The Project Gutenberg eBook of Around the clock in Europe, by Charles Fish Howell

Title: Around the clock in Europe

A travel sequence

Author: Charles Fish Howell

Release Date: June 26, 2023 [eBook #71043]

Language: English

Credits: Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Page 76—conquerers changed to conquerors

Page 171—expecially changed to especially

Page 226—Funicolà changed to Funiculà

PIAZZA SAN MARCO FROM THE GRAND CANAL Page 305

AROUND THE CLOCK IN EUROPE

A Travel-Sequence

BY

CHARLES FISH HOWELL

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

HAROLD FIELD KELLOGG

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

1912

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY CHARLES FISH HOWELL

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published October 1912

TO

HELEN EDITH HOWELL

[ix]

IN EXPLANATION

The pages that follow should best account for themselves, of course, but for the satisfaction of those who very properly require some general conception of a project before definitely entering upon it, the author begs to say that he has here sought to visualize to the reader the appearance and the life of these cities at the hours indicated, and to preserve, as well, the distinctive atmosphere of each. He has endeavored to catch and present faithful impressions of the streets, their kaleidoscopic animation, and the activities and characteristics of the people; to touch the pen-pictures with a light overwash of the racial and national peculiarities that distinguish each, and to invest them with what insight, sympathy, and enthusiasm he is capable of. It is “fitting the scene with the apposite phrase,” as Mr. Howells has so aptly described the process and as he himself has so wonderfully exemplified it. A formidable undertaking? Indeed, yes; but there is the dictum of Mr. Browning that the purpose swells the account.

These, then, are impressionistic sketches. They are of the moment only. It has been sought, most of all, to give them just that character. They have been written as reflecting the probable observations and emotions of visitors of normal enthusiasm during these hours and in [x] these environs. Under such conditions, it is well to remember, every active mind has its sudden, drifting excursions afield; something in the visible, present surroundings whimsically invokes the subtle genii of Memory and Imagination, and one is whisked off in a breath, and without rhyme or reason, to the most ultimate and alluring Isles of Thought. These swift and scarcely accountable flights are the common experience of all travelers, and the author has felt it to be a part of his task to take proper cognizance of them.

Travel is generally conceded to be one of the most informing and diverting of engagements, and to gain in both particulars in proportion to the favorableness of the conditions under which it is prosecuted. It is, therefore, a satisfaction to be in position to afford readers advantages scarcely obtainable elsewhere. Discarding conventions of time and space, the author undertakes to give them twelve consecutive happy hours in Europe,—once around the clock,—always endeavoring to secure the most favorable union of hour and place. And though there may be dissent from his judgment concerning the superiority of this combination or that, there can hardly be two opinions as to the perfection of the transportation facilities. The latter eliminate time and space, and convey the reader from city to city and from point to point, with no discomfort or inconvenience whatever, and without the loss of so much as a tick of the watch.

[xi]

With foot in the stirrup, it may be added that there has been an earnest desire to entertain those whom circumstances have hitherto kept at home, as also to revive to memory golden recollections for travelers who have already passed along these pleasant ways. What is here offered is just a new portfolio of sketches from Nature; the touch of another but reverent hand on the old and well-loved scenes. Surely there can be no better reason for any book than a desire to share with others the happiness experienced by

The Author.

[xii]

[xiii]

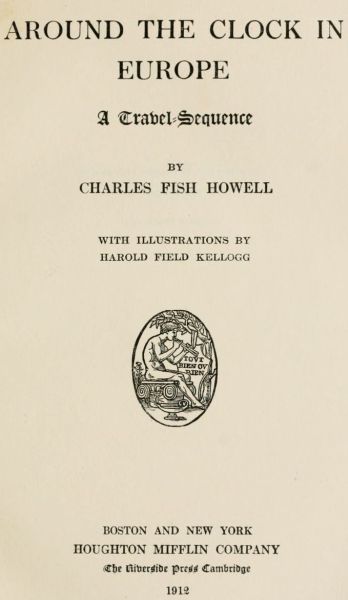

| EDINBURGH—1 P.M. TO 2 P.M. | 1 |

| ANTWERP—2 P.M. TO 3 P.M. | 33 |

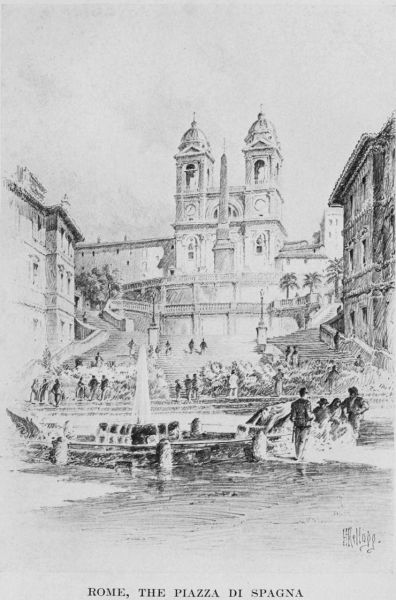

| ROME—3 P.M. TO 4 P.M. | 69 |

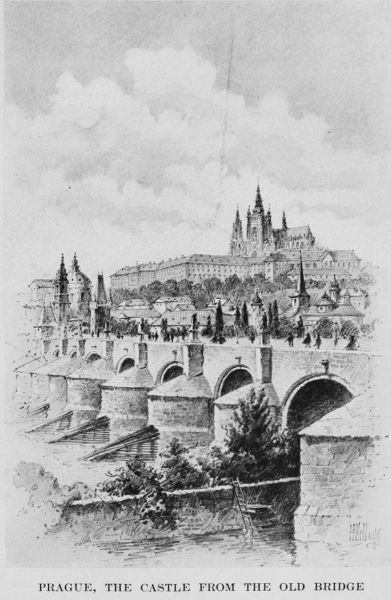

| PRAGUE—4 P.M. TO 5 P.M. | 101 |

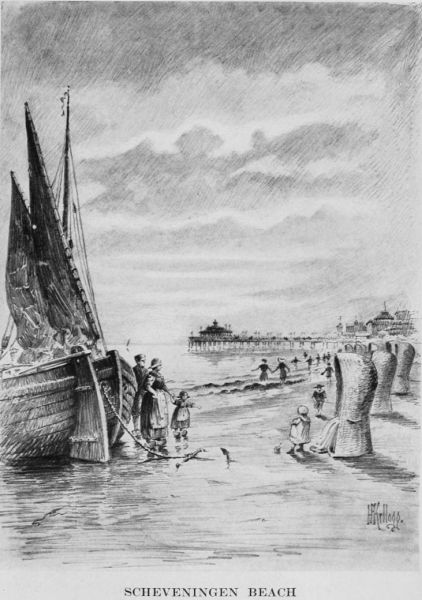

| SCHEVENINGEN—5 P.M. TO 6 P.M. | 135 |

| BERLIN—6 P.M. TO 7 P.M. | 153 |

| LONDON—7 P.M. TO 8 P.M. | 183 |

| NAPLES—8 P.M. TO 9 P.M. | 215 |

| HEIDELBERG—9 P.M. TO 10 P.M. | 249 |

| INTERLAKEN—10 P.M. TO 11 P.M. | 273 |

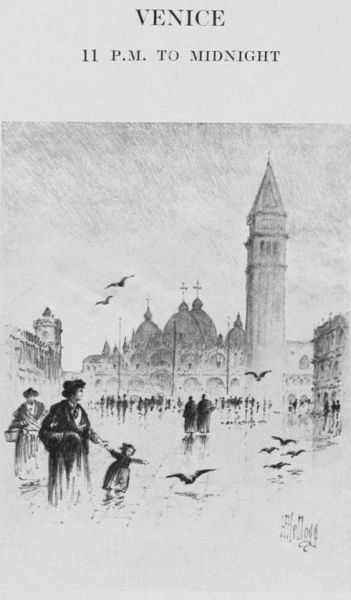

| VENICE—11 P.M. TO MIDNIGHT | 299 |

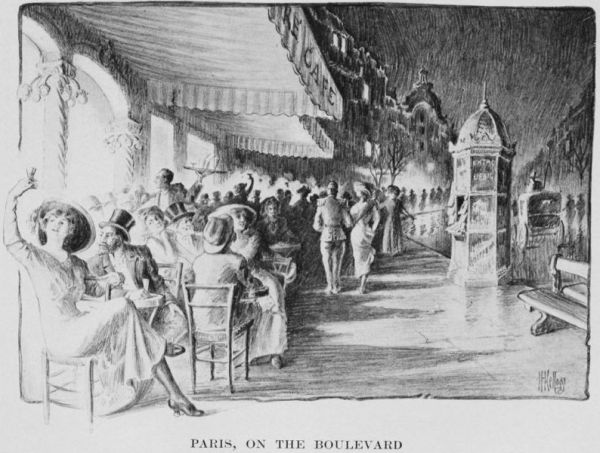

| PARIS—MIDNIGHT TO 1 A.M. | 329 |

| Piazza San Marco from the Grand Canal (page 305) | Frontispiece |

| Edinburgh Castle | 1 |

| Edinburgh, Princes Street | 4 |

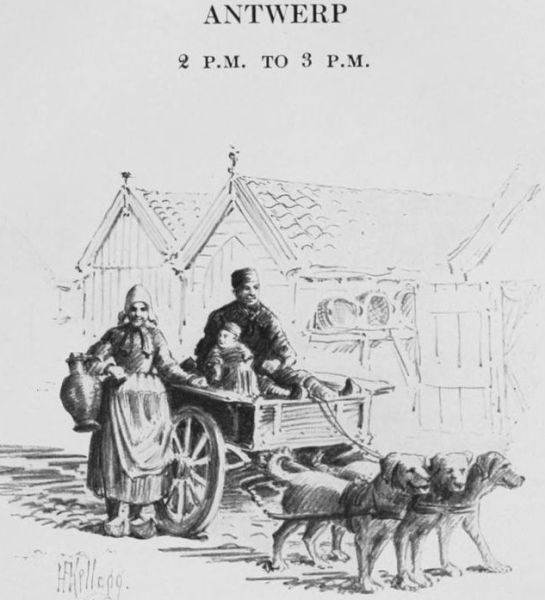

| The Whole Family | 33 |

| Antwerp, from the Scheldt | 42 |

| In the Gardens of the Vatican | 69 |

| Rome, The Piazza di Spagna | 90 |

| The Pulverturm | 101 |

| Prague, The Castle from the Old Bridge | 108 |

| Dutch Girls are always Knitting | 135 |

| Scheveningen Beach | 140 |

| In the Sieges-Allée | 153 |

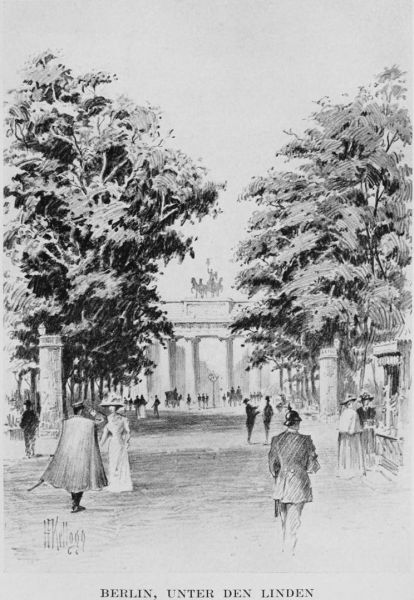

| Berlin, Unter den Linden | 160 |

| Trafalgar Square | 183 |

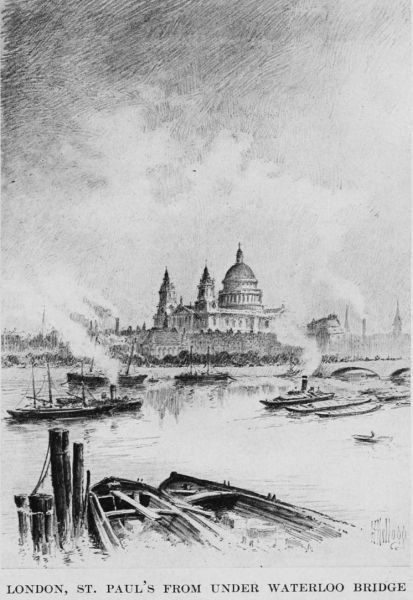

| London, St. Paul’s from under Waterloo Bridge | 212 |

| Margherita | 215 |

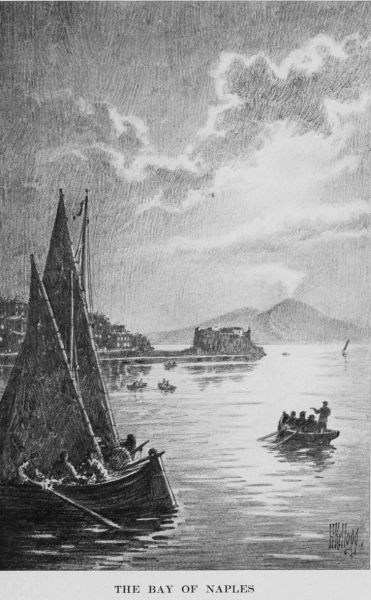

| The Bay of Naples[xvi] | 220 |

| A Heidelberg Student | 249 |

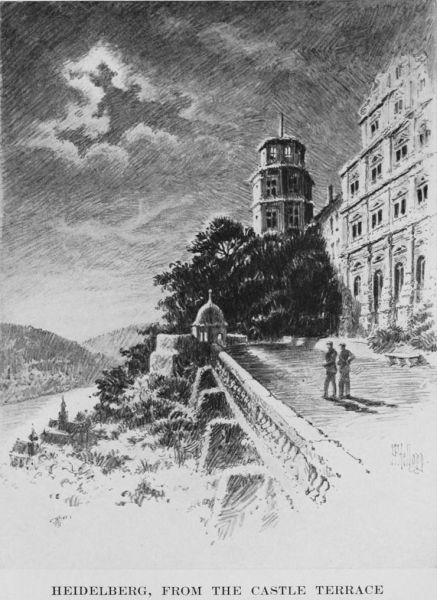

| Heidelberg, From the Castle Terrace | 252 |

| Down from the Mountain | 273 |

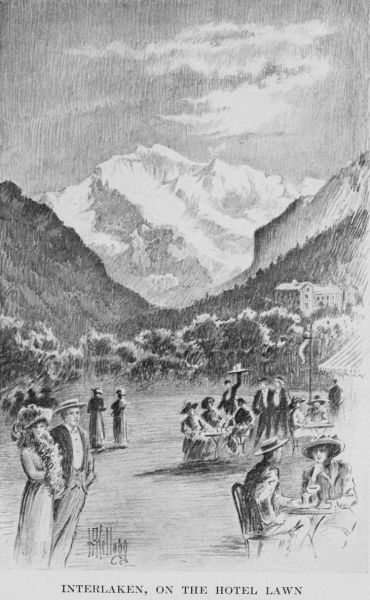

| Interlaken, On the Hotel Lawn | 282 |

| Piazza San Marco | 299 |

| Venice, Grand Canal from the Piazzetta | 304 |

| A Gargoyle of Notre Dame | 329 |

| Paris, On the Boulevard | 334 |

[3]

IN EUROPE

1 P.M. TO 2 P.M.

Up there on the gusty heights of Edinburgh no one ever inquires the time at one o’clock in the afternoon. Precisely at the second, a ball flutters to the top of the Nelson flagstaff on Calton Hill and a cannon booms from a battery at Castle Rock; and watches are then set by merchants all over town, by shepherds on the shaggy Pentland Hills, and sailors on ships in the lee of Leith. And one o’clock is the very best time Edinburgh could have fixed upon to encourage her people to look up and about and behold her at her finest. It is luncheon-hour, and when the sun is kindly, “Auld Reekie” is just about as garish and stimulating as it is possible for a town of such dignified traditions and questionable climate ever to become. The air freshens in from blustering Leith, and fair Princes Street wears its most beguiling smiles. One thrills with the joy of being alive in so brave and bonny a world, with the bluebells and heather of Old Scotland about him and this town of song and story at his feet. He gazes at the cheerful crowds moving[4] leisurely along the valley gardens elegant with statues and flowered lawns, or across at the frowzy heads in rickety garret windows away up among the palsied gables of ancient High Street, and he knows that over there is the Canongate of stern tradition and the storied St. Giles’ and black Holyrood, and beyond them he sees the Salisbury Crags, a gaunt palisade halfway up to lofty Arthur’s Seat. He has just arrived, perhaps, with the glow on his face of all he has read and heard of this famed place, and the bugles are singing on Castle Hill and the Edinburgh bells are ringing.

There is little opportunity for preliminary impressions while arriving. The train darts up a valley before you have finished with the suburban cottages of the laboring men, and with an ultimate shriek of relief abruptly dives into its cave, as it were, and deposits you unceremoniously in the esplanaded Waverley Station, with flowered walks above and a market just at hand. The wise traveler gathers up his luggage and fares eagerly forth to Princes Street, as a matter of course. There, on the way to his hotel, he finds a good part of Edinburgh idling pleasantly after luncheon, for Princes Street is the dear delight of the loiterer be he old or young, Robin or Jean. He is studied as he passes through the crowds, curiously, smilingly, critically, tolerantly. His clothing may excite disapproval, his baggage amusement, and his intentions speculation. [5]Curiosity “takes the air” at noon. Arrived in a moment at a Princes Street hotel and duly registered, he is handed a curious disk of white cardboard the size of an after-dinner coffee-cup’s top, upon which is blazoned the number of the room to which he has just been assigned. Preceded by a chambermaid gowned in black and aproned in white and followed by a porter with his traps, he advances grandly to his quarters, according to the tag, and hurries to a window for his first keen impression of the “Modern Athens.”

EDINBURGH, PRINCES STREET

Just why it should be called an “Athens” would scarcely be apparent from a Princes Street hotel window. The literary rights to the title might be conceded, but the stranger will need to view the town from some neighboring height to appreciate the physical similarity between the two cities and to observe the suggestiveness of the Castle and the reminder of the Acropolis in the “ruin”-crowned summit of Calton Hill. What he does see from his window is sufficiently inspiring. At his feet stretches Princes Street which he has heard called the finest avenue in Europe, and along its other side terraces of vivid turf, set with shade trees and statues and flowered walks, drop down in graceful steps to the lawns in the bottom of the valley that was once the North Loch’s basin and where now, to Edinburgh’s chagrin, are the railroad tracks. Across these gardens vaults a boulevard styled “The Mound,” and on their farther side is the gray old Castle on its precipitous crag with a soft sweep of green braes at its base. On[6] the Castle side of the valley the far-famed High Street turns the venerable backs of its tall, tottering, weather-blackened rookeries on the frivolity of Princes Street, and scornfully gives its laundry to the breeze in hundreds of heaped and crooked gable-windows. Centuries before any of us were born those fantastic and whimsical family nests were lined up as we see them to-day. One could fancy them a row of colossal, prehistoric giraffes with their tails all our way, nibbling imaginary tree-tops on High Street. The stranger will lean out of his window and look down Princes Street and start with delight to see that “sublimest monument to a literary genius,” the lace-like Gothic spire to Scott, where, under a springing canopy of arches and aspiring needles studded with statues of the immortal characters he created, sits the great Sir Walter himself in snowy Carrara, with his favorite hound at his feet. And one’s heart warms to this romantic Edinburgh so beloved of him and of the fiery Burns, the passionate Chalmers, the gentle Allan Ramsay, and Jeffrey of the brilliant “far-darting” criticisms. Here, in their time, mused Robert Fergusson and David Livingstone and Smollett and Hume and Goldsmith and De Quincey and “Kit North” and Carlyle; and but yesterday has added the name of Stevenson, not the least loved of them all. What inspiration this region must have kindled to have given to Art such sons as Gordon, Drummond, Nasmyth, Wilkie, Raeburn,[7] and Faed! Could the roster of old Greyfriars Burying-Ground be called, one would marvel at the number of great names there memorialized that are familiar and beloved to the remotest, out-of-the-way corners of the earth. And so the new arrival closes his window more slowly than he raised it and steals reverently down into the street to meet this Edinburgh face to face.

You might think, to hear Americans talk at home, that every other Edinburgh man carries a dirk or a claymore under a tartan and wears a ferocious red beard like the pictures of Rob Roy; that people go about in plaid shawls and tam o’shanters, and that most society functions end up with a Highland fling. One may see at wayside railroad stations, as in our own country, wild, hair-blown lassies with flaming cheeks running in from the hills to have a look at the train; but with some such mild exception, if it is one, the Scots on their native heath are, of course, precisely what we are used to elsewhere. Types apart, the man of the streets of Edinburgh looks entirely familiar—shrewd and combative, rugged and perhaps hard, slouchy and indifferent in the matter of dress, hobnailed and be-capped. There is something tremendously genuine and wholesome about him. He is merry and brisk and lively, often; but you would not call him ever quite gay—at least with that sparkle that dances in the eyes you look into on the Paris boulevards. You could scarcely, for instance, imagine a Scotchman singing a barcarolle![8] Best of all they are honest and sincere, and one takes to them at once. Here are the lassies and laddies you have long sung about, fresh-faced and debonair. Cheerful fearlessness shines out of their frank blue eyes, and they look to dare all things and be utterly unafraid. The square foreheads of the older men, the austere cheek bones and strong chins, unscroll history to the observer and make him think of savage broils along the border, of fierce finish-fights throughout the wild Highlands, and of the deathless Grays of Waterloo. You may defeat a Scotchman, but he will never admit it, and if he is all-Scotch he will not even know it. They are brave, witty, and devoted, and many a person will take issue with Swift for finding their conversation “hardly tolerable,” and with Lamb for pronouncing their “tediousness provoking” and for giving them up in despair of ever learning to like them.

The new arrival plunges into Princes Street, accepts inspection good-naturedly, and soon feels entirely at home. He may even find the day bright and cheerful, in spite of apprehension over the dictum of Stevenson that this climate is “the vilest under heaven.” The street is quite unusual—one side a terraced valley, the other a splendid line of shops, clubs, and hotels, with gay awnings. Paris and London novelties fill the windows. A throng of vehicles bustles up and down—motor-busses, double-decked trolley cars, taxi-cabs, hired Victorias, two-wheeled carts, brewery wagons, station[9] lorries, tourists’ chars-à-bancs with drivers in scarlet liveries, private carriages and bicycles. The stream of people on either pavement is of the holiday cheeriness that comes with the luncheon recess from office and shop, though here and there one may occasionally discover some “sour-looking female in bombazine” that recalls R. L. S.’s “Mrs. McRankin” and who appears as ready as she to inquire whether we attend to our “releegion.” The restaurants are plying a brisk trade, contenting their tarrying guests, speeding the parting and hailing the coming. Whole coveys of pretty shop-girls with brilliant cheeks, wholesome and vivacious, come chattering and laughing out of tea- and luncheon-rooms and flutter back to work with frequent enthusiastic stops before alluring windows. Workmen in tweed caps and clerks in straw hats pass by, to or from their occupations, and always with lingering looks toward the Princes Street Gardens, so that one can accurately guess whether they are coming from or going to office by applying the reliable Shakespearean formula—

The air is rhythmic with the up-and-down slur of this speech of “aye” and “na.” Curious faces flash past. Threadbare lawyers argue pompously as they saunter back arm in arm toward Parliament Close, and the[10] ruddy-cheeked girls, by contrast, seem so distracting that a foreigner rages at the sentiment that “kissing is out of season when the gorse is out of bloom.” Occasionally, even at so early an hour, there is evidence of the passion for drink. “Willie brew’d a peck o’ maut” flashes to mind, and one fancies the unsteady ones are trying to hum, “We are na fou, we’re no that fou, but just a drappie in our ee.” When night comes on, sober men in the streets have reason to frown censoriously; and if it be a Saturday night, they may even feel lonesome.

A passing regiment is a welcome interruption and a brave spectacle. It is always hailed with shouts of joy. All Edinburgh turns in its bed Sunday mornings at nine to see the Black Watch come out from the Castle for “church parade” at St. Giles’s. Nothing stirs Princes Street on any week day like a military display. It is a thrilling moment to a stranger, perhaps, when he has his first glimpse of a young Tommy Atkins, and he stops stock-still to take in the bright scarlet, tailless jacket, the tight trousers, the “pill-box” perilously cocked over an ear, and the inevitable “swagger cane” with which he slaps his leg as he braves it along. But what is that to the passing of a company of Highlanders! Along they come, kilts and plaids, sporrans swinging, claymores rattling, and jolly Glengarry bonnets poised rakishly to the falling point. Ten pipers are droning and three drummers are pounding; and one watches, as they pass, for the holly sprig, or what-not, they wear in[11] their bonnets as a badge of the clan. The best show is made by the King’s Highlanders from up Balmoral way; and splendid they are in royal Stuart tartan, with the oak leaf and thistle in their bonnets and each man carrying a Lochaber axe. If there is anything more inspiriting than cheery bagpipe music at such a time, no one to laugh foolishly at it and every one to love it, and the men stepping proudly and the crowd applauding,—I, for one, do not know it.

Keenness of impressions, as we all know, may depend on the most trivial circumstances of time and place. I recall, for example, a sharp and thrilling musical experience in Scotland, with the instrument nothing more than the despised and humble mouth-organ. Perhaps it was the mood, perhaps the setting, perhaps the unexpectedness of it; there was so little and yet so much. At all events, I shall not soon forget the sparkle and stir of “The British Grenadiers” as it ripped the sharp night air of quiet Melrose to the approach of three English soldiers, one with the mouth-organ and the others whistling in time as they marched briskly along. I shall always remember the rhythmic beat of their feet as they swung across the murky, deserted square, the loudness, the thrill, and the lilt of that historic melody, and the flicker of a lamp in a window here and there and the pleasant sting of the keen night air.

There is no better place for a stranger to “get his bearings” in Edinburgh than out on that valley-spanning[12] boulevard they call “The Mound.” He then has the Old Town to one side and the New Town to the other, and on opposite corners, as if to maintain the balance, the Castle and Calton Hill. He also takes note of the several bridges that clamp the town together, as it were; and he may look down into the gardens before him and watch the children playing as far as the promenade-covered Waverley Station, or he may turn and look the other way and see quite as many more all the way along the pleasant green to the old battle-scarred West Kirk of St. Cuthbert’s where De Quincey lies in his quiet grave. Thus he will find himself of a sunny afternoon between the pleasant horns of a most agreeable dilemma. He must choose whether to spend his first hour in the New Town or the Old. If he remembers what Ruskin said he will fly from the New; but then he may go there, after all, if he recalls the opinion of the old skipper cited by Stevenson, whose most radiant conception of Paradise was “the New Town of Edinburgh, with the wind the matter of a point free.” He must decide whether his present inclination is for latter-day city features, like conventional streets lined with substantial gray stone buildings looking all very much alike, for the fashionables of Charlotte Square and Moray Place and the bankers and brokers of St. Andrew Square, or the historic ground of crowded old High Street and the Castle and Holyrood. He would find in the New Town some old places, too, for it is one hundred and fifty years old,[13] and there are the literary associations of the last century and the house on Castle Street where Scott lived more than a quarter-century—“poor No. 39,” as he called it in his Journal—and wrote the early Waverley Novels, and rejoiced along with his mystified friends in the tremendous success of “The Great Unknown.” He would find it a rapidly modernizing city; no longer may the children salute the lamplighter on his nightly rounds with “Leerie, Leerie, licht the lamps!” But he would find the most interesting things there the oldest things, and they all in the Antiquarian Museum—and what a show! John Knox’s pulpit, the banners of the Covenanters, the “thumbikins” that “aided” confession and the guillotine “Maiden” that rewarded it, the pistols Robert Burns used as an exciseman, and the sea-chest and cocoanut cup of Alexander Selkirk, the real Robinson Crusoe; and there, too, is Bonnie Prince Charlie’s blue ribbon of the Garter and the ring Flora Macdonald gave him when they parted. If historic paraphernalia is alluring, however, the scenes of its associations are much more so; and our friend would doubtless hesitate no longer, but turn to the Old Town and trudge up the steep way to the Castle.

and if the song had kept to geography it would probably have added, “And we’ll meet at the bonny Castle o’[14] Auld Reekie.” Such, at least, has been a Scotch custom for thirteen hundred years; and with every reason. Through the long and cruel centuries it has gathered to its flinty gray bosom memories of every possible phase of national mutation, desperate or glorious, gloomy or gay. One approaches it with awe. So long has it gripped the summit of that impregnable rock, half a thousand feet sheer on three of its sides, that it has blended into the life and color of its foundations, like a huge chameleon, until one could scarcely say where rock leaves off and castle begins. A stern and pitiless object, tolerating only here and there a grassy crevice at its base, and a clinging tree or two. In the great “historic mile” of High Street, lifting gradually from Holyrood to this rugged elevation, one feels the illusion of an enormous scornful finger extended dramatically westward toward the traditional rival, Glasgow. There is no need to see Highland regiments drilling on its broad esplanade, or to enter its sally-port or penetrate the dungeons in its rocky depths to have confidence that the royal regalia of “The Honours of Scotland” are safe enough here, on the red cushions in their iron cage. One enters, and there settles upon him a feeling of sharing in every grim tradition since the doughty days “when gude King Robert rang.” It is not a visit; it is an initiation.

Quite worthy of this savage stronghold is the inspiring outlook from its parapets over hills and rivers and storied glens. One turns impatiently from “Mons[15] Meg,” which may have been a big gun in some past day of little ones, to gaze afar over the carse of Stirling and the trailing silver links of the Forth to where the snow shines in the clefts of Ben Ledi, or out over the Pentland Hills where the “Sweet Singers” awaited the Judgment. The sportsman will think of the grouse-shooting at Loch Earn; the sentimentalist will reflect that when night settles over Aberdeenshire the pipers will strike up their strathspeys and there will be Scotch reels by torchlight. Scotland seems unrolled at your feet and Scottish songs rush to mind until you fairly bound the region in verse and story: To the north and northwest, “Bonnie Dundee,” the glens of “Clan Alpine’s warriors true,” Bannockburn and “Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,” and “The Banks of Allan Water”; to the north and east, the Firth of Forth where the fishwives’ “puir fellows darkle as they face the billows”; to the west and southwest, “The banks and braes o’ bonnie Doon,” “Tam o’Shanter’s” land, “Sweet Afton” and “Bonnie Loch Leven” whence “the Campbells are comin’”; and to the south, “The braes of Yarrow,” “Norham’s castled steep, Tweed’s fair river, broad and deep, and Cheviot’s mountains lone,” and, most sung of all, “The Border”:—

The afternoon sun rests brightly on the pretty glen[16] in the foreground where lie the dismal, bat-flown ruins of Rosslyn Castle, loopholed for archers and shadowed in ancient yews that have overhung the Esk for a thousand years, and on the delicate chapel of stone-lace where the barons of Rosslyn await the Judgment in full armor with finger-tips joined in prayer. And there, too, are the cool, dark thickets of Hawthornden, recalling the ever-popular

One cannot forbear a smile as he surveys the noble bridge that spans the Forth and recalls the insistent pride of Edinburgh in the same. Here is an achievement over which all visitors are expected to exclaim in amazement—and engineers, I presume, invariably do. On this point your Edinburgh man is immovable. He scorns to elaborate and he will not descend to eulogy. He merely indicates it with a reverent inclination of the head, and turns and looks you in the eye; you are supposed to do the rest. Personally, while I give the great structure its dues, which are many, I like what flows under it more.

And there is one thing about the Forth that Edinburgh people never forget, nor do the visitors who find it out: “Caller herrin’!” It must have taxed the resources of even such a genius as Lady Nairne, whose home one may see if he looks beyond Holyrood to the villas of[17] Duddingston, to have written two such dissimilar songs as the heart-melting “Land o’ the Leal” and the cheery “Caller Herrin’.” There’s the king of all marketing songs. It really compels one to think with despair of what a dreary mockery life would be were this, of all harvests, to fail. For love of that song I could defend the Forth herring against all competitors whatsoever. Loch Fyne herring? Fair fish, yes; but really, now, you would hardly say they have that racy flavor we get in the Forth article. Caller salmon? Oh, pshaw, you are from Glasgow; you have been swearing by caller salmon for five hundred years; have it on your coat of arms; used to draw it on legal papers as other people do seals;—but, honestly, have you ever seen a salmon in the Clyde, anywhere near Glasgow, in all your life? And if you did, would you eat it? Certainly not! So “give over,” as they say in England. Certainly there never was such pathos and unction devoted to just such a subject. And the music, too! How it compels you with its appealing monotones and rebukes you with the brave huckster cries on high F! So when you are passing near Waverley Market and encounter one of the picturesque Scandinavian fishwives, who has trudged in with her “woven willow” from her little stone house at Newhaven with the patched roof and quaint fore-stairs, unless you are willing to buy a herring then and there and carry it around in your pocket, run for your life before she starts singing:—

[18]

To stroll down High Street is to unscroll Scottish history and survey Edinburgh of to-day at one and the same time. “Hie-gait,” as the old fellows still occasionally call it, is the “historic mile” par excellence of Scotland. In its independent fashion it assumes new names as it meanders along, first Castle Hill, then Lawnmarket, then High Street, and finally Canongate. Even the afternoon sun ventures guardedly among the nest of tall, gaunt lands that scowl at each other across its war-worn way. Bleak and glum to the peaked and gabled roofs, eight and ten stories above the sidewalk, they have resisted dry rot by a miracle of mortar and still hang together, doubtless to their own amazement, huddling a perfect enmeshment of tiny homes like some ingenious nest of boxes. It would be hard to imagine more drear and rickety domiciles or any more nervously overshadowed with an impending doom of dissolution. One looks anxiously about to see some venerable veteran give it up with a dismal, weary groan and collapse in a vast huddle of domestic wreckage. Fancy living[19] where you have to scale breakneck stairs to a dizzy height and then reach your remote eyrie by a trembling gangway over an air well! The closes or wynds that are engulfed among these flat-chested ancients are equally surprising. One passes in from the street through a dirty entrance with a worn stone sill and a rudely carven doorhead inscribed with Scriptural and moral injunctions, and finds himself in an inner court fronted by dirty doors and palsied windows full of frowzy women, a cobbled pavement littered with refuse and a patch of sky half-hidden by fragments of laundry. And, mind you, these retreats are not without pride of tradition; many of them have entertained riches and royalty—but that was not last week. Lady Jane Grey was once hidden in famous White Horse Close, which must have fallen further than Lucifer to reach its present condition. Douglas Tavern was in one of them, where Burns and his brethren of the “Crochallan Club” were wont to revel with “Rattlin’, roarin’ Willie, and amang guid companie.” Legends, of course, abound. There was the case of the two stubborn sisters who quarreled one night and never spoke to each other again, though they lived the remainder of their lives together in the selfsame room. There’s Scotch persistence! Deacon Brodie was another instance, the “Raffles” of his time. He it was who used to ply his nefarious trade by night on the friends who knew him by day as a highly respectable cabinet-worker; and if you look furtively aloft at some dusty,[20] closed shutter you can fancy the dark lantern glowing and the file rasping and the black mask drawn to his chin. Happily, they hanged him eventually; and, singularly enough, on the very gallows for which he had himself invented a very superior drop.

A close, therefore, is so cheerless a spot that you could not well be worse off if you were to dive down the steep, wet steps of a neighboring slit of an alley and come out on the old Grassmarket of sinister renown where they hanged the Covenanters of the Moss Hags. As you gaze about on this ill-omened slum, once the home of many a prosperous and respected “free burgess,” but now given over to drovers and visiting farmers, and peer suspiciously up the adjoining West Port where Burke and Hare conducted their murders to get bodies for the surgeons, you are very apt to beat a hurried retreat and cry out with Claverhouse, “Come, open the West Port and let me gang free!”

After one or two such explorations a stranger is content to pursue his investigation in the broad light of High Street. It seems delightful then to watch the barefooted boys in the street and the little girls in aprons and “pigtails.” And happily he may come across a shaggy steely-eyed old Highlander growling to a comrade in the guttural Gaelic, or perhaps a soldier in kilts and sporan. At this hour he will certainly see around Parliament Square groups of advocates and solicitors and “writers to the Signet,” and, it may be, some judge of[21] the “Inner House” or “Outer House,” and possibly the Lord President himself. Otherwise he can take note of the uninviting shop-windows and the piles of merchandise on the sidewalks, and find entertainment in such unfamiliar signs as “provisioners,” “spirit merchants,” “bootmakers,” “hairdressers,” etc., with prices set forth in shillings and pence, or rejoice in a hostelry with so unusual a name as “The Black Bull Lodgings for Travellers and Working Men.”

There are pleasant surprises. For instance, you find in the cobbled pavement the outline of a heart—and you do not have to be told that you are standing on the site of the terrible old Tolbooth prison, at the Heart of Midlothian. And what rushes to mind and displaces all other associations if not the fine story Sir Walter gave us under that name! Here, then, the Porteous mob swarmed and raged in its struggle to burn this savage Bastile, and here they tried and condemned poor Effie Deans and locked her up while the faithful Jeanie turned heaven and earth to save her, and the heart of old David broke. “The Heart of Midlothian!” Why, it is like being a boy all over again!

Encouraged by this discovery, like a man who has just found a gold-piece, you keep a sharp lookout on the pavements, and presently comes a second reward in the shape of a brass tablet in the ground marking the last resting-place of stern John Knox. “There!” say you; “Dr. Johnson said he ought to be buried in the public[22] road, and sure enough, he is!” What a man! He dared all things and feared nothing. How many a long discourse did Queen Mary herself supply him a topic for, and how often did he assail even her with personal rebukes and virulent public tirades! Thanks to the Free Church, his dwelling stands intact, farther down the street at the site of the Netherbow; and a fine specimen it is of sixteenth-century domestic Scotch architecture, with low ceilings and stairways scarce two feet wide—but, like its former austere tenant, narrow, cornery, and unpleasant. Implacable, unbending old John Knox! There is nothing in Browning more shuddering in imaginative flight than the quatrain:—

One makes a long stop before the far-famed church of St. Giles, half a thousand years old and the battle-ground of warring creeds. Its crown-shaped tower top is one of the familiar landmarks of Edinburgh. Within you may study to heart’s content the grim barrel vaulting and massive Norman piers and the tattered Scottish flags in the nave, but there is scope for many an agreeable thought outside if one conjures up the little luckenbooth shops that once clustered between its buttresses, and imagines Allan Ramsay in his funny nightcap selling wigs, or “Jingling Geordie” Heriot, of[23] “The Fortunes of Nigel,” gossiping with his friend King James VI over his jewelry counter. Nor would you forget Jenny Geddes and how she seized her stool in disgust when the Dean undertook to introduce the ritual, and let it fly at the good man’s head with the sizzling invective, “Deil colic the wame o’ ye! Would ye say mass i’ my lug!”

Old Tron Kirk, farther on, is still an active feature of Edinburgh life, and particularly on New Year’s Eve when the crowds rally here as the old year dies. Beyond it the Canongate extends itself in a rambling, happy-go-lucky fashion, lined with curious timber-fronted houses with “turnpike” stairs. It is like sitting down to “Humphrey Clinker” once more; or better still, perhaps, to the poems of Fergusson; and we smile at thoughts of the scowling, early-risen housewives of other days who would

and fancy how the convivial revelers would foregather by night and

But lingering along the Canongate is a negligible pleasure. There is nothing in the whole architectural world more jailish and pitiless than the gaunt Tolbooth and all its grim neighbors. It is as if the conception[24] of anything suggestive of beauty or ornamentation had been harshly repressed, and ugliness and the most naked utility sternly insisted upon. One may, however, if he is interested in slums, pause a moment to look down through the railings of the South Bridge on the screaming peddlers and flaunting shame of bedraggled Cowgate, and behold a district which stands to Edinburgh in the relative position of Rivington Street to New York, or Petticoat Lane to London, or Montmartre to Paris.

The end of the Canongate, a few steps farther on, debouches unexpectedly, and with a sudden unpreparedness for the stranger, on the great open square before Holyrood. There it stands, black and dismal; more like a prison than a palace! The Abbey ruins, in the rear, supply all the atmosphere of romance that the eye will get here. But the eye is better left as a secondary aid in comprehending Holyrood; history and imagination do the work. Cowering sorrowfully in its gloomy hollow, it has the look of a moody, forsaken thing brooding over a neglectful world. Its memories are of the dead. Its sole companionship is in the mosses and grassy aisles of the crumbling Abbey chapel, where lie the bones of Scottish royalty that ruled and reveled here its allotted time and left scarce a memory behind. It was here they slew Rizzio as he dined with Queen Mary; and perhaps that is romance enough.

The fumes and cobwebs of murky tradition dissipate[25] in the keen, vigorous air of Calton Hill. Breezes from over the level shore-sands of Leith taste sharp of salt and excite bracing thoughts of the sea. Like a map, the whole environ of Edinburgh lies exposed from the Pentlands to the Firth. There is the steepled city, rising over its ridges and dropping down its valleys like billows of a troubled ocean, and there, too, is the enveloping sweep of suburbs dotted with villas or cross-thatched with streets of workingmen’s cottages, and farther still the Meadows and their archery grounds, “the furzy hills of Braid” and their golf links, Blackford Hill whence “Marmion” and his bard looked down on “mine own romantic town,” and, on the southern horizon, the heathery Pentlands, low and shaggy, with the kine that graze over them low and shaggy too. To the northward, away beyond the cricket greens of Inverleith Park, the blue Firth sparkles in the offing, dotted with fleet steamers and the white spread sails of stately ships laying courses for the Baltic. In the distance, over Leith, looms the tall lighthouse of the Inchcape Rock that Southey made famous with a ballad. Beyond the west end of the city a wavy blue line marks the course seaward of the bustling little Water of Leith, where “David Balfour” kept tryst with “Alan Breck,” and many a sturdy little “brig” leaps across it as it hurries along, “brimmed,” wrote Stevenson, “like a cup with sunshine and the song of birds.” Still farther to the westward, where the old Queens Ferry Coach Road[26] appears as a faint white tracing, within many “a mile of Edinborough Town,” thin vapors of smoke rise from the chimneys of white cottages on peasant greens by brooksides; and one knows that the rowans there are white with bloom and the meadows flecked with daisies, and that bees are droning in the foxglove and blackbirds singing in the hawthorn.

Calton Hill itself scarcely improves on acquaintance, but loses rather. Its meagre scattering of monuments would barely excite a passing interest were it not for their conspicuous location and that suggestion of the Athenian Acropolis. A paltry array—a tall, ugly column to Nelson, a choragic monument like the one to Burns on a hillside near Holyrood, an old observatory with a brown tower and a new one with a colonnaded portico and a dome, and, most mentioned of all, the so-called “ruin” of the proposed national monument to the Scotch dead of Waterloo and the Peninsula, which got no farther than a row of columns and an entablature when funds failed and work stopped. Many a bitter shaft of scorn and mockery has this ill-starred undertaking pointed for the disparagers of Scotland. However, in its present condition it has done more than any other agency to stimulate the pleasant illusion of the “Modern Athens.” The hill itself is a favorite resort, lofty, and with a broad, rounded top. The eastern slopes are terraced and set with gardens, and the western and northern sides are steep verdant braes. One yields[27] the palm for reckless daring to Bothwell; not every one would care to speed a horse down such a course even to win attention from eyes so bright and important as Queen Mary’s.

It was on Calton Hill I had my first experience of the old school of Scotchmen, in the person of a dry and withered chip of Auld Reekie, combative, peppery, brusque and sententious, and abounding in that peculiar admixture of braggadocio and repression so characteristic of the class. He had evidently been nurtured from infancy on Allan Ramsay’s collection of Scotch proverbs, for he quoted them continually, giving the poet credit for their origin. He was sitting in the shade of Nelson’s column in shirt sleeves and cap, absorbed to all appearances in a copy of “The Scotsman,” though I suspect he had been regarding me for some while with quite as much curiosity as I now did him. He was a grim, self-contained old party, as dignified as the Lord Provost himself, with gray, shaggy eyebrows and a thin, wry mouth that gripped a cutty pipe; and he looked so much a part of the surroundings, so settled and weather-beaten, that one might almost have passed him over for some memorial carving or, at least, an “animated bust.” Him I beheld with vast inner delight and gingerly approached, giving “Good day” with all the cordiality in the world. The reward was a curt nod and a keen scrutiny from a pair of hard and twinkling blue eyes that had an appearance under the grizzled brows[28] of stars in a frosty sky. I observed upon the fineness of the day; he opined “There had been waur, no doot.” I noted what a capital spot it was for a quiet smoke; he allowed I might “gang far an’ find nane better.” Here I made proffer of a cigar and, presumably, with acceptable humility, for he took it with an “Ah, weel, I dinna mind,” of gloomy resignation—and so we got things going.

The conversation that followed I venture to give in some detail as illustrating, possibly, the peculiarities of a type to be encountered on every Edinburgh street corner—whimsical, conservative, witty, cautious in opinion, and surcharged with local pride.

“A man can take life pleasantly here,” said I, when we had lighted up.

“Aye, aye,” said he; “even a hard-workin’ one like mysel’, as Gude kens. But a bit smoke frae ane an’ twa o’ the day hurts naebody, I’m thinkin’; an’ auld Allan Ramsay was richt eneuch, ‘Light burdens break nae banes.’”

“You will never be leaving Edinburgh, I’ll warrant.”

“Na, na. Ye’ll have heard tell the sayin’, ‘Remove an auld tree an’ it will wither.’”

“There’s more money to be made elsewhere, perhaps.”

“I’m no so sure o’ that. Forbye, ‘Little gear the less care.’”

“One wouldn’t find a handsomer city than this, at all events.”

[29]

“Aweel, aweel, a’body kens that. Ye’ll no so vera frequently see the bate o’ it, I’m thinkin’. Them that should ken the best say sae.”

“How many people are there here, sir?”

“Mare than three hunner an’ fifty thoosan’, I’m telt.”

“No more? It is small for its fame. Why, Glasgow must be three times as large,” I ventured, resolved to stir him up a little.

“Glesgie, is it! Think shame o’ yersel’, mon, to say the same! A grippie carlin, Glesgie! Waur than the auld wife o’ the sayin’, ‘She’ll keep her ain side o’ the hoose, and gang up an’ doon in yours.’ Ye canna nay-say me there. Gae wa’ wi’ ye!”

“But you must admit it is a great port. The receipts are enormous, I’m told.”

“Aye, an’ it’s muckle ye’ll be telt ye’ll never read in the Guid Buik! Port, are ye sayin’? Hae ye na thought o’ Leith? Or the bonny sands an’ gardens o’ Portobello? Or Granton, forbye, wi’ the three braw piers o’ the Duke o’ Buccleuch? Ye’ll no be kennin’ they’re a’ a part o’ Ed’nboro, maybe.”

“But how about the ship-building on the Clyde?”

“An’ what wad ye make o’ that? How ony mon in his senses could gang to think sic jowkery-packery wi’ the gran’ brewin’ ayont the Coogait is mair than ever I could win to understan’. It’s by-ordinar, fair! An’ dinna loup to deecesions frae the claver an’ lees aboot muckle things. ’Twas Allan Ramsay himsel’ said,[30] ‘Mony ane opens their pack an’ sells nae wares.’ It’s unco strange that a body should tak nae notice o’ the learnin,’ an’ the gran’ courts, an’ the three hunner congregeetions, an’ a’ the bonny kirks we hae in Ed’nboro, but must ever be spairin’ o’ the siller. Do ye think, noo, it’s sae vera wonderful to ‘Put twa pennies in a purse, an’ see them creep thegither’? Glesgie may ken a’ sic-like gear, I’m nae sayin’; but there’s no sae muckle worth in that, as ye’ll be findin’ oot, though ye read in the books til the morn’s mornin’. It’s a fair disgrace to hae sic thochts. Mon can sae nae mair.”

“At any rate, there’s a fine university there.”

“It’s easy sayin’ sae. Muckle service is it! Gude kens a’ they learn there! Gin it’s cooleges ye’ll be admirin’, maybe ye’ll no be so vera well acquaint wi’ our ain toun? There’s nane in a’ Glesgie like the ane ye see the day. Mon, it’s fair dementit ye’ll be.”

It took time and diplomacy and many a round compliment on Edinburgh to bring him out of his sulk; but eventually he yielded.

“Aye,” said he, “I believe ye’ll be in the richt the noo. It’s gran’ up here, dinna misdoot it. Mony’s the braw sicht to be had, that’s a fac’, an’ I ken them a’ like the back o’ my hand. Sin lang afore yon trees were plantit, mare than ane fine dander hae I taen mysel’, bonny simmer days, lang miles o’er the heather. Ye’ll believe me, I’d gang hame and sleep soun’. It’s na sae pleesant, maybe, in winter, wi’ the dour haars an’ the fog an’ the[31] east winds. But I aye like it fine in simmer, wi’ a bit nip o’ wind betimes an’ then fair again. At the gloaming it’s quaiet an’ cauller, and then aiblins I bide a blink an’ hae a bit puff o’ my cutty, an’ syne I’ll gang to my bed wi’ an easy hairt. But, wheesht, mon! It’ll be twa o’ the day by the noo, I’m thinkin’? Is it so! Be gude to us! Weel, weel, I’ll gang my gait. I maunna be late to the wark; it’s a fearsome example to the laddies. ‘A scabbed sheep,’ says auld Allan, ‘smites the hale hirsel’.’ Guid day to ye; an’ keep awa’ frae Glesgie.” And with many a sigh and rheumatic hitch he shuffled off to the steps.

The old man was right. “Frae ane an’ twa o’ the day” a blither or more inspiring spot than Calton Hill would be hard to find. What more could possibly be desired, with a city so fair and famous at one’s feet and the air tonic with the sweetness of the heather and the brine of the sea! Fancy plays an amiable rôle and adds to one’s contentment with shadowy illusions of the Canongate of bygone days acclaiming Scotland’s kings and queens as they ride forth in pomp and pageantry, with trains of fierce clansmen from the furtherest Highlands, with pibrochs screaming, bonnets dancing, and axes and claymores rattling. And Montrose may pass with his Graham Cavaliers, or Argyle leading the Campbells of the Covenant. With our eyes on Holyrood, pathetic visions float before us of fair Mary of many sorrows, over whose gilded gloom the poets have loved[32] to linger. One moment she looms in the heroic martyrdom conceived by Schiller, and the next we see her as Swinburne did in “Chastelard,” with

Welcome apparitions of later days throng about us on the hill: Ramsay and his “Gentle Shepherd,” young Fergusson and his wild companions, Burns with his jovial cronies, the scholarly Jeffrey, the learned Hume, the inspired Sir Walter, the delightful revelers of the “Noctes Ambrosianæ,” the gentle Lady Nairne, the eager, brilliant Stevenson, and Dr. Brown with the faithful “Rab” and Ollivant with “Bob, Son of Battle.” The crisp sunshine lies golden on Princes Street and all her flowered terraces; it glints the grim redoubts of the Castle and lingers on the crooked gables of High Street. From the brown heather of the Pentlands to the distant sparkle of the Firth stretches a vigorous and comely land. What man so callous as to feel no joy in “Scotia’s Darling Seat”!

[33]

[35]

2 P.M. TO 3 P.M.

A table in the lively little Café de la Terrasse, up on the broad stone promenoir overhanging the Antwerp docks, is one place in a thousand for the man who is inclined toward any such unusual combination as a maximum of twentieth-century business activity in a setting of the Middle Ages. He is fortunate in locality and happy in surroundings. A Parisian waiter removes the remains of his light luncheon of a salad of Belgian greens fresh this morning from a trim truck garden beyond the ramparts, refills the thin tumbler to the taste of the guest with foaming local Orge or light Brussels Faro or the bitter product of Ghent or the flat, insipid stuff they boast about at Louvain, and supplies a light for an excellent cigar made here in Antwerp of the best growth of Havana. Supposing it to be two o’clock of the usual mottled, doubtful afternoon,—for Antwerp’s weather, like Antwerp’s history, is mingled sunshine and shadows,—the loiterer may look out at his ease on a notable and fascinating panorama. Beneath him and to either side extend miles of massive docks of ponderous masonry, upon and about which swarms an ant-like multitude of nimble and active longshoremen plying[36] a network of ropes and tackle, and directing the labors of vast, writhing derricks that toil like a mechanical Israel in bondage. Snuggling close to the grim granite walls are merchant mammoths from the ends of the earth, and into these, with the ease of a man stooping for a pin, gigantic steel arms sweep tons of casks and bales that they have lightly plucked out of long wharf trains lying alongside. There is a prodigious bustling of porters in long blue blouses, shouts and cries from the riverful of shipping, trampling of thousands of hobnailed shoes, and an incessant clatter of the wooden sabots of little Antwerp boys in peaked caps and baggy blue trousers and of little Antwerp girls in bright skirts and curious white headdress.

This sort of thing is proceeding for miles up and down the river front, and all through the intricate series of locks and bassins and canals that quadruple the wharfage of this rejuvenated old Flemish city. They are receiving whole argosies of raw material in the shape of hides, tobacco, and textiles, and are sending away fortunes in cut diamonds, delicate laces, linens, beer, sugar, and innumerable clever products of human hands from fragile glass to ponderous machinery. And they do it with more ease and, it seems necessary to add, with less profanity than any other port of Europe. What, then, could have possessed the genial Eugene Field to pass along that ancient slander on the excellent burghers of Flanders?

[37]

While I should not wish to take such extreme ground as that assumed, in another connection, by a New York police inspector, when he observed that “every one of them facts has been verified to be absolutely untrue,” still I must say that, as far as I could notice, there is nothing notable about the Flemish oath as employed to-day. Indeed, it is more than likely that one could pass a long and pleasant evening loitering among the tavernes and recreation haunts of the Belgian soldier and civilian and come across nothing more vocally spirited than robust guffaws, possibly punctuated discreetly, or heavy fists thundering the time as a couple of comrades scrape over the sanded floor in the contagious rhythm of that venerable and favorite waltz of the Netherlands,—

On the other hand, if, with this much of an excuse, a stranger should go exploring Antwerp between two and[38] three o’clock in quest of “verkoop men dranken” signs, he would be quite otherwise repaid in the discovery of charming huddled and crooked streets and a wealth of architectural quaintness and beauty. He would have no difficulty in finding tavernes and drinking-places, particularly along the river front, where they abound. As he passed them he would encounter robust whiffs of acrid and penetrating odors with tar and fish in the ascendancy, and catch glimpses of a wooden-shod peasantry fraternizing with evil-eyed “water-rats” and devouring vast quantities of salmon and sauerkraut washed down with ale and white beer. There is no charge now, as once there was, for noise made by patrons. The silk-fingered gentry overreached themselves here, for when, a number of years ago, they had carried the robbing of foreign sailors to the point of international notoriety, the authorities took a hand and devised a system of payment for Jack ashore; then the American and English ministers and consuls established and made popular the Sailors’ Bethel on the quay, with its clean and attractive reading- and amusement-rooms, and the Sailors’ Home on Canal de l’Ancre, where, for fifty-five cents a day, Jack can have a neat little room to himself and four excellent meals in the bargain. For these reasons among others, a visitor, even by night, finds much less of noise and revelry than he had anticipated, and beholds the thirsty Antwerpian content himself with a final “nip” at an estaminet or even make shift of a “nightcap”[39] of mineral water or black coffee at one or another of the city’s innumerable cafés. In these he will himself be welcome to read the news of the day in the columns of “Le Précurseur” or “De Nieuwe Gazet,” or, better still, in the venerable “Gazet van Gent,” one of the oldest of existing newspapers, with nearly two hundred and fifty years of publication behind it. The real drinking will have been in progress where the out-of-town people have been dining à prix fixe, and clinking their burgundy and claret glasses at the great hotels on the Quai Van Dyck, the Place de Meir, or the Place Verte. The palm should really go to the amusement seekers of the latter little square; for nothing this side the capacity of an archery club at a July kermess can compare with the thirst of the music lovers who throng the tables on the sidewalks before the restaurants and cafés of jolly Place Verte when the band is playing, on balmy summer evenings. Instead of dissipation, the man who explores Antwerp makes constant discovery of unanticipated delights. He observes about him in the surprising little streets of the old section an amazing collection of absurd roofs slanting steeply up for several stories, pierced with owl-like, staring, round windows; house fronts by the hundreds with denticulated gables stepping upward like staircases toward the sky; and pots of flowers and immaculate muslin curtains in tiny doll-house windows peering out from the most unexpected and impossible places away up among the eaves[40] and chimneys. He will catch an occasional glimpse of massive old four-poster beds with green curtains and yellow lace valances; of shining oak chests, and high-back chairs, and brown dining-rooms wainscoted in polished oak and most inviting with ponderous side-boards set with Delft platters and gleaming copper and pewter pieces. From time to time he will see large, cool living-rooms in which the father enjoys his paper and meerschaum pipe, while the placid-faced mother employs herself with lace or embroidery and the fair-haired daughter at the piano tells how

As I previously observed, there is no better place for a preliminary impression of Antwerp than along the docks. There one acquires some adequate idea of the amazing extent of its industrial operations and enjoys, at the same time, an extraordinary panorama of a river choked with shipping in the immediate foreground, and, on the opposite bank, the sombre redoubts of Tête de Flandre and Fort Isabelle keeping watch and ward over the flat little farms that extend seaward in fields of pale-green corn and barley. For any one who has done the proper amount of preparatory reading on Antwerp, it will inspire stirring thoughts of the musical, artistic, and martial career of this rare old Flemish town.

[41]

If the visitor be a lover of music—of Wagner’s music—the surrounding uproar and confusion will shortly fade into a charming reverie as he gazes far down the glittering zigzag of the Scheldt and some distant glimmer will take the form of the swan-boat of Lohengrin with the Grail knight leaning on his shining shield. The docks and quays will have disappeared, and in their place will once more lie the old low meadows, and, under the Oak of Justice, King Henry the Fowler will take seat on his throne with the nobles of Brabant ranged about him. Fair Elsa, charged with fratricide, moves slowly forward, sustained by her dream of a champion who is to come to her defense; and the heralds pace off the lists and appeal to the four quarters in the sonorous chant,—

And suddenly the peasants by the water’s edge cry out in amazement and point down the reaches of the river, and there comes glittering Lohengrin in the “shining armor” of Elsa’s dream. The champion steps ashore and gives no heed to the awe-hushed company until he has sung to his feathered steed what now every child in Germany could sing with him, “Nun sei bedankt, mein lieber Schwan.” And then the contest rages and the false Frederick falls, and the royal cortège retires to the neighboring old fortress of the Steen. All[42] night the treacherous Ortrud and her defeated Frederick plot by the steps of yonder cathedral, and there, in the morning, Lohengrin weds Elsa and the immortal Wedding March welcomes the “faithful and true” back to their fortress home. The black night of mistrust and carnage follows, and when day dawns Lohengrin bids farewell to his suspicious bride in these green Scheldt meadows and sails sadly away in his resplendent boat drawn by the dove of the Grail.

On the other hand, if the visitor has a mind for history, he may scorn the pretty Grail story and look with stern eyes on this Scheldt and the battle-scarred city beside it, mindful of the deeds of blood and fire that fill the hypnotic pages of Schiller, Prescott, and Motley. The monk of St. Gall could have appropriately dedicated to the war-ravaged Antwerp of those days his solemn antiphonal “media vita in morte sumus.” The grim, turreted Steen, just at hand, recalls the bloody reign of Alva and how he condemned a whole people to death in an order of three lines. In its present rôle of museum it houses hundreds of implements of torture that once were drenched in the blood of the heroic burghers of Antwerp. Not all the horrors of the “Spanish Fury,” when eight thousand citizens of this town were butchered in three days, nor the stirring memory of the “French Fury,” with Antwerp triumphant, can dim the glory of the heroic resistance the “Sea Beggars” made to the advance of the Duke of Parma up the Scheldt.

ANTWERP, FROM THE SCHELDT

[43]

From the cathedral tower one may see the little towns of Calloo and Oordam, on either bank of the river; it was between them that Parma built his bridge to obstruct navigation, and against it the men of Antwerp sent their famous fire-ships to open up a passage for the Zeelander allies. Gianibelli, who devised them, and whom Schiller styled “the Archimedes of Antwerp,” builded better than he knew, for with one ship he destroyed a thousand Spaniards and heaped up their defenses into a labyrinth of ruin. Could Antwerp have risen then above the clash of factions, there would have been no need later to tear down the dikes and present the strange spectacle of ships sailing over the land, and their story might have been as triumphant as Holland’s, and a united Netherlands have issued from those long wars with Spain.

Here where the visitor takes his afternoon ease many a brave pageant foregathered in the troubled, olden days. In the magic pages of old Van Meteren’s chronicles we see them pass again: Cold, gloomy, treacherous Philip stepping from his golden barge to walk under triumphal arches on a carpet of strewn roses, surrounded by magistrates and burghers splendid in ruffs and cramoisy velvet; later on, the Regent, Margaret of Parma, strident and gouty, whom Prescott has called “a man in petticoats”; and then the bloodthirsty Alva; then the dashing “Sword of Lepanto,” the brilliant and romantic Don John of Austria; next, the atrocious[44] Requesens; and, last of all, the revengeful Alexander of Parma. Hopeful, stolid, impassive Antwerp, ever the sheep for the shearers, ever believing that at last the worst was over, rejoices in her welcome to each as though the millennium had finally dawned on all her troubles and sets cressets to blazing in the cathedral tower and roasts whole oxen in the public squares.

The scream of a river siren will arouse the visitor from the Past to the Present, and, with a sigh, he will saunter forth to see the places that cannot come to him. He will leave with regret this busy, fascinating river—“the lazy Scheldt” that Goldsmith loved. Excited little tugs are bustling busily about, queer-coated dock-hands struggle mightily with their mammoth burdens, and ships of every shape and pattern throng the roadstead before him. The sharp and trim Yankee sloop, the ponderous German tramp, the fastidious British freighter, the clean-cut ocean liner, and, best of all, the round-sterned, wallowing Dutch craft, green of hull and yellow of sail,—all are here, and, he can think, for his especial diversion. A canal barge crawls laboriously by, and in that floating home which she seldom cares to leave, a much-be-petticoated mother of Flanders busies herself with her many children and looks after the care of her tiny house;—and looks after it well, as you may see by the spotless little curtains that flutter in the windows and the bright pots of geraniums that stand on the sills. One recalls the keen delight this[45] singular craft afforded Robert Louis Stevenson at the time he made his charming “Inland Voyage” from Antwerp. Quoth he: “Of all the creatures of commercial enterprise, a canal barge is by far the most delightful to consider. It may spread its sails, and then you see it sailing high above the tree-tops and the windmill, sailing on the aqueduct, sailing through the green corn-lands; the most picturesque of things amphibious.... There should be many contented spirits on board, for such a life is both to travel and to stay at home.”

Along the front there is also opportunity to expend a couple of francs to advantage for a ticket on the comfortable little steamer that is just impatiently casting off from the embarcadère, and to go sailing with her on an hour’s voyage up the river to Tamise to view the shipping at greater length, to see the merchants’ villas at Hoboken, and finally the famous picture of the Holy Family at the journey’s end. Otherwise the visitor may take a parting look up the Quay van Dyck and the Quay Jordaens, examine once more the striking Porte de l’Escaut that Rubens decorated, and so turn a reluctant back on the bright life of the river to thread a crooked street or two, cobbled and tortuous, and issue forth on the Grand Place before the immense, fantastic Hôtel de Ville.

In the drowsy early afternoon this quaint and curious old city hall wears a most friendly and reposeful air. To one who has never before seen any of these extraordinary[46] Old-World buildings such a one as this will move such incredulity as mastered the countryman at the first sight of a giraffe;—“Shucks!” said he when he had looked it all over, “there never was such an animal!” Fancy a rambling, picture-book of a structure a hundred yards long, made up of the oddest combination of architectural orders—massive pillars for the first story, Doric arcades for the second, Ionic for the third, and last of all, an abbreviated colonnade supporting a steep, tent-like, gable-pierced roof! As though some touch of the whimsical might even so have been neglected, behold a pompous central tower, decorated to suffocation, arched of window and graven of column, rearing itself in three diminishing, denticulated stories above the long, sloping roof, until the singular, box-like ornaments on the very tiptop appear tiny Greek tombs of a cloud-hung Acropolis. The statues of Wisdom and Justice could pass for Æschylus and Sophocles, and the Holy Virgin on the summit might very well be Athena. The friendly air to which I have referred extends even to these statues, who have the appearance of shouting down to you to come in out of the heat and have a look at the great stairway of colored marbles and rest awhile before the splendid chimney-piece of delicately carved black-and-white stone in the elaborate Salle des Mariages. Subtle matchmakers, those statues! And, indeed, if Antwerp is the first steamer-stop of the visitor, he may well be pardoned for reveling in this[47] Hôtel de Ville as something that for picturesque beauty he may not hope to better elsewhere. And yet that would only be because he had not seen the glorious one at Brussels, or the grim and huddled caprice at Mechlin, or the incredible Halle aux Draps at Ypres, or the amazing Rabot Gate or Watermen’s Guild House of Ghent. And even these will fall back into the commonplace once he has drifted along the Quai du Rosaire of drowsy old Bruges and been steeped in picturesqueness and color that is beyond any man’s describing.

No one who cares for structural quaintness and originality can fail to find especial delight in the surroundings of this venerable Grand Place. Along one entire side, like prize competitors in an architectural fancy ball, shoulder to shoulder, stiff and precise, range the old Halls of the Guilds. The Archers, the Coopers, the Tailors, the Carpenters, and all the others of that most unusual alignment, present themselves in full regalia of characteristic ornament and design. As though in keeping with their ancient traditions of stout rivalry, there is a very real air of vying between themselves for some coveted palm for fantastic bizarreness; and all the while with a solemn innocence of being at all grotesque or unusual. One could laugh at their naïve unconsciousness of the prodigious show they make, with sculptures and adornments of bygone days and a combined violent sky-line slashed with long eaves and bitten out in serrated gable ends. But there is little of merriment[48] and very much of reverence in the thoughts they excite of worthy pride in skill of craftsmanship and the glory their masters brought to this city in the sixteenth century in winning from Venice the industrial supremacy of the world. In those days there were no poor in all Antwerp and every child could read and write at least two languages, and the Counts of Flanders were more powerful than half the kings of Europe.

But the Grand Place has more to show than the guild halls. The apogee of the whimsical and fantastic has been attained in the choppy sea of red-tiled roof-tops that eddies above this huddled neighborhood. Grim old dormered veterans, queer and chimerical, palsied and askew, have here held their own stoutly through the centuries. They have echoed back the shouts of the crusaders, the triumphal cannon of Spanish royalty, and the free-hearted welcomes to foreign princes come to curry favor with the Flemish merchant rulers of the world. They have turned gray with the groans of their nobles writhing under the Inquisition and rosy with approval of the adroit and courageous William of Nassau. From their antique windows have leaned the burgomasters of Rubens and the cavaliers of Velasquez, brave in ruffs and beards; and out of the most hidden nests of their eaves the wan and pallid faces of their hunted sons have been raised to watch the approach of the ruthless soldiery of Requesens and Parma. These old roofs look down to-day on a rich and happy people[49] whose skill and tireless industry have reared a commercial fabric that astonishes the world.

At this afternoon hour the Grand Place betrays little of its early-morning activity, when it is thronged with the overflowing stands of busy marketmen in baggy trousers, and banks of rich colors of the flower-women in immaculate linen headdress proffering the choice output of their scrupulously tilled farms. Scarcely less picturesque are these oddly garbed country-folk than the famous fish-venders over at Ostend, and certainly they are a more fragrant people to shop among. A curious and colorful picture they present with the long lines of gayly painted dog-carts blazing with peonies and geraniums. Huddled around the great statue of Brabo they quite throw into limbo the Daughters of the Scheldt that are disporting in bronze on the pedestal. Brabo himself, Antwerp’s Jack-the-Giant-Killer, pauses on high in the act of hurling away the severed hand of the vanquished Antigonus as though he could see no unoccupied spot to throw it in. Should he let go at random, and hit house Number 4, he could surely expect to be hauled down forthwith, for the great Van Dyck was born there, and Antwerp is nothing if not reverent of the memory of her glorious sons of Art. And Brabo cannot afford to take too many chances with the security of his own position, for he himself has a rival; Napoleon the Great was really a greater champion of Flanders than he, and overthrew a worse enemy of[50] Antwerp’s than the fabled Antigonus when he raised the embargo on the Scheldt, that had existed for a century and a half under the terms of the outrageous Treaty of Westphalia, until scarcely a rowboat would venture over the silt-choked mouth of the river, and only then to find the famous capital a forsaken village of empty streets and abandoned factories. The dredging of the channel, the expenditure of millions in construction of wharves and quays, and the restoration of the city to its high place in the commercial world was a greater and more difficult work than Brabo’s.

The varied and vivid life of Antwerp unfolds itself strikingly in the early afternoon to one who exchanges the sleepy, mediæval Grand Place for the broad, curving, crowded boulevard of the popular Place de Meir. It was just such clean and handsome streets as this that inspired John Evelyn to write so delightedly of Antwerp two hundred and fifty years ago, describing them in his famous “Diary” as “fair and noble, clean, well-paved, and sweet to admiration.” Indeed, everything seemed to have charmed Evelyn here, as witness his inclusive approval, “Nor did I ever observe a more quiet, clean, elegantly built, and civil place than this magnificent and famous city of Antwerp.” Rubens, the name of names in Flanders, was then too recently dead to have come into the fullness of his fame; whereas to-day one thinks of him continually here and likes nothing better than the many opportunities to study him in the completeness[51] of his wonderful career—“the greatest master,” said Sir Joshua Reynolds, “in the mechanical part of the art, that ever exercised a pencil.” Even trivial associations of his activity are cherished; as we find them, for instance, in the little woodcut designs he made for his famous friend, Christopher Plantin, the greatest printer of the era, and which one handles reverently in the old Plantin house in the Marché du Vendredi—that picture-book of a house, where corbel-carved ceiling-beams overhang antique presses, types, and mallets, and great windows of tiny leaded panes let in a flood of light from the rarest and mellowest old courtyard in the whole of the Netherlands.

The Place de Meir is Antwerp’s Broadway; and an afternoon stroll along it affords a constantly changing view of stately public and private buildings, no less attractive to the average man than those “apple-green wineshops, garlanded in vines” that delighted Théophile Gautier on the river front. Little corner shrines, so numerous in this city, shelter saints of tinsel and gilt and receive the reverence of a population that has four hundred Catholics to every Protestant. One must necessarily delight in a street whose houses are all of delicately colored brick, with stone trimmings carved to a nicety and shutters painted in softest greens. The imposing Royal Palace is graceful and beautiful, but human interest goes out to the stone-garlanded house across the way,—old Number 54,—where[52] Rubens was born and where he lived so many years and took so much pleasure in making beautiful for his parents. On either hand one sees solid residences of the most generous proportions, and all in tints of pink and gray, and busy hotels with red-faced porters hurrying about in long blouses. Picture stores and bookshops scrupulously stocked with religious volumes beguile lingering inspection. There are establishments on every hand for the sale of ecclesiastical paraphernalia, with windows hung with confirmation wreaths, crucifixes, rosaries, and what-not. Occasionally, even here, one discovers, crushed in between more consequential businesses, the celebrated little gingerbread-shops of which so much amused notice has been taken. Restaurants and cafés abound. One sees them on every hand, with their characteristic overflow of tables and chairs on the sidewalk, always thronged, both inside and out, with jolly, chattering patrons and gleaming in sideboard and shelf with highly polished vessels of brass and pewter. Here and there one passes the confectionery shops, called pâtisseries, where ices, mild liqueurs, and mineral waters refresh a thriving trade. Stevenson found no relish for Flemish food, pronouncing it “of a nondescript, occasional character.” He complained that the Belgians do not go at eating with proper thoroughness, but “peck and trifle with viands all day long in an amateur spirit.” “All day long” is apt enough, for Antwerp’s restaurants and cafés are always thronged.

[53]

These ruddy-faced and placid Belgians are a very serene and contented people. It is pleasant and even restful to watch them; they go about the affairs of life with such an absence of fret and fever. Spanish-appearing ladies float gracefully past in silk mantillas; priests by the hundreds shuffle along leisurely in picturesque hats and gowns; the portly merchant, on his way at this hour to the moresque, many-columned Bourse, proceeds in like deliberate and unhurried fashion. Street venders, in peaked caps and voluminous trousers, approach you with calm deliberation and retire unruffled at your dismissal. On every sunny corner military men by the score “loafe and invite their souls.” Tradesmen in the shops and cabmen in the open go about their business as though it were a matter of infinite leisure. Even the day laborers in the streets, whose huge sabots stand in long rows by the curb, survey life tranquilly; why worry when a good pair of wooden shoes costs less than a dollar and will last for five or six years?

The snatches of conversation one catches betray the confusion of tongues inseparable from a nation of whom one half cannot understand the other, and whose cousins, once or twice removed, are of foreign speech to either. The Dutch spoken in the Scheldt country is said to be as bewildering to a German, as is the French the Walloons employ in the valley of the Meuse to a Parisian. But although the Flemish outnumber their[54] fellow countrymen of Wallonia two to one, still French is the tongue of the court, the sciences, and all the educated and upper circles. It is like Austria-Hungary all over again. And French continues steadily to gain ground in spite of the utmost efforts of the enthusiasts behind the new “Flemish Movement.” One sees both classes on the Place de Meir,—the stolid, light-haired man of Flanders and the nervous, swarthy Walloon. The beauty of the blue-eyed, belle Flamande is in happy contrast with that of the slender, dark-eyed Wallonne, and their poets have exhausted themselves in efforts to do justice to either side of so delicate and distracting a dilemma. Our grandmothers heard much of the charms of La Flamande when Lortzing’s melodious “Czaar und Zimmermann” was so popular, seventy-five years ago:—

The complexion of the life on the Place de Meir changes with the hours. Between two and three o’clock we find it disposed to adapt itself as closely as possible along lines of personal comfort. By five it will be lively with carriages and automobiles bound for the driving in the prim little Pépinière, or the bird-thronged Zoölogical gardens, or around the lake in the central park, with a turn up the fashionable Rue Carnot to the stately boulevards of the new and exclusive Borgerhout section.[55] At that hour one may count confidently upon seeing every uniform of the garrison among the crowds of officers who turn out to have a part in the beauty show. On the other hand, if it were early morning—very early morning—and the sun were still fighting its way through the mists and vapors of the Scheldt, the Place de Meir would resound with rattling little carts by the hundreds, bearing great milk cans of glittering, polished brass packed in straw, by whose sides patient, placid-faced women would trudge along in quaint thimble-bonnets, with plaid shawls crossed and belted above voluminous skirts and their feet set securely in the clumsy wooden sabots of the Fatherland. Market gardeners in linen smocks and gray worsted stockings would be bringing Antwerp its breakfast in carts only a little larger than the milk-women’s, and butcher boys would be scurrying by with meat trays on their heads or suspended from yokes across their shoulders. And all the echoes of the city would be forced into feverish activity to answer the wild clamor of the barking and fighting dogs, shaggy and strong, that draw all these picturesque little wagons. Assuredly there are few sights in Antwerp so impressive to the stranger as this substitution of dog for horse. It has been celebrated in prose and verse, with Ouida possibly carrying off the palm with her canine vie intime, “A Dog of Flanders.”

As the loiterer continues his afternoon stroll to the large and central Place de Commune, crosses into the[56] chain of transverse boulevards, and returns riverward to that choicest spot of all, the tree-shaded, memory-haunted Place Verte, he is bound to reflect upon the vast changes that Antwerp, above all other Continental cities, has experienced in the last quarter-century. He will marvel, too, that Robert Bell should have lamented in his charming “Wayside Pictures” the paucity of gay life here and particularly the lack of theatrical entertainment. It may have been so when Bell wrote, fifty years ago, but it is decidedly otherwise to-day. So far as theatres go, they simply abound; nor could city streets be gayer than these, thronged with a merry, happy people and bright with the uniforms of artillery-men and fortress engineers, grenadiers of the line and the dashing chasseurs-à-cheval. Every hotel and café has its orchestra; and in the early evening practically every square of the city has its concert by a band from a regiment or guild. There is no suburb, they say, but has its own band or orchestra, or both. Indeed, Antwerp is nearly as music-mad as art-mad.