CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

FOOTNOTES

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

By Dr. GORDON STABLES, R.N.

Crown 8vo. Cloth elegant. Illustrated.

In the Great White Land

A Tale of the Antarctic. 3s. 6d.

“Full of life and go, and just the kind that is beloved of boys.”—Court Circular.

In Quest of the Giant Sloth. 3s. 6d.

“The heroes are brave, their doings are bold, and the story is anything but dull.”—Athenæum.

Kidnapped by Cannibals

A Story of the Southern Seas. 3s. 6d.

“Full of exciting adventure, and told with spirit.”—Globe.

The Naval Cadet

A Story of Adventure on Land and Sea. 3s. 6d.

“An interesting traveller’s tale with plenty of fun and incident in it.”—Spectator.

To Greenland and the Pole. 3s.

“His Arctic explorers have the verisimilitude of life.”—Truth.

Westward with Columbus. 3s.

“We must place Westward with Columbus among those books that all boys ought to read.”—Spectator.

’Twixt School and College. 3s.

“One of the best of a prolific writer’s books for boys, being full of practical instructions as to keeping pets, and inculcates, in a way which a little recalls Miss Edgeworth’s ‘Frank’, the virtue of self-reliance.”—Athenæum.

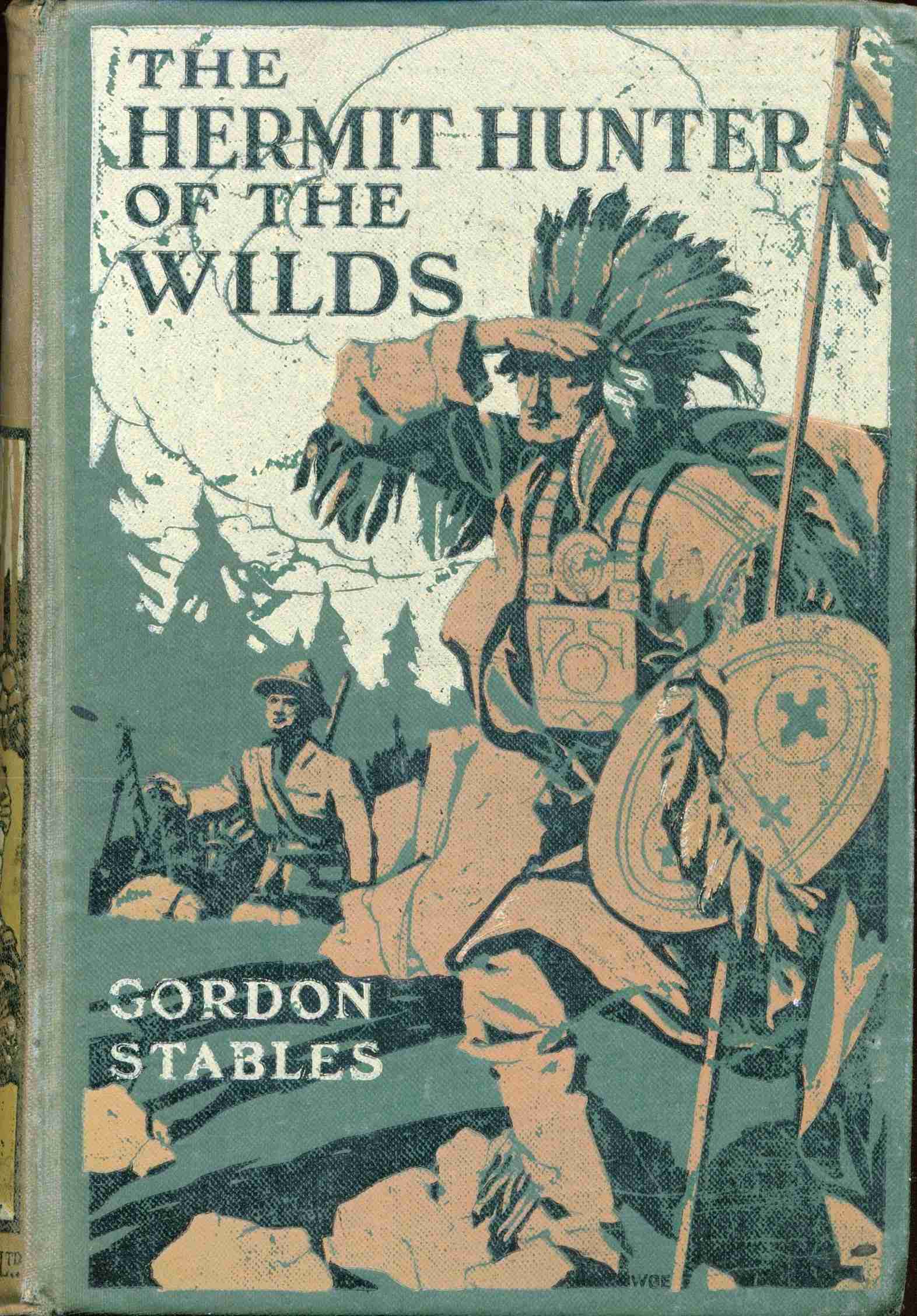

The Hermit Hunter of the Wilds. 2s. 6d.

“Pirates and pumas, mutiny and merriment, a castaway and a cat, furnish the materials for a tale that will gladden the heart of many a bright boy.”—Methodist Recorder.

In Far Bolivia

A Story of a Strange Wild Land. 2s.

“An exciting and altogether admirable story.”—Sheffield Telegraph.

————

London: BLACKIE & SON, Limited.

BY

GORDON STABLES, C.M. M.D. R.N.

Author of “’Twixt School and College” “To Greenland and the Pole”

“The Naval Cadet” “Westward with Columbus” &c.

WITH FOUR PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

| “Tom crouched lower and lower” [Image unavailable.] | Frontis. 100 |

| Tom introduces His Cat | 84 |

| “Behold your chief!” she cried | 145 |

| Giant Tortoise Riding | 216 |

THE HERMIT HUNTER OF THE WILDS.

OMMY TALISKER was probably one of the most unassuming boys that ever

lived. At all events everybody said so. And this is equivalent to

stating that the boy’s general behaviour gave him a character for

modesty.

OMMY TALISKER was probably one of the most unassuming boys that ever

lived. At all events everybody said so. And this is equivalent to

stating that the boy’s general behaviour gave him a character for

modesty.

He was the youngest of a family of five; the eldest being his only sister, and she, like her mother, made a good deal of Tommy, and thought a good deal about him too in certain ways.

“I don’t think,” said Tommy’s father to Tommy’s mother one evening as they all sat round the parlour hearth; “I don’t think we’ll ever be able to make much of Tommy.”

Perhaps Tommy’s father was at present merely speaking for speaking’s sake; for there had been general silence for a short time previously, broken only by the sound of mother’s knitting-wires, the{10} crackle of uncle’s newspaper as he turned it, and the howthering of the wind round the old farmhouse.

Tommy’s mother looked at Tommy, and heaved a little bit of a sigh, for she was very much given to taking everything for granted that her husband said.

But Tommy’s sister, who always sat in the left-hand corner of the fireside, with Tommy squatting on a footstool right in front of her, drew the lad’s head closer to her knee, and smoothed his white brow and his yellow hair.

Tommy took no notice of anything or anybody, but continued to gaze into the fire. That fire was well worth looking at, though I am not at all sure that Tommy saw it. It was a fire that made one drowsily contented and happy to sit by,—a comfort-giving, companionable sort of a fire. Built on the low hearth, with huge logs of wood sawn from the trunk of a poplar-tree that had succumbed to a summer squall, logs sawn from the roots of a sturdy old pine-tree that had weathered many and many a gale, and logs sawn from the withered limbs of a singularly gnarled and ancient pippin-tree that had grown and flourished in the orchard ever since this farmer’s father was a boy. There were huge lumps of coals there also, and a wall round the whole of dark-brown peats, hard enough to have cut and chiselled the hull of a toy yacht from.{11}

It is not to be wondered at that Tommy took no notice of the somewhat commonplace talk that went on around him; he was listening to a conversation that was being carried on in the fire between the blazing wood and the coals and the peat.

“You have no idea, my friends,” said the poplar log, after emitting a hissing jet of steam by way of drawing attention and commanding silence—“you have no idea what a stately and beautiful tree I was when in my prime. I and my fellows, who were all alive and well when I heard from them last, were the tallest and most gracefully-waving trees in the country-side. Poets and artists, and clever people generally, used to say we gave quite a character to the landscape. We knew we were very beautiful, because the broad winding river went through the meadow where we stood, and all day long we could see our faces therein. O, we were very beautiful! I do assure you. The seasons thought so, and every one of them did something for us. Spring came first, as soon as she had fastened the downy buds on the waving willows; placed wee crimson-topped anemones on the hazel boughs—five to each nodding catkin; scattered the burgeons over the hawthorn hedges; tasselled the larches with vermilion and green; adorned the rocks with lichen and moss; brought early daisies to the meadow-lands, the gold of the celandine to the{12} banks of the streamlets, and the silver of a thousand white starry buttercups to float on the ponds; breathed through the woods and awakened the birds to light, love, and song; led the bee to the crocus, the butterfly to the primrose; awakened even the drowsy dormouse and the shivering hedgehog from their long winter’s slumber, to peep hungrily from their holes and wearily wonder where food could be found. Then Spring came to us. Spring came and kissed us, and we responded with green-yellow leaves to her balmy caress. Ah, the sun’s rays looked not half so golden anywhere else, as seen through our glancing quivering foliage. We raised our heads so high in air, that the larks seemed to sing to us alone, and the very clouds told us their secrets.

“But Summer came next and changed our leaves to a darker, sturdier green. And she brought us birds. The rooks themselves used to rest and sway on our topmost branches, lower down the black-bibbed sparrows built; in our hollows the starlings laid their eggs of pearl, while even the blackbird had her nest among the ivy that draped our shapely stems.

“We were things of beauty even when winds of Autumn blew; and Winter himself must clothe our leafless limbs with its silvery hoar-frost, till every branch and twiglet looked like radiant coral against the deep blue of the cloudless sky.{13}”

“Hush! hush!” cried the pine-tree root. “Dost thou well, O poplar-tree log, to boast thus of thy beauty and stateliness? I lived on the mountain brow not far off. I marked your rise and fall. Out upon your beauty! Where was your strength? To me thou wert but as a sapling, or a willow withe bending in the summer air. But my strength was as the strength of nations. On the hill yonder I flourished for hundreds of years; my foot was on the rocks, my dark head swept the clouds, my brown stem was a landmark for sailors far at sea. In the plains below I saw the seasons come and go. Houses were built, and in time became ruins; children were born, grew up, grew old and died, but I changed not. The wild birds of the air, of the rock, and the eyrie were my friends—the eagle, the osprey, the hawk, and curlew. The deer and the roe bounded swiftly past me, the timid coney and the hare found shelter near me. I have battled with a thousand gales; thunders rolled and lightnings flashed around me, and left me unscathed. I stood there as heroes stand when the battle rages fiercest, and my weird black fingers seemed to direct the hurricane wind. I was the spirit of the storm.

“And I too had beauty, an arboreal beauty that few trees can lay claim to; whether in autumn with the crimson heather all around me, in summer with the last red rays of sunset lingering in my foliage, or in winter itself—my branches sil{14}houetted against the green of a frosty sky. But I fell at last. We all must fall, and age had weakened my roots. But I fell as giants fall, amidst the roar of the elements and chaos of strife. The skies wept over my bier, rain clouds were my pall, and the wild winds shrieked my dirge.”

There was silence in the fire for some little time after the pine log had finished speaking, and Tommy thought the conversation had ceased; but presently a voice, soft and musical as summer winds in the linden-tree, came from the gnarled pippin log:

“O men of pride and war!” said the voice, “I envy neither of you. Mine was a life of peace and true beauty; and had I my days to live over again, I would not have them otherwise. My home was in the orchard, and the seasons were good to me too, and all things loved me. In spring-time no bride was ever arrayed as I was; the very rustics that passed along the roads used to stop their horses to gaze at me in open-mouthed admiration. Then all the bees loved me, and all the birds sang to me, and the westling winds made dreamy music in my foliage. Lovers sat on the seat beneath my spreading branches, when the gloaming star was in the east, and told their tales of love heedless that I heard them. In summer merry children played near me and swung from my boughs, and in autumn and even winter{15} many a family showered blessings on the good old pippin-tree. ‘Peace, my friends, hath its victories not less renowned than war.’”

“O dear me!” sighed a smouldering peat, “how humble I should feel in such company. I really have nothing to say and nothing to tell, for my life, if life it could be called, was spent on a lonesome moor; true, the heath bloomed beautiful there in autumn, but the wintry winds that swept across the shelterless plain had a dreary song to sing. The will o’ the wisp was a friend of mine, and an aged white-haired witch, that at the dead hours of moonlight nights used to come groaning past me, culling strange herbs, and using incantations that I shudder to hear. There were many strange creatures besides the witch that came to the moor where I dwelt; and even fairies danced there at times. But for the most part the strange creatures I saw took the form of creeping or flying things; fairies changed themselves into beautiful moths and wild bees, but brownies and spunkies to crawling toads and tritons. But heigho! I fear a poor peat has few opportunities of doing good in the world.”

“Say not so!” exclaimed a blazing lump of coal; “even a humble peat is not to be despised. How often have you not brought joy and gladness to the poor man’s fireside, caused the porridge-pot to boil and the bairns to laugh with glee, banished the cold of winter, and infused comfort{16} and warmth into the limbs of the aged. But you are modest, and modesty is ever the companion of genuine merit.”

“And you, sir,” said the peat to the coal, “you are very, very great and very, very old—are you not?”

“I am very, very old, and I am no doubt very, very powerful. Yet my powers are gifts of the great Creator, and it is mine to distribute them to toiling and deserving man. Ages and ages ago before this ancient pine log was thought of or dreamt of, before mankind even dwelt on these islands, when its woods were the home of the wildest of beasts, when gigantic woolly elephants with curling tusks roamed free in its forests, and its marshes and lakes swarmed with loathsome saurians, I dwelt on earth’s surface. But changes came with time, and for thousands of years I was dead and buried in the earth’s black depths. The ingenuity of man has resuscitated me, and now I have gladly become his servant and slave. I warm the castle, the palace, and the humble cot. I give light as well as heat; I am swifter than the eagle in my flight. I am more powerful than the wind; I drag man’s chariots across the land, I waft his ships to every clime and every sea. I move the mightiest machinery; I am gentle in peace and dreadful in war.

“Nay more, the great wizard Science has but to lift his wand, and lo! I yield up products more{17} wonderful than any yet on earth. Gorgeous were the colours that adorned the flowers of the land in ages long gone by, delicate and delightful were their perfumes; but these perfumes and these colours I have carefully stored, and give them now to man.”

What more Tommy would have overheard, as he sat there at his sister’s knee, it is impossible to say, for the boy had fallen asleep.

“NO,” repeated Tommy’s father as he proceeded to refill his pipe; “we mustn’t expect to make much of Tommy.”

“Tommy may be president of America yet,” said Uncle Robert, looking quietly up from his paper. “Stranger things have happened, brother; much stranger.”

“Pigs might fly,” said Tommy’s father, somewhat unfeelingly. “Stranger things have happened, brother; much stranger.”

Tommy’s brothers laughed aloud.

Tommy’s mother smiled faintly.

But the boy slept on, all unconscious that he was being made the butt of a joke.{18}

Tommy was not an over-strong lad to look at. About eleven or twelve years old, perhaps. He had fair silky hair, regular features, and great wondering blue eyes that appeared to look very far away sometimes. For Tommy was a dreamy, thinking boy. To tell the truth, he lived as much in a world of his own as if he were in the moon, and the man of the moon away on a long holiday. He seemed to possess very little in common with his brothers. Their tastes, at all events, were infinitely different from his; in fact they were lads of the usual style or “run” which you find reared on such farms as those of Laird Talisker’s—called laird because he owned all the land he tilled. Dugald, Dick, and John were quite en rapport with all their surroundings. They loved horses and dogs and riding and shooting, and they had to take to farming whether they liked it or not. Dugald was the eldest; he was verging on seventeen, and had long left school. Indeed he was his father’s right hand, both in the office and in the fields. His father and he were seldom seen apart, at church or market, mill or smithy; and as time rolled on and age should compel Mr. Talisker to take things easy, Dugald would naturally step into his father’s shoes.

Dick was sixteen, and Jack or John about fourteen; and neither had as yet left the parish school, which was situated about a mile and a half beyond the hill. All boys in Scotland receive{19} tolerably advanced education if their parents can possibly manage to keep them at their studies, and these two lads were already deeply read in the classics and higher branches of mathematics.

What were they going to be? Well, Dick said he should be a clergyman and nothing else, and Jack had made up his mind to be a cow-boy. He had read somewhere all about cow-boys in the south-western states of America, and the life, he thought, would suit him entirely. How glorious it must feel to go galloping over a ranche, armed with a powerful whip; to bestride a noble horse, with a broad hat on one’s head and revolvers at one’s hip! Then, of course, every other week, if not oftener, there would be wild adventures with Comanche red-skins, or Indians of some other equally warlike tribe; while now and then this jolly life would be enlivened by hunting horse-stealers across the boundless prairie, and perhaps even lynching them if they happened to catch the thieves, and there was a tree handy.

Jack’s classical education might not be of much service to him in the wild West, either in fighting bears or scalping Indians; though it would be easily carried. He determined, however, not to neglect the practical part of the business; and so whenever opportunity favoured him he used to mount the biggest horse in the stable and go swinging across the fields and the moors, leaping{20} fences and ditches, and in every way behaving precisely as he imagined a cow-boy would.

Several times Jack had narrowly escaped having his neck broken in teaching Glancer—that was the big horse’s name—to buck-jump. Glancer was by no means a bad-tempered beast; but when it came to slipping a rough pebble under the saddle, then he buck-jumped to some purpose, and Jack had the worst of it.

Mrs. Talisker herself was a somewhat delicate, gentle English lady, whom the laird had wooed and won among the woodlands of “bonnie Berkshire.” Her daughter Alicia, who was but a year older than Dugald, took very much after the mother, and was in consequence, perhaps, the worthy laird’s darling and favourite.

One thing must be said in favour of this honest farmer-laird: his whole life and soul were bound up in his family, and his constant care was to do well by them and bring them up to the best advantage. But he did not think it right to thwart his boys’ intentions with regard to the choice of a profession. There was admittedly a deal of difference between a clergyman of the good old Scottish Church and a cow-boy. However, as Jack had elected to be a cow-boy, a cow-boy he should be—if he did not break his neck before his father managed to ship him off to the wild West.

But as to Tommy, why the laird hardly cared{21} to trouble. Tommy was Uncle Robert’s boy. Uncle Robert, an old bachelor, who had spent his younger days at sea, had constituted himself Tommy’s tutor, and had taught the boy all he knew as yet. Uncle Robert ruled the lad by love alone, or love and common sense combined. He did not attempt to put a new disposition into him, but he did try to make the very best of that which he possessed. In this he showed his great wisdom. In fact, in training Tommy he followed the same tactics precisely as those that successful bird and beast-trainers make such good use of. And what I am going to say is well worth remembering by all boys who wish to teach tricks to pets, and make them appear to be supernaturally wise. Do not try to inculcate anything, in the shape of either motion or sound, which the creature does not evince an inclination or aptitude to learn. Take a white rat for example, and after it is thoroughly tame and used to running about anywhere, loving you, and having therefore no fear, begin your lessons by placing the cage on the table with the door open. It will run out and presently show its one wondrous peculiarity of appropriation. In very wantonness it will pick up article after article and run into its house with it—coins, thimbles, apples, cards, &c. Now, I hinge its education in a great measure on this, and in a few months I can teach it to tell fortunes with cards, and spell words even. A rat{22} has two other strange motions; one is standing like a bear, another is climbing poles. By educating it from each of these stand-points you can make the creature either a soldier or a sailor, or even both, and teach it tricks and actions the glory of which will be reflected on you, the teacher.

Tommy was exceedingly fond of Uncle Robert, to begin with, and never tired listening of an evening to his wonderful stories of travel and adventure.

Uncle lived in a little cottage not very far from the farm; and if he was not at the laird’s fireside of a winter evening he would generally be found at his own, and Tommy would not be far away. They used to sit without any light except that reflected from the fire. Stories told thus, Tommy thought, were ever so much nicer, especially if they were tales of mystery and adventure. For there were the long shadows flickering and dancing on the wall, the darkness of the room behind them, and the fitful gleams in the fire itself, in which the lad sometimes thought he could actually see the scenery and figures his uncle was describing; and all combined to produce effects that were really and truly dramatic.

Well, if by day Dugald was his father’s constant companion, Tommy was his uncle’s; and the one hardly ever went anywhere without the other.{23}

School hours were from nine till one o’clock; and uncle was a strict teacher, though by no means a hard task-master. Then the two of them had all the rest of the long day to read books, to wander about and study the great book of nature itself, to fish, or do whatsoever they pleased. It must be said here that Uncle Robert was almost quite as much a boy at heart as his little nephew. He was a good old-fashioned sailor, this uncle of Tommy, and a man who never could grow old; because he loved nature so, and nature never grows old: it is the same yesterday, to-day, and for ever.

Uncle Robert was quite as good-natured as the big horse Glancer. But Glancer drew the line at pebbles under his saddle. The best-tempered horse in the world will draw the line at something or other. And uncle was the same. If anyone wanted to annoy him they had only to mention Tommy in a disparaging sort of way; then, like Glancer, Uncle Robert buck-jumped at once.

So, on that particular evening—a wild and stormy one it was in the latter end of April—when Tommy’s father talked about the improbability of pigs flying, and Tommy’s brothers had all laughed, Uncle Robert had felt a little nettled.

“Ah, you may laugh, lads,” he said, putting his paper down on his knee and thrusting his spectacles up over his bald brow—“you may laugh,{24} lads, and you may talk, brother, but I tell you that there is more in that boy than any of you are aware of; and mark my words, he is not going to remain a child all his life. Boys will be men, and Tommy will be Tom some day.”

Mrs. Talisker looked fondly over at her brother, and she really felt grateful to him for taking her boy’s part.

Whoo—oo—oo! howled the wind round the chimney, and doors and windows rattled as if rough hands were trying their fastenings. Every now and then the snow and the fine hail were driven against the panes, with a sound like that produced by the spray of an angry sea against frozen canvas.

At this very time, away down in the midlands of England, spring winds were softly blowing and the buds appearing on the trees; but on the west coast of Scotland, where the farm of Craigielea was situated, winter still held all the land, the moors, the lakes, and woods, firm in his icy grasp.

To-night the moon had sunk early in a purple-blue haze—a new moon it was, and looked through the mist like a Turkish scimitar wet with blood. The stars had been bright for a short time afterwards. But the wind rose roaring from the east, driving great dark clouds before it, that soon swallowed everything else up. Then it was night in earnest.{25}

Whoo—oo—oo! What a mournful sound it was, to be sure! You might have imagined that wild wolves were howling round the house, and stranger voices still rising high over the din of the raging storm.

Whoo—oo—oo!

“What a fearful night!” said Mrs. Talisker.

“Ay, sister,” said Uncle Robert; “it is blowing half a gale outside to-night, I’ll warrant, and may be more.”

By “outside” he did not mean out of doors simply. It is a sailor’s expression, and refers to the sea away beyond the harbour-mouth.

“It was on just such a night as this, sister, though not on such a cold sea as that which is sweeping over our beach to-night, that the Southern Hope was lost on the shores of Ecuador. Heigho-ho! My dear friend Captain Herbert has never been the same man since.

“And do you know, my dear, it happened exactly six years ago this very night.”

“How very strange!” said Tommy’s mother.

“Strange, my dear? Not a bit of it. What is strange, and how should it be strange—eh?”

“Oh, I meant, brother, that you should think of it. I believe that was what I meant.”

“You’re not very sure. But let me tell you this, that there never does pass a single 25th of February that I do not think of that fearful shipwreck. Ay, girl, and pray too. I’ve been pray{26}ing as I sat here—praying with my eyes on the newspaper, when you all thought I was reading it. You look at me, sister; and Tommy has woke up, and he is looking at me too. Well, you little know how often old sailors like me pray, and what strange things we do pray for, and how our prayers are often heard. You see, sister, those who go down to the sea in ships, and see the wonders of the Lord in the mighty deep, get a kind of used to thinking more than shore-folks do. In many a dark black middle watch, we are alone with the ocean, one might say, and that is like being in the presence of the great Maker of all. Verily, sister, I think the waves on such nights seem to talk to us, and tell us things that the ear of landsman never listened to. No one could long lead the life of a sailor and not be a believer. Do you mind, sister, that New Testament story of our Saviour being at sea one night with some of his disciples, when a great storm arose, and the craft was about to founder? How he was asleep in the stern-sheets, how in an agony of terror they awoke him, how his words ‘Peace, be still’ fell like oil on the troubled waters, and how they all marvelled, saying, ‘What manner of man is this, that even the wind and sea obey him?’

“Well, sister, I never knew nor felt the full meaning of those words until I became a sailor. But sometimes on dreamy midnights, when darkness and danger were all around us, I have in my{27} thoughts accused the ocean of remorselessness, the winds of cruelty; and, as I did so, seemed to hear that answer come to me up from the black vastness, ‘We obey Him.’ The winds sang it as they went shrieking through the rigging, the waves sang it as they went toiling past: ‘We obey Him,’ ‘We obey Him.’ Then have I turned my thoughts heavenward and been comforted, knowing in whose good hands we all were.

“A sailor’s prayer, sister, on a night like this, while he sits comfortably by the fireside, is for those in danger far at sea or on some surf-tormented lee shore. But on this particular evening, on this 25th of February, I always add a prayer for my good old shipmate, Captain Herbert—and may heaven give him peace.”

“Captain Herbert is still at sea, brother?”

“Ay, sister, and will be, if spared, for many a year. He seems unable to rest on shore, although he is rich enough to retire. You see, he never had but the one boy, Bernard; and, foolish as it may appear, he cherishes the notion that he still lives, and that some day he will meet him again.

“And never a strange sailor does he meet in any part of the world, or any port of the world, but he questions concerning all his life and adventures. More than once has my friend been thus led astray, and has sailed to distant shores where he had heard some English lad was held prisoner by Indians or savages. But all in vain.{28}

“It was a sad story, you say, sister? Indeed, lass, it was. Shall I repeat it?

“Well, stir the fire, Tommy, and make it blaze and crackle. How the storm roars, to be sure.”

Whoo—oo—oo! Whoo—oo—oo! howled the wind again; but the fire only burned the brighter, and the fireside looked the cheerier for the sound.

UNCLE ROBERT sat for some little time with his eyes fixed on those burning logs before he commenced to speak, the firelight flickering on his face. But bygone scenes were being recalled, and events long past were being re-enacted in his memory as he sat thus.

He spoke at length; quietly at first, dreamily almost, as if unconscious of the presence of anyone near him, apparently addressing himself to no one, unless it were to the faces in the fire:—

Six years!—six years ago, and only six, and yet it seems like a lifetime, because I, who have been a rover and a wanderer since my boyhood, have come to settle down on this peaceful farm.{29} Yet I have been happy, quietly happy, in my sister’s family, and with the companionship of her dear children; but the afternoon of a sailor’s existence must ever be a somewhat restless one. Like the sea over which he has sailed so long, it is seldom he can be perfectly still. In spite of himself he feels a longing at times to revisit scenes of former days, and the lovely lands and sunny climes that time has hallowed and softened till they resemble more the phantasies of some beautiful dream than anything real and earthly.

A vision like this rises up before me even now, as I sit here. The wintry winds are howling round the house, but I hear them not, nor noise of hail or softer snow driving against the window panes. I am far away from Scotland, I am in a land whose rocky shores are laved by the blue rolling waves of the Pacific, I am in Ecuador. Ecuador! land of the equator; land of equal day and night; land that the swift-setting sun leaves to be plunged into darkness Cimmerian, or bathed in moonlight more tranquil and lovely than poets elsewhere can ever dream of; land of mighty mountains, whose snow-capped summits are lost in the blue vault of heaven or buried in clouds of rolling mist; land of ever-blazing volcanic fires, wreathing smoke, and muttering thunders; land of vast plains and prairies; land of swamps that seem boundless; land of forests whose depths are dark by daylight—forests that bathe the valleys,{30} the cañons, the glens with a foliage that is green, violet, and purple by turns, darkling as they climb the hills half-way to their rugged crests; land of waterfalls and foaming torrents, over which in the sunlight rainbows play against the moss-grown rocks or beetling cliffs beyond; land of mighty rivers, now sweeping through dreamy woods, now roaring green over the lava rocks, now broadening out into peaceful lakes or inland seas, with shores of silvery sand; land of tribal savages, wild and warlike or peaceful and uncouth; land of the Amazons; land of the fern, the moss, and the wild-flower; land of giant butterflies, with wings of bronzy silken velvet, or wings of colours more radiant than the humming-bird itself, or wings of transparent gauze that quiver and shimmer in the sunlight like plates of mica; land of strange birds; land of the vampire or blood-sucking bat, the tarantula, the centiped, and many a creeping horror besides; land, too, of the condor, the puma, the jaguar, the peccary, the tapir, the sloth, and agouti; land of romance, and a history going back, back, back into the remotest regions of the past;—truly a strange and wondrous land! I seem to see it all, everything, among those blazing logs to-night.

I lived in Ecuador for many, many months. I roughed it with the Indians, the Zaparos, the Napos, and Jivaros; I wandered over forest-land and plain and by the banks of the streams; I{31} hunted in the jungle and on the prairies, and after escaping many a danger I returned to the sea-coast, laden with skins and curios and a wealth of specimens that would have made the eyes of a naturalist sparkle with very joy.

During all my long wanderings my servants had been faithful; and although our lives had oftentimes been in danger from wild beasts and wilder men, here we were once more at Guayaquil safe and sound.

I was lucky enough to find a small Spanish vessel to take me and my treasures to Callao; and here, at this somewhat loud-smelling seaport, my good star was once more in the ascendant; and though I had arrived three weeks before my promised time, the Southern Hope was lying waiting for me.

My welcome on board was a very joyful and gratifying one. Captain Herbert himself met me in the gangway, and behind him was little Bernard. The boy was not content with shaking hands. He must jump joyfully into my arms and up and on to my shoulder; and thus he rode me aft to where good little Mrs. Herbert sat in her deck-chair nursing baby, with Lala, her sable ayah, standing near.

“Now, don’t rise,” I cried. “I won’t permit it. How well you look, Mrs. Herbert! The roses have quite returned to your once wan cheeks.{32}”

“A nice compliment, Mr. Robert Sinclair,” she replied, smiling. “And you too are looking well.”

“Have I got roses on my cheeks?” I said.

“Yes,” she said; “peony roses.”

“And how is baby?”

“O, look at her; isn’t she charming?”

I gave baby a finger, which she at once proceeded to eat with as much relish as if she had been a young cannibal. And so our reunion was complete. At dinner that day we were all exceedingly happy and full of mirth and fun. We had so much to tell each other, too; for during my sojourn in Ecuador the Southern Hope had been on a long cruise among the Pacific islands, where everything had seemed so strange and delightfully foreign to both Captain and Mrs. Herbert, that, they told me, it was like being in another world.

The steward—I have good reason for mentioning this—was most assiduous in his attentions at table that day. He was a short, broad-shouldered, strong-jawed, half-caste Spaniard, exceedingly clever, as Mrs. Herbert assured me, but possessed of those dark shifty eyes that seem unable to trust anyone, or to inspire trust in others.

When dessert was put on the table—a dessert of such fruits as princes in England could not procure—Mrs. Herbert motioned to him that he might now retire. He only smiled and shrugged{33} his shoulders in reply, and presently he was entirely forgotten.

So our conversation rattled on. I told my adventures much to the delight of every one, but especially to that of our young mate and little Bernard, although the child was barely seven years of age.

“And those mysterious boxes, Mr. Sinclair,” said Mrs. Herbert, “when will you open those?”

“O, not before we get to San Francisco; when, you know, I must leave you all, and make my way home overland.”

From this reply, it will be understood that I was but a passenger on the Southern Hope. I was travelling, indeed, for pleasure and health combined, but had been altogether nearly a year and a half in this hitherto happy ship; which had been baby’s birthplace, for little Oceana was born on the ocean wave. Hence her name, which we always pronounced ’Theena.

“No, my dear Mrs. Herbert,” I continued, “those boxes contain greater treasures than ever were brought from the diamond mines of Golconda; treasures more beautiful, and rarer far than all the gold in rich Peru.”

“Well, Robert,” said the captain laughing heartily, “they are heavy enough for anything; and by St. George and merry England, my friend, you do well to keep such treasures in your own cabin.{34}”

I was at that moment engaged fashioning some marvellous toy for Bernard from a piece of orange peel, but happening to look up I found the evil, sinister eyes of Roderigo the steward fixed on me with a look I did not half like.

I took occasion that same evening to ask Mrs. Herbert some particulars of this man’s history; for he had not been in the ship when I left it. She had little to tell me. James, the old steward, had run away or mysteriously disappeared somehow or other at Callao, and the very next day this Roderigo had applied for the situation. Captain Herbert had waited for his steward for a whole week; but as there were no signs of his coming, and no trace of him on shore, it was concluded he had gone to Lima. So, as he seemed eminently fitted for the duties of the post, the half-caste Spaniard was installed in his place. He proved to be all they could desire, Mr. Herbert continued, although he certainly was not handsome; but he was very fond of Bernard, and doated on baby ’Theena. I asked no more, but I felt far from content or easy in my mind.

We left Callao at last, and proceeded on our voyage to San Francisco. The Southern Hope was a good sea vessel; so our voyage was favourable, though the winds were light until we reached the equator, which we crossed in baffling winds, about 85° west longitude. We soon got enveloped in dense wet fogs, and for{35} days it was all but a dead calm. A breeze sprang up at last, however, and we kept on our course, and by and by the sky cleared and we saw the sun.

None too soon; for not ten miles to the east of us loomed the rocky cliffs of Northern Ecuador. They could be none other, yet why were we here?

Captain Herbert could not understand it for a time. He was as good a sailor as ever stood down the English Channel or crossed the far-famed Bay of Biscay. He was not left long in doubt, however.

There was villainy on board. Treachery had been at work, and the compass had been tampered with.

It was about two bells in the afternoon watch when he made the discovery. I heard him walking rapidly up and down the deck first, as some sailors do when deep in thought. Then he came below.

“Are your pistols all ready?” he said to me.

“Yes,” I answered; “but I sincerely hope there will be no need of them.”

Then he told me what he had discovered, and that he felt sure mutiny was intended.

He broke the news as gently as possible to his wife, and gave orders that she should keep to the cabin with the ayah and the children.

Then he and I went on deck together.{36}

As I passed the steward’s pantry I tried the door. It was locked, and I could see through the jalousies that no one was inside.

My doubts of the half-caste had become certainties.

“Call all hands, and let the men lay aft, mate!”

This was Herbert’s stern command.

“Ay, ay, sir,” came the cheerful reply.

The Southern Hope was but a moderate-sized ship, and our men, all told, were but nineteen hands.

The mate’s sonorous voice and the sound of his signalling boot on the deck could easily be heard all over the ship.

Captain Herbert and I waited uneasily and impatiently by the binnacle. His face was very pale, but firm and set, and I knew he would fight to the death, if fighting there was going to be.

Alas! we were not left long in doubt as to the exact position of affairs. Out of all the crew—which were mostly a mixed class of foreigners—only five lay aft.

“Where are the others?” shouted the captain.

Groaning and yelling came from below forward as a reply.

“The men have mutinied,” said the mate.

The words had scarcely left his lips ere, headed by Roderigo himself, the mutineers rushed on deck.

“You wanted us to lay aft,” cried Roderigo.{37} “Here we are. What do you want, Mr. Herbert, for I am captain now?”

Before the captain could reply, either by word of mouth or ring of pistol-shot, the mate had felled the steward with a capstan-bar. It was a blow that might have killed a puma; but, though bleeding like an ox, the half-caste drew his knife as he lay on deck, and next moment had sprung on the first officer as a jaguar springs on a deer.

The fight now became general; but in a very few minutes the mutineers were triumphant. Our mate was slain; while, whether dead or alive, the other poor fellows who had so nobly stuck by us were heaved into the sea.

A worse fate was probably intended for Captain Herbert and myself; but meanwhile, our hands were tied, and we were led to the after-cabin and there locked up. No one came near us all that afternoon, nor was there any sound that could give us even an inkling as to the fate of poor Mrs. Herbert, the children, and the ayah. Had they been murdered or even molested, we surely should have heard shrieks or appeals for mercy.

I did my best to keep up my companion’s heart, but there were moments when I thought he would lose his very reason in the depth of his despair.

About an hour afterwards it was quite dark,{38} and we could tell from the singing and roystering forward that the mutineers had broken into the spirit-room and were having a debauch. It had come on to blow too, and the motion of the vessel was uneasy and jerking. Evidently she was being badly steered, and an effort was also being made to shorten sail.

The storm increased till it blew all but a gale. Some sails had been rent in ribbons, and the noise of the flapping was like that of rifle platoon firing.

I was standing close by the cabin door, my ear anxiously drinking in every sound, when suddenly I was thrown violently on the deck, and by the dreadful grating and bumping noises under us we could tell that the vessel had struck heavily on a rock. Almost at the same moment there was the noise of falling spars and crashing wreck. Then a lull, succeeded by the sound of rushing footsteps overhead and cries of “Lower away the boats!”

The fearfulness of our situation after this can hardly be realized. Nothing was now to be heard except the roar of the winds and the thumping of the great seas against the vessel’s sides. Hopeless as we were, we longed for her to break up. Had she parted in two we felt that we could have rejoiced. Death by drowning would not seem so terrible, I thought, could we but see the stars above us or even feel the wind in our faces;{39} but to die shut up thus in the darkness like rats in a hole was too dreadful to think of—it was maddening!

In the midst of our despair, and just as we were beginning to think the end could not be far off, we heard a voice outside in the fore-cabin.

“Husband! husband!” it cried in pitiful tones; “where are you?”

“Here! here!” we both shouted in a breath.

Next minute a light shone glimmering through the keyhole, and we knew Mrs. Herbert had lit the lamp.

Then an axe was vigorously applied to our prison door, and in a short time we were free.

Mrs. Herbert had fainted in her husband’s arms.

She slowly recovered consciousness, and then could tell us all she knew.

The mutineers had rifled the ship; they had broken open my cabin and boxes, expecting to find treasure, and as soon as the vessel struck had lowered the boats and left the ship.

But where was Bernard?

And where was the ayah?

Alas! neither could be found. And from that day to this their fate is a mystery.

The storm was little more, after all, than a series of tropical squalls. The vessel did not break up just then, and when daylight broke the sea all around us was as calm and blue as baby ’Theena’s eyes.{40}

In the course of the day we managed to rig a raft and thereby reach the shore.

It was a wild and desolate beach on which we landed, and glad we were to find even the huts of Indians in which to shelter.

There we lived for three long weeks, making many trips in the canoes of the Indians to the ship, and bringing on shore as many of the necessaries of life as we could find.

But alas! the loss of Bernard and the terror of that terrible night had done their work on poor Mrs. Herbert. She gradually sunk and died.

We buried her near the beach on that strange wild shore, and raised a monument over the grave, roughly built in the form of a cross, from green lava rocks.

Our adventures after that may be briefly told.

The ship did not break up for many weeks, and where the carrion is there cometh the “hoody crow.” The first coasting vessel that found out the wreck plundered it, and sailed away leaving us to perish for aught they cared. But with the captain of the next we managed to come to terms, and the promise of a handsome reward secured us a passage to Callao, and there we found a Christian ship and in due time arrived in England.

“And what about Bernard?” said Tommy with eager eyes.

“The mystery about Bernard still remains, dear{41} boy. He may be living somewhere yet in the interior of Ecuador, or he may have been taken away by some passing ship, or—and this is my own opinion—he is dead.”

“And the baby ’Theena is living, isn’t she?” said Alicia.

“She was, dear, when last I heard of her, and the father too is well. Heigh-ho! I wonder if he knows I am thinking about him to-night, and telling his strange story and my own?”

Whoo—oo—oo! roared the storm. The wind-wolves still shrieked around the house. But suddenly Laird Talisker lifts a finger as if to command silence.

All listen intensely.

“That is something over and above the ‘howthering’ of the gale,” he says. “Hark!”

Rising unmistakably above the din of the storm-wind could now be heard the barking of dogs, as if in anger.

“Someone is coming undoubtedly,” says Uncle Robert.

Then the door opens and old Mawsie the housekeeper enters, looking so scared that the borders of the very cap or white linen mutch she wore seem to stand straight out as if starched.

“What can be the matter, Mawsie?” asks the laird.

“O, sir!” gasps old Mawsie, “on this awfu’ nicht—through the snaw and the howtherin{42}’ wind-storm—a carriage and pair drives up to the door, and a gentleman wi’ a bonnie wee lady alichts—”

What more Mawsie would have said may never be known, for at that moment straight into the room walk the arrivals themselves, and in his eagerness to get towards them Uncle Robert knocks over his chair, and the long stool on which the boys are sitting goes down with it, boys and all.

“By all that is curious!” cries Uncle Robert, giving a hand to each. “However did you come here? Talk of angels and lo! they appear.”

He shakes Captain Herbert by the hand as if he had determined to dislocate his elbow, and he fairly hugs little ’Theena in his arms.

“And this is baby,” he cries to Tommy’s mother, “and here is good old Captain Herbert himself. Why, this is the most joyful 25th of February I ever do remember.”

WITH the arrival of Captain Herbert and little ’Theena a fresh gleam of sunshine appeared to have fallen athwart our young hero’s pathway in life.{43}

As he sat in his corner that evening thoughtfully gazing on her sweet face, while her father and his uncle kept talking together as old friends and old sailors will, Tommy thought he had never seen anything on earth so lovely before, and albeit he was about half afraid of her he made up his mind to fall in love with her as early as possible. He really was not quite certain yet, however, that he might not be dreaming. Had he fallen asleep again, he wondered, after Uncle Robert had finished his story? and was ’Theena but a vision? She looked so ethereal and so like a fairy child that he could not help giving his own arm a sly pinch to find out whether he really was awake or not. He did feel that pinch, so it must be all right.

Next he wondered if his two big brothers would appropriate ’Theena almost exclusively to themselves while she stayed here. He determined to circumvent them, however. He had a hut and a home in the wild woods not far from the romantic ruin of Craigie Castle, and he felt sure that ’Theena would be delighted with this hermitage of his. She did not look very strong, but she would soon be rosier. He would wander through the woods and wilds and cull posies of wild-flowers, and by the sea-shore and gather shells for her—shells as prettily pink as those delicate ears of hers. What a pity, he thought, that it was still winter! But never mind, spring{44} would come, and he knew where nearly all the song-birds dwelt and built. And O! by the way, ’Theena’s eyes were as blue as the eggs of the accentor or hedge-sparrow. Even deeper, they were more like the blue of the pretty wee germander speedwell that before two months were past would be peeping up through the grass by the hedge-foot. Then further on there would be the wild blue hyacinth and the blue-bells of Scotlands (the hare-bell of English waysides), and the bugloss and milk-wort and succory—all of them more or less like ’Theena’s eyes—and a score of others besides, he could find and fashion into garlands.

’Theena smiled so sweetly when she bade him good-night, and was upon the whole so self-possessed and lady-like, that the boy felt infinitely beneath her in every way. But that did not matter; he would improve day by day, he felt certain enough on this point. So he went off to bed, and dreamed that he and ’Theena were up in a balloon together, sailing through the blue sky, and that down beneath them was spread out just such a romantic land as that of Ecuador, which his uncle had described. It was more like a scene of enchantment than anything else. But lo! even as he gazed in rapture from the car of the balloon, it entered a region of rolling clouds and snow mists; it became darker and darker, the gloom was only lit up by the hurtling fires of terrible{45} volcanoes, while all around the thunders pealed and lightnings flashed. Then the balloon seemed to collapse, and after a period of falling, falling, falling that felt interminable, suddenly the sun shone once more around them—’Theena was still by his side—and they found themselves in a kind of earthly arboreal and floral paradise. Near them stood a tall and handsome young man, dressed, however, like a savage, and armed with bow and arrow.

He advanced, smiling, to the spot where they stood, and extending a hand to each:

“Dear sister and brother,” he said, “do you not know me? Behold I am the long-lost Bernard!”

Then Tommy awoke and found it was daylight, and that the robin was singing on his windowsill expectant of crumbs.

. . . . . . .

Spring came all at one glad bound to the fields and woods of Craigielea this year.

Three weeks had passed away since the night Tommy had dreamt that strange dream. Captain Herbert had gone south. He would sail round the world before he returned to Craigielea to take his “little lass,” as he called ’Theena, away with him again. Meanwhile he knew she would be well cared for, and grow bigger and stronger.

Tommy’s brothers had made no attempt, or very little of an attempt, to win ’Theena over. True, Jack had mounted her once or twice on{46} Glancer; but Glancer, knowing the responsibility of such a charge, could not be induced to break even into a decent trot. So Jack got tired of ’Theena, and told her she might never expect to make a cow-boy.

And Dick could not get the girl to race, or play cricket or hockey, though he tried hard; and she was not even good at climbing trees nor riding on fences, and was positively afraid of Towsie, the white, shorthorn bull, because he had red eyes and tore up the ground with a fore-foot, while he bellowed like distant thunder.

“It’s no good, Jack,” said Dick; “we couldn’t make anything of ’Theena if we tried ever so long.”

“I don’t think so, Dick,” was Jack’s reply. “Besides, what is the use of girls anyhow?”

“Not much. I really want to know what they are put into the world for at all.”

“Well,” said Jack, “we’ll give her up, won’t we? Little Cinderella can have her for a plaything, can’t he?”

“Yes, Jack, she’ll just suit little Cinderella.” This was the name his brothers always called Tommy by, because he always sat by his sister’s knee close to the fire, and looked at it for hours.

“Dick,” said Jack, “there’s nothing like boys, is there?”

“Nothing much.{47}”

“And there’s nobody like you and me. Hurrah! come and give me a leg up to mount Glancer, and just see me clear that farther fence. Besides, I’ve got a new way of making Glancer buck-jump. Hurrah, Dick! Cow-boys for ever!”

As the two went tearing along towards the paddock where Glancer was browsing, they met Tommy and ’Theena on their way to the woods. Tommy had a fishing-basket on his back, ’Theena carried the rod. Tommy had a bow and arrows besides, and ’Theena carried a real Arab spear.

“Hullo, Cinderella!” shouted Dick.

“Hurrah, Cinder!” cried Jack. “Why, where ever are you off to with all that gear?”

“We’re going to the hermitage,” said Tommy proudly. “I’m the Hermit Hunter of the Wilds.”

“Ha, ha, ha!” from both the bigger boys.

“And,” continued Tommy, “we’re going to play at wild man in the woods; and we’re going to gather flowers, and find birds’-nests, and fish in the Craigieburn, and perhaps go for a sail on the sea.”

“Ha, ha, ha! Well, don’t you dare to fall in anywhere and drown your little self,” said Jack; “else you will catch it. Good-bye, Cinder. Take care of baby. Good-bye, Eenie-’Theenie.”

And away went Dick and Jack whooping.

“I don’t love your brothers much,” said ’Theena, almost crying. “What makes them call you Cinder?{48}”

“I don’t know, I’m sure, ’Theena; but I don’t mind it if you don’t.”

“I shall call you Tom.”

“Thank you; but really I don’t mind, you know, and if you would prefer—”

“No, no, no. I don’t like Cinderella. You’re not a girl.”

“O, no. I’m a boy, and Uncle Robert says I shall soon be a man. Wouldn’t you like to be a boy, ’Theena?”

“Yes, dearly.”

“It would be so nice if you were. We could have even better fun than we have now, and you would be able to get up trees, and shoot, and do everything I do.”

Talking thus they reached the great pine-wood, and entered among the trees. In this silent forest-land there was not a morsel of undergrowth, only the withered needles that had fallen from the pines and larches and formed a thick soft carpet. And the great tree-stems went towering skywards, brown for the pines, gray for the larches, till they ended far above in a canopy of darkest green that would hardly admit a ray of sunshine without breaking it all up into little patches of gold and silver.

’Theena felt somewhat afraid now, and crept closer to Tom, who took her hand, and thus they wandered on and on. And very small the two of them looked among those giant timber trees.{49}

“You’re not very much afraid, are you?” said Tom. “You needn’t be, you know, for I’m the Hermit Hunter of the Wilds, and could protect you against anything; and Connie here would protect us both.”

Connie was the long-haired collie dog, who followed his master everywhere like his shadow.

“You could shoot straight with your bow and arrow, couldn’t you, Tom, if any wild beast came upon us?”

“O, very straight.”

They were following a tiny beaten path that led them through the pine-wood. But it also led them up and up, and sometimes it was so steep that they had to scramble on their hands and knees.

By and by the pines gave place to silver-stemmed birch-trees, with shimmering, shivering leaves that reflected the sunshine in all directions. The perfume from these trees was delightful in the extreme.

They reached a clearing at last, where the heather grew green all round, and where there were lichen-clad stones to sit upon. Here one or two large and lovely lizards were basking, and a splendid green speckled snake went gliding away at their approach. Tom, being a Highland lad, was not afraid of either snakes or lizards. Neither was ’Theena; for though she was only seven years old she had been in strange countries with her{50} papa, and had seen far bigger snakes and lizards too than any we have in Scotland.

Having rested for a short time, they resumed their upward journey, and soon came to a little table-land about an acre in extent, and near it, in the shelter of a tall gray rock, with drooping birch-trees, and broom, and whins, lo! the hermitage and woodland home of the Hermit Hunter.

What a business the making of this hut had been, nobody ever knew except Tommy himself, Uncle Robert, and the collie dog Connie.

But now that it was made, it looked a very complete dwelling indeed, just such as a Crusoe would have delighted to live in.

’Theena was overjoyed.

“O!” she cried, “I would love to stay here always; a table and cupboard, and real seats, and real plates and things, and a window, and books and all! I can’t read much, can you?”

“Yes,” said Tom. “Uncle taught me. He teaches me always up here in summer, and he shall teach you too.”

After ’Theena had admired everything sufficiently long, they commenced to climb again, and soon rose out of the greenery of the woods entirely, high up the hill into the very sky itself; and, wonderful to say, here was a noble castle, though now but little more than a ruin.

“My ancestors,” said Tommy proudly, “once dwelt here, and they were great soldiers and{51} warriors. Dick and Jack don’t care anything about ancestors; but I do, Theena. And do you know what I am going to do?”

“No,” said ’Theena.

“After I grow a big man, I mean.”

“Yes, after you grow a big man.”

“Well, I’m going to make lots of money first, you know. For I shall be a sailor, and sail away to strange countries where the gold lies in heaps in the woods and wilds, watched over by terrible dragons.”

“Yes, Tom, I suppose there would be dragons.”

“Well, I shall kill the dragons, and bring away, O, ever so much gold! Then I will sail home in my ship, and I shall furnish this castle all splendid and new again, with beautiful furniture and pictures, and all sorts of nice things. O, but stop, there is something I am going to do before then.”

“Yes, Tom, something to do before then.”

“I’m going to find your brother Bernard.”

“O, that would be nice!”

“Yes, very. And I’ll bring him home, and we’ll all live happy here in this splendid castle; your father and my father, and mother, and uncle, and Bernard, and Alicia, and Connie and all.”

“Will your brothers be here too?”

“N—no, I think it better not, perhaps. Of course Dugald would be at the farm, and we could see him sometimes, but Dick and Jack better go away and preach and be a cow-boy.{52}”

“And then,” said ’Theena, “they would never call you Cinder any more. But how very nice it will all be. And O, Tom, look at the waves!”

From the window of the room in which they stood the view was grand and imposing. Hills and rocks and woods on one side, the lovely glen on the other, and down yonder, stretching away and away to the illimitable horizon, the blue Atlantic dotted here and there with white sails, with one or two steamers in the far offing, ploughing their way northwards, and leaving their trailing wreaths of smoke and long white wakes.

And up from the woods beneath them came a chorus of bird songs. The mellow fluting of the blackbird, the sweat clear notes of the mavis, and bold bright lilt of chaffinch. Nearer still the linnet perched on the whin-bush, and high, high in air, dimly seen against a white fleecy cloud, but easily heard, was the laverock itself.

And the bright pure sunshine was over everything; glittering on the rippling sea, sparkling on the mountain-tops where the snow still lay, patching the woods with light and shadow, heightening the green of moss and heather, changing the streams into threadlets of silver, spreading out the petals of half-open flowers, the gowans on the lea, goldilocks by the meadow’s brink, awakening the bees, and causing ten thousand, thousand rainbow-coloured insects to join in the song of{53} gladness that rose everywhere on this lovely spring morning, from nature to nature’s God.

Tom and his companion stood long enough at the window to drink in the essence of the glorious scene, but no longer. The day was young, and they were young. There was a moping owl up in the ivy yonder; they would leave the ruined castle to him, while they should go forth and mingle with, and become part and parcel of, all the light and loveliness that made up the day.

“Come, ’Theena, we mustn’t keep the fish waiting. Come, Connie; and you must not go and bathe and splash to-day in the stream where we are fishing. ’Theena, I want to get a basket full to the top with such trout that will make Dick and Jack want to kick themselves with jealousy.”

And off they went, and no one saw either of them again till the sun was going down behind the sea, and changing the waves into billows of blood.

“WELL,” said Uncle Robert one morning some time after this, “if anybody twenty years ago had prophesied that I should become a schoolmaster in my declining years, I should have{54} laughed at him. But come, there is no help for it, and by good luck I’ve got two of the dearest and best little pupils that ever any teacher could desire.”

Perhaps, though, no boy or girl either was ever taught on so delightful a system before. For, every morning after breakfast—well rolled in fear-nothing plaids if it happened to be raining—Uncle Robert, with Tom and ’Theena, took their way towards the pine-wood and the hermitage. If Dick and Jack happened to be about when they started, they were sure to give them a hail.

“Good-bye, Eenie-’Theenie,” Dick would cry.

“Fare thee well, Old Cinder,” Jack would shout.

And Uncle Robert would pretend to growl like an old sea-lion, and shake his stick at the pair of them as they scampered off, looking nearly all legs, like the figures on the old Manx pennies.

Young as Tommy was, he had a very complete knowledge of geography, and even a smattering of navigation; for he had declared his intention of becoming a sailor, and nothing else. But this knowledge of his was not such as you learn in books alone; but from books, and maps, and charts, and the big globe itself. Tommy actually knew and felt he was in the world, and not inside the cover of a book. And if you asked him where any country was he pointed in the direction of it at once, taking his bearings as it were{55} by the sun or stars, and the time of day or night it happened to be at the time the question was put.

Their school was the hermitage in the woods, and here they laboured away most earnestly all the forenoon. Then they laid aside their books, and while uncle and ’Theena went outside to squat on the green-sward, Tom—we shall not call him Tommy any more—got ready the luncheon. A very simple repast it was—cheese and cake, and creamy milk.

Then uncle would light his pipe and perhaps tell a story, and after this they started off in pursuit of pleasure.

Were there not fish in the rivers, and shells by the sea-shore, and wondrous creatures of fur and feather in the woods and on the hills, beautiful insects everywhere, and wild-flowers everywhere?

So passed one summer quickly away; and another summer and another winter after that, and now Tom was thirteen and ’Theena was nine and over. Tom was a man, at least he thought he was; and now, dearly though he loved his old home, an almost irresistible longing took possession of him to go to sea—to sail away and see the world and all that is in it.

For Tom was already a sailor. One might hardly think this possible, until told that for a year and more hardly a fine day dawned that did not see Uncle Robert and him, and as often{56} as not little ’Theena also, afloat in uncle’s little yacht-boat. This saucy wee craft had been a man-o’-war’s cutter, sold as unfit for further service. But Uncle Robert had bought her, and had her brought round to the bay of Craigie, and there turned bottom upwards in old Dem Harrison’s boat-shed. And between the pair of them, aided by Tom and ’Theena, who did the looking-on, they soon made the hull seaworthy.

No flimsy work either. Wherever a plank was in the slightest degree decayed, it was taken out and a light, hard new one put in; the very best of copper nails being used, and nothing else. Then she was painted inside and out. This done, she was “whomeld,” as old Dem called it—that is, turned right side up; and so they proceeded to put a raised deck upon her, and step a nice raking mast with fore-and-aft mainsail and topsail and jibs to match. Fine big jibs they were too; honest spreads of canvas, having no resemblance to either a baby’s blanket or a biscuit sack. The wee yacht had an excellent rudder also, and a false keel that could be raised or lowered at pleasure, or to suit circumstances.

You must understand that the Oceana, as she was called, after ’Theena, had the most darling little saloon it is possible to imagine. To be sure, Uncle Robert looked a bit crowded in it; but when Tom and ’Theena were there by themselves, with only uncle’s legs dangling down the{57} companion as he sat steering, the place seemed just made for them. There was a couch at each side, supported by lockers, and prettily upholstered in crimson. There was a lamp in gimbals to burn at night, a natty little locker containing all sorts of dishes and all kinds of dainties, and brackets in the corners with pockets for flowers, and sconces for coloured candles; besides a rack for arms and fishing-gear; while the white paint, the gilding, and the mirrors completed the picture and made the place double the size it really was.

Just imagine if you can how delicious it was to go sailing away over the summer seas in a fairy-like yacht such as the Oceana—the blue above and the blue below, white-winged gulls tacking and half-tacking in the air around. Perhaps a shoal of porpoises in the offing, and great jelly-fishes floating everywhere in the water like animated parasols.

They were entirely independent of the land when once fairly afloat; for the Oceana was well provisioned, and had over and above all her other stores a tiny library of the most readable books of adventure and poetry.

No, it was little wonder that Tom became a sailor under so pleasant a captain as Uncle Robert, and on board so fairy-like a yacht.

But neither on shore was Tom’s nautical studies neglected; for in a room of uncle’s cottage was situated a huge toy ship, which he had built and{58} rigged himself, and which he and his pupils often dismantled and rigged up again. Full rigged she was, with every spar, bolt, and stay in its proper place—a very model of perfection.

But the most curious thing I have to relate is that ’Theena learned every branch of the seafarer’s craft quite as readily as, and even more quickly than, Tom himself. Born and brought up at sea, she appeared to take to everything intuitively.

Taking it all in all, both Uncle Robert and his pupils enjoyed themselves very much, indeed, both on shore and afloat; but whether most on shore or most afloat, it would have been difficult to say.

“My dear children,” said uncle one day at the hermitage, just as they had finished luncheon and were preparing for a long ramble—“my dear children, I shall miss you very much when you go away. I expect I’ll begin to get old very quickly after that.”

“Dear unky,” said Tom, “you are never going to grow old. Don’t you believe it.”

“And we are never going to grow any older either, unky,” said ’Theena.

Uncle Robert laughed.

“Well,” he said, “I should have no objections to make a bargain of that sort with old Father Time if we could fall in with him. But, my dears, changes will come, you know. The whole{59} world is full of changes, and the whole universe too for that matter. And you, Tom, will be going away to sea, and ’Theena will have to go to school. I might make a sailor of her, but, bother me if I could teach her the piano and dancing and the like of that, unless it were a hornpipe such as the sailors dance on a Saturday night. Yes, my dears, changes must and will come.”

Black Tom came up at this moment and began rubbing his great head against the boy’s arm as he lay on the grass. Black Tom was a cat, and a very wonderful specimen he was; elephantic in size as far as the term could be applied to any grimalkin, with an enormous broad and honest-looking face of his own. He was probably not more than two years of age at this time; but Tom—the boy Tom—had saved his life when he was little more than full-grown. It was quite a little adventure for the young Hermit Hunter of the Wilds. As far as could be known, the cat had attempted the abduction of a young or puppy-fox, but the mother coming home in time a furious battle had ensued. The hermit came up at the very moment the fox had scored victory, and was proceeding to break the cat up, as some day the dogs might break her up. But a well-directed arrow from Tom’s cross-bow sent her yelping to her den, and then the boy picked up the half-dead cat and carried him to the hermitage. He{60} recovered after a few weeks of careful nursing; and since then, wherever the boy went the cat followed, all through the woods and over the hills, and even out to sea in the Oceana yacht. Boy and cat were inseparable, and throughout the length and breadth of the parish they were known to everybody as “the two Toms.” When at peace, Tom the cat was very contented-looking, though no great beauty, his shoulder and head having been terribly scarred in that encounter with the fox; but he could be very fierce when he pleased. He tolerated Connie the collie dog, and even slept in his arms; but if any strange dog came into the hut Tom mounted his back and rode him out, whacking him all the way.

. . . . . . .

Changes must and will come. Yes, and changes came to all about Craigielea before very long. First and foremost Dick went away to Oxford. He had a cousin there who would look after him while at college, and, as Uncle Robert phrased it, put him up to the ropes.

Then an American farmer called at Craigielea and stayed for a week, telling very wonderful stories indeed about life and adventures in the sunny south of the United States, to all of which Jack listened with open-mouthed earnestness. And when this farmer went away he left poor Mrs. Talisker in tears, for her dear boy Jack went away with him.{61}

Dear boy Jack did not himself take on much about the matter, however. Indeed, though he did manage to screw a tear or two out when saying good-bye to his mother and Alicia, there certainly were no tears in his eyes as he parted with Tom.

“Ta, ta, Old Cinder!” he said, shaking his brother’s hand. “Take care of yourself, my Cinder; and if ever you are out our way drop round and see us, and I’ll let you ride a buck-jumper that will toss you half-way to the moon. Ta, ta! Be good.”

The old farm was a deal quieter after Dick and Jack had gone. There was far less whooping, or barking of dogs, or cracking of whips. Uncle Robert said the place was not the same at all.

Then came another change. For Captain Herbert walked into the house one forenoon as quietly and coolly as if he had not been from home for over a week. This caused the greatest change of all, for Tom had to get ready for sea at once. His uncle took him straight away to Glasgow to get his outfit; and when the boy was rigged out in his pilot suit, with gilt buttons and cap with badge and band, very natty and neat he looked. ’Theena was very proud of him now; but at the same time she was very sad, for those brass buttons and that blue pilot-jacket meant separation for many and many a long day.{62}

When Tom awoke one morning and looked out of his window he could see a beautiful black painted barque lying at anchor in the bay, with tall tapering spars shining white in the sunlight, as if they had been formed of satin-wood. Then Tom knew that his time had come.

He was not very elated about it at first. It was so sudden; and I do trust the reader will not think him any the less brave when I confess that he sat down beside the window and indulged in the luxury of a good cry. For remember that the boy was not very old yet. No; and I have known many much older boys than he shed tears at the prospect of leaving home.

He was to sail on the very next morning; and that day he and ’Theena went to take one last look at the hermitage and the old castle, and the woods and wilds generally. And Tom the cat followed them and kept close by his master all the way.

“Poor fellow!” said the boy, stooping down to caress his favourite; “he seems to know we are to be parted.”

“Purr-rrn!” said Tom the cat. That was all he could say, but there was more in it than either the boy or ’Theena understood just then.

“Mind,” said Tom to ’Theena, as they stood together at the window of the old castle overlooking the woods and the sea, “I am going to come back rich and bring your brother with me.{63}”

“I don’t care so much for my brother as for you,” said ’Theena candidly. “You know you are my brother now.”

“Yes,” answered Tom abstractedly.

Then hand in hand they went down the hill and through the woods and forest, and so back home again.

Tom’s mother came to see him to bed this last sad night, and sat long with him in the moonlight giving him good advice—the best of which was that he was to read the little Bible she gave him every night, and never to forget to pray.

The bustle of starting saved everybody next day from making much display of grief, and everybody was thankful accordingly. Only poor little ’Theena was half frantic, and could hardly tear herself away from the only brother she had ever known or loved—that is, as far as she could remember.

But the parting was all over at last; and when the sun sank slowly behind the waves that night the Caledonia was far away on the western waters, ploughing her way southward, with the coast of Ireland a long distance on the weather-bow.

Tom was to be apprentice, and, as he was the only one on board, he messed in the saloon along with Captain Herbert and the first and second mate.

The boy had knocked about too long in his{64} uncle’s little yacht to feel the effects of the ship’s motion in the shape of sea-sickness, so he sat down to supper that evening in very good spirits and with a healthy appetite.

They were just about to commence that meal, when in at the saloon door, with tail erect and something like a smile on his broad face, walked Tom the black cat.

“Purr-rrn!” he said well-pleasedly as he jumped on his master’s knee and rubbed his head against the boy’s chest.

Tom was too much surprised to speak, but the captain and mates laughed heartily.

“A stowaway!” said the former.

“Yes,” said Tom. “I have no idea how he got on board.”

“Well, never mind. I’ll wager a shilling he will bring us good luck.”

Black Tom was henceforth installed as ship’s cat; and the men were all most kind to him, for every sailor of them knew that though black cats will bring good luck to a ship, nevertheless if ill treated or lost overboard, the luck is sure to turn.{65}

IT is not often that the lines of young sailor-lads fall in such pleasant places as did those of Tom Talisker on first going to sea. To begin with, he had no extra rough work to do, as is too often the case with apprentices, and even midshipmen, on first going afloat—scrubbing and scraping all day long, their hands in a bucket of tar one minute, and in a bucket of “slush” the next.

“Make a man of my lad,” had been about the last words of Uncle Robert to his friend Captain Herbert; and that honest old tar had proceeded to do so forthwith, not on the old plan of first breaking a boy’s heart, and then making a bully of him if he survived it. No, the captain put Tom into the second mate’s watch, with a request that he should do the best he could for the lad; and as Holborn himself, as this officer was called, was an excellent sailor, and a kindly-hearted though somewhat rough and uncouth individual, he set about putting Tom up to the ropes without loss of time.

Captain Herbert himself superintended the lad’s book-studies, so on the whole he was well off; and it is no wonder, therefore, that before he had been to sea for three years he was able to reef, steer, and do his duty both on deck and below almost as well as Holborn could.

But all this time the Caledonia had never once been back to England.

For Captain Herbert was quite a wandering Jew of a sailor, and the reasons for this are not far to seek. First and foremost, he had never yet given up hopes that he would one day find his lost son, and he certainly left no stone unturned to bring about so wished-for an event. Secondly, he was his own master, the barque he sailed being his own property. And thirdly, it paid him to keep going from country to country, as long as there was no real necessity for docking the ship. Not that he valued riches for his own sake, but for the sake of ’Theena and the son he ne’er again might look upon.

If Tom had felt a man before leaving England, he now almost looked one. Indeed, in size and strength he was a man quite; for whatever some may say, the ocean certainly never stunts a youth’s growth.

He was a good sailor, too, taking the adjective “good” in every sense of the word. Neither his mother’s advice, the second mate’s care, nor Captain Herbert’s kindness had been thrown away on the boy; and on many a dark and stormy{67} night he proved that he was just as good as brave.

Another year of voyaging here and there across the face of the great waters passed away. The Caledonia was lying at San Francisco, and the captain intimated to the officers his intention of bearing up for home. They would double the Horn for the last time; then hurrah for merry England!

There was rejoicing fore and aft at the glad news; for if there is one word in our language that can convey a thrill of happiness to a sailor’s heart, that word is “home.” And every seaman on board a ship carries about with him all over the world affections and ties with the dear ones he has left behind that nothing but death itself can sever.

“In nine months’ time, my lad,” said Captain Herbert cheerily to Tom, who was walking the deck with his constant companion the cat at his heels. “In nine months’ time I hope we’ll be sailing up the Clyde. We shall touch at Ecuador and at Callao, then steer away south.”

It was not the first time since they had sailed from England that the Caledonia had touched at Ecuador, so Tom was not surprised at what the captain now told him; for the grave of his wife was there on that rugged shore, and it was there, too, he had lost his boy.

“I’m getting old, Tom,” he added. “I cannot{68} do now what I could have done ten years ago, and I fear I may never be on this coast again.”

Tom could hardly repress a sigh as he looked at him. He certainly was getting old, and very white in hair and beard; but probably it was his never-ending sorrow that had aged him quite as much as his years.

The Caledonia lay for many days near the spot where the Southern Hope was lost. Captain Herbert seemed to find a difficulty in tearing himself away this time. But when at last the wind began to blow high off the land, sail was set and away southwards once more went the good ship.

The captain was inexpressibly sorrowful as the vessel left the land, and Tom felt he could have given all he possessed in the world to dispel the clouds that hung so heavily over his dear old friend’s heart.