F. Jones, lith.

Day & Son, Lithrs. to the Queen

Published by Smith, Elder & Co. 65 Cornhill, London.

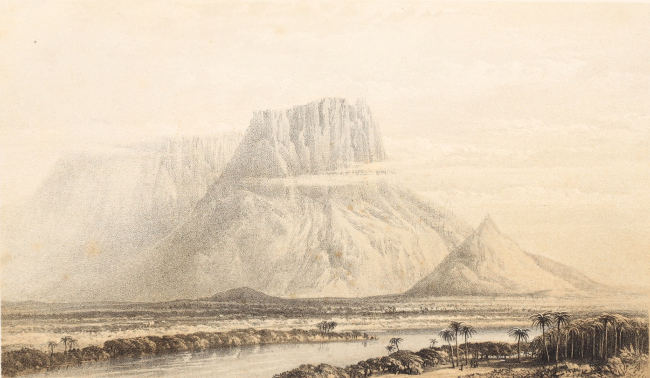

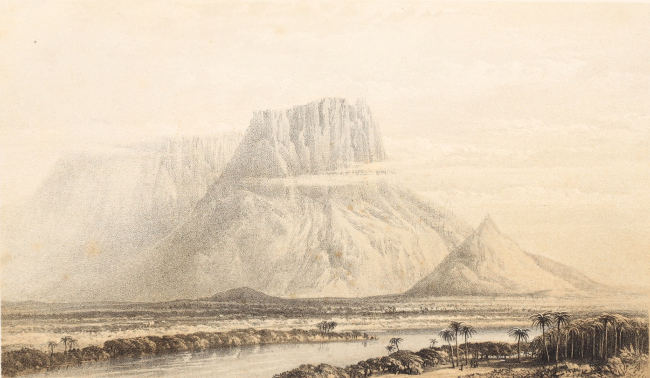

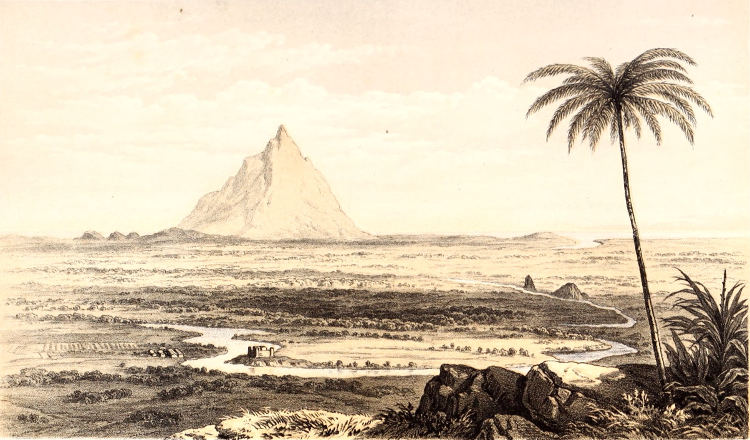

KINA BALU FROM THE LOWER TAMPASUK.

Title: Life in the forests of the Far East (vol. 1 of 2)

Author: Spenser St. John

Release Date: September 14, 2023 [eBook #71643]

Language: English

Credits: Peter Becker, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

LIFE IN THE FORESTS

OF

THE FAR EAST.

F. Jones, lith.

Day & Son, Lithrs. to the Queen

Published by Smith, Elder & Co. 65 Cornhill, London.

KINA BALU FROM THE LOWER TAMPASUK.

BY

SPENSER ST. JOHN, F.R.G.S., F.E.S.,

FORMERLY H.M.’S CONSUL-GENERAL IN THE GREAT ISLAND OF BORNEO,

AND NOW

H.M.’S CHARGÉ D’AFFAIRES TO THE REPUBLIC OF HAYTI.

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

SMITH, ELDER AND CO., 65, CORNHILL.

M.DCCC.LXII.

[The right of Translation is reserved.]

[vii]

I have explained in a short introduction the object and plan of the present volumes, and have little more to say, beyond a reference to the assistance I have received, and the plates and maps which accompany and illustrate them. In order to prevent mistakes, and correct my own impressions, I submitted a series of questions to four gentlemen who were intimately acquainted with the Dayak tribes, and they gave me most useful information in reply. To Mr. Charles Johnson and the Rev. William Chalmers I am indebted for very copious and valuable notes on the Sea and Land Dayaks; and to the Rev. Walter Chambers and the Rev. William Gomez for more concise, yet still interesting accounts of the tribes with whom they live.

To Mr. Hugh Low, the Colonial Treasurer of Labuan, I am under special obligations, as he freely placed at my disposal the journals he had kept during our joint expeditions, as well as those relating to some[viii] districts which I have not visited. It is to be regretted that he has not himself prepared a work on the North-West Coast, as no man possesses more varied experience or a more intimate knowledge of the people.

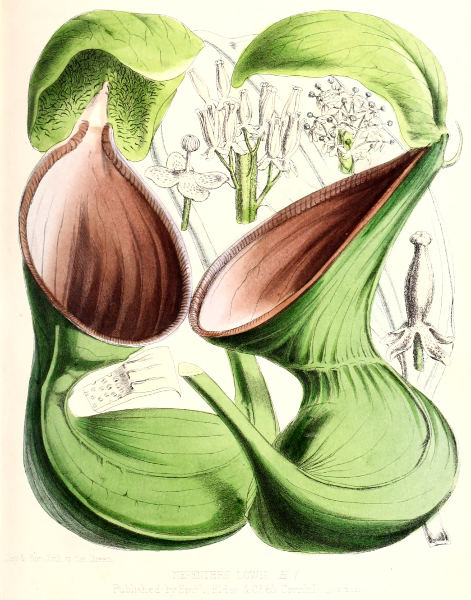

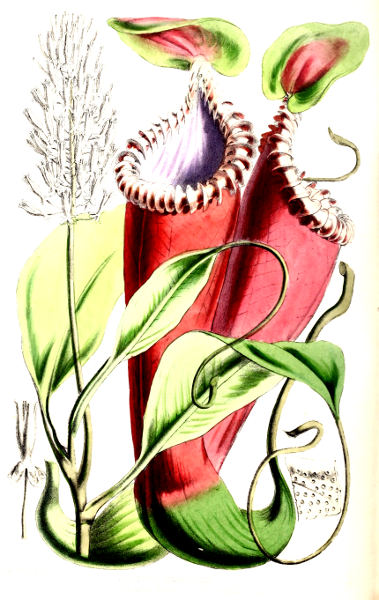

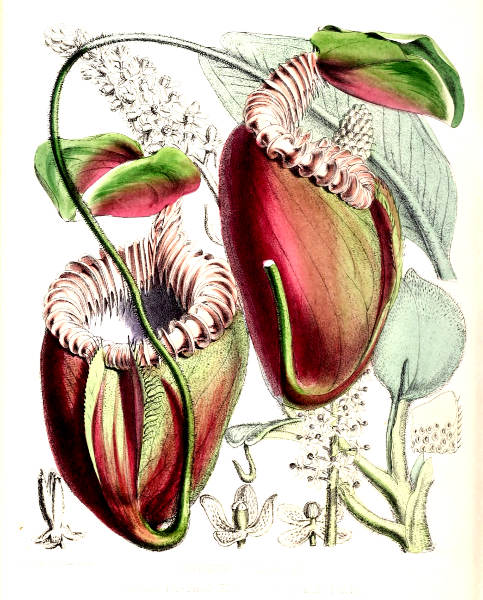

With regard to the plates contained in this work, I am indebted to the courtesy of George Bentham, Esq., the President of the Linnean Society, for permission to engrave the figures of the Nepenthes from the admirable ones published in Vol. XXII. of that Society’s Transactions, and which being of the size of life are the more valuable.

I have inserted, with Dr. Hooker’s permission, his description of the Bornean Nepenthes; and it will always be a subject of regret that the British Government did not carry out their original intention of sending this able botanist to investigate the Flora of Borneo, which is perhaps as extraordinary as any in the world.

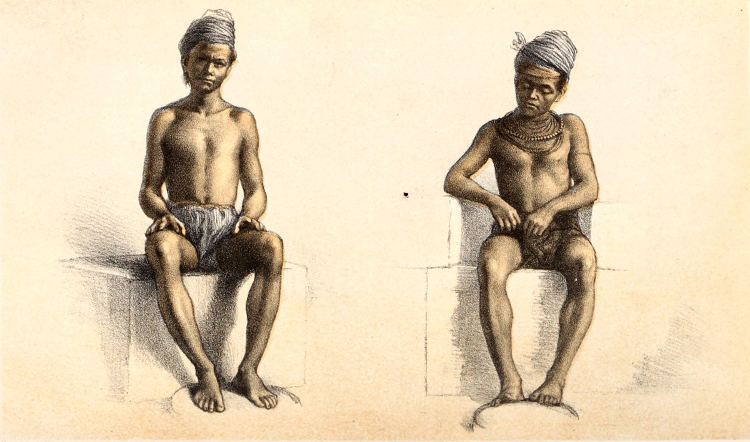

I have also to thank the Rev. Charles Johnson, of White Lackington, and Charles Benyon, Esq., for the photographs which they placed at my disposal, and which have enabled me to insert, among other plates, the most life-like pictures of the Land and Sea Dayaks I have ever seen. To the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel I am also indebted for their generous offer to place all their drawings at my disposal.

[ix]

I must likewise draw attention to the exquisite manner in which the plates of the Nepenthes are coloured, and to the beauty of the engravings in general. They are admirably illustrative of the country, and do very great credit to the lithographers, Messrs. Day and Son, and to their excellent draughtsmen. I ought also to mention that the Nepenthes are drawn less than half the natural size, as it was found impracticable to introduce the full size without many folds, which would have speedily destroyed the beauty of the plates.

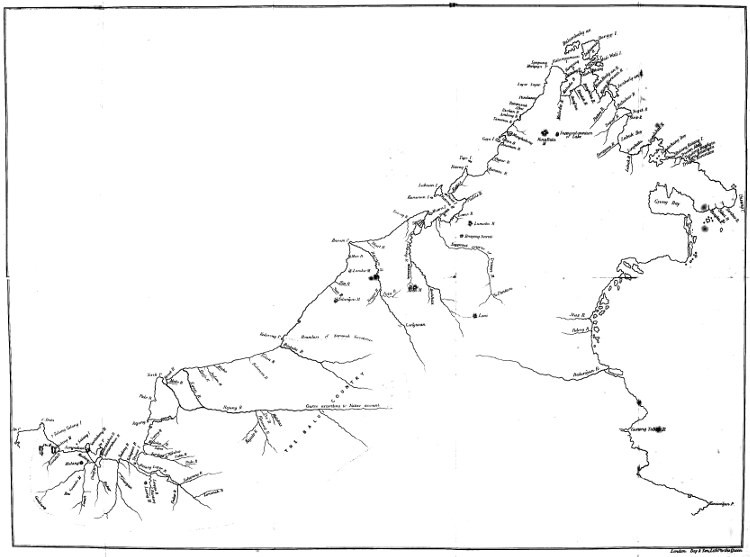

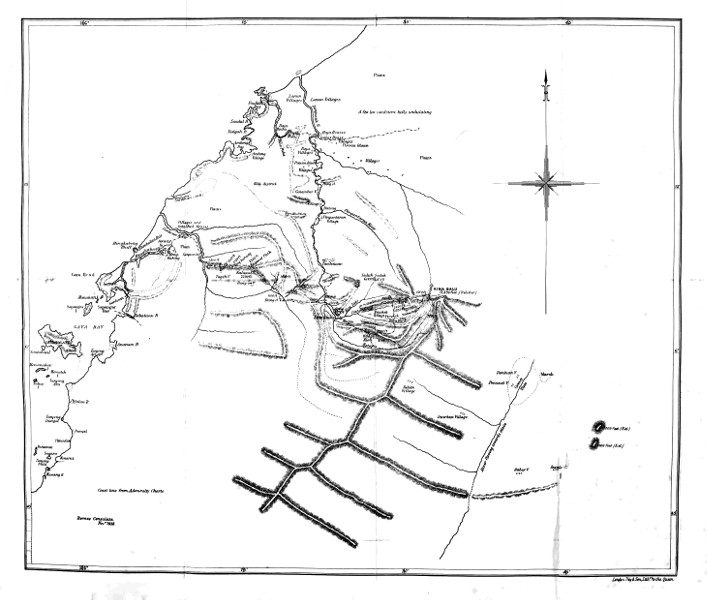

I will add a few words respecting the maps. The one of the districts around Kina Balu was constructed from the observations made during our two expeditions to that mountain. The map of the Limbang and Baram rivers is the result of many observations, and with regard to the position of the main mountains, I think substantially correct, as they were fixed with the aid of the best instruments. The third map is inserted in order to give a general idea of the North-West Coast, though the run of the rivers is often laid down by conjecture.

[xi]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| Chapter I. | |

| THE SEA DAYAKS. | |

| Habitat of the Sea Dayaks—Start for the Lundu—Inland Passages—Fat Venison—The Lundu—Long Village House—Chinese Gardens—Picturesque Waterfall—The Lundu Dayaks—Their Village—Gradual Extinction of the Tribe—A Squall—Childbirth—Girl Bitten by a Snake—Mr. Gomez—His Tact—A Boa Seizes my Dog—Stories of Boa Constrictors—One Caught in a Cage—Invasion of a Dining-room—Capture of a large Boa—Boa and Wild Boar—Native Accounts—Madman and Snake—Boas used as Rat Catchers—Floating Islands—A Man found on one—Their Origin—The Batang Lupar—The Lingga—Alligators Dangerous—Method of Catching them—Their Size—Hair Balls—Death of an Acquaintance—The Balau Lads—The Orang-Utan—A large one killed—Banks of the River—The Fort at Sakarang—The late Mr. Brereton—Sakarang Head-hunting—Dayak Stratagem—Peace Ceremonies—Sacred Jars—Farmhouse—Love of Imitation—Illustrated London News—Women—Men—Poisoning—Workers in Gold and Brass—Anecdote—Rambi Fruit—Pigs Swimming—The Bore—Hunting Dogs—Wild Boar—Respect for Domestic Pig—Two Kinds of Deer—Snaring—Land and Sea Breezes—The Rejang—Lofty Millanau House—Human [xii]Sacrifices—Swings—Innumerable Mayflies—Kanowit Village—Kayan Mode of Attack—Kanowit Dayaks—Men with Tails—Extraordinary Effect of Bathing in the Nile—Treachery—Bier—Customs on the Death of a Relative—Curious Dance—Ceremonies on solemnizing Peace—Wild Tribes—Deadly Effect of the Upas | 5 |

| Chapter II. | |

| SOCIAL LIFE OF THE SEA DAYAKS. | |

| Ceremonies at the Birth of a Child—Infanticide—Desire for Children—A Talkative and Sociable People—Great Concord in Families—Method of Settling Disputes—Marriage Ceremonies—Pride of Birth—Chastity—Punishment of Indiscreet Lovers—Bundling and Company-keeping—Love Anecdotes—Separations—Division of Household Duties—Flirting—Divorce—Burials—Religion—Belief in a Supreme Being—Good and Evil Spirits—The Small-pox—Priests—Some dress as Women—Mourning—Sacrifices—Human Sacrifices—Unlucky Omens—Reconciliation—Belief in a Future State—The other World—Dayaks Litigious—Head-feast—Head-hunting—Its Origin—Horrible Revenge—Small Inland Expeditions—Cat-like Warfare—Atrocious Case—Large Inland Expeditions—War-boats—Edible Clay—Necessity for a Head—Dayaks very Intelligent—Slaves—Objections to Eating certain Animals, or Killing others—Change of Names—Degrees of Affinity within which Marriages may take place—Sickness—Cholera—Manufactures—Agriculture—Method of taking Bees’ Nests—Lying Heaps—Passports—Ordeals—Language | 47 |

| Chapter III. | |

| THE KAYANS OF BARAM. | |

| Unaccountable Panic—Man Overboard—Fishing—Coast Scenery—Baram Point—Floating Drift—Pretty Coast to Labuan—Thunder and Lightning Bay—Bar of the Brunei—River Scenery—The Capital—Little Children in Canoes—Floating [xiii]Market—Kayan Attack—The Present Sultan’s Story—Fire-arms—Devastation of the Interior—Customs of the Kayans—Upas Tree—View of the Capital—The Fountains—The Baram—Kayan Stratagem—Wild Cattle—Banks of the River—Gading Hill—Ivory—Elephants on North-east Coast—Hunting—Startling Appearance—Town of Langusin—Salutes—First Interview—Graves—Wandering Kanowits—Appearance of the Kayans—Visit Singauding—Religion—Houses—Huge Slabs—Skulls—Women tattooed—Mats—Visit the Chiefs—Drinking Chorus—Extempore Song—Head-hunting—Effect of Spirits—Sacrifice—Ceremony of Brotherhood—Effect of Newly-cleared Jungle—War Dance—Firewood—Customs—Origin of Baram Kayans—Vocabularies—Trade—Birds’ Nests—Destruction of Wealth—Manners and Customs—Iron—Visit Edible Birds’ Nest Caves—The Caves—Narrow Escape—Two Kinds of Swallows—Neat House—Visit of Singauding—Visit to Si Obong—Her Dress—Hip-lace—Her Employments—Farewell Visit—Fireworks—Smelting Iron—Accident—Departure—Kayans Cannibals—Anecdotes—Former Method of Trading—Unwelcome Visitors | 79 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| THE LAND DAYAKS. | |

| Visit to the Left-hand Branch of the Sarawak River—Attack of Peguans—Sarawak River—Capture of English Ship—The Durian Fruit—Iron-wood Posts—Rapids—Rapid of the Corpse—Mountains—Village of San Pro—Lovely Scenery—Head-house—Cave—Upper Cave—Unfortunate Boast—Pushing up the Rapids—Story of the Datu Tamanggong—Invulnerable Men—How to become one—Grung Landing-place—Sibungoh Dayaks—Dayak Canoes—Lovely Scenery—Uses of the Bambu—Fish—Sharks in the Upper Waters—Repartee—Pigs Swimming—Farmhouses in Trees—Floods—Suspension Bridges—Chinese Traders—Dress of Land Dayaks—System of Forced Trade—Interesting Tribe—Story of the Murder of Pa Mua—The Trial—Painful Scene—Delightful Bathing—Passing the Rapids—Walk to Grung—Dayak Paths—Village of Grung—Warm Reception—Ceremonies—Lingua Franca—Peculiar Medicine—Prayer—Sacred Dance—Sprinkling [xiv]Blood—Effect of former System of Government—Language | 125 |

| Chapter V. | |

| LAND DAYAKS OF SIRAMBAU.—THEIR SOCIAL LIFE. | |

| Madame Pfeiffer—Chinese Village—Chinese Maidens—Sirambau—Ascent of the Mountain—Difficult Climbing—Forests of Fruit Trees—Scenery—Sirambau Village—Houses—The “Look-out”—Scenery—Head-houses—Orang Kaya Mita—His modest Request—Sir James Brooke’s Cottage—Natural Bath-house—Chinese Gold Workings—Tapang Trees—Social Life of the Land Dayaks—Ceremonies at a Birth—Courtship—Betrothment—Marriage—Burial—Graves—The Sexton—Funeral Feast—Children—Female Chastity—Divorces—Cause of Separations—Anecdote | 152 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| SOCIAL LIFE OF THE LAND DAYAKS—Continued. | |

| Religion—Belief in Supreme Being—Traces of Hinduism—Sacrifices—Pamali or Interdict—Mr. Chalmers’s Account of the Dayak Religion—A Future State—Spirits by Nature—Ghosts of Departed Men—Transformations—Catching the Soul—Conversion of the Priest to Christianity—Story—Other Ghosts—Custom of Pamali, or Taboo—Sacrifices—Things and Actions Interdicted—Not to Eat Horned Animals—Reasons for not Eating Venison—Of Snakes—The Living Principle—Causes of Sickness—Spirits Blinding the Eyes of Men—Incantations to Propitiate or Foil the Spirits of Evil—Catching the Soul—Feasts and Incantations connected with Farming Operations—The Blessing of the Seed—The Feast of First Fruits—Securing the Soul of the Rice—Exciting Night Scene—The Harvest Home—Singular Ceremony—Head Feasts—Offering the Drinking Cup—Minor Ceremonies—Images—Dreams—Love—Journeys of the Soul—Warnings in Sleep—Magic Stones—Anecdote—Ordeals—Omens—Birds of Omen—Method of Consulting them—Beneficial Effects of the Head Feasts—Languages of the Land Dayaks—Deer—The Sibuyaus free from Prejudice—Story of the Cobra de Capella—Names—Change of Name—Prohibited Degrees of Affinity—Heights—Medical Knowledge—Priests and Priestesses—Origin of the latter—Their Practices—Manufactures—Agriculture—Story of the Origin of [xv]Rice—The Pleiades | 168 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| THE SAMARAHAN RIVER AND THE CAVES OF SIRIH. | |

| A Storm—The Musquito Passage—The Samarahan—Rich Soil—The Malays—The Dayaks—The Malay Chief—The Sibuyau Village—A Pretty Girl—Dragons’ Heads—Climbing Pole—Drinking—“The Sibuyaus get no Headaches”—Force repelled by Force—Gardens—Left-hand Branch—Difficult Path—Hill of Munggu Babi—Former Insecurity—The Village—Welcome—Deer Plentiful—Walk to the Sirih Caves—A Skeleton—Illustrative Story—Method of Governing—Torches—Enter the Recesses of the Cave—Small Chambers—Unpleasant Walking—Confined Passage—The Birds’ Nests’ Chamber—Method of Gathering them—Curious Scene—The Cloudy Cave—Wine of the Tampui Fruit—Blandishments—Drinking—Dancing—Bukars Hairy—Scenery—Walk—“The Sibuyaus do get Headaches”—Lanchang—Rival Chiefs—Ancient Disputes—Deer Shooting—Wanton Destruction of Fruit Trees—Choice of an Orang Kaya—Return to Boat—The Right-hand Branch—The San Poks—Hot Spring—Tradition—Hindu Relics—The Female Principle—The Stone Bull—Superstition—Story | 205 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| THE MOUNTAIN OF KINA BALU. | |

| FIRST EXPEDITION. | |

| First Ascent by Mr. Low—Want of Shoes—Set Sail for the Tampasuk—Beautiful Scenery—The Abai—Manufacture of Nipa Salt—Uses of the Nipa Palm—A Lanun Chief—Baju Saddle—Baju a Non-walker—Our ride to the Tampasuk—Gigantic Mango Trees—The Datu’s House—Its Arrangements—The Datu and his People—Piratical Expedition—A Bride put up to Auction—The Bajus—Mixed Breeds—Quarrels with the Lanuns—Effect of Stealing Ida’an Children—Fable of the Horse and his Rider—Amount [xvi]of Fighting Men—Freedom of the Women— Killing the Fatted Calf—Beautiful Prospect—A new Gardinia—Pony Travelling—Difficulty of procuring Useful Men—Start—An Extensive Prospect—Cocoa-nuts and their Milk—A View of Kina Balu—Granite Débris—Our Guides—Natives Ploughing—Our Hut—Division of Land—Ginambur—Neatest Village-house in the Country—Its Inhabitants—Tatooing—Curiosity—Blistered Feet—Batong—Granite Boulders—Fording—Fish-traps—Tambatuan—Robbing a Hive—Search for the Youth-restoring Tree—Our Motives—Appearance of the Summit of Kina Balu—A long Story—Swimming the River—Koung—Palms not plentiful—Lanun Cloth—Cotton—Nominal Wars—The Kiladi—Attempt to Levy Black-mail at the Village of Labang Labang—Resistance—Reasons for demanding it—Bamboo flat-roofed Huts—Ingenious Contrivance—Kiau—Dirty Tribe—Recognition of Voice—A Quarrel—Breaking the Barometer—Opposition to the Ascent of Kina Balu—Harmless Demonstration—Thieves—Mr. Low unable to Walk—Continue the Expedition alone—Cascade—Prayers to the Spirit of the Mountain—Flowers and Plants—Beautiful Rhododendrons—Cave—Unskilful Use of the Blow-pipe—Cold—Ascent to the Summit—Granite Face—Low’s Gully—Noble Terrace—Southern Peak—Effect of the Air—The Craggy Summit—Distant Mountain—Dangerous Slopes—Ghostly Inhabitants—Mist—Superstitions—Collecting Plants—Descent—Noble Landscape—Difficult Path—Exhaustion—Mr. Low not Recovered—Disagreeable Villagers—Recovering the Brass Wire—Clothing—Distrust—A lively Scene—Our Men behave well—Return on Rafts to the Datu’s House | 230 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| SECOND ASCENT OF KINA BALU. | |

| Cholera in Brunei—Start from Labuan—Coal Seams—View of Tanjong Kubong—Method of working the Coal—Red Land—Method of cultivating Pepper—Wild Cattle—The Pinnace—Kimanis Bay—Inland Passage—Kimanis River—Cassia—Trade in it stopped—Smooth River—My first View of Kina Balu—Story of the Death of Pangeran Usup—Anchor—Papar—A Squall—Reach Gaya Bay—Noble [xvii]Harbour—Pangeran Madoud—My first Visits to him—Method of making Salt—Village of Menggatal—Ida’an—His Fear of them—Roman Catholic Mission—Cholera—Mengkabong—Manilla Captives—The Salt-water Lake—Head-quarters of the Bajus—Their Enterprise—Find Stranded Vessels—Tripod Masts—Balignini Pirates—Their Haunts—Spanish Attack—Great Slaughter—Savage-looking Men—Great Tree—Unreasoning Retaliation—Energy of M. Cuarteron—Lawlessness of the Bajus—Pangeran Duroup, the Governor—Anecdote of a drifting Canoe—Inhospitable Custom—Origin of the Bajus—Welcome by Pangeran Sirail—Love of Whiskey overcomes Prejudice—Night Weeping—A Market—The Datu of Tamparuli—The Pangeran’s Enthusiasm—Path to the Tawaran—Fine Scene—Fruit Groves—Neat Gardens—The Tawaran—Sacred Jars—The Talking Jar—Attempted Explanation—Efficacy of the Water—Carletti’s Account—Fabulous Value—The Loveliest Girl in Borneo—No Rice—Advance to Bawang—Our Guides—Steep Hill—Extensive View—Si Nilau—Unceremonious Entry into a House—The Nilau Tribe—Kalawat Village—Tiring Walk—Desertion of a Negro—Numerous Villages—Bungol Village Large—Deceived by the Guide—Fatiguing Walk—Koung Village—Black Mail—Explanation—Friendly Relations established—Labang Labang Village—Change of Treatment—Kiau Village—Warm Reception—Houses—No Rice—Confidence | 280 |

| Chapter X. | |

| SECOND ASCENT OF KINA BALU—Continued. | |

| Return of the Men for Rice—Readiness to assist us—New Kinds of Pitcher Plants—The Valley of Pinokok—Beautiful Nepenthes—Kina Taki—Description of the Nepenthes Rajah—Rocks Coated with Iron—Steep Strata—The Magnolia—Magnificent Sunset Scene—Fine Soil—Talk about the Lake—Change of Fashions—Effect of Example—Rapid Tailoring—Language the same among Ida’an, Dusun, and Bisaya—Reports—Start for Marei Parei—The Fop Kamá—Prepare Night Lodgings—Fragrant Bed—Stunted Vegetation—Appearance of Precipices—Dr. Hooker—Botanical Descriptions—Nepenthes Rajah—Manner [xviii]of Growing—Great Size—Used as a Bucket— Drowned Rat—Nepenthes Edwardsiana—An Account of it—Beautiful Plants—Botanical Description of Nepenthes Edwardsiana—Extensive Prospects—Peaked Hill of Saduk Saduk—Noble Buttress—Situation for Barracks—Nourishing Food—Deep Valleys—Familiar Intercourse with the Villagers—Turning the Laugh—Dirty Faces—Looking-glasses—Their Effect—Return of our Followers—Start for the Mountain—Rough Cultivation—The Mountain Rat used as Food—Our Old Guides—Difficult Walking—Scarlet Rhododendron—Encamp—Double Sunset—Nepenthes Lowii—Botanical Description—Nepenthes Villosa—Botanical Description—Extensive View of the Interior of Borneo—The Lake—The Cave—Ascend to the Summit—Its Extent and Peculiarities—Distant Views—North-western Peak—Severe Storm—Injured Barometer—Useless Thermometers—Dangerous Descent—Accidents—Quartz in Crevices—Clean and Pleasant Girls—Friendly Parting—Ida’an Sacrifices—Return by Koung—Kalawat and Nilu—Death of Sahat—A Thief—Cholera—Incantations and Method of Treatment—Arrival at Gantisan—Fine Wharf—The Pangeran—Bad Weather—Heavy Squall—Little Rice to be had—Sail—Anchor at Gaya Island—Curious Stones—Fish—Description of a magnificent Kind—Poisonous Fins—Set Sail—Awkward Position—Water-spout—Admiralty Charts—Names require Correcting—Serious Mistake—Among the Shoals—Fearful Squall—Falling Stars and Brilliant Meteor—Arrival at Labuan | 314 |

| Chapter XI. | |

| THE PHYSICAL AND POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE DISTRICTS LYING BETWEEN GAYA BAY AND THE TAMPASUK RIVER; WITH A GEOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF MALUDU BAY AND THE NORTH-EAST COAST OF BORNEO. | |

| The Coast Line—The Rivers—The Bays—Gaya Bay—Abai—Character of Interior Country—Plains—Hills—Kina Balu—First Ascent by Mr. Low—Description of Summit—The Peaks—The Northern Ranges—Steep Granite Slopes—The Spurs—The Main Spur—Interior Country—Distant Mountains—Plain—Villages—The Lake—Vegetation [xix]on Kina Balu—The Rivers—The Ananam—The Kabatuan—The Mengkabong—The Tawaran—The Abai—The Tampasuk—Its Interior—Political Geography—Inhabitants—The Lanuns—The Bajus—Mahomedans—Appearance—Their Women—Their Houses—Love of Cockfighting—Fine Breed of Fowls—Other Inhabitants—The Ida’an—Their Houses—Their Women—Tattooing—Comfortable House—Method of Government—No Wars—Aborigines Honest—Exceptions—Agriculture—Ploughing—Remnant of Chinese Civilization—Tobacco—Cotton—Good Soil—Amount of Population—Numerous and Extensive Villages—The Tampasuk—The Tawaran—Mengkabong—Other Districts—Enumeration—Manufactures—Lanun Cloths—Trade—Difficult Travelling—Languages—Geology—Sandstone—Greenstone—Climate of Kina Balu temperate—Map—Addition—Maludu Bay—Western Point—Western Shore—Mountains—Head of Bay—Population—Accounts compared—Bengkoka—Minerals—Eastern Point—Banguey—Difficult Navigation—Small Rivers and Bays—Paitan—Sugut—Low Coast—Labuk Bay—High Land—Benggaya—Labuk—Sandakan—Story of the Atas Man—Kina Batangan—Cape Unsang—Tungku—Population—The Ida’an—The Mahomedans | 356 |

| I. | Kina Balu from the Lower Tampasuk | Frontispiece | |

| II. | The Sea Dayaks | To face page | 5 |

| III. | City of Brunei. Sunset | „ | 89 |

| IV. | The Land Dayaks | „ | 125 |

| V. | View from near the Rajah’s Cottage | „ | 156 |

| VI. | Nepenthes Rajah | „ | 317 |

| VII. | Kina Balu from the Pinokok Valley | „ | 318 |

| VIII. | Nepenthes Edwardsiana | „ | 327 |

| IX. | Nepenthes Lowii | „ | 336 |

| X. | Nepenthes Villosa | „ | 337 |

MAPS.

| I. | Map of North-West Coast of Borneo | To face page | 1 |

| II. | Map of Districts near Kina Balu | „ | 230 |

ERRATA.

Page 317, line 9, for “four,” read “fourteen.”

„ „ 17, for “was,” read “that of the others is.”

London. Day & Son, Lithrs. to the Queen

[1]

LIFE IN THE

FORESTS OF THE FAR EAST.

The wild tribes of Borneo, and the not less wild interior of the country, are scarcely known to European readers, as no one who has travelled in the Island during the last fourteen years has given his impressions to the public.

My official position afforded me many facilities for gratifying my fondness for exploring new countries, and traversing more of the north of Borneo than any previous traveller, besides enabling me to gain more intimate and varied experience of the inhabitants.

In the following pages I have treated of the tribes in groups, and have endeavoured to give an individual interest to each; while, to preserve the freshness of my first impressions, I have copied my journal written at the time, only correcting such errors as are inseparable from first observations, and comparing them with the result of subsequent experience.

[2]

Preserving the natural order of travel, I commence with an account of my expeditions among the tribes living in the neighbourhood of Sarawak; then follow narratives of two ascents of the great mountain of Kina Balu, the loftiest mountain of insular Asia, of which I have given a full account, as it is a part of Borneo but little known, and rendered still more curious by the traces we find of former Chinese intercourse with this part of the island; my personal narrative being concluded by the journal of a distant expedition I made to explore the interior of the country lying to the south and south-east of Brunei, the capital of Borneo Proper.

The starting-point of the first journeys was Kuching, the capital of Sarawak, where I was stationed in the acting appointment of H. M.’s Commissioner in Borneo. I lived so many years among the Dayaks, that the information I give of their mode of life may be relied on; and I have received so much assistance from others better acquainted with individual tribes, that I can place before the public, with great confidence in the correctness of detail, the chapters on the Manners and Customs of these people. I persuade myself that the more the natives of Borneo are studied, the more lively will be the interest felt in them. The energy displayed by the Sea Dayaks, gives much hope of their advancement in civilization at a future time; and a few years of quiet and steady government would produce a great change in their condition. The Land Dayaks scarcely display the same aptitude for improvement, but patience may do much with them also; their modes of thought, their customs, and the traces of Hinduism in their religion,[3] render them a very singular and interesting people.

Of the Kayans we know less; and I have only been able to give an account of one journey I made among them, very slightly corrected by subsequent experience. They are a strange, warlike race, who are destined greatly to influence the surrounding tribes. They have already penetrated to within thirty miles of Brunei, the capital, spreading desolation in their path.

For ten years, every time I had entered the bay near the Brunei river, I had speculated on what kind of country and people lay beyond the distant ranges of mountains that, on a clear day, appeared to extend, one behind the other, as far as the eye could reach. I constantly made inquiries, but never could find even a Malay who had gone more than a few days’ journey up the Limbang, the largest river which falls into the bay. In 1856, I took up my permanent residence in Brunei as Consul-General, and, after many minor attempts, I was at last enabled to organize an expedition to penetrate into the interior, and, hoping it might prove interesting, every evening, with but two exceptions, I wrote in my journal an account of the day’s proceedings. I have printed it, as far as possible, in the same words in which it was originally composed. As this country was never before visited by Malay or European, I hope there will be found in my narrative some fresh and interesting matter.

The Malays being a people about whom much has been written, I have refrained from dwelling on their characteristics.

[4]

I conclude with a sketch of the present condition of Brunei and Sarawak, of the Chinese settlers, and of the two missions which have been sent to Borneo, one Roman Catholic, the other Protestant.

It was with much regret that I gave up the idea of penetrating to the opposite side of Borneo, starting from the capital, and crossing the island to Kotei or Baluñg-an, on the eastern coast; but the expense would have been too great: otherwise, with my previous experience of Borneo travelling, I should have had no hesitation in attempting the expedition.

Having thus briefly indicated the plan of the work, I will commence with an account of my journeys among the Sea Dayaks.

G. Mc Culloch, Lith.

Day & Son, Lithrs. to the Queen

Published by Smith, Elder & Co. 65 Cornhill, London.

THE SEA DAYAKS.

[5]

Habitat of the Sea Dayaks—Start for the Lundu—Inland Passages—Fat Venison—The Lundu—Long Village House—Chinese Gardens—Picturesque Waterfall—The Lundu Dayaks—Their Village—Gradual Extinction of the Tribe—A Squall—Childbirth—Girl Bitten by a Snake—Mr. Gomez—His Tact—A Boa Seizes my Dog—Stories of Boa Constrictors—One Caught in a Cage—Invasion of a Dining-room—Capture of a large Boa—Boa and Wild Boar—Native Accounts—Madman and Snake—Boas used as Rat Catchers—Floating Islands—A Man Found on one—Their Origin—The Batang Lupar—The Lingga—Alligators Dangerous—Method of Catching them—Their Size—Hair Balls—Death of an Acquaintance—The Balau Lads—The Orang-Utan—A large one killed—Banks of the River—The Fort at Sakarang—The late Mr. Brereton—Sakarang Head-hunting—Dayak Stratagem—Peace Ceremonies—Sacred Jars—Farmhouse—Love of Imitation—Illustrated London News—Women—Men—Poisoning—Workers in Gold and Brass—Anecdote—Rambi Fruit—Pigs Swimming—The Bore—Hunting Dogs—Wild Boar—Respect for Domestic Pig—Two kinds of Deer—Snaring—Land and Sea Breezes—The Rejang—Lofty Millanau House—Human Sacrifices—Swings—Innumerable Mayflies—Kanowit Village—Kayan Mode of Attack—Kanowit Dayaks—Men with Tails—Extraordinary Effect of Bathing in the Nile—Treachery—Bier—Customs on the Death of a Relative—Curious Dance—Ceremonies on Solemnizing Peace—Wild Tribes—Deadly Effect of the Upas.

The Sea Dayaks are so called from their familiarity with the sea, though many live as far inland as any of the other aborigines. They inhabit the districts lying to the eastward of Sadong, and extend along[6] the coast to the great river of Rejang. They are the most numerous and warlike of the Dayaks; and the most powerful of their sections formerly indulged in the exciting pastime of piracy and head-hunting. The next river to the east of Sadong is the Sibuyau, whose inhabitants were scattered and had fled to the districts around Sarawak.

The first village of these Sibuyaus, to whom we paid a long visit, was situated on the Lundu, the most westerly river in the Sarawak territories.

We started in March; and the north-east monsoon still blowing occasionally, made it necessary to watch our time for venturing to sea, as the waves would soon have swamped our long native prahu.

From the Santubong entrance of the Sarawak River to the Lundu, there are passages which run behind the jungle that skirts the sea-shore, enabling canoes to hold communication between those places thirty miles apart without venturing to sea; but our boat being fifty feet long was unable to pass at one place, so during a lull in the weather we pushed out, calling at the little island of Sampadien, where Mr. Crookshank was preparing the ground for a cocoa-nut plantation. He brought us down a fine haunch of venison, covered with a layer of fat, a very rare thing in Borneo, where the deer generally are destitute of that sign of good condition. He had employed himself the first few days in clearing the island of game, and his dogs had on the previous evening been fortunate enough to bring this fine animal to bay, when he speared it with his own hands.

Pushing off quickly, as the sea breeze was blowing[7] in strongly, we sailed and pulled away for the river of Sampadien, and after a narrow escape from not hitting the right channel, found ourselves clear of the breakers and safe in still water. An inland passage then took us to the Lundu.

The banks of this river are very flat and the plains extend for a considerable distance, but the scene is redeemed from tameness by the mountains of Gading and Poè. There is a flourishing appearance about the place; all were engaged in some occupation. We were received by Kalong, the Orang Kaya’s eldest son, the chief himself being absent collecting the fruit of the mangkawan, from which a good vegetable oil is extracted: the natives use it for candles and for cookery, but it is also exported in quantities to Europe.

The landing-place is very picturesque, being overshadowed by a grove of magnificent palms, under which were drawn up the war-boats of the tribe. A passage raised on posts three feet above the ground, led to the great village-house, which extended far on either side, and was then hidden among the fruit-trees. It was the longest I had seen, measuring 534 feet, and contained nearly five hundred people. There are various lesser houses about of Malays and Dayaks, forming a population of about a thousand. The Orang Kaya lived in the largest house, which was certainly a remarkably fine one: the broad verandah, or common room, stretched uninterruptedly the whole length, and afforded ample space for the occupations of the tribe. The divisions appropriated to each family were comparatively large, and all had an air of comfort; while in front of the house were[8] bamboo platforms, on which the rice is dried and beaten out.

No village in Sarawak is blessed with greater prosperity than this. The old Orang Kaya, being of a most determined character, has reversed the usual order of things; and the Malays, instead of being the governors, are the governed. Having for years been little exposed to exactions, they are flourishing and exhibit an air of great contentment.

They made us comfortable in the long public room, and placed benches around a table for our accommodation. I confess to prefer the clean matted floor. After the first burst of curiosity was over, the people went on with their usual avocations, and did not make themselves uncomfortable about us.

We walked in the evening among the Chinese gardens extending over about a hundred acres of ground, and neatly planted with various kinds of vegetables, among which beans and sweet potatoes appeared most numerous. There were here about two hundred Chinese, most of them but lately arrived, so that the cultivated ground was continually increasing. A large market was found for their sweet potatoes among the sago growers and workers of the rivers to the north.

Next day we started for a waterfall, which we were told was to be found on the sides of the Gading mountain, a few miles below the village. After leaving our boat, the path lay through a jungle of fruit-trees; but as we ascended the spur of the mountain these ceased. In about an hour we came to a very deep ravine, where the thundering noise of falling water gave notice of the presence of a cataract. This[9] is by far the finest I have yet seen: the stream, tumbling down the sides of the mountain, forms a succession of noble falls: the first we saw dashed in broken masses over the rocks above, and then descended like a huge pillar of foam into a deep, gloomy basin, while on either side of it rose smooth rocks, crowned with lofty trees, and dense underwood, that threw their dark shadows into the pool.

A slight detour brought us to a spot above the cascade, and then we could perceive that it was but the first of a succession. One view, where six hundred feet of fall was at once visible, is extremely fine: the water now gliding over the smoothest granite rock, then broken into foam by numerous obstructions, then tumbling in masses into deep basins,—the deafening roar, the noble trees rising amid the surrounding crags, the deep verdure, the brightness of the tropical sun, reflected from burning polished surfaces, then deep shade and cooling air. This varied scene was indeed worth a visit. We ascended to the top of the mountain, though warned of the danger we incurred from a ferocious dragon which guarded the summit.

The Sibuyaus are only interlopers in the Lundu, as there is a tribe, the original inhabitants of the country, who still live here. One day we visited them.

After pulling a few miles up the river we reached a landing place, where the chief of the true Lundus was waiting to guide us to his village. For six or seven miles our path lay through the jungle over undulating ground, and we found the houses situated at the commencement of a great valley lying between the mountains[10] of Poè and Gading. The soil is here excellent, but now little of it is tilled, though there are thousands of acres around that might support an immense population. Most of it, however, had, in former times, been cleared, as we saw but very little old forest.

The Lundu houses, on the top of a low hill, are but few in number, neat and new. The tribe, however, has fallen; they fear there is a curse on them. A thousand families, they say, once cultivated this valley, but now they are reduced to ten, not by the ravages of war, but by diseases sent by the spirits. They complain bitterly that they have no families, that their women are not fertile; indeed, there were but three or four children in the whole place. The men were fine-looking, and the women well favoured and healthy—remarkably clean and free from disease. We could only account for their decreasing numbers by their constant intermarriages: we advised them to seek husbands and wives among the neighbouring tribes, but this is difficult. Their village is a well-drained, airy spot.

On our return, one of those sudden squalls came on that are so frequent in Borneo: we were among the decayed trees that still stood on the site of an old farm. As a heavier gust swept from the hills, the half-rotten timber tottered and fell with a crash around us, rendering our walk extremely dangerous. I was not sorry, therefore, to find myself in the boat on the broad river. The banks are tolerably well cleared by Chinese, Malays, Millanaus, and Dayaks. A few months after this, a sudden squall struck the British brig “Amelia,” and capsized her: ninety-three[11] went down with her, but twenty escaped in the jolly-boat.

In the evening Kalong’s wife was taken in the pains of childbirth. The Rev. F. Dougall, now Bishop of Labuan, offered his medical assistance, as it was evident the case was a serious one, but they preferred following their own customs. The child died, and we left the mother very ill.

A young girl, bitten by a snake, was brought in; the wound was rubbed with a piece of deer’s horn, she became drowsy and slept for several hours, but in the morning she was about her usual occupations.

A year after this visit, the Rev. W. Gomez was established there, to endeavour to convert the Sibuyau Dayaks. At first, he did not press religious instruction upon them, but opened a school. I mention this circumstance on account of the very remarkable tact he must have exercised to induce the children to attend as they did. His system of punishment was admirable, but difficult to be followed with English boys. He merely refused to hear the offending child’s lesson, and told him to go home. A friend, who often watched the progress of the school, has told me that instead of going home the little fellows would sob and cry and remain in a quiet part of the school till they thought Mr. Gomez had relented. They would rarely return to their parents, if it could be avoided, before their lessons were said.

On our journey along the coast, while walking at the edge of the jungle, a favourite dog of mine was seized by a boa-constrictor, perhaps twelve feet in length. Fortunately, Captain Brooke was near, and[12] sent a charge of shot into the reptile, which then let go its hold and made off. The dog had a wound on the side of his neck.

The natives tell many stories of these monstrous snakes; but rejecting the testimony of those who say they have seen them so large as to mistake them for trees, I will mention three cases where the animals were measured. A boa one night got into a closely-latticed place under a Dayak house, and finding it could not drag away a pig which it had killed there, on account of the wooden bars, swallowed the beast on the spot. In the morning the owner was astonished to find the new occupant of the sty; but as the reptile was gorged, he had no difficulty in destroying it. Its body was brought to Sarawak and measured by Mr. Ruppell, when it was found to be nineteen feet in length.

The next was killed in Labuan, and without head and a large portion of its neck, it measured above twenty feet. I heard the story told how the reptile was secured. One day, a dog belonging to Mr. Coulson disappeared, and a servant averred that it was taken by an enormous snake. The following week, as the same servant was laying the cloth for dinner, he saw, to his horror, a huge snake dart at a dog, that was quietly dozing in the verandah, and carry it off. The master, alarmed at the cries of his follower, rushed out, and, on hearing the cause, gave chase, spear in hand, followed by all his household. They tracked the reptile to his lair, and found the dead dog opposite a hole in a hollow tree; placing a man with a drawn sword to watch there, Mr. Coulson thrust a spear into an upper hole, and struck the[13] boa, which, feeling the wound, put its head out of the entrance, and instantly lost it by a blow from the Malay. I believe that when it was drawn from its hiding-place it measured about twenty-four feet; the before-mentioned length was taken by me from the mutilated skin.

Mr. Coulson was also fortunate enough to secure the largest boa that has ever been obtained by a European in the north-west part of Borneo.

In March, 1859, a Malay, his wife, and child, accompanied by a little dog, were walking from the Eastern Archipelago Company’s house, at the entrance of the Brunei towards the sea-beach. The path was narrow; the little dog trotted on first, followed by the others in Indian file. Just as they reached the shore, a boa darted on the dog and dragged him into the bushes. The Malays fled back to the house, where they found Mr. Coulson, who, on hearing of the great size of the serpent, determined to attempt the capture of its skin. He loaded a Minié rifle, and requested three English companions who happened to be there to accompany him with drawn swords. He made them promise to follow his directions. His intention was to walk up to within a fathom of the boa, and then shoot him through the head; if he were seized, then his companions were to rush in with their swords, but not before, as he wished to preserve the skin uninjured. They found the reptile on the same spot where it had killed the dog, that still lay partly encoiled: on the approach of the party, it raised its head, and made slight angry darts towards them, but still keeping hold of its prey. Mr. Coulson coolly approached to within five feet of[14] the animal, which kept raising and depressing its head, and, seizing a favourable opportunity, fired; the ball passed through its brain and it lay dead at his feet—a prize worthily gained. They raised the boa up while still making strong muscular movements, and carried it back to the house; there they measured it—it was twenty-six feet two inches. Mr. Coulson immediately skinned it, and, shortly after, brought it up to the consulate. When I measured it, it had lost two inches, and was exactly twenty-six feet in length.

These boas must have occasionally desperate struggles with the wild pigs. I one day came upon a spot where the ground was torn up for a circle of eight or nine feet, and the branches around were broken. The boar, however, had evidently succumbed, as we could trace with ease the course it had been dragged through the jungle. We followed a little distance, but evidently no one was very anxious in pursuit. I knew the animal killed on this occasion to be a boar, from finding his broken tusk half-buried in the ground.

I may mention one or two incidents which I heard from very trustworthy Malays. Abang Hassan was working in the woods at the Santubong entrance of the Sarawak river, when he came upon a huge boa, completely torpid; it had swallowed one of the large deer, whose horns, he said, could be distinctly traced under the reptile’s skin. He cut it open and found that the deer was still perfectly fresh. The boa measured about nineteen feet.

Abang Buyong, a man whose word is trusted by all the Europeans who know him, told us that one[15] day he was walking through the jungle with a drawn sword, looking for rattans, when he was suddenly seized by the leg; he instinctively cut at the animal, and fortunate for him that he was so quick, as he had struck off the head of a huge boa before it had time to wind its coils around him. He said he carefully measured him, and it was seven Malay fathoms long—that is, from thirty-five to thirty-seven feet. Dozens of other stories rise to my memory, but they were told me by men in whom I have not equal confidence. The largest I have myself killed was fourteen feet.

I will mention an incident that took place in July, 1861, during the Sarawak expedition to the Muka river. A Malay, subject to fits of delirium, sprang up suddenly one day in a boat, drew a sword, killed two and wounded several men; he then dashed overboard, and fled into the jungle. Ten days after, he was found wandering starving on the beach. He appeared quite in his senses, and perfectly unaware of the act he had committed. He said, one night that threatened heavy rain, he crawled into a hollow tree to sleep. He was suddenly awakened by a choking sensation in his throat. He instinctively put up both his hands, and tore away what had seized him; it was a huge boa, which in the confined space could not coil around him. The Malay quickly got out of the serpent’s lair and fled, leaving his sword behind him. When found, there were the marks of the fangs on the sides of the torn wound, which was festering. The last news I heard of the man was that he was expected to die.

Many persons are very partial to small boas, as wherever they take up their abode all rats disappear;[16] therefore they are seldom disturbed when found in granaries or the roofs of houses, though the reptile has as great a partiality for eggs as for vermin. Our servants killed one, and found fourteen eggs in its stomach.

Passing, on our way to the great tribes of Sea Dayaks, through Sarawak, we picked up our home letters and newspapers, and transferred our baggage to a larger prahu, very comfortably fitted up, with a spacious cabin in the centre.

At Muaratabas we joined the Jolly Bachelor pinnace, sending our boat on in shore. Setting sail with a fair breeze, we soon reached the entrance of the Batang Lupar, which is marked by two conical hills,—one the island of Trisauh, in the centre of the river, the other on the right bank. During our passage we observed some of those floating islands which wander over the face of the sea, at the mercy of wind and wave. I remember once that the signalman gave notice that a three-masted vessel was ahead. We all fixed our telescopes on her, as at sea the slightest incident awakens interest: her masts appeared to rake in an extraordinary manner. As we steamed towards her our mistake was soon discovered; it was a floating island, with unusually tall nipa palms upon it, that were bending gracefully before the breeze.

On one occasion a man was found at sea making one of these his resting-place. Doubtless he abandoned his island home cheerfully, though he fell into the hands of enemies. He told us that his pirate companions, in hurried flight, had left him on the bank of a hostile river, and so seeing a diminutive island[17] floating to the sea, he swam off and got upon it, and he had been there many days, living upon the fruit he had found on the palm stems.

The origin of the islands is this: The stream occasionally wears away the steep bank under the closely united roots of the nipa, and some sudden flood, pressing with unusual force on the loosened earth, tears away a large portion of the shore, which floats to the mouth of the river to be carried by the tides and currents far out to sea. Some fifteen miles off Baram Point, mariners tell of a great collection of floating trees and sea-weed, that forms an almost impassable barrier to ships in a light breeze. Some action of the currents appears to cause this assemblage of floating timber always to keep near one spot, and to move with a gyrating motion.

The Batang Lupar is in breadth from two to three miles, and occasionally more: we never had a cast of less than three fathoms on the bar, and inside it deepens to six. The banks are low, composed entirely of alluvial soil. Wind and tide soon carried us to our first night’s resting-place at the mouth of the Lingga river, some twenty miles from the embouchure of the Batang Lupar. It is small, and its banks have the usual flat appearance, relieved, however, by some distant hills and the mountain of Lesong (a mortar), from a fancied resemblance to that article to be seen in every Malay house.

We found our boat here, together with a large force from Sarawak. I had taken advantage of the chance to accompany Captain Brooke on one of his tours through the Sarawak territories. This was to induce all the branches of the Sea Dayaks to make[18] peace with each other, and with the towns of the coast, some of which they had so long harried.

While business detains the force at the mouth of the Lingga, I will describe Banting, the chief town of the Balau Dayaks, about ten miles up that stream. There are here about thirty long village houses, half at the foot of a low hill, the others scattered on its face, completely embowered in fruit-trees. From the spot where Mr. Chambers, the missionary, has built his house, there is a lovely view,—more lovely to those who have long been accustomed to jungle than to any others. For here we have the Lingga river meandering among what appear to be extensive green fields, reminding me of our lovely meadows at home. We must not, however, examine them too closely, or I fear they will be found swamps of rushes and gigantic grass. Still the land is not the less valuable, being admirably adapted in its present state for the best rice cultivation.

The Lingga river is famous for its alligators, which are both large and fierce; but, from superstitions to which I shall afterwards refer, the natives seldom destroy them. In Sarawak there is no such prejudice. It is a well-known fact, that no alligator will take a bait that is in any way fixed to the shore. The usual mode of catching them is to fasten a dog, a cat, or a monkey to a four or five fathom rattan, with an iron hook or a short stick lightly fastened up the side of the bait. The rattan is then beaten out into fibre for a fathom, to prevent its being bitten through by the animal when it has swallowed the tempting morsel. Near a spot known to be frequented by alligators, the bait, with this long appendage, is[19] placed on a branch about six feet above high-water mark. The cries of the bound animal soon attract the reptile; he springs out of the water and seizes it in his ponderous jaws. The natives say he is cunning enough to try if it be fastened to the bank; but the real fact appears to be that the alligator never eats its food until it is rather high. So that when fastened, finding he cannot take away his prize to the place where he usually conceals his food, he naturally lets it go. Gasing, a Dayak chief, saved his life when seized by an alligator, by laying hold of a post in the water: the animal gave two or three tugs, but finding its prey immovable, let go.

Two or three days after the bait has been taken, the Malays seek for the end of the long rattan fastened to it. When found, they give it a slight pull, which breaks the threads that fasten the stick up the side of the bait, and it spreads across the alligator’s stomach. They then haul it towards them. It never appears to struggle, but permits its captors to bind its legs over its back. Till this is done they speak to it with the utmost respect, and address it in a soothing voice; but as soon as it is secured they raise a yell of triumph, and take it in procession down the river to the landing-place. It is then dragged ashore amid many expressions of condolence at the pain it must be suffering from the rough stones; but being safely ashore, their tone is jeering, as they address it as Rajah, Datu, and grandfather. It then receives its death at the hands of the public executioner. Its stomach is afterwards ripped open, to see if it be a man-eater. I have often seen the buttons of a woman’s jacket, or the tail of a Chinese, taken out.[20] The alligator always appears to swallow its food whole. Some men are very expert in catching these reptiles; I remember one Malay, who came over from the Dutch possessions, capturing thirteen during a few months, and as the Sarawak Government pay three shillings and sixpence for every foot the beast measures, the man made a large sum.

Alligators sometimes attain to a very large size. I have never measured one above seventeen feet six inches, but I saw a well-known animal, the terror of the Siol branch of the Sarawak, that must have been at least twenty-four or twenty-five feet long. The natives say the alligator dies if wounded about the body, as the river-worms get into the injured part, and prevent its healing; many have been found dying on the banks from gunshot wounds. In the rivers are occasionally found curious balls of hair, five or six inches in diameter, that are ejected from these reptiles’ stomachs,—the indigestible remains of animals captured.

I once lost an acquaintance in Sarawak who was killed by an alligator. He was seized round the chest by the jaws of an enormous beast that swam with his prey along the surface of the water. His children, who had accompanied him to bathe, ran along the banks of the river shouting to him to push out the animal’s eyes; they say he looked at them, but that he neither moved nor spoke, paralyzed, as it were, by the grip.

I am very partial to this tribe of Lingga Dayaks; they have always shown so unmistakable a preference for the English—faithful under every temptation, and ready at a moment’s warning to back them up with a force of a thousand men.

[21]

The lads, too, have a spirit more akin to English youths than I have yet seen among the other tribes. I well remember the delight with which they learnt the games we taught them—joining in prisoner’s base with readiness, hauling at the rope, and shouting with laughter at French and English, represented by the names of two Dayak tribes. There is good material to work on here, and it could not be in better hands than those of their present missionary, Mr. Chambers. That his teaching has made any marked difference in their conduct I do not suppose, but he has influenced them, and his influence is yearly increasing.

It is pleasing to record a little success here, at the Quop, and at Lundu, or we should have to pronounce the Borneo mission a complete failure.

The largest orang-utans I have ever heard of are in the Batang Lupar districts. Mr. Crymble, of Sarawak, saw a very fine one on shore, and landing, fired and struck him, but the beast dashed away among the lofty trees; seven times he was shot at, but only the eighth ball took fatal effect, and he came crashing down, and fell under a heap of twigs that he had torn in vain endeavours to arrest his descent. The natives refused to approach him, saying it was a trick—he was hiding to spring upon them as they approached. Mr. Crymble, however, soon uncovered him, and measured his length as he lay: it was five feet two inches, measuring fairly from the head to the heel. The head and arms were brought in, and we measured them: the face was fifteen inches broad, including the enormous callosities that stick out on either side; its length was fourteen inches; round the[22] wrist was twelve inches, and the upper arm seventeen. I mention this size particularly, as my friend, Mr. Wallace, who had more opportunities than any one else to study these animals, never shot one much over four feet, and perhaps may doubt the existence of larger animals; but he unfortunately sought them in the Sadong river, where only the smaller species exists.

The Dayaks tell many stories of the male orang-utans in old times carrying off their young girls, and of the latter becoming pregnant by them; but they are, perhaps, merely traditions. I have read somewhere of a huge male carrying off a Dutch girl, who was, however, immediately rescued by her father and a party of Javanese soldiers, before any injury beyond fright had occurred to her.

During the time I lived at Sarawak, we had many tame orang-utans; among others, a half-grown female called Betsy. She was an affectionate, gentle creature that might have been allowed perfect liberty, had she not taken too great a liking for the cabbage of the cultivated palms. When she climbed up one of these, she would commence tearing away the leaves to get at the coveted morsel, but shaking or striking the tree with a stick, would induce her to come down. Her cage was large, but she had a great dislike to being alone, and would follow the men about whenever she had an opportunity. At night, or when the wind was cold, she would carefully wrap herself in a blanket or rug, and of course choose the warmest corner of her cage.

After some months, we procured a very young male, and her delight was extreme. She seemed to[23] take the greatest care of it; but like most of the small ones brought in, it soon died.

When I lived in Brunei, a very young male was given me. Not knowing what to do with it, I handed it over to a family where there were many children. They were delighted with it, and made it a suit of clothes. To the trousers it never took kindly; but I have often seen him put on his own jacket in damp weather, though he was not particular about having it upside down or not. It was quite gentle and used to be fondled by the very smallest children.

I never saw but one full-grown orang-utan in the jungle, and he kept himself well sheltered by a large branch as he peered at us. He might have shown himself with perfect safety, as I never could bring myself to shoot at a monkey; but a friend who was collecting specimens saw an enormous one in a very high tree: he fired ten shots at him with a revolver, one of which hit him on the leg. As in the case when I saw the orang-utan, he kept himself well sheltered, but whenever a bullet glanced on a tree or branch near him, he put out his hand to feel what had struck the bark. When he found himself wounded, he removed to the topmost branches, and was quite exposed, but my friend’s guns were left behind him, and he failed to obtain this specimen.

It is singular that most of the orang-utans die in captivity, from eating too much raw fruit. Betsy, that was fed principally on cooked rice, must have lived a twelvemonth with us. I was not in Sarawak when she died, and do not remember the cause.

On my return, finding that the arrangements were made, we started for a fort built at the entrance of[24] the Sakarang, which was under the command of Mr. Brereton, accompanied by the Sarawak forces and the Balau Dayaks. The real value of the Batang Lupar as a river adapted for ships ceases shortly after leaving the junction, as sands begin, and a bore renders the navigation dangerous to the inexperienced; but it presents a noble expanse of water. As we started after the flood tide had commenced, the bore had passed on, and only gave notice of its late presence by a little bubbling in the shallower places.

The banks of the river continue low, with only an occasional rising of the land; nothing but alluvial plains, formerly the favourite farming grounds of the Dayaks, then completely deserted, or tenanted only by pigs and deer; but it was expected that as soon as the peace ceremonies were over, the natives would not allow this rich soil to remain uncultivated, and the expectation has been fulfilled, as this abandoned country was, on my last visit, covered with rice farms, while villages occupied the banks.

After we had passed Pamutus, the site of the piratical town destroyed by Sir Henry Keppel, the river narrows, and is not above a hundred yards broad at the town of Sakarang, built at the confluence of a river of the same name. The fort was rather an imposing-looking structure, though built entirely of wood. It was square, with flanking towers, and its heavy armament completely commanded the river, and rendered it secure against any Dayak force.

This country was at the time influenced, rather than ruled, by the late Mr. Brereton, as his real power did not extend beyond the range of his guns. I never met a man who threw himself more enthusiastically[25] into a most difficult position, or who, by his imaginative mind and yet determined will, exercised a greater power over Dayaks by the superiority of his intellect. A stranger can scarcely realize a more difficult task than that of endeavouring to rule many thousands of wild warriors without being backed by physical force; but he did a great deal, though his exertions were too much for his strength, and he died a few years after, while engaged in his arduous task. In him the Sarawak service lost an admirable officer, and we an affectionate friend.

When we landed at the fort, we found a great crowd assembled to meet us, among whom were the principal Sakarang chiefs, as Gasing and Gila. Many were fine-looking men of independent bearing and intelligent features. There were a few women about, but until the preliminaries of peace had been settled, they were not encouraged to come into the town.

It was found impossible to inquire into the origin of many of the quarrels, so Captain Brooke settled the matter by agreeing to give each party a sacred jar (valued at 8l.), a spear, and a flag. This was considered by them as satisfactory, and it was immediately determined that the next day the formal ceremonies should take place to ratify the engagement.

There is comparatively little difficulty in putting a stop to the piratical acts of the Sakarangs, as the fort commands the river; but it is almost impossible to prevent them head-hunting in the interior, there being so many unguarded outlets by which the hostile tribes can assail each other. The Bugau Dayaks—a numerous and powerful tribe, living on the Kapuas,[26] and tributary to the Dutch—were principally exposed to their expeditions, and their justifiable retaliations kept up the hostile feeling.

Whenever a head-hunting party was expected to be on its return, a strict watch was kept to prevent it passing the fort. One day, at sunset, a couple of light canoes were seen stealing along the river bank, but a shot across their bows made them pull back: they dared not come up to the fort, having three human heads with them. The sentries were doubled, and Mr. Brereton kept watch himself. About two hours before dawn, something was seen moving under the opposite bank. A musket was fired; but as the object continued floating by, it was thought to be a trunk of a tree; but no sooner had it neared the point than a yell of derision arose, as the swimming Dayaks sprang into the boat, and pulled off in high glee up the Sakarang.

To prevent all chance of the hostile tribes of Sakarangs and Balaus quarrelling before the treaty was concluded, it was arranged that the latter tribe should remain at the entrance of the Undup, a stream about two miles below the town, and that we should drop down to that spot next day.

We found a covered stage erected, and a crowd of nearly a thousand Balau men around it, and in their long war boats: the Sakarangs came also in large force, and our mediating party of about five hundred armed men was there likewise.

Captain Brooke clearly explained the object of the meeting, when the topic was taken up by the Datu Patinggi of Sarawak, who, with easy eloquence, briefly touched on the various points in question.[27] The Dayak chiefs followed; each protested that it was their desire to live in peace and friendship; they promised to be as brothers and warn each other of impending dangers. They all appear to have a natural gift of uttering their sentiments freely without the slightest hesitation.

The ceremony of killing a pig for each tribe followed; it is thought more fortunate if the animal be severed in two by one stroke of the parang, half sword, half chopper. Unluckily, the Balau champion struck inartistically, and but reached half through the animal. The Sakarangs carefully selected a parang of approved sharpness, a superior one belonging to Mr. Crookshank, and choosing a Malay skilled in the use of weapons placed the half-grown pig before him. The whole assembly watched him with the greatest interest, and when he not only cut the pig through, but buried the weapon to the hilt in the mud, a slight shout of derision arose among the Sakarangs at the superior prowess of their champion. The Balaus, however, took it in good part and joined in the noise, till about two thousand men were yelling together with all the power of their lungs.

The sacred jar, the spear, and flag, were now presented to each tribe, and the assembly, no longer divided, mixed freely together. The Balaus were invited to come up to the town, and thus was commenced a good understanding which has continued without interruption to the present time—about eleven years.

There are many kinds of sacred jars. The best known are the Gusi, the Rusa, and the Naga, all most probably of Chinese origin. The Gusi, the most valuable[28] of the three, is of a green colour, about eighteen inches high, and is, from its medicinal properties, exceedingly sought after. One fetched at Tawaran the price of four hundred pounds sterling to be paid in produce; the vendor has for the last ten years been receiving the price, which, according to his own account, has not yet been paid, though probably he has received fifty per cent. over the amount agreed on from his ignorant customer. They are most numerous in the south of Borneo. The Naga is a jar two feet in height, and ornamented with Chinese figures of dragons; they are not worth above seven or eight pounds. While the Rusa is covered with what the native artist considers a representation of some kind of deer, it is worth from fifteen to sixteen pounds. An attempt was made to manufacture an imitation in China, but the Dayaks immediately discovered the counterfeit.

We pulled up the Sakarang river to visit Gasing in his farmhouse, which was large, neat, and comfortable; in form and general appearance like their usual village houses. These Sea Dayaks are a very improvable people. I have mentioned the tender point of their character as displayed in Mr. Gomez’s school at Lundu, and another is their love of imitation. A Sakarang chief noticed a path that was cut and properly ditched near the fort, and found that in all weathers it was dry, so he instantly made a similar path from the landing place on the river to his house, and I was surprised on entering it to see coloured representations of horses, knights in full armour, and ships drawn vigorously, but very inartistically, on the plank walls. I found, on inquiry, he had been given some[29] copies of the Illustrated London News, and had endeavoured to imitate the engravings. He used charcoal, lime, red ochre, and yellow earth as his materials.

The Sakarang women are, I think, the handsomest among the Dayaks of Borneo; they have good figures, light and elastic; with well-formed busts and very interesting, even pretty faces; with skin of so light a brown as almost to be yellow, yet a very healthy-looking yellow, with bright dark eyes, and long glistening black hair. The girls are very fond of using an oil made from the Katioh fruit, which has the scent of almonds. Their dress is not unbecoming, petticoats reaching from below the waist to the knees, and jackets ornamented with fringe. All their clothes are made from native cloth of native yarn, spun from cotton grown in the country. These girls are generally thought to be lively in conversation and quick in repartee.

The Sakarang men are clean built, upright in their gait, and of a very independent bearing. They are well behaved and gentle in their manners: and, on their own ground, superior to all others in activity. Their national dress is a chawat or waistcloth, and in warlike expeditions they are partial to bright red cloth jackets, so that when assembled at a distance, they look like a party of English soldiers. The Sakarang and Seribas men have the peculiar practice of wearing rings all along the edge of their ears, sometimes as many as a dozen. I thought this custom confined to them, but I find the Muruts of Padas, opposite Labuan, also practise it.

Their strength and activity are remarkable. I have[30] seen a Dayak carry a heavy Englishman down the steepest hills; and when one of their companions is severely wounded they bear him home, whatever may be the distance. They exercise a great deal from boyhood in wrestling, swimming, running, and sham-fighting, and are excellent jumpers. When a little more civilized they would make good soldiers, being brave by nature. They are, however, short—a man five feet five inches high would be considered tall, the average is perhaps five feet three inches.

We did not visit the interior of the Batang Lupar, but it is reported to be very populous, and the Chinese are now working gold there. I have penetrated to the very sources of the Sakarang, and found it, after a couple of days’ pull, much encumbered by drift-wood and rocks, with shallow rapids over pebbly beds. This interior is very populous, and from a view we had on a hill over the upper part of the Seribas River, as far as the hills in which the Kanowit rises, we could perceive but little old forest.

I may mention that the crime of poisoning is almost unknown on the north-west coast, but it is very generally believed the people of the interior of the Kapuas, a few days’ walk from the Batang Lupar, are much given to the practice. Sherif Sahib, and many others who visited that country, died suddenly, and the Malays assert it was from poison; but of this I have no proof.

Near the very sources of the Kapuas live the Malau Dayaks, who are workers in gold and brass, and it is very singular that members of this tribe can wander safely through the villages of the head-hunting Seribas and Sakarang, and are never molested,—on[31] the contrary, they are eagerly welcomed by the female portion of the population, and the young men are not indifferent to their arrival; but the specimens of their work that I have seen do not show much advance in civilization. The Malau districts produce gold, and it is said very fine diamonds.

I will insert here an anecdote of the public executioner of Sakarang. Last year, a native was tried and condemned to death for a barbarous murder, and according to the custom in Malay countries, the next day was fixed for carrying out the sentence. A Chinese Christian lad, who was standing near the executioner, said to him earnestly, “What! no time given him for repentance?” “Repentance!” cried the executioner, contemptuously. “Repentance! he is not a British subject.” A curious confusion of ideas. Both were speaking in English, and very good English.

I tasted here, for the first time, the rambi fruit, that looks something like a large grape, growing in bunches, pleasantly sweet, yet with a slight acidity, yellow skin, with the interior divided into two fleshy pulps.

At the broadest part of the Batang Lupar, nearly four miles across, I saw a herd of pigs swimming from one shore to the other. If pigs do this with ease, we need not be surprised that the tigers get over the old Singapore Strait to devour, on a low average, a man a day.

On our return, while anchored at Pamutus, we saw the bore coming up, and it was a pretty sight from our safe position. A crested wave spread from shore to shore, and rushed along with inconceivable speed, to subside as it approached deep water, to commence[32] again at the sands with as great violence when it had passed us. At full and change, few native boats escape which are caught on the shallows, but are rolled over and over, and the men are dashed breathless on the bank, few escaping with life.

Some of our Malays went ashore last night to snare deer, while the Balaus tried for pigs. It used to be a very favourite hunting ground of the Dayaks, who are expert in everything appertaining to the jungle; they nearly always employ dogs, which are very small, not larger than a spaniel, sagacious and clever in the jungle, but stupid, sleepy-looking creatures out of it, having all the attributes of bad-looking, mongrel curs as they lurk about the houses; but when some four or five are led into the jungle, dense and pathless as it is in most places, then they are ready to attack a wild boar ten times their size. And the wild boar of the East is a very formidable animal. I have seen one that measured forty inches high at the shoulder, with a head nearly two feet in length. Sir Henry Keppel also was present when this was shot, and he thought a small child could have sat within its jaws. Captain Hamilton of the 21st M. N. I., a very successful sportsman, killed one forty-two inches high. Native hunting with good dogs is easy work; the master loiters about gathering rattans, fruit, or other things of various uses to his limited wants, and the dogs beat the jungle for themselves, and when they have found a scent, give tongue, and soon run the animal to bay: the master knowing this by the peculiar bark, follows quickly and spears the game.

I have known as many as six or seven pigs killed[33] before midday by Dayaks while walking along a beach: their dogs searching on the borders of the forest, bring the pigs to bay, but never really attack till the master comes with his spear to help them. The boars are very dangerous when wounded, as they turn furiously on the hunter, and unless he has the means of escape by climbing a tree, he would fare ill in spite of his sword and spear, if it were not for the assistance of his dogs. These creatures, though small, never give in unless severely wounded, and by attacking the hind legs, keep the pig continually turning round.

The Dayaks are very fond of pork, and fortunately it is so, or they would be much more easily persuaded to become Mahomedans. They have a sort of respect for the domestic pig, and an English gentleman was in disgrace at Lingga on account of allowing his dogs to hunt one that they met in the fruit-groves, which in any civilized country would have been considered wild. The European sportsman said in his defence, that he could not help clapping his hands when he heard his dogs give tongue in chase. Upon a hot day a deer is soon run down by them; in fact, hunters declare that they could easily catch them themselves in very dry weather, when the heat is extremely oppressive. The deer have regular bathing-places to which they resort, sometimes during the day, and at others by night.

There are, I believe, only two kinds of deer in Borneo, one Rusa Balum, and the other Rusa Lalang. The former frequents low swampy ground, and has double branched horns, averaging about eighteen inches in length. The Rusa Lalang is a small,[34] plump, hill deer, with short horns, and having one fork branch near the roots.

The Dayaks say there is another kind; but after making many inquiries, it appears to be the same as Rusa Balum. Occasionally you meet with deer whose horns are completely encased in skin.

The natives snare them with rattan loops and nooses, fastened on a long rope. They are of different lengths, varying from twenty to fifty feet. A number of these attached to each other, and resting on the tops of forked sticks, they stretch across a point of land where they have previously ascertained that deer are lying. After they have arranged the snares, the party is divided, one division watching them, and the other landing on the point; barking dogs and yelling men rush up towards the snare, driving the game before them; the deer, though they sometimes lie very close, generally spring up immediately and dart off bewildered, rushing into the nooses, catching their necks or their fore legs in them; the men on the watch dash up and cut them down, or spear them before they can break through. They sometimes catch as many as twenty in one night, but generally only one or two; snaring may be carried on either in the light or dark.

The evening we set sail from the Batang Lupar, we had a discussion on Marsden’s theory of the land and sea breezes; one of our party denied the correctness of the authority whom we looked upon as not to be challenged in all that relates to the Eastern Archipelago. At midnight the land breeze commenced blowing, as the ocean does retain the heat longer than the land, and at midday the sea breeze set in, which[35] carried us pleasantly onward, passing the mouths of the Seribas and Kalaka, to our anchorage in the noble river of Rejang. We did not triumph over our adversary, but recommended him to study Marsden more carefully. On the bar at the entrance of this river at dead low water, we had one cast which did not exceed three fathoms, but I do not think we were in the centre of the channel.

At the entrance of the Rejang is a small town of Milanaus, a people differing greatly from the Malays in manners and customs; some converted to Islamism are clothed like other Mahomedans, while those who still delight in pork dress like Dayaks, to which race they undoubtedly belong. Their houses are built on lofty posts, or rather whole trunks of trees are used for the purpose, to defend themselves against the Seribas.

It is stated that at the erection of the largest house, a deep hole was dug to receive the first post, which was then suspended over it; a slave girl was placed in the excavation, and at a signal the lashings were cut, and the enormous timber descended, crushing the girl to death. It was a sacrifice to the spirits. I once saw a more quiet imitation of the same ceremony. The chief of the Quop Dayaks was about to erect a flag-staff near his house: the excavation was made, and the timber secured, but a chicken only was thrown in and crushed by the descending flag-staff.

I made particular inquiries of Haji Abdulraman, and his followers, of Muka, whilst I was in Brunei last year. They said that the Milanaus of their town who remained unconverted to Islamism have within the last few years sacrificed slaves at the death of a respectable[36] man, and buried them with the corpse, in order that they might be ready to attend their master in the other world. This conversation took place in the presence of the Sultan, who said he had often heard the report of such acts having been committed. One of the nobles present observed that such things were rare, but that he had known of a similar sacrifice taking place among the Bisayas of the River Kalias, opposite our colony of Labuan. He said a large hole was dug in the ground, in which was placed four slaves and the body of the dead chief. A small supply of provisions was added, when beams and boughs were thrown upon the grave, and earth heaped to a great height over the whole. A prepared bamboo was allowed to convey air to those confined, who were thus left to starve. These sacrifices can seldom occur, or we should have heard more of them. There were rumours, however, that at the death of the Kayan chief Tamawan, whom I met during my expedition to the Baram, slaves were devoted to destruction, that they might follow him in the future world.

In front of the houses were erected swings for the amusement of the young lads and the little children. One about forty feet in height was fastened to strong poles arranged as a triangle, and kept firm in their position by ropes like the shrouds of a ship. From the top hung a strong cane rope, with a large ring or hoop at the end. About thirty feet on one side was erected a sloping stage as a starting-point. Mounting on this, one of the boys with a string drew the hoop towards him, and making a spring into it, away he went. Other lads were ready, who successively sprung upon the ring or seized the rope, until there were[37] five or six in a cluster, shouting, laughing, yelling and swinging. For the younger children smaller ones were erected, as it required courage and skill to play on the larger.

The Rejang is one of the finest rivers in Borneo, and extends far into the interior. We ascended it upwards of one hundred miles, and never had less than four fathoms. Mr. Steel, who lived many years at the Kanowit fort, told me that it continued navigable for about forty miles farther, then there were dangerous rapids, but above them the water again deepened. The Rejang has many mouths, but the principal are the one we entered, and another to the eastward of Cape Sirik, called Egan. Its tributaries below the rapids are the Sirikei, the Kanowit, and the Katibas, the last two very populous.

Above the junction, the Rejang is about a mile and a half broad, with islets scattered over it, but afterwards it contracts to about a thousand yards, and has a fine appearance. The scenery here is not varied by hill or dale; the land is low, but the banks were rendered interesting by the varied tints of the jungle; blossoms and young leaves were bursting out in every variety of colour, from the faintest green to the darkest brown.

The air was filled with a kind of may-fly in astonishing numbers; I have never seen anything like it before or since: they fell by myriads into the water, and afforded a feast to thousands of fish that rose with a dash to the surface, covering the river with tiny widening circles.

During our passage up we had an instance of the insecurity to which the head-hunters formerly reduced[38] this country. We landed at a place called Munggu Ayer (water hill) to bathe; a party of our men insisted on keeping watch over us, as many people had lost their lives here. Being a good spot to procure water, boats are accustomed to take in their supplies at this well, and the Dayaks lurked in the neighbouring jungle to rush out on the unwary.