Lewanika

Late Paramount Chief of the Barotse Nation

Frontispiece. Photo by Mrs. Marshall

Title: Barotseland: eight years among the Barotse

Author: D. W. Stirke

Author: Sir Harry Johnston, G.C.M.G., K.C.B

Release Date: August 4, 2023 [eBook #71338]

Language: English

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BAROTSELAND:

EIGHT YEARS AMONG THE BAROTSE PEOPLE

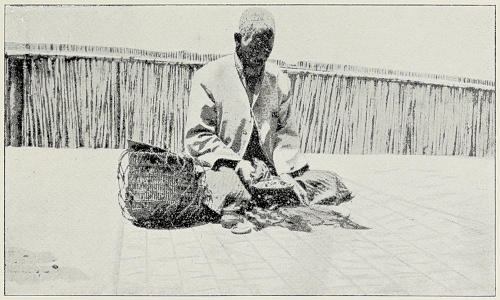

Lewanika

Late Paramount Chief of the Barotse Nation

Frontispiece. Photo by Mrs. Marshall

BAROTSELAND:

Eight Years among the Barotse

BY

D. W. STIRKE

Native Commissioner Northern Rhodesia

WITH AN INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER BY

SIR HARRY JOHNSTON, G.C.M.G., K.C.B.

At one time H.M. Commissioner &c., for Northern Zambezia

LONDON:

JOHN BALE, SONS & DANIELSSON, LTD.

OXFORD HOUSE

83-91, GREAT TITCHFIELD STREET, OXFORD STREET, W.1

In presenting this book to the public I would like to register my appreciation of the kindness of various friends who have materially assisted me in its production. My brother-officials Messrs. Helm and Palmer and my friend the Rev. V. Ellenberger, of the Paris Huguenot Mission, have greatly assisted me with advice and information, while my sincere gratitude is due to Mr. Coxhead (Secretary for Native Affairs), Mrs. Marshall, Mr. Walton (Assistant Native Commissioner), and Mr. Thomas (Vice-Principal of the Barotse National School) for photographs.

The greatest care has been taken in checking and rechecking any and all portions of the book and several items have been deleted as lacking confirmation, which was unavoidable in handling such a mixed race as the present day Barotse.

I would also wish it to be fully understood that this work has been compiled by me, aided by my friends as mentioned before, but with no official assistance from the Administration, and[vi] this work must in no way be considered “Official” or “Approved by the British South African Co.” The information to be found in the book is however fairly accurate, in spite of not being written under the ægis of the Administration.

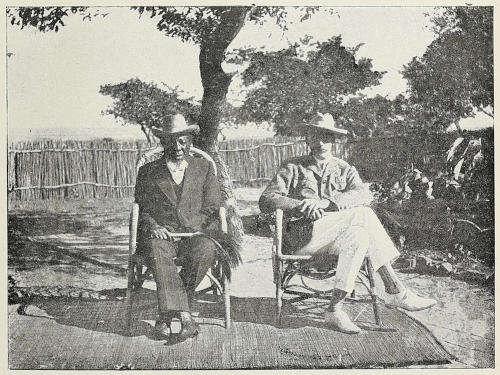

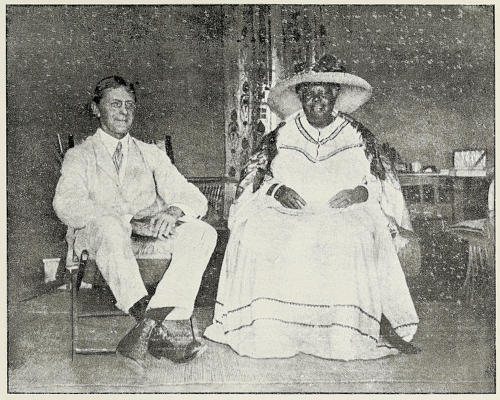

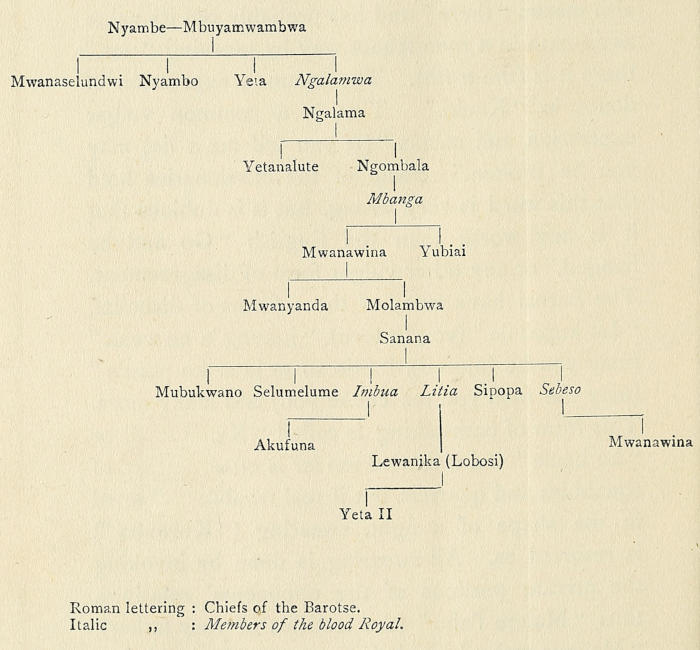

Since finishing the book the death of the Paramount Chief Lewanika has occurred, and he has been succeeded in his position by his eldest son, Yeta, who has taken the title of Yeta II.

Lewanika was a man of about 70 years of age, and had a hold on his people that no Murotse chief will ever have again. He will, for generations, be remembered as the chief who did most for the improvement and consolidation of his people. Lewanika travelled to England for the late King Edward’s coronation, and it was always a great delight to him to talk about the friends he made and the sights he saw while going to, staying in, and returning from England.

Early in his reign he was deposed by a relative of his named Tatila; but Tatila had not the grip over his people nor the statesmanship to hold the chieftainship, with the result that Lewanika was reinstated after a couple of battles. To the surprise of all he showed great clemency and pardoned most of the rebels. A notable example of his clemency is the induna Noyōō, who was very prominent in killing off Lewanika’s women and children during Tatila’s brief rule. Lewanika told me himself that his reason for sparing Noyōō[vii] was because he and Noyōō had herded cattle together when very small boys.

Lewanika led many successful raids against the neighbouring tribe of the Mashukulumbwe, and he was the first Barotse Chief who accepted their homage and counted them as a portion of his people.

He had a great belief in acquiring knowledge of other native races and chiefs, and sent embassies to Chitimukulu the Awemba Chief and to Khama the Bamangwato Chief (the Bamangwato being better known nowadays under the general term Bechuana).

Lewanika was a man of most charming and courteous manners and had always a very sincere regard for Europeans, while his loyalty to the Empire has repeatedly proved itself, more especially since the beginning of the German War. A visit by a European, accompanied by his wife, was always considered a great compliment by the late chief.

Missionaries always received support from Lewanika, and were given grants of land for their stations and many other privileges. The Chief himself never professed Christianity, but set an example to his people by attending church services and by supporting the Missions generally.

D. E. C. S.

| PAGE | |

| Preface by the Author | v |

| Introductory Chapter by Sir Harry Johnston | 1 |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Barozi and their Origin | 37 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| The Administration of Barotseland | 42 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Native Administration | 46 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Barozi Industries | 55 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Customs (Mikwa) | 61 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Riddles and Conundrums | 80 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Barozi Songs and Dances | 85 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Barozi Legends | 93 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Barozi Laws | 108 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| General | 115 |

| To face p. | |

| Lewanika, late Paramount Chief of the Barotse Nation | Frontispiece |

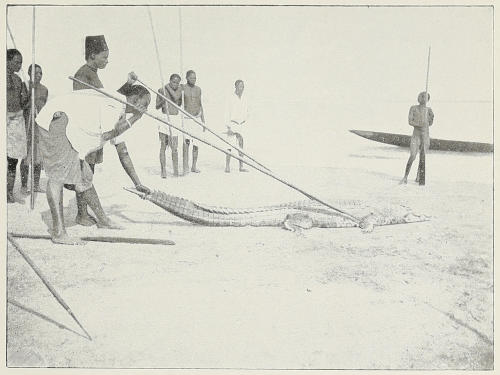

| The Skull of Homo rhodesiensis from the Specimen at the British Museum | 1 |

| The Giant Sable Antelope of Eastern Angola | 28 |

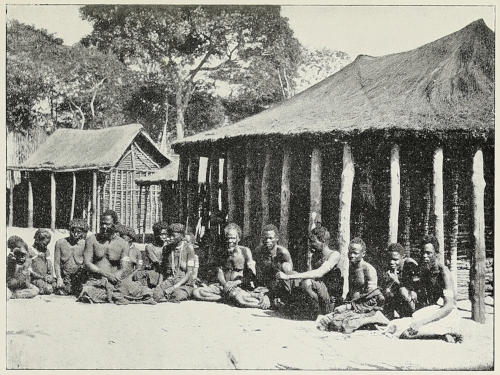

| The Mokwai Mataŭka of Nalolo with her husband (standing) and interpreter (sitting) | 37 |

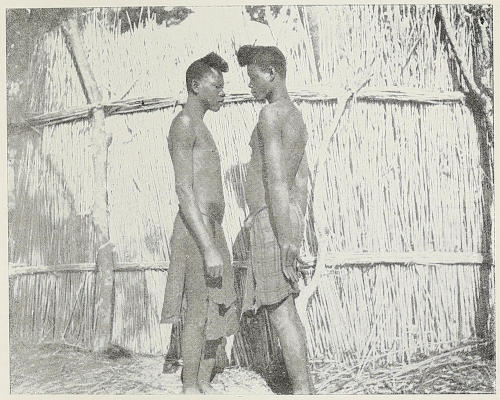

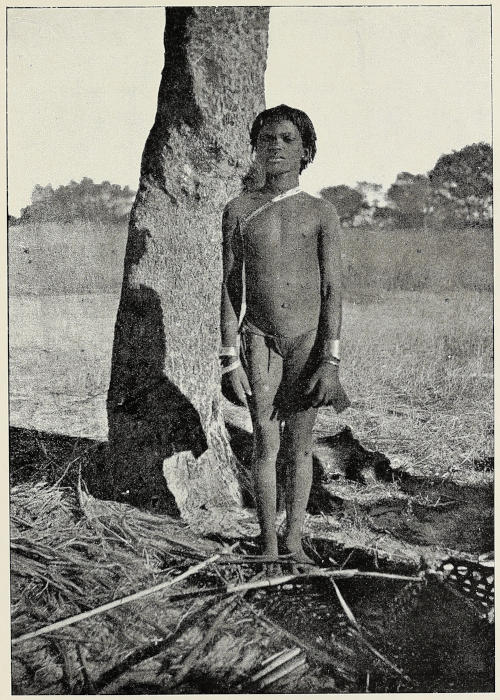

| One of Lewanika’s Aunts with Attendant | 40 |

| Lewanika’s Band (Mirupa and Silimba) | 40 |

| A Lujazi Village | 44 |

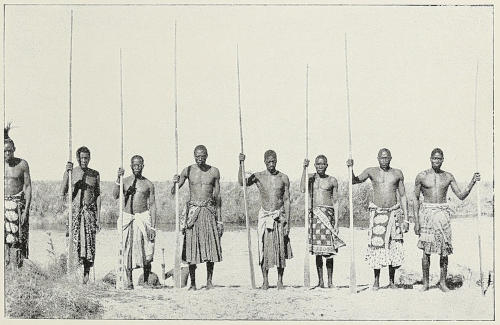

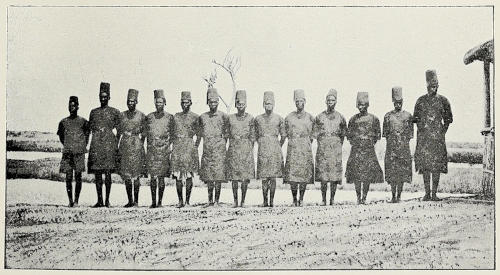

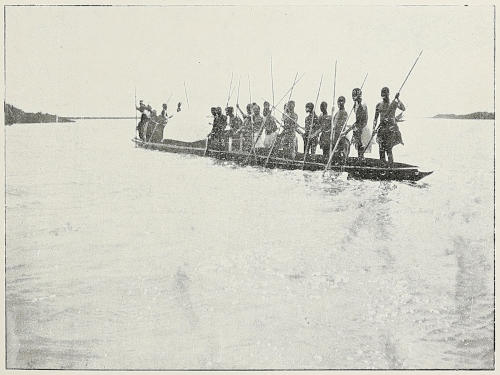

| Lewanika’s Head Paddlers | 44 |

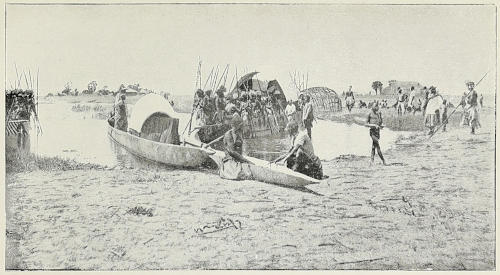

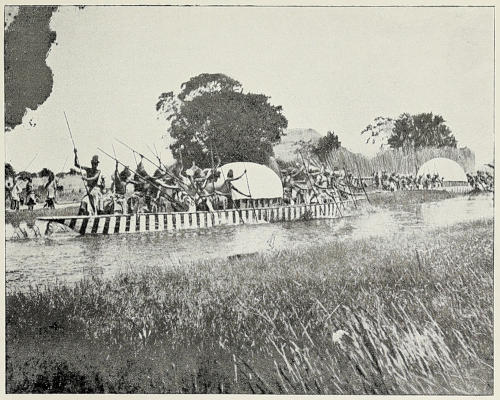

| Arrival of the Nalikwanda | 52 |

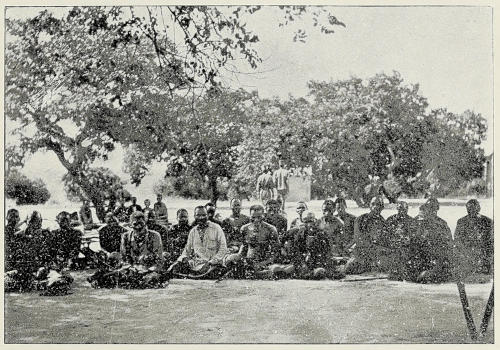

| The Secretary for Native Affairs and the late Paramount Chief | 52 |

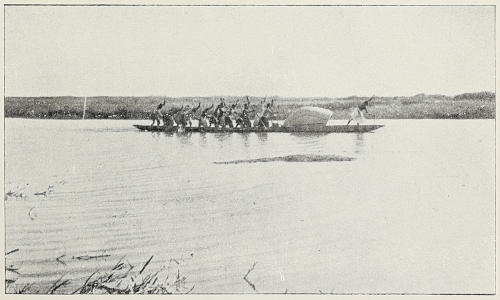

| The Nalikwanda | 56 |

| Government Messengers and a Post-runner at Nalolo | 56 |

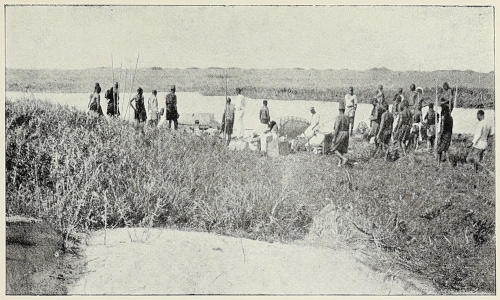

| Crossing Cattle over the Zambezi | 58 |

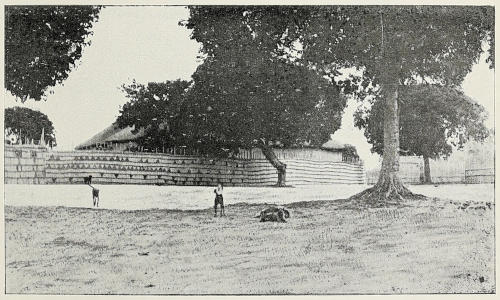

| The Mokwai’s House and Fence at Nalolo | 58 |

| Capture of a young Crocodile | 62 |

| Arrival of Lewanika’s Subsidy at Lialui: carried by British South Africa Company’s Messengers | 62 |

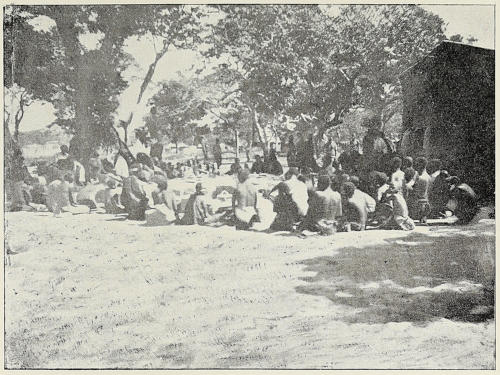

| Tax-payers | 66 |

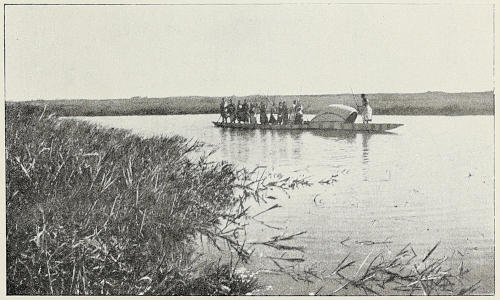

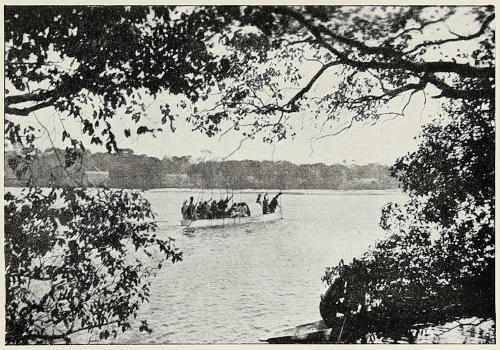

| Royalty travelling by Boat | 66 |

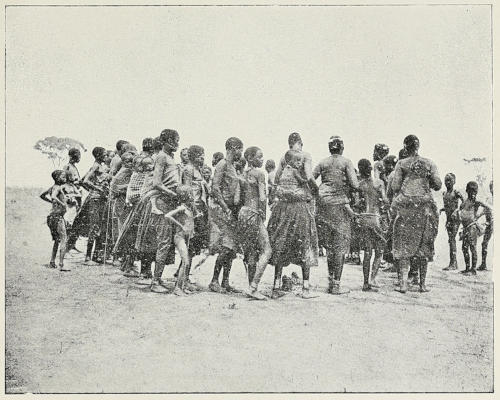

| Mankoya Women dancing | 70 |

| “Well in swing” | 70 |

| Mambalangwe “Nuts” | 74 |

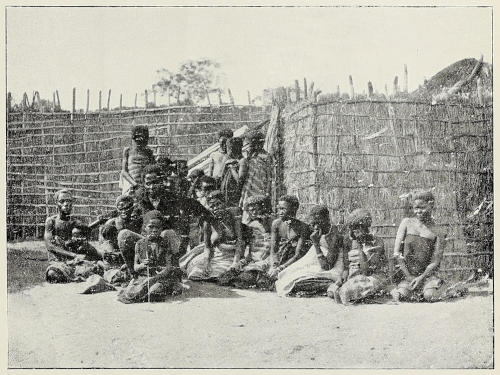

| Mat-makers, with Mats for Sale | 78 |

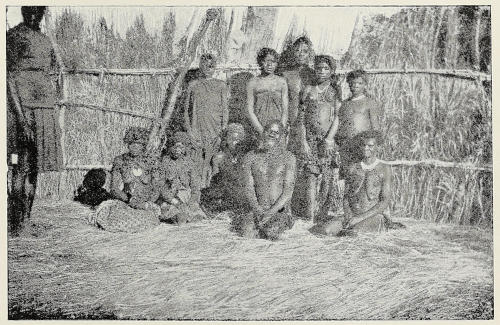

| A Mambalangwe Family | 78 |

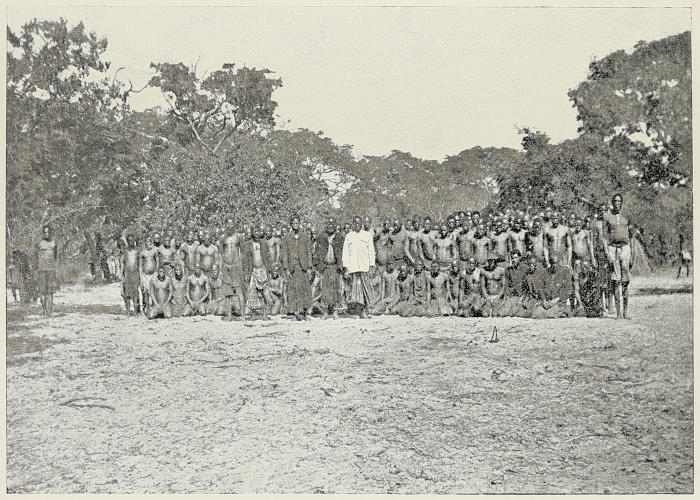

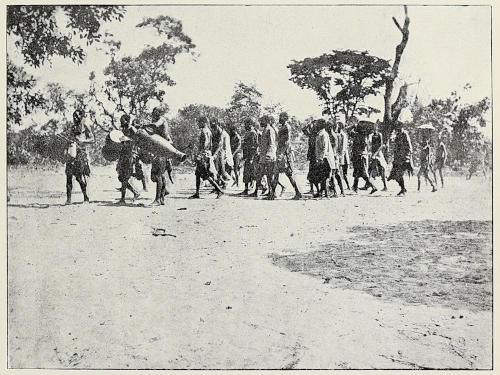

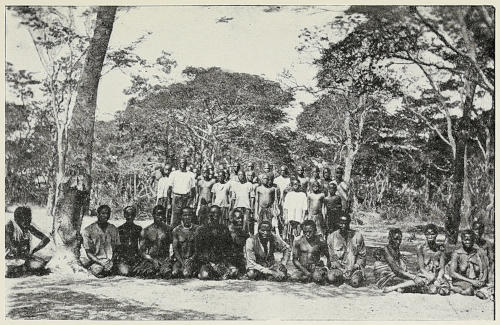

| Gang of Natives proceeding to the Mines in Southern Rhodesia | 82 |

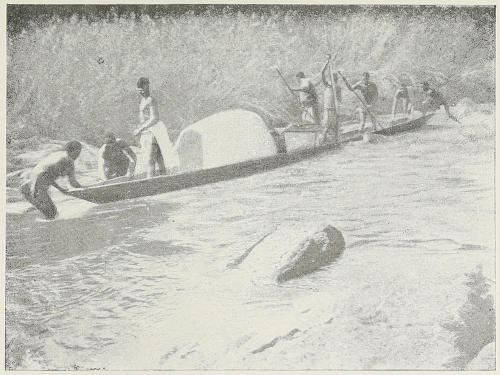

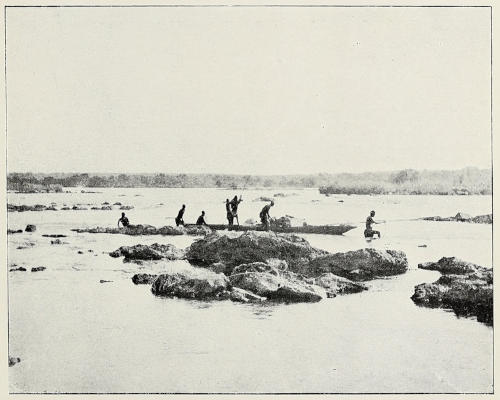

| Shooting Rapids | 86 |

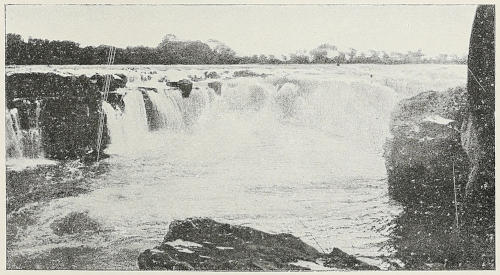

| Ngonya Falls at Sioma, Barotseland | 86 |

| Food for Sale | 88[xii] |

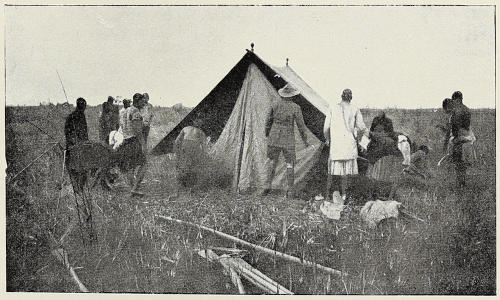

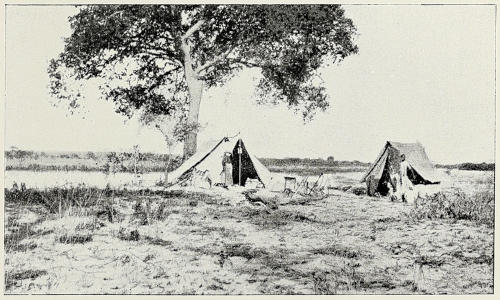

| The End of the Day’s Journey | 88 |

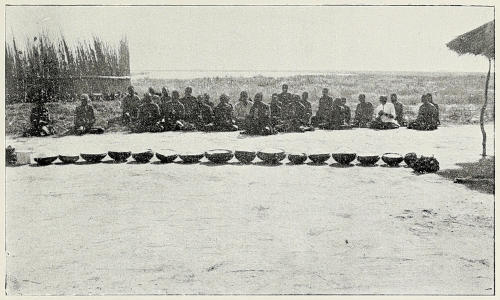

| “Liyumbo,” or Food-tribute | 92 |

| Travelling in Barotseland | 92 |

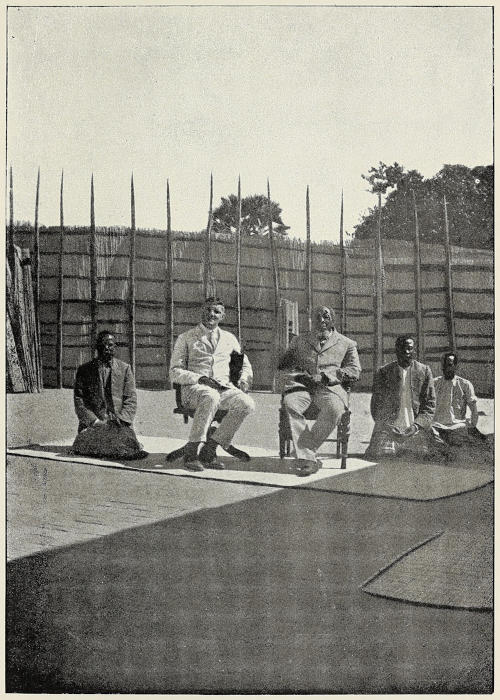

| The Author and the Mokwai of Nalolo | 100 |

| A Mrozi Boat and Crew | 100 |

| The Author and Lewanika | 104 |

| A Mumbunda Witch Doctor telling Fortunes | 106 |

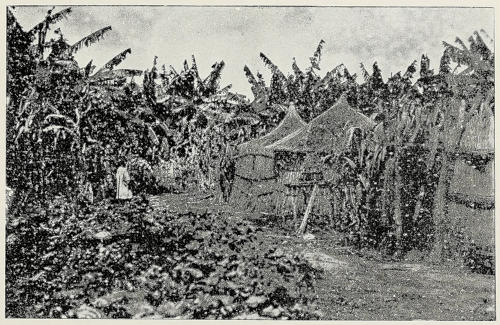

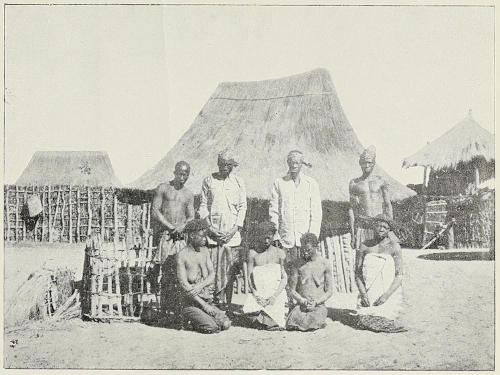

| A Barotse Village | 106 |

| Start of a River Trip | 110 |

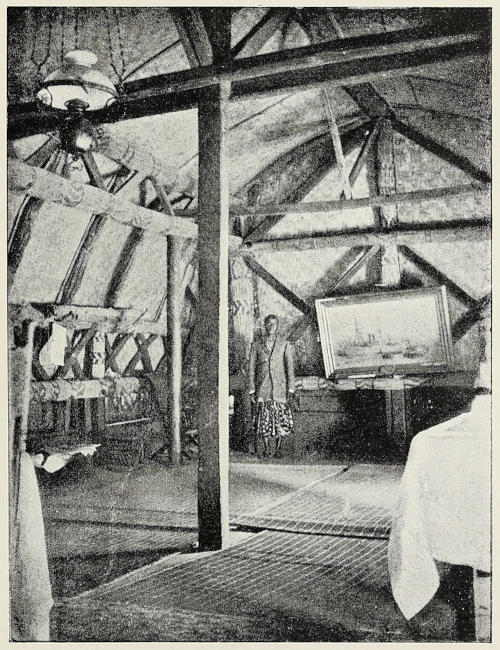

| Interior of Lewanika’s Dining-room | 110 |

| A Mambalangwe Belle | 114 |

| A Mankoya Chief and Retinue | 118 |

| A Traveller on the Zambezi | 122 |

| The Mankoya Chief, Mweni-Mutondo, and Band | 122 |

| Village School Boys, with Parents in foreground | 128 |

| Hauling Boats through Rapids | 128 |

| Portion of a Lubale Village | 134 |

| The Lunda Chief, Sinde, and Harem | 134 |

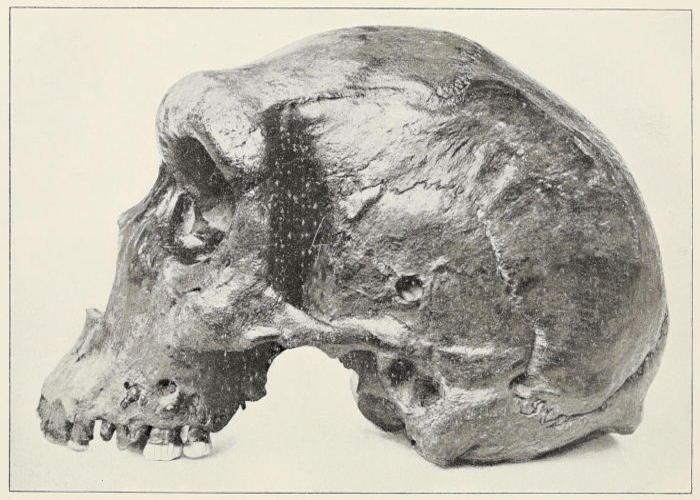

The Skull of an ancient North Rhodesian Type of Man (Homo rhodesiensis).

(From a photograph kindly lent by Dr. Smith Woodward, British Museum).

Face p. 1

By Sir HARRY JOHNSTON, G.C.M.G., K.C.B.

Sometime H.M. Commissioner, &c., for Northern Zambezia.

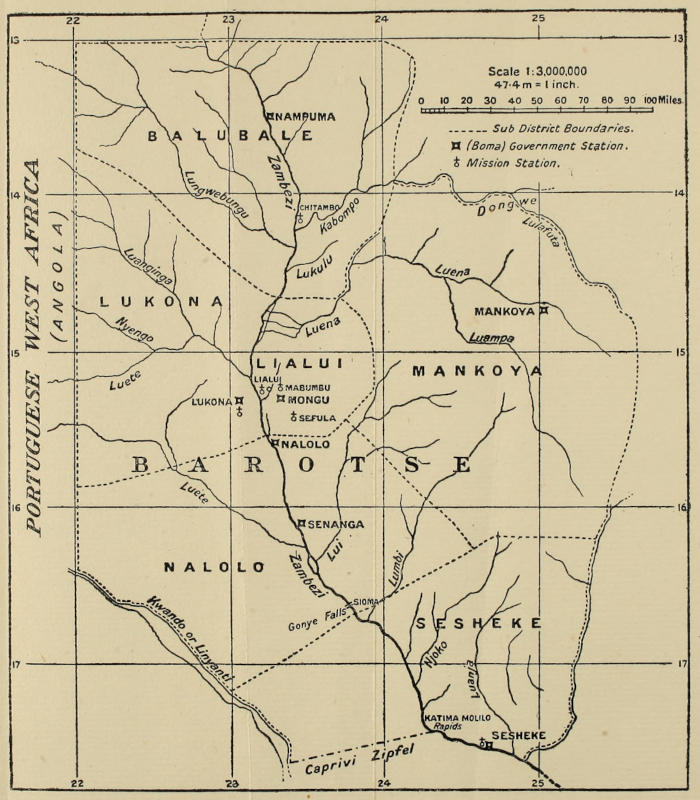

Barotseland at the present day is mainly defined as the kingdom of the recently dead Lewanika which lies both to the east and west of the Upper Zambezi, north of Sesheke, the Katima Rapids, the “Caprivi” boundary line of former German South West Africa. The western boundary line of Barotseland is the east bank of the Kwando river up stream to its intersection with the 22nd degree of E. longitude; the northern boundary is the 13th degree of S. latitude; and the eastern limit is a line drawn from the 13th degree of S. latitude to the upper waters of the Kabompo-Lulafuta, and then southward to the Majili river and along the Majili down to its union with the Upper Zambezi near Sesheke.

The master people, still, in this Upper Zambezi state are the A-luyi, who seem to have entered the lands of the Upper Zambezi from the direction of Eastern Angola, if vague tradition be anything to rely on. At any rate the A-luyi became the dominant tribe in this region some three hundred years ago, if not much earlier. Prior to their[2] dominancy the Upper Zambezi regions had been invaded by terrible armies of cannibals, the “Bazimba” of Portuguese East African records and the “Giagas,” “Jaggas” of Portuguese Congo and Angola history. The term “Jagga” seems to have been derived from the title Jaga, which they gave to their chiefs; amongst themselves this tribe or congeries of tribes which played such an amazing part in the history of Central Africa in the latter half of the 16th century was known either as the “Imbángala” of the middle course of the Kwango river or the Va-chibokwe, Va-kioko, Va-chokwe, Bajoko (according to Livingstone), or Ba-jok of South-west Congoland and the Kasai sources. This boiling over of the Va-chokwe—as they are nowadays termed in their original home—caused terrific, population-destroying raids to be made across Northern Angola into Luango and the Congo coast region, and southwards over Barotseland, Central Zambezia, Southern Nyasaland and Moçambique, and northwards up the East Coast to the surroundings of Mombasa. The Va-chokwe were known by several names in the Portuguese records, the Jagga, Ba-zimba, and Bambo (sing. “Mumbo.”) “Ba-zimba” seems to have died out as a tribal name, but the Bambo still inhabit the region through which the Lower Shire flows, and the original Va-chokwe, Va-kioko, Va-chibokwe, or Ba-jok are prominent inhabitants in the basin of the extreme upper Kasai, and come into Barotseland[3] or Angola on trading expeditions. They are a singularly independent, quarrelsome, warlike people, not unlikely to give trouble yet to the Belgian controllers of Congoland, to the British peace-keepers in North-West Zambezia, or to the Portuguese in Eastern Angola.

But though Upper Zambezia was traditionally overrun by the Va-chokwe three hundred and fifty years ago, the A-luyi seem soon afterwards to have absorbed the invasive quota of peoples and to have settled down as the rulers of Upper Zambezia till their land was first invaded from the south about one hundred and twenty years ago.

This invasion took place from the direction of Lake Ngami and the invaders seem to have been a section of the Ba-hurutse division of the Bechuana people. They reached the Upper Zambezi—traditionally—at the end of the 18th century, whether as friends or foes, tradition does not say; probably in small numbers and with no racial feud against the A-luyi. Their descendants may be the “Njenji” or “Zinzi” tribe who still speak a dialect of Sechuana and are settled rather high up the Zambezi. They seem however to have long retained the tribal name—Ba-hurutse—which became shortened into Ba-rotse.

These Ba-hurutse colonists of the Upper Zambezi valley apparently preserved some slender connection with the remainder of the great area of Bechuanaland, and had allowed news to reach the[4] Fatherland of their tribe regarding the well-watered region in which they had made a new home. At any rate Sebituane, the son of an erratic woman chief in Basutoland, who in the second decade of the 19th century led her people forth on a mad excursion, gradually found his way to the north-west, and finally at the close of the eighteen-twenties had crossed the Zambezi and brought his followers—now called the Makololo—to the conquest of its upper valley.

By about 1840, he had conquered the A-luyi, whom he and his people called the “Ba-rotse” (Ba-hurutse), by the name of the earlier Bechuana colonists. Livingstone found him a fine-looking, copper-coloured man. “He was far and away the finest Kafir I ever saw,” wrote W. C. Oswell at the time—1851; and many years afterwards (in 1890) he repeated the same thing to me. “Sebituane is a gentleman in life and manner” exclaimed his surprised guests in 1851, when they appreciated to the full his gracious and thoughtful hospitality.

One feels on reading the remembrances of Livingstone and Oswell how intense must have been their regret when a few days after their arrival this great chief fell ill with inflammation of the lungs and passed away. Sebituane’s last days of life were taken up with recounting in a subdued voice (he was suffering from an old wound in the lungs) his wonderful adventures since he had first reached the Zambezi and found his way into[5] Barotseland as a ruler. To the east of his moving horde of Bechuana or Makololo, were the fierce Tebele Zulus under Umsilikazi or Mosilikatse,[1] who likewise strove to conquer for themselves a state in North Zambezia. The pressure of the Amandebele drove Sebituane to the more swampy regions of “Barotseland.”

After Sebituane’s death Livingstone and Oswell left his country, promising to return. His son Sekeletu—inferior to his splendid father in height, physique, and appearance—was placed on the throne and ruled Barotseland for some twelve years. Livingstone had returned to the Upper Zambezi in 1853, determined then to discover the whole secret of its course and of its main tributaries, and to follow up the trail of the Ba-joko traders and the “Mambari” or half-caste Portuguese, who were beginning to renew their trading enterprize with the Upper Zambezi, and ascertain if through Sekeletu’s kingdom they could find their way “á contra costa”—to Portuguese Zambezia and Moçambique.

Livingstone traversed Barotseland (or Uluyi, as it was still more anciently called). Makololo porters and soldiers—some of whom were really A-luyi subjects of Sekeletu—accompanied him to São Paulo de Loanda, and turned back with him from Portuguese civilization to deliver him safely again at Sekeletu’s capital, whence, after many adventures on the Tonga highlands and along the cataract-strewn[6] Zambezi, he reached that river’s delta and the settled towns of the Portuguese.

He returned in 1858 and, accompanied by Charles Livingstone and John Kirk, he once more entered Barotseland and sat with Sekeletu and his subordinate chiefs. But Livingstone had become by then more deeply interested in the problems, geographical and political, of Lake Nyasa and the Shiré river, the ravages of the Yao and Arab slave-traders, the courses of rivers west and north of the Nyasa watershed. Barotseland simmered on; scarcely visited by any European—unless it was some stray hunter who had found his way to the Zambezi. At last, in the year 1878, the pioneers of the great French Protestant Mission—notably Monsieur François Coillard—came into the Lake Ngami basin from Bechuanaland, and thence travelled to Upper Zambezi.

They found this former kingdom of Sebituane and Sekeletu ruled intermittently and disturbedly by a young chief of the old Aluyi dynasty—Lewanika. Sekeletu had died in 1864, and a period of struggle then arose in which the Aluyi and allied peoples, with possibly the remnant of the old settlement of the “Barotse” (Ba-hurutse), overcame the fighting caste of the Makololo, killed the males and married the females; and at the end of the struggle—about 1870—-the former dynasty of Aluyi chiefs was re-established.

The French Protestant missionaries (some of[7] whom were Swiss) did much to keep Lewanika and his people in touch with British South Africa, after they were well-established in his country. He was made aware, at the close of the ’eighties, of German ambitions, of Portuguese desires to “protect” his territory—the journeys of Serpa Pinto and Capello and Ivens (1878-1883) had kept him advised of this; and at the same time of the formation of a great Chartered Company which had come to terms with the Matebele Zulus and was extending British political influence over the regions north of the Zambezi.

The “Barotse” people had heard something about the Arabs far back in the 19th century, for Livingstone found an intelligent, enquiring, civil-spoken Arab staying at or near the Barotse capital on the Zambezi in 1855.

Lewanika came to hear of the war with the Arabs in Nyasaland and on Tanganyika into which Germans and English were led, and his sympathies lay with the Europeans. Though Sekeletu had been a slave-trader on rather a considerable scale, Lewanika held such a policy in abhorrence. In 1891 he came to a preliminary understanding with the Chartered Company which has been strengthened by later agreements. In 1902, Lewanika, who had been born and brought up in the heart of Central Africa, travelled via Cape Town to England and was present at the coronation of King Edward VII. He looked a fine and imposing[8] figure in Westminster Abbey, where I—recently returned from Uganda—was presented to him, after the ceremony was over. He had, indeed, as the author of this book says in his introduction, “most charming and courteous manners.” Further, it should be added that in regard to the kingdom of the Barotse, the British South Africa Chartered Company has taken no false step, has incurred no unfavourable criticism, and has received praise for its control of native customs and defence of native rights from the French Protestant and the Church of England missionaries at work in this country and its neighbour states.

The Barotse country, as defined on the sketch map accompanying this book, includes a number of interesting and distinct Bantu languages. It is even possible that a traveller who pushed his explorations to the south-western limits of the kingdom and of the British sphere might find in the valley of the Kwando river a few nomad Bushmen of more normal stature than the stunted Bushmen of Cape Colony, but speaking a tongue of Bushman and not Bantu affinities. The Bushmen were more anciently inhabitants of this land than the Bantu Negroes; but not far away, to the east of Barotseland, we have had a sensational discovery within the last twelve months of a different and peculiar species of man which once inhabited South Central Africa, prior to the penetration thither of[9] the Negro sub-species. This was Homo rhodesiensis, the skull, jaw, and limb-bones of which were found in close association with rudely-chipped quartz knives and scrapers, and with the broken bones of antelopes still living in Rhodesia. The place of discovery was some sixty feet below the surface in a cave at the Broken Hill Mine almost in the middle of Northern Rhodesia. The bones found are attributable to at least two personages, the limb-bones and the skull having belonged to a tall man perhaps not less than six feet in height. He possessed tremendously-developed brow ridges, a feature in which Negro man is as a rule more deficient than the European. These, and the large flat face and comparatively small front teeth and other features, suggest an affinity with Neanderthal man (Homo primigenius) of Europe. Other points show some resemblance to the black Australian. But the brain-case measured in space only about 1,280 cubic centimetres—a capacity much inferior to the ordinary brain-cases of the Neanderthaloids and Australoids, though, of course, there are occasional examples of Australoid women’s skulls that have a brain capacity of under 1,000 cubic centimetres.

These bony remains of Rhodesian man may have been living creatures as much as forty thousand or as little as ten thousand years ago: there is not enough surrounding evidence to fix the date of them more precisely. All we can say is that the bones of the beasts they hunted and ate are nearly if not[10] quite identical with those of existing species. Probably at the time when this big-browed, gorilla-faced man was alive, the Upper Zambezi, which flows through Barotseland three or four hundred miles westward of Broken Hill Mine, formed a great longitudinal lake in the heart of the Barotse[2] country, the greater part of which still remains very swampy. And when it issued from this expansion it joined the Kwando, the Okavango, and the Zuga to form a vast lake in what is now the North Kalahari Desert. The Guay river was then the Upper Zambezi and the Kafue river joined it as now.

The Kalahari Desert which well nigh ruins the north-western part of South Africa is probably “younger” as a desert even than the Sahara—and the Sahara Desert is a thing of yesterday, possibly much more recent than the existing human species. In the days when Rhodesian man with the huge brow-ridges, long, ape-like face and poorly developed brain ranged across all of Northern Rhodesia that was not under water, he might have passed between the vast Zambezi Lake on the west and the sources of the Guay on the east, and have wandered down into a green, tree-besprinkled South Africa, where he was no doubt killed out by the smaller but far[11] more cunning Bushman or the intelligent Strandloopers who painted pictures on the rock surfaces like their relatives of Europe, the Crô-Magnon men. Long after these antecedent types of invaders had died away came in the vigorous Negroes...? Two thousand years ago? ... who spoke Bantu languages. Whether, between the Strandloopers, Bushmen and Hottentots who invaded the southern portion of South Africa thousands—who yet can say how many?—of years ago and the Bantu Negroes of yesterday (so to speak), other races entered and dwelt in southern and South-Central Africa, we do not know. I have given reasons elsewhere for premising that the flocking south from Equatoria of the Zulus, Bechuana, Karaña, Nyanja, Tonga, Luyi, Hérero, Angola, Luba, Lunda, Yao and Makua tribes and their allies and embranchments was quite a recent episode in the history of Africa, perhaps not more than two thousand years old. We have at present absolutely no knowledge of the incoming of any other type of inhabitant later than the Hottentot and before the Bantu; though there may have been many Negro immigrants belonging to neither group linguistically.

Barotseland, as its recent past becomes revealed to us from the second half of the sixteenth century, seems to have had as a dominant people the Aluyi; and as other tribes of importance the Tonga group (Ila-Tonga-Subia) in the south and south-east, the[12] Luena or Lubale, Mbunda, and Lujazi tribes of northern Barotseland and the adjoining parts of Angola, the Nkoya-Mbwela peoples of eastern Barotseland; and a section of the southern Luba folk. Sporadically there has also occurred a strong invasion of the Lunda people (Ma-bunda) into the northernmost basin of the Zambezi, but it is doubtful whether these immigrants penetrate into the political limits of Barotseland. Similarly a section of another vigorous South Congo people has colonized the Northern Zambezi basin; the Luba, who are known in North-Eastern Barotseland as the Kahonde or Kaondi. Then again the enterprising, uppish, cheeky Va-chokwe or “Ba-joko” traders—once the slave-traders of South Congoland and Eastern Angola—circulate through Northern Barotseland and add yet another type of Bantu language to its markets and meetings.

The dominant language at Court and in trade to-day is an almost artificially-manufactured tongue which had come into existence during the last fifty years—Si-kololo. This will be found illustrated in its most modern form in the first volume of my Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages (Oxford, 1919). My information has been mainly derived from the Sikololo Grammar and Vocabulary published in London by Dr. Stanley Colyer in 1917, and from a Sikololo Phrase-book produced two years’ earlier by Mr. Stirke, the author of this book, in conjunction with a very[13] noteworthy colleague, Mr. A. W. Thomas, formerly master of the Barotse National School.

Sikololo which has gradually displaced and superceded the Sechuana or Sesuto language of the original Bechwana invaders of a hundred years ago, is a far easier language to speak and pronounce than the difficult and highly peculiar idiom of Central South Africa. To philologists, Sechuana and its later southern specialization, Sesuto, are intensely interesting. Sechuana entered South Africa at as ancient a date as any other Bantu tongue—say sixteen or seventeen hundred years ago, coming thither from South-East Africa. But since then it has become highly specialized. The most specialized form of it was the southernmost, Sesuto, scarcely distinguishable a hundred or more years ago from the Sepedi of the Western Transvaal.

The chief Sebituane, born some hundred and twenty years ago, was a Mosuto, the son of a great crazy woman-chief known as Mantatisi. He carried his Sesuto tongue with him on the amazing journey he made with half his tribe across Bechuanaland to Lake Ngami and the Zambezi. Sechuana or Sesuto was the Court language in Barotseland when Livingstone first reached the Upper Zambezi in 1851. As the years rolled by, and after the Makololo (Basuto) dynasty had given place to a restoration of the Aluyi chieftainship, the original Sesuto spoken by Sebituane and well understood by Livingstone[14] (who could converse in it freely) became greatly changed. It has remained the governing language of Barotseland and has succeeded almost in replacing and killing the remarkable Siluyi of the old rulers; and neither of the beautiful languages of the Tonga-Subia group of Southern and South-Eastern Barotseland has been allowed to take its place.

In Sikololo the pronunciation is much simplified. The rough guttural combination kx—of Sechuana-Sesuto gives way to the simple k; a hiatus formed by a dropped consonant is filled by h; ts is generally changed to z; e in the prefixes becomes i; f which had become h in Sesuto is generally replaced; the uncouth tl, tlh or the aspirated th and kh return to the simple t and k; and in general the pronunciation of Sikololo is brought into conformity with the harmonious phonology of the Zambezi languages.

A far more interesting tongue is Siluyi, the nearly extinct language of the Aluyi; in its older form, that is to say, as it was spoken round about Lialui (the original governing centre, near the left bank of the Zambezi, in about 15° 15´). Here it was a stately language, using preprefixes, and possessing all the seventeen customary prefixes of the Bantu languages. The second (Ba-) and eighth (Bi-) of these were in an abbreviated form, because the Luyi tongue had rather a dislike to an initial b, though it turned the sixteenth[15] prefix—Pa- into Ba-, following a practice which recurs a good deal in the Angola tongues.

The principal form in which I have presented this language in the First Volume of my Comparative Study is derived from the studies of Luyi (Siluyi) compiled some twenty to twenty-five years ago by the Rev. E. Jacottet, of the French Protestant Mission. It was soon evident, when the British South Africa Co. officials got to work, that there was at least one separate dialect of Luyi spoken to the East and North-East of the main Zambezi. This was the Si-kwango or Si-kwangwa, a tongue in which the preprefixes are dropped. Si-kwangwa seems still to be a living speech among the people in the East-Central part of Barotseland; but the much nobler Luyi of the Zambezi vicinity is dying out, even among the natives of Luyi stock, dying out in favour of mongrel Sikololo.

Allied to Siluyi apparently, is the Nyengo language of the Bampukushu people, a scattered tribe living still (perhaps) in the South-Western portion of Barotseland, on the banks of the Kwando or Linyanti river. There has been no record of this speech since that which was compiled by Livingston about 1853, and which I have reproduced (numbered 82) in my Comparative Study of the Bantu Languages.

Still farther south, in the northern part of the basin of Lake Ngami, there were, down to quite recently, the Ba-yeye or Makoba people, whose[16] language also seemed to show kinship with Luyi as well as with the Subia-Tonga group. The imperfect record of this is numbered 81 in my book. It may be extinct as a spoken tongue by now. But its existence where it last lingered on the northern side of Lake Ngami would seem to show that this basin of the shrinking lake (which received a vast but diminishing tribute of water from the Okavango river, and earlier still from the present “Upper Zambezi”) was colonized by the Bantu from the north before it was found and peopled by the Bechuana tribes from the south-east.

So much does Sikwangwa differ from Siluyi nowadays, that it is almost a separate language. If this be so, the Western Zambezi group of my formation would contain at least four languages, Yeye, Nyengo, Luyi and Sikwangwa. I am also informed that Sikwangwa is not the only existing dialect of Luyi, but that two others exist, and are spoken to the North-West and North-East of Lialui and the Zambezi: Si-koma and Si-kwandi. These have only been recorded in name, and I have seen no specimens of their vocabularies. It would be interesting to ascertain whether, like Luyi, they retain the use of preprefixes; or whether they have dropped them, as have most of the languages in the western half of the Zambezi basin.

There is a tendency in Siluyi for b and p to take the place of v or f as the initial of the root, although in the prefixes b and p are inclined to drop out: so[17] that Aba- becomes Aa-; Ibi-, I; Ubu-, Uu-; and Apa-, Aba-. Thus we have -pumo for “belly,” instead of the familiar -fumo; -bumu for “chief,” in place of -fumu; -pumbu for “ground” (ordinarily -vu) -buu for “hippopotamus” (-vubu), -bula for “rain” (-vula); and -pi for “war” (-vita). The roots for the numerals “six,” “seven,” “eight” and “nine” were in Livingstone’s day, very peculiar and unlike those of any other Bantu tongue; though to-day they are supplemented by paraphrases meaning “five-and-one,” “five-and-two,” etc.

The Rev. Mr. Jacottet has shown how rich Siluyi was in folk-lore and legends. It is a great pity this particularly interesting, expressive Bantu tongue should be allowed to die out through the vogue given to the artificial amalgam of speech known as Sikololo.

Subia, spoken in Southern Barotseland, on and near the Zambezi at its bend eastward, is also a language of great interest, said likewise to be dying out under the rivalry of mongrel Sikololo. It was first noticed by Livingstone about 1851, and a grammatical sketch of it was given by Jacottet in 1896. But in the present century, F. V. Worthington and C. F. Molyneux, officials of the Chartered Company, supplied me with a full vocabulary and grammatical information which has been reproduced in my Comparative Study, Vols. I and II. Subia is spoken to the south of the Zambezi as far eastward as Pandamatenka; but it belongs to the West[18] Central Zambezia Group, mainly in use on the north side of the great river, and including the Tonga, Ila and Lenje tongues and their dialects. This group is related to the Luba languages of Southern Congoland and to the tongues of the Bangweulu basin and of the Luangwa valley. They are all beautiful-sounding and expressive languages, representing Bantu speech in an attractive form.

The Tonga language is spoken in South-East Barotseland in one or more dialects. The Tonga people are a series of vigorous tribes not very likely to give up their expressive language in favour of the bastard Sikololo or the crabbed Sechuana. They attained some degree of civilization two centuries ago under the teaching of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries. Their attitude towards Livingstone and later travellers, down to the incoming of the British South Africa Company, was hostile. James Chapman, the great explorer of Southern Zambezia and even of Barotseland—in some senses the rival of Livingstone—suffered much from attacks at their hands. So did F. C. Selous. They also warred incessantly against the Zulu invasions under Umsilikazi and Lobengula, and checked the Zuluizing of central Northern Zambezia, which, in default of similar vigorous opposition, took place in the regions east of the Luangwa river.

Similarly related to Tonga and Subia are the Ila (Shukulumbwe) and Lenje tongues, though both lie almost or wholly outside the limits of[19] Barotseland, in the central part of Northern Rhodesia. The Ba-ila tribes, two divisions of which are also known as the Ba-lumbu and Ba-shala, are a splendid-looking folk in physical development, who were long recalcitrant to European influence. In fact their healthy plateau country has only been opened up to knowledge during the last twenty years. When they were first seen in the latter part of the nineteenth century they were found to be—the men especially—living in a state of complete nudity, except in the case of the married women. But to make up for the complete neglect of clothing the men devoted particular attention to their head-hair. This was pulled up, greased, lengthened by the insertion of ancestral hair pullings, and fastened to a supple arched, recurved whip, so that it rose a foot to two feet above the occiput. Nowadays I imagine that their complete nudity is modified. The mining surveys, motor roads, and suggestions of railways, together with good and wise government, in and out of the Barotse kingdom, have succeeded in taming the Ba-ila and in drawing them into paid employment; though it is still feared by watchful administrators that they tend to diminish owing to sexual vice which causes the women to become infertile.

Another language of interest and importance is that of the Nkoya and Mbwela tribes living in East Barotseland. It has affinities jointly to the Luyi[20] Group and to that of the North-West Zambezia languages. Preprefixes are not used, but the seventeen prefixes-with-concords seem to be fully represented in primitive forms, except that the seventh prefix (Ki-) is represented by Shi-, which brings it near to the Si- of Luyi. The tenth prefix is lisped as Thi-, Thin-, &c., a feature reappearing in one or two other tongues of the Group. The eighth prefix is Bi- and the locative prefix is Pa-. The root for ‘two,’ in the numerals is the East and South Africa form, -bidi or -biji (for -bili); not the -bali root that obtains in the other members of the North-West Zambezian Group. Another peculiarity that signalizes Nkoya is the root -mwa- for ‘all,’ only to be met with elsewhere in two of the Manyema languages of East Congoland. In Nkoya there is none of that dislike to the consonant p, which recurs over and over again in Bantu Africa. But in the other members of the North-West Zambezia Group this obtains, and in these—Luena, Mbunda, Lujazi and Chokwe—the 16th prefix is given as Ha- or A- instead of Pa-. Otherwise they are fairly orthodox, betraying little more “West African” affinities than the use of the -bali root for ‘two’ (instead of -bili), which is a characteristic of West Central Africa.

The Luena or Lubale language only enters the north-western part of Barotseland; Mbunda is spoken in separate parts on either side of the Upper Zambezi, also in the north of this state;[21] Lujazi extends from South-East Angola to the western limits of Barotse territory; and Chokwe comes in as a trading language in the extreme north. None of these North-West Zambezia languages use preprefixes.

One other great Bantu Group may be met with in the northern part of Barotseland. Here there are outlying dialects of Luba and Lunda which have penetrated into Barotseland comparatively recently. The Luba tongues of South Congoland are represented by Kahonde, a form of South Luba illustrated in my Comparative Study under the designation of 105a. This is spoken on the North-Eastern verge of Barotseland in the basin of the Upper Kabompo river. Southern Lunda, introduced into the northern part of this territory goes under the name of “Ma-bunda,” the root of which—bunda—is the same as that of “Mbunda,” a quite distinct language of the North-West Zambezia Group allied to Luena, Lujazi, Nkoya, and Chokwe. “Bunda” is evidently a language and tribal name which in the shapes of -bundu, -bundo, and -bunda haunts Angola and Western Zambezia without implying close relationship between the different forms of speech thus termed. The “Ma-bunda” dialect of Lunda may represent an older form of the latter name, which seems to be a contraction of Lu-unda for Lu-bunda. The language (No. 111) which I have styled “Western Lunda” in my Comparative Study was originally[22] called by its discoverer, the Revd. S. Koelle, “Ru-unda,” suggesting that Ru- (= Lu-) was the familiar language prefix and -unda or -bunda the root. The loss of an initial b is a frequent occurrence in the Lunda languages.

The distribution of tongues southward from Angola and the Congo Basin over the regions north of the main Zambezi river indicates no causes of hesitancy, no interruptions in the north-to-south progress of the Bantu peoples. But westward of the course of the Luangwa river, as far as the Barotse country extends, or at any rate as far as the main stream of the Zambezi flows, this great river seems to have been a very decided and arresting barrier in the distribution not only of African tribes and languages but of the larger or more remarkable mammals and birds.

With regard to man of course the barrier has not been so effective. Evidently the Aluyi people of long ago crossed the Upper Zambezi and penetrate to the Lower Kwando or Chobe, and across this stream to the vicinity of Lake Ngami, though not much farther west; and in return, immigrants of Bechuana stock entered Barotseland from Lake Ngami in the last century. But there seems to have been a not easily explained halt in human migrations between Western Zambezia and South-West and South Africa. It would be comparatively easy to account for, if one could presume that the[23] present sterile influence of the Kalahari desert prevailed two thousand or even one thousand years ago, and earlier still. But on the contrary from the many indications we can collect and from the legends of the natives in the regions south of the Zambezi, we are inclined to believe that the present arid nature of the lands on the western side of South Africa is quite a modern feature which has gone on rapidly increasing. So rapidly that even I who made a journey in 1882 to the Kunene river from Mossamedes can remember flowing streams (in the dry season) and forests, where the rivers and rivulets are now dry and the woodland is dead.

There seem, in addition, to have taken place in comparatively recent times, changes in the disposition of water supplies, which have diverted much useful moisture from inner South Africa into the Atlantic Ocean. Not such a very long time ago the Kunene river, which brings an abundant supply of fresh water from the great knot of highlands in Southern Angola, bore this water into Lake Etosha in Ovampoland, and beyond that towards the course of the Okavango or the great vanished lake of which Ngami is the surviving vestige: Ngami, which even in Livingstone’s day—the end of the ’forties, some seventy-two years ago—was twice its present size. Into the same basin flowed the mighty Okavango (known much farther north as the Kubango), the Kwando and the upper Zambezi, then the outlet of another vast lake in the[24] Barotse country. Quite possibly these two shallow lakes of huge size sent their overflow of water through the Guay river into the bed of the Zambezi-Kafue, and so out into the Indian Ocean after all; for these waters of Central Africa were completely hemmed in southwards by the plateaux of Damaraland, Bechuanaland and Matebeleland. But in those days the ultimate source of the Zambezi would have lain in the Benguela highlands near the Atlantic Ocean, and not in the Luvale country near to the upper Kasai.

As regards the mammalian fauna and some of the more striking or peculiar of African birds, Barotseland, east of the Upper Zambezi, appears, in common with all the rest of South Central Africa up to the east coast of Lake Nyasa and down to the main course of the Zambezi, to be deficient as compared with Portuguese West Africa, South Africa, and (in a lesser degree) Moçambique. It probably has more in common as a distributional area with the southern part of the Congo basin outside the forest area, and west of the Luapula-Lualaba streams. Down to recent times Barotseland possessed great herds, enormous numbers of a few species of game animals, but not such a great variety of species. Like South Congoland outside the forest zone, it seems never to have had any example of the rhinoceros: indeed, I have no confirmatory evidence of the existence of a[25] rhinoceros or a giraffe, west of the eastern rise of the Nyasa-Tanganyika plateau, or of the waters of Lake Nyasa. The rhinoceros begins to show itself south of Lake Nyasa and east of the Shire river. It recurs in Southern Angola and Damaraland, up to the vicinity of the Western Zambezi, and as far north as the beginning of the lofty plateaux where the Kwanza river rises.

The Kwanza, which divides Angola into two unequal portions, is very noteworthy as a boundary. Its ultimate sources are in the Ngangela, Bihé and Lujazi highlands (plateaus and mountains) which connect the mountain ranges of Benguela on the west with the 5,000-feet-high plateau dividing the Southern Congo basin from that of the Zambezi. This undulating line of heights (rising on several peaks to nearly 8,000 feet) really marks off Southern from Northern Angola; and zoologically Southern Angola extends eastwards almost to the banks of the Upper Zambezi and covers the western limits of Barotseland.

Here you have a remarkable extension of the South African area of zoological distribution. East of this, from the Upper Zambezi to the Shire river and the east coast of Lake Nyasa (with the Zambezi as a southern boundary) there is an interruption in distributional area which affects certain mammals and birds very curiously. For some the interruption is complete. The Ostrich, the true Gazelles, the Oryxes, the Secretary bird,[26] certain types of Vulture, the Striped Hyena, the Chita or Hunting Leopard, the Caracal Lynx, the Aard Wolf (Proteles), the Big-eared Fox (Otocyon), the small Desert Foxes, the Black-backed Jackal, the Pedetes or Cape Jumping Hare, the Elephant-shrews, the Mountain Zebras, the White Rhinoceros and, in a lesser degree, the Black, are in a measure confined to north-east and eastern Equatorial Africa on the one hand, and to Africa south of the Zambezi and to Southern Angola on the other. Some of the examples cited stretch across to the Bahr-al-ghazal and even Northern Nigeria from Abyssinia and the Eastern Sudan; others reach Senegal and Western Nigeria beyond the forest zone. But all of the examples cited (besides many more less well-known birds and mammals) seem to be absent from North Angola, Northern Zambezia and Nyasaland, and apparently also from Moçambique. In Moçambique, numerous forms may have been exterminated by the white man and the black hunters, who began shooting here in the 17th century. Yet it is difficult to understand that they could thus have eliminated the Ostrich, Springbok, Striped Hyena (represented in South Africa and Angola by the Brown Hyena), Chita, Caracal, Aard Wolf, and Pedetes rodent, or even the Giraffe.

The Giraffe’s distribution conforms somewhat, but not so closely, to similar restrictions. Its least specialized form, perhaps, is the Reticulated Giraffe[27] of Somaliland, whereon the original markings are seen to be white stripes, horizontal and perpendicular, on a red ground. From Somaliland the Giraffe radiates over the eastern Sudan to Northern Nigeria and thence (with gaps) to Senegal. It entirely avoids forested Central and West Africa, though it has a near relation, the Okapi, in the forests of Equatorial Africa east and north of the main Congo river. The distribution of the Giraffe continues south from Uganda and Somaliland to the east of Tanganyika and Nyasa down to the neighbourhood of the Ruvuma river. It has never been reported south of that stream, or until the Lower Zambezi has been crossed. A hundred years ago and down to about 1900 it was found in various sub-species and varieties south and west of the Zambezi to Cape Colony and into Southern Angola. But it has never been shown to exist between the Upper Zambezi and the Moçambique coast, north of that river system.

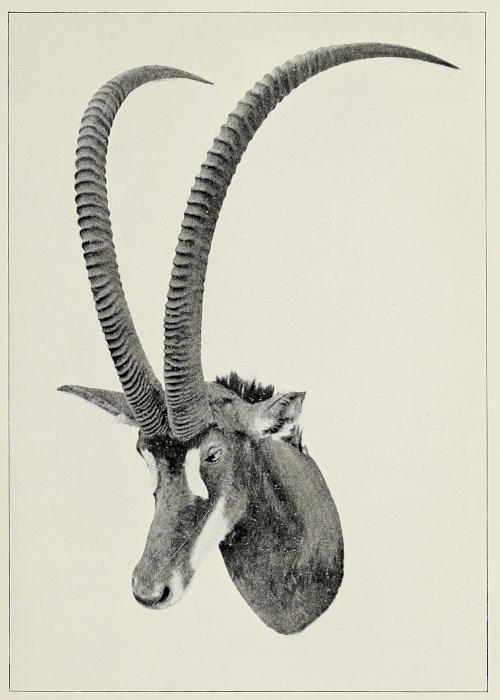

On the other hand the range of the Sable Antelope does not leave out Northern Zambezia and Barotseland. It begins in Eastern Africa, in the latitude and neighbourhood of Mombasa (a fact first suggested in my book on Kilimanjaro, published in 1885), broadens over what was formerly “German East Africa,” passes round the south end of Tanganyika into Southern Congoland and crosses Barotseland into Eastern Angola. Here, in the south-eastern basin of the Kwanza,[28] and possibly in north-western Barotseland as well, it develops its most superb form—Hippotragus variani, generally called the Giant Sable—with magnificently developed horns, longer than those of any other type found elsewhere, and a longer, narrower skull. It is possible (from heads I once saw, shot to the west of the main Upper Zambezi and specimens of horns) that the Giant Sable may be found just within the limits of Barotseland.[3]

North of the belt of dense forest between the Liba and Kabompo, on the spongy plains near to the river, Livingstone noticed in the rainy season large numbers of Buffaloes, Elands, Kudus, Roan Antelopes, Gnus, and other game. He even avers that farther north he saw a White Rhinoceros. It was on a Sunday and his encampment was almost surrounded by herds of astonished Mpala antelopes, tsesebes (“bastard hartebeests”), zebras and buffaloes. But although the Black Rhinoceros is undoubtedly found in Southern Angola close up to the Barotse frontier, and the White has been shot immediately south of the Upper Zambezi, no word has come from any other quarter as to the existence of the monstrous White square-lipped species in the direction of the Upper Zambezi and the Congo watershed; so it is possible his eye-sight was deceived.

Giant Sable Antelope, from Angola

(From a specimen in the Museum of the New York Zoological Society presented by John Jay Paul.)

In general, Barotseland, east of the main Zambezi and of its great north-western affluent the Lungo-e-bungo, seems to possess the mammal and bird fauna of Northern Angola, Southern Congoland, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Moçambique is richer—up to the Shire river—in possessing the Black (I used to think also the White, and perhaps was not wrong) Rhinoceros, and a few other creatures found also in Eastern Equatorial and in Trans-zambezian Africa. Otherwise Moçambique remains rather an unsolved problem, as to why and how it served as an interruption in the spread of the vertebrate fauna of Pliocene and Pleistocene North Africa down to South Africa, an extension which as regards West-Central and Western Africa may have been barred by the former enormous area of dense forest growth.

In botany, as in vertebrate zoology, Barotseland is part of the region which lies between the Kwanza and Zambezi rivers on the south, and the main-stream of the Congo on the north, from Lake Mweru to the Atlantic Ocean. It has a sufficient rainfall, from 22 inches in the south-west to 42 inches in the north-east, to maintain a fairly luxuriant flora as well as powerful rivers. North of the confluence of the Kabompo and the Liambai or Liba (the Upper Zambezi), there seems to have been seventy years ago a luxuriant belt of forest stretching northwards and occupying the mountainous region between[30] the Liba-Zambezi and the Kabompo or Lulafuta.

The average elevation of the Barotse Valley, south of this confluence, ranges from a little under 3,000 feet at Sesheke to about 3,600 feet at the juncture of the Zambezi and the Kabompo; but the forested country between these rivers must rise in part to at least 4,500 feet. The richness of this forest seems to have made an immense impression on Livingstone in the middle of the ’fifties. Up till then, coming from South Africa through Bechuanaland, he had at most seen scattered trees with occasionally a fine solitary umbrageous specimen, or a palm thicket. But above the confluence of these two rivers he evidently plunged (when he had to land) into a woodland comparable with the splendid forests of the Congo or the Cameroons. His Missionary Travels contains some very good word-painting of the grand growth of the trees, the deep gloom of the forest depths as contrasted with the shadeless glare of Bechuanaland. In spite of the incessantly rainy weather—and in this little-explored region the yearly rainfall must be far in excess of the modest estimate quoted by travellers in the Barotse park-land and plateaux—Livingstone found considerable pleasure in here seeing—for the first time—the real forest display of Central Africa.

North of the Zambezi-Kabompo junction Livingstone noticed the increasing growth of the bamboo on the uplands, as a skirting of the great display of[31] tropical forest which so deeply impressed him as he followed the northward course of the main Zambezi. This—or these—bamboos recur on the elevated plateaux of Eastern Barotseland, and extend over a good deal of the upland on either side of the Upper Kafue, as well as over the five thousand feet crest of the Congo boundary. No doubt they may also be observed within the north-western limits of Barotseland. They are seemingly of the same types as the bamboos of Nyasaland and the elevated portions of Northern Rhodesia south of Tanganyika, and in such case belong to the Oxytenanthera and Arundinaria genera. The only other genus of arboreal bamboo in Africa is Oreobambos; but that, I think, is confined in its range to Abyssinia and the Snow mountains of East Equatorial Africa.

The forests of Northern Barotseland have one or more species of wild plantain (Musa) and either wild or introduced examples of the oil palm, where the rainfall is over fifty inches per annum. This may have been introduced from Congoland or Northern Angola by the natives, who in the north of the Barotse country are so closely connected with the peoples of the Congo basin; or as in the case of North Nyasaland and Zanzibar Id., it may be a separate species or sub-species of the Elaïs genus.

According to the reports of later travellers, there is much woodland and scrub on the higher land—4,000[32] to 4,500 feet—on the west side of the Zambezi, south of the Kabompo-Zambezi junction. This woodland is also repeated, less markedly, to the east of the great river where the land likewise rises. The Mankoya country (Eastern Barotseland) has a larger, steadier rainfall than Sesheke and the southern regions; and the Mashukulumbwe table-land, and the valley of the upper Kafue are said to be well and regularly watered countries. The more scattered growth of trees (occasional fine and large trees are common) seems due to human intervention. The natives of the Lukona province, towards Angola, are a wilder, less intelligent race than folk of Tonga kinship on the east, and not so eager to promote tree planting. Bulovale (the region between the Luena and Kabompo rivers) and north of the Kabompo up to the boundary of the Zambezi watershed are well forested regions.

The central valley of the Zambezi—“Borotse proper,”[4] as it might be called, the region which the Barotse (really the Aluyi) have so long dominated—ranges from below the Zambezi-Kabompo confluence on the north to the Gonye Falls on the south, and is about 150 miles long and 60 miles broad. It is the bed—most observers think—of the old lake of the Upper Zambezi, and presents[33] to-day an utterly flat and treeless aspect. Then ensue from Gonye to Katima, some eighty miles of rapids or falls. From Katongo to Mambova, past the now world-famed Sesheke, where Livingstone and Oswell first “discovered” the Zambezi, there are fifty miles of navigable river; then two more rapids at Mambova and Nkalata, and then another navigable stretch of some sixty miles to the vicinity of the Victoria Falls. (These lie well outside the political limits of Barotseland, the boundary striking north along the Majili river, ten miles east of Sesheke.) The plain of the extinct lake is much flooded during the winter rains, when a good deal of central Barotseland is under water. The rainy season seems, however, to be tending more and more towards the spring months (the autumn of South Central Africa).

The geology of Barotseland may be summarized thus: In the north-west, north, east and south-east the surface is a red laterite clay, superimposed on granite which in the higher portions obtrudes itself in mountains and hills. The central valley and most of the south-west has a heavy, white, sandy soil, but with a good deal of alluvium laid down on the sand by river courses or in the bed of the ancient lake. There is a basaltic outbreak in the neighbourhood of the Victoria Falls, but this lies outside Barotseland limits. In the eastern half of the country gold, copper—connected with the copper deposits of Katanga—tin, lead, zinc and[34] iron have been discovered, chiefly in regions between four and five thousand feet in altitude.

In this little book and in the first and second volumes of my Comparative Studies of the Bantu Languages (fed from much the same source) our information concerning Barotseland and its peoples has been greatly implemented. But that fact does not conceal from us that the country, its zoology, botany, peoples, and even its geography (to say nothing of geology) are still far too little known. The portions that lie to the west and south-west of the main Zambezi remain almost unknown and undescribed, or are only made known to us in works of travel fifty, sixty, seventy years old, which even if accurate in what particulars they give were written at a much lower level of knowledge than exists concerning Africa in general to-day. We know more about Eastern Angola than we do of Western Barotseland. Recent discoveries concerning Angolan Antelopes, Zebras, Rhinoceroses, and other mammalian types make us eager to ascertain how these discoveries affect Barotseland west of the Zambezi. How far do the Bushman tribes extend into Western Barotseland? Are they of normal human stature, like those of South-East Angola? Do they speak languages akin to the Bushman tongues and use clicks? Have they greatly projecting brows like certain Bushmen of the Northern Kalahari, or are they without brow projections at all but very[35] prognathous in the lower part of the face? What is the full tale of the Bantu tribes of Western Barotseland? Are there still unrecorded Bantu languages on the Kwando river? Do the tongues recorded south-west of the Upper Zambezi by Livingstone, seventy-two years ago, still exist?

Does Livingstone’s great forest between the course of the Upper Zambezi and that of the Kabompo still maintain itself, in spite of the reckless spirit of destruction inherent in all uneducated Negro tribes, who since the imposition of peace by the white man have been largely increasing the area of their settlement in Northern Barotseland? If the forest is still there, in whole or in part, why are no botanical reports and collections available? The botany of Barotseland, in common with its zoology, has never been efficiently explored and reported on since the land was first entered. Cattle apparently prosper in the whole country; yet the tsetse fly exists seemingly everywhere. Does it, north of the Zambezi and west of the Luañgwa, convey no germs? The time—it seems to me—has come when the British Empire, from London or from Cape Town, should have this country examined scientifically from west to east and north to south; not with anything but benevolent intentions towards its natives—Aluyi and Batonga, Basubia and Mabunda, Batonga and Baila, Bankoya and Kahonde, Valujazi and Valubale—but with the earnest endeavour to make[36] fully known its resources and defects, its wonders and survivals, and the relation that Western Barotseland bears to the growing menace of South Africa: the spread of the Kalahari Desert, the drying up of once fully habitable land, the cause of ruin in South Angola, in Eastern Damaraland, and the vast, dead region north, east, south, and west of Lake Ngami.

H. H. Johnston.

The Mokwai Mataŭka of Nalolo with her husband (standing) and interpreter (sitting)

Photo by Mrs. Marshall

The origin of the Barotse is a matter of conflicting conjecture. It has been suggested by the Abarozwi of Southern Rhodesia that the Barotse are descendants of theirs and that Lewanika is a direct descendant from their royal house. The Barotse of Barotseland deny this in toto. They aver that they came south from the Congo Basin and found the Alunda and Balubale living in their country (vide map). The Alunda and Balubale confirm the statement of the Barotse, and it is known that the Barotse lived for some years among the Lunda, gradually working south till they left the forest country on the Zambezi and came out on to the flat swampy country known to-day as the Barotse Valley.

They were then sometimes called by foreigners the Barozi or Barotse, but were better styled the A-luyi and spoke Siluyi and in our days Sirozi or Sikololo.

During the chieftainship of Mbukwano, the A-luyi were conquered by Sebituane, a roving Mosutu with a band of warriors. Sebituane not only re-christened the A-luyi as “Makololo,” but forced Sesuto as a language on them. Sebituane[38] and his followers were not called Basuto by the A-luyi but Makololo, which name, according to the Rev. E. Smith, once of the Batonga-Baila mission, was derived from the fact that Sebituane’s favourite wife was a Makololo woman.

Sikololo (a mongrel form of Sesuto) is the lingua franca of the Barozi to-day. The greatest difficulty is found in getting any well-authenticated information from the Barozi as to their past history.

The origin of the name “Murozi” (a native of the Barozi country) is peculiar. The true name of the people is the A-luyi; the prefix A or Ba being the plural of Mu and applied to mean “people.” When the Makololo under Sebituane first invaded the southern portions of the country, they found a subordinate tribe called the Masubia living near Sesheke. These people told the Makololo that their overlords living to the north were the “A-luyi.” The Makololo converted this into “Ba-luizi,” “Ba-ruizi” (L and R being interchangeable) and finally “Ba-rozi.” Why the foreign missionaries decided to call it “Barotse” is best known to themselves; certainly no one else can imagine or find any reason for it at all. There is no possible reason for mistaking the “z” in Barozi for “ts”.[5]

Whether from the vicissitudes of their southern trek or from natural laziness is unknown, but they[39] have no system of record, nor, as is the case in many native tribes, have the village elders ever acted as historians and handed their knowledge on from father to son. The Barozi themselves say that owing to their numerous raids and their intermarriage with the aboriginal tribes and with women raided from other tribes, they have lost all purity of race and incidentally all remembrance of their former history. They certainly are to-day a very mixed race, and nearly all their songs, dances, customs and legends are either borrowed wholly or in part from other tribes. They are quite positive that the Abarozwi of Southern Rhodesia are related to them, but they state that these people are a branch that left them and trekked south into Matebeleland where they settled. If this is correct it must have been previous to the Matebele settling in Southern Rhodesia under Mosilikatse, as the Barozi, though fond of raiding weaker or more divided people, were too canny to try conclusions with a powerful and warlike people like the Matebele. Besides the raid of Sebituane and his Makololo, several raids by the Matebele are known of, and although the Barozi certainly suffered at the raiders’ hands, they generally got rid of them by strategy and cunning. Their own successes over people like the Bashukulumbwe and Batonga were nearly always gained by treachery, superior numbers, superior weapons, or else by internal dissensions amongst the people they raided.

The Barozi were very fortunate in the class of people they found occupying the country they settled in; the more timid tribes were at once enslaved, while more powerful people were propitiated and gradually absorbed. Unfortunately, the conquerors readily acquired all the vicious and degraded habits of the conquered, and are to-day, both physically and morally, a far poorer type of native than they were on entering the country, always providing their statements are true. Natural laziness and the rapidity with which they acquired the demoralizing customs of their subject people have practically eliminated the true Muluyi nature in so much that the real Sirozi or Siluyi language is gradually dying out and to-day is known to but a few of the blood royal, sons of Indunas and the like. Sikololo, which is a mongrel Sesuto, is the commonest language in use in the country and even amongst the outlying tribes such as the Alunda, Balubale, Bankoya, Batotela, Bandundulu and others, it is always possible to find one or more persons in every village with a slight knowledge of Sikololo. The missionaries possibly made a mistake in not working up Sikololo on their arrival in the country, but having Sesuto text-books and grammars to hand they commenced to teach Sesuto. Sikololo is now being reverted to and this should simplify matters to a great extent. Many pure Siluyi words are in use in Sikololo, for which there are no equivalents in Sesuto. For example, river work such as paddling and other matters connected[41] with boats are unrepresented in Sesuto, as there is no river work in Basutoland, and the words in use in Sikololo are practically all Siluyi.

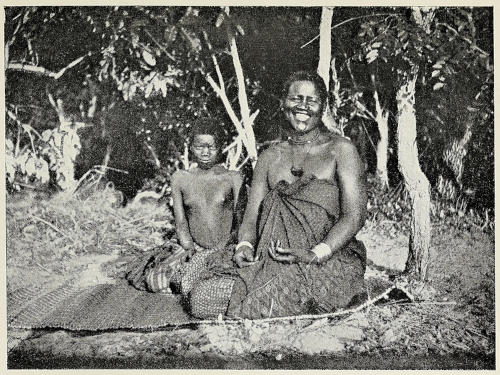

One of Lewanika’s Aunts with Attendant

Photo by J. C. Coxhead, Esq.

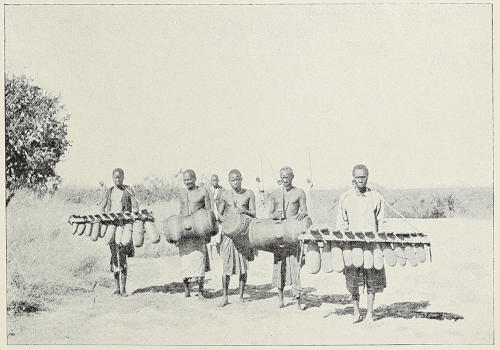

Lewanika’s Band (Mirupa and Silimba)

Photo by J. C. Coxhead, Esq.

Siluyi itself is doubtless a corruption of an older Siluyi language, but this is hard to prove owing to the lapse of time and lack of authentic records.

The Bambowe, an aboriginal tribe on the Zambezi, living south of the Balunda, corroborate the statement made by Alunda and Balubale, that the Barozi or Aluyi lived amongst them while coming from the Congo Basin. The Bakwangwa, another aboriginal tribe living east of the Zambezi, say the Barozi found them there and absorbed them, and yet Sirozi (Siluyi) is clearly the language of which Simbowe and Sikwangwa are dialects. Any one conversant with one of these languages, understands and is understood by speakers of the others. Some idea of the composition of the Barozi people of to-day can be gained when one realizes that they are composed of Bambowe, Bakwangwa, Bahoombi, Bakoma, Makololo, Bandundulu, Bambunda, Bankoya, Bashasha, Alunda, Balubale, Bambalangwe, Batonga, Basubia, Mashukulumbwe, Bakwande, Batotela, Bakwangali, Bakwengo, Balojazi, Vachibokwe, Basanjo and other tribes. Many of the above tribes were, so far as can be gathered, aboriginal owners of the Barozi country, others were raided from time to time and slaves (chiefly women) taken back to the homes of the raiders, where they in time intermarried and became Barozi.

The Barotse Reserve is administered by the British South Africa Company in agreement with the Paramount Chief Lewanika. By this agreement the Chief Lewanika has handed over certain powers and privileges to the B.S.A. Co. The company is empowered to collect a poll-tax, of which a percentage is set aside for the Barotse nation. Out of this percentage the Barotse National School and its industrial branch is maintained. The school is controlled by a European principal and vice-principal, as well as a European instructor, at the head of the industrial side, supported by an effective staff of native teachers. The B.S.A. Co. further have a resident magistrate near Lewanika’s capital at Lialui, who is supported by two Northern Rhodesia police officers and a company of native police (recruited in Angoni and Awembaland). Native commissioners are maintained at Lialui, Nalolo, Balovale, Mankoya, and Lukona, with an assistant magistrate and a native commissioner at Sesheke.

Lewanika has ceded all judicial rights to the B.S.A. Co. with the exception of very minor items[43] and of civil cases between natives. At the same time the B.S.A. Co. recognizes native laws where such native laws are not repugnant to British ideas of justice.

At present Lewanika has his capital at Lialui, where his Kotla (Parliament)[6] sits daily. His sister Mataŭka is Mokwai of Nalolo (Mokwai being a title designating a woman of royal blood on the father’s side).

A younger sister, Mbwanjikana, is Mokwai of Libonda, and Lewanika’s eldest son Litia (or Yeta, as he is now called by all Barozi since his youth) is stationed at Sesheke. (Yeta, styled Yeta II, has since succeeded his father as Paramount Chief.) The two sisters and Yeta are subordinate to Lewanika, but all three have their Kotlas (Parliaments) and Prime Ministers. There is a right of appeal from any of these subordinate Kotlas to the Lialui Kotla.

The Barozi Reserve is closed against farming or mining, and is reserved for the Barozi only. Trading is allowed, but any applicant for a licence has to be proved by the Administrator, Resident Magistrate, and the Chief Lewanika—Lewanika getting a half share of all gun and store licences issued throughout Barotseland.

Liquor is naturally not allowed to be sold in the Reserve, nor are powder, caps, nor guns. The[44] Administrator will grant permission to the Chief, at his request, for any of the more important Indunas to buy sporting guns and a limited amount of ammunition.

Slavery has been suppressed, although, in due justice to the Barozi, it does not appear to have existed in its more brutal form in this country. The B.S.A. Co. has given every encouragement to the Paris Huguenot Mission in the Reserve, and the Mission have several privileges to assist them, such as free inspection of their schools by the Principal of the Barozi National School, the reservation of vacancies in the Barozi National School for members of the Mission Schools and other items. The Chief Lewanika has always lent the mission the support of his approval, although he himself has not become converted.

The B.S.A. Co. has endeavoured in every possible way to protect the interests of the Barozi people and their Chief Lewanika. The Resident Magistrate at Mongu, besides his magisterial duties, acts as adviser to the Chief and the Kotlas (or Parliament) as well. The native is safeguarded against himself as regards his cattle by restrictions placed on the local traders as to numbers purchased annually—restrictions on breeding stock being much more stringent than on bulls and bullocks. The Rhodesian Native Labour Bureau is given free access to the country to recruit labour, but is under close Government supervision.

A Lujazi Village

Photo by J. C. Coxhead, Esq.

Lewanika’s Head Paddlers

Photo by J. C. Coxhead, Esq.

Besides all these safeguards, there is a Resident Commissioner stationed at Salisbury in Southern Rhodesia, a large part of whose duties is the protection of natives’ rights. Beyond him again is the High Commissioner for all native protectorates, who directly represents His Majesty King George V, and is also Governor-General for the Union of South Africa.

A poll tax of 10s. is collected, which is very much lighter than the tax collected from any native race south of the Zambezi. This tax is collected from adult males only, boys, old men and women not being taxed, with the exception of second and other wives of polygamous marriages. A man’s first wife does not have to be paid for, but, as a man who marries more than one wife is nearly always a man of means, he is responsible for the tax of his second and other wives. Exemptions are granted from payment of tax, either for a number of years or for life, for sickness, disease or old age.

The Administrator of Northern Rhodesia pays a visit to the Barozi Reserve in person or by proxy every year, and during his visit the Chief and the people are at liberty to bring any complaints and grievances before him. No matter is too trifling or insignificant to receive the fullest and most careful attention and it is doubtless the care taken over these minor points that has solidified the excellent relations at present existing between the Chief Lewanika and the officials of the B.S.A. Company.

The Paramount Chief of the Barozi is the head of the nation and, in the eyes of his subjects, can do no wrong. His actions are nevertheless curtailed by the national assembly, which was called in the early days of the Aluyi, the “Namōō,” but after the Makololo invasion, the “Kotla.”

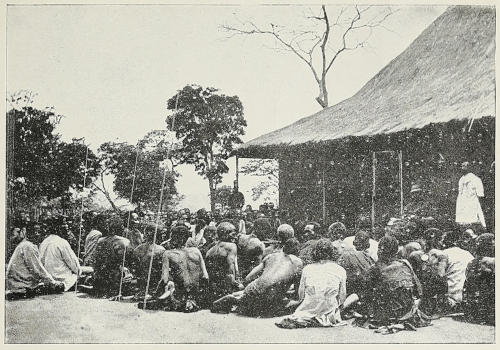

On state occasions the Chief sits in the middle of the Kotla which holds its daily meetings in a long rectangular building open on three sides. Half-way along the fourth side, which is walled, sits the Paramount Chief on a raised daïs. On his immediate right sits the “Ngambela” or Prime Minister and the various Indunas in order of the responsibility of their positions. On the immediate left of the Chief sits Ingangwana the Induna at the head of the “Likombwa,” a division of the people who supervise the Chief’s food and all his personal property (as different from his property as Chief). On the left of the Likombwa sit all sons-in-law of the Chief, with the exception of those who hold positions as Indunas of the people,[47] in which case they sit to the right in order of seniority of position.

In any discussion the “Left” supports the Chief while the Ngambela and the “Right” oppose the Chief, should his wishes clash with the national welfare. There are two rules for the conduct of business in the Kotla which will be dealt with separately. No state affairs are discussed in the presence of the Chief by the assembled Kotla. The reason for this is that out of respect for the Chief’s person, it is argued that discussion would be cramped and restrained and that the best and wisest solution of the question would not be arrived at. So the arrangement of the Kotla may be placed under the following two headings: (1) with the Chief present; (2) in the absence of the Chief. (1) The Chief comes practically daily and sits in the Kotla to show himself to his loyal subjects, and to let them see that he is well. Trivial matters only are discussed, the Chief asking any questions he wishes of the Ngambela or any of the indunas.

Should there be embassies from other people, they are received while the Chief is present and the Chief may, at will, call up the head of the embassy and inquire of him as to the health of the Chief who sends the embassy, the state of crops and general welfare of the nation represented, or as to how the embassy like the Barotse country; but all these questions are polite nothings.

While the Chief is present, the Left sits as previously stated but the Right is slightly different. First comes the Prime Minister (or Ngambela), after him comes Solami. Solami is the man who represents the father of the Chief. As is easily understood no Chief, whose father held the chieftainship, ever held sway during his father’s lifetime. This is not stipulated by law but has always been the case—the death of a Chief’s father often having been arranged by his son to secure succession. So we find Solami is the man who has married the Chief’s mother. Here again it might be suggested that a Chief’s mother might also be dead by design or by course of nature. This is guarded against by the Barotse custom “ku yola” (to appoint), which appoints a successor to take the name and position of any male or female person of importance. Makoshi, the mother of the present Chief, Lewanika, died about ten years ago and a daughter of Lewanika’s (Ngula by name) was at once appointed Makoshi. Her husband is Solami and, though a son-in-law, yet represents the father of the Chief.

On Solami’s right sits Natamoyo. “Natamoyo” means the “father of life” according to the Siluyi meaning of the word “moyo,” and he has or rather had, a position of great value and power. Should any man—Chief, induna, or private person—be pursuing anyone with the desire or intention of killing him, the hunted person was safe directly[49] he could reach the Natamoyo or his palisade. Natamoyo was in fact very similar to the “city of refuge” of the Old Testament. Natamoyo also had the power to veto an execution when discussed in the Kotla, but his chief value lay in his being a haven of refuge. He had as well the following privilege. If the Chief committed any act of injustice to any of his people, the injured party could complain to the Natamoyo, who then went to the Chief’s palisade and abused him roundly. The Chief would then desist from the course of action which was objected to. Needless to say this privilege was very great and valuable amongst a people over whom order was only maintained by the exercise of great brutality, persecution and very often injustice. It is hardly needful to point out that anyone else having the temerity to resent any action of the Chiefs would have paid for it with his life, in all probability being assisted out of the world, with torture and various most revolting cruelties.

After Solami comes Mukulwakashiku, an Induna who acts as Prime Minister during the absence of the Ngambela. On Mukulwakashiku’s right sit the various indunas who take precedence by the relative value of their positions.

(2) When the Chief leaves the Kotla, the business of the people is discussed; cases are tried and new laws talked over, or old laws amended. The “Right” sits in the same order, but the positions[50] of Solami and Natamoyo are now of little value and the two leading men are the Ngambela and Mukulwakashiku. Other divisions of the people for legislative purposes will be described later, but the method of the procedure of the Kotla will now be given. The Ngambela calls Mukulwakashiku and instructs him to inform the assembled Kotla of the matter under discussion. This is done and the assembled Barozi are called on to express their opinions. The smallest man (in position) on the “Right” starts the ball rolling, and utters his views on the matter. He must be a free-born Murozi, but not of necessity even the headman of a village. All the divisions have different values for each member and the junior member of each division speaks first. In a large assembly the first speakers are always members of the “Ikatengo,” a division which comprises the people, petty headmen and very minor indunas. Headmen of more important villages and sub-Indunas of the “Lukaya” division speak after the Ikatengo have finished. When the “Lukaya” have finished, the indunas of importance who comprise the Saa division speak next. Following them, the Sikalu expresses its opinion; this division is composed of the higher indunas. Members of the three division, Lukaya, Saa and Sikalu of the “Right” alternate with members of the “Left,” and when the head “Sikombwa” of the “Left” has finished, Mukulwakashiku gives his personal[51] opinion. He is the last speaker before the Ngambela. The Ngambela then gives a brief résumé of the various pros and cons and shows the weak points in the different arguments.

Should he disagree with the majority, a lively discussion takes place, and should the majority still disagree, the matter is laid before the Chief by one of the “Sikombwa” (Left) and his decision is final. This is seldom if ever the case—especially nowadays—as the present Ngambela is a man of great cleverness, tact and diplomacy, and can always command a great following. When the matter is settled in the Kotla, one of the “Sikombwa” is sent with word to the Chief who sends word back by the same man as to his approval or otherwise. In the event of his disapproval he gives his reasons by the same channel, and these reasons are announced to the Kotla by Mukulwakashiku at the Ngambela’s orders. When the Kotla hear the Chief’s reasons, they signify their agreement thereto by clapping their hands (kandelela), and their resolutions are rescinded or else they refuse to be guided by the Chief. The Ngambela then goes to the Chief and explains the matter and urges his acceptance of the ruling of the Kotla. This he generally gets.

This is a brief description of the working of the chief legislative organ as regards the making of laws, settling of cases, &c. Their methods of administering the law are as follows: Any private[52] person, free or serf, brings his case to the headman of his village, the headman takes it to the resident induna of the native district in which the village may lie, the country being divided off into a large number of districts, like parishes in England, though much bigger in area; the resident induna carries the case to the Kotla induna who represents that native district in the Kotla and the representative induna takes the case to the Ngambela who hears the case at his own residence. Should the parties agree to the Ngambela’s finding the case is settled, but should there be any dissatisfaction the matter is discussed before the assembled Kotla, each party speaking in turn with their respective witnesses.

The divisions enumerated earlier in this chapter have each and all of them certain duties and privileges. The “Sikalu” is a Privy Council and consists of a score or so of the highest indunas. They are divided again into two divisions which have their respective duties. The “Sikalu” of the night sits together with the Chief in a very humble sort of hut, a good distance from any chance of eavesdropping, and these indunas when so employed do not “kandelela” when speaking to the Chief. The Ngambela is one of the night Sikalu. The Sikalu discusses any new law to be made or any important matter which it is necessary to keep very secret, and these discussions are always held in whispers and at a good distance from any likely shelter for eavesdroppers.

Arrival of the Nalikwanda

Photo by J. C. Coxhead, Esq.

The Secretary for Native Affairs and the late Paramount Chief

Photo by J. C. Coxhead, Esq.

The Sikalu of the day is sometimes taken on one side in the Kotla by the Ngambela if any little unforeseen piece of news or information crops up in any discussion. Their conversation is also strictly private and is held entirely in whispers.