The Project Gutenberg eBook of Alexander's Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 1, May 15, 1905), by various

Title: Alexander's Magazine (Vol. 1, No. 1, May 15, 1905)

Author: various

Release Date: May 9, 2023 [eBook #70720]

Language: English

Produced by: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note: A reprint edition provided by the Negro Universities Press, New York, 1969.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain. Obvious typos were corrected.

Vol. 1 Boston, Mass., May 15, 1905 No. 1

From The Baptist Missionary Magazine

Mystery becomes opportunity. Mr. Mott’s book, “The Pastor and Modern Missions,” contains the following summary: “One hundred years ago Africa was a coast line only. Even one generation ago, when Stanley emerged from that continent with the latest news of Livingstone, nine tenths of inner Africa remained unexplored. More than 600 white men have given their lives to explore this one continent. Now, however, H. R. Mill, D. Sc., formerly librarian of the Royal Geographical Society, can well say, ‘The last quarter of the nineteenth century has filled the map of Africa with authentic topographic details, and left few blanks of any size.’ Bishop Hartzell says: ‘Yesterday Africa was the continent of history, of mystery, and of tragedy; today it is the continent of opportunity.’ When Stanley, starting in 1874, made his journey of 999 days across Africa, in the course of 7,000 miles he never met a Christian. There was not a mission station, or church, or school on all that track. Now the chain of missions is almost complete from Mombasa to the mouth of the Congo, and there are scattered through inner Africa hundreds of churches and Christian schools and over 100,000 native Christians.”

“Three distinct Africas are known to the modern world—North Africa, where men go for health; South Africa, where they go for money; and Central Africa, where they go for adventure. The first, the old Africa of Augustine and Carthage, every one knows from history; the geography of second, the Africa of the Zulu and the diamond, has been taught us by two universal educators, war and the stock exchange; but our knowledge of the third, the Africa of Livingstone and Stanley, is still fitly symbolized by the vacant look upon our maps which tells how long this mysterious land has kept its secret.” So said Henry Drummond in “Tropical Africa” in 1888; the mystery is now revealed; we see an open door for the gospel of love, light and life.

The African work of our Missionary Union is in the Congo Free State. The mission was adopted by us in 1884. There are now 8 stations; 31 missionaries and were last year 306 native helpers; 13 churches with 3,3692 members; 135 schools, with 4,456 pupils. [Transcriber’s Note: obviously, 3,3692 is a misprint. 3,692 members seems most likely (= about 250 per church), but 33,692 is also plausible.]

Rev. Henry Richards

Who says that the next 25 years will surely determine what Central Africa is to be. Considering what has been done in Uganda and Congo land, we ought fully to expect that the gospel tree will have so grown that its branches with healing leaves will overshadow the whole land.

Told at the 35th Anniversary Exercises of that Splendid Seat of Learning

By E. Jay Ess

Written for Alexander’s Magazine

Hampton Institute, Va., May 3rd, 1905.—This has been anniversary week at Hampton Institute. The spirit of Armstrong—the courageous and strong—has been all about and in everything. The famous Ogden Party headed by Dr. Robert C. Ogden, trustee of Hampton and of Tuskegee, has been in attendance and has given to the occasion an importance of overwhelming interest.

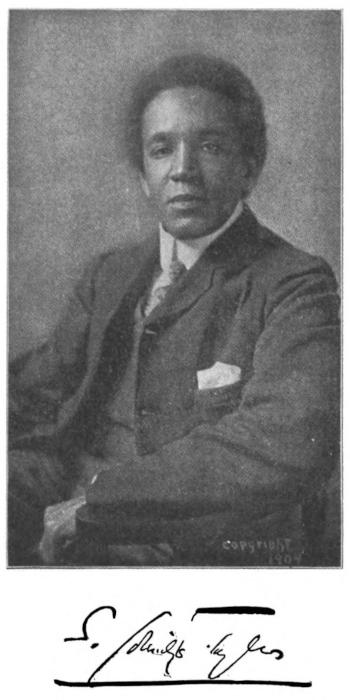

DR. H. B. FRISSELL

First of all the weather has been perfect. Everything whether of exhibit or address has been in perfect good taste and the 35th anniversary exercises have been voted the most successful in the history of the school—made so in large part because of the presence upon Hampton’s grounds of her most famous and eloquent son, Dr. Booker T. Washington, who delivered the principal address upon both days—“Virginia Day,” May 2, when nearly 300 White Virginians from Richmond attended in a body—and upon Wednesday, May 3, when the anniversary exercises proper were held. He has been lionized wherever he has gone and has been as cordially sought after by banker, prelate, educator and what not, as by those who are students or have been students of Hampton.

A report of Tuesday’s exercises may be interesting:

The spacious room was handsomely decorated with flags and bunting. The exercises were of an exceptionally interesting character, the opening service being followed by plantation songs from the chorus of Negro and Indian students of the school. J. Enoch Blanton, a member of the class of 1905 in agriculture, read an essay on “Changed Ideas of Farming.” Francis E. Bolling, a graduate of the class of 1905, in domestic science spoke of “What Hampton Has Meant to Me,” paying a glowing tribute to his Alma Mater. Dr. John Graham Brooks of Harvard University, spoke on the “Fruits of Hampton.” He said that as the race problem is probably the hardest with which the world has to deal, and one of which we are the most profoundly ignorant, he would avoid the big and keep near the little. “One of the truest things about Hampton,” he said, “is that she is finding[12] out her own business, the real business of Hampton is to learn how a race can be disciplined into independence and how success is to be won. In this Hampton succeeds admirably.”

Dr. Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute was then introduced and received a splendid ovation. After Doctor Washington’s address, President Boatwright of Richmond College spoke on “The Educational Problem,” in which he paid a glowing tribute to the work of the Hampton Institute. Dr. R. E. Blackwell of Randolph-Macon College followed and spoke of the misgiving with which Southern men approach the problem of education, and expressed the opinion that if respect and co-operation between the races is to be restored, it must be through such institutions as Hampton and Tuskegee. Dr. Robert C. Ogden made a few remarks in which he gave a hearty welcome to the guests present. He also paid a very high tribute to Doctor Frissell, whom he said, was the real founder of the Conference for Education in the South. He briefly reviewed the work in the institution and spoke of the American fellowship existing between Massachusetts and Virginia, of Boston and Richmond which binds the hearts of all together.

HUNTINGTON MEMORIAL LIBRARY

On Wednesday representatives of the several classes spoke most acceptably after which Dr. Robert C. Ogden, president of the Hampton board of trustees, presented the diplomas and trade certificates to the young men and women of the several academic and industrial departments. Of these 13 were awarded to post-graduates, 23 to members of the senior class, and 45 trade certificates to those who had finished trades. After this ceremony Dr. Booker T. Washington again spoke. He said in part:

“When I was a student at this institution I was taught that Ponce de Leon spent years in search of a fountain of perpetual youth. In my opinion there is no spot in America where one can more nearly renew his youth and strengthen his faith in the wisdom and perpetuity of our institutions than at Hampton.

“To the students who are to go out from the Hampton institute today to begin what I hope are to be careers of usefulness, I wish to say: I hope that you will learn to be even tempered, self-controlled and hopeful. You will find many conditions that will try your soul, but the test of Hampton’s training will be shown by the ability with which you are able to choose the fundamental things in life and stick to them and not become discouraged because of the temporary and non-essential. The great thing is for you to conduct yourselves so as to become worthy of the privileges of an American citizen and these privileges will come. I hope you will not yield to the temptation of becoming grumblers and whiners, but will hold up your head and march bravely forward, meeting manfully and sensibly all the problems that may confront you. Place[13] emphasis upon your opportunities rather than upon your disadvantages; place emphasis upon achievement rather than upon the injustices to which you will be subjected. As you go out into the world you may expect rebuffs, sometimes insults, opposition, injustice. You will meet with race prejudice in many forms, but if you are true to Hampton and its traditions you will meet and overcome all of these conditions with a calm and patient spirit.

VIRGINIA AND CLEVELAND HALLS

“No one can degrade you; you, yourselves, are the only individuals who can inflict that punishment. I hope that you will pursue the policy of making yourself so indispensably useful in every community into which you go that the members of that community, black and white, will feel that they cannot dispense with your services. The race that goes quietly and contentedly on doing things day by day will reap its reward. It often requires more courage to suffer in silence than to retaliate; more courage not to strike back than to strike; more courage to be silent than to speak. We must not permit ourselves to harbor the belief that our friends among the white people in the south are disappearing. If we pursue the sensible and conservative course, the number of such friends will multiply. There are great opportunities for us here in the south in education, industry, business and the professions. The race that gets most out of the soil, out of the wood, out of the kitchen, out of the school room, the doctor’s office or the pulpit, is the race that is going to succeed regardless of all obstacles.”

The signal tribute to Dr. Frissell was received with every manifestation of pride on the part of the students and alumni, and of gratification upon the part of Dr. Frissell himself, the board of trustees and the distinguished visitors present. Some of those who have been here as members of Mr. Ogden’s party and as guests of Hampton and friends of Negro Education—many of whom have spoken during the two days stay—are: Dr. John Graham Brooks, Cambridge, Mass.; Dr. Wallace Buttrick, executive secretary of the General Education Board, New York; Mr. E. H. Clement, editor Evening Transcript, Boston; Dr. A. S. Draper, State Committee of Education, New York; Rev. Paul Revere Frothingham, Boston; Mr. Frederick T. Gates, confidential secretary to Mr. John D. Rockefeller; Hon. Seth Low, New York; Dr. St. Clair McKelway of the Brooklyn Eagle; Mr. W. R. Moody, East Northfield, Mass.; Mr. Robert Treat Paine, Boston; Mr. and Mrs. J. G. Thorpe, Cambridge, Mass.; Dr. F. G. Peabody, Cambridge, Mass.; Mr. Geo. Foster Peabody, New York and a great number of others—some 95 in all—many with their wives.

A great number of prominent Colored persons have also been present,[14] including Hon. Harry S. Cummings of Baltimore; Rev. M. J. Naylor of Baltimore; Mr. Emmett J. Scott, secretary to Dr. Booker T. Washington and many others.

MEMORIAL CHAPEL, HAMPTON INSTITUTE

By Reverdy C. Ransom.

What do the Socialists propose to do with the Negro question? One says, he is willing to treat a black man as he would a white man; that is, when Socialism is fully established. Another tells us, he has never considered the subject, besides he is too busy considering the question of “class consciousness.” The Socialistic cult in this country, under whatever name it may act, is bound to consider the Negro and the questions growing out of his presence here. Nine million people cannot be ignored. They are the storm centre for the exhibition of vigorous racial prejudices and animosities.

REV. R. C. HANSON, D. D.

Mr. Eraste Vidrine, a socialistic organizer in the Southern states, in the International Socialist Review for January, says: “The socialist organizations are restricted to whites, who refuse admission to Negroes.” This is God’s world and not a devil’s world.

Of all the numerous attempts through the ages to read the teachings of Jesus into widely differing schools of thought, that of socialism is nearest.

Karl Marx is the high priest of modern socialism, and Joseph Mazzini, Count Tolstoi, and Henry George are of the same company. It will take years for the ruling ideas of the present age to spend themselves. New England is conservative. Precedent, custom, the old-established order of things, hold sway. In the west, it is different. The immense distances of her prairies, and the lofty altitudes of her mountains are congenial soil for the growing of great ideas.

Theories, economic, populistic, socialistic, coming out of the west, strike the staid people of the east as being quite grotesque. But it must ever be that true prophets and reformers are made out of cranks and heretics.

With those who advocate the Negroes, forced elimination or self-effacement from politics, we have nothing but uncompromising dissent.

The obsequious, cringing, sycophantic man, with his hat under his arm, is only a thing to be despised. To be a man, one must stand erect, and contend for the recognition of all that belongs to a man. The Democratic party does not seek the Negro; the Republican party uses him, but has small use for him, in the paths that lead to honor and to power.

Those who falsely picture the Negro as indolent, shiftless, lazy, are one with those who seek to keep him in a condition of social, political and economic inferiority. The Negro is industrious and aspiring and is seeking to mount each round in the ladder of moral, social, industrial and political strength and progress.

Seventy percent of our women are wage-workers, with the overwhelming majority of our men. Organized labor may discriminate, but there can be no permanent advance while one-eighth of our population is ignored.

The program of socialism is begirt with the spirit of righteousness and seeks to establish itself on the foundations of justice. Sooner or later, in the affairs of men, there must come a levelling process. The Negro needs to take a broader outlook and a larger view of himself in relation to his surroundings.

Within the present century the mightiest battle of all the ages will be fought right here in the United States. It will be that of the people coming into their own. I have used the term socialism loosely; but I mean what Chicago meant when it voted to own its street railways; I mean what Kansas meant when it sought to establish its own oil refineries; I mean the spirit of what Edward Bellamy said in his “Looking Backward,” I mean in fine, that the wheels and spindles, the wealth of the bowels of the earth, and the produce of the soil shall be justly shared by the producers. The Negro’s cue for all time to come, is to preach brotherhood and to practice it. He or some other race, whom God shall choose, has it in his power to more mightily enrich the world than did Egyptian or Jew, Greek, Roman, or Anglo-Saxon, this by consecrating himself to a mission of unselfishness, to war against social, political and economic inequalities, and for a bringing in of the realization of the brotherhood of man.

New Bedford, Mass.

In Andrew Carnegie’s “Empire of Business” he sets down the prime conditions of success as they appear to him. Above all, he says, a young man should concentrate his energy, thought and capital exclusively on the business which he has adopted. If he has begun on one line, he should fight it out on that line.

The concerns which fail are those which have scattered their capital, which means that they have scattered their brains also. They have investments in this, or that, or the other, here, there and everywhere. “Don’t put all your eggs in one basket” is all wrong. I tell you “Put all your eggs in one basket, and then watch that basket.” Look round you and take notice; men who do that do not often fail. It is easy to watch and carry the one basket. It is trying to carry too many baskets that breaks most eggs in this country. He who carries three baskets must put one on his head, which is apt to tumble and trip him up. One fault of the American business man is lack of concentration.

To summarize what I have said: Aim for the highest; never enter a barroom; do not touch liquor, or if at all, only at meals; never speculate; never indorse beyond your surplus cash fund; make the firm’s interests yours; break orders always to save owners; concentrate; put all your eggs in one basket and watch that basket.

Said the man about town as he pushed a coin across the table and poked several bank notes into his vest[16] pocket: “Have you ever seen a waiter who stands in with the cashier in a fashionable hotel, cafe or rathskeller dress up his change as you’d dress a window, so that you’re tempted to tip him? No matter what denomination you pay in, between them they’ll always make one bill look as if it had been broken up with dynamite. If your check calls for half a dollar you never get half a dollar back from a dollar. There’ll be a quarter and two 10-cent pieces and a nickel. If you’re generous you won’t pick up the quarter; if you’re kind of stingy you’ll leave a dime, and you’ll pass over the nickel anyway, even if you’re tighter than a tight shoe.”

“Let me ask you a harder one,” replied the man addressed. “Have you ever seen a waiter who didn’t stand in with the cashier in a fashionable hotel, cafe or rathskeller?”

“I believe that any man’s life will be filled with constant unexpected encouragements if he makes up his mind to do his level best each day of his life—that is, tries to make each day reach as nearly as possible the high-water mark of pure, unselfish useful living.”—Booker T. Washington.

“The ability to live and thrive under adverse circumstances is the surest guarantee of the future. The race which at the last shall inherit the earth will be the race which remains longest upon it. The Negro was here before the Anglo-Saxon was evolved, and his thick lips and heavy-lidded eyes looked out from the inscrutable Sphynx cross the sands of Egypt while yet the ancestors of those who now oppress him were living in caves, practicing human sacrifices, and painting themselves with woad—and the Negro is here yet.”—Charles W. Chesnutt.

Fortune is often too kind and generous to the mentally, morally delinquent and too often covers the path of the undeserving with flowers, while real merit and genius is allowed to starve and die.

BY WILFRED H. SMITH

From the Outlook

As an American Negro I feel compelled to take issue with the Hon. John B. Knox of Alabama, in his article in The Outlook of January 21, on the “Reduction of Southern Representation,” and challenge his statement that the recent Constitution of Alabama does not disfranchise the Negro as such, but only prescribes an educational and property qualification test for both races; and his further statement that in case a Negro is discriminated against by the registrars, an appeal to the courts of Alabama will not be in vain.

On the contrary, the fact is that the suffrage provisions of the new Constitution of Alabama are an open disavowal and nullification of the Fifteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, and an exclusion of the Negro from the electorate on account of his race and previous condition; also the law providing for an appeal to the courts of the State of Alabama, where a Negro is refused registration, is only a snare, and affords him no relief whatever.

In considering this question the following undeniable facts should be borne in mind:

1. The Twelfth Census of the United States shows the population of the State of Alabama to be 1,001,152 whites and 827,545 Colored; and in 20 counties the Negroes largely outnumber the whites.

2. That since 1875 or thereabouts, up to the adoption of the new Constitution, the Negro vote in the State of Alabama has been suppressed by intimidation and false returns; so that during the entire time the complete control of the state government has been in the hands of white men and the Democratic party.

3. That not a single Negro delegate held a seat in the convention which enacted this Constitution; it was composed exclusively of white men.

4. That the constitutional convention was called upon a party platform[17] in which there was a pledge that no white man, however poor or ignorant, should be deprived of the franchise.

Upon the authority of Judge Cooley’s work on Constitutional Limitations, and the case of Ah Kow vs. Nunan, 5th Sawyer, 560, it is proper to refer to statements in debate on the passage of a law, for the purpose of ascertaining the general object of the legislation proposed, and the mischief sought to be remedied. If, then, we wish to know the purpose of the law, we have but to read the words of Mr. Knox himself, in his opening address as president of the constitutional convention:

“If the Negroes of the south should move in such numbers to the State of Massachusetts, or any other northern state, as would enable them to elect the officers, levy the taxes, and control the government and policy of that state, I doubt not they would be met in the spirit that the Negro laborers from the south were met in the State of Illinois, with bayonets led by a Republican governor, and firmly but emphatically informed that no quarter would be shown them in that territory.

“And what is it that we do want to do? Why, it is, within the limits imposed by the Federal Constitution, to establish white supremacy in this state.”

And so throughout the debate on these provisions the same or similar language was indulged in. Some of the delegates proposed openly to defy the Fifteenth Amendment by frankly writing it in the law that no Negro should be eligible to vote in Alabama. The prevailing opinion seemed to be that the enfranchisement of the Negro in the beginning was an insult and an outrage upon the southern white people to humiliate and degrade them, and it now became their duty in self-defense to disfranchise him as far as they could under the Amendment to the Federal Constitution.

Upon the authority of the Supreme Court of the United States, one cannot do indirectly unlawfully what one cannot do directly lawfully.

How could Mr. Knox keep his pledge not to disfranchise a single white man, made to his party, and at the same time keep his oath to support the Constitution of the United States? Which, think you, had the greater building force upon him? There being only white and black men in Alabama, and the convention being pledged not to disfranchise the whites, who else were there to be disfranchised but the Blacks. No matter how the thing was done, whether by a soldier clause or a grandfather clause, a temporary plan or a permanent plan, its purpose was unlawful and repugnant to the Fifteenth Amendment.

The well-settled rule of construction is that the form of a law by which an individual is deprived of constitutionality is immaterial. The test of the law’s constitutionality is whether it operates to deprive any person of a right guaranteed by the Constitution. If it does, it is a nullity, whatever may be its form.

Only one of many similar illustrations can be given of the administration of this law.

In the postoffice at Montgomery there are about eight or ten Colored clerks and carriers, all of them qualified under the United States Civil Service, who own their homes, each valued at upwards of a thousand dollars. Not one of these men, however, has been able to satisfy the board of registrars in Montgomery county of his good character, his ability to read or write, or that he was assessed with three hundred dollars’ worth of property. The Constitution thus administered has brought about the following results:

In the county of Montgomery, where there are more than 5000 qualified Negro electors, only 47 were allowed to register. And in the whole State of Alabama, with about two hundred thousand qualified Negro electors, only about two thousand five hundred were allowed to register; while all the white men in the state who applied—183,234—were given certificates of qualification for life.

Mr. Knox is also in error when he says that the Negroes of Alabama disqualify themselves by failing to pay their capitation tax, which is a prerequisite for voting.

The payment of the poll tax without[18] also being registered does not give the right to vote in Alabama; and the payment of this tax is not a prerequisite for registration. The truth is, the boards of registrars refuse to register qualified Negroes, no matter what their qualification, or what property they own, or what taxes they have paid, except in such cases as seem to suit their whims. The qualified Negro thus refused is wholly remediless.

The Alabama Constitution provides that any person to whom registration is denied shall have the right of appeal to the Circuit Court. At the trial the solicitor for the state shall appear and defend against the petitioner on behalf of the state. The judge shall charge the jury only as to what constitutes the qualifications to entitle the applicant to become an elector at the time he applied for registration, and the jury shall determine the weight and effect of the evidence and return a verdict. From the judgment rendered an appeal lies to the Supreme Court in favor of the petitioner.

This law, we submit, is an absolute farce. It provides for an appeal from a partisan board to a partisan jury, composed exclusively of white men with the state solicitor, a partisan officer, appearing for the state against the elector. The hands of the trial judge are tied, so that he can only charge the jury as to what constitutes qualifications. The jury are thus made the sole judges of the case, and their decision is final, because nothing but an issue of fact can arise at the trial. Every lawyer knows that an appellate court cannot disturb the verdict of a jury on any disputed issue of fact, and hence on appeal to the Supreme Court the appeal was dismissed, the Court would avail nothing.

The case of the state vs. Crenshaw, 138 Alabama, 506, from Limestone county, referred to by Mr. Knox, in no way supports his contention, and really decides nothing. It has been ascertained that this case was specially made up to induce Negroes to abandon the Federal Courts and seek the State Courts. As arranged, the jury in the Circuit Court reversed the registrars, but on appeal to the Supreme Court the appeal was dismissed, the Court holding that the Constitution gave the right of appeal only to the person refused registration and not to the registrars.

The deception becomes obvious when we consider how utterly impossible it would be for the courts of Alabama, as at present constituted, to carry on their regular business and determine the cases of two hundred thousand qualified Negroes refused registration.

BY H. D. SLATTER

Of a truth we may say that the upward career of the average Negro reads like a romance of the wildest creation. The terrible struggle to overcome the ignorance and superstition which slavery imposed upon him, the bitter contest with the phantoms of darkness, the persistent advancement into the light of intelligence with the shadow of a long record of intense cruelty and suffering constantly threatening before him and with the gloom of an inexorable race prejudice threatening his onward march toward a higher and grander civilization, this new citizen, undaunted by barriers of whatever sort, is forging his way to the front in every noble cause. Many inspiring examples of usefulness on the part of earnest young men who have received their training at such Institutions as Hampton and Tuskegee may be found in all sections of the south; but we know of few who are so unselfishly devoted to the work of elevating the masses of the race as Prof. William H. Holtzclaw, principal of the Utica Normal and Industrial institute, located one mile from the town of Utica, on a branch of the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley railroad in the very heart of the Black Belt of Mississippi, where the Negroes outnumber the whites seven to one.

Professor Holtzclaw was born in Roanoke, Alabama in 1872. At an early age he heard of Dr. Booker T. Washington and later attended the Tuskegee Institute where he received such convictions as to the wisdom of the principal’s course as to inspire him with the ambition to supplement, if possible, this great work. After his[19] graduation he went to Snow Hill, also where he worked for four years in the Snow Hill institute, rising to the responsible position of treasurer of that institution. While at Snow Hill he made a very careful study of the condition of the Colored people in various parts of the south and settled upon Mississippi as the state in which he might render most valuable service.

In October, 1902, leaving his wife in Alabama, he started for Utica, where, with unflagging industry he succeeded in opening a school under an oak tree in the forest one mile from the town. As soon as he was able to secure a cabin in which to teach the young people flocked in great numbers to his school. In a very short while he had 200 pupils in daily attendance. One teacher after another was employed; but the struggle was most distressing when he found that he could not raise money enough to pay them. During all this time he was trying to arouse the interest of the people. He went from door to door explaining his efforts, then made a tour of the churches; after riding or walking ten miles at night, he would return and teach the next day. After a protracted struggle of this kind and after visiting nearly everybody for miles, he secured about $600.

Forty acres of land were purchased and part of the lumber for a comfortable building was put on the ground. Some of the trustees in New York City and Boston came to his assistance and with this and contributions from a few other friends, he was able to get through that first year. Although it was a struggle, he found in it some pleasure. To know that you are doing the work that the world needs and must have done is a pleasure, even under trying circumstances. It is doubtful if any school started as a result of Tuskegee’s teaching ever accomplished more in the same length of time, during its first year of existence than was true of the Utica Normal and Industrial Institute.

Starting in October, 1902, without a cent, in the open air, he succeeded in one year in establishing a regularly organized institution, incorporated under the laws of the state of Mississippi,[20] with 225 students and seven teachers, and the property valued at $4000. On 40 acres of good farm land, about a mile from town, a model crop had been grown. He had erected a two-story frame building, at a cost of something over $4000. But in all this noble work Professor Holtzclaw was assisted by teachers whose co-operation made it possible for him to accomplish so much in so short a period.

PROF. W. H. HOLTZCLAW

Miss Ada L. Hicks, lady principal of the institute, a graduate of the Snow Hill school and for a number of years a student at Spelman seminary, Atlanta, Ga., is one of the most helpful workers associated with the professor. She is deeply concerned about the work and is painstaking in every effort.

Miss Clara J. Lee, head of the academic work of the institute was born on a farm in the neighborhood of Utica. She finished the normal course in Tongaloo university, located in the beautiful little village of Tongaloo, in the very middle of the state of Mississippi, just a few miles from Jackson, the capital. She started to work with Professor Holtzclaw immediately upon her graduation and her services have been invaluable. Her endeavors are highly appreciated by the principal.

The work which Professor Holtzclaw is doing in the Black Belt of Mississippi is of incalculable value.

A THRILLING STORY OF HOW LOVE

PLAYS UPON THE HEART AND SOUL

BY ALICE MAUD MEADOWS

Written for Alexander’s Magazine

“I wish,” Nora Desmond colored ever so slightly, “one of you would tell me what Mr. Le Strange is like!”

Mrs. Desmond and Nancy Desmond looked at one another sharply, something like a warning glance passed between them.

“Like?” Mrs. Desmond repeated, faintly.

“Yes—like,” Nora returned. “I know he’s tall and big. I know he has a pleasant voice, a merry laugh; I know”—her strange, pretty eyes grew shy, though they saw nothing, never had seen anything since her fourth birthday—“he is the kindest man in the whole wide world; but I want to know what his face is like—that’s natural, isn’t it, since”—a trifle defiantly—“since we are such good friends?”

“Quite natural,” Mrs. Desmond answered. “What would you like to know—the color of his eyes?”

Once more she looked at Nancy; the girl shrugged her shoulders, and made a helpless sort of gesture.

“Of course,” Nora said, “the color of his eyes, his hair, what sort of a nose and mouth he has, whether he wears a mustache. I should like a word picture of him. You know,” she sighed softly, “it’s all the picture I can see.”

For some reason or other, both Mrs. and Miss Desmond looked relieved.

“John Le Strange has very good features, indeed,” Mrs. Desmond answered; “a straight nose, a good mouth and really beautiful eyes. His hair is brown, with a natural wave in it. I don’t think there’s anyone in the world who could deny John has good features. As for the nature of the man, it’s absolutely the sweetest I have ever known.”

A very pretty smile crossed Nora’s lips, a tender expression entered the sightless eyes.

“The sweetest nature you have ever known,” she repeated. “One couldn’t have a nicer thing said than that. Looks are a great deal, of course—I so love everything beautiful, but a lovely nature is even more than a lovely exterior. I—why, that’s John’s footstep; he’s earlier than usual today, isn’t he?”

John Le Strange boarded in the house of Mrs. Desmond; had lived in her house now for ten years, almost ever since the death of Terrence Desmond, leaving his widow not very well provided for.

A look of pleased expectancy shone[22] upon the girl’s face; then, as the footsteps passed the door, went slowly upstairs, it died away.

“His footfall sounds tired tonight,” she said, more to herself than the others, “as though some trouble is upon him. I wish, mother”—it was curious how directly she seemed to look at her mother—“you would go up to him, just to see that nothing is wrong. He’s been an inmate of your house so long now, you must feel almost like a mother to him.”

Once more Mrs. Desmond glanced at Nancy.

“I dare say he’s fagged out,” she answered. “Men mostly are when they come home from their work. Why not go and ask him yourself, Nora? You’re his favorite.”

A smile flashed into the girl’s face, in her eyes, on her lips, dimpling her cheeks. She had been beautiful before; she was absolutely lovely now.

“His favorite!” she repeated. “Mother, do you really think so? Of course, he pities me—everyone does; everyone is kind to me—but, apart from that, do you really, really think I am his favorite—in spite of my blindness?”

Mrs. Desmond rose, cross the room, put her hand upon the girl’s shoulder.

“I don’t think—I know,” she returned. “He thinks more of you than he thinks of anyone in the wide, wide world! That’s something to be proud of, Nora.”

She rose slowly, her little hands tightly clasped.

“Something to be very, very proud of!” she returned. “But how wonderful that is, mother!”

She moved across the room without stretching out her hands. No one who did not know would have supposed her to be blind.

“She will marry him, of course,” Nancy said, when she was out of hearing, “because she is blind; she never would if she could see!”

Just as quietly as she had gone from her mother’s sitting room, Nora mounted the stairs, knocked at the door, and, in answer to a quiet “Come in,” uttered in a singularly beautiful voice, entered.

By a table, with the full glare of a lamp shining upon him, sat a man. So far as his features went, Mrs. Desmond’s description had been accurate. The eyes that softened so wonderfully as he saw the girl were beautiful; for all that, the man was not pleasant to look upon. Smallpox of the most virulent type had seamed and scarred his face, making what should have been very fair almost terrible.

“You, Nora!” he said, springing to his feet. “How good of you to come and see me!” He made use, without thought, of the ordinary words. “Come to this chair; it’s the most comfortable in the room. You know that, don’t you?”

“And so you always give it to me, John,” she said. “I think you can’t help being like that—the best invariably for some one else. I wonder,”—her soft fingers closed on his hand as he led her to a chair—“why you are sad tonight—unhappy?”

He started, ever so slightly.

“How did you know?” he asked. “How wonderful you are, Nora!”

She was sitting now; he standing close beside her, worshipping her with his beautiful eyes, feeling he would give the whole world, were it his, to take this dear, blind girl in his arms and kiss her sweet lips.

“I suppose I know,” she answered, “because God, who is very just, has given me a greater power of perception of some things than those who can see—a fuller sympathy. Tell me[23] what is wrong, John—why you are sad?”

He hesitated a moment; then very slowly, half timidly, he sank upon his knees.

“This is why,” he answered, and his hungry lips almost kissed her hand. “I want something that I dare not ask for, and yet if it could be mine how I would love and cherish it! I want something—some one to work for, to make money for; some one to surround with adoration and comfort, but I dare not—I dare not say to her I love you, because——”

He paused. She stretched out her hand and laid it unfalteringly upon his shoulder.

“Because she is blind, John?”

He covered her hand with his—then he covered it with kisses.

“No, no! A thousand times no!” he answered. “Oh, Nora, you know I love you—want you—you know your blindness makes you all the dearer to me! But you don’t know me as others know me—you have never seen me. If—if you should give yourself to me, you would be giving yourself to an unknown man. I think you care for me—but——”

“There is no but,” she interrupted. “I love you. As for knowing you, there is no one in the world I know so well. And today my mother has told me just what you are like—has so to speak, painted the picture of your every feature. I can look at you now with my mind’s eye—I am so glad, dear!”

He put his arm round her; he drew her gently to him; he kissed her lips.

“Little sweetheart!” he said. “Little wife to be! So your mother told you all? Are you sure you did not dislike the picture?”

With her slender, sensitive fingers she touched his features, one by one, smiling, but a little puzzled.

“Quite,” she answered; “and mother was right; your features are beautiful. Your skin is rough and rugged, different from mine—that is because you are a man, but you must not think”—one could scarcely believe she was not looking at the scarred face—“I love you for your beauty; I love you just because I love you—because I can’t help it. And I hope—I do hope, with all my heart—you will never regret your goodness in taking a blind girl to your heart—wanting her for your wife.”

Many times during their short engagement something almost compelled John Le Strange to paint a word picture of himself as he really was, not as he knew she believed him to be; but, after all, is it necessary? She loved him, and, God knows, he loved her! She would never look upon his face; always to her he would be beautiful. So far as utter affection could, he would keep all sorrow from her, surround her with every comfort. She was more helpless than most women; would need all her life more care and cherishing.

More than once he asked Mrs. Desmond if it would not be better to undeceive the girl. She, however, was emphatic in her negative.

“You’ll just spoil her life and her happiness if you do,” she answered. “What the eye does not see, the heart does not grieve for; as every one knows, the blind in their hearts and souls worship at the shrine of beauty more ardently than those who see. To her you are all that is desirable in every way; let that content you.”

And so, with the truth still untold, the two married, and in the whole wide world there was no happier wife than Nora Le Strange. Never once did he let her feel her blindness; never[24] did he tire of telling her of beautiful things, describing every place he took her to so vividly, with such care, that always she smiled and nodded as she pressed the hands she held.

“I see—I see it all quite plainly!” she would say. “Oh, John, what a beautiful place this world is! And what a pair of seeing eyes you lend to me!”

It was not until her little son was born that Nora craved passionately to see, if only for a moment. Time after time, as she held the little creature, as she passed her fingers ever so gently across his downy head, his tiny features, over and over again, John described just what the little one was like—the most beautiful baby in the world. But for once, she seemed hardly satisfied.

“Oh, if I could only see him!” she said; “just once. John, I’ve wanted terribly sometimes to see you, though I know just what you are like. I want even more to see him, because he’s you and me, and our dear love all rolled up in this sweet, warm bundle.”

It was just about this time that a stranger, meeting John, Nora and the beautiful child in a public conveyance, looked at the girl’s eyes with an interested, professional glance. A day later, having discovered where they lived, he called upon John Le Strange.

“Your wife is blind,” he said, after a preliminary word or two. “I think, however, she was not blind from birth?”

“No,” he answered, “she was not blind until her fourth year. Her blindness is the outcome of some juvenile complaint.”

“And can, I believe, be cured,” the doctor said, gently.

John’s heart gave a great leap. Nora’s blindness cured! That would mean that she would see him; look upon the man she had believed beautiful—see how he had deceived her—perhaps hate him!

“Cured!” he repeated, and Dr. Winter wondered why the man’s scarred face grew so pale.

“Will you allow me to examine your wife’s eyes?” the oculist said. “From what I have observed, I have little doubt that your wife may yet see.”

There was a struggle for a moment in John’s heart. The happiness of his life, the dear, utter happiness, seemed slipping away. Then the beauty of the man’s nature conquered; he fetched his wife.

Trembling, he stood by while the beautiful eyes were examined; slowly he sat down as the doctor gave his verdict.

“The operation would be painful,” he said, “but I have no doubt whatever of its success.”

With a laugh of excitement, Nora spoke:

“Painful, John? That won’t matter; I can bear pain. Think of it, dear! I shall see the sky, the flowers—see you, and the baby! Oh, John—John, it’s too good to be true! No, no—I won’t say that. John, how quiet you are!”

As the days passed on, and certain preparations for the operation were made, John grew more quiet than ever; a silent tragedy had come into his happy life. Within another week his wife would see—would look at him, perhaps with aversion!

“Will you tell her,” he said to Mrs. Desmond, “before she sees—will you tell her? Directly the bandages are removed, she will turn to me, and she won’t know me. Will you prepare her?”

“It’s most unfortunate,” she said, slowly. “Yes, I mean it; I look upon this hope for Nora’s sight as a great misfortune. She was perfectly happy, perfectly content, I know”—neither of them heard a soft step coming along the passage—“she longed to see the child, but, after all, her sense of touch is so delicate, she knows as well as I know what he is like. This interfering doctor had better have left things alone.”

The soft steps stopped outside the door. The blind girl stood and listened, her heart beating strangely. Sight a misfortune for her! Why—why? She could not understand.

“After all,” Mrs. Desmond went on, slowly, “she loves you dearly; she will grow used to your looks in time; even if she is shocked at first, it will wear off, and any one can see that it’s your misfortune that you’re not a handsome man; your features, as I have told Nora often, are beautiful. You ought to be a handsome man, and but for the smallpox marks you certainly would have been.”

The blind girl, standing so motionless outside the door, shivered a little.

“I shan’t be able to bear it,” John said. “Blind as she is, she worships beauty. What will she feel when she sees she is bound for life to me! I ought not to have married her; but when a man loves”—he made a hopeless gesture—“and I wanted to take care of her.”

Mrs. Desmond rose, and walked about the room.

“You’re her husband,” she said; “you have the remedy in your own hands—forbid the operation!”

“And rob her of one of life’s greatest blessings?” he answered. “No, I’m not so selfish as that, and she wants to see the little one. Ah, well; he, at all events, is perfectly beautiful; she will turn from me, perhaps; but she can feast her eyes on our little son.”

As quietly as she had come, the blind girl stole away, up the stairs to her little one’s nursery, where he lay crooning in his cot. With a half sob, she bent over him, kissed him—touched the tiny face.

A little later, with a quick, light step, she ran down the stairs, her hand just touching the banisters; listened an instant, then went straight to the room in which John sat. He glanced up, and she went to him, kissed him softly.

“John,” she said, a tremble in her voice, “dear John, don’t be angry with me—I know you’ve been put to trouble—trouble and expense, but—I’m a coward, dear—the doctor said it would be painful; I can’t”—she almost sobbed now—“I can’t face the operation!”

He held her from him for a minute; no inkling of the truth entered his mind. Then he snatched her to his heart. Was he wicked, selfish, to be so glad?

“Not to face it!” he returned. “But think, Nora, just a little pain, or even a great deal, and then to see! To see,” he said the words bravely, “to see baby!”

She trembled from head to foot. Oh, to see—to see!

“Yes, I know,” she answered. “I have wanted to, but after all, you have been my eyes—such good eyes, John—and I’m not brave at bearing pain. You’re not vexed with me?”

“No, darling—no; but think, think again.”

“I have thought;” she answered, “and I can’t risk it. You must thank the doctor, and tell him I’m afraid. John, I don’t seem selfish to you because I won’t bear pain—because I must be your blind wife, and baby’s blind mother always?”

“No,” he whispered. Was he selfish, wicked, that so great a glow of joy pervaded his whole being? “But, dearest, to be blind all your life, when you might see!”

She lifted her lips and kissed him—kissed the scarred cheek, the beautiful eyes.

“I don’t mind,” she answered. “Why should I, John, when the most beautiful thing in the world is blind?”

“The most beautiful thing?”

A WEIRD STORY FULL OF PATHOS SETTING

FORTH THE DEVOTION OF A NATIVE HEROINE

BY A NATIVE HAWAIIAN

Written for Alexander’s Magazine

Three riders came out of the woods, and, turning into the road leading from Napoopoo to the uplands, slowly began the ascent. As they went up, the long plains, reaching from the forest covered heights of Mauna Loa to the ocean, seemed to grow broader, and the sea rose higher, till the far away horizon almost touched the sinking sun. Lanes of glassy water stretched from the shore into illimitable distance. A ship lying motionless looked as if hanging in mid-air. Under the cliff the delicate lines of cocoanut and palm trees were silhouetted against the ocean mirror. Far to the south ran the black and frowning coast, relieved here and there by white lines or foam creeping lazily in from the ocean, only to look darker as the surf melted from sight. On the plain, little clusters of trees, or a house, or a thin curl of smoke, indicated the presence of men; and back of all rose the forest, vast, dim and mysterious, stretching away for miles till lost in the clouds resting softly on the bosom of the mountain.

Such a scene could not fail to arrest attention, and, though our riders were tired, they reined in their horses to enjoy its quiet beauty.

“What a wonderful scene! I have been through Europe, feasted my eyes on the Alps, and have seen the finest that America can produce, but I never saw its equal,” said the tourist.

“It looks as if such a picture might be the theatre of thrilling romance and history,” said the Coffee Planter. “Is it not here that Captain Cook was killed? And I think I have heard that a famous battle was fought somewhere near: the last struggle of the past against advancing Christianity.”

“Yes,” replied the Native, slowly, with a lingering look in his eyes, as he turned from the inspiring view to his companions. “Yes, this is all historic ground. Over there under the setting sun, at Kuamoo, was fought the battle of Kekuaokalani, and there a heroic woman braved and met death with her husband, a rebel chief. On these plains below and on yonder[27] heights there have been many thrilling scenes in Hawaii’s history. But all of the romance is not in the past. Do you see those houses away down the coast, this side of the high lands of Honokua? See how they glow in the setting sunlight. That is Hookena, and only a few years ago it witnessed the last act in a simple drama, which can hardly be excelled in all the tales of heroism in the past. It was told me in part by the woman who was or is the heroine, for she yet lives. And I looked at her in wonder, because she was so unconscious of it all.”

“Let us hear the story,” said the planter. “We will sit on that high point and watch this glorious scene fade into moonlight, while we rest and listen.” They dismounted and stepped from the road to a projecting rock and, throwing themselves on the grass where none of the wonderful vision could be missed, listened. The native looked a little embarrassed at his sudden transformation from guide to story-teller, but accepted the position and began.

“Many years ago a native family lived a few miles above Hookena, on land which had been occupied by their ancestors for generations, for they belonged to the race of chiefs. The house was hidden from the road, in the midst of a grove of orange, breadfruit, mango, banana and other trees.

It is on storied ground, for many stirring events in the past history of Hawaii had occurred here. A son and three daughters were the children.

They received more than the usual care and attention given to Hawaiian children, and had grown to man and womanhood serious and reflective. The young man, Keawe, was filled with a desire to do something noble for his dying race. Though he had travelled over the Islands and had been well received everywhere, yet he was heart-free and said he would never marry, but wait untrammelled till his time for action should come. With eagerness he watched political developments at the capital. His heart beat wildly when the last Kamehameha died, and Kalakaua was elected King.

Such a method of King-making did not suit his chivalric ideas. The records of personal prowess, of brave chiefs and noble women were his delight. He mourned that such records belonged to the well-nigh forgotten past. His ambition was not ignoble. He wanted the Hawaiians to be worthy of the best civilization, to maintain a Hawaiian Kingdom, because that the native was equal to it. While he mourned, he condemned the frequent failures, under which the native was forfeiting the confidence of his white friends. He was one of the overwhelming majority who regarded Kalakaua’s accession unworthy, and as the beginning of the end of Hawaiian supremacy.

One day, while fishing at the beach where he was doing more dreaming than fishing; sometimes idly watching a laughing company of girls who were bathing and surf-riding; he was startled by a cry of terror. Springing to his feet, he saw that one of the girls was desperately struggling to swim ashore, where her affrighted companions were running wildly about crying for help. Looking towards the sea he saw a large fin on the surface rapidly following the swimmer. Accustomed to every athletic sport; perfectly at home in[28] the water; always cool and self possessed, he saw, that to overtake her, the shark must pass a low rocky headland, and in an instant he was there with a long knife in his hand. He remembered seeing the face of the girl as she struggled desperately to escape. There was a single terrified glance, but he saw a beautiful woman, with a face indicating a higher type than usual. There was no time for admiration. The shark was turning and, with a horrid open mouth, was about to rush upon its victim. Ho gave a loud shout, jumped full upon the huge beast, and in an instant had plunged his knife to the hilt again and again into its body. Then he was hurled into the seething brine, as the frightened animal with frantic plunges rushed seaward. Coming to the surface and looking about he saw the body of the girl near by. He thought her dead. She was indeed stunned and hurt, for the shark gave her a fearful blow in turning. It was the work of only a minute to drag her out. There for a moment he saw the full measure of her youth and beauty, but did not wait for returning consciousness. Seeing that she was recovering he walked swiftly away.

But he was wounded, and, denounce and reproach himself as he would, the sweet face ever and anon came before his eyes, and sent the blood tingling and dancing through his veins. He tried to crush out the image, and determined to enter into active life; to cease dreaming, and begin then and at once to accomplish his high aims.

The political campaign, culminating in the election of 1886, had commenced. Kalakaua had announced the aim of his reign: to increase and develop the Hawaiian people. “Hawaii for the Hawaiians” made an inspiring war cry. Keawe entered with energy and hope into the conflict. Yet it troubled him, and it seemed as if there was something wrong in opposing the noble Philipo, who had so long faithfully represented the people of Kona in the National Legislature. But Kalakaua declared that Philipo must be replaced by another man, and was himself coming to assist in the conflict. With the ancient faith and confidence in the chief, Keawe put aside his doubts and worked day and night for the success of the holy cause. It was holy to him and as the day of election drew near, his belief grew stronger, that at last a deliverer had come and Hawaii was to be redeemed. Already he saw, in a bright future, a government by Hawaiians with full friendship for all nations, and cordial relations with those who had helped his people into the best light of civilization. The King came, and with him a troop of palace guards from Honolulu. When all of these were, by the royal will, duly registered as voters, and means, other than argument and persuasion, were used to help on the good cause, a chilly sense of something wrong cooled Keawe’s ardor. He met the King and was cordially received. His heart bounded with pleasure at words of praise for his work. An invitation to a feast and dance was accepted, and only when he went and saw, did he realize the mockery and sham behind the fine words. Heart sick, dizzy with a sore disappointment, early the next morning, when all were sleeping,[29] he mounted his horse and stole away alone. The cold mountain air relieved the pain in his head, but his heart was weary and the future looked dark. He saw that if there was momentary triumph, all the sooner disaster must come; and he longed to know how to avert the danger. He grew weary thinking and trying to hope, and his thoughts went to other things. Again he was in the water, struggling to save her life. Again the sweet face appeared before him, so fair and gentle. The sun was hot now; he had ridden for hours, and, alighting, threw himself on the grass and looked up through the leafy bower at the bright sky. Perhaps he slept; at any rate be dreamed that a sweet voice was singing “Aloha oe.” He sat up and listened. It was not a dream, and a strong desire to see the face of the singer possessed him. The voice drew nearer, then she passed near by carrying a pitcher, and went to a spring. It was the girl he had saved from the shark! She wore a loose flowing gown of white and a maile branch twisted about her head hardly confined the silky hair which floated down her back. A coral pin held the gown about her neck. Short sleeves only partly hid her graceful and shapely arms.

Keawe arose and stood watching. His heart beat tumultuously. No other woman had so strongly moved him, and now he would speak and not run again. A movement startled her, and rising with the dripping pitcher in her hand, she turned and saw him. That she knew him was instantly evident; but her eyes modestly dropped and she moved as if to go. But he was in the path, and seeing that, she hesitated and turned to go through the woods, but could not and stood again, looking at her feet which just peeped from the gown. Keawe stepped towards her and said, “Do you remember the shark?” “Yes, I know you,” she replied. Her eyes said more and he saw it again. As he stepped nearer she said. “Why did you not let me thank you? I thought you might come.” It flashed through his mind that he wasted two months pursuing an ignis fatuus, only to have nothing but bitterness at the end, when it might have been——! “I was afraid to come,” he replied. “I wanted to work for Hawaii and our people.” “Yes, I know,” she said. “You have spoken bravely. All Kona trusts in your words!” “Did you believe them?” he quickly asked. “Do you believe in me?” A look was her reply. “Will you believe in me if I say that I am done with ‘Hawaii for the Hawaiians,’ under such leadership?” “I will always believe in you. But come, you are tired. My father will be glad to meet you,” she said quickly. “May I drink?” he said, and held out his hand. She gave him the pitcher, which he held and looked at the pretty figure standing near the spring. “You are Rebecca at the well.” “And are you Abraham’s servant?” “No, I am Isaac himself,” he replied and tried to take her hand. “Oh! but Isaac did not meet Rebecca at the well!” And, laughing merrily, she ran down the path towards her home. He followed but though he wanted, the opportunity for other words did not come; she was so very coy. But that was not the only visit. Very[30] often business calls took him along that lovely mountain road and there was always a welcome at the home of Lilia. He told her of his love, and in April they were married.

They built a little cottage which nestled snugly in a quiet valley on the mountain side, and there they passed a few months of perfect happiness. All loved them. He was regarded as the wise adviser and friend of the country-side. She became the gentle sister of those who were ill, or suffering or wayward, and their home was the center of an influence which helped and lifted.

But a shadow came into their lives. He grew silent, reserved, almost afraid of beautiful Lilia. She watched with eager anxiety and entreated his confidence, but his lips were sealed. Only his tremulous voice and shaking hand betrayed suffering. Sometimes she fancied that his hands grew palsied and his bright eye was dim, but repelled the fancy with terror. One day he came home with such a look that her heart stood still, and words died upon her lips. He gazed into her eyes with passionate agony and, taking her hands, said “Will you still believe in me if I say we must part; that I must leave you and go away, and you must stay here and live out your life—your precious life, so dear to me—all, all alone?” Then her courage came, and she said, “No, I will never leave you. You are mine. I must go too, wherever you go!” “But,” said he, “I have seen the examining surgeon today, and he says I must go by the next trip of the steamer to Honolulu.” And then the full measure of her woe dawned upon the stricken wife. With unutterable anguish she threw her arms about his body and clasped him tightly to her breast. “I was allowed to come here and prepare to go, and to bid a last farewell to all I hold so dear. I shall never see these trees, the flowers, this house, my friends, nor you, my precious wife, again.” But her face had grown hard and stern, and, relaxing the hold, she told her plan. It was to take him into a far off deep recess in the woods. There was up the mountain side a deep crater, overgrown with trees, ferns, vines and a wild luxurious growth, which kindly nature had draped so softly that its hideousness was lost. It was considered inaccessible, and only the family knew of an ancient lava cavern which entered its deepest recess. One of several mouths of the cavern was near the house. “But the law says that I must go” he urged. “There is no law higher than my love for you,” and he yielded to her imperious urgency. Quickly and stealthily she carried such articles as the simplest life might require, and a few days later, when the officers of the law came, Keawe was not to be found and no one knew where they had gone.

With untiring love the wife watched and aided her husband. Together they built a little bower out of view from the upper edges of the crater, under the spreading branches of a kukui tree. A little pool, fed by the constant drip from the over-hanging wall, supplied them with pure water. Near at hand, under a mass of ferns, maile and ieie, was the mouth of the cavern. She grew familiar with its turns and windings, till she almost[31] dared to brave its black recesses without a torch. In one of its dry and sheltered windings, she stored articles of food and clothing thinking that sometime a watch might be stationed at the home on the hill-side and she could not venture out. But days melted into weeks; weeks became months: two years passed, and their hiding place was not discovered. No one came, though Keawe often longed to see the faces of friends. But they were afraid to venture near and the cavern echoed only to her feet, and the silence of the deep pit was only broken by their voices and the music of the birds. At times a sudden gust rushed down the steep sides and every tree waved and bowed and quivered. The sunlight only touched the bottom in summer and then for a few minutes only. But it was not gloomy, the glorious sky was always there and the brilliant light, and the bloom and fragrance filled the air. No, it was not always bright, sometimes tempests whirled far over their heads; trees in the world above tossed their branches over the abyss, leaves and twigs fell gently, or branches, and once, a tree, were hurled down with deafening noise. The roar of thunder, and vast sheets and torrents of rain filled the pit. Once, in a still night, they were startled and terrified by a sudden boom far below their feet and the earth shook, stones rattled down the rocky sides of the abyss, and they remembered the dread power of the volcano. “It is Pele! she is angry with us!” cried Lilia. “No,” replied her husband, “we have thrown ourselves into the protecting bosom of the Goddess! We are safe in her arms.” They were safe from human sight and interference, and Lilia’s soul feasted in the presence of him she loved. She poured out upon him such a wealth of devotion, that a miser might have envied. But alas, though safe from man, he was under the fell power of disease, and slowly yielded. Day after day he grew weaker and less able to help himself, until the fond wife performed the most menial tasks. But they were not menial to her. Everything for him was a glory and a joy. “I cannot last long” he said one day, “and I want you to have my lands. Get your mother’s young husband, the lawyer, to come, that it may be settled.” He came, and, looking wonderingly about, prepared a deed which he said would accomplish the object. Keawe was not satisfied. “It sounds wrong—why should the name of your wife appear?” he asked. “She’s your wife’s mother,” was the reply, “and you cannot convey to your wife direct. When this deed is recorded my wife can then convey to your wife. You must hurry or it will be too late,” said the coming man. With some doubt still, but trusting to his friend’s good faith, knowing he was alone, cut off from all the world, Keawe signed, and the deed was taken away. Patiently they waited for weeks to finish the business, “and then,” said Keawe, “you will have a home.” But the lawyer did not come, and evaded Lilia’s eager questions.

One day when returning to the cavern, her heart stood still as she saw slowly emerging from its mouth, several police officers, bearing on a rough litter the helpless form of her beloved[32] Keawe. At a glance she saw the whole base deception. Her stepfather had betrayed their secret hiding place, and the end had come! With a frantic wail of despair, she flung herself at their feet and begged and implored. But her entreaties were vain, and the sick man was taken to Hookena where the steamer was waiting. At the landing, as the boat drew near the shore, she learned that he was to go alone and then her grief knew no bounds. As he was put on board and turned his imploring eyes on her she made a desperate attempt to go too, and in her struggle her clothing was almost torn away. The officers of the law thought they were doing their duty, but their eyes were full of pity. “Keawe! Oh Keawe, my beloved husband!” she cried, “let me go with you!” But no answer came. The steamer turned her head towards the sea, and he was gone. She fell to the earth, and lay with buried face for many minutes. It seemed to her that nothing was left and bitterly she mourned her loss. But suddenly starting, she asked eagerly for a horse, which was furnished at once by a sympathetic friend. Mounting, she went without stopping for rest or food until, on the second day, Kawaihae was reached. Soon a steamer came, and she went to Honolulu, only to hear on landing that Keawe had died on the trip down. Giving way to despair, she dejected, sought the house of an aunt, where she was kindly received, and there she remained for several months.

“And that is the story,” said the Native.

“It is rather sad, but she was a heroine sure enough,” said the Planter.

The pale light of the crescent moon served only to render the landscape shadowy. All nature rested. An owl fluttered slowly by and a soft murmur from far below told that the restless sea alone moved. There was no other sound. The riders mounted and silently stole away.

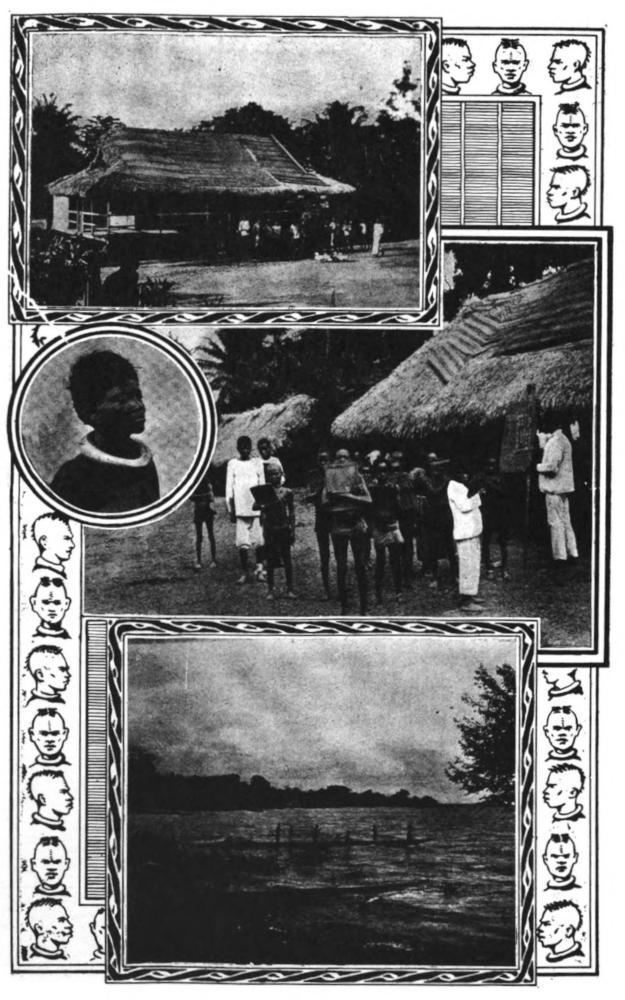

It is given to but few men in so short a time to create for themselves a position of such prominence on two continents as has fallen to the lot of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Born in London, August 15, 1875, Mr. Coleridge-Taylor is not yet thirty. His father, an African and a native of Sierra Leone, was educated at King’s college, London, and his medical practice was divided between London and Sierra Leone.

As a child of four Coleridge-Taylor could read music before he could read a book. His first musical instruction was on the violin. The piano he would not touch, and did not for some years. As one of the singing boys in St. George’s church, Croydon, he received an early training in choral work. At fifteen he entered the Royal College of Music as a student of the violin. Afterwards winning a scholarship in composition he entered, in 1893, the classes of Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, with whom he studied four years or more.

Mr. Coleridge-Taylor early gave evidence of creative powers of a higher order, and today he ranks as one of the most interesting and remarkable of British composers and conductors. Aside from his creative work, he is actively engaged as a teacher in Trinity college, London, and as conductor of the Handel society, London, and the Rochester Choral society. At the Gloucester festival of 1898 he attracted general notice by the performance of his Ballade in A minor, for orchestra, Op. 33, which he had been invited to conduct. His remarkable sympathetic setting in cantata form of portions of Longfellow’s Hiawatha, Op. 30, has done much to make him known in England and America. This triple choral work, with its haunting, melodic phrases, bold harmonic scheme, and vivid orchestration, was produced one part or scene at a time. The work was not planned as a whole, for the composer’s original intention was to set Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast only. This section was first performed at a concert of the Royal College of Music under the conductorship of Stanford, November 11, 1898. In response to an invitation from the committee of the North Staffordshire Musical Festival The Death of Minnehaha, Op. 30, No. 2, was written, and given under the composer’s direction at Hanley, October 26, 1899. The overture to The Song of Hiawatha, for full orchestra, Op. 30, No. 3, a distinct work, was composed for and performed at the Norwich musical festival of 1899. The entire work, with the added third part—Hiawatha’s Departure, Op. 30, No. 4—was first given by the Royal Choral society in Royal Albert hall, London, March 22, 1900, the composer conducting.

The first performance of the entire work in America was given under the direction of Mr. Charles E. Knauss by the Orpheus Oratorio society in Easton, Penn., May 5, 1903. The Cecilia society of Boston, under Mr. B. J. Lang, gave the first performance of Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast on March 14, 1900; of Hiawatha’s Departure on December 5, 1900; and on December 2, 1902, The Death of Minnehaha, together with Hiawatha’s Departure.

In 1902 Mr. Coleridge-Taylor was invited[34] to conduct at the Sheffield musical festival his orchestral and choral rhapsody Meg Blane, Op. 48. The fact that this work was given on the same program with a Bach cantata, Dvorak’s Stabat Mater and Tschaikowsky’s Symphonie Pathetique indicates the high esteem in which the composer is held.

A sacred cantata of the dimensions and style of a modern oratorio. The Atonement, Op. 53, was first given at the Hereford festival, September 9, 1903, under the composer’s baton, and its success was even greater at the first London performance in the Royal Albert hall on Ash Wednesday, 1904, the composer conducting. The first performance of The Atonement in this country was by the Church Choral society under Richard Henry Warren at St. Thomas’s church, New York, February 24 and 25, 1904. Worthy of special mention are the Quintet for Clarinet and Strings, Op. 6 (1897), which Joachim has given, and the Sorrow Songs, Op. 57 (1904), a setting of six of Christina Rossetti’s exquisite poems.

Beside the work already mentioned are a Nonet for Piano, Strings and Wind, Op. 3 (1894), Symphony in A minor, Op. 7 (1895), Solemn Prelude for Orchestra, Op. 40, (1899), between thirty and forty songs, various piano solos, anthems, and part songs, and part works in both large and small form for the violin with orchestra or piano.

Mr. Coleridge-Taylor has written much, has achieved much. His work, moreover, possesses not only charm and power, but distinction, the individual note. The genuineness, depth and intensity of his feeling, coupled with his mastery of technique, spontaneity, and ability to think in his own way, explain the force of the appeal his compositions make. Another element in the persuasiveness of his music lies in its naturalness, the directness of its appeal, the use of simple and expressive melodic themes, a happy freedom from the artificial. These traits, employed in the freedom of modern musical speech, coupled with emotional power and supported by ample technical resource, beget an utterance quick to evoke response.

The paternity of Mr. Coleridge-Taylor and his love for what is elemental and racial found rich expression in the choral work by which he is best known and more obviously in his African Romances, Op. 17, a set of seven songs; the African Suite for the piano, Op. 35; and Five Choral Ballads, for baritone, solo, quartet, chorus and orchestra, Op. 54, being a setting of five of Longfellow’s Poems on Slavery. The transcription of Negro melodies recently published is, however, the most complete expression of Mr. Coleridge-Taylor’s native bent and power. Using some of the native songs of Africa and the West Indies with songs that came into being in America during the slavery regime, he has, in handling these melodies, preserved their distinctive traits and individuality, at the same time giving them an art from fully imbued with their essential spirit.

It is especially gratifying that at this time, when interest in the plantation songs seems to be dying out with the generation that gave them birth, when the Negro song is in too many minds associated with “rag” music and the more reprehensible “coon” song, that the most cultivated musician of his race, a man of the highest esthetic ideals, should seek to give permanence to the folk songs of his people by giving them a new interpretation and an added dignity.

A STORY

BY KELT-NOR

What you want to press upon your brethren of African descent is (1) hard work, (2) the earnest use in that work of all the brains with which the Almighty has blessed them, (3) the acquirement of knowledge whereby that work may become better paid, and (4) chiefest of all the highest possible standard of morality, higher therefore than has been reached by any people in the old or new world, in this first decade of the 20th century.

Now the most bigoted citizen north or south, of European or Asiatic extraction, has always been only too glad to concede to your people the[35] first mentioned of these blessings; but, in the southern part of our country at least, he is very apt to do all in his power to prevent his fellow citizens, with African blood in their veins, from acquiring the last three.

As I sat pondering on this melancholy fact and on how best to enforce the precepts of which I have spoken, my eyes fell on the theme which my little girl had just written for humble submission to her school ma’am. It seemed to me to the point, and I straightway copied it out for you, just as written. Here it is:

The Students’ Adventure.

Two German students, Dietrich and Hans, wished to get for their Botany Professor a specimen of a particular kind of rare pine which grew only on the Hartz mountains. They were natives of a district near there; so, when they went home for their Christmas vacation, they went on a snowshoeing trip, to get some.

They gave, on their way, in return for food and lodging, such songs and stories as they knew; and so they traveled on pleasantly enough until, on the third day, they found themselves near the lonely tract on which grew the pines. As there were no more farmhouses at which they could stop, they hurried forward, hoping to get to the trees and back before nightfall.

The snow was deep, but as they were young and strong, and more than that had on snow shoes, they had no difficulty. But alas! about half a mile from the pines, the strap of one of Hans’ snowshoes broke. He took his snowshoes off and carried them, but found doing so hard work, and when they reached the pines the sun had almost set, and Hans was tired. “You rest old boy,” said Dietrich (in German of course) “and I’ll get the boughs.”

It was easier said than done, for when he got to the trees he had to take off his snowshoes and shin up. The huge trunk was hard to grapple, but he managed it, and after about 20 minutes had two fine specimens. But when Dietrich was safe on the ground again the sun had set, there were only a few golden clouds floating on the horizon, and the light was waning fast.

“Oh, beloved Heaven! We must hasten wind-fast” (literal translation), exclaimed he, and, when he reached Hans, “Get up, old fellow!”

Hans got up, and they started home by moonlight.

Now there happened to be a devil on that mountain—the devil of ignorance—and, of all that he hated, professor and students he abhorred most; for did not they forward learning more than any one? Hearing these students talking he gathered—being a German devil, and so understanding them—that they were students, and that they were going to forward his enemy, Learning, by giving some pine-boughs off his mountain to a hated professor.

“This must not be!” he stormed; so he took hold of the heels of Dietrich’s snow shoes, and putting his tail round Hans’ waist, for every step they took he pulled them back three; so they went backwards towards his cave.

Now Hans wore spectacles, and he saw what the devil was doing, reflected in them. He told Dietrich, in Latin, what went on, and the devil, being very ignorant did not understand. So they figured out by geometry that if they turned round and walked the other way they would get shelter even sooner than before.

They carried out this plan so scientifically that the devil, being also very unperceptive, did not find out how they were fooling him, until he saw the farmhouse lights. Then, being very much frightened he let go of the students and fled shrieking and howling up the mountain. That was the last they ever saw of him—which they did not regret.

When the students went back to the university, they triumphantly gave the pine-boughs to the professor.

Goodness knows how the young person who wrote that story got it into her head that one is justified in tricking even the good old-fashioned Nick with his horns and hoofs, for any purpose whatever. Myself I disclaim any responsibility for the morality involved. But this I will say that if trickery and “lying low” of any kind is ever justified, or (I may rather say) not much noticed by the recording angel, it must be when they are[36] brought to bear on the very Evil Spirit which grudges to any race the attainment of more knowledge and a higher civilization than that to which their ancestors, near or remote had arrived.

KELT-NOR.

(By Carolyn Schlesinger.)

Orville Wright, the flying machine man, told a reporter this story:

“A little boy bustled into a grocery one day with a memorandum in his hand.

“‘Hello, Mr. Smith,’ he said, ‘I want 13 pounds of coffee at 32 cents.’

“‘Very good,’ said the grocer, and he noted down the sale, and set his clerk to packing the coffee. ‘Anything else, Charlie?’

“‘Yes, 27 pounds of sugar at 9 cents.’

“‘The loaf, eh? And what else?’

“‘Seven and a half pounds of bacon at 20 cents.’