Title: A Virginia cavalier

Author: Molly Elliot Seawell

Illustrator: F. C. Yohn

Release Date: September 19, 2023 [eBook #71672]

Language: English

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, with special thanks to Abbey Maynard, Courtesy Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections and University Archives, Northwestern University Libraries for providing the missing illustrations, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

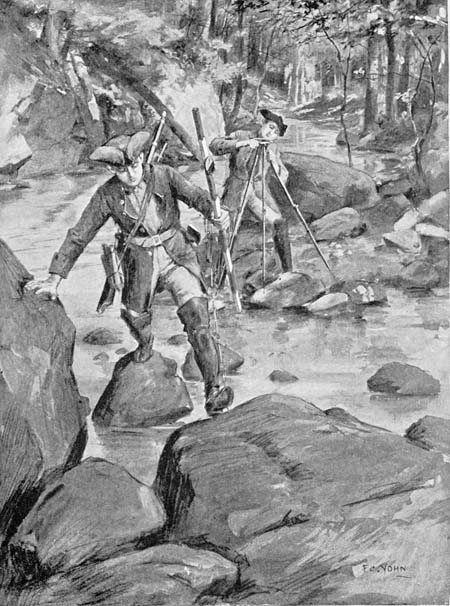

[P. 147

“‘NEVER DRAW IT IN AN UNWORTHY CAUSE’”

BY

MOLLY ELLIOT SEAWELL

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

1903

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers.

All rights reserved.

“Nature made Washington great—but he made himself virtuous”

| “‘NEVER DRAW IT IN AN UNWORTHY CAUSE’” | Frontispiece |

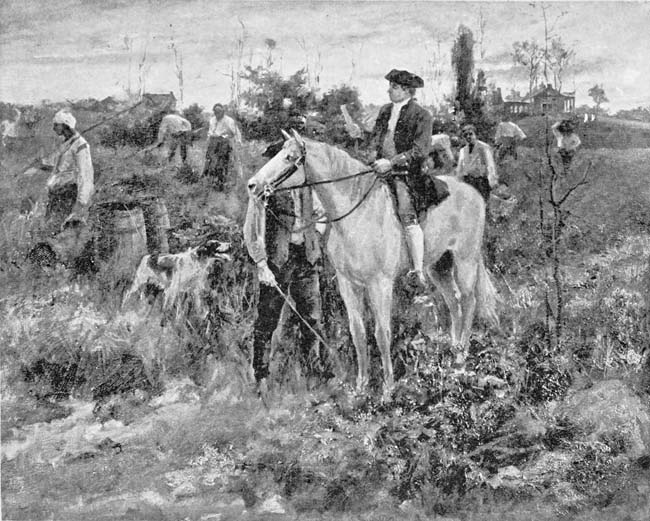

| “‘THIS IS MY SON, MR. WASHINGTON’” | Facing p. 18 |

| GEORGE BIDS BETTY GOOD-BYE | “ 54 |

| SKETCHING THE DEFENCES ON THE SCHELDT | “ 72 |

| “‘IS MARSE GEORGE WASHINGTON HERE, SUH?’” | “ 100 |

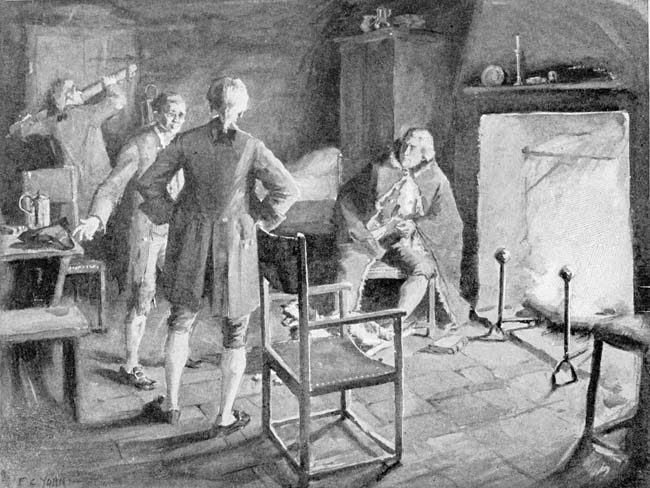

| THE DAILY LESSON IN ARMS | “ 122 |

| THE FIGHT IN THE KITCHEN PASSAGE | “ 136 |

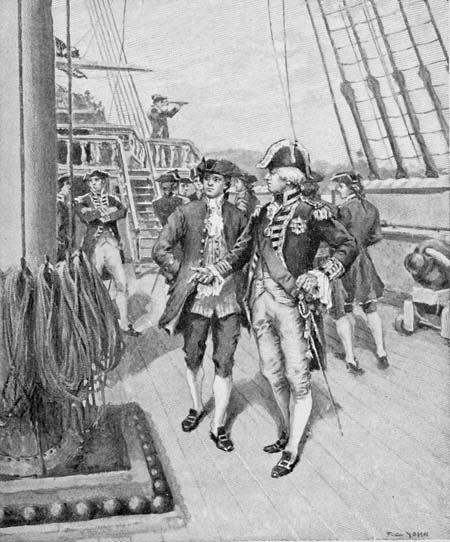

| “SHE WAS THE STATELIEST BEAUTY OF A SHIP HE HAD EVER SEEN” | “ 168 |

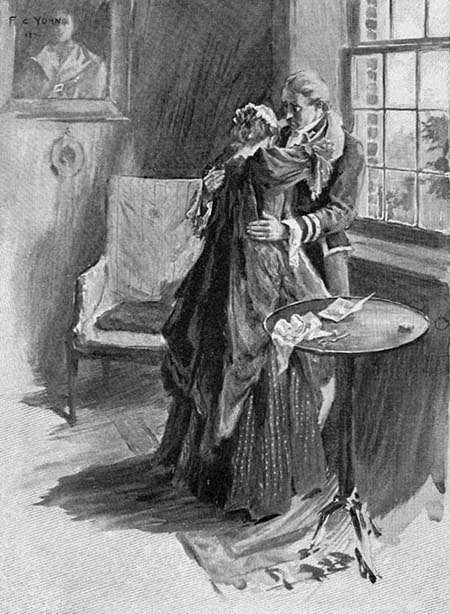

| “‘MY SON, MY BEST-LOVED CHILD’” | “ 192 |

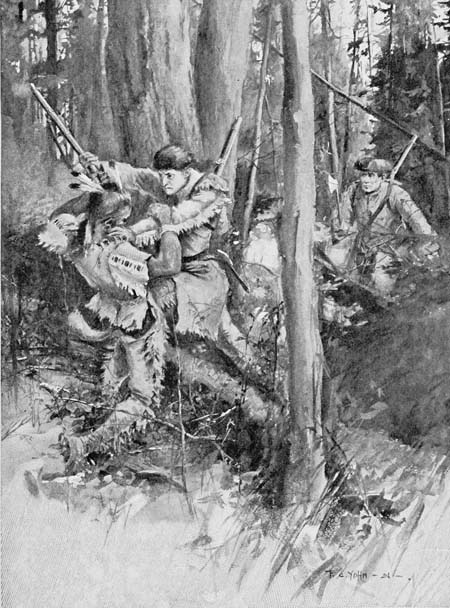

| “THEY STRUCK NOW INTO THE WILDERNESS” | “ 218 |

| “BY DAYLIGHT GEORGE WAS IN THE SADDLE” | “ 236 |

| “‘NEVER WILL YOU BE HALF SO BEAUTIFUL AS OUR MOTHER’” | “ 246 |

| THE GOVERNOR’S LEVEE | “ 260 |

| “GEORGE HAD THE SAVAGE BY THE THROAT” | “ 296 |

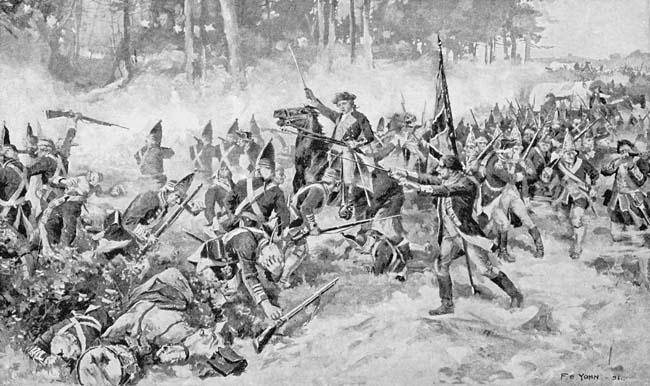

| “WITH DRUMS BEATING AND COLORS FLYING” | “ 314 |

| “GEORGE DID ALL THAT MORTAL MAN COULD DO” | “ 342 |

A VIRGINIA CAVALIER

“Nature made Washington great; but he made himself virtuous.”

The sun shines not upon a lovelier land than midland Virginia. Great rivers roll seaward through rich woodlands and laughing corn-fields and fair meadow lands. Afar off, the misty lines of blue hills shine faintly against the deeper blue of the sky. The atmosphere is singularly clear, and the air wholesome and refreshing.

Never was it more beautiful than on an afternoon in late October of 1746. The Indian summer was at hand—that golden time when Nature utters a solemn “Hush!” to the season, and calls back the summer-time for a little while. The scene was full of peace—the broad and placid Rappahannock shimmering in the sun, its bosom unvexed except by the sails of an occasional grain-laden vessel, making its way quietly and slowly down the blue river. The quiet homesteads[2] lay basking in the fervid sun, while woods and streams and fields were full of those soft, harmonious country sounds which make a kind of musical silence.

A mile or two back from the river ran the King’s highway—a good road for those days, and showing signs of much travel. It passed at one point through a natural clearing, on the top of which grew a few melancholy pines. The road came out of the dense woods on one side of this open space, and disappeared in the woods on the other side.

On this October afternoon, about three o’clock, a boy with a gun on his shoulder and a dog at his heels, came noiselessly out of the woods and walked up to the top of the knoll. The day was peculiarly still; but only the quickest ear could have detected the faint sound the boy made, as with a quick and graceful step he marched up the hill—for George Washington was a natural woodsman from his young boyhood, and he had early learned how to make his way through forest and field without so much as alarming the partridge on her nest. No art or craft of the woods, whether of white man or Indian, was unknown to him; and he understood Nature, the mighty mother, in all her civilized and uncivilized moods.

[3]A full game-bag on his back showed what his employment had been, but now he gave himself over to the rare but delicious idleness which occasionally overtakes everybody who tramps long through the woods. He sat down and took off his cap, revealing his handsome, blond head. The dog, a beautiful long-eared setter, laid his nose confidentially upon his master’s knee, and blinked solemnly, with his large, tawny eyes, into his master’s blue ones. The boy’s eyes were remarkable—a light but beautiful blue, and softening a face that, even in boyhood, was full of resolution and even sternness. His figure was as near perfection as the human form could be—tall, athletic, clean of limb and deep of chest, singularly graceful, and developed, as the wise old Greeks developed their bodies, by manly exercises and healthful brain-work and the cleanest and most wholesome living. Neither the face nor the figure could belong to a milksop. The indications of strong passions, of fierce loves and hates and resentments, were plain enough. But stronger even than these was that noble expression which a purity of soul and a commanding will always writes upon the human countenance. This boy was a gentleman at heart and in soul—not because he had no temptation to be otherwise, but because he chose to be a gentleman.[4] He sat in silence for half an hour, the dog resting against him, the two communing together as only a boy and a dog can. The sun shone, the wind scarcely ruffled a dying leaf. A crow circled around in the blue air, uttering a caw that was lost in the immensity of the heavens. The silence seemed to grow deeper every moment, when, with a quick movement, George laid his ear to the ground. To an unpractised ear there was not the slightest break in the quiet, but to the boy’s trained hearing something was approaching along the highway, which induced him to sit still awhile longer. It was some time in coming, for the heavy coaches in those days hung upon wide leather straps, and with broad-tired wheels made much commotion as they rolled along, to say nothing of the steady beat of the horses’ hoofs upon the hard road. George’s eyes were as quick as his ears, but he caught nothing of the approaching travellers until the cavalcade flashed suddenly into the sun, and with its roar and rattle seemed to spring out of the ground.

First came four sturdy negro outriders, in a gorgeous livery of green and gold, and mounted upon stout bay horses, well adapted for hard travel. Then came a magnificent travelling-coach, crest emblazoned, which would not have discredited[5] the king’s levee. It was drawn by four superb roans, exactly matched in form, color, and action. They took the road as if they had just warmed up to their work; but from the dust on the whole cavalcade it was plain they had travelled far that day. With heads well in the air the horses threw their legs together with a style and at a gait that showed them to be of the best blood in the horse kingdom. A black postilion in green and gold rode the off horse of the leaders, while a black coachman handled the reins. On the box, next the coachman, sat a white man, evidently a servant out of livery. One glance told that he was an old soldier. He had at his side one of the huge holsters of the day, in which he carried a pair of long horse-pistols, and a stout wooden box, upon which he rested his feet, showed that the party had means of defence had it been attacked.

George was so stunned with admiration at the splendor of the equipage that he scarcely glanced at the interior of the coach until the sunlight flashed upon something that fairly dazzled him. It was a diamond-hilted dress-sword, worn by a gentleman of about fifty, who sat alone upon the back seat. The gorgeous sword-hilt was the only thing about him that shone or glinted, for his brown travelling-suit was as studiously simple[6] as his equipage was splendid. He wore plain silver buckles at his knees and upon his handsome, high-arched feet, and his hair, streaked with gray, was without powder, and tied into a club with a black ribbon.

One glance at his face fixed George’s attention. It was pale and somewhat angular, unlike the type of florid, high-colored Virginia squires with which George was familiar. He had been handsome in his youth, and was still handsome, with a stately, grave beauty; but even a boy could see that this man had had but little joy in life.

From the moment that George’s eyes fell upon this gentleman he looked upon nothing else. Neither the great coach nor the superb horses had any power to attract his gaze, although never, in all his short life, had he seen anything so splendid. His mother had a coach, and so had most of the people round about, but all had a common air of having once been handsome, and of having reached the comfortable, shabby-genteel stage. And many persons drove four horses to these great lumbering vehicles, but all four would not be worth one of the gallant roans that trotted along the road so gayly.

It was out of sight in a few minutes, and in a few minutes more it was out of hearing; but in[7] that time George, who was quick-witted, had shrewdly guessed the name and rank of the gentleman with the plain clothes and the diamond-hilted sword. It was the great Earl of Fairfax—the soldier, the wit, the rich nobleman—who for some mysterious reason had chosen to come to this new land, and to build a lodge in the wilderness. The boy had often heard his mother, Madam Washington, speak of Earl Fairfax. Meeting with him was one of the events of that great journey she had made in her girlhood to England, where for a time she lived in the house of her brother Joseph Ball, at Cookham, in Berkshire, who had left his Virginia home and had taken up his residence in England. Here Mary Ball had met Augustine Washington, then in England upon affairs connected with his property. Augustine Washington was one of the handsomest men of his day, and from him his eldest son George inherited the noble air and figure that marked him. Mary Ball was a Virginia beauty, and although admired by many Englishmen of distinction, she rather chose to marry Augustine Washington, albeit he had been married before, and had two motherless boys. In England, therefore, were they married, sailing soon after for Virginia, and within twelve years Mrs. Washington was a[8] widow with five children. She loved to talk to her children of those happy English days, when she had first pledged herself to Augustine Washington. It had also been the only time of excitement in her quiet life, and she had met many of the wits and cavaliers and belles of the reign of George the Second. She sometimes spoke of Lord Fairfax, but always guardedly; and George had conceived the idea that his mother perhaps knew Lord Fairfax better, and the reasons for his abandonment of his own country, than she cared to tell.

He began to wonder, quite naturally, where the earl was bound; and suddenly it came to him in a flash—“He is going to pay his respects to my mother.” In another instant he was on his feet and speeding like a deer through the woods towards home.

The house at Ferry Farm, which was home to him, was a good four miles by the road, but by paths through the woods and fields, and a foot-bridge across a creek, it was barely a mile. It took him but a short time to make it, but before he could reach the house he saw the coach and outriders dash into sight and draw up before the porch. The old soldier jumped from the box and opened the door and let down the steps, and the earl descended in state. On the porch stood Uncle[9] Jasper, the venerable black butler, in a suit of homespun, with a long white apron that reached from his chin to his knees. George saw him bowing and ushering the earl in. The outriders loosened their horses’ girths, and, after breathing them, led them to the watering-trough in the stable-lot back of the house. They then watered the coach-horses, the coachman sitting in solitary magnificence on his box, while the old soldier stretched his legs by walking about the lot. George saw this as he came through the stable way, his dog still at his heels. Uncle Jasper was waiting for him on the back porch.

“De madam,” he began, in a mysterious whisper, “will want you ter put on yo’ Sunday clo’es fo’ you come in ter see de Earl o’ Fairfax. He’s in de settin’-room now.”

George understood very well, and immediately went to his room to change his hunting-clothes, which were the worse for both dirt and wear. It was a ceremonious age, and the formalities of dress and manners were very strictly observed.

Meanwhile, in the sitting-room, on opposite sides of the fireplace, sat Madam Washington and the earl. Truly, the beauty that had distinguished Mary Ball remained with Madam Washington. Her figure was slight and delicate[10] (not from her had her eldest son inherited his brawn and muscle), and in her severely simple black gown she looked even slighter than usual. Her complexion was dazzlingly fair, and little rings of chestnut hair escaped from her widow’s cap; but her fine blue eyes were the counterpart of her eldest son’s. The room was plainly furnished, even for the times, but scrupulously neat. A rag-carpet covered the middle of the floor, while around the edges the polished planks were bare. In one corner a small harpsichord was open, with music on the rack. Dimity curtains shaded the small-paned windows, and a great fire sparkled in the large fireplace. Over the mantel hung the portrait of a handsome young man in a satin coat with lace ruffles. This was a portrait of Augustine Washington in his youth. Opposite it was a portrait of Madam Washington as a girl—a lovely young face and figure. There were one or two other portraits, and a few pieces of silver upon a mahogany buffet opposite the harpsichord—relics of Wakefield, the Westmoreland plantation where George was born, and of which the house had burned to the ground in the absence of the master, and much of the household belongings had been destroyed.

The earl’s eyes lingered upon the girlish portrait[11] of Madam Washington as the two sat gravely conversing.

“It was thus you looked, madam, when I first had the honor of knowing you in England,” he said.

“Time and sorrow and responsibilities have done their work upon me, my lord,” answered Madam Washington. “The care of five children, that they may be brought up to be worthy of their dead father, the making of good men out of four boys, the task of bringing up an only daughter to be a Christian gentlewoman, is no mean task, I assure you, and taxes my humble powers.”

“True, madam,” responded the earl, with a low bow; “but I know of no woman better fitted for so great an undertaking than Madam Washington.”

Madam Washington leaned forward and bowed in response, and then resumed her upright position, not once touching the back of her chair.

“And may I not have the pleasure of seeing your children, madam?” asked the earl, who cared little for children generally, but to whom the children of her who had once been the beautiful Mary Ball were of the greatest interest.

“Certainly, my lord,” answered Madam Washington,[12] rising, “if you will excuse me for a moment while I fetch them.”

The earl, left alone, rose and walked thoughtfully to the portrait of Mary Ball and looked at it for several minutes. His face, full of melancholy and weariness, grew more melancholy and weary. He shook his head once or twice, and made a motion with his hand as if putting something away from him, and then returned to his chair by the fire. He looked into the blaze and tapped his foot softly with his dress-sword. This beautiful, grave widow of forty, her heart wrapped up in her children, was not the girl of eighteen years before. There was no turning back of the leaves of the book of life for her. She had room now for but one thought in her mind, one feeling in her heart—her children.

Presently the door opened, and Madam Washington re-entered with her usual sedate grace. Following her was a young girl of fourteen, her mother’s image, the quaintest, daintiest little maiden imaginable, her round, white arms bare to the elbow, from which muslin ruffles fell back, a little muslin cap covering her hair, much lighter than her mother’s, and her shy eyes fixed upon the floor. Behind her were three sturdy, handsome boys of twelve, ten, and eight, as alike as peas in a pod. In those days the children of[13] gentlepeople were neither pert and forward nor awkward and ashamed at meeting strangers. Drilled in a precise etiquette, they knew exactly what to do, which consisted chiefly in making many low bows to their elders, and answering in respectful monosyllables such questions as were asked them. They learned in this way a grace and courtesy quite unknown to modern children.

“My daughter, Mistress Betty Washington, my Lord of Fairfax,” was Madam Washington’s introduction.

The earl rose from his chair and made the little girl a bow as if she were the princess royal, while Mistress Betty, scorning to be outdone, courtesied to the floor in response, her full skirt making a balloon as she sunk and rose in the most approved fashion.

“I am most happy to meet you, Mistress Betty,” said he, to which Mistress Betty, in a quavering voice—for she had never before seen an earl, or a coach like the one he came in—made answer:

“Thank you, my lord.”

The three boys were then introduced as Samuel, John, and Charles. To each the earl made a polite bow, but not so low as to Mistress Betty. The boys returned the bow without the slightest[14] shyness or awkwardness, and then took their places in silence behind their mother’s chair. They exchanged keen glances, though, among themselves, and wondered when they would be allowed to depart, so that they might further investigate the coach and the four roan horses. Madam Washington spoke.

“I am every moment expecting my eldest son George; he is out hunting to-day, and said that he would return at this hour, and he is always punctual to the minute. It will be a severe disappointment to me if I should not have the pleasure of showing your lordship my eldest son.”

It did not take a very acute person to note the tone of pride in madam’s voice when she said “my eldest son.”

“It will be a disappointment to me also, madam,” replied the earl. “I hope he is all that the eldest son of such a mother should be.”

Madam Washington smiled one of her rare smiles. “’Tis all I can do, my lord, to keep down the spirit of pride, so unbecoming to all of us, when I regard my son George. My other sons, I trust, will be as great a comfort to me, but they are still of too tender years for me to depend upon.” Then, turning to the three boys, she gave them a look which meant permission to leave the room. The boys bowed gravely to[15] their mother, gravely to the earl, and walked more gravely out of the room. Once the door was softly closed they made a quick but noiseless dash for the back door, and were soon outside examining the roans and the great coach, chattering like magpies to the negro outriders, until having made the acquaintance of the old soldier, Lance by name, they were soon hanging about him, begging that he would tell them about a battle.

Meanwhile, within the sitting-room, Madam Washington heard a step upon the uncarpeted stairs. A light came into her eyes as she spoke.

“There is my son now, going to his room. He will join us shortly. I cannot tell you, my lord, how great a help I have in my son. As you know, my step-son, Captain Laurence Washington, late of the British army, since leaving his Majesty’s service and marrying Mistress Anne Fairfax, has lived at the Hunting Creek place, which he has called Mount Vernon, in honor of his old friend and comrade-in-arms, Admiral Vernon. It is a good day’s journey from here, and although Laurence is most kind and attentive, I have had to depend, since his marriage, upon my son George to take his father’s place in the conduct of my affairs and in my household. It is he who reads family prayers night and morning[16] and presides with dignity at the foot of my table. It might seem strange to those who do not know his character how much I rely upon his judgment, and he but fifteen. Even my younger sons obey and respect him, and my daughter Betty does hang upon her brother. ’Tis most sweet to see them together.” At which Mistress Betty smiled and glanced at the earl, and saw so kind a look in his eyes as he smiled back at her that she looked at him quite boldly after that.

“It is most gratifying to hear of this, madam,” replied the earl; “but it is hardly merciful of you to a childless old man, who would give many worldly advantages had he but a son to lean upon in his old age.”

“You should have married twenty years ago, my lord,” answered Madam Washington, promptly.

Something like a gleam of saturnine humor appeared in the earl’s eyes at this, but he only replied, dryly, “Perhaps it is not wholly my fault, madam, that I find myself alone in my old age.”

At that moment the door opened, and young Washington stood upon the threshold.

The full flood of the sun, now low in the heavens, poured through the western windows upon the figure of the boy standing in the doorway. The room was beginning to darken, and the ruddy firelight, too, fell glowingly upon him.

The earl was instantly roused, and could scarcely persuade himself that the boy before him was only fifteen; seventeen, or even eighteen, would have seemed nearer the mark, so tall and well-developed was he. Like all creatures of the highest breeding, George looked handsomer the handsomer his dress; and although his costume was really simple enough, he had the splendid air that made him always appear to be in the highest fashion. His coat and knee-breeches were of dark-blue cloth, spun, woven, and dyed at home. His waistcoat, however, was of white brocade, and was made of his mother’s wedding-gown, Madam Washington having indulged her pride so far as to lay this treasured garment aside for waistcoats for her sons, while[18] Mistress Betty was to inherit the lace veil and the string of pearls which had gone with the gown.

George’s shoebuckles and kneebuckles were much finer than the earl’s, being of paste, and having been once worn by his father. His blond hair was made into a club, and tied with a black ribbon, while under his arm he carried a smart three-cornered hat, for the hat made a great figure in the ceremonious bows of the period. His dog, a beautiful creature, stood beside him.

Never in all his life had the Earl of Fairfax seen so noble a boy. The sight of him smote the older man’s heart; it flashed through him how easy it would be to exchange all his honors and titles for such a son. He rose and saluted him, as Madam Washington said, in a tone that had pride in every accent:

“My lord, this is my son, Mr. Washington.” George responded with one of those graceful inclinations which, years after, made the entrance of Colonel Washington at the Earl of Dunmore’s levee at Williamsburg a lesson in grace and good-breeding. Being “Mr. Washington” and the head of the house, it became his duty to speak first.

“I am most happy to welcome you, my lord, to our home.”

“‘THIS IS MY SON, MR. WASHINGTON’”

[19]“And I am most happy,” said the earl, “to meet once more my old friend, Madam Washington, and the goodly sons and sweet daughter with which she has been blessed.”

“My mother has often told us of you, sir, in speaking of her life during the years she spent in England.”

“Ah, my lord,” said Madam Washington, “I perceive I am no longer young, for I love to dwell upon those times, and to tell my children of the great men I met in England, chiefly through your lordship’s kindness.”

“It was my good-fortune,” said the earl, “to be an humble member of the Spectator Club, and through the everlasting goodness of Mr. Joseph Addison I had the advantage of knowing men so great of soul and so luminous of mind that I think I can never forget them.”

“I had not the honor of knowing Mr. Addison. He died before I ever saw England,” replied Madam Washington.

“Unfortunately, yes, madam. But of those you knew, Mr. Pope, poor Captain Steele, and even Dean Swift, with all his ferocious wit, his tremendous invective, his savage thirst for place and power, respected Mr. Addison. He was a man of great dignity—not odd and misshapen, like little Mr. Pope, nor frowzy like poor Dick[20] Steele, nor rude and overbearing like the fierce Dean—but ever gentle, mild, and of a most manly bearing. For all Mr. Addison’s mildness, I think there was no man that Dean Swift feared so much. When we would all meet at the club, and the Dean would begin his railing at persons of quality—for he always chose that subject when I was present—Mr. Addison would listen with a smile to the Dean as he lolled over the table in his huge periwig, and roared out in his great rich voice all the sins of all the people, always beginning and ending with Sir Robert Walpole, whom he hated most malignantly. Once, a pause coming in the Dean’s talk, Mr. Addison, calmly taking out his snuffbox, and helping himself to a pinch, remarked that he had always thought Dean Swift’s chiefest weakness, until he had been assured to the contrary, was his love for people of quality. We each held our breath. Dick Steele quietly removed a pewter mug from the Dean’s elbow; Mr. Pope, who sat next Mr. Addison, turned pale and slipped out of his chair; the Dean turned red and breathed hard, glaring at Mr. Addison, who only smiled a little; and then he—the great Dean Swift, the man who could make governments tremble and parliaments afraid; who made duchesses weep from his rude sneers, and great ladies almost go down on their[21] knees to him—sneaked out of the room at this little thrust from Mr. Addison. For ’twas the man, madam—the honest soul of him—that could cow that great swashbuckler of a genius. Mr. Addison abused no one, and he was exactly what he appeared to be.”

“That, indeed, is the highest praise, as it shows the highest wisdom,” answered Madam Washington.

George listened with all his mind to this. He had read the Spectator, and Mr. Addison’s tragedy of “Cato” had been read to him by Mr. Hobby, the Scotch school-master who taught him, and he loved to hear of these great men. The earl, although deep in talk with Madam Washington, was by no means unmindful of the boy, but without seeming to notice him watched every expression of his earnest face.

“I once saw Dean Swift,” continued Madam Washington. “It was at a London rout, where I went with my brother’s wife, Madam Joseph Ball, when we were visiting in London. He had great dark eyes, and sat in a huge chair, and called ladies of quality ‘my dear,’ as if they were dairy-maids. And the ladies seemed half to like it and half to hate it. They told me that two ladies had died of broken hearts for him.”

[22]“I believe it to be true,” replied the earl. “That was the last time the Dean ever saw England. He went to Ireland, and, as he said, ‘commenced Irishman in earnest,’ and died very miserably. He could not be bought for money, but he could very easily be bribed with power.”

“And that poor Captain Steele?”

The earl’s grave face was suddenly illuminated with a smile.

“Dear Dick Steele—the softest-hearted, bravest, gentlest fellow—always drunk, and always repenting. There never was so great a sermon preached on drunkenness as Dick Steele himself was. But for drink he would have been one of the happiest, as he was by nature one of the best and truest, gentlemen in the world; but he was weak, and he was, in consequence, forever miserable. Drink brought him to debts and duns and prison and rags and infamy. Ah, madam, ’twould have made your heart bleed, as it made mine, to see poor Dick reeling along the street, dirty, unkempt, his sword bent, and he scarce knowing what he was doing; and next day, at home, where his wife and children were in hunger and cold and poverty, behold him, lying in agony on his wretched bed, weeping, groaning, reproaching himself, and suffering tortures for one hour’s wicked indulgence! Then would he[23] turn gentleman again, and for a long time be our own dear Dick Steele—his wife smiling, his children happy. I love to think on honest Dick at these times. It was then he wrote that beautiful little book, which should be in every soldier’s hands, The Christian Hero. We could always tell at the club whether Dick Steele were drunk or sober by Mr. Addison’s face. When Steele was acting the beast, Mr. Addison sighed often and looked melancholy all the time, and spent his money in taking such care as he could of the poor wife and children. Poor Dick! The end came at last in drunkenness and beastliness; but before he died, for a little while, he was the Dick Steele we loved, and shall ever love.”

“And Mr. Pope—the queer little gentleman—who lived at Twickenham, and was so kind to his old mother?”

“Mr. Pope was a very great genius, madam, and had he not been born crooked he would have been an admirable man; but the crook in his body seemed to make a crook in his mind. He died but last year, outliving many strong men who pitied his puny frame. But let me not disparage Mr. Pope. My Lord Chesterfield, who was a very good judge of men, as well as the first gentleman of his time, entertained a high esteem for Mr. Pope.”

[24]“I also had the honor of meeting the Earl of Chesterfield,” continued Madam Washington, with animation, “and he well sustained the reputation for politeness that I had heard of him, for he made as much of me as if I had been a great lady instead of a young girl from the colonies, whom chance and the kindness of a brother had brought to England, and your lordship’s goodness had introduced to many people of note. ’Tis true I saw them but for a glimpse or two, but that was enough to make me remember them forever. I have tried to teach my son Lord Chesterfield’s manner of saluting ladies, in which he not only implied the deepest respect for the individual, but the greatest reverence for all women.”

“That is true of my Lord Chesterfield,” replied the earl, who found it enchanting to recall these friends of his youth with whom he had lived in close intimacy, “and his manners revealed the man. He had also a monstrous pretty wit. There is a great, lumbering fellow of prodigious learning, one Samuel Johnson, with whom my Lord Chesterfield has become most friendly. I never saw this Johnson myself, for he is much younger than the men of whom we are speaking; but I hear from London that he is a wonder of learning, and although almost indigent[25] will not accept aid from his friends, but works manfully for the booksellers. He has described my Lord Chesterfield as ‘a wit among lords, and a lord among wits.’ I heard something of this Dr. Johnson, in a late letter from London, that I think most praiseworthy, and affording a good example to the young. His father, it seems, was a bookseller at Lichfield, where on market-days he would hire a stall in the market for the sale of his wares. One market-day, when Samuel was a youth, his father, being ill and unable to go himself, directed him to fit up the book-stall in the market and attend it during the day. The boy, who was otherwise a dutiful son, refused to do this. Many years afterwards, his father being dead, and Johnson, being as he is in great repute for learning, was so preyed upon by remorse for his undutiful conduct that he went to Lichfield and stood bareheaded in the market-place, before his father’s old stall, for one whole market-day, as an evidence of his sincere penitence. I hear that some of the thoughtless jeered at him, but the better class of people respected his open acknowledgment of his fault, the more so as he was in a higher worldly position than his father had ever occupied, and it showed that he was not ashamed of an honest parent because he was of a humble class. I[26] cannot think, madam, of that great scholar, standing all day with bare, bowed head, bearing with silent dignity the remarks of the curious, the jeers of the scoffers, without in spirit taking off my hat to him.”

During this story Madam Washington fixed her eyes on George, who colored slightly, but remarked, as the earl paused:

“It was the act of a brave man and a gentleman. There are not many of us who could do it.”

Just then the door opened, and Uncle Jasper, bearing a huge tray, entered. He placed it on a round mahogany table, and Madam Washington proceeded to make tea, and offered it to the earl with her own hands.

The earl while drinking his tea glanced first at George and then at pretty little Betty, who, feeling embarrassed at the notice she received, produced her sampler from her pocket and began to work demurely in cross-stitch on it. Presently Lord Fairfax noticed the open harpsichord.

“I remember, madam,” he said to Madam Washington, as they gravely sipped their tea together, “that you had a light hand on the harpsichord.”

“I have never touched it since my husband’s death,” answered she, “but my daughter Betty can perform with some skill.”

[27]Mistress Betty, obeying a look from her mother, rose at once and went to the harpsichord, never thinking of the ungraceful and disobliging protest of more modern days. She seated herself, and struck boldly into the “The Marquis of Huntley’s Rigadoon.” She had, indeed, a skilful little hand, and as the touch of her small fingers filled the room with quaint music the earl sat, tapping with his foot to mark the time, and smiling at the little maid’s grave air while she played. When her performance was over she rose, and, making a reverence to her mother and her guest, returned to her sampler.

The earl had now spent nearly two hours with his old friend, and the sun was near setting, but he could scarcely make up his mind to leave. The interest he felt in her seemed transferred to her children, especially the two eldest, and the resolve entered his mind that he would see more of that splendid boy. He turned to George and said to him:

“Will you be so good, Mr. Washington, as to order my people to put to my horses, as I find that time has flown surprisingly fast?”

“Will you not stay the night, my lord?” asked Madam Washington. “We can amply accommodate you and your servants.”

“Nothing would please me more, madam, but[28] it is my duty to reach Fredericksburg to-night, where I have business, and I am now seeking a ferry where I can be moved across.”

“Then you have not to seek far, sir, for this place is called Ferry Farm; and we have several small boats, and a large one that will easily hold your coach; and, with the assistance of your servants, all of them, as well as your horses, can be ferried over at once.”

The earl thanked her, and George left the room promptly to make the necessary arrangements. In a few moments the horses were put to the coach, as the ferry was half a mile from the house; and George, ordering his saddle clapped on his horse, that was just then being brought from the pasture, galloped down to the ferry to superintend the undertaking—not a light one—of getting a coach, eight horses, and eight persons across the river.

The coach being announced as ready, Madam Washington and the earl rose and walked together to the front porch, accompanied by little Mistress Betty, who hung fondly to her mother’s hand. Outside stood the three younger boys, absorbed in contemplation of the grandeur of the equipage. They came forward promptly to say good-bye to their mother’s guest, and then slipped around into the chimney corner that[29] they might see the very last of the sight so new to them. Little Betty also disappeared in the house after the earl had gallantly kissed her hand and predicted that her bright eyes would yet make many a heart ache. Left alone on the porch in the twilight with Madam Washington, he said to her very earnestly:

“Madam, I do not speak the language of compliment when I say that you may well be the envy of persons less fortunate than you when they see your children. Of your eldest boy I can truly say I never saw a nobler youth, and I hope you will place no obstacle in the way of my seeing him again. Greenway Court is but a few days’ journey from here, and if I could have him there it would be one of the greatest pleasures I could possibly enjoy.”

“Thank you, my lord,” answered Madam Washington, simply. “My son George has, so far, never caused me a moment’s uneasiness, and I can very well trust him with persons less improving to him than your lordship. It is my wish that he should have the advantage of the society of learned and polished men, and your kind invitation shall some day be accepted.”

“You could not pay me a greater compliment, madam, than to trust your boy with me, and I shall claim the fulfilment of your promise,”[30] replied Lord Fairfax. “Farewell, madam; the sincere regard I have cherished during nearly twenty years for you will be extended to your children, and your son shall never want a friend while I live. I do not know that I shall ever travel three days’ journey from Greenway again, so this may be our last meeting.”

“Whether it be or not, my lord,” said Madam Washington, “I can only assure you of my friendship and gratitude for your good-will towards my son.”

The earl then respectfully kissed her hand, as he had done little Betty’s, and stepped into the coach. With a great smacking of whips and rattle and clatter and bang the equipage rolled down the road in the dark towards the ferry.

A faint moon trembled in the heavens, and it was so dark that torches were necessary on the river-bank. George had dismounted from his horse, and with quiet command had got everything in readiness to transport the cavalcade. The earl, sitting calmly back in the chariot, watched the proceedings keenly. He knew that it required good judgment in a boy of fifteen to take charge of the ferriage of so many animals and men without haste or confusion. He observed that in the short time George had preceded him everything was exactly as it should[31] be—the large boat drawn up ready for the coach, and two smaller boats and six stalwart negro ferry-men to do the work.

“I have arranged, my lord, with your permission,” he said, “to ferry the coach and horses, with your own servants, over first, as it is not worth while taking any risks in crowding the boats; then, when the boats return, the outriders and their horses may return in the large boat.”

“Quite right, Mr. Washington,” answered the earl, briskly; “your dispositions do credit to you, and I believe you could transport a regiment with equal ease and precision.”

George’s face colored with pleasure at this. “I shall go on with you myself,” he said, “if you will allow me.”

The boat was drawn up, a rude but substantial raft was run from the shore to the boat, the horses were taken from the coach, and it was rolled on board by the strong arms of a dozen men. The horses were disposed to balk at getting in the boat, but after a little coaxing trotted quietly aboard; the ferry-men, reinforced by two of Lord Fairfax’s servants, took the oars, and the boat, followed by two smaller ones, was pulled rapidly across the river. After a few minutes, seeing that everything was going right, George entered the coach, and sat[32] by the earl’s side. The earl lighted his travelling-lamp, and the two sat in earnest conversation. Lord Fairfax wished to find out something more about the boy who had made so strong an impression on him. He found that George had been well taught, and although not remarkable in general literature, he knew more mathematics than most persons of twice his age and opportunities. He had been under the care of the old Scotchman, Mr. Hobby, who was, in a way, a mathematical genius, and George had profited by it.

“And what, may I ask, Mr. Washington, is your plan for the future?”

“I hope, sir,” answered George, modestly, “that I shall be able to get a commission in his Majesty’s army or navy. As you know, although I am my mother’s eldest son, my brother Laurence, of Mount Vernon, is my father’s eldest son, and the head of our family. My younger brothers and I have small fortunes, and I would like to see something of the world and some service in arms before I set myself to increasing my part.”

“Very creditable to you, and you may count upon whatever influence I have towards getting you a commission in either branch of the military service. I myself served in the Low Countries[33] under the Duke of Marlborough in my youth, and although I have long since given up the profession of arms I can never lose my interest in it. Your honored mother has promised me the pleasure of your company for a visit at Greenway Court, when we may discuss the matter of your commission at length. I am not far from an old man, Mr. Washington, but I retain my interest in youth, and I like to see young faces about me at Greenway.”

“Thank you, my lord,” answered George, with secret delight. “I shall not let my mother forget her promise—but she never does that.”

“There is excellent sport at Greenway, and I have kept a choice breed of deer-hounds as well as fox-hounds. I brought with me from England a considerable library, and you can, I hope, amuse yourself with a book; but if you cannot amuse yourself with a book, you will always be dependent upon others for your entertainment.”

“I am fond of reading—on rainy days,” said George, at which candid acknowledgment the earl smiled.

“My man, Lance, is an old soldier; he is an intelligent man for his station and a capital fencer. You may learn something from him with the foils. He was with me at the siege of Bouchain.”

[34]What a delightful vista this opened before George, who was, like other healthy minded boys, devoted to reading and hearing of battles, and fencing and all manly sports! He glanced at Lance, standing erect and soldierly, as the boat moved through the water. He meant to hear all about the siege of Bouchain from Lance before the year was out, and blushed when he was obliged to acknowledge to himself that he had never heard of the siege of Bouchain.

Next morning, as usual, George was up and on horseback by sunrise. Until this year he had ridden five miles a day each way to Mr. Hobby’s school; but now he was so far ahead of the school-master’s classes that he only went a few times a week, to study surveying and the higher mathematics, and to have the week’s study at home marked out for him. Every morning, however, it was his duty to ride over the whole plantation before breakfast, and to report the condition of everything in it to his mother. Madam Washington was one of the best farmers in the colony, and it was her custom, after hearing George’s account at breakfast, to mount her horse and ride over the place also, and give her orders for the day.

The first long lances of light were just tipping the woods and the river when George came out and found his horse held by Billy Lee, a negro lad of about his own age, who was his[36] body-servant and shadow.[A] Billy was a chocolate-colored youth, the son of Aunt Sukey the cook and Uncle Jasper the butler. He had but one idea and one ideal on earth, and that was “Marse George.” It was in vain that Madam Washington, the strictest of disciplinarians, might lay her commands on Billy. Until he had found out what “Marse George” wanted him to do, Billy seemed unconscious of having got any orders. Madam Washington, who could awe much older and wiser persons than Billy, had often sent for the boy, when he was regularly taken into the house, and after reasoning with him, kindly explaining to him that both “Marse George” and himself were merely boys, and under her authority, would give him a stern reproof, which Billy always received in an abstracted silence, as if he had not heard a word that was said to him. Finding that he acted throughout as if he had not heard, Madam Washington turned him over to Aunt Sukey, who, after the fashion of those days, with white boys as well as black, gave him a smart birching. Billy’s[37] roars were like the trumpeting of an elephant; but within a week he went back to his old way of forgetting there was anybody in the world except “Marse George.” Then Madam Washington turned him over to Uncle Jasper, who “lay” that he would “meck dat little triflin’ nigger min’ missis.” A second and much more vigorous birching followed at the hands of Uncle Jasper, who triumphed over Aunt Sukey when Billy for two days actually seemed to realize that he had something else to do besides following George about and never taking his eyes off of him. Uncle Jasper’s victory was short-lived, though. Within a week Billy was as good-for-nothing as ever, except to George. Madam Washington then saw that it was not a case of discipline—that the boy was simply dominated by his devotion to George, and could neither be forced nor reasoned out of it. Therefore it was arranged that the care of the young master’s horse and everything pertaining to him should be confided to Billy, who would work all day with the utmost willingness for “Marse George.” By this means Billy was made of use. Nobody touched George’s clothes or books or belongings except Billy. He scrubbed and then dry-rubbed the floor of his young master’s room, scoured the windows, cut the wood and made[38] the fires, attended to his horse, and when George was there personally to direct him, Billy would do whatever work he was ordered. But the instant he was left to himself he returned to idleness, or to some perfectly useless work for his young master—polishing up windows that were already bright, dry-rubbing a floor that shone like a mirror, or brushing George’s clothes which were quite spotless. His young master loved him with the strong affection that commonly existed between the masters and the body-servants in those days. Like Madam Washington, George was a natural disciplinarian, and, himself capable of great labor of mind and body, he exacted work from everybody. But Billy was an exception to this rule. It is not in the human heart to be altogether without weaknesses, and Billy was George’s weakness. When his mother would declare the boy to be the idlest servant about the place, George could not deny it; but he always left the room when there were any animadversions on his favorite, and could never be brought to acknowledge that Billy was not a much-injured boy. Serene in the consciousness that “Marse George” would stand by him, Billy troubled himself not at all about Madam Washington’s occasional cutting remarks as to his uselessness, nor his father’s and mother’s more outspoken[39] complaints that he “warn’t no good ’scusin’ ’twas to walk arter Marse George, proud as a peacock ef he kin git a ole jacket or a p’yar o’ Marse George’s breeches fur ter go struttin’ roun’ in.” Aunt Sukey was very pious, and Uncle Jasper was a preacher, and held forth Sunday nights, in a disused corn-house on the place, to a large congregation of negroes from the neighboring places. But Billy showed no fondness whatever for these meetings, preferring to go to the Established Church with his young master every Sunday, sitting in a corner of the gallery, and going to sleep with much comfort and regularity as soon as he got there. Madam Washington always exacted of every one who went to church from her house that he or she should repeat the clergyman’s text on coming home, and Billy was no exception to the rule. On Sunday, therefore, instead of joining the gay procession of youths and young men, all handsomely mounted, who rode along the highway after church, George devoted his time on his way home to teaching Billy the text. The boy always repeated it very glibly when Madam Washington demanded it of him, and thereby won her favor, for a short time, once a week.

On this particular morning, as George took the reins from Billy and jumped on the back of[40] his sorrel colt, and galloped down the lane towards the fodder-field, Billy, who was keen enough where his young master was concerned, saw that he was preoccupied. Contrary to custom, he would not take his dog Rattler with him, and Billy, dragging the whining dog by the neck, hauled him back into the house and up into George’s room, where the two proceeded to lay themselves down before the fire and go to sleep. An hour later the indignant Aunt Sukey found them, and but for George’s return just then it would have gone hard with Billy, anyhow.

As George galloped briskly along in the crisp October morning, he felt within him the full exhilaration of youth and health and hope. He had not been able to sleep all night for thinking of that promised visit to Greenway Court. He had heard of it—a strange combination of hunting-lodge and country-seat in the mountains, where Lord Fairfax lived, surrounded by dependants, like a feudal baron. George had never in his life been a hundred miles away from home. He had been over to Mount Vernon since his brother Laurence’s marriage, and the visit had charmed him so that his ever prudent mother had feared that the simpler and plainer life at Ferry Farm would be distasteful to him; for Mount Vernon was a fine, roomy country-house,[41] where Laurence Washington and his handsome young wife, both rich, dispensed a splendid hospitality. There was a great stable full of saddle-horses and coach-horses, a retinue of servants, and a continual round of entertaining going on. Laurence Washington had only lately retired from the British army, and his house was the favorite resort for the officers of the British war-ships that often came up the Potomac, as well as the officers of the military post at Alexandria. Although he enjoyed this gay and interesting life at Mount Vernon, George had left it without having his head turned, and came back quite willingly to the sober and industrious regularity of the home at Ferry Farm. He was the favorite over all his brothers with Laurence Washington and his wife, and it was a well-understood fact that, if they died without children, George was to inherit the splendid estate of Mount Vernon. Madam Washington had been a kind step-mother to Laurence Washington, and he repaid it by his affection for his half-brothers and young sister. In those days, when the eldest son was the heir, it seemed quite natural that George, as next eldest, should have preference, and should be the next person of consequence in the family to his brother Laurence.

He spent an hour riding over the place, seeing[42] that the fodder had been properly stripped from the stalks in a field, looking after the ferry-boats, giving an eye to the feeding of the stock, and a sharp investigation of the stables, and returned to the house by seven o’clock. Precisely at seven o’clock every morning all the children, servants, and whatever guests there were in the house assembled in the sitting-room, where prayers were read. In his father’s time the master of the house had read these prayers, and after his death Laurence, as the head of the family, had taken up this duty; but since his marriage and removal to Mount Vernon it had fallen upon George.

When he entered the room he found his mother waiting for him, as usual, with little Mistress Betty and the three younger boys. The servants, including Billy, who had already been reported by Aunt Sukey, were standing around the wall. After an affectionate good-morning to his mother, George, with dignity and reverence, read the family prayers in the Book of Common Prayer. His mother was as calm and as collected as usual, but in the small velvet bag she carried over her arm lay an important letter, received between the time that George left the house in the morning and his return. Prayers over, breakfast was served, George sitting in his father’s place at the head of the table, and Madam[43] Washington talking calmly over every-day matters.

“I do not know what we are to do with that boy Billy,” she said. “This morning, when he ought to have been picking up chips for the kitchen, he was lying in front of your fireplace with Rattler, both of them sound asleep.”

George, instead of being scandalized at this, only smiled a little.

“I do not know which is the most useless,” exclaimed Madam Washington, with energy, “the dog or that boy!”

George ceased smiling at this; he did not like to have Billy too severely commented on, and deftly turned the conversation. “Lord Fairfax again asked me, when we were crossing the river last night, to visit him at Greenway Court. I should like very much to go, mother. I believe I would rather go even than to spend Christmas at Mount Vernon, for I have been to Mount Vernon, but I have never been to Greenway, or to any place like it.”

“The earl sent me a letter this morning on the subject before he left Fredericksburg,” replied Madam Washington, quietly.

The blood flew into George’s face, but he spoke no word. His mother was a person who did not like to be questioned.

[44]“You may read it,” she continued, handing it to him out of her bag.

It was sealed with the huge crest of the Fairfaxes, and was written in the beautiful penmanship of the period. It began:

“Honored Madam.—The promise you graciously made me, that your eldest son, Mr. George Washington, might visit me at Greenway Court, gave me both pride and pleasure; and will you not add to that pride and pleasure by permitting him to return with me when I pass through Fredericksburg again on my way home two days hence? Do not, honored madam, think that I am proposing that your son spend his whole time with me in sport and pleasure. While both have their place in the education of the young, I conceive, honored madam, that your son has more serious business in hand—namely, the improvement of his mind, and the acquiring of those noble qualities and graces which distinguish the gentleman from the lout.

“He would have at Greenway, at least, the advantage of the best minds in England as far as they can be writ in books, and for myself, honored madam, I will be as kind to him as the tenderest father. If you can recall with any pleasure the days so long ago, when we were both twenty years younger, and when your friendship, honored madam, was the chief pleasure, as it always will be the chief honor, of my life, I beg that you will not refuse my request. I am, madam, with sentiments of the highest esteem,

“Your obedient, humble servant,

“Fairfax.”

“Have you thought it over, mother?”

“Yes, my son; but, as you know I am a[45] person of deliberation, I will think it over yet more.”

“I will give up Christmas at Mount Vernon, mother, if you will let me go.”

“I have already promised your brother that you shall spend Christmas with him, and I cannot recall my word.”

George said no more. He got up, and, bowing respectfully to his mother, went out. He had that morning more than his usual number of tasks to do; but all day long he was in a dream. For all his steadiness and willingness to lead a quiet life with his mother and the younger children at Ferry Farm, he was by nature adventurous, and for more than a year he had chafed inwardly at the narrow and uneventful existence which he led. He had early announced that he wished to serve either in the army or the navy, but, like all people, young or old, who have strong determination, he bided his time quietly, doing meanwhile what came to hand. He had been every whit as much fascinated with Lord Fairfax as the elder man had been with him; and the prospect of a visit to Greenway—of listening to his talk of the great men he had known, of seeing the mountains for the first time in his life, and of hunting and sporting in their wilds, of taking lessons in fencing from old Lance, of looking[46] over Lord Fairfax’s books—was altogether enchanting. He had a keen taste for social life, and his Christmas at Mount Vernon, with all its gayety and company, had been the happiest two weeks of his life. Suppose his mother should agree to let him go to Greenway with the earl and then come back by way of Mount Vernon? Such a prospect seemed almost too dazzling. He brought his horse down to a walk along the cart-road through the woods he was traversing while he contemplated the delightful vision; and then, suddenly coming out of his day-dream, he pulled himself together, and, striking into a sharp gallop, tried to dismiss the subject from his mind. This he could not do, but he could exert himself so that no one would guess what was going on in his mind, and in this he was successful.

Two o’clock was the dinner-hour at Ferry Farm, and a few minutes before that time George walked up from the stables to the house. Little Betty was on the watch, and ran down to the gate to meet him. Their mother, looking out of the window, saw them coming across the lawn arm in arm, Betty chattering like a magpie and George smiling as he listened. They were two of the handsomest and healthiest and brightest-eyed young creatures that could be imagined, and Madam Washington’s heart glowed with a[47] pride which she believed sinful and strove unavailingly to smother.

At dinner Madam Washington and George and Betty talked, the three younger boys being made to observe silence, after the fashion of the day. Neither Madam Washington nor George brought up the subject of the earl’s visit, although it was a tremendous event in their quiet lives. But little Betty, who was the talkative member of the family, at once began on him. His coach and horses and outriders were grand, she admitted; but why an earl, with bags of money, should choose to wear a plain brown suit, no better than any other gentleman, Mistress Betty vowed she could not understand. His kneebuckles were not half so fine as George’s, and brother Laurence had a dozen suits finer than the earl’s.

“His sword-hilt is worth more than this plantation,” remarked George, by way of mitigating Betty’s scorn for the earl’s costume. Betty acknowledged that she had never seen so fine a sword-hilt in her life, and then innocently remarked that she wished she were going to visit at Greenway Court with George. George’s face turned crimson, but he remained silent. He was a proud boy, and had never in his life begged for anything, but he wanted to go so badly that[48] the temptation was strong in him to mount his horse without asking anybody’s leave, and, taking Billy and Rattler with him, start off alone for the mountains.

Dinner was over presently, and as they rose Madam Washington said, quietly:

“My son, I have determined to allow you to join Lord Fairfax, and I have sent an inquiry to him, an hour ago, asking at what time to-morrow you should meet him in Fredericksburg. You may remain with him until December; but the first mild spell in December I wish you to go down to Mount Vernon for Christmas, as I promised.”

George’s delight was so great that he grew pale with pleasure. He would have liked to catch his mother in his arms and kiss her, but mother and son were chary of showing emotion. Therefore he only took her hand and kissed it, saying, breathlessly:

“Thank you, mother. I hardly hoped for so much pleasure.”

“But it is not for pleasure that I let you go,” replied his mother, who, according to the spirit of the age, referred everything to duty. “’Tis because I think my Lord Fairfax’s company will be of benefit to you; and as there is but little prospect of a school here this winter, and I have[49] made no arrangements for a tutor, I must do something for your education, but that I cannot do until after Christmas. So, as I think you will be learning something of men as well as of books, I have thought it best, after reflecting upon it as well as I can, to let you go.”

“I will promise you, mother, never to do or say anything while I am away from you that I would be ashamed for you to know,” cried George.

Madam Washington smiled at this.

“Your promise is too extensive,” she said. “Promise me only that you will try not to do or say anything that will make me ashamed, and that will be enough.”

George colored, as he answered:

“I dare say I promised too much, and so I will accept the change you make.”

Here a wild howl burst upon the air. Billy, who had been standing behind George’s chair, understood well enough what the conversation meant, and that he was to be separated until after Christmas from his beloved “Marse George.” Madam Washington, who had little patience with such outbreaks of emotion, sharply spoke to him. “Be quiet, Billy!”

Billy’s reply was a fresh burst of tears and wailing, which brought home to little Betty that[50] George was about to leave them, and caused her to dissolve into tears and sobs, while Rattler, running about the room, and looking from one to the other, began to bark furiously.

Madam Washington, standing up, calm, but excessively annoyed at this commotion in her quiet house, brought her foot down with a light tap, which, however, meant volumes. Uncle Jasper too appeared, and was about to haul Billy off to condign punishment when George intervened.

“Hold your tongue, Billy,” he said; and Billy, digging his knuckles into his eyes, subsided as quietly as he had broken forth.

“Now go up to my room and take the dog, and stay there until I come,” continued George.

Billy obeyed promptly. Betty, however, having once let loose the floodgates, hung around George’s neck and wept oceans of tears. George soothed her as best he could, but Betty would not be comforted, and was more distressed than ever when, in a little while, a note arrived from Lord Fairfax, saying he would leave Fredericksburg the next morning at sunrise if it would be convenient to Mr. Washington to join him then.

Before daybreak the next morning George came down-stairs, Billy following with his portmanteau. Madam Washington, little Betty, and all the house-servants were up and dressed, but it was thought best not to waken the three little boys, who slept on comfortably in their trundle-beds. The candles were lighted, and for the last time for two months,—which seems long to the young, George had family prayers. His mother then took the book from him and read the prayers for travellers about to start on a journey. She was quite composed, for no woman ever surpassed Madam Washington in self-control; but little Betty still wept, and would not leave George’s side even while he ate his breakfast. There had been some talk of Betty’s going to Mount Vernon also for Christmas, and George, remembering this, asked his mother, as a last favor, that she would let Betty meet him there, whence he could bring her home. Madam Washington agreed, and this quickly dried Betty’s[52] tears. Billy acted in a mysterious manner. Instead of being in vociferous distress, he was quiet and even cheerful, so much so that a grin discovered itself on his countenance, which was promptly banished as soon as he saw Madam Washington’s clear, stern eyes travelling his way. George, feeling for poor Billy’s loneliness, had determined to leave Rattler behind for company; but both Billy and Rattler were to cross the ferry with him, the one to bring the horse back, and the other for a last glimpse of his master.

The parting was not so mournful, therefore, as it promised to be. George went into the chamber where his three little brothers slept, who were not wide-awake enough to feel much regret at his departure. The servants all came out and he shook the hand of each, especially Uncle Jasper’s, while Aunt Sukey embraced him. His mother kissed him and solemnly blessed him, and the procession started. George mounted his own horse, while Betty, seated pillion-wise behind him, was to ride with him to the ferry. Uncle Jasper and Aunt Sukey walked as far as the gate, and Billy, with Rattler at his heels and the portmanteau on his head, started off on a brisk run down the road. The day was breaking beautifully. A pale blue mist lay over the river and the woods. The fields, bare and brown, were[53] covered with a white hoar-frost, and harbored flocks of partridges, which rose on whirring wings as the gray light turned to red and gold. In the chinquapin bushes along the road squirrels chattered, and a hare running across the lane reminded George of his hare-traps, which he charged Betty to look to. But although Betty would have died for him at any moment, she would not agree to have any hand in the trapping and killing of any living thing; so she would only promise to tell the younger boys to look after the traps.

“And it won’t be long until Christmas,” said George, turning in his saddle and pressing Betty’s arm that was around him as they galloped along briskly; “and if I have a chance of sending a letter, I will write you one. Think, Betty, you will have a letter all to yourself; you have never had one, I know.”

“I never had a letter all to myself,” answered Betty. For that was before the days of cheap postage, or postage at all as it is now; and letters were rare and precious treasures.

“And it will be very fine at Mount Vernon—ladies, and even girls like you, wearing hoops, and dancing minuets every evening, while Black Tubal and Squirrel Tom play their fiddles.”

[54]“I like minuets well enough, but I like jigs and rigadoons better; and mother will not let me wear a hoop. But I am to have her white sarcenet silk made over for me. That I know.”

“You must practise on the harpsichord very much, Betty; for at Mount Vernon there is one, and brother Laurence and his wife will want you to play before company.”

Mistress Betty was not averse to showing off her great accomplishment, and received this very complaisantly. Altogether, what with the letter and the white sarcenet, she began to take a hopeful rather than a despairing view of the coming two months.

Arrived within sight of the ferry, George stopped, and lifted Betty off the horse. There was a foot-path across the fields to the house which made it but a short walk back, which Betty could take alone. The brother and sister gave each other one long and silent embrace—for they loved each other very dearly—and then, without a word, Betty climbed over the fence and walked rapidly homeward, while George made for the ferry, where Billy and the portmanteau awaited him. One of the small boats and two ferry-men, Yellow Dick and Sambo, took him across the river. The horse was to be carried across for George to ride to the inn where Lord Fairfax awaited him, and Billy was to take the horse back again.

GEORGE BIDS BETTY GOOD-BYE

[55]The flush of the dawn was on the river when the boat pushed off, and George thought he had never seen it lovelier; but like most healthy young creatures on pleasure bent, he had no sentimental regrets. The thing he minded most was leaving Billy, because he was afraid the boy would be in constant trouble until his return. But Billy seemed to take it so debonairly that George concluded the boy had at last got over his strong disinclination to work for or think of anybody except “Marse George.”

The boat shot rapidly through the water, rowed by the stalwart ferry-men, and George was soon on the opposite shore. He bade good-bye to Yellow Dick and Sambo, and, mounting his horse, with Billy still trotting ahead with the portmanteau, rode off through the quaint old town to the tavern. It was a long, low building at the corner of two straggling streets, and signs of the impending departure of a distinguished guest were not wanting. Captain Benson, a militia officer, kept the tavern, and in honor of the Earl of Fairfax had donned a rusty uniform, and was going back and forth between the stable and the kitchen, first looking after his lordship’s breakfast[56] and then after his lordship’s horses’ breakfasts. He came bustling out when George rode up.

“Good-morning, Mr. Washington. ’Light, sir, ’light. I understand you are going to Greenway Court with his lordship. He is now at his breakfast. Will you please to walk in?”

“No, I thank you, sir,” responded George. “If you will kindly mention to Lord Fairfax that I am here, you will oblige me.”

“Certainly, sir, certainly,” cried Captain Benson, disappearing in the house.

The travelling-chariot was out and the horses were being put to it under the coachman’s superintendence, while old Lance was looking after the luggage. He came up to George, and, giving him the military salute, asked for Mr. Washington’s portmanteau. George could scarcely realize that he was going until he saw it safely stowed along with the earl’s under the box-seat. He then determined to send Billy off before the earl made his appearance, for fear of a terrible commotion, after all, when Billy had to face the final parting.

“Now, Billy,” said George to him, very earnestly, “you will not give my mother so much trouble as you used to, but do as you are told, and it will be better for you.”

[57]“Yes, suh,” answered Billy, looking in George’s eyes without winking.

“And here is a crown for you,” said George, slipping one into Billy’s hand—poor George had only a few crowns in a purse little Betty had knitted for him. “Now mount the horse and go home. Good-bye, Rattler, boy—all of Lord Fairfax’s dogs, of every kind, shall not make me forget you.”

Billy, without the smallest evidence of grief, but with rather a twinkle in his beady eyes, shook his young master’s hand, jumped on the horse, and, whistling to Rattler, all three of George’s friends disappeared down the village street. George looked after them for some minutes and sighed at what was before Billy, but comforted himself by recalling the boy’s sensible behavior in the matter of the parting. In a few moments Lord Fairfax came out. George went up the steps to the porch, and, making his best bow, tried to say how much he felt the earl’s kindness. True gratitude is not always glib, and was not with George, but the earl saw from the boy’s face the intense pleasure he experienced.

“You will sit with me, Mr. Washington,” said Lord Fairfax, “and when you are tired of the chariot I will have one of my outriders give[58] you a horse, and have him ride the wheel-horse.”

“Anything that your lordship pleases,” was George’s polite reply.

The earl bade a dignified farewell to Captain Benson, who escorted him to the coach, and in a little while, with George by his side and the outriders ahead, they were jolting along towards the open country.

The earl talked a little for the first hour or two, pointing out objects in the landscape, and telling interesting facts concerning them, which George had never known before. After a while, though, he took down two books from a kind of shelf in the front of the coach, and handing one to George, said:

“Here is a volume of the Spectator. You will find both profit and pleasure in it. Thirty years ago the Spectator was the talk of the day. It ruled London clubs and drawing-rooms, and its influence was not unfelt in politics.” The other book, George saw, was an edition of Horace in the original. As soon as the earl opened it he became absorbed in it.

Not so with George and the Spectator. Although fond of reading, and shrewd enough to see that the earl would have but a low opinion of a boy who could not find resources in books,[59] what was passing before him was too novel and interesting, to a boy who had been so little away from home, to divide his attention with anything. The highway was fairly good, but the four roans took the road at such a rattling gait that the heavy chariot rolled and bumped and lurched like a ship at sea. So well made was it, though, and so perfect the harness, that not a bolt, a nut, or a strap gave way. The country for the first thirty miles was not unlike what George was accustomed to, but his keen eyes saw some difference as they proceeded towards the northwest. The day was bright and beautiful, a sharper air succeeding the soft Indian summer of the few days preceding. The cavalcade made a vast dust, clatter, and commotion. Every homestead they passed was aroused, and people, white and black, came running out to see the procession. George enjoyed the coach very much at first, but he soon began to wish that he were on the back of one of the stout nags that rode ahead, and determined, as soon as they stopped for dinner, to take advantage of Lord Fairfax’s offer and to ask to ride.

They had started soon after sunrise, and twelve o’clock found them more than twenty-five miles from Fredericksburg. They stopped at a road-side tavern for dinner and some hours’ rest. The[60] tavern was large and comfortable, and boasted the luxury of a private room, where dinner was served to the earl and his young guest. The tavern-keeper himself carved for them, and although he treated the earl with great respect, saying “My lord” at every other word, according to the custom of the day, there was no servility in his manner. Like everybody else, he was struck with George’s manner and appearance on first seeing him, and, finding out that he was the son of the late Colonel Augustine Washington, made the boy’s face glow with praise of his father. When the time came to start George made his request that he be allowed to ride a horse, and he was immediately given his choice of the four bays. He examined them all quickly, but with the eye of a natural judge of a horse, and unerringly picked out the best of the lot. “Do not feel obliged to regulate your pace by ours,” said the earl. “We are to sleep to-night at Farley’s tavern, only twenty miles from here, and so you present yourself by sundown it is enough.”

George mounted and rode off. He found the bay well rested by his two hours’ halt and ready for his work. He felt so much freer and happier on horseback than in the chariot that he could not help wishing he could make the rest[61] of the journey in that way. But he thought it would scarcely be polite to abandon the earl altogether, and determined to make the first stage in the coach every day. He rode on all the afternoon, keeping the high-road with ease, although towards the end it began to grow wilder and rougher. He reached Farley’s tavern some time before sundown, and his arrival giving advance notice of the earl, everything was ready for him, even to a fine wild turkey roasting on the kitchen spit for supper. Like most of the road-houses of the day, Farley’s was spacious and comfortable, though not luxurious. There was a private room there, too, with a roaring fire of hickory logs on the hearth, for the night had grown colder. At supper, when there was time to spare, old Lance produced a box, out of which he took some handsome table furniture and a pair of tall silver candlesticks. The supper was brought in smoking hot, Lance bearing aloft the wild turkey on a vast platter. He also brought forth a bottle of wine of superior vintage to anything that the tavern cellar could produce.

The earl narrowly watched George as they supped together, talking meanwhile. He rightly judged that table manners and deportment are a very fair test of one’s training in the niceties of life, and was more than ever pleased the[62] closer he observed the boy. First, George proved himself a skilful carver, and carved the turkey with the utmost dexterity. This was an accomplishment carefully taught him by his mother. Then, although he had the ravenous appetite of a fifteen-year-old boy after a long day’s travel, he did not forget to be polite and attentive to the earl, who trifled with his supper rather than ate it. The boy took one glass of wine, and declined having his glass refilled. His conversation was chiefly replies to questions, and were so apt that the earl every moment liked his young guest better and better. George was quite unconscious of the deep attention with which Lord Fairfax observed him. He thought he had been asked to Greenway out of pure good-nature, and rather wished to keep in the background so he should not make his host repent his hospitality. But a feeling, far deeper than mere good-nature, inspired the earl. He felt a profound interest in the boy, and was enough a judge of human nature to see that something remarkable might be expected of him.

Soon after supper occurred the first inelegance on George’s part. In the midst of a sentence of the earl’s the boy suddenly and involuntarily gave a wide yawn. He colored furiously, but[63] Lord Fairfax burst into one of his rare laughs, and calling Lance, directed him to show Mr. Washington to his room. George was perfectly willing to go; but when Lance, taking one of the tall candlesticks, showed him his room, his eyes suddenly came wide open, and the idea that Lance could tell him all about the siege of Bouchain, and marching and starving and fighting with Marlborough, drove the sleep from his eyes like the beating of a drum.

Reaching the room Lance put the candle on the dressing-table, and, standing at “attention,” asked:

“Anything else, sir?”

“Yes,” said George, seating himself on the edge of the bed. “How long will it be before my Lord Fairfax needs you?”

“About two hours, sir. His lordship sits late.”

“Then—then—” continued George, with a little diffidence, “I wish you would tell me something about campaigning with the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene, and all about the siege of Bouchain.”

Lance’s strong, weather-beaten face was suddenly illuminated with a light that George had not seen on it before, and his soldierly figure unconsciously took a more military pose.

“’Tis a long story, sir,” he said, “and I was[64] only a youngster and a private soldier; it is thirty-five years gone now.”

“That’s why I want you to tell it,” replied George. “All the books are written by the officers, but never a word have I heard from a man in the ranks. I have read the life of the great Duke of Marlborough, and also Prince Eugene, but it is a different thing to hear a man tell of the wars who has burned powder in them.”

“True, sir. And the Duke of Marlborough was the greatest soldier of our time. We have the Duke of Cumberland now—a brave general, sir, and brother to the king—but I warrant, had he been at the siege of Bouchain and in the Low Countries, he would have been licked worse than Marshal Villars.”

“And Marshal Villars was a very skilful general too,” said George, now thoroughly wide-awake.

“Certainly, sir, he was. The French are but a mean-looking set of fellows, but how they can fight! And they have the best legs of any soldiers in Europe; and I am not so sure they have not the best heads. I fought ’em for twenty-five years—for I only quitted the service when I came with my Lord Fairfax to this new country—and I ought to know. My time of enlistment was up, the great duke was dead, and[65] there had been peace for so long that I thought soldiers in Europe had forgot to fight; so when his lordship offered to bring me, I, who had neither wife nor child, nor father nor mother, nor brother nor sister, was glad to come with him. I had served in his lordship’s regiment, and he knew me because I had once—but never mind that, sir.”

“No,” cried George. “Go on.”