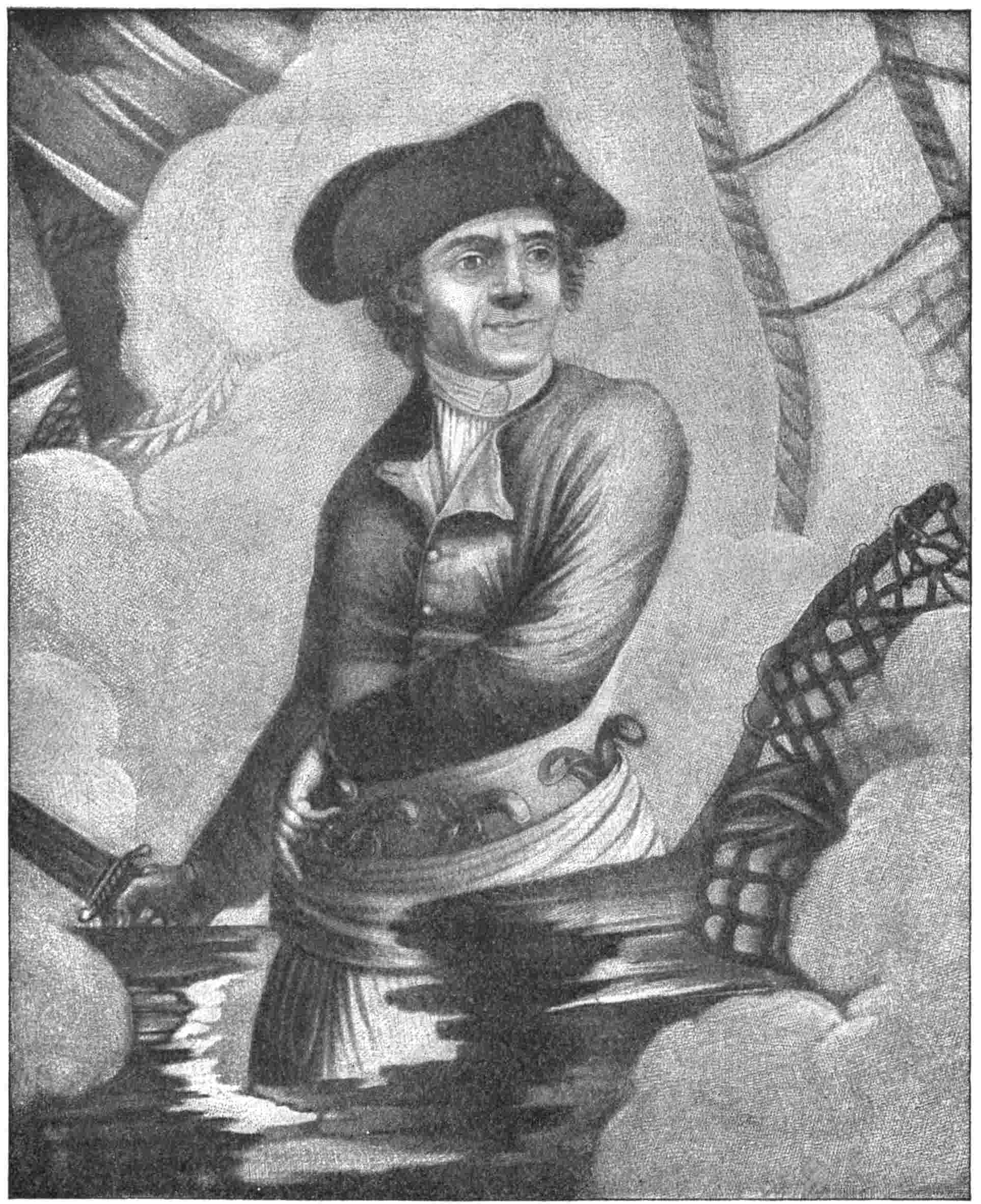

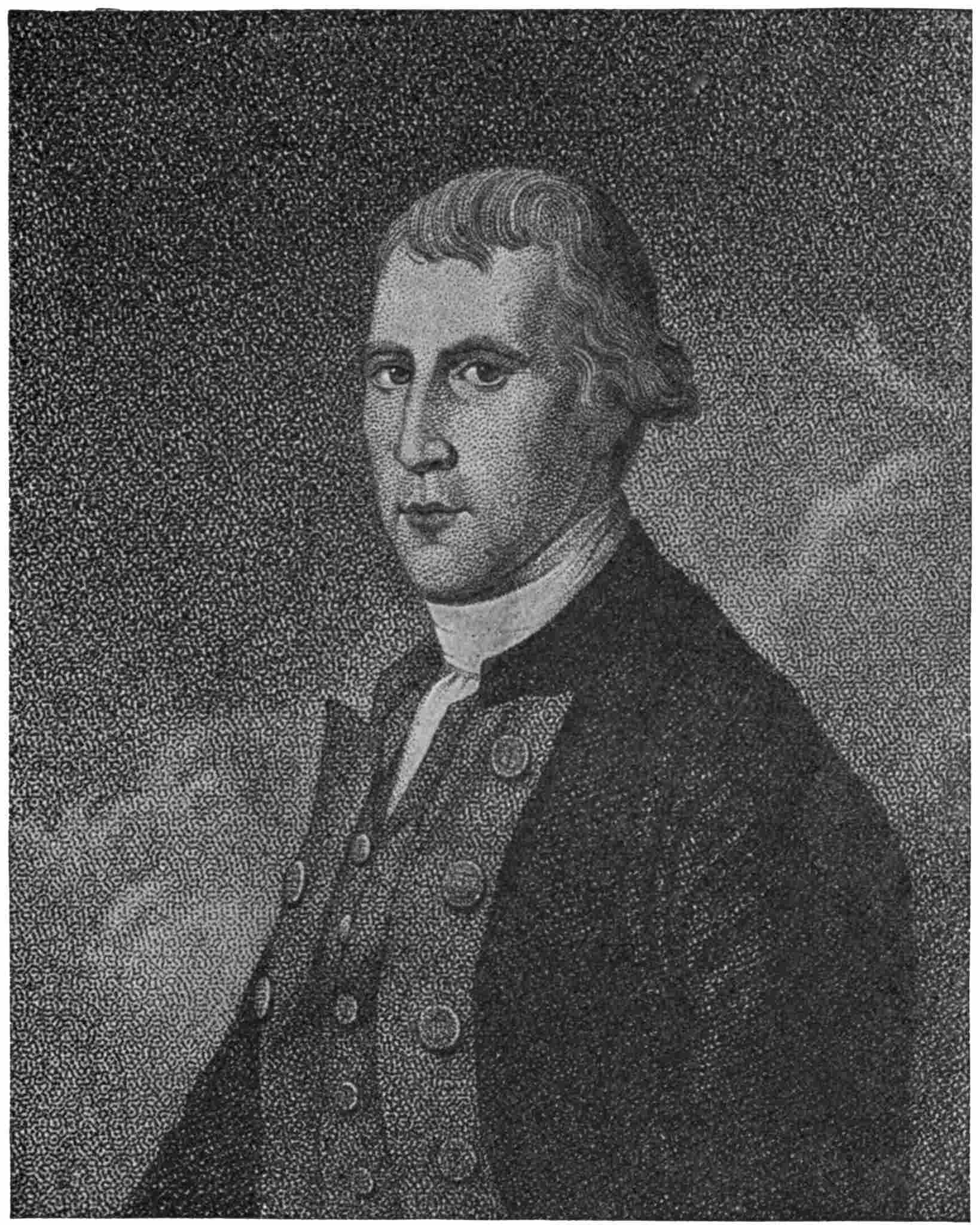

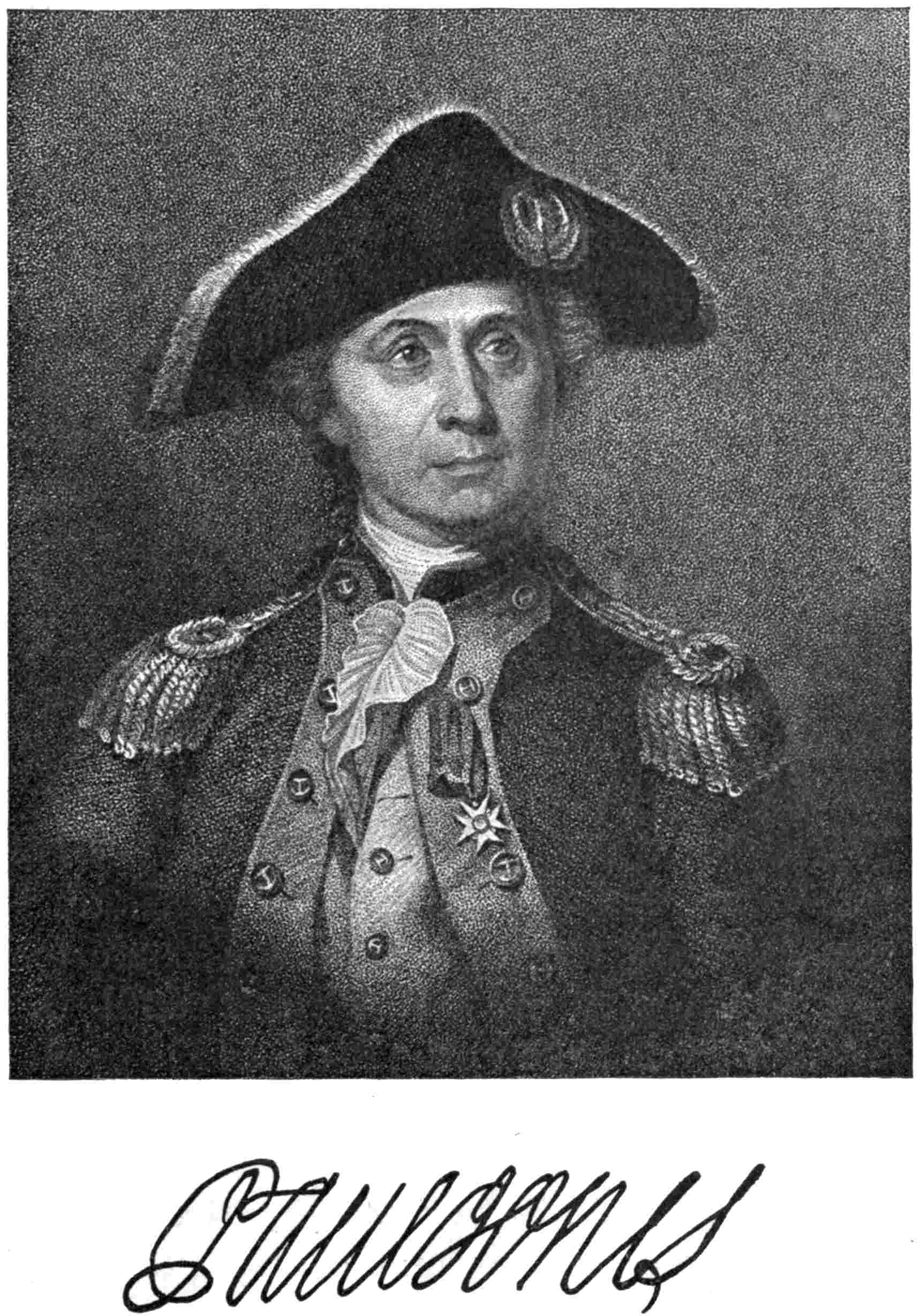

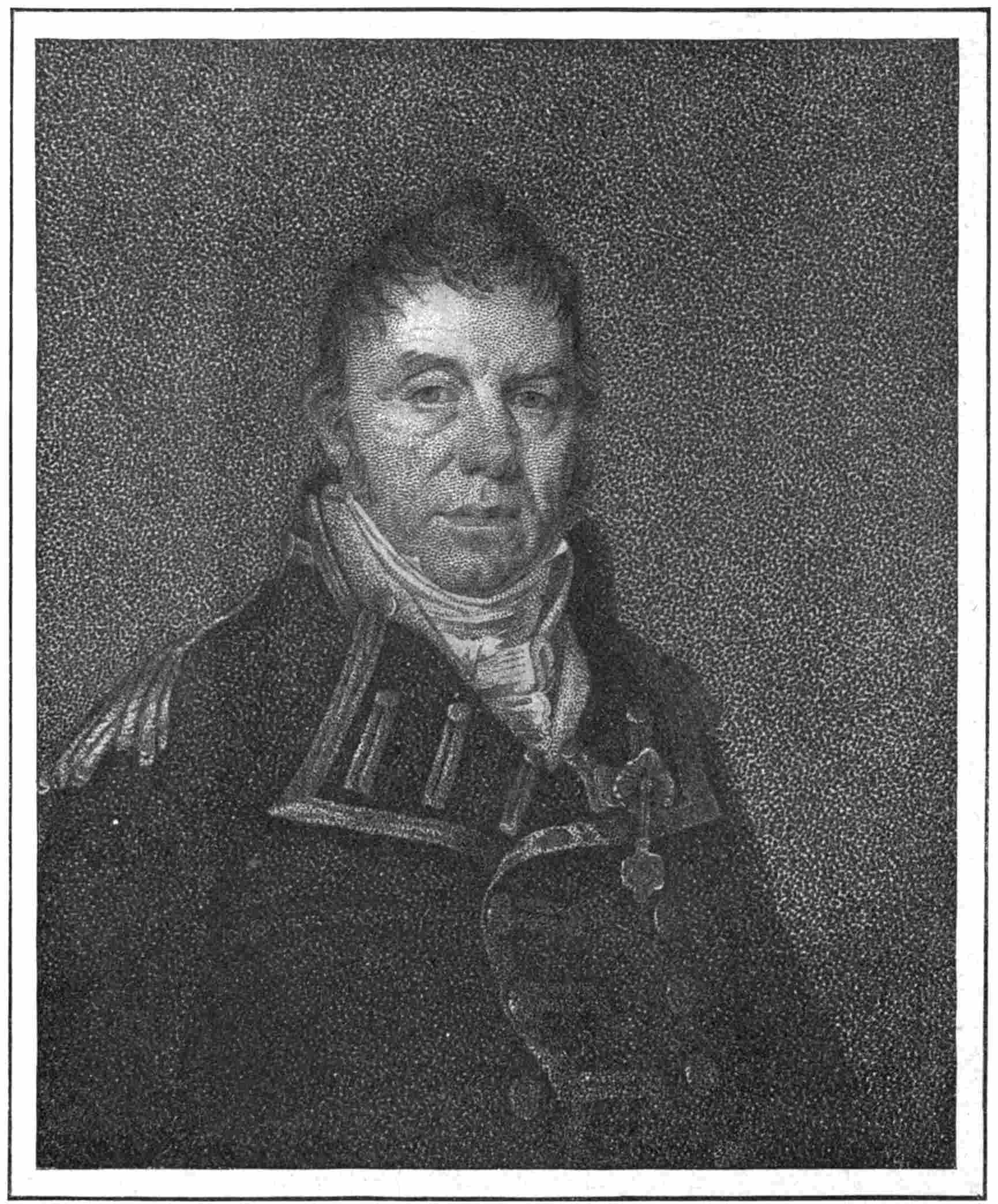

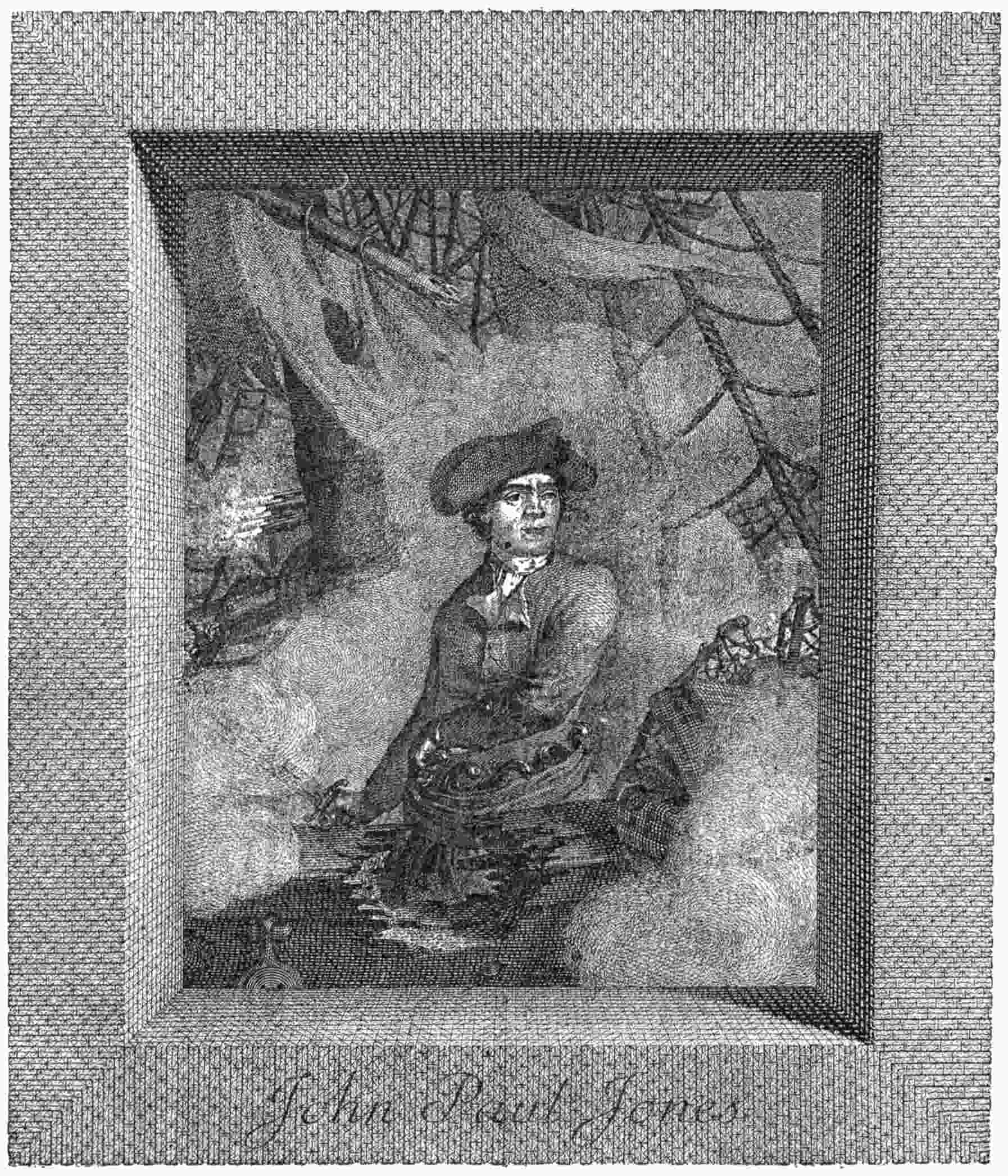

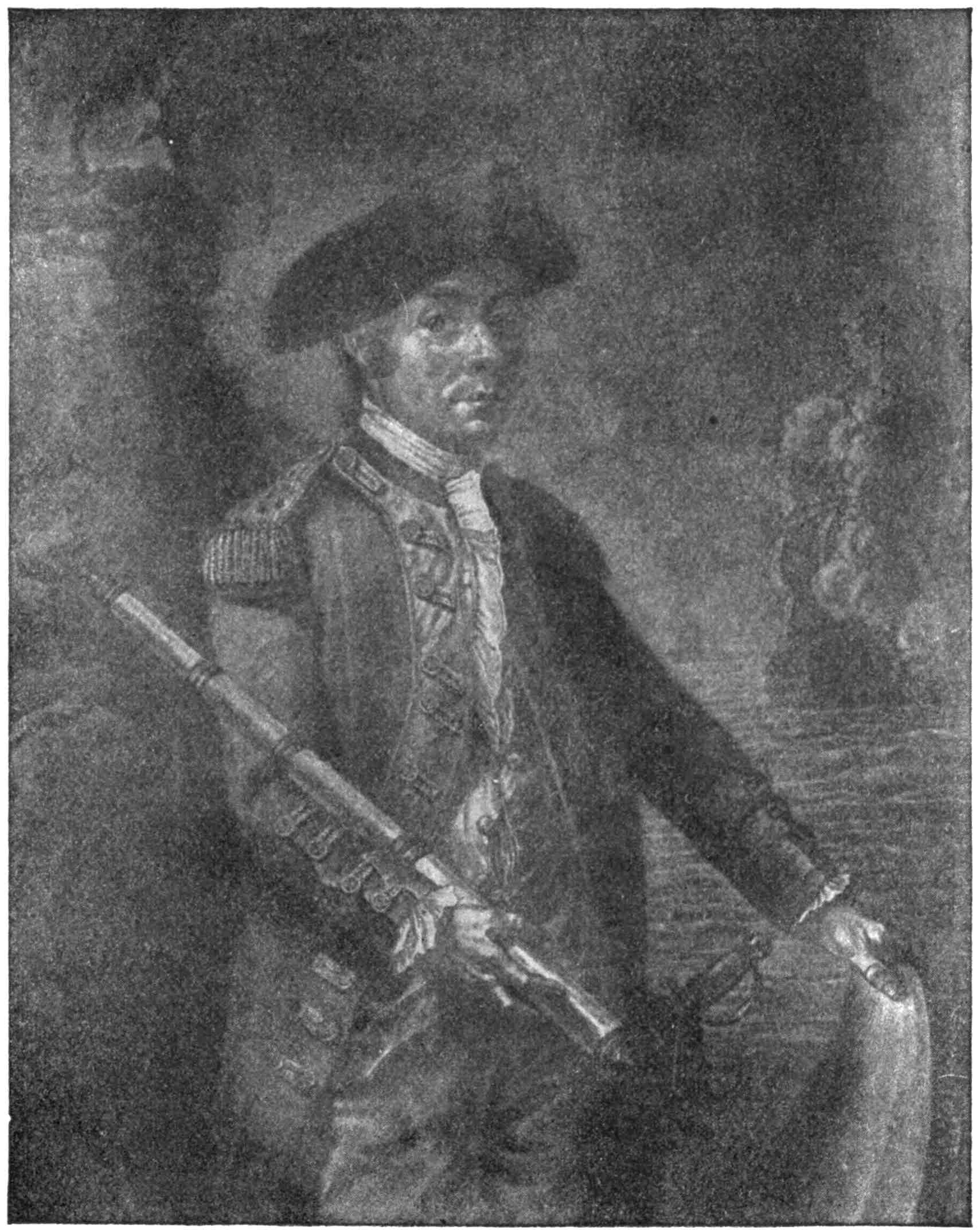

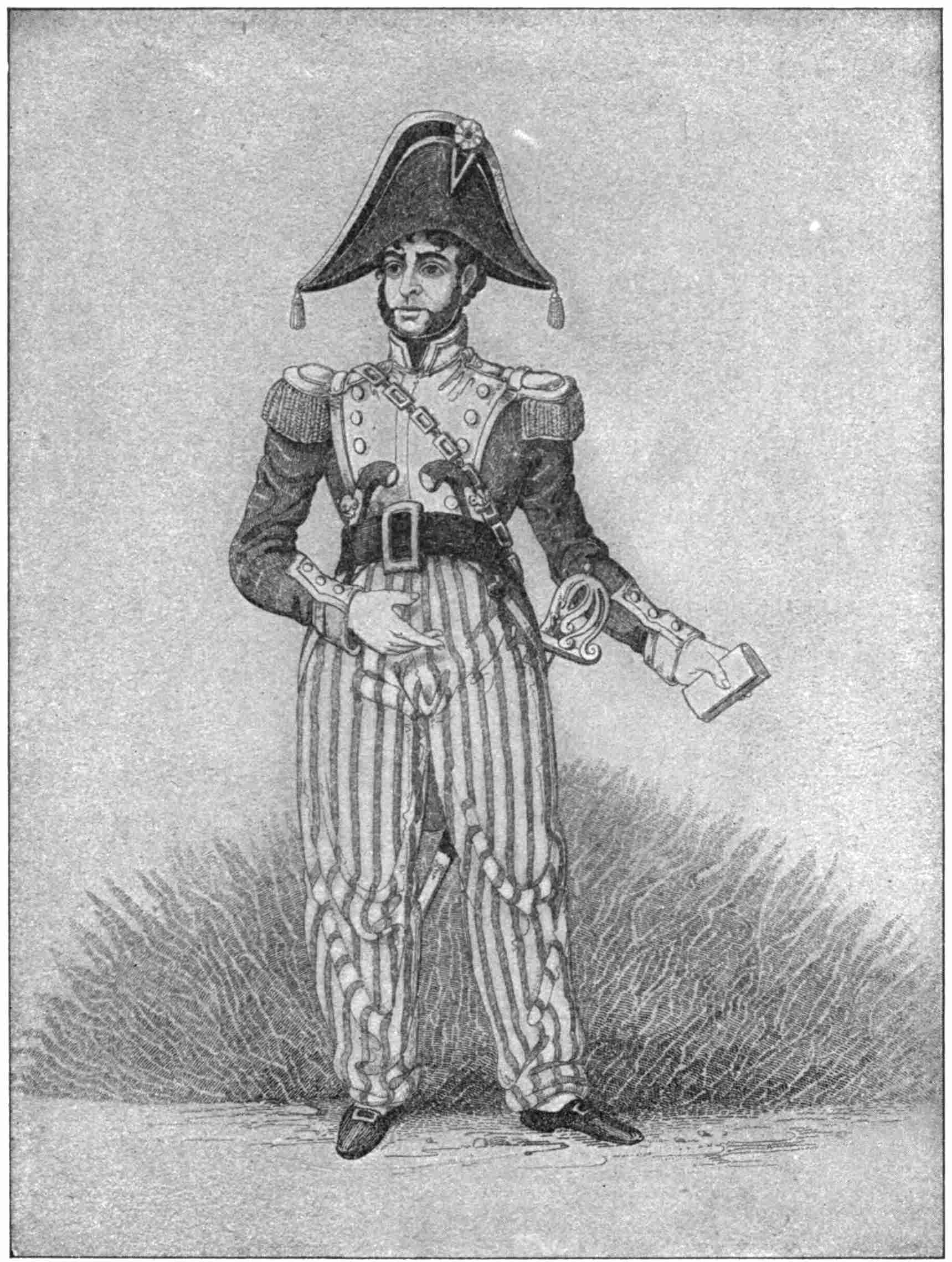

JOHN PAUL JONES.

From a mezzotint of the painting by Notté.

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

JOHN PAUL JONES.

From a mezzotint of the painting by Notté.

THE

HISTORY OF OUR NAVY

FROM ITS ORIGIN TO THE PRESENT DAY

1775–1897

BY

JOHN R. SPEARS

AUTHOR OF “THE PORT OF MISSING SHIPS,”

“THE GOLD DIGGINGS

OF CAPE HORN,” ETC.

WITH MORE THAN FOUR HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

IN FOUR VOLUMES

VOLUME I.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

MANHATTAN PRESS

474 W. BROADWAY

NEW YORK

TO ALL WHO WOULD SEEK PEACE

AND PURSUE IT

ix

This work is to tell the story of the American navy from the time when the fathers of the nation first conceived the idea of sending warships to sea “at the expense of the Continent” down to this year of our Lord 1897. It seems to me that the memory of what the naval heroes of the nation have done is worth preserving if only as a mark of gratitude—gratitude to the men whose sole incentive was patriotism and whose only greed was for honor. It seems worth while to tell anew the story of these men who had a noble ambition. It may help to prevent their race becoming extinct. But if that appeal does not secure the attention of the reader, let me say that self-interest demands that he heed the lessons in the story of the navy.

Because naval officers and their friends are very properly jealous of their rights in the matter of titles and rank, it is necessary to explain that officers have very often held one rank on the naval list while entitled to a higherx one by courtesy. Farragut was a midshipman under Porter, and yet, for a time, while in command of a captured ship, was by courtesy called captain. Lieutenant Macdonough was entitled to the title of commodore while in command on Lake Champlain. I have in nearly all instances used the title which courtesy demanded, but, for reasons which I hope will be apparent, the title of actual rank seemed proper at times.

To sum it all up, I am bound to say I have tried to tell the story accurately, interestingly, and usefully. If there are errors, they are unpardonable blunders; if the story lacks interest or usefulness, the fault is entirely with the writer. Any story of the navy—even this one—should rouse the enthusiasm of the patriot because of the stirring character of the deeds that must be described; and I believe that when the reader has considered it well, he will conclude, as I do, that because of the growth of civilization and the spread of the pure doctrines of Christianity throughout the world, and the progress in the arts of making guns and armor-plate in the United States, we shall continue to pursue, for many years, our daily vocations in peace.

J. R. S.

xi

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. Origin of the American Navy | 1 |

| The Curious Chain of Events that Led to the Creation of a National Sea Power—The Gaspé Captured by Men Armed with Paving-stones—Tea Destroyed in Boston—The Battle of Lexington and the Attack of the Machias Haymakers on the Margaretta—British Vengeance on Defenceless Portland and its Effect on the Continental Congress—The “Colonial Navy” Distinguished from the Temporary Cruisers—The First Officers and the First Ships of the American Navy—John Paul Jones and the First Naval Ensign—The Significant “Don’t Tread on me”—Putting the First American Naval Ships in Commission. | |

| Chapter II. First Cruise of the Yankee Squadron | 48 |

| A Fairly Successful Raid on New Providence, but they Let a British Sloop-of-war Escape—Character of the First Naval Commander-in-chief and of the Material with which he had to Work—Esek Hopkins, and his Record as Commander of the Fleet—Crews Untrained and Devoid of Esprit de Corps—Good Courage, but a Woeful Lack of other Needed Qualities—Hopkins Dismissed for Disobedience of Orders. | |

| Chapter III. Along Shore in 1776 | 63 |

| Brilliant Deeds by the First Heroes of the American Navy—Why Nicholas Biddle Entered Port with but Five of the Original Crew of the Andrea Doria—Richard Dale on the sleek Lexington—The Racehorse Captured in an even Fight—Captain Lambert Wickes in the Reprisal Beats off a Large Vessel—John Paul Jones in his Earlier Commands—A Smart Race with the Frigate Solebay—Sixteen Prizes in Forty-seven Days in Cape Breton Region—Poking Fun at the Frigate Milford—The Valuable Mellish—An Able Fighter who Lacked Political Influence.xii | |

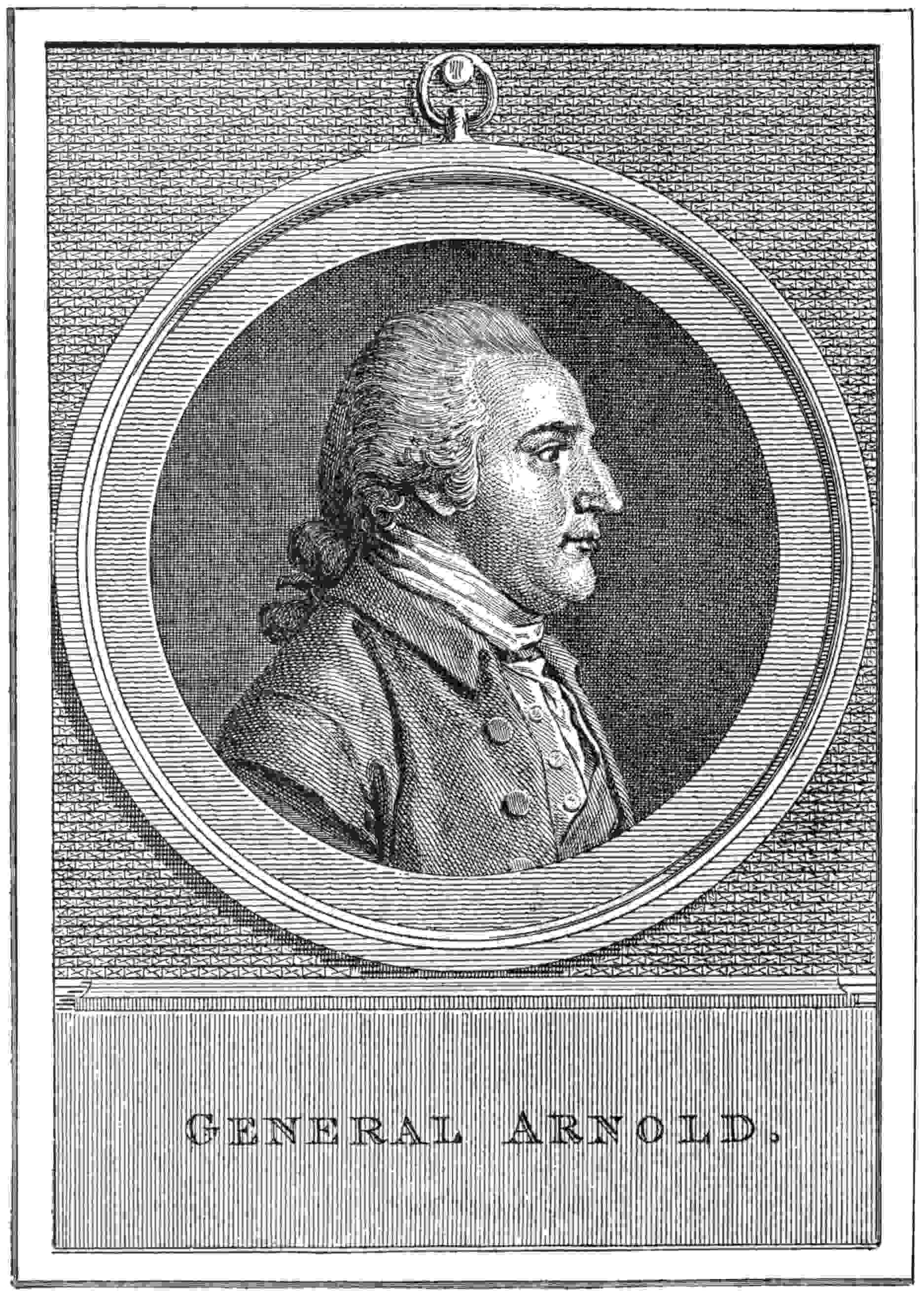

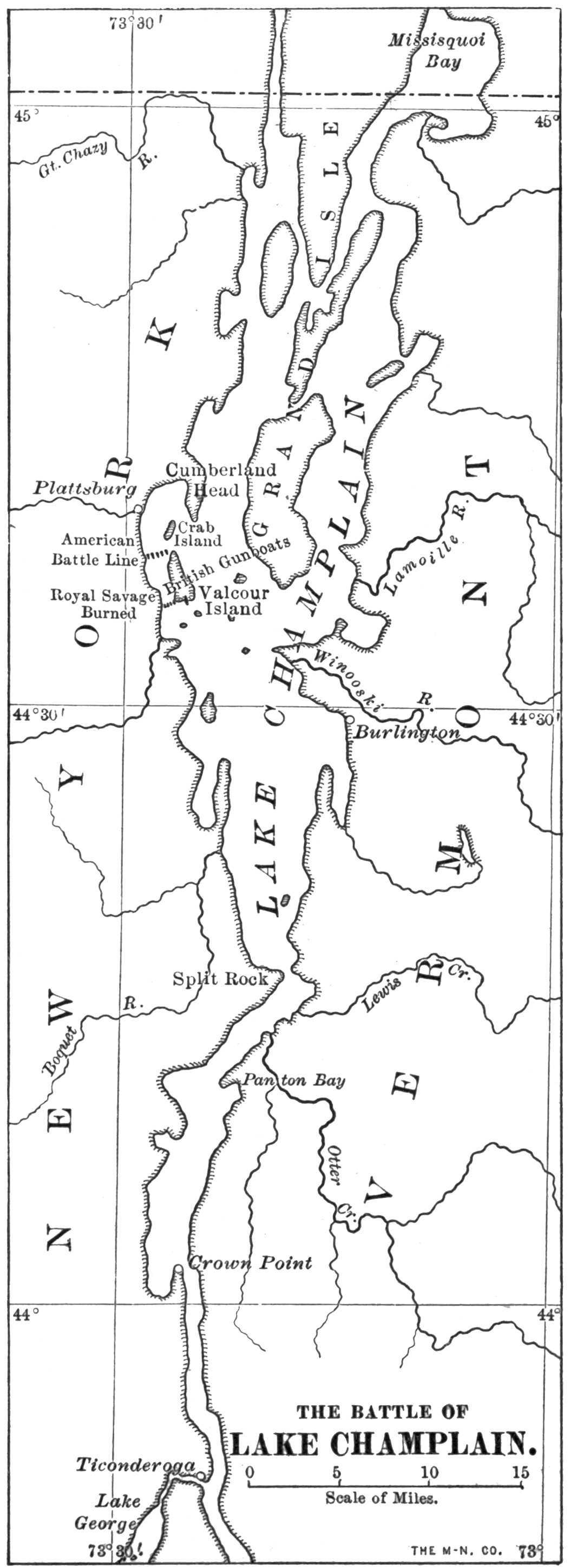

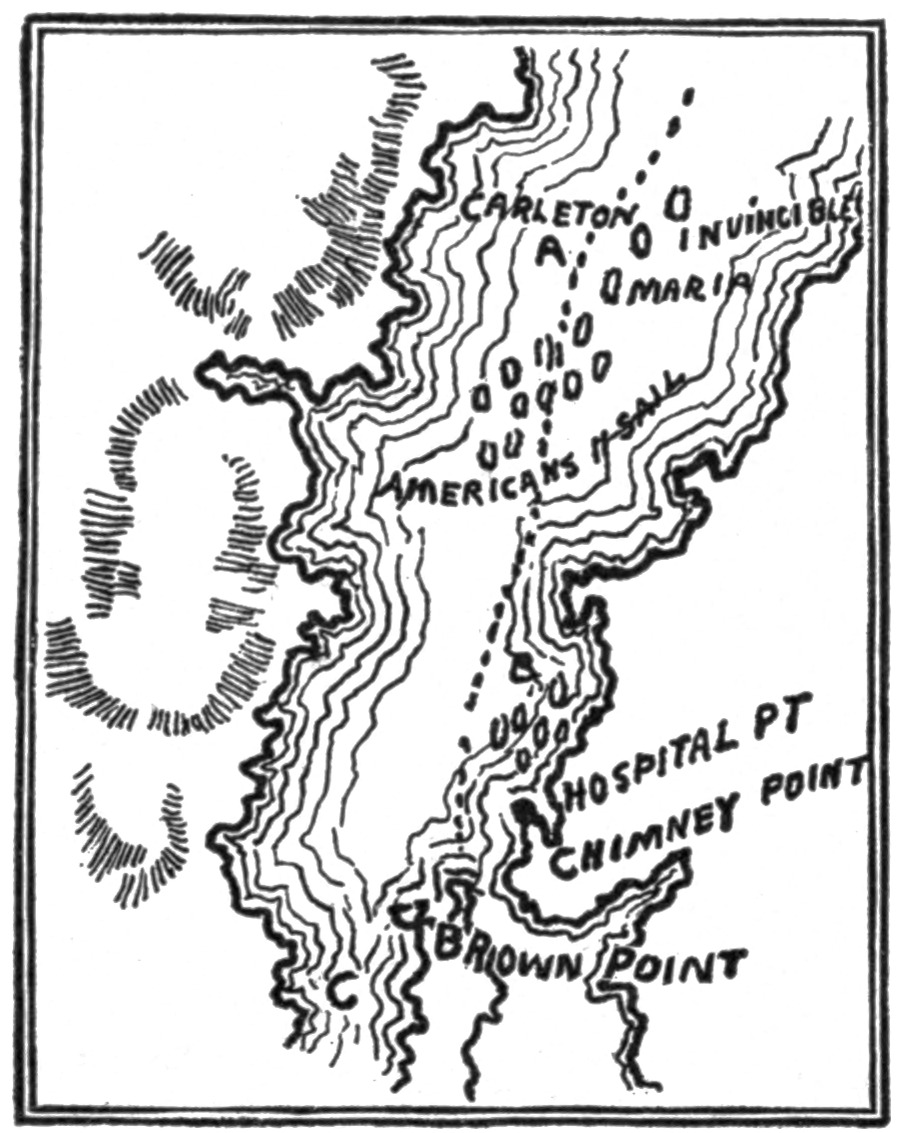

| Chapter IV. He Saw “the Countenance of the Enemy” | 84 |

| The Story of Arnold’s Extraordinary Fight against Overwhelming Odds on Lake Champlain—A Thousand Sailors, of whom Seven-tenths were Picked Men, Armed with the Heaviest Guns, were Pitted under a Courageous Leader against 700 Yankees, chiefly Haymakers, Poorly Armed and with Insufficient Ammunition—Savages with Scalping Knives Aided the British—A Desperate Struggle at the End—The Best All-around Fighter under Washington. | |

| Chapter V. Under the Crags of the “Tight Little Isle” | 112 |

| The Saucy Yankee Cruisers in British Waters—When Franklin Sailed for France—Wickes in the Reprisal on the Irish Coast—Narrow Escape from a Liner—A Plucky English Lieutenant—Harsh Fate of the Americans in the British Prison—Starved by Act of Parliament—Deeds of the Gallant Connyngham—Well-named Cruisers—A Surprise at a Breakfast Table—Taking Prizes Daily—Why Forty French Ships Loaded in the Thames—Insurance Rates never before Known. | |

| Chapter VI. John Paul Jones and the Ranger | 134 |

| The First Ship that Carried the Stars and Stripes—Dash at a Convoy that Failed—When the Dutch were Browbeaten—The Ranger Sent on a Cruise in English Waters—A Ship Taken off Dublin—The Raid on Whitehaven—When one Brave Man Cowed more than a Thousand—The Whole Truth about Lord Selkirk’s Silverware, with the Noble Lord’s Expression of Gratitude when he Got it Back—How Captain Jones Missed the Drake at First, but Got her Later on in a Fair and Well-fought Battle. | |

| Chapter VII. The First Submarine Warship | 157 |

| It was Small and Ineffective, but it Contained the Germ of a Mighty Power that is as yet Undeveloped—When Nicholas Biddle Died—He was a Man of the Spirit of an Ideal American Naval Officer—Fought the Ship against Overwhelming Odds till Blown out of the Water—The Loss of the Hancock—An American Captain Dismissed for a Good Reason—Captain Rathburne at New Providence—Loss of the Virginia—Captain Barry’s Notable Exploit—Withxiii Twenty-seven Men to Help him, he Captured a Schooner of Ten Guns by Boarding from Small Boats in Broad Daylight, although the Schooner was Manned by 116 Sailors and Soldiers. | |

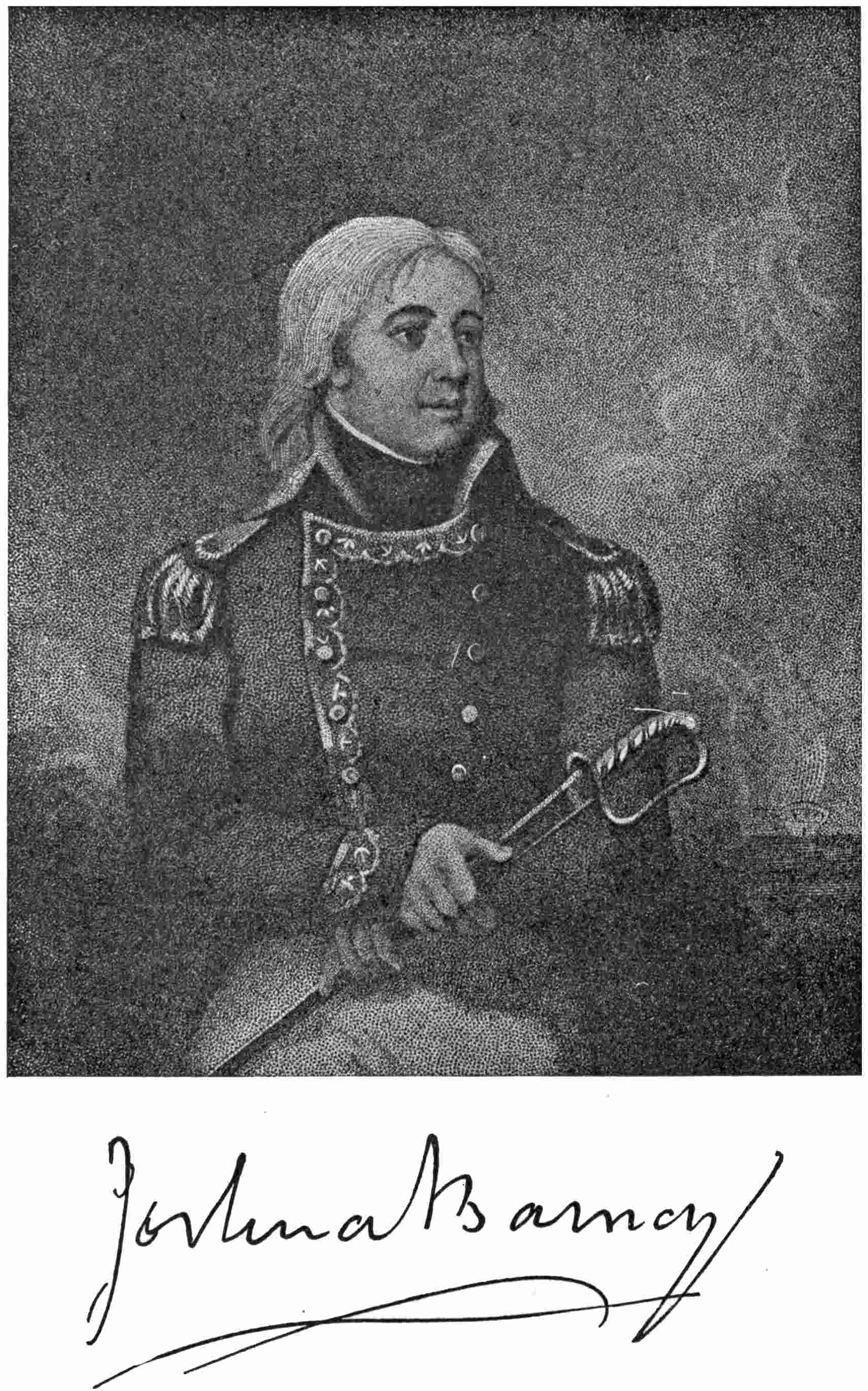

| Chapter VIII. Privateers of the Revolution | 196 |

| A Tale of the American Patriots who Went Afloat outside of the Regular Navy—Their Part in Driving the British from Boston—Remarkable Work of the Lee—Truxton as a Privateer—Daring Capt. John Foster Williams—When Capt. Daniel Waters, with the Thorn of Sixteen Guns, Whipped Two Ships that Carried Thirty-four Guns between them—Great was Joshua Barney—The Story of the most Famous State Cruisers of the Revolution—Won against Greater Odds than were Encountered by any Successful Sea Captain of the War—British Account of the Work of American Privateers—The Horrors of the Jersey Prison Ship. | |

| Chapter IX. John Paul Jones and the Bonhomme Richard | 227 |

| A Condemned Indiaman, Ill-shaped and Rotten, Fitted as a Man-o’-war—A Disheartening Cruise with Incapable and Mutinous Associates—Attempt to Take Leith, and the Scotch Parson’s Prayer—Meeting the Serapis—When John Paul Jones had “not yet Begun to Fight”; when he had “Got her now”; when he would not “Surrender to a Drop of Water”—Ready Wit of Richard Dale—Work of a Bright Marine—A Battle Won by Sheer Pluck and Persistence. | |

| Chapter X. After the Serapis Surrendered | 260 |

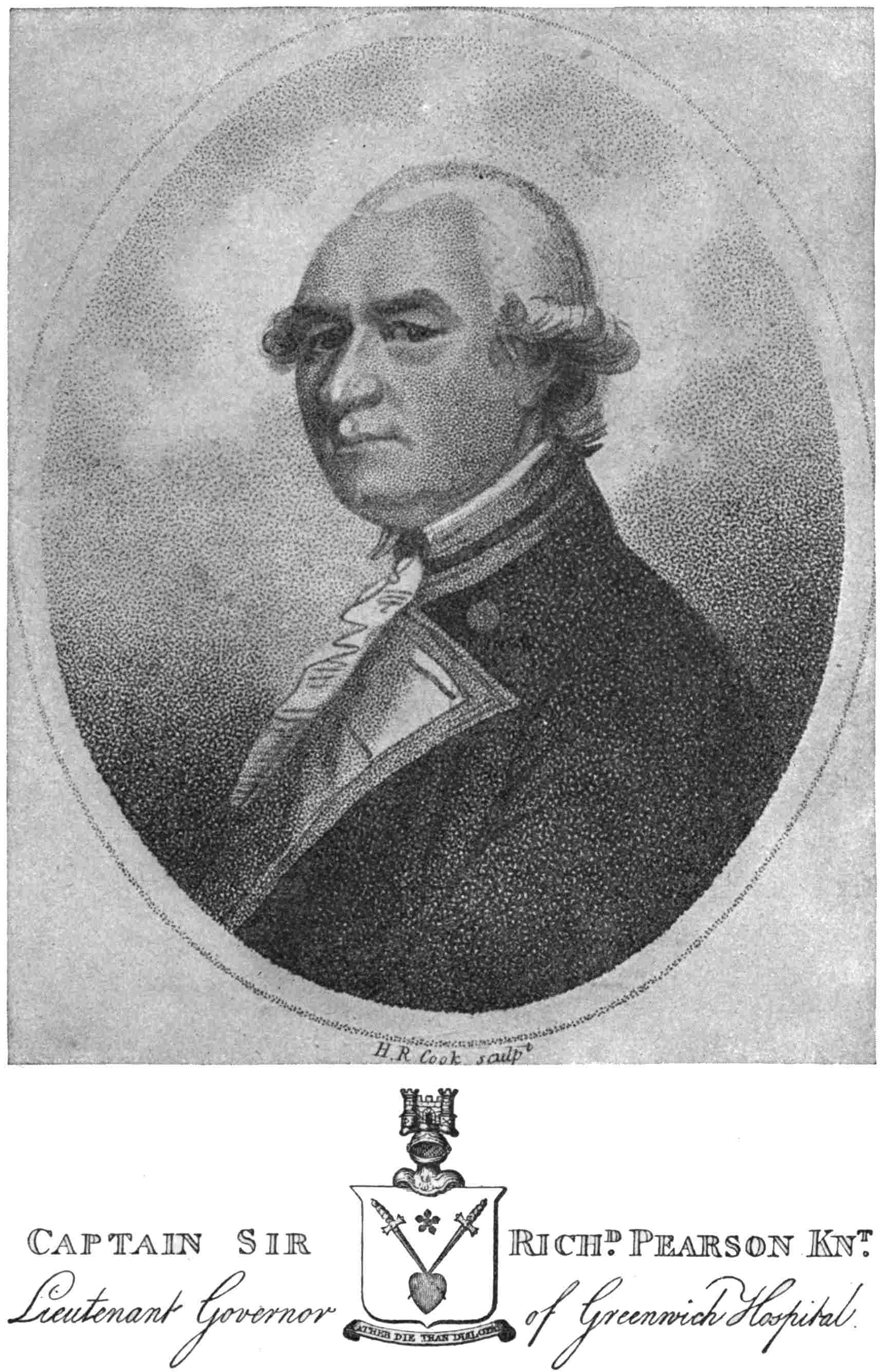

| Richard Dale too Bright for the British Lieutenant—A Fair Estimate of Captain Pearson of the Serapis—The Treachery of Landais—Remarkable Escape from Texel—Honors for the Victor—“The Fame of the Brave Outlives him; his Portion is Immortality.” | |

| Chapter XI. The Year 1779 in American Waters | 280 |

| Lucky Raids of British Transports and Merchantmen—Disastrous Expedition to the Penobscot—The Trumbull’s Good Fight with the Watt—The First Yankee Line-of-battle-ship—When Nicholson, with a Wrecked Ship and Fifty Men, Fought for an Hour against Two Frigates, each of which was Superior to the Yankee Ship—Captain Barry’s Exasperating Predicament in a Calm—The Last Naval Battle of the Revolution.xiv | |

| Chapter XII. Building a New Navy | 303 |

| When England, in her Efforts to Wrest Commerce from the Americans, Incited the Pirates of Africa to Activity, she Compelled the Building of the Fleet that was, in the End, to Bring her Humility of which she had never Dreamed—Deeds of the Barbary Corsairs—American Naval Policy as Laid down by Joshua Humphreys—The Wonderful New Frigates—Troubles with the French Cruisers on the American Coasts—Trick of a Yankee Captain to Save a Ship—A Midshipman who Died at his Post—Capture of the Insurgent—A Long Watch over the French Prisoners—Escape of a Twice-beaten Ship—The Valiant Senez—Story of Isaac Hull and the Lucky Enterprise. | |

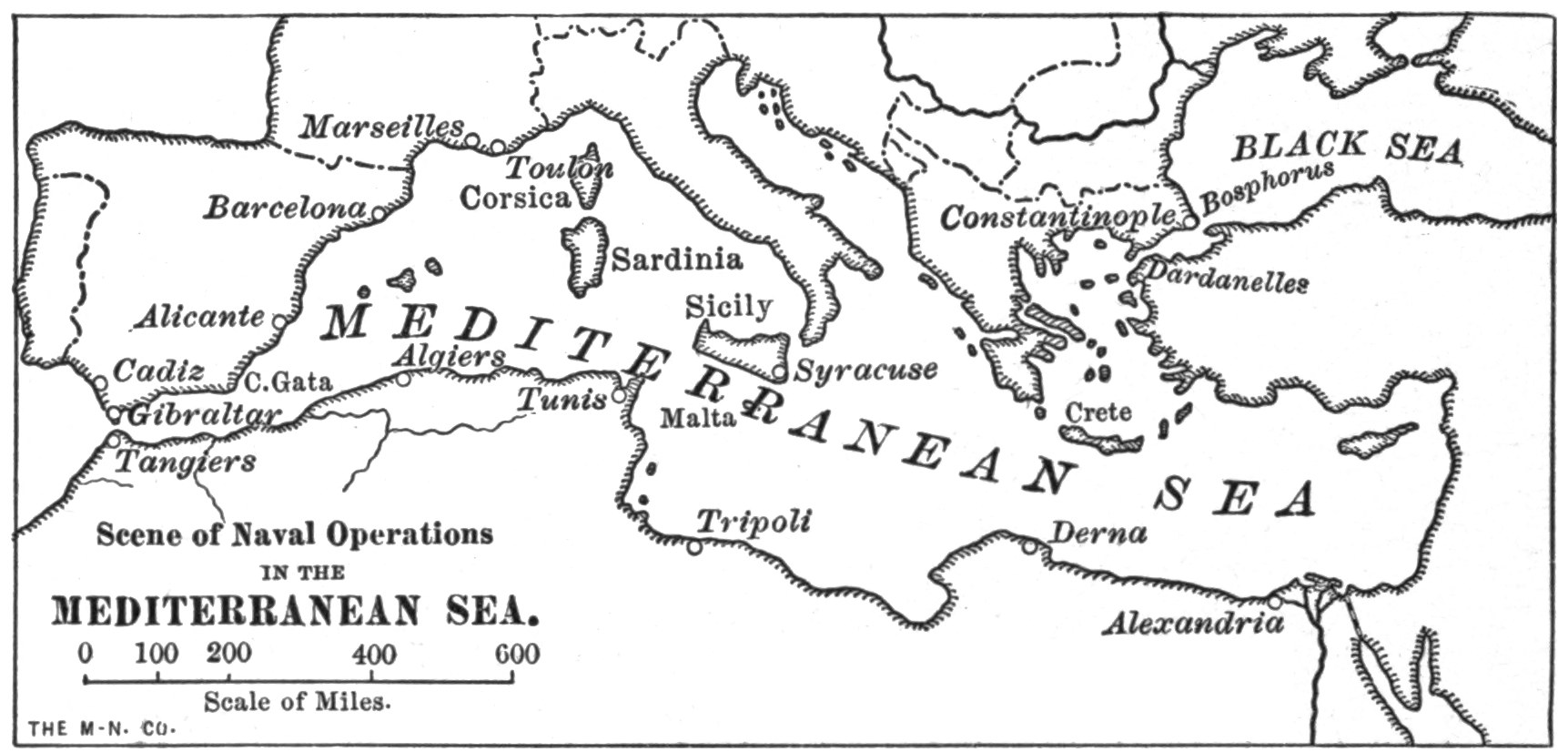

| Chapter XIII. War with Barbary Pirates | 333 |

| A Squadron under Richard Dale Sent to the Mediterranean—The Dey of Algiers became Friendly, but the Bashaw of Tripoli Showed Fight—Fierce Battle between the Schooner Enterprise and the Treacherous Crew of the Polacre Tripoli—Slaughter of the Pirates—Tripoli Blockaded—Grounding and Loss of the Philadelphia. | |

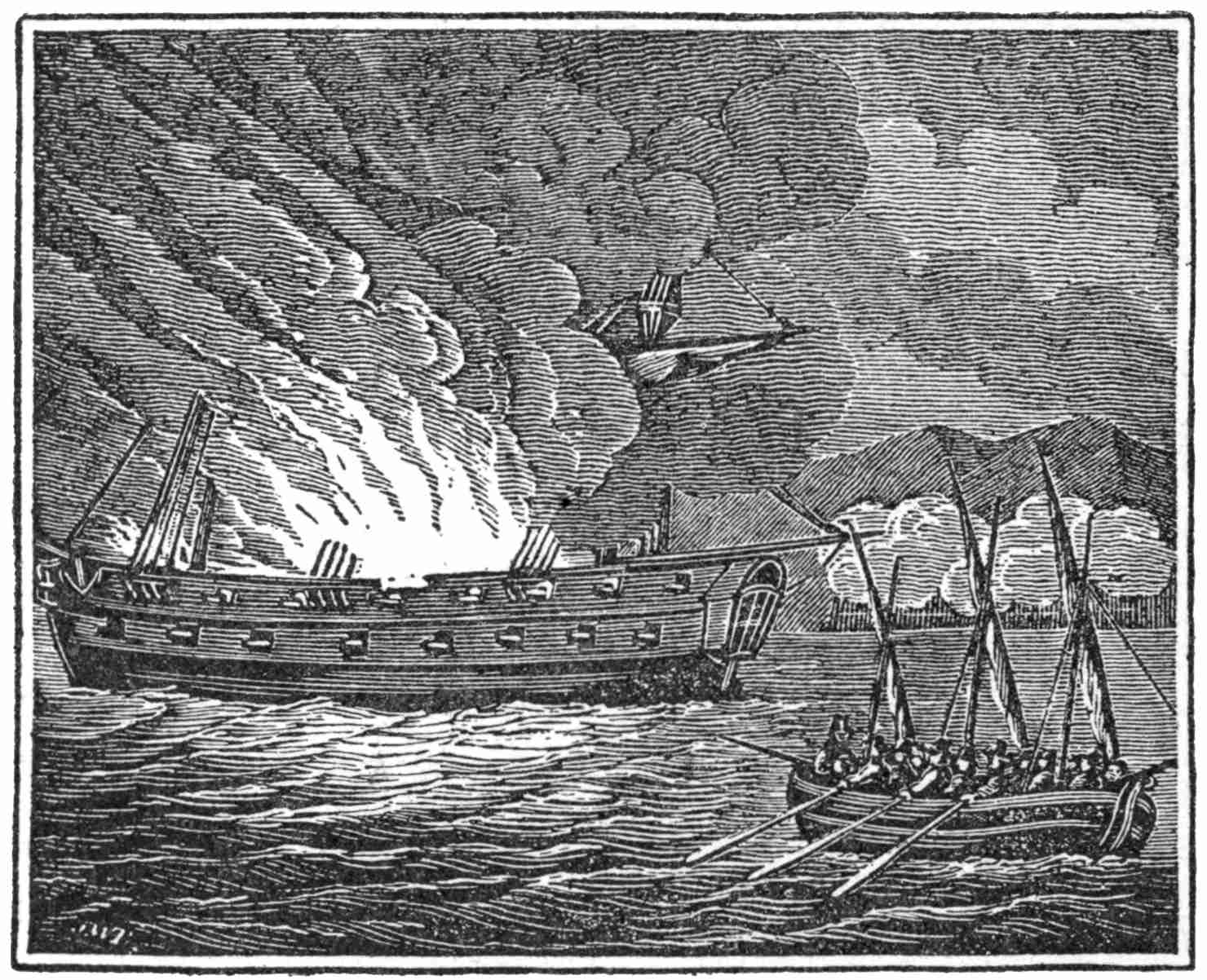

| Chapter XIV. Decatur and the Philadelphia | 345 |

| Story of the Brave Men who Disguised a Ketch as a Merchantman and Sailed into the Harbor of Tripoli by Night, Drew up alongside the Captured Philadelphia, and then, to the Order “Boarders Away!” Climbed over the Rail and through the Ports, and with Cutlass and Pike Drove the Pirates into the Sea or to a Worse Fate—“The most Bold and Daring Act of the Age.” | |

| Chapter XV. Hand-to-hand with the Pirates | 359 |

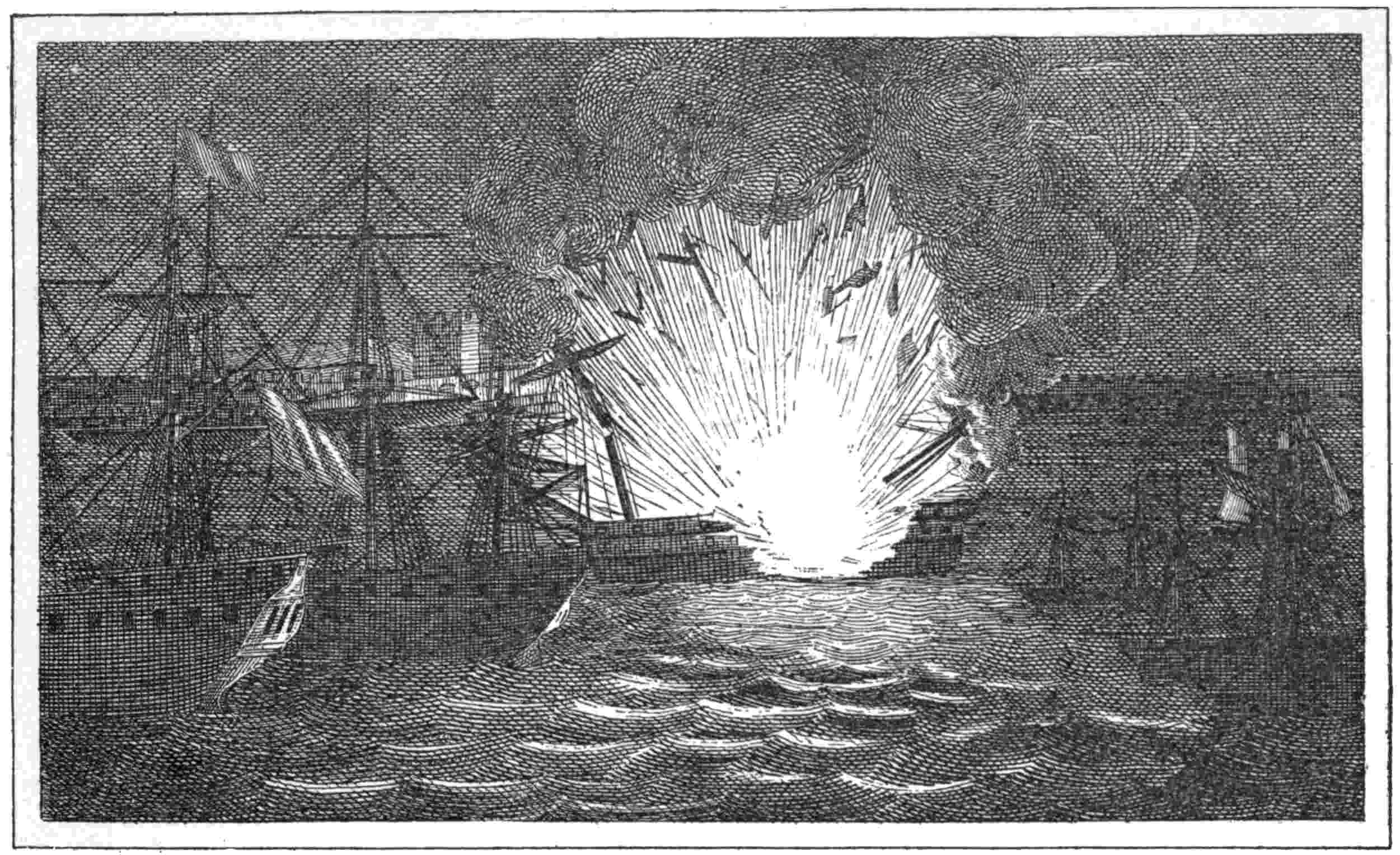

| A Fight against Odds of Three Gunboats to One—Decatur and Macdonough Leading the Boarders—Cold-blooded Murder and the Vengeance that Followed—When Reuben James Won Fame—Eleven against Forty-three in a Hand-to-hand Struggle, and the Remarkable Result—The Handy Constitution—Fired their Gun as the Boat Sank under them—When Somers and his Mates Went to their Death in a Fireship—End of the War with the Pirates. | |

| Chapter XVI. Why We Fought in 1812 | 383 |

| A Stirring Tale of the Outrages Perpetrated on American Citizens by the Press-gangs of the British Navy—Horrors of Life on Shipsxv where the Officers Found Pleasure in the Use of the Cat—Doomed to Slavery for Life—Impressed from the Baltimore—A British Seaman’s Joke and its Ghastly Result—The British Admiralty’s Way of Dealing with Deliberate Murder in American Waters—Assault of the Leopard on the Chesapeake to Compel American Seamen to Return to the Slavery they had Escaped—Building Harbor-defence Boats to Protect American Seamen from Outrage on the High Seas—Other Good Reasons for Going to War. | |

| Appendix | 415 |

xvi

xvii

| PAGE | |

| John Paul Jones. (From a mezzotint of the painting by Notté), Frontispiece | |

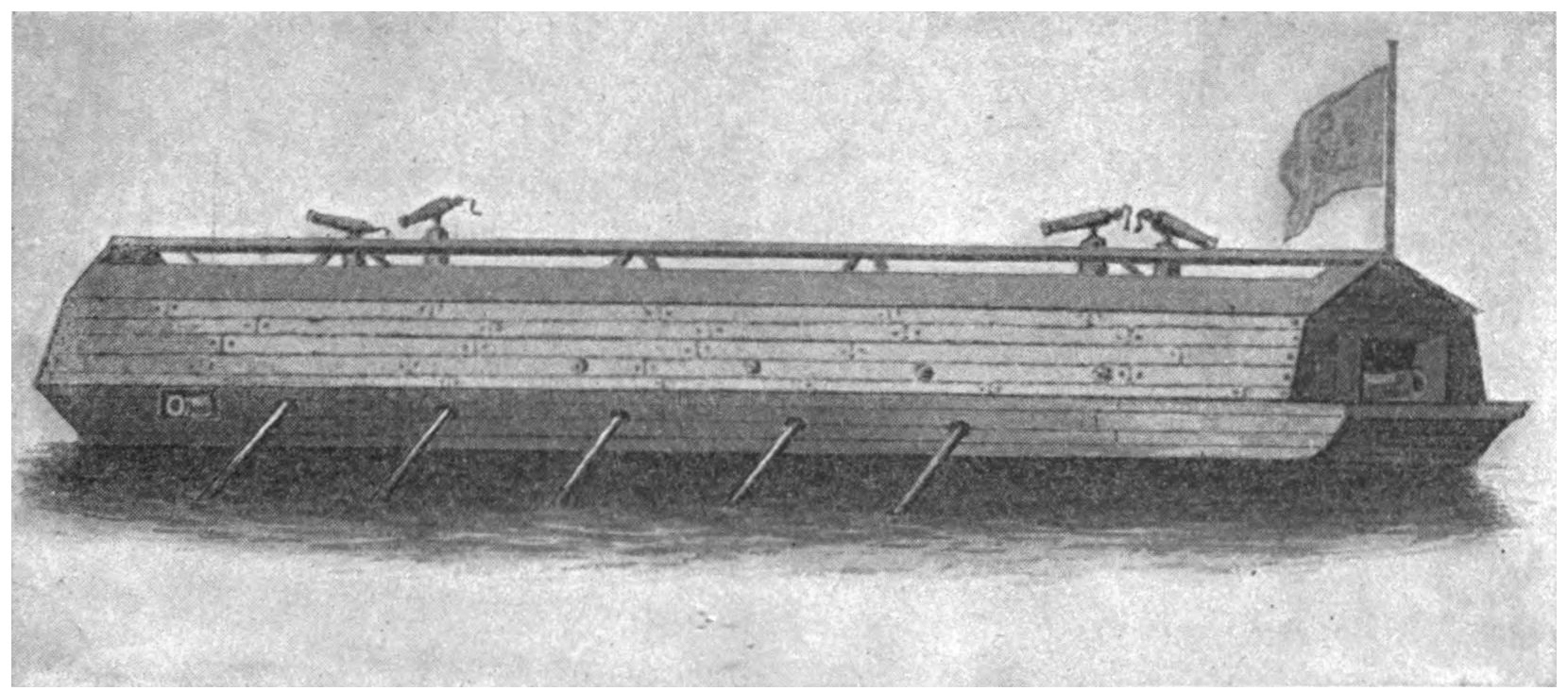

| An Early American Floating Battery, | 1 |

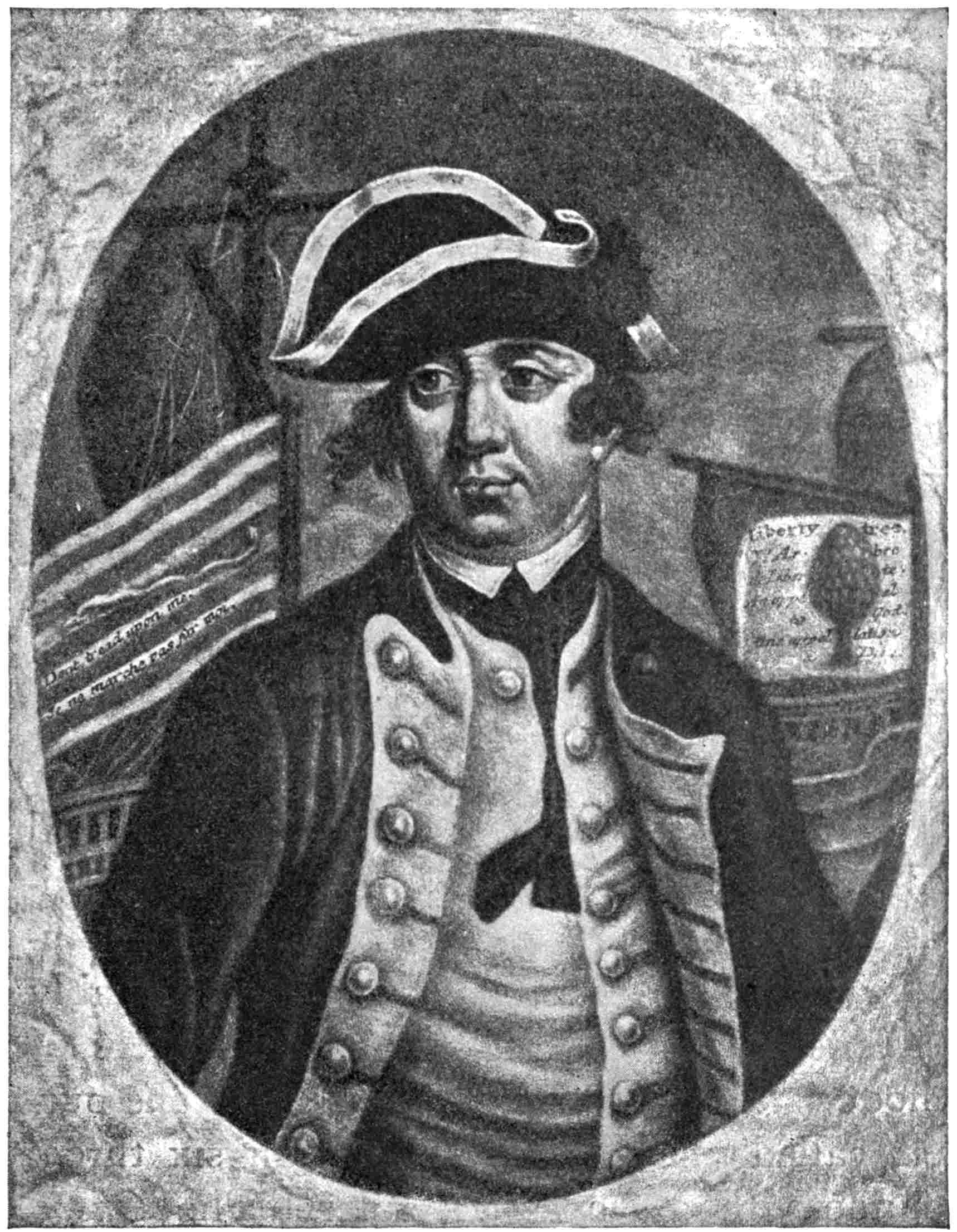

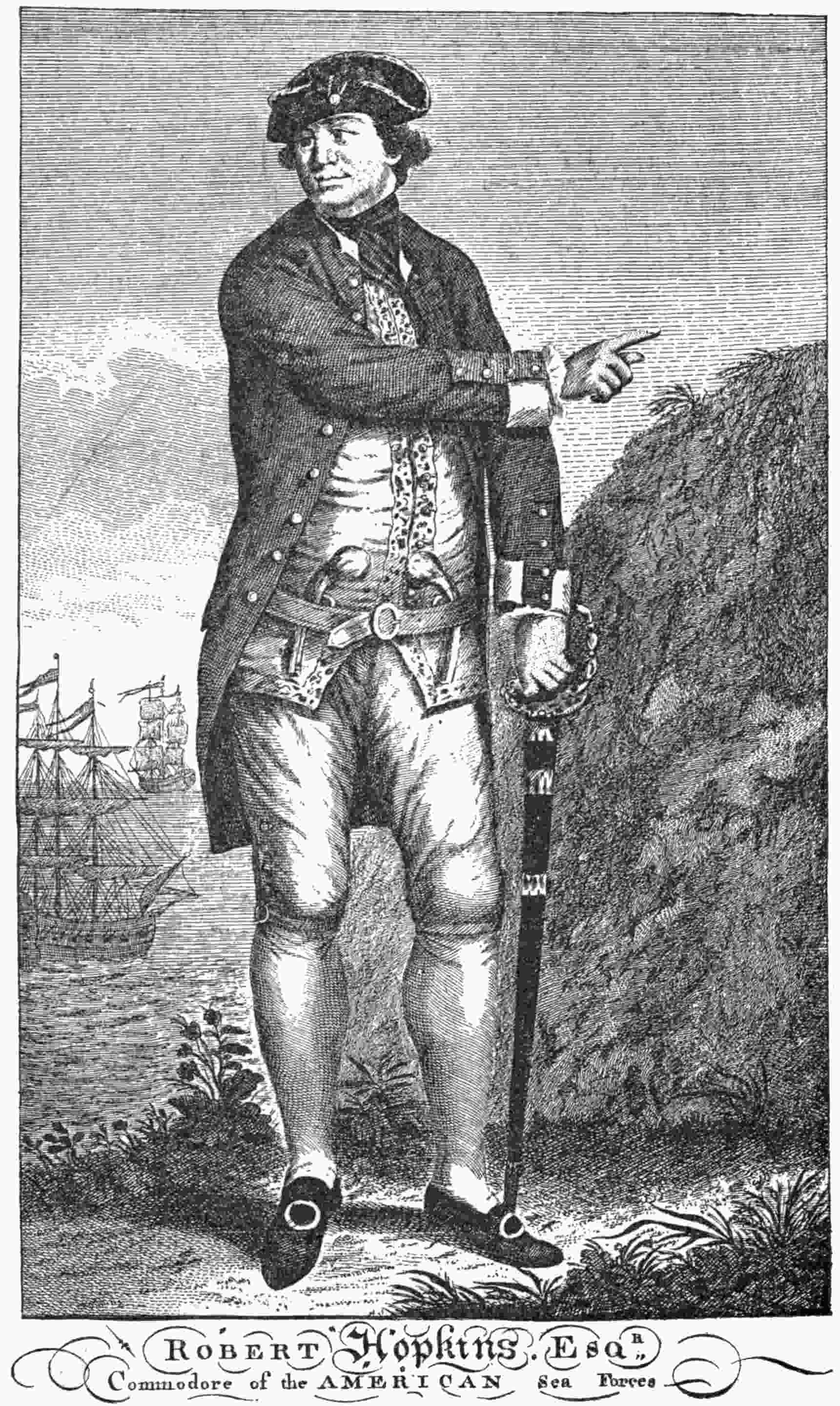

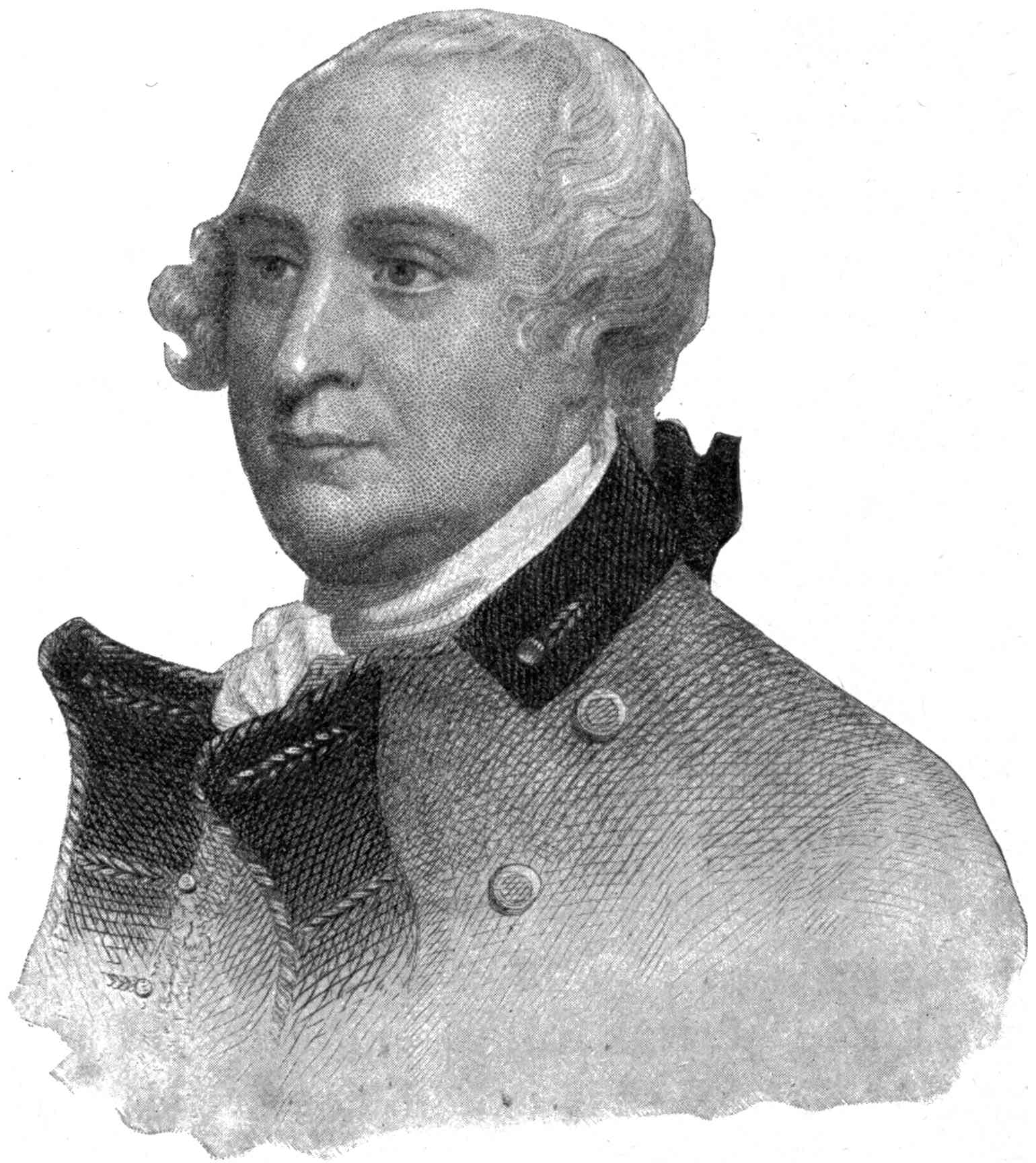

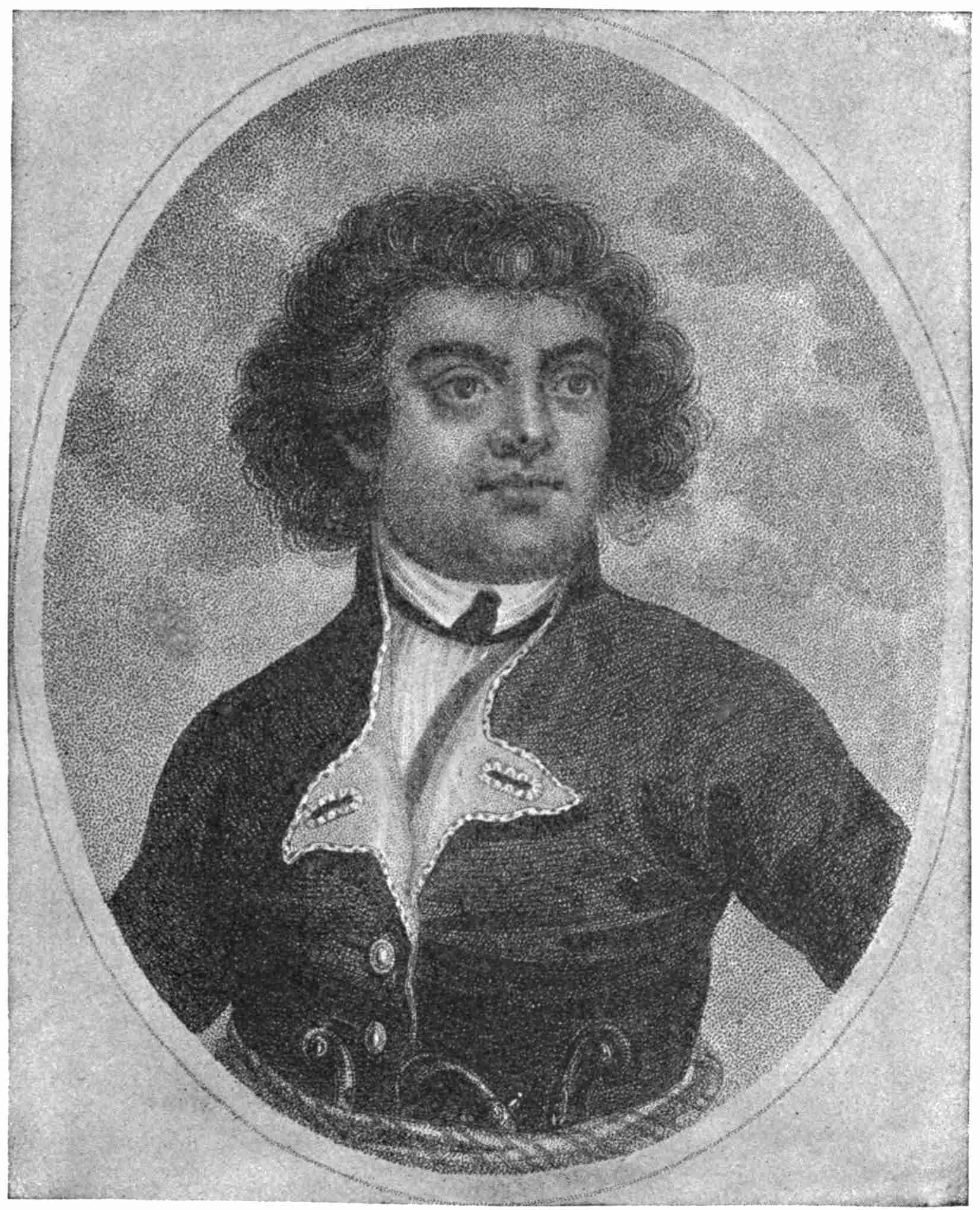

| Commodore Esek Hopkins. (From a French engraving of the portrait by Wilkinson), | 3 |

| The First Naval Flags, | 4 |

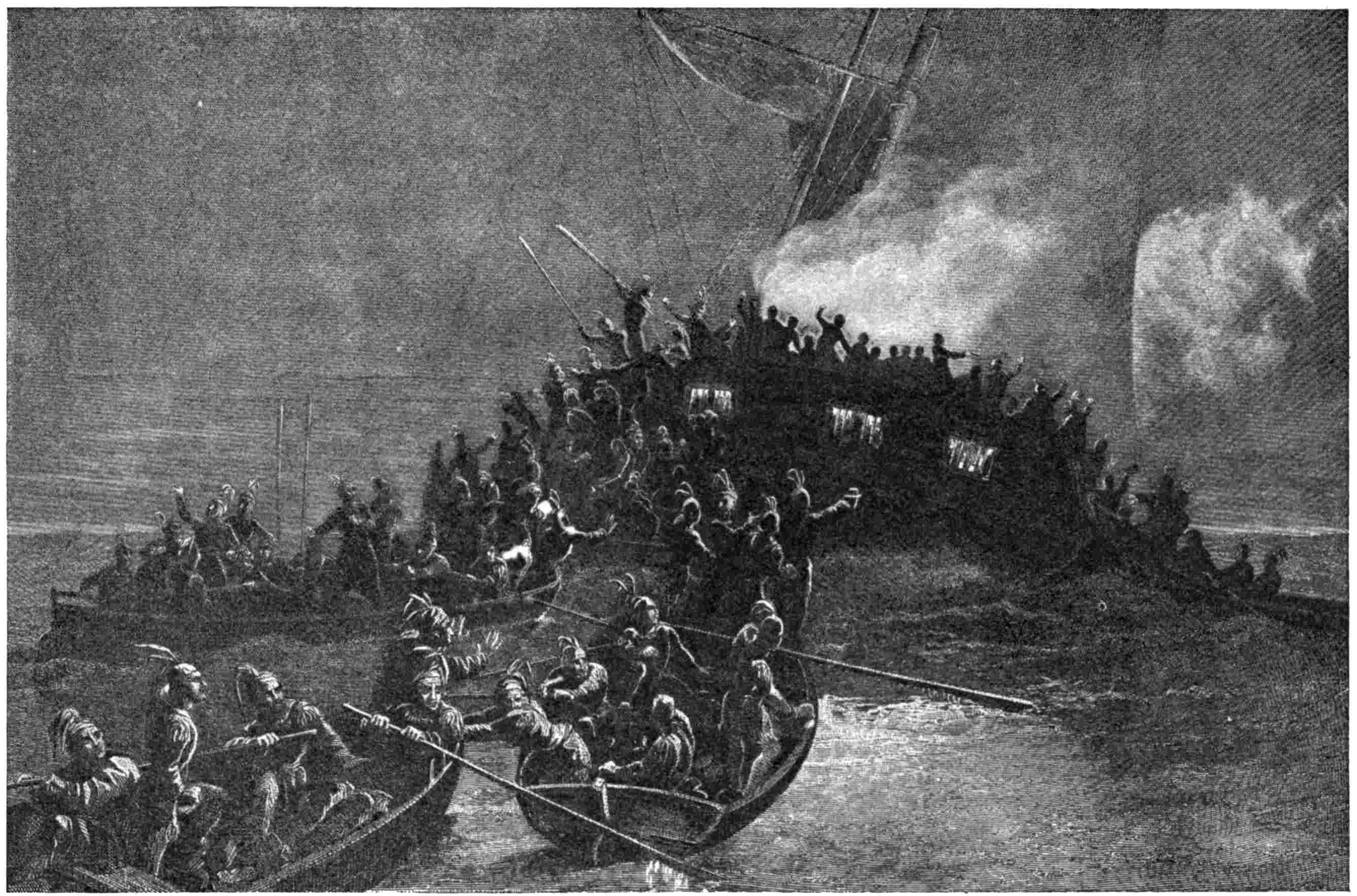

| Destruction of the Schooner Gaspé, 1772. (From an engraving by Rogers of the painting by McNevin), | 7 |

| The State House at Newport, Showing the Gaspé Affair. (From an engraving in Hinton’s “History of the United States”), | 10 |

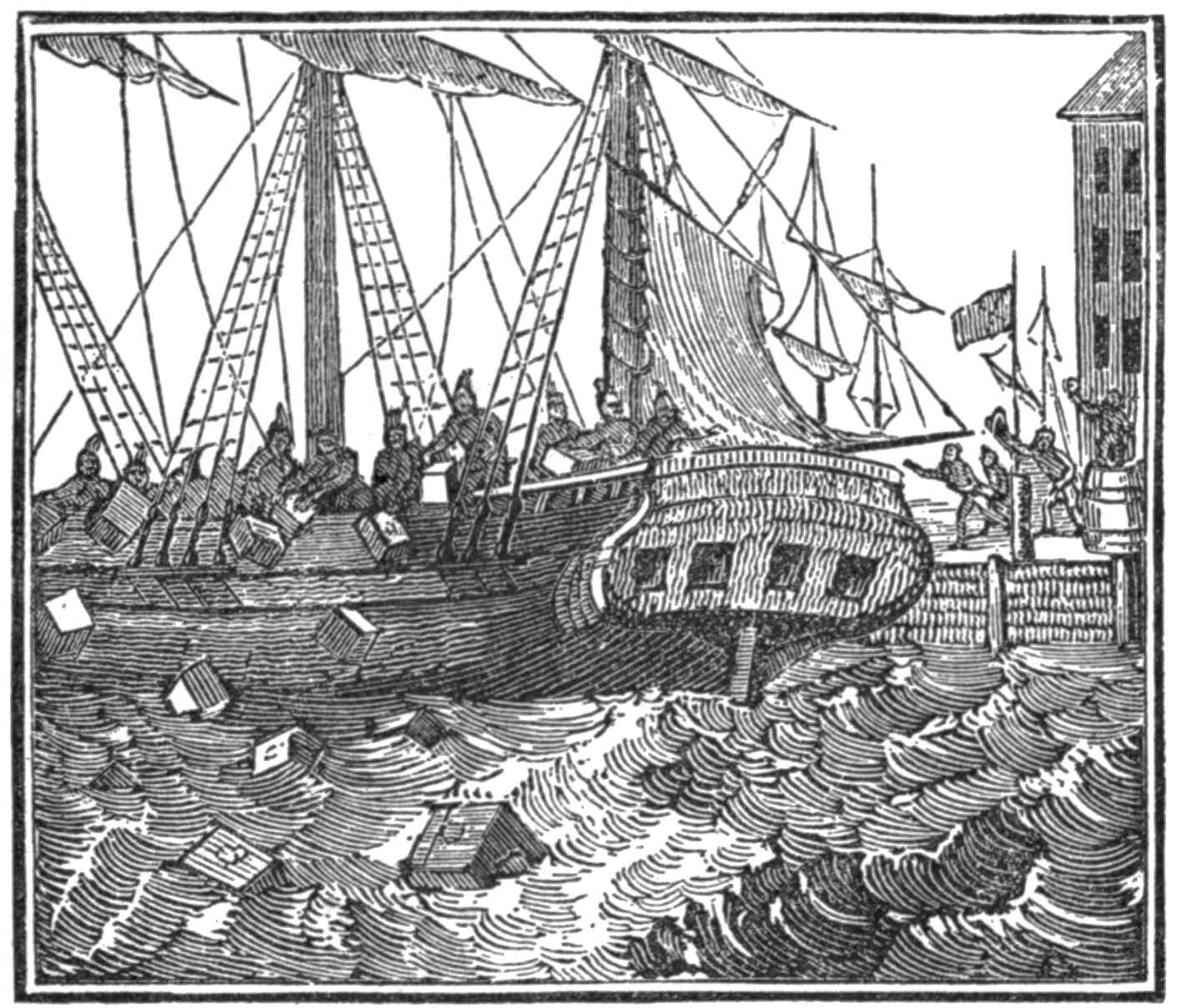

| The “Boston Tea-Party.” (From an old engraving), | 13 |

| A British Armed Sloop. (From a very rare engraving, showing the first lighthouse erected in the United States—on Little Brewster Island, Boston Harbor), | 19 |

| A Brig of War Lowering a Boat. (From a picture drawn and engraved by Baugean), | 29 |

| The Admiralty Seal, | 33 |

| The Founders of the American Navy. (Drawn by I. W. Taber—the portraits from engravings), | 37 |

| Vessel of War Saluting, with the Yards Manned. (From an old French engraving), | 40 |

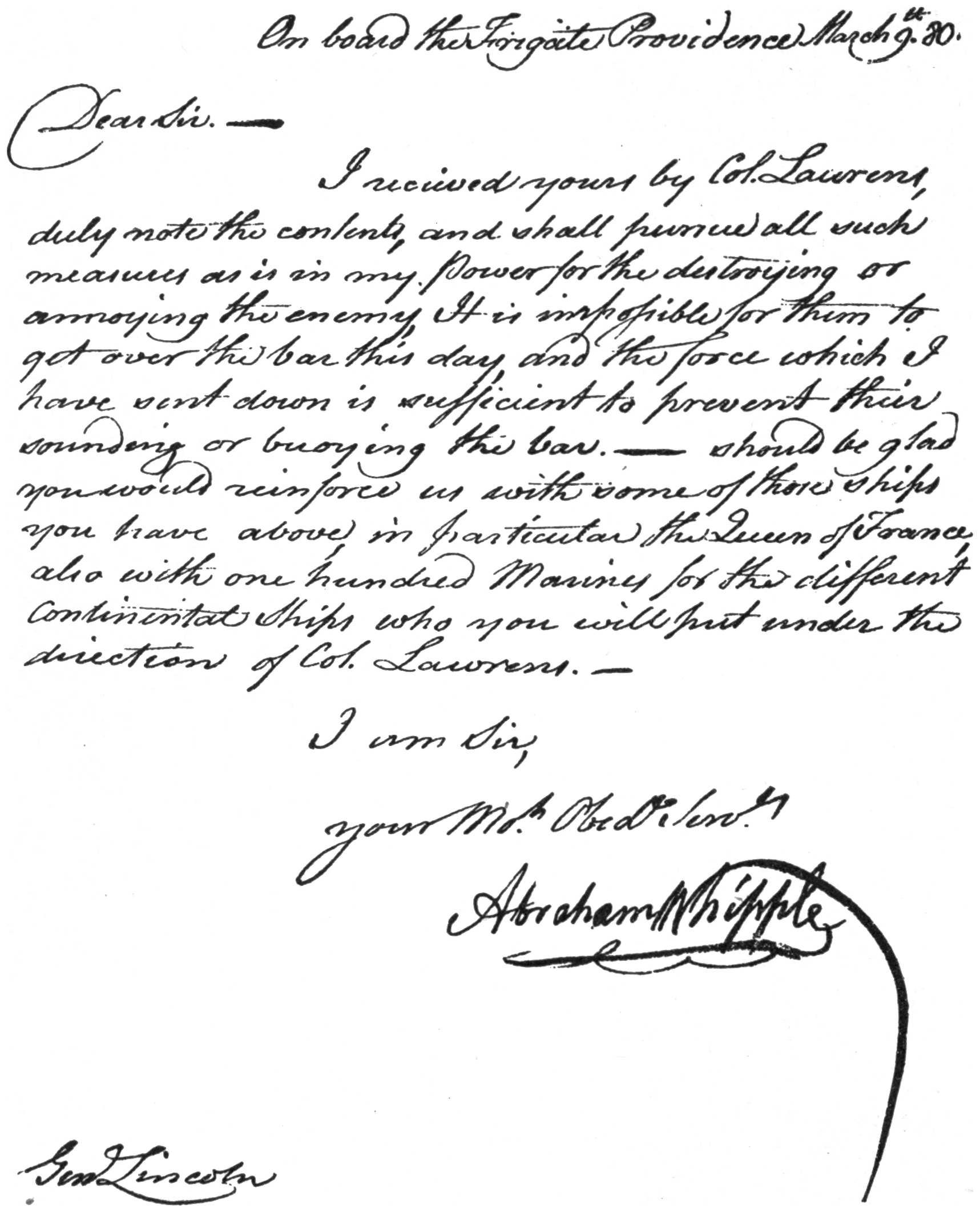

| Facsimile of a Letter from Abraham Whipple to General Lincoln during the Siege of Charleston. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 42 |

| Nicholas Biddle. (From an engraving by Edwin), | 45 |

| A Frigate Chasing a Small Boat. (From an old French engraving), | 48 |

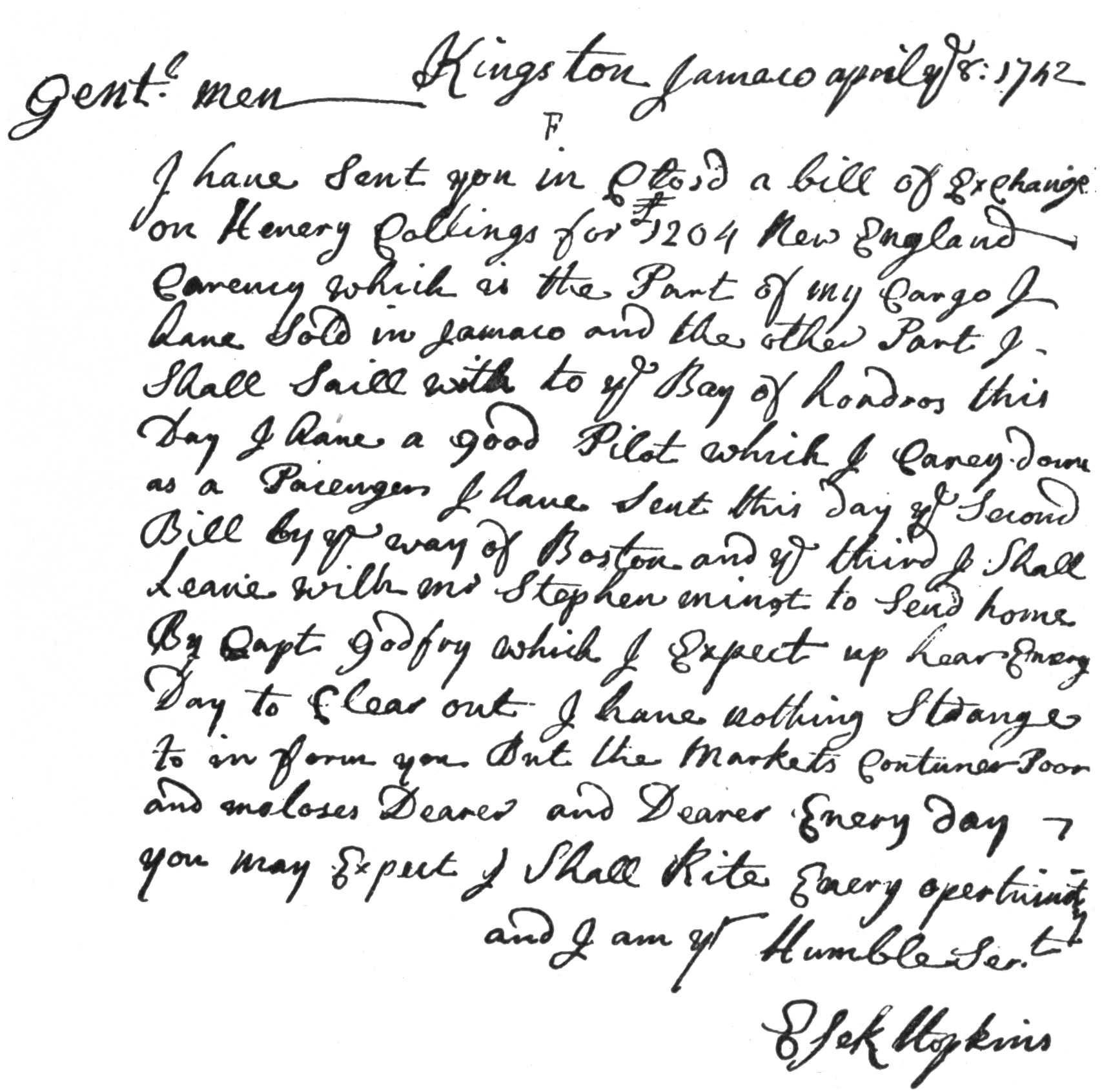

| A Letter from Esek Hopkins. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 50 |

| A Corvette. (From an old French engraving), | 52xviii |

| Commodore Esek Hopkins. (From a very rare English engraving), | 55 |

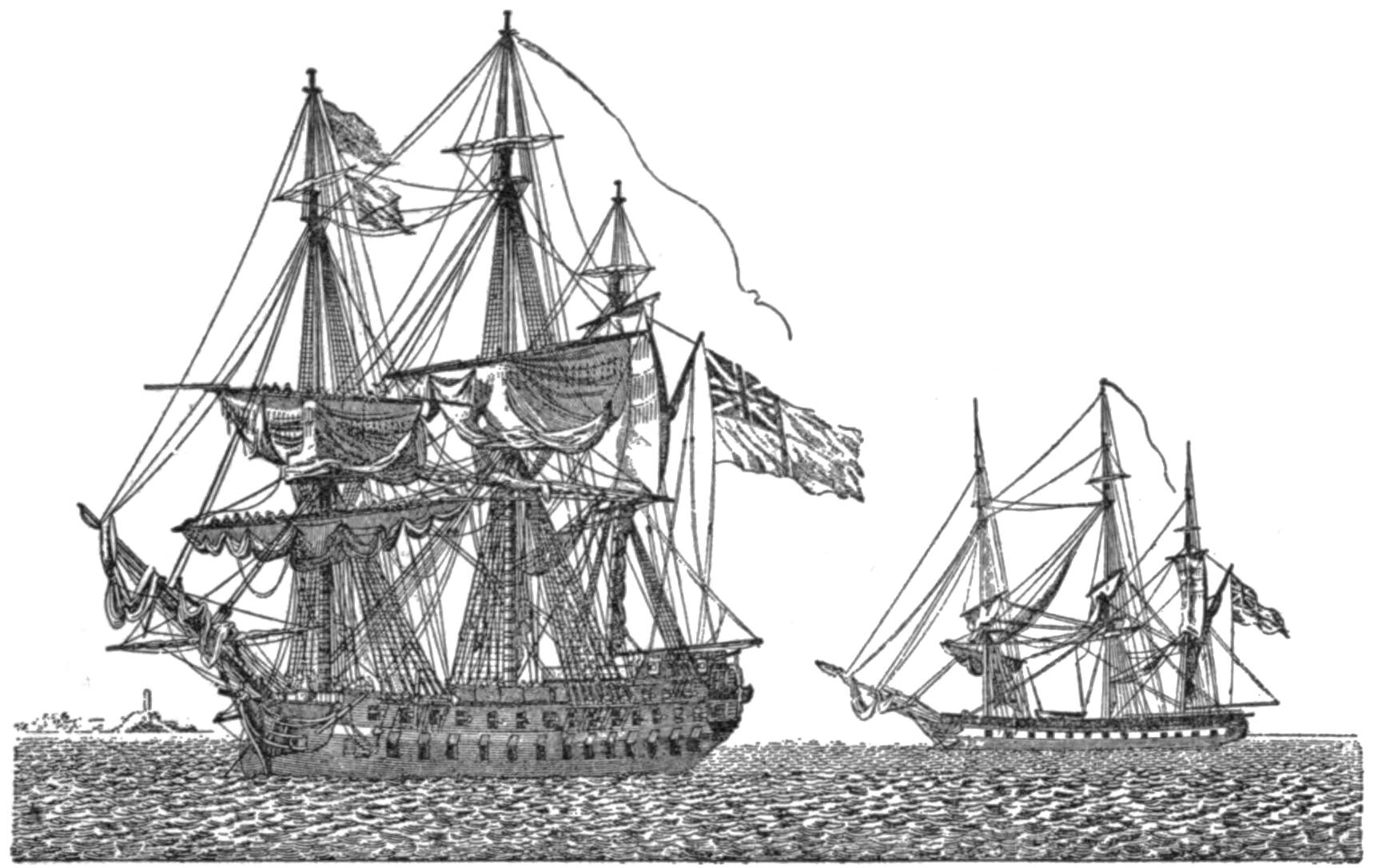

| An English “Seventy-four” and a Frigate Coming to Anchor. (From an old engraving), | 59 |

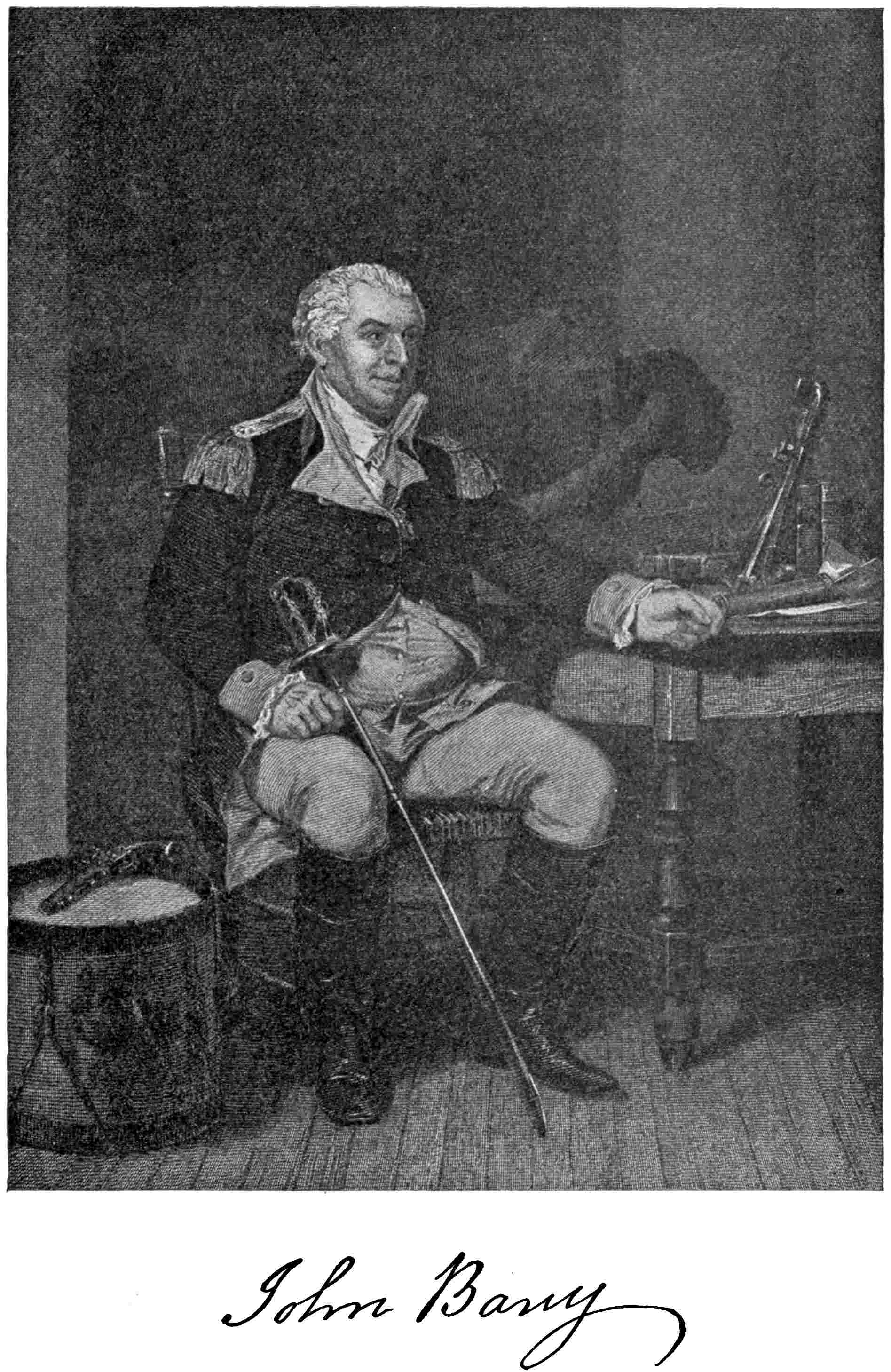

| John Barry. (From an engraving of the portrait by Chappel), | 65 |

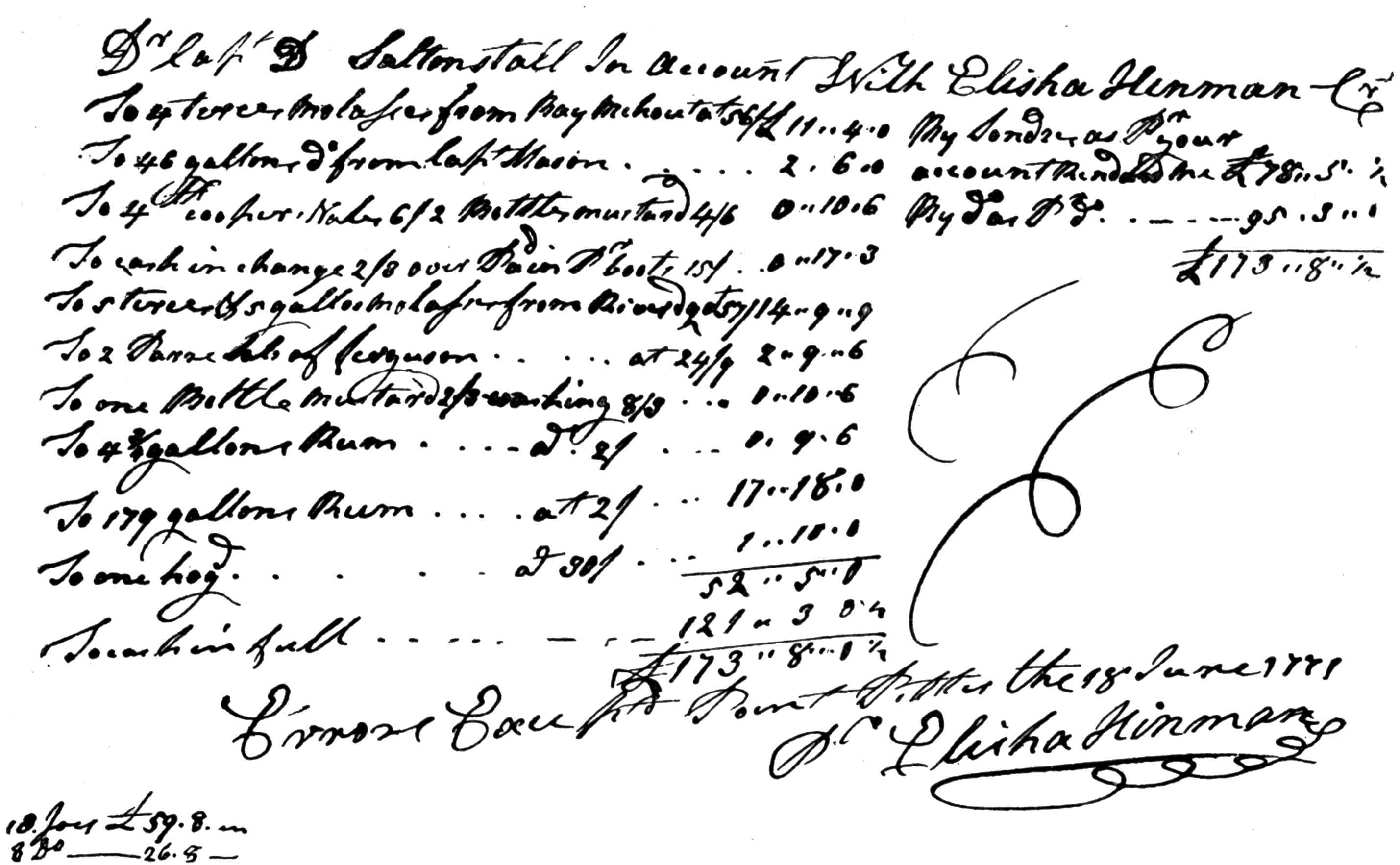

| Facsimile of Account between Dudley Saltonstall and Elisha Hinman. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 67 |

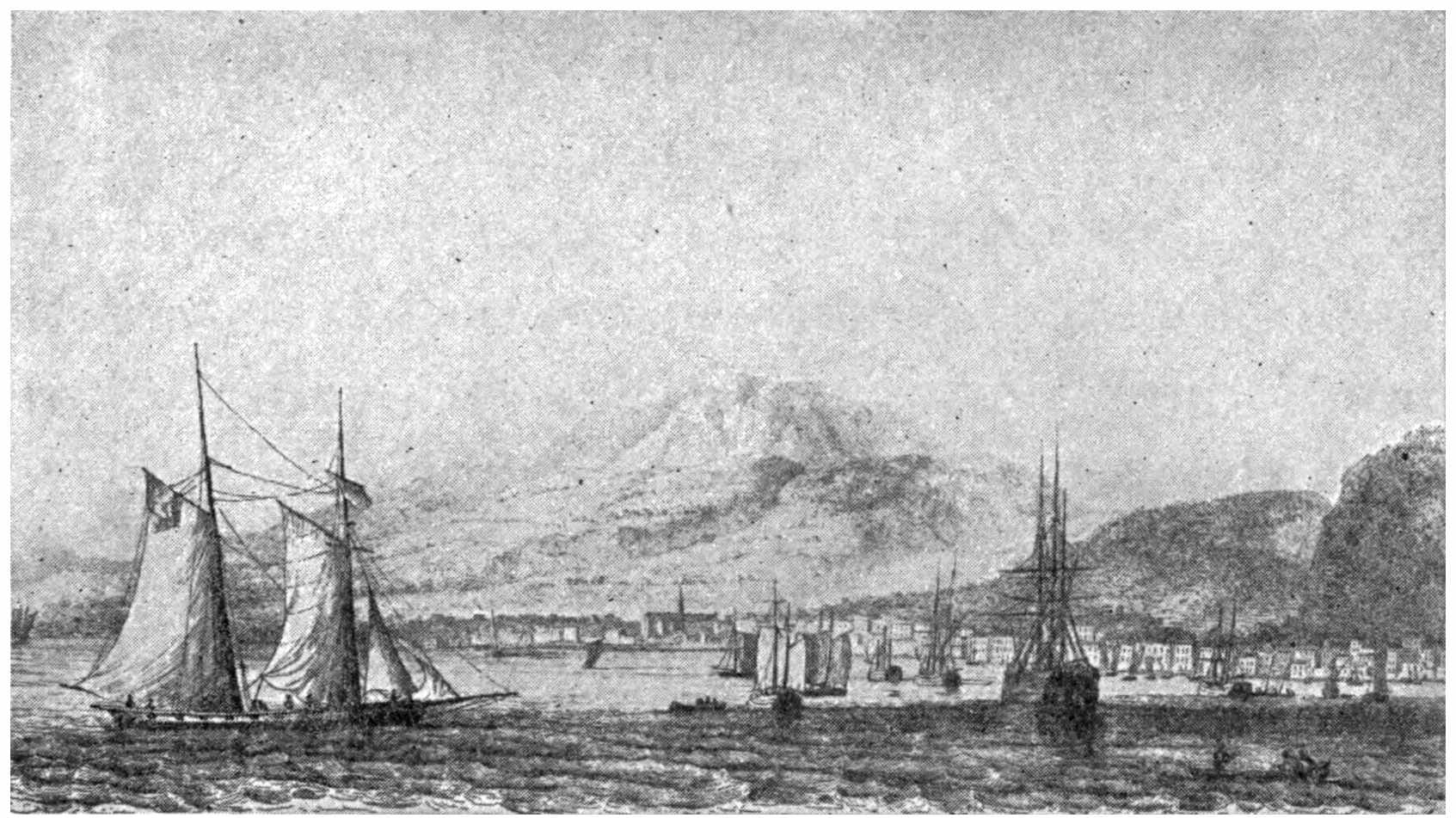

| St. Pierre, Martinique. (From an old engraving), | 70 |

| John Paul Jones. (From an engraving by Longacre of the portrait by C. W. Peale), | 75 |

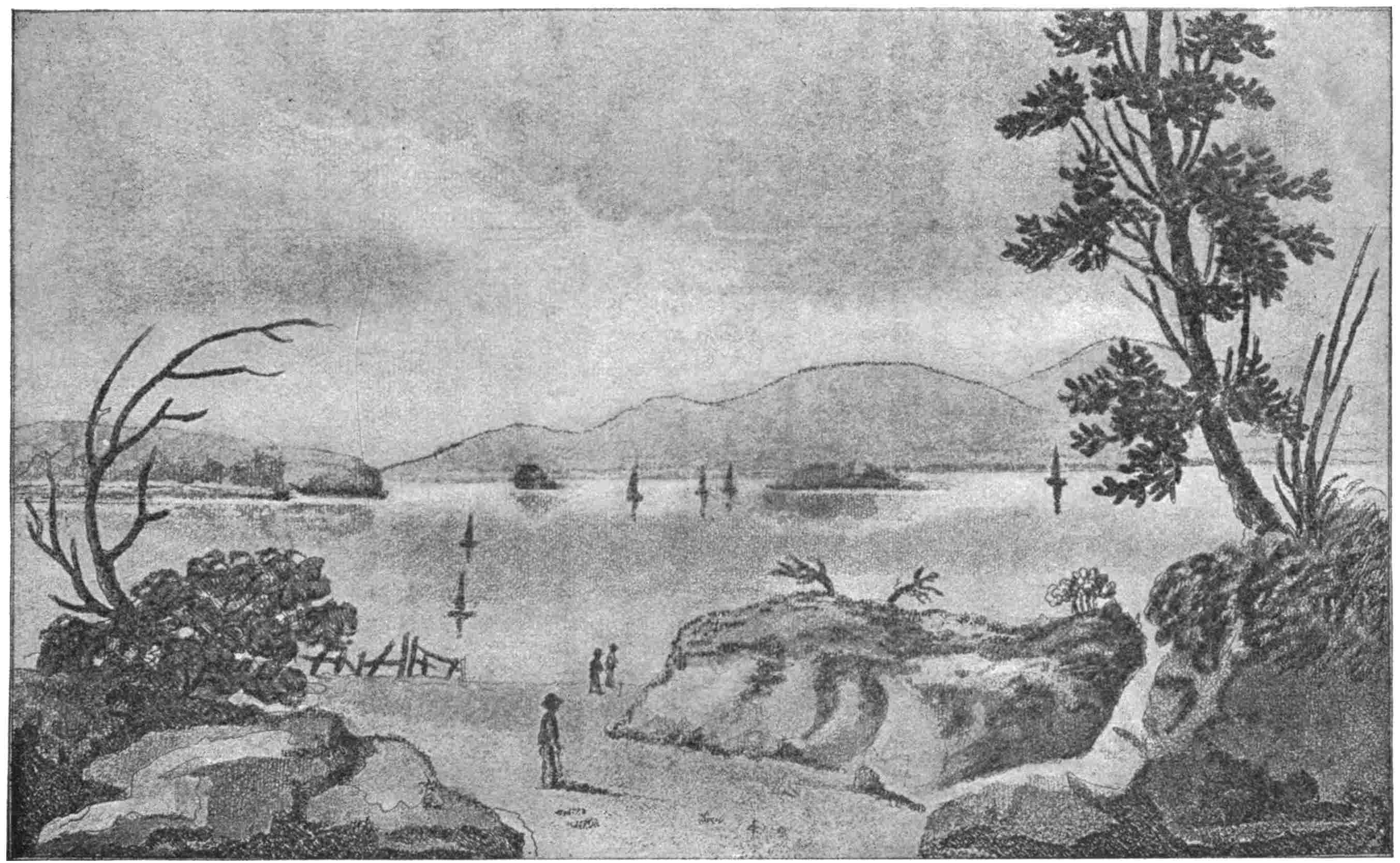

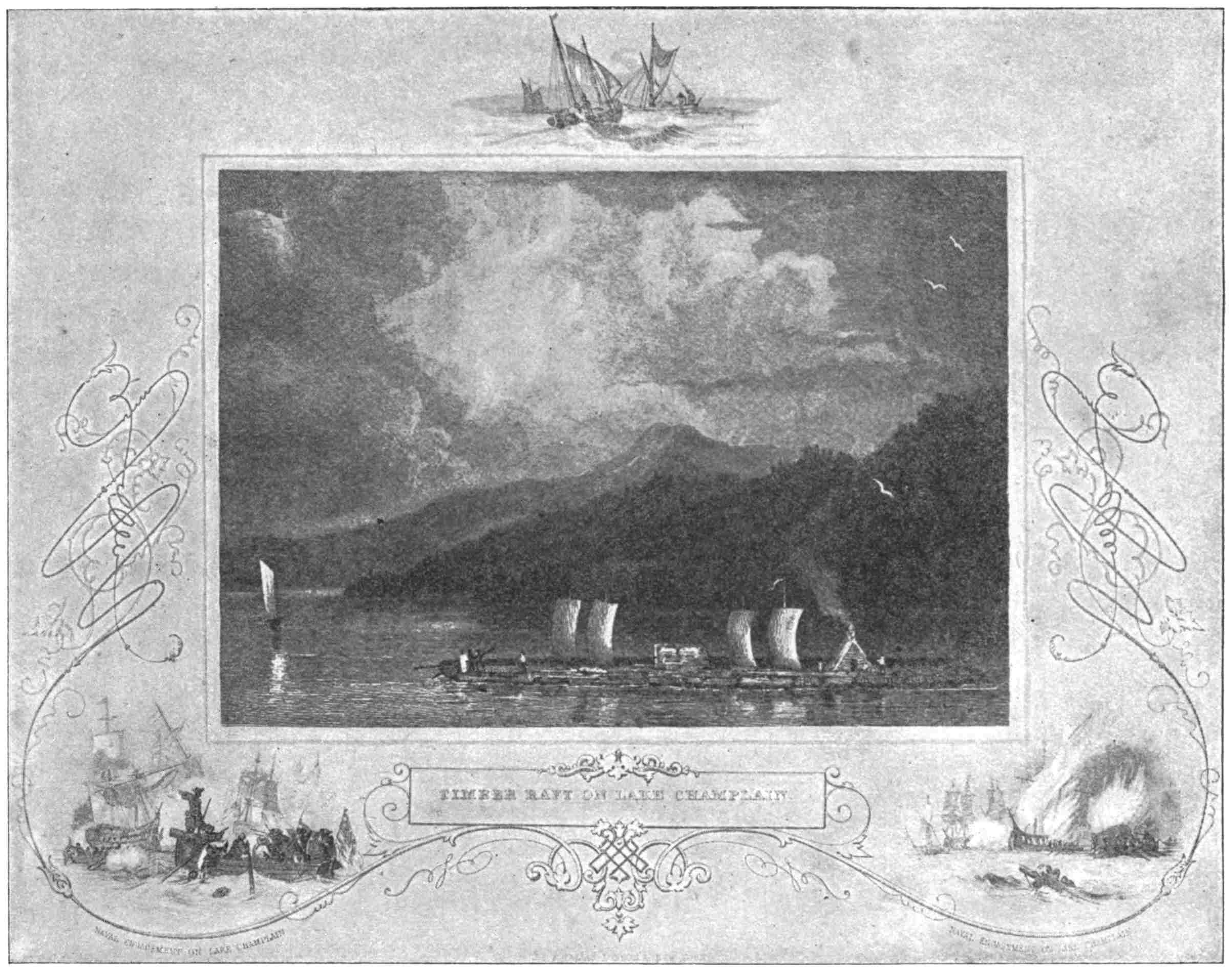

| Burlington Bay on Lake Champlain. (From an old engraving in the collection of Mr. W. C. Crane), | 83 |

| Sir Guy Carleton. (From an engraving by A. H. Ritchie), | 86 |

| Gen. Benedict Arnold. (Drawn from life at Philadelphia by Du Simitier), | 88 |

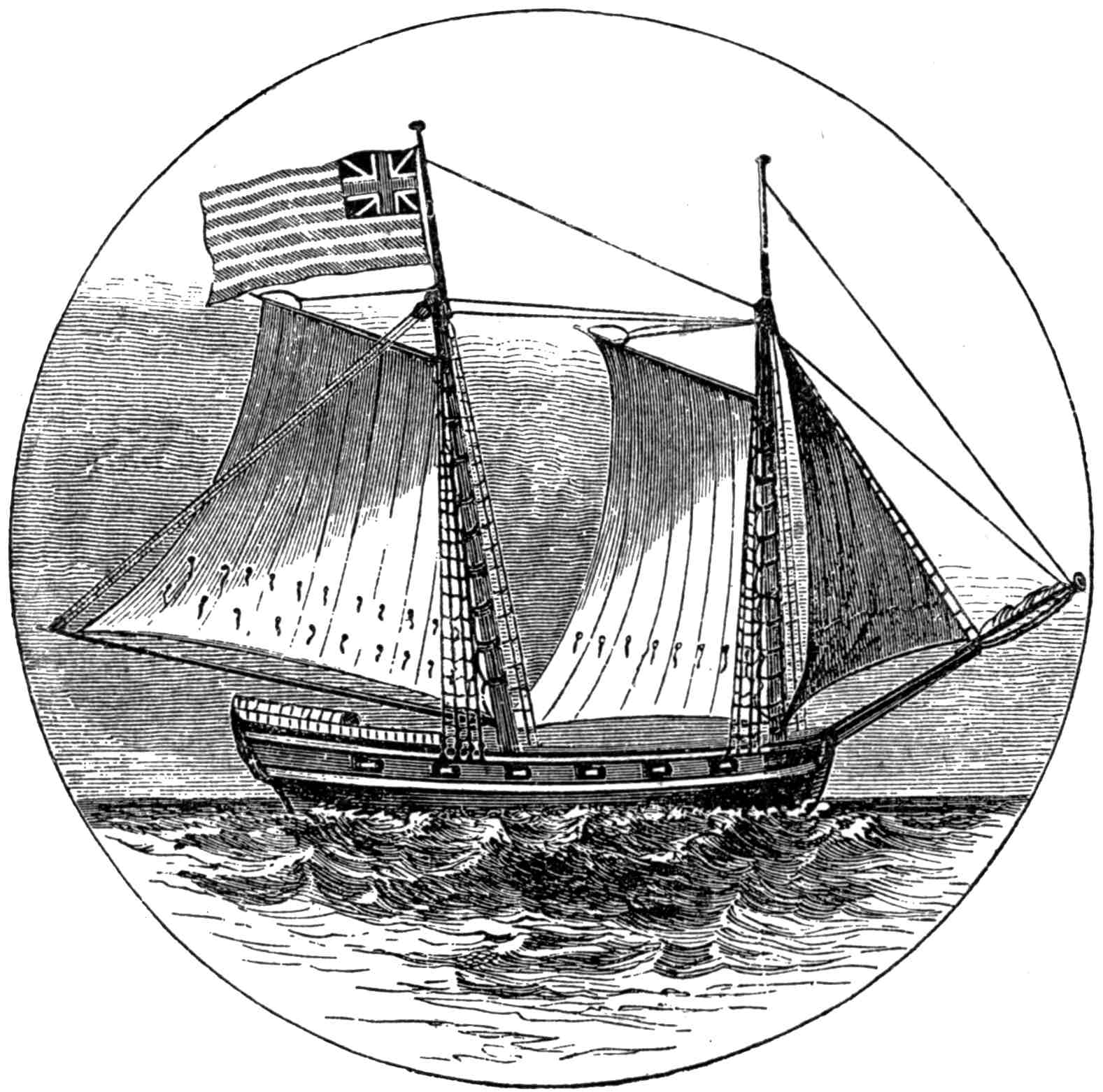

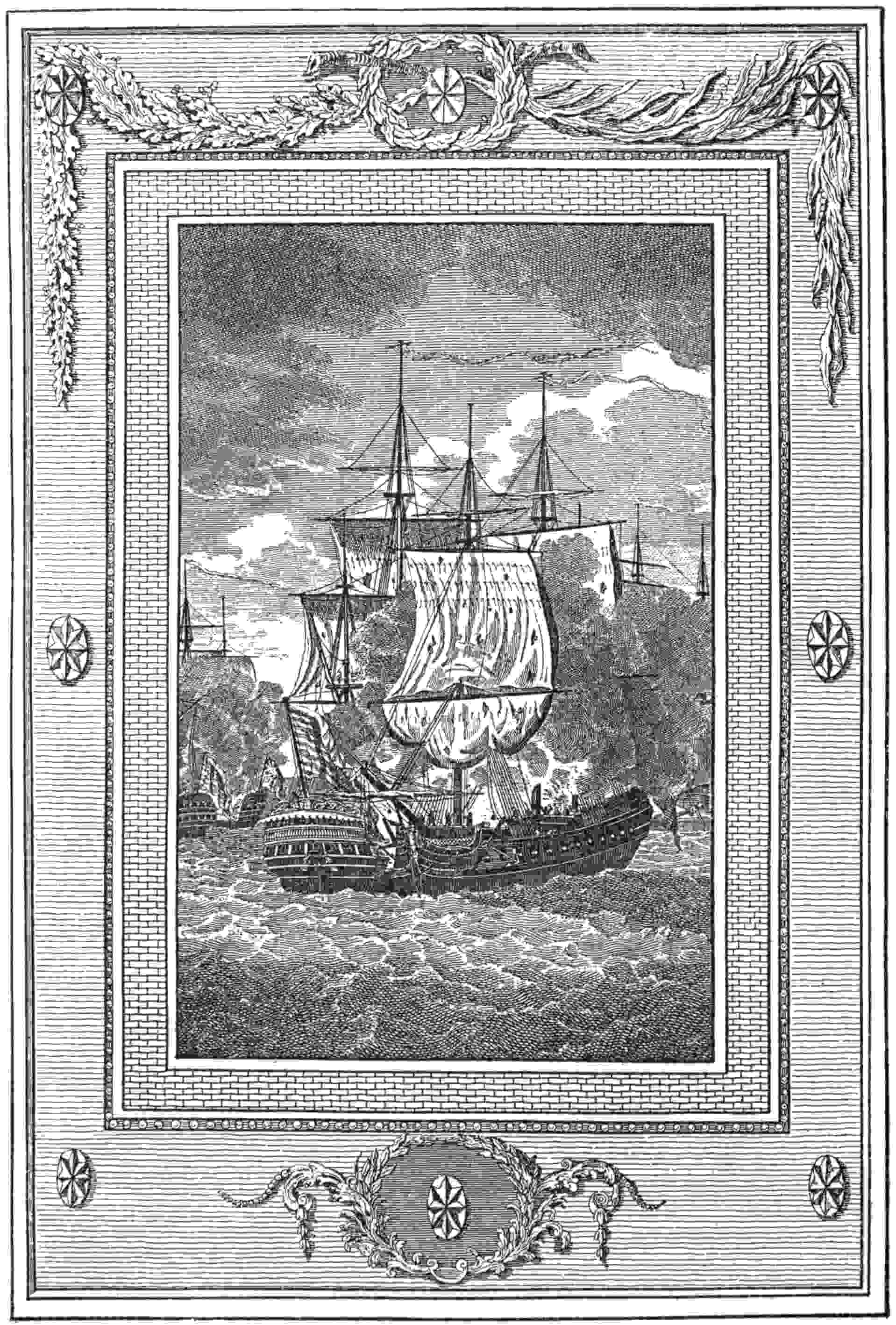

| The Royal Savage. (After an old painting), | 90 |

| The Battle of Lake Champlain, | 92 |

| Plan of the Action of October 12, 1776, | 93 |

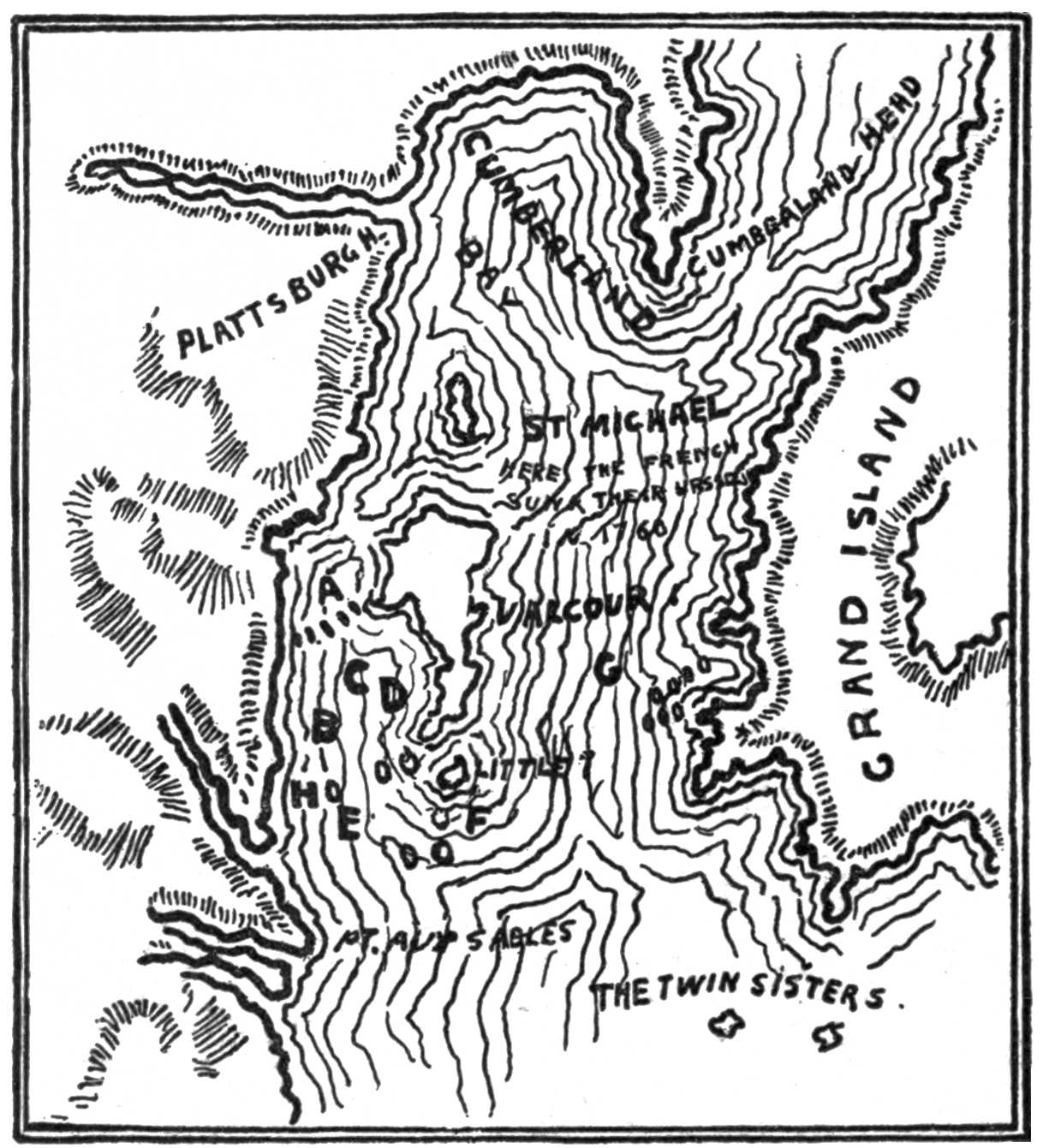

| Map of the Fight on Lake Champlain, 1776, | 94 |

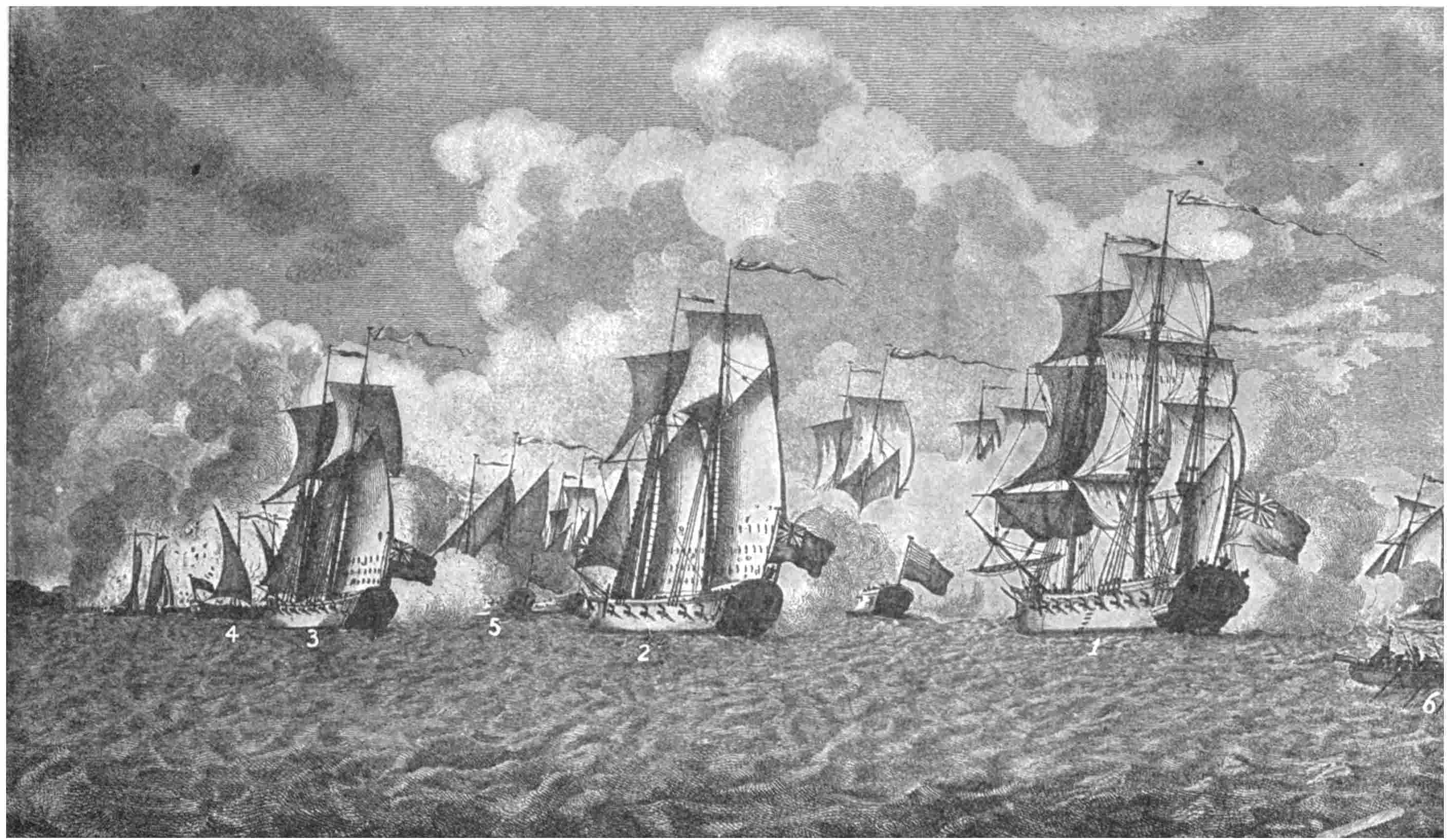

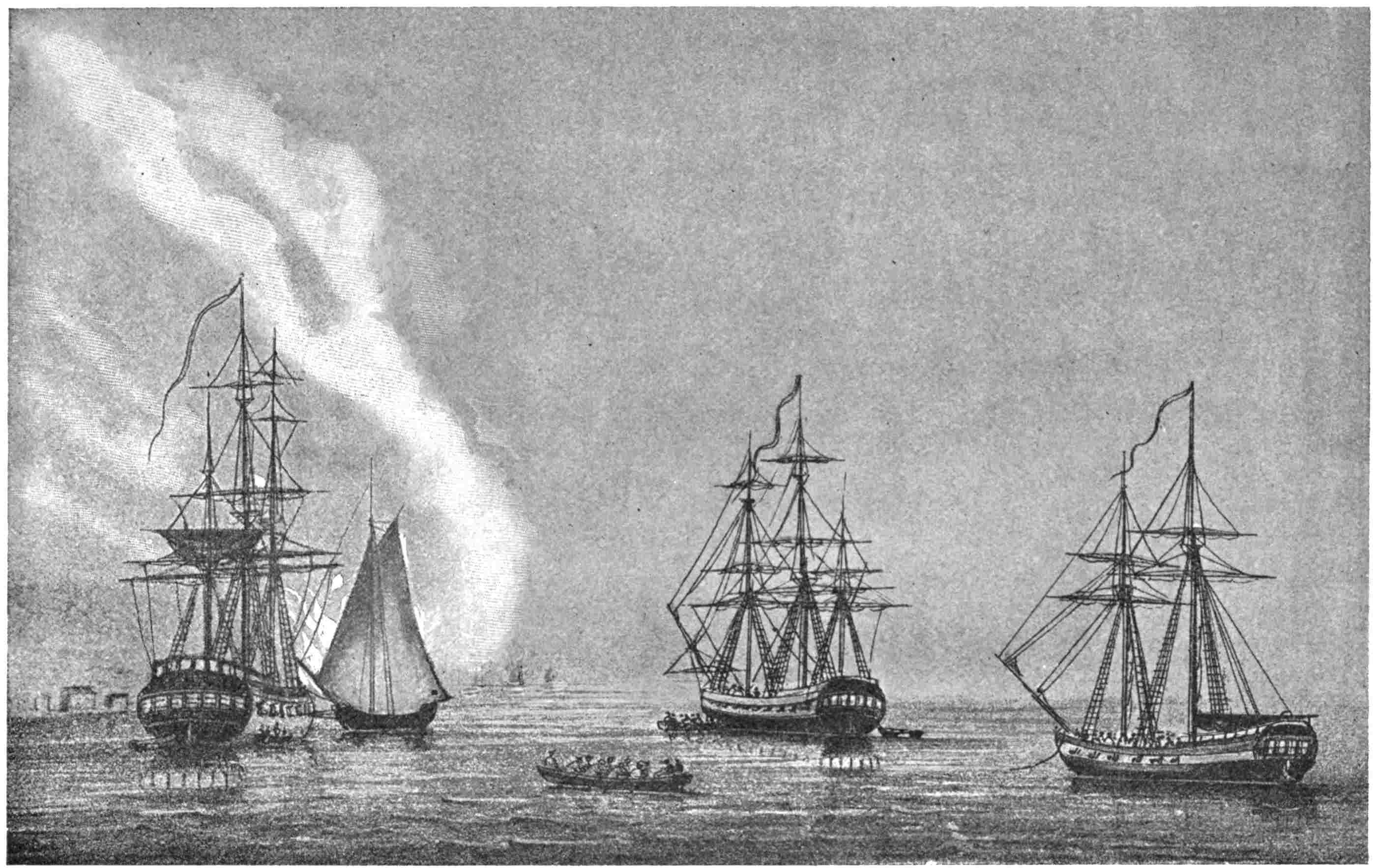

| The Fight on Lake Champlain, October 13, 1776. (From a contemporary English engraving), | 97 |

| A View on Lake Champlain, Showing the Fight of 1776. (From Hinton’s “History of the United States”), | 101 |

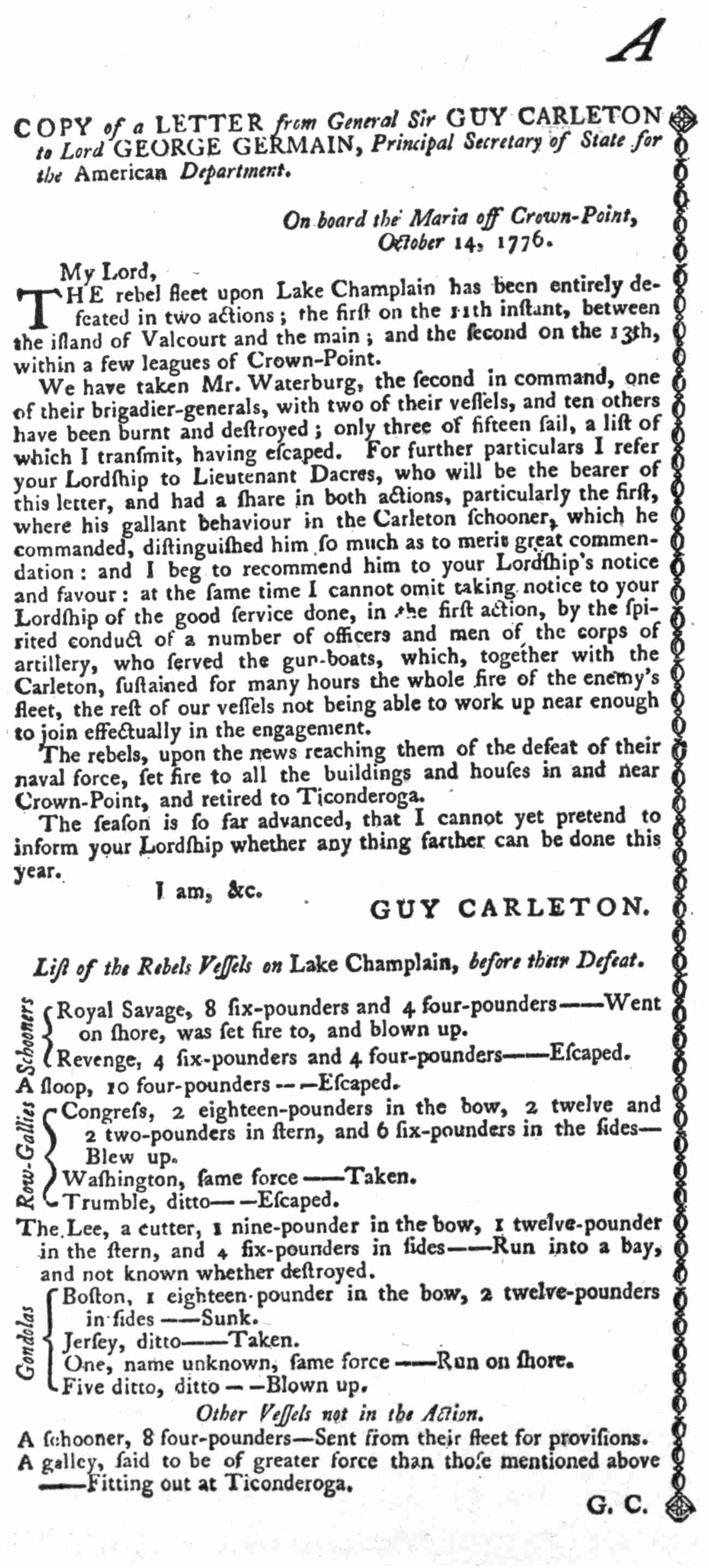

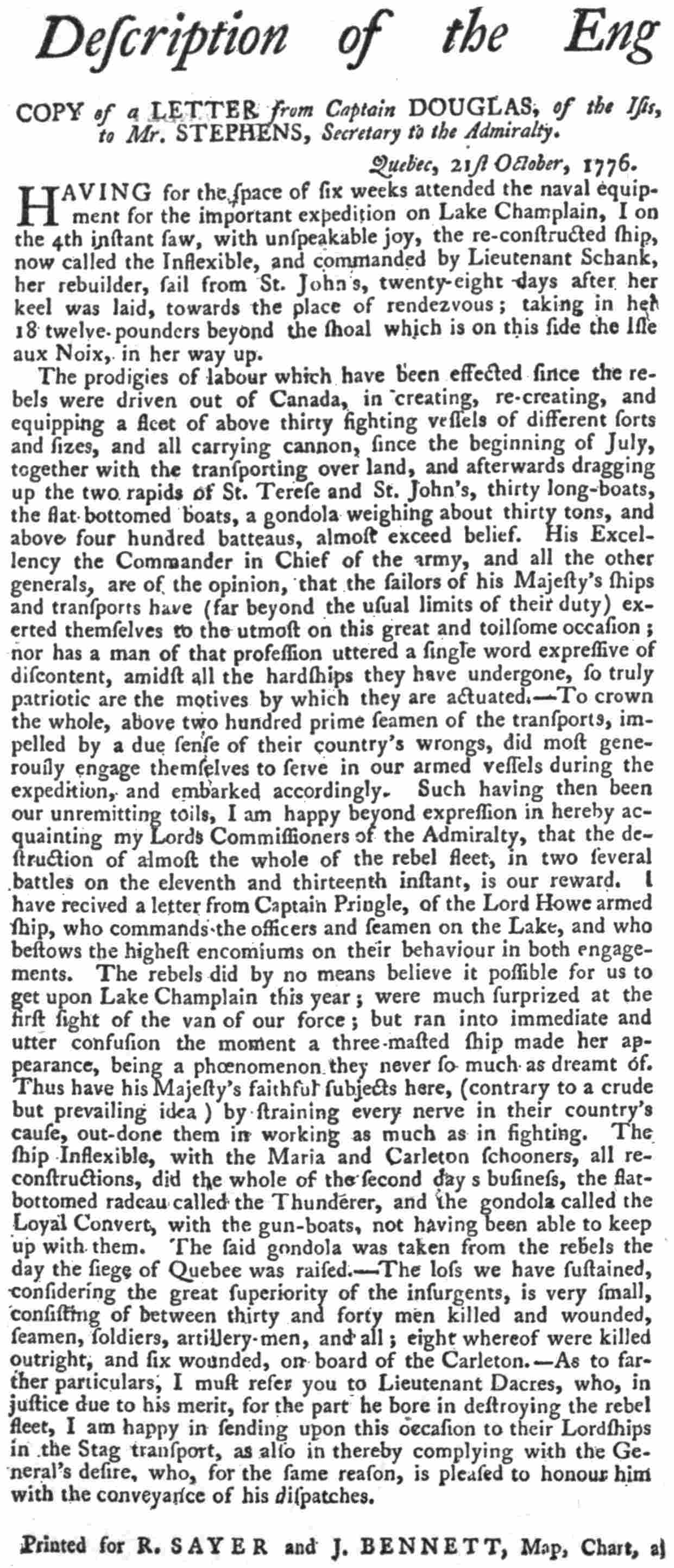

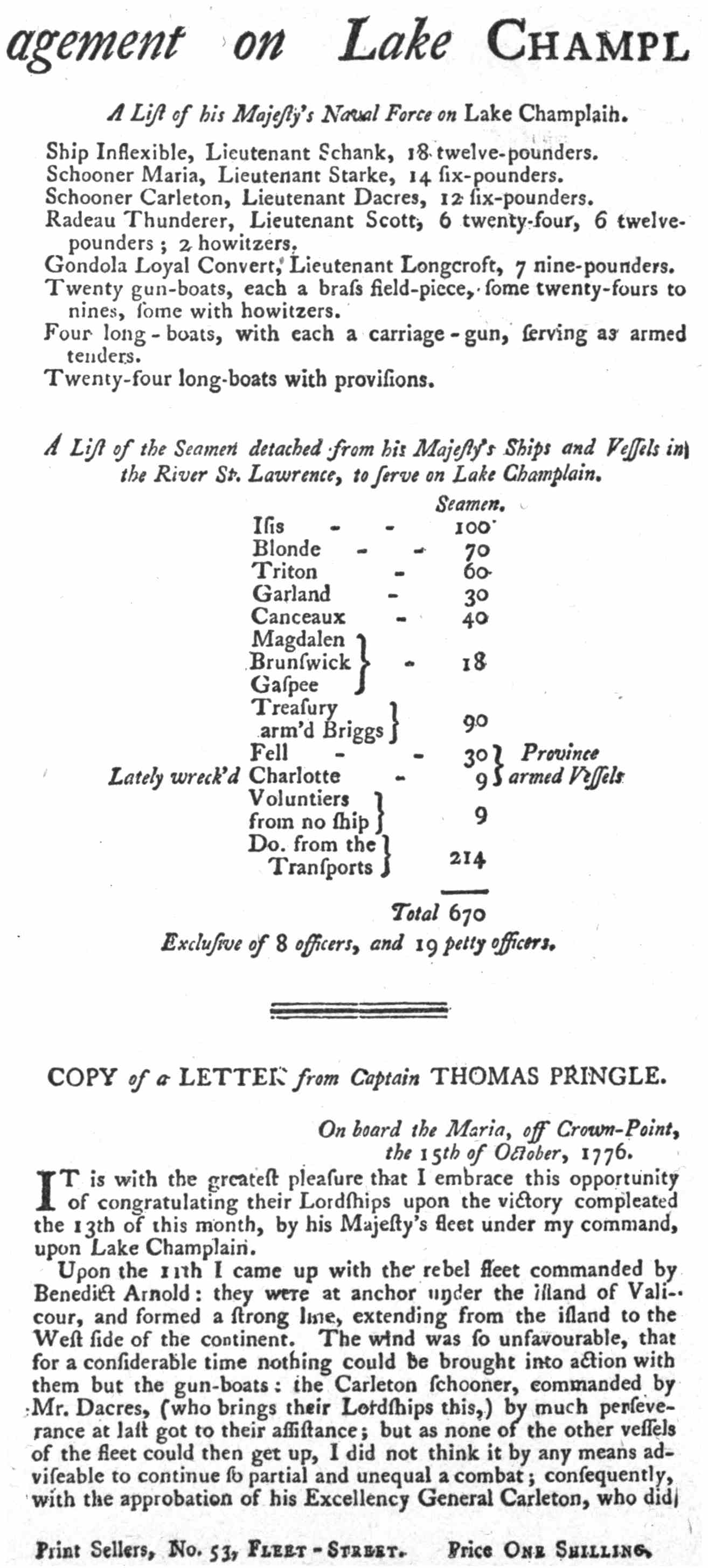

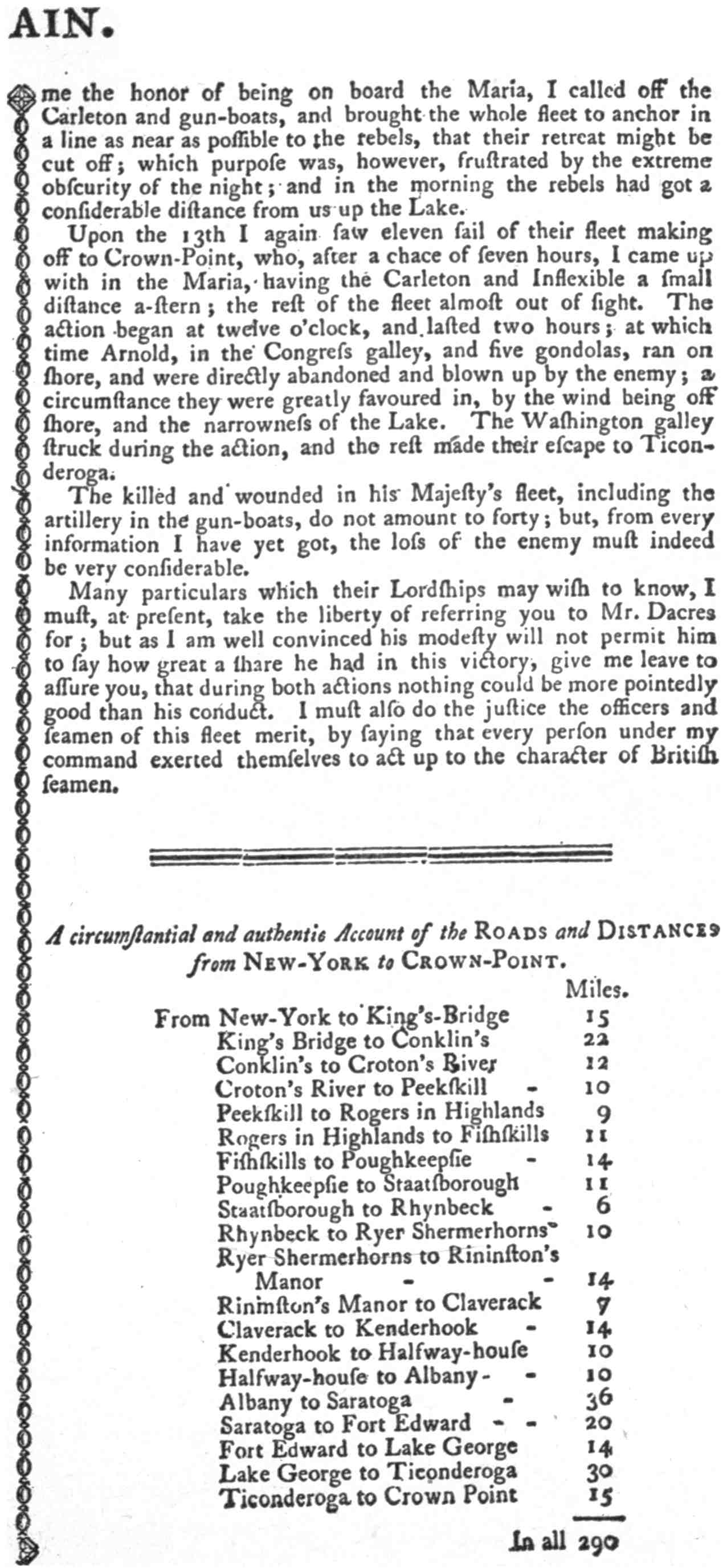

| Broadside Describing the Engagement on Lake Champlain. (From a copy at the Lenox Library), | 106–109 |

| The Phœnix and the Rose Engaging the Fireships on the Hudson River. (From a lithograph of the painting by Serres after a sketch by Sir James Wallace), | 115 |

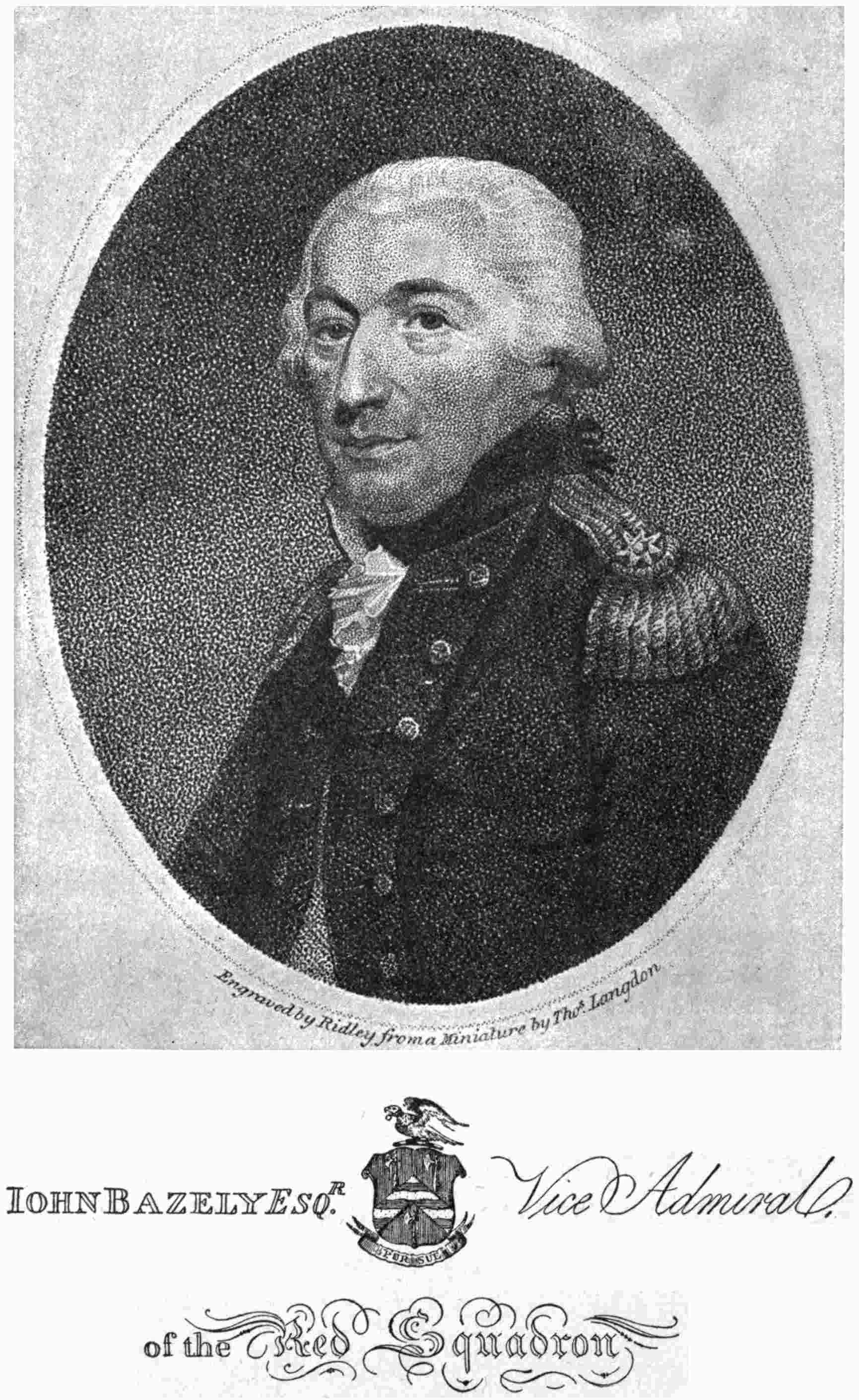

| John Bazeley. (From an engraving by Ridley of a miniature by Langdon), | 120 |

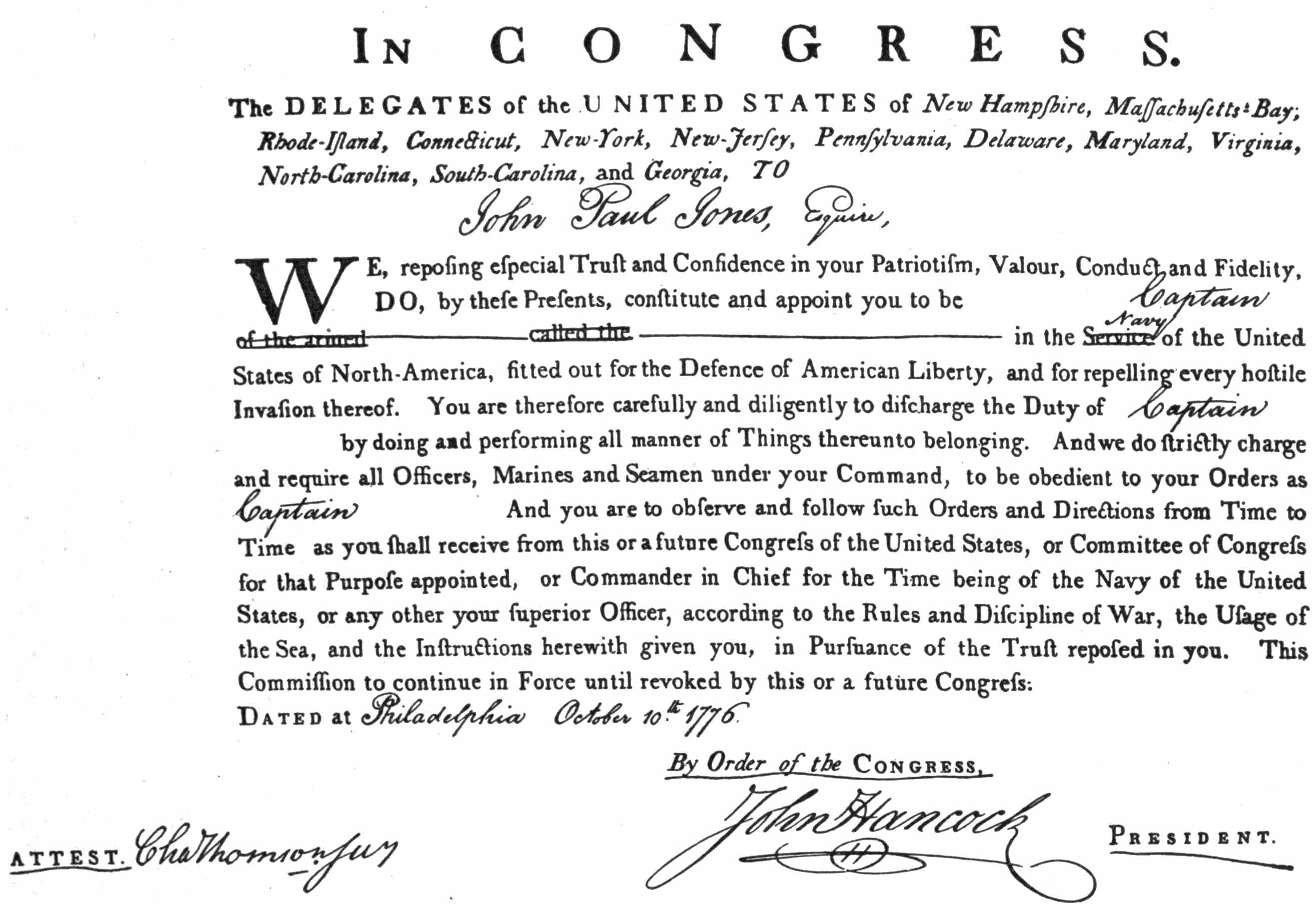

| John Paul Jones’s Commission, | 136 |

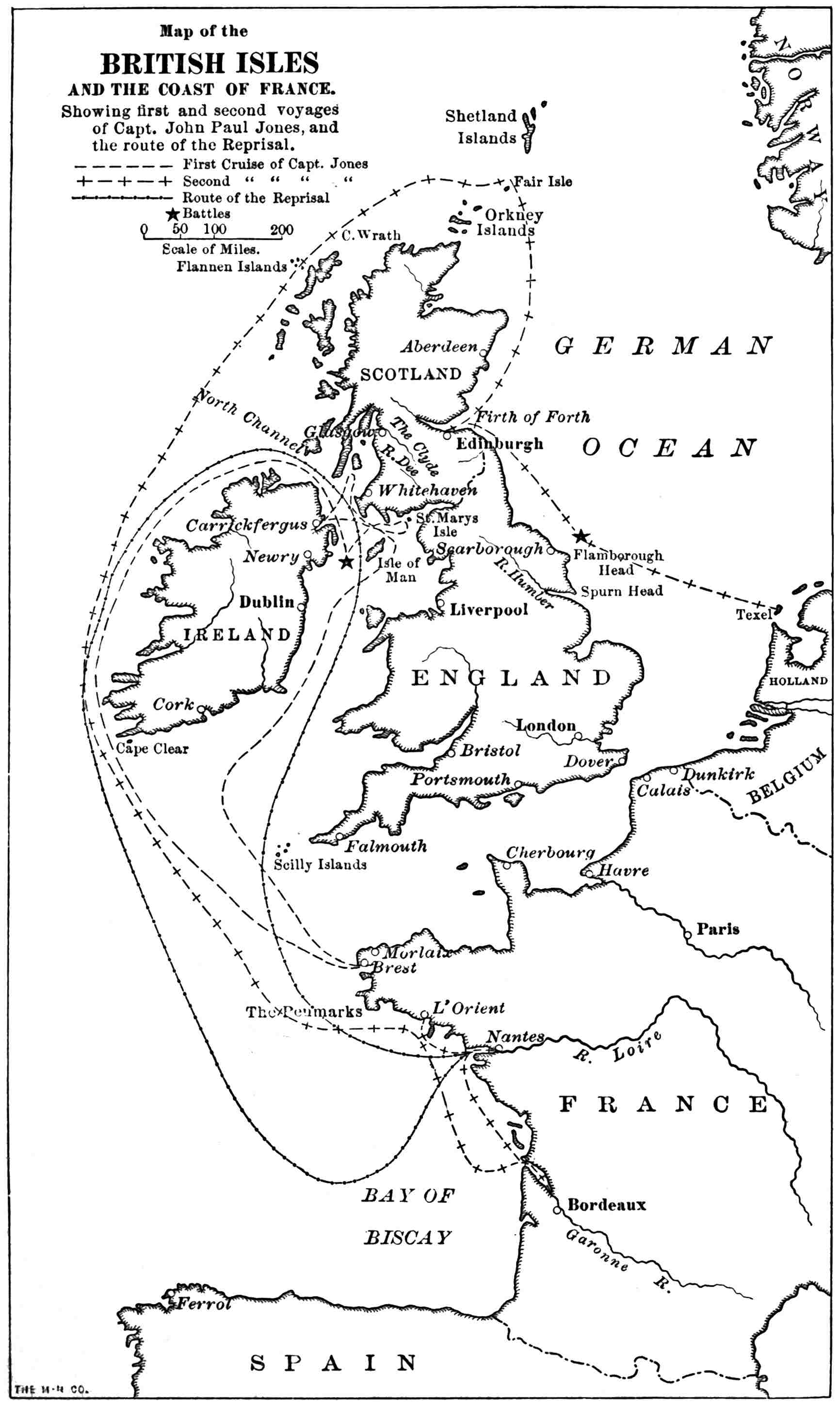

| Map of the British Isles. (Showing Captain Jones’s two voyages and the route of the Reprisal), | 139 |

| An English Caricature of John Paul Jones. (Published in London, October 22, 1779), | 143 |

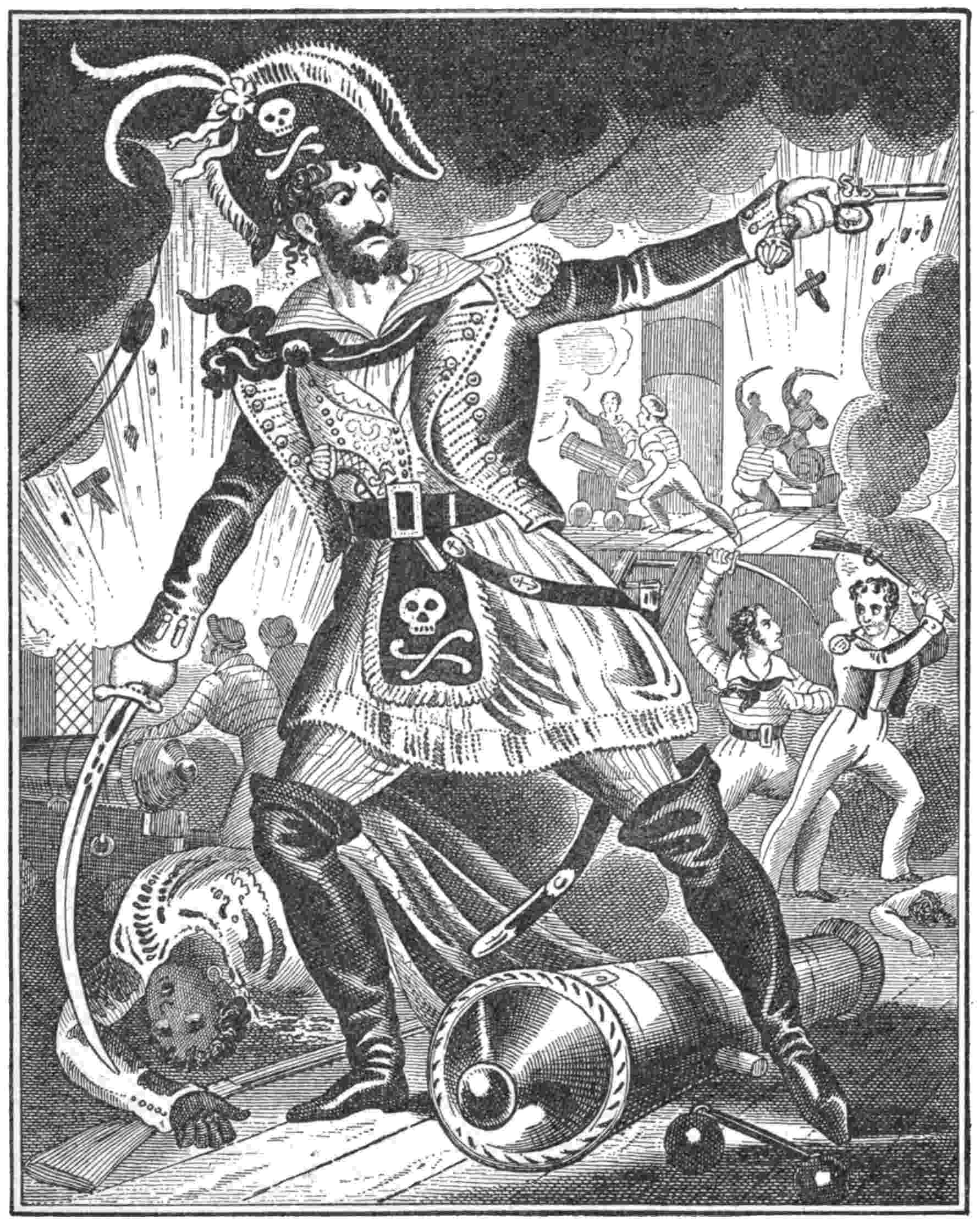

| “Paul Jones the Pirate.” (From an old engraving in the collection of Mr. W. C. Crane), | 149 |

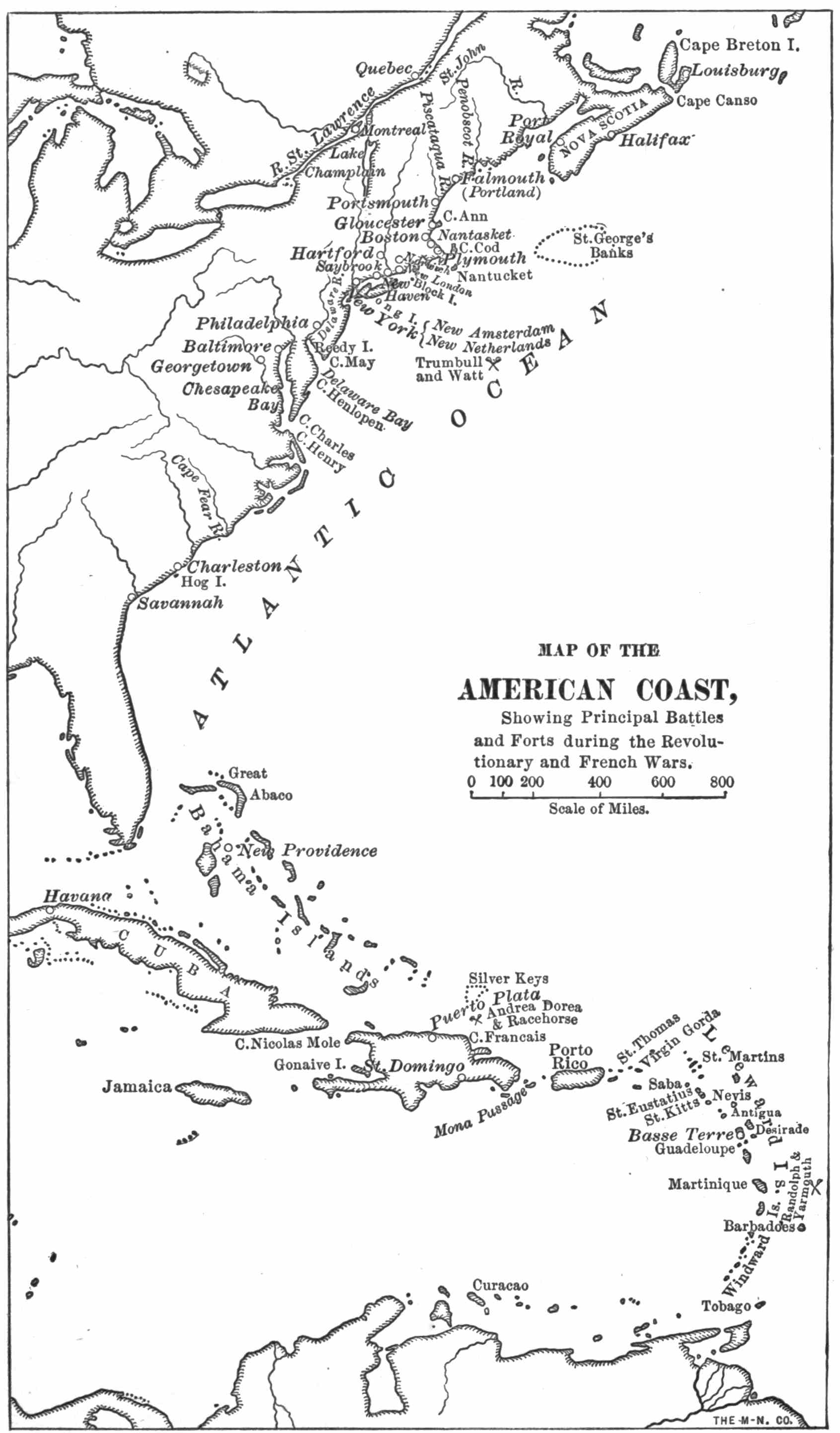

| Map of the American Coast, | 161 |

| Signatures of John Manly and Hector McNeil, | 181 |

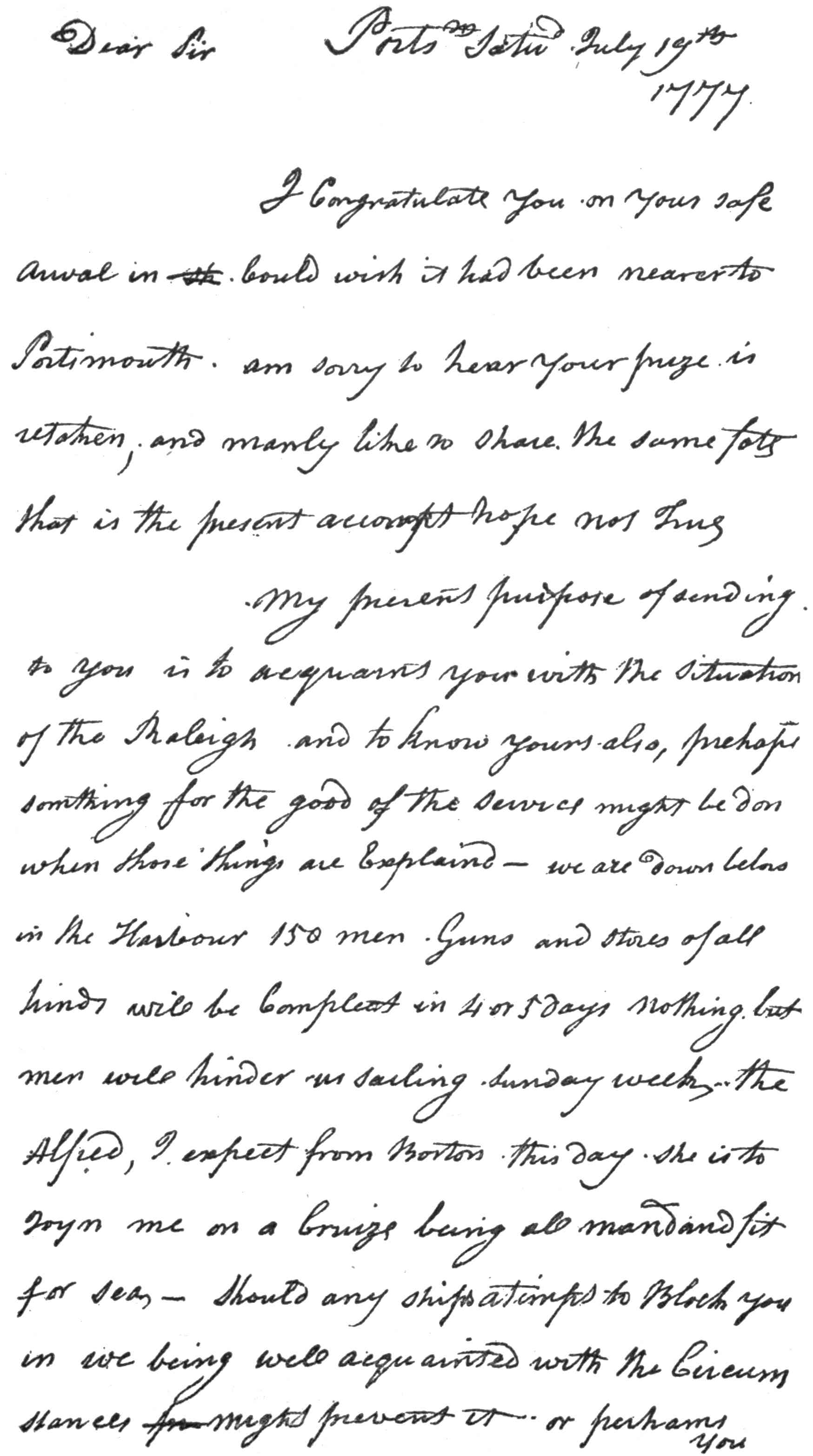

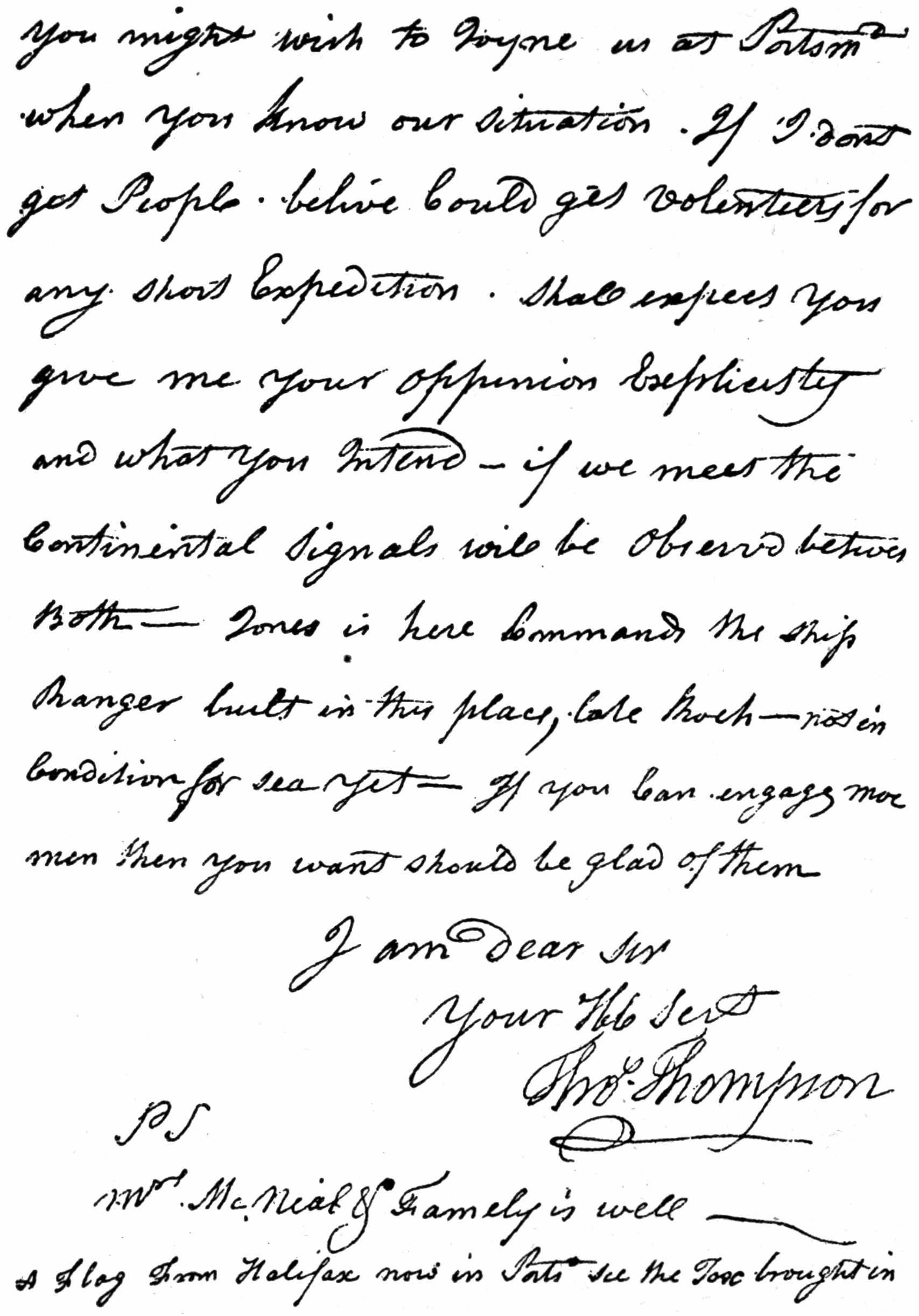

| Facsimile of a Letter from Thomas Thompson to Captain McNeil. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 183–4xix |

| A Typical Nassau Fort—Fort Fincastle. (From a photograph by Rau), | 187 |

| An English Frigate of Forty Guns. (From an engraving by Verico), | 191 |

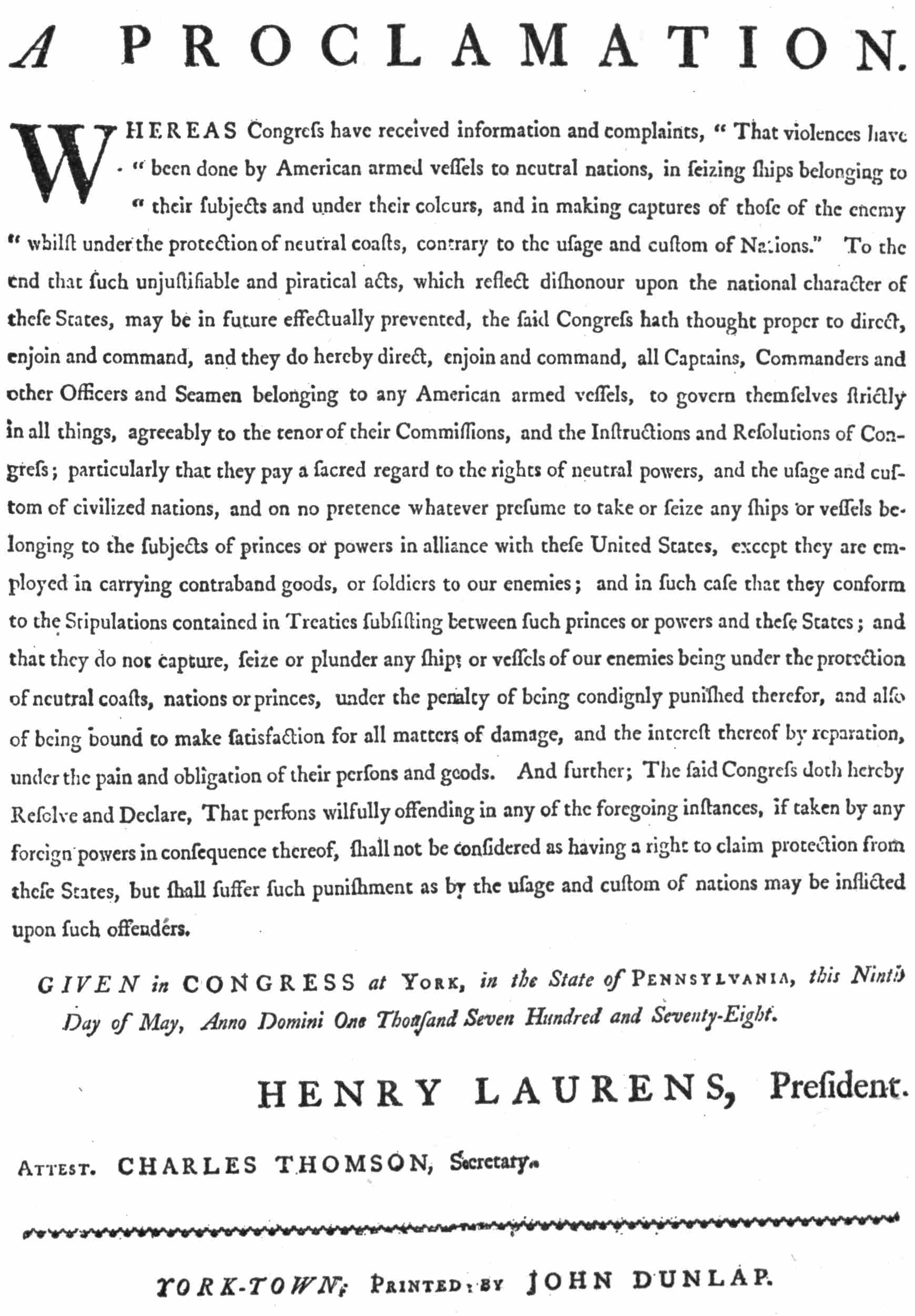

| “A Proclamation.” (From the copy at the Lenox Library), | 198 |

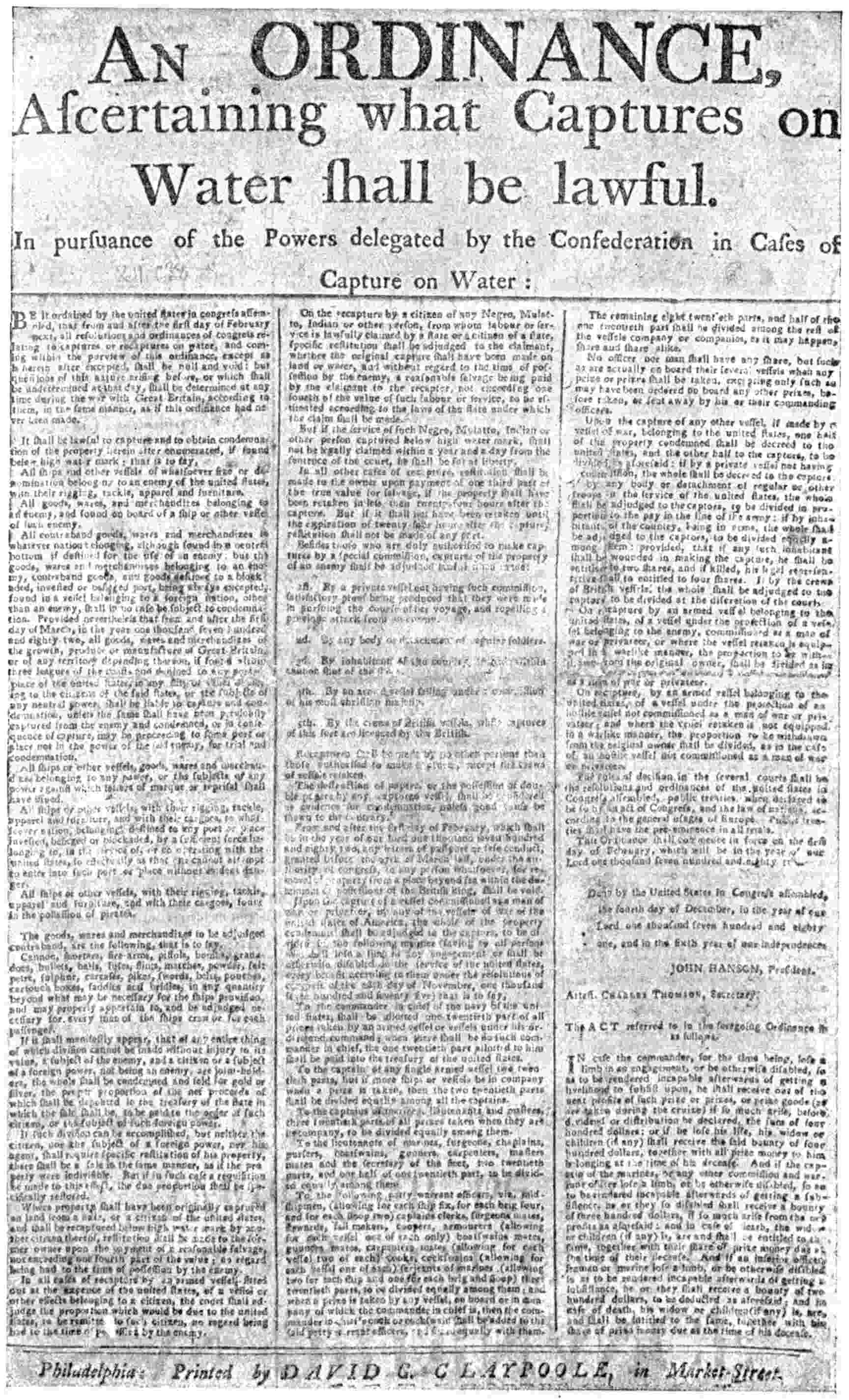

| “An Ordinance Ascertaining what Captures on Water shall be Lawful.” (From the copy at the Lenox Library), | 202 |

| Alexander Murray. (From an engraving by Edwin of the painting by Wood), | 208 |

| Joshua Barney. (From an engraving by Gross after a miniature by Isabey), | 210 |

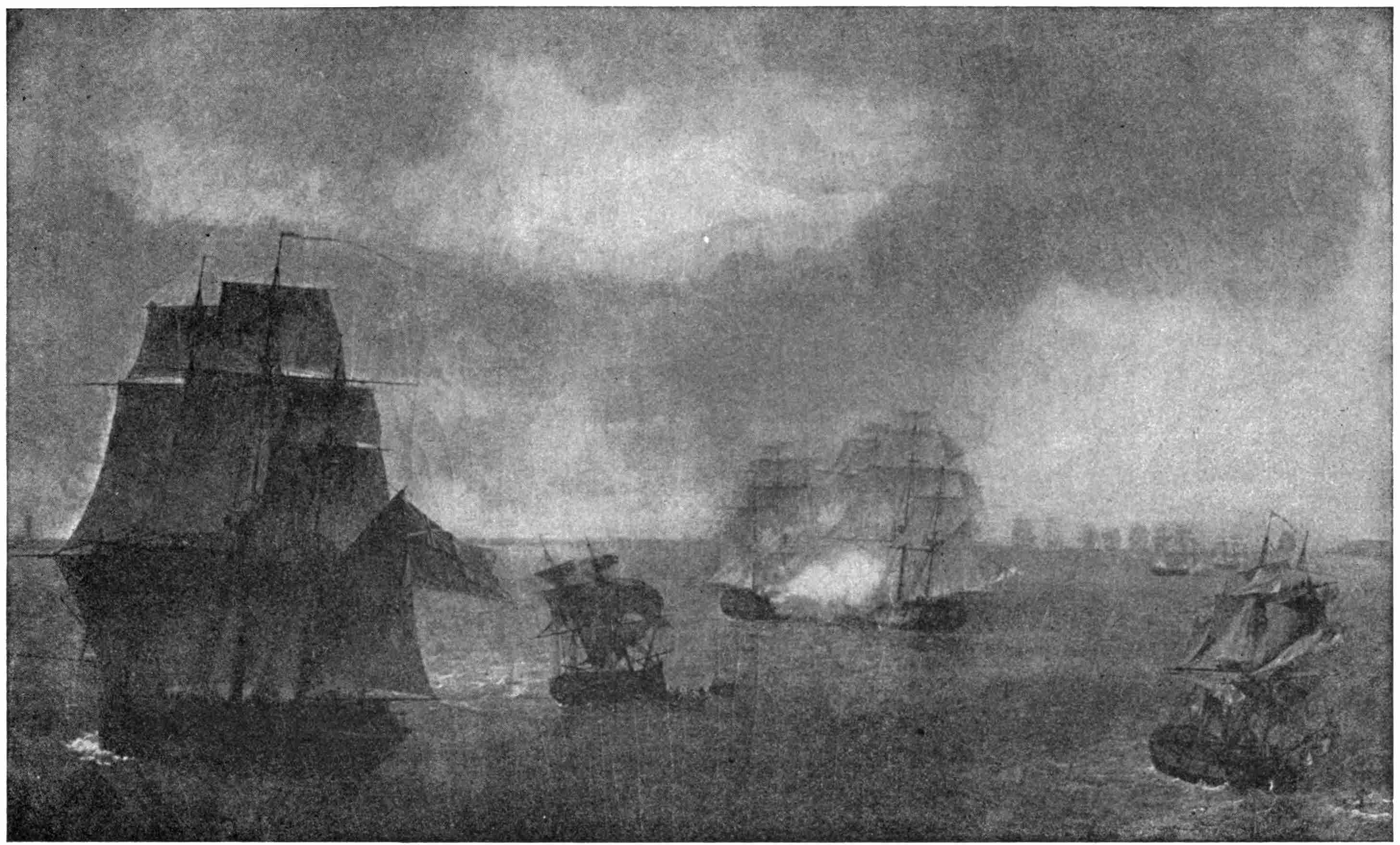

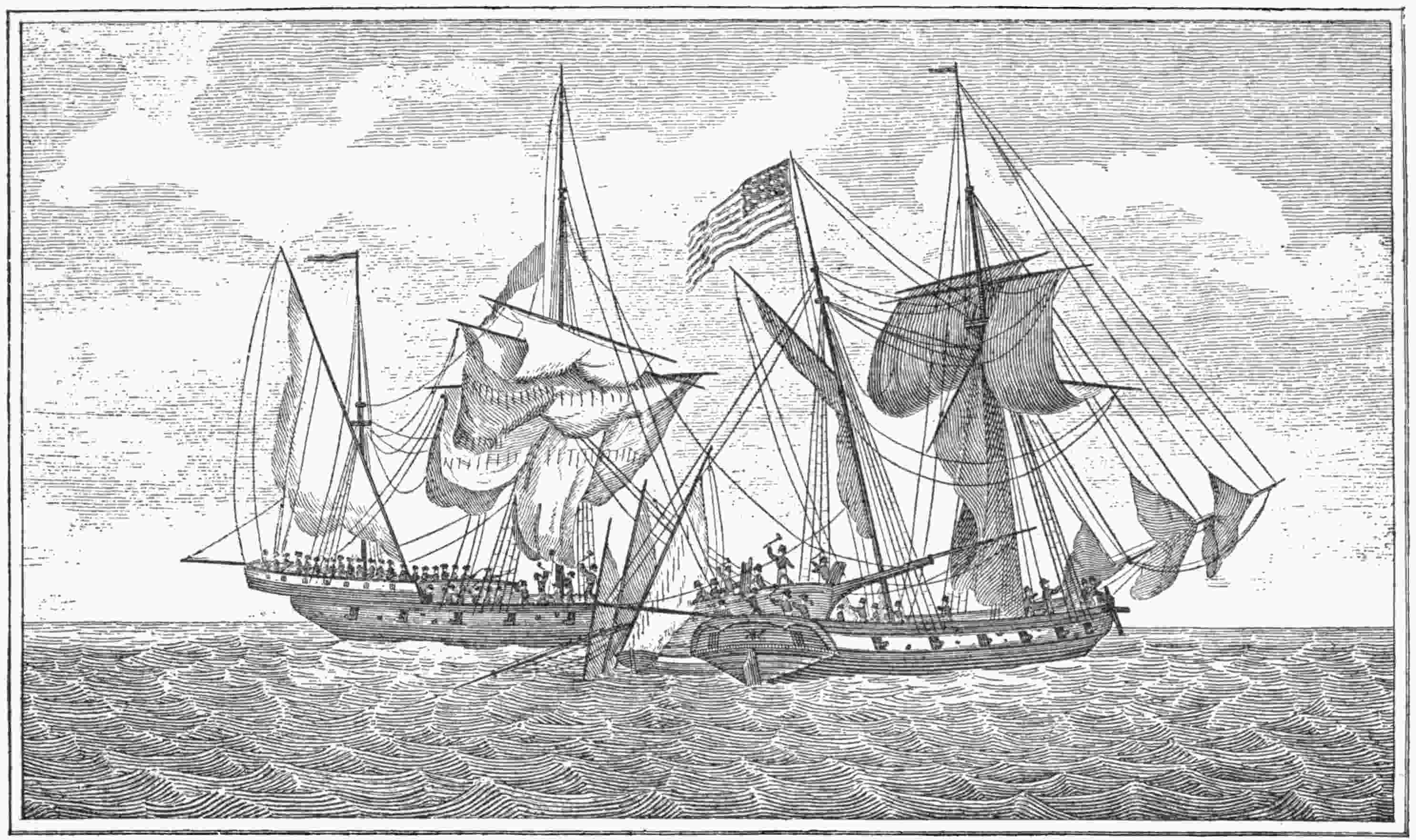

| Fight of the Hyder Ali with the General Monk, 1782. (From a painting by Crépin at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 213 |

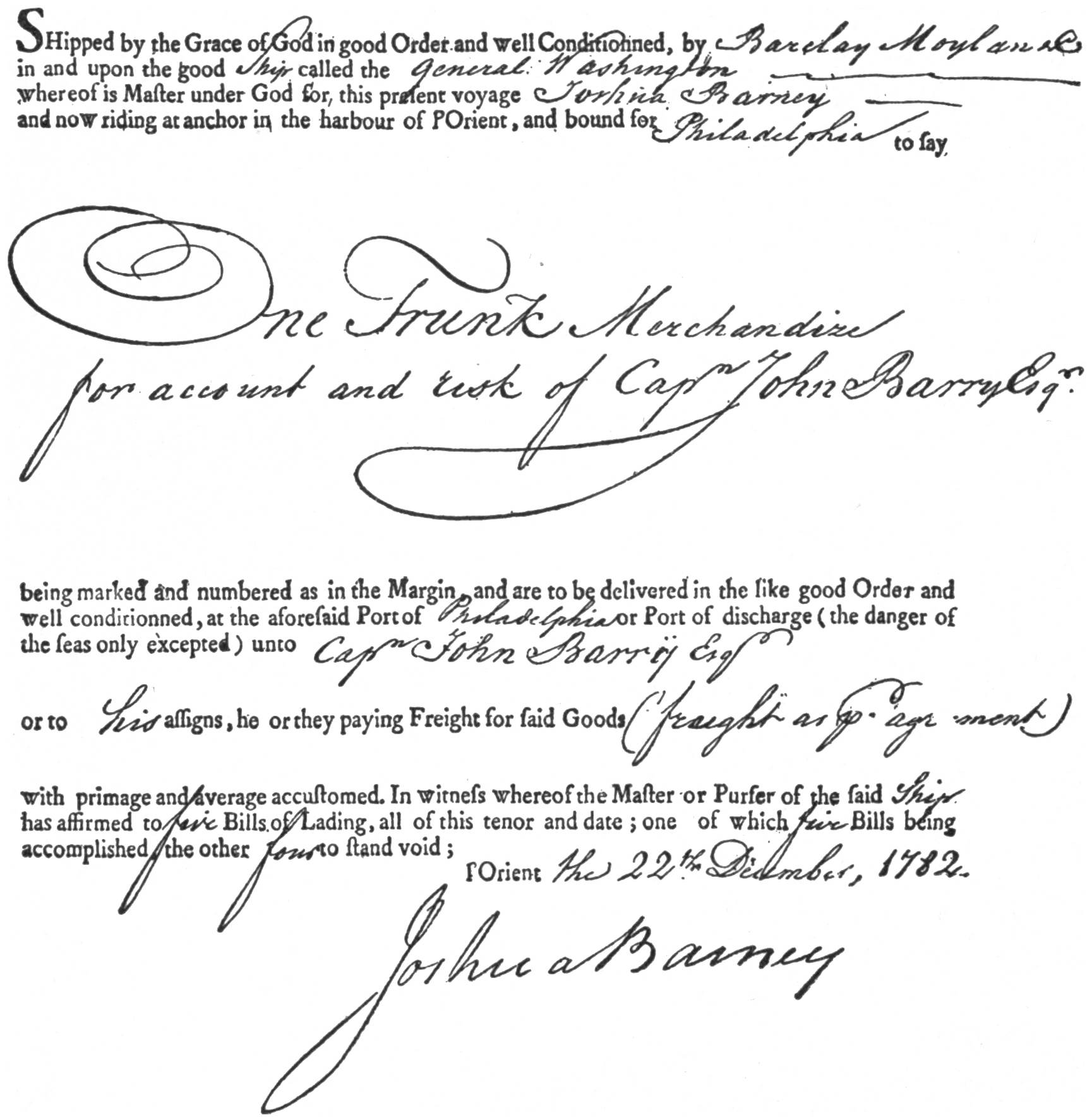

| A Relic of Two Revolutionary Captains—Bill of Lading for John Barry Signed by Joshua Barney. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 216 |

| “The Howes Asleep in Philadelphia”—A Caricature Drawn forth by the Doings of Revolutionary Privateers, | 219 |

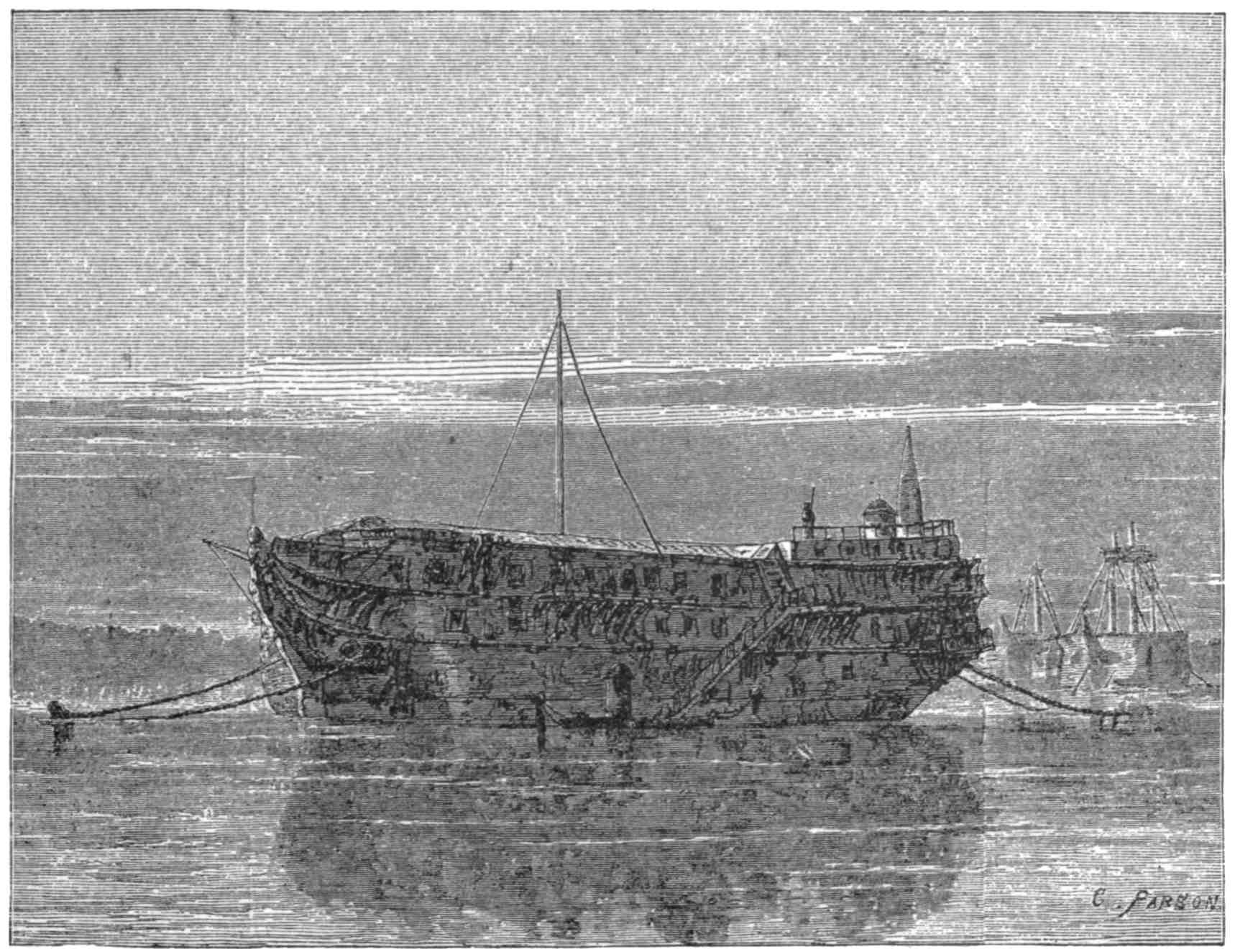

| The British Prison Ship Jersey. (From an old wood-cut), | 221 |

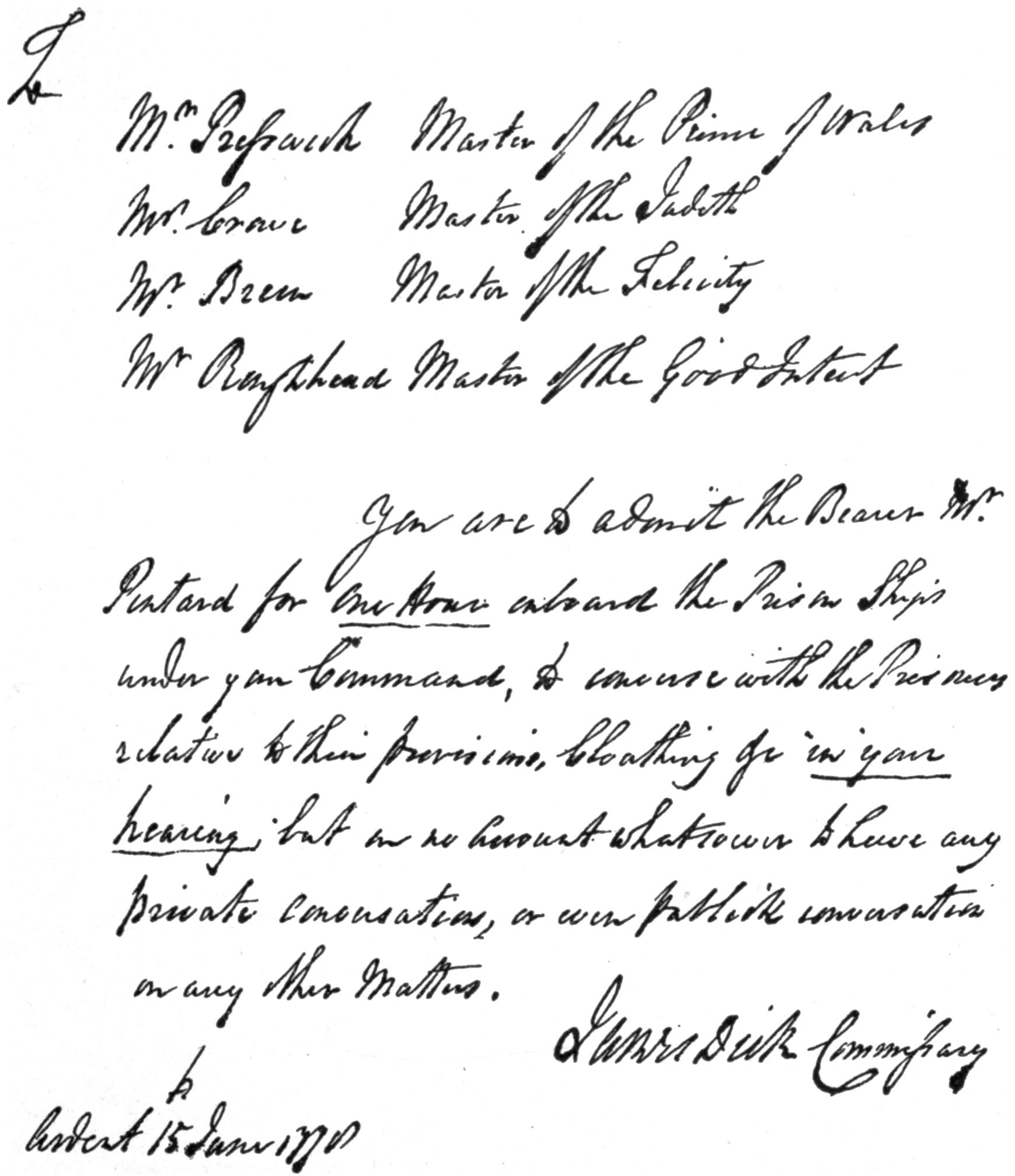

| A Permit to Visit One of the Prison Ships. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 223 |

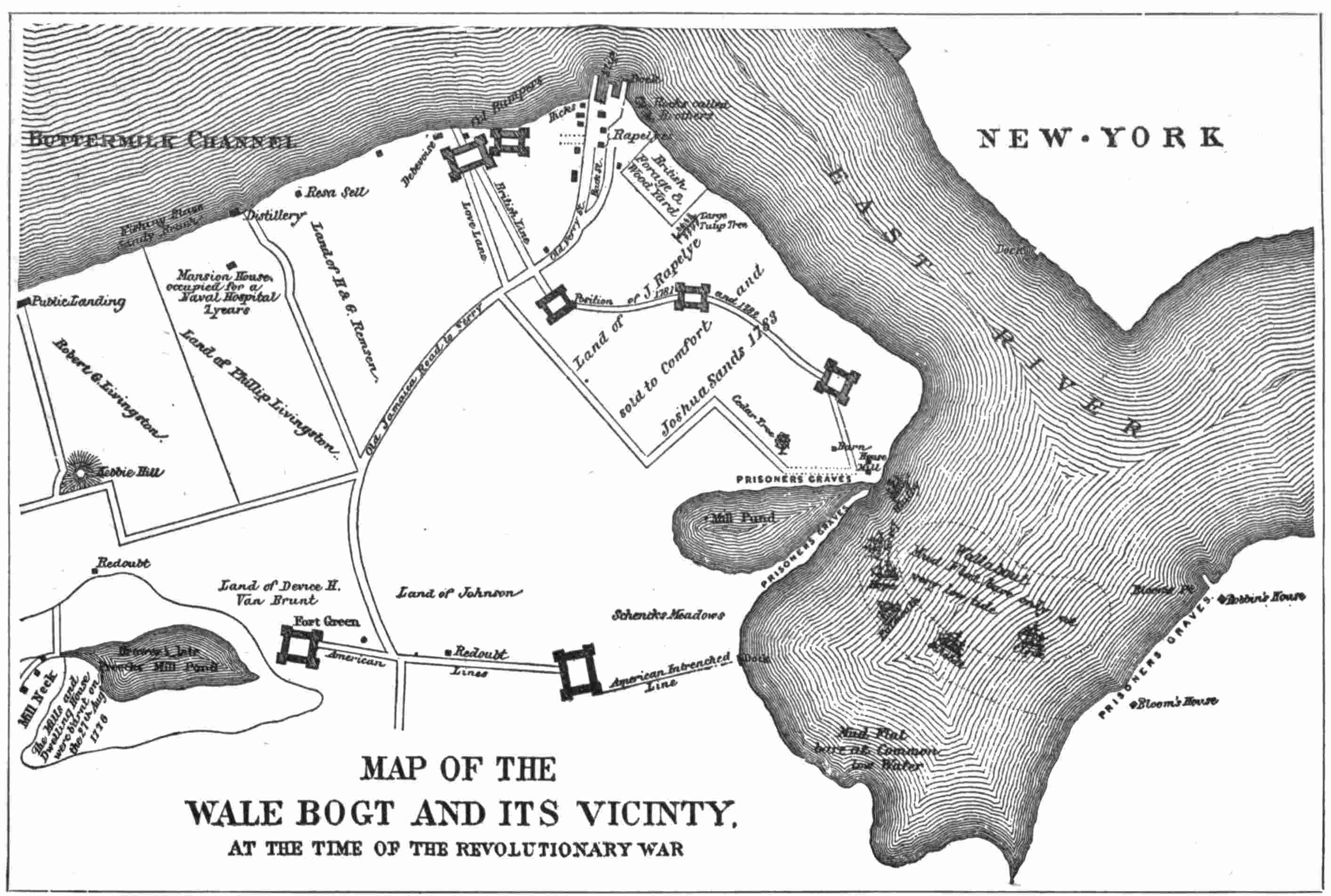

| Map of the Wale Bogt and its Vicinity, | 225 |

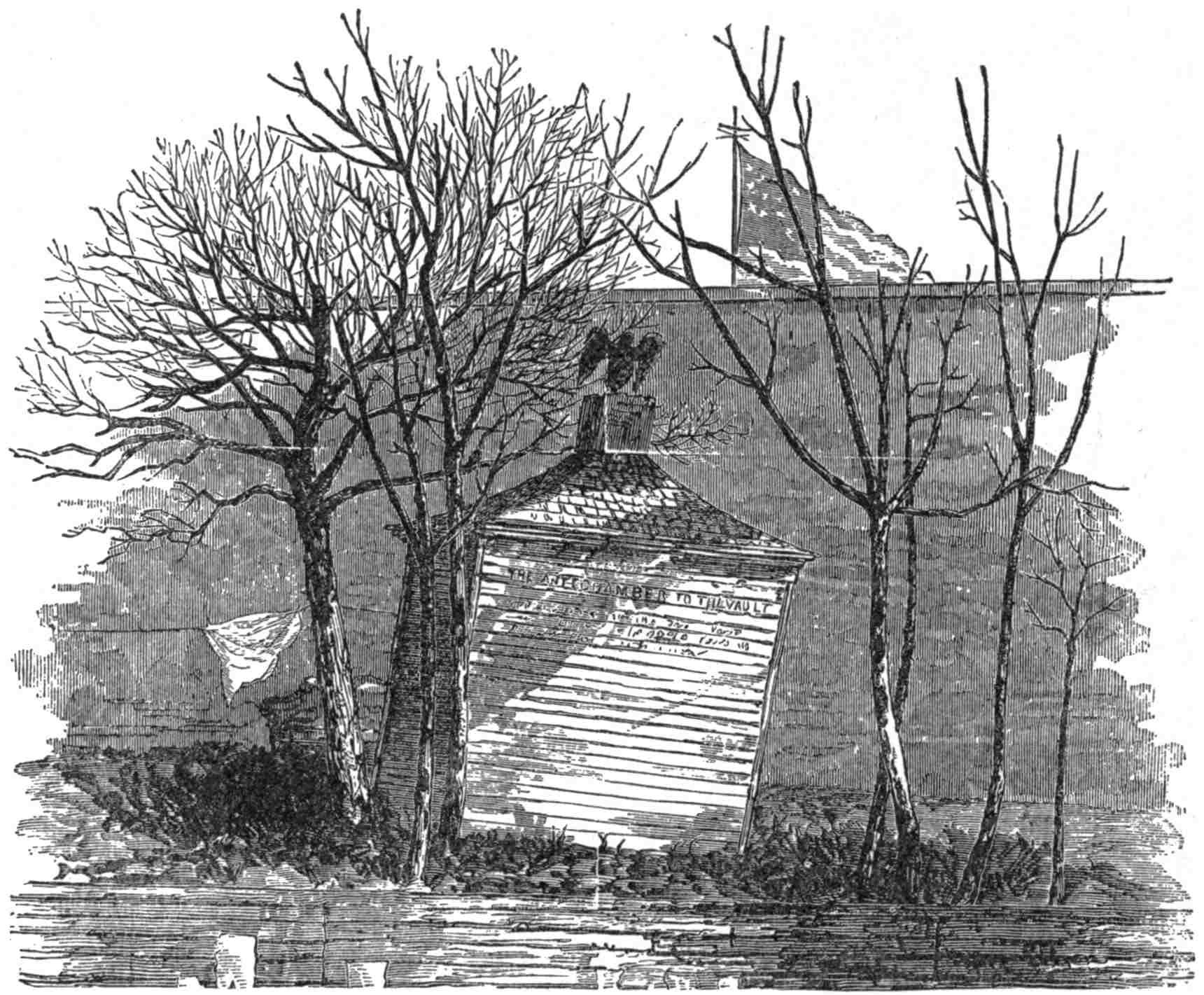

| A Relic of the Prison Ships: Entrance to the Vault of the Martyrs. (From an old wood-cut), | 226 |

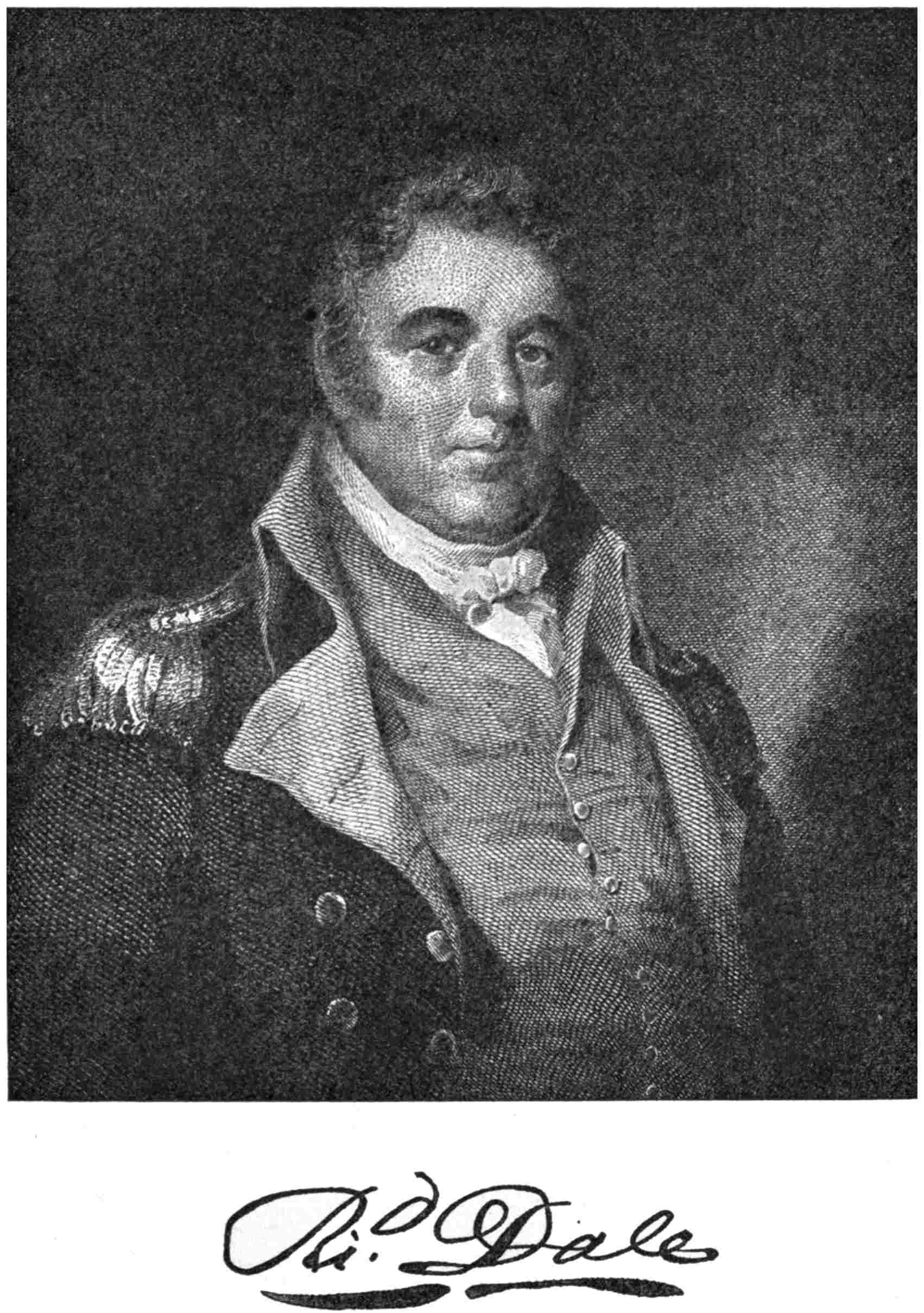

| Richard Dale. (From an engraving by Dodson after the portrait by Wood), | 231 |

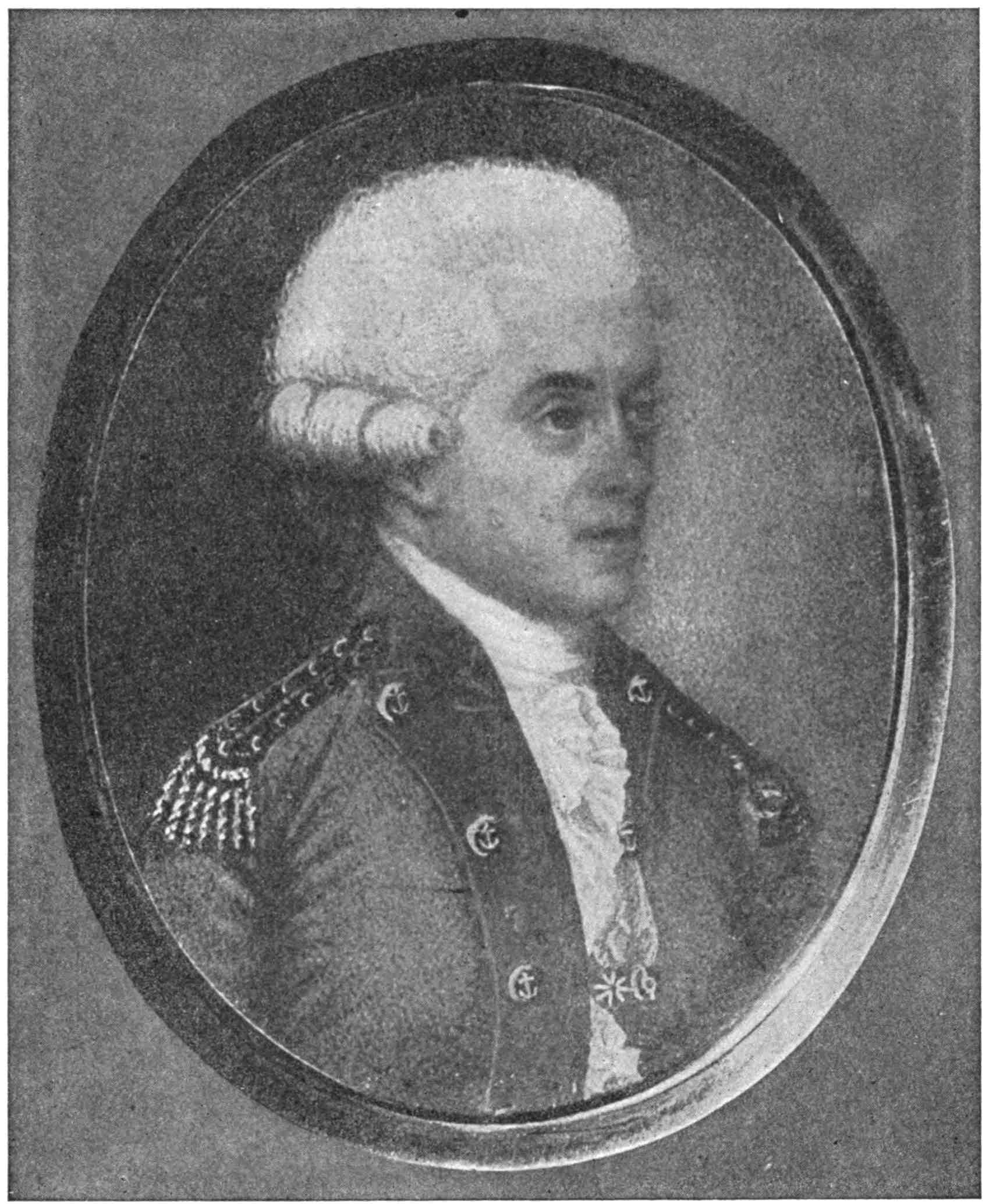

| Pierre Landais. (From a copy, at the Lenox Library, of a miniature), | 236 |

| Leith Pier and Harbor. (From an old engraving), | 239 |

| John Paul Jones. (From an engraving by Guttenberg, after a drawing by Notté, in the collection of Mr. W. C. Crane), | 242 |

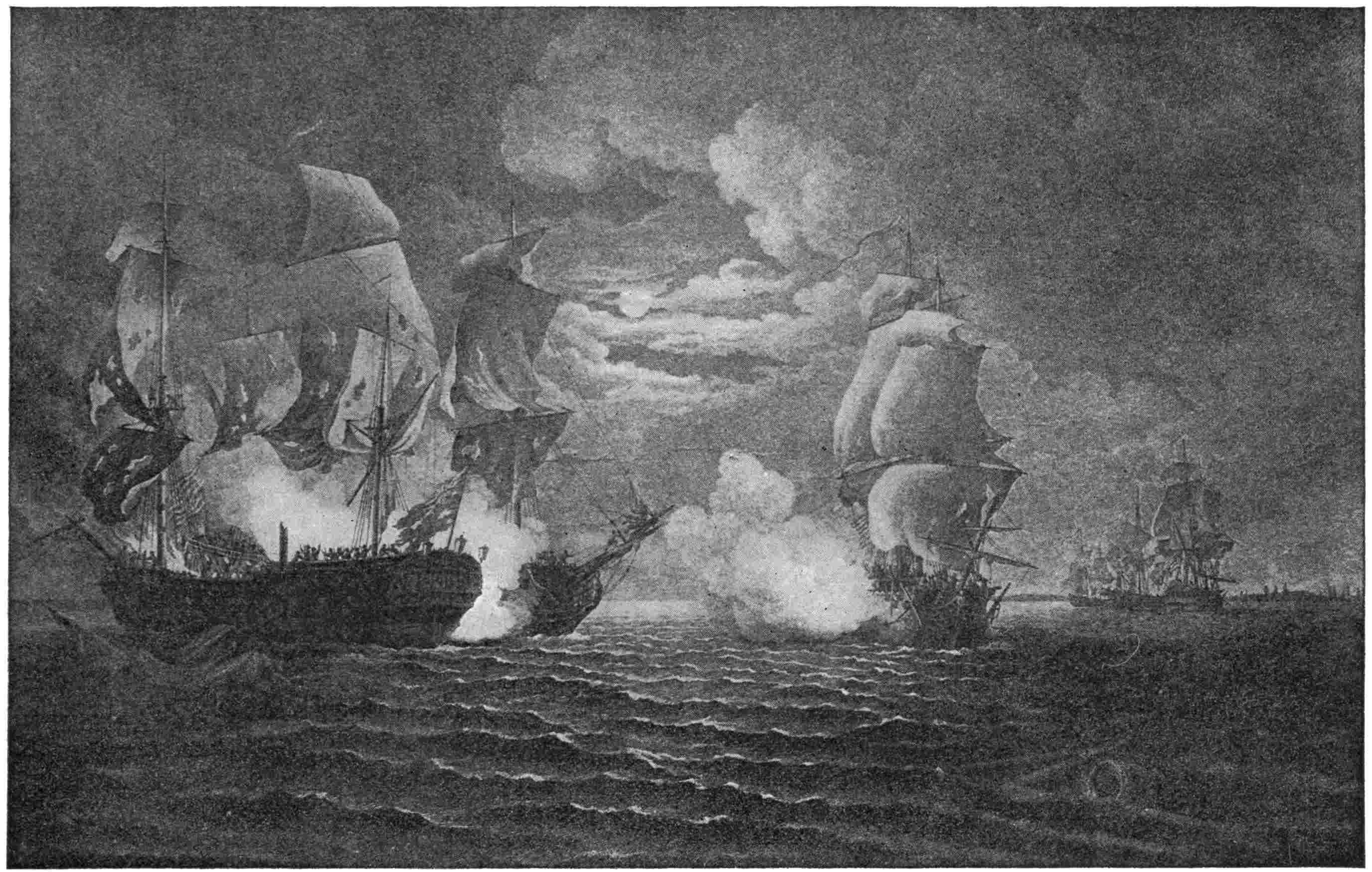

| The Engagement between the Bonhomme Richard and Serapis. (From an engraving by Hamilton of a drawing by Collier), | 246 |

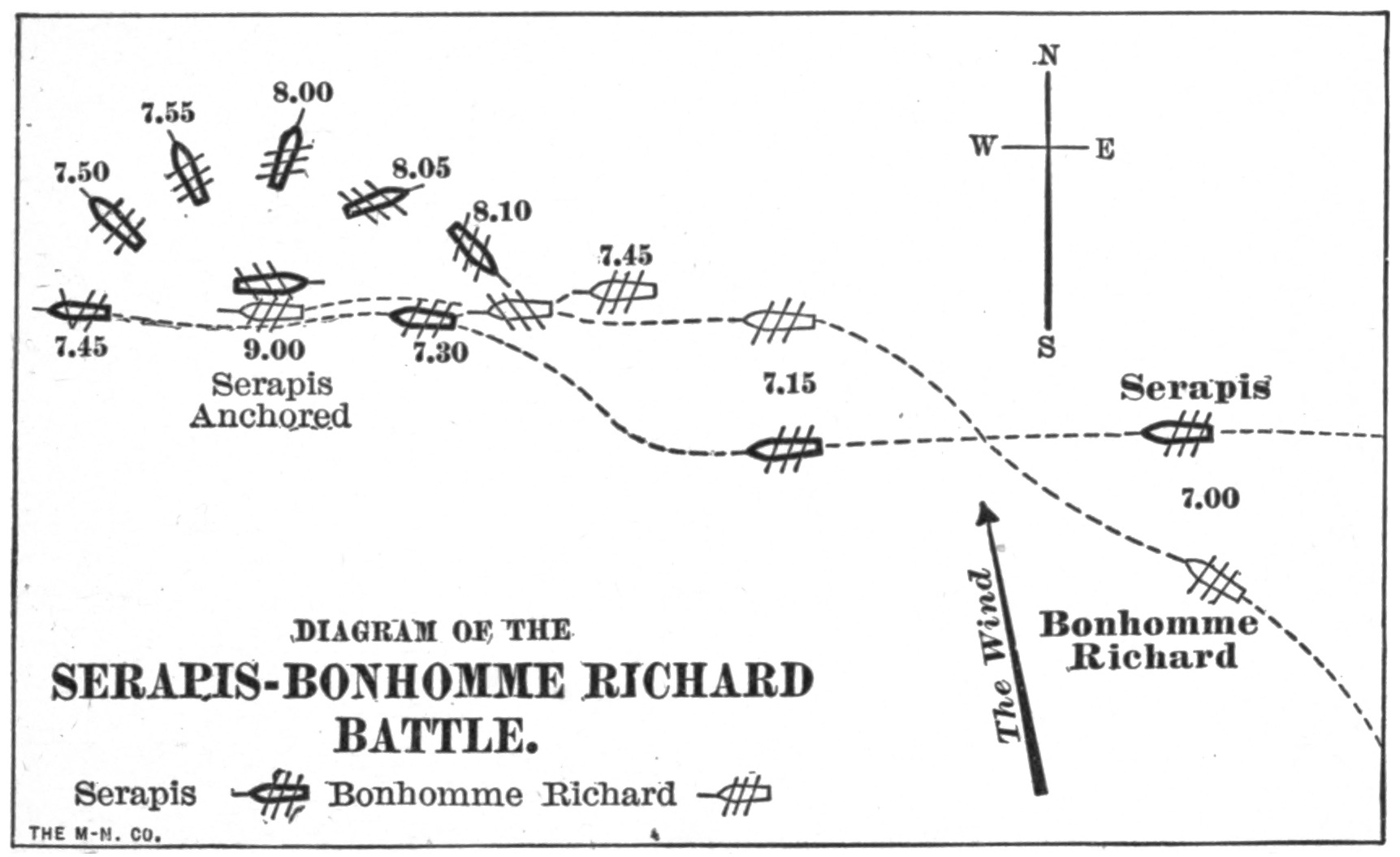

| Diagram of the Serapis-Bonhomme Richard Battle, | 249 |

| The Serapis and the Bonhomme Richard. (From an engraving by Lerpinière after a drawing by Fitler), | 252xx |

| Paul Jones Capturing the Serapis. (From an engraving of the picture by Chappel), | 258 |

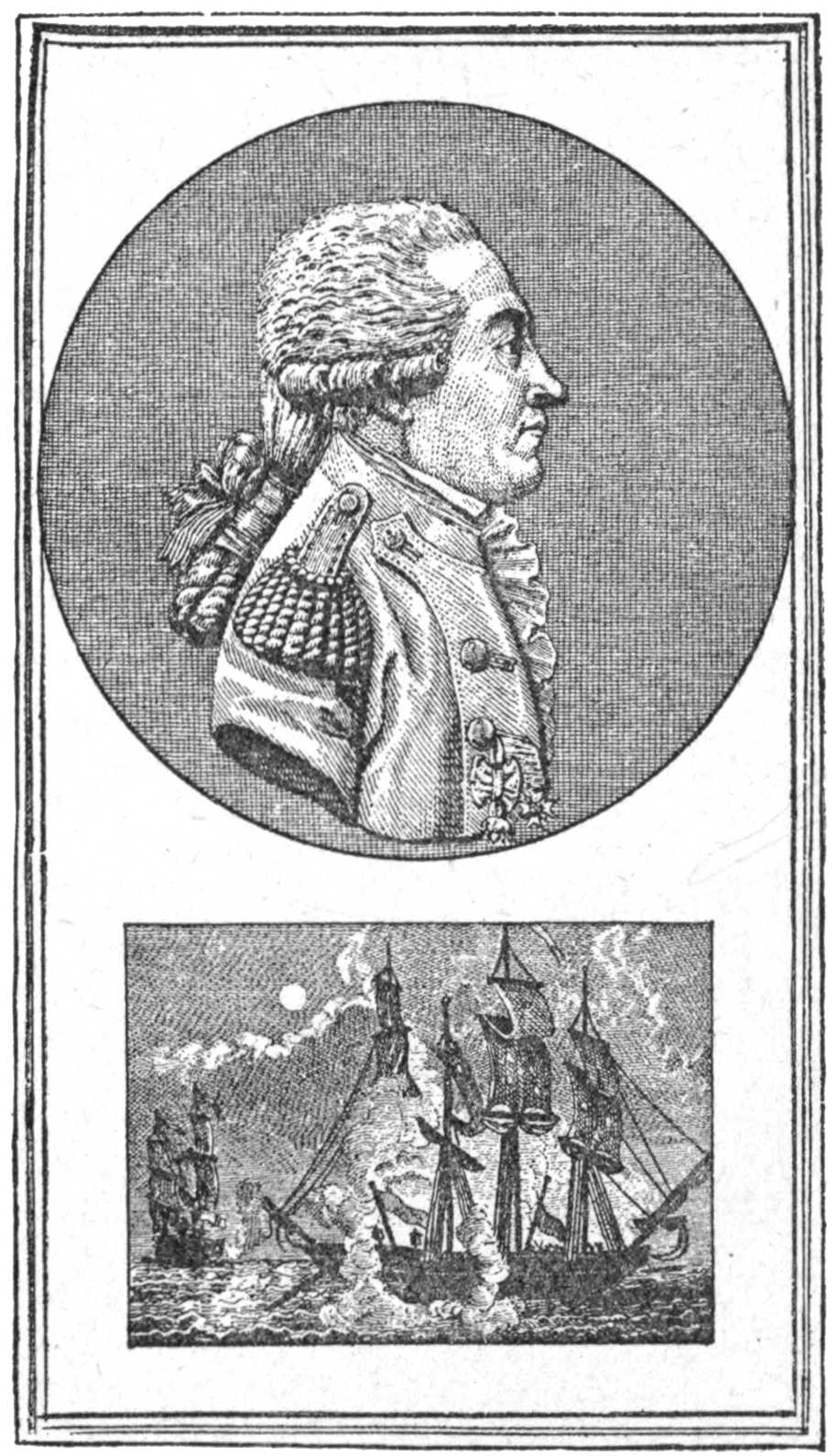

| Capt. Sir Richard Pearson. (From an engraving by Cook), | 261 |

| John Paul Jones. (After a rare engraving), | 263 |

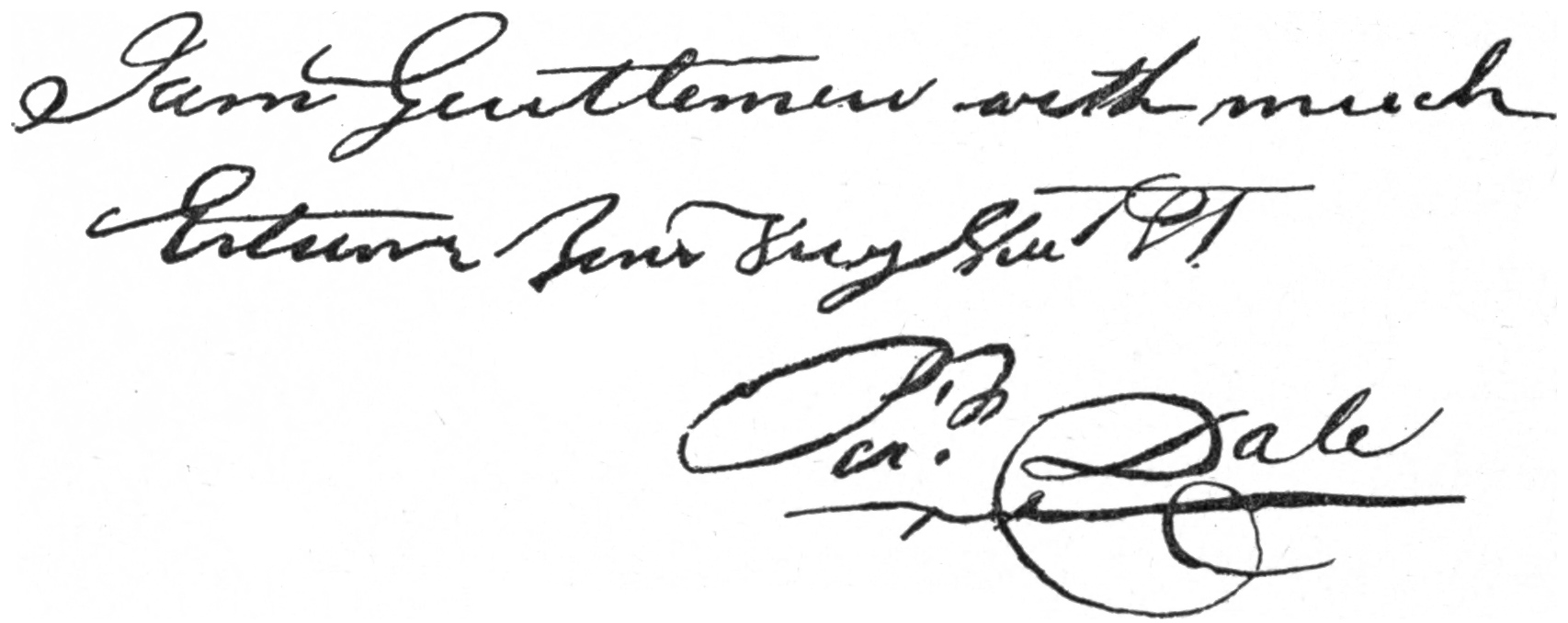

| Signature of Richard Dale. (From a letter at the Lenox Library), | 266 |

| A Letter from Pierre Landais. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 268 |

| John Paul Jones. (From a miniature recently found [1897] in a cellar at the Naval Academy), | 269 |

| John Paul Jones (in Cocked Hat). (From a very rare engraving at the Navy Department, Washington), | 271 |

| John Paul Jones. (From an engraving by Chapman in the collection of Mr. W. C. Crane), | 273 |

| John Paul Jones’s Medal, | 276 |

| John Paul Jones and the Serapis Fight. (From an engraving in the collection of Mr. W. C. Crane), | 278 |

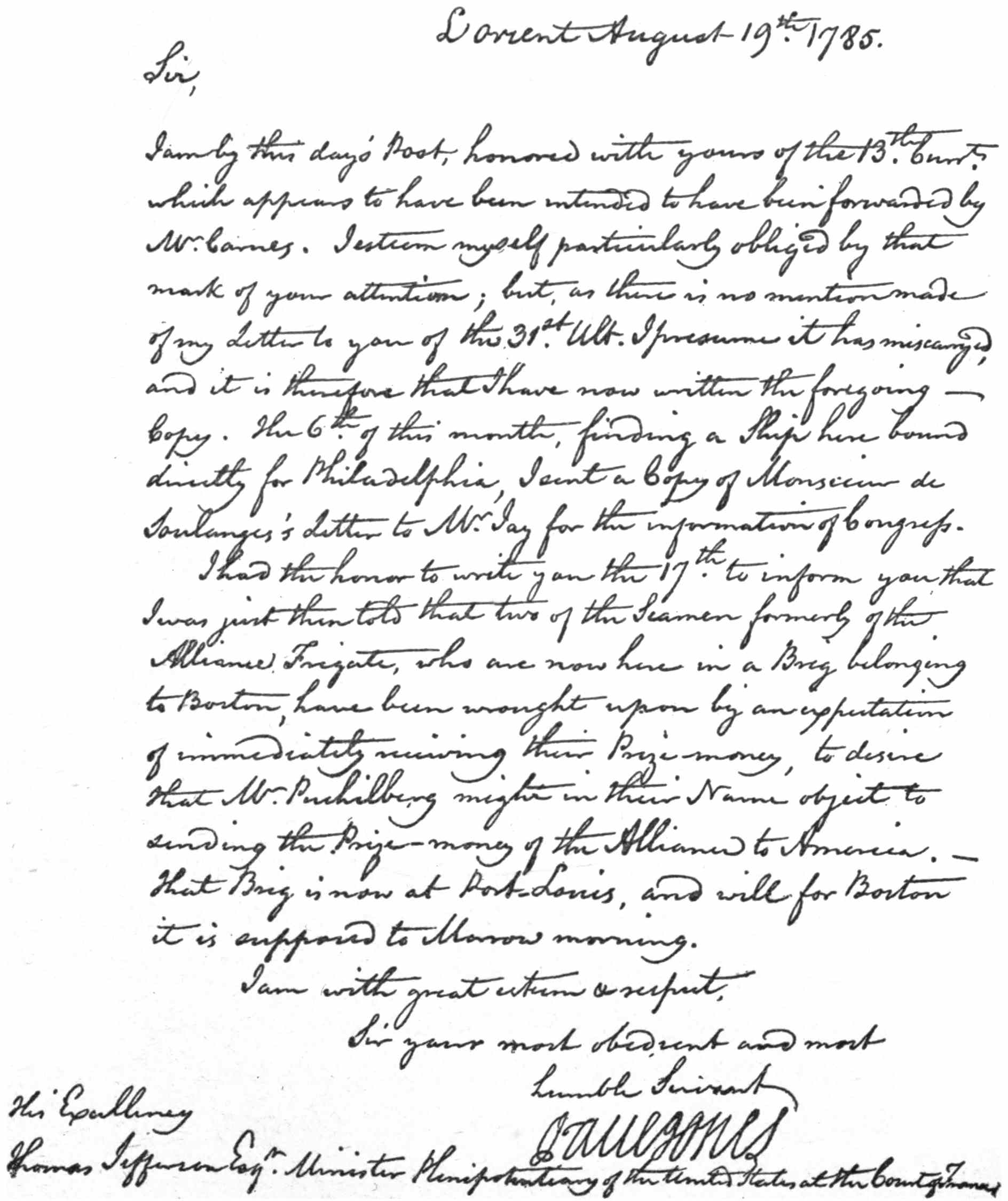

| A Letter from John Paul Jones to Thomas Jefferson. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 279 |

| Signature of Hoysted Hacker. (From a letter at the Lenox Library), | 283 |

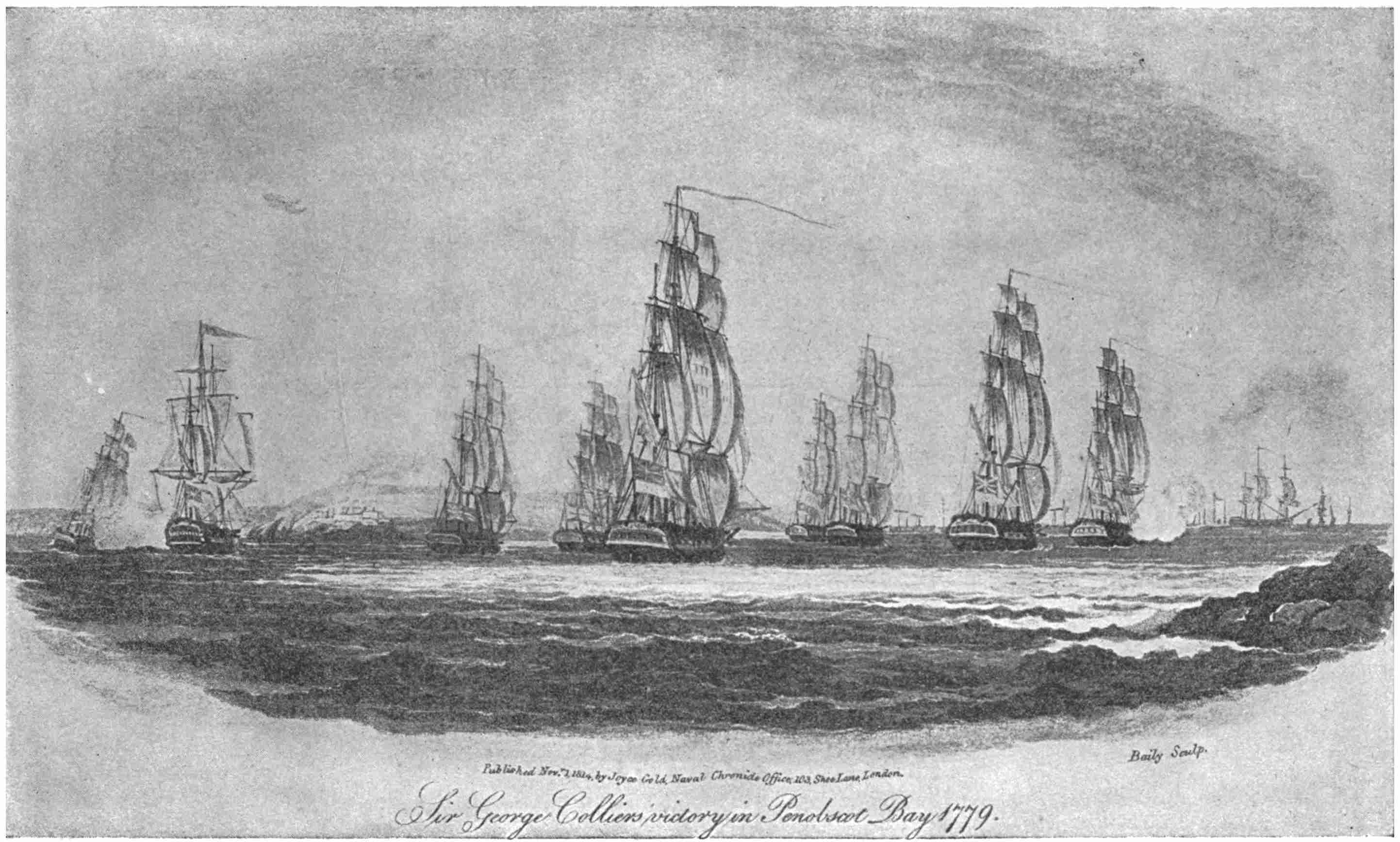

| Sir George Collier’s Victory in Penobscot Bay, 1779. (From a very rare engraving at the Lenox Library), | 285 |

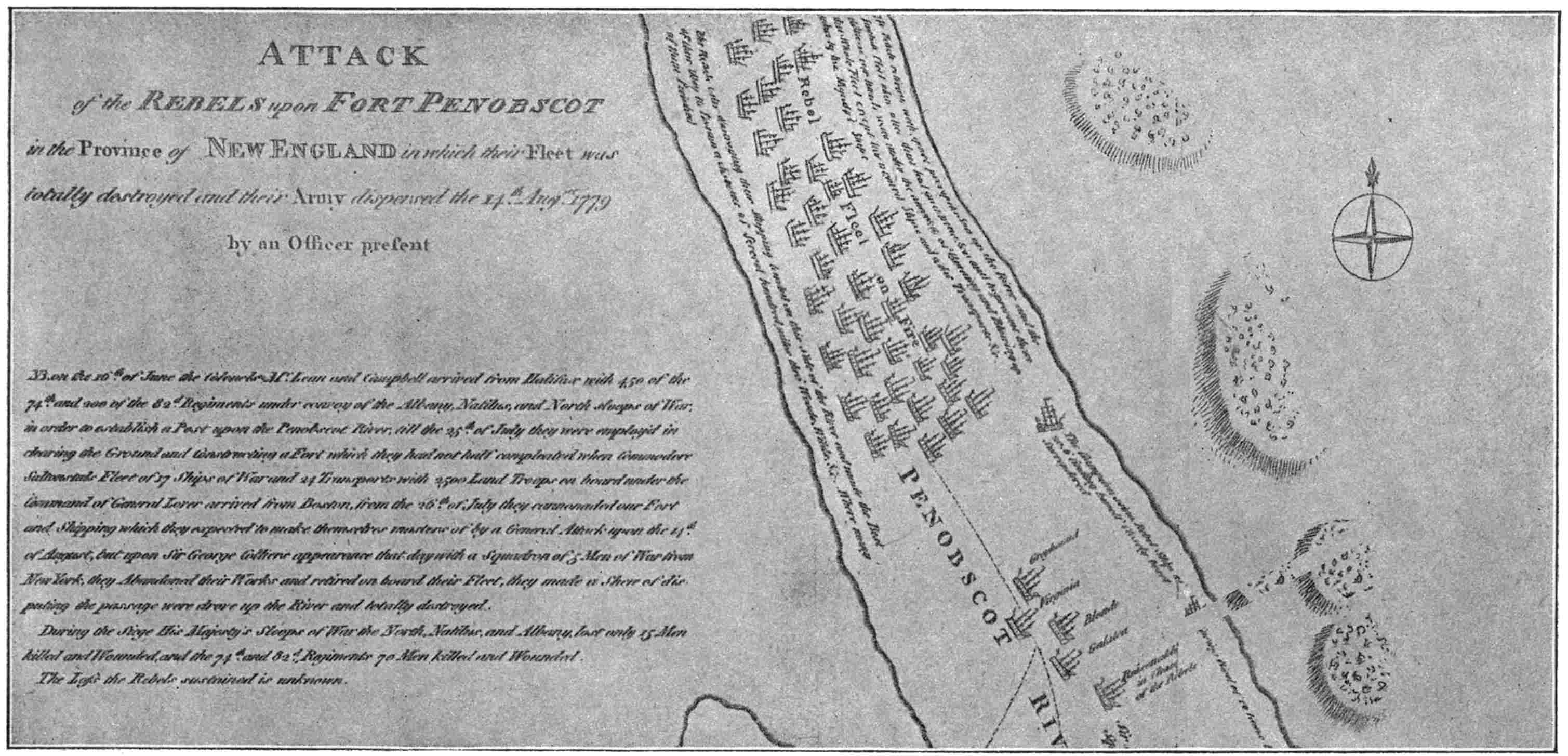

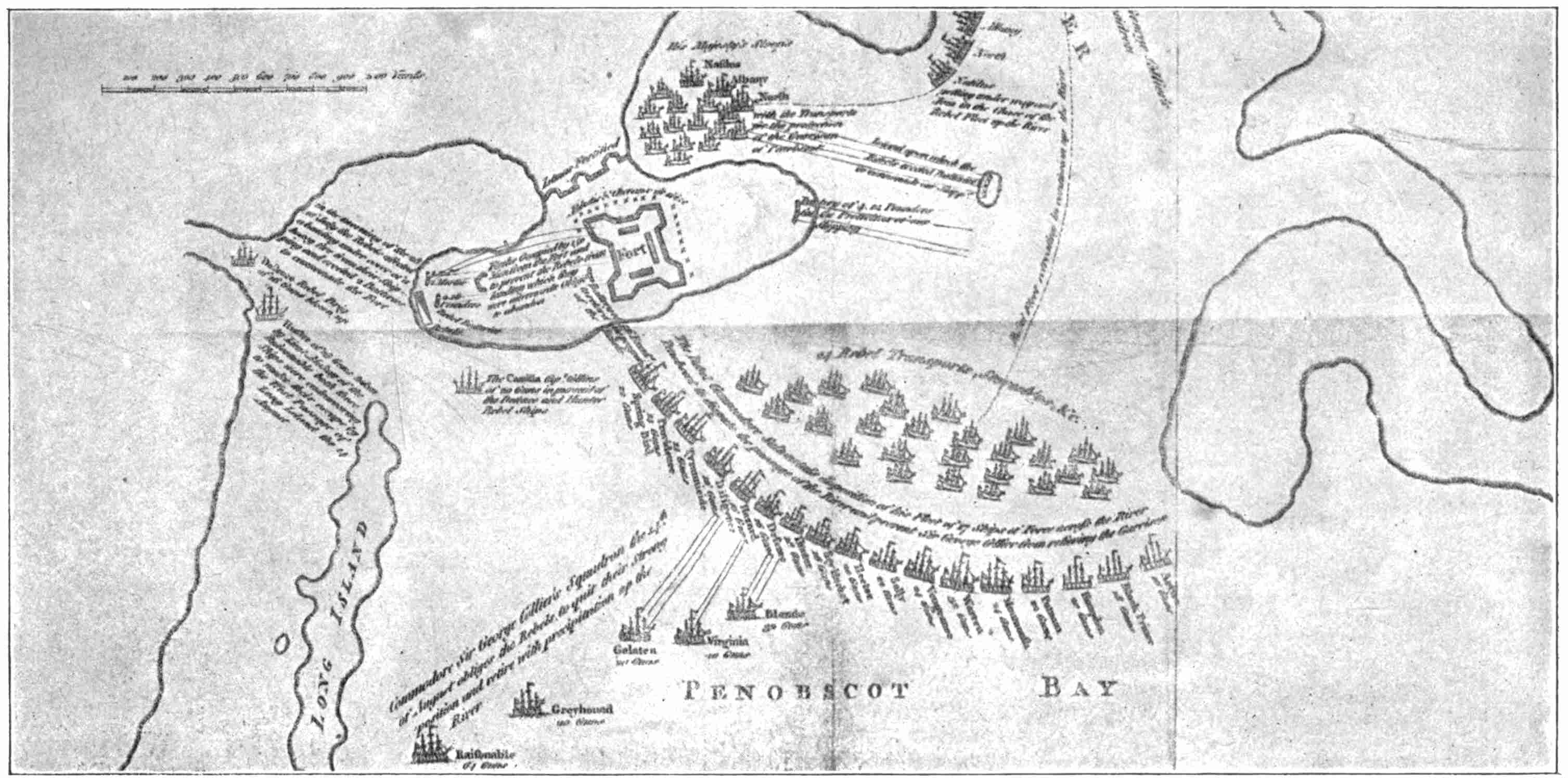

| Map of the Attack on the Penobscot Fort. (From a contemporary map at the Lenox Library), | 288–9 |

| Signature of Samuel Nicholson. (From a letter at the Lenox Library), | 290 |

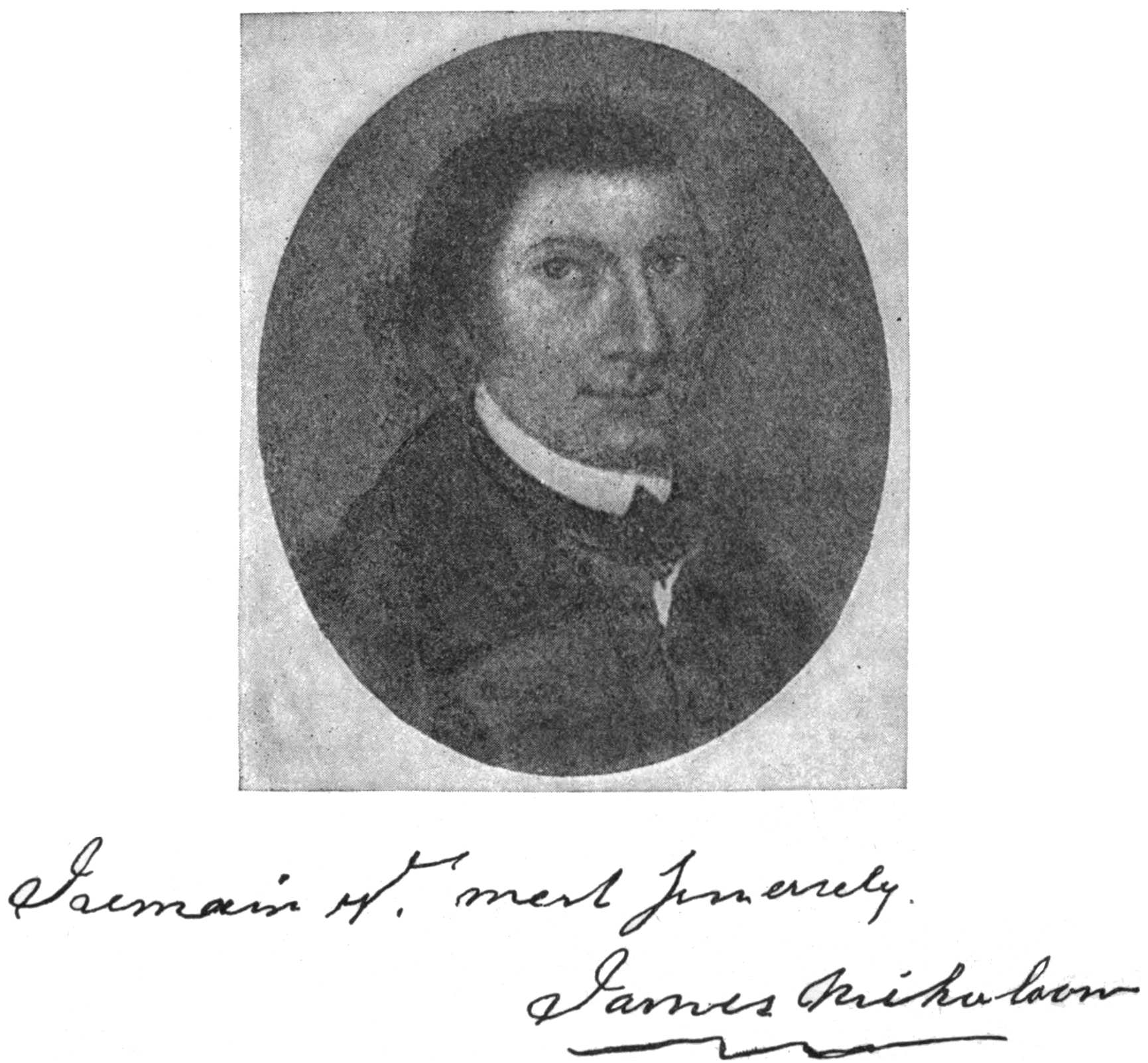

| James Nicholson. (After a miniature in the possession of Miss Josephine L. Stevens), | 296 |

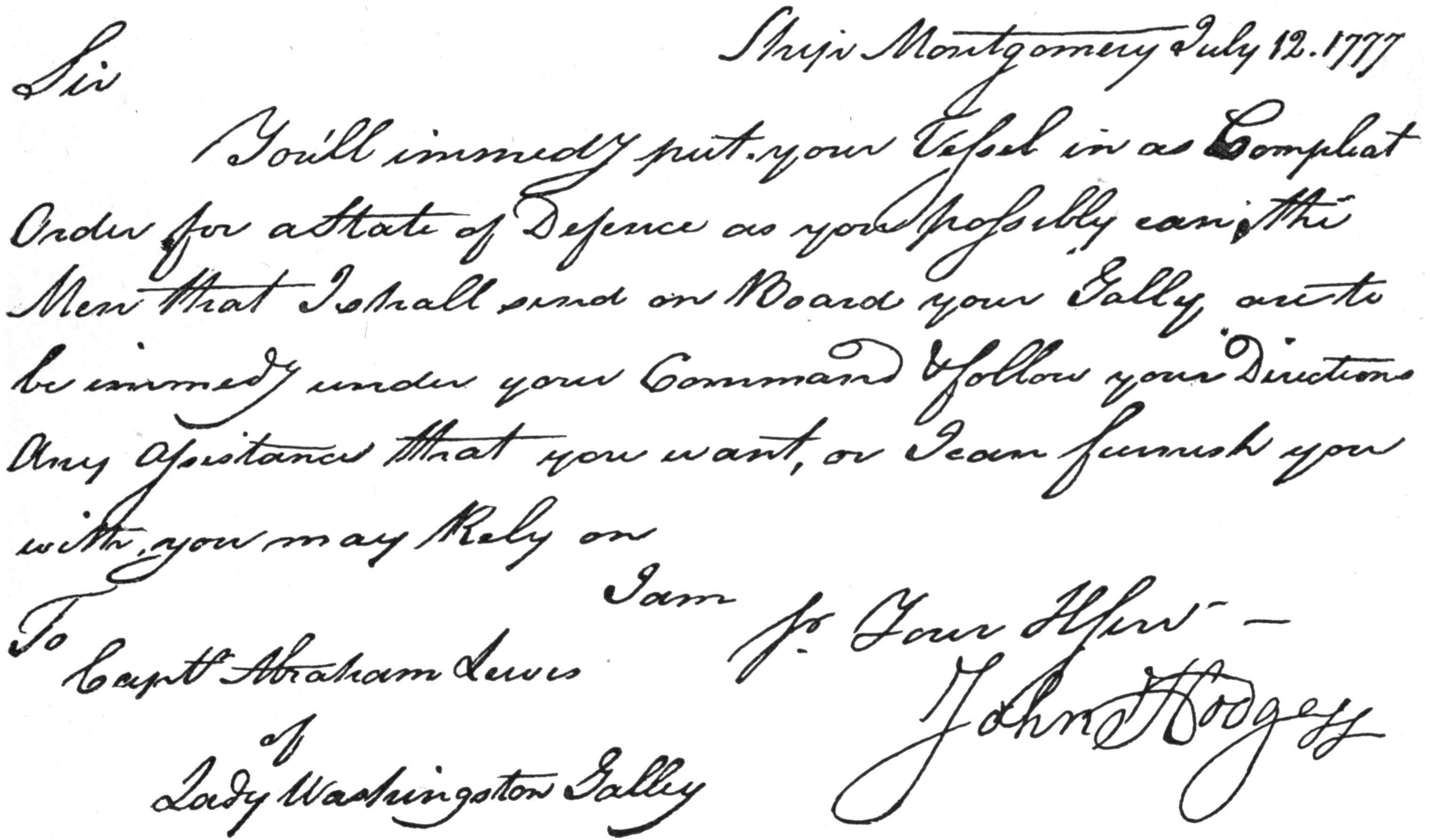

| An Old Naval Order. (From the original at the Lenox Library), | 301 |

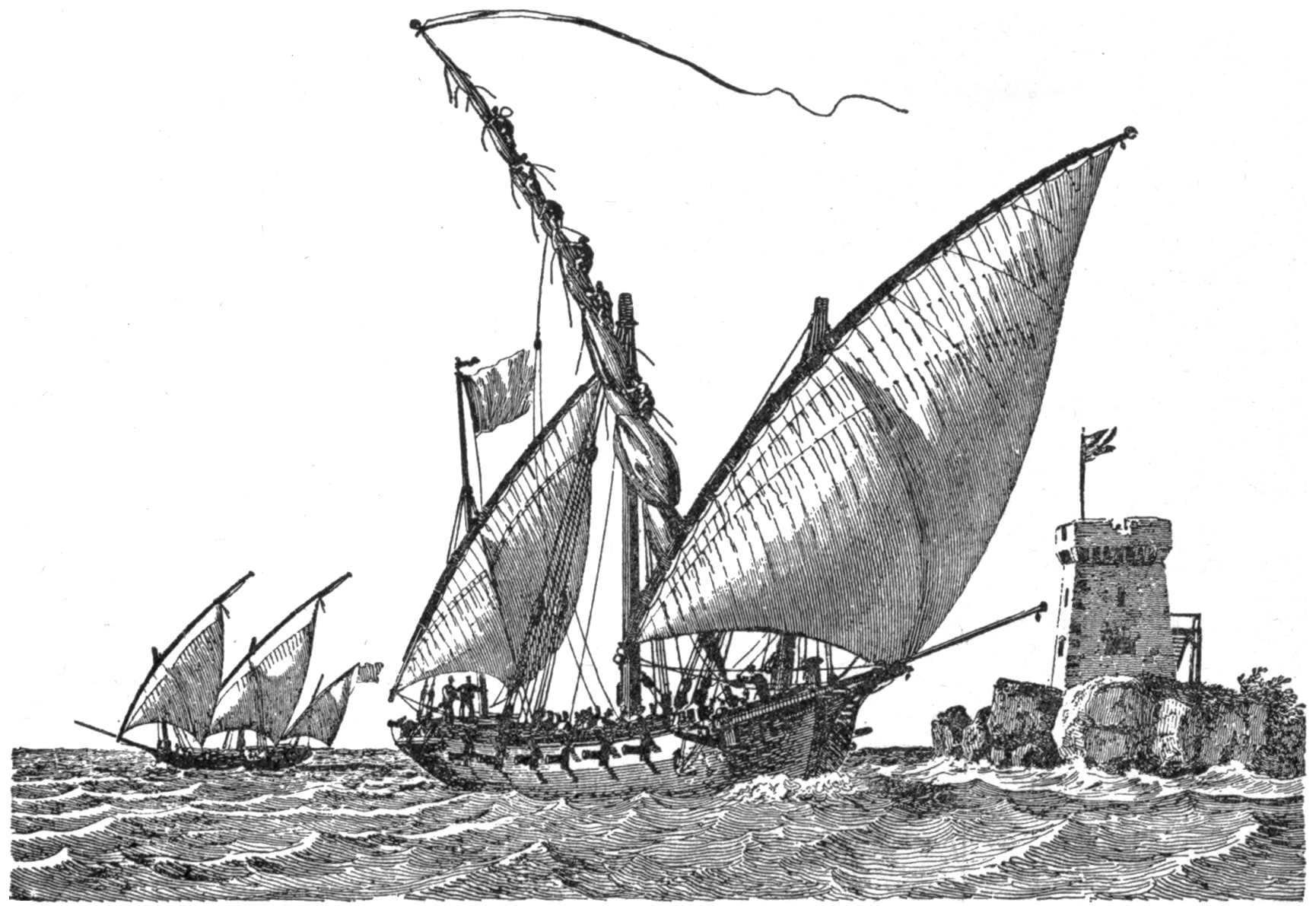

| A Mediterranean Corsair Anchoring. (From a picture drawn and engraved by Baugean), | 306 |

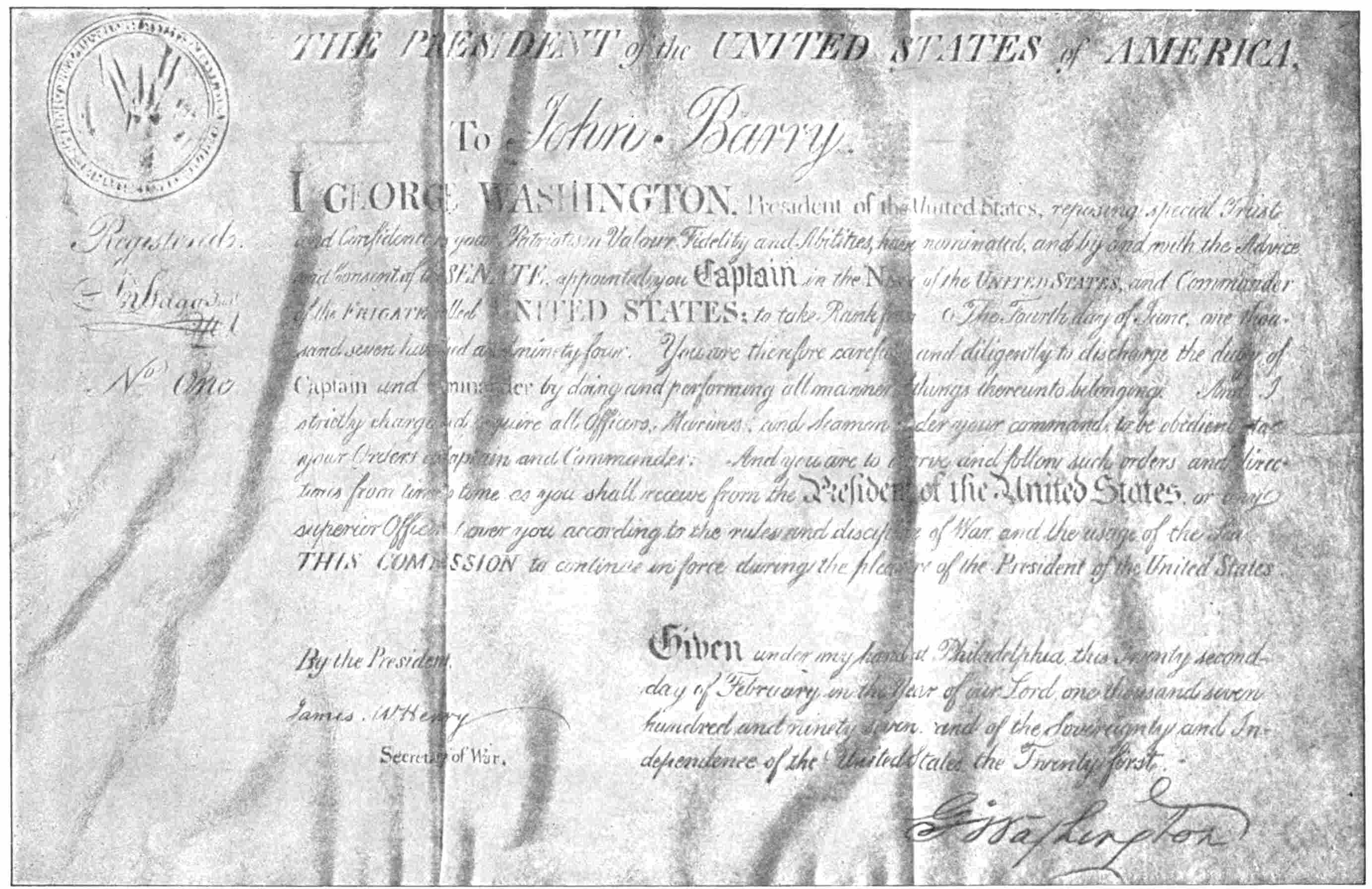

| John Barry’s Commission as Commander of the United States. (From the original at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 313 |

| A French Vessel of 118 Guns, a Century Ago. (From an engraving by Canali), | 318 |

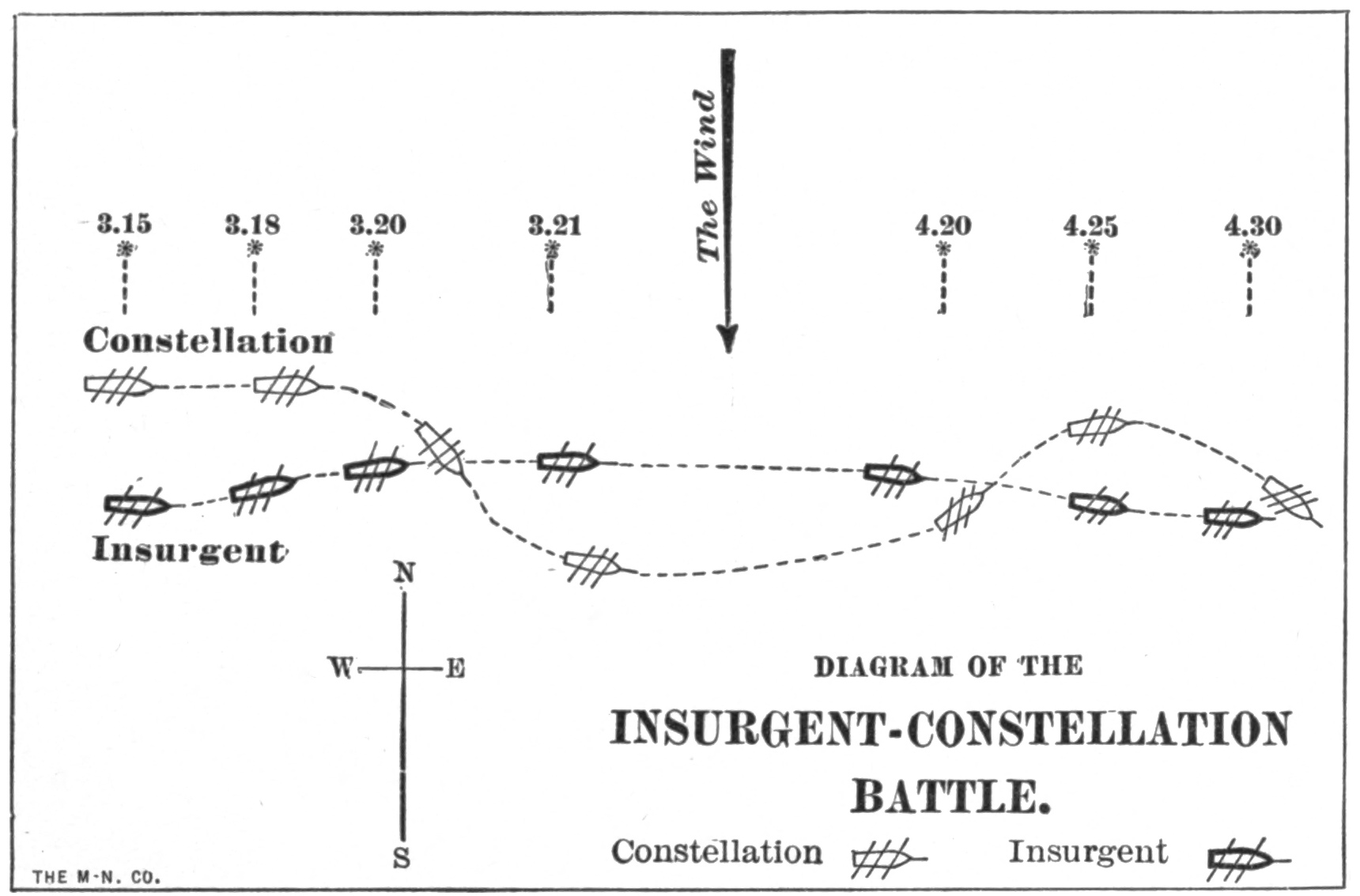

| Diagram of the Insurgent-Constellation Battle, | 321 |

| A French Vessel of 120 Guns. (From an engraving by Orio), | 322xxi |

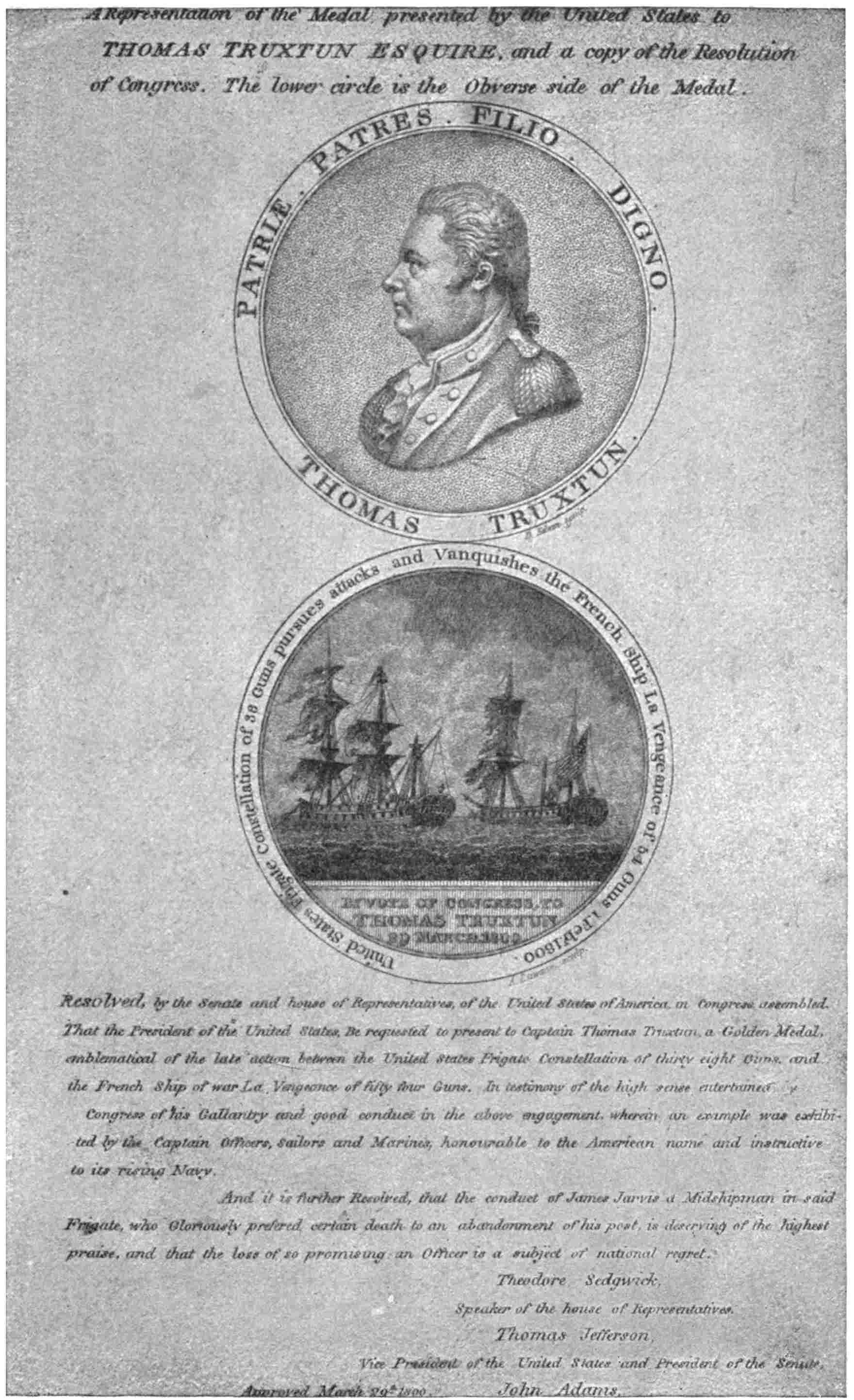

| Medal Awarded to Thomas Truxton, | 325 |

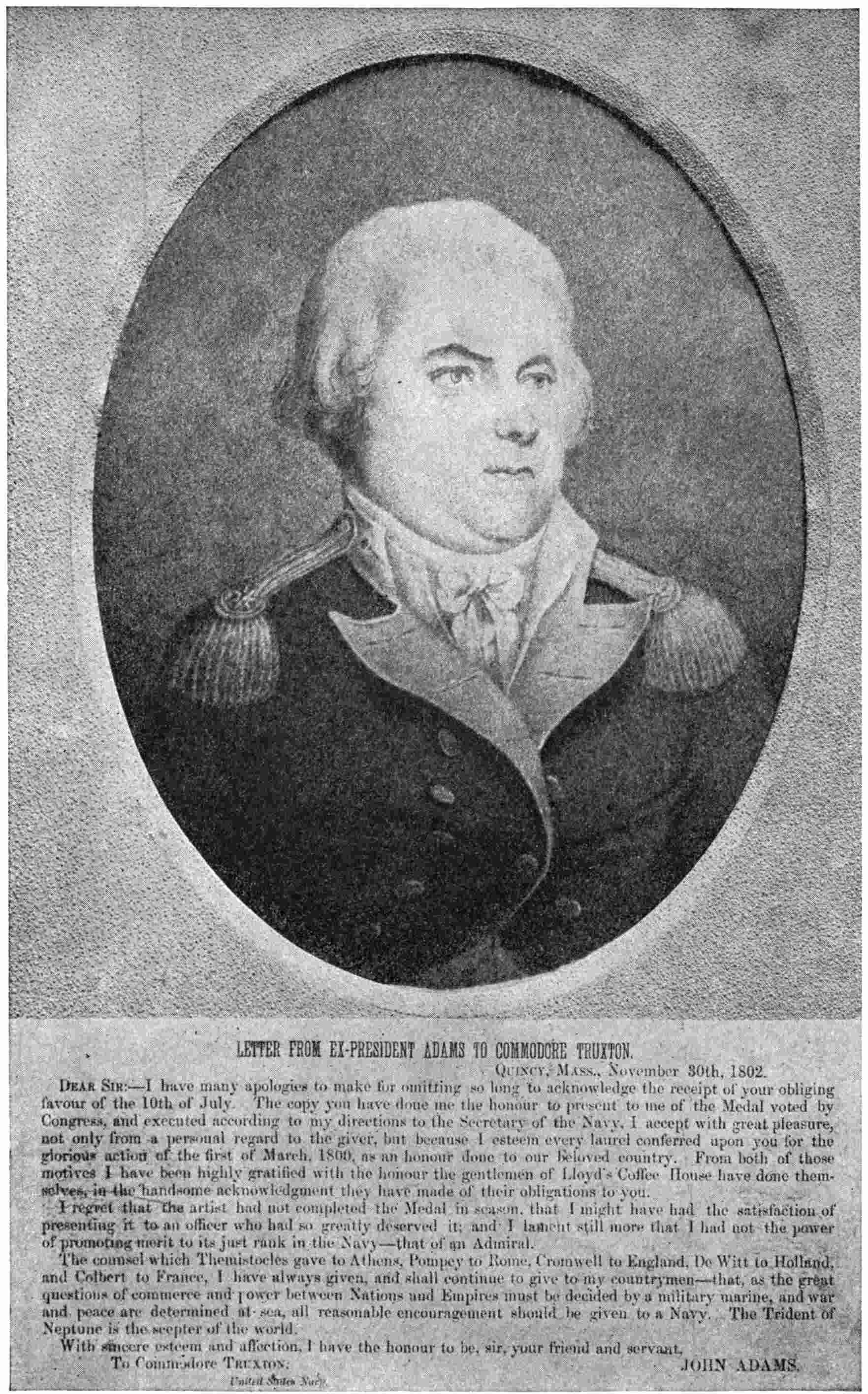

| Portrait of Truxton and President Adams’s Letter to him. (From a lithograph at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 326 |

| Truxton’s Medal and the Congressional Resolution Awarding it to him, | 327 |

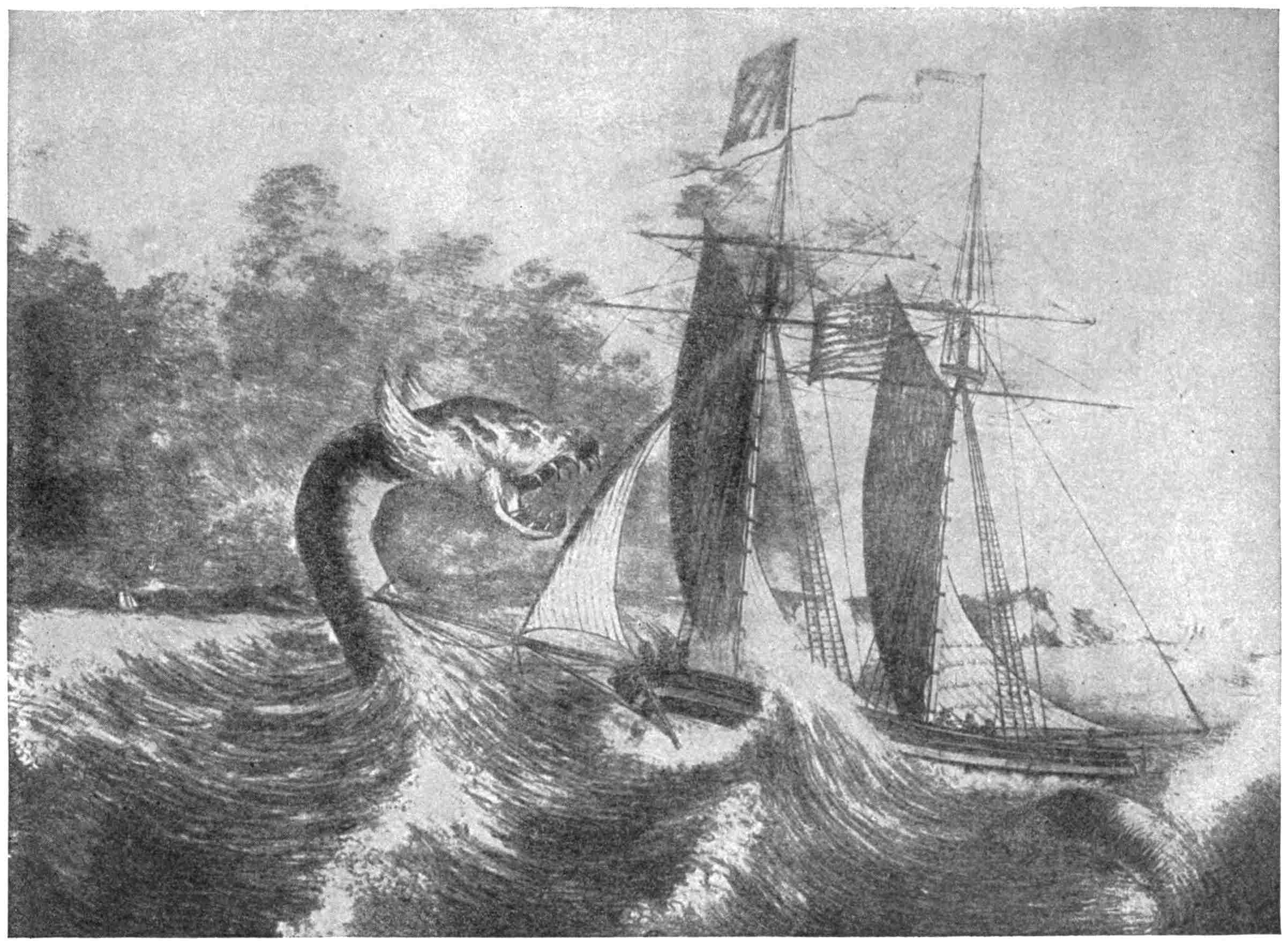

| The Sally Attacked by a Sea-Serpent off the Shore of Long Island. (From a French engraving), | 331 |

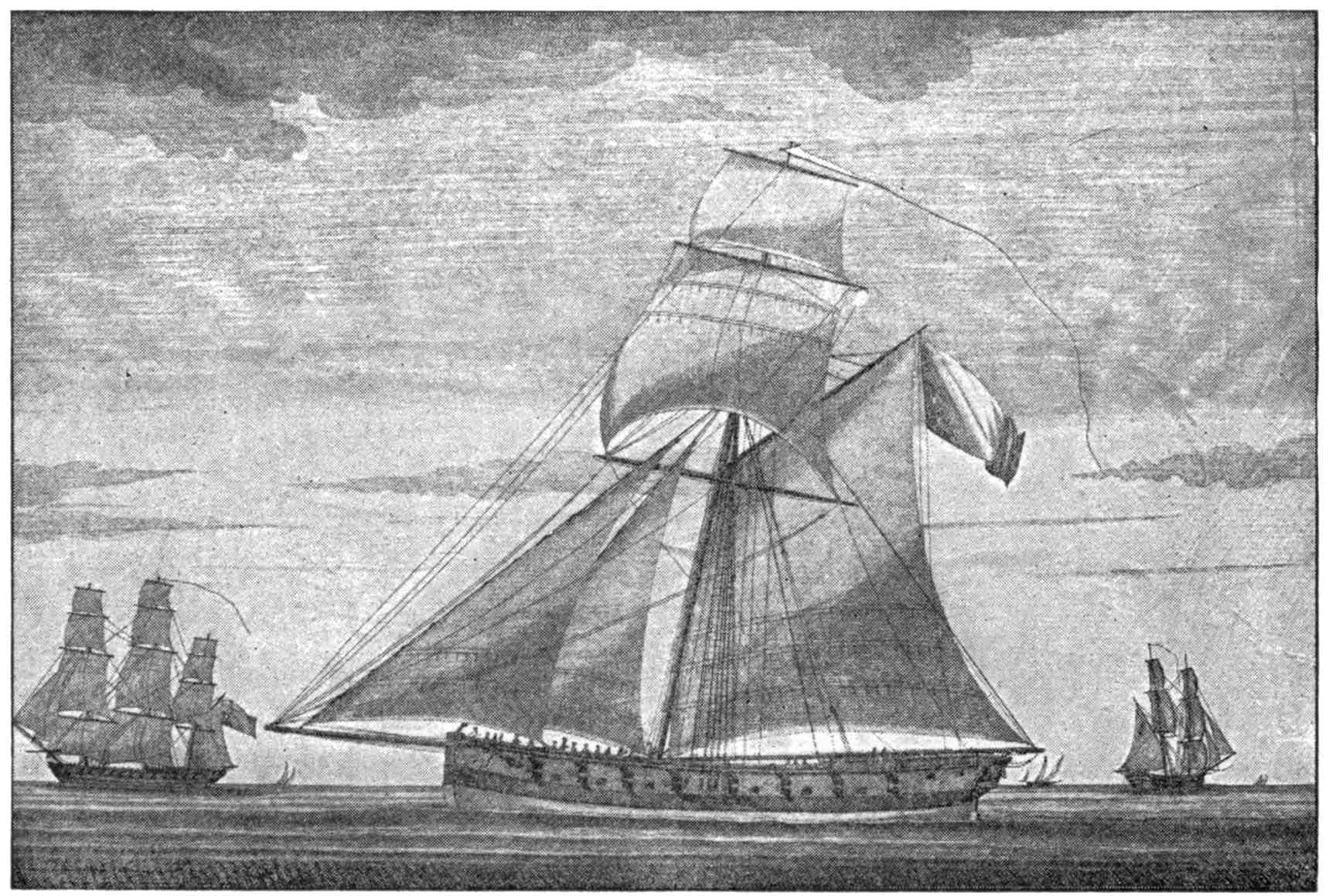

| A French Cutter of 16 Guns. (From an engraving by Merlo), | 332 |

| Benjamin Stoddert. (From a painting at the Navy Department, Washington), | 334 |

| “Captain Sterrett in the Enterprise, Paying Tribute to Tripoli.” (From an old wood-cut), | 337 |

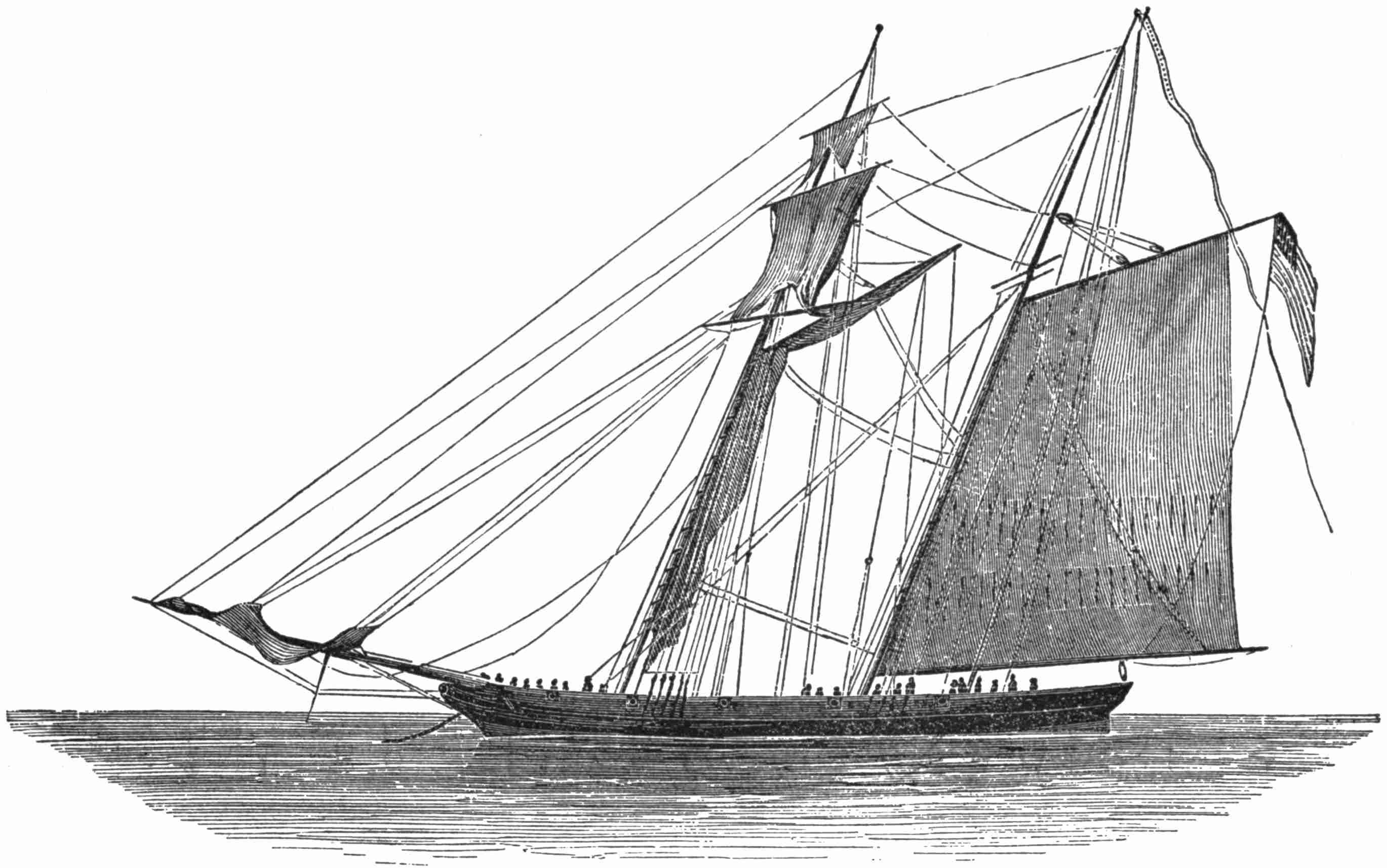

| A Schooner-of-War, Like the Enterprise. (From a wood-cut in the “Kedge Anchor”), | 339 |

| Map of the Mediterranean Sea, | 340 |

| William Bainbridge. (From an engraving by Edwin), | 341 |

| Stephen Decatur. (From an engraving by Osborn of the portrait by White), | 347 |

| Burning of the Frigate Philadelphia by Decatur. (From an old wood-cut), | 352 |

| The Blowing up of the Frigate Philadelphia. (From an engraving in Waldo’s “Decatur”), | 355 |

| A Piece of the Philadelphia’s Stern. (From the original piece at the Naval Institute, Annapolis), | 358 |

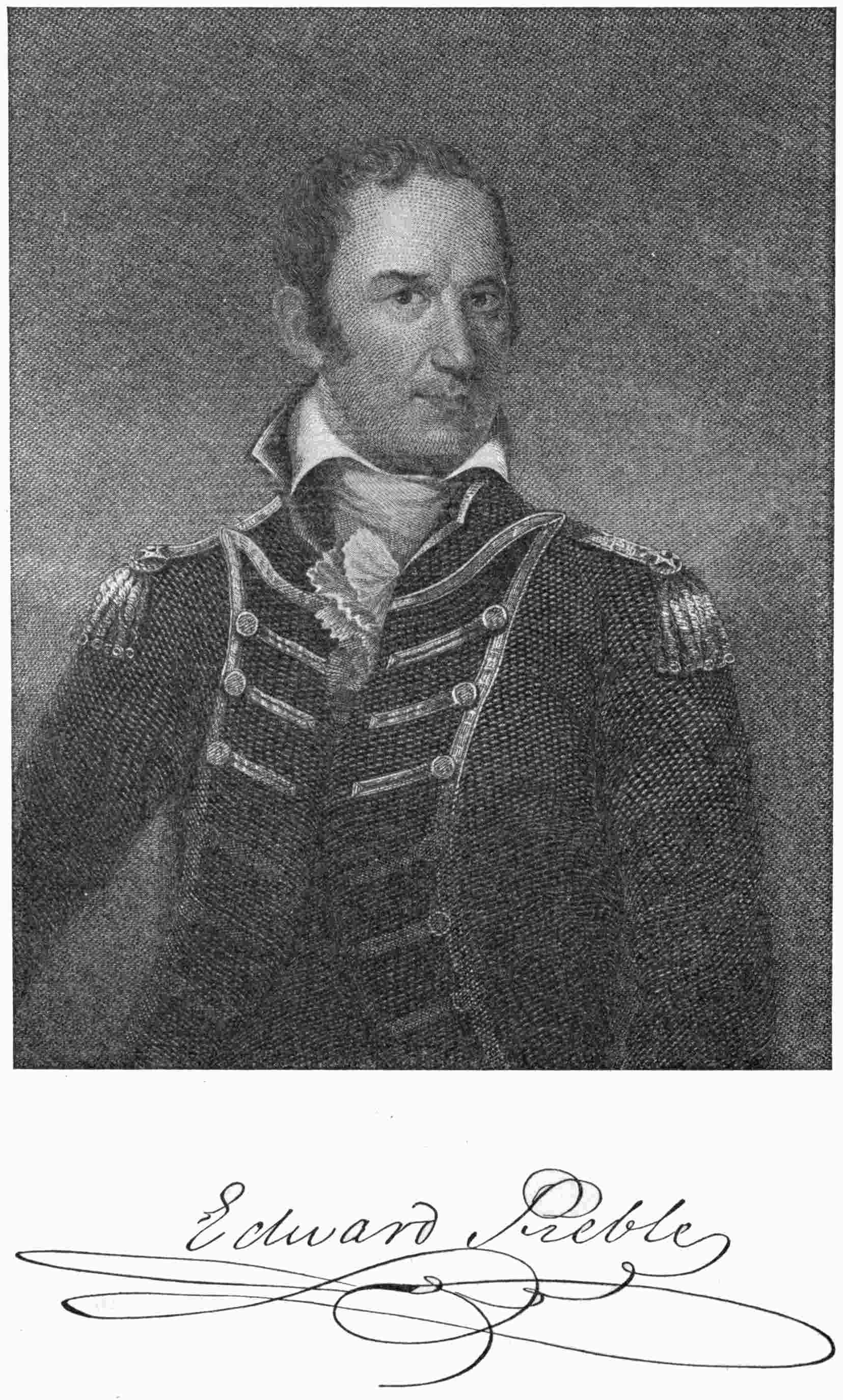

| Edward Preble. (From an engraving by Kelly of the picture in Faneuil Hall, Boston), | 360 |

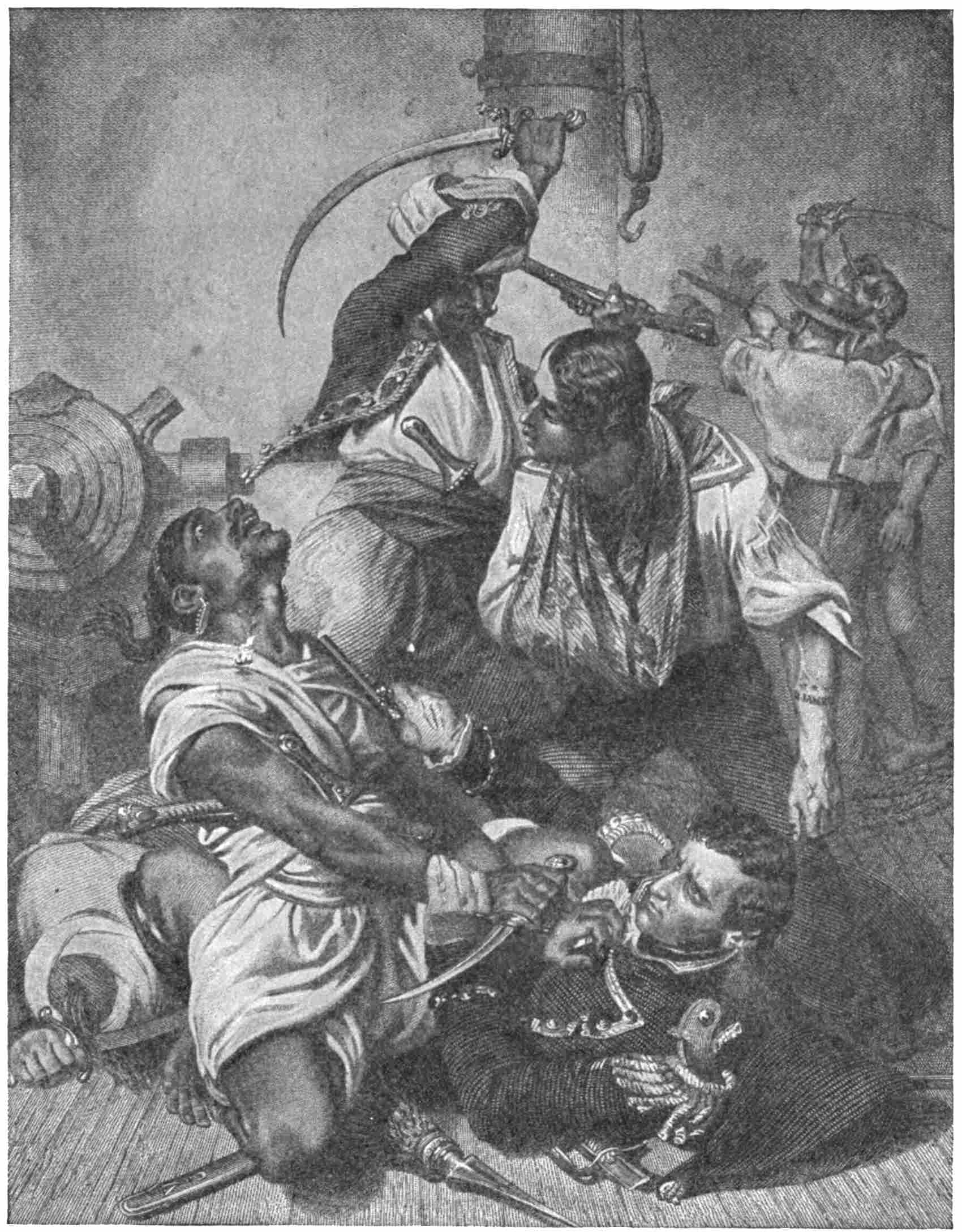

| Decatur Avenging the Murder of his Brother. (From an engraving in Waldo’s “Decatur”), | 363 |

| Reuben James Saving Decatur’s Life. (From an engraving of the picture by Chappel), | 365 |

| John Trippe. (After a French engraving), | 367 |

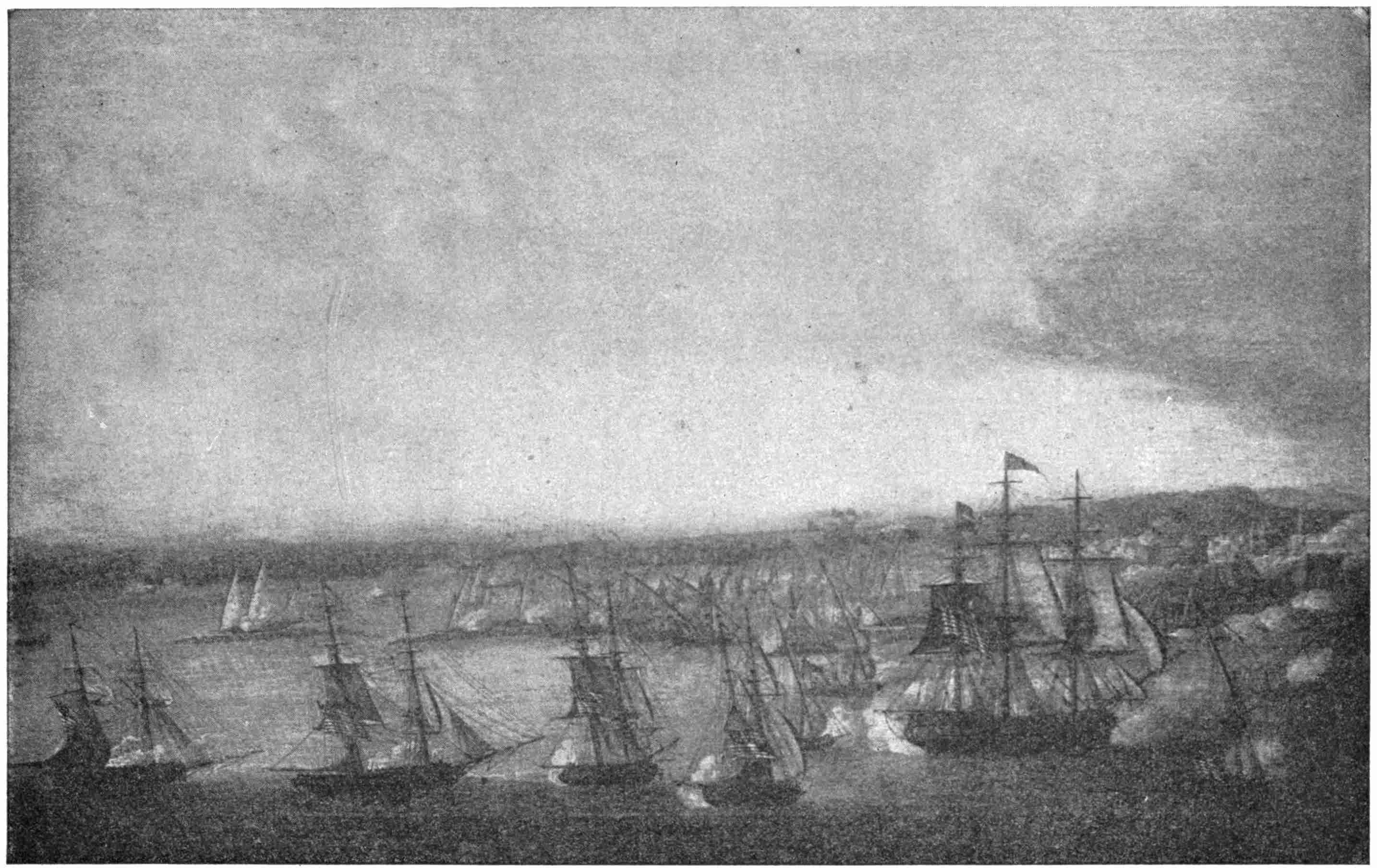

| The Battle of Tripoli, August 3, 1804. (From the painting by Corné, 1805, at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 369 |

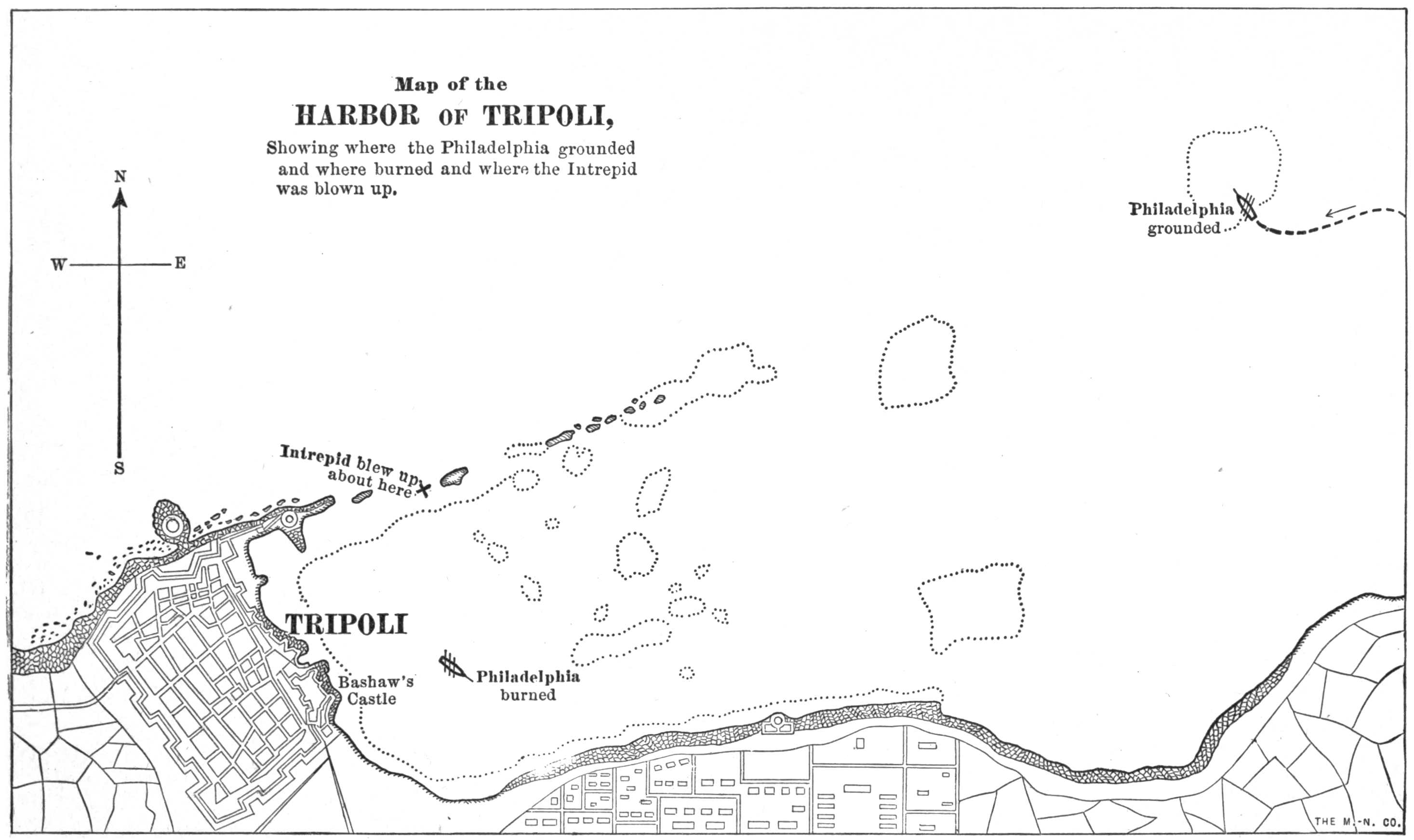

| Map of the Harbor of Tripoli, | 372 |

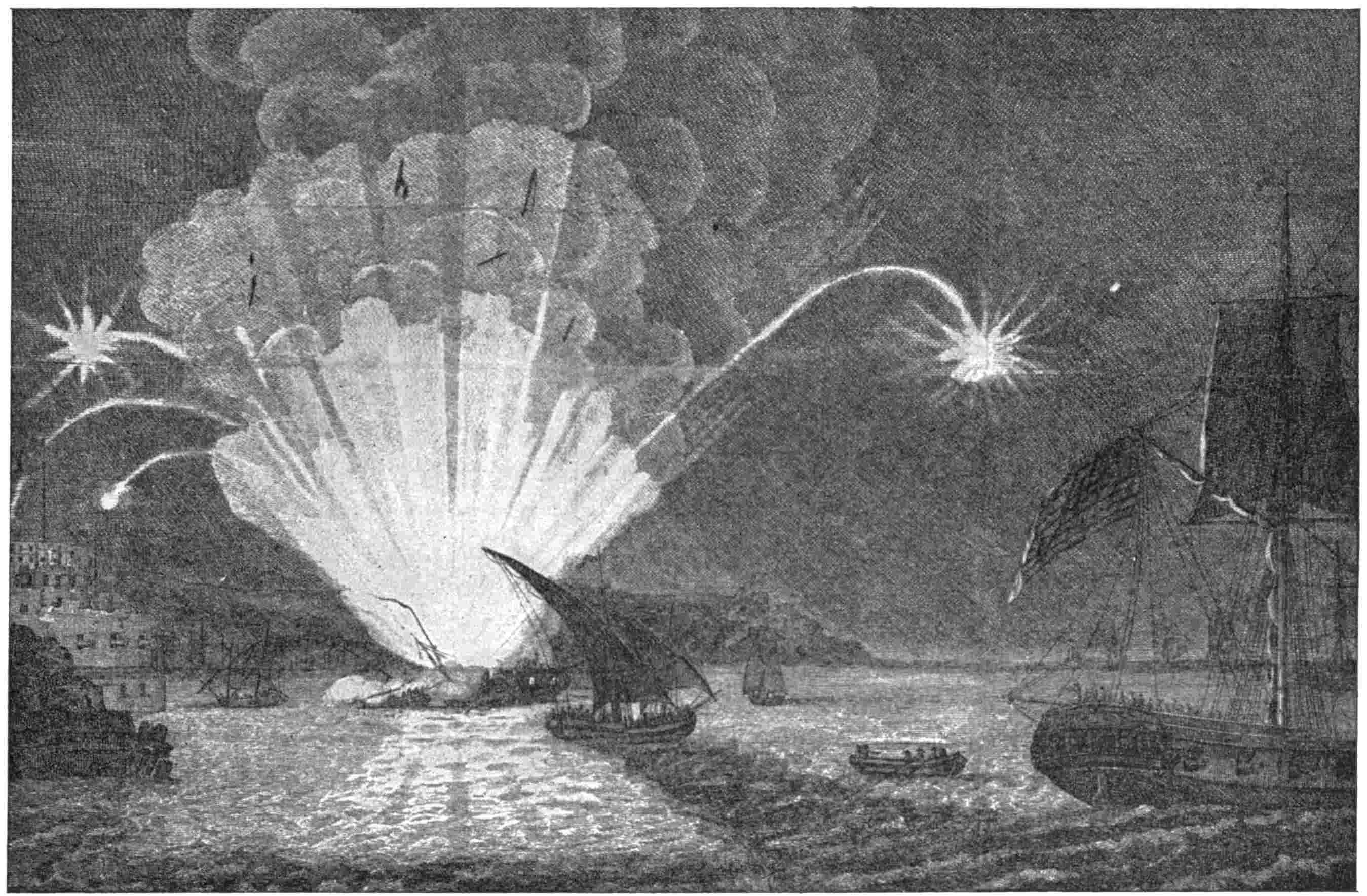

| The Explosion of the Intrepid. (From an old engraving), | 375 |

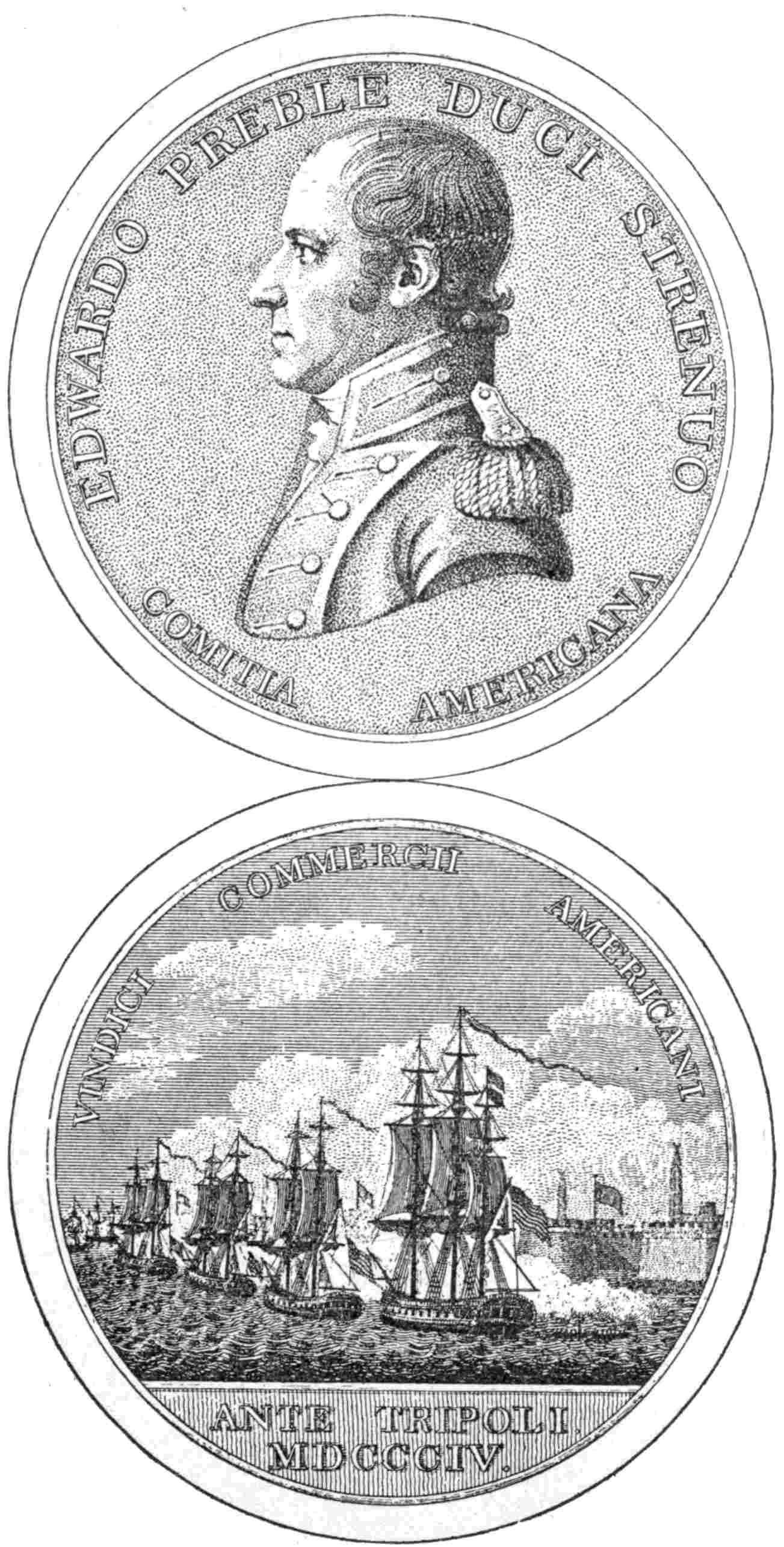

| Preble’s Medal, | 379 |

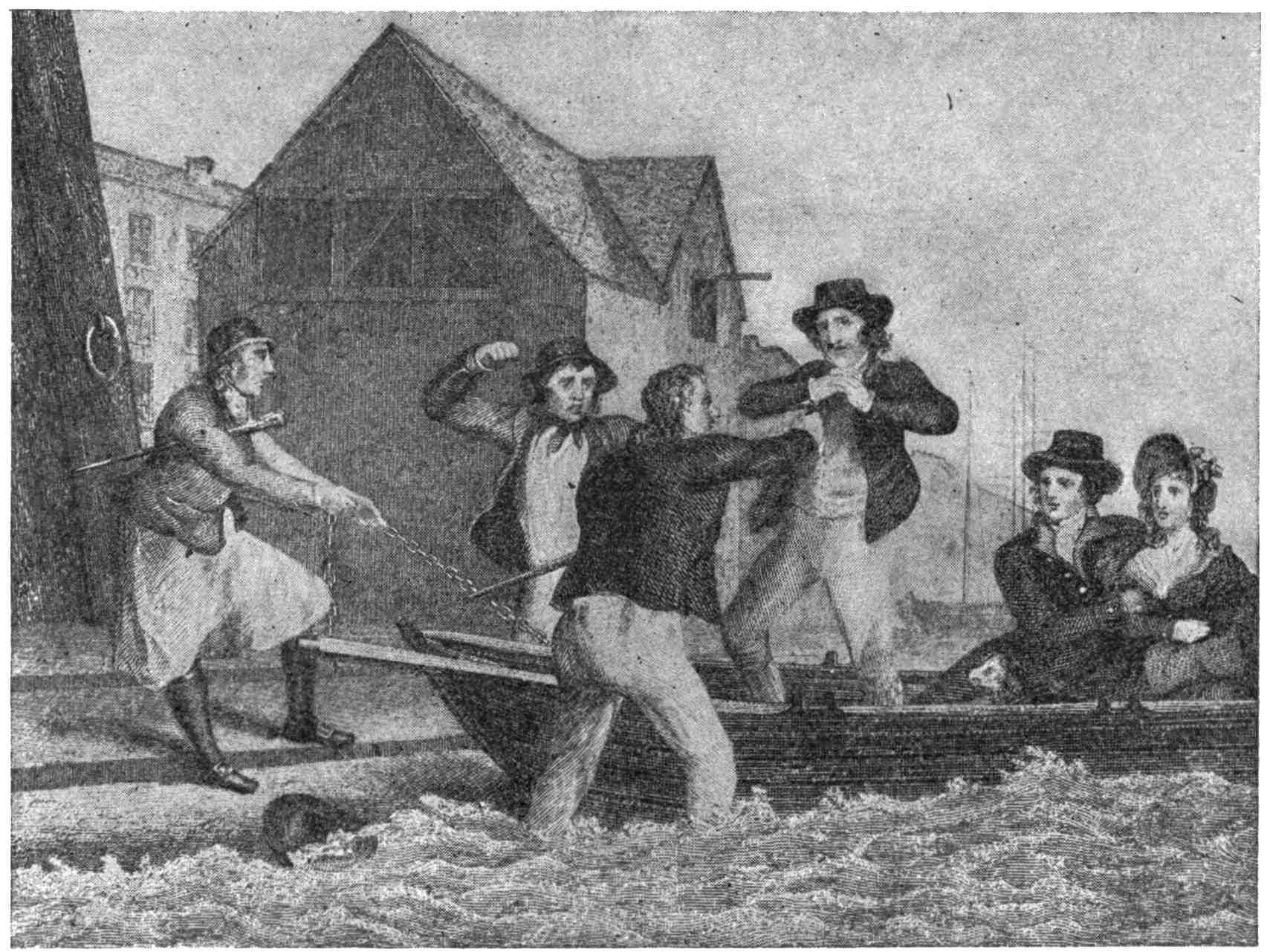

| “The Press-Gang Impressing a Young Waterman on his Marriage Day.” (From an English engraving, illustrating an old song), | 386xxii |

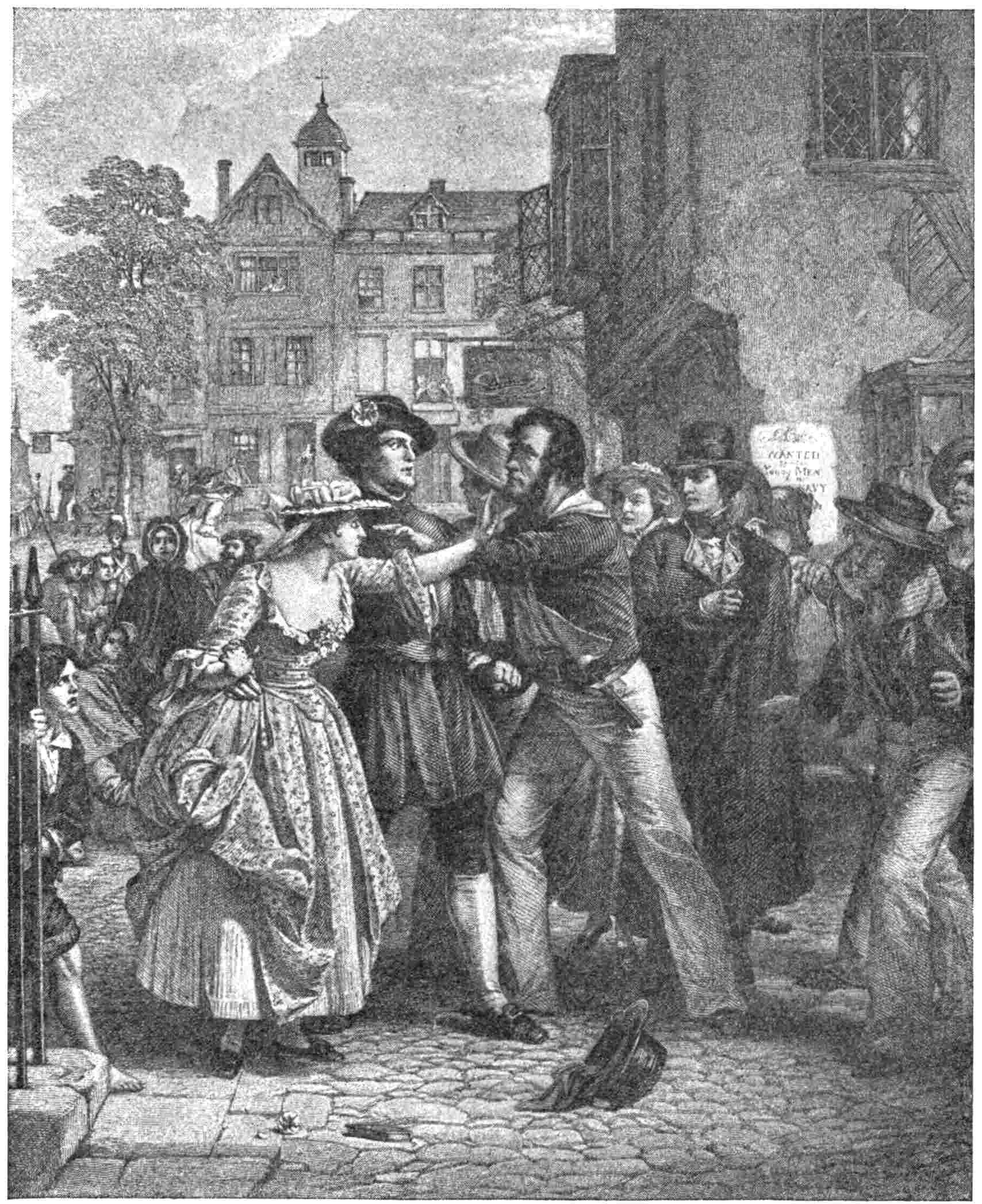

| Another View of the “Young Waterman” and the Press-Gang. (From an English engraving), | 388 |

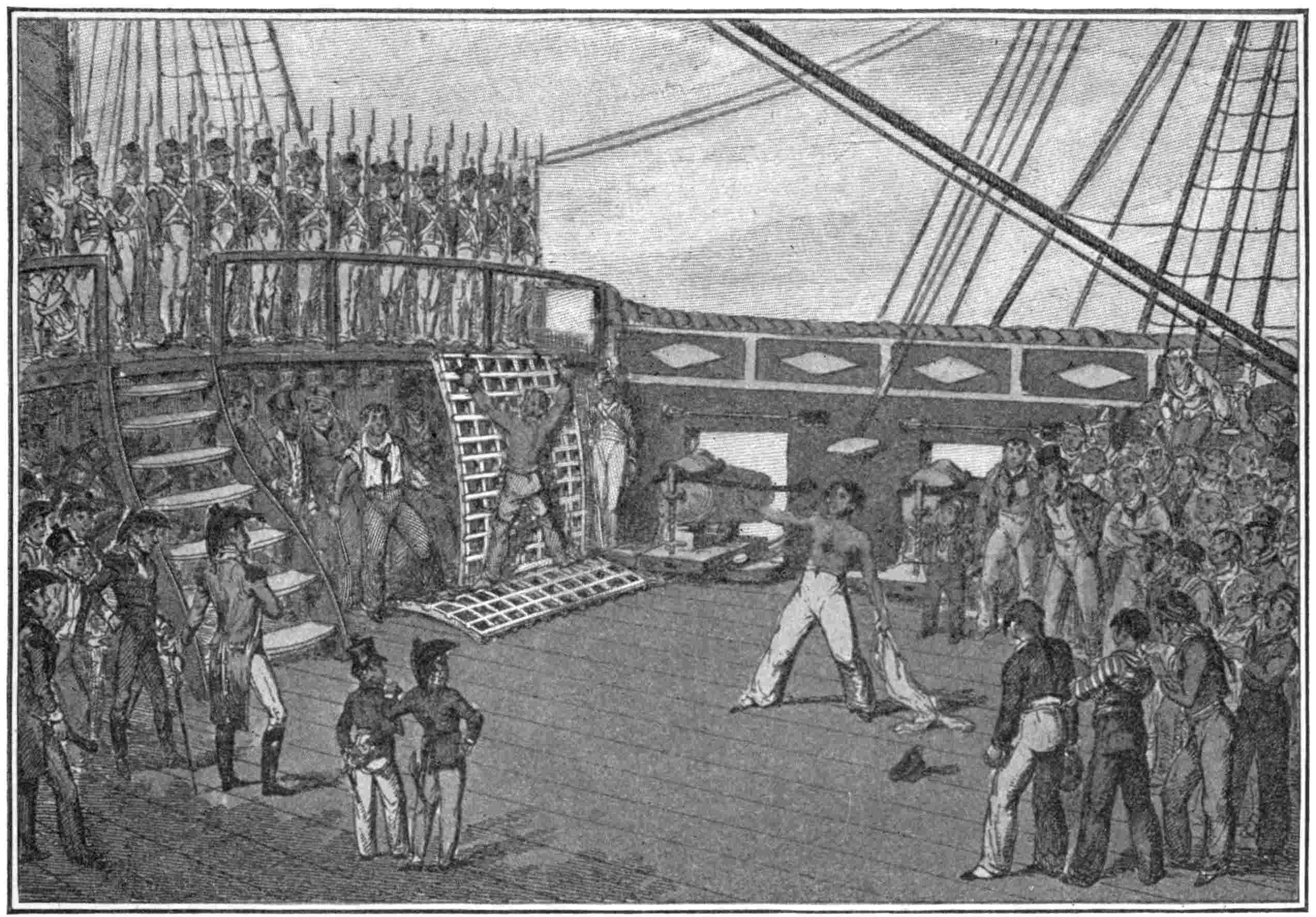

| A Flogging Scene. (“The Point of Honor.” A sailor about to be flogged is saved by a comrade’s confession.) (From a drawing by George Cruikshank), | 391 |

| The United States Frigate Essex. (From a lithograph at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 393 |

| Capt. Henry Whitby, R. N. (From an engraving by Page), | 405 |

| Capt. Salusbury Pryce Humphreys, R. N. (From an English engraving), | 411 |

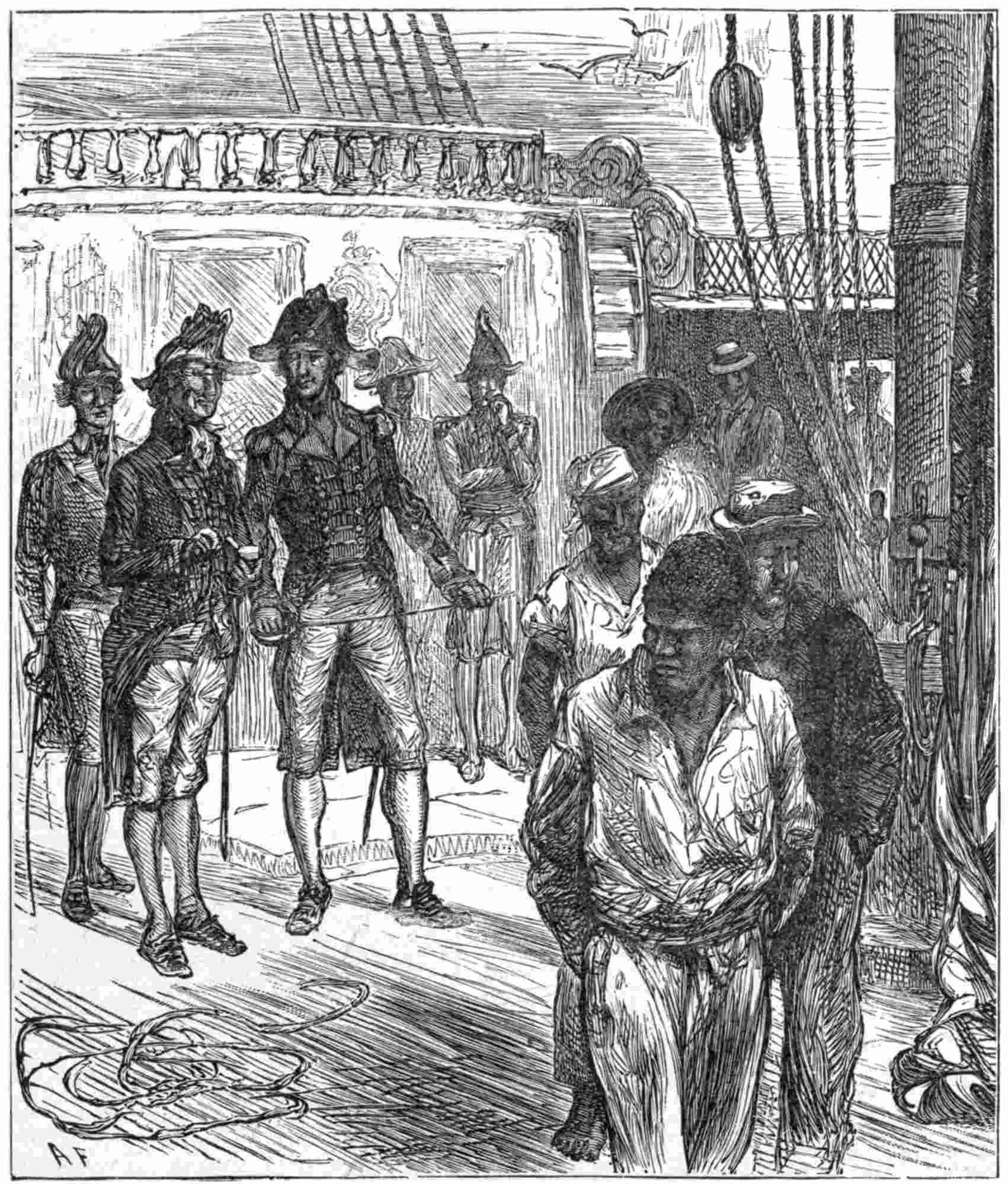

| Taking Deserters from the Chesapeake, | 413 |

1

THE CURIOUS CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT LED TO THE CREATION OF A NATIONAL SEA POWER—THE GASPÉ CAPTURED BY MEN ARMED WITH PAVING-STONES—TEA DESTROYED IN BOSTON—THE BATTLE OF LEXINGTON AND THE ATTACK OF THE MACHIAS HAYMAKERS ON THE MARGARETTA—BRITISH VENGEANCE ON DEFENCELESS PORTLAND AND ITS EFFECT ON THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS—THE “COLONIAL NAVY” DISTINGUISHED FROM THE TEMPORARY CRUISERS—THE FIRST OFFICERS AND THE FIRST SHIPS OF THE AMERICAN NAVY—JOHN PAUL JONES AND THE FIRST NAVAL ENSIGN—THE SIGNIFICANT “DON’T TREAD ON ME”—PUTTING THE FIRST AMERICAN NAVAL SHIPS IN COMMISSION.

Of all the dates in American history not yet so commemorated, there is none so well worthy of recognition as a national holiday as the 22d of December; for it was on December 22, 1775, that the American navy came into existence. And there is no part of the story of the American nation of more thrilling interest than that including the events which2 compelled the establishment of this branch of the public service, nor is there any part of the nation’s story as a whole that so stirs the patriotic pride of the American people as that which tells of the deeds of the heroes whose names have been inscribed upon the American naval registers.

It is a grateful task to recount once more how it was that an American navy was demanded for the preservation of American liberties, and what has been accomplished by that navy since the day when Commodore Esek Hopkins received his commission, and then stood by on the deck of his flagship while John Paul Jones flung to the breeze the broad folds of the flag that bore as a symbol the picture of a rattlesnake coiled to strike, with the significant and appropriate motto,

“DON’T TREAD ON ME.”

Commodore Esek Hopkins.

From a French engraving of the portrait by Wilkinson.

The salt-water Lexington, that is to say, the first fight afloat of the Revolutionary war, occurred on the night of June 17, 1772, in the waters of Rhode Island, and the fact that it was in Rhode Island will be recalled later on. The war of Great Britain against France for dominion in America, “though crowned with success, had engendered a progeny of discontents in her colonies.” “Her policy toward them from the beginning had been purely4 commercial.” And that is to say that the English, even in their dealings with their own colonies, were animated solely by greed. The stamp act; the levying of taxes on intercolonial commerce; the imposition of duties on glass, pasteboard, painters’ colors, and tea, “to be collected on the arrival of the articles in the colonies”; worse yet, the “empowering of naval officers to enforce the acts of trade and navigation,” grew out of “the spirit of trade which always aims to get the best of the bargain,” regardless of right.

It was through this empowering of naval officers to enforce the acts of trade and navigation that the first sea-fight of the Revolution occurred. A vessel of war—presumably a ship—had been stationed in the waters of Rhode Island, with a schooner of 102 tons burden, called the Gaspé, armed with six three-pounders, to serve as a tender. The Gaspé was under the command of Lieut. William Duddingstone. Duddingstone was particularly offensive in his treatment of the coasting vessels, every one of which was, in his5 view, a smuggler. He had a crew of twenty-seven men.

On June 17, 1772, a Providence packet, named the Hannah and commanded by Captain Linzee, came in sight of these two war-vessels while she was on her regular passage from New York to Providence. As the Hannah ranged up near the war-vessels she was ordered to heave to in order that her papers might be examined, but Captain Linzee being favored by a smart southerly wind that was rapidly carrying him out of range of the man-of-war guns, held fast on his course.

At this the schooner Gaspé was ordered to follow and bring back the offending sloop, and with all sail drawing, she obeyed the order. For a matter of twenty-five miles that was as eager and as even a race as any sailorman would care to see, but when that length of course had been sailed over, the racers found themselves close up at the Providence bar. The Yankee knew his ground as well as he knew the deck of his sloop, but the captain of the Gaspé was unfamiliar with it. A few minutes later the shoal-draft Hannah was crossing the bar at a point where she could barely scrape over, and the deeper-draft Gaspé, in trying to follow at full speed, was grounded hard and fast.

To make matters still worse for the Gaspé,6 the tide had just begun to run ebb; not for many hours could her crew hope to float her.

Leaving the stranded schooner to heel with the falling tide, Captain Linzee drove on with the wind to Providence, where he landed at the wharf and spread the story of his trouble with the coast guard. Had it happened in the days before the French war, or before the persistent efforts of the British ministry to levy unjust taxes on the colonies had roused such intense opposition in New England, this affair would have been considered as a good joke on a revenue cutter, and that would have been the end of it so far as the people of Providence were concerned.

Now, however, the matter was taken in a most serious light. As the sun went down, the town drummer appeared on the streets, and with the long roll and tattoo by which public meetings were called he gathered the men of the town under a horse-shed that stood near one of the larger stores overlooking the water. While yet the people were coming to the rendezvous, a man disguised as an Indian appeared on the roof and invited all “stout hearts” to meet him on the wharf at nine o’clock, disguised as he was.

Destruction of the Schooner Gaspé, 1772.

From an engraving by Rogers of the painting by McNevin.

As one may readily believe, nearly every man of Providence came to the pier at the9 appointed hour. From this crowd sixty-four men were selected. They chose as their commander, so tradition asserts, Abraham Whipple, who, later on, became one of the first-made captains of the American navy, and then all embarked in eight long-boats gathered from the different vessels lying at the wharves, and pulled away for the Gaspé.

That was a most remarkable expedition in the matter of armament, for, although there were a few firearms in the boats, the crews depended for the most part on a liberal supply of round paving-stones that they carried for weapons of offense.

It was at two o’clock in the morning when this galley-fleet arrived in sight of the stranded Gaspé. The tide had turned by this time, and the schooner had begun to right herself somewhat. A sentinel, pacing to and fro with some difficulty, saw the approaching boats and hailed them. A shower of paving-stones was the most effective if not the only reply he received, and he tumbled down below precipitately. The rattle and crash of the paving-stones on the deck routed the crew from their berths, and, running hastily on deck, the captain of the Gaspé fired a pistol point-blank at his assailants.

At that a single musket was fired from the boats, by whom will never be told, and the10 captain dropped with a bullet in his thigh. Then the boats closed about the stranded vessel and their crews swarmed over the rails. The sailors of the Gaspé strove to resist the onslaught, but they were quickly knocked down and secured.

As soon as this was done the schooner was effectually fired, and her captors, with their prisoners, pulled away; but they remained within sight until the early dawn appeared, when the schooner blew up, and the boats were rowed hastily home with the tide.

The State House at Newport, Showing the Gaspé Affair.

From an engraving in Hinton’s History of the United States.

11

The indignation of the British officials over this assault on a naval vessel was so great that a reward of £1,000 was offered for the leader of the expedition, with £500 more and a free pardon to any one of the offenders who would turn informer. But, “notwithstanding a Commission of Inquiry, under the great seal of England, sat with that object, from January to June, during the year 1773,” not enough evidence was obtained to warrant the arrest of a single man.

Although it was not an affair of the sea, strictly speaking, it is worth recalling here that within six months after this Commission of Inquiry had failed to learn the names of the men, disguised as Indians, who had burned the Gaspé, another party of men in another colony disguised themselves as Indians, and helped amazingly in making the history of the times. It was on the night of Friday, the 17th of December, 1773, as the reader will remember. The ship Dartmouth, laden with tea, was lying at her wharf in Boston. She had been lying there since the 28th of the preceding month, and during all those days the people of Boston had labored unceasingly to get her away to sea without discharging her cargo. It is even recorded that “the urgency of the business in hand overcame the sabbatarian scruples of the people,” and that in Boston!12 Meetings too great for “the Cradle of Liberty” (Faneuil Hall) were adjourned to the Old South Meeting-House. The people were “determined not to act (in offense) until the last legal method of relief should have been tried and found wanting.” But at last, on the night of this 17th day of December, as the great throng of more than seven thousand people waited in and about “the church that was dimly lighted with candles,” a messenger arrived from the British Governor to say that the last legal resource had failed. The Governor had refused to allow the ship to go. And “then, amid profound stillness, Samuel Adams arose and said, quietly but distinctly, ‘this meeting can do nothing more to save the country.’”

A war-whoop was heard a moment later without the church, and fifty men, disguised as Indians, just as Captain Whipple’s men were when they fired the Gaspé—disguised as Indians because Captain Whipple’s men had successfully eluded the British detectives—these fifty citizens of Boston ran away to the wharf where the Dartmouth lay.

One John Rowe had asked during the meeting earlier in the evening, “Who knows how tea will mingle with salt water?” He had now his opportunity to learn, for when the Indians reached the ship they quickly brought13 her cargo on deck, and smashing open the chests with hatchets, tumbled the tea over the rail, while a vast host stood by in the moonlight and silently watched the work.

There was a significance in the silence of the work that might have been, but was not, heeded by those in authority, for it portrayed the feelings and the character of the men engaged in it, and foreshadowed the grim determination of the people during the conflict that was fast coming on.

The “Boston Tea-Party.”

From an old engraving.

Then followed, as the reader will remember very well, the Boston Port Bill closing that port. Then followed the bill by which any14 magistrate, soldier, or revenue officer, accused of murder in Massachusetts, was to be taken to England for trial—a bill justly stigmatized as an act to encourage the soldiery in shooting down peaceful citizens. Then followed other acts equally or still more unjust and tyrannous that need not be mentioned here, the indignation of the colonists growing deeper as their distress under the oppression increased, until war was inevitable. And on the 19th of April, 1775, when the profane Pitcairn discharged his “elegant pistol” at the minute-men of the veteran Capt. John Parker on the village green in Lexington, war came.

Now, it was because of the stir caused by the story of this battle at Lexington that the second sea-fight of the Revolution occurred.

The reader must keep steadily in mind that not only were churches lighted by candles in those days, but mails were carried up and down the country by stage coaches and on horseback and by the oft-times slower water route—in sloops and schooners. The fight at Lexington occurred on April 19th, but the news of it did not reach Machias, Maine, until Saturday, the 9th of the following month. On that day word was brought by sea to Machias, telling how the British troops had fired on the minute-men, whose present offense was that they had refused to obey when Pitcairn had15 shouted, “Disperse, ye villains! Damn you, why don’t you disperse?” How some had been killed and others wounded by this first onslaught; how the minute-men had at first retreated and then gathered anew for the attack; how the British were first brought to a stand and then started in a retreat so swift that when at last they were rescued by fresh troops from Boston they fell to the ground with “their tongues hanging out of their mouths like those of dogs after a chase”—when all this was related in Machias, Maine, it stirred the men of the town to do a stroke against the oppressive ministry on their own account.

There was at this time in the port of Machias an armed schooner called the Margaretta, Captain Moore, in the service of the crown, with two unarmed sloops in convoy which were loading with lumber, according to the American account, for the British in Boston, but an English account speaks of the schooner as “a mast ship,” i.e., a vessel loading with logs suitable for the masts of a warship. As the reader will remember, the grants of land from the crown in those days, always retained for the use of the crown all trees suitable for masts of ships that might be found on the land.

On hearing of the fight at Lexington the16 bolder spirits of the town, considering that affair as the beginning of war, determined to capture the king’s schooner Margaretta. Their first plan turned on the fact that the day after the news arrived was Sunday. The news was kept secret among those who laid the plan, and Captain Moore came ashore to attend church on Sundays as usual. Then these men started to capture him at the church, but their haste and excitement alarmed Captain Moore, and he jumped through the church window and fled to the beach, where he was protected by his schooner’s guns.

On reaching his schooner, Captain Moore fired several shots over the town to intimidate the people; but not liking the looks of things on shore after the firing, he got up his anchor and dropped down-stream for a league, where he came to anchor foolishly under a high bank. The townspeople who had followed him, quickly took places on this bank, and a man named Foster called on him to surrender, but Captain Moore got his anchor again and ran out into the bay, apparently unmolested by those who had summoned him to surrender.

It looked as if the proposed capture would not be made. But on Monday morning (May 11, 1775) two of the young men of the town, Joseph Wheaton and Dennis O’Brien, met on17 the wharf, when Wheaton proposed taking possession of one of the lumber sloops, raising a crew of volunteers and going after the Margaretta. Peter Calbreth and a man named Kraft happened along and agreed to join in, and the four went on board the sloop and took possession.

Three rousing cheers were given over the success of their effort, and that brought a crowd to the wharf—among the rest, Jeremiah O’Brien, “an athletic gallant man,” to whom, as to a village leader, Wheaton explained the project.

“My boys, we can do it,” said Jeremiah with enthusiasm, and at that every one in the throng skurried off for arms.

The equipment which they brought together for that cruise is worth describing in detail. They had twenty guns, of which one is described as a “wall-piece.” It was a musket too heavy to hold offhand when fired; it needed a wall, so to speak, to support its weight when it was aimed. For all these guns they had but sixty bullets and sixty charges of powder—three loads for each weapon. In addition they carried thirteen pitchforks and twelve axes (a formidable weapon in the hands of a Maine man). For food they carried a few pieces of pork, a part of a bag of bread, and a barrel of water.

18

Out of a throng of volunteers thirty-five of the most athletic were selected to go, and, this done, they hoisted sail and boldly headed away before a northwest breeze to capture the Margaretta.

It should be noted here that these sloops were single-masted vessels, as was the one in the Providence affair. They were in form and rig very much like the one-masted vessels employed at the time of this writing (1897) in carrying brick from the yards on the Hudson River to New York City, but they were not nearly as large as the brick-carriers, though they probably stood as high out of water, if not higher. A “sloop of war” was a very different vessel, as will appear further on.

Captain Moore saw the sloop coming from afar, and realized that the crowd upon her deck meant trouble for him. So, being still anxious to avoid a conflict (just why he was anxious does not appear), he up anchor and once more ran away. But luck was against him—perhaps his frustrated state of mind brought him ill-luck. At any rate, although the wind was in the northwest and he was bound south, he got up his mainsail with the boom to starboard, and soon found himself obliged to jibe it over to port. With a fresh breeze that was a task needing care, and yet,21 when he came to swing the boom across, he let it go on the run, and it brought up against the backstays with such a shock that it was broken short off in the wake of the rigging.

A British Armed Sloop

From a very rare engraving, showing the first lighthouse erected in the United States—on Little Brewster Island, Boston Harbor.

Rendered desperate by this accident, Captain Moore now turned to a merchant schooner that he saw at anchor not far away, and bringing to alongside of her, he robbed her of her boom to replace his own and again headed for the open sea, and then, to still further aid his flight, cut adrift every one of his boats.

But it was all in vain, for the sloop was much the swifter vessel, and Captain Moore was at last compelled to fight.

The Margaretta was armed with four six-pounders and twenty swivels—short and thick guns firing a one-pound ball, and mounted on swivels placed on the vessel’s rail. It was an armament that should have been more than sufficient to repel the Machias men armed with pitchforks and axes. Moreover, the crew of the Margaretta outnumbered that of the sloop. But there was a difference in the character of the two crews—a difference for which abundant cause will be shown further on—and the issue of the contest was never for a moment in doubt after the haymakers had gone afloat.

The first discharge of guns on the schooner22 killed one man on the sloop. A man of the name of Knight on the sloop returned the fire, using the wall-piece. He was probably from the backwoods and a moose hunter, for he was bright enough and skilful enough to pick off the man at the schooner’s helm. And that shot drove everybody off the schooner’s quarter-deck, so she was left, as a sailor might say, to take charge of herself.

Then the schooner broached to, the sloop crashed into her, and the men from Machias, with swinging axes and poised pitchforks, climbed over her rail.

It is said for Captain Moore that at this point he fought gallantly, throwing hand-grenades “with considerable effect,” but he was quickly shot to death, and then his crew surrendered.

In all, twenty men were killed and wounded in this fight, showing that it was a desperate conflict when once the two crews got within range of each other, man to man, for twenty was more than one-fourth of all engaged in it. The crew of the Margaretta numbered forty, all told.

On the Margaretta the captors found two wall-pieces, forty cutlasses, forty boarding axes, two boxes of hand-grenades, forty muskets, and twenty pistols, with an ample supply of powder and shot.

23

When one with a full knowledge of the naval tar’s contempt for “a haymaker’s mate” recalls the story of this Machias fight, he cannot help thinking that some of the crew of the Margaretta must have suffered as much in mind as they did from their wounds after being impaled on the two-pronged pikes—the pitchforks of these Yankee haymakers.

Not only was the fight between the Margaretta’s crew and the haymakers interesting in itself; it was followed by consequences of the most important nature in connection with the establishment of the American navy.

The commander of the haymakers, elected in good American fashion after they were afloat, was Jeremiah O’Brien. Having secured the Margaretta and his prisoners, Captain O’Brien shifted the cannon and swivels, with the ammunition and small arms, from the captured schooner over to his fleeter sloop, and set forth in search of more prizes and glory. Straightway the efforts of the British naval authorities to punish him for his assault on the Margaretta gave him the opportunity to acquire both. Two schooners, the Diligence and the Tapanagouche, were sent from Halifax to bring the obstreperous Irish-Yankee in for trial. But Captain O’Brien was a sailorman as well as a haymaker. By skilfully handling his sloop he separated the cruisers,24 and then captured them one at a time by the bold dash that had succeeded in the assault on the Margaretta. This done, Captain O’Brien, with his prizes, sailed into Watertown, Massachusetts, where the provincial legislature was sitting, and delivered up everything to the colonial authorities.

Such brave deeds as these did not go unrewarded in those days. Captain O’Brien received a commission from the colony, and, with the three vessels well refitted, he was sent once more to sea to cruise for vessels bringing supplies to the British troops.

As said, not only was this an interesting fight, but it was one with far-reaching consequences. The deeds of Captain O’Brien, followed by others of a like nature performed by men who were stirred by his example, so exasperated Admiral Graves, the British commander-in-chief on the coast, that he sent a squadron of four vessels under Captain Mowat to take revenge in such a manner as would fill, as he supposed, the hearts of the people of the whole coast with terror. Portland (then called Falmouth), Maine, was the port selected for destruction.

The British account of what was done after Captain Mowat’s fleet arrived before the town, shall be given for a reason that will appear further on in this history. The “Annual Register”25 for 1776 (Dodsley’s, London), in its “Retrospective view of American affairs in the year 1775,” says (page 34):

“About 9 o’clock in the morning, a canonade was begun, and continued with little intermission through the day. About 3,000 shots besides bombs and carcases, were thrown into the town, and the sailors landed to compleat the destruction, but were repulsed with the loss of a few men. The principal part of the town, (which lay next the water) consisting of about 130 dwelling houses, 278 stores and warehouses, with a large new church, a new handsome courthouse, with the public library, were reduced to ashes; about 100 of the worst houses being favored by the situation and distance, escaped destruction, though not without damage.”

In Allen’s “Battles of the British Navy,” the “new edition revised and enlarged” and published by George Bell & Sons, London, in 1893 (note that it was published in 1893), we get a modern British view of this important assault. On page 227 it says:

“Lieutenant Mowat’s instructions were tempered with moderation. He was directed to confine his operations to certain enumerated towns which had rendered themselves conspicuous by open acts of hostility.”

The town was destroyed on the 16th day of26 October, and in Maine. Under instructions that, to an Englishman’s mind, tempered with moderation, “a thousand unoffending, men women and children were thus turned out of doors” just as the fierce Maine winter was coming down upon them.

It should be told here that among the children who were thus obliged to seek shelter in brush and bark huts was a lad of fourteen years, named Edward Preble, of whom something will be told further on.

Meantime the Congress of the thirteen United Colonies had been in session at Philadelphia, resolving itself into a committee of the whole, from day to day, to consider “the state of trade in the colonies.” Patriots by the thousand had answered the cries of distress at Lexington by gathering with their muskets about Boston. The battle of Bunker Hill, the most glorious defeat recorded in the annals of American warfare, had been fought and lost, because the supplies of gunpowder, brought by the colonists in the old-fashioned cowhorns, had failed them. Of missiles there was apparently no lack—they would have used pebbles from the beach had no others been available and powder abundant. But the want of gunpowder became chronic, and in considering the state of trade in the colonies the Congress found that of all branches of that trade the one needing27 their most careful attention was the trade in gunpowder. It was a trade that did not thrive under the circumstances; but there was one source of supply that did not escape the attention of such able-minded as well as able-bodied citizens as Capt. Jeremiah O’Brien and his ilk afloat. That source was in the supply ships that provided for the British forces, and in the smaller cruisers that waited on the great ships of the British fleet. The sailormen of the coast pointed to the supplies afloat, and the legislators adopted the views of the sailormen. Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut provided small cruisers on their own account and sent them out seeking the enemy’s supply ships, which, because the rebellious colonies had theretofore no sort of a navy, came to Boston and other ports in the king’s possession, unarmed and without convoy. The far-sighted Washington, who had been placed in command of the heterogeneous forces about Boston, took hold of this matter and brought it to the attention of the Congress. In the mind of Washington it was an expedient well worth trying, but apparently he regarded it only as a temporary expedient. For during the summer and early fall of 1775, when the need of gunpowder became and remained most urgent, the colonies were fighting only for their rights as British subjects, as the reader remembers,28 and not for national independence. A few long-headed leaders undoubtedly saw the drift of current events, but with every address to the throne there was sent a protestation of loyalty.

The earliest reference to this temporary expedient for getting gunpowder which is found in the printed reports of the doings of the Congress is in the minutes for Thursday, October 5, 1775. It was then resolved to inform General Washington that the Congress had “received certain intelligence of the sailing of two north country built brigs, of no force, from England on the 11th of August last, loaded with arms, powder and other stores for Quebec without convoy, which it being of importance to intercept,” Washington was requested to “apply to the Council of Massachusetts-Bay for the two armed vessels in their service,” and send them “at the expense of the continent” after the brigs. Moreover, he was informed that “the Rhode Island and Connecticut vessels of force will be sent directly to their assistance.” Further still, it was resolved that “the general be directed to employ the said vessels and others, if he judge necessary.” That was a very important set of resolutions in connection with the history of the navy. And the same may be said of the resolutions of Friday, October 13th, when it29 was provided that “a swift vessel to carry ten carriage guns and a proportionable number of swivels, with eighty men, be fitted out with all possible despatch for a cruise of three months,” and, further, “that another vessel be fitted out for the same purposes.” Deane, Langdon, and Gadsden were chosen as a committee of the Congress to look after the fitting out of the vessels. Further than that, on Monday, October 30, 1775, it was resolved that the second vessel previously ordered should “carry fourteen guns and a proportionate number of swivels and men,” while two other ships, “one to carry not exceeding twenty guns and the other not exceeding thirty-six guns,” were to30 be chartered for the same purpose—to cruise “eastward” to intercept the British store-ships.

A Brig of War Lowering a Boat.

From a picture drawn and engraved by Baugean.

How under the resolutions of October 5th Captain Manly of the schooner Lee was sent “eastward”; how he captured a large brigantine loaded with munitions of war; how, in consequence of this capture, “a long, lumbering train of wagons, laden with ordnance and military stores, and decorated with flags, came wheeling into camp”—Washington’s camp—the next day after a host of Connecticut troops had deserted the cause, and “it was feared their example would be contagious”; how “such universal joy ran through the whole camp as if each one grasped victory in his own hands,”—all are parts of a story that may not be wholly omitted here; but the resolutions of the Congress did not provide, properly speaking, for an American navy. They only provided temporary means for obtaining supplies. The Congress was not yet ready to take the important step of establishing a navy as a branch of the public service.

But the thought of a colonial navy was abroad—it was even then officially before the Congress, although it had not been acted upon. Officially, the subject of establishing a colonial navy came from Rhode Island, where Capt. Abraham Whipple and his paving-stones31 had conquered the schooner Gaspé. On August 26, 1775, the two houses of the Rhode Island legislature concurred in ordering their representatives in the Congress to propose the establishment of a navy “at the expense of the continent.” So cautious were the members of the Congress in handling the matter that, when, on October 3d, one of the Rhode Island delegates—presumably Samuel Ward, who was their leader—called the attention of the Congress to the proposal of his legislature, they did not even mention the matter definitely in the minutes of the day. The minutes read: “One of the delegates for Rhode Island laid before the Congress a part of the instructions given them,” etc. “The proposal met great opposition,” and even the briefest consideration of the matter had to go over to a later day. “In the Congress at Philadelphia, so long as there remained the dimmest hope of favor to its petition, the lukewarm patriots had the advantage.”

But a time was coming when they were to change their feelings in this matter radically and in a day. They had ordered the forces afloat and ashore “carefully to refrain from acts of violence which could be construed as open rebellion,” but before the end of the year they had taken such a long step toward the32 Declaration of Independence that to turn back was impossible.

It was on October 31st that the change of sentiment was wrought. One cannot help wishing that what a newspaper man in these days would call “a crackerjack reporter” might have been present to describe the stir in the Congress when, on that day, one messenger arrived to announce that the British king had succeeded in hiring 20,000 of “the finest troops in Europe”—Germans—to fight against the colonists, while a second messenger followed with the story of the desperate plight of the people of Falmouth, who had been driven from their homes to face a Maine winter by the assault of the infamous Mowat. But if we lack the picture we have the record of what was done in consequence of the news then received.

Though stirred as never before since they had come together, the members of the Congress moved with judicial moderation, and it was not until Saturday, November 25th, that they resolved to make an aggressive fight at sea. On this day they adopted a preamble that eloquently told how “orders have been issued ... under colour of which said orders the commanders of his majesty’s said ships have already burned and destroyed the flourishing and populous town of Falmouth,33 and have fired upon and much injured several other towns within the United Colonies, and dispersed at a late season of the year, hundreds of women and children, with a savage hope that those may perish under the approaching rigours of the season who may chance to escape destruction from fire and sword.” And then they resolved that all armed British vessels, and all “transport vessels in the same service,” “to whomsoever belonging,” with their cargoes, that might fall into the hands of the colonists, “shall be confiscated.” Further than that, commissions not only for the captains of the colonial cruisers, but for the commanders of privateers as well, were ordered to be issued under proper regulations. The colonies were recommended to “erect courts of justice” to dispose of the prizes to be so captured, and a scheme for distributing prize money to the crews of both cruisers and privateers was approved.

Three days later—on November 28, 1775—the minutes contain the first adopted “Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies,” and that34 was the first occasion on which the term navy of the United Colonies appears in the minutes of the proceedings.

Very curious and well worth the study of any one interested in history are those first rules adopted for the American navy—a navy not yet actually in existence. But for the present purpose it is necessary to note only the thoughtfulness of the Congress for the comfort of the members of the crews—especially the comfort of the men before the mast. A remarkably large space in the printed report of these regulations relates to the feeding of the men, and if to this space be added that devoted to the regulations for the care of the sick and wounded, together with what was ordered for the preservation of the property rights of the sailors, then more than one-half of all that was decided upon was in the interest of the men in the forecastle. The bearing of this policy on the future of the American navy will appear further on, but it may be said here that it was not for nothing that grave legislators were concerned to provide that “a proportion of canvas for pudding-bags, after the rate of one ell for every sixteen men,” should be served out at proper intervals.

Thereafter the making of a navy went on more rapidly. Within a week word came that Lord Dunmore, with a fleet in the Chesapeake35 Bay, was aiding the Tories there to engage in trade with the West Indies, contrary to the colonial regulations, and, worse yet, was stirring up a race war. In consequence of this the Congress resolved, on December 5th, that all the vessels engaged in the trade established by Dunmore, with their cargoes, should be seized when possible and held “until the further order of this Congress.” And that is a matter of importance, because it was the first warrant of the Congress permitting the capture of merchant ships of the enemy when engaged in another traffic than the carrying of supplies to the enemy’s military or naval stations.

Next (on December 11th) the Congress ordered that “a committee be appointed to devise ways and means for furnishing these colonies with a naval armament.” The alacrity with which that committee acted was something phenomenal, for in two days they brought in their report, “which being read and debated,” was adopted. They had determined to build “five ships of 32 guns, five of 28 guns, three of 24 guns, making in the whole thirteen.” These were to be constructed, one in New Hampshire, two in Massachusetts, one in Connecticut, two in Rhode Island, two in New York, four in Pennsylvania, and one in Maryland. They were expected to go afloat36 “by the last of March next,” and the cost was not to be “more than 66,666⅔ dollars each, on an average, allowing two complete suits of sails for each ship.” So far as the committee could see, there would be but one difficulty in the way of sending all these ships to sea well found for the service, and that was in the lack of canvas and gunpowder. They would need 7,500 pieces of canvas for the sails and 100 tons of powder for the magazines, and there was not any of either in the market.

In the meantime the marine committee appointed under the resolution of October 13th to fit out two vessels to “cruise eastward” after the king’s transports, had been increased in number, and in December consisted of Silas Deane, Christopher Gadsden, John Langdon, Stephen Hopkins, Joseph Hewes, and Richard Henry Lee. John Adams, who was an enthusiastic supporter of the project to create a navy from the moment it was discussed, had been at first a member of this committee, but because of other duties he left it, and Gadsden took the place. The names of these men are well worth remembering, for they were the originators of the American navy. While the Congress was preparing to build the navy these men had labored faithfully, and with success, to provide one ready made out of the ships that could be purchased along the coast.

37

Christopher Gadsden. John Langdon. Richard Henry Lee.

Stephen Hopkins. Joseph Hewes. Silas Dean.

The Founders of the American Navy.

39

Vessel of War Saluting, with the Yards Manned.

From an old French engraving.

The Congress had, on November 2d, placed $100,000 at their disposal. With this they went about buying ships and supplies for them. A London packet called the Black Prince came into port under command of that Captain John Barry who, later on, was a captain in the American navy. She was of good scantling, and was considered a vessel worthy of becoming the flagship of the new fleet. The committee purchased her, and, after renaming her the Alfred, after Alfred the Great, they mounted twenty nine-pounders on deck, with four (it is said) smaller guns—presumably four-pounders—on the forecastle and poop. Another merchant ship, called the Sally, was purchased and renamed Columbus, for the great explorer, after which she received eighteen or twenty (authorities vary) nine-pounders. She is said to have been crank (top-heavy) and of small value. Two brigs were purchased and renamed the Andrea Doria, for the famous Genoese sailor, and the Cabot, for the early explorer of North America. These are set down as carrying fourteen four-pounders each. A third brig was purchased in Providence and named for that town, because, according to John Adams, that town was “the residence of Governor Hopkins and his brother Esek, whom we appointed the first Captain.” She carried twelve guns—sixes or fours. In addition40 to these, the committee obtained a sloop of ten guns, called the Hornet, and an eight-gun schooner named the Wasp. These were purchased and equipped in Baltimore, and then brought around to Philadelphia. The Fly, an eight-gun schooner, completed the list.

While the committee were gathering this fleet at Philadelphia, the Congress showed its appreciation of the work in hand by voting that the crews should be engaged to serve41 until January 1, 1777—practically for one year. They further voted $500,000 of the continental currency to the use of the naval committee.

Then, on Tuesday, December 19th, the Congress still further showed their appreciation of the situation of affairs by resolving “that the Committee of Safety of Pennsylvania be requested to supply the armed vessels, which are nearly ready to sail, with four tons of gunpowder at the continental expense”; and, further, “that the said committee be requested to procure and lend the said vessels as many stands of small arms as they can spare, not exceeding 400.”

Facsimile of a Letter from Abraham Whipple to General Lincoln during the Siege of Charleston.

From the original at the Lenox Library.

The Pennsylvania people had already agreed to furnish these necessaries; the resolutions of the Congress were only in the nature of vouchers, and, twenty-four hours later, the first American fleet was found and fitted for service. Only the crews for the ships were needed, and these the committee had provided ready for the occasion, so all that was then required to man the ships was for the Congress to confirm the appointment of the officers. And this was done on the memorable date, Friday, December 22, 1775. The resolutions of the Congress shall be given in full, because it was upon this legal warrant that the American navy was founded. They were as follows:

42

“The committee appointed to fit out armed vessels, laid before congress a list of the officers by them appointed agreeable to the powers to them given by Congress, viz:

Esek Hopkins, esq. comander in chief of the fleet—

43

Dudley Saltonstall, Captain of the Alfred.

Abraham Whipple, Captain of the Columbus.

Nicholas Biddle, Captain of the Andrea Doria.

John Burrow Hopkins, Captain of the Cabot.

First lieutenants, John Paul Jones, Rhodes Arnold, —— Stansbury, Hoysted Hacker, Jonathan Pitcher.

Second Lieutenants, Benjamin Seabury, Joseph Olney, Elisha Warner, Thomas Weaver, —— McDougall.

Third Lieutenants, John Fanning, Ezekiel Burroughs, Daniel Vaughn.

Resolved, That the Pay of the Comander in-chief of the fleet be 125 dollars per calender month.

Resolved, That commissions be granted to the above officers agreeable to their rank in the above appointment.

Resolved, That the committee for fitting out armed vessels, issue warrants to all officers employed in the fleet under the rank of third lieutenants.

Resolved, That the said committee be directed (as a secret committee) to give such instructions to the commander of the fleet, touching the operations of the ships under his command, as shall appear to the said committee most conducive to the defence of the United Colonies, and to the distress of the enemy’s naval forces and vessels bringing supplys to their fleets and armies, and lay such instructions before the Congress when called for.”

44

The thirteen United Colonies had at last a naval fleet, armed, equipped, and manned, and legally authorized to sail away on the secret expedition the committee had planned. But before Commodore Hopkins might up anchor and spread his canvas to the breeze there was one ceremony to be performed which, though not mentioned in any colonial law, was (and it still is) considered of the utmost importance. He must “put his ships in commission”—must “pipe all hands on deck,” and then “hoist in their appropriate places the national colors and the pennant of the commanding officer,” after which he must address the crew and “read to them the order by virtue of which he assumes command.”

That is a most impressive ceremony, and it was now to be performed for the first time in the American naval fleet.

Important—even thrilling as was the occasion, there is no known record by which the date on which this ceremony was performed may be definitely located. But it is unquestioned that the naval committee of the Congress had, on this December 22d, secured the crews as well as the ships for a fleet, and that the crews were then on board awaiting the coming of properly authorized officers. There is, therefore, no reason to doubt that as soon as the Congress had passed the resolutions45 above quoted, and the commissions therein mentioned had been signed, the commodore and his officers immediately went on board to take formal possession.

Captain Nicholas Biddle.

From an engraving by Edwin.

But whatever the date, it is recorded that it was on a beautiful winter day when the commodore46 and his officers made their way to the foot of Walnut Street, Philadelphia, where a ship’s long-boat awaited them. A great throng of patriots gathered along shore on the arrival of the officers, and the shipping along the whole river front was not only decorated with bunting, but decks and rails and rigging were occupied by enthusiastic spectators.

Pushing off and rowing away through the floating ice, Commodore Hopkins reached the ladder at the side of the Alfred, and, followed by all his officers, mounted to the deck. The shrill whistle of the boatswain called the crew well aft in the waist of the ship. The officers gathered in a group on the quarterdeck. A quartermaster made fast to the mizzen signal halliards a great yellow silk flag bearing the picture of a pine tree with a coiled rattlesnake at its roots, and the impressive motto “Don’t Tread on Me.” This accomplished, he turned toward the master of the ship, Capt. Dudley Saltonstall, and saluted.

And then, at a gesture from the captain, the executive officer of the ship, the immortal John Paul Jones, eagerly grasped the flag halliards, and while officers and seamen uncovered their heads, and the spectators cheered and cannon roared, he spread to the breeze the first American naval ensign.

The grand union flag of the colonies, a flag47 of thirteen stripes, alternate red and white, with the British jack in the field, and the pennant of the commander-in-chief, were then set, and the resolutions of the Congress read. The first American naval fleet was in commission.

48

A Frigate Chasing a Small Boat.

From an old French engraving.

A FAIRLY SUCCESSFUL RAID ON NEW PROVIDENCE, BUT THEY LET A BRITISH SLOOP-OF-WAR ESCAPE—CHARACTER OF THE FIRST NAVAL COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF AND OF THE MATERIAL WITH WHICH HE HAD TO WORK—ESEK HOPKINS, A LANDSMAN, SET TO DO A SAILOR’S WORK—CREWS UNTRAINED AND DEVOID OF “ESPRIT DE CORPS”—GOOD COURAGE, BUT A WOEFUL LACK OF OTHER NEEDED QUALITIES—HOPKINS DISMISSED FOR DISOBEDIENCE OF ORDERS.

The career of Commodore Esek Hopkins as commander-in-chief of the American navy lasted for a year and ten days. If it was not a glorious career it was at least an instructive one, and the candid student is likely to conclude that, under the circumstances, it was creditable to his reputation. He was badly handicapped from the beginning in a variety49 of ways, but in spite of this he accomplished something.

As already noted, Commodore Hopkins received his appointment chiefly through the influence of John Adams, and because he was the brother of the capable Governor of Rhode Island. The student of American history should keep in mind that the colonists were still monarchists in 1775, and that they followed the monarchial system of appointing favorites to office. That is to say, the man who had the most influence, who had what politicians call a “pull,” got the appointment, regardless, usually, of his fitness for the place. Commodore Hopkins had been a brigadier-general in the Rhode Island militia by appointment of his brother. He had served in various capacities at sea, but it is likely that training had made him a soldier rather than a sailor, and no greater mistake can be made by executive authority than to appoint a soldier to do a sailorman’s work.

Further than this, the vessels under the command of Hopkins were all built for carrying cargoes and not for fighting—they were not as swift or as handy as fighting ships of the same size. Worse yet, they were manned by crews brought together for the first time—men who were not only unacquainted with each other, and therefore devoid of esprit de50 corps, but who were unaccustomed, for the most part, to the discipline necessary on a man-of-war and untrained in the use of great guns. When compared with the crews of the British warships they were more inferior in these two respects than were the raw militia around Boston when compared with the British regulars. The raw militia could at least shoot well.

A Letter from Esek Hopkins.

From the original at the Lenox Library.

With these facts in mind it is worth while51 comparing the American ships with the British naval forces on the coast. As said, Commodore Hopkins had eight vessels, of which two only were ships, and the others were brigs or smaller, and all were lubberly merchantmen. All told, this squadron mounted just 114 guns, of which the largest was a cannon that could throw a round cast-iron ball weighing nine pounds. Even of these there were less than fifty. And the powder to load them and the muskets with which the seamen had been armed were all borrowed from the commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Yet this puny squadron, “poor and contemptible, being for the greater part no better than whale boats,” as a British authority truly says, was to go to sea to make war—against what force does the reader suppose? A navy of 112 ships, carrying 3,714 guns, of which force no less than seventy-eight ships, carrying 2,078 guns, were either already on the American coast or under orders to go there.

A Corvette.

From an old French engraving.

Nor does a comparison of the number of guns—114 against 2,078—give an idea of the utter inefficiency of the American sea power; for, while the best of the American guns was but a nine-pounder, at least a fourth of the guns on the British ships—at least 500 of them—were eighteen-pounders or heavier. For every nine-pounder in the American ships there were52 at least ten of double that size in the British, not to mention the 1,500 and more guns in the fleet that included six-pounders, nine-pounders, and twelve-pounders. “Poor and contemptible” were just the words for describing the comparative merits of the American warships. And in the matter of experience and training the American crews were but little better than their ships and guns. As will appear further on, there were to be fights between British ships manned by experienced, thoroughly disciplined crews of full numbers against Yankee53 ships that were manned for the greater part by seasick landsmen, and short-handed at that.

The secret orders that had been given to Commodore Hopkins commanded him to go in search of Lord Dunmore, who had been making so much trouble along the shores of Chesapeake Bay as to cause Washington to write that “if this man is not crushed before spring he will become the most formidable enemy America has.” The ships were to gather at Cape Henlopen, and sail thence for the Chesapeake. But the Delaware River was full of ice, and it was not until February 17, 1776, that the squadron finally passed out to sea. Then, on the night of the 19th, while running along with a fresh breeze, the Hornet and the Fly became separated from the others, and did not again join the squadron.

It appears from the meagre record that Hopkins did not enter the Chesapeake at all. Instead of that he sailed away to the Bahama Islands, because he had learned that a large quantity of military supplies were stored at New Providence, with only a few men to guard them. He was determined to capture the supplies.

On reaching Abaco, Hopkins divided his forces by sending 300 men under Capt. Samuel Nichols, in ten small sloops found at Abaco, to capture New Providence. Hopkins54 supposed the force would surprise the garrison, but the commander was found ready to repel an attack, and the Providence and the Wasp had to be sent over to assist the men in landing.

It was at this point that a branch of the American naval personnel, of which too little notice has been taken by historians, first made a record for gallantry. Captain Nichols was the first captain of marines in the American naval service, the organization of the marine corps having been ordered by the Congress on November 10, 1775.

Under cover of the guns of the Providence and the Wasp, Captain Nichols and his marines landed on the beach, and then “behaved with a spirit and steadiness that have distinguished the corps from that hour down to the present moment.” They carried the forts by assault. “A hundred cannon and a large quantity of stores fell into the hands of the Americans,” but because the Governor had been apprised of the coming of the Americans, he succeeded in sending away in a small coaster 150 barrels of powder.

It is worth noting that Commodore Hopkins not only loaded his vessels with these stores, but that the stores made a heavy cargo for them, and they were deep in the water when they turned toward home. It should be56 further noted that the Governor of the island “and several of the more prominent inhabitants” were carried away for use as hostages to compel the British authorities to modify the harsh treatment American prisoners were receiving.

Commodore Esek Hopkins.

From a very rare English engraving.

New Providence was taken in the middle of March, 1776. Elated by the success of his expedition, Commodore Hopkins set sail for the north on the 17th of that month. How much more elated he and his crews would have felt could they have known that at four o’clock on that morning the British were hurriedly, and in great confusion, leaving Boston through fear of an assault by the troops of Washington, may be easily imagined.

Two weeks later the American fleet had arrived off the east end of Long Island, where, on April 4th, the tender Hawke, of six guns, and the bomb-brig Bolton, of twelve guns, were captured. And then followed a conflict that well-nigh ruined the reputation of the first American fleet commander. It began soon after midnight on the morning of April 6th.

With a gentle breeze, the fleet, well scattered out—too well, in fact—was washing along over the smooth sea between Block Island and the Rhode Island shore. Only those who have floated and dreamed in the soft light57 of a warm night on these waters can fully appreciate the influences of sea and air over a sailor on such an occasion, but it was, last of all, a night for thoughts of bloodshed. Suddenly a large strange ship appeared in the midst of the fleet. From the way the narrative reads one is forced to the conclusion that the lookouts were all at least half asleep. The stranger was heading for the flagship Alfred, but before she could close in, the crew of the little brig Cabot, Capt. John Burrows Hopkins, woke up, and, ranging alongside, they hailed her.

For a reply the stranger fired a broadside, and so began the first naval battle of the first American squadron.

The brave captain of the Cabot returned the fire, in spite of the great superiority of the stranger, and still bravely stood to his duty, even after a second broadside from the stranger had partly disabled his brig, killed a number of his crew, and wounded himself.

The Alfred, the flagship, soon came ranging up beside the stranger and opened fire, whereat the stranger turned his attention to her; and then came the Providence, Captain Hazard, who secured a position on the lee quarter (they were all close hauled) of the enemy, where she opened an effective fire.

By this time the Cabot was drifting out of58 range, but the Andrea Doria came up to take her place. For an hour thereafter the stranger maintained the unequal contest, while the fleet drifted along over the smooth sea. At one time a shot from the stranger cut away the tiller ropes of the Yankee flagship, leaving her to broach to where she could not use her own guns. At that the stranger raked her fore and aft with a number of broadsides. But when repairs had been made the Alfred closed in once more, and then, at about two o’clock in the morning, the stranger found it too hot, and, putting up his helm, he squared away for Newport and safety.

Commodore Hopkins pursued the stranger until after daylight. The course lay along the Rhode Island coast, and the people of the region, awakened by the roar of the guns, came hurrying to the cliffs to look away over the smooth water, where one ship, badly cut up aloft, was still able to keep ahead of the fleet that followed, and fired at frequent intervals upon the pursued.

But the ships of the American fleet were cargo-carriers deeply loaded with the spoils of New Providence, and the stranger was a man-o’-war well formed and fitted for the sea. So the chase ended when it was found that the stranger steadily gained, and the distance from Newport was growing so short as to warrant59 the belief that the cannonading would call out the British fleet then lying there. So the Yankee fleet “hauled its wind,” captured a small tender that had been in company with the stranger, and then made port at New London.

An English “Seventy-Four” and a Frigate Coming to Anchor.

From an old engraving.

When there Commodore Hopkins learned that the stranger he had encountered was the British sloop-of-war Glasgow, Capt. Tyringham Howe, a full-rigged ship (three masts), carrying twenty guns, and a crew of 150, all told. She had lost one man killed and three wounded, while the American loss had been in all twenty-four killed and wounded, of whom the little brig Cabot lost four killed and seven wounded.

60

Nothing more is needed to show the superiority of the British naval crews over the American, at this time, than the above statement of casualties. How that superiority was overcome at the last will appear later on; but if all British warships in the contests that followed this one had been handled as Captain Howe handled the Glasgow the story of the American navy would not have appealed to patriotic American pride as it now does.