The Project Gutenberg eBook of Celtic Scotland, Volume I (of 3), by William Forbes Skene

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Celtic Scotland, Volume I (of 3)

A history of ancient Alban

Author: William Forbes Skene

Release Date: July 23, 2023 [eBook #71258]

Language: English

Credits: MWS, KD Weeks, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CELTIC SCOTLAND, VOLUME I (OF 3) ***

Footnotes were numbered beginning afresh with each chapter. They have

been resequenced across the entire text for uniqueness. On occasion,

notes are referred to in other notes by number. These references have

been changed as well.

Footnotes have been collected at the end of each chapter, and are

linked for ease of reference.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

Printed by Thomas and Archibald Constable,

FOR

DAVID DOUGLAS, EDINBURGH

| LONDON |

HAMILTON, ADAMS, AND CO. |

| CAMBRIDGE |

MACMILLAN AND BOWES. |

| GLASGOW |

JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS |

CELTIC SCOTLAND:

A HISTORY OF

Ancient Alban

BY

WILLIAM F. SKENE, D.C.L., LL.D.

HISTORIOGRAPHER-ROYAL FOR SCOTLAND.

Volume I.

HISTORY AND ETHNOLOGY.

SECOND EDITION.

EDINBURGH: DAVID DOUGLAS

1886

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION.

The first volume of Celtic Scotland being out of

print, the Author has very carefully revised the

text, with a view to a new edition; but he has,

after mature consideration, found nothing to alter

in the views of early Scottish history expressed in

it. He has therefore confined himself to correcting

obvious mistakes and misprints, and, with these

exceptions, this edition is substantially a reprint.

Edinburgh, 27 Inverleith Row,

4th September 1886.

vii

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

Each volume of this work may be regarded as complete

in itself so far as the object of the volume is

concerned, and will be issued separately.

The principal aim of the Author in this first

volume of Celtic Scotland has been to endeavour to

ascertain the true facts of the early civil history.

For this purpose the narratives of her early historians

afford no available basis. The artificially-constructed

system of history first brought into shape by John

of Fordun, and elaborated in the more classical text

of Hector Boece, must, for the Celtic period of our

history, be entirely rejected. To attempt to found

a consecutive historical narrative on the scattered

notices in the Roman writers and in the Chronicles,

which consist merely of lists of kings with the

length of their respective reigns, and notices of a

few isolated battles, would be merely to produce an

unsatisfactory and unreadable book. On the other

hand, a succession of general views of the early

periods of its history, founded upon a superficial

and uncritical use of authorities, or the too readily

accepted conclusions of more painstaking writers,

viiihowever lively and graphic they may be, might

furnish very pleasant reading, but would be worthless

as a work of authority.

The first thing to be done is to lay a sound foundation

by ascertaining, as far as possible, the true

facts of the early history, so far as they can be fairly

extracted from the more trustworthy authorities.

There is, unfortunately, no more difficult task than

to substitute the correct ‘sumpsimus’ for the long-cherished

and accepted ‘mumpsimus’ of popular

historians. All that the Author has attempted in

this volume is to show what the most reliable

authorities do really tell us of the early annals of

the country, divested of the spurious matter of supposititious

authors, the fictitious narratives of our

early historians, and the rash assumptions of later

writers which have been imported into it.

The Author is glad to take this opportunity of

acknowledging the valuable assistance which his

excellent publisher, Mr. David Douglas, has freely

and ungrudgingly given him in carefully revising

the proof-sheets. They could have been submitted

to no more intelligent supervision.

Edinburgh, 20 Inverleith Row,

1st May 1876.

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

| |

|

PAGE |

| Name of Scotia, or Scotland |

1 |

| Ancient extent of the kingdom |

2 |

| Physical features of the country |

7 |

| Mountain chains |

9 |

| |

The Cheviots |

9 |

| |

The Mounth |

10 |

| |

Drumalban |

10 |

| |

The Grampians |

11 |

| The Debateable lands |

14 |

| Periods of its history |

16 |

| Celtic Scotland |

17 |

| Critical examination of authorities necessary |

17 |

| Spurious authorities |

21 |

| Plan of the work |

26 |

BOOK I.

HISTORY AND ETHNOLOGY.

CHAPTER I.

ADVANCE OF THE ROMANS TO THE FIRTHS OF

FORTH AND CLYDE.

| Early notices of the British Isles |

29 |

| B.C. 55. Invasion of Julius Cæsar |

31 |

| A.D. 43. Formation of province in reign of Claudius |

33 |

| A.D. 50. War with the Brigantes |

36 |

| A.D. 69. War with the Brigantes renewed |

39 |

| xA.D. 78. Arrival of Julius Agricola as governor |

41 |

| A.D. 79. Second Campaign of Agricola; overruns districts on the Solway |

43 |

| A.D. 80. Third summer; ravages to the Tay |

45 |

| A.D. 81. Fourth summer; fortifies the isthmus between Forth and Clyde |

46 |

| A.D. 82. Fifth summer; visits Argyll and Kintyre |

47 |

| A.D. 83-86. Three years’ war north of the Forth |

48 |

| A.D. 86. Battle of ‘Mons Granpius’ |

52 |

| A.D. 120. Arrival of the Emperor Hadrian, and first Roman wall between the Tyne and the Solway |

60 |

CHAPTER II.

THE ROMAN PROVINCE IN SCOTLAND.

| Ptolemy’s description of North Britain |

62 |

| |

The coast |

65 |

| |

The Ebudæ |

68 |

| |

The tribes and their towns |

70 |

| A.D. 139. First Roman wall between the Forth and Clyde. Establishment of the Roman province in Scotland |

76 |

| A.D. 162. Attempt on the province by the natives |

79 |

| A.D. 182. Formidable irruption of tribes north of wall repelled by Marcellus Ulpius |

79 |

| A.D. 201. Revolt of Caledonii and Mæatæ |

80 |

| A.D. 204. Division of Roman Britain into two Provinces |

81 |

| A.D. 208. Campaign of the Emperor Severus in Britain. Situation of the hostile tribes |

82 |

| Roman roads in Scotland |

86 |

| Severus’s wall |

89 |

| A.D. 287. Revolt of Carausius; Britain for ten years independent |

91 |

| A.D. 289. Carausius admitted Emperor |

92 |

| A.D. 294. Carausius slain by Allectus |

93 |

| A.D. 296. Constantius Chlorus recovers Britain |

93 |

| A.D. 306. War of Constantius Chlorus against Caledonians and other Picts |

94 |

| Division of Roman Britain into four provinces |

96 |

| A.D. 360. Province invaded by Picts and Scots |

97 |

| A.D. 364. Ravaged by Picts, Scots, Saxons, and Attacotts |

98 |

| xiA.D. 369. Province restored by Theodosius |

100 |

| A.D. 383. Revolt by Maximus |

104 |

| A.D. 387. Withdrawal of Roman troops from Britain; first devastation of province by Picts and Scots |

105 |

| A.D. 396. Repelled by Stilicho, who sends a legion to guard the northern wall |

105 |

| A.D. 402. Roman legion withdrawn; second devastation of province |

106 |

| A.D. 406. Again repelled by Stilicho, and army restored |

107 |

| A.D. 407. Constantine proclaimed Emperor. Withdraws the army from Britain; third devastation by Picts and Scots |

108 |

| A.D. 409. Gerontius invites Barbarians to invade empire. Termination of Roman Empire in Britain |

111 |

CHAPTER III.

BRITAIN AFTER THE ROMANS.

| Obscurity of history of Britain after the departure of the Romans |

114 |

| Settlement of barbaric tribes in Britain |

114 |

| Ignorance of Britain by writers of the sixth century |

115 |

| Position of Britain at this time as viewed from Rome |

117 |

| The four races in Britain |

119 |

| |

The Britons |

120 |

| |

The Picts |

123 |

| |

The Scots |

137 |

| |

The Saxons |

144 |

| War with Octa and Ebissa’s colony |

152 |

| Kingdom of Bernicia |

155 |

| A.D. 573. Battle of Ardderyd |

157 |

| A.D. 603. Battle of Degsastane or Dawstane |

162 |

CHAPTER IV.

ETHNOLOGY OF BRITAIN

| Inquiry into Ethnology of Britain proper at this stage |

164 |

| An Iberian or Basque people preceded the Celtic race in Britain and Ireland |

164 |

| xiiEthnologic traditions |

170 |

| |

British traditions |

171 |

| |

Irish traditions |

172 |

| |

Dalriadic legend |

184 |

| |

Pictish legends |

185 |

| |

Saxon legends |

189 |

| Languages of Britain |

192 |

| |

Anglic language |

193 |

| |

British language |

193 |

| |

Language of the Scots |

193 |

| |

The Pictish language |

194 |

| Evidence derived from topography |

212 |

CHAPTER V.

THE FOUR KINGDOMS.

| Result of ethnological inquiry |

226 |

| The four kingdoms |

227 |

| |

Scottish kingdom of Dalriada |

229 |

| |

Kingdom of the Picts |

230 |

| |

Kingdom of the Britons of Alclyde |

235 |

| |

Kingdom of Bernicia |

236 |

| |

The Debateable lands |

237 |

| |

Galloway |

238 |

| A.D. 606. Death of Aidan, king of Dalriada; Aedilfrid conquers Deira, and expels Aeduin |

239 |

| A.D. 617. Battle between Aeduin and Aedilfrid |

239 |

| A.D. 627. Battle of Ardcorann between Dalriads and Cruithnigh |

241 |

| A.D. 629. Domnall Breac becomes king of Dalriada |

242 |

| A.D. 631. Garnaid, son of Wid, succeeds Cinaeth mac Luchtren as king of the Picts |

242 |

| A.D. 633. Battle of Haethfeld. Aeduin slain by Caedwalla and Penda |

243 |

| A.D. 634. Battle of Hefenfeld. Osuald becomes king of Northumbria |

244 |

| A.D. 635. Battle of Seguise, between Garnait, son of Foith, and the family of Nectan |

246 |

| A.D. 634. Battle of Calathros, in which Domnall Breac was defeated |

247 |

| xiiiA.D. 638. Battle of Glenmairison, and siege of Edinburgh |

249 |

| A.D. 642. Domnall Breac slain in Strathcarron |

250 |

| A.D. 642. Osuald slain in battle by Penda |

252 |

| A.D. 642-670. Osuiu, his brother, reigns twenty-eight years |

253 |

| Dominion of Angles over Britons, Scots, and Picts |

256 |

| A.D. 670. Death of Osuiu, and accession of Ecgfrid his son |

260 |

| A.D. 672. Revolt of the Picts |

260 |

| A.D. 678. Wilfrid expelled from his diocese |

262 |

| Expulsion of Drost, king of the Picts, and accession of Brude, son of Bile |

262 |

| A.D. 684. Ireland ravaged by Ecgfrid |

264 |

| A.D. 685. Invasion of kingdom of Picts by Ecgfrid; defeat and death at Dunnichen |

265 |

| Effect of defeat and death of Ecgfrid |

267 |

| Position of Angles and Picts |

267 |

| Position of Scots and Britons |

271 |

| Contest between Cinel Loarn and Cinel Gabhran |

271 |

| Conflict between Dalriads and Britons |

273 |

CHAPTER VI.

THE KINGDOM OF SCONE.

| State of the four kingdoms in 731 |

275 |

| Alteration in their relative position |

276 |

| Legend of St. Bonifacius |

277 |

| A.D. 710. Nectan, son of Derili, conforms to Rome |

278 |

| Establishment of Scone as capital |

280 |

| The Seven provinces |

280 |

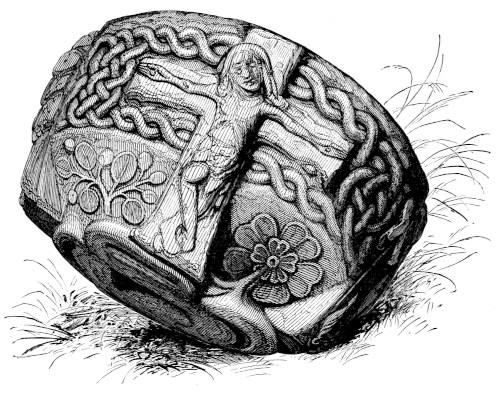

| The Coronation Stone |

281 |

| A.D. 717. Expulsion of Columban clergy |

283 |

| Simultaneous revolution in Dalriada and kingdom of the Picts |

286 |

| A.D. 731-761. Aengus mac Fergus, king of the Picts |

289 |

| Suppressed century of Dalriadic history |

292 |

| Foundation of St. Andrews |

296 |

| A.D. 761-763. Bruide mac Fergusa, king of the Picts |

299 |

| A.D. 763-775. Ciniod, son of Wredech, king of the Picts |

300 |

| A.D. 775-780. Alpin, son of Wroid, king of the Picts |

301 |

| xivA.D. 789-820. Constantin, son of Fergus, king of the Picts |

302 |

| Norwegian and Danish pirates |

302 |

| A.D. 820-832. Aengus, son of Fergus, king of Fortrenn |

305 |

| A.D. 832. Alpin the Scot attacks the Picts, and is slain |

306 |

| A.D. 836-839. Eoganan, son of Aengus |

307 |

| A.D. 839. Kenneth mac Alpin invades Pictavia |

308 |

| A.D. 844. Kenneth mac Alpin becomes king of the Picts |

309 |

| The Gallgaidhel |

311 |

| Obscurity of this period of the history |

314 |

| Causes and nature of revolution which placed Kenneth on the throne of the Picts |

314 |

| Where did the Scots come from? |

316 |

| What was Kenneth mac Alpin’s paternal descent? |

321 |

| A.D. 860-864. Donald, son of Alpin, king of the Picts |

322 |

| A.D. 863. Constantin, son of Kenneth, king of the Picts |

323 |

| A.D. 877-878. Aedh, son of Kenneth, king of the Picts |

328 |

| A.D. 878-889. Girig mac Dungaile and Eochodius, son of Run |

329 |

CHAPTER VII.

THE KINGDOM OF ALBAN.

| A.D. 889-900. Donald, son of Constantin, king of Alban |

335 |

| A.D. 900-942. Constantin, son of Aedh, king of Alban |

339 |

| A.D. 937. Battle of Brunanburg |

352 |

| A.D. 942-954. Malcolm, son of Donald, king of Alban |

360 |

| A.D. 945. Cumbria ceded to the Scots |

362 |

| A.D. 954-962. Indulph, son of Constantin, king of Alban |

365 |

| A.D. 962-967. Dubh, son of Malcolm, king of Alban |

366 |

| A.D. 967-971. Cuilean, son of Indulph, king of Alban |

367 |

| A.D. 971-995. Kenneth, son of Malcolm, king of Alban |

368 |

| A.D. 995-997. Constantin, son of Cuilean, king of Alban |

381 |

| A.D. 997-1004. Kenneth, son of Dubh, king of Alban |

382 |

CHAPTER VIII.

THE KINGDOM OF SCOTIA.

| A.D. 1005-1034. Malcolm, son of Kenneth, king of Scotia |

384 |

| A.D. 1018. Battle of Carham, and cession of Lothian to the Scots |

393 |

| xvA.D. 1034-1040. Duncan, son of Crinan, and grandson of Malcolm, king of Scotia |

399 |

| A.D. 1040-1057. Macbeth, son of Finnlaec, king of Scotia |

405 |

| A.D. 1054. Siward, Earl of Northumbria, invades Scotland, and puts Malcolm, son of King Duncan, in possession of Cumbria |

408 |

| A.D. 1057-8. Lulach, son of Gilcomgan, king of Scotia |

411 |

| A.D. 1057-8-1093. Malcolm, eldest son of King Duncan, king of Scotia |

411 |

| Malcolm invades Northumbria five times |

417 |

| A.D. 1092. Cumbria south of the Solway Firth wrested from the Scots |

429 |

| State of Scotland at King Malcolm’s death |

432 |

CHAPTER IX.

THE KINGDOM OF SCOTIA PASSES INTO FEUDAL SCOTLAND.

| Effects of King Malcolm’s death |

433 |

| A.D. 1093. Donald Ban, Malcolm’s brother, reigns six months |

436 |

| A.D. 1093-1094. Duncan, son of Malcolm, by his first wife Ingibiorg, reigns six months |

437 |

| A.D. 1094-1097. Donald Ban again, with Eadmund, son of Malcolm, reigned three years |

439 |

| A.D. 1097-1107. Eadgar, son of Malcolm Ceannmor by Queen Margaret, reigns nine years |

440 |

| A.D. 1107-1124. Alexander, son of Malcolm Ceannmor by Queen Margaret, reigns over Scotland north of the Firths of Forth and Clyde as king for seventeen years |

447 |

| A.D. 1107-1124. David, youngest son of Malcolm Ceannmor by Queen Margaret, rules over Scotland south of the Forth and Clyde as earl |

454 |

| A.D. 1124-1153. David reigns over all Scotland as first feudal monarch |

457 |

| A.D. 1130. Insurrection of Angus, Earl of Moray, and Malcolm, bastard son of Alexander I. |

460 |

| A.D. 1134. Insurrection by Malcolm mac Eth |

462 |

| A.D. 1138. David invades England; position of Norman barons |

465 |

| Composition of King David’s army |

466 |

| A.D. 1153-1165. Malcolm, grandson of David, reigns twelve years |

469 |

| xviA.D. 1154. Somerled invades the kingdom with the sons of Malcolm mac Eth |

469 |

| A.D. 1160. Revolt of six earls |

471 |

| A.D. 1160. Subjection of Galloway |

472 |

| A.D. 1160. Plantation of Moray |

472 |

| A.D. 1164. Invasion by Somerled. His defeat and death at Renfrew |

473 |

| A.D. 1166-1214. William the Lyon, brother of Malcolm, reigns forty-eight years |

474 |

| A.D. 1174. Revolt in Galloway |

475 |

| A.D. 1179. King William subdues the district of Ross |

475 |

| A.D. 1181. Insurrection in favour of Donald Ban Macwilliam |

476 |

| A.D. 1196. Subjection of Caithness |

479 |

| A.D. 1211. Insurrection in favour of Guthred Macwilliam |

482 |

| A.D. 1214-1249. Alexander the Second, son of King William the Lyon, reigned thirty-five years. Crowned by the seven earls |

483 |

| A.D. 1215. Insurrection in favour of Donald Macwilliam and Kenneth Maceth |

483 |

| A.D. 1222. Subjection of Arregaithel or Argyll |

484 |

| A.D. 1235. Revolt in Galloway |

487 |

| A.D. 1249. Attempt to reduce the Sudreys, and death of the king at Kerrera |

488 |

| A.D. 1249-1285. Alexander the Third, his son, reigned thirty-six years. Ceremony at his coronation |

490 |

| A.D. 1250. Relics of Queen Margaret enshrined before the seven earls and the seven bishops |

491 |

| A.D. 1263. War between the kings of Norway and Scotland for the possession of the Sudreys |

492 |

| A.D. 1266. Annexation of the Western Isles to the Crown of Scotland |

495 |

| A.D. 1283. Assembly of the baronage of the whole kingdom at Scone, on 5th February, to regulate the succession |

496 |

| A.D. 1285-6. Death of Alexander the Third |

496 |

| Conclusion |

497 |

| Remains of the Pictish Language |

501 |

| Map showing mountain chains |

to face page |

8 |

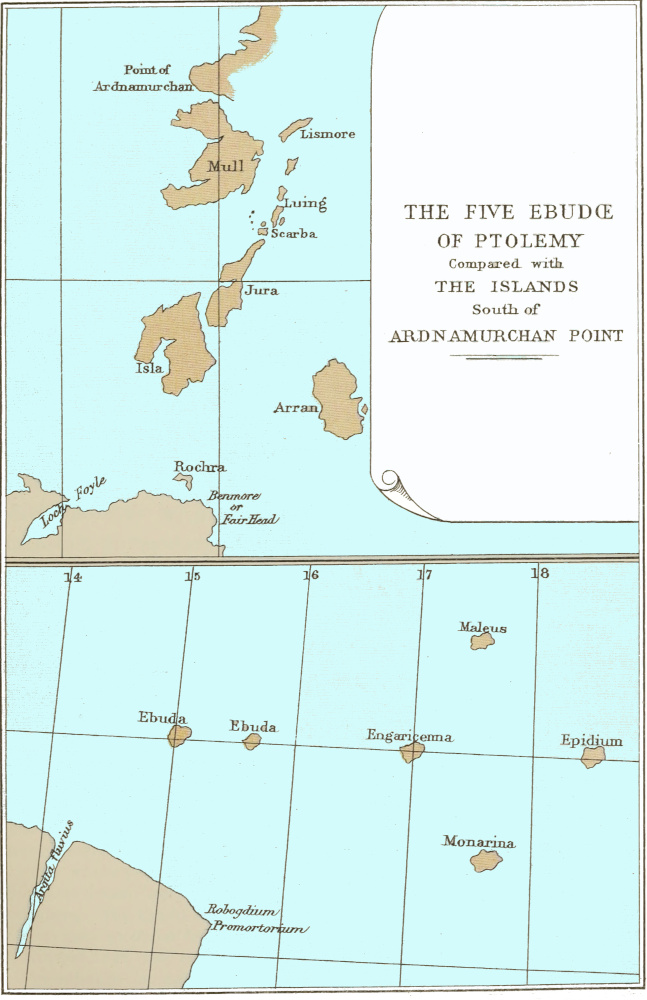

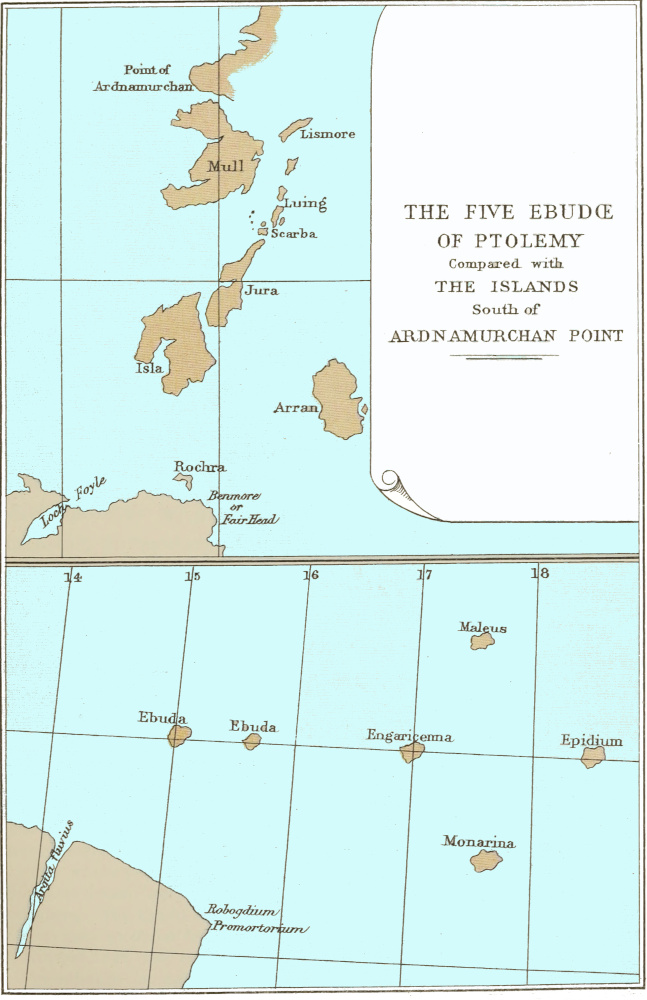

| The five Ebudæ of Ptolemy compared with the islands south of Ardnamurchan Point |

” |

68 |

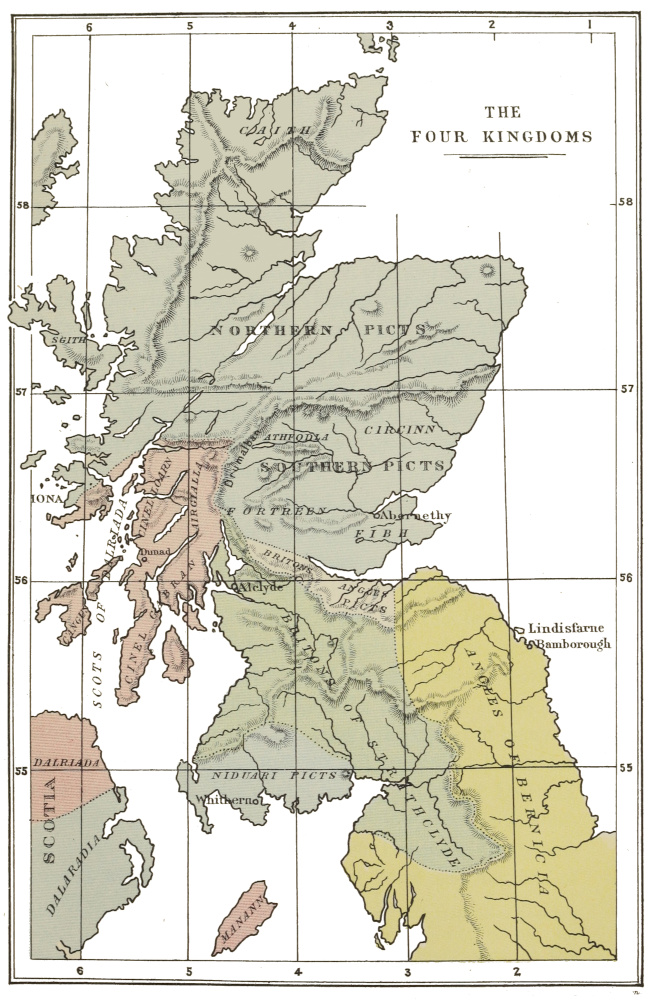

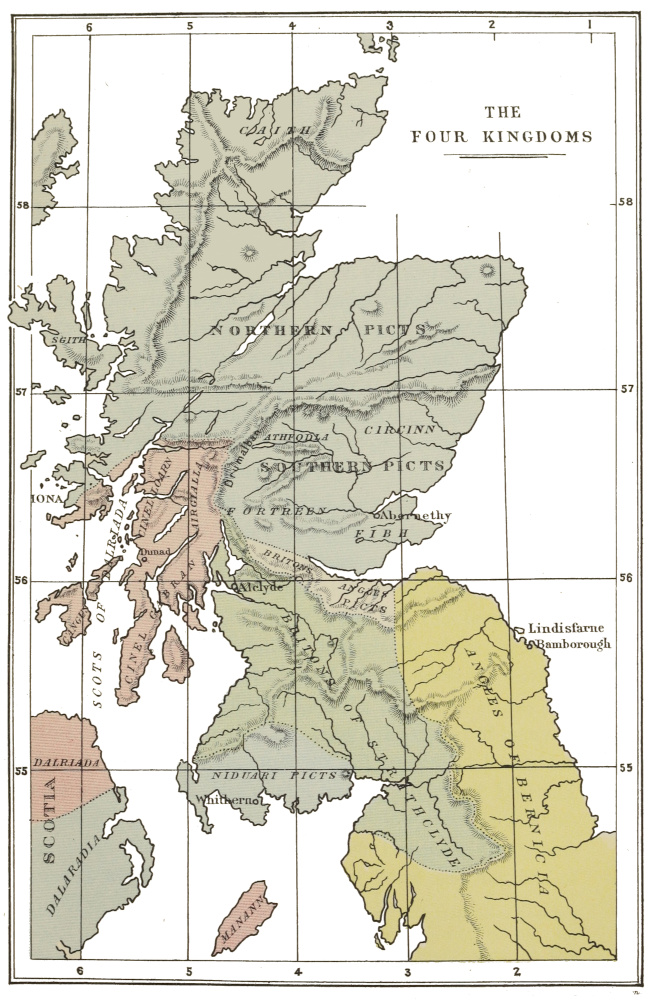

| The four Kingdoms |

” |

228 |

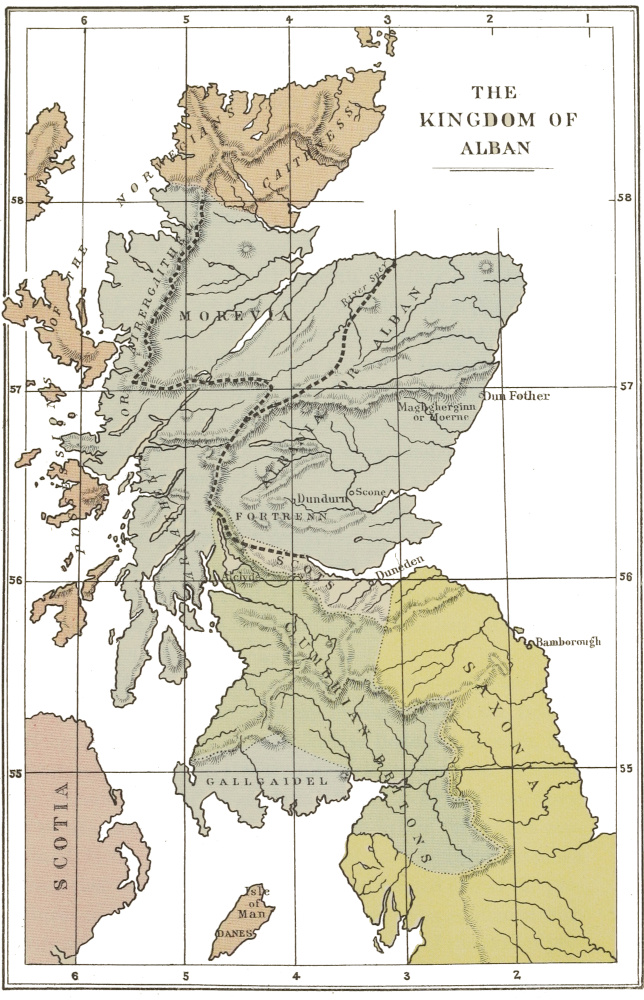

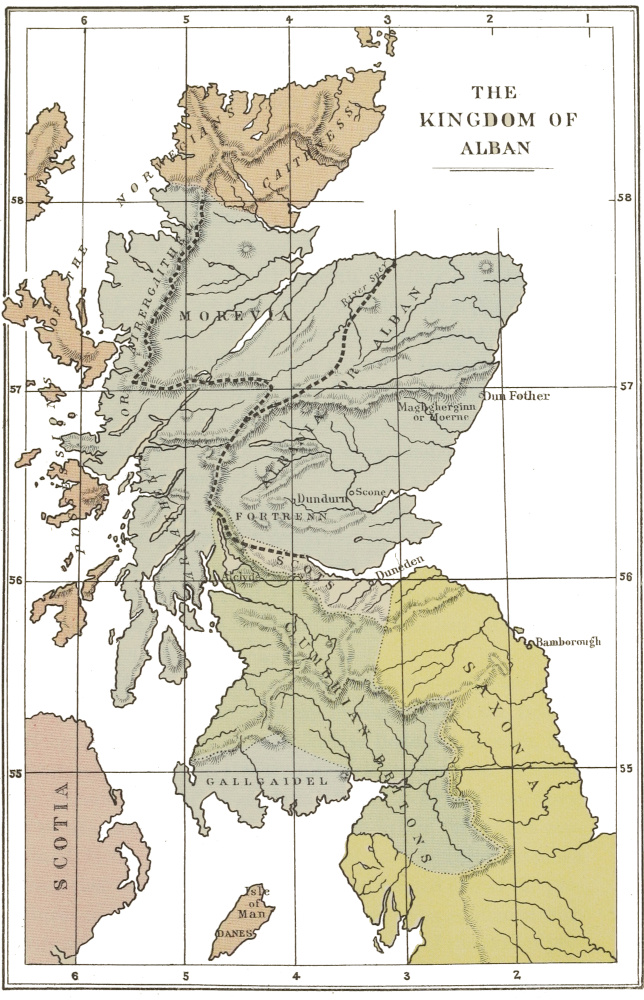

| The Kingdom of Alban |

” |

340 |

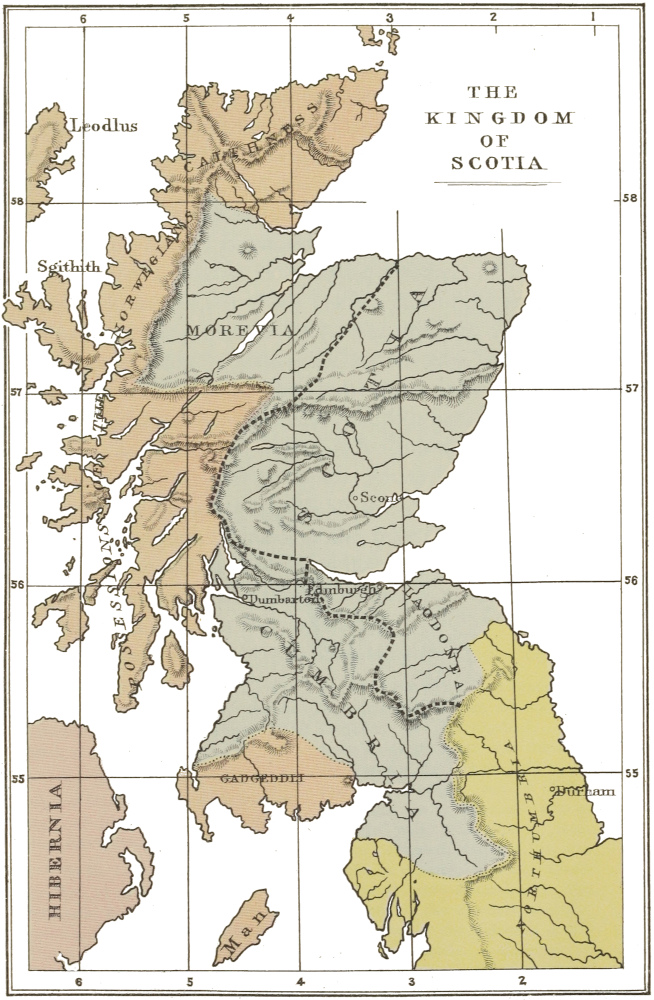

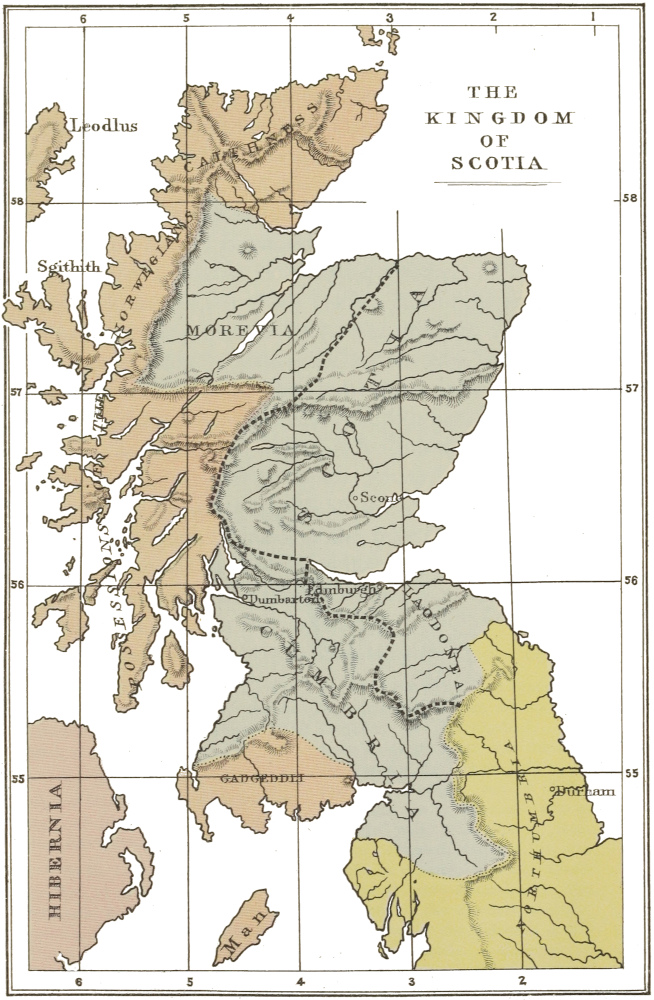

| The Kingdom of Scotia |

” |

396 |

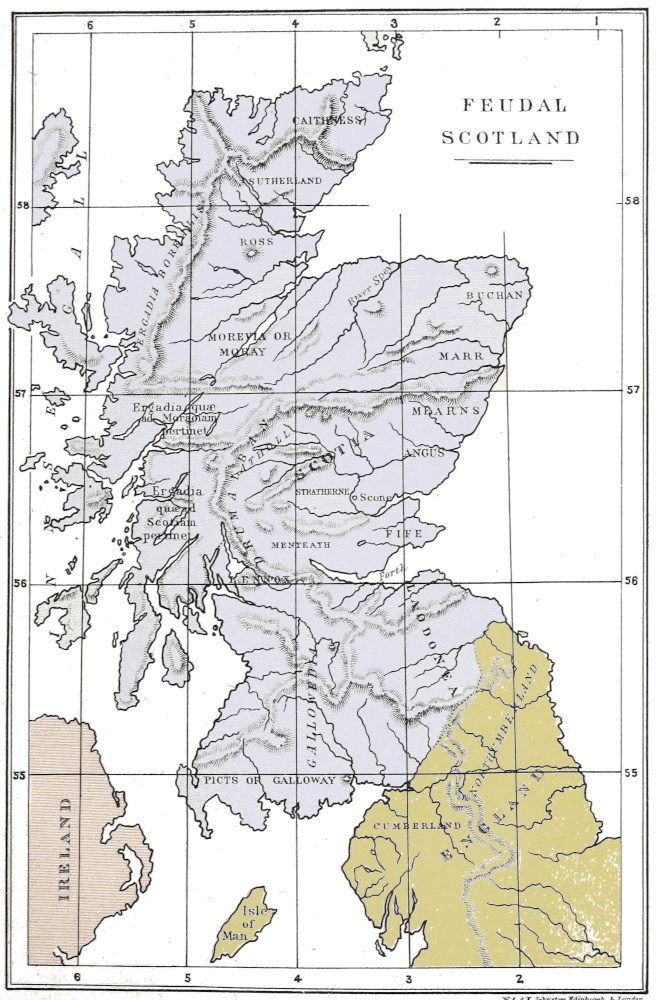

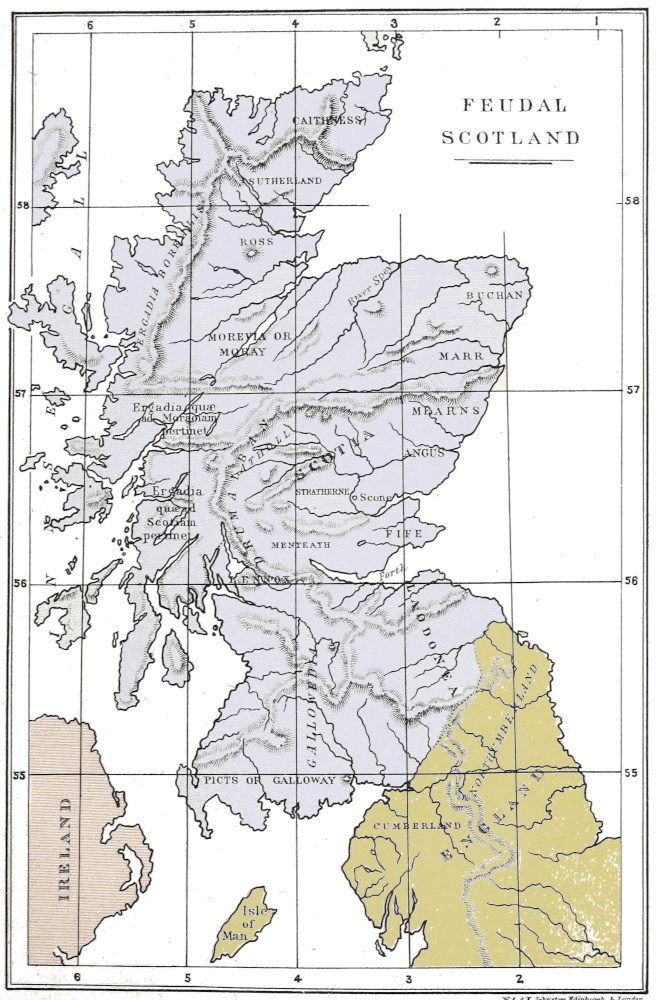

| Feudal Scotland |

” |

496 |

1

INTRODUCTION.

Name of Scotia, or Scotland.

The name of Scotia, or Scotland, whether in its Latin or its

Saxon form, was not applied to any part of the territory

forming the modern kingdom of Scotland till towards the

end of the tenth century.

Prior to that period it was comprised in the general appellation

of Britannia, or Britain, by which the whole island

was designated in contradistinction to that of Hibernia, or

Ireland. That part of the island of Britain which is situated

to the north of the Firths of Forth and Clyde seems indeed

to have been known to the Romans as early as the first

century by the distinctive name of Caledonia,[1] and it also

appears to have borne from an early period another appellation,

the Celtic form of which was Albu, Alba, or Alban,[2] and

its Latin form Albania.

2The name of Scotia, however, was exclusively appropriated

to the island of Ireland, which was emphatically

Scotia, the ‘patria,’ or mother country, of the Scots;[3] and

although a colony of that people had established themselves

as early as the beginning of the sixth century in the western

districts of Scotland, it was not till the tenth century that

any part of the present country of Scotland came to be

known under that name, nor did it extend over the whole

of those districts which formed the later kingdom of the

Scots till after the twelfth century.

Ancient extent of the kingdom.

From the tenth to the twelfth or thirteenth centuries the

name of Scotia, gradually superseding the older name of

Alban, or Albania, was confined to a district nearly corresponding

with that part of the Lowlands of Scotland which

is situated on the north of the Firth of Forth. The Scotia

of these centuries was bounded on the south by the Firth of

Forth; on the north by the Moray Firth and river Spey;

on the east by the German Ocean; and on the west by the

range of mountains which divides the modern county of

Perth from that of Argyll. It excluded Lothian, Strathclyde,

and Galloway, on the south; the great province of

Moravia, or Moray, and that of Cathanesia, or Caithness, on

3the north; and the region of Argathelia, or Argyll, on the

west.

Subsequently the name of Scotia extended over these

districts also, and the kingdom by degrees assumed that

compact and united form which it ever afterwards exhibited.

The three propositions—1st, That Scotia, prior to the

tenth century, was Ireland, and Ireland alone; 2d, That

when applied to Scotland it was considered a new name

superinduced upon the older designation of Alban or Albania;

and 3d, That the Scotia of the three succeeding

centuries was limited to the districts between the Forth,

the Spey, and Drumalban,—lie at the very threshold of

Scottish history.[4]

4The history of the name of a country is generally found

to afford a very important clue to the leading features in the

5history of its population. This is remarkably the case with

regard to the history of Scotland, and the facts just indicated

6in connection with the application of its name at different

periods throw light upon the corresponding changes in the

race and position of its inhabitants. They point to the fact

that, prior to the tenth century, none of the small and

independent tribes which originally occupied the country,

and are ever the characteristic of an early period in their

social history, or of the petty kingdoms which succeeded

them, were sufficiently powerful and extended, or predominated

sufficiently over the others, to give a general

name to the country; and they point to a great change

in the population of the country and the relative position

of these kingdoms to each other in the tenth century,

and to the elevation, by some important revolution, of the

race of the Scots over the others, whose territory formed

a centre round which the formerly independent petty kingdoms

now assumed the form of dependent provinces, and

from which an influence and authority proceeded that

7gradually extended the name of Scotia over the whole of

the country, and incorporated its provinces into one compact

and co-extensive monarchy.

Physical features of the country.

The great natural features of a country so mountainous

and intersected by so many arms of the sea as that of Scotland,

seem at all times to have influenced its political divisions

and the distribution of the various races in its occupation.

The original territories of the savage tribes of Caledonia

appear to have differed little from those of the petty kingdoms

which succeeded them, and the latter as little from

the subsequent provinces of the monarchy. The same great

leading boundaries, the same natural defences, are throughout

found occupying a similar position and exercising a

similar influence upon the internal history of the country,

while, amidst the numerous fluctuations and changes which

affected the position of the northern tribes towards the

southern and more civilised kingdoms of Britain, the two

ever showed a tendency to settle down upon the great

natural bulwarks of the south of Scotland as their mutual

boundary, to which, indeed, the independent position of

the northern monarchy in no slight degree owed its existence.

Where the great arm of the western sea forming the

Solway Firth contracts the island to a comparatively narrow

breadth, not exceeding seventy miles, a natural boundary was

thus partially formed, which had its influence at the very dawn

of Scottish history; but, if during the occupation of the island

by the Romans, who placed their trust more in the artificial

protection of a rampart guarded by troops, the comparatively

level ground in this contracted part of the country presented

facilities for such a construction, the great physical bulwark

of the Cheviot Hills had an irresistible attraction to fix the

boundary eventually between the Solway and the Tweed,

where that chain of hills extending between them proved

so effectual a defence to the country along the whole of its

8range, that every hostile entrance into it was made either

at the eastern or the western termination of that mountain

chain.

Farther north is the still more remarkable natural boundary

where the Eastern and the Western Seas penetrate into

the country in the Firths of Forth and Clyde, and approach

within a comparatively short distance of each other, separating

the northern from the southern regions of Scotland by an

isthmus not exceeding thirty-five miles in breadth. This was

remarked as early as the first Roman invasion of Scotland,

when the historian Tacitus observes that these estuaries

almost intersect the country, leaving only a narrow neck of

land, and that the northern part formed, as it were, another

island.[5]

Proceeding farther north, the great series of the mountain

ranges, stretching from the south-west to the north-east, present

one continuous barrier, intersected indeed by rivers

forming narrow and easily defended passes, but exhibiting

the appearance of a mighty wall, which separates a wild and

mountainous region from the well-watered and fertile plains

and straths on the south and east; and, while the latter have

been at all times exposed to the vicissitudes of external

revolution, and the greatly more important and radical change

from the silent progress of natural colonisation, the recesses

of the Highlands have ever proved the shelter and protection

of the descendants of the older tribes of the country, and the

limit to the advance of a stranger population.

MAP

SHEWING

MOUNTAIN CHAINS

W. & A.K. Johnston, Edinburgh & London.

The territory which forms the modern kingdom of Scotland

is thus thrown by its leading physical features into

three great compartments. First, the districts extending

from the Solway, the Cheviots, and the Tweed, on the south,

9to the Firths of Forth and Clyde on the north; secondly, the

low country extending along the east coast from the Forth

as far as the Moray Firth, and lying between the sea and

the great barrier of the Grampians; and thirdly, the Highland

or mountainous region on the north-west.

Mountain chains.

In each of these great districts natural boundaries are

again found exercising their influence on the subordinate

political divisions. |The Cheviots.| In the first of these great compartments,

the lofty range of the Cheviots, which forms the southern

boundary and presents a steep face to the north, extends

from the Cheviot Hill on the north-east by Carter Fell to

Peel Fell on the south-west; and from thence a range of

hills, sometimes included in the general name of the Cheviots,

separates the district of Liddesdale from that of Teviotdale,

and has its highest point in the centre of this part of the

island, in a group of hills termed the Lowthers, where the

four great rivers of the Tweed, the Clyde, the Annan, and

the Nith, take their rise. From thence it extends westward

to Loch Ryan, separating the waters which pour their streams

into the Solway Firth from those which flow to the north.

From the centre of this range a smaller and less remarkable

chain of hills branches off, which, running eastward by

Soutra and Lammermoor, end at St. Abb’s Head, at the

entrance to the Firth of Forth, separating the tributaries of

the Tweed from the streams which flow into the Firth of

Forth. In the centre of the island, a barren and hilly

region divides the districts watered by the rivers flowing

into the east sea from those on the west coast.

The same natural boundary which separated the eastern

from the western tribes afterwards divided the kingdom of

the Strathclyde Britons from that of the Angles; at a

subsequent period, the province of Galweia from that of Lodoneia

in their most extended sense; and now separates the

counties of Lanark, Ayr, and Dumfries from the Lothians

and the Merse. Galloway in its limited sense was not more

10clearly separated by its mountain barrier on the north from

Strathclyde, than were the Pictish from the British races by

the same chain, and the earlier tribes of the Selgovæ and

Novantæ from the Damnii.

In the other two great compartments situated on the

north of the Firths of Forth and Clyde, two great mountain

chains and two large rivers formed the principal landmarks

in the early history of the social occupation of these districts.

These two principal mountain chains were in fact the great

central ridges from which the numerous minor chains proceed,

and the rivers flow in opposite directions, forming that

aggregate of well-watered glens and rocky defiles which

characterise the mountain region of Scotland, till its streams,

uniting their waters into larger channels, burst forth through

the mountain passes, and flow through the more fertile plains

of the Lowlands into the German Ocean.

The Mounth.

The first of these two great mountain chains was known

by the name of the Mounth, and extends in nearly a straight

line across the island from the Eastern Sea near Aberdeen to

the Western Sea at Fort-William, having in its centre and

at its western termination the two highest mountains in

Great Britain—Ben-na-muich-dubh and Ben Nevis.

Drumalban.

The second great chain, less elevated and massive in its

character, but presenting the more picturesque feature of

sharp conical summits, crosses the other at right angles,

running north and south, and forming the backbone of Scotland—the

great wind and water shear, which separates the

eastern from the western districts, and the rivers flowing

into the German Ocean from those which pour their waters

into the Western Sea. It is termed in the early records of

Scottish history Dorsum Britanniæ, or Drumalban—the

dorsal ridge or backbone of Scotland. It commences in

Dumbartonshire, and forms the great separating ridge

between the eastern and western waters from south to north,

till it terminates in the Ord of Caithness.

11These two mountain chains—the Mounth and Drumalban,

the one running east and west, the other south and

north, and intersecting each other—thus divided the country

north of the Firths of Forth and Clyde into four great districts,

two extending along the east coast, and two along the

west, while each of the two eastern and western divisions

were separated from each other by the Mounth. The two

eastern divisions are watered by the two great rivers of the

Tay and the Spey and their tributaries, the one flowing south

and the other north from these mountain chains. The two

western divisions are intersected by those arms of the sea or

lochs, which form so peculiar a feature in the West Highlands.

The Grampians.

The lesser mountain ridges which proceed on either side

of the Mounth, and separate the various streams which flow

into the two great rivers from each other, terminate as the

waters enter the plains of the Lowlands, and present the

appearance of a great barrier stretching obliquely across each

of the two eastern districts and separating the mountain

region from the plain; but, although this great barrier has

an appearance as if it were a continuous mountain range, and

is usually so considered, it is not so in reality, but is formed

by the termination of these numerous lesser ridges, and is

intersected by the great rivers and their tributaries. This

great barrier forms what was subsequently termed the Highland

line, and that part of it which extends across the south-eastern

district from Loch Lomond to the eastern termination

of the Mounth was known under the general but loosely

applied name of the Grampians.[6]

12Within is a wild and mountainous region full of the most

picturesque beauty which the ever-varied combination of

mountain, rock, and stream can afford, but adapted only for

pasture and hunting, and for the occupation of a people still

in the early stage of pastoral and warlike life; while every

stream which forces its way from its recesses through this

terminating range forms a pass into the interior capable of

being easily defended.

Throughout the early history of Scotland these great

mountain chains and rivers have always formed important

landmarks of the country. If the Mounth is now known as

the range of hills which separate the more southern counties

of Kincardine, Forfar, and Perth from those of Aberdeen

and Inverness on the north, it was not less known to the

13Venerable Bede, in the eighth century, as the steep and

rugged mountains which separate the provinces of the

southern from those of the northern Picts.[7] If Drumalban

now separates the county of Argyll from that of Perth, it

formed equally in the eleventh century the mountain range

which separated Arregaithel from Scotia,[8] and at an earlier

period the boundary between the Picts and the Scots of

Dalriada.[9]

The river Spey, which now separates the counties of

Aberdeen and Banff from those of Moray and Nairn, was for

three centuries the boundary between Scotia, or Scotland

proper, and Moravia, or the great province of Moray. The

Tay, which separates the districts of Stratherne and Gowry,

formed for half a century the limit of the Anglic conquests

14in the territory of the Picts, and at the very dawn of our

history interposed as formidable a barrier to the progress of

the Roman arms. The Forth, which for three centuries was

the southern boundary of Scotia, or Scotland proper, during

the previous centuries separated the Pictish from the British

population.

The debateable lands.

The tract of country in which the frontiers of several independent

kingdoms, or the territories in the occupation of

tribes of different race, meet, usually forms a species of debateable

land, and the transactions which take place within its

limits afford in general a key to much of their relative history.

Such were the districts extending from the river Tay to the

minor range of the Pentland hills and the river Esk, which

flows into the Firth of Forth on the south. These districts

fall naturally into three divisions. The region extending

from the Tay to the river Forth, and containing part of

Perthshire, was included in that part of the country to

which the name of Alban, and afterwards that of Scotia, was

given. The central district between the rivers Forth and

Carron consisted of the whole of Stirlingshire and part of

Dumbartonshire, and belonged more properly to Strathclyde.

The region extending from the Carron to the Pentlands and

the river Esk on the south comprised the counties of West

and Mid Lothian, and was attached to Northumbria; but all

three may be viewed as outlying districts, having a mixed

population contributed by the neighbouring races.

Situated in the heart of Scotland, and having around it

tribes of different races, and subsequently the four kingdoms

of the Picts, the Scots, the Angles, and the Britons, surpassing

the other districts in fertility, and possessing those

rich carses which are still distinguished as the finest agricultural

districts of Scotland, this region was coveted as the

chief prize alike by the invaders and the native tribes. The

scene of the principal Roman campaigns, it appears throughout

the entire course of Scottish history as the main battlefield

15of contending races and struggling influences. Roman

and Barbarian, Gael and Cymry, Scot and Angle, contended

for its occupation, and within its limits is formed

the ever-shifting boundary between the petty northern

kingdoms, till in the memorable ninth century a monarchy

was established, of which the founder was a Scot, the chief

seat Scone, and that revolution was accomplished, which

it is difficult to say whether it was more civil or ecclesiastical

in its character, but which finally established the supremacy

of the Scottish people over the different races in the

country, and led to their gradual combination and more

intimate union in the subsequent kingdom of Scotland. The

kingdom of the Scots soon extended itself over these

central plains. Its monarchs usually had their residence

within its limits, and the capital, which had at first been

Scone, on the left bank of the Tay, eventually became

established at Edinburgh, within a few miles of its southern

boundary.

During the few succeeding centuries of Scottish rule,

after the establishment of the Scottish monarchy in the ninth

century, it remained limited to the districts bounded by the

Forth on the south, the mountain chain called Drumalban on

the west, and the Spey on the north. The Scots had rapidly

extended their power and influence over the native tribes

within these limits; but beyond them (on the north and west)

they held an uncertain authority over wild and semi-independent

nations, nominally dependencies of the kingdom, but

in reality neither owning its authority nor adopting its name.

It was by slow degrees that the peoples beyond these

limits were first subjugated and then amalgamated with the

original Scottish kingdom; and it was not till the middle of

the thirteenth century, when the annexation of the Western

Isles by Alexander the Third finally completed the territorial

acquisitions of the monarchy, that its name and authority

became co-extensive with the utmost limits of the country,

16and Scotland was consolidated in its utmost extent of

territory into one kingdom.

Periods of its history.

The early history of Scotland thus presents itself to the

historian in five distinct periods, each possessing a character

peculiar to itself.

During the first period of three centuries and a half

the native tribes of Scotland were under the influence

of the Roman power, at one time struggling for independent

existence, at another subject to their authority,

and awaking to those impressions of civilisation and

of social organisation, the fruits of which they subsequently

displayed.

A period of rather longer duration succeeded to the

Roman rule, in which the native and foreign races in the

country first struggled for the succession to their dominant

authority in the island, and then contended among themselves

for the possession of its fairest portions.

The third period commences with the establishment of

the Scottish monarchy in the ninth century, and lasted for

two centuries and a half, till the Scottish dynasty became

extinct in the person of Malcolm the Second.

There then succeeded, during the fourth period, which

lasted for a century, a renewed struggle between the different

races in the country, which, although the Scoto-Saxon

dynasty, uniting through the female line the blood of the

Scots and the Saxons, succeeded in seating themselves firmly

on the throne, cannot be said to have terminated in the

general recognition of their royal authority till the reign of

David the First.

The fifth period, consisting of the reigns of David I., Malcolm

IV., William the Lion, and Alexander the Second and

Third, was characterised by the rapid amalgamation of the

different provinces, and the spread of the Saxon race and of

the feudal institutions over the whole country, with the

exception of the Highlands and Islands, and left the kingdom

17of Scotland in the position in which we find it when

the death of Alexander the Third, in 1286, terminated the

last of the native dynasties of her monarchs.

Celtic Scotland.

During the first three periods of her early history, Scotland

may be viewed as a purely Celtic kingdom, with a population

composed of different branches of the race popularly called

Celtic. But during the subsequent periods, though the

connection between Scotland with her Celtic population and

Lothian with her Anglic inhabitants was at first but

slender, her monarchs identified themselves more and more

with their Teutonic subjects, with whom the Celtic tribes

maintained an ineffectual struggle, and gradually retreated

before their increasing power and colonisation, till they

became confined to the mountains and western islands. The

name of Scot passed over to the English-speaking people,

and their language became known as the Scotch; while the

Celtic language, formerly known as Scotch, became stamped

with the title of Irish.

What may be called the Celtic period of Scottish history

has been peculiarly the field of a fabulous narrative of no

ordinary perplexity; but while the origin of these fables can

be very distinctly traced to the rivalry and ambition of ecclesiastical

establishments and church parties, and to the great

national controversy excited by the claim of England to a

feudal supremacy over Scotland, still each period of its early

history will be found not to be without sources of information,

slender and meagre as no doubt they are, but possessing

indications of substantial truth, from which some perception

of its real character can be obtained.

Critical examination of authorities necessary.

Before the early history of any country can be correctly

ascertained, there is a preliminary process which must be

gone through, and which is quite essential to a sound treatment

of the subject; and that is a critical examination of

the authorities upon which that history is based. This is

especially necessary with regard to the early history of Scotland.

18The whole of the existing materials for her early

history must be collected together and subjected to a critical

examination. Those which seem to contain fragments

of genuine history must be disentangled from the less trustworthy

chronicles which have been tampered with for ecclesiastical

or national purposes, and great discrimination exercised

in the use of the latter. The purely spurious matter must be

entirely rejected. It is by such a process only that we can

hope to dispel the fabulous atmosphere which surrounds

this period of Scottish history, and attempt to base it upon

anything like a genuine foundation.

The first to attempt this task was Thomas Innes, a priest

of the Scots College in Paris, who published in 1729 his

admirable Essay on the ancient inhabitants of Scotland. In

this essay he assailed the fabulous history first put into

shape by John of Fordun and elaborated by Hector Boece,

and effectually demolished its authority; but he attempted

little in the way of reconstruction, and merely printed a few

of the short chronicles, upon which he founded, in an appendix.

Lord Hailes, who in 1776 published his Annals of Scotland,

from the Accession of Malcolm III., surnamed Canmore,

to the Accession of Robert I., abandons this period of Scottish

history altogether, with the remark that his Annals

‘commence with the accession of Malcolm Canmore, because

the history of Scotland previous to that period is involved

in obscurity and fable.’

The first to attempt a reconstruction of this early history

was John Pinkerton, who published in 1789 An Enquiry

into the History of Scotland preceding the reign of Malcolm

III., or the year 1056, including the authentic history of

that period. It is unquestionably an essay of much

originality and acuteness; and Pinkerton saw the necessity

of founding the history of that period upon more trustworthy

documents, but they were to a very limited extent

accessible to him. The value of the work is greatly impaired

19by the adoption, to an excessive extent, of a theory of early

Teutonic settlements in the country and of the Teutonic

origin of the early population, and by an unreasoning

prejudice against everything Celtic, which colours and

biasses his argument throughout.

Pinkerton was followed in 1807 by George Chalmers,

with his more elaborate and systematic work, the Caledonia,

based, however, to a great extent upon the less trustworthy

class of the early historical documents, which had been

tampered with and manipulated for a purpose. He, too,

was possessed by a theory which influences his views of the

earlier portion of the history throughout; and where John

Pinkerton could find nothing but Gothic and the Goths,

George Chalmers was equally unable to see anything but

Welsh and the Cymry.

In 1828 the first volume of a History of Scotland by

Patrick Fraser Tytler appeared, which he continued to the

accession of James VI. to the throne of England; but Tytler

not only abandons this early part of the history as hopelessly

obscure, but also a great part of the field occupied by Hailes

in his Annals, and commences his history with the accession

of Alexander the Third in 1249.

In 1862 a very valuable contribution to the early history

of Scotland was made by the late lamented Mr. E. William

Robertson in his Scotland under her Early Kings, in which

the attempt is once more made to fill up the early period

left untouched by Hailes and Tytler. It is a work of great

merit, and exhibits much accurate research and sound judgment.[10]

Such is a short sketch of the attempts which have been

made to place the early history of Scotland upon a sound

basis, and to substitute a more trustworthy statement of it

for the carefully manipulated fictions of Fordun, and the still

20more fabulous narrative of Hector Boece and his followers,

prior to the appearance of Mr. Burton’s elaborate History of

Scotland, from Agricola’s Invasion to the Extinction of the last

Jacobite Insurrection, the first edition of which appeared in

1867, and the second, in which the early part is revised and

much altered, in 1873.

These works, however, are all more or less tainted by the

same defect, that they have not been founded upon that

complete and comprehensive examination of all the existing

materials for the history of this early period, and that critical

discrimination of their relative value and analysis of their

contents, without which any view of this period of the annals

of the country must be partial and inexact. They labour, in

short, under the twofold defect, first, of an uncritical use of the

materials which are authentic; and second, of the combination

with these materials of others which are undoubtedly

spurious. The early chronicles are referred to as of equal

authority, and without reference to the period or circumstances

of their production. The text of Fordun’s Chronicle, upon

which the history, at least prior to the fourteenth century,

must always to a considerable extent be based, is quoted as

an original authority, without adverting to the materials he

made use of and the mode in which he has adapted them to a

fictitious scheme of history; and the additions and alterations

of his interpolator Bower are not only founded upon

as the statements of Fordun himself, but quoted under his

name in preference to his original version of the events.

The author has elsewhere endeavoured to complete the

work commenced by Thomas Innes. He has collected together

in one volume the whole of the existing chronicles

and other memorials of the history of Scotland prior to the

appearance of Fordun’s Chronicle, and has subjected them,

as well as the work of Fordun, to a critical examination and

analysis.[11]

21He now proposes to take a farther step in advance, and

to attempt in the present work to place the early history of

the country upon a sounder basis, and to exhibit Celtic

Scotland, so far as these materials enable him to do so, in a

clearer and more authentic light. By following their guidance,

and giving effect to fair and just inferences from their

statements unbiassed by theory or partiality, and subjected

to the corrective tests of comparison with those physical

records which the country itself presents, it is hoped that

it may not be found impossible to make some approximation

to the truth, even with regard to the annals of this

early period of Scottish history.

It may be said that this task has been rendered unnecessary

by the appearance of Mr. Burton’s History of Scotland,

which commences the narrative with the invasion of

Agricola, and claims ‘the two fundamental qualities of a

serviceable history—completeness and accuracy;’[12] but, with

much appreciation of the merits of Mr. Burton’s work as a

whole, the author is afraid that he cannot recognise it as

possessing either character, so far as the early part of the

history is concerned, and he considers that the ground which

the present work is intended to occupy remains still unappropriated.

Spurious authorities.

It remains for him to indicate here at the outset the

materials founded upon by the previous writers which he

considers of questionable authority, or must reject as entirely

spurious.

22Among the first to be rejected as entirely spurious is the

work attributed to Richard of Cirencester, De situ Britanniæ

et Stationum quas Romani ipsi in ea insula ædificaverunt.

It was published in 1757 from a MS. said to be discovered

at Copenhagen by Charles Julius Bertram, and was at once

adopted as genuine. The author at a very early period came

to the conclusion that the whole work, including the itineraries,

was an impudent forgery, and this has since been so

amply demonstrated, and is now so generally admitted, that

it is unnecessary to occupy space by proving it.[13] The whole

of the Roman part of Pinkerton’s Enquiry and of the elaborate

work of Chalmers is tainted by it; and, what is perhaps

more to be regretted, the valuable work of General Roy[14] on

The Military Antiquities of the Romans in Britain, published

in 1793. He says in his introduction, ‘From small beginnings

it is, however, no unusual thing to be led imperceptibly

to engage in more extensive and laborious undertakings, as

will easily appear from what follows, for since the discovery

of Agricola’s camps, the work of Richard of Cirencester

having likewise been found out in Denmark and published

to the world, the curious have thereby been furnished with

many new lights concerning the Roman history and

23geography of Britain in general, but more particularly the

north part of it,’ and by this unfortunate adoption of the

forged work by General Roy, there has been lost to the

world, to a great extent, the advantage of the commentary

of one so well able to judge of military affairs. Horsley’s

valuable work, the Britannia Romana, was fortunately

published in 1732 before this imposition was practised on

the literary world; but Stuart has not been equally fortunate

in his Caledonia Romana, published in 1845, the usefulness

of which is greatly impaired by it.

Among the Welsh documents which are usually founded

upon as affording materials for the early history of the

country, there is one class of documents contained in the

Myvyrian Archæology which cannot be accepted as genuine.

The principal of these are the so-called Historical Triads,

which have been usually quoted as possessing undoubted

claims to antiquity under the name of the Welsh Triads;

the tale called Hanes Taliessin, or the history of Taliessin;

and a collection of papers printed by the Welsh ms. Society,

under the title of the Iolo MSS. These all proceeded from

Edward Williams, one of the editors of the Myvyrian

Archæology published in 1801, and who is better known

under the bardic title of Iolo Morganwg. The circumstances

under which he produced these documents, or the motives

which led him to introduce so much questionable matter into

the literature of Wales, it is difficult now to determine; but

certain it is that no trace of them is to be found in any

authentic source, and that they have given a character to

Welsh literature which is much to be deplored. In a former

work, the author in reviewing these documents merely said,

‘It is not unreasonable therefore to say that they must be

viewed with some suspicion, and that very careful discrimination

is required in the use of them.’ He does not hesitate

now to reject them as entirely spurious.[15]

24It will of course be impossible to write upon the Celtic

period of Scottish history without making a large use of Irish

materials; and it is difficult to over-estimate the importance

of the Irish Annals for this purpose; but these too must

be used with some discrimination. The ancient history of

Ireland presents the unusual aspect of the minute and

detailed annals of reigns and events from a period reaching

back to many centuries before the Christian era, the whole

of which has been adopted by her historians as genuine.

The work of Keating, written in Irish in 1640, a translation

of which by Dermod O’Connor was published in 1726, may

be taken as a fair representation of it. The earlier part of

this history is obviously artificial, and is viewed by recent

Irish historians more in the light of legend; but there is

nothing whatever in the mode in which the annals of the

different reigns are narrated to show where legend terminates

and history begins, and there is a tendency among even the

soundest writers on Irish history to push the claims of these

annals to a historical character beyond the period to which

it can reasonably be attached. For the events in Irish

history the Annals of the Four Masters are usually quoted.

There is a certain convenience in this, as it is the most

complete chronicle which Ireland possesses; but it was

compiled as late as the seventeenth century, having been

commenced in 1632 and finished in 1636. The compilers

were four eminent Irish antiquaries, the principal of whom

was Michael O’Clery, whence it was termed by Colgan the

Annals of the Four Masters. These annals begin with the

year of the Deluge, said to be the year of the world 2242, or

2952 years before Christ, and continue in an unbroken series

to the year of our Lord 1616. The latter part of the annals

25are founded upon other documents which are referred to in

the preface, and from which they are said to be taken, but

the authority for each event is not stated, and some of those

recorded are not to be found elsewhere, and are open to

suspicion.[16] The earlier part of the annals consists simply

of a reduction of the fabulous history of Ireland into the

shape of a chronicle, and, except that it is thrown into that

form instead of that of a narrative, it does not appear to the

author to possess greater claims to be ranked as an authority

than the work of Keating. He cannot therefore accept it

as an independent authority, nor can he regard the record

of events to the fifth century as bearing the character of

chronological history in the true sense of the term, though

no doubt many of these events may have some foundation

in fact.[17]

The older annals stand in a different position. Those of

Tighernac, Inisfallen, and the Annals of Ulster, are extremely

valuable for the history of Scotland; and, while the latter

commence with what may be termed the historic period in

26the fifth century, the earlier events recorded by Tighernac,

who died in the year 1088, may contain some fragments of

genuine history.

Plan of the work.

The subject of this work will be most conveniently treated

under three separate heads or books.

The first book will deal with the Ethnology and Civil

History of the different races which occupied Scotland. In

this inquiry, it will be of advantage that we should start

with a clear conception of the knowledge which the Romans

had of the northern part of the island, and of the exact

amount of information as to its state and population which

their possession of the southern part of it as a province affords.

This will involve a repetition of the oft-told tale of the

Roman occupation of Scotland. But this part of the history

has been so overloaded with the uncritical use of authorities,

the too ready reception of questionable or forged documents,

and the injurious but baseless speculations of antiquaries,

that we have nearly lost sight of what the contemporary

authorities really tell us. Their statements are, no doubt,

meagre, and may appear to afford an insufficient foundation

for the deductions drawn from them, but they are precise;

and it will be found that though they may compress the

account of a campaign or a transaction into a few words, yet

they had an accurate knowledge of the transactions, the

result of which they wished to indicate, and knew well

what they were writing about. It will be necessary, therefore,

carefully to weigh these short but precise statements,

and to place before the reader the state of the early inhabitants

of Scotland as the Romans at the time knew them

and viewed them, not as what by argument from other

premises they can be made to appear.[18]

27This will lay the groundwork for an inquiry into their

race and language; and an attempt will then be made to

trace the history of these different races, their mutual

struggle for supremacy, the causes and true character of

that revolution which laid the foundation of the Scottish

monarchy, and the gradual combination of its various heterogeneous

elements into one united kingdom; and thus by

a more complete and critical use of its materials, to place

the early history of the country, during the Celtic period,

upon a sounder basis.

The second book will deal with the Early Celtic Church

of Scotland and its influence on the language and culture

of the people. The ecclesiastical history of Scotland has

shared the same fate with its civil history, and is deeply

tainted with the fictitious and artificial system which has

perverted both; but the stamp of these fables upon it is

less easily removed. It has also had the additional misfortune

of having been made the battle-field of polemical controversy.

Each historian of the Church has viewed it

through the medium of his ecclesiastical prepossessions, and

from the standpoint of the Church party to which he

belonged. The Episcopal historian feels the necessity of

discovering in it his Diocesan Episcopacy, and the partisan

28of Presbyterian parity considers the principles of his

Church involved in maintaining the existence of his early

Presbyterian Culdees. One great exception must be made,

however, in Dr. Reeves’s admirable edition of Adamnan’s

Life of St. Columba, which has laid the foundation for a

more rational treatment of the history of the early Church

in Scotland.

The subject of the third and last book will be the Land

and People of Scotland. It will treat of the early land

tenures and social condition of its Celtic inhabitants. The

publication of the Brehon laws of Ireland now enables us

to trace somewhat of the history and character of their

early tribal institutions and laws, and of their development

in Scotland into those communities represented in

the eastern districts by the Thanages, and in the western

by the Clan system of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

29

BOOK I.

HISTORY AND ETHNOLOGY.

CHAPTER I.

ADVANCE OF THE ROMANS TO THE FIRTHS OF FORTH AND CLYDE.

Early notices of the British Isles.

As early as the sixth century before the Christian era, and

while their knowledge of Northern Europe was still very

imperfect, the Greeks had already become aware of the

existence of the British Isles. This comparatively early

knowledge of Britain was derived from the trade in tin, for

which there existed at that period an extensive demand in

the East. It was imported by sea by the Phœnicians, and

by their colony, the Carthaginians, who extended their

voyages beyond the Pillars of Hercules; and was subsequently

prosecuted as a land trade by their commercial

rivals, the Greek colonists of Marseilles.

A Greek poet, writing under the name of Orpheus, but

whose real date may be fixed at the sixth century, mentions

these remote islands under the name of the Iernian Isles;[19]

but in the subsequent century they were known to Herodotus

as the Cassiterides, or Tin Islands,[20] a name derived from the

chief article of the trade through which all report of their

existence was as yet derived.

In the fourth century they are alluded to by Aristotle

30as two very large islands beyond the Pillars of Hercules;

and, while the name of Britannia was now from henceforth

applied, especially by the Greek writers, to the group of

islands, of whose number and size but vague notions were

still entertained, the two principal islands appear for the

first time under the distinctive appellations of Albion and

Ierne.[21]

Polybius, in the second century before Christ, likewise

alludes to the Britannic Islands beyond the Pillars of Hercules,

and to the working of the mines by the inhabitants.[22]

Besides these direct allusions to the British Isles, we

have preserved to us by subsequent writers an account of

these islands from each of the two sources of information—the

Phœnician voyages and the land trade of the Phocæans

of Marseilles—in the narratives of the expeditions of

Himilco and Pytheas.

Himilco was a Carthaginian who was engaged in the

Phœnician maritime trade in the sixth century, and the

traditionary account of his voyage is preserved by a comparatively

late writer, Festus Rufus Avienus. In his

poetical Description of the World, written from the account

of Himilco, he mentions the plains of the Britons and the

distant Thule, and talks of the sacred isle peopled by

the nation of the Hiberni and the adjacent island of the

Albiones.[23]

Pytheas was a Massilian. His account of his journey

is preserved by the geographer Strabo, and appears to have

been received with great distrust. He stated that he had

sailed round Spain and the half of Britain; ascertained that

the latter was an island; made a voyage of six days to the

island of Thule, and then returned. From him Strabo, Diodorus

Siculus, and Pliny derived their information as to the

31size of the islands, and his statement made known for the

first time the names of three promontories—Cantium or

Kent, Belerium or Land’s End, and Orcas, or that opposite

the Orkneys.[24]

But although the existence of the British Isles was thus

known at an early period to the classic writers under specific

names, and some slender information acquired through the

medium of the early tin trade as to their position and magnitude,

it was not till the progress of the Roman arms and

their lust of conquest had brought their legions into actual

contact with the native population, that any information as

to the inhabitants of these islands was obtained.

B.C. 55.

Invasion of Julius Cæsar.

The invasion of Britain by Julius Cæsar in the year 55

before the Christian era, although it added no new territory

to the already overgrown empire of the Romans, and was

probably undertaken more with the view of adding to the

military renown of the great commander, for the first time

made the Romans acquainted with some of the tribes inhabiting

that, to them, distant and almost inaccessible isle,

and added distinctness and definiteness to their previously

vague conception of its characteristics. Its existence was

now not merely a geographical speculation, but a political

fact in the estimation of those by whom the destinies of the

world were then swayed—an element that might possibly

enter into their political combinations.

The conquests of Julius Cæsar in Britain, limited in

extent and short-lived in duration, were not followed up.

The policy of the subsequent emperors involved the neglect

of Britain as an object of conquest; and, while it now

assumed a more definite position in the writings of Greek

and Roman geographers, they have left us nothing but the

names of a few southern tribes and localities which do not

concern the object before us, and a statement regarding the

general population which is of more significance.

32Cæsar sums up his account by telling us that the interior

of Britain was inhabited by those who were considered to be

indigenous, and the maritime part by those who had passed

over from Belgium, the memory of whose emigration was

preserved by their new insular possessions bearing the same

name with the continental states from which they sprang.

He describes the country as very populous, the people as

pastoral, but using iron and brass, and the inhabitants of the

interior as less civilised than those on the coasts. The

former he paints as clothed in skins, and as not resorting to

the cultivation of the soil for food, but as dependent upon

their cattle and the flesh of animals slain in hunting for

subsistence. He ascribes to all those customs which seem to

have been peculiar to the Britons. They stained their bodies

with woad, which gave them a green colour, from which the

Britons were termed ‘Virides’ and ‘Cærulei.’ They had

wives in common. They used chariots in war, and Cæsar

bears testimony to the bravery with which they defended

their woods and rude fortresses, as well as encountered the

disciplined Roman troops in the field. He mentions the

island Hibernia as less than Britannia by one-half, and about

as far from it as the latter is from Gaul, and an island termed

‘Mona’ in the middle of the channel between the two

larger islands.[25]

Strabo and Diodorus Siculus have preserved any

additional accounts of the inhabitants which the Romans

received during the succeeding reigns of Augustus and

Tiberius. They describe the Britons as taller than the Gauls,

with hair less yellow, and slighter in their persons; and

Strabo distinguishes between that portion of them whose

manners resembled those of the Gauls and those who were

more simple and barbarous, and were unacquainted with

agriculture—manifestly the inhabitants of the interior whom

Cæsar considered to be indigenous. He describes the peculiarity

33of their warfare, their use of chariots, and their towns

as enclosures made in the forests, with ramparts of hewn

trees. He mentions the inhabitants of ‘Ierne’ as more

barbarous, regarding whom reports of cannibalism and the

promiscuous intercourse of the sexes were current.[26] Diodorus

gives a more favourable picture of the inhabitants who

were considered to be the aborigines of the island, and

attributes to them the simple virtues of the pure and early

state of society fabled by the poets. He alludes to their use

of chariots and their simple huts, and adds to Strabo’s account

that they stored the ears of corn under ground. He represents

them as simple, frugal, and peaceful in their mode of

life. Those near the promontory of Belerion or Land’s End

he describes as more civilised, owing to their intercourse

with strangers.[27]

Thus all agree in distinguishing between the simple and

rude inhabitants of the interior, who were considered to be

indigenous, and the more civilised people of the eastern

and southern shores who were believed to have passed over

from Gaul.

A.D. 43.

Formation of province in reign of Claudius.

It was not till the reign of Claudius that any effectual

attempt was renewed to subject the British tribes to the

Roman yoke; but the second conquest under that emperor

speedily assumed a more permanent character than the first

under Julius Cæsar, and the conquered territory was formed

into a province of the Roman empire. During this intervening

period of nearly a century, we know nothing of the

internal history of the population of Britain; but the

indications which have reached us of a marked and easily-recognised

distinction between two great classes of the

inhabitants, and of the progressive immigration of one of

them from Belgium, and the analogy of history, lead to the

inference that during this period—ample for such a purpose—the

stronger and more civilised race must have spread over

34a larger space of the territory, and the ruder inhabitants of

the interior been gradually confined to the wilder regions of

the north and west. The name of Britannia having gradually

superseded the older appellation of Albion, and the latter, if

it is synonymous with Alba or Alban, becoming confined to

the wilder regions of the north, lead to the same inference.

As soon as the conquests of the Romans in Britain

assumed the form of a province of the empire, all that they

possessed in the island was termed ‘Britannia Romana,’ all

that was still hostile to them, ‘Britannia Barbara.’ The conquered

tribes became the inhabitants of a Roman province,

subject to her laws, and sharing in some of her privileges.

The tribes beyond the limits of the province were to them

‘Barbari.’ An attention to the application of these terms

affords the usual indication of the extent of the Roman

province at different times, and, if the history of the more

favoured southern portion of the island must find its earliest

annals in the Roman provinces of Britain, it is to the

‘Barbari’ we must turn in order to follow the fortunes of

the ruder independence of the northern tribes. It will be

necessary, therefore, for our purpose, that we should trace

the gradual extension of the boundary of the Roman province

and the advance of the line of demarcation between what was

provincial and what was termed barbarian, till we find the

independent tribes of Britain confined within the limits of

that portion of the island separated from the rest by the

Firths of Forth and Clyde.

It was in the year of our Lord 43, and in the reign of the

Emperor Claudius, that the real conquest of Britain commenced

under Aulus Plautius, and in seven years after the

beginning of the war a part of the island had been reduced

by that general and by his successor into the form of a province,

and annexed to the Roman empire,—a result to which

the valour and military talent of Vespasian, then serving

under these generals, and afterwards Emperor, appears

35mainly to have contributed. In the year 50, under Ostorius,

and perhaps his successor, the Roman province appears

to have already extended to the Severn on the west, and to

the Humber on the north.[28]

Beyond its limits, on the west, were the warlike tribes

of the Silures and the Ordovices, against whom the

province was defended by a line of forts drawn from the

river Sabrina or Severn, to a river, which cannot be identified

with certainty, termed by Tacitus the Antona.[29] On the

north lay the numerous and widely-extended tribes of the

Brigantes, extending across the entire island from the

Eastern to the Western Sea, and reaching from the Humber,

which separated them from the province on the south, as

far north, there seems little reason to doubt, as the Firth of

Forth.[30] Beyond the nation of the Brigantes on the north,

the Romans as yet knew nothing save that Britain was

believed to be an island, and that certain islands termed

Orcades[31] lay to the north of it; but the names even of the

more northern tribes had not yet reached them.

A.D. 50. War with the Brigantes.

36It is to the war with the Brigantes that we must mainly

turn, in order to trace the progress of the Roman arms, and

the extension of the frontier of the Roman province beyond

the Humber. The Romans appear to have come in contact

with the Brigantes for the first time in the course of the war

carried on by Publius Ostorius, appointed governor of

Britain in the year 50. That general had arrived in the

island towards the end of summer; and the Barbarians, or

those of the Britons still hostile to the Romans, believing he

would not undertake a winter campaign, took advantage of

his arrival at so late a period of the year to make incursions

into the territory subject to Rome. Among these invading