The Project Gutenberg eBook of The Summers readers: second reader, by Maud Summers

Title: The Summers readers: second reader

Author: Maud Summers

Release Date: June 22, 2023 [eBook #71019]

Language: English

Credits: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

SECOND READER

BY

MAUD SUMMERS

ILLUSTRATED FROM ORIGINAL DRAWINGS BY

LUCY FITCH PERKINS

AND

MARION L. MAHONY

FRANK D. BEATTYS AND COMPANY

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1909, by

Frank D. Beattys and Company

New York

THE DE VINNE PRESS

Thanks are due to the following publishers and authors for permission to reprint poems and to adapt stories on which they hold copyright:

Charles Scribner’s Sons:

“Singing”; “Autumn Fires” by Robert Louis Stevenson from “Poems and Ballads” (copyright 1895, 1896).

Houghton, Mifflin & Company:

“Sir Robin” from “Childhood Songs” by Lucy Larcom; “A Flock of Doves” from “Poems for Children” by Celia Thaxter; “What the Winds Bring” by Edmund Clarence Stedman; “Hiawatha”; “The Children’s Hour”; “Christmas Bells” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow; “The Miraculous Pitcher”; “The Pomegranate Seed” by Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Kindergarten Literature Company:

“The Bluebird” from “Songs from the Nest” by Emily Huntington Miller.

Little, Brown & Company:

“September” by Helen Hunt Jackson.

Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Company:

“The Caterpillar” from “Finger Plays” by Emilie Poulsson.

The Macmillan Company:

“The Fairy’s Love Song” by Ella Higginson.

Milton Bradley Company:

“Patty’s New Dress” from “More Mother Stories” by Maud Lindsay; “The Teeter” from “Rhymes for Little Fingers” by Maud Burnham.

Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge:

“Mary’s Meadow” by Juliana Horatio Ewing.

The Phelps Publishing Company:

“Pop-corn Song” by Sophia T. Newman. From “Good Housekeeping.”

The Youth’s Companion:

“The Calico’s Story”; “The Nixie’s Strain” by Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen.

F. A. Owen Publishing Company:

“The Story of a Little Water Drop” by Eva Mayne.

| PAGE | ||

| SEPTEMBER: | Helen Hunt Jackson | |

| Indian Corn | 11 | |

| The Coming of the Corn—Henry W. Longfellow (Adapted) | 14 | |

| Arabella’s Party | 16 | |

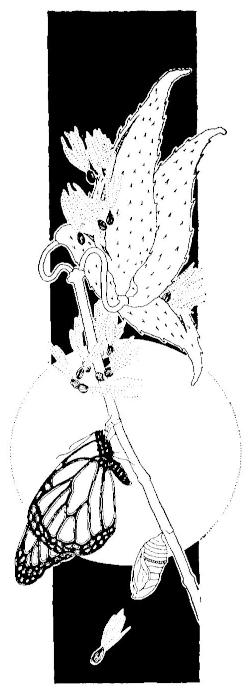

| The Caterpillar—Emilie Poulsson | 18 | |

| Rumpel-Stilts-Kin—Jacob and William Grimm (Adapted) | 19 | |

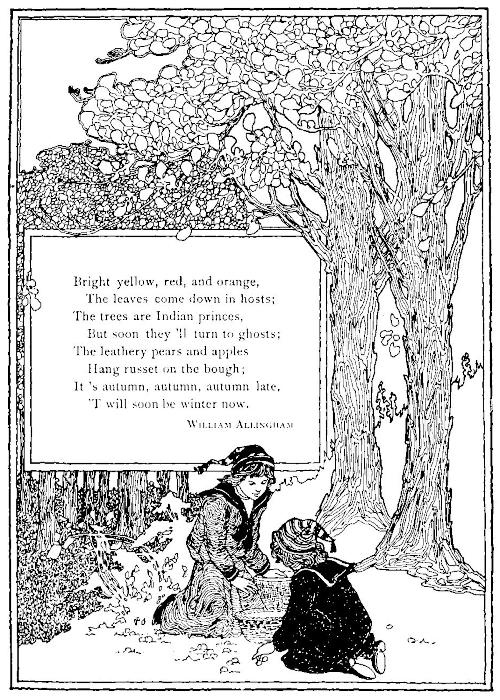

| OCTOBER: | William Allingham | |

| Hiawatha’s Canoe—Henry W. Longfellow (Adapted) | 25 | |

| Hiawatha’s Sailing—Henry W. Longfellow (Adapted) | 26 | |

| Lady Gray | 27 | |

| The Elves and the Shoemaker—Jacob and William Grimm | 29 | |

| Hallowe’en | 31 | |

| Pop-corn Song—Sophia T. Newman | 34 | |

| Philemon and Baucis—Nathaniel Hawthorne (Adapted) | 35 | |

| NOVEMBER: | John G. Whittier | |

| The First Thanksgiving Day | 41 | |

| Thanksgiving Day Long Ago | 44 | |

| Thanksgiving Day—Lydia Maria Child | 46 | |

| Whittier | 48 | |

| Pattie’s New Dress—Maud Lindsay (Adapted) | 51 | |

| DECEMBER: | Old Song | |

| Christmas Carol | 56 | |

| The Birds’ Christmas Feast | 57 | |

| Piccola | 59[vi] | |

| The Star-Children—Fraulein Meissner (Adapted) | 62 | |

| The Stars—May Moore Jackson | 65 | |

| Raphael—Louise de la Ramée (Adapted) | 67 | |

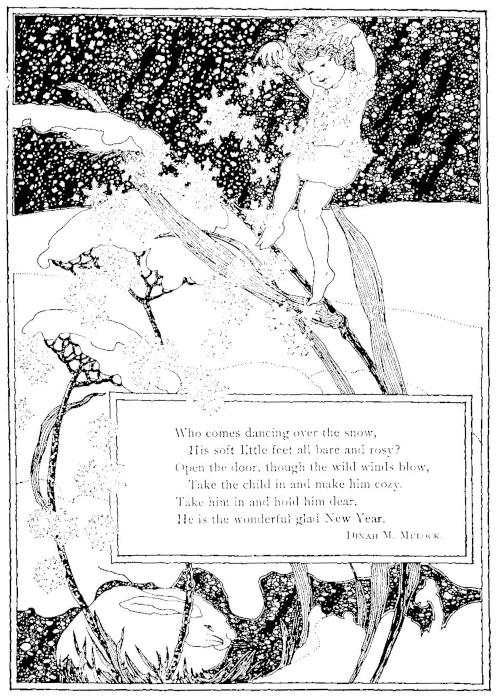

| JANUARY: | Dinah M. Mulock | |

| The Great White Stove—Louise de la Ramée (Adapted) | 71 | |

| The Flock of Doves—Celia Thaxter | 75 | |

| The Midnight Sun | 77 | |

| Michael Angelo | 80 | |

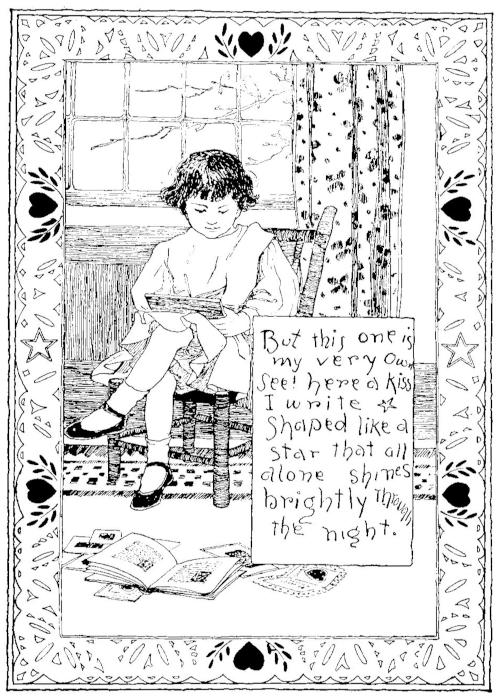

| FEBRUARY: | Eve Brodlique Summers | |

| A Valentine—Eve Brodlique Summers | 83 | |

| Abraham Lincoln | 84 | |

| The First Flag | 87 | |

| Longfellow’s Arm-chair | 88 | |

| The Road of the Loving Heart | 89 | |

| Singing—Robert Louis Stevenson | 91 | |

| MARCH: | Celia Thaxter | |

| The Four Winds—Edmund Clarence Stedman | 93 | |

| The Bag of Winds | 94 | |

| The Feast of Dolls | 97 | |

| The Feast of Flags | 98 | |

| Franklin’s Kite | 100 | |

| Boats Sail on the Rivers—Christina G. Rossetti | 102 | |

| The Story of a Water-drop—Eva Mayne (Adapted) | 103 | |

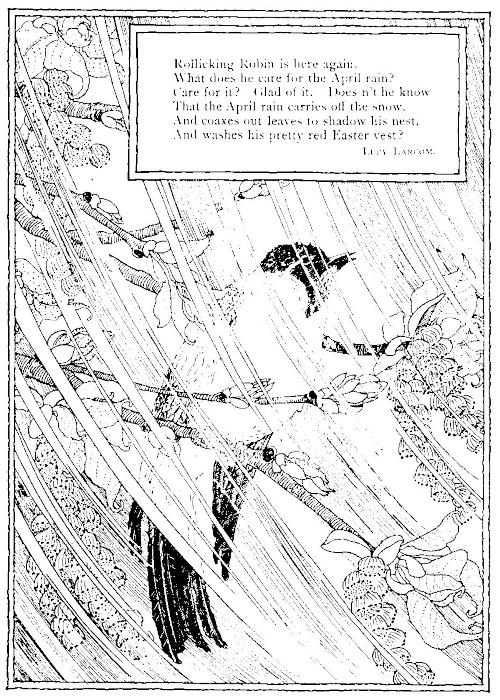

| APRIL: | Lucy Larcom | |

| The Sleeping Princess—Jacob and William Grimm (Adapted) | 106 | |

| An Open Secret—Unknown | 110 | |

| The Feast of Eggs—Christoph Schmid (Adapted) | 111 | |

| The Easter Egg—Christoph Schmid (Adapted) | 114 | |

| The Farmer and the Birds | 116[vii] | |

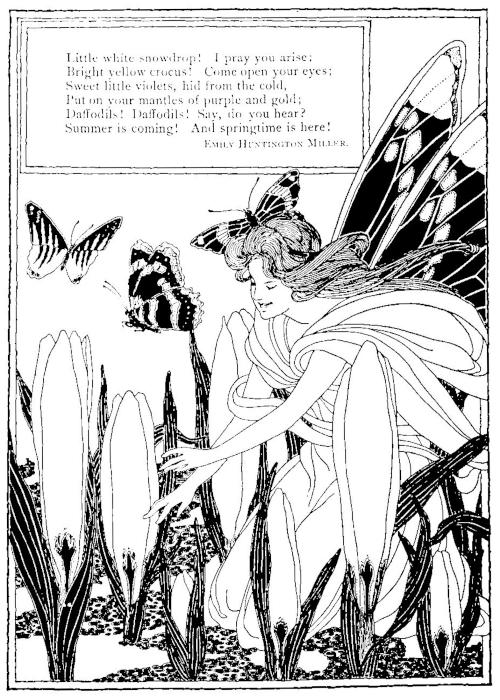

| MAY: | Emily Huntington Miller | |

| Mary’s Meadow—Juliana Horatio Ewing (Adapted) | 119 | |

| The May Party | 122 | |

| Come, My Dolly—Lydia Avery Coonley-Ward | 124 | |

| Proserpina—Nathaniel Hawthorne (Adapted) | 125 | |

| Hawthorne and His Children | 131 | |

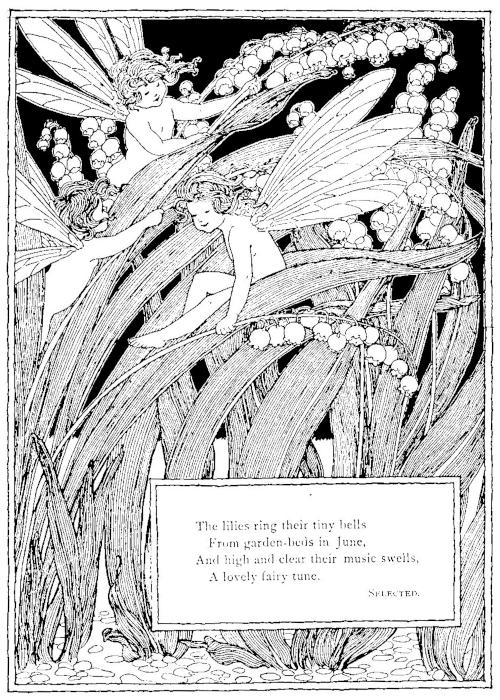

| JUNE: | Selected | |

| Thumbling—Hans Christian Andersen (Adapted) | 134 | |

| Midsummer Night—Shakespeare (Adapted) | 143 | |

| The Teeter—Maud Burnham | 144 | |

| The Nixie’s Music—Hjalmar Hjorth Boyesen (Adapted) | 145 | |

| JULY: | Francis Scott Key | |

| America—Samuel F. Smith | 150 | |

| Liberty Bell | 152 | |

| The Soldier Bird | 155 | |

| The Calico’s Story—The Youths’ Companion (Adapted) | 157 | |

| AUGUST: | Ella Higginson | |

| The Six Little Sea-Maids—Andersen (Adapted) | 162 | |

| The Singer and the Cricket | 166 | |

| King Solomon and the Bees | 168 | |

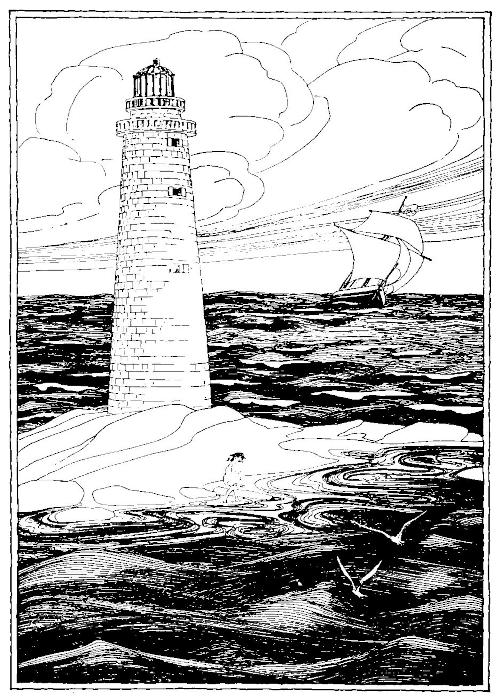

| The Little Maid of the Lighthouse | 169 | |

| Good Night and Good Morning—Lord Houghton | 173 | |

| WORD LIST | 177 | |

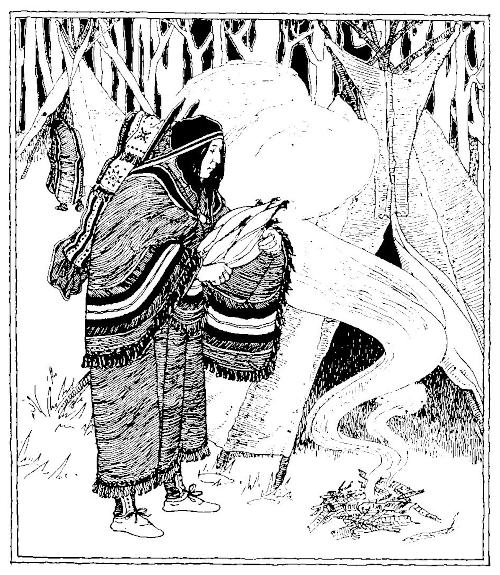

Long ago the Indians lived where we now live.

The Indian house was a tent covered with skins or bark. These tents were called wigwams.

The Indians wore clothes made of deerskin. Often these were covered with pretty beads.

Indian boys played ball, and swam in the rivers. Sometimes they went into the woods to hunt with their bows and arrows.

Indian girls played with dolls made of deerskin. Sometimes they helped their mothers plant the corn or cook the food.

The Indian baby’s cradle was a bag made of skin. It was tied to a board.

The Indian mother carried the baby on her back in this cradle.

Often she hung the cradle on a branch of a tree. The wind rocked the little cradle.

Sometimes the Indian father wore feathers in his hair, and painted his face. This made him look very fierce.

Indian children never cried. More than anything else they wanted to be brave.

One day some white people came over the sea in a ship. They were called Pilgrims.

It was cold, and snow was on the ground.

The Pilgrims sent out some men to walk along the shore.

They were looking for a good place to build their log-houses.

They soon came to a pile of sand. They began to dig, and found a basket full of corn. It belonged to the Indians.

The Pilgrims did not know that the Indians could make such large, strong baskets. It took two men to lift the basket of corn from the ground.

The white men had never seen Indian corn.

“How beautiful it is!” they said.

The Pilgrims took some of the corn to plant in the spring. The next summer they paid the Indians for all they had taken.

A kind Indian taught them how to plant the corn. He also taught them how to cook it.

Indian corn is one of the most useful of all the plants that grow.

Hiawatha, the young Indian chief, was alone in the woods.

He was thinking what he could do to help his people.

He could not rise from his bed of leaves, as he had not eaten anything for three days.

Then a young man dressed in green and yellow came to him.

“Oh, my Hiawatha!” he said. “I am Mondamin, the friend of man.

“I have come to tell you how you can help your people. Arise from your bed and wrestle with me.”

Hiawatha grew stronger and stronger as he wrestled with Mondamin. Three times Mondamin came and wrestled with Hiawatha.

Then Mondamin said, “The next time we wrestle you will win. Take off my green and yellow clothes. Make a bed for me to lie in where the sun may come and warm me.

“No one but you must watch beside me, until I come again with the sunshine.”

Hiawatha made the bed as Mondamin had told him, and then went home. Every day he watched the place where Mondamin was lying.

At last he saw a small green feather coming up from the earth.

Before the summer was over, the corn with its soft yellow hair stood before him, tall and beautiful.

Then Hiawatha was glad, and cried, “It is Mondamin, the friend of man!”

He called the Indians and showed them the corn. Then he said, “It is a gift for you, my people, and it will always be your food.”

Henry W. Longfellow’s “Hiawatha” (Adapted).

“Grandma, Arabella wants a party, and there are no dolls to come to it,” said Ruth.

“Peter has been lying in my room a great many years,” said Grandma. “I think he would like to come to a party.”

Ruth laughed when Grandma gave her the rag baby. He wore such queer clothes.

“Your father played with Peter when he was a little boy,” said Grandma. “He liked Sally Squash, too. Shall we ask her to the party?”

Ruth followed Grandma into the garden. They soon found a long squash.

Grandma cut a face in the small end, and put[17] a white paper dress on the squash. Then Sally was ready for the party.

“I should like to ask Patty Corncob,” said Grandma. “I played with her when I was a little girl.”

Grandma tied a head and arms made of paper on a corncob. Then she made a pink paper dress and cap.

“Oh, how pretty!” said Ruth as she looked at Patty Corncob. “I like her almost as well as Arabella.”

Grandma drew a face in the head of a clothespin, and put on a blue paper dress and hat.

“This is Betty Clothes-pin,” said Grandma. “She came to my parties long ago.”

Ruth could not tell which she liked the better, Patty or Betty.

They all sat down under a tree, and ate the cake that Dinah had baked for the party.

Arabella did not look like the other dolls. She had blue eyes and yellow hair, and wore a beautiful silk dress.

But she smiled and seemed to have almost as good a time as Grandma and Ruth.

There was once a wicked miller who said to his king, “I have a beautiful daughter who can spin straw into gold.”

The king loved gold more than anything else, so he carried the miller’s daughter away to his castle.

He filled a large room with straw, and said to her, “If you do not spin this straw into gold before morning, you must die.”

Then the king went out and locked the door.

The miller’s daughter sat down and began to cry. She did not know how to spin straw into gold.

Soon a brownie came in, and said, “What will you give me if I spin this straw into gold?”

“My gold chain,” said the miller’s daughter.

The brownie sat down beside the spinning-wheel, and sang,

Around went the wheel, and soon all the straw was spun into gold.

When the king came in the next morning, he was very glad to see so much gold. But he wanted more.

So he locked the miller’s daughter into a larger room filled with straw.

Again the brownie came in, and said, “What will you give me if I spin this straw into gold?”

The miller’s daughter said, “My gold ring.”

So again he sang,

The king was so glad to see all the gold, that he filled a much larger room with straw.

“Now,” he said, “if you spin this straw into gold I will make you my queen.”

When the brownie came that night, the miller’s[22] daughter said, “I have nothing else to give you.”

“Will you give me your first little child, when you are queen?” said the brownie.

“Yes,” said the miller’s daughter.

Once more the brownie sang. The wheel went round, and soon the room was filled with gold.

The king was so glad that he made the miller’s daughter his queen.

When she held her first little child in her arms, she was so happy that she did not think about the brownie.

But one day he came to take away the baby. The poor queen was very unhappy.

Then the brownie said, “If in three days you can find out my name, I will not take away your child.”

The queen sent all over the land to find out the queerest names.

The first day passed, and the second day passed, and she could not tell the brownie his name.

On the third day a man came to the queen and[23] said, “Last night as I was walking through the woods, I saw a brownie dancing around a bonfire and singing,

This made the queen very happy. When the brownie came in she said,

“Is your name Tom?”

“No, my queen.”

“Is it John?”

“No, my queen.”

“Is it Robert?”

“No, my queen.”

“Can your name be Rumpel-Stilts-Kin?”

“An old fairy has told you! An old fairy has told you!” he cried. Then he ran away.

The queen laughed and said,

“Good morning to you, Mr. Rumpel-Stilts-Kin.”

Jacob and William Grimm (Adapted).

Hiawatha, the young Indian chief, lived in the woods, by the Big Sea Water. He wanted to make a canoe.

He said to the Birch-tree, “Take off your white cloak, for the summer is coming, and you will not need it.”

The Birch-tree waved its branches in the wind and said, “Take my cloak, O Hiawatha!”

So Hiawatha cut the beautiful white bark from the tree.

Then he said to the Cedar, “Give me your branches, so my canoe will be strong.”

There was a cry from the top of the Cedar, but it said, “Take my branches, O Hiawatha!”

So Hiawatha cut them off and bent them, to make a frame for his canoe.

“Give me your roots, O Larch-tree,” Hiawatha said, “to hold the ends of my canoe together.”

The Larch-tree said sadly, “Take them all, O Hiawatha!”

Hiawatha pulled up the roots of the Larch-tree,[26] and sewed the bark together. Then he said to the Fir-tree, “Give me your balm, so that the water may not come into my canoe.”

And the tall dark Fir-tree said, “Take my balm, O Hiawatha!”

So Hiawatha made his birch canoe. And it lay upon the water like a yellow leaf in autumn.

Henry W. Longfellow’s “Hiawatha.” (Adapted).

One summer Robert and his father and mother lived in a little house in the woods.

They saw a squirrel running about in the trees.

Robert put some nuts on the ground and hid behind a tree. Soon the squirrel came and carried them away.

The next day he put the nuts nearer the house. The squirrel came again and carried them away.

So it went on for some time. Each day Robert put the nuts nearer the house.

They named the squirrel Lady Gray.

One day Robert’s mother sat down in a chair on the porch. She put some nuts on the floor and kept very still.

After a while Lady Gray came up on the porch. She looked at Robert’s mother, then she took a nut and ran away as fast as she could.

By and by Lady Gray became so gentle that she would hunt for nuts in their pockets.

One morning Father put a nut on his shoulder. Lady Gray jumped on Father’s shoulder and ate the nut. How they all laughed.

The next summer Robert went again to the little house in the woods.

Robert’s father wanted the house to look pretty, so he painted it white and green.

In the morning Robert called out, “Mother! Mother! See what the squirrels have done!”

The porch was covered with marks of little feet.

Lady Gray saw Robert and came up on the porch. A baby squirrel was with her. They named it Little Son.

Soon Little Son was as gentle as Lady Gray. Sometimes he would let them put their hands on his soft fur.

One day Robert was out walking with his father. They saw a hole in an old tree.

Robert’s father held him up so that he could put his hand in the hole. The squirrel’s nest was almost full of nuts.

All summer Robert had good times, playing with Lady Gray and Little Son.

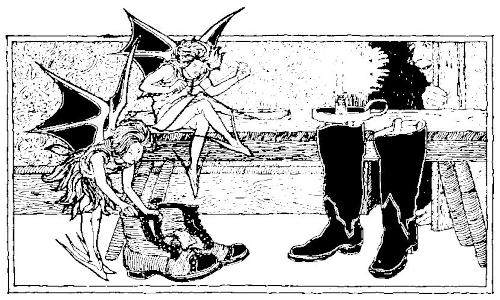

There was once a kind old shoemaker who was very poor. He had leather to make only one pair of shoes.

He cut these out and went to bed. The next morning the shoes were standing ready upon the table.

The shoemaker sold them and bought leather to make two pairs of shoes.

He cut these out, and again found the shoes made when he got up in the morning.

He sold the shoes and bought leather to make four pairs. The work he cut out was always done in the morning.

One evening the shoemaker said to his wife, “I should like to sit up to-night and see who it is that makes the shoes.”

In the night two little elves ran in. They sewed and rapped and tapped so quickly that the shoes were made long before morning. Then the elves ran away.

The next day the shoemaker’s wife said, “These elves have made us rich. I should like to do something for them. You make each of them a little pair of shoes, and I will make them some clothes.”

On Christmas eve they put the shoes and the clothes on the table. Then they hid behind the door to see what the elves would do.

When the elves saw the clothes, they quickly put them on. They laughed and danced and jumped about.

At last they danced out of the door and across the grass and were seen no more. But the kind shoemaker and his wife lived a long and happy life.

Jacob and William Grimm (Adapted).

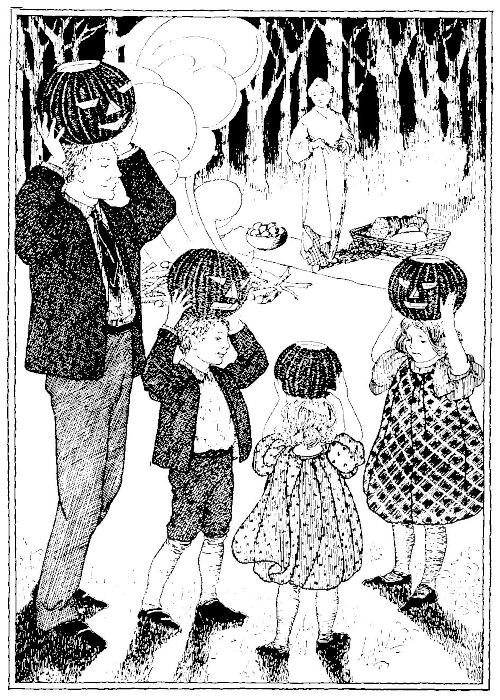

Big Brother Ben, Sister Polly and little Martha sat talking together under the old oak-tree.

Father went out to see what the children were doing.

“Oh, Father,” said Polly, “to-night is Hallowe’en!”

“May we have some pumpkins to make Jack-o’-lanterns?” asked Ben.

“Yes,” said Father. “Come with me.”

They went down to the corn-field and each chose a yellow pumpkin.

Brother Ben cut a round piece out of the stem-end of each pumpkin. The little girls then went to work to dig out the pumpkins.

After this Brother Ben cut eyes, nose, and mouth on the outside. The last thing was to make a little hole in which to set a candle.

“How would you like a bonfire to-night?” asked Father.

This pleased Brother Ben so much that he threw his cap in the air and cried,

“Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!”

When evening came Father and Brother Ben made a large bonfire near the corn-field.

They all sat around the bonfire and ate the good things which Mother and Sister Polly carried down in a basket.

Father showed them how to toast apples, pop corn and roast nuts in the fire.

“Now let us march around with the pumpkins on our heads,” said Brother Ben.

Mother sat on a rug and watched them. After a while little Martha joined her and soon the rug held them all.

“Please, Mother, tell us a story,” said little Martha.

Mother told them about the brownies and elves who come out on Hallowe’en to help the farmer, and all the busy people who work for us.

“I know a story about them, Mother,” said little Martha.

“Let us hear it, dear,” said Mother.

So little Martha told them about the Elves and the Shoemaker.

“I’ll tell about Cinderella and her Pumpkin Coach,” said Polly.

Father told them the story of Mondamin and his gift of corn to the Indians.

“I can say the poem,” said Brother Ben. “We learned it in school.”

Brother Ben gave the poem so well that they were all very still for a few moments.

Then Mother said softly, “It is bedtime now.”

As they turned away from the fire Polly said, “The Jack-o’-lanterns were fun, but I like the stories best of all.”

A long time ago, on a high hill, lived old Philemon and his good wife Baucis.

They were poor, but they were two of the kindest[36] old people that ever lived. Often they went without their supper to give it to some traveler.

One evening, Philemon and Baucis sat on their door-step looking at the sunset.

Soon they saw two travelers coming up the hill. Some children ran after them, shouting and setting their dogs on them.

“Come, Wife,” said Philemon. “Let us go and meet these travelers.”

“You go to them,” said Baucis, “while I get them some bread and milk.”

Philemon went to meet the travelers and said, “Welcome, strangers! Welcome!”

He asked them to come in to supper. Baucis gave the travelers bread and milk and honey.

On the table stood a pitcher half full of milk.

The travelers quickly drank the milk.

“What good milk!” said one of them. “May I have a little more, kind Baucis?”

“I am sorry,” said Baucis, “but there is no more milk.”

“Why,” said the traveler, “here is more milk!”

He took the pitcher and filled both bowls.

Baucis looked into the pitcher, and saw the[37] white milk running in from the side. Soon it was full.

“May I have some bread, Mother Baucis,” said the traveler, “and a little of that honey?”

Baucis cut him some and found that the bread was no longer old and hard as it was when she and Philemon ate of it.

And, oh, the honey! It was better than any honey they had ever eaten.

“Who are you, wonderful travelers?” said Philemon.

“Your friends, my good Philemon. After this the pitcher will always be full of milk for you and Baucis, and for poor travelers.”

The next morning the travelers asked Philemon and Baucis to walk with them and show them the road.

When Philemon and Baucis turned to go back, the older traveler said, “Good Philemon and Baucis, you gave us not only milk and bread but also a kind welcome. Ask for anything you want, and you shall have it.”

Philemon and Baucis looked at each other and said, “Grant that we may die together.”

“You shall have your wish,” said the traveler. “Now look at your home.”

They saw a beautiful white castle standing where their little house had been.

The old people fell on their knees to give thanks. When they looked up, the travelers were not there.

Philemon and Baucis lived in the castle a long, long time. One morning they could not be found.

The people looked everywhere for them. At last they saw two large trees standing in front of the castle.

One was an oak, the other was a linden-tree. The people wondered where they came from. Just then the wind began to blow, and the trees seemed to be talking.

“I am Philemon,” said the Oak.

“I am Baucis,” said the Linden.

Whenever a traveler rested under the trees, the leaves seemed to say, “Welcome, dear traveler! Welcome!”

Nathaniel Hawthorne (Adapted).

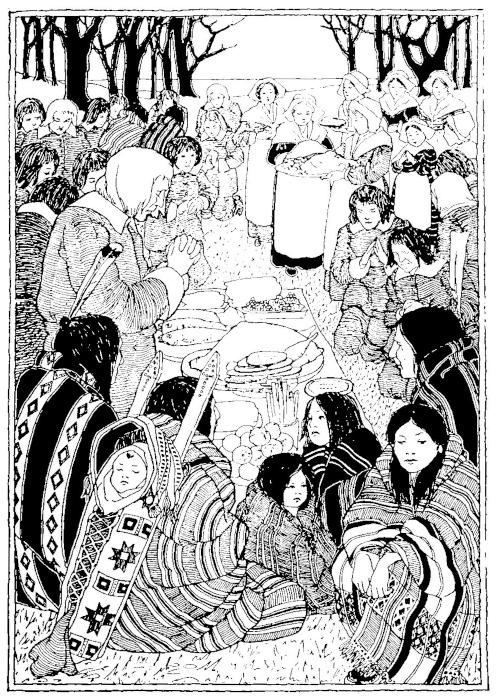

One spring the Pilgrims planted corn as the Indians had taught them.

Summer brought the sunshine and the rain to ripen the corn.

Such a harvest as there was when autumn came!

“Let us have a day of thanksgiving for this great blessing,” said the Governor.

“A Thanksgiving Day! A Thanksgiving Day!” cried the Pilgrims.

“The Indians have been kind to us. We will ask them to our feast,” said the Governor.

So they began to get ready for the first Thanksgiving Day.

The Pilgrim fathers went hunting and fishing. They carried home duck, turkey, and fish.

The Pilgrim mothers made bread and cake from the corn. They baked plenty of pumpkin-pies.

What a good time the children had getting ready for the feast! They gathered the wild plums and grapes. They put pop-corn in the ashes of the wide fireplace. Then they watched until the “Snap! Crack! Snap!” was heard.

The Indians came, gaily dressed in skins, and paint, and feathers. They brought five large deer to the feast.

The Indians came in time for breakfast and stayed three whole days. So they must have had a good time. They played games, and danced, and sang.

Before the feast the Indians and the Pilgrims thanked God for His goodness to them.

Ever since then the people have kept Thanksgiving Day.

The large kitchen was a busy place on Thanksgiving morning.

A log fire was burning in the fireplace. On the walls hung strings of dried apples. Long, yellow squashes hung up above.

A little girl sat beside the spinning-wheel dressing corncob dolls. She was taking care of the baby that lay in the queer old cradle.

Mother put the pudding in the kettle that hung before the fire. Then she said, “Come, Patty! It is time to set the table.”

Patty looked at the turkey that was roasting before the fire.

“I wish Thanksgiving came every day,” she said.

“What hard work that would make for Mother!” said Grandma, looking at the rows of pies.

After a while a loud shout made them all run to the door.

“Here they come! Here they come!” said Patty, dancing around the room.

Uncle John stopped the sleigh and out jumped Aunt Mary and the children.

What a good dinner it was! They all said that the turkey was the best they ever ate. And, oh, the pudding and the pies!

After dinner the fun began. There were games and songs, and at last a dance.

Grandma and Grandpa stood at one end. Father and little Patty stood at the other end. Then up and down the long kitchen they went, laughing all the time.

In the evening they sat around the log fire. They told stories, roasted apples, and ate the nuts the children had gathered.

At last they said good night. Then Uncle John put Aunt Mary and the children in the sleigh, and drove home through the softly falling snow.

Soon every one in the old farm-house was in bed and asleep.

Pussy sat in the warm firelight, alone, in the large kitchen.

When Whittier was a little boy, he lived on a farm.

In the summer he ran about with bare feet. He went swimming and fishing.

His merry whistle could be heard as he hunted for strawberries.

He knew the songs of the birds. He liked to watch them make their nests and feed their young.

When he went into the woods, the squirrels played about him. They let him see where they hid their nuts.

He watched the bee gather honey from the flowers. He knew how it made its house.

Often, at night, he sat on the door-step to eat bread and milk.

Then he could see the clouds and hear the frogs. Sometimes the fireflies flew about looking like little lanterns.

He tells of all those happy times in a poem called “The Barefoot Boy.”

In another poem called “Snow-Bound,” Whittier tells what he did in the winter.

One morning they looked out to find everything covered with snow.

“See the well!” said one of the boys. “It looks like a castle.”

“That pole looks like an old man,” said another.

Just then their father called out, “Boys! Make a path.”

With merry shouts they made a path to the barn. In one place the snow was so deep that they played it was a cave.

The old horse heard them and put his head out of the barn window to see the fun.

The rooster heard them coming and crowed a good morning.

They fed the farm-yard animals and gave them straw for their beds.

In the evening they all gathered around the fireplace.

The dog lay asleep in the warm firelight. The cat opened and closed her yellow eyes as she sat beside him.

The boys roasted apples and ate the nuts which they had gathered.

Then their father told them a story about the Indians. Mother talked of the days when she was a little girl.

When bedtime came, they said good night.

The wind roared around the house. The snow fell through the roof upon their beds. But the children did not know it, for they were soon fast asleep.

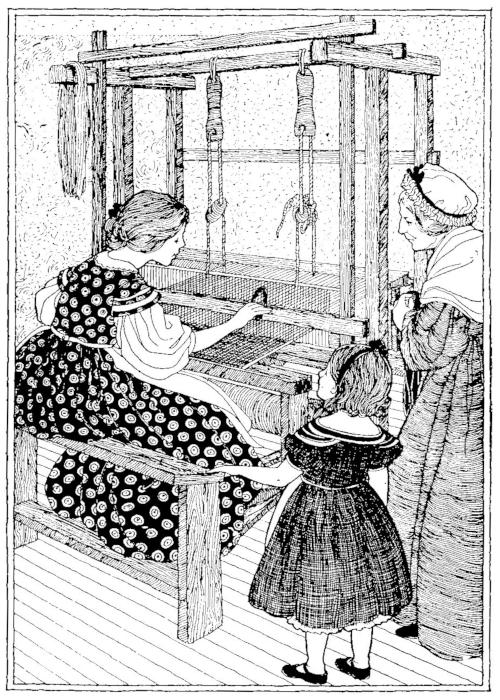

When Pattie was a little girl, long ago, she needed a warm new dress.

Grandmother said, “I’ll spin the wool for it.”

“And I’ll weave the cloth,” said Sister Rachel.

“And I’ll make the dress,” said the little girl’s mother.

The sheep had given the wool from their backs for Pattie’s new dress.

“It is as soft as down, and as white as milk, and as beautiful as snow,” said Pattie.

Grandmother carded the wool fine and smooth. Then she fastened it on her spindle and sent the spinning-wheel whirling round.

“Zu-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-m!” sang the wheel, as it turned. “Zu-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-m!”

Pattie’s brother said it sounded as if there were bees in the room. “Zu-m-m-m-m-m-m-m-m!”

As Grandmother drew the thread out from the fleecy wool she said,

Pattie stood by to watch her spin. She asked more questions than Grandmother had time to answer.

“Will there be a pocket in my new dress,” she asked, “and buttons down the back?”

“And, oh, Grandmother! What color is it going to be?”

“I know,” said Brother Joe. He had just come in from the woods with some walnut bark.

“It will be the color of a—chestnut.”

“Brown, brown, brown!” cried Pattie.

Mother made a dye with the walnut bark. Sure enough, when she dipped the yarn into the dye it came out a beautiful brown just as Pattie had guessed.

Then Sister Rachel fastened the yarn in the loom and began to weave.

The treadle went up and the treadle went down with a click and a clack. Such a merry sound!

Away the shuttle went to carry the thread under and over, and in and out.

When the cloth was woven Sister Rachel took[54] it out of the loom. Mother was all ready to begin the dress.

“Snip, snip, snip!” went her sharp scissors.

“Stitch, stitch, stitch!” flew her shining needle.

Long after Pattie was in bed and fast asleep that night, Mother was busy sewing.

Grandmother and Rachel helped, too, and the dress was ready the very next day.

It had pockets, two of them, bound with red.

It had buttons down the back like a row of red berries.

Jack Frost had come in the night and the cold winds had begun to blow. But Pattie did not care.

“I’m warm as toast in my new woolen dress,” said little Pattie.

Maud Lindsay (Adapted).

OLD SONG.

Far away across the sea, there is a very cold country.

The ground is covered with snow almost all the year, and the birds cannot get enough to eat.

So every Christmas the children are the birds’ Santa Claus.

In the summer the children go into the fields and gather grain for the birds.

The day before Christmas such a wonderful thing happens!

Over the snow the birds come from north, south, east, and west.

They sit upon the porch, upon the roof of the house, and sometimes look in at the windows.

“Here we are, little friends!” they seem to say.

On Christmas morning, a tall pole with a bunch of grain on the top is set before every door.

Then such a twittering is heard from the birds, and such merry shouts from the children!

It would be hard to tell which has the better time, the birds or the happy children.

Suggested by Celia Thaxter’s Poem, “The Sparrows.”

Fred and May lived one winter in a country where the sun was always bright and warm.

What good times they had playing in the garden!

One day they saw a queer little girl watching them. She did not look like the little girls they played with at home.

She wore a long red dress. On her feet were little wooden shoes.

She said that her name was Piccola. She told them that she was alone all day, because her mother went out to work.

Fred and May asked her to come and play with them in the garden.

One day the children were talking about Santa Claus.

“Who is that?” asked Piccola.

“Why, Piccola!” said May. “Did you never hear of Christmas?”

“Yes,” said Piccola. “We go to church on Christmas Day, and hear beautiful singing.”

Then the children told her all about Santa Claus.

“Hang up your stocking on Christmas Eve,” said May. “He will come down the chimney and fill it with toys.”

Piccola could hardly wait to tell her mother about Santa Claus.

“I wonder what he will give me,” she said.

“Do not look for him this year, little daughter,” said her mother. “I shall be thankful if we have enough to eat.”

But Piccola knew that Santa Claus would not forget her.

On Christmas Eve Piccola did not have any stocking to hang up. So she put her little wooden shoe in front of the fireplace.

“I’m sure Santa Claus will not care if it is a shoe,” she said.

The next morning Piccola awoke before it was light. She ran softly to the fireplace to see what was in her shoe.

“Oh, Mother, Mother!” cried the happy little girl. “See what Santa Claus has given me!”

She ran to her mother with the shoe in her hand.[61] A little bird had come down the chimney. There it lay in the shoe, looking up at her with its two bright eyes.

Piccola fed it and warmed it. Then she carried it into the garden to show it to Fred and May.

They gave her candy, and toys, and a doll. But Piccola liked the gift of Santa Claus best of all.

Suggested by Celia Thaxter’s Poem, “Piccola.”

Queen Sunshine lived in a wonderful red and blue castle.

She wore a dress of gold. Whenever she came out from her castle everything became light.

She had many children whom she loved very dearly, and they also wore dresses of gold.

Their good servant, the Moon, who followed after them, wore a dress of shining silver.

In another country across the sea lived Queen Darkness.

She always wore the same black dress. Wherever she went all things became dark.

She was alone and unhappy and often wished that she had children like those of Queen Sunshine.

One day when Queen Sunshine’s children were playing on the seashore, a little boy fell into the water.

“Oh, help me! Help me!” he cried.

One of his sisters tried to help him, and she, too, fell into the sea.

By and by, when the Moon came to take them home, not one child was on the shore. They had all fallen into the water.

The Moon looked at the sea, and saw that it was black.

“Oh!” she cried. “Queen Darkness is there! She has taken all the dear children.”

The Moon was so sorry for Queen Sunshine that she would not go home and tell her that Queen Darkness had taken the children.

She said to Queen Darkness, “Let me go with the children.”

Queen Darkness gladly carried their good servant, the Moon, to her dark castle to live with Queen Sunshine’s children.

She named them the Star-children. Queen Darkness always keeps the Star-children near her. The little ones are so close together that they look like a silver ribbon on her dress.

Ever since, their mother, Queen Sunshine, has been looking for her children.

Whenever she comes in her golden dress to[65] the shore of the sea, the water is so bright that she cannot find them.

Queen Darkness does not let the Star-children go out when it is light, but once every night she leads them across the sky.

Their mother always follows after them. Sometimes she sees one of her children far away.

The kind old servant, the Moon, sometimes runs away and comes to Queen Sunshine to tell her about her children.

From the German of Fraulein Meissner (Adapted).

Long, long ago, across the sea, there lived a master artist.

He made, in clay, such beautiful bowls and vases, that people came from far and near to buy them.

Some young men lived with him. The master artist taught them how to make the same beautiful things.

One summer day, one of these young men was very sad. A little boy with golden hair ran up to him and said, “Dear Luca, why are you so unhappy?”

“Oh, Raphael!” said Luca. “The great duke wants us to paint him a bowl and a vase. The master says that the artist who makes the most beautiful one may live with him always. He will also have a gift from the duke.”

“When must the bowl and the vase be ready?” said Raphael.

“In three months,” answered Luca.

Raphael threw his arms around Luca’s neck.

“Let me try to paint them for you,” said the little boy with golden hair.

“You dear child!” cried Luca. “You are only seven years old. You cannot help me.”

Raphael was very sorry for his dear Luca.

“Oh, Luca, I love you so! Please let me try,” he said again.

Then Luca said, “You may try, Raphael. It can do no harm. I can never paint the vase and the bowl.”

Raphael was glad now that his father had taught him how to draw.

He was glad, too, that the master artist had taught him how to put the colors on the clay.

All through the long summer days the child worked alone. He would not let any one see his painting till it was done.

One day he showed Luca his work.

“Dear Luca, see!” he said. “There are the vase and the bowl for you to give the duke!”

Luca fell on his knees before the little boy.

“Wonderful child!” he said. “I cannot call this beautiful work mine. It would not be right.”

The next day the duke came to look at all the vases and the bowls.

“Here is something very beautiful,” he said, taking a bowl in his hand. “Who painted this?”

The master artist turned to the young men and said, “Who did this work?”

But no one answered.

Then a little boy with golden hair went to him. “I painted it,” he said. “I, Raphael.”

Tears of joy came into the great duke’s eyes. He took a golden chain from around his neck and gave it to Raphael.

The little boy said, “But it is Luca’s. I painted the bowl for him to give to you.”

But Luca did not hear him. He was kneeling again at the feet of the wonderful child.

Louise de la Ramée’s “The Child of Urbino” (Adapted).

Karl had no mother and his father was very poor.

The only beautiful thing in their little house was a white stove. It was very large, and it had wonderful colored pictures all over it.

Karl and his brothers and sisters loved it dearly. In the summer they covered it with flowers.

In the winter the children sat around the stove, while Karl drew them pictures and told them stories.

One cold winter night the father came home very late. He could not find work, and the children had not enough to eat.

By and by the little ones went to bed.

Then the father told Karl and his sister that he had sold the great white stove.

“Oh, no, Father!” cried Karl. “You will not send our dear stove away.”

“I must,” said his father. “It is a wonderful stove. There is a man who will give me a great[72] deal of gold for it. I must have gold to buy bread for my little ones.”

“Wait awhile,” said Karl. “I will help. I am sure there is work I can do.”

Karl’s father shook his head and went away. He thought such a very little boy could not help him.

All that night Karl lay on the floor beside his dear white stove.

In the morning the man came and carried the stove away in a wagon. Karl was so unhappy that he could do nothing but cry and cry.

“I love it so,” he said. “Better than anything on earth.”

Then he said, “I will go with it.”

He ran quickly after the wagon and climbed into it.

By and by when no one was looking, he hid inside the great white stove. It was very dark, but it was warm, and soon he was fast asleep.

When Karl opened his eyes, he wondered where he could be. He lay quite still and listened.

He traveled a long, long time. At last the stove[73] was set down on a soft rug. Then some one said, “What a wonderful stove!”

The door was opened, and Karl jumped out. He fell on his knees before a man who had a very kind face.

“Oh,” cried he, “please do not send me away! Let me stay here with my dear white stove.”

“Poor child!” said the man, as he laid his hand on Karl’s hand. “Why did you hide in the stove? Tell me for I can help you. I am the king.”

Karl was glad to tell the king all about the great white stove. He told him how much they all loved it. He said that they had to send it away because they had no bread to eat.

“Do let me stay with it,” he said again. “I will cut wood for it and feed it. The stove loves to have me feed it, for I have done it so long.”

“But what else do you wish to do?” said the king.

“I should like to paint pictures, beautiful pictures, like those on the stove,” said the little boy.

So the king told Karl that he could stay in the castle with the great white stove.

Karl became a great artist and painted beautiful pictures. Then the king gave him the stove.

Karl sent it back to the little house where his father still lived. He often went there to see his father and the great white stove.

He was thankful that he had traveled so far inside of the stove that winter day.

Louise de la Ramée’s “The Nurnberg Stove” (Adapted).

Naka lives where it is very cold. There is snow and ice nearly all the year.

Naka lives in a queer little round house made of cakes of snow. The door is so close to the ground that she has to creep in and out on her hands and knees.

One day Naka’s mother dressed the little girl in her warm fur clothes.

She first put on stockings made of bird skins. The soft feathers kept her feet very warm. Over the stockings she wore another pair made of bearskin.

Next she put on a white bearskin coat. This had a hood which she put over Naka’s short, dark hair.

It was almost noon when they crept out into the dim light.

They climbed a hill and saw the sun just rising; the beautiful, bright sun which they had not seen for so long!

It soon went away, but the next day it came again and stayed longer. After a while it did not go away at all.

All day and all night the bright sun was shining on the earth. Naka had a merry time playing in the warm sunshine.

She ran about on the soft green grass and picked the pretty flowers.

She found some berries one day and carried them home to her mother.

She watched the great white birds that came to lay their eggs among the rocks.

Best of all, the reindeer came back and gave her milk to drink.

By and by the sun went slowly away. But Naka was happy.

In the winter she had no sun. But the moon and the stars were bright.

Then, too, she saw again the beautiful northern lights, which are brighter than fireworks.

Long ago in a country over the sea there lived a Grand Duke.

He had a garden in which he put some beautiful statues.

A boy artist named Michael Angelo often came there to study. One day he saw across the garden the statue of a faun that had no head.

“I will make a head for that statue,” said Angelo.

He made a head of a laughing faun. The mouth was open so that the teeth could be seen.

About this time the Grand Duke was walking in his garden. He stopped to look at the statue made by the boy artist.

“Well done, Angelo!” said the Grand Duke. “But, see! You have made an old faun. He should not have all his teeth.”

“That is so,” said Angelo, and he quickly took out some of the teeth.

This pleased the Grand Duke so much that he asked Angelo to live with him in his castle.

The years Michael Angelo spent among the beautiful statues in the Grand Duke’s garden helped him to become a great artist.

When Abraham Lincoln was a little boy, he lived in a log house in the woods.

He could not go to school, for he worked on a farm with his father. He went to school only one year.

His mother taught him how to read and write in the evenings. When everybody had gone to bed, he would sit and read by the light of a log fire.

There were only two or three books in the house. Lincoln read them over and over.

One day a man let him take a book about George Washington. When he went to bed, Lincoln put it between the logs of the house.

When he awoke he found that the snow had fallen upon the book and spoiled it. He took it back to the man and told him he was very sorry.

The man said, “You must either pay for the book, or work three days in my corn-field.”

At the end of the three days the man said, “You are an honest boy, Abe. You may keep the book.”

Lincoln did not like to see any one unkind to animals.

Once, when he was a boy, Lincoln was standing on a log making a speech. The boys were clapping their hands and shouting.

One of the boys saw a turtle. He picked it up and threw it down at Lincoln’s feet. The poor turtle could not crawl away with its broken shell.

Lincoln did not like this. He jumped off the log and said, “Whoever did that is a coward!”

The boys were sorry for the poor turtle. They gently picked it up and carried it down to the water.

One day when Lincoln was a man, he saw a pig trying to get out of the mud.

Lincoln had on some new clothes. He did not want to get them muddy, so he passed on.

But he could not help thinking about the poor pig. He turned back and helped the pig out.

Lincoln became a very great man. He was so wise and kind that the people made him President.

He did so much for his country that we keep his birthday on the 12th of February.

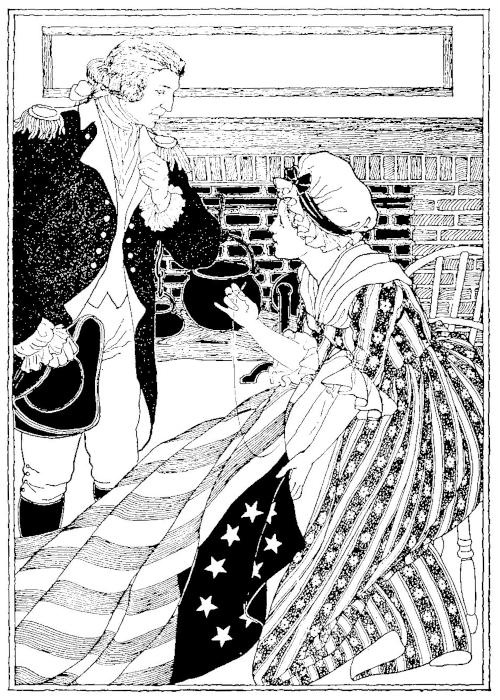

Over one hundred years ago, there lived in Philadelphia a young woman named Betsy Ross.

From the time she was a little girl she liked to sew. When her husband died she made money by her needlework.

One day there came to her little brown house the great General Washington.

He wanted a new flag for his soldiers to carry in their war against the King of England.

When he heard of the beautiful needlework of Betsy Ross, he came to ask her to help him.

Together they planned a flag that had thirteen stripes and thirteen stars.

A few days later Betsy Ross showed General Washington the flag. She had cut it and sewed it with her own hands.

General Washington was so pleased that he told his soldiers to have their flags made at once.

Soon the beautiful stars and stripes were flying all over the country.

In Philadelphia, the little house where Betsy Ross lived is still standing.

Near the poet Longfellow’s home there was a blacksmith shop. A beautiful chestnut tree grew beside it and spread its branches over the shop.

Little children often looked in at the open door on their way home from school. They liked to see the sparks fly from the anvil.

The poet Longfellow sometimes passed by the shop. He thought it was such a pretty picture that he wrote a poem about it. He called the poem “The Village Blacksmith.”

Longfellow loved the tree and felt sorry when it was cut down. He and the chestnut tree had grown old together.

About that time Longfellow had a birthday. He was an old, white-haired man.

The children wanted to show their love for him. They had the wood from the tree made into a chair and gave their pennies to pay for it.

This gift made Longfellow very happy. He thanked the children by writing a beautiful poem, called “From My Arm-Chair.”

Robert Louis Stevenson wrote the beautiful poem called “Singing.” It is in a book which he named “A Child’s Garden of Verses.”

He was sick much of the time and had to live in a warm country. His home was far away in the South Seas on a beautiful island.

Robert Louis Stevenson built his house on a hillside among the large forest trees. Here the flying foxes came to rest. At night great bats flew about.

The house was three miles from the nearest town. The trees grew close and high along the path that led to it. They used packhorses to carry things from the town to the house.

A beautiful stream ran through the ground. Orange trees grew along the banks. Here Robert Louis Stevenson came to bathe and swim.

Mrs. Stevenson had a garden in which grew oranges, lemons, bananas, and breadfruit trees.

She had cows, and pigs, and chickens in the barn-yard.

Robert Louis Stevenson had a brown pony named Jack. He and Jack were great friends and had many fine rides together.

In this warm country Robert Louis Stevenson grew so much better that he once said,

“It is like a fairy story that I should become well and strong. I go boating, riding, bathing, and work hard with my wood-knife in the forest.”

The people on the island do not look as we do. Their skin is brown. Many bright flowers grow on the island. The women always wear flowers in their hair.

The people loved Mr. Stevenson very dearly. When they learned that he wrote stories, they named him Tusitala. That means The Story Writer.

Once some of the chiefs were put in prison. Robert Louis Stevenson did not think this was right.

He went to the prison to see the chiefs and was very kind to them.

At last the chiefs were set free. They wanted[91] to show their love for Mr. Stevenson, so they made a road from the town to his house.

It was a hard piece of work. It took many men a long time to do it.

When the road was made the chiefs gave a great feast. All the people on the island came to it.

These are some of the words which they put on a board beside the road,

“To show our great love for Tusitala we have made this gift. It shall never be muddy. It shall go on forever, this road that we have dug.”

Long ago there was a man named Ulysses who had been traveling for many years.

He was sailing toward home one day when he came to the land where Æolus lived. Æolus was king of all the winds that blow.

Sometimes he sent soft winds to fill the sails of the ships at sea. Sometimes he sent winds that made the waters roar. Then he called them back and the sea would become quiet again.

Ulysses and his sailors were glad to stay for a time in the land of Æolus. They were tired of traveling so long.

When they were ready to go away, King Æolus filled their boat with food and many gifts. One of these gifts was a large bag made of skin.

King Æolus said to Ulysses, “In this bag I have tied all the winds that blow. If you wish to go more quickly toward home, open the bag and let one of the winds fly out. Then tie the bag again.”

Æolus said good-by to Ulysses and sent a soft wind to carry him from the land.

Day after day Ulysses sailed his boat safely over the sea. But one night when he was asleep, his sailors wondered what was in the large bag made of skin.

“It must be full of gold,” they said. “Let us take it.”

The sailors opened the bag and at once all the winds flew out.

How they made the waters roar around the boat! Even Ulysses could do nothing to quiet them. For many days the boat was tossed about by the waves.

At last the sailors saw land. They were very glad to pull the boat upon the shore, and rest.

They did not know where they were. The winds had made the boat go far from its path.

The sailors were sorry that they had opened the bag which King Æolus had given Ulysses.

A long-time afterward the travelers came home. Ulysses often told the story of his friend, King Æolus, and his gift of the Bag of Winds.

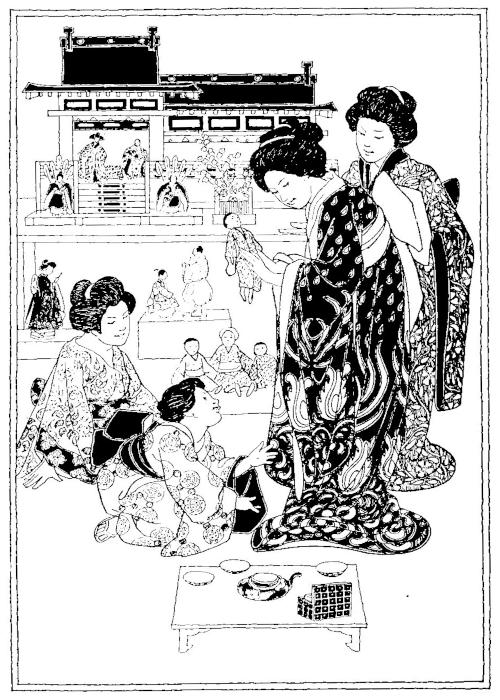

The Feast of Dolls is the happiest day in the year for the little girls in Japan. It is the third day of March.

The night before, while the little girls are asleep, great boxes of dolls are taken from the store-room.

There are all kinds,—large dolls, small dolls, girl dolls, and boy dolls.

The mothers and grandmothers of the little girls played with some of these. Others are very much older.

On the day of the Feast of Dolls, the little girls wake up early and run to the feast room.

Each doll must be dressed. This takes a long time, for some of the little girls have a great many dolls.

By this time the feast is ready. The dolls cannot eat the rice cakes and drink the tea, so their little mothers do this for them.

When the long, happy day is over, the dolls are undressed. Then they are put away until the Feast of Dolls comes again.

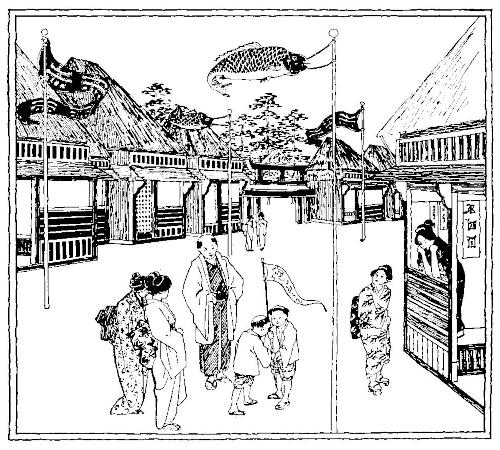

The fifth of May is the great day for boys in Japan. It is called the Feast of Flags.

Everywhere poles with gold paper balls on the top may be seen. Paper flags of all colors fly from these.

The boys get up early on the day of the Feast[99] of Flags. They go to the room where the dolls had their feast.

Now the room is filled with flags, toy soldiers, and the games that boys like. Their grandfathers and great-grandfathers played with some of these.

All day long the boys play at war with their soldiers. Sometimes they go into the garden and shoot at straw soldiers.

On the morning of the Feast of Flags each father gives his son a paper fish.

Every one in the house stands near while the boy ties this to a string. Then they watch him raise it to the top of the pole which is set before the house.

The wind fills out the hollow body of the fish. It pulls at the end of the string as if it were alive.

The name of this fish is the carp. It is so strong that it can swim very fast and even jump over waterfalls.

In America, fathers tell their sons to be brave and strong like the eagle. But in Japan, they tell them to be brave and strong like the carp.

A long time ago there lived a wise man named Benjamin Franklin.

People did not know much about lightning in those days. Franklin made a kite to catch some of it.

He knew that rain would spoil paper, so he covered his kite with silk. He put a piece of pointed wire at the top of the kite to draw the lightning into it.

At the end of the string he tied a key for the lightning to follow. Then he tied a piece of ribbon to the string and held it in his hand.

One rainy night when it was lightning he went out to fly his kite.

After a while he held his hand near the key. He saw a little spark of lightning go from the key to his hand.

After that he brought the lightning into his house on wires. He made it ring bells and do many strange things.

Other wise men have told us how to make lightning without drawing it from the skies.

It lights houses, runs street-cars, and does many other useful things.

It is called electricity.

Once there was a little drop of water. It lived in the great sea with hundreds of other water-drops.

When the sun shone all the little water-drops danced up and down. They looked like diamonds sparkling in the sunshine.

One day something happened. The little water-drop broke into a great many tiny drops.

At the same time it went up in the air. Other drops were going up, too. Up, up, they went, higher, and higher.

At last the water-drops were sailing far above the sea. A strong wind blew them over the land.

A man looked up at them and said, “See this big dark cloud. I think it is going to rain.”

As they sailed along, the air grew very cold. This made the little water-drops creep so close together that they became a shining raindrop.

Soon all the other little water-drops ran together and became raindrops.

They were so heavy that they could not float in the air. So down they all went toward the earth.

Pitter-patter! Pitter-patter! They fell upon the grass, the trees, and the fields.

“It is raining!” cried the children as they ran into the house.

When the rain was over, out came the sun. Then a wonderful thing happened.

Some of the water-drops were not heavy enough to fall to the earth. As the sun shone through them they changed into beautiful colors.

These colors were red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. They formed a bow across the sky.

“Oh, look!” cried the children. “Look at the beautiful rainbow.”

Eva Mayne (Adapted).

Once upon a time there lived a king and a queen who had no children.

They were so happy when a little daughter came that they gave a great feast.

The king asked the fairies to come because he wished them to be kind and good to the little princess.

There were thirteen fairies in the land. But the king had only twelve golden dishes. So one fairy was not asked to come to the feast. This made her very angry.

The twelve fairies came and gave all their best gifts to the little princess.

Just then the door opened and the angry fairy came into the room.

“When the princess is fifteen years old she shall prick her finger with a spinning needle and die,” said the angry fairy.

But there was one kind fairy who had not made her wish.

“No!” she said. “The princess shall not die. She shall fall asleep for a hundred years.”

The king and the queen were frightened. So they said that no spinning-wheel should be used in all the land.

One day, when the princess was fifteen years old, she went into a high tower of the castle. There sat an old woman spinning.

“Good morning,” said the princess. “What are you doing?”

“I am spinning,” said the old woman.

“Oh,” cried the princess, “how I should like to spin!”

The old woman gave the needle to the princess. She pricked her finger and fell back fast asleep.

The king and the queen and every one in the castle fell asleep.

The fire in the kitchen stopped burning and the cook fell asleep.

The horses in the barn went to sleep.

The dogs stopped barking and fell asleep.

The doves on the housetop put their heads under their wings and went to sleep.

Even the flies on the walls stopped buzzing and fell asleep.

A hedge of thorns soon grew around the castle. It was so high and thick that no one could pass through it.

One hundred years after, a king’s son was hunting. He saw the towers of a castle far away.

He rode toward the castle and at last came to the hedge of thorns. As the prince looked he saw that it was not a hedge of thorns, but a hedge of beautiful flowers.

The prince passed through the hedge of flowers and followed a path to the castle.

He went into the castle and saw the king and the queen fast asleep.

Then he looked in all the rooms. By and by the prince came to the high tower.

There lay the princess fast asleep. She was so beautiful that the prince kissed her hand.

The princess opened her eyes and said, “My prince, I have waited for you here a hundred years.”

Then the prince and the princess went out of the high tower together.

At once the king and the queen and every one in the castle awoke.

The fire in the kitchen burned, and the cook began to get the dinner.

The horses in the barn awoke, and the dogs jumped about and barked.

The flies on the wall buzzed, and the doves flew about the housetop.

That night there was a great feast in the castle. Ever after the prince and the princess lived happily together.

Jacob and William Grimm (Adapted).

There was once a princess who left her beautiful castle. She went to live in a little house in the country.

One day she told her servant to go to the village and buy some eggs for supper.

“Eggs!” said the servant. “There are no birds’ eggs.”

“I did not ask for birds’ eggs,” said the princess. “Buy hens’ eggs, of course.”

The servant shook her head and said, “We have no hens. I do not know what kind of birds they are.”

The princess thought that she would surprise the boys and the girls of the village. So she sent an old man far away.

When he came back the old man carried a chicken coop on his head.

All the children of the village ran after him. They wanted to know what he was carrying on his head.

The old man set the coop down, opened the little door, and a large rooster stepped out.

The children all cried, “Oh, what a wonderful bird that is!” They did not know what to call him.

Then out stepped the hens. There was a white one, and one that was brown, and one that had tall red combs.

The princess gave the chickens some corn. When they had eaten it the rooster crowed.

How the children laughed! “Ki-ki-ri-ki!” they cried, like the rooster.

The children ran home to tell about the wonderful birds that had come to live in the village.

Not long after, the princess showed the children one of the hens that was sitting.

“Fifteen eggs!” they cried. “The doves lay only two, and the other birds only five. How will the hens feed so many little ones?”

The children watched the chickens when they came out of the eggs. They were surprised that the little chickens were covered with yellow down.

“It is wonderful!” they cried. “Other little birds have no feathers. And see! They know how to run. Oh, there are no birds like them!”

By and by the princess asked the people of the village to a feast of eggs. They all sat down at a long table in the garden.

The eggs were in large baskets on the table. They were as white as snow.

The princess showed them how to break the eggs. Then she cooked them in many ways.

The people of the village liked the feast of eggs. When they went home, the princess gave them some chickens.

After that the children had merry times hunting for the white eggs.

From the German of Christoph Schmid (Adapted).

On Easter Day, a princess gave a party to the children of the village.

She had no apples and nuts to give them. So she colored some eggs red, blue, and yellow.

When the children came, the princess took them into the woods. She told them to make nests out of the grass and leaves.

They left the nests under the trees. Then they went into the garden where a feast was waiting for them.

While they were eating, the princess carried the colored eggs into the woods. She filled the nests with them.

Then she went back to the children and said, “Come, now! Let us look for our nests.”

The children hunted everywhere. When they found the nests, they clapped their hands for joy. In each nest lay five colored eggs.

“Red eggs! Red eggs!” cried one. “In my nest all are red!”

“In mine are blue ones,” cried another. “All blue like the sky!”

“And mine are as yellow as the butterfly that is flying around us,” said another.

“Oh,” they all cried, “how we should like to see the chickens that lay such beautiful eggs!”

“Of course hens do not lay them,” said one little girl. “Hens’ eggs are white.”

“I saw a rabbit running away from my nest,” said another. “I believe a little rabbit laid them.”

All the children laughed and said, “Yes, yes! The rabbits laid the colored eggs!”

From the German of Christoph Schmid (Adapted).

It was springtime. The birds were singing merrily as they built their nests.

But the farmers were angry. They did not want the birds to eat the corn in the fields, and the cherries on the trees.

The farmers said that all the birds must be killed. But the birds had one friend.

This friend stood up before the farmers and said, “Think of your woods and fields without the birds! Who will drive the worms from your fields and gardens?

“The birds pay you well for the grain and the[117] cherries that they eat. What will you do without their sweet music?”

The farmers laughed and would not listen to the friend.

They sent men and boys into the fields and the woods to kill the birds. The little ones were left to die in their nests.

When summer came, there was not a bird to be seen. Hundreds of worms ate everything that grew in the gardens and fields.

That autumn there were no red and yellow leaves on the trees. The branches were dry and brown.

Then the farmers were sorry. The next spring they sent a man away to bring the birds from all the country around.

One day the man drove a wagon covered with green branches into the village. Cages filled with singing birds hung upon the branches.

The farmers opened the doors, and the birds flew out.

Once more the woods and the fields were filled with sweet music.

Suggested by Longfellow’s poem, “The Birds of Killingworth.”

Mary liked to plant flowers beside the road and in the fields.

She told her father that she wanted to make people happy who had no gardens. So Father called her The Traveler’s Joy.

But Mary liked best of all to play in the Squire’s meadow. It was filled with beautiful flowers and singing birds.

Mary cried when her father told her that he and the Squire were no longer friends. He said she must not play in the meadow with the Squire’s great dog, Saxon.

One day, the gardener gave Mary some pretty cowslips. She forgot what her father had told her, and ran down to the Squire’s meadow to plant them.

Soon she heard a loud shout. She looked up and saw the old Squire running toward her. With one hand he held his dog, Saxon, who was trying to get away.

Mary was so frightened that she did not hear what the Squire was saying. She told him that[120] she was not digging up his cowslips, but planting them.

Just then Saxon came running toward her. The Squire stopped shouting to her, and called to Saxon. He did not know that Mary and Saxon were such good friends.

Mary threw her arms around Saxon’s neck, and began to cry. Then she picked up her basket and ran home as fast as she could.

Every day she thought the old Squire would come and tell her father. But he never came.

The next spring it was great fun to look for the flowers which The Traveler’s Joy had planted.

One day Mary’s father sent for her. When she came home, she found the old Squire talking to her father. He held some cowslips in his hand.

He gave them to Mary, and said, “My dear, I am sorry that I sent you out of the meadow.”

“But I was not digging up your cowslips,” Mary said.

The old Squire put his hand on her head. “I know, my child,” he said. “You are The Traveler’s Joy.”

“I am glad the cowslips grew,” Mary said. “I hope they will grow all over your meadow.”

Then the Squire said, “It is not my meadow now. I have given it away.”

“Oh, please, please, do not give it away!” cried Mary. “Can’t I play there with Saxon, and plant flowers?”

The Squire smiled at her father, and said, “Yes, Mary! You may play, and plant, and do what you like there.”

Father put his arm around the little girl. “You do not know what the Squire means. Do you, dear?” he said. “The Squire has given it to you. Now we shall always call it Mary’s Meadow.”

Juliana Horatio Ewing’s “Mary’s Meadow” (Adapted).

A bright, happy crowd of children marched to the woods for a May party.

First came two boys carrying a May-pole to which bright ribbons were tied.

Then came the May Queen with a crown of flowers on her head, and a long wand in her hand.

The girls marched behind the May Queen, carrying the pretty May baskets which they had made. The boys were waving flags and blowing horns.

When they came to the woods, the boys set[123] up the May-pole and all the children danced around it.

In and out they went weaving the bright ribbons. The girls went to the left, the boys to the right. They bowed as they passed each other, and sang the pretty May-pole song.

Soon the pole was wound with the bright ribbons.

Then some of the children ran down to the water to sail boats, and others went up, up, in the swings.

The older girls set the table. What a beautiful table it was! There were sandwiches, and oranges, and cakes, and nuts, and candy.

After the children had eaten all the good things, they went through the woods gathering flowers.

They filled the pretty baskets with flowers, and stood them side by side. But the children could not tell which they liked the best.

That night, when it was dark, each girl and boy put a basket on the door-step of a friend, then rang the bell and ran away.

They had such a good time that they wished May-day came oftener than once a year.

It was harvest-time and the grain was ready to be gathered.

Mother Ceres was very busy, for she had the care of every seed that grows.

She put on her hat made of poppies. Then she stepped into a chariot drawn by a pair of winged dragons.

“Dear Mother,” said Proserpina, “may I go down to the shore and play with the sea-maids?”

“Yes, child,” answered Mother Ceres, “but you must not go alone into the fields.”

The sea-maids heard Proserpina calling. Soon she saw them coming up out of the water. They made a chain of beautiful shells and hung it around Proserpina’s neck.

“How pretty it is!” said Proserpina. “Wait for me here while I run into the fields. I want to make each of you a chain of flowers.”

Proserpina’s hands were soon full of flowers. She was turning to go back, when she saw a beautiful plant near her.

“I will put it in my garden,” said Proserpina. She pulled and pulled. Soon Proserpina held the plant in her hands. She was surprised to see the deep hole which its roots left in the ground.

The hole grew deeper and wider, and Proserpina heard a loud noise under the ground.

Four black horses jumped out of the hole, drawing a golden chariot. In it sat a very dark man, with a crown of diamonds on his head.

The man caught Proserpina in his arms, and shouted to his horses. They went so fast that they seemed to fly through the air.

Proserpina was frightened and called out, “Mother! Mother Ceres! Come quickly and help me!”

But Mother Ceres was a great way off, and could not hear her cry.

“I will not harm you,” said the man. “I am King Pluto. All the gold and silver under the ground belong to me.

“I will give you a garden full of prettier[127] flowers than those in your hand. Where I live all the flowers are made of pearls and rubies.”

Just then Proserpina saw Mother Ceres in a field far away. She gave a loud cry, but King Pluto only made the horses go faster.

As they went under the earth it grew darker and darker. By and by they came to his castle. It was made of gold and lighted with lanterns made of diamonds. There was no sunshine in King Pluto’s country.

“Try to be happy, little Proserpina,” he said. “You may have my crown to play with. If you like, you may sit beside me and be my little queen.”

“I do not want golden castles and crowns,” sobbed Proserpina. “Please carry me back to my mother.”

Dinner was ready for them but Proserpina would eat nothing. She knew that if she ate the food or drank the water of King Pluto’s country, she could never see her mother again.

Mother Ceres heard Proserpina’s loud cry. She looked all around but could not see her. Then she drove home quickly, but she could not find her in the house.

She heard the sea-maids singing, and ran down to ask them about Proserpina.

“She left us this morning to gather flowers,” said one of them. “We have not seen her since.”

It was now almost dark. Mother Ceres lighted her torch, and went from house to house asking every one about her child.

Day and night for six long months she hunted for her little girl. Her torch burned dimly by day but at night it lighted her path.

At last some one told her that Proserpina had been carried off by King Pluto.

Then Mother Ceres said, “The grain shall not grow, nor the flowers bloom, until my little girl is given back to me.”

The earth turned brown, and there was no food for men nor animals. So they asked King Pluto to make the earth green by sending Proserpina home.

Proserpina had grown very hungry. She had just begun to eat some fruit when King Pluto told her she could go back to her mother.

As she walked along, everything turned green. Beautiful flowers grew in her path. The cows[130] and the sheep began to eat the grass and the birds to sing in the trees.

Mother Ceres was sitting on the door-step when she heard Proserpina say, “Here I am, Mother dear.”

How happy Mother Ceres was, to hold her little girl in her arms once more. Proserpina told her all about King Pluto’s castle.

“I was so unhappy, Mother dear,” she said, “that I did not eat anything until to-day. Then King Pluto gave me some fruit that had grown in one of your gardens.”

“Oh, my little Proserpina!” said Mother Ceres. “Why did you eat it?”

“I did not eat all of it,” said the little girl. “I swallowed only six seeds.”

“My child,” said Mother Ceres sadly, “you ate those six seeds in King Pluto’s castle. So you will have to spend six months of every year under the ground with him. While you are gone nothing shall grow. But when you come back to me in the spring, we will make the world beautiful.”

Nathaniel Hawthorne (Adapted).

Nathaniel Hawthorne had three children. They had great fun together.

In the spring he made them boats to sail on the lake, and kites to fly in the air.

In the summer he went fishing with them and took them into the woods to gather flowers.

In the autumn they went nutting.

One day the children were standing at the foot of a tall walnut tree. Soon they heard a shout.

When they looked up the children saw their father high up in the top of the tree. Then down came the nuts! The children put them into bags and carried them home.

When the snow came, their father took them coasting. Sometimes as they went down the hill they fell into the snow.

Then how they shouted and laughed!

Hawthorne liked to take long walks with his son. The little boy thought that his father was the best playmate in the world.

Once when they were out walking, they passed through some tall grass and weeds. They played these were giants and dragons which had to be cut down.

Hawthorne struck so hard that he broke his cane. Then he sat down and watched the little boy fighting with the giants and dragons.

Hawthorne loved children so much that he wrote books for them.

His three children loved his stories. They read his Wonder Book and Tanglewood Tales so often that they knew them almost by heart.

There was once a woman who had no little child. So one day she went to see a Wise Fairy.

“I wish for a tiny, little child,” she said. “Can you tell me where I can get one?”

“Here is a grain of corn,” said the Wise Fairy. “Plant it in a flower-pot. Then you will see what is to be seen.”

“Thank you,” said the woman.

Then she went home and planted the corn in a flower-pot.

The next day a large flower came up. It looked like a tulip bud.

The woman kissed the red and yellow leaves. As she kissed it the flower opened with a loud snap.

In the middle of the tulip there was a little tiny girl. She was only an inch high. So they named her Thumbling.

“Thumbling must have a cradle,” said the woman. So she made her one out of a walnut shell.

Thumbling slept on the blue velvet leaves of a violet. Her cover was a pink rose leaf.

One night a great Ugly Toad hopped in at the window.

“What a pretty little girl!” she said. The Ugly Toad took the walnut shell and hopped down into the garden. A brook ran through the garden.

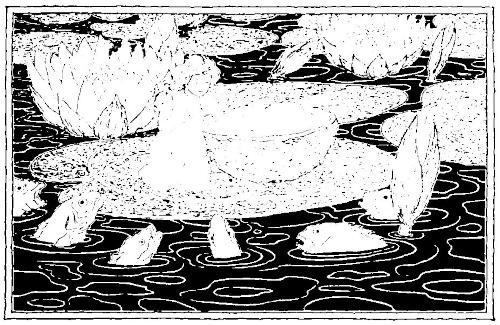

“I will put her out in the brook on a water-lily leaf,” said the Ugly Toad. “Then she cannot get away.”

On the largest leaf the Toad laid the walnut shell. Thumbling was in it fast asleep.

In the morning Thumbling awoke and began to cry. The Fishes looked up and saw poor little Thumbling.

“Why are you crying, little girl?” they said.

“I do not want to live with the Ugly Toad,” said Thumbling.

“Live with the Toads?” said the Fishes. “No, that must never be.”

They cut the stem of the lily leaf with their sharp teeth.

The lily leaf floated down the brook and carried Thumbling away from the Ugly Toads.

By and by a large May-bug came flying along.

He caught Thumbling with his long claws. Then he flew with her into a tree. How frightened little Thumbling was!

Soon many other May-bugs came into the[137] tree, to look at poor frightened little Thumbling.

“Why!” said one. “She has no claws.”

“She has only two legs,” said another. “She should have six.”

“How ugly she is!” said all the others.

When the May-bug heard this he flew down with her from the tree. He set her upon a large daisy and left her there.

All summer Thumbling lived alone in the great woods.

She wove a bed out of the leaves of grass. She hung the bed under a large leaf to keep out the rain.

Thumbling ate the honey from the flowers. She drank the dew that stood every morning upon the leaves.

Then winter came, and it began to snow. Poor little Thumbling! She was very cold.

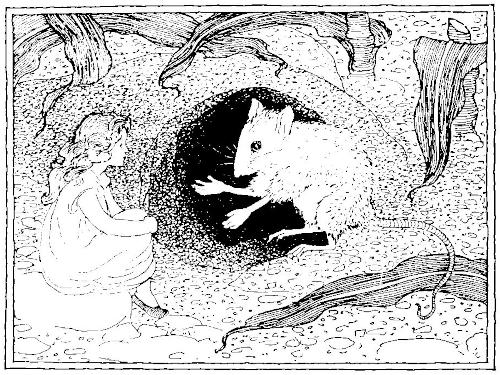

A Field Mouse lived in a corn-field close to the woods.

“I will ask the Field Mouse for something to eat,” she said.

Poor Thumbling stood at the door like a little beggar girl.

“You dear child!” said the Field Mouse. “Come into my warm house. You may eat dinner with me.”

“Would you like to stay with me all winter?” said the Field Mouse.

“You may keep my house clean, and you may tell me pretty stories.”

The winter was long and cold. But Thumbling was happy with the kind Field Mouse.

One day Thumbling found a poor bird lying near the Field Mouse’s door. Thumbling was very sorry. She thought the bird was dead.

“Poor little Swallow!” she said. “You must not lie on the cold snow.”

Thumbling wove a mat of hay. Then she laid it over the Swallow. She found some soft wool and made a warm bed.

“Good-by, you pretty little Swallow,” she said.

Then Thumbling laid her head against the bird. The Swallow moved. It was not dead. It was only cold.

The Swallow opened its eyes and looked at Thumbling.

“Thank you, pretty child,” he said. “I am warm now. Soon I shall fly about in the bright sunshine.”

“Oh!” said Thumbling. “You cannot live out of doors. Cold winter is here. You must stay in the Field Mouse’s home.”

The Field Mouse did not like birds. But she liked Thumbling and wished to make her happy.

So all winter the Swallow lived in the Field Mouse’s warm home.

At last spring came.

“I must go now,” said the Swallow. “Will you go with me, Thumbling? You may sit upon my back and I will fly out into the bright sunshine.”

“No!” said Thumbling. “The kind Field Mouse will be sorry to have me leave her.”

“Good-by, then, dear little Thumbling,” said the Swallow.

“No, no!” said Thumbling. “I will go with you. I do not like to live in the dark ground when it is so beautiful above.”

Thumbling sat upon the Swallow’s back. Then he flew high up into the air.

By and by they came to a warm country.

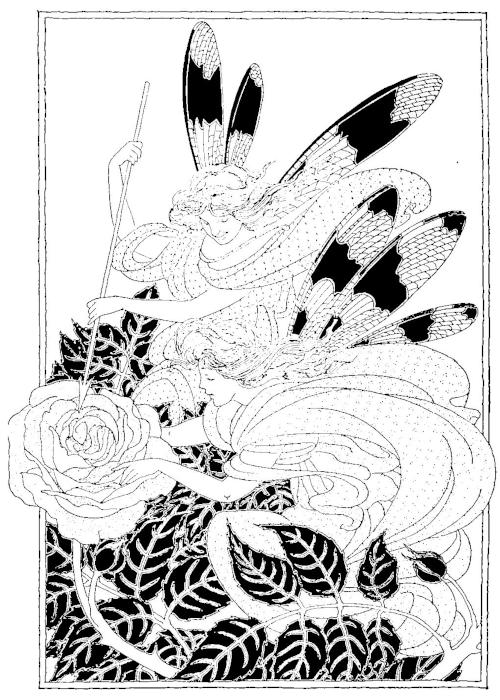

A large white flower was growing in a garden. The Swallow flew down and set Thumbling upon one of its broad leaves.

In the middle of the flower she saw a little tiny man. He was no larger than Thumbling.

The tiny man was as pure and white as if made of glass. He had a gold crown on his head and bright wings on his shoulders.

He was the King of the flower fairies.

“Oh, how beautiful he is!” said Thumbling to the Swallow.

The fairy King was glad to see Thumbling. He took off his crown and put it on her head.

“You shall be Queen of all the flower fairies,” he said.

How happy every one was! Out of every flower came a tiny flower fairy.