THIRD EDITION. REVISED AND ENLARGED.

A GENUINE HISTORY OF PERILS OF THE DEEP,

AND

AN AUTHENTIC RECORD OF THE MOST IMPORTANT SHIPPING

CASE EVER DEALT WITH IN THE SUPREME

COURTS OF AUSTRALASIA.

COMPILED BY

J. ARBUCKLE REID

AUTHOR OF “THE AUSTRALIAN READER,” “SEAMEN AND SHIPWRECKS,” ETC.

“Truth is always strange; stranger than fiction.”

Byron.

LONDON

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & CO., LTD.

PRINTED BY

HAZELL, WATSON, AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

| PAGE | |

| Among the Billows | 54 |

| Application for New Trial | 216 |

| Battling with Waves and Lawyers | 197 |

| Discovery of Ponting | 33 |

| Division of the Spoil | 275 |

| Final Battle with the Lawyers | 243 |

| Gratitude | 85 |

| Hints on Swimming | 82 |

| Introductory | 17 |

| Landing | 74 |

| Morning | 70 |

| New Trial | 236 |

| Night | 63 |

| Plaintiff’s Case | 90 |

| Sorrento | 27 |

| The Voyage | 45 |

| The Defence | 141 |

| Among the Billows | 62 |

| Cape Schanck | 47 |

| Lord Brassey | 13 |

| Captain Mathieson | 15 |

| Ocean Beach | 75 |

| Ponting and “Victor Hugo” | 81 |

| Ponting and his Friend “Victor Hugo” in 1899 | 161 |

| Rescue of Ponting | 31 |

| Sorrento | 25 |

| S.S. Alert | 41 |

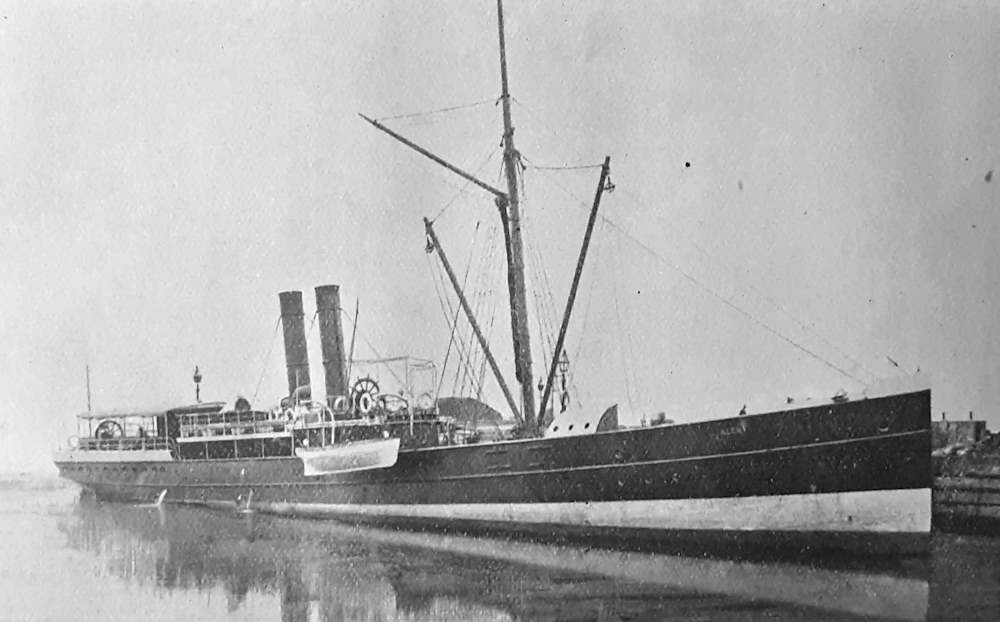

| S.S. Alert before Alterations | 89 |

| S.S. Alert Sinking | 55 |

| S.S. Sunbeam | 137 |

| Supreme Court Buildings | 243 |

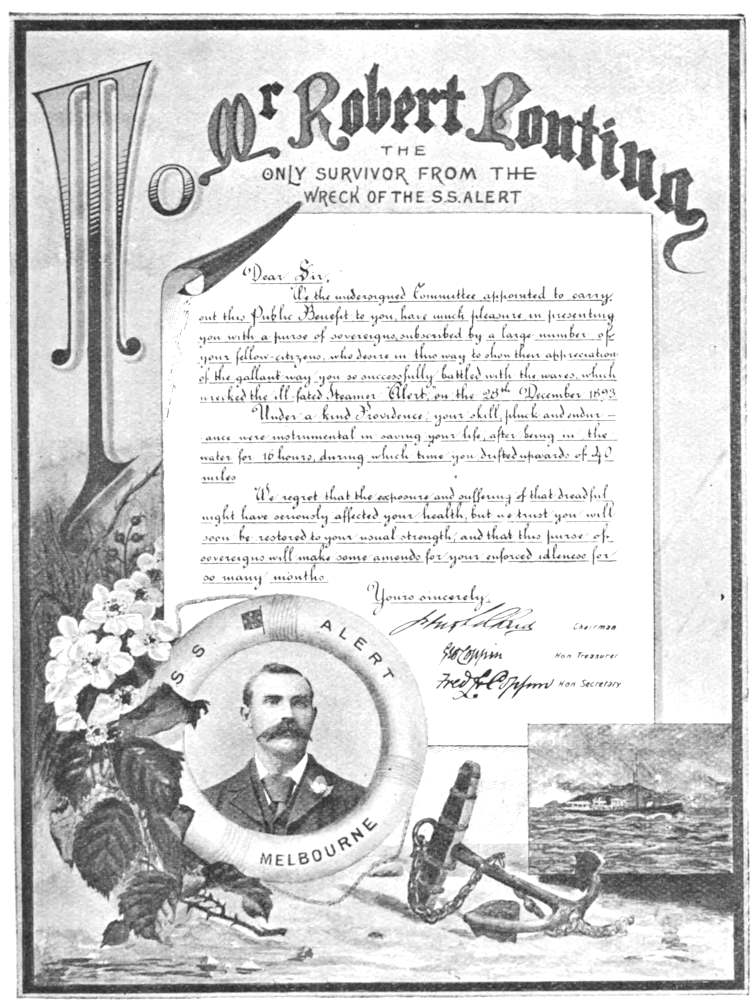

| Testimonial | at End of Book |

| The Pantry Window | 151 |

TO

LORD BRASSEY,

IN HIS TRIPLE CAPACITY OF LAWYER, MASTER-MARINER,

AND MEMBER OF THE ROYAL COMMISSION

ON UNSEAWORTHY SHIPS,

THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY

THE AUTHOR.

LORD BRASSEY AS A MASTER-MARINER.

THE LATE CAPTAIN MATHIESON,

S.S. Alert.

[Pg 17]

Battling with the Waves.

A shipwreck, at all times and under any circumstances, is a lamentable occurrence, but it is peculiarly so in instances where out of a whole ship’s company only one solitary individual is left to tell the tale. So far as is known to the compiler of the present work there have been only two such shipwrecks in Australian waters. One was the wreck of the emigrant ship Dunbar near Sydney Heads, Port Jackson, on the 20th August, 1857, when a seaman named Johnson—who is still living and permanently employed by the New South Wales Government, as a lighthouse-keeper at Newcastle—was the sole survivor out of 121 persons.

The other was that of the steamer Alert, near Melbourne Heads, Port Phillip, Victoria, on the 28th of[Pg 18] December, 1893, and the relation of which forms the subject matter of these pages. The last named vessel had 16 persons on board and all, save one, perished either by drowning, or by being dashed to pieces against the cruel rocks. Disaster comes to us in all forms, but the stirring story told by Robert Ponting, the survivor from the Alert, partly lifts the veil and shows us how brave men can, and do, even under the most adverse circumstances, battle to the last against the mighty raging sea which finally engulphs them.

It might be fitly said in the language of the poet.

To do his duty and face death on the battlefield the soldier requires great courage, even although there he has only his fellow man—and the instruments created by him—to contend against. The seaman’s courage is, however, of a very different sort. In a storm he has to war with something infinitely more awe-inspiring than anything puny man can make! Hence, however sorrowful and heartrending the detail of suffering and death at sea, still we who read of such cannot but admire the indomitable pluck which characterises the conduct of mariners, even when they believe and feel that all hope has fled. Death is the[Pg 19] portion of all; yet, although we are aware it is inevitable, there is a something—call it what we will—that instinctively impels us to fight and struggle for existence. During this struggle there are some well authenticated instances wherein men seem to have passed through the very gates of death, and yet, by the mysterious workings of Divine providence, have been for a time brought back, so to speak, into the land of the living until some purpose or aim had been accomplished. A clear case of the latter sort came within the experience of the present writer, and he hopes that the relation of the incident here will not be considered out of place by his readers:—

We were coming from Quebec, Canada, bound to Milford, England, with a timber-laden ship called the Marmion. When about half way across the Atlantic the captain became very ill with something understood by us to be British cholera. He was confined to bed, but persisted, every day the sun was to be seen, in being carried up on deck to take observations at noon. We could all see he was dying, and though every attention was paid to him, we expected each day to be his last. Just three days before we sighted land our captain died apparently, and it being cold winter weather, we determined, if possible, to bring his body on for burial when we arrived in port. To our astonishment, some hours after we believed him dead, he suddenly revived, and asked for something to eat! He continued improving so much that one night about six o’clock, when we had just sighted Kinsale light, on the Irish coast, he, without any assistance, came up on deck, took the[Pg 20] bearings of the light, and altered the ship’s course. A heavy gale was blowing, and the weather as thick as a hedge; still the ship, under close reefed topsails, was kept running all night before the wind, the captain, meanwhile, against all persuasion, insisting upon remaining on the poop. At noon next day, when the ship was still rushing along in the midst of a thick fog which prevented any land from being seen, the captain said quietly to the man at the wheel: “If the ship has been steered properly since we saw Kinsale light, she will be in Milford Haven in about three hours’ time; if she hasn’t been steered properly, she will be God knows where.” Almost immediately after speaking to the helmsman the skipper muttered in a bitter tone, as if communing with himself: “Anyway, it won’t make much difference to me.” In two hours more the weather cleared a bit, the we saw the land very “close to,” and we were heading straight for St. Ann’s—an island which lies in the entrance to Milford—as an arrow from a bow. By three p. m. we were safe in port with the anchor down. In the flurry of letting the anchor go we, for the time being, forgot all about our captain’s condition, but on walking aft and going below, we found him lying on the sofa in the saloon, dead for certain, as it proved, this time! He was, physically, a weak man, but had a powerful will and a taciturn nature. The anxiety of getting the ship safe into port had no doubt kept him supernaturally alive. The anchor down, he felt his task was done; he had quietly gone below, and unseen, passed away beyond the cares and troubles incidental to human life!

[Pg 21]

The voyage of life is anything but plain sailing, and whether we like it or not—aye, whether our duty lies in the hut of the shepherd—in the palace of the prince—in the workshop—in the forest—in the camp—or on the ocean—we may expect to encounter some phase or other of that perpetual conflict with the material forces of the universe, or that scarcely less persistent conflict with the moral force of circumstances, which, together, make up so much of the tragedy of life, and after all, impart to it so much of its dignity. Knowing then that storms and trials have to be encountered it is clearly our duty, so far as we are able, to take every precaution to minimise disaster of every kind. Disasters, of course, will occur, both on sea and shore, even when everything has been done that thought and skill can suggest, but with regard to shipping matters can we say that, in the interests of life and property, all is done that could and should be? Without presuming here to enter into the cause, or causes, of the Alert going to the bottom, it is saddening to think that though the vessel went down in broad daylight, and not far from the shore, still the accident was not seen. It may be that even if it had been seen, nothing, owing to the state of the weather, could have been done to help the sixteen men who were left to buffet with the waves, but, nevertheless, it must have added another pang to the suffering of these men to see and know the land was “So near and yet so far.”

The incidents which occurred after the foundering of the Alert are so extraordinary that if they were not authenticated beyond a doubt, the recital of them[Pg 22] would at once be classed as a narrative from the prolific pen of a dealer in romance. Indeed, it might be fittingly said that the wonderful endurance displayed by the survivor, Robert Ponting, in battling with the waves for fifteen hours on what must have been to him a terribly long, and dreary night—his being cast upon the beach—his curious discovery and ultimate resuscitation—all partake of the miraculous!

Moreover, as if to make matters still more sensational, somebody conveyed the news to Ponting’s wife, at South Melbourne, that her husband was amongst the lost, and Messrs. Huddart, Parker, and Co., the owners of the Alert, also, on the 4th January, 1894—six days after the date of the wreck—sent a cablegram to London, stating that Ponting was drowned.

The following extract from a letter, lately received at Melbourne by Mr. Robert Ponting from his brother-in-law, Mr. Thomas Hutton, in London, clearly gives the particulars of this unaccountable blunder:—

“Dear brother Bob,—

We heartily congratulate you on your wonderful escape from the sad fate that befel your shipmates through the foundering of the Alert. You also have our sincere sympathy for the terrible ordeal and physical suffering you have passed through. At the same time I may tell you that all your relations here had five weeks’ mental suffering on your account. It came about thus—On Saturday, 30th December, 1893, I read in the “London Morning Post” a telegraphic report of the loss of the Alert, in which it stated there was only one survivor, but no name was given. Of course we all[Pg 23] hoped that you were the survivor, and in order to ascertain this I went, on the 2nd of January, as soon as the office opened after the holidays, to Mr. James Huddart’s office, 22 Billiter street, London, but they could give me no information. They told me they would bring my request for information before Mr. Huddart, and that evening I got a letter from him stating that he would be glad to cable to his Melbourne branch if I wished, at my expense. I sent him, as desired, a cheque for £1 18s 8d, or 4s 10d per word for eight words—five words for the message and three for the answer. He deeply deplored the sad necessity there was for such a cable, but stated that he would send it on at once, and immediately communicate the result to me. Mr. Huddart got the reply from his Melbourne office on the 4th January, and then he forwarded a telegram to me as follows:— ‘Much regret to inform you, brother (R. Ponting) drowned in the Alert.’ Of course I had the sad duty of letting mother and father and all the other members of the family know the mournful news that had reached me. You, dear Bob, can imagine our feelings when we thus knew for certain that you were lost. We all purchased mourning clothes and wore them for five weeks, until, on 6th February last, we received a letter from Mr. James Huddart which filled us all with joy. This letter enclosed a cutting from a Geelong paper, stating that you had been saved and that you were the sole survivor. Mr. Huddart’s welcome communication also stated that owing to a strange error, on the part of his Melbourne branch, the word “drowned” had been cabled[Pg 24] instead of “saved.” In reply I thanked Mr. Huddart for his kindness in sending the good news to us, but I did not further refer to the painful mistake they had made, although it had caused us such grief. I need scarcely tell you we are all truly thankful that God in his mercy, saved you from the dangers of the deep.”

It will be seen from the foregoing that Robert Ponting was placed in the unique position of being able to read of incidents which took place after his supposed death.

[Pg 26]

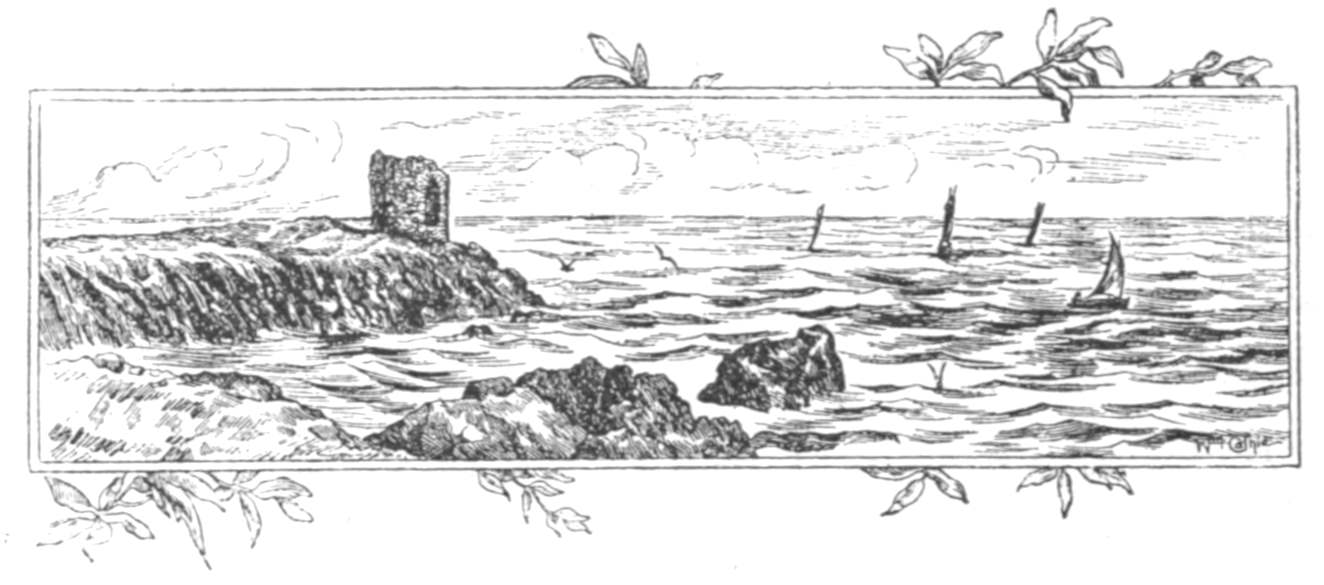

SORRENTO.

From a Photo by the late J. Dodd, lost with the S.S. Alert.

[Pg 27]

In order to give those of our readers who have not visited Sorrento a clearer idea of the coast whereon the S.S. Alert was wrecked, it has been deemed necessary to give, by way of preliminary, a brief outline of the locality.

On the S.E. side of Port Phillip bay, about 40 miles south of Melbourne, lies the pretty little township of Sorrento. It has a population of some 300 persons, but during the summer months this number is largely increased as the neighborhood, principally owing to the enterprise of the Hon. George Coppin, M.L.C., is a favorite resort for pleasure seekers and picnic parties, who arrive, per train or steamboat, from Melbourne and suburbs. In addition to its notoriety as a bathing and health giving place, Sorrento possesses a historic interest which is at once instructive, amusing and contradictory.[Pg 28] Here it was that Colonel Collins, in October, 1803, landed, from the ships Calcutta and Ocean, 350 British convicts, with the intention of forming a permanent penal settlement in accordance with instructions received from the Imperial Government. After staying a few months, he, however, abandoned the locality as it was, to use his own words, “an inhospitable spot not fit for a white man to live in.”

In one sense it was providential that the Colonel condemned the place, otherwise the record of the origin of Victoria, as a colony, would not have been very edifying. One of the principal reasons given by Collins for deserting the settlement was “want of water,” but wells, dug by the members of the expedition, still exist to prove how easily water could have been obtained. Other proofs are not lacking to show that the gallant Colonel must have had other reasons than the ones he gave for taking his departure. For instance, Mrs. Hopley, wife of one of the officers of the expedition, according to Rusden’s “Discovery and Settlement of Port Phillip,” wrote to her friends in England, thus—“My pen is not able to describe half the beauties of that delightful spot. We were four months there. Much to my mortification, as well as loss, we were obliged to abandon the settlement through the whim and caprice of the lieutenant governor. Additional expense to the government and loss to individuals were incurred by removing to Van Dieman’s land. Port Phillip is my favorite and has my warmest wishes. During the time we were there (Sorrento), I never felt one ache, or pain, and I parted with the[Pg 29] place with more regret than I did my native land.” Further, one of the officers wrote—“It was one of the most healthy and enjoyable spots that it has been my good fortune to find in the course of my travels. Why it should have been abandoned is a mystery. Climate, prospect, and every natural advantage were in its favor, and water was to have been obtained in abundance if there had been any desire to have found it.” Amongst the members of the Collins party were two men who afterwards became famous though their stations in life were widely apart. One was William Buckley—a convict who made his escape and lived for 32 years amongst the native blacks as “the wild white man,”—and the other was the late Hon. John Pascoe Fawkner—then a boy in charge of his parents—who had an excellent claim to be considered the founder of Victoria, and was beyond all doubt the founder of the City of Melbourne. At the rear of Sorrento, across a narrow neck of land about a mile and a quarter wide, lies the Ocean Beach—or as landsmen love to call it, the “Back Beach,”—where the ever surging South Pacific rolls in its mighty waves on to a bleak and barren shore, which embraces a stretch of coast line extending from Cape Schanck to Port Phillip Heads, a distance of about 20 miles. The fore-shore, or rocky beach, is here flanked by a sort of amphitheatre of high cliffs, from whence a magnificent view seaward can be obtained, and, when a strong southerly wind is blowing, the commotion of the waters, as seen from this vantage ground, forms a remarkably imposing picture. Here one can gaze on what Tennyson[Pg 30] describes as “The long wash of Australasian Seas.” Now, with sullen roar, racing swiftly along, now leaping high over the outlying reefs, then dashing with irresistible force against the jutting rocks, and finally spending their fury by lashing themselves into a fringe, or belt, of creamy foam which extends as far as the eye can reach. If there be one place more than another to which the grand lines of Gordon, the Victorian poet, are appropriate, that place is Sorrento Ocean Beach.

[Pg 32]

RESUSCITATION OF ROBERT PONTING.

[Pg 33]

On Thursday, the 28th December, 1893, a large number of visitors were, as is usual at holiday times, down at Sorrento. All day a heavy gale of wind and rain had been blowing along the Victorian coast, and visitors were, of course, thereby prevented from enjoying themselves on the ocean beach. Next day, however, the weather was considerably finer, and the sun shone out, although a pretty stiff cool breeze was still coming in from the south, or seaward. Taking advantage of the gleams of sunshine and the receding[Pg 34] tide, four young ladies, namely—Miss L. Armstrong, of 397 Station-street, North Carlton; Miss E. Duggin, of St. Belades, Kasouka-road, Camberwell; Miss K. E. Davis, of 97 Webb-street, Fitzroy; and Miss M. Moorman, of 349 Smith-street, Fitzroy, were down strolling on the only bit of sandy beach there is below the cliffs, when suddenly they came across the body of a partially dressed man lying half-buried in the drifting sand. Although frightened at first, instead of running away screaming at the unwonted sight, as many of their sex at their age would have done, these brave girls, with a promptitude which reflects credit on their heads, as well as their hearts, quickly determined on their line of conduct, and added another proof of the truth of Scott’s opinion:—

The following account was given to the present writer by Miss Davis, one of the foregoing young ladies:—“We left ‘Lonsdale House’ directly after breakfast on Friday morning for Jubilee Point. We got down the cliff about half-past ten, intending to look for shells and seaweed. We had just reached the end of the railing, and were looking at some ‘natural aquariums,’ as they are called, when our attention was drawn to a man stretched on the sand to all appearance dead. Miss Moorman said, ‘I believe it’s a drunken man,’ but on looking closer we saw that he had a life-belt around him. We went near to him and noticed that his eyes were moving. Finding that he[Pg 35] was not dead, I knelt down and asked, ‘Are you ship wrecked, Mr.?’ After a minute or two he replied in a faint whisper, ‘Yes,’ and shortly afterwards he gasped out ‘Refreshments,’ then immediately swooned away. We then arranged that two of us should stay by the man, dead or alive, and the other two go at once to obtain help of some kind. We saw that the man’s life-belt was clogged with sand, and also his eyes, nose and ears. With some difficulty we undid the belt, and dipping our handkerchiefs in water we wiped the sand from his face. He then came to a little, and said he felt better, but all the time till assistance came, and even after, he kept swooning away, and each time he went off we thought he was dead. We put our cloaks over him, and sheltered him from the cold wind as much as we could with our parasols, till Messrs Ramsay and Stanton came and applied the treatment usual in cases of the apparently drowned. In our small way we gave all the aid in our power. The scene was one which none of us will fail to remember, and although we do not wish to be in such another incident, still we feel it did us good to be there, for we got an object lesson, and any of us know now how to treat a person rescued from the water.” The two young ladies who ran back for assistance luckily had not gone far when they met Mr. J. Douglas Ramsay, the well-known dentist, of Elsternwick. By a strange coincidence Mr. Ramsay had been in former years a medical officer on board several ships belonging to the “Loch” line, and hence he was just the very man required for the emergency. What took place[Pg 36] afterwards cannot be better told than in the graphic language of Mr. Ramsay himself, as given at the official enquiry, held a few hours after the discovery already related. In giving evidence Mr. Ramsay stated, “I, with my wife and her sister, Mrs. Whitelaw, went to the Ocean Beach by trap at about 10 a. m. this day (Friday, 29th December) and then walked on towards St. Paul’s, one of the highest points around. When we were within a few hundred yards of it I saw two ladies hurrying up. They came towards us and one said, ‘There is a shipwrecked sailor down there. Can you tell us where to get some stimulant?’ I replied ‘Thank God! we have some here in a flask.’ I ran down in the direction pointed out and found a man lying on the sand about seven yards from the water’s edge. He appeared to be dead. He was clad in black trousers and white shirt, stockings were on his feet, but no boots. I immediately tried if I could discover any signs of life, but could find no pulse, everything he had on was covered with sand, and his body was stiff and cold. I prized open his teeth, and poured some brandy down his throat and then commenced to work his arms to restore animation if possible. After 10 minutes I saw a few signs of life and then, assisted by my wife and the other ladies, I dragged him behind a rock for shelter from the cold wind which was blowing strong. I continued working at him for about half-an-hour and the whole of the ladies assisted me materially by rubbing, in turns, the man’s hands and arms. As soon as I saw it was likely that the man would be saved, I sent Mrs. Ramsay and her sister back[Pg 37] to get more assistance and they both cheerfully started on the journey. Meanwhile Mr. Austin Stanton, of Collins-street, Melbourne, in company with Miss Hill, came on the scene, and he at once took off his great coat, and spread it over the man’s body, while Miss Hill took off her jacket and wrapped it round his feet, which were very much bruised. Mr. Stanton had his large St. Bernard dog, “Victor Hugo,” with him, and as warmth was now the great thing necessary, Stanton got the docile animal to lie down and nestle up close to the man’s body. It was indeed a strange sight, and one which called up feelings which I will not readily forget, to see a huge dog, in faithful obedience to his master’s orders, lying close to an apparently dead man! One could almost imagine that the intelligent animal knew the effect its conduct would produce; be this as it may, the increased warmth soon became apparent. The man opened his eyes and drew a long breath. I at once gave him some more brandy, and a better color began to appear in his face. A few moments after, he suddenly exclaimed: ‘Where is my life-belt?’ I told him it was all right, having been taken off previously. He then said: ‘Could some one go round the beach? Some of my mates might be washed up.’ In answer to questions he said his name was Bob Ponting, that he had been cook on board the steamer Alert, and that she had foundered the previous day when about three miles off the coast. From the weak state our patient was in we dared not question him further, but some of us went along the beach, without, however, finding[Pg 38] or seeing any traces of his mates. About two hours from the time Ponting was found additional assistance came. Constable Nolan, of Sorrento, brought a party of men in a buggy. They also brought a stretcher, on which we placed the poor man, and between us we carried him up the cliffs and across to the buggy. It was no easy task, even with half a dozen willing hands, as the cliffs at this point are very steep, and after getting to the top the scrub is very thick and hard to walk through. We got Ponting into the buggy and brought him to Clark’s Mornington Hotel, Sorrento, where we arrived about 1.30 p. m. He is now receiving all care and attention. I fancy he will pull through with good nursing. Had he not been such a powerful man, he could not have stood the terrible exposure. It is a miracle that he is alive at all. He is a fine-looking man of about 30 years of age. He was only married three months ago, and was very anxious that a telegram should be sent to his wife. Of course we complied with his request as soon as possible.”

On arrival at the hotel Ponting was immediately attended to by Dr. Browning, the Government medical officer of the Quarantine Station, Point Nepean, and also by Drs. Mullen, Hutchinson and Cox, but in spite of all their skill the poor fellow showed unmistakable signs of collapsing. The life color, which had been coming back to his skin, now gradually disappeared, his body got cold and rigid and he relapsed into a complete state of coma, so much so that the medical gentlemen despaired of his case as utterly hopeless. However, after rubbing two bottles of brandy through[Pg 39] his skin, applying hot bricks to his feet, and rolling him in warm blankets, the doctors saw that their patient was likely to recover. As the wounds on Ponting’s body—caused by the nails in the raft on which he had floated—showed signs of engendering blood-poisoning, blisters were applied to the various places with good effect. Nearly all the forepart of Friday night he lay tossing in a delirious condition and talked wildly of the terrible experience of the preceding twenty-four hours. His wife was sent for, and aided by her careful nursing the doctors knew that their combined efforts were being crowned with success. Meantime search parties had been scouring the rocky coast and they succeeded in finding seven of the ill-fated ship’s company, but they were battered and bruised almost beyond recognition. The bodies were removed from the beach and laid in a row side by side in a shed at the rear of the Mornington Hotel, and on the following day (Saturday) Ponting, having recovered consciousness and improved considerably, was carried there for the purpose of identifying his dead comrades. It was an affecting scene, and a trying ordeal for Ponting in his weak state as one by one the bodies were uncovered to his gaze. No. 1 was J. Williamson, one of the sailors; No. 2 was Page, a steerage passenger; No. 3, D. McIvor, a fireman; No, 4, W. Thompson, also a fireman; No. 5, W. Stewart, the other steerage passenger; No. 6, J, Thompson, the chief engineer, and the seventh was Captain Mathieson, the commander of the Alert.

[Pg 40]

[Pg 42]

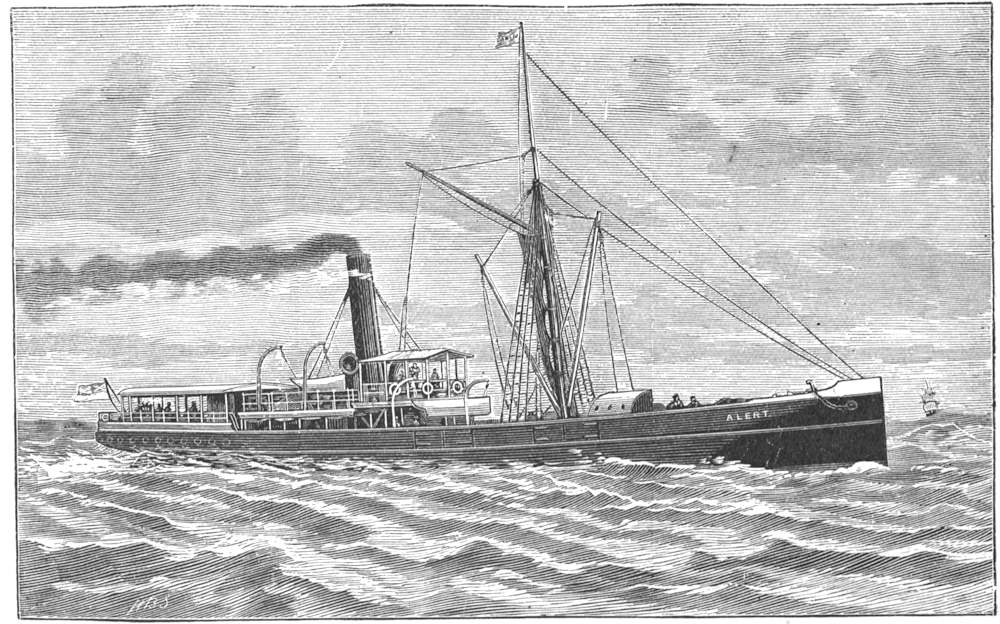

S.S. ALERT.

From a Photo by the late J. Dodd, lost with the S.S. Alert.

[Pg 43]

The following is a complete description of the S.S. Alert:—

Owners, Messrs Huddart, Parker and Co., Melbourne. She was an iron screw Steamer of 243 tons gross measurement, built at Port Glasgow, Scotland, in 1877. Her length was 169 feet. Breadth of beam, 19 feet 6 in., and depth of hold, 9 feet 8 inches, In other words, her length was nearly eighteen times her depth, and nearly nine times her width. She came out to Melbourne under sail, and rigged as a three masted Schooner.

From the time of her arrival here until the month prior to her loss, she had been trading inside Port Phillip Heads, from Melbourne to Geelong and vice versa. All the time she was engaged in the Geelong trade, and up till the period of her loss, she was rigged[Pg 44] with a foremast only, and hence she was not capable of carrying sail aft.

The cargo she had on board when she left Metung, (Gippsland Lakes) her last port of call, consisted of 25 tons wattle bark, 20 bags maize, 14 empty casks, 40 bales wool, 55 sheepskins, one box tools and 20 packages furniture. In all estimated about 44 tons.

With regard to her draught of water when on the fatal voyage, it is alleged that she was drawing 9 feet 6 inches aft, and 5 feet 9 inches forward.

Complete list of the persons on board the Alert at the time of the disaster.

Drowned—

Albert Mathieson, captain, age 35, married, no children; residence. St. Vincent-street, South Melbourne

J. G. Hodges, chief officer, 32, married, no children; Yarraville.

J. Mattison, second officer, 43, single; South Melbourne.

J. Thompson, chief engineer, 48, single: South Melbourne.

J. Kilpatrick, second engineer, 33, married; one child; Williamstown.

J. Dodd, steward, 32, married, one child; Carlton.

T. Thompson, A.B., 45, married, two children; South Melbourne.

J. Williamson, A.B., 27, single; South Melbourne.

J. Arthurson, A.B., 25, single; South Melbourne.

J. Coutts, A.B., 42, married, three children; South Melbourne.

W. Thompson, fireman, 30, single, Williamstown.

D. McIvor, fireman, 28, single, Balaclava.

J. Newton, saloon passenger, 29, single; Beechworth.

W. Stewart, steerage passenger, 60, married, seven children; Collingwood.

— Page, steerage passenger, Steiglitz.

Saved—

R. Ponting, cook, 30, married, no children; South Melbourne.

[Pg 45]

The subjoined narrative is given, as nearly as possible, in the words of Robert Ponting, the sole survivor.

The S.S. Alert left Melbourne at mid-day on Saturday, December 23rd, 1893. Proceeding down Hobson’s Bay we called at Portsea and Queenscliff, and finally cleared through Port Phillip Heads at 5.30 p. m. We had moderately fine weather along the coast and rounded Wilson’s Promontory at 4 a. m. on Sunday. Four hours after, we reached Port Albert, lay there all day, discharged cargo early Monday morning (Christmas Day), and sailed at 7.30 a. m. for Gippsland Lakes. Had moderate sea and cloudy weather along the “90[Pg 46] mile beach” and got to Lakes entrance about 4 p. m. Proceeded up the lakes, called on the way at Metung and Paynesville, and arrived at Bairnsdale, our destination, at 8 p. m., in the midst of a heavy thunderstorm. Next day, Tuesday, being Boxing Day, no cargo was put out. On Wednesday, 27th, discharged all cargo and shipped a small quantity of wattlebark, wool and some cases of furniture, the latter belonging to Mr. Deasy, inspector of police. We sailed same day at 2 p. m. for Melbourne, having three passengers on board, one, Mr. J. Newton, in the saloon, and two in the fore-cabin, whose names I did not then know, but I have since ascertained their names were Stewart and Page. There were several other passengers expected but they did not turn up. On the way down the lakes, we called at Metung and shipped a little more wattlebark, making our cargo as I have since been informed, in all about 44 tons. Just before dark we passed out through the Lakes entrance. Outside we met with misty weather, a smooth sea and a light breeze from the south-west. At 2 o’clock on Thursday morning (28th), I was awakened by the stopping of the propellor—I slept in the stern sheets immediately over it—I went on deck to see what was the matter, and was informed that, owing to the thick weather, the red light on Cliffy Island could not be picked up. We lay “hove to” for nearly four hours, then, as the wind rose and lifted the fog we found we were well on our proper course. The ship was again kept on her way and we rounded Wilson’s Promontory a little before 7 a. m. Soon after, the wind chopped round from south west to [Pg 47]south-east, enabling us to set the trysail and staysail. We passed through between the islands all right and then fell in with a heavy rising S.W. swell and a choppy sea from S.E. This caused the vessel, being very light, to get very lively and take on board large quantities of heavy spray. At 8 a. m. the crew came for their breakfast, but the steward told me that no one in the after part of the ship wanted any breakfast. I was not surprised at this as I had often seen the Alert make things so lively that no one on board required anything to eat for the time being. I went forward to ask whether the two steerage passengers wanted breakfast, but they would not have any. About 11 a. m. when off Cape Liptrap, the sea was very much higher, but we did not give much heed to this as we had always found it a bit rougher when passing headlands. At noon the crew came along for their dinner and they brought their beds with them. They placed these on the engines to dry, grumbling very much as they did so that the ship was so dirty they could keep nothing dry either above or below. I told the men they might have their dinner in the galley, but after looking in they declined, remarking it was worse than the forecastle. Tea and toast was all they required aft for their midday meal. By 3 p. m. we were about two miles off Cape Schanck and the wind having gone round to S.W. again, blowing a steady gale, there was a heavy sea breaking just off the point. In order to avoid these breakers, Captain Mathieson altered the ship’s course and headed out seaward for a while, till the Schanck was given a wide berth, then the course was shaped for Port Phillip Heads,[Pg 48] The Alert now began to roll very much and take heavy lurches to leeward at the same time taking lots of water on board. A great many articles in the galley were thrown down and smashed or washed away. It was impossible for me to help this, although the steward said there would be a jolly row when we got into port over losing so many things.

CAPE SCHANCK

At 4 p. m. the watch came from below but all hands remained on deck and went up on the poop as it was the driest part of the ship, and, but for the rain, fairly comfortable. The steward told me not to attempt to get any tea ready till we got inside, so I went below with him into the saloon. We had not been there many minutes till we heard a tremendous sea break on board on the lee side. It made the ship shiver like a leaf and listed her over to starboard so much that the two lamps hanging in the saloon were thrown violently up against the deck overhead and smashed to pieces. We ran up on deck to see what was the matter and found the lee side of the vessel full of water, the bulwarks amidships being clean out of sight. Two men were at the wheel and the Captain was on the bridge evidently trying to get the ship’s head up to the sea and wind. The next wave came right up on the lee side of the poop—where I was standing holding on to a stay—and washed me overboard, but I managed to grasp the poop railing and held on for bare life. Just as the chief mate, Mr. Hodges, was coming to my rescue another heavy roller threw me inboard again and dashed me up against the companion with such force that I thought for a time my legs were broken. I asked Mr. Hodges whether he[Pg 49] thought the ship was in danger. He replied, “No, I think she will come up to it,” meaning that when the vessel got her head to windward she would free herself from the water on deck. Meantime, Captain Mathieson had taken the wheel himself and sent the two men to join the others in taking in sail foreward. As soon as the canvas was taken off the ship another attempt was made to bring her up, but all efforts were useless. She would “come to” a little bit, then the sea and wind would sling her off again, like a gate swinging on its hinges. Each time she went off she seemed to become more helpless and dipped nearly her whole broadside into the hissing waters. The steward and I went down into the saloon and found the water about three feet deep on the starboard, or lee, side of the floor. Every roll the vessel took dashed the water over Mr. Newton where he lay. We assisted him up on deck and then tried to discover where the water was coming in. We found that the pantry window—which looked out on the starboard side of the main-deck—had been burst in by the pressure of water from the outside. We blocked the aperture up as well as we could and then went up on the poop. The Captain was still at the wheel and the men were foreward securing things about the deck in the best way they could. Captain Mathieson beckoned me and asked if there were any water below in the saloon. I told him there was and it was still rising. His countenance changed, but he made no reply. By the beating of the engines I could hear they were commencing to work more slowly, and the ship seemed as though she were becoming[Pg 50] entirely unmanageable. The chief engineer, Mr. Thompson, called out to Mr. Kilpatrick, the second engineer, who was on duty below, “Give it to her, Jack,”—meaning for him to keep the engines working as fast as he could. In answer to the steward’s question, “Is there no show to get the vessel head on?” Mr. Hodges said, “I am afraid she won’t come to. She is too light foreward and we have no sail aft to help her round. Everything is against her at present as it happens. There is that upper deck and the foreward boat, all on the starboard side. What with the big funnel and bridge, the life-boat on the engine-room skylights, the awning of wood instead of canvas and too little cargo, she’s all top and no bottom.” The ship now began to lie down almost steadily on her beam ends, the big seas dashing over her as if she were a half tide rock, and pouring down into the engine-room and stoke-hole. The second engineer, Mr. Kilpatrick, and W. Thompson, the fireman, came up and stated that there was too much water below for them to stay any longer. The Captain sang out from the bridge, where he had been standing exposed from early morning, “Call all hands aft, passengers and everybody.” As soon as we were mustered together he gave orders, “Now boys, get out the life-belts and put them on.” Matters now began to wear a serious aspect, and although there was no panic, everybody felt that a great change was at hand. The steward and I started throwing the life-belts from the racks underneath the awning and in a few minutes everybody had one on. Poor Mr. Newton, who seemed downhearted, asked “How do[Pg 51] you put this on?” By way of reply the steward fastened it properly round him at once, and also on the two steerage passengers. The next order given by the Captain, was, “Now then my lads, bear-a-hand and get the life-boat out.” The words were scarcely out of his mouth when the ship took a fearfully sudden lurch to starboard and away went the life-boat, chocks and all, clean over the ship’s side. Two lines that were fast to the boat kept it from washing away. The crew soon made the boat fast properly, and though she was half full of water, Mr. Hodges jumped into her and called out for all the spare life-belts to be thrown to him so that he might fasten them on to the boat’s thwarts while some of the sailors were keeping her clear of the ship’s side. He had got about six of them tied on when we saw a heavy sea coming and sang out to him, “Look out.” He leaped back to the ship just in time as in less than a minute the boat was either smashed to pieces or swamped; for we saw no more of her. Orders were then given to get the foreward boat ready but as the waves were breaking clean over it, nothing could be done. The ship now lay over so much that we could not stand on the deck. The Captain got over the bridge railing and stood on the end of the bridge, while the rest of us got on the outside of the weather (port) bulwarks. Though we were all crowded close together very little was said, each one kept looking at the big breakers, knowing that the time had come when each man would have to enter on a desperate struggle for life. Almost the only remark made was by one of the sailors, who said, “We can see the Schanck lighthouse,[Pg 52] quite plain, and no doubt the people there see us and will send help of some kind.” Prior to putting on the life-belt I took off all superfluous clothing, leaving nothing on but my white cap, shirt, trousers and socks. The steward followed my example but kept his boots on. All the others were fully dressed and a few of them had even their oilskins on beneath the life-belts. The seas now rolled relentlessly over us, each one holding on as best he could. The wooden awning was wrenched off its stanchions and swept away to leeward. Some one suggested that there would be more safety further foreword both from the sea and the propellor, as the latter was still slowly revolving, and a number of our crowd crept as far foreword as the bridge. I decided to keep aft as I was afraid the boiler would burst and blow us all into the air. Whilst standing alone, holding on to the rail opposite the saloon companion, a tremendous sea broke over the ship’s quarter and swept me fathoms away from the vessel. I swam some distance clear and then turned to see how my mates were getting on. They were all still clinging on to the weather bulwarks and from the way their faces were turned, I saw they were watching me. The ship for a little while looked as if she were going to uprighten then she began to sink slowly, stern first. I saw Captain Mathieson still holding on to the railing at the port end of the bridge. I think he must have told the men to jump into the sea, for I saw one after the other spring clear of the vessel, then, last of all, he jumped himself. The Alert’s bow then rose in the air till I could see many feet of her keel clear of the water. She hung in[Pg 53] that position for a minute or two as if she hesitated to sink. It flashed across my mind that as there was no water in the forehold, perhaps she was going to keep afloat after all. The hope raised by the thought, however, soon left me as the ship gave a sort of plunge and then gradually disappeared. Fire and steam burst up through the funnel just before the waters closed over it!

[Pg 54]

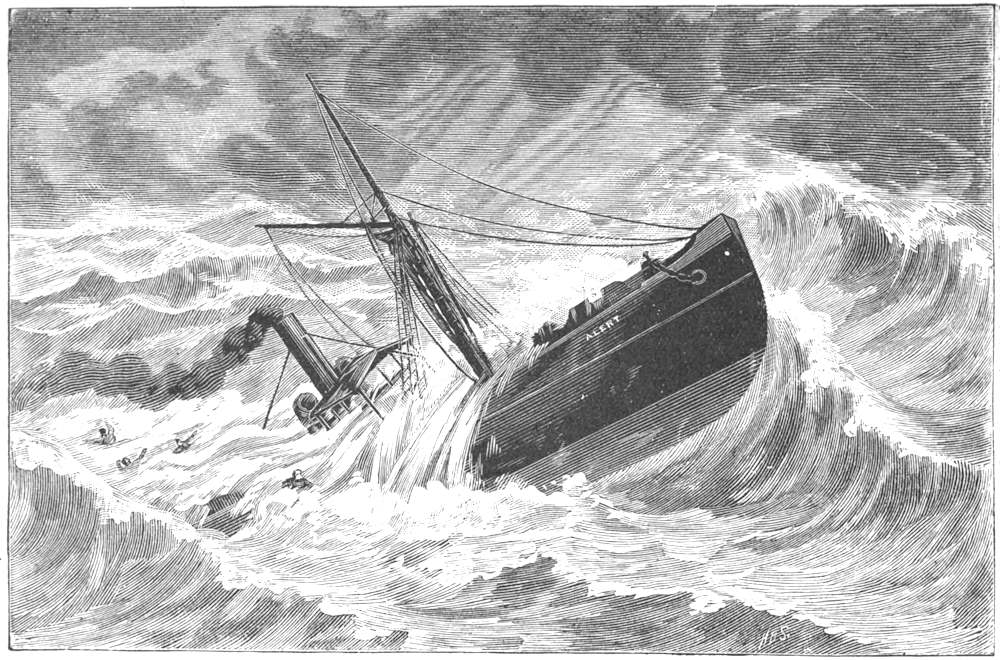

Owing to the manner in which the ship went down she created little or no suction. A slight swirl and wreckage—principally pieces of the awning, a few gratings and life-buoys—were all that denoted where our vessel had been. She sank about 4.30 p. m., and just then the thick weather cleared off a little so that when I rose on top of a wave I could see a considerable distance off. The shore was plainly visible and I judged we were about three miles S.W. of Cape Schanck. I saw that the whole fifteen of my companions had managed to get hold of some wreckage. The Captain, chief mate and two firemen were all grouped together on some pieces of weather-board, and the others were scattered in twos and threes, each on top of something. [Pg 57]My first fear was that the sharks would get hold of me, then it struck me that the water was too rough for them to attack any one. I could only see some single pieces of board near me, so I was puzzled for a bit as to how to steer for something larger. All of a sudden I saw a lot rise on the top of a big wave right ahead of me. I soon reached it and thought I was quite as well off as the rest of my mates. My raft consisted of eleven or twelve pieces of weather-board all nailed together on a crosspiece. I got on top, and then every single piece of plank that came near me I pulled on board, till I succeeded in piling them up high enough to keep me out of the water. The sixteen of us were at this time all floating nearly in a line. Two sailors and the steward were about thirty yards seaward of me, the captain, chief mate, and two firemen about 50 yards off landward, and the rest a little distance further inward still. A large number of Mullihawks collected and kept hovering above our heads. I had no sooner got my raft put together, to the best advantage, when a heavy sea came, and turned all clean over on top of me. The nails in the planks caught my clothes and pierced my skin so that I had great difficulty in clearing myself from underneath. When I succeeded in getting on top again I saw that all my mates to windward of me had also been washed off their wreckage, and a similar fate shortly after befel those to leeward. It almost seemed as if the same wave had capsized the lot of us one after the other. Everyone, however, succeeded in catching their planks and getting on them again. After the[Pg 58] capsize I found my raft in a very different condition to what it was previously. All the loose planks were gone and a number of the ones nailed to the crosspiece had also disappeared. All of my mates, when on top of their wreckage, knelt on the boards with their heads facing the shore, and held on in that position. The noise made by the wind and waves made it useless, at the distance I was off, for me to call to my companions, but I made signs, and tried to show them, by lying down flat on my raft, what I believed to be the surest way of holding and keeping on, with my head facing the seas.

FOUNDERING OF THE S.S. ALERT, THREE MILES S.W. OF CAPE SCHANCK. DECEMBER 28, 1893.

As we drifted nearer the shore the seas got larger and more powerful still, so that in spite of all our precautions we could not retain our hold on the boards for any length of time. The frequent turning over of my raft knocked me sort of stupid every time I went under, and I have no doubt that the rest of my companions had similar experience. I reckon it must have been about 6 p. m. when I saw the steward washed away a great distance from the wreckage he had been on. After a long struggle he succeeded in getting back to his mates, but he evidently had completely exhausted himself in the effort, for he had hardly been a minute on the top of the boards till he fell from his kneeling position forward, with his head on the edge of the raft. He seemed to be smothering in the foam of the sea, so I shouted to his raft mates to hold his head up till I came to help him if I could. I knew poor Dodd was not strong, still I thought we might be able to keep him alive until the life-boat, or some other assistance, came from the shore.[Pg 59] I left my raft and swam towards him as quickly as I could, but before reaching him a big sea buried me. When I got to the surface again I saw the steward had been washed off the boards and was floating some distance away in a position that told me he was dead. It greatly grieved me to see that my most intimate companion was the first to go out of our number, and for the time being I felt unnerved enough almost to give up hope myself. Then I thought it useless brooding over the matter, and determined to struggle on while I had any strength left. For a while I swam towards the raft on which were the captain, the chief officer and the two firemen. As I got near I saw a large breaker turning them clean over. They had their feet to the sea, and as their raft capsized I saw the legs of the whole four in the air at the same time. Finding it out of my power to help them, and thinking that matters might be made worse by crowding too close together, I started back to my boards again. Quite exhausted I reached my raft. As I lay on it I began to think it was time the life-boat was in sight. I could see a good distance around, the shore being plainly visible, but no sign of any help coming. It could not have been more than 7 p. m., yet it seemed to me that I had been days, instead of hours, in the water. I noticed that all had got on their boards again. The different groups were all ranged round in a semi-circle, and all, except myself, heading shoreward. I had found, by bitter experience, that in heading shoreward I was more exhausted—when turned over, or washed off my raft by a sea—in getting back to my boards than when I faced[Pg 60] and headed the sea. At the same time, this method of going head first into the seas kept myself and my raft from drifting shoreward as quickly as the others. I did not mind this drawback, as my hope was strong that the life-boat would pick us all up before dark. Various currents now began to scatter our rafts in all directions. Both Coutts and Williamson (two of the sailors), drifted so close to me that I could speak to them. One after the other I asked how they were getting on. I got no reply and I could plainly see that they were so exhausted that they could not keep up the life struggle much longer. The boards to which Coutts held on were being carried seaward, while those belonging to Williamson were drifting in shore, towards the place where the four-masted ship Craigburn was wrecked. I reckoned we had all drifted some miles shoreward—from where the Alert had foundered—before the tide began to turn, and take our various rafts hither and thither. The seas, if possible, began to get bigger, and break irregularly in all directions around us. I caught sight of Mattison, the second officer, Thompson, the sailor, Kilpatrick, the second engineer, and Mr. Newton, the saloon passenger, all being carried by a current which I judged would take them round Cape Schanck whilst the rest of our number were going, some towards the shore, and some out seaward.

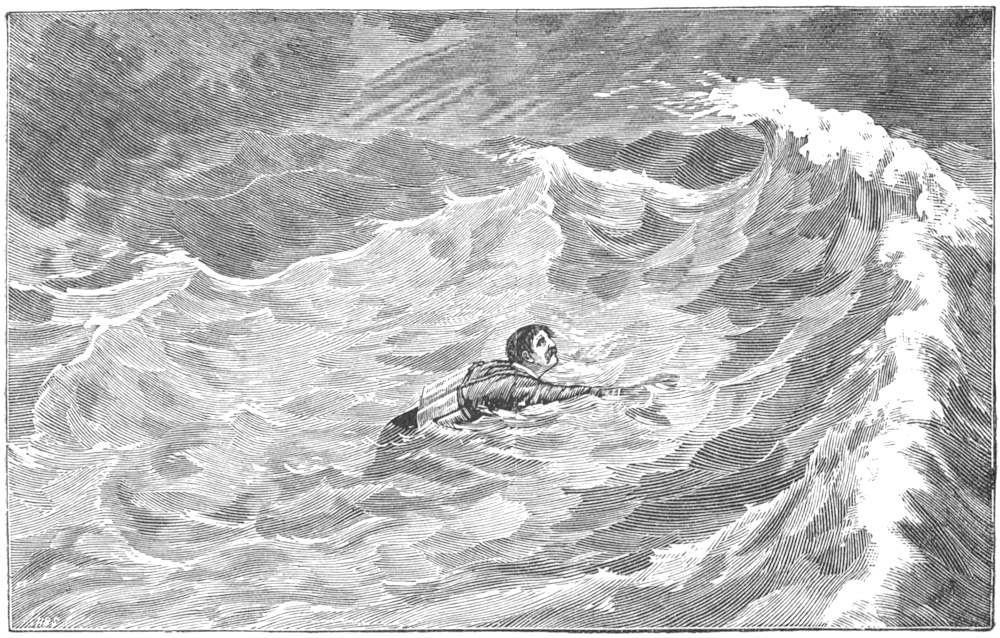

[Pg 62]

ROBERT PONTING “AMONG THE BILLOWS” ON THE NIGHT OF DECEMBER 28, 1893.

[Pg 63]

Darkness began to set in, and I soon lost sight of everybody and everything except the light on Cape Schanck. With the daylight fled my hope of a life-boat coming to our assistance. I had all along been under the impression that the sinking of our ship had been seen by the people in the lighthouse, and that it was only a question of time when help would come. I began to give way to despondency! While the daylight lasted I expected assistance, and my attention, when not struggling under water, was taken up watching my mates and the shore. Now night had come, and I felt as if I were left alone in the midst of the raging waters. Was it worth while trying to continue what seemed to be a hopeless struggle for life? I thought of my poor[Pg 64] wife, who, just then, would be expecting me home! I remembered, too, that Captain Mathieson—who knew my life was insured—had asked me, on the way from Melbourne to Port Albert, if I had made my will. When I told him “No,” he said, “You should have done so, as no one knows what may occur.” I gave little heed to his words at the time, but now they seemed to have all the meaning of a presentiment. Under the circumstances, thoughts like these were anything but cheering, but nevertheless I made up my mind that, while God gave me strength, I would battle on to the end. My raft, through being so frequently turned over, had got reduced to three boards and the crosspiece. At first I thought this was a misfortune, but I found that, being smaller, it was more easily managed, and less liable to be capsized. The wind began to be very cold, and a heavy shower of rain came on. As I lay on my boards, the raindrops felt to me like spots of ice as they fell upon my body. Strange as it may seem, I believe I must have perished with the cold, but the frequent washings off the raft, and my struggles in swimming to get on again, always kept my blood in circulation, and made me feel fairly warm. Meanwhile, the tide was slowly setting me down towards Cape Schanck, I saw the light burning brightly, and it seemed no great distance off. As I drew nearer and nearer, the breakers I got amongst were terribly heavy. From the peculiar thunder-like roar they made in rushing along, I could hear them coming in time to get ready for them. This I did by turning myself on the raft with my head and face seaward. These[Pg 65] tremendous waves generally ran in threes, one after the other in succession. The first would dash me off my boards and bury me in a half-senseless state under water; then by the time I got to the surface again, and had a breath or two, the second sea would be on me, repeating the burying process, so that I used to reckon the third would completely finish me. After recovering from these dashings my next great trouble was to find my boards. I was anxious to keep them, as they not only gave me a rest, but they also seemed to be kind of company for me. In the dark I could see them always a little distance off; as they shone on the water with a ring of phosphorus around them. I feel certain that if I had been unable to get on to my boards during the short intervals (about fifteen minutes) between these terrible breakers I would not have had sufficient strength left to resist them. I think it must have been about midnight when I was off the Schanck, but time seemed to be getting beyond my comprehension. I fancied that away back in the dim past I had seen, as in a dream, the Alert sink and leave us all to struggle each one for himself. Then, as I gradually remembered the event took place only a few hours before, the thoughts arose where were my mates and how many of them living. Were they, like myself, still battling for life, or had they all perished in the pitiless storm?

The gale seemed now at its height, and my heart sank within me as I reflected that assistance from the shore had become an impossibility. No boat could face and live in such a sea as now swept along with a force[Pg 66] at least double that of the time when the ship went down. How I longed for daylight! But would it ever come for me, or any of my companions? If to be rescued depended on endurance, then I felt sure the chief officer, Mr. Hodges, would be almost certain to hold out, for he was, far more than ordinary, a powerful man, and his action, up to the period of the vessel leaving us, showed he was clearly and collectedly helping everyone, and preparing for the worst. Whether the foregoing thoughts crowding in on me, caused me to be less watchful, or whether the continued strain on brain and muscle made me stupid and weak, I cannot say, but in the midst of my reflections I got caught in a sort of swirl, or whirlpool. I was rapidly turned round and round, then quickly, raft and all, sucked under water. Whilst below this time I felt, as my boards were wrenched away from my instinctive, but nerveless grasp, that all was over. Thanks, however, to my life-belt, more than my own exertions, I was thrown to the surface just as I was choking for want of air. Some minutes after, my boards came up a little distance off, and I managed with great difficulty to reach them and drag myself on top again. As I lay on my raft, resting and trying to collect my scattered senses, I turned my head shoreward, for a bit, to watch the Cape Schanck light. I had not been able, during the forepart of the night, to see the light continuously owing to the heavy showers of rain which had passed over. Now I began to realise that it seemed farther off than before. I was getting into comparatively smoother water, and this fact together with the receding light told me plainly[Pg 67] that the tide was carrying me seaward. While nearing the light it helped to revive my drooping spirits—not that I expected any help from it, for by this time I had abandoned all idea that the lighthouse people could assist—but still the sight of it, gleaming out like a “star of hope,” encouraged me to struggle on.

A new idea seized me. Instead of allowing myself to drift out to sea again, I would leave the raft and make a last desperate effort to swim for the shore. A little reflection, however, showed me the hopelessness of making the attempt. In the dark I could not see the smoothest place to steer for, and being weak, stiff, and sore, I felt that I would most likely be dashed to pieces amongst the rocks. Therefore, I decided to stick to my boards, so long as they stuck to me. My feet now began to trouble me very much, and their cold numbness seemed inclined to creep up my legs. I knew I had made a great mistake in taking off my boots. Had I kept them on they would not only have helped to keep my feet warm, but they would also have prevented my feet from being bruised, and battered against the boards, with the action of the water. Besides, I found by experience that whether in the water, or on the raft, my feet were too light, and needed weight to keep them down. My woollen socks—although I was kept continually pulling them up—were of great service in keeping some heat in, and, though it might have been fancy, my white cotton cap kept my head a bit warm. I think I must have drifted about ten miles past, or south-east of Cape Schanck, and was nearly out of sight of the light before the current began to set in again. The sea[Pg 68] had by this time moderated a good deal and I was enabled to keep longer resting on my boards. I tried all ways of reclining on the raft but I found it the safest plan to lie on my left side, thus I got a good grip of the crosspiece with my left hand and one of the boards with my right. In this position I had a chance to watch the heavy seas when they were going to break. I now began to get very cold, and every now and then was seized with cramp in both legs. The working of the life-belt caused my body, and also the inside of my arms, to get raw and sore. To make matters worse, I felt terribly thirsty at times, and a sort of drowsiness seemed to steal over me as if tempting me to go to sleep. I, however, fought against the latter feeling, for I had an inward conviction that if I once gave way to sleep I should never wake again. Meanwhile, I kept gradually nearing the Schanck light once more, but as no signs of daylight were yet visible, I began to fear it would never come for me. The pain in my neck through my head hanging over the life-belt, was getting almost unbearable. Now and then, when I got a chance, I propped my head up with my left hand while keeping the elbow resting on the boards. This gave me ease but I dared not do it so often as I wished for fear of being caught unawares and washed off the raft. All of a sudden I saw a light flashing away in the direction where I deemed Port Phillip Heads would be. My first thought was that it must be a search-light to find out our whereabouts. I kept anxiously watching, but as it did not again appear I came to the conclusion that it had been a flash-light from one of the pilot schooners a long way off, and the hope raised by it died[Pg 69] away as quickly as it came. Racked with thirst and pain, and under the impression that it was impossible for me to hold out much longer, my thoughts flew back over my past life. Matters long forgotten rose up swiftly in my memory, and the acts of my whole career seemed to pass in review before me. After the past came the questions of the present and the future. Must I go now, and was I fit to die?

[Pg 70]

At length—and what a length—the day began to dawn, and with it came renewed hope that I might be rescued. As the welcome light crept slowly in I kept straining my eyes, when I got a chance on top of a sea, for some signs of my shipmates, but in no direction could I see the slightest trace. Had they been picked up? Had they reached the shore? or had they, unable to withstand the tossing and exposure during the fearful night, all been drowned? The sight of even one of them would have helped to revive my drooping spirits. Whilst it was dark night I clung to the thought that although I could not see my mates, still some of them might be near me. Now, however, I realised that I was alone amidst the seething waters. Then I[Pg 71] remembered that when darkness closed in on the previous day the majority of my companions were a good distance inshore of me, and it was just possible that they had got safely to land. This reflection helped me to make up my mind to struggle on while there was a bit of life left in me. A number of albatrosses now began to hover around, and two of them swooped down close to my head. I raised my arms as well as I could and thereby succeeded in frightening them away. Seeing me lying on the boards I dare say they thought I was dead! By the time daylight came thoroughly in I was able to see the land stretching along at no great distance off. I think it must have been about 5 a. m. when I found myself right abreast of the Schanck with a strong current sweeping round it and setting me towards the Heads. The tide, wind and sea all bore directly on my raft and seemed to be taking me rapidly nearer the shore.

Quite plainly I could see the Rotunda on St. Paul’s, and by all appearance I was being driven in a little to the westward of it. When lifted up by the seas, as I came nearer and nearer the shore, I saw what looked like a little bay with a belt, or patch, of sandy beach at the head of it. Whilst earnestly praying that I might be fortunate enough to be drawn into the bay, my heart went down again when I caught sight of the fearful breakers that were running across its entrance. These breakers lay directly in front of me, and I could see no way in, except by passing through them. Gathering my scattered senses together as well as I could, I took a fresh hold of my boards, and prepared for a last desperate[Pg 72] effort. As I got close to the broken waters I could hear their thundering roar, although they were still to leeward of my raft. After some minutes’ anxious suspense, I reached the dreaded breakers; then almost instantly my boards were ruthlessly snatched away, in spite of my best efforts to retain them. I felt myself being turned over and over like a rolling ball; at the same time I experienced, more than at any previous period, an awful sense of utter helplessness. The thick foam filled my mouth and nostrils so much that I felt all the sensations of suffocation, and believed my end had come. Just then another sea threw me clear of the foam and dashed me, face and knees downwards, on to some rocks which were sunk a little under water. Instinctively I threw out my arms, and thus prevented my face from striking the jutting stones, while the thickness of the life-belt kept the blows from my body. Dazed, and almost senseless as I was, I could see that the sandy patch was still a distance off, too far away for me to expect the incoming breaker to carry me there. My strength being gone, I felt it utterly useless to attempt to swim to the beach, and hence I came to the conclusion that if the next wave did not take me in, it would dash me against the rocks and knock out the little life I had left. Along, it came roaring, but being too weak and stupid to make ready for it, I was caught broadside on, lifted high above the rocks, and whirled away helpless as a log, right up on the sandy shore, As I rolled over and over on the sand the motion made my neck and head feel as if they were going to burst in pieces. Suddenly the rolling ceased, then I became[Pg 73] aware that the back-wash of the wave was taking me out again. In sheer desperation I clutched the sand, but my fingers, being numbed and nerveless, had no power of grasping. Then I dug my knuckles in as well as I could, but all to no purpose, out I kept going, as helpless as when I came in!

[Pg 74]

Just as I had given myself up for lost, providentially I was washed sideways against a jutting rock, and this enabled me to stem the recoiling water until it passed away. Although powerless to do anything I had sense enough left to know that unless I managed to get further inshore the back-wash of the next wave would certainly carry me off and finish me outright. I strove to get on my hands and knees, and with great difficulty succeeded in doing so. I crawled along, in what direction I knew not, for the sand in my eyes had made me partially blind, and my neck, which seemed to have given way altogether, rendered me incapable of holding my head up. Unable to creep another yard, I tumbled over on to the sand, and, while lying exhausted, the succeeding wave came up close [Pg 77]enough to touch my feet. I knew then that, instinctively I had been going in the right direction and was safe, so far, from the sea. After resting for a brief space, I again essayed the creeping, and painfully dragged myself over the sand and rocks towards a small cave in front, and at foot of the cliffs. The distance I had to go was only a few yards, but in the condition I was it seemed a mile to me. I think it must have been about 8 a. m. when I got inside the cave. My reason for going there was a sort of confused idea that I might get shelter from the cold wind which felt as if it were blowing right through my very bones. I crouched in a corner on top of some seaweed, but obtained no relief from the change, indeed, the cold seemed, if possible, worse than ever, and sharp shooting pains now and then darted over my whole body.

SORRENTO OCEAN BEACH (from a Photo).

The White Cross indicates where Ponting landed. Showing Jubilee Point in the distance.

I endeavored to collect my wandering thoughts concerning the position I was now in. While on the water I had, at first, strong hope that assistance would come, then latterly, when nearing the shore, hope rose again that if I succeeded in getting to the beach I would soon be right. Now that I was on land, I was helpless to do anything for myself and there seemed no appearance of aid coming. Evidently the loss of our vessel was still unknown, otherwise there would have been somebody on the beach before this time looking for us. Where were my shipmates? Were they all drowned, or were some of them lying like myself on other parts of the shore? As these thoughts rushed through my mind I began to feel that I must abandon all hope of being rescued. Yet it seemed hard that I should be saved from the waves only to perish through weakness and exposure on the rocky[Pg 78] beach! One minute I prayed for help and the next I almost longed for death to come and end my troubles!

I had not been lying down for very long when I began to feel much easier. The extreme cold had departed and the twitching pain in my limbs had gradually abated; but, meanwhile, the thirsty craving came back, and my head got still more dull and leadenlike. I took these symptoms to mean that I was getting weaker, and slowly dying. The struggle for life had been a protracted one, but it could not be kept up much longer. I had striven hard to keep my spirits up and live, but God had willed that I must go! My poor wife would soon know the worst. The end of my troubles would be the beginning of hers. My life being insured, she would not be left altogether penniless, but still the news of my death would be a sad blow to her and our relations. God help her, and them! A burning sensation seemed to shoot through my head! A strange buzzing sound filled my ears, and then I lost all consciousness!

How long I lay in the cave, or whether in a swoon or sleeping, I cannot say, but when my senses returned I had a vivid impression that I had just awoke out of a fearful dream. The state of my body, and a glance at the rocks around, however, soon convinced me that the incidents of the past day and night were reality indeed. I now not only felt sore and numbed, but my whole body tingled with a peculiar sensation similar to that which a person feels when his leg, or foot, is said to be “asleep.” On looking outward, I fancied, in my half blind condition, that the sun was shining brightly on the sand, and I made up my mind, if possible, to get[Pg 79] out to the heat. After a number of ineffectual attempts, I managed to rise once more on hands and knees, and got outside, although, when on the way, I reeled over, like a drunken man, at least a dozen times. With my back on the sand, I lay head up hill towards the cliffs, but was not there long till I felt sorry I had left the cave, for the sun seemed to have no heat in it, and the sand, drifting with the strong wind, flew all over me. I knew I was too far gone to attempt to return to the cave, and thought my time had come at last!

Concerning the incidents which took place some time after my coming out of the cave on to the beach, the reader is already acquainted with them from the narrations given by others in the former portions of this book. Personally I have no clear recollection of these matters. Excepting during intervals of consciousness, all is blank to me up till Saturday morning, 30th December, when I found myself in bed at Clark’s hotel, Sorrento, surrounded with the best of comfort and attention. I distinctly remember hearing the voices of ladies coming nearer and nearer on the beach, and of my being ungracious enough to feel no joy at the sound. The thought uppermost in my mind then was “It’s all over. Too late, too late!”

I also remember speaking to the ladies and subsequently to some gentlemen. I saw too, as in a dream, a group of people and a dog, and wondered what they were all doing. During the five days I remained at Sorrento I received nothing but the greatest care and attention from everybody. Then I was removed to my own home at South Melbourne, where through starting[Pg 80] to walk too soon, my legs and feet got bad again and I was confined to bed for six weeks. I believe I will ultimately get all right, but up to present time of writing, I still feel, in nerves and muscles, the effects of the long exposure. Frequently at night I wake up suddenly, suffering from severe cramps and under the impression that I am on the raft at sea! This reminds me of a remark I overheard the other day in Melbourne that “the survivor of the Alert stuck to his raft because he could not swim.” No greater mistake could be made. I am a native of Tortworth, near Bristol, England, and when at school there was taught to swim by the clergyman of the parish. Afterwards I removed to Clevedon, in the Bristol Channel, where I practised daily, during summertime, swimming in the surf. Without reckoning myself an expert, I purpose in the next chapter to make a few remarks on this important subject.

[Pg 81]

R. PONTING AND MR. A. STANTON’S DOG “VICTOR HUGO.”

From a Photo taken after the Wreck.

[Pg 82]

I have had a good deal of experience in the matter and my advice to any person swimming towards heavy seas is this—When a large wave is coming, don’t wait till it breaks on you, dive under it to save being struck and carried away. On the other hand, if swimming with the seas—that is, in the direction in which they are going—and a larger one than usual is coming along behind you, turn round, face it, and dive as in the former case. I don’t know whether Shakespeare could swim, or not, but in his play of “The Tempest” he describes exactly the mode of procedure in rough water, thus—

I am so convinced of the merits of swimming, that if I had the power I would make a law compelling everybody, male and female, to learn the art when young. Once learnt—like riding on horseback—it is an exercise having a method that can never be forgotten, even although years may elapse between the times of practice. It may be said that everyone is not called upon to swim, but no one knows how soon he, or she, may be placed in a position requiring the use of it, and the fact of being able to do something for oneself inspires confidence—the great thing needed—to a person in the water, whether there voluntarily, or by accident.

Nowadays, everyone knows by reading, that the human body will not sink in water—and especially salt water—unless the lungs are filled with it instead of air. Yet each one, except a swimmer, when fallen into the water, either does not believe in the truth of this natural law, or else gets so frightened as to forget all about it! No one can become a swimmer till he possesses thorough confidence in the power of the water to support him, and he can easily get this confidence by a little practical lesson:—Go down to the beach at Port Melbourne, or any other where having a sloping sandy beach, strip off your clothes, take a small white stone in one hand, wade out from the shore till the water rises as high as your waist. Then turn face shoreward[Pg 84] and throw the stone to the bottom, the water being clear you will see the stone plainly. Stoop down and try to pick it up. You will find the water, even against your inclination, prevents you from sinking to the stone, and if you want to get it, you must use active force by diving. To encourage you to dive, remember that you are in shallow water, and can put your feet to the ground at any moment you wish to stand upright. Having this practical knowledge, if a person unacquainted with swimming should happen, accidentally, to fall into the water, all he has to do when he comes to the surface—which he must do if he keeps his mouth shut and does not attempt to breathe while under—is to turn on his back, refrain from struggling and plunging, or raising his hands above his head. He can easily keep himself from turning over face downwards by putting his arms a little distance out from his sides, at the same time taking care that the hands are open and flatly in line with the surface of the water. In this position he can float in safety for hours, if the water be smooth, and call for assistance meanwhile. This method is very well in its way, but the better plan is to learn swimming, and then, under ordinary circumstances, a man can help himself confidently.

My story now draws to a close, but I feel that it would be the height of ingratitude for me to conclude without a few special words to my many benefactors.

[Pg 85]

So far as ability and memory would permit I have given a plain unvarnished account of the incidents connected with the most trying time that I have ever experienced. Each day removes the date of the Alert disaster further off; still, in quiet moments, when I look back on the 28th and 29th of last December, I cannot prevent a saddening sensation from stealing over me.

Mingled with the feeling, however, comes the thought that I can never be grateful enough, firstly to God, and secondly to the many kind friends by whose assistance I was snatched from the grave! I will be unworthy of the life they recalled if ever I forget those who befriended me in my need, therefore, through the pages of this little book I take the opportunity of publicly conveying some token of my heartfelt gratitude to the Misses Armstrong, Davies, Duggin, Hill, Moorman, and the nurses, Miss Skelton and Mrs.[Pg 86] Keating, to Mrs. J. D. Ramsay and Mrs. Whitelaw, to Drs. Browning, Cox, Hutchinson, Hewlett, and Mullen, to the six gentlemen who carried me up the cliffs, namely, Constables Conroy and Nolan, Messrs. Knowles, J. D. Ramsay, J. F. Watts and W. D. Watts, also to Messrs. Clark, Cousins, Maillard, McWalter, Stanton, and others whose names have not been supplied to me. To each and all of the above ladies and gentlemen I owe a debt which I never can repay. Further, these friends have not only aided me as the “poor shipwrecked mariner,” but also, since the wreck, they have in various ways laid me under a load of obligation to them. There is still another friend whose kind services to me must be acknowledged, although it is not an easy task for me to convey my thanks to him. I allude to Mr. Austin Stanton’s St. Bernard dog, “Victor Hugo.” He, by the instructions of his owner, took an important part in the proceedings outside the cave on the Ocean Beach, and the very least that can be said of him is that he is a worthy descendant of the noble animal described in Crabbe’s lines—

CONCLUSION.

On the 2nd of February, 1894, the Melbourne Marine Court, consisting of Mr. J. A. Panton, Police Magistrate, Captain A. J. Roberts, and Mr. Douglas Elder, concluded their investigation into the circumstances surrounding the foundering of the Alert. The decision given was as follows:—

[Pg 87]

“We find that when the Alert left Metung, she was properly equipped in every respect, and apart from the manner in which she was laden, was in a good and sea-worthy condition. She was a suitable vessel, having regard to her build, for the trade in which she was engaged, as it was shown in evidence that she was classed for any trade. In view of the vessel’s construction and the manner in which laden on her last voyage—having on board only about forty four tons of cargo—the Alert in the opinion of the Court, had not sufficient stability, and in view of the weather experienced, she had too much freeboard for the voyage she was on. Considering the trim of the vessel and the state of the weather, it would have been more prudent had the Alert run into Western Port for shelter. In the opinion of the Court, the Master should have kept her head to sea when the vessel first commenced to take in lee water. There was not any neglect on the part of the lighthouse keeper at Cape Schanck, and existing regulations appear to have been carefully observed. The crew of the life-boat at Queenscliff appears to have been properly directed, and, in the opinion of the court, they did all that could have been done, having in view all the existing circumstances. A proper look-out was kept on board the pilot schooner on the cruising station. The reason the boats on the Alert were not made use of would appear to be attributable to the fact that when the vessel heeled over, the forward boat could not be got at, and the after life-boat was washed away about the moment when the vessel foundered, and there is no evidence to show what became of it. There was a sufficient supply of proper life belts on board, and they were easily available. There is no evidence before the Court to show that the late Master, Alexander Mathieson, did not use every precaution in handling the vessel. There is no evidence to justify the Court in expressing an opinion as to the immediate cause of the foundering of the steamship Alert.”

A perusal of the foregoing shows that, while almost everything else has been commented on, no mention, whatever, is made of the fact that the rig of the vessel did not permit of sail being set aft. In view of[Pg 88] the great length of the Alert—as compared with her depth—the above fact constituted, in the opinion of the compiler of this book, a very grave defect. Further, no vessel, whatever her length, or whether steamer or sailing ship, should be classed by the Government officials as fit to go outside Port Phillip Heads, unless she is rigged in a suitable manner to enable her to carry sail aft, as well as foreward. No doubt in these “hurry skurry” days the tendency of the time is to make steam machinery take the place of sail, but until man can control wind and waves, machinery can never wholly supersede canvas. The latter is not only required to steady a steamship in a seaway, but is indeed an actual necessity during emergencies brought about by either a breakdown of machinery, or stress of weather.

It is not so very long since a large steamer, the Age, was tossing about, for a week or so, in Bass’ Straits, as helpless as a log, because her machinery had met with a mishap, and she was unable to set canvas enough to keep her side down, let alone bring her into port!

Moreover, it may be added that there is scarcely a single sea-going steamer, which, at the present time, carries half the canvas she ought to. In the interests of life and property this is a matter that should be carefully seen to in future, and, if need be, enforced by legal enactment.

[Pg 89]

S.S. ALERT BEFORE ALTERATIONS.

KILPATRICK v. HUDDART, PARKER & CO., LTD.