Title: An English woman-sergeant in the Serbian Army

Author: Flora Sandes

Author: Slavko Y. Grouitch

Release Date: August 19, 2023 [eBook #71442]

Language: English

Credits: MWS, Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries.)

There is no page 244 in the book, as mentioned on the ‘Colonel Militch on Diana’ illustration on Page 220.

The words Topolchar and Topolchor have been left as spelt.

The words wagons and waggons have been left as spelt.

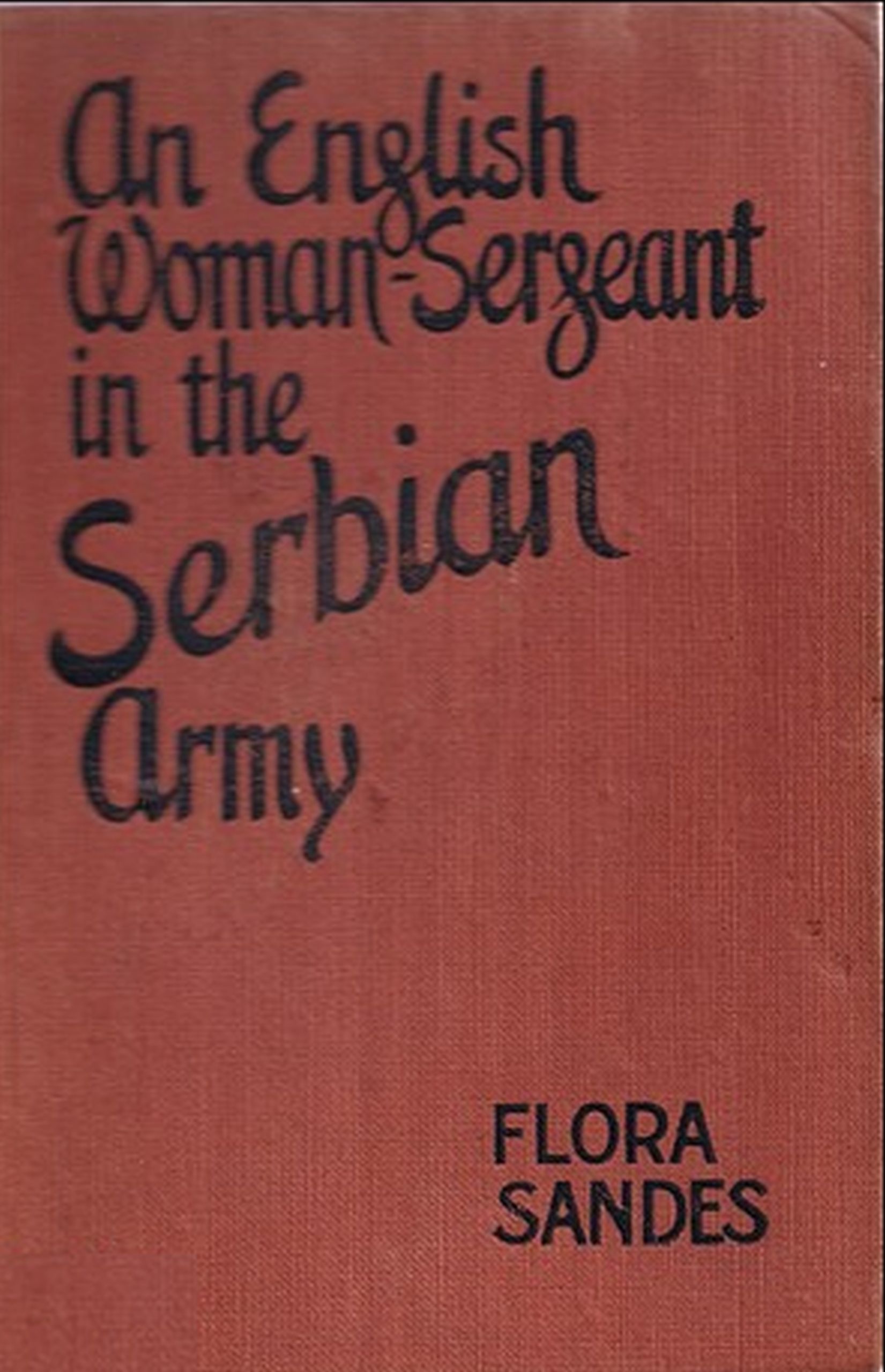

COLONEL MILITCH, COMMANDANT OF THE SECOND REGIMENT (ON THE LEFT) AND HIS CHIEF OF STAFF; WITH THE REGIMENTAL FLAG

Frontispiece

BY FLORA SANDES

With an Introduction by SLAVKO Y. GROUITCH Secrétaire-Général of the Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs

HODDER AND STOUGHTON LONDON, NEW YORK, TORONTO

[v]

Innumerable have been the manifestations of sympathy, generosity, and of the sincere desire to help Serbia given by the British people to their little Ally since the very beginning of the War. No words could ever express the deep gratitude of the Serbian Nation for the splendid services rendered by the many British Medical Missions, whose staffs, men and women, have nursed the sick and wounded without a thought for the hardships and dangers to which they have been personally exposed, and which, especially during the typhus epidemic and, later on, during the Great Retreat, were very serious indeed. British women, have played a [vi] most prominent part in this humanitarian work of charity and mercy, and some of them have even given their lives for the Cause.

When the history of their splendid achievements is written—as I hope will be done some day—the name of Miss Flora Sandes will certainly figure in it with a special acknowledgment. In the interesting pages which follow she will herself give a vivid description of her experiences during the Retreat in the ranks of the Serbian Army, in which, I believe, she was the only foreign woman allowed to serve in a fighting capacity. That in itself speaks very highly of the esteem and confidence in which she is held in Serbia. But she only took to a rifle when there was no more nursing to be done, as, owing to [vii] the Army retreating, the wounded could not be picked up and had to be left behind. Before that she had worked in Serbia for eighteen months as a voluntary nurse, practically without interruption, having left the country but twice, and that on a short visit to London to collect funds and bring back with her dressings and other hospital supplies which were badly wanted. During the typhus epidemic she volunteered to go to Valjevo, which was the centre of the disease and where eight Serbian doctors and many nurses had already succumbed. The same fate very nearly overtook her, but fortunately she recovered and resumed immediately her self-imposed duty.

Such examples of self-sacrifice, added to so many others given by British men and [viii] women in Serbia, have implanted in the hearts of the Serbians a deep love and admiration for Great Britain, who may well be proud of such sons and daughters.

SLAVKO Y. GROUITCH,

Secrétaire-Général of the

Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[ix]

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Rejoining the Serbians, November, 1915—The Second Regimental Ambulance | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| A Serbian Ambulance at Work—We Start to Retreat | 22 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| A Ride to Kalabac and a Battle in the Snow | 46 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| I Meet the Fourth Company—A Cold Night Ride | 77 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| We Say Good-bye to Serbia and take to the Albanian Mountains | 104[x] |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Fighting on Mount Chukus | 126 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Elbasan—We push on towards the Coast | 148 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Serbian Christmas Day at Durazzo—Aeroplane Raids | 170 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| We Go to Corfu | 192 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The “Slava Day” of the Second Regiment | 230 |

REJOINING THE SERBIANS, NOVEMBER, 1915—THE

SECOND REGIMENTAL AMBULANCE

Events moved so rapidly in Serbia after the Bulgarians declared war that when I reached Salonica last winter I found it full of nurses and doctors who had been home on leave and who had gone out there to rejoin their various British hospital units, only to find themselves unable to get up into the country.

I had been home for a holiday after working in Serbian hospitals since the very beginning of the war, but when things began to look so serious again I[2] hurried back to Serbia. We had rather an eventful voyage, as the French boat I was on was carrying ammunition as well as passengers, and the submarines seemed to make a dead set at us. At Malta we were held up for three days, waiting for the coast to clear. The third night I had been dining ashore, and on getting back to the boat, about eleven, found the military police in charge, and the ship and all the passengers being searched for a spy and some missing documents. We were not allowed to go down to our cabins until they had been thoroughly ransacked, but as nothing incriminating was found we eventually proceeded on our way, with a torpedo-destroyer on either side of us as an escort. The boats were always slung out in[3] readiness, and we were cautioned never to lose sight of our life-belts. We had to put in again at Piræus, and again at Lemnos for a few days, so that it was November 3rd before we finally reached Salonica—having taken fourteen days from Marseilles—only to find that the railway line had been cut, and there was no possible way of getting up into Serbia.

My intention had been to go back into my old Serbian hospital at Valjevo to work under the Serbian Red Cross as I did before; that was out of the question now, of course, as Valjevo was already in the hands of the Austrians, but I thought I might get up to Nish and get my orders from the President of the Serbian Red Cross there. I inquired from a Serbian officer staying at the hotel, who had just[4] ridden down from Prisren, if it would be possible to ride up into Serbia, but he most strongly discouraged all idea of riding, saying that with every facility at his disposal, and relays of fresh horses all along the route, it had taken him ten days to ride from Prisren to Salonica, and that during that time he had frequently been unable to obtain food either for himself or his horses; that, furthermore, it was very dangerous even with an escort, as part of the way was through hostile Albania, and that all the horses were needed for the Army. I gave up that idea, therefore, and set to work to find out where I could come into touch with the Serbians, and finally found I could go to Monastir, or, to call it by its Serbian name, Bitol. Accordingly, I, with four[5] other nurses and a doctor whose acquaintance I had made on the boat, who also found themselves unable to reach their original destinations, left for Bitol the next day.

Arrived at Bitol, I at once made inquiries about the next step farther, and found that Prilip, about twenty-five miles farther on, was still in the hands of the Serbians, though its evacuation was expected any minute, and even now the road from Bitol to Prilip was not considered safe on account of marauding Bulgarian comitadjes, or irregulars. However, the English Consul had to go out there, and he said he would take us with him to see how the land lay, and whether we were needed in the hospital there.

I spent the afternoon prowling round Bitol, mostly in the Turkish quarter.

[6]

The next day we went with the Consul to Prilip—though up to the last moment I was afraid we should not go, as there was so much talk about the road not being safe—some of us in the touring car and the rest in a motor-lorry, with an escort of Serbian soldiers, all armed to the teeth. I took my camp bed and blankets with me, on the off chance of being able to stay at Prilip, as I was gradually edging my way up to the Front, leaving the rest of my baggage in Bitol to be sent after me. We got there without any mishap, keeping a sharp look-out for Bulgarian patrols. We found a Serbian military hospital at Prilip, and I asked the Upravnik or Director if I might stay and work there, to which he consented, but added that he was afraid that it would not be for long,[7] as they were expecting to have to fly before the Bulgarians any day. I accordingly got a room at the hotel, and the Consul left me an orderly to look after me, named Joe, who could speak a little English. I was very pleased at getting into a Serbian hospital again in spite of all difficulties, as the opinion in Salonica seemed to be that it was impossible; but I must say I felt rather lost when the cars went back that evening and I was left alone, the only Englishwoman in Prilip.

The first thing I did was to turn all the furniture, including the bed, out of the room in the tenth-rate pub., which was the best hotel that Prilip boasted, and made Joe scrub the floor and put in my own camp bed.

I take the following extract out of my[8] diary, written on my first night in Prilip:

“Monday, 8th, 8.30 p.m.—I am sitting up in bed in my sleeping sack, writing this in a very small room in S—— Hotel, Prilip. The room contains (besides my camp bed) a rickety chair, and a small table with my little rubber basin, a cracked mirror and my faithful tea-basket. From the café below comes a deafening chorus of Serbian soldiers. I am glad there is a good lock on the door, as someone is making a violent effort to come in, and from the fierce altercation going on between him and the boy-chambermaid, scraps of which I can understand, he is apparently under the impression that I have taken his room—I may have for all I know, but anyhow the proprietor gave it to me.

[9]

“The view from my window is not calculated to inspire confidence either. It looks on to a stableyard full of pigs, donkeys and the most villainous-looking Turks squatting about at their supper. These, I tell myself, are the ones who will come in and cut my throat if Prilip is taken to-night, as I don’t think any responsible person in the town knows I am here. However, if I live through the night things will probably look more cheery in the morning.”

In the middle of the night I was awakened by another fearful racket in the passage. “That’s done it,” I thought, sitting up in bed with my electric torch in one hand and my service revolver in the other, “it’s like my rotten luck that the Bulgars should pitch on to-night to[10] come in and sack the town.” However, a very few minutes convinced me that it was only two drunks coming up to bed, and, telling myself not to be more of a fool than nature intended, I turned over and went to sleep again.

I think my morbid reflections must have been brought on by the supper I had had. Joe, my orderly, had, for reasons best known to himself, taken me to a different restaurant to the one where we had been to lunch with the Consul, assuring me that it was much better; it was not, very much worse, in fact, though I should not have thought such a thing could be possible. It was full of soldiers and comitadjes drinking. At first I could get no food at all, and when it did come it was uneatable. I had supper with an[11] American doctor I met in the town next night, and he informed me that food was so scarce and dear in Prilip that to get anything of a meal you had to have your meat in one restaurant, your potatoes in another, and your coffee in a third!

Next morning I went round to the hospital, and in the afternoon one of the doctors took me round and introduced me to the Serbian Chief of Police, who was most friendly and polite, got me a nice little room close to the hospital, and apologised for not being able to ask me to come to his house as his guest as his wife was ill. This is the sort of courtesy that has always been extended to me in Serbia; they think the best of everything they can offer is not too good for the[12] stranger within their gates, and I began to feel much cheered up.

There were not very many wounded in the hospital, but a great many sick, and dysentery cases beginning to come in rapidly. I was soon quite at home there, being used to the ways of Serbian hospitals. The Director was going to Bitol for a few days, and I asked him to ask the head of the Sanitary Department there, Dr. Nikotitch, if I might join a regimental ambulance as nurse, as I heard that the ambulance of the Second Regiment was some miles farther up the road, just behind the Front. The Second and Fourteenth Regiments were then holding the Baboona Pass, a very strongly fortified position in the mountains, against the Bulgarians.

[13]

I stayed about a week in the hospital; there was plenty of work to do—in fact, to have done it properly there would have been enough for a dozen nurses, as dysentery was rapidly becoming an epidemic, and the hospital was soon full up; we could take in no more. We were fearfully short of everything, beds, bedding, drugs, and we simply had to do the best we could with practically no kind of hospital appliances. Any kind of proper nursing was impossible, most of the patients lying on the floor in their muddy, trench-stained uniforms.

One afternoon two of the doctors motored out to the ambulance of the Second Regiment and took me with them. We stopped first at the ambulance of the Fourteenth, where we found twenty[14] unfortunate dysentery cases lying on the bare ground in two ragged tents groaning. We had a long chat with the doctor of the Second Regimental ambulance, and had coffee and cigarettes in his room—a loft over the stable. That is to say, I did not do much of the talking as he was a Greek, and besides his own language only talked Turkish and not very fluent Serbian, although later on, strange to say, when I joined the same ambulance, we used to carry on long conversations together in a kind of mongrel lingo very largely helped out by signs.

We visited a large empty barracks on our way back, and made arrangements for it to be turned into a dysentery hospital, as this disease was beginning to assume serious proportions, and our [15]hospital was full up. This was never carried out, however, owing to the Bulgarians’ rapid advance a few days later.

The next day the Director came back, and brought with him papers whereby I was officially attached to the ambulance of the Second Regiment; and it was part of my extraordinary luck to have just hit on this particular regiment, which is acknowledged to be the finest in the Serbian Army. Everybody was extremely kind to me in the hospital, and all the doctors asked me to stay there and work, saying I could have no idea of the hardships of ambulance life; but as I knew that it would not be many days before we all had to clear out of Prilip before the advancing Bulgarians, and that would mean my going back to Salonica, and[16] losing all chance of staying with the Serbians (whom I had grown thoroughly attached to in my work among them for the last year and a half), I adhered to my resolution to throw in my lot with the Army.

I always had my meals at the hospital now, and we had quite a merry supper that night, and they all drank my health, declaring they would see me back in three days, when I had been frozen out of my small tent on the hills, where it was already bitterly cold. The next afternoon I went all round the hospital and said good-bye to everyone; I was very sorry to leave my patients, they are so affectionate, and always so grateful for anything one does for them. One young soldier was my special pet; he had been driven mad[17] from the shock of a shell bursting close to him, though he was not wounded. He was such a nice gentle lad, and I used to spend a good bit of time with him, coaxing him to swallow spoonfuls of milk, as he would not take anything from anyone else, though the Bolnichars—hospital orderlies—were very kind to him. I heard afterwards that he lived till the hospital was evacuated, but died at Bitol. A good many of the men were from the Second Regiment, and when they heard I was going to their ambulance we only said au revoir. They assured me we should meet again when they were sent back to their regiment, as they would come and see me directly they had the smallest pain.

It was rather late in the day when Joe[18] and I finally set out in a very rickety carriage commandeered by martial law, with a very unwilling driver, and a horse that could hardly crawl. The harness, which was tied up with bits of string, kept coming to pieces, and the driver kept stopping to repair it. Joe began to look very uneasy, and kept peering round in the gathering dusk for any signs of wandering Bulgarian patrols, or comitadjes, as it was a very lonely road. At last, after what seemed an interminable time, we arrived at the ambulance, which was on the grass by the side of the road. They were not expecting me then as it was late, and the Serbians turn in soon after sunset. There was apparently nowhere to sleep and nothing to eat. One of them took us round to the doctor’s quarters,[19] the same loft I had visited a few days before, not far from the ambulance. He turned out full of apologies, and said that he had had notice that I was coming that day, but that as it was so late he had given me up.

It seemed a bit of a problem where I was to sleep, but eventually some of the soldiers turned out of one of their small bivouac tents. These tents are only a sort of little lean-to’s, which you crawl into, just the height of a rifle, two of which can be used instead of poles. You seem a bit cramped at first, but after I had lived in one for a couple of months I did not notice it. All the tents were bunched up together, touching each other, with four soldiers, or hospital orderlies, in each. I insisted, to their great surprise,[20] in having mine moved to a clean spot about fifteen yards away from the others, and some more or less clean hay put in to lie upon. There was a good deal of excitement and confusion, the whole camp turning out and assisting. They could not imagine why I wanted it moved, and declared that the Bulgarian comitadjes would come down in the night and cut my throat before the sentry knew they were there. Afterwards, when I was more used to war, and accustomed to sleeping in the middle of a regiment, and to sleeping when and where one could, in any amount of noise, I used to laugh at my scruples then, and only wondered they were all as good-tempered and patient as they were with what must have seemed to them my extraordinary English ideas. The doctor[21] sent me down some supper of bread and cheese and eggs, and presently came down himself and sat on the grass beside me as I ate it, and altogether they all did their best to make me comfy, and were as amiable as only Serbians can be when you rouse them out in the middle of the night and turn everything upside down. It reminded me somewhat of my arrival in Valjevo, at the beginning of the typhus epidemic, when owing to the vagaries of the Serbian trains I was landed at the hospital at 3 a.m., after everyone had given me up. After I had finished my supper I crawled into my tent, tightly rolled myself up into the blankets as it was a very cold night, and slept like a top on my bed of hay.

[22]

A SERBIAN AMBULANCE AT WORK—WE

START TO RETREAT

Next morning we all turned out at daybreak, and I got a better view of my surroundings. The ambulance itself consisted of one largish tent, where the patients lie on their clothes on very muddy straw, until they can be removed to the base hospital by bullock-wagon. This is done as often as transport permits. There were a few cases of dressings, drugs, etc., in the tent, and a small table for writing at. There were about twenty patients in at one time, some of them sick[23] and some wounded. About a dozen little tents, similar to mine, for the soldiers and ambulance men, and two or three wagons completed the outfit.

There was a Serbian girl, about seventeen, helping; she was very unlike any other Serbian woman I had ever met, lived and dressed just like the soldiers, and was very good to the sick men. She spoke German very well, so that we understood each other and became very good friends; she gave me lots of tips, and though I had been under the impression that I knew something about camping out and roughing it, having done so already in various parts of the world, she could walk rings round me in that respect. The first thing the men did after I had had some tea with them by[24] the camp fire was to set to work to convince me of the error of my ways, and to move my little tent back to its old spot before any harm could happen to me. We don’t have breakfast in Serbia, but have an early glass of tea, very hot and sweet, without milk.

The doctor came down shortly afterwards to prescribe for the men who were sick, and then a couple of orderlies and myself dressed the wounded ones, those who were able to walk coming out of the tent and squatting down on the grass outside, where there was more room, and light enough to see what you were doing. They kept straggling in all day from Baboona, where there was a battle going on; it was not far away, and the guns sounded very plain. There were not very[25] many seriously wounded, but I am afraid that was because the path down the mountains is so steep that it is almost impossible to get a badly wounded man down on a stretcher. Any who are able to walk down do so, and they were glad to get their wounds dressed and be able to lie down. At lunch-time we knocked off for a couple of hours, and I went back with the doctor to his loft. We had lunch in great style, sitting on his bed, there being no chairs, and with a blue pocket-handkerchief spread out between us for a table-cloth. He said they were expecting to have a retreat at any moment, and that we must always be in readiness for it as soon as the order arrived. All the patients we had were to go off that afternoon if the bullock-wagons arrived. This question[26] of transport is always a terrible problem; in many cases bullock-wagons are the only things that will stand the rough tracks, although here there was a good road all the way to Bitol, and had we had a service of motor-cars we could have saved the poor fellows an immense amount of suffering. Imagine yourself with a shattered leg lying in company with three or four others on the floor of a springless bullock-wagon, jolting like that over the rough roads for twenty or thirty miles. When I was in Kragujewatz we used to get in big batches of wounded who had travelled like that for three or four days straight from the Front, with only the first rough dressing which each man carries in his pocket.

The wagons came that afternoon, but[27] only two or three for the lying down patients; several poor chaps who were so sick they could hardly crawl had to turn out and start on a weary walk of a good many miles to the nearest hospital at Prilip. One man protested that he would never do it, and I really didn’t think he could, and said so; however, the ambulance men, who were well up to their work, explained that it was absolutely imperative that all should get off into safety day by day, otherwise when the order came suddenly to retreat we might find ourselves landed with an overflowing tentful of sick and wounded men, and no transport available on the spot. “Go, brother,” they said kindly, “Idi polako, polako” (“Go slowly, slowly”), and fortified with a drink of cognac from the ambulance[28] stores, and a handful of cigarettes from me, he and the others like him set off.

We all turned in prepared that evening, and I was cautioned to take not even my boots off. Later on, sleeping in one’s clothes didn’t strike me as anything unusual; in fact, two months later, when we had finished marching and arrived at Durazzo, it was some time before I remembered that it was usual to undress when you went to bed, and that once upon a time, long, long ago, I used to do the same.

In the middle of the night a special messenger arrived with a carriage from the English Consul at Bitol, advising me to come back at once, and that a motor-car would meet me in Prilip, and take me back to Bitol. I knew perfectly well that[29] I should not be able to find the motor-car in the middle of the night in Prilip, which is as dark as the nethermost regions, there not being a lamp in the town, and that it would probably mean sitting up in the carriage in one of those dirty little streets all night; so I said all right, I would see about it in the morning, and went to bed again. In the morning I had another look at the telegram, and as it was not an order to go back, but only advising me strongly to do so, I said I meant to stop. They all seemed very pleased because I said I wanted to stick with the Serbians, and, as we all sat round the camp fire in the bitter cold of a November sunrise, we drank the healths of England and Serbia together in tin mugs full of strong, hot tea.

[30]

Later on during the day came another telegram, and I must say that the English Consul at Bitol was a perfect trump in the way he did his duty by stray English subjects and looked after their safety, before he finally had himself to leave for Salonica. A Serbian officer was sent out from somewhere, and he said that if I liked to throw in my lot with them and stop he would send out a wagon and horses, in which I could live and sleep, and in which I could carry my luggage. I hadn’t very much of the latter, and what I had I was perfectly willing to abandon if it was any bother, but he wouldn’t hear of that; and in due course the wagon arrived, and proved, when a little hay had been put on the floor to sleep on, a most snug abode.

[31]

The next day the wounded kept straggling in all day, faster than we could evacuate them, and when the order came at ten o’clock that night that the regiment was forced to retreat from Baboona, and that the ambulance was to start at once, we had sixteen wounded in the tent, twelve of them unable to walk. The Serbian ambulances travel very light, and half an hour after receiving our orders we were on the move, the men being adepts at packing up tents and starting at a moment’s notice. At the last moment, while the big ambulance tent was being taken down, a man with a very bad shrapnel wound in the ankle was carried in, and as it was blowing a gale, and we couldn’t keep a lamp alight, I dressed it by the light of a pocket electric torch,[32] which I fortunately had with me. They said at first that he would have to go on as he was, but as I knew very well that it might be three or four days before he would get another dressing I insisted on them getting out some iodine, gauze, etc., and kneeling in the mud, and with some difficulty under the circumstances as the tent was being taken down over my head, I cut off his boot and bloody bandages (he had been wounded in the morning) and cleaned and dressed the wound. He was awfully good, poor fellow, though it hurt him horribly, and he hardly made a murmur. Then two ambulance men carried him out to the ox-wagon, three of which had appeared from somewhere, I don’t know where. I found the Kid, as I called her, had been working like a[33] Trojan in the pitch dark and pelting rain helping the men through the thick slippery mud down the bank to the road, and had settled four men, lying down, in each wagon, that being all they could hold, and had also decided the knotty point which should be the four unlucky ones who had to walk—these four being, I may say, quite well enough to walk, but naturally not being anxious to do so. When they were all started off, she and I clambered into our wagon, and the whole cavalcade set off in the pitch dark, not having the faintest idea (at least, we had not, I don’t know if anybody else had) where we were going to travel to or how long for. We were a long cavalcade with all the ambulance staff, the Komorra or transport, and a good many soldiers all[34] armed, and a most unpleasant night we had rumbling along in the dark, halting every few miles, not knowing whether the Bulgars had got there first and cut the road in front of us, or what was happening. It was bitterly cold besides, and as the Kid and I were black and blue from jolting about on the floor of our wagon I began to wonder how the poor wounded ever survived it at all.

A little way on we picked up a young recruit who said he was wounded and couldn’t walk; our driver demurred, saying that he had had orders that no one else was to use our wagon, but we said, of course, the poor boy was to come in if he was wounded. He lay on my feet all night, which didn’t add to my comfort, though it kept them warm. He[35] was evidently starving, so we gave him half a loaf of bread that we had with us, and some brandy out of my water-bottle, and he went to sleep.

Putting brandy in my water-bottle had been suggested to me by a tale a young Austrian officer, a prisoner, who was one of my patients in Kragujewatz hospital, told me. Poor boy, he had been badly wounded in the leg, and was telling me some of his experiences during the war and about the terrible journey after he was wounded, travelling in a bullock cart. He said he had a flask full of brandy, and that was a help while it lasted. When that was all gone he filled up the flask with tea, which was pretty good, too, as it had a stray flavour of brandy still, and then when he had drunk all that he put[36] water in, and that had the flavour of tea!

The next morning our “wounded hero” hopped off quite unhurt, and we couldn’t help laughing at the way we had been done. It was a bitterly cold dawn, and we found to our sorrow that the recruit had not put the cork back in my water-bottle, and the rest of the brandy had upset, as had also a bottle of raspberry syrup which the Kid set great store by. I once upset a pot of gooseberry jam in a small motor-car, and it permeated everything until I had to take the car to a garage to be washed, and go and take a bath myself before I could get rid of it; but it was not a patch in the way of stickiness to a pot of raspberry syrup let loose in a jolting wagon, and we were very[37] glad to get out at daybreak, after eight hours’ travelling, to walk a bit to stretch our legs, and also to wipe off some of the stickiness with some grass.

We came through Prilip that night, and were rather doubtful how we should get through, but though the people standing about glowered at us, and we heard a few shots in the distance, nothing much happened, and only one man got slightly hurt.

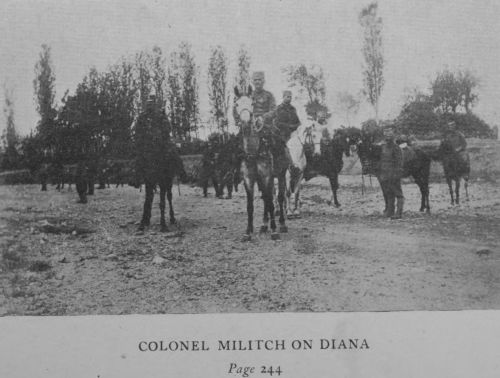

We arrived somewhere between Prilip and Bitol at sunrise, and made a big fire and waited for further orders when the Colonel of the regiment should arrive. Presently he rode up with his staff, and I was introduced to Colonel Militch, the Commandant of the Second Regiment. My first impression of him was that he[38] was a real sport, and later on, when I got to know him very well and had the privilege of being a soldier in his regiment, I found out that not only was he a sport, but one of the bravest soldiers and most chivalrous gentlemen anyone ever served under. We stood round the fire for some time and had a great powwow; my Serbian was still in an embryo stage, but the Colonel spoke German.

We were all very cold and hungry, but one of the officers of the staff, who was a person of resource, made some rather queerish coffee in a big tin mug on the fire, and we all had some, and it tasted jolly good and hot, and then the Colonel produced a bottle of liqueur from a little handbag, and we drank each other’s healths. I got to know that little handbag[39] well later—it used always to miraculously appear when everybody was cold, tired and dying for a drink.

After a couple of hours the ambulance went on about a mile and pitched camp, and I went with them. The Kid went to sleep in the wagon and I did the same outside on the grass. The doctor sent me a piece of bread and cheese, which I casually ate on the spot, not liking to wake the Kid up, but afterwards I was filled with remorse for my thoughtlessness, when I was convicted by her later on for not being a good comrade at all, as it appeared it was the only eatable thing in camp; but, as I was new and green at “retreating,” at that time it never dawned on me: I learnt better ways later on. I made her some tea with[40] my tea-basket, but it was not very satisfying.

Later on in the day the Commandant of the Bitol Division, Colonel Wasitch, and an English officer came up in a car. I was introduced to them, and went with them in the car somewhere up the road to visit a camp. The Commandant of the division went off to attend to business, leaving the English officer and myself to amuse ourselves as we liked.

Here we were witnesses of a case of corporal punishment. I relate it because some people think this is quite a common occurrence; it is not, cruelty is absolutely foreign to their natures. Some people once talked of setting up a branch of the “Prevention of Cruelty to Animals” in Serbia, and were[41] asked in astonishment what work they supposed they would find to do; who ever heard of a Serbian being cruel to child or animal? Corporal punishment, that is to say, a certain number of strokes with a stick (maximum 25—schoolboys will know on what part), is the legitimate and recognised way of punishing in the Serbian Army, and the sentence is carried out by a non-commissioned officer. As an officer once explained to me, some punishment you must have in the interests of discipline, and what else can you do in wartime, when you are on the move every day? Particularly was it so at this most critical juncture, when it would have been fatal for the whole Army had the men been allowed to get out of hand.

[42]

This question of corporal punishment in the Serbian Army has so frequently been brought up to me by English and French officers that I purposely mention it, as I have always tried to thoroughly disabuse their minds of any idea that the men were indiscriminately knocked about. I may add that it is not so very many years since flogging was abolished in our own Navy, and no doubt in course of time the Serbian Army will follow suit. The most popular officer I knew, who was absolutely adored by his own men, was extremely ready to award corporal punishment. “My soldiers have got to be soldiers,” he replied curtly to me once, and his men certainly were. These things always depend largely on the particular officer, of course. I think the[43] Serbian soldier, more than anyone else I have ever come across, can excel as a “passive resister” when he is under an unpopular officer; while all the time keeping himself just within the bounds of discipline, he will contrive to avoid doing anything he does not wish to do, while he is extraordinarily “clannish” and loyal to one whom he likes. In the critical moments in a battle it is not the question whether an officer is “active” or “reserve” that counts, or whether he has passed through his military academy or risen from the ranks, but whether the men will follow him or not.

Captain —— and I walked back to the ambulance together and found that some of the orderlies had got a pig from somewhere and were roasting it with a long[44] pole through it over the camp fire: it smelt jolly good, and as we were very hungry, having had nothing to eat but a piece of bread and cheese, we accepted their invitation to have supper with them with alacrity. As soon as it was cooked we all sat round the big fire in a semicircle, and ate roast pig with our fingers, there being no plates or cutlery available, and Captain —— said he had never tasted anything so good in his life, and wished he could come and join our ambulance altogether.

At some of the other fires dotted about they were roasting some unwary geese which had been foolish enough to stray round our camp. As the inhabitants of the houses had fled leaving them behind we certainly could not call it looting.[45] Looting was very firmly checked; the Serbian is far from being the undisciplined soldier in that respect that some people suppose.

[46]

A RIDE TO KALABAC AND A BATTLE IN THE

SNOW

It snowed hard in the night and most of the next day and was bitterly cold, blowing a gale, but my wagon was a good bit snugger than the tent. The Colonel and his staff had quarters in a loft over a little café just along the road, and after lunch the Commander of the division, who came with two English officers, took the Kid and me with them in their cars some miles back along the road towards Prilip, where we all walked about and inspected the new positions part of the regiment[47] was to take up. The Kid went back to Bitol in the car with them that evening to fetch some clothes, and I never saw her again, though I believe she did want to come back to us later on.

I used to sit over the camp fires in the evenings with the soldiers, and we used to exchange cigarettes and discuss the war by the hour. I was picking up a few more words of Serbian every day, and they used to take endless trouble to make me understand, though our conversations were very largely made up of signs, but I understood what they meant if I couldn’t always understand what they said. It was heartbreaking the way they used to ask me every evening, “Did I think the English were coming to help them?” and “Would they send cannon?” The Bulgarians[48] had big guns, and we had nothing but some little old cannon about ten years old, which were really only what the comitadjes used to use. If we had had a few big guns we could have held the Baboona Pass practically for any length of time, for it was an almost impregnable position. I used to cheer them up as best I could, and said I was sure that some guns would come, and that even if they did not they must not think that the English had deserted them, as I supposed they had big plans in their head that we knew nothing about, and that though we might have to retreat now everything would come right in the end. It was touching the faith they had in the English, whom they all described as going “slowly but surely.” They were very much[49] excited when they saw the two English officers, as they were sure they had come to say some English troops were coming.

One day, however, one thousand new English rifles did come, and there was great rejoicing thereat.

With the courtesy which always distinguishes the Serbian peasant, they used always to stand up and make room for me, and bring a box for me to sit on in the most comfortable place by the fire, out of the smoke, and I used to spend hours like this with them. Under happier circumstances they would all have been singing their national songs and dancing, but, though there were many fine singers among them, nothing would induce them to sing: they were too broken-hearted at being driven back. One man did start a[50] song one night to please me, but he broke down in the middle and said he knew I would understand why he could not sing.

There was deep snow on the ground, and it was bitterly cold, and the men used to anxiously ask me if I managed to keep warm at night, as they huddled up together, four in one tiny tent, for warmth, and seemed to rather fear that they might find me frozen to death some morning in my wagon, but I was really quite warm enough.

The next day, while we were doing the dressings, a man came in who had walked from Nish, twenty-two days’ tramp. He was a cheery soul, and said he felt very fit, but he looked as thin as a rake. We all crowded round him to hear the news. He [51]said that the town of Nish was evacuated and everyone gone to Krushavatz.

Commandant Militch told me he was sending for his second horse, so that I could ride her. When she arrived she proved to be a very fine white half-Arab, who could gallop like the wind, and I grew very fond of her. She had a passion for sugar, and always expected a bit when she saw me. The Commandant had moved his quarters a few miles farther up the road towards Prilip to a small deserted hahn, or inn, consisting of two small rooms by the roadside. It was close to the village of Topolchar. I had been cautioned not to stray away from the camp by myself, as it was very unsafe; only a few days before Bulgarian comitadjes had swooped down and taken[52] prisoner a Serbian soldier who had gone to fetch some water not a quarter of a mile from his own camp. One bright sunny morning, however, the hills looked so tempting that I went for a stroll and wandered on farther than I intended. I was out of sight of the camp, when suddenly I heard voices behind some trees, though I could not see anybody, and I knew that none of our men were camping near. Discretion conquering curiosity, I beat a dignified retreat at a brisk walk, as I was quite unarmed at the time, and they told me when I got back it was a good thing I did. I took no more constitutionals over the hills while in that neighbourhood, anyhow, for I had no wish to cut off my career with the Army by suddenly disappearing, as no[53] one would know what had become of me.

One day I rode over on Diana, my white mare, to see the Commandant and his staff at the hahn. They all welcomed me most warmly, inviting me to stop to supper, sleep there, and ride out next day with them to the mountain of Kalabac, to visit the positions there. I accepted joyfully. They said I could either sleep there near the stove or have my wagon brought up, if I was not afraid of being too cold. I decided in favour of the wagon, as the hahn was already pretty crowded; so they telephoned for it, and in due course it arrived with my orderly. It was a grey-covered wagon, and I had christened it “My little grey home in the west.” A house on wheels is[54] an ideal arrangement, as if you take it into your head to sleep anywhere else you go off and your house simply follows you. It was planted exactly opposite the door, with a sentry to guard me.

The Commandant, in spite of all his troubles, was full of fun, and even in the darkest and most anxious hours in the tragic weeks that followed kept up everyone’s spirits and thought of everyone’s comfort before his own. After a most hilarious supper I turned in, as we were to make an early start next morning.

Next day the Commandant, his Adjutant and I, with four armed gendarmes, rode off to Kalabac. It was a lovely day, and we had about two hours’ ride across country to the first line of trenches. The Commandant and I used to have a[55] race whenever we got to a good bit of ground. He was a fine rider, and, as the horses were pretty well matched, we used to get up a break-neck speed sometimes, and had some splendid gallops. About a year before in Kragujewatz I was riding with a Serbian soldier who had been sent with a horse for me, and he said: “What did I want to be a nurse for?” and tried to persuade me not to go back to the hospital, but to join the Army then and there, regardless of my poor patients expecting me back.

The first line of trenches that we came to were little shallow trenches dotted about on the hillside, with about a dozen men in each. We sat in one of them and drank coffee, and I thought then that I should be able to tell them at home that[56] I had been in a real Serbian trench, little thinking at the time that I was going to do it in good earnest later on under different circumstances.

After that we went on up to another position right at the top of Kalabac. It was a tremendous ride, and I could never have believed that horses could have climbed such steep places, or have kept their feet on some of the obstacles we went over, but these horses were trained to it, and could get through or over anything. Just the last bit of the way we all had to dismount, and, leaving the horses with the gendarmes, did the rest on foot. There was no need for trenches there, as it was very rocky, and there was plenty of natural cover. Major B—— and another officer met us[57] near the top, and he and the Commandant went off to discuss things. It happened to be Captain Pesio’s “Slava” day. This “Slava” day is an institution peculiar only to the Serbians, and which they always keep most faithfully. Every family and every regiment has one. It is the day of their particular patron saint, and is handed down from father to son. It is kept up for three days with as much jollification as circumstances permit, even in wartime. I have been the guest at plenty of other Slava days in Serbia, but I never enjoyed anything so much as I did that one. We sat round the fire on boxes or logs of wood under the shelter of a big overhanging rock, with a most gorgeous panorama of the country stretching for miles round, and had a very festive[58] lunch, and all drank Captain Pesio’s health. In the middle of lunch I had my first sight of the enemy, a Bulgarian patrol in the distance, and orders were promptly given to some of our men to go down and head them off. The men all seemed to be in high spirits up there, in spite of the cold, and some of them were roasting a pig, although I suppose that was a “Slava” luxury for them, not to be had every day.

It was evening by the time we left, and we slipped and slid down the mountain again by moonlight. When we got back to the first trenches which we had visited we made a short halt, and sat in an officer’s little tent and drank tea. He had certainly not been at war for four years without learning how to make himself[59] comfortable under adverse circumstances, and had brought it down to a fine art. He had a tiny little tent, one side of which was pitched against a bank, and in the bank there was a hole, with a large fire in it, and a sort of tunnel leading up to the outer air for a chimney. His blanket was spread on some boughs woven together for a bed, and he was as snug and warm as a toast when he did get a chance to sleep in his tent, which was apparently not very often. He was very popular with everyone, and the Commandant spoke particularly of his bravery. We were quite sorry to leave and turn out into the cold night air.

We had a long ride home, ending up with a hard gallop along the last bit of road, and it was late when we got back to[60] the hahn. There was a big fire going in the iron stove, and we soon thawed out. The Commandant sat down at his table and dictated endless despatches to his Adjutant, while I dosed on his camp bed till about ten, when he finished his work for the time being and we had supper. Every now and then there would be a rap at the door, and an exhausted, half-frozen rider would come in bearing a despatch from one of the outlying positions on the hills.

I was very sorry afterwards that I had not taken my camera with me up to the positions, but I was not sure at the time if they would like me to, though afterwards they told me I might take it anywhere I liked.

There was another small ambulance here in charge of the proper regimental[61] doctor, and in the afternoon everyone was ordered to move up into the village, Topolchor, and find rooms there. The soldiers were all delighted at the prospect of getting under a roof of any kind, though I felt quite sorry at leaving my Little Grey Home. The doctor got me a nice big empty room in what was formerly the school. There was a pile of desks and tables filling up one side of it, and a stove, but otherwise no furniture. After my orderly had unpacked my camp bed and lit the stove I had some visitors: three or four old native women, who came up and inspected me and all my belongings closely, and seemed deeply impressed with the extraordinary luxury in which an Englishwoman lived, with a room to herself, a bed and a rubber bath! I had[62] been making futile efforts, by the way, for the last few days to make use of this same bath, in spite of my orderly’s repeated assurances that you could not have a bath in wartime, which I found afterwards to be strictly true. I did not succeed even here, owing to the lack of water and anything to carry it in.

The villagers themselves, those who had not already fled in terror, seemed to live in the most abject poverty, huddled together in houses no better than pigsties. The place was infested by enormous mongrel dogs, which used to pursue me in gangs, barking and growling, but they had a wholesome respect for a stone, and never came to close quarters.

Next morning I went for a long ride with the Commandant to inspect some[63] more of the positions. He had to hold an enormous front with only two regiments, and, as we were outnumbered by the Bulgarians by more than four to one, when the latter could not break through our lines they simply made an encircling movement and walked round them, and, as there were absolutely no reserves, every available man being already in the fighting line, troops had to abandon some other position in order to cut across and bar their route. Thus we were constantly being edged back, and were very many times in great danger of being surrounded. We were fighting a rear-guard action practically all the time for the next six weeks—a mere handful of troops, worn out by weeks of incessant fighting, hungry, sick, and with no big guns to back them up,[64] retreating slowly and in good order before overwhelming forces of an enemy who was fresh, well equipped and with heavy artillery. It was no use throwing men’s lives away by holding on to positions when no purpose could be gained by it, though the Colonel felt it keenly that the finest regiment in the Army should have to abandon position after position, although contesting every inch, without having a chance of going on the offensive. It was heartbreaking work for all concerned, and the way they accomplished it is an everlasting credit to officers and men alike.

My orderly told me he had heard we were going that evening, so he packed up everything, camp bed included, and put it in my wagon. We hung about all the evening[65] expecting to get the order to go at any moment, as the horses were always kept ready saddled in the stable, and you simply had to “stand by” and wait until you were told to go, and then be ready to get straight off. Eventually, however, the Commandant came back and said we were not going that night, and we had a quiet supper about ten o’clock and turned in, with a warning to be up early in the morning. As my bed was packed up I rolled myself up in a blanket on the floor, and my orderly did likewise at the other side of the stove and kept the fire up. It was snowing hard and frightfully cold. At daybreak we did move, but not very far, only to the little hahn by the roadside; and there we stood about in the snow and listened to a battle which was apparently[66] going on quite close; although we strained our eyes we could see nothing—there was such a frightful blizzard. A company of reinforcements passed us and floundered off through the deep snow drifts across the fields in the direction of the firing. There was no artillery fire (I suppose they could not haul the guns through the snow), but the crackle of the rifles got nearer and nearer, and at last about midday they were so close that we could hear the wild “Hourrah, Hourrahs” of the Bulgarians as they took our trenches, and as the blizzard had stopped for a bit we could see them coming streaking across the snow towards us, our little handful of men retreating and reforming as they went. The Bulgarians always give the most blood-curdling yells when they charge.[67] The ambulance was already gone, and there were only the Colonel and his staff, myself and the doctor left. The horses were brought out, and the order came to go, but only about three miles to where the big ambulance was camped with whom I had been at first.

There was a river between the hahn and this ambulance, and the road went over a bridge. This bridge was heavily mined and was to be blown up as soon as our men were over, thus cutting off, or anyhow considerably delaying, the Bulgarians, as the river was now a swollen icy torrent. We sat round the fire of the ambulance and dried our feet. Some of the men were soaking to the knees, having no boots, but only opankis, leather sandals fastened on with a strap which winds[68] round the leg up to the knee. Later on some wounded were brought in, given a very hurried dressing, and despatched at once to the base hospital. The majority of them seemed to be hit in the right arm or wrist, but I am afraid perhaps the worst wounded never reached us. One poor fellow who was hit in the abdomen was, I am afraid, done for; he would hardly live till he got to the hospital.

We heard no more firing till late in the afternoon, when all at once it broke out again quite close, and with big guns as well this time. We wondered how on earth they had been able to get them across the river, but the explanation was forthcoming when we heard that the bridge, although it had ten mines in it, had failed to blow up—the mines would not[69] explode; no one knew why. I floundered through the snow up a little hill with some of the others to see if we could see anything, but we could not see much through the winter twilight except the flashes from the guns momentarily lighting up the snow banks, and hear the noise of the shells as they whistled overhead.

This had been going on for a couple of hours now, and the Greek doctor was getting into a regular funk because they had had no orders to move, though it was all right as we had no wounded in the tent to be carried away, and no one else was worrying about it; but he finally sent a messenger up to the Commandant, as he seemed to think the ambulance had been forgotten. A couple of days afterwards the men told me[70] with much scorn that that afternoon had been too much for him, and that he did a retreat on his own and never came back to the ambulance again. I was just thinking of looking round for something to eat, as I had had neither breakfast nor lunch, and had been much too busy to think about it, when the order arrived for the ambulance to pack up and move, and the tents came down like lightning. The soldiers were all retreating across the snow, and I never saw such a depressing sight. The grey November twilight, the endless white expanse of snow, lit up every moment by the flashes of the guns, and the long column of men trailing away into the dusk wailing a sort of dismal dirge—I don’t know what it was they were singing—something[71] between a song and a sob, it sounded like the cry of a Banshee. I have never heard it before or since, but it was a most heartbreaking sound.

My saïs (groom) brought Diana round to me. I asked him if he had been told to do so, and he said “No,” but that I “had better go now.” He shook his head dubiously, murmuring, “Safer to go now,” when I told him I was coming later on with the Commandant and his staff.

War always seems to turn out exactly the opposite to what you imagine is going to happen. Such a great proportion of it consists of “an everlastin’ waiting on an everlastin’ road,” as someone has already written. Bairnsfather hits it off exactly in his picture of the young officer with his new sword: how he pictures himself[72] using it, charging at the head of his company, and how he really does use it, toasting bread over the camp fire! I had some wild visions in my head—as I knew the Commandant would wait until the last moment—of a tremendous gallop over the snow, hotly pursued by Bulgarian cavalry. I imagine I must once have seen something like it on a cinematograph. What, however, really did happen was that, having received permission to stop, I sat for four hours in company with seven or eight officers who were waiting for orders, on a hard bench in a freezing cold shed, which in its palmier days might have been a cowhouse. I was ravenously hungry, and sucked a few Horlick’s milk tablets I found in my pocket, but they did not seem so satisfying[73] as the advertisements would lead one to suppose. However, presently the jolly little captain, whose tent I described on Kalabac, came in, followed by his soldier servant bearing a hot roast chicken wrapped up in a piece of paper! Where in the world he got it I can’t think. We had no knives or forks, but we sat side by side, and each took hold of a leg and pulled till something gave. It tasted delicious! He shared it round with everybody, and I don’t think had much left for himself. Although he came straight from the trenches, where he had been fighting incessantly and had not slept for three nights himself, he was full of spirits and livened us all up, and we little thought that it was the last time we were to see him. I was terribly sorry to hear a few[74] days later of the tragic death of my gay little friend.

The firing had ceased, as it usually does at night, and at last, about nine o’clock, the Commandant appeared and the horses were brought out, and instead of the wild cinema gallop I had pictured we had one of the slowest, coldest rides you can imagine. There was a piercing blizzard blowing across the snowy waste, blinding our eyes and filling our ears with snow; our hands were numbed, and our feet so cold and wet we could hardly feel the stirrups. We proceeded in dead silence, no one feeling disposed to talk, and slowly threaded our way through crowds of soldiers tramping along, with bent heads, as silently as phantoms, the sound of their feet muffled by the snow.[75] I pitied the poor fellows from the bottom of my heart—they were so much colder and wearier even than I was myself, and I wondered where the “glory” of war came in. It was exactly like a nightmare, from which one might presently wake up. My dreams of home fires and hot muffins were brought to an abrupt termination by the Commandant suddenly breaking into a trot, when I found my knees were “set fast” with the cold, and I had a very painful five minutes till they loosened up.

After a long time we turned off the road across some snowy fields. I followed close behind the Commandant, who always made a bee line straight ahead through everything; and after our horses had slipped and scrambled through a hedge, a couple of deep ditches and a[76] stream we eventually got to the village of Mogilee, I think it was called. The soldiers bivouacked in some farm out-houses, and we were received by some officers in a big loft. They had a huge stove going and supper ready for us. We finished up the long day quite cheerily, even having a bottle of champagne that a comitadje brought as a present to the Commandant. We all slept that night in the loft on the floor, I being given the place of honour on a wide bench near the stove, while the other six or seven selected whichever particular board on the floor took their fancy most, and spread their blankets on it. Turning in was a simple matter, as you only have to take off your boots; and, though the atmosphere got a bit thick, we all slept like tops.

[77]

I MEET THE FOURTH COMPANY—A COLD

NIGHT RIDE

We were all up at daybreak next morning as usual; no good Serbian sleeps after the first streak of light. It was still snowing fearfully hard, making it impossible to go out, though the Commandant and his Staff Captain rode out somewhere all the morning. We had sundry cups of tea and coffee during the morning and a pretty substantial snack of bread and eggs and cold pig about ten. I protested that I was not hungry, and that we should have lunch when the Commandant came in,[78] but they reminded me of what had happened to me yesterday in the matter of meals, and might possibly happen again to-morrow, and advised me to eat and sleep whenever I got a chance. They were old soldiers and spoke from experience, and I subsequently found it to be very good advice.

It was a long day, as we had nothing to do. In the afternoon the doctor started to teach me some Serbian verbs, and afterwards we all played “Fox and Goose,” and I initiated them into the mysteries of “drawing a pig with your eyes shut,” and any other games we could think of with pencil and paper to while away the time.

About dusk we set forth again to a small village, Orizir, close to Bitol. It was pitch dark as we splashed across a field[79] and a couple of streams to another little house which we occupied. It consisted of two tiny rooms, up a sort of ladder, with a fair-sized balcony in front. The balcony was quite sheltered with a big pile of straw at one end, and I elected to sleep there, though they were fearfully worried about it, and declared I should die of cold, in spite of my protestations that English people always sleep much better in the open air than in a hot room with all the windows shut. Foreigners always look upon English people as more than half mad on the subject of fresh air, especially at night. The next day my orderly, who was in a great state of mind, and seemed to think that I would lose caste with his fellow orderlies if I persisted in sleeping on the balcony, told[80] me that he had found another room for me in a hahn by the roadside, where I accordingly slept the next night, and subsequently we all moved down there. I actually got my long-sought-for bath that day, my resourceful man borrowing a sort of stable for me for an hour and fixing it up for me. As all old campaigners know, a certain kind of live stock, and plenty of them, is the inevitable accompaniment to this sort of life, and is one of its greatest trials, though you do get more or less used even to that. I burnt a hole in my vest cremating some of them, but judging by the look of my bathroom, where the soldiers had been sleeping, I am not at all sure that I did not carry more away with me than I got rid of. While I was engaged in this interesting[81] occupation my orderly called out that the English Consul was there and wished to see me, so I hastily dressed and went out to interview him. He had come in a car to take me back to Salonica with him if I wanted to go, which of course I did not; so he just drove me into town to pick up a large case of cigarettes which I had previously ordered from Salonica for myself and the soldiers and anyone else who ran short of them, and he also gave me a case of tins of jam and one of warm woollen helmets, which were very much appreciated by the men. He said he thought I was quite right to stop, and we parted warm friends.

When I got back I found the Staff Captain, who was the Commandant’s right hand, just going out for another[82] cold ride. He had had fever for the last two or three days, and looked so fearfully ill that I begged him not to go, as, however much he might, and did, boss everybody when he was well, he might let himself be looked after a little bit when he was ill. Rather to my surprise he submitted quite meekly, and let me dose him with quinine, and tuck him up in his blankets by the stove, and as he was shivering violently I told his orderly to make him some hot tea and stand outside the door to see that no one came in to disturb him. As the tea did not seem to be forthcoming, I went out presently to see what was up, and found him with several of his fellow orderlies sitting in the snow round the camp fire having a meal of some kind. He said he had made the tea, but had not[83] any sugar; so I asked some of the others.

“Now, don’t you say ‘Néma’ to me,” I said, before he had time to speak, “but go and find some, because I know perfectly well you have got it.” It is a Serbian peculiarity, which I had found out long ago, that whenever you first ask for a thing they invariably say “Néma” (“There isn’t any”). I have frequently been told that in a shop with the thing lying there under my eyes, because the man was too lazy to get up and get it. They thought it a great joke, and of course produced it, and “Don’t say ‘Néma’ to me” became a sort of laughing byword amongst some of the men afterwards whenever I asked for anything. They have a keen sense of humour, and are always[84] ready for a laugh and a joke, and their gaiety and high spirits bubble up even under the most adverse circumstances.

The rest of the Staff and I then made a fire in the other little room, and sat there and played chess and auction bridge, and were making a terrific noise over the latter, when the Commandant came back. If you really want an amusing occupation, likely to give rise to any amount of discussion and argument, try teaching auction bridge to three men who have never seen it played before, in a language your knowledge of which is so slight that you can only ask for the simplest things in the fewest possible words. You’ll find the result is a very queer and original game.

The next afternoon, it having at last stopped snowing, I walked over to visit [85]my old friends in the ambulance a couple of miles up the road, and we sat by the camp fire and pored over the map of Albania, whither we should soon be going, and discussed the war as usual. When I got back about sunset I found the Commandant had gone to visit a company who were camped about a mile and a half up the road, and his Adjutant was waiting for me, as we thought it would be a good opportunity to give away some of the warm woollen helmets while it was so cold. Accordingly, followed by a couple of men carrying the wool helmets, some cigarettes and a few pots of jam, we started for the camp. It turned out to be the Fourth Company of the First Battalion, strange to say, the very company that I afterwards joined, though I didn’t guess that[86] at the time. It was a most picturesque scene with the little tents all crowded together, and dozens of big camp fires blazing in the snow with soldiers sitting round them; they all seemed very cheery in spite of the bitter cold. We had a great reception, the whole company was lined up, and under the direction of their Company Commander I gave every seventh man a white woollen helmet—unfortunately there were not enough for each man to have one—and every man a couple of cigarettes, and my orderly followed with half a dozen large pots of jam and a spoon, the men opening their mouths like young starlings waiting to be fed. This is a national custom in Serbia; directly you visit a house your hostess brings in a tray with a pot of jam, glasses[87] of water and a dish with spoons on it. You eat a spoonful of jam, take a drink of water, and put your spoon down on another dish provided for that purpose. It is very amusing to see a stranger the first time this is presented to him; he generally does not know what he is supposed to do, or whether he is to dip the jam into the water, or vice versa, and how many spoonfuls it would be polite to eat, Serbian jam being extraordinarily good. One Englishman I knew wanted to go on eating several spoonfuls, and I had gently but firmly to check him.

I was introduced to all the officers, and a great many of the men who were pointed out to me as having done something very special. One of the men was wearing an English medal for[88] “distinguished conduct in the field.” The men seemed awfully pleased with their little presents; they never have anything in the way of luxury—no jam, sweets or tobacco served out to them with their rations, no parcels or letters from home (at this time), no concerts or amusements got up for their benefit, none of the things that our Tommies hardly regard in the light of luxuries, but necessities. No one who has not lived with them can imagine how simply they live, how much they think of a very little, and what a small thing it takes to please them. After that little ceremony was over we sat round the officers’ camp fire and a young sergeant—a student artist—played the flute very well indeed, and they sang some of their national songs. It was all so friendly and[89] fascinating that we were very loath indeed to tear ourselves away, and I promised to come back next day and take their photographs, but next day they were not there, having been ordered off at dawn to hold some positions up on the hills.

Among other sundry oddments in my luggage I had a box of chessmen and a board, and as several of them could play we whiled away many weary hours when we had nothing else to do playing chess. The Commandant and I were very evenly matched, and we used to have some tremendous battles, sometimes long after everyone else was asleep, and always kept a careful record of who won. Some of the others were very keen on it too, and those who were not playing would stand round and offer advice. I used sometimes[90] to think, as I listened to the sounds of hurried packing up going on all round while we sat calmly playing chess, that the Bulgars would walk in one day and capture the lot of us, chessboard and all.

About 9 p.m. next night the Commandant gave the order to start, and we walked the first mile, the horses being led behind, I suppose to get used to the roads, which were one slippery sheet of ice. When we got to Bitol, which was quite close, we went to the headquarters of the Commandant of the division, and sat there till about midnight, while he and our Commandant discussed matters. We met Dr. Nikotitch there again, and he and Commandant Wasitch asked me if I really had made up my mind to go on. They said the journey through Albania would[91] be very terrible, that nothing we had gone through so far was anything approaching it, and that they would send me down to Salonica if I liked. I was not quite sure whether having a woman with them might not be more of an anxiety and nuisance to them than anything else, though they knew I did not mind roughing it; and I asked them, if so, to tell me quite frankly, and I would go down to Salonica that night. They were awfully nice, though, and said that “for them it would be better if I stopped, because it would encourage the soldiers, who already all knew me, and to whose simple minds I represented, so to speak, the whole of England.” The only thought that buoyed them up at that time, and still does, was that England would never forsake them. So that settled the matter,[92] as I should have been awfully sorry if I had had to go back, and I believe the fact that I went through with them did perhaps sometimes help to encourage the soldiers.

We left there soon after midnight, and rode all night and most of the next day. The Commandant and his Staff Captain drove in a wagon, the same one that the Kid and I had driven in on the first night of the retreat. They asked me whether I would rather come in the wagon with them or ride, as the roads were simply terrible, but I elected to ride and chance Diana going on her head, which she did not do, however, as the Commandant, with his usual thoughtfulness, had had her roughed for me a few days before. We rode very, very slowly, always through crowds of soldiers, pack-horses and[93] donkeys, halting about every hour at little camp fires along the roadside made by our front guard, where we sat and warmed our feet for about a quarter of an hour till the tired soldiers could catch us up, there being frequent halts for them to rest for a few minutes. I rode alongside the Adjutant and another officer, and was very glad that my orderly had filled my thermos flask with hot tea, with a good dash of cognac in it, which the three of us consumed while riding along. The roads were really fearful, one solid sheet of ice, and the Adjutant’s horse came down so often that eventually he had to walk and lead it. Occasionally we all used to get down and walk for a bit to warm our feet, which became like blocks of ice, but the going was[94] so hard that we were glad to mount again. I say “mount,” but in reality, what between wearing a heavy fur coat and getting colder and stiffer and wearier, it was more a sort of crawl up Diana’s side that I did; fortunately she was a patient animal, and used to stand still. It soothed my feelings to see that I was not the only one, several of the others having nearly as much difficulty in mounting. They were all so friendly, and I had more than one “Good luck to you” shouted after me. It was not really such a hard ride as we had expected, though, as stopping at the little camp fires and chatting with the men round them made a nice break.

About daybreak we arrived at a hahn, where we found the ambulance again, and the Commandant and the Captain[95] got their horses there, and we all walked, and later on rode, up and up a winding road, up a mountain. It was bitterly cold, and every few yards we passed horrible looking corpses of bullocks, donkeys and ponies, with the hides and some of the flesh stripped from them; sometimes there were packs, ammunition and rifles thrown away by the roadside, but very, very few of the latter; a soldier is very far gone indeed before he will part with that. Of course everywhere swarmed with spies, and we stopped a man and a boy in civilian clothes carrying baskets; they protested that they were going down to do some marketing or something of that sort, but whatever it was they wanted to do they were told they could not do it, and gently but firmly turned back.

[96]

At the very top we stopped at the ruins of a filthy little hut, where a halt was called and the field telephone rigged up. We built a fire outside—it was too dirty to go inside—under the wall, and had some coffee, and tried, very unsuccessfully, to get out of the howling, bitter wind. The soldiers sat about and rested, and we stayed there until late in the afternoon. We were to spend the night at Resan, some way down the other side, and about 3 o’clock the doctor said he was going down there, and I might as well come down with him and look for a room. Wily young man, he was petrified with cold himself and didn’t like to say so, so had previously told the Staff Captain that I was cold and wanted to go into the town, and that, as I could not go by myself,[97] hadn’t he better escort me? He let this out afterwards, and I was very indignant with him, but he was quite unabashed. He used to love teasing me, calling me “Napoleon” because I rode a white horse, and we were constantly sparring. My orderly, after a long search, found me quite a decent little room in a house close to the Caserne, where the staff were to be quartered. The family consisted of two old ladies and a girl, who all fell on my neck and hugged me, rather to my embarrassment. One of the old ladies explained volubly that she had once had something—I never could quite make out whether it was a husband or a cat—and had lost it, and I was now to take its place in the family circle.

We all sat round the stove in my little[98] room, which seemed quite a luxurious palace to me now, and I made them real English tea with my little tea-basket, and the poor old things seemed quite enchanted, as they had neither tea nor sugar in the house, and they fussed over me, and could not do enough for me.

The next morning I stayed in bed till nearly eight, and, after dressing leisurely, went up to see the Commandant and staff, who said they had begun to think they had lost me. About five o’clock my orderly came in in a great state of excitement and wrath, declaring that he did not know what to do with my things as the wagon had been taken for something else, and that the Commandant and staff were all gone. He was an excitable person, and used to get these panics occasionally,[99] and, as I knew perfectly well that whatever happened they would not leave me behind, I told him not to be such an ass, but to go and get my horse and I would go and find out for myself, as I could not get any sense out of him. I happened to meet the Commandant in the street, and, as I fully expected, we had supper quietly, and did not stir till 9 p.m. We nearly always did ride at night. We left very quietly, and walked the first bit of the way through the mud, and then rode up a beautiful serpentine road, which had originally been made by the Turks, through what looked as if it might be beautiful country if you could only see it. All the way along there were soldiers and camp fires, which looked so pretty twinkling all over the hills through the fir trees, and we[100] made frequent halts while the Commandant gave his orders.

I thought we were going to ride all night, and it was a pleasant surprise when we turned off the road, and put our horses at a steep muddy bit of mound at the top of which was an old block-house, one of the many built by the Turks and dotted all over that part of the country. The telephone was rigged up there, and it was full of officers and soldiers; the ground all round was a perfect sea of mud, and there were soldiers everywhere. I had not the faintest idea whether we were going to stop there half an hour or for the rest of the night, and I don’t suppose anybody else had either, except, perhaps, the Commandant. I sat by the stove for some time, and finally lay down on the[101] floor on some straw that looked not quite so dirty as the rest, though that is not saying much, but when I woke up some hours later I got the impression that I had strayed into a new version of the Black Hole of Calcutta. The whole floor was absolutely covered so thickly with sleeping men that you could not put your feet down without treading on them. I counted up to twenty-nine and then gave it up because I saw several more come in afterwards, though where they managed to wedge themselves in I do not know. The Commandant had left the telephone and was sleeping peacefully among the others; the only person awake was a very big, good-looking gendarme, who was keeping the stove stoked up, although it was already suffocatingly hot. The Serbians[102] laugh at me because I declare that they always pick their gendarmes for their good looks; they are certainly a magnificent set of men. This one inquired if I wanted anything, as soon as he saw that I was awake, and I asked him if he would fetch me my thermos flask full of tea, which he would find in Diana’s saddle-bag. He had never seen a thermos flask before, and when he brought it back and I shared the tea with him he was perfectly thunderstruck to find it still hot. He couldn’t make it out at all, and seemed to think that in some extraordinary way Diana must have had something to do with it, and I shouldn’t be surprised if next day he put a bottle of tea in his own saddle-bag to see if his horse would be equally clever.

[103]

About 5 a.m., while it was still dark, I woke up again so boiling hot that I could not stand it any longer, and crawled out cautiously over the sleeping men, treading on a good many, I am afraid, though they did not seem to object, and took a walk round; but, as it was raining and the mud appalling, I did not stay outside long. There was one camp fire still going, and what I took to be a large bundle covered over with a sack beside it. Here’s luck, I thought, something to sit on beside the fire, and down I plumped, but got up again quickly when it gave a protesting grunt and a heave, and I found I had sat down on a man. After that I sat on a tin can in the cold passage for some time and waited for daybreak.

[104]

WE SAY GOOD-BYE TO SERBIA AND TAKE TO

THE ALBANIAN MOUNTAINS