The Project Gutenberg eBook of Rules for compositors and readers at the University Press, Oxford, by Horace Hart

Title: Rules for compositors and readers at the University Press, Oxford

Author: Horace Hart

Contributors: James A. H. Murray

Henry Bradley

Release Date: July 14, 2023 [eBook #71188]

Language: English

Credits: Richard Tonsing, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

This was a reference book for typesetters and proofreaders at the University Press, Oxford. While primarily covering English words and grammar, it also addresses French, German, Latin and Greek text in UP books.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each major section. Many footnotes have more than one anchor; in these cases the second and third anchors have been denoted by {number}.

Most handheld devices are not able to display the German Fraktur (blackletter) characters. These are used primarily in Appendix III, but elsewhere in the book as well. Some devices running epub3 will display these characters correctly. Modern browsers display Unicode Fraktur as expected.

Appendix III addresses German text, both in roman lettering and 𝔉𝔯𝔞𝔨𝔱𝔲𝔯 (blackletter). There are many digraphs (a pair of letters printed as one type-letter) in 𝔉𝔯𝔞𝔨𝔱𝔲𝔯 text in this book. They do not have a separate Unicode representation, and are indicated by the letter pair in [ ], for example [𝔠𝔥], [𝔠𝔨], [ſ𝔱], [ſ𝔷].

The printed long-s character, ſ in roman lettering, does not have a blackletter Unicode encoding. The roman ſ has been used in preference to the Fraktur short 𝔰 in all the relevant text and digraphs, such as 𝔈𝔯 ſ𝔞𝔤𝔱𝔢 — 𝔫𝔦[𝔠𝔥]𝔱 𝔬𝔥𝔫𝔢 ℨ𝔞𝔲𝔡𝔢𝔯𝔫 —, 𝔡𝔞[ſ𝔷] 𝔢𝔯 𝔤𝔢𝔥𝔢𝔫 𝔪𝔲̈ſſ𝔢.

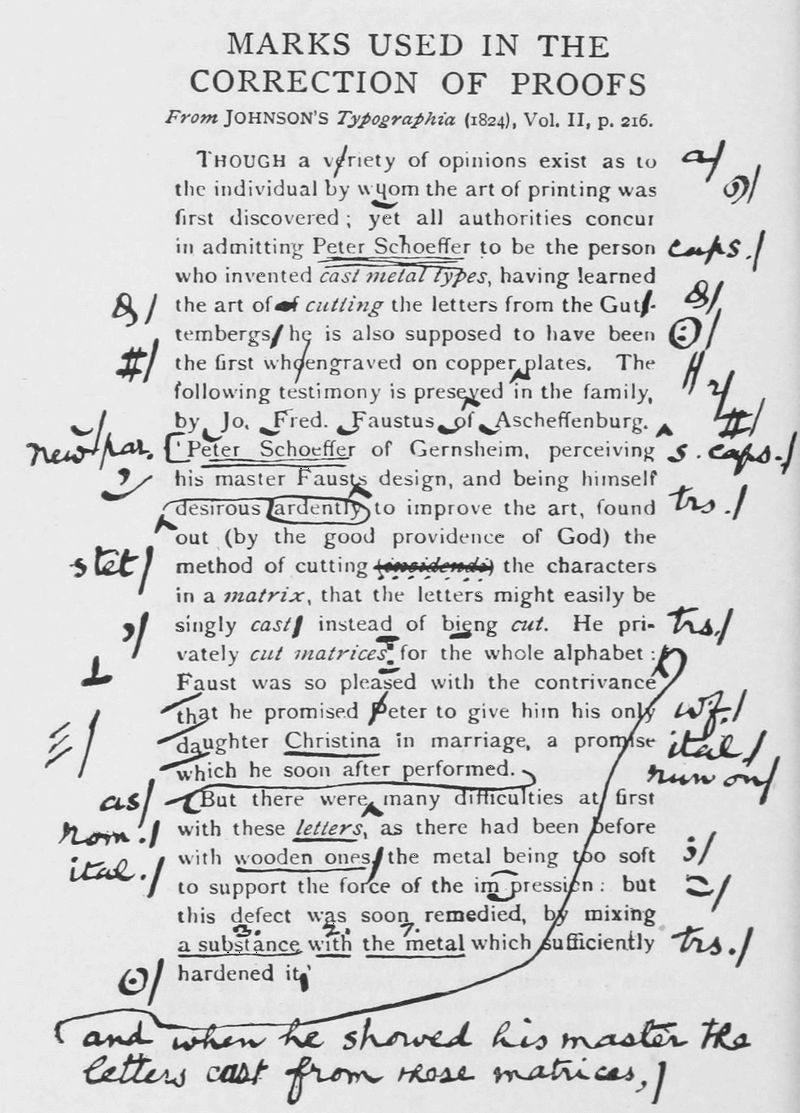

Page 98 shows a page of printed text with dozens of handwritten proofreading correction marks and notes. Page 99 has the corrected version of that marked-up text.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain. It is based on the original cover, which was damaged.

BY

HORACE HART, M.A.

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

THE ENGLISH SPELLINGS REVISED BY

SIR JAMES A. H. MURRAY, M.A., D.C.L., LL.D., D.Litt.

AND

HENRY BRADLEY, M.A., Ph.D.

EDITORS OF THE OXFORD DICTIONARY

TWENTY-SECOND EDITION

(THE EIGHTH FOR PUBLICATION)

LONDON

HENRY FROWDE, AMEN CORNER, E.C.

OXFORD: 116 HIGH STREET

1912

These Rules apply generally, and they are only to be departed from when the written instructions which accompany copy for a new book contain an express direction that they are not to be followed in certain specified cases.

First Edition, April 1893. Reprinted, Dec. 1894.

Reprinted with alterations—

Jan. 1895; Feb. 1895; Jan. 1896; July 1897;

Sept. 1898; April 1899; Aug. 1899; Jan. 1901;

Feb. 1901; Jan. 1902; March 1902; May 1903.

Fifteenth Edition, revised and enlarged

the first for publication March 1904.

Sixteenth Edition, April 1904.

Seventeenth Edition, April 1904.

Eighteenth Edition, revised and enlarged July 1904.

Nineteenth Edition, July 1905.

Twentieth Edition, July 1907.

Twenty-first Edition, January 1909.

Twenty-second Edition, January 1912.

It is quite clearly set out on the title-page in previous editions of these Rules and Examples, that they were intended especially for Compositors and Readers at the Clarendon Press. Consequently it seems necessary to explain why an edition or impression is now offered to so much of the General Public as is interested in the technicalities of Typography, or wishes to be guided to a choice amidst alternative spellings.

On the production of the First Edition at the Oxford Press, copies were placed at the disposal of all Readers, Compositors, and Compositor-apprentices; and other copies found their way into the possession of Authors and Editors of books then in the printers’ hands. Subsequently, friends of authors, and readers and compositors in other printing-offices, began to ask for copies, which were always supplied without charge. By and by applications for copies were received from persons who had no absolute claim to be supplied gratuitously; but as many of such requests came from Officials of the King’s Government at Home, in the Colonies, and in India, it was thought advisable, on the whole, to continue the practice of presentation.

Recently, however, it became known that copies of the booklet were on sale in London.[4] A correspondent wrote that he had just bought a copy ‘at the Stores’; and as it seems more than complaisant to provide gratuitously what may afterwards be sold for profit, there is no alternative but to publish this little book.

As to the origin and progress of the work, it was begun in 1864, when the compiler was a member of the London Association of Correctors of the Press. With the assistance of a small band of fellow members employed in the same printing-office as himself, a first list of examples was drawn up, to furnish a working basis.

Fate so ordained that, in course of years, the writer became in succession general manager of three London printing-houses. In each of these institutions additions were made to his selected list of words, which, in this way, gradually expanded—embodying what compositors term ‘the Rule of the House’.

In 1883, as Controller of the Oxford Press, the compiler began afresh the work of adaptation; but pressure of other duties deferred its completion nearly ten years, for the first edition is dated 1893. Even at that date the book lacked the seal of final approval, being only part of a system of printing-office management.

In due course, Sir J. A. H. Murray and Dr. Henry Bradley, editors of[5] the Oxford Dictionary, were kind enough to revise and approve all the English spellings. Bearing the stamp of their sanction, the booklet has an authority which it could not otherwise have claimed.

To later editions Professor Robinson Ellis and Mr. H. Stuart Jones contributed two appendices, containing instructions for the Division of Words in Latin and Greek; and the section on the German Language was revised by Dr. Karl Breul, Reader in Germanic in the University of Cambridge.

The present issue is characterized by many additions and some rearrangement. The compiler has encouraged the proofreaders of the University Press from time to time to keep memoranda of troublesome words in frequent—or indeed in occasional—use, not recorded in previous issues of the ‘Rules’, and to make notes of the mode of printing them which is decided on. As each edition of the book becomes exhausted such words are reconsidered, and their approved form finally incorporated into the pages of the forthcoming edition. The same remark applies to new words which appear unexpectedly, like new planets, and take their place in what Sir James Murray calls the ‘World of Words’. Such instances as[6] air-man, sabotage, stepney-wheel, will occur to every newspaper reader.

Lastly, it ought to be added that in one or two cases, a particular way of spelling a word or punctuating a sentence has been changed. This does not generally mean that an error has been discovered in the ‘Rules’; but rather that the fashion has altered, and that it is necessary to guide the compositor accordingly.

H. H.

January 1912.

| Page | ||

| Some Words ending in -able | 9 | |

| Some Words ending in -ible | 11 | |

| Some Words ending in -ise or -ize | 12 | |

| Some Alternative or Difficult Spellings, arranged in alphabetical order | 15 | |

| Some Words ending in -ment | 24 | |

| Hyphened and non-hyphened Words | 25 | |

| Doubling Consonants with Suffixes | 29 | |

| Formation of Plurals in Words of Foreign Origin | 31 | |

| Errata, Erratum | 33 | |

| Plurals of Nouns ending in -o | 34 | |

| Foreign Words and Phrases, when to be set in Roman and when in Italic | 35 | |

| Spellings of Fifteenth to Seventeenth Century Writers | 38 | |

| Phonetic Spellings | 38 | |

| A or An | 39 | |

| O and Oh | 39 | |

| Nor and Or | 40 | |

| Vowel-ligatures (Æ and Œ) | 41 | |

| Contractions | 41 | |

| Poetry: Words ending in -ed, -èd, &c. | 45 | |

| Capital Letters | 46 | |

| Lower-case Initials | 47 | |

| Small Capitals | 47 | |

| Special Signs or Symbols | 48 | |

| Spacing | 49 | |

| Italic Type | 50 | |

| References to Authorities | 52 | |

| [8] Division of Words—English, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish | 53 | |

| Punctuation | 55 | |

| Figures and Numerals | 68 | |

| Appendix I | } | 71 |

| Possessive Case of Proper Names | ||

| By Sir J. A. H. Murray | ||

| Appendix II | } | 73 |

| Works in the French Language | ||

| Appendix III | } | 88 |

| Works in the German Language | ||

| Appendix IV | } | 95 |

| Division of Latin Words | ||

| By Prof. Robinson Ellis | ||

| Appendix V | } | 97 |

| Division of Greek Words | ||

| By Mr. H. Stuart Jones | ||

| Marks used in the Correction of Proofs | 98 | |

| Some English Names of Types | 100 | |

| GENERAL INDEX | 103 |

RULES FOR SETTING UP

ENGLISH WORKS[1]

Words ending in silent e generally

lose the e when -able is added, as—

But this rule is open to exceptions upon which authorities are not agreed. The following spellings are in The Oxford Dictionary, and must be followed:

If -able is preceded by ce or ge, the e should be retained, to preserve the soft sound of c or g, as—

Words ending in double ee retain both letters, as—agreeable.

In words of English formation, a final consonant is usually doubled before -able, as—

[1] At Oxford especially, it must always be remembered that the Bible has a spelling of its own; and that in Bible and Prayer Book printing the Oxford standards are to be exactly followed.—H. H.

[2] For an authoritative statement on the whole subject see The Oxford Dictionary, Vol. I, p. 910, art. -ble.

The principle underlying the difference between words ending in -able and those ending in -ible is thus stated by The Oxford English Dictionary (s.v. -ble): ‘In English there is a prevalent feeling for retaining -ible wherever there was or might be a Latin -ibilis, while -able is used for words of distinctly French or English origin.’ The following are examples of words ending in -ible:

The following spellings are those adopted for The Oxford Dictionary:

MORE OR LESS IN DAILY USE, ARRANGED IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER FOR EASY REFERENCE

[3] Compound words of this class form their plurals by a change in the first word.—H. H.

[4] ‘The Eng. form alinement is preferable to alignment, a bad spelling of the French.’—O.E.D.

[5] But the k is retained in The Oxford Almanack, following the first publication in 1674.—H. H.

[6] ‘In derivatives formed from words ending in c, by adding a termination beginning with e, i, or y, the letter k is inserted after the c, in order that the latter may not be inaccurately pronounced like s before the following vowel.’—Webster.

[7] In The Oxford Dictionary, Vol. I, p. 598, Sir James Murray says, ‘The spelling ax is better on every ground ... than axe, which has of late become prevalent.’ (But as authors generally still call for the commoner spelling, compositors must follow it.—H. H.)

[8] The sign [¨] sometimes placed over the second of two vowels in an English word to indicate that they are to be pronounced separately, is so called by a compositor. By the way, this sign is now used only for learned or foreign words; not in chaos or in dais, for instance. Naïve and naïveté still require it, however (see pp. 35, 37).—H. H.

[9] In 1896, Mr. W. E. Gladstone, not being aware of this rule, wished to include, in a list of errata for insertion in Vol. II of Butler’s Works, an alteration of the spelling, in Vol. I, of the word ‘forgo’. On receipt of his direction to make the alteration, I sent Mr. Gladstone a copy of Skeat’s Dictionary to show that ‘forgo’, in the sense in which he was using the word, was right, and could not be corrected; but it was only after reference to Sir James Murray that Mr. Gladstone wrote to me, ‘Personally I am inclined to prefer forego, on its merits; but authority must carry the day. I give in.’—H. H.

[10] ‘This is now usual. See O.E.D., s.v. Enq-.’—J. A. H. M.

[11] But Linnean Society.

[12] Compound words formed of two nouns connected by a preposition form their plurals by a change in the first word.—H. H.

[13] Sir James Murray thinks that where there is any ambiguity a hyphen may also be used, as ‘bad printers’-errors,’—H. H.

[14] ‘Etymology is in favour of reflexion, but usage seems to be overpoweringly in favour of the other spelling.’—H. B.

[15] The older form ‘rime’ is occasionally used by modern writers, and in such cases the copy should be followed.—H. H.

[16] ‘Shakspere is preferable, as—The New Shakspere Society.’—J. A. H. M. (But the Clarendon Press is already committed to the more extended spelling.—H. H.)

[17] The ‘sycomore’ of the Bible is a different tree—the fig-mulberry.—H. H.

[18] It is generally agreed that words ending in ll should drop one l before less (as in skilless) and ly; but there is not the same agreement in dropping an l before ness.—H. H.

[19] ‘But the bicycle-makers have apparently adopted the non-etymological tyre.’—J. A. H. M.

In words ending in -ment print the e when it occurs in the preceding syllable, as—abridgement, acknowledgement, judgement, lodgement.[20] But omit the e in development, envelopment, in accordance with the spelling of the verbal forms develop, envelop.

[20] ‘I protest against the unscholarly habit of omitting it from “abridgement”, “acknowledgement”, “judgement”, “lodgement”,—which is against all analogy, etymology, and orthoepy, since elsewhere g is hard in English when not followed by e or i. I think the University Press ought to set a scholarly example, instead of following the ignorant to do ill, for the sake of saving four e’s. The word “judgement” has been spelt in the Revised Version correctly.’—J. A. H. M.

The hyphen need not, as a rule, be used to join an adverb to the adjective which it qualifies: as in—

a beautifully furnished house,

a well calculated scheme.

When the word might not at once be recognized as an adverb, use the hyphen: as—

a well-known statesman,

an ill-built house,

a new-found country,

the best-known proverb,

a good-sized room.

When an adverb qualifies a predicate, the hyphen should not be used: as—

this fact is well known.

Where either (1) a noun and adjective or participle, or (2) an adjective and a noun, in combination, are used as a compound adjective, the hyphen should be used:

a poverty-stricken family, a blood-red hand, a nineteenth-century invention.

A compound noun which has but one accent, and from familiar use has become one word, requires no hyphen. Examples:

The following should also be printed as one word:

Compound words of more than one accent, as—ápple-trée, chérry-píe, grável-wálk, wíll-o’-the-wisp, as well as others which follow, require hyphens:

Half an inch, half a dozen, &c., require no hyphens. Print the following also without hyphens:

[21] See Oxford Dict., Vol. I, page xiii, art. ‘Combinations’, where Sir James Murray writes: ‘In many combinations the hyphen becomes an expression of unification of sense. When this unification and specialization has proceeded so far that we no longer analyse the combination into its elements, but take it in as a whole, as in blackberry, postman, newspaper, pronouncing it in speech with a single accent, the hyphen is usually omitted, and the fully developed compound is written as a single word. But as this also is a question of degree, there are necessarily many compounds as to which usage has not yet determined whether they are to be written with the hyphen or as single words.’

And again, in The Schoolmasters’ Year-book for 1903 Sir James Murray writes: ‘There is no rule, propriety, or consensus of usage in English for the use or absence of the hyphen, except in cases where grammar or sense is concerned; as in a day well remembered, but a well-remembered day, the sea of a deep green, a deep-green sea, a baby little expected, a little-expected baby, not a deep green sea, a little expected baby.... Avoid Headmaster, because this implies one stress, Héadmaster, and would analogically mean “master of heads”, like schoolmaster, ironmaster.... Of course the hyphen comes in at once in combinations and derivatives, as head-mastership.’

[22] ‘The hyphen is often used when a writer wishes to mark the fact that he is using not a well-known compound verb, but re- as a living prefix attached to a simple verb (re-pair = pair again); also usually before e (re-emerge), and sometimes before other vowels (re-assure, usually reassure); also when the idea of repetition is to be emphasized, especially in such phrases as make and re-make.’—The Concise Oxford Dictionary (1911), p. 694.

[23] As, up-to-date records; but print ‘the records are up to date’.—H. H.

Words of one syllable, ending with one consonant preceded by one vowel, double that consonant on adding -ed or -ing: e.g.

| drop | dropped | dropping |

| fit | fitted | fitting |

| stop | stopped | stopping |

Words of more than one syllable, ending with one consonant preceded by one vowel, and accented on the last syllable, double that consonant on adding -ed or -ing: e.g.

| allot | allotted | allotting |

| commit | committed | committing |

| infer | inferred | inferring |

| trepan | trepanned | trepanning |

But words of this class not accented on the last syllable, do not double the last consonant[25] on adding -ed, -ing: e.g.

In words ending in -l, the final consonant is generally doubled, whether accented on the last syllable or not: e.g.

[25] ‘We must, however, still except the words ending in -el, as levelled, -er, -ing; travelled, -er, -ing; and also worshipped, -er, -ing.’—J. A. H. M.

Plurals of nouns taken into English from other languages sometimes follow the laws of inflexion of those languages. But often, in non-technical works, additional forms are used, constructed after the English manner. Print as below, in cases where the author does not object. In scientific works the scientific method must of course prevail:

| SING. | addendum | PL. | addenda[26] |

| alkali | alkalis | ||

| alumnus | alumni | ||

| amanuensis | amanuenses | ||

| analysis | analyses | ||

| animalculum | animalcula | ||

| antithesis | antitheses | ||

| apex | apices | ||

| appendix | appendices | ||

| arcanum | arcana | ||

| automaton | automata | ||

| axis | axes | ||

| bandit | banditti | ||

| basis | bases | ||

| beau | beaux | ||

| bronchus | bronchi | ||

| calculus | calculi | ||

| calix | calices | ||

| chrysalis | chrysalises | ||

| coagulum | coagula | ||

| corrigendum | corrigenda{26} | ||

| cortex | cortices | ||

| crisis | crises | ||

| [32] | criterion | criteria | |

| datum | data | ||

| desideratum | desiderata | ||

| dilettante | dilettanti | ||

| effluvium | effluvia | ||

| elenchus | elenchi | ||

| ellipsis | ellipses | ||

| ephemera | ephemerae | ||

| epithalamium | epithalamia | ||

| equinox | equinoxes | ||

| erratum | errata | ||

| focus | focuses (fam.) | ||

| formula | formulae | ||

| fungus | fungi | ||

| genius | geniuses[27] | ||

| (meaning a person or persons of genius) | |||

| genus | genera | ||

| helix | helices | ||

| hypothesis | hypotheses | ||

| ignis fatuus | ignes fatui | ||

| index | indexes[28] | ||

| iris | irises | ||

| lamina | laminae | ||

| larva | larvae | ||

| lemma | lemmas[29] | ||

| libretto | libretti | ||

| matrix | matrices | ||

| maximum | maxima | ||

| medium | mediums (fam.) | ||

| memorandum | memorandums[30] | ||

| (meaning a written note or notes) | |||

| [33] | metamorphosis | metamorphoses | |

| miasma | miasmata | ||

| minimum | minima | ||

| nebula | nebulae | ||

| nucleus | nuclei | ||

| oasis | oases | ||

| papilla | papillae | ||

| parenthesis | parentheses | ||

| parhelion | parhelia | ||

| phenomenon | phenomena | ||

| radius | radii | ||

| radix | radices | ||

| sanatorium | sanatoria | ||

| scholium | scholia | ||

| spectrum | spectra | ||

| speculum | specula | ||

| stamen | stamens | ||

| stimulus | stimuli | ||

| stratum | strata | ||

| synopsis | synopses | ||

| terminus | termini | ||

| thesis | theses | ||

| virtuoso | virtuosi | ||

| volsella | volsellae | ||

| vortex | vortexes (fam.) | ||

[27] Genius, in the sense of a tutelary spirit, must of course have the plural genii.—H. H.

[28] In scholarly works, indices is often preferred, and in the mathematical sense must always be used.—H. H.

[29] But lemmata in botany or embryology.—H. H.

[30] But in a collective or special sense we must print memoranda.—H. H.

Do not be guilty of the absurd mistake of printing ‘Errata’ as a heading for a single correction. When a list of errors has been dealt with, by printing cancel pages and otherwise, so that only one error remains, take care to alter the heading from ‘Errata’ to ‘Erratum’. The same remarks apply to Addenda and Addendum, Corrigenda and Corrigendum.

The plurals of nouns ending in -o, owing to the absence of any settled system, are often confusing. The Concise Oxford Dictionary says (p. vi): ‘It may perhaps be laid down that on the one hand words of which the plural is very commonly used, as potato, have almost invariably -oes, and on the other hand words still felt to be foreign or of abnormal form, as soprano, chromo, have almost invariably -os.’ The following is a short list, showing spellings preferred:

Print the following anglicized words in roman type:

The following to be printed in italic:

The modern practice is to omit accents from Latin words.

For further directions as to the use of italic in foreign words and phrases see pp. 50-1.

[31] For this and nearly all similar words, the proper accents are to be used, whether the foreign words be anglicized or not.—H. H.

[32] Employee is more legitimate when it is used in contrast with the English word employer.—H. H.

[33] Omit the accent from étiquette.—H. H.

[34] Omit the hyphen from rendez-vous.—H. H.

When it is necessary to reproduce the spellings and printed forms of old writers the following rules should be observed:

Initial u is printed v, as in vnderstande. Also in such combinations as wherevpon.

Medial v is printed u, as in haue, euer.

Initial and medial j are printed i, as in iealousie, iniurie.

In capitals the U is non-existent, and should always be printed with a V, initially and medially, as VNIVERSITY, FAVLCONRIE.

In ye and yt the second letter should be a superior, and without a full point.

Some newspapers print phonetic spellings, such as program, hight (to describe altitude), catalog, &c. But the practice has insufficient authority, and can be followed only by special direction.

Print a, not an, before contractions beginning with a consonant: e.g. a L.C.C. case, a MS. version.

[36] This is in accordance with what seems to be the preponderance of modern usage. Originally the cover of The Oxford Dictionary had ‘a historical’, and the whole question will be found fully treated in that work, arts. A, An, and H.—H. H.

When used in addressing persons or things the vocative ‘O’ is printed with a capital and without any point following it; e.g. ‘O mighty Caesar! dost thou lie so low’; ‘O world! thou wast the forest to this hart’; ‘O most bloody sight!’ Similarly, ‘O Lord’, ‘O God’, ‘O sir’. But when not used in the vocative, the spelling should be ‘Oh’, and separated[40] from what follows by a punctuation mark; e.g. ‘Oh, pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth’; ‘For if you should, oh! what would become of it?’

Print: (1) Neither one nor the other; neither Jew nor Greek; neither Peter nor James. (2) Either one or the other; either Jew or Greek; either Peter or James.

Never print: Neither one or the other; neither Peter or James;—but when the sentence is continued to a further comparison, nor and or must be printed (in the continuation) according to the sense.[37]

Likewise note that the verb should be in the singular, as ‘Neither Oxford nor Reading is stated to have been represented’.

[37] The necessity of giving strict attention to this rule was once exemplified in my experience, when the printing of a fine quarto was passing through my hands in 1882. The author desired to say in the preface, ‘The writer neither dares nor desires to claim for it the dignity or cumber it with the difficulty of an historical novel’ (Lorna Doone, by R. D. Blackmore, 4to, 1883). The printer’s reader inserted a letter n before the or; the author deleted the n, and thought he had got rid of it; but at the last moment the press reader inserted it again; and the word was printed as nor, to the exasperation of the author, who did not mince his words when he found out what had happened.—H. H.

The combinations ae and oe should each be printed as two letters in Latin and Greek words, e.g. Aeneid, Aeschylus, Caesar, Oedipus; and in English, as mediaeval, phoenix. But in Old-English and in French words use the ligatures æ, œ, as Ælfred, Cædmon, manœuvre.

NOTE.—Some abbreviations of Latin words such as ad loc., &c., to be set in roman, are shown on page 51.

Names of the books of the Bible as abbreviated where necessary:

Old Testament.

New Testament.

Apocrypha.

Abbreviate the names of the months:

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | June |

| July | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. |

Where the name of a county is abbreviated, as Yorks., Cambs., Berks., Oxon., use a full point; but print Hants (no full point) because it is not a modern abbreviation.

4to, 8vo, 12mo,[39] &c. (sizes of books), are symbols, and should have no full point. A parallel case is that of 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and so on, which also need no full points.

Print lb. for both sing. and pl.; not lbs. Also omit the plural -s in the following: cm., cwt., dwt., gr., grm., in., min., mm., oz.

When beginning a footnote, the abbreviations e.g., i.e., p. or pp., and so on, to be all in lower-case.

Use ETC. in a cap. line and ETC. in a small cap. line where an ampersand (&) will not range. Otherwise print &c.; and Longmans, Green & Co.; with no comma before ampersand in the name of a firm.

Print the symbolic letters I O U, without full points.

The points of the compass, N. E. S. W., when separately used, to have a full point: but print NE., NNW. These letters to be used only in geographical or similar matter: do not, even if N. is in the copy, use the contraction in ordinary composition; print ‘Woodstock is eight miles north of Carfax’.

MS. = manuscript, MSS. = manuscripts, to be spelt out when used in a general sense. But in printing bibliographical details, and in references to particular manuscripts, the contracted forms should be used; e.g. the Worcester MS., the Harleian MSS., Add. MS. 25642.

Print PS. (not P.S.) for postscript or postscriptum; MM. (messieurs), SS. not S.S. (steamship); but H.M.S. (His Majesty’s Ship); H.R.H.; I.W. (Isle of Wight); N.B., Q.E.D., and R.S.V.P., because more than one word is contracted.

Print ME. and OE. in philological works for Middle English and Old English. When an author prefers M.E., O.E., do not put a space between the letters.

Abbreviations of titles, such as M.P., D.D., M.A., or of occupations or parties, such as I.C.S., I.L.P., to have no space between the letters.

When titles of books are represented by initials, put a thin space only between each letter; e.g. J. T. S., S. B. E.

Mr., Mrs., Dr., &c. must be printed with a full point, but not Mme, Mlle.

In printing S. or St. for Saint, the compositor must be guided by the manuscript. Ordinarily St. should be used, but if S. is consistently written this must be assumed as the form in which the author wishes it printed.

Print Bt. for Baronet, and Kt. for Knight.

Apostrophes in similar abbreviations to the following should join close up to the letters—don’t, ’em, haven’t, o’er, shan’t, shouldn’t, ’tis, won’t, there’ll, I’d, I’ll, we’ll.[40]

An apostrophe should not be used with hers, ours, theirs, yours.

Apostrophes in Place-Names.[41]—1. Use an apostrophe after the ‘s’ in Queens’ College (Cambs.). But

2. Use an apostrophe before the ‘s’ in Connah’s Quay (Flints.), Hunter’s Quay (N.B.), Orme’s Head (Carn.), Queen’s Coll. (Oxon.), St. Abb’s Head (N.B.), St. John’s (Newfoundland), St. John’s Wood (London), St. Mary’s Loch (N.B.), St. Michael’s Mount (Cornwall), St. Mungo’s Well (Knaresboro’), St. Peter’s (Sydney, N.S.W.).

3. Do not use an apostrophe in—All Souls (Oxon.), Bury St. Edmunds, Husbands Bosworth (Rugby), Johns Hopkins University (U.S.A.), Millers Dale (Derby), Owens College (Manchester), St. Albans, St. Andrews, St. Bees, St. Boswells, St. Davids, St. Helens (Lancs., and district in London), St. Heliers (Jersey), St. Ives (Hunts. and Cornwall), St. Kitts (St. Christopher Island, W.I.), St. Leonards, St. Neots (Hunts., but St. Neot, Cornwall), Somers Town (London).

[38] The separately written oe, ae are ‘digraphs’, because the sounds they represent are in modern pronunciation not diphthongs, though they were such in classical Latin; but ch, ph, sh are also digraphs. Æ, æ, Œ, œ, are rather single letters than digraphs, though they might be called ligatured digraphs.—H. B.

[39] To justify the use in ordinary printing of these symbols (as against the use of 4o, 8o, 12o, a prevailing French fashion which is preferred by some writers), it may suffice to say that the ablative cases of the ordinal numbers quartus, octavus, duodecimus, namely quarto, octavo, duodecimo, are according to popular usage represented by the forms or symbols 4to, 8vo, 12mo; just as by the same usage we print 1st and 2nd as forms or symbols of the English words first and second.—H. H.

[41] The selection is arbitrary; but the examples are given on the authority of the Oxford University and Cambridge University Calendars, the Post Office Guide, Bartholomew’s Gazetteer, Bradshaw’s Railway Guide, Crockford’s Clerical Directory, Keith Johnston’s Gazetteer, and Stubbs’s Hotel Guide.

Words ending in -ed are to be spelt so in all cases; and with a grave accent when the syllable is separately pronounced, thus—èd. (’d is not to be used.)

This applies to poetical quotations introduced into prose matter, and to new works. It must not apply to reprints of standard authors, nor to quotations in works which reproduce old spellings, &c.

Whenever a poetic quotation, whether in the same type as the text or not, is given a line (or more) to itself, it is not to be placed within quotation marks; but when the line of poetry runs on with the prose then quotation marks are to be used.

On spacing poetry, see p. 49.

Avoid beginning words with capitals as much as possible; but use them in the following and similar cases:

Act, when referring to Act of Parliament or Acts of a play; also in Baptist, Christian, Nonconformist, Presbyterian, Puritan, Liberal, Conservative, and all denominational terms and names of parties.

His Majesty, Her Royal Highness, &c.

The King of England, the Prince of Wales.

The Duke of Wellington, Bishop of Oxford, Sir Roger Tichborne, &c.

British Army, German Navy.

Christmas Day, Lady Day, &c.

Dark Ages, Middle Ages.

House of Commons, Parliament, &c.

Government, Cabinet, Speaker.

In geography: Sun, Earth, Equator, the Continent.

In geological names: Upper Greensand, London Clay, Tertiary, Lias, &c.

In names of streets, roads, &c., as—Chandos Street, Trafalgar Square, Kingston Road, Addison’s Walk, Norreys Avenue.

Figure, Number, Plate (Fig., No., Pl.), should each begin with a capital, whether contracted or not, unless special instructions are given to the contrary.

Pronouns referring to the Deity should begin with capitals—He, Him, His, Me, Mine, My, Thee, Thine, Thou; but print—who, whom, and whose.

Also capitalize the less common adjectives derived from proper names; e.g. Homeric, Platonic.

FOR ANGLICIZED WORDS, ETC.

christianize, frenchified, herculean, italic, laconic, latinize, puritanic, quixotic, roman, satanic, tantalize, vulcanize.

Also for the more common words derived from proper names, as—boycott, doily, guernsey, hackney, hansom-cab, holland, inverness, japanning, latinity, may (blossom), morocco, russia, stepney-wheel.

When ‘In the press’ occurs in publishers’ announcements, print ‘press’ with a lower-case initial.

Put a hair space between the letters of contractions in small capitals:

| A.U.C. Anno urbis conditae | |

| A.D. Anno Domini | A.H. Anno Hegirae |

| A.M. Anno mundi | B.C. Before Christ. |

a.m.[42] (ante meridiem), p.m.{42} (post meridiem), should be lower-case, except in lines of caps. or small caps.

When small caps, are used at foot of title-page, print thus: M DCCCC IV[43]

Text references to caps. in plates and woodcuts to be in small caps.

The first word in each chapter of a book is to be in small caps. and the first line usually indented one em; but this does not apply to works in which the matter is broken up into many sections, nor to cases where large initials are used. (See p. 50 as to indentation.)

[42] It is a common error to suppose that these initials stand for ante-meridian and post-meridian. Thus, Charles Dickens represents one of his characters in Pickwick as saying ‘Curious circumstance about those initials, sir,’ said Mr. Magnus. ‘You will observe—P.M.—post meridian. In hasty notes to intimate acquaintance, I sometimes sign myself “Afternoon”. It amuses my friends very much, Mr. Pickwick.’—Dickens, Pickwick Papers, p. 367. Oxford edit., 1903.—H. H.

[43] ‘Or better M CM IV’—J. A. H. M.

The signs + (plus), - (minus), = (equal to), > (‘larger than’, in etymology signifying ‘gives’ or ‘has given’), < (‘smaller than’, in etymology signifying ‘derived from’), are now often used in printing ordinary scientific works, and not in those only which are mathematical or arithmetical.

In such instances +, -, =, >, <, should in the matter of spacing be treated as words are treated. For instance, in—

spectabilis, Bœrl. l. c. (= Haasia spectabilis)

the = belongs to ‘spectabilis’ as much as to ‘Haasia’, and the sign should not be put close to ‘Haasia’. A thin space only should be used.

In Philological works an asterisk * prefixed to a word signifies a reconstructed form, and must be so printed; a dagger † signifies an obsolete word. The latter sign, placed before a person’s name, signifies deceased.

In Medical books the formulae are set in lower-case letters, j being used for i both singly and in the final letter, e.g. gr.j (one grain), ℥viij (eight ounces), ʒiij (three drachms), ℈iij (three scruples), ♏︎iiij (four minims).

Spacing ought to be even. Paragraphs are not to be widely spaced for the sake of making breaklines. When the last line but one of a paragraph is widely spaced and the first line of the next paragraph is more than thick-spaced, extra spaces should be used between the words in the intermediate breakline. Such spaces should not exceed en quads, nor be increased if by so doing the line would be driven full out.

In general, close spacing is to be preferred; but this must be regulated proportionately to the manner in which a work is leaded.

Breaklines should consist of more than five letters, except in narrow measures. But take care that bad spacing is not thereby necessitated.

Poetical quotations, and poetry generally when in wide measure, should be spaced with en quadrats. But this must not be applied to reprints of sixteenth and seventeenth century books: in such cases a thick space only should be used.

Avoid (especially in full measures) printing at the ends of lines—a, l., ll., p. or pp., I (when a pronoun).

Capt., Dr., Esq., Mr., Rev., St., and so on, should not be separated from names; nor should initials be divided: e.g. Mr. W. E. | Gladstone; not Mr. W. | E. Gladstone.

Thin spaces before apostrophes, e.g. that’s (for ‘that is’), boy’s (for ‘boy is’), to distinguish abbreviations from the possessive case.

In Greek, Latin, and Italian, when a vowel is omitted at the end of a word (denoted[50] by an apostrophe), put a space before the word which immediately follows.

Hair spaces to be placed between lower-case contractions, as in e.g., i.e., q.v.

Indentation of first lines of paragraphs should be one em for full measures in 8vo and smaller books. In 4to and larger books the indentation should be increased.

Sub-indentation should be proportionate; and the rule for all indentation is not to drive too far in.

Quotations in prose, as a rule, should not be broken off from the text unless the matter exceeds three lines.

Use great care in spacing out a page, and let it not be too open.

Underlines, wherever possible, to be in one line.

NOTE.—A list of foreign and anglicized words and phrases, showing which should be printed in roman and which in italic, is given on pp. 35-7.

In many works it is now common to print titles of books in italic, instead of in inverted commas. This must be determined by the directions given with the copy, but the practice must be uniform throughout the work.

Words or phrases cited from foreign languages (unless anglicized) should be in italic.

Short extracts from books, whether foreign or English, should not be in italic but in roman (between inverted commas, or otherwise, as directed on p. 63).

Names of periodicals should be in italic. Inconsistency is often caused by the prefix[51] The being sometimes printed in italic, and sometimes roman. As a rule, print the definite article in roman, as the Standard, the Daily News. The Times is to be an exception, as that newspaper prefers to have it so. The, if it is part of the title of a book, should also be in italic letters.

Print names of ships[44] in italic. In this case, print ‘the’ in roman, as it is often uncertain whether ‘the’ is part of the title or not. For example, ‘the King George’, ‘the Revenge’; also put other prefixes in roman, as ‘H.M.S. Dreadnought’.

ad loc., cf., e.g., et seq., ib., ibid., id., i.e., loc. cit., q.v., viz.[45], not to be in italic. Print c. (= circa), ante, infra, passim, post, supra, &c.

Italic s. and d. to be generally used to express shillings and pence; and the sign £ (except in special cases) to express the pound sterling. But in catalogues and similar work the diagonal sign / or ‘shilling-mark’ is sometimes preferred to divide figures representing shillings and pence. The same sign is occasionally used in dates, as 4/2/04.

In Mathematical works, theorems are usually printed in italic.

[44] Italicizing the names of ships is thus recognized by Victor Hugo: ‘Il l’avait nommé Durande. La Durande,—nous ne l’appellerons plus autrement. On nous permettra également, quel que soit l’usage typographique, de ne point souligner ce nom Durande, nous conformant en cela à la pensée de Mess Lethierry pour qui la Durande était presque une personne.’—V. Hugo, Travailleurs de la mer, 3rd (1866) edit., Vol. I, p. 129.—H. H.

[45] This expression, although a symbol rather than an abbreviation, must be printed with a full point after the z.—H. H.

Citation of authorities at the end of quotations should be printed thus: Homer, Odyssey, ii. 15, but print Hor. Carm. ii. 14. 2; Hom. Od. iv. 272. This applies chiefly to quotations at the heads of chapters. It does not refer to frequent citations in notes, where the author’s name is usually in lower-case letters, and the title of the book sometimes printed in roman.

As an example: Stubbs, Constitutional History, vol. ii, p. 98; or the more contracted form—Stubbs, Const. Hist. ii. 98, will do equally well; but, whichever style is adopted after an examination of the manuscript, it must be uniform throughout the work.

References to the Bible in ordinary works to be printed thus—Exod. xxxii. 32; xxxvii. 2. (For full list of contractions see p. 41.)

References to Shakespeare’s plays thus—I Henry VI, III. ii. 14; and so with the references to Act, scene, and line in other dramatic writings.

Likewise in references to poems divided into books, cantos, and lines; e.g. Spenser, Faerie Queene, IV. xxvi. 35.

References to MSS. or unprinted documents should be in roman.

As to use of italic, see also above, p. 50.

I. English

Such divisions as en-, de-, or in- to be allowed only in very narrow measures, and there exceptionally.

Disyllables, as ‘into’, ‘until’, &c., are only to be divided in very narrow measures.

The following divisions to be preferred:

Avoid such divisions as—

but put starva-tion, &c.

The principle is that the part of the word left at the end of a line should suggest the part commencing the next line. Thus the word ‘happiness’ should be divided happi-ness, not hap-piness.[46]

Roman-ism, Puritan-ism; but Agnosti-cism, Catholi-cism, criti-cism, fanati-cism, tauto-logism, witti-cism, &c.

The terminations -cial, -cian, -cious, -sion, -tion should not be divided when forming one sound, as in so-cial, Gre-cian, pugna-cious, condescen-sion, forma-tion.

Atmo-sphere, micro-scope, philo-sophy, tele-phone, tele-scope, should have only this division. But always print episco-pal (not epi-scopal), &c.[47]

A divided word should not end a page, if it is possible to avoid it.

II. Some Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish Words

Italian.—Divide si-gnore (gn = ni in ‘mania’), trava-gliare (gli = lli in ‘William’), tra-scinare (sci = shi in ‘shin’), i.e. take over gn, gl, sci. In such a case as ‘all’ uomo’ Italians divide ‘al-l’ uomo’ when occasion arises.[48]

Portuguese.—Divide se-nhor (nh = ni in ‘mania’), bata-lha (lh = lli in ‘William’), i.e. take over nh, ll.

Spanish.—Divide se-ñora (ñ = ni in ‘mania’), maravi-lloso (ll = lli in ‘William’), i.e. take over ñ, ll.

III.

For the division of French words, see p. 81; German, p. 90; Latin, p. 95; and Greek, p. 97.

[46] I was once asked how I would carry out the rule that part of the word left in one line should suggest what followed in the next, in such a case as ‘disproportionableness’, which, according to Sir James Murray, is one of the longest words in the English language; or ‘incircumscriptibleness’, used by one Byfield, a divine, in 1615, who wrote, ‘The immensity of Christ’s divine nature hath ... incircumscriptibleness in respect of place’; or again, ‘antidisestablishmentarians’, quoted in the biography of Archbishop Benson, where he says that ‘the Free Kirk of the North of Scotland are strong antidisestablishmentarians’.—H. H.

[47] ‘Even the divisions noted as preferable are not free from objection, and should be avoided when it is at all easy to do so.’—H. B.

[48] Italians follow this rule, but it is better avoided in printing Italian passages in English books.—H. H.

The compositor is recommended to study attentively a good treatise[49] on the whole subject. He will find some knowledge of it to be indispensable if his work is to be done properly; for most writers send in copy quite unprepared as regards punctuation, and leave the compositor to put in the proper marks. ‘Punctuation is an art nearly always left to the compositor, authors being almost without exception either too busy or too careless to regard it.’[50] Some authors rightly claim to have carefully prepared copy followed absolutely; but such cases are rare, and the compositor can as a rule only follow his copy exactly when setting up standard reprints. ‘The first business of the compositor’ says Mr. De Vinne, ‘is to copy and not to write. He is enjoined strictly to follow the copy and never to change the punctuation of any author who is precise and systematic; but he is also required to punctuate the writings of all authors who are not careful, and to make written expression intelligible in the proof.... It follows that compositors are inclined to[56] neglect the study of rules that cannot be generally applied.’[51]

It being admitted, then, that the compositor is to be held responsible in most cases, he should remember that loose punctuation,[52] especially in scientific and philosophical works, is to be avoided.[53] We will again quote Mr. De Vinne: ‘Two systems of punctuation are in use. One may be called the close or stiff, and the other the open or easy system. For all ordinary descriptive writing the open or easy system, which teaches that points be used sparingly, is in most favor, but the close or stiff system cannot be discarded.’[54] The compositor who desires to inform himself as to the principles and theory of punctuation will find abundant information in the works mentioned in the footnote on p. 55; in our own booklet there is space only for a few cautions and a liberal[57] selection of examples; authority for the examples, when they are taken from the works of other writers, being given in all cases.

The Comma.

Commas should, as a rule, be inserted between adjectives preceding and qualifying substantives, as—

An enterprising, ambitious man.

A gentle, amiable, harmless creature.

A cold, damp, badly lighted room.[55]

But where the last adjective is in closer relation to the substantive than the preceding ones, omit the comma, as—

A distinguished foreign author.

The sailor was accompanied by a great rough Newfoundland dog.{55}

Where and joins two single words or phrases the comma is usually omitted; e.g.

The honourable and learned member.

But where more than two words or phrases occur together in a sequence a comma should precede the final and; e.g.

A great, wise, and beneficent measure.

The following sentence, containing two conjunctive and’s, needs no commas:

God is wise and righteous and faithful.{55}

Such words as moreover, however, &c., are usually followed by a comma[56] when used[58] at the opening of a sentence, or preceded and followed by a comma when used in the middle of a sentence. For instance:

In any case, however, the siphon may be filled.[57]

It is better to use the comma in such sentences as those that immediately follow:

Truth ennobles man, and learning adorns him.[58]

The Parliament is not dissolved, but only prorogued.

The French having occupied Portugal, a British squadron, under Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood, sailed for Madeira.

I believed, and therefore I spoke.

The question is, Can it be performed?

My son, give me thy heart.

The Armada being thus happily defeated, the nation resounded with shouts of joy.

Be assured, then, that order, frugality, and economy, are the necessary supporters of every personal and private virtue.

Virtue is the highest proof of a superior understanding, and the only basis of greatness.{58}

When a preposition assumes the character of an adverb, a comma should follow it, to avoid awkwardness or ambiguity: ‘In the valley below, the villages looked very small.’

The Semicolon.

Instances in which the semicolon is appropriate:

Truth ennobles man; learning adorns him.

The temperate man’s pleasures are always durable, because they are regular; and all his life is calm and serene, because it is innocent.

Those faults which arise from the will are intolerable; for dull and insipid is every performance where inclination bears no part.

Economy is no disgrace; for it is better to live on a little than to outlive a great deal.

To err is human; to forgive, divine.[59]

Never speak concerning what you are ignorant of; speak little of what you know; and whether you speak or say not a word, do it with judgement.{59}

Semicolons divide the simple members of a compound sentence, and a comma and dash come after the last sentence and before the general conclusion:

To give an early preference to honour above gain, when they stand in competition; to despise every advantage which cannot be attained without dishonest arts; to brook no meanness, and stoop to no dissimulation,—are the indications of a great mind, the presages of future eminence and usefulness in life.[60]

The Colon.

This point marks an abrupt pause before a further but connected statement:

In business there is something more than barter, exchange, price, payment: there is a sacred faith of man in man.

Study to acquire a habit of thinking: no study is more important.[61]

Always remember the ancient maxim: Know thyself.

The Period or Full Stop.

Examples of its ordinary use:

Fear God. Honour the King. Pray without ceasing.

There are thoughts and images flashing across the mind in its highest moods, to which we give the name of inspiration. But whom do we honour with this title of the inspired poet?

The Note of Interrogation.

Examples of its ordinary use:

Was the prisoner alone when he was apprehended? Is he known to the police? Has he any regular occupation? Where does he dwell? What is his name?

What does the pedant mean?

Cases where the note of interrogation must not be used, the speaker simply stating a fact:

The Cyprians asked me why I wept.

I was asked if I would stop for dinner.

The Note of Exclamation.

Examples of its ordinary use:

Hail, source of Being! universal Soul!

How mischievous are the effects of war!

O excellent guardian of the sheep!—a wolf![62]

Alas for his poor family!

Alas, my noble boy! that thou shouldst die!

Ah me! she cried, and waved her lily hand.

O despiteful love! unconstant womankind!

Marks of Parenthesis.

Examples:

I have seen charity (if charity it may be called) insult with an air of pity.

Left now to himself (malice could not wish him a worse adviser), he resolves on a desperate project.[63]

The Bracket.

These marks are used chiefly to denote an interpolation or explanation. For example:

They [the Lilliputians] rose like one man.

The Dash.

Em rules or dashes—in this and the next line an example is given—are often used to show that words enclosed between them are to be read parenthetically. Thus a verbal parenthesis may be shown by punctuation in three ways: by em dashes, by ( ), or by commas.[65]

Omit the dash when a colon is used to preface a quotation or similar matter, whether at the end of a break-line or not.

The dash is used to mark an interruption or breaking off in the middle of a sentence.[66]

Marks of Omission.

To mark omitted words three points ... (not asterisks) separated by en quadrats are sufficient; and the practice should be uniform throughout the work. Where full lines are required to mark a large omission, real or imaginary, the spacing between the marks should be increased; but the compositor should in this case also use full points and not asterisks.

Punctuation Marks generally.

The following summary is an attempt to define in few words the meaning and use of punctuation marks (the capitals are only given for emphasis):

A Period marks the end of a sentence.

A Colon is at the transition point of the sentence.

A Semicolon separates different statements.

A Comma separates clauses, phrases, and particles.

A Dash marks abruptness or irregularity.

An Exclamation marks surprise.

An Interrogation asks a question for answer.

An Apostrophe marks elisions or possessive case.

Quotation marks define quoted words.

Parentheses enclose interpolations in the sentence.

Brackets enclose irregularities in the sentence.[67]

Quotation Marks, or ‘Inverted Commas’ (so-called).

Omit quotation marks in poetry, as instructed on p. 45. Also omit them in prose extracts broken off in smaller type, unless contrary instructions are given.

Insert quotation marks in titles of essays: e.g. ‘Mr. Brock read a paper on “Description in Poetry”.’ But omit quotation marks when the subject of the paper is an author: e.g. ‘Professor Bradley read a paper on Jane Austen.’

Single ‘quotes’ are to be used for the first quotation; then double for a quotation within a quotation. If there should be yet another quotation within the second quotation it is necessary to revert to single quotation marks. Sometimes, as in the impossible example in the footnote, quotation marks packed three deep must be omitted.

All signs of punctuation used with words in quotation marks must be placed according to the sense. If an extract ends with a point, then let that point be, as a rule,[68] included[64] before the closing quotation mark; but not otherwise. When there is one quotation within another, and both end with the sentence, put the punctuation mark before the first of the closing quotations. These are important directions for the compositor to bear in mind; and he should examine the examples which are given in the pages which follow:

‘The passing crowd’ is a phrase coined in the spirit of indifference. Yet, to a man of what Plato calls ‘universal sympathies’, and even to the plain, ordinary denizens of this world, what can be more interesting than ‘the passing crowd’?[69]

If the physician sees you eat anything that is not good for your body, to keep you from it he cries, ‘It is poison!’ If the divine sees you do anything that is hurtful for your soul, he cries, ‘You are lost!’[70]

‘Why does he use the word “poison”?’

But I boldly cried out, ‘Woe unto this city!’[71]

Alas, how few of them can say, ‘I have striven to the very utmost’!{71}

Thus, notes of exclamation and interrogation are sometimes included in and sometimes follow quotation marks, as in the sentences above, according to whether their application is merely to the words quoted or to the whole sentence of which they form a part. The sentence-stop must be omitted after ? or !, even when the ? or ! precedes the closing ‘quotes’.

In regard to the use of commas and full[65] points with ‘turned commas’, the general practice has hitherto been different. When either a comma or a full point is required at the end of a quotation, the almost universal custom at the present time is for the printer to include that comma or full point within the quotation marks at the end of an extract, whether it forms part of the original extract or not. Even in De Vinne’s examples, although he says distinctly, ‘The proper place of the closing marks of quotation should be determined by the quoted words only’, no instance can be found of the closing marks of quotation being placed to precede a comma or a full point. Some writers wish to exclude the comma or full point when it does not form part of the original extract, and to include it when it does form part of it; and this is doubtless correct.

There seems to be no reason for perpetuating a bad practice. So, unless the author wishes to have it otherwise, in all new works the compositor should place full points and commas according to the examples that follow:

We need not ‘follow a multitude to do evil’.

No one should ‘follow a multitude to do evil’, as the Scripture says.

Do not ‘follow a multitude to do evil’; on the contrary, do what is right.

When a number of isolated words or phrases are, for any reason, severally marked off by ‘turned commas’ (e.g. in order to show that they are not the expressions which the author would prefer to use, or that they are used in some technical sense), the closing[66] quotation mark should precede the punctuation mark, thus:

‘Such odd-sounding designations of employment as “scribbling miller”, “devil feeder”, “pug boy”, “decomposing man”, occur in the census reports.’

in my voice, ‘so far as my vote is concerned’. parlous, ‘perilous’, ‘dangerous’, ‘hard to deal with’.

But when a quotation is complete in itself, either as a sentence or a paragraph, the final quotation mark is to be placed outside the point. For example:

‘If the writer of these pages shall chance to meet with any that shall only study to cavil and pick a quarrel with him, he is prepared beforehand to take no notice of it.’ (Works of Charles and M. Lamb, Oxford edition, i. 193.)

Where a quotation is interrupted by an interpolated sentence, the punctuation must follow the sense of the passage, as in the following examples:

1. ‘At the root of the disorders’, he writes in the Report, ‘lies the conflict of the two races.’ In this example the comma is placed outside the quotation mark, as it forms no part of the original punctuation.

2. ‘Language is not, and never can be,’ writes Lord Cromer, ‘as in the case of ancient Rome, an important factor in the execution of a policy of fusion.’ In this example the comma is placed inside the quotation mark, as it forms part of the original punctuation.

In the case of dialogues, the punctuation mark should precede the quotation mark, as:

‘You hear him,’ said Claverhouse, smiling, ‘there’s the rock he splits upon; he cannot forget his pedigree.’

Punctuation in Classical and Philological Notes.

In notes on English and foreign classics, as a rule[72] follow the punctuation in the following examples:

5. Falls not, lets not fall. (That is, a comma is sufficient after the lemma where a simple definition follows.)

17. swoon. The spelling of the folios is ‘swound’. (Here a full point is used, because the words that follow the lemma comprise a complete sentence.)

Note, as to capitalization, that the initial letter of the word or phrase treated (as in Falls not above) should be in agreement with the text.

The lemma should be set in italics or clarendon, according to directions.

Punctuation Marks and References to Footnotes in juxtaposition.

The relation of these to each other is dealt with on p. 70. Examples of the right practice are to be found on many pages of the present work.

Points in Title-pages, Headlines, &c.

All points are to be omitted from the ends of lines in titles, half-titles, page-headings, and main cross-headings, in Clarendon Press works, unless a special direction is given to the contrary.

[49] e.g. Spelling and Punctuation, by H. Beadnell (Wyman’s Technical Series); The King’s English (Clarendon Press), containing a valuable chapter on Punctuation; Stops; or, How to Punctuate, by P. Allardyce (Fisher Unwin); Correct Composition, by T. L. De Vinne (New York, Century Co.); or the more elaborate Guide pratique du compositeur, &c., by T. Lefevre (Paris, Firmin-Didot).

[50] Practical Printing, by Southward and Powell, p. 191.

[51] De Vinne, Correct Composition, pp. 241-2.

[52] How much depends upon punctuation is well illustrated in a story told, I believe, by the late G. A. Sala, once a writer in the Daily Telegraph, about R. B. Sheridan, dramatist and M.P. In the House of Commons, Sheridan one day gave an opponent the lie direct. Called upon to apologize, the offender responded thus: ‘Mr. Speaker I said the honourable Member was a liar it is true and I am sorry for it.’ Naturally the person concerned was not satisfied; and said so. ‘Sir,’ continued Mr. Sheridan, ‘the honourable Member can interpret the terms of my statement according to his ability, and he can put punctuation marks where it pleases him.’—H. H.

[53] Below is a puzzle passage from the Daily Chronicle, first with no points, and then with proper marks of punctuation: ‘That that is is that that is not is not is not that it it is.’ ‘That that is, is; that that is not, is not; is not that it? It is.’—H. H.

[54] De Vinne, Correct Composition, p. 244.

[55] Beadnell, pp. 99, 100.

[56] Nevertheless the reader is not to be commended who, being told that the word however was usually followed by a comma, insisted upon altering a sentence beginning ‘However true this may be,’ &c., to ‘However, true this may be,’ &c. This is the late Dean Alford’s story. See The Queen’s English, p. 124, ed. 1870.—H. H.

[57] Beadnell, p. 101.

[58] Id., pp. 95-107.

[59] Beadnell, pp. 109, 110.

[60] Id., p. 111.

[61] Id., p. 112.

[62] All the examples are from Beadnell, pp. 113-17.

[63] Beadnell, pp. 118-19.

[64] Id., p. 120.

[65] Some writers mark this form of composition quite arbitrarily. For instance Charles Dickens uses colons: ‘As he sat down by the old man’s side, two tears: not tears like those with which recording angels blot their entries out, but drops so precious that they use them for their ink: stole down his meritorious cheeks.’—Martin Chuzzlewit, Oxford ed., p. 581.

[66] There is one case, and only one, of an em rule being used in the Bible (A.V.), viz. in Exod. xxxii. 32; where, I am told by the Rev. Professor Driver, it is correctly printed, to mark what is technically called an ‘aposiopesis’, i.e. a sudden silence. The ordinary mark for such a case is a two-em rule.—H. H.

[67] De Vinne, Correct Composition, p. 288.

[68] I say ‘as a rule’, because if such a sentence as that which follows occurred in printing a secular work, the rule would have to be broken. De Vinne prints:

‘In the New Testament we have the following words: “Jesus answered them, ‘Is it not written in your law, “I said, ‘Ye are gods’”?’”’ [H. H.]

[69] Beadnell, p. 116.

[70] Id., p. 126.

[71] Allardyce, p. 74.

[72] There are exceptions, as in the case of works which have a settled style of their own.

IN ARABIC OR ROMAN

Do not mix old-style and new-face figures in the same book without special directions.

Nineteenth century, not 19th century.

Figures to be used when the matter consists of a sequence of stated quantities, particulars of age, &c.

Example: ‘Figures for September show the supply to have been 85,690 tons, a decrease on the month of 57 tons. For the past twelve months there is a net increase of 5 tons.’

‘The smallest tenor suitable for ten bells is D flat, of 5 feet diameter and 42 cwt.’

In descriptive matter, numbers under 100 to be in words; but print ‘90 to 100’, not ‘ninety to 100’.

Spell out in such instances as—

‘With God a thousand years are but as one day’; ‘I have said so a hundred times’.

Insert commas with four or more than four figures, as 7,642; but print dates without commas, as 1908; nor should there be commas in figures denoting pagination or numbering of verse, even though there may be more than three figures. Omit commas also in Library numbers, as—British Museum MS. 24456.

Roman numerals to be preferred in such cases as Henry VIII, &c.—which should never be divided; and should only be followed by a full point when the letters end a sentence. If, however, the author prefers the full title, use ‘Henry the Eighth’, not ‘Henry the VIIIth’.

Use a decimal point · to express decimals, as 7·06; and print 0·76, not ·76. When the time of day is intended to be shown, the full point . is to be used, as 4.30 a.m.

As to dates, in descriptive writing the author’s phraseology should be followed; e.g. ‘On the 21st of May the army drew near.’ But in ordinary matter in which the date of the month and year is given, such as the headings to letters, print May 19, 1862; not May 19th, 1862,[73] nor 19 May, 1862.

To represent pagination or an approximate date, use the least number of figures possible; for example, print:

pp. 322-30; pp. 322-4, not pp. 322-24. But print: pp. 16-18, not pp. 16-8; 116-18, not 116-8.

In dates: 1897-8, not 1897-98 (use en rules); and from 1672 to 1674, not from 1672-74.

Print: 250 B.C.; but when it is necessary to insert A.D. the letters should precede the year, as A.D. 250. In B.C. references, however, always put the full date, in a group of years, e.g. 185-122 B.C.

When preliminary pages are referred to by lower-case roman numerals, no full points should be used after the numerals. Print:

p. ii, pp. iii-x; not p. ii., pp. iii.-x.

When references are made to two successive text-pages print pp. 6, 7, if the subject is disconnected in the two pages. But if the[70] subject is continuous from one page to the other, then print pp. 6-7. The compositor in this must be guided by his copy. Print p. 51 sq. if the reference is to p. 51 and following page; but pp. 51 sqq. when the reference is to more than a single page following.[74]

In a sequence of figures use an en rule, as in the above examples; but in such cases as Chapters III—VIII use an em rule.

Begin numbered paragraphs: 1. 2. &c.; and clauses in paragraphs: (1) (2) (3), &c. If Greek or roman lower-case letters are written, the compositor must follow copy. Roman numerals (I. II. III.) are usually reserved for chapters or important sections.

References in the text to footnotes should be made by superior figures—which are to be placed, as regards punctuation marks, according to the sense. If a single word, say, is extracted and referred to, the reference must be placed immediately after the word extracted and before the punctuation mark. But if an extract be made which includes a complete sentence or paragraph, then the reference mark must be placed outside the last punctuation mark. Asterisks, superior letters, &c., may be used in special cases. Asterisks and the other signs (* † ‡ &c.) should be used in mathematical works, to avoid confusion with the workings.

In Mathematics, the inferior in P1′ should come immediately after the capital letter.

[73] Sir James Murray says, ‘This is not logical: 19 May 1862 is. Begin at day, ascend to month, ascend to year; not begin at month, descend to day, then ascend to year.’ (But I fear we must continue for the present to print May 19, 1862: authors generally will not accept the logical form.—H. H.)

[74] In references of this nature different forms are used, as—ff., foll., et seq. Whichever form is adopted, the practice should be uniform throughout the work.

Use ’s for the possessive case in English names and surnames whenever possible; i.e. in all monosyllables and disyllables, and in longer words accented on the penult; as—

In longer names, not accented on the penult, ’s is also preferable, though ’ is here admissible; e.g. Theophilus’s.

In ancient classical names, use ’s with every monosyllable, e.g. Mars’s, Zeus’s. Also with disyllables not in -es; as—

Judas’s Marcus’s Venus’s

But poets in these cases sometimes use s’ only; and Jesus’ is a well-known liturgical archaism. In quotations from Scripture follow the Oxford standard.[75]

Ancient words in -es are usually written -es’ in the possessive, e.g.

Ceres’ rites Xerxes’ fleet

This form should certainly be used in words longer than two syllables, e.g.

To pronounce another ’s (= es) after these is difficult.

This applies only to ancient words. One writes—Moses’ law; and I used to alight at Moses’s for the British Museum.

As to the latter example, Moses, the tailor, was a modern man, like Thomas and Lewis; and in using his name we follow modern English usage.

J. A. H. M.

French names ending in s or x should always be followed by ’s when used possessively in English. Thus, it being taken for granted that the French pronunciation is known to the ordinary reader, and using Rabelais = Rabelè, Hanotaux = Hanotō, as examples, the only correct way of writing these names in the possessive in English is Rabelais’s (= Rabelès), Hanotaux’s (= Hanotōs).—H. H.

The English compositor called upon to set works in the French language will do well, first of all, to make a careful examination of some examples from the best French printing-offices. He will find that French printers act on rules differing in many points from the rules to which the English compositor is accustomed; and he will not be able to escape from his difficulties by the simple expedient of ‘following copy’.

For works in the French language, such as classical text-books for use in schools, the English compositor generally gets reprint copy for text and manuscript for notes. It is, as a rule, safe for him to follow the reprint copy; but there is this difficulty, that when the work forms part of a series it does not always happen that the reprint copy for one book corresponds in typographical style with reprint copy for other works in the same series. Hence he should apply himself diligently to understand the following rules; and should hunt out examples of their application, so that they may remain in his memory.[76]

1. Capital and lower-case letters.—In the names of authors of the seventeenth century,[74] which are preceded by an article, the latter should commence with a capital letter: La Fontaine, La Bruyère.[77] Exceptions are names taken from the Italian, thus: le Tasse, le Dante, le Corrège.[78] As to names of persons, the usage of the individuals themselves should be adopted: de la Bruyère (his signature at the end of a letter), De la Fontaine (end of fable ‘Le Lièvre et la Tortue’), Lamartine, Le Verrier, Maxime Du Camp. In names of places the article should be small: le Mans, le Havre, which the Académie adopts; la Ferté, with no hyphen after the article, but connected by a hyphen with different names of places, as la Ferté-sous-Jouarre.

Volumes, books, titles, acts of plays, the years of the Republican Calendar, are put in large capitals: An IV, acte V, tome VI; also numerals belonging to proper names: Louis XII; and the numbers of the arrondissements of Paris: le XVe arrondissement.

Scenes of plays, if there are no acts, are also put in large caps.: Les Précieuses ridicules, sc. V; also chapters, if they form the principal division: Joseph, ch. VI. If, however, scenes of plays and chapters are secondary divisions, they are put in small capitals: Le Cid, a. I, sc. II; Histoire de France, liv. VI, ch. VII. The numbers of centuries are generally put in small capitals: au XIXe (or XIXème) siècle.

The first word of a title always takes a capital letter: J’ai vu jouer Les Femmes[75] savantes; on lit dans Le Radical. If a substantive in a title immediately follows Le, La, Les, Un, Une, it is also given a capital letter, thus: Les Précieuses ridicules. If the substantive is preceded by an adjective, this also receives a capital letter: La Folle Journée; if, however, the adjective follows, it is in lower-case: L’Âge ingrat. If the title commences with any other word than le, la, les, un, une, or an adjective, the words following are all in lower-case: De la terre à la lune; Sur la piste.

In titles of fables or of dramatic works the names of the characters are put with capital initials: Le Renard et les Raisins; Le Lion et le Rat; Marceau, ou les Enfants de la République.

In catalogues or indexes having the first word or words in parentheses after the substantive commencing the line, the first word thus transposed has a capital letter: Homme (Faiblesse de l’); Honneur (L’); Niagara (Les Chutes du).

If the words in parentheses are part of the title of a work, the same rule is followed as to capitals as above given: Héloïse (La Nouvelle); Mort (La Vie ou la).

The words saint, sainte, when referring to the saints themselves, have, except when commencing a sentence, always lower-case initials: saint Louis, saint Paul, sainte Cécile. But when referring to names of places, feast-days, &c., capital letters and hyphens are used: Saint-Domingue, la Saint-Jean. (See also, as to abbreviations of Saint, Sainte, p. 82.)

I. Use capital letters as directed below:

(1) Words relating to God: le Seigneur, l’Être suprême, le Très-Haut, le Saint-Esprit.

(2) In enumerations, if each one commences a new line, a capital is put immediately after the figure:

1o L’Europe.

2o L’Asie, &c.

But if the enumeration is run on, lower-case letters are used: 1o l’Europe, 2o l’Asie, &c.

(3) Words representing abstract qualities personified: La Renommée ne vient souvent qu’après la Mort.

(4) The planets and constellations: Mars, le Bélier.

(5) Religious festivals: la Pentecôte.

(6) Historical events: la Révolution.

(7) The names of streets, squares, &c.: la rue des Mauvais-Garçons, la place de la Nation, la fontaine des Innocents.

(8) The names of public buildings, churches, &c.: l’Opéra, l’Odéon, église de la Trinité.

(9) Names relating to institutions, public bodies, religious, civil, or military orders (but only the word after the article): l’Académie française, la Légion d’honneur, le Conservatoire de musique.

(10) Surnames and nicknames, without hyphens: Louis le Grand.

(11) Honorary titles: Son Éminence, Leurs Altesses.

(12) Adjectives denoting geographical expressions: la mer Rouge, le golfe Persique.

(13) The names of the cardinal points designating an extent of territory: l’Amérique du Nord; aller dans le Midi. (See II. (2).)

(14) The word Église, when it denotes the Church as an institution: l’Église catholique; but when relating to a building église is put.

(15) The word État when it designates the nation, the country: La France est un puissant État.

II. Use lower-case initials for—

(1) The names of members of religious orders: un carme (a Carmelite), un templier (a Templar). But the orders themselves take capitals: l’ordre des Templiers, des Carmes.

(2) The names of the cardinal points: le nord, le sud. But see I. (13) above.

(3) Adjectives belonging to proper names: la langue française, l’ère napoléonienne.

(4) Objects named from persons or places: un quinquet (an argand lamp); un verre de champagne.

(5) Days of the week—lundi, mardi; names of months—juillet, août.

In plays the dramatis personae at the head of scenes are put in large capitals, and those not named in even small capitals:

SCÈNE V.

TRIBOULET, BLANCHE, HOMMES,

FEMMES DU PEUPLE.

In the dialogues the names of the speakers are put in even small capitals, and placed in the centre of the line. The stage directions and the asides are put in smaller type, and are in the text, if verse, in parentheses over the words they refer to. If there are two stage directions in one and the same line, it will be advisable to split the line, thus:

(Revenu sur ses pas.)

Oublions-les! restons.—

(Il l’assied sur un banc.)

Sieds-toi sur cette pierre.

Directions not relating to any particular words of the text are put, if short, at the end of the line:

Celui que l’on croit mort n’est pas mort.—

Le voici!

(Étonnement général.)

2. Accented Capitals.—With one exception accents are to be used with capital letters in French. The exception is the grave accent on the capital letter A in such lines as—

A la porte de la maison, &c.;

A cette époque, &c.;

and in display lines such as—

FÉCAMP A GENÈVE

MACHINES A VAPEUR.

In these the preposition A takes no accent; but we must, to be correct, print Étienne, Étretat; and DÉPÔT, ÉVÊQUE, PRÉVÔT in cap. lines.[79] Small capitals should be accented throughout, there being no fear of the grave accent breaking off.

3. The Grave and Acute Accents.—There has been an important change in recent years as to the use of the grave and acute accents in French. It has become customary[79] to spell with a grave accent (`) according to the pronunciation, instead of with an acute accent (´), certain words such as collège (instead of collége), avènement (instead of avénement), &c. The following is a list of the most common:

4. Hyphens.—Names of places containing an article or the prepositions en, de, should have a hyphen between each component part, thus: Saint-Germain-des-Prés, Saint-Valery-en-Caux, although the Académie leaves out the last two hyphens.

Names of places, public buildings, or streets, to which one or more distinguishing words are added, take hyphens: Saint-Étienne-du-Mont, Vitry-le-François, rue du Faubourg-Montmartre, le Pont-Neuf, le Palais-Royal, l’Hôtel-de-la-Monnaie.

In numbers hyphens are used to connect quantities under 100: e.g. vingt-quatre; trois cent quatre-vingt-dix; but when et joins two cardinal numbers no hyphen is[80] used, e.g. vingt et un; cinquante et un. But print vingt-et-unième.

5. Spacing.—No spaces to be put before the ‘points de suspension’, i.e. three points close together, cast in one piece, denoting an interruption (...). In very wide spacing a thin space may be put before a comma,[82] or before or after a parenthesis or a bracket. Colons, metal-rules, section-marks, daggers, and double-daggers take a space before or after them exactly as words. Asterisks and superior figures, not enclosed in parentheses, referring to notes, take a thin or middle space before them. Points of suspension are always followed by a space. For guillemets see pp. 86, 87.

A space is put after an apostrophe following a word of two or more syllables (as a Frenchman reckons syllables, e.g. bonne is a word of two syllables):—

Bonn’ petite... Aimabl’ enfant!...

Spaces are put in such a case as 10 h. 15 m. 10 s. (10 hours 15 min. 10 sec.), also printed 10h 15m 10s.

Chemical symbols are not spaced, thus C10H12(OH)CO.OH.

6. Awkward divisions: abbreviated words and large numbers expressed in figures.—One[81] should avoid ending a line with an apostrophe, such as: Quoi qu’ | il dise?

If a number expressed in figures is too long to be got into a line, or cannot be taken to the next without prejudice to the spacing, a part of the number should be put as a word, thus: 100 mil- | lions.