ON THE GREAT ASWAN DAM

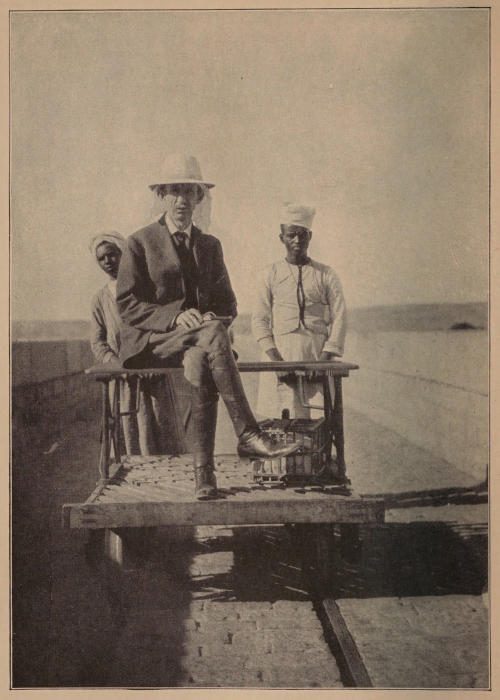

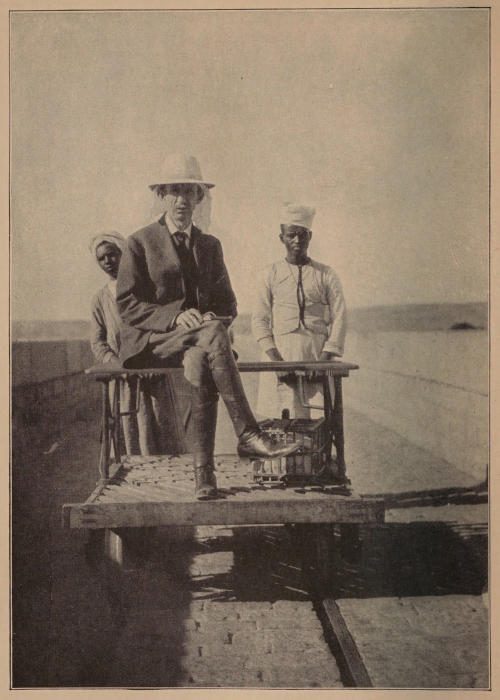

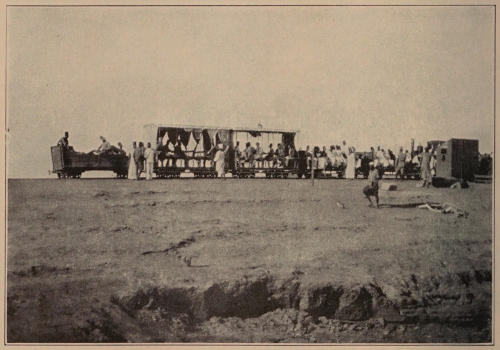

“The dam serves also as a bridge over the Nile. I crossed on a car, my motive power being two Arab boys who trotted behind.”

Title: Cairo to Kisumu

Subtitle: Egypt--The Sudan--Kenya Colony

Author: Frank G. Carpenter

Release Date: September 14, 2023 [eBook #71651]

Language: English

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CARPENTER’S

WORLD TRAVELS

Familiar Talks About Countries

and Peoples

WITH THE AUTHOR ON THE SPOT AND

THE READER IN HIS HOME, BASED

ON THREE HUNDRED THOUSAND

MILES OF TRAVEL

OVER THE GLOBE

CAIRO TO KISUMU

EGYPT—THE SUDAN—KENYA COLONY

ON THE GREAT ASWAN DAM

“The dam serves also as a bridge over the Nile. I crossed on a car, my motive power being two Arab boys who trotted behind.”

CARPENTER’S WORLD TRAVELS

CAIRO TO KISUMU

Egypt—The Sudan—Kenya

Colony

BY

FRANK G. CARPENTER

LITT.D., F.R.G.S.

WITH 115 ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS

AND TWO MAPS IN COLOUR

GARDEN CITY NEW YORK

DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY

1923

COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY

FRANK G. CARPENTER

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED, INCLUDING THAT OF TRANSLATION

INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES, INCLUDING THE SCANDINAVIAN

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES

AT

THE COUNTRY LIFE PRESS, GARDEN CITY, N. Y.

First Edition

In the publication of this book on Egypt, the Sudan, and Kenya Colony, I wish to thank the Secretary of State for letters which have given me the assistance of the official representatives of our government in the countries visited. I thank also our Secretary of Agriculture and our Secretary of Labour for appointing me an Honorary Commissioner of their Departments in foreign lands. Their credentials have been of the greatest value, making available sources of information seldom open to the ordinary traveller. To the British authorities in the regions covered by these travels I desire to express my thanks for exceptional courtesies which have greatly aided my investigations.

I would also thank Mr. Dudley Harmon, my editor, and Miss Ellen McBryde Brown and Miss Josephine Lehmann for their assistance and coöperation in the revision of the notes dictated or penned by me on the ground.

While most of the illustrations are from my own negatives, these have been supplemented by photographs from the Publishers’ Photo Service and the American Geographic Society.

F. G. C.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Just a Word Before We Start | 1 |

| II. | The Gateway to Egypt | 3 |

| III. | King Cotton on the Nile | 13 |

| IV. | Through Old Egypt to Cairo | 22 |

| V. | Fellaheen on Their Farms | 29 |

| VI. | The Prophet’s Birthday | 41 |

| VII. | In the Bazaars of Cairo | 49 |

| VIII. | Intimate Talks with Two Khedives | 58 |

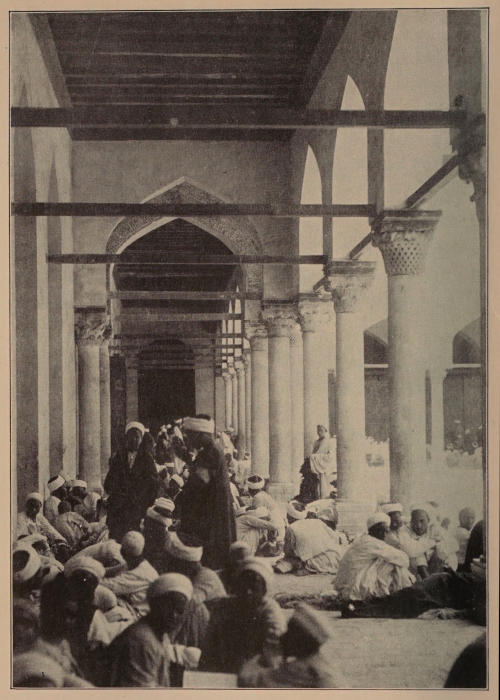

| IX. | El-Azhar and Its Ten Thousand Moslem Students | 70 |

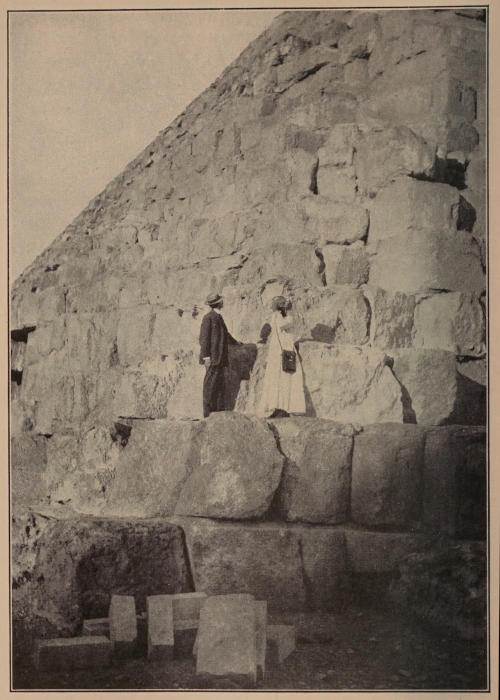

| X. | Climbing the Great Pyramid | 79 |

| XI. | The Pyramids Revisited | 87 |

| XII. | Face to Face with the Pharaohs | 96 |

| XIII. | The American College at Asyut | 106 |

| XIV. | The Christian Copts | 112 |

| XV. | Old Thebes and the Valley of the Kings | 117 |

| XVI. | The Nile in Harness | 128 |

| XVII. | Steaming through the Land of Cush | 140 |

| XVIII. | From the Mediterranean to the Sudan | 149 |

| XIX. | Across Africa by Air and Rail | 160[x] |

| XX. | Khartum | 167 |

| XXI. | Empire Building in the Sudan | 175 |

| XXII. | Why General Gordon Had No Fear | 181 |

| XXIII. | Omdurman, Stronghold of the Mahdi | 187 |

| XXIV. | Gordon College and the Wellcome Laboratories | 200 |

| XXV. | Through the Suez Canal | 208 |

| XXVI. | Down the Red Sea | 218 |

| XXVII. | Along the African Coast | 224 |

| XXVIII. | Aden | 229 |

| XXIX. | In Mombasa | 236 |

| XXX. | The Uganda Railway | 243 |

| XXXI. | The Capital of Kenya Colony | 252 |

| XXXII. | John Bull in East Africa | 261 |

| XXXIII. | With the Big-Game Hunters | 269 |

| XXXIV. | Among the Kikuyus and the Nandi | 277 |

| XXXV. | The Great Rift Valley and the Masai | 285 |

| XXXVI. | Where Men Go Naked and Women Wear Tails | 293 |

| See the World with Carpenter | 303 | |

| Bibliography | 305 | |

| Index | 309 | |

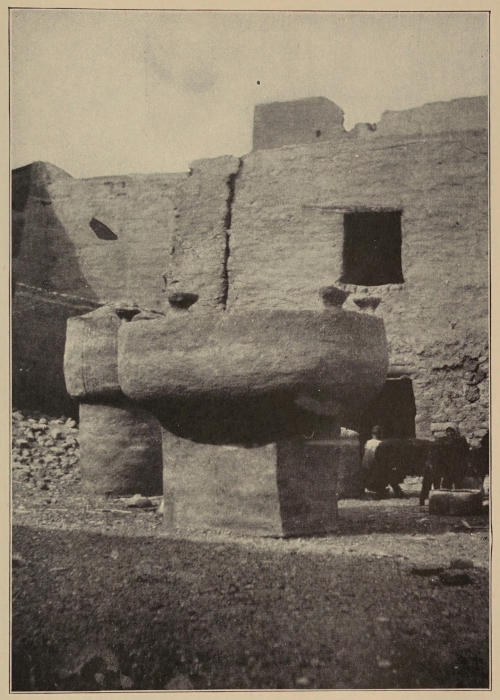

| On the great Aswan Dam | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

| The bead sellers of Cairo | 2 |

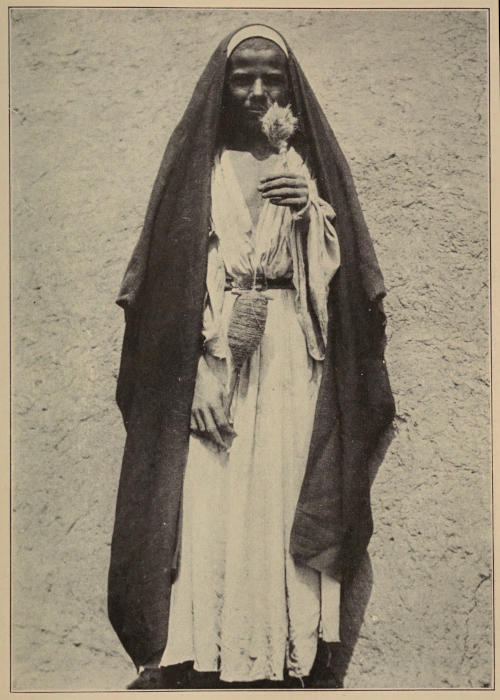

| The veiled women | 3 |

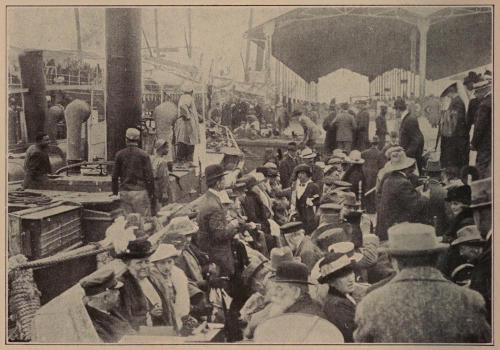

| On the cotton docks of Alexandria | 6 |

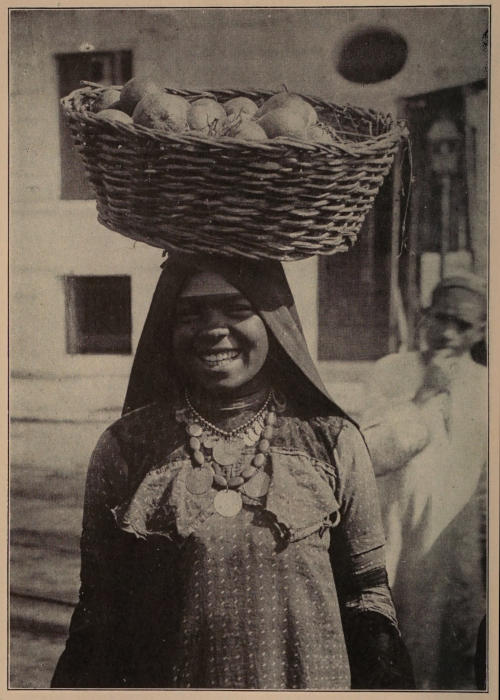

| Nubian girls selling fruit | 7 |

| Woman making woollen yarn | 14 |

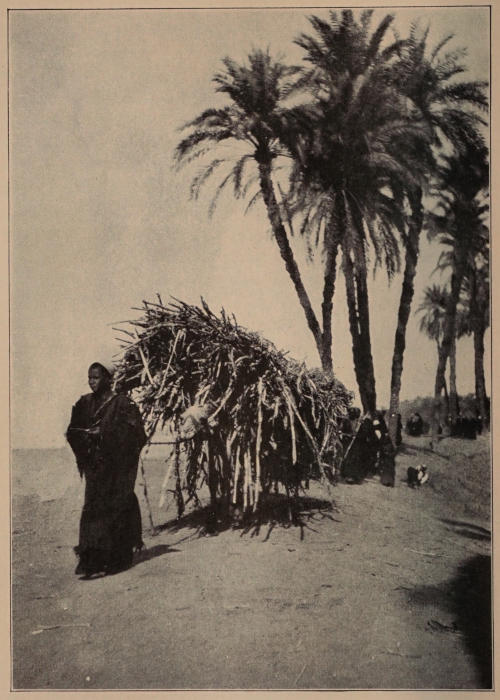

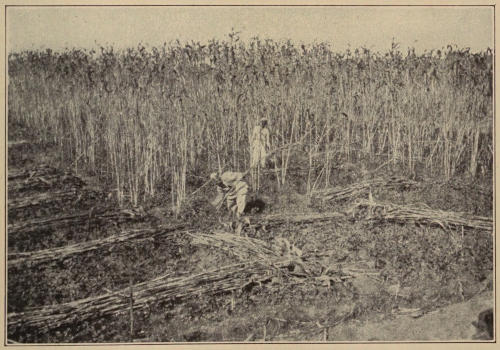

| Fresh-cut sugar cane | 15 |

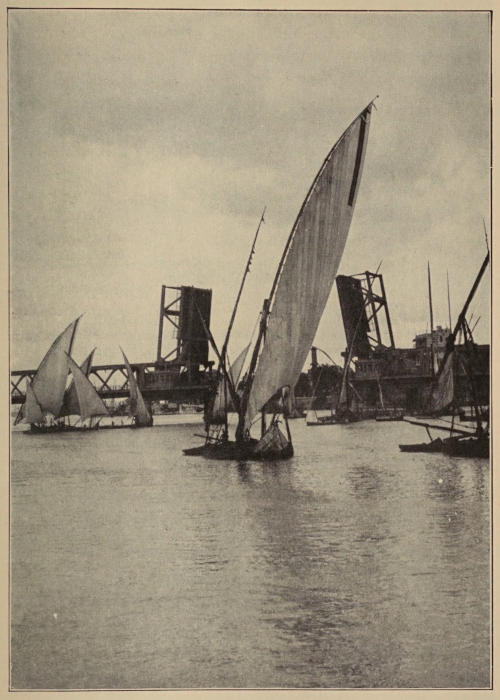

| One of the mill bridges | 18 |

| The ancient sakieh | 19 |

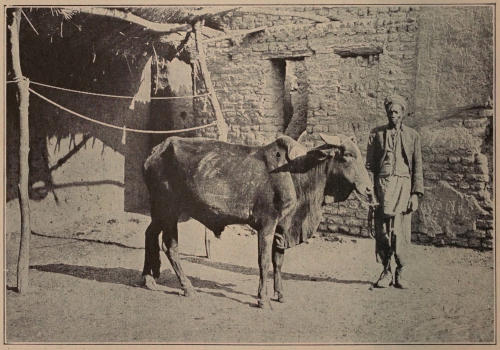

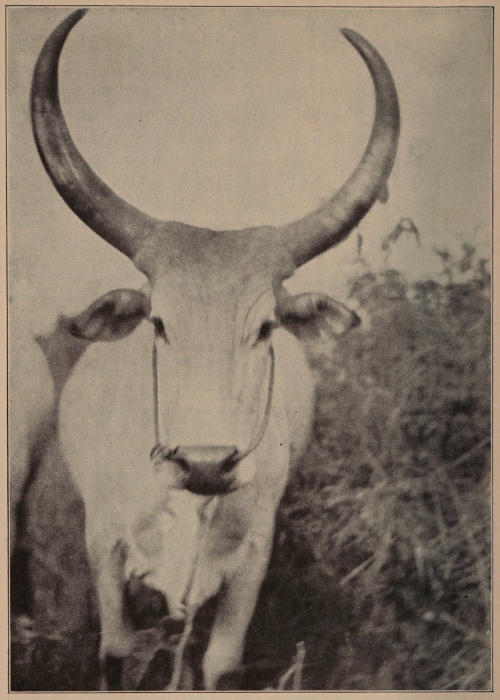

| The native ox | 19 |

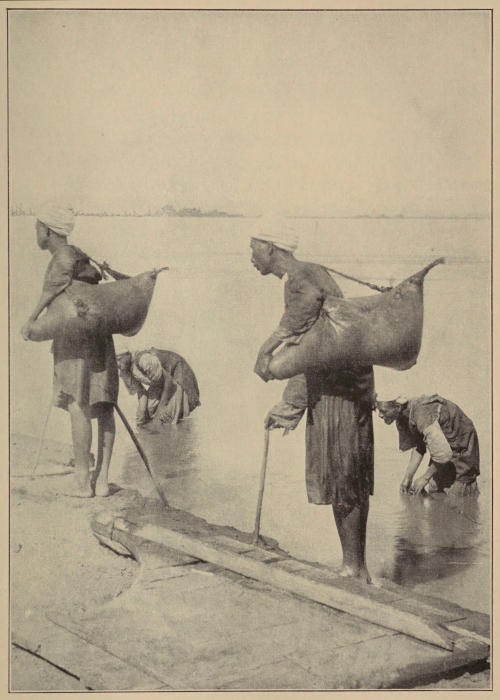

| Water peddlers at the river | 22 |

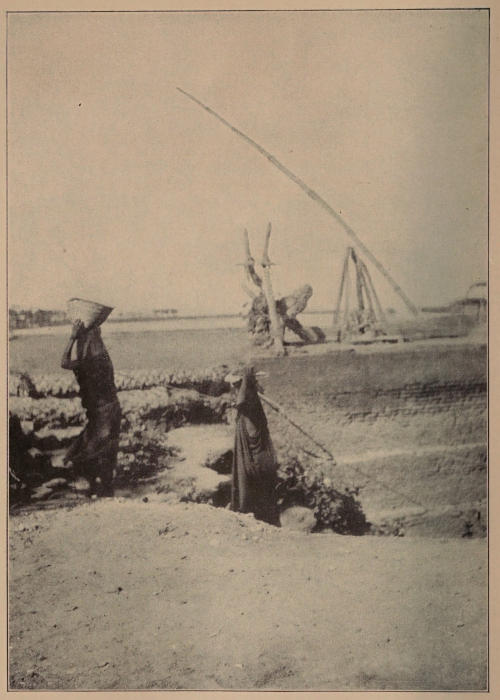

| Women burden bearers | 23 |

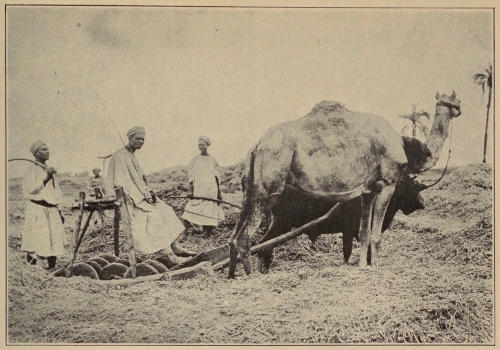

| Threshing wheat with norag | 30 |

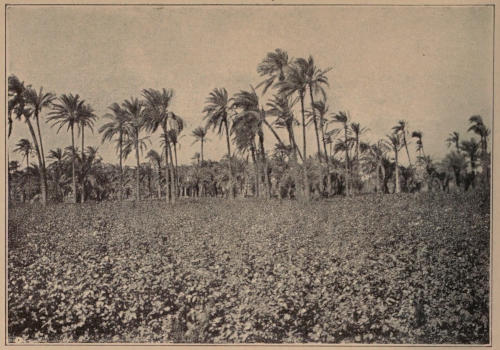

| A corn field in the delta | 30 |

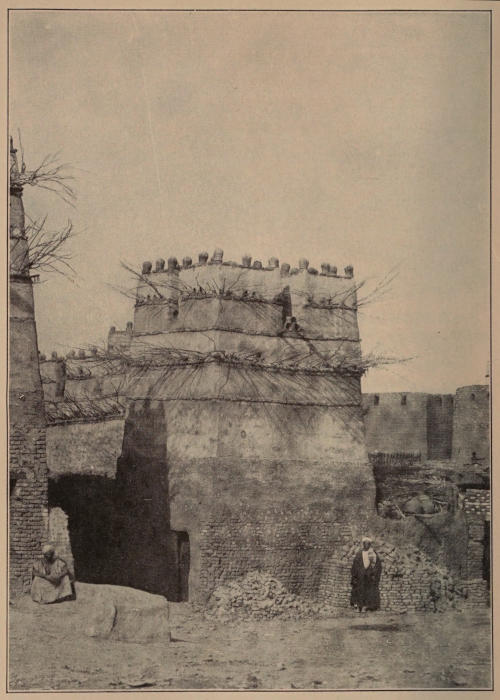

| The pigeon towers | 31 |

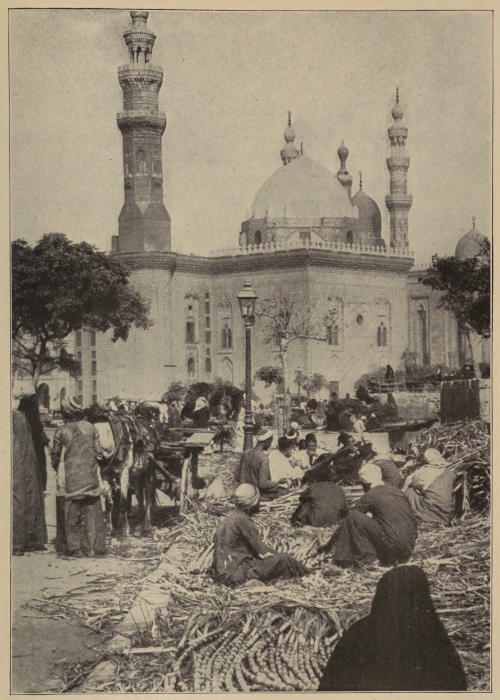

| In the sugar market | 38 |

| Flat roofs and mosque towers of Cairo | 39 |

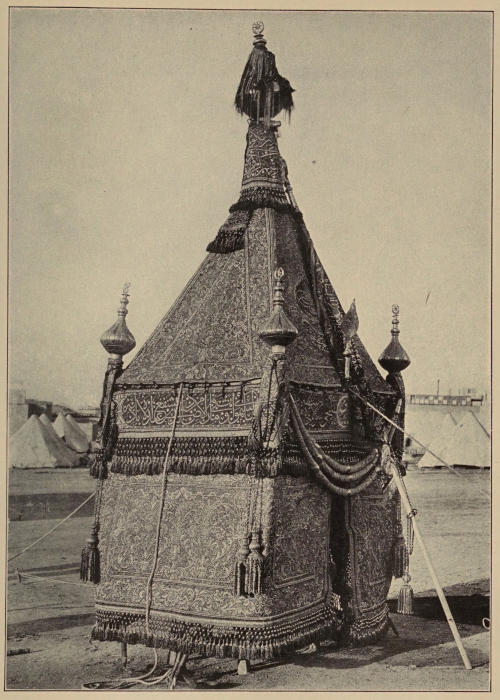

| Tent of the sacred carpet | 46 |

| The Alabaster Mosque | 47 |

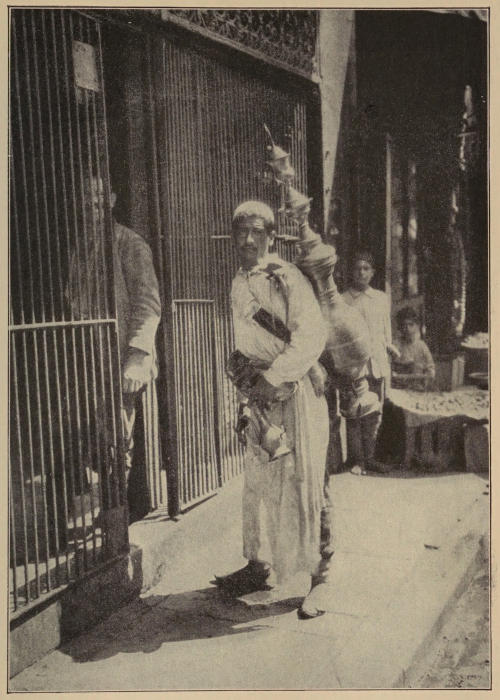

| “Buy my lemonade!” | 54 |

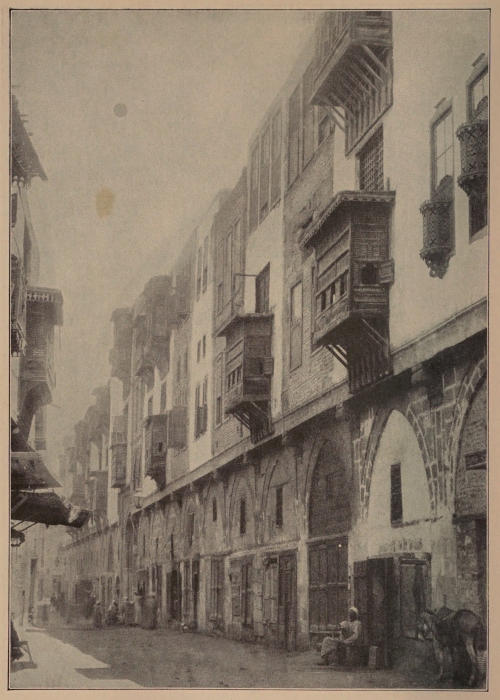

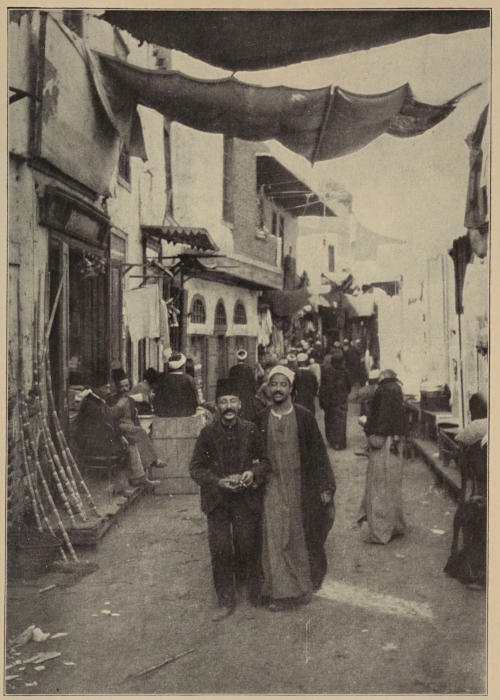

| A street in old Cairo | 55 |

| Gates of the Abdin Palace | 62 |

| The essential kavass | 63 |

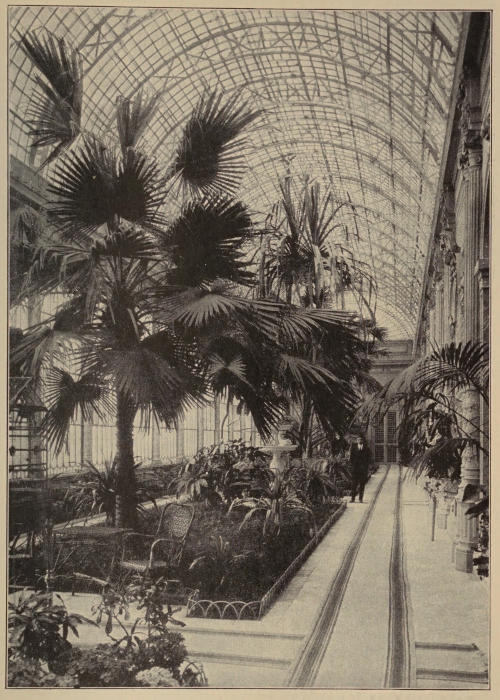

| In the palace conservatory | 66 |

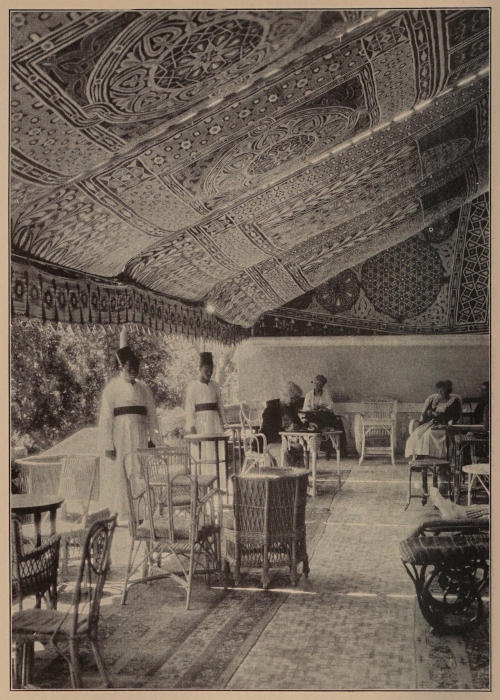

| The famous Shepheard’s Hotel | 67[xii] |

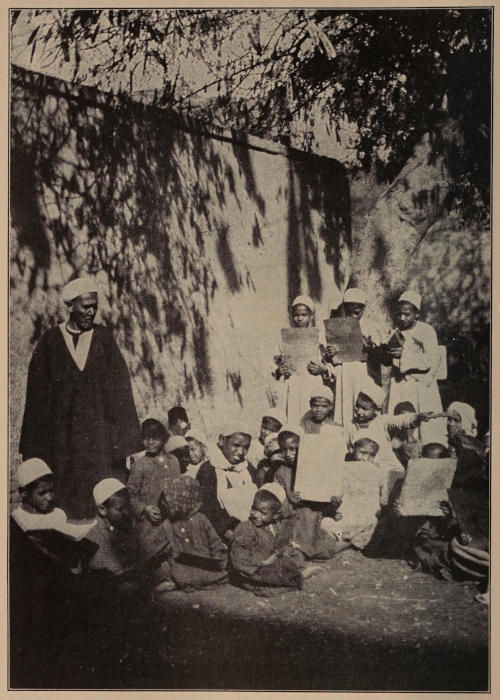

| Learning the Koran | 67 |

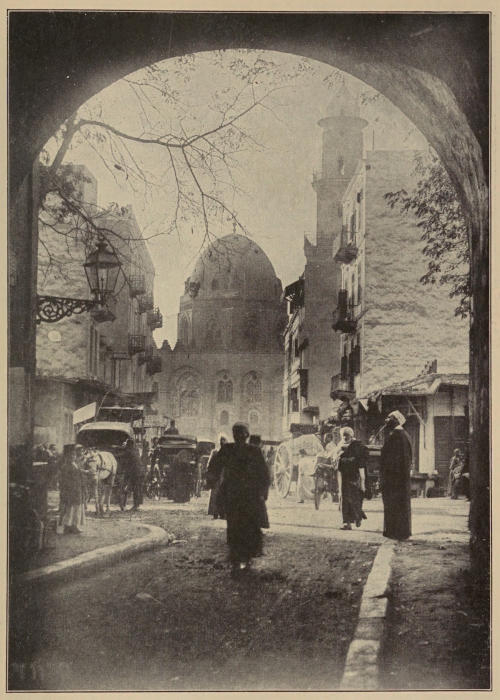

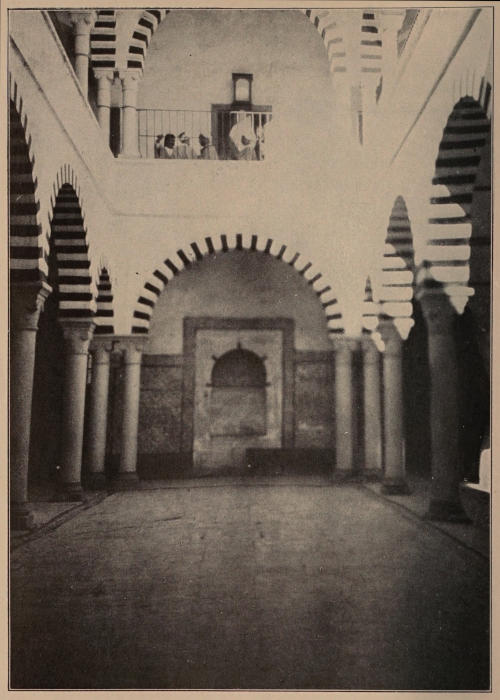

| Approaching El-Azhar | 70 |

| In the porticos of El-Azhar | 71 |

| The Pyramids | 78 |

| Mr. Carpenter climbing the Pyramids | 79 |

| Standing on the Sphinx’s neck | 82 |

| Taking it easy at Helouan | 83 |

| View of the Pyramids | 86 |

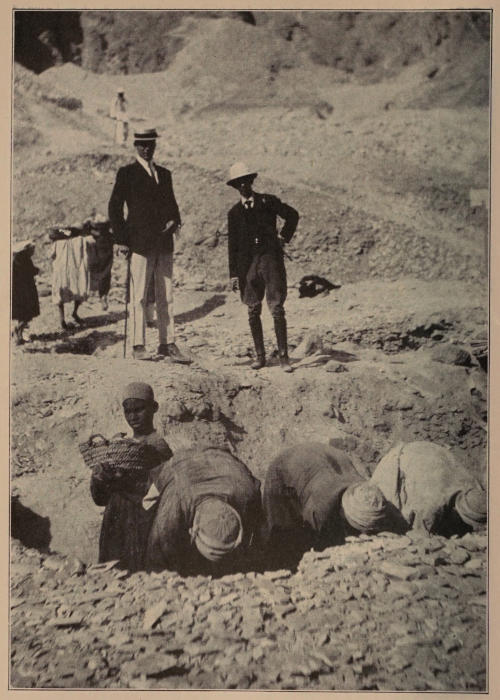

| Uncovering tombs of ancient kings | 87 |

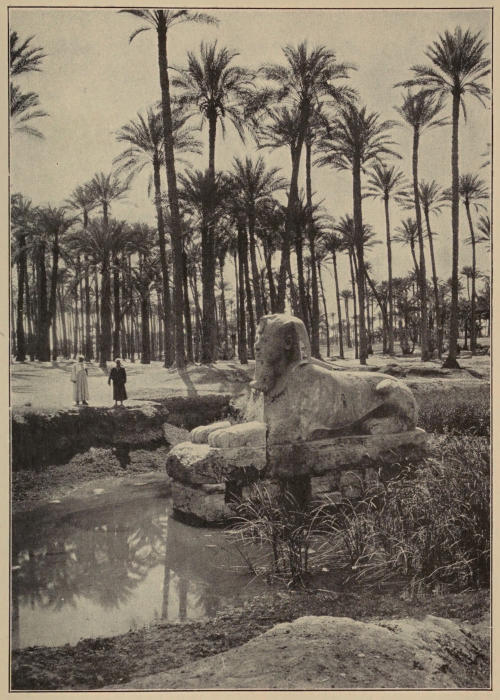

| The alabaster Sphinx | 94 |

| The great museum at Cairo | 95 |

| Students at Asyut College | 102 |

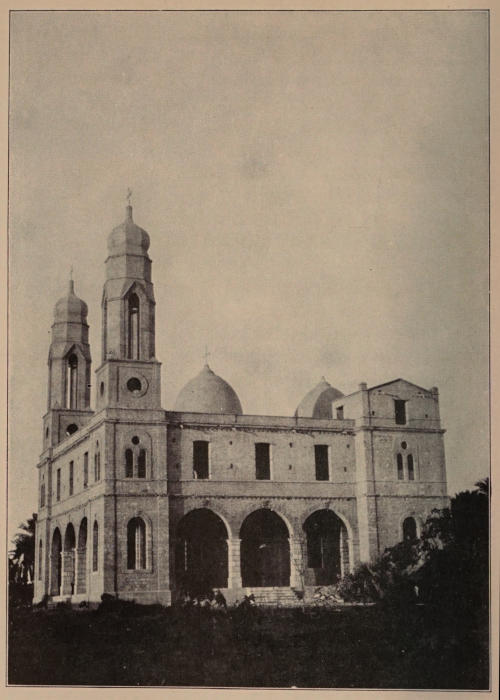

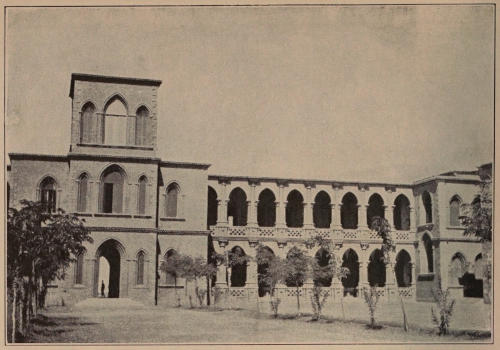

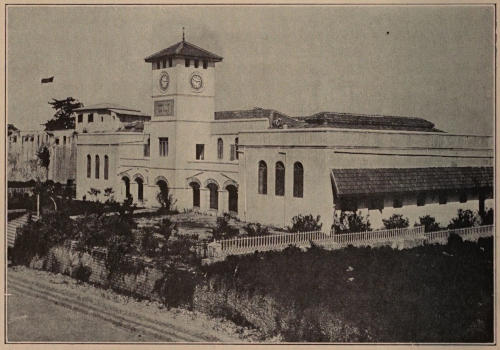

| American College at Asyut | 103 |

| Between classes at the college | 103 |

| In the bazaars | 110 |

| A native school in an illiterate land | 111 |

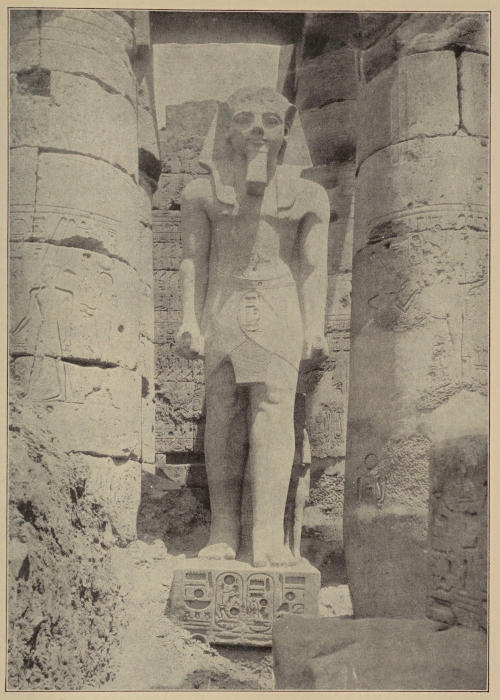

| The greatest egoist of Egypt | 118 |

| The temple tomb of Hatshepsut | 119 |

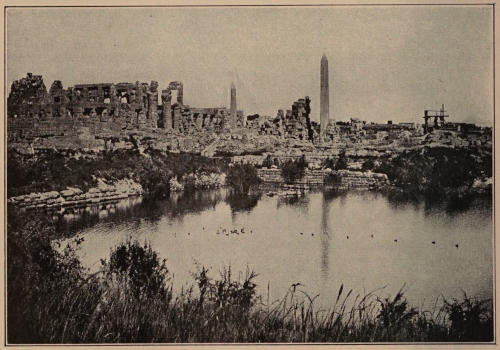

| Sacred lake before the temple | 119 |

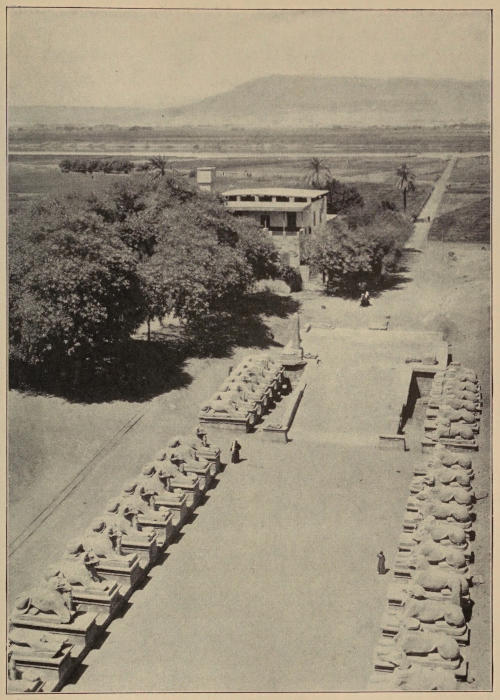

| The avenue of sphinxes | 126 |

| The dam is over a mile long | 127 |

| Lifting water from level to level | 134 |

| Where the fellaheen live | 135 |

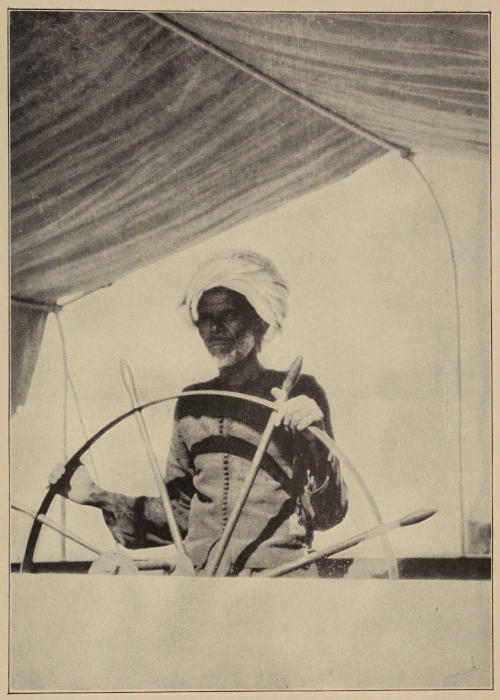

| A Nubian pilot guides our ship | 142 |

| Pharaoh’s Bed half submerged | 143 |

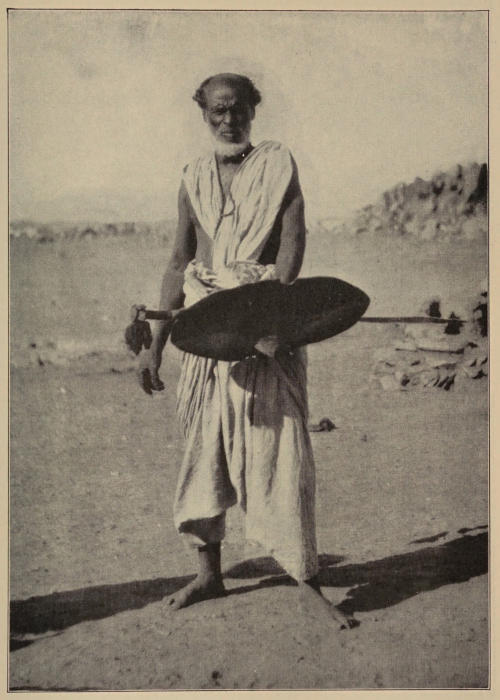

| An aged warrior of the Bisharin | 150 |

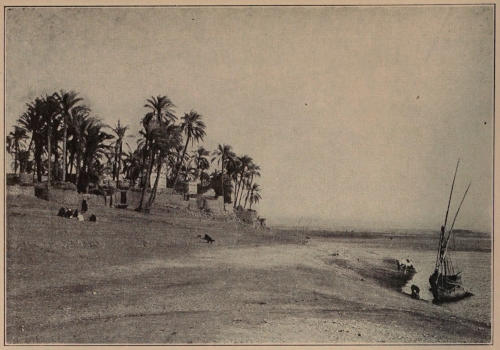

| A mud village on the Nile | 151 |

| Where the Bisharin live | 151 |

| A safe place for babies | 158 |

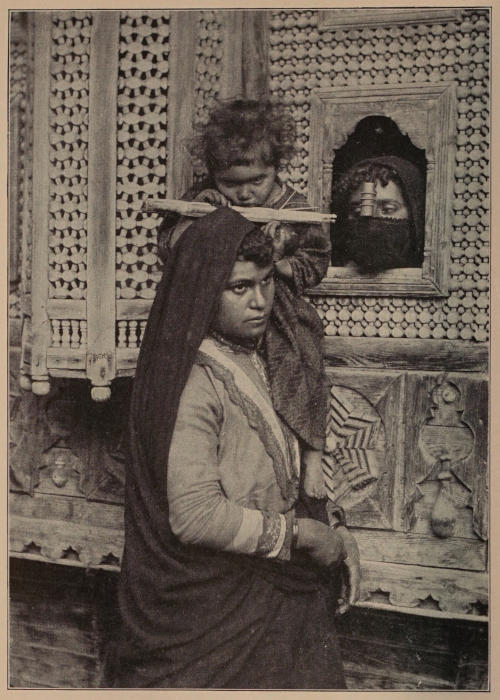

| Mother and child | 159 |

| A bad landing place for aviators | 162 |

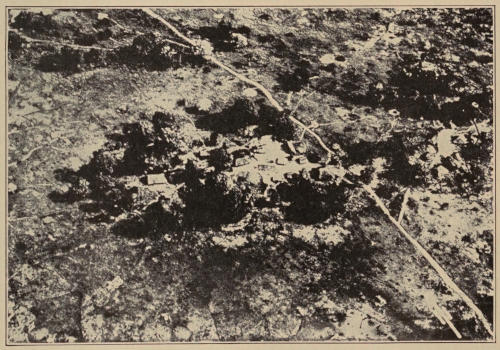

| Over the native villages | 162[xiii] |

| The first king of free Egypt | 163 |

| Soldiers guard the mails | 166 |

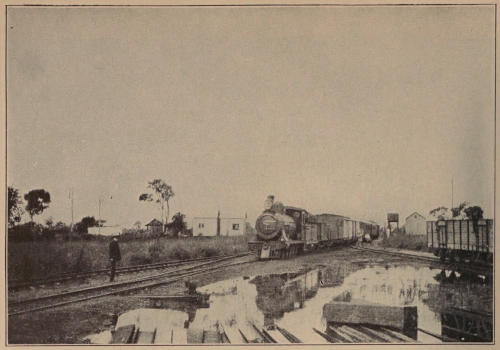

| An American locomotive in the Sudan | 167 |

| Light railways still are used | 167 |

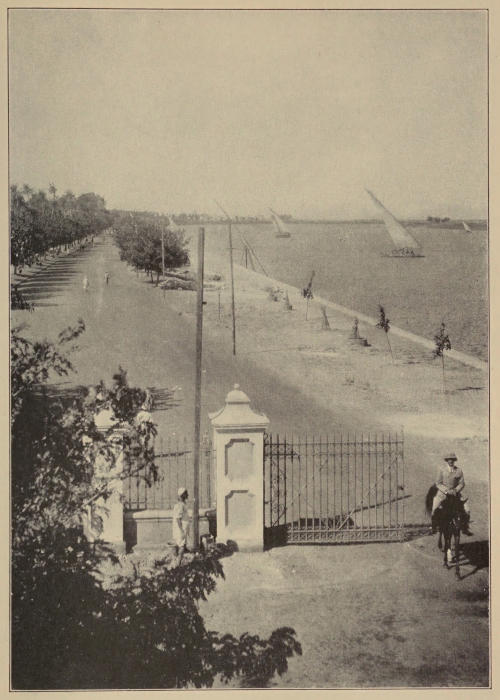

| Along the river in Khartum | 174 |

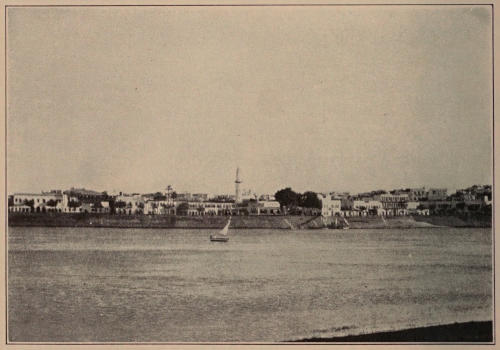

| Where the Blue and the White Nile meet | 175 |

| The modern city of Khartum | 175 |

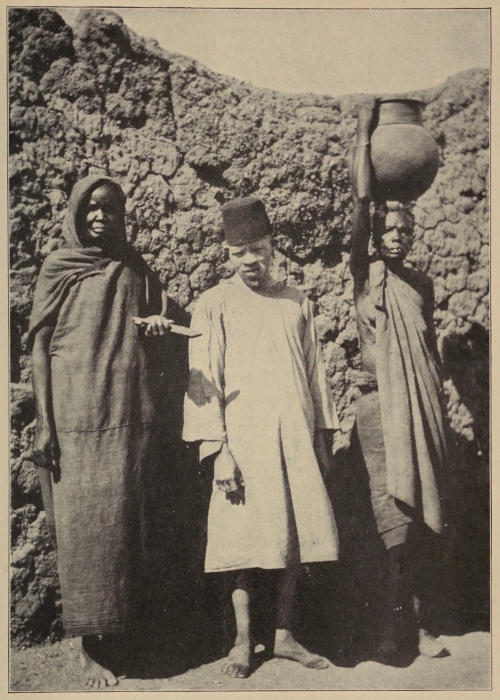

| A white negro of the Sudan | 178 |

| Where worshippers stand barefooted for hours | 179 |

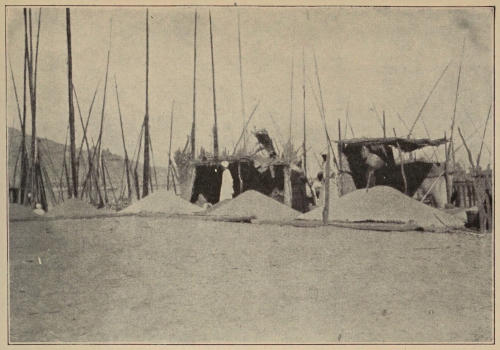

| Grain awaiting shipment down river | 182 |

| “Backsheesh!” is the cry of the children | 182 |

| Cotton culture in the Sudan | 183 |

| The Sirdar’s palace | 183 |

| The bride and her husband | 190 |

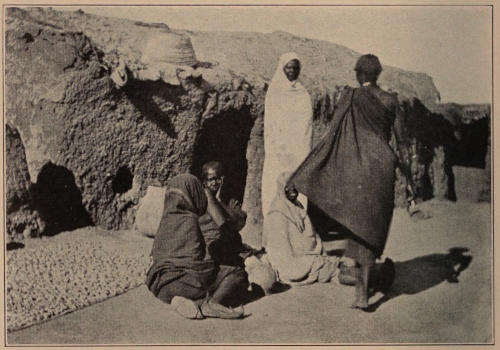

| Omdurman, city of mud | 191 |

| Huts of the natives | 191 |

| A Shilouk warrior | 198 |

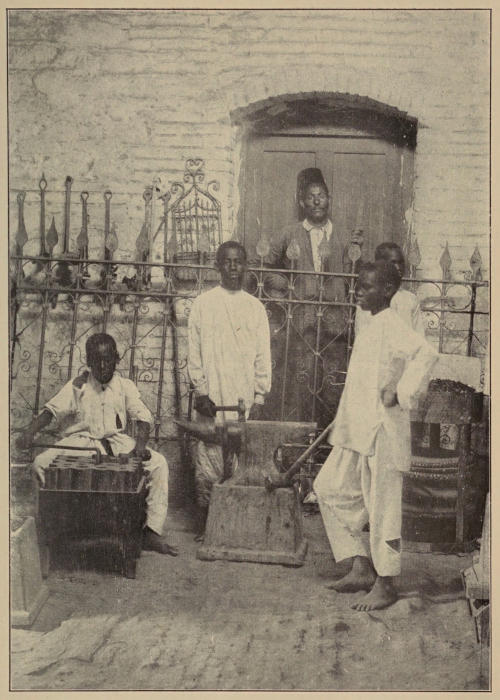

| In Gordon College | 199 |

| Teaching the boys manual arts | 206 |

| View of Gordon College | 207 |

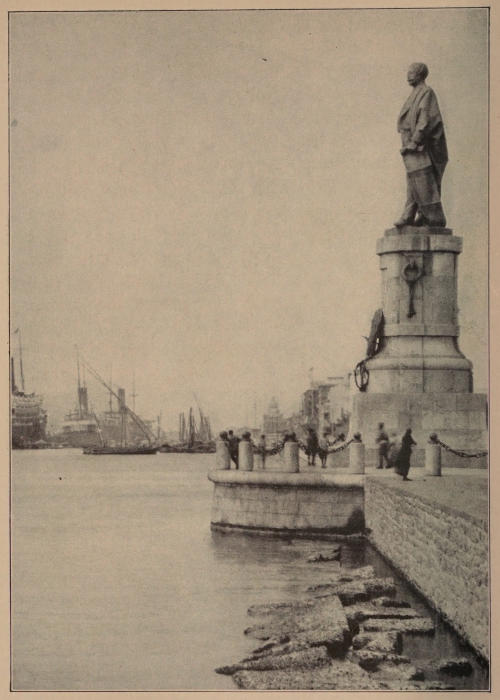

| On the docks at Port Said | 207 |

| Fresh water in the desert | 210 |

| The entrance to the Suez Canal | 211 |

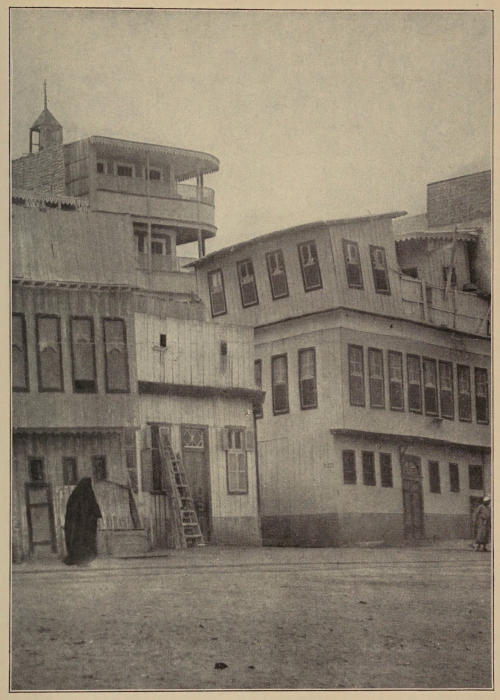

| A street in dreary Suez | 226 |

| Ships passing in the canal | 227 |

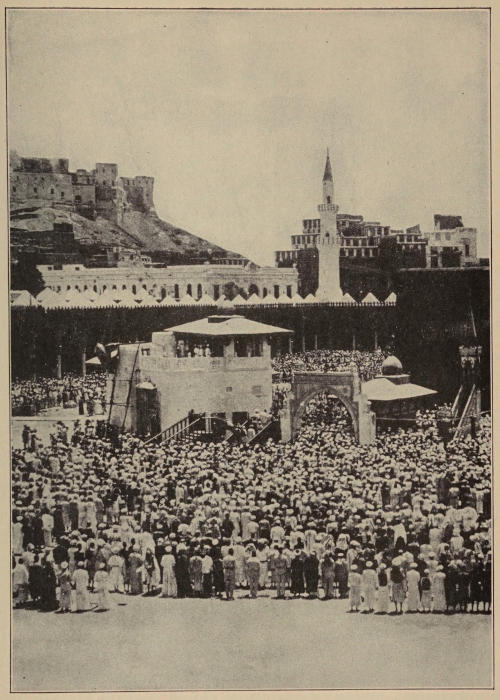

| Pilgrims at Mecca | 230 |

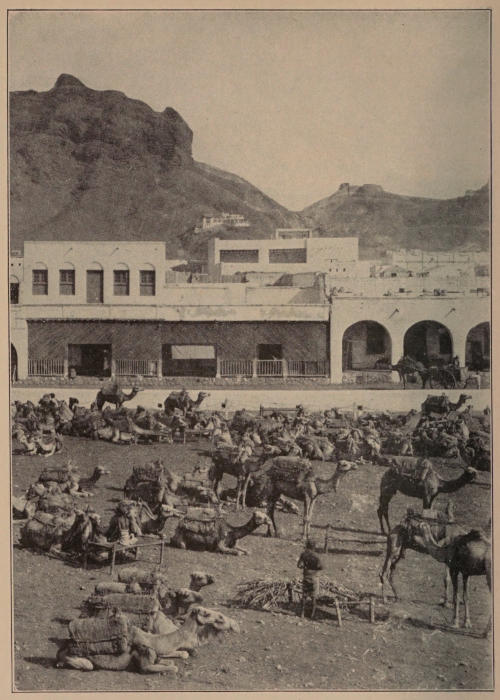

| Camel market in Aden | 231 |

| Harbour of Mombasa | 238 |

| Where the Hindus sell cotton prints | 239 |

| The merchants are mostly East Indians | 239 |

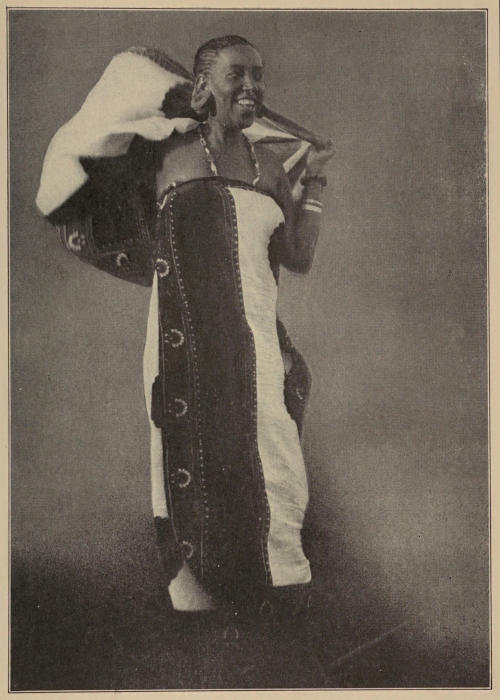

| A Swahili beauty | 242 |

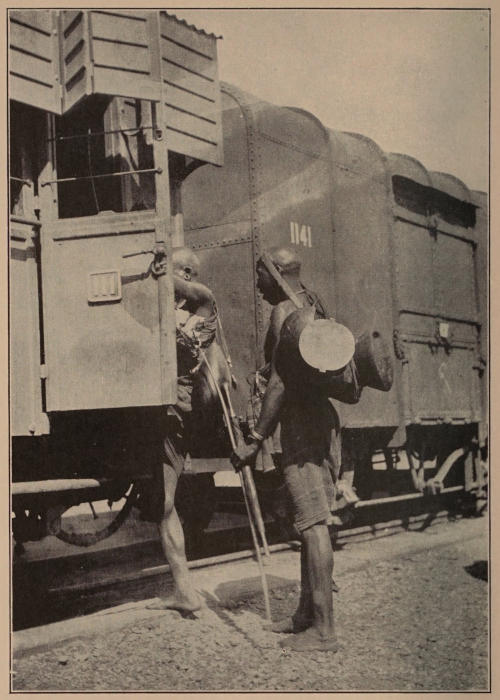

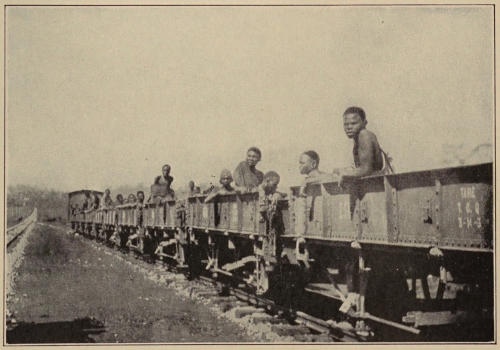

| Passengers on the Uganda Railroad | 243[xiv] |

| An American bridge in East Africa | 246 |

| Native workers on the railway | 246 |

| Why the natives steal telephone wire | 247 |

| In Nairobi | 254 |

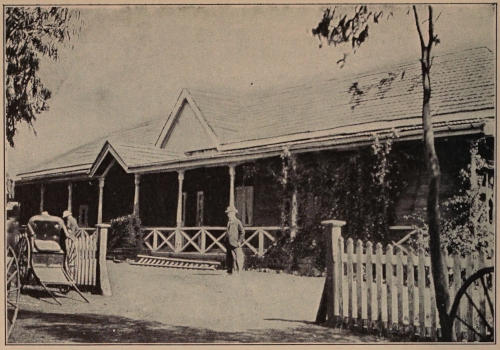

| The hotel | 255 |

| Jinrikisha boys | 255 |

| A native servant | 258 |

| Naivasha | 259 |

| The court for white and black | 259 |

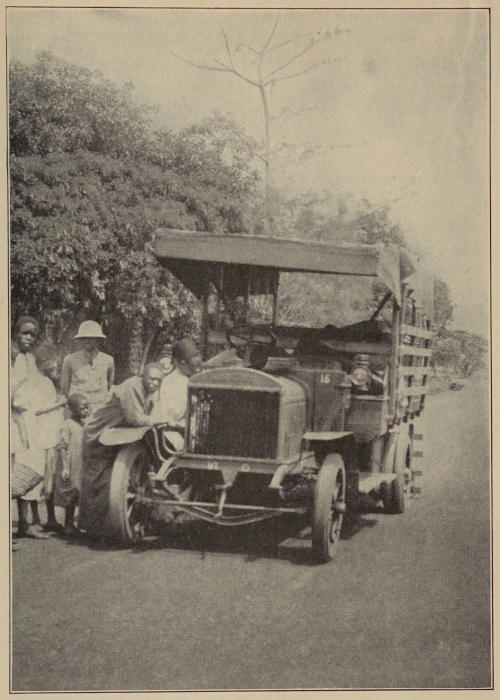

| Motor trucks are coming in | 262 |

| How the natives live | 263 |

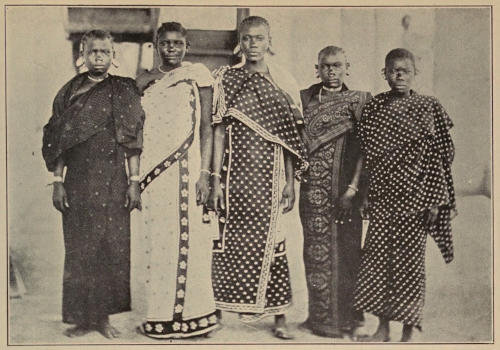

| Native taste in dress goods | 266 |

| The Kikuyus | 266 |

| Wealth is measured in cattle | 267 |

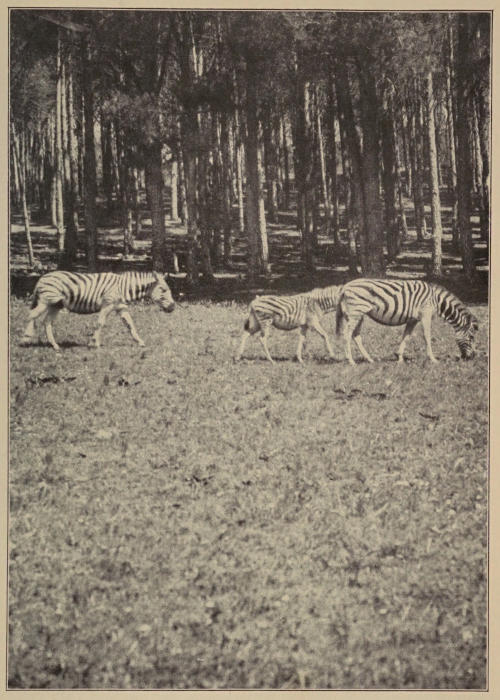

| Zebras are frequently seen | 270 |

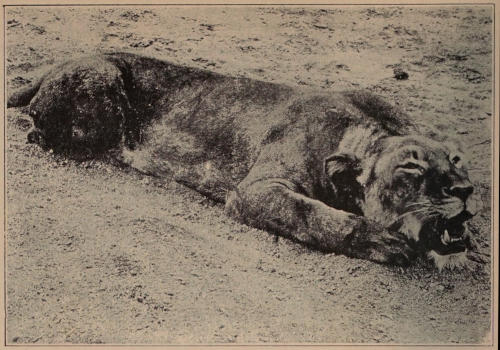

| Even the lions are protected | 271 |

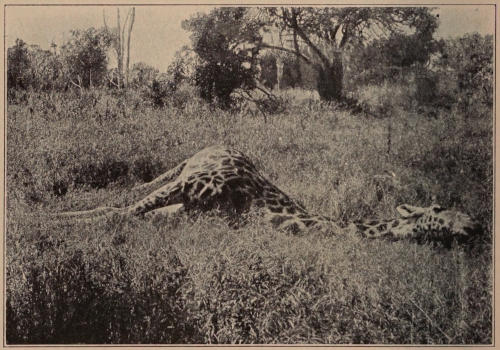

| Giraffes are plentiful | 271 |

| Elephant tusks for the ivory market | 278 |

| How the mothers carry babies | 279 |

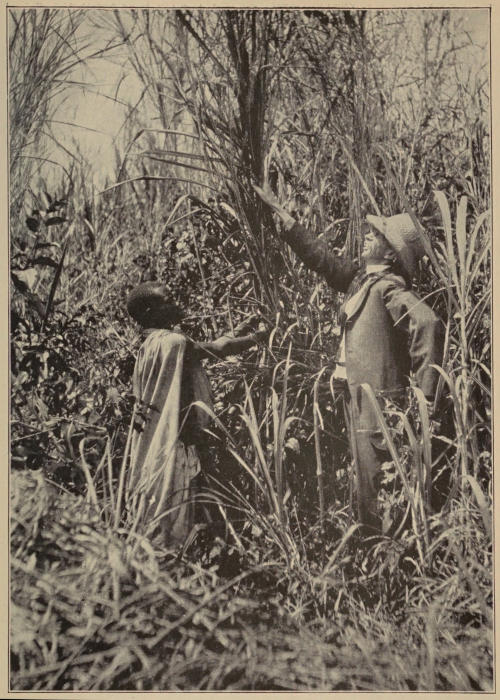

| Mr. Carpenter in the elephant grass | 286 |

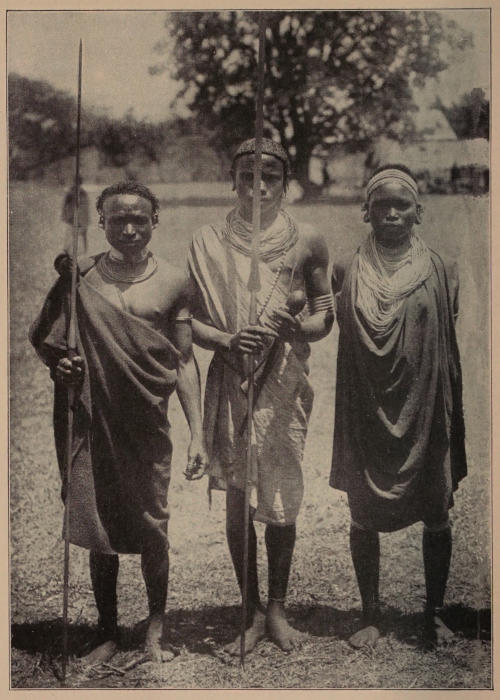

| Nandi warriors | 287 |

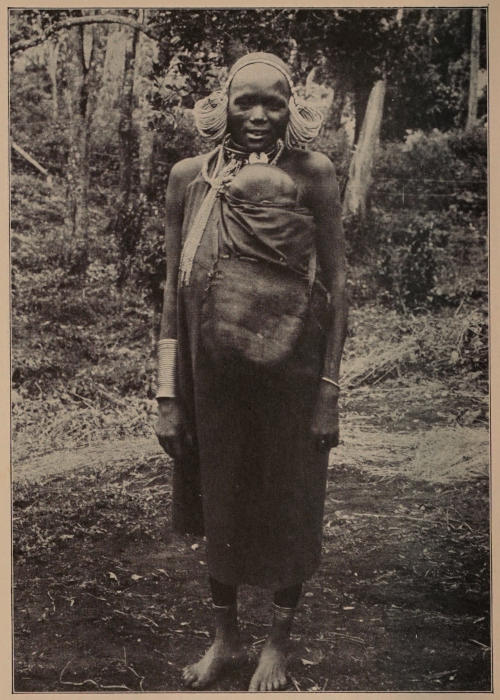

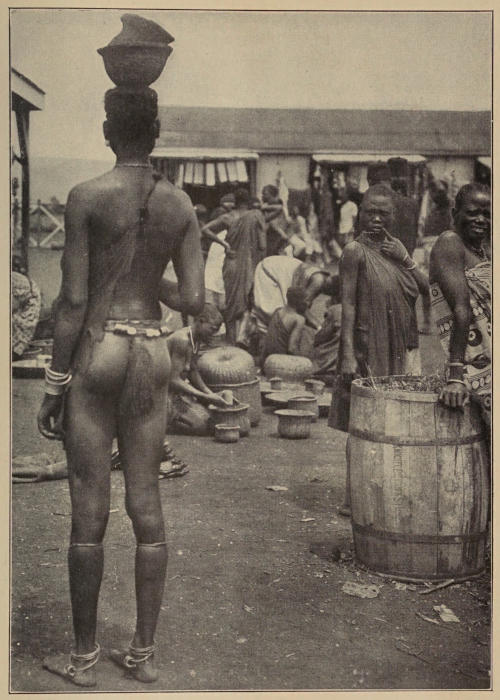

| Woman wearing a tail | 290 |

| How they stretch their ears | 291 |

| The witch doctor | 298 |

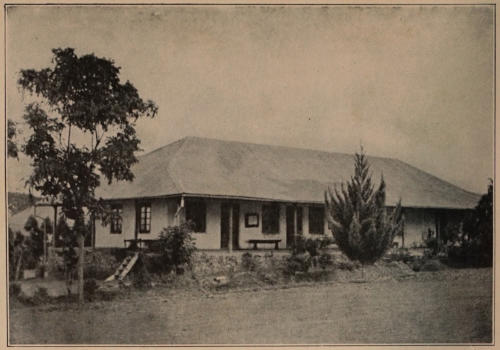

| Home of an official | 299 |

| The mud huts of the Masai | 299 |

| MAPS | |

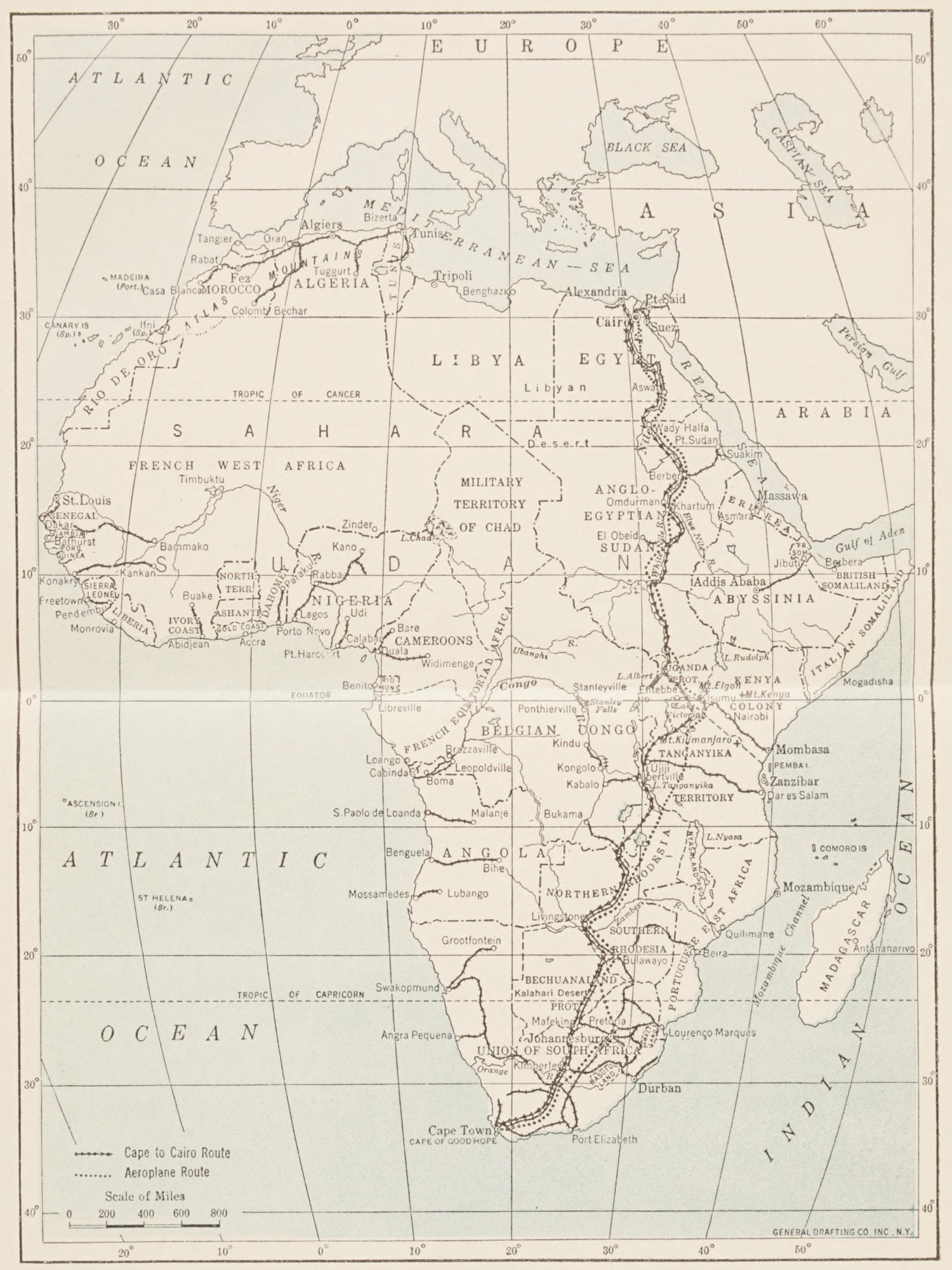

| Africa | 34 |

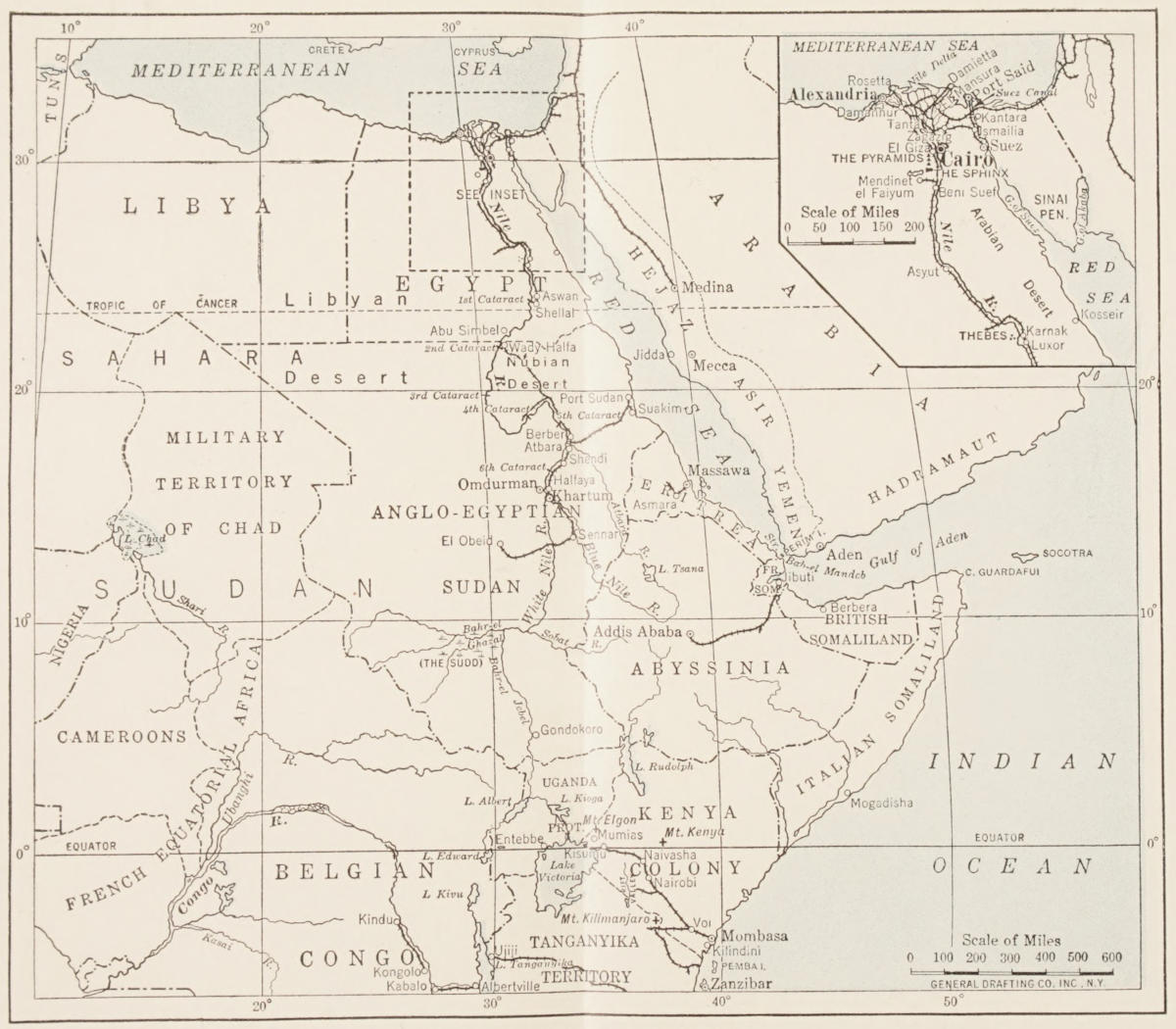

| From Cairo to Kisumu | 50 |

This volume on Egypt, Nubia, the Sudan, and Kenya Colony is based upon notes made during my several trips to this part of the world. At times the notes are published just as they came hot from my pen, taking you back, as it were, to the occasion on which they were written. Again they are modified somewhat to accord with present conditions.

For instance, I made my first visit to Egypt as a boy, when Arabi Pasha was fomenting the rebellion that resulted in that country’s being taken over by the British. I narrowly escaped being in the bombardment of Alexandria and having a part in the wars of the Mahdi, which came a short time thereafter. Again, I was in Egypt when the British had brought order out of chaos, and put Tewfik Pasha on the throne as Khedive. I had then the talk with Tewfik, which I give from the notes I made when I returned from the palace, and I follow it with a description of my audience with his son and successor, Abbas Hilmi, sixteen years later. Now the British have given Egypt a nominal independence, and the Khedive has the title of King.

In the Sudan I learned much of the Mahdi through[2] my interview with Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, then the Governor General of the Sudan and Sirdar of the British army at Khartum, and later gained an insight into the relations of the British and the natives from Earl Cromer, whom I met at Cairo. These talks enable one to understand the Nationalist problems of the present and to appreciate some of the changes now going on.

In Kenya Colony, which was known as British East Africa until after the World War, I was given especial favours by the English officials, and many of the plans that have since come to pass were spread out before me. I then tramped over the ground where Theodore Roosevelt made his hunting trips through the wilds, and went on into Uganda and to the source of the Nile.

These travels have been made under all sorts of conditions, but with pen and camera hourly in hand. The talks about the Pyramids were written on the top and at the foot of old Cheops, those about the Nile in harness on the great Aswan Dam, and those on the Suez Canal either on that great waterway or on the Red Sea immediately thereafter. The matter thus partakes of the old and the new, and of the new based upon what I have seen of the old. If it be too personal in character and at times seems egotistic, I can only beg pardon by saying—the story is mine, and as such the speaker must hold his place in the front of the stage.

Beggars and street sellers alike believe that every foreigner visiting Egypt is not only as rich as Crœsus but also a little touched in the head where spending is concerned, and therefore fair game for their extravagant demands.

Among the upper classes an ever-lighter face covering is being adopted. This is indicative of the advance of the Egyptian woman toward greater freedom.

I am again in Alexandria, the great sea-port of the valley of the Nile. My first visit to it was just before Arabi Pasha started the rebellion which threw Egypt into the hands of the British. I saw it again seven years later on my way around the world. I find now a new city, which has risen up and swallowed the Alexandria of the past.

The Alexandria of to-day stands upon the site of the greatest of the commercial centres of antiquity, but its present buildings are as young as those of New York, Chicago, or Boston. It is one of the boom towns of the Old World, and has all grown up within a century. When George Washington was president it was little more than a village; it has now approximately a half million inhabitants.

This is a city with all modern improvements. It has wide streets as well paved as those of Washington, public squares that compare favourably with many in Europe, and buildings that would be an ornament to any metropolis on our continent. It is now a city of street cars and automobiles. Its citizens walk or ride to its theatres by the light of electricity, and its rich men gamble by reading the ticker in its stock exchange. It is a town of big hotels, gay cafés, and palaces galore. In addition to its several hundred thousand Mohammedans, it has a large population[4] of Greeks, Italians, and other Europeans, among them some of the sharpest business men of the Mediterranean lands. Alexandria has become commercial, money making, and fortune hunting. The rise and fall of stocks, the boom in real estate, and the modern methods of getting something for nothing are its chief subjects of conversation, and the whole population is after the elusive piastre and the Egyptian pound as earnestly as the American is chasing the nickel and the dollar.

The city grows because it is at the sea-gate to Egypt and the Sudan. It waxes fat on the trade of the Nile valley and takes toll of every cent’s worth of goods that comes in and goes out. More than four thousand vessels enter the port every year and in the harbour there are steamers from every part of the world. I came to Egypt from Tripoli via Malta, where I took passage on a steamer bound for India and Australia, and any week I can get a ship which within fifteen days will carry me back to New York.

One of the things to which Alexandria owes its greatness is the canal that Mehemet Ali, founder of the present ruling dynasty of Egypt, had dug from this place to the Nile. This remarkable man was born the son of a poor Albanian farmer and lived for a number of years in his little native port as a petty official and tobacco trader. He first came into prominence when he led a band of volunteers against Napoleon in Egypt. Later still he joined the Sultan of Turkey in fighting the Mamelukes for the control of the country. The massacre of the Mamelukes in 1811 left the shrewd Albanian supreme in the land, and, after stirring up an Egyptian question that set the Powers of Europe more or less by the ears with each[5] other and with the Sultan of Turkey, he was made Viceroy of Egypt, with nominal allegiance to the Turkish ruler. When he selected Alexandria as his capital, it was a village having no connection with the Nile. He dug a canal fifty miles long to that great waterway, through which a stream of vessels is now ever passing, carrying goods to the towns of the valley and bringing out cotton, sugar, grain, and other products, for export to Europe. The canal was constructed by forced labour. The peasants, or fellaheen, to the number of a quarter of a million, scooped the sand out with their hands and carried it away in baskets on their backs. It took them a year to dig that fifty-mile ditch, and they were so overworked that thirty thousand of them died on the job.

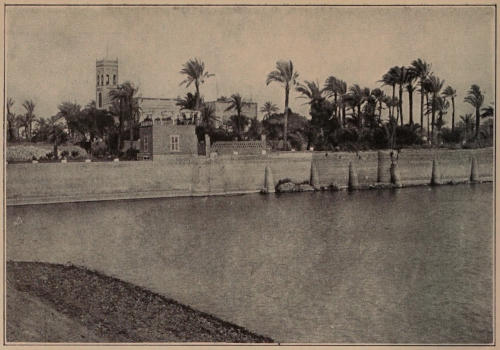

Ismail Pasha, grandson of Mehemet Ali, made other improvements on the canal and harbour, and after the British took control of Egypt they bettered Alexandria in every possible way.

It has now one of the best of modern harbours. The port is protected by a breakwater two miles in length, and the biggest ocean steamers come to the quays. There are twenty-five hundred acres of safe anchorage inside its haven, while the arrangements for coaling and for handling goods are unsurpassed.

These conditions are typical of the New Egypt. Old Mother Nile, with her great dams and new irrigation works, has renewed her youth and is growing in wealth like a jimson weed in an asparagus bed. When I first saw the Nile, its valley was a country of the dead, with obelisks and pyramids as its chief landmarks. Then its most interesting characters were the mummified kings of more than twenty centuries ago and the principal visitors were[6] antiquity hunters and one-lunged tourists seeking a warm winter climate. These same characters are here to-day, but in addition have come the ardent dollar chaser, the capitalist, and the syndicate. Egypt is now a land of banks and stock exchanges. It is thronged with civil engineers, irrigation experts, and men interested in the development of the country by electricity and steam. The delta, or the great fan of land which begins at Cairo and stretches out to the Mediterranean, is gridironed with steel tracks and railroad trains, continuing almost to the heart of central Africa.

I find Egypt changing in character. The Mohammedans are being corrupted by the Christians, and the simple living taught by the Koran, which commands the believer to abstain from strong drink and other vices, has become infected with the gay and giddy pleasures of the French. In many cases the system of the harem is being exchanged for something worse. The average Moslem now has but one wife, but in many cases he has a sweetheart in a house around the corner, “and the last state of that man is worse than the first.”

The ghouls of modern science are robbing the graves of those who made the Pyramids. A telephone line has been stretched out of Cairo almost to the ear of the Sphinx, and there is a hotel at the base of the Pyramid of Cheops where English men and women drink brandy and soda between games of tennis and golf.

Cotton warehouses and docks extend for a mile along the Mahmudiyeh Canal connecting the port of Alexandria with the Nile River, and the prosperity of the city rises and falls with the price of cotton in the world’s markets.

Nubian women sell fruit and flowers on the streets of Alexandria to-day, but once their kings ruled all Egypt and defeated the armies of Rome. They became early converts to Christianity but later adopted Mohammedanism.

The Egypt of to-day is a land of mighty hotels and multitudinous tourists. For years it has been estimated that Americans alone spend several million dollars here every winter, and the English, French, and other tourists almost as much. It is said that in the average season ten[7] thousand Americans visit the Nile valley and that it costs each one of them at least ten dollars for every day of his stay.

When I first visited this country the donkey was the chief means of transport, and men, women, and children went about on long-eared beasts, with Arab boys in blue gowns following behind and urging the animals along by poking sharp sticks into patches of bare flesh, as big as a dollar, which had been denuded of skin for the purpose. The donkey and the donkey boy are here still, but I can get a street car in Alexandria that will take me to any part of the town, and I frequently have to jump to get out of the way of an automobile. There are cabs everywhere, both Alexandria and Cairo having them by thousands.

The new hotels are extravagant beyond description. In the one where I am now writing the rates are from eighty to one hundred piastres per day. Inside its walls I am as far from Old Egypt as I would be in the Waldorf Astoria in New York. The servants are French-speaking Swiss in “swallow-tails”, with palms itching for fees just as do those of their class in any modern city. In my bedroom there is an electric bell, and I can talk over the telephone to our Consul General at Cairo. On the register of the hotel, which is packed with guests, I see names of counts by the score and lords by the dozen. The men come to dinner in steel-pen coats and the women in low-cut evening frocks of silk and satin. There is a babel of English, French, and German in the lounge while the guests drink coffee after dinner, and the only evidences one perceives of a land of North Africa and the Moslems are the tall minarets which here and there reach above the other buildings of the city, and the voices of the muezzins[8] as they stand beneath them and call the Mohammedans to prayer.

The financial changes that I have mentioned are by no means confined to the Christians. The natives have been growing rich, and the Mohammedans for the first time in the history of Egypt have been piling up money. Since banking and money lending are contrary to the Koran, the Moslems invest their surplus in real estate, a practice which has done much to swell all land values.

Egypt is still a country of the Egyptians, notwithstanding the overlordship of the British and the influx of foreigners. It has now more than ten million people. Of these, three out of every four are either Arabs or Copts. Most of them are Mohammedans, although there are, all told, something like eight hundred and sixty thousand Copts, descendants of the ancient Egyptians, who have a rude kind of Christianity, and are, as a body, better educated and wealthier than the Mussulmans.

The greater part of the foreign population of Egypt is to be found in Alexandria and Cairo, and in the other towns of the Nile valley, as well as in Suez and Port Said. There are more of the Greeks than of any other nation. For more than two thousand years they have been exploiting the Egyptians and the Nile valley and are to-day the sharpest, shrewdest, and most unscrupulous business men in it. They do much of the banking and money lending and until the government established banks of its own and brought down the interest rate they demanded enormous usury from the Egyptian peasants. It is said that they loaned money on lands and crops at an average charge of one hundred and fifty per cent. per annum.

This was changed, however, by the establishment of[9] the Agricultural Bank. The government, which controls that bank, lends money to the farmers at eight per cent. to within half of the value of their farms. To-day, since the peasants all over Egypt can get money at this rate, the Greeks have had to reduce theirs.

The Italians number about forty thousand and the French twenty thousand. There are many Italian shops here in Alexandria, while there are hundreds of Italians doing business in Cairo. They also furnish some of the best mechanics. Many of them are masons and the greater part of the Aswan Dam and similar works were constructed by them.

There are also Germans, Austrians, and Russians, together with a few Americans and Belgians. The British community numbers a little over twenty thousand. Among the other foreigners are some Maltese and a few hundred British East Indians.

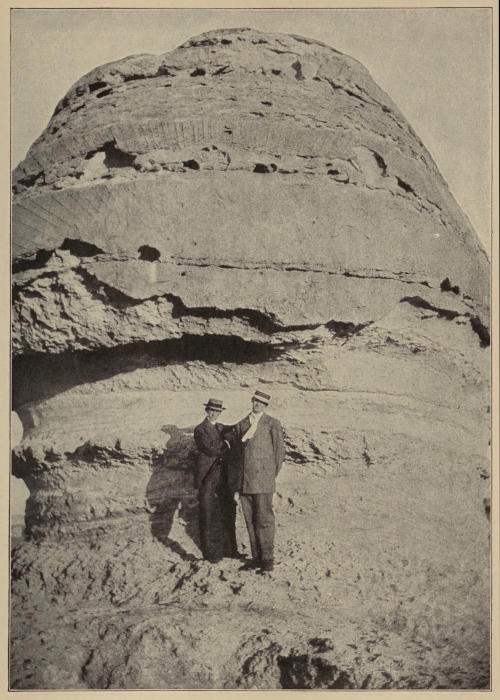

Sitting here at Alexandria in a modern hotel surrounded by the luxuries of Paris or New York, I find it hard to realize that I am in one of the very oldest cities of history. Yesterday I started out to look up relics of the past, going by mile after mile of modern buildings, though I was travelling over the site of the metropolis that flourished here long before Christ was born. From the antiquarian’s point of view, the only object of note still left is Pompey’s Pillar and that is new in comparison with the earliest history of Old Egypt, as it was put up only sixteen hundred years ago, when Alexandria was already one of the greatest cities of the world. The monument was supposed to stand over the grave of Pompey, but it was really erected by an Egyptian prefect in honour of the Roman emperor, Diocletian. It was at one time a landmark for sailors,[10] for there was always upon its top a burning fire which was visible for miles over the Mediterranean Sea. The pillar is a massive Corinthian column of beautifully polished red granite as big around as the boiler of a railroad locomotive and as high as a ten-story apartment house. It consists of one solid block of stone, standing straight up on a pedestal. It was dug out of the quarries far up the Nile valley, brought down the river on rafts and in some way lifted to its present position. In their excavations about the pedestal, the archæologists learned of its comparatively modern origin and, digging down into the earth far below its foundation, discovered several massive stone sphinxes. These date back to old Alexandria and were chiselled several hundreds of years before Joseph and Mary brought the baby Jesus on an ass, across the desert, into the valley of the Nile that he might not be killed by Herod the King.

This city was founded by Alexander the Great three hundred and thirty-two years before Christ was born. It probably had then more people than it has to-day, for it was not only a great commercial port, but also a centre of learning, religion, and art. It is said to have had the grandest library of antiquity. The manuscripts numbered nine hundred thousand and artists and students came from all parts to study here. At the time of the Cæsars it was as big as Boston, and when it was taken by the Arabs, along about 641 A.D., it had four thousand palaces, four hundred public baths, four hundred places of amusement, and twelve thousand gardens. When Alexander the Great founded it he brought in a colony of Jews, and at the time the Mohammedans came the Jewish quarter numbered forty thousand.

At Alexandria St. Mark first preached Christianity to[11] the Egyptians, and subsequently the city became one of the Christian centres of the world. Here Hypatia lived, and here, as she was about to enter a heathen temple to worship, the Christian monks, led by Peter the Reader, tore her from her chariot and massacred her. They scraped her live flesh from her bones with oyster shells, and then tore her body limb from limb.

Here, too, Cleopatra corrupted Cæsar and later brought Marc Antony to a suicidal grave. There are carvings of the enchantress of the Nile still to be seen on some of the Egyptian temples far up the river valley. I have a photograph of one which is in good preservation in the Temple of Denderah. Its features are Greek rather than Egyptian, for she was more of a Greek than a Simon-pure daughter of the Nile. She was not noted for beauty, but she had such wonderful charm of manner, sweetness of voice, and brilliancy of intellect, that she was able to allure and captivate the greatest men of her time.

Cleopatra’s first Roman lover was Julius Cæsar, who came to Alexandria to settle the claims of herself and her brother to the throne of Egypt. Her father, who was one of the Ptolemies, had at his death left his throne to her younger brother and herself, and according to the custom the two were to marry and reign together. One of the brother’s guardians, however, had dethroned and banished Cleopatra. She was not in Egypt when Cæsar came. It is not known whether it was at Cæsar’s request or not, but the story goes that she secretly made her way back to Alexandria, and was carried inside a roll of rich Syrian rugs on the back of a servant to Cæsar’s apartments. Thus she was presented to the mighty Roman and so delighted him that he restored her to the[12] throne. When he left for Rome some time later he took her with him and kept her there for a year or two. After the murder of Cæsar, Cleopatra, who had returned to Egypt, made a conquest of Marc Antony and remained his sweetheart to the day when he committed suicide upon the report that she had killed herself. Antony had then been conquered by Octavianus, his brother-in-law, and it is said that Cleopatra tried to capture the heart of Octavianus before she took her own life by putting the poisonous asp to her breast.

The whole of to-day has been spent wandering about the cotton wharves of Alexandria. They extend for a mile or so up and down the Mahmudiyeh Canal, which joins the city to the Nile, and are flanked on the other side by railroads filled with cotton trains from every part of Egypt. These wharves lie under the shadow of Pompey’s Pillar and line the canal almost to the harbour. Upon them are great warehouses filled with bales and bags. Near by are cotton presses, while in the city itself is a great cotton exchange where the people buy and sell, as they do at Liverpool, from the samples of lint which show the quality of the bales brought in from the plantations.

Indeed, cotton is as big a factor here as it is in New Orleans, and the banks of this canal make one think of that city’s great cotton market. The warehouses are of vast extent, and the road between them and the waterway is covered with bales of lint and great bags of cotton seed. Skullcapped blue-gowned Egyptians sit high up on the bales on long-bedded wagons hauled by mules. Other Egyptians unload the bales from the cars and the boats and others carry them to the warehouses. They bear the bales and the bags on their backs, while now and then a man may be seen carrying upon his head a bag of loose cotton weighing a couple of hundred pounds. The[14] cotton seed is taken from the boats in the same way, seed to the amount of three hundred pounds often making one man’s load.

Late in the afternoon I went down to the harbour to see the cotton steamers. They were taking on cargoes for Great Britain, Russia, France, Germany, and the United States. This staple forms three fourths of the exports of Egypt. Millions of pounds of it are annually shipped to the United States, notwithstanding the fact that we raise more than two thirds of all the cotton of the world. Because of its long fibre, there is always a great demand for Egyptian cotton, which is worth more on the average than that of any other country.

For hundreds of years before the reign of that wily old tyrant, Mehemet Ali, whose rule ended with the middle of the nineteenth century, Egypt had gone along with the vast majority of her people poor, working for a wage of ten cents or so a day, and barely out of reach of starvation all the time. Mehemet Ali saw that what she needed to become truly prosperous and raise the standard of living was some crop in which she might be the leader. It was he who introduced long-staple cotton, a product worth three times as much as the common sort, and showed what it could do for his country. Since then King Cotton has been the money maker of the Nile valley, the great White Pharaoh whom the modern Egyptians worship. He has the majority of the Nile farmers in his employ and pays them royally. He has rolled up a wave of prosperity that has engulfed the Nile valley from the Mediterranean to the cataracts and the prospects are that he will continue to make the country richer from year to year. The yield is steadily increasing and with the improved irrigation[15] methods it will soon be greater than ever. From 1895 to 1900 its average annual value was only forty-five million dollars; but after the Aswan Dam was completed it jumped to double that sum.

Though cotton is the big cash crop of Egypt, small flocks of sheep are kept on many of the farms and the women spin the wool for the use of the family.

Sugar is Egypt’s crop of second importance. Heavy investments of French and British capital in the Egyptian industry were first made when political troubles curtailed Cuba’s production.

The greater part of Upper and Lower Egypt can be made to grow cotton, and cotton plantations may eventually cover over five million five hundred thousand acres. If only fifty per cent. of this area is annually put into cotton it will produce upward of two million bales per annum, or more than one sixth as much as the present cotton crop of the world. In addition to this, there might be a further increase by putting water into some of the oases that lie in the valley of the Nile outside the river bottom, and also by draining the great lakes about Alexandria and in other parts of the lower delta.

Egypt has already risen to a high place among the world’s cotton countries. The United States stands first, British India second, and Egypt third. Yet Egypt grows more of this staple for its size and the area planted than any other country on the globe. Its average yield is around four hundred and fifty pounds per acre, which is far in excess of ours. Our Department of Agriculture says that our average is only one hundred and ninety pounds per acre, although we have, of course, many acres which produce five hundred pounds and more.

It is, however, because of its quality rather than its quantity that Egyptian cotton holds such a commanding position in the world’s markets. Cotton-manufacturing countries must depend on Egypt for their chief supply of long-staple fibre. There are some kinds that sell for double the amount our product brings. It is, in fact, the best cotton grown with the exception of the Sea Island[16] raised on the islands off the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina. The Sea Island cotton has a rather longer fibre than the Egyptian. The latter is usually brown in colour and is noted for its silkiness, which makes it valuable for manufacturing mercerized goods. We import an enormous quantity of it to mix with our cotton, and we have used the Egyptian seed to develop a species known as American-Egyptian, which possesses the virtues of both kinds.

There is a great difference in the varieties raised, according to the part of the Nile valley from which each kind comes. The best cotton grows in the delta, which produces more than four fifths of the output.

A trip through the Nile cotton fields is an interesting one. The scenes there are not in the least like those of our Southern states. Much of the crop is raised on small farms and every field is marked out with little canals into which the water is introduced from time to time. There are no great farm houses in the landscape and no barns. The people live in mud villages from which they go out to work in the fields. They use odd animals for ploughing and harrowing and the crop is handled in a different way from ours.

Let me give you a few of the pictures I have seen while travelling through the country. Take a look over the delta. It is a wide expanse of green, spotted here and there with white patches. The green consists of alfalfa, Indian corn, or beans. The white is cotton, stretching out before me as far as my eye can follow it.

Here is a field where the lint has been gathered. The earth is black, with windrows of dry stalks running across it. Every stalk has been pulled out by the roots and piled[17] up. Farther on we see another field in which the stalks have been tied into bundles. They will be sold as fuel and will produce a full ton of dry wood to the acre. There are no forests in Egypt, where all sorts of fuel are scarce. The stalks from one acre will sell for two dollars or more. They are used for cooking, for the farm engines on the larger plantations, and even for running the machinery of the ginning establishments. In that village over there one may see great bundles of them stored away on the flat roofs of the houses. Corn fodder is piled up beside them, the leaves having been torn off for stock feed. A queer country this, where the people keep their wood piles on their roofs!

In that field over there they are picking cotton. There are scores of little Egyptian boys and girls bending their dark brown faces above the white bolls. The boys for the most part wear blue gowns and dirty white skullcaps, though some are almost naked. The little girls have cloths over their heads. All are barefooted. They are picking the fibre in baskets and are paid so much per hundred pounds. A boy will gather thirty or forty pounds in a day and does well if he earns as much as ten cents.

The first picking begins in September. After that the land is watered, and a second picking takes place in October. There is a third in November, the soil being irrigated between times. The first and second pickings, which yield the best fibre, are kept apart from the third and sold separately.

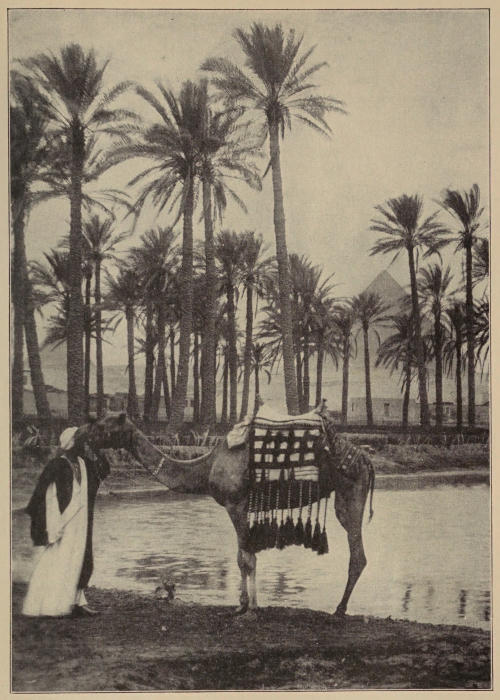

After the cotton is picked it is put into great bags and loaded upon camels. They are loading four in that field at the side of the road. The camels lie flat on the ground, with their long necks stretched out. Two bags, which together[18] weigh about six hundred pounds, make a load for each beast. Every bag is as long and wide as the mattress of a single bed and about four feet thick. Listen to the groans of the camels as the freight is piled on. There is one actually weeping. We can see the tears run down his cheeks.

Now watch the awkward beasts get up. Each rises back end first, the bags swaying to and fro as he does so. How angry he is! He goes off with his lower lip hanging down, grumbling and groaning like a spoiled child. The camels make queer figures as they travel. The bags on each side their backs reach almost to the ground, so that the lumbering creatures seem to be walking on six legs apiece.

Looking down the road, we see long caravans of camels loaded with bales, while on the other side of that little canal is a small drove of donkeys bringing in cotton. Each donkey is hidden by a bag that completely covers its back and hides all but its little legs.

In these ways the crop is brought to the railroad stations and to the boats on the canals. The boats go from one little waterway to another until they come into the Mahmudiyeh Canal, and thence to Alexandria. During the harvesting season the railroads are filled with cotton trains. Some of the cotton has been ginned and baled upon the plantations, and the rest is in the seed to be ginned at Alexandria. There are ginning establishments also at the larger cotton markets of the interior. Many of them are run by steam and have as up-to-date machinery as we have. At these gins the seed is carefully saved and shipped to Alexandria by rail or by boat.

The Nile bridge swings back to let through the native boats sailing down to Alexandria with cargoes of cotton and sugar grown on the irrigated lands farther upstream.

A rainless country, Egypt must dip up most of its water from the Nile, usually by the crude methods of thousands of years ago. Here an ox is turning the creaking sakieh, a wheel with jars fastened to its rim.

Egypt is a land that resists change, where even the native ox, despite the frequent importation of foreign breeds, has the same features as are found in the picture writings of ancient times. He is a cousin of the zebu.

The Egyptians put more work on their crop than our[19] Southern farmers do. In the first place, the land has to be ploughed with camels or buffaloes and prepared for the planting. It must be divided into basins, each walled around so that it will hold water, and inside each basin little canals are so arranged that the water will run in and out through every row. The whole field is cut up into these beds, ranging in size from twenty-four to seventy-five feet square.

The cotton plants are from fourteen to twenty inches apart and set in rows thirty-five inches from each other. It takes a little more than a bushel of seed to the acre. The seeds are soaked in water before planting, any which rise to the surface being thrown away. The planting is done by men and boys at a cost of something like a dollar an acre. The seeds soon sprout and the plants appear in ten or twelve days. They are thinned by hand and water is let in upon them, the farmers taking care not to give them too much. The plants are frequently hoed and have water every week or so, almost to the time of picking. The planting is usually done in the month of March, and, as I have said, the first picking begins along in September.

I have been told that cotton, as it is grown here, exhausts the soil and that the people injure the staple and reduce the yield by overcropping. It was formerly planted on the same ground only every third year, the ground being used in the interval for other crops or allowed to lie fallow. At present some of the cotton fields are worked every year and others two years out of three. On most of the farms cotton is planted every other year, whereas the authorities say that in order to have a good yield not more than forty per cent. of a man’s farm should be kept to this crop from year to year. Just as in our Southern[20] states, a year of high cotton prices is likely to lead to overcropping and reduced profits, and vice versa. Another trouble in Egypt, and one which it would seem impossible to get around, is the fact that cotton is practically the only farm crop. This puts the fellaheen more or less at the mercy of fluctuating prices and changing business conditions; so that, like our cotton farmers of the South, they have their lean years and their fat years.

Egypt also has had a lot of trouble with the pink boll weevil. This pestiferous cotton worm, which is to be found all along the valley of the Nile, has also done great damage on the plantations of the Sudan, a thousand miles south of Alexandria. It is said that in one year it destroyed more than ten million dollars’ worth of cotton and that hundreds of the smaller farmers were ruined. The government has been doing all it can to wipe out the plague, but is working under great disadvantages. The Egyptian Mohammedans are fatalists, looking upon such things as the boll weevil as a judgment of God and believing they can do nothing to avert the evil. Consequently, the government had to inaugurate a system of forced labour. It made the boys and men of the cotton region turn out by the thousands to kill the worms under the superintendence of officials. The results were excellent, and as those who were forced into the work were well paid the farmers are beginning to appreciate what has been done for them.

The government helps the cotton planters in other ways. Its agricultural department sends out selected seed for planting a few thousand acres to cotton, contracting with each man who takes it that the government will buy his seed at a price above that of the market. The seed coming[21] in from that venture is enough to plant many more thousands of acres, and this is distributed at cost to such of the farmers as want it. More than one quarter of all seed used has latterly been supplied in this way.

The government has also induced the planters to use artificial fertilizers. It began this some years ago, when it was able to distribute thirty thousand dollars’ worth of chemical fertilizer, and the demand so increased that within a few years more than ten times as much was distributed annually.

On my way to Cairo I have taken a run through the delta, crossing Lower Egypt to the Suez Canal and returning through the Land of Goshen.

The soil is as rich and the grass is as green now as it was when Joseph picked out this land as the best in Egypt for his famine-stricken father Jacob. Fat cattle by the hundreds grazed upon the fields, camels with loads of hay weighing about a ton upon their backs staggered along the black roads. Turbaned Egyptians rode donkeys through the fields, and the veiled women of this Moslem land crowded about the train at the villages. On one side a great waste of dazzling yellow sand came close to the edge of the green fields, and we passed grove after grove of date-palm trees holding their heads proudly in the air, and shaking their fan-like leaves to every passing breeze. They seemed to whisper a requiem over the dead past of this oldest of the old lands of the world.

The sakka, or water carrier, fills his pigskin bag at the river, and then peddles it out, with the cry: “O! may God recompense me,” announcing his passage through the streets of village or town.

Up and down the slippery banks of the Nile goes the centuries-long procession of fellah women bearing head burdens—water-jars or baskets of earth from excavations.

As we neared Cairo and skirted the edge of the desert, away off to the right against the hazy horizon rose three ghost-like cones of gray out of the golden sand. These were the Pyramids, and the steam engine of the twentieth century whistled out a terrible shriek as we came in sight of them. To the left were the Mokattam Hills, with the citadel which Saladin built upon them, while to the right[23] flowed the great broad-bosomed Nile, the mother of the land of Egypt, whose earth-laden waters have been creating soil throughout the ages, and which to-day are still its source of life.

Egypt, in the words of Herodotus, is the gift of the Nile. This whole rainless country was once a bed of sterile sand so bleak and bare that not a blade of grass nor a shrub of cactus would grow upon it. This mighty river, rising in the heights of Africa and cutting its way through rocks and hills, has brought down enough sediment to form the tillable area of Egypt. South of Cairo, for nearly a thousand miles along its banks, there extends a strip of rich black earth which is only from three to nine miles wide. Below the city the land spreads out in a delta shaped somewhat like the segment of a circle, the radii of which jut out from Cairo, while the blue waters of the Mediterranean edge its arc. This narrow strip and fan form the arable land of Egypt. The soil is nowhere more than thirty-five feet deep. It rests on a bed of sand. On each side of it are vast wastes of sand and rock, with not a spot of green to relieve the ceaseless glare of the sun. The green goes close to the edge of the desert, where it stops as abruptly as though it were cut off by a gardener. Nearly everywhere up the Nile from Cairo the strip is so narrow that you can stand at one side of the valley and see clear across it.

Thus, in one sense, Egypt is the leanest country in the world, but it is the fattest in the quality of the food that nature gives it. Through the ages it has had one big meal every year. At the inundation of the Nile, for several months the waters spread over the land and were allowed to stand there until they dropped the rich, black fertilizing[24] sediment brought down from the African mountains. This sediment has produced from two to three crops a year for Egypt through the centuries and for a long time was the sole manure that the land had. The hundreds of thousands of cattle, donkeys, camels, and sheep that feed off the soil give nothing back to it, for their droppings are gathered up by the peasant women and girls, patted into shape, and dried for use as fuel. Until late years the only manure that was used in any part of the country was that of pigeons and chickens, or the crumbled ruins of ancient towns, which, lying through thousands of years, have become rubbish full of fertilizing properties. Recently, as I have said, the use of artificial fertilizers has been encouraged with excellent results.

The irrigation of Egypt is now conducted on scientific lines. The water is not allowed to spread over the country as it was years ago, but the arable area is cut up by canals, and there are immense irrigating works in the delta, to manage which during the inundation hundreds of thousands of men are required. Just at the point of the delta, about twelve miles above Cairo, is a great dam, or barrage, that raises the waters of the Nile into a vast canal from which they flow over the fan-like territory of Lower Egypt. All through Egypt one sees men scooping the water up in baskets from one level to another, and everywhere he finds the buffalo, the camel, or donkey turning the wheels that operate the crude apparatus for getting the water out of the river and onto the land.

But let me put into a nutshell the kernel of information we need to understand this wonderful country. We all know how Egypt lies on the map of northeastern Africa, extending a thousand miles or more southward from the[25] Mediterranean Sea. The total area, including the Nubian Desert, the region between the Nile and the Red Sea, and the Sinai Peninsula, is more than seven times as large as the State of New York, but the real Egypt, that is, the cultivated and settled portion comprising the Nile valley and delta, lacks just four square miles of being as large as our State of Maryland. Of this portion, fully one third is taken up in swamps, lakes, and the surface of the Nile, as well as in canals, roads, and plantations of dates, so that the Egypt of farms that actually supports the people is only about as big as Massachusetts. Though this contains little more than eight thousand square miles, nevertheless its population is nearly one eighth of ours. Crowd every man, woman, and child who lives in the United States into four states the size of Maryland, and you have some idea of the density of the population here. Belgium, that hive of industry, with its mines of iron and coal and its myriad factories, has only about six hundred people per square mile; and China, the leviathan of Asia, has less than two hundred and fifty. Little Egypt is supporting something like one thousand per square mile of its arable area; and nearly all of them are crowded down near the Mediterranean.

Of these people, about nine tenths are Mohammedans, one twelfth Christians, Copts, and others; and less than one half of one per cent. Jews. Among the Christians are many Greeks of the Orthodox Church and Italian Roman Catholics from the countries on the Mediterranean Sea.

Nature has much to do with forming the character and physique of the men who live close to her, and in Egypt the unvarying soil, desert, sky, and river, make the people[26] who have settled in the country become, in the course of a few generations, just like the Egyptians themselves. Scientists say that the Egyptian peasantry of to-day is the same as in the past, and that this is true even of the cattle. Different breeds have been imported from time to time only to change into the Egyptian type, and the cow to-day is the same as that pictured in the hieroglyphics of the tombs made thousands of years ago. The Egyptian cow is like the Jersey in shape and form save that its neck is not quite so delicate and its horns are a trifle shorter. Its colour is a rich red. Its milk is full of oil, and its butter is yellow. It has been asserted that the Jersey cow originally came from Egypt, and was taken to the Island of Jersey by the Phœnicians in some of their voyages ages ago.

But to return to the Nile, the source of existence of this great population. Next to the Mississippi, with the Missouri, it is the longest river of the world. The geographers put its length at from thirty-seven hundred to four thousand miles. It is a hundred miles or so longer than the Amazon, and during the last seventeen hundred miles of its course not a single branch comes in to add to its volume. For most of the way it flows through a desert of rock and sand as dry as the Sahara. In the summer many of the winds that sweep over Cairo are like the blast from a furnace, and in Upper Egypt a dead dog thrown into the fields will turn to dust without an offensive odour. The dry air sucks the moisture out of the carcass so that there is no corruption.

Nearly all of the cultivated lands lie along the Nile banks and depend for their supply of water on the rise of the river, caused by the rains in the region around its sources. When[27] the Nile is in flood the waters are coloured dark brown by the silt brought down from the high lands of Abyssinia. When it is low, as in June, they are green, because of the growth of water plants in the upper parts of the river. At flood time the water is higher than the land and the fields are protected by banks or dikes along the river. If these banks break, the fields are flooded and the crops destroyed.

We are accustomed to look upon Egypt as a very hot country. This is not so. The greater part of it lies just outside the tropics, so that it has a warm climate and a sub-tropical plant life. The hottest month is June and the coldest is January. Ice sometimes forms on shallow pools in the delta, but there is no snow, although hail storms occur occasionally, with very large stones. There is no rain except near the coast and a little near Cairo. Fogs are common in January and February and it is frequently damp in the cultivated tracts.

For centuries Egypt has been in the hands of other nations. The Mohammedan Arabs and the Ottoman Turks have been bleeding her since their conquest. Greece once fed off her. Rome ate up her substance in the days of the Cæsars and she has had to stake the wildest extravagancies of the khedives of the past. It must be remembered that Egypt is almost altogether agricultural, and that all of the money spent in and by it must come from what the people can raise on the land. The khedives and officials have piped, and Egypt’s farmers have had to pay.

It was not long before my second visit to Egypt that the wastefulness and misrule of her officials had practically put her in the hands of a receiver. She had gone into[28] debt for half a billion dollars to European creditors—English, French, German, and Spanish—and England and France had arranged between them to pull her out. Later France withdrew from the agreement and Great Britain undertook the job alone.

At that time the people were ground down to the earth and had barely enough for mere existence. Taxes were frightfully high and wages pitifully low. The proceeds from the crops went mostly to Turkey and to the bankers of Europe who had obtained the bonds given by the government to foreigners living in Egypt. In fact, they had as hard lives as in the days of the most tyrannical of the Pharaohs.

But since that time the British have had a chance to show what they could do, irrigation projects and railroad schemes have been put through, cotton has come into its own, and I see to-day a far more prosperous land and people than I did at the end of the last century.

For the last month I have been travelling through the farms of the Nile valley. I have visited many parts of the delta, a region where the tourist seldom stops, and have followed the narrow strip that borders the river for several hundred miles above Cairo.

The delta is the heart of Egypt. It has the bulk of the population, most of the arable land, the richest soil, and the biggest crops. While it is one of the most thickly settled parts of the world, it yields more to the acre than any other region on earth, and its farm lands are the most valuable. I am told that the average agricultural yield for all Europe nets a profit of thirty-five dollars per acre, but that of Lower Egypt amounts to a great deal more. Some lands produce so much that they are renting for fifty dollars an acre, and there are instances where one hundred dollars is paid.

I saw in to-day’s newspapers an advertisement of an Egyptian land company, announcing an issue of two and one half million dollars’ worth of stock. The syndicate says in its prospectus that it expects to buy five thousand acres of land at “the low rate of two hundred dollars per acre,” and that by spending one hundred and fifty thousand dollars it can make that land worth four hundred dollars per acre within three years. Some of this land[30] would now bring from two hundred and fifty to three hundred dollars per acre, and is renting for twenty dollars per acre per annum. The tract lies fifty miles north of Cairo and is planted in cotton, wheat, and barley.

Such estates as the above do not often come into the market, however. Most of Egypt is in small farms, and little of it is owned by foreigners. Six sevenths of the farms belong to the Egyptians, and there are more than a million native land owners. Over one million acres are in tracts of from five to twenty acres each. Many are even less than an acre in size. The number of proprietors is increasing every year and the fellaheen, or fellahs, are eager to possess land of their own. It used to be that the Khedive had enormous estates, but when the British Government took possession some of the khedivial acres came to it. These large holdings have been divided and have been sold to the fellaheen on long-time and easy payments. Many who then bought these lands have paid for them out of their crops and are now rich. As it is to-day there are but a few thousand foreigners who own real estate in the valley of the Nile.

The farmers who live here in the delta have one of the garden spots of the globe to cultivate. The Nile is building up more rich soil every year, and the land, if carefully handled, needs but little fertilization. It is yielding two or three crops every twelve months and is seldom idle. Under the old system of basin irrigation the fields lay fallow during the hot months of the summer, but the canals and dams that have now been constructed enable much of the country to have water all the year round, so that as soon as one crop is harvested another is planted.

The primitive norag is still seen in Egypt threshing the grain and cutting up the straw for fodder. It moves on small iron wheels or thin circular plates and is drawn in a circle over the wheat or barley.

The Egyptian agricultural year has three seasons. Cereal crops are sown in November and harvested in May; the summer crops are cotton, sugar, and rice; the fall crops, sown in July, are corn, millet, and vegetables.

The mud of the annual inundations is no longer sufficient fertilizer for the Nile farm. The fellaheen often use pigeon manure on their lands and there are hundreds of pigeon towers above the peasants’ mud huts.

The whole of the delta is one big farm dotted with farm villages and little farm cities. There are mud towns everywhere, and there are half-a-dozen big agricultural centres outside the cities of Alexandria and Cairo. Take, for instance, Tanta, where I am at this writing. It is a good-sized city and is supported by the farmers. It is a cotton market and it has a great fair, now and then, to which the people come from all over Egypt to buy and sell. A little to the east of it is Zagazig, which is nearly as large, while farther north, upon the east branch of the Nile, is Mansura, another cotton market, with a rich farming district about it. Damietta and Rosetta, at the two mouths of the Nile, and Damanhur, which lies west of the Rosetta branch of the Nile, not far from Lake Edku, are also big places. There are a number of towns ranging in population from five to ten thousand.

The farms are nothing like those of the United States. We should have to change the look of our landscape to imitate them. There are no fences, no barns, and no haystacks. The country is as bare of such things as an undeveloped prairie. The only boundaries of the estates are little mud walls; and the fields are divided into patches some of which are no bigger than a tablecloth. Each patch has furrows so made that the water from the canals can irrigate every inch.

The whole country is cut up by canals. There are large waterways running along the branches of the Nile, and smaller ones connecting with them, to such an extent that the face of the land is covered with a lacework veil of little streams from which the water can be let in and out. The draining of the farms is quite as important as watering, and the system of irrigation is perfect,[32] inasmuch as it brings the Nile to every part of the country without letting it flood and swamp the lands.

Few people have any idea of the work the Egyptians have to do in irrigating and taking care of their farms. The task of keeping these basins in order is herculean. As the Nile rushes in, the embankments are watched as the Dutch watch the dikes of Holland. They are patrolled by the village headmen and the least break is filled with stalks of millet and earth. The town officials have the right to call out the people to help, and no one refuses. If the Nile gets too high it sometimes overflows into the settlements and the mud huts crumble. During the flood the people go out in boats from village to village. The donkeys, buffaloes, and bullocks live on the dikes, as do also the goats, sheep, and camels.

The people sow their crops as soon as the floods subside. Harvest comes on within a few months, and unless they have some means of irrigation, in addition to the Nile floods, they must wait until the following year before they can plant again. With a dam like the one at Aswan, the water supply can be so regulated that they can grow crops all the year round. This is already the condition in a great part of the delta, and it is planned to make the same true of the farms of Upper Egypt.

As for methods of raising the water from the river and canals and from one level to another, they vary from the most modern of steam pumps and windmills to the clumsy sakieh and shadoof, which are as old as Egypt itself. All the large land owners are now using steam pumps. There are many estates, owned by syndicates, which are irrigated by this means, and there are men who are buying portable engines and pumps and hiring them out to the smaller[33] farmers in much the same way that threshing machines are rented in the United States and Canada. Quite a number of American windmills are already installed. Indeed, it seems to me almost the whole pumping of the Nile valley might be done by the wind. The breezes from the desert as strong as those from the sea sweep across the valley with such regularity that wind pumps could be relied upon to do efficient work.

At present, however, water is raised in Egypt mostly by its cheap man power or by animals. Millions of gallons are lifted by the shadoof. This is a long pole balanced on a support. From one end of the pole hangs a bucket, and from the other a heavy weight of clay or stone, about equal to the weight of the bucket when it is full of water. A man pulls the bucket down into the water, and by the help of the weight on the other end, raises it and empties it into a canal higher up. He does this all day long for a few cents, and it is estimated that he can in ten days lift enough water to irrigate an acre of corn or cotton. At this rate there is no doubt it could be done much cheaper by pumps.

Another rude irrigation machine found throughout the Nile valley from Alexandria to Khartum is the sakieh, which is operated by a blindfolded bullock, buffalo, donkey, or camel. It consists of a vertical wheel with a string of buckets attached to its rim. As the wheel turns round in the water the buckets dip and fill, and as it comes up they discharge their contents into a canal. This vertical wheel is moved by another wheel set horizontally, the two running in cogs, and the latter being turned by some beast of burden. There is usually a boy, a girl, or an old man, who sits on the shaft and drives the animal round.

The screech of these sakiehs is loud in the land and almost breaks the ear drums of the tourists who come near them. I remember a remark that one of the Justices of our Supreme Court made while we were stopping together at a hotel at Aswan with one of these water-wheels in plain sight and hearing. He declared he should like to give an appropriation to Egypt large enough to enable the people to oil every sakieh up and down the Nile valley. I doubt, however, whether the fellaheen would use the oil, if they had it, for they say that the blindfolded cattle will not turn the wheel when the noise stops.

I also saw half-naked men scooping up the water in baskets and pouring it into the little ditches, into which the fields are cut up. Sometimes men will spend not only days, but months on end in this most primitive method of irrigation.

The American farmer would sneer at the old-fashioned way in which these Egyptians cultivate the soil. He would tell them that they were two thousand years behind the time, and, still, if he were allowed to take their places he would probably ruin the country and himself. Most of the Egyptian farming methods are the result of long experience. In ploughing, the land is only scratched. This is because the Nile mud is full of salts, and the silt from Abyssinia is of such a nature that the people have to be careful not to plough so deep that the salts are raised from below and the crop thereby ruined. In many cases there is no ploughing at all. The seed is sown on the soft mud after the water is taken off, and pressed into it with a wooden roller or trodden in by oxen or buffaloes.

AFRICA

Last of the continents to be conquered by the explorers, and last to be divided up among the land-hungry powers, is now slowly yielding to the white man’s civilization.

Where ploughs are used they are just the same as those of five thousand years ago. I have seen carvings on the[35] tombs of the ancient Egyptians representing the farm tools used then, and they are about the same as those I see in use to-day. The average plough consists of a pole about six feet long fastened to a piece of wood bent inward at an acute angle. The end piece, which is shod with iron, does the ploughing. The pole is hitched to a buffalo or ox by means of a yoke, and the farmer walks along behind the plough holding its single handle, which is merely a stick set almost upright into the pole. The harrow of Egypt is a roller provided with iron spikes. Much of the land is dug over with a mattock-like hoe.

Most of the grain here is cut with sickles or pulled out by the roots. Wheat and barley are threshed by laying them inside a ring of well-pounded ground and driving over them a sledge that rests on a roller with sharp semicircular pieces of iron set into it. It is drawn by oxen, buffaloes, or camels. Sometimes the grain is trodden out by the feet of the animals without the use of the rollers, and sometimes there are wheels of stone between the sled-runners which aid in hulling the grain. Peas and beans are also threshed in this way. The grain is winnowed by the wind. The ears are spread out on the threshing floor and the grains pounded off with clubs or shelled by hand. Much of the corn is cut and laid on the banks of the canal until the people have time to husk and shell it.

The chief means of carrying farm produce from one place to another is on bullocks and camels. The camel is taken out into the corn field while the harvesting is going on. As the men cut the corn they tie it up into great bundles and hang one bundle on each side of his hump. The average camel can carry about one fifth as much as one horse hitched to a wagon or one tenth as much as a[36] two-horse team. Hay, straw, and green clover are often taken from the fields to the markets on camels. Such crops are put up in a baglike network that fits over the beast’s hump and makes him look like a hay or straw-stack walking off upon legs. Some of the poorer farmers use donkeys for such purposes, and these little animals may often be seen going along the narrow roads with bags of grain balanced upon their backs.

I have always looked upon Egypt as devoted mostly to sugar and cotton. I find it a land of wheat and barley as well. It has also a big yield of clover and corn. The delta raises almost all of the cotton and some of the sugar. Central and Upper Egypt are grain countries, and in the central part Indian and Kaffir corn are the chief summer crops. Kaffir corn is, to a large extent, the food of the poorer fellaheen, and is also eaten by the Bedouins who live in the desert along the edges of the Nile valley. Besides a great deal of hay, Egypt produces some of the very best clover, which is known as bersine. It has such rich feeding qualities that a small bundle of it is enough to satisfy a camel.

This is also a great stock country. The Nile valley is peppered with camels, donkeys, buffaloes, and sheep, either watched by herders or tied to stakes, grazing on clover and other grasses. No animal is allowed to run at large, for there are no fences and the cattle thief is everywhere in evidence. The fellaheen are as shrewd as any people the world over, so a strayed animal would be difficult to recover. Much of the stock is watched by children. I have seen buffaloes feeding in the green fields with naked brown boys sitting on their backs and whipping them this way and that if they attempt to get into the[37] crops adjoining. The sheep and the goats are often watched by the children or by men who are too old to do hard work. The donkeys, camels, and cows are usually tied to stakes and can feed only as far as their ropes will reach.

The sheep of Egypt are fine. Many of them are of the fat-tailed variety, some brown and some white. The goats and sheep feed together, there being some goats in almost every flock of sheep.

The donkey is the chief riding animal. It is used by men, women, and children, and a common sight is the veiled wife of one of these Mohammedan farmers seated astride one of the little fellows with her feet high up on its sides in the short stirrups. But few camels are used for riding except by the Bedouins out in the desert, and it is only in the cities that many wheeled vehicles are to be seen.

Suppose we go into one of the villages and see how these Egyptian farmers live. The towns are collections of mud huts with holes in the walls for windows. They are scattered along narrow roadways at the mercy of thick clouds of dust. The average hut is so low that one can look over its roof when seated on a camel. It seldom contains more than one or two rooms, and usually has a little yard outside where the children and the chickens roll about in the dust and where the donkey is sometimes tied.

Above some of the houses are towers of mud with holes around their sides. These towers are devoted to pigeons, which are kept by the hundreds and which are sold in the markets as we sell chickens. The pigeons furnish a large part of the manure of Egypt both for gardens and fields. The manure is mixed with earth and scattered over the soil.

Almost every village has its mosque, or church, and often, in addition, the tomb of some saint or holy man who lived[38] there in the past. The people worship at such tombs, believing that prayers made there avail more than those made out in the fields or in their own huts.

There are no water works in the ordinary country village. If the locality is close to the Nile the drinking and washing water is brought from there to the huts by the women, and if not it comes from the village well. It is not difficult to get water by digging down a few feet anywhere in the Nile valley; and every town has its well, which is usually shaded by palm trees. It is there that the men gather about and gossip at night, and there the women come to draw water and carry it home upon their heads.

The farmers’ houses have no gardens about them, and no flowers or other ornamental decoration. The surroundings of the towns are squalid and mean, for the peasants have no comforts in our sense of the word. They have but little furniture inside their houses. Many of them sleep on the ground or on mats, and many wear the same clothing at night that they wear in the daytime. Out in the country shoes, stockings, and underclothes are comparatively unknown. Only upon dress-up occasions does a man or woman put on slippers.

The cooking and housekeeping are done entirely by the women. The chief food is a coarse bread made of corn or millet baked in thick cakes. This is broken up and dipped into a kind of a bean stew seasoned with salt, pepper, and onions. The ordinary peasant seldom has meat, for it is only the rich who can afford mutton or beef. At a big feast on the occasion of a wedding, a farming nabob sometimes brings in a sheep which has been cooked whole. It is eaten without forks, and is torn limb from limb, pieces being cut out by the guests with their knives.

Next to the market where sugar cane is sold is the “Superb Mosque,” built by Sultan Hassan nearly 600 years ago. Besides being a centre for religious activities, it is also a gathering place for popular demonstrations and political agitation.

Cairo is the largest city on the African continent, and one of the capitals of the Mohammedan world. Its flat-roofed buildings are a yellowish-white, with the towers and domes of hundreds of mosques rising above them.

Of late Egypt has begun to raise vegetables for Europe. The fast boats from Alexandria to Italy carry green stuff, especially onions, of which the Nile valley is now exporting several million dollars’ worth per annum. Some of these are sent to England, and others to Austria and Germany.

As for tobacco, Egypt is both an exporter and importer. “Egyptian” cigarettes are sold all over the world, but Egypt does not raise the tobacco of which they are made. Its cultivation has been forbidden for many years, and all that is used is imported from Turkey, Greece, and Bosnia. About four fifths of it comes from Turkey.

Everyone in Egypt who can afford it smokes. The men have pipes of various kinds, and of late many cigarettes have been coming into use. A favourite smoke is with a water pipe, the vapour from the burning tobacco being drawn by means of a long tube through a bowl of water upon which the pipe sits, so that it comes cool into the mouth.

The chicken industry of Egypt is worth investigation by our Department of Agriculture. Since the youth of the Pyramids, these people have been famous egg merchants and the helpful hen is still an important part of their stock. She brings in hundreds of thousands of dollars a year, for her eggs form one of the items of national export. During the last twelve months enough Egyptian eggs have been shipped across the Mediterranean to England and other parts of Europe to have given one to every man, woman, and child in the United States. Most of them went to Great Britain.

The Egyptians, moreover, had incubators long before artificial egg hatching was known to the rest of the world.[40] There is a hatchery near the Pyramids where the farmers trade fresh eggs for young chicks at two eggs per chick, and there is another, farther down the Nile valley, which produces a half million little chickens every season. It is estimated that the oven crop of chickens amounts to thirty or forty millions a year, that number of little fowls being sold by the incubator owners when the baby chicks are about able to walk.

Most of our incubators are of metal and many are kept warm by oil lamps. Those used here are one-story buildings made of sun-dried bricks. They contain ovens which are fired during the hatching seasons. The eggs are laid upon cut straw in racks near the oven, and the firing is so carefully done that the temperature is kept just right from week to week. The heat is not gauged by the thermometer, but by the judgment and experience of the man who runs the establishment. A fire is started eight or ten days before the eggs are put in, and from that time on it is not allowed to go out until the hatching season is over. The eggs are turned four times a day while hatching. Such establishments are cheaply built, and so arranged that it costs almost nothing to run them. One that will hatch two hundred thousand chickens a year can be built for less than fifty dollars, while for about a dollar and a half per day an experienced man can be hired to tend the fires, turn the eggs, and sell the chickens.

Stand with me on the Hill of the Citadel and take a look over Cairo. We are away up over the river Nile, and far above the minarets of the mosques that rise out of the vast plain of houses below. We are at a height as great as the tops of the Pyramids, which stand out upon the yellow desert off to the left. The sun is blazing and there is a smoky haze over the Nile valley, but it is not dense enough to hide Cairo. The city lying beneath us is the largest on the African continent and one of the mightiest of the world. It now contains about eight hundred thousand inhabitants; and in size is rapidly approximating Heliopolis and Memphis in the height of their ancient glory.

Of all the Mohammedan cities of the globe, Cairo is growing the fastest. It is more than three times as big as Damascus and twenty times the size of Medina, where the Prophet Mohammed died. The town covers an area equal to fifty quarter-section farms; and its buildings are so close together that they form an almost continuous structure. The only trees to be seen are those in the French quarter, which lies on the outskirts.

The larger part of the city is of Arabian architecture. It is made up of flat-roofed, yellowish-white buildings so crowded along narrow streets that they can hardly be seen at this distance. Here and there, out of the field[42] of white, rise tall, round stone towers with galleries about them. They dominate the whole city, and under each is a mosque, or Mohammedan church. There are hundreds of them in Cairo. Every one has its worshippers, and from every tower, five times a day, a shrill-voiced priest calls the people to prayers. There is a man now calling from the Mosque of Sultan Hasan, just under us. The mosque itself covers more than two acres, and the minaret is about half as high as the Washington Monument. So delighted was Hasan with the loveliness of this structure that when it was finished he cut off the right hand of the architect so that it would be impossible for him to design another and perhaps more beautiful building. Next it is another mosque, and all about us we can see evidences that Mohammedanism is by no means dead, and that these people worship God with their pockets as well as with their tongues.

In the Alabaster Mosque, which stands at my back, fifty men are now praying, while in the courtyard a score of others are washing themselves before they go in to make their vows of repentance to God and the Prophet. Not far below me I can see the Mosque El-Azhar, which has been a Moslem university for more than a thousand years, and where something like ten thousand students are now learning the Koran and Koranic law.