“Here is a pretty, new book, made to catch the attention of my darling.”

COBWEBS TO CATCH FLIES.

“Here is a pretty, new book, made to catch the attention of my darling.”

OR,

Dialogues in Short Sentences.

ADAPTED TO CHILDREN FROM THE AGE OF THREE

TO EIGHT YEARS.

A NEW EDITION, REVISED AND ILLUSTRATED.

NEW YORK:

C. S. FRANCIS & CO., 252 BROADWAY.

BOSTON:

J. H. FRANCIS, 128 WASHINGTON STREET.

1851.

ADVERTISEMENT.

The writer of these volumes was advised by a friend to prefix an Advertisement to them, explaining their design. Her answer to that friend was to this effect:

“Those for whom they are designed will not need an explanation; and others will not regard it. The mother, who is surrounded by smiling prattlers, will enter with spirit into my first Dialogues: will declare that they are such as she has wished for a thousand times; and that she esteems herself obliged to me, for having condescended to march in shackles, for the sake of keeping pace with her infant; she will be aware of some difficulty in the task; she will (to pursue the metaphor) allow that it is not easy to move gracefully, when we shorten our steps to those of a child. She will, therefore, pardon such inaccuracies as arise from the necessity of confining the language to short words.

“For the rest, I am persuaded (from experience and[Pg vi] the remarks of the most judicious mothers) that a book of this kind will be acceptable.

“The mother who herself watches the dawn of reason in her babe; who teaches him the first rudiments of knowledge; who infuses the first ideas in his mind; will approve my Cobwebs. She will, if she be desirous of bringing her little darling forward; (and where it can be done with ease and satisfaction, who is not?) she will be aware of the consequence of the first lessons, where nothing meets the eye of the learner but objects with which he is already familiar; nothing arises to his mind, but subjects with which he begins to be acquainted; sentiments level to his capacity, explained in words which are suited to his progress.

“Such is the Cobwebs designed to be; if such it be, it will meet the smile of Mothers. It was written to please a set of children dear to the writer; and it did please them; and in the hope that it may be agreeable to other little people, it is given to the public.”

[Pg vii]

TO MY LITTLE READERS.

My Dears:

Do not imagine that, like a great spider, I will give you a hard gripe, and infuse venom to blow you up. No; I mean to catch you gently, whisper in your ear,

and then release you, to frisk about in pursuit of your innocent pastimes.

Dear little creatures! enjoy your sports; be as merry as you will; but remember the old proverb,

Your whole duty is contained in one short precept,

Happy little creatures! you will never taste such careless hours as you do now; when you grow up, you will have many cares; you may have many sorrows; yet assure yourselves, if you be good, you will be happy; be happy for ever. Remember this, my dear little readers, from

Your Friend,

THE AUTHOR.

[Pg 9]

COBWEBS TO CATCH FLIES.

Frederick. I saw a rat; and I saw the dog try to get it.

Ann. And did he get it?

Frederick. No: but the cat did.

Ann. My cat?

[Pg 10]

Frederick. No: it was the old cat.

Ann. How did she get it? Did she run for it?

Frederick. No: it is not the way:—she was hid—the rat ran out; and, pop! she had him.

Ann. A dog can run.

Frederick. Yes; but a cat is sly.

Ann. The kit can not get a rat.

Frederick. No; she can not yet; but she can get a fly. I saw her get a fly.

[Pg 11]

Boy. See our cat! she can see a rat. Can she get it and eat it up?

[Pg 12]

Mother. Yes, she can: but she was bit by an old rat one day.

Boy. Ah! my Kit! why did you try to get the old rat! One day the dog bit our cat; he bit her jaw. Did the cat get on my bed?

Mother. Yes; but she is off now.

Boy. Why did she get on the bed?

Mother. To lie on it, and purr.

Boy. Now, Puss, you are up. Why do you say Mew? Why do you say purr?

You may lie by me, Cat. See her joy as I pat her ear.

Why do you get off the bed? Why do you beg to be let out?

[Pg 13]

Mother. So she may go to her kit.

Boy. Has she a kit? Why do you go to the kit? Is she to go?

Mother. Yes; let her go.

Mother. Now get up; it is six.

Boy. O, me! is it six?

Mother. Yes, it is; and the dew is off.

Boy. I see the sun. Is it fit for me to go out?

[Pg 14]

Mother. Now it is; but by ten it may be hot. So get up now.

Boy. May I go to-day, and buy my top?

Mother. Yes, you may.

Boy. A peg-top? Sam has a peg-top. He has let me use his. One day he did.

[Pg 15]

I met Tom one day, and he had a top so big!

I can hop as far as Tom can.

Tom has a bat too! and Tom is but of my age.

Let us buy a cup and a mug for Bet.

And let us get a gun for Sam.

And a pot and an urn for Bet.

An ant has bit my leg. See how red it is!

May I get a bag for Sue?

Mother. Can you pay for it?

Boy. O, no! but you can pay for all. May the dog go?

Mother. Yes, he may go.

Boy. I see him: may I let him in?

[Pg 16]

First Boy. I see a man! The man has a dog. The man has got in.

The dog has not got in: but the man has got in.

Mother. Do not cry, dog; you will see the man by-and-by. Dog! why do you cry?

Second Boy. I can not see.

First Boy. You are too low. Get up.

Second Boy. I can not get up.

First Boy. Try;—now you are up.

[Pg 17]

Second Boy. I see the cow.

First Boy. I see two. I see the red cow; and I see the dun cow.

Second Boy. I see a hog. Pig! pig! pig! why do you run?

First Boy. Now I see one, two, six—yes, ten hogs. Why do you all run?—Now let us go off.

Second Boy. You can not see me.

First Boy. You are hid.

Second Boy. I see you. Can you not see me?

First Boy. O, now I can get up.

Second Boy. No, I can run; you can not get me.

[Pg 18]

First Boy. Yes, I can.

Second Boy. Let us go to Tom.

First Boy. We must not go out.

Second Boy. I can get out.

First Boy. So can I; but do not go yet.

Second Boy. Why may not we go yet?

First Boy. Do as you are bid, and do not ask why, is the law for a boy.

[Pg 19]

Boy. I love the dog. Do not you?

Mother. Yes, sure.

Boy. Wag! do you love me?

Mother. You see he does; he wags his tail. When he wags his tail, he says, I love you.

[Pg 20]

Boy. Does his tail tell me so?

Mother. Yes; it says, I love you; I love you; pray love me.

Boy. When we go out, he wags his tail: what does his tail say then?

Mother. It says, Pray let me go; I wish to go with you.

Boy. I love to have him go with me.

Mother. Here is a cake for you.

Boy. Nice cake! See the dog! how he wags his tail now! Why do you wag your tail? Why do you look so? Why does he wag his tail so much?

Mother. To beg for some cake. His tail says, I love you; you have a cake,[Pg 21] and I have none: will you not be good to me? Will you not give some of your cake to your poor dog?

Boy. Poor dog! do you want some cake? take a bit. Here! I hold it to him, but he does not take a bit.—Take some; O, he has got it all! he was not to take all. Fie, Wag! to take all! Now I have none left. You are rude, Wag.

Mother. He did stay some time.—Here, I will give you a plum-cake.

Boy. Now you are to have none, Wag. You are to have none of this cake; you were rude.

Mother. He did not know that he[Pg 22] was not to take all. He can not know all that you say.

Boy. Well, you may have a bit of this. I will take a bit off and give it to him.

Mother. Do so. You are a good boy. We must be kind to all. We must give to them who want.

Boy. Why do you ask for more?

Mother. He has not had a meal to-day. He had not a bit till now. You have had food.

Boy. I hope he will have meat at noon. I will ask cook to give him a bone; and he may have some milk, and[Pg 23] he can have some bran. Cook will boil them for him. Poor dog! he can not ask as we can, so I will ask for him. Wag, I wish you could talk. Why does he bark at poor men?

Mother. When he sees a man whom he does not know, then he says, “Who are you?—who are you?—why do you come?—what do you do here?—I am at home—I must tell the folks—I must tell that you are here—I will call our folks to look at you. Come out, man; come out, maid—see who this is.—Bow, wow, wow, wow!”

Boy. Does the dog say all that?[Pg 24] Why does he stop as soon as the folks come out?

Mother. He is so wise as to know that he need bark no more then. If he means to call them out, he will stop when they are come out.

Boy. Wag, why do you gape when you are hot? Can you tell me why he does so?

Mother. To cool his tongue.

[Pg 25]

Boy. I do not love pigs.

Maid. A pig is not so nice as a fowl; yet we must feed the pigs. Pigs[Pg 26] must eat as well as boys. Poor pigs want food.

Boy. Do they cry for food? I hear them cry.

Maid. They cry to me for food; in the way they can call, they call—“Pray feed me; pray feed me! do pray feed me now!”

Boy. What do you give them?

Maid. This pail full of milk. Will you not like to see them? They will be so glad!

Boy. How they jump! how they run to the gate! why do they run so?

Maid. They are glad to see me.[Pg 27] They know me; I feed them when they want food; and you see they love me.

Boy. I like to see them so glad. I like to see a pig fed; but I love a lamb; may I not love a lamb more than I do a pig?

Maid. Yes; but you must be good to all.

Boy. My aunt has a tame lamb, I love to give him milk; once I saw a fawn, I do not mean in a park, but I saw a tame fawn; the old doe was dead, so we fed the fawn at home. We kept him a long time, but he bit off the buds.

Maid. Have you seen a goat?

[Pg 28]

Boy. Yes; he has not wool; he has hair.

Maid. Now you may go with me. We will go and see the cows.

Boy. Why is one duck by itself?

Maid. The duck sits; she has a nest just by. I must feed her: she will not go far from her nest. The rest can get food. You may give her some corn; we will get some for her. Come.

Boy. I like to feed the poor duck.

[Pg 29]

Girl. What a nice doll! I like this; pray may I have this? I wish to have a wax doll.

Mother. You must then take care to keep her cool, else you will melt her face; and she must be kept dry, or this nice pink on her face will be lost.

Girl. What a neat coat! I love a blue silk. And her hat! I love a doll in a hat. What sort of a cap have you, miss! but a poor one; but it is not much seen. She has some soil on the neck. I can rub it off, I see. No, that[Pg 30] will not do; I must not wet her skin. What sort of a foot have you? O! a nice one; and a neat silk shoe: a blue[Pg 31] knot, too; well, that is what I like; to suit her coat. I am fond of blue, too. Now, miss, when I have you home with me, then I am to be your maid; to wait on you. Will not that be nice! I will take care of you, and keep you so neat! and I will work for you; you can not sew, nor hem; and I will read to you in my new book; and I will take you out with me when you are good. You shall sit by me near the tree, on a low seat, fit for you. I wish you to walk. Can not I make you walk? so—step on—see how my new doll can walk!

Mother. You will pull off her legs, my dear.

[Pg 32]

Girl. Now if I had a pin to pin this sash back. Stay, I can tie it. O me! see! here is a bag for her work! who has seen the like? a bag for her work! I must have this doll—if you like it, I mean.

Mother. You must then work for her. You will have much to do. To make and mend all that your doll will want to wear. Will not you wish her in the shop? I fear that you will; you who are so fond of play.

Girl. Work for my doll will not tire me.

Mother. Take it, then.

Girl. You are so good! pray let me[Pg 33] kiss you. I must kiss you too, my dear doll, for joy.

Girl. I like this frock; but it will not keep on. Why will it not keep on?

Maid. It is too big for you, miss.

Girl. It is off; it will fall off.

Maid. You had best lay it down, miss.

Girl. I like to have it; I will put it on.

[Pg 34]

Mother. My dear! lay it down when you are bid to do so; do not wait to be made to do well.

Girl. I will not, mamma. Jane, I will be good. Pray may I look in this box?

Mother. You see it is shut now; you may see it by-and-by.

Girl. I will not hurt the lock.

Mother. You must not try.

Girl. May I play with your muff?

Mother. You may.

Girl. What is this made of?

Mother. Fur; and fur is skin with the hair on.

[Pg 35]

Girl. It is like puss; how soft it is! How warm it is when I hold it to my nose! it is like wool.

Mother. Now come and kiss me; I am sure you will be good to John; go and play with him.

Girl. Do you stay all day? do you stay till John is in bed?

Mother. Yes; till you are both in bed. Now go.

Girl. Pray let me get my work-bag first. May I get my work-bag?

Mother. Why do you want it?

Girl. I want some silk out of it, that I may work a ball for John.

[Pg 36]

Lady. What does the baby want? what does that mean?

Girl. It is his way to say please.

Lady. And what does he wish?

Girl. To have your fan: but he will tear it.

Lady. Can you take care of it?

Girl. O yes; I can show it to him.

Lady. Take it; and let him see it.

Girl. Now sit by me. Pray sit him down by me. Look! no, you must not[Pg 37] have it. I must keep it in my hand. You can not hold it. Here is a boy. See, he runs to get that bird. O fie! do not get the bird. No! you must not put the bird in a cage. Let the bird fly; let him sing; and let him help to make a nest. Do not hurt the poor bird. You must be good and kind. You must not vex the bird. Here is a girl. Look at her pink coat. Here is her foot. She has a blue shoe. She is at play with the boy. Miss! you must be good. You must tell the boy to be good, that we may love him. All good folks will love him, if he be good, not else. Now let us turn the fan. Now we will look[Pg 38] at this side. Here is a nice pink. This is a rose. That is a fly.

Mother. Now John will walk. Ring the bell. Go and walk with the maid.

Girl. Am I to go?

Mother. As you like.

Girl. I like best to stay; but John says with his hand, “pray go.” I will go then; dear boy! I will go with you.

Mother. Good girl.

Girl. John! you must love me; I wish to stay here, and you hear that I may stay.

Mother. Take hold of him and lead[Pg 39] him out. You will meet the maid at the door.

Boy. I will have a book. I will have one with a dog in it. May I not?

[Pg 40]

Mother. Yes, you may.

Boy. Let me see, here is a goat. Do look at his face; how like it is to a goat! Here is a ball, and a lamb with wool on it, just like my lamb that I feed at home. And here is a cock. Can you crow? Crow and tell us that it is time to rise. Can you not? What a tail he has! a fine tail! No, I will not have that, for his tail will soon be off. Some part of it is come off now.

Mother. You must not pull; you do harm.

Boy. I did not pull hard.

Mother. You are a long time.

[Pg 41]

Boy. O, here is a fine horse! I like this horse. I like his long tail. You shall not have your tail cut—no, nor your ears: but you can not feel. Come, sir, walk and trot. Do you move well? I will rub you down, and give you oats and hay, and chop straw for you. I will be good to you, not whip you much—No more than just to say—Now go on;—nor spur you, nor gall your poor skin; no, nor let the hair rub off. So—you set your tail well; but if you did not, Tom must not nick you; no, nor yet dock your poor tail; you will want it to keep the flies from you when it is hot.[Pg 42] I see poor Crop toss his head all day; he does it to keep the flies from him; but it is all in vain, he can not keep them off. I will be good to you; I will tend and feed you; and I will not ride too hard, and hurt your feet; nor trot on hard road, so as to make you fall and cut your knees; but I will pat your neck when I get up, and I will make you know me: so that you will turn your head, and seem to like to have me get on your back. At night, you must have a warm bed. When I have rode you in the day, I will see that you have good corn, and hay, and straw; and Tom[Pg 43] must wash the hot sand out of your poor feet, so that they may not ache, and make you grow lame.

Mother. I can not but give you the horse, as you seem to plan so well for him; I hope you will be good and kind to all things.

Boy. I do not care now for the lamb, nor for the—

Mother. My dear, I would have you know your own mind; if you get the trick to like now this, now that, and now you know not what, it will do you harm all your life.—So it is that boys and men spend too much; so it is that they act like fools. I would give you all the[Pg 44] toys in the shop, if it were for your good to have them: the horse you have; now take something else; take the book, do you like the book?

Boy. I do; I thank you, mamma. I will keep the horse, and I will give the book to Jack. O! my dear horse, how I love you!

[Pg 45]

Father. Shall we take a walk, my son?

[Pg 46]

Boy. Yes, sir, where shall we go?

Father. Let us go by the farm yard into the fields.

Boy. See! a horse and a cow stand by the fence in the yard. Now we are in the field. Is it full of nettles?

Father. No, not so, it is hemp.

Boy. What is that for, papa?

Father. To make cloth of; the stalk has a tough peel on it, and that peel is what they make thread of. The thread they weave, and make strong cloth.

Boy. I want to know all the trees: pray what leaf is this?

Father. That is an oak; that bush[Pg 47] is May; we call it too White-thorn; it blooms late in May; its fruit are called Haws; so we call it Haw-thorn. The birds eat the fruit. That is Black-thorn; that blooms soon in Spring; it has a white bloom, and has then few or no leaves. The fruit is a sloe. They are like a small blue plum; but so sour that you can not eat them.

Boy. What is this?

Father. Wild rose; its fruit are Hips; they are kept, and we take them for coughs. That is broom; it has a bloom like a pea in shape, but it is yellow.

[Pg 48]

Boy. There is a bush of it in bloom.

Father. No: that is Furze, such as you see on heaths. Feel this; Broom does not prick like this.

Boy. I will keep a leaf of each to show to James.

Father. You may put them in a book, and write what I have told you.

Boy. I will get all sorts of plants; and I will mark by each the name, the place, the bloom, the time when it blows, and the use which is made of it.

[Pg 49]

First Girl. My doll’s quilt is of chintz. What is this?

Second Girl. French Print.

First Girl. Let us take the doll up.

Second Girl. With all my heart.

First Girl. Where are her clothes?

Second Girl. Here they are; some in this trunk, and some hang in the press.

First Girl. Bless me! what a nice press! I have a trunk at home, in my doll’s house; but I have no press.

[Pg 50]

Second Girl. Here are her linen and coat; those shoes are her best, do not put them on; take these.

First Girl. What gown does she put on?

Second Girl. Her white one. I will take it out, whilst you lace her stays.

First Girl. What is her best cloak?

Second Girl. White; with a neat blond-lace round it.

First Girl. Mine has a muff; has your doll a muff?

Second Girl. No, she has not; my aunt says she will teach me to do chain stitch; and then I am to work one.

[Pg 51]

First Girl. What is her best dress?

Second Girl. You shall see them all; there is the dress which I like best.

First Girl. Why do you like it best?

Second Girl. It is my dear mother’s work; see how neat it is; and there is a green silk.

First Girl. My doll’s best dress is brown with a stripe of blue; and she has a white, wrought with a moss rose, a pink, and a large bunch of leaves: that was her best, but it is just worn out now; she must leave it off soon.

Second Girl. Why does she wear it so long?

[Pg 52]

First Girl. I had a half-dollar to buy her a piece of silk; as I went in the coach with my aunt to buy it, we met a poor child who had no clothes, but the worst rags which you can think.

Second Girl. And you gave it to her. My doll should wear her old gown for a long time, for the sake of such a use to put my half-dollar to.

First Girl. I had more joy in that, than I could have had in my doll’s new dress. Dolls can not feel the want of clothes.

Second Girl. Now let us go down stairs.

[Pg 53]

First Boy. I see no toys—How do you pass your time?

[Pg 54]

Second Boy. I feed the hens, and the ducks; I see the calf fed.

First Boy. And what do you do else?

Second Boy. I go out and see the men plough; I see them sow; and when I am good, they give me some corn.

First Boy. And what do you do with it?

Second Boy. I sow it; I love to see it come up. I have some oats of my own; they are just come up; I wish they were ripe, we would cut them.

First Boy. What is done with oats?

Second Boy. Horses eat them.

[Pg 55]

First Boy. We eat wheat. John says the bread is made of wheat.

Second Boy. I make hay; I have a rake and a fork; and I ride in the cart. I rode last year.

First Boy. I ride in papa’s coach; and I walk when it is fair and warm; but I have no tools to work with; I wish I had. I love a toy when it is new, just the first day I love it; the next day I do not care for it.

Second Boy. I have a spade and a hoe, and a rake; and I can work with them; and am never tired of them. When I am a man I will have a scythe,[Pg 56] and mow in the fields. I have a bit of ground of my own to work in.

First Boy. Where is it? pray show it to me.

Second Boy. Here; come this way. There; you see I have a rose bush; I wish I could find a bud. Here is a white pink: they blow in the spring. Do you like pinks?

First Boy. We have fine large pinks at home; but these are as sweet—I thank you.—I should like pinks of my own.

Second Boy. I will give you some slips in June; and show you how to[Pg 57] plant them; and I can give you some seeds which I took care of last year.

First Boy. You are good to me I am sure; when you come to see me, I will ask for some fruit to give to you.

Second Boy. I have a pear tree; that tree is mine, and we get nuts from it.

First Boy. We have grapes, and figs, and plums; but I love a peach best, it is so full of juice.

Second Boy. We have none of them; I shall like to taste them. Now I will show you our bees; the hives stand just by. When we take them up, you shall have some comb.

[Pg 58]

Miss. How do you do, nurse? I am come to see you. Mamma gave me leave to come and spend the day with you.

Woman. I am glad to see you here, Miss.

[Pg 59]

Miss. Pray call me as you did when I came to you to stay; you were so good to me! you soon made me well. I like you should say, My dear. I love you.—I ought to love those who are kind to me, and nurse me.

Woman. I did not think you would have me say so. But, my dear, if you are so good, I think I cannot but love you.

Miss. Where is Betsy? I want to see her.

Woman. She shall come; she longs to see you; I see her; she is just by.

Little Girl. How do you do; I am glad to see you here, Miss.

[Pg 60]

Miss. Ah, Betsy! how you are grown! I should scarce know you.

Little Girl. You are as much grown, Miss; you were but so tall when you were here.

Miss. Let us run and jump; and I want to see all your things.

Little Girl. Will you like to see the cows? or shall we go and see the lambs?

Miss. O, yes! let us go.

Little Girl. They are just by. I have a tame lamb; I reared it with milk, warm from the cow.

Miss. I like sheep, they look so mild; when I went home I had a great[Pg 61] deal to tell my sister. She did not know that a lamb was a young sheep.

Woman. How could she, my dear, till she was told?—you would not have known, if you had not been told.

Miss. I told her that we cut the wool off the backs of the sheep, and wore it. I told her how I had seen the lambs frisk and jump. I told her that I had seen you milk, and make cheese;—she did not know that cream came off the milk!

Woman. Did you know when you came to me?

Miss. No—I did not.

[Pg 62]

Woman. You cannot know what you are not taught.

Miss. Tell me more, and when I go home I will tell my sister.

Woman. Come with me and we will talk; and I will show you the cow and her calf.

[Pg 63]

Boy. Where is James.

Lady. He is in the house; you may go to him there.

[Pg 64]

Boy. If you please, I like to stay here.

Lady. What shall we do?

Boy. I wish to have my knife and a stick; then with this small piece of board I will make a chair for Jane’s doll.

Lady. That will please Miss Jane; that piece will do for a couch; you might stuff it with wool.

Boy. I wish I could; pray will you teach me how to do it?

Lady. If you make the frame well, I will stuff it for you.

Boy. Thank you; I think Jane will dance for joy.

[Pg 65]

Lady. She does not dream of such a nice chair; stay, this is the right way to cut it; you must not notch it so.

Boy. I think I hear Jane’s voice; I would not have her come till it is done. Will she thank me?

Lady. Yes, sure; she ought to thank you.

Boy. Why does she sleep in the day?

Lady. She is a babe—you slept at noon, when you were so young.

Boy. Now I do not sleep till night. I hear my ducks; what do you quack for?—May I fetch them some bread? Here is a crust which I left; pray may I give it to them?

[Pg 66]

Lady. If it be clean, some poor child would be glad of it; that is a large piece—We will give chaff to the ducks.

Boy. This bread is made of wheat; wheat grows in the earth; wheat is a grain. I am to see Tom bind a sheaf: and when Tom goes home to shear his sheep, I am to see him. He will throw them in a pond: plunge them in! Our cloth is made of wool; how can they weave cloth, and how can they stain it? How light this chair will be! it will not weigh much.

Lady. Who heard the clock; I meant to count it. I left my watch in my room.

[Pg 67]

Boy. Why did you leave it?

Lady. The chain was broken last night.

Boy. I like to have my couch of green. Jane loves green. What do you call this?

Lady. A blush, or faint bloom; some call it bloom of peach; it is near white. That is quite white.

Boy. May I sit on the grass? I love to sit in the shade, and read my book.

Lady. The earth is as dry as a floor now.

Boy. If I could reach those sweet[Pg 68] peas I would get some seed; they are such nice round balls. Jane likes them to play with.

Lady. You may go now and fetch a quill for me; do not put it in your mouth. While you go, I shall go on with the work.

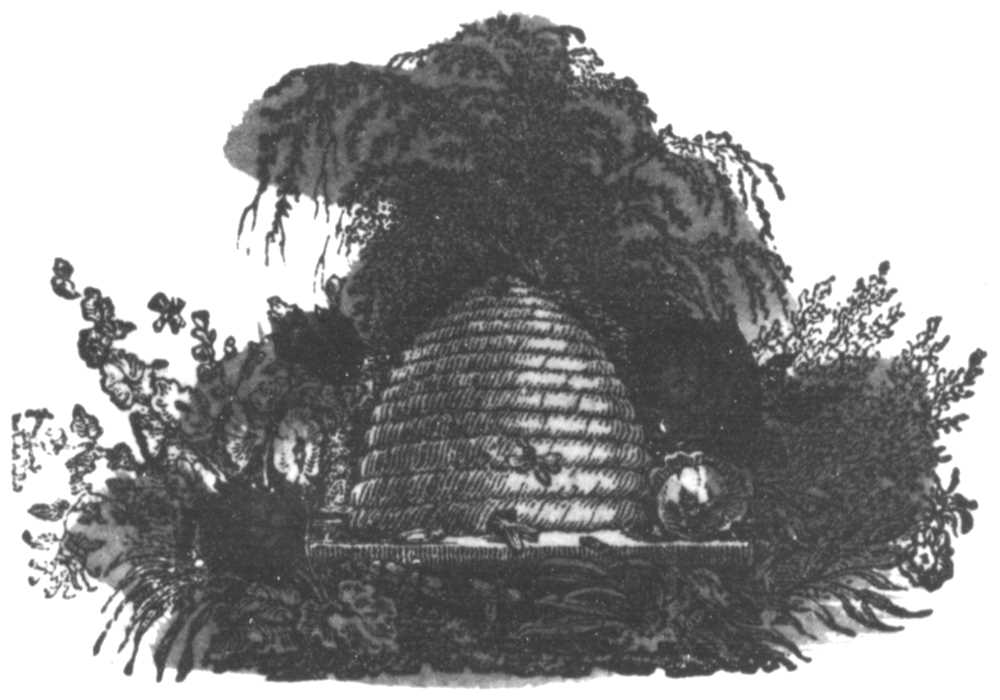

A little girl was eating her supper; it was bread and milk, with some honey. “Pray,” said the little girl, “who makes honey for my supper?”

Mother. The bees collect it.

[Pg 69]

Girl. Where do they find it?

Mother. In the flowers.

Girl. Where do the bees live?

Mother. Those which supply us with honey, live in a hive.

Girl. What is it made of?

Mother. Ours are made of straw.

Girl. Pray, mamma, tell me a great deal about the bees, whilst I eat my milk.

Mother. In the night, and when the weather is cold, they keep in the hive. When the sun shines, and the days are warm, they fly abroad. They search far and near for such flowers as supply[Pg 70] them with honey or wax. Of the wax they make cells which we call comb. In some of the cells they lay up stores of honey to support them in the winter, when they can not venture out to seek for food. In some of the cells they nurse their young ones, who have no wings. They are very neat creatures; they keep the hive quite clean. They carry out the dead bees.

[Pg 71]

The next morning this same little girl was eating her breakfast. It chanced that the maid had let fall a drop of honey as she mixed her milk; and a fly came and stood on the edge of her basin to suck it.

The good child laid aside her spoon to avoid frightening the poor fly.

What is the matter, Sarah? are you not hungry?

Yes, mamma; but I would not hinder this little fly from getting his breakfast.

Good child! said her mother, rising from her tea; we will look at him as he[Pg 72] eats. See how he sucks through his long tube. How pleased he is!

Mother, can not flies make honey? said the little girl.

“No,” said her father, “they are like you, they can not make honey, but they are very fond of eating it.”

What do flies do, father?

Father. They are as idle as any little girl of you all; they frisk and buzz about all the summer, feeding upon what is made by others.

Girl. And in winter what do they do?

Father. Creep into some snug corner.

Girl. But what do they eat then?

Father. They sleep, and want no food.

[Pg 73]

A little boy saw a spider; its legs were all packed close to its body; the boy thought it was a bit of dirt, and was going to pick it up.

His father stopped him, lest he should chance to hurt the spider; he told him that the poor creature had rolled himself up from fear; that if he stood still he would soon see the spider move.

The little boy kept close and quiet some time, watching the spider; he saw it unfold one leg, then another, till at last they were all loose, and away it ran. Then the little boy ran after his father, and heard the history of spiders.

[Pg 74]

He told him a great deal about them. Then he talked to him of other insects, which disguise themselves to escape the dangers which they meet with.

He picked up a wood-louse, and laid it gently in his little hand. There, said he, you see the wood-louse roll itself into a little ball, like a pea: let it lie awhile and when it thinks that you do not observe it—

Boy. Ah! it unrolls.—O! it will run away: shall I not hold it?

Father. No, my dear, you would hurt it.

Boy. I would not hurt any creature.

Father. No! surely—He who made you, made all creatures to be happy.

[Pg 75]

A boy was walking with his mother; he saw a bird fly past, with some food in its mouth.

Boy. Is not that bird hungry? for I[Pg 76] see that he carries his meat fast in his mouth.

Mother. She is a mother bird, and has young ones in her nest.

Boy. Who makes the nest?

Mother. The old birds.

Boy. How do they make the nests?

Mother. Some make their nests of sticks; some of dry leaves; some use clay; some straw: they use all sorts of things; each kind of bird knows what is fit for its use.

Boy. What do they make nests for?

Mother. To nurse their young in.

Boy. And are they warm?

[Pg 77]

Mother. The old birds line them with moss, with wool, or with feathers, to make them warm and soft.

Boy. Where do they get all these things?

Mother. They fly a great way to fetch them; and sometimes they pluck their own breasts to supply down for their young to lie upon.

Boy. How kind they are!

Mother. So kind are good parents to their children.

Boy. Pray why do the birds sing?

Mother. One old bird sings whilst one sits on the eggs.

Boy. Why do they sit on the eggs?

[Pg 78]

Mother. To keep them warm, so that they may hatch.

Boy. What do you mean by that, pray, mother?

Mother. The young birds break the shells and come out.

Boy. What do they do then? do they fly?

Mother. Not at first: babes, you know, cannot walk.

Boy. But what do young birds do?

Mother. They lie in the nests, and gape for food.

Boy. And do they get it?

Mother. The old birds fly far and[Pg 79] near to fetch it. You saw one with some in its bill.

Boy. I see a bird now with some in its mouth.

Mother. Do not make a noise, lest you fright the poor thing.—Hush! hush!—let us creep gently, and see the bird go to her nest.

They saw the bird alight on a bush just by: she hopped from twig to twig till she got to the nest: she gave the little worm which she had in her beak to her young, and then flew away in search of more.

Boy. Now may I talk?

[Pg 80]

Mother. Yes, my dear;—are you not pleased to see the birds?

Boy. Yes, mother.—When will the little ones fly?

Mother. When they have got all their feathers.

Boy. How will they learn?

Mother. The old birds will teach them to fly as I taught you to walk.

Boy. I hope the little birds will always love their mothers. I shall always love you; mother, pray kiss me.

[Pg 81]

There were eight boys and girls of the name of Freelove; their kind parents taught them to do as they were bid in all things. They were the happiest children in the world; for, being used to control, they thought it no hardship to obey their friends. When one of them[Pg 82] had a mind to do anything, and was not sure whether it would be right, he went in to inquire, and was always content with the answer. If it was proper, he was certain to have leave: and if it was not proper, he had no longer a wish to do it, but was glad that he had asked.

Mr. and Mrs. Freelove took great pains with their children, and taught them, as soon as they could learn, all that was proper for their age; and they took delight in learning, so that it was a pleasure to teach them.

Such a family is the most pleasing scene upon earth.

The children were all very fond of[Pg 83] each other. No one had an idea of feeling joy in which the rest did not share. If one child had an apple, or a cake, he always parted it into eight pieces; and the owner kept the smallest for himself; and when any little treasure was given which could not be so divided, the rest were summoned to see it, to play with it, and to receive all the pleasure which it could afford.

The little folks were fond of books: the elder ones would often lay aside their own, to read aloud to the younger ones in such as were suited to them. In short, they were a family of perfect love. Each boy had a little piece of ground[Pg 84] for a garden, in which he might work to amuse himself. It would have made you smile to see how earnest they were at their work—digging, planting, weeding, and sometimes they had leave to water. Each was ready to lend any of his tools to his brother. Each was happy to assist in any plan, if his brother needed help.

The boys did the chief work in their sisters’ gardens; and their greatest joy was to present little nosegays to their mother and sisters.

There were sheep kept upon the lawn; the pretty creatures were so tame that they would eat out of a person’s hand.[Pg 85] You may believe that the children were very fond of feeding them; they often gave them their little barrow full of greens. There was no danger of the little folks not thinking to perform so pleasing a task as this. One day George was reading aloud to a younger brother, whose name was William—‘Do as you would be done by.’

William. Pray what does that mean?

George. I will show you now; you hear the sheep bleat.

So he ran and got some greens, and gave to the sheep.

George. You see what it is to do as[Pg 86] we would be done by; the poor sheep are hungry and I feed them.

William. I should like to feed them; but I have no greens.

George. Here are some of mine: take some, and give to them.

William. I thank you, brother; now you do to me as you would wish to be done by.

The next day, William saw a poor woman standing on the outside of the iron gates. She looked pensive; and the child said:

What do you want, poor woman?

[Pg 87]

Woman. A piece of bread; for I have had none to eat.

William had a bit in his hand; he had just begun to eat it. He stopped, and thought to himself—If I had nothing to eat, and I saw a person who had a great piece of bread, what should I wish?—that he should give me some. So the good child broke off all but a very little bit, (for he was very hungry) and said,

You shall have this bread which the maid gave me just now. We should ‘do as we would be done by.’

Good boy! said his mother, who chanced to pass that way, come and[Pg 88] kiss me. William ran to his dear mother, and hugged her; saying, I am never so happy as when you say, good boy.

Mother. I was seeking for Mary to tell her that Mrs. Lovechild has sent to have you all go with us: but for your reward, you shall carry the message to the rest. Go; I know it will give you great pleasure to rejoice your brothers and sisters.

[Pg 89]

James and Edward Franklin, with their Sisters, had leave to walk about, and amuse themselves in a fair. They saw a great many people who seemed very happy, many children merry and joyous, jumping about, and boasting of their toys. They went to all the stalls and bought little presents for those who were at home. They saw wild beasts; peeped in show-boxes; heard drums, trumpets, fiddles, and were as much pleased with the bustle around them, as you, my little reader, would have been, had you been there.

[Pg 90]

Mrs. Franklin had desired them not to ride in a Merry-go-round, lest they should fall and hurt themselves.

Did you ever see a Merry-go-round? If you never passed through a country fair, I dare say you never did.

As they passed by, the children who were riding called, “will you ride? will you ride?”

James. No, I thank you, we may not.

Edward. I should like it, if I might.

One girl called, “See how we ride!” One said, “O! how charming this is!” One boy said, “You see we do not fall!”

[Pg 91]

James. I am not fearful; but my mother forbade us to ride.

One boy shouted aloud, “Come, come, you must ride; it will not be known at home. I was bid not to ride, but you see I do.”

Just as he spoke, the part upon which he sat broke, and down he fell.

In another part of the fair, the boys saw some children tossed about in a Toss-about.

They were singing merrily the old nurse’s ditty:

[Pg 92]

The voices sounded pleasantly to Ned’s ear; his heart danced to the notes; jumping, he called to his brother James, “Dear James! look! if I thought our mother would like it, I would ride so.”

James. My dear Ned! I am sure that mother would object to our riding in that.

Ned. Did you ever hear her name the Toss-about?

James. I am certain that if she had known of it, she would have given us the same caution as she did about the Merry-go-round.

Ned paused a moment; then said,[Pg 93] “How happy am I to have an elder brother who is so prudent!”

James replied—“I am not less happy that you are willing to be advised.”

When they returned home, each was eager to relate his brother’s good conduct; each was happy to hear his parents commend them both.

Mr. Steady was walking out with his little son, when he met a boy with a satchel on his shoulder, crying and sobbing dismally. Mr. Steady accosted[Pg 94] him, kindly inquiring what was the matter.

Mr. Steady. Why do you cry?

Boy. They send me to school: and I do not like it.

Mr. Steady. You are a silly boy! what! would you play all day?

Boy. Yes, I would.

Mr. Steady. None but babies do that; your friends are very kind to you.—If they have not time to teach you themselves, then it is their duty to send you where you may be taught; but you must take pains yourself, else you will be a dunce.

[Pg 95]

Little Steady. Pray, may I give him my book of fables out of my pocket?

Mr. Steady. Do, my dear.

Little Steady. Here it is—it will teach you to do as you are bid—I am never happy when I have been naughty—are you happy?

Boy. I cannot be happy; no person loves me.

Little Steady. Why?

Mr. Steady. I can tell you why; because he is not good.

Boy. I wish I was good.

Mr. Steady. Then try to be so; it[Pg 96] is easy; you have only to do as your parents and friends desire you.

Boy. But why should I go to school?

Mr. Steady. Good children ask for no reasons; a wise child knows that his parents can best judge what is proper; and unless they choose to explain the reason of their orders, he trusts that they have a good one; and he obeys without inquiry.

Little Steady. I will not say why again, when I am told what to do; but will always do as I am bid immediately. Pray, sir, tell the story of Miss Wilful.

Mr. Steady. Miss Wilful came to[Pg 97] stay a few days with me; now she knew that I always would have children obey me: so she did as I bade her; but she did not always do a thing as soon as she was spoken to; and would often whine out why?—that always seems to me like saying—I think I am as wise as you are; and I would disobey you if I durst.

One day I saw Miss Wilful going to play with a dog, with which I knew it was not proper for her to meddle; and I said. Let that dog alone.

Why? said Miss—I play with Wag, and I play with Phillis, and why may I not play with Pompey.

[Pg 98]

I made her no answer—but thought she might feel the reason soon.

Now the dog had been ill-used by a girl, who was so naughty as to make a sport of holding meat to his mouth and snatching it away again; which made him take meat roughly, and always be surly to girls.

Soon after Miss stole to the dog, held out her hand as if she had meat for him, and then snatched it away again. The creature resented this treatment, and snapped at her fingers. When I met her crying, with her hand wrapped in a napkin. “So,” said I, “you have been[Pg 99] meddling with the dog! Now you know why I bade you let Pompey alone.”

Little Steady. Did she not think you were unkind not to pity her? I thought—do not be displeased, father—but I thought it was strange that you did not comfort her.

Mr. Steady. You know that her hand was not very much hurt, and the wound had been dressed when I met her.

Little Steady. Yes, father, but she was so sorry!

Mr. Steady. She was not so sorry for her fault, as for its consequences.

[Pg 100]

Little Steady. What, father?

Mr. Steady. Her concern was for the pain which she felt in her fingers; not for the fault which had occasioned it.

Little Steady. She was very naughty, I know; for she said that she would get a pair of thick gloves, and then she would tease Pompey.

Mr. Steady. Naughty girl! how ill-disposed! then my lecture was lost upon her. I bade her while she felt the smart, resolve to profit by Pompey’s lesson; and learn to believe that her friends might have good reasons for their orders; though they did not think[Pg 101] it proper always to acquaint her with them.

Little Steady. I once cut myself with a knife which I had not leave to take; and when I see the scar, I always consider that I ought not to have taken the knife.

Mr. Steady. That, I think, is the school-house; now go in, and be good.

Mrs. Lovechild had one room in her house fitted up with books, suited to little people of different ages.—She had[Pg 102] likewise toys, but they were such as would improve, as well as amuse her little friends.

The book-room opened into a gallery, which was hung with prints and pictures, all chosen with a view to children. All designed to teach little folks while they were young; in order that when they grew up, they might act worthily.

There were written accounts of each picture, with which her ladyship would often indulge good children.

Sometimes she walked about herself and explained a few of the pictures to her little guests.

[Pg 103]

One day I chanced to be present when she was showing a few of them to a little visiter; and I think my young reader may like to hear what passed.

Mrs. Lovechild. That is Miss Goodchild.—I have read an account of her, written by her mother.

Miss. Pray, madam, what was it?

Mrs. Lovechild. It is too long to repeat now, my dear; but I will tell you a part.—She was never known to disobey her parents; never heard to contradict her brothers or sisters; nor did she ever refuse to comply with any request of theirs.—I wish you to read her[Pg 104] character, for she was a pattern of goodness.

Miss. Pray, madam, was she pretty?

Mrs. Lovechild. She had a healthful color: and her countenance was sweet, because she was always good-humored.—That smile on her mouth seems to say—I wish you all happy; but it was not for her beauty, but her goodness, that she was beloved: and on that account only did I wish for her picture.

Miss. Pray, madam, why is that boy drawn with a frog in his hand?

Mrs. Lovechild. In memory of a kind action which he did to a poor harmless[Pg 105] frog.—You shall hear the whole story.—I was taking my morning walk pretty early one day, and I heard a voice say, “Pray do not kill it; I will give you this penny, it is all I have, and I shall not mind going without my breakfast, which I was to have bought with it.”

“You shall not lose your meal!” exclaimed I; “nor you, naughty boys, the punishment which you deserve for your cruel intention.”

Miss. Pray, madam, what was the good boy’s name?

Mrs. Lovechild. Mildmay! he was always a friend to the helpless.

[Pg 106]

Miss. How cruel it is in a great boy to be a tyrant!

Mrs. Lovechild. Dunces are often cruel.—My young friend redeemed a linnet’s nest from a stupid school-fellow, by helping him in his exercise every day for a fortnight, till the little birds were flown.

Here a servant entered the gallery, and announced company, which put an end to Mrs. Lovechild’s account of the picture.

[Pg 107]

Master William Gentle was riding on the back of his dog Cæsar, when his[Pg 108] grandfather called to him and invited him to take a walk. They went out together, and as they were walking, they met some boys who had a hedge-hog, which they were going to hunt.—Mr. Gentle ordered them to release it.—The boys pleaded that the hedge-hog would injure the farmers by sucking their cows, and that it therefore ought to be killed.

Mr. Gentle. If it were proper to deprive the animal of life, it would be a duty to do it in as expeditious a manner as possible, and very wicked to torment the poor creature; but the accusation is false, and you are unjust as well as cruel.—Release it this instant!

[Pg 109]

William. Will the hedge-hog be glad when he gets loose?

Grandfather. Very glad.

William. Then I shall be glad too.

Grandfather. I hope that you will always delight in making other creatures happy: and then you will be happy yourself.

William. I love to see the dog happy, and the cat happy.

Grandfather. Yes, surely; and you love to make them happy.

William. How can I make them happy?

[Pg 110]

Grandfather. By giving them what they want, and by taking kind notice of them, and when you get on Cæsar’s back again, as he lets you ride, do not strike him, but coax him gently.

William. Can I make my brothers and sisters happy?

Grandfather. You can each of you make yourself and all the rest of the children happy, by being kind and good-humored to each other; willing to oblige, and glad to see the others pleased.

William. How, pray?

Grandfather. If you were playing with a toy, and Bartle wished to have[Pg 111] it, perhaps you would part from it to please him; if you did, you would oblige him.

William. Should not I want it myself?

Grandfather. You would be pleased to see him delighted with it, and he would love you the better, and when George goes out, and you stay at home, if you love him as well as you do yourself, you will be happy to see his joy.

William. I shall be happy to see his joy.

Grandfather. Your parents are always watching over you all, for your[Pg 112] good; in order to correct what is amiss in your tempers, and teach you how you ought to behave; they will rejoice to see you fond of each other, and will love you all the better.

William. Grandpa, I remember that my brother wrote a piece last Christmas, which you called Brotherly Love.—I wish I could remember it.

Grandfather. I recollect it;—you shall learn to repeat it.

William. I shall like that; pray let me hear it now, sir.

Grandfather. You shall.

“The children of our family should[Pg 113] be like the fingers on a hand; each help the other, and each in his separate station promote the good of the whole. The joy of one should be the joy of the whole. Children in a house should agree together like the birds in a nest, and love each other.”

William. I thank you grandpa: I remember Watts’ hymn:

The master Rebels often fight; many say that it is jealousy that makes them do so.—Pray, grandpa, what is jealousy?

[Pg 114]

Grandfather. A passion which I hope will never enter your breast. Your excellent parents love you all equally, and take care to make it appear that they do so. A good parent looks around with equal love on each child, if all be equally good, and each be kind to the rest. When a family is affectionate, how happy is every member of it! each rejoiceth at the happiness of the rest, and so multiplies his own satisfactions. Is any one distressed? the tender and compassionate assistance of the rest mitigates where it cannot wholly relieve his pain!

[Pg 115]

First Girl. Let us lay words. Where is the box?

Second Girl. How do you play?

First Girl. I will show you. Here I give you c, e, u, h, q, and n; now place them so as to make a word.

Second Girl. It is quench!

First Girl. You are quick; now let us pick out some words for Charles. What shall we choose?

Second Girl.

| Let us lay | thrust, | thresh, | branch, |

| ground, school, | thirst, | quince, | quail, |

| and dearth. |

[Pg 116]

First Girl.

| I will | lay | plague, | and | neigh, | and |

| nought, | and | naught, | and | weight, | and |

| glare, | and | freight, | and | heart, | and |

| grieve, | and | hearth, | and | bathe, | and |

| thread, | and | vaunt, | and | boast, | and |

| vault, | and | tongue, | and | grieve, | and |

| beard, | and | feast, | and | friend, | and |

| fraught, | and | peace, | and | bread, | and |

| grape, | and | breath, | or the verb | to | |

| breathe, | and | thought, | and | grace, | and |

| mouse, | and | slave, | and | chide, | and |

| stake, | and | bought. | |||

Second Girl. I shall like the play, and it will teach Charles to spell well.

First Girl. That is its use: we have sports of all kinds to make us quick: we have[Pg 117] some to teach us to count; else I could not have been taught to do sums at three years old.

Second Girl. Were you?

First Girl. Yes; I was through the four rules by the time that most boys learn that two and two make four.

Second Girl. I wish you would teach me some of your sports; that I could teach Charles.

First Girl. Print words on a card; on the back write the parts of speech; let it be a sport for him to try if he can find what each one is; let him have the words, and place them so as to make sense; thus I give you these words:

you, done, do, be, would, by, as.

[Pg 118]

Place them in their right order, and make

Do as you would be done by.

Or give him two or three lines: here and there scratch out a word; let him tell what those words must be to make sense.

Second Girl. The card on which you have a, b, c, and so on, might have a, b, c, made with a pen at their backs, to teach written hand.

First Girl. I have a set of those; I could read my mother’s writing when I was four years old.

Second Girl. I will buy some prints or cuts, and paste at the back of cards, for our little ones; so they will soon learn to distinguish nouns. On one side shall be DOG; I will ask what part of speech is that?[Pg 119] Charles will say, Is it not a noun?—He will turn the card, and find a cut.

First Girl. Let us prepare some words of all kinds; we can lay sentences for little ones to read. For Lydia, we will place them thus:

My mother says that three words are as much as a child could read in a breath at first.

Second Girl. Where there is a house full of young folks, it might be good sport to teach and learn in these ways.

First Girl. It is; we play with our words thus; mother gives to one some words; he is to place them so as to make sense: one is[Pg 120] to parse them: one to tell more than the parts of speech, as the tense, mode and so on, of the verbs.—George and I have false English to correct; verse to turn to prose; we write out a passage which we like; we write letters upon given subjects; we read a story, and then write it in our own words.

Second Girl. Do you repeat much?

First Girl. To strengthen our memories, we learn to repeat passages in prose—we also repeat verse, and read it aloud.

Second Girl. That is a great pleasure.

First Girl. Yes, and my mother reads aloud to us; this teaches us to read with propriety; and she often stops to inquire whether we understand any expression which is not perfectly plain.

THE END.