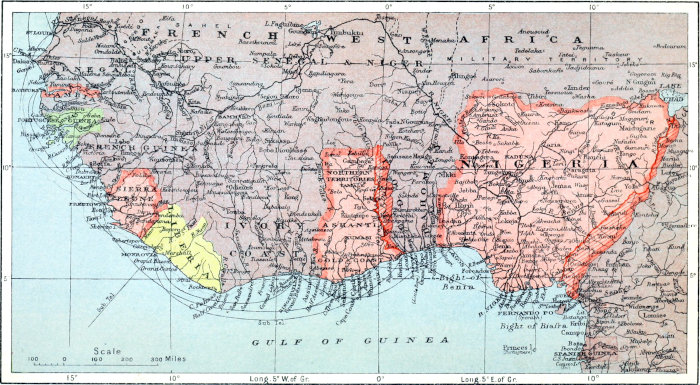

WEST AFRICA

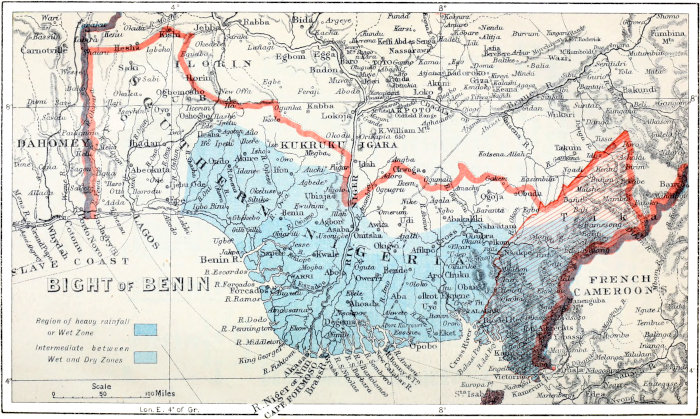

Territory held by Great Britain

under Mandate is hatched in Red. ![[Legend]](images/legend.jpg) |

Stanford’s Geogl. Estabt., London. |

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The agricultural and forest products of British West Africa, by Gerald C. Dudgeon

Title: The agricultural and forest products of British West Africa

Author: Gerald C. Dudgeon

Editor: Wyndham R. Dunstan

Release Date: June 14, 2023 [eBook #70973]

Language: English

Credits: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

IMPERIAL INSTITUTE HANDBOOKS

THE AGRICULTURAL AND

FOREST

PRODUCTS OF BRITISH WEST AFRICA

IMPERIAL INSTITUTE SERIES OF HANDBOOKS TO THE COMMERCIAL RESOURCES OF THE TROPICS, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO BRITISH WEST AFRICA

ISSUED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE

SECRETARY

OF STATE FOR THE COLONIES

EDITED BY

WYNDHAM R. DUNSTAN, C.M.G., M.A., LL.D., F.R.S

DIRECTOR OF THE IMPERIAL

INSTITUTE; PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL

ASSOCIATION FOR TROPICAL AGRICULTURE

WEST AFRICA

Territory held by Great Britain

under Mandate is hatched in Red. ![[Legend]](images/legend.jpg) |

Stanford’s Geogl. Estabt., London. |

IMPERIAL INSTITUTE HANDBOOKS

BY

GERALD C. DUDGEON,

C.B.E.

LATELY CONSULTING AGRICULTURIST AND

DIRECTOR-GENERAL

OF AGRICULTURE IN EGYPT; PREVIOUSLY

INSPECTOR OF

AGRICULTURE FOR BRITISH WEST

AFRICA

WITH A PREFACE

BY

WYNDHAM R. DUNSTAN, C.M.G., M.A., LL.D.,

F.R.S.

DIRECTOR OF THE IMPERIAL INSTITUTE

SECOND EDITION

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1922

All Rights Reserved

Since the first edition of this book appeared, British West Africa has experienced a serious set-back in its development through the occurrence of the Great European War. From that war, however, many lessons will have been learnt, which will, it is hoped, make the course of progress in the future more sure and perhaps more rapid.

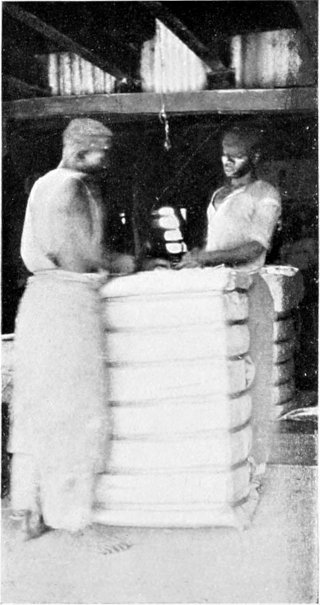

The cultivation of cotton has now been shown to be successful and profitable in Nigeria. In the Northern Provinces great progress has been made in perfecting a cotton originally grown from “American Upland” seed, whilst the Southern Provinces have produced increasing quantities of an improved native cotton of the type of “Middling American.” The future of cotton production in Nigeria is now assured, and its further development chiefly depends on effective action being taken on commercial lines.

The products of the oil palm and especially palm kernels have been in increased demand for edible purposes, the war having led to a far greater use of margarine and similar materials. The perfection of processes for the better extraction of palm oil from the fruits which had nearly reached success at the outbreak of war now awaits completion, when a large additional source of edible oil will be available. In the meantime the trial cultivation of this palm in other countries has been attended with remarkable success, the growth of the palm in plantations having been entirely satisfactory and furnished yields of oil which exceed those given by the wild palm in West Africa. The Dutch East Indies, where large plantations have been made, and also British Malaya, where similar enterprise has been shown, may before long be formidable rivals to West Africa in the production of palm kernels and palm oil. The neglect in West Africa of the wild trees, the imperfect methods followed in extracting the palm oil, and the large number of palms unutilised are questions which now need renewed attention, and in fact the entire subject of the development of the palm-oil industry in West Africa demands the most serious[vi] study in all its aspects if the industry is not to be supplanted by the enterprise of other countries.

In this and other directions where the continuous acquisition of new knowledge is requisite, it is satisfactory to learn that the staffs of the Agricultural Departments in West Africa are to be extended and better remunerated. In addition to this step, and perhaps equally important, will be the increased interest and activity of those merchants and manufacturers who utilise the raw materials of the country, and to whom the commercial development of West Africa has hitherto owed so much.

There are many other subjects which, it will be seen from the new edition of this book, have come to the front since the first edition appeared, and now need increased attention.

The only rubber tree which has survived as a producer in the years of strenuous competition is Hevea brasiliensis, from which Para rubber is obtained. Successful plantations of this tree have been established both in the Southern Provinces of Nigeria and in the Gold Coast, and from the former commercial rubber is now being produced of quality equal to that of the rubber plantations of the East.

The Gold Coast has become the chief cocoa producer of the world, but it is clear that unremitting care and attention in connection with the cultivation and the preparation of cocoa in that country will be necessary if that supremacy is to be maintained.

In connection with the production of fibres, cinchona bark, cinnamon, tobacco, and many other materials, there are promising possibilities in various parts of West Africa, including those new territories for which, as a result of the war, Great Britain is now responsible. Above all, there is the dominant problem of the growth of foodstuffs sufficient to maintain the native populations of these countries.

Mr. Dudgeon, within the limits imposed in the production of a revised but not greatly enlarged edition, has successfully brought this Handbook up-to-date, and it is hoped that it will continue to serve as a standard guide to all those who require general information respecting the agricultural and forest products of West Africa.

WYNDHAM R. DUNSTAN.

Imperial Institute,

March 1921.

The present series of Handbooks is intended to present a general account of the principal commercial resources of the tropics, and has been written with special reference to the resources of British West Africa. These Handbooks will furnish a description of the occurrence, cultivation and uses of those tropical materials, such as cotton and other fibres, cocoa, rubber, oil-seeds, tobacco, etc., which are of importance to the producer in the tropics, as well as to the manufacturer and consumer in Europe.

Without attempting to include all the detailed information of a systematic treatise on each of the subjects included, it is believed that these Volumes will contain much information which will be of value to the tropical agriculturist as well as to the merchant and manufacturer. They will also be of importance to Government Officials in tropical Colonies where the advancement of the Country and the welfare of its inhabitants depend so largely on the development of natural resources. In recent years those candidates who are selected for administrative appointments under the Colonial Office in British West Africa are required to pass through a short course of instruction in tropical cultivation and products, which is now arranged at the Imperial Institute. For these prospective officials the present series of Handbooks will be helpful in the study of a large and generally unfamiliar subject. Similarly it is believed that the series will provide a valuable aid to the teaching of commercial geography. It is hoped also that the Handbooks will not be without interest for the student of Imperial and national problems.

The increase in the productivity of the tropics, and especially of the tropical regions within the British[viii] Empire, is important, not only for the natives of those countries, and others who are actually engaged in tropical enterprise, but for the merchant and manufacturer at home. The preparation for general use of cotton and other fibres, of tea, coffee and cocoa, of oils, of tobacco, and of numerous other products exported from the tropics, provides the means of employment and livelihood for a very large proportion of the working population of this country, whilst every one at home is interested in securing an adequate supply at a moderate cost of these necessaries and luxuries of life.

The subjects of these Handbooks, treated as they will be, as far as possible, in non-technical language, should therefore appeal to a large class of readers.

The present Handbook deals with the Agricultural and Forest Products of British West Africa and serves as an introduction to this series. Mr. Dudgeon, who until lately was Inspector of Agriculture in the West African Colonies and Protectorates, writes with an unrivalled knowledge of his subject, and gives a comprehensive account of the vegetable products of that country, which will afford to the general reader some idea of the enormous possibilities of this British territory now in the process of rapid commercial development.

WYNDHAM R. DUNSTAN.

Imperial Institute, S.W.

March 1911.

| PART I | |

| PAGES | |

| The Gambia | 1-14 |

| PART II | |

| Sierra Leone | 15-42 |

| PART III | |

| The Gold Coast, Ashanti, and the Northern Territories | 43-92 |

| PART IV | |

| Nigeria—Southern Provinces | 93-119 |

| PART V | |

| Nigeria—Northern Provinces | 120-164 |

| INDEX | 165-176 |

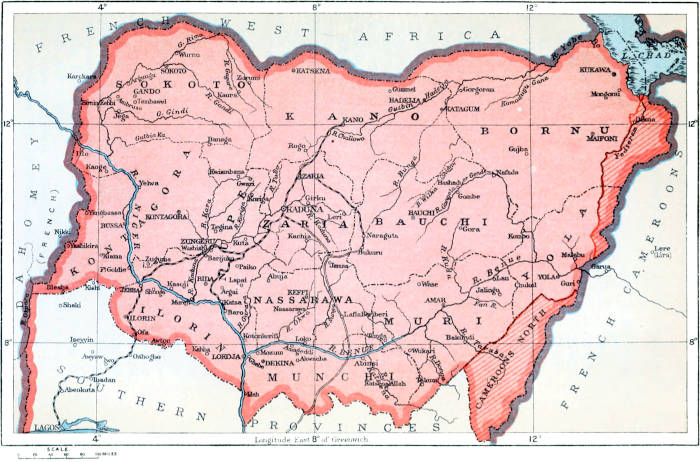

| Sketch Map of British West Africa | Frontispiece |

| GAMBIA AND SIERRA LEONE | |

| OPPOSITE PAGE | |

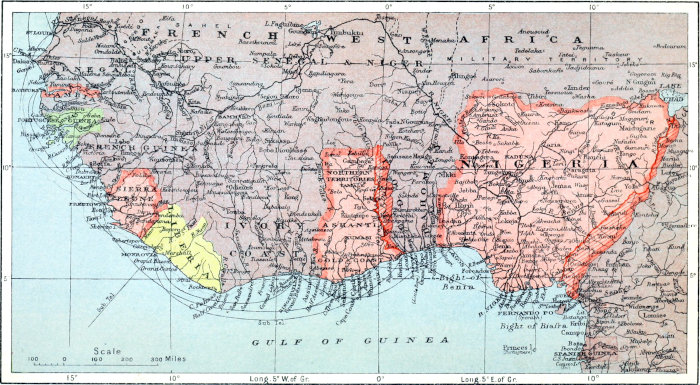

| Jolah with Native Hand-plough, Bullelai, Fogni | 3 |

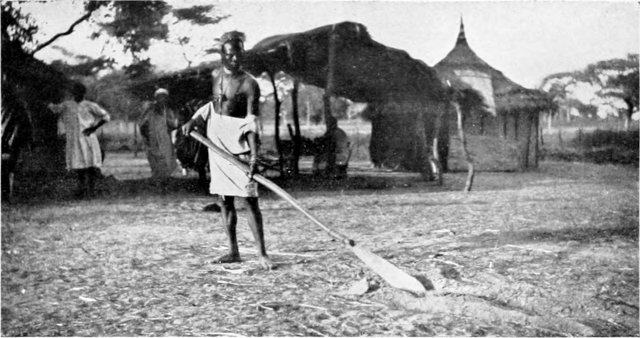

| Canary Island Plough, Agricultural School, Abuko | 3 |

| Rubber Tree (Ficus vogelii) at Bathurst | 3 |

| Rubber Vine (Landolphia heudelotii) at Kotoo | 9 |

| Ceara Rubber Tree (Manihot glaziovii) at Bakau | 9 |

| Rubber Tree (Castilloa elastica) at Kotoo | 9 |

| Fruits of Oil Palms, Sierra Leone | 13 |

| Sweet Cassava, with Baobab Trees, Bakau | 13 |

| Indigo Dyers, McCarthy Island | 13 |

| Sketch Map of Gambia and Sierra Leone | 15 |

| Oil Palms (Elæis guineensis), Mafokoyia | 21 |

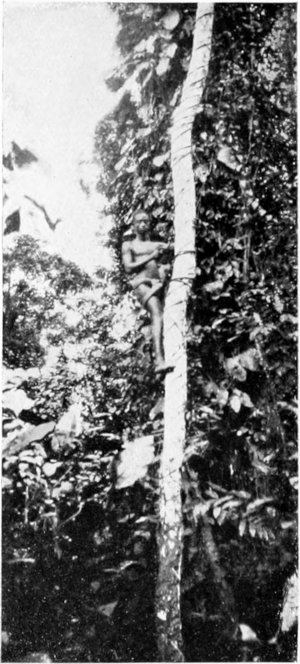

| Native collecting Oil Palm Fruit, Blama | 21 |

| Kola Tree at Mano | 21 |

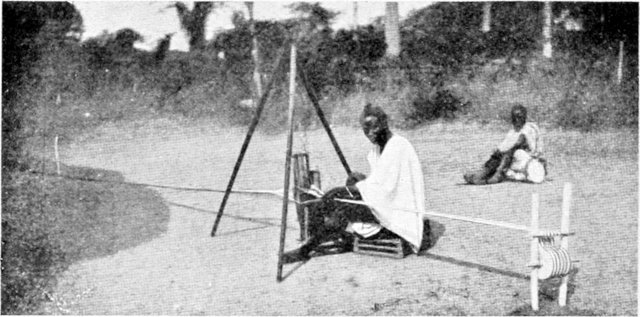

| Native Weaver at Pendembu | 35 |

| GOLD COAST | |

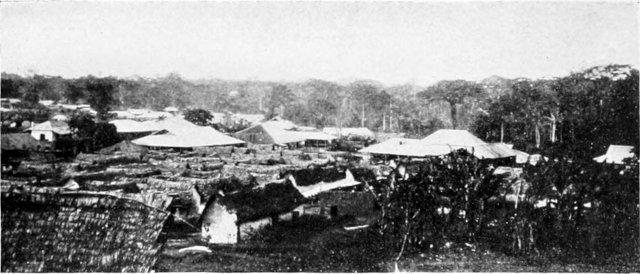

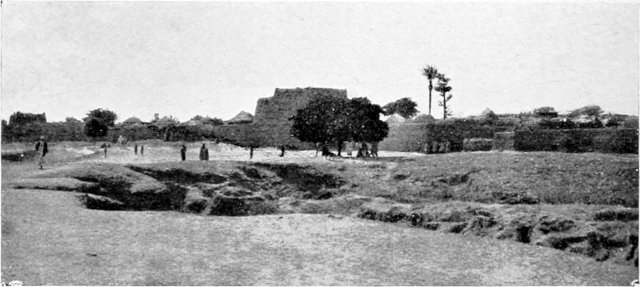

| Kumassi, the Capital of Ashanti | 35 |

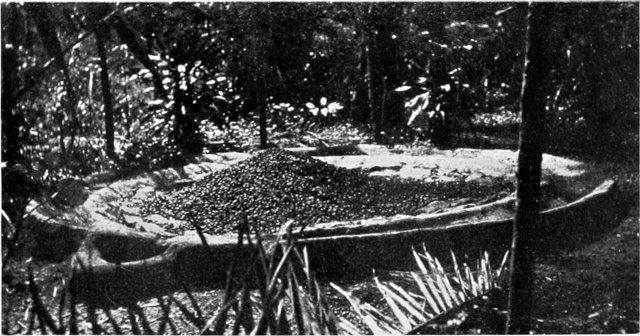

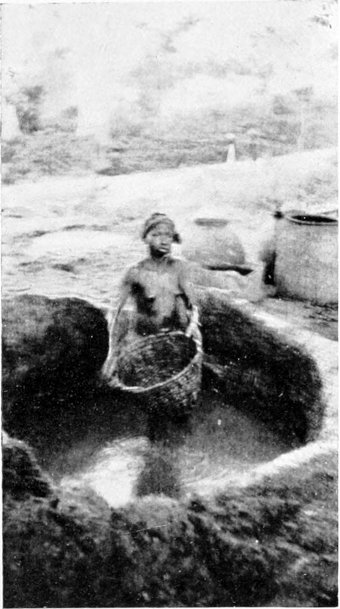

| Stone Vat for pounding Palm Fruits, with surrounding Gutter and Oil Well, Krobo Plantations | 35 |

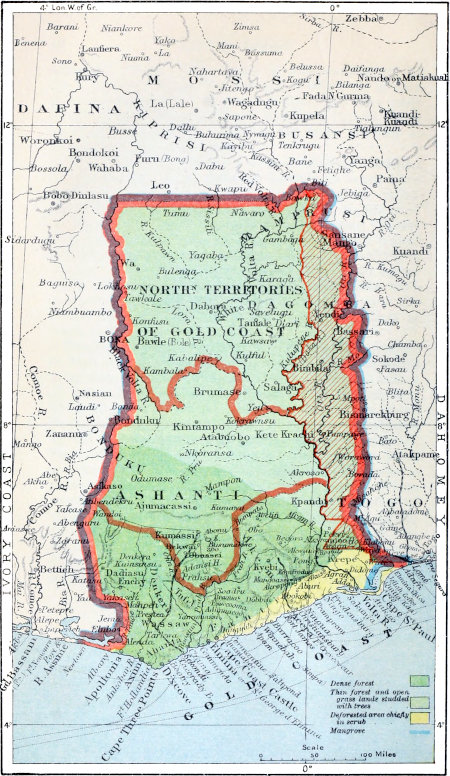

| Sketch Map of Gold Coast | 43 |

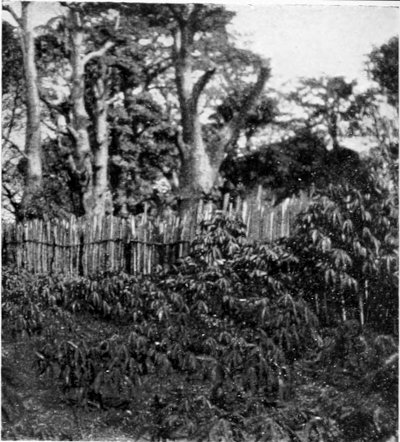

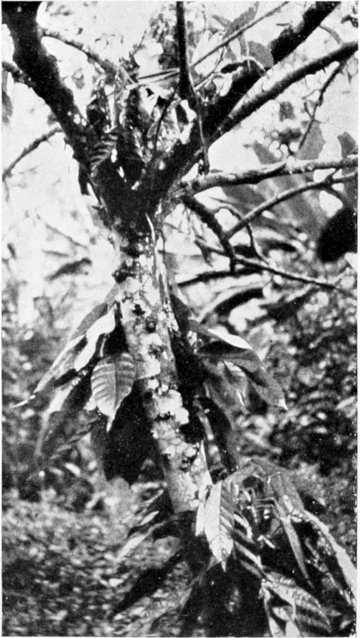

| Cocoa at Mramra attacked by Black Cocoa-bark Bug | 51 |

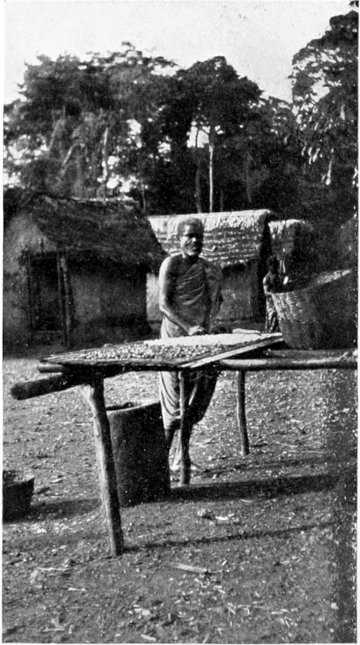

| Drying Cocoa Beans at Mramra | 51 |

| Native tapping Indigenous Rubber Tree (Funtumia elastica), Oboamang, Ashanti | 51 |

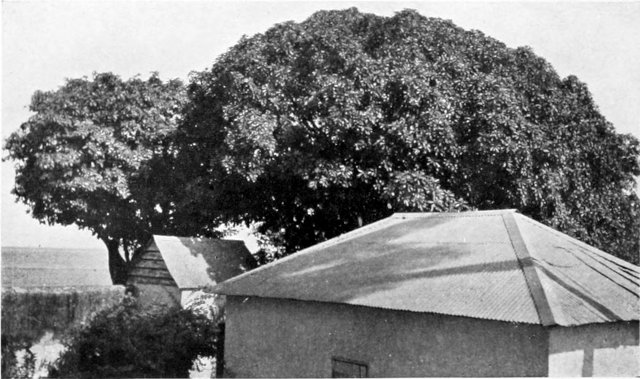

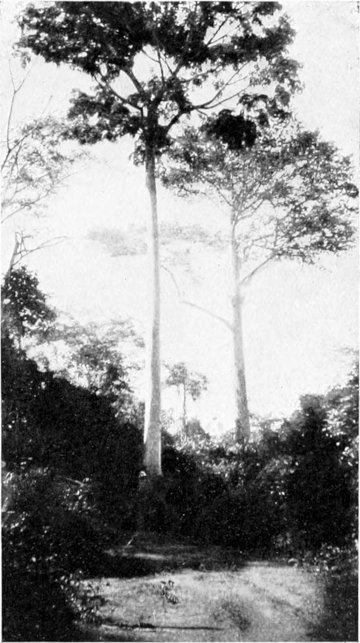

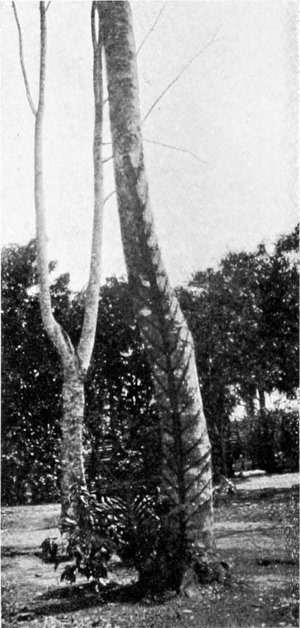

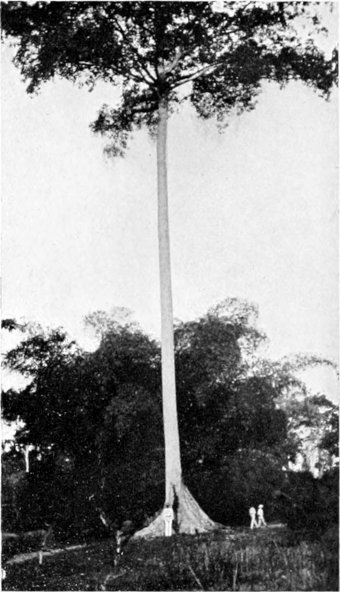

| “Odum” Trees (Chlorophora excelsa) | 61 |

| [xii]Para Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis), tapped at Aburi | 61 |

| Rubber Tree tapped, Herring-bone System Imperfect, Aburi | 61 |

| NIGERIA—SOUTHERN PROVINCES | |

| Sketch Map of Southern Nigeria | 93 |

| Straining Oil from the Fibrous Pulp of the Oil Palm, Oshogbo | 97 |

| Cotton Bales, Marlborough Ginnery, Ibadan | 97 |

| Afara Tree (Terminalia superba) at Olokomeji | 97 |

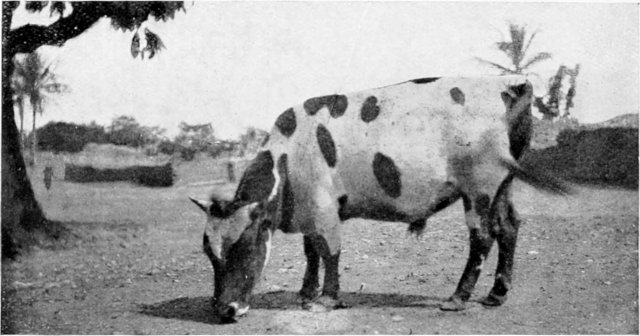

| Dwarf Cattle, Illara | 119 |

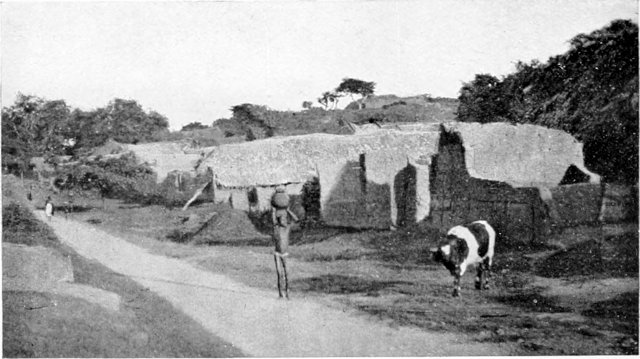

| Owo | 119 |

| NIGERIA—NORTHERN PROVINCES | |

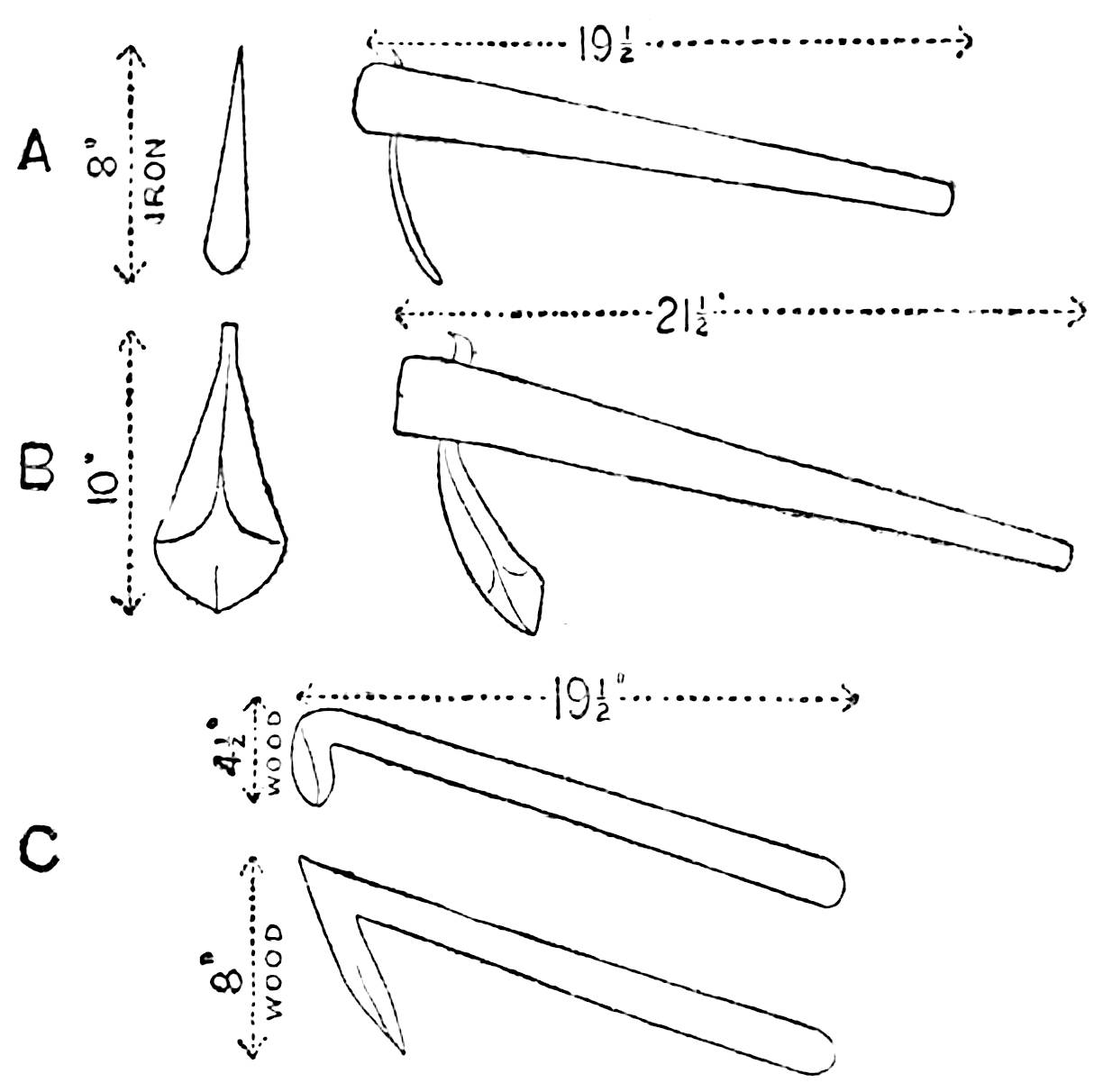

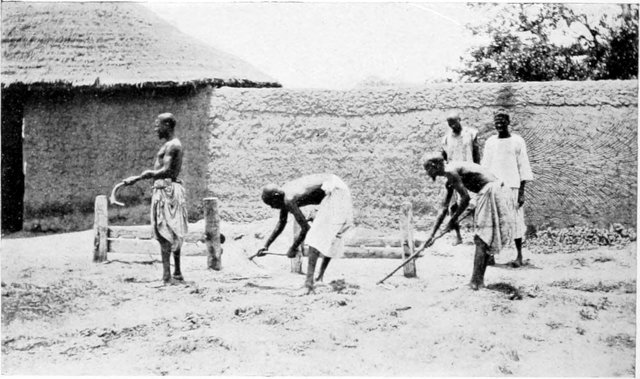

| Haussa cultivating Implements (Left to Right: I. Fatainya, II. Garma, III. Sangumi), Northern Provinces | 119 |

| Sketch Map of Northern Nigeria | 120 |

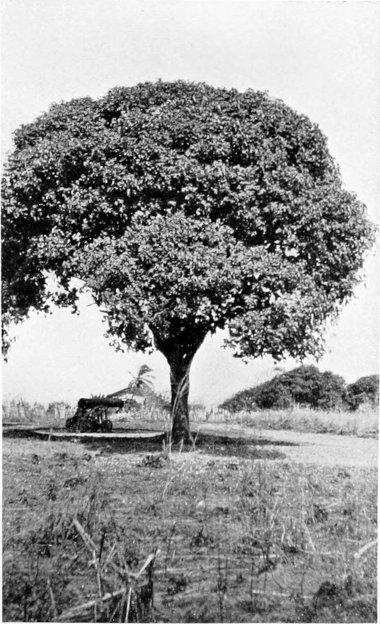

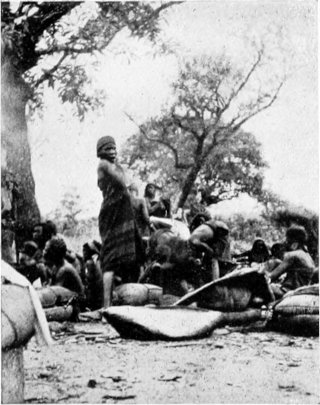

| Shea-butter Tree (Butyrospermum Parkii), with Nut-collectors, Ilorin | 130 |

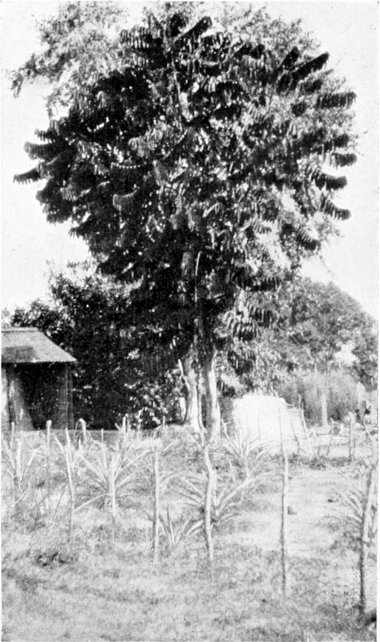

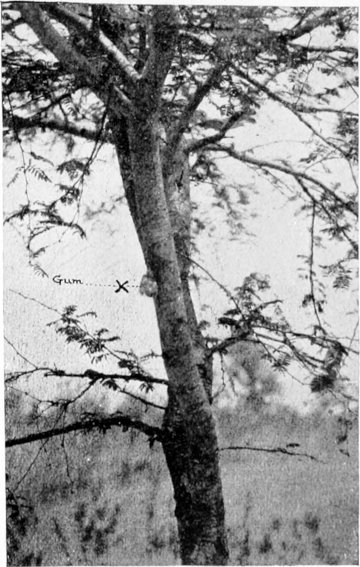

| Yielding Gum Tree (Acacia caffra) at Kontagora | 130 |

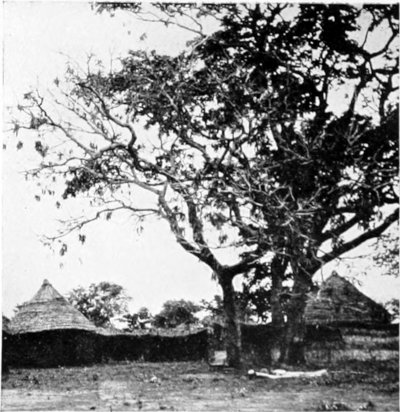

| Locust-bean Tree (Parkia filicoidea) at Ilorin | 130 |

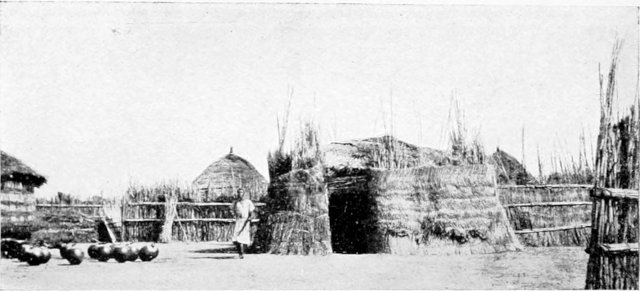

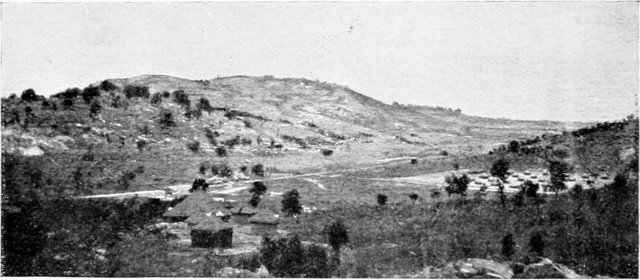

| Village of Fogola, built of Guinea-corn Stalks | 137 |

| Outside the Emir’s Palace, Kano | 137 |

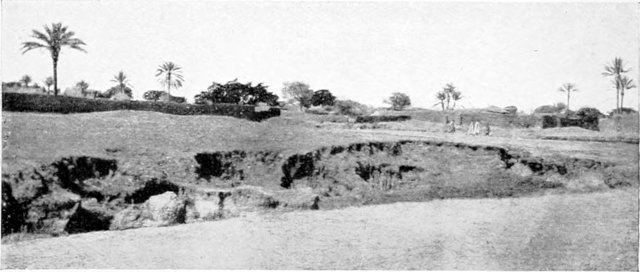

| Near the Southern Gate, Zaria | 137 |

| British Cotton Growing Association Ginnery, Ogudu, Ilorin | 155 |

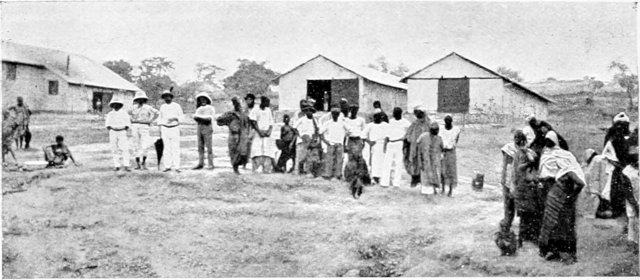

| Gwari Town, opposite Minna, South of Zaria | 155 |

| Cow Fulani Woman selling Milk at Gwari | 155 |

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS. Geographical Position.—The Gambia Colony and Protectorate consists of a narrow tract of country following the winding course of the river from which it takes its name, for a distance of about 250 miles, and extending approximately four miles from the river on both banks.

The whole country lies between 12° 10′ and 13° 15′ north latitude and 13° 50′ and 16° 40′ west longitude. It is the most northerly of the British West African possessions.

Area and Population.—The extent of territory is said to be 3,619 square miles, much of which consists of low-lying land intersected by creeks and rivers, which under tidal influence are often densely afforested with mangroves.

According to the census of 1911 the Colony and Protectorate had populations of 7,700 and 138,401 respectively, totalling 146,101. The total of 90,404 given in the previous census is now admitted to have been below the actual amount. A large migratory farming community exists, coming annually from the adjoining countries, for the purpose of raising groundnut crops. This in 1911 numbered 3,367. Many of these immigrants are reported to have remained and established themselves permanently under the British flag.

Tribes.—The principal tribes inhabiting the Gambia are the Mandingoes, Foulahs, Joloffs, and Jolahs. The first-named are the most numerous, and are, generally speaking, Mohammedans, although there are many “Sonninkis” or spirit drinkers among them. The Foulahs are identical with the Fulanis of the Gold Coast and Northern Nigeria, and are frequently fair-skinned[2] without negroid features. They are said to be strictly Mohammedan, and to have originated from the country near the source of the Senegal river. The Joloffs occupy the northern bank of the Gambia river, and extend well into Senegal. The Jolahs inhabit the province of Fogni, and spread into the confines of French territory towards the Casamance river. They are a curious race, given to living in small family villages, and are said to be vindictive. They are of a lower type than the three other tribes mentioned, and are jealous of their rights.

Political Divisions.—The Protectorate is divided into five districts, each under the control of a Travelling Commissioner. These districts are named in accordance with their positions: North Bank, South Bank, M‘Carthy Island, Kommbo and Fogni, and Upper River.

Natural Conditions.—The climatic conditions of the country are favourable to the breeding of cattle and horses, although in the vicinity of the river and creeks two species of tsetse fly are common. By carefully preventing animals from straying into these infested tracts the spread of fly-borne disease is held in check, and cases are comparatively rare.

During the dry season, which often occupies seven months in the year, from November to May, the highest maximum and the lowest minimum temperatures are recorded; the range being from 41° (lowest minimum, March 1909) to 105° (highest maximum, March 1909 and April 1911). The rainfall, of which official records are kept at Bathurst, varies considerably, as the following extract will serve to show:

| 1901 | 45·31 | inches | 1910 | 44·00 | inches |

| 1902 | 29·42 | „ | 1911 | 28·14 | „ |

| 1903 | 57·13 | „ | 1912 | 33·99 | „ |

| 1904 | 38·02 | „ | 1913 | 23·68 | „ |

| 1905 | 66·07 | „ | 1914 | 48·91 | „ |

| 1906 | 64·36 | „ | 1915 | 47·64 | „ |

| 1907 | 34·00 | „ | 1916 | 38·02 | „ |

| 1908 | 43·54 | „ | 1917 | 37·68 | „ |

| 1909 | 56·59 | „ | 1918 | 54·03 | „ |

Soil.—The soil generally is of a light sandy nature, becoming stiffer as the undulating regions of the upper[3] river are approached. The low countries are subject to flood in the rainy season, and are only favourable for rice cultivation.

JOLAH WITH NATIVE HAND-PLOUGH, BULLELAI, FOGNI.

Fig. 1, p. 3.

CANARY ISLAND PLOUGH, AGRICULTURAL SCHOOL, ABUKO.

Fig. 2, p. 3.

RUBBER TREE (FICUS VOGELII) AT BATHURST.

Fig. 3, p. 9.

Chief Crops.—The country is rather sparsely populated, but, on the whole, the people are fair cultivators and prepare their lands in a careful manner. Practically the only crop grown for export is the groundnut, monkey-nut, or earth-pea (Arachis hypogæa), which forms by far the most important article of cultivation. Alternating this with the staple food-crops of the country, namely, guinea-corn, maize, millet, and cassava, a fairly useful form of rotation is obtained.

Implements.—Cultivation among the Mandingoes and Joloffs is performed by means of a large wooden-bladed, iron-shod hoe, with which the loose earth ridges are thrown up. A small iron hoe is used for keeping down weeds and clearing. In the Jolah country a handplough is employed, consisting of a flat blade attached to a pole, and pushed in front of the operator, so as to throw up a shallow ridge. This is shown in the picture which represents a native with the implement at Bullelai (Fig. 1).

Ploughing.—Cattle are plentiful, even to the extent of there being an insufficiency of fodder for them in the dry season in some localities. They are chiefly kept for the purpose of displaying the wealth of their owners, and are not employed for any kind of farm work. Notwithstanding the shortage of manual labour and the successful demonstrations made by the Government, through the agency of the Roman Catholic Fathers at the Abuko Agricultural School, to prove the value of substituting animal draught for manual labour in tilling the land, the prejudice on the part of the natives against the use of their cattle for ploughing or cartage has not been overcome. A photograph is given showing a native with a Canary Island plough drawn by locally-trained bullocks (Fig. 2). Owing to the failure attending the efforts to introduce ploughing and cattle breeding at Abuko, where, for the latter purpose, some Ayrshire bulls were provided, the Govermnent withdrew the provisional subsidy in 1911.

Land Tenure.—Land ownership is hereditary and descends from father to son among the Mandingoes and[4] Joloffs. No fees are paid or presents given to chiefs when a transfer is made. Europeans can rent land from Government in cases where it is not held or claimed by a native. Grants are apparently issued for various periods, but freehold rights are not given.

The rules regarding the itinerant, so-called “strange farmers,” who annually visit the country to plant groundnuts, vary to some extent in different parts of the Protectorate. Where hereditary ruling chiefs exist, a tax of 4s. per head is paid to them. In other places, half of this tax goes to Government, one-quarter to the chief, and one-quarter to the farmer’s landlord. The landowner generally gives the groundnut seed and food as well as a piece of land to be cultivated. In payment for the seed and food, it is a rule to give one-tenth of the crop. During the time the strange farmer is in occupation he is expected to give one or two days’ work each week on the landowner’s own farm.

Labour.—There is no fixed rate paid by the Government for labour. All the work on a farm is done by the owner and his own boys, but occasionally others come in to assist from the neighbouring farms, but no payment is made—only a present of kolas being usually given.

Agricultural Schools.—An agricultural school, previously referred to, was started at Abuko, near Lammin, under the Roman Catholic Fathers there, and a subsidy was granted by the Government especially for the purpose of educating the sons of large cultivators and chiefs in the use of ploughs and other labour-saving implements. A stipulation was made that the work should be inspected by a Government officer from time to time.

In spite of this a fear was expressed at the outset that the attendance at these schools would be disappointing, in view of the fact that Mohammedan chiefs would be restrained by their mallams from sending their children where there might be a risk of their religious conversion. Although it had been specially laid down that no religious teaching would be insisted upon, the fear proved justified and the school never became a success, the attendance being only of a few aliens. Since the closing of this school no renewal of agricultural instruction seems to have been made.

[5]Chief Exports.—The following table gives the average amounts and values of the chief exports for 1900-10, and the individual figures for the remaining years to 1918.

| Year | Groundnuts tons and value | Rubber lbs. and value | Beeswax lbs. and value | Palm Kernels tons and value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1900-10 Av. | 39,000 tons | 46,000 lbs. | 45,500 lbs. | 255 tons |

| £250,000 | £3,500 | £2,000 | £2,260 | |

| 1911 | 47,931 tons | 10,733 lbs. | 33,871 lbs. | 443 tons |

| £437,472 | £836 | £1,514 | £4,758 | |

| 1912 | 64,169 tons | 4,335 lbs. | 30,830 lbs. | 445 tons |

| £502,069 | £409 | £1,164 | £6,518 | |

| 1913 | 67,404 tons | 12,995 lbs. | 31,518 lbs. | 546 tons |

| £622,098 | £1,027 | £990 | £9,026 | |

| 1914 | 66,885 tons | 3,548 lbs. | 15,513 lbs. | 495 tons |

| £650,461 | £102 | £473 | £7,815 | |

| 1915 | 96,152 tons | 1,171 lbs. | 9,563 lbs. | 326 tons |

| £400,435 | £31 | £311 | £5,457 | |

| 1916 | 46,366 tons | 355 lbs. | 6,950 lbs. | 669 tons |

| £506,098 | £23 | £104 | £14,671 | |

| 1917 | 74,300 tons | 1,753 lbs. | 3,962 lbs. | 532 tons |

| £869,790 | £187 | £247 | £7,994 | |

| 1918 | 56,489 tons | 564 lbs. | 8,626 lbs. | 644 tons |

| £800,319 | £40 | £501 | £9,800 |

Note.—Cotton exports were 59,828 lbs. and 2,572 lbs. in 1904 and 1905 respectively. None has been exported since.

GROUNDNUTS.—This commodity is by far the most important exported product, and is alone subject to a duty levied by the Administration.

Uses.—The undecorticated nuts are shipped, chiefly, to the French ports and to Hamburg, for the expression of an oil of excellent quality, of which they yield on an average about 30 per cent., estimated on the weight of the raw material. This is equivalent to about 44 per cent. of the weight of the extracted kernels.

The mode of extraction in general employment in France is to grind the kernels into a fine meal, from which the first quality of oil is extracted by cold expression, yielding about 18 per cent. The meal is then moistened with cold water, and at the second expression 6 per cent. more is obtained. Both of these oils are useful for alimentary purposes. A third expression is made from the residue treated with hot water, and gives a further 6 per cent., which is chiefly employed for lighting purposes, lubricating and soap-making. The fine oils are substituted for, or mixed with, the olive-oils of commerce for salad oils, and enter[6] into the manufacture of oleo-margarine. After these expressions of oil have been made, the meal is pressed into cakes and used for cattle-food and manurial purposes.

Classification and Description of the Groundnut Plant.—The groundnut belongs to the Sub-Order Papilionaceæ, of the Order Leguminosæ, and is termed Arachis hypogæa, Linn.

The plant cultivated in Senegal and the Gambia grows in a spreading form, with branches of from 12 to 18 inches in length, and possesses oval leaflets given off in double pairs. A large number of conspicuous yellow flowers appear from the upper leaf axils, but are not capable of fertilisation. Those springing from the lower leaf axils nearest the ground are small and generally hidden, but produce fruitful pods. After fertilisation the stems of these flowers become elongated, and are directed downwards, forcing the ovary into the ground, in which it commences to swell to the mature size, frequently penetrating to a depth of two inches beneath the surface.

The fruit is a pale straw-coloured, irregularly-cylindrical pod, with the surface of the shell pitted and longitudinally ribbed. In the Gambian variety, which is identical with the common Senegalese kind, there are usually two kernels in each pod, but three or one are also found.

The plant is of doubtful origin, but it is generally supposed that it may have been introduced into Africa from Brazil (where the genus Arachis is well represented) nearly four centuries ago, by the Portuguese slave-traders.

About 1840 groundnuts began to attract the attention of European manufacturers, on account of the value of the oil obtained from them, and, in common with the Senegalese, the Gambian natives were induced to undertake cultivation upon a large scale.

The nuts grown in the Gambia and in Saloum, in the French territory adjoining on the north, are classed as of second quality; those from Cayor and Rufisque holding the first, and those from the Casamance and Portuguese Guinea the third, places.

The seeds are sown upon ridges with flattened tops,[7] and the crop occupies the ground for about four months—July to October—corresponding to the period of heavy rainfall in the country. When the branches commence to wither, the whole plant is carefully pulled up, so that the pods, which are then mature, remain attached. The plants are then stacked in the fields, and are often covered over with the leaves of the fan-palm. The green parts dry into a hay, which, when the pods have been beaten out, is used as horse-fodder. The advent of rain after stacking often does great damage to the crop, but the occurrence is so rare that it has been found difficult to induce the native to take common precautions against it. During the last two years, however, the Government have taken steps to enforce a regulation with regard to this, and in consequence drains are now generally cut around the stacks, and coverings of palm-leaves are left on until the nuts are ready to be beaten out.

In the Jolah country raised platforms are constructed for stacking this crop as well as others. After the nuts have been beaten out from the dried plants, they are winnowed by allowing them to fall from a slight elevation in a gentle breeze.

A good crop of nuts in the Gambia is estimated at about 44 bushels per acre, equivalent to over half a ton, but larger yields are frequently obtained. The Government standard bushel is used throughout the country, and may contain from 25 to 31 lbs. of undecorticated nuts.

Experiments have been made from time to time, to establish a three-kernel nut instead of the two-kernel one, but the results obtained have not shown that any advantage could be gained in this way. Other varieties of nuts have been introduced and cultivated, but no extensive planting of new kinds has yet been found worth adoption.

The plant seldom suffers from severe attacks of disease, although a white fungus was prevalent in some localities in 1906. This affection was termed “tio jarankaro” by the Mandingoes. In the succeeding year it completely disappeared, and has not been reported to have occurred since. The extermination of this disease was doubtless in a large measure due to the careful way in which[8] the selection and distribution of seed had been carried out. For several years the Government has been accustomed to purchase a certain quantity of the best nuts each season, and to distribute these at sowing time to the cultivators, on credit. Without this precaution, in a season when the prices for nuts were high, the thriftless native would be induced to sell every nut, reserving nothing for sowing the next year. The system adopted is greatly appreciated by the cultivators and merchants alike, and has without doubt contributed largely to the prosperity of the country. Seed is not only interchanged, in this manner, with advantage between different districts, but fresh seed is sometimes also provided from Senegal.

The immigrant or “strange farmers” are generally welcomed by the land-owners, who usually manage to lease them the fields which require the most cleaning. After the immigrant farmer has reaped his groundnut crop, the field is left in a good state of tilth for the owner to sow his guinea corn.

The occurrence of ruinous competition among merchants at Bathurst induced them to form a “combine” to regulate the buying price of nuts; the purchases being pooled and then divided according to a fixed scale. A recent attempt to divert Gambian nuts to Senegal ports for shipment, by the levy of an import tax at Marseilles, was opposed by the French and British merchants alike, and the fear that the produce might only be diverted to another destination led to its abandonment. For further information regarding the cultivation, varieties and uses of groundnuts, see Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol. viii. (1910), pp. 153-72.

RUBBER.—A good quality of rubber is produced in the Jolah country, in particular, from Landolphia Heudelotii, an apocynaceous vine, which grows commonly in the grass lands of Fogni.

The vine is tapped by women, who, after digging a hole near the root of the plant, make a number of transverse cuts upon the root-stem. The latex flows rapidly from such cuts, and is coagulated by throwing salt water on the wound. The scrap rubber which forms is collected the following day, and the pieces are attached to one another, forming an open sponge-like ball of a pinkish-white colour. Sand is often present in these[9] balls owing to the fallen latex being added to the rest.

RUBBER VINE (LANDOLPHIA HEUDELOTII) AT KOTOO.

Fig. 4. p. 9.

CEARA RUBBER TREE (MANIHOT GLAZIOVII) AT BAKAU.

Fig. 5, p. 10.

RUBBER TREE (CASTILLOA ELASTICA) AT KOTOO.

Fig. 6, p. 10.

In addition to the inhabitants themselves collecting rubber, natives belonging to a tribe from Portuguese Guinea, called “Manjagos,” travel through the country for the purpose; the rubber which they obtain being sold in the French Colony to the south of the Gambia. The “Manjagos” are said to make a semicircular cut upon the thick vine-stems just above the ground, to induce the better flow of latex. This, they maintain, is not a destructive method, and that, as the root stock is uninjured, the plant continues to yield latex for a long time. At one time the rubber vine must have been plentiful, but the rush for it which occurred at the beginning of the present century has had the effect of exterminating it, except in the more inaccessible places. The export has declined and is now insignificant. The plant is known to the Mandingoes as “Folio.” An illustration is given showing this plant at Kotoo (Fig. 4).

Landolphia florida, Benth., is common in places similar to those where the last-mentioned vine occurs, but the latex is not used in any way to adulterate the good rubber, nor is inferior “paste” rubber made from it, as in other places in West Africa. Ficus Vogelii, known as “Kobbo” (Mandingo), has recently been used for extracting an inferior rubber, which has been shipped in small quantities. This tree is found growing in Bathurst as well as in many of the large towns, where it often attains a large size, and affords an excellent shade for native markets, etc. A view of a tree in Bathurst is shown (Fig. 3). Information regarding the composition and value of the rubber of Ficus Vogelii is given in the Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol. vii. (1909), p. 260.

Some of the South American species of rubber trees have been planted at different places, but for the most part the climatic conditions have proved unsuitable for their establishment. An exception to this is the Ceara rubber (Manihot Glaziovii), large trees of which were to be seen in Bathurst and at Bakau, but in the latter locality appear to have been cut down during recent years. It is generally acknowledged that Ceara[10] rubber has not proved successful in plantations made in different parts of West Africa, for, although rubber of the finest quality can be easily prepared from the latex, the tree furnishes an extremely inconstant yield of latex. In the Gambia the tree reproduces readily, and, as far as can be judged, produces a latex capable of being coagulated into good rubber. As a shade tree it is recommended to be grown along public roads, and it might prove expedient in the country to make small experimental plantations, in the manner adopted in Togoland and elsewhere. By this system, tapping is continued for a few years, and whole blocks of trees are cut out as they cease to yield latex—the seedlings which have sprung up beneath these trees being permitted to take the place of the original trees. An illustration showing a Ceara rubber tree at Bakau is given (Fig. 5).

One specimen of Castilloa elastica, of which a photograph is given (Fig. 6), is growing in the Kotoo farm, about 12 miles from Bathurst. This tree has not, so far, proved successful in West Africa, and the example photographed is apparently in better condition than those grown in the Botanic Gardens of the Gold Coast and Southern Nigeria.

Funtumia elastica, the Lagos silk rubber tree, does not thrive in the Gambia, and the rainfall has been found to be insufficiently distributed for the cultivation of the Para rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis).

The observed facts point to the conclusion that further experimental trials of certain species of rubber trees in the Gambia should be made.

BEESWAX.—It will be observed that a large quantity of beeswax is annually exported, the quality of which is high. The native bee is a small form of Apis mellifera, var. Adansonii. It is found in a wild state forming nests in hollow trees or rock cavities. The Mandingoes collect the wild swarms and confine them in basket-hives, cylindrical in form and sometimes plastered over with mud. These are placed in high trees or in abandoned huts. The wax is sold in a crude form to the Bathurst merchants, who boil it down and strain it previous to shipment. The European market value of the cleaned wax is from £5 to £6 per cwt. A detailed description[11] of methods for the refining of wild bees’ wax for export is published in the Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol. viii. (1910), pp. 23-31.

PALM KERNELS.—The West African oil palm, Elæis guineensis, is found commonly in some parts, but the heads produced are small and carry small fruits, containing little oil. This oil is used locally, and the kernels from the nuts alone are shipped. The palm is chiefly valued for the production of palm wine, which is tapped from the base of the fruiting stems into funnelled gourds, hung beneath the holes. The tree is apparently never felled for the purpose, and, by limiting the amount of wine extracted, it survives for a long period.

COTTON.—The Mandingoes and Jolahs cultivate cotton for making the yarn used in their native looms, in which they weave the strips of cloth called “pagns.” These strips are afterwards sewn together along their lateral edges and made into gowns.

The native cotton plant varies somewhat in appearance. In Kommbo, a long straggling form occurs, which is retained for two seasons to produce cotton, but in the Jolah country a small annual is most frequently seen. The former is grown as a mixed crop and the latter in separate patches.

In quality, from the European spinner’s point of view, the Mandingo cotton lint compares favourably with the commercial type called “middling American” as far as length of staple is concerned, although it is not so white, nor is there so much silkiness apparent. It has been rightly remarked that the native variety, if properly cultivated, would probably give a better result than would be obtained from the introduction of American seed. The Jolah cotton is short-stapled and woolly, though whiter than the Mandingo. It would be more difficult to improve this kind sufficiently to suit the European demand.

Egyptian cotton seed was tried in the Gambia about twenty years ago, and the variety was at first considered suitable; the cultivation was, however, not proceeded with, owing to local difficulties.

The obstacles which hindered the development of cotton-growing in the Gambia for export were the same[12] as those experienced in Sierra Leone. The local demand for raw cotton precluded it from being obtained at a sufficiently low price to leave a margin of profit to exporters, and in addition to this, labour was not sufficiently abundant, nor were the natives familiar with labour-saving methods in cultivation. Attempts to establish an interest in the matter produced a fair amount of raw cotton in 1904, but since that year the exported quantity rapidly diminished and has now ceased altogether. For reports on the quality of the cotton produced in the Gambia see Professor Dunstan’s British Cotton Cultivation (Colonial Reports—Miscellaneous Series, Cd. 3997, 1908), p. 26, and Bull. Imp. Inst., 1921. Samples may be seen in the Imperial Institute Collections.

GRAIN CROPS.—No grain is exported, as owing to the work of the scanty population being so largely applied to the cultivation of groundnuts, scarcely sufficient food-stuff is grown for their own requirements. Guinea-corn (Sorghum vulgare), the two most important varieties of which are known as “Bassi” and “Kinto” in the Mandingo language, are commonly used for food, but during recent years, owing to the repeated annual attacks on the crop by Aphis sorghi, maize-growing was substituted in some parts of the country. White maize seed was obtained from Lagos, and yellow maize seed from the Canary Islands, but the grain is not appreciated to the same extent as Guinea corn. Pennisetum typhoideum, the large millet, of which the commonest variety is known in Mandingo as “Sannio,” is alternated with Guinea corn or maize, but is often badly affected by a “smut fungus” (Ustilago sp.), which also attacks the “Kinto” variety of Guinea corn. A small grass is often grown in the millet fields, yielding a crop of fine seed which is made into flour for the preparation of a kind of porridge. This is termed “Findi” locally. Rice (Oryza sativa) is somewhat extensively grown in the swamp lands, but the success of the crop is very largely dependent on the distribution of the rainfall. Whole tracts of rice fields are destroyed in some years, owing to excessive floods, as no precautions are taken to guard against them. It is chiefly on account of the uncertainty of the grain crops, that a large quantity of rice has to be imported annually to supplement that[13] produced in the country. These imports often amount to six or seven thousand tons.

FRUITS OF OIL PALMS, SIERRA LEONE.

Fig. 9, p. 21.

SWEET CASSAVA, WITH BAOBAB TREES, BAKAU.

Fig. 7, p. 13.

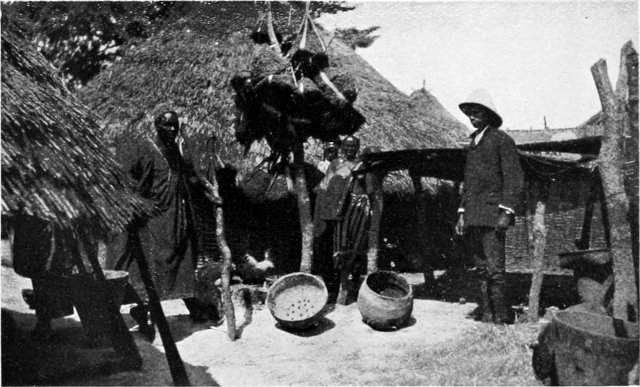

INDIGO DYERS, McCARTHY ISLAND.

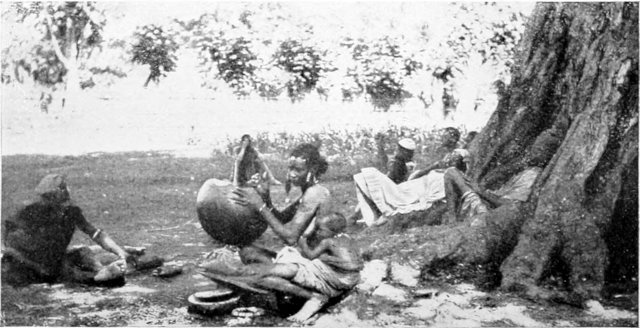

Fig. 8, p. 13.

ROOT AND OTHER CROPS.—Sweet cassava (Manihot palmata) is frequently planted as a terminal crop in the crude rotation employed. This variety can be eaten without previously washing or cooking. An illustration of a cassava field is given (Fig. 7). Two or three kinds of beans are planted, though not extensively in spite of a good local demand for them. Okra (Hibiscus esculentus), cultivated for the edible fruit pods, indigo (Indigofera sp.) employed for making the local blue dye, and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), are planted near houses. A photograph is given exhibiting the different utensils required for the preparation of indigo, and cakes of the dried and fermented indigo stalks, in the form in which they are preserved, are shown suspended in the illustration (Fig. 8). The tobacco prepared is usually ground into snuff, in which form it is used for chewing as well as for smoking.

TANNING.—Goat-skins are tanned in the manner similar to that employed by the Haussas; Acacia arabica pods being used in the process. The people who perform the work of preparing and working leather are termed “Korankos.” Red and black inks, purchased from the European merchants, are used for staining the leather, which is inferior to that produced in Northern Nigeria (see p. 142).

FIBRES.—The country seems to be plentifully supplied with fibre plants in a wild state, chiefly belonging to different species of Hibiscus. These are of the jute class, and are used throughout the country for making native ropes. Indian jute (Corchorus capsularis) has been tried experimentally at Kotoo, and excellent samples were obtained, but the quantity of fibre per acre turned out to be small, and the working proved to be too expensive.

The preparation of piassava, which had been abandoned for many years, is said to have been taken up again by a British firm in 1915. The fibre is obtained from the leaf sheath of a palm (Raphia vinifera) which grows plentifully along the banks of the Gambia in places. For further information see Selected Reports from the Imperial Institute, Pt. I., Fibres, and Bull. Imp. Inst., 1915.

TIMBER.—There are no trees of commercial importance,[14] accessible for felling for export, although Gambian mahogany (Khaya senegalensis) and Gambian rosewood (Pterocarpus erinaceus) occur in many parts of the country. In some remote districts the former tree is said to attain large dimensions (Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol. viii. (1910), p. 244).

TRADE.—The following extracts from the Colonial Reports show the diversion of destination of Gambian exports which has occurred in recent years. For this purpose groundnuts are regarded as representing the whole of the trade, of which they normally constitute about 90 per cent.

Percentages of Exports from the Gambia

| Destination | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Great Britain and British Possessions | 6·30 | 9·00 | 6·72 | 9·92 | 39·45 | 53·56 | 79·56 |

| France and French Possessions | 84·80 | 76·00 | 59-10 | 79·34 | 48·60 | 36·58 | 20·35 |

| Holland | 3·20 | 9·00 | 6·03 | — | — | 4·20 | — |

| Germany | — | 3·64 | 24·56 | 6·80 | — | — | — |

| Denmark | — | — | — | 1·99 | 7·68 | 5·63 | — |

| Spain | — | — | — | ·35 | 4·24 | — | — |

| Other countries | 5·70 | 2·36 | 3·59 | 1·60 | 0·03 | 0·03 | 0·09 |

| 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

From the above it will be noted that Germany began to appear in the market in 1912, and, in 1913, had taken nearly one-quarter of the output. This is probably accounted for by the rapid growth of the vegetable oil industry in Germany and the attempt on the part of Hamburg crushers to capture the Gambia trade from Marseilles. It will be seen that a proportionate decrease occurred in exports to French ports coincident with the increased shipments to German ports. The European war put Germany out of the market, and in 1914 France took nearly her normal share. In 1915 and 1916, however, Great Britain felt the lack of imported vegetable oils to such an extent that factories for their extraction sprang up in the country; thus it is seen that in 1915 Great Britain took nearly 40 per cent. against France’s 48½ per cent., and in 1916, Great Britain, for the first time in the last fifty years, took a larger portion of the Gambian groundnut crop than France.

GAMBIA & SIERRA LEONE

Stanford’s Geogl. Estabt., London.

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS. Geographical Position.—The Colony and Protectorate of Sierra Leone are bounded upon the north and west by French Guinea, and upon the east by Liberia. The Colony is confined to the hill country of the Sierra Leone Peninsula and Sherbro Island; the remainder being Protectorate.

Area and Population.—The area of the country according to the Blue Book of 1911 is 31,000 sq. miles. The greater part is undulating, well watered and fairly fertile, traversed by short ranges of mountains, mostly running north and south. The population of the Colony, by the census taken in 1911, was 75,572, and of the Protectorate 1,327,560.

Administrative Divisions.—The country is divided into seven administrative districts, two of which are in the Colony and five in the Protectorate. The latter have been formed primarily in accordance with tribal settlements, due to the expediency of recognising in each the native customary law; the exception to this is the Railway district, in which other considerations of greater importance are involved.

Natural Features.—Although the country is largely of a slightly undulating type, in the north a curious formation of hills exists, in the Koinadugu district; each hill bearing a curiously-formed pinnacle of rock on its summit, and presenting a most striking appearance. The valleys between these hills contain some of the richest soil found in the country. Farther north, above the 9th degree of latitude, the country is composed chiefly of grass land interspersed with stunted trees. Approaching the coast, secondary forest or scrub occurs, which is constantly being cleared for farms; being so used for a year or two and then allowed to revert to “bush” for long periods.

[16]Natives.—The inhabitants of the Colony are chiefly the descendants of liberated slaves from North America and the West Indies, but a number were rescued by British war-vessels from slave ships, and represent races from all parts of West Africa. The language adopted by these people is a “pidgin English” of a peculiar kind, and is easily understood after a few of the curious idiomatic phrases have been learnt.

The most important tribes are the Mendis, Timanis, Limbas and Sherbros. These are followed in number by the Konnohs, Port Lokkos, Susus, Korankos, Bulloms, Krims, Yalunkas, Mandingoes, Gbemas, Foulahs, Gallinas or Veis and Gpakas. The Mendis are the largest tribe, and are entirely pagan; they cultivate in a wasteful manner and are otherwise improvident. The Timanis are more intelligent and careful, and the Veis, occupying the sea coast to the south, who have recently adopted cocoa planting, are not only considered the most intelligent, but, alone among West African natives, have a written language.

Land Tenure.—The land in the Colony is held by the Crown, and is granted on the authority of the Governor. All grants made contain reservations with regard to roads and other public requirements. The tenure of Crown lands is fee simple, but occupation is also sanctioned under squatters’ licence at a nominal rent, and the tenure is then in the nature of a tenancy at will. Under Ordinance No. 14 of 1886, real and personal property may be taken, acquired, held or disposed of by any alien in a manner similar to that allowed to a British-born subject.

Fields or waste lands outside town or village limits in the Sierra Leone Peninsula and Sherbro Island must be taken up in lots of not less than 20, or more than 200, acres. Such lots are disposed of at auction, at an upset price of 4s. 2d. per acre in the former, and 8s. in the latter locality. Up to 1902 the question of land grants in the Protectorate was unsettled, but arrangements may now be come to with the chiefs for the lease of tracts of land for long periods on an annual rental, agreed to between the applicant and the tribal council; the title requiring the confirmation of the Government. According to native law, it is generally recognised that the lands of a chiefdom are not the property of the chief, but are[17] held in trust by him for the tribe. A chief has no power to alienate any portion of the land of a chiefdom, or to grant to any one perpetual rights to any portion, but the lease of land by an arrangement with the tribal council, and with the approval of Government, should be satisfactory for all requirements with regard to legal title.

Labour.—Plantations worked by chiefs at the instigation of Government are usually supplied with labour by the chief, although monetary assistance in the form of bonuses is occasionally given. Under such conditions experimental plantations of fibre, rubber, kola, etc., have been made. There is no fixed rate of pay for labourers, but the usual wage for an adult man, when hired, is from 6d. to 1s. per day.

Cultivation.—Throughout the country a shallow type of cultivation is common, and one in which the bush stumps and roots are not removed. The seeds of a number of different kinds of agricultural crops are generally mixed together before being sown broadcast over the lightly scraped soil of the burnt bush area.

The object of retaining the bush stumps and roots in the fields is that, after two or three years of cultivation, the bush may be easily reinstated, and again after ten or fifteen years, when cut down and burnt, it furnishes a supply of wood ash for the fertilisation of the field. This application of ash constitutes the only form of artificial renovation which the soil ever receives.

Recently experiments have been made in the presence of natives, in order to show the advantages of deep cultivation. To effect this, without the employment of ploughs, the fork kodalli hoe, recommended by the writer, has been introduced and generally adopted. The substantial increase in the production of their rice fields obtained by the use of this implement made a fortunate impression among the natives.

The native agricultural implements consist of a straight-handled, narrow-bladed hoe called “kari” (Mendi), or “katala” (Timani), and one formed from an angled stick with a charred point, called “baowe” (Mendi), or “kalal” (Timani). This last is used for drilling. In addition to these, a large broad-bladed hoe, called “karu wai” (Mendi), or “katala kabana” (Timani), is employed for cleaning out weeds and scraping the soil surface;[18] the latter being the only cultivation the growing crop receives. These implements are illustrated below.

A. “KARI” (MENDI), “KATALA” (TIMANI).

B. “KAKU WAI” (MENDI), “KATALA KABANA” (TIMANI),

C. “BAOWE” (MENDI), “KALAL” (TIMANI).

Agricultural Schools, etc. Chiefs’ Sons’ College.—In 1906 a college for the sons of chiefs was established at Bo, and it was intended that, in addition to the ordinary course of instruction, the rudiments of improved agriculture should be taught. This was subsequently found to interfere with the teaching of other subjects which were considered more necessary, and was abandoned in consequence. The omission of agricultural training from the course did not preclude the scholars from cultivating small patches of vegetables for their own use, upon ground allowed to them for the purpose.

Thomas Agricultural College.—In 1908 the erection of an Agricultural College was commenced at Mabang, under the terms of the will of Mr. Thomas, a native who bequeathed a large sum of money to be devoted to this purpose. The College was expected to be completed in June 1910, when a commencement of lectures and general[19] instruction was to be made. Scholarships and some official control were provided for by the terms of the trust, but the project was never developed, and the buildings were not even completed.

Principal Crops.—The most important food crop is rice, but two varieties of maize are also cultivated for local consumption; one of these is quick maturing, and is probably identical with the white variety which is exported from Lagos, from which country it is said to have been introduced into Sierra Leone. The other kind is of slower growth, and bears a yellow grain. Yams, sweet potatoes, and cassava are grown, especially where there is a heavy rainfall.

Forest Products.—Besides the agricultural crops, the forests yield palm oil and kernels, and kola nuts are planted for the much appreciated seed which their pods contain. The latter nut is said to have a stimulating effect, and to allay hunger and thirst when chewed. The nut is in such great demand throughout Northern Africa that a large trade exists between Sierra Leone and the coast countries to the north.

The more important exported products are accorded the foremost positions in the following account.

OIL PALM. Localities and the Influence of Position.—Elæis guineensis is found generally throughout the country from the sea-board towards the interior, diminishing in those districts where the climate becomes drier or where rocky and mountainous tracts intervene. In places, owing, doubtless, to the wasteful methods of treatment and the carelessness in burning the “bush” for farms, extensive areas without palms are occasionally met with, even where the soil and climatic conditions are not unfavourable to their growth. In the extreme north, where the rainfall diminishes, the tree is only found in the vicinity of streams. The most suitable situation for growth seems to be one in which the soil is generally rather moist, although swampy, ill-drained land is not favourable. In those parts of the country where a gravelly laterite appears as a surface soil over a deep substratum of syenite, trees may often be met with in considerable numbers, but it is observed that the trunks of such trees do not acquire the same thickness as those[20] growing in a damper and lighter soil. It is probable, although no experiments have yet been made affording direct evidence for the conclusion, that the fertility and yield of fruits of the trees growing upon the flat lands are greater than those established upon the higher undulating country because they are subject to less wash and more natural irrigation. It is also quite possible that the variety of palm fruit produced in the former places will be found to furnish better commercial results. No distinct varieties are, however, recognised by the natives, although distinctive names are applied to the same fruit in different stages of development.

The oil palm does not appear to be able to thrive in heavy forest, and in a natural state occupies open valleys with low undergrowth, but upon the clearance of primary forest it soon becomes established.

The seeds or nuts, which are large and heavy, are distributed by the agency of frugivorous birds and mammals. The grey parrot, for example, may be observed extracting the ripe fruits from the heads or picking them from the ground where they have fallen, and, after conveying these to a convenient tree, carefully removing the oily pericarp before dropping the nut in a new position. Monkeys doubtless convey the fruits to even greater distances in their cheek-pouches.

Owing to the presence of rocky and swampy strips of country in the Protectorate, and the direction in which farm fires have been carried by the prevailing winds, the distribution of palms has been thought to assume the character of “belts,” defined by fairly well-marked boundaries. When looked into more closely, however, the distribution appears to be better described as consisting of dense patches linked sometimes by almost unrecognisable chains of widely scattered trees, and often broken into by short ranges of hills which are completely destitute of palms.

The patches referred to may bear 500 palm trees to the acre, and these may represent 80 to 100 per cent. of the total tree-growth on the patch. The area of such a patch may be roughly estimated at from ¼ acre to 15 sq. miles, or even more, but it should be added that, where such extensive tracts as these occur, the difficulties of transport and the scarcity of the population have[21] constituted obstacles to working, and to the means of preserving the trees. Oil palms near Mafokoyia are shown in the picture (Fig. 10).

OIL PALMS (ELÆIS GUINEENSIS), MAFOKOYIA.

Fig. 10, p. 21.

The appearance of a young tree is that of a thick stem throwing out annulate series of long feathery leaf fronds, upon petioles, which bear roughly-formed spines. As the tree increases in height the lower petioles are shed, and the trunk assumes a narrower but more regular form; indistinct rings being traceable, formed by the bases of the fallen leaf stems. A mature tree will measure about one foot in diameter at four feet from the ground, and at the ground surface the diameter will be two and a half to nearly three times as much. The male flowers are collected in the form of a number of tassel-like pendants, springing from a common stalk, and one such bunch is usually found above and upon each side of the female inflorescence. Both sexes of flowers usually occur upon the trees, but the natives recognise the existence of a non-fruiting tree, and one which only produces male flowers. The number of fruit heads and the weight of these vary according to the position, age, and treatment of the tree. An idea may be given of the fruitfulness of trees, from the accounts obtained from natives in different parts of the country. The palm has two fruiting seasons, one during the dry weather and another during the rainy season, the latter being generally the lighter crop. It is estimated that a tree in full bearing will yield from twelve to twenty fruiting heads in one year, each of a fairly large size. A younger tree may only produce four to eight heads, but usually of a larger size; and a tree of only five or six years old may give about the same number of heads, but of smaller dimensions. From very old trees small heads with fruits of a diminished size are obtained. The weight of a moderately large head will be about thirty pounds, and will contain about twelve hundred fruits weighing roughly 23 lbs. An illustration showing two fruiting heads is given (Fig. 9).

The ripe fruiting heads are gathered by a man using a climbing sling, with which he encircles the tree and his waist, and by means of a skilful manipulation of the part in contact with the trunk and remote from the body, he proceeds to ascend the tree rapidly, almost[22] as though walking up it. On reaching the crown, a number of dead leaves have to be removed in order to get at the fruit stem. These are cut by means of a “cutlass” or “machete,” which the climber carries, and are thrown to the ground. Only one head ripens at a time upon each tree, and the time occupied in climbing and cutting out the fruit head is estimated at about eight minutes. A photograph showing a native climbing a palm tree is reproduced (Fig. 11).

Both the Mendi and Timani races distinguish the fruit, at different periods during the advance towards maturity, by special names given with regard to the appearance. Identifications of the same series of fruits by different individuals have shown that these names are widely used.

Although it will be seen that in the Gold Coast and Nigeria the natives recognise a number of different varieties of fruit, this does not appear to be the case in Sierra Leone. The thin-shelled forms, so well known to the natives of the former countries, appear unknown, except around Sherbro, where there are a few trees recognised as productive of this type of fruit. In the appearance of the mature fruit, the presence or absence of black at the apex seems to be of equally common occurrence, but no importance is attached to this feature.

The Sierra Leone form appears to be at a disadvantage with regard to the proportion of oily pericarp covering the nut, as well as in the great thickness of its shell. Comparing it with the varieties obtained in the Gold Coast, it is probably nearest to, if not identical with, that called “Abe pa.”

When the percentage of oil extracted from the fruit of the Sierra Leone trees is compared with that from other parts of West Africa, it at once becomes apparent that the amount is small. The results of three series of experiments, made in different parts of the country, showed that the fibrous pericarp, which contains the oil, constituted only about 30 per cent. of the whole, the nut containing the kernel being large and approximating 70 per cent. Palm oil extracted by native methods gave 1·201, 5·47, 5·637, and 8·326 per cent. respectively in four tests. If these results are compared[23] with the extractions of oil from the several Gold Coast varieties, the deficiency is very marked. Compare Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol. vii. (1909), pp. 364-71.

A close examination of the local fruit shows that the outer fibrous portion or pericarp, which alone contains the palm oil, is very thin, whereas the hard shell surrounding the kernel is thick. The kernel represents about 15 per cent. of the total weight of the fruit, and is largely exported from the country for the extraction of another kind of oil.

Small Export of Oil compared with Kernels.—The proportionately larger weight of kernel than of palm oil capable of extraction, accounts for the large quantities of kernels exported compared with palm oil. As an example of this, it may be mentioned that in the year 1906 Sierra Leone exported only 12½ gallons of palm oil to each ton of kernels, whereas Southern Nigeria figures for the same year showed 142 gallons of oil per ton of kernels. Since this date, up to the beginning of the war, a comparison of the annual exports of oil and kernels shows a fluctuation between about 12 and 19 gallons of pericarp oil for every ton of kernels; the latter still remaining disproportionately high.

Proposal to introduce New Varieties.—Since it has begun to be realised that the local variety of palm is probably constantly inferior as an oil producer to some of the varieties found farther to the south, it has been suggested that some of the forms, with a thicker fibrous pericarp and a thin-shelled kernel, should be introduced and planted upon an extensive scale. It is assumed that by doing so, a better type would become established. Experiments made in the Kamerun show, however, that the progeny of palms having a thin-shelled fruit (Lisombe) do not necessarily retain their important characters. Dr. Strunk has suggested that, in the variety mentioned, the characters are not fixed or susceptible of transmission, but the experiments are not considered as yielding conclusive evidence, and it is advisable that experimental plots should be planted with the more useful forms in Sierra Leone and elsewhere, the seed being obtained from artificially fertilised sources.

[24]Improvements in the Local Manufacture.—During recent years great efforts have been made by the Administration to increase the exports of both palm oil and kernels by opening up the previously rather inaccessible areas in which palm trees were found growing almost untouched. The first step in this direction was the extension of the Sierra Leone Railway line from Boia, a small village just beyond the Headquarters District boundary, to Mafokoyia, lying a short distance to the north. From here a road was made eastwards towards Yonnibannah, passing through country fairly well studded with oil palms. Later from Yonnibannah the objective of the railway became Baga, a town on the Maybole river, again to the north. At the present time this line has reached Kamabai, at the foot of the Koinadugu mountains and to the west of Bumban, passing the town of Makump on its way there. The whole of this route has been chosen in order to make the oil palm regions more accessible, and the increase in exports of both oil and kernels between 1907 and 1913 is almost entirely attributable to this development.

Not only was it desirable to open up new areas from which palm fruits could be gathered, but, owing to the deficiency of pericarp oil shipped from the country in comparison with palm kernels, it was thought that, by the introduction of improved methods for extracting the pericarp oil, more of this commodity might be obtainable in the future.

The prospect of working a large area both experimentally and commercially for oil extraction in situ, attracted Messrs. Lever Brothers, who installed ample mechanical apparatus at Yonnibannah in 1914. The Government had granted this firm a concession to work several hundred square miles on the understanding that the local traders and merchants were not thereby to be debarred from buying the hand-prepared oil from the natives as before. The scheme was intended to demonstrate the advantages of mechanical means of extraction over those of hand power; and it was thought that, by the introduction of these greater facilities for dealing with the oil palm products, labour would be liberated and would be employed to a greater extent in the less heavy and more remunerative direction of plantation and field[25] work. Messrs. Lever Brothers’ factory was one designed to be equipped both from a mechanical and research standpoint, and a special shunting yard on the railway was leased to the firm by the Government to deal with the anticipated work. The project seemed so promising that local firms were contemplating following Messrs. Lever Brothers’ example in other localities. The whole scheme was, however, abandoned after a short trial; Messrs. Lever Brothers having probably discovered two facts in connection with the oil palm industry in Sierra Leone which had been lost sight of. The first is that the pericarp of the common type of palm fruit found in Sierra Leone, as pointed out in the first edition of this book, is very thin and therefore contains very little oil, and that the shell of the nuts in this thin-pericarped fruit is extremely thick. The common Sierra Leone kind is therefore of less economic value both in respect to pericarp oil and kernel contents than the common kind found in the Gold Coast, Nigeria and Kamerun. The second point is that the Mendis and Timanis occupying this part of the Protectorate are a lower type and generally poorer workers by comparison with the Fanti tribes of the Gold Coast or the Yorubas of Nigeria.

One explanation given for the failure of Messrs. Lever Brothers’ effort in Sierra Leone was that they did not offer a sufficiently high price for the oil palm fruit heads to induce the natives to collect and carry them to the factory. As the chiefs and villagers saw that by selling the fruits to the factory the main occupation of their wives (the preparation of palm oil and the cracking of nuts for the extraction of palm kernels) would be taken away, they were said to be averse to the establishment of a new condition of enforced idleness, which would impose greater difficulties on them of keeping their wives in order. The offer by the factory to return the nuts for cracking in the villages, did not dispose of this difficulty, as the villagers only saw in it an arrangement involving them in extra transport. Messrs. Lever Brothers have now transferred their work to the Belgian Congo, where, by reason of the better type of palm fruit commonly obtainable, the conditions are more satisfactory for the development of the mechanical extraction of palm oil on a commercial scale, and where the inhabitants are[26] less independent and more accustomed to co-operate with European enterprise.

Export Figures.—The average annual export of palm oil and kernels for the first nine years of the century, and the annual total of the subsequent ten years are given:

| Palm oil | Palm kernels | |

|---|---|---|

| Year | Gallons | Tons |

| 1900-1908 Av. | 303,790 | 26,630 |

| 1909 | 851,998 | 42,897 |

| 1910 | 645,339 | 43,031 |

| 1911 | 725,648 | 42,892 |

| 1912 | 728,509 | 50,751 |

| 1913 | 617,088 | 49,201 |

| 1914 | 436,144 | 35,915 |

| 1915 | 481,576 | 39,624 |

| 1916 | 557,751 | 45,316 |

| 1917 | 543,111 | 58,020 |

| 1918 | 260,442 | 40,816 |

RUBBER.—Until 1907 the African tree rubber (Funtumia elastica) had not been recorded from any part of the country, although its congener, F. africana, was found everywhere. A number of trees of the first-named species have been recently discovered in the Panguma and Gola forests, and have been carefully examined. The latex, from trees tapped in the former locality, yielded a good quality of rubber when boiled with three volumes of water.

Native Method of Preparation.—The tree is known to the Mendis as “Gboi-gboi,” and in order to obtain the latex it is customary to fell the tree, afterwards ringing it at intervals of about one foot. The latex, which flows, is collected in leaf cups or other receptacles, and is heated in an iron pot. When in a state of semi-coagulation, induced by heat, it is poured upon plantain leaves, placed on the ground. Another plantain leaf is then used to cover the mass, which is stamped out with the feet into a rough sheet. The sheet is hung up to dry in a hut, in which it obtains the benefit of the fumes from the wood fires used by the occupants. The next process is to cut the sheet into strips, which are subsequently[27] wound into large oval balls and enter the Freetown market under the name of “Manoh twist.”

Owing to the wasteful method of tapping the trees, the species has been exterminated in many places, and the local Government have had under consideration the formulation of an ordinance to prevent the continuance of such destruction. As the existing trees are now practically only found in the dense forests near the Liberian frontier, and are probably widely scattered over a large area, it will prove a difficult matter to enforce any regulations with regard to collection.

Vine Rubber: Method of Preparation.—Landolphia owariensis, var. Jenje, is said to be the species of vine from which the Sierra Leone “Red Nigger” rubber is obtained. The Mendi name for the plant is “Djenje.” A very destructive method is usually employed in the preparation of the rubber. The vine is cut down and the roots dug out, both of which are cut into small pieces and soaked in water for several weeks. The bark is then removed, and the wood is pounded and washed repeatedly until a reddish mass of rubber remains, which usually contains a large amount of woody matter. This is sold in the form of balls. It is less common for the native to tap the vine and to coagulate the latex upon the wound with the addition of salt or lime juice, but this is occasionally done, and balls of scrap rubber collected in this way are sold in some localities.

Another vine (Clitandra laxiflora), which yields an inferior rubber by means of boiling the latex, is termed “Jawe” by the Mendis. This was at first considered to be Clitandra Manni, but more recent investigation has proved that C. Manni, although called by the same native name, produces a latex incapable of coagulation.

The Quality of Indigenous Rubbers and the Export.—The prices obtained for Sierra Leone rubbers compare favourably with those of the other British West African countries. Funtumia rubber, which is generally largely adulterated in the Gold Coast and Nigeria, is apparently not so in Sierra Leone, when prepared in the form of “Manoh twist.” The vine rubber, made from the scrap, is also of good quality, and the root rubber is not inferior to that shipped from the other countries. The trade of Sierra Leone is, however, small, and it is probable that[28] the larger part of that exported from Freetown is obtained from the adjoining countries of Liberia and French Guinea. The export of rubber declined since 1906, when it amounted to 107 tons, to only 6 tons in 1913, while in 1916 and 1917 none was exported. The composition and quality of Sierra Leone rubbers is given in the Bulletin of the Imperial Institute, vol. iv. (1906), p. 29; vol. vi. (1908), p. 24; vol. viii. (1910), p. 16; and vol. xii. (1914), p. 371.

Rubber Plantations.—No plantations of Funtumia rubber have been made although small plots have been planted with the South American Para tree (Hevea brasiliensis) on an experimental scale at different times and in various parts of the country and a mixed plantation of rubber, cocoa, coffee and fruit has been made near Waterloo. Up to 1909, it should be remarked, the work was in the hands of the Agricultural Service, but from 1910, on the formation of the Forestry Department as well as the reorganisation of an Agricultural Department, all forest and plantation work was transferred to the first-named Department. No plantation rubber has yet reached the commercial stage, although further trials are still in progress, and much experience has been gained.

A few Para trees were planted at the beginning of the present century in the Botanic Gardens at Freetown, but the locality was found unsuitable, and the trees grew slowly and yielded unsatisfactorily. A small plantation was made at Moyamba by Madam Yoko, the late chief of the Mendis, and was well looked after until she died, since when it seems to have been somewhat neglected. At Mano, the chief of the town made a good plantation in 1906, and, as the locality was apparently well selected, the trees have shown satisfactory growth. Small plots have been put out under Para at the Roman Catholic Mission station at Serabu, at Segbwema, Tinainahun and the Bo school, with variable success, in accordance with the cultivation and care bestowed on the plants. Except in the gravelly positions the tree succeeds well.

Landolphia owariensis and L. Heudelotii have been planted in forested patches in different parts of the country, the supervision of such planting having been entrusted to a native who had seen similar work performed by the French authorities in the neighbouring colony. Near Batkanu, a few plants can still be seen.

[29]KOLA NUTS.—The importance of the kola nut in West Africa is very high. Sierra Leone produces generally a better quality, for local consumption and export, than other countries. The kola trees (Kola acuminata and K. vera) do not, however, occur in a wild state in the country, and the whole produce is obtained from plantations, which are to be seen near almost every village in the moist region. A photograph is given showing a kola tree at Mano (Fig. 12). The destination of the exported kola is chiefly Bathurst (Gambia), Dakar (Senegal), Bissao (Portuguese Guinea), and to a small extent Dahomey. The exports of this commodity in recent years are given below as well as their average annual values per ton, which, as will be seen, exhibit great fluctuation.

| Tons | Valued at | Equal to £ per ton | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | 1,155 | £104,084 | £90 |

| 1907 | 1,374 | £113,674 | £83 |

| 1908 | 1,162 | £108,895 | £94 |

| 1909 | 1,320 | £153,848 | £116 |

| 1910 | 1,508 | £191,878 | £127 |

| 1911 | 1,597 | £194,260 | £121 |

| 1912 | 1,649 | £276,473 | £167 |

| 1913 | 1,865 | £328,003 | £176 |

| 1914 | 1,924 | £279,185 | £145 |

| 1915 | 2,041 | £233,388 | £119 |

| 1916 | 2,484 | £302,720 | £122 |

| 1917 | 1,702 | £321,105 | £188 |

| 1918 | 2,302 | £397,726 | £173 |

Kola nuts are second only to palm kernels in Sierra Leone in importance as an export, although they are practically entirely consigned to other coast ports; an insignificant amount of dried kolas only being destined for Europe.

RED PEPPER.—Capsicum annuum and C. frutescens are both grown among the multitude of plants, the seeds of which are mixed and broadcasted in the farms; but whereas most of the other plants are annuals, these are left in the ground for two years or more, and yield almost continuous crops during that period. The country of origin of these plants is probably South America, but the date of their introduction is unknown.

Beside the extensive local use of the pods, the export statistics of 1909 show that 41 tons were shipped.

[30]GINGER.—Zingiber officinale is not found in a wild state in Africa, but has been widely introduced throughout the tropical portions, although in Sierra Leone, alone among the West African countries, has it reached the important position of an export.

Owing to the defective methods of agriculture employed in the Colony, where for the most part ginger is cultivated, the roots or rhizomes do not attain a large size, and, in consequence, present great difficulties in decortication.

The common native method of preparation is to rub the washed and partially dried rhizomes in sand, and then to dry them more or less completely in the sun. The effect of this treatment is to remove a small portion of the outer skin from those prominences which come into contact with the sandy surface more readily, the depressions being left untouched. The native has found that the weight of the prepared ginger is increased by the adhesion of sand, and therefore prefers to employ this method to that of using a knife. The result is a very inferior product.

During the last few years attempts have been made among the ginger growers to deal directly with the European buyers, and a Farmers’ Association was formed with this object in view. Government assistance was obtained on the assurance that better methods of cultivation and preparation would be adopted, and this was done to a certain extent, but greater dependence seems to have been placed upon the supposed advantage to be obtained from shipping ginger of the usual inferior quality, without it passing through the local merchants’ hands. The result was, that a small quantity of selected ginger was sold at a good price, and a large quantity of common grade obtained a lower price than previously.

Recent experiments have shown that good results can be obtained with ginger in Sierra Leone if care be taken to deep-hoe the ground and then plant out the selected eyes from clean rhizomes. The custom of attempting to grow a crop in hard laterite gravel without proper cultivation is the chief cause of the malformed and small rhizomes usually obtained in native cultivation. Under improved conditions a crop of five tons per acre of good quality ginger has been procured.

[31]Export Trade.—The following amounts of ginger have been shipped during the last decade:

| Tons | Value | Tons | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1906 | 579 | 10,879 | 1913 | 2,048 | 35,468 |

| 1907 | 618 | 11,578 | 1914 | 1,213 | 15,639 |

| 1908 | 637 | 11,871 | 1915 | 567 | 8,091 |

| 1909 | 722 | 14,147 | 1916 | 971 | 25,814 |

| 1910 | 1,093 | 33,288 | 1917 | 1,136 | 25,863 |

| 1911 | 1,692 | 44,668 | 1918 | 1,576 | 39,306 |

| 1912 | 2,200 | 44,864 |

It is reported that, owing to the decline in price paid for Sierra Leone ginger in 1913, about one-third of the crop was left unharvested, and that the depreciation experienced was due to the competition from other sources of a better marketed product. It would be a pity if the promising opportunity of the country to become established as a large producer of ginger were altogether lost, owing to the want of a little care in cultivation and preparation of the product for the market.

The plant is essentially suited to certain parts of the Colony and Protectorate and is not subject to any serious diseases, the only recorded one being a fungus which attacks the rhizomes and causes yellowing of the leaves. This can be prevented from spreading if the plants be removed and burned as soon as the signs of attack are apparent on them.

FIBRES. Jute Class.—In the last few years several fibre plants indigenous to the country have been experimented with at the Imperial Institute, in order to ascertain whether any were capable of being exported for use as substitutes for Indian jute.