![[The image of

the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: The life and works of Sir Charles Barry

Author: Alfred Barry

Release Date: September 16, 2023 [eBook #71663]

Language: English

Credits: Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

FOOTNOTES

By REV. ALFRED BARRY, D.D.,

PRINCIPAL OF CHELTENHAM COLLEGE.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

1867.

The right of Translation is reserved

{ii}

LONDON: PRINTED BY W. CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET,

AND CHARING CROSS.

{iii}

The objects which I have had in view in the following pages, and the spirit in which I have endeavoured to pursue them, are referred to in the opening paragraphs of the first chapter. It remains to say a few words on the nature of the materials at my command, and the authorities on which my statements of fact and opinion are based.

For all narrative purposes, I have found an abundance of excellent and trustworthy materials. My father’s architectural life is written in outline in his own professional journals, and, in its more important periods, has left its memorials in public and official documents of unquestionable authority. Some of these I have quoted in the Appendix; in other cases I have given summaries of their contents, and references to the original documents. In all cases I may venture to profess, that I have taken the greatest pains to ascertain clearly the facts which I have here recorded. When I could not consult official documents, I have depended only on personal recollection and the testimony of {iv}eye-witnesses. Of any errors, which may still have crept in, I shall thankfully receive correction.

I could indeed have wished to present to my readers more original letters and extracts from Journals. These form the most valuable part of many biographies; for, independently of any intrinsic excellence of their own, they are full of interest, as bearing the marked impress of personal character, and enabling the subject of the biography to speak for himself. But here my materials fail me. My father was no great letter-writer. His pen was indeed constantly busy in valuable professional notes and official reports, clear in style and comprehensive in scope, of which specimens are given in the Appendix. But I find few characteristic letters, embodying his personal opinions and feelings; and he does not appear to have preserved, except in a few cases, the numerous letters from eminent persons, which he must have received. I have had therefore to rely on personal recollection to supply the deficiency, and to endeavour in the last chapter to describe his private life and character, as it appeared to those who knew him and loved him best. Nor are his Journals altogether fit for reproduction. They are indeed invaluable as authorities. During his foreign tours they were copious and detailed, and almost the whole of Chapter II. is drawn {v}from them. But they were mostly notes for practical use, and, before they could be published, they would need alterations and developments, which he alone had the right to give them. During his professional life they contained simply brief memoranda of every day’s work. I could not therefore quote them with advantage, but I have found them of the greatest value in ascertaining facts and fixing dates, which otherwise might have escaped me.

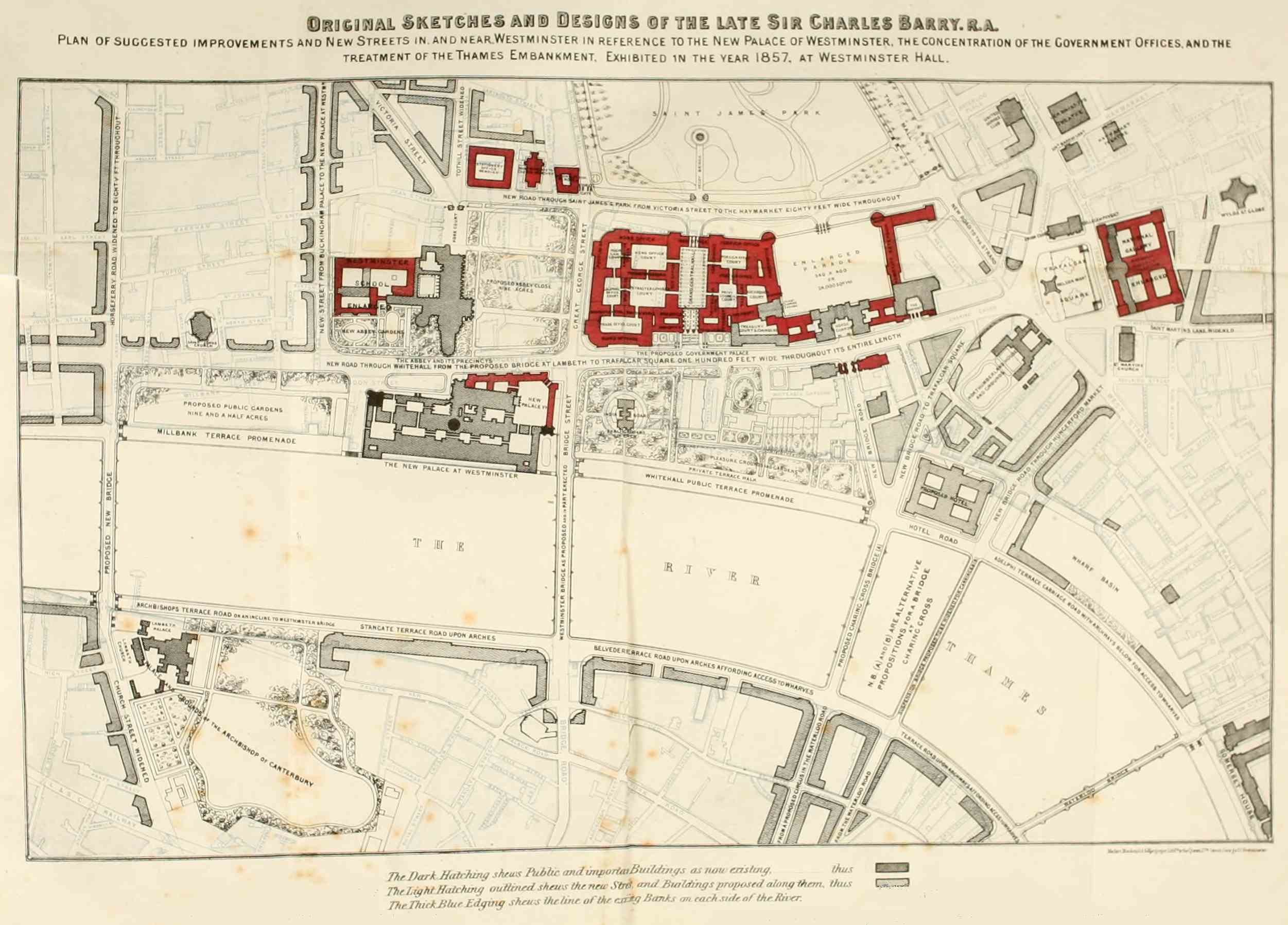

For all professional information and opinion,—for all, in fact, which may give any value to the work,—I have been able to refer to my brothers, in regard to the later part of my father’s career, with every fact of which they were intimately acquainted. For the earlier portion I have depended mainly on J. L. Wolfe, Esq., who was to my father the true friend of a lifetime, almost the only person who knew well his opinions and principles, and to whose aid and criticism he was materially indebted. He has given me notes and information, which I have found invaluable, especially in regard of the story of the New Palace at Westminster, which must be the central feature of the biography. For all the letterpress, however, I hold myself responsible. The choice of the illustrations is due to my eldest brother. We have to acknowledge with thanks the permission given us to use in some cases illustrations which{vi} have already appeared. Believing that an architectural record must speak mainly to the eye, we should gladly have given further illustrations; instead of some which are here found, we should have wished to represent more of the unexecuted designs, had authentic drawings been at hand; but we conceive that those actually given, especially the large illustrations of the Westminster Improvements, will be of great interest, both to the profession and to the public.

With these materials at command, and with these authorities to refer to, I have tried to tell my story, without tincturing the record with undue partiality, or introducing into it those merely private details, either of fact or of feeling, which appear to me to be utterly out of place in a published narrative.

I trust also, that, in speaking of controversies, and in dwelling on some parts of my father’s life, on which I cannot but feel strongly, I shall be thought to have observed due moderation of expression, and due respect for the reputation of others. In some cases I have simply stated facts, and left it to others to draw inferences and make comments upon them. It will not, I hope, be supposed that reticence in such cases implies any want of strong conviction or strong feeling on my own part. In fact, as the work has proceeded, I have felt more and more that such reticence is forced upon a son, when he is writing{vii} his father’s life, and I do not think that it need necessarily interfere with the impression which the record ought to create.

The story itself may perhaps be mainly one of professional interest. But this is a time in which Art is beginning to be recognised as an important subject to the public; and the record of a career not unimportant in regard of artistic progress, of the erection of one of the largest and most important buildings of modern times, and of designs and opinions bearing upon most public improvements now actually in contemplation, may therefore commend itself to general notice.

I have only to say in conclusion, that the inevitable difficulties in the task of preparation, the duty of wading through long official documents, and the necessity of seeking in many quarters information (which, even now, has occasionally arrived too late for use),[1] have delayed the publication of this Memoir to a period far later than that originally contemplated. I am far, however, from regretting this enforced delay. Whatever interest there may be in the record of works and opinions here given, it is not of a temporary character; and it is clear, from many indications, that even the time, which{viii} has already elapsed, has served to bring out public opinion more clearly, and has tended to the formation of a true estimate of Sir Charles Barry’s architectural genius, and of the position which his works must hold in the progress of English Art.

A. B.

Cheltenham, April, 1867.

Since this work was printed, the risk alluded to in page 195, as likely to arise from the employment of the late Mr. A. W. Pugin on the New Palace at Westminster, has been unexpectedly realized fifteen years after his death by some extraordinary claims put forward by his son. These claims, referring as they do to a question raised and settled in the life-time of those concerned, have not appeared to me to require any notice in these pages. I have therefore left the whole passage in pp. 194-198 precisely as it was originally written, without the alteration of a single word. It contains the exact account of the connexion which existed between Mr. A. W. Pugin and my father, and which, I repeat, so far as Sir Charles Barry’s knowledge and feeling were concerned, was never broken by any dispute or estrangement, from the day when Mr. Pugin (then a young man of 23) was first employed on the drawings of the New Palace, until the day of his death in 1852.

A. B.

October 22nd, 1867.{ix}

| I. 1795-1817. EARLY LIFE AND EDUCATION. | |

|---|---|

| Object of the work—Birth of Charles Barry—His childhood, schooldays, and apprenticeship—His early efforts and amusements—His self-education and its effects on his character—His determination to travel—His matrimonial engagement | Page 1 |

| II. 1817-1820. TRAVELS IN FRANCE, ITALY, GREECE, EGYPT, AND THE EAST. | |

| I. France and Italy.—General effects of travel—Study of classical architecture—Observation of natural scenery—Universality and accuracy of examination. II. Greece and Constantinople.—Growth of artistic power—Impressions of Athens and Constantinople—Contrast of the Turkish and Greek characters. III. Egypt and the East.—Great effect of Egyptian architecture upon him—Mehemet Ali’s government—Dendera, Esneh, Edfou, Philæ, Abousimbel, Thebes—Return to Cairo—Palestine—Jerash—Baalbec—Damascus—Palmyra. IV. Sicily and Italy.—Syracuse, Messina, Agrigentum, and Palermo—Return to Rome—Meeting with Mr. J. L. Wolfe—Systematic architectural study—Effects of Egyptian impressions—Italian palaces at Rome, Florence, Vicenza, and Venice—Italian churches—St. Peter’s, the Pantheon, the cathedrals at Florence and Milan—The bridge of La Santa Trinita at Florence—The {x}growth of his architectural principles—Return to England | 15 |

| III. 1820-1829. EARLY PROFESSIONAL LIFE. | |

| Early difficulties and failures—Thought of emigration—Non-publication of his sketches—Holland House—Revival of Gothic—His Manchester churches, and their peculiarities—Marriage—Church at Oldham—Alarm at Prestwich Church—Designs for King’s College, Cambridge—Royal Institution at Manchester—Gradual relinquishment of Greek architecture—St. Peter’s Church, Brighton—Sussex County Hospital—Petworth Church—Queen’s Park, Brighton, his first Italian design—Islington churches—His relations to church architecture generally—Removal to Foley Place—Subsidiary work—Travellers’ Club—General character of his life at this period | 64 |

| IV. CHIEF ITALIAN WORKS. | |

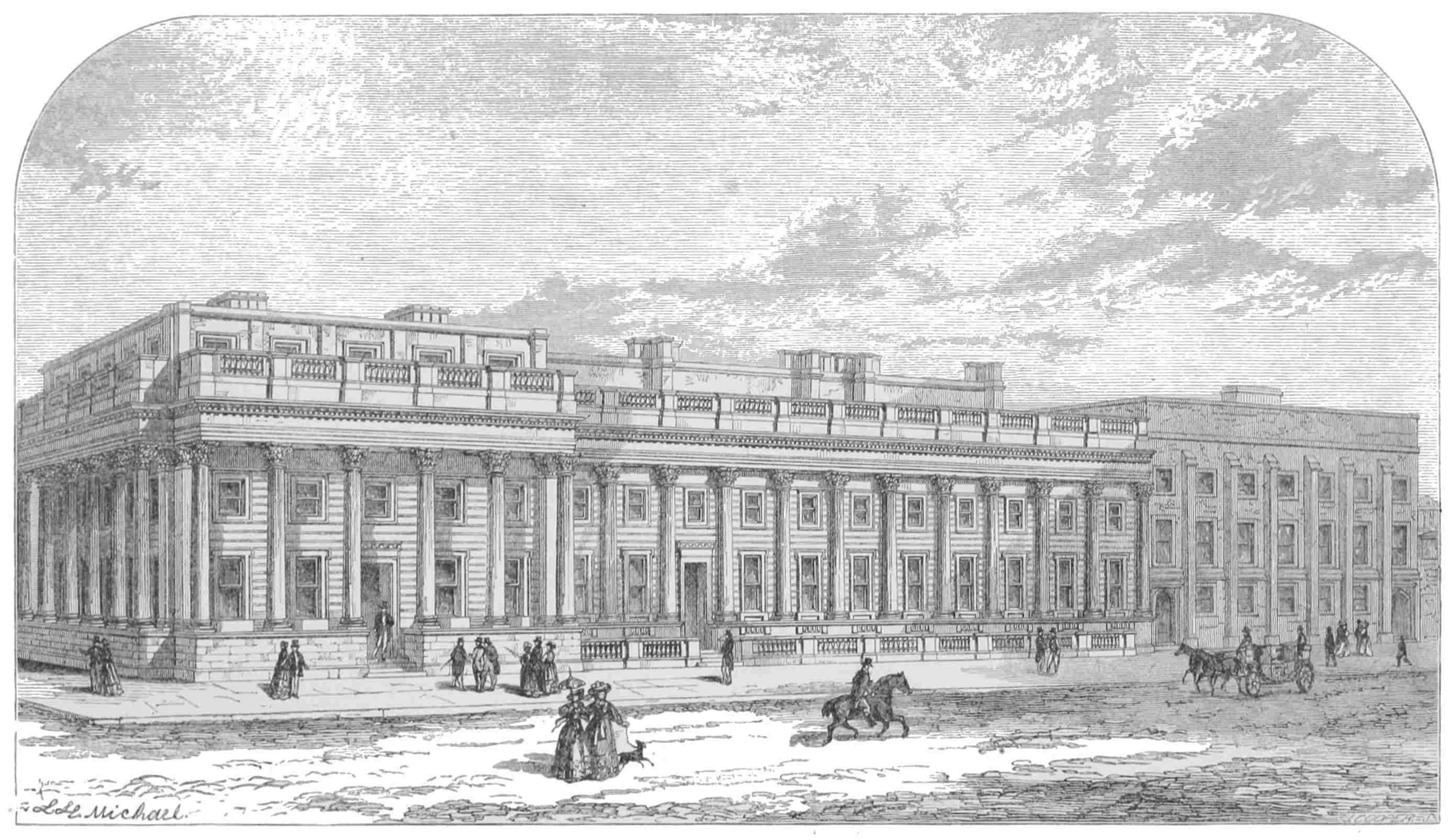

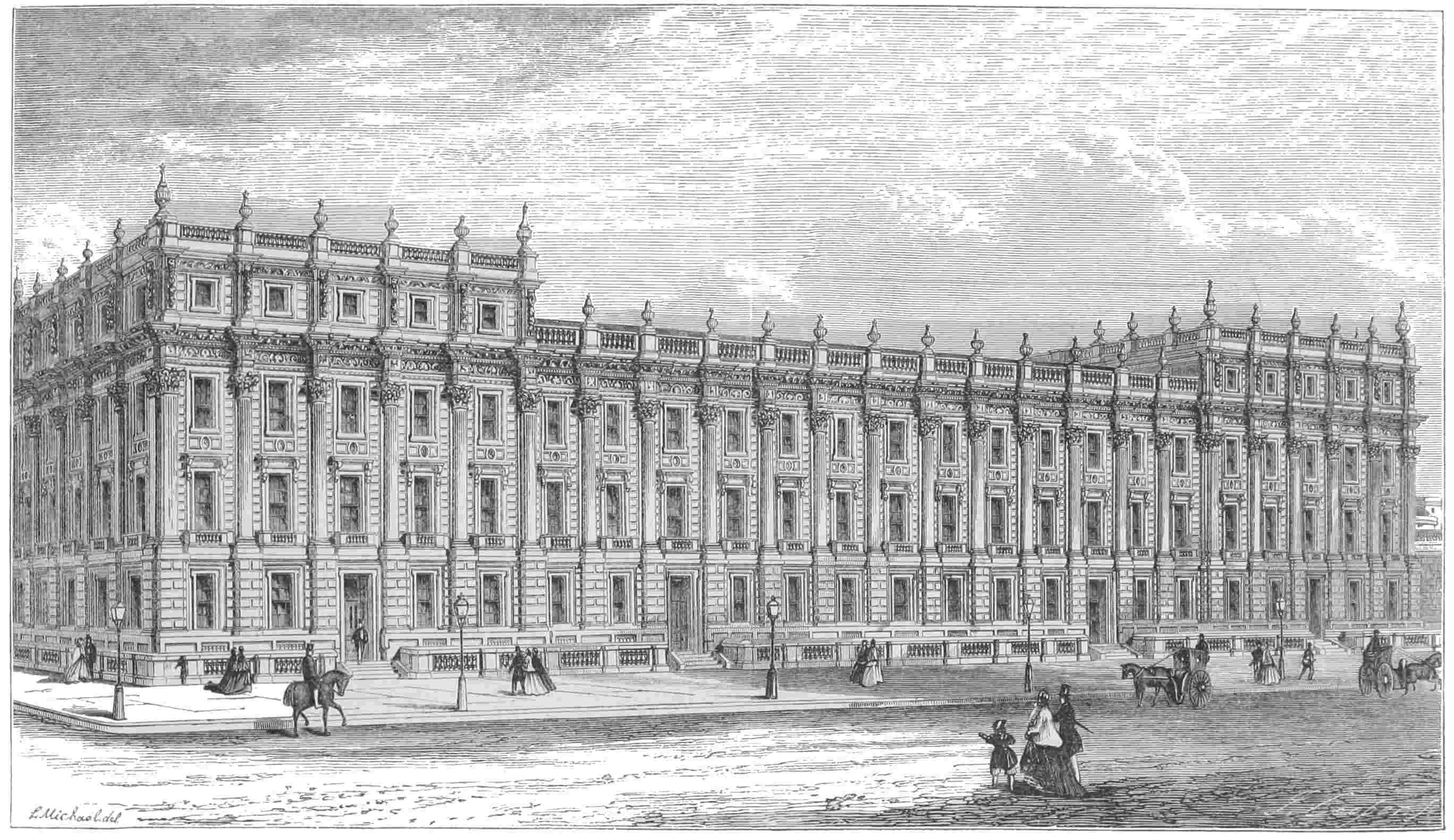

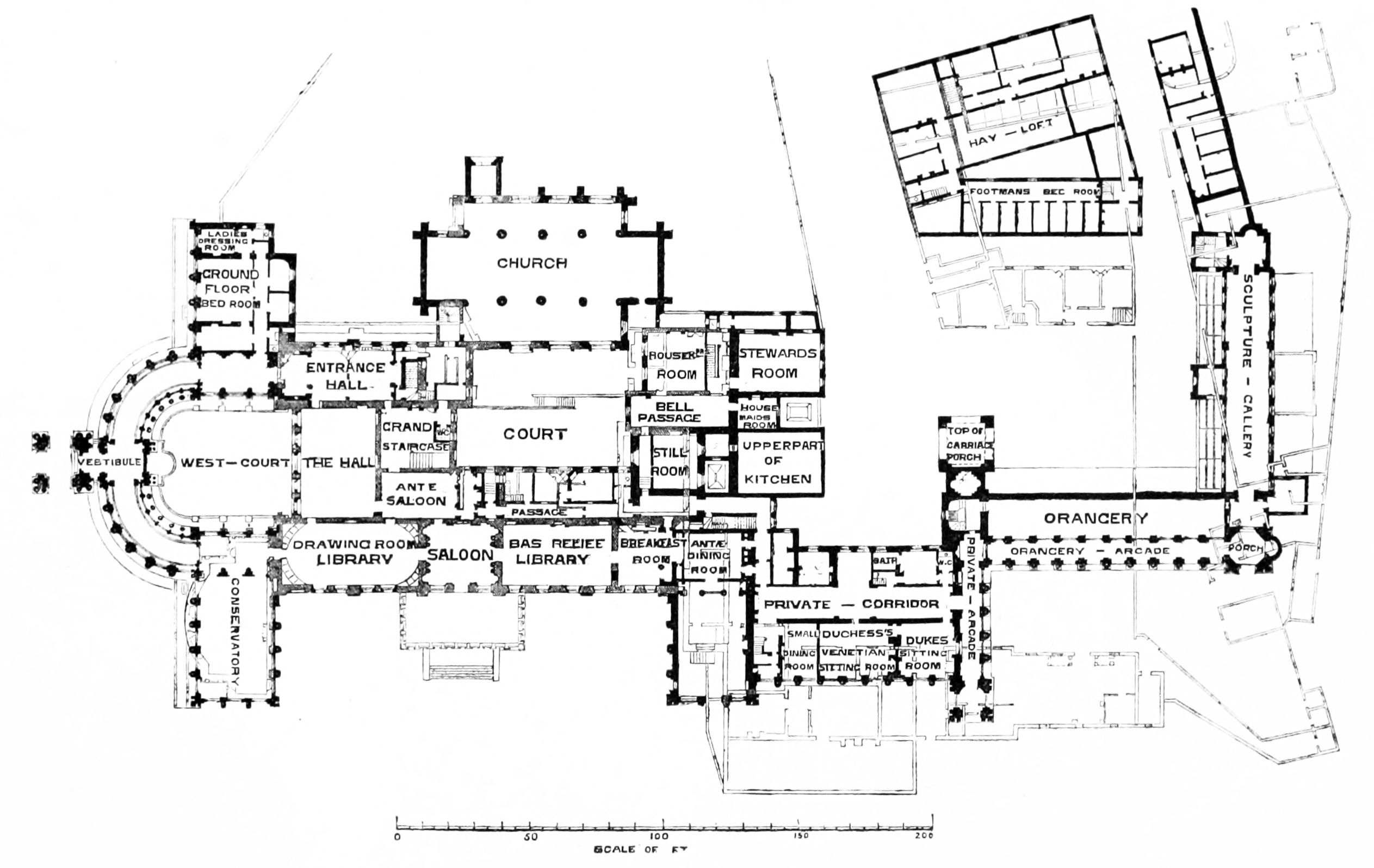

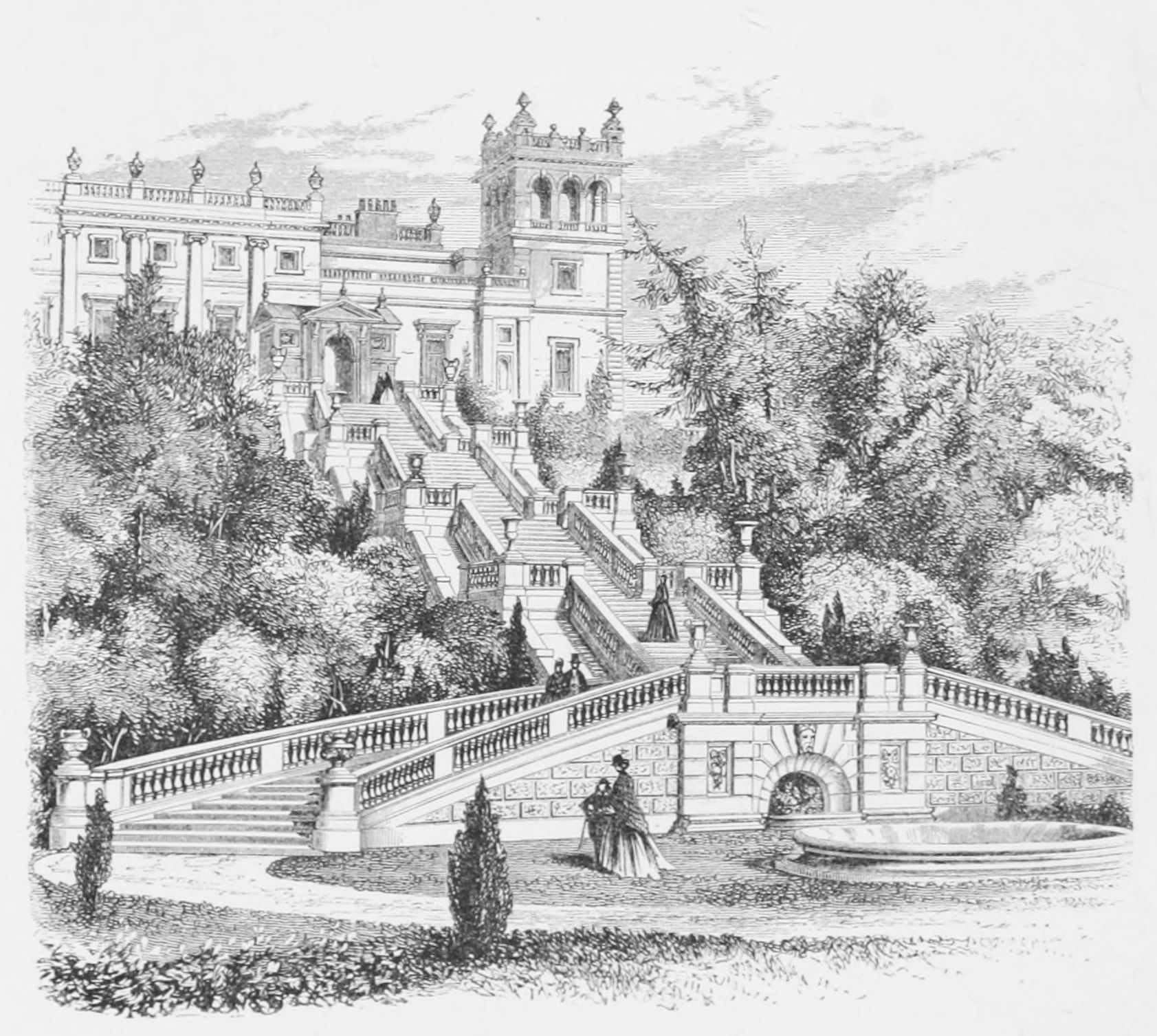

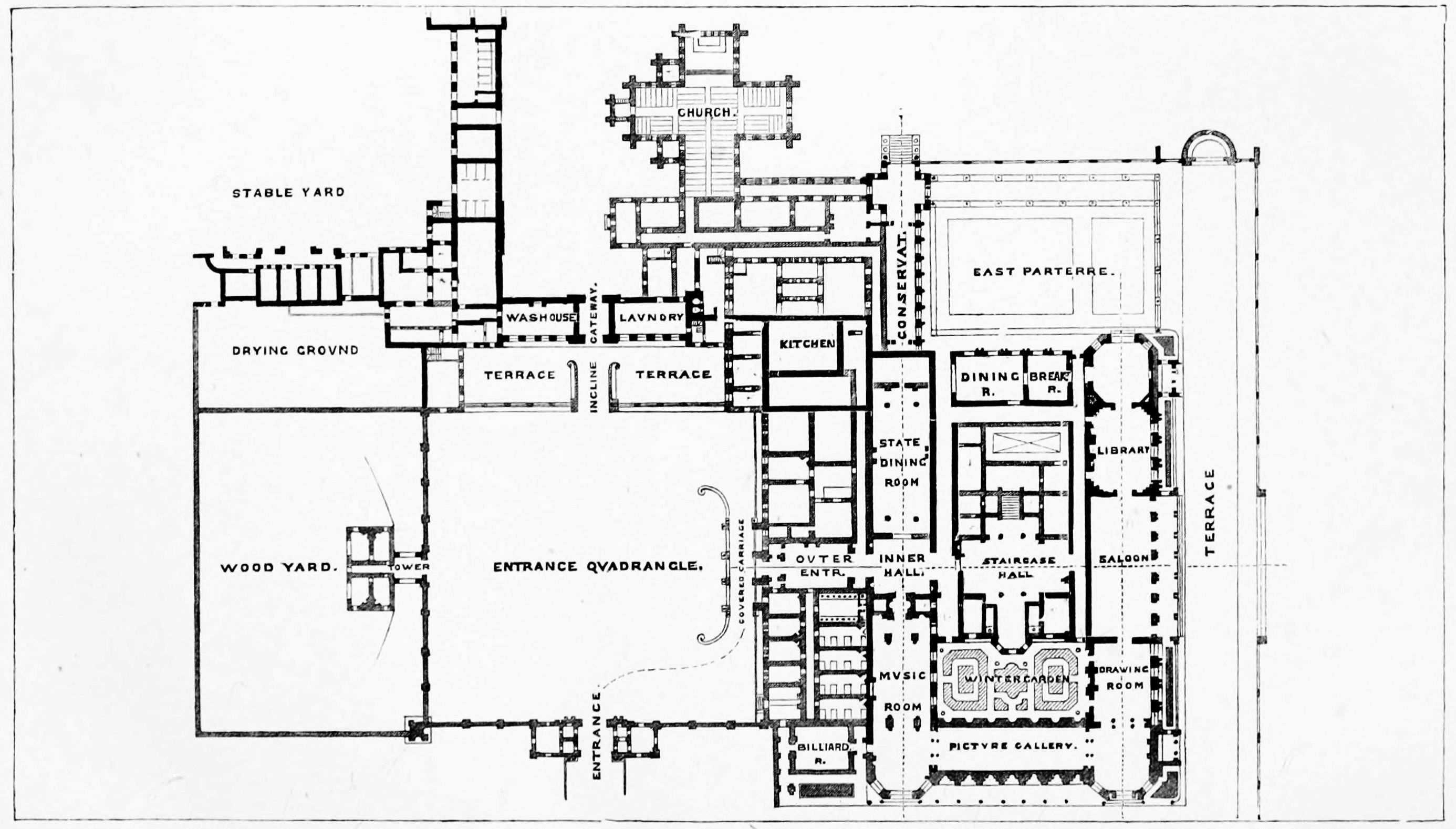

| Plan of the Chapter. (A.) Original Buildings—Varieties of his Italian style—First manner—Reform Club—Manchester Athenæum—New wing at Trentham—Second manner—Bridgewater House—Third manner—Halifax Town Hall. (B.) Conversions and Alterations—College of Surgeons—Walton House—Highclere House—Board of Trade—Architectural gardening—Trentham Hall—Duncombe Park—Harewood House—Shrubland Park—Cliefden House—Laying out of Trafalgar Square. (C.) Designs carried out by others—Keyham Factory—Ambassador’s Palace at Constantinople—General remarks on his Italian architecture | 89 |

| V. MINOR GOTHIC WORKS. | |

| Progress of the Gothic revival—Birmingham Grammar School—First acquaintance with Mr. Pugin and Mr. Thomas—Alterations at Dulwich College—Unitarian chapel at Manchester—Additions to University College, Oxford—Hurstpierpoint Church—Canford {xi}Manor—Gawthorpe Hall—Designs for Dunrobin Castle | 128 |

| VI. THE NEW PALACE AT WESTMINSTER. | |

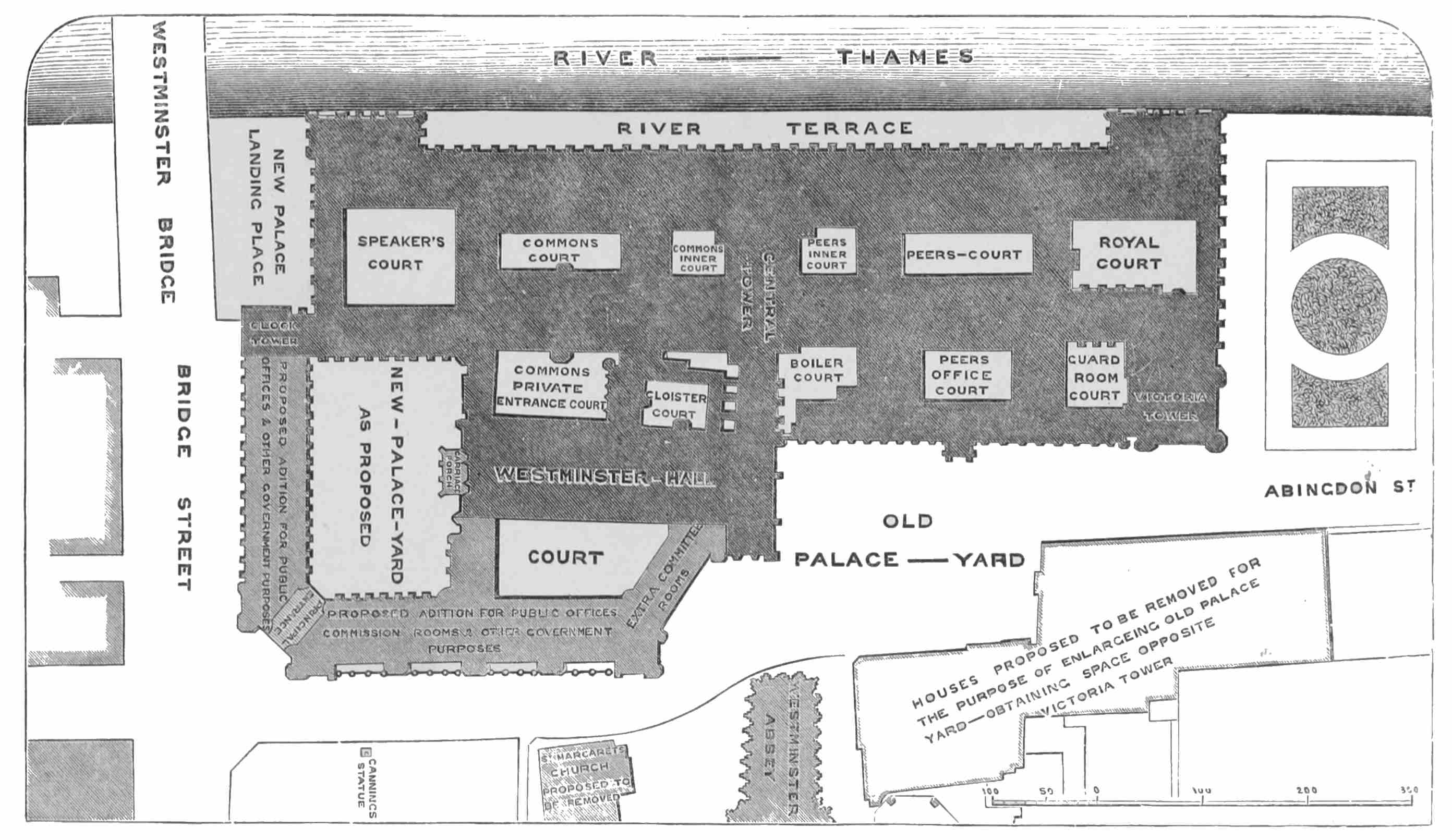

| Plan of the Chapter. Section I. History of the Competition—Burning of the old Houses of Parliament—Opening of the Competition for the New Building—Award of the Commissioners—Approved by the Select Committee of the Houses—Protest of the advocates of Classical Architecture—Critical controversy—Personal attacks on Mr. Barry—Meeting of unsuccessful Competitors—Presentation of Petition by Mr. Hume—Opposition quashed by Sir Robert Peel—Protest against it by Professor Donaldson and others. Section II. Progress of the Building—Difficulties as to the Foundation—Commission of Inquiry as to the Stone to be used—First Stone laid—Unavoidable delays—Committee of the Peers—Generous support of Earl of Lincoln—Committee of the Commons—Appointment of New Palace Commissioners—Appointment of Dr. Reid—Difficulties arising therefrom, and arbitration of Mr. Gwilt—The Great Clock—Competition and success of Mr. Dent—Professor Airy and Mr. E. B. Denison referees—Mr. Denison the chief Director—His tone and method of controversy—The Great Bell and its disasters—The Fine Arts Commission—The Architect’s exclusion from it—His scheme for the Decoration of the Building—The scheme of the Commissioners—Its ideal excellence and practical drawbacks—Connection with Mr. Pugin—Real nature of the aid given by him—Mr. Thomas and the stone carving—Mr. Meeson and the practical engineering—Other assistants in the work—Opening of the House of Peers—Opening and alteration of the House of Commons—The Architect knighted in 1852—The Great Tower hardly completed at his death. Section III. The Remuneration Question—Its points of public interest—General question of architectural percentage—Its bearing on the particular work—Original attempt at a bargain by Lord Bessborough—Accepted under protest—Re-opening of the question—First Minute of the Treasury, and reply—Mr. White acts for Sir C. Barry—Second Minute of the Treasury—Counter statement—Third Minute of the Treasury—Submitted to by Sir C. Barry—Protest of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and reply—Practice of the Government after Sir C. Barry’s death—General reference to the question {xii}of expenditure—Summing up of the chief points of the controversy | 143 |

| VII. The NEW PALACE AT WESTMINSTER. | |

| I. History of the Growth of the Design.—Influence of external circumstances on the design—Lowness and irregularity of site—Limitation of choice to Elizabethan and Gothic styles—Choice of Perpendicular style—Original conception of the Plan—Question of restoration of St. Stephen’s Chapel—Use of Westminster Hall as the grand Entrance to the building—Simplicity of plan—Principle of symmetry and regularity dominant—Enlargement of Plan after its adoption—Conception of St. Stephen’s porch—The Central Hall—The Royal entrance and Royal Gallery—The House of Lords, its construction and decoration—The House of Commons, and its alteration—Great difficulty of the acoustic problem—Enlargement of public requirements—Alterations of design in the River Front—The Land Fronts—The Victoria Tower—The Clock Tower—General inclination to increase the upward tendency of the design, and the amount of decoration. II. Brief Description of the Actual Building.—Its dimensions—Its main lines of approach; the public approach—The Royal approach—The private approaches of Peers and Commons—General character of the plan—The external fronts—The towers—Criticisms on the building by independent authorities | 236 |

| VIII. CHIEF DESIGNS NOT EXECUTED. | |

| Large number of designs not executed—Views of Metropolitan Improvement—Reasons for notice of such designs—Clumber Park—New Law Courts—National Gallery—Horse Guards—British Museum—General scheme laid before the late Prince Consort—Design for new Royal Academy—Crystal Palace—Alterations of Piccadilly and the Green Park—Prolongation of Pall Mall into the Green Park—Westminster Bridge—Extension of the New Palace at Westminster round New Palace Yard—Great Scheme of Metropolitan Improvements—Plan and description—General remarks {xiii}thereon | 266 |

| IX. GENERAL NOTICE OF PUBLIC LIFE. | |

| Public action—His natural dislike of publicity—His characteristics as a Commissioner—Royal Academy—Scheme for Architectural Education—Royal Institute of British Architects—Scientific Societies—Royal Commission of 1851—Exposition Universelle of 1855—Professional arbitrations at Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Leeds—St. Paul’s Cathedral Committee | 302 |

| X. PRIVATE LIFE AND DEATH. | |

| Leading events of his life—General habits of work—Domesticity and privacy of life—Acquaintances and friendships—Distaste of publicity—Leading features of character—Personal appearance—Failure of health—Death—Funeral in Westminster Abbey—Erection of Memorial Statue—Conclusion | 323 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| (A.) List of Architectural Designs | 355 |

| (B.) Letter to his Royal Highness the Prince Consort as to the South Kensington Scheme | 358 |

| (C.) Papers on the Remuneration Controversy | 369 |

| (D.) List of Subscribers to the Memorial Statue | 405 |

Object of the work—Birth of Charles Barry—His childhood, schooldays, and apprenticeship—His early efforts and amusements—His self-education and its effects on his character—His determination to travel—His matrimonial engagement.

In the compilation of this memoir of my late father I have endeavoured to keep two objects in view. It is desired, on the one hand, to preserve for his family and his many personal friends some record of his private life and character. It is thought, on the other, that there will be some public value and interest in a notice of his opinions, designs, and works, and a general record of his professional career.

Even to the public at large it is conceived that his life, though it presents but little variety of incident, may yet be worth telling. He started with no advantages of birth, and with an imperfect education;{2} he was supported by no influential connection or school of art, and was aided by no patronage except that which his own merit commanded. He won for himself a place among the foremost architects of Europe, not more by his talents than by a life-long devotion to his art, and an extraordinary power of work. Having earned this high position, he paid its usual penalty in the many difficulties and misrepresentations, which are inevitable to a professional career, and which, though they may be stoutly met, tend, far more than any mere work, to wear out the energies and shorten the life. The interest of biography seems to lie, not so much in variety of event, as in its illustration of human character, and the ordinary conditions of human life. It is hoped that this interest may not be altogether wanting in the following pages.

By his professional brethren it will probably be thought, that the history of so many public and private works, and of the questions raised and decided in connection with them, may bear on some points important to the profession at large, and that the grounds and the nature of the architectural principles, which he maintained, may excite interest, even where they do not secure agreement. It is not unlikely that the record of such a life as his may throw some light on the remarkable progress and diffusion of artistic taste, which appear to mark our own time, transforming the whole aspect of our country, and not indirectly affecting our national character. Since he entered on his career the forms of Art have changed, and its principles have been{3} developed or modified. With some of these changes he strongly sympathized; others he strenuously resisted. But, in either case, the record of a life of ceaseless architectural activity, and of a mind keenly alive to artistic influences—readily impressible, and bound to no special school—must tend to illustrate the movements which have taken place, and are taking place still, in his own special province of Art.

It is for these reasons that the following memoir has been undertaken. In performing such a duty, it would be useless and unbecoming in a son to affect a position of independent criticism, or to claim credit for a strict impartiality. It can only be expected that he should record his father’s career as it was seen from his own point of view, and sketch his character as it appeared to those who loved him best. It can only be required that he observe strict truthfulness and accuracy as to facts, and due consideration for the feelings of others. If these limitations be observed (and I trust that in the following pages they will be observed most sacredly), experience has shown that such a record is likely to contain at least a large and essential portion of the whole truth. There will be subjects indeed on which it can only give the materials for judgment; for, where criticism is precluded, eulogium is at least equally out of place. But such correction and completion as it requires may be safely left to the impartial judgment of its readers.

In most cases its influence on the reputation of its subject is but a secondary one. The true and lasting reputation of a man will depend very little on any other memorial than the work which he has done, and{4} the influence which he has exerted in his life-time; and on the results which he has thus left behind for the use and the verdict of posterity.

Charles Barry, the fourth son of Walter Edward and Frances Barry, was born in Bridge Street, Westminster, on the 23rd of May, 1795, in a house which (until last year) lay under the shadow of the Clock Tower of the New Palace at Westminster.

His father was a stationer of great respectability and some wealth,[2] as is seen by the fact that he supplied, in the course of his business, the materials used at the Government Stationery Office. His mother died in 1798, when he was a little more than three years old; but her place was supplied (so far as a mother’s place can be) by the care and affection of his stepmother, Sarah, to whom his father was married shortly after, and to whom, at his death in 1805, he left the care of his children, and of the business which was to support them. Most thoroughly did she fulfil the charge, and reap her due reward of respect and gratitude. Of the whole family he alone, even from his childhood, manifested artistic taste and capacity, and chose for himself, in spite of all difficulties, a new path in life. These difficulties were then far greater than they would be now, in a less stationary condition of society, with greater facilities for change and travel, and greater opportunities of artistic and general education. There was little in his home life to foster any high aspirations, although{5} perhaps its wholesome atmosphere of honesty and regularity, of steady industry and “habits of business,” supplied a corrective influence much needed by an enthusiastic and artistic temperament.

He had little advantage of education. He went with his brothers to various private schools, such as schools then were. The first seems to have been a mere preparatory school; of the second, the only account preserved is that the “master paid little attention to it, being very dissolute, and absenting himself for weeks together;” and the last school, though perhaps rather better than the rest, was apparently one of those which attempted only mechanical teaching and severe discipline. Education, in the highest sense of the word, seems hardly to have been dreamt of. He carried away from it little except a superficial knowledge of English, a good proficiency in arithmetic, and a remarkably beautiful handwriting.

The account of his early days speaks of him as merely a warm-hearted and spirited boy, handsome and engaging in appearance, not very studious, full of fun, and by no means averse to mischief. His only remarkable talent was his taste for drawing; in this he was taught by a most incompetent man, and his best practice was in caricatures, especially of his drawing-master. The imperfection of his early training he always felt and regretted, in spite of his zealous efforts to supply its deficiencies. For, not to speak of the external difficulties which it threw in his way, it is obvious enough that his impulsive disposition, quick observation, and susceptible mind,{6} especially needed the bracing and strengthening influence of a good education.

On leaving school, at the age of fifteen, he was articled to Messrs. Middleton and Bailey, architects and surveyors, of Paradise Row, Lambeth. With them he remained six years. Both took a strong and affectionate interest in him, and from them he received all the professional training which he ever enjoyed. Their business was mainly that of surveying; he could have learnt little with them of the artistic element of architecture. But his time was not wasted; for he studied accurately and industriously the “business” of his profession. Lists of prices, calculations of dimensions, methods of measuring and valuation, crowd his note-book, side by side with studies from Chambers’ Architecture, and sketches of such details and ornaments as struck his own fancy. In the later part of his time much responsibility was thrown upon him, and responsibility he never refused. The fruit was seen in after life in his excellent habits of business, and his ability to prepare his own working drawings, make out his own specifications and estimates, and form a sound judgment of materials and work. This knowledge stood him in good stead; he never failed to impress its importance on young architects; and, though he would not for a moment have allowed it to take equal rank with artistic power, he regarded the frequent neglect of it, and the increasing tendency to separate it from the higher province of art, as a serious evil, both in theory and in practice.

But he could not be satisfied with this semi-{7}mechanical work. His name appears regularly in 1812, 1813, 1814, and 1815 in the architectural part of the catalogue of the Royal Academy. His first drawing, there exhibited when he was seventeen years old, still remains. It was a drawing of the interior of Westminster Hall, the building which (as has been well said) “was in after-days to give the key-note to his greatest work.” His other designs “For a Church,” “A Museum and Library,” “A Nobleman’s Mansion,” &c., have all perished. They had served their purpose, and were no doubt destroyed by himself, for he was always ruthless both in his criticism and his treatment of his early designs.

At an earlier age (about fifteen or sixteen) his artistic taste had found a much more curious development. There was much of the boy in him still (as indeed there was in all his after-life), and he did not disdain boyish fancies and amusements. Accordingly he resolved to transform his small attic bedroom into a “hermitage,"—“a rocky interior,” “with openings looking out on a sunny landscape.” The mechanical work and the painting he did entirely himself, working at it in all his spare time with constant delight; and when it was done, he kept up its character by using it as a painting-room, and drawing constantly figures of all kinds on a large scale on its walls. His family noticed all this with some wonder and amusement; he himself, though he used to laugh at it in after-life, remembered it with a kind of pleasure. These details may seem trivial, but they were certainly characteristic. The work must have given boldness to his hand (as scene-painting has done to some of{8} our great painters); it may not improbably have helped to kindle and foster his imagination, and at the same time to satisfy that delight in alteration and contrivance which always was conspicuous in him.

In every respect his home was a simple and a happy one. If it did not stimulate artistic tastes, it certainly allowed them perfect freedom, and gave them the support of admiration and sympathy. His character, in spite of his fondness for change and amusement, was always strongly domestic. In his work, and the society of his mother (for so he always esteemed her) and his brothers, he found all the interest he cared for. Such are the records of his early days. They are scanty enough; but they are corroborated by the recollections of his later life, for his was a character that changed but little.

It is evident from these that he was in every sense of the word a self-educated man, and the recognition of this fact is most important, for the true appreciation of his character, and a right understanding of his career.

Even in general education this was strikingly the case. He carried away very little from school. His very journals show that he had to acquire for himself not only a knowledge of French and Italian (which he mastered sufficiently for all practical purposes), but even correctness and fluency of English. They show, during his foreign journey, almost as great progress in style as in thought—a progress gained, as usual with him, not so much by systematic study as by a certain “readiness of mind” and an unwearied practice. Mathematics and theoretical mechanics he{9} had studied but little, and in fact he had little taste for such study. Their practical conclusions, as bearing on his own profession, he knew familiarly enough; and his mind was not only quick in its deductions from them, and bold even to the verge of rashness, but singularly fertile in all kinds of mechanical contrivance. But of systematic study of theory he was impatient. He could often, though at some risk, supersede it for himself by a kind of intuition, and he perhaps never estimated it at its true value.

But much more was this the case in all that regarded his own profession. No powerful mind had by its contact fired and influenced his; no deep course of study had imbued him with profound and systematic principles. He had gained “business” experience and practical knowledge; his strong natural tastes and powers had been cordially and kindly recognised, but in all that concerns the higher element of his profession he was left alone to find his way by his own observations and inductions to the first principles of Art. His natural character—vigorous, impulsive, and energetic—was allowed to grow by its own power, and to choose for itself both the method and the direction of growth.

The chief consequence was, as usual, an intense and absorbing devotion to the art which he had chosen as his work in life. He found it difficult to take any deep interest in anything else. In the political and social questions of the day he would often adopt the opinions of others. All his originality and his thought were already pre-occupied. In the service of architecture he held everything cheap; time,{10} labour, and health were sacrificed as a matter of course; and keenly sensitive as he was to blame, yet he would defy the opinion of the world in search of what he deemed perfection.

His art was scarcely at any time absent from his mind, even in times of social relaxation or of more serious employment. He could hardly enter a room without seeing capabilities in it, and longing to develope them. But when an important design was in progress, it seemed to take entire possession of his mind. It was his custom to work it out almost wholly for himself, in its scientific and financial as well as its artistic bearings. His extraordinary rapidity of execution and untiring industry enabled him to keep up this custom to a great extent, even in his busiest times. In fact, when a design was once conceived—when it had once taken possession of his imagination—hard work at it was a relief. The idea of it would occur to him at his first waking, and he could not but rise, however early the hour, and set to work. Adverse criticism at such a time was rejected or disregarded, but a few days later it would be found to have sunk into his mind unconsciously; then it would be rapidly seized upon as if original, and its results, often greatly modified and reconstructed, would be produced in the most perfect good faith as new, perhaps to the very person who had first made the criticism. Difficulties were forgotten or defied in the attempt to perfect the idea conceived; drawings of the more important parts of the work altered scores of times until his fastidious taste was satisfied. He could not conceive the idea of resting contented with{11} what was acknowledged to be defective, and he held that the word “impossible” was to be erased from his dictionary. In this absorbing devotion to his art lay the cause of infinite labour, many troubles, and much misapprehension, but in it lay, as usual, the secret of success.

Another effect of this early freedom and self-direction was a vigorous growth of self-reliance and originality. It perhaps entailed some want of philosophic symmetry and largeness of view, especially at a time when there was comparatively little study of great principles of art as based on substantial reason. Grounds of criticism were then sought by the generality in conventional rules, and by the more active minds in arbitrary conceptions of “taste,” till society was divided into the connoisseurs, who were to pronounce their arbitrary judgment, and the “ignobile vulgus,” who were obediently and ignorantly to accept their conclusions. Yet it gave him the power of progress, and it kept him also free from any tendency to bigotry and copyism. There is indeed the highest kind of originality, which combines philosophic knowledge and study with the power of a true development. But in practice, especially in the domain of art, the most important steps of progress are probably due to men of a happy intuition and an unscientific audacity, and such men are usually men who have guided and educated themselves.

He himself was avowedly and on principle an eclectic. He could not help recognising the excellences of various schools: but he knew too much to{12} be satisfied with any single one, as if it were all-comprehensive, and to conclude accordingly that to it alone praise and devotion are due. His principles of design and construction had been worked out for himself, the fruit of many crude conceptions in theory and many trials in practice. For that very reason they became so deeply rooted in his mind, that, when he attempted to change his course, he found himself insensibly returning to them. His early study of Greek architecture did not prevent his appreciation of Italian and Gothic; and so he stood apart from the exclusive devotion to one or other style which now seems to divide the architectural profession. Such a position is a difficult and dangerous one, in art, as well as in politics or theology, but those who occupy it supply the chief resisting influence to stagnation, and open some of the chief avenues of progress. In his case it was all but inevitable; his natural character, and his early freedom from the trammels of any school of art, forbade his taking any other course. For even in his early days those characteristics were fixed which determined his after career.

With these capabilities, and with a fixed and hopeful resolution to cut out a path for himself, he passed through his time of pupilage, and attained his majority in 1816. He now began to act for himself, and he at once conceived, or perhaps after long consideration declared openly, a determination on which much of his future success depended. He was naturally formed to make his way in the world. To the mental qualities already enumerated he added the{13} advantages of a handsome person, great fascination of manner, high spirits, and a sanguine temperament, which was well calculated to inspire confidence and win affection. He believed that he had the elements of success in him, and that he only needed freedom of scope and a more extended sphere than he could obtain at home. The result verified his belief. Perhaps the prophecy fulfilled itself.

By his father’s will, he and each of his brothers had inherited a certain sum of money, and the remainder of this inheritance, diminished by the expense of his education and his articles, now came into his hands. The sum was not a large one, and it was his all, for he had little expectations of assistance from without in entering on the risks of a professional career. He resolved to devote the whole, or the greater part of it, to an architectural tour.

The Continent was just opened by the peace of 1815. All English society was awaking from the torpor and isolation of the great European war. Architecture was receiving a fresh stimulus by the cessation of external difficulties, and fresh principles and models from abroad were breaking in upon its stereotyped forms. He naturally felt, with all the impressibility of his character, the influence of this universal movement; and at the same time, from deliberate consideration, he saw that his only chance of developing the power and satisfying the desires of which he was conscious, his only chance of gaining a thorough grasp of his art, and taking a high stand in his profession, lay in foreign travel. His mind wanted objects which the narrow and prosaic character of{14} his home life could not supply. It wanted the intercourse of a society from which conventional barriers shut it out in England; it wanted scope for activity, and models by which its activity might be guided. Without foreign travel he might have had the certainty of a respectable position and sufficient emoluments in his profession; with it he took the risk of delay and difficulty, and the chance of a noble career.

The choice was not likely to cause him much hesitation. He decided at once, and kept to his decision firmly, in spite of the natural remonstrances of his family, who felt the risk, but did not understand the necessity. Travel was then comparatively rare, and thought by many to be needless. It seemed madness to risk on it so much of his slender resources. His stepmother alone was led by her own strong good sense, and by her unlimited confidence in him, to give him her decided support. At last his plans were fixed, and his journey, the length of which he did not anticipate, or at any rate did not disclose, was determined upon.

Before he left England he was engaged to Miss Sarah Rowsell. Her father, Mr. Samuel Rowsell, was employed in the same line of business which his own father had followed. After about a year’s acquaintance, the engagement was made on the eve of his departure; and with this fresh tie to home, and fresh incentive to exertion, he left England in June, 1817.{15}

I. France and Italy.—General effects of travel—Study of classical architecture—Observation of natural scenery—Universality and accuracy of examination. II. Greece and Constantinople.—Growth of artistic power—Impressions of Athens and Constantinople—Contrast of the Turkish and Greek characters. III. Egypt and the East.—Great effect of Egyptian architecture upon him—Mehemet Ali’s government—Dendera, Esneh, Edfou, Philæ, Abousimbel, Thebes—Return to Cairo—Palestine—Jerash—Baalbec—Damascus—Palmyra. IV. Sicily and Italy.—Syracuse, Messina, Agrigentum, and Palermo—Return to Rome—Meeting with Mr. J. L. Wolfe—Systematic architectural study—Effects of Egyptian impressions—Italian palaces at Rome, Florence, Vicenza, and Venice—Italian churches—St. Peter’s, the Pantheon, the cathedrals at Florence and Milan—The Bridge of La Santa Trinita at Florence—The growth of his architectural principles—Return to England.

On June 28th, 1817, Mr. Barry left England, and remained abroad for more than three years. During that time he travelled, first, chiefly alone, in France and Italy; next with Mr. (afterwards Sir C.) Eastlake, and Messrs. Kinnaird and Johnson, in Greece and Turkey; thirdly, with Mr. D. Baillie, Mr. Godfrey, and Mr. (afterwards Sir T.) Wyse, in Egypt, Palestine, and Syria; and lastly, chiefly in company with Mr. J. L. Wolfe, in Sicily and Italy, returning alone through France in August, 1820.{16}

His travels had, at the time, a considerable interest of their own: few had gone so far as the second cataracts of the Nile; still fewer had added to their Egyptian experiences so great an extent of Eastern and Western travels. Accordingly, on his return to Rome, he was one of the lions of the season, and his portfolio of sketches excited unbounded interest, as much by their novelty as by their intrinsic excellence. All this is, of course, greatly changed; scenes then little known have become almost hackneyed; what were then difficult and even hazardous journeys, are now pleasant summer excursions. The intrinsic interest of any narrative of his travels (such as might easily be drawn from his copious journals) is therefore to a great extent lost. But the importance of their effect on his own mind can hardly be exaggerated, and it is to this, therefore, that attention must here be drawn.

In the first period of his travels, the point most deserving notice is the exciting and enlarging effect of novelty and beauty on a mind, which had hitherto been cooped up within narrow limits, and had lacked its own congenial food. The change was infinite, after the narrowness of home experience, and the depression of all artistic and scientific energy in England by the long war. It seemed to be the entrance on a new life, one day of which (to use his own constant expression) was “worth a year at home.” His frank and buoyant spirit, his love of adventure, and good-humoured determination in all his purposes, answered readily to its call.

There is little at first in his journals of a strictly{17} professional character; the architect is merged in the artist; and even the artistic element has by no means an exclusive dominion; observations of all kinds throng his journals, as impressions of all kinds evidently crowded on his mind. The external aspect of the country, both as to its scenery and its life, social peculiarities, and differences from English customs,[3] political feelings and tendencies, aspects of individual life and character—all claim their place, side by side with the records of sketches taken and buildings criticized.

Such a process, as it was the most natural, was also probably the most beneficial, if travel was really to enlarge his mind and to educate his whole nature. The work of life would soon narrow, and so deepen, the stream of thought and observation; and, indeed, at all times, he possessed the power of subordinating all his various interests and enjoyments to his one important business. He always liked the greater freedom of foreign life and foreign society, as compared with the conventions and formality which, then especially, clung to the social system of England. But Paris and Rome, with all their various enchantments fully appreciated and enjoyed, never drew him away from the hard work which was the real object of his travels.{18}

At first, of course, all study was devoted to classical architecture alone. It is curiously characteristic of the time, that at Rouen, while he thought it worth while to sketch and criticize a small Corinthian church, all the glories of the cathedral and of St. Ouen are dismissed in one line, as being “examples of a rich florid Gothic;” and at Paris, the cathedral of Notre Dame and the Sainte Chapelle are noticed in the same spirit, as having an antiquarian interest, and a certain irregular beauty of their own; but not as deserving any high admiration or study. Milan Cathedral is noted for its grandeur and richness, but with no criticism as to its architectural details. All this gradually changed as the revival of mediæval architecture began. On his return over the same ground the contrast seen in his journals is remarkable; and Gothic, though not studied or understood as it would be now, was regarded by him with keen interest and deep respect.

Art of all kinds, not exclusively architectural, attracted him at once. At Paris the Louvre occupied him for days together; and it was characteristic of his taste (which always inclined to the real rather than the ideal) that, on the one hand, he passed by at once as “showy and unnatural” the then popular school of David and Gérard, and, on the other, devoted more attention to the grand historical series of Rubens’ pictures, the Claudes, and the Dutch pictures (which reminded him of Wilkie), than to those of a higher and more imaginative kind. At Rome (thanks to the kindness of Canova, to whom he had letters of introduction) he spent whole days in{19} sketching among the antiquities, the sculptures, and the paintings of the Vatican, and of other galleries. In fact, at this time he often seemed to turn aside from architecture to woo the sister arts, although afterwards his own art gradually asserted an almost exclusive dominion, and he was accused, with some truth, of looking at the others as merely her handmaids.

Travelling as he was in Italy, he could not fail to be impressed by the artistic influences of painting, sculpture, architecture, and, above all, of music, which the Church of Rome presses into the service of her religious ceremonies. He first saw these displayed (and he could hardly have seen them more gloriously) when he entered Milan Cathedral on the feast of St. Carlo. He had fuller opportunities still, in his long sojourn at Rome, of witnessing all the splendours of Christmas and Easter. They could not but appeal to his artistic tastes, and especially to his great love of music; but they seem never to have laid hold of his mind. The sense of the artificiality and cumbrousness of ceremony spoilt the effect to his taste; and neither the time nor his own disposition was such as to appreciate any devotion, in which superstition might appear to lurk, whether in the wayside chapels of Switzerland or under the dome of St. Peter’s itself. He felt in it occasionally “something awful and divine;” but his feeling was marred by the prevailing sense of unreality. Even his friend Pugin’s enthusiasm in after days, though it commanded respect, could win no real sympathy from him.{20}

With regard to natural scenery, though his observation of it was always keen, he delighted in what was rich and beautiful, rather than in the highest forms of grandeur. The love of mountain scenery was not then a fashion, which few, even in a Journal, would dare to disregard. His admiration of it was blended with the notion of something strange and almost grotesque in it. He speaks of it as exhibiting “the freaks and outrageous effects of Nature” in its wilder features, and the beauties of an Alpine pass seemed to him to present something “appalling,” calculated to excite a kind of awe, too oppressive for genuine admiration. He delighted more in the Apennines, rising in mountains of equal height “like the waves of the sea,” and disclosing in their lateral valleys scenes of quiet beauty and richness, or in the scenery of the Saronic Gulf, with its bright colour and picturesque variety. Colour, indeed, at this time, seems to have impressed him more than form: sunsets, or moonlight effects, and the contrasts of white cities with the verdure surrounding them, are constant themes of notice and admiration. He cared for what was bright and beautiful more than for any sombre and awful grandeur; and he was always master of his impressions rather than overmastered by them.

His examination of buildings was always comprehensive, and his criticisms, even from the first, audaciously defiant of all fashion and authority.[4]

{21} In entering a town he always estimates its general effect before proceeding to details; and his impressions seem often divided between an artistic love of the picturesque and a determined architectural preference for regularity. In proceeding to greater particularity, no buildings came amiss to him. Besides the churches and palaces, which have a prescriptive right to precedence, he seems to have had a special taste for two most opposite specimens of architectural effect. Cemeteries, on the one hand, always attracted his notice, both as to their arrangement and their accompanying buildings, and in their case he had a strong dislike of over-embellishment. The sombre solemnity of a Turkish burial-ground was his ideal. The same taste which attached brightness and cheerfulness in buildings that ministered to life, inclined to solemnity and sadness in all that suggested the idea of death. On the other hand, theatres greatly interested him at all times, from the Scala at Milan to the little theatres of Italian country towns. He thought that they gave a grand opportunity for architectural effect, which was generally frittered away. And his note-books abound in plans and criticisms of existing buildings, and ideas as to their best theoretical construction. It was curious enough that a theatre was almost the only kind of public building which it never fell to his lot to execute.

Perhaps the one point especially to be noticed in all his examinations of buildings is the extreme care for accuracy which distinguishes them; measurements are always given, plans generally accompany{22} the descriptions in his journals; he would take any trouble to obtain measurements and details, even if it risked his neck, or threw him into the hands of the police.[5] What was vague seemed to him worthless, and difficulties rather excited than daunted him.[6]

In this way the first nine months of his travels passed over—a good preparation, but only a preparation, for professional study. It became a question whether he should return home, or visit Greece in the congenial company of Mr. (afterwards Sir C.) Eastlake, already distinguished as an artist; Mr. Kinnaird, an architect, afterwards editor of the last volume of Stuart’s ‘Athens;’ and Mr. Johnson, afterwards a Professor at Haileybury College. Home ties and considerations of economy drew him back; he consulted his friends at home, and especially his future father-in-law, Mr. Rowsell, and by his sensible advice he determined to disregard difficulties, and give full scope to his tastes and powers. It was a wise resolution; he had left England inexperienced and unknown; he was now recognised as an artist of talent and promise, and was to travel with men of acknowledged ability, generally his superiors in education and knowledge both of books and men. His journals show clearly the effect of his past{23} experience in greater maturity of judgment, greater taste for antiquity, and general growth of mind.

Athens and Constantinople were their two main objects. The season was rather advanced, so they hurried on, paying but a hasty visit to Naples[7] and Pompeii, then across Calabria to Bari, while he made the most of his time by sketching incessantly under a great umbrella, and managing to give careful descriptions and rough plans of all that he visited. Thence they crossed to Corfu;[8] and there first the richness and picturesque beauty of the island seem to have captivated him, and stirred up anew the artistic power within. His pencil was never out of his hand, but it was employed almost entirely on the beauties of nature, and his delight in the scenery itself evidently increased with his power of representing it.

This was even more strikingly the case in a visit to Parnassus and Delphi, where they spent some ten days in the hut of a poor cottager, and were richly compensated for their disappointment at finding no traces of the old temple, and no remains worthy of notice, by the extraordinary beauty of the country, and the opportunity which it gave them for countless sketches. They even offered a reward from the minaret of the village for one of the great vultures of the mountain, and obtained, for sketching purposes, a magnificent bird, measuring nine feet from tip to tip{24} of his wings. “I drank,” he says, “deeply of the Castalian spring, but did not find my poetic faculty improved thereby.” Yet the genius loci did not fail him entirely. It was here more especially that a change and growth of artistic power in him struck his fellow-travellers.[9] Before he left Rome, his drawings had been only careful and elaborate; now there began to show itself in them that indescribable power of insight and imagination, which distinguishes the true artist from the mere draughtsman. Conventionalities were shaken off, and nature represented as it was; laboured and ineffective drawing gave place to a bold and masterly grasp of the leading lines, and the general effect of the scene represented; and his journals show an ever-increasing admiration for natural and artificial beauty, and an absorbing delight in the task of representing it. The progress, once begun, never ceased. Every day witnessed a progress in his power, till his sketches in Egypt showed those powers in full maturity, and astonished those who had known him only in Italy and in Greece.

At Athens they stayed about a month, in despite of some danger of plague which hung over the city. Here unfortunately his journals fail us for a time, and there is no means of supplying the deficiency. It is easy to imagine his intense delight in seeing the buildings which he had so long considered not only as the masterpieces of Greek art, but as the highest forms in which the architectural idea of beauty had clothed itself. We know, what might{25} easily have been conceived, that his admiration did not evaporate in mere enthusiasm, but gave rise to careful study and thoughtful criticism; and that such study, while it deepened his original admiration, yet led him to feel that changes of circumstances, needs, and conceptions might well limit that imitation of Greek models, which had hitherto exercised a despotic influence over modern architecture. But beyond this, there is no memorial of what he perhaps at that time felt to be the crowning pleasure of his architectural tour, except some sketches, made always entirely on the spot, and remarkable for uniting great accuracy and truthfulness of effect to free and spirited drawing.

He left Athens on June 25th, 1818, with Mr. Johnson, and passed by Ægina, and through the Cyclades, touching at Delos, to Smyrna, and thence by land to Constantinople. The voyage was “one continued delight;” full of architectural and antiquarian interest, and even fuller of natural beauty, seen under cloudless skies and glorious sunsets.

They were now having their first experience of countries under Turkish rule, just at the beginning of Mahmoud’s reign, when lawlessness was at its height, scarcely kept down by his bloody justice, or awed by the suspicions of the coming revolution. It is not uninteresting to gather from the journals the impressions made upon the travellers even then by the Turkish and the Greek characters.

The Turks seemed essentially barbarians, not without some excellences (which probably have been deteriorated in late years), such as simplicity and sincerity of religious devotion, dignity, truthfulness,{26} and even generosity of character. They appeared to occupy rather than inhabit the country, allowing its richest regions to fall into desolation, and its commerce (except where the Greeks or English[10] sustained it) to languish and decay. The relics of its former grandeur were transformed for their own purposes, or watched over as antiquities with a jealous and ignorant churlishness;[11] their general insolence and violence were unbridled. At Constantinople Mr. Barry, by attempting a panorama of the city from the Galata tower, grievously offended the Turkish women, who, after abusing him with all their powers of vituperative eloquence, called up the guard to dismiss him summarily, and incited a mob of boys to pursue him with stones, and cries of “Giaour” through the city. Such insults were common then, and had to be borne patiently even by those under ambassadorial protection.

The Greeks, on the other hand, wherever, as at Iverli, Scio, and Patmos, they managed to secure self-government by payment of tribute, appear to have shown that activity and intellectual capacity which the modern kingdom of Greece, with all its defects, has since exemplified. They had schools and universities, in spite of the jealousy and ill-will of the Turks, libraries ancient and modern, and even scien{27}tific instruments from Paris. It was a matter of regret, but, after ages of slavery, hardly a matter of surprise, that their honesty and truthfulness did not keep pace with their intellectual progress. But there seemed then grounds for hope of improvement in them, and none for their Turkish masters.

Constantinople itself surpassed even his high-wrought expectations, as seen, first from the Asiatic heights, and afterwards on approaching it from the water. His journals are full of enthusiastic description; and in after life he often spoke of it as “the most glorious view in the world.” In spite of all difficulty he managed to see it thoroughly, both as to its architecture, and as to its Turkish life: but again his pencil was too busy to give much time for the use of his pen. Except to testify his impression of the magnificence of St. Sophia, there is little record or criticism of individual buildings. He spent a month of never-forgotten interest and enjoyment in the city, and then prepared to turn homewards, in August, 1818.

Once more an opportunity presented itself which could not be passed by. Mr. David Baillie, whom he had met at Athens, was preparing for a journey to the East; and, struck by the beauty of Mr. Barry’s sketches, he offered to take him, at a salary of 200l. a year, and to pay all his expenses, in consideration of retaining all the original sketches he might make. The artist was to be allowed to make copies for himself. The offer was too tempting to be refused,[12]

{28} for it gave him his only opportunity of visiting Egypt and Syria, and of doing so with a man of high cultivation and refinement, who treated him at all times with great kindness and liberality. He hesitated but little; and set out on September 12th, full of delight and expectation.

The third period of his travels was more important to him than all which had gone before. “Egypt,” he remarked, “is a country which, so far as I know, has never yet been explored by an English architect.” Besides the members of the French Institute, only Captains Irby and Mangles, and Belzoni, had gone before him. He felt keenly the novelty and magnificence of the scene thus opened to him. The remains of Egyptian architecture made a far deeper impression upon him than all Italy and Greece combined; and from this time architectural study seems to have assumed in his mind that predominant and almost exclusive influence which it never lost. His journals are kept with far greater accuracy and copiousness. Every great temple is described in outline and in detail, with notes of its present condition, and of the traces of its former greatness. His observation seemed to be stimulated, without being overwhelmed, by the inexhaustible profusion and magnificence of the Egyptian remains. He must certainly have thought of publishing to the world the information he had so carefully collected on a field hitherto little known, and engrafting on it the criticism and evolution of principles, which in the whirl of ceaseless change and activity he had no time to record in his journals. That intention bore no{29} immediate fruit; but the effects of the study sank deep in his own mind. It is hardly too much to say that he entered Egypt merely under the influence of vague artistic interest, and left it with the leading principles of his architectural system fixed for ever.

They passed first through the Troad, and thence by Assos and Pergamus to Smyrna, a brief journey, but one which was remarkable for the varied associations of legendary, classical, Byzantine, and modern times, such as perhaps no other part of the world can offer. Thence they sailed (with Messrs. Godfrey and Wyse) to Alexandria.

The impression then made by Mehemet Ali’s government of Egypt was very much the same which after experience has confirmed. It was a wonderful contrast with Turkish lawlessness; the country was well ordered, and perfectly open to Europeans; public works of all kinds were progressing; commerce and agriculture were pushed on under the guidance of European science, and with all the power of a despotic government. But there was another side to the picture: the pasha urged on his work in utter disregard of the rights, happiness, or lives of his subjects; “in fact,” he was “the chief merchant in Egypt, and did not mind sacrificing all other interests to his own.” The natural results among the people were infinite distress, and a deep though impotent hatred of the Government, solaced only by the common belief that the English (whose glory in Egypt was still fresh) would soon seize and emancipate the country.

Cairo itself was a remarkable evidence of the state of Egypt. The busy crowds of all nations which{30} streamed through its streets, “from the stately Turk to the half-naked and miserable Arab,” gave proof of a vigour and activity very different from the listless and apathetic aspect of most Turkish cities. In the city itself, though it seemed peculiarly Oriental in its general sombreness of aspect, relieved by “bursts of Saracenic magnificence,” yet buildings in European style, and silk and cotton manufactures under European guidance, indicated the quarter whence this vivifying influence came. There was no danger of molestation in sketching here, for, though the city was full of rejoicing and illuminations for Ibrahim Pasha’s victory over the Wahabbees, the strong hand of the Government, which left its bloody traces here and there visible in the streets, effectually checked the spirit of turbulence. The whole country was full of life and energy and progress, but its progress was maintained by force and purchased by misery.

From this point the journals contained a careful and elaborate description of the journey up the Nile. The first place noticed especially is Siout (Lycopolis?), where they landed to obtain permission from Ibrahim Pasha to visit Upper Egypt, and to examine the great catacombs; of these Mr. Barry made a careful ground-plan, as well as a sketch of the frontispiece. To the S.E. of the catacombs they saw “a kind of amphitheatre formed by the mountains, the whole of which was perforated for tombs, one range rising above another.” There was a beautiful contrast between the “gloom of this city of the dead” and the view from the height overlooking it, over the “rich{31} plain of the Nile, level as water, and in the highest cultivation, mostly covered with the rising crops, now of a beautiful green, and laid out” (as of old) “with geometrical exactness.”

From this point the ruins of temples began to show themselves, and on November 29th they came in sight of the great temple of Dendera, lying “on a low ridge of land all in shadow, with a pretty foreground of palm-trees, and the Libyan mountains in the distance.” Full of excitement they hurried on shore to see this first specimen of Egyptian grandeur. “It astonished us,” he says, “by its unexpected magnitude, and gave me a high idea of the skill and knowledge of the principles of architecture displayed by the Egyptians. There is something so unique and striking in its grand features, and such endless labour and ingenuity in its ornaments and hieroglyphics, that it opens to me an entirely new field. No object I have yet seen, not even the Parthenon itself (the truest model of beauty and symmetry existing), has made so forcible an impression upon me. The most striking feature of the building is its vast portico, six columns in front and four in depth, giving a depth of shadow and an air of majestic gravity such as I have never before seen.”

As soon as the first impressions of the grandeur of the great temple had passed away there followed, as usual, a most accurate examination of the whole. The three temples are described with the greatest exactness, every dimension, even of the details, being carefully recorded. All stood before them in complete preservation, in spite of the 4000 years which{32} had passed over the scene. “Even the hieroglyphics and the most delicate parts of the ornamentation were as sharp and vigorous as when they were first executed.” All was studied con amore. He seems to have been especially struck with the variety and beauty of the Egyptian capitals, all of which he sketched and criticised, evidently seeking to emancipate himself from the limits of the five orders, and longing for greater variety and scope for imagination.

The impression made on him by the mixture of general grandeur of outline and dimension with profuse richness of detail was never effaced. It seems at this time to have kindled in his mind an intensity of devotion to his art hitherto unknown, and to have stirred him up to extraordinary labour and study. Temple after temple opened upon him till the view of Philæ crowned the magnificence of the whole. Sketching for Mr. Baillie, copying sketches, where possible, for himself, elaborately describing in his journal what was then an almost unknown treasure-house of ruins, “in comparison with which even those of Greece and Rome sink into insignificance, although the Parthenon and the Pantheon still keep their places as models of architectural excellence"—he drank in deeply the influence of the scene, and seemed in three months to have lived through whole years of study.

Esneh, their next halting-place, appeared then less striking than Dendera; but his second visit corrected the impression, and led him to think the great portico “the finest of all he had seen in Egypt,” half{33} concealed though it was by rubbish and by modern excrescences. Both at Esneh and at Dendera he gives an elaborate description of the remarkable zodiacs, which appeared to show a knowledge of the precession of the equinoxes, and which were then little known except from the Memoirs of the French Institute, a work of which he remarks elsewhere that he found it “full of glaring and unpardonable errors.”

Edfou was then being excavated by M. Drouetti, sufficiently for examination; the sculpture appeared to be of a high order, but the general effect of the temple with the grand peristyle of columns (enclosing an area of 146 ft. by 108 in front) unsatisfactory in spite of its size, for want of due proportion and symmetry in its parts. On the other side of the river they visited the ruins of the temples at Eleithias, some half-excavated in the rock, and the famous tombs, which had then recently been opened, and had given by their hieroglyphics and painting a new glimpse of the life of the ancient Egyptians.

A few days now brought them to Assouan, whence they visited the islands of Elephantina and Philæ. At the former the ancient Nilometer attracted their attention, and was accurately measured and described. The latter island, now, and at his return in January, was felt by him to be the centre of attraction. He felt “it impossible to conceive anything more magnificent than Philæ in the zenith of its prosperity; when all, Egyptians and Ethiopians alike, venerated it as the burial-place of Osiris, and lavished on it the treasures of ages.” He speaks of the long ranges of columns{34} as the characteristic features of the ruins, and as producing even now an “enchanting effect,” and notices the traces of painting in the great portico, as showing great taste in the harmonizing of colours, and giving some idea of the brilliant effect which must have been produced in the days of its splendour. Even then, when the island was a mass of ruins, they lingered over it, carefully examining it at every step; and when at last they left it, it was with deep regret, and a feeling that only in leaving it could they fully appreciate its grandeur. The natural beauty of the view of the first cataracts, far superior in his opinion to that of the second cataracts, or to any point of the Nile, claimed its due share in their delight, and it was evidently the one spot in Egypt to which he most delighted to recur.

At Philæ they left their large vessel and proceeded in four small boats up the river. The whole scenery was now changed: mountains bounded the narrow strips of cultivated land on the banks of the river, and occasionally approached close to the water’s edge; villages numerous, but miserable enough, fringed the banks; and the finer barbarian race of Nubia contrasted favourably with the abject and miserable Egyptians. The ruins still showed themselves in almost uninterrupted series on either side, interesting in themselves, but still more interesting as memorials of the various civilisations which had passed over the country. Most belonged to the earlier Egyptian days: but, combined with these, or superimposed upon them, were the signs of the Greek and Roman dominion; and these in their turn were remodelled{35} or defaced by Christian hands. Greek, Latin, and Coptic inscriptions were mingled with the hieroglyphics; ancient deities were transformed into saints; and a rough daub of the Madonna was often seen on the very plaster which covered the symbols of old Egyptian idolatry.

They proceeded slowly, both in their ascent and return, and found abundant occupation by the way. Above all others, the ruins of Abousimbel claimed careful examination and accurate description. The temples, as being entirely excavated from the rock, and having the greater portion of their fronts occupied by colossal figures, were entirely new to them, and produced as great an effect on their minds as those of Dendera or Philæ. The entrance to the great temple, opened the year before by Mr. Salt, was now again closed by sand and rubbish, and had to be re-opened with much labour. The sculpture of the interior struck them greatly as spirited, and free from the conventionality of most of those which they had seen. The painting was in most places fresh and bright, but the intense heat (98°) and moisture of the interior had made the surface soft, and threatened rapid decay. He was even obliged to sketch on a board, because the paper was so soft that the pencil could not be used upon it, and to work with light almost insufficient for accurate examination. He carried away a drawing of the exterior, seen by a bright moonlight, and partly lit up by the fire of their Arab crew, as a memorial of a place which made a permanent impression on his mind.

A few days brought them to the second cataracts,{36} where they stayed only long enough to admire the picturesque aspect of the scenery, wilder, though less beautiful, than that near Philæ; and then they returned leisurely down the stream, stopping generally rather longer than on the ascent.

At Koum Ombos they now stayed to visit the great temple, with its many traces of crocodile worship, and to examine some of the mummies there found in abundance.

Thebes, which they had passed before, now detained them several days. The ruins of Luxor and Karnac, by their overwhelming magnitude and variety, seemed to throw all others into the shade; and at Medinet Habou, the temples and the recently discovered Tombs of the Kings possessed hardly inferior interest. Even Dendera, which had seemed so marvellous at first, now held only a secondary place. In fact, the rich abundance of architectural treasures presented to their eyes seems almost to have outstripped all attempt at description, and to have left neither time nor room for criticism.

Finally they arrived at Cairo on March 1st; thence duly ascended the great pyramids of Ghizeh, and penetrated into their interior; and on March 12th, 1819, Mr. Barry left Egypt. Little more than four months had elapsed since he first entered Cairo; but the fruits of that short time had been valuable beyond all description.

Their journey across the desert to Gaza, and thence to Jaffa and Jerusalem, with excursions to Bethlehem, the Dead Sea, and the convent of St. Saba, lay over a more beaten track, and produced far less effect upon his mind. It could not fail to be full of interest, and{37} gave opportunity for numberless sketches;[13] they carried on their examination with their usual vigour, visiting all the “Holy Places,”[14] and, as they arrived at Easter, had abundant evidence of the feuds of the Greeks and Latins, and witnessed the notorious miracle of the “Holy Fire.” They carried away from the Latin Patriarch certificates of their presence at the Easter ceremonies (which gave them a certain sacred character as pilgrims), and rosaries, blessed at the Holy Sepulchre, which were highly prized in Italy and France; but the journal adds, “I wish I could say that my faith had been strengthened by a pilgrimage in the Holy Land,” and goes on to express the predominant feeling of disgust at the superstitions and impostures, which swarm on that sacred ground, and mar its holy associations.

A visit to Jerash, in Arab costume and under Arab guidance, had in it more of novelty. They found its remains situated in a well-wooded valley, and embosomed in trees. The ruins were then carefully examined, and some sketches made, but disputes between their Arab guards, and strong symptoms of violence, hastened their departure. “The remains (all of Roman origin) much resemble those of Antinoöpolis, and are probably of the same age; there is too great a profusion of ornament and feebleness of general design; but the effect of the great street, 740 yards in length, flanked by long colonnades of{38} Roman, Ionic, and Corinthian, crossed by triumphal arches, and terminating in a circus surrounded by a peristyle of Ionic columns, must have been magnificent, in spite of many faults of detail.”

Their journey northward, through the Lebanon country, to Beyrout, was highly interesting, not only for the grandeur and beauty of the scenery, but because it brought them in contact with the Maronites and Druses. Among the Maronites they always found industry, especially silk-weaving and the raising of silkworms, and considerable prosperity, wherever they enjoyed a quasi-independence of Turkish rule. At Deh-el-Kams the Emir (who was secretly a Christian) was full of interest in the West, a man of taste[15] and energy, who, like other Orientals, worshipped the memory of Sir S. Smith. The great Maronite convent of St. Anthony had a printing-press at work, and was a centre of cultivation and industry. They heard much of the Druses, and the jealous care with which they guarded the secret of their religion, the Acchals, or stricter Druses, living a recluse and ascetic life, the Jechaird Druses mingling with all, and professing themselves indifferently Christian or Mohammedan. Their relations were then peaceful; but the peace was jealous and precarious, and the Turkish authority (as usual) seemed weak to protect, and powerful only to oppress.

Baalbec, Damascus, and Palmyra, were their chief objects of attraction. The situation of Baalbec, in the midst of its forest of walnut-trees, delighted the eye of{39} the artist, but accurate plans and descriptions of the magnificent ruins (then but little known, and even now described with much discrepancy of authorities), gave evidence of more elaborate architectural study. The great encircling wall of the citadel, within which the ruins stand, formed of huge blocks of stone, some as much as 30 feet long, 13 feet high, and 10 feet thick, the fragments of the Greater Temple (of the Sun?), 270 feet by 165 feet, the extensive remains of the Smaller Temple (of Jupiter?), and a third circular Corinthian temple, with their decorations and masterly bas-reliefs, in which the Roman eagle was conspicuous, gave them the idea of that union of power with richness, which well deserves the title of “magnificence.”[16]

It was a curious transition from the silent grandeur of Baalbec to the bustle and life of Damascus. The first view of the city struck them, as it strikes all travellers, as one perfectly unique in its beauty,—“a boundless plain, with surface and horizon level as the sea,” but covered with masses of dark verdure, out of which the city of Damascus rises, “bright as the whitest marble.” The city itself hardly corresponded{40} with this glorious appearance. The travellers were probably taken for Turks, and so were able to see, without molestation, all the parts of this city,—the very home of Turkish fanaticism; but with the exception of a few of the larger buildings, which were full of Oriental magnificence, there was little to justify the glowing descriptions of former travellers. They quitted it without regret; for Palmyra lay before them.

In this expedition they encountered their only noteworthy adventure. The country was beset with the Bedouin Arabs, half obedient, half hostile to the Turkish Government. Every city and village was in a “state of siege;” and when the travellers arrived at the village of Kâl, they were taken for Arabs, and received with a dropping fire of musketry, till the presence of the Aga of Baalbec put an end to the mistake. However, they arrived safely at Homs; and there their dangers began. By the help of the Governor, who treated them most kindly and honourably, a negotiation was made with two Bedouin Arabs, professing to be envoys from the chief of the neighbouring tribe, for their safe conveyance to and from Palmyra.

They set out accordingly, eight in number, with an escort of twelve Arabs, who soon began to play them false, and led them out of the way to a large encampment of their tribe, where they were kept prisoners, and assailed with all kinds of lies and threats to extort money. The Arabs, of course, could not conceive the true object of their visit to Palmyra; but settled at once that they must be seekers of hidden{41} treasures, and that Mr. Baillie’s eye-glass, which excited their greatest astonishment, was the talisman, by which the treasures were to be revealed. The whole party had, for some extraordinary reason not mentioned, come out unarmed; there was not even a pistol among them; and they were therefore wholly in the power of the Arabs. However, they stood firm with true English coolness, till, after long negociation, they found proceeding hopeless, and resolved to return with their escort to Homs.

This they did at full speed, starting about 4 p.m., and galloping over the desert all night by starlight, the Arabs hurrying on in order to leave them under the walls of Homs before daybreak, and so to escape the vengeance of the Governor. About two hours before sunrise, they arrived at Dehr Balbah, near Homs. Here the Arabs by their signal made the dromedaries kneel down, and then tried, first to induce, and then to force, the travellers to dismount. This they refused to do, and, unarmed as they were, resisted for some minutes, wresting the spears and matchlocks from the hands of the Arabs. One or two of the party were slightly wounded, and the thrust of an Arab spear from behind at Mr. Barry would have been serious, and perhaps fatal, had it not been turned aside by the loose burnoose which he wore; as it was, it passed under his arm, and merely grazed his hand. A short struggle proved that the odds were too great, and so the Arabs gained their point, and galloped off to the desert.

Next morning the travellers went on to Homs, having previously sent a despatch to the Governor.{42} On their way they met droves of camels and Bedouin drivers, hastening with all speed to the desert, and cavalry of the Turkish Governor in pursuit. Several Arabs were killed, and three heads brought into Homs in triumph. The Governor behaved most honourably; he felt the danger of provoking the Arabs (for, in fact, out of this incident arose a petty war), but felt also that his own faith had been pledged to the Englishmen, and that it must not be violated with impunity. Some of the money still in his hands he insisted on returning, and, though full of anxiety as to the consequences of the affair, he dismissed them with all honour and courtesy. So ended the only failure, and almost the only serious danger, of their journey.