Title: Cringle and cross-tree

Subtitle: Or, the sea swashes of a sailor

Author: Oliver Optic

Release Date: August 24, 2023 [eBook #71482]

Language: English

Credits: hekula03, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

THE UPWARD AND ONWARD SERIES.

OR,

BY OLIVER OPTIC

AUTHOR OF "YOUNG AMERICA ABROAD," "THE ARMY AND NAVY STORIES,"

"THE WOODVILLE STORIES," "THE BOAT-CLUB STORIES,"

"THE STARRY FLAG SERIES," "THE LAKE-SHORE SERIES," ETC.

WITH FOURTEEN ILLUSTRATIONS.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD, PUBLISHERS.

NEW YORK:

LEE, SHEPARD AND DILLINGHAM.

1873.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871,

By WILLIAM T. ADAMS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

ELECTROTYPED AT THE

BOSTON STEREOTYPE FOUNDRY,

19 Spring Lane.

TO

MY YOUNG FRIEND

JOSEPH H. KERNOCHAN

This Book

IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED.

"Cringle and Cross-Tree" is the fourth of the Upward and Onward Series, in which Phil Farringford, the hero of these stories, appears as a sailor, and makes a voyage to the coast of Africa. His earlier experience in the yacht on Lake Michigan had, in some measure, prepared him for a nautical life, and he readily adapts himself to the new situation. Being a young man of energy and determination, who puts his whole soul into the business in which he is engaged, he rapidly masters his new calling. His companions in the forecastle are below the average standard of character in the mercantile marine; but Phil, constantly true to his Christian principles, obtains an influence over some of them,—for vice always respects virtue,—which results in the permanent reform of two of his shipmates.

Fifteen years ago the fitting out of a slaver in New York harbor was not an uncommon occurrence, though, happily, now the business is wholly suppressed. What was possible then is not possible now; but the hero of the story, and many of his shipmates, regarded the horrible traffic with abhorrence, and succeeded in defeating the purposes of the voyage upon which they were entrapped. In such a work their experience was necessarily exciting, and the incidents of the story are stirring enough to engage the attention of the young reader. But they were battling for right, truth, and justice; and every step in this direction must be upward and onward.

In temptation, trial, and adversity, as well as in prosperity and happiness, Phil Farringford continues to read his Bible, to practise the virtues he has learned in the church, the Sunday school, and of Christian friends, and to pray on sea and on land for strength and guidance; and the writer commends his example, in these respects, to all who may be interested in his active career.

Harrison Square, Boston, August 21, 1871.

OR,

"I have a very decided fancy for going to sea, father."

"Going to sea!" exclaimed my father, opening his eyes with astonishment. "What in the world put that idea into your head?"

I could not exactly tell what had put it there, but it was there. I had just returned to St. Louis from Chicago, where I had spent two years at the desk. I had been brought up in the wilds of the Upper Missouri, where only a semi-civilization prevails, even among the white settlers. I had worked at carpentering for two years, and I had come to the conclusion that neither the life of a clerk nor that of a carpenter suited me. I had done well at both; for though I was only eighteen, I had saved about twelve hundred dollars of my own earnings, which, added to other sums, that had fallen to me, made me rich in the sum of thirty-five hundred dollars.

My life in the backwoods and my campaign with the Indians had given me a taste for adventure. I wished to see more of the world. But I am sure I should not have yielded to this fancy if it had been a mere whim, as it is in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred with boys. I had never left, of my own accord, a place where I worked: the places had left me. The carpenter with whom I had served my apprenticeship gave up business, and the firm that had employed me as assistant book-keeper was dissolved by the death of the junior partner. I was again out of business, and I was determined to settle what seemed to be the problem of my life before I engaged in any other enterprise.

For eleven years of my life I had known no parents. They believed that I had perished in the waters of the Upper Missouri. I had found my father, who had been a miserable sot, but was now, an honest, sober, Christian man, in a responsible position, which yielded him a salary of three thousand dollars a year. But while he was the degraded being I had first seen him, his wife had fled from him to the protection and care of her wealthy father. My mother had suffered so much from my father's terrible infirmity, that she was glad to escape from him, and to enjoy a milder misery in her own loneliness.

Though my father had reformed his life, and become a better man than ever before, he found it impossible to recover the companion of his early years. She had been in Europe five years, where the health of her brother's wife required him to live. My father had written to Mr. Collingsby, my grandfather, and I had told him, face to face, that I was his daughter's son; but I had been indignantly spurned and repelled. My mother's family seemed to have used every possible effort to keep both my father and myself from communicating with her. She had spent the winter in Nice, and was expected to remain there till May.

Phil's Interview with his Grandfather.

I had never seen my mother since I was two years old. I had no remembrance of her, and I did not feel that I could settle down upon the business of life till I had told her the strange story of my safety, and gathered together our little family under one roof. Existence seemed to be no longer tolerable unless I could attain this desirable result. Nice was on the Mediterranean, and, with little or no idea of the life of a sailor, I wanted to make a voyage to that sea.

I had served the firm of Collingsby & Faxon in Chicago as faithfully as I knew how; I had pursued and captured the former junior partner of the firm, who had attempted to swindle his associate; and for this service my grandfather and his son had presented me the yacht in which the defaulter had attempted to escape. In this craft I had imbibed a taste for nautical matters, and I wished to enlarge my experience on the broad ocean, which I had never seen.

In pursuing Mr. Collingsby's junior partner, I had run athwart the hawse of Mr. Ben Waterford, a reckless speculator, and the associate of the defaulter, who had attempted to elope with my fair cousin, Marian Collingsby. I had thus won the regard of the Collingsbys, while I had incurred the everlasting hatred of Mr. Waterford, whose malice and revenge I was yet to feel. But in spite of the good character I had established, and the service I had rendered, the family of my mother refused to recognize me, or even to hear the evidence of my relationship. I thought that they hated my father, and intended to do all they could to keep him from seeing her. Her stay in Europe was prolonged, and I feared that her father and brother were using their influence to keep her there, in order to prevent my father or me from seeing her.

I was determined to see her, and to fight my way into her presence if necessary. At the same time I wanted to learn all about a ship, and about navigation. I had flattered myself that I should make a good sailor, and I had spent my evenings, during the last year of my stay in Chicago, in studying navigation. Though I had never seen the ocean, I had worked up all the problems laid down in the books. I wanted to go to sea, and to make my way from a common sailor up to the command of a ship. I say I wanted to do this, and the thought of it furnished abundant food for my imagination; but I cannot say that I ever expected to realize my nautical ambition. I had borrowed a sextant, and used it on board of my boat, so that I was practically skilled in its use. I had taken the latitude and longitude of many points on Lake Michigan, and proved the correctness of my figures by comparing them with the books.

I intended to go to Nice, whether I went to sea as a sailor or not. I had sold my boat for eight hundred dollars, and with seven hundred more I had saved from my salary, I had fifteen hundred dollars, which I was willing to devote to the trip to Europe. But somehow it seemed to go against my grain to pay a hundred dollars or more for my passage, when I wanted to obtain knowledge and experience as a sailor. I preferred to take a place among the old salts in the forecastle, go aloft, hand, reef, and steer, to idling away my time in the cabin.

"I want to be a sailor, father," I added. "I want to know the business, at least."

"I'm afraid that boat on the lake has turned your head, Philip," said my father. "Why, you never even saw the ocean."

"Well, I have seen the lake, and the ocean cannot be very much different from it, except in extent."

"But the life of a sailor is a miserable one. You will be crowded into a dirty forecastle with the hardest kind of men."

"I am willing to take things as they come. I am going to Nice, at any rate, and I may as well work my passage there, and learn what I wish to know, as to be a gentleman in the cabin."

"You are old enough to think for yourself, Philip; but in my opinion, one voyage will satisfy you."

"If it does, that's the end of the idea."

"Do you expect to go to work in a ship just as you would in a store, and leave her when it suits your own convenience?" asked my father, with a smile.

"I can ship to some port on the Mediterranean, and leave the vessel when she reaches her destination."

"I think not. I believe sailors ship for the voyage out and home, though you may be able to make such an arrangement as you propose. I don't like your plan, Philip. You are going to find your mother. It is now the middle of March. If you get off by the first of April, you may make a long passage, and perhaps not reach Nice till your mother has gone from there."

"I shall follow her, if I go all over Europe," I replied.

"But don't you think it is absurd to subject yourself and me to all this uncertainty?"

"Perhaps it is; but I wanted to kill two birds with one stone."

"When you throw one stone at two birds, you are pretty sure to hit neither of them. Be sensible, Philip. Go to New York, take a steamer to Liverpool or Havre, and then proceed to Nice by railroad. You will be there in a fortnight after you start."

My father was very earnest in his protest against my plan, and finally reasoned me out of it. I believed that fathers were almost always right, and I was unwilling to take the responsibility of disregarding his advice, even while he permitted me to do as I pleased. I had been idle long enough to desire to be again engaged in some active pursuit or some stirring recreation. I abandoned my plan; but circumstances afterwards left me no alternative but to adopt it again.

I immediately commenced making my preparations for the trip to Europe, and in three days I was ready to depart. I had called upon and bade adieu to all my friends in St. Louis, except Mr. Lamar, a merchant who had been very kind to me in the day of adversity. On the day before I intended to start, I went to his counting-room, and found him busy with a gentleman. I waited till he was disengaged, and picked up The Reveille to amuse myself for the time. Before I could become interested in the contents of the newspaper, the voice of the gentleman with whom the merchant was occupied attracted my attention. I looked at him a second time, and as he turned his head I recognized Mr. Ben Waterford.

I was conscious that this man was my enemy for life. I was rather startled, for I assure my sympathizing reader that I was not at all anxious to meet him. The last time I had seen him was on the bank of Lake Michigan, at the mouth of a creek where I had left him, having taken possession of his yacht, after a hard battle with him, in order to prevent him from running away with my fair cousin, Miss Marian Collingsby. I had entirely defeated his plans, as well as those of Mr. Whippleton, Mr. Collingsby's partner; and when the business affairs of the latter were examined, they involved those of the former. He was driven into bankruptcy, and did not again show his face in Chicago. Very likely, if I had not thwarted him, he would have married the daughter of Mr. Collingsby, and, perhaps, at the same time, have saved himself from financial ruin.

I read my newspaper, and hoped Mr. Ben Waterford would not see me. I was rather curious to know what business he had with Mr. Lamar. I could hear an occasional word, and I was soon satisfied that the parties were talking about lands. The Chicago gentleman was at his former business, evidently; for then he had been a speculator in lands. I could not understand how one as effectually cleaned out as he was represented to be could have any lands to sell, or any funds to buy them.

"How are you, Phil? How do you do?" said Mr. Lamar, as, for the first time, he happened to discover me.

"Don't let me disturb you, sir. I will wait," I replied.

"Ah, Phil! how do you do?" added Mr. Waterford; and I thought or imagined that there was a flush on his face, as though the meeting was no more agreeable to him than to me.

I shook hands with Mr. Lamar, but I had not the hypocrisy to do so with the Chicago swindler, though he made a motion in that direction. He was not glad to see me, though he smiled as sweetly as the rose in June.

"Take a seat, Phil," continued Mr. Lamar. "I will think of the matter, Mr. Waterford," he added, as the latter turned to leave the counting-room.

"Do you know that gentleman, Phil?" asked Mr. Lamar, when Waterford had gone.

"Yes, sir; I know him, and he knows me as well as I know him," I replied, cheerfully.

"He has some land to sell in the vicinity of Chicago."

"He! He don't own a foot of land on the face of the earth."

"Perhaps he don't own it himself, but is authorized to sell it."

"That may be. Where is the land, sir?"

"In Bloomvale, I think. By the way, he is connected with the former partner of your uncle, Mr. Richard Collingsby."

"So much the worse for him."

"I am thinking of buying this land."

"Don't think of it any more, Mr. Lamar."

"But he offers to sell it to me for half its value, for he is going to leave the country—"

"For his country's good," I suggested.

"That may be; but he wants the money."

I inquired into the matter a little more closely, and found the land was that which had ruined Mr. Charles Whippleton, and which he had deeded to Mr. Collingsby in settlement for the deficiencies in his accounts. It was a fraud on the face of it, and I explained the matter to Mr. Lamar so far as I understood it; but I could not see myself in what manner Waterford expected to convey the property, since he had already deeded it to Whippleton. The two speculators had owned the land together, but Waterford had conveyed his share to Whippleton, who was to pay ten thousand dollars from his ill-gotten gains for the deed, when they ran away together. I had prevented them from running away together, and Mr. Whippleton from running away at all; consequently, the ten thousand dollars had never been paid, though the deed had been duly signed and recorded. The property had since been mortgaged to Mr. Collingsby, who held it at the present time.

It appeared that Waterford had given the deed, but had not received the payment. He was sore on the point, and claimed that the deed for his share of the land was null and void, and that he had a right to sell it again. He had borrowed the money to enable him to purchase it, and the debts thus contracted had caused his failure. But I do not propose to follow Waterford in his land speculations, and I need only say that he was engaged in an attempt to swindle my friend. My statement opened the eyes of Mr. Lamar, and he investigated the matter. Once more I was a stumbling-block in the path of Ben Waterford.

On the day the steamer in which I had engaged my passage to Pittsburg was to sail, I called upon Mr. Lamar again; for I was curious to know the result of the business. Waterford had been to see him again, and the negotiation had been summarily closed. I was thankful for the opportunity of saving one of my friends from loss; for Waterford was a very plausible man, and had grown reckless by misfortune. I had no doubt Mr. Whippleton, who was now in business in Cincinnati, was concerned in the affair.

I bade adieu to all my friends in St. Louis. Mrs. Greenough cried heartily when I took leave of her, and declared that she never expected to see me again, I was going away so many thousand miles. My father went with me to the steamer, and gave me much good advice, which I gratefully treasured up. I found my state-room, and having placed my trunk in it, I spent my last hour in St. Louis in talking with my father. I hoped to bring my mother there in a few months. With a hearty shake of the hand we parted, when the steamer backed out from the levee.

I went to my room then, for I wanted to be alone. I was going away on a long journey, and upon my mission seemed to hang all the joys of life. I prayed to God for strength to be true to the principles in which I had been so faithfully instructed, and that our little family might soon be reunited, after a separation of about sixteen years. I thought of the past, and recalled all the friends who had been kind to me. The Gracewoods were uppermost in my thoughts; for they were among the first who had loved me. To Mr. Gracewood I owed my education, and he had taken pains to give me high principles, upon which to found my life-structure. Ella Gracewood, whom I had saved from the Indians, was an angel in my thoughts. She was beautiful to look upon, though it was four years since I had seen her. She was seventeen now, and my imagination was active in picturing her as she had become during this long absence.

Ella Gracewood was something more than a dream to me; she was a reality. I had the pleasant satisfaction of knowing that she had not forgotten me; for I had received an occasional letter from her, in which she reviewed the stirring scenes of the past, and spoke hopefully of meeting me again at no distant period in the future. I took from my pocket a letter which had come to me from her father only a few days before, and which had given direction, in part, to my thoughts at the present time. The family had passed the winter in Rome, and intended to sail for home about the last of April. Mr. Gracewood had a friend who was in command of a ship which was to sail for New York at this time from Messina, and he had decided to come with him. The ship was the Bayard, Captain Allyn.

I expected to reach Nice by the middle of April, and after I had found my mother, I intended to go to Rome, where I should arrive before the Gracewoods departed for home. The prospect was very pleasant and very satisfactory. I pictured to myself the joy of meeting Ella in that far-off land, and of wandering with her among the glorious relics of the past, and the grand creations of the present. I was sorry to leave my father, but I was very happy in what the future seemed to have in store for me.

From these reflections I passed to more practical ones. I opened my trunk, and looked over its contents, in order to satisfy myself that I had forgotten nothing. I had with me all the letters which Ella had ever written to me, and I had read each of them at least a score of times, weighing and measuring every sentence, the better to assure myself that she had a sincere and true regard for me. I wondered whether she read my letters with the same degree of interest. I could hardly persuade myself that she did. I found myself troubled with a kind of vague suspicion that her regard was nothing more than simple gratitude because I had rescued her from the hands of the Indians. However, I could only hope that this sentiment had begotten a more satisfactory one in her heart.

From these lofty thoughts and aspirations my mind descended to those as material as earth itself—to the yellow dross for which men sell soul and body, of which I had an abundant supply in my trunk. I had fifteen hundred dollars in gold, with which I intended to purchase a letter of credit in New York, to defray my expenses in Europe. Being a young man of eighteen, I was not willing to rest my hopes upon drafts and inland bills of exchange, or anything which was a mere valueless piece of paper. I left nothing to contingencies, and determined to give no one an opportunity to dispute a signature, or to wonder how a boy of my age came by a draft for so large a sum. Gold is substantial, and does not entail any doubts. If the coin was genuine, there was no room for a peradventure or a dispute. In spite of the risk of its transportation, I felt safer with the yellow dross in my trunk than I should with a draft in my pocket.

I had fifteen hundred dollars in gold in a bag, deposited beneath my clothing. I counted it over, to see that it was all right. I had also the relics of my childhood in my trunk, for I expected to see my mother, and I wanted the evidence to convince her that I was what I claimed to be, if the sight of my face did not convince her. Besides my gold, I had about a hundred dollars in cash in my pocket, to pay my expenses before I sailed from New York. I felt that I was provided with everything which could be required to accomplish my great mission in Europe.

Fortunately I had a state-room all to myself, so that I had no concern about the treasure in my trunk. I remained in my room the greater part of the time; for from the open door I could see the scenery on the banks of the river. I assured myself every day that my valuables were safe, and I believe I read Ella's letters every time I opened the trunk. The steamer went along very pleasantly, and in due time arrived at Cincinnati. As she was to remain here several hours, I took a walk through some of the principal streets, and saw the notables of the city. When I went on board again, I bought a newspaper. The first thing that attracted my attention in the news columns was the announcement of a heavy forgery in the name of Lamar & Co. Two banks where the firm did their business had each paid a check, one of six and the other of four thousand dollars. No clew to the forger had been obtained. This was all the information the paper contained in regard to the matter; but as the banks, and not my friend Mr. Lamar, would be the losers, I did not think any more of the subject.

Before the boat started, I assured myself that my trunk had not been robbed in my absence. The bag was safe. At Cincinnati many of the passengers from St. Louis had left the boat, and many new faces appeared. I looked around to see if I knew any one on board. I did not find any one, though, as I walked along the gallery near my room, I saw a gentleman who had a familiar look; but I did not obtain a fair glance at his face. I thought it was Mr. Ben Waterford; but he had no beard, while my Chicago friend had worn a pair of heavy whiskers. I kept a sharp lookout for this individual during the rest of the day, but, strange as it may seem, I did not see him again.

Mr. Ben Waterford had no reason for avoiding me, and if he had he was too brazen to do anything of the kind. I concluded that I had been mistaken; for I could not find him at the table, in the cabin, or on the boiler deck. When I had seen the gentleman whom I supposed to be Mr. Ben Waterford, he was on the point of entering a state-room adjoining my own. I went to the clerk, and found against the number of the room the name of "A. McGregor;" and he was the only person in the room. I heard the creak of his berth when he got into it that night, and I heard his footsteps in the morning. In the course of the next day I inquired about Mr. A. McGregor, but no one knew him.

I watched the door of the room, but no one came out or went in. I only wanted to know whether Mr. A. McGregor was Mr. Ben Waterford with his whiskers shaved off; but that gentleman failed to gratify my reasonable curiosity, though I worked myself up to a very high pitch of excitement over the subject. I was determined to see his face again, if possible, and very likely I might have succeeded under ordinary circumstances; but a startling catastrophe intervened to disappoint me.

On the day after we left Cincinnati, towards evening, I was sitting on the gallery, when, without any warning whatever, I heard a tremendous crash, and felt the steamer breaking in pieces beneath me. I had seen a boat coming down the river a moment before, and I quickly concluded that the two steamers had run into each other.

I realized that the steamer was settling under me. Ladies were shrieking, and even some gentlemen were doing the same thing. I rushed into my state-room, intent upon saving my gold and my relics. I had taken out the key of my trunk, when I heard the door of the adjoining room open. I glanced towards the gallery, and saw Mr. A. McGregor flash past the door. He looked like Mr. Ben Waterford; but I was not confident it was he. Before I could use my key, the disabled steamer rolled over on one side, and the water rose into the gallery, and even entered my state-room.

By the time I was ready to open my trunk, the steamer had settled upon the bottom of the river, which was not very deep at this point. Finding the boat was going down no farther, I dragged my trunk up into the cabin. I do not believe in making a fuss when there is no occasion for a fuss. My property was safe, and so far as I was able to judge, my fellow-passengers were equally fortunate. A few of the ladies insisted upon screaming, even after the danger was past; but it is their prerogative to scream, and no one had a right to object.

I did not object, and I believe everybody else was equally reasonable. I heard a burly gentleman swearing at the pilot for the collision in broad daylight, without a fog or even a mist to excuse him. I do not know whose fault it was, and not being an accident commissioner, I did not investigate the circumstances attending the collision. I only know that no lives were lost, though a great deal of heavy freight on the main deck and in the hold was badly damaged. The crew, and a few of the passengers who happened to be below, were subjected to a cold bath; but I have not heard that any one took cold on account of it.

After a few minutes, some of the gentlemen seemed to consider the calamity a rather pleasant variation of the monotony of the trip, and not a few of the ladies to regard themselves as the heroines of a disaster. The floor of the saloon was still dry and comfortable, though it had an inclination of about thirty degrees from its proper horizontal position, and therefore was not comfortable for ladies to walk upon.

The steamer which had caused the mischief had not been disabled. She had run her solid bow into the quarter of the other, and stove in the side of the hull. She ran alongside the wreck, and the passengers were able to step on board of her without wetting a foot, or even crossing a plank. I took my trunk on my shoulder, and effected a safe retreat, inspired by the same wisdom which induces all rats to desert a sinking ship, and especially one already sunk. Myself, my trunk, and my treasure were safe. I was happy in the result, and doubly so because all my fellow-passengers were equally fortunate. I am sure, if a single life had been sacrificed, I should not have been happy. As it was, I was disposed to be jolly.

I put my trunk in a safe place in the cabin of the steamer which had made the mischief, and turned my attention to the people and the events around me. I found a lone woman, who insisted upon being very much distressed, when there was not the least occasion for any such display of feminine weakness. She had saved herself, but had not saved her baggage, which the deck hands were transferring from the sunken boat with all possible expedition. The lady was sure her trunk would go to the bottom; but when she had told me the number of her room, I conveyed it to the cabin, and placed it above my own. The lady was happy then, and twenty-five per cent. was added to my own felicity by her present peace of mind. She sat down upon her trunk, and did not seem disposed to abandon it. As in watching her own she could not well help watching mine, which was beneath it, and finding it so well guarded, I left the place, and went on the hurricane-deck to take a survey of the lost craft.

In this elevated locality a violent discussion between the two captains and the two pilots of the steamers was in progress. The representatives of each boat blamed those of the other. I listened with interest, but not with edification, for I could not ascertain from anything that was said which of the two was the more to blame. Each pilot had mistaken the intention of the other, and probably both had become rather reckless from long experience. I had often noticed on the Mississippi and the Ohio, as well as in other places, that pilots are disposed to run their boats as close as possible to other boats, when there is not the least necessity for doing so. There is a kind of excitement in going as near as possible without hitting. Men and boys, in driving horses, are apt to be governed by the same principle, and laugh at the timid reinsman who gives a wide berth to the vehicle he encounters.

I have had considerable experience now, and I have come to the conclusion that it is always best to keep on the safe side. It is folly to incur useless risks; and as a venerable young man of twenty-eight, I would rather be laughed at for going a good way to avoid even a possible peril than be applauded for making "a close shave." It is criminal vanity to run into danger for the sake of the excitement of such a situation, and people who do it are not really courageous. On the contrary, it is cowardly in the moral sense, for the person is not brave enough to face a smile or a word of ridicule.

One or both of these pilots had been trying to make "a close shave," where the river was broad enough for them to keep their boats a quarter of a mile apart. If the loss of the boat and the damage to the freight had fallen upon them alone, it would have served them right; but I doubt whether either of them even lost his situation. One boat was smashed and sunk, the other was not much injured. It was a pity that the loss could not have been equally divided between the two; but as it could not be so, of course the captain who had lost his boat was much the more uncomfortable of the two.

I listened to the profitless discussion till I was tired of it, and examined the position of the sunken boat. I should have been very glad to take the job of raising her, if I had not had a mission before me. Leaving the excited little group on the hurricane-deck, I went down into the saloon again. The old lady was still seated on her trunk and mine, and I continued my walk around the steamer. I wanted to see Mr. A. McGregor again; indeed, I was in search of him, for I had made up my mind that he was Mr. Ben Waterford, though I could not see why he was so particular to keep out of my way. Of course I was not sure that the gentleman was my Chicago acquaintance. The lack of a beard on the face of Mr. A. McGregor was an argument against the truth of the supposition; but the form, and as near as I could judge from a single glance, the features, were those of Mr. Waterford.

I could not find him. The passengers were continually moving about the galleries and saloons, and if he was trying to avoid me, he could easily do so. But why should Mr. Ben Waterford wish to avoid me? He did not love me, I knew. I could even understand why he should hate me. If he had met me face to face, abused me and worried me, kicked me, tripped me up in the dark, or pushed me into the river, I might have explained his conduct. I had seen him in St. Louis, and he had greeted me very pleasantly. Now he shunned me, if I was not mistaken in the person. My best efforts failed to afford me a fair view of his face. I had become quite interested, not to say excited, about the matter, and I was determined, if possible, to solve the mystery of Mr. A. McGregor.

As soon as the steamer alongside had taken on board all the passengers, and all the baggage that was above water, she started for Marietta. Those who wished to land at this town, and wait for another steamer, did so; but most of them continued in the boat to Parkersburg, where they took the train immediately on their arrival for Baltimore. As this latter arrangement would enable me to see Baltimore, I concluded to go with the majority, for I was afraid I might be detained three or four days on the river. We arrived just in time to take a night train, and I received a check for my trunk. As soon as the cars were in motion, I passed through all of them in search of Mr. A. McGregor. If he was on the train, I should have a chance to see him where he could not dodge me, and if he proved to be my old yachting friend, I was determined to speak to him, and ascertain where he was going.

Mr. A. McGregor was not on the train. I had missed him somewhere, for in my anxiety for my baggage I had not thought of him till I took my place in the car. He had either stopped at Marietta, or remained in Parkersburg. But after all, I was actuated only by curiosity. I had no special interest either in Mr. A. McGregor or Mr. Ben Waterford. Whoever he was, if I had not imagined that he wished to avoid me, I should not have bothered my head about him. However, we had parted company now, and I was willing to drop the matter, though I was no wiser than at first.

I arrived at Baltimore the next day, astonished and delighted at the beautiful scenery of the Potomac, along whose banks the train passed. My trunk was delivered to me, and I went to a small hotel, where the expense for a day would not ruin me. I was in a strange city, but one of which I had heard a great deal, and I was anxious to see the lions at once. I opened my trunk, and having satisfied myself that my bag of gold was safe, I did not stop to open it, but hastened up Baltimore Street, intent upon using my limited time in the city to the best advantage.

The next day I went to Philadelphia, remaining there a day, and left for New York, only sorry that my great mission would not allow me to remain longer. I was excited all the time by the wonders that were continually presented to me. I was not "green" now, but I was interested in new objects and new scenes, both in the cities and on the routes between them.

On the ferry-boat from Amboy I met a plain-looking man, and a question which I asked him, in regard to a vessel in the bay, opened the way to a longer conversation. He was dressed in blue clothes, and by the manner in which he spoke of the vessel, I concluded that he was a sailor. He criticised rigging and hull with so many technicalities that I was bewildered by his speech. He answered my questions with much good-nature; and when I found he was going to the Western Hotel, I decided to go there with him. Rooms adjoining each other were assigned to us, and we went down to dinner together. I saw by the register that his name was Farraday, and the hotel clerk called him captain. When he ascertained that I was a stranger in the city, he seemed to take an interest in me, and very kindly told me some things worth knowing.

"Do you remain long in New York, Captain Farraday?" I asked, pleased with my new acquaintance, though his breath smelled rather strong of whiskey, which was the only thing I disliked about him.

"No; I mean to be off to-morrow. I expect my mate to-day, and we are all ready to sail," he replied. "I am going on board this afternoon. Perhaps you would like to see my vessel."

"Very much indeed, sir."

"We will go down after dinner."

I wanted to go on board of a sea-going vessel, and I was delighted with the opportunity.

"I believe you said you came from the west," said Captain Farraday; and we walked down to the North River, where his vessel lay.

"Yes, sir; I was born in St. Louis, but have lived a great portion of my life on the Upper Missouri."

"I don't know that I have heard your name yet."

"Philip Farringford, sir."

"Do you ever take anything, Mr. Farringford?"

"Take anything?" I replied, puzzled by the question.

"Anything to drink."

"No, sir; I never drink anything stronger than tea and coffee."

"That's the safest plan; but we old sailors can't get along without a little whiskey. Won't you have a drop?"

"No, I thank you. I never drank a drop in my life, and I don't think I shall begin now."

"Will you excuse me a moment, then?" he added, halting before a drinking-shop.

"Certainly, Captain Farraday," I answered; but I confess that I excused him against my own will and wish.

I stood on the sidewalk while he entered the shop and imbibed his dram.

"I feel better," said he, when he returned. "My digestive rigging don't work well without a little slush."

"I have heard that much grease is bad for the digestion."

"Well, whiskey isn't. If you should go to sea for two or three years, you would find it necessary to splice the main brace, especially in heavy weather, when you are wet and cold."

"I should try to keep the main brace in such condition that it would not need splicing," I replied, laughing, for I considered it necessary to be true to my temperance principles.

"Cold water is a good thing; but when you have so much of it lying loose around you on board ship, you need a little of something warm. That's my experience, young man; but I don't advise any one to drink liquor. It's a good servant, but a bad master."

"It is certainly a bad master," I replied, willing to accept only a part of the proposition.

"Yes; and a good servant to those who know how to manage it. Are you much acquainted out west, Mr. Farringford?" he asked, changing the subject, to my great satisfaction.

"I am pretty well acquainted in Chicago and St. Louis."

"Not in Michigan?"

"Not much, sir."

"Do you happen to know the Ashborns, of Detroit?"

"No, sir; never even heard of them."

"There are two of them out there now; but the third of them came back to New York, and owns two thirds of the bark I sail in. I own the other third. John Ashborn calls himself a Michigan man because the family is out there, and named the bark after the state."

"The Michigan?"

"Yes; and she's a good vessel."

"Where do you go?"

"We are bound to Palermo."

"Palermo!" I exclaimed. "I wish I was going there with you."

"I wish you were. We are to have three or four passengers," added the captain. "I rather like you, from what I have seen of you."

"But I should like to go as a sailor."

"A sailor! You, with your good clothes?"

"I could change them. I know all about a boat, and I should like to learn all about a ship."

"Well, if you want to go, I will ship you. I want two or three more hands."

"I am sorry I can't go. I must be in Nice by the twentieth of next month."

"There are steamers every few days from Palermo and Messina to Marseilles, and that's only a short run from Nice."

"I want to be a sailor; but I shall not be able to ship at present."

"My mate is a western man, too," added the captain, as we stepped on board his vessel—the bark Michigan. "He is a nephew, a cousin, or something of that sort, of Mr. Ashborn. They say he is a good sailor, and has made two voyages as second mate, and one as chief mate. He's smart, and went into business out west; but he failed, and now wants to go to sea again," continued Captain Farraday, as he led the way into the cabin.

I looked through the main cabin, examined the state-rooms, and then went on deck. The master answered all my questions with abundant good-nature. Indeed, he had taken another dram in the cabin, and he appeared to be growing more cheerful every moment. I had seen a square-rigged vessel before, and was tolerably familiar with the names of the spars, sails, and rigging, and I astonished the old salt by calling things by their right names. I told him I could sail a boat, and I thought a few weeks would make a salt sailor of me.

"Well, Mr. Farringford, if you want to ship, you can't find a better vessel than the Michigan," said Captain Farraday. "I have had college-larnt men before the mast with me, and though I expect every man to do his duty, we make the hands as comfortable as possible."

"I have no doubt of it, sir. You don't seem at all like the hard and cruel shipmasters we read of in the newspapers."

"Not a bit like 'em. I'm human myself, and I know that sailors are human, too. They can't help it; and I always try to use 'em well, when they will let me. I haven't seen my new mate yet; but they say he is a gentleman and a scholar, besides knowing a buntline from a broomstick."

I had no doubt that the new mate was a very wonderful man, and I was only sorry that the circumstances would not permit me to enjoy his kind and gentlemanly treatment on the passage to Palermo.

"Mr. Ashborn says his nephew is really a brilliant man, and I suppose, if I was only out of the way, he would have the command of the bark," the captain proceeded. "Well, I'm fifty now, and I don't mean to go to sea all the days of my life. I've been knocked about in all sorts of vessels ever since I was a boy. I didn't crawl in at the cabin window; I went through the hawse-hole; and I can show any man how to knot, and splice, and set up rigging. But I've had about enough of it. I've got a little farm down in Jersey, and when I've paid off the mortgage on it, I shall quit going to sea. It's all well enough for a young man; but when one gets to be fifty, he wants to take it a little easier."

Captain Farraday showed me the quarters of the crew, in a house on deck, instead of the forecastle, where the hands are generally lodged. It was rather dirty, greasy, and tarry; but I was satisfied that I could be comfortable there. It was even better than the log cabin where I had spent my earlier years; and neither the smell nor the looks would have deterred me from going to sea in the Michigan, if I had not felt obliged to follow the instructions of my father.

I liked the bark very much. Her captain pleased me, and I had no doubt I should be captivated by the graces and accomplishments of the new mate. I was sorry I could not go in her. Captain Farraday took another drink before I left the vessel, and I was glad then that his duties required his presence on board, for he told me that, in the absence of the mate, he was obliged to attend to the details of the bark himself. I walked up to Broadway, and examined the wonders of the city on my way. I wanted to find the office of the steamers for Europe, and a handbill gave me the necessary information. It was now Saturday, and one of them would sail on the following Wednesday. I spoke for a berth in the second cabin, which I thought would be good enough for me, after having seen the forecastle of the Michigan.

I then visited a banker's, and ascertained on what terms I could obtain a letter of credit. I did not care to keep my gold any longer than was necessary, and I hastened back to the hotel to obtain it, rather than leave it in my trunk till Monday. When a man's conscience is all right, money is a great blessing to him, and may make him very happy, if he knows how to use it; but when a man's conscience is not all right, neither money nor anything else can make him happy. My bag of half eagles was a great luxury to me. I could even spend a year in Europe without troubling myself about my finances. There is something in this consciousness that future wants are provided for, which affords a very great satisfaction; and as I walked back to the hotel, I was in the full enjoyment of this happy state of mind. I could look into the shop windows without wanting anything I saw, unless I needed it; but the lack of means suggests a thousand things which one never wants when he has the ability to buy them.

I reached the hotel, and went up stairs to my room. My trunk was on the chair where the porter had placed it; and every time I saw it safe, it afforded me a new sensation of enjoyment. I experienced it more fully on this occasion, for in half an hour more I should be relieved of all responsibility in regard to it. I could have all the benefit of it, without being burdened with the care of it. I could cross the ocean, and in whatever city I happened to be, I could step into the banker's and provide myself with funds as long as the fountain now in my possession should hold out.

I opened my trunk. It was a very nice trunk, which my father had furnished for me, expressly for travelling in foreign lands. It was made of sole leather, and strong enough to resist all reasonable assaults of the baggage smashers, though of course I could not have entire confidence in it, when pitted against the violence of those worthies. I was rather proud of my trunk, for I have always thought that a nice-looking, substantial one adds very much to the respectability of the traveller. I have imagined that the landlord bows a shade lower to the owner of well-ordered baggage, and that gentlemanly hotel clerks pause before they insult the proprietor of such goods. I considered my trunk, therefore, as a good investment for one about to cross the ocean, and wander in foreign lands. I had heard a western hotel-keeper speak very contemptuously of those people who travel with hair trunks, and I was very happy in not being counted among the number.

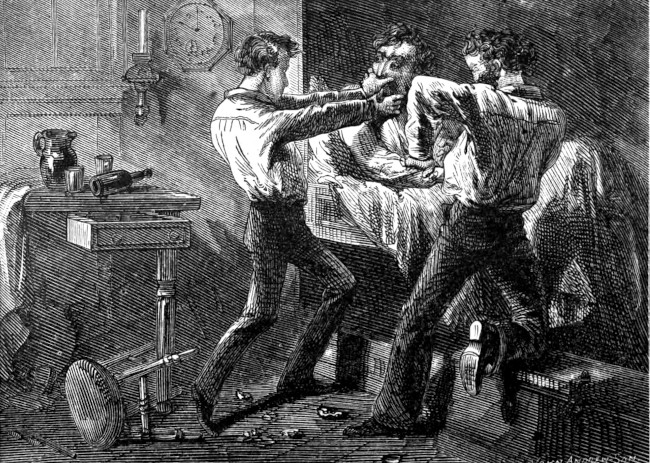

I opened my trunk, and found my clothes just as I had left them the last time I examined my treasure, or rather the last time I had looked at the bag which contained it, for I had not counted the gold since I left the steamer on the Ohio. I took out the various articles at the top of the trunk, and soon reached the bag. It lay in the corner, distended just enough to hold the fifteen hundred dollars. It was a pleasant sight to look upon, and I could not help congratulating myself upon the fact that I had brought so large a sum in safety from St. Louis to New York. Perhaps it was not a great feat; but I could not help feeling that it was just a little "smart," for specie is always a dangerous commodity to transport.

The bag lay in the corner just as it had when I glanced at it in Baltimore and in Philadelphia. As the sight of the distended bag had satisfied me then, so it would have satisfied me now, if I had not intended to dispose of its contents. I took hold of the bag, and lifted it up. It was very light compared with what it ought to have been, and with what it had been when I had last raised it.

In a word, my gold was not there.

My Gold was not there.

The bag which had contained my gold was distended as though the treasure were still there; but it was light, and I was satisfied that it contained nothing more substantial than paper. I need not say that a feeling akin to horror chilled the very blood in my veins, for without this money it seemed to me that all my plans would be defeated. I could not travel in Europe without it. I could not even purchase the steamer ticket for which I had spoken.

Grief, despair, and even shame, overwhelmed me, and I dropped into my chair utterly disconsolate for the moment. I held the bag in my hand, and felt that the solid, substantial hopes with which I had cheered and gladdened my soul had suddenly changed into airy phantoms. My gold had become waste paper. If I ever felt like using wicked language, it was then; but I thank God I did not profane his name, and pollute my own lips by any uttered word of irreverence. But I did feel as though God had forgotten and deserted me; as though he had cruelly and unreasonably mocked my hopes. Yet these thoughts were but the momentary spasm of a disappointed soul, and I trembled when I realized that such wickedness was in my heart.

God had given me all that I was and all that I had. What I had lost was not the half even of my worldly wealth, and it was impious to repine, though but for an instant. When I weighed this handful of gold against all my other blessings, against my Christian father, who prayed for me morning and night, and against the good I had been permitted to do for myself and others, the treasure was but a trifle. If it had cost me two years to save it, I was thankful that it was not the only saving of that precious period.

I rebuked myself severely for the wicked thoughts which had been engendered by my misfortune, and tried to take a more reasonable view of the loss I had sustained. I thanked God for all his mercies, and asked for strength to sustain me in this new trial. Having conquered the rebellious thoughts which the loss occasioned, I opened the bag, and attempted to fathom the mystery of its emptiness. There was nothing in it but an old newspaper rolled up into a ball. That was the only fact I had to work with. The bag had contained fifteen hundred dollars in ten and twenty dollar gold pieces when I left St. Louis; and the money was all right when I counted it on board of the steamer.

It was evident, therefore, that I had been robbed after the boat entered the Ohio River; but whether at Cincinnati, Parkersburg, Baltimore, Philadelphia, or New York, I had no idea whatever. I threw the bag back into the trunk. My father had insisted that the safest way for me to convey my money to New York was in the form of a draft; but I was afraid that, being a minor, the banker would refuse to pay me, or that something else might occur to make me trouble. I could not help thinking again that fathers are almost always right. At any rate I was wrong, and too late I regretted that I had persisted in my own way. I had lost my money by it, though my father would have been just as correct in his position if I had not lost it.

While I was thinking of the disagreeable subject, I unrolled the ball into which the newspaper had been formed. One of the first things that attracted my attention as I did so, was the announcement of the "Heavy Forgery in St. Louis." One of the corners of the paper was lapped over in printing it, and this circumstance enabled me to identify it as the one I had purchased in Cincinnati, and read after I came on board of the steamer. One more fact was added to my knowledge of the robbery. My trunk had been rifled after I left Cincinnati.

This fact did not help me much; but it suggested an examination of the lock on my trunk. I could see the marks of some sharp instrument in the brass around the key-hole, and I remembered that I had had some difficulty in opening the trunk just before the collision on the Ohio. If the robber had left my trunk unlocked, I had not discovered the fact. The bolt had evidently been moved back by a bent file, or something of that kind. I cudgelled my brains severely to recall all the circumstances of my last day on board of the steamer. I had opened my trunk after dinner, and read all the letters of Ella Gracewood, not only because I had nothing else to do, but because it was the pleasantest occupation in the world to me. I was persuaded that my bag had been emptied that afternoon, probably while I was walking on the hurricane-deck, where I spent an hour just before the collision in obtaining my daily exercise, walking back and forth.

I could not help connecting the robbery with "Mr. A. McGregor;" but it was too late now to do anything. The money had gone, and so had Mr. A. McGregor. I could not find him if I tried. It was better for me to regard the treasure as lost, than to entertain the absurd proposition of finding it. What should I do? It was impossible to go to Europe without money, and a liberal supply of it, too. I still had two thousand dollars in the savings bank in St. Louis; but I regarded this as my capital for the future, when I should have an opportunity of going into business. I did not like to draw it, and I did not like the delay which it would require to obtain it. If I wrote to my father immediately, it would require a week to receive an answer from him. Then he would be obliged to give notice to the savings bank, and wait for regular days for drawing out money.

I must certainly wait a week, and perhaps a fortnight, before I could receive funds from St. Louis. I might miss my mother at Nice, and I was tolerably certain to miss the Gracewoods at Messina. I was vexed at the thought of this delay, and I am not sure but the fear of not seeing the Gracewoods fretted me more than the contingency of not meeting my mother, for the latter was to remain in Europe another summer, and I could follow her wherever she went.

Worse, if possible, than all this, I was ashamed of myself, because I had permitted myself to be robbed. It is not for me to say whether or not I am conceited; but I certainly had a great deal of pride of character. A mistake was not half so bad as a crime, in my estimation; but it was still very bad. I did not wish to be regarded, even by my father, whose judgment would be very lenient, as a young man who had not the ability to take care of himself. I did not like to confess that in neglecting the advice of my father, and following the behests of my own head, I had come to grief. Without doubt I was wrong; but I had been taught to depend solely upon myself, and to rely upon no arm but that of God. A blunder, therefore, was more to me than it would have been under other circumstances. While I was thinking of the matter, there was a knock at my door. It was Captain Farraday, and I admitted him.

"Well, Mr. Farringford, you seem to be busy," said he, glancing at my clothing laid upon the bed and chairs, as I had taken it from my trunk.

"Not very busy, sir, except in my head," I replied.

"Young men's heads are always busy," he added, with a jolly laugh, for he was still under the influence of the liquor he had drank, though he was not much intoxicated.

"I am full of misfortunes, mishaps, and catastrophes," I answered.

"You!"

"Yes, sir."

"You don't mean it! If I were a young fellow like you, I should be as jolly as a lark always and everywhere. In fact, I am now."

But I could not help feeling that his whiskey was the inspiration of his merriment, and that he must have times when the reaction bore severely upon him.

"I have met with a heavy loss," I continued.

"Sorry for that; what is it?"

"I had a bag containing fifteen hundred dollars in gold in my trunk. It is gone now."

"Gone!" exclaimed he.

"The bag is empty."

"I am sorry for it; but I think you almost deserve to lose it for leaving it in your trunk."

"I acknowledge that I was imprudent; but I thought it was safe there, because no one knew that I had it."

I told him enough of my story to enable him to understand my situation.

"It's a hard case; but you know it's no use to cry for spilt milk; only don't spill any more."

"But all my plans are defeated. I can't go to Europe without money."

"That's true; a man wants money in Europe, if he don't in America. Where did you say your mother was?"

"At Nice."

"Just so; you can go in my vessel to Palermo, and then to Genoa and Nice by the steamers. If you want to learn how to knot and splice, reef and steer, you shall go before the mast and work your passage. It will do you good, besides what you learn."

"But I shall have no money when I get to Nice," I suggested.

"What of that? You say your mother belongs to a rich family, and of course she has money enough."

This idea struck me very favorably. I had about sixty dollars in my pocket, which would more than pay my expenses from Palermo to Messina, where Mr. Gracewood would lend me a further sum. If I missed them, I could even go to Nice, where my mother would be glad to supply all my wants. I liked the plan, but I was not quite prepared to decide the matter. The Michigan would sail the next day, and I could at least think of it over night.

Captain Farraday pressed the matter upon me, and declared it was a great pity that a good sailor should be spoiled to make an indifferent merchant or mechanic. I promised to give him an answer the next morning; and the prospect of being a sailor, even for the brief period of three or four weeks, seemed to be some compensation for the loss of my money. I was not disposed to be a fatalist; but it passed through my mind once, that, as I was destined to be a sailor, I had lost my money so that I might not miss my destiny.

I went down to supper with Captain Farraday, who still plied his favorite topic, and gave me a rose-colored view of "a life on the ocean wave." He stopped at the bar on the way to the dining-room, and he was not agreeable company after he had taken one more dram. After supper, I left him, and went to the post office, for I had been expecting a letter from my father ever since I arrived in the city.

I found one this time. It was full of good advice and instructions, forgotten before I left St. Louis. He gave me fuller particulars than I had obtained from the newspaper in regard to the forgery of Mr. Lamar's name. I learned with surprise that Mr. Ben Waterford was now strongly suspected of the crime, and his visits to Mr. Lamar, ostensibly to sell land, were really to enable him to see the check book of the firm. The evidence was not conclusive, but it was tolerably strong.

I had no difficulty in believing that Mr. Ben Waterford was a rascal and a swindler, but it was hard to realize that one who had occupied so respectable a position in Chicago had sunk so low as to commit the crimes of forgery and robbery. With my father's letter before me, I was satisfied that Mr. A. McGregor was no other than Mr. Ben Waterford. After he had committed forgery in St. Louis, he had abundant reason for wishing to remain unseen and unknown.

He had obtained the money on the forged checks, crossed the country to Cincinnati, and joined the steamer in which I had taken passage. It was possible, and even probable, that he knew I had a considerable sum of money with me, and that he had come on board for the purpose of obtaining it, as much for revenge on account of the check I had put upon his operations as for the sake of the money. My friends in St. Louis all knew that I was going to Europe, and I had procured my gold at a broker's. His iniquity seemed to be prosperous at the present time, for so far as I had learned, he had yet escaped detection.

My desire to be a sailor, even for a few weeks, got the better of other considerations, and before the next morning I had about decided to take passage in the Michigan, or rather to ship as one of the crew for the outward voyage to Palermo. I met the captain at breakfast, and he was quite sober then. I supposed that he kept sober on board ship, for the discharge of his responsible duties required a clear head, though the wonderful mate was competent to handle the vessel. He was just as persistent sober as he had been drunk, that I should embark in the Michigan, and I was weak enough to believe that I had made a strong friend in him. I might never again have such an opportunity to go to sea, with the master interested in me, and desirous of serving me.

I am satisfied that, if I had not met Captain Farraday, I should have asked my father to send me the money needed for my trip, and taken the steamer, as I had intended. Such a powerful friend in the cabin would necessarily afford me a very comfortable berth in the forecastle. He was the superior even of the wonderful mate; and, if the latter did not take a fancy to me, as the friend of the captain I should not be likely to suffer any great hardships. I might even expect an occasional invitation to dine in the cabin, and certainly, if I was not comfortably situated on board, I should have the courage to inform my excellent friend of the fact, and he would set me right at once.

I wrote a long letter to my father, detailing the loss of my money, and the reasons why I had changed my plans. I thought that the circumstances justified the change; but my strongest reason was, that Captain Farraday was my friend, and I should never have so favorable an opportunity again to learn seamanship. After I had written the letter, I read it over, and I concluded that my argument was strong enough to convince my father. Having mailed this letter, I looked about me for the captain. I found him at dinner, rather boosy again, but very kind, considerate, and friendly.

"Well, my hearty, are you ready yet for a life on the ocean wave?" said he.

"I have about concluded to go with you," I replied.

"Have you? Well, you have about concluded to do the biggest thing you ever did in your life."

"I have written to my father that I should go in the Michigan."

"Good, my hearty! You are on the high road to fortune now," added the captain, rubbing his hands.

"I don't expect to make my fortune. All I desire is to work my passage," I replied, rather amused at his enthusiasm.

"Fortunes have been made by a single voyage. I mean this shall be my last cruise."

"I hope you will make your fortune, sir."

"I expect to do it on this trip. Then I shall pay off the mortgage on my farm, and keep quiet for the rest of my life."

"I hope you will. But what time do you sail, sir?"

"Some time this afternoon. The new mate hasn't come yet; but he's in the city, for I've heard from him. He's the owner's nephew, you see, and I can't drive him up, as I should another man. We will go on board about three o'clock."

After dinner I went up to my room, and put on the suit of old clothes which I had brought with me to wear on board of the steamer. It was not a salt rig, but I have since learned that it is not the tarpaulin and the seaman's trousers that make the sailor. I procured a carriage to convey my trunk to the wharf, and Captain Farraday rode with me. We called a shore boat, and were put on board of the bark, which had hauled off into the stream. She lay with her anchor hove short, and her topsails loosed, ready to get under way the moment the order was given.

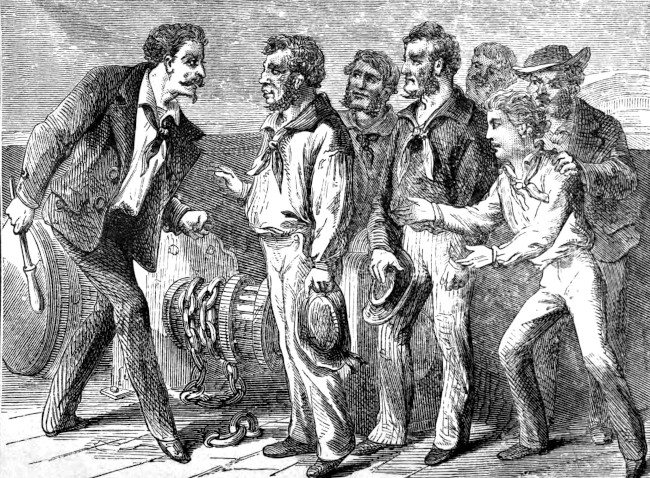

The crew had been put on board by a shipping agent, who remained by the vessel, to see that none of them deserted. I should say that the majority of them were beastly drunk, while all of them were under the influence of liquor. Without exception they were the hardest looking set of men I had ever seen collected together. I listened for a moment to the wild curses that rang through the air, and my heart was sick. The idea of being for three weeks in the same vessel with such a set of wretches was intolerable. They were of all nations, and the lowest and vilest that the nations could contribute.

The sight of them was a terrible shock to me, and my romantic notions about a "life on the ocean wave," so vividly set forth by my friend Captain Farraday, were mocked by the stern reality. I had taken my elegant trunk on board; if it had only been in the boat, I should have returned to the shore, without stopping to say good by to the captain. I fled from the forecastle to escape the ringing oaths and the drunken orgies of the crew. How vividly I recalled all that my father had told me about the character of the sailor of the present day! All that he had said was more than realized in the actions and appearance of the crew of the Michigan; but, in justice to the sailor, I ought to add in the beginning, that they were not a fair specimen of the class of men who sail our ships. I walked aft filled with loathing and disgust. The captain was giving some directions to the second mate, who was performing mate's duty in the absence of that worthy. Even the second mate was drunk; and, between him and the captain, it was difficult to tell which was the more sober.

"Well, Farringford, did you find a place for your trunk in the forecastle?" said the captain, as he saw me.

"No, sir; I did not look for a place."

"What's the matter, my hearty? You look down in the mouth," he added, thus assuring me that the feeling in my heart had found expression in my face.

"I don't exactly like the looks of things," I replied, trying to smile.

"What's the trouble?"

"I would like to go on shore again," I added, candidly.

"On shore again! I didn't take you for a chicken."

"I don't think I am a chicken, but I don't like the idea of being with those fellows forward."

"What's the matter with them?"

"They are all drunk."

"Drunk! What of it? So am I. That is, I'm reasonably drunk. I know what I'm about, and so do they."

"I don't think many of them do know what they are about. I never heard such awful profanity before in my life."

"O, well, my lad, you will soon get used to that," laughed Captain Farraday.

"Not if I can help it, sir."

"But you are not going to back out now, Farringford?"

"I don't like to back out, but I can't stand it to live in the same forecastle with such miserable wretches as those men."

"Be reasonable, Farringford. Don't you see they are drunk?"

"Yes, sir; and I consider that a serious objection to them; for men in their sober senses would not use such horrible curses as those men use."

"That's it, exactly, Farringford. It's only because they are drunk. When they are sober they will be as pious as parsons."

"If you have no objection, I think I will go on shore again."

"Of course you can go on shore if you like, but you will make a blunder if you do, Farringford. I advise you as a friend. Do you expect the crew will be drunk all the time?"

"I don't know anything about it; but I don't like the looks of them."

"These men have just come on board. Sailors always go on a spree before they go on a voyage. They don't have any liquor at sea. Every man's kit is searched to see that he brings none with him. Before eight bells, to-night, they will all be as sober as judges, and you won't see one of them drunk again till we get to the coast of—to Palermo; and not then, unless we give them a day on shore."

"That alters the case," I replied, perceiving the force of his argument.

"That's one of the best crews that ever was shipped out of New York. You can't tell what they are when they are drunk. Why, one third of them are church members."

If the captain had not been tipsy himself, I should have believed he intended to deceive me; but he had been very kind to me, and I charged his exaggerated remarks to the whiskey he had drank. If the crew were only sober, and ceased swearing, I was confident I could get along three weeks with them. I had read in my Sunday school library books of ships which were sailed without rum or profanity, and perhaps I had taken my ideal from too high a pitch. If these men were not fed upon liquor I did not believe they could be as they were now.

"I can't go into the forecastle with them while they are in their present state," I added.

"O, well, we will make that all right. I will give you a place in the cabin till to-morrow. By that time you will find the crew are like so many lambs. Bring your trunk this way."

I obeyed, though I was not quite satisfied. I carried my trunk below, and put it into the steerage, which was appropriated to the use of the cabin steward. The captain told me I might sleep that night anywhere I could find a place. I was so infatuated with the desire to go to sea as a sailor, that I flattered myself the crew would appear better when sober, and I tried to persuade myself that the adventure would come out right in the end.

"Here, Farringford, sign the papers," said the captain, pointing to a document on the cabin table.

"But I don't ship as a regular seaman," I replied.

"It's only a form," he added. "You shall leave when you please, but the law requires that every seaman shall sign the papers."

I did so as a matter of form, and went on deck. The new mate was coming alongside. He was in a boat with two other men; and, as he was practically to be my master during the voyage, I regarded him with deep interest. I did not see his face at first, but as he rose from his seat I recognized him.

The new mate was Mr. Ben Waterford, from the west!

As soon as I saw the face of Mr. Ben Waterford, I retreated to the cabin, and then to the steerage, where my trunk had been deposited. I felt as though I had seen the evil one, and he had laid his hand upon me. I was disgusted and disheartened. I had signed the shipping articles, and it was not easy to escape. Captain Farraday wanted me, or he would not have taken so much pains to induce me to ship. If my trunk had been on deck, I would have hailed a boat and escaped at all hazards; but I could not abandon the relics of my childhood, for I depended upon them to prove that Louise Farringford was my mother.

I asked myself what wicked thing I had done to deserve the fate which was evidently in store for me if I remained on board of the Michigan. Whatever I had done, it seemed to me that my punishment must be more than I could bear. Ben Waterford would be a demon in his relations to me, after the check I had been upon his evil deeds in Chicago. He was a man of violent temper when excited, and I regarded him as a malicious and a remorseless man.

It seemed stranger to me than it will to any of my readers, that this man should now appear in New York as the mate of the bark in which I had shipped. Still there was nothing which could not be easily reconciled, except the fact itself. I had myself heard him say, on board his yacht, when we were sailing on Lake Michigan, that he had been a sailor; that he had made several voyages—two of them as second mate, and one as chief mate. This was precisely the recommendation which had been given to Captain Farraday of his qualifications. He was a good sailor, and I had learned a great deal about vessels from him.

I concluded, after passing the circumstances through my mind, that he had failed in every other kind of business, and had been obliged to go to sea again. But if he was guilty of the forgery in St. Louis of which he was suspected, and of the robbery of my trunk, of which I was tolerably confident, he was well provided with funds; and certainly he was not compelled to go to sea to earn his living, though it would be convenient for him to be in any other locality than the United States for the next few months or years, till the excitement about the forgery had subsided.

The steward's room, where my trunk had been placed, was in the steerage—a rude apartment between decks, next to the cabin. Several rough pine bunks had been built here, for the cabin steward, carpenter, and sail-maker. The two latter were unusual officers on board a Mediterranean vessel. I was thinking in what manner I could get out of the bark, and I walked from the steerage forward. The hatches were off, and the hold was open. The vessel had but little freight, and was really going out in ballast, for a cargo of fruit. I did not wish to show myself to Ben Waterford, if I could possibly avoid it. I concluded that he would be on the quarter-deck with the captain. I went to the hatch, and ascended by the notched stanchion.

The crew were still engaged in their wild orgies, which they considered as mere skylarking; but the oaths and the roughness of their manners led me to avoid them. The captain and the mate were standing near the wheel, talking. I went to the side, and looked over into the water. The boat which had brought off the mate was still there. Two men sat in it, and I hoped I might be able to make a bargain with them to convey me to the shore. If I could escape, I intended to denounce Ben Waterford to the police on shore as the forger and robber, for in this way there was a chance that I might recover my gold.

I went to an open port, and beckoned to the two men in the boat, who appeared to be waiting for something. They obeyed my summons, and came up beneath the port.

"What do you want?" demanded one of them, as he stuck the boat-hook into the side of the bark.

"I will give you five dollars if you will take me and my trunk on shore," I replied, as loud as I dared speak.

"All right; I'll do it," replied the man, evidently satisfied with the liberal offer I made. "Hand down the trunk."

"What are you waiting for?" I added.

"The captain wants to send his papers to the custom-house; but never mind that. We will take you on shore as soon as you are ready."

"I will be ready as soon as I can get my trunk on deck," I answered.

"Hurry up. I understand the case. You are sick of your ship, and want to leave her. That's none of my business. I'll help you off, if you will hand over the money."

I gave the man one of the sovereigns I had purchased with the sixty dollars which remained of my funds.

"Bear a hand," said the man, as he glanced at the coin, and slipped it into his pocket.

"I will be ready in less than five minutes."

"Don't let them see you if you can help it."

I had already decided how the plan was to be carried out. A piece of whale line lay on the deck near the mainmast, one end of which I dropped down the hatch, making the other end fast at a belaying-pin on the fiferail. Fortunately for me, the men were forward of the house on deck, and the officers were on the quarter-deck, busily engaged in discussing some difficult subject, I judged, by the energy they used in their discourse. The two men who had come off with the mate were taking part in the discussion, and I was confident that Captain Farraday had forgotten all about me.

I descended to the between-decks after I had satisfied myself that I was not observed. Conveying my trunk to the hatch, I attached the whale line to one of the handles. Running up the notched stanchion again, I reached the deck, and took another careful survey of the surroundings before I proceeded any further. The men were still skylarking; the shipping agent sat on the rail watching them, and the group on the quarter-deck had not yet settled the dispute in which they were engaged. The open port was abreast of the hatch. Grasping the line, I hauled my trunk on deck. Dragging it to the port-hole, I lowered it into the boat, where it was taken by the two men.

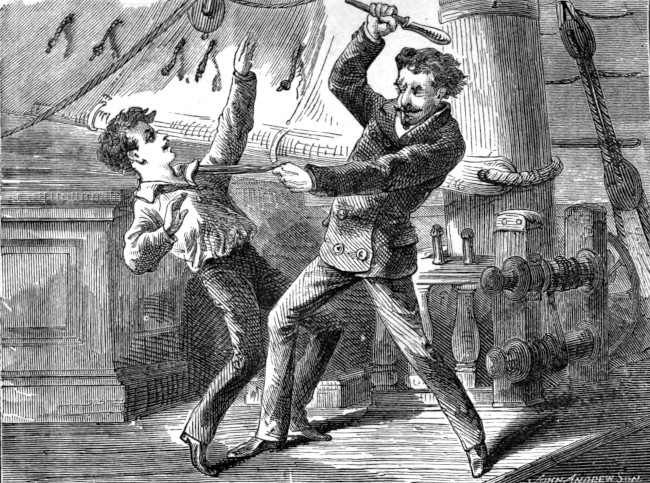

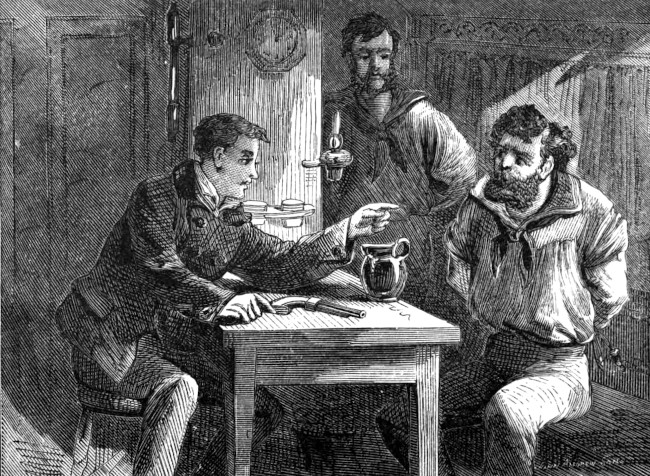

"Hallo, there, Farringford! What are you about?" shouted Captain Farraday, rushing into the waist, followed by the mate and the two passengers.

I was just congratulating myself on my success in getting away, when my ears were saluted by this unwelcome call. I was determined not to be cast down by the unfortunate discovery, and seizing the rope by which I had lowered my trunk, I slid down upon it into the boat. I considered myself all right then; but youth is proverbially over-confident and over-enthusiastic. The men in the boat cast off the line from my trunk, and pushed off from the bark.

"Hallo, Farringford! Where are you going?" shouted the captain through the open port.

"I have concluded to go on shore again," I replied, with great equanimity, for I felt considerable assurance for the future, now that I was actually out of the bark.

"But you have signed the papers, and belong to the vessel now," replied Captain Farraday.

"I will thank you to scratch my name from the papers," I added.

"Phil Farringford!" shouted the wonderful mate, as he thrust his head out of the port-hole, and apparently for the first time saw and recognized me. "Don't let him get off!"

The head of the mate disappeared. I saw the interest he felt in the matter, and as soon as he comprehended the situation he was very active.

"Pull away!" said I to the men in the boat with me.

"Your chances are small, my lad," added the one with whom I had made my trade.

"We have the start of them."

"Not much."

"They have no boat ready."

"Yes, they have. The shipping master's boat is pulling around the bark to keep any of the crew from getting off. There it is; he has hailed it."

I saw a sharp and jaunty-looking boat pull up to the accommodation ladder. Captain Farraday and the new mate leaped into it, and the men gave way with a will.

"Pull, my men," I said, when I saw that my companions were not disposed to use their muscles very severely.

"No use; we can't pull this boat against that one."

"I will give you another sovereign if you will keep out of their way, and land me anywhere in the city," I added, feeling that I had lost all influence over the oarsmen because I had already paid them.

"We will do the best we can for you. Pull, Tom," replied the spokesman.

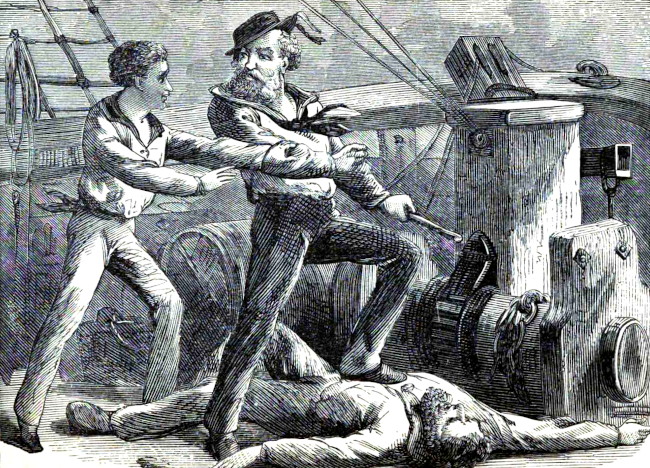

Then commenced an exciting race; and I will do my men the justice to say that they did the best they could. But the shipping master's boat was lighter and sharper, and his men were exceedingly well trained. Ben Waterford was in earnest, and not only crowded his oarsmen to their utmost, but he took a spare oar and helped them with his own muscle. Our pursuers were gaining upon us, and my heart sank within me.

"We are losing it," said the man at the stroke oar. "I am sorry for you, for I don't believe that bark is going to Palermo, or anywhere else up the Mediterranean."

"Where is she going?" I asked, startled by this suggestion.

"Of course I don't know; but, in my opinion, she is going to the coast of Africa."

"Coast of Africa!" I exclaimed.

"I don't know, but I think so."

"Her shipping papers say Palermo."

"Shipping papers are not of much account on such voyages."

"Pull away!" I cried, as I saw the other boat gaining upon us.

My men increased their efforts; and, as talking diminished their activity, I did not say any more, though I was anxious to know more about the Michigan. I did not yet understand why the bark should go to the coast of Africa, instead of Palermo.

"I put the Spaniard that went off with the first mate on board of a vessel a few months ago, which was seized before she got out of the harbor," said the boatman.

"Pull with all your might," I added, trying to help the man nearest to me.

"We are doing the best we can."