Title: The cave dwellers of Southern Tunisia

Subtitle: Recollections of a sojourn with the Khalifa of Matmata

Author: Daniel Bruun

Translator: L. A. E. B.

Release Date: September 7, 2023 [eBook #71585]

Language: English

Credits: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE BEY OF TUNIS.

RECOLLECTIONS OF A SOJOURN WITH THE

KHALIFA OF MATMATA

TRANSLATED FROM THE DANISH OF

DANIEL BRUUN

BY

L. A. E. B.

London: W. THACKER &

CO., 2 Creed Lane, E.C.

Calcutta: THACKER, SPINK, & CO.

1898

[All Rights Reserved]

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

My journey among the cave dwellers of Southern Tunisia was essentially one of research, since I was entrusted by Doctor Sophius Müller, Director of the Second Department of the National Museum, with the honourable task of purchasing ethnographical objects for the said museum.

On submitting this work to the public, it is incumbent upon me to offer my sincere thanks to all those who afforded me support and help in my travels: the Minister of Foreign Affairs, at whose recommendation Cubisol, the Danish Consul in Tunis, addressed himself to the French Regency, and obtained permission for me to travel through the country, and also an escort, guides, etc. Doctor Müller and Chamberlain Vedel, whose respective introductions, given from the National Museum and the Society concerned with ancient manuscripts, and addressed to other similar institutions, introduced me not only to these, but also to those remarkably scientific men, Gauckler and[vi] Doctor Bertholon, whose friendship I have to thank for much information and assistance.

England’s Representative in Tunis, Drummond Hay, may be said to have traced my path through Tunisia, as, on the basis of his remarkable knowledge of both individuals and of relative circumstances, he sketched a plan of my journey, from which I required to make little or no deviation. The Government and officers in El Arad, the officials, both military and civilian, showed me the greatest hospitality, and assisted me in the highest degree; Colonels Billet and Gousset especially claim my warmest gratitude.

Much of what I have recorded has been left in its original form, namely, as letters written home, some to my wife, some to other persons, as, for instance, to the publisher, Herr Hegel. I have not altered these lest they might lose the fresh impression under which they were written. Several portions were composed with a view to publication in the French journal the Revue Tunisienne, and in the Parisian magazine Le Tour du Monde.

The illustrations were obtained from various sources. Albert, the photographer in Tunis, obligingly allowed me to make use of a number of photographs, from which were chiefly drawn the views of the town and of the sea-coast. With a detective camera I myself took some[vii] instantaneous photographs on the journey from Gabés to the mountains, of which a number are introduced. Besides these, Mr. Knud Gamborg has engraved some drawings of my own. Mr. Gauckler also gave me the free use of the sketches already published in his Collection Beylicale, from which were selected the pictures of the villages in the Matmata mountains. Lastly, from the wife of Consul Henriksen at Sfax I received two paintings, which are reproduced.

When, in the spring, I made an expedition to Greenland, I left my manuscript with my friend Doctor Kragelund, of Hobro, who had already afforded me his assistance, and gave him full powers to arrange the somewhat heterogeneous materials. In my absence he corrected the proofs as they came from the press, and has therefore taken a very important part in my work, and enabled it to be published in its present form. For this act of friendship I tender him my warmest thanks.

Daniel Bruun.

November 1894.

Note.—The fact of three years having elapsed since the Danish original of the Cave Dwellers was published, renders the letter form of which the[viii] author speaks somewhat unsuitable for translation. It has been necessary, therefore, in many cases to modify that form, and also to omit certain passages in the work as being of little or no interest to English readers.

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | WITH DRUMMOND HAY IN TUNIS | 1 |

| II. | SUSA | 5 |

| III. | FROM SFAX TO GABÉS | 17 |

| IV. | FROM GABÉS TO THE MATMATA MOUNTAINS | 32 |

| V. | RETURN TO GABÉS | 59 |

| VI. | OF THE MATMATA MOUNTAINS AND THEIR INHABITANTS | 93 |

| VII. | FROM GABÉS TO THE OASIS OF EL HAMMA—THE SHOTTS | 116 |

| VIII. | THE OASIS OF EL HAMMA | 129 |

| IX. | OVER AGLAT MERTEBA TO THE MATMATA MOUNTAINS | 152 |

| X. | BRIDAL FESTIVITIES IN HADEIJ | 158 |

| XI. | OVER THE MOUNTAINS AND ACROSS THE PLAIN FROM HADEIJ TO METAMER | 197 |

| XII. | METAMER AND MEDININ | 217 |

| XIII. | SOUTHWARDS OVER THE PLAIN TO TATUIN | 233 |

| XIV. | DUIRAT | 243 |

| XV. | THE TUAREG | 253 |

| XVI. | BACK TO TUNIS | 274 |

| XVII. | TUNIS | 285 |

| SUPPLEMENT—THE TRIBES OF TUNISIA: A SYNOPSIS | 292 | |

| COSTUMES—THE DRESS OF THE COUNTRYWOMEN | 324 | |

| POSTSCRIPT | 334 |

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

| PAGE | |

| THE BEY OF TUNIS | Frontispiece |

| DRUMMOND HAY, BRITISH CONSUL-GENERAL AT TUNIS | 3 |

| SUSA | 8 |

| TWO KHRUMIR WOMEN | 13 |

| AT SFAX | 20 |

| TOWER IN THE VILLAGE OF MENZEL | 24 |

| JEWESSES AT MENZEL | 25 |

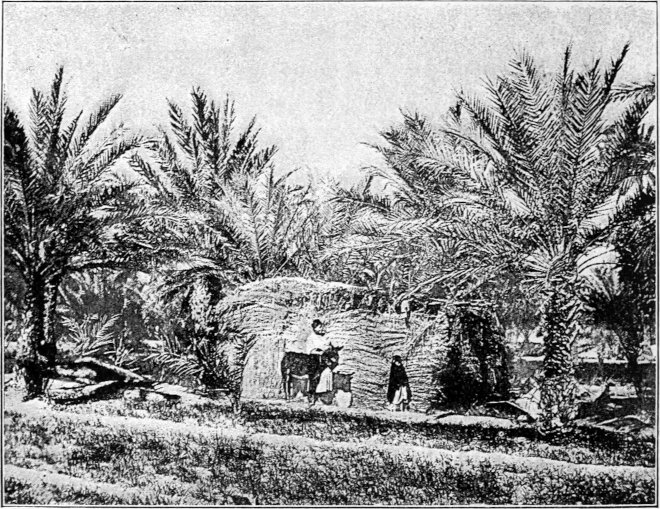

| ON THE OASIS OF GABÉS | 28 |

| WASHERWOMEN AT THE JARA BRIDGE | 30 |

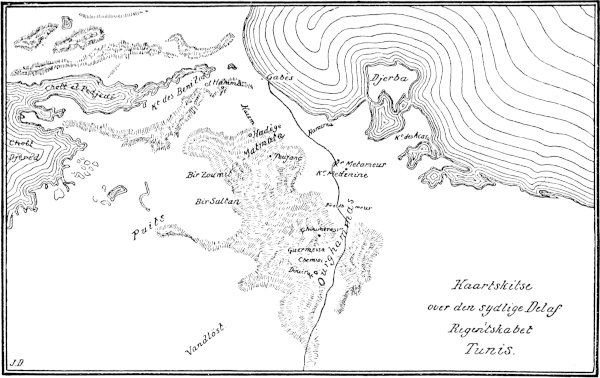

| MAP OF SOUTHERN TUNISIA | 33 |

| PLOUGHING—GABÉS | 37 |

| JEWISH FAMILY IN A CAVE DWELLING IN HADEIJ | 43 |

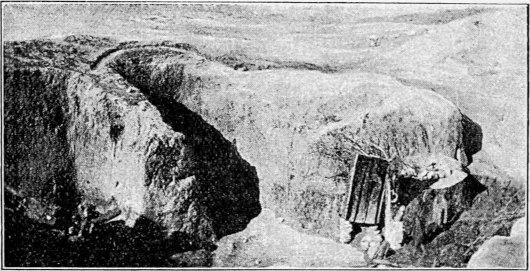

| CAVES IN MATMATA | 45 |

| A CAVE DWELLING, MATMATA | 46 |

| THE BRIDAL FESTIVITIES | 49 |

| HOLD UP! | 59 |

| EXCAVATED STABLE | 62 |

| BERBER WOMAN OF THE VILLAGE OF JUDLIG | 65 |

| A CAVE INTERIOR | 66 |

| FALCONERS | 77 |

| MANSUR | 100 |

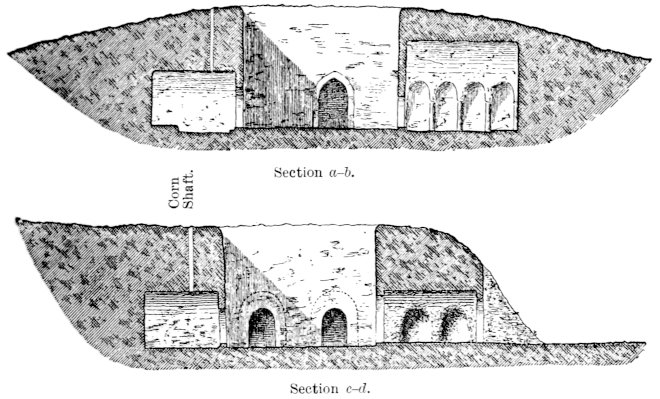

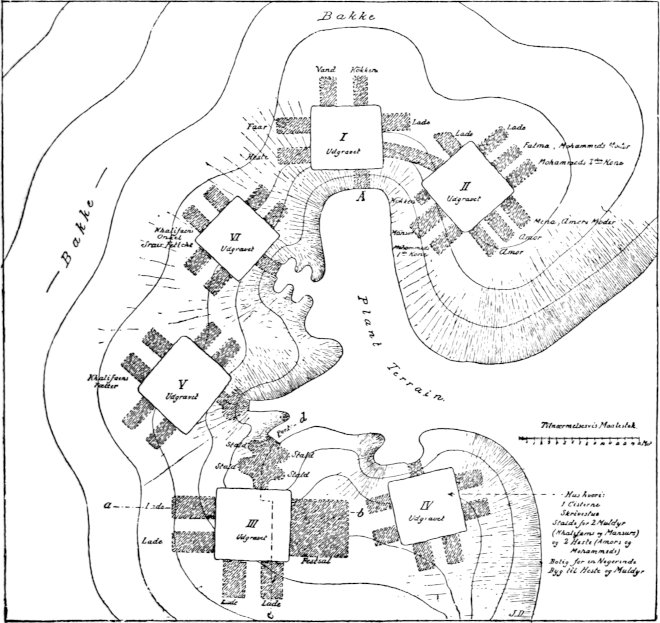

| SECTIONS OF DWELLING IN MATMATA WHERE I LIVED—PLAN | 103 |

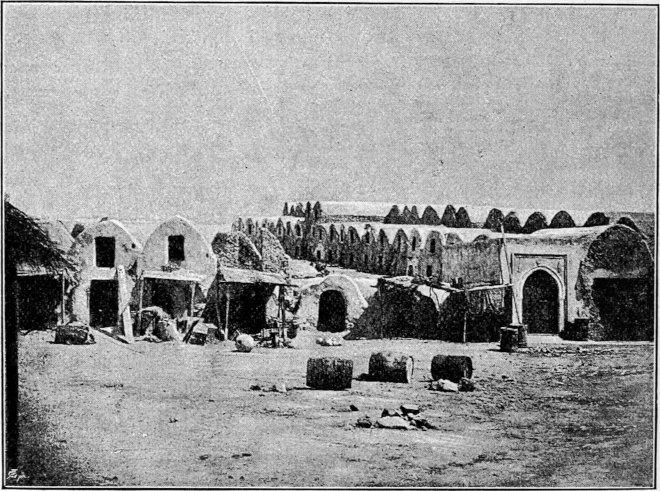

| MEDININ | 112 |

| BEDOUIN WOMEN GROUPED BEFORE THEIR HUT | 113 |

| AT GABÉS | 117 |

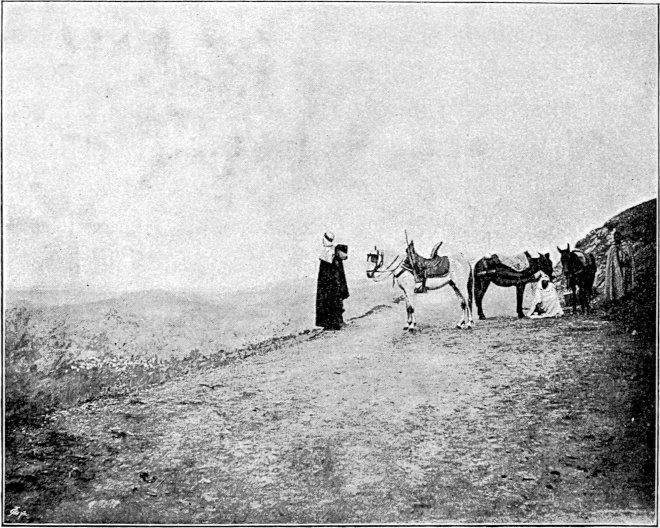

| IN THE MOUNTAINS—ON THE ROAD TO AIN HAMMAM | 120 |

| [xii]REARING | 156 |

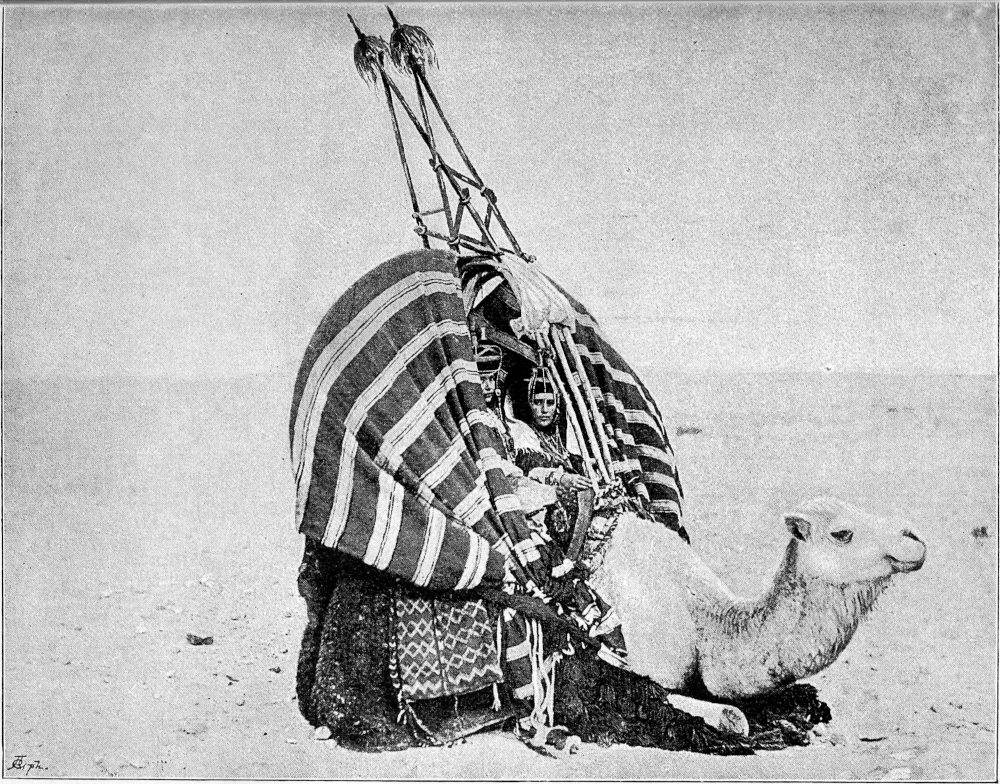

| CAMEL WITH CANOPY | 169 |

| THE BRIDE ESCORTED OVER THE MOUNTAINS | 176 |

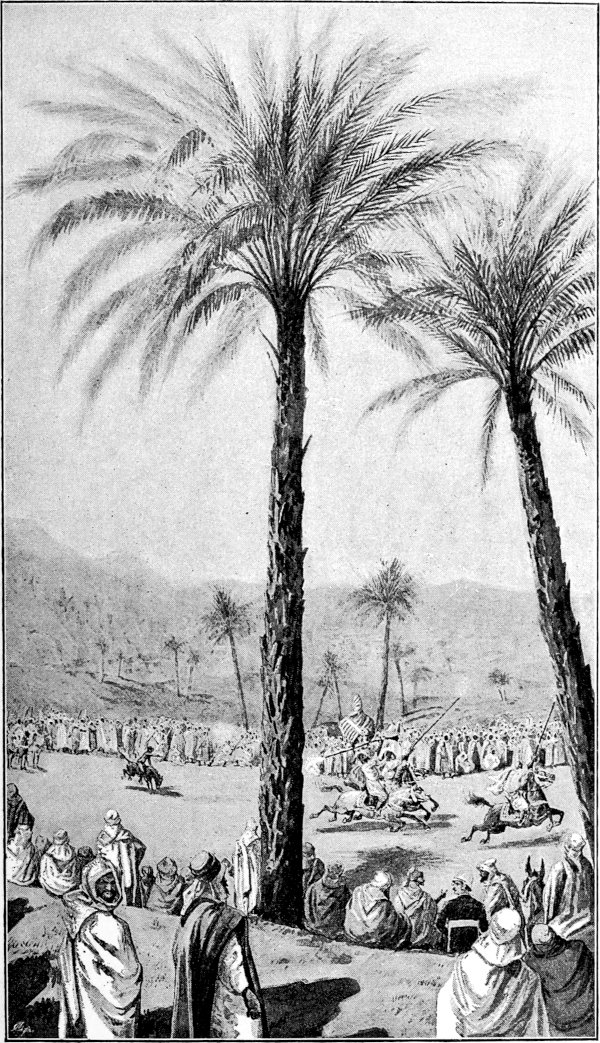

| FANTASIA | 179 |

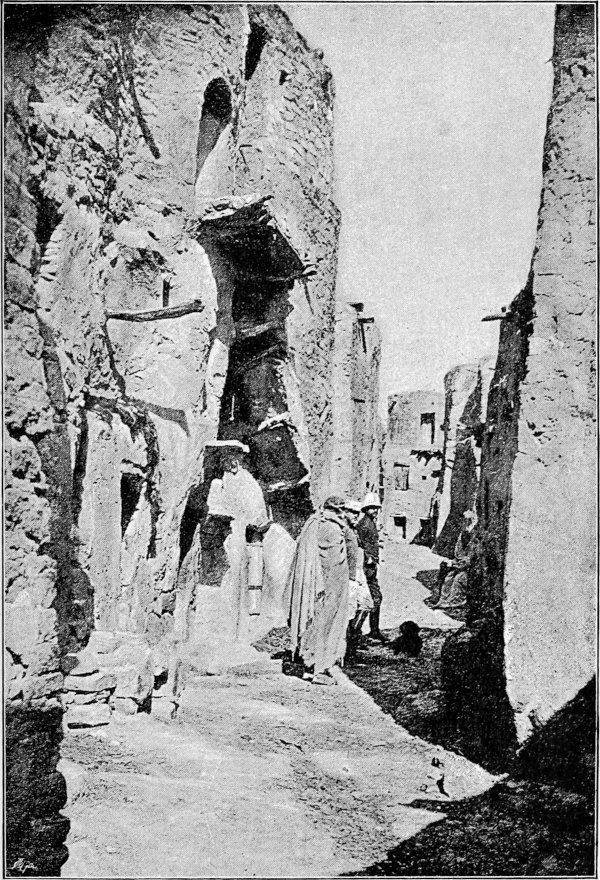

| A STREET IN BENI BARKA | 219 |

| MEDININ | 224 |

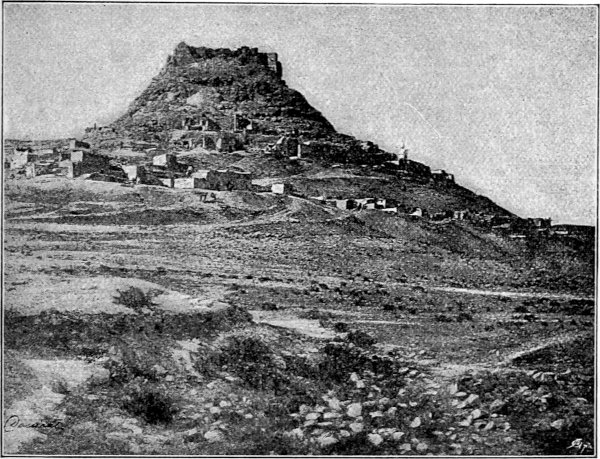

| DUIRAT | 245 |

| SHENINI | 248 |

| A HALT IN THE DESERT—TENT OF A TRIBAL CHIEF | 251 |

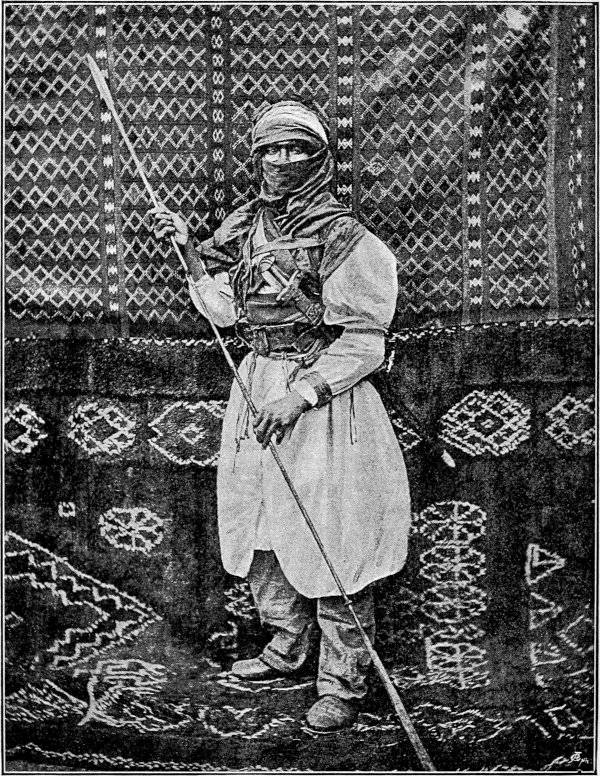

| A TUAREG | 254 |

| A TUAREG | 262 |

| MOORISH WOMEN IN A STREET IN TUNIS | 289 |

[1]THE CAVE DWELLERS OF

SOUTHERN TUNISIA

![[Decoration]](images/decor1.jpg)

Though the midday sun still shone bright and hot, I sat at my ease and breathed again in the pleasant atmosphere of a cool drawing-room, from which the stifling air and the flies were excluded by closely drawn blinds.

I had just arrived from Tunis by rail, over the scorching hot plain, and past the milky-white shallow lagoon known as the Lake of Tunis. Beyond Goletta the blue hills seemed to quiver beneath the rays of the sun, and my eyes were blinded by the dazzling white walls of the cathedral standing on the heights, where, in olden days, Byrsa, the fortress of Carthage, stood, defying the invader and the storm.

As we sped over the traces of the mighty circular wall, which formerly enclosed the town, I[2] caught a glimpse of a white roof amongst the green trees of a wood, and requested the conductor to stop the train at the English Consul’s summer abode.

Down a pretty shady avenue I walked to the white summer palace, with its beautiful columned portico, the finest in all Tunisia.

It is a proud name that my host bears,—a name associated with unfailing honour in the history of Morocco. His late father, Sir J. H. Drummond Hay, as England’s Representative, practically led Morocco’s policy during the past forty years. He represented Denmark also, and under him his son won his diplomatic spurs.

My host had invited me that we might quietly arrange a plan for my intended expedition to visit the Berber tribes of Tunisia.

I was aware that in the south-west mountains of the Sahara I should meet with Berbers of a pure race such as are scarcely to be found elsewhere. Our country’s excellent Representative, Consul Cubisol, had procured me a French permit for the journey, without which it would be difficult for a lonely traveller to visit regions unfrequented by Europeans.

In the spring, Drummond Hay had made a tour on horseback over the greater part of Southern Tunisia; he was therefore acquainted, not only with[3] the localities, but also with several of the native chiefs who would be able to assist me. He understands the people and their country thoroughly, for he speaks Arabic like a native, and is quite conversant with the life, opinions, manners, and customs of the inhabitants. His wife had travelled far and wide with him in Morocco when he was serving under his father, and accompanied him to the capital of Morocco; so she also is well versed in Oriental life.

DRUMMOND HAY, BRITISH CONSUL-GENERAL AT TUNIS.

Together we traced the plan of my journey, which, in the main, I afterwards followed. Here I will not anticipate what I shall relate later; only premising this—that I owe first and foremost to Drummond Hay the fact of having comprised in my journey those regions which no traveller has as yet described. To him I was also afterwards indebted for the elucidation and explanation of what I had seen and heard.

[4]Both my host and hostess had resided for many years in Stockholm, when Drummond Hay was Consul there. The north has great attractions for them, as Drummond Hay’s mother was a Dane, a Carstensen, being daughter of the last Danish Consul-General at Tangier.

England has great interests in Tunis, not only directly on account of the many Maltese living there under British protection, but also indirectly, more especially since the French settled in the country; it will therefore be understood that the post of British Representative is one of confidence.

“A happy journey until our next meeting, and may Allah preserve you from cholera!”

These were the parting words of my friend Gauckler, Inspector of Antiquities and Arts, who bade me a last farewell at the Italian railway station of Tunis.

Numbers of flamingoes stalked along the shores of the lagoon, showing like white patches on the blue-grey expanse of water. Out on the horizon, where the lake ended, I could see Goletta’s white houses, and beyond them a deep, dark blue line—the Mediterranean.

At midday the heat was stifling, but after we reached Goletta Bay the sun sank rapidly, and the air grew cooler as a little steamer took us through the entrance to the harbour, past the homeward-bound fishing-boats. Just at sunset we reached our large steamer. To the north, Carthage’s white church on the heights near Marsa appeared on the horizon, and, in the south, the blue mountains of Hammamlif.

[6]Amid the noisy whistling of the steamer, mingled with screams and shouts, I tumbled on board with my numerous bundles and packages; finding my way at last to the saloon, where a frugal dinner awaited us.

Next morning, when I went on deck, the coast lay like a flat, grey stripe ahead of us. I went forward and enjoyed the fresh sea breeze for which I had so longed in Tunis. Near the bows of the ship were two dolphins. One of them rose to the surface of the water and spouted a stream of spray through the little orifice in its head, then sank again. The other then rose in its turn.

The white bundles on the fore part of the deck now began to stir into life, and each as it rose threw back its burnous, and showed a dark face. One Arab had with him his whole family. He had spread a rush mat on which, amongst their numerous belongings, lay, closely packed, husband, wife (perhaps wives), several children and a large poodle. A roguish little girl came to discover what I was contemplating. She was sweet, brown, and clean, and peeped up at me, hiding her face the while with one hand, evidently conscious of wrong-doing. The tips of her fingers and toes were stained red with henna, which was not unpleasing. Soon after, a closely veiled figure, apparently the mother, came to fetch the little one. I had just time to perceive[7] that she was pretty, as she threw back a fold of her haik to wrap round her child and herself. What a charming picture they made as they leant against the bulwarks and gazed towards the land!

Upon a slope, quite near, lay Susa—white, white, everything was white.

On the summit of the slope were some towers and a crenelated wall, and on the seashore beneath, yet another wall. Below lay the harbour, too shallow, however, for our ship to enter; we had therefore to lie out in the open.

A boat took me to the quay, where some twenty black-eyed boys of all ages, with gleaming teeth and red caps, lay watching for their prey. As the boat drew alongside, they rushed down to seize my luggage. The boatmen attempted to push them aside, but, nevertheless, one caught up my little handbag, another my umbrella, and a third my photographic apparatus. There was nothing for me to do but to jump ashore and chase the thieves. It was long before I could collect everything under the charge of one lad. Then, with a couple of smart taps right and left, my little guide and I marched up to the Kasba, where the Commandant lives. Here are the magazines and barracks, and here, too, I knew that I should find a collection of antiquities.

Susa was originally a Phœnician colony, and[8] played no small part in the Punic Wars. Trajan called it “Hadrumetum,” and made it the capital of the province. It was laid waste by the Vandals, rebuilt by Justinian, and destroyed by Sid Obka, who utilised the greater portion of its ancient materials to build the holy city of Kairwan. Later the town was rebuilt by the Turks, who had here for a long time one of their hiding-places for their piratical fleets. The town was therefore assaulted by Charles V. in 1537, and again by Andreas Doria in 1539, and, lastly, was occupied without a struggle on the 10th of September 1881, by a force under General Etienne. It is, after Tunis, the most[9] important town in the Regency, and is governed by a Khalifa in the name of the Bey.

SUSA.

Numerous remains of all these periods are to be found in Susa. In the houses, mosques, and in the surrounding country, antiquities and ancient ruins abound. From the Commandant I learnt that the foundations of the Kasba date from the time of the Phœnicians. Later, the Romans, as also those conquerors who followed them, built over these.

In the salle d’honneur are arranged many earthen vessels of Phœnician origin found in tombs, together with other objects of the same period.

From Roman times remain magnificent mosaics, partly buried in the walls; vessels, vases, and broken fragments of marble figures. The Kasba itself, with its many arches, gateways, turrets, and walls inlaid with tiles, dates from the days of the Arabs or Turks.

In nearly every instance the mosaics depict horses, their names being introduced beside them. Evidently, in those days, this was already deemed an important mart for horses bred in the country. The breeding of Barbs appears to date further back than is generally believed, and, in fact, to be older than the Arabian conquest of this land. One sees horses depicted with red head-stalls, decorated on the top with tufts of feathers, and with their near[10] quarters branded, exactly as seen on the troop horses of to-day.

The outlines of the horses on the mosaics prove that the Barbs of that period were the same in type as those of the present age; also that their careful treatment is not of recent date. Even the same class of flat iron shoes is used now, as then, on the horses’ forefeet.

I inquired of the Commandant whether particularly fine horses were reared in this region. He replied in the affirmative, and that in the direction of Kairwan there are nomad tribes whose horses are of noble race.

I climbed the high tower of the Kasba,—now used as a lighthouse,—whence I overlooked the town which lay below me encircled by its protecting wall. Over the country, on all sides, olive woods met my view, and far away on the horizon I could catch a glimpse of villages, looking like white specks. There dwell the ill-disposed tribes who, in 1881, held out against the French. They never ventured on an open engagement, but at night assembled in their hundreds and kept up an incessant fire on the French lines; killing a number of both officers and men. These were avenged by heavy levies and fines on the inhabitants. Poor people, they had only defended their hearths and homes.

My boy guide followed me through the streets,[11] where drowsy lazy Moors crouched, half asleep in their shops, waiting for purchasers. The loveliest small boys and girls were lying about in the streets, much to the obstruction of traffic, here conducted by means of small donkeys and large mules.

Stepping into a little Moorish coffee-house, I found, to my astonishment, that the interior resembled in construction an old Byzantine basilica, its dome being supported on arches and pillars. The whole was white-washed, but well preserved. The coffee-house was named “el Kaunat el Kubba,” which may be translated Church Café.[1] Nothing could be more artistic than the cooking utensils, mats, and pottery scattered here and there about this very old building.

At five o’clock it was dark. The stream of wayfarers diminished, and the streets were deserted and empty. I dined at the Hotel de France on the seashore, not far from the esplanade, and sat after dinner reading my papers, till I heard a frightful noise outside, and, peering out, saw a crowd of Arabs gathered behind an unfurled banner. They shouted and yelled in measured time. One of them said a few words which all the others repeated. I was told that they were praying to Allah for rain. They halted a few paces from a kubba, called Bab el Bahr,[12] and the procession dispersed, the banner being taken into the kubba.

I went for a turn on the seashore by the road which leads along the walls to Bab el Jedir. The sun was melting hot. Against the walls were built a number of mud huts and sheds, in which, amongst carriages and carts, horses and donkeys were stabled.

Outside were piles of pottery, vessels of all shapes and sizes, from the largest receptacles for wine or water—reminding one of those found belonging to the Roman age—to cups and jars of spiral or other strange forms, such as I have seen in the museum at Carthage.

This clay ware is brought from Nebel, where, since very ancient times, there has been a manufactory that produces pottery the same to-day as it was a thousand years ago.

The gateway is deep, and has, as have most gates in this country, recesses with seats on both sides, always filled by idlers and beggars. Indeed, it is quite an Eldorado for the blind, halt, and maimed, as well as for many who have nothing the matter with them. The whole day they sit there and stretch out their hands for alms.

I placed myself near the corner stone of the gate, where the shade was cool and pleasant; through the dark archway I could see the sun blazing on the shore, and the road looking like a bright streak of[15] light, and, beyond it, the harbour and the beautiful blue sea.

TWO KHRUMIR WOMEN.

In the space of half an hour, at least a hundred little donkeys passed me, laden with vessels of water or bundles of straw, with often a man or boy perched behind the load. A solitary rider also passed, his small but wiry horse going at an amble. Along the seashore came, picking their way, a herd of goats, most of them wearing small bells that rang incessantly. The herd settled in the corner outside the gates between the towers and the town wall. Then came unveiled Bedouin women, dark-skinned almost as negresses, but with very fine features. Then other veiled Arab women with black masks that covered their faces. A number of boys followed these, all good-looking and black-eyed. One held out his hand; they are accustomed to European good-nature, and a copper is a foretaste of Paradise to an Arab boy.

Lastly passed a strange couple. On an ordinary Arab saddle a veiled woman rode astride, and behind her, on her horse, a little boy; he held the reins in one hand, and a parasol in the other.

Towards evening it grew cooler. Amongst the shipping lay the Ville d’Oran, which next morning was to take me south. It was lit up with numbers of lanterns, and the town was illuminated and hung everywhere with flags, in honour of the Russian[16] fleet, which that day was to enter Toulon. Festival was kept, not only all over France, but also in her colonies. Illustrated editions of French newspapers, with coloured pictures of Russian and French admirals and of the ships of both countries, were displayed on the walls of all cafés, tobacco shops, taverns and drinking booths in Susa.

The light on the Kasba had been lit. The moon rose over the town, and lanterns gleamed along the seashore and the promenade. The irregular line of the wall and the Kasba tower showed dark against the heavens. Mingling with the ripple of the water against the quay, I heard the Marseillaise played, followed by cheers, and on the terraces and balconies appeared dark figures, enjoying the cool air and the music.

At 9 a.m. on the morning of the 14th October, the Ville d’Oran weighed anchor and left the roadstead of Susa in brilliant weather for Monastir.

Monastir, or Mistir, has a population of nine thousand inhabitants, of whom one thousand are Europeans. It was originally a Carthaginian town; later, the “Ruspina” of the Romans. It is now surrounded by battlemented walls interspersed with towers and pierced by five gates. Ornamented with coloured tiles, the minarets of several mosques rise here and there above the houses.

I crossed the town from the south to the opposite side. Here I found an immense cemetery; grave upon grave grouped about kubbas. In the very midst of the cemetery is a cistern, which must supply remarkably good water!

Following along the walls of the town I soon reached the beach, where before me lay three small islands—Jezirel el Hammam (Pigeon Island), Jezirel Sid Abd el Fairt el R’dani (so called after a Marabout[18] whose kubba crowns its summit), and the third island named Jezirel el Austan (Central Island).

Still following the walls, I passed Moorish women and children washing clothes on the shore. A number of boats were lying in the shallow water under the lea of the islands.

At ten o’clock I was again on board, and at eleven we started, steering for Mehdia, some thirty-six miles farther south.

On the way we passed Cape Diauros, the site of ancient Thapsus. It was a Carthaginian colony where fought Cæsar Scipio and Cato. Numerous ruins recall the old times.

In Mehdia harbour we anchored about three o’clock. Mehdia was once a very important town; now it has only some ten thousand inhabitants. The Sicilians besieged it in 1147; the Arabs in 1160; the Duke of Bourbon in 1390; and Charles V. in 1557. The knights of Malta took part in this last assault, and the grave of one of these knights is still shown.

Some Europeans carry on a trade here in oil, dried fruits, sponges, coral, and sardines. In the months of May and June there are often a couple of hundred boats lying off the shore fishing for sardines, and generally making good hauls. In one night a single boat may take even as much as from four to six hundredweight of fish.

Large vessels do not follow the coast from[19] Mehdia to Sfax, but make a long circuit round the island of Kirkennah, the water along the coast being shallow. Along this stretch of sea have been placed light-buoys to mark the course. These buoys are filled with compressed oil, and burn incessantly day and night. They are constructed to burn three months, but are inspected monthly.

Early in the morning of the 15th October we cast anchor about two miles outside Sfax, of which the white walls glistened in the morning sun. A steam tug took us ashore. The ebb and flow of the tide here is very strong, with a possible rise and fall of as much as eight feet, which accounts for the flatness of the beach.

The only ship in the roadstead was the Fæderlandet from Bergen, lying-to and discharging timber.

Sfax was taken on the 16th July 1881 by a force under Admiral Garnault, after a serious bombardment which laid waste a great part of the ramparts and the town.

The walls enclosing the European quarter, which faces the sea, have been pulled down lately, and here the French have established themselves. To the rear lies the Arab town, still surrounded by its walls and towers.

On landing I met the Vice-Consul for Sweden and Norway, Olaf Henriksen, a young man who in[20] the course of a few years has made for himself a good position as partner in the large, and perhaps sole, firm of timber traders in the place. His office and warehouses are on the quay. Olsen, his co-partner, is likewise a Northerner. Henriksen is agent for the United Shipping Co., but it is seldom that Danish vessels touch here.

AT SFAX.

(From a painting by Mrs. Henriksen.)

After a stroll through the town, Mr. Henriksen[21] led me to his home and introduced me to his wife, a Norwegian lady from Christiania. I spent a comfortable and most enjoyable day in their house, which is outside the town and commands a view of the harbour.

Mrs. Henriksen is a very fair artist. On the walls hung sketches of her northern home and of Sfax, painted by herself and showing considerable talent. The tombs of Marabouts, the cemeteries outside the walls, and the Arab tents in the vicinity were the subjects that pleased me most. She most amiably promised to be my collaborator, by allowing me to make use of a couple of her sketches for my book.

Sfax is a large town, with about fifty thousand inhabitants, of whom the eighth part are Europeans. A considerable trade is carried on in sponges, oil, and esparto grass, this last being worked by a Franco-Anglo-Tunisian Company; in addition to these, there is a trade in fruit and vegetables, more especially cucumbers, called in Arabic “Sfakus,” from which, no doubt, arises the name of the town.

In the neighbourhood are many villas and gardens, where the townsfolk take refuge in the hot season, but beyond these is the sandy desert.

In ancient days the Romans had here a large city, of which many traces are found. In the[22] covered streets I saw arches, which by their capitals and columns were of Roman origin, and heard of old Roman graves and foundations being frequently discovered.

Sfax is a garrison, and amongst the soldiers is a fine body of Spahis, but at the time of my visit many were absent at the manœuvres.

During the night we steamed in four hours from the roadstead of Sfax to Gabés.

A golden strand: in the background some white houses, and to the right a palm grove. Such is the view of Gabés from the sea.

The landing-place was only a short distance from the European quarter. I called on the commanding officer, Colonel Gousset of the Spahis, to whom the Regency at Tunis had recommended me, directing that he should assist me by word and deed in my journey to the cave dwellers (troglodytes) of the southern mountains.

It was the hour of muster, and the Colonel introduced me to many of the officers, one of whom, Captain Montague of the General’s staff, lent me his horse, and a Spahi was told off as my guide.

“When one wanders towards the Syrtes and ‘Leptis Magna,’ one finds in the midst of Afric’s sands a town called Tacape; the soil there is much cultivated and marvellously fruitful. The town extends in all directions to about three thousand[23] paces. Here is found a fountain with an abundant supply of water, which is only used at stated times; and here grows a high palm, and beneath that palm an olive, and under that a fig tree. Under the fig tree grows a pomegranate, and beneath that again a vine. Moreover, beneath these last are sown, first oats, then vegetables or grass, all in the same year. Yes, thus they grow them, each sheltered by the other.”

Thus wrote Pliny of the oasis near Gabés over eighteen hundred years ago, and this description can be applied in the main at the present day.

Of this town, created by the Carthaginians, colonised by the Romans, and later the seat of an archbishopric, and which stood nearer the ocean than the existing villages, there remain now only some crumbled ruins on the hills near Sid Bu’l Baba’s Zauia, now difficult even to trace.

Remains of cisterns can be seen, built with the imperishable cement of which the Romans alone understood the preparation. But the stones have long since been removed to Jara, Menzel, and Shenini, villages of the oasis, where are still to be found, in the wretched native buildings, carved capitals and bas-reliefs, side by side with sun-dried bricks and uncut stones.

But it is long since this old town vanished. The Arab geographers in the eleventh and twelfth[24] centuries, as also Leo Africanus in the sixteenth century, mention Gabés as a large town surrounded by walls and deep trenches, which latter could be flooded with water. They tell us of a great fortress there, and that the town had a large population and extensive suburbs. Then the Mohammedan conquerors laid their iron hand over the country, and the inhabitants were dispersed and gathered in the villages Jara and Menzel, each now containing some four thousand inhabitants. Both villages were situated near the river and close to the market-place, and were continually fighting amongst themselves for[25] the possession of these; whilst other villages, of which Shenini is the largest, concealed themselves amidst their palm groves.

TOWER IN THE VILLAGE OF MENZEL.

JEWESSES AT MENZEL.

To keep these rival villages in subjection, the Turks erected, just between them, a fort—Borj Jedia (the new fort). It was blown up by French marines on the 21st July 1881,[26] when they assaulted, stormed, and seized the villages.

Later there arose by the seashore, huts, taverns, and eating-houses, and, after the first occupation, these formed a place of resort for all sorts of adventurers, and was therefore wittily named “Coquinville” by the soldiers. Out of this has grown quite a little town, known as the Port of Gabés. This is occupied by the European colony, consisting of from one to two thousand persons of various Mediterranean origins. The residence of General Allegro, the Bey’s governor of El Arad, the most southern district of Tunisia, was originally the only building on the spot, and here he still resides; but now in the long streets there are commandants’ houses, officers’ quarters, the Hotel de l’Oasis, and a large number of offices of all descriptions. Behind the town to the south, lie the barracks for the garrison of Spahis and infantry. In former days the troops were quartered farther inland, on a height near the Gabés River, as the water was better; but now drinking-water has been brought to the town from a near-lying oasis.

Wad Gabés, or the Gabés River, has its source about a score of miles inland, and flows over its broad bed, through saline and lime-charged soil, down to the oasis, wherefore the water contains much magnesia, and is in consequence most unwholesome,[27] and has caused the death of many a young colonist and soldier. It is said that the age of the eldest soldier buried in the churchyard was but five-and-twenty.

In old times the water must naturally have been as unhealthy as now, but the Romans, those masters of colonisation, used, on that account, rain water collected in cisterns. Remains of such tanks are found everywhere in the south.

The Arab rider, given me as guide, and I rode along the northern bank of the river so as to cross the Gabés oasis from the sea towards the interior.

It was the most enjoyable excursion I can remember ever having made.

The sea roared behind the sand cliffs, while the horses panted through the deep sand. From behind the cliffs appeared the tops of palm trees, and presently we were in the shade.

The light gleamed through the palm leaves on lemon, orange, and pomegranate trees, and on the trailing vines, trained up to the beloved sun, and stretched from tree to tree in graceful festoons.

In the open spaces between the palms lay the orchards, where grew all kinds of fruit trees—peaches, apples, pears, plums, apricots, figs, olives, and many others.

The air was pregnant with the scent from the[28] trees and plants. Beneath the shade of the thick foliage overhead spread the most beautiful green sward, intersected by flowing rivulets of water and small canals, dammed by means of dykes and low banks, as in our own land irrigation.

ON THE OASIS OF GABÉS.

By small paths and roads we wandered on, following the turns of the canals, riding sometimes on a narrow track between two banks, and if we then met Arabs on their little overladen mules it was a squeeze to pass by them.

There was silence amongst the trees. Only now and then, when we drew near to tents, or some straw[29] hut concealed amidst the foliage, could we hear voices and the barking of dogs. Women and children peeped at us through the branches, and we saw men in scanty clothing working with hoes in their gardens, or women weeding the beds and gathering henna in baskets.

Birds flew from branch to branch, or across the open spaces. Wood pigeons called, and turtle-doves cooed, whilst the chaffinch fluttered about on the tops of the almond trees, and in the distance the sound of a shot proclaimed that a sportsman in a clearing on the borders of the oasis had fired at hare, quail, or partridge. On the extreme border, by the sea, was the tomb of a Marabout, built from the ancient remains of the town of olden days, blended with new materials. The columns supporting the entrance were of new rough stone, with handsome carved capitals.

We emerged on the barren plain, and saw in the far distance, on rising ground, other palm groves, but hurried back again into the fascinating wood, till, by paths and over small stone bridges, beneath which streams rippled sheltered by the arching palms, we came to a broader road between high dykes. There it was difficult to advance, as some artillerymen with baggage carts drawn by mules had stuck fast in the mud, the waggons being overladen with stone.

[30]The way now turned towards the river. As we left the palm grove by the miry road to cross the bridge, the grey walls of a village lay before us on the opposite side. The river bank was crowded with women and children washing; clothes were hanging to dry on the bushes, whilst shortly-kilted figures waded into the water, or sat on the stones by the river side beating clothes with flat boards. Most of them pretended not to see us, some turned their backs, and a very few stole roguish glances at us.

WASHERWOMEN AT THE JARA BRIDGE.

The whole scene was worthy of the brush of a good artist. The grey-yellow water, the yellow shore and green wood under the deep blue sky, and[31] against this background the many-coloured figures of women and children. All were in constant movement and chattering loudly.

We rode through the gate. The village consists of narrow streets and lanes of wretched low houses. The air was oppressively hot, and dirt was everywhere. My guide rode in front, pushing people aside with loud exclamations. They submitted quietly to being hustled; “Kith to kin is least kind.” Then, again crossing the river, we rode through the oasis to other villages and as far as the poor huts of Shenini, then turned again down to the stream, which here ran between high banks, and after visiting, just at nightfall, some encampments close by, we hastened on our way back to Gabés.

Crouched in a wretched hut, which seemed to me then the perfection of comfort, I sat writing by the light of a flickering candle at the village of Zaraua, on the top of a mountain of the Matmata range, south of Gabés.

Outside I could hear my horse munching, as he stood, his well-earned barley; farther away dogs were barking. The moon sent her rays through my doorway; and now and then came to my ear the sound of human voices, but this soon ceased as the sun had long since set: for in these regions all retire to rest early so as to rise at daybreak.

The two previous days had sped as in a fairy tale. As I opened my window at the Hotel de l’Oasis at 4.30 a.m. on the 17th October, it was still half-dark, but I could distinguish a little way down the street an Arab horse, saddled, and by its side a white bundle lying on the footway. It was Hamed, the Arab horseman, whom the bureau de renseignement had placed at my disposal, and who was now waiting for five o’clock, the hour fixed for[35] our start. A little later arrived my brown steed, supplied by the Spahi regiment.

MAP OF SOUTHERN TUNISIA.

My small travelling kit, photographic apparatus, and breakfast were packed on Hamed’s horse. The revolver I slung on my own saddle, little realising that the same afternoon I should fire it on a festive occasion; and we started, wending our way amongst the showy, newly-built European houses.

Outside the town, the country is somewhat flat; we followed the road. To our right, towards the north, was Gabés’ winding river, but invisible to us, as it lies low. On the other side, the palm groves showed us a dark forest. The villages by the river stood out clearly against this dark background, and the rising sun shone on the white kubba to our left of Sid Bu’l Baba.

On the road we met little groups of natives driving camels and tiny donkeys, all laden with esparto straw. Their houses were many a mile away over the blue mountains, which were dimly distinguishable on the horizon, for they came from Hadeij, our destination, to sell this, about the only product in which they can deal during the hot summer season.

Now and again we also met small caravans of donkeys carrying light loads of dry wood.

After a quick trot, that warmed us at this early chilly hour, we turned to the left in a southerly[36] direction, taking a path that wound along slightly undulating ground. A brace of partridges rose, and we heard the quail calling, and saw young larks running on the barren ground. On a hill to the north-west we spied the camp of Ras el Wad, erected by General Boulanger in his day. Once and again we indulged in a quick gallop, but only in short stretches, when the paths were not muddy or too winding.

Here and there stood a parched olive tree or date palm, on spots where, in the wet season—if it ever come—a little water would reach them. We were overtaken by a horseman closely enveloped in a white burnous, the hood drawn over his head and sticking up in the air in a peak. It was “Amar” from Hadeij on his slight but wiry pony. He was acquainted with Hamed, so wished to join us. His hair, beard and eyes were black, his expression good-natured, with an open brow, and his teeth milk white.

After two hours’ ride, during which we only once met any people, we reached the oasis of El Hamdu; near by roamed some miserable cattle, grazing under the care of an old man; with these were also a couple of goats.

On the border of the oasis we watered our horses at a fountain surrounded by palms. Women peeped shyly at us over the walls of the only stone building of the village that we could make out.

[37]Riding on, we passed several tombs of Marabouts. On our left, the palms of the oasis seemed drawn up in a long line, and smoke could be perceived rising heavenwards from huts and tents beneath the trees. From an encampment on the edge of the oasis the dogs rushed out barking, the inhabitants standing stiffly, like statues, and staring at us.

PLOUGHING-GABÉS.

Along a shallow, stony, river bed—rough ground for the horses—we pursued our way towards our destination in the hills, whilst the sun burnt so fiercely that our senses were dulled.

After a couple more hours, we again met laden[38] camels, and with them some travellers on foot, one without a burnous or head-covering, and clothed only in a shirt confined at the waist by a strap. He wore his hair in a tuft on the nape of his neck, and carried in his hand a banner on a pole. Amar told me he was a Marabout from one of the villages near Gabés.

Of Marabouts there is no lack. This one was very poor, and was returning from the mountains, where he had been begging for money which he imagined was due to him. The banner he carried that everyone might see that a holy man was coming.

I gave him a few coppers, and the young fellow kissed my hand, and wished me good luck on my journey. It is not everyone who is wished good luck on their travels by a Marabout. I bought my blessing cheap.

We now rode some distance amongst small hills, which are scattered in the foreground of the mountains like islands on a coast-line. On some eminences were heaps of stones.

“Those were there before our time,” said Amar.

In places where the ground was more or less level it was slightly scratched round about the dry bushes. This is the arable land, that is to say, it would be cultivated if rain fell.

We halted beneath some bushes to eat our breakfast.[39] The bread, butter, and cheese we could all enjoy, but I alone the wine and meat. A pomegranate supplied our dessert.

Whilst we sat there, five women in blue dresses came by, preceded by an old man driving half a score of camels. The women wore bracelets and anklets. They glanced furtively at us and trudged past. A negress only, who lagged behind, tried to attract our attention. She was evidently not accustomed to be taken notice of.

Travelling was now easy, the track leading upwards over smooth calcareous ground. In little watercourses, now dry, were planted clumps of palm and olive trees, the soil being banked about them to form dams. On an adjoining slope were numbers of small caves, inhabited only in harvest time, when watch is kept over the crops.

We ascended higher and higher amongst the mountains, until suddenly, as I turned in my saddle, I saw the Mediterranean like a blue streak in the distance. We were at that moment at the highest point we were to reach that day. At a distance here and there dogs appeared, barking at us, and occasionally in their vicinity white figures and rising smoke. Hamed said that these people were cave dwellers, but were only a small tribe. A little later we were to arrive at quite a subterranean town.

[40]I halted abruptly on seeing below me a valley with, comparatively speaking, many trees. On the farther side rose a long range of high mountains. The valley itself was exactly like a large, old sand or clay ditch, with sloping sides, pierced by a great number of neglected and long-disused shafts, but planted with trees—palms, olives, and figs.

“Is that Hadeij?” I asked. Hamed nodded, and I pulled up to take a photograph.

It was then exactly two o’clock, and we continued on our way, walking for a time beside our horses. Just as we were about to remount, a white sheep-dog bounded out of a hole we had not noticed; it bayed at us in a most dismal fashion, and from the nearest points of vantage its companions joined in chorus.

I rode up to look at the dogs, and caught sight of a deep pit with perpendicular sides that had been dug in the ground from the top of the ascent. Down at the bottom a camel stood resting. Round a hearth were household chattels and large bins made of rushes, containing barley, and amongst these a few fowls. Some women and children looked up on hearing the tramp of my horse, stared at me for a moment, and then fled into recesses in the walls.

Hamed now suggested that I should not remain standing there, and I followed his good advice.

[41]A path had been dug into the hillside, and terminated in a large door or gate. This evidently led to a long underground passage, and ended in the square yard, open to the air, which I had just seen, and whence are entered the excavated rooms or caves, used as dwelling-places, stores, and stables.

On the horizon the straight stems of palms stood out sharply against the mountains. In the foreground were olive trees, and, mingled with them, a few palms; beneath one of these was gathered a group of men, amongst whom, Hamed said, was the great Khalifa. I therefore drew rein. An old greybeard rose and strode forward, offering his hand and bidding me welcome, the other men following his example. They were fine specimens of humanity, with regular features, black eyes, and straight noses—one saw at once that they were not of the ordinary Arab type.

From an open space, or square, several passages led into the hills, affording admission to the cave dwellers’ abodes, which are all of similar construction to that already mentioned. I was allotted quarters in one of the caves, and stepped from the outer air into the hill through a wooden gate on heavy hinges, and proceeded through a long passage, cut in the rocks, a little over a man’s height. On either side were excavated large stalls for horses, the covered way ending in an open[42] square court with perpendicular walls some thirty feet high and about the same in width. From this court one steps into symmetrical caves with vaulted roofs.

In the underground guest-chamber I stretched myself comfortably on a couch covered with handsome carpets from Kairwan. A table and some chairs completed the furniture of this room, specially set apart for European guests. The Khalifa is rich, very rich, so that he can permit himself this luxury, though it is but seldom that he has a European visitor. He told me with pride that General Boulanger had in his time been his guest.

After my long ride I required rest; the doors in the yard were therefore closed, so that it was quite dark in my room. The flies did not worry me, and I had quite a refreshing sleep until I was awakened by the neighing of the horses in the passages. A little later the light streamed in through my door; a figure stepped in, and for a moment it was again dark whilst the newcomer passed through the doorway.

It was the Khalifa; behind him came Hamed and several other persons, sons or people of the house.

I expressed my pleasure at being the guest of so hospitable a man, and the Khalifa responded with compliments. Coffee was served, and the party[43] grouped themselves about me on the floor, with the exception of the Khalifa who seated himself by me on the divan, and conversation flowed easily with the help of Hamed.

The contents of my saddle-bags, the photographic apparatus, and especially an entomological syringe, underwent careful investigation.

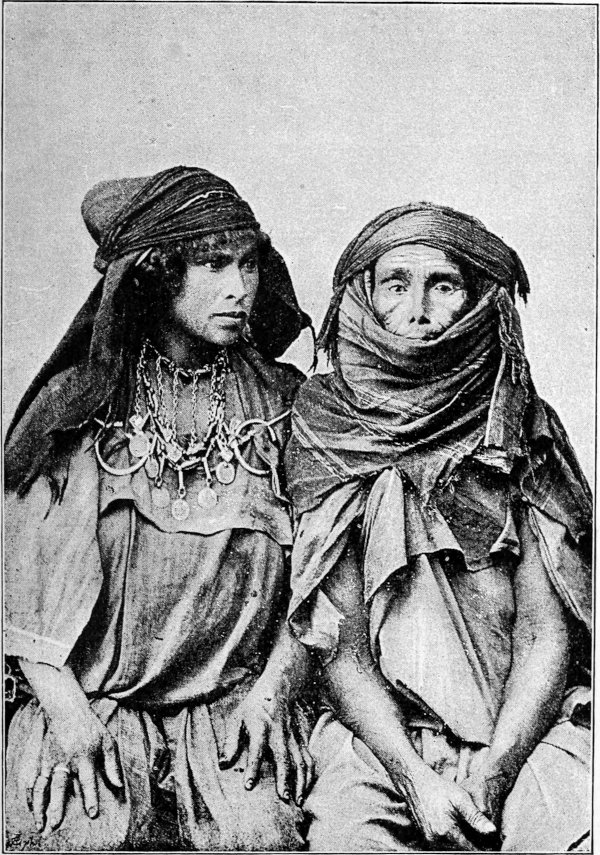

JEWISH FAMILY IN A CAVE DWELLING IN HADEIJ.

But I could not afford to sit and idle the time away, so went out to look about me. Through Hamed I expressed my desire to examine the interior of a dwelling, and was promised that I should see everything; but several times we passed the square openings on the tops of the hills, as also the entrances to houses, without anyone making a sign to us to enter.

At last we arrived at a house into which I was invited. On the whole it much resembled that from which we came, and was inhabited by a Jew and a poor Berber family.

The yard was dirty; cooking utensils lay[44] scattered about, intermingled with a few rush corn-bins and some goats and poultry.

A woman, old, wrinkled, and tattooed, and both hideous and dirty, was brought forward for me to see. It was, of course, the Jew’s wife. His fellow-lodgers, the Berbers, I did not see; but as I stepped into the dwelling, a vision of blue skirts and bare legs vanished into the side caves.

Already I began to feel impatient and to fear that I was being made a fool of and should never see, as I longed to do, where and how the Berbers lived. Fortunately I had later a splendid opportunity of studying the whole subject.

Accompanied by two sons of the Khalifa and some other persons I walked round the valley and up the slopes, whence I could peer down into the caves at the bottom of the valley, and could see women going through the entrances to their dwellings, to the palm and olive trees, followed by dogs and inquisitive children.

My camera I had with me, and used it frequently.

As the sunset hour approached, the heat relaxed, and one breathed with ease.

In a great open square, beautified with palms, at least fifty young men and boys were running from side to side. They had cast aside the burnous, and wore only red caps and shirts, which fluttered as[45] they ran. With long sticks, bent at one end, they struck at a soft ball which flew to and fro, sometimes in the air, sometimes on the ground.

It was beautiful to watch these bold muscular figures, so straight and supple, with their light brown skins, regular features and bright eyes, reminding me that thus must the Greek and Roman boys have played on the plains beneath their blue mountains.

CAVES IN MATMATA.

The game was kept up without a pause, until the sun sank suddenly behind the mountains, and it was no longer possible to see, for twilight is unknown in these regions.

[46]I returned to my cave, lit my candle, smoked cigarettes and waited until my dinner should be served.

Five figures appeared, each carrying a dish which was placed on a table before me, and a pitcher of water was deposited beside me. The meal consisted of soup with lumps of meat highly peppered, a stew of chicken, and an enormous dish of kus-kus, made of barley meal with goat’s flesh, and, finally, honey and bread; this last was of barley meal, dry but well flavoured.

A CAVE DWELLING, MATMATA.

A knife I had with me; but a spoon, that treasure to a European in these regions, was provided.[47] Hamed stood by my side, filled my glass whenever it was empty, and served the dinner. On one side sat Mansur, the Khalifa’s third son, as ordained by their customs and usages. I requested him to join me at dinner. With a graceful motion of his hand to his breast, he bowed his head and begged me to excuse him.

Hamed informed me that honoured guests always dine alone.

On the floor, somewhat aside, sat a row of white figures all staring at me whilst I ate.

A great silence reigned.

This procedure rather disturbed me at first, but one soon gets accustomed to this sort of thing.

Hamed constantly pressed me to eat. I thought it could be of no consequence to him; but discovered later that he was prompted by delicacy of feeling. For when I had concluded my meal, it was his turn, with Mansur and others, to eat the remains. All the scraps of meat, bones, etc. left were then put back into the dishes, and these were carried into the adjoining room where the rest of the men gathered round them; but before doing so, they poured water in a basin and moistened their lips and fingers.

I peeped in on them, and was greeted by the sound of noisy mastication.

Their shoes had been left beyond the edge of[48] the rush mat on which they were seated. Fingers were used in place of spoons or forks.

At last they were satisfied. The remnants were again collected in a dish, and it was then probably the turn of the boys and negroes, and, after them, of the dogs; but the end I did not see.

After enjoying coffee I went out into the court where the stars twinkled overhead. In the distance I heard a strange humming noise, and the sound as of far-off explosions. After a little while the Khalifa arrived to invite me to be present at the first day’s fête held to celebrate his son Mohammed’s wedding to a second wife, and I then understood that the sounds I had heard had been the hum of many voices and of gunshots.

The moon rose in the vault of heaven, and disclosed in front of me, and on either side of the slopes, forms wrapped each in his burnous, squatting side by side. From above, the moonlight shone on the white crowd, giving them the appearance of spectres. The group opposite looked as though moulded half in black, and half in dazzling white.

Up above and to the left were depicted against the light a crowd of black, pointed figures. These were men of the Matmata mountains; they sat silent, watching apparently the dark corner in front of me, where no light penetrated, as the moon rose high on her course.

[49]

THE BRIDAL FESTIVITIES.

(From a sketch by Knud Gamborg.)

[51]The Khalifa ordered chairs to be brought. On these we seated ourselves, Hamed standing behind us, and bending forward to each of us in turn, like a mechanical contrivance through which we carried on our conversation.

Groups of men sat behind and beside us; they continued arriving until the square was full to where the Matmata men sat on the banks.

Right in front, on the level ground, I distinguished a dark compact mass. These were the women, closely enveloped in their sombre garments; they were seated by the entrance to the caves.

A lantern was now lit and placed on the ground near my feet. At first its light confused me, but without it I could not have seen what took place.

One of the Khalifa’s horsemen named Belkassim, a relative and an elderly man, was deputed to maintain order, and at once cleared a little space between us and the women. He then led forward two negroes, who performed a dance to the sound of a drum and a clarionet. They marched towards us side by side, then retired backwards, then again forward and back. This was repeated some half-dozen times, with a swinging movement from the hips. Every time they approached us, they waved the drum and the clarionet over our heads, then turned towards the women before stepping backwards[52] again. The Khalifa raised his hand. The negroes bent their heads backwards that he might place a coin on the forehead of each. I followed his example; with the result that they continued their parade and deafening noise of slow, harsh, wheezy, jerky music.

Suddenly it increased in pace, and both negroes whirled violently round. The time then became slower, the parade recommenced, and my sense of hearing was again endangered each time the loud drum was swung over my head.

The din ceased abruptly, and from the rows of women came a strange clucking sound as of the hurried calling of fowls, “Lu, lu, lu, lu, lu, lu, lu.” This was a sign of approval. At the same moment a gun was fired. The flash lit up the rows of women. The shots were repeated again and again. It was the bridegroom’s nearest friends firing a salute in his honour. The women responded with the “Yu, yu” cry, the negro musicians joined, and more shots followed.

Then it struck me that I also would join in the festive demonstration, so I told Hamed to bring me my revolver, and I fired the six chambers into the air, one after the other.

The women at once broke into the cry of joy. Drums and clarionets joined in.

“I am much gratified,” I said to the Khalifa,[53] “that you have introduced me to the circle of your people. Here is my hand in token of my gratitude. May Allah protect you and yours.”

“Thanks for your good wishes,” he replied. “You come from a strange and distant land. You are my friend and my brother, one for whom I am responsible so long as you remain in the Matmata mountains. You are free to travel anywhere you please; no one will injure you.”

I said, “When I came I knew you would treat me as you would a brother; I was told so by the Khalifa of Gabés; but I was not aware that you had authority over all the tribes of the Matmata. But now I know it. I arrived with this weapon by my side, as you may have seen it hung by my saddle when you received me. Now I realise that it is superfluous, and that I shall have no need of it so long as I am amongst your people. As a sign, therefore, of my sincerity, and as a token of my respect for and gratitude to yourself, my brother, I present you with my weapon. But before I place it in your hands, permit me to salute with it, after the manner of your countrymen, as an expression of the pleasure I derive at being in your company during the celebration of these festivities.”

Retiring outside the circle of spectators, I again fired the six chambers of my revolver.

[54]Then arose from the women a high-pitched and long-drawn “Yu, yu, yu,” followed by some musket shots.

Bowing to the Khalifa I presented him with the revolver. He gave me his hand, bringing it afterwards to his lips. This was the seal of our friendship.

“Would you like the women to sing for you, or would you prefer men-singers?” asked the Khalifa.

“As you will, brother; I do not wish to interrupt your fête; let it go on as arranged before my arrival.”

However, the old man insisted on my deciding which I preferred, so I could not deny that I was inclined to hear the women sing.

They sat before me; I could not distinguish their features. Amongst them, I was told, sat the first wife of the bridegroom Mohammed—sharing in the universal rejoicings.

According to report, she is comparatively young and still pretty, and who knows but that her heart aches at the thought that soon she must share her husband with a younger rival—or perhaps it may seem to her quite natural, and she congratulates herself on the prospect of having someone to help in her work, which is not of the lightest.

The Khalifa laid his hand on my shoulder to[55] warn me that the performance was about to begin.

In somewhat drawling measure, a sweet female voice improvised a solo, the chorus being taken up by the surrounding women, interrupted now and again by the shrill “Yu, yu.”

Hamed told me it was of myself they sang.

“This morning he came with weapons and followers—perhaps straight from Paris. The pistol hung on his saddle; his horse was red. The proudest charger you could see. He sat straight as a palm on his horse, right over the steep hillside. Yu, yu, yu.

“Now he sits with us as a brother. Yes, like the Bey himself, by the side of Sid Fatushe, our old Khalifa. He has given him his pistol, a costly gift, of greater value than even the best camel. Yu, yu, yu.

“If he will be our friend and remain with us, we will find him a wife. Fatima awaits him—of the beautiful eyes, her nails stained with henna; on her hands are golden bracelets, and anklets on her feet.

“Yu, yu, yu.”

There was a great deal more sung about me which I am too modest to repeat.

The women sang for about an hour, improvising my praises, giving honour to the Khalifa in flattering[56] phrases, and not omitting my friend and guide, Hamed and his horse.

At last the song ceased, and I thanked the Khalifa and begged him to believe in my sincere appreciation.

Next stepped forward a mulatto. Amongst the Arabs these play the part of the jesters of the Middle Ages. Accompanied by the drum and the shrill notes of the clarionet, he delivered a lampoon in verse, directed against the women, since they had not sung in praise of him whom they knew, but, forsooth, had extolled the stranger whom they saw for the first time.

He abused them in language far from decorous, and reaped applause in half-stifled laughter from the men, who spent the whole evening on the self-same spot where they had originally settled; only now and then did one of them rise to wrap his burnous better about him; his figure standing out sharply against the vault of heaven above the edge of the bank.

There were many children and half-grown lads present. At the commencement they were rather noisy, but were scolded by Belkassim, or the Khalifa, and were kicked aside. Later, several fell asleep enveloped in their burnouses and leaning against the elder men.

When the negro singer had finished his song[57] it was again the women’s turn, and they paid him off for having ventured to imagine that they might have sung in praise of him, a wretched creature, who did not even possess a decent burnous.

The drum and clarionet again did their duty; after which the negro took up his defence. They were not to suppose that he was poverty-stricken; and he was the boldest rider amongst the Matmata (the Khalifa told me the man had never mounted a horse). When he appeared in flowing burnous, the hood thrown back as he sang the war song, he rivalled the Khalifa himself when marching to battle.

He and the women continued squabbling in this fashion for some time. No doubt the women carried the day, for the negro was finally shoved back upon the spectators, and hustled by them from one group to another, until at last he vanished in the darkness.

Two men then performed a stick dance to the tripping time of drum and clarionet, and towards the end the women joined in a song with a chorus. They prayed Allah for rain and a good harvest. Then sang of Mena, the married woman who took to herself a lover and paid for her indiscretion with her life; of the hunter who bewitched a lion with his flute, thus saving the life of a little girl; of love; of charming cavaliers; of the Khalifa; and, finally, of myself; but, strangely enough, not of the[58] bridegroom, so far as I could gather, and very slightly of the bride.

The wedding feast was to last eight days. On the last the bride would be brought home. During these eight days Mohammed, the bridegroom, was not to show himself in either his own or his father’s house. He must remain concealed amongst his friends, and not attend openly at the rejoicings, though he was probably present incognito.

At last the Khalifa rose and bade me good-night. The men dispersed and went their ways homewards, the women following.

I expressed a wish to leave next morning, and, in accordance with my plans, to take a two days’ journey into the mountains to visit a number of Berber villages, returning afterwards to be again the Khalifa’s guest before finding my way back to Gabés.

The same evening the Khalifa sent an express courier to the sheikhs of the villages with instructions that I should be well received.

This arranged, I retired to rest. As I passed up the dark underground passage, I patted my horse and wished my friends good-night.

The door closed behind me, and soon I was sleeping as quietly and peacefully in the caves of the Matmata mountains as I should in my own bed at home.

Hamed woke me at sunrise. I was soon dressed, my saddle-bags packed and coffee heated.

HOLD UP!

The horses had been led out from their underground stable. Outside the dwelling I met the Khalifa, coming evidently fresh from his devotions as he still grasped his rosary. Smiling, he held out his hand to take leave bidding me “Farewell till to-morrow evening.”

As we rode over the hill, a rider galloped up and took the lead; it was Belkassim, the Khalifa’s relative, who was to show me the way. I followed him, and Hamed became the arrière garde.

[60]There are no springs or wells in these regions; water, therefore, is collected in deep tanks. By one of these was a woman filling her pitcher.

The rays of the rising sun gleamed on Belkassim’s white burnous and the silver-inlaid gun which lay across his saddle-bow, on the tips of the palm trees, on the mountain peaks, and on the woman at the cistern. Snatching a rapid glance I saw she was pretty, but she at once turned her back; so I could only admire her slender feet and silver anklets as she placed the pitcher on the side of the tank and drew her blue-striped kerchief over her head.

“That is Mansur’s wife; his only wife,” said Belkassim.

Happy son of the Khalifa of Matmata!

When we had crossed to the other side of the vale I turned in my saddle; she still stood there, and in the distance below I saw her face indistinctly, like a pale spot amidst its dark blue wrappings. She remained long standing thus and looking after us; then disappeared, carrying the dull grey pitcher on her back, and up the slope other blue figures came tripping along to the same spot.

The valley is very uneven, rising and falling, as it is furrowed and cut up by watercourses. The palm and olive trees scattered along these crevasses are protected by stone enclosures and ditches.

Just as we passed the last dip in the valley[61] before climbing the hill, there rushed out three dogs which had evidently been watching us.

I looked about me, for it dawned on my mind that there must be a habitation in the vicinity. I was right; for, by standing in my stirrups and stretching my neck, I got a glimpse of the square upper rim of a cave yard.

The dogs rushed on Hamed’s horse which was last, and had possibly approached too close to the entrance of the dwelling. The attack was so violent that we were obliged to turn and assist him. The furious brutes held fast on to the tail of his horse, fearing to come within reach of Hamed’s whip; but one of them succeeded in biting the horse’s near hind-leg, drawing blood and laming it—a pleasant beginning to our mountain trip!

We dismounted and threw stones at these furious white sheep-dogs, and at last they retired, showing their teeth and ready to resume the attack the moment we remounted. Fortunately a man and a boy appeared and called the dogs off. Believing the man to be their owner, I ordered Hamed to rate him soundly and threaten that I would report what had occurred to the Khalifa. The man took the rebuke quietly, but told us humbly that he was a poor devil who possessed nothing—not even a dog. The proprietor of the dwelling was absent.

“Then greet him from us and say that he[62] should have his dogs under better control, or he will have the Khalifa after him.”

The wrongly accused man kissed a fold of my burnous, and we again mounted our horses and climbed the mountain in a zigzag course, by difficult paths over loose stones.

Belkassim rode only a few paces in front of me, yet I saw his horse above the level of my head, whilst Hamed, who was a couple of paces behind dragging along his lame horse, appeared to be far beneath me.

From the summit I looked back along the valley and to a high undulating stretch, where the trees showed like spots on a panther’s skin.

EXCAVATED STABLE.

Over the valley to the north rose the mountains, and beyond them stretched an indistinct light blue plain, melting far away into a darker blue—this was the sea.

Step by step, slowly but surely, our horses paced[63] down the long valley into which we descended. Now and again we put up a covey of partridges that flew up the mountain, and the larks started in couples from amongst the palms and stones. We presently hurried on at the quick pace to which the Berber horses are accustomed; Hamed singing, as we went along, a song that echoed above us and on every side.

Perched on some stones at the bottom of the dry bed of a torrent were three pretty little girls, who leaned against the bank and peeped shyly at us over it. Their goats jumped from stone to stone seeking food amongst the scanty forage afforded by the dry burnt pasture.

The tallest of the little girls ran suddenly away from the others when I rode towards them. She scrambled up the rocky bank like a squirrel, and paused on the top of a large boulder; the flock of black goats following her. She was evidently old enough to know that speech with a strange man is forbidden.

Belkassim tried to coax her down again; he assured her that the kind stranger would give her money if she would come to him. But no, she would not respond, remaining where she was and calling to the two other little ones. These pressed nervously against each other, in their thin blue garments, and, when I offered them some coppers,[64] shut their eyes as they extended their hands to me to receive the money, and then took flight.

We were near some native dwellings. Dogs barked, under an olive tree stood a donkey munching straw, and we perceived some of the familiar blue figures, which looked nearly black against their light brown surroundings. In the distance their ornaments glittered in the light of the setting sun. Belkassim shouted to them to come forward as it was a friend and brother of the Khalifa who wished to see them. Most of them remained standing where they were and stared at us. The men were apparently all away, either amongst the mountains, busy with the date harvest, or building tanks in the valleys, so from them there was naught to fear.

We dismounted and had a chat with the women. I unpacked my camera and tried to take their portraits, but these girls and women are so restless that it is difficult to make them keep still. There was one exception, however, a pretty fresh young girl who came out of one of the dwellings—a cave like those near Hadeij—and stared and stared at the camera.

An old woman next came tripping up to offer herself, evidently of a mind that coppers are worth having. I should have preferred her good-looking daughters, who were engaged in driving a restive camel into the cave passage. But this I saw plainly[65] was not to be, for she ordered the girls in and placed herself before me, and I had to be satisfied.

This was the village of Judlig. The population cannot be large, but by me it will always be remembered as the village of many women.

Continuing along the base of the valley for about an hour, we then entered another valley through the great deep bed of a broad river now dry; the banks were quite perpendicular. This river is the Sid Barrak. The horses had difficulty in keeping their footing on the stony bottom.

BERBER WOMAN OF THE VILLAGE OF JUDLIG.

On a slight rise our guide bade us halt, so we drew rein while he pointed out Sid ben Aissa, but I could see nothing.

When we had ridden some way down the valley, we saw some half-score white burnouses coming towards us. These proved to be the Sheikh and his people, who came to bid me welcome; his brown-clad followers walked beside their horses. In time, the old greybeards and dark-eyed merry lads joined our party.

[66]Dogs barked, sombre clad females with peaked white headgear peered over the crest of the mound, and terrified little children fled to their mothers and hid themselves in the folds of their garments.

Palm trunks raised their lofty crowns towards the blue heavens, where, on the mountains and in the valley, they grew mingled with olive and fig trees, and the hot air of midday quivered about us as we made our entry.

A CAVE INTERIOR.

(From a sketch by Knud Gamborg).

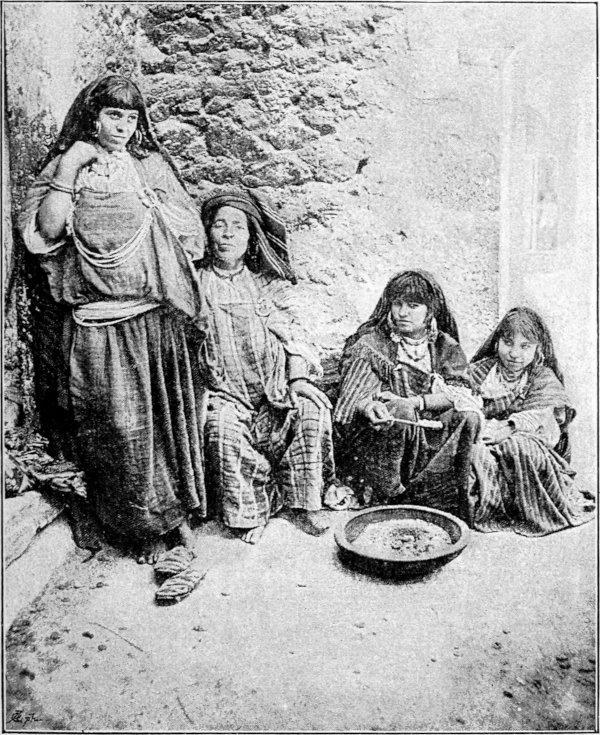

The village contains some fifty underground dwellings like those of Hadeij, and about five[67] hundred inhabitants. The approach to the Sheikh’s dwelling was not covered in. From the highest point of the hill a slope led through a gate to the great square court. In addition to this entrance from the slope, one could enter from the hillside through a deep excavated passage that ran parallel with the slope, but naturally at a lower level.

Close to the point where the descent began was erected a thatched roof of dry twigs and palm branches, supported on four palm tree trunks. On this roof lay red and yellow bunches of freshly gathered dates, and beneath its shade sat a few men. My horse was tied up close by.

Hamed had told the Sheikh that I wished to see the interior of a dwelling, so they at once led me into the courtyard and thence into the long underground chamber.

In the courtyard a camel stood chewing the cud. It was pushed aside, fowls fluttered out of our way, and a kid and several sheep sprang on to some heaps of garnered dates, or hid behind the great egg-shaped reservoirs, woven of rushes, used for storing corn.

In the caves I found it dark, chiefly because my eyes had been dazzled by the daylight outside. Within were women, some grinding corn, others weaving. None were very young, but all were overladen with ornaments. They were quite friendly; one offered me dates, another water, only one of[68] them, probably a young wife or daughter, hid in a corner and turned her back on me. The children flocked about me without fear, one of the boys even pulling roguishly at my burnous.

During my visit, Hamed and the other men had remained outside. Hamed was very proud of having obtained permission for me to see the cave. Usually, he said, no strangers are admitted into a house where there are women. But I fancy my good reception was due as much to the Khalifa’s influence as to Hamed’s.

On our way to the cave we had passed the vaulted guest-room, tastefully excavated out of the soft calcareous soil. Here I stretched myself on costly carpets whilst I ate my meal; my escort afterwards consuming the remainder.

As I wished to learn all particulars concerning the costume of both men and women, they brought me clothes and ornaments in quantities. To the great amusement of those present, Belkassim was dressed up in woman’s attire, the property of the Sheikh’s first wife. Afterwards, I photographed him in the same dress, together with the Sheikh and his boys in a group outside the caves.

After a stay of a couple of hours we rode on, being set on our way by the Sheikh and his people.

We now followed the bed of the river Barrak, amongst rocks and ridges and over rolling stones[69] and rough pebbles. We saw a party of women leave the valley for a deserted village, of which the ruins showed waste and grim on the mountain-top. They were taking food up to the shepherds in charge of the sheep and goats there, and would take advantage of the cooler air of the heights to have a midday nap in the shade of the ruins. In olden days the Beni Aissa dwelt on these heights, but it was very trying, especially for the women who had every day to descend to the plain to fetch water; so, when more peaceful times came, they moved down to the caves at the base of the valley.

This valley wound round the foot of the mountain, so for a couple of hours we had the picturesque ruins to our right. At last we lost sight of them, and then began a stiff ascent through wild and desolate gorges, and, finally, we clambered up a very steep mountain side where the stones rolled from under our horses’ feet. Hamed thought it too bad, so dismounted, letting his horse follow him; while we, by endless zig-zags, wound our way to the summit. Here we waited a few moments to recover breath and give time to the loiterer, whilst enjoying the lovely view over the Matmata mountain peaks and vales.

Once more we descended into a valley, then[70] toiled up another mountain side, afterwards riding along the ridge at the summit to reach “Tujud,” one of the eyries on the top of the Matmata heights.

On the horizon we could distinguish the low land to the south of Gabés, and, beyond it, the sea. Farther east lay the mountain chain of Jebel Teboga, a long blue line, and between it and us stretched a level plain, partly concealed by the adjacent hilly ground, of which the ridges surmounted each other in undulating lines. Below us, to the north, was a deep valley.

Scanning the stony surface of the bridle-path, I discovered accidentally some outlines scratched on the stones. They were mostly of footprints, and later I was informed that these are said to be carved by pious friends, in memory of the dead, on the spot where they had last met the deceased.

Tujud lay before us. In the distance it resembles somewhat an old German castle of the Middle Ages, with the usual mass of houses attached thereto. The summit of the pile of dwellings was crowned by a couple of camels, showing like black silhouettes against the sky. On the flat grey plain, dark specks were moving: these were women.

The Sheikh came to meet and conduct me[71] into the town, through steep narrow alleys. The houses were all built of uncut stone, and not whitewashed. The style of building was most irregular. As the rock was very precipitous, the little dwellings were extraordinarily varied in height and appearance. Their courtyards were crowded with bleating sheep and goats, a few camels, various household chattels, braziers, and all manner of dirt. In the doorways, and on the flat roofs, women and children stood watching us.

Of men there were not many at home; at this season they are probably mostly guarding their flocks on the far plains to the south-west.

On a height close by, were a couple of Marabout tombs with whitewashed walls; and in the distance to the north we could see, over the mountain ridge, a village on a height. This was Zaraua; and towards the west we sighted another, Tamezred. They both looked like fortified castles.

After a short halt we continued our way towards Zaraua, the Sheikh giving us a guide, quite a young fellow. He tried to slip off when we had ridden about half-way; as it was near sunset he most likely wished to return to his home before dark. Belkassim gave him a sound thrashing and forced him to go on, as we could not distinguish the bridle-road from the footpath. When we reached the foot of the hill and could see the village at[72] the summit, I dismissed the lad, who quickly vanished behind us.

No one came to meet us until, when quite near the town, a young man at last appeared, who welcomed me, announcing that he was a near relative of the Sheikh who, he said, was absent.

Both Hamed and Belkassim told me they detected an intention to slight me, therefore they abused the unlucky fellow because I had not been received at the proper distance from the town, and with the honours due to me.

Twelve years ago these natives tried to assert their independence of French rule, and many of the brave fellows fell fighting here among the mountains. From that time, therefore, they do not entertain a friendly recollection of the French; and they supposed me to be a Frenchman. However, they did not openly venture to run counter to the safe conduct the Khalifa had given me, so they went through the forms of hospitality; but my guides were in the right—my hosts were, to say the least, unwilling.

I walked up a path which led towards the cemetery. On the precipitous slope lay mound on mound, composed of small stones. Here rested, perhaps, the defenders of their fatherland, laid low by the bullets of the French.

From the tanks beneath the slopes the women[73] drew water. They carried the huge pitchers on their backs, bound to their foreheads by a towel. Each turned away her face, or concealed it in her towel, as they approached us. The men stood, like rigid statues, without looking at us; not one extended the hand of welcome.