BOOKS BY STEPHEN GRAHAM

THE GENTLE ART OF

TRAMPING

THE DIVIDING LINE OF

EUROPE

IN QUEST OF EL DORADO

TRAMPING WITH A POET

IN THE ROCKIES

EUROPE-WHITHER BOUND?

THE CHALLENGE OF THE DEAD

CHILDREN OF THE SLAVES

A PRIVATE IN THE GUARDS

THE QUEST OF THE FACE

RUSSIA IN 1916

PRIEST OF THE IDEAL

THROUGH RUSSIAN CENTRAL

ASIA

THE WAY OF MARTHA

AND THE WAY OF MARY

RUSSIA AND THE WORLD

WITH POOR EMIGRANTS

TO AMERICA

WITH THE RUSSIAN PILGRIMS

TO JERUSALEM

CHANGING RUSSIA

A TRAMP’S SKETCHES

UNDISCOVERED RUSSIA

A VAGABOND IN THE

CAUCASUS

THE GENTLE ART

OF TRAMPING

BY

STEPHEN GRAHAM

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

MCMXXVI

COPYRIGHT — 1926 — BY

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

Chapter Headings by R. H. Hull

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | We Set Out | 1 |

| II | Boots | 7 |

| III | The Knapsack | 15 |

| IV | Clothes | 22 |

| V | Carrying Money | 32 |

| VI | The Companion | 38 |

| VII | Whither Away? | 47 |

| VIII | The Art of Idleness | 78 |

| IX | Emblems of Tramping | 88 |

| X | The Fire | 97 |

| XI | The Bed | 103 |

| XII | The Dip | 114 |

| XIII | Drying after Rain | 121 |

| XIV | Marching Songs | 128 |

| XV | Scrounging | 135 |

| XVI | Seeking Shelter | 142 |

| XVII | The Open | 152 |

| XVIII | The Tramp as Cook | 160 |

| XIX | Tobacco | 173 |

| XX | Books | 179 |

| XXI | Long Halts | 189 |

| XXII | Foreigners | 195 |

| XXIII | The Artist’s Notebook | 208 |

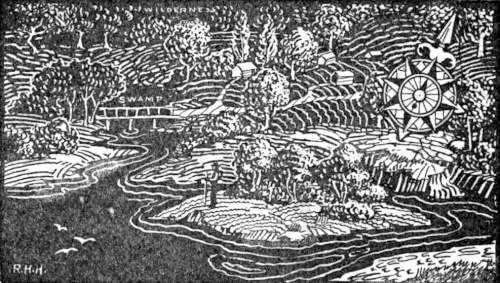

| XXIV | Maps | 233 |

| XXV | Trespassers’ Walk | 240 |

| XXVI | A Zigzag Walk | 251 |

THE GENTLE ART

OF TRAMPING

[Pg 1]

CHAPTER ONE

WE SET OUT

IT is a gentle art; know how to tramp and you know how to live. Manners makyth man, and tramping makyth manners. Know how to meet your fellow wanderer, how to be passive to the beauty of Nature and how to be active to its wildness and its rigor. Tramping brings one to reality.

If you would have a portrait of Man you must not depict him in high hat and carrying in one hand a small shiny bag, nor would one draw him in gnarled corduroys and with red handkerchief about his neck, nor with lined[Pg 2] brow on a high bench watching a hand that is pushing a pen, nor with pick and shovel on the road. You cannot show him carrying a rifle, you dare not put him in priest’s garb with conventional cross on breast. You will not point to King or Bishop with crown or miter. But most fittingly you will show a man with staff in hand and burden on his shoulders, striving onward from light to darkness upon an upward road, shading his eyes with his hand as he seeks his way. You will show a figure something like that posthumous picture of Tolstoy, called “Tolstoy pilgrimaging toward eternity.”

So when you put on your old clothes and take to the road, you make at least a right gesture. You get into your right place in the world in the right way. Even if your tramping expedition is a mere jest, a jaunt, a spree, you are apt to feel the benefits of getting into a right relation toward God, Nature, and your fellow man. You get into an air that is refreshing and free. You liberate yourself from the tacit assumption of your everyday life.

What a relief to escape from being voter,[Pg 3] taxpayer, authority on old brass, brother of man who is an authority on old brass, author of best seller, uncle of author of best seller.

What a relief to cease being for a while a grade-three clerk, or grade-two clerk who has reached his limit, to cease to be identified by one’s salary or by one’s golf handicap. It is undoubtedly a delicious moment when Miles the gardener seeing you coming along in tramping rig omits to touch his hat as you pass. Of course it is part of the gentle art not to be offended. It is no small part of the gentle art of tramping to learn to accept the simple and humble rôle and not to crave respect, honor, obeisance. It is a mistake to take to the wilderness clad in new plus-fours, sports jacket, West-End tie, jeweled tie pin, or in gaiters, or carrying a silver-topped cane. One should not carry visiting cards, but try to forget the three-storied house remembering Diogenes and his tub.

I suppose one should draw a distinction between professional tramping and just tramping, especially as this whole book is to be called The Gentle Art of Tramping. I am not[Pg 4] writing of the American hobo, nor of the British casual, nor of railroaders and beach combers or other enemies of society—“won’t works” and parasites of the charitable. While among these there are many very strange and interesting exceptions, yet in general they are not highly estimable people, nor is their way of life beautiful or worth imitation. They learn little on their wanderings beyond how to cadge, how to steal, how to avoid dogs and the police. They are not pilgrims but outlaws, and many would be highway robbers had they the vitality and the pluck necessary to hold up wayfarers. Most of them are but poor walkers, so that the word tramp is often misapplied to them.

The tramp is a friend of society; he is a seeker, he pays his way if he can. One includes in the category “tramp” all true Bohemians, pilgrims, explorers afoot, walking tourists, and the like. Tramping is a way of approach, to Nature, to your fellowman, to a nation, to a foreign nation, to beauty, to life itself. And it is an art, because you do not get into the spirit of it directly you leave your[Pg 5] back door and make for the distant hill. There is much to learn, there are illusions to be overcome. There are prejudices and habits to be shaken off.

First of all there is the physical side: you need to study equipment, care of health, how to sleep out of doors, what to eat, how to cook on the camp fire. These things you teach yourself. For the rest Nature becomes your teacher, and from her you will learn what is beautiful and who you are and what is your special quest in life and whither you should go. You relax in the presence of the great healer and teacher, you turn your back on civilization and most of what you learned in schools, museums, theaters, galleries. You live on manna vouchsafed to you daily, miraculously. You stretch out arms for hidden gifts, you yearn toward the moonbeams and the stars, you listen with new ears to bird’s song and the murmurs of trees and streams. If ever you were proud or quarrelsome or restless, the inflammation goes down, fanned by the coolness of humility and simplicity. From day to day you keep your log, your daybook[Pg 6] of the soul, and you may think at first that it is a mere record of travel and of facts; but something else will be entering into it, poetry, the new poetry of your life, and it will be evident to a seeing eye that you are gradually becoming an artist in life, you are learning the gentle art of tramping, and it is giving you an artist’s joy in creation.

[Pg 7]

CHAPTER TWO

BOOTS

BOOTS and the Man I sing! For you cannot tramp without boots. The commonest distress of hoboes is thinness of sole.

The sad heart, in this case, often has just a thin sole. Two friends set out last spring to tramp from Bavaria to Venice, luggage in advance, knapsack on shoulder. But they had not the right sort of boots, and they lingered[Pg 8] in the mountain inns quaffing steins of brown beer to take their thoughts away from their toes. They are in those mountains yet.

You should have leather-lined boots with most substantial soles. They may squeak, they may feel clumsy as sabots when you first put them on. They may feel like comfortable baskets on your feet. Slight and elegant boots seldom stand the strain, or, if they do, your feet do not. I have tramped in little steel-soled boots in the Caucasus, and in plaited birch-bark boots, lapti, in the North, but I do not recommend novelties in footwear. It is difficult to better a new pair of Army boots. But the best I ever had were a pair of chrome leather fishing boots which I once bought in a wayside shop in the Catskill Mountains. My feet were in a poor state, having got frozen by night and blistered by day in a disgusting pair of light boots. I got into these capacious fishing boots one evening and never felt another twinge all the way to Chicago. As regards Army boots, men suffered on the march because often they were wearing other men’s boots worn and shaped already to a different[Pg 9] pair of feet and then patched and cobbled. One cannot with advantage wear dead men’s boots.

Of course, one should go gradually with a really stout pair of boots. Beware of the zest of the first and second day’s tramping. It is so easy to cripple oneself on the second day out. You dispose of the first surface blisters, and then you get the deeper, more painful, blisters, and those you cannot squeeze. They intend to squeeze you. One should wear thick woolen socks, or even two pairs of socks at the same time. When the socks wear out one can even increase the number of pairs to three, though it is better to discard socks that have worn to hard shreds. I do not believe in soaping socks, though it does not hurt to put them on damp. One should try to get a dip every day, in mountain stream or lake. An ideal combination is sea-bathing and tramping. The salt-water exercise certainly helps the feet. It takes several days to get town-nurtured feet into condition. With that in mind one should not overdo it at the beginning. Mile averages are a curse. So are definite programs. Like[Pg 10] a good cricketer, you should play yourself in before you begin to score.

Of all tramping the most delightful is in the mountains; the most trying is along great highways. Both have their place in the ideal tramp’s life. But experience teaches where the most fun is to be found. Mountain walking is really much less tiring because, first of all, there is no dust, then there is more contrast and mental distraction, and last, not least, one’s feet hit the earth at varying angles, employing more muscles. The sole does not hit a road with monotonous regularity upon the same dry spot of blistering skin.

I find that in the mountains a boot of rather lighter sole is preferable, with either brads or Phillips rubbers. One must nevertheless beware of shoddy. After the second scramble amid rocks I have seen the whole sole of a boot part company with the upper. I have seen the heel come off. Well established lines of workingmen’s boots are safer than fair-seeming boots for clerks. On the other hand, boots whose nails come through are a nuisance, digging holes in the soles of one’s feet. Boots[Pg 11] which are letting iron in should be hammered inside with a stone, but if, as often happens, some sharp nail edge cannot be smoothed it is as well to put in a certain amount of paper till a cobbler can be found to right the wrong.

Metal plates, “bradies,” on the outside of the soles are of little use as they get very smooth and slippery. Brads also wear to be more slippery than plain leather. The new type of very hard rubber patches made by Phillips and others are ideal for climbing. It is to be remembered that tramping across country in the mountains one comes to steep and dangerous descents, and upon occasion one risks one’s neck on the grip of one’s feet. That is where the Army type of rubbers comes in. As an auxiliary it is not a bad plan to have a light pair of tennis shoes in the pack, as you can get over some obstacles in prehensile rubber shoes which one could never negotiate in boots. But hard rubber bars across one’s leather soles are in any case very good. These rubbers would “draw” your feet on an exposed level road. But in the mountains one’s feet[Pg 12] keep cooler, and the comfort of a safe grip on slippery rocks is not to be disdained. When in the Rockies with Vachel Lindsay he had bradded boots, but they got very shiny and smooth, and he could slide in them. In certain dangerous descents we made I could see that much-worn bradded boots were clearly at a disadvantage.

It is a good plan on a long tramp to carry a duplicate pair of boots in the pack. While it adds to the weight carried there is a counter-balancing pleasure in a change of footgear now and then. It is moreover possible that in wild country one may wear out one solid pair of boots in a month or so. Uppers have a way of bursting in the mountains, especially when one indulges in rushing down great slopes of silt with myriads of knife-edged little stones. By the way, one should beware of toasting one’s feet in front of camp fires, or of leaving one’s boots too near the embers when sleeping out. If not using them as the foundation of a pillow, it is well to put them in a fresh and airy place, smearing a little grease on them perhaps, to keep the uppers soft and pliable.[Pg 13] Beware, however, of the grease getting near the bread.

Boots are, of course, not a poetic subject. Kipling used the word to express the boredom of route marching:

The boot, like the thumbscrew, was an instrument of torture of the Inquisition. But nevertheless, it must be remembered, old boots bring good luck. That is why one ties them to the hymeneal coach. On life’s tramp together, may the blissful pair have the comfort and easy-going happiness of a well-worn boot.

The tramp gets affectionately attached to his boots when they have served him long and well, and may even wax patriotic in looking at them and say, like Dickens in America, “This, sir, is a British boot.”

Poems addressed to boots are hard to find, and one must assume that poets for the most part do not tramp. For if they tramp there inevitably comes the pathetic moment when[Pg 14] looking upon discarded boots by starlight the poet says: “Oh, boot, have you not served me well, old boot, old friend!” There is a lost poetry in boots—“lines addressed to my favorite boots,” “lines written after taking off my most cruel boots,” “lines written before putting on my boots.” The last, on the occasion of putting them on swollen and blistered feet, might be the occasion of a long, reflective poem.

But enough, we at least have our boots on, and are ready to proceed with the story of our tramping art.

[Pg 15]

CHAPTER THREE

THE KNAPSACK

IT is wonderful how much you can carry when it is for pleasure. Soldiers grumble like camels at the loads put on their shoulders. Under some one’s orders they shall march with packs on their backs to such a point to-day, to such another point

The camel groans, the soldier grouses, but the gay tramp puts ever something more into his capacious rucksack for pleasure or profit.[Pg 16] There’s a hunk of tobacco, there’s his favorite volume of poems, his sketchbook—his danger is in putting in too much and not putting in the right things.

I assume he is to be equipped for sleeping à la belle étoile. I may mention one or two things he might overlook. First, the pack itself should be well made. I have found in the past that Germans and Austrians make the best rucksacks, and even the best in London seemed to be imported from these countries. The one I have now was purchased some years ago in Vienna, but I think it was the best to be found there. There were many shoddy ones about. The shopkeeper pretended that the one I chose was not for sale, and I spent twelve hours getting it. Not that it is remarkable, but it is a genuinely well made article. Exterior pockets which will not burst are a necessary; interior pockets are also useful.

The worst of the interior of a rucksack is that after a while everything in it gets mixed. Spare boots and linen get sprinkled with coffee; different foods mingle. Some paper[Pg 17] wrapper bursts and the sugar spills over everything. Then writing papers, books, or notebooks get greasy. But this is avoided if one provides oneself with half-a-dozen cotton bags which tie with tapes. If these are not obtainable at home they are to be found in some sort of form at a Woolworth’s or a cheap draper’s. It is a small detail, but a matter of comfort: if you feel so disposed you wash out these little cotton bags when they get dirty.

Another valuable extra to put in the rucksack is a few yards of mosquito netting which can be bought quite cheaply, sometimes called brides’ veil in the shops, sometimes leno, sometimes butter-muslin. With this you can defy the mosquito at nights, and by day you can enjoy the luxury of a sun-bath siesta watching the flies which cannot bite your nose. Apropos of the mosquito netting the choice of hat is important. Do not take a cap. You need a brim. And do not take a straw hat. You cannot lie down comfortably with a straw hat on. A tweed hat is best. The brim has a double use. It shields your eyes from the sun, but also, when you lie down where flies[Pg 18] and mosquitoes abound, you had best sleep in your hat and use the brim to lift the mosquito net an inch from your face. N.B.—A tramping hat does not get old enough to throw away. The old ones are the best. Of course, once you have slept a night wearing your hat it is not much more use for town wear. It has become more tramp than you are.

I am in favor of carrying a blanket. It is less cumbersome than a sleeping sack and more hygienic. If, however, insects are very troublesome, as in the tropics, and there are “land crabs” and scorpions and tarantulas and what not about, a light sleeping sack may be improvised by sewing together three sides of a pair of small sheets. This I have done: it gets rather airless and smelly. It is best to turn it inside out in the morning and give it plenty of sun. But a blanket will do: take a couple if you are chilly. This makes weight on the back, but it is also a softening comfort and fits the rucksack upon the shoulders on a long hike.

There is no point whatever in carrying an overcoat, though a waterproof cape or an oilskin[Pg 19] comes in useful. A blanket and a cape form a useful combination. One can sleep on the cape with the blanket over one.

In one of the little cotton bags you will carry your toilet requisites, soap and towel and comb. Some men like to let their beard grow on a long tramp and thus dispense with razor and brush. Still, there are few things more refreshing than the cold shave at dawn, the rushing stream, the lather scattering itself on ferns and flowers, the brandishing arm, the freshening cheek.

A vital consideration at that time in the morning is the coffeepot. I am in favor of carrying an ordinary metal cafetière; some prefer a kettle, but it bumps too much on the back; others a pail, but the water in it is apt to get smoky. In the United States there are so many clean empty cans lying about that it is perhaps unnecessary to carry anything of the kind. The cowboys never carry anything in the nature of a coffeepot. They confidently reckon on finding a lard can. Indeed, if you make camp in the West or South where some have camped before you, you may find carefully[Pg 20] preserved the coffee can used by the last party. All America is camping out in the summer, so it is a simple matter to find the black patch of some one else’s erstwhile sleeping pitch.

However, I dislike the places where people have been before, their orange peel and biscuit wrappings, their trampled grass and jaded scrub. Give me a virginal patch of woodland or moorland, or a happy grassy corner of the long dusty road, and there startle the earwigs and the birds with the crackle of a first bonfire. Therefore, I consider it ideal to take a coffeepot with you, a metal one that gets blacker and blacker as you go along. It can best be carried outside the knapsack, angling from the center strap and resting in the hollow between the bulging pockets.

I had forgotten the enamel mug, the knife and the spoon. But you must not. Do not carry a fork; it is unnecessary. A small enamel plate is useful. Pepper and salt mixed to taste may be carried in a little bag. Some sort of safe box for butter is to be recommended. Take plenty of old handkerchiefs[Pg 21] or worst quality new ones; they come in useful. Remember a glove for taking the coffeepot off the fire. If you do not you will be burning all your handkerchiefs, your hat, your shirt, or anything else that you may be tempted to use. There are occasions when the coffeepot seems to get almost red hot before it boils. There are giddy moments when it loses its balance and will topple over and spill its precious contents unless you are ready to dash in with gloved hand to save it.

For the rest of the contents of your knapsack you will be guided by your special desires and aims. Loaded and bulging in the morning, it will gradually feel lighter and look more shapely as movement sorts the various things into their best positions. At night you turn out many things and use what remains as a pillow. Some carry a pillow, but it is too bulky. An air pillow is not to be despised, but it generally seems to let you down during the night. Your knapsack will grudge being left in the dew. It will feel happier with your head resting upon it.

[Pg 22]

CHAPTER FOUR

CLOTHES

1. Attire

NEEDY knife grinder,” said the poet, “your hat has got a hole in it, and so have your breeches.” That was not necessary. You should carry a housemaid’s tidy, or whatever it may be called, the tiny compendium of needles and thread sometimes offered upon hotel dressing tables, and sew up the holes. I fear the knife grinder’s hat was of felt, a broken billycock hat, but we tramps have nothing to do with felt hats. The bowlers and the[Pg 23] derbys and the trilbys are not our style. There was a time when men tramped in shovel hats, and I can see Parson Adams trudging along, his lank locks crowned with this lugubrious headgear. And Abraham Lincoln walked abroad in his rusty topper. But we have changed all that. We tramp in tweed hats or caps or without hats at all. We do not feel superior, but we know we are more comfortable.

Also we no longer wear cravats. In fact, a collar and tie may be secreted in a pocket of the knapsack to be unwillingly put on when it is necessary to visit a post office or a bank, a priest, or the police. But otherwise we go forth with free necks and throats, top button of shirt preferably undone.

And we do not tramp in spats or gaiters, nor in fancy waistcoats. The waistcoat is an article of attire which can be cheerfully eliminated as entirely unwanted. Undervests also are rather de trop. There are many things a man can shed. I am not qualified to say what a woman can do without, but she needs no hat with feathers, no hatpin. As I think of her[Pg 24] in the wilderness it seems to me she can get rid of everything she commonly wears with the exception perhaps of a hair net, and then dress herself afresh in “rational attire.” The green and brown misses in the “lovely garnish of boys” are now so familiar in the United States that it is almost superfluous to describe them. A khaki blouse and knickers, green putties or stockings, and a stout pair of shoes are almost everything; very simple, very practical, and if one must think of looks while on tramp, not unbecoming.

Materials are more important than shapes. A homespun, a tweed, a cord, are better than flannel or serge or shoddy cloth. Tramping is destructive of material; sun, rain, camp-fire sparks, and hot smoke seem to reduce the resistance of cloth very rapidly. After a month, a sort of dry rot will show itself, and as you go through a wood every rotten stick or tiny thorn you happen to touch will tear a tatter in your trousers. It can be annoying and amusing. “When I am tired of looking at the view I look at your trousers,” said Lindsay to me, in the Rockies, he in the virtuous[Pg 25] superiority of green corduroy; I in old clothes which I thought I might as well wear out on tramp. I certainly wore them out: in fact, we had to turn from the wilds towards civilization, and the poet bought me a ready-to-wear pair of cowboy’s bags.

But workmen’s trousers, suspended by workmen’s braces, are the best. Braces marked “For Policemen and Firemen” are sold in the United States. They are undoubtedly stout and will stand the strain of many jumps. You will have a cosy feeling of nothing defective in your straps, a feeling akin to that of a good conscience—much to be desired.

What remains? A jacket. It may as well be a tweed one with half-a-dozen roomy pockets. I once saw a character reader at a fair who said: “Show me your hat and I will tell you who you are.” He had plenty to guide him. I gave him mine. He said: “You, sir, are a thinker. Your thoughts have been oozing out of your head and have spoilt an excellent lining.” He held my hat up to the crowd. “This is the hat,” said he, “of a man who buys at the best shop, but wears his[Pg 26] hat a very long while. He is both proud and economical, and is probably a Scotsman.”

Had I taken off my jacket he could probably have told me a good deal more; made bulgy with books, yet pinched by the clips of fountain pens, ink-stained, wine-stained, sun-bleached and rain-washed, fretted by camp-fire sparks, frayed and yet not torn by envious thorns; the whole well stretched, well slept in, well tramped in. Other parts of one’s attire wear out, come and go, but the jacket remains, granted a good sound indestructible jacket.

Such a jacket is warm wear. No, not in the morning, not for some hours after sunrise; not in the evening, not during the twilight hours. During the heat of the day if you wish you can take it off and, tying it into a neat bundle, fix it to the knapsack. It is pleasant to have the air break fresh on one’s perspiring chest. But the warm jacket is your friend, and after two days’ out of home you understand it. The stout jacket stands by you in the hours when you need support. You soon get used to its weight, and its thickness[Pg 27] helps to bed the knapsack between the shoulders.

Carlyle wrote a book on clothes, the inwardness of which was that man, the straggling bifurcate animal, discovered in Eden that he was really ugly and a shame to be seen, and he has been trying to hide himself ever since, in fig leaves and phrases, phylacteries and philosophies. That shall provide the tramp’s motto: a fig leaf and a phrase. But, oh, Sartor, oh, Mr. Mallaby-Deeley, a stout fig leaf!

2. Motley

“Invest me in my motley; give me leave to speak my mind.... Motley’s the only wear.”

The privilege of the Court Fool is that he can tell the plain ordinary truth to the King, even with the executioner standing by, ax in hand, and risk not his head. But he must be wearing his cap and bells. Let him come but dressed as a courtier and make the same painful jest, and the headsman will step forth to relieve him of his poor-quality thinking piece. The Greek who was employed to tell[Pg 28] his Alexander after each glorious triumph that he too must die, must have worn some shred of motley. You cannot say that sort of thing without the dress which liberates. It was the same with Diogenes. He got in so many home truths in an intolerant age because he lived in a tub. That tub was his motley. Our tramps’ gear is ours.

There are clothes which rob you of your liberty, and other clothes which give it you again. In the sinister garb called morning dress you are a close prisoner of civilization; but in the tramp’s morning dress you do not need to “mind your step.” Oh, the difference between one who has worn silk in the Temple and the same man lying in a cave in smoke-scented tweeds. Of course, it takes some time to break him down. He is still wearing a shadow topper and invisible cutaway coat weeks after he has started into the wilds. The same with a lady of fashion; she puts a hat over the glory of her hair to hide the primitive Eve—she will be still thinking of this false headgear long after she has changed into a forest nymph.

[Pg 29]

Motley has a double advantage not used by Shakespeare in his admirable clownings. It not only perhaps enables a man to jest shrewdly with the prince; it enables a prince, if he will put it on, to talk freely with an ordinary poor man. The cat can look at the King and the King can look at the cat.

Class is the most disgusting institution of civilization, because it puts barriers between man and man. The man from the first-class cabin cannot make himself at home in the steerage. He can have conversations with his fellow man down there, but fellow man will be standing to attention like private in presence of officer, or standing defiant like prisoner in presence of a condemnatory court. It is not the fault of the bottom dog, the proletarian. He scents a manner. Your bearing cannot be adjusted to equality. You are not on the level with him. You cannot rid your voice of its kind note. “Damn it, don’t be kind to me,” say the eyes of the third-class passenger. But you cannot get rid of that absurd, unwanted, kind look—that “tell me, my dear man” expression.

[Pg 30]

Yes, whatever he replies will seem a little bit irrelevant, like the answers to the visiting rector going the round of his parish, he having the next drag hunt on his mind.

But in the tramps’ motley you can say what you like, ask what questions you like, free from the taint of class.

It also puts you right with regard to yourself. You see yourself as others see you, and that is a refreshing grace wafted in upon an opinionated mind. The freedom of speech and action and judgment which it gives you will breed that boldness of bearing which, after all, is better than mere good manners. It allows you to walk on your heels as well as on your toes, and to eat without a finicking assortment of forks. It aids your digestion of truth and of food, and aids nutrition as good air does good porridge. All that highfalutin’ advice which Kipling wrote in “If” may be left in its glum red lettering pasted on your bedroom[Pg 31] wall, if you will only put on your tramp’s motley.

“What must I do to inherit eternal life?” The answer to that question is not adequately stated in that “If” of talking to mobs without losing your virtue and to Kings without losing the common touch, or in the “If” of making a heap of all your winnings and staking them in a game of pitch and toss. The answer of the Evangel is Take up the Cross and Follow Me, which may be interpreted indulgently for our purpose here: Take up thy staff and the common burden for thy shoulders, the motley of the pilgrim and the tramp.

[Pg 32]

CHAPTER FIVE

CARRYING MONEY

PUT money in thy purse,” is often given to the young man as a jewel of wisdom. But we give the contrary advice: take it out. The less you carry the more you will see, the less you spend the more you will experience. Of course, if you have a strong enough will to resist temptation you can carry what you like, but even then you are at the disadvantage of being worth a robber’s attention.

I sometimes pride myself that I set out for Jerusalem with the Russian pilgrims having ten pounds, and that I brought back five of the[Pg 33] pounds to Russia. The most I paid for lodging in Jerusalem was three farthings a day. Had I quit for a hotel I should have lost most of the experience of the pilgrimage. When I made my study of the emigrants to America I went steerage and came back steerage. I stayed in a workman’s lodging house in New York and I tramped to Chicago on less than a dollar a day. Of course it is very expensive in America, always was, unless you care to work your way. For my part, I think working one’s way even more expensive.

A shilling a day ought to be ample for tramping in any part of the world—if you cook on your own camp fire and sleep out. But America is an exception. There you will need three-parts of a dollar. In Europe generally, after the War, one needs to consider the currency situation. The Tyrol has been a place of cheap food and wine; now it is much dearer. France and Italy, on the other hand, are cheaper.

It is well to carry notes of low denominations, as it is almost always difficult to get change in the country. If you have a larger[Pg 34] note, a reserve, to take you, let us say, by boat or train somewhere, at some point of your adventure, or to bring you home, it is as well to sew it in your jacket lining. It is a mistake to put it in your knapsack or in a pocket of a shirt. Once I put a five-pound note in a secret pocket of a shirt and forgot all about it till after I received my linen one day, washed and ironed, from a peasant girl. Suddenly I remembered, and feverishly picked up the shirt and went to the secret pocket, the girl smiling at me as I did so. The note was there, fresh and crisp. I was astonished. “You washed and ironed this bit of paper?” I asked. “No,” she said simply, “I found it in and took it out. But I put it back after ironing.”

In America it is as well to carry travelers’ checks, as they can be cashed even in a small village, and they are safer than notes. In Europe such checks are difficult to cash except in large cities. They are unfamiliar to the bankers of provincial towns. Even in large towns you may have to wander from bank to bank seeking a correspondent of the original[Pg 35] bank from which you have taken the traveler’s check.

A good plan is to have five-pound notes sent to you by registered post by a bank at the time at which you are likely to require them. They can be sent poste restante, but it is unwise to leave the packet too long unclaimed, as in some countries they send back letters to sender after a week. Money can be sent by wire in this way. Money can also be sent by a bank in response to a wire if you have arranged a code signature before leaving home. This is a very simple matter if you are bad enough tramp to have a balance intact.

After two months, or less, in the open, living the life of a tramping hermit, you are likely, upon occasion, to have a joyous reaction towards excess. And this may express itself in a gay and giddy week-end, in hotels and restaurants and places of music and dance. You may spend more on a romp than you do on the tramp. Round and round the market place the monkey chased the weasel! You are that monkey never catching that weasel.[Pg 36] That’s the way the money goes. Pop goes the weasel!

Oh, that weasel, that weasel of false heart’s desire! Haven’t we chased it upon occasion!

Thus sang the banjo in the wilderness. You lie in the heights of the mountain under the stars, with empty pockets and empty stomach, and you look at the many lights, the blent illumination of the Milky Way, and think—of Broadway, the Great White Way, burning its great stream of electricity, burning your candle and its own.

The spree is not, however, entirely legitimate to the tramping expedition. Tramping is first of all a rebellion against housekeeping and daily and monthly accounts. You may escape from the spending mania, but first of all you escape from the inhibition, that is the word, the inhibition of needing to earn a living. In tramping you are not earning a living, but earning a happiness.

There was a verse of poetry of which[Pg 37] Ruskin, in his satirical mood, was inordinately fond:

Well, ours is the morning concert, without ticket and without program, without classification of box or stall. You do not pay as you enter, nor grumble as you go out. Indeed there is a very good reason. Performers and friends of the performers do not pay. You come as a friend of the thrush, or you are a thrush yourself. We shall see as we tramp the woods together which it is. But in any case the thrush never takes round the hat.

[Pg 38]

CHAPTER SIX

THE COMPANION

GIVE me a companion of my way, be it only to mention how the shadows lengthen as the sun declines,” wrote Hazlitt. An ideal companion is ideal. However, we all know that companionship prolonged may be trying even to good friends. If you live for some time in the same room with any one you discover that fact. Indeed, you discover a good deal about your companion that you had not suspected before you were intimate, and he about you. Eventually a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand becomes a storm, and[Pg 39] you quarrel over what seems afterwards to have been nothing at all. Even man and wife of ideal choice find that out.

But there is perhaps no greater test of friendship than going on a long tramp. You discover to one another all the egoisms and selfishnesses you possess. You may not see your own: you see your companion’s faults. In truth, if you want to find out about a man, go for a long tramp with him.

Still there are rewards. If you do not quarrel irreparably and part on the road you will probably find your friendship greatly increased by the experience of the wilds together. I like tramping alone, but a companion is well worth finding. He will add to the experience; perhaps double it.

You have naturally long conversations. You comment on Nature around you, and on tramping experiences. You talk of books and pictures, of poems, of people, but above all, almost inevitably, of yourself. Tramping makes you self-revelatory. And this is an enormous boon. If you have patience you will get to see your friend in a new light; you will[Pg 40] fill in the picture which up to then you have but vaguely sketched. The richest people in life are the good listeners. If, however, you also must talk, must reveal your life, your heart, your prejudices and passions, it will often happen that you will express yourself to yourself, as much as to your friend. Self-confession is growth of the mind, an enriching of the consciousness. In talk which seems idle enough you may be reaching out toward the infinite.

The early morning tramp is a striving time, one of reaching out, of vigorous assertions. The afternoon may mock the morning with jesting, with ribald songs,

as Kipling says. But the evening will make amends. There is a great poetic time after the camp fire has been lit, the coffee brewed, the sleeping place laid out. You sit by the embers as the twilight deepens and talk till the stars shine brightly upon you. That is the time of confidences, of tenderness, of melancholy, of the “might-have-been” and the “if[Pg 41] only.” You are full of the songs of the birds to which you have listened all day. Music will come out again.

But there are many types of companionship: the two undergraduates en vacance, the two cronies of the same town, the middle-aged man and his young disciple, sweethearts, bachelor girls, father and son, man and wife, friend and friend.

Young athletes will go to the furthest distance; lovers the shortest. But the lovers may be out the longest time. I am inclined to measure a tramp by the time taken rather than by the miles. If a hundred miles is covered in a week it is a longer tramp than if it is rushed in three days. There is great happiness in taking a month over it. However, it is hardly possible to walk less than seven miles a day if one sleeps out of doors.

A point to make sure about in companionship is distribution of kit. You do not need two coffeepots, two sugar bags—a number of duplicates can be avoided. See your companion has the right boots. The slower walker should set the pace. It is absurd for one to[Pg 42] walk the other off his feet just to show what a walker he is. There is great difference in walking capacity. Some can do forty miles a day without turning a hair; many can hardly keep up fifteen. If your companion breaks his feet or turns an ankle you may have to wait some days with him while he recovers. The first days of tramping are in this respect the most dangerous. It is so easy to blister the feet if one marches too far in hot weather. One or two blisters may be remedied, but there comes a morning when you cannot get your boots on.

The best companions are those who make you freest. They teach you the art of life by their readiness to accommodate themselves. After freedom, I enjoy in a companion a well stocked mind, or observant eyes, or wood lore of any kind. It is nice sometimes to tramp with a living book.

Of course, one should carry a notebook or diary or some broad-margined volume of poems. You can annotate Keats from your life on the road. But whether you do that or merely record the daily life in a page-a-day[Pg 43] journal, you are enriching yourself enormously by what you can write about.

Lovers, I imagine, will carry no diary. Their impressionable hearts are the tablets on which they write. Every one has a tendency to write down the unforgettable: it is obviously unnecessary. Loving pairs, however, seldom take their staffs and their packs and make for the wild. Even in our free days they are somewhat afraid of it. But it is to be recommended as an admirable preparation for married life. It is a romantic adventure, but it leads to reality. If you have to carry your beloved, you will probably have to carry her for the rest of your life. You cannot tell till you’ve spent a night in the rain, or lost the way in the mountains, and eaten all the food, whether you have both stout hearts and a readiness for every fate. If not a tramp before marriage, then a tramp directly after comes not amiss, a honeymoon spent tramping. It is an ideal way to begin life. For tramping is the grammar of living. Few people learn the grammar—but it is worth while.

There are few more felicitous proposals of[Pg 44] marriage set down in literature than the Autocrat at the Breakfast Table’s, “Will you take the long road with me?”

Life à deux is much more of an adventure than life seul, much more of a tramping expedition, less of a “carriage forward,” “fragile,” “lift with care,” and “use no hooks” affair. One, be it the man, be it the woman, pulls the other from security. It is a more difficult way of life; it needs learning.

On the road the weak and strong points of character are revealed. There are those who complain, making each mile seem like three; there are those who have untapped reserves of cheerfulness, who sing their companions through the tired hours. But in drawing-rooms, trains, tennis parties, theater, and dance hall, they would never show either quality. The road shows sturdiness, resourcefulness, pluck, patience, energy, vitality, or per contra, the lack of these things. It is something to face the first night together under the stars, the fears of lurking robbers or wild animals, fears of the unnamed.

The first night out together of a man and[Pg 45] his wife is a memorable occasion. You go back to the primitive, but there is something very cosy and comfortable about it—the only man in the world with the only woman. Darkness settles down upon you in a stranger way than it does upon man and man. There is more poetry in the air and in your mind. More tenderness is enkindled than ceiling and walls of house ever saw, tenderness of a certain sheltering care which it is luxurious to give.

Night is dark and still and intense, and you can hear two hearts beating while you look outward and upward, and dimly discern the passage of bats’ wings in the air.

The first night, however, is seldom without alarm; the cold wet nose of a hedgehog touching your beloved’s cheek may cause her to rend the air with a shriek, a field mouse at her toes cause her scarcely less alarm. It is good to pack her in a really capacious sleeping bag; it excludes rodents. And if you are not too big you can snuggle into it yourself, if the lady proves to be nervous and you are on such terms of fellowship as to make it possible.

[Pg 46]

A night of murmurings and deepening shadows and freshness, and then, perhaps, of a gentle rain before dawn, and of glimmerings of new day and sweetness of wild flowers and birds’ songs before sunrise. You watch the boles of the great trees grow into stateliness in the twilight, and the night is over. With an arm round your fair one you go to the point where in orange and scarlet the great friend of all the living is lifting himself once more out of the east to show us the way of life.

[Pg 47]

CHAPTER SEVEN

WHITHER AWAY?

THE principle motive of the wander-spirit is curiosity—the desire to know what is beyond the next turning of the road, and to probe for oneself the mystery of the names of the places in maps. In a subconscious way the born wanderer is always expecting to come on something very wonderful—beyond the horizon’s rim. The joys of wandering are often balanced by the pains; but there is something which is neither joy nor pain which makes the desire to wander or explore almost incurable in many human beings.

[Pg 48]

The child experiences his first wander-thrill when he is taken to places where he has never been before. I remember from the age of nine a barefoot walk with my mother along the Lincolnshire sands from Sutton to Skegness, and the romantic and strange sights on the way. What did we not build out of that adventure? And who does not remember the pleasurable thrill, the pleasure that’s all but pain, of being lost in a wood, or in a strange countryside, and meeting some crazy individual who humored the idea by apostrophizing a little brook in this style: “I am now marching upon the banks of the mighty Congo”? The imagination wishes to be stirred with the romance of places, and is stirred. In a great city like London or New York, even though living there, certainly I for one am homesick; not for a home and an armchair, but for a rolling road and a stout pair of boots, and my own stick fire by the roadside at dawn, and the old pot which is slow to boil.

“Where,” I am asked, “would you go a-tramping now if you were absolutely fancy-free and passports and Bolsheviks were unknown?”[Pg 49] It would probably be in Russia, where I have vagabondized over thousands of miles already. I should like to resume my six-thousand-mile journey southwest to northwest, which was interrupted by the War in August, 1914. But, alas, the Moscow of the Bolsheviks does not encourage adventure of that kind.

Again, I’d like to buy a boat at Perm and slip down to the Petchora River, and go with the stream thousands of miles north, selling the boat to the Samoyedes at the mouth of the river, thence tramping perhaps by the tundra roads or sledging it to Mesen. What a romance, what a journey, as it seems to me now, in complete inexperience of it!

Or I’d like to take a party of literary men across the Altai, and in a verdant valley live for half a year without letters and newspapers, and each write his own book, express his own peculiar happiness in his own words.

Or I’d like to plunge south from Verney, in Seven-Rivers-Land, or from Kashgar, and climb to the mountain passes into India; and[Pg 50] as I think of it a sense of the last poem of Davidson creeps into the memory:

So much for Russia. I’d love to tramp the whole length of Japan, and peer into all the ways of the modern Japanese. There, however, speaks another interest, and that is not so much to explore strange lands as to explore strange people. Life teaches the wanderer that peoples are extra pages to geography, and the fascination can at times be irresistible. You long to be familiar with Russians, Frenchmen, Germans, Chinamen, Arabs, Americans, and the rest. And it takes you afield, it takes you far, far away from 1, Alpha Villas, or the sweet shady side of Pall Mall.

I’ve long wished to wander for years in the tents of the nomads of the Central Mongolian Plain. I came on them accidentally, tramping in Turkestan; surely among the most interesting peoples in the world, and the oldest, with customs of the most intense human interest. Nothing less than a year with them would do;[Pg 51] and that means a year without civilization, for no postman seeks the wandering tents of the Kirghis and the Kalmouk.

I should like also to pursue a study which I once began of the monasteries of the Copts, and tramp in the Sahara desert, to follow the clues of early Christianity up the Nile from Alexandria and the Thebaid, and I would make some study of Abyssinian Christianity in its native haunts. Or, on the other side of the world, I’d like to tramp the communal estate of the Dukhobors, of which I obtained a glimpse in 1922 in western Canada. Or I’d like just now to tramp as a beggar through the heart of the new Ireland.

These, and many other fascinating adventures, haunt the mind like Maeterlinck’s souls of the unborn children in that charming drama of the ideal—“The Betrothal.” If I don’t do them this time on earth, and can’t do them, friends are apt to say: “Well, next time.” One lifetime will hardly suffice to find out all there is to know and to enjoy in the world and in man.

Vachel Lindsay, with whom I enjoyed a[Pg 52] wonderful six weeks when we crossed Glacier Park, going by compass, and passed the frontier between the United States and Canada, is eager for a resumption of the trail. Next time it shall be Mount McKinley in Alaska, or Crater Lake, in the far northwest of the States. Perhaps some day I’ll go. Only recently I received from him, by one post, six long letters and a packet of coffee from Going-to-the-Sun Mountain. “Come at once,” said Vachel. But I was in Finland at the time. Otherwise I’d have flung off for Alaska or Crater Lake. The difficulty is to say “No” to such suggestions. It would be a traveling more with Nature than with man—through enormous wildernesses. Imagination could draw a wonderful picture of what such places would be like, but there is one crude unmannerly truth that the traveler always comes upon in the course of his experience of new places, and that is, that imagination, though very charming, is nearly always wrong. Knowledge of living detail shows the world to be full of the unexpected, the unanticipated, the unimagined.

[Pg 53]

There is a type of tramping which belongs more to the future; a new type, and an even more fascinating one, and that is the taking of cross sections of the world, the cutting across all roads and tracks, the predispositions of humdrum pedestrians, and making a sort of virginal way across the world. This can be tried first of all as a haphazard tramp—a setting out to walk without the name of any place you want to get to. Hence the zigzag walk, of which I write later. Keep taking the first turning on the left and the next on the right, and see where it leads you. In towns this gives you a most alluring adventure. You get into all manner of obscure courts and alleys you would never have noticed in the ordinary way. But in the country, beaucoup zigzag, as they say in France, does not work. You get tied up in a hopeless tangle of lanes which go back upon themselves. As a result of a week’s tramping you may find yourself only two steps from the place you started from. You feel like a lost ant that, after infinite trouble, has got back to the heap. It is dull to be an ant.

[Pg 54]

In the country a real cross section and haphazard adventurous tramp is one which can be known as “Trespasser’s Walk.” You take with you a little compass, decide to go west or east, as fancy favors, and then keep resolutely to the guidance of the magnetic needle. It takes you the most extraordinary way, and shows what an enormous amount of the face of the earth is kept away from the feet of ordinary humanity by the fact of “private property.” On the other side of the hedge that skirts the public way is an entirely different atmosphere and company. In ten minutes in our beautiful Sussex you can find yourself as remote from ordinary familiar England as if you were in the midst of a great reservation. And you may tramp a whole day upon occasion without meeting a single human being.

I want to do it in Russia some time—tramp across her by the compass, visit the hamlets which are five miles from the road, visit those which are fifty from the road, a hundred and fifty from the road. In that way I should find a Russia as yet unknown, unrevealed. It[Pg 55] would be a strange and fantastic quest of happiness.

“There’s no sense in it,” I can hear the stay-at-home repeat. And if he came with me it would not be long before he parted company and went back. “There’s no sense in going further.” And he is quite right if he doesn’t hear the explorer’s whisper in his heart:

The Japanese question to the Polar explorer: “What did you find when you got to the Pole?” is a foolish one. You may bring nothing back in your hands from an expedition, but you have garnered within. You have garnered for yourself and also for others. It is always worth while to quit for a time the rabbit hutches of civilization and do something which stay-at-home folk call flying in the face of fortune. “Is it not comfortable enough where you are?” they ask.

[Pg 56]

However, tramping, as I am writing of it, is not Polar exploration, nor footing it along the rocky ways of the mountains to Lhasa. It is a smaller, gentler, matter. It is merely accepting the call of Nature; taking those two weeks which Wells described in his Modern Utopia—and taking more. But it matters greatly where one chooses to go. Some countries are better than others, some districts better than other districts.

England cannot be said to be excellent tramping country; very good for a walking tour where one seeks an inn each night, but not good for a tramp in which one hopes to sleep à la belle étoile. Even when the weather is fine the dews are heavy. In the occasional dry, hot summers which occur it is however, delightful to adventure forth in the West Country or in Cumberland, or even in the Highlands. One or two jaunts are very attractive, for instance, to tramp the old Roman Wall from Carlisle to Wallsend at Newcastle, or to tramp the Scottish border from Berwick to the Solway. One passes over remarkably wild and desolate country. I think especially[Pg 57] of the track from Jedburgh to Newcastleton, and a forlorn district called, if I remember rightly, Knot of the Hill, which, however, is very much of the hill. One meets upon occasion uncouth, friendly mountain shepherds with plenty of philosophy in them. There are some wild tramps in Wales, especially in the marches. The Shropshire border is most interesting. If, however, one dives westward for places such as Dinas Mawddy or Dolgelly, one should take provisions for a couple of days. It is easy to lose yourself, and when you come upon people they speak only Welsh, and one has some trouble in making oneself understood. Dartmoor and western Ireland and the mountains and coastways of Donegal afford remarkable scope for adventurers with pack on back.

One ought to be very careful in Great Britain about wayside fires. Even when one is careful to put them out thoroughly with water before leaving one is apt to get into trouble with the farmers, the police, etc. One should also remember that if found sleeping behind haystacks, or in barns, one is liable to be haled[Pg 58] before the justice and charged with vagrancy. Not that the tramp need be ashamed, when motorists appear there in strings charged with obstruction and speeding and the like. As a practical detail, however, it may be mentioned that sleepers are very rarely discovered.

America is, of course, the tramp’s paradise, a country made by tramps. I do not mean the hoboes which infest the railroads to-day, but the Johnny Appleseeds of time past, who went exploring beyond the horizon and the sunset. The first thing to be said about the New World is its enormous stretch and variety. Many people have walked the three thousand miles from New York to San Francisco. I even came across a woman who had done it in high-heeled boots. It is no novelty. A more difficult transcontinental jaunt would be the four thousand miles of the Unguarded Line—the frontier of Canada and the United States. This is a good literary expedition, and any one who did it and described it well would make his name. My friend Wilfrid Ewart had it in mind to do, and he went prospectively over the details of such a vagabondage. But he was[Pg 59] unfortunately killed in Mexico. Such a tramp would not be confined to frontier posts, but should be crisscross, now in the Republic, now in the Empire.

Another tramp which has seldom been done, except by laborers, is to follow the wheat harvest north from Texas. The harvesting starts in June in the South, and great gangs of harvesters work northward with the summer. This implies a readiness to work in the fields. It is arduous, but a great experience. You garner wheat: you garner gold. If you take lifts when offered you may get all the way to Oregon by September and find the corn still standing there.

In America, however, the roads are killing. You can only tramp in the early hours of the morning and the cool of the evening—at least, in summer. The noontide is too hot, the many cars throw up too much dust. Cross-country tramping is much happier and provides more adventures.

But the man in the car is much more hospitable in America than in any other part of the world. When tired of some waterless, treeless[Pg 60] countryside, you can come on to the highway, hail a passing car, and be taken a long step further forward. The leisured and educated Americans do not tramp for pleasure and find some difficulty in understanding it. There is a well-known motto: Why walk if you can ride? And Americans without automobiles make their more fortunate brothers carry them. A hand wave from a pedestrian brings a car to a halt and you jump in. Journeys have been made from New York to Los Angeles, Boston to New Orleans, “stepping cars,” all the way. It is not to be recommended, however, as it is an abuse of a delightful hospitality.

Still, unless you are studying American civilization, it is hardly worth while to tramp from town to town. The wildernesses are so much more interesting. It is worth while for any one thinking out a novel walk to apply to the Department of Forests and National Parks at Washington. A National Park, conventional as it sounds, may easily prove to be a reserve of territory as extensive as an English county. They are commonly referred to[Pg 61] by propagandists as “vast natural playgrounds”—but as yet they are but little used. Yellowstone Park is the only one which is visited by great numbers of people. The others are in nowise overrun. Indeed, the railway journeys to them are generally so long that the masses of the eastern cities cannot profit by them. There are two specially marvelous ones, Sequoia and Yosemite, notable for their trees; the highest and the oldest trees in the world are to be found in these primeval wildernesses.

The Grand Canyon can afford at least a week’s walking. It is a mistake to go down it on horse or mule, and when down in the depths there is a marvelous journey for the pedestrian along the rocky flank of the fast-running Colorado River. If at Grand Canyon in August it is well to visit the Hopi Indians and see the Snake Dance. However, it is really better to visit the Canyon later in the year. At Christmas it is delightful. At midsummer it is really too oppressive down below. When I went down there was snow above and soft vernal airs three thousand feet under,[Pg 62] spring flowers in bloom, and one could sit happily by one’s wood fire in the afternoon sunshine.

Tramping in the South of the United States is very pleasant in autumn and spring, especially in Florida and Alabama. In the summer it is too hot and the mosquitoes unusually thick. A very interesting November tramp is from Atlanta, the largest city in Georgia, to Savannah on the coast. In this way you can follow, as I did, the track of Sherman’s army in its famous march to the sea.

But there are places less far afield than these. There is hardly any wilder country anywhere than in upper New York State. A tramp through New England is likely to be congenial to most Englishmen: the people are so much nearer to the English. Canada also presents enormous fields for pleasure tramping, or for tramping which is almost exploration. The far Northwest especially is wild and little traversed.

Europe, however, has equally strong claims on those who tramp, being even more diversified than is America. The language difficulty[Pg 63] is the chief drawback. There are a hundred or so tongues. Customs and laws are also bewildering. Still, the best way to see the Pyrenees or the Alps is pack on back. The charming works of Hilaire Belloc on the “Path to Rome” and the Pyrenees are memorials of excellent tramping in Europe.

A pilgrimage from inn to inn in France, especially going south through the wine country, is utterly pleasant. One dispenses with a coffeepot in these parts, a liter bottle is better. Fill it with the vin du pays wherever you go; a bottle of Chablis in the village of Chablis, a bottle of Nuits St. Georges in the village of Nuits St. Georges, a bottle of Pommard at Pommard, identifying the country by the wine of wayside inns. It is well to taste and try what any countryside, town, or hostelry is famous for, be it Creole gumbo or stuffed peppers, be it even snails, even frogs’ legs. I remember in younger days the disgust of the waiter in a little hotel opposite Chartres Cathedral when I rejected a plateful of snails which, with a clatter, he had put before me—a flagon of red wine, a chunk of bread, and a[Pg 64] plateful of Roman snails. I said “No! Take them away!”

The waiter shrugged his shoulders. Que diable! If I didn’t want snails why did I come to that hotel? Snails were their specialty. However, I confess now I have eaten snails. The first time was at Pont de Vaux, near Mâcon of Burgundy fame. The snails came on as a third course at the Hôtellerie de la Renaissance, cleverly disguised, and before I knew it I was saying, “I like these; I wonder what they are!”

They were purveyed upon a silver tray, or nickel, I suppose; they had been taken out of their shells and put into tiny pots, one snail one pot. There were a dozen or so tiny pots on the tray, each no more than half an inch across the top, and in each a snail floated in a little bath of melted butter and spice. There was a slender two-pronged fork which looked like a toothpick, and you ate the snail with that.

Very tasty! Very novel! Perhaps that was how the Romans ate them. Perhaps in ancient Egypt they ate them in that way, and these[Pg 65] are the original fleshpots. Be that as it may, I felt much amused and intrigued and turned with a friendly gesture to my bottle of local Mâcon. I was more pro-French after that, having got over a prejudice, I could no longer say, “Disgusting people; they eat snails!”

France is a delightful country for a spring escapade. Go South and stay in the country inns, and disenchant the Northern seriousness! It’s a great idea. Go out from Paris to Fontainebleau, where the birds are singing in choirs in the silvery lichened trees. You can sprawl at your length in the sun in May. It is cold sleeping out, but there are inns. You will walk amid wild daffodils and budding hyacinths. Summer is coming north to meet you at Joigny or Dijon. You enter the Côte d’Or country and spectacular stone villages among green hills. From Dijon by red-earth vineyards whence the well cut vines are sprouting an elemental eye-placating green. Your eyes need placating after the dreary North with its cities and industries. The vineyards have low stone walls which incidentally make excellent seats for the wanderer on which to[Pg 66] munch his bread and Camembert and stand his bottle of Burgundy. You come to Beaune, a name on a bottle, on a wine list, now a place well established in your mind and heart. So also Pommard, Volnay, Mersault, Nuits, Mâcon, to mention but a few.

It is a longish distance, but another journey or a continuation might be from Lyons along the banks of the Rhône or eastward to Lake Geneva and Switzerland. It is very hot on the Rhône, but there is an added interest in the old Roman cities you pass through. Avignon might be your center, and from Avignon there are delightful pilgrimages to the fountain of Vaucluse, where Petrarch and Laura met, to Tarascon, the byword for obscurity in France, to famous Arles and its amphitheater. But certainly the most wild and delightful tramp would be over the mountains by compass to Cannes, through untraversed and solitary Provence. This can be done in later summer. For although it is extremely hot on the Riviera, the whole way there is at a height, and one drops down to the coast by a precipitous road from the perfume factories of Grasse.

[Pg 67]

Tramping expeditions of even more beauty can be made on the French side of the Pyrenees, in the country of the Basques. Pious Catholics may be inclined to make for Lourdes and will encounter the sick in body going for health, and perhaps coming in the opposite direction, rejoicing cripples who have been made whole. Whether credulous or incredulous, the tramp will find Lourdes a religious curiosity well worth approaching in the spirit of a true pilgrim on foot. A tramp from Biarritz to Carcassonne, across the ankle of the Franco-Iberian peninsula holds many picturesque sights of strange people and of feudal towns. But mountainous Nature will rule the hearts of all those who come under the influence of the sublime. This is delightful country for sleeping out, provided mosquito netting be carried. Inns, however, are not so numerous, and one should be prepared to make one’s own coffee on one’s own brushwood fire.

Spain, despite some pleasant volumes recording walking tours, is really untouched. It is a remarkable country, and the people, the most conservative and delightful in[Pg 68] Europe, look somewhat askance upon Bohemians. There are tens of thousands of beggars who are accepted as philosophically as flies in summer, but the man in tweeds with knapsack on his back is regarded as some sort of strange wild animal. One is almost bound to be called upon to explain oneself to the police, and to find oneself described officially as a vagrant. Jan and Cora Gordon, two delightful vagabonds, got over the difficulty by carrying guitars, and they were understood as itinerant musicians. In the end, because they played so well, they won over the affections of many somber Spaniards. Among other tramping friends of mine, I ought to mention Mr. Forse, the tramping vicar of Southborne, who has made several tours on foot in Spain and issues his impressions as supplements to his parish magazine. I often envied him his experiences.

It was my impression in Spain that it is not wise to wear tweeds. Black is the accepted color for all people. All respectable beggars wear black. On the other hand, state visits are also made in black. With regard to the climate of Spain, it is easy to be deceived. It is[Pg 69] much colder than most people think. Northern Spain is mostly elevated plateau and is exposed to bitter winds in the spring. Andalusia, however, and the South generally, is serene and warm, hot even, but subject to unpleasant dust storms. Incidentally, it may be mentioned that the easiest way to get to Spain is via Southampton and Gibraltar. The railway journey from France is apt to be very uncomfortable.

After these two countries, northern Italy, Switzerland, and Germany come naturally to mind. Of these, by far the cheapest is northern Italy, and there is more untrodden ground. It is well to take passports for Austria as well, so as to be free of the Austrian Tyrol if you wish to enter. Austria, however, as a result of the War, lost a great deal of magnificent territory to Italy, and there is plenty of room in the latter country. Southern Germany is, of course, very fine, and not inhospitable, though the cost of provisions has gone up prodigiously. Perhaps that will be remedied—as one remembers Germany in the old days as one of the cheapest countries for travel in the world.[Pg 70] Bavaria is, however, still Bavaria, and if beer attract, the brown brau is as good as ever. The Bavarians were the only Germans who did not Gott-strafe England, America, and the rest, and they are quite pleasant neighbors. The Germans themselves are good walkers, love rucksacks, and the tramp will attract no unpleasant curiosity as in Spain. Switzerland may best be enjoyed afoot. It is common ground for the walkers of all nationalities—a League of Nations center for those who love God’s handiwork in Nature. It is, however, a rendezvous for the lazier type of tourist, and the “lounge lizard” is apt to set the pace for all. It is dangerous to spend more than one night consecutively in one of the large hotels or tourist round-ups. It is a desecration of one’s opportunities to use them for dancing and gentle promenades. The program of the visitor to Switzerland is apt to be a little unambitious. People go with heaps of luggage and find themselves tied to it, returning inevitably to it even from delightful daily expeditions, like cows from pasture. The end of a happy day should be the stepping-stone[Pg 71] to one still happier. A fortnight or three weeks spent going continuously with sunset and dawn joined by your resting place in the hills has a larger content that the equivalent days spent going out to a certain point and then returning to a hotel.

Czechoslovakia is also a country of athleticism, and one encounters good will there at every point. There is a good deal of delightful ground, especially in the Carpathians. It is rougher going than in France, but the people you meet are simpler. More rations need to be carried as villages are further apart and are apt to have less in them than one might imagine. Here are few canned goods. But there is plenty of good fruit. An expedition well worth making is to Ushorod, in the long narrow strip of territory inhabited by the Carpathian Russians.

As regards the rest of Southern Europe, conditions are frequently difficult. The Balkans are bare and sun-beaten, and largely uncivilized. There is plenty of scope for adventure, especially in Albania, where an armed guard is usually required. Dalmatia[Pg 72] is extremely interesting, especially the primitive Croats living in the interior. But the country is mostly treeless and subject to the southern sun and the Sirocco. Early morning is the best time for walking. It is often very cool then—but there is little shelter from the noontide ardor. Spalato and Ragusa are excellent starting points, especially the former. Montenegro has very interesting people and the country is obscure enough to please the stoutest adventurer.

I have written considerably in my books concerning tramping in Russia and Siberia. I have been over many thousands of miles of Russia afoot. The happiest times were in the Caucasus, by the Gorge of Dariel road, over the Cross Pass, or by the Rion valley over Mamison, or on the Caucasian shore of the Black Sea. When it is too hot to live in a house in a town, it is heaven on the mountains. Since the War, and the Revolution, the Caucasus has, unfortunately, become much more dangerous for travelers of all kinds. The tribes are warlike, and have been badly treated by Bolsheviks and Europeans in general.[Pg 73] Robbers are merciless. Pacification should, however, succeed within the next ten years, and the Caucasus become open again. Weapons are not of much use to a tramp in these parts. If he carry a revolver he should be secretive about it—for a revolver is a great lure. You are almost certain to be robbed if it is known you have a revolver—for the revolver’s sake. It is best to go unarmed and match intelligence against force when necessary. The native horsemen will be found to be of a brow-beating kind, carrying perchance several mortal weapons. It is best to meet them face to face—but smiling—never let them get you scared. They may want to turn you back or force you to work in their fields. But a smiling answer turneth away wrath, and it is well to keep them talking and watch for your chance to escape. It should be remarked that the scope for tramping is not great before the middle of May, or after the middle of October. The passes, the lowest of which is over nine thousand feet, fill up with snow; you get into whirling blizzards and lose the only trail. On Mamison, especially, it is easy[Pg 74] to go wrong, as it is extremely desolate. I crossed once before the snows had melted, an experience never to be forgotten or to be repeated.

It is better in the Caucasus to provide for sleeping out. There are inns, dukhans, bedless, dirty, and you can obtain hospitality in the villages. But the guest is scared only as long as he is under the roof. Next morning, after an hour’s grace wherein to hide his tracks, he may become the quarry of mine host.

Villages, the native auli, may be entered by day, but it is safer to keep out of them. They do not possess much which cannot be found in the wayside inn. Provisions are very scarce; such things as tea, sugar, bread, ham, generally unobtainable. Eggs, and a species of bread baked from millet seed, are the commonest fare. The latter needs a good deal of red wine to wash even a small quantity down. It is called churek, and it is good for chickens.

In the summer and autumn wild fruits of many kinds abound; strawberries, plums, grapes, and a number of species not known or sold in towns. The kizil, with its bloodlike[Pg 75] juice, is excellent boiled with plenty of sugar. Wild grapes make good fruit but are inclined to blister the lips. There is an endless abundance of grapes upon the slopes of the Black Sea shore. The wine is heady, and is apt to put you to sleep in the noontide. It is better enjoyed in the evening. It is marketed in skins—but is none the less good for coming out of a tight pig.

The only other parts of Russia to compare with the Caucasus are the Crimea, the Urals, and the Altai. The delightful Crimea is all too limited in extent. It is very beautiful, and possessed of marvelously good air. It is more invigorating in the Crimea than in the Caucasus. It is also easier and safer tramping. It may take some time to recover from Bolshevism, but I daresay it is more delightful in desolation than it was in the days when it was the national pleasure ground of the Russian middle and upper classes.

The Urals are tame beside the Caucasus, but they have a poetry of their own. The many lakes and little hills and birch forests make a welcoming land. One ought to know[Pg 76] something of geology and mineralogy when tramping in the Urals. It is one of the most remarkable parts of Europe from a geological point of view. Every stone is interesting. The man who can combine geology and tramping is likely to have a very interesting experience, and one that might even add to science in its results. The Ural region, it should be noted, is very extensive, and is for the most part unprospected—especially northward. The chief difficulty in tramping becomes ultimately absence of people, and of food. The gnats also swarm badly at night.

The Altai is also more or less untrodden country; vast majestic mountain ranges separating Siberia from China, forested and beautiful, now rather difficult of access, even for a starting point.

Of course, I went to Russia, not merely to tramp for tramping’s sake, but in order to fill in life, which is limited at home. I found tramping to be the quickest way to a nation’s heart. Many regions in which I have tramped I could not recommend for the pleasure—thus, Archangel to Moscow through the wet and[Pg 77] gloomy forests of the North, or Tashkent to Vernoe, across the Central Asian desert. That sort of expedition I would call student tramping, and recommend it heartily as a means of learning the truth about a country. No number of museums or handbooks or columns of statistics can give you the sum of reality obtained quite simply and without particular effort, upon the road. I have not tramped in India or China or Japan, these problematical countries. But, while there may not be much pleasure in footing it there, I believe it to be a way toward the understanding of their peoples.

[Pg 78]

CHAPTER EIGHT

THE ART OF IDLENESS

THE world is large enough, or is only too small, as takes your fancy or speaks your experience. But blue sky by day and fretted vault of heaven by night give you the foil of the infinite, making your petty exploit a brave adventure. After surveying the map of the world, thinking on this country and on that with gusto of a Marco Polo, you may modestly decide to take a little trip in Hertfordshire, like Mr. Wyndham Lewis, who, on a certain journalistic occasion, set forth to the discovery of Rutland. Instead of going, like[Pg 79] Kennan, into the wilds of Siberia for a year or so, you may decide to go across the New Forest during the Whitsuntide week-end, a little voyage au tour de ma chambre. There are thrills unspeakable in Rutland, more perhaps than on the road to Khiva. Quality makes good tramping, not quantity.

The virtue to be envied in tramping is that of being able to live by the way. In that indeed does the gentle art of tramping consist. If you do not live by the way, there is nothing gentle about it. It is then a stunt, a something done to make a dull person ornamental. I listen with pained reluctance to those who claim to have walked forty or fifty miles a day. But it is a pleasure to meet the man who has learned the art of going slowly, the man who disdained not to linger in the springy morning hours, to listen, to watch, to exist. Life is like a road; you hurry, and the end of it is grave. There is no grand crescendo from hour to hour, day to day, year to year; life’s quality is in moments, not in distance run.

Fallen trees are to be sat on, laddered trees to climb, flowers to be picked, nests to be[Pg 80] looked into, song birds to hear, falcons to be watched. The river invites you to strip. You sit under the cascade in the noontide; you climb into caves to cool and dry. The green roof of the mole’s track is to be followed till you find the gentleman in velvet in his home. The sound of the tapping of the woodpecker shall guide you to the loose-barked tree where with watchful eye a bird of beauty is hunting the unmannerly wood louse. You shall approach gently the deer who, in a group, wait for you with startled eyes. They run from the crashing and speedy—they can be won by the gentle. Wild nature is not so wild as we think, or we are wilder—it is not so far from us, and we are nearer.

You can enter a wider family if you are gentle. The rabbit which tempts your stones will come and smell at your toes, the birds will hop on you and sing as you lie in the grass, even the alleged ferocious animals, such as bears, will come and take bread from your hands—if they feel you are near to them.

[Pg 81]