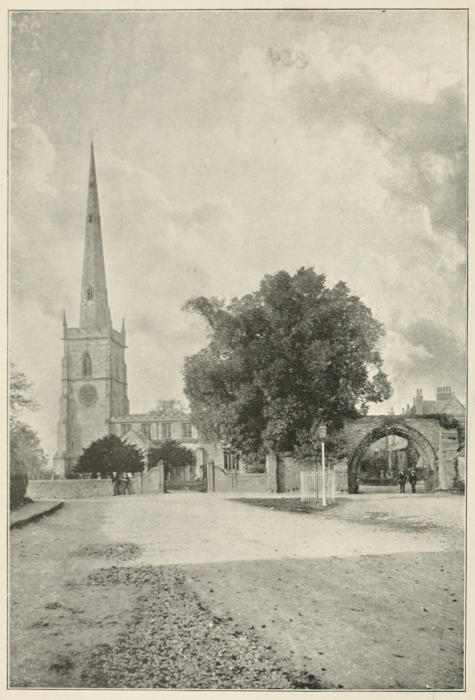

Plate 1.

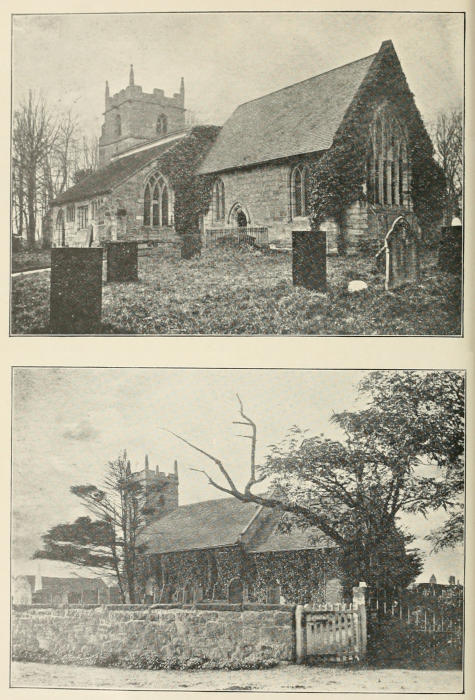

Repton Church.

Title: Repton and its neighbourhood

Subtitle: a descriptive guide of the archæology, &c. of the district

Author: Frederick Charles Hipkins

Release Date: September 21, 2023 [eBook #71701]

Language: English

Credits: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Plate 1.

Repton Church.

A DESCRIPTIVE GUIDE OF

THE ARCHÆOLOGY, &c., OF THE DISTRICT.

Illustrated by Photogravures, &c.

BY

F. C. HIPKINS, M.A., F.S.A.,

ASSISTANT MASTER AT REPTON SCHOOL.

SECOND EDITION.

A. J. LAWRENCE, PRINTER, REPTON.

MDCCCXCIX.

REPTON:

A. J. LAWRENCE, PRINTER.

In the year 1892, I ventured to write, for Reptonians, a short History of Repton, its quick sale emboldened me to set about obtaining materials for a second edition. The list of Authors, &c., consulted (printed at the end of this preface), will enable any one, who wishes to do so, to investigate the various events further, or to prove the truth of the facts recorded. Round the Church, Priory, and School centre all that is interesting, and, naturally, they occupy nearly all the pages of this second attempt to supply all the information possible to those who live in, or visit our old world village, whose church, &c., might well have served the poet Gray as the subject of his Elegy.

In writing the history of Repton certain events stand out more prominently than others, e. g., the Conversion of Mercia by Diuma, its first bishop, and his assistant missionaries, Adda, Betti, and Cedda, the brother of St. Chad: the Founding of the Monastery during the reign[iv] of Peada or his brother Wulphere (A.D. 655-675): the coming of the Danes in 874, and the destruction of the Abbey and town by them: the first building of Repton Church, probably during the reign of Edgar the Peaceable, A.D. 957: the Founding of the Priory by Maud, Countess of Chester, about the year 1150, its dissolution in 1538, its destruction in 1553, and the Founding of the School in 1557. Interwoven with these events are others which have been recorded in the Chronicles, Histories, Registers, &c., consulted, quoted, and used to produce as interesting an account as possible of those events, which extend over a period of nearly twelve hundred and fifty years!

The hand of time, and man, especially the latter, has gradually destroyed anything ancient, and “restorations” have completely changed the aspect of the village. The Church, Priory, Hall, and “Cross,” still serve as links between the centuries, but, excepting these, only one old house remains, in Well Lane, bearing initials “T.S.” and date “1686.”

Even the Village Cross was restored! Down to the year 1806, the shaft was square, with square capital, in which an iron cross was fixed. In Bigsby’s History of Repton, (p. 261), there is a drawing of it, and an account of its restoration, by the Rev. R. R. Rawlins.

During the last fifteen years the old house which stood at the corner, (adjoining Mr. Cattley’s house,) in which the “Court Leet” was held, and the “round-house” at the back of the Post Office, with its octagonal-shaped[v] walls and roof, and oak door, studded with iron nails, have also been destroyed.

The consequence is that the History of Repton is chiefly concerned with ancient and mediæval times.

The Chapters on the Neighbourhood of Repton have been added in the hope that they may prove useful to those who may wish to make expeditions to the towns and villages mentioned. More might have been included, and more written about them, the great difficulty was to curtail both, and at the same time make an interesting, and intelligible record of the chief points of interest in the places described.

In conclusion, I wish to return thanks to those who by their advice, and information have helped me, especially the Rev. J. Charles Cox, LL.D., Author of “Derbyshire Churches,” &c., J. T. Irvine, Esq., and Messrs. John Thompson and Sons who most kindly supplied me with plans of Crypt, and Church, made during the restorations of 1885-6.

For the many beautiful photographs, my best thanks are due to Miss M. H. Barham, W. B. Hawkins, Esq., and C. B. Hutchinson, Esq., and others.

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, (Rolls Series).

Bassano, Francis. Church Notes, (1710).

Bede, Venerable. Ecclesiastical History.

Bigsby, Rev. Robert. History of Repton, (1854).

Birch, W. de Gray. Memorials of St. Guthlac.

Browne, (Right Rev. Bishop of Bristol). Conversion of the Heptarchy.

Cox, Rev. J. Charles. Churches of Derbyshire.

Derbyshire Archæological Journal, (1879-98).

Eckenstein, Miss Lina. Women under Monasticism.

Diocesan Histories, (S.P.C.K).

Dugdale. Monasticon.

Evesham, Chronicles of, (Rolls Series).

Gentleman’s Magazine.

Glover, S. History of Derbyshire, (1829).

Green, J. R. Making of England.

Ingulph. History.

Leland. Collectanea.

Lingard. Anglo-Saxon Church.

Lysons. Magna Britannia, (Derbyshire), (1817).

Paris, Matthew. Chronicles, (Rolls Series).

Pilkington, J. “A View of the Present State of Derbyshire,” (1789).

Repton Church Registers.

Repton School Register.

Searle, W. G. Onomasticon Anglo-Saxonicum.

Stebbing Shaw. History of Staffordshire.

” ” Topographer.

Tanner. Notitia Monastica.

| page | |

| List of Illustrations | ix |

| Chapter I. | |

| Repton (General) | 1 |

| Chapter II. | |

| Repton (Historical)—The place-name Repton, &c. | 6 |

| Chapter III. | |

| Repton’s Saints (Guthlac and Wystan) | 11 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| Repton Church | 17 |

| Chapter V. | |

| Repton Church Registers | 25 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| Repton’s Merry Bells | 42 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| The Priory | 50 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| Repton School | 61[viii] |

| Chapter IX. | |

| Repton School v. Gilbert Thacker | 65 |

| Chapter X. | |

| Repton Tile-Kiln | 71 |

| Chapter XI. | |

| Repton School Tercentenary and Founding of the School Chapel, &c. | 75 |

| Chapter XII. | |

| School Houses, &c. | 81 |

| Chapter XIII. | |

| Chief Events referred to, or described | 87 |

| Chapter XIV. | |

| The Neighbourhood of Repton. | 91 |

| Ashby-de-la-Zouch | 92 |

| Barrow, Swarkeston, and Stanton-by-Bridge | 99 |

| Bretby and Hartshorn | 104 |

| Egginton, Stretton, and Tutbury | 108 |

| Etwall and its Hospital | 115 |

| Foremark and Anchor Church | 121 |

| Melbourne and Breedon | 124 |

| Mickle-Over, Finderne, and Potlac | 127 |

| Newton Solney | 130 |

| Tickenhall, Calke, and Staunton Harold | 132 |

| Index | 137 |

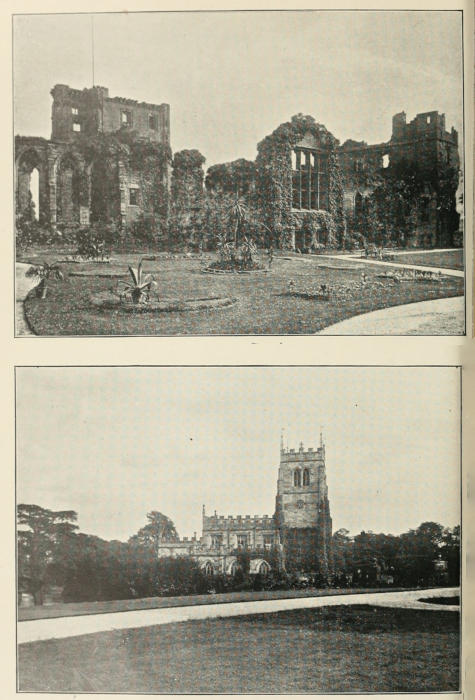

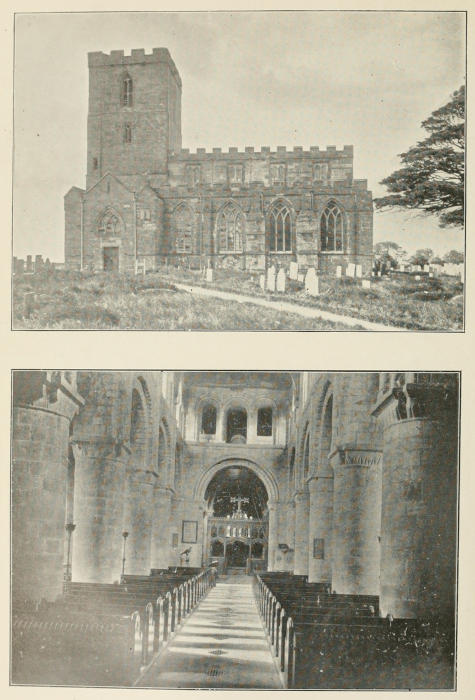

| Plate | |||

| 1. | Repton Church | frontispiece | |

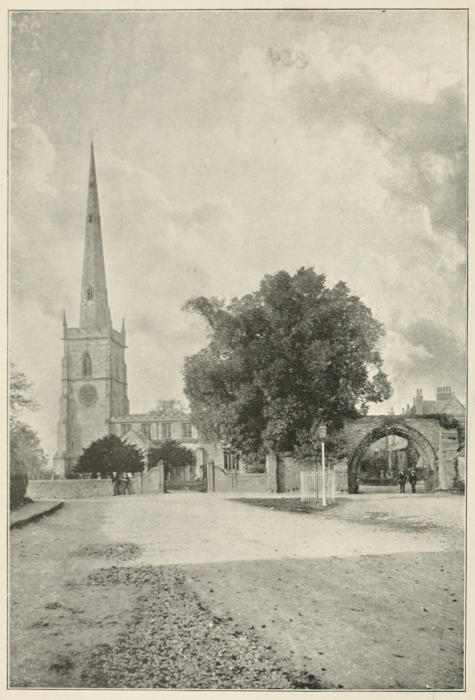

| 2. | Prior Overton’s Tower | to face page | 1 |

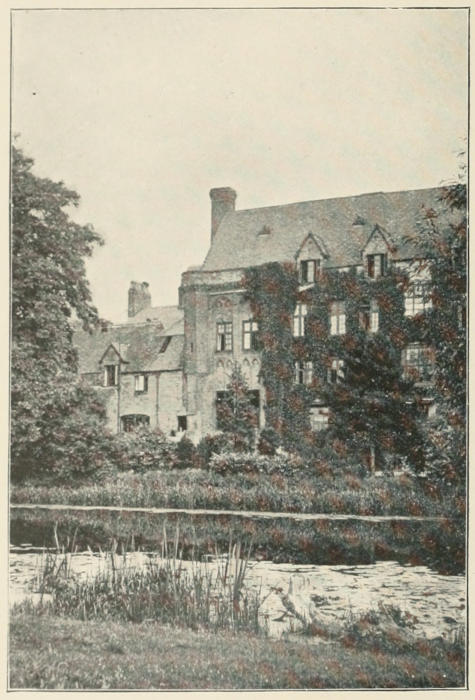

| 3. | Repton Church Crypt | ” | 17 |

| 4. | Repton Camp and Church | ” | 22 |

| 5. | Plans of Church and Priory | ” | 25 |

| 6. | Bell Marks | ” | 46 |

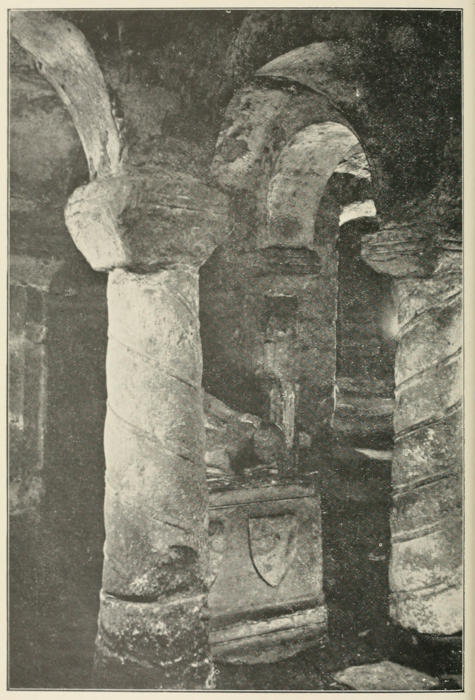

| 7. | Repton Priory | ” | 51 |

| 8. | Sir John Porte and Gilbert Thacker | ” | 54 |

| 9. | The Outer Arch of Gate House | ” | 61 |

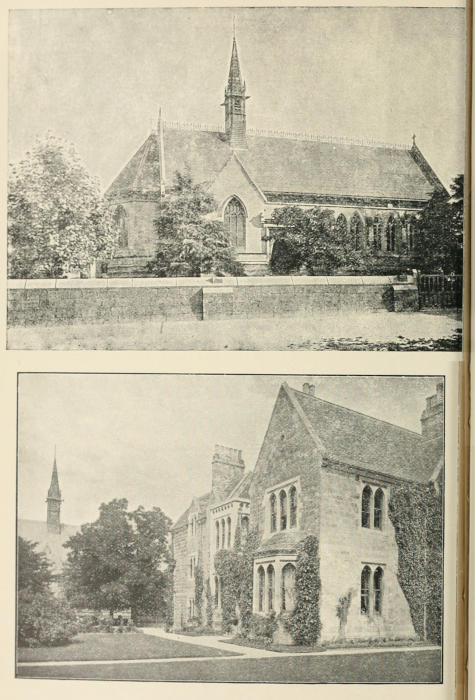

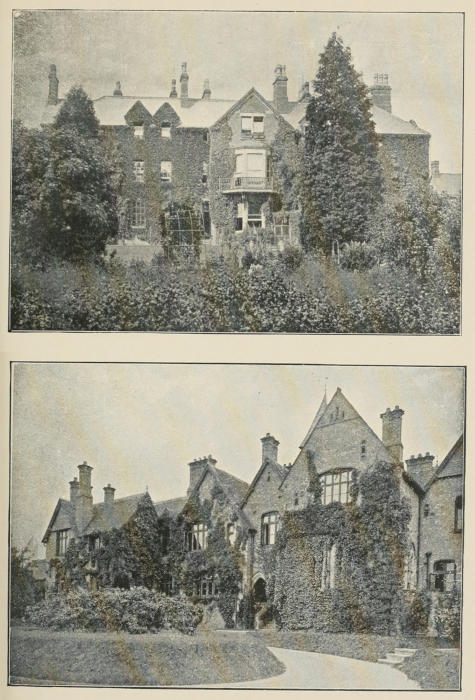

| 10. | Repton School Chapel and Mr. Exham’s House | ” | 75 |

| 11. | The Hall and Porter’s Lodge | ” | 81 |

| 12. | Pears Memorial Hall Window | ” | 83 |

| 13. | Mr. Cattley’s, Mr. Forman’s and Mr. Gould’s Houses | ” | 85 |

| 14. | Mr. Estridge’s and Mr. Gurney’s Houses | ” | 86 |

| 15. | Cricket Pavilion, Pears Memorial Hall, &c. | ” | 90 |

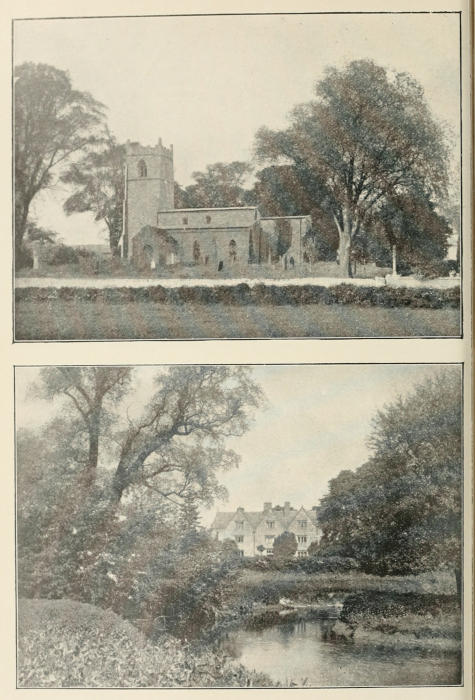

| 16. | Ashby Castle and Staunton Harold Church | ” | 93 |

| 17. | Barrow Church and Swarkeston House | ” | 99 |

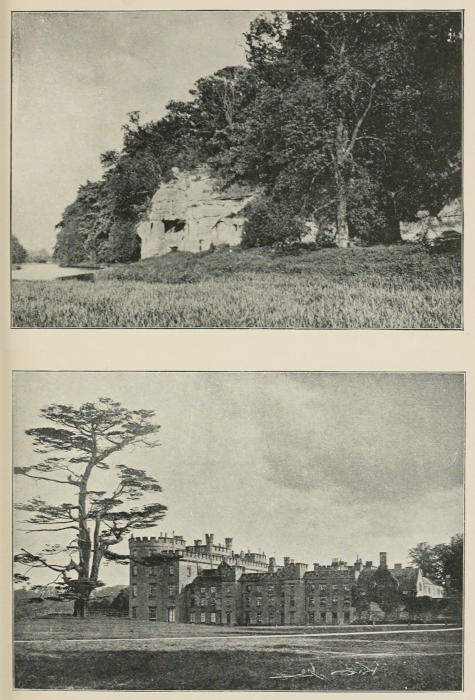

| 18. | Anchor Church and Bretby Hall | ” | 104 |

| 19. | Egginton Church and Willington Church | ” | 109 |

| 20. | Etwall Church and Hospital | ” | 115 |

| 21. | Breedon Church and Melbourne Church | ” | 125 |

| 22. | Tickenhall Round House | ” | 136 |

| Page | 12. | For | Eaburgh | read | Eadburgh. |

| ” | 14. | ” | Ggga | ” | Egga. |

| ” | 74. | ” | Solwey | ” | Solney. |

| ” | 96. | ” | Grindley | ” | Grinling. |

| ” | 99. | ” | preceptary | ” | preceptory. |

| ” | 111. | ” | now | ” | father of the. |

| ” | 115. | ” | Bumaston | ” | Burnaston. |

Transcriber’s Note: These corrections have been made to the text.

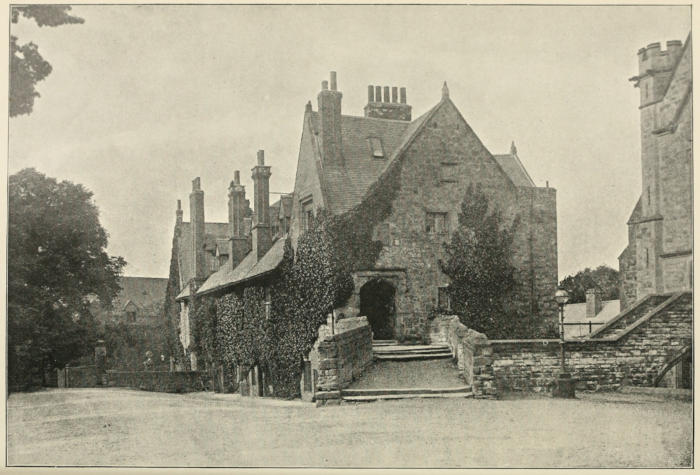

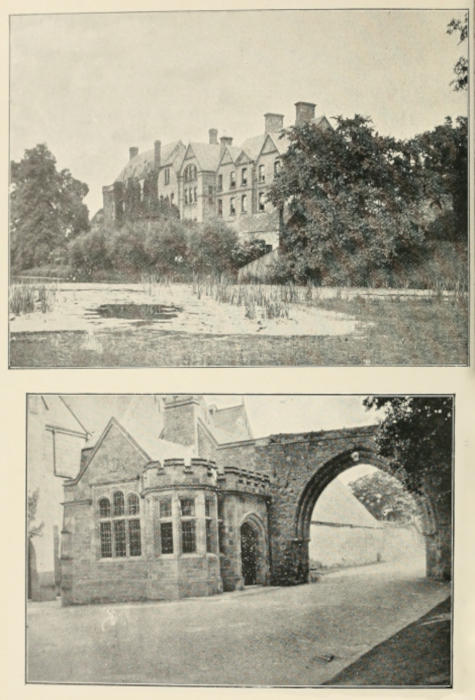

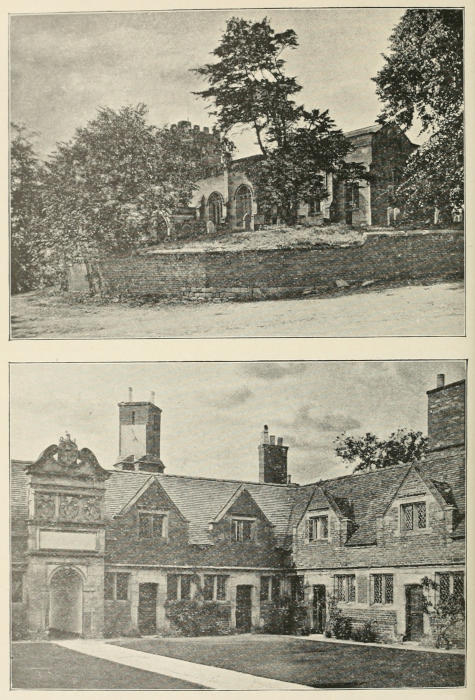

Plate 2.

Repton Hall. (Prior Overton’s Tower, page 81.)

Repton is a village in the County of Derby, four miles east of Burton-on-Trent, seven miles south-west of Derby, and gives its name to the deanery, and with Gresley, forms the hundred, or division, to which it belongs.

The original settlers showed their wisdom when they selected the site: on the north flowed “the smug and silver Trent,” providing them with water; whilst on the south, forests, which then, no doubt, extended in unbroken line from Sherwood to Charnwood, provided fuel; and, lying between, a belt of green pasturage provided fodder for cattle and sheep. The hand of time and man, has nearly destroyed the forests, leaving them such in name alone, and the remains of forests and pasturage have been “annexed.” Repton Common still remains in name, in 1766 it was enclosed by Act of Parliament, and it and the woods round are no longer “common.”

Excavations made in the Churchyard, and in the field to the west of it, have laid bare many foundations, and portions of Anglo-Saxon buildings, such as head-stones of doorways and windows, which prove that the site of the ancient Monastery, and perhaps the town, was on that part of the village now occupied by church, churchyard, vicarage and grounds, and was protected by the River Trent, a branch of which then, no doubt, flowed at the foot of its rocky bank. At some time unknown, the course of the river was interfered with. Somewhere,[2] above or about the present bridge at Willington, the river divided into two streams, one flowing as it does now, the other, by a very sinuous course, crossed the fields and flowed by the town, and so on till it rejoined the Trent above Twyford Ferry. Traces of this bed can be seen in the fields, and there are still three wide pools left which lie in the course of what is now called the “Old Trent.”

There is an old tradition that this alteration was made by Hotspur. In Shakespeare’s play of Henry IV. Act III. Hotspur, Worcester, Mortimer, and Glendower, are at the house of the Archdeacon at Bangor. A map of England and Wales is before them, which the Archdeacon has divided into three parts. Mortimer is made to say:

The “dear Coz” Hotspur, evidently displeased with his share, replies, pointing to the map;—

Whether this passage refers to the alteration of the course of the Trent at Repton, or not, we cannot say, but that it was altered is an undoubted fact. The dam can be traced just below the bridge, and on the Parish Map, the junction of the two is marked.[3] Pilkington in his History of Derbyshire refers to “eight acres of land in an island betwixt Repton and Willington” as belonging to the Canons of Repton Priory. They are still known as the Canons’ Meadows. On this “island” is a curious parallelogram of raised earth, which is supposed to be the remains of a Roman Camp, called Repandunum by Stebbing-Shaw, O.R., the Historian of Staffordshire, but he gives no proofs for the assertion. Since the “Itineraries” neither mention nor mark it, its original makers must remain doubtful until excavations have been made on the spot. Its dimensions are, North side, 75 yards, 1 foot, South side, 68 yards, 1 foot, East side, 52 yards, 1 foot, West side, 54 yards, 2 feet. Within the four embankments are two rounded mounds, and parallel with the South side are two inner ramparts, only one parallel with the North. It is supposed by some to be “a sacred area surrounding tumuli.” The local name for it is “The Buries.” In my opinion it was raised and used by the Danes, who in A.D. 874 visited Repton, and destroyed it before they left in A.D. 875.

Before the Conquest the Manor of Repton belonged to Algar, Earl of Mercia. In Domesday Book it is described as belonging to him and the King, having a church and two priests, and two mills. It soon after belonged to the Earls of Chester, one of whom, Randulph de Blundeville, died in the year 1153. His widow, Matilda, with the consent of her son Hugh, founded Repton Priory.

In Lysons’ Magna Britannia, we read, “The Capital Messuage of Repingdon was taken into the King’s (Henry III.) hands in 1253.” Afterwards it appears to have passed through many hands, John de Britannia, William de Clinton, Philip de Strelley, John Fynderne, etc., etc. In the reign of Henry IV., John Fynderne “was seised of an estate called the Manor of Repingdon alias Strelley’s part,” from whom it descended through George Fynderne to Jane Fynderne, who married Sir Richard Harpur, Judge of the Common Pleas,[4] whose tomb is in the mortuary chapel of the Harpurs in Swarkeston Church. Round the alabaster slab of the tomb on which lie the effigies of Sir Richard and his wife, is the following inscription, “Here under were buryed the bodyes of Richard Harpur, one of the Justicies of the Comen Benche at Westminster, and Jane his wife, sister and heyer unto Thomas Fynderne of Fynderne, Esquyer. Cogita Mori.” Since the dissolution of the Priory there have been two Manors of Repton, Repton Manor and Repton Priory Manor.

From Sir Richard Harpur the Manor of Repton descended to the present Baronet, Sir Vauncey Harpur-Crewe. Sir Henry Harpur, by royal license, assumed the name and arms of Crewe, in the year 1800.

The Manor of Repton Priory passed into the hands of the Thackers at the dissolution of the Priory, and remained in that family till the year 1728, when Mary Thacker devised it, and other estates, to Sir Robert Burdett of Foremark, Bart.

The Village consists of two main streets, which meet at the Cross. Starting from the Church, in a southerly direction, one extends for about a mile, towards Bretby. The other, coming from Burton-on-Trent, proceeds in an easterly direction, through “Brook End,” towards Milton, and Tickenhall, &c. The road from Willington was made in 1839, when it and the bridge were completed, and opened to the public. A swift stream, rising in the Pistern Hills, six miles to the south, runs through a broad valley, and used to turn four corn mills, (two of which are mentioned in Domesday Book,) now only two are worked, one at Bretby, the other at Repton. The first, called Glover’s Mill, about a mile above Bretby, has the names of many of the Millers, who used to own or work it, cut, apparently, by their own hands, in the stone of which it is built. The last mill was the Priory Mill, and stood on the east side of the Priory, the arch, through which the mill-race ran, is still in situ, it was blocked, and the stream diverted to its present course, by Sir John Harpur in the year 1606. On the left bank[5] of this stream, on the higher ground of the valley, the village has been built; no attempt at anything like uniformity of design, in shape or size, has been made, each owner and builder erected, house or cottage, according to his own idea or desire; these, with gardens and orchards, impart an air of quaint beauty to our village, whose inhabitants for centuries have been engaged, chiefly, in agriculture. In the old Parish registers some of its inhabitants are described as “websters,” and “tanners,” but, owing to the growth of the trade in better situated towns, these trades gradually ceased.

During the Civil War the inhabitants of Repton and neighbourhood remained loyal and faithful to King Charles I. In 1642 Sir John Gell, commander of the Parliamentary forces stormed Bretby House, and in January, 1643, the inhabitants of Repton, and other parishes, sent a letter of remonstrance to the Mayor and Corporation of Derby, owing to the plundering excursions of soldiers under Sir John’s command. In the same year, Sir John Harpur’s house, at Swarkeston, was stormed and taken by Sir John Gell.

In 1687 a wonderful skeleton, nine feet long! was discovered in a field, called Allen’s Close, adjoining the churchyard of Repton, now part of the Vicarage grounds. The skeleton was in a stone coffin, with others to the number of one hundred arranged round it! During the year 1787 the grave was reopened, and a confused heap of bones was discovered, which were covered over with earth, and a sycamore tree, which is still flourishing, was planted to mark the spot.

During the present century few changes have been made in the village; most of them will be found recorded, either under chief events in the History of Repton, or in the chapters succeeding.

The first mention of Repton occurs in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, under the year 755. Referring to “the slaughter” of King Ethelbald, King of Mercia, one out of the six MSS. relates that it happened “on Hreopandune,” “at Repton”; the other five have “on Seccandune,” “at Seckington,” near Tamworth. Four of the MSS. spell the name “Hrepandune,” one “Hreopadune,” and one “Reopandune.”

Under the year 874, when the Danes came from Lindsey, Lincolnshire, to Repton, “and there took winter quarters,” four of the MSS. spell the name “Hreopedune,” one “Hreopendune.” Again, under the year 875, when they left, having destroyed the Abbey and the town, the name is spelt “Hreopedune.” The final e represents the dative case. In Domesday Book it is spelt “Rapendune,” “Rapendvne,” or “Rapendvn.” In later times, among the various ways of spelling the name, the following occur:—Hrypadun, Rypadun, Rapandun, Rapindon, Rependon, Repindon, Repingdon, Repyndon, Repington, Repyngton, Ripington, Rippington, &c., and finally Repton; the final syllable ton being, of course, a corruption of the ancient dun or don.

Now as to the meaning of the name. There is no doubt about the suffix dun, which was adopted by the Anglo-Saxons from the Celts, and means a hill, and was[7] generally used to denote a hill-fortress, stronghold, or fortified place. As to the meaning of the prefix “Hreopan,” “Hreopen,” or “Repen,” the following suggestions have been made:—(1) “Hreopan” is the genitive case of a Saxon proper name, “Hreopa,” and means Hreopa’s hill, or hill-fortress. (2) “Hropan or Hreopan,” a verb, “to shout,” or “proclaim”; or a noun, “Hrop,” “clamour,” or “proclamation,” and so may mean “the hill of shouting, clamour, or proclamation.” (3) “Repan or Ripan,” a verb, “to reap” or a noun, “Rep, or Rip,” a harvest, “the hill of reaping or harvest.” (4) “Hreppr,” a Norse noun for “a village,” “a village on a hill.” (5) “Ripa,” a noun meaning “a bank,” “a hill on a bank,” of the river Trent, which flows close to it.

The question is, which of these is the most probable meaning? The first three seem to suit the place and position. It is a very common thing for a hill or place to bear the name of the owner or occupier. As Hreopandun was the capital of Mercia, many a council may have been held, many a law may have been proclaimed, and many a fight may have been fought, with noise and clamour, upon its hill, and, in peaceful times, a harvest may have been reaped upon it, and the land around. As regards the two last suggestions, the arrival of the Norsemen, in the eighth century, would be too late for them to name a place which had probably been in existence, as an important town, for nearly two centuries before they came.

The prefix “ripa” seems to favour a Roman origin, but no proofs of a Roman occupation can be found. If there are any, they lie hid beneath that oblong enclosure in a field to the north of Repton, near the banks of the river Trent, which Stebbing Shaw, in the Topographer (Vol. II., p. 250), says “was an ancient colony of the Romans called ‘Repandunum.’” As the name does not appear in any of the “Itineraries,” nor in any of the minor settlements or camps in Derbyshire, this statement is extremely doubtful. Most probably the camp was constructed by the Danes when they wintered there in[8] the year 874. The name Repandunum appears in Spruner and Menke’s “Atlas Antiquus” as a town among the Cornavii (? Coritani), at the junction of the Trent and Dove!

So far as to its name. Now we will put together the various historical references to it.

“This place,” writes Stebbing Shaw, (O.R.), in the Topographer, Vol. II., p. 250, “was an ancient colony of the Romans called Repandunum, and was afterwards called Repandun, (Hreopandum,) by the Saxons, being the head of the Mercian kingdom, several of their kings having palaces here.”

“Here was, before A.D. 600, a noble monastery of religious men and women, under the government of an Abbess, after the Saxon Way, wherein several of the royal line were buried.”

As no records of the monastery have been discovered we cannot tell where it was founded or by whom. Penda, the Pagan King of Mercia, was slain by Oswiu, king of Northumbria, at the battle of Winwadfield, in the year 656, and was succeeded by his son Peada who had been converted to Christianity, by Alfred brother of Oswiu, and was baptized, with all his attendants, by Finan, bishop of Lindisfarne, at Walton, in the year 632. (Matt. Paris, Chron. Maj.) After Penda’s death, Peada brought from the north, to convert Mercia, four priests, Adda, Betti, Cedda brother of St. Chad, and Diuma, who was consecrated first bishop of the Middle Angles and Mercians by Finan, but only ruled the see for two years, when he died and was buried “among the Middle Angles at Feppingum,” which is supposed to be Repton. In the year 657 Peada was slain “in a very nefarious manner, during the festival of Easter, betrayed, as some say, by his wife,” and was succeeded by his brother Wulphere.

Tanner, Notitia, f. 78; Leland, Collect., Vol. II., p. 157; Dugdale, Monasticon, Vol. II., pp. 280-2, all agree that the monastery was founded before 660, so Peada, or his brother Wulphere could have been its founder.

The names of several of the Abbesses have been recorded. Eadburh, daughter of Ealdwulf, King of East Anglia. Ælfthryth (Ælfritha) who received Guthlac, (see p. 12). Wærburh (St. Werburgh) daughter of King Wulphere. Cynewaru (Kenewara) who in 835 granted the manor and lead mines of Wirksworth, on lease, to one Humbert.

Among those whom we know to have been buried within the monastery are Merewald, brother of Wulphere. Cyneheard, brother of the King of the West Saxons. Æthelbald, King of the Mercians, “slain at Seccandun (Seckington, near Tamworth), and his body lies at Hreopandun” (Anglo-Saxon Chron.) under date 755. Wiglaf or Withlaf, another King of Mercia, and his grandson Wistan (St. Wystan), murdered by his cousin Berfurt at Wistanstowe in 850 (see p. 15). After existing for over 200 years the monastery was destroyed by the Danes in the year 874. “In this year the army of the Danes went from Lindsey (Lincolnshire) to Hreopedun, and there took winter quarters,” (Anglo-Saxon Chron.), and as Ingulph relates “utterly destroyed that most celebrated monastery, the most sacred mausoleum of all the Kings of Mercia.”

For over two hundred years it lay in ruins, till, probably, the days of Edgar the Peaceable (958-75) when a church was built on the ruins, and dedicated to St. Wystan.

When Canute was King (1016-1035) he transferred the relics of St. Wystan to Evesham Abbey, where they rested till the year 1207, when, owing to the fall of the central tower which smashed the shrine and relics, a portion of them was granted to the Canons of Repton. (see Life of St. Wystan, p. 16.) In Domesday Book Repton is entered as having a Church with two priests, which proves the size and importance of the church and parish in those early times. Algar, Earl of Mercia, son of Leofric, and Godiva, was the owner then, but soon after, it passed into the hands of the King, eventually it was restored to the descendants of Algar, the Earls of Chester.[10] Matilda, widow of Randulph, Earl of Chester, with the consent of her son Hugh, enlarged the church, and founded the Priory, both of which she granted to the Canons of Calke, whom she transferred to Repton in the year 1172.

“The sober recital of historical fact is decked with legends of singular beauty, like artificial flowers adorning the solid fabric of the Church. Truth and fiction are so happily blended that we cannot wish such holy visions to be removed out of our sight,” thus wrote Bishop Selwyn of the time when our Repton Saints lived, and in order that their memories may be kept green, the following account has been written.

At the command of Æthelbald, King of the Mercians, Felix, monk of Crowland, first bishop of the East Angles, wrote a life of St. Guthlac.

He derived his information from Wilfrid, abbot of Crowland, Cissa, a priest, and Beccelm, the companion of Guthlac, all of whom knew him.

Felix relates that Guthlac was born in the days of Æthelred, (675-704), his parents’ names were Icles and Tette, of royal descent. He was baptised and named Guthlac, which is said to mean “Gud-lac,” “belli munus,” “the gift of battle,” in reference to the gift of one, destined to a military career, to the service of God. The sweet disposition of his youth is described, at length, by his biographer, also the choice of a military career, in which he spent nine years of his life. During those years he devastated cities and houses, castles and villages, with[12] fire and sword, and gathered together an immense quantity of spoil, but he returned a third part of it to those who owned it. One sleepless night, his conscience awoke, the enormity of his crimes, and the doom awaiting such a life, suddenly aroused him, at daybreak he announced, to his companions, his intention of giving up the predatory life of a soldier of fortune, and desired them to choose another leader, in vain they tried to turn him from his resolve, and so at the age of twenty-four, about the year 694, he left them, and came to the Abbey of Repton, and sought admission there. Ælfritha, the abbess, admitted him, and, under her rule, he received the “mystical tonsure of St. Peter, the prince of the Apostles.”

For two years he applied himself to the study of sacred and monastic literature.

The virtues of a hermit’s life attracted him, and he determined to adopt it, so, in the autumn of 696, he again set out in search of a suitable place, and soon lost himself among the fens, not far from Gronta—which has been identified with Grantchester, near Cambridge—here, a bystander, named Tatwine, mentioned a more remote island named Crowland, which many had tried to inhabit, but, owing to monsters, &c., had failed to do so. Hither Guthlac and Tatwine set out in a punt, and, landing on the island, built a hut over a hole made by treasure seekers, in which Guthlac settled on St. Bartholomew’s Day, (August 24th,) vowed to lead a hermit’s life. Many stories are related, by Felix, of his encounters with evil spirits, who tried to turn him away from the faith, or drive him away from their midst.

Of course the miraculous element abounds all through the narrative, chiefly connected with his encounters with evil spirits, whom he puts to flight, delivering those possessed with them from their power. So great was his fame, bishops, nobles, and kings, visit him, and Eadburgh, Abbess of Repton, daughter of Aldulph, King of East Angles, sent him a shroud, and a coffin of Derbyshire lead, for his burial, which took place on the 11th of April, A.D. 714.

Such, in briefest outline, is the life of St. Guthlac. Those who wish to know more about him, should consult “The Memorials of St. Guthlac,” edited by Walter de Gray Birch. In it he has given a list of the manuscripts, Anglo-Saxon, Latin, and Old English Verse, which describe the Saint’s life. He quotes specimens of all of them, and gives the full text of Felix’s life, with footnotes of various readings, &c., and, what is most interesting, has interleaved the life with illustrations, reproduced by Autotype Photography, from the well known roll in Harley Collection of MSS. in the British Museum. The roll, of vellum, is nine feet long, by six inches and a half wide, on it are depicted, in circular panels, eighteen scenes from the life of the Saint. Drawn with “brown or faded black ink, heightened with tints and transparent colours, lightly sketched in with a hair pencil—in the prevailing style of the twelfth century—the work of a monk of Crowland, perhaps of the celebrated Ingulph, the well known literary abbot of that monastery, it stands, unique, in its place, as an example of the finest early English style of freehand drawing,” one or more of the cartoons are missing.

The first cartoon, the left half of which is wanting, is a picture of Guthlac and his companions asleep, clad in chain armour.

The 2nd. Guthlac takes leave of his companions.

The 3rd. Guthlac is kneeling between bishop Headda, and the abbess, in Repton abbey. The bishop is shearing off Guthlac’s hair.

The 4th. Guthlac, Tatwine, and an attendant are in a boat with a sail, making their way back to the island of Crowland.

The 5th. Guthlac, with two labourers, is building a chapel.

The 6th. Guthlac, seated in the completed chapel, receives a visit from an angel, and his patron saint Bartholomew.

The 7th. Guthlac is borne aloft over the Chapel by five demons, three of whom are beating him with triple-thonged[14] whips. Beccelm, his companion, is seated inside the Chapel, in front of the altar, on which is placed a chalice.

The 8th. Guthlac, with a nimbus of sanctity round his head, has been borne to the jaws of hell, (in which are a king, a bishop, and two priests) by the demons, and is rescued by St. Bartholomew, who gives a whip to Guthlac.

The 9th. The cell of Guthlac is surrounded by five demons, in various hideous shapes. He has seized one, and is administering a good thrashing with his whip.

The 10th. Guthlac expels a demon from the mouth of Egga, a follower of the exiled Æthelbald.

The 11th. Guthlac, kneeling before bishop Headda, is ordained a priest.

The 12th. King Æthelbald visits Guthlac, both are seated, and Guthlac is speaking words of comfort to him.

The 13th. Guthlac is lying ill in his oratory, Beccelm is kneeling in front of him listening to his voice.

The 14th. Guthlac is dead, two angels are in attendance, one receiving the soul, “anima”, as it issues from his mouth. A ray of light stretches from heaven down to the face of the saint.

The 15th. Beccelm and an attendant in a boat, into which Pega, sister of Guthlac, is stepping on her way to perform the obsequies of her brother.

The 16th. Guthlac, in his shroud, is being placed in a marble sarcophagus by Pega and three others, one of whom censes the remains.

The 17th. Guthlac appears to King Æthelbald.

The 18th. Before an altar stand thirteen principal benefactors of Crowland Abbey. Each one, beginning with King Æthelbald, carries a scroll on which is inscribed their name, and gift.

The Abbey of Crowland was built, and flourished till about the year 870, when the Danes burnt it down, four years later they destroyed Repton.

Guthlaxton Hundred in the southern part of Leicestershire, and four churches, dedicated to him, retain his name. The remains of a stone at Brotherhouse, bearing[15] his name, and a mouldering effigy, in its niche on the west front of the ruins of Crowland Abbey, are still to be seen. His “sanctus bell” was at Repton, and as we shall see, in the account of the Priory, acquired curative powers for headache.

Among “the Chronicles and Memorials of Great Britain and Ireland during the Middle Ages,” published by the authority of Her Majesty’s Treasury, under the direction of the Master of the Rolls is the “Chronicon Abbatiæ de Evesham,” written by Thomas de Marleberge or Marlborough, Abbot of Evesham. In an appendix to the Chronicle he also wrote a life of St. Wystan from which the following facts, &c., have been gathered.

Wystan was the son of Wimund, son of Wiglaf, King of Mercia, his mother’s name was Elfleda. Wimund died of dysentery during his father’s life-time, and was buried in Crowland Abbey, and, later on, his wife was laid by his side. When the time came for Wystan to succeed to the crown, he refused it, “wishing to become an heir of a heavenly kingdom. Following the example of his Lord and master, he refused an earthly crown, exchanging it for a heavenly one,” and committed the kingdom to the care of his mother, and to the chief men of the land. But his uncle Bertulph conspired against him, “inflamed with a desire of ruling, and with a secret love for the queen-regent.” A council was assembled at a place, known from that day to this, as Wistanstowe, in Shropshire, and to it came Bertulph and his son Berfurt. Beneath his cloak Berfurt had concealed a sword, and (like Judas the traitor), whilst giving a kiss of peace to Wystan, drew it and smote him with a mortal wound on his head, and so, on the eve of Pentecost, in the year 849, “that holy martyr leaving his precious body on the earth, bore his glorious soul to heaven. The body was conveyed to the Abbey of Repton, and buried in the mausoleum of his grandfather,[16] with well deserved honour, and the greatest reverence. For thirty days a column of light, extending from the spot where he was slain to the heavens above, was seen by all those who dwelt there, and every year, on the day of his martyrdom, the hairs of his head, severed by the sword, sprung up like grass.” Over the spot a church was built to which pilgrims were wont to resort, to see the annual growth of the hair.

The remains of St. Wystan rested at Repton till the days of Canute (1016-1035), when he caused them to be transferred to Evesham Abbey, “so that in a larger and more worthy church the memory of the martyr might be held more worthily and honourably.” In the year 1207 the tower of Evesham Abbey fell, smashing the presbytery and all it contained, including the shrine of St. Wystan. The monks took the opportunity of inspecting the relics, and to prove their genuineness, which some doubted, subjected them to a trial by fire, the broken bones were placed in it, and were taken out unhurt and unstained. The Canons of Repton hearing of the disaster caused by the falling tower, begged so earnestly for a portion of the relics, that the Abbot Randulph granted them a portion of the broken skull, and a piece of an arm bone. The bearers of the sacred relics to Repton were met by a procession of prior, canons, and others, over a mile long, and with tears of joy they placed them, “not as before in the mausoleum of his grandfather, but in a shrine more worthy, more suitable, and as honourable as it was possible to make it,” in their Priory church, where they remained till it was dissolved in the year 1538.

In memory of St. Wystan, the first Parish Church of Repton was dedicated to him, as we shall see in our account of Repton Church.

Plate 3.

Repton Church Crypt. (Page 17.)

Repton Church is built on the site of the Anglo-Saxon Monastery, which was destroyed by the Danes in the year 874. It was most probably built in the reign of Edgar the Peaceable (959-975), as Dr. Charles Cox writes:—“Probably about that period the religious ardour of the persecuted Saxons revived ... their thoughts would naturally revert to the glories of monastic Repton in the days gone by.” On the ruins of the “Abbey” they raised a church, and dedicated it to St. Wystan. According to several writers, it was built of stout oak beams and planks, on a foundation of stone, or its sides might have been made of wattle, composed of withy twigs, interlaced between the oak beams, daubed within and without with mud or clay. This church served for a considerable time, when it was re-built of stone. The floor of the chancel, supported on beams of wood, was higher than the present one, so the chancel had an upper and lower “choir,” the lower one was lit by narrow lights, two of which, blocked up, can be seen in the south wall of the chancel. When the church was re-built the chancel floor was removed, and the lower “choir” was converted into the present crypt, by the introduction of a vaulted stone roof, which is supported by four spirally-wreathed piers, five feet apart, and five feet six inches high, and eight square responds, slightly fluted, of the same height, and distance apart, all with capitals with square abaci,[18] which are chamfered off below. Round the four walls is a double string-course, below which the walls are ashlar, remarkably smooth, as though produced by rubbing the surface with stone, water and sand. The vaulted roof springs from the upper string-course, the ribs are square in section, one foot wide, there are no diagonal groins, it is ten feet high, and is covered with a thin coating of plaster, which is continued down to the upper string-course. The piers are monoliths, and between the wreaths exhibit that peculiar swell which we see on the shafts of Anglo-Saxon belfry windows, &c.

The double string-course is terminated by the responds. There were recesses in each of the walls of the crypt. In the wall of the west recess there is a small arch, opening into a smaller recess, about 18 inches square. Many suggestions have been made about it: (1) it was a “holy hole” for the reception of relics, (2) or a opening in which a lamp could be kept lit, (3) or that it was used as a kind of “hagioscope,” through which the crypt could be seen from the nave of the church, when the chancel floor was higher, and the nave floor lower than they are now.

There are two passages to the church, about two feet wide and ten feet high, made from the western angles of the crypt.

A doorway was made, on the north side, with steps leading down to it, from the outside, during the thirteenth century; there is a holy water stoup in the wall, on the right hand as you enter the door.

For many years it has been a matter of dispute how far the recesses in the crypt, on the east, north, and south sides, extended. Excavations just made (Sept. 1898), have exposed the foundations of the recesses. The recess on the south side is rectangular, not apsidal as some supposed, it projects 2 ft. 2 in. from the surface of the wall, outside, and is 6 ft. 2 in. wide. About two feet below the ground level, two blocks of stone were discovered, (each 2 ft. × 1 ft. 4 in. × 1 ft. 9 in.), two feet apart, they rest on a stone foundation. The inside[19] corners are chamfered off. On a level with the stone foundation, to the south of it, are two slabs under which a skeleton was seen, whose it was, of course, cannot be said. The present walls across the recesses, on the south and east, block them half up, and were built in later times.

The recess on the east end was destroyed when a flight of stone steps was made leading down to the crypt. These steps (there are six of them) are single, roughly made stones of varied length, resting on the earth, without mortar. When the flight was complete there would have been twelve, reaching from the top to the level of the crypt floor.

The steps would afford an easier and quicker approach to the crypt and church, but when they were made cannot now be said.

The recess on the north side was also destroyed when the outer stairway, and door, were placed there, probably, as before stated, in the thirteenth century. On the outside surface of the three walls, above the ground level, are still to be seen traces of the old triangular-shaped roofs which covered the three recesses, and served as buttresses to the walls. Similar “triangular arches” are to be seen at Barnack, and Brigstock.

The eastern end of the north aisle is the only portion of the ancient transepts above the ground level. During the restorations in 1886 the foundations of the Anglo-Saxon nave were laid bare, they extend westward up to and include the base of the second pier; the return of the west-end walls was also discovered, extending about four feet inwards.

Over the chancel arch the removal of many coats of whitewash revealed an opening, with jambs consisting of long and short work; a similar opening to the north of it used to exist, it is now blocked up.

The Early English Style is only represented by foundations laid bare during the restoration in 1885, and now indicated in the north and south aisles, by parallel lines of the wooden blocks, with which the church is paved.[20] In the south aisle the foundations of a south door were also discovered (see plan of church). To this period belong the windows in the north side of the chancel, and in the narrow piece of wall between the last arch and chancel wall on the north side of the present choir. There were two corresponding windows on the south side, one of which remains. All these windows have been blocked up.

The Decorated Style is represented in the nave by four out of the six lofty pointed arches, supported by hexagonal columns; the two, on either side, at the east end of the nave, were erected in the year 1854.

The tower and steeple were finished in the year 1340. Basano, in his Church Notes, records the fact—“Anᵒ 1320 ?40. The tower steeple belonging to the Prior’s Church of this town was finished and built up, as appears by a Scrole in Lead, having on it these words—“Turris adaptatur qua traiectū decoratur. M c ter xx bis. Testu Palini Johis.”

A groined roof of stone, having a central aperture, through which the bells can be raised and lowered, separates the lower part of the tower from the belfry.

The north and south aisles were extended to the present width. The eastern end of the south aisle was also enlarged several feet to the south and east, and formed a chapel or chantry, as some say, for the Fyndernes, who were at one time Lords of the Repton Manor. A similar, but smaller, chapel was at the east end of the north aisle, and belonged to the Thacker family. They were known as the “Sleepy Quire,” and the “Thacker’s Quire.” Up to the year 1792 they were separated by walls (which had probably taken the place of carved screens of wood) in order to make them more comfortable, and less draughty! These walls were removed in 1792, when “a restoration” took place.

The square-headed south window of the “Fynderne Chapel” composed of four lights, with two rows of trefoil and quatrefoil tracery in its upper part, is worthy of notice as a good specimen of this style, and was[21] probably inserted about the time of the completion of the tower and spire. The other windows in the church of one, two, three, and four lights, are very simple examples of this period, and, like the chancel arch, have very little pretensions to architectural merit, in design at least.

The Perpendicular Style is represented by the clerestory windows of two lights each, the roof of the church, and the south porch.

The high-pitched roof of the earlier church was lowered—the pitch is still indicated by the string-course on the eastern face of the tower—the walls over the arcades were raised several feet from the string-course above the arches, and the present roof placed thereon. It is supported by eight tie-beams, with ornamented spandrels beneath, and wall pieces which rest on semi-circular corbels on the north side, and semi-octagonal corbels on the south side. The space above the tie-beams, and the principal rafters is filled with open work tracery. Between the beams the roof is divided into six squares with bosses of foliage at the intersections of the rafters.

The south porch, with its high pitched roof, and vestry, belongs to this period. It had a window on either side, and was reached from the south aisle by a spiral staircase (see plan of church).

The Debased Style began, at Repton, during the year 1719, and ended about the year 1854. In the year 1719 a singers’ gallery was erected at the west end of the church, and the arch there was bricked up.

In the year 1779 the crypt was “discovered” in a curious way. Dr. Prior, Headmaster of Repton School, died on June 16th of that year, a grave was being made in the chancel, when the grave-digger suddenly disappeared from sight: he had dug through the vaulted roof, and so fell into the crypt below! In the south-west division of the groined roof, a rough lot of rubble, used to mend the hole, indicates the spot.

During the year 1792 “a restoration” of the church took place, the church was re-pewed, in the “horse-box” style! All the beautifully carved oak work “on pews[22] and elsewhere” which Stebbing Shaw describes in the Topographer (May, 1790), and many monuments were cleared out, or destroyed. Some of the carved oak found its way into private hands, and was used to panel a dining-room, and a summer-house. Some of the carved panels have been recovered, and can be seen in the vestry over the south porch. One of the monuments which used to be on the top of an altar tomb “at the upper end of the north aisle,” was placed in the crypt, where it still waits a more suitable resting-place. It is an effigy of a Knight in plate armour (circa Edward III.), and is supposed to be Sir Robert Francis, son of John Francis, of Tickenhall, who settled at Foremark. If so, Sir Robert was the Knight who, with Sir Alured de Solney, came to the rescue of Bishop Stretton in 1364, and is an ancestor of the Burdetts, of Foremark.

The crypt seems to have been used as a receptacle for “all and various” kinds of “rubbish” during the restoration, for, in the year 1802, Dr. Sleath found it nearly filled up, as high as the capitals, with portions of ancient monuments, grave-stones, &c., &c. In the corner, formed by north side of the chancel and east wall of the north aisle, a charnel, bone, or limehouse had been placed in the Middle Ages: this house was being cleaned out by Dr. Sleath’s orders, when the workmen came upon the stone steps leading down to the crypt, following them down they found the doorway, blocked up by “rubbish,” this they removed, and restored the crypt as it is at the present day.

During the years 1842 and 1848 galleries in the north and south aisles, extending from the west as far as the third pillars, were erected.

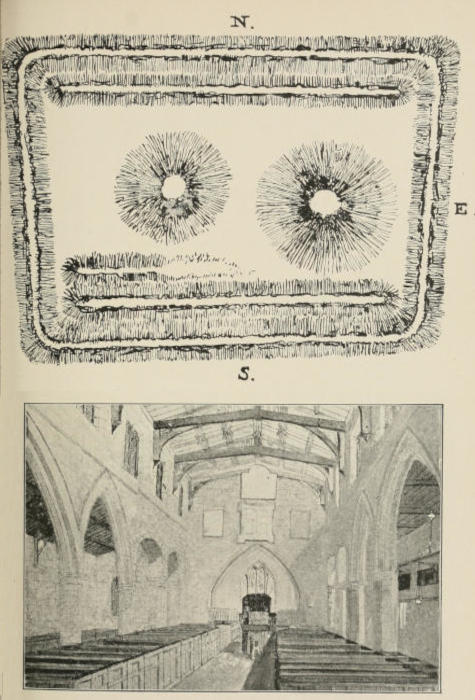

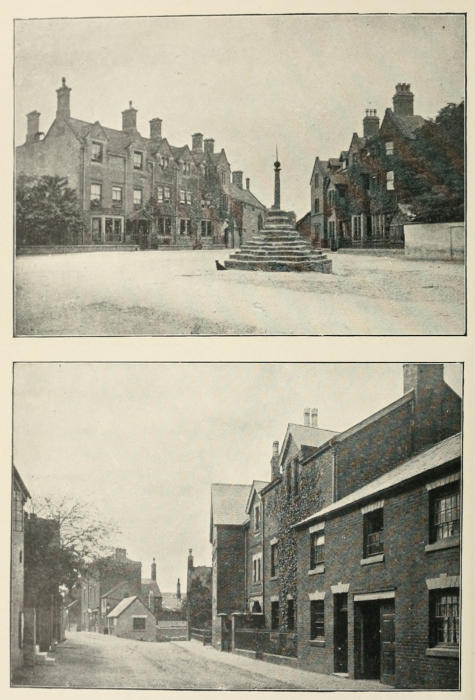

Plate 4.

Repton Camp. (F. C. H.) (Page 3.)

Repton Church. (Before 1854.) (Page 22.)

In 1854, the two round arches and pillars, on either side of the eastern end of the nave, were removed, and were replaced by the present pointed arches and hexagonal piers, for, as before stated, the sake of uniformity! Thus an interesting portion belonging to the ancient church was destroyed. The illustration opposite was copied from a drawing done, in the year[23] 1847, by G. M. Gorham, then a pupil in the school, now Vicar of Masham, Bedale. To him our thanks are due for allowing me to copy it. It shows what the church was like in his time, 1847.

In 1885 the last restoration was made, when the Rev. George Woodyatt was Vicar. The walls were scraped, layers of whitewash were removed, the pews, galleries, &c., were removed, the floor of the nave lowered to its proper level, a choir was formed by raising the floor two steps, as far west as the second pier, the organ was placed in the chantry at the east end of the south aisle. The floor of nave and aisles was paved with wooden blocks, the choir with encaustic tiles. The whole church was re-pewed with oak pews, and “the choir” with stalls, and two prayer desks. A new pulpit was given in memory of the Rev. W. Williams, who died in 1882. The “Perpendicular roof” was restored to its original design: fortunately there was enough of the old work left to serve as models for the repair of the bosses, &c. The clerestory windows on the south side were filled with “Cathedral” glass. The splendid arch at the west end was opened.

The base of the old font was found among the débris, a new font, designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield, (the architect employed to do the restoration), was fixed on it, and erected under the tower.

Since that restoration, stained glass windows have been placed in all the windows of the north aisle by Messrs. James Powell and Sons, Whitefriars Glass Works, London; the one in the south aisle is also by them. The outside appearance of the church roof was improved by the addition of an embattled parapet, the roof itself was recovered with lead.

In 1896 all the bells were taken down, by Messrs. John Taylor, of Loughborough, and were thoroughly examined and cleansed, two of them, the 5th and 6th (the tenor bell), were re-cast, (see chapter on Bells).

The only part of the church not restored is the chancel, and we hope that the Lord of the Manor, Sir Vauncey[24] Harpur-Crewe, Bart., will, some day, give orders for its careful, and necessary restoration.

INCUMBENTS, &c. OF REPTON.

| Jo. Wallin, curate. Temp. Ed. VI. | |

| 1584 | Richard Newton, curate. |

| 1602 | Thomas Blandee, B.A., curate. |

| ” | John Horobine |

| 1612 | George Ward, minister |

| Mathew Rodgers, minister | |

| 1648 | Bernard Fleshuier, ” |

| 1649 | George Roades, ” |

| 1661 | John Robinson, ” |

| 1663 | John Thacker, M.A., minister. |

| ” | William Weely, curate. |

| 1739 | Lowe Hurt, M.A. |

| 1741 | William Astley, M.A. |

| 1742 | John Edwards, B.A. |

| 1804 | John Pattinson. |

| 1843-56 | Joseph Jones, M.A. |

| 1857-82 | W. Williams. |

| 1883-97 | G. Woodyatt, B.A. |

| 1898 | A. A. McMaster, M.A. |

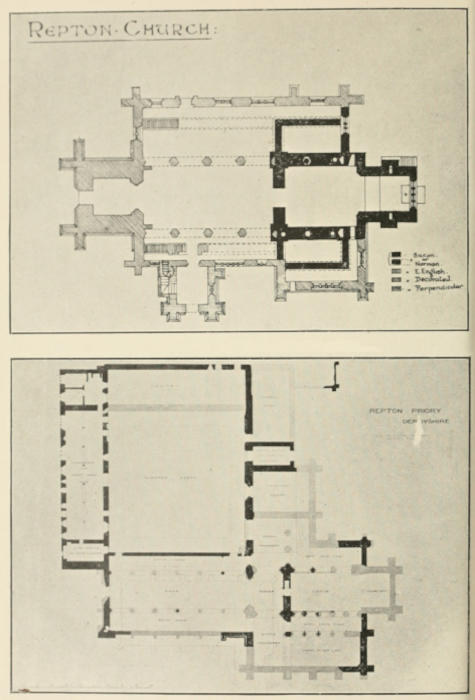

Plate 5.

Plan of Repton Church. (F. C. H.)

Plan of Repton Priory. (W. H. H. ST. JOHN HOPE, Mens et Del.) (Page 25.)

There are three ancient register books of births, baptisms, marriages and burials, and one register book of the Churchwardens’ and Constables’ Accounts of the Parish of Repton. They extend from 1580 to 1670.

The oldest Volume extends from 1580 to 1629: the second from 1629 to 1655: the third from 1655-1670. The Churchwardens’ and Constables’ Accounts from 1582 to 1635.

The oldest Volume is a small folio of parchment (13 in. by 6 in.) of 45 leaves, bound very badly, time-stained and worn, in parts very badly kept, some of the leaves are loose, and some are quite illegible. It is divided into two parts, the first part (of thirty pages) begins with the year 1590 and extends to 1629: the second part begins with “Here followeth the register book for Ingleby, formemarke and Bretbye,” from 1580 to 1624.

The Second Volume consists of eighteen leaves of parchment (13 in. by 6 in.), unbound, the entries are very faded, only parts of them are legible, they extend from 1629 to 1655.

The Third Volume has twenty-six leaves (11½ in. by 5½ in.). The entries are very legible, and extend from 1655 to 1670.

On the first page is written:

December yᵉ 31, 1655.

Geo: Roades yᵉ day & yeare above written approved & sworne Register for yᵉ parrish of Repton in yᵉ County of Derby

By me James Abney.

THE FOLLOWING ENTRIES OCCUR.

Across the last page of the register is written this sage piece of advice:

“Beware toe whome you doe commit the secrites of your mind for fules in fury will tell all moveing in there minds.”

Richard Rogerson, 1684.

NAMES OF REPTON FAMILIES IN REGISTERS.

The Register book of the Churchwardens’ and Constable’s Accounts extends from 1582 to 1635, and includes Repton, and the Chapelries of Formark, Ingleby, and Bretby.

It is a narrow folio volume of coarse paper, (16 in. by 6 in., by 2 in. thick), and is bound with a parchment which formed part of a Latin Breviary or Office Book, with music and words. The initial letters are illuminated, the colours, inside, are still bright and distinct.

At the beginning of each year the accounts are headed “Compotus gardianorum Pochialis Eccle de Reppindon,” then follow:

(1) The names of the Churchwardens and Constable for the year.

(2) The money (taxes, &c.,) paid by the Chapelries above mentioned.

(3) The names and amounts paid by Tenants of Parish land.

(4) Money paid by the Parish to the Constable.

(5) Money “gathered for a communion,” 1st mentioned in the year 1596. At first it was gathered only once in July, but afterwards in January, June, September, October, and November.

The amounts vary from jd to vjd.

(6) The various “items” expended by the Churchwardens and Constable.

Dr. J. Charles Cox examined the contents of the Parish Chest, and published an account of the Registers &c., and accounts, in Vol. I. of the Journal of the Derbyshire Archæological Society, 1879. Of the Accounts he writes, “it is the earliest record of parish accounts, with the exception of All Saints’, Derby, in the county,” and “the volume is worthy of a closer analysis than that for which space can now be found.” Acting on that hint, during the winter months of 1893-4, I made most copious extracts from the Accounts, and also a “verbatim et[31] literatim” transcript of the three registers, which I hope will be published some day.

Dr. Cox’s article is most helpful in explaining many obsolete words, curious expressions, customs, and references to events long ago forgotten, a few of the thousands of entries are given below:

The first five leaves are torn, the entries are very faded and illegible.

Thus does a local poet compare Repton bells with those of neighbouring parishes. It is not intended to defend the comparison, for as Dogberry says, “Comparisons are odorous”! but to write an account of the bells, derived from all sources, ancient and modern.

Llewellynn Jewitt, in Vol. XIII. of the Reliquary, describing the bells of Repton, writes, “at the church in the time of Edward VI. there were iij great bells & ij small.” Unfortunately “the Churchwardens’ and Constables’ accounts of the Parish of Repton” only extend from the year 1582 to 1635. I have copied out most of the references to our bells entered in them, which will, I hope, be interesting to my readers.

Extracts from “the Churchwardens’ and Constables’ accounts of the Parish of Repton.”

Extract from the diary of Mr. George Gilbert.

“A.D. 1772, Oct. 7th. The third bell was cracked, upon ringing at Mr. John Thorpe’s wedding. The bell upon being taken down, weighed 7 cwt. 2 qr. 18lb., clapper, 24lb. It was sold at 10d. per lb., £35. 18s. Re-hung the third bell, Nov. 21st, 1774. Weight 8 cwt. 3 qr. 24lb., at 13d. per lb., £54. 7s. 8d., clapper, 1 r. 22 lb., at 22d., £1. 2s. 10d. £55. 9s 6½d.”

This is all the information I can gather about “Repton’s merry bells” from ancient sources.

For some time our ring of six bells had only been “chimed,” owing to the state of the beams which supported them, it was considered dangerous to “ring” them.

During the month of January, 1896, Messrs. John Taylor and Co., of Loughborough, (descendants of a long line of bell-founders), lowered the bells down, and conveyed them to Loughborough, where they were thoroughly cleansed and examined. Four of them were sound, but two, the 5th and 6th, were found to be cracked, the 6th (the Tenor bell) worse than the 5th. The crack started in both bells from the “crown staple,” from which the “clapper” hangs; it (the staple) is made of iron and cast into the crown of the bell. This has been the cause of many cracked bells. The two metals, bell-metal and iron, not yielding equally, one has to give way, and this is generally the bell metal. The “Canons,” as the projecting pieces of metal forming the handle, and cast with the bell, are called, and by which they are fastened to the “headstocks,” or axle tree, were found to be much worn with age. All the “Canons” have been removed, holes have been drilled through the crown, the staples removed, and new ones have been made which pass[46] through the centre hole, and upwards through a square hole in the headstocks, made of iron, to replace the old wooden ones. New bell-frames of iron, made in the shape of the letter H, fixed into oak beams above and below, support the bells, which are now raised about three feet above the bell chamber floor, and thus they can be examined more easily.

During the restoration of the Church in 1886, the opening of the west arch necessitated the removal of the ringers’ chamber floor, which had been made, at some period or other, between the ground floor and the groined roof, so the ringers had to mount above the groined ceiling when they had to ring or chime the bells. There, owing to want of distance between them and the bells, the labour and inconvenience of ringing was doubled, the want of sufficient leverage was much felt: now the ringers stand on the ground floor, and with new ropes and new “sally-guides” their labour is lessened, and the ringing improved.

When the bells were brought back from Loughboro’ I made careful “rubbings” of the inscriptions, legends, bell-marks, &c., before they were raised and fixed in the belfry. The information thus obtained, together with that in Vol. XIII. of the Reliquary, has enabled me to publish the following details about the bells.

The “rubbings” and “squeezes” for the article in the Reliquary were obtained by W. M. Conway (now Sir Martin Conway) when he was a boy at Repton School.

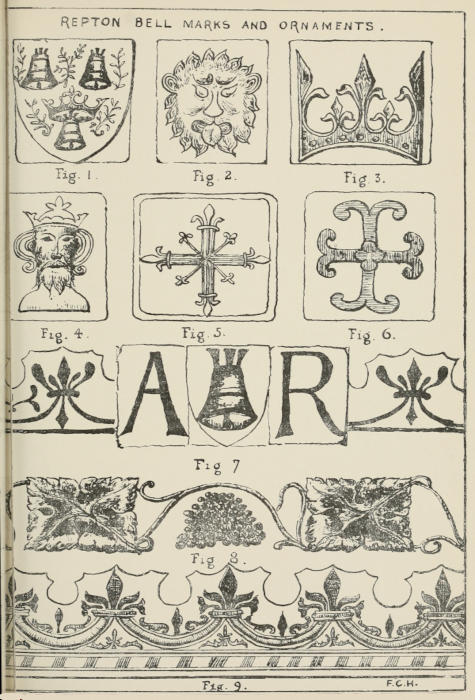

Plate 6.

REPTON BELL MARKS AND ORNAMENTS.

The 1st (treble) Bell.

On the haunch, between three lines, one above, two below,

FRAVNCIS THACKER OF LINCOLNS INN ESQᴿ, 1721.

a border: fleurs-de-lis (fig. 7): Bell-mark of Abraham Rudhall, (a famous bell-founder of Gloucester): border (fig. 7).

A catalogue of Rings of Bells cast by A. R. and others, from 1684-1830, is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford: this bell is mentioned as the gift of Francis Thacker.

At the east end of the north aisle of our Church there is a mural monument to his memory.

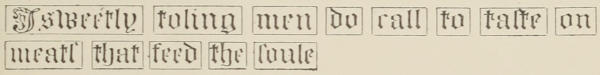

The 2nd Bell.

On the crown a border of fleurs-de-lis (fig. 9). Round the haunch,

Is sweetly toling men do call to taste on meats that feed the soule

between two lines above and below, then below the same border (fig. 9) inverted.

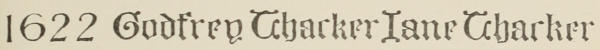

1622 Godfrey Thacker Iane Thacker

This bell is referred to in the Churchwardens’ accounts under dates 1615 and 1623.

The 3rd Bell.

Round the haunch, between two lines,

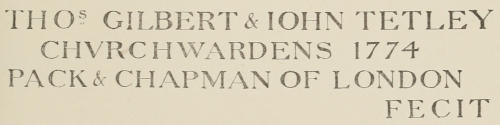

THOˢ. GILBERT & IOHN TETLEY CHVRCH WARDENS 1774 PACK & CHAPMAN OF LONDON FECIT

Below, a border, semicircles intertwined.

This is the bell referred to in the extract quoted above from George Gilbert’s diary.

The 4th Bell.

Round the haunch, between six lines (3 above and 3 below),

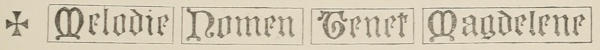

✠ Melodie Nomen Tenet Magdelene

a shield: three bells (two and one), with a crown between them (fig. 1), (Bell mark of Richard Brasyer, a celebrated[48] Norwich Bell founder, who died in 1513) a lion’s head on a square (fig. 2): a crown on a square (fig. 3); and a cross (fig. 5).

The 5th Bell.

Round the haunch, between two lines, one above, one below,

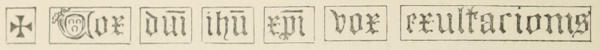

✠ Vox du̅i̅ ihū x̅r̅i̅ vox exultarionis

same marks (except the crown) as No. 4 Bell: a king’s head crowned (fig. 4): and a cross (fig. 6). Below this, round the haunch, a beautiful border composed of a bunch of grapes and a vine leaf (fig. 8), alternately arranged.

Below, the Bell mark of John Taylor and Co. within a double circle, a triangle interlaced with a trefoil, and a bell in the centre. Above the circle the sacred emblem of S. John Baptist, the lamb, cross, and flag. The name of the firm within the circle.

RECAST 1896.

The 6th Bell (the tenor Bell).

Round the haunch, between four lines, two above, and two below,

Hec Campana Sacra Fiat Trinitate Beata GILB THACKAR ESQ IC MW CH WARDENS 1677

(no bell marks).

Below, a border like that on the fifth Bell.

RECAST 1896.

| G. WOODYATT, | VICAR. | |

| J. ASTLE, | } | CHURCHWARDENS. |

| T. E. AUDEN, | } |

Bell mark of J. Taylor and Co. on the opposite side.

(Owing to the difference of the type of the inscription, and names, it is supposed that this bell was recast in 1677, so it may have been one of the “three great bells” in Edward VI.’s time.)

The following particulars of the bells have been supplied by Messrs. John Taylor & Co.

| Diameter. | Height. | Note. | Weight. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ft. | in. | ft. | in. | cwt. | qr. | lbs. | |||

| No. | I. | 2 | 9½ | 2 | 3 | C♯ | 7 | 3 | 19 |

| ” | II. | 2 | 10¾ | 2 | 4½ | B | 7 | 2 | 27 |

| ” | III. | 3 | 0½ | 2 | 4½ | A | 8 | 1 | 18 |

| ” | IV. | 3 | 2 | 2 | 6½ | G♯ | 9 | 2 | 21 |

| ” | V. | 3 | 6 | 2 | 10 | F♯ | 12 | 2 | 26 |

| ” | VI. | 3 | 11 | 3 | 1 | E | 17 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 3 tons | 4 cwts. | 0 qrs. | 27 lbs. |

Key-note E major.

To complete the octave, two more bells are required, D♯ and E, then indeed Repton will have a “ring” second to none.

Before we write an account of the next most important event in the history of Repton, viz., the founding of Repton Priory, we must go back to the year 1059, when Calke Abbey is supposed to have been founded by Algar, Earl of Mercia. Dr. Cox is of opinion that it was founded later, at the end of the reign of William (Rufus), or at the beginning of that of Henry I. circa 1100. About that date a Priory of Canons regular of St. Augustine, dedicated to St. Giles, was founded. Many benefactors made grants of churches, lands, &c., a list of all these will be found in Cox’s Derbyshire Churches, vol. iii., p. 346. There is a curious old Chronicle, written in Latin, by one T(h)omas de Musca, Canon of Dale Abbey. Each section of the Chronicle begins with a letter which, together, form the Author’s name, a monkish custom not uncommon. The section beginning with an E. (Eo tempore) records the arrival, at Deepdale, of the Black Canons, as they were called, from Kalc (Calke). Serlo de Grendon, Lord of Badeley or Bradeley, near Ashbourne, “called together the Canons of Kalc, and gave them the place of Deepdale.” Here, about 1160, the Canons “built for themselves a church, a costly labour, and other offices,” which became known as Dale Abbey, in which they lived for a time, “apart from the social intercourse of men,”[51] but “they began too remissly to hold themselves in the service of God; they began to frequent the forest more than the church; more to hunting than to prayer or meditation, so the King ordered them to return to the place whence they came,” viz., Calke. During the reign of Henry II., Matilda, widow of Randulf, 4th Earl of Chester, who died 1153, granted to God, St. Mary, the Holy Trinity, and to the Canons of Calke, the working of a quarry at Repton, (Repton Rocks), together with the advowson of the church of St. Wystan at Repton, &c., &c., on condition that as soon as a suitable opportunity should occur, the Canons of Calke should remove to Repton, which was to be their chief house, and Calke Abbey was to become subject to it. “A suitable opportunity occurred” during the episcopate of Walter Durdent, Bishop of Coventry only, at first, afterwards of Lichfield. He died at Rome, Dec. 7th, 1159. The usual date given for the founding of Repton Priory is A.D. 1172, but this must be wrong for the simple reason that Matilda addresses the Charter of Foundation to Bishop Walter Durdent, who died, as we saw, in 1159: moreover, the “remains” of the Priory belong to an earlier date; probably the date 1172 refers to the coming of the Canons from Calke to Repton, as Dugdale writes, “About the year 1172, Maud, widow of Randulf, removed the greater part of them here (Repton), having prepared a church and conventual buildings for their reception.” To those interested in Charters, copies of the original, and many others, can be read in Bigsby’s “History of Repton,” Dugdale’s “Monasticon,” and Stebbing-Shaw’s Article in Vol. II. of “the Topographer,” in which he has copied several “original Charters, not printed in the Monasticon,” which were in the possession of Sir Robert Burdett, Bart., of Foremark, and others.

Plate 7.

Repton Priory.

The Charters, containing grants, extend from Stephen’s reign, (1135-1154), to the reign of Henry V., (1413-1422), and include the church of St. Wystan, Repton, with its chapels of Newton Solney, Bretby, Milton, Foremark, Ingleby, Tickenhall, Smisby, and Measham, the church[52] at Badow, in Essex, estates at Willington, including its church, and Croxall.

In 1278 a dispute arose between the Prior of Repton and the inhabitants of the Chapelry of Measham, which had been granted to the Priory about 1271. The chancel of Measham Church was “out of repair,” and the question was, who should repair it? After considerable debate, it was settled that the inhabitants would re-build the chancel provided that the Priory should find a priest to officiate in the church, and should keep the chancel in repair for ever after, both of which they did till the dissolution of the Priory.

In the year 1364 Robert de Stretton, Bishop of Lichfield (1360-1386), was holding a visitation at Repton in the Chapter House of the Priory. For some reason or other, not known, the villagers, armed with bows and arrows, swords and cudgels, with much tumult, made an assault on the Priory gate-house. The Bishop sent for Sir Alured de Solney, and Sir Robert Francis, Lords of the Manors of Newton Solney and Foremark, who came, and quickly quelled this early “town and gown” row, without any actual breach of the peace. The monument in the crypt of Repton Church, where it was placed during the “restoration” of 1792, is supposed to be an effigy of Sir Robert Frances. “The Bishop proceeded on his journey, and, on reaching Alfreton, issued a sentence of interdict on the town and Parish Church of Repton, with a command to the clergy, in the neighbouring churches, to publish the same under pain of greater excommunication.” See Lichfield Diocesan Registers.

On October 26th, 1503, during the reign of Henry VII., an inquisition was held at Newark. A complaint was heard against the Prior of Repton for not providing a priest “to sing” the service in a chapel on Swarkeston Bridge, “nor had one been provided for the space of twenty years, although a piece of land between the bridge and Ingleby, of the annual value of six marks, had been given to the Prior for that purpose.”

The Priory of Repton was dissolved in the year 1538. By the advice of Thomas Cromwell—malleus monachorum—the hammer of the monks—Henry VIII. issued a commission of inquiry into the condition, &c., of the monasteries in England. A visitation was made in 1535, the results were laid before the House of Commons, in a report commonly known as the “Black Book.” In 1536 an Act was passed for the suppression of all monasteries possessing an income of less than £200. a year. By this Act 376 monasteries were dissolved, and their revenues, £32,000. per annum, were granted to the King, by Divine permission Head of the Church! Repton Priory was among them. In the Valor Ecclesiasticus (27 Henry VIII.) the gross annual value of the temporalities and spiritualities is given as £167. 18s. 2½d. In 1535, Dr. Thomas Leigh and Dr. Richard Layton, visited Repton and gave the amount as £180. Also they reported, as they were expected, that the Canons were not living up to their vows, &c., &c., and “Thomas Thacker was put in possession of the scite of the seid priory and all the demaynes to yᵗ apperteynying to oʳ sov’aigne lorde the Kynges use the xxvj day of October in the xxx yere of oʳ seid sov’aigne lorde Kyng henry the viijᵗʰ.” There is a very full inventory of the goods and possessions in the Public Record Office, Augmentation Office Book, 172. A transcript of this inventory is given by Bigsby in his History of Repton, also by W. H. St. John Hope, in Vol. VI. of the Derbyshire Archæological Journal. From this inventory, and Mr. St. John Hope’s articles in the journal, a very good account and description can be given of the Priory as it was at the time of its dissolution.

The dissolved Priory was granted to Thomas Thacker in 1539, he died in 1548, leaving his property to his son Gilbert. He, according to Fuller (Church History, bk. vi., p. 358), “being alarmed with the news that Queen Mary[54] had set up abbeys again (and fearing how large a reach such a precedent might have), upon a Sunday (belike the better day, the better deed) called together the carpenters and masons of that county, and plucked down in one day (churchwork is a cripple in going up, but rides post in coming down) a most beautiful church belonging thereto, saying “he would destroy the nest, for fear the birds should build therein again”.” The destruction took place in the year 1553. How well he accomplished the work is proved by the ruins uncovered during the years 1883-4.

This Gilbert died in 1563, as set forth on the mural tablet in the south aisle of Repton Church, a copy of which I have made, so that my readers may see what sort of a person he was who “wrought such a deed of shame.” Gilbert sold the remains of the Priory to the executors of Sir John Port in 1557, he and his descendants lived at the Hall till the year 1728, when Mary Thacker, heiress of the Manor of Repton Priory, left it, and other estates, to Sir Robert Burdett, of Foremark, Bart. Since that time the Hall has been occupied by the Headmasters of Repton School.

The Priory followed the usual plan of monastic buildings, differing chiefly in having the cloister on the north of its church, instead of the south. This alteration was necessary owing to the river Trent being on the north. In choosing a site for monasteries the water supply was of the first consideration, as everything, domestic and sanitary, depended on that. The Conventual buildings consisted of Gate-house, Cloister, with Church on its south side, Refectory or Fratry on its north. The Chapter Rouse, Calefactorium, with Dormitory above them, on its east side. Kitchens, buttery, cellars, with Guest Hall over them, on its west side. The Infirmary, now Repton Hall, “beside the still waters” of the Trent, on the north of the Priory. The Priory precincts, (now the Cricket ground), were surrounded by the existing wall on the[55] west, south, and east sides; on the north flowed, what is now called, “the Old Trent,” and formed a boundary in that direction.

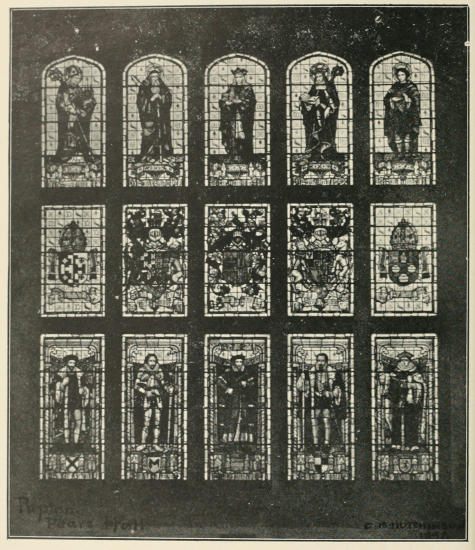

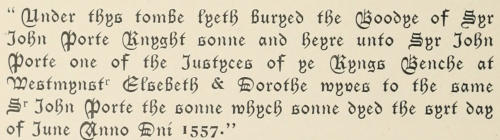

Plate 8.

Sir John Porte Knt. The Founder of Repton School. (F. C. H.) (Page 62.)

Gilbert Thacker. (Page 54.)

On the east side of the Priory was the Mill. The wall, with arch-way, through which the water made its way across the grounds in a north-westerly direction, is still in situ in the south-east corner of the Cricket ground. The Priory, and well-stocked fish ponds, were thus supplied with water for domestic, sanitary, and other purposes.

The bed of the stream was diverted to its present course, outside the eastern boundary wall, by Sir John Harpur, in the year 1606.

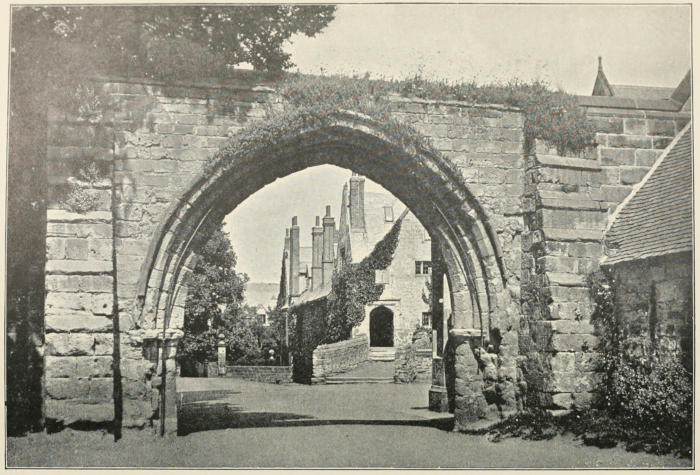

The Gate-house (now represented by the School Arch, which was its outer arch, and wall) consisted of a square building with an upper chamber, and other rooms on the ground floor for the use of the porter. Two “greate gates,” with a wicket door let into one of them, for use when the gates were closed, or only pedestrians sought for admission, provided an entrance to the Priory. Proceeding through the arch-way of the Gate-house, we find ourselves in the precincts. In the distance, on our left hand, was the Parish Church of St. Wystan, on our right the Priory Church and conventual buildings.

The Priory Church consisted of nave, with north and south aisles, central tower, north and south transepts, choir, with aisles, and a south chapel, and a presbytery to the east of the choir. The Nave (95 ft. 6 in. long, and, with aisles, 51 ft. 8 in. wide) “was separated from the aisles by an arcade of six arches, supported by clustered pillars of good design, and must have been one of the most beautiful in this part of the country, all of exceptionally good character and design, and pertained to the transitional period of architecture which prevailed during the reign of Edward I., (1272-1307), when the severe simplicity of the Early English was merging into the more flowing lines of the Decorated.” In the north aisle the foundations of an older church, perhaps the original one, were discovered in 1883-4.

There were several Chapels in the Nave, two of which are named, viz., “Oʳ lady of petys Chapell” and the “Chapell of Saint Thomas,” with images, “reredoses, of wood gylte, and alebaster,” “and a partition of tymber seled ouerin seint Thom’s Chapell.” “vij. peces of tymber and lytell oulde house of tymber,” probably the remains of a shrine, and “xij. Apostells,” i.e. images of them. “j sacrying bell,” sanctus bell, used during the celebration of the mass. In the floor, in front of the central tower arch, a slab was discovered, (6 ft. 4 in. by 3 ft. 2 in.), bearing a rudely cut cross, with two steps, and an inscription, in Old English letters, partly obliterated, round the margin “(Orate pro) anima magistri edmundi duttoni quondam canonici huius ecclisie qui obiit ... januarii anno diu mcccclᵒ cui’ ppic (deus Amen).” This slab is now lying among the ruins at the east end of the Pears School.

Central Tower (25 ft. by 21 ft. 6 in.) supported by four large piers. Between the two eastern piers there was a pulpitum, a solid stone screen (5 ft. 4½ in. deep), with a door in the centre (4 ft. 4½ in. wide). In the northern half was a straight stone stair leading to the organ loft above, where was “j ould pair of Organs,” a phrase often met with in old inventories, and church accounts, in describing that instrument of music. Through the passage under the screen we enter the Choir. The step leading down to the choir floor, much worn by the feet of the canons and pilgrims, is still in situ. The Choir (26 ft. wide, 31 ft. long) was separated from the south Choir aisle, by an arcade of five arches, from the north choir aisle, by an arcade of three arches. All traces of the Canons’ stalls have gone, but there was room for about thirty-four, thirteen on each side, and four returned at the west end of the Choir. In the Choir was the High Altar with “v. great Images” at the back of which was a retable, or ledge of alabaster, with little images, (on a reredos with elaborate canopies above them). “iiij lytle candlestyks” and “a laumpe of latten,” i.e., a metal chiefly composed of copper, much used in church vessels, also “j rode” or cross.

On the south of the choir was a chapel dedicated to St. John, with his image, and alabaster table, similar to that in the choir. To the south of St. John’s Chapel was the “Chapel our Lady” similarly ornamented, these two chapels were separated from the south transept by “partitions of tymber,” or screens, the holes in which the screens were fixed are still to be seen in the bases of the pillars. On the east of the choir was the Presbytery. In the South Transept was the Chapel of St. Nicholas with images of St. John and St. Syth, (St. Osyth, daughter of Frithwald, over-lord of the kingdom of Surrey, and Wilterberga daughter of King Penda). Of the North Choir Aisle nothing remains: it is supposed that in it was the shrine of St. Guthlac, whose sanctus bell is thus referred to by the visitors in their report “superstitio—Huc fit peregrinatio ad Sanctum Guthlacum et ad eius campanam quam solent capitibus imponere ad restinguendum dolorem capitis.” “Superstition. Hither a pilgrimage is made to (the shrine of) St. Guthlac and his (sanctus) bell, which they were accustomed to place to their heads for the cure of headache.” The North Transept was separated from the north choir aisle by an arcade of three arches, immediately to the east of which the foundations of a wall, about six feet wide, were discovered, which, like those in the north nave aisle, belonged to an older building. Many beautiful, painted canopies, tabernacle work, &c., were found among the débris of the north transept and aisle, which no doubt adorned the shrines, and other similar erections, which, before the suppression of the monasteries, had been destroyed, and their relics taken away—that is, probably, the reason why we find no mention of the shrines of St. Guthlac, or St. Wystan in the Inventory.

In the western wall of the North Transept there was a curious recess (13 ft. 10 in. by 4 ft. 10 in.) which may have been the armarium, or cupboard of the Vestry, to hold the various ornaments, and vestments used by the Canons, “j Crosse of Coper, too tynacles, (tunicles), ij albes, ij copes of velvet, j cope of Reysed Velvet, iiij[58] towels & iiij alter clothes, ij payented Alterclothes,” &c., &c.

Leaving the Church, we enter the Cloister, through the door at the east end of the Nave, it opened into the south side of the Cloister (97 ft. 9 in. long by 95 ft. wide). Here were “seats,” and “a lavatory of lead,” but, owing to alterations, very little indeed is left except the outside walls. Passing along the eastern side we come to the Chapter House, the base of its entrance, divided by a stone mullion into two parts, was discovered, adjoining it on the north side was a slype, or passage, through which the bodies of the Canons were carried for interment in the cemetery outside. The slype (11¾ ft. wide by 25½ ft. long) still retains its roof, “a plain barrel vault without ribs, springing from a chamfered string course.” Next to the slype was the Calefactorium or warming room. Over the Chapter House, Slype, and Calefactorium was the Dormitory or Dorter, which was composed of cells or cubicles.

The Fratry or Refectory occupied the north side of the Cloister, here the Canons met for meals, which were eaten in silence, excepting the voice of the reader. A pulpit was generally built on one of the side walls, from which legends, &c., were read. Underneath the Fratry was a passage, leading to the Infirmary, and rooms, used for various purposes, Scriptorium, &c. At the east end of the Fratry was the Necessarium, well built, well ventilated, and well flushed by the water from the Mill race.