THE

CHICKAMAUGA

DAM

and its environs

by

robert sparks walker

Title: The Chickamauga dam and its environs

Author: Robert Sparks Walker

Release Date: August 18, 2023 [eBook #71437]

Language: English

Credits: Bob Taylor, Lisa Corcoran and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

[Pg 1]

and its environs

by

robert sparks walker

[Pg 2]

The Chickamauga Dam and Lock

[Pg 3]

THE CHICKAMAUGA DAM

AND ITS ENVIRONS

BY ROBERT SPARKS WALKER

ANDREWS PRINTING COMPANY

Chattanooga, Tennessee

1949

[Pg 4]

Copyright, 1949

by

ROBERT SPARKS WALKER

Price 50 Cents

Companion Book:

THIS IS CHATTANOOGA

Price 75 Cents

Printed and bound in the United States of America

[Pg 5]

The Chickamauga Dam

and Its Environs

Well, here we are, standing on the top of a huge pile of concrete 129 feet above the ground floor, about seven miles from the center of Chattanooga.

What a beautiful body of water it is that spreads before us to the east! It is a lovely creation. I think you will agree that its shoreline warrants its claim to as much beauty as the water itself. Really, I find it so inviting that I would like to join you in a hike all the way along its many little peninsulas, capes, inlets and tiny bays, halting long enough to see the loveliest wild flowers, vines, trees and birds, especially the waterfowls which have been attracted here chiefly because they find good fishing. Suppose we pause a moment and do a little figuring. If we should walk twenty miles each day, it would take us forty days to walk around the shoreline of this lake. On our way up the river, fifty-nine miles from here, we would walk directly into the Watts Bar Dam. There we would cross over to descend the east side of the Chickamauga Lake. While we were at Watts Bar Dam, surely some person would tell us that seventy-two miles farther upstream is the Fort Loudon Dam, whose waters back up as far as Knoxville, Tennessee, a city that is 650 miles from where the Tennessee empties into the Ohio. By the time we had walked back to our starting point, we would have trekked 810 miles.

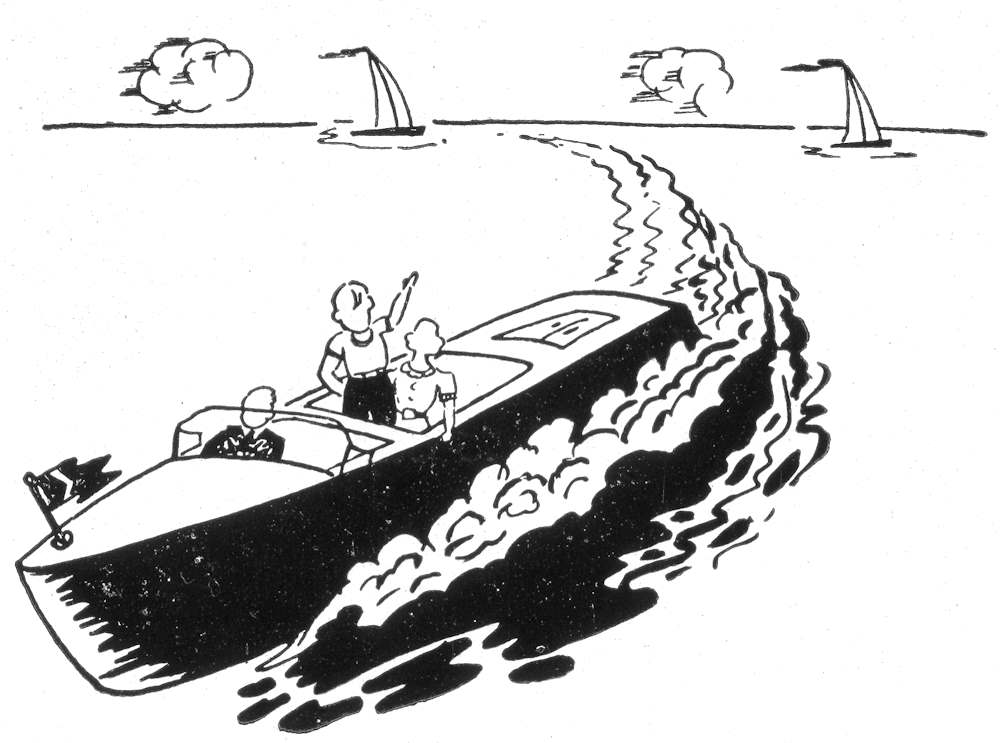

If the water that is now passing by could talk so we could understand, some of it would tell us that it has come from storage dams that have been built on the tributaries of the Tennessee River. The dams thus reporting would be, Hiwassee, Norris, Fontana, Cherokee, Douglas, Ocoee, Apalachia and Chatuge. The TVA also has control of the water of the following five dams of the Aluminum Company of America: Calderwood, Cheoah, Glenville, Nantahala, and Santeetlah.

What do you really see here? Briefly, there are a navigation lock 60 by 360 feet, a concrete spillway, a concrete powerhouse intake section, a concrete bulkhead section, and an earth embankment on each side. It calls for a long stretch of the legs to walk from one end to the other. The spillway section which includes eighteen piers, is 864 feet long. The eighteen gates are forty feet wide and forty feet high. The earth embankment to our left on the north side, is 1,390 feet in length;[Pg 6] the embankment on our right, or south side, is 3,000 feet long. The total length is approximately 5,800 feet or a little more than a mile.

The spillway section has a width of eighty-two feet at its base. Including the apron, its width increases to a hundred and twenty-five feet. The power station with its three units has a generating capacity of 81,000 kilowatts. There are three hydraulic turbines, and one more can be added.

The Tennessee Valley Authority Act of 1933, passed by Congress, gave power to the board to construct dams in the Tennessee River. Accordingly, the TVA began work on the Chickamauga Dam, January 13, 1936. The project was finished January 31, 1941, or five years after the work was started. The filling of the reservoir was begun January 15, 1940. In that time 2,510,800 cubic yards of earth were handled and 491,800 cubic yards of concrete poured. The total cost of constructing the Chickamauga Dam, including the cost of acquiring all the lands, totaled thirty-eight million dollars.

It is well to remember that the water shed of the Tennessee River embraces 40,910 square miles. Believe it or not, about half of that area is found above the Chickamauga Dam. This upper basin has an average rainfall of 50.8 inches.

Let us now turn our backs to the Chickamauga Lake for a glimpse towards the west. To the southwest, we see Lookout Mountain standing like a bright cameo in a position as if it were looking down on Chattanooga. To our right, we view the head of another rocky monster that is looking southward. This is Signal Mountain, which is simply the local name for the southern end of Waldens Ridge. A little to our left, in the background between Signal and Lookout Mountains, stands Raccoon Mountain. These are parts of the Cumberlands and are plateaus, each of them being quite flat on its top. Their average altitude is approximately 2,000 feet above the sea. The Cumberlands were so named by Dr. Thomas Walker in 1748 in honor of the Duke of Cumberland, William Augustus, who two years previous had defeated the Scotch in the battle of Culloden. Following that bloody event, the Duke was so bitterly hated that the early Scotch settlers in America refused to call the mountains by the name Cumberland, preferring to speak of them by their Cherokee name Ouisoto Mountains, (pronounced We-soto).

If we could leap like a giant kangaroo, the first kick of our hind legs down the Tennessee River would leave us standing on the dam at Hales Bar, forty miles from here. Another leap of eighty-two miles and we would rest on Guntersville Dam in Alabama. Our third leap would take us seventy-four miles farther on where we would strike the Wheeler Dam. Next a kitten’s spring of only sixteen miles and we would strike the Wilson Dam. A sudden jump of 52 miles would leave us astride the Pickwick Dam, and then a tremendous long leap of 184 miles and we would find ourselves perched on the Kentucky Dam, only twenty-three miles from the mouth of the Tennessee River at Paducah, Kentucky. If we chose to continue the journey to the[Pg 7] mouth of the river we would find ourselves 471 miles from where we now stand on the Chickamauga Dam.

DIAGRAM OF

TVA

WATER CONTROL

SYSTEM

MAP OF THE TENNESSEE RIVER

The high railroad bridge we see directly in front of us is where the Cincinnati-Chattanooga division of the Southern Railway crosses the river. This railroad is owned by the city of Cincinnati and leased by the Southern Railway. The creek a few rods to our right is the North Chickamauga. It has its source on Waldens Ridge and leaves the mountain about fifteen miles from here at Daisy, Tennessee, where it has chiseled out a marvelously beautiful gulch of rustic beauty. When the Chickamauga Dam was begun, this creek emptied into the[Pg 8] river a short distance above the dam, but after an artificial bed was dug, its course was changed so that it would find the river below the dam.

To our left, on the south side, we can see where the South Chickamauga Creek empties into the Tennessee. It was there that the Federal troops under General W. T. Sherman crossed on pontoon bridges at daylight, November 24, 1863. The steamer Dunbar assisted in transporting Sherman’s division to the other side of the river. A pontoon was also laid across the mouth of the Chickamauga. It was then that Sherman attacked the right wing of General Bragg’s Confederate forces, which occupied Missionary Ridge from this north end to the south. Sherman was fighting throughout the day while the battle of Lookout Mountain was raging to our southwest. Because Missionary Ridge ends near the Chickamauga Dam, and since the battle fought there on November 25, 1863, has been regarded by some historians as the turning point in the Civil War, a little later I shall describe briefly that battle. For the present we shall leave some of the interesting places below the dam in order to tell about a few sites and historical events that took place above the dam and along the South Chickamauga Creek.

The waters that gather above the Chickamauga Dam have quite naturally obliterated some old village sites and some prehistoric mounds. It was fortunate, however, that the Department of Archaeology, under the direction of T. M. N. Lewis, of the University of Tennessee, made scientific explorations of the ancient dwelling places and the mounds. The facts and the artifacts thus obtained have been preserved for posterity.

On February 26, 1940, when the navigation lock at the Chickamauga Dam was opened, since there was no Cherokee Indian to represent the aborigines who used the Tennessee to make the initial trip through it, it was a fortunate circumstance that Nature stepped in and saved the day on that memorable occasion and let a large turtle swim through. It was a splendid model for a river boat, somewhat made on the order of a submarine, a natural boat propelled by living paddles and guided by a live rudder. It passed through the lock as freely as if it had been commissioned to serve as the official representative of the river’s inhabitants.

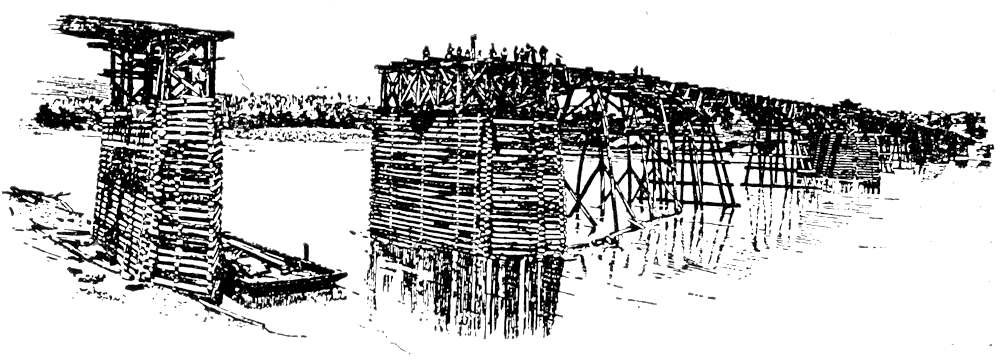

Military Bridge over the Tennessee River at Chattanooga in 1863

[Pg 9]

Among the historical places blotted out by waters of Chickamauga Dam was Oo-le-quah, or Dallas Island, situated a few miles upstream. On the higher ground overlooking the isle was the village of Dallas, which, in 1819, became the seat of government at the time Hamilton County, in which the Chickamauga Dam is situated, was carved out of the Hiwassee Purchase. The new county’s south boundary at that date was the Tennessee River, which up to about the year 1800, had been known to the Indians as the Hogohegee River. The Cherokees still remained in possession of the land south of the river.

When the state of Georgia, by force, took possession of the Cherokee lands within her borders, some of the prominent Indians sought refuge in Tennessee. Among those who were chased out of Georgia was Joseph Vann of Spring Place, a dozen miles east of Dalton. James Vann, the father of Joseph, had married a full-blooded Cherokee. He was a prosperous farmer. The two and a half-story brick residence he erected about the year 1797 still stands at Spring Place and has been tenanted through the years. It is looked on today as a splendid example of early architecture.

An old boatman on the Tennessee River operating his hand-propelled paddle wheel boat.

After leaving Georgia, Joseph Vann settled on the south bank of the Tennessee River, a few miles above the Chickamauga Dam. He was very industrious, and soon there were thirty-five houses erected and occupied on his property. The village was known as Vanntown. There was scarcely a moment’s rest, however, for the poor Indians. The greedy whites kept encroaching on their real estate until only a small portion of their once large territory remained. Several years previously the government had induced some of the Cherokees to [Pg 11]move to the Arkansas, west of the Mississippi. The last of the Cherokees departed in 1838. At that time the white settlers took possession of the lands lying south of the Tennessee River. Three years previous to that date, however, the whites had slowly been slipping into their lands. Hamilton County’s boundary was then extended to take in the Cherokee lands from the Tennessee River to the Georgia line. It was at that time that Dallas lost the county seat, since Vanntown was chosen and a court house was erected. This happened about the time that William H. Harrison was elected President of the United States, so Vanntown became Harrison, Tennessee.

A Near View of the Chickamauga Dam and Lock.

About the year 1815, following the close of the Creek War, John Ross, Cherokee, and Timothy Meigs, son of Return J. Meigs, the Indian Agent, established a trading post seven miles south of the Chickamauga Dam. They operated a ferry as well as a general store. The place became known as Ross’ Landing, but when the Indians had departed for the lands in the West, the whites had the town surveyed, and the name was changed to Chattanooga. John P. Long became the first postmaster, March 22, 1837. However, this was not the first post office established in the old Cherokee lands, for on April 5, 1817, Rossville post office was established four miles to the south with John Ross as postmaster. This was said to have been the first post office established in this part of the Cherokee Nation.

The word Chattanooga is a corruption in the spelling of the Muskogean word Chatanugi, which years previously had been the name of Lookout Mountain, meaning “rock coming to a point.” In the narrow valley between the east side of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge is a small stream which was also known as Chatanugi Creek. Near its mouth where it empties into the Tennessee was, in the 18th century, a small Indian village by the same name.

It is an interesting geological fact that in ages past the water we now know as the Tennessee River flowed south of the east base of Lookout Mountain and emptied into the Coosa River in what is now Alabama. A later upheaval blocked its southern passage and forced it to seek a new route, which it did by cutting out its way through the rough rocks of the Cumberlands.

The town of Chattanooga kept growing and was chosen as the county seat. Harrison, which for many years had been full of promise for growing into a large and thriving city, began to dwindle until it was left behind as an ordinary village, which was wiped off of the map by the waters after the building of the Chickamauga Dam. The forming of the Chickamauga Lake created so many beautiful sites along its margin that hundreds of families could not resist the advantages offered by the board of the TVA to take up sites for summer homes and camps. At various places on the lake are to be found beautiful cottages and bungalows where families enjoy recreation as well as the pure atmosphere and the cool currents of air that come from the fresh waters. There they enjoy boating, fishing and other sports, not only along the shores of Harrison Bay State Park, but also at Soddy and other choice situations. When the town of Harrison was obliterated by the impounded waters of Chickamauga Lake, there came into existence new Harrison, whose people today enjoy boating and fishing[Pg 12] where Joseph Vann and other Cherokees once produced crops of hay and corn.

A few miles upstream from the obliterated Dallas Island there was located until the completion of the Chickamauga Dam, the second largest island in the Tennessee River. This was Hiwassee Island, which contained 781 acres, was two miles long, and a mile wide. It received its name from the Hiwassee River, which finds the Tennessee east of the island.

Beginning in 1937 and continuing for two consecutive years the Archaelogical Department of the University of Tennessee succeeded in completing the excavations of all village sites and mounds on this historical island. The result of these investigations were published in 1946 by the University Press, Knoxville, in a book entitled the Hiwassee Island, by T. M. N. Lewis and Madeline Kneberg.

When the white settlers came into Tennessee, they found Hiwassee Island was being ruled by the honest and kind-hearted Cherokee Chief Oolooteeskee, popularly known as John Jolly. In 1809, when Sam Houston was 16 years old, he visited Hiwassee Island. Chief Jolly became so fond of the lad that he adopted him, rechristening him The Raven.

Several years previous, Jolly’s brother, Tahkinsteeska, had moved to Arkansas and was the principal chief of the Cherokees in the West. In 1818, John Jolly decided to join his brother. Although agents of the United States had been persuading the Cherokee to move to the new lands west of the Mississippi, it was necessary that when they chose to do so they must obtain a permit to make the change, as indicated in the following official paper:

“John Jolly, the bearer, having under his superintendence 16 boats laden with Cherokee families and their property are on their way to the Arkansas River to enter lands designated for them by the Treaty in July last, in exchange for lands here relinquished by them to the United States, which Treaty was constitutionally ratified the 25th of December, 1817. The said Cherokee Nation being at peace and friendship with the United States, are entitled to the confidence and friendly offices of the citizens, and therefore recommended to all such with whom they may meet on their passage to the place of their destination. They are hereby particularly recommended for aid (should their circumstances need it) to the officers commanding military posts, or stations on their line of movement.

“Given under my hand and seal of the Cherokee Agency the 26th day of January, 1818, and in the 43rd year of American Liberty and Independence.”

(SEAL)

RETURN J. MEIGS.

Sam Houston, however, did not go with his foster-father on this long journey. He remained in Tennessee and studied law. A few years later, Houston was elected governor of Tennessee. Not long thereafter he married a Miss Allen of Nashville, Tennessee, and in three months he left her and resigned as governor. Houston then[Pg 13] sought his old friend and foster-father on the Arkansas River and married Chief Jolly’s niece, a Cherokee by the name of Tiana Rogers. Houston’s next move took him to Texas where he became commander-in-chief of the Texan army. After defeating Santa Ana in April, 1836, thereby winning the independence of Texas, Houston became the first president of the republic of Texas. It was due to his negotiations that Texas was annexed by the United States in 1845. The flooding of the Hiwassee Island by the waters of the Chickamauga Dam put an end to its history as a place where human beings might reside.

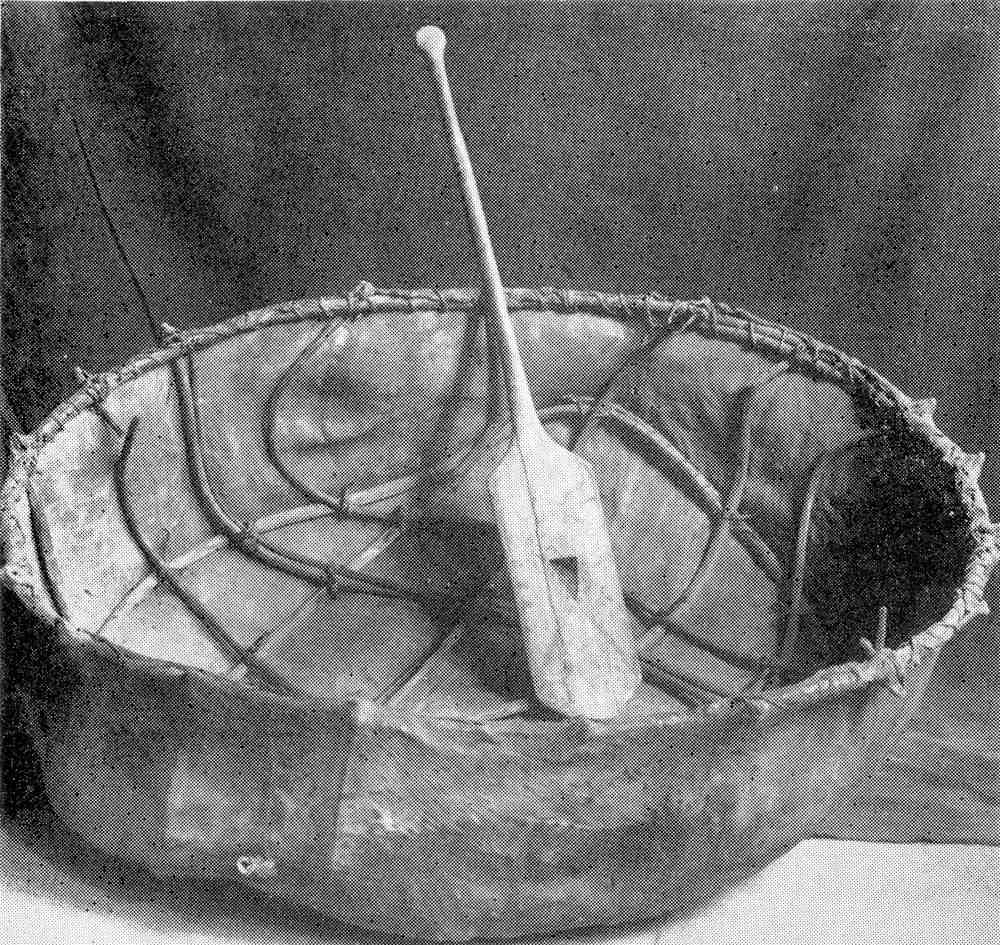

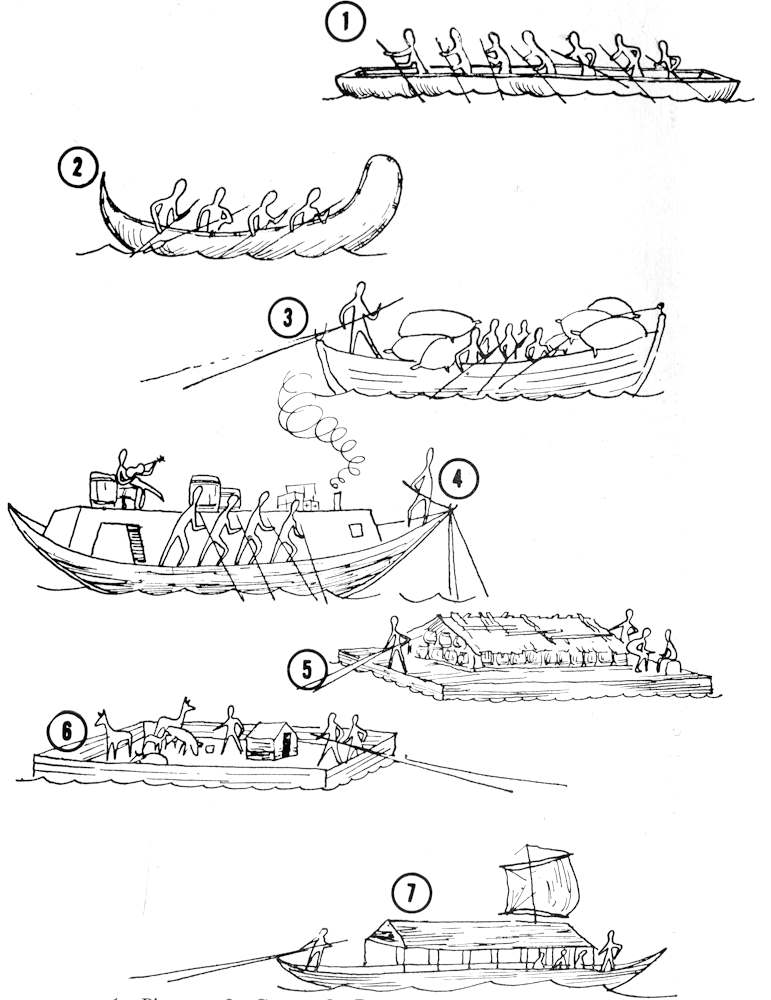

If we could have stood on the bank of the river here almost 200 years ago, we would have been amazed at the sight of the curious kinds of watercraft floating by. Perhaps, the most primitive type would have been the bullboat, which was made by stretching a wet buffalo hide with hair on the inside over a framework of willow strips, in the shape of a tub or a canoe, about seven feet in diameter. The bowl-shaped type would carry about 700 pounds. It was propelled with a paddle made of wood, or with the shoulder blade of a buffalo fastened to a stick for a handle.

Every now and then would have passed us a big flat boat resembling in shape a big box floating on the water, carrying as its cargo human families with their possessions. This rather frail boat was known as an ark, because it suggested the Biblical boat made by Noah. The ark served the early American settler so well that one writer at least has aptly asserted that “it was out of the womb of an ark that our nation was born.”

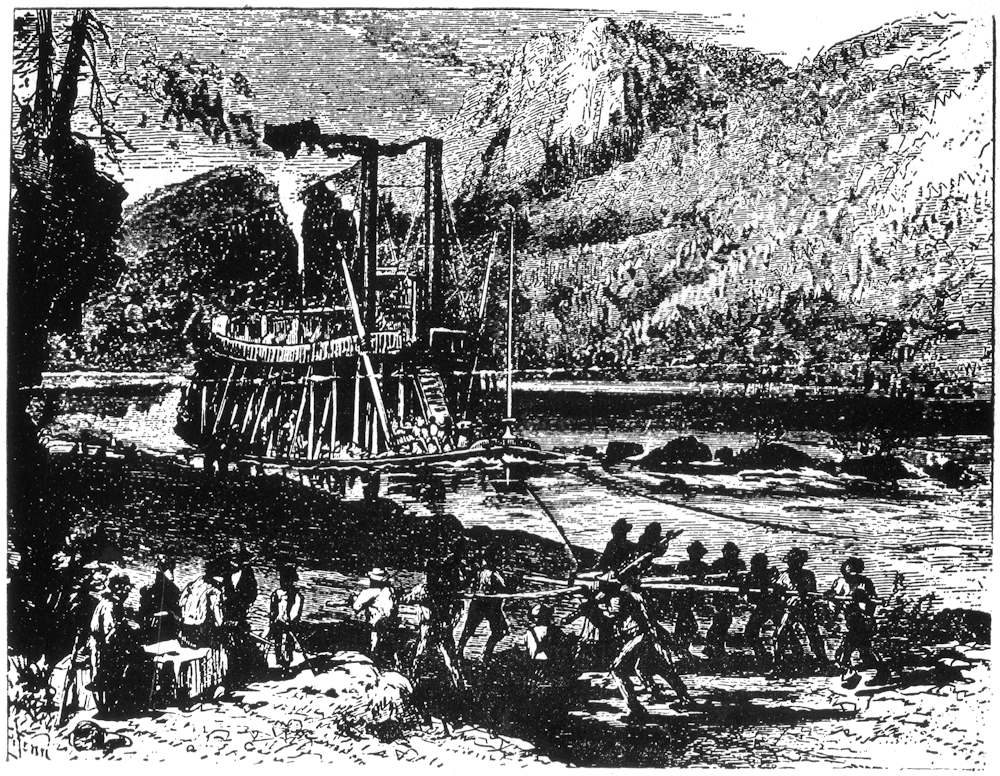

Steamboat being warped through “The Suck”

[Pg 14]

We would have been well entertained by the frequent passing of the flatboats. The average rivercraft of this sort would carry about 400 barrels of goods. About two-thirds of the flatboat was roofed like an ordinary house to keep families and cargo dry.

There also would have been seen many popular keelboats. Compared to the boxlike ark, the keelboat was graceful, long and slender, ranging in length from forty to eighty feet, sharp at each end and with a shallow keel. Most of the keelboats were well roofed. Sometimes a sail was hoisted to aid the crew in the difficult task of rowing the boat.

Bullboat made of buffalo skin and used by the Indians on the Tennessee River

We would have seen some barges, too. The average length of this kind of boat was from fifty to one hundred twenty feet with a width from twelve to twenty feet. A cabin was built at the stern, and fastened to the one or two masts were square sails.

Primitive types of boats that were used on the Tennessee River

1—Pirogue; 2—Canoe; 3—Bateau; 4—Keelboat; 5—Flatboat; 6—Ark; 7—Barge.

Besides the light canoes, we would have noticed the passing of the dug-out, known as a pirogue. A boat of this kind was made by hollowing out a log of cottonwood, tulip, sycamore or other tree with an adz or by fire. One or both ends were left square. A very large pirogue would have passed which was made by chopping out two [Pg 16]large trees, and using one tree for each side of the boat, filling in the middle with planks, and then sealing the bottom so that it was watertight. Such a boat would carry several tons of produce and as many as twenty-five men.

There would be passing a few flattened boats with tapering ends known as bateaux. A bateau was not as clumsy as the pirogue to handle in the water. The very light bateau was known as a skiff. The sizes of the bateaux varied, and each of the larger kinds used on the river was able to carry fifty tons of cargo.

I shall now resume the story of the Battle of Missionary Ridge, a brief reference to it having been previously made when General Sherman’s crossing the river near this point was mentioned. On September 19 and 20, 1863, the Federals in command of General Rosecrans had suffered a defeat at the battle of Chickamauga, in which a total of about 34,000 men were killed and wounded, the casualties being about evenly divided. In the battle of Lookout Mountain, November 24, the Confederates suffered severe losses, including that strategic point. During that night the Confederates withdrew their forces to Missionary Ridge where they joined General Bragg’s troops. Throughout the day of the battle of Lookout Mountain Sherman persisted in pounding at Bragg’s right wing, the object being to force him to weaken his center by strengthening his right wing. If this had happened, General Grant, then stationed on Orchard Knob, a few miles south of this dam, would have struck a heavy blow to Bragg’s center and split the Confederates in two, making their capture a certainty. This was November 25th. At 2:30 o’clock in the afternoon the Federals were in battleline facing Missionary Ridge and were waiting patiently for official orders to attack. Notice was given them to be ready to advance at a signal of the firing of six cannons two seconds apart from Orchard Knob.

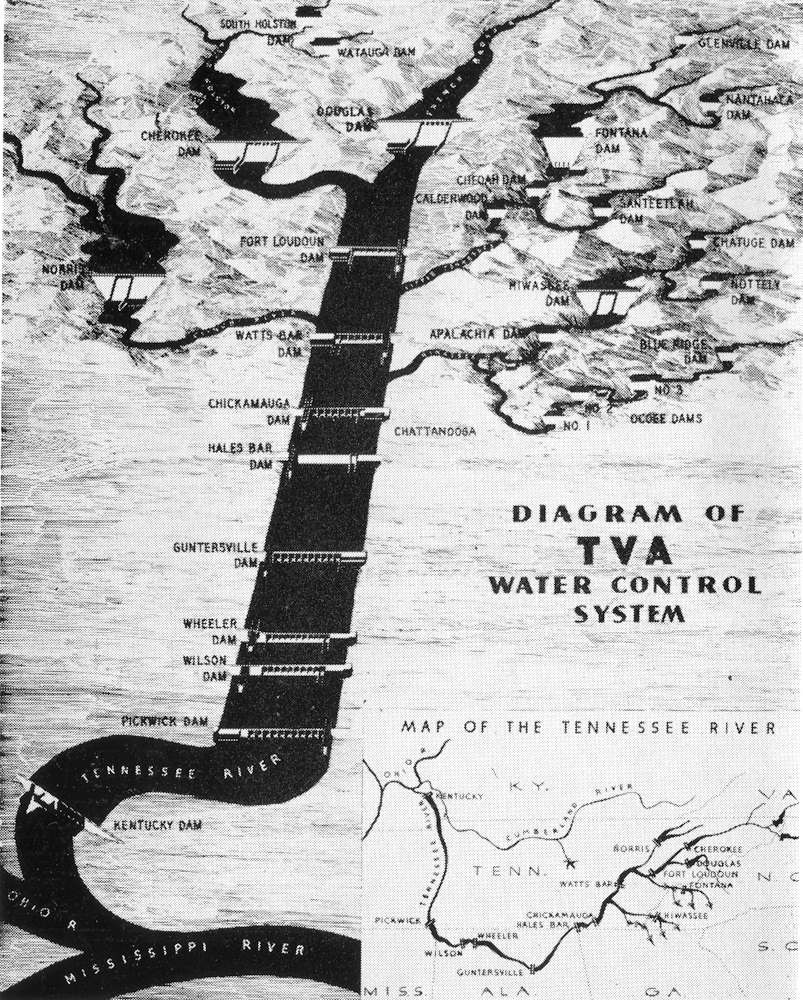

Passing through the Chickamauga Lock

Eight sail boats racing on Chickamauga Lake

Impatient soldiers anxiously counted the minutes waiting for the booming of the six cannons. The thrill came promptly at 3 o’clock, when the noise of the half dozen cannons startled their ears. With a wild rush, even though they were under terrific fire from Bragg’s army on Missionary Ridge, the Union soldiers succeeded in driving the Confederates from the first line of trenches. There they had been ordered to halt and wait for further orders. After a moment’s pause, as if for the purpose of gaining a deep breath, there was a roar and shout from thousands of throats along the entire Federal line, as the troops plunged forward without official orders from commanding officers. In the next few moments there was made one of the most remarkable charges that was ever recorded in military history. Just as General Hooker’s troops had the previous day enthusiastically stormed the Confederates stationed on the slopes of Lookout Mountain, so on the following day, did the Federal army under Grant sweep up the western slopes of Missionary Ridge, taking the advance line of the Confederates before them. Because of the nearness of the two contending forces the Confederate batteries stationed on the crest of the ridge could not be used. The Union men moved forward yelling as they fired their muskets, whereupon Bragg’s line broke in wild [Pg 19]confusion and was swept entirely from Missionary Ridge’s full length, except a small section near the railroad tunnel at the north end. Bragg’s men fled eastward and the Union troops pursued them as far as the Georgia line. The Confederates lost forty cannon, 7,000 stand of arms, and 6,687 men. The Federals lost 5,815 men. The battle of Missionary Ridge was so closely connected with that of Lookout Mountain, some students of military history at least think of it as the second day’s battle of Lookout Mountain.

John P. Long, Chattanooga’s first postmaster, who lived among the Cherokees, stated that the meaning of the word Chickamauga is “sluggish water.” J. P. Brown, however, in his book entitled Old Frontiers says the word means “dwelling place of the war chief.” The Chickamauga Dam was so named because of its being situated near the mouth of the North and South Chickamauga Creeks. In the early days of the Indians’ occupancy of this territory there was a village at the mouth of the South Chickamauga known as Bulltown.

About eighty miles northeast of the Chickamauga Dam, in the Little Tennessee River near old Fort Loudon, was Mialoquo, a very prominent island where lived many prominent Cherokees. Dragging Canoe was the leader of the militant minded Indians there.

In 1770 there passed down the Tennessee River at the site of the Chickamauga Dam a Scotch trader by the name of John McDonald. With him was a half-breed Cherokee by the name of William Shorey. They turned their boats which held their possessions up the South Chickamauga Creek and paddled and poled for about seven miles upstream, halting at the crossing of the Great War Path where the Lee Highway now crosses the Chickamauga Creek.

At this point, John McDonald decided to establish a trading post. The old Scotchman soon proved himself a good business man because he became very prosperous. At the outbreak of the American Revolution the Cherokees aligned themselves on the side of the British. McDonald was appointed the sub-agent for the King’s service, and his place was the headquarters for Tories and Indians south of the Ohio River.

John McDonald married Anna Shorey, daughter of William Shorey. The location of his home and store is now the site of the Brainerd Mission, which was established in later years. Directly across the Chickamauga from McDonald’s was Chickamauga Town, that stretched a mile on the higher ground, ending at the present Chattanooga Airport. In 1849, when the state of Georgia finished the Western and Atlantic Railroad, a station and post office was established there known as Chickamauga, Tennessee. It became a busy village where thousands of dollars worth of farm produce was bought and shipped. After General Bragg abandoned Chattanooga, Chickamauga became the terminus where the Confederate troops and supplies were loaded and unloaded.

In 1777 the Cherokee settlements from Virginia to the Chattahoochee River were destroyed by the whites. Following these heavy losses, the Lower Cherokees gave up all their lands lying in South[Pg 20] Carolina, except a very small strip on their western boundary. Two months later, the Middle and Upper Cherokees signed away their lands lying east of the Blue Ridge. About the same time they ceded their lands in northeast Tennessee to the white man. Most of the Cherokees, feeling helpless, accepted the unjust treatment, but the loss of their most valuable ground was more than Dragging Canoe could endure. This patriotic Cherokee declared that before he would submit to such an outrageous treaty, which swindled his people boldly, he would go to war. There were hundreds of other brave Indians who felt as did Dragging Canoe and were awaiting an opportunity to strike back at the greedy whites, hoping thereby to regain some of their lost property. When Dragging Canoe made his intentions known, there were attracted to him the bravest of his tribe, who seceded from the Cherokee, organizing themselves into a militant wing which became known as the Chickamaugas. They settled at various places on the Chickamauga Creek.

This beautiful stream of water is formed by the aquatic contributions of many other creeks. It rises in northwest Georgia, and as it flows northwest it collects the waters from other sources. One mile above the site of John McDonald’s trading post it receives the water from the West Chickamauga, which has its source at the junction of Pigeon and Lookout Mountains, thirty-five miles south of Chattanooga. This is the Chickamauga Creek which gave the name to the battle of Chickamauga. It might properly be stated here that the many references to it in Civil War history as meaning “the river of death” is an error.

Henry Hamilton, British Governor of the Northwest Territory, stationed at Detroit, had transported on horseback from Pensacola thousands of dollars in army supplies, which were stored at McDonald’s for the Cherokees to use in their warfare against the Americans. Hamilton had offered so many rewards to the Indians for the scalps of revolutionists that he was popularly dubbed the Hair Buyer. John Stuart was the British Agent for the South who had charge of seeing that the war supplies were kept at McDonald’s. Everything went well until the Americans, in command of Colonels Evan Shelby and Montgomery, got into boats at Kingsport, Tennessee, in the spring of 1779, and descended the Tennessee River. Soon after passing where the Chickamauga Dam now stands, they piloted their boats to the south side, where they found an Indian fishing. They made a prisoner of him and forced him to guide them to Chickamauga Town, Dragging Canoe’s headquarters. On reaching Chickamauga, they took the Indians by surprise, captured all of the supplies the British had stored with McDonald, and burnt the buildings to the ground. Among the spoils were 150 head of horses which the officers employed for riding back home. Dragging Canoe’s brother, Little Owl, who settled two miles upstream at the same time Chickamauga Town was selected, had his village destroyed by Shelby’s men shortly after they had reduced to ashes the capital of the Chickamaugas. There were many prominent Cherokees living at Chickamauga Town, among them was one named Long Fellow, a son of Nancy Ward, the beloved Cherokee [Pg 22]woman. Dragging Canoe and Little Owl were first cousins of Nancy Ward.

Motor boats speeding on Chickamauga Lake

In 1785 an Indian trader by the name of Mayberry left Baltimore with a supply of goods. Daniel Ross, a young man from Sutherlandshire, Scotland, met Mayberry, and being full of adventure joined him on the proposed journey south. They took to the Tennessee River at Kingsport and on their way down stream learned from a Chickasaw Indian, who was a passenger on the boat, that both Ross and Mayberry were to be captured. When they landed at Brown’s Ferry, a short distance below Ross’ Landing, the Indians were suspicious of the new arrivals. Chief Bloody Fellow asked for an immediate execution, but before a definite decision was reached, a messenger was sent to confer with John McDonald at Chickamauga. McDonald was able to secure the release of the two men. Later, Daniel Ross married Molly McDonald, daughter of John McDonald, and John Ross, who later became the most distinguished Chief of the Cherokee Nation, was their son. Ten miles northeast of Dragging Canoe’s Chickamauga Town was another Cherokee settlement known as Ooltewah. Some of the Cherokees most prominent men once lived in that region, especially along Ooltewah Creek, which name has been corrupted to Wolf Tever. Much of the land there which was formerly occupied by the Cherokees, has been inundated by the Chickamauga Dam. Among the Cherokees once living there was Ostenaco, popularly known in history as Judd’s Friend.

Following the disgraceful treaty of Long Island, in 1777, Ostenaco joined the Chickamaugas and moved to Ooltewah. In 1760, when the British troops surrendered Fort Loudon, Ostenaco was one of the chiefs to march out with the conquered soldiers. The day’s trek took the 180 soldiers 15 miles where they encamped on Cane Creek. At daybreak the next morning the British were attacked by several hundred Cherokees, and after they had killed Paul Demere, who had been in command of the fort, and 23 of his men, Ostenaco ran about the field yelping like a wolf in an effort to stop the Indians from fighting. He thus saved the lives of many white soldiers.

After the restoration of peace Ostenaco went on a visit to Williamsburg, Virginia, and there saw a picture of King George III. This fired his ambition to make a journey to England, as his old friend, Chief Little Carpenter, had once done. After Ostenaco’s persistent pleading the governor of Virginia gave his consent. Ostenaco with two attendants and with William Shorey of Chickamauga as interpreter set sail with Lieutenant Henry Timberlake as guide. Before reaching England William Shorey took sick and died. On their arrival they were presented to King George by Lord Eglinton. The Indians attracted considerable attention. Sir Joshua Reynolds, eminent artist, made a group painting of the Indians, and then he made a separate painting of Ostenaco.

Without an interpreter Ostenaco suffered a serious handicap. He was unable to deliver an address he had prepared for King George. He was determined that the King should know what he had to say and on his return to America, November 3, 1762, he gave the following[Pg 23] address to Governor Bull of Charleston, S. C., to be translated and transmitted to King George:

“Some time ago, my nation was in darkness, but that darkness has now cleared up. My people were in great distress, but that is ended. There will be no more bad talks in my nation, but all will be good talks. If any Cherokee shall kill an Englishman, that Cherokee shall be put to death. Our women are bearing children to increase our nation, and I will order those who are growing up to avoid making war with the English. If any of our head men retain resentment against the English for their relations who have been killed, and if any of them speak a bad word concerning it, I shall deal with them as I see cause. No more disturbances will be heard in my nation. I speak not with two tongues, and ashamed of those who do.”

Ostenaco was seasick on his way over the big pond, and the following brief report hints as to what impressed him most on the long journey:

“Although I met with a good deal of trouble going over the wide water, that is more than recompensed by the satisfaction of seeing the King and the reception I met from him being treated as one of his children and finding the treatment of every one there good to me.

“The number of warriors and people all of one color which we saw in England, far exceeded what we thought possibly could be. That we might see everything which was strange to us, the king gave us a gentleman to attend to us all the day, and at night till bedtime.

“The head warrior of the canoe who brought us over the wide water, used us very well. He desired us not to be afraid of the French for he and his warriors could fight like men, and die rather than be taken.”

The Chickamaugas were not ready to give up after their towns had been destroyed in 1779. They rebuilt Chickamauga Town, but in 1782 John Sevier, in command of a troop of mounted Tennesseeans, descended on them, and after burning Chickamauga, marched up the creek and destroyed Little Owl’s village. Fourteen years later John Sevier became the first governor of Tennessee.

It is of interest to note that the land on which Little Owl’s village was situated, containing 105 acres, has been The Elise Chapin Wild Life Sanctuary, owned by the Chattanooga Audubon Society. On the property is an Indian cabin which, according to reports and records handed down by the earliest white settlers, was the birthplace of Spring Frog, or Tooantuh, the Cherokee sportsman and naturalist. The cabin has been preserved by Mrs. Sarah Key Patten and is one of the oldest found in this part of the Cherokee country. Tooantuh was born about the year 1754, fought with Andrew Jackson in the Creek war, and was praised for his bravery at the battle of Horseshoe Bend. He went West and took up the life of a farmer at Briartown, Oklahoma, where he died. He was a man of great influence and was among the chiefs whose portrait was painted for the War Department.

I have already acquainted you with John McDonald, Scotch[Pg 24] trader, and Dragging Canoe’s Chickamauga Town across the creek from McDonald’s home. Before the removal of the Cherokees there was more history made at that place, which at the time attracted visitors from as far away as England, and yet it is in less than 10 miles of the Chickamauga Dam.

After a hundred years of warfare, not until the year 1800 were the Cherokees able to rest. That year the Moravians established a mission at Spring Place, Georgia. Before selecting that place they visited McDonald’s on the Chickamauga and, after examining it closely, rejected it because they judged it to be an unhealthy place in which to live. In 1816, when the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, of Boston, sent Cyrus Kingsbury to the Cherokee country, he purchased the identical place that the Moravians had rejected. It was directly across the Chickamauga Creek from Chickamauga Town.

On his way South, Kingsbury stopped in Washington and laid his plans for establishing a mission and school before President James Madison, who heartily approved it and tendered government assistance in equipping it. The school was opened in January 1817 and had the distinction of being the first school in North America where domestic science and agriculture were taught. It preceded the Gardiner Institute of Maine by four years.

The institution grew rapidly. At one time there were forty buildings of one kind and another standing on its grounds. Some of the outstanding men and women of New England were its leaders and teachers. Its first superintendent was Ard Hoyt, who left many prominent descendants. Hundreds of Cherokees were educated and Christianized during its twenty-one years of existence.

At first the mission was called Chickamauga, but since Chickamauga Town was situated on the other side of the creek, visitors coming to the school often became confused and went to the Indian village. It was decided to correct the handicap by changing the name to Brainerd, in honor of David Brainerd, the pioneer missionary among the Indians of New England and New York. David Brainerd had been in his grave seventy years before the founding of this namesake of his.

Many were the visitors of prominence who came to Brainerd. Perhaps the most noted person was President James Monroe, who paid the mission a surprise visit May 27, 1819, and spent the night there. Monroe took a deep interest in the institution and gave it the material support of the Federal Government.

John Howard Payne, author of the famous song, Home Sweet Home, while collecting data for a history he was preparing of the Cherokee, spent two weeks at Brainerd, and the fourteen large volumes of his manuscripts now at the Newberry Library in Chicago contain copies of many letters written by the pupils of this mission school.

Dr. Samuel Worcester, one of the founders of the American Board and its first secretary, who was largely responsible for founding Brainerd Mission, visited the institution in 1821. He was ill when he left his home in Boston and traveled by boat as far as New Orleans. After[Pg 25] driving a horse and buggy from that southern city to Brainerd, he arrived there on May 25 a very sick man. On June 7 he passed away. His funeral in the Brainerd cemetery on June 9, 1821, was attended by hundreds of Cherokees riding horseback from all parts of the nation, who came to show their respect for a man they had not seen but whom all had learned to love.

Little Owl’s village site on the Elise Chapin Wildlife Sanctuary

Sequoya, the inventor of the Cherokee syllabary, also came for a visit. The first translations of the Bible in Cherokee was made by another Indian by the name of Atsi, but who was known to the whites as John Arch. This took place at Brainerd. John Arch was the interpreter at Brainerd. When he arrived at the school, after having walked to the mission from the Nantahala Valley of Western North Carolina, now a part of the Smoky Mountain Park, he was so raggedly dressed and so wild looking that the missionaries were three days deciding whether to accept him as a pupil or not. He had only one possession, a gun, which he gladly exchanged for some warm clothes. Much to their surprise John Arch proved an apt pupil, and after receiving a few years’ education, he became one of the strongest supporters of the school.

Sequoya spent a dozen years perfecting his alphabet. It was judged by competent critics as ranking second to the English alphabet, which required several hundred years to perfect. By Sequoya’s alphabet of 85 characters a Cherokee was able to read and write in a[Pg 26] few hours. The inventor of this alphabet received many honors. He had the distinction of being the only literary person in the United States to receive a pension, which came from the Cherokee Nation. The Big Trees of California were also named Sequoia in his honor. His alphabet enabled the Indians to make rapid progress in education, and after type had been cast in Boston, The Cherokee Phoenix, a newspaper, was established and published at their capitol in New Echota, near the present town of Calhoun, Georgia. Elias Boudinot, a full-blooded Cherokee who had been educated at Brainerd Mission and Cornwall, Connecticut, was chosen as its editor.

John Ross, who became one of the most influential and renowned Cherokees, was a frequent visitor at Brainerd and was its chief supporter, so was Andrew Jackson. Jackson was the first white man to assist Cyrus Kingsbury in his initial meeting with the Cherokees at Turkeytown near the present town of Centre, Alabama, when the plan of the mission and school was approved by the Cherokees.

In 1817, Elias Cornelius, representing the American Board, the founders of the Brainerd Mission, came to Brainerd for a visit. Cornelius was on a good will tour among the Indians of the South and Southwest where the Board planned to establish more missions and schools. On November 15 he left Brainerd on horseback with three companions en route for New Orleans. After traveling about 200 miles, he reached Caney Creek, which was swollen from recent rains. Cornelius did not dare risk swimming his horse, but selected a camp site nearby. Soon he saw a band of Cherokee approaching on the opposite side of the creek. They plunged their horses into the swollen stream and swam successfully across. Night was speeding on, and the Indians encamped in the woods nearby.

In the early part of the evening Cornelius went to pay his neighbors a friendly visit. On approaching the open fire he saw tomahawks, corn, skins of wild animals, and bows and arrows spread before the fire. Fortunately, there was one Indian in the crowd who was able to speak English. When Cornelius saw the arrows were bearing the stain of fresh blood, he learned that this band of Cherokees was returning from west of the Mississippi, some 30 miles from the Dardanelles, where they had fought a battle with the Osage tribe. About 800 Cherokees, including their allies, the Delawares and Shawnees, had participated. Some of the Cherokees had been taken prisoners, and the Cherokees had captured a few of the Osages. Among them was a little Osage girl, about five years old, whom they were taking back to their homes as one of their valued war trophies.

When Cornelius queried them about the little girl’s father and mother, one of the Indians reached into a rough looking bag, fumbled around inside, and drew out two human scalps. Holding them up in plain view he said, “Here they are!”

Cornelius’ heart was deeply touched. He took the little girl in his arms, whereupon she screamed from fear because she had been taught to shun white men as being very cruel to Indian children. Remembering that kindness is the only universal language that is understood by beasts and birds, by all wild flowers and trees and every living[Pg 27] thing, Cornelius spoke kindly and sympathetically to the girl and gave her a piece of sweet cake, which she knew not how to use. Then he presented her with a pretty cup, and thus he won her confidence and friendship. Before leaving them, he told the Indians about the Brainerd Mission, and although the Cherokee who claimed possession of the little girl intimated that he might be willing to sell her, he promised faithfully that he would place her in the Brainerd school on his arrival at the mission. Cornelius learned before leaving them that the Indian who owned her had not captured her, but that he had swapped a horse for her with the Cherokee who had taken her as a prisoner.

The next day Cornelius proceeded on his way. After reaching Mississippi, while he was entertaining some friends in Natchez, Mr. Cornelius related the story of the little Osage captive, whereupon a Mrs. Lydia Carter, who was touched with the pathetic story, gave Cornelius $150 with which to purchase the little girl’s freedom. Soon Cornelius received a letter from Brainerd stating that the Indian had not brought the little girl to the school as he had promised. When interviewed, the Indian refused to part with her unless the missionaries would give him in return a Negro girl as a servant. Such thoughts were repulsive to the missionaries. On Cornelius’ return to Brainerd he rode 60 miles to call on the Indian who held the little girl. On seeing him approaching, she did not become frightened, but ran to greet him. Her owner, however, stubbornly refused to release the little girl.

On his way back to Boston, Cornelius called on the President of the United States. Then he interviewed the Secretary of War who handed him written authority to demand possession of the little Osage girl. On receipt of the order, Ard Hoyt, superintendent of Brainerd Mission, went after the little girl and paid the Indian for her release. On his way back to the Mission, Hoyt, christened her Lydia Carter in honor of the benevolent woman of Natchez. Lydia was adopted by Mr. and Mrs. Chamberlain, missionaries at Brainerd, and she became a sister of their own little daughter, Catherine.

A few days later rumors reached the missionaries that the Cherokees held two other Osage children, a boy and a girl, and that Lydia was their sister. The boy had been sold first for $20 and resold so many times that the last price brought $150. Return J. Meigs, the Indian Agent, gave the missionaries authority to take possession of the boy and place him in the Brainerd school. John Ross, then a dashing young man, went to Brainerd and tendered his services in rescuing the boy. Ross rode horseback for 250 miles to the mouth of the Catawba River. He handled the situation with skill. Before going to the house of the Indian who held the boy, Ross hid his horse in the woods and stealthily approached on foot. When he glimpsed the lad, entirely nude, playing about the hut, as agile as a deer, Ross leaped the fence gracefully, and in another moment he had the boy securely in his arms. In great excitement the owner came rushing out. Ross turned a deaf ear to the pleading of the Indian, who tried all kinds of schemes to prevent Ross from taking the boy away. In a [Pg 29]few moments Ross had the boy riding behind him on the horse, and they were hastening on their way to Brainerd Mission. After 13 days, riding through forests, swimming rivers, fording streams, Ross returned with his human prize. During this time he had traveled more than 600 miles. On his return the Osage boy was christened John Osage Ross in honor of the young man who had rescued him.

Mayor Hugh P. Wasson of Chattanooga, standing by the side of President Dutra of Brazil, points to an interesting feature of the Chickamauga Dam

The story of these two children was so remarkable that Elias Cornelius wrote a book entitled The Little Osage Captive, which was published in Boston, also in York, England. The book had a wide sale.

Later when John Rogers, Cherokee, came from Arkansas to take Lydia Carter and John Osage Ross back to the Osages, there was great sadness at Brainerd when the missionaries had to part with the children. John Rogers was an antecedent of the late humorist Will Rogers and a relative of Tiana Rogers, Sam Houston’s Cherokee wife.

The Brainerd Mission was closed on August 19, 1838, at the time of the removal of the Cherokees to the West. Many of the missionaries chose to accompany them to the new lands and there resumed their labors as they had done so unselfishly at Brainerd. It should be remembered that Brainerd Mission gave the name to Missionary Ridge, and on August 19, 1938, at the identical hour marking the 100th anniversary of the closing of the Brainerd Mission, a meeting was held on the grounds attended by hundreds of Chattanoogans.

A few months before the Chickamauga Dam was completed in 1940, its historical name, with so much beauty and clear, sweet music in its pronunciation, was threatened with extinction.

Persons who were interested in preserving the original Cherokee names became anxious over the safety of the name Chickamauga Dam. Through the columns of The Chattanooga News a protest was registered daily for about a week. The beginning interview came from the historian of the University of Chattanooga, who was strongly opposed to changing the name to the McReynolds’ Dam, in honor of Chattanooga’s Congressman. On succeeding days, similar protests were published from Chattanooga’s leading citizens, each of them giving logical reasons for the retention of the name Chickamauga. At the close of the series of interviews the public had been thoroughly awakened to the importance of holding on to this beautiful historical name which had been given to some of this region’s loveliest streams by its aborigines. Irvin Cobb once declared that the word Chattanooga was the most beautiful of any word he knew in the English language. Could not the well known humorist writer also have made the same assertion about the word Chickamauga?

To climax the movement to hold on to the historical name, the Chickamauga Chapter of the DAR of Chattanooga, at the last moment when the bill was up for its final reading, the members voted unanimously for the retention of the name Chickamauga. When Congressman S. D. McReynolds received notice of its action, he withdrew his name, and the name Chickamauga Dam was thereby saved for posterity.

[Pg 30]

Old Grist Mill at Brainerd Mission as seen from Chickamauga Town.

[Pg 31]