Title: Robespierre

Subtitle: The story of Victorien Sardou's play adapted and novelized under his authority

Author: Ange Galdemar

Release Date: September 25, 2023 [eBook #71538]

Language: English

Credits: Al Haines

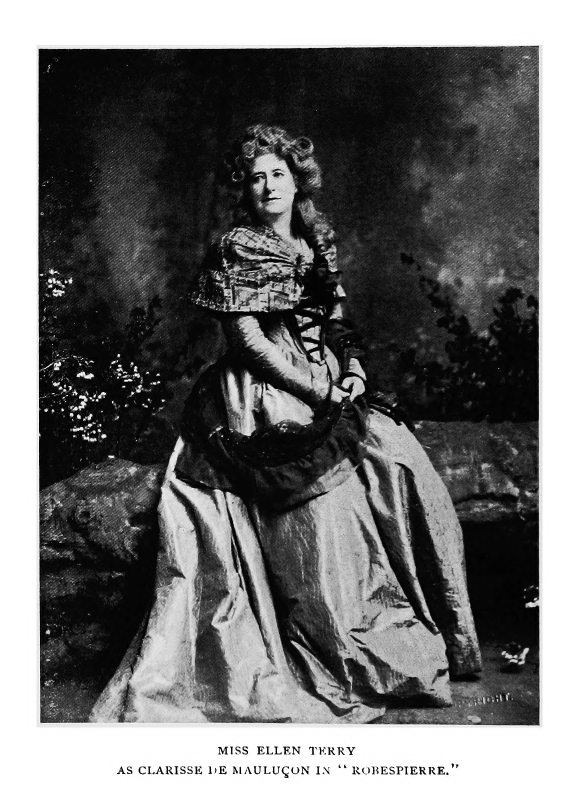

MISS ELLEN TERRY

AS CLARISSE DE MAULUÇON IN "ROBESPIERRE."

The Story of Victorien Sardou's Play

Adapted and Novelized under

his authority

BY

ANGE GALDEMAR

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1899

Copyright, 1899,

BY ANGE GALDEMAR.

University Press:

JOHN WILSON AND SON, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

[Transcriber's note: The chapter titles below do not all match the titles at the chapters.]

Contents

CHAPTER

III The Englishman

IV The Arrest

VII The Fête of the Supreme Being

VIII Beset by Memories and Forebodings

XIII A Broken Idol

MON CHER GALDEMAR,—

J'achève la lecture du roman qu'avec mon autorisation vous avez tiré de mon drame "Robespierre." Je ne saurais trop me féliciter de vous avoir encouragé à entreprendre ce travail, où vous avez, de la façon la plus heureuse, reproduit les incidents dra-matiques de ma pièce et préparé votre lecteur à apprécier l'admirable évocation du passé que Sir Henry Irving lui présente sur la scène du Lyceum. Je ne doute pas que le succèes de votre livre ne soil tel que vous le souhaite ma vieille et constante amitié.

[Signature: Victor Sardoz]

MARLY-LE-ROI.

Robespierre

The Hôtel de Pontivy was situated in the Rue des Lions-Saint-Paul, in the very heart of the Marais Quarter, which as early as the opening of this story, the June of 1775, seemed to form by itself a little province in Paris.

It was a magnificent spring night. The sky, luminous with a galaxy of stars, was reflected on the dark waters of the Seine lazily flowing by. A hush rested on the Rue des Lions-Saint-Paul, which lay enshrouded in gloom and silence, indifferent to the fairy charms of the hour.

Enclosed in high walls thickly clad with ivy, dark and mysterious as a prison, the Hôtel de Pontivy had all the aspect of some chill cloister apart from men and movement. And yet behind those shutters, where life seemed to pause, wrapped in slumber, some one is keeping watch—the master of the house, Monsieur Jacques Bernard Olivier de Pontivy, Councillor to the King's Parliament, sits late at his work, taking no count of time.

But Monsieur de Pontivy has at last decided; he raises his eyes to the clock.

"Twenty past two!" he exclaims. "I really cannot wake that poor fellow!"

Through the deep stillness of the vast room, with blinds and curtains drawn, a stillness enhanced by the glare of candelabra lighted up, as if in broad day, the heavy, green-repp armchairs, and bookshelves of massive oak ornamented with brass rose-work, passing a litter of cardboard boxes and waste-paper basket, and in the centre the ministerial desk overladen with books and bundles, the councillor makes his way towards a bureau that he has not yet opened.

"Perhaps it may be here," he says, as he turns over a whole file of letters, old and new, receipts, accounts, plans and invoices—one of those mixed files put aside for future classification. Perhaps the paper had been slipped in there by mistake? Monsieur de Pontivy set to work methodically, turning the papers over one by one, stopping here and there to read a word that caught his attention, or threw a sudden light on things long forgotten, and awakened projects long dormant.

"Oh! I must think over that," he exclaimed, as he put one or another aside.

Now and again a ray of joy lit up his countenance, as he thought he had found the missing paper, and as disappointment followed he renewed the search with unabated ardour.

For more than half an hour he went on thus, seeking the lost document, a lawyer's opinion recently received, which would assist him in elucidating a difficult point which was to be secretly debated the next day in Parliament, before judgment was delivered. He had thoughtlessly let his young secretary retire without asking him the whereabouts of this document, which he alone could find.

Monsieur de Pontivy had hastened to his study this evening directly dinner was over, to mature in solitude the arguments which were to triumph on the morrow, and of which he wished to make a short, concise summary before retiring to rest.

Having returned home sooner than usual that afternoon, the fancy had seized him to advance the dinner-hour, but learning that his daughter had not returned, he was obliged to forego his whim. This hour was rarely changed, the regulations of the house being rigorous to a degree, but Monsieur de Pontivy in the excess of his despotic authority was none the less displeased, being early himself, to find no one awaiting him. So when he heard the rumbling of the heavy coach which brought back Clarisse and her governess, Mademoiselle Jusseaume, he sought for a pretext to vent his ill-humour on them.

He had commenced to walk impatiently backwards and forwards the whole length of the room, casting hasty glances out of the window, wondering at the child's delay in coming to him, when the door opened and a head appeared in the doorway, fair, with pale, delicate features, large blue eyes, wide open to the day, in whose clear depths, half-hidden by the fresh candour of first youth, lay a tinge of melancholy.

It was Clarisse.

What an apparition, in such an austere and dreary place, that frail, white-robed form standing on the threshold, a tender smile of dawn in the dark room! She entered on tip-toe, approaching her father with greeting in her eyes and on her lips; he, continuing his walk, had his back towards her.

"Already here?" she asked, and her voice fell on the silence like an angelus.

Monsieur de Pontivy turned abruptly.

"How is it that you enter without knocking?"

The smile died on the child's lips. She murmured, disconcerted and abashed—

"I never used to knock, father, on entering your room."

"Then make it a point to do so in future. You are no longer a child; so learn to be discreet and to respect closed doors. A closed room, mademoiselle, is a sanctuary."

The young girl was accustomed to sermons, but had not expected one of that kind just then. She stood irresolute, hesitating whether to advance or retire.

"Must I go?" she hazarded, trembling.

Monsieur de Pontivy, satisfied at having vented his ill-humour, stooped to kiss his daughter's forehead, and then added, as if to soften the effects of his reception—

"Where have you been to-day?"

"On the boulevards."

"Were there many people?"

The young girl, reassured by this encouragement, began brightly—

"Oh yes, and only imagine...!"

"That will do! You can tell me that at table."

But at table she was supposed only to reply to her father, and he, lost in meditation, did not question her that day. And so passed all the meals she partook of with her father and young de Robespierre, Monsieur de Pontivy's secretary, whom the councillor made welcome every day at his table, glad to have so near at hand one whose memory and aid were easily available.

Timid at first, confining himself to the points put to him, the young secretary had gradually become bolder, and sometimes, to Clarisse's great delight, would lead the conversation on to subjects of literature and art, opening out a new world before her, and shedding rays of thought in her dawning mind. She found a similar source of pleasure on Sundays in the reception-room, while Monsieur de Pontivy's attention was absorbed by his dull and solemn friends in interminable games of whist, and Robespierre entertained her apart, quickening her young dreams by the charm of an imagination at once brilliant and graceful. It was as dew falling from heaven on her solitude.

Alas, how swiftly those hours flew! Clarisse was just sixteen. She could not remember one day of real joy. Her mother she had lost long ago; her brother Jacques, two years younger than herself, was always at school at the College de Navarre, and she saw him only once a fortnight, at lunch, after mass, on Sunday. At four o'clock an usher fetched him, when he had submitted his fortnight's school-work for the inspection of his father, who more often than not found fault with his efforts, so that the lad frankly confessed to his sister that, upon the whole, he preferred those Sundays on which he remained at school.

From her cradle Clarisse had been given over to nurses and chamber-maids, and at the age of eight she was confided to the care of nuns, just when she was emerging from the long torpor of childhood. Here she remained until the day when Monsieur de Pontivy, whose paternal solicitude had, up to then, been limited to taking her to the country for the holidays, claimed her, and installed her in his town residence under the charge of a governess. But Clarisse had only changed convents. For going out but seldom, except to mass and vespers on Sundays, at St. Paul's Church, or on fine days for a drive in the great coach with her governess, she continued to grow like a hot-house plant, closed in by the high walls of the house where nothing smiled, not even the garden uncultivated and almost abandoned, nor the courtyard where a few scattered weeds pushed their way between the stones.

It is true the young girl fully made up for this in the country, during the summer months at the Château de Pontivy, two miles from Compiègne, where her father spent his holidays. But they were so short, those precious holidays! The autumn roses had scarcely unfolded when she was compelled to return with her father to Paris; and all the charm and sweetness of September, with the tender tints of its dying leaves, were unknown to her, though a semblance of its grace crept into her room sometimes in the Rue des Lions-Saint-Paul, and stole like melancholy into her young soul, but new-awakened to the ideal, arousing a regret for joys denied.

These holidays were shorter since Monsieur de Pontivy recommenced his duties as councillor to the Parliament which the King had just re-established, and Clarisse began again to feel lonely, so lonely that she looked forward impatiently to the dinner-hour, when the young secretary brought with him some gay reports and rumours of Paris, planted germs of poetry in her soul, and initiated her into those charming trifles which constitute fashionable life.

All her suppressed tenderness and affection, which asked nothing better than to overflow, were concentrated on her governess, Mademoiselle Jusseaume, an excellent creature, upright and generous, but impulsive, inconsequent, and without authority. She was a good Catholic, and saw that her charge scrupulously observed her religious duties. She kept her place, was submissive, discreet, and always contented; and this was more than enough to satisfy Monsieur de Pontivy, who classed all womankind in one rank, and that the lowest.

Of his two children the one in whom Monsieur de Pontivy took the greater interest was his son, the heir to his name, and to whom would descend later on the office of councillor. But as this was as yet a distant prospect, he contented himself with superintending his education as much as possible, absorbed as he was in high functions which he fulfilled with that perseverance and assiduity, that desire to give incessant proofs of staunch fidelity, which arise from an immeasurable pride.

Such a character can well be imagined. Heartless, hard, and implacable, strictly accomplishing his duty, honest to a fault, making ever an ostentatious display of his principles, doing no man harm, but also suffering no man to harm him, under an apparent coldness he masked an excess of violence that the least suspicion or provocation would arouse.

Clarisse had her black-letter days—days of scolding, when with eyes brimful of tears she retired to her room, forbidden even to seek refuge with her governess; and looking back through the mists of childhood, she endured again those terrible scenes of anger, the horror of which haunted her still.

The two women understood each other instinctively, almost without the aid of words, living as they did that sequestered existence, in constant communion, both losing themselves in the same vague dreams, trembling on the borders of the unknown; each leaning on the other, with this only difference that Clarisse with an indefinable feeling of dawning force took the lead.

The same dim future smiled on both, the same far-off paradise of delusive hopes in which they would gladly lose themselves, until Mademoiselle Jusseaume, suddenly conscious of responsibility, would rouse herself, blushing and trembling, as if at some guilty thought. For in their day-dreams Monsieur de Pontivy had no part, did not exist. Was he to disappear? Was he to die? In any case he was always absent from these speculations, and Mademoiselle Jusseaume, the soul of righteousness, felt that this was altogether wrong.

"You must love your father," she would say, as if stirred by some secret impulse, and the remark fell suddenly and unexpectedly on the silence of the little room where the two were apparently deeply absorbed in the mazy dancing of the flies.

"But I do love him!" Clarisse would answer without surprise, as if replying to some inner thought.

She was, indeed, convinced of it, poor child! Filial love beamed in her eyes, love for her father: a mixture of respect for his age and position, and of gratitude for his rare kindnesses, while he did not realise the gulf that separated him from his daughter, a gulf which a little tenderness, an occasional response, a smile however slight, might have sufficed to bridge. He did not realise the riches of this mine, or seek its treasures of youth, of grace, and of love abounding in every vein. He had but to bend down, look into her large blue eyes, those eyes where the dreams floated, to find a world of love.

However, he had other things to think about; Monsieur de Pontivy, King's Councillor to the ancient Parliament, and unanimously returned to the new; a man of position, rich, influential, highly connected, of the old provincial noblesse, admitted to the council of the King, honoured at Court, respected in the town, feared at home by a whole crowd of cringing lackeys trembling before this potentate of fortune and intellect, who seemed to them the very embodiment of justice. His daughter, indeed! He had three years before him to think of her, which meant in his acceptance of the term but a speedy riddance of her, to his own and her best advantage, a chance to establish her well in the world in which he moved, in which his position would enable him to procure for her without much difficulty an alliance worthy of her name and rank. Meanwhile he was happy, or rather contented with his lot. Had not the young King but lately said to him, when he was admitted to a private audience to render homage and tender his assurances of fidelity and respect to the successor of Louis XV.:—

"Monsieur de Pontivy, I know the services you have rendered to France, and I can only ask you to continue them."

These words had spread through Versailles. The Councillor was overwhelmed with compliments of the kind more acceptable to certain natures for the spice of envy they contain, for is not the envy of our fellows the very sign and seal of our success?

Thus the influential Abbé de Saint-Vaast, the future Cardinal de Rohan, remarked to him some days after, whilst walking in the suite of the Queen at Versailles, "Such words, Monsieur de Pontivy, stand you in better stead than sealed parchment."

A smile of superiority, which he quickly changed to one of patronising condescension, played round the Councillor's lips at the thought that for a Rohan to compliment him meant that he sought something in return. Monsieur de Pontivy was not mistaken. The Abbé de Saint-Vaast wished to place with some lawyer in search of a secretary a young man who, having finished his college studies, intended to prepare for the Bar.

"I can recommend him," said the Abbé, "as intelligent, industrious, and of an excellent character; one of the best pupils of Louis-le-Grand, and recently chosen as most worthy the honour of welcoming the King and Queen, who visited the college on their way to the Pantheon."

"And his name?" asked Monsieur de Pontivy.

"Maximilien de Robespierre."

"And may I ask your lordship's reason for the particular interest taken in this young man?"

"Why, yes, of course! He comes from Arras, and was commended to me by the bishop of that town, with excellent testimonials from a priest of my diocese. I gave him a grant for the college, and as he has succeeded so far, I shall be glad to see him make his way. And, after all, are we not generally interested in the welfare of those we have helped—a feeling which you doubtless understand, Monsieur de Pontivy, since it is but human?"

"I understand it so well that I will take your nominee."

"Into your own service?"

"Yes, into my service. Pray do not thank me. I was in urgent need of one, and am too glad to accept him on your recommendation."

It was true, for Monsieur de Pontivy with his manifold occupations was at the moment without a secretary, and anxious to fill up the post so soon as he could find a worthy candidate. The offer of the Abbé was doubly acceptable to him as an opportunity to oblige a Rohan, and to enlist in his service a young man who had been chosen before all his fellow-students as most worthy to welcome the King and Queen.

The next day Robespierre was installed at the Hôtel de Pontivy. After some preliminary questions as to his parentage, his studies, his college life, Monsieur de Pontivy had adroitly brought the conversation to bear on the visit of Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette. The young man gave a detailed account, standing in a respectful attitude, his eyes lowered, and with an appearance of modesty, which to a mind less vain than that of Monsieur de Pontivy's would have suggested more self-sufficiency than was desirable.

"And the King, what did he say? And the Queen?"

"Their majesties did not speak to me," said the young man, rather confused.

"Ah!" exclaimed Monsieur de Pontivy, visibly satisfied.

"But the King smiled," continued Robespierre, "and received me graciously."

"And the Queen?"

The young man hesitated, but drawing himself up resolutely under the searching glance of the Councillor, he answered—

"Her Majesty was equally gracious."

But he was not telling the truth, for the Queen's thoughts had been bent all the time on hastening her departure. Monsieur de Pontivy examined the young man critically. He was dressed with the utmost simplicity, but a certain air of distinction was apparent in his whole person and manners. Spruce and neat in appearance, sprightly and brisk in manner, and at the same time respectful, decision of character and firm will were written on his brow; his eyes of a pale green were restless and piercing, though their gleam under the gaze of others was veiled, and so subdued as to lend to the whole countenance an unexpected tenderness.

"The young man is not so bad after all," mused Monsieur de Pontivy, and he thought he was justified in admitting him to his table now and again. Had he not been honoured with a royal glance? He could by no means be looked upon as a chance comer.

A chance comer he certainly was not, as Monsieur de Pontivy soon discovered by his work, quick, neat, perfectly accurate and orderly, and his method in arrangement and classification, rare in a young man of his years. Pursuing his law studies, he was naturally interested in the difficult and delicate questions which Monsieur de Pontivy had so often to treat, elucidating them under his direction, and astonishing him sometimes by his sagacious remarks, in which were revealed a rare instinct for solving legal subtleties.

There is a certain kinship of the mind, a certain intellectual affinity, which creates sympathy between those who may be separated by a wide social gulf. They certainly were so separated, this master and his secretary: the one jealously asserting his prerogative, proud of his name, of that noblesse de robe of which he was one of the ornaments, and which, seeing its growing influence on the destinies of France, he had exalted to the highest rank; the other of doubtful origin, hesitating even to make use of the titular prefix of nobility, but shrewd and ambitious, and seeking to supply his deficiencies of birth in the reflected light of the patrician world.

For, after all, who were the de Robespierres? The tangled narrative of the young man had but half satisfied Monsieur de Pontivy. There was, first and foremost, his father, who left his four children, when mad with grief at the loss of his wife, and disappeared in Germany in most mysterious fashion. But was young Robespierre responsible for all this misty past?

That which pleased Monsieur de Pontivy most in his young secretary were his orderly habits and his method of classifying and arranging everything to hand. So continuing that evening to look for the report he wanted, he had hesitated to wake him. He had seemed so sleepy before going to bed, and it was the first time a document had not been forthcoming. The Councillor had looked everywhere—on the files, under the blotters, and even in the waste-paper basket. Had the young fellow thrown it in the fire by mistake? Naturally distrustful, suspicions began gradually to form in his mind. Had Robespierre made use of it? Had he given it to an attorney? Once doubting Monsieur de Pontivy did not rest. Had he sold it? Yes, perhaps sold it to the counsel for the adverse party! Everything is possible! One is never sure.... At any rate he would ease his mind and ascertain at once. Monsieur de Pontivy looked at his watch.

"Three o'clock! So you have kept me up till this hour, my fine fellow! Now it is your turn!"

He took down a candlestick, lighted it at one of the chandeliers, and went towards the door. The whole house was wrapped in sleep. Oh! the awful stillness of that vast house, where not a soul seemed to breathe, that house with its interminable corridors, so high and so cold, like long, deserted lanes. Thus alone, in the silence of the night, he experienced a new sense of satisfaction, for was not the house absolutely his? Every living occupant, man or beast, was at his bidding, under his sway; and at this hour, when all slept under his protection, his proprietorship was accentuated, and he realised to the full that he was absolute master. In his long flowered dressing-gown, holding the candlestick aloft in his right hand, with his iron-grey head, clean-shaven visage, and true judge's nose, large and massive as if hewn in one piece, and in keeping with the cold, hard expression of his countenance, he could have been taken for the spirit of avenging justice, or for some statue, descended from its pedestal to carry light into the surrounding darkness.

Monsieur de Pontivy crossed a long passage, turned to the left, then went up three steps, and turning again, found himself on a narrow staircase leading to the second floor. It was there that the young secretary slept, in a little room looking on the courtyard. He lifted the candle to assure himself he was not mistaken, then knocked softly, twice. Receiving no answer he knocked again, somewhat louder.

"He sleeps soundly enough," he muttered; "at that age it comes easy."

The Councillor was on the point of returning. After all, it would be time enough to speak of the paper at breakfast, and already day was beginning to break. But again those subtle, insinuating suspicions crept into his mind. Yes! he must assure himself at once! And he knocked again, this time almost pushing the door. It was not fastened, and gave way, disclosing an empty room and a bed untouched. With a rapid glance he searched the room. All was in order.

"What!" he exclaimed, "at his age! This is promising, certainly."

And he began to wonder which servant was accessory to these midnight rambles, for this was surely not the first. The hall door was barred and double-barred when young Robespierre took leave of Monsieur de Pontivy. The porter was certainly culpable. Yes, the whole domestic staff was privy to the misconduct of his secretary! The very next day the Councillor would have a reckoning with them all, and it would be a terrible reckoning! But just at that moment, when Monsieur de Pontivy was about to leave the room, he noticed the young man's hat and stick lying near. He stopped in surprise.

Was Robespierre in the house, then?

Monsieur de Pontivy again looked at the bed. No, it had not been slept in. Other details struck him: the coat and vest hanging up, and the frilled waistcoat carefully folded on a chair. It was enough,—the young man had not gone out.

Where was he? In Louison's room, undoubtedly, on the third floor! Louison, his daughter's maid! She was from Perigord, sprightly and complaisant, cunning enough, a veritable soubrette, with her sly ways and her round cheeks. Ah! how stupid he had been to have taken her into the house, considering her age and bearing, scarcely twenty-two, and dark and passionate as a Catalonian.

"I ought to have known as much," he said.

His daughter's waiting-woman! The thought was distracting. That she should enter Clarisse's room every morning, carry her breakfast, see her in bed, assist at each detail of her toilet, fresh from the young man's embraces, his caresses still warm on her lips! And these things were taking place under his roof!

He left the room agitated but resolved. It was very simple. To-morrow she would be discharged the first thing, and he also should be turned out, the hypocrite who, with all his smiling, respectful airs, defiled his roof. He did well to get himself protected by priests, and Monsieur de Rohan, a nice present he had made!

All the young man's qualities, all the satisfaction he had given him, disappeared before this one brutal fact. He would not be sorry, either, to be able to say to the Abbé de Saint-Vaast—

"You know the young man you recommended me. Well, I surprised him in the garret with a servant-maid, and I turned him out like a lackey. But even lackeys respect my house."

He had now crossed the corridor and was descending the stairs, still rehearsing the scene in his mind. Smarting under his wounded self-love, he exaggerated everything. Had they not forgotten the respect due to him, Monsieur de Pontivy, to his house, and worse still, had they not mockingly set him at defiance? He smiled grimly at the thought. He had now reached the last step of the second staircase, and was turning into the corridor of the ground floor.

"Decidedly," he muttered, "I was mistaken in my estimate of that young man. He is a fool!"

All at once he stopped. He caught the sound of whispering, and the noise of a door being softly and cautiously closed. Some one here, at this hour! Who can it be? He blew out the candle, and gliding along the wall, he approached, but suddenly recoiled, for in the grey light of the dawn he had recognised Robespierre. The young man was advancing quietly in the direction of the stairs.

The truth, all the awful, maddening truth, the endless shame and dishonour, rushed on Monsieur de Pontivy in a moment, and stunned him like a blow.

Robespierre had come from Clarisse's room!

Everything swam before him. He held in his hand the extinguished candle, with such force that the bronze candlestick entered his flesh. He made a movement as if to use it as a weapon, and kill the wretch there and then. At that instant the young man saw him. He turned deadly pale and tried to escape, but Monsieur de Pontivy threw himself on him, and seized him by the throat.

"Where do you come from?" he almost hissed.

The young man swayed with the shock, his knees, bent under him.

Monsieur de Pontivy, mad with rage, repeated—"Where do you come from?"

He was strangling him.

Robespierre gave a hoarse scream.

"You are hurting me!" he gasped.

"Hurting you! Hurting you! did you say? What if I kill you, knock out your cursed brains with this"—brandishing the bronze candlestick—"yes, kill you, wretch, for bringing dishonour on my house...."

But just then Monsieur de Pontivy felt a hand laid on his arm arresting the blow.

It was Clarisse, drawn by the noise, half-dressed, her hair hanging in disorder down her back.

"Oh, father!" she sobbed, falling on her knees, as if for pardon.

It was dishonour, yes, dishonour complete, palpable, avowed, dishonour that flowed with his. daughter's tears, and covered her face with shame. The agony of the father was augmented by that of the head of the family, whose record of austerity and uprightness was thus dragged in the mud.

The young man, having regained his self-possession, was about to speak, but Monsieur de Pontivy gave him no time.

"Silence!" he thundered. "Not a word! Do you hear, sir? Not a word! To your room, and await my orders!"

The command was accompanied with such a gesture that Robespierre could only obey, and silently moved towards the staircase.

Then, turning towards Clarisse, he continued, "As to you ..."

But she lay lifeless on the floor. He bent down, lifted her in his arms, and carried her to her room; exhausted by her weight, he laid her on the first armchair.

The young girl regained consciousness. She opened her eyes and recognised her father, and a sob rose in her throat, suffocating her. She could not speak, but a word she had not pronounced for ten years, a word from her far-off childhood, came to her lips, and she murmured softly through her tears, "Papa! papa!"

Under what irresistible spell had she fallen? Through what intricate windings had the subtle poison entered the young girl's pure and innocent soul, then steeped in the fresh dew of life's dawning hopes? What sweet vision had the young man held out to her, to which she had yielded in all innocence, her eyes dreamily fixed on the vague unknown, and from which she had awaked, all pale and trembling, her heart smitten with unspeakable dismay?

Or had they both been the puppets of Destiny, of blind Chance which at so tender an age had brought them together under the same roof, in an intimacy of daily intercourse, increased by the sadness of their cloistered existence, so that they had been the victims of their extreme youth, of the attraction they unconsciously exercised over each other, both carried away by the strong currents of life.

She, influenced by a train of incidents insignificant in themselves, rendered dangerous by repetition, details of every-day life which had gradually drawn her towards the young man, whose presence at last became a sweet necessity to her lonely existence.

He, suddenly stirred during the first few days of his residence in the Hôtel Rue des Lions; never for a moment thinking of the distance which separated him from the daughter of Monsieur de Pontivy. Think? How could he think, thrilling under the first revelation of love disclosed to him with the eloquence of Rousseau in la Nouvelle Héloïse, that romance of burning passion then in vogue? He had commenced to read the novel, by stealth, at Louis-le-Grand, and finished it in three nights of mad insomnia, in his little room on the third floor at the Hôtel de Pontivy. All the sap of his youth beat at his temples and throbbed in his veins at that flaming rhetoric; every phrase burned like kisses on his lips.

He recited portions aloud, learned them by heart, found them sublime in utterance. He yearned to repeat them to others, as one does music. And to whom could he repeat them but to Clarisse, placed there as if expressly to hear them? So he did repeat them to her. At all times and everywhere when alone with her. At the harpsichord, on long winter evenings, when the guests gravely and silently played at cards, and he turned the pages of her music. Out walking, when he met her, as if by chance, and spoke to her—while the eyes of Mademoiselle Jusseaume wandered absently from them—of Paris which she knew so little, the gay fêtes and gossip of the town, thus opening out to her endless vistas of happiness until then unknown, which involved promises of future joy.

He recited verses to her, pastorals, such as were then upon men's lips, mythologic madrigals made for rolling round a bonbon. She found them charming, and sought to learn them by heart. He copied them and gave them to her. This was a dangerous game. He became bolder, copied love-letters, then wrote them himself and compared them with Rousseau's. She read them, delighted at first, then trembling, and when she trembled it was too late.

She was unconsciously dragged into a world of fancy and illusion by the very strength of his youth and enthusiasm. His presence in that dull dwelling had seemed a ray of sunlight under which the bud of her young life had opened into flower. Thus, all unconscious of the poisonous mist that was more closely enveloping her from day to day, she found herself gliding insensibly down a steep declivity which gave way under her feet as she advanced, and before she could recover possession of her senses, or stay her quick descent to question whereto it led, she was undone!

"Every girl who reads this book is lost," Rousseau had written at the beginning of la Nouvelle Héloïse. And she had done far worse. Alone, given up to her own devices, just awakening to the mystery of existence, pure, innocent, and guileless, she had imbibed its insidious poison from the lips of one she had learned to love. And now she had fallen from these dizzy heights, dazed and crushed, lonelier than ever, for Monsieur de Pontivy had turned Robespierre out of the house soon after the fatal discovery.

The decision had been brief, in the character of a command:

"Of course, it is understood that what passed between us last night shall go no further," Monsieur de Pontivy had said to the young secretary, called to the Councillor's study at breakfast-time. "You can seek some pretext to treat me disrespectfully at table before the servants, and I shall beg you to leave my house."

The young man listened respectfully.

"But I am willing to make reparation," he said.

The Councillor drew back under this new affront.

"You marry my daughter! You forget who you are, Monsieur de Robespierre! You, the husband of Mademoiselle de Pontivy! Enough, sir, and do as I have said!"

The departure of young Robespierre took place as the Councillor desired. No one had the slightest suspicion of the real reason, and Clarisse, who was suffering from a severe attack of brain fever, kept her bed.

In refusing to give the hand of his daughter, even dishonoured, to any one who was not of her rank, Monsieur de Pontivy was but true to his principles, to his own code of morals, based upon caste prejudice and foolish pride.

Could he have read the future of the young man he would not have acted otherwise, and yet that young man was destined to become one of the masters of France—but at what a price and under what conditions!

Nineteen years had passed since then, nineteen years in which events succeeded each other with a rapidity and violence unparalleled in the previous history of Europe. The excesses of an arbitrary government, added to universal discontent, had led to the Revolution. But this act of deliverance and social regeneration was unhappily to develop even worse excesses. The Reign of Terror was now raging. Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette had perished on the scaffold, followed by a large number of nobles and priests, victims of the tempest now at flood, and drowning in its crimson tide numberless victims with no respect of persons. The whole nation, in the country and in Paris, was perishing in the iron grasp of a new and more despotic government. Terror, monstrous parody of liberty, ruled the State, which was adrift without rudder on the storm, while all its people were driven to distraction by wild advocates of the guillotine.

Prominent among these fanatics, raised to power by the very suddenness of events, was Maximilien de Robespierre, once the young secretary of Monsieur de Pontivy, now styled simply Robespierre, President of the National Assembly, or Convention, the most powerful and most dreaded of the twelve conventionnels who, under the name of members of the Committee of Public Safety, ruled the destinies of France.

History is the romance of nations, more abundant in wild improbabilities than the most extravagant fairy tale; and the French Revolution stands out from the events which have perplexed the mind of man since the world began, a still unsolved enigma. The actors in this fearful drama move like beings of some other sphere, the produce of a wild imagination, the offspring of delirium, created to astound and stupefy. And it was the destiny of the secretary of Monsieur de Pontivy to become one of these. Still in the prime of his life, scarcely thirty-six, he was one of the principal if not the chief personage of the Revolution.

However signal his success, the course of events left him unchanged. During the slow accession of a man to the summit of human aspiration, his deficiences are sometimes dwarfed and his powers developed and strengthened; but the foundation remains the same—just as trees which ever renew their leaves, and absorb from the same soil a perennial flow of life.

After nineteen years, marked by a succession of events so rapid, so tumultuous, and of such moment that they would have sufficed to fill a century of history, the secretary of Monsieur de Pontivy, whom we last saw awake to love under the influence of Rousseau, found himself, on a day given up to retirement and study, at l'Ermitage of Montmorency, in the very room where the great philosopher wrote la Nouvelle Héloïse, whose burning pages had been a revelation to his youth.

He had come there to seek inspiration for the speech he was to deliver on the Place de la Révolution at the approaching festival in honour of the Supreme Being, a ceremony instituted and organised under his direction, and which had been suggested to him by the spiritualistic theories of Rousseau.

It was Friday, the 6th of June, 1794, or, to use the language of the time, the 20th prairial of the second year of the Republic. Robespierre, having left Paris the evening before, had come down to sleep in that quiet and flowery retreat, built at the entrance of the forest of Montmorency, like a nest hidden in the under branches of a tree. Rousseau's Ermitage, which became State property after the Revolution, had been secretly sublet to him by a friend and given over to the care of a gardener, who also acted as sole domestic during his visits, which were very frequent. For he often fled from Paris secretly, seeking solitude and calm, and a little of that poetry of nature in which the fiercest Revolutionists, his peers in crime, loved sometimes to refresh themselves in the short pauses of their fratricidal and sanguinary struggles.

Robespierre descended to the garden soon after daybreak, inhaling the fresh morning air, wandering under the shade of those great trees where Rousseau used to walk, or sitting in his favourite nooks; dreaming the while, his soul drinking to the full the infinite sweetness of Nature's magic charms, quickened into life at the rosy touch of morn. He would busy himself in rustic pursuits, botanising, or gathering periwinkles, the master's favourite flowers; thus occupied he used to prolong his walk into the forest of Montmorency, which seemed but a continuation of the garden. Here, he would sometimes find friends awaiting him, an intimate circle which he was wont to gather round him to share a rustic meal upon the grass.

That morning he had awakened earlier than usual, beset with ideas for his forthcoming speech, the first that he was to deliver at a public ceremony, whose anticipated success would, like an apotheosis, deify him in the eyes of the people, and set a decisive and brilliant seal to that supremacy of power which was the goal of his boundless ambition. It was important that he should finish before noon, when he had arranged an interview in the forest, a political interview of the highest importance, which would perhaps effect a change in the foreign policy of France.

Robespierre had slept in the very room which Rousseau had occupied on the first floor, and in which were gathered all the furniture and possessions of the great man, left behind in the haste of removal, after his famous quarrel with the fair owner of l'Ermitage. The bed was Rousseau's, as were two walnut cabinets and a table of the same rich wood, the very table on which the philosopher wrote the first part of la Nouvelle Hèloïse; then a small library, a barometer, and two pictures, one of which, by an English painter, represented "The Soldier's Fortune," and the other "The Wise and Foolish Virgins." In these surroundings Robespierre seemed to breathe more intimately the spirit of the master for whom he had such an ardent admiration.

Robespierre had passed a sleepless night, judging from his pale, feverish face and swollen eyelids. Outwardly he was little changed. Monsieur de Pontivy would have recognised his former secretary in this man before whom all France trembled. It was the same dapper figure, spruce and neat as ever, with that nervous, restless manner which time had but accentuated. This nervousness, apparent in his whole person, was visible even in his face, which, now deeply marked with small-pox, twitched and contracted convulsively. The high cheek-bones and the green, cat-like eyes, shifting about in an uneasy fashion, added to the unpleasant expression of the whole countenance.

He threw open the three windows of his room, which looked out on the garden. A whiff of fresh air fanned his face, charged with all the sweet perfumes of the country. Day had scarcely dawned, and the whole valley of Montmorency was bathed in pale, uncertain light, like floating mist. He remained at one of the windows, gazing long and earnestly out on awakening nature, watching the dawn as it slowly lifted the veil at the first smiles of morning. Then he seated himself at the little table prepared for work, with sheets of paper spread about, as if awaiting the thoughts of which they were to be the messengers. He slipped his pen in an inkstand ornamented with a small bust of Rousseau, and commenced.

Jotting down some rough notes and sentences, he stopped to look out of the window in a dreamy, absent manner, apparently without thought. Thirty-five years ago, amid the same surroundings, in that same room, on that very table, Rousseau had written those burning pages of romance under whose influence Robespierre had stammered forth his first love tale on the shoulder of Clarisse. Did he ever think of that drama of his youth, of that living relic of his sin wandering about the world perhaps, his child, the fruit of his first love, whose advent into life Clarisse had announced to him some months after the terrible scene at the Rue des Lions-Saint-Paul? Think? He had more important things to trouble him! Think indeed! The idea had never entered his head. For many years the intellectual appetite had alone prevailed in him;—egoism, and that masterful ambition which asks no other intoxicant than the delirium of success, and the thought of realising one day, by terrorism even if necessary, Utopian theories of universal equality. And yet the letter in which Clarisse had apprised him of her approaching motherhood would have moved a stone:—

"DEAR MAXIMILIEN,—I never thought to write to you after the solemn promise torn from me by my father, the day he declared I should never be your wife. An unexpected event releases me from my oath, and brings me nearer to you.

"I am about to become a mother.

"My father knows this. I thought that the announcement would conquer his resistance, but I was mistaken. My supplications were vain.

"He persists unshaken in his refusal, exasperated at my entreaties, and is resolved to send me to a convent, where the innocent being whose life is already considered a crime will first see the light. My heart bleeds at the thought of the wide gulf that must separate you from your child, orphaned before its birth. And what pain for you to have a child that you must never know! But I will spare you this. You are the disposer of our destiny, Maximilien. We are yours.

"I have some money saved, which, in addition to the kind help of Mademoiselle Jusseaume, would enable us to cross to England, where a priest of our faith will bless our union. We can return afterwards to France, if you wish; that shall be as you judge best, for you will have no wife more submissive and devoted than the mother of your child.

"I am sending this letter to your aunt's at Arras, requesting them to forward it to you. Write to me at the Poste Restante, Rue du Louvre, under the name of the kind-hearted Mademoiselle Jusseaume, who is reading over my shoulder while I write, her eyes full of tears. Wherever I may be, your reply will always reach me.

"I kiss thee from my soul, dear companion of my heart—that heart which through all its sufferings burns with an undying love and is thine forever.

"CLARISSE DE PONTIVY."

This letter remained unanswered. Had it reached its destination? Yes; young Robespierre had actually received it, eight days after, in Paris, at the Hôtel du Coq d'Argent, on the Quai des Grands-Augustins, where he had hired a room after leaving Monsieur de Pontivy's house. He had read and re-read Clarisse's letter, then, on consideration, he burnt it, so that no trace of it should be left. Clarisse's proposal was a risky adventure. What would become of them both in England when her meagre resources were exhausted? Return to France? Implore Monsieur de Pontivy's pardon? A fine prospect! He would cause the marriage to be annulled, for it was illegal both in England and in France, as the young people were not of age. As to him, his fate was sealed in advance. He would be sent to the Bastille. And the child? He scarcely gave a thought to it. So much might happen before its birth!

This, however, was made known to him, soon after, in another letter from Clarisse. The child—a boy—was born. If he did not decide to take them the child would be abandoned, and she sent to a convent. Robespierre hesitated, crushing the letter between his fingers, then resolutely burnt it, as he destroyed the first. Paugh! The grandfather was wealthy. The child would not starve. Clarisse had told him that she had given him Monsieur de Pontivy's Christian name—Olivier. The Councillor would eventually relent. And was it not, after all, one of those adventures of common occurrence in the life of young men? He, at least, had done his duty by offering to make reparation by marriage. Monsieur de Pontivy would not hear of it. So much the worse!

Ah! he was of mean birth, was he!—without ancestry, without connections, without a future.... Without a future? Was that certain, though?

Monsieur de Pontivy's refusal, far from humiliating him, gave a spur to his ambition. All his latent self-esteem and pride rose suddenly in one violent outburst. Full of bitterness and wounded vanity he finished his law studies in a sort of rage, and set out for Arras, his native place, which he had left as a child, returning to it a full-fledged lawyer. No sooner was he called to the Bar than he came into public notice, choosing the cases most likely to bring him renown.

But these local triumphs, however flattering, only half-satisfied his ambition. He cared little or nothing for provincial fame. He would be also foremost in the ranks of those who followed with anxious interest the great Revolutionary movement now astir everywhere, in the highways and byways of France, with its train of new ideas and aspirations. Robespierre took part in this cautiously and adroitly, reserving ample margin for retreat in case of future surprises, but already foreseeing the brilliant career that politics would thenceforth offer to ambition.

At the Convocation of the States-General, the young lawyer was sent to Versailles to represent his native town. Success was, at length, within his grasp. He was nearing the Court, and about to plunge into the whirl of public affairs, in which he thought to find an avenue to his ambition.

And yet he did not succeed all at once. Disconcerted, he lost command of himself, became impatient and excited by extreme nervousness. He had developed such tendencies even at Arras, and time seemed only to increase them. In the chamber of the States-General, still ringing with the thunderous eloquence of Mirabeau, the scene of giant contests of men of towering mental stature, Robespierre vainly essayed to speak. He was received with mockery and smiles of ridicule. He appeared puny and grotesque to these colossal champions of Liberty, with his falsetto voice, his petty gestures, his nervous twitches and grimaces, more like a monkey who had lost a nut than a man.

But Robespierre's colleagues would have ceased their raillery perhaps had they gone deeper into the motives and character of the man, and sounded the subtle intricacies of his soul. They would have found in those depths a resolute desire to accomplish his aim, an insatiable pride joined to the confidence of an apostle determined to uphold his own doctrines, and to promote theories of absolute equality, and of a return to the ideal state of nature. They would have perhaps discovered that this ambitious fanatic was capable of anything, even of atrocious crime, to realise his dreams.

The impetuous tribune Mirabeau had said at Versailles: "That man will go far, for he believes in what he says." Mirabeau ought to have said, "He believes in himself, and, as the effect of his mad vanity, he looks upon everything he says as gospel truth." And in this lay his very strength. This was the source of his success, founded on that cult of self, and a confidence in his own powers carried to the point of believing himself infallible. Through all the jolts and jars of party strife, the thunder and lightning contests, the eager enthusiasm or gloomy despondency, the grand and tumultuous outpourings of the revolutionary volcano through all this hideous but sublime conflict, and amid dissensions of parties swarming from the four corners of France, tearing each other to pieces like wild beasts, Robespierre cunningly pursued a stealthy course, sinuously ingratiating himself now with the more advanced, now with the more moderate, always faithful to his original plan and policy.

Words! Rhetoric! these were his arms. Speech was not incriminating, but actions were. Words were forgotten, actions lived as facts, and Robespierre kept as clear of these as possible. During the most startling manifestations of that horrible revolutionary struggle, he was never seen, though the work of his hand could be traced everywhere, for far from retiring he carried fuel to the flames, knowing well that every one would be swallowed up in the fratricidal strife. When the danger was over and victory assured, he would re-appear fierce and agitated, thus creating the illusion that he had taken part in the last battle, and suffered personally in the contest.

Where was he at the insurrection of Paris, the 10th of August, 1792, when the populace invaded the Tuileries, and hastened the fall and imprisonment of the King, whom they sent to the scaffold some months later? Where was he a few days later, the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th of September, when armed bands wandered through Paris, forcing the prison doors, and butchering the hostages? Where was he during the riots of February, 1793, when the famished populace prowled about Paris asking for bread? Where was he the evening of the 1st of May, when eighteen thousand Parisians assailed the National Convention to turn out the traitor deputies? Where was he two days after, on the 2nd of June, when the insurrection recommenced?

Hidden, immured, barricaded, walking to and fro like an encaged tiger-cat, excited and agitated, shaken with doubts, cold beads of perspiration standing on his forehead, breathless to hear any news which his agents and detectives might bring him, and only breathing freely again when the result was known.

For this man was a coward. And was this known? No! Not then! All that was known was what he wished to make public; that he was poor, that he was worthy in every respect of the title of "Incorruptible" given to him by a revolutionist in a moment of enthusiasm. And, in truth, he was free from any venal stain, and knew that in this lay the greater part of his strength.

What was also known was that he was temperate and chaste. His private life, from the time he left Versailles with the States-General to come to Paris and install himself in a humble lodging in the Rue de Saintonge, would bear the closest scrutiny. He lived there frugally and modestly, his only resource being the deputy's fees of eighteen francs a day, part of which he ostentatiously sent to his sister at Arras. Then suddenly he established himself in the house of Duplay the carpenter, in the Rue Saint-Honoré, a few steps from his club, the Jacobin Club; or, more properly speaking, he was established there by force, by the carpenter himself, an ardent admirer of his, who took advantage of a chance hospitality during the riots to press him to remain indefinitely. He occupied a room under their roof where he had now lived a year, surrounded by the jealous care of the whole family, in republican simplicity, after the true patriarchal manner.

All this was well known, or if it had not been Robespierre would have proclaimed it, for from this Spartan setting an atmosphere of democratic virtue enveloped him, and raised him in solitary state above his fellows.

Yes, he was above them! Others gave themselves away, but he never! Others had revealed their characters in unguarded moments, and laid bare to the world their frailties and their virtues. He had never betrayed himself, for he never acted on impulse. The others were well known to be made of flesh and blood, of idealism, and dust, but who knew the real Robespierre? The very mystery and doubt in which his true character was wrapped had lent credence to the common rumour which attributed to him supernatural qualities. He was compared to the pure source, high among virgin snows, from which the Revolution sprung.

He stood alone on his pedestal, inaccessible, unassailable. All the great leaders of the Revolution, his predecessors or his rivals, had disappeared, carried off in the whirlwind, victims of their exaggerated enthusiasm, as Mirabeau and Marat, or of Robespierre's treachery, as Danton and Camille Desmoulins, ground in the sanguinary mill of the Revolutionary Tribunal, on his sole accusation.

Thus when his path was cleared of those who stood most in his way, he anticipated the time when he should hold the destiny of France in his hand, aided by the Convention now subdued to his will, and the whole armed force grovelling at his feet.

Yet one obstacle remained to be surmounted: the Committee of Public Safety to whom the Convention had transferred its authority, and of which he was a member, but where he felt a terrible undercurrent of animosity directed against him.

At this point Robespierre realised that he must either cajole or conquer them. For if they were curbed and reduced to silence, he would have all power absolutely in his own hands. The hour was approaching. It was necessary to strike a decisive blow, and he thought to have found the means to do so, and to overawe the Committee, at his Festival of the Supreme Being, which would take place in a couple of days, when he would speak to the assembled multitude, and dominate his colleagues in his quality of President of the Convention, a post he had sought in order to have an opportunity to assert himself at this lay ceremony, this parody of the religious celebrations of the old regime.

His intention was to confirm in public, amid the acclamations of the populace, the religion of a new God, whose existence he had just proclaimed—the God of Nature, a stranger to Christianity, borrowed entire from Rousseau's famous pages in le Vicaire Savoyard. Robespierre's sectarian temperament experienced a deeper satisfaction than he had perhaps ever felt, at the thought that he was to declaim, among flowers and incense, those empty, sonorous phrases which he was writing on the little walnut table where his master had found some of his most burning inspirations. He became in his own eyes the high priest of the Republic, offering incense on the altar of his own superhuman sovereignty. Yes, Robespierre could already hear the enthusiastic applause of the multitude! Who would dare to stand in his way after such public consecration in the immense Place de la Révolution, where for a week past the platform was being prepared.

Such was the man shadowed by Destiny, the further course of whose chequered career, with its startling incidents, we are now to follow.

Robespierre had just finished his first discourse, for he was to deliver two. He closed it with a menace. "People," it ran, "let us under the auspices of the Supreme Being give ourselves up to a pure joy. To-morrow we shall again take arms against vice and tyrants!"

This was his note of warning to those who, he felt, ranged themselves against him. Completely satisfied with himself, he read and re-read his sentences, stopping to polish periods and phrases, or seeking graceful and sonorous epithets. One passage especially pleased him, for a breath of le Vicaire Savoyard seemed to pervade it. He spoke of the presence of the Supreme Being, in all the joys of life. "It is He," he said, "who adds a charm to the brow of beauty by adorning it with modesty; it is He who fills the maternal heart with tenderness and joy; it is He who floods with happy tears the eyes of a son clasped in his mother's arms." Robespierre smiled at the music of the phrasing which in his pedantry he thought his master would not have disowned.

But he stopped. After all, was it not a reminiscence of le Vicaire Savoyard? Perhaps he had made use of the same metaphor as Rousseau? He would be accused of feeble imitation! This could be easily ascertained, as the book was near at hand, in the little bookcase that once belonged to the master. He had but to take it from the case. The key was in the lock, but it resisted, though he used all his strength. Growing impatient, he was about to break open the door, but paused as though this would be sacrilege, and at last sent for the gardener.

"This lock does not act, does it?" he said.

The gardener tried it in his turn, but with no better success.

"It is of the utmost importance for me to have a book which is in there," said Robespierre, visibly annoyed.

"That can be easily managed, citizen; there is a locksmith a few steps from here, on the road to the forest. I will go and fetch his apprentice."

The gardener ran downstairs, and Robespierre returned to his work. He was soon aware of footsteps advancing. It was the gardener returning with the apprentice.

"This way, citizen," said the gardener.

The two men entered. Robespierre had his back to them, and continued to write, a happy inspiration having occurred to him, which he was shaping into a sentence. After they had tried several keys the door yielded at last.

"Now it's right, citizen!" said the gardener.

"Thanks!" said Robespierre, still bending over his work, and absorbed in his sentence.

Suddenly the sound of a voice floated up through the casement:—

"Petits oiseaux de ce viant bocage...."

It was the young apprentice returning home across the garden, singing. Robespierre stopped in his writing, vaguely surprised. He had heard that air before! But where? When? This he could not tell. It was the echo of a distant memory. He turned his head slowly in the direction of the cadence, but the song had ceased.

The fleeting impression was soon effaced, and Robespierre, having already forgotten the coincidence, rose and went towards the now open bookcase. Taking Rousseau's volume, he opened it at these words: "Is there in the world a more feeble and miserable being, a creature more at the mercy of all around it, and in such need of pity, care, and protection, as a child?" He passed over two chapters, turning the pages hastily. The phrase he wanted was undoubtedly more towards the end. As one of the leaves resisted the quick action of his hand, he stopped a moment to glance at the text: "From my youth upwards, I have respected marriage as the first and holiest institution of nature..." Now he would find it. The phrase he wanted could not be much further! It soon cheered his sight: "I see God in all His works, I feel His presence in me, I see Him in all my surroundings."

Robespierre breathed freely again. Here was only an analogy of thought, suggested, hinted at by Rousseau, and which he, Robespierre, had more fully developed. Smiling and reassured he returned to his place.

These words of Rousseau read before the open bookcase, suggestive as they were of voices from the past still echoing through his memory, had no meaning for him. They kindled no spark in the dead embers of his conscience to reveal the truth. And yet it was a warning from heaven—a moment of grave and vital import in the life of this man, who, had he not been blinded by an insane ambition, might have recognised in the passing stranger a messenger of Fate.

For the voice which had distracted him from his work was the voice of Clarisse, and the young apprentice who had just left him was his son.

The outcast child, now grown to manhood, had been within touch of his own father, but unseen by him. No mysterious affinity had drawn them together, though the voice had vaguely troubled him as he returned to his work.

The young man on leaving l'Ermitage took the path that led to the forest. He was a fine, stoutly built lad, with a brisk lively manner, strong and supple, revealing in spite of his workman's garb an air of good breeding which might have perhaps betrayed his origin to a keen observer. His hair was dark brown, his blue eyes looked out from the sunburnt and weather-beaten face with an expression of extreme sweetness, and his full lips smiled under a downy moustache. He walked with rapid strides, a hazel stick in his hand, towards the forest, which he soon reached, threading the paths and bypaths with the assurance of one to whom the deep wood and its intricate labyrinths was familiar. He slackened his pace now and then to wipe the perspiration from his forehead, keeping to the more shady side of the way, for the sun, already high in the heavens, shed its rays in a burning shower through the leaves, scorching the very grass in its intensity. At last, overcome by the heat, he took off his coat and hung it at the end of the stick across his shoulder.

Presently he turned into an avenue of oak saplings through which a green glade was visible, an oasis where refreshing coolness told of the presence of running water. Here he shaded his eyes with his hands to make out a form outlined against the distance, and a smile lit up his face as he recognised the approaching figure. Hastening his steps he called out—

"Thérèse!"

A fresh, clear voice answered—

"Good morning, Olivier! Good morning!" as a young girl came towards him with outstretched hands. She was tall and lithe, of a fair, rosy complexion, and wore a peasant's dress from which the colour had long since faded. She advanced rapidly, now and then replacing with a quick, graceful movement the rebel locks of fair hair that caressed her cheeks, all in disorder from the air and exercise.

"You bad boy! Auntie and I have been quite anxious about you; but where do you come from?"

For only answer the young man kissed her upturned forehead, and allowed her to take the stick at the end of which his coat still hung.

"And where is mamma?" he asked, continuing to walk on.

"Why, here, of course!" called another voice, a woman's also, gay and joyous as the other, but more mellow in tone, and Clarisse's head appeared above the tall grass.

Instantly the young man was in his mother's arms, and seated by her side on the trunk of a fallen chestnut lying parallel with the stream, which in his haste he had cleared at a bound, discarding the assistance of the little bridge of trees of which the young girl was more prudently taking advantage.

"Ah! my poor Olivier! What anxiety you have caused us! Why are you so late? And after being out all night, too?"

"Did you not know that I should not be back?" the young man asked, looking at his mother.

"Yes, but we expected you earlier this morning."

"It does certainly seem as if it had happened on purpose," he said, as he explained to them why he was so late, and he went on to tell them how he had been kept at the last moment by his employer for some pressing work at Saint-Prix, a little village then in full gala, and distant about a league from the forest. The Democratic Society of the district had joined for this occasion with the Montmorency Society, and there were of course masts to put up, a stand to erect, or rather to improvise, for everything was behindhand. Olivier had been told off to fix iron supports to the steps raised for the convenience of the populace. They had worked, he said, till late in the night by candle light, and in the morning, when he was preparing to come home, he had to go to l'Ermitage to open a bookcase, just to oblige the gardener who was such a good fellow, though the tenant...

"Who is he?" interrupted Clarisse, always fearful and uneasy at the thought of her son going to a stranger's house.

"I don't know at all," replied Olivier. "I only know that he didn't even disturb himself to thank me. They have pretty manners, these Republicans; the old aristocracy were at least polite."

But his mother stopped him.

"Oh, hush! Do not speak like that; suppose you were heard!"

And, putting her arms round his neck, as if to shield him from some possible danger, she asked him what news he brought from the workshop.

"Nothing but the same string of horrors at Paris, and it was even said that the number of victims had sensibly increased."

Carried away by his subject, he detailed to the two women scraps of conversation overheard that night at the village of Saint-Prix. As he spoke, Marie Thérèse, now seated near him on the grass, with his coat spread before her, silently smoothed out the creases, and his mother drank in every word with breathless attention.

Nothing was left of the Clarisse of sixteen but the velvet softness of the blue eyes, and the sweet charm of their expression, with all the pristine freshness of a pure soul still mirrored in their depth. The thin, colourless face seemed modelled in deep furrows, and the fair hair was already shot with silver. Though poorly clad in the dress of a peasant, she also might have betrayed her better birth to a practised observer by her white hands, with tapered fingers and delicate wrists, and by the supple grace of her bearing. But who could regard as an aristocrat this poor woman, almost old, sheltering under her maternal wing the stout young workman, with his resolute air and hands blackened at the forge?

She now went under the name of Durand, as did her son and her niece, Marie Thérèse, who passed as the child of her brother-in-law. The young girl was, in reality, the daughter of her own brother, the young student of the College of Navarre, who had been killed the preceding year in Vendée, fighting in the ranks of the Chouans, in the Royalist cause. Clarisse's husband also met his fate at one of these sanguinary combats, for he was so dangerously wounded that a few days after he had been secretly conveyed to London he died in great agony.

For Clarisse had been married, and was now a widow.

And her past: it could be written in a page—a little page; yet in writing it her hand would have trembled at every line. Deserted by her betrayer, receiving no reply to her letters, she realised, when too late, his cold egoism and ambition. She had been separated from her child, who was born in the retirement of a little village of Dauphiné, whither her father had taken her, and had been immediately confided to the care of peasants, where she was allowed to visit him once a fortnight, subject to a thousand precautions imposed by Monsieur de Pontivy.

And yet, with all this weight of sadness, Clarisse retained her native grace. Misfortune had but added charm to her delicate and melancholy beauty.

It sometimes happened, though very seldom, that she was obliged to accompany her father into society. On one of these rare occasions she attracted the notice of a young captain of the Queen's Guards, Monsieur de Mauluçon, who sought her society assiduously, fell in love with her, and asked Monsieur de Pontivy for her hand.

"Your offer does us much honour," the Councillor had replied, "but I should wish you to see Mademoiselle de Pontivy herself, before renewing your request to me."

And Monsieur de Pontivy notified the fact to Clarisse the same evening with characteristic formality:

"Monsieur de Mauluçon," he said, "whose affection, it appears, you have won, has done me the honour of asking for your hand. I gave him to understand that you alone would dispose of it. He will be here to-morrow afternoon to confer with you. I do not know if he pleases you, but this I know, that if you wish to accept his offer you must lay before him the story of your past. And I need not tell you that if, after this, he persists in making you his wife, you can rely on my consent."

"It shall be as you wish, father," Clarisse answered.

That open nature, which was her most touching trait, made her father's attitude seem quite natural. She did not wait to think that Monsieur de Pontivy could have spared her the shame of this avowal by making it himself, for the fault of another is more easily confessed than our own. Clarisse only felt that, having inflicted a wrong on her father, she was in duty bound to expiate it. And, in truth, it did not cost her so much to make the confession to Monsieur de Mauluçon as it would to have broken it to any other, for he had from the first inspired her with unbounded confidence. She had read a manly generosity in the kindly expression of his frank, open face. She would never have dreamt of becoming his wife, but since he had offered himself why not accept the proffered support of so strong an arm? She well knew in her lonely existence that her father would never be the loving friend and protector that, in the utter weakness of her betrayed and blighted womanhood, she had yearned for through so many long days!

But her child, her little Olivier, would he be an obstacle? At the thought her eyes filled with tears. What did it matter? She would only love him the more, the angel, and suffering would but bind them closer together! However, it was now to be decided, and both their destinies would be sealed, for she well knew that if Monsieur de Mauluçon drew back after her confession, all prospects of marriage would be over, for never again could she so humiliate herself, though she could bring herself to it now, for she had read a deep and tender sympathy in her lover's eyes. And, after all, what mattered it if she were not his wife? She would at least remain worthy of his pity, for he could not despise her. Her confession would create a tie between them which he would perhaps remember later on, when her little Olivier engaged in the battle of life.

When Monsieur de Mauluçon came again to her, innocent of all suspicion, he found her grave and deeply moved. In a few brief words she laid bare to him the history of her past, and he was too high-souled, too strong and generous, to feel anything but an immense pity for a heart of exquisite sensibility, wrecked by its own confiding impulses, misunderstood, misled, and then forsaken.

He took both her hands in his and pressed them to his lips respectfully.

"And the child," he said; "whose name does he bear?"

"Luc-Olivier. Olivier is my father's Christian name."

"But he must have a name! We will give him ours. Mauluçon is as good as Pontivy."

"How can that be?" Clarisse answered, thinking she must be dreaming. "Do you mean you will adopt my child? ... Oh! Monsieur! ... Monsieur!..." and she stammered incoherent words of gratitude, struggling with an emotion which seemed to strangle her.

"I also have a Christian name"—and he bent low, whispering softly in her ear—"my name is Maurice."

She turned towards him with a wan smile, and as he stooped to kiss his affianced bride she melted into tears.

The child was just two years old. The young couple took him with them in their travels. They then established themselves at Pontivy, near the grandfather, who had softened towards his daughter since her marriage, partly won by the baby charm of his grandchild. Their visits to Paris became less frequent, for Monsieur de Mauluçon, in order better to enjoy his home life, obtained an unlimited leave of absence. He now devoted himself to Olivier's education, who was growing up a bright, frank, and affectionate boy. Except Monsieur de Pontivy and Clarisse's brother Jacques, no one but themselves knew the story of his birth. Jacques de Pontivy, recently married, had kept it even from his wife, who died, however, some months after giving birth to a baby girl, whom Clarisse now loved as much as her own Olivier.

Life seemed to smile at last upon the poor woman, when the Revolution broke out. Jacques de Pontivy, who had intended to succeed his father in Parliament, seeing the Royal Family menaced, entered the army, which Monsieur de Mauluçon had also rejoined. Both endeavoured several times to give open proof of their loyal sentiments. They covered the flight of Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette, and were nearly taken at the arrest of the King and Queen on their way to Varennes, and the next year they were obliged to fly from France, and both sought refuge in England, resolved to serve the Royalist cause with all their energy and devotion to the last.

Clarisse, who had remained at Paris with her husband during those stormy times, now rejoined her father at the Château de Pontivy, with Olivier and little Marie Thérèse.

Monsieur de Pontivy, whose health was fast failing, was struck to the heart by the rapid march of events and the sudden collapse of all his most cherished surroundings.

"There is nothing left but to die," he would say sometimes, looking on with indifference at the vain attempts of his son and son-in-law, whose firm faith and enthusiasm he no longer understood, tired and disgusted as he was with everything.

Another tie which bound Clarisse to France was the charge of the two children. Almost grown up now, they were still too young to be exposed to the danger of travelling in such uncertain times, when the frontiers were scarcely guarded, and France was committed to a course which had estranged her from the nations of Europe.

But when Clarisse heard that Monsieur de Mauluçon and her brother were on the eve of leaving London for Southampton to rejoin the royal army in Vendée, she hesitated no longer.

Confiding the children to their grandfather's care, she left Pontivy, and arrived in London, to find her husband and brother at the house of a mutual friend, Benjamin Vaughan, whose acquaintance they had made at the American Embassy in Paris, at a reception on the anniversary of the United States Independence, and with whom they had become intimate.

But Clarisse had hardly rejoined her husband, when a letter reached her from Pontivy telling her that if she wished to hear her father's last words she must come at once. She returned to France almost beside herself with grief, giving her whole soul to her husband in a parting kiss.

It was to be their last.

Misfortune followed misfortune with astounding rapidity. Monsieur de Mauluçon and Jacques de Pontivy soon landed at Saint-Paire, and joined the Vendean army. At the first encounter Jacques was killed by a Republican bullet, and Monsieur de Mauluçon mortally wounded. He was secretly conveyed to London with other wounded royalists, and in spite of the fraternal welcome and care he found under the roof of the faithful friend who had always received them with open arms, he died there of his wounds. Clarisse learnt her double bereavement at the time when her father was breathing his last.

Thus she became a widow and an orphan in that brief space of time.

Prostrated by this double blow, she was for some time at death's door. When she came to herself after a delirium which lasted nearly a week, she saw her children—for Marie Thérèse, now doubly orphaned, was more her child than ever—seated at her bedside awaiting in unspeakable anxiety her return to consciousness. She drew them to her, and covered them with kisses.

"Console yourselves," she said, "I shall live, since you are here."

At this moment a man advanced smilingly towards her, his eyes glistening with tears of joy.

"Leonard!" she said, "you here?"

It was an old servant of Monsieur de Pontivy, who had come in all haste from Montmorency, where he lived, to attend the funeral of his late master.

"Ah!" he cried, "Madame can rest assured Leonard will not leave her till she is herself again."

"Then I shall remain ill as long as possible," she replied laughing, and she held out her hands to him.

Her convalescence was short, and as soon as she was on her feet again she began to think of the future. But Leonard had already thought of this. "You cannot remain here," he said. "Your name, your connections, your fortune—everything denounces you, and exposes you to the ill-treatment of so-called patriots. You must leave Pontivy."

"Go? But where?" asked Clarisse, "Abroad? I have already thought of that, but how can I reach the frontier with my young people without passport, and without guide?"