Title: Even Stephen

Author: Charles A. Stearns

Release Date: September 20, 2023 [eBook #71694]

Language: English

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By CHARLES A. STEARNS

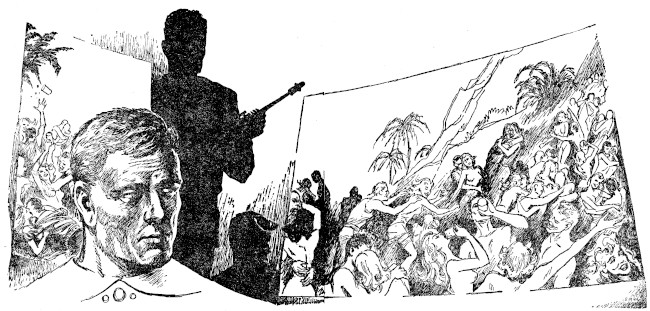

Illustrated by EMSH

It only takes one man to destroy a pacifist

Utopia—if he has a gun, and will use it!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Infinity July 1957.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The henna-haired young man with the vermilion cape boarded Stephen's vehicle on the thirty-third air level, less than two whoops and a holler from a stationary police float, by the simple expedient of grappling them together with his right arm, climbing over into the seat beside Stephen, and allowing his own skimmercar to whisk off at a thousand miles an hour with no more control than its traffic-dodging mechanism afforded.

The peregrinator was barbarically splendid, and his curls showed the effect of a habitual use of some good hair undulant. More to the point, he had a gun. It was one of those wicked moisture rifles which can steam the flesh off a man's bones at three hundred paces. Quite illegal.

He smiled at Stephen. His dentures were good. They were stainless steel, but in this day and time that was to be expected. Most of his generation, in embryo during the last Blow-down, had been born without teeth of their own.

"Sorry to inconvenience you, Citizen," he said, "but the police were right on my brush that time. Please turn right at the next air corridor and head out to sea."

And when Stephen, entranced, showed no inclination to obey, he prodded him with the weapon. Prodded him in a most sensitive part of his anatomy. "I have already killed once today," he said, "and it is not yet eleven o'clock."

"I see," Stephen said stiffly, and changed course.

He might simply have exceeded the speed limit in the slow traffic stream and gotten them arrested, but he sensed that this would not do. A half-memory, playing around in his cranium, cried out for recognition. Somewhere he had seen this deadly young man before, and with him there was associated a more than vague unpleasantness.

Soon the blue Pacific was under them. They were streaming southwest by south at an altitude of eighty miles. Stephen was not terrified at being kidnapped, for he had never heard of such a thing, but there was one thing that did worry him. "I shall be late for work," he said.

"Work," the young man said, "is a bore."

Stephen was shocked. Work had always been the sacred principle of his life; a rare and elevating sweetness to be cultivated and savored whenever it might be offered. He, himself, had long been allotted alternate Thursday afternoons as biological technician at Mnemonic Manufactures, Plant No. 103, by the Works Administration, and he had not missed a day for many years. This happened to be one of his Thursdays, and if he did not arrive soon he would be late for the four-hour shift. Certainly no one else could be expected to relinquish a part of his shift to accommodate a laggard.

"Work is for prats," the young man said again. "It encourages steatopygia. My last work date was nine years ago, and I am glad that I never went back."

Stephen now felt a surge of fear at last. Such unregenerates as this man were said to exist, but he had never met one before. They were the shadowy Unemployed, who, barred from government dispensation, must live by their wits alone. Whimsical nihilists, they, who were apt to requisition human life, as well as property, at a breath's notice.

Small lightning sheeted in front of their bow. A voice crackled in the communications disk. "Attention! This is an official air barricade. Proceed to Level Twelve to be cleared."

"Pretend to comply," the young man said. "Then, when you are six or eight levels below these patrol skimmers following us, make a run for it toward that cloud bank on the horizon."

"Very well," Stephen said. He had quickly weighed the gloomy possibilities, and decided that his best chance for survival lay in instant compliance with this madman's wishes, however outrageous they might seem.

He nosed down, silently flitting past brightly painted fueling blimp platforms and directional floats with their winking beacons. To the east, the City lay, with its waffle-like subdivisions, its height-foreshortened skyscrapers, and its vast Port, where space rockets winked upward every few minutes.

"If you were only on one of those!" Stephen said feelingly.

His abductor smiled—a rather malicious smile. "Who wants to go to Mars?" he said. "Earth is such a fascinating place—why leave it? After all, only here, upon this exquisitely green, clean sphere of ours can the full richness of man's endeavors be enjoyed. And you would have me abandon it all!"

"I was only thinking aloud," Stephen said.

The smile withered. "Mind your altitude," the young man said. "And try no tricks."

Twenty seconds had passed. Thirty-five....

"Now."

Tight-lipped, Stephen nodded, leveled off, and energized the plates with their full, formidable power. They shot past the police stationary, and into the great, azure curve of the horizon at a pace which would have left Stephen breathless at any other time. There came a splutter of ether-borne voices.

The henna-haired young man turned off the receiver.

In an instant there were skimmers in hot pursuit, but the cloud bank loomed close, towering and opaque. Now the wisps of white were about them, and a curious, acrid smell filtered in through the aerating system. The odor of ozone. The skimmer began to shudder violently, tossing them about in their seats.

"I have never experienced such turbulence," Stephen exclaimed. "I believe this is no ordinary cloud!"

"You are right," the henna-haired young man said. "This is sanctuary."

"Who are you?" Stephen said. "Why are you running from the police?"

"Apparently you don't read the newspapers."

"I keep abreast of the advances in technology and philosophy."

"I meant the tabloid news. There is such a page, you know, in the back of every newspaper. No, no; I perceive that you never would allow yourself to become interested in such plebeian goings-on. Therefore, let me introduce myself. I am called Turpan."

"The Bedchamber Assassin! I knew that I'd seen your face somewhere."

"So you do sneak and read the scandals, like most of your mechanics' caste. Tch, tch! To think that you secretly admire us, who live upon the brink and savor life while it lasts."

"I could hardly admire you. You are credited with killing twelve women." Stephen shuddered.

Turpan inclined his handsome head sardonically. "Such is the artistic license of the press. Actually there were only nine—until this morning, I regret to say. And one of those died in the ecstacy of awakening to find me hovering over her virginal bed. I suppose she had a weak heart. I kill only when it is unavoidable. But so long as my lady will wear jewels and keep them on her boudoir dressing table—" He shrugged. "Naturally, I am sometimes interrupted."

"And then you murder them."

"Let us say that I make them a sporting proposition. I am not bad to look upon—I think you will admit that fact. Unless they happen to be hysterical to begin with, I can invariably dominate them. Face the facts, my stodgy technician. Murder is a term for equals. A woman is a lesser, though a fascinating, creature. The law of humane grace does not apply equally to her. It must be a humiliating thing to be a woman, and yet it is necessary that a supply of them be provided. Must we who are fortunate in our male superiority deny our natures to keep from trampling them occasionally? No indeed. 'Sensualists are they; a trouble and a terror is the hero to them. Thus spake Zarathustra'."

"That is a quotation from an ancient provincial who was said to be as mad as you are," Stephen said, rallying slightly, but revising his opinion of the uncouthness of his captor.

"I have studied the old books," Turpan said. "They are mostly pap, but once I thought that the answers might be discovered there. You may set down now."

"But we must be miles from any land."

"Take a look," Turpan said.

And Stephen looked down through the clearing mists and beheld an island.

"It happens to be a very special island," Turpan said. "The jurisdiction of no policeman extends here."

"Fantastic! What is it called?"

"I should imagine that they will call it 'Utopia Fourteen', or 'New Valhalla'. Idealists seldom possess one iota of originality. This is the same sort of experiment that has been attempted without success from times immemorial. A group of visionaries get together, wangle a charter from some indulgent government and found a sovereign colony in splendid isolation—and invariably based upon impossible ideas of anarchism."

The skimmercar shook itself like a wet terrier, dropped three hundred feet in a downdraft, recovered and glided in to a landing as gently as a nesting seabird. They were upon a verdant meadow.

Stephen looked around. "One could hardly call this splendid isolation," he remarked. "We are less than five minutes from the City, and I am sure that you will be reasonable enough to release me, now that I've brought you here, and allow me to return. I promise not to report this episode."

"Magnanimous of you," Turpan said, "but I'm afraid that what you ask is impossible."

"Then you refuse to let me go?"

"No, no. I merely point out that the cloud through which we arrived at this island was not, as you noted, a natural one. It had the ominous look of a Molein Field in the making. In other words, a space distortion barrier the size of which Earth has never seen."

And Stephen, looking around them, saw that the cloud had, indeed dispersed; and that in its place a vast curtain of shifting, rippling light had arisen, extending upward beyond sight and imagination, to the left and to the right, all around the circle of the horizon, shutting them in, shutting the rest of the universe out. Impenetrable. Indestructible.

"You knew of this," Stephen accused. "That's why you brought me here."

"I admit that there were rumors that such a project might be attempted today. The underworld has ears," Turpan said. "That we arrived just in time, however, was merely a circumstance. And even you, my stolid friend, must admit the beauty of the aurora of a Molein Field."

"We are lost," Stephen said, feeling stricken. "A distortion barrier endures forever."

"Fah!" the Bedchamber Assassin replied. "We have a green island for ourselves, which is much better, you'll agree, than being executed. And let me tell you, there are many security officials who ache to pump my twitching body full of the official, but deadly, muscarine. Besides, there is a colony here. Men and women. I intend to thrive."

But what of me! Stephen wanted to cry out. I have committed no crime, and I shall be lost away from my books and my work! However, he pulled himself together, and noted pedantically that the generation of a Molein Field was a capital offense, anyway. (This afforded little comfort, in that once a group of people have surrounded themselves with a Molein Field they are quite independent, as Turpan had observed, of the law.)

When they had withdrawn a few yards from the skimmercar, Turpan sighted upon it with the moisture rifle and the plastic hull melted and ran down in a mass of smoking lava. "The past is past," Turpan said, "and better done with. Come, let us seek out our new friends."

There were men and there were women, clamorously cheerful at their work, unloading an ancient and rickety ferrycopter in the surprise valley below the cliffs upon which Stephen and Turpan stood. Stephen, perspiring for the first time in his life, was almost caught up in their enthusiasm as he watched that fairy village of plasti-tents unfold, shining and shimmering in the reflected hues of the Molein aurora.

When Turpan had satisfied himself that there was no danger, they descended, scrambling down over rough, shaly and precipitous outcroppings that presented no problem for Stephen, but to which Turpan, oddly enough, clung with the desperation of an acrophobe as he lowered himself gingerly from crag to crag—this slightly-built young man who had seemed nerveless in the sky. Turpan was out of his métier.

A man looked up and saw them. He shouted and waved his arms in welcome. Turpan laughed, thinking, perhaps, that the welcome would have been less warm had his identity been known here.

The man climbed part way up the slope to meet them. He was youthful in appearance, with dark hair and quick, penetrating eyes. "I'm the Planner of Flight One," he said. "Are you from Three?"

"We are not," Turpan said.

"Flight Two, then."

Turpan, smiling like a basilisk, affected to move his head from side to side.

And the Planner looked alarmed. "Then you must be the police," he said, "for we are only three groups. But you are too late to stop our secession, sir. The Molein barrier exists—let the Technocracy legislate against us until it is blue in the face. And there are three hundred and twelve of us here—against the two of you."

"Sporting odds," Turpan said. "However, we are merely humble heretics, like yourselves, seeking asylum. Yes indeed. Quite by accident my friend and I wandered into your little ovum universe as it was forming, and here we are, trapped as it would seem."

The crass, brazen liar.

The Planner was silent for a moment. "It is unlikely that you would happen upon us by chance at such a time," he said at last. "However, you shall have asylum. We could destroy you, but our charter expressly forbids it. We hold human life—even of the basest sort—to be sacred."

"Oh, sacred, quite!" Turpan said.

"There is only one condition of your freedom here. There are one hundred and fifty-six males among us in our three encampments, and exactly the same number of females. The system of numerical pairing was planned for the obvious reason of physical need, and to avoid trouble later on."

"A veritable idyl."

"It might have been. We are all young, after all, and unmarried. Each of us is a theoretical scientist in his or her own right, with a high hereditary intelligence factor. We hope to propagate a superior race of limited numbers for our purpose—ultimate knowledge. Naturally a freedom in the choice of a mate will be allowed, whenever possible, but both of you, as outsiders, must agree to live out the rest of your natural lives—as celibates."

Turpan turned to Stephen with a glint of humor in his spectacular eyes. "Celibacy has a tasteless ring to it," he said. "Don't you think so?"

"I can only speak for myself," Stephen replied coldly. "We have nothing in common. But for you I should still be in my world. Considering that we are intruders, however, the offer seems generous enough. Perhaps I shall be given some kind of work. That is enough to live for."

"What is your field?" the Planner asked Stephen.

"I am—or was—a biological technician."

"That is unfortunate," the Planner said, with a sudden chill in his voice. "You see, we came here to get away from the technicians.

"I," said Turpan haughtily, "was a burglar. However, I think I see the shape of my new vocation forming at this instant. I see no weapons among your colonists."

"They are forbidden here," the Planner said. "I observe that you have a moisture rifle. You will be required to turn it over to us, to be destroyed."

Turpan chuckled. "Now you are being silly," he said. "If you have no weapons, it must have occurred to you that you cannot effectively forbid me mine."

"You cannot stand alone against three hundred."

"Of course I can," Turpan said. "You know quite well that if you try to overpower me, scores of you will die. What would happen to your vaunted sexual balance then? No indeed, I think you will admit to the only practical solution, which is that I take over the government of the island."

The officiousness and the élan seemed to go out of the Planner at once, like the air out of a pricked balloon. He was suddenly an old young man. Stephen saw, with a sinking feeling, that the audacity of Turpan had triumphed again.

"You have the advantage of me at the moment," the Planner said. "I relinquish my authority to you in order to avoid bloodshed. Henceforth you will be our Planner. Time will judge my action—and yours."

"Not your Planner," Turpan said. "Your dictator."

There could be but one end to it, of course. One of the first official actions of Dictator Turpan, from the eminence of his lofty, translucent tent with its red and yellow flag on top, was to decree a social festival, to which the other two settlements were invited for eating, drinking and fraternization unrestrained. How unrestrained no one (unless Turpan) could have predicted until late that evening, when the aspect of it began to be Bacchanalian, with the mores and the inhibitions of these intellectuals stripped off, one by one, like the garments of civilization.

Stephen was shocked. Secretly he had approved, at least, of the ideals of these rebels. But what hope could there be if they could so easily fall under the domination of Turpan?

Still, there was something insidiously compelling about the man.

As for Stephen, he had been allotted his position in this new life, and he was not flattered.

"You shall be my body servant," Turpan had said. "I can more nearly trust you than anyone else, since your life, as well as mine, hangs in the balance of my ascendance."

"I would betray you at the earliest opportunity."

Turpan laughed. "I am sure that you would. But you value your life, and you will be careful. Here with me you are safer from intrigue. Later I shall find confidants and kindred spirits here, no doubt, who will help me to consolidate my power."

"They will rise and destroy you before that time. You must eventually sleep."

"I sleep as lightly as a cat. Besides, so long as they are inflamed, as they are tonight, with one another, they are not apt to become inflamed against me. For every male there is a female. Not all of them will pair tonight—nor even in a week. And by the time this obsession fails to claim their attention I shall be firmly seated upon my throne. There will be no women left for you or me, of course, but you will have your work, as you noted—and it will consist of keeping my boots shined and my clothing pressed."

"And you?" Stephen said bitterly.

"Ah, yes. What of the dictator? I have a confession to make to you, my familiar. I prefer it this way. If I should simply choose a woman, there would be no zest to it. Therefore I shall wait until they are all taken, and then I shall steal one—each week. Now go out and enjoy yourself."

Stephen, steeped in gloom, left the tent. No one paid any attention to him. There was a good deal of screaming and laughing. Too much screaming.

He walked along the avenue of tents. Beyond the temporary floodlights of the atomic generators it was quite dark. Yet around the horizon played the flickering lights of the aurora, higher now that the sun was beyond the sea. A thousand years from now it would be there, visible each night, as common to that distant generation as starlight.

From the shadow of the valley's rim he emerged upon a low promontory above the village. Directly below where he stood, a woman, shrieking, ran into the blackness of a grove of small trees. She was pursued by a man. And then she was pursued no more.

He turned away, toward the seashore. It lay half a mile beyond the settlement of Flight One.

Presently he came upon a sandy beach. The sea was dark and calm; there was never any wind here. Aloft the barrier arose more plainly than before, touching the ocean perhaps half a mile from shore, but invisible at sea-level. And beyond it—he stared.

There were the lights of a great city, shining across the water. The lights twinkled like jewels, beckoning nostalgically to him. But then he remembered that a Molein Field, jealously allowing only the passage of photonic energy, was said to have a prismatic effect—and yet another, a nameless and inexplicable impress, upon light itself. The lights were a mirage. Perhaps they existed a thousand miles away; perhaps not at all. He shivered.

And then he saw the object in the water, bobbing out there a hundred yards from the beach. Something white—an arm upraised. It was a human being, swimming toward him, and helplessly arm-weary by the looks of that desperate motion! It disappeared, appeared again, struggling more weakly.

Stephen plunged into the water, waded as far as he could, and swam the last fifty feet with a clumsy, unpracticed stroke, just in time to grasp the swimmer's hair.

And then he saw that the swimmer, going down for the last time, was a girl.

They rested upon the warm, white sand until she had recovered from her ordeal. Stephen prudently refrained from asking questions. He knew that she belonged to Flight Two or Flight Three, for he had seen her once or twice before this evening at the festival. Her short, platinum curls made her stand out in a crowd. She was not beautiful, and yet there was an essence of her being that appealed strongly to him; perhaps it was the lingering impression of her soft-tanned body in his arms as he had carried her to shore.

"You must have guessed that I was running away," she said presently.

"Running away? But how—where—"

"I know. But I had panicked, you see. I was already dreadfully homesick, and then came this horrid festival. I couldn't bear seeing us make such—such fools of ourselves. The women—well, it was as if we had reverted to animals. One of the men—I think he was a conjectural physicist by the name of Hesson—made advances to me. I'm no formalist, but I ran. Can you understand that?"

"I also disapprove of debauchery," Stephen said.

"I ran and ran until I came, at last, to this beach. I saw the lights of a city across the water. I am a strong swimmer and I struck out without stopping to reconsider. It was a horrible experience."

"You found nothing."

"Nothing—and worse than nothing. There is a place out there where heaven and hell, as well as the earth and the sky, are suspended. I suddenly found myself in a halfworld where all directions seemed to lead straight down. I felt myself slipping, sliding, flowing downward. And once I thought I saw a face—an impossible face. Then I was expelled and found myself back in normal waters. I started to swim back here."

"You were very brave to survive such an ordeal," he said. "Would that I had been half so courageous when I first set eyes upon that devil, Turpan! I might have spared all of you this humiliation."

"Then—you are the technician who came with Turpan?"

He nodded. "I was—and am—his prisoner. I have more cause to hate him than any of you."

"In that case I shall tell you a secret. The capitulation of our camps to Turpan's tyranny was planned. If you had counted us, you would have found that many of the men stayed away from the festival tonight. They are preparing a surprise attack upon Turpan from behind the village when the celebration reaches its height and he will expect it least. I heard them making plans for a coup this afternoon."

"It is ill-advised. Many of your men will die—and perhaps for nothing. Turpan is too cunning to be caught napping."

"You could be of help to them," she said.

He shrugged. "I am only a technician, remember? The hated ruling class of the Technocracy that you left. A supernumerary, even as Turpan. I cannot help myself to a place in your exclusive society by helping you. Come along. We had better be getting back."

"Where are we going?"

"Straight to Turpan," he said.

"I cannot believe that you would tell me this," Turpan said, striding back and forth, lion-like, before the door of his tent. "Why have you?"

"Because, as you observed, my fate is bound with yours," Stephen said. "Besides, I do not care to be a party to a massacre."

"It will give me great pleasure to massacre them."

"Nevertheless, their clubs and stones will eventually find their marks. Our minutes are numbered unless you yield."

Turpan's eyes glowed with the fires of his inner excitement. "I will never do that," he said. "I think I like this feeling of urgency. What a pity that you cannot learn to savor these supreme moments."

"Then at least let this woman go. She has no part in it."

Turpan allowed his eyes to run over the figure of the girl, standing like a petulant naiad, with lowered eyes and trembling lip, and found that figure, in its damp and scanty attire, gratifying.

"What is your name?"

"Ellen," she said.

"You will do," Turpan said. "Yes, you will do very well for a hostage."

"You forget that these men are true idealists," Stephen said. "Yesterday they may have believed in the sanctity of human life. Today they believe that they will be sanctified by spilling their own blood—and they are not particular whether that blood is male or female. If you would survive, it will be necessary for us to retrench."

"What is your suggestion, technician?"

"I know a place where we can defend ourselves against any attack. There is an elevation not far from here where, if you recall, we stood that first time and spied upon the valley. It is sheer on all sides. We could remain there until daylight, or until you have discouraged this rebellion. It would be impossible for anyone, ascending in that loose shale, to approach us with stealth."

"It is a sound plan," Turpan said. "Gather a few packages of concentrates and sufficient water."

"I already have them."

"Then take this woman and lead the way. I will follow. And keep in mind that in the event of trouble both of you will be the first to lose the flesh off your bones from this moisture rifle."

Stephen went over and took Ellen by the hand. "Courage," he whispered.

"I wish that both of us had drowned," she said.

But she came with them docilely enough, and Stephen drew a sigh of relief when they were out of the illuminated area without being discovered.

"Walk briskly now," Turpan said, "but do not run. That is something that I have learned in years of skirmishing with the police."

At the foot of the cliff Stephen stopped and removed his shoes.

"What are you doing?" Turpan demanded suspiciously.

"A precaution against falling," Stephen said.

"I prefer to remain fully dressed," Turpan said. "Lead on."

Stephen now found that, though the pain was excruciating, his bare feet had rendered him as sure-footed as a goat, while Turpan struggled to keep his footing. Between them the girl uncomplainingly picked her way upward.

And then they came to a place, as Stephen had hoped, where it was necessary to scale a sheer scarp of six or seven feet in order to gain a shelf near the summit. He had to kneel in order to help the girl up. Turpan, not tall enough to pull himself up with his arms, cursed as his boots slipped.

"Extend the barrel of your rifle to me," Stephen said, "and I will pull you up until you are able to reach that overhanging bush. It will support your weight."

Turpan nodded curtly. He was not happy about this. He was never happy when playing a minor role, but he appreciated the urgency of the moment.

Stephen pulled and the Bedchamber Assassin strained upward. Then he grasped at the bush, and at the same moment Stephen gave a sharp, Herculean tug.

Turpan snatched for the bush with both hands. "Got it," he said, and swung himself upon the ledge.

"Yes," agreed Stephen, "but I have the rifle."

Turpan, fettered like a common criminal, lay upon his couch in the tent where he had sat not long ago, a conqueror. The powerful floodlight that shone in his face did nothing to sooth his raw temper. Someone entered the tent and he strained in his bonds to see who it was. Stephen came and stood over him.

Turpan licked his dry lips. "What time is it?" he asked.

"It is almost midnight. They have destroyed your rifle, but it has been decided that, in view of your predatory nature, it would be dangerous to release you again upon this colony. Are you prepared to meet your fate?"

Turpan sneered. "Destroy me, fool—eunuch! It will not change your lot here. You will remain an untouchable—an odd man out. May your books comfort your cold bed for the rest of your life. I prefer death."

Stephen removed the hypodermic needle from the kit which they had furnished him and filled it. He bared Turpan's arm. The muscles of that arm were tense, like cords of steel. Turpan was lying. He was frightened of death.

Stephen smiled a little. He looked a good deal younger when he smiled. "Please relax," he said. "I am only a biological technician; not an executioner."

Two hours later Stephen emerged from the tent, perspiring, and found that the revel in the encampment continued unabated even at this time of morning. Few suspected what had been going on in Turpan's tent. These few now anxiously awaited his verdict.

"How did it go?" the former Planner of Flight One asked. "Was—the equipment satisfactory? The drugs and chalones sufficient?"

He nodded wearily. "The character change appears to have been complete enough. The passivity will grow, of course." A group of men and women were playing a variety of hide-and-seek, with piercing shouts and screams, among the shadows of the tents, and it was no child's game.

"Don't worry about them," the Planner said. "They'll be over it in the morning. Most of them have never had anything to drink before. Our dictator's methods may have been cruder than we intended, but they've certainly broken the ice."

"When will we see—Turpan?" someone asked. It was Ellen.

Stephen had not known that she was waiting. "Any moment now, I believe," he said. "I will go in and see what is keeping him."

He returned in a few seconds. "A matter of clothing," he said with a smile. "I warned you that there would be a complete character change."

The garments were supplied. Stephen took them in. The floodlight had been turned off now, and it was fairly dark in the tent.

"Hurry up," Stephen said gently.

"I can't—I cannot do it!"

"Oh, but you can. You can start all over now. Few of the colonists ever knew you by sight. I am sure that you will be warmly enough received."

Stephen came out. Ellen searched his face. "It will not be much longer now," he told her.

"And to think that I doubted you!"

"I am only a technician," he said.

"There are one hundred and sixty-two male high scientists upon this island," she said, coming forward and putting her arms around him, "but only one, solid, unimaginative, blessed technician. It makes a nice, even arrangement for us women, don't you think?"

"Even enough," he said. And at that moment Turpan stepped out of the tent, and all of them looked. And looked. And Turpan, unable to face that battery of eyes, ran.

Ran lightly and gracefully through the tent village toward the cliffs beyond. And all along that gauntlet there were catcalls and wolf whistles.

"Don't worry," the Planner said. "She will come back to us. After all, there is a biological need."