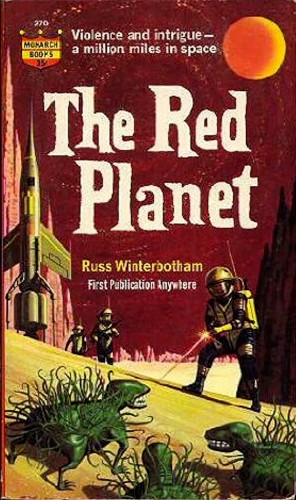

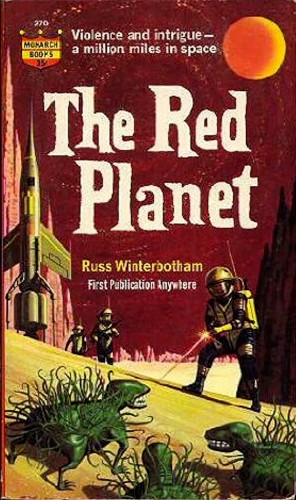

The Project Gutenberg eBook of The red planet, by Russ Winterbotham

Title: The red planet

Author: Russ Winterbotham

Illustrator: Ralph Brillhart

Release Date: June 26, 2023 [eBook #71049]

Language: English

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Russ Winterbotham

A Science Fiction Novel

MONARCH BOOKS, INC.

Derby, Connecticut

Published in August, 1962

Copyright © 1962 by Russ Winterbotham

[Transcriber's Note: Extensive research did not uncover any

evidence that the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Cover Painting by Ralph Brillhart

Monarch Books are published by MONARCH BOOKS, INC., Capital Building, Derby, Connecticut, and represent the works of outstanding novelists and writers of non-fiction especially chosen for their literary merit and reading entertainment.

Printed in the United States of America

All Rights Reserved

REVENGE IN AN ALIEN WORLD

When Gail Loring chose Bill Drake to be her husband—in name only—for the duration of the flight to Mars, she didn't know that she had just signed his death warrant.

Jealous Dr. Spartan, leader of the expedition, swore to get revenge and force Gail to share his maniacal plan for power.

Bound together in space, five men and a woman strained against the powerful tug of twisted emotions and secret ambitions.

But all plans were forgotten when they landed on the Red Planet and encountered the Martians—half animal, half vegetable—with acid for blood and radar for sight.

When the Martians launched an assault against the spaceship, linking their electrical energy in an awesome display of power, Spartan realized that this was the perfect moment for personal revenge—and touched off his own diabolical plan of destruction against his fellow crewmen....

I got no sleep that Thursday night. I tossed and dozed and tossed again. Operation Jehad and Willy Zinder were on my mind. Operation Jehad was the designation given to the proposed first manned flight to Mars, and Willy was our last chance to fill the six-man crew.

If Willy didn't make it, Doc Spartan would be fit to be tied in a hangman's knot. More than anything else, he had insisted on a six-man crew and, if he couldn't get six qualified astronauts, including himself, on the Jehad ship, he was as likely as not to postpone the voyage for 26 months, when Mars would be in the right spot again and by which time more men could be trained.

While I rolled and tossed in my bed sheets, Willy Zinder was playing carousel in his Jupiter capsule three hundred miles above old Momma Earth. And I hated to speculate about what had happened to him. When I'd watched him get into the cherry-picker Thursday morning, he'd been a poor, frightened kid. He'd probably been suffering ever since. And now, after this dreadful night, re-entry was staring him in the face.

Feeling scared was natural and nothing to be ashamed of, because we all got butterflies on our first solo orbit. But when I took my ASD tests, I'd managed to keep my teeth from chattering. Willy hadn't and somehow I got the feeling that he was suffering as much as all the rest of us combined. He looked so ready to collapse that I wondered what was holding him up.

Finally I gave up trying to sleep. It was daylight anyhow and I dressed, hurried to a restaurant and had scrambled eggs and coffee. Then I went over to the reservation to see how things were going. Dr. Spartan probably had spent the night there, but the rest of us had knocked off when the midnight operations shift came on duty. If they'd all spent a night like I had, the other members of the Jehad crew would be on hand almost as soon as me.

Besides Spartan, the others were Axel Ludkin, the big Swede from Minnesota; Dr. Warner Joel, who probably would hide his feelings by slapping people on the back and trying to joke about inconsequential things; and Morrie Grover, who was a pink-cheeked kid. We, plus Dr. Lewis Spartan, had already qualified for the first manned trip to Mars.

But plans had been made for six and Willy Zinder was our last candidate. To say we were scraping the bottom of the barrel would be selling Willy short. He was Number 12 out of 100 fine physical and mental specimens who had been selected for astronaut training three years before. Eighty-eight others had been washed out, one way or another, before twelve were fingered for Operation Jehad—so named because Jehad means holy war to Moslems. We were going to Mars, which was named after the Roman war god, so that accounted for the war part of the name, but I don't know what was holy about it except that going to Mars would materialize an ancient dream of man to travel through space to another world.

Willy was as healthy as a mountain and even if he looked scared I could tell he had guts. By the time the lift-off date of the operation got a few months away, Willy had climbed to position Number Six. Two higher numbers had flunked the ASD—Aeronautical Systems Division—tests, Dr. Spartan had said two others wouldn't do—the space boys in Washington took Doc's word as gospel—one had been banged up in a car wreck and was still in the hospital, and the sixth man had undergone an emergency appendectomy which left him too weak to lift off for Mars at the scheduled time.

There wasn't time now to train more men for the job, which meant that Willy had to pass and Doc Spartan was enough of a perfectionist to insist that Willy get as thorough a testing as the others of the crew.

Sure, there were other astronauts. There were ten or twelve working on other projects, but the plasma space engine isn't an ordinary spaceship that anybody can take on a 150,000,000-mile round trip without rigorous training.

I reached the gate that separated spacemen from mere Earthlings and flashed my badge on the security guard.

"William Drake," he said, grinning. "Sure hope you have luck today, Mr. Drake."

"Thanks," I said. "How's Zinder doing?"

"Very well, the last I heard. The boys coming off the last Operations shift said he'd handled everything pretty well."

I went through the gate. Almost anybody can get through this one, but there are other security officers, at other gates further on down, to keep the place from being overrun by tourists, newspaper guys and people looking for rest rooms. How far you got depended on the color of your badge. Mine was blue, for the wild blue yonder, and I could walk right into Dr. Spartan's office with it, provided I had business there. And I wouldn't dare call on Dr. Spartan unless I did have it. He could eat a man out better than acid.

Finally I reached the bunker. I glanced into the room filled with the Operations staff which was keeping track of Willy—communicating with him, tabulating his heartbeats, respiration and maybe his thoughts—and checking the behavior of his capsule. I wasn't interested in them. I went to the end of the hall, flashed my badge again, and entered the room reserved for the panel that was going to pass or flunk Willy Zinder.

Doc Spartan was the man in charge. He was the leader of our little group, but that was no break for Willy Zinder. Doc Spartan was an old space hand. He'd been to the moon and he had conducted the trial flight of the plasma engine. First, last and middle, he was a perfectionist. I hated him, so did everyone else, but there was one thing that we all could say: if Doc stamped you okay, you were as good as he expected to find. And there was another thing that could be said: Doc Spartan made a top sergeant of the Marine Corps look like Peter Pan.

He was there, along with three other men who looked as if they'd been without sleep for a week. Maybe they'd taken a few naps during the twenty-four hours, but it didn't show. They were red-eyed, their hair was uncombed and they each showed a day's growth of beard. Although the room was air-conditioned, they looked sweaty and hot. Mugs full of black coffee were on their desks and there were bread crusts and half-eaten sandwiches on trays nearby.

Axel Ludson stood back against the rear wall. Like me, he had nothing to do but watch and he had probably hurried over after eating breakfast, just as I had, in order to be on hand when Willy made his re-entry.

Axel was a big, raw-boned Swede, which is a description you could give of a large portion of the male population of his home town in Minnesota. He had light brown hair, blue eyes and a long straight nose. His jaw looked big and solid enough to crush concrete. He winked at me and I walked over to him.

"Willy is doing fine," he said, which was an accolade. Axel made his words count. "Doc has thrown everything at him but a flock of asteroids and Willy hasn't missed a pitch."

"Good!" I said. "Where is Willy now?"

Axel nodded toward a screen on the left wall. On it was projected a portion of a globe showing Northern Siberia. A little spot of light showed up in the middle of it.

"In thirty minutes he'll begin his last orbit."

"How did he do on the emergencies?" I asked.

Axel grinned. "He acted like they were the real thing."

The space capsule carrying Willy was the old-fashioned type, with room enough for only one man. However, it had special controls which made its manual operation similar to that used on the plasma craft. Throughout the flight, Willy was in charge of the operation. Without warning, certain simulated emergencies were signaled to instruments aboard the capsule and Willy was expected to meet them.

Although space flight sounds dangerous, most of it isn't because space is more empty than anything most of us ever saw. The only critical times are usually at the lift-off, the re-entry and the landing. However, other emergencies can arise. The worst would be the sudden appearance of a large meteor, meaning a pebble a quarter of an inch in diameter or bigger. Since about 95 per cent of the meteors in space are less than that size, chances of meeting one, even on a trip lasting two-and-a-half years, are remote. But it could happen.

The plasma ship was equipped with meteor bumpers which would vaporize anything smaller than a quarter of an inch. Larger ones might puncture the sides, but even then there was patching fluid in the walls of the craft which would prevent too much air loss. A tremendously large meteor can be detected by radar and avoided. Willy'd had to make the right maneuver to avoid such a meteor.

Radiation in space also poses some problems. Space travel requires high speed, and astronauts can pass through a radiation belt in so short a time that the exposure isn't harmful. But a very large cloud might pose problems and Willy would have to meet such an emergency by determining the size of the cloud and the best way to pierce it.

Another hazard could be faulty astrogation. On a 75,000,000-mile trip—the distance we were to travel to reach Mars—a small error at the start might put the ship too far from Mars to be caught by the planet's gravity at the end of the voyage. Willy had to make observations throughout the test flight and go through operations necessary to correct his trajectory. There might be other minor emergencies, such as failure of equipment and instruments, but Willy had demonstrated his ability to cope with them in tests conducted on the ground.

Dr. Warner Joel entered the room. A few months ago he had been overweight, but stringent diet had cut his weight down enough to allow him to qualify for our crew. He was a short, stocky man, with a smooth face and nervous manner. However, his knowledge of geology had made him almost indispensable. Rarely do you find a man with his experience in this particular field who can also qualify for the stringencies of space flight.

There was one thing against Joel that I was determined to overlook and this was his rather ingratiating manner, his eagerness to appear to be more than he was, and his intense desire to win favor from Dr. Spartan.

As he entered he hailed everyone in a loud voice, speaking to no one in particular. And no one in particular answered. Ignoring the rebuff, and with a strict eye to protocol, he walked over to the control board where Dr. Spartan was seated.

"Great show, Doctor! Brilliant show!" Joel exclaimed, extending his hand as if he were congratulating a playwright on opening night.

Spartan, his dark eyes glued to the instruments in front of him, ignored Joel.

"Yes, sir!" the geologist continued, putting his hand in his coat pocket, probably to give it warmth after Spartan's coolness. "We've got a good man in Willy Zinder. I always did say this boy was a sleeper. Better than a lot of men in our group, in fact."

Axel nudged me in the ribs and, as I turned, he winked one of his ice-blue eyes. "Meaning me or you, Bill?"

"You, you big Swede," I said, winking back. "But my opinion puts Willy several notches above Joel, too."

Axel chuckled softly.

"I won't worry with Willy Zinder on the crew," Joel was saying loudly. "No, sir—"

"Why don't you sit down?" snarled Spartan, still not turning his head. "You drive me crazy."

"Uh—ah—why yes, of course! I didn't realize—"

"Then do it!" snapped Spartan.

Joel almost stumbled as he backed away. Now, as he spotted Axel and me, he decided we were appropriate sympathizers. He walked over to us and said, "He's understandably touchy."

"I never pet rattlesnakes," said Axel.

Willy's voice, surprisingly cheerful, came over the loud-speaker. He was A-okay and was passing over the North Pole for the fifteenth time.

Communications responded and wished him good luck.

Dr. Spartan nodded. Then he turned his head and called out: "Miss Loring!"

I turned my head. I hadn't seen Gail Loring when I entered the room. She must have been in Operations and had entered through the door in the other end of the room. Now I saw her fine-featured face as she replied, "Yes, Dr. Spartan?"

"Come here!"

She came over to his control board briskly, holding her head high, paying no attention to anyone but Dr. Spartan. She was all business.

It was a pitiful waste, because she was an attractive girl and so untouchable. She wasn't beautiful in the sense that a stage or screen star is. She was good-looking, the kind of girl who wore well. Without lace or fancy trimmings, she was solid, durable, functional—and feminine, in spite of herself. She'd made a successful landing on the moon and had accompanied Dr. Spartan on the trial flight of the plasma ship. Now she was preparing for some other project—only the NASA knew what it was.

Surprisingly enough, I'd found out in the three or four times we'd met that she had a pleasant disposition, in spite of her businesslike manner. She liked to laugh and she was intelligent, which of course she'd have to be as a woman astronaut. Up to the time I'd met her informally, I'd classified her as a female Dr. Spartan.

"Please take over the control panel for a few minutes," Spartan said. "I'm going to get some breakfast before the re-entry."

"Certainly, Doctor," she said. "Any special orders?"

"None," he said. "Operations has alerted the Navy carrier and it is in position to pick up Zinder after the re-entry, on his next orbit. All you have to do is be ready to switch over to ground control in the event of an emergency."

I felt Axel's elbow shudder against my arm. Resorting to ground control would wash Willy Zinder off the project because it was his job to handle the capsule from beginning to end of his flight. Only during the lift-off and re-entry was there automatic operation—Willy had to take over again after re-entry.

Dr. Spartan rose and Gail took his seat. She glued her eyes on the instruments with all the instinct of a good pointer flushing a covey of quail.

I watched her. Even in slacks she looked good; a statement I could make about no other women I've ever seen. She wore no make-up, except lipstick, and that didn't hurt her. She had brown hair cut close, almost mannish style, and still she looked like a woman.

The disappointing thing about her was that she would not allow a man to become part of her life. Not that she was cold. No one could tell me that a woman who tried so hard to forget she was feminine had nothing to forget. It was simply that men were "out" until she'd got enough of her career.

I turned my head and noticed that young Morrie Grover had come in and was too busy watching Gail Loring to take much interest in what was going on in space.

Morrie was the fifth man in our crew—Willy was qualifying as sixth. Morrie was the youngest of our group, being a couple of years my junior by the calendar. Actually I felt at least ten years older because Morrie was one of those eager young lads who keep too busy learning about the universe to understand what is going on in this world. No doubt he'd grow up a lot on the Martian adventure. The fact that he was looking hungrily at Gail didn't mean his thoughts were grown up. High school boys have the same thoughts.

He watched her until he decided, apparently, that she was less likely to move than the faces on Mt. Rushmore, then he took off his glasses, began rubbing them with a clean white handkerchief and squinted at me.

"Hello, Bill," he said condescendingly. "Is Willy on his last lap yet?"

"He will be in about two minutes," I said, glancing at the clock on the wall. I could have told him about the map and explained that he could see for himself, but that would have been rude. I would have to live with this guy for thirty months and it was best that I learn to get along with him.

Dr. Spartan came in again, carrying a bacon-and-egg sandwich in his left hand.

"Hello, Doctor Spartan," said Morrie.

"Wmpf!" replied Spartan, chomping on the sandwich. He didn't even give Morrie a glance.

Morrie looked shook up.

"Don't mind him, kid," said Axel. "He hates everybody. Especially today."

Morrie did not reply. He blew heavily on his glasses, wiped off the moisture with his handkerchief and held them up to the light. He squinted, nodded with satisfaction and put them on his nose. Then he turned to resume watching Gail Loring.

Though Dr. Spartan had taken a position behind Gail so that he blocked the view, Morrie wasn't going to miss the pleasure of ogling the prettiest girl astronaut in the world. He moved over to the left for an unobstructed view. Realizing there would be about ninety idle minutes to kill, I moved to the right, deciding that I could get even more pleasure out of watching her than Morrie could.

Axel and Dr. Joel remained where they were, Axel watching the little light on the screen map and Dr. Joel bobbing his head, smiling and waving at everyone who looked in his direction.

Gail turned her head and looked up at Dr. Spartan. "You want to take over now, Dr. Spartan?" she asked.

"Go ahead," said Spartan. "I haven't finished breakfast, my dear."

She turned her head in a businesslike manner and glanced at the clock, then at the instrument panel. Finally she picked up the microphone and held it to her lips. She waited a moment, still watching the instrument panel.

"Last orbit!" she said. Her words were echoed by the speaker in the room. "We'll start our countdown for re-entry five minutes before you've completed the turn, Zinder. At zero, set the automatic control to take over."

"A-okay," said Willy's voice. He spoke calmly. Apparently he was no longer frightened.

"Remember," she said, "precisely at zero."

"A-okay."

Gail put the microphone back on its hook. She watched the instruments. Suddenly she tensed. Her voice rose as she spoke to Dr. Spartan.

"Doctor, look!"

She gestured excitedly at the panel.

"Good God in heaven!" Spartan reached out, snatched up the microphone. "Zinder! Zinder, you fool! What have you done? Are you crazy?"

"Hey!" Willy's cry was full of fear, but he was not speaking to Dr. Spartan. He was yelling to no one. "Help me! I'm accelerating—decelerating! Something's gone haywire! I'm starting to re-enter—"

The voice broke off as a crash came from the speaker.

"He hit something!" somebody yelled.

"Hell, he probably fell to the floor," said Axel. "He wouldn't have his harness on now."

"He cut in the automatic," Spartan said. "Did you tell him this was the last lap, Miss Loring?"

"Oh, no, Doctor! I told him it was the next to last!"

"He must have misunderstood."

I squirmed to catch a glimpse of the instrument panel, but Spartan's bulk hid it from my eyes. Willy should have known he had another lap to go. There was a clock in front of him. I shifted my position. I could see Gail's hands flying to this button and that as if she were trying desperately to check the fall with the ground controls. But she must have known it was useless to try. Once the re-entry cycle is started, nothing can shut it off till the parachute opens in the earth's atmosphere. Willy Zinder was being returned to a world unready for his arrival.

"Willy! Willy! Please answer!" Gail screamed above the excited voices in the room.

No reply came from the speaker.

Then the intercom from Operations cut in. "The medical section says Zinder may have been injured by sudden deceleration," said the voice. "His heart action is very weak."

"Oh, dear God!" moaned Gail Loring. "It's all my fault!"

Ordinary human reflexes, which respond to tangible, near-at-hand crises, were woefully inadequate for the dozen or so men and women in that room. What could anyone do to save Willy Zinder, so far away that he could only be detected by instruments, and whose future and very existence depended upon electronic gadgets which went about their task more cold-bloodedly even than Dr. Spartan?

In fact, Spartan himself seemed to lose his poise for a moment. He appeared to freeze as he stood directly behind Gail, staring at the dials that told what was happening to Willy. At last he seemed to see her hands, fluttering aimlessly from button to switch. He reached out, swept them away.

"Stop it!" he said hoarsely. "Nothing you can do will stop the automatic action of the capsule now!"

Gail seemed to wilt. Spartan released her hands and she sat there helplessly. Behind her Spartan looked like some kind of understudy of Satan, his black beard, dark eyes and sharp features blending into the illusion. He was tall and gaunt to begin with—now he looked taller and more gaunt. Was it a suspicion of a smile that I saw on his face for a brief, fleeting instant? But surely he didn't want Willy to fail. He had a greater stake in this operation than any of us. For him it would mean immortality as the leader of the first manned flight to Mars.

Again the fleeting smile. I tried to tell myself that it was the result of nervousness. I'd often seen men under stress grinning like fools, because laughter is an emotional reflex. But I'd never suspected Spartan of having emotions before. He'd had a wealth of experience and had seen men die in space.

For ten years he'd been one of the top astronauts of the nation—ever since he had risen to fame as the genius who had developed a certain method of converting nuclear energy directly into electricity. In those days he'd been a poorly paid instructor at some obscure mid-western college. Now he was famous as a spaceman, and wealthy from his discoveries.

His apparent nervousness lasted only an instant. Then he became his cold self again. Not that it served to reassure anybody—we all knew that northeast of where we stood, far out over the Atlantic, Willy's capsule was screaming into the atmosphere. It mattered little that the parachutes were open, since the men who had been watching the instruments recording Willy's heartbeat said he had been hurt badly.

There was no button to push, no knob to turn, no switch to flip which would make everything A-okay. And there certainly was no magic wand to break the evil enchantment of the moment.

The loud-speaker squawked out a report from the Navy carrier. Its helicopters were airborne, attempting to reach the place where Willy would come down, but they were hundreds of miles west—at the place where Willy would have come down after his next lap, not this one.

Then there was an awful silence, broken only by a sob from Gail. Spartan looked down at her, his lips curling with displeasure. She clasped her hands to her face and swayed in her chair. Spartan growled with annoyance, then turned his head and saw me.

"Drake!" he bellowed. He gestured a slim finger toward Gail. "Get that hysterical woman out of here!"

I didn't like the way he gave the order, but it made sense and I started forward to obey. Gail jerked her hands away from her face and turned toward him. She stopped her swaying, turned her eyes on Dr. Spartan and tilted her chin upward with indignation.

"I'm not hysterical! I've never been hysterical!"

"Take her outside, Drake," said Dr. Spartan, as if she'd never spoken.

It did seem like the best idea. Every dial in front of her was an instrument of torture. Whatever happened to Willy Zinder, she believed it to be her fault.

I stepped forward and took Gail by the arm. "Please come," I said. "There's nothing you can do."

She jerked her arm out of my grip, then got up by herself. "Willy must have misunderstood me," she said. Suddenly her shoulders sagged. "Yes, Bill Drake, I'll go. You're right. There's nothing I can do."

Her eyes were moist but her voice was firm. She was not crying like a hysterical woman. I believe that, at that moment, if there was anything she could have done, she would have done it as efficiently as anyone in that room, including Dr. Spartan.

She let me take her arm again as I guided her through the door, out of the bunker and into the refreshing warmth of the outside air.

"I told him to switch on the automatic controls precisely at zero," she said. "Those were my words: 'Precisely at zero!' He must have misunderstood. He thought I said it was precisely zero at that moment. He lost track of time."

"Don't think about it," I said. "It wasn't your fault."

"It was my fault. People under tension are in a highly suggestible state. I should have chosen my words more carefully, so that he could not possibly misunderstand—"

"If Willy was capable of such confusion, it's best that we know about it now. In space that kind of a misunderstanding could cost lives."

"Willy may be dying," she said. "Even if he isn't, the Mars project is down the drain for twenty-six months."

"Maybe," I said, "and maybe not. Spartan says he's gotta have a six-man crew, but I don't follow him. It's better to try it short-handed than to get there after the Commies."

"But I've heard him say a dozen times that there must be six men," she said. "Dr. Spartan doesn't change his plans once he makes up his mind."

Certainly that was true, but Dr. Spartan was too intelligent to insist on the impossible. Six men could operate the plasma ship efficiently: two could be on watch, two could rest, two could care for the needs of the others—prepare the meals, do cleaning, and operate the water and air regeneration machinery, check the course and so on. But a system could be worked out for five, four, three—even two or one. The fewer the number, the greater the risk, but the important thing was to achieve a successful mission. The risks could never deter him from trying for a first landing on Mars.

We reached the pad which the big Jupiter rocket had carried Willy Zinder into space twenty-four hours before. Gail stood there looking at it, choking back a sob, and then turned around and started back toward the bunker.

"I could take Willy's place, if he's—he's hurt," she said softly. She probably had been thinking about this while we stood at the launching pad.

I tried to smile at her. "That would cause complications."

"Why? I'm as qualified as you, Bill Drake. I made a test flight in the plasma ship along with Dr. Spartan and Mr. Ludson. I've passed every test you and the others passed and I've made a flight to the moon."

"You've already been assigned to a project," I told her, hoping it would end the talk.

"That can wait," she insisted. "Besides, there are others who could be trained for my job and there's time to train them, whereas Operation Jehad begins its final phase in five days."

"I wasn't selling your qualifications short," I said. "What I meant was—you're a woman."

"Good Lord! Would Dr. Spartan discriminate against me because I'm not a man?"

"Dr. Spartan wouldn't care if you were an ape. But a lot of people would wonder what one pretty girl was doing up in space with five men."

"Not really! You mean they'd think my honor and virtue would be—lost?" For an instant there was the faintest trace of a smile on her face.

"Exactly," I said. "This world has some queer standards of propriety—especially the good old U.S.A. with its puritan traditions. A lot of people would take the stand that an unmarried young woman could hardly expect to spend two-and-one-half years in close quarters with five unmarried men and expect to come back chaste."

She laughed and I joined her.

"Ridiculous."

"Yes, but that's what they'd think," I insisted.

"Do you imagine I give a hoot about what people think?" she asked. "And what does Victorian decorum have to do with going to Mars?"

"Nothing at all, but there are bureaucrats and politicians who could spike Project Jehad on moral grounds. These hypocrites wouldn't give you credit for being a virtuous young woman, nor us credit for being gentlemen with restraint. No doubt they'd judge us all by their own past behavior."

"There were no objections when I went on a test flight with two men."

"You weren't gone overnight. At least, it wasn't night on the puritan side of the earth," I explained. "These people think all sins occur at night. Besides, you were in communication with the earth the whole time. You had a radio chaperon."

"Holy cow!" she said. "Can't we make people see that it doesn't matter if the world thinks I'm a fallen woman? The success of the project is more important than my reputation, my morals, or even my life. I'm going to offer to go in Willy's place."

"Good luck," I said, quite certain she wouldn't have any.

Axel Ludson was waiting for us outside the bunker with the bad news.

Although the Navy had been alert and had done everything possible to reach the scene of the capsule's landing, it had been too far away to arrive in time. Helicopters had been sent aloft immediately, but they arrived at the capsule just in time to see it sink into the ocean, a mile and a half deep at that point.

"How horrible!" said Gail.

"We're not sure he could have survived his injuries," said Axel. "The medical observers believe his neck was broken and that he was dying as his capsule floated down to the sea."

Gail shuddered. "It was my fault."

"You mustn't say that, Miss Loring," said Axel. "The only way it could have been your fault was if you had touched the automatic control button yourself. Did you? Even by accident?"

"No. No, of course not," she said. "My hands were in my lap. I was talking into the mike just a moment before. There was no reason to take over control of the capsule."

Axel nodded. "I was watching you," he said. "That is my recollection. That leaves only two ways for the accident to have happened. Either Willy put the ship into automatic himself or there was a malfunctioning that set it off spontaneously."

Neither theory seemed to fit. In the first place, Willy had been drilled on what to do before re-entering. One of the first things—something even a novice would realize—would have been to get into his harness. Furthermore, Willy had instruments, including a chronometer, in front of him and he should have known he had to spend ninety more minutes in space.

Faulty mechanism might have accounted for the accident, but everything had been tested, checked and double-checked. Dr. Spartan himself had gone over everything.

"Dr. Spartan would like to talk to you, Miss Loring," Axel went on. "There will be an inquiry, but he wants to hear your story as soon as you feel up to it."

Gail moistened her lips. "I'd like to get it over with now," she said. "Thanks for telling me—everything." She turned back to me. "And thanks to you, Bill Drake. I feel much better after talking to you."

I remained outside the bunker while Axel took her in.

Later I made a statement, along with everyone else who had had an official part in the test. Dr. Spartan announced that the fate of the Martian expedition would be decided within a few days and if it was decided to go ahead with a short crew, the lift-off would take place on schedule.

I was not surprised, therefore, when I was called into his office the next morning. Dr. Joel was there and so were Morrie Grover and Axel. We sat down in straight-backed chairs opposite his desk to wait. About five minutes later Dr. Spartan accompanied by Gail, came into the room.

My first thought was that he was extending the investigation of the accident, and then I recalled Gail's decision to volunteer for the Mars expedition in Willy's place. Dr. Spartan was as dedicated as Gail and the idea of flaunting convention and risking a lot of condemnation wouldn't have bothered him. But there were powers higher than Dr. Spartan who would step in and halt the project if public pressure were applied.

We greeted him formally. No one ever became informal with Dr. Spartan in his office. In fact, I couldn't remember anyone but Axel who had ever tried to kid Spartan. But Axel was a special case. Even Dr. Spartan secretly admitted that Axel was the most reliable astronaut on the project.

"Thanks for being here punctually, gentlemen," said Dr. Spartan, sitting down behind his desk. Again he looked like the Devil himself, just as he had yesterday when Willy's capsule went out of control. "As you know, the fate of the Martian operation is uncertain because of yesterday's unfortunate accident. But there is an outside chance we can go ahead with it, if an obstacle or two are removed."

He paused, letting his cold black eyes sweep our group, finally resting on Gail Loring who was seated facing us in a chair at the end of Dr. Spartan's desk. She smiled, showing her pretty dimples.

"Miss Loring is willing to fill the vacancy in our crew," Spartan said quietly.

No one spoke. We all looked at Gail, every last man of us thinking what a wonderful trip it would be with her aboard. And every last man realized that with a woman aboard there would be complications.

"She's a fully qualified astronaut," Spartan went on. "No further tests would be needed to prove that she could step into the vacant spot in our crew and hold up as well as any of us during the long, tedious trip through space. However, she is a woman."

"I guess we can all see that," said Dr. Joel, in a feeble attempt to be funny. No one laughed but Joel. Spartan's hard eyes cut him short.

"I wasn't so sure you could, Warner," said Spartan, his voice full of sarcasm. "But your half-witted wisecrack brings the big objection into full focus. A woman, especially an attractive woman—" Spartan bowed toward Gail and permitted himself to smile with all the graciousness he could muster. "—well, it complicates matters."

Again we held our silence. Joel choked back whatever comment he'd been about to make as Spartan glanced at him again.

"A woman, alone with a large group of men, would bring dissension and emotional factors into the situation which would not arise if all our crew were men. Besides, there is convention to worry about. Certain prudish individuals, of which there are far too many on earth, would accuse us of promoting some sort of Saturnalia in space—free love, even licentiousness."

"It would be a lie," said Gail. "I have nothing to fear from any of you in that respect."

"Not here and now, perhaps," Spartan replied, "but two-and-one-half years in space might have a cumulative effect. None of us are properly called old men, my dear. Besides, we'll be making history, and we'll have to appear to be, as well as be, above reproach."

"Oh, come on," said Gail, resenting the trend of the conversation. "History has never been that pure—"

Spartan scowled. He resented her remark. "I know that, Miss Loring," he replied. "But the fact that we are making history will cause politicians and bureaucrats, who have the power to call off the project, to fear the loss of public support. Votes are what they want, more than scientific achievement. All of you know our plans call for a six-man crew. Fewer than six would require a revision of plans, redistribution of duties, and a slighting of many important aims. In order to justify the expenditure of billions of dollars of taxpayer money we must show results."

"That's the first time I ever heard of a taxpayer being considered in a space operation," said Joel, once more trying to be funny.

"But it's a point," said Axel, nodding his head and glancing around first at me and then at Morrie Grover, who had sat through the session watching Gail as if he were hypnotized.

"Does anyone have a constructive idea?" Spartan asked coldly. He was trying to keep the discussion from getting out of hand and, from this, I suspected he had his own plans fully worked out.

"It's your show," I said. "What's your idea?"

Spartan did not like to have anyone reading his mind and he honored me with one of his stern glances. "In the interest of science," he said, "I'm proposing marriage to Miss Loring."

I expected almost anything but that. My mouth flew open.

"In the interest of science? Good Lord!" said Morrie Grover.

Gail half rose from her seat, then settled down. "Doctor!" she exclaimed. "Why didn't you discuss this with me beforehand? That's the least I would expect—"

"This, as I said, is a proposal made purely in the interest of our mission," Spartan said.

"Well, I resent it," she said. I rather guessed that she was showing a natural, female resistance to so cold and unfeeling a proposition.

"You shouldn't," said Spartan. "There's nothing wrong with the idea. I have much to offer you—or any other woman. I have substantial wealth. I have a long list of accomplishments. I am famous and will be even more so at the end of this trip. And certainly I'm not repulsive."

His chin tilted upward slightly as he displayed his profile. I'm sure he didn't pose intentionally; his conceit was subconscious, but nevertheless amazing.

Gail pressed her lips tightly together. For an instant I had a terrible fear that she was going to laugh. Then I was even more frightened at the thought that she might possibly accept this proposal. It would be a waste of such a beautiful, attractive young woman.

"Actually, Doctor," she said after some deliberation, "you're suggesting I prostitute myself for science. If I ever decide to do that, I'll do it on my own terms."

Spartan seemed to stagger mentally, as if she'd landed an uppercut on his subconscious conceit. "But, Miss Loring," he said, "if you were married to me, it would erase whatever objections there'd be to the idea of a woman going to Mars with five men. The unconventionality would become respectability. The puritans would have no reason to object to the space trip and the men in Washington wouldn't need to fear the loss of votes."

"Couldn't we make the trip with a five-man crew?" I asked.

Spartan glared at me as if I'd suggested we organize a Communist cell.

"I told you I want to get maximum results from our trip," he said. "I won't be satisfied with less." He turned to the others to amplify his statement. "There must be a full crew and Miss Loring is the only qualified astronaut available. And the only way she can go with us is as a married woman." Now he turned to Miss Loring. "Certainly you'll not refuse?" he demanded.

"I understand the problem thoroughly, Dr. Spartan," Gail told him. "But I won't consider marriage in the generally accepted sense. If we must conform to convention, we can have a ceremony; everything and anything that may follow a normal wedding will be of my own choosing."

"I'm not sure I understand," said Spartan.

"I mean it will be a marriage in name only. I won't even share quarters with my husband. I've been aboard the plasma ship. As spaceships go, it's a palace. There's room for six men, provisions and equipment for two-and-a-half years. At each end there are observation cabins used in getting the parallax in astrogation. I'll use one of them for living quarters. The rest of you will bunk in the main cabin of the ship. Furthermore, the marriage will end when we return to the earth. A quiet divorce or, possibly, annulment will be arranged. Do you object to divorce, Dr. Spartan?"

"No," said Spartan with ill-concealed temper.

"Does anyone else object to divorce on religious or other grounds?"

She paused, awaiting an answer. Axel finally spoke. "I do not object to divorce," he said. "However, I do not believe in this kind of marriage, either."

"What about you, Bill Drake?"

"Anything for science," I said. But deep in my heart I knew that if I was ever fortunate enough to go through a marriage ceremony with Gail, I'd move heaven and earth, and all the planets between, to make the union a permanent one.

"And you, Dr. Joel?"

Joel cleared his throat. "I'd take you under any conditions, Miss Loring."

"Morrie Grover?"

"I have no objections." He looked at her hungrily.

"Am I to understand that you intend to pick one of the others?" asked Dr. Spartan. "I've already asked you to be my bride. I suppose your conditions are reasonable. I will accept them."

"That's very generous of you, Doctor," said Gail. "And my reason for turning you down is not to be taken as a criticism of you as a man or as a lover-in-name-only. It's simply that as leader of the expedition you must have disciplinary control over all members of the crew. As your wife, I'd be tempted to ask for privileges, even though I am not a believer in favoritism—especially in space where the line between life and death is as thin as a quarter-inch meteor. It would not be to the best interests of this expedition for you to have a wife. However, I have proposals for marriage from Bill Drake, Dr. Joel and Morrie Grover. Am I right? Any of you is free to back out."

"I won't back out," said Morrie breathlessly.

"I won't either," I said quickly.

Joel cleared his throat. "I said I'd take you under any conditions."

"I feel honored, gentlemen." Gail smiled at us, showing her dimples. I decided that, under different circumstances, I could have proposed to her on my own initiative and been as conventional as hell about it. But this was like a political convention.

"Which?" asked Morrie.

"Not you," she said. "You're younger than I am. And not Dr. Joel—he's at least ten years older." She paused, stared at me and then went on. "Because this marriage is one of convenience—a propaganda wedding to satisfy propriety—we ought to be convincing. Bill Drake is the pin-up boy to millions of panting secretaries and shopgirls who see his picture in newspapers and on television. Would this public believe in a marriage between us? I think so. For no one could possibly imagine I could resist such a prize."

She paused and waited for comments. None came. Five astronauts, including Dr. Spartan, sat tensely waiting for her inevitable decision.

"Believe me," Gail went on, "I could resist this handsome young astronaut very well. He's somewhat conceited, you know, and he is too much aware that he's the answer to a maiden's prayer. But millions of man-hungry women wouldn't see it that way. I'm not panting over Bill Drake, and that's why he's the logical choice. It'll look like a love match and who'll know the difference?"

She paused once more, then turned to me. "Forgive the insults, Bill. Will you marry me? Or do you want to back out?"

It was the first time she had ever called me Bill without adding my last name. I sat there for a moment, somewhat dazed by the outcome. Should I take her in my arms and kiss her tenderly, passionately? Hardly. My ears still burned from her statement that I considered myself the answer to a maiden's prayer, and that I was a conceited pin-up boy. Considering her attitude, should I back out? Or should I cold-bloodedly allow her the use of my last name for the sake of science? My male ego told me she cared a little, secretly, or at the very least, would learn to care before Operation Jehad ended. I began to feel happy about the whole deal.

Dr. Spartan's voice came through my thoughts. "You're not acting very enthusiastic, Drake."

"I was thinking of the conditions," I said.

"I won't sue for breach of promise if you want to back out," said Gail.

That decided me. "When's the wedding?" I asked.

As I spoke, Joel and Morrie looked at me with ill-concealed disappointment. They'd hoped, down to the wire, that something would happen which would turn the scales in their favor. Even now, I noticed that Morrie hadn't quite given up. He turned his eyes toward Gail. You could practically see him hoping that, in reality, it would turn out to be a marriage in name only, that he'd have a chance to win her before we returned.

"Just before the lift-off," said Gail.

"Humph," said Dr. Spartan. "That settles it, I suppose." He didn't like it, but he couldn't back out now.

He turned his eyes toward me.

They were full of hatred.

Some unscrupulous public relations genius attached to Operation Jehad was informed of Gail Loring's betrothal and, in the remaining four days before the lift-off, the entire world was told the most romantic story since Romeo and Juliet—and it was lies, mostly.

Only the marriage was a fact. But the world was informed that William Drake and Gail Loring, high ranking astronauts, had fallen deeply in love some months before. They had secretly agreed to be married after the completion of Operation Jehad. Drake, brave man that he was, and Gail, self-sacrificing young woman that she was, had pushed their personal desires into the background for science; the cruel, tragic death of Willy Zinder had left a vacancy in the Jehad crew and Gail and Bill had agreed to marry immediately so that both could further this important expedition into the unknown. The fact that inadvertently the trip would also serve as a honeymoon cruise, put the whole project on a more romantic note.

Space officials in Washington, fully apprised of the reasons for the wedding, and sold on the idea by Dr. Spartan, were not only gratified by the world-wide acceptance of these lies, but they announced that the ceremony would be included as part of the countdown proceedings prior to the launching of the big Saturn that would carry us all to the plasma ship, already in orbit around the earth.

The bride and groom and all of the members of the wedding party, with the exception of a federal judge who was to perform the rites, would be wearing spacesuits. The only charitable thing the officials did was to forbid interviews with either the bride-to-be or her intended. There just wasn't time, they said. Actually they didn't trust us to conceal the real reason behind the marriage. The project's publicity team, however, issued handouts of purported interviews, a fictional history of our love affair, and pictures.

On the day before the launching, I received two mail sacks full of letters from the panting shopgirls mentioned by Gail and a United States post-office truck delivered a full cargo of gifts to Gail. I didn't read the mail, and the gifts were stored in a government warehouse, pending our return from Mars. I don't know how much mail and parcel post came the fourth day. We were too busy to find out.

I developed a monumental guilty feeling when I realized the magnitude of our deception. I was sick of the whole business. There had been many marriages of convenience, of course, and some had turned out better than marriages for love, but this was pure fraud. The only consolation was that through it we had acquired a full crew. Still, I couldn't help feeling that a quiet, secret ceremony would have accomplished the same purpose. Why compound a fraud with a spectacle?

Twelve precious minutes were squeezed out of the countdown for the ceremony. We marched in spacesuits, sans helmets, to the launching pad—five male astronauts and one female, accompanied by a federal judge named Lockhart who had no part in the conspiracy but who had been asked to perform the rites because he was a friend of some governor.

No ring was used, since it would have been impossible to slip it over the spacesuit glove Gail wore. We joined hands while the judge spoke into a microphone and the words were carried, via radio and television, to the far reaches of our planet, even to the fur-clad outposts at Thule and Antarctica.

Nearby were photographers to record the lie for posterity.

A conventional bridegroom is in a state of shock and he scarcely realizes what is going on. I heard everything, realizing I was perjuring myself every step of the way. I accepted Gail as my lawful, wedded wife, knowing we would not really be married. She accepted me as her lawful, wedded husband, knowing it was all a lie.

Finally it ended. Judge Lockhart said, "You may kiss the bride."

This I could do without faking. I took her in my arms and drew her close. As she turned her face to mine, I thought for a moment that this, at least, would be real. But when I started to meet her lips with mine, she quickly turned her cheek.

The kiss, too, turned out to be a fraud.

My four companions also kissed her—on the cheek. Then we stepped into the cherry-picker which would lift us to the nose capsule of the Saturn.

Two technicians rode with us to help adjust our harnesses and to make sure we were snug in our seats before the lift-off.

The seats were backed against the wall in a hexagonal arrangement, with a small instrument panel directly in front of Spartan's position.

"Sit on my left, Ludson," said Spartan. "Joel, you sit on my right. I think we can allow the bride and groom to sit side-by-side, since this is to be their honeymoon ride."

Morrie Grover snickered.

"There's no cause for mirth," said Spartan sharply. "There's going to be nothing funny about this trip."

Morrie sobered and grew red-faced. I felt sorry for the kid. The laugh had been caused by nervousness. All of us had been in space, of course, but this trip was anything but routine. The lift-off and the re-entry are the most dangerous phases of space flight, any way you look at it.

We put on our helmets and the technicians adjusted them. There was a microphone in each so that we could communicate, but no one, not even Spartan, said anything.

"Sixty minutes!" came the voice from the countdown.

Sixty long minutes of sitting. I wondered how I could stand the strain. Turning my head, I looked at Gail Loring beside me. She stared straight ahead, her lips pressed tight and her eyes glistening. She must have seen my head move, for she turned and looked at me.

"Good luck, Mrs. Drake," I said.

"The name is Gail Loring, and don't forget that, Bill Drake," she said.

I could have slapped her.

But after a time I was glad she had said it. My angry thoughts kept me occupied and that helped pass the time. Almost before I knew it, I heard the voice outside say:

"Fifteen minutes!"

I am a congenital heathen. This is not to say that I'm an atheist or anything of the sort. It's simply that I've never accepted religion the way most people do. In a way, I think I've missed something and I envy those who can accept their faiths without question or doubt, and mold their lives accordingly. For the first time, I wished I knew how to pray.

"Ten minutes!" said the voice of doom.

It seemed as if the words were still echoing in my ears when I heard: "Five minutes—four—three—two—sixty seconds—"

And then came the final ten seconds, ticked off one by one, ending in:

"Zero!"

The huge Saturn shuddered as the fuel ignited. It seemed to hesitate, as if unwilling to leave the earth. I held my breath. Then I felt the seat pressing against my buttocks and I knew we were on our way.

With each second the acceleration increased, the pressure grew greater.

I heard Morrie groan, but I knew he was all right. He was merely expressing his reaction to the tension. Out of the corner of my eye I saw Gail, her face contorted, her jaw firmly set. Spartan's eyes were on the instruments, although his face revealed that he, too, was under strain. Axel Ludson seemed to bear up best, probably because his body was the strongest of all and his rugged frame could absorb the shock. Dr. Warner Joel looked the most frightened and his eyes were fixed on Dr. Spartan as if that man represented all of the security in the universe at that instant.

Although the long wait before the lift-off had seemed unbelievably short—just as the last hour would seem to a condemned criminal in his death cell—the flight to the plasma ship, which had been nicknamed the Jehad, after our own code name, was interminably long. We felt the momentary halt and resurgence of acceleration as each successive stage of the rocket was dropped. Then, after the third stage had burned out, Spartan's hands grasped the controls, his eyes on a small television screen in front of him.

"Right on the nose," he said, as if talking to himself. "At least, Operations has done one thing right."

It was a typical remark, because as a perfectionist, Dr. Spartan was aware of and magnified each minor imperfection in everyone else. So far as I knew the entire operation had gone smoothly and without a hitch.

Spartan continued to operate the controls. I felt slight pressures as the ship adjusted its orbit. We were moving alongside and close to the plasma ship.

Six years, and as many billions of dollars, had been spent to build the Jehad, which was the most revolutionary space craft ever to be put in orbit.

To be accurate, the Jehad never had been put in orbit in one piece. Each part, and all of the equipment needed to put those parts together, had been rocketed into orbit from the ground. A team of highly skilled scientists and construction workers had pieced it together, an amazing job considering they had done this in a state of weightlessness. Eight men had lost their lives as a result of punctured spacesuits.

The strange thing about the Jehad was that it could never have lifted off the earth under its own power. Although the twelve generators which would drive the Jehad to Mars produced fantastic voltage, their force would not have knocked down a child—in fact, the push from a single motor was about equal to the power exerted by a pigeon in flight.

However, it was the most efficient and most economical motor man could use to travel ninety million miles to Mars—which is not the shortest route, but the most practical since it makes use of the earth's motion and the sun's gravitational power.

The plasma motor, more correctly the traveling-wave plasma motor, was developed after several years of research at the NASA laboratories near Cleveland, expressly for space propulsion. The first big breakthroughs, which led to the eventual perfection of the machine, were made in 1961. Because the machine was so complicated, involving principles laymen found hard to understand, it had received very little publicity.

In the simplest terms, the plasma engine, like the rocket, makes use of Newton's law on the conservation of energy—for every action there is a corresponding and opposite reaction. But here the similarity with rockets ends.

In effect, it means that if you throw a ball, as much pressure and force is backward thrust on the hand as forward thrust on the ball. Since the ball has smaller mass, it sails through the air while your hand and body stay put because you are anchored by your weight and gravity. But in space you would go back in proportion to your mass, just as the ball goes forward. And if you continued to throw balls you would accelerate with each toss.

The plasma motor is an electric generator, "spread out." That is, the rotor—the part that revolves—is removed, the motor opened up and flattened. Then it is coiled into a tube so that the field travels at right angles to its normal direction. This makes the electrical field run down the tube in waves, instead of in a circular motion.

Instead of a rotor, some lightweight element is ionized—heated and vaporized until the electrons and protons of the atoms are torn apart—and the resulting plasma rides down the tube on the waves as circulating systems of positive (protons) and negative (electrons) charges. When they are expelled there is a good-sized kick—kinetic energy. In space, any kick, no matter how small, results in motion, which will continue unless another force is applied to stop it. But in this case the only applied force is more kicks forward, thus there is acceleration.

The chief advantage of the plasma motor is that it can give a very good thrust with a very small amount of fuel. Even the earliest calculations disclosed that the amount of fuel needed to accelerate and decelerate the ship amounted to practically nothing compared to the payload it could push through space. A one-hundred-pound thrust would suffice to drive a 150-ton spaceship to Mars. Compare this with the one thousand pounds of thrust necessary to lift one pound of payload by rocket from the surface of the earth.

The fuel used on the Jehad was lithium, the third-lightest element. It had been used in the first experiments with the plasma engine but, since it had to be heated to 2500 degrees in order to vaporize it, argon—which was a gas to begin with—was experimented with. However, it had been decided to use lithium, for two reasons: one, heat to vaporize it could easily be obtained through high frequency heaters powered by solar batteries; two, lithium is lighter than argon. Thus was gained double advantage.

In theory, the Jehad could travel five-ninth's the speed of light, or about one hundred thousand miles per second. As yet the Jehad had never attained this velocity, because building up to that speed would take months. In the 12-hour test flight, Spartan, Ludson and Gail Loring reported that the craft behaved according to expectations and there was reason to believe that, in practice, it would not fall short of its theoretical speed.

However, speed was not important, since a good part of the time on the trip would be spent in waiting for the earth and Mars to get into proper positions. It was necessary only to be fairly close to schedule in arriving on Mars.

I had been trained in the operation of the plasma ship and to me it represented the summit of safety in space. That's why the trip to the Jehad seemed so long. I didn't feel secure in the Saturn capsule and I knew I'd be much safer on the Jehad.

We were weightless now as we orbited close to the plasma-powered ship. Spartan, Joel and Ludson could see the craft on a small television screen near the control panel. I couldn't see it from where I sat, but I was familiar with its appearance. It looked something like an elongated sausage with a small glass knob on each end. It was 185 meters long from the center of its forward cabin—an astrogation observatory—to the center of the rear. This base line had been measured to compute distances by parallax during the flight to Mars.

The center section was partitioned to contain motors, control and communications room, storage and living quarters for the crew. There was a difference, however, inasmuch as the entire interior could be utilized as floor. Small rockets in the side would start the cylinder spinning to give a weak but effective artificial gravity so that we could walk, rather than float, during our weightless voyage. This pressure would be equal on all walls, so it was possible for us to be suspended from what earthbound people call the "ceiling," or to stand out at right angles from the walls, without fear of falling. No matter where we stood, the centrifugal force would always be outward.

"We're less than fifty yards from the Jehad," Dr. Spartan announced. "This is about as close as I dare bring us. Drake, you'll carry a line to the Jehad—make it fast to the door of the locks. We'll follow you across."

"Yes, sir," I said.

I unbuckled the straps to my harness, taking a great deal of care with my movements. I was weightless, and the slightest exertion might send me spinning away in another demonstration of Newton's law on the conservation of energy.

Grasping a grab rail, I pulled myself upward to the escape hatch. In a rack were six aluminum tanks filled with oxygen. I slipped the straps over my shoulders, tightened them, brought the flexible tube around to my chest and fastened it into the fitting. Then I disconnected the long air hose that fed oxygen to my helmet from the Saturn's supply and opened the hatch. A gentle push of my toes on the grab rail sent me floating into the air lock.

A reel of thin, stout copper wire was fastened to the wall near the outside hatch. I slipped the end of this through a ring on my spacesuit and ran out about a dozen feet, leaving a loose end, twice my height, trailing.

Then I opened the hatch. A small amount of air in the locks escaped, sucking me with it into outer space. For the first time I had a glimpse of the universe, unshielded by atmosphere or clouds.

At my feet lay the earth, looking up with a bluish-white countenance. To my left was the half moon, peeking over the dark blue horizon, its craters plainly visible. Above was the sun, too dazzling to look at, and all around were brilliant stars and planets, although I had no time to pick them out, much as I would have liked to spot Mars, our destination.

I was aimed toward the long sausage-shaped Jehad, but my trajectory would take me above it and I had to make immediate adjustment. To do this, I used a petcock on the belt of my spacesuit, which released a very tiny jet of oxygen from the tank on my back. I twisted my body so the force would send me in the right direction.

One little push was all I needed and now I had to somersault quickly, and, at the same time, push out the long loose end of copper wire so that it would strike the side of the Jehad before I did. This was very important, for the electrical potential of the Jehad must be adjusted to that of the Saturn capsule to guard against being struck by a bolt of lightning as I contacted the sides of the craft. Apparently there was not much of a differential for I saw no sparks against the black sky.

My feet struck the sides of the Jehad gently, and magnetic strips in my boots held me fast.

Walking with soft footfalls, because even a slightly heavy push might tear me loose and send me out into space, making it necessary for me to maneuver my way back to ship again, I approached the locks. I opened the outer door and then made my line of copper wire fast to an eye just above the opening.

"A-okay, Dr. Spartan!" I announced into my helmet microphone. "The line's fast. I'll stand by to assist you folks aboard."

"Roger!" Spartan's voice echoed in my ears.

They came one by one, hand over hand, with safety hasps fastened over the wire. First Morrie, then Gail, then Axel, Joel and Dr. Spartan, playing his role of captain to the hilt, being the last to leave the ship.

I pulled them into the locks. There had been a little danger from meteors, of course, but the experts had figured that the chance of a meteor large enough to penetrate a spacesuit hitting an individual was one in 241 years. So far the estimate had been holding up. The nineteen men who built the Jehad had worked six years in space—a total of 114 man years. We had yet to experience a meteor casualty.

None of my companions seemed afraid. All were a little glad to be aboard the Jehad.

As Spartan came into the locks, he unfastened the wire line that held us to the Saturn capsule. Then he closed the door. He turned a valve, filling the chamber with air, and after a few seconds he opened the inside locks and we all walked into the large, roomy interior of the little planet of our own.

You could call those five days aboard the Jehad a honeymoon, although the usual definition did not apply to Mr. and Mrs. William Drake. Not only had I promised to keep the marriage on a purely platonic level, but Gail, by her actions and formality, gave me to understand that I was not expected to even go through the motions of playing the newlywed husband.

However, it was a happy time for all of us, and I include Dr. Spartan, even though he might never again be described as being in sympathetic rapport with the rest of us.

As soon as we had cut loose from the capsule and filled the plasma craft with air, we got the artificial gravity in operation by starting some auxiliary rockets which made the ship rotate slowly. The gravity was only ten per cent, but it was sufficient to keep us from floating around the room. We took off our spacesuits and laughed uproariously at our costumes—shorts, T-shirts and lightweight sandals which had magnetic strips in the soles to assist the artificial gravity in holding us to the floor.

Axel relayed our messages back to the earth, telling of our safe arrival, and Dr. Spartan and Warner Joel got the plasma motors going. There were four banks of three motors each encircling the ship. Although we had twelve engines, we planned to use only eight at a time. Four were for emergencies and extra power, when needed.

There were no portholes except in the control room and even here the outside view was partially blocked by a huge nuclear reactor, well shielded and stuck out in front of the ship. This supplied all our electrical power. However, there were video cameras on the outside—in the front and rear of the craft—so that we could always see the heavens about us on the monitor screens. There were four of these in the control room and four more in the main cabin, which was the middle segment of the ship. There were six sections, not counting the rear cupola where Gail was quartered. The control dome was in front. Dr. Spartan's private cabin, which was partitioned for sleeping and working, was second.

The large main cabin was where we did most of our living, if you can call it that. Directly behind it was a small galley and storeroom for our food supplies. Next was the lavatory and shower room, and the rear segment was filled with machinery—air and water-cycling equipment, laundry, and some electrical tools for repairing the ship.

There wasn't much to see outside after we got in space but, during those early days when we circled the earth and gained momentum, we had a beautiful view of our world. There was also a procession of multicolored and unwinking stars. The sun, too, was beautiful because the corona could always be seen.

Probably it was because we were so busy in those first days that we got along so well. Or maybe it was the excitement of finding everything so new and different. From the moment we boarded the ship, we were in another world, an independent planet, no longer associated with the earth.

We had to learn to walk in diminished gravity; we had to accustom ourselves to looking up and finding a companion sleeping on the ceiling as if he were stuck there. Even the day was changed. Because there were five of us, we had a 25-hour day, each man, with the exception of Dr. Spartan, taking a five-hour control-room shift. The terrestrial day no longer had any meaning, since our little planet rotated once every 30 seconds.

We had a garden—two trays, one above and one below the tube that carried electrical wiring the length of the ship. We planted hybrid vegetables in the garden—plants using a minimum of water and converting a maximum of carbon dioxide into oxygen. However, the air-cycling machinery was sufficient for most purposes.

Our biggest problem was water. Due to its weight and bulk, we carried as little water as possible, since a great deal of it was already being used to shield the nuclear reactor. For all other purposes—drinking, preparation of dehydrated foods, laundry, sanitation and irrigation of the garden—there was a tank containing 35 gallons. Excess water, removed from the air and extracted from all waste products, was purified and distilled twice, then used again.

At first, Gail Loring made the trip pleasant by her very presence. She was pretty and cheerful, and the fact that she revealed so much in the way of feminine charm in her space clothing caused the usual male response. Not that we were a pack of wolves. There is nothing wrong with looking, or even giving a mental whistle. I think Gail read our minds and I'm sure she enjoyed it.

Axel's face mirrored his thoughts in a slow grin. Dr. Joel, who was acting with the vigor of a sales manager at a customers' convention, treated her to adoring, but not necessarily fatherly, witticisms. Morrie Grover positively drooled when she was around and made a great thing of helping her out with various tasks, even though I think Gail would have preferred not to have the help. Spartan watched her, too, but it was impossible to read his thoughts. As I said, everything was milk and honey in those days.

But after we had the ship functioning, the garden growing, and our schedules perfected, we suddenly found that there was not enough to do. The looks that had been innocently male, began slowly to change to something else.

Gail, who had usually shown me less attention than the others, apparently because I had a greater legal right to claim more attention, spoke of it one day when she came through the machinery room while I was washing out the dirty uniforms.

I'd brought a projector and a microfilm of a book on astrogation and was reading when she paused beside the washer. "Need help, Bill Drake?" she asked in a friendly tone.

I looked up and smiled. "Now that was a nice, wifely thing to say." I told her. "Unfortunately it's my turn to do the laundry so you don't have to help."

"But you wouldn't throw me out if I did?" she asked.

"There's really nothing to do," I said, nodding toward the automatic washer which was halfway through its cycle. "But if you'd like to join in a little small talk about the universe at large, I'll be thankful for company. You realize, don't you, that this is the first time the bride and groom have really been alone together since they were married?"

She frowned. "Let's not talk about that, Bill Drake," she said.

"Why not? Afraid that if we mention it too often we might suddenly realize we're married?"

She nodded her head slowly. "Something like that."

I shut off the projector. I had no interest in astrogation at the moment. "Is that why you avoid me?"

"I don't avoid you."

"You always find time to horse around with Morrie," I said.

Now she smiled. "Are you by any chance jealous?" she asked. "If you are, you have no right."

"Damnit, I'm not. I just want equal time," I said. "I should have the right to want as much time with my legal wife as those other bums."

"I'm doing the laundry with you," she said teasingly. "That's the first time I've done that with anybody on this ship."

"I'm in your debt, gracious lady," I said. There was a trace of sarcasm, less than I felt, in my voice.

She heard it, too, and gave me a sharp glance. "I do want to talk to you about something, Bill Drake," she said.

"Sure. The laundry doesn't need attention. Let's talk."

"You've noticed that we're not the jolly little group we started out to be when we first boarded the ship, haven't you?"

"Yes, but it's because we're getting bored. We've been going around the earth in a spiral, like a merry-go-round. We don't seem to be getting anyplace."

"That's not what I mean," she said. "We are getting someplace. The spiral widens a little more each turn. Very soon now—perhaps within hours—we'll break away from the earth. We all realize it. And the farther away from earth we go, the less we'll feel bound by standards of the earth."

I frowned. "I don't see what you're driving at, Gail."

She glanced toward the bulkhead door at the end of the room. It led to the shower room and lavatory. She glided toward it, using the familiar "space walk" we all had learned in order to conform to the very light, artificial gravity. She opened the door, peered in, then closed it and returned. "Just wanted to be sure we really were alone," she said. "What I wanted to talk about was Dr. Spartan. It—it's the way he looks at me."

"We all look at you," I said. "I thought most girls liked it and felt like they were slipping when men stopped looking."

"That's right, when you speak of a normal male look," she said. "But the bearded monster frightens me."

"Relax," I said. "He won't get out of hand. That old boy is no fool and he won't pull any raw deals. The one I'd look out for is Morrie. He acts like a crazy kid sometimes. You can't always figure him."

"Morrie!" she exclaimed. "Bill Drake, you are jealous! He's just a kid."

"That's what I said, a crazy kid."

"And I'm two years older than he is." The washer stopped spinning and I went over and began removing the duds and putting them in the dryer.

She started to get up to help me. She'd been sitting cross-legged on the floor, as we all did because we had no chairs aboard. "Don't bother," I told her. "This isn't hard work."

She sat down again. "Do you realize, Bill Drake, that there are no laws here in space excepting those laid down by Spartan?"

"I can think of a few of Newton's laws that he has no control over."

"I'm not talking about physical laws. Spartan is more powerful than any nabob who ever lived on earth—he is a greater despot than Caesar, than the Pharaohs. That's why he's stand-offish with everyone. He has the power of life and death over us all."

I closed the dryer and set the timer. "Forget it, Gail," I told her, dropping down beside her. "Spartan's like a military commander. Not only our lives, but the success of this mission are his responsibility. He can't very well get chummy with buck privates." I didn't particularly love the guy, but I thought—then—that I understood him.

"We're not buck privates," she said, with a woman's logic and hatred of metaphor.

"Okay. We're second looeys. Now, what shall I do? Go to Spartan and say, 'Listen, you old goat, stop looking lecherously at my wife-in-name-only'?"

"This is no joking matter, Bill Drake. I may be your wife-in-name-only but there was a good sound reason for our marriage. You have to keep me from—uh—well, getting involved. You're a sort of chaperon."

I groaned.

"Let me tell you something," she went on. "During my first trick in the control room—not long after we started our routine on this ship—Spartan came in and spent almost the five hours with me. He talked to me as I'd never been talked to before, Bill Drake. He told me to move my sleeping bag into his compartment and live there. He made it sound as if it were my duty and that I'd be shirking if I didn't."

I gaped at her. "The hell he did!" I just couldn't believe it. "You must have misunderstood him—"

"I most certainly did not!" she said. "Don't you believe me?"

"Well, the guy isn't any tin god," I said. "But he didn't force you to do what he'd suggested."

"Do you know why?" she asked. When I didn't answer she went on. "Because I told him that if he did, he'd have to explain to the whole crew. He'd wind up with a red-hot mutiny on his hands. And when we returned from Mars, I'd nail his hide to the Pentagon, or some other conspicuous place."

I whistled. "And he took it?"

"Not meekly. He said that if he wished, he could "take care" of the whole crew. And if I repeated what he said to me, to anyone, he'd brand it as a pack of lies. He particularly cautioned me against telling you. He said he didn't want to be forced into "taking care" of you."

"But you told me," I said.

"I'm warning you, Bill Drake. Watch out for Spartan. He doesn't intend for you to return alive—or anyone else who opposes him."

I no longer understood Spartan. Would he kill to have his way? I had suspected his hatred since the day the wedding was agreed upon. "He wanted to marry you," I said, "but you changed the plan. Why didn't he object then?"

"Because he couldn't on the earth. And when I made a point of platonic marriage he thought he could fit it into his plan."

My heart bounded hopefully. "It wasn't a platonic marriage you wanted?" I asked softly. I tried to take her hand but she pulled it away.

"No, Bill!" It was the first time since we'd left the earth, that she used my first name alone. "I really meant it when I suggested it. I knew Spartan. I'd been in space with him before, but I managed him. This is different. I wanted you to protect me—but not as a husband."

My heart sank and I felt helpless. I walked over to the dryer. "Lots of dirty laundry today," I said.

"You can say that again," she replied.

Spartan's voice came over the intercom as I started to take the laundry from the dryer.

"Attention, please. Just fifteen seconds ago, the Jehad reached the escape velocity for this distance from the earth. We have broken away from terrestrial gravity. Mr. Ludson and I are now computing the necessary corrections to put us on the proper orbit to reach Mars."

Gail looked at me and I stared back at her. We had gone beyond the point of no return.

After that talk with Gail, I had my first thoughts of mutiny. But I'd been raised with a good, healthy respect for authority and, because most persons I'd come in contact with who had it, used judgment in administering it, I had seen no reason for changing my attitude. Even Spartan, when he was drilling us for this trip, had seemed to be right, in spite of his toughness. But as the earth grew smaller behind us, I began to look for allies, in case we were ever forced into a showdown with Spartan.