a Peacemaker Jasper actually fomented the hostility of these two young men. He seemed to delight in it and it enabled him subsequently to report to Crisparkle that Neville was “murderous.” Indeed he went so far as to assert that he “might have laid his dear boy at his feet, and that it was no fault of his that he did not.”

The Revd. Mr. Crisparkle talked with Helena and Neville on the latter’s rash conduct, and he expressed extreme regret and promised to exercise more caution in future. On another occasion Crisparkle visited Jasper, who read to him passages from his diary expressing fears for Drood’s safety. A few days later Drood, at the suggestion of Jasper, wrote and agreed to dine with him and Neville on Christmas Eve at the Gate house, Cloisterham—in order that the two young men should become friends. Their walk after dinner is evidence that this object was fully achieved.

We submit that, the whole plans having thus been prepared, the murder of Edwin Drood took place after the parting of the young men, and that John Jasper and no other was the murderer. In support of this we shall produce evidence to prove that Jasper acted in a highly incriminatory manner.

The next morning whilst great commotion was raging in the vicinity of the cathedral over the damage done by the storm, John Jasper broke into the crowd crying: “Where is my nephew?” as if everybody knew he was missing, whereas no one but the prisoner had any reason to think he was not in the Prisoner’s rooms. He even volunteered the statement that Drood had gone “down to the river last night, with Mr. Neville, to look at the storm, and had not been back?” and demanded that Mr. Neville should be called.

These utterances were made to the Revd. Canon, and showed clearly that the murderer felt so confident that he had executed his deed with perfect thoroughness that no fear of discovery need enter his mind. But knowing his nephew was murdered he tried immediately to fix the deed upon another.

I must direct your attention to one other matter. John Jasper, whether guilty or not of murder, is indisputably a hypocrite, leading a double life. Like most criminals he was also capable of foolish mistakes. Had he not killed his “dear boy,” as he called him, he would have made investigations of his whereabouts, he would have refrained from courting inquiries, and would not have excited the hostility of Rosa Bud.

But, gentlemen, most criminals of the John Jasper type, make at least one error in the execution of their crime, which ultimately finds them out. Jasper made his. Having as I have said, divested Edwin Drood of his watch and chain and scarf pin, all the jewellery he was aware Drood had upon his person, he felt safe. But he left, unknown to him, on the person of the young man a valuable gold ring set with rubies and diamonds, and this ring quicklime could not consume. The ring was once the property of Rosa Bud’s mother and had been handed to Edwin Drood by Mr. Grewgious, Rosa Bud’s guardian, with strict instructions that he should give it to Rosa if he intended to marry her, or return it to Mr. Grewgious should Edwin and Rosa decide, as seemed likely, to break their betrothal.

This was a faithful promise and was witnessed by one, Bazzard, the clerk to the said Mr. Grewgious.

It so happened that on December 24th the young couple did break off their engagement. Therefore if Drood, by any chance, were now alive, that ring would have been[Pg 16] returned to Mr. Grewgious, in accordance with his promise. But, gentlemen, it never has been returned, and why? We say because Drood is no longer alive, but dead, and that where the body was hidden after the murder, there that ring was hidden also.

Jasper knew of all the articles that were on the person of Edwin Drood, except that ring. He did not know of that because it had only been handed to Drood on the previous day.

Nor did Jasper know of the breaking off of the betrothal, else would there have been no object in his committing the murder. Evidence will be given that Drood promised Rosa he would not spoil his Uncle’s Christmas festivities by telling him of their decision to part as lovers.

The first time Jasper learnt the fact was on the day following the murder, when he heard it from Mr. Grewgious. He then instantly “gasped, tore his hair, shrieked,” swooned and “fell a heap of torn and miry clothes upon the floor.” From this we infer that the information was unexpected and a shock to him.

Sometime afterwards the Revd. Canon Crisparkle found the watch and chain and scarf pin, when walking near the weir, and he will be called to give evidence on this and other facts.

Now, gentlemen, let me read to you an extract from the diary of Jasper entered after this discovery. It reads thus—

“My dear boy is murdered. The discovery of the watch and shirt pin convinces me that he was murdered on that night, and that his jewellery was taken from him to prevent identification by its means.”

The word “murdered” was frequently in the mind of Jasper at this time, and he made use of it in several phrases in his diary, which clearly demonstrates that he was attempting to create the impression that his nephew was murdered, and, by using the words, hoped to divert attention from himself.

But he became so nervous of what he had written, that he declared to the Revd. Canon that he meant to “burn this year’s diary at the year’s end” and by so doing, as he evidently thought, destroy all evidence of his guilty conscience.

There is one more phase to touch upon.

It is admitted that John Jasper was secretly addicted to opium smoking and frequented a certain opium den in London kept by a person known as the “Princess Puffer.” Whilst under the influence of opium he babbled strangely, moaned, and uttered significant words in the hearing of the opium woman. This woman followed him more than once to Cloisterham and on one of these occasions, the fateful 24th December, she accosted Edwin Drood, and for the price of three and sixpence offered to tell him something. He paid her the money and she asked him first his name, and when he told her Edwin, she wanted to know, “Is the short of that name Eddy?...” Drood answered “It is sometimes called so.” “You be thankful your name is not Ned,” she next replied, “because it is a threatened name: a dangerous name.” “Threatened men live long,” he assured her. Her reply was—

“Then Ned—so threatened is he, wherever he may be while I am a-talking to you, deary—should live to all eternity!”

Now, gentlemen, it is a striking and amazing fact that Jasper, and he only, called Edwin Drood “Ned”—the threatened name.

That very night Edwin Drood disappeared, and he has “never revisited the light of the sun.”

A few months passed and no trace of the body of the ill-fated young man having been found, Jasper, feeling he had cleared his way effectively, called at the Nun’s House[Pg 17] (Miss Twinkleton’s Academy) one afternoon in the vacation, and taking Rosa unawares made passionate love to her. On being repulsed he vowed vengeance on Neville Landless—the man against whom he had already directed suspicion. So horrified was Rosa, she flew for safety to her guardian Mr. Grewgious at Staple Inn. A strict watch was kept upon Jasper by a person calling himself Mr. Datchery, with the result that he was eventually arrested.

Gentlemen, that is the case put to you as briefly as possible—it is the case you have to try.

We feel confident that the evidence we shall place before you will convince you that the prisoner has committed a foul crime, and that we can safely leave the issue to you. Painful as your duty may be, we look to you to give your verdict faithfully and fearlessly in the interests of justice and your fellow-men.

The Foreman: My Lord, one word. Did I understand the learned gentleman to say that he was going to call evidence?

Mr. Matz: Certainly.

The Foreman: Well, then, all I can say is, that if the learned gentleman thinks the convictions of a British jury are going to be influenced by evidence, he little knows his fellow countrymen!

Judge: At the same time, in spite of this somewhat intemperate observation——[The remainder of his Lordship’s words were inaudible.]

[Evidence of Anthony Durdles.]

Mr. Matz: Call Anthony Durdles.

Usher: Anthony Durdles! [That gentleman immediately entered the witness-box.]

Clerk of Arraigns: The evidence that you shall give before the Court and Jury, shall be the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

Mr. Walters: Your name is Durdles?

Witness: Durdles is my name.

Mr. Walters: Do you always call yourself Durdles?

Witness: I do; ’cause my name is Durdles.

Mr. Walters: You are a stonemason, I believe?

Witness: Ay; Durdles is a stonemason.

Mr. Walters: Would you mind telling us where you work?

Witness: Durdles works anywhere he can, up and down, round about the Cathedral.

Mr. Walters: Round about the Cathedral. Thank you. Very good. Do you happen to know the prisoner, John Jasper?

Witness: Ay; I knows John Jarsper.

Mr. Walters: And did you ever happen to meet him anywhere near the Cathedral?

Witness: Yes; Durdles met Mister Jarsper near the Cathedral.

Mr. Walters: Perhaps you met him more than once?

Witness: Twice.

Mr. Walters: You met him twice. What did you go with him to the Cathedral for?

[Pg 18]

Witness: Well, sir; he——

Mr. Walters: Yes: speak up, please.

Judge: I must interpose. The witness cannot possibly know what Mr. Jasper went to the Cathedral for.

Mr. Walters: My Lord, with respectful submission to you, the prisoner might have told him.

Judge: But for that purpose you must examine the prisoner in chief.

Mr. Walters: I think, my Lord, that you will find a conversation took place between Durdles and the prisoner, and that I am perfectly justified in asking what the conversation was.

Judge: Yes; I think so.

Mr. Walters (to witness): Let us know what the conversation was between you and Mr. Jasper.

Witness: He says to me, “Is there anything new in the crypt?” and I says, “Anything new! Anything old, you mean.”

Mr. Walters: Yes?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: What happened then?

Witness: We went down in the crypt, and he give me a drink out of his bottle. Fine stuff it was, too.

Mr. Walters: And what about that bundle which I believe you carried?

Witness: He asked me if he could carry my bundle.

Mr. Walters: Yes?

Witness: Ay.

Mr. Walters: What was in your bundle?

Witness: Durdles knows what was in his bundle. Keys, among other things.

Mr. Walters: Oh, keys. And I suppose you let him carry your bundle?

Witness: I did. Well, I had another drink out of his bottle.

Mr. Walters: Did you happen on that occasion to see any quicklime lying about?

Witness: Well, there’s always quicklime lying about the crypt. Always.

Mr. Walters: You noticed it. Did Jasper happen to notice it?

Witness: He did. He asked me what it was for.

Mr. Walters: Oh, he asked you what it was for. And did you tell him?

Witness: Yes; I told him it ’ud burn anything; burn your boots, and with a little handy stirring, it ’ud burn your bones.

Mr. Walters: It would burn your bones with handy stirring. And when he put that curious question to you, did it occur to you there was a reason for it?

Witness: Durdles thinks everybody ’as a reason for everything they says and does.

Mr. Walters: When he asked you would that quicklime burn, you thought he must have a reason for it?

[Pg 19]

Witness: Yes; so I did.

Mr. Walters: People use quicklime for quite innocent purposes, I believe, don’t they?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: They use it for cement?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: What else do they use it for?

Witness: Bodies.

Mr. Walters: Did you think, by the way he was making his inquiries, that he wanted to know if it would burn something else besides ordinary stuff?

Witness: I didn’t think as ’ow he wanted a heap of quicklime to burn his waste paper with.

Mr. Walters: What happened next? You had a drink out of the bottle, and you had a little talk: what happened then? Did you go home?

Witness: No; I fell asleep.

Mr. Walters: Oh, you fell asleep?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Anything else?

Witness: I had a dream.

Mr. Walters: You had a dream before you woke up?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: What was the nature of that dream?

Witness: I dreamt that Mister Jarsper was a-moving around me, handling my keys, and I thought I was left alone in the dark. Then I see a light coming back, and then I found Mr. Jarsper waking me up, saying “Hi! wake up!”

Mr. Walters: Did you wake up?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did you remember how long you had been asleep?

Witness: A long time. I remember the clock struck two.

Mr. Walters: And you went in about midnight?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: You had two hours’ sleep?

Witness: Yes, I suppose so.

Mr. Walters: Anything else? Did you notice anything?

Witness: When I woke up, I sees my key on the ground, and I says, “I dropped you, did I?” So I picks it up, and asks Mister Jarsper for my bundle.

Mr. Walters: Did he give it to you?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: I think you had on that occasion a little conversation about a curious art of yours—tapping the tombs?

[Pg 20]

Witness: Yes; oh, yes—yes.

Mr. Walters: Would you mind telling the court?

Witness: I told him, with my little hammer I could tap and go on tapping, and I could tell whether anything was solid or whether it was hollow. For instance, I says, “Tap, tap, old ’un crumbled up in stone coffin in the vault!”

Mr. Walters: That’s what you said, is it?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: And what did Mr. Jasper say to that?

Witness: He said it was wonderful, and I says, “No; I ain’t going to take it as a gift, ’cause it’s all out o’ my own head.”

Mr. Walters: I understand you told him what you could do by tapping the walls—tell whether it was hollow or solid?

Witness: Yes, Durdles can tell whether it’s hollow or solid by its tap.

Mr. Walters: Was he interested in your conversation?

Witness: Very much, sir.

Mr. Walters: Did you happen to notice the Sapsea tomb?

Witness: Durdles knows the Sapsea tomb.

Mr. Walters: There is only one body in that tomb at present?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did you tap the Sapsea tomb with your hammer, and did it sound surprising there?

Witness: It sounded more solid than usual.

Mr. Walters: Since then, you have tapped it lately, and it sounds a little more solid?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Chesterton: This is contrary to an understanding. This is a formal witness, not to be cross-examined.

Mr. Walters: Very well, I will go on. (To witness.) Did you meet him at another time?

Mr. Chesterton: This is only formal evidence.

Judge: What is the point?

Mr. Chesterton: You will find before you, my Lord, a document, and you will find there that certain witnesses who are to be cross-examined at length will be free to go beyond certain admitted evidence. The formal witnesses are not to do so.

Judge (after perusing the “Conditions”): Yes, I think I take your point, Mr. Chesterman—or Chesterton—whatever it is. The point, I understand, is that you are cross-examining this witness as if he were a principal witness of the trial.

Mr. Chesterton: In the second paragraph I think you will notice——

Mr. Walters: It is not of great importance to me.

Judge: One moment: I will see. (After reading the paragraph referred to.) I think you are justified up to the point to which you have gone, but I should recommend you to terminate it with some rapidity.

[Pg 21]

Mr. Walters: I only want to ask one question. (To witness.) You did have a conversation with Mr. Datchery?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Chesterton: I ask you to say, my Lord, that the Jury must entirely disregard the statement about the tapping.

The Foreman: How are we to dismiss it from our minds, my Lord? It is a very difficult point.

Mr. Walters: I think I shall leave the Jury to draw their own conclusions. All I want to know from Durdles is, did he have a conversation with Datchery?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Thank you. That is all.

Witness: Thank you, sir. I’ll drink your health on the way home, p’raps twice, and I won’t go home till morning.

[Durdles Cross-examined.]

Mr. Crotch: One moment, please.

Witness: Oh, beg pardon, sir, beg pardon.

Mr. Crotch: Now, Durdles, you know all about the destructive qualities of quicklime?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Crotch: Do you say that quicklime will not destroy metals?

Witness: No; I don’t think quicklime will destroy metals.

Mr. Crotch: You don’t think it will?

Witness: No, I knows it won’t.

Mr. Crotch: Now, Durdles——

Judge: I must ask you to address the witness in more respectful terms, such as “Mr.” Durdles.

Mr. Crotch: Very well, my Lord.

Witness: Mister Durdles, sir.

Mr. Crotch (to witness): I understand you were employed round about the Cathedral, and that you know all about the crypt?

Witness: Yes, sir.

Mr. Crotch: Now, tell me what was the state of the windows in 1860.

Witness: Ay?

Mr. Crotch: I put it to you again. In what state were the windows of the crypt in 1860?

Witness: Do you mean clean or dirty?

Mr. Crotch: I put it to you they were in a very broken condition?

Witness: Yes, sir; always broken.

Mr. Crotch: As a matter of fact, they were not only broken, weren’t they, but partially boarded up?

Witness: Well, I can’t remember, sir.

[Pg 22]

Mr. Crotch: Can’t remember! You were constantly in the crypt!

Witness: Some of ’em.

Mr. Crotch: How many windows are there?

Witness: I don’t know.

Mr. Walters: I don’t suppose the witness is expected to count windows!

Witness: Thank you, sir.

Mr. Crotch: Well, now, Mr. Durdles, I will ask you another question. As a matter of fact, have you not on many occasions chased little boys and others out of the crypt?

Witness: Yes, and they’ve chased me.

Mr. Crotch: Where did these boys find their way into the crypt?

Witness: Ay?

Mr. Crotch: You don’t know?

Witness: No, I don’t.

Mr. Crotch: You swear you don’t know?

Witness: Ay, I swear I don’t know.

Mr. Crotch: You have never seen them creeping through the windows of the crypt?

Witness: Might be; when I’ve been sober.

Mr. Crotch: That’ll do. Now, you tell us that you met Mr. Datchery. Is that so?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Crotch: Have you ever admitted Mr. Datchery to the Sapsea vault?

Mr. Walters: This is going far beyond—

Mr. Chesterton: If my learned friend will look at the first paragraph he will see that in cross-examination the formal witnesses may, in response to specific questions, give explanations not expressly contained in the book.

Mr. Walters: Then I must re-examine the witness.

Mr. Chesterton: Certainly.

Mr. Crotch: Now, Mr. Durdles, have you ever admitted Mr. Datchery to the Sapsea vault?

Witness: Not that I can remember.

Mr. Crotch: If you cannot remember admitting Datchery, do you at any time remember admitting anybody else?

Witness: No; I can’t say as I do.

Mr. Crotch: Thank you, Mr. Durdles.

Mr. Walters: I won’t trouble you to re-examine you, Mr. Durdles.

Witness: Well, good day. I’ll drink your health on the way home, and I won’t go home till morning—I beg your pardon, my Lord.

[Evidence of Reverend Canon Crisparkle.]

Mr. Walters: The Reverend Canon Crisparkle.

[Pg 23]

Usher: Reverend Canon Crisparkle.

[That gentleman responded to the call, and entering the witness box, was duly sworn.]

The Foreman: May I interpose for a moment? This gentleman has been called as the Reverend Septimus Crisparkle. I submit to your Lordship that his real name is Christopher Nubbles, a man who was tried before you on the information of a certain Mr. Chuckster, on the charge of being a snob, and you, in one of those summings-up which have made your name famous wherever the English language is spoken, found that the charge brought by Mr. Chuckster was well and truly proved. Now, I contend that Mr. Christopher Nubbles has gone to Cloisterham, become a Minor Canon, taken the name of Crisparkle, and is here obviously a more intolerable snob than ever.

Mr. Walters: Mr. Crisparkle; I believe you are a Minor Canon of Cloisterham Cathedral?

Witness: I am, sir.

Mr. Walters: I believe your identity has never been disputed until this moment?

Witness: Never. I am glad to be able to answer that impertinent reflection.

Mr. Walters: Do you happen to know John Jasper?

Witness: Very well. He was associated with me daily in the duties of the Cathedral.

Mr. Walters: Did he ever tell you about his affection for his nephew, Edwin Drood?

Witness: Constantly.

Mr. Walters: And did he, while in this confidential mood, also tell you of his great affection for Miss Rosa Bud?

Witness: No, I cannot charge my memory that he ever mentioned affection for her.

Mr. Walters: Well, then, in that matter John Jasper deceived you?

Witness: Well, shall we say deceived? Guilty of a lapse of confidence to a priest. Theologically speaking it would be deceit, perhaps.

Mr. Walters: I believe, Mr. Crisparkle, that you have been acting as tutor to Neville Landless?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Do you mind telling the court the opinion you formed of that man’s character?

Witness: I should say a very impulsive man, but responsive to influence of any kind.

Mr. Walters: I think he has a sister?

Witness: Oh, yes: Miss Helena Landless.

Mr. Walters: Is he under her influence at all?

Witness: Yes, I should say she exercises a good and strong influence upon him.

Judge: I should suggest that question is very improper. We are all under the influence of each other to a great extent. I am as much under the influence of the foreman of the Jury that I almost entirely agree with the view that he takes of the situation when he mentions it. But I think it is not quite proper to say “Is he under the influence of his sister?” Surely?

Mr. Walters: But, my Lord, this gentleman knows both parties, and is perfectly acquainted with their relationships.

[Pg 24]

Witness: Yes, well.

Judge: I——

Mr. Walters: I will not press the point. I will ask you, Mr. Crisparkle, have you any influence?

Witness: Is that proper, my Lord?

Judge: Quite proper.

Witness: I should say I have done my best. I have talked to him from time to time and found him very anxious to profit by any words I was able to say.

Mr. Walters: You said he was impetuous. Perhaps he has one or two little faults of that sort. Would you regard them as dangerous?

Witness: No, no; oh no. The faults of an undisciplined boy.

Mr. Walters: Has he any good qualities?

Witness: Many, which appear to me to far outweigh the others.

Mr. Walters: Suppose Neville Landless had a little quarrel with another young man. Would you attach much importance to it?

Witness: No, I think not: very little, I think. Hot-tempered youth—soon over. He would be the first to regret it.

Mr. Walters: Did you know Edwin Drood?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: And you heard of a quarrel between him and Neville Landless?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Who told you about that quarrel?

Witness: Well, in the first instance, Neville Landless mentioned it to me when he came back to my house. He said he had made a bad beginning and was sorry. But immediately afterwards John Jasper came to the house, and gave me what I am bound to say was a very different account indeed.

Mr. Walters: This is the John Jasper who had already deceived you?

Witness: Who had perhaps misled me by suppression.

Mr. Walters: He was the John Jasper who was Edwin Drood’s rival for Rosa Bud?

Witness: It would appear so.

Mr. Walters: You say he gave a strong account of the quarrel—Is that correct?

Witness: It is more than correct. He said, when he came into the room, that he had had an awful time with him. I said, “Surely not as bad as that!” and he said “Murderous—murderous!”

Mr. Walters: Are you sure he used the word “Murderous”?

Witness: I am absolutely certain.

Mr. Walters: What did you say to that?

Witness: I said, “I must beg you not to use quite such strong language.” He continued to use even stronger terms. He said there was something tigerish in Neville’s blood. He was afraid he would have struck his dear boy, as he called him, down at his feet.

[Pg 25]

Mr. Walters: You are quite sure those were his words?

Witness: Absolutely.

Mr. Walters: And I suppose, following on that, you asked for an explanation from Neville? Did you have any conversation with him?

Witness: Yes, a long conversation with him in company with his sister.

Mr. Walters: Was Jasper satisfied with the explanation given to him?

Witness: No, I’m afraid not. A few days afterwards, when I was endeavouring to make peace between the two combatants, and arranged a meeting, Jasper took the opportunity to show me his diary, in which he had written his fears and suspicions in regard to his dear boy’s safety.

Mr. Walters: Fears and suspicions?

Witness: That was the phrase.

Mr. Walters: May we take it then, that this man was always harping on danger and using the word “Murder,” and influencing your mind against Neville Landless?

Witness: I am afraid that was the impression which I derived.

Mr. Walters: Was that the impression left in your mind after the conversation with John Jasper?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: I think you know that on the Christmas Eve following, there was a friendly little party?

Witness: Yes; I was instrumental in arranging it.

Mr. Walters: Following on that, Neville Landless was, on the following day, to start on a walking expedition?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did he tell you all about it?

Witness: Oh, yes.

Mr. Walters: He was quite frank?

Witness: Quite frank.

Mr. Walters: Did he start to carry out his plans?

Witness: He started.

Mr. Walters: On the Christmas morning, early?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Do you remember that Christmas Eve?

Witness: Perfectly.

Mr. Walters: Why?

Witness: Especially because of the beauty of Evensong that day. John Jasper was in splendid voice that day, and I congratulated him when he came out of the Cathedral. I said he must be in very good health.

Mr. Walters: Very good health: did he say anything?

Witness: He said he was in very good health, and that the black humours were[Pg 26] passing from him, and that he would have to burn his diary—consign it to the flames—that was the phrase.

Mr. Walters: He also laughed?

Witness: He went laughing up the postern gate.

Mr. Walters: Do you mind telling us whether laughing was common with John Jasper.

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: In short, you thought it an exceptional piece of good humour?

Witness: Yes; he made that impression on me.

Mr. Walters: Do you remember what sort of night it was?

Witness: A terrible night of storm.

Mr. Walters: Let us get on to the next morning. The next morning what happened?

Witness: Before I was about, while I was still in my dressing room, I was aware of a great noise at my gate, and there I saw John Jasper, insufficiently attired, crying very loudly to me in the house. I looked out, and asked what was the matter, and he said, “Where is my nephew?” Naturally, I said to him, “Why should you ask me?” and he said, “Last evening, very late, he went down to the river to see the storm, in company with Mr. Neville Landless,” since when nothing had been heard of him. And then he said, “Call Mr. Neville.” I told him Neville had already started.

Mr. Walters: When this conversation took place between you and John Jasper, did it occur to you that he was dazed, as if suffering from the effect of drugs?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: Did it strike you that he was particularly clear-headed?

Witness: I think so. Yes: he was very clear-headed.

Mr. Walters: Was he concise and clear in his remarks?

Witness: Yes, perfectly clear.

Mr. Walters: If anybody told you he was suffering from the effect of drugs, or was dazed or bewildered, would your observation bear that out?

Witness: No, indeed.

Mr. Walters: What did you do in respect of Mr. Neville?

Witness: We sent some men after him, and Mr. Jasper and I followed. Directly we came up with him, Jasper said, “Where is my nephew?” and Neville said, “Why do you ask me?”

Mr. Walters: What did Jasper say?

Witness: He said, “He was last seen in your company”—or words to that effect.

Mr. Walters: When he said that, what sort of impression did it cause on you? What did you think it meant?

Witness: I am sorry to say I had the unpleasant impression that he meant to suggest that Neville Landless was in some way responsible for Drood’s disappearance.

Mr. Walters: Once more he was suggesting murder?

[Pg 27]

Witness: Yes, that was the impression.

Mr. Walters: And once more suggesting that Neville Landless was the murderer?

Witness: That was so, undoubtedly.

Mr. Walters: This man, Neville Landless, with this terrible charge hanging over him; did he come back readily?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did he answer any questions put to him?

Witness: Quite frankly.

Mr. Walters: Some time afterwards, you made a discovery, I think. Would you mind telling the Court what it was?

Witness: I was walking along by the river, some two miles above where these young men had gone for their walk—by the weir, in fact,—when I saw something shining brightly. Looking more closely, I thought it was a jewel. I immediately dived in, being fortunately a good swimmer, and found that it was a gold watch and chain. The chain was hanging on the timbers. Later I found in the mud a gold scarf-pin. The watch had the initials E. D. engraved on it.

Mr. Walters: Did you tell Jasper you had discovered these things?

Witness: At once.

Mr. Walters: Did he say anything about it?

Witness: Nothing at the time, but a few days later, when we were disrobing in the vestry, he showed me the diary to which I have alluded.

Mr. Walters: Did it contain any reference to it?

Witness: I cannot charge my memory with the exact words, but something to this effect—“My poor boy is certainly murdered. The discovery of the watch and scarf-pin leaves that beyond doubt. They were no doubt thrown away to prevent identification of the body”—or words to that effect.

Mr. Walters: One moment, Mr. Crisparkle. Am I right in saying that once more Murder was suggested to you?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: And that Neville Landless was pointed to as the murderer?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: And so that would be the impression left on your mind by your conversation with Jasper?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Whether it was right or wrong, that would be the impression left?

Witness: Whether right or wrong, that would undoubtedly be the impression.

Mr. Walters: Thank you, Mr. Crisparkle.

The Foreman: May I ask one question, my Lord?

Judge: Certainly.

The Foreman: Do I understand the witness to say that the prisoner was a musician?

Witness: He was, my Lord.

[Pg 28]

Foreman: His case looks black indeed.

[Canon Crisparkle Cross-examined.]

Mr. Crotch: Canon Crisparkle, you referred to the night of the preliminary quarrel and the return of Neville Landless. Do you remember accusing Neville of intoxication?

Witness: Quite well.

Mr. Crotch: You said, “You are not sober”?

Witness: I did so.

Mr. Crotch: Do you remember his reply?

Witness: He said, “Yes; I am afraid that is true, although I took very little to drink.”

Mr. Crotch: “Although I can satisfy you at another time that I had very little to drink.” I put it, those were the words he used?

Witness: Doubtless.

Mr. Crotch: You said you went down to the weir, which is two miles from the river?

Witness: No; two miles from the point at which Edwin Drood and Neville Landless went down to watch the storm. It is two miles higher up.

Mr. Crotch: And it was there you found the articles you have described?

Witness: That is so.

Mr. Crotch: What was the position of the watch and chain?

Witness: It was adhering to the timbers. Where two timbers crossed, it had become fixed.

Mr. Crotch: As though somebody had gone down with a hammer and nail and hung it up deliberately?

Witness: No, that I would not say.

Mr. Crotch: Was the pin in the mud?

Witness: In the mud.

Mr. Crotch: This was ordinary loose mud?

Witness: Yes, a kind of sludge.

Mr. Crotch: Did you find anything else?

Witness: No.

Mr. Crotch: Nothing else at all?

Witness: No.

Mr. Crotch: Now, Canon Crisparkle, I have just one question of some delicacy to ask. I hope you won’t be offended. Is it not a fact that you are in love with Helena Landless?

Mr. Walters: My lord, my lord, I must object. I think this is a secret to a man’s breast, and my friend has no right to try to get it out.

Witness: My Lord, I have no objection to answer the question. The lady will appear before you shortly, and when you see her you will not be surprised that my heart is a little affected.

[Pg 29]

Mr. Crotch: Thank you, Canon Crisparkle.

Mr. Walters: Canon Crisparkle, one word please, as to the exact position of the weir. I think you have not been carefully examining the exact position lately? You could not testify whether it was two miles, one mile, or one and a half miles, and would not commit yourself to an actual distance?

Witness: No; we are not in mathematics.

Mr. Walters: If I told you it was a little nearer the Cathedral, you would not dispute it?

Witness: Not for a moment.

Mr. Walters: Thank you, Canon Crisparkle. That will do.

[Evidence of Helena Landless.]

Mr. Walters: Call Helena Landless.

Usher: Helena Landless!

[That lady was conducted to the witness-box, and duly sworn.]

Mr. Walters: What is your name, please?

Witness: Helena Landless.

Mr. Walters: And you have a brother named Neville?

Witness: Yes; a twin brother.

Mr. Walters: Is there a great bond of sympathy between you and your brother?

Witness: A very great bond.

Mr. Walters: Is it so strong that you have an intimate understanding of each other?

Witness: We almost know each other’s thoughts.

Mr. Walters: And I think you are accustomed to exercise influence on him—perhaps to lead him?

Witness: It always has been so.

Mr. Walters: Where did you live when young?

Witness: In Ceylon.

Mr. Walters: With your parents?

Witness: No. My parents died when we were young, and a step-father brought us up.

Mr. Walters: How did he treat you?

Witness: Very badly indeed. He was always cruel and harsh to us.

Mr. Walters: Ever beat you?

Witness: We were whipped like dogs, and we ran away.

Mr. Walters: How old were you when you first ran away?

Witness: Seven.

Mr. Walters: Who suggested running away?

Witness: I did.

Mr. Walters: And did your brother follow you?

Witness: He always followed me.

[Pg 30]

Mr. Walters: You planned everything?

Witness: I always planned.

Mr. Walters: Weren’t you afraid to run away?

Witness: I was afraid of nothing to be free.

Mr. Walters: What did you do in order to make a flight successful?

Witness: I cut off my hair, and dressed myself as a boy.

Mr. Walters: That needed a great amount of daring?

Witness: Well, the occasion needed all the daring I could command.

Mr. Walters: And when it needs all the daring you can command, you don’t mind daring?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: As a matter of fact, you did it, I think, not only for yourself, but for your brother?

Witness: I think more for him than for myself.

Mr. Walters: And you love your brother very much?

Witness: Dearly.

Mr. Walters: Still?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Would you do as much again, Miss Landless?

Witness: I would; and more.

Mr. Walters: As much for anybody else you love?

Witness: If I loved them dearly enough.

Mr. Walters: You have lately come to England. When you came, tell us where you resided.

Witness: I went to Miss Twinkleton’s at the Nun’s House, and my brother went to Mr. Crisparkle’s.

Mr. Walters: I believe the Nun’s House is an Academy?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Other girls there?

Witness: Yes, several.

Mr. Walters: Miss Rosa Bud there?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Ever meet her?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Ever become friends with her?

Witness: Yes; very great friends.

Mr. Walters: Did you form an estimate of her character?

Witness: I thought she was a sweet, lovable girl, but shy and timid.

[Pg 31]

Mr. Walters: Not got your daring?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: She was learning music, I think? Who was her tutor?

Witness: John Jasper.

Mr. Walters: Do you remember a party at Canon Crisparkle’s shortly after your arrival?

Witness: On the night of our arrival.

Mr. Walters: Who was there?

Witness: Myself, Miss Twinkleton, and Rosa Bud, and Edwin Drood, and John Jasper.

Mr. Walters: You are sure John Jasper was there?

Witness: Yes; I noticed him particularly.

Mr. Walters: Why?

Witness: Because of his strange manner towards Rosa Bud.

Mr. Walters: How?

Witness: He watched her closely. During the evening she sang to his accompaniment, and his eyes were fixed on her the whole time with a most peculiar expression, and this seemed to trouble Rosa, although she was not looking at him. Suddenly she covered her face with her hands, burst into tears, and said she was frightened and wanted to be taken away.

Mr. Walters: You don’t think it was pure imagination on her part? She was frightened?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: When people are frightened there is danger about generally. Did you think there was any danger in his looking at her?

Witness: I thought there was danger in his looks.

Mr. Walters: Did you ever speak to her about it?

Witness: Yes. She said she was terrified at him; that he haunted her like a ghost, and that he made secret love to her.

Mr. Walters: And she didn’t like it?

Witness: She begged me to take care of her, and stay with her.

Mr. Walters: Did you promise to do so?

Witness: I said I would protect her.

Mr. Walters: Be very careful. If this man frightened her, would he not equally frighten you?

Witness: In no circumstances.

Mr. Walters: That is because you are a woman of daring?

Witness: I suppose so.

Mr. Walters: If you promised to shield and protect her, you did not content yourself with words. Did you take any action?

[Pg 32]

Witness: I kept a sort of watch on John Jasper.

Mr. Walters: Why on Jasper?

Witness: Because I felt that he menaced Rosa’s peace and happiness.

Mr. Walters: You thought he was the source of the danger?

Witness: No one but Jasper.

Mr. Walters: Had she any enemies?

Witness: No; she was too sweet and lovable.

Mr. Walters: And you thought it was John Jasper, and John Jasper alone?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: We will leave that for a moment, and come to your brother. You are very intimate with your brother, and he confides in you. Were he and Drood friendly?

Witness: Yes, but they had a little misunderstanding.

Mr. Walters: Misunderstanding?

Witness: Only a difference of opinion.

Mr. Walters: Did you think it would lead your brother to make an attack on him?

Witness: The idea is preposterous.

Mr. Walters: They had a quarrel at the outset?

Witness: My brother did not like the way in which Edwin Drood spoke of Rosa Bud. He thought he was too patronising. John Jasper came up, made a great deal more of it than it warranted, and then insisted on the young men going back with him to have a glass of wine—stirrup-cup, he called it.

Mr. Walters: What was the effect on your brother?

Witness: Both became flushed and excited.

Mr. Walters: Was it very usual with your brother?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: Yet a small quantity had this effect on him. Did you suspect anything of the wine?

Witness: I am morally certain the wine was drugged.

Mr. Walters: I believe after that there was to be a little patching up?

Witness: That was owing to Canon Crisparkle. They were all to meet and shake hands.

Mr. Walters: Was it to be a large party, or confined to themselves?

Witness: Only my brother and Edwin Drood and John Jasper, who had invited them to his house.

Mr. Walters: That was on the Christmas Eve?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did you know anything about your brother’s plans for the next day?

Witness: He had planned to go on a walking tour.

Mr. Walters: You knew all about it?

Witness: Yes.

[Pg 33]

Mr. Walters: All arranged?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: No secret?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: And to the best of your knowledge, he started on that tour next morning?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Now, to get back to the party: you saw your brother just before he went?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Was he happy and jolly going to the party?

Witness: No. He was ready to shake hands with Edwin Drood, but he had a strange dread of the gatehouse.

Mr. Walters: He did not object to going?

Witness: No; because he wanted to shake hands with Edwin Drood.

Mr. Walters: Then the main object of his going was, not to enjoy himself, but to shake hands with Edwin Drood?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: And you think that was practically the only motive?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: We are told that Neville was fetched back after starting on his journey.

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Was it a surprise he was fetched back after Drood’s extraordinary disappearance was mentioned?

Witness: It was.

Mr. Walters: But when you heard who had fetched him back, was that a surprise?

Witness: No; because Jasper had always been his enemy from the first.

Mr. Walters: You thought he had cast suspicion on him?

Witness: Jasper had hinted in Cloisterham to many people that if anything ever happened to his nephew my brother would be responsible for it.

Mr. Walters: And so you knew that your brother was under deep suspicion when brought back to Cloisterham?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did you take that very much to heart?

Witness: I did, indeed, seeing it concerned the one I loved best in the world.

Mr. Walters: There were two persons you wanted to protect?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Who were they?

Witness: My brother, and Rosa Bud.

[Pg 34]

Mr. Walters: You had a double motive, and you thought the danger came from one and the same man?

Witness: I certainly did.

Mr. Walters: Who was that?

Witness: John Jasper.

Mr. Walters: What did your brother do after all this?

Witness: He was so sad and unhappy that he left Cloisterham, and took lodgings in London.

Mr. Walters: You went with him?

Witness: No, I stopped there to live it down.

Mr. Walters: That is where your courage came in again?—But you need not reply. I shall leave it to the Jury to draw their own conclusions. And now, all this time you were watching Jasper? Did you discover anything about his actions?

Witness: Nothing definite.

Mr. Walters: Did you hear of his going here and there?

Witness: Yes; there were periodical disappearances.

Mr. Walters: Did you know where he went on those occasions?

Witness: Yes, he went to London.

Mr. Walters: And when in Cloisterham, how did he behave?

Witness: He went about always throwing out hints that he had thought my brother so hot tempered that he was afraid for his nephew to meet him.

Mr. Walters: Did he meet Rosa Bud again?

Witness: He made love to her.

Mr. Walters: Did she receive him kindly?

Witness: Hated him, loathed him, was terrified at him.

Mr. Walters: Did he say anything to her when he discovered what her attitude was?

Witness: He told her that nothing should prevent him from having her himself. No one should stand against him.

Mr. Walters: Did he threaten anyone who did stand against him?

Witness: Yes; he threatened my brother’s life.

Mr. Walters: You mean, he said to Rosa Bud something which amounted to a threat against your brother’s life?

Witness: He said he could place him in the greatest jeopardy and danger.

Mr. Walters: Then you thought his danger would increase?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: I suppose you went to London occasionally to see your brother?

Witness: Not often.

Mr. Walters: Did you ever see Rosa Bud in London?

[Pg 35]

Witness: Yes. She fled to London, so terrified was she at Jasper with his desperate love-making. She went to Mr. Grewgious, her guardian.

Mr. Walters: And you determined to shield her as much as possible?

Witness: More than ever.

Mr. Walters: Did you ever recall those words, that you would not, in any circumstances, be afraid of Jasper?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Not a mere idle boast?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: You meant it?

Witness: I did.

Mr. Walters: Six months went by, and no progress made?

Witness: I found out nothing.

Mr. Walters: Yet the danger remained, and increased?

Witness: I grew more and more anxious.

Mr. Walters: It was the woman against the man, and the woman was making no headway?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did you think it was about time to change your course of action?

Witness: I did.

Mr. Walters: What did you do?

Witness: I remembered how, as a little girl, I dressed myself as a boy, and now I determined to dress myself as a man.

Mr. Walters: That was the result of recalling what you had done as a girl?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: What you had done in the past you could do again?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: It was difficult, you realised?

Witness: Yes, it was difficult, but I determined to overcome every difficulty.

Mr. Walters: You did not shrink?

Witness: Naturally I shrank, but the end was worth all the sacrifice.

Mr. Walters: You determined to go through with it?

Witness: I did.

Mr. Walters: Because you had this double motive?

Witness: That is so.

Mr. Walters: The overpowering motive which overcame everything else?

Witness: Yes.

[Pg 36]

Mr. Walters: Very well, now; if you could have avoided dressing yourself as a man, if some other course had been open to you, would you have taken it?

Witness: If I could have felt sure of success.

Mr. Walters: But you felt this was the last resource, and determined to do it?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: In order to appear as a man, you had to adopt a very complete disguise indeed. Did you remember what you did when you were a little girl? Did you cut off your hair again?

Witness: No, I thought I could manage.

Mr. Walters: Miss Landless, I don’t want to press you, but was there any particular, personal reason why you didn’t wish to sacrifice your hair?

Witness: Am I obliged to answer that question?

Judge: No.

Mr. Walters: His Lordship says you need not answer that question. I think we may leave it to the Jury, as human beings, to give their own answer. But, at all events, we understand that you did not cut off your hair. Did you whiten your eyebrows?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: You thought you could manage?

Witness: I did.

Mr. Walters: How did you disguise yourself effectively?

Witness: I put on a large wig of white hair.

Mr. Walters: To conceal your own luxuriant tresses?

Witness: I bound them well down underneath.

Mr. Walters: What else?

Witness: I thought, in keeping with a large head of white hair, I had better assume the free and easy manners of an elderly man, and I tried to put a little dash of swagger, and I wore a blue coat and buff waistcoat.

Mr. Walters: It was not so difficult, after all, in some respects, for you are a rapid and fluent talker—you need not be shy, you are—and therefore, as Dick Datchery, the affable old gentleman, a bit garrulous, you did not find much difficulty?

Witness: No: I did not find it very difficult.

Mr. Walters: What did you do in Cloisterham?

Witness: I put up at the Crozier Inn.

Mr. Walters: Where is that?

Witness: In the High Street.

Mr. Walters: Far from the Gate House?

Witness: No.

Mr. Walters: Did you try the effect of your disguise on the people in the neighbourhood?

[Pg 37]

Witness: Yes, at the Crozier I walked in, asked a few questions, and ordered a man’s dinner.

Mr. Walters: You ordered a man’s dinner?

Witness: You would not have had me ask for a glass of milk and a Sally Lunn!

Judge: What is a man’s dinner?

Witness: I called for a fried sole, and a veal cutlet, and a pint of sherry. Something like a man’s dinner!

Mr. Walters: And did you consume this gargantuan feast?

Witness: I think you are an intelligent gentleman, and I will leave it to you.

Mr. Walters: You may. Now let us come to your inquiries. I suppose you wanted lodgings?

Witness: I asked the waiter if he could direct me to any.

Mr. Walters: And did he?

Witness: I asked for something old, architectural, and inconvenient.

Mr. Walters: And he directed you?

Witness: He did.

Mr. Walters: Very far?

Witness: No; not far: Mrs. Tope’s house.

Mr. Walters: Did you find it easily?

Witness: No. That would not have done. I wandered about a bit in the wrong direction, and inquired, and at last found it.

Mr. Walters: The reason for all that?

Witness: I wanted to put everybody off the scent, and tried to act as to the manner born, so that if anybody were watching me they would really take me for the man I wanted to be.

Mr. Walters: You thought it best to take every precaution, in case you were watched?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: And they would think you had lost your way, and were a stranger?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: As a matter of fact, you were not a stranger. Did you meet Mr. Jasper?

Witness: I made an excuse, and I went up and asked him if he could tell me anything as to the respectability of the Tope family.

Mr. Walters: So that you bearded the lion in his den. Did he recognise you?

Witness: No; he did not know the mouse.

Mr. Walters: There are other ways of detecting people than by appearance. Jasper is a musician with a very delicate ear. What about your voice?

Witness: Mr. Jasper had only heard it once, and that was months ago, and, besides, I can change it (changing her voice)—change the tone of my voice, and speak like a man.

[Pg 38]

Mr. Walters: You can disguise it, Miss Landless, so that people would really think it was a man’s voice?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Tell us what you discovered as to Mr. Jasper’s movements at this time.

Witness: He absented himself from the Cathedral every now and then, and made periodical disappearances.

Mr. Walters: Where did he go?

Witness: To London.

Mr. Walters: Were you in correspondence with Mr. Grewgious, the family solicitor, in London?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did he tell you he had seen Jasper?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: So that, between you, you knew all about him?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: In the character of Datchery, did you meet people?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Durdles?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: The old opium woman?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Mr. Sapsea, the Mayor?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Did you talk to them familiarly?

Witness: Yes. I really knew their idiosyncrasies—everyone of them—so I fooled them to the top of their bent, and got everything out of them.

Mr. Walters: I have no doubt but that you asked the old opium woman some questions?

Witness: She had been following Jasper to the Gate House, and she asked me, in a whisper, would I mind telling her who he was, his name, and where he lived.

Mr. Walters: And you said it was John Jasper?

Witness: Yes. She asked, would I give her three-and-sixpence to buy some opium. She said that on Christmas Eve a young gentleman gave her three-and-sixpence, and he said that his name was Edwin. And she said where could she see Jasper? And I told her in the Cathedral.

Mr. Walters: Did she go to the Cathedral next morning?

Witness: Yes; I saw her behind a pillar, shaking her fist at him.

Mr. Walters: You think she knew something about him?

Witness: Yes; that she knew more about his character than anybody else suspected.

Mr. Walters: May I take it that the results of your investigations led you to the conclusions about John Jasper—that they increased your suspicions?

[Pg 39]

Witness: I had my suspicions from the first.

Mr. Walters: Did you keep a record of your successes at the time?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: How?

Witness: In chalk marks.

Mr. Walters: Why in chalk marks?

Witness: I like the old tavern way of keeping scores. You may make a little mark, and nobody but the scorer knows what it means: a small mark for a small success, and a big mark for a big one.

Mr. Walters: Was another reason that you did not wish your woman’s handwriting to be discovered?

Witness: That would never have done.

Mr. Walters: Did you adopt any device to bring Jasper into your presence, or not?

Witness: Yes; Mr. Grewgious had told me that he had given a ring to Edwin Drood.

Mr. Walters: And did you use that ring in any way?

Witness: Yes; it was this ring that I used to lure him.

Mr. Walters: And then, when you confronted Jasper, you felt that you had sufficient to go upon to accuse him openly of murder?

Witness: I did. His appearance and agitation were sufficient.

Mr. Walters: And so he was accused of murder; and your motives throughout were disinterested motives for the protection of Rosa Bud and your brother?

Witness: That is so.

Mr. Walters: You knew Edwin Drood?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Walters: Do you think that if he had voluntarily disappeared while all this trouble was going on, he would have communicated with his friends?

Witness: Yes, he was a kind-hearted lad.

Mr. Walters: You cannot understand him being silent while Rosa was in danger?

Witness: I am sure he would not be.

Mr. Walters: You think that, wherever he was, he would have spoken, if alive?

Witness: I do.

Mr. Walters: Thank you, that will do.

[Helena Landless Cross-examined.]

Mr. Chesterton: Miss Landless, you say you knew the prisoner to some extent before the disappearance of Edwin Drood?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Chesterton: When did you learn that the prisoner was addicted to opium smoking—or have you learned it?

Witness: Mr. Tope told me of a seizure he had in the Cathedral.

[Pg 40]

Mr. Chesterton: When was that, approximately?

Witness: As far as I can remember, about a few weeks after I came to Cloisterham as Dick Datchery. Rosa told me how frightened she was of him after he had had a dream; that he used to go into a peculiar kind of dream, and a film came over his eyes, and then she was more terrified of him than before.

Mr. Chesterton: But you are putting two very different dates. I want to know when you realised he was addicted to opium smoking.

Witness: It takes a little time to realise anything. We hear this and that, and we put two and two together.

Mr. Chesterton: When Rosa gave you that information, did you suspect opium smoking?

Witness: I had a faint suspicion.

Mr. Chesterton: It occurred to you that it was probably opium. You knew Edwin Drood, Miss Landless?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Chesterton: Was he a conspicuous person—a person to notice very much?

Witness: Not very much, with the exception of this: that he was rather patronising, and had the air of a lad who was very much at home with himself.

Mr. Chesterton: He dressed like ordinary young men?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Chesterton: Wore trousers?

Witness: Yes, certainly, I believe so.

Mr. Chesterton: Do you understand that the ring was found in the quicklime?

Witness: I believe so.

Mr. Chesterton: Oh! you believe so!

Witness: It was found there.

Mr. Chesterton: Were any buttons found there?

Witness: No, I believe not.

Mr. Chesterton: I suppose Mr. Drood would presumably have on either a belt or braces. Was a buckle or a belt or braces found in the quicklime?

Witness: No.

Mr. Chesterton: Nothing was found in the lime except this ring?

Witness: No.

Mr. Chesterton: Thank you.

Witness: I could throw some light on that.

Mr. Chesterton: Your Counsel will no doubt re-examine you. Now, I want to know about this disguise of yours. You told us that it was no new thing to disguise yourself, because you dressed up as a boy in Ceylon. Would you kindly tell me how old you were the last time you did it?

Witness: Thirteen.

[Pg 41]

Mr. Chesterton: Do you really suggest that a little girl of thirteen dressing up as a little boy—dressing up as a boy of thirteen—is any sort of qualification for a young lady of 21 dressing up as an “old buffer living idly on his means”?

Witness: Yes; the girl is mother to the woman, as the boy is father to the man.

Mr. Chesterton: Well, now, you have told us, Miss Landless, that in dressing up as Datchery, you wore a white wig, blue coat, buff waistcoat, and so on. Did you do anything to your face?

Witness: No.

Mr. Chesterton: You did not paint your face at all?

Witness: I always have enough colour in my face without paint.

Mr. Chesterton: You did not make up your face in any way?

Witness: No.

Mr. Chesterton: Do you ask the Jury to believe that you had been going about Cloisterham as Helena Landless for more than six months—ever since you came to Canon Crisparkle’s—that you had been going about as Miss Helena Landless; that you did not alter your face in any way, and went about as Dick Datchery, seeing the same people? Do you ask the Jury to believe that you were not recognised?

Witness: I ask them to believe it, because it is the truth.

Mr. Chesterton: Very well; the Jury will decide that for themselves. You say you went to Cloisterham and put up at the Crozier?

Witness: Yes.

Mr. Chesterton: You also told us that you ordered a certain meal—a fried sole, a veal cutlet, and a pint of sherry. When my learned friend asked you, you said you would leave it to us. I must ask you: did you consume that meal?

Witness: I am a healthy young woman, but I did not eat it all. I had a little of the fish, some of the cutlet, and some of the sherry.

Mr. Chesterton: How much sherry?

Witness: I had a glass.

Judge: It is important to insist whether the glasses were ordinary wine glasses.

A Juryman (Mr. Edwin Pugh): I think it is not a fair question.