The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Republic of Costa Rica, by Gustavo Niederlein

Title: The Republic of Costa Rica

Author: Gustavo Niederlein

Release Date: May 9, 2023 [eBook #70725]

Language: English

Produced by: John Campbell, Adrian Mastronardi and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Table of Contents was created by the Transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Several tables in this book were very wide, and have been split into two or more parts.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

BY

Gustavo Niederlein

CHIEF OF THE SCIENTIFIC DEPARTMENT

THE PHILADELPHIA

COMMERCIAL MUSEUM

THE

PHILADELPHIA MUSEUMS,

Established by Ordinance of City Councils, 1894.

233 South Fourth Street.

| Page | ||

| Introduction | 5 | |

| Chapter I. | TOPOGRAPHY, GEOLOGY AND MINERAL WEALTH. | 7 |

| Chapter II. | CLIMATE OF COSTA RICA. | 25 |

| Chapter III. | CHARACTER OF VEGETATION. | 32 |

| Chapter IV. | FAUNA. | 43 |

| Chapter V. | THE ABORIGINAL INHABITANTS. | 46 |

| Chapter VI. | POPULATION. | 51 |

| Chapter VII. | IMMIGRATION AND COLONIES. | 74 |

| Chapter VIII. | PUBLIC INSTRUCTION. | 77 |

| Chapter IX. | TRANSPORTATION, POST AND TELEGRAPH. | 81 |

| Chapter X. | AGRICULTURE AND LIVE STOCK. | 90 |

| Chapter XI. | COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY. | 96 |

| Chapter XII. | FINANCE AND BANKING. | 108 |

| Chapter XIII. | POLITICAL ORGANIZATION. | 121 |

| Chapter XIV. | HISTORY. | 125 |

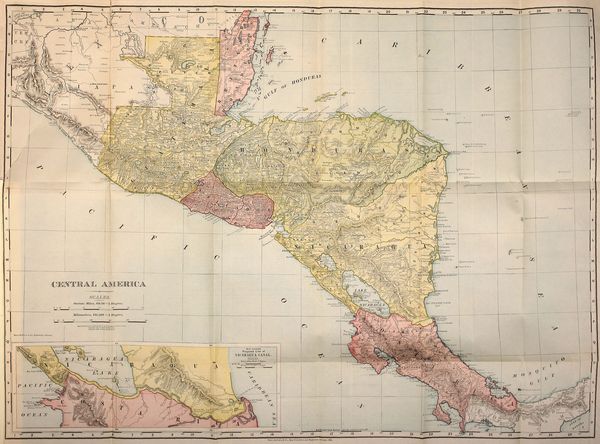

| Map of Central America | end of book (128) | |

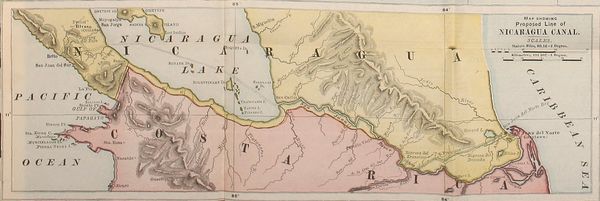

| Proposed line of Nicaragua Canal | end of book (128) | |

| Reverse side of Map | end of book (129) | |

[Pg 5]

THIS monograph treats of the topography, geology, mineral wealth and soils of Costa Rica; it describes its climate and presents the details of its flora and fauna with reference to their economic value; it displays the distribution of population according to race, wealth, communities and social conditions; it examines the agricultural development of the Republic, including its live stock and forests; and, finally, it recounts the most important features of its commerce, industry, finance, and of its economic and political conditions.

It is made up of observations and studies pursued in 1897 and 1898, during seven and a half months of economic and scientific explorations in Central America, and of facts garnered with great care from authoritative manuscripts, books and official documents and publications. Respect has been shown to the work of men of originality in research and thought, and care has been taken to adhere closely to the original text when either quoting or translating. I am especially indebted to Professor H. Pittier, whose great qualifications for a scientific exploration of Costa Rica cannot be overestimated; to Mr. Anastasio Alfaro, the Director of the National Museum; to Mr. Manuel Aragon, the Director General of the National Statistical Department; to Dr. Juan Ullua, the Minister of Fomento; to Joaquin B. Calvo, Minister Resident in Washington; and Mr. Rafael Iglesias, the able President of the Republic of Costa Rica.

[6]

[7]

The State of Costa Rica.

Costa Rica, the southernmost Republic of Central America, is advantageously situated within the North tropical zone, adjoining Colombia, the most northern state of South America. It is between the two great oceans, having also the prospect of one inter-oceanic ship-canal at one extremity and another ship-canal near the other.

Costa Rica is between 8° and 11° 16′ N. latitude and 81° 35′ and 85° 40′ W. longitude from Greenwich. Its area is between 54,070 and 59,570 sq. kilometers, the difference arising from the boundary line unsettled with Colombia. We follow here Colonel George Earl Church’s paper in the London Geographical Journal of July, 1897, which gives in a condensed form all important results of extensive explorations by Professor H. Pittier as well as well-written abstracts of important publications of the “Instituto fisico geografico Nacional” and of the “Museo Nacional” of Costa Rica.

The mountains of Costa Rica are not a continuous Cordillera, although in general they extend from the frontier of[8] Colombia to within a few miles of Brito. The entire country may properly be divided into two distinctive groups by a natural line running between the mouths of the Reventazon and Rio Grande de Pirris; groups which can be called “volcanic mountains” or “mountains of the northwest,” and “Talamanca mountains” or “mountains of the southeast.” It is clear that the Caribbean Sea once joined the Pacific Ocean through this valley of the river Reventazon in which the Costa Rica Railway now climbs to reach Cartago. In weighing existing data there seems to be no room for doubt that the highlands of Costa Rica once formed part of a vast archipelago extending from Panama to Tehuantepec. The lowest inter-oceanic depressions between the Arctic Ocean and the Straits of Magellan are the divide between the two oceans at Panama which is 286 feet above the sea-level, and the narrow strip of land separating Lake Nicaragua from the Pacific, which has only about 150 feet elevation.

The “volcanic mountains” or “the mountains of the northwest” can again be divided into two sections. The first comprises the part situated between the Rio Reventazon and a depression which connects San Ramon with the water-shed of San Carlos, including the groups of the volcanoes Turialba (11,000 feet), Irazú (11,200 feet), Barba (9335 feet) and Poas (8675 feet). The second section comprises the part which extends from the Barranca River to the Lake of Nicaragua with the groups of Tilaran, Miravalles, La Vieja and Orosi.

The first section may be called “Cordillera Central” or “Cordillera del Irazú” and the second “Cordillera del Miravalles.” The three masses which form the volcanic Cordillera of Irazú are separated by two depressions: first by that of La Palma, 1500 meters above the sea, between Irazú and Barba, and second by that of Desengaño, 1800 meters above the sea, between Barba and Poas.

The basis of the two western masses seems to be formed of basaltic rocks, while the trachytes dominate in the eastern mass. Irazú and Turialba, which is part of the same mass, seem to have ejected lavas in a compact state. The height of volcanoes diminishes towards the west.

The three orographic groups which dominate the[9] northern central plateau do not show the regular conical form which usually characterizes a volcano. The general line of the southern slopes ascends in an imperceptible manner towards the summit, notwithstanding that they are composed of a succession of terrace plains. On the Irazú, for instance, eight such terraces are observable from Cartago to the summit. The northern declivity is more precipitous, being over 60° on the Irazú.

The peak of the Irazú is a point from which go various spurs and secondary mountains in opposite directions, one to the west and one to the east, the latter terminating in a crater where the Parismina River takes its origin. The western mountains trend first in a westerly direction to the Cerro Pelon, where they divide, one part descending south to the pass of Ochomogo, 1540 meters above sea-level; the other, after taking a northwesterly direction, terminating in the plain of La Palma, which is a part of the water-shed of the two oceans. On the south various mountains follow the rivers Pirris and Turialba. The Irazú has various craters, formed successively, each one contributing to the gradual rising of the mass.

The Irazú, which had eruptions in 1723, 1726, 1821 and 1847, has now an altitude of 3414 m. (11,200 feet), and from its summit both oceans are visible, and also the great valleys of San Juan and of Lake Nicaragua, as well as the mountains of Pico Blanco, Chirripo, Buena Vista and Las Vueltas. Turialba had a famous eruption of sand and ashes which began on the 17th of August, 1864, and lasted to March, 1865. Its heaviest ejected matter fell to the west, and Seebach classifies it as andesite. Another eruption, occurring on February 6, 1866, was accompanied by heavy earthquakes and sent its ashes as far as Puntarenas.

The Cordillera del Miravalles commences with the volcano Orosi, situated near the southwest extremity of Lake Nicaragua. In its southeast trend it recedes more and more from the lake and the San Juan River. It is an irregular, broad and volcano-dotted chain, about sixty geographical miles long, breaking down gradually on the northwest from Orosi to the Sapoa River, one of the southern boundaries of[10] Nicaragua. In this short distance are found the Cerro de la Vieja (6508 feet), the Montemuerto (8000 feet), the beautiful volcano Tenorio (6700 feet), the volcanoes Miravalles (4665 feet), the Rincon (4498 feet), and the Orosi (5195 feet).

These mountains, as far as they have been examined, are found to be of eruptive origin, basalts and trachytes predominating, but extensive sedimentary rock formations are also found upon their slopes, as well as vast deposits of boulders, clay, earth and volcanic material.

The peninsula of Nicoya, forming a part of Guanacaste, is partly an elevated plain and partly consists of hills and mountain ridges seldom attaining a greater elevation than 1500 feet. It is also composed of eruptive rocks and sedimentary formations, the latter being especially visible in the valley of Tempisque.

Between the northern volcanic section and the more regular Talamanca range is the notable “Ochomogo” Pass, about twenty miles broad, and a little more than 5000 feet above the sea-level at the water parting.

To the eastward through this gap, and in a broad, deeply eroded valley, runs the tumultuous Reventazon River, and to the westward the Rio Grande de Pirris. On the south of this depression the Chirripo Grande mountain mass sends off east and west two immense flanking ranges. A part of the western range, lying between San Marcos and Santa Maria, for a length of about six miles, is known as the Dota ridge, to which former explorers gave great importance.

This lofty, transverse and precipitous mountain system almost forbids communication between the northern and southern halves of the Republic, and, as Colonel Church says, must at all times have had a marked influence on the movement of races in this part of Central America. Both the northern and Talamanca sections present mountains in masses instead of sierrated like many Andean chains of North America. Those of the Talamanca section are Rovalo (7050 feet), Pico Blanco (9650 feet). Chirripo Grande (11,850 feet) and Buena Vista (10,820 feet). There are no signs of recent volcanic activity in the Talamanca range. The Talamanca mountains have narrow crests and are very precipitous[11] on the Atlantic side, with evidences of extensive denudations and erosions caused by the ceaseless rain-laden trade-winds.

Professor William M. Gabb, in his geological sketch of Talamanca, observes that the geological structure of the entire region is very simple. The greatest expanse is occupied by recent sedimentary rocks raised and nearly entirely metamorphosed by the action of volcanic masses.

At several points along the Atlantic coast, there are found masses of rocks of still later date. Professor Gabb maintains that the nucleus of the great Cordillera of the interior is formed by granites and syenites, which, like the sediment that covers them, are broken through here and there by dikes of volcanic origin identical with the eruptive material found on a greater scale in the northern part of Costa Rica. The syenites are intrusive and have their culminating point and greatest development in the Pico Blanco or Kamuk, a mountain of great altitude, unusual ruggedness and scarred with deep and precipitous cañons. All these dikes are of more modern formation and are porphyritic. Professor Gabb also notes a thick deposit of conglomerates and sandstones, schists and limestones, the schists being the most abundant; although the conglomerates, found all over the region, indicate the previous existence of an older sedimentary formation.

The pebbles which form the conglomerates are composed of metamorphic clay, having a character distinct from all the other rocks found in the country. The cement is also clay or sand. The absence of crystalline rocks in the conglomerates is irrefutable proof that, when these were deposited, the syenites and granites had not yet appeared from the interior of the earth. The limestone and sandstone represent a less developed geographical horizon of the sedimentary group, the latter appearing occasionally in layers, interstratified with conglomerates or more recent schists. In no place in Talamanca have fossils been found in these sandstones, although the same rocks are very fossiliferous near Zapote on the River Reventazon.

In regard to fossils, Professor Gabb saw at Las Lomas Station, about seven hundred feet above the sea, in the Bonilla[12] Cliffs cutting, shark’s teeth, compact masses of sea shells, fish, etc., and at an elevation of 2500 feet large deposits of compact shell limestone.

The schists have a fine, leaf-like texture, and are easily decomposed and reduced to a black mud, if they have not been metamorphosed. In this rock fossils have been found which belong to a Miocene age.

Along the Talamanca coast calcareous deposits are found in horizontal layers, and are probably elevated coral reefs, a rock which Professor Gabb calls “antillite,” and which is developed in the entire Caribbean region. It belongs to the post-Pliocene formation, the last of the Tertiary series.

In the interior valleys a thick deposit of pebbles and clays of recent origin is observed. The limit between the syenites of the high mountains and the metamorphosed Miocene formation is found in proximity to the Depuk River. In the slopes of the hills the schists are usually decomposed and covered with red clay, a sub-soil above which is found a small cap of fertile vegetable mold. In the valley of Tsuku the schists are profoundly altered and transformed in a magnesic or semi-talcous rock. The schists are more silicified in coming near to the limits of the syenites.

Higher up, the granitic rocks extend in the direction of the Pico Blanco without interruption. The Pico Blanco itself is of granite. Three hundred feet below the summit porphyry is observed, while the summit itself shows a greenish-brown trachyte with black spots.

In regard to the Pacific side of this Talamanca section, Professor H. Pittier says, “The southern coast Cordillera, as a whole, is formed of a nucleus of basaltic or syenitic rocks, above which are found successively limestone in very deep banks and sometimes fossiliferous: then argillaceous and marly schists; again, sandstone and conglomerates, the latter forming generally the crests of the hills and giving way very easily to atmospheric action, which produces its decomposition and is the cause of sterile lands characterized by savannas and the absence of forests on the upper parts of the mountains, as well as in certain lower and denuded parts.[13] The conglomerates are made up of heterogeneous elements whose resistance to erosion is variable. Some disintegrate as soon as they are exposed to erosion, while others remain unaltered for a long time. For this reason the savannas are in many places covered with stones of varied sizes.”

The lower valley of the Pirris presents a cap of impervious red clay, and, as the waters do not readily drain off they become stagnant and make an unhealthy district.

Dr. Frantzius, referring to the same region, speaks of diorites and syenites, also of calcareous deposits of the Miocene age covered with sandstone formations containing useful lignites. In his opinion the mountain of Dota is formed almost entirely of dioritic rocks with some syenitic nucleus. The same scientist says further that the high plains of Caños Gordas are formed of conglomerates of ashes ejected by the volcano of Chiriqui and brought there by the trade-winds which prevail in Central America.

The Pacific slope, which comes boldly to the water’s edge, is margined almost throughout by headlands and lofty hills, and has fewer evidences of extensive denudations and erosions than the Atlantic coast.

There is also a notable difference between the outlines of the two coasts. The eastern is regular and slightly concave to the southwest, while the western is indented with large and small bays and gulfs.

The most northern of these bays is the Salinas, belonging partly to Nicaragua and partly to Costa Rica. It is a spacious deep-water harbor, overlooked by the volcanic peak of Orosi. It is separated from the adjoining bay, the Santa Elena, by Sacate Point.

Continuing south, we come, south of Cacique Point, to Port Culebra, which is a mile wide, with a depth of eighteen fathoms. At the outlet of this harbor lies Cocos Bay, capacious enough for a thousand ships to anchor in the roadstead. The coast line south of Cocos Bay, bordered by numerous and lofty hills and cut into gorges by small impetuous water courses, presents no harbor as far as Cape Blanco, which is at the western entrance of the extensive Gulf of Nicoya. The gulf extends fifty miles to the northwest and is[14] a magnificent sheet of water, surrounded by green scenery, rivaling, if not surpassing, that of the Bay of Naples, the Bosphorus, or the harbor of Rio de Janeiro. Some twenty islands, large and small, nearly all bold, rocky and covered with vegetation, contribute to its beauty, while many small rivers, draining the slopes of the Miravalles and Tilaran sierras and the mountains of the peninsula of Nicoya, flow into it and diversify the scenery. The principal river, the Tempisque, enters at the head of the gulf, and with numerous small branches irrigates much of the province of Guanacaste.

All of the streams have bars at their mouths, composed generally of mud and broken shells, and but few of them are navigable even for a short distance inland, and then by very small craft. The whole eastern part of the peninsula of Nicoya is broken into hills and low mountains, wild and rarely cultivated, although there are many beautiful and fertile valleys. The west side of the gulf is full of reefs, rocks, violent currents, eddies that run from one to three and a half miles an hour, and is subject to violent squalls coming from the northwestern sierras. The eastern shore is less beset by obstructions, and small craft go along it with ease, and at high tide penetrate a few of its many rivers. It rises rapidly a short distance inland, but is at times bordered by mangrove swamps.

Near the mouth of the river Aranjuez, on a sand spit three miles long, stands Puntarenas, the only port of entry of Costa Rica on the Pacific coast, and which had, from 1814 until recently, nearly the entire foreign trade of the country. Ocean vessels anchor from one to two miles off in the roadstead. There is an iron pier for loading and discharging.

From Puntarenas southward to the unnavigable Barranca River there is a broad beach lying at the foot of the high escarpment of Caldera.

The Rio Grande de Tarcoles, which enters the gulf south of the Barranca, has a dangerous bar, but once inside it may be navigated a few miles. Its upper waters irrigate the table-land of San José, Alajuela and Heredia. In the neighborhood of these towns is garnered nearly the entire coffee crop of Costa Rica. The coast line south is rocky and precipitous[15] until near Punta Mala, or Judas, at the southeastern mouth of the gulf, and is low and surrounded by reefs and rocks.

From Point Judas, low and covered with mangrove swamps, the coast trends southeast in a long angular curve for about one hundred marine miles to Point Llorena. It is dominated by lofty hills, cut through at intervals by short impetuous streams and a few estuaries. The only safe and excellent anchorage in this one hundred miles is Uvita Bay, behind a rocky reef. From the precipitous headline, called Punta Llorena, to Burica Point, the southern limit of Costa Rica, the coast is abrupt, soon rising into ridges and peaks from 300 to 700 meters high (985 to 2300 feet). These give birth to a few short turbulent streams. About half way between these two points the great Golfo Dulce, having a main width of six miles, penetrates inland northwest about twenty-eight miles. It has an average depth of one hundred fathoms.

Cape Matapalo, which marks its western entrance, is deep and forest-covered, but Banco Point, opposite to it, is low. At the head of the gulf is found the little Bay of Rincon. From here to the Esquinas River, at the northeast angle of the gulf, the shore is hilly, and thence to the harbor of Golfito, which is surrounded by high hills, the country rises rapidly inland, but between Golfito and the entrance to the gulf it is lower and less broken, and thence to Platanal Point and Burica Point, the coast is bold, the country descending gradually from the northeast.

From Point Llorena to Point Burica the coast is wild and almost uninhabited. The coasts of Golfo Dulce have but a few hundred half-breeds as their sole occupants.

There are but two rivers in the long coast line from the Gulf of Nicoya to the Golfo Dulce, the Rio Grande de Pirris, and the Rio Grande de Terraba, the head waters of the former flowing through deep canyons with steep sides, which are almost bare of vegetation until the region of Guaitil is reached, where dense forests are encountered. The valley of the Rio Grande de Terraba is one of the most beautiful, extensive and fertile of Costa Rica, but is occupied by only a few families. Formerly it was the home of a large indigenous population.

[16]

In the angle made by the River Buena Vista and Chirripo there is a vast ancient cemetery, the graves of which contain many ornaments of gold, principally eagles. An ancient road runs by near this place.

Turning to the hydrographic basin of the San Juan River and Lake Nicaragua, the northeastern slope of the Miravalles range is found to send off several small streams to the lake.

Between Cuajiniquil, two and one-fourth miles east of Rio Sapoa, and Tortuga, six miles further east, are the little streams, Lapita, El Cangrejo, Puente de Piedra, La Vivora, Guabo, Genizaro and Tortuga, the latter the greatest in volume, being about one hundred and sixty feet wide at its mouth and navigable. In the further distance of seventeen miles going east, we cross the rivers Zavalos, Cañitas, Quesera, Mena, Mico, Sapotillo, Quijada, Quijadita, Santa Barbara, Sardinia, Barreal, Cañas, Perrito and, finally, Las Haciendas which is navigable by small boats. From here to San Carlos, at the outlet of Lake Nicaragua, the distance is sixty-four kilometers, and the principal rivers which cross this tract are El Pizote, Papalusco, Guacolito, Zapote, Caño Negro and Rio Frio. The Rio Frio is of considerable magnitude, and with its many branches drains a large area of the territory lying on the slopes of the volcanoes of Miravalles and Tenorio. It pours much sedimentary matter into Lake Nicaragua, and has thrown an extensive mudbank across the lake entrance to the River San Juan.

For three or four miles above the mouth of the River Frio the lands are low and swampy. Several of its branches can be reached and navigated by canoe, and even a small river steamer can ascend a few miles from the lake.

The San Carlos River joins the San Juan sixty-five miles from Lake Nicaragua. The depth of its mouth, which is obstructed by a sand-bar, varies from eight to twenty feet, according to the season.

The San Carlos has numerous affluents which at times have a volume of water altogether disproportionate to their lengths. The distance up to the first rapid of the San Carlos River, which is at El Muelle de San Rafael where there are from four to six feet of water is roughly fixed at sixty-two[17] miles by the course of the river. Small steamers could reach this point, although with difficulty on account of many snags. The floods sometimes rise to their full height in twenty-four hours and carry with them a great number of trees and much sand, from which floating islands are formed.

Should the plans of Engineer Menocal for the Nicaragua Canal be realized, the waters of the upper San Juan and the lower San Carlos would be impounded and form an arm of Lake Nicaragua, which would flood a large area in Costa Rica. The interval between the San Carlos and the River Frio is an extensive forest, covering an undulating plain with occasional low hills and watered by numerous little streams. This territory is fertile and beautiful.

The next great river, the Sarapiqui, reaches the San Juan about twenty miles east of San Carlos. It is 600 feet wide at its mouth, and has numerous affluents from the sides of the volcanoes Poas, Barba and Irazú, the principal ones being the Toro Amarilla and Sardinal from the west, and the River Sucio from the east. The river is navigable for large canoes up to its confluence with the Puerto Viejo. Its banks as high up as to the River Sucio are low. The lands are extremely fertile. El Muelle Nuevo is the head of navigation, forty-five miles from the River San Juan and sixty-six miles by the road across the mountains from San José.

From the Sarapiqui River to the River Colorado, a branch or bayou of the San Juan, the banks of the latter in Costa Rica are but slightly elevated. The lands are low and swampy, but occasionally a hill is found from fifteen to eighteen feet high.

Below the Machuca Rapids the San Juan River is broad and deep as far as the junction with its Colorado outlet, about seventeen miles from the sea. Here it turns about nine-tenths of its volume of water into the Colorado. It is navigable for river steamers at all seasons, but has a dangerous bar at its mouth where the sea breaks heavily, and on which there are only from eight to nine feet of water.

From the Colorado Junction to Greytown, some twenty miles distant, the San Juan averages about three hundred[18] feet in width for sixteen miles and 100 feet for the remaining four, with a depth at high water of from six to eight feet.

The Colorado has several islands in its course, but has excellent anchorage at its mouth. This river forms several lagoons which communicate with each other by caños or bayous perfectly navigable, the principal being the Agua Dulce, a short distance from the sea, eleven miles in length, 800 feet in width and from ten to forty feet in depth.

Passing from the difficult Caño de la Palma in the midst of swamps, the Caño de Tortuguero is reached, the entrance to which from the sea is called Cuatro Esquinas. It is approximately thirty-eight miles long, about one thousand feet in width, with a depth of from fifty to sixty feet. The rivers Palacio and Penetencia, navigable for boats, empty into this caño. The River Tortuguero, which gives name to the plains watered by its affluents, is formed from several of these caños, as the Caño Desenredo, Caño Agua Fria and Caño de la Lomas. The Caño de Tortuguero communicates with the Parismina by the caños California and Francisco Moria Soto, which are also navigable. The margins of the Parismina are swampy. It has as its affluents the Guasimo, Camaron, Novillos and the Destierro.

The lower district drained by the Tortuguero is raised but little above the ocean, and in flood time the river communicates by several caños with the Matina and with the delta of the Colorado, as well as with the lagoon of Caiman, lying south of the Colorado. Its numerous upper streams rise in the spurs of Irazú and Turialba.

The Sierpe and Parismina rivers flow into the sea south of Tortuguero. The former is short, but the Parismina with its several branches is a child of Irazú. Its lower course is sometimes considered to be a part of the River Reventazon, which however has its confluence with the former a few miles from the sea.

The Reventazon River has carved its way to a profound depth around the south and southeastern bases of Irazú and Turialba, and, flanking the latter volcano, it turns northward to join the Parismina. It receives many tributaries from the northern slope of the Talamanca range, and interweaves its[19] head waters with those of the Rio Grande de Tarcolles and the Rio Grande de Pirris, which flow into the Pacific Ocean.

The Pacuare River, once known as Suerre, enters the sea about half way between the mouth of the Reventazon and that of the Matina. Its waters, in 1630, instead of flowing to the sea, joined the Reventazon, closing the port of Suerre, but in 1651 Governor Salinas closed the northern channel, deflecting its waters and restoring the port.

The Matina River is a short stream with a large volume of water, which enters the sea just north of Port Limon near the roadstead of Moin, where, up to 1880, ocean craft anchored. The River Matina is navigable by small steamers over the bar and by large ones above the bar to the point where it receives its principal affluents, the Chirripo, Barbilla and Zent. It yearly overflows its lower valley, depositing an inch or two of exceedingly fertile mud highly appreciated by the banana planters.

The entire mainland of the coast, from the River Colorado to the Matina, is separated from the Caribbean Sea by a continuous narrow sand bank, between which and the mainland is a lagoon, said to be navigable the whole distance by boats. The intermediate rivers pour into this narrow lagoon, driving their currents across it, and, cutting through the sand bank, enter the sea. Sometimes a violent gale closes one of the openings, which are all shallow, but the river again forces an exit to the ocean through the obstruction. This whole coast for sixty-five miles, is forbidding and dangerous, and has but little depth of water within a mile of the shore, upon which a monotonous, heavy surf breaks during the entire year. It is only frequented from April until August by fishermen, who find their way to the River San Juan through the intricate system of rivers and caños described.

Port Limon, in latitude 10° north and longitude 83° 3′ 13″ west from Greenwich, is the only port of entry of Costa Rica on the Caribbean Sea. The first house was built there in 1871. The harbor faces the south, and is formed by a little peninsula on which Limon is situated. It is behind a narrow coral reef. The site, which now has perhaps 3500 to 4000 population, is being raised with earth about four[20] feet, and its port will become one of the smoothest of the Caribbean Sea. A small island, called Uvita, lies east at a distance of 3660 feet from the town. Port Limon has a wooden pier 930 feet long, accommodating two sea-going ships, but an iron pier is about to replace it, which will berth four large ones of deep draught.

The Talamanca coast lying south of Limon is low, flat and swampy, except where it is broken by hills. The little River Banana is the first one met with going south, and its valleys produce large quantities of timber and bananas. Next comes the Estrella, also a short stream; then follows the Teliri, called in its lower course the Sicsola. It is the largest stream in Costa Rica south of Port Limon. It runs along the southern base of the great eastern mountains of the Talamanca range, through a spacious, undulating, wooded valley of 100 to 150 square miles area, partly low grounds in some places dry and in others swampy. It has several branches, like the Uren coming from the slopes of the Pico Blanco, the Supurio and others. At the entry of the high valleys of the Teliri and Coen rivers, the pyramid-like mountains of Nefomin and Nenfiobete appear, at the foot of which the interior plain of Talamanca, fifteen kilometers in length and eight kilometers in width, extends from southwest to northeast, and so uniformly that the water courses run indifferently and frequently change their beds.

Southward of Sicsola is the Tilorio or Changuinola, which makes a turbulent way to the sea from the Talamanca mountains. Along its lower margin mud flats spread to a great width, and, from its mouth towards the northwest, cover a region which surrounds also the lagoon of Sansan, and extends up the rivers Zhorquin and Sicsola. Behind the muddy zone the lands rise rapidly into hills, which in a few miles reach an altitude of several thousand feet, at times intermingling with the Cordillera. Along the entire sea margin of Talamanca runs a narrow sand-belt of firm land, at times not a hundred feet wide, like that described between the Matina and San Juan rivers.

Within this sand-belt are long, narrow, deep lagoons filled with half-stagnant water from the mud flats. These[21] lagoons usually open into the rivers which descend from the mountains.

Between the Sicsola and the Tilorio lies the already mentioned, crooked and deep lagoon called the Laguna de Sansan.

At Limon, Cahuita and Puerto Viejo, the hills, which are connected by spurs with the more elevated country of the interior, extend to the ocean coast. Between them, in plains extending from one to five miles inland, are forest-covered swamps, overflowed with not less than ten feet of water in the rainy season and only traversable in the dry.

Costa Rica claims sovereignty on the Atlantic side southeast as far as the Island of Escudo de Veragua, including the ancient Ducado de Veragua, whose frontier follows the coast of Chiriqui Viejo to the crest of the Cordillera, and crosses it to the head waters of the River Calobebora, then down this stream to the Escudo de Veragua.

Since their independence Colombia and Costa Rica have been in dispute in regard to their boundary line. Colombia has never ceased to claim jurisdiction over the entire Caribbean coast of Costa Rica, and even over that of Nicaragua as far north as Cape Gracias á Dios. In November, 1896, both governments signed a convention submitting their dispute to the arbitration of the President of the French Republic, or, in the event of his failure to act, to the President of Mexico or of the Swiss Confederation.

The principal lakes of Costa Rica are the Laguna Manatí, northwest from the Sarapiqui River; the Lagunas de Poas and de Barba, each on a volcano bearing its name; Lagunas de Sansan and Samay, towards the east and near the Sicsola River, in Talamanca; Laguna Tenoria, in Guanacaste; Laguna San Carlos, in the plains of San Carlos; Laguna de Arenal, between Las Cañas and San Carlos, and Laguna de Sierpe, in the south, northward from the Golfo Dulce.

Far away from Costa Rica, in the Pacific Ocean, lies the Cocos Island, about two hundred and sixty-six miles to the southwest of the Golfo Dulce, in N. latitude 5° 32′ 57″ and longitude 86° 58′ 25″ W. of Greenwich. Its highest point reaches 2250 feet, whence the descent is gradual to a bold,[22] steep coast, which has many irregularities and rocks and a surf-beaten shore. Chatham Bay is its best harbor, having room for a dozen ships. The interior is broken into numerous fertile valleys, but there is probably not a square kilometer of level ground in the entire island. Other islands are Chira, Venado, San Lucas, Caño, etc.

Mineral Wealth.—In regard to the mineral wealth of Costa Rica, petroleum has been discovered near Uruchiko on the Talamanca coast, and coal in certain sandstone formations on both the Atlantic and Pacific sides of the Talamanca section.

In the province of Alajuela, a little to the north of the cart-road which runs from San José to Puentarenas, is Monte Aguacate, part of an old mountain range which extends far to the northwest, and not very distant from the Gulf of Nicoya. In general, it is of metamorphic formation, principally of diorite and porphyry.

Here, in a good climate, at 2000 feet elevation, are found auriferous veins of great richness. They are of quartz mixed with decomposed feldspathic rocks, and have yielded very lucrative bonanzas. The first mine was Guapinol, one bonanza of which produced $1,000,000. Several other mines were worked, from one of which (Los Castros) $2,000,000 were taken in a few years. It is estimated, from the best data obtainable, that about £1,000,000 have been taken from Monte Aguacate. Several of these veins are from six to seven feet wide, but that called the Quebrada Honda is sixteen feet wide. Most of the ore is of a high grade and of refractory character. It is probable that the whole southwestern slope of the Guatusos and Miravalles ranges of mountains is auriferous. The rocks in the northwestern extension of this district consist principally of feldspar, porphyry, basalt and dolorite.

The gold veins nearly all ran northeast and southwest, and are encased in feldspar, sometimes in porphyry, and occasionally in basalt. They consist, in great part, of crystalline quartz, and are from two to forty feet wide. Professor Pittier also found gold in the slopes of the Buena Vista mountain. Gold is further found in the Talamanca mountains, especially[23] in the placer grounds of the Duedi River, and on the inferior hills between the Lari and Coen rivers.

Along the latter, and near Akbeta, also on the shore of Puerto Viejo, iron exists.

Copper and silver, Professor Pittier says, have been discovered in Diquis, between Paso Real and Lagarto, and native copper in Puriscal. Other mines are included in the following table:

The Principal Mines Registered in 1892.

| Name of Mine. | Canton. | Location. | Product. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Trinidad | Esparza | Rio Ciruelitas | Gold and silver ores. | |

| La Union | Puntarenas | Shores of Rio Seco | ” | ” |

| Sacrafamilia | Alajuela | Monte de Aguacate | ” | ” |

| La Minita | ” | ” ” | ” | ” |

| Mina de los Castros | ” | Corralillo | ” | ” |

| San Rafael | ” | ” | ” | ” |

| Mina de los Oreamuno | ” | ” | ” | ” |

| Quebrada Honda | ” | Quebrada Honda | ” | ” |

| Machuca | ” | Corralillo | ” | ” |

| Trinidad de Aguacate | ” | ” | ” | ” |

| Peña Grande | San Ramon | Cerro de San Ramon | ” | ” |

| Mina de Acosta | ” | Shores of Rio Jesus | ” | ” |

| Palmares | ” | Cordillera de Aguacate | Gold, silver and lead ores. | |

| Las Concavas | Cartago | Rio de Agua Caliente | Copper ore. | |

| Mancuerna | Sardinal | Sardinal | ” | |

| Mata Palo | ” | ” | ” | |

| Puerta de Palacio | ” | ” | ” | |

| Hoja Chiques | ” | ” | ” | |

| Chapernal | ” | ” | ” | |

It should be stated that, with the exception of gold and some silver, little is mined. The deposits of coal, petroleum, copper and silver have thus far yielded, under present methods of management, outputs of no commercial value.

However, anthracite is found at Santa Maria Dota, Department of Puriscal. A specimen of it, analyzed by Dr. L. J. Mátos, chief of the laboratories of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum, gave these results:

It is a good quality of anthracite coal and compares very favorably with the best grades that are mined in Pennsylvania. Color, black; slight tendency to show iridescence; fracture, conchoidal, brittle; analysis, specific gravity, 1,343; weight per cubic foot, 83.93 pounds.

[24]

Proximate composition:

| Moisture | 2.60 | per cent. |

| Volatile matter | 3.56 | ” |

| Fixed carbon | 88.20 | ” |

| Ash | 5.64 | ” |

| Total | 100 | ” |

| Sulphur | .4319 | ” |

| Coke | 93.84 | ” |

| Coke per ton of coal | 2002.01 | pounds. |

| Fuel value | 9.14 | ” |

| Fuel ratio | 1 : 24.77 |

There are to be mentioned also some mineral waters, as, for instance, those near the mouth of the Isqui River, on the Talamanca coast; those in Agua Caliente, about five miles from the City of Cartago and belonging to the Bella Vista Company; those of Orosi and Salitral, of Poas, Miravalles, Ausoles, Bagaces, San Carlos, Liberia, San Roque, etc.

[25]

The climate of Costa Rica depends on its situation in the tropics, on the position of the sun at different times of the year, and on the topography, but, owing to the narrowness of the country and its situation between the two great oceans, it is well-tempered by the alisios (northeast trades) and other winds.

I begin this chapter with the following table which gives the

Meteorological Conditions in San José During the Year 1896.

| Temperature in C.° | Evaporation. | Humidity. | Atm’sph’ic Pressure. |

|||

| Max. | Min. | Average. | Average. | Average. | Average in mm. |

|

| Per cent. | ||||||

| January | 28.5 | 10.8 | 18.60 | 26.97 | 78 | 665.86 |

| February | 31.8 | 10.5 | 19.24 | 33.97 | 74 | 665.39 |

| March | 32.4 | 12.2 | 19.84 | 42.77 | 70 | 665.38 |

| April | 28.4 | 14.8 | 20.13 | 19.65 | 84 | 664.87 |

| May | 29.2 | 15.8 | 20.10 | 19.84 | 83 | 665.32 |

| June | 28.8 | 14.9 | 20.32 | 18.67 | 84 | 665.09 |

| July | 29.2 | 15.8 | 20.10 | 19.84 | 83 | 665.32 |

| August | 29.2 | 14.7 | 20.17 | 22.81 | 82 | 664.38 |

| September | 26.6 | 14.4 | 19.97 | 17.87 | 85 | 664.83 |

| October | 28.4 | 14.8 | 20.13 | 19.65 | 84 | 664.87 |

| November | 29.0 | 14.2 | 19.78 | 19.93 | 84 | 664.70 |

| December | 27.7 | 11.9 | 19.30 | 25.29 | 80 | 665.36 |

| Average | 28.71 | 13.73 | 19.81 | 23.94 | 81 | 665.21 |

First Half of 1897.

| Temperature in C.° | Evaporation. | Humidity. | Atm’sph’ic Pressure. |

|||

| Max. | Min. | Average. | Average. | Average. | Average in mm. |

|

| Per cent. | ||||||

| January | 29.5 | 13.1 | 19.25 | 30.77 | 78 | 665.53 |

| February | 31.9 | 8.2 | 19.78 | 44.89 | 70 | 666.52 |

| March | 31.7 | 10.9 | 20.51 | 36.68 | 72 | 665.70 |

| April | 32.7 | 12.2 | 21.02 | 36.80 | 74 | 665.59 |

| May | 30.3 | 14.0 | 20.52 | 24.29 | 82 | 665.52 |

| June | 29.3 | 15.5 | 20.40 | 16.40 | 85 | 665.32 |

[26]

The average atmospheric pressure of San José, the capital of the country, is 665.21 mm. The maximum occurs regularly during the months from October to March inclusive, at nine o’clock a. m., and during the rest of the year at eleven o’clock p. m. The minimum occurs always in the afternoon at four o’clock during the first eight months of the year, and at three o’clock during the last four months.

The prevailing wind is from the northeast, or, better, north-northeast and east. During August, September and October an increase of the northwest winds causes the heavy rains of that season. West-northwest and northwest winds blow also from May to August.

The daily variation of winds is generally as follows:

At seven a. m. the most frequent winds blow from S. E., to N. E.; at ten o’clock a. m. from E. to N. N. E; at one o’clock and at four o’clock p. m. from E. N. E. to N.; from seven o’clock p. m. the movement is retrograde. The velocity is least from seven to ten o’clock a. m., and most from one to four o’clock p. m.

In 1889, during the time of observations at San José, there were noted 13 hours of north winds, 186 N. N. E., 571 N. E., 227 E. N. E., 93 E., 58 E. S. E., 25 S. E., 6 S. S. E., S. none, S. S. W. none, 1 S. W., 3 W. S. W., 4 W., 83 W. N. W.

The number of calms is small. The wind is nearly always moderate, but during the dry season the dust whirled up in the cities is very disagreeable. The climate of the uplands is an eternal spring.

The coldest month is January; December and February are relatively cold. The hottest months are May and June. The heat is, at all times, moderate and agreeable. The course of the temperature has all the characters of an insular climate, without having so much humidity. The oscillation of the average temperature is greatest in March and during the dry season, as at that time the sky is clear and the soil exposed to uninterrupted insolation during the day, while the earth’s radiation of heat during the night is rapid. Also the daily oscillation is considerable during the dry season, and continues during the first month of the rainy season, according to the condition of the sky.

[27]

In 1890 the sun shone in San José 1911 hours, that is an average of five hours and fourteen minutes per day. February is the month of most sunshine and least nebulosity. The hour of most sunshine during the year is that between eight and nine a. m., and that of the least is in the afternoon.

The oscillation of the temperature of the soil is, at a depth of one meter, 2, 13° C., per year. At a depth of three meters, the temperature of the soil is lowest in February and March, when it is 20, 48° C., and highest in August, when it is 20, 75° C.

The daily variation is almost nothing during the first three months of the year, and the sky is relatively clear, while, from May to October, not one day is clear. During the hottest hours of the day the sky begins regularly to be darkened by clouds, due to ascending atmospheric currents.

In San José the sky is ordinarily clear between midnight and noon, even during the most rainy months, and cloudy the rest of the twenty-four hours. Although the rainfalls are abundant here from May to October, with rare exceptions they do not last more than a few hours each day. The mornings are generally splendid and the air very pure, and nearly every day the sunset can be clearly observed.

From May to November there are about two hours of copious rain daily between one and four o’clock in the afternoon, averaging, with great regularity, from ten to twelve inches a month, and from seventy to eighty inches during the year. Towards the end of June there is a short dry period called “Veranillo de San Juan.”

Through the Desengaño and Palma Passes the northern rains penetrate a short distance every day, and the northern descent of the Palma towards Carillo is probably the most rainy district of the Republic.

At Tres Rios, having an elevation of 4140 feet, six miles east of San José, at the western foot of the Ochomogo Pass, the rain record for 126 days out of ten months showed a fall of 100 inches, while at San José, during the same period of ten months there were 147 rainy days, with a fall of eighty-four inches. In the month of May Professor Pittier, to whom we owe these excellent data, measured nine inches in rainfall in one and one-half hours.

[28]

Rainfall in 1896 at Stations of Costa Rica of Different Altitudes,

by Days and Precipitation in Mm.

| (Part 1 of 2) | Alt. = Altitude in meters. | ||||||||||||

| Alt. | Jan. | Feb. | Mch. | April. | May. | June. | |||||||

| Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | ||

| Boca del Rio Banana | 3 | 15 | 292 | 16 | 184 | 17 | 140 | 24 | 1030 | 19 | 132 | 13 | 272 |

| Port Limon | 3 | ? | 224 | ? | 210 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Gute Hoffnung | 40 | — | — | 18 | 443 | 14 | 132 | 24 | 1065 | 19 | 302 | 11 | 182 |

| La Colombiana | 250 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Juan Viñas | 1140 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Aragon (Turialba) | 600 | 21 | 353 | 12 | 49 | 12 | 65 | 22 | 629 | 23 | 237 | 17 | 267 |

| Tuis | 650 | 21 | 291 | 12 | 159 | 14 | 44 | 22 | 403 | 19 | 270 | 19 | 223 |

| San Rafael de Cartago | 1476 | 15 | 106 | 12 | 72 | 6 | 20 | 16 | 141 | 14 | 123 | 16 | 153 |

| San Diego de la Union | 1300 | 7 | 49 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 227 | 16 | 190 | 12 | 239 |

| La Palma | 1400 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| San Fransisco Guadelupe | 1200 | 10 | 55 | 0 | 0 | — | 1 | 12 | 138 | 19 | 173 | 16 | 182 |

| San José | 1160 | 6 | 54 | — | — | 1 | 1 | 12 | 132 | 11 | 167 | 19 | 165 |

| La Verbena | 1140 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Nuestro Amo | 850 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| (Part 2 of 2) | Alt. = Altitude in meters. | ||||||||||||||

| Alt. | July. | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Year. | ||||||||

| Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | Days. | mm. | ||

| Boca del Rio Banana | 3 | 24 | 405 | 23 | 477 | 14 | 109 | 15 | 262 | 17 | 335 | 23 | 481 | 220 | 4119 |

| Port Limon | 3 | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Gute Hoffnung | 40 | 24 | 399 | 25 | 414 | 14 | 95 | 11 | 106 | 16 | 318 | 23 | 569 | — | — |

| La Colombiana | 250 | 28 | 269 | 23 | 378 | 12 | 129 | 11 | 114 | 16 | 280 | 22 | 564 | — | — |

| Juan Viñas | 1140 | 19 | 205 | 11 | 183 | 14 | 194 | 11 | 121 | 19 | 247 | 16 | 515 | — | — |

| Aragon (Turialba) | 600 | 25 | 257 | 20 | 327 | 14 | 298 | 25 | 142 | 19 | 210 | 15 | 475 | 225 | 3310 |

| Tuis | 650 | 21 | 267 | 23 | 204 | 21 | 254 | 20 | 134 | 19 | 217 | 27 | 366 | 238 | 2831 |

| San Rafael de Cartago | 1476 | 17 | 132 | 16 | 72 | 18 | 97 | 9 | 125 | 16 | 135 | 17 | 164 | 172 | 1339 |

| San Diego de la Union | 1300 | 11 | 110 | 9 | 46 | 19 | 377 | 17 | 239 | 16 | 179 | 8 | 66 | 131 | 1728 |

| La Palma | 1400 | 30 | 370 | 30 | 272 | 21 | 229 | 24 | 241 | 25 | 360 | 29 | 835 | — | — |

| San Fransisco Guadelupe | 1200 | 21 | 232 | 17 | 127 | 21 | 190 | 21 | 241 | 19 | 304 | 11 | 78 | 157 | 1721 |

| San José | 1160 | 19 | 209 | 17 | 124 | 23 | 207 | 20 | 200 | 18 | 300 | 8 | 77 | 154 | 1642 |

| La Verbena | 1140 | 16 | 156 | 10 | 86 | 24 | 238 | 16 | 117 | 19 | 260 | 5 | 41 | — | — |

| Nuestro Amo | 850 | 13 | 136 | 8 | 143 | 21 | 376 | 9 | 212 | ? | ? | ? | ? | — | — |

[29]

The daily curve of rainfall shows a minimum very accentuated in the first half of the day. Rain begins to fall about eleven o’clock, and continues to augment rapidly from hour to hour until it reaches its maximum between four and five o’clock p. m.; from this time on it diminishes gradually until morning. The daily maximum of rain is reached about sunset, although in January the heaviest rainfalls are observed between one and two o’clock p. m. The most probable hour of rain is between four and five o’clock p. m. It seldom rains between three and four o’clock, and very seldom during the morning hours.

Thunderstorms reach their maximum in May. The relative humidity of the air is such that the climate can be considered a favored one. Its annual curve shows three minima and three maxima. The minima are observed between February and March, in July, and between November and December; the maxima in June, September and December. These lines, of course, are parallel with those indicating the distribution of rain. The maximum is noted at sunrise, the minimum at two o’clock p. m., with an average oscillation of twenty-four per cent.

From 1866 to 1880, the rain gauge record kept by Mason at San José shows a yearly average precipitation of sixty-four and one-fourth inches, or 1631 millimeters.

It is as follows:

The Rainfall in San José from 1866 to 1880 in Mm.

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May. | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | Total. | |

| 1866 | 33 | 7 | — | 29 | 139 | 123 | 320 | 156 | 274 | 250 | 171 | 122 | 1619 |

| 1867 | 98 | 56 | 7 | 98 | 209 | 206 | 214 | 190 | 314 | 213 | 244 | 14 | 1397 |

| 1868 | — | — | 181 | 13 | 83 | 150 | 102 | 130 | 224 | 393 | 144 | 17 | 1436 |

| 1869 | 7 | — | 7 | 28 | 202 | 218 | 150 | 132 | 393 | 281 | 78 | 102 | 1562 |

| 1870 | 1 | 6 | 31 | 17 | 333 | 276 | 240 | 284 | 240 | 262 | 184 | 33 | 1905 |

| 1871 | 28 | 3 | 8 | 13 | 290 | 203 | 364 | 307 | 245 | 333 | 114 | 11 | 1925 |

| 1872 | 3 | 3 | 15 | 50 | 244 | 255 | 192 | 378 | 397 | 504 | 142 | 21 | 2197 |

| 1873 | 64 | — | 3 | 71 | 64 | 205 | 145 | 85 | 387 | 262 | 121 | 11 | 1418 |

| 1874 | 46 | 1 | 20 | 60 | 336 | 167 | 162 | 181 | 319 | 191 | 42 | 20 | 1543 |

| 1875 | — | — | — | 28 | 252 | 180 | 93 | 294 | 279 | 339 | 21 | 32 | 1492 |

| 1876 | 14 | — | 11 | 6 | 247 | 237 | 153 | 192 | 206 | 117 | 70 | 28 | 1282 |

| 1877 | 14 | — | — | — | 240 | 167 | 223 | 159 | 259 | 95 | 121 | 79 | 1357 |

| 1878 | — | — | 38 | 50 | 142 | 187 | 205 | 149 | 329 | 238 | 223 | 20 | 1580 |

| 1879 | 13 | — | 45 | 192 | 220 | 330 | 460 | 283 | 351 | 231 | 61 | 8 | 2193 |

| 1880 | 8 | — | — | 15 | 254 | 210 | 104 | 436 | 165 | 278 | 92 | — | 1562 |

| Average | 22 | 5 | 24 | 44 | 217 | 208 | 208 | 222 | 299 | 266 | 122 | 35 | 1631 |

[30]

There is every year a number of slight earthquakes in San José, generally undulating from west to west-northwest, and occurring mostly between eleven p. m. and six a. m. The greatest number are observed at the beginning of the rainy season.

The rainy season on the Caribbean slope of the country does not correspond to that of the Pacific. In fact there are no continuously dry months, and on the northern declivities of the volcanoes of Turialba, Irazú, Barba and Poas, it rains more or less during the entire year; also near Lake Nicaragua it rains nearly continuously, and the mountains of the Guatuso country and the surroundings of the volcano of Orosi are seldom without clouds. At times there are cloud-bursts of tremendous power, broadening rivers for miles. Port Limon is said to have an annual rainfall of eighty-nine inches, but it is greatly exceeded by that of Colon, which averages 120 inches. The mean rainfall at Greytown for 1890, 1891, 1892, was 267 inches yearly. The late United States Commission estimated the average at Lake Nicaragua at eighty inches, and in the basin of the San Juan River at 150 inches.

The climate of Talamanca is for the same reason very unhealthy in the proximity of the coast, and also in the lower course of the rivers a similarly deadly climate prevails. In normal years there are two dry and two wet seasons. The rains commence regularly in May or June and last until the end of July. The months of August and September are more or less dry. In October there are some heavy showers, and extensive rains begin which characterize the months of November, December and January. The driest months are February, March and April. The high region is extremely humid, giving rise to fogs and rains. The mosses which almost completely envelop the stems of the trees are constantly dropping water, and the rivers in this section are almost impassable.

The climate of the great valley of the Rio Grande de Terraba is similar to that described for the terrace lands. Both regions have distinctly marked characters. Rains begin in April, grow heavier towards September, and cease about the[31] end of November. During the rest of the year dry weather prevails, although sometimes heavy showers relieve this arid condition. In the lower zone pronounced radiation causes a heavy dew and extensive fogs, and both are characteristic of this section.

The excessive heat felt on the lowlands diminishes gradually with the rising of the land towards the high mountains, but at times a height of 1500 feet will be found cooler than one of 3000 feet. In the Santa Clara district, for instance, it is cooler at 500 feet elevation than it is in the Reventazon valley at 1500 feet. In general, the torrid lands of the country, ranging from the sea to 150 feet above it, and, if not clear and well-drained, even up to 400 and 500 feet, abound in malarial fevers; but as high ground, having an elevation of from 1500 to 3000 feet is reached, the fevers are of light type and not dangerous, while from 3000 to 5000 feet the diseases are those of the temperate zone, and are due less to local conditions of soil and climate than to personal neglect.

There were no epidemic diseases in 1897. In October 30, 1894, sixteen medical districts were established by law, and so were a number of hospitals and quarantine stations in the ports of the Republic.

[32]

This chapter I begin with a phyto-geographical classification given by Dr. Carl Hoffman and published in Bonplandia in 1858. He distinguishes:

First.—Coast regions (sea shores and salt swamps).

Second.—Regions of tropical forests and savannas, stretching from the coast regions to a height of 900 meters.

Third.—Regions of high plains, lying between 900 to 1500 meters of elevation.

Fourth.—Region of upper tropical forests, situated between 1500 to 2150 meters of altitude.

Fifth.—Region of oaks, from 2150 to 2750 meters in height.

Sixth.—Region of chaparrales, from 2750 to 3050 meters up.

Seventh.—Region of subalpine or subandine flora, from 3050 meters up to the tops of the high mountains.

Dr. Polakowsky enumerates cultivated lands, virgin forests, open forests and savannas.

Another division is given by Dr. Moritz Wagner. He mentions a littoral (as appears on next page) zone, a tropical forest zone and a zone of savannas.

He also distinguishes on the volcano of Chiriqui the following successive regions:

First.—Regions of evergreen forest trees and palms, bananas, Araceæ, etc., to a height of 550 meters, with an average temperature of 26° to 24° C.

Second.—Region of tree ferns and mountain orchids, from 550 to 1220 meters, with an average temperature of 23° to 18° C.

Third.—Region of Rosaceæ, Senecionodeæ, Gramineæ and Agave americana, from 1220 to 1585 meters.

Fourth.—Region of Cupuliferæ and Betulaceæ, mostly oaks and alders, from 1585 to 3050 meters.

Fifth.—Higher region above 3050 meters.

[33]

Dr. Wagner calls special attention to a noted uniformity of the flora on the coasts of both oceans, and Professor Pittier affirms that the vegetation between Colon and Greytown on one side, and between Panama and San Juan del Sur on the other side, is remarkably uniform. The littoral zone has a width of about four maritime miles. The predominating flora is composed of Rhizophora mangle, Hippomane mancinella, Cocos nucifera, Chrysobalanus icaco, Crescentia cujete, Acacia spadicigera, Cæsalpinia bonducella and other Leguminosæ; Acrostichum aureum, Ipomœa pescapræ, Avicennia nitida, Uniola Pittierii and also Euphorbiaceæ, etc.

The zone of tropical forests shows, especially on the Atlantic side behind the coast region, a strip of from twenty to twenty-two miles in width, with lofty trees of Rubiaceæ, Myrtaceæ, Melastomaceæ, Sterculiaceæ, Euphorbiaceæ, Meliaceæ, Urticaceæ, Moraceæ, Anacardiacæ, Sapindaceæ, Leguminosæ and Palmæ. It is relatively free from ligneous undergrowth, having more monocotyledonous plants, such as Cycadeæ, Scitamineæ, Cannaceæ, Marantaceæ, Cyperaceæ, Filices and Bromeliaceæ, underneath. The latter orders figure, also with Orchideæ and Loranthaceæ among the epiphytes and parasites which cover the trees. Among the most characteristic plants of this region we name the coyol palm (Acrocomia), corozo (Attalea cohune), biscoyol (Bactris horrida), palmiche (Elæis melanococca) and Raphia nicaraguensis which forms almost forests along the River San Juan; further, Tecoma pentaphylla, Bombax ceiba, Eriodendron, Spondias, Croton gossypifolius, Hymenæa courbaril, rubber trees (Castilloa costaricencis and C. elastica), Geoffræa superba, Simaba cedron, species of Enterolobium, Cæsalpinia, Liquidambar, Copaifera, Cedrela, Swietenia, Sapota, Pithecolobium, Palicourea, Cinchona, Piper, Ficus, Cecropia; still further, smilax, vanilla, etc. Many of these characteristic plants are largely social, such as the piper, ferns, palms and others.

Moritz Wagner states that all along the southern limits of Costa Rica a likeness of climatic and geological conditions gives to the vegetation a nearly uniform character, while further northward a notable contrast is observed between the Atlantic and Pacific slopes of the mountain groups[34] and on the interior terrace lands. The Atlantic slope, with more constant humidity of air, is characterized by vast, dense, evergreen, virgin forests, while the Pacific lands, with a relatively dry climate and rainless summer, present more open forests and savannas, with many deciduous trees and shrubs. However, deep river valleys and some slopes near the water-shed have dense, evergreen forests, and their vegetation does not differ much from that of the Atlantic slope. The flora of the high terrace lands has been so altered by thorough cultivation as to have almost lost its original character.

The Atlantic virgin forests, as well as those in the region of the San Juan River and of Lake Nicaragua, which comprise two-thirds of Costa Rican territory, show such a dense vegetation that its interior can be penetrated almost only by way of the rivers, and its general character and its enormous extension be studied only from high mountains. Owing to the very mountainous character of the country, over half of its area lies between 900 and 2100 meters above the sea, and is almost wholly covered with virgin forest. This forest here and there ascends still higher, reaching the upper limit of the oak region about 2700 meters above the sea.

Dr. Polakowsky, in an interesting publication entitled “Flora of Costa Rica,” calls the forest region of the San Juan River, in view of its luxuriant character, “The Central American Hylæa,” and this name Professor Pittier applies also to the entire Atlantic region, attributing to it a distinctly South American character.

The zone of the open forests and savannas, which has park-like features, is rarely found away from the Pacific side, where it forms a belt from sixteen to eighteen miles in width, interspersed with more densely forested river valleys, islands of higher and thicker virgin forests, isolated trees or groups of trees, sometimes also with catingas and meadows flecked with shrubs and matorrales.

The savannas and open forests spread to a considerable extent over Guanacaste, where they are a continuation of those of Rivas in Nicaragua; also over the plains of Terraba, especially in the region of Buenos Aires and Terraba; and over the coast-lands of Golfo Dulce. There are some[35] small similar tracts near Alajuela, Turialba, Santa Clara and at some other points, as well as catingas and paramos in the high mountain ridges of the south. The paramos are found on poor soil and have a vegetation more herbaceous than ligneous, which, when moist, takes on the character of turf.

The trees of the savannas are generally of little height, excepting the Enterolobium cyclocarpum (the guanacaste), the pochote and ceiba. The grass lands are almost wholly composed of Gramineæ and Cyperaceæ, especially in the savannas of Guanacaste. The most characteristic plants are Digitaria marginata and Paspalum notatum, besides species of Setaria, Panicum, Eragrostis, Andropogon, Isolepis, Cyperus, Rhynchospora and Scleria, as well as of ferns (Pteris aquilina) and Schizæa occidentalis.

Other abundant plants in the open forests and savannas are Compositæ (Zemenia, Pectis, Spilanthes); Rubiaceæ (Spermacoce); Polygalaceæ; Iridaceæ; Moraceæ (Maclura, Ficus); Melastomaceæ (Miconia, Clidemia, Conostegia, Leandra); Cyperaceæ; Convolvulaceæ; Euphorbiaceæ; Bombacaceæ; Sauvagesia. Further, Myrtaceæ (Psidium, Alibertia edulis); Curatella americana (chamico); Roupala (danto hedliondo); Byrsonima crassifolia (nance); Miconia argentea DC. (santa maria); guacimo macho (Luhea), guacimo de ternero (Guazuma ulmifolia); burio (Bombax apeiba); ñambar (Cocobola); Davilla lucida; Duranta Plumieri; Proteaceæ; and Acacia scleroxyla Lonchocarpus atropurpureus, Dalbergia and many other Leguminosæ, especially Mimosa pudica, which gives large tracts in many places a special character, and still more so as, being often very abundant and the plants tangled together, a general movement all around is caused when one is touched.

Among the epiphytes and parasites may be mentioned small ferns, Peperomia, Epidendrum, Loranthus, Aroideæ, Tillandsia and other Bromeliaceæ, mosses, lichens, etc.

Professor Pittier attributes to this flora of the Pacific slope a more northern origin.

During the dry season the vegetation of the savannas almost disappears, the greater part of the trees and bushes shed their leaves and herbs become dry and brittle. Only[36] along the rivers is some freshness observable. Toward the border of Nicaragua cacti appear, mostly species of Cereus, Opuntia, Phypsalis and Mammilaria. Professor Pittier also mentions an oak forest of Quercus citrifolia between Liberia and the Rio de los Ahogados, at a height of about one hundred meters above the sea. The peninsula of Nicoya is noted for a large lumber industry among its different cedars (Cedro dulce, C. amargo, C. real, etc.), mora and other trees. Towards the upper limits of the Atlantic tropical forests, below the oak region, Chamædorea, Geonoma, Bactris, Euterpe longepetiolata and other palms of the same groups, as well as Gulielma utilis (the pijivalle palm) and Carludovica microphylla are seen in great abundance, mixed with tree ferns like Alsophylla pruinata, Hemitelia horrida, Hemitelia grandifolia, etc. Higher up appears the region of oaks, principally Quercus retusa, Quercus granulata, Quercus citrifolia and Quercus costaricensis, with Buddleia alpina, Rubus, Lupinus, etc. Here is also the region of the common potato. This oak region slopes gradually down from east to west. The vegetation on the summits of the high mountains of Costa Rica is of a marked subalpine character, having a great number of northern genera, as Vaccinium, Pernettya, Alchemilla, Cardamine, Calceolaria, Spiræa, etc.

Certain types of vegetation are often more due to the sterile nature of the soil than to elevation.

Although a northern flora is frequent on the high terraces of San José and Cartago, that character is not general because of the introduction of cultivated tropical and other plants peculiar to Costa Rica.

On the southern high mountains two species of Podocarpus (P. taxifolia and P. salicifolia), one of Alnus (Alnus Mirbelii Spach.) and one of Weinmannia occur quite generally among the oak forests. Other distinct floral groups are represented by the vegetation along roads and fences, on potreros, in cultivated regions and along river shores. The latter especially are rich in herbaceous plants, grasses, bushes and woods of Bignoniaceæ, Myrtaceæ, Euphorbiaceæ, Mimoseæ, etc.

The potreros are characterized by Tagetes, Sida, Hyptis,[37] olanum, Salvia, Mimosa pudica and M. sensitiva, etc. Along fences there grow nearly everywhere Erythrina corallodendron, Yucca aloifolia, Bromelia pinguin, Agave americana, Cereus, Spondias, Bursera, Cestrum, etc.

Prominent characteristic plants, besides the already mentioned species and genera, are the Piperaceæ and Melastomaceæ; further, species of Iriartea, Bactris and Raphia of the palm order, and Alsophylla, Schizæa occidentalis and Pteris aquilina of the ferns; still further Castilloa costaricana, Gunnera insignis, Ochroma lagopus, Gliciridia, Inga edulis, Chusquea maurofernandeziana, Erythrina corallodendron, Drymis Winterii Forst., Acacia Farnesiana, etc.

The passage from one flora to another is one of insensible gradations. Cultivated lands, as already stated, do not show any longer the original vegetation.

The plants which are now mostly cultivated are: Coffea arabica (coffee), Saccharum officinarum (sugar cane), Zea mays (corn), Musa paradisiaca and Musa sapientium (bananas), Phaseolus (beans), Oryza sativa (rice), Solanum tuberosum (potato), Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco), Batatas dulcis (sweet potato), Lycopersicum esculentum and Lycopersicum Humboldtii (tomatoes), Capsicum annuum (chile), Ananas sativa (pine-apple), Carica papaya (papaya), Persea gratissima (aguacate), Anona cherimolia (cherimoya), Manihot aipi and Manihot utilissima (yucca or mandioca), Indigofera anil (indigo), Gossypium barbadense (cotton), Cichorium Intyous (chicory), Asparagus officinalis (asparagus), Psidium guava (guayaba), Mammea americana (mamey), Theobroma cacao (cacao), etc.

Before giving the lists of the woods, tannings, dyeings, gums, balsams, resins, rubber, waxes, textile and medicinal plants, oils and oil seeds, etc., of Costa Rica, it is advantageous to research to name those collectors and scientists who, having traveled through Costa Rica or established themselves there, have especially contributed to the knowledge of the natural resources of the country. They are Professor H. Pittier, A. S. Oersted, Dr. C. Hoffmann, Dr. H. Polakowsky, Dr. M. Wagner, Captain J. Donnel Smith, C. Warszewicz, Neudland, A. Tonduz, P. Biolley, Dr. A. von Frantzius, Dr.[38] Franc Kuntze, Professor W. M. Gabb, José C. Zeledón, Anastasio Alfaro, Juan J. Cooper, and Bishop Bernardo Augusto Thiel, D. D.

Native Names of the Woods of Costa Rica.

[39]

[40]

Native Names of the Medicinal Plants of Costa Rica.

[41]

Native Names of Costa Rican Tanning and Dyeing Plants.

| Name. | Commercial Part. | Use. |

| Achiote | Seed | Dyeing. |

| Aguacate | Seed | Tanning. |

| Añil | Extract | Dyeing. |

| Brazil | Wood | ” |

| Catazin | Wood | ” |

| Encino blanco | Bark | Tanning. |

| Encino colorado | Bark | ” |

| Gavilan | Bark | ” |

| Guanacaste | Bark | ” |

| Guanacaste | Fruit | Dyeing and tanning. |

| Mangle | Bark | ””” |

| Mora | Wood | Dyeing. |

| Nacascolo | Fruit | Dyeing and tanning. |

| Nancite | Bark | ””” |

| Ojo de venado | Seed | Dyeing. |

| Ratoncillo | Bark | Tanning. |

| Sacatinta | Plant | Dyeing. |

| Sangre de drago | Sap | ” |

| Yuquilla | Root | ” |

[42]

Native Names of Costa Rican Gums, Resins, Rubber, Etc.

| Name. | Character. | Name. | Character. |

| Acacia | Gum. | Gallinazo | Gum. |

| Arrayan | Wax. | Guapinol | Resin. |

| Aroma | Gum. | Hule | Rubber. |

| Balsamo negro | Balsam. | Incienso | Resin. |

| Barillo | Resin. | Jinote | Gum-resin. |

| Copal, fossil amber | ” | Jocote | Gum. |

| Copal | ” | Jobo | ” |

| Camibar | Balsam. | Jenizaro | Gum-resin. |

| Caraña | Resin. | Mangle | Gum. |

| Copaiba | Balsam. | Mastate | Milk. |

| Cedro | Gum. | Nispero | Chewing gum. |

| Cera vegetal | Wax. | Ojoche colorado | Milk. |

| Cerillo | ” | Ojoche macho | ” |

| Chilamate | Milk. | Pochote | Gum. |

| Chirraca | Balsam. | Quiebracha | ” |

| Espino blanco | Gum. | Sangre de drago | Sap. |

| Guanacaste | ” | Tuno macho | Chewing gum. |

| Guayacan | Resin. | Palo de vaca | Milk. |

Native Names of Costa Rican Oilseeds.

Native Names of Costa Rican Textile Plants.

| Name. | Product. | Name. | Product. |

| Algodon | Cotton. | Limon montes | Bast. |

| Balsa | Silk-cotton. | Luffa | Fruit. |

| Banana | Leaves. | Majagua | Bast. |

| Barrigona | Silk-cotton and bast. | Maguey | Leaves. |

| Burio | Bast. | Mastate | Bast. |

| Cabuya | Leaves. | Palma | Leaves. |

| Ceiba | Silk-cotton. | Peine de mico | Bast. |

| Corteza blanca | Bast. | Pie de venado | Bast. |

| Coco | Fruit fibre. | Piña | Leaves. |

| Cucanilla | Bast. | Piñuela | Leaves. |

| Guarumo | Bast. | Pochote | Bast and silk-cotton. |

| Itavo | Leaves. | Pita | Leaves. |

| Juco | Bast. | Ramio | Bast. |

| Junco | Leaves. | Soncollo | Bast. |

[43]

In regard to the fauna, there are in Costa Rica about one hundred and twenty-one species of mammalia, of which ten are domesticated and four of Mus introduced, leaving 107 as indigenous to Costa Rica.

There are only a few species peculiar to Costa Rica, and also but a small number peculiar to Central America, among which are the Tapirus dowi alston and three species of monkeys. About one-fifth of the total number also belong to South America and one-seventh to North America. The rest are found as well in North as in South America. With respect to the avifauna, there are 725 known species. This great variety of the avifauna is due to especial climatic conditions, to the very rich flora, to the geographical position between two oceans and to the vicinity of so many islands of the Caribbean Sea.

It is composed of 67 Neoarctic species, which are also found in the north of Mexico; of 247 Neotropical or South American species, of 260 autochthonous or exclusively Central American species, and 128 newly described species which live as well in the northern as in the southern continent. The rest, comprising 23 species, have a doubtful origin. The best singing birds are the Gilguero, Yigüerro, Toledo, Mozotillo, Cacique, Mongita, Comemaiz, Setillero and Agüillo.

There are over 130 species of Reptilia and Batrachia in Costa Rica. Those known and described are 36 Batrachia, 28 Lacertilia, 60 Ophidia and 6 Testudinata. Poisonous snakes are the Toboba, Bocaracá, Oropel, Terciopelo and Cascabel.

[44]

Costa Rica is also very rich in Fishes. Those in the Pacific are almost entirely different from those of the Atlantic Ocean. Also its tributary waters have more varied species than those of the Atlantic slope.

In correspondence with the varied topographical, climatological, and botanical conditions of Costa Rica is also the invertebrate fauna. And here the National Museum, under Mr. Anastasio Alfaro, and the “Instituto fisico geografico Nacional.” under Professor H. Pittier, are doing equally excellent work in bringing them to our knowledge, as they have done like service in other branches of Natural History.

The most interesting species of the fauna in Costa Rica among the mammalia are the monkeys (Mycetes palliatus, Ateles geoffroyi, and Cebus hypoleucus), the tigre (Felis onca), marrigordo (Felis pardalis), puma (Felis concolor), the coyote (Canis latrans), tigrillo (Urocyon cinereo), pisote (Nasua narica), martilla (Cercoleptes caudivolvulus), comadreja (Mustela brasiliensis), chulomuco or tolumuco (Galictis barbara), Zorro hediondo (Conepatus mapurito), nutria or perro de agua (Lutra felina), manati or vaca marina (Trichecus australis), danta (Elasmognathus bairdii and E. Dowi), salimo (Dicotyles tajacú) cari blanco (Dicotyles labiatus), venado (Dorcelophus clavatus), cabro de monte (Mazama temama), ardillas (Sciurus hypopyrrhus, Sc. æstuans hoffmanni, Sc. Alfari), puerco espino (Synetheres mexicanus), guatusa (Dasyprocta isthmica, D. punctata), tepeizcuintle (Coelogenys paca), conejo (Lepus graysoni, L. gabbi), perico ligero (Bradypus castaneiceps), perezoso (Choloepus hoffmanni), armado de zopilote (Dasypus gymnurus), armadillo (Tatusia novemcincta), oso hormiguero (Myrmecophaga jubata), oso colmeno or tejon (Myrmecophaga tetradactyla), serafin de platanar (Cyclothorus didactylus), zorro pelon (Didelphis marsupialis aurita), zorro isi (Marmosa cinerea) and zorrito de platanar (Marmosa murina).

Among the birds the following may be mentioned, following the enumeration of José C. Zeledón: The sensontle (Mimus gilous), the jilguero (Melanops), the yigüerro (Turdus grayi), the picudos (Cæreba cyanea and C. lucida), the rualdo (Chlorophonia callophrys), the caciquita (Euphonia[45] elegantissima), the monjita fina (Euphonia affinis), and other species of Euphonia; further pipra mentalis, la viuda (Tanagra cana), el cardenal (Pyranga leucoptera and P. rubra), cyanospiza, sps., alcalde mayor (Rhamphocœlus) the oropéndula (Ocyalus waglieri and O. montezumæ), the choltote or trupial (Icterus pectoralis and I. giraudi), the rajon (Cotinga amabilis), colibris or gorriones (Trochilidæ), the quetzal (Pharomacrus costaricensis), resplandor (Muscivora mexicana), the curré (Ramphastus carinatus), the quioro (R. tocard), the curré verde (Aulacorhamphus cæruleigularis), carpintero (Campephilus guatemalensis and Centurus hoffmanni), the lapas rojas and lapas verdes (Ara militaris and Chryosotis diademata, C. guatemalæ and C. auripalliata), the periquitos (Conurus petzii and Brotogerys tovi).

Further mention is made of the aguila (Trasætus harpyia), camaleon (Falco sparverius), carga-hueso (Polyborus cheriway), the rey de zopilote (Gyparchus papa), the zopilote (Catharista atrata) and the zonchiche (Cathartes aura). To these may be added the tortolita (Columbigallina passerina), the pavon (Crax globicera), the pava (Penelope cristata), pava negra (Chamæpetes unicolor), the codorniz (Ortyx leylaudi) and chirraxua (Denitortyx leucophrys); still further, the martin peña (Ardea virescens) and other garza (Tigrisoma cabanisi, Nycticorax americanus, Gallina aquatica, Eurypyga major), zarzetas (Numenius and Totanus); also the pijijes (Totanus flavipes and Charadrius vociferus), the patillo (Colymbus dominicus), the piche (Dendrocigna autumnalis), pelicanos and alcatraz (Pelecanus), etc.

We have further to mention the great turtles from both oceans, the (Nacar de perlas) or pearl shells from Golfos Dulce and Nicoya, the oysters from Puntarenas, the purple snail (Murex), also sponges, corals, etc.

[46]

Colonel George Earl Church says in regard to the Indians: “There are many indications that Costa Rica was once the debatable ground between the powerful Mexican invader and the warlike Caribs of northern South America.”

“The Caribs were a tall, muscular, copper colored race who, when the New World was discovered, occupied the coast from the mouth of the River Orinoco to that of the River Amazon, and stretched inland over all the half-drowned districts and far up the valley of the Orinoco. Their nomadic spirit led them to the conquest of many of the Windward Islands, and, I am disposed to believe, urged them to invade all the countries bordering the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico having estuaries and rivers which could be penetrated by their war canoes. These carried from twenty-five to one hundred men each and were of sufficient size to make long voyages.”

Along all the Caribbean coast districts of Yucatan, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Chiriqui, and throughout the province of Panamá, the Carib has left traces of his presence.

It is evident that an offshoot of the highland Mexican race pressed south and east from Chiapas, Mexico, into and through the long strip of the Pacific coast occupied by the Chorotegas or Mangues, followed the Pacific slope of the Cordilleras and the narrow space between Lake Nicaragua and the Ocean, penetrated into northwestern Costa Rica, settled and helped the Mangues to develop a considerable civilization in the district of Guanacaste and Nicoya, and in[47] part subdued all the volcanic region lying north and west of the valley of the River Reventazon.

It is notable that inhabitants of volcanic countries crowd around the slopes of its volcanoes, due probably to the fertilizing quality of the ejected ash.