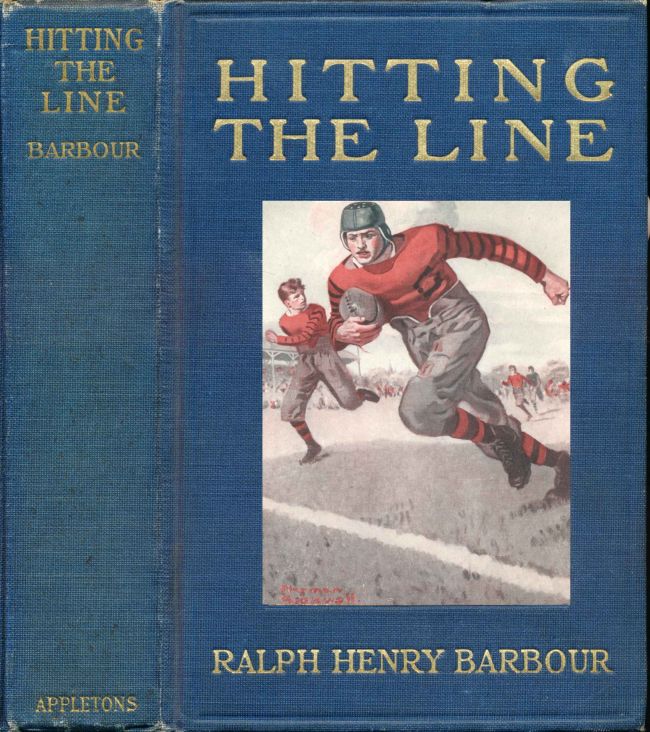

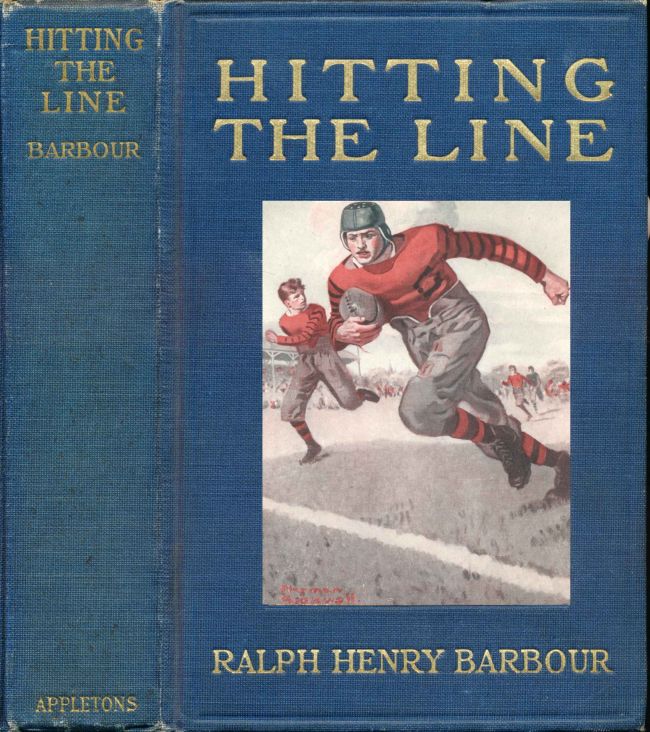

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Hitting the line, by Ralph Henry Barbour

Title: Hitting the line

Author: Ralph Henry Barbour

Illustrator: Norman Rockwell

Release Date: July 13, 2023 [eBook #71181]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Donald Cummings and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

HITTING THE LINE

By Ralph Henry Barbour

Purple Pennant Series

Yardley Hall Series

Hilton Series

Erskine Series

The “Big Four” Series

The Grafton Series

Books not in Series

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY, Publishers, New York

BY

AUTHOR OF “RIVALS FOR THE TEAM,” “THE PURPLE PENNANT,”

“DANFORTH PLAYS THE GAME,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

NORMAN ROCKWELL

Copyright 1917, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | A Chance Encounter | 1 |

| II. | The Boy from Out West | 12 |

| III. | Monty Crail Changes His Mind | 25 |

| IV. | “Out for Grafton!” | 36 |

| V. | A Room and a Roommate | 48 |

| VI. | Battle Royal | 63 |

| VII. | Monty Shakes Hands | 77 |

| VIII. | The New Chum | 88 |

| IX. | Soap and Water | 103 |

| X. | Some Victories and a Defeat | 121 |

| XI. | Monty is Bored | 135 |

| XII. | Keys: Piano and Others | 144 |

| XIII. | Standart Gets Advice | 155 |

| XIV. | The Middleton Game | 168 |

| XV. | Monty Goes Over | 178 |

| XVI. | Coach Bonner Talks | 190 |

| XVII. | Back of the Line | 203 |

| XVIII. | What’s in a Name? | 216 |

| XIX. | “Bull Run” | 229 |

| XX. | Tackled | 240 |

| XXI. | Standart Plays the Piccolo | 250 |

| XXII. | Hollywood Springs a Surprise | 262 |

| XXIII. | Monty Finds a Soft Place | 275 |

| XXIV. | The “Blue” | 288 |

| XXV. | “Fire!” | 300 |

| XXVI. | Monty Receives Callers | 313 |

| XXVII. | Hitting the Line | 323 |

Two boys alighted from a surface car in front of the big Terminal in New York and dodged their way between dashing taxicabs, honking motor cars and plunging horses to the safety of the broad sidewalk. Each boy carried a suitcase, and each suitcase held, amongst the more or less obliterated labels adorning it, a lozenge-shaped paster of gray paper, bearing, in scarlet, the letters “G. S.,” cunningly angulated to fit the space of the rhombus.

If I were Mr. Sherlock Holmes I should write, as a companion work to the famous monograph on tobacco ashes, a Treatise on the Deduction of Evidence from Hand Luggage. For one can learn a great deal from a careful scrutiny of, say, a suitcase or kit bag. As for example. Here is one bearing the initials “D. H. B.” on its end. It is quite an ordinary affair, costing when new in the neighborhood of six dollars perhaps. Its color has deepened to a light shade of mahogany, from which we deduce that its age is about three years. While it is[2] still in good usable condition, it is not a bit “swagger,” and we reach the conclusion that its owner is in moderate circumstances. There are no signs of abuse and so it is apparent that the boy is of a careful as well as a frugal turn of mind. A baggage tag tied to the handle presumably bears name and address. Therefore he possesses forethought. The letters “D. H. B.” probably stand for David H. Brown. Or possibly Daniel may be the first name. We select David as being more common. As to the last name, we frankly own that we may be mistaken, but Brown is as likely as any other. The letters “G. S.” on the label indicate that he belongs to some Society, but the G puzzles us. It might stand for Gaelic or Gallic—or Garlic—but we’ll let that go for the moment and look at the other bag.

This bears the initials “J. T. L.,” not in plain block letters but in Old English characters. It is of approximately the same age as the first one, but cost nearly twice as much, and has seen twice as much use and more than twice as much abuse. The handle is nearly off and those spots suggest rain. There is no tag on it. The initials probably stand for John T. Long. The gray label with the scarlet letters indicate that the owner of the suitcase is also a member of the mysterious Society. Other facts show that he is wealthy, careless, not over-neat, fond of show and lacks forethought. There!

And just at this moment “J. T. L.” lays a detaining[3] hand on his companion’s arm and exclaims: “Wait a shake, Dud!” And we begin to lose faith in our powers of deduction and to fear that we will never rival Mr. Holmes after all!

Dud—his full name, not to make a secret of it any longer, was Dudley Henry Baker—paused as requested, thereby bringing down upon him the ire of a stout gentleman colliding with the suitcase, and followed his friend’s gaze. A few yards away, in a corner of the station entrance, two newsboys were quarreling. Or so it seemed at first glance. A second look showed that one boy, much larger and older than his opponent, was quarreling and that the other was trying vainly to escape. The larger boy had the smaller youth’s arm in a merciless grip and was twisting it brutally, eliciting sharp cries of pain from his victim. The passing throng looked, smiled or frowned and hurried by.

“The brute!” cried Dud indignantly, and started across the pavement, his companion following with the light of battle in his eyes. But the pleasure of intercession was not to be theirs, for before they had covered half the distance a third actor entered the little drama. He was a sizable youth of about their own age, and he set the bag he carried down on the ledge of the step beside him, stuffed a morning paper in his pocket, seized hold of the larger boy with his left hand, placed his right palm under the boy’s chin and pushed abruptly backward.

Needless to say, the smaller boy found himself free instantly. The bully, staggering away, glared at his new adversary and rushed for him, uttering an uncomplimentary remark. The new actor in the drama waited, ducked, closed, crooked a leg behind the bully and heaved. The bully shot across the sidewalk until his flight was interrupted by the nearest pedestrian and then, his fall slightly broken by that startled and indignant passer, measured his length on the ground. At the same instant a commotion ensued near the curb and the rescued newsboy sensing the reason for it, exclaimed: “Beat it, feller! The cop’s coming!” and slid through the nearest door. His benefactor acted almost as quickly, and when the policeman finally pushed his way to the scene he found only a dazed bully and an irate pedestrian as a nucleus for the quickly-forming crowd.

Dud and his companion, grinning delightedly, followed the youth with the bag. The newsboy had utterly vanished, but his rescuer was a few yards away, crossing the waiting-room. On the impulse Dud and his companion hurried their steps and drew alongside him, the latter exclaiming admiringly: “Good for you, old man! That was a peach of a fall!”

The other turned, showing no surprise, and smiled slowly and genially. “Hello,” he responded. “What did you remark, Harold?”

“I said that was a peach of a fall.”

“Oh! Were you there? I guess we’d have had some real fun if the cops hadn’t butted in. Is this the way to the trains, Harold?”

“Yes, but my name isn’t Harold,” answered the other, slightly exasperated. “What train do you want?”

The boy observed the questioner reflectively for a moment. Then: “What trains have you got?” he inquired politely.

“Come on, Jimmy,” said Dud, tugging at his friend’s sleeve. “He’s too fresh.”

“Thought you might be a stranger, and I was trying to help you,” said James Townsend Logan stiffly. “You find your own train, will you?”

They had emerged into the concourse now and the stranger stopped and put his bag down, facing Jimmy with a quizzical smile. “I guess you’re an artist,” he said. “Making believe to get mad would fool most any fellow. What is it now? Eskimo Twins? Or——”

“That’ll be about all for you!” said Jimmy hotly. “If I’m an Eskimo you’re——”

“Back up, Harold! You don’t savvy. Far be it from me to take a chance on your nationality——”

“Oh, dry up!” growled Jimmy, turning away.

“Well, but you’re not going, are you?” called the stranger in surprised tones. Jimmy was going, and Dud was going with him. And on the way to the[6] gate they exchanged short but succinct verdicts on the youth behind.

“Flip kid!” sputtered Jimmy.

“Crazy!” said Dud, disgustedly.

The subject of the uncomplimentary remarks had watched them amusedly as long as they were in sight. Outraged dignity spoke eloquently from Jimmy Townsend’s back. When the two boys were hidden by the throng about the gate the stranger chuckled softly, took up his bag again and moved toward a ticket window. He had a long, easy stride, and the upper part of his body, in spite of the heavy kit-bag he carried, swung freely, giving the idea that he was used to much walking and in less crowded spaces.

“One of your very best tickets to Greenbank, please,” he said to the man behind the window.

“Any special Greenbank?” asked the latter, faintly sarcastic.

“Which one would you advise?”

The man shot an appraising look at the boy, smiled, pulled a slip of cardboard from a rack, stamped it and pushed it across the ledge. “Two-sixty-eight, please.”

“Thank you. You think I’ll like this one?”

“If you don’t, bring it back and I’ll change it.”

“That’s fair. Good-morning.”

At the news-stand he selected two magazines, paid for them and then glanced at the clock. Twenty[7] minutes past eleven exactly. He drew a watch from his pocket and compared it with the clock. “Is that clock about right?” he asked the youth behind the counter.

“Just right,” was the crisp reply.

“Honest? I make it three minutes slow.” He held his own timepiece up in evidence. The youth smiled ironically.

“Better speak to the President about it,” he advised. “He just set that clock this morning.”

“Wouldn’t he be too busy to see me?” asked the other doubtfully.

“Naw, he never does nothin’! He’d be glad to know about it.”

“Well, I’m sure I think he ought to know. I guess he wouldn’t want folks to be too early and miss their trains!” He smiled politely and moved away, leaving the news-stand youth to smile derisively and murmur: “Dippy Dick!”

The sign “Information” above a booth in the center of the concourse met his gaze and he turned his steps toward it. “Will you please give me a timetable showing the train service between New York and Greenbank?” he asked gently.

“Greenbank, where?” demanded the official bruskly.

“Yes, sir.”

“Come on! Greenbank, Connecticut? Greenbank, Rhode Island? Greenbank——”

“Which do you consider the nicest?” asked the boy anxiously.

“Now, look here! I haven’t got time to fool away. Find out where you want to go first.”

“I’m so sorry! I saw it said ‘Information’ here and thought I’d get a little. If I’m at the wrong window——”

“This is the Information Bureau, son, but I’m no mind reader. If you don’t know which Greenbank you want—Yes, Madam, eleven-thirty-two: Track 12!”

“Maybe this ticket will tell,” hazarded the boy, laying it on the ledge. The man seized it impatiently.

“Of course it tells! Here you are!” He tossed a folder across. “You oughtn’t to travel alone, son,” he added pityingly.

“No, sir, I hope I shan’t have to. There’ll be other people on the train, won’t there?”

“If there aren’t—Yes, sir, Stamford at twelve, sir—you’d better put yourself in charge of the conductor!”

“I shall,” the other assured him earnestly. “Good-morning.”

“Just plain nutty, I guess,” thought the man, looking after him.

Eleven-twenty-four now, and the boy approached the gate, holding his bag in front of him with both hands so that it bumped at every step and fixing his[9] eyes on the announcement board, his mouth open vacuously.

“Look where you’re going!” exclaimed a gentleman with whom the boy collided.

“Huh?”

“Look where you’re going, I said! Stop bumping me with your bag!”

“Uh-huh.”

The gentleman pushed along, muttering angrily, and the boy followed, his bag pressed against the backs of the other’s immaculate gray trousered knees. “Greenbank, Mister?” he inquired of the man at the gate.

“Yes. Ticket, please!”

“Huh?”

“Let me see your ticket.”

“Ticket?”

“Yes, yes, your railway ticket! Come on, come on!”

“I got me one,” said the boy.

“Well, let me see it! Hurry, please! You’re keeping others back.”

“Uh-huh.” The boy set down his bag and began to dig into various pockets. The ticket examiner watched impatiently a moment while protests from those behind became audible. Finally:

“Here, shove that bag aside and let these folks past,” said the man irascibly. “Did you buy your ticket?”

“Huh?”

“I say, did you buy your ticket?”

“Uh-huh, I got me one, Mister.”

“Well, find it then! And you’d better hurry if you want this train!”

“Huh?”

“I say, if you want this—Here, what’s that you’ve got in your hand?”

“This?” The boy looked at the small piece of cardboard in a puzzled manner. “Ain’t that it?” he asked. But the man had already whisked it out of his hand, and now he punched it quickly, thrust it back to the boy and pushed him along through the gate.

“Must be an idiot,” he growled to the next passenger. “Someone ought to look after him.”

“All aboard!” shouted the conductor as the boy with the bag swung his way along the platform. “All aboard!”

“Is this the train for Greenbank?”

The conductor turned impatiently. “Yes. Get aboard!”

“Pardon me?” The boy leaned nearer, a hand cupped behind his ear.

“Yes! Greenbank! Get on!”

“I’m so sorry,” smiled the other. “Would you mind speaking a little louder?”

“Yes, this is the Greenbank train!” vociferated the conductor. “Get aboard!”

“Thank you,” replied the boy with much dignity, “but you needn’t shout at me. I’m not deaf!” Whereupon he climbed leisurely up the steps of the already moving train and entered a car.

Jimmy Logan and Dud Baker discussed the eccentricities of the obnoxious youth they had encountered in the waiting-room for several minutes after they were seated in the train. (By arriving a good ten minutes before leaving time they had been able to take possession of two seats, turning the front one over and occupying it with their suitcases.)

“Know what I think?” asked Jimmy, his choler having subsided. “Well, I think he was having fun with us. There was a sort of twinkle in his eye, Dud.”

“Maybe he was,” agreed the other. “He was a nice-looking chap. And the way he lit into that big bully of a newsboy was dandy!”

“Guess he knows something about wrestling,” mused Jimmy. “Wish I did. Let’s you and I take it up this winter, Dud.”

“That’s all well enough for you. Seniors don’t have anything to do. I’m going to be pretty busy,[13] though. Say, you don’t suppose that fellow is coming to Grafton, do you?”

“If he is, he’s a new boy,” was the response. “Maybe he’s a Greenie. A lot of Mount Morris fellows go back this way. It’s good we got here early. This car’s pretty nearly filled. I wish it would hurry up and go. I’m getting hungry.”

“How soon can we have dinner?” asked Dud.

“Twelve, I guess. They take on the diner down the line somewhere. Got anything to read in your bag?”

Dud opened his suitcase, lifted out several magazines and offered them for inspection. He was a slim boy of sixteen, or just short of sixteen, to be exact, with very blue eyes, a fair complexion and good features, rather a contrast to his companion who was distinctly stocky, with wide shoulders and deep chest. Jimmy’s features were a somewhat miscellaneous lot and included a short nose, a wide, humorous mouth, a resolutely square chin and light brown eyes. His hair was reddish-brown and he wore it longer than most fellows would have, suggesting that Jimmy went in for football. Jimmy, however, did nothing of the sort. In age he was Dud’s senior by four months. Both boys wore blue serge suits, rubber-soled tan shoes and straw hats, all of a style appropriate to the time of year, which was the third week in September. The straw hats were each encircled by a scarlet-and-gray band, scarlet and gray being the[14] colors of Grafton School, to which place the two boys were on their way after a fortnight spent together at Jimmy’s home. The similarity of attire even extended to the shirts, which were of light blue mercerized linen, and to the watch-fobs, showing the school seal, which dangled from trousers’ pockets. It ended, however, at ties at one extreme and at socks at the other, for Jimmy’s four-in-hand was of brilliant Yale blue, and matched his hosiery, while Dud wore a brown bow and brown stockings.

Jimmy turned over the magazines uninterestedly. “Guess I’ve seen these,” he said, tossing them to the opposite seat. “I’ll buy something when the boy comes through. I wonder what the new room’s like, Dud.”

“It’s bound to be better than the old one. I’m sorry we didn’t get one on the top floor, though.”

“Guess we were lucky to get into Lothrop at all. That’s what comes of leading an upright life, Dud, and standing in with Charley and faculty. Bet you a lot of fellows got left this fall on their rooms. Gus Weston has been trying for Lothrop two years. Wonder if he made it. Hope so. Gus is a rattling good sort, isn’t he?”

“Yes. Do you suppose he will be the regular quarter-back this year?”

“Not unless Nick Blake breaks his neck or something. Gus will give him a good run for it, though.[15] Still, Bert Winslow and Nick are great friends, and I guess Nick will naturally have the call.”

“Winslow never struck me as a fellow who would play a favorite,” objected Dud.

“Of course not, but if you’re football captain and there are two fellows who play about the same sort of game, and one is a particular friend and the other isn’t, and——”

“Here we go,” interrupted Dud as the conductor’s warning reached them through the open window.

“Good work! That’s what I meant, you see. Bert will naturally favor Nick. No reason why he shouldn’t. Besides, Nick was quarter last year and he was a peach, too. Bet you we have a corking team this fall, Dud. Look at the fellows we’ve got left over! Nick and Bert and Hobo and Musgrave——”

“Look!” exclaimed Dud in a low voice, nudging his companion. The train had begun to move. Following the direction of Dud’s gaze, Jimmy’s eyes fell on the form of the boy he had accosted in the station. The latter was coming leisurely down the car aisle, looking on each side for a seat. But the weather was warm and the passengers who were so fortunate as to be sitting alone were loathe to share their accommodations. The newcomer, however, displayed neither concern nor embarrassment. Something about him said very plainly that if he didn’t take this seat or that it was only because he chose not to, and[16] not because he was intimidated by scowls or chilly glances.

“Maybe,” began Dud, looking about the car, “we’d ought to turn this over, Jimmy.”

But before Jimmy had time to answer the boy had paused in his progress along the aisle and was smiling genially down on them.

He was, first of all, an undeniably good-looking youth. Even Jimmy was forced to acknowledge that, although he did it grudgingly. In age he appeared to be about sixteen, but he was tall for his years and big in a well-proportioned way. He had brown hair that was neither light nor dark, and eyebrows and lashes several shades paler. His face was rather long and terminated in a surprisingly square chin. His brown eyes were deeply set and looked out very directly from either side of a straight nose. The mouth was a trifle too wide, perhaps, but there was a pleasant curve to it, and at either end hovered two small vertical clefts that were like elongated dimples. Face, neck and hands were deeply tanned. For the rest, he was square-shouldered, narrow-waisted and deep-chested, and there was an ease and freedom in his carriage and movements that went well with the careless, self-confident look of him.

“Hello, fellows!” he said. “Mind if I sit here?” Whereupon, and without waiting for reply, he lifted Jimmy’s suitcase to the rack above, piled his own[17] bag on top of Dud’s and settled himself opposite the latter. “Warm, isn’t it?” he observed, removing his soft straw hat and putting it atop his bag. As he did so his gaze traveled from Jimmy’s hat to Dud’s, and: “Belong to the same Order, don’t you?” he said affably. “Is it hard to get in?”

“School colors,” answered Dud stiffly.

“Oh! Thought maybe you were Grand Potentates of the High and Mighty Order of Kangaroos or something.”

“You’re chock full of compliments, aren’t you?” asked Jimmy. “Called us Eskimos a few minutes ago, I think.”

“No, you got that wrong, Harold. What I meant——”

“Cut that out! My name isn’t Harold.”

“Oh, all right. I couldn’t know, could I?” asked the other innocently. “About the Eskimo Twins, though. It’s like this. You see, this is my first visit to your big and wicked city and the fellows out home told me I’d surely be spotted by the confidence men. Well, I’ve been in New York since yesterday afternoon and not a blessed one of them’s been near me. Made me feel downright lonesome, it did so! And when you fellows came along I just naturally thought someone was going to take a little notice of me at last. You didn’t look like con men, but they say you can’t tell by appearances. Sorry I made the mistake, fellows. Dutch Haskell—he’s Sheriff out in Windlass—got[18] to talking with a couple of nice-looking fellows in Chicago once and they invited him to go and see the Eskimo Twins, and Dutch fell for it and it cost him four hundred dollars. That’s why I mentioned the Twins. Wanted you fellows to know I wasn’t as green as I looked, even if I did come from the innocent west.”

“That’s rot,” said Jimmy severely. “You didn’t mistake us for confidence men. You only pretended to.”

Dud was secretly rather amused at Jimmy’s ruffled temper. This breezy stranger was the first person Dud had ever seen who was capable of causing Jimmy to forget his highly developed sense of humor.

“Well,” answered the boy in the opposite seat, smilingly, “I dare say you are a little too young for a life of crime.”

“I guess we’re not much younger than you are,” replied Jimmy, with the suggestion of a sneer.

“No, about the same age, probably. I’m sixteen and seven-eighths. Is there a parlor car on this train?”

“Yes, it’s about two cars forward,” answered Dud.

“Oh, that’s why I didn’t see it. Back home we generally put them on the rear of the train.”

“You can find it easily enough,” said Jimmy meaningly. “Don’t let us keep you.”

The boy smiled amusedly. “Thanks, Harold, I won’t. But I guess——”

Jimmy tried to stand up, but the confusion of legs and a sudden lurch of the car defeated his purpose and his protest lost effect. “Cut that out, Fresh!” he said angrily. “You do it just once more and I’ll punch your head.”

“My, but you fellows in the East are a hair-trigger lot,” said the other, shaking his head sadly. “Maybe you’d better tell me your name so I won’t get in trouble. Mine’s Crail.”

“I don’t care what it is,” growled Jimmy, observing the other darkly. “You’re too flip.”

The boy opposite raised a broad and capable-looking hand in front of him and observed it sorrowfully. “Monty,” he said severely, “didn’t I tell you before you left home you were to behave yourself? Didn’t I?” The fingers crooked affirmatively. “Sure I did! I told you folks where you were going mightn’t understand your playful ways, didn’t I?” Again the fingers agreed, in unison. “Well, then, why don’t you act like a gentleman? Want folks to think you aren’t more’n half broke?” The fingers moved agitatedly from side to side. “You don’t?” The fingers signaled “No!” earnestly. “Then you’d better behave yourself, Monty,” concluded the boy sternly. “No sense in getting in wrong right from the start. Going to be good now?” The fingers nodded vehemently, and the boy took the offending[20] right hand in his left and placed it in his pocket. “We’ll see,” he said, with intense dignity.

By that time Dud was laughing and the corners of Jimmy’s mouth were trembling. The stranger raised a pair of serious brown eyes to Jimmy as he said gravely: “I have to be awfully strict with him.”

Jimmy’s mouth curved and a choking gurgle of laughter broke forth. “Gee, you’re an awful fool, aren’t you?” he chuckled. “Where do you come from?”

The boy brought the offending hand from the pocket and clasped it with its fellow about one knee and leaned comfortably back. “Windlass City, Wyoming, mostly,” he replied. “Sometimes I live in Terre Haute.”

“Where’s Terre Haute?” asked Dud.

“Indiana. Next door to Wyoming,” he answered unblinkingly.

“No, we know better than that,” laughed Dud. “Indiana’s just back of Ohio, and Wyoming’s away out beyond Nebraska and Oklahoma and those places. Do you live on a ranch?”

Crail shook his head. “No, there isn’t much ranching up our way. It’s mostly mining. Snake River district, you know. Windlass City’s about a hundred miles northwest of Lander. Know where the Tetons are? Or the Gros Ventre Range? We’re in there, about ten miles from where Buffalo Fork[21] and Snake River join. Some country, Har—I mean friend.”

“Is it gold mining?” asked Jimmy interestedly.

“No, coal. That’s better than gold. There’s more of it.”

“And you live there, Creel?”

“Crail’s the name. Only in summer. I’ve been there pretty late, though. Winters I go back east to Terre Haute. Last year I was at school, though. Ever hear of Dunning Military Academy at Dunning, Indiana?”

The boys shook their heads.

“It’s not so worse, but they teach you so much soldiering that there isn’t much time for anything else. And you have to live on schedule all day long, and that gets tiresome. I kicked myself out last May. Couldn’t stand it any longer.”

“Kicked yourself out?” echoed Dud questioningly.

“Yes, they wouldn’t do it so I had to. I tried about everything I could think of, but the best they’d do was to put me in the jug and feed me bread and water. I spent so much time in ‘solitary’ that I got so I liked it. It gives you a fine chance to think, and I’m naturally of a very thoughtful disposition. Say, I used to think perfectly wonderful thoughts in the jug, thoughts that made a better boy of me!”

Jimmy grinned. “What did you do to get punished?” he asked with lamentable eagerness.

“What little I could,” sighed Crail. “There wasn’t much a fellow could do. You see, you’re dreadfully confined. The last time I set a bucket of water outside the commandant’s door and rang the fire gong. He came out in a hurry and didn’t see the bucket and put his foot in it. He was awfully peeved about it. I told him he ought to blame his own awkwardness.”

“And they fired you then?”

“Oh, no, they jugged me again. Six days that time. Six days is the limit.”

“What did you do when they kicked you out?” asked Dud.

“They didn’t kick me out. I gave them all the chance in the world, but they wouldn’t part with me. Stubborn lot of hombres. So I held a court martial on myself one afternoon, found myself guilty of gross disobedience and conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman and sentenced myself to dishonorable discharge. Then I wrote down the finding of the court, tucked it under the commandant’s door and mushed out of there. They came after me but I doubled back, and swapped clothes with a fellow I met on the road—he didn’t want to swap, but I persuaded him to—and then walked back to Dunning and took a train for home. Military academies are all right for some fellows, but they irk me considerable.”

“Where are you going now?” asked Jimmy.

“School. I told Jasper—Jasper’s my guardian[23] since dad died—that I wanted to go to Mexico and be an army scout or something, and he said an army scout ought to know a heap more than I did and he reckoned I’d better find me a school and go to it. I thought maybe there was a heap in what he said and decided I’d hike east here where learning comes from. So here I am, Ha—fellows. I don’t know what sort of a place this Mount Morris is, but I don’t have to stay if I don’t like it.”

“Mount Morris!” exclaimed Dud and Jimmy in one breath.

“Yes. Know it?”

They nodded.

“Aren’t going there yourselves, are you?” asked Crail.

Jimmy snorted with disgust. “I should say not! We’re Grafton fellows.”

“Are you? What’s Grafton, another school?”

“No, it’s not ‘another’ school,” replied Jimmy with great dignity. “It’s the school, the only school.”

“Think of that! Then this place I’m going to doesn’t stack up very high, eh?”

“Oh, Mount Morris is all right,” replied Jimmy, carelessly condescending, “if you aren’t particular. A lot of fellows do go there.”

“Just like that, eh?” asked Crail, grinning. “Well, aside from that it’s pretty good, isn’t it?”

“We naturally like Grafton a good deal better,” said Dud seriously. “And I guess it really is better.[24] But Mount Morris is good, too. That is so, isn’t it, Jimmy?”

“Oh, it’s good enough, I suppose,” answered Jimmy without enthusiasm. “We generally manage to beat it at about everything from chess to football, and we have a lot more fellows, and better buildings and better faculty, but it’s fair.”

“I savvy. This place you go to and Mount Morris are rivals, eh? Play football together?”

“Sure.”

“And you fellows always win?”

“Well, not always,” granted Jimmy, “but pretty generally. We won last year and——”

“First call for dinner in the dining car!” announced a waiter, passing through the car. “Three cars forward!”

“Me for that!” exclaimed Crail. “You fellows eating?”

“You bet! I’m starved. Hurry up before the seats are all gone.” Jimmy struggled heroically and finally disentangled his legs and stood up. “Get a move on, Dud! Maybe if we go now we can get three seats together.”

Three minutes later they were established at a table and had ordered the first two courses, oysters and soup, accompanied by such trifles as celery and olives and mango pickles. They were already consuming bread and butter with gusto, or, at least, Jimmy and Dud were, for they had breakfasted very early. Crail was less enthusiastic about food, and while the others ate he took up the interrupted subject of Mount Morris School.

“The way I came to know about this place was seeing an advertisement in a magazine,” he confided. “It certainly did read well, fellows. I sort of got the idea that it was the leading educational institution of the country. Maybe I was wrong, though.”

“You certainly were,” said Jimmy, speaking rather indistinctly by reason of having his mouth very full. “Mount Morris never led in anything. Why didn’t you pick out a good school while you were picking?”

“I suppose it’s a mistake to believe all the advertisements tell you,” said Crail. “Well, I guess it’ll[26] be good enough for me. I’m not very particular. If they give me enough to eat and treat me kindly and beat a little algebra and history and a few languages through my skull I won’t kick. Know whether I have to take Latin, fellows?”

“Depends on what class you enter, I suppose,” replied Dud, helping himself to Jimmy’s butter, to that youth’s distress and muffled remonstrances. “I guess you’ll have to take one year of it, anyway.”

“Snakes!” said Crail. “That’s sure disappointing. I never did have any luck with Latin. Sort of a half-baked language, I call it.” His sorrow was dispelled by the appearance of the waiter with the oysters, and he beamed approval and beckoned with his fork. “Sam,” he said confidingly, “you bring in six more of these little birds. I haven’t eaten a real nice fresh oyster for a long time.”

“Can’t serve no more, sir,” replied the waiter. “Only one order goes with a dinner.”

“That’s all right, Sam,” said Crail untroubledly. “You don’t have to sing when you bring them in. Just do it unostentatiously.”

“Can’t be did, sir. I’d like to oblige you, but——”

“I know you would,” interrupted Crail earnestly. “I just feel it, Sam. Say no more about it, but get busy. And put them right here when you bring them. Try for the plump ones, Sam. These look sort of—sort of emaciated.”

“You won’t get them,” laughed Dud. “The steward would take them away from him.”

“I’ll get them all right,” was the reply. “Say, fellows, they sure are good! I used to think I’d like to live by the ocean and raise my own oysters. A fellow could, eh?”

“Where do they find oysters?” inquired Jimmy. “In the ocean or rivers or where?”

“Both,” said Dud. “They sow the young oysters and——”

“Sow them!” exclaimed Jimmy. “Oh, sure! Just like wheat or oats, I suppose. Where do you get that stuff?”

“They do, don’t they, Creel?”

“It’s still Crail. Search me, though. I never saw an oyster field. Ah, that’s the good old scout, Sam. Place them right here and remove this devastated affair.”

“Yes, sir. I’m sorry those wasn’t good, sir.” The waiter uttered the regret loudly, evidently for the benefit of the near-by diners, or, possibly, the eagle-eyed steward.

“Couldn’t eat them, Sam,” replied Crail cheerfully. “Don’t let it happen again.”

“No, sir. Now what can I bring the rest of you gentlemen?”

“Do you always get what you want like that?” inquired Jimmy enviously after the waiter had departed with their order. “If I’d asked for a second[28] helping of oysters they’d have thrown me off the train!”

“The main thing to do,” answered Crail, holding an oyster up on his fork and viewing it approvingly, “is to think you’re going to get what you want and let the other fellow know you think it. That gets him to thinking so too, you see. How’s that soup?”

“Punk,” said Dud.

“I’ll pass it. Say, have you fellows got any names?”

“A few,” replied Jimmy. “His is Baker and mine’s Logan.”

“Thanks. I was afraid I’d call you Harold again and get beat up.” Crail didn’t look vastly alarmed, however, and Jimmy secretly congratulated himself on not having to carry out his threat of punching his head. Crail didn’t quite look like a fellow who would stand around idle during such a process! “I know a fellow named Baker out in Wyoming. He’s foreman on the Meeteetse Ranch. Might be kin to you, eh? He comes from back here somewhere. I don’t know what his first name is, though. He’s generally called ‘Soapy.’ Any of your folks out my way?”

“Not that I know of,” replied Dud. “Why do they call him ‘Soapy’?”

“Search me! You get all kinds of names out there. Up at the mines there’s a choice collection: ‘Pin Head’ Farrel, ‘Snub’ Thompson, ‘Tejon’ Burns, ‘Last Word’ MacTavish: a bunch of them. Sometimes[29] they sort of earn their names and sometimes they just stumble on them, I guess. ‘Pin Head,’ he’s a big, tall chap with a head six sizes too small for him, and MacTavish is a Scotsman who is always saying ‘If it’s my last wor-r-rd on airth!’ But I don’t know why Thompson is called ‘Snub.’ Nor where Burns gets his nickname.”

“What were you called?” asked Dud.

“Just Monty. That’s my middle name, or part of it. The whole of it’s Montfort. That was my mother’s name. She was French.”

“What’s your first name?” Dud inquired.

“A.”

“A?”

“Yes, A Montfort Crail.”

“But—but doesn’t the A stand for anything?”

“Not a thing. Snakes, fellows, if I eat all this truck I’ll pass in my chips! Where’s this Grafter School you tell about at?”

“Grafton, not Grafter, if you please. Grafters is what the Greenies call us.”

“Who are the Greenies?”

“The Mount Morris fellows. Their color is green, you know.”

“Seems like it would be a good place for me,” chuckled Crail, transferring a large slice of roast beef to his plate and starting to work on it. (The others observed with interest as the meal progressed that their new acquaintance dealt with one thing at[30] a time. He consumed his beef to the last portion before he paid any attention to the vegetables and then ate each vegetable by itself.) “Which comes first, Grafton or Greenbank?”

“Grafton, in everything,” laughed Dud. “We get to Needham Junction about half-past two. That’s where we change. You stay on and get to Greenbank about an hour later.”

“I didn’t know it took so long,” said Crail. “Tell me about your school, fellows. What’s it like? What do you do there? How many of you are there?”

“We had two hundred and sixteen last year,” replied Jimmy, “and I guess we’ll have a few more this year. I suppose the faculty would take more if we had dormitory room. We have three big dormitories and two small ones. Dud and I are in Lothrop this year. That’s the newest one, and it’s a peach. Then there’s Manning, where the younger fellows live, and Trow, the oldest one. And there’s Fuller and Morris, but they’re just wooden houses on the Green. They look after about twenty fellows altogether.”

“Don’t any of you live around?” asked Crail. “In the town, I mean?”

“No, the school’s about a half-mile from the town. Of course, we have some fellows who live in Grafton, you know, but not many.”

“I guess I’d rather live outside the school,” said[31] Crail. “You don’t have to toe the mark so much, eh?”

“You won’t do that at Mount Morris,” said Dud, “because you’re nowhere near the village there. The school’s about three miles from Greenbank; and it’s up-hill all the way, too. I know, for I walked it once.”

“Oh, you’ve been there?”

“Yes,” answered Dud grimly. “Last June. Jimmy was with me. We got left at Webster and had to foot it most of the way. We found a handcar after awhile and did pretty well until a train came sneaking up on us and we had to throw the handcar down the bank. That was some journey, Jimmy.”

Jimmy smiled reflectively. “It certainly was! And say, Crail, what do you suppose this idiot did after we got to Greenbank? Well, he went in and pitched three innings and won the game for us!”

“Good leather!” Crail viewed Dud with new interest. “Pitched, eh? Say, that’s something I’d like mighty well to do. I tried baseball at Dunning last spring, but the captain and I had a falling-out and I got fired.”

“What position did you play?” asked Dud.

“First base—when I played. There was another fellow, though, that had me beat. Football is what I’m crazy about, though. What sort of a team do you have at Grafton?”

“Good enough to win from Mount Morris two[32] years out of three,” answered Jimmy. “We’ll have a wonder this year, for we’ve got a lot of good men left from last season. Do you play?”

“I tried it a little last fall,” answered Crail, “but I didn’t make the team. I’d never seen football near-to until then. I guess it takes a pile of learning, that game. I’m sure fond of it, though, and I’m going to try it again this time.”

“You ought to make good at it,” said Jimmy, running an appreciative eye over Crail’s muscular body. “Guard is your place, I guess.”

“They had me trying for tackle, but I’m heavier now. I bought me a book about football and I’ve been studying it. Say, there’s a lot to it, isn’t there? Is it hard to get on the team at your school?”

“N-no, not if you show something,” answered Jimmy. “Of course, there are a good many fellows turn out every fall and you’ve got to work like an Indian to make it, but——”

“Work like an Indian, eh?” laughed Crail. “Say, did you ever see an Indian work? Well, I did, just once. He was plowing a piece of ground about eight times the size of this car and it took him three days to do it. It’s Mrs. Indian who does the work, partner. I guess I’d have to work a sight harder than any Indian to get a place on a football team. But I sure mean to do it, Har—I mean Logan. Sam, I’ll have a dish of ice cream and a man-size cup of coffee. Don’t fetch me one of those thimbles now![33] I suppose they make you study pretty hard, eh?”

“You bet they do!” said Jimmy feelingly. “And then some!”

“Harder than at this place I’m headed for?”

“N-no, I guess about the same.”

“Maybe it costs more money at Grafton?”

“Tuition, you mean? That’s about the same, too, I suppose. I don’t know how much it is at Mount Morris, do you, Dud?”

Dud shook his head, but Crail supplied the information. “A hundred and fifty,” he said. “Seventy-five down and seventy-five in January. And anywhere from two hundred to five hundred for board and lodging. Education sure costs a heap of money in this part of the world. I know a fellow went through college in Nebraska, and it cost him less than six hundred for the whole three years!”

“Two hundred and fifty is the least you can pay for a room at Grafton,” said Jimmy, “and that means either Trow or one of the houses. But the tuition is the same, except that we pay in three installments.”

“Well, I got two hundred and seventy dollars with me,” said Crail, “and I guess that would see me through for one term, eh? Only thing is, though, will they let me in?”

“Why, you’ve taken an exam, haven’t you?” asked Dud.

Crail shook his head. “No, they said at Mount[34] Morris that I could do that after I got there. Won’t they let me?”

“Oh, yes, only fellows usually enter by certificate after the junior year. Let’s go back. We’ll be at the Junction in a few minutes.”

“What did you mean by entering by a certificate?” asked Crail, when they were once more in their seats in the day coach. “Where do you catch these certificates?”

Dud explained and Crail frowned a moment. Then his face cleared, and he laughed. “Well, I guess they wouldn’t have given me any kind of a certificate at Dunning that would have helped me much, fellows! I’ll just have to go up against the examination. Will it be hard, do you think?”

“I don’t believe so,” Jimmy reassured him. “They’ll probably let you in, and then sock it to you afterwards. I guess they want all the fellows they can get at Mount Morris.”

“Mount Morris, yes, but how about this Grafton place?” said Crail. “What about the examinations there?”

Jimmy shrugged. “I never took them. Neither did Dud. You’d be sure to pass for the lower middle, though, if you failed for the upper. They call them third and second at Mount Morris. We’d better get our bags closed, Dud. There’s the whistle.”

Crail arose and took his kit-bag out of the way,[35] and set it in the aisle while Dud stuffed the magazines back into his suitcase, and Jimmy rounded up his own belongings. The train slowed down gradually, and finally came to a stop, and a trainman sent the stentorian cry of “Needham Junction!” through the car. “Needham! Change here for Grafton!”

“Well, I’m glad to have met you,” said Jimmy, holding out his hand to Crail. “And if you ever come to one of the games— Say, hold on! This isn’t your station! You’ve got another hour yet, Crail.”

But Crail, bag in hand, shook his head. “Fellows, I’m plumb tired of traveling,” he said, “and I sort of think I’ll get off right here.”

“But you’ll have three hours to wait, nearly!” Jimmy expostulated to Crail’s broad back. “There isn’t another train to Greenbank until five!”

Crail smiled over his shoulder as he pushed through the car door.

“Oh, I’ve changed my mind about that place,” he answered. “You see, I don’t know anybody at Mount Morris, and I sort of like you fellows, and I guess one school’s as good as another. Which side do we get off at?”

“Do you really mean that you’re coming to Grafton?” demanded Dud when they had reached the station platform.

“If they’ll have me,” replied Crail, looking about him curiously. “What do we do now? Take another train?”

“Yes, that one there. But—but——”

“Shut up, Dud,” said Jimmy. “If he wants to, what’s the difference? He isn’t bound to go to Mount Morris if he doesn’t want to, is he? He isn’t entered there, you idiot. Come on, Crail. Talk about your brands snatched from the burning! Say, Dud, maybe they’ll give us a commission on him! Hello, Pete! I didn’t see you on the train. Who’s with you? All by your lonesome? You know Dud Baker, don’t you? And this is Mr. Crail. Crail, shake hands with Mr. Gowen. Crail has just been rescued from a horrible fate, Pete.”

Gowen, a big, good-natured chap, who played guard on the football team, smiled. “What was[37] that, Jimmy?” he asked, as they climbed into the single coach of the branch line and found seats.

“Why, he was on his way to Mount Morris, and we spoke so eloquently of Grafton that he saw the error of his way, and decided to turn back into the path of righteousness.”

“I suppose Jimmy’s stringing me, Crail,” said Pete Gowen, “but I’m glad you’re coming our way. Football man?”

“Not much. I’m going to have a try, though. Say, I’d ought to get me a ticket, eh?”

“Never mind it. Pay the conductor,” said Dud. “It’s really a fact, Gowen. Crail was on his way to Greenbank and changed his mind, and decided to come with us.”

“It was our personal charm that did the business,” said Jimmy. “What do you think of him for a lineman, Pete?”

“If Dave Bonner sees him,” laughed Pete, “he will be eating dirt no later than tomorrow P. M.”

“Eating dirt, eh? Sounds fine, but what does it mean?” asked Crail.

“Tackling the dummy,” explained Pete. “We have very tasty loam in our pits. You’re sure to like it.”

“I’m willing. Only thing is, you fellows, I may get the gate when I run up against the examination. Think they’ll let me by, eh?” He appealed a bit anxiously to Pete, and Pete smiled.

“If Bonner and Bert Winslow were on the committee you wouldn’t have much trouble,” he replied, “but I don’t know how hard those entrance exams are. Hope you pass, though, Crail. We need a few fellows of about your build this fall. How did you happen to change your mind about Mount Morris?”

A Montfort Crail smiled. “Well, I’d made up my mind to go somewhere. You see, I’ve never had much schooling. I’m a good deal of a dunce, I suspect. I saw this Mount Morris Academy advertised in a magazine I picked up one day, and wrote to them and got a sort of a circular. That was last month. So I asked them could I get in if I came, and they said I could if I ‘met the requirements.’ I didn’t know just what those were, but I thought I’d take a chance. Then I ran across Harold and his friend——”

“Who?” asked Pete.

“I mean Logan and Baker here,” corrected Monty with an apologetic grin at Jimmy. “They told me about this place, and I thought ‘What’s the good of going to Mount Morris when Grafton’s an hour nearer?’ You see, I’ve had two days on the cars, and I’m sort of tired of them.”

“That’s one reason for coming,” laughed Pete. Then he added, more seriously, “I’d advise you to be prepared for a disappointment, Crail. I’ve an idea they’re pretty well filled up, and you may find[39] that they can’t take you. In that case you could go on to Mount Morris, though.”

“Sure.” Monty nodded carelessly. “I guess there are plenty of schools in this part of the country, eh?”

“What ought he to do?” asked Jimmy. “Go to Pounder, and tell him he wants to enter, or—or what?”

“If it was me,” replied Pete, “I’d see Charley and tell him just what had happened. I have an idea Charley would think it was a kind of a joke on Mount Morris, and so he might stretch a point, and make it all right for your friend. Pounder might just say that they were filled up and all that, you know.”

“Think Charley would see him?” asked Jimmy doubtfully.

“Why not? Go to his house if he isn’t at the office. If there’s anything I can do, Crail, look me up. I’m in Trow; Number 16. Jimmy’ll show you.”

Monty thanked him, and the talk wandered to other subjects; such as who was coming back, and who wasn’t, the rumored changes in the faculty, the prospects for the football team, and what progress had been made by the squad that, following a custom of several years’ duration, had been practising at Grafton for the last week. Pete explained his absence from the preliminary session. He had[40] spent the summer in the Southwest with a surveying party, and had only finished his work five days before. Evidently, the hardships, some of which he jokingly alluded to, had agreed with him, for the big fellow looked as hard as nails, and wore the complexion of a Comanche Indian. Monty Crail listened politely, and in silence for the most part, dividing his attention between his companions and the landscape moving leisurely past the window. Needham Junction is only four miles from Grafton, but the train doesn’t hurry, and somehow usually manages to consume the better part of twenty minutes on the journey, making five stops at cross-roads stations, and lingering socially at each. There were few other Grafton students amongst the passengers sprinkled through the car, for the train that Jimmy and Dud had selected was not a favorite with the fellows. The real influx would occur later in the afternoon when the two expresses came in. Dud and Jimmy had chosen to arrive early for the reason that they were to have a new room this fall, and there would be some work to be accomplished before they would be fairly settled.

Monty viewed the country with favor. It was all very different from both Indiana and Wyoming. There was a softness and a peacefulness that were attractive, and which, in spite of novelty, seemed to the boy very homelike. Only once before had he been in the east, and that had been when he was[41] nine years of age, and his father had taken him on a hurried trip to Washington and New York. Monty couldn’t remember many of the details of that visit nor much of the places he had seen. As he recalled it now, much of the time had been spent by him awaiting his father in hotel rooms. From the train window his gaze fell on restful, still, green meadows, outlined by stone walls, on patches of woodland, on squatty white farmhouses that seemed rather to have grown than been built, on distant hills, hazy blue in the afternoon light, on fields of corn and blue-green cabbages, and potatoes and golden pumpkins.

Everything was very different, even the trees and the fences, and the faces he glimpsed at the little stations, but there was no feeling of loneliness in Monty. He was used to strange scenes, used to being by himself and looking after himself. Even before his father had died—he remembered nothing at all of his mother—he had been left a good deal to his own devices, and since then he had fended entirely for himself, for Mr. Holman, his guardian, attempted to exercise but slight control over the boy. Monty was practically incapable of ever being homesick, for the simple reason that for five years he had had no real home, spending his summers as it pleased him, usually at Windlass City, sometimes on a ranch, and his winters in or around Terre Haute. What had bothered him most the winter[42] before, at Dunning Academy, had been the “staying put,” as he called it. Accustomed to moving about as, and when he pleased, being tied to a few acres had proved a new and unpleasant experience. Just now he was wondering whether he could accustom himself to similar conditions this winter. He meant to try hard, for here he was sixteen years old and with less “book-learning” than most fellows two years younger, and he realized that if he was to get an education he must buckle down to it, and restrain those restless feet of his. He didn’t want to grow up an ignoramus. And then, too, Dunning had given him a taste for the companionship of persons of his own age, something he had enjoyed but little. Until he had gone to the military school his friends and acquaintances had been, with few exceptions, men; Joe Coolidge, the mine superintendent; “Snub” Thompson, “Tejon” Burns, Garry Waters, who ranched on Little Horse Creek, “Soapy” Baker, of the Meeteetse outfit, and a few more commonplace and less picturesque gentlemen in Terre Haute. Monty had begun to feel the need of boy friends and boy interests, and perhaps it was as much that need as a desire for knowledge that had led him to fall in so readily with his guardian’s suggestion. So far as making his way in the world was concerned, Monty might have gone along with no more knowledge of Ancient and Modern Languages, higher mathematics, and the[43] rest of the curriculum, than he possessed, for Mr. Crail had left a good-sized fortune in trust for the boy, and the Gros Ventre Coal Company, under present management, was doing better than ever, and that Monty would ever have to work for a living if he didn’t want to was inconceivable.

When he had said that he had decided to go to Grafton instead of Mount Morris, because it was nearer he had spoken only part of the truth. The chief reason had been that he had found in Jimmy and Dud a hint of the companionship he craved. An uneventful journey east and a night spent alone in a New York hotel had left him ready to make friends with almost anyone of his kind on slight provocation. He was always able to amuse himself very satisfactorily for awhile, as witness his efforts with the news vendor, the information bureau man and the conductor, but that sort of fooling palled eventually, and having made the acquaintance of Jimmy and Dud he felt it the part of wisdom to continue it. He might, he told himself, speaking from experience gained at Dunning, remain at Mount Morris a month before he would get on such friendly footing with anyone. And already he had increased his circle of acquaintances by one more, he thought, glancing appreciatively at Pete Gowen’s homely and kindly face, and that was doing pretty well. He had come east prepared for hard sledding in the matter of making friends, for[44] he had heard all his life of the Easterner’s aloofness, but here, with scarcely an effort, he was already in possession of three—well, if not friends, at least friendly acquaintances! If, he said to himself as the engine announced the end of its leisurely journey by a shrill whistle, the rest of the Grafton fellows were as human and likeable as the three he had so far encountered he was going to like the place fine!

A minute or two later they were out on the platform, bags in hand. And a minute later still they were, all four, together with nine other lads, settled in the queer vehicle that Jimmy called a “barge.” The barge was long and open all around, and had seats running lengthwise, seats upholstered in faded crimson plush. There was a crosswise seat in front for the aged driver, and the vehicle was drawn by a pair of likely-looking gray horses. Although the two long seats were designed to accommodate some two dozen passengers, thirteen boys and thirteen bags, with a sprinkling of golf-bags, tennis rackets, cameras and overcoats, used about all the space. The road did not enter the town of Grafton, but skirted it, and almost before Monty had begun to entertain any curiosity as to the school itself the barge swung around a corner into River Street, and the buildings and the campus were before him.

Dud, sitting beside him with his suitcase on his[45] knees that Monty might have room for his kit-bag on the floor, pointed out the buildings. “That’s Lothrop, the one ahead there, nearest the street. Jimmy and I room there this year. It’s the best of the lot. Trow’s behind it. The next is School Hall, and Manning’s the last in the row. The gymnasium is back of Manning, but you can’t see it yet. The frame house at the other side of the campus, behind the trees, is Doctor Duncan’s. He’s the principal, you know.”

Monty listened and looked with interest. As the barge rolled down the freshly sprinkled macadamized street, through alternating patches of sunlight and shadow, he looked under the branches of the bordering maples and saw a wide expanse of turf across which marched a row of brick buildings, the newer ones graced with limestone trimming, the older one, School Hall this, saved from monotony only by the ivy that clothed its lower story. Gravel paths, shaded by tall elm trees, led across the turf, and a wide walk of red brick ran from one side of the campus to the other in front of the buildings. A fence of roughly squared granite posts connected by timbers enclosed the grounds. Further away, in the direction of the river whose existence Dud dwelt on, a second smoothly paved street proceeded at right angles with the one they were on, and beyond that was a second and narrower stretch of turf—“the Green,” Dud called it—with two comfortable,[46] immaculately white dwellings nestling on the nearer corner of it. “Morris and Fuller Houses,” said Dud, waving a hand toward them. “They’re dormitories, too. Small ones. Some fellows like them, but I never thought I should. The Field’s on the other side. You can see the grandstand if you look quick.”

But Monty failed, for just then the barge turned in at the carriage gate, and the trees closed in on his view.

“Who’s for Lothrop?” asked the driver over his shoulder as he pulled up at the corner of the newest dormitory.

“We are,” announced Jimmy rather importantly, as it seemed to Monty. “Come on, Crail. We’ll leave the bags, and then go over to School.” Pete Gowen and two other boys followed them out, and then the barge rolled on to repeat the process at Trow, and, finally, Manning.

Monty gave a sigh of satisfaction as he stood on the edge of the turf and felt the grateful coolness of the shadow cast by the big dormitory. They had been cutting the grass that day, and the languorous warmth of the air was scented with the wonderful fragrance of it. In a near-by tree a locust rasped shrilly, and Monty gazed curiously in its direction. He would have asked what it was, but Jimmy was leading the way toward the nearer entrance, and so Monty took up his bag again and followed.

It was a wonderful building that, Monty thought. He glimpsed a wide carpeted hallway from which opened comfortably, even luxuriously furnished apartments, while, at the far end of the corridor, a bewilderingly long way off, wide-open doors afforded a view of white-draped tables with peaked napkins like tiny Indian teepees dotting them and the shimmer of polished silverware.

“Snakes,” murmured Monty, “this isn’t much like Dunning!”

But the others didn’t hear him, for they were chattering busily as they climbed the slate stairway to the floor above. A corridor slightly narrower than the one below ran the length of the building, and on either side numbered doors, some open, some closed, marched away.

“Here it is,” announced Jimmy, in the lead, and pushed open one of the portals. “Say, Dud, this is perfectly corking! And we’ve got a fireplace! And look at the view, will you? Maybe this doesn’t beat Trow, what?”

Monty Crail sat in a spindle-backed wooden armchair with his feet on the sill of the low window, and his hands clasped behind his head, and dreamily watched a solitary star—it happened to be Venus, but Monty wasn’t aware of the fact—brighten momentarily in the western sky. It hung just midway between the topmost branches of the two elms across the street, and it required little imagination to almost detect the wire that held it there! Supper was over, and the other inhabitants of Morris House, saving Mrs. Fair and the maids, had either wandered off to other scenes or were loitering outside on the steps. Monty could hear the voices from around the corner of the house. Monty’s room was numbered—or, rather, lettered—“F,” and was on the second floor. There were three windows in it, one looking down on a small patch of lawn, and then across River Street, and, finally, in the general direction of Grafton Village, and two others, side by side, staring rather blankly[49] at this season against the leafy screen of a big horse chestnut tree. Later, when the leaves were gone, those windows afforded a fine view of Lothrop Field and the tennis courts, and the diamond and the gridiron and running track, and, further away, glimpses of the Needham River that wound its quiet way past the southern confines of the school property. The twin casements were dormered, and the small alcove so formed was occupied on one side by a washstand, and on the other, a long shelf, which, with the aid of bright-hued cretonne curtains, formed a supplementary wardrobe designed to eke out the meager accommodations offered by a tiny closet.

The room, though small, was attractive. There were two cot beds, one on each side of the chamber, a brown oak study table in the center, two chiffoniers to match, the aforementioned washstand, two arm chairs of the Windsor pattern, a like number of straight-backed chairs, and a small stand. The center of the floor was spread with a brown grass rug and smaller ones lay in front of the door, and in the alcove. And there were, of course, lesser furnishings, such as a green-shaded electric drop-light on the table, a waste-paper basket with the appearance of having been used at some time as a football, a scarlet-and-gray cushion, which, because there was neither window-seat nor couch, led a restless life. Four pictures of no importance, and a[50] large Grafton banner adorned the walls, and on one chiffonier were several photographs, framed and unframed. The walls were covered with a paper of alternating white and buff stripes which gave a sunshiny effect to the room. On the whole, Monty’s new home was cheerful and comfortable, and, while he would have preferred a study and bedroom in one of the campus dormitories, he was not at all dissatisfied.

He had been at Grafton twenty-eight hours, and, to be exact, fourteen minutes, reckoning from the time he had stepped from the barge at the corner of Lothrop, and in that time much of a not exciting nature had happened. He was reviewing that period now, his gaze fixed intently on the star. He had been conducted by Jimmy Logan in the august presence of Doctor Duncan, the principal, and had told his story. The Doctor—the fellows called him “Charley,” but Monty had not achieved that familiarity yet—had been visibly interested and amused. In the end he had picked up the telephone and consulted the school secretary with the result that Monty, bag in hand, had presently followed Jimmy across the campus to Morris House.

There Jimmy had left him, after extracting a promise to return later to 14 Lothrop, and Monty had been conducted upstairs by a stout and short-breathed lady whom the boys called “Mother Morris,” but whose real name was Mrs. Fair. Mrs.[51] Fair was the matron, and what the fellows termed “a good sort.” Left to himself, Monty had wandered about the room, hands in pockets, looked out the windows, and finally unpacked his bag. After that there had seemed nothing to do save look up Jimmy and Dud, and so he had returned to Lothrop. By that time the campus and the dormitories presented a quite different appearance, for another train had come in, and boys of all sorts were in evidence on walks and in doorways, and on the stairs and in the corridors. One fell over a bag at every turn. Jimmy and Dud were hanging pictures and arranging their belongings, their trunks having arrived, and Monty had helped to the best of his ability. Now and then a boy had wandered in to say “Hello,” pour out a rapid fire of questions and answers, shake hands with Monty and hurry out again. And finally supper time had come, and Monty had gone back to Morris House and partaken of cold lamb and chicken salad and graham muffins and pear preserve and three glasses of milk at a long table, and in the presence of eleven other youths of assorted ages, sizes and looks. Monty had been introduced to them all, but acquaintanceship had for the time ended there. After supper he had wandered off for a walk along the twilight roads, and across the campus and past the buildings and had returned to Morris tired enough to go to bed and sleep.

He had found Room F in possession of a tall, loose-jointed youth, with tow-colored hair plastered greasily to his head, and a pair of pale, near-sighted eyes under colorless lashes. This was Alvin Standart, the rightful owner of one-half of Room F. Monty had met him at supper, but had not thought of him as a roommate. Standart seemed anything but delighted with the idea of sharing the apartment with the newcomer, and Monty, for his part, was not sensible of any particularly joyous emotions. Standart hadn’t impressed him favorably. He didn’t yet, after a day’s acquaintance. Standart, in the first place, didn’t look clean. Monty seriously doubted that he was. And he had unpleasant manners. Standart was the one fly in Monty’s ointment this evening. Everything else had turned out beautifully. The examination, conducted by Mr. Rumford, the assistant principal, had been far less severe than Monty had feared. He and three other rather anxious looking youths had assembled in a classroom in School Hall that morning after breakfast, and had been questioned as to their previous studies. Two simple problems in algebra, a sight translation of a dozen lines of Ovid, a test in German grammar, and the ordeal was over. Two of the applicants were passed into the Junior Class, and two into the Lower Middle, Monty being one of the latter. He had not impressed the instructor very deeply, he concluded, for “Jimmy”[53] Rumford had viewed him for several long moments with an expression plainly dubious.

“Passing this test,” said the Assistant Principal, in conclusion, “doesn’t mean very much, young gentlemen. It means only that the school is giving you an opportunity. Whether you remain with us or flit away to other fields depends entirely on you. We don’t encourage loafers here. If you’ll all remember that it may save you future sorrow and regrets. Hand these slips to Mr. Pounder, the secretary, please, and he will assign you to your classes. If there is anything you want to know, you will find me here between eight and nine in the morning, and from five to six in the afternoon. You, er—Crail, ought to be in the Upper Middle Class, sir, but I don’t see my way to placing you there. If you’ll take my advice you will do your best to make the jump at the beginning of the next term. I think you can do it. That is all. Good morning, young gentlemen. Success to you.”

Recitations that day had been short, the time in each case having been largely consumed in arranging for future work. Monty found that his schedule included Latin, Mathematics, English, German (he had selected it instead of the alternative Greek) and Physical Training. Dud had, however, informed him that Physical Training was only for those who did not go in for a regular sport. The studies footed up to twenty hours a week, and Monty wondered[54] whether he would survive the first week! That afternoon he had joined Dud and Jimmy and a new acquaintance named Brooks, and with them watched football practice. The fact that his playing togs were in his trunk, and that his trunk had scarcely yet started from New York prevented him from joining the candidates that afternoon. He had purposely refrained from checking his baggage to Greenbank yesterday, preferring to make certain first that he was to remain there, and while he had delivered the check to the agent here in Grafton at noon with reiterated requests to have the trunk forwarded as soon as possible, it was not likely that he would receive it before the next afternoon.

Football practice at Grafton was quite different from the same thing at Dunning Military Academy, he decided. At Dunning the squad seldom exceeded thirty candidates, while here the field was literally thronged with ambitious youths. At Dunning only the “hefty” ones were encouraged, but at Grafton it seemed that any size or shape of a boy could have a try-out. Only the juniors were barred, Jimmy explained. Ed Brooks—Brooks was a catcher on the baseball nine, Monty learned later—estimated the number of candidates in sight as close on eighty, which was very nearly a third of the total enrollment.

“There won’t be so many next week, though,” he[55] added, pessimistically. “They fade away fast! Say, Bonner’s got a peach of a tan, hasn’t he?”

Bonner, Monty gathered, was the coach, a middle-sized man of just under thirty, alert and quick, with a peremptory voice and a settled scowl. Or, at least, Monty concluded that the scowl was settled until “Dinny” Crowley, the assistant athletic director, had tossed a word to him in passing, and the coach’s face had lighted with a smile that chased the scowl away, and made Monty smile in sympathy. Practice was not very interesting that afternoon. Only the fact that nothing more exciting offered itself kept the spectators there until the squads were sent back to the field house. After that, Jimmy had suggested walking to the river, and they had done so, and Monty had had his first sight of a canoe in actual use, and had mentally registered a vow to become the proud possessor of one at the earliest possible opportunity, and spend all his spare time paddling up and down the little stream.

Still later, he had joined the Morris House fellows on the steps before the supper time, and, without taking much part in the talk, had in a way established himself as one of the crowd. Of the eleven youths, who, with Monty, made up the roster at Morris, seven were what Monty unflatteringly termed “Indians.” Monty would have had some difficulty in explaining just what he meant by the term, but it satisfied him. Perhaps when we remember[56] that in the neighborhood of Windlass City, Wyoming, the noble Red Man is not held in high regard we may form a fair estimate of the seven. Further light is shed by the fact that Monty secretly dubbed Alvin Standart a “Digger.” I believe that the Digger Indian is considered especially low caste and subsists principally on such luxuries as wild roots!

Monty’s verdict regarding the seven was hasty, and later he revised it with regard to several of them. It is a mistake to judge others on the evidence of a day’s acquaintance, and so Monty found it.

After supper he had climbed to the room, Standart being out, and had seated himself in the chair, and propped his feet comfortably, if inelegantly, on the sill to think things over. He decided that he was going to like Grafton School; that, on the whole, he was glad he had substituted it for Mount Morris; that he would have to do some hard studying if he was to secure that promotion in January; that he would certainly “have a stab at it”; that Alvin Standart was a most undesirable roommate, but would have to be made the best of; and that if he got a chance to show this eastern bunch how to play tackle or guard, why, they’d learn something!

The evening sky grew a deeper blue. Somewhere afar off in the direction of the town a light glowed wanly. The air that entered the open window still[57] held the heat of the sun, and, while fresher than before supper, gave no promise of a cool night. Sitting indoors until bedtime did not appeal to Monty, but neither did joining the crowd outside on the steps. He would have looked up Dud and Jimmy again, but didn’t want them to think that he meant to fasten himself on them for the rest of the school year. He supposed that it would be all right to pay a visit to Gowen, but Gowen’s invitation might have been more polite than sincere, and Monty still clung to his belief that easterners were stand-offish and resentful of anything that looked like “butting-in.” But not going over to Lothrop was not, after all, a great deprivation, for, while Monty liked Dud and Jimmy, and was grateful to them for their friendship, they did not fill the want that he felt. Dud and Jimmy had each other, and although they always made him feel that he was welcome, still he realized that he was by no means essential to their happiness, and that what liking they had for him was, so far at least, due to the fact that he was a bit different from the run of the fellows they knew, and that he amused them. What Monty really wanted was a chum of his own, someone he could talk to about the little, intimate things of life, someone who would like him because he was just Monty Crail, and not merely because he was “western” and amusing. It would, he thought; a trifle wistfully, be a wonderful thing to have a[58] real chum. Well, that sort of thing just happened, he supposed. You didn’t go out and find a fellow whose looks you approved of and link arms with him and say, “Hello, hombre, let’s you and I be friends!” Monty grinned at the mental picture of what would happen if he followed such a course.

“Guess,” he muttered, as he dropped his heels from the sill, and heaved himself from the chair, “the poor fellow would drop dead of heart disease!”

He clapped his straw hat to his head—Monty’s hat had no regular position, but stayed wherever it happened to land, even if it happened to be over one ear—“cinched” up his belt another hole, and went downstairs. The group on the steps was reduced to a quartette now, and although no one said anything to the new boy each looked at him as invitingly as dignity permitted. But Monty failed to read invitation in their glances, and so passed on down the steps and turned into the well-worn path that led back between Morris and Fuller across the Green to Front Street and the athletic field. Set in the right-hand pillar of the ornamental gateway was a bronze tablet on which, enclosed by a border of laurel leaves, was the inscription: “Lothrop Field. In Memory of Charles Parkinson Lothrop, Class of 1911.” Monty wondered what deed Charles Parkinson Lothrop had performed to be so honored. And then the real portent of the phrase, “In Memory of” came to him, and his face sobered[59] and the brick and stone pillars and the wrought-iron gates took on a new dignity in his eyes. And standing on the steps that led down to the broad path of the field, looking over the acres of level turf dotted with white figures where the tennis players were wresting a last hour of pleasure from the growing twilight, he thought that the boy could scarcely have had a finer memorial than this.

He paused outside one of the back nets and watched two youths send the balls back and forth with what seemed to him miraculous ease and certainty. The players were in white flannel trousers and white, short-sleeved shirts open at the necks. They wore no caps, and their hair was damp with perspiration. Monty had never played tennis, had scarcely ever watched it played, and the way in which the contenders darted on silent, rubber-shod feet here and there about the court, always anticipating the ball correctly, struck him as surprising. He stood there for quite a while, nibbling a blade of grass, and watched. Other courts held two, three or four players, and through the deepening dusk came the soft pat of ball against racket, the swish of hurrying feet, the occasional voices of the players, mellowed, as it seemed, by the warm twilight. The boys before him played swiftly and silently. They seldom spoke. When they did it was only a few brisk words, as “Hard luck, Hal!” when the effort of one went for naught, or “I’m[60] sorry!” when a ball rolled into an adjacent court and had to be chased. There was no announcing of the score between aces. A wave of a racket seemed to answer for speech in most cases. Probably, thought Monty, they were chums and knew each other so well they didn’t have to speak! He envied them as he turned away at last, and went on along the path between the courts and the curve of the running track. Against the purpling sky the football goals stood out like giant H’s.

The gravel path ended where a backwater of the river, known as the Cove, stretched into the field. It gave forth the stagnant, but not unpleasant, odor of rotting vegetation, and over its quiet surface the mosquitos hovered in swarms, and a dissipated dragon-fly who should have been at home long since darted and swooped above the still reflections. Two skiffs lay half pulled out on the muddy bank, and one held a pair of weather-stained, broken-bladed oars. Monty would have preferred a canoe, and there were plenty of them further down the Cove, as he knew, but canoes were liable to have jealous owners, whereas he couldn’t imagine anyone caring a whit whether he helped himself to one of the leaky skiffs. So he shoved one off, put his feet out of the way of the water that swished about in the bottom, and dropped the oars into the locks. Monty was not a skilled rower, and he ran into the mud twice before he succeeded in getting the craft[61] into the wider part of the Cove. On his left a grove of trees came to the water’s edge, and a few yards of mingled sand and pebbles there had been ironically named The Beach. This was the bathing spot approved of by the faculty, but few except timid juniors used it. The others preferred the boathouse float further up the river. Under the trees, back of the beach, a dozen or more upturned canoes rested, and as Monty went past another was being put in place by returned mariners. Monty could see the boys’ forms only dimly in the gloom of the grove, but their voices and laughter came to him distinctly.

“Lift your end, Hobo! Ata boy! Where’s the other paddle? Oh, all right. I see it.”

“I say, do you know my arm’s lame, Nick? You wouldn’t think a chap would get out of practice, like that, eh?”

“Shows the enervating effect of the soft and flabby life you’ve led this summer. Everyone knows that your English climate is punk, anyway. Come on, and—Geewhilikins! I walked square into a tree!”

“’Ware timber!”