The Project Gutenberg eBook of The children's book of Christmas, by J. C. Dier

Title: The children's book of Christmas

Compiler: J. C. Dier

Release Date: May 5, 2023 [eBook #70702]

Language: English

Produced by: Bob Taylor, Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON · BOMBAY · CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

THE

CHILDREN’S BOOK

OF CHRISTMAS

Compiled by

J. C. DIER

The MACMILLAN COMPANY

1911

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1911,

BY

THE MACMILLAN

COMPANY

Set up and electrotyped.

Published, October, 1911.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

[Pg v]

[This question addressed to The Sun, New York, received this reply.]

We take pleasure in answering at once and thus prominently the communication below, expressing at the same time our great gratification that its faithful author is numbered among the friends of The Sun:—

Virginia, your little friends are wrong. They have been afflicted by the scepticism of a sceptical age. They do not believe except they see. They think that nothing can be which is not comprehensible by their little minds. All minds, Virginia, whether they be men’s or children’s, are little. In this great universe of ours man is a mere insect, an ant, in his intellect, as compared with the boundless world about him, as measured by the intelligence capable of grasping the whole of truth and knowledge.

Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus. He exists as certainly as love and generosity and devotion exist, and you know that they abound and give to your life its highest beauty and joy. Alas! how dreary would be the world if there were no Santa Claus! It would be as dreary as if there were no Virginias. There would be no childlike faith then, no poetry, no romance, to make tolerable this existence. We should[Pg vi] have no enjoyment, except in sense and sight. The eternal light with which childhood fills the world would be extinguished.

Not believe in Santa Claus! You might as well not believe in fairies. You might get your papa to hire men to watch in all the chimneys on Christmas Eve to catch Santa Claus, but even if they did not see Santa Claus coming down, what would that prove? Nobody sees Santa Claus, but that is no sign that there is no Santa Claus. The most real things in the world are those that neither children nor men can see. Did you ever see fairies dancing on the lawn? Of course not, but that’s no proof that they are not there. Nobody can conceive or imagine all the wonders that are unseen and unseeable in the world.

You may tear apart the baby’s rattle and see what makes the noise inside, but there is a veil covering the unseen world which not the strongest man, nor even the united strength of all the strongest men that ever lived, could tear apart. Only faith, fancy, poetry, love, romance, can push aside that curtain and view and picture the supernal beauty and glory beyond. Is it all real? Ah, Virginia, in all this world there is nothing else real and abiding.

No Santa Claus! Thank God! he lives, and he lives forever. A thousand years from now, Virginia, nay, ten times ten thousand years from now, he will continue to make glad the heart of childhood.

[Pg vii]

| PAGE | ||

| Is there a Santa Claus? | v | |

| An Editorial by the late Frank P. Church in the New York Sun. | ||

| Christmas Greens | 1 | |

| Adapted from Some Curiosities of Popular Customs by William S. Walsh. | ||

| I Saw Three Ships come Sailing in | 2 | |

| A Kentish Version of an old English Christmas Carol. | ||

| The Angels and the Shepherds | 4 | |

| The Gospel Story as in the Children’s Series of the Modern Reader’s Bible, edited by R. G. Moulton. | ||

| While Shepherds Watched | 6 | |

| The famous Christmas hymn written in about 1700 and attributed to Nahum Tate. | ||

| The Wise Men from the East | 7 | |

| The Gospel Story as in the Children’s Series of the Modern Reader’s Bible, edited by R. G. Moulton. | ||

| Strooiavond in Holland | 9 | |

| Adapted from Holland by Beatrix Jungman in the Peeps at Many Lands Series, with one paragraph simplified from Servia and the Servians by Chedo Mijatovich. | ||

| How St. Nicholas came To Volendam | 12 | |

| From the volume on Holland by Beatrix Jungman in the Peeps at Many Lands Series. | ||

| Keeping Christmas in the Old Way | 16 | |

| From an entertaining old pamphlet published in 1740 entitled “Round about Our Coal Fire, or Christmas Entertainments,” quoted in Christmas: Its Origin and Associations by W. F. Dawson. | ||

| As Joseph was A-walking | 20 | |

| An Old English Christmas Carol known as The Cherry-tree Carol. In many versions another stanza said to be of later origin is added. | ||

| The “Jule-Nissen” and Blowing in the Yule | 21[Pg viii] | |

| From The Old Town by Jacob A. Riis, copyright by The Macmillan Company, 1909. | ||

| Christmas Eve in Merry England | 23 | |

| From Marmion by Sir Walter Scott. | ||

| When Christmas was not Merry | 25 | |

| Compiled from Christmas: Its Origin and Associations by W. F. Dawson, and from general sources. | ||

| Going Home for Christmas | 28 | |

| From Old Christmas at Bracebridge Hall by Washington Irving. | ||

| God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen | 31 | |

| An Old English Carol. | ||

| The Date of Russia’s Christmastide | 33 | |

| Compiled from general sources, and in part from Russia by L. Edna Walter in the Peeps at Many Lands Series. | ||

| St. Barbara’s Grain | 37 | |

| Adapted from an unsigned article in Macmillan’s Magazine and from creole folk-lore. | ||

| Before the Paling of the Stars | 38 | |

| By Christina Rossetti. | ||

| A Midnight Mass in France | 39 | |

| Adapted from an article in Macmillan’s Magazine with added details drawn from an article in The Century by Mme. Th. Bentzon. | ||

| The Christchild and the Pine Tree | 42 | |

| A weaving together of bits of folk-lore drawn chiefly from The Child and Childhood in Folk-thought by Alexander F. Chamberlain. | ||

| A Birthday Gift | 44 | |

| Part of a hymn for children by Christina Rossetti. | ||

| The Christmas Fire in Servia | 45 | |

| Adapted from Servia and the Servians by Chedo Mijatovich. | ||

| The Day of the Little God | 47 | |

| From Servia and the Servians by Chedo Mijatovich. | ||

| Nature Folk-lore of Christmastide | 50[Pg ix] | |

| Compiled from several sources, including The Old Town by Jacob A. Riis and magazine articles. | ||

| Good King Wenceslas | 53 | |

| An Old English Carol in the version by John Mason Neale. | ||

| A Mexican “Mystery” seen by Bayard Taylor | 54 | |

| From Eldorado by Bayard Taylor. | ||

| Breaking the Piñate | 57 | |

| Collated from Mexico, the Wonderland of the South by W. E. Carson, copyright by The Macmillan Company, 1909. | ||

| Christmas upon a Greenland Iceberg | 59 | |

| Collated from Christmas: Its Origin and Associations by W. F. Dawson, and The Great White North by Helen S. Wright. | ||

| Luther’s Christmas Carol for Children | 61 | |

| Translator unknown. | ||

| The Good Night in Spain | 63 | |

| Adapted from the account by Ferdinand Caballero, translated by Katharine Lee Bates. | ||

| A Christmas Tree in Japan | 66 | |

| From Letters from Japan by Mary Crawford Fraser, copyright by The Macmillan Company, 1899. | ||

| From Far Away | 72 | |

| A Christmas Carol by William Morris. | ||

| Lordings, Listen to our Lay | 73 | |

| A fragment of the earliest existing carol; sung in the thirteenth century. | ||

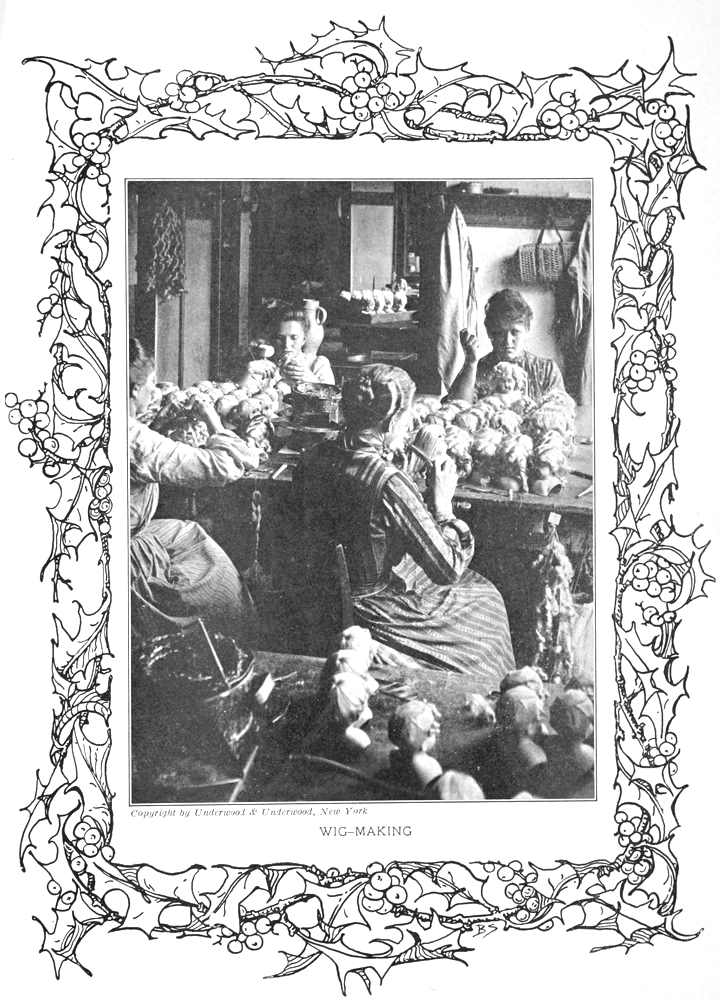

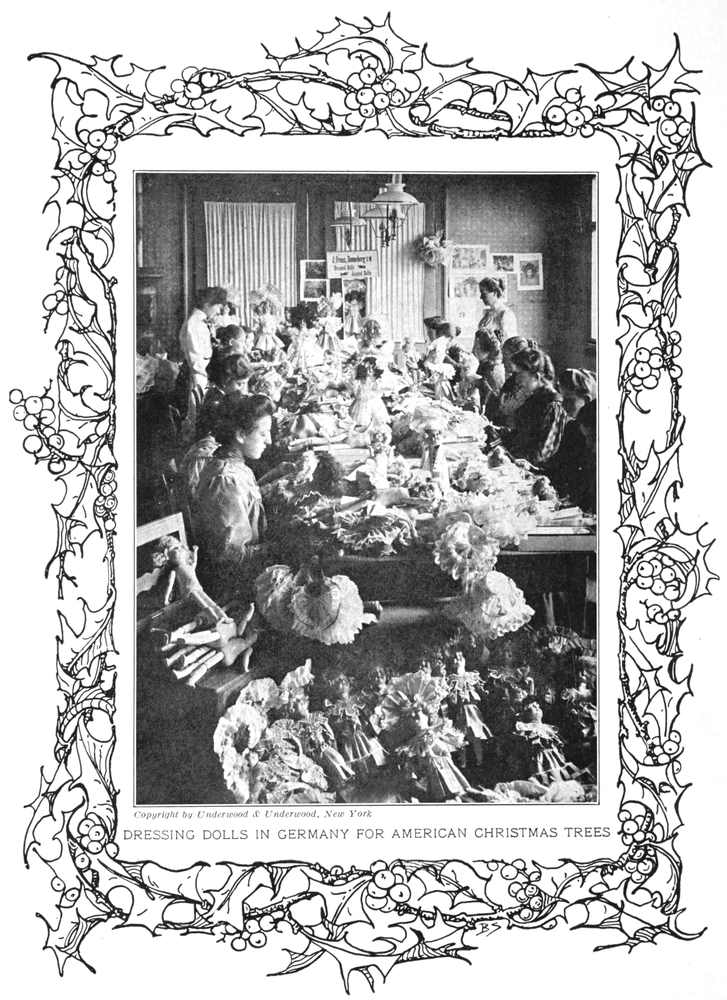

| Where the Christmas Toys come From | 74 | |

| Compiled from general sources, including In Toyland, an article in The Royal Magazine, copyright by C. Arthur Pearson, Ltd. | ||

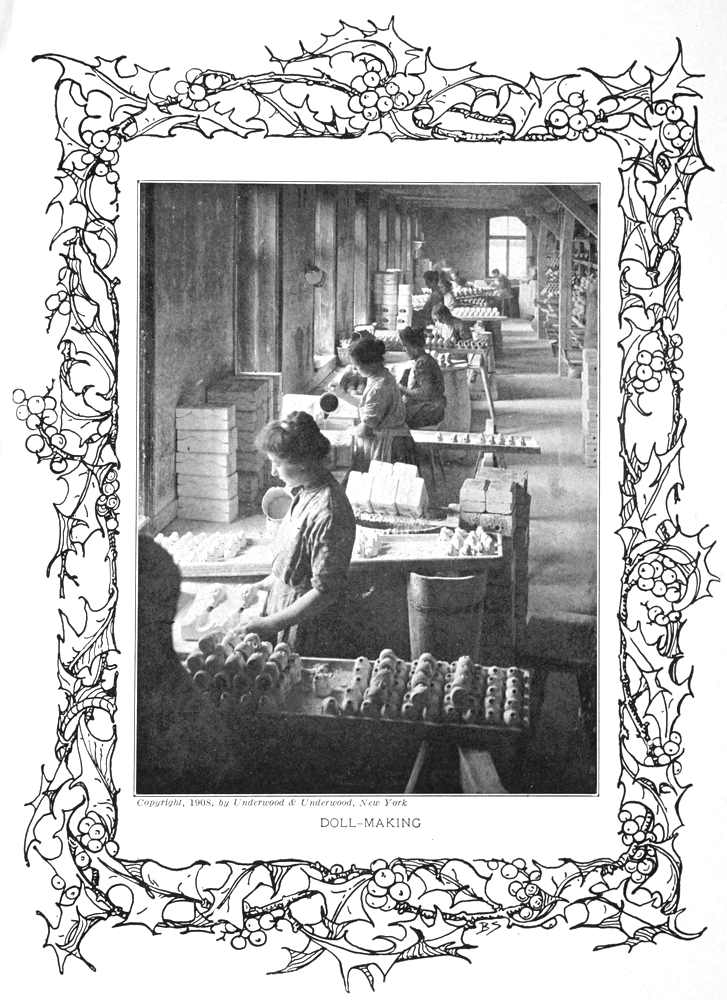

| The Making of a Christmas Doll | 76 | |

| The material of this article also has been drawn from The Royal Magazine by permission of its publishers, C. Arthur Pearson, Ltd. | ||

| Irina’s Day on the Estates | 79 | |

| Adapted from Russia by L. Edna Walter in the Peeps at Many Lands Series. | ||

| A Visit from St. Nicholas | 83[Pg x] | |

| By Clement C. Moore. | ||

| The Cratchits’ Christmas Dinner | 85 | |

| From A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. | ||

| After the Christmas Dinner | 88 | |

| From The Old Town by Jacob A. Riis, copyright by The Macmillan Company, 1909. | ||

| Hang up the Baby’s Stocking | 89 | |

| Author unknown. | ||

| A German Christmas | 90 | |

| Collated from Home Life in Germany by Mrs. Alfred Sidgwick, Music Study in Germany by Amy Fay, and Elizabeth and Her German Garden. | ||

| Crowded Out | 95 | |

| By Rosalie M. Jonas. | ||

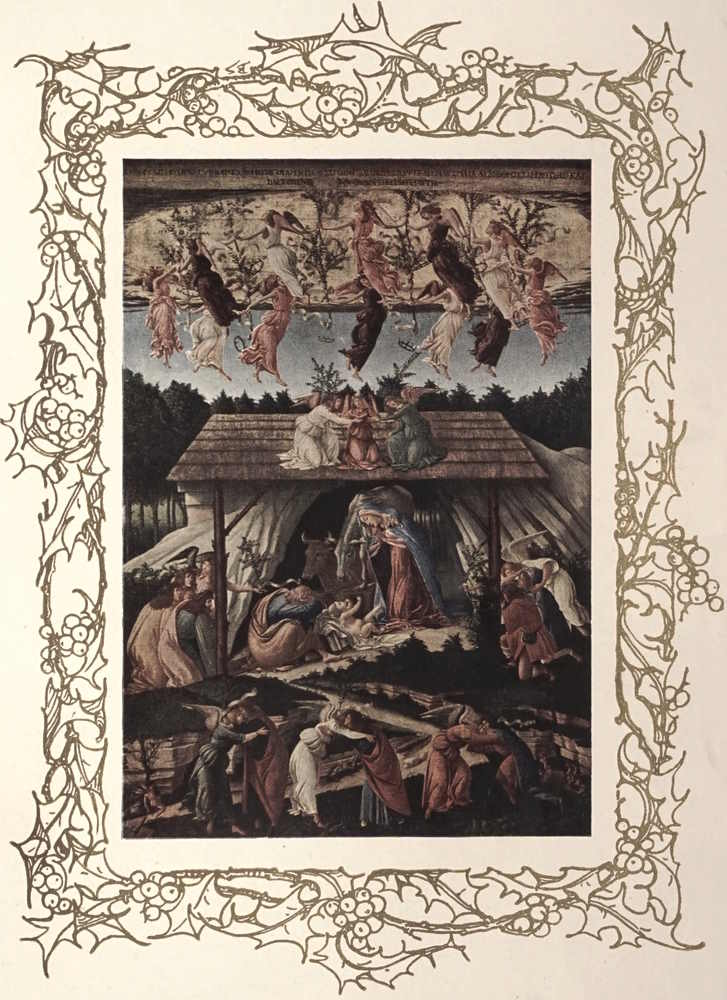

| An English “Adoration” | 96 | |

| Adapted from The Children’s Book of Art by Miss A. E. Conway and Sir Martin Conway. | ||

| The Children’s Own Saint | 99 | |

| Based on legends chiefly drawn from Curiosities of Popular Customs by W. S. Walsh. | ||

| The Befana Fair in Rome | 102 | |

| From Ave Roma Immortalis by F. Marion Crawford, copyright by The Macmillan Company, 1898. | ||

| The Golden Carol | 104 | |

| An Old English Epiphany Carol. | ||

| Babouscka | 105 | |

| By Carolyn S. Bailey. Copyright by the Milton Bradley Company. Reprinted by permission from For the Children’s Hour. | ||

| The Three Kings | 107 | |

| Adapted by permission from The Memoirs of Mistral, copyright by the Baker and Taylor Company, 1907. | ||

| Christmas Peace | 110 | |

| From The Little City of Hope by F. Marion Crawford, copyright by The Macmillan Company, 1907. | ||

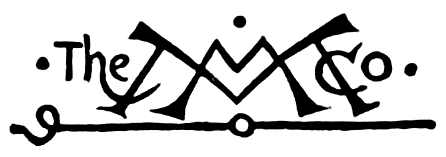

| The Annunciation | Dante Gabriel Rossetti | Frontispiece[Pg xi] |

| PAGE | ||

| The Nativity | Botticelli | Facing 4 |

| Shepherds and Shepherd Boy | 20 | |

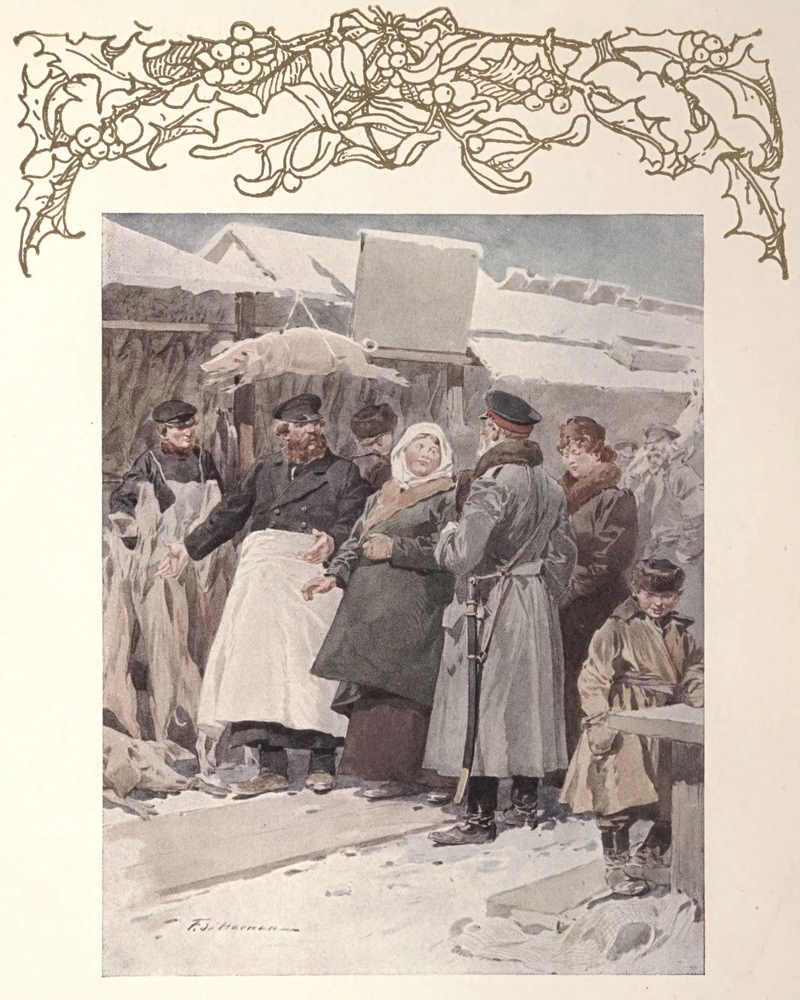

| In a Christmas Market on the Neva | 36 | |

| The Yule Sheaf | 52 | |

| Nuremberg Where the Toys are Made | 72 | |

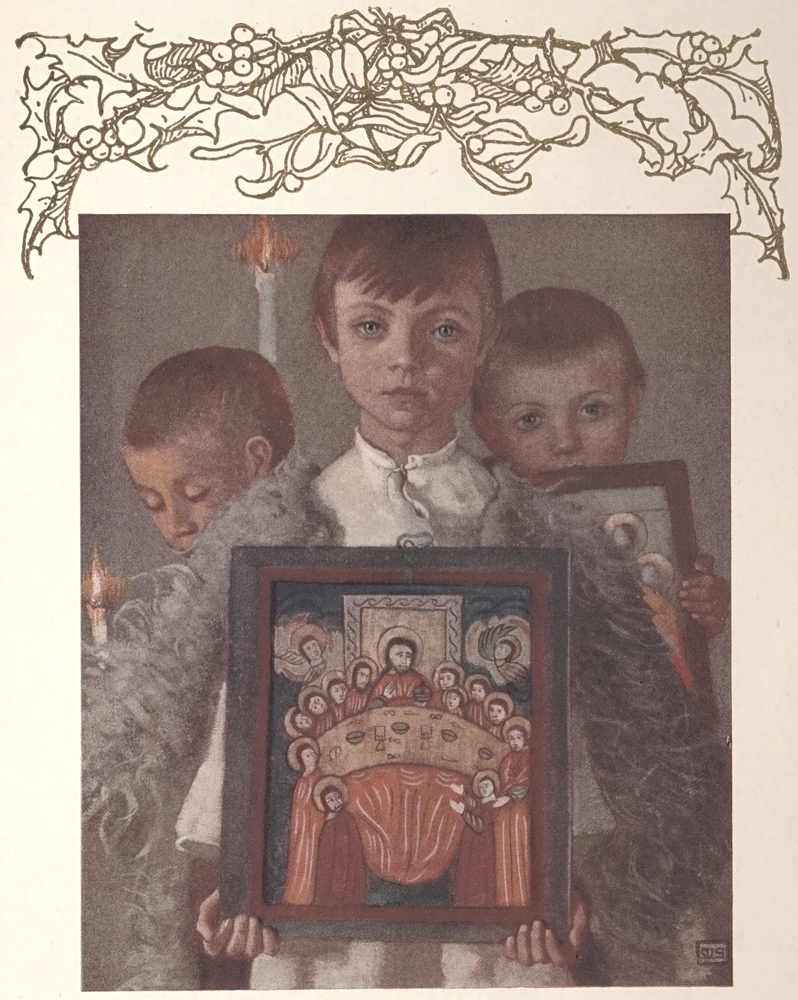

| Roumanian Boys in a Religious Procession | 80 | |

| An English “Adoration” | 96 | |

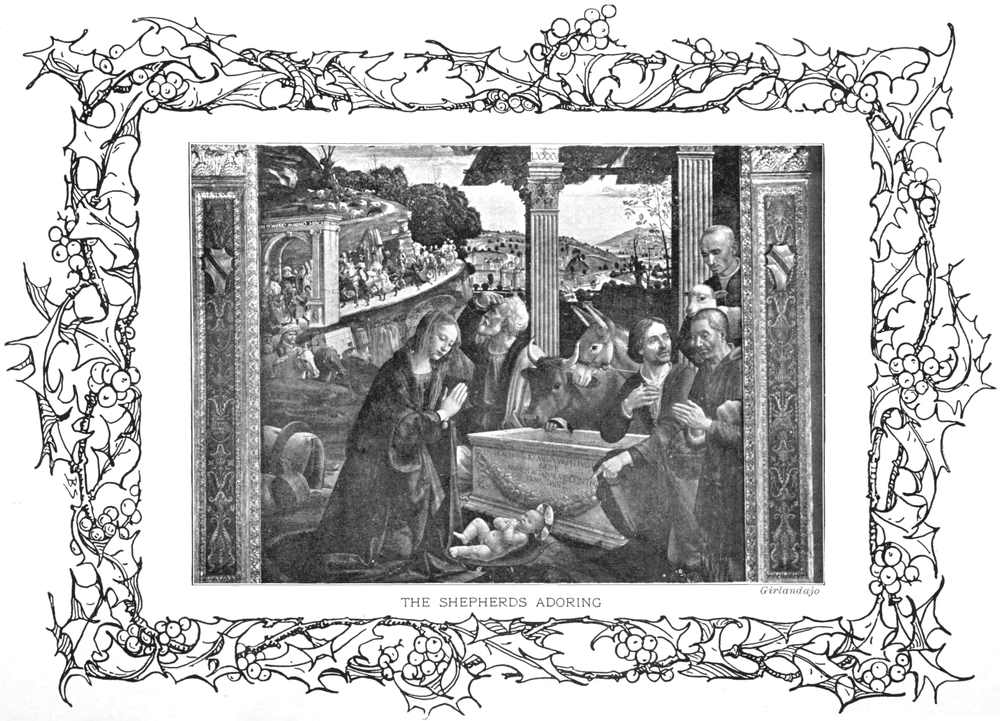

| The Shepherds Adoring | Ghirlandajo | 8 |

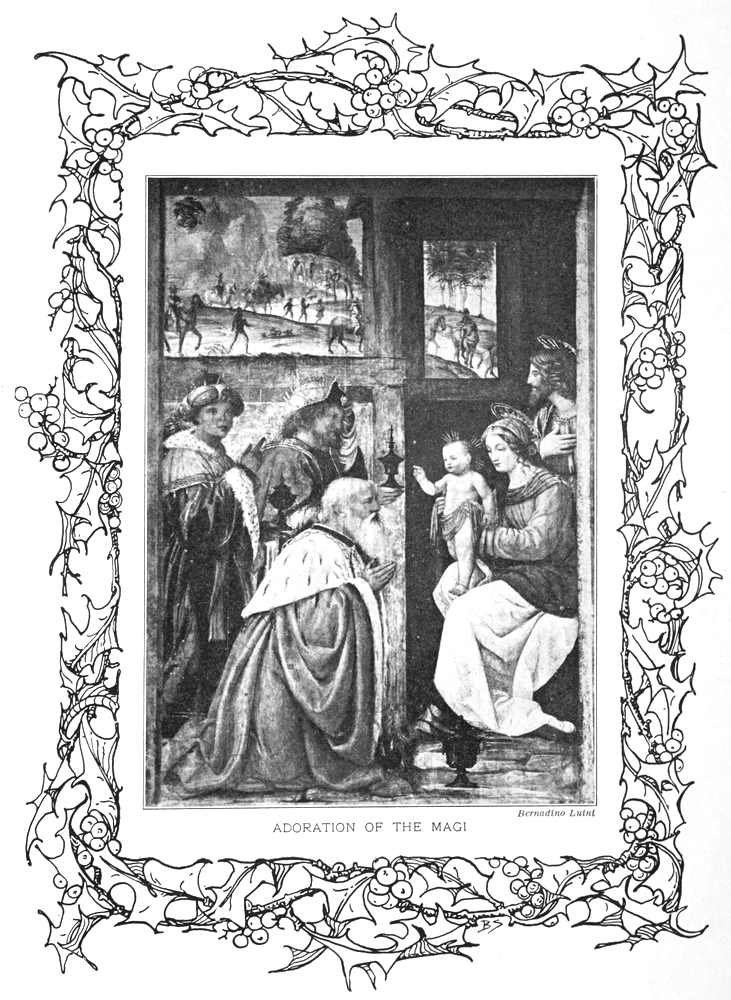

| The Adoration of the Magi | Bernadino | 12 |

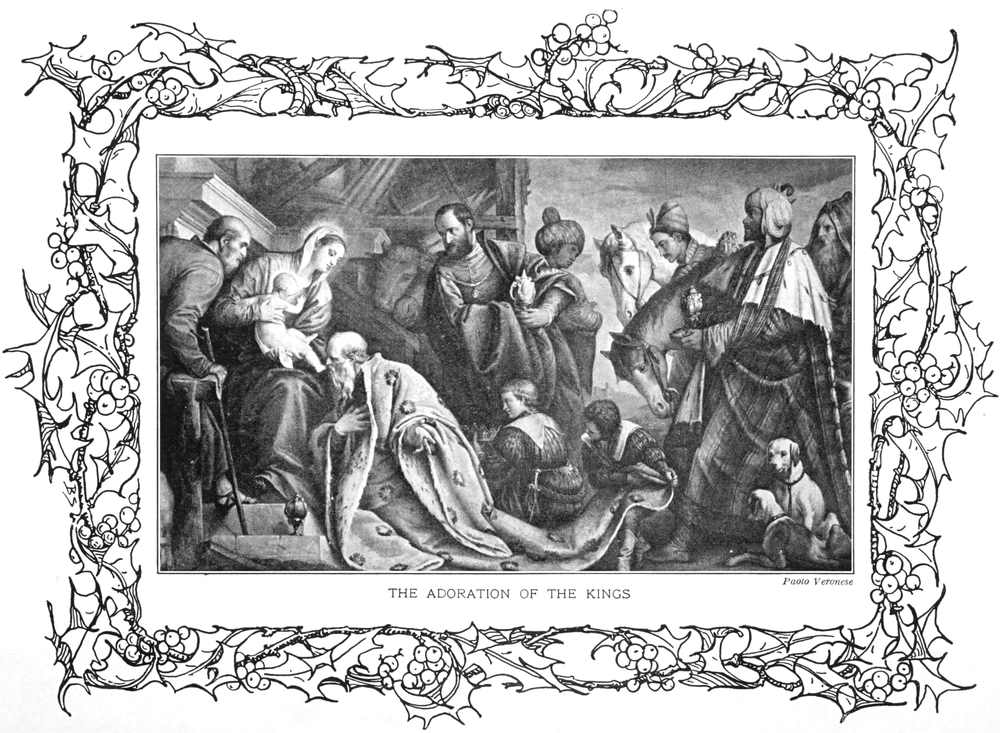

| The Adoration of the King | Veronese | 16 |

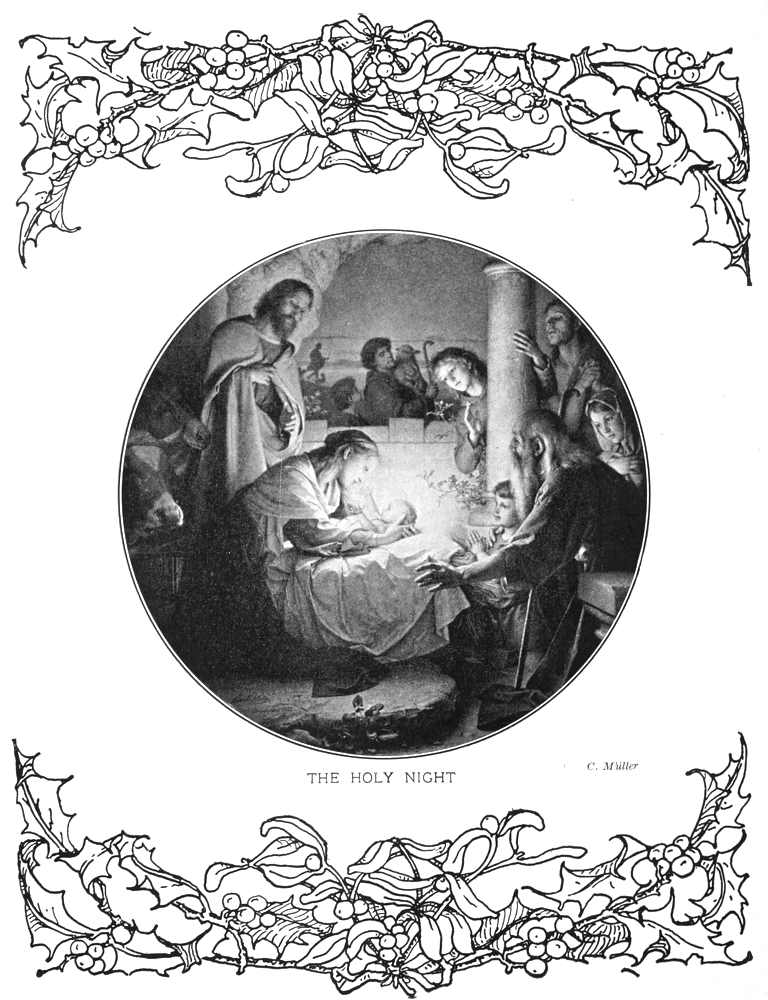

| Holy Night | C. Müller | 24 |

| A Christmas Gift on the Way to Christmas Dinner | 28 | |

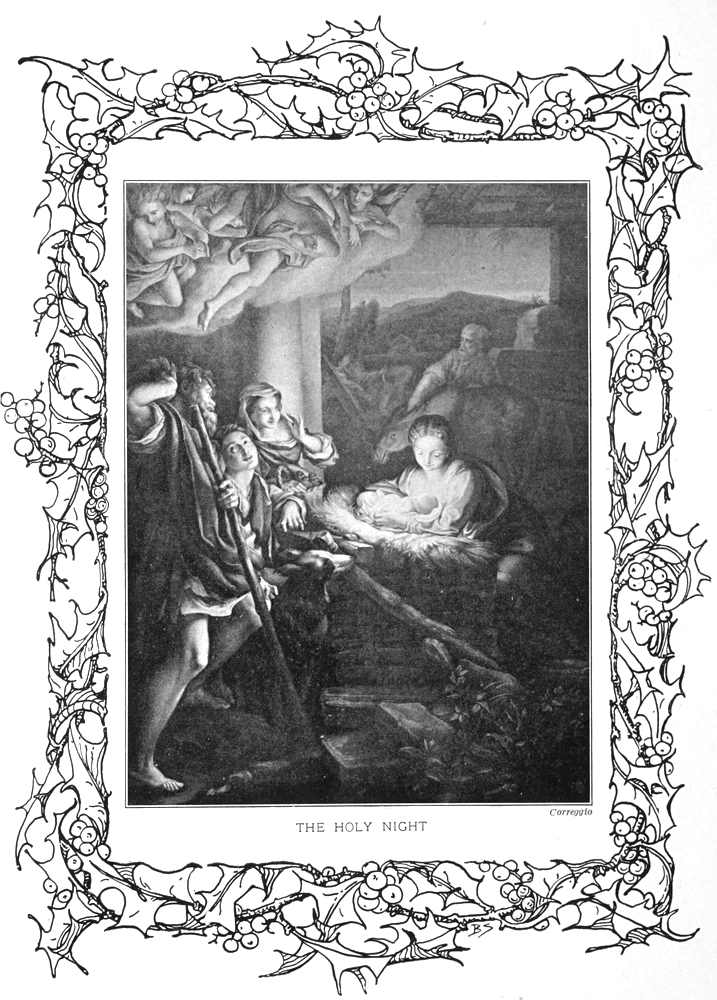

| The Holy Night | Correggio | 32 |

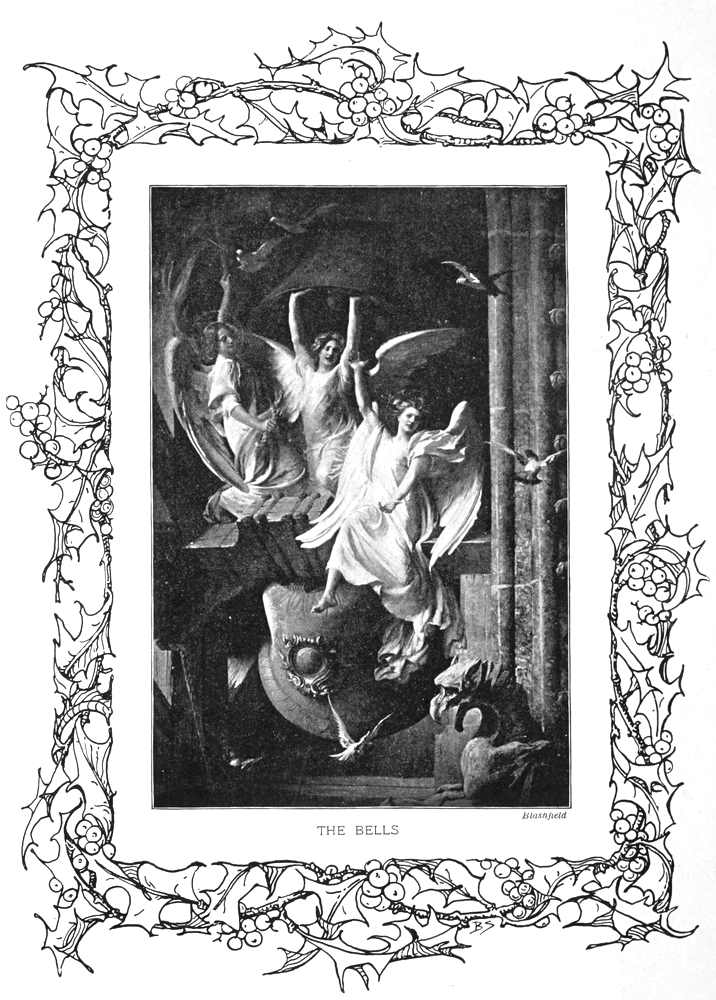

| The Bells | Blashfield | 40 |

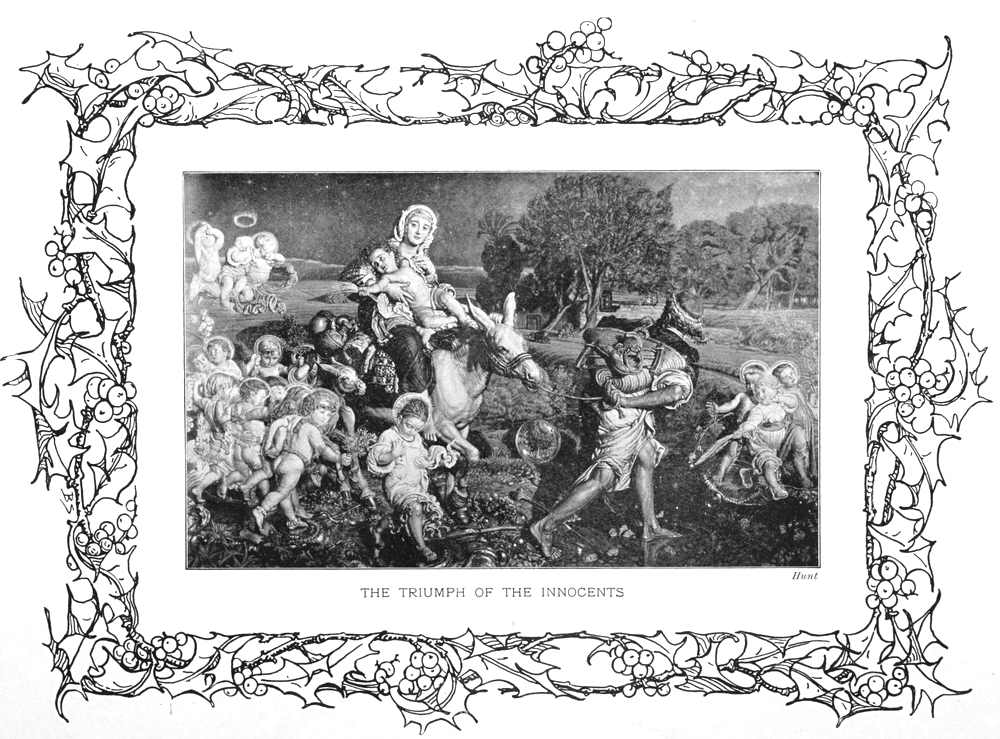

| The Triumph of the Innocents | Hunt | 44 |

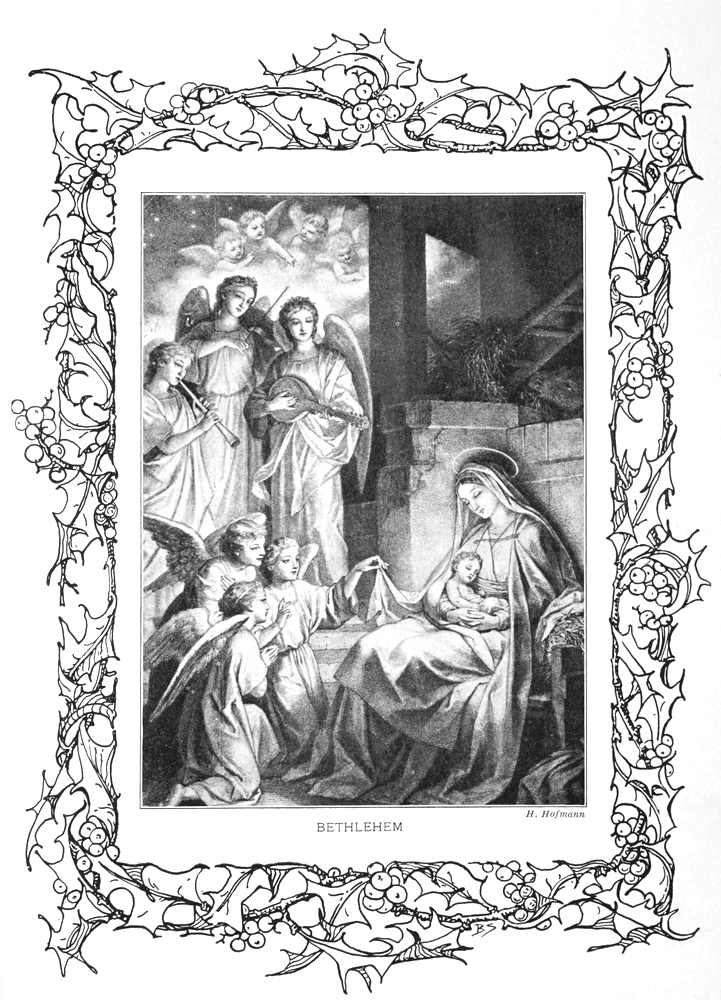

| Bethlehem | Hofmann | 48 |

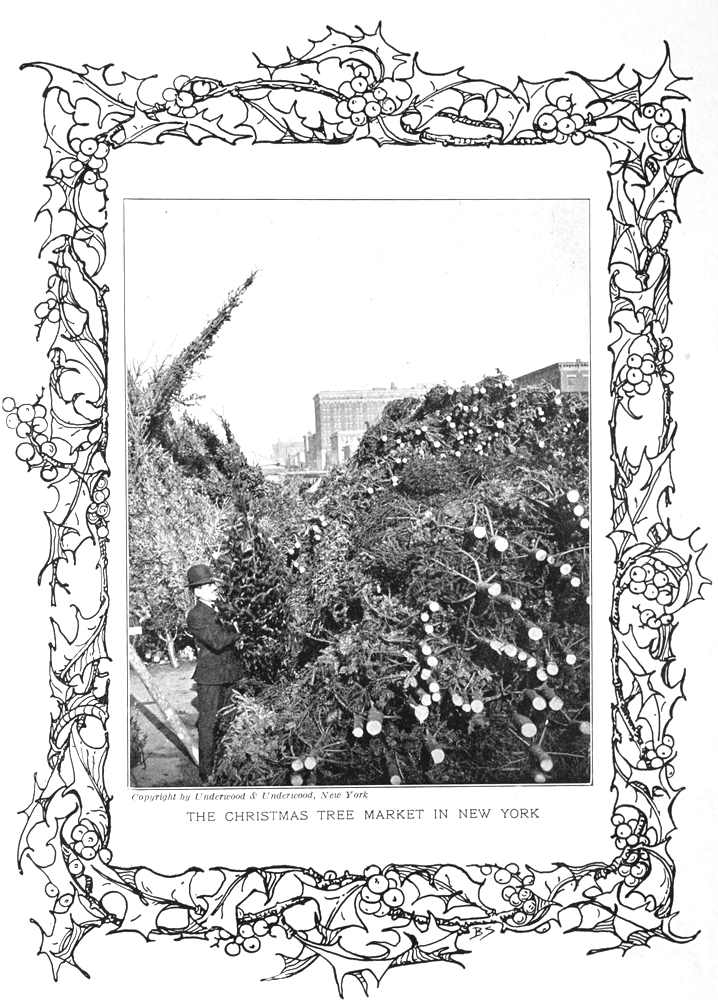

| The Christmas Tree Market in New York | 56[Pg xii] | |

| Heads of the Christ Child from Raphael’s Paintings | 60 | |

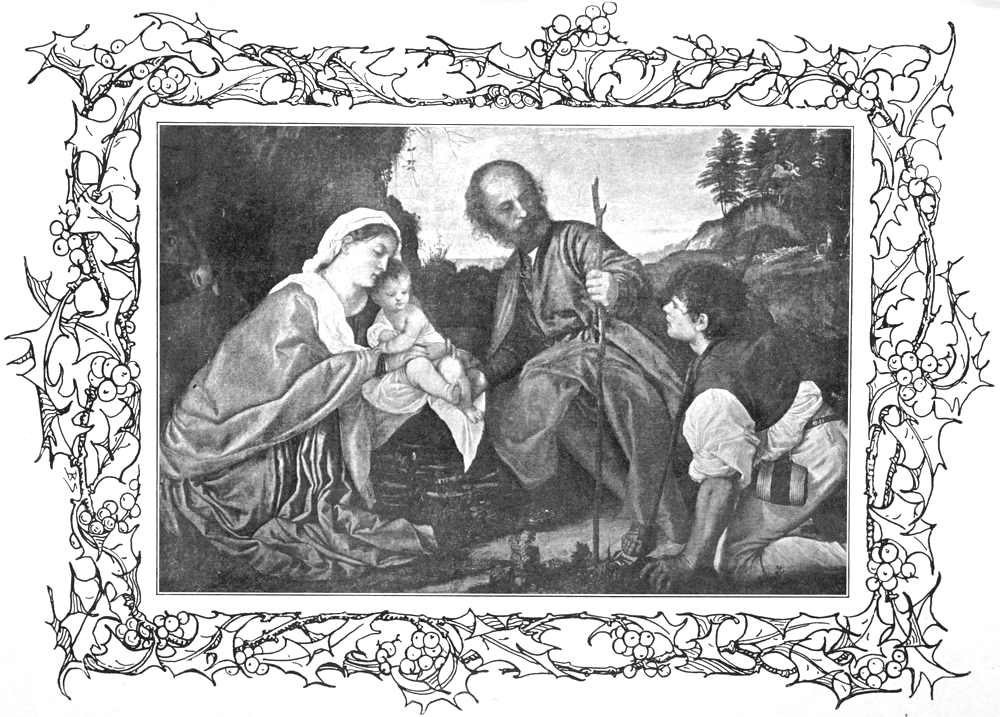

| The Holy Family with the Shepherds | Titian | 64 |

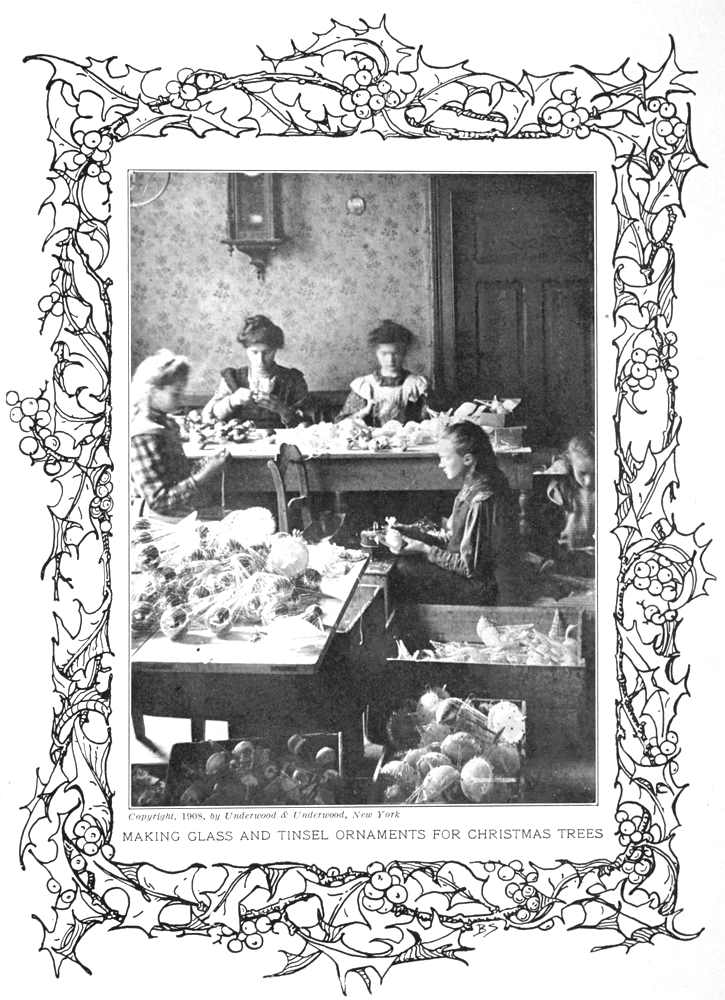

| Making Glass and Tinsel Ornaments for Christmas Trees | 68 | |

| Doll-making | 76 | |

| Wig-making | 78 | |

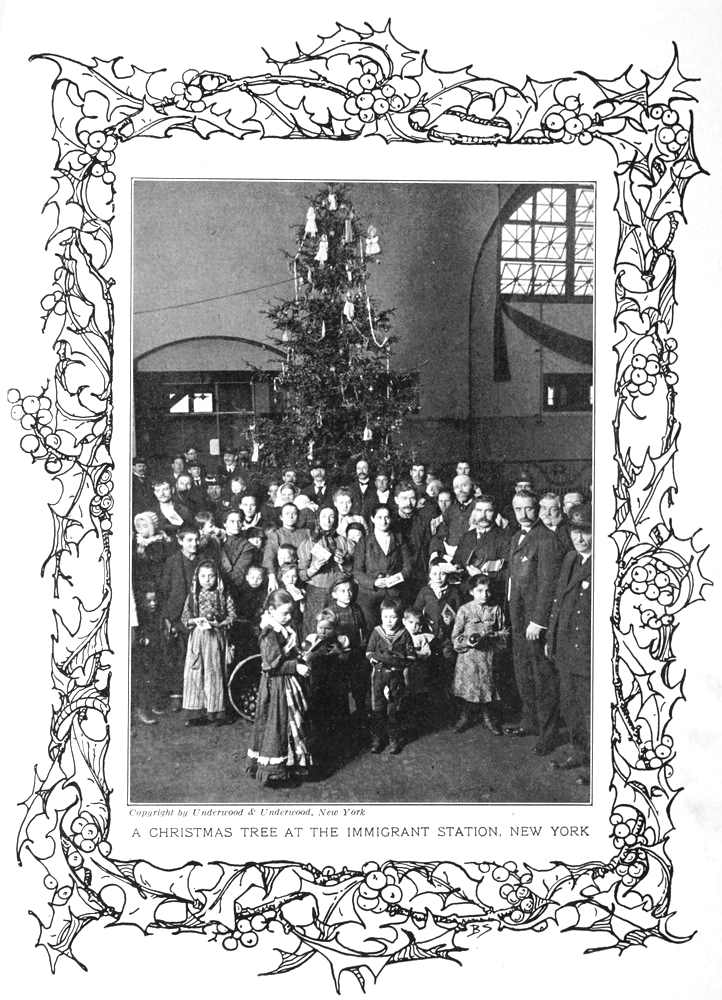

| A Christmas Tree at the Immigration Station, New York | 84 | |

| “We joined hands and danced around the tree” | 88 | |

| Dressing Dolls in Germany for American Christmas Trees | 92 | |

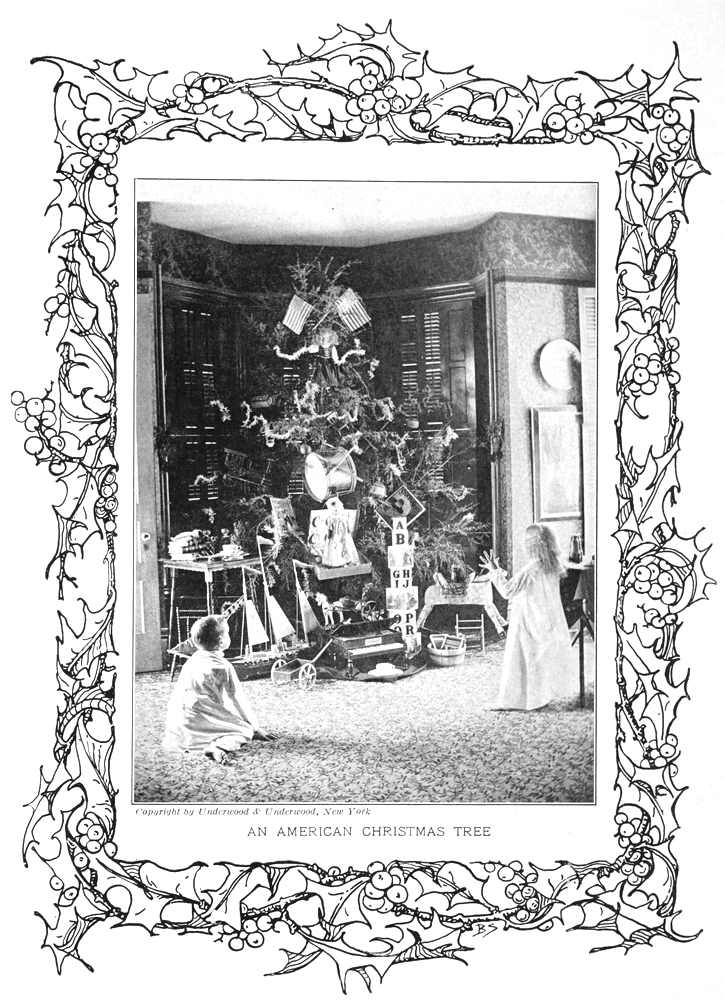

| An American Christmas Tree | 100 | |

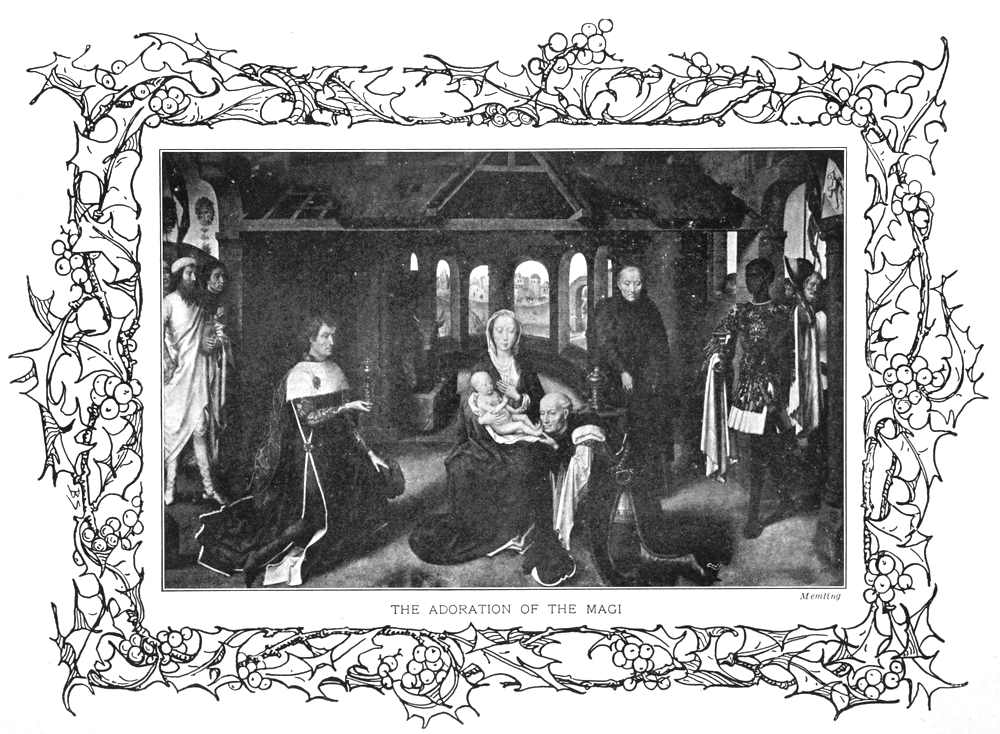

| The Adoration of the Magi | Memling | 104 |

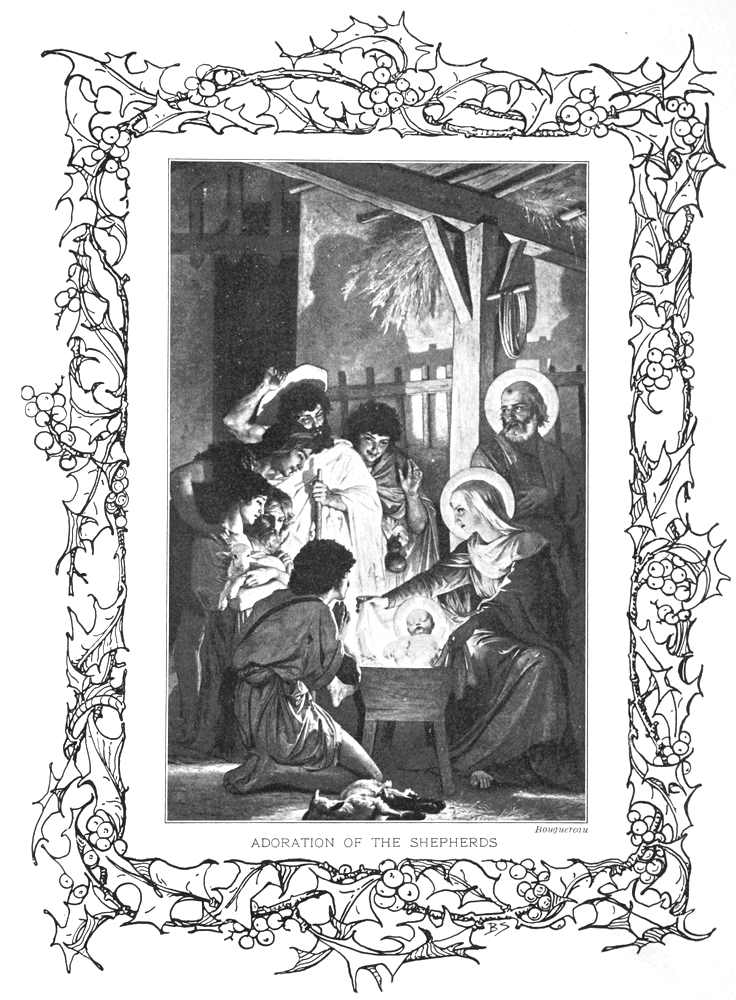

| The Adoration of the Shepherds | Bouguereau | 108 |

Wherever it has been possible, the material used has been quoted in the exact words of the writer. In some cases omissions have been made of sentences which would be unintelligible because that part of the original book to which they refer is not herein included. In a very few cases where the books quoted were not written for children, the selections have been condensed and the language simplified. It is hoped that injustice has been done to none.

[Pg 1]

THE CHILDREN’S BOOK OF

CHRISTMAS

It is hard for you who have never felt the lack of heat and light to know what the long dark winter must have meant to the men of long ago who first kept the midwinter feast. Many of them really believed that as the days grew shorter and shorter, and the nights long and cold, there was danger that the sun might go out altogether and the whole world die in the darkness. When, late in December, the days began to lengthen, and they saw that the sun was coming back to bring again the flowers and the summer heat, they fancied that a new sun had been born. So then for gladness they kept a feast which naturally in later years was changed into a festival in honor of the birth of Christ, “the sun of righteousness.”

With the feast itself some other of their old customs have been handed down to us, and among them is that of bringing into the house in midwinter the boughs of Christmas green. For these far-away folk believed that wood-spirits—you know them as brownies, fairies, and elves—were living in the forests outside, and were so sorry to think of them shivering under the snow-laden trees and in damp icy caves, that they used to place in the corners of their houses great branches of hemlock and balsam fir, that “the good little people” might creep into[Pg 2] the sort of shelters they loved and be warm. And as the heat of the fire brought out the sweet smell of the fir, it seemed to them like a “thank you” from their friends of the summer woods. Thus they, first of all men, felt the wish to give which is the heart of the Christmas spirit. And soon they began to hang little gifts for their unseen guest upon the green boughs, and to make them bright with the berries of holly and ash. After that it may be that some night hunter, crouching in the underbrush, looked up to the stars, and felt that his tree was incomplete without twinkling lights. However that may be, the custom of trimming the house with evergreens, holly, and lights at Christmas time is an old, old one.

[Pg 4]

Now in the days of Herod, King of Judea, the angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city in Galilee named Nazareth, unto a virgin whose name was Mary, to whom he said: Hail, thou that art highly favored! the Lord is with thee! blessed art thou among women! But she was greatly troubled by his greeting and wondered what such words could mean. Fear not, Mary! for thou hast found favor with God, he said, and went on to tell her of the Son who should be hers, and whom she was to call Jesus. He shall be great, she was told, and shall be called the Son of the Most High; and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David; and he shall reign over the house of Jacob forever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end.

Now it came to pass there went out a decree from Cæsar Augustus, that all the world should be enrolled. And all went to enroll themselves, every one to his own city. And Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem, because he was of the house of the family of David; to enroll himself with Mary. And it came to pass, while they were there she brought forth her firstborn son; and she wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger, because there was no room for them in the inn.

And there were shepherds in the same country abiding in the field, and keeping watch by night over their flock. And an angel of the Lord stood by them, and the glory of the [Pg 5]Lord shone round about them: and they were sore afraid. And the angel said unto them, Be not afraid; for behold I bring you good tidings of great joy which shall be to all the people: for there is born to you this day in the city of David, a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord. And this is the sign unto you; ye shall find a babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, and lying in a manger. And suddenly there was with the angel a multitude of the heavenly host praising God, and saying:

And it came to pass, when the angels went away from them into heaven, the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem, and see this thing that is come to pass, which the Lord hath made known unto us. And they came with haste, and found both Mary and Joseph, and the babe lying in the manger. And when they saw it they made known concerning the saying which was spoken to them about this child. And all that heard it wondered at the things which were spoken unto them by the shepherds. But Mary kept all these sayings, pondering them in her heart. And the shepherds returned, glorifying and praising God for all the things that they had heard and seen, even as it was spoken unto them.

And when eight days were fulfilled his name was called

JESUS.

[Pg 6]

[Pg 7]

Now when Jesus was born, behold, Wise men from the east came to Jerusalem, saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? for we saw his star in the east, and are come to worship him. And when Herod the king heard it, he was troubled, and all Jerusalem with him. And gathering together all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Christ should be born. And they said unto him, In Bethlehem of Judea: for thus it is written by the prophet: And thou Bethlehem, land of Judah, art in no wise least among the princes of Judah: for out of thee shall come forth a governor, which shall be shepherd of my people Israel. Then Herod privily called the Wise men, and learned of them carefully what time the star appeared. And he sent them to Bethlehem, and said, Go and search out carefully concerning the young child; and when ye have found him, bring me word that I also may come and worship him. And they, having heard the king, went their way; and lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. And when they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy. And they came into the house and saw the young child with Mary his mother; and they fell down and worshipped him; and opening their treasures they offered unto him gifts, gold and frankincense and myrrh. And being warned of God in a dream that they should not return to Herod, they departed into their own country another way.

[Pg 8]

Now when they were departed, behold an angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise and take the young child and his mother and flee into Egypt, and be thou there until I tell thee: for Herod will seek the young child to destroy him. And he arose and took the young child and his mother by night, and departed into Egypt; and was there until the death of Herod. Then Herod, when he saw that he was mocked of the Wise men was exceeding wroth, and sent forth, and slew all the male children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the borders thereof, from two years old and under, according to the time which he had carefully learned of the Wise men. Then was fulfilled that which was spoken by Jeremiah the prophet, saying: A voice was heard in Ramah, weeping and great mourning, Rachel weeping for her children; and she would not be comforted, because they are not.

But when Herod was dead, behold, an angel of the Lord appeareth in a dream to Joseph in Egypt, saying, Arise and take the young child and his mother, and go into the land of Israel: for they are dead that sought the young child’s life. And he arose and took the young child and his mother, and came into the land of Israel. But when he heard that Archelaus was reigning over Judea in the room of his father Herod, he was afraid to go thither; and being warned of God in a dream, he withdrew into the parts of Galilee, and came and dwelt in a city called Nazareth: that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophets, that he should be called a Nazarene.

Girlandajo

THE SHEPHERDS ADORING

[Pg 9]

A Dutch boy does not have to wait until December 25 for the great gift-day of the year. He is one of those who look for the gift-bringing saint on the eve of his own day which falls on December 6. For days beforehand the shops have been filled with toys and gaily trimmed, and on the evening of December 5 St. Nicholas is supposed by the little ones to make choice of the special treasure intended for little Dutch Jan or Martje. Indeed, it is one of the children’s treats to go out on that night to see the shops; and in the doorway of many of them stands a gorgeously clad likeness of the saint.

At home the children in turn are visited by the saint; in he walks carrying a big sackful of candies, oranges, apples, and so forth, which he scatters on the floor. Indeed, the Eve of St. Nicholas is called in Holland Strooiavond, which means “strewing evening.” This idea of a strewing evening crops up curiously often as one reads of the various customs connected with the December holidays the world over. In southern France the Provençal women strew wheat on the surface of shallow dishes of water, planting St. Barbara’s grain; in Mexico the children try to break with a long stick a bag or jug swung high above their heads, scattering the contents at last all over the floor.

In some parts of Servia there is found among the Christmas customs one which is probably the remnant of an early rite from which all of these “strewing evenings” come. In[Pg 10] that country, after the Christmas fire has been started with due ceremonies, the mother of the family brings in a bundle of straw which has been made ready early in the day. All the young children arrange themselves behind her in a row. She then starts walking slowly about the hall, and all the adjoining rooms, throwing on the floor handfuls of straw, and at the same time imitating the hens sounds, “Kock ... kock ... kock;” while all the children, representing the hen’s little chickens, merrily follow shouting, “Peeyoo! ... peeyoo! ... peeyoo!” The floor well strewn with straw, and the little folk in breathless heaps upon it, the oldest man of the family throws a few walnuts in every corner of the hall. After this a large pot, or a small wooden box, is filled with wheat and placed a little higher than a man’s head in the east corner of the hall. In the middle of the wheat is fixed a tall candle of yellow wax. The father of the family then reverently lights the candle, and, folding his arms on his breast, he prays, while all who are present stand silently behind him, asking God to bless the family with health and happiness, to bless the fields with good harvests, the beehives with plenty of honey, the sheep with many lambs, the cows with rich creamy milk, and so on. When he finishes his prayer, he bows deeply before the burning candle, and all those standing behind him do the same. He then turns toward them and says, “May God hear our prayer, and may He grant us all health!” to which they answer, “God grant it. Amen!”

In Holland the very little children believe that while they are busy gathering up the saint’s goodies, or else in the[Pg 11] night, he hides away the presents meant for them all over the house. Before they go to bed they place their largest shoes—wooden sabots, such as you see in almost every picture of Dutch children—in the chimney place, where in the morning they find them stuffed with fruit, nuts, and sweets. There are no lie-a-beds in Holland on St. Nicholas’ morning. There is a glorious game of “seek-and-find” going on in every house where there are children. Piet takes down one of the shining copper saucepans hanging beside the chimney place and finds curled up inside it the many-petticoated doll which of course he hands over to a delighted little sister, who has somewhere discovered his box of gaily painted leaden soldiers. There are plenty of hiding holes in an old Dutch house; thick oak beams support the walls and roofs and make wide ledges upon which Rupert may find a packet containing two flat silver buttons which once belonged to his great-grandfather. He is the oldest son, beginning to be particular about his striped waistcoats and the tight fit of his blue or red coat. He will be immensely proud to wear, as every other man in the old village does, two silver buttons at the waist of his baggy trousers. In the parts of Holland where the new fashions have not spoiled the old, silver buttons are to the men what such coral necklaces as Rupert’s sister wears are to the women. These buttons are always as big as the men can afford, and sometimes are like saucers; the little boys, even the tiniest ones, are dressed exactly after the pattern of their fathers, but their two flat buttons are smaller, about as large as fifty-cent pieces, and stamped with some design, the favorite one being a ship.

[Pg 12]

When all the gifts have been hunted out (down to a pair of skates with long curved tips for a boy so little that you would think St. Nicholas must have made a mistake if you did not know that Dutch children learn to skate almost as early as you learn to walk), the children are ready for the season’s other special treat, the gingerbread cakes. Delicately spiced gingerbread is made into many fantastic shapes, but every one, young or old, receives a gingerbread doll. Figures of men are given to the women folk, and of women in ruffles and straight skirts to the men. It is interesting to see how exactly like these gingerbread figures are in outline to those in early Dutch paintings. The models from which they are patterned frequently date from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

One winter I was staying with my husband at the little fishing village of Volendam, and we wished that the little Volendamers, who are all very poor, should for once have a splendid St. Nicholas. A French artist, who was there at the same time, was of our opinion, and we were equally supported by our host Spaander and his wife and their family of blooming daughters. In the wooden hotel there is a “coffee-room,” long and low, of really vast proportions. In the summer-time half of it forms the drawing-room. At the farther end of this apartment is a small stage, with wings. On this occasion (thanks to Spaander) the whole of it was covered in spotless white, tables were [Pg 13]erected, and upon their surface were arranged about a thousand toys and as many oranges and cakes. A white throne was placed for St. Nicholas, whose part was taken by the Frenchman. He wore a long white woollen robe falling over a purple silk underdress, a cape of costly old yellow brocade, and a gorgeous jewelled mitre, and he was made venerable by long white hair and beard. The dress of the black slave, whose part was taken by my husband, was equally correct and effective—a long tight-fitting garment of green velvet, showing a white robe underneath; an orange silk turban was wound round the black locks of a disguising wig and lit up his cork-black face. So much for the preparations, completed with considerable trouble and a great deal of amusement.

Bernadino Luini

ADORATION OF THE MAGI

My husband painted a large poster, on which was set forth a notice to all the children of Volendam that at 6.30 a boat would land upon the quay, bearing St. Nicholas and his faithful slave laden with gifts. One may easily imagine the joy and delight of these poor fisher-children, into whose uneventful lives what English children call a treat hardly ever enters. They crowded about the announcement, and read that St. Nicholas would come laden with gifts. Who can say what wild, beautiful hopes filled their hearts? Before five o’clock the youngsters began to assemble. The quay was crowded with them, so was the narrow road leading from the quay to the hotel. The parents also were there, quite as excited and almost as credulous as their children. Indeed, all Volendam[Pg 14] turned out to welcome the saint. Rain began to fall; but, although it soaked their poor clothes, it seemed to have no damping effect upon their spirits, all afire as they were with expectation. Meanwhile, the saint and his slave rowed out to their boat. It was now almost dark, but in the faint light one could still distinguish the fishing-boats which always crowd the harbor, their tall masts and sails dimly defined against the gray sky, and their narrow flags gently flapping in the rain. At one point there was an opening between the boats, a glimmering waterway, where those who were in the secret expected the boat to appear. The time passed slowly. It was seven o’clock; and every one was very wet. Still, all Volendam was full of cheerful good humor.

At length a blaze of bright light far out on the water revealed the saint—a venerable figure standing in the boat, crosier in hand, evidently blessing the expectant crowd. In a few moments the boat reached the landing-place. With blare of trumpets, and by the light of the torches, a procession was formed. How radiant were the faces illumined by the flickering glow! Soon the warm, well-lighted café was reached. The saint sat on his throne, and his good slave rapidly distributed presents to the little ones, safely housed from the inclement weather! Alas! they were very wet; but, as not one of the seven hundred coughed during the distribution, it may be concluded that the young Volendamers do not easily take cold. Their surroundings are so damp that they are almost amphibious.

[Pg 15]

Every face beamed with happiness. The genial St. Nicholas and his hard-worked slave; the Spaander family all helping vigorously; the three fine, tall Volendamers, who, in their yellow scarves of office, kept order so gently and gaily; down to the very youngest child,—all the faces were sweet and patient, and aglow with the pleasure either of giving or receiving.

The crowd of children looked plump and healthy, and although many garments were much patched, there were no rags; the poorest seemed to be well cared for and comfortable.

Seven hundred of them were made happy with toys and fruit; but there was no scrambling or pushing, nothing but happy expectation, and then still more happy satisfaction. All too soon it was over; the last child clattered down the long room with its precious armful.

Afterwards we heard from the schoolteachers and the children’s parents that most of them believed firmly that it was the real saint descended from heaven who had laid his hands on their heads in benediction as they received their presents from the black slave.

Beatrix Jungman.

[Pg 16]

There is an amusing account of how Christmas used to be observed in England in the time of George II, in a little book called “Round about our Coal Fire, or Christmas Entertainments,” published in 1740. The author begins:——

“First acknowledging the sacredness of the Holy Time of Christmas, I proceed to set forth the Rejoicings which are generally made at the great Festival.

“You must understand, good People, that the manner of celebrating this great Course of Holydays is vastly different now to what it was in former days: There was once upon a time Hospitality in the land; an English Gentleman at the opening of the great Day, had all his Tenants and Neighbours enter’d his Hall by Day-break, the strong Beer was broach’d, and the Black Jacks went plentifully about with Toast, Sugar, Nutmeg, and good Cheshire Cheese; the Rooms were embower’d with Holly, Ivy, Cypress, Bays, Laurel, and Misselto, and a bouncing Christmas Log in the Chimney glowing like the cheeks of a country Milk-maid; then was the pewter as bright as Clarinda, and every bit of Brass as polished as the most refined Gentleman; the Servants were then running here and there, with merry Hearts and jolly Countenances; every one was busy welcoming of Guests, and look’d as smug as new licked Puppies; the Lasses as blithe and buxom as the maids in good Queen Bess’s Days, when they eat Sir-Loins of Roast Beef for Breakfast; Peg would scuttle about to make Toast for John, while Tom run [Pg 17]harum scarum to draw a Jug of Ale for Margery: Gaffer Spriggins was bid thrice welcome by the ’Squire, and Gooddy Goose did not fail of a smacking Buss from his Worship while his Son and Heir did the Honours of the House: in a word, the Spirit of Generosity ran thro’ the whole House.

Paolo Veronese

THE ADORATION OF THE KINGS

“In these Times all the Spits were sparkling, the Hackin (a great sausage) must be boiled by Day-break, or else two young Men took the Maiden (the cook) by the Arms, and run her round the Market-place, till she was ashamed of her Laziness. And what was worse than this, she must not play with the Young Fellows that Day, but stand Neuter, like a Girl doing penance in a Winding-sheet at a Church-door.

“But now let us enquire a little farther, to arrive at the Sense of the Thing; this great Festival was in former Times kept with so much Freedom and Openess of Heart, that every one in the Country where a Gentleman resided, possessed at least a Day of Pleasure in the Christmas Holydays; the Tables were all spread from the first to the last, the Sir-loins of Beef, the Minc’d Pies, the Plum-Porridge, the Capons, Turkeys, Geese, and Plum-puddings, were all brought upon the board; and all those who had sharp stomachs and sharp Knives eat heartily and were welcome, which gave rise to the Proverb—

Merry in the Hall, when Beards wag all.

“A merry Gentleman of my Acquaintance desires I will insert, that the old Folks in the Days of yore kept open House at Christmas out of Interest; for then, says he, they[Pg 18] receive the greatest part of their rent in Kind; such as Wheat, Barley or Malt, Oxen, Calves, Sheep, Swine, Turkeys, Capon, Geese, and such like; and they not having Room enough to preserve their Cattle or Poultry, nor Markets to sell off the Overplus, they were obliged to use them in their own Houses; and by treating the People of the country, gained credit amongst them, and riveted the Minds and Goodwill of their Neighbours so firmly in them that no one durst venture to oppose them. The ’Squire’s Will was done whatever came on it; for if he happened to ask a Neighbour what it was a Clock, they returned with a low Scrape, it was what your Worship pleases.

“The Dancing and Singing of the Benchers in the great Inns of the Court in Christmas, is in some sort founded upon Interest; for they hold, as I am informed, some Priviledge by Dancing about the Fire in the middle of their Hall, and singing the Song of Round about our Coal Fire, &c.

“This time of the year being cold and frosty, generally speaking, or when Jack-Frost commonly takes us by the Nose, the Diversions are within Doors, either in Exercise or by the Fire-side.

“Country-Dancing is one of the chief Exercises....

“Then comes Mumming or Masquerading, when the ’Squire’s Wardrobe is ransacked for Dresses of all Kinds, and the coal-hole searched around, or corks burnt to black the Faces of the Fair, or make Deputy-Mustaches, and every one in the Family except the ’Squire himself must be transformed from what they were....

[Pg 19]

“Or else there is a match at Blind-Man’s-Buff, and then it is lawful to set anything in the way for Folks to tumble over....

“As for Puss in the Corner, that is a very harmless Sport, and one may romp at it as much as one will....

“The next game to this is Questions and Commands, when the Commander may oblige his Subject to answer any lawful Question, and make the same obey him instantly, under the penalty of being smutted, or paying such Forfeit as may be laid on the Aggressor; but the Forfeits being generally fixed at some certain Price, as a Shilling, Half a Crown, &c., so every one knowing what to do if they should be too stubborn to submit, making themselves easy at discretion.

“As for the game of Hoop and Hide, the Parties have the Liberty of hiding where they will, in any part of the House; and if they happen to be caught the Dispute ends in Kissing, &c.

“Most of the Diversions are Cards and Dice, but they are seldom set on foot, unless a Lawyer is at hand, to breed some dispute for him to decide, or at least to have some Party in.

“And now I come to another Entertainment frequently used, which is of the Story-telling Order, viz. of Hobgoblins, Witches, Conjurors, Ghosts, Fairies, and such like common Disturbers.”

[Pg 20]

[Pg 21]

I do not know how the forty years I have been away have dealt with “Jule-nissen,” the Christmas elf of my childhood. He was pretty old then, gray and bent, and there were signs that his time was nearly over. So it may be that they have laid him away. I shall find out when I go over there next time. When I was a boy we never sat down to our Christmas Eve dinner until a bowl of rice and milk had been taken up to the attic, where he lived with the marten and its young and kept an eye upon the house—saw that everything ran smoothly. I never met him myself, but I know the house-cat must have done so. No doubt they were well acquainted; for when in the morning I went in for the bowl, there it was, quite dry and licked clean, and the cat purring in the corner. So, being there all night, he must have seen and likely talked with him.... The Nisse was of the family, as you see, very much of it, and certainly not to be classed with the cattle. Yet they were his special concern; he kept them quiet and saw to it, when the stableman forgot, that they were properly bedded and cleaned and fed. He was very well known to the hands about the farm, and they said that he looked just like a little old man, all in gray and with a pointed red nightcap and long gray beard. He was always civilly treated, as he surely deserved to be, but Christmas was his great holiday, when he became part of it, indeed, and was made much of. So, for that matter, was everything that lived under the husbandman’s roof, or within reach of it.

[Pg 22]

Blowing in the Yule from the grim old tower that had stood eight hundred years against the blasts of the North Sea was one of the customs of the Old Town that abide, that I know. At sun-up, while yet the people were at breakfast, the town band climbed the many steep ladders to the top of the tower, and up there, in fair weather or foul,—and sometimes it blew great guns from the wintry sea,—they played four old hymns, one to each corner of the compass, so that no one was forgotten. They always began with Luther’s sturdy challenge, “A Mighty Fortress is Our God,” while down below we listened devoutly. There was something both weird and beautiful about those far-away strains in the early morning light of the northern winter, something that was not of earth and that suggested to my child’s imagination the angel’s song on far Judean hills. Even now, after all these years, the memory of it does that.

[Pg 23]

C. Müller

THE HOLY NIGHT

[Pg 25]

Christmas was not always “Merry Christmas” in old England, for at one time a strong effort was made to do away with the holiday entirely, after some of the older ways of celebrating the season had become too boisterous for decent God-fearing folk. “At this season,” says old Dr. Stubbs, “all the wild-heads of the parish flocking together choose them a grand captain of Mischief, whom they crown with great solemnity and the title of Lord of Misrule, who chooseth as many as he will to guard his noble person. Then every one of these men he dresseth in liveries of green, of yellow, or other light color; and as though they were not gaudy enough, they bedeck themselves with scarves, ribbons, laces, and jewels. This done they tie about either leg twenty or forty bells, with rich handkerchiefs on their heads, and sometimes laid across their shoulders and necks.... Then march this heathenish company to the church, their pipes piping, their drums thundering, their bells jingling, their handkerchiefs fluttering about their heads like madmen, their hobby horses, dragoons, and other monsters skirmishing among the throng. And in this sort they go to church though minister be at prayer or preaching,—dancing and singing with such a confused noise that no man can hear his own voice.” “My Lord of Misrule’s badges” were given to those who contributed money to pay the expense of this wild fooling; those who refused were sometimes ducked in the cow pond, he adds. It is admitted that these abuses were[Pg 26] quite as bad as he described, and that they were among the chief reasons why, in the seventeenth century, Cromwell tried to put down the great old holiday. His Puritan government ordered that the shops were to be opened, that markets were to be held, that all the work of the world should go on as if there had never been carols sung or chimes set ringing “on Christmas Day in the morning.” Instead of merry chimes, people heard a criers harsh-sounding bell and his monotonous voice telling every one “No Christmas! No Christmas!”

In Scotland about the same time bakers were ordered to stop baking Yule cakes, women were ordered to spin in open sight on Yule day, farm laborers were told to yoke their ploughs. In both countries the masks, or Christmas plays, which had been so popular in the houses of rich nobles, were absolutely forbidden; and if one were given, those who merely looked on might be fined and the actors whipped.

But the people would not have their holiday taken away. Shops might open, but few would come to buy. In Canterbury on one Christmas Day the townspeople asked the tradesmen to close their shops. The tradesmen feared the law’s penalties, so refused. In the riot that followed the mob broke the shop windows, scattered the goods, and roughly handled the shopkeepers.

In London even Christmas decorations were forbidden, but when the Lord Mayor sent a man to take down some holiday greens from one of the houses, the saucy London ’prentice-boys swarmed out with sticks and stones and sent him flying. Then came on horseback, fat and lordly, even the great Lord Mayor[Pg 27] himself, who thought his dignity would overawe the unruly boys. But they only laughed and shouted until his horse took fright and ran away—and perhaps he was glad to be let off so easily. Even where the people dared not openly fight the new laws, they did not obey them more than they could help. Spinning-wheels were idle because there was no flax, and ploughs were “gone to be mended” on Christmas Day in many an English village until after the death of Cromwell, when the holiday came to its own again in “merrie England.”

The same dislike for the festival of Christmas, with its drinking, dancing, and stage plays, came over to the New World with the Puritans. Only a year after the landing at Plymouth Governor Bradford called his men out to work, “on ye day called Christmas Day,” as on other days. But certain young men, who had just come over in the little ship Fortune, held back and said it went against their consciences to work on that day. So the governor told them that he would spare them till they were better informed. But when he and the rest came home at noon from their work, he found them in the street at play openly, some pitching the bar and some at ball and such like sports. So he went to them and took away their implements and told them it was against his conscience that they should play and others work. If they made the keeping of it matter of devotion, he said, let them keep their houses, but there should be no gaming or revelling in the street. Later, in 1659, a law was made that anybody found to be keeping “by feasting, or not working, or in any other way, any such day as Christmas Day, shall pay for every offense five shillings.”

[Pg 28]

In the course of a December tour in Yorkshire, I rode for a long distance in one of the public coaches, on the day preceding Christmas. The coach was crowded, both inside and out, with passengers, who, by their talk, seemed principally bound to the mansions of relations or friends to eat the Christmas dinner. It was loaded also with hampers of game, and baskets and boxes of delicacies; and hares hung dangling their long ears about the coachman’s box—presents from distant friends for the impending feast. I had three fine rosy-cheeked schoolboys for my fellow-passengers inside, full of the buxom health and manly spirit which I have observed in the children of this country. They were returning home for the holidays in high glee, and promising themselves a world of enjoyment. It was delightful to hear the gigantic plans of pleasure of the little rogues, and the impracticable feats they were to perform during their six weeks’ emancipation from the abhorred thraldom of book, birch, and pedagogue. They were full of anticipations of the meeting with the family and household, down to the very cat and dog; and of the joy they were to give their little sisters by the presents with which their pockets were crammed; but the meeting to which they seemed to look forward with the greatest impatience was with Bantam, which I found to be a pony, and, according to their talk, possessed of more virtues than any steed since the days of Bucephalus. How he could trot! how he could run! and then such leaps as he would take—there was not a hedge in the whole country that he could not clear.

Copyright by Underwood & Underwood, New York

A CHRISTMAS GIFT ON THE WAY TO A CHRISTMAS DINNER

[Pg 29]

They were under the particular guardianship of the coachman, to whom, whenever an opportunity presented, they addressed a host of questions, and pronounced him one of the best fellows in the whole world. Indeed, I could not but notice the more than ordinary air of bustle and importance of the coachman, who wore his hat a little on one side, and had a large bunch of Christmas greens stuck in the buttonhole of his coat. He is always a personage full of mighty care and business, but he is particularly so during this season, having so many commissions to execute in consequence of the great interchange of presents....

Perhaps the impending holiday might have given a more than usual animation to the country, for it seemed to me as if everybody was in good looks and good spirits. Game, poultry, and other luxuries of the table were in brisk circulation in the villages; the grocers’, butchers’, and fruiterers’ shops were thronged with customers. The housewives were stirring briskly about, putting their dwellings in order; and the glossy branches of holly, with their bright red berries, began to appear at the windows. The scene brought to mind an old writer’s account of Christmas preparations: “Now capons and hens, besides turkeys, geese, and ducks, with beef and mutton—must all die; for in twelve days a multitude of people will not be fed with a little. Now plums and spice, sugar and honey, square it among pies and broth. Now or never must music be in tune, for the youth must dance and sing to get them a heat, while the aged sit by the fire. The country maid leaves half her market, and must be sent again,[Pg 30] if she forgets a pack of cards on Christmas Eve. Great is the contention of Holly and Ivy, whether master or dame wears the breeches. Dice and cards benefit the butler; and if the cook do not lack wit, he will sweetly lick his fingers.”

I was roused from this fit of luxurious meditation by a shout from my little travelling companions. They had been looking out of the coach windows for the last few miles, recognizing every tree and cottage as they approached home, and now there was a general burst of joy—“There’s John! and there’s old Carlo! and there’s Bantam!” cried the happy little rogues, clapping their hands.

At the end of a lane there was an old sober-looking servant in livery waiting for them; he was accompanied by a superannuated pointer, and by the redoubtable Bantam, a little old rat of a pony, with a shaggy mane and long rusty tail, who stood dozing quietly by the roadside, little dreaming of the bustling times that awaited him.

I was pleased to see the fondness with which the little fellows leaped about the steady old footman, and hugged the pointer, who wriggled his whole body for joy. But Bantam was the great object of interest; all wanted to mount at once; and it was with some difficulty that John arranged that they should ride by turns, and the eldest should ride first.

Off they set at last; one on the pony, with the dog bounding and barking before him, and the others holding John’s hands; both talking at once, and overpowering him by questions about home, and with school anecdotes. I looked after them with a feeling in which I do not know whether pleasure[Pg 31] or melancholy predominated; for I was reminded of those days when, like them, I had neither known care nor sorrow, and a holiday was the summit of earthly felicity. We stopped a few moments afterwards to water the horses, and on resuming our route, a turn of the road brought us in sight of a neat country-seat. I could just distinguish the forms of a lady and two young girls in the portico, and I saw my little comrades, with Bantam, Carlo, and old John, trooping along the carriage road. I leaned out of the coach window, in hopes of witnessing the happy meeting, but a grove of trees shut it from my sight.

Correggio

THE HOLY NIGHT

[Pg 33]

Real winter in Russia is supposed to start on the feast of St. Nicholas of which the date, written in Russian style, is December 6/19. The first figure gives the date of the month as it is known in Russia and Greece, the second the date according to the calendar in use in all other civilized countries.

The calendar which was brought into use by Julius Cæsar, and was carried all over the then known world by the Romans, aimed to measure the year by the time it takes the earth to move once around the sun. His Egyptian astronomer figured that this required 365¼ days, so the practice was begun of having three years of 365 days, followed by a leap year, to which an extra day is given. As a matter of fact, the length of the average year is not exactly 365¼ days. To be sure, that is only 11¼ seconds or so out of the way, and this may seem a very small matter out of a whole year; but what happens is that every 128 years or so the calendar of Julius Cæsar or the Julian Calendar, as it is called, gets a day behind. By the year 1582, when Gregory XIII was Pope, the calendar was ten days slow. So Pope Gregory issued an order that the year was to take a new start and that thereafter three leap years out of every four centuries should be omitted, which keeps the calendar very nearly correct. But though Pope Gregory might decree, it did not follow that every one would obey at once; the ignorant thought[Pg 34] that by the change of date they were losing ten days of time and, of course, of wages. After some confusion all the Roman Catholic countries obeyed. England, being a Protestant country, ignored Pope Gregory’s commands. But it could not so easily dismiss the knowledge of its own astronomers that the Gregorian Calendar, as it is called, is nearer the truth than the Julian. In 1752, therefore, the date of the day of the year was changed by an Act of Parliament. The day after September 3 was to be called September 14, which it would have been if the calendar had not been slow. And naturally the change was also made in America, to which the new style had been brought already by French and Spanish settlers from Catholic countries.

There were always hot jealousies between the Eastern Church, ruled from Constantinople, and the Western, ruled from Rome. The Eastern or Greek churches refused to change their calendar on the order of a Latin Pope, and to this day retain the old style, the Julian dates. This is why their Christmas follows our Twelfth Day, for by this time their calendar is thirteen days behind the Gregorian. But to avoid confusion the double date is very generally in use.

During the time between the Day of St. Nicholas and Christmas it seems as if half Russia streams out upon the ice of the river Neva in St. Petersburg. All through the summer the boats come and go, bringing food, fuel, building materials, everything the city needs, from the[Pg 35] interior; but the river is frozen for six months of the year, and in those months it is used as if it were public land. St. Petersburg is a very gay capital in winter, when the wealthier Russian nobles have left their country estates, and come down to exchange visits, to give balls, or go dashing about in gay sleighs to join the sleighing or skating contests for which a part of the frozen river is reserved. All around the cleared spaces on the ice, merchants have set up temporary booths; here you may buy tea and nutcakes; there holy pictures, or ikons, pictures of all the possible saints, some costing a few pennies, others with gold and silver backgrounds costing many roubles, a rouble being worth about fifty cents. On another part of the river a great provision market is held a little before Christmas, and the booths stretch for miles. Everything is frozen. Countless oxen, piles of sheep and goats, pyramids of pigs, form a frozen range of hillocks to which the butcher comes to make his choice. With hatchet or saw he divides the animal, ox, or pig, or it may be a bear, into sections which his customers store in the ice-cellars which have all been freshly filled. Thousands of workmen are engaged during the winter in cutting and drawing the ice from yet another part of the Neva, and on a still frosty morning the clink of their axes against iron ice-breakers can be heard at a long distance from the river.

A great ceremony of the Greek Church takes place each year at the end of their Christmas season—the Benediction of the Waters—in every town and village in Russia and[Pg 36] down along the coasts of Greece. In St. Petersburg the ceremony is performed by the Czar outside the Winter Palace. A wooden temple is put up out on the ice, decorated with gilt and paintings within, and surrounded by a hedge of fir boughs without. A hole is made in the ice, and to this a long procession makes its way; troops with bright banners, gorgeously robed bishops, and priests carrying lighted tapers and big ikons, are followed by more soldiers, the Czar and Czarina in magnificently jewelled robes, and after them their Court brilliant in uniforms and beautiful fur-trimmed dresses. They have all attended one service in the Imperial Chapel; they now have another on the ice. The water is blessed, evil spirits flee away, the soldiers fire a salute, and every one is sprinkled with the now holy water. The procession returns to the city, carrying with it great vessels of the holy water to be used later in all the churches. Then the people who have been looking on try to get to the hole; some draw up pailfuls of the cold liquid; others plunge bodily into the icy water, believing that so they will be cleansed from sin or sickness; many have even plunged delicate babies into it, content, if the child does not survive the shock, in the belief that its soul is forever saved. And over every door in the great city on that day rests the sign of the cross, lest the evil spirit expelled from the water should enter any home.

[Pg 37]

Only in the south of France, they say, is to be found the custom of planting St. Barbara’s grain on the fourth of December. Earthenware dishes an inch or two in depth are half filled with water, on the surface of which wheat is scattered, or the small, flattened seeds of the lentil, a leafy-stemmed plant whose honey-laden blossoms will, later in the year, draw swarms of golden bees to the fields where it is planted. The dish is then set in the warm ashes of the fireplace, or on the deep stone sill of a sunny window, and the grain is left to sprout and grow so that on the table of the Christmas Eve supper there may be this tender promise of the harvest of the year to come—a pale, delicate young greenness in strong contrast with the darker evergreens. The bent old gran’mère by the hearth will tell you, that as the growth is thick and sturdy or scattered and thin, so will be the later harvests of grain, or honey.

The yellow daffodil, or narcissus, is a plant which first grew in southern France, and along the Mediterranean, and it may be that it was some early settler from Languedoc or Provence, who introduced into Louisiana a custom common half a century ago, that had a dim resemblance to this planting of St. Barbara’s grain. The daffodil bulbs were planted in shallow earthenware dishes on the eve of All Saints, and set for three weeks in the warm dark, and later in the sun. The older creoles foretold a fruitful year if the flower bud were well formed by St. Barbara’s day.

[Pg 38]

[Pg 39]

The great time for making gifts in France is the Jour de l’An, the day of the year, our New Year’s Day, when there is a great exchange of cards, good wishes, visits, and presents. On Christmas Eve, everything else used to pale before the exciting adventure of going to the church at midnight. After church came the Grand Supper, a family gathering from which the children were sent to bed long before they were ready to go, comforting themselves as they climbed the stair by asking each other, “What do you think P’tit Noël will put in your shoe?” But they were always too sleepy to lie awake long enough to see whose hand it was that dropped into each little shoe under the mantelpiece a few goodies or bits of silver coin. Sometimes one was guiltily afraid that a black record of naughtiness deserved the disgracing gift of a few pebbles, but then,—surely Petit Jesus was forgiving and next year one would be very good, yes, of a certainty, most good.

Earlier in the evening the children had been allowed to play any game they liked, however noisy, quite up to eleven o’clock, which was unusual enough by itself. Then began a great bundling up in furs and mufflers before the plunge from the warm candle-lighted room into the frosty night, where stars shone like gold nails driven into blue-black velvet; the frost crunched under wooden shoes; the lanterns threw strange, wavering shadows; a dry branch fell with a sudden crackle; far away a horse whickered and stamped just as[Pg 40] one was coming toward the deepest blackness of all, where the great gray church and the tall buildings about it threw the Grande Place into densest shadow. Nothing in that sound should frighten one, but every child had heard the peasants tell of this enchanted hour when animals in their stables could talk like men; still, nothing could harm a child on the way to mass, of course, so one plucked up courage and sang out extra loudly in the refrain of whatever carol was being rung on the chimes in the ivy-covered tower.

The old church had always seemed large, very large for the few who worshipped in it, but now it was majestic, reaching up toward the skies as if to gather from the angelic choir the great waves of music that rolled down the valley to be heard miles away. And how could one help gasping when a gust of wind swept him suddenly into the porch; there through the open door he was caught and drawn forward, adoring, by the full splendor of the altar, studded with lights, dazzling against dark walls, green with pine and laurel.

At one side was the crêche, the miniature stable scene, where the mother ever watched in wondering love the Holy Child. Down the long nave, from the damp stone floor which had never known the luxury of matting, great pillars lost themselves in the blackness of the arches. But each who entered brought his lantern and set it on the stones in front of him; one after another the little lights like stars came twinkling out all over the church. And each newcomer joined in the carols sung before the mass was [Pg 41]begun—old, old carols with beloved refrains which one heard only at Christmas time.

Blashfield

THE BELLS

The old mysteries, quaint plays in which long ago the peasants of Southern France acted the simple stories of the adoration of the Babe by the angels, the shepherds, and the Wise Men, are seen no more, but it is said that until very recently, in some of the provinces, at a certain pause in the mass, a shepherd knocks loudly on the great church door, the hollow sound echoing in the solemn hush. From without is heard singing, the voices of shepherds asking to come in. Slowly the doors swing back, the people part and the shepherds enter, passing up the nave between a double row of worshippers. In front are two or three boys playing softly on simple musical instruments, one has a flute, another a tambourine. Then begins a quaint musical dialogue between these peasants in their long, weather-stained cloaks, and those who stand on either side.

From one hand comes the question, in high treble,

Where hast thou been?

And it is echoed from the other,

What hast thou seen?

And the deep musical voices of the shepherds answer:—

So they move slowly, carrying a little fruit, a measure of grain, a pair of pigeons, to where the priest stands waiting to bless their simple gifts and lay them at the foot of the altar.

[Pg 42]

On the Holy Night when the Christchild was born, the earth lay very near to heaven; all the world was at peace, and there was no noise of war to keep men on earth from hearing the angels sing.

Animals and birds and trees alike were glad because of the coming of the Holy Babe, and like the shepherds and the Wise Men came to bring to Him their gifts. Most of all the little pine tree beside the road longed to take something to the Christchild.

The cedars, instead of pointing their branches upward in pointed slender trees, spread their branches wide, as Cedars of Lebanon do to this day, and bent low to shelter the Mother and Child. But the little pine was too small to shelter anything, and though he stretched and stretched, he was not even tall enough to keep the sun out of the eyes of the Wonderful Babe. He was barely tall enough for the wind to make a whispering sound in the tips of his little branches.

The thorn, although it was midwinter, suddenly blossomed out and brought its white flowers to make a coverlet for the Child’s cradle. And the little pine tree tried so hard to blossom that pine-needles came out in tufts all over him, but that was all; only the wind through his branches now sounded like a sigh.

The “bird of God,” which we call the wren, flew quickly and brought soft moss and feathers to make His cradle[Pg 43] warm. “I will pull off all my needles to make a bed for Him,” the pine tree said. But when he began to do that, Mother Mary smiled and shook her head. “Your needles would only prick Him, little pine,” she said. And the little pine rocked in pain and the wind sighed through his branches.

The olive came and brought sweet-smelling oil, with which to rub the Christchild’s little limbs; and the pine tree saw her and ached so for something to give that the resin stood out in big drops along his stem. “Oh!” he cried joyfully, “I, too, have oil to give.” And Mother Mary’s smile was very tender as she shook her head again and said gently, “But your drops are sticky, and they would hurt His tender skin, dear little pine.” So the little pine was very unhappy because it had nothing to offer the Christchild. And year by year as he grew taller, and remembered the Holy Night, the wind swept through his branches with a sound that was almost a moan; and ever since you can hear that sound from pine trees all the world over.

Now for hundreds of years after, on each Christmas Eve, the Christchild comes again, in the likeness of a poor child, gathering fallen sticks in the forest. Up and down the hills He goes, shivering in the icy cold, knocking at every door, whether it is of a cabin or a castle, until He finds some one who, remembering His lesson of love, calls Him in to find warmth and shelter; and such a home He blesses. Some there are who, like the pine tree, long to serve Him, and these place a candle in the window, that if He pass along their way, He may see it and come in.

[Pg 44]

But one night there was no door open and as He walked wearily through the pine wood the wind shrieked through the trees bending before Him. Then the Christchild turned aside and crept under the low branches of a pine tree, which was large enough now to shelter Him; and the moss lifted itself from the snow to make a soft bed for the tired Child. And the pine tree, drawing its branches close above Him, was so happy that tears of joy ran down his branches and freezing, hung in slender icicles. And as the first red rays of the sun on Christmas morning shone upon them they glittered like the candles on your Christmas tree, and the Christchild opened His eyes and smiled.

Hunt

THE TRIUMPH OF THE INNOCENTS

[Pg 45]

Servia is one of the countries in which the old, old customs have lasted longest. They began in the times when men looked forward longingly to “the days in which the sun, having gone far enough into the snowy plains of the winter, turns back toward the green fields of summer.” The celebration begins on the day before Christmas, which the older Servian songs call “the day of the old Badnyak.” No one seems to know who Badnyak was; but some have believed that the fast-day was first kept in honor of the old sun-god, who was thought of as grown weak and faint, and as giving place to a younger. For on the next day was the feast of “the little God,” the new sun who was to bring summer back again. Nowadays, the name is given to logs cut for the Christmas fire.

Every Servian boy is up before daylight on the day before Christmas, for he, of course, must be on hand when the strongest young men of the family start out with a cart and a pair of oxen to cut a young oak tree and bring it home. Upon the chosen tree they throw a handful of wheat with the greeting, “Happy Badnyi Day to you!” Then they begin to cut it very carefully, timing the strokes of the axes and placing them so that the tree shall fall directly toward the rising sun, and at the exact moment when its red ball begins to show at the edge of the world. If by any mischance, or a stroke of the axe in the wrong place, the tree falls toward the west, there will be great distress, for this is thought to mean that very bad luck will follow the family through all the[Pg 46] coming year. If the tree should fall in the right direction but catch in the branches of another, the good fortune of the family will only be delayed for a while. The small boy’s part is to watch very closely where the first chip falls, for it is most important to carry home that first oak chip. The trunk of the tree is trimmed and cut into two or three logs, of which one is a foot or more longer than the others. They are then dragged to the house, but are not taken inside until sunset; in the meantime they stand in the courtyard on either side the door. The house mother leaves her work as they are brought home to break a flat cake of purest wheat flour upon the longest log, while the little girls sing special songs. But soon she goes back to her work, for there is a deal to be done before sunset; the women are making Christmas cakes in the shape of lambs and chickens, and most often of little pigs with blunt-pointed noses and curly tails. For the pig belongs to a Servian Christmas as much as turkey does to an American Thanksgiving. Long ago the pagan Servians used to sacrifice a pig to the sun-god on the day of the old Badnyak; and to this day you will not find one Servian house in which “roast pig” is not the chief dish of the Christmas dinner. While the women bake, the men prepare the pig for the next day’s roasting. The boy who so carefully brought home that first oak chip put it at once into a wooden bowl, and his little sister and he cover the chip, and fill the bowl with wheat.

Just at sunset the whole family gathers in the big kitchen. The mother of the family gives a pair of woollen gloves to one of the men—most often to the father, sometimes to the[Pg 47] strongest of her sons, who goes outside to bring in the Badnyak. Tall wax candles are set on either side the open door, and in front of it the mother stands with the wooden bowl in her hands. As the log is brought in she throws a handful of wheat at the bearer, who says, “Good evening, and may you have a happy Badnyi Day.” He is answered by a chorus of greetings from all in the room. In some parts of the country each man present brings in a log and at each is thrown a little wheat in sign of the wish that, in the year to come, food may be plenty enough to throw away. A glass of red wine is then sprinkled on the log, and the oldest and the strongest of the family together place it on the burning fire in such a way that the thick end of the log sticks out above the hearth for about a foot. And sometimes you may see a prudent father smear the end of it with honey and place on it a bowl of wheat, an orange, and the ploughshare, that they may be so warmed by the Christmas fire that the cattle shall be fed, the bees industrious, and the trees and fields be fruitful, through all the year.

There is so little sleep for the Servian peasant on a Christmas morning that very few except the old and the babies go to bed at all on the night before “the day of the little God,” as it is called. For one thing, the new Badnyak, the great log on the Christmas fire, must be kept burning all the time, and brightly. Then the all-important pig must be set to roast early. When it is ready and laid before the fire,[Pg 48] some one goes outside and fires off a gun or pistol; and when the roasted pig is taken from the fire, the shooting is repeated. From four to eight o’clock on a Christmas morning every Servian village reëchoes as if it were celebrating the Fourth of July with cannon crackers.

Just before sunrise some young girl of the family goes to the fountain, or the brook from which they usually get their drinking water. Before she fills her pots or jars she greets the water, wishing it a happy Christmas, and throws into it a handful of wheat. The first cupfuls of water drawn are put into a special jar and are used to make the “Chesnitza,” the Christmas cake, which is to be divided into a piece for each member of the family, present or absent. A small silver coin baked into it is supposed to fall to the lot of that member of the family who is to meet with special good fortune during the coming year.

H. Hofmann

BETHLEHEM

No other visitor is allowed to enter the house before the “Polaznik,” the Christmas guest, has come. The part is usually taken by some boy from a neighbor’s family, who comes very early and brings with him a woollen glove full of wheat. When at his knock the door is opened, he showers the wheat over those around the brightly burning fire and into all corners of the room with the greeting, “Christ is born.” The mother of the family throws a handful of wheat at him and all the others shout, “In truth, He is born!” The guest then walks straight to the fire, and with the heavy shovel strikes the burning log with all his force repeatedly, so that thousands of sparks rise high in the chimney, while he says, [Pg 49]“May you have this year so many oxen, so many horses, so many sheep, so many pigs, so many beehives of honey, so much good luck, so much success and happiness.” After this good wish he kisses his host, drops to his knees before the Christmas log on the fire, kisses one end of it, which sticks out of the fireplace into the room, and places a coin upon it as his gift. As he rises, a woman offers him a low wooden chair, but just as he seats himself draws it away so that he sits down hard upon the ground, and is thus supposed to fix to it firmly every good wish he has spoken. Finally he is wrapped in a thick blanket, and with it around him sits quietly for a few minutes while the young folks who are to tend the flocks and herds in the coming year come to the hearth and kiss each other solemnly across the Christmas log. The wearing of the blanket is said to insure thick cream in the next year, and the shepherds’ kisses will make for peace and plenty among the cattle.

Before the chief meal of the day, all the members of the family gather about its head, each with a lighted candle in hand, while he prays briefly. Then they turn and kiss each other with such greetings as: “Peace of God be with us!” “Christos is born!” “In truth, He is born!” “Therefore let us bow before Christos and His birth.” And toward the end of the meal all stand to drink “to the glory of God and of the birth of Christ,” which marks the end of the Christmas celebration.

[Pg 50]

Among all the older peoples of Europe there are many bits of folk stories which tell of the wonderful peace which fell upon the world on the night of the Holy Eve. A Bosnian legend says that at the time of the birth of Christ “the sun in the east bowed down, the stars stood still, the mountains and the forests shook and touched the earth with their summits, and the green pine tree bent, ... the grass was beflowered with opening blossoms, incense sweet as myrrh pervaded upland and forest, birds sang on the mountain top, and all gave thanks to the great God.” This belief in the holy and gracious kinship of all nature at this season finds expression in many countries in an added tenderness for all living things during Yuletide. The very sparrows, whose nests the boys are free to raid at any other time, have a sheaf of rye set up for their Christmas feast, says Mr. Riis, who tells that once, stranded in a Michigan town, he was wandering about the streets and came upon such a sheaf raised upon a pole in a dooryard. “I knew at once,” he says, “that one of my people lived in that house and kept Yule in the old way. So I felt as if I were not quite a stranger.”

In England, robins are the birds of Christmas time; an old legend has it that on the day of Christ’s suffering the robin fluttered beside Him, and in trying to pluck thorns from His crown stained its breast crimson.

The Spanish show special kindness at this time to any ass or cow, believing that on Holy Night they breathed upon the Christchild to keep Him warm. Many other quaint old beliefs used to be common about how the animals act at Christmas time. From northern Canada comes the Indian saying that on the Holy Night the deer all kneel and look up to the Great Spirit, but that whoever spies upon them will have stiffness in his knees for all the year to come. In the German Alps it was believed that animals have the gift of speech on Christmas Eve, but that he who listens will surely hear them foretell some evil for the listener. Of a like belief Mr. Riis says that, when he was a boy:—

“All the animals knew perfectly well that the holiday had come, and kept it in their way. The watch-dog was unchained. In the midnight hour on the Holy Eve the cattle stood up in their stalls and bowed out of respect and reverence for Him who was laid in a manger when there was no room in the inn, and in that hour speech was given them, and they talked together. Claus, our neighbor’s man, had seen and heard it, and every Christmas Eve I meant fully to go and be there when it happened; but always[Pg 52] long before that I had been led away to bed, a very sleepy boy, with all my toys hugged tight, and when I woke up the daylight shone through the frosted window-panes, and they were blowing good morning from the church tower; it would be a whole year before another Christmas. So I vowed, with a sigh at having neglected a really sacred observance, that I would be there sure on the next Christmas Eve. But it was always so, every year, and perhaps it was just as well, for Claus said that it might go ill with the one who listened, if the cows found him out.”

In the older parts of Montenegro, the head of the family and his shepherd boy still follow the quaint old custom of lighting the animals to their stalls on Christmas Eve. Each takes a lighted wax candle and they go together into every stall in turn, holding the candles for a moment in each of its corners. Then, at the stable door they take stand, one at each side of it, and hold their candles high while the little shepherdess drives the animals in. One by one, sheep, goats, and oxen, they pass between the flickering lights. After that, the shepherd boy and the little shepherdess kiss each other “that the cattle may live in peace and love,” they say.

[Pg 53]

Against the wing-wall of the Hacienda del Mayo, which occupied one end of the plaza, was raised a platform, on which stood a table covered with a scarlet cloth. A rude bower of cane leaves on one end of the platform represented the manger of Bethlehem, while a cord stretched from its top across the plaza to a hole in the front of the church bore a large tinsel star, suspended by a hole in its centre. There was quite a crowd in the plaza, and very soon a procession appeared, coming[Pg 55] up from the lower part of the village. The three kings took the lead; the Virgin, mounted on an ass that gloried in a gilded saddle and rose-besprinkled mane and tail, followed them, led by the angel; and several women, with curious masks of paper, brought up the rear. Two characters, of the harlequin sort—one with a dog’s head on his shoulders, and the other a bald-headed friar, with a huge hat hanging on his back—played all sorts of antics for the diversion of the crowd. After making the circuit of the plaza, the Virgin was taken to the platform, and entered the manger. King Herod took his seat at the scarlet table, with an attendant in blue coat and red sash, whom I took to be his Prime Minister. The three kings remained on their horses in front of the church; between them and the platform, under the string on which the star was to slide, walked two men in long white robes and blue hoods, with parchment folios in their hands. These were the Wise Men of the East, as one might readily know from their solemn air, and the mysterious glances which they cast toward all quarters of the heavens.