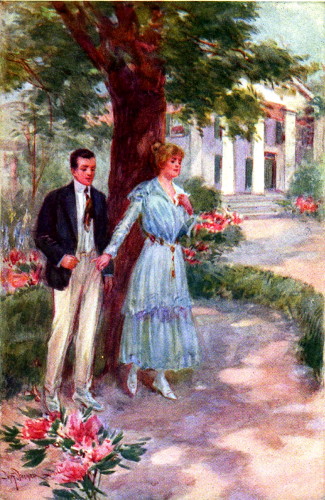

SHE DREW THE RING FROM HER FINGER AND WITH AVERTED FACE HELD IT OUT

Title: Nancy first and last

Author: Amy E. Blanchard

Illustrator: Will F. Stecher

Release Date: August 4, 2023 [eBook #71334]

Language: English

Credits: David Edwards, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

BY AMY E. BLANCHARD

AUTHOR OF "BETTY OF WYE," "GIRLS TOGETHER," ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

WILL F. STECHER

PHILADELPHIA AND LONDON

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1917

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY AMY E. BLANCHARD

PUBLISHED SEPTEMBER, 1917

PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS

PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A.

SHE DREW THE RING FROM HER FINGER AND WITH AVERTED FACE HELD IT OUT

| I. | A Parting of the Ways |

| II. | A Revelation |

| III. | Creeping Back |

| IV. | Mother! |

| V. | Other Names and Places |

| VI. | O las Piedras! |

| VII. | A Clue |

| VIII. | At a Fiesta |

| IX. | In Barcelona |

| X. | A Fruitless Search |

| XI. | In the Cathedral |

| XII. | Help from England |

| XIII. | Primrose Cottage |

| XIV. | War! |

| XV. | The News of a Day |

| XVI. | Cousin Prudencia Writes |

| XVII. | Convalescents |

| XVIII. | A Puzzled Patient |

| XIX. | My Boy! |

| XX. | Opened Eyes |

| XXI. | Farewell |

The garden was too peaceful and fair for a scene of discord. From behind the sun-warmed box hedges came the odor of clove pinks, hundred-leaf roses and heliotrope, while breezes, passing by the porch of the old-fashioned, high-pillared house, brought the cloying sweetness of honeysuckle and jessamine blooms. Along the gravelled paths paced a man and a girl, both young and good to look upon. The girl, slender, brown-eyed, fair-haired, white-skinned, discoursed passionately; the man, with steady blue eyes, broad brow and firm chin, listened, turning toward her once in a while a half-bewildered look.

"You do not understand, you cannot," the girl was saying excitedly. "You are nothing but ice and snow, a creature of marble. If you had ever met love face to face, had ever felt its real power I would not need to question you, but it has to filter through your body and never reaches your soul. There is so little spiritual essence in what you offer that it is valueless to me."

"But, Nancy, what is it you want me to do?" asked the man, still looking bewildered.

The girl made a despairing gesture. "You ask me to tell you what to do!" she cried. "If your own heart cannot tell you, it is no use, no use to go on. Have you ever stood at night in the shadows gazing at my window till my light went out?"

He shook his head. "I don't think so," he answered slowly.

"Did you ever lie awake, Terrence Wirt, thinking of me, and find yourself here in the garden at dawn waiting for me to appear?"

"Why, no. I didn't need to do that. I know your breakfast hour and I never like to intrude too early," replied the man still with a puzzled look. "Would you like me to come before breakfast?"

"Not unless you can't help coming."

"I hope I have myself well enough in hand not to act on an impulse which would mean impoliteness to your mother."

"It's no use, no use," Nancy repeated. "You cannot understand."

"But I do want you to be happy. It is my dearest wish to make you so. Can't you explain so I will understand wherein I fail?"

"It has been two whole days since you asked me if I loved you."

"But, dear, you told me so in the beginning. Do you want me not to believe you?"

Nancy turned away and, leaning against a tree began to weep convulsively. Terrence tried to take her hand but she snatched it away. "Go! Go!" she cried passionately. "Do not touch me. From henceforth we are parted forever." She drew the ring from her finger and with averted face, held it out.

Silence fell between them. The gentle rustle of leaves overhead, the drone of a bee making ready to clasp a flower, the opening and shutting of a door in the house, these were the only sounds audible. Presently Nancy felt the touch of fingers; the ring was withdrawn from her palm. In another moment she heard footsteps treading the gravel, the gate clicked and she knew she was alone. She stood for a moment leaning against the tree, then she dashed to the house, pushed open the outer door, darted up to her room and flung herself, face downward on the bed, where she sobbed her heart out, refusing her midday meal and asking to be left alone. The sun was low in the skies when, pale and still, she went slowly down stairs. Mrs. Loomis, who was sitting in the broad hall which opened east and west upon porticos, looked up as Nancy paused upon the lowest step before coming forward, but she made no remark. Nancy sat down on the carved bench opposite Mrs. Loomis's high-backed chair. She spread wide her arms and rested a hand on either arm of the bench, fixing her burning eyes upon space. She might have been posing for some figure of Tragedy.

"Is your headache better, daughter?" asked Mrs. Loomis, drawing a needle from the row of knitting she had just finished. She was a frail looking woman with fast-graying hair, a low voice and a quiet manner.

Nancy's great dark eyes rested somberly upon the questioner. "I didn't have a headache. I have parted forever from Terrence Wirt, and my heart is broken," she replied in an intense tone.

"Why, Nancy!" Mrs. Loomis laid down her knitting. "What in the world did you quarrel about?"

"We didn't quarrel. He doesn't love me. At least his love is of such poor quality that it might better be called a mild liking. Compared to mine it is as lukewarm as milk is to wine."

"Lukewarm milk is very nourishing and often to be greatly preferred to wine," remarked Mrs. Loomis with a little smile as she resumed her knitting. "You are too exacting, Nancy."

"I want no more than has been given to other women. I want only what Romeo gave to Juliet, what Dante gave to Beatrice."

"But Terrence is not a poet, my dear," Mrs. Loomis counted her stitches, "though he appears to me to be very true and steadfast. He may not be exactly what you might consider temperamental, but certainly he is appreciative and devoted to you; moreover, he is a young man of fine character, and that is worth everything. I am sure he loves you deeply."

"No, no," Nancy sprang to her feet and waved away the suggestion with a dramatic gesture, then she seated herself at her mother's feet on the doorsill, resting her chin in her hands. "No man who was devoted to a girl could be content with such a humdrum, settled state of affairs. No romance, no poetry, no jealousy, no wild heart yearnings, no sleepless nights. All these have been mine. I loved him so. Oh, I loved him so." Her lips trembled and she turned to bury her face in her mother's lap.

Mrs. Loomis stroked her hair softly. "Well, my dear, if you love him so much as all that I cannot imagine why you sent him away. Perhaps when you see him again it will all come right, since he seems to have had no fault to find with you."

"We shall not meet again. He took me at my word. He may have no fault to find, but he does not love me or he would not have gone," persisted Nancy, lifting wet eyes.

"He loves you in a very quiet, manly way, no doubt, but that is not saying that it is not a very strong and enduring love which is much better than a wild passion. However, if it does not satisfy you there is nothing more to say. You have dismissed him, which I consider a mistake, and there is nothing left for him but to accept your decree."

"But I don't want him to," cried Nancy. "Why didn't he get down on his knees and beg me not to give him up? Why didn't he tell me that I had broken his heart, that I had clouded his life, that existence would be unbearable to him without me? I expected him to. I thought the test would bring forth at least some anguished protest."

"What did he say?"

"He didn't say a word, not a word. He just took the ring when I gave it to him and walked away." Nancy gave a little choking sob.

"Still waters run deep; shallow streams make the most noise," remarked Mrs. Loomis.

"Do you think I am a shallow stream because I cry out in my pain?"

"No, dear, but you are a highly emotional child, and demand more of life than you are liable to receive."

"I flew to the very heights of love; he was content to grope below the stars."

"Oh, you child, you child, you are so young, and you do love to talk like a tragedy queen. When real trouble comes you will lose all those romantic ideas, and will not look to have a man express his deepest emotions in poetry. Real trouble will come soon enough; it is our portion in this life, and you must learn not to dwell in the clouds, but to gain a more practical outlook."

"And while I am learning I shall be very, very unhappy."

"Perhaps so; I am afraid so. Unhappiness comes to each one in some form or other, but we need not magnify it, dwell on it, nurse it, hug it to our breasts. We need not be selfish about it and imagine our griefs greater than those of any other. We must rise above them and try to help those whose sorrows are greater than ours."

Nancy gave a deep sigh. At that moment she did not think any sorrow could be greater than her present one. She was emotional, enthusiastic, with an eager belief that life must hold for her all that her ardent nature could demand. Unhappiness had been given no place in her dreams heretofore and she was not armed to meet it. She had planned out an interview with her lover, an interview which she believed would terminate exactly as she fancied it would. She had wanted to make this a supreme test and she was aghast that it had resulted so disastrously. Bubbling over with joy, full of appreciation, of fresh and pretty fancies, with a keen sense of humor, yet thrilled by more serious things, it is no wonder that Terrence Wirt found her charming. Her beauty, versatility of mind and her enthusiasm were liable to impress a more mature and more exacting man. That he had been the first to become her suitor was due to chance, Fate, Nancy called it, and the romantic manner of their meeting had much to do with the rapidity with which she fell in love. Probably her heart was standing tiptoe waiting for the possible prince, and any who bore the slightest semblance to a knightly figure would have been welcomed. As it was, when the girth of her saddle broke, she was dumped upon a country road and a good-looking young man suddenly galloped up, dismounted and insisted upon leading his and her own horse to her home, in her eyes he appeared as truly a Paladin as if he had worn shining armor and had carried a shield. Straightway he filled her dreams day and night. She did not fall in love; she flung herself in.

Mrs. Loomis, at first amused, was next bewildered, then concerned at discovering that a perfect stranger had so completely carried Nancy off her feet. But when she learned that the young man was the guest of a sister who had lately married into one of the old families of the neighborhood, that his parents were people of standing in the city, that he was just graduated from college and bore a record above reproach,—"sans peur, sans reproche," as Nancy loved to say,—she made no objection to the engagement.

Indeed, Mrs. Loomis was not a born objector. The line of least resistance was usually hers, partly no doubt because of physical weakness. Ira and Parthenia, commonly known as Unc. Iry and Aunt Parthy, relieved her of most of her household cares. She occupied the ancestral home of the Loomises, which she was able to keep up by means of an income inherited from her husband. Her business matters were looked after by the old lawyer who had managed Loomis affairs since the day that he took his father's place in the dingy office on the main street of the county town.

As for Nancy, she had grown up pretty much as she pleased, had been under the care of governesses good, bad or indifferent, had read, not wisely but too well, whatever came her way, had been away at school for two years, coming home always for week-ends and between whiles, too, if she felt so disposed, but in one way or another absorbing a deal of information of a desultory sort. Languages she found easy and a French governess had trained her into a sufficient knowledge of her tongue to enable her to speak it rather fluently. Music was her chief talent. She played readily by ear, but hated to be bound down by technical exercises, and in her earlier years was not compelled to do so, since Mrs. Loomis did not insist. However, the old German professor at school scared her into a carefulness she had previously scorned, and at last she came to be his star pupil, continuing her lessons after she had left school. As for her schoolmates, most of them lived too far away for her to visit after her school days were over, and though she kept up a desultory correspondence with one or two she was not intimate with any special one. One or two holiday visits to New York had given her some idea of life in the metropolis, but the days spent in a big hotel did not specially charm her, and, while they dispelled some of her illusions, they did not interfere with her day dreams. Back again in her country home she was ready to enter again her world of romance and dream away the hours.

On this special evening she sat on the doorsill, silently brooding and looking off into the garden which so lately had been a paradise to her. It was impossible, she told herself, that she would never again pace the walk with Terrence by her side. She would go half way, yes, she was willing to do even more at the slightest sign from him. They could not avoid meeting; perhaps it would be at church, when she would find herself smiling wistfully across the aisle at him. He would be assured then that she was not angry with him; he would join her on the way out and ask if they could not be at least friends. She would accord him the privilege and after a while they would drift back into their old relation. Or it might be that they would meet at the house of some acquaintance. She would be making a call, would be waiting for her friend to appear. Suddenly Terrence would come in. "You!" he would exclaim agitatedly. She would hold out her hand and look up into his face beseechingly. "Let us be friends," she would say. Oh, she could not be content to accept the fact that they were parted forever!

Her musings were interrupted by the gray-haired old butler who came softly into the hall. "Miss Jenny, ma'am," he said, "Parthy say ef de ladies ready suppah is."

Mrs. Loomis drew Nancy close to her as they went out together into the lofty dining-room where pale shifting lights were playing over the wall and touching up the old mahogany and silver as the western sky received its last benefice from the sun.

It was but a few days later that Nancy came in with the local paper and, with pale cheeks, pointed tragically to an item which read: "As a fitting conclusion to his studies at college, Mr. Terrence Wirt, lately visited his sister, Mrs. Lindsay, at Heathworth, will travel abroad. He sails from New York to-morrow on the St. Paul."

"He has gone!" quavered Nancy. "Gone without a word!"

Mrs. Loomis laid down the paper with a troubled look, but presently her habit of taking the easiest way out, asserted itself. "Oh, well, Nancy," she said, "I wouldn't take it to heart. There are as good fish in the sea as ever yet were caught. You are very young and there are plenty of nice young men in the world."

"Not for me," responded Nancy, gloomily.

"Of course you think so now; that is perfectly natural. Every girl feels so at first, till some one else comes along. Of course I haven't a word against Terrence, and his people are all right, but for my own part I'd much rather see you settled in this neighborhood, than to see you married to some one who would take you away off to New York or some other big city. There are a number of nice boys whose families have lived here for generations; there's Patterson Lippett, for instance."

"Pat Lippett!" exclaimed Nancy with fine disdain. "He is no more to be compared to Terrence than an earth worm is to a jewelled humming-bird; besides, I have known him all my life."

"I don't see why that isn't so much the better. I am sure Pat has been to college, and so have several of the other boys you know. The Lippetts are a good old family, so are the Carters and the Gordons. Don't look so tragic, dear. I declare when those big eyes of yours get that expression you fairly frighten me. Why I had had half a dozen affairs before I met Mr. Loomis and I am sure no one could have been happier than we were. There is no more beautiful memory to me than our honeymoon in Cuba and Mexico. Everyone has said they never knew anything more romantic." She sighed a little.

"That is why you love Spanish, isn't it mamma?" said Nancy. "I wish I had studied it."

"It is not too late now," returned Mrs. Loomis. "I could help you. Why don't you take it up this summer, Nancy? It would occupy your time and perhaps take your mind away from this affair."

"It might help," returned Nancy, in a melancholy tone, "but nothing could make me forget."

"Not at once, of course, but you might gain quite a good knowledge in a year's time and then we might make a visit to Cuba."

This prospect appealed to Nancy, and she showed enough interest in the proposition to say: "Mademoiselle said I had a gift for languages."

"Naturally," responded Mrs. Loomis, with a thoughtful look.

"Do you think that I inherited the gift from you or from my father?"

Mrs. Loomis started. "From your father," she said, and immediately changed the subject.

Nancy took the paper she had brought in, meaning to preserve the notice of Terrence Wirt's departure. So did she mean to preserve any word of him. She found an ancient vellum-bound album in a pile of books packed away in the attic, appropriated it and dedicated it to her lost lover with a queer ceremony of her own invention, in which a dead rose, broken heart and a dying candle figured. No consolatory words of Mrs. Loomis's availed to change her conviction that the separation was final, and for the first time in her life she turned a shrinking front toward the future.

The summer days dragged on monotonously. The gallants who rode that way rode off again, for Nancy would have none of their invitations to picnics, dances or tournaments. She always had a flimsy excuse: she was tired; she didn't care for picnics; she was busy; her mother might need her, and so the offended young squires finally turned their attentions to more complaisant maidens. The Loomis homestead stood a couple of miles out of the small town, upon an unfrequented road, so that visitors were rather rare, even at best, and it might be said that they were not encouraged, if one judged by the infrequency of Mrs. Loomis's calls upon her neighbors. She was naturally indolent, and in the past few years had been warned by her doctor not to exert herself unnecessarily, so she was quite content to sit on the porch with a book or with fancy work, while Nancy wandered about at will, or spent her time poring over some old volume of poetry. Many of the more prosperous neighbors, the Lindsays among them, had gone to the Springs to enjoy greater gayeties, so there were few young persons left, and these Nancy declared she did not miss.

It grew hotter and hotter. Nancy's pallor increased day by day, and at last Mrs. Loomis noticed it and looked at the girl with concern.

"I wish I felt able to make the journey to the North," she said. "This excessive heat is pulling us both down. I feel as limp as a rag and you look as if you had been drawn through a knot-hole. I hope you haven't been poring over those Spanish books too steadily. Perhaps we'd better stop the lessons till it grows cooler. Would you like to join the Lippetts at Greenbriar, Nancy?" she inquired with a half hope of bringing Nancy into the daily society of Patterson.

"I shouldn't care a rap about it," returned Nancy, quickly nipping the hope in the bud. "I would much rather stay alone with you than be thrust into a little hot room and have to dress half a dozen times a day, and for what purpose?" she added sighing.

Mrs. Loomis laid her cheek against the girl's slim hand. "After all," she said, "I suppose one is more comfortable at home, and I must confess I feel like undertaking anything but a journey, myself. Any exertion makes me feel as if I should collapse utterly."

Nancy bent to kiss her. "Perhaps you need a tonic. Shall I call up Dr. Turner and ask him to stop in?"

Mrs. Loomis shook her head. "No, it isn't worth while. I know exactly what he would say. It is the same old trouble. He wouldn't give me anything new. I am out of the drops he ordered the last time, but I will send for them to-morrow."

"Mañana; that old mañana," returned Nancy, playfully. "Why not send at once?"

"One more day will not make any difference," protested Mrs. Loomis. "Iry is busy cutting the grass and I don't want to take him away from his work."

"I could go."

"In this heat? No, indeed. I should be afraid of sunstroke, and should be so worried every minute you were gone that it would do me twice the harm it would to wait."

So Nancy yielded, but told herself that she would take an early morning ride into the town and bring out the medicine before breakfast the next morning.

But the dawning of the morning was not on this earth for Virginia Loomis, for, while the world was yet in half light, old Parthy came to Nancy's door, tears rolling down her dark cheeks. "De white hoss done been hyar, honey," she said. "I been a-lookin' fo' him. Udder day a li'l buhd fly into Miss Jinny's room, an' a dawg been howlin' uvver night fo' a week."

Nancy, sitting up in bed, gazed at the woman with startled eyes. "What? Who?" she began, but could not go on, feeling the weight of some tragedy imminent.

"Las' night 'pears lak Miss Jinny skeerce kin drag huhse'f up stairs," Parthy went on, "an' dis mawnin' airly when de roosters a-crowin', three o'clock, I reckons, I jes' kaint sleep, an' wakes up Iry an' says ef dat dawg don' stop dat howlin' I los' my min', an' Iry gits up, too, fo' I feels sumpin bleedged mek me go up an' see ef Miss Jinny want nothin' I dunno de whys an' wharfores of dat but I feels lak I bleedged ter go." She paused and Nancy, never moving, kept her eyes fixed in the same startled gaze.

"Go on," she whispered. Faint light was creeping into the room. A gentle breeze drifted in through the open windows, swaying the curtains ever so gently. There were one or two twittering cheeps from newly awakened birds. A wagon rattled clumsily along the stony road. "Go on," again whispered Nancy.

"I goes up an' knocks at Miss Jinny's do', but she ain' give no 'sponse, den I opens de do' an' goes in, an'—an'" Parthy broke off short in her speech and, burying her face in her apron, she rocked back and forth moaning.

Nancy slipped out of bed and crept toward her. "If mamma is ill, send for the doctor at once," she said, in a strained voice.

"Iry done been, but 'tain' no use, 'tain' no use. Po' li'l chile. Po' li'l chile," she wailed.

Nancy darted from the room to be met at her mother's door by the old doctor. "Go back, my child," he said, tenderly. "Go back, you can be of no use now. She is safe."

"Safe fo' evahmo'," chanted Parthy, who had followed Nancy. "She happy an' safe. She done gone to meet Mars Jeems."

With one wild cry Nancy flung herself upon Parthy's broad breast, was picked up in her strong arms and carried back to her room.

The days that followed passed for Nancy she scarce knew how. Kind neighbors tried to comfort her; the good old doctor spared no pains to ease her grief, telling her that if her mother had lived she would have suffered greatly. "It was her heart, my child," the doctor said, "and it is a merciful Providence who has allowed her to leave this world so peacefully."

But Nancy would not be comforted. She felt that Heaven had dealt her a double blow, that in her cup of bitterness had been mixed still more bitter draughts till it overflowed.

It was not till the lean old lawyer, Silvanus Weed, came to consult her about her mother's affairs that Nancy realized that she must rouse herself and make an effort to understand what he was trying to say.

She met him in the library, a room seldom used, for Mrs. Loomis had always preferred her own more cheerful sitting-room upstairs. On this occasion Nancy felt that its memories were too tender, its associations too dear to be desecrated by discussions such as she knew must take place, so to the sombre library she went and established herself in a stiff chair facing the table. She looked very wan, very young and helpless, and Mr. Weed felt that seldom had a more difficult duty been assigned to him.

He cleared his throat once or twice after he sat down and turned over the papers he drew from his bag, then he said suddenly, "You know, Miss Nancy, Mrs. Loomis had only a life interest in this estate in the event of her dying without issue. Should such be the case the estate would revert to the Loomis heirs, nieces and nephews of the late Mr. James Loomis. Beyond this in her own right she had not a large income. This, of course, is left by will to you. I cannot state the exact sum at this moment, as there are some stocks which I have not looked into; they might realize you more if well handled."

"But,—but,—" Nancy roused herself to say, "as I am the only child, surely I inherit all. You meant that it—the place—my father's property, would go to his family only in case there were no children, wasn't that what you meant, Mr. Weed?" She fixed her great, mournful eyes upon his face and his own gaze fell.

"I meant," he said hesitatingly, "that if there were no legal heirs, all Mr. Loomis's property would go to his family. Yes, that is what I meant." He fidgeted with the papers on the table and seemed unable to go on although Nancy waited expectantly.

"I wished to say," he spoke again after what seemed an unnecessarily long pause, "that Mrs. Weed, at least we both would feel gratified if you would come to us until all these legal matters are settled. You will scarcely wish to remain alone with servants, and we would be much gratified to receive you under our roof till your plans are made."

"But, Oh, Mr. Weed, I would so much rather stay right here. It would break my heart to go away so soon. I could get some one, some nice, quiet, respectable person to stay with me, couldn't I?"

"No doubt, no doubt," Mr. Weed answered nervously. "I think perhaps," he added, "that the next thing to be done is to go over such papers of Mrs. Loomis's as have not been entrusted to me. There may be matters which need legal attention, and we would best see to such as soon as possible. You have the keys, of course."

"Yes. At least I know where they are," Nancy replied in a disheartened voice. Why all this red tape, this caution when it seemed a very simple thing that she be allowed to retain what was hers, her inheritance by right of descent? "I suppose there has to be something done about a will," she said, "it has to be—probated, do they call it? Does it take long?"

"Not so very, and an estate is usually settled up within the year."

"Oh, a year, then I need not hurry."

The lawyer gave his dry little cough as he began to gather up his papers. He had an angular face, square forehead, blocked in nose, and eyes which seemed like two triangles set beneath indefinite brows, but his smile was kindly as he said: "Now, don't worry, Miss Nancy. There will probably be no objection to your staying here as long as you wish, though I wish to impress it upon you that our home is open to you at any time that you may feel you would be ready to come to it."

"I do appreciate your saying so," returned Nancy earnestly, "but you can understand that my own home must seem more of a refuge than any other place just now. It is all so dear to me, hallowed by so many precious memories. Parthy and Ira will take good care of me."

"I am sure of that," Mr. Weed replied in his stiff little manner. "So then, Miss Nancy, we will leave the question open for the present and in the meantime you can be looking over the papers. You can let me know when you wish to consult me about them and I will advise you to the best of my ability. I trust you will believe that I wish to spare you all the trouble that I can, and that I will serve you as faithfully as I would any of the family. We Weeds have attended to the Loomis's legal matters for generations and I think we have never failed them yet. Now, no matter what happens, you must not worry." He gave her shoulder a wooden sort of pat and went out, leaving the girl to ponder over what he had said, but, as he walked down the gravelled path he murmured to himself. "I could not do it. Not yet, not yet. Let her find it out for herself."

"Better get it over with," sighed Nancy, as she watched the lawyer's stiff figure mount his buggy. "Ah, me, I wish mamma's sisters had not died young. I wish I had a real live aunt or an older sister to help me through all this terrible business. I must be brave," she told herself. "I have to be," she repeated as she searched for the keys. In time she found them and sat down before the old escritoire which was a familiar object in Mrs. Loomis's sitting-room. "I cannot, oh, I cannot," she whispered chokingly as she began to draw out papers from the various pigeon-holes. The papers were thrust rather loosely into the most convenient spot, or, unlabeled, were scattered about in a drawer. Most of these she was able to sort without difficulty. A packet of letters, tied with a black ribbon was marked "From my dear husband." These Nancy put aside reverently, then removed a smaller packet which had lain beneath them. There was nothing to indicate the correspondent, but some were post-marked Havana, some New Orleans. There were not more than half a dozen and, because they were so few, Nancy decided to read them.

As her eyes followed the lines of the first letter her breath was drawn in sharply. She hastily glanced at the signature, José Beltrán. This letter she flung aside and eagerly glanced through the remaining ones. At last she started to her feet with a wild cry, staggered to the door, still grasping the letter, and found her way gropingly to her own room. "Not that! Not that!" she moaned, and sank in a heap on the floor.

There Parthy found her. "Po' little lamb! Po li'l lamb," she murmured as she lifted her in her arms and laid her on the bed. "De good Lord done stricken huh fo' sho. He done lay his han' heavy on huh." She loosened the girl's clothing, then sent a call below for Iry. "Miss Nancy done give out at las'," she said. "You bleedged to fetch de doctah, Iry. She done come to de een' o' huh rope."

For days Nancy lay babbling in delirium, her head, shorn of its golden locks, tossing from side to side. When he was first called in, Dr. Plummer shook his head dubiously. "Who is with you here, Aunt Parthy?" he asked.

"'Tain't nobody, doctah, jes' at de present 'ceptin' Iry. Miss Ober she been an' stay a while, an' Miss Greenway she stay a while, dat jes' at fust, when Miss Nancy lef' by huhse'f. Den she up an' say she don' want nobody but jes' Iry an' me; she don' want no strangers meddlin' wif her ma's things. She don' say dat to dem, min' yuh, but she say so to me, an she jes' sweet an' perlite to 'em but she let 'em all know she radder be lef' alone."

"She must have a trained nurse at once," decided the doctor.

"I kin nuss huh," declared Parthy, looking anxiously from the bed to the doctor. "Dese yer train' nusses a lot o' trouble, dey tells me. Dey say yuh bleedged wait on 'em han' an' foot, an' dey so high an' mighty yuh kaint please 'em nohow. Dat what dey tells me. I kin nuss huh."

"No, Aunt Parthy, I'm afraid you can't," decided the doctor.

"What de reason I kaint?" persisted Parthy. "Ain't I nuss huh when she have de measles an' de whookin' cough, an de chicken pox? Ain't I? What Miss Jinny know 'bout nussin'. Law, doctah, I teks ker o' Miss Jinny an' Miss Nancy bofe."

"I know that Parthy, and you did well, but this is quite a different case and will require a skilful hand. I know you would do your best, and we shall probably have to call on you to help out, but this child has every symptom of brain fever. This ordeal has been too much for her."

"Ain't it de troof now?" exclaimed Parthy. "I say she boun' be sick ef she don' look out. Why, doctah, she ain't been eatin' nuff ter keep a buhd alive, dis month pas', an' den de heat an' all huh trouble comin' so sudden. Co'se huh brain giv out when she ain't feed it up."

Even the gravity of the situation did not prevent a little smile from lurking around the doctor's lips at this speech. "Well, Parthy," he said, "a trained nurse is an absolute necessity. I think I know just the right person, and I can promise you she will give no more trouble than is required. In the meantime I want you to carry out these instructions"—he gave them to her—"and then I will go back and return as soon as I can with Mrs. Bertram, the nurse I spoke of. With her help and the Lord's I hope we can pull her through. Poor little thing! Poor little thing!" So he left Nancy to Aunt Parthy's tender mercies.

Thus it was when at last Nancy opened her eyes to an actual world, instead of the weird, and often terrible one, in which she had been for so long, she beheld a strange, but kind and sympathetic face bent above her. She gazed long and earnestly before she whispered faintly "Mamma!"

The nurse stroked the frail little hand which lay outside the coverlet, but said nothing though her eyes were full of tenderness.

"Who are you?" Nancy added faintly. "I want mamma."

"I am your nurse, Mrs. Bertram," was the answer. "Don't try to talk, dear. You have been very ill and must keep quiet."

Nancy, too weak to do else, closed her eyes, but gradually the recollection of all that had happened returned to her, and tears began to trickle from beneath her closed eyelids. But presently she heard a soft voice ask: "She in her conscience yet, Mis' Bertry?" and opening her eyes again she beheld Aunt Parthy standing by her bedside and looking down upon her with loving concern. Nancy tried to lift a feeble hand, murmuring "Oh, Mammy, Oh, Mammy," and the tears flowed faster.

"Dere, honey chile, dere now," said Parthy, soothingly, taking the slim white hand in her strong black one. "Yo' ole Mammy gwine stay right hyar whar yuh kin see huh ole black face. Don' yuh mou'n fo' yo' ma, chile; she wid de angels a-lookin' down at yuh dis blessed minute. She gone whar dey ain' no mo' weepin' an' sighin' er no mo' sickness er dyin'. Jes yuh think o' dat. Hyah come de doctah. I say he be mighty glad yuh come back outen dem shadders whar yuh been stayin'."

Dr. Plummer came near and smiled down benevolently upon his patient. "Well, little one," he said, "you're better. Now we shall have you up in no time."

"Why, why did you let me come back?" whispered Nancy. "They are all gone, all gone, and no one wants me."

The doctor turned away and furtively wiped his glasses with what might seem unnecessary fierceness. "Tut! Tut!" he exclaimed as he again addressed his patient "We're not all gone, not a bit of it. You've more friends in this place than you can count, beginning with myself and Mrs. Bertram, not to mention Aunt Parthy. You'll be coming on finely now. I expect you to be laughing at my stale old jokes before the week is out."

Before the week was out she was not exactly laughing, but she was ready to admit that life still held hopes for her, that the world offered her beauty, that Heaven had given her friends. The presence of her nurse was a great comfort, and she began to give her a devotion born of helplessness and dependence. But even the doctor's jokes, Parthy's pleasantries, or the tender, encouraging words of her calm and capable nurse failed to alter the sad expression of her face or the sombre look of her eyes, now all the larger because of the thinness of her face.

"Laws, chile," said Aunt Parthy one morning when she was anxiously watching her nursling's attempts at eating breakfast, "I 'clar dem eyes o' you'n teks up nigh de whole o' yo' purty li'l face. Kaint yuh eat no mo' dan dat? Yuh 'min's me o' one dese yer li'l yaller chicks, picky, picky, picky. Ain' dey nothin' yuh relishes? Ef dey anythin' yuh laks Iry go right down town an' git it fo' yuh ef he have to comb de town wif a fine toof comb ter git it. How yuh relishes a nice li'l weenty piece o' duck er a slice o' young tu'key?"

Nancy shook her head. "I couldn't eat anything more, Mammy dear," she said, "but I should like to see Mr. Weed. I think I am strong enough now."

"Dat ole atomy? Honey, he so dry in de j'ints I don' know ef he kin git hyar 'thout crackin', but Iry kin go fo' him ef yuh says so. He ole atomy, dat man is. Ain't got no juice lef' in him. He 'minds me o' one o' dese yer places in de woods whar dey ain' nothin' growin', nothin' on de groun' but jes' pine needles. But yo' ma she trusses him, an' all de Loomises trus' him so I reckons we bleedged trus' him, but he dat dry he mos' choke yuh when yuh talks ter him."

Nancy smiled faintly. Nothing brought a smile to her lips more surely than Aunt Parthy's rambling comments. She was sitting in a big chair by the window of Mrs. Loomis's favorite room when Mr. Weed arrived. Between the branches of the great trees she could see a far stretch of country, the little town at the foot of the hills, and the railway trains crossing a shining river and winding along in the distance. She could also see the nearer view of the box-edged garden borders and the gravelled path along which Mr. Weed was moving stiffly. She smiled as she remembered Parthy's criticism, for his movements did suggest that he might creak as he walked, but the smile faded away as she remembered why she had sent for him, and she drew a deep sigh. She sat motionless when he entered the room. She must brace herself for this ordeal. She scarce paid attention to his inquiries after her health, his felicitations upon her recovery, but cut these short by saying: "Please sit down, Mr. Weed. I have something important to say to you," and she did not wait a moment before making the announcement. "This place is not mine, and I want you to tell me what I must do. Did you know, Mr. Weed? Did you know?"

Mr. Weed regarded the floor for a moment before he answered, "Yes, I knew."

Nancy drew a quick breath of relief and said with a sad little half smile. "Then it would have been of no use if I had tried to keep it to myself. I was tempted to at first, but I couldn't be so dishonorable, of course. I think it was more because I hated to give up the name than anything else."

Mr. Weed nodded. "I can believe that," he said. "It would have been unnatural if you had not been tempted at first."

"But why, Mr. Weed, why was I not told in the first place? It would have been so much easier for me if I had grown up with a knowledge of the truth. But to come now, now, on top of everything else, I feel as if I could not bear it." She gave a quick sob, but steadied herself at once and said in a controlled voice, "Please tell me what you know and why you didn't tell me."

The lawyer gave his sudden dry cough. "I couldn't, Miss Nancy, I suppose it was cowardly, but I simply couldn't bring myself to the task of hurting you. I told myself that it would be better for you to make the discovery yourself, and that is why I suggested that you examine Mrs. Loomis's papers. You found them, I conclude."

"Yes, I found them, papers, letters which told me——"

"Letters from your—from José Beltrán?"

"Yes. You have seen them?"

"I saw them a long time ago, when Mrs. Loomis first came to this place after her husband's death."

"And she brought me with her. Why did she conceal the fact that I was not her own child?"

"Because she meant to adopt you legally in place of the child she had lost, to give you a legal right to the name she bore. She always meant to do that, but, like many, many others, she deferred it from time to time. She had a feeling that if it were known by her husband's family you might not be treated with proper deference, and she was jealous for you. She hoped to live to see you well married, then the name would have made little difference. It was a wrong view which she took, but it came more from a natural disinclination to trouble herself about business than from any desire to harm you. I was able to persuade her to make a will in which she left you all that was her own."

Nancy was silent before she asked: "Would I have had more if I had been legally adopted?"

"Possibly; but we need not go into that now. The will was made long ago."

"Poor, dear mamma," sighed Nancy. "At first, Mr. Weed, I felt very bitterly toward her, as if she had done me a great wrong. I was very wicked to feel so, for I know she thought she was doing her best, and I have come to see that my feeling should be one of deep gratitude rather than of bitterness. She did so much for me, me, a poor little waif but it is a shock to know that my name is Anita Beltrán and not Nancy Loomis, to know little of my father and nothing of my own mother. Do you know anything more about me than is contained in those letters?"

"Nothing. I know only that you were deserted by your own mother; that your father, in political difficulties, was obliged to leave Mexico, that he went first to Cuba and then to New Orleans, where he died of fever; that Mrs. Loomis took you, at the time of your father's flight, brought you back with her from Mexico and reared you as her own."

"And her own child?"

"Was born in Mexico, lived but a short time and died there. Mr. Loomis died while they were on their way home, and she came here a widow with one child whom all believed to be her own. I think I was the only person who was informed of the truth, and this because of necessity rather than choice. Mrs. Loomis was still rather a young woman, and it seemed possible that she might live for many years. I was not aware that she had serious heart trouble till I learned so from Dr. Plummer after her death."

"I never knew it, either. I knew she was not very strong, but that there could be anything serious the matter never occurred to me. If I had known"—she gave a little sob—"it might have been different. I would have been more careful of her, more attentive."

"Ah, my dear, do not reproach yourself. You did not know and therefore acted according to your lack of knowledge. I can appreciate your feeling, for it has been my own in this case."

"It is good of you to say so," returned Nancy gratefully. "Most of what you have been telling me, Mr. Weed, I gathered from those letters. I shall keep them sacredly, all I have, all I shall ever have, probably, of my own people. Now, will you please tell me what you think I should do? I cannot live here under obligations to strangers upon whom I have no claim. Will I have enough to live upon?"

"I would not worry about that yet. There are still some months in which to settle up the estate. You can surely remain during the winter."

"I would rather not if it can be avoided. I have not much ready money."

"I will see that you are provided with sufficient for your needs until your affairs are settled."

"Thank you. I suppose I could find a place where I could board cheaply, but as soon as I am really well I must have something to employ my time. I have been thinking that I might be able to teach. I know most persons want trained teachers nowadays, but perhaps a family might be willing to take me. I am rather a good musician, and I am quite familiar with French. I know a little of Spanish, too. I see now why Spanish was so easy to me, and why I am fond of it. I thought it was because mamma liked it. My father was her teacher for a time, wasn't he?"

"He was; and it was during that time that Mrs. Loomis saw you and was so captivated by your charms, as others have been since." Mr. Weed made a little bow.

But Nancy waved the compliment aside. "What do you think of my trying to get a position to teach?" she asked. "It would perhaps save me from loneliness and keep me from brooding."

"For those reasons it might be wise, yet it seems to me that I would not undertake it, at least I would not at present."

"Shall I have enough without? If not, what would you advise me to do?"

Mr. Weed put the tips of his fingers together and gave a few moment's frowning consideration to the question, while he sat back with pursed-up mouth and head a little to one side. "I would advise you to stay here for a few months," he said finally. "In the meantime we can find out exactly the state of your finances, and then you can determine upon your best course. It would be well if you could have some older woman with you. Could Mrs. Bertram remain?"

"I do not know, but I shall scarcely be able to pay her, dearly as I should love to have her with me. She has been so devoted, so helpful in every way, and I have learned to love her very dearly."

"Then I should not be in haste to let her go."

"Can I afford to keep up this place with Parthy and Ira?"

"For the present it appears to me the best plan. I think you should do everything possible to establish your health before taking up the problem of a changed manner of life."

"And the doctor's bills, the druggist?"

"I will attend to them when I settle up the estate. Do not give yourself any uneasiness about those things."

"How good you are," sighed Nancy. "I feel much more hopeful, much easier in my mind. I thought it was wrong to let things go, but it is a relief not to grapple with difficulties just yet. I cannot tell you what a help you are, the one person who knows all, whose advice I can rely upon."

Mr. Weed drew himself up stiffly and moistened his dry lips, frowning the while, moved to the soul by the girl's words, yet fearing to show his emotion. "I trust you will not fail to confide in me and ask my advice whenever you desire," he said even more coldly than usual.

"And if I find I must go to work you will help me find something to do?"

He smiled in a manner which one who did not know him well might consider sarcastic, but the smile brought to Nancy only added assurance of his desire to befriend her. "You must get strong and well before we talk about that," he said.

"I will try my best to get well," returned Nancy, "for I know it is important that I should. Can you keep my secret a while longer, Mr. Weed? I am afraid I do not feel equal yet to the ordeal of meeting curious eyes and of answering curious questions. It would be intolerable to me to face everyone and have them know I have been—been an impostor all these years."

Mr. Weed shook his head and frowned. "That is morbid, entirely morbid," he said. "Don't get such notions into that innocent head of yours."

"But I have felt so, ever since I came back to my reason and could think. Sometimes I have thought I would steal away by myself, without letting anyone know. I may do it yet," she said half under her breath.

Mr. Weed wheeled around suddenly and faced her. "Are you a coward?" he asked sharply. "If I do not mistake you are far from it. When you have back your health you will throw aside such a thought; you will face the world bravely. All such romantic and foolish ideas will drop from you. I am an old man and have seen much of people. I have had opportunities of studying character and I can tell you that you will never be a coward. I know you better than you know yourself."

The tears rose to Nancy's eyes. "I suppose I deserve to be scolded," she said, "but I cannot help shrinking from what is ahead of me."

"You do not know what is ahead of you, none of us know. My advice is for you to rest quietly, leave your affairs in my hands and think only of what is contained in the day before you. I will guard your secret until it becomes necessary to divulge it. The Loomis heirs do not live here; they may never wish to. They may decide to sell the property. Until we are assured of what their intentions are there is no use in making any hard and fast plans."

"I feel so much better, oh, so much," Nancy told him. "I wish I could thank you properly, but please to believe that I am very, very grateful for your interest and your counsel, even for your scolding;" she smiled up at him. "I am not going to be a coward. Whenever I feel like running away I will notify you so you can head me off." She gave him her hand which he took in both of his for a moment, then, as if half ashamed of having been at all demonstrative, he quickly resumed his most business-like manner and bowed himself out as if their talk had been upon anything but intimate matters.

Nancy was watching him from the window when Parthy appeared. "Hyar him creak, Miss Nancy?" she asked, ducking her head and chuckling.

"He is a dear, good man," said Nancy, gravely, "the best friend I have in the world. He may be crusty on the outside, but he is fine and soft within."

"Jes' like a croquette," agreed Parthy, not meaning to be anything but amiably concurrent. "Dey do say he hones'," she went on, "an' dat he nuvver 'low his lef' han' know de performers of his right, dey do say dat."

"I can well believe it. Where is Mrs. Bertram, Parthy?"

"Mis' Bertry? She down in de gyarden. I ain't zackly proceive what she doin'. She demonstrate wif Iry awhile ago' bout de way he doin' dem crystyanthem baids. She say he ain't richen 'em 'nuff, an' dey too full o' buds to come to anythin'. She know a lot 'bout flowers, Miss Bertry do. She sutt'nly is one nice lady, rale lady ef she is a nuss. I knows. I kin spot de quality. She ain't no po' white. No suh, dat she ain't. I tells Iry she got good blood an' he say de same. Yas'm, Miss Nancy, she got good blood. How long she gwine stay, Miss Nancy?"

"Not very long, I am afraid. I can't afford to keep her much longer."

"Law, honey, what yuh talkin' 'bout, 'fordin' fo'? Ain't yuh got as much as yo' ma?"

"No, I haven't, Parthy. Some of all this goes to my father's—to Mr. Loomis's family. Mamma had only a life interest in it."

"What dat? You means dat huh chile ain't gwine to have huh house an' lam's? Humph! tell me dat ole atomy Weed hones'; no, he are not, not ef he cheats yuh outen yo' rights."

"He has nothing whatever to do with it. He doesn't make the law."

"What he lawyer fo' den? He ain't no kin' o' lawyer ef he kaint mek laws. Iry a gyardner an' he mek gyarden. I a cook an' I does cookin'. What kin' o' lawyer dat ole atomy, kaint mek laws?"

Nancy had to laugh. "Well, but Parthy," she argued, "Ira is a coachman but he doesn't make coaches."

Parthy disconcertedly stroked her chin. "Dat so, Miss Nancy, dat so," she acknowledged. "I reckons yuh got de right ob it dis time. Yuh wants see Mis' Bertry?"

"Yes, if she is not busy."

"She come anyway. 'Tain't nothin' she won't leave ef yuh calls." And Parthy went out leaving Nancy to smile over her arguments.

Very frail and pathetic looked Nancy to the nurse who entered the room a little later. Beneath the frill of the little cap the girl wore to cover her shorn head, her dark eyes looked sadly out of proportion to the wan face with its milky white skin. Her little pointed chin was sharper, her nose with its sensitive nostrils more aquiline, her hands more transparent than before her illness. Mrs. Bertram's quick eye perceived that she looked tired. "Don't you think you'd better lie down, dear?" she asked.

"Not yet," returned Nancy. "There are so many things to think about."

"And can't you think lying down?" Mrs. Bertram smiled at her.

"Perhaps I can. Very well, I will lie down if you will sit by me. I shall not have you much longer and I want all I can have of you while I can get it."

"Please don't speak of sending me away. I want to see you well and rosy before I go," said Mrs. Bertram as she settled the cushions of the couch around her.

"I don't want to speak of it. I would like to keep you with me always, dear Mrs. Bertram. I can't tell you what it has meant to have a person like your dear self to help and comfort me, but I do not know yet how long I can afford such a luxury as you are."

"It has meant as much to me as to you," Mrs. Bertram answered earnestly, "and please, please don't speak again of the sordid money side of it. Such a sweet, peaceful haven as this is for a storm-tossed soul is not to be found every day, and I have learned to love my little patient almost too well, for it gives me a pang even to think of leaving her."

Nancy leaned over to lay her hand upon that of her nurse who was now seated in a low chair by her side. "Have you been unhappy, too?" she asked.

"I have been. I still am very unhappy at times. It is only when I lose myself in my work, only when I am caring for those who suffer, does my life seem at all worth living."

Nancy looked with deeper interest at the calm brow, the steady blue eyes, the sweet mouth, the fast-graying hair of the woman before her. "You are very brave," she said, "and very unselfish if you can forget your own troubles in doing for others. I am afraid I can never do that. It must be very, very hard not to dwell upon one's own griefs."

"It was hard at first, but one learns. To centre one's entire thoughts upon one's own sorrows that way madness lies. If we can not busy ourselves in some vital way we become worthless to ourselves and the world."

Nancy sighed. It would be hard to disengage her thoughts from her present sorrows, she considered, yet, for the second time that day she had been made to realize that life was a battle, and that one must not be a coward. One must look for defeats, for weariness of soul and body, for privations and sufferings, but one must not desert the ranks. "Would you mind telling me about the way you learned to be brave?" she said presently. "Would it hurt you to tell me of your sufferings? Were you very young when they came to you?"

"I was young—less than twenty-four—when the storm broke which threatened to destroy me. If it will help you I am ready to tell you, although I seldom speak of it now to anyone. Let me get my knitting first, for it is something of a long story."

She found her knitting and returned with it. Nancy lay back upon the pillows to listen. "If it will sadden you, please don't tell it," she said.

Mrs. Bertram smiled and shook her head. "Sometimes it is good discipline to be saddened," she said. "Many of us try to avoid anything that is not perfectly agreeable to see or to hear; that, too, is selfish. As our good Quaker friends say: it is borne in upon me to tell you. As you already know, I was born in a little town in Sussex, England, near the sea. My father was a clergyman. When I was seventeen he died and my mother and I were left with very small means to battle with the world. I had been carefully educated and a year later there came a chance for me to go to Mexico as governess in an English family. The pay was so good, the opportunity so unusual, that we decided it would be best for me to go. To leave my mother was a great grief to me; to lose me, her only child, was heartbreaking to her, but we made many plans and as the period of separation promised to be but two years we thought we must endure it. Well, I went, and all seemed as fair and promising as we had hoped. I was very young, only eighteen, and with little knowledge of the world."

"Only a year younger than I am," responded Nancy.

"Then you can understand the impression which would be made upon a young and romantic creature when she meets a man who answers to her girlish ideal, a man full of enthusiasm, ardent, imaginative, a musician, a writer, full of schemes which to him, and to so young a girl, appeared such as would work wonders in this sorry world. I was fairly carried off my feet, swept along by the current of his passion. His lovemaking was such as one reads of, but which does not always bring the happiest issues, yet to me a man so eager, so enthusiastic, so full of sentimentality could not fail to seem wonderful. That I, a simple girl, should be wakened by a serenader in picturesque cloak who sang fervid love songs under my window, who would tell me that night after night he watched in the shadows till my light went out; whom I saw waiting below to behold my face when I drew my curtain in the early morning, was nothing less than ideal. Of course all these things made their appeal as they have done a thousand times to a thousand other foolish maids. He questioned me about my home, my family. Did I have another lover? Was he the first? Had I left anyone in England whom I had reason to think might care for me? I had to confess that there was one who had liked me well enough to beg me to remain as his wife, but that I had not thought of him in any such relation, that he was only a poor curate, and that my mother was my first thought. Of this possible admirer he was madly jealous and seemed to think if I did not consent to an immediate marriage that he might lose me. So at last I yielded to the intensity of his persuasions and one night I slipped away secretly and married him, a man I knew scarcely more about than I have told you. The good people whom I left so abruptly were naturally furiously indignant, and I lost a friendship which might have served me well in later days if I had not been so foolishly precipitate."

"But it must have been an ideal love," murmured Nancy.

"It seemed so to me then, and it was for the time being. We were deliriously happy for a year, then my little son came and my husband began to resent my devotion to the child, although he adored him, for none loves and considers his children more than a Spaniard."

"He was a Spaniard? You didn't tell me that," remarked Nancy, who was intensely interested in the story.

"Yes, he was a Spaniard living in Mexico. He came to that country when he was about eighteen, from northern Spain. There was much that was fine about him, but his too impossible ideals led him into difficulties. After the baby's birth he absented himself from home very often to plot with others against the government. Perhaps he was right, perhaps wrong; I do not know. He wrote flaming articles which, in many cases, were published outside of Mexico. He helped to lay underhand schemes for the overthrow of the authorities then in power. These things did not bring him much in the way of money, but he had pupils, English or Americans, who wished to learn the pure Castilian rather than the cruder speech frequently spoken in Mexico. So we managed to get along. He would come home moody, depressed, or in a rage against those whom he called his enemies, yet always he was devoted to me and the child, only that smouldering fire of jealousy, that lack of faith, that unworthy suspicion was ready to burst into flame at a moment's provocation. I could never mention a return to England without bringing forth a tirade. I was tired of him. He could bring me no happiness. I wanted a lover of my own people, he would declare. He was a doting, mistaken imbecile to think I could continue to be true to him. Then he would regret his wild words, say that he would turn his attention to making more money, would give up his intriguing friends, and we would send for my mother and we would all be happy together. There came another baby, a little girl. Such darling children they were." Mrs. Bertram paused. Her eyes had a faraway look, and her knitting lay untouched upon her lap. Nancy, absorbed and excited, did not dare to interrupt by asking where these children were at the present time, although she longed to know.

Presently Mrs. Bertram took up her needles again. "My little girl was two years old," she went on, "when a message came that my mother was dangerously ill, and probably could not live long. She begged me to come to her. Could I do so? The message was sent by the young curate who was devoted to her. My husband was away. I made every effort to reach him but without avail. I had but little money, yet I felt I must go at all hazards. My precious, patient mother! Nothing at that moment seemed so important as the granting of her wish. I calculated that I could make the trip, spend a little time with her and return within six weeks or two months at the furthest. I hesitated about leaving the children, but they had a faithful, devoted nurse, and I knew that my husband would be inconsolable if I took them with me, so, hard as it was, I made up my mind to leave them. I borrowed the money, received the promise of my nearest neighbors to look in once in a while upon the children and then I started off, praying that I might reach my mother in time."

"And did you?" asked Nancy eagerly.

"Yes, and my coming was such a joy to her that sometimes I have let that thought compensate for all the trouble that came after. When I saw her I realized how cruel I had been to sacrifice her to my own desires. How could I have left her? How could I have married so precipitately? Why did I not wait? Well, dear, when one is young one does many foolish things, yet who can expect level judgment from young, inexperienced persons? If they do nothing to bring lifelong regrets I suppose it is the best that can be expected of them. Pray Heaven you may never do such."

"Oh, but I have, I have done just that," murmured Nancy. "But never mind, please go on, Mrs. Bertram, I never heard such an exciting story. Did you go back, and—and?"

"I went back as soon as I could, though not as soon as I expected, for after my dear mother's death there were necessary things to be attended to, but I wrote very, very often to my husband, and never received a word in reply. During the first weeks I had one or two post-cards from a neighbor to say the children were well, but after that nothing. I knew that my husband's insane jealousy had probably led him to believe that I had made my mother's illness an excuse to leave him. The message I received I had enclosed in a note which I left for him, in my anxiety forgetting that the name signed was Ernest Kirkby, the curate's."

"Oh, dear, oh, dear, but it was unfortunate under the circumstances," exclaimed Nancy.

"Terribly so, for I believe it was that which did the mischief. Well, at last I returned to the little city where we had lived, only to find my husband and children gone, none could tell me where. Poor, unhappy boy, he was not so much to blame. His plottings with revolutionists brought suspicion upon him. He was a marked man, and one night his friends hustled him on board a ship about to sail for Cuba, in order to prevent his arrest, perhaps his assassination, for it was that way, rather than another, that they were doing things in Mexico at that time. A number of his fellow-plotters did meet death by stealthy means; others fled the country, so there were few to give me any news of my husband. At last I learned where he had gone, was told he had taken the children and the nurse with him, and had left the town where we had lived, this shortly after my departure, about the time the post cards from our neighbor ceased to come. This kind neighbor, supposing I was in communication with my husband, and having nothing more to report about the children, had not troubled to write again. After learning that he sailed for Cuba I went there, and in time found that he had gone to the United States. It is a large place, my dear, and I never found him nor my children. The last news I received was from a relative of his in Spain to whom I wrote as a last resort. I had a short reply which said that he was dead and that no information could be given about the children."

"Oh, me, what a grief!" cried Nancy. "Dear Mrs. Bertram, you are right, your sorrow is heavier than mine. How could you have borne it?"

"I had hope left. I have never given up hope. At first I felt that I could never forgive my husband for robbing me of my children, for his unjust and cruel suspicions, for his lack of faith in me. But, as time went on, I realized that I must have something to fill my heart and mind, and at the advice of my good physician I studied nursing. I was still young, and I knew I might have many years to live. There seemed but one way to atone for the sorrow I had brought to my mother, and that was to relieve the sufferings of others; but one way to forget my own griefs and that was to help others bear theirs."

"That is very noble, very wonderful," said Nancy thoughtfully, "I am afraid I could never rise to such heights as you have done."

Mrs. Bertram ignored this remark and said, "So now you see how I came by my profession. I have visited most of the large cities in this country, always hoping to discover some clue which would lead me to my children. I adopted the Anglicized version of my husband's name at the outset, because I feared he might discover me in my searchings, and in his resentment might spirit away the children before I could see him and explain."

"And what is the Spanish version of your name?" inquired Nancy.

"Beltrán. My husband's name was José Beltrán. In English Joseph Bertram."

"Beltrán! Beltrán!" Nancy sat up with a sharp cry, clasped her hands over her heart and gazed at the nurse with startled eyes. "There could not be two, could there? No, there could not. Wait!" She sprang from the couch with more energy than prudence and ran to a drawer, produced a key, then opened the old escritoire bringing back the letters which had so overcome her upon first reading them. These, scattered upon the floor Ira had carefully gathered together after Nancy had left them there, and had as carefully locked them up in the desk, putting the key where he knew it belonged.

The girl was so agitated when she returned to Mrs. Bertram that she could scarcely speak. She thrust the packet into the nurse's hands. "Read them! Read them!" she cried, then sank back against the pillows, to watch every expression of Mrs. Bertram's face.

First there was curiosity, then wonder, then agitation. The usually self-controlled woman leaned forward trembling. "Tell me, tell me," she said, in a tense voice, "where did you get these?"

"They were written to my adopted mother, Mrs. Virginia Loomis," answered Nancy, scarce above her breath.

"Your adopted mother!" cried Mrs. Bertram. "You are not actually the child of Mrs. Loomis? Oh, you must be; the doctor would have known. Oh, you must be."

"I am not," declared Nancy, sitting up and clasping her hands together. "I am not. Mr. Weed knows. Oh, I have been so unhappy. I have felt so alone since I found it out, but now—but now!"

Mrs. Bertram leaned back and pressed her hands against her eyes. "It is a dream," she murmured. "Oh, yes, it is a dream. I have dreams such as this." Then she steadied herself, grasping the arms of her chair and saying with assumed composure. "If you are an adopted daughter, if you are not Nancy Loomis, what is your true name?"

"It is Anita Beltrán," replied Nancy, tremulously. "I am your daughter. José Beltrán was my father. Mother! Mother! Love me, oh, please love me."

With a little moaning sound Mrs. Bertram gathered the girl into her arms and kissed her eyelids, her cheeks, her hands, murmuring, "My baby, my little Nita, my baby girl. Oh, dear God I thank Thee! I thank Thee. My darling, oh, my darling! Let me hold you close. No, it is not a dream. My darling! My darling!"

Nestled in her mother's arms the girl sat, a feeling of great content stealing over her. "No more alone, no more alone," she whispered. "Now, I want to get well," she said at last, as she lifted her head.

Her mother held her off a little way. "Let me look at you, my precious," she said. "Why did I not see it before? You have your father's eyes, great, melting, brown eyes; you have my English skin, but for the rest you are a mixture, but why did I not know instinctively?"

"With this funny shaved head, and this cap how could you see any resemblance?" asked Nancy. "Have I a brother, too, do you think? I am sure I have. He is somewhere. I must hurry and get well, then we will go away together and look for him. What is his name?"

"He is little Joseph, Pepé, as they call it in Spain."

"Nancy is the diminutive of Anna, just as Anita is in Spanish. Hereafter I am Anita Beltrán, and we will go away together and find my brother Pepé."

The remaining period of Nancy's convalescence meant days of happy intercourse, hours of confidences, nights of peace for both mother and daughter. Mr. Weed was sent for and agreed with them that for the present it might be as well not to announce the news of the discovery. He showed as much interest and sympathy as it was in him to display, which was much less than that which would have been manifested by any other person, yet Nancy was convinced of his real pleasure in the matter.

"While you remain here, and until everything is settled it would be best that you retain your name of Nancy Loomis," he advised. "Mrs. Bertram, for the same obvious reasons, will not desire to resume the name of her husband."

"I certainly do not want to be considered a seven days' wonder, and to feel that everyone is staring at us and whispering about us every time we appear in public; that would be intolerable," declared Nancy. "No, dear Mr. Weed, we will just jog along as we have been doing, and will go quietly away together when I am strong enough. No one will think it peculiar that Mrs. Bertram should be going with me. We shall begin immediately to search for my brother, and we shall find him, if he is to be found."

"I trust you will not fail in your search, and I wish you all possible success," returned Mr. Weed, which was a good deal for him to say, Nancy thought. "You may be interested to know," he went on, "that Mr. Adrian Loomis and his sisters do not care to reside in this place, and have decided to offer this property for sale. They will come down to look it over in course of time. They have requested me to secure proper caretakers for such time as it may lie idle. If you have no other plans for Parthenia and Ira I have thought they might very properly be offered the place."

"Indeed, I think they would be the very ones," replied Nancy, "and I am sure it will be a great comfort to the poor old souls to be left in charge. It will be hard for me to part from them," she sighed. "Indeed, it will be hard for me to part from a great many things, from a great many persons, yourself in particular, Mr. Weed." The chief reason why Nancy had endeared herself to this very diffident man was that she seemed intuitively to be able to penetrate beneath his reserve, and to accept him as quite as responsive a person as any other. He was known to be a man of ability, honest and astute, consequently was held in high esteem, but there were none who treated him with Nancy's informality, who gave him such easy confidence, such unabashed trust, consequently she occupied a place in his barred and locked heart that no other possessed.

He bowed stiffly at Nancy's implied compliment, but was more wooden than ever as he continued. "If you desire me to continue to take charge of your affairs I can assure you of my conscientious attention to them."

"Oh, dear me, yes, do please look after them always, Mr. Weed. I shouldn't be happy if anyone else took charge of them, no matter where I might be. Will it make any difference, Mr. Weed, if I happen to be away off somewhere?"

"Not in the least. There are the mails, you know, and in emergencies there is the telegraphic means of communication."

"That will be comforting to remember. If I lose my pocket-book or find I can't pay my board bill, I shall wire you straight off, and you will come to my rescue, won't you?"

"I will endeavor to do so," replied Mr. Weed very stiffly.

Nancy laughed, "You always take me so terribly in earnest," she said, "but joking aside, Mr. Weed, I think we shall be able to get along. My mother has a small income and with that added to mine, we believe it will serve if we are economical. If we do not find my brother in this country we shall go abroad."

"I suspected that would be your intention. Probably it would not be amiss, in any event. Then I am to understand, Miss Nancy, that I am not to disclose the fact of your change of name until it appears a necessity?"

"Oh, please don't say anything yet. Let the story leak out by degrees after a while, after we have been gone for some time and people are forgetting about me; that will mean less talk and comment, don't you think?"

"I agree with you, and will endeavor to follow out your wishes in this, as in every other respect." So he took up his hat, but at the door gave his little habitual cough and said, "I regret that necessity urges you to leave us, Miss Nancy, but I trust you will not forget your old friends, your old home, and that some day you will return to us."

"I shall never forget, never," answered Nancy, emphatically, "and I shall be writing to you, of course."

"I am gratified that occasion will require it," responded Mr. Weed, and went out.

Nancy returned to the house. She felt very hopeful, almost buoyant. Something of her own mother's brave spirit was reflected in her. She had grown immeasurably in character since trouble had befallen her, and in the hours of self-communion, which a sick-bed must always induce, she had come face to face with the invisible powers which encourage a view of spiritual realities. Her mother's story enabled her better to understand values, though with this understanding came a truer realization of what she had given up in dismissing Terrence Wirt.

To the faltering tale of her romance her mother listened with grave interest. "No wonder, my darling, that all these shocks were too much for your poor little brain," she said. "How true it is that when troubles arrive they are so liable not to come singly but in battalions. It may be that it is to test our strength, our faith, our courage to the uttermost. Even a knowledge of enduring love comes to us many times in the midst of adversity."

"How well you understand. It is so comforting that you do understand, madre, and it is because you, too, had such great sorrows coming one after another. Yet how much braver you were than I. You did not succumb to them, but went right on."

"Ah, no. You must not think that. I did not go right on. At first I seemed paralyzed. I sank down, down into a gulf of despair, and only the necessity of action, the glimmer of that spark of hope led me forward."

"It will still lead you forward to find Pepé." She sat leaning against her mother's shoulder in silence for a moment, then she said wistfully, "Dear madre, do you think there is a faint glimmer, the faintest sort of glimmer of hope that I shall ever meet Terrence again? Of course I realize," she added quickly, "that everything is changed. We are poor. I am no longer the daughter of Mrs. James Loomis, no longer the heiress to this estate, but only the child of José Beltrán, whom no one ever heard of. In this locality family counts for everything, even for more than money. With my own precious mother I can face anything; I do not care for any of the things I have been taught to believe are the most worth while, yet I believe I shall always care for Terrence."

"He would be a very snobbish person if he were to avoid you for any reason except the one which sent him from you. If he truly loves you it is yourself only which counts."

"I wonder if he did truly love me," returned Nancy meditatively. "Could he have given me up if he had done so? No, I cannot believe yet that he really cared."

Mrs. Bertram looked at her wistfully. Her impulse was to remind the girl that it was she who had done the giving up, and it was a temptation to reassure her, yet why attempt it when there appeared little hope that the affair would ever be resumed! From what Nancy had told her she believed young Wirt to be worthy of the girl's love, but, until she had a personal knowledge, she felt that she must guard against bringing any more unhappiness into her daughter's life. The child has suffered enough as it is, she told herself.

The days slipped by until one afternoon came a tearful parting from the old home, from Parthy and Ira, both of whom openly lamented, yet looked forward to Miss Nancy's return in the spring. "Gwine souf fo' de wintah," was the word passed by the old retainers. "Tek de nuss. She dat sot on Miss Nancy kaint hire huh to leave, no way you fix it," Parthy told a neighbor. "When she comin' back? Laws, honey, she don' know no mo'n de daid. She boun' ter git her healf 'stored, Mis' Bertry say. Yas'm, me an' Iry stay right hyar." So even the most curious gossips had no idea of the true state of things when Nancy's farewells were made.

More than one well-known face was seen in the group gathered at the station. Good Mrs. Lippett, Patterson, his sister Betty, the Carters, the Browns, Dr. Plummer and, last of all, Mr. Weed. To him Nancy stretched forth her hand from the car window as the train began to move. He ran like a marionette to give her a final hand-clasp. "Good-bye, my best friend, good-bye," said Nancy brokenly. Then as the train moved faster it seemed as if it were the group which slipped away. With misty eyes she watched the little crowd disperse, her last impression being that of a sobbing old mammy, and the wooden features of the lawyer strangely distorted into something like emotion.

"I believe he was ready to cry," said Nancy half hysterically as she drew in her head. Then she turned her face toward the window while the tears rolled down her own cheeks. She was leaving forever the only home she had ever known.

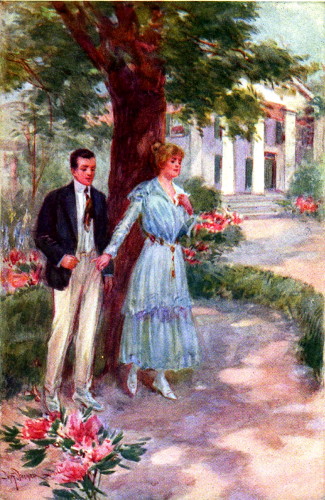

It was one morning of the following spring that from the deck of a vessel lying off the little white city of Cadiz, the mother and daughter looked earnestly toward land. The girl's short curly hair was blown about her face by the wind from the sea, and she pushed it back from her eager eyes that she might better take in the view of the wide granite quay, the great sea walls and projecting bastions; then her eyes traveled further to where the tall houses rose, silver-white, against an intensely blue sky. "Spain!" murmured the girl, clasping her hands closely. "Spain! The home of my father's people. I know I shall love it."

"SPAIN," MURMURED THE GIRL