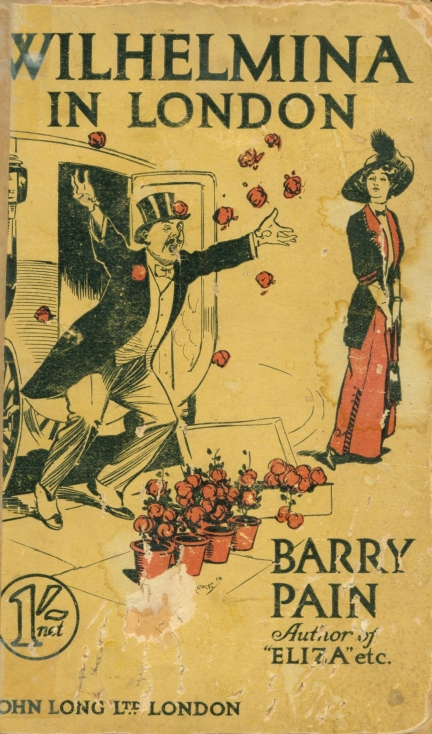

By

Barry Pain

Author of “Eliza,” “Eliza Getting On,”

“Exit Eliza,” etc.

NEW EDITION

London

John Long, Limited

Norris Street, Haymarket

1912

Contents

I. STRANDED

II. MR. NATHAN GOULD

III. THE MAN OF MEANS

V. THE SPIRITS OF HANFORD GARDENS

VI. UNREWARDED

VII. A QUEER COMMISSION

VIII. THE PEGASUS CAR

Wilhelmina in London

It is quite possible to love a person whom one does not respect, of whom one even disapproves. I loved my father, but I certainly did not respect him. He did not even respect himself.

When he married my mother, much against the wishes of his family, my grandfather bought him an annuity of two hundred a year, and desired to have nothing more to do with him. My mother died when I was quite a little girl, but I have a vivid recollection that she was just about as helpless as my father. In times of financial crisis—and, thanks to my father, these were very frequent—the two would sit staring at one another over the fire, and say that this was the beginning of the end, or exhort each other to hope and courage, but never, by any chance, take any practical way of dealing with the situation. On these gloomy occasions my father generally made a will. I do not think he, at any time, had anything to leave us worth mentioning, but the sonorous phrases and the feeling that he was doing something business-like seemed to give him a melancholy satisfaction. I have the last will that he made before me now. It begins: “I, Bernard Castel, being of sound mind and understanding, and at peace with God and man, do hereby give and bequeath all my real and personal estate, of whatsoever kind, to my only beloved daughter, Wilhelmina.” There followed directions as to the ways of disposing of this estate, supposing it should exceed twenty-five thousand pounds at the time of his death, and further directions if it should exceed fifty thousand. At that time we were as usual skating on the very edge of bankruptcy. I remember my father returned in triumph from dealing with the local tradesman who was his principal creditor. “I have done it, Wilhelmina,” he said. “And I doubt if any other man in the world could have done it. Another coat of paint and there would have been a collision.”

I suppose he really loved me. He often told me, especially when a financial crisis was at its worst, that I was all he had in the world. But he never insured his life, and never made any provision for me after his death. After all, I believe that a father and a girl of sixteen, even if they happen to be gentle-folks, can live in the country on two hundred a year, and even put by a few pounds for insurance. The trouble was that my father could not let his income alone. Every quarter-day brought some new scheme, generally of a wildly speculative and gambling character. And before next quarter-day we were terribly hard up. At first my father confided these schemes to me, but I am quite practical, and I hated them, and told him so. Then he kept his schemes to himself, merely observing, in the deepest despondency when the bottom had dropped out of them, “Wilhelmina, I fear that I have made a fool of myself again.” He sometimes earned a little money by writing, and I think might have earned more. He wrote stories of the most extreme sentimentality and of the most aggressively moral character; and one of the Sunday magazines used to publish them. He and I have screamed over them many a time. Shortly after one quarter-day he went down to a land auction in Essex and bought a small plot for ten pounds. When I remonstrated, he said feebly that an excellent free luncheon had been provided for all who attended the sale, and that, after all, much money had been made by poultry farming. I asked him if either he or I knew one single fact about poultry, except that they never laid as many eggs as one expected. He admitted it, and in a rare fit of remorse sat down at once and wrote a story about a girl with consumption which brought him in nearly enough to cover the difference between the price he had paid for the land and the price he sold it for a few days later.

He was popular, as most extravagant men with a sense of humour are, but his sense of humour had a blind point. He could never see that any of his wild-cat business was utterly ridiculous, or understand why sometimes in the middle of our deepest distress I could not help laughing at him. Yet he did not take his literary work seriously at all, and it used to be my chief amusement to get him to read out his own stories, with his own parenthetical comments. His popularity certainly served him at some of the times of crisis, and made his creditors lenient with him. During his last illness several people to whom he owed money, and had owed money for a long time, sent him presents. I thought it was rather touching. We were living then at a village called Castel-on-Weld, and we lived there simply and solely because my father happened to come upon the name in an old Bradshaw, and thought that it would be nice and hereditary to be Bernard Castel, Esq., of Castel-on-Weld. I am not aware that any of his ancestors had ever lived within a hundred miles of the place.

On the day after the funeral I got the only letter I ever received from my grandfather. It did not pretend to any grief over the dead, and it informed me, in a courteously acidulated way, that he did not wish to see me and that I had nothing to expect from him. But it enclosed a cheque for two hundred pounds, to cover present expenses and until I was able to get work.

Now, I think a really fine and high-spirited girl out of a penny book would have torn that cheque in half and sent it back to him with a few dignified words. But I did not see why my butcher and baker and candlestick maker should be called upon to finance my exhibition of a proud and imperious nature. That was what it would have come to, for we owed money to the butcher and the baker, and I do not doubt we should have owed it to the candlestick maker as well, but for the fact that there was no candlestick maker in the village. So I wrote:—

“DEAR GRANDPAPA,—Thanks very much for the two hundred pounds, which will be most useful, but you don’t seem to know how to write a letter to a girl who has just lost her father. I shan’t bother you.—Your affectionate granddaughter,

“WILHELMINA.”

Then the parson and the doctor came round, and they were two good men. The doctor said that medical etiquette did not permit him to make any charge to an orphan girl, and that if he took my money he would be hounded out of the profession, and quite properly. But I told him that I thought he was lying, and made him take the money. As it was, he had given us any amount of his care and time and charged about half nothing for it. He was not a rich man either. The parson said that his wife wanted someone to act as a companion and to assist in looking after the little girls. I thanked him very much, but I said that I believed, if she thought it over, she would find that she didn’t. They gave me lots of good advice, and when I sold all the furniture and effects they bid frantically against one another for the six bottles of distinctly inferior sherry which at that time constituted our entire cellar. Other friends did similar acts of kindness at the sale. I had meant it to be a perfectly genuine sale, but all the time I felt that I was passing round the hat. I do not think the auctioneer has ever forgotten it. The way that sherry, with the maker’s name giving it away on every bottle, fetched the price of a vintage Chateau d’Yquem of great age, must have made an indelible impression.

I had thought it all out. I really did not want to take from these good people what was given in the merest charity. I was not, as a matter of fact, very intimate with any of them. I did not want to be a companion, even if the parson’s wife had had any sort of use for a companion. I had quite clearly made up my mind that there was no work in the world that I should be ashamed to do, if I could do it; but that I would not take up anything which could not possibly lead to anything. Now, nearly every feminine occupation recommended to the distressed but untrained gentlewoman is a cul-de-sac, and when you get over the wall at the end of the cul-de-sac you are in the workhouse. I had also decided that I must get out of Castel-on-Weld, because things did not happen there, and in consequence I could not take advantage of things happening. I determined to go to London.

Beyond the general principles which I have indicated I had no clear idea of what I was going to do, but I had got new clothes, no debts, and about seventy-five pounds in cash. I think I was well educated, though rather in a general and erratic way. My father, who had never been in France in his life, spoke the most idiomatic, and even the most argotic, French, with the vilest of accents. He infinitely preferred French fiction to English, and I will do him the justice to say that he generally remembered to look it up. It is possible that, with my knowledge of French, music and literature, I might have become a governess, but to become a governess is to walk deliberately into the cul-de-sac. I had vague ideas that I should like to get into some kind of business, and by cleverness, and practicality, and temperance, and early rising, and the rest of the bag-of-tricks, worm my way slowly upwards until I was a manageress and indispensable. All the time I should be saving money, and should then be ready to start for myself. I had not decided what the business was to be; once in London I should have time to look about me.

I had also thought of marriage. Even if I had not thought of it, the fact that the doctor proposed to me twice would have reminded me of it. I was pretty enough, and though the idea of falling in love never occurred to me, I thought that I might marry rather well one day. That was an additional reason for leaving Castel-on-Weld. I had already twice refused the only marriageable man in the neighbourhood. But in any case I was only eighteen and I did not mean to marry for some time to come.

I was going to play a lone hand, and the honest truth is that I rather enjoyed the prospect. I was going to London, a place where things happen, and I was going to do what I wanted in the way I wanted. And perhaps I should starve, and perhaps I should have fun. So one morning I got into a third-class railway carriage, and an old woman talked to me at length about her somewhat unseemly physical infirmities. I hope I was sympathetic, but my mind was already in London, looking out for the possibility of adventure.

I did not have to wait long in London to discover that strange things happen there. The first thing that I noticed on my arrival at Charing Cross was that on the platform, under the clock, there were some fifteen girls, all of whom wore the closest possible physical resemblance to myself. We might all have been sisters.

It was something of a surprise.

If on my arrival in London I had found waiting on the platform at Charing Cross one girl of the same height as myself, the same colour of hair, the same type of face, and the same style of clothes, I might have thought it merely a coincidence. But here were fifteen girls, all, so far as I could see, exactly similar. They were not in groups, but scattered about the platform under the clock. They never spoke to one another, but it struck me that they looked at one another curiously and with something like veiled hostility. I saw the same expression on their faces whenever one of them happened to pass me. I could not imagine what it meant, and I wanted to find out. I sent a porter to the cloak-room with my belongings, and stood against the bookstall waiting events. It was then two minutes to one.

At one o’clock precisely a man of about thirty-five, in a light overcoat, with a folded newspaper in his hand, walked rapidly into the station and stood still, looking about him. His personal appearance was not in his favour. He wore too much jewellery, and the expression on his face was one of furtive spite. One of the girls who were waiting walked close past him very slowly. He looked at her intently, but made no sign, and she then passed out of the station. A second girl did the same thing, except that she lingered at a little distance from him. A third was just approaching, when he came rapidly forward to me and raised his hat.

“I think,” he said, in a slightly foreign accent, “I am right in presuming that you are here in response to my advertisement in this morning’s Mail.”

“No,” I said, “I have seen no advertisement. I don’t know you, and don’t understand why you should speak to me.”

“I hope,” he said, “you will give me an opportunity of explaining. It can do you no harm, and may be very profitable to you. It is a matter of life and death, or I would not trouble you. I assure you that I mean no disrespect whatever.”

By his tone and manner it was perfectly evident that he was not talking to me merely because I was a pretty girl. He was the kind of man whom anyone would distrust at sight, but of whom no one could have been afraid. I was not in the least afraid. I shrugged my shoulders.

“This is wildly unusual,” I said, “and I don’t like it. You may begin your explanations. If at any moment I think them at all unsatisfactory, I shall send you away. Begin by showing me the advertisement.”

He handed me the paper in his hand, with the advertisement marked, and I read as follows:—

“If the lady of eighteen with dark hair and blue eyes, pale complexion, good-looking, height five-foot-seven, will be on the platform of Charing Cross, under the clock, at 1 p.m. precisely this morning, the man in the light overcoat, with the folded newspaper, will meet her there and liberally reward her services.”

“Well?” I said.

“The advertisement was not addressed to any particular lady. I merely wanted to find one who would bear a close resemblance to my half-sister, who died about a month ago. My mother is seriously ill, and the death of my half-sister, to whom she was devoted, has been kept from her. If she knew of that death there is no doubt that she would succumb at once. She has been told that my half-sister is away in the country, but she has begun to suspect, and we have had to promise to produce her. You are exactly like her, you have the same tone of voice, you spoke to me exactly as she would have spoken if a stranger had addressed her. The impersonation will be a very easy one; you will have to be in the same room with my mother for a few moments, and will have little to say. The room will not be brightly lit, and the doctor would not permit any but the briefest interview. You will be prolonging her life for a few days—at the best I fear it cannot be for more than that—and you will remove a load of terrible suffering from her mind. For this I am ready to pay you five pounds now, and one pound for every day that you remain at my house. My name is Gould—Mr. Nathan Gould. Here is my card.”

The card bore an address in Wilbraham Square, Bloomsbury. I thought the matter over for a few seconds. One can do a great deal of thinking in a few seconds. “Mr. Gould,” I said, “if I believed your story entirely I would do what you want for nothing. I neither believe it nor disbelieve it entirely. I have the impression that you are keeping something back.”

“Not intentionally. I explained myself as quickly and briefly as possible, but I am ready to answer any questions.”

“Possibly I am not in a position to ask the questions which would be material.” At this I thought he winced slightly. “I consider that I take a great risk, and I do not take a great risk unless the consideration is proportionately great. If you will pay me fifty pounds in cash now, and five pounds for every day that I remain in your house, I will come. I have only just arrived in London, have no friends here, and was on the point of going to an hotel. If you accept my terms I can come at once. If not, there is no more to be said.”

He did not seem much surprised. “Is that your last word?” he asked.

“It is.”

“Very well. You shall have my cheque for fifty pounds as soon as we reach my house, and the rest of the money will be paid you day by day.”

“That will not do,” I said. “We will drive now to your bank, and you will draw fifty pounds in notes or gold. We shall then go on to my bank, where I shall deposit the money. After that I am at your service.”

“You are a business-like woman,” he said. “It is queer to be distrusted when one is really perfectly honest, but it shall be as you wish. If you will come with me I will call a cab.”

“You will call two,” I said. “A four-wheeler for myself and my luggage, and a hansom for yourself.”

My programme was punctually carried out. As it happened, we both banked in Lombard Street, and it was not long before that part of the business was concluded and we had arrived at the house in Wilbraham Square. It was a good Georgian house, and looked well kept. Gould paid the cabman and introduced his latch-key.

“No,” I said, “ring. I prefer it.” I wanted particularly to see who would answer the door. An extremely commonplace and honest-looking parlourmaid answered it. When she saw me she staggered back aghast.

“That’s all right, Annie,” said Mr. Gould reassuringly. “The resemblance is striking, isn’t it?”

“Yes, sir,” said the maid. “It took me very much by surprise.”

“All right upstairs?” asked Gould.

“I believe so. The doctor is just leaving.”

By this time the man had brought my luggage into the hall. At the same moment a grey-headed old gentleman came down the stairs, slipping a stethoscope into his side-pocket. He also seemed startled at seeing me.

I trusted that old gentleman, and I trusted the maid who had opened the door, and I did not trust Mr. Nathan Gould a bit. At this moment his air was far more that of a man who has recently pulled off a clever financial coup than of a son who has succeeded in saving a mother to whom he is devoted from a great sorrow. Gould went forward to the doctor at once.

“How is she?” he asked eagerly.

“No change,” said the doctor. He looked across at me. “Really,” he said, “the resemblance is astounding.”

Gould brought him up to me. “This is our doctor,” he said. “Dr. Wentworth.” Gould hesitated. I had not given him my name.

“I am Miss Tower,” I said.

The doctor bowed. “May I ask,” I said, “if you have been attending Mrs. Gould for some time?”

“Certainly,” he said. “For the last five years.”

“I should like very much to speak with you alone for a few minutes. Have you the time, and would you be so very kind as to do this for me?”

The doctor looked inquiringly at Gould. Gould was furious. He knew, of course, that I was about to ask for his character. But he restrained himself. “Miss Tower,” he said, with a touch of bitterness, “has already made it quite clear to me that she must have her own way. I believe there is no one in the drawing-room.” The doctor held open the door for me.

“I will give you as many minutes as you want, with pleasure,” he said.

I gave him my story as briefly as I could, and told him all that had passed between Mr. Gould and myself. “I am going to be quite frank,” I went on. “I do not trust the man in the least. I do not believe he has one atom of love or respect for his mother.”

“He has not,” said the doctor.

“Why then does he want this impersonation?”

“What he has told you is true. Mrs. Gould is very ill. There are various complications, but it is the heart which we have to fear principally. It is impossible to cure her, but I confidently believe that by coming here you will prolong her life and make her last days much happier. As to Mr. Gould’s motives, I have perhaps no right to speak. He has not confided in me. I will only give you the facts. Mrs. Gould is one of two sisters, of equal fortune, and bitterly jealous of one another. The elder sister died in her seventy-fourth year. She did not wish Mrs. Gould to have any advantage over her, and left her money to accumulate until Mrs. Gould’s seventy-third birthday, when Mrs. Gould comes into it. She was a cranky old woman, and did not like the idea of her sister having any more money than she had. Mrs. Gould is a wealthy woman now, and on her seventy-third birthday, which will be in a few days’ time, will be twice as wealthy. If she does not live till her seventy-third birthday, the whole of her sister’s money goes to the London Hospital. Do you see?”

“Yes,” I said, “I see. She has doubtless left her money to her son, and in the event of her surviving until her seventy-third birthday he will profit.”

“Precisely. Her entire estate is left equally between Mr. Gould and his half-sister, and in the event of the death of either the whole goes to the survivor. That is the situation in a nutshell.”

“Then what have I to fear?”

“Nothing at all until after that seventy-third birthday.”

“I see,” I said meditatively. I could imagine that after that date Mr. Gould’s filial affection might undergo some remarkable changes.

The doctor gave me some useful information about the half-sister and explained to me exactly what I was to do when I was admitted to his patient’s room. He also gave me his address. “You may find that useful in a week’s time,” he said.

My luggage had already been taken up and the maid showed me the way to my room. On the stairs we met Mr. Gould. “It is all right,” he said in a low voice, “I have just come from my mother’s room. She is overjoyed. You will see her this evening.” He paused and added, “And have you heard the worst of me?”

“Not yet,” I said. “That will come.”

Then he guessed how much I knew, and hated me almost as much as I hated him.

The maid who was unpacking for me asked me if I would lunch downstairs with Mr. Gould, or if I preferred to lunch in my own room. It is always well to get to know one’s enemy, and I did not hesitate. A few minutes later I was sitting down to lunch alone with a man whom two hours before I had never seen in my life, and of whom I now knew very little, and nothing which was not dead against him.

He was really very clever. He hardly spoke of his mother at all, he was quiet in his manner, and showed himself most attentive to my personal comfort. I was not to consider myself a prisoner at all. I could have the brougham that afternoon and go anywhere I liked. If it was convenient to me to be back at six o’clock, that would be the best time for me to see his mother. But if not, some other arrangement might be made. Did I like the room that had been given me? If not, it could be changed. There was another little room just opposite to it in the same passage, which was being got ready to serve as a private sitting-room for me.

I thanked him, and said I was not going out. Turning the conversation away from myself, I made him talk to me about his half-sister. He talked about her in the most easy and matter-of-fact way. I do not suppose he ever cared for her or for anybody except himself. All the same, the information that I got as to minute points of her personal appearance and her manner of speaking were very useful.

At six o’clock I was quite ready. Mr. Gould now seemed a little nervous and excited. He kept on giving me fragments of stupid advice and telling me things that he had told me before. The interview was to be a very short one, and the doctor and the nurse were both in the dimly lit room when I entered it, though they stood at some distance from the bed. On the bed lay the dying woman—a handsome old Jewess, with white-yellow skin of one even tint, colourless lips, and blazing eyes. I went straight up to the bed and took her claw of a hand and bent over her and kissed her. She spoke in a very low voice, and I just caught the words, “Thought I’d lost you.”

“No,” I said, “I’m here, and I will not leave you again until you get better.”

Her eyes closed and opened again and fixed themselves on me. “Pray for me,” she said.

Still holding her hand, I dropped down on my knees by her bedside. My thoughts flew frantically in unlikely directions. I remembered my own mother sitting before the fire and saying with helpless solemnity that it was the beginning of the end. I was not quite sure where I had put my watch-key, and puzzled about it. I recalled vividly a fat old woman who had travelled up in the same compartment with me and I wondered where she had gone. And all the time I was holding the old woman’s hands and trying to pray, and hearing the clock on the mantelpiece tick, as it seemed to me, constantly quicker and quicker.

Presently the doctor touched me on the shoulder. I opened my eyes and saw that the old woman had fallen asleep. I released her hand gently, and slipped out of the room. When I got outside I was shaking like a leaf, and there was Mr. Gould full of eager questions. I answered him as well as I could. He was delighted.

“Now,” I said, “let me go to my own rooms for the rest of the day.”

He looked at me curiously. “Why,” he said, “you seem upset. I suppose you are not as used to it as we are. You ought to have a brandy-and-soda. Let me get it for you.”

I refused that, went off to my own room, lay down on the bed, and began to cry. I had not the faintest idea what I was crying about. It was all so strange and horrible. But soon I sat up and bullied myself. I could see that there might be much to do which would want all my sense and none of my emotion. I dined in my own room, and with my dinner there was brought to me a letter from Mr. Gould, thanking me for my kindness and enclosing a five-pound note.

The next two days passed quietly enough. I now saw the old woman two or three times a day. The third day was the day before the birthday. In the afternoon Mrs. Gould, who had been getting much better, became rapidly worse, fainted, and was unconscious for quite a long time. Gould made a fool of himself. He whipped the doctor off into the dining-room, and talked so loudly that I could hear in the drawing-room. “Look here, doctor,” he said, “you must keep her alive for another nine hours. You can do it if you like, you know. Use more stimulants. You want to flog that heart. Keep it going somehow. Were you trying oxygen?”

“Mr. Gould,” said the doctor, “you know that your mother refuses to see any other doctor, and that any attempt to force one upon her would certainly be fatal. Otherwise I should have thrown up this case before. As it is, I am not going to enter into any consultation with yourself or any other ignorant and unqualified person. And it would help me to keep my temper, and would therefore facilitate my work, if I had no interviews with you of any kind. Send your inquiries through the servant.”

The doctor came out and shut the door. He looked into the drawing-room for a moment. “Miss Tower,” he said, “if Mrs. Gould lives until after twelve to-night, look out.”

“I had meant to,” I said.

Then he went up to his patient.

At twelve that night Mrs. Gould was alive and sleeping peacefully. As soon as Mr. Gould had heard this glad news he went up to bed. That night, for the first time, I had not received my fee. At breakfast next morning he was distinctly disrespectful in his manner. “Look here,” he said, “the best of friends must part. You’ve done all I wanted, and there is no doubt my mother will get on all right without you now. She has got rid of the idea that my half-sister is dead, and that was the main point. I’ve told them to pack your things, and as soon as you’re ready to go you shall have that last fiver you managed to screw out of me. You’ve been paid a sight too well, but I’m a man of my word.”

“I’m not going,” I said.

“Not going? Don’t talk in that silly way. You’ll have to go. I can starve you out—I can throw you out by force if you like. Still, I don’t want a scene. I suppose I must make it two fivers instead of one. That’s what you’re after.”

I took out the slip of paper on which Dr. Wentworth had written down his address for me. “It’s quite true,” I said. “You may have my things packed and put on a cab, and may ask me to leave the house. If I do so that will be the address to which the cabman will drive, and the consequences are likely to be serious for you.”

He raved and abused like a drunken cad for a few moments, and then went out of the room—and, a moment later, out of the house.

At eleven that morning Mrs. Gould died suddenly in my arms. It was a quick and painless ending. A telegram was sent to Mr. Gould’s office in the City, and the reply came back that he was not there. Dr. Wentworth came down to the drawing-room with me and seemed slightly hesitating. “Excuse me,” he said, “for asking the question, but have you any friends in London?”

“None,” I said.

“And have you any plans?”

“None; except to leave this place immediately. I shall see what happens. It was through seeing what happened that I came here. At any rate, I’m not going to take on any of the underpaid work leading to nothing of which women seem to be so fond.”

“I don’t quite like this,” he said. “I rather wish you’d go and talk things over with my wife. But you won’t, and after all, I don’t know that it would do much good. You’re playing a lone hand and you rather like it, and you can take care of yourself.”

I talked to him a little longer and then my cab came. As I drove away I saw Mr. Gould approaching the house. He was not helpless, but he was a little more than half drunk. I wondered for what act he had been trying to find the courage.

My principal feeling on leaving Mr. Gould’s house was one of extreme weariness. The emotions wear one out more than work does. I had been living idly and even luxuriously, but I was more tired than I used to be in the days when I lived with my father and during some financial or domestic crisis the whole of the housework fell to my lot. I had Mr. Gould’s five-pound notes in my pocket, and I drove to a good hotel. I stopped there for three days, and I think I spent most of my time in bed and asleep. Then I said to myself, “Wilhelmina, this will not do. You are spending too much, and you are earning nothing, and you are not even looking about you.” So I left my good hotel and went to a cheap boarding-house. And on the second night that I was there a young Hindoo proposed marriage to me. Also the cooking was very bad. So I left.

While I was there I had calculated that I had enough money to furnish a very small flat and to live for very nearly a year. I found my flat in a Brompton back street. It was not one of the mansions with lifts and liveried porters and electric light and lots of white paint. It was a little thirty-pound house which had been ingeniously converted into three flats. One was in the basement, and you entered it down the area steps, and paid seven shillings a week when you got there. The ground-floor flat was eight shillings, and the upstairs flat seven-and-six. I went in for luxury and eight shillings. I had a separate entrance, and when I shut my front door I was alone in my own little world. The world contained a sitting-room, bedroom and kitchen, and was extremely dirty and horrible until I set to work on it. I need not say that I spent more money than I had intended on cleaning, furnishing and decorating. Everybody does that. As an economy and a punishment I did everything for myself. The flat above me was occupied by a horse-keeper from one of the ’bus-yards and his wife. The wife did a little intermittent cheap dressmaking. They both drank, used improper language, and occasionally flung paraffin lamps at one another. The flat below had been occupied by an old man who lived alone, and had got tired of it and died. I met his dead body coming up those area steps as I moved in. After that the flat remained untenanted. Every Saturday a knowing-looking young man with a pencil behind his ear, and an account book and a black bag, called for the eight shillings. And as long as you paid that, nobody cared who you were, or what you did, or why you did it. I rather liked that.

When I was comfortably installed I began to think things out. I decided at first to go in for the gratitude of the aged. You know the kind of thing. You render the old gentleman or old lady some slight service in a ’bus or railway carriage, and a month later they die and leave you all their money. I think I was right in believing in the gratitude of the aged. Compared with the young they are very grateful. But I fancy they have a great tendency to have wives and children or other near relations, and to abstain from leaving their money to the entire stranger who has opened the carriage door for them. One day, in Chancery Lane, a horse in a hansom cab came down rather excessively, and a very aged solicitor shot out in a miscellaneous heap into the middle of the road. I helped him up, saved his hat from the very jaws of an omnibus, so to speak, and said I was sorry for him. He did not even ask for my name and address, and at the moment of going to press I have heard nothing further from him. The other old people to whom I was able to offer some slight service seemed to think that a few words of warm thanks would be all I required. I began to disbelieve in the familiar stories of the wills of the wealthy.

And then I embarked on a business which I am afraid must prove conclusively that I was a daughter of my father, for it was just the mad, wild-cat kind of thing that he would certainly have embarked on himself, if he had ever thought of it. Briefly, I put an advertisement in one of the most popular of the Sunday papers, and also in the Morning Post, addressed to all who were unhappy in love. “I know the heart, and I know the world,” was the way I began. I pointed out cunningly that however much one might need advice in these matters, there was always a feeling of embarrassment in consulting anyone who knew you. The only person in whom one could confide was the entire stranger. I pointed out, moreover, that real names and addresses need never be given to me. I only required to know the facts, and I would send a letter of advice specially written for each case for the sum of half a crown. Their letters were to be directed to “Irma.” And I gave the address of a little newsagent, who took in letters for me.

I ran this business for about two months. It began slowly, but after the first fortnight I really had as much as I could do. I always asked the people to whom I sent letters to recommend me to their friends, and in many cases I know that they did so. I gave the best advice that I could, and I had a small shilling book on the marriage laws which I found very useful. Not one couple in a hundred that wants to get married really knows how it may or may not be done. My clients were chiefly women, and I have grave doubts as to the seriousness of some of the few men who applied to me. But I did not mind in the least so long as their postal orders were enclosed. The women seemed to belong almost exclusively to two sets—domestic servants and foolish people in smart society. The middle-class would have nothing to do with me, and I am not sure, although I always gave the best advice I could, that the middle-class was not right. Only once or twice, in the curious confessions that were poured out on me, did I come upon anything that I should have called real romance. There was plenty of vanity, there was plenty of sentimentality, and there was a good deal of acute money-grubbing. It was really interesting work, though it kept me a great deal indoors, and though I am not sure even now that it was quite honest.

At the end of the first month some blessed young man, whom I am glad to have this opportunity of thanking, wrote a short and chaffing article about my advertisement. For days after this I was simply inundated with letters, and I had to send out post cards to my clients explaining that, owing to the pressure of business, my letters of advice to them would probably be delayed for some days. Among those letters was one bearing the address of a house in Berkeley Square, which was so extraordinary that I give it in full. It was one of the few letters that I received from men:—

“DEAR MADAM,—I have seen your advertisement, and also the short article upon it in the Daily Courier, and my own case is so curious that I have decided to address you. I enclose a postal order for half a crown as required, but I am a man of means, and in the event of your being able to assist me I shall, as you will see, propose a more adequate remuneration. I have been a great traveller and sportsman, and you may possibly have come upon my recent work on Sport in Thibet. I have now returned to England and am anxious to marry. But I am prevented by a strange psychological characteristic of my own.

“The fact, put briefly, is that I cannot stand fear. Any evidence of timidity in a man inspires me with rage, and in a woman with disgust. However attractive she may be, at the slightest sign that she fears me, love vanishes completely. I cannot stand her, I cannot bear to be with her. This is the more unfortunate because I am by nature a dominant person. I have been told that my eyes are mesmeric. I do not believe in this nonsense, but certainly women seem to find it difficult to meet my gaze fairly and squarely. I have a somewhat hasty temper, and nothing exasperates it more than the attempt to smooth it down, accompanied as it always is by fear of what I may do next. I want a woman who does not care one straw what I do next—who will be absolutely free from every form of cowardice, physical or moral, as I am myself. The mother of my children must not be a coward.

“I am thirty-seven years of age, wealthy, and not, I believe, much uglier than other men, and I cannot find the woman that I require. Possibly, among the many cases which must have been brought to your notice, you will have come across some such woman. If so, and if you will arrange a meeting between her and me, I will pay you the sum of one hundred pounds, provided, of course, that I am satisfied on the question of her courage. If, though satisfied on this point, I do not wish to marry her, I will pay her also the sum of one hundred pounds for the trouble which I have given her. She must, of course, not be older than I am myself, and I confess that good looks are a great consideration with me. Social standing is of no importance whatever. I do not allow popular prejudices to interfere with my actions, even when they are of the least importance, and far less do I admit of such interference in my choice of a wife.—I am, my dear madam, faithfully yours, ——.”

I do not give his signature. It is a name that you will find in Debrett, though I did not look it up at the time. That letter gave me a great deal to think over. There was a queer mixture of bragging and modesty about it. Yet, I asked myself, how could he give me the facts which it was necessary for me to know without appearing to brag? The commission of one hundred pounds was certainly tempting, but none of my correspondents occurred to me as being likely to meet his requirements, even if they had not had their own affairs on their hands. Fear is a feminine quality. Women have a right to it; without being cowardly, they may be able to realise a danger, and they may have delicate nerves. Nor can I see that they are any the worse for it. After a little reflection I wrote to say that I believed I should be able to assist him if he could wait for about a fortnight. And I had a reply on the following day to say that he would wait with pleasure.

I was not, decidedly not, thirty-seven, and I was as pretty as I thought he had any right to expect. I was not the creature of steel that he required, but, none the less, my nerves were in fairly good order, and I thought that I could get through, at any rate, any of the preliminary tests to which he might subject me. Two hundred pounds are better than one hundred. Possibly I might marry this man. I did not know, and did not want to marry anybody. But he might take his chance and, in case of failure, fall in line with the doctor at Castel-on-Weld and the young Hindoo in the boarding-house. It is wonderful how many excuses one can find for an action which brings in two hundred pounds.

At the end of the fortnight I wrote and gave him an appointment for the afternoon of two days later, outside the Stores in Victoria Street, when I said that the young lady whom I had selected as likely to meet his requirements would meet him. I suggested that there should be some sign by which he might be known. Next day I received a telegram in these words:—

“I shall come dashing up. The red rose is, and always has been, my sign.”

I thought over that telegram for a long time, and I did not quite like it. It was altogether too queer. But I meant to see the thing through. After all, I had given him no sign by which he could recognise me, and I could always back out at the last moment if I thought it necessary. So, at the time appointed, which was at three in the afternoon, I was in Victoria Street at some little distance from the Stores, waiting to see what might happen.

What actually happened was rather grotesque. A four-wheeled cab drove up, and an old gentleman got out. He wore a red rose in his button-hole and another in his hat. He took four rosebushes in pots from the interior of the cab and placed them on the pavement; dived back into his cab once more, and came out with a large florist’s box. This was packed with red roses which he proceeded to scatter broadcast. His cabman laughed till he nearly fell off the box, and a large crowd quickly gathered round. The crowd seemed to annoy the old gentleman. I heard him shouting in a querulous voice, “I am here for a special purpose. Kindly go away. I require this street for the afternoon.” A small boy knocked over one of the little rose-bushes, and this exasperated the old gentleman still further. In a moment he had whipped a revolver out of his pocket, and began firing it up into the air in an indiscriminate manner. The police very promptly got him. And I said nothing to anybody and went home.

Naturally the case was reported in all the papers. The old man had been strange in his manner for some time, but his relations had not apprehended anything serious. This afternoon he had been particularly enraged because he could not get a four-wheeler, and he was too nervous to ride in hansoms.

I never heard any more of the case, but it gave me a dislike of the business which I was engaged upon and the dislike was increased a few days later. I was looking out of my windows when I saw a woman of common appearance give an almost imperceptible nod to a passing policeman. She then came on to my flat and knocked. I let her in.

“You are the lady who advertises as ‘Irma’?” she said.

“I am. How did you know that I lived here?”

“They told me at the tobacconist’s where your letters are sent. Now, I want you to give me some help. I have got the money here, and I can pay well.”

“What is it you want?” I asked.

“Well, I’m told that you are a wise woman and know the future. A man, rather younger than myself, has every appearance of being attracted by me, but I don’t know whether he means anything serious or not. I thought perhaps you’d look at my hand and tell me what was destined.”

I sent her away at once. It was a police trap, of course. When you receive many letters, containing many postal orders, and you cash those orders all at one office, I suppose the police become interested. It seemed degrading, and I hated it. Also I had reflected that this was not really work that would lead to anything.

I sat down there and then and wrote letters withdrawing the “Irma” advertisements. My total profit, after all expenses were paid, amounted to a little over twenty pounds.

Being still young and passably beautiful, I had no wish to become a cynic. But the events of the next fortnight tended to make me so. I reverted to my old idea of making a conquest of some big business firm in my belief that I had ideas and could make suggestions and that these were worth money.

I still believe that ideas and suggestions are worth money—pots of money. I also believe that it is extremely difficult to get a guinea for the best of them.

I tried an inflated and gigantic shop, one of the stores where you buy everything, and I asked to see the manager. I do not suppose I did see the manager, but I saw someone who was more or less in authority in a back office. There was a clerk at work in that office, and the clerk made me nervous. If I could have rung and had him removed I might have got on better. As I was pretty and well dressed and did not look poor, and might have called to complain of the quality of the bacon supplied, the managerial person was at first extremely polite, and asked in what way he could serve me.

“I believe,” I said, “that this is a business in which new ideas are of value.”

“Yes,” he said suavely, “in fact, we’ve already noticed it.” He was still polite, but one could detect a slight shade of irony.

“Well,” I said blunderingly, “I am a woman with ideas—heaps of ideas. I have thought about your business particularly, and I am full of suggestions. I believe them to be valuable, but before I hand them over to you I should like to come to some business arrangement; either in the way of a cash payment, or, where practicable, a percentage on profits. In the latter case, of course, I should expect permission to inspect your books and——”

At this moment the clerk, who had been writing at a side table, with his back to me, went off like a soda-water bottle. I am inclined to think now that for some moments he must have been suffering severely.

“Shut up, or get out!” said the manager to the clerk.

The clerk, being unable to shut up, got out at once. Then the manager turned to me.

“Extraordinary!” he said seriously. “Most extraordinary. And yet you don’t look as if you’d been drinking.”

Then I got up. “My proposal seems to you very silly,” I said. “And, because I was nervous, I put it all very badly. But I do not think that justifies you in behaving like a cad.”

He gave a jump in his chair. Being a person in authority, he did not get a chance to hear the plain truth about himself often.

“Nor do I,” he said reflectively. “I beg your pardon. Still, the thing was so outrageous; you must see, my dear young lady, that we could not dream for one moment——”

“Thanks,” I said. “I won’t trouble you any further.”

If I had stuck to that man and given him one or two of my ideas in advance, reserving the question of terms, I am not sure that I might not have done something. He would have liked to compensate for his rudeness, if he could have done it. But, being proud and angry and an idiot, I walked out. My one idea was to get out of the awful place.

I tried two or three other shops, and began at the right end, but did very little better. One man listened to three of my ideas for Christmas novelties, very politely regretted that he could not avail himself of them, and showed me out. He used two of those ideas subsequently and made money with them, and I hope it may choke him. Another man listened to a still longer list and, while disclaiming any legal liability, offered me five shillings for my trouble.

So, as things were going rather badly, I was particularly glad of the windfall which came to me in connection with the man behind the door. It was one of those queer things that cannot happen except in big cities. It is part of the fascination of London that every moment of the day and night something more wicked and more strange is happening than one could ever invent.

I had been into the North End Road to do a little shopping. I had got six eggs and a pound of tomatoes and a new tooth-brush and some other luxuries, and my hands were full. I managed to get my door open with the latch-key, but in trying to get it out again I nearly dropped those eggs. So I went through into my little sitting-room, put my parcels down carefully, and was just going back to shut the outer door and get my key, when I distinctly heard the door shut. It did not shut with a bang, as if it had been blown to; it was shut very gently and carefully, as if the object had been to avoid noise. So I was just about as frightened as a school girl in a barrel of live mice. But I went out into the passage all the same.

There, in the passage behind the door, stood a tall and extremely well-dressed gentleman of about forty. His frock-coat was buttoned and fitted his good figure to perfection. In one hand he held the glossiest of silk hats, and in the other his gloves and walking-stick. His appearance was foreign; his hair was not grotesque, but it was longer than an Englishman generally wears it. He wore a pointed beard and, for a man, he was by no means ugly. He spoke good enough English, though with a slight accent.

“Pardon me, mademoiselle,” he said. “I would not have taken this liberty except under great compulsion. If you will permit me to remain here for a few minutes you will be doing me a very important service. I assure you of my good intentions, and of my reluctance to annoy you in this way. Only,” he paused and shrugged his shoulders, “one is reluctant to die also. Permit me to hand you your latch-key.”

I suppose I ought to have thought the man was mad, or worse. But it never occurred to me. He had not the manner of it.

“Thanks,” I said, as I took the key. “You may wait a few moments if you like, and if you will tell me what is the matter. Won’t you come into the sitting-room?”

“You are too kind, mademoiselle. I will explain myself fully. But may I ask, in your sitting-room should I be seen from the street?”

“Not if you stand at the back of the room.”

“That is very good. I shall stand at the back of the room. If you would do me one more favour, you would stand at the window and tell me who comes past.”

I went to the window without a word, and turned back to him. “There is a policeman,” I said.

“Ah, the London policeman. He is a charming man. I love him. And next?”

“A lady in black.”

“Possibly bereaved. Poor lady. But I know nothing of her. But do you not see a man of much the same appearance as myself?”

“No. I mean, yes. He has just come into view. He is remarkably like you. He walks very fast.”

At this the man in my room sat down and looked very white and shaky. His back-bone seemed to have been taken out and he was all huddled up.

“You can’t faint in here, you know,” I said sharply.

“Has he gone?” he asked hoarsely.

“Gone? Of course he’s gone. He’s at the other end of the street by this time.” As I spoke I poured out a glass of water and handed it to him. He thanked me, protested that he was not in the least faint, and took a sip of the water. Then he turned to me.

“Now, mademoiselle, I must really explain myself.”

“Well?” I said. I rather liked the idea of having helped him to escape. Any woman would help anyone to escape from anything. And after all, this was more romantic than talking about corkscrews to a shopman who did not want to listen.

“I have been hunted,” he said. “I have been hunted all the morning. Three years ago I left France to get away from this man who, by the way, is my brother. For those three years I have been in England. You see I speak the English very nicely—is it not so?”

“Yes, you speak it well enough. Go on.”

“During the whole of that time I never met my brother. This morning I came upon him, face to face, at Charing Cross Station. I walked away, and he came after me. I went down the steps to the underground station and booked to Wimbledon. He followed and did the same. I got out at Gloucester Road, and he stepped out of the next compartment after me. I took a hansom back to Charing Cross. He followed in another. Then I tried to tire him out with walking. I have walked all the way here, and have not come directly, but by the most circuitous routes. Always he was a little way behind me. As we drew near to this street I quickened my pace very much. He was tired, and I saw there was no cab. I got round the corner, nearly a hundred yards ahead of him, and saw your door open. What a chance!”

“It sounds queer enough to be true.”

“Mademoiselle,” he said in a pained voice, “I would not repay your kindness by deceiving you.”

“But I don’t understand. What did your brother say when you met?”

“Nothing. Nor I. We shall not speak again, except perhaps at the very last.”

“But why? Why do you run away from him? What does he want?”

“He wants,” said the man dreamily, “and I think that it is the only thing in the world that he does want, to kill me. He has wanted that for just a little more than three years. He does not wish for any publicity or, if possible, any scandal. He would have liked this morning to have found out where I lived and then made his opportunity.”

“But this is perfectly absurd. The law does not permit anything of the kind. If you thought your brother was following you with the intention of injuring you in any way, you had only to speak to the nearest policeman.”

“Ah, mademoiselle,” he said, with an indulgent smile, “there are just a few matters on which one does not speak to the nearest policeman, and this is one of them. It is a private matter—a family matter. The honour of three women is involved in it. Our family name is involved in it. We do not want talk in the newspapers.”

“What a cold-blooded brute your brother must be!”

“Really, I do not think so. I can quite understand his desire to kill me. If he succeeded it would be but just. All the same I do not wish to die. I have escaped him for three years, and I propose to go on escaping. But here I babble of my own affairs and do not even thank you for having saved my life. You have done me a great service, mademoiselle—a very great service. I shall not forget it.”

At this I laughed. “It is not a very great matter. Indeed, it is hardly worth thanks.”

“You shall not find me ungrateful. But I must not inflict myself upon you longer than is necessary. If the coast is clear now, I can get away with safety. Might I ask you to inspect from the window once more?”

I went to the window and turned back to him. “It is no good,” I said, “your brother has come back again. He is standing on the opposite side of the road.”

“He saw you?”

“Yes, I think so. Indeed, I am sure of it.”

“Then he saw, as I did, that you gave a little start. Possibly he also saw you watching at the window when he passed the first time. He is rather a clever man, and he can make deductions. I fear, mademoiselle, that in a few moments you will be troubled with a visit from my brother.”

“But you,” I said, “what about you?”

“If I got through the window of the room at the back of this flat where should I be?”

“You would drop into the little yard of the flat below this. It is at present untenanted, and you might make your way into it, or else climb the wall and get——”

My electric bell purred loudly. A shower of light taps came from the knocker of the door.

“Keep him back for a minute or two, if you can!” said my guest in a whisper.

I waited until the kitchen door had closed on him, and then opened the front door to his brother.

Seeing him now close at hand, I found that he differed in many ways from the man that he was pursuing. He was much older and his hair was beginning to go grey. He gave me the impression of being a better man altogether than his brother. I do not know and shall never know what the quarrel between them was, but I feel sure it was his brother who was in the wrong.

He told me with a pleasant smile that he had come from the house agents who had the letting of these fiats. He could not remember their names; he was a foreigner and these English names easily escaped him. But he believed that there was a flat to be let in that block.

“Yes,” I said, “the basement flat is to let. You understand—the basement flat? You go down the area steps to get to it. Why ring here in order to tell me that?”

He was desolated. “Because, mademoiselle, I have had the very great misfortune to lose the key of that basement flat. Possibly your own latch-key would fit it.”

“No, it would not. But you need not mind, for you would not have taken the flat in any case. They are not intended for rich people.”

He laughed. “Appearances are so deceptive,” he said. Then quite suddenly and rather adroitly he stepped past me into the passage. “Ah,” he said, looking round, “if I could have a little place like this, furnished and arranged with the exquisite taste that is shown here, I should be perfectly content.”

“Will you please go away?” I said.

“Certainly, mademoiselle, in one moment. Your kindness will permit me just to see the arrangement of the rooms, so that I may determine whether a flat here would be suitable for me. You have made me a little nervous by casting doubt upon it.”

“You cannot see any of the rooms,” I said. “You must go at once.”

“And if not?” He smiled.

“If not, I shall fetch a policeman and hand you over to him.”

He still smiled. “Believe me,” he said, “I am sorry indeed to give you this extra trouble, but I am afraid I must ask you to fetch that policeman. In your absence I can inspect the rooms at my leisure. I can at least promise you that I will take the greatest care not to injure them in any way.”

Quickly and adroitly he slipped past me again and went straight into the kitchen. I held my breath and listened, and did not fetch the policeman. In a moment he came out of the kitchen again.

“No policeman yet?” he said. “You are kind to me, and I will repay it by leaving at once. I see,” he added meaningly, “that you keep your kitchen window wide open. The English love fresh air, do they not? Good morning.”

So that was all right. The man behind the door had escaped.

* * * * * *

Two days later I received two surprises. The van of a West-End florist degraded itself by stopping at my flat and delivered a hamper of exquisite flowers and fruit. I had ordered nothing, and could not at first believe that they were intended for me. But a short note was enclosed.

“Permit me, dear mademoiselle, with these few flowers to make my apologies look prettier than my rudeness the other day. I shall not take the basement flat after all.”

The evening post brought me another letter, registered, containing five Bank of England twenty-pound notes, and another letter.

“You seemed, mademoiselle, to think so little of your great kindness to me on Tuesday, that I think you should have some souvenir of it. It would be idle of me to match my taste against yours, and with renewed gratitude I leave the choice to you.”

Neither letter bore any address or any signature. At first I was a little puzzled to make out how they had got my name. But there were many ways in which that might have been managed. A simple inquiry at the house agents would have been one of them. It was impossible to return their presents, and, to be quite honest, I doubt if I should have returned them if it had been possible. For the next few days I fed on peaches and bought things and lived gloriously.

* * * * * *

About a year later I read in a newspaper a curious story. A man had jumped overboard in mid-Channel and another had immediately gone over after him. It was supposed to be a gallant attempt at rescue, and the statement of a passenger that he saw the rescuer grip the other man by the throat as if to choke him was not credited. The men bore different names, but in personal appearance were remarkably like one another. The phrase used was, “They might have been brothers.” A description of the appearance left little doubt in my mind, and I could fully believe that passenger’s story.

The windfall which came to me from my adventure with “The Man behind the Door” tempted me to engage some help in the domestic work of my little flat. I cooked admirably, but I did other things less well and they bored me; so I talked to my baker, a man of genial and mature wisdom, and he said that I couldn’t do better than take Minnie Saxe if I could get her. So I set out to engage Minnie Saxe; and in the end Minnie Saxe engaged me.

She was a girl of sixteen, as flat as a board, with a small bun of sand-coloured hair, a mouth like a steel vice, and an eye like a gimlet.

Given the sex and the opportunities she would have been Napoleon. As it was, she was a manager, given up to managing everything and everybody, including her own weak-kneed father. To see her was to know that she was capable, but I thought I ought to put the usual questions as to previous experience and character. She waived them aside.

“You don’t want to trouble about that, miss. I’m all right. If I say I’ll do for you, I will, and you won’t ’ave no fault to find. Now then, what do you do for yerself—I mean, for a livin’?”

“Well,” I said, “I have some independent means.”

“I see—money of yer own.”

“Yes, though not much. Then I had thoughts of some business. Lately I’ve been writing a little—stories for a magazine.”

“I see, miss. Unsettled. Well, church or chapel?”

I fenced with that question discreetly, and she came off it at once to tell me, almost threateningly, that I couldn’t have my breakfast before eight. I said that even so late an hour as nine would suit me.

“And what time should I ’ave finished doin’ of you up if you didn’t breakfast afore nine? That wouldn’t do neither. Well, I shall be there soon after seven. You’ll ’ave your breakfast at eight and I shall go as soon as I’m through with what’s wanted. I may look in in the evening again, but that ’ull be accordin’. And my money will be four shillin’ a week. I can but try it.”

So I was engaged as mistress to Minnie Saxe, and I am glad to say that I gave satisfaction. On the first morning, just before she went, she asked candidly if there was anything I “wanted done different,” and the few suggestions which I made were never forgotten. “And there’s just one thing,” she said at the door. “If my fawther comes round ’ere subbin’—I mean wanting a shillin’ or two o’ my money what’s comin’—’e ain’t to ’ave nutthink. If ’e says I sent ’im, jest tell ’im ’e’s a liar.”

“Do you have trouble with your father?”

“Should do, if I took my eye off of ’im. ’E’s afride of me.”

I could understand that. I tried to say something delicate and sympathetic about the wide spread evils of intemperance, Minnie Saxe looked puzzled.

“Watcher mean, miss? Drink? Why, ’e’s a life-long teetotal. No, it’s sweets as ’e can’t keep awye from—sugar an’ choclit, an’ pyestry, and ice-creams from the Italyuns. ’E’s no better nor a child—mikin’ ’isself a laughin’-stock an’ wyestin’ ’is money. And if I ’ont give ’im none for such truck ’e’s as cunnin’ as a cart-load of monkeys about gettin’ it. That’s why I dropped you that word o’ warnin’.”

The word of warning was wanted. Her father called a few days later to say that Minnie had asked him to look in on his way back from work to ask the kindness of sixpence in advance as they had friends to supper. He was a fat little man with a round innocent face, and really looked much younger than his daughter. I lectured him severely and he made no defence. “I did think that sixpence was a cert,” he said sadly. “But there—she don’t leave one no chawnst.”

I consoled him with a large slice of cake. But unfortunately Minnie found him in the street in the act of devouring it. “And,” she told me, “of course I knowed that kike by sight. And a pretty dressin’-down I give ’im fur ’is cadgin’ wyes.” He worked for a book-binder when he could get a job, and was also intermittently a house-painter and a night-watchman.

I got on very well with Minnie. She shopped admirably and got things cheaper and better than I had ever done. Owing to her fine independence of character she was occasionally rude, but there was always a penitential reaction; she did not apologise or even allude to the past, but for a few days she would call me “m’lady,” give me more hot water than usual in the morning, and bring every bit of brass in the place to a state of brilliant polish that seemed almost ostentatious. She respected my cooking and despised my story-writing, and I am inclined to think she was right. “You can cook my ’ead off,” she said in a complimentary moment; but I never attempted that delicacy. The trouble with my stories was that I had not got my poor dear papa’s style and could not get it. The children in my stories were just as consumptive and just as misunderstood as in his; they forgave their mother and saved the kitten from drowning and died young. And the excessively domestic magazine that always accepted him almost always refused me.

I began to get rather nervous. I had given up the notion of capturing some big business by the sheer brilliance of my ideas. I had no business training and no familiarity with the ways of it. I was unproved, and firms would not let me begin at the top to prove me. Perhaps it was not unnatural, though I still feel sure that some of the ideas had lots of money in them, if only I could have found any backing. I did not make anything like enough by story-writing to pay my expenses, and in consequence I was eating up my capital. “Wilhelmina Castel,” I said to myself severely, “this cannot go on.” I could not hope for a continual supply of windfalls. My hatred of the usual feminine professions, with thirty shillings a week as the top-note and a gradual diminuendo into the workhouse, was as strong as ever. Yet I questioned whether it would not be better for me to spend capital in learning shorthand and typewriting, worm my way into a good business house as a clerk, and then trust to my intelligence to find or make the opportunities that would ultimately lead to a partnership. I wished I had someone with whom I could talk it over. But what Minnie Saxe said was perfectly true.

“You ain’t got no friends seemingly,” said Minnie Saxe.

“Yes, I have, Minnie, but not here. In London I’m playing a lone hand, as they say.”

“Well, it ain’t right. And I shan’t be lookin’ in We’n’sday night, ’cos I’ve promised to do up Mrs. Saunders.” She always spoke of her employers as if they were parcels.

It is easy enough for a girl who is alone in London to make friends, but in nine cases out of ten they are not friends. The friend is not made but arrives in the usual formal channels. And when these usual channels are closed it is perhaps better to do without friends. Yet I had made one or two acquaintances.

One of them was a neat little woman in a brown coat and skirt. We had come across one another while shopping in the North End Road. One day when we were both in the grocer’s shop her string-bag collapsed and I assisted at a rescue of the parcels. She thanked me; she had a musical voice and spoke well—with a slight American accent. After that, we always spoke when we met; it was mostly about the weather, but gradually she told me one or two things about herself. She was married and had no children and wanted none. She liked old houses, and lived in one. “There are plenty of them in Fulham, if you know where to look,” she added.

On the night that Minnie was “doing up” Mrs. Saunders, I dined at a little confectioner’s near Walham Green. That is to say, I had a mutton chop, a jam tartlet, and a glass of lemonade there. One took this weird meal in a little place at the back of the shop, just big enough to hold two small tables and the chairs thereof, and decently veiled by a bead curtain from the eye of the curious. I sat waiting for my chop and reading the evening paper when a rattle of the curtain made me look up. In came the little woman in brown. She seemed rather bewildered at seeing me, said “Good evening,” and modestly took her place at the other table. But she had clearly hesitated about it, and I could not seem too unsociable.

“Won’t you come and sit here?” I said. “Unless, of course, you are expecting anybody.”

“Thanks so much, I’m quite alone. I didn’t know—I thought you might be waiting for a friend.”

I laughed. “No, I have no friends—in London at any rate.”

“I am sure you have no enemies,” she said with conviction.

“I don’t think I have. I’m all alone, you see. Do you often come here? It’s a quaint little place.”

“Not very often. But to-night my husband is out—professionally engaged—he is a spiritualist, you know. So I let my maid go out too, and locked up the house and came here.”

“So your husband is a spiritualist. That sounds interesting. Does he see visions and make tables jump, and do automatic writing, and all those things?”

“Oh, no! He has been for years a student of spiritualism. And, of course, he is, as I am, a profound believer in it. He understands the best ways to conduct a séance, and mediums like to work with him for that reason, but he is not a medium himself. I am a medium—at least, I was.” She fiddled with a little pepper-pot on the table, turning it round and round. “Oh, I wish I were you!” she said suddenly.

I was astonished. “But why?” I asked.

“Well, the story is no secret if it won’t bore you. It’s known to many people already. Have you ever heard of Mr. Wentworth Holding?”

“Of course. You mean the financier and millionaire.”

“Yes. Well, he heard of my husband and of his medium, Una. I was always known as Una. I have heard it said that these hard men of business are often superstitious. I should put it that they are shrewd enough to see that there is something beyond them. Mr. Holding wrote to my husband to ask him to find out the future of a certain stock. Now that money-making kind of question is one which the spirits always dislike. As a rule they refuse to answer, or answer ambiguously. My husband did not expect much, but he gave me the question, and as soon as it was controlled my hand wrote, ‘Heavy fall in three days.’ My husband telegraphed this at once to Holding. The financier could not quite believe or quite disbelieve. He did not bear the stock, but also he did not buy it—as in his own judgment he had intended to do. The fall took place, and he sent my husband the biggest fee we have ever received, and said we should hear from him again.”

“But why does all this make you wish you were I?”

“That’s soon told. Holding has written again and wishes to engage the services of my husband and his medium exclusively. My husband has warned him that the spirits will not continue to interest themselves in his business, but he says that he does not mind that and that there are other things that interest him as much as business. The terms he offers are princely. The work would delight us both. And here comes the trouble: from the moment that I answered that question about the stock—perhaps because I answered it—I have lost power. My husband has searched London for a medium to take my place and can find none. Some of them drink, and very many of them cheat, and those who are decent and honest very often fail to get the results. And that is why I wish I were you; for I feel just as sure that you are an excellent medium as I am that you are good and above any kind of trickery. You won’t think me impertinent? I’ve always studied faces, you know.”

“But how can I be a medium? I have never done anything of the kind in my life.”

“But that does not matter—not in the very least. I am quite sure of what I say. I only wish you had some spare evenings, and wanted to make money, and could help us.”

“All my evenings are spare evenings, and I do want to make money. But I fear my help would be worth nothing.”

“Come and see at least.” She glanced at her watch. “My husband will be back in a few minutes. We live at 32 Hanford Gardens—quite near here.” Perhaps she noticed the look of cautious hesitation on my face. “Or would you rather come later? You might prefer to——”

“No,” I said, “I’ll come now.” I confess that I felt rather curious. I was not in the least a believer in spiritualism, but I did believe—and do still believe—that things happen for which no known law supplies the explanation.

No. 32 Hanford Gardens was a little box of a place with a small walled garden. It was an old house, and the tiny room into which my new friend brought me was panelled. The panels had been painted a dark green, and the thick noiseless carpet was of the same colour. It struck me, I remember, that they must have given a good price for that carpet. It was scantily furnished with a square table, a few solid mahogany chairs, and a couch in the recess by the fireplace. A man sat by the table, and in front of him was what looked like a glass ball, the size of a cricket-ball, resting on a strip of black velvet. He rose as we came in. The light was dim—for the room was lit only by one small shaded lamp in a sconce on the wall—but I could see that he was a gaunt man of forty, hollow-eyed, with a strong blue chin, looking like a tired actor.

I had already given my new acquaintance my name and learned that she was Mrs. Dentry. She presented her husband, and in a few words explained the situation. He had a pleasant voice and rather a dreamy, abstracted manner.

“It is very kind of you,” he said hesitatingly. “I do not know, of course, if you have a spiritual power, and one meets with many disappointments—as I have already done this evening. Still, one can try.”

“My husband,” said Mrs. Dentry, in explanation, “has been to-night to see a medium who professed to get most wonderful results. So he was no good, Hector?”

“Worse than that. Conjuring tricks—and not even new conjuring tricks.”

Then he turned to me with a host of rapid questions, and seemed satisfied with my answers. “We may have no results, but at any rate there will be no trickery.” He glanced at his watch. “Unfortunately, I have to go out for half an hour to see a client of mine. But my wife knows what to do—you will be able to make your first experiments without me.”

He went out and presently I heard the front door bang. Mrs. Dentry made me sit at the table and place my hands on it. “Wait,” she said, “until you are sure that the spirits are present, and then ask them aloud to raise the table from the floor.”

She went over to the other end of the room and turned out the lamp; then she lit a lamp that gave a little blue flicker, by which I could distinguish nothing except the face of Mrs. Dentry standing beside it.

For a few moments nothing happened; then loud raps came from all parts of the room, and the pictures rattled on the walls, and a cold wind blew sharply across my face and hands. I was astounded. Mrs. Dentry had not moved from her position at the other end of the room, and I could just see that she was smiling.

“I knew it would be all right,” she said softly. “Go on, please.”

“If there are spirits here,” I said—and somehow the voice hardly sounded like my own—“I ask them to raise this table from the ground.”

Very gradually I felt the table—which was fairly solid and heavy—begin to rise. It rose about two feet in the air and remained suspended. I pressed on it with my hands and could not force it down. After a moment or two it fell to the ground with a bang, and I removed my hands.

“That will do,” I said faintly, and Mrs. Dentry struck a match and re-lit the lamp. Then she and I sat on the sofa and talked. She said that I was wonderful and must certainly come and help them. If she might mention terms, she knew that her husband would pay a guinea for each sitting; at any rate I must come while the Wentworth Holding business was on. She urged that I owed it to myself to develop my marvellous powers. As she was talking I heard the click of a key in the front door and Mr. Dentry entered, his hat and gloves still in his hands.

“Well?” he said eagerly. “Did you get anything?”

“Anything?” said his wife. “Everything. Miss Castel is a really wonderful medium.”

We talked on for some time. I would promise them nothing definitely. But I gave them my address, and said that I would probably come once again at any rate. They were in despair that I would not give them any further assurance, but I was obstinate. I regarded the whole thing with a curious mixture of curiosity and repulsion.

* * * * * *

Next morning Mrs. Dentry called to see me. Wentworth Holding was sending a man of science that night to examine into the whole thing; it was essential that I should be there.

“If I go,” I said, “I do not want my name given.”

“Certainly,” said Mrs. Dentry. “You will be addressed as Una.”

“Then,” I said, “Mr. Holding’s tame investigator would be made to believe that I was the same medium that foretold the fall of the stock. I don’t like that.”

“True,” said Mrs. Dentry. “I hadn’t thought of that. It doesn’t really much matter. But you’d better be called Una all the same; there’s no cheating about it, because you’re ever so much better than the original Una.”

“I don’t think so. This morning, for instance, I tried the automatic writing and got nothing.”

“That’s because you don’t know how to set about it. My husband will show you. I myself failed scores of times at first. But as for the name, that must be just as you wish. You may be quite nameless if you like.”

“I should prefer it.”

“And please don’t make any more experiments without us. If the conditions are not right you will get no results, and in any case you will be tiring yourself. We want you to-night to be as fresh and full of vitality as possible. If you could get an hour’s sleep this afternoon it would be all the better.”

But I could not sleep that afternoon although I made the attempt. There were things in my interview with Mrs. Dentry that I did not quite like. I began to wish that I had never gone into the business at all.

* * * * * *

I kept my appointment at nine that night, and the Dentrys’ rather frowsy maid showed me into the room where I had been on the previous evening. Two men in evening dress stood by the fireplace. One was Dentry; the other was a short, solid-looking man with a closely clipped grey beard. At the table sat an elderly lady in black, with tight lips and a proud, disapproving face. Dentry thanked me for coming, and explained that his wife could not be present. “She is, in fact, taking some of my regular work in order that I may be free.” The grey-bearded man was introduced to me as Dr. Morning. The elderly lady, to whom I was not presented, was his wife.