Title:The beautiful garment and other stories

Author: A. L. O. E.

Release Date:August 26, 2023 [eBook #71492]

Language:English

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

"You'll find our Lydia a child after your own heart, Martin," said Captain Neill, a retired officer, to his elder brother, who had lately returned from India.

"She seems to be a quick, intelligent girl," answered Mr. Neill, in a less enthusiastic tone.

"She is that, and a great deal more!" cried the father. "It is wonderful to see the good that child does! From cottage to cottage she goes, reading, talking—really like a grown-up woman; it would surprise you were you to hear her."

"Perhaps it would," said his brother, a pale, reserved man, with dark, thoughtful eyes, and a face on which love to God and good-will to man seemed to have set their stamp.

"Certainly, dear Lydia is a very uncommon child," lisped Mrs. Neill from the sofa, to which long and tedious, though not dangerous illness had confined her for several months.

"You see," pursued the captain, "we've no child but Lydia, so we've devoted all our care to our pet."

"An only child runs some danger of being spoilt," observed Mr. Neill, with a smile.

"Yes, yes, but we never spoil ours," answered the father, quickly.

"Oh, dear, no!" said the lady, from the sofa.

"We have always from the first taught Lydia her duty; and I must say that we've found her an apt pupil," continued the captain. "Would you believe it—though she is just twelve years old, that child has twice read through the Bible, and has started on the third reading of her own accord!"

The partial father looked into his brother's face, expecting to see depicted there admiration and surprise. There was, however, no expression of the kind. Perhaps Mr. Neill was thinking that one verse of the Holy Scriptures, treasured in the heart, might do more for the soul than the whole Bible read hastily over for the sake of boasting that so much had been done.

"And then her charity," recommenced Captain Neil; but he was interrupted by the entrance of a fine-looking girl, who came in with a quick step and self-possessed manner, her checks glowing beneath her white hat from the exercise which she had been taking.

"Where have you been, my darling?" asked her father.

"Oh, round by the mill, and as far as the seven cottages. Poor Jones is getting worse and worse; his wife says that he cannot last long. I tried to get Mrs. Brown to send all her children to school, but she tells me they can't go in such rags. I'm about to make a parcel of my old clothes, my green dress, and a lot of other things—"

"But, my dear," said Lydia's mother, "that dress was quite new this spring; I don't wish—"

"I'm tired of it," interrupted Lydia; and seeing that her mother was about to speak, she cut her short by a decided, "I hate green dresses, and I'm not going to wear it again."

The mother looked vexed, but said nothing. "You've had a long round, my darling; sit down and rest," said Captain Neill, kindly.

"I'm not tired, and would rather stand," replied Lydia, in her short, decided manner, as she flung her hat back on her shoulders, and shook the curls from her heated face. Then, turning to her mother, she said, "Whom do you think I met on the way? All the Thomsons on ponies. I wish I had a pony, too, I should so enjoy riding about."

"Could we afford it, you should have one," said her father, who, though very fond of riding, had never mounted a horse since he had quitted the army. It pained him that his child should ever form a wish which he had not the power to gratify.

"I don't see why the Thomsons should ride when we walk!" observed Lydia, with a little toss of the head. "We are as good as they any day. Their mother was no fine lady, I've heard, and they say in the village that Mr. Thomson is deep in debt, and will have to sell his fine house."

"People say ill-natured things, my love; I would not repeat them," observed Mrs. Neill, mildly.

Lydia looked annoyed at the gentle reproof, and began humming an air to herself, to show that she did not mind it.

"Have you written the notes as I desired you, my dear?" asked the sick mother, after a silence.

"No, I've been busy, and shall be busy all day; I'll write them to-morrow," replied Lydia, sitting down, and carelessly opening a book.

"Did you carry your missionary subscription to the Vicarage?" asked the captain. "My girl keeps a collection box," he added, smilingly turning towards his brother to explain.

"No; I did not," replied Lydia, shortly.

"And why? for the clergyman told us he was anxious to send in the subscriptions directly."

"I would rather wait till I have collected more," answered Lydia. "The Barnes had one pound nine in their box."

"But we cannot attempt to compete with the Barnes, my love; we can give but little, but we give it cheerfully."

"I will wait till I have collected more," repeated Lydia. "I should be ashamed to send in less than my neighbors."

"It is a great privilege to be able to help a good cause," said the captain, again addressing his brother. "My girl does not content herself with gathering money; she gives her work, which is something better. Her little fingers were busy for the fancy fair held for our schools: she made two bags and seven purses—"

"Four bags and eight purses," interrupted Lydia, "and six round pincushions besides. The Charters did not furnish so much, though there are three of them to work. But they are such an idle set of girls, and I don't think they care about schools."

"Four bags and eight purses, to say nothing of the pincushions; pretty well for one little pair of hands!" said the captain, turning again to his brother, in expectation of an approving smile or word; but no smile was given, no word was uttered. Lydia glanced at her uncle in surprise, but could not understand the almost sad expression on her relative's kind face. Could she have read his thoughts, they would have run somewhat as follows:

"It is clear that these fond parents are content with their child, and that the child is content with herself; she has enough of the sweet poison of flattering praise without my pouring out more from a selfish desire to make myself a favorite here. My brother thinks his Lydia perfect, and believes that the soil, cultivated with tender care, is already covered with a glorious harvest. But what is it that eyes less blinded by partial affection see there? In ten minutes I have unwillingly beheld the weeds of pride, selfishness, and disobedience, a disposition to evil speaking, covetousness, and a silly thirst for praise. Small indeed the faults now appear, as weeds scarce showing above the soil; but it is evident that the roots are there, and I fear that the harvest will be different indeed from what my brother expects. What shall I do? Speak openly to him? I fear that the only result would be to wound—perhaps to offend him; he would think me unjust or severe, and retain his own opinion. I must gain some quiet opportunity of speaking a word to Lydia herself; she is an intelligent, sensible girl; but I can see too plainly by her manner toward her mother that nothing will be welcome to the young lady that comes in the shape of reproof. My conscience will not suffer me to leave my niece to her blind security; I will make at least an attempt to open her eyes to the truth."

The party now dispersed—Lydia to take off her hat and cape; the two gentlemen to visit a friend. During their walk, Captain Neill could scarcely discourse on any subject but that of his daughter. He told anecdote after anecdote, which had been treasured up in his affectionate heart; but his conversation only served to convince Mr. Neill that Lydia, brought up in a pious family, had acquired but a sort of hothouse religion, that could stand no blast of temptation. He felt that though his niece might do many things that were certainly proper and right, she only did them when they suited her pleasure; her proud will was yet unbroken—her impatient temper unsubdued.

In the evening, Mr. Neill was sitting alone in the little study, when Lydia entered the room. The girl was anxious to please her uncle, of whose character she had heard high praise, and whose gentle, courteous manner was well suited to win young hearts.

"I like him," thought Lydia, "and I will make him like me." So approaching Mr. Neill, and laying her hand on the back of his chair, she said in her most pleasing manner, "Can I do anything for you, dear uncle?"

"Yes, my dear, you can read the Bible to me; I shall be glad of the help of your young eyes, for mine have suffered from the climate of India."

"I will read with pleasure," said Lydia, taking up the Bible; and she spoke no more than the truth. She was glad to do a kindness to her uncle, but was more glad still of an opportunity of showing him how beautifully she could read aloud.

"Do you wish any particular chapter?" she inquired.

"Pray, begin the twenty-second chapter of St. Matthew."

In a tone very clear and distinct, Lydia commenced her reading—

"And Jesus answered, and spake unto them again by parables, and said, 'The kingdom of heaven is like unto a certain king, which made a marriage for his son, and sent forth his servants to call them that were bidden to the wedding; and they would not come. Again, he sent forth other servants, saying, Tell them which are bidden, Behold, I have prepared my dinner; my oxen and my fatlings are killed and all things are ready; come unto the marriage. But they made light of it, and went their ways, one to his farm, another to his merchandise; and the rest laid hold on his servants, and treated them spitefully, and slew them. But when the king heard thereof, he was wroth; and he sent forth his armies, and destroyed those murderers, and burned up their city.'"

"Do you understand the meaning of the parable?" asked Mr. Neill.

"Yes," replied his niece, looking up from her book; "the Jews, to whom the invitation of the gospel was first sent, in their pride, would not accept it, but rejected and slew the Lord, and some of His faithful servants; and so the armies of the Romans were sent to take and to burn Jerusalem. The command was given that the gospel should be preached to every creature, as we hear." And Lydia proceeded to read aloud:

"'Then saith he to his servants, The wedding is ready, but they which were bidden were not worthy. Go ye therefore into the highways, and as many as ye shall find, bid to the marriage. So those servants went out into the highways, and gathered together all, as many as they found, both bad and good; and the wedding was furnished with guests.'"

"'And when the king came in to see the guests, he saw there a man which had not on a wedding-garment: he saith unto him, Friend, how earnest thou in hither, not having a wedding-garment? and he was speechless. Then said the king to the servants, Bind him hand and foot, and take him away, and cast him into outer darkness; there shall be weeping and gnashing of teeth. For many are called but few are chosen.'"

"Was it not strange," said Mr. Neill, "that a poor man, taken from the common highway, should be expected to be found in a wedding-garment at the feast of the mighty king?"

"No," replied Lydia, without hesitation, "for it was the custom in the East to provide wedding-garments for the guests, and this man must, through pride, have refused to accept one, thinking his own dress good enough to wear."

"And what is the deeper—the spiritual meaning of this parable?" inquired her uncle.

"The merits of our Lord form the wedding-garment, which all must wear who would enjoy the feast of heaven. If we try to appear in our own righteousness, we shall be cast out like the miserable man of whom we have just been reading."

"You have been well-instructed in the Bible, Lydia."

The girl colored at the praise, and said, "I ought to know it well, for I read four chapters every day, and a great deal more on Sundays, and can repeat hundreds of verses by memory."

"And yet," observed Mr. Neill, "there is a wide difference between head-knowledge and heart-knowledge, between understanding the meaning of the Scriptures, and making their truths our own. I suspect that many of us fall unconsciously into the error of the man in the parable, and fancy that there is something in ourselves to make us acceptable in the presence of our Heavenly King. When you came into the room, Lydia, my mind was dwelling upon the very subject, and I was forming a little allegory, or story, about the garment of human merits."

"I wish that you would tell me your allegory," said Lydia; "I often make such stories myself."

"Close the Bible, and place it on the table, my child, and you shall know what thoughts were suggested to my mind by the parable of the wedding-garment."

Lydia obeyed and listened with some interest and curiosity to this, the first story which she had ever heard from the lips of her uncle. Mr. Neill thus began:

"Ada was a bright young creature, brought up in a happy and a holy home, where, almost as an infant, she had been taught to pray, and where Scripture had been made familiar to her from the earliest dawn of reason. Ada was an invited guest to the feast of the great King, and she had accepted the invitation. She knew that she must appear in His courts robed in righteousness not her own, a garment provided by the Lord of the feast, spotless, holy, and white."

"But Ada had a friend, or rather let me term her an enemy, in a companion named Self-love, whose society was so delightful to the girl that they were constantly found together. It was wonderful to behold the influence quietly exerted by Self-love over the mind of her young companion. She joined Ada in her amusements, assisted at her studies, went with her wherever she went, even to the cottages of the poor, even to the house of prayer. But Self-love was treacherous as well as pleasing; her influence was never exerted for good; her one great object was to draw Ada away from religion, and cause her to be rejected at the great banquet, to which Self-love never herself could be admitted."

"'Is it not hard,' whispered Self-love one night, 'that all the guests at the banquet are to wear the same kind of dress, whatever their former character or station may have been? I can well believe that poor wanderers from the highways, and beggars from the street, will be glad enough to lay aside their rags, and wear the garments provided; but you have a white robe of your own, fit to be worn in any palace, even the robe of innocence, embroidered all over by your hands with the silver blossoms of good works. How often has the world admired you in it! How it has been praised by your family and friends! It would, at least, form a beauteous addition to what you must wear at the banquet of Heaven."

"Ada turned her eyes towards the robe of which Self-love had spoken, which was spread out on a table before her. Very beautiful indeed, and very white, it appeared to the admiring eye of the girl. Hundreds of delicate silver flowers, work of charity, faith, and obedience, glittered in the light of a large flaring torch which Self-love had placed beside it. The robe was studded with innumerable pearls, which Ada knew to be her prayers, so that nothing could seem more splendid than the robe which Ada had prepared for herself."

"I suppose," interrupted Lydia, "that this Ada was really a very excellent girl. I do not wonder that she was unwilling that so lovely a robe should be laid entirely aside, and not be worn at all at the banquet."

"Ada listened and looked," continued Mr. Neill; "and the more she looked and listened, the more she regretted that ragged beggars should one day be clothed in just the same manner as the possessor of a garment so fine. 'I almost think that I might wear both,' she murmured, half aloud; 'I might appear in my own beauteous robe, and if my dress should be not quite complete, the King's mantle would cover all defects.'"

"'Ada, Ada!' whispered a voice in the air. The girl started and gazed around, but no human form was to be seen."

"'Ada, my name is Conscience,' continued the voice, 'and my accents fall not on the ear; they are heard in the depths of the heart. I have read thy thoughts, I know thy desires, and I come unto thee with a message. If thou, for but one day, canst keep thy garment quite white and fair, thou mayest wear it with joy and honor. But thou must see it by sunlight, and not by torchlight, and thine eyes must be anointed with Self-knowledge,—a salve which thou shalt find close to thy Bible when thou lookest on it first in the morning.'"

"'Be content, Ada,' said Self-love, with a smile, 'a single day is no long time of trial, and thou hast hitherto kept thy garment so fair, that thou hast small reason to fear a stain.'"

"The first thing that Ada did in the morning was to anoint her eyes with the golden salve which, as Conscience had promised, she found lying close to her Bible. She resolved not to look at her robe till a part of the day should be over, and then to examine it closely, to see whether the smallest speck or stain had sullied its pearly whiteness."

"Had I been Ada, I should have been very careful in my conduct on that day," observed Lydia, with a smile.

"So Ada determined to be. She resolved to crowd it with fresh good works. She read double her usual number of chapters, was very long at her prayers, though it must be confessed that all the time that she was perusing God's holy Word, or making show of pleading with her Maker, her thoughts were wandering in every direction—now to her birds, now to her new book, now to her plans for the morrow, and now, alas! resting with bitterness upon some affront received from a neighbor. While Ada read or knelt, a dim, misty stain was slowly spreading over her white garment; that which she believed to be a merit, in God's eyes was full of sin."

"But Ada was not always in the quietness of her own room; she had to go forth and mix with others. She determined to visit a great many poor people, and do a great deal of good; but she lost her temper twice before she set out. First, with the servant, for keeping her waiting while preparing some broth for a poor invalid; then with her mother for sending her to change her dress for one of coarser material, as it seemed likely to rain. That half-hour of peevish impatience left its mark on the beautiful garment."

"Oh, uncle, such trifles could never be counted," exclaimed Lydia.

"Life is made up of trifles, Lydia, and especially the life of a child. But to return to the story of Ada. On her way to the cottages, she met with a companion, a silly, frivolous girl, and they entered into such conversation as that which is known by the name of gossip. They spoke not of the beauties of nature, or the wonders of art, or of the deeper things of God; they spoke of their neighbors, and their neighbors' affairs, and the ill-natured remarks, silly jests which they made, were certainly not such as beseem the lips of youthful Christians. Ada was very amusing and very merry; but her face would have worn a graver expression had she but seen how, at each foolish and unkind word, there fell a speck, as if of ink, on the folds of her beautiful garment."

"A carriage, splendid and gay, drove past the girls, as, heated and tired, they walked along the dusty road. Ada knew the young ladies within, and, as she returned their bow, thoughts of discontent, covetousness, and envy possessed the mind of the girl."

"'How hard it is to walk when others are rolling in their carriages,' was the secret reflection of Ada. 'I wonder why things are so unequal. I'm sure we've a better right to comforts than those girls, whose father made all his money by manufacturing tapes and bobbins.' Ada expressed not her thoughts aloud; but she fostered and indulged them in her heart, and deeper and duller grew the stain that clouded her beautiful garment."

"Uncle, uncle," exclaimed Lydia, who now perceived pretty clearly that Ada represented herself, "I think that you are hard on your heroine. It is almost impossible to govern our words, and quite impossible to control our thoughts."

"If so," replied Mr. Neill, "would the Bible have contained such verses as these, 'Keep thy tongue from evil, and thy lips from speaking guile,' 'Covetousness, let it not once be named amongst you, as becometh saints; neither filthiness, nor foolish talking, nor jesting, which are not convenient'? When our Lord declared what doth defile a man, evil thoughts were the first things mentioned, the sin that cometh from the heart."

Lydia looked grave, and was silent.

"Ada paid many visits, read the Bible in several cottages, and returned home with a comfortable persuasion that she had passed a most useful morning. She felt herself wonderfully better than the ignorant creatures who had listened with admiring attention to the words of 'the dear young lady.' Ada was impatient to look at her robe, and could not, as she had at first intended, wait till evening before she did so. What was her astonishment and distress when she cast her gaze on the treasured garment! With the salve of Self-knowledge on her eyes, she could no longer flatter herself that it was anything approaching to white. A dull, dirty hue overspread it; it was besprinkled here and there with dark and unsightly stains. Poor Ada was so badly disappointed, that she could scarcely restrain her tears, till Self-love whispered, 'It is somewhat soiled, it must be owned, yet see, it is embroidered all over with the silver flowers of good works.'"

"Yes, that was some consolation," murmured Lydia.

"Then again the low voice of Conscience was heard, piercing the inmost soul, 'Ada, Ada! there is indeed a blessing on works done for the love of God; precious and bright is such silver. But while man sees our actions, God sees our motives, and tarnished with sin is the work, be it ever so good in itself, which is done from vainglory, emulation, or self-pleasing.' As the words were uttered, to Ada's dismay she beheld every one of her silver flowers become tarnished and dull; some, indeed, less so than others; but not one remained that retained its brightness, while some appeared actually black."

"Poor Ada had nothing left but her pearls, her prayers," observed Lydia, with something like a sigh.

"Nay, the pearls shared the fate of the flowers. What is the worth of prayers uttered from habit, or fear, or love of praise, prayers with which the heart has nothing to do? The pearls appeared pearls no longer, but dull, discolored, unsightly beads."

"Oh, what a wretched discovery!" cried Lydia.

"Self-knowledge showed Ada something besides," pursued Mr. Neill, without looking at his niece as she spoke. "On bending over her garment, Ada perceived many large rents, which seemed to grow in number and size the longer she examined the robe. Again was heard the whisper of Conscience—'These are thy sins of omission, neglected opportunities of serving God, acts of kindness or obedience left undone, a tender mother's wishes disregarded, duties put off in order to gratify the idle whims of self-love.'"

Lydia remembered the notes which she had put off writing for so long that her sick mother had that morning done the little business herself. This had been but one of a series of trifling neglects for which Lydia had never before felt self-reproach; for she had not reckoned them to be sins. Tears started into her eyes, and she wished that the story would come to an end.

"'I can never wear this,' exclaimed Ada; 'it would take me months to repair these rents.' As she spoke she bent down to lift the garment that she might examine it more closely; to her astonishment, the whole fabric came to pieces in her hands. The moth of Pride had fretted the garment, and not only was it tarnished and stained, but no sound piece was to be found in the whole of the once goodly robe."

"Oh, I can't bear this story of yours," exclaimed Lydia; "it is one to put us all in despair."

"If it puts us in despair of ourselves, my child," replied Mr. Neill, laying his hand gently on the arm of his niece, "it will prove a story not without profit."

"Ada seemed such a good girl at first, and you have made all her righteousness fall to pieces in the end! How could any one go to a banquet in such soiled and miserable rags?"

"The knowledge of our helplessness and sin, Lydia, is beyond measure precious to our souls. While we wrap ourselves in our fancied merits, while we nourish a secret hope that we can stand before a holy God in the garment of our own poor works, we will never earnestly and thoroughly seek for the grace which alone can save. Let us ask for the gift of self-knowledge, that we may see that we are in His sight."

"Self-knowledge only makes us miserable," exclaimed Lydia, whose pride had been deeply wounded.

"It would be so indeed, were it not united to knowledge of the blessed Redeemer; if the same Bible which shows us that our fancied righteousness is but as a moth-eaten rag, did not show us, also, the spotless robe washed white in the blood of the Lamb, prepared for the meek and lowly in heart who come to the banquet of heaven. Let this then, dear child, be our constant prayer to the Giver of good— 'Lord, show me myself—my nothingness, my sin. Lord, show me Thyself—Thy holiness, Thy love. Pour Thy Spirit into my heart; let it rule my lips and my life, and clothe me in the robe of righteousness, even the merits of my blessed Redeemer.'"

It was with a thankful and joyous heart that Grace Milner wended her way through the crowded streets of London. She had just been granted her heart's desire; she had been accepted as a female teacher by a missionary society for the conversion of the Jews, and a life which few, perhaps, would covet, but which to her appeared one of delight, was opening before the clergyman's orphan. It was a life of independence, and Grace had an honest pleasure in earning her own bread, and having the means even to assist others; it was a life of usefulness, and Grace longed to be able to do some good in the world. And the teacher was young, and of an ardent spirit; to her the very journey offered great attractions: traveling gave her exquisite pleasure, all the greater, perhaps, because she had hitherto seldom enjoyed opportunities of traveling. Grace had not a single relative from whom it would be a pain to part—she stood alone in the world, except so far as she belonged to the family of God. She was full of hope that she might be made a blessing where she was going. Grace had a great talent for learning foreign languages, and what to many is a weary task, to her was only an amusement. She felt that she was peculiarly suited for the position in which Providence had placed her, and would not have exchanged her lot for that of any queen in the world.

"Oh! to think of visiting the land in which my Saviour lived and died!" was the reflection of the young teacher as she threaded her way, careless of all that was passing around her; "to think of gazing upon Jerusalem, the guilty, yet sacred city, of standing in the garden of Gethsemane, where the Holy One knelt and prayed! And then to be permitted to lead the little ones of Israel to the footstool of the Saviour! To be surrounded by young descendants of Abraham, to whom I can speak of their fathers' God! Oh! Sweet command of the risen Saviour, 'Feed my lambs!' With what delight shall I obey it, with what delight shall I seek out His jewels, to be my joy and crown of rejoicing when He comes in the clouds with glory! Blessed work to labor for Him! I thank God for the talents which He has given me; I thank Him for the opportunity of spending them all in His service; I thank Him for the hope that I—even I—may one day hear from my Saviour the transporting words, 'Well done, good and faithful servant, enter thou into the joy of thy Lord.'"

Grace was startled from her dream of happiness by a sudden shock! Absorbed in thought, she had not taken sufficient precaution in crossing a road, and was struck down by a cab that had, unnoticed, turned sharply round the corner of a street.

The young teacher uttered no cry; she fell stunned and senseless to the ground. She saw not the pitying crowd who thronged around her. When raised from the ground, and carried on a shutter to the nearest hospital, she felt no pain from the motion. It was not for some hours that Grace had sufficiently recovered her senses to know what had happened, or to comprehend the nature of the injury which she had received.

Great indeed was the trial to the poor girl when she awoke to a sense of what was before her. Her spine had sustained an incurable injury, such as might not perhaps shorten life, but which might render her utterly helpless as long as that life should last. The once active, energetic young woman would never again be able even to sit up in bed, and all her hopes of usefulness as a teacher were crushed in a moment for ever!

Dark indeed were the prospects of the orphan, when this cloud of misfortune so suddenly swept over her sky! Where should she go—what should she do—when dismissed, as she soon must be, from the hospital which had received her? Her little savings as a governess had all been expended; she had no home to which to return, no friend wealthy enough to be burdened with the support of a helpless cripple. There was sympathy shown to Grace by the supporters of the charity which had so lately accepted her services. There was even a subscription raised for her; but the assistance thus given was far too small to render the lady independent. As she was unable, and would always be unable, to rise from a lying position, it would be hopeless to attempt to gain a miserable pittance by her needle. Drops of agony stood upon the brow of the poor young lady, as the terrible truth forced itself upon her mind, that, henceforth, the only home that she could look to on earth was the poorhouse.

Grace could not at first bend her spirit to submit to a fate which she looked upon as worse than death. She quitted the hospital for a lodging where the kindness of strangers enabled her to struggle on for a time. But she knew that this could not last; the evil day might be put off, but was certain at length to arrive. Grace thought that it was wrong to draw so heavily upon the charity of others, when so many of her fellow-creatures were in want of common necessaries. What was given to her lessened the power of the generous to assist them; and Grace was of too unselfish a spirit to bear to encroach on the kindness of the rich, or draw away relief from the poor. So she made up her mind at last she would go where she had a right to food and shelter; she would claim the support of her parish, now that she could not support herself.

Deep gloom was upon the soul of poor Grace, when she was carried to the large, dull, cheerless-looking building, which to her appeared but as a prison. She sank beneath the weight of her cross, and even her religion seemed for a time to bring her no comfort. Satan, ever busy to tempt us, whether in days of wealth or tribulation, was whispering hard thoughts of God. Grace saw in her trial no sign of the love of her Heavenly Father; she thought herself forsaken—forgotten; she longed for death, little conscious at that moment that she was unfit to die!

"Oh! That I should ever be brought down to this!" was her thought, as she was borne across the court-yard of the poorhouse, where a few old women, in pauper's dress, scarcely turned their heads to observe a new sufferer carried to a place where sickness and sorrow were things too common to attract much notice. "I, well-born, highly educated, degraded to the position of a pauper! Why has God, in whom I trusted, forsaken me? Why has He placed me in a position where I can be but a burden to myself and to others? God gave me talents, and with a willing mind I had devoted all my powers to His service; but now He has taken away the opportunities which once I possessed, of exercising my talents to His glory, and the good of my fellowmen."

Grace was wrong in three important points: first, She was wrong in thinking herself degraded by becoming a pauper, when she was so not from idleness, nor extravagance, nor any other sin of her own. It was God who had appointed her place, and the post which He assigns to His people must be a post of honor to those who faithfully fill it. Oh! Let the lowly ones of Christ remember this to their comfort! Can poverty be a disgrace when it was the state chosen by the Son of God for Himself, when He deigned to visit the earth? The Lord's people are kings and priests unto God, heirs of a crown, and inheritors of heaven, whether they dwell in a palace, or lie in a poorhouse ward.

Secondly, Grace was wrong in doubting for one moment the loving care of her God, because He was trying her faith in the heated furnace of affliction. "Whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth." Grace had been an earnest and active Christian; but she had little knowledge of the weakness and sin of her own heart, till affliction stirred up the quiet waters, and showed her what evil lay below. She had hoped and believed that her will was conformed to the will of God, till sudden misfortune revealed how much of self-pleasing, pride, and unbelief had lurked behind her devotion. Grace now thought herself worse than she had ever thought herself before, only because she now knew herself better; the medicine for pride was most bitter, but it was the hand of love that had mixed it.

And thirdly, Grace was wrong in supposing that all opportunity of glorifying God and of serving others had been taken from her for ever. Never, perhaps, does the Christian's light shine more brightly, or more profitably, to those who behold it than from the bed of sickness and pain. Wherefore glorify God in the fires! is the watchword for the suffering saint. Happy those who to the words, "We rejoice in hope of the glory of God," can add, And "not only so but we glory in tribulations also," knowing that tribulation worketh patience, and patience experience, and experience hope; and hope maketh not ashamed, because the love of God is shed abroad in our hearts by the Holy Ghost which is given unto us!

Grace was carried to a ward containing twelve of the aged or sick, and placed on a bed in a corner of the room. The ward was clean and airy, and, in some respects, more comfortable than Grace had been led to expect; but she was little disposed to see in it anything but the dreary aspect of a prison. She looked with sadness on the bare walls, the high windows—affording no prospect but the sky—and the rows of beds occupied by those with whom she deemed that she would have not a single feeling in common. Grace particularly shrank from the pauper whose bed was next to her own. Ann Rogers, a coarse-looking, red-faced woman, with a rough manner and loud voice, which jarred on the nerves of the sufferer.

"Well, poor soul, how came you into your troubles?" were the words with which Ann first addressed Grace, standing beside her with her arms akimbo, and surveying the newcomer with a look of mingled curiosity and pity.

Grace flinched like one who had a rough hand laid on a wound, and murmuring a short reply, she closed her eyes in the hope of stopping further conversation.

"You have seen better days, I take it, and so have I. I was cook in a gent'man's family, I was, and little thought of ever coming to this—." Ann added an epithet so coarse that I do not choose to repeat it.

"Oh, misery! can I not even suffer in silence?" thought the poor girl. "Must I have that horrible voice for ever dinning in my ears?" Grace said nothing aloud, but her face probably betrayed something of her feelings, for Ann went on in the tone of one who is offended. "There's no use in anybody's playing the fine lady here, or turning up her nose at the company she meets with. This ain't the place for airs, and I'd advise no one to try 'em upon me!"

The heart of Grace sank within her. Weak as she was, and in constant pain, she needed gentle sympathy, tender care, and perfect quiet; and it appeared that none of these could ever be her own. She had no spirit to bear up against the thousand petty annoyances inseparable from her condition. She resolved that she would never complain, but the resolve, it must be confessed, came as much from pride as from patience. She would shut herself up in her sorrow, and have nothing to do with her companions. In her desponding gloom, Grace forgot that those around her were God's creatures as well as herself: that they, like herself, were afflicted, and that the command, "Love one another," is as binding in the poorhouse as in the brightest, happiest home.

The poor lady might long have remained in this miserable state, with her mind suffering still more than her body, impatient, despairing under her cross, unloved, unloving, and desolate; but for a seemingly trifling incident which occurred a few days after her arrival. This was a visit to the ward from a lady who came regularly once a week to read the Bible to its inmates. Mrs. Grant was not gifted with talent: she had little power of influencing others; she could not, like some more honored servants of God, so plead with sinners that the hardened heart should be touched with the holy eloquence of love. She was a plain, quiet woman, somewhat stiff in her manner, who did her duty indeed as unto God, but who in herself was little capable of making any impression on others. Conscious perhaps of her own defects, the lady contented herself with reading the Scripture without making any remarks upon it. The portion which she chose upon this occasion was the parable of the talents. Grace listened in deep depression; the words reminded her so painfully of her own shattered hopes, of her joyous praises on the morning on which her accident had occurred—"I thank God for the talents which He has given me: I thank Him for the opportunity of spending them all in His service."

But the parable does not end with the account of the "good and faithful servants who entered into the joy of their Lord.' There is a second part, and it was this which especially fixed the attention of Grace as she lay on her couch of pain.

"Then He which had received the one talent, came and said, 'Lord, I know thee that thou art a hard man, reaping where thou didst not sow, and gathering where thou didst not scatter; and I was afraid, and went away and hid thy talent in the earth: lo, thou hast thine own.'"

"His Lord answered and said unto him, 'Thou wicked and slothful servant—'" And then followed the stern but just rebuke, closing with the terrible sentence—"'Cast ye out the unprofitable servant into the outer darkness: there shall be the weeping and the gnashing of teeth.'"

The plain, forcible lesson from Scripture went straight to one heart in that ward—a loving, obedient heart, that received the truth in simplicity. Grace did not turn from the light, because it showed her a blemish in herself; she did not try to persuade herself that the lesson was meant for some character quite different from her own.

"Is not this God's message to me," thought the sufferer; "and is not this warning for me? Would not I have been glad to have been trusted with the ten talents, or the five; but when only one was left to me, did I not, in discontent, despair, bury it deep and hide it? And why, why have I done so? Because I have dared to entertain gloomy ideas of my God. I have thought His dealings hard, and my faith and patience have failed! But have I, indeed, one talent: I who am so feeble that my voice could scarcely reach beyond the bed next to mine? Yes, there is one soul at least in this ward which I might influence for good: there is one at least to whom I ought to show how meekly a Christian can suffer. There is great ignorance which I have made no attempt to enlighten. I have even repelled my fellow-sufferers by coldness that looked like pride. I have been gloomy—perhaps sullen in my grief. Alas! alas! I have buried my talent. God help me to use it ere it be too late!"

In the meantime Mrs. Grant had quitted the ward, and some of the paupers began to make observations upon her.

"I daresay, now that 'ere lady thinks she has done a mighty good deed in sitting there starched and stiff for ten minutes, and then sweeping away in her rustling silk, without so much as asking one of us how we be!" said Ann Rogers, in her harsh and insolent tone.

"Yes," observed the nurse, "she's different from the lady who visited the ward that I had down below. That lady smiled so kind, and talked so pleasant that it was a real pleasure to see her; and she made everything in the Bible so plain. Then, it seemed as if she really did care for us; she talked to us quietly one by one, and was as sorry for any one sick or in pain as if she had been an old friend. That's the kind of visitor for me."

"I knew a lady, afore I came into the house, who allowed a poor old soul as lived in a garret a pound of tea every month, and a sack of coal at Christmas. That's what I calls a friend," said Ann Rogers.

"The kindest thing I ever heard of," observed an old, bedridden pauper, "was a clergyman's taking in my poor brother, who had chanced to fall down in a fit at his gate, and nursing him, and paying his doctor, and giving him a half-crown and a good warm coat when he left. A real kind Christian was that parson, who knew how to practice what he preached."

There was a general murmur of assent through the room. When it was silenced, Grace Milner said, in her soft, faint voice, "If you are comparing deeds of kindness, I think that I know of one greater than any that you have mentioned. I do not mean to undervalue the generosity of either the clergyman or the lady; but I could tell you of one who, without spending a farthing, did more than either of the two. My story is a true one, and belongs to the history of the famous general, Sir David Baird."

"A story—let's have that," said the nurse, who, like most of those in the poorhouse, was glad of anything that gave promise of affording five minutes' amusement.

"So you've found your tongue at last," observed Ann Rogers, who had been inclined to take offence at the previous silence of the invalid lady.

Grace slightly flushed at the rude remark; but without appearing to take notice of it, and lifting up her heart to God to ask for His blessing on her attempting to use her one talent to His glory, she recounted the following little anecdote, in the hope of drawing from it some spiritual lesson.

"Some seventy or eighty years ago a fierce war raged in India between the English and a native monarch called Tippoo Saib. In the course of this war, which ended at last triumphantly for our country, our troops sustained a terrible disaster, and some of our most gallant officers fell into the enemy's hands."

"And mighty little mercy they found, I'll warrant you," observed Ann Rogers.

"The officers, amongst whom was Baird, then a young man, were thrown into a horrible prison, where those who had been brought up amidst the comforts of an English home were exposed to hunger and miseries untold. What made their condition yet more wretched was that some of the officers had been wounded—Baird, in particular, had been shot in the leg, and pain and weakness were added to confinement, want, and anxious fears for the future. A wild beast was at one time kept near the prison of the unfortunate English, and its howls greatly disturbed them; for a dread arose in their minds that the tyrant Tippoo intended to give his captives as a prey to the savage animal."

"Poor souls, they were worse off than we," said the nurse, who had seated herself on the edge of Grace's bed, to listen to her tale.

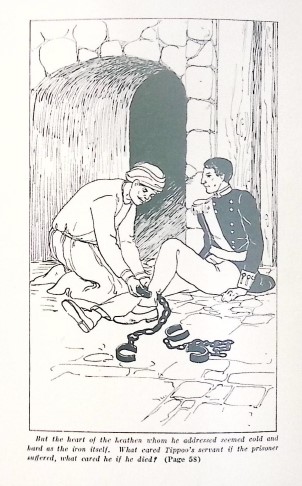

"One day the English were further alarmed by a great clanking noise just outside their prison. The door opened, and a number of native smiths came in, bearing a quantity of iron fetters, which they flung down on the floor. The wretched captives too easily guessed who were to wear these chains. A native officer then entered, who gave command that a pair of fetters should be fixed upon the legs of each of the unhappy gentlemen."

"What! The wounded and all?" exclaimed Ann.

"A gray-haired officer," continued Grace,—"I grieve that I have forgotten his name—determined to make an effort to save poor Baird from the agony to which he was destined. 'It is impossible,' said he to the dark Indian, 'that you can think of putting chains upon that suffering young man. A bullet has been cut from his leg; his wound is fresh and sore; the chafing of the iron must cost him his life.' But the heart of the heathen whom he addressed seemed cold and hard as the iron itself. What cared Tippoo's servant if the prisoner suffered; what cared he if the prisoner died!"

"'There are just as many pairs of fetters as there are captives,' he said; 'let what may come of it, every pair must be worn.'"

"'Then,' said the noble officer, 'put two on me; I will wear his as well as my own.'"

"Bless him," exclaimed the nurse, warmly. "That was a friend indeed; and what was the end of the story?"

"The end of the story is that Baird lived to regain his freedom, Jived for victory and reward, lived to besiege and take the very city in which he had so long lain a wretched captive. In the last deadly struggle, Tippoo was slain."

"And the kind officer?" interrupted Ann.

"The generous friend died in prison," replied Grace.

"Well," said the nurse, with a sigh, "he did more indeed than either the clergyman or the lady. To be willing to wear two chains, and all for the sake of his friend!"

"What would you have thought," asked Grace, "if he had borne the fetters of all in the prison? What would you have thought if instead of being a captive himself, he had been free, and wealthy, and great, and, for the sake of the unhappy sufferers, had quitted a glorious palace to live in their loathsome dungeon, to wear their chains, to bear their stripes, to suffer and die in their stead that the captives might go free?"

"Such a thing would never be done," cried Ann Rogers.

"Such a thing has been done," exclaimed Grace. There was a murmur of surprise from her hearers; she paused a minute, and went on, clasping her hands as she spoke. "Helpless captives of sin, doomed to wear the heavy chain of God's wrath, trials in this world, endless woe in the next; such are we all by nature—such would we all have remained, had not the Son of God himself deigned to visit our prison. He bore the weight of all our guilt, He endured the punishment which we had deserved; and now, for all who receive His grace, the prison is thrown wide open; victory over sin here, and glory in heaven—such are the blessings bought for His people by the blood of our Lord Jesus Christ."

"Ah!" observed the nurse, in an undertone, "that's how my lady used to speak. Many a time has she told me that there's no friend like the Lord; for there's no one on earth would do for us what He did of His own free will."

Grace felt joyful surprise on finding that there was some one in the ward who looked to the blessed Saviour. An ignorant but simple-minded Christian was near her, ready and glad to be instructed; and the lady reproached herself for having ever thought that her own work for God was ended.

"Well," observed Ann, in her blunt manner, "I went to school when I was young, and I learned a good deal of the Bible there, which I've not all forgotten yet. I know that the Lord died for us, and that, when we've done with the troubles of this life, we shall go and be happy in heaven."

Grace had already heard enough of the bad language, and seen enough of the bad temper of this woman, to fear that Ann was deceiving herself; believing her soul to be safe, although she had never yet repented of sin, or struggled against its power; never yet given her heart to the Lord. Oh! Fearful mistake of multitudes deceived by Satan, who, because salvation's stream flows within their reach, believe that its blessings are theirs, though they never have tasted of its waters. Grace felt that the conscience of Ann was asleep, and she silently prayed that God might awaken it.

"Suppose that the generous officer during his captivity," said Grace, "had called Baird to his side, had entreated him to do something for his sake whenever he should quit the prison; suppose that, when Baird was free, and rich, and happy, he had totally forgotten his friend, had quite neglected his dying wish, and had even done dishonor to his name, what should we think of such conduct?"

"Think," exclaimed the indignant nurse, "we should think it shamefully ungrateful."

"The world's bad enough, I take it," cried Ann; "but there's none of us bad enough to neglect the dying wish of a friend like that."

"Ah! let us take heed that our own words condemn us not," faltered Grace. "We have seen that the love of the Saviour to us has exceeded all other love; has not our ingratitude to Him exceeded all ingratitude beside? On the very night before He suffered, did not the Lord utter the words, 'If ye love me, keep my commandments?' And how has that dying charge been fulfilled? Have we not, at least too many of us, quite forgotten the Saviour? Have not our hearts been as cold and dead, our conduct as careless and sinful as if we had never known His love, or heard of His holy commandments?"

"Well, well, we all go wrong sometimes; but the Lord won't judge his poor servants," said Ann, in a tone which seemed to say, "Let's have no more of this preaching."

"If we be His servants!" exclaimed Grace, with earnestness, "but let us not forget that God's Word declares, that 'if any man have not the Spirit of Christ, he is none of His'; yea, the Lord Himself hath said, 'He that is not with me is against me; no man can serve two masters,'—if we be not heartily upon the Saviour's side, we are upon the side of the world and Satan."

"It's just like this, I take it," said the nurse, "it's just as if Baird had chosen to forget all about his country and his duty, and had gone into the service of Tippoo, and had even fought in his cause."

"He'd have been a vile rebel," cried Ann.

"And have been punished as such," observed Grace. "What would have been to him the name of Englishman? It could only have increased his shame; and what to us will be the name of Christians, if we are found in the ranks of Christ's foes? Oh, let us pray that we may be of the number of those who are saved from wrath by His death, and freed from sin's prison by His grace, and who bravely fight in His cause against the world, the flesh, and the devil! To such the victory is certain, to such the crown is sure; we shall be 'more than conquerors through Him who loved and gave Himself for us.'"

Grace ceased, for her strength was exhausted; but a feeling of peace and hope, such as she had not known before since her accident, stole over the lady's soul. She felt that she had done what she could; however little that might be, and that the Lord would not despise the one talent which she sought to lay out for Him. Grace sank into refreshing sleep, with the promise sounding in her ears, "They that be wise shall shine as the brightness of the firmament, and they that turn many to righteousness as the stars for ever and ever."

"Oh! is not this delightful!" exclaimed little Minnie Mayne, as she sprang upon the deck of the steamer which was to take herself and her mother back to their beautiful home in Scotland.

Mrs. Mayne, a widow lady, was returning from a visit to an aged parent in London. Her child had become very weary of dull brick streets, and the noise and smoke of the city. Minnie longed to see her bright home by the sunny lake, to feel the breeze on the healthy mountains, which to her young eyes were more beautiful than any other scene upon earth. Mrs. Mayne and her daughter had come to London by land, so this was the first time that Minnie had ever entered a steamer. Everything was new, and everything seemed delightful. The child promised herself great enjoyment from the voyage, as well as from the arrival at home.

With curiosity and pleasure Minnie surveyed the scene around her. The deck piled with luggage, the funnel black with smoke, the compass in its little glass frame, the pilot at the wheel, the hurrying to and fro, the sailors busy with the rope, and outside the vessel the view of the river crowded with shipping—boats, steamers, and barges; all afforded intense amusement to the light-hearted, intelligent child, who was full of eager questionings about each new object that caught the eye.

"Oh, mamma! What a noise the steam makes! I can hardly hear myself speak. I wish that the vessel would begin to move; but I can't think how it will ever make its way through such a crowd of boats! What a number of passengers there are; and, oh! What a lot of carpetbags and boxes! I don't think that any more people can be coming; the sailors had better pull up the plank that joins us to the shore, and let us be off at once. Oh! no; there are some more people arriving. Such a grand gentleman and lady, mamma! And a little girl so splendidly dressed! They had better make haste and get on deck, or the vessel will move off without them."

As Minnie concluded her sentence, a stout man passed along the plank, followed by his wife and daughter. The child wore a pink frock, and pea-green silk tippet, and a quantity of light curls streamed on her shoulders from a hat adorned with a long drooping feather. While Minnie surveyed the girl's finery with admiration approaching to envy, Mrs. Mayne glanced at the mother with an impression that that face was familiar to her, though she could not for some time recollect where she had seen it before. While the woman was bustling about her baggage, and in a loud voice disputing with the porter about his dues, the lady recalled to memory that the person before her was Mrs. Lowe, a greengrocer's wife, who had provided Mrs. Mayne's mother with vegetables nearly ten years previous. Mrs. Mayne recollected also the circumstances under which her family had given up employing the Lowes. The ladies had in vain tried to persuade the greengrocer to close his shop on Sundays; his wife had even been insolent when the duty of obeying the third commandment had been pressed home on her conscience, and had thus lost her customers, as well as her temper. Mrs. Mayne was not sure whether the greengrocer's wife now recognized her, but felt sorry that such a person was to be her companion on the voyage to Scotland.

"She looks as though her business had prospered," thought the lady, "to judge by her comfortable appearance and dress; and she has decked out her poor child in finery purchased by her ill-gotten gains. But how impossible it is to tell who is happy by mere outside show! However, those who wilfully break God's laws may appear to prosper, yet in the end it shall be seen that 'the blessing of the Lord it maketh rich, and He addeth no sorrow with it.'"

In the meantime, the plank had been raised; the huge paddles had slowly begun to go around, and a stream of foam, white as cream, on either side, marked the track of the steamer down the river. Minnie watched the banks with delight, as they appeared to move faster and faster with the vessel's increasing speed. There was so much to see, so much to wonder at, as every bend of the river brought new objects to view. The child's delight reached its height, when the noble hospital of Greenwich appeared with its stately park rising behind, and at the same time from the deck of a passing steamer, gliding with fairy speed, sounded the air of "Rule Britannia," borne towards them by the fresh breeze.

"How happy she is!" thought her mother, looking fondly at the child by her side. "She is like some joyous young creature just beginning the voyage of life, to whom all around seems beautiful, and everything bright ahead. She is troubled by no thought of storm or trial; she rejoices that she is going to a home, and she trusts to a parent's care to provide all things needful on the way. Lord, give me this childlike spirit of trust, and hope, and love, as I journey to the heavenly home, which my dear husband has long since reached."

Pleasure seldom lasts long without a check. Shortly before passing the Nore, as evening was coming on, a shower of rain warned the voyagers to seek shelter below. Minnie had not yet seen the place in which two nights were to be passed, and it was with some curiosity that she descended the steep stairway that led to the ladies' cabin.

"What a dark, dull room!" she exclaimed, as she entered and looked around; "and how hot and close it feels! I wish that we could stop all night on deck. Why, where are we to sleep?" she added; "not in those little pigeonholes surely! Are twelve or fourteen ladies to be crowded together in a room no bigger than our parlor, and not nearly so nice and high?"

"These are our berths," said Mrs. Mayne, with a smile, showing to her daughter a little recess, almost perfectly dark, in which were four "pigeonholes," as Minnie called them, two on each side, one above another, each containing a bed; while in the centre was a space only wide enough to turn round in. "The berths on the right hand are ours. You shall have the one over mine."

Minnie laughed at the idea of clambering up to her little nest, though she did not much like its appearance. "And will two other ladies," she asked, "be packed into these tiny berths on the left?"

"No doubt, as the steamer is full."

"I hope they'll be quiet and pleasant," murmured Minnie, who was quite unaccustomed to be brought into such very close contact with strangers. She had scarcely spoken, when Mrs. Lowe and her Jemima came bustling up to the recess.

"What a wretched dark hole it is!" exclaimed the greengrocer's wife, in disgust, as with her dress spreading out like a balloon, she almost entirely blocked up the entrance.

"Mamma, we can't sleep in such a place," cried Jemima. Minnie wondered to herself in what corner the pea-green jacket and plumed hat could be stowed, and for the first time felt glad that her own dress was so simple and plain.

While the Lowes went for their bandboxes and provision bag, Minnie whispered to her mother, "So they are to be our companions in this funny little place! I would rather have had some people not quite so dashing and grand."

Mrs. Mayne smiled to herself at the ignorance of her child, whose eye had been caught by mere outside glitter. "She will know better in time," thought the lady, "and learn to distinguish between tinsel and real gold."

The Lowes returned to their little recess, which, small as it was, they made smaller, by stuffing it full of their luggage, without the least regard to the comfort of their unfortunate fellow travelers. The night had now come on, and a lamp was lighted near the end of the cabin, which threw but a dull gleam into the part portioned off for the four. The steamer had entered the open sea, and to other discomforts was added that of a heaving motion, which, with the close air, gave to Minnie a tightness and pain in the head.

"Mamma," said she, sadly, to Mrs. Mayne, who was sitting beside her on a sofa near the recess, but in a more open part of the cabin; "mamma, I am afraid that we shall find this a miserable voyage after all."

"It is something like the voyage of life, my darling, in which we must all expect to find some things to annoy and try; but let us make little of trifling discomforts, and cheerfully look to the end. We know that we are going home—the voyage will soon be over."

"Yes, mamma; and the less we like the way, the more glad shall we be to get home. It makes one think of the verse about our heavenly rest:"

"'There fairer bowers than Eden's bloom,

Nor sin nor sorrow see;

Blest land, o'er rude and stormy waves,

I onward press to thee.'"

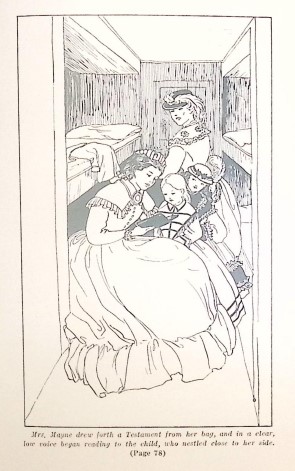

"And now, Minnie," said her mother, "the sooner you can forget your discomforts in sleep, the better. I will just read a small portion of the Bible to you as usual, and then you shall climb up into your berth, and, I hope, slumber quietly till the morning."

"Mamma, you can't read the Bible here," whispered Minnie, "where there are so many strangers;" and she glanced timidly at the tall, portly figure of Mrs. Lowe, who was standing very near her.

"Why should we not read it, my child? It makes no difference in the importance of a duty whether we perform it quietly in our own room, or with many around us. You know that you are not able to read to yourself, and must therefore hear your mother."

So saying, Mrs. Mayne drew forth a Testament from her bag, and in a low, clear voice began reading to the child, who nestled close to her side. Minnie felt shy and uneasy. Though her mother read softly, the Lowes were so near that they must overhear every word; and the child fancied that she saw a scornful look on the face of the elder, and on that of Jemima a wondering smile, as though hearing the Bible read was something strange to both. It is very possible that Mrs. Mayne wished to be overheard; and it was with more than usual earnestness that she prayed God to bless the reading of His Holy Word.

"'Then shall the kingdom of heaven be likened unto ten virgins, who took their lamps, and went forth to meet the bridegroom. And five of them were foolish, and five were wise. For the foolish, when they took their lamps, took no oil with them: but the wise took oil in their vessels with their lamps.'"

"Mamma," whispered Minnie, "I do not understand what is meant by the virgins and their lamps."

"The virgins, my child, are the whole Christian world, now expecting the coming of their Lord. The oil is God's grace in the soul, shining forth in a holy life. What would a lamp be without oil? What would a soul be without grace?—a dark and a worthless thing!"

Minnie fixed her eyes upon the lamp, which was now throwing around its yellow light, and thought what a fearfully gloomy place that cabin would be, but for its cheering gleam. Mrs. Mayne turned her page, so that the light should fall upon it, and continued reading the parable, so full of deep and solemn meaning:—

"'Now while the bridegroom tarried, they all slumbered and slept. But at midnight there is a cry, Behold, the bridegroom! Come ye forth to meet him!'"

"'And the foolish said unto the wise, Give us of your oil; for our lamps are gone out. But the wise answered, saying, Peradventure there will not be enough for us and you; go ye rather to them that sell, and buy for yourselves.'"

"We see here," observed Mrs. Mayne, pausing in her reading, "that no human being has power to save the soul of another, or to share with him that grace which is the gift of God alone. The wise cannot supply the foolish; each must answer for himself before God."

"'And while they went away to buy, the bridegroom came; and they that were ready went in with him to the marriage feast: and the door was shut.'"

"'Afterward came also the other virgins, saying, Lord, Lord, open to us. But he answered and said, Verily I say unto you, I know you not.'"

"Oh!" exclaimed Minnie, "Does that mean that the foolish virgins—the people who have no grace in their souls—will be shut out from heaven for ever?"

"Shut out from light—shut out from glory—shut out from the presence of the Lord! To me few words in the Bible are so fearfully solemn as those, 'The door was shut!' Mercy's door is wide open now, open to all who repent and believe. All are invited guests to heaven. All are welcome now to the Saviour. All may have grace for the asking; yea, 'without money and without price'; it is promised to the prayer of faith. But a time will come when it will be too late for sinners to seek for grace—too late to sue for pardon, when mercy's door will be shut upon those who would not repent and be saved. 'Watch therefore; for ye know neither the day nor the hour wherein the Son of man cometh.'" And with this solemn warning on her lips, Mrs. Mayne closed the Testament.

"Mamma," said Minnie, resting her little hand on the arm of her mother, and looking earnestly into her face, "do you think that the Lord will come soon?"

"God only knows the time," was the reply; "but it is for us to live as those who are ready and waiting for His coming. Of one thing we all are assured—death is not very far off; it may come soon to the young; it must come soon to the aged: and death is as the midnight cry, 'Behold, the bridegroom cometh!'"

"I can't imagine," said Mrs. Lowe, addressing herself to Jemima, but in a tone to be overheard, "why people who are strong and hearty should always be thinking about death. I for one never trouble myself with sickly fancies;" and as she spoke, she plunged her hand deep into her provision bag, and brought out of its depths a rather suspicious-looking flask.

Little Minnie, assisted by her mother, was soon safe in her tiny nest, which she found less uncomfortable than she had expected. The child did not, however, feel disposed to sleep. She seemed in a strange, new world, and sat up for some time in her berth, watching the movements of the Lowes by the light of the lamp, and listening to the voices of the ladies who occupied the cabin. Presently, however, the motion of the vessel became so disagreeable to Minnie that she was glad to lay down her aching head. She heard poor Jemima complaining bitterly, and Mrs. Lowe abusing steamers and all their arrangements, and scolding the stewardess for not attending at once to her unreasonable wants.

"It's a comfort," thought poor little Minnie, "that the voyage can't last for ever. I wonder if any people feel the same way about the voyage of life—if any are really glad to know that it soon may come to an end! Ah! Only the wise virgins, who had oil in their lamps, could start up with joy at the midnight cry! They were glad at the thought of seeing the bridegroom, for they were ready to go to the feast. I wonder how I should feel, if I heard that I soon should meet my Lord."

As the night advanced, the sounds in the cabin became gradually stilled; Jemima ceased to complain, and her mother to scold; both showed by their welcome silence that they were fast asleep. The weather was by no means stormy; there was nothing to disturb or alarm, and an occasional heavy step on the deck overhead, or a slight creaking in the cordage, with the constant beat of the paddles, were all the noises now heard. Minnie, wearied by the day's excitement, sank into peaceful slumber at last; she knew that her mother was close beneath her, and that God was watching above.

Suddenly every occupant of the ladies' cabin was startled from sleep by the sound of great commotion on deck, tramping of feet, and loud and repeated cries of alarm, that thrilled every heart with fear. Anxious faces were bent forward from every berth, and eager questions were passed from mouth to mouth, to which none seemed able to reply. "What is that noise? What can have happened? Has the ship struck? Have we run down some vessel?" And as the sound above continued and increased, rapid movements were made on all sides, as the ladies began hasty preparations for appearing on deck, should there prove to be real cause for alarm.

"Stewardess, stewardess!" called out Mrs. Lowe, as she searched here and there for her mantle, "run up-stairs; ask what is the matter; I'm sure something dreadful has occurred. If ever I travel by steamer again—"

"Mamma, mamma!" cried the terrified Jemima, "How awfully hot it has grown!"

"I feel half stifled," murmured pour Minnie, as, half dizzy with sleep, and trembling with fright, she held out her arms to her mother, who lifted her down from her berth.

The stewardess hurried to the door. The instant that she opened it, to the horror of all in the cabin, in rolled a suffocating volume of smoke, and only too distinctly sounded the voices above—"Fire! Fire!" was the terrible cry.

"Don't let the women come up—they must keep down—we can't have them here on deck!" called out the loud voice of the captain. Several of the ladies attempted to rush up the hatchway, but were roughly ordered back by the sailors.

"You would but hinder us here; go down and pray," cried a tar, all begrimed with smoke.

"Yes, let us pray," re-echoed the voice of Mrs. Mayne, as she sank on her knees in the cabin, her hands clasped, and her arms enfolding her daughter.

In that hour of terror and danger, the varied characters of those in that crowded cabin showed in strange distinctness. Differences of rank and age were quite forgotten—a common fear seemed to level all; while far more marked than before grew the contrast between the foolish virgins and the wise. Poor Jemima stood trembling in the recess, unconsciously trampling under foot the plumed hat which had once been her pride. Mrs. Lowe was almost mad with terror. Wringing her hands, and imploring those to save her whose peril was as great as her own—wildly asking those who knew as little as herself whether there were no hope of deliverance—she stood a fearful picture of one who has lived for the world and self. What were then to her the comforts or pleasures bought at the price of conscience! With what feelings did she then recall warnings despised and duties neglected! Could all her unrighteous gains—gains by petty fraud, by bold Sabbath-breaking—procure her one moment's peace when she feared that, within an hour, she might be standing before an angry God? No; those very gains were as fetters, as dead-weights, to sink her soul down to destruction. "Your gold and silver is cankered, and the rust of them shall be a witness against you, and shall eat your flesh as it were fire. Ye have heaped up treasure for the last days."

Mrs. Mayne was pale but calm. Her best treasure was safe where neither storm nor fire could touch it. She knew that a sudden death is, to the Christian, but a shorter passage home, a quicker entrance into glory. The grace which she had sought for by prayer in time of safety, shone out brightly now in time of danger, and she was able to sustain others by the light which cheered her own trusting soul. Mrs. Mayne prayed aloud, and many in the cabin fervently joined in her prayers.

"I can't pray, I can't pray!" cried Mrs. Lowe, sinking her face on her hands, while her long, loose black hair streamed wildly over her shoulders. Then suddenly changing her tone, and stretching out her arms, she exclaimed, "O God! Spare me, spare me yet a while; I will lead a different life, I will turn from my sins; mercy, mercy on a wretched sinner! Let not the door yet be shut; save me, save me from this terrible death!"

Minnie clung round her mother; the greater the danger, the greater the fear, the closer she clung! "We shall not be separated!" she gasped forth; and Mrs. Mayne, bending down, whispered in her ear, "'And who shall separate us from the love of Christ?' My precious one, He is with us now; He has power to subdue the fire, or to bear us safe through it to glory."

It was a strange and awful scene, and strange and wild were the mingling sounds that rose from the ship on fire. Shouting, shrieking, praying; the clank of the pump incessantly at work, voices giving hurried commands, the crackling of flame, the gurgle of water, the rushing of feet to and fro. Then—oh, blessed hope!—can that sudden, sharp clatter be indeed that of rain, pelting rain, against the window of the cabin, that dark window, which has only been lightened now and then by a terrible gleam from the fire?

"Rain, blessed rain!" exclaimed Mrs. Mayne, starting up. "Rain, rain!" repeated every joyful tongue; and then there was a momentary silence to listen to the clattering drops, as thicker and faster they fell, as if in answer to the fervent prayers that were rising from every heart. Surely never was shower more welcome!

"Oh, God sends the rain!" exclaimed Minnie. "There's no red glare now to be seen. It is pelting, it is pouring; it comes down like a stream!" And even as the words were on her tongue, a loud, long, glad cheer from above gave welcome tidings that the fire was subdued.

"Thank God, ladies, the danger is over," said the captain, at the door. He was now, for the first time, able to leave his post-upon deck, to relieve the terrors of his passengers below.

Then was there a strange revulsion of feeling amongst those who had lately been almost convulsed with terror. Strangers embraced one another like sisters, sobbing, laughing, congratulating each other; the passengers seemed raised at once from the depth of misery to the height of rapture. This, also, soon subsided, and it became but too evident that, with some, gratitude was almost as short-lived as fear, and that God's warning made no more lasting impression on the heart than the paddle-wheels on the water—creating a violent agitation for a few minutes, leaving a whitened track for a brief space longer, which, melting away from view, all became as it had been before.

Mrs. Lowe was very angry at the carelessness which had occasioned her such a fright; she was angry with the captain, the sailors, the passengers; in short, angry with every one but herself.

"I'll never set my foot in a steamer again! As if all the discomfort were not enough to drive one out of one's wits, one is not left to sleep for a moment in peace. Ah, tiresome child!" she exclaimed, almost fiercely, turning upon poor Jemima, "What have you done! Trampled your new hat, crushed the feather to bits!"

Jemima, who had by no means recovered from the shock of the alarm, made no attempt to reply to her mother, but sat crying in the corner of her berth. Mrs. Lowe, declaring that she would stay no longer to be stifled down below, made her way up to the deck, though the first faint streak of dawn was but beginning to flush the sky.

Minnie was on her mother's knee, peaceful, happy, thankful. From that dear resting-place she looked upon the poor little girl, whom she had half envied on the preceding evening, but whom she regarded now only with a feeling of pity. Mrs. Mayne saw that the child's nerves had been severely shaken, and, bending forward, she gently drew the weeping Jemima to her side.

"God has been very good to us; shall we not love Him, and thank Him?" said the lady.

Jemima squeezed her hand in reply.

"And shall we not try to set our affections on things above, so that, trusting in our Saviour God, our hearts may fear no evil?"

The tears were fast coursing one another down the pale cheeks of Jemima, and Minnie, with an impulse of joy, raised her head from her mother's bosom, and kissed her little companion.

This trifling act of kindness quite opened the heart of the girl. Jemima threw her little arms round the neck of Minnie, and, burying her face on her shoulder, sobbed forth, "Oh, where shall I get the grace, the oil for my lamp, that I may never be so frightened, so miserable again, when I hear the midnight cry!"

Never had Mrs. Mayne and her daughter spent a holier or more peaceful hour than that which followed, as in that narrow recess of the cabin, while the morning sun rose over the sea, the lady spoke to a trembling inquirer of the Saviour who died for sinners.

"Do you, my child, long for more grace to make you holy in life, and happy at the hour of death? 'Blessed are they who hunger and thirst after righteousness, saith the Lord, for they shall be filled.' It is the Spirit of God in your soul that alone can make that soul holy. Kneel, and ask for it in the name of the Saviour, who hath promised, 'Ask, and ye shall receive; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.' Sweet is His service, rich its reward; pardon and peace, happiness and heaven, such are His gifts to His children. The world and all within it must soon pass away; its pleasures, its riches, its glory: for 'the day of the Lord will come as a thief, in the which the heavens shall pass away with a great noise, and the elements shall be dissolved with fervent heat, and the earth and the works that are therein shall be burned up.' But is there anything in this to terrify the Christian? Oh, no! For to him 'the day of the Lord' will be the day of joy, and thanksgiving, and triumph. For the Lord himself shall descend from heaven, with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God: and the dead in Christ shall rise first; then we that are alive, that are left, shall together with them be caught up in the clouds, to meet the Lord in the air: and so shall we ever be with the Lord.'"

Deep sank the words of Scripture into the hearts of the two little girls. Each in her different path trimmed her lamp with the oil of grace, and the holy life of a wise virgin waiting for the coming of her Lord.