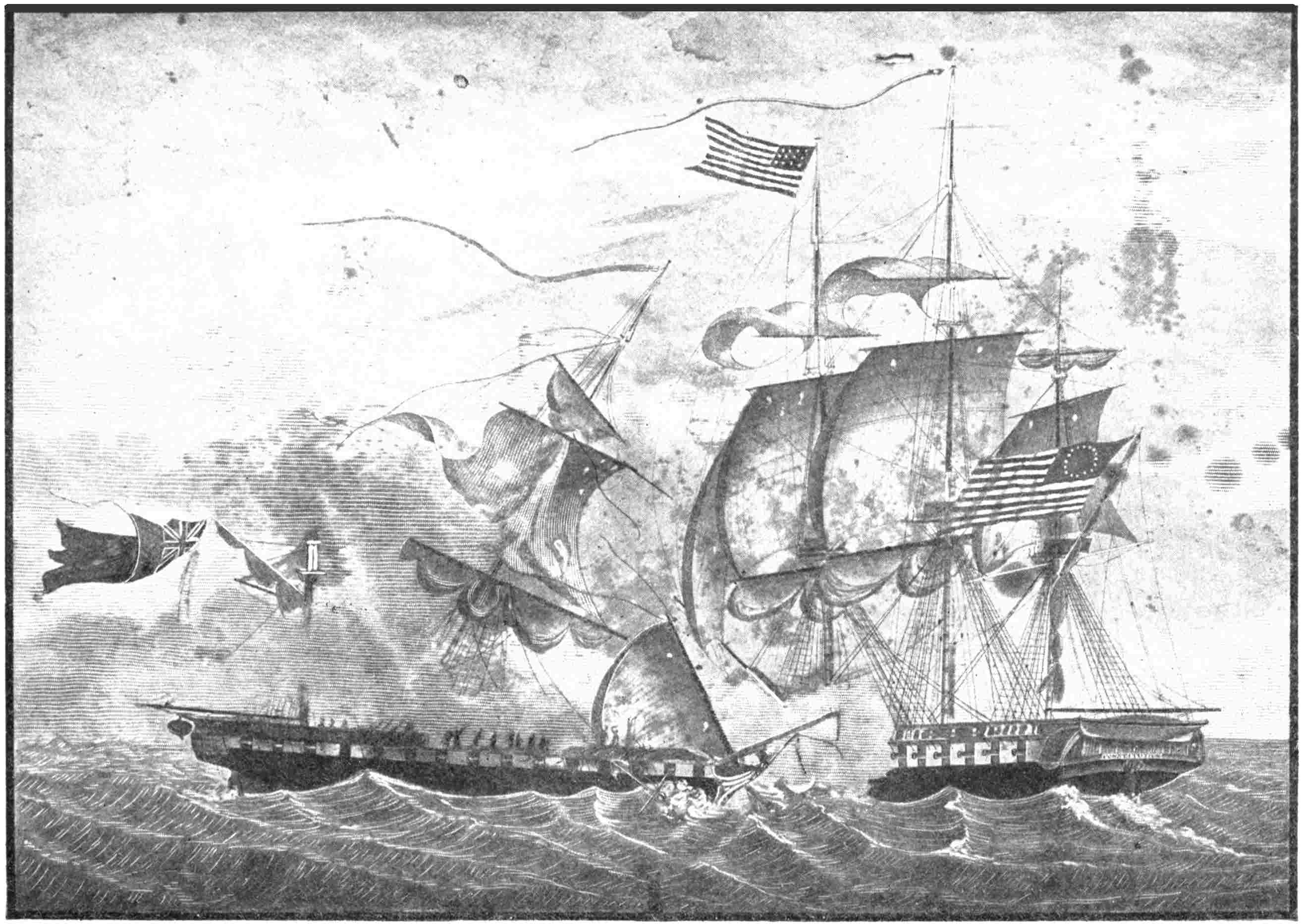

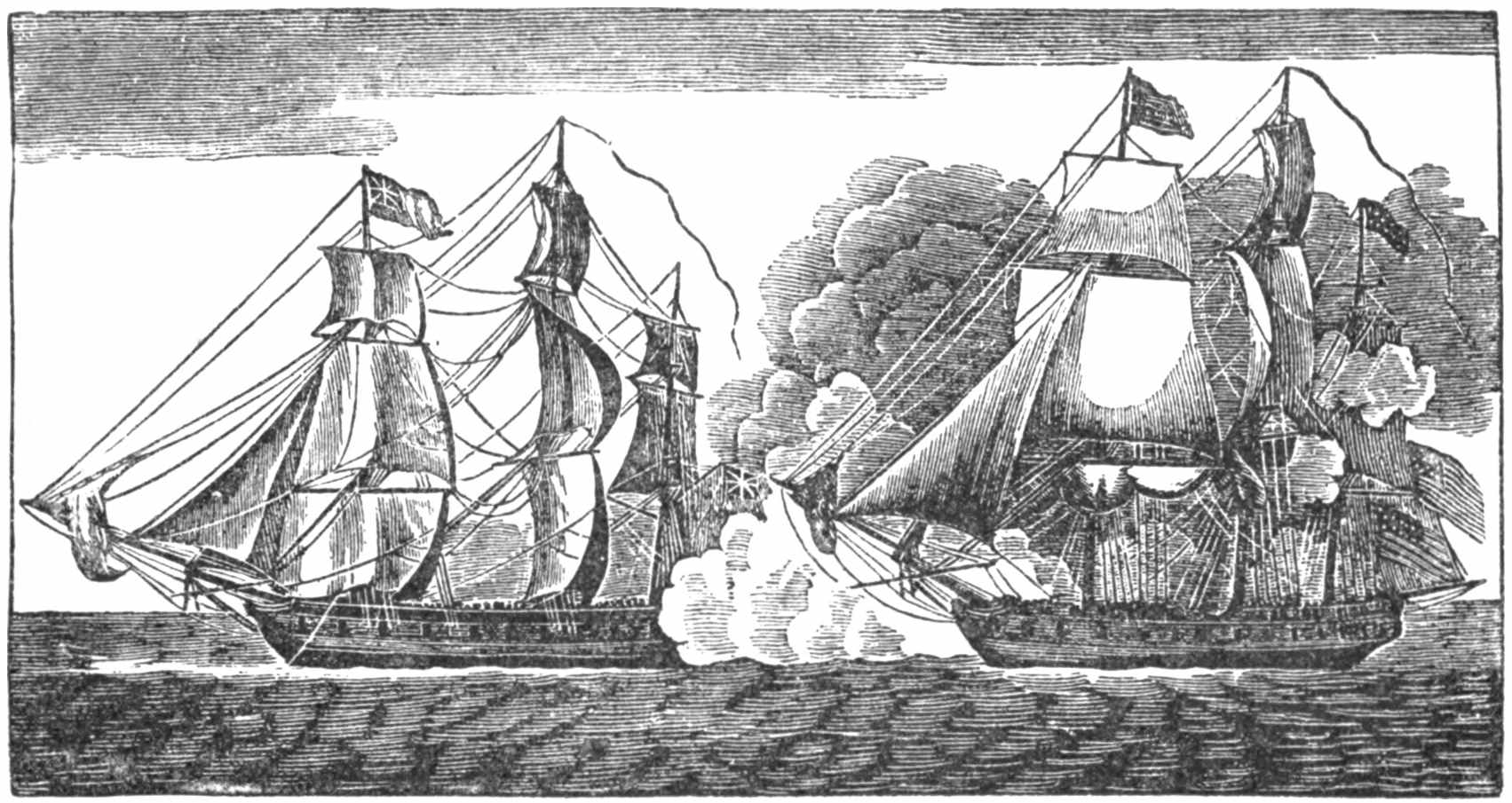

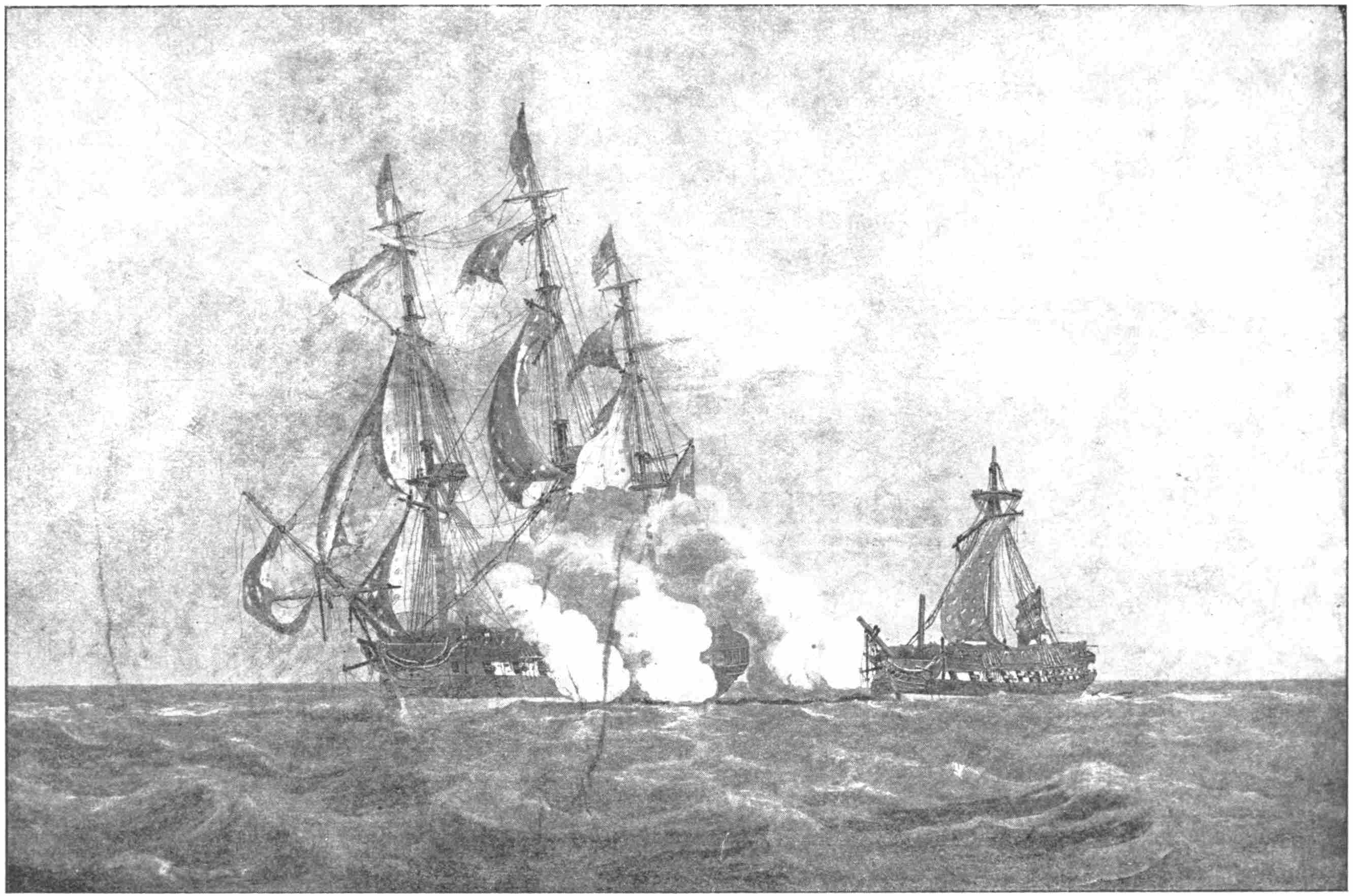

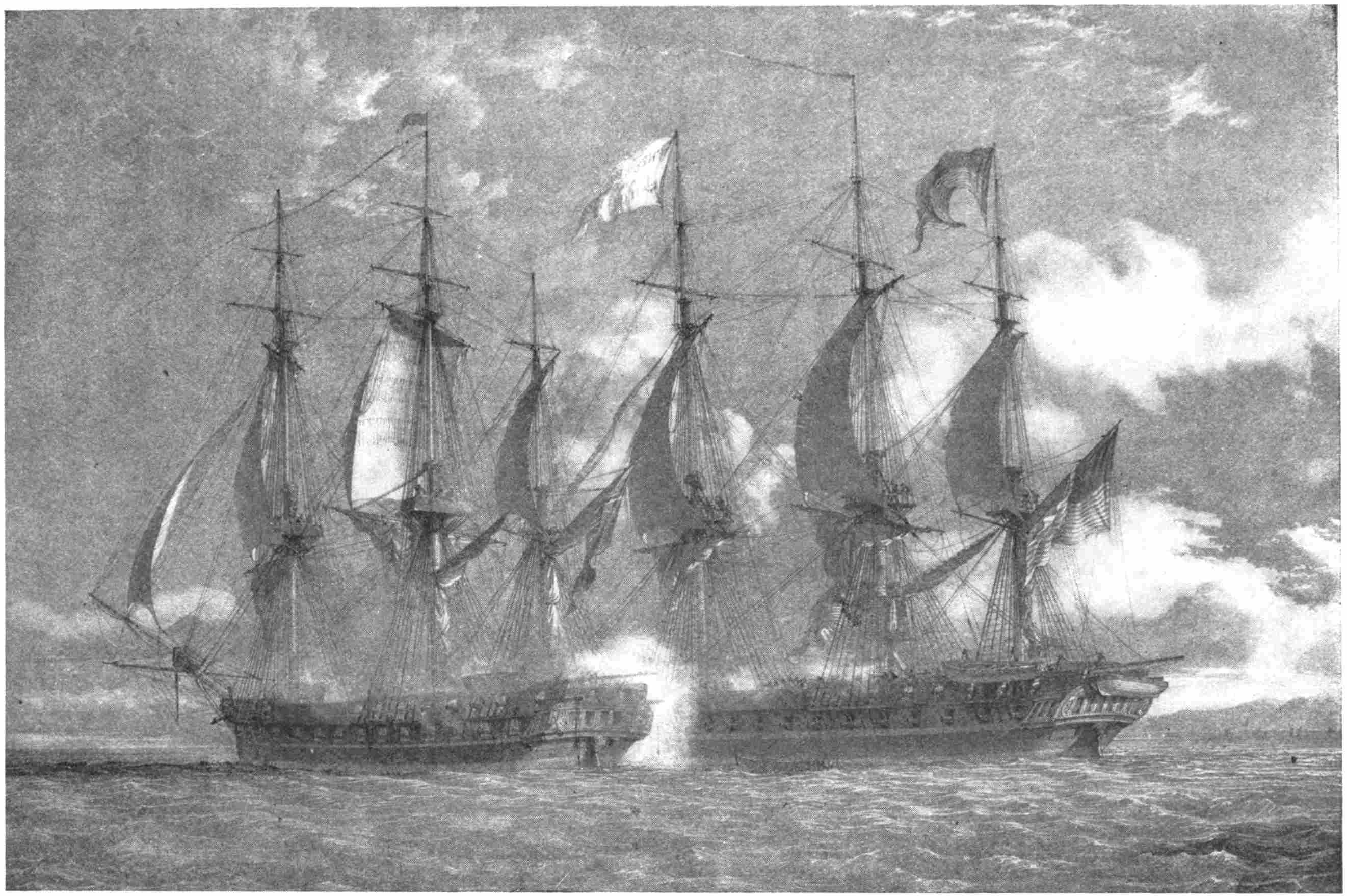

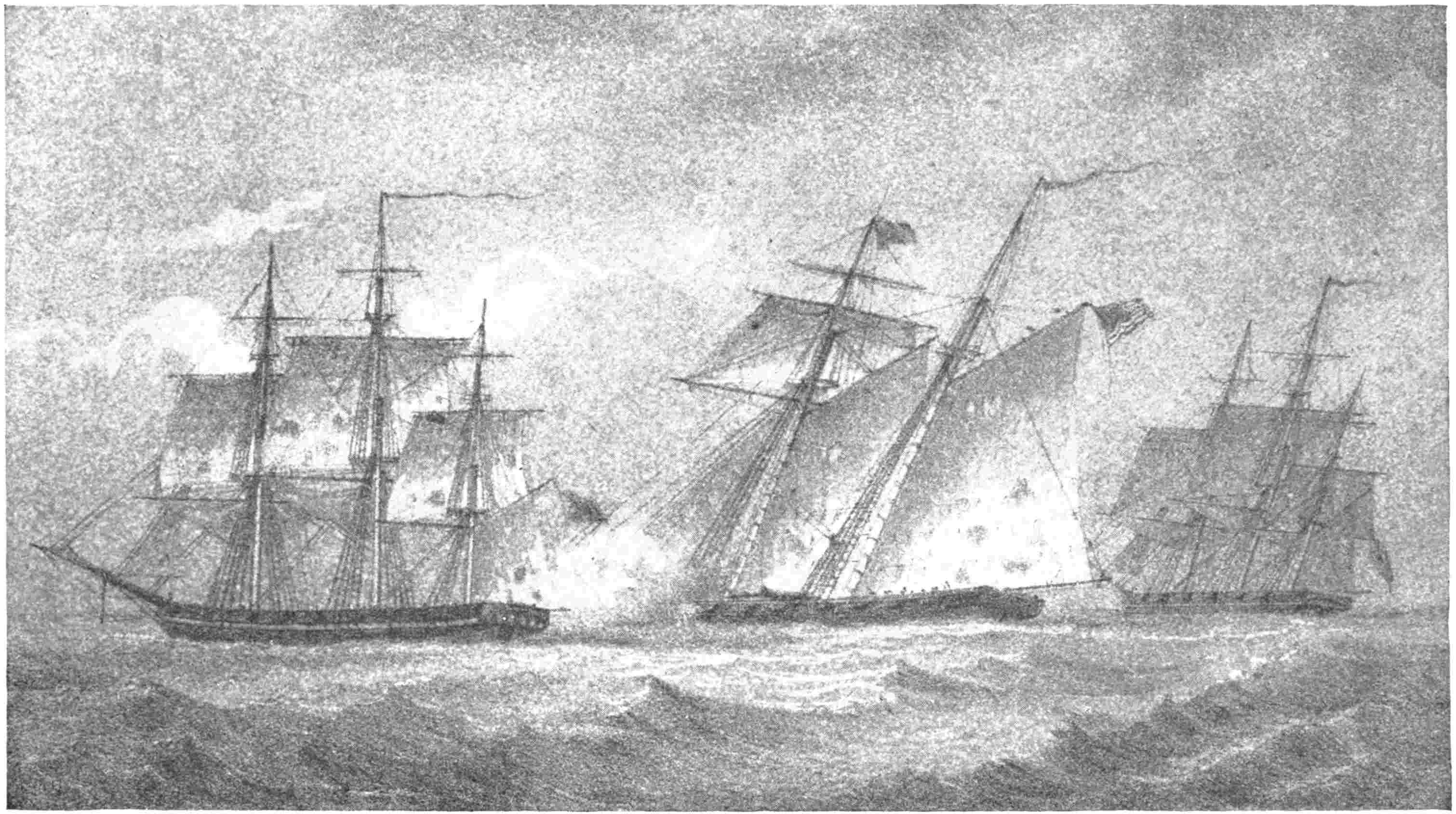

THE CONSTITUTION AND GUERRIÈRE.

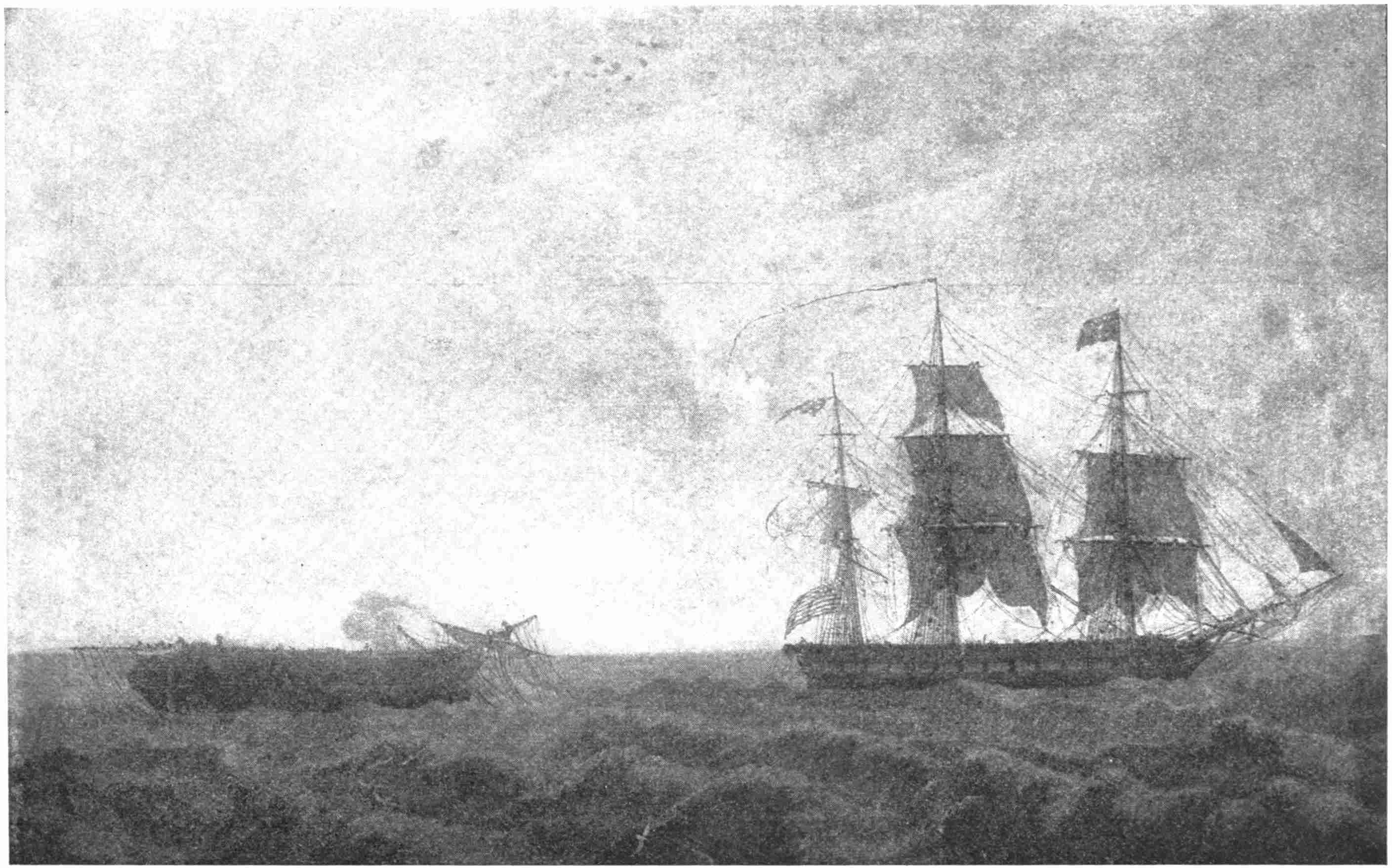

From a French water-color drawing in the possession of Mr. W. C. Crane.

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

THE CONSTITUTION AND GUERRIÈRE.

From a French water-color drawing in the possession of Mr. W. C. Crane.

THE

HISTORY OF OUR NAVY

FROM ITS ORIGIN TO THE PRESENT DAY

1775–1897

BY

JOHN R. SPEARS

AUTHOR OF “THE PORT OF MISSING SHIPS,”

“THE GOLD DIGGINGS

OF CAPE HORN,” ETC.

WITH MORE THAN FOUR HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

IN FOUR VOLUMES

VOLUME II.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

MANHATTAN PRESS

474 W. BROADWAY

NEW YORK

vii

TO ALL WHO WOULD SEEK PEACE

AND PURSUE IT

viii

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. Troubles on the Eve of War. | 1 |

| A Fair Estimate of the Number of Americans Enslaved by the Press-Gangs—A Braggart British Captain’s Work at Sandy Hook—A Search for the Guerrière—Attack on the British Ship Little Belt—A Feature of the Battle that was Overlooked—When the Constitution Showed her Teeth the British Ship Brailed its Spanker and Headed for Safer Waters—An Eager Yankee Sailor who Couldn’t Wait for an Order to Fire—War Unavoidable. | |

| Chapter II. The Outlook Was, at First, not Pleasing | 20 |

| The Silly Cry of “On to Canada!”—The Naval Forces of the United States Compared with Those of Great Britain—The Foresight and Quick Work of Captain Rodgers in Getting a Squadron to Sea—But he Missed the Jamaica Fleet he was After, and when he Fell in with a British Frigate, the Results of the Affair were Lamentable. | |

| Chapter III. The First Exhibit of Yankee Mettle | 33 |

| Captain David Porter’s Ideas about Training Seamen—The Guns of the Essex—Taking a Transport out of a Convoy at Night—A British Frigate Captain who was Called a Coward by his Countrymen—Captain Laugharne’s Mistake—A Fight that began with Cheers and ended in Dismay for which there was Good Cause—Work that was Done by Yankee Gunners in Eight Minutes—When Farragut Saved the Ship—An Attack on a Fifty-gun Ship Planned.x | |

| Chapter IV. A Race for the Life of a Nation | 51 |

| Story of the Constitution’s Escape from a British Squadron off the Jersey Beach—Four Frigates and a Liner were after her—For more than two Days the Brave Old Captain Stood at his Post while the Ship Tacked and Wore and Reached and Ran, and the tireless Sailors Towed and Kedged and Wet the Sails to Catch the Shifting Air—Though once Half-surrounded and once within Range, Old Ironsides Eluded the whole Squadron till a Friendly Squall Came to Wrap her in its Black Folds and Carry her far from Danger. | |

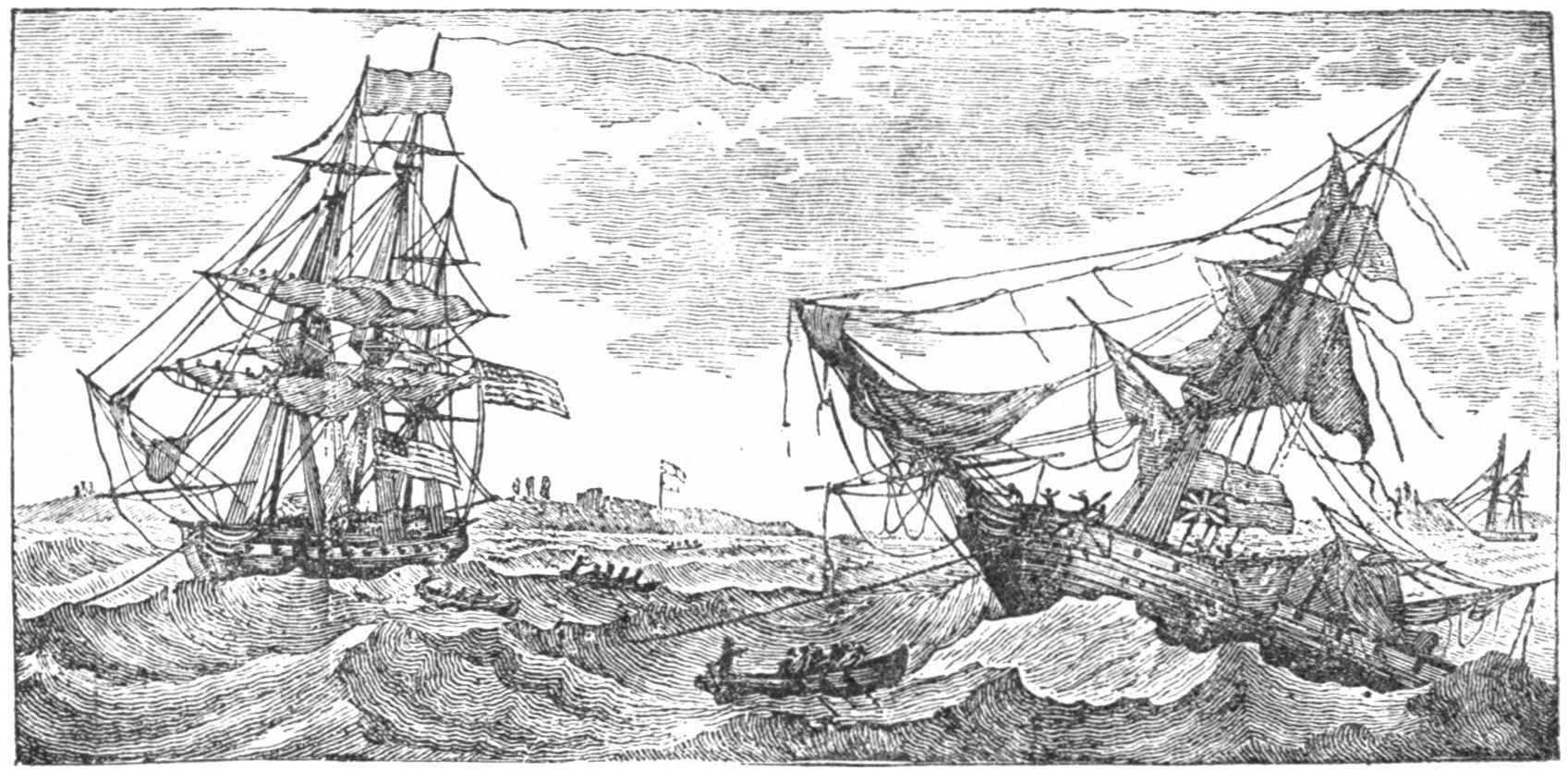

| Chapter V. The Constitution and the Guerrière | 71 |

| The British Captain could scarcely Believe that a Yankee would be Bold Enough to Attack him, and was Sure of Victory in Less than an Hour, but when the Yankees had been Firing at the Guerrière for Thirty Minutes she was a Dismantled Hulk, Rapidly Sinking out of Sight—“The Sea never Rolled over a Vessel whose Fate so Startled the World”—Sundry Admissions her Loss Extorted from the Enemy—A Comparison of the Ships. | |

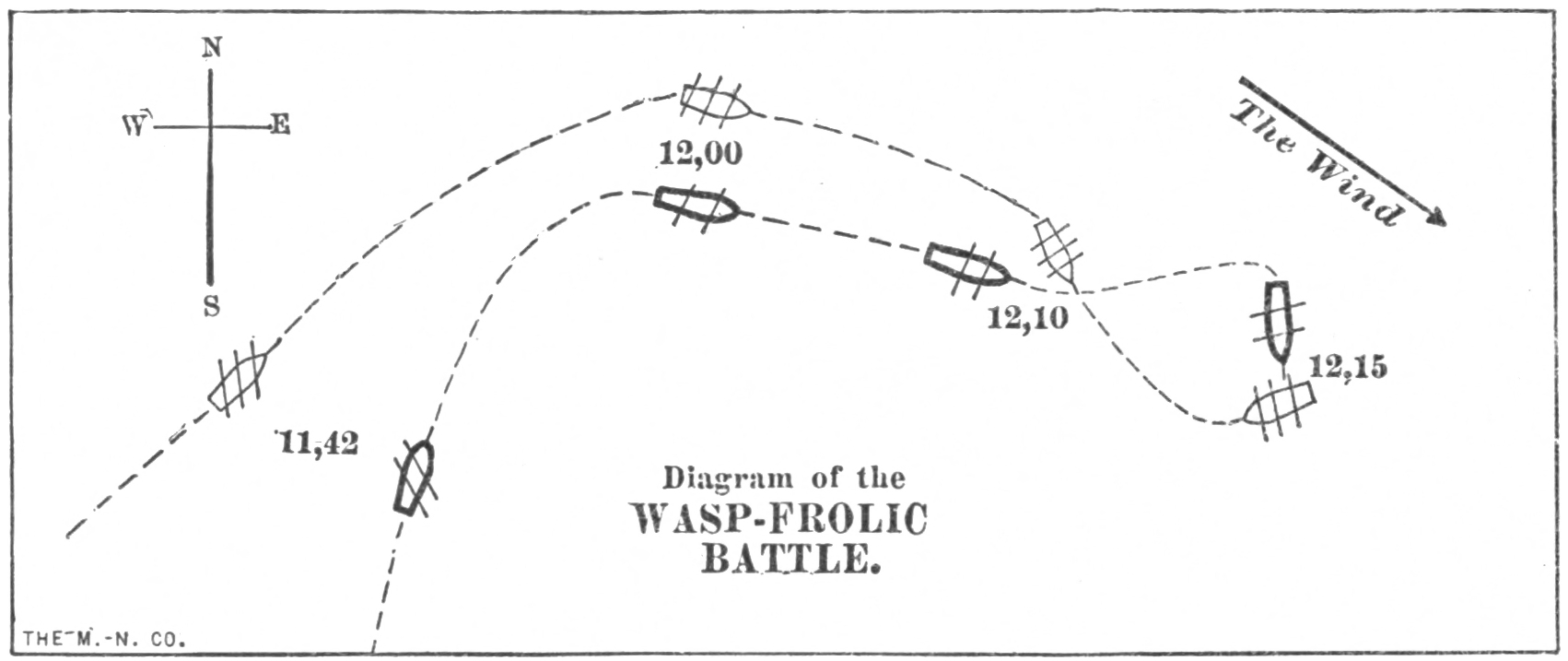

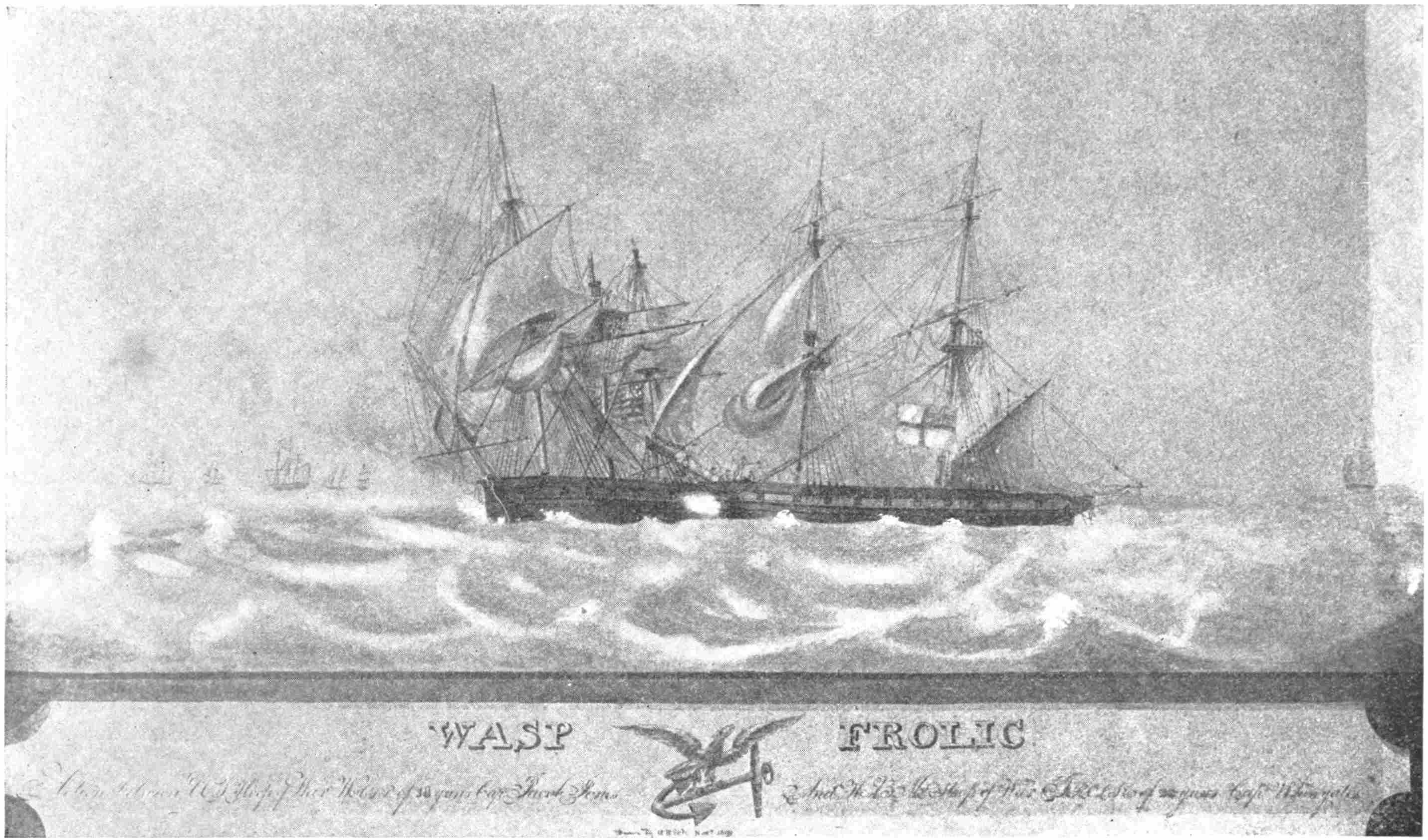

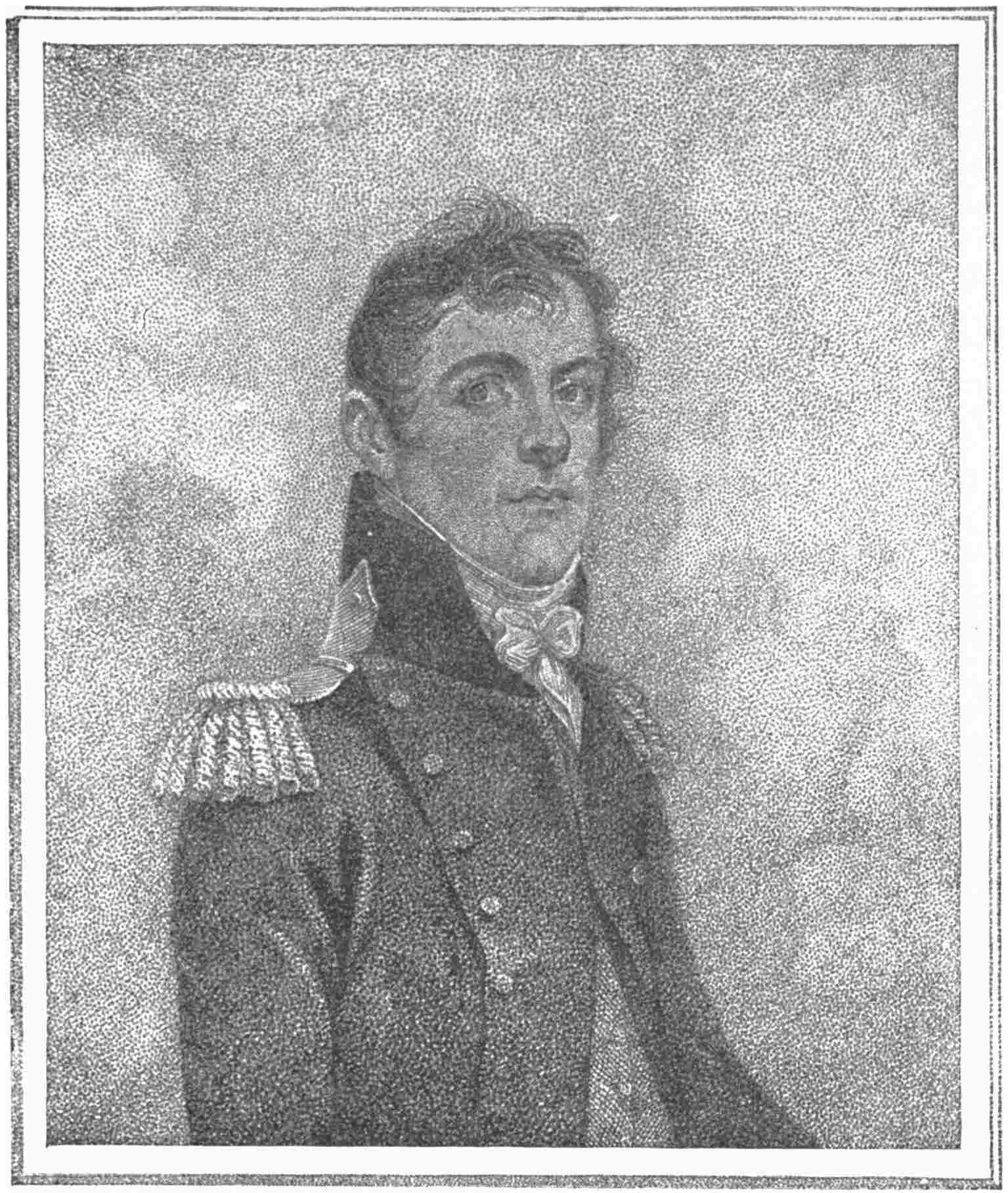

| Chapter VI. Fought in a Hatteras Gale | 104 |

| When the Second Yankee Wasp Fell in with the British Frolic—They Tumbled about in the Cross Sea in a Way that Destroyed the British “Aim,” but the Yankees Watched the Roll of their Ship, and when they were Done they had Killed and Wounded Nine-tenths of the Enemy’s Crew and Wrecked his Vessel—the Frolic was a Larger Ship, carried more Guns, and had all the Men she could Use, “Fine, Able-bodied Seamen,” sure enough! | |

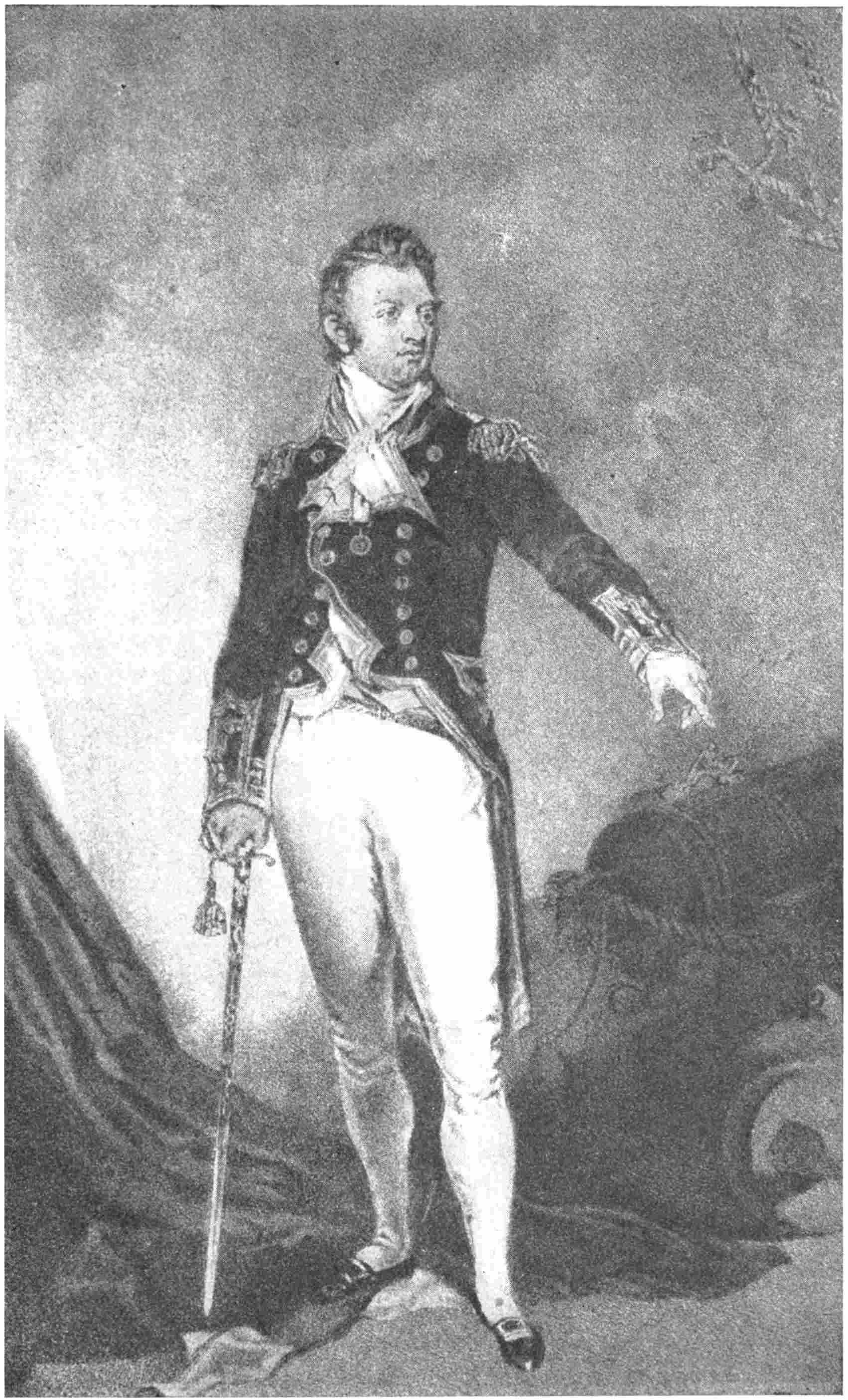

| Chapter VII. Brought the Macedonian into Port | 120 |

| Story of the Second Frigate Duel of the War of 1812—The Macedonian was a new Ship, and had been Built with a full Knowledge of the Yankee Frigates—Whipped, but not Destroyed—Estimating a Crew’s Skill by the Number of Shots that Hit—Suppose the Armaments of the Ships had been Reversed—Impressed Americans Killedxi when Forced to Fight against their own Flag—“The Noblest Sight in Natur’”—A First-rate Frigate, as a Prize, Brought Home by Brave Decatur—Enthusiastic Celebrations of the Victory throughout the United States. | |

| Chapter VIII. When the Constitution Sank the Java | 152 |

| The British had Plenty of Pluck, and Lambert was a skilful Seaman; but his Gunners had not Learned to Shoot, while the Yankees were able Marksmen—The Java was Ruined beyond Repair—Proof that the British Published Garbled Reports of Battles with the Americans—Though Twice Wounded, Bainbridge Remained on Deck—Wide Difference in Losses—Story of a Midshipman—When Bainbridge was a Merchant Captain. | |

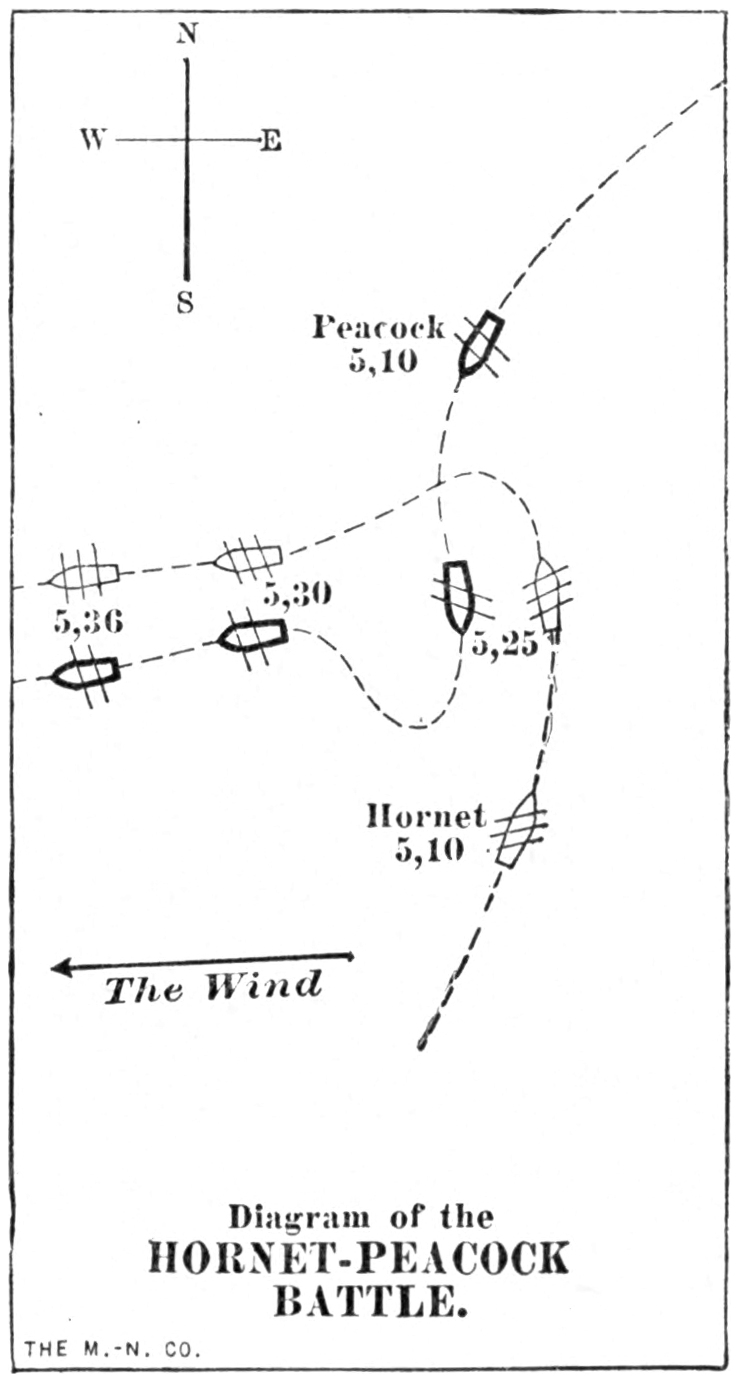

| Chapter IX. Whipped in Fourteen Minutes | 178 |

| The Remarkable Battle between the Yankee Hornet and the British Peacock—The British Ship was so Pretty she was Known as “The Yacht,” but her Gunners could not Hit the Broadside of the Hornet when the Ships were in Contact—As her Flag came Down a Signal of Distress went Up, for she was Sinking—The Efforts of two Crews could not Save her—“A Vessel Moored for the Purpose of Experiment could not have been sunk Sooner”—Infamous Treatment of American Seamen Repaid by the Golden Rule—Captain Greene, of the Bonne Citoyenne, did not dare Meet the Hornet. | |

| Chapter X. Loss of Lawrence and the Chesapeake | 193 |

| The Yankees had Won so Often that they were Underestimating the Enemy and were Over-confident in Themselves—A Mixed Crew, Newly Shipped, Untrained and Mutinous, Ten Per Cent. of them being British—The Result was Natural and Inevitable—Chivalry a Plenty; Common-sense Wanting—The “Shannons” were Trained like Yankees—A Fierce Conflict—Significance of the Joy of the British over the Shannon’s Victory. | |

| Chapter XI. The Privateers of 1812 | 233 |

| Property Afloat as a Pledge of Peace—Foreign Aggression had Taught the Americans how to Build and Sail swift Cruisers—Oddxii Names—The First Prizes—Commodore Joshua Barney and the Rossie—A Famous Cruise—Some Rich Prizes were Captured, but only a Few of the Privateers made Money—Beat off a War-ship that Threw Six Times her Weight of Metal—A Battle in Sight of La Guayra. | |

| Chapter XII. Early Work on the Great Lakes | 259 |

| It was a beautiful Region unmarred by the Hand of Man in those Days—The Long Trail to Oswego—The First Yankee War-ship on Fresh Water—The British Get Ahead of us on Lake Ontario—Good Work of “The Old Sow” at Sackett’s Harbor—A Dash into Kingston Harbor—The Story of the Brilliant Work by which Jesse D. Elliott Won a Sword and the Admiration of the Nation. | |

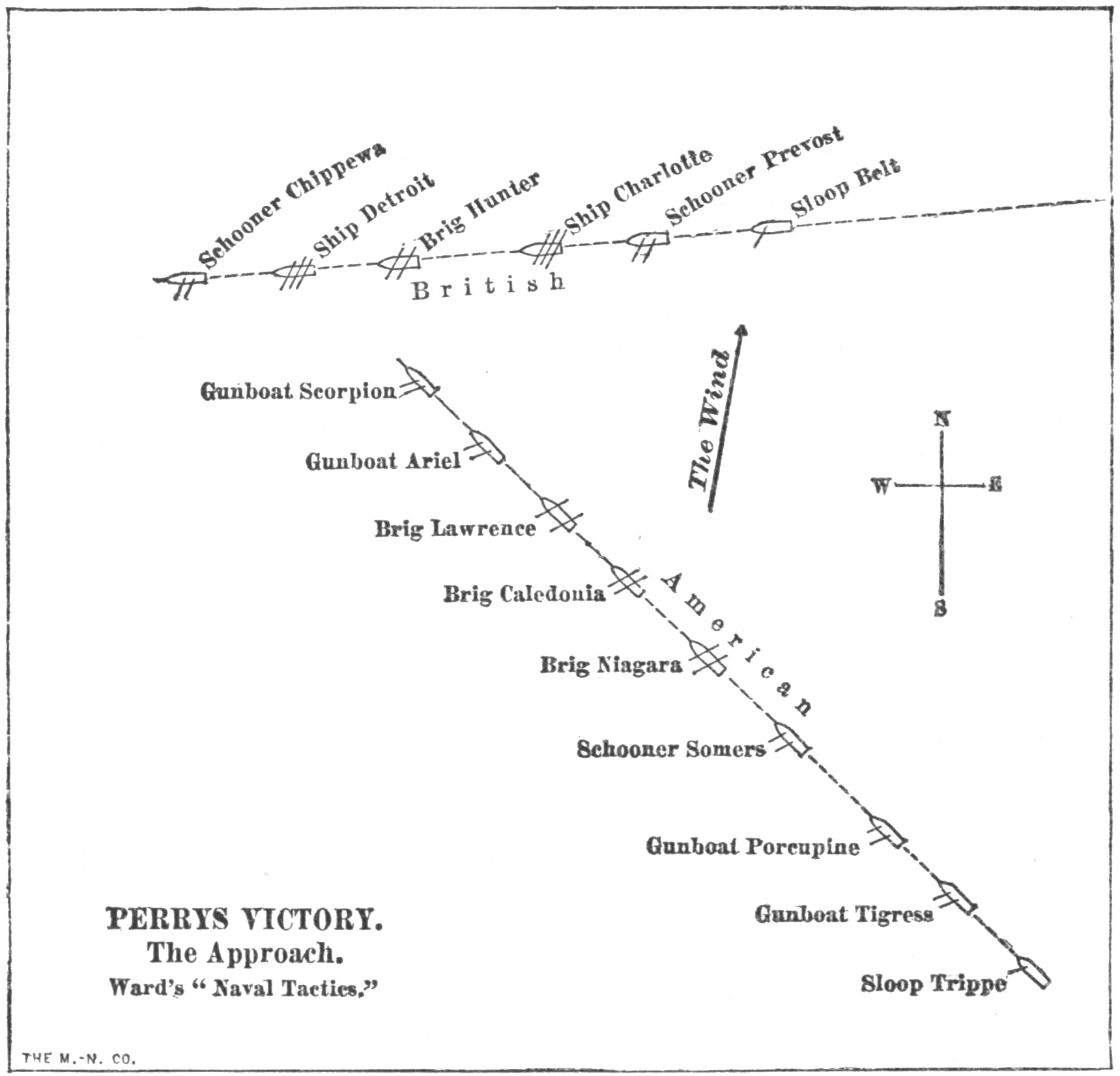

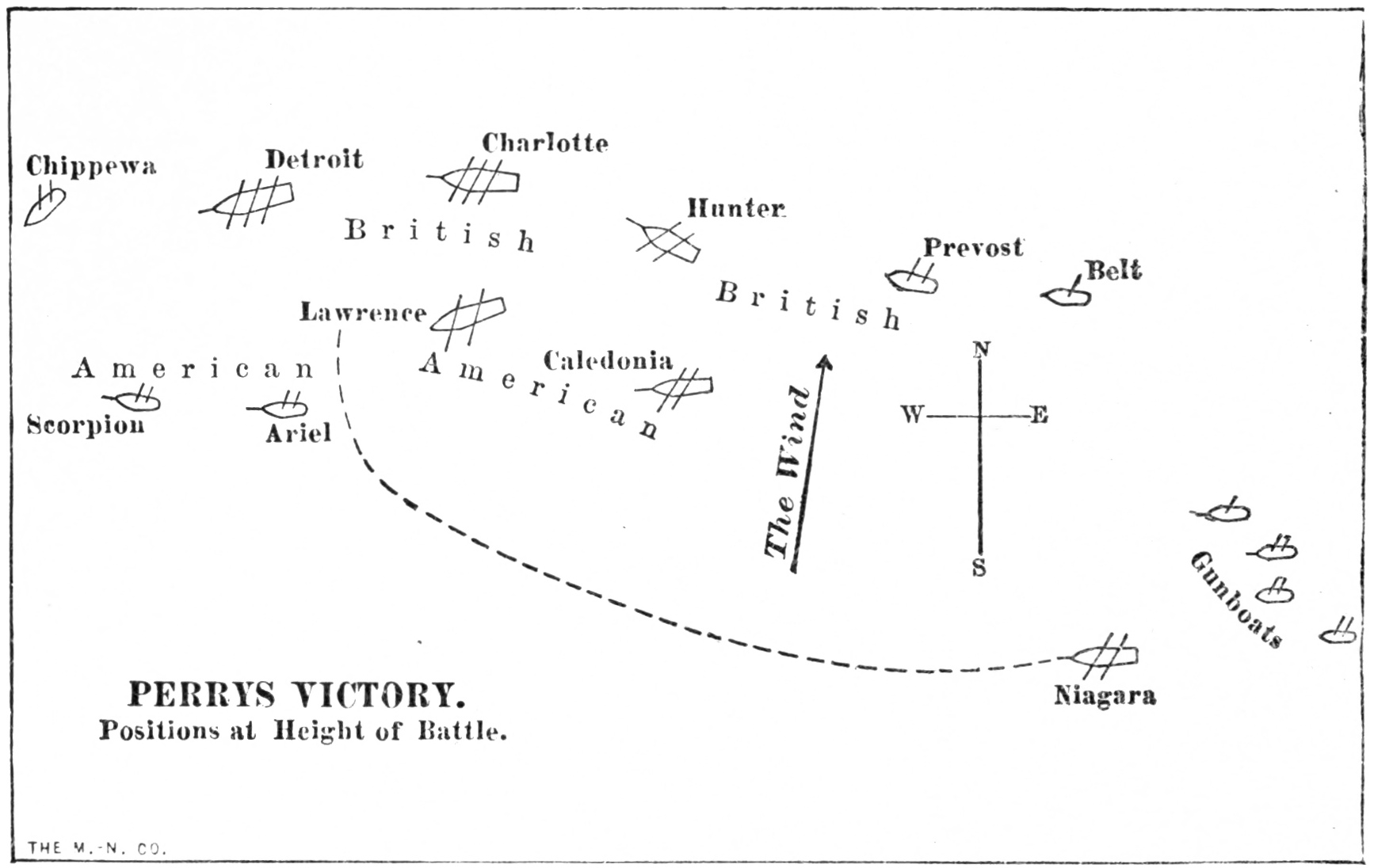

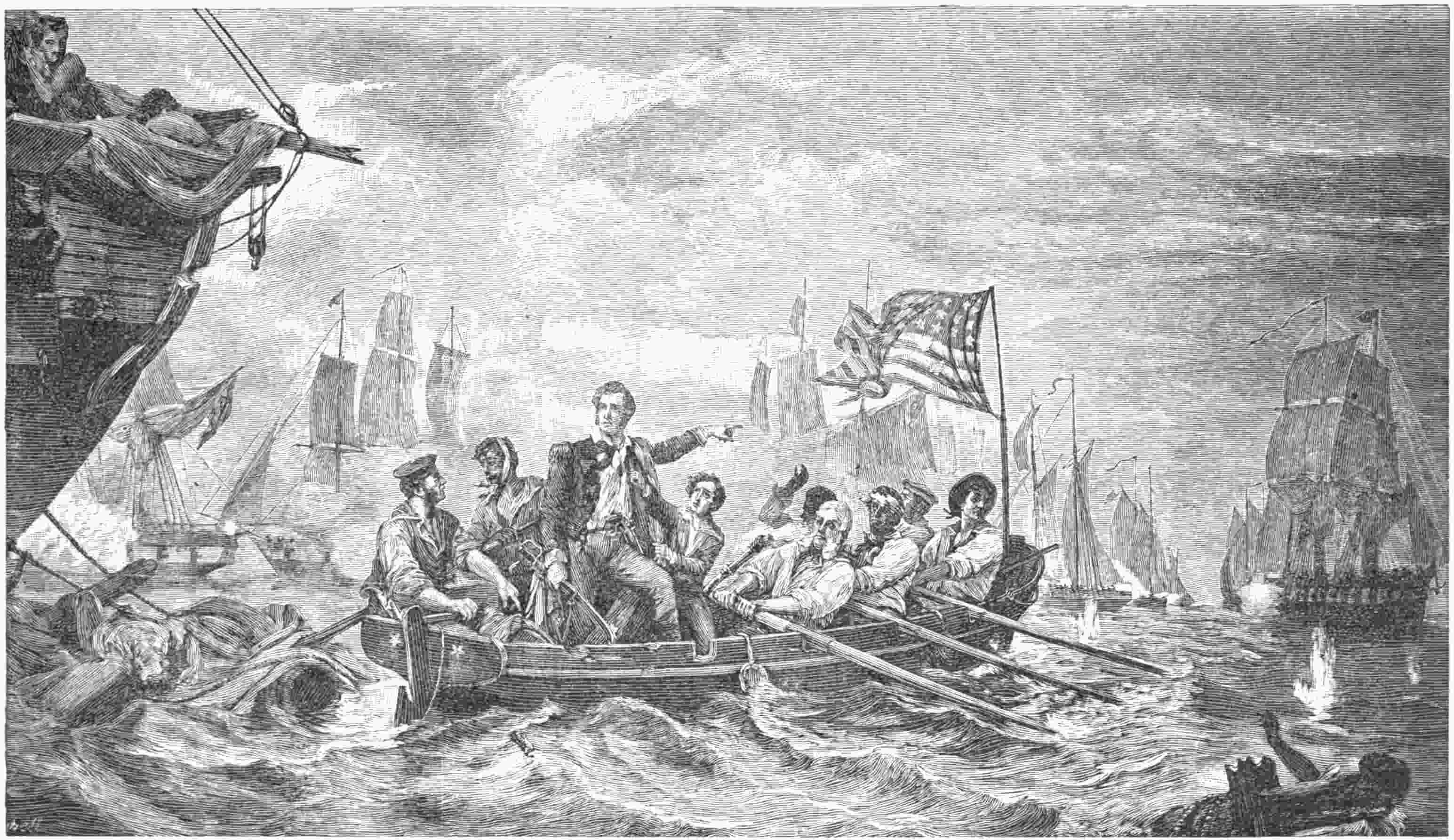

| Chapter XIII. The Battle on Lake Erie | 280 |

| Building War-ships and Gun-boats in the Wilderness—Lifting the Vessels over a Sand-bar—Fortunately the British Commander was Fond of Public Entertainments—The two Squadrons and their Crews Compared—The Advantage of a Concentrated Force was with the British—On the Way to Meet the Enemy—“To Windward or to Leeward they shall Fight To-day”—The Anglo-Saxon Cheer—The Brunt of the Fight Borne by the Flag-ship—A Frightful Slaughter there in Consequence—When Perry Worked the Guns with his own Hands, and even the Wounded Crawled up the Hatch to Lend a Hand at the Side-tackles—An Able First Lieutenant—Wounded Exposed to the Fire when under the Surgeon’s Care—The Last Gun Disabled—Shifting the Flag to the Niagara—Cheers that were Heard above the Roar of Cannon—When the Wounded of the Lawrence cried “Sink the Ship!”—Driving the Niagara through the British Squadron—The White Handkerchief Fluttering from a Boarding-pike—“We have Met the Enemy, and they are Ours.” | |

| Chapter XIV. Incidents of the Battle on Lake Erie | 326 |

| Two of the Enemy’s Vessels that Tried to get Away—A Yankee Sailor’s Reason for Wanting one more Shot—When Perry Returned to the Lawrence—The Dead and Wounded—Effect of the Victory onxiii the People—Honors to the Victors—The Case of Lieutenant Elliott—Ultimate Fate of some of the Ships. | |

| Chapter XV. the War on Lake Ontario | 339 |

| The Capture of York (Toronto) by the Americans—A Victory at the Mouth of the Niagara River—British Account of the Attack on Sackett’s Harbor—Tales of the Prudence of Sir James Yeo and Commodore Chauncey—The Americans did somewhat Better than the British, but Missed a great Opportunity—Small Affairs on Lake Champlain during the Summer of 1813. | |

| Chapter XVI. Loss of the Little Sloop Argus | 356 |

| She was Captured by the Pelican, a Vessel that was of slightly superior Force—A Clean Victory for the British, but one that in no Way Disheartens the Fiercest of the American Patriots—Ill-luck of “the Waggon.” | |

| Chapter XVII. the Luck of a Yankee Cruiser | 372 |

| There was never a more fortunate Vessel than the Clipper-schooner Enterprise—As originally Designed she was the Swiftest and Best All-around Naval Ship of her Class Afloat—Men she made Famous in the West Indies—A Glorious Career in the War with the Mediterranean Pirates—Even when the Wisdom of the Navy Department Changed her to a Brig and Overloaded her with Guns so that she “Couldn’t Get Out of her own Way,” her Luck did not Fail her—Her Fight with the Boxer—Even a good Frigate could not Catch her. | |

| Chapter XVIII. Gun-boats not Wholly Worthless | 388 |

| Even in the worst View of them they are Worth Consideration—The Best of them Described—The Hopes of those who, like Jefferson, Believed in them—Reasons for their General Worthlessness that should have been Manifest before they were Built—Promoted Drunkenness and Debauchery—They Protected Yankee Commerce inxiv Long Island Sound—A Fight with a Squadron in Chesapeake Bay—When the Braggart Captain Pechell Met the Yankees—Sailing-master Sheed’s Brave Defence of “No. 121”—Commodore Barney in the Patuxent River—When Sailing-master Travis of the Surveyor made a good Fight—A Wounded Yankee Midshipman Murdered—Men who made Fame in Shoal Water below Charleston. | |

xv

| PAGE | |

| The Constitution and Guerrière. (From a French water-color drawing in the possession of Mr. W. C. Crane), Frontispiece. | |

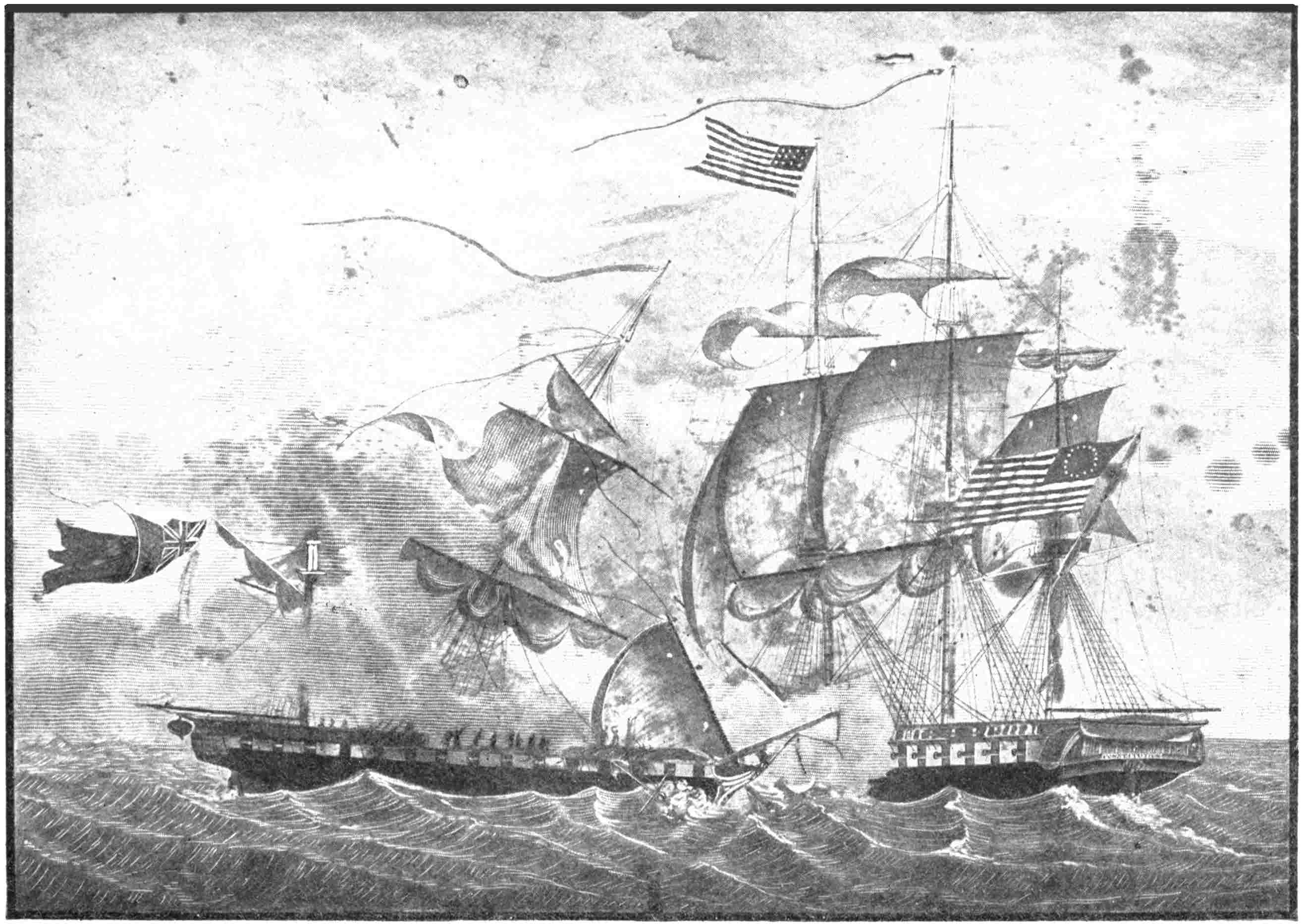

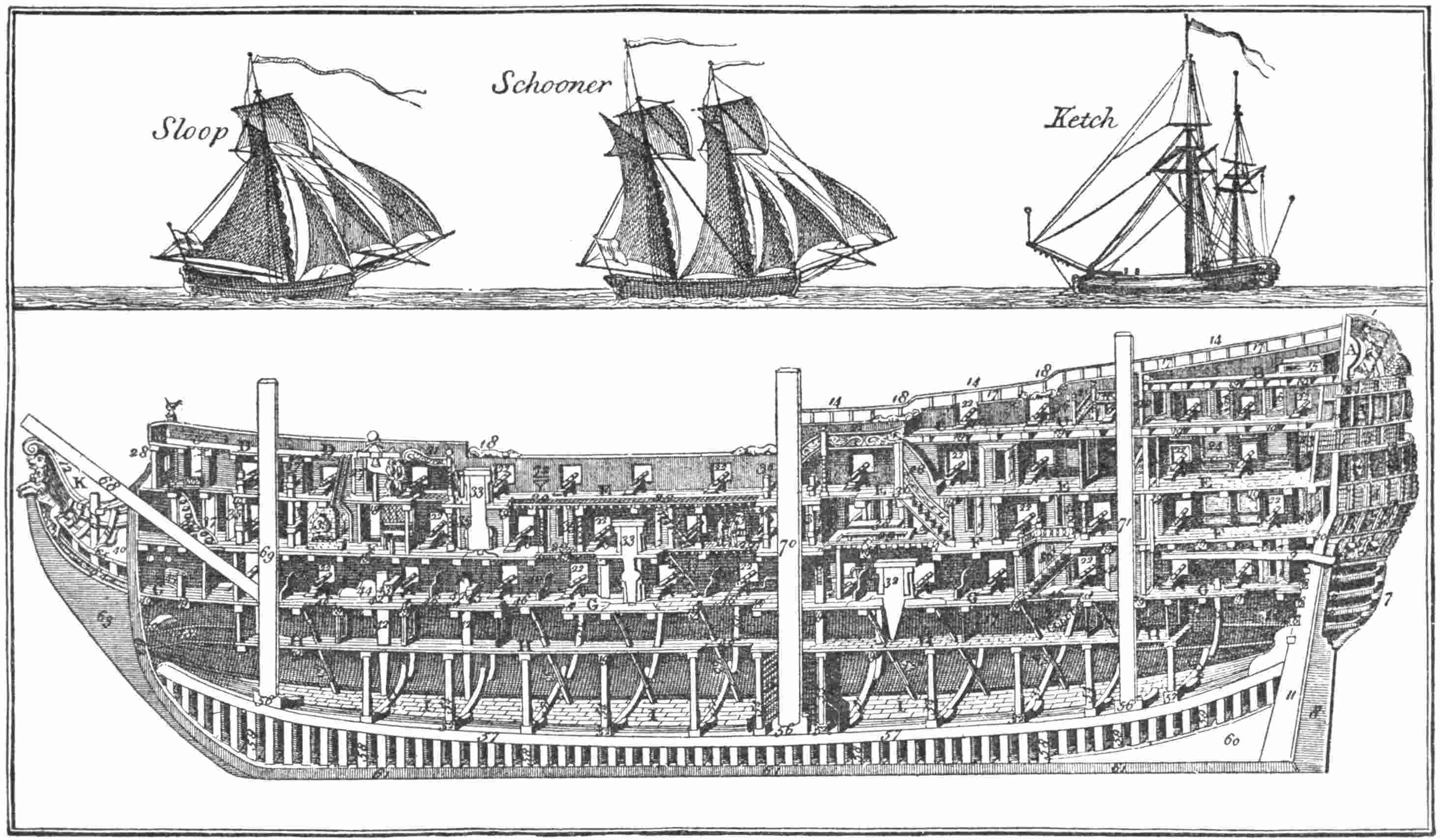

| English Vessel of One Hundred Guns. (From an engraving by Verico), | 3 |

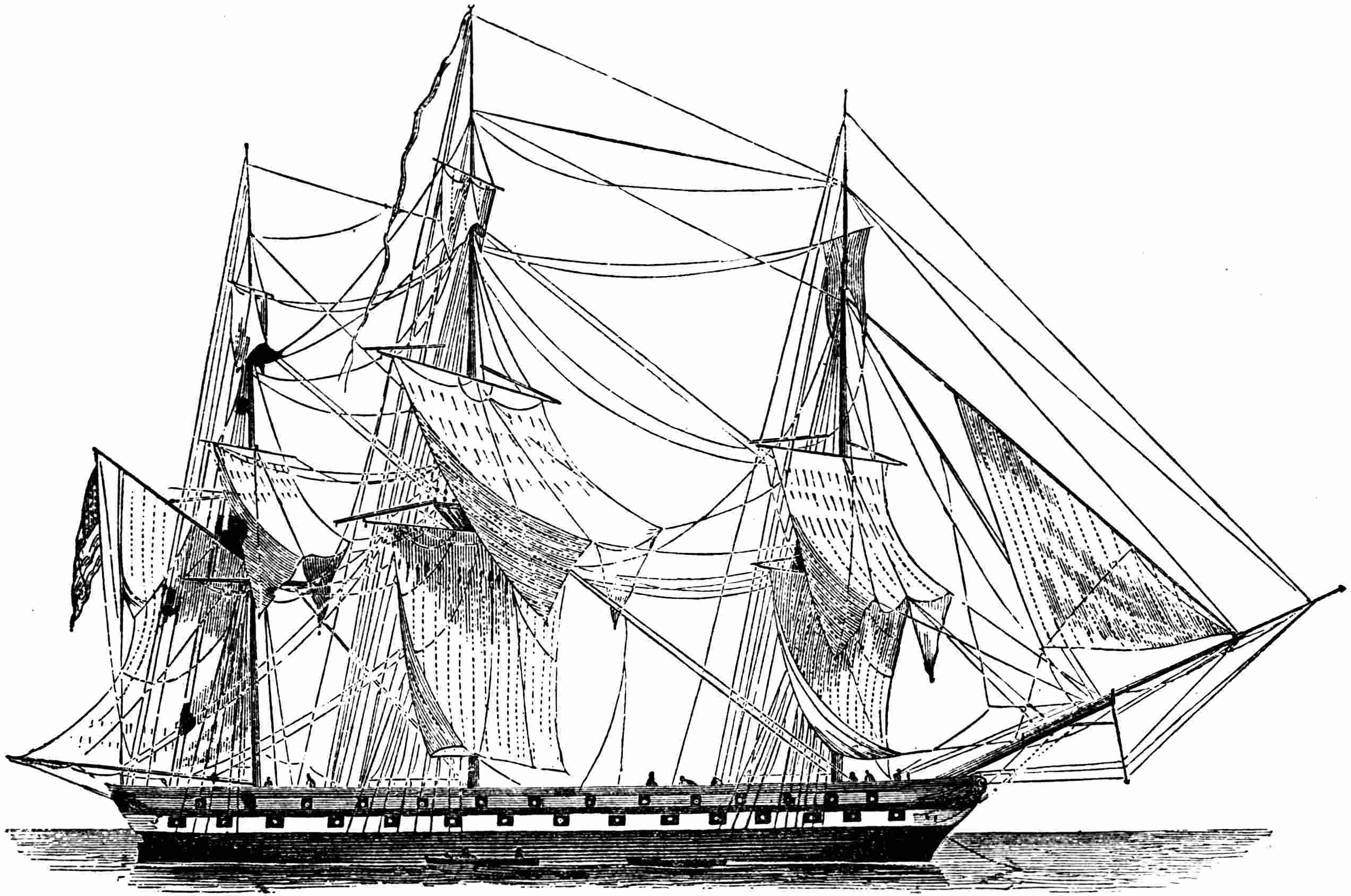

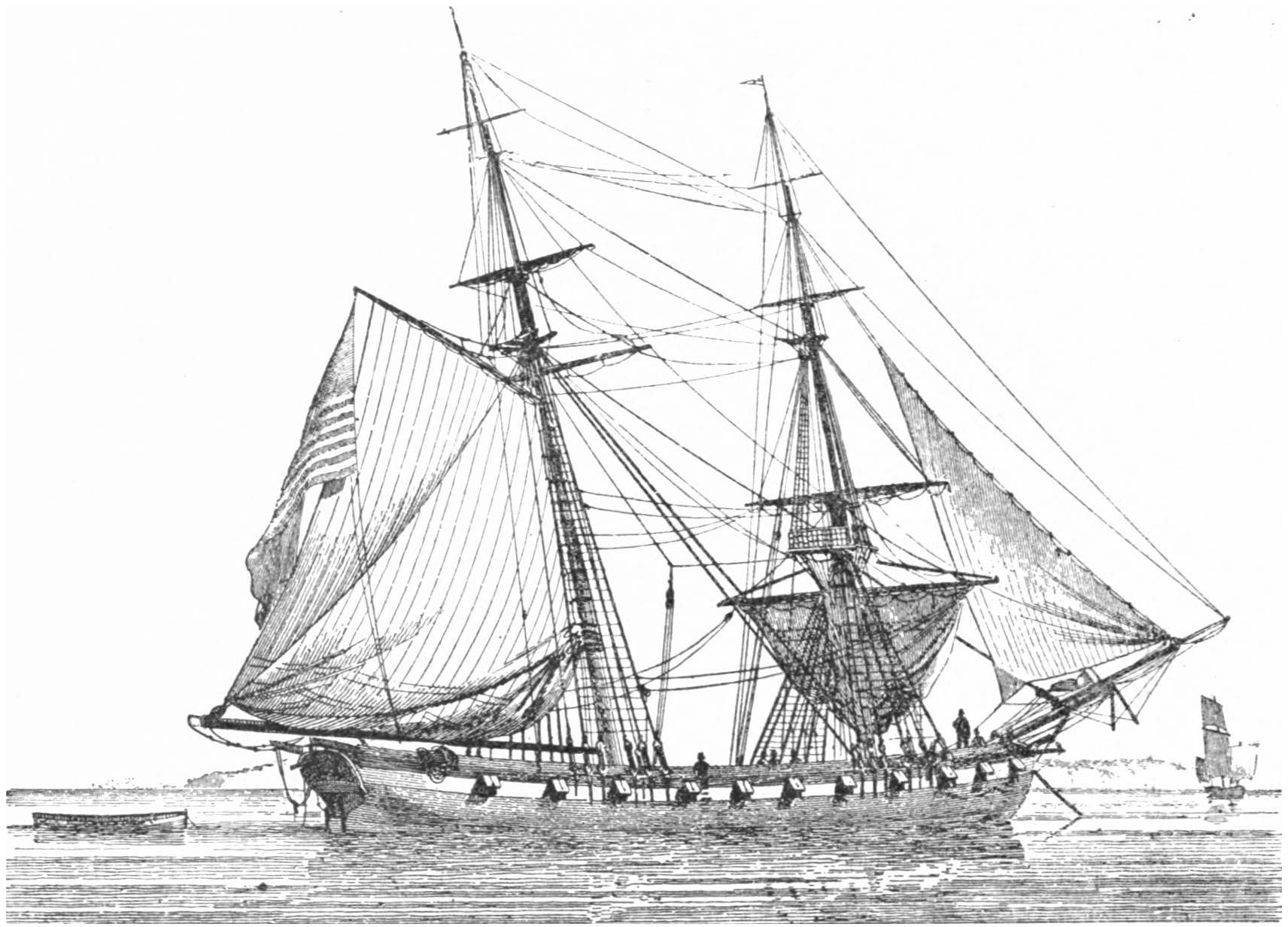

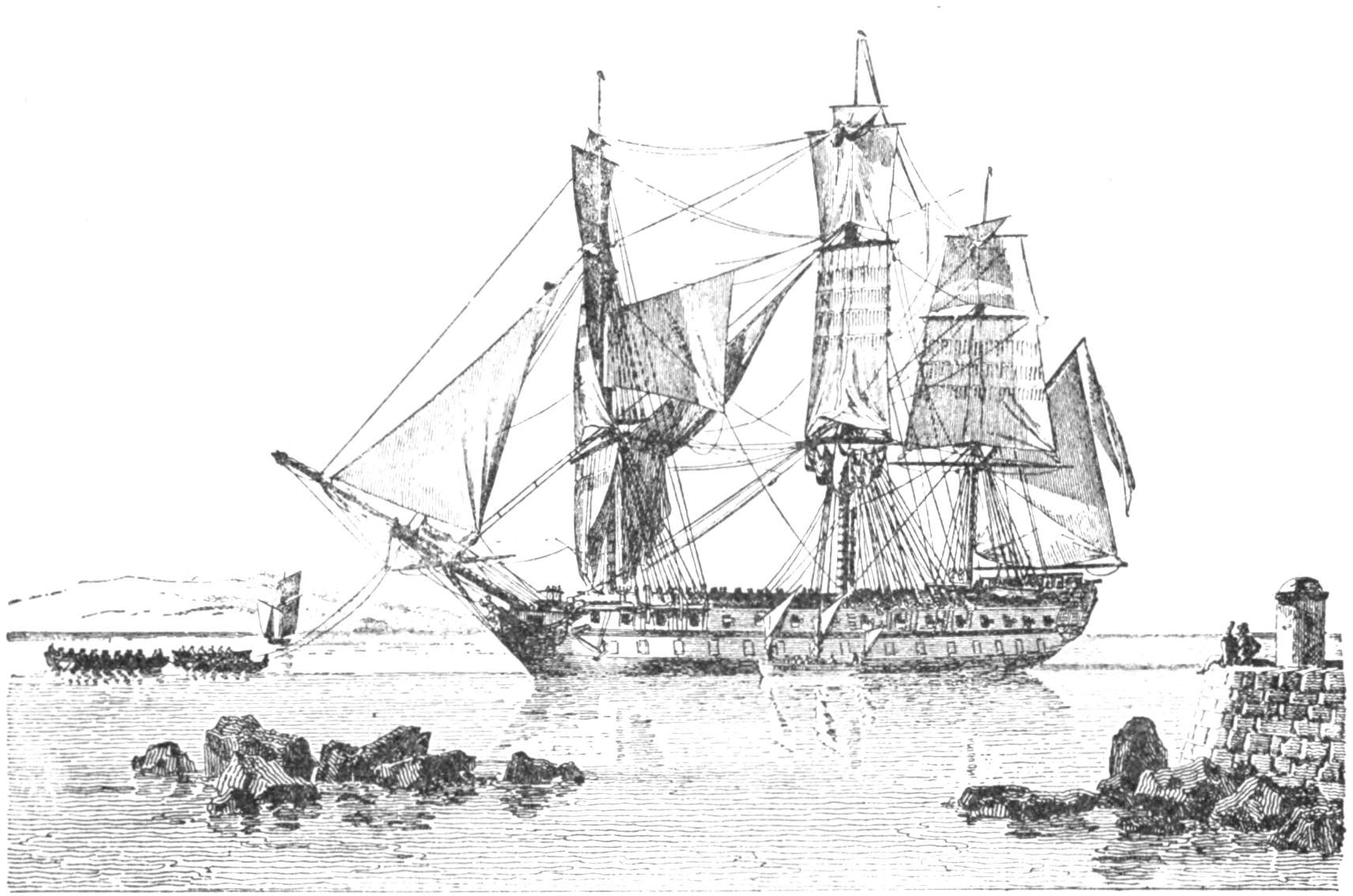

| A Frigate with her Sails Loose to Dry. (From a wood-cut in the “Kedge Anchor”), | 5 |

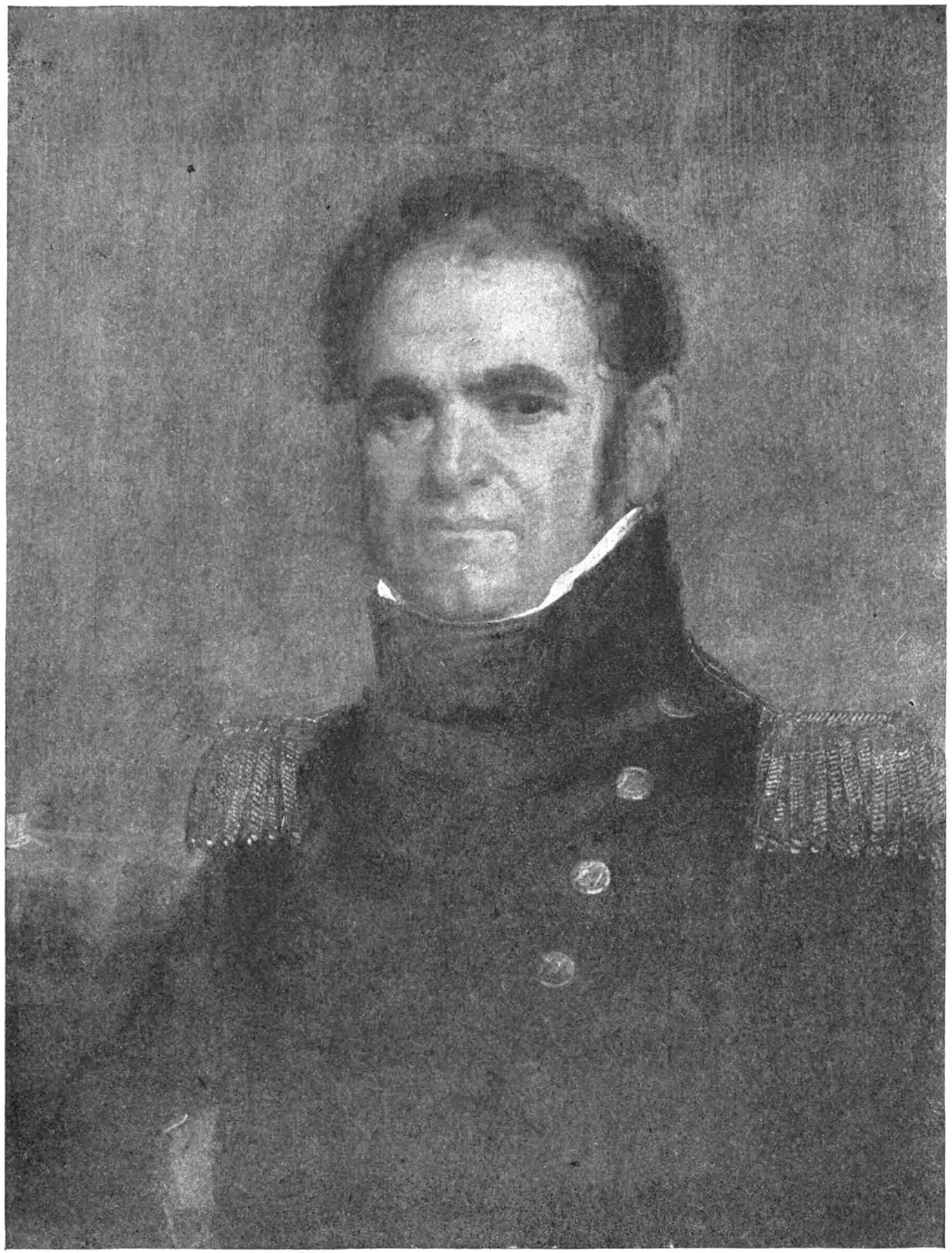

| John Rodgers. (From the portrait by Jarvis at the Naval Academy), | 9 |

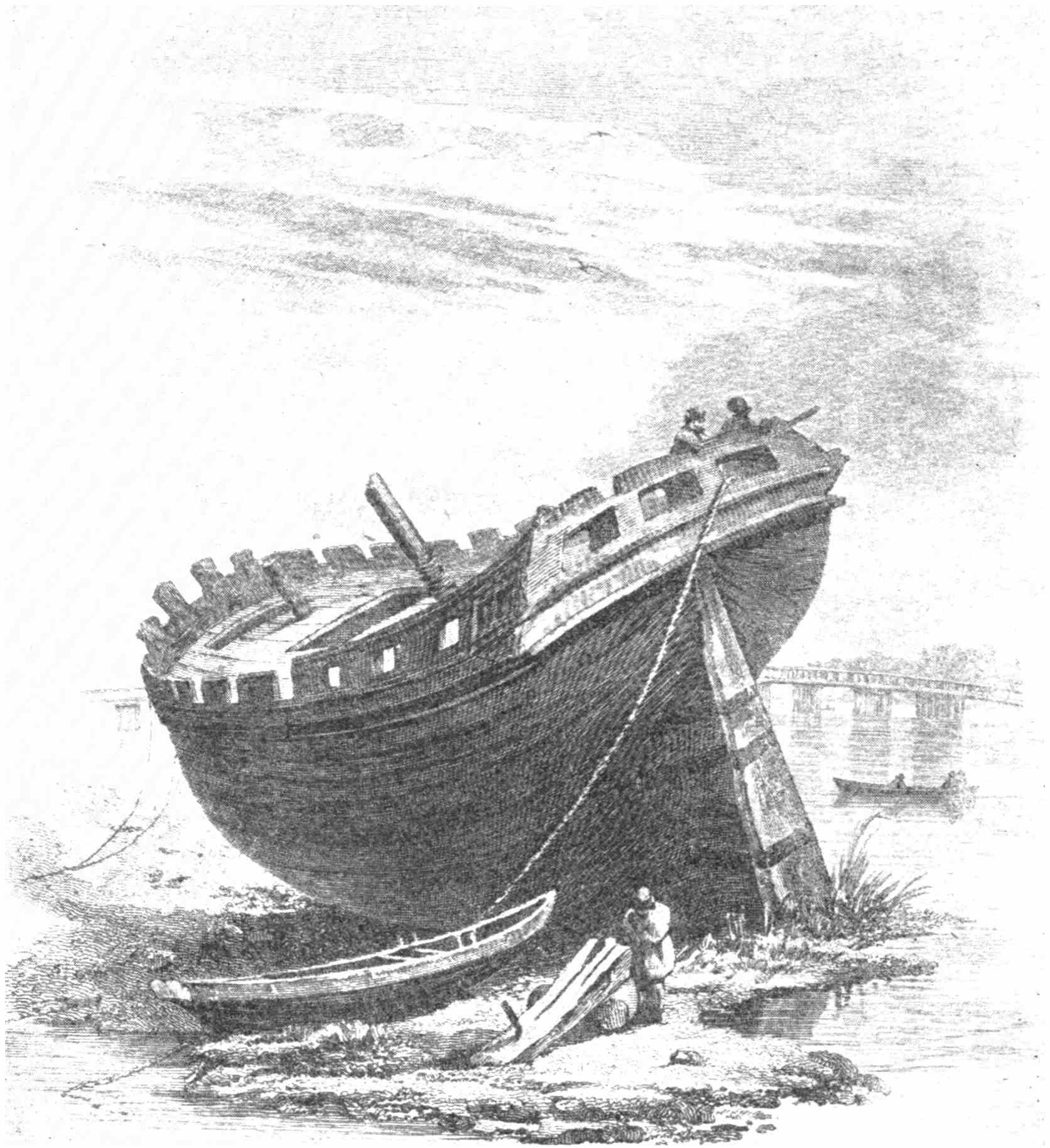

| The Little Belt Breaking up at Battersea. (From an engraving by Cooke of a drawing by Francia), | 12 |

| The Section of a First-rate Ship. (From an old engraving), | 17 |

| A Brigantine of a Hundred Years Ago at Anchor. (From a picture drawn and engraved by Baugean), | 22 |

| An English Admiral of 1809. (From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington), | 24 |

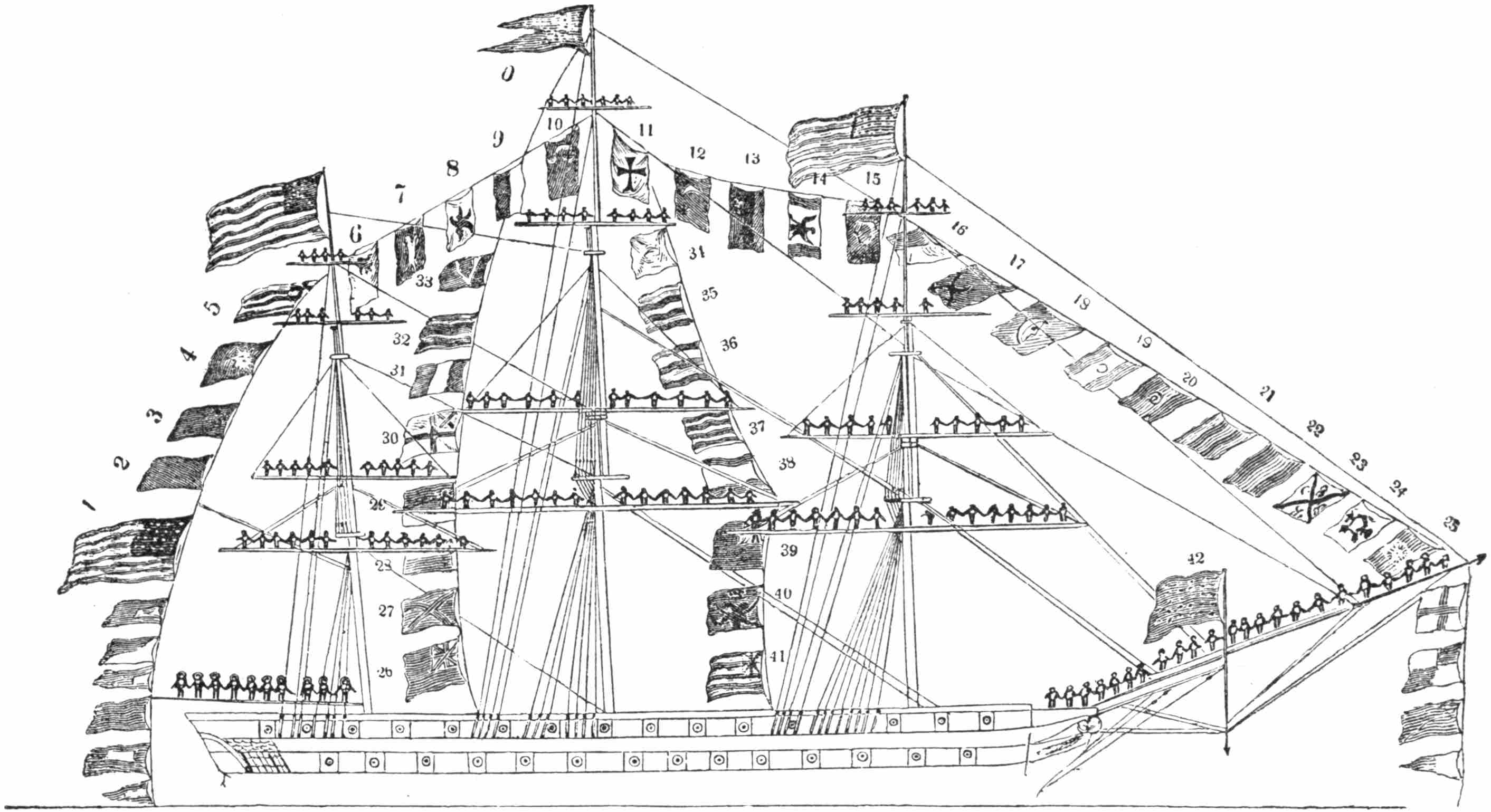

| Representation of a Ship-of-war, Dressed with Flags, and Yards Manned. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 27 |

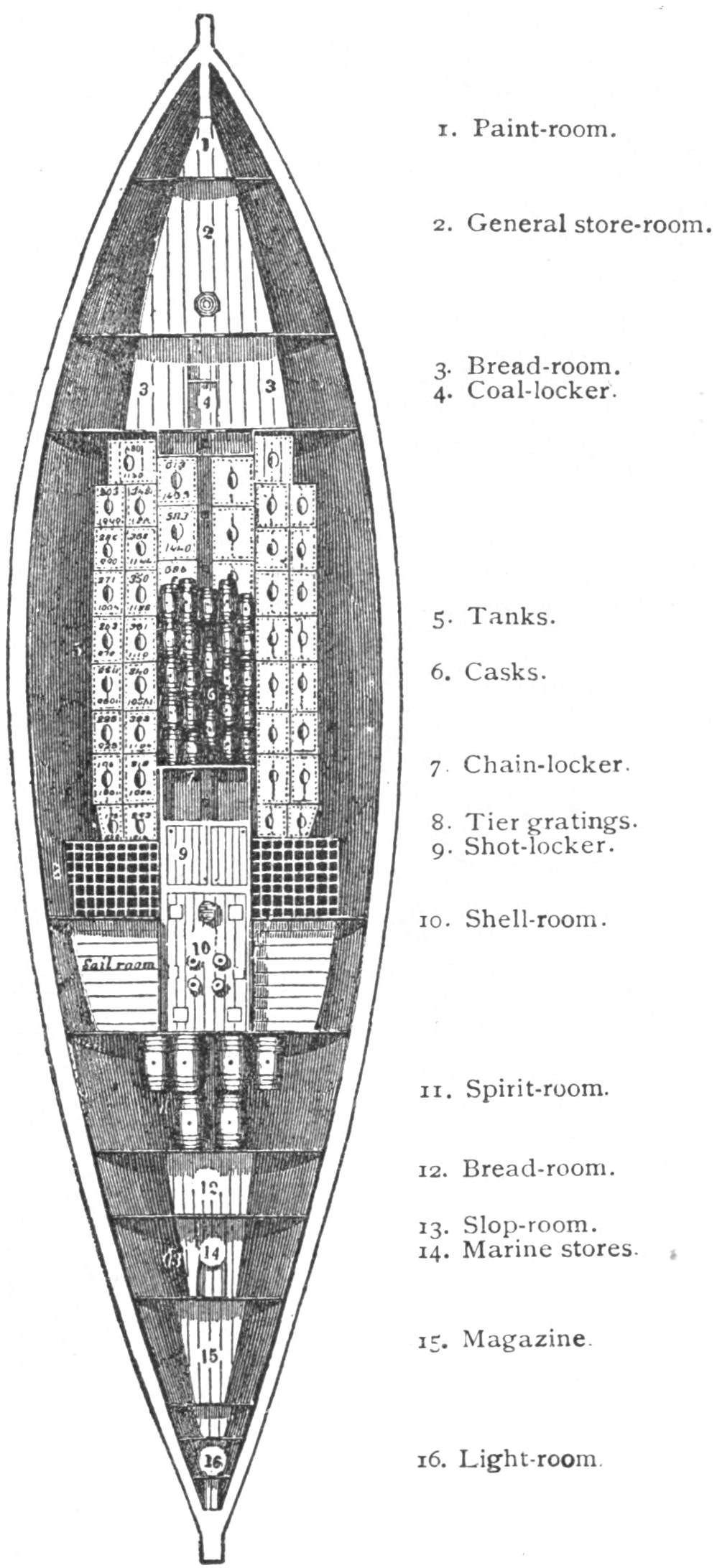

| The Internal Arrangements and Stowage of an American Sloop-of-war. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 28 |

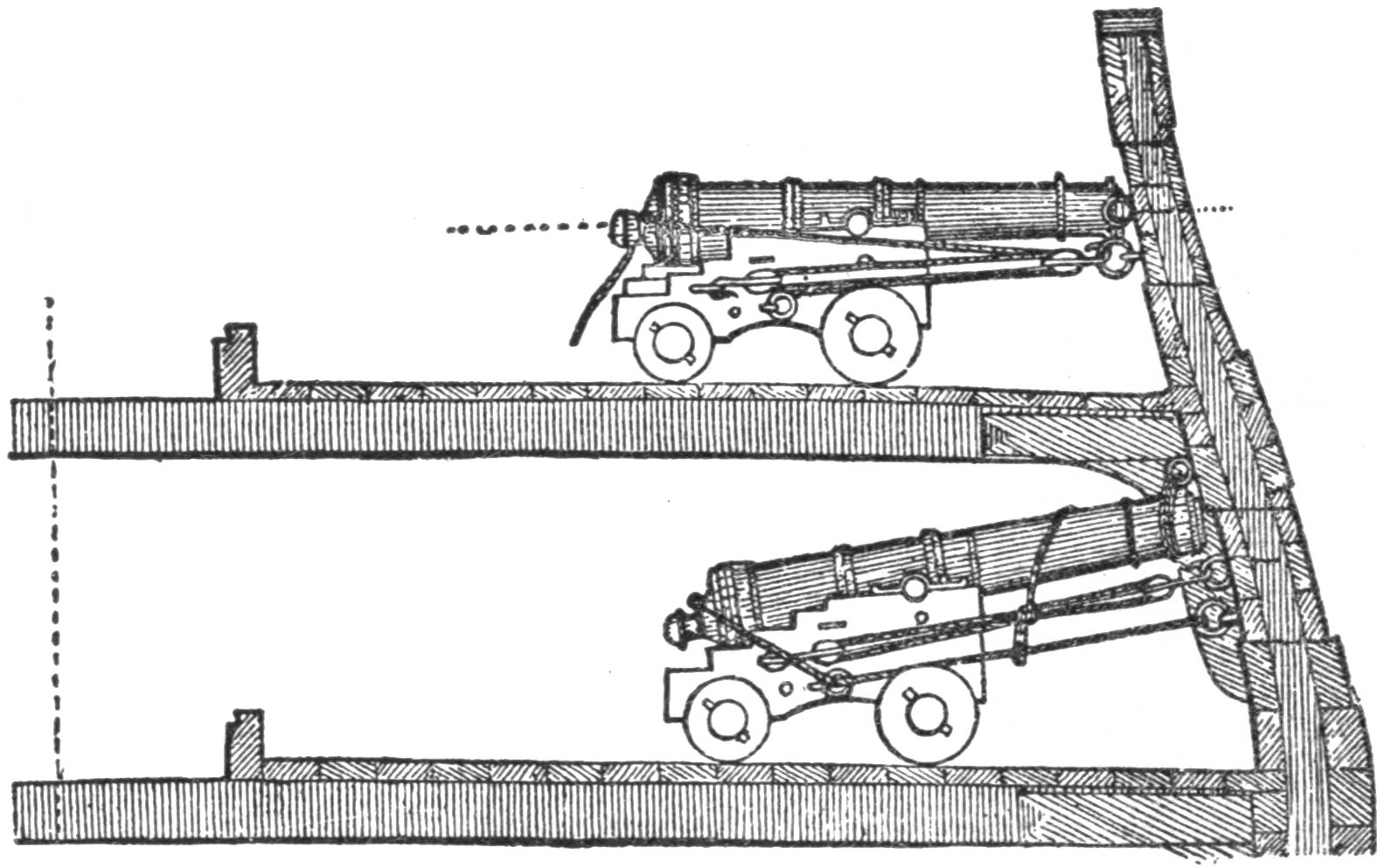

| Guns Secured for a Gale. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 30 |

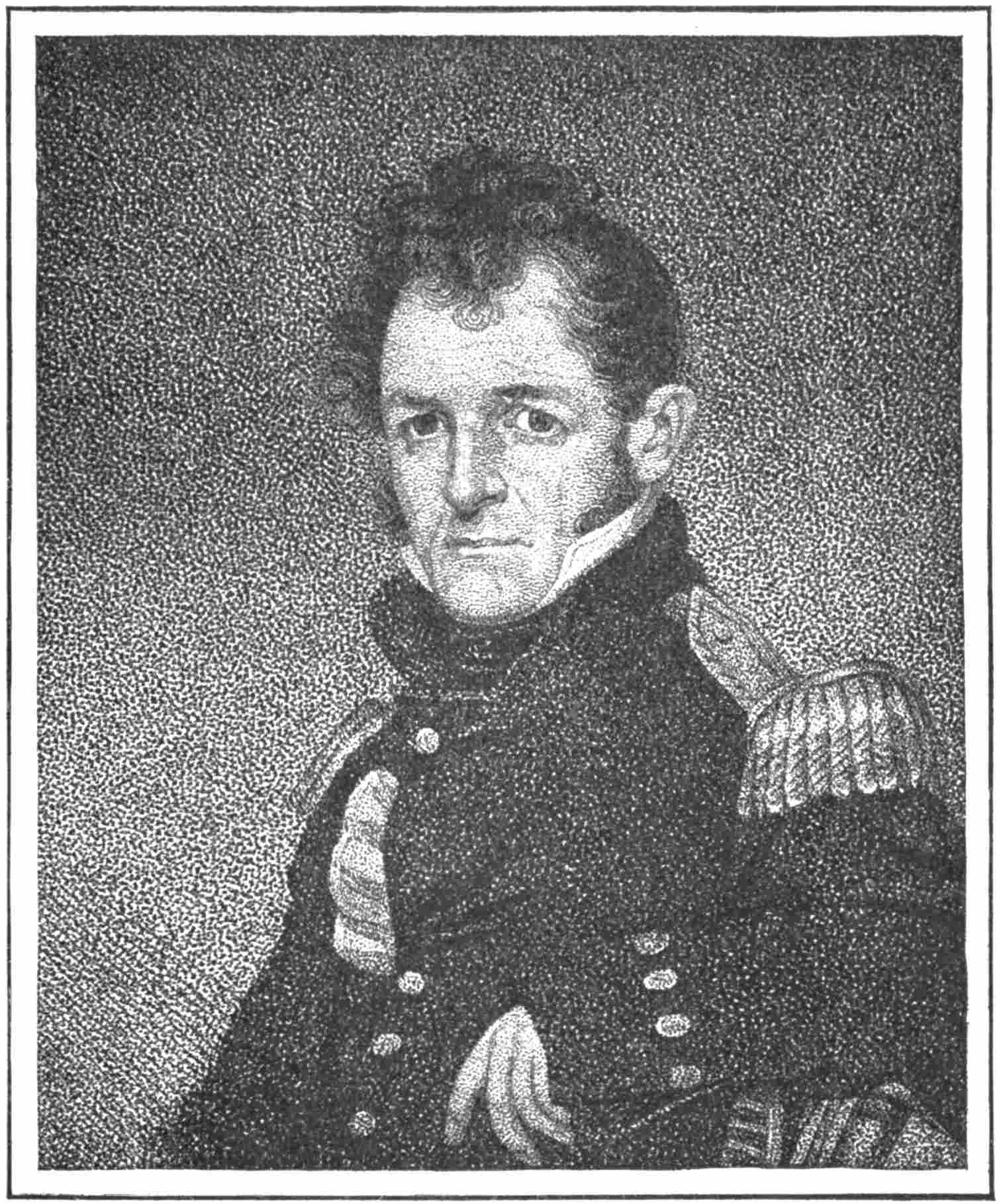

| David Porter. (From an engraving by Edwin of the portrait by Wood), | 35 |

| Fight of the Essex and the Alert. (From an old wood-cut), | 41 |

| An English Thirty-gun Corvette. (From an engraving by Merlo in 1794), | 45 |

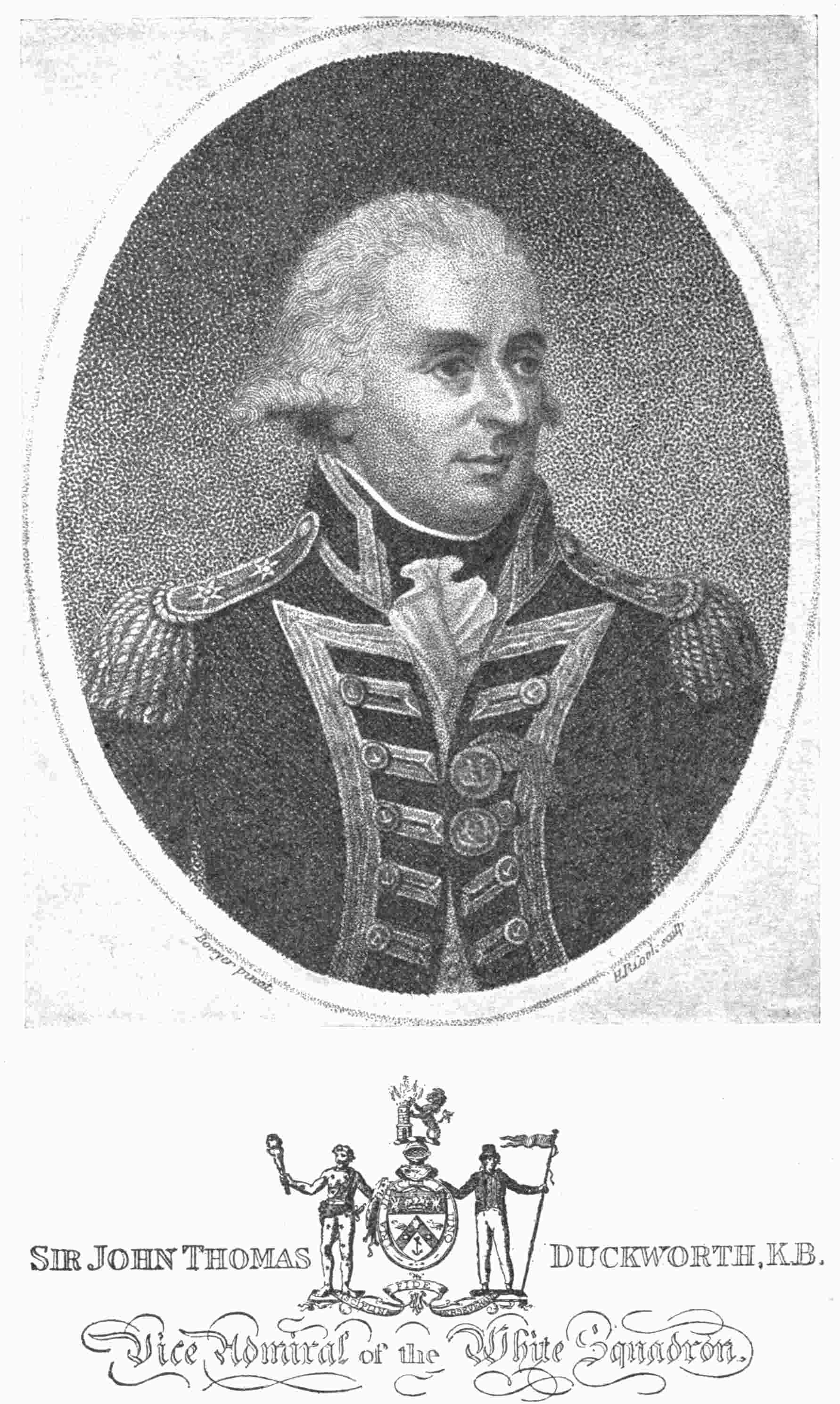

| Sir John Thomas Duckworth. (From an English engraving), | 48xvi |

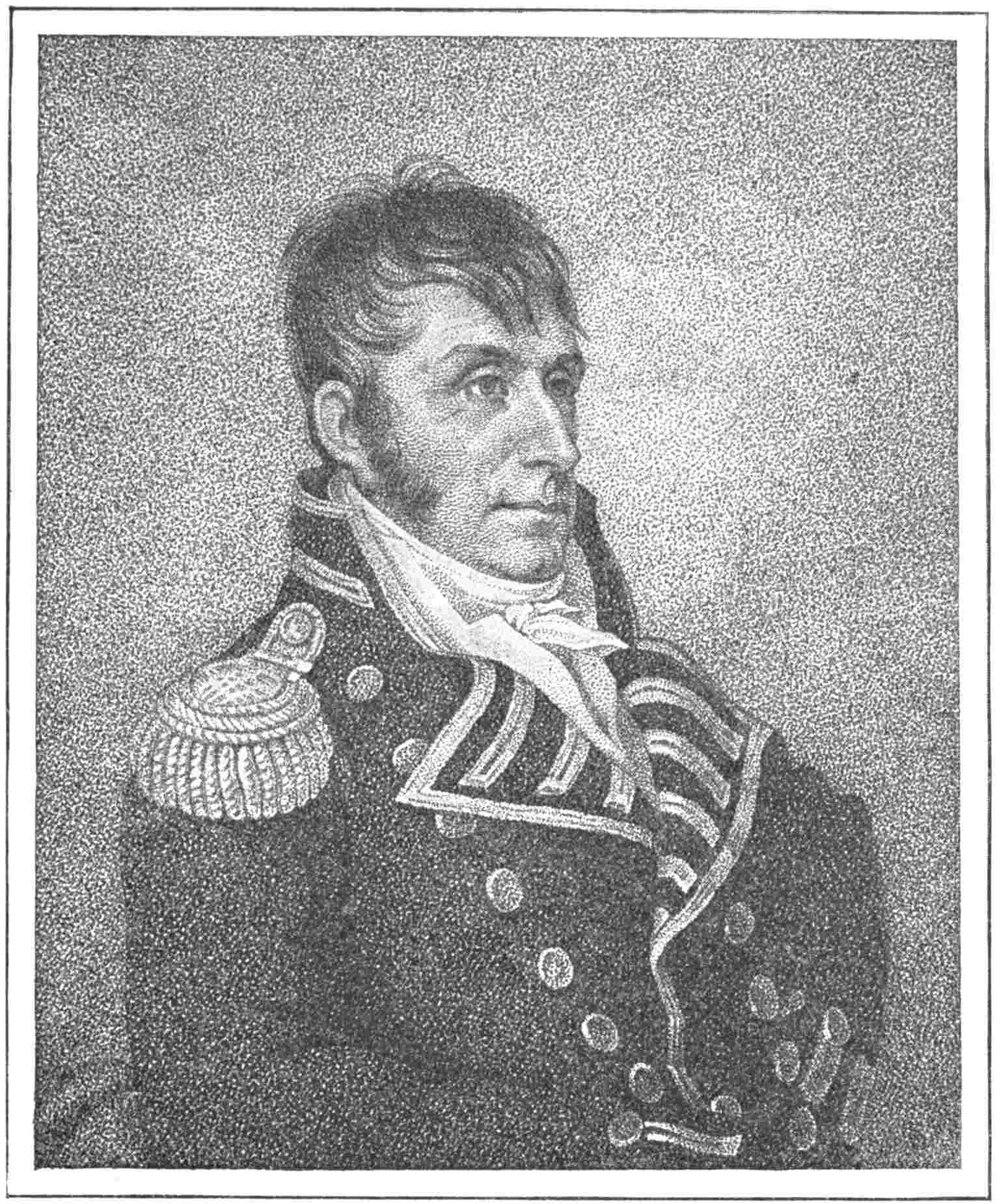

| Isaac Hull. (From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington, of the painting by Stuart), | 54 |

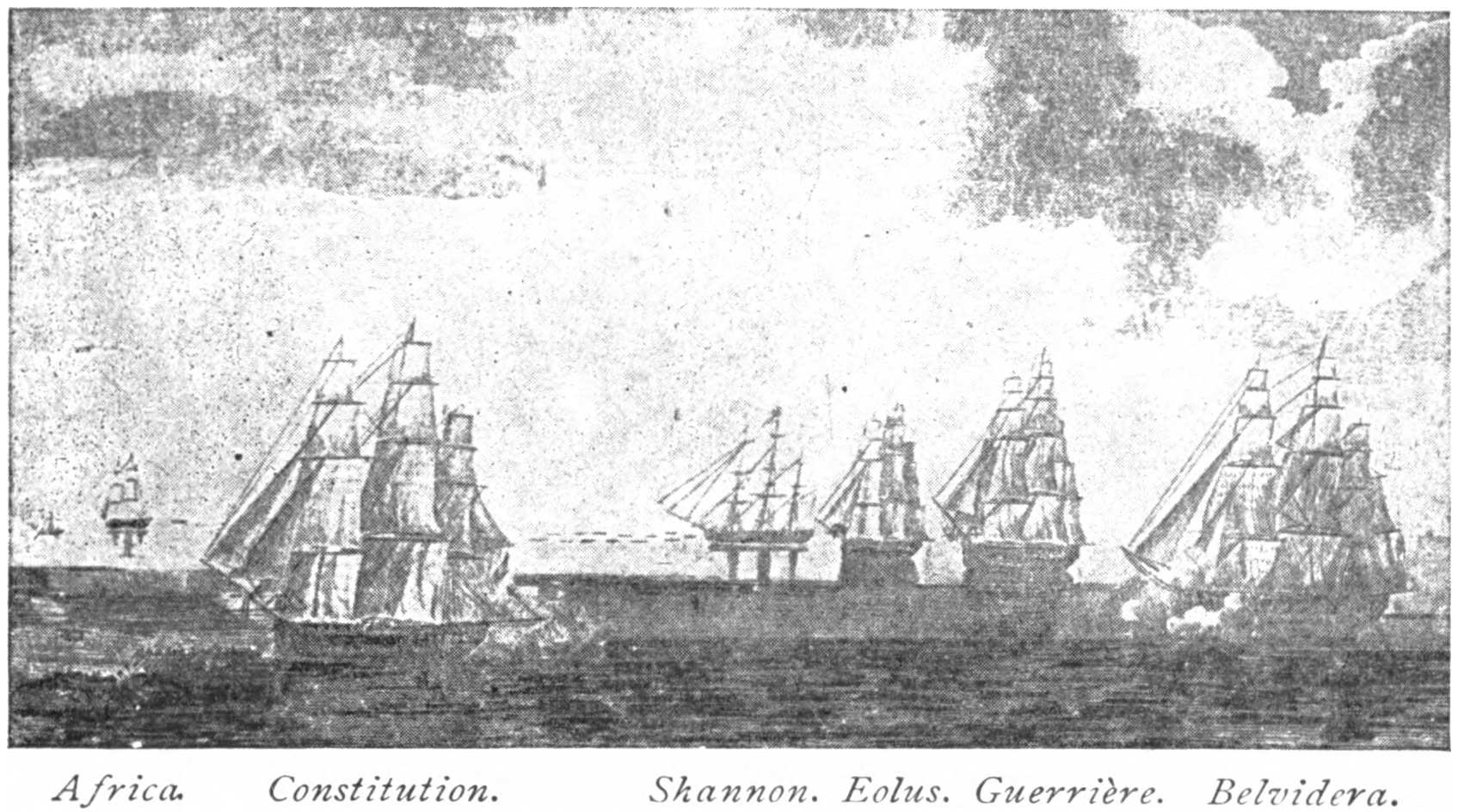

| The Constitution’s Escape from the British Squadron after a Chase of Sixty Hours. (From an engraving by Hoogland of the picture by Corné), | 57 |

| Towing a Becalmed Frigate. (From a picture drawn and engraved by Baugean), | 59 |

| Chase of the Constitution off the Jersey Coast. (From the painting by Inch at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 65 |

| The Constitution Bearing Down for the Guerrière. (From an old wood-cut), | 71 |

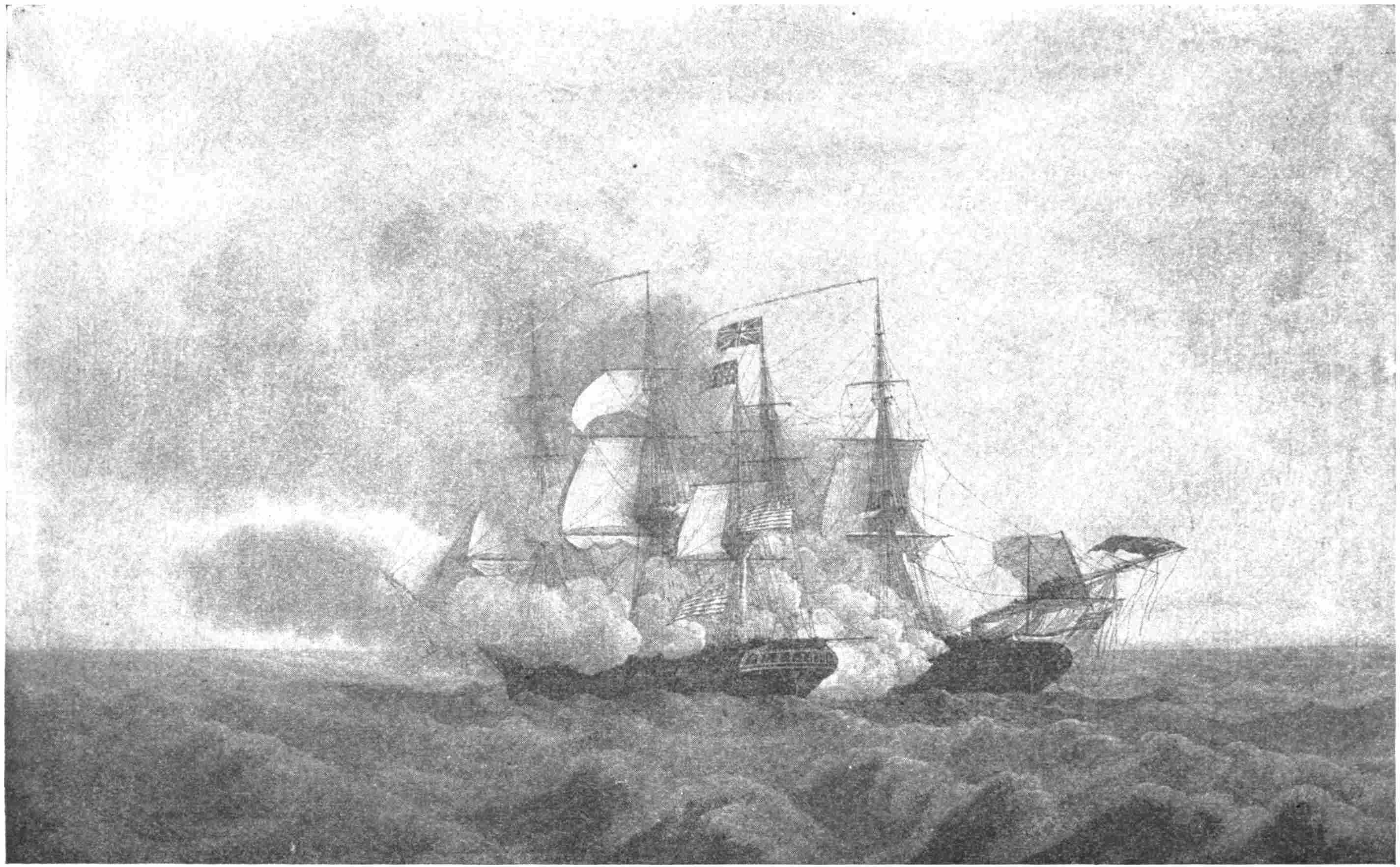

| Action between the Constitution and the Guerrière.—I. (From the painting by Birch at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 77 |

| Action between the Constitution and the Guerrière.—II. (From the painting by Birch at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 81 |

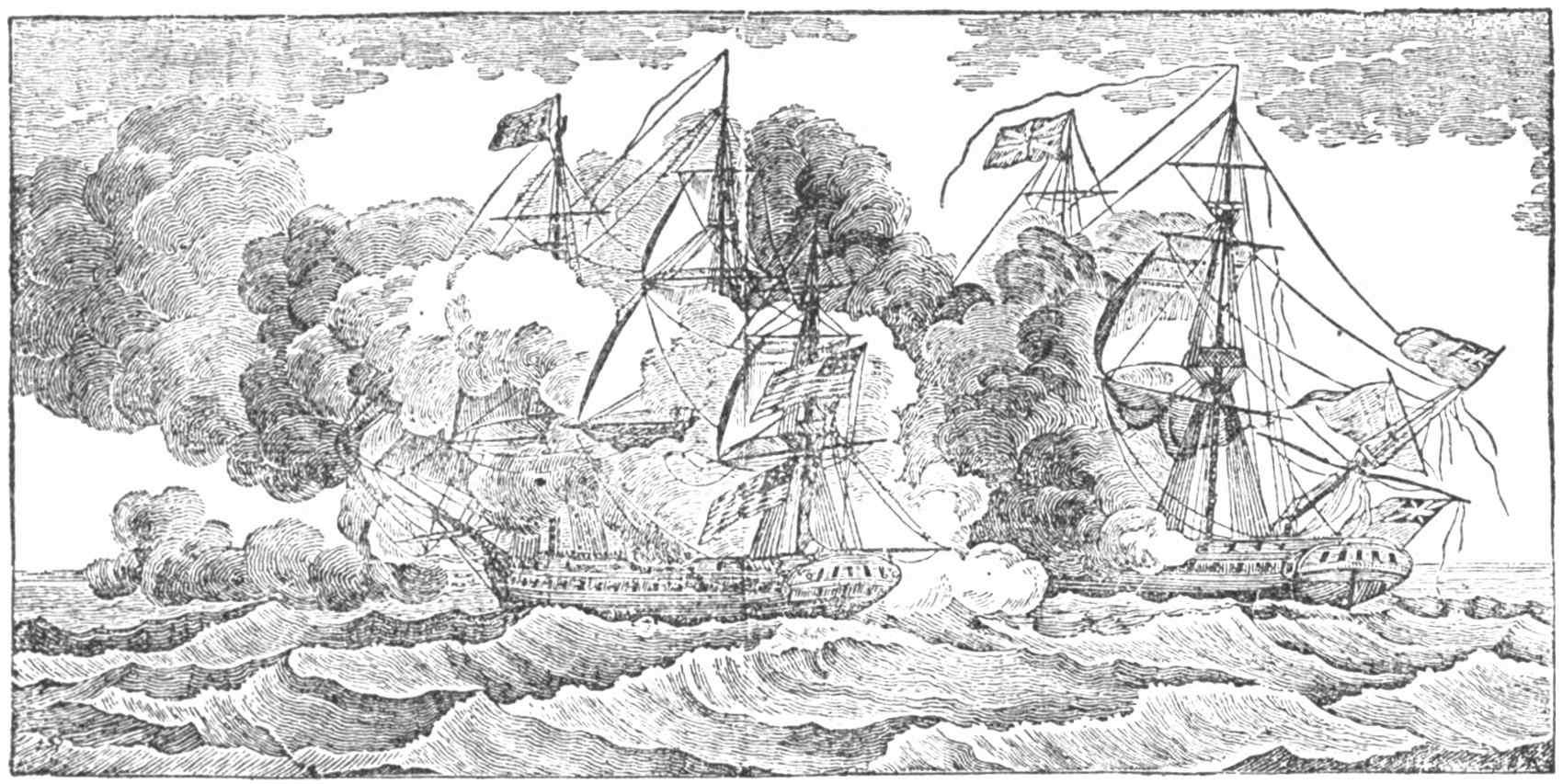

| The Constitution in Close Action with the Guerrière. (From an old wood-cut), | 83 |

| Action between the Constitution and the Guerrière.—III. (From the painting by Birch at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 85 |

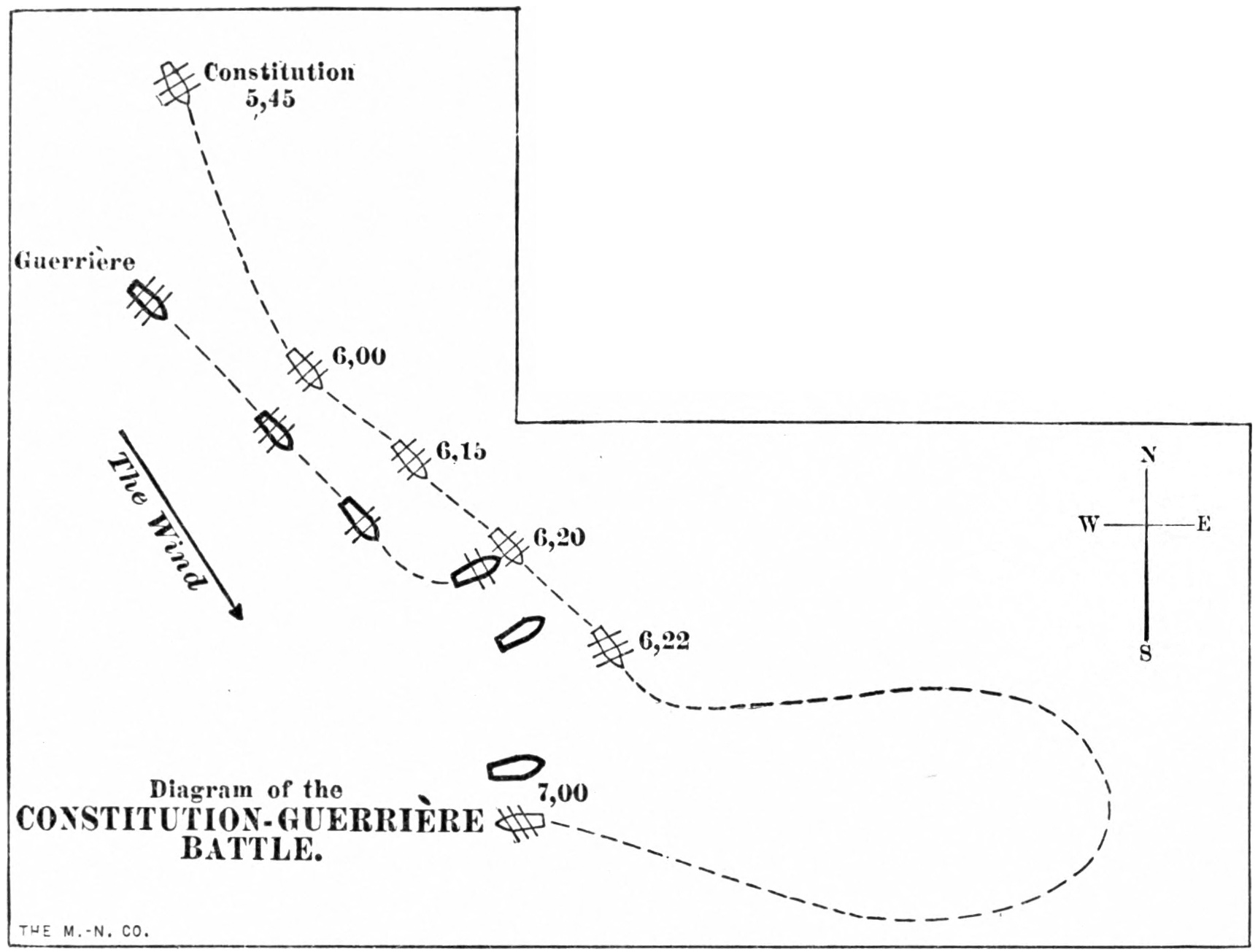

| Diagram of the Constitution-Guerrière Battle, | 87 |

| Action between the Constitution and the Guerrière.—IV. (From the painting by Birch at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 89 |

| Sir James Richard Dacres. (From an English engraving published in 1811), | 93 |

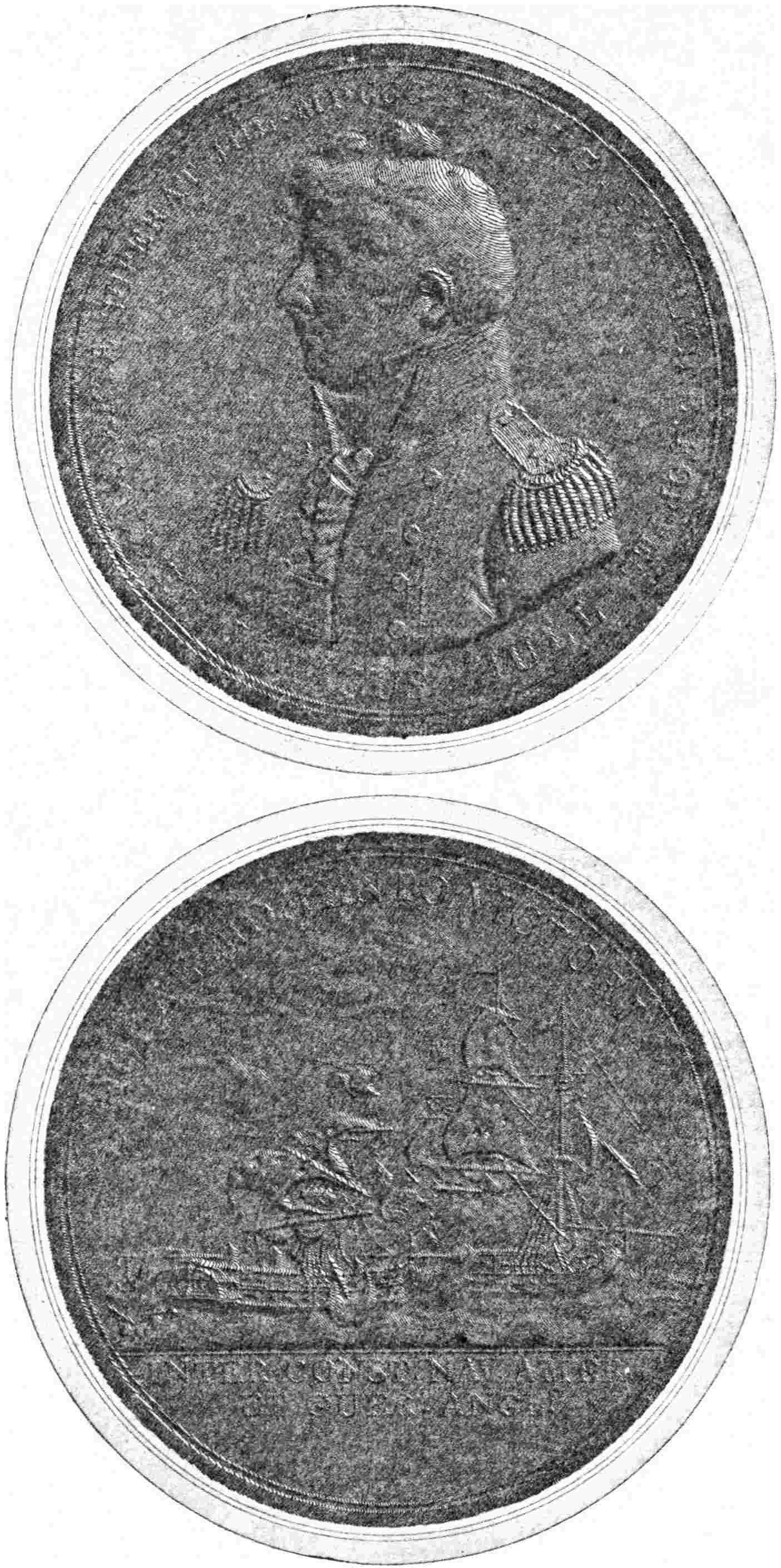

| Medal Awarded to Isaac Hull after the Capture of the Guerrière by the Constitution, | 102 |

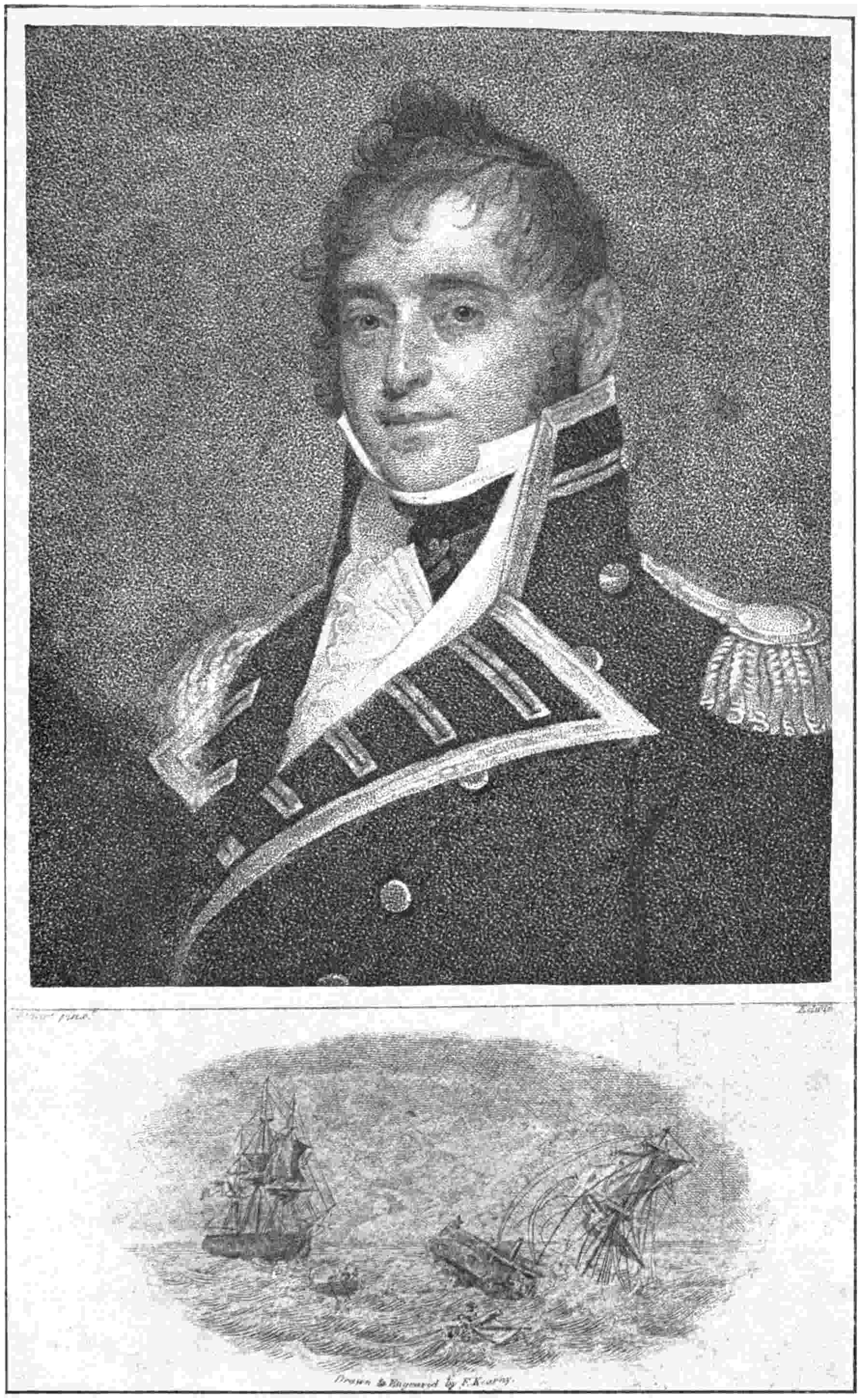

| Jacob Jones. (From an engraving by Edwin of the portrait by Rembrandt Peale), | 105 |

| Diagram of the Wasp-Frolic Battle, | 108 |

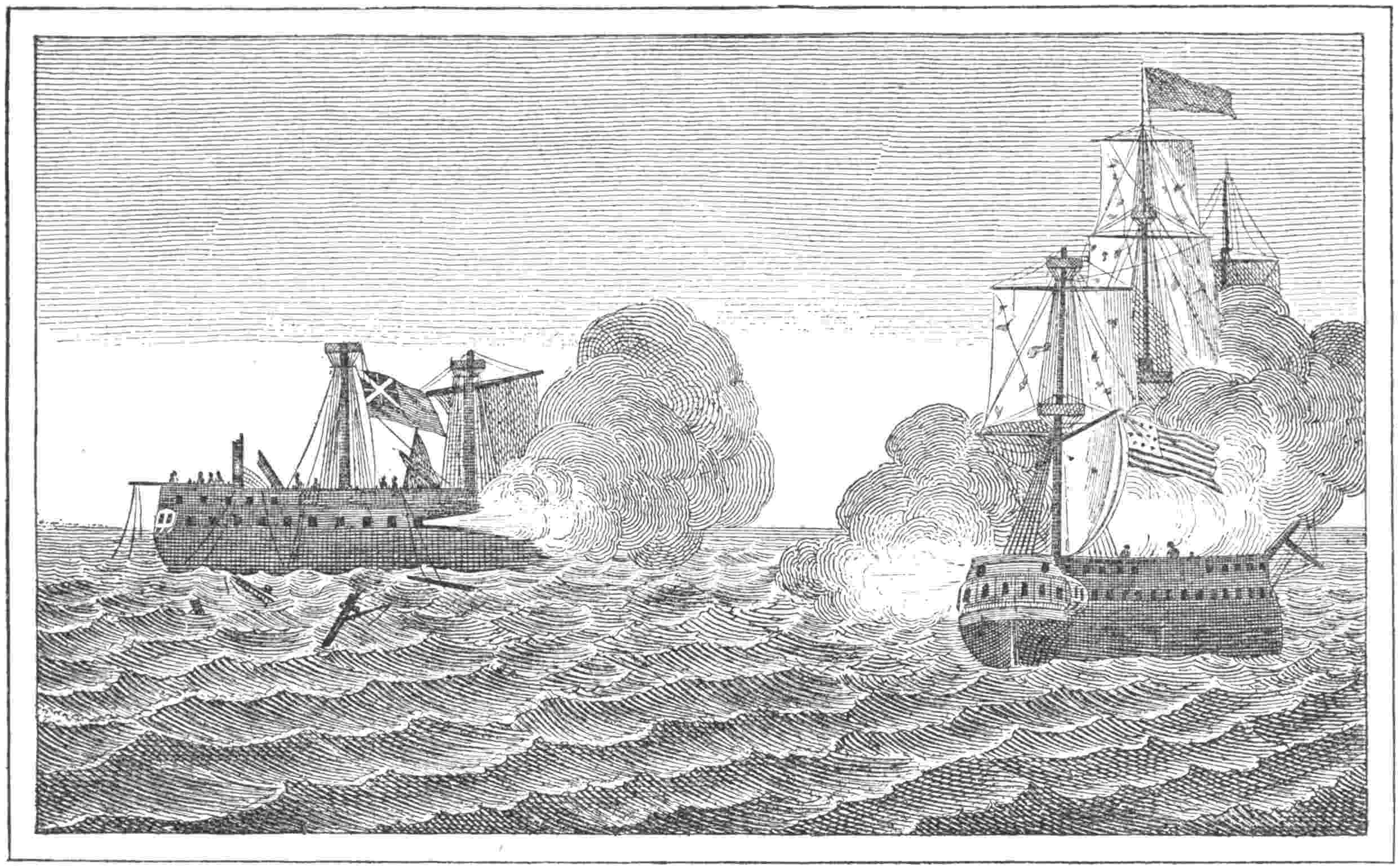

| The Wasp Boarding the Frolic. (From an old wood-cut), | 111 |

| The Wasp and Frolic. (From an original water-color by H. Rich, at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 113 |

| James Biddle. (From an engraving by Gimbrede of the portrait by Wood), | 115 |

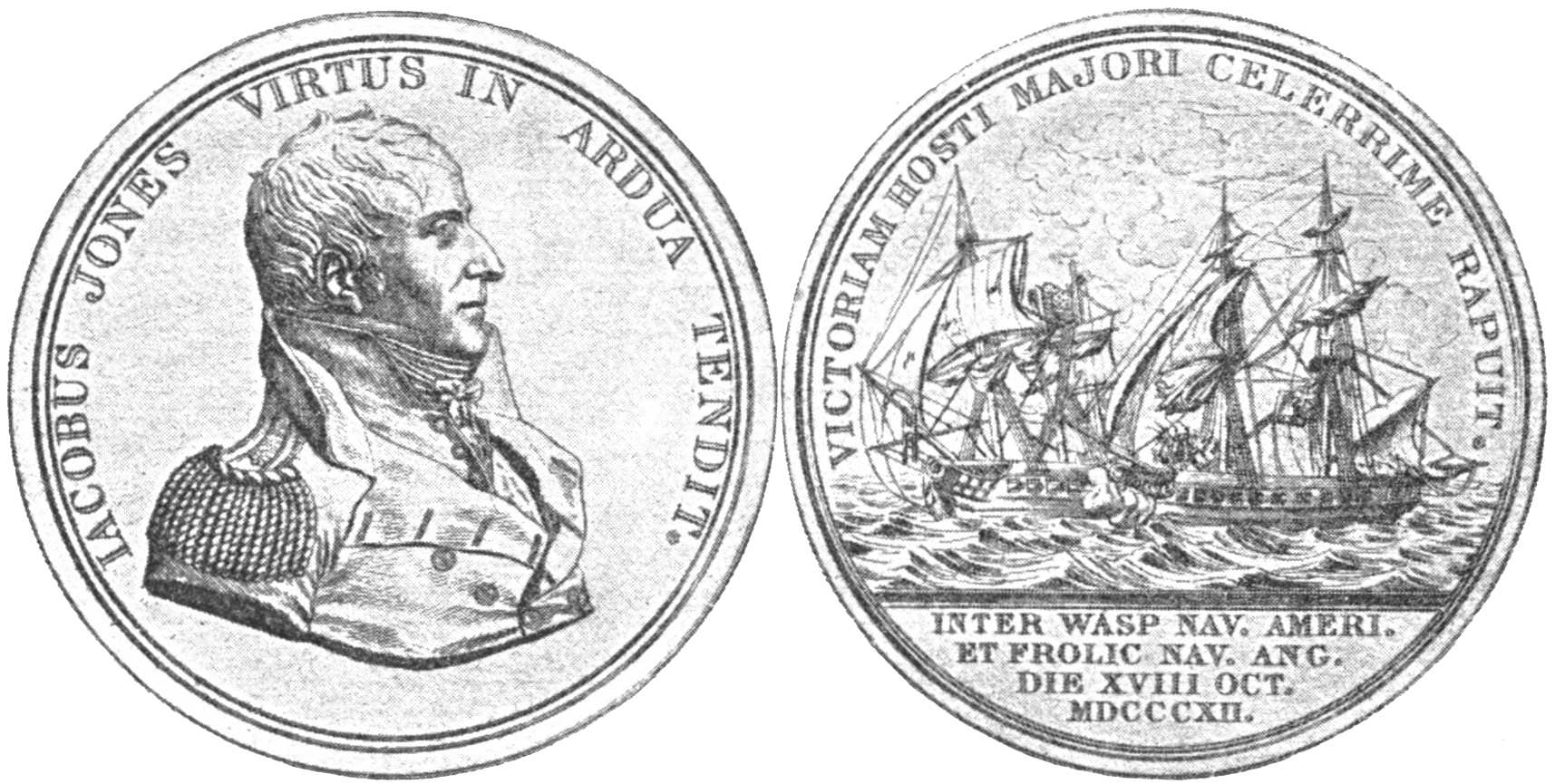

| Medal Awarded to Jacob Jones after the Capture of the Frolic by the Wasp, | 118xvii |

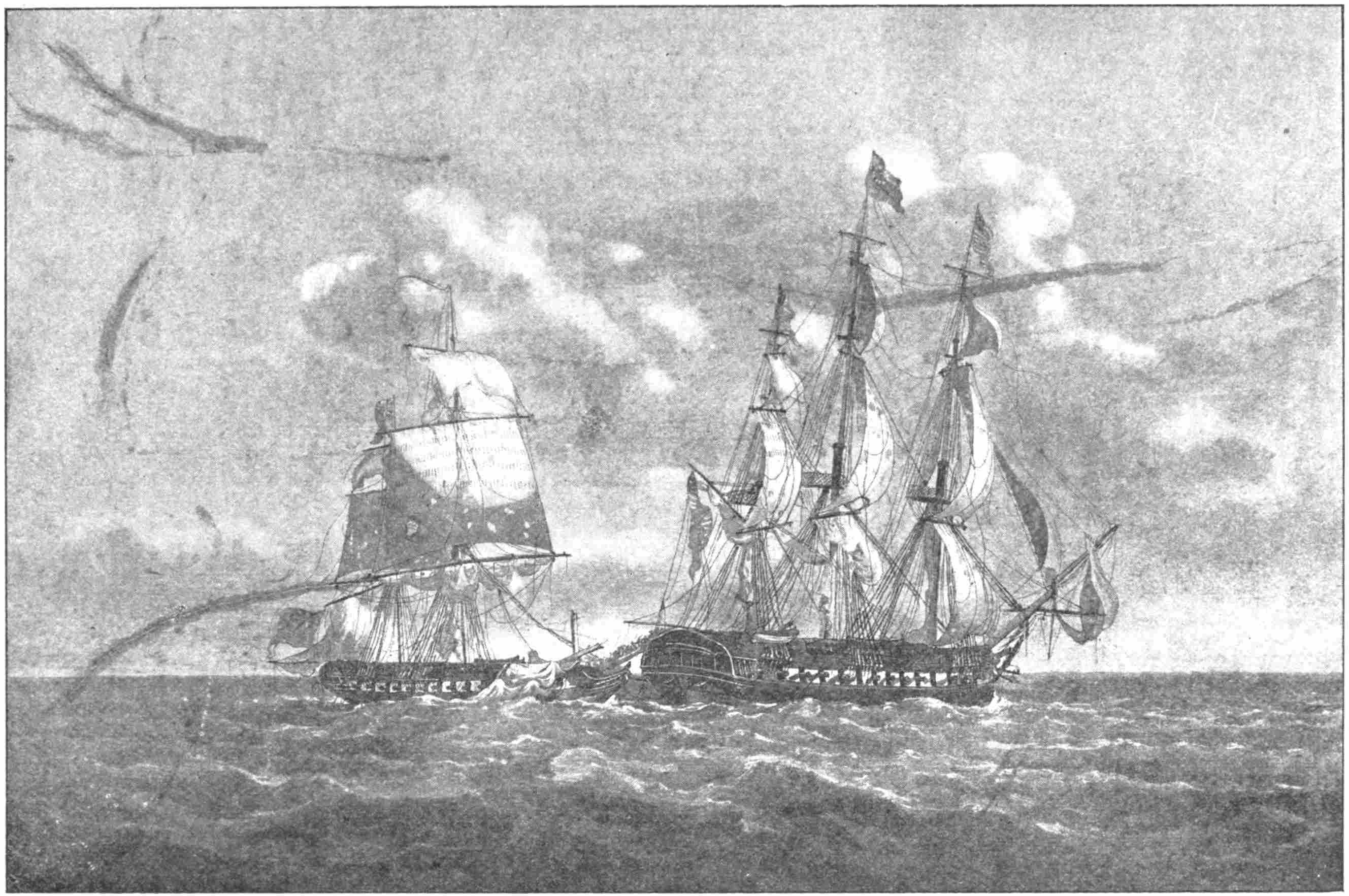

| Capture of the Macedonian. (From an engraving in Waldo’s “Decatur”), | 123 |

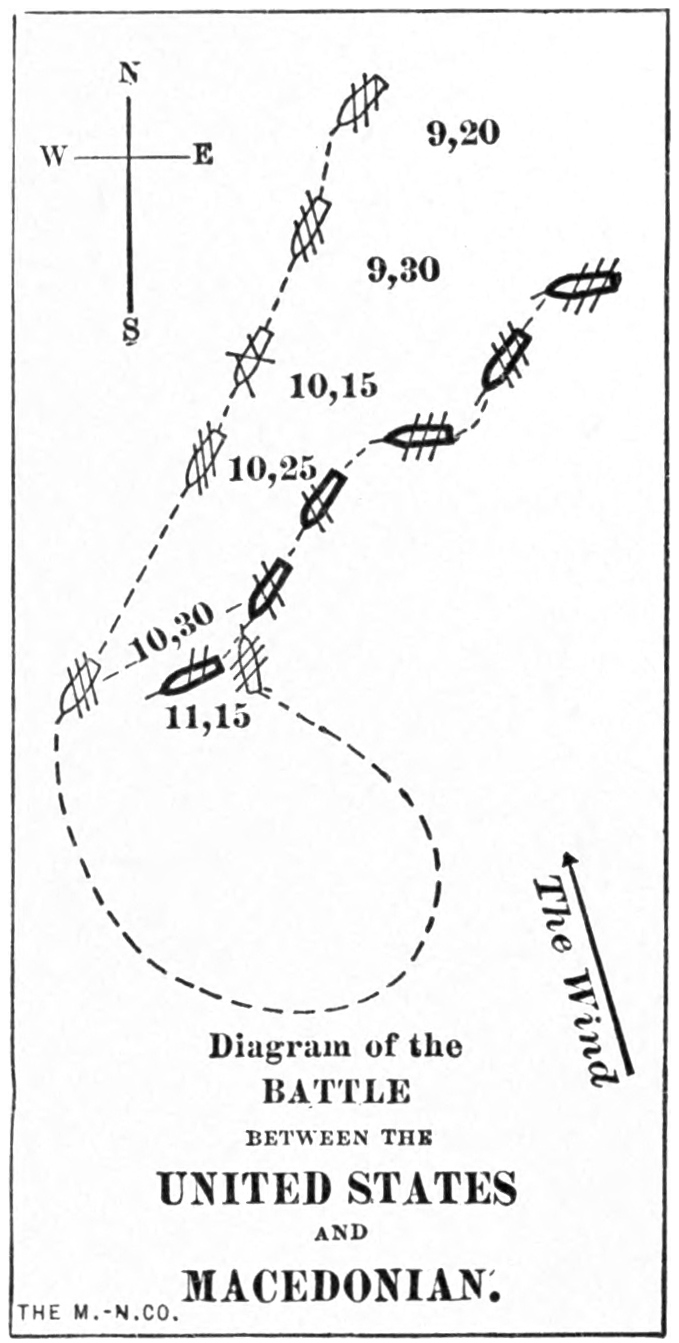

| Diagram of the Battle between the United States and Macedonian, | 127 |

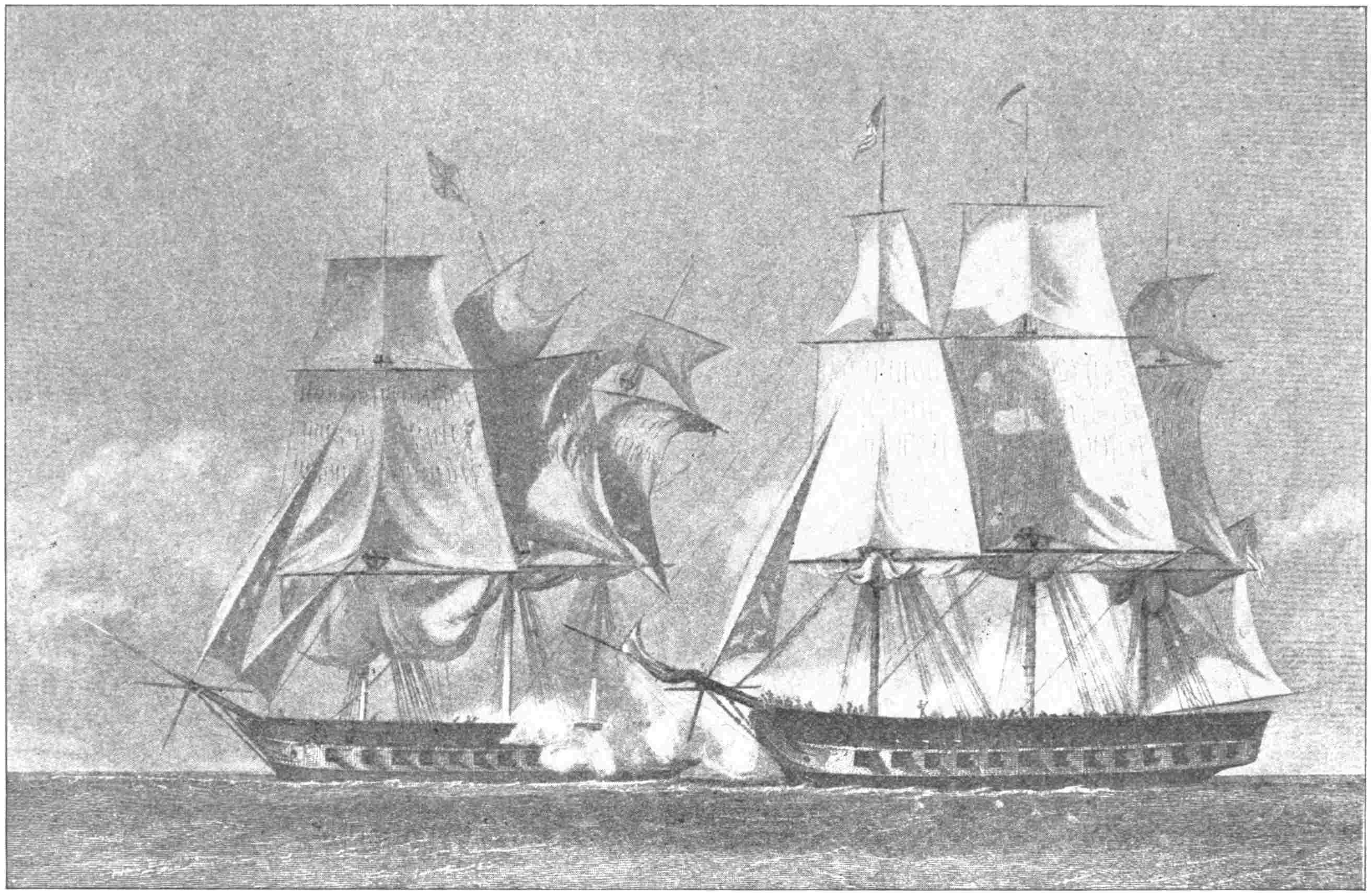

| Battle between the United States and the Macedonian. (From an engraving by Duthie of the drawing by Chappel), | 129 |

| The Battle Between the United States and the Macedonian. (Drawn by a sailor who was on the United States. From the original drawing at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 135 |

| Stephen Decatur. (From the portrait by Thomas Sully at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 145 |

| Medal Awarded to Stephen Decatur after the Capture of the Macedonian by the United States, | 150 |

| Billet-head of the Constitution. (From the original at the Naval Institute, Annapolis), | 153 |

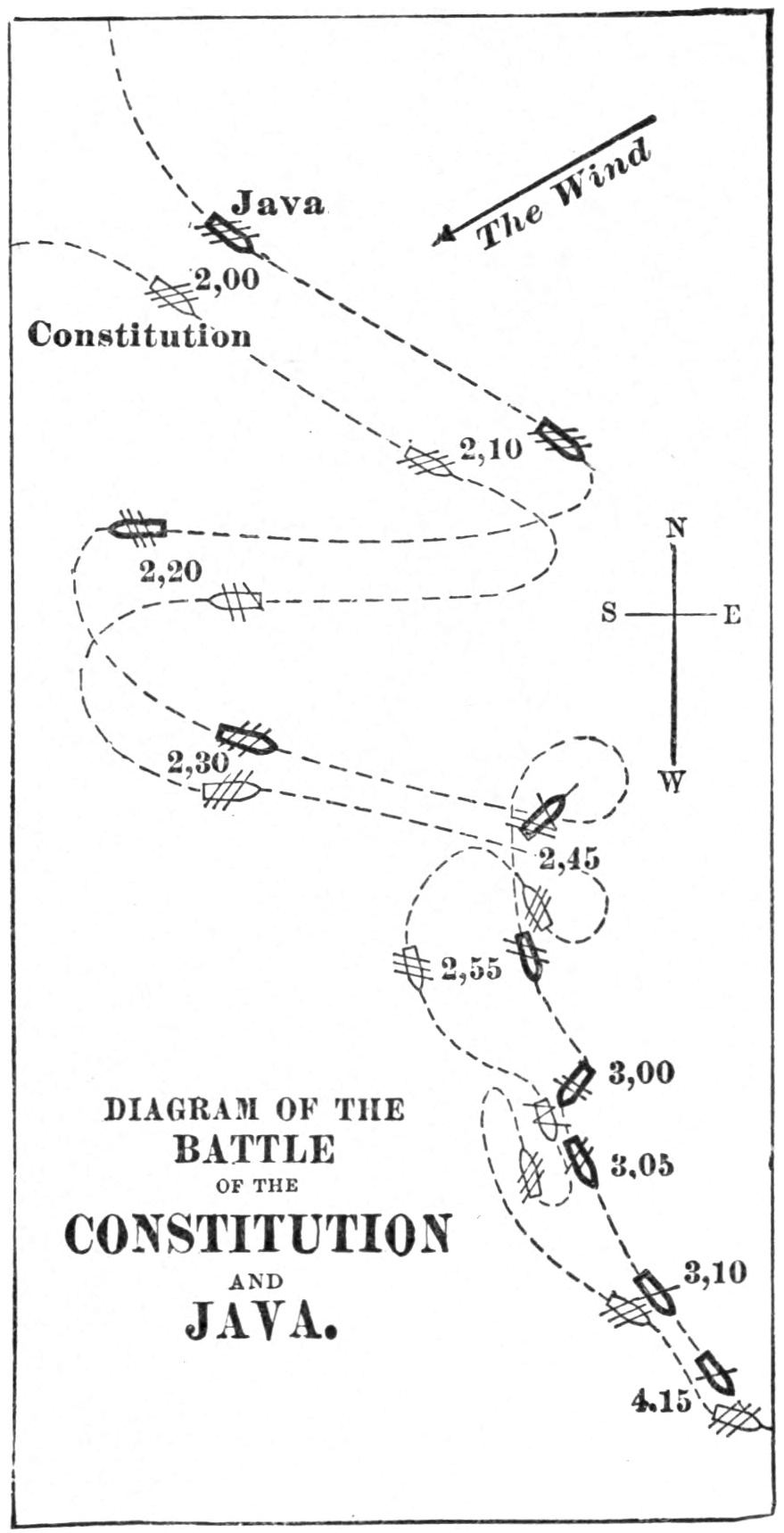

| Diagram of the Battle of the Constitution and Java, | 158 |

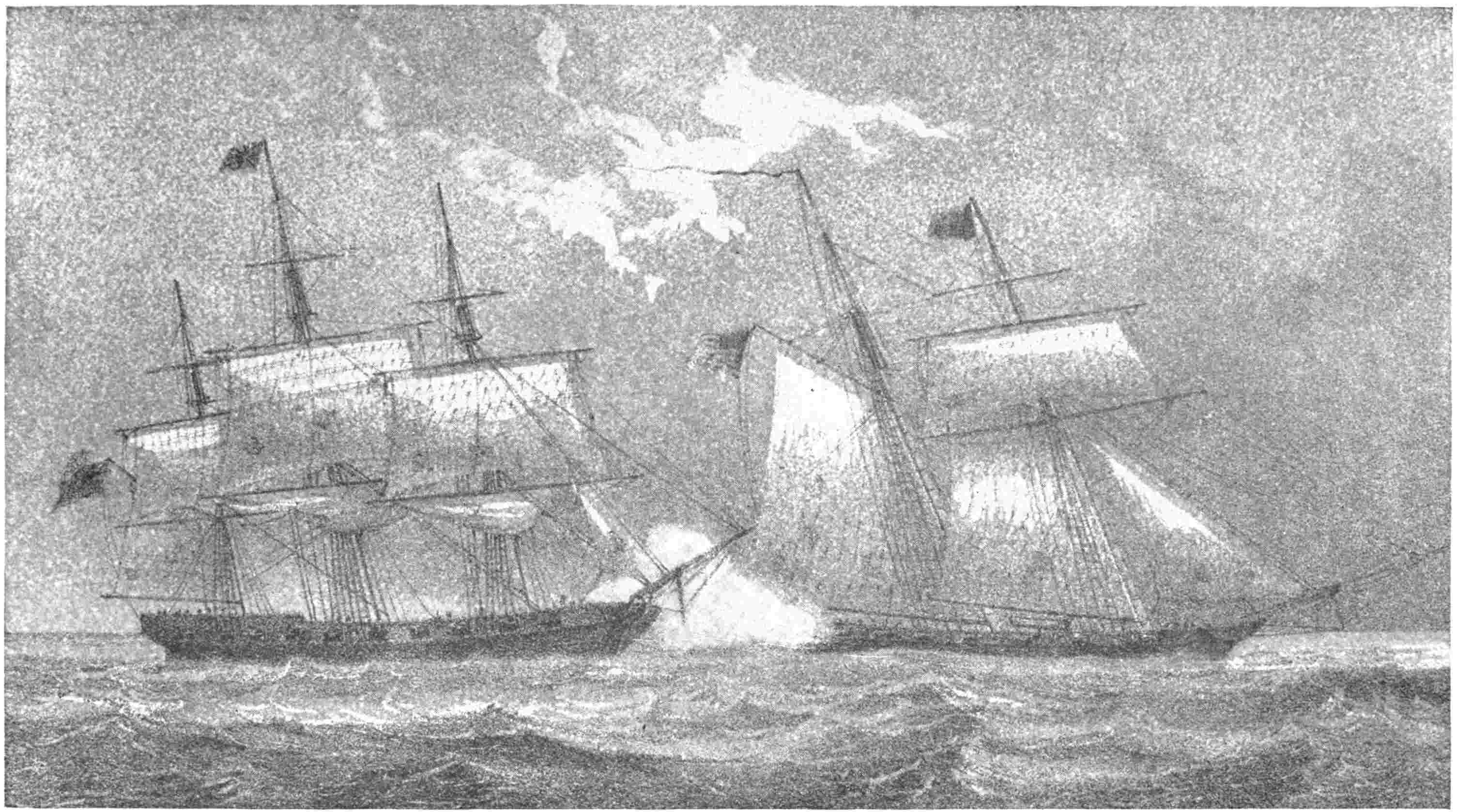

| The Battle between the Constitution and the Java.—I. (“At five minutes past three o’clock, as the Java’s foremast fell.” From an engraving by Havel, after a sketch by Lieutenant Buchanan), | 159 |

| The Battle between the Constitution and the Java.—II. (“At half-past four o’clock, as the Constitution began to make sail.” From an engraving by Havel, after a sketch by Lieutenant Buchanan), | 163 |

| The Java Surrendering to the Constitution. (From an old wood-cut), | 167 |

| Medal Awarded to William Bainbridge after the Capture of the Java by the Constitution, | 175 |

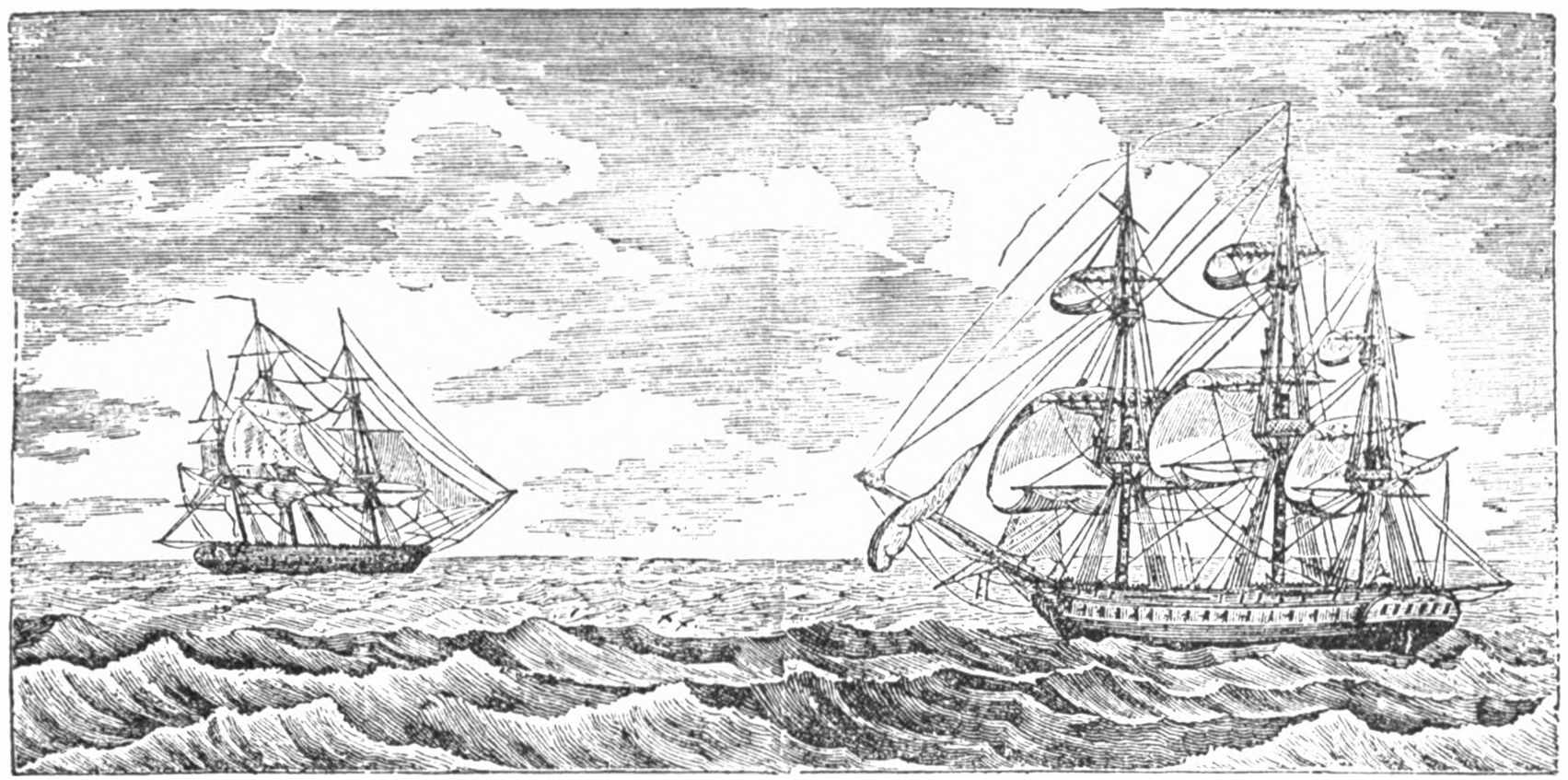

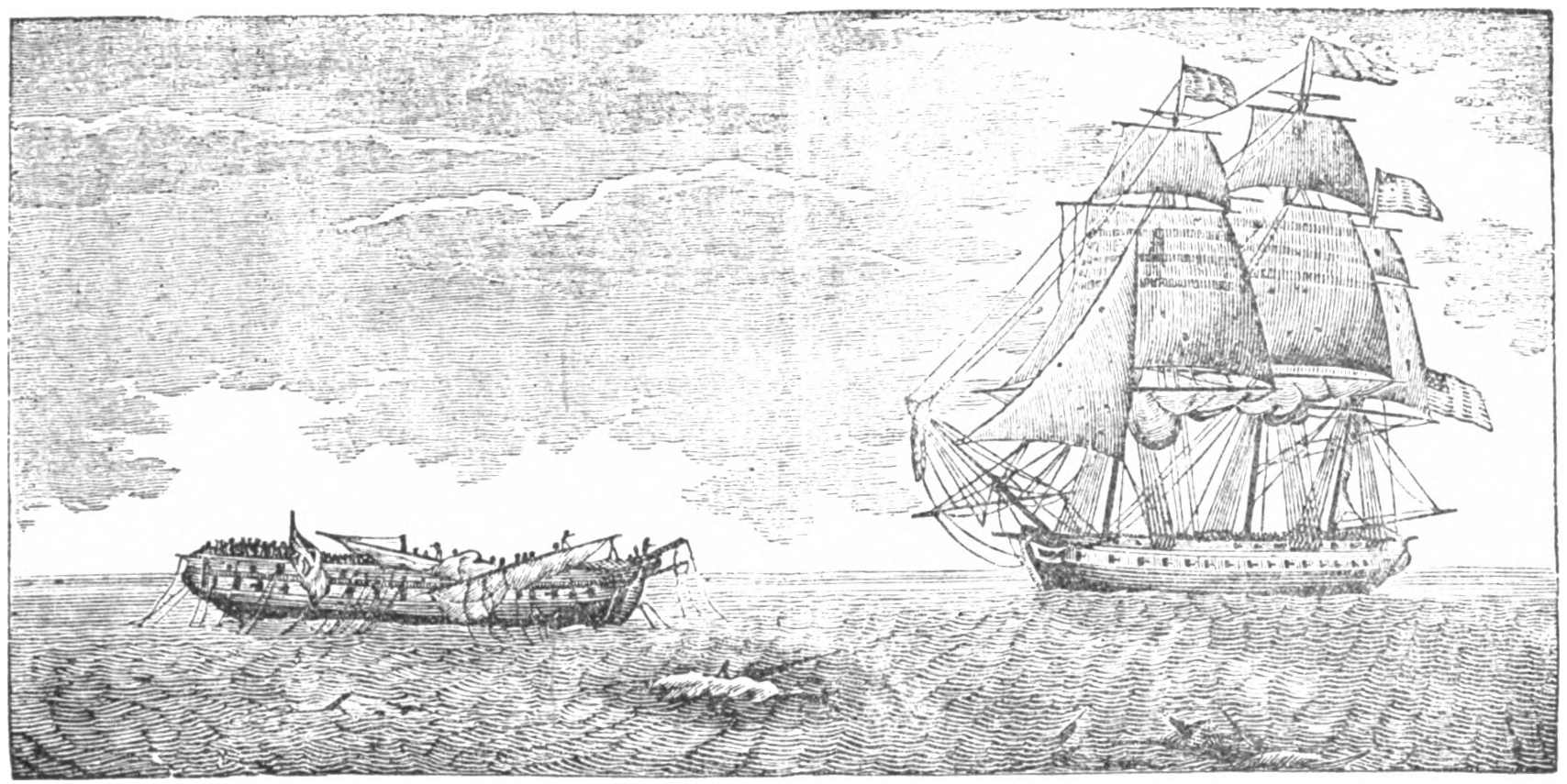

| The Hornet Blockading the Bonne Citoyenne. (From an old wood-cut), | 180 |

| Diagram of the Hornet-Peacock Battle, | 183 |

| John T. Shubrick. (From an engraving by Gimbrede), | 185 |

| The Hornet Sinking the Peacock. (From an old wood-cut), | 186 |

| Medal Awarded to James Lawrence, after the Capture of the Peacock by the Hornet, | 191 |

| James Lawrence. (From an engraving by Edwin of the portrait by Stuart), | 195 |

| Sir Philip Bowes Vere Broke, Bart. (From a lithograph of the portrait by Lane), | 201xviii |

| James Lawrence. (From an engraving by Edwin), | 205 |

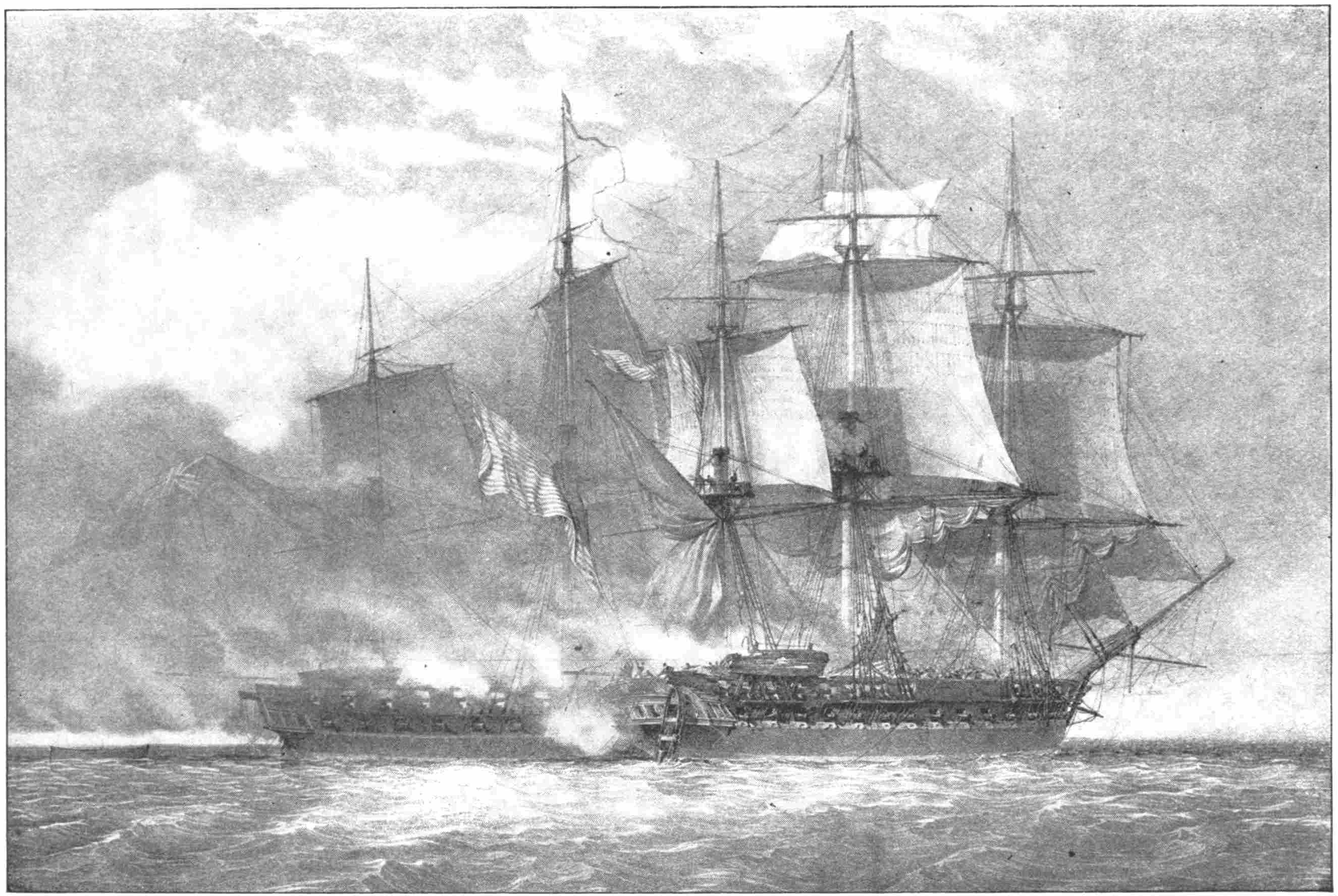

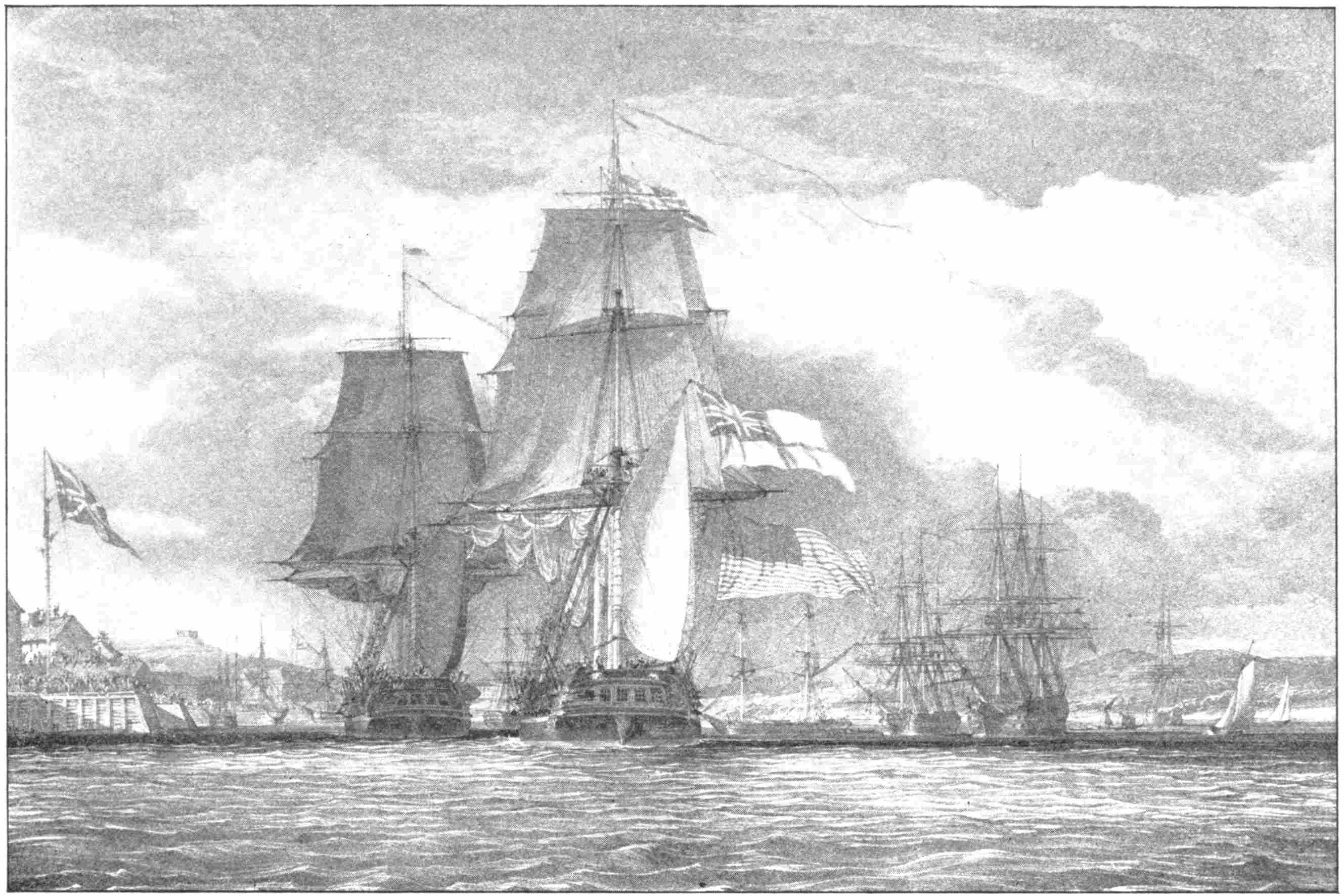

| The Chesapeake and Shannon.—Commencement of the Battle. (From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington), | 207 |

| The Chesapeake and Shannon.—After the First Two Broadsides from the Latter. (From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington), | 211 |

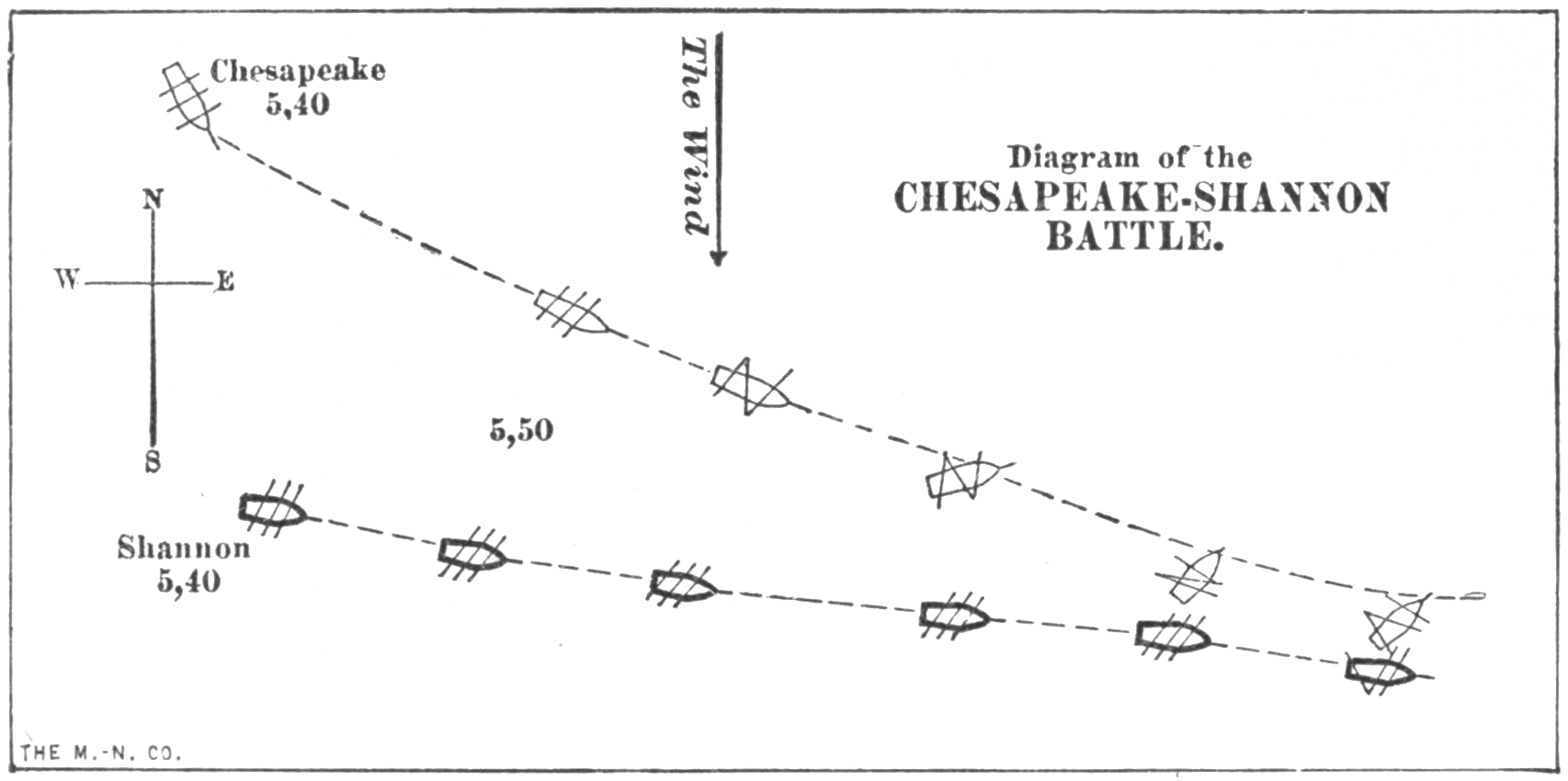

| Diagram of the Chesapeake-Shannon Battle, | 213 |

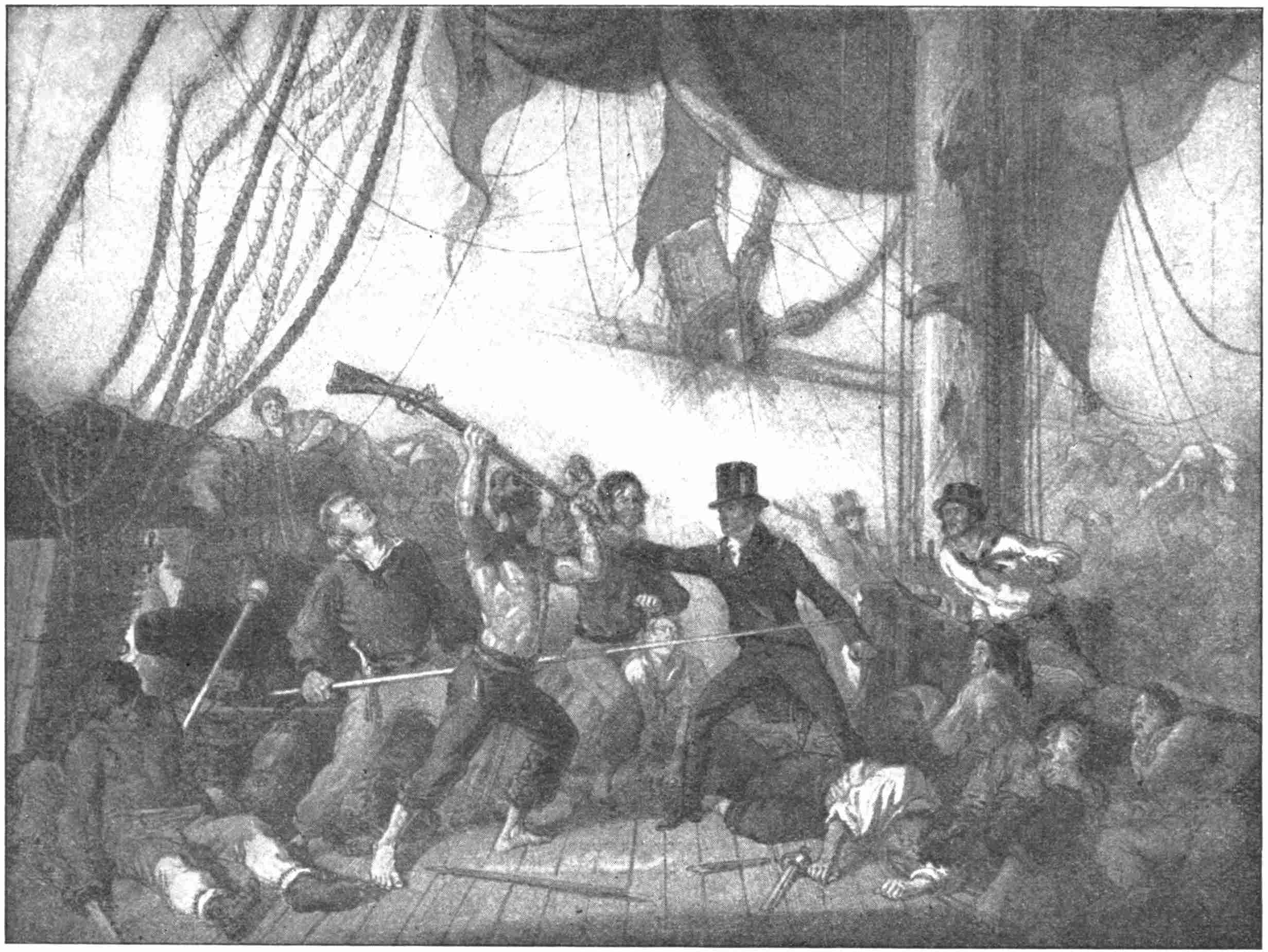

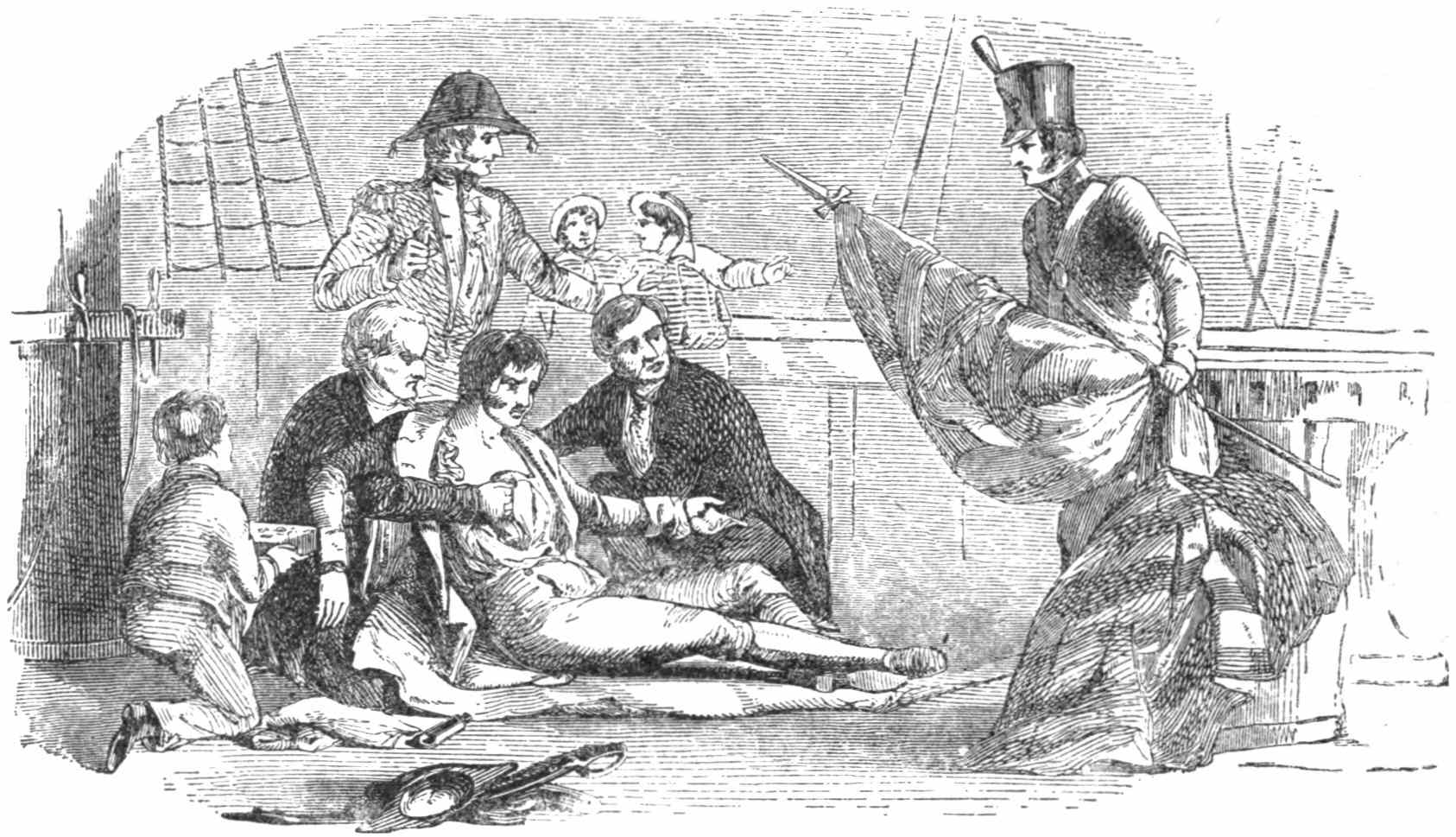

| “Don’t Give Up the Ship!”—Death of Captain Lawrence. (From an engraving by Hall of the picture by Chappel), | 215 |

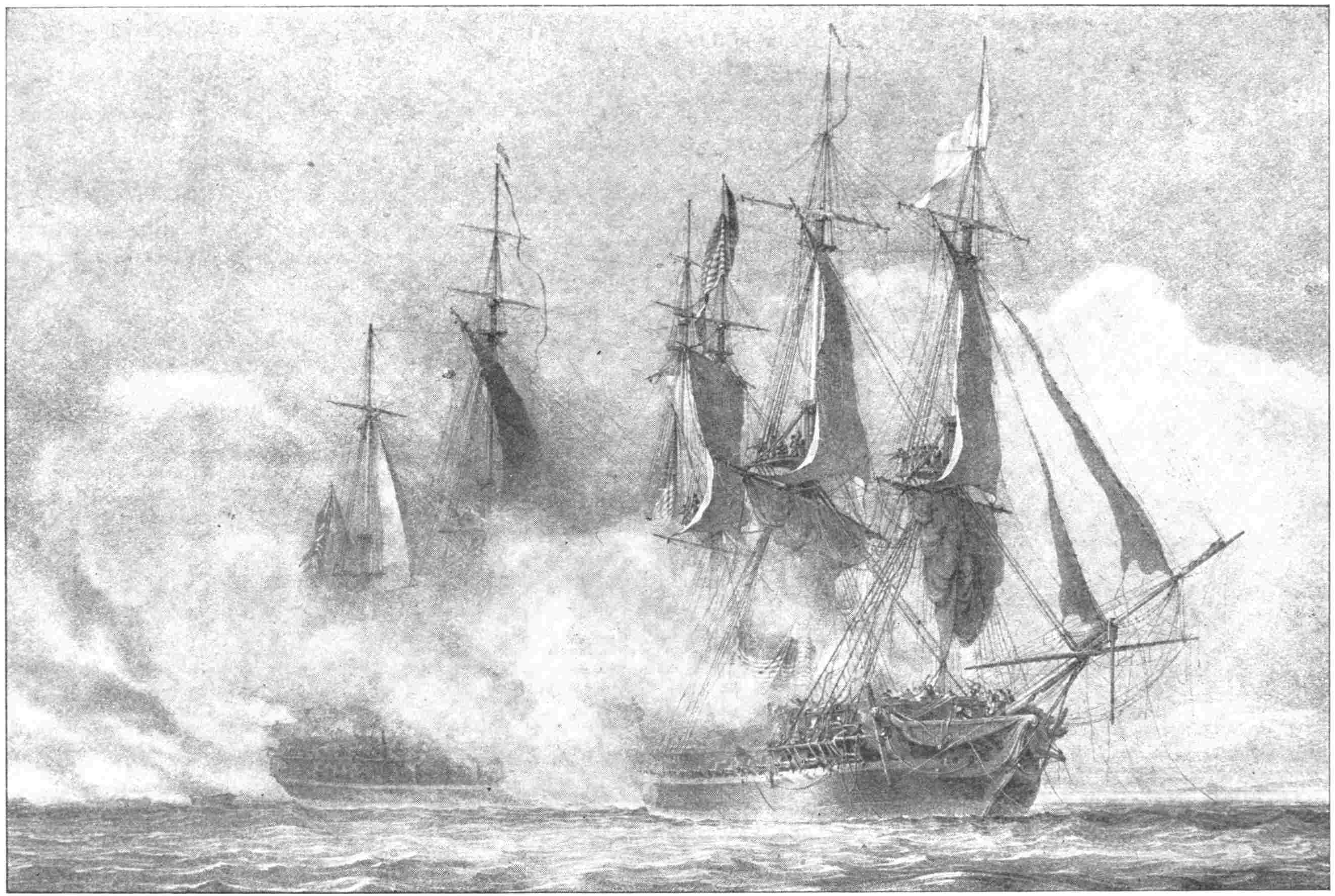

| The Chesapeake and Shannon.—The Shannon’s Men Boarding. (From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington), | 219 |

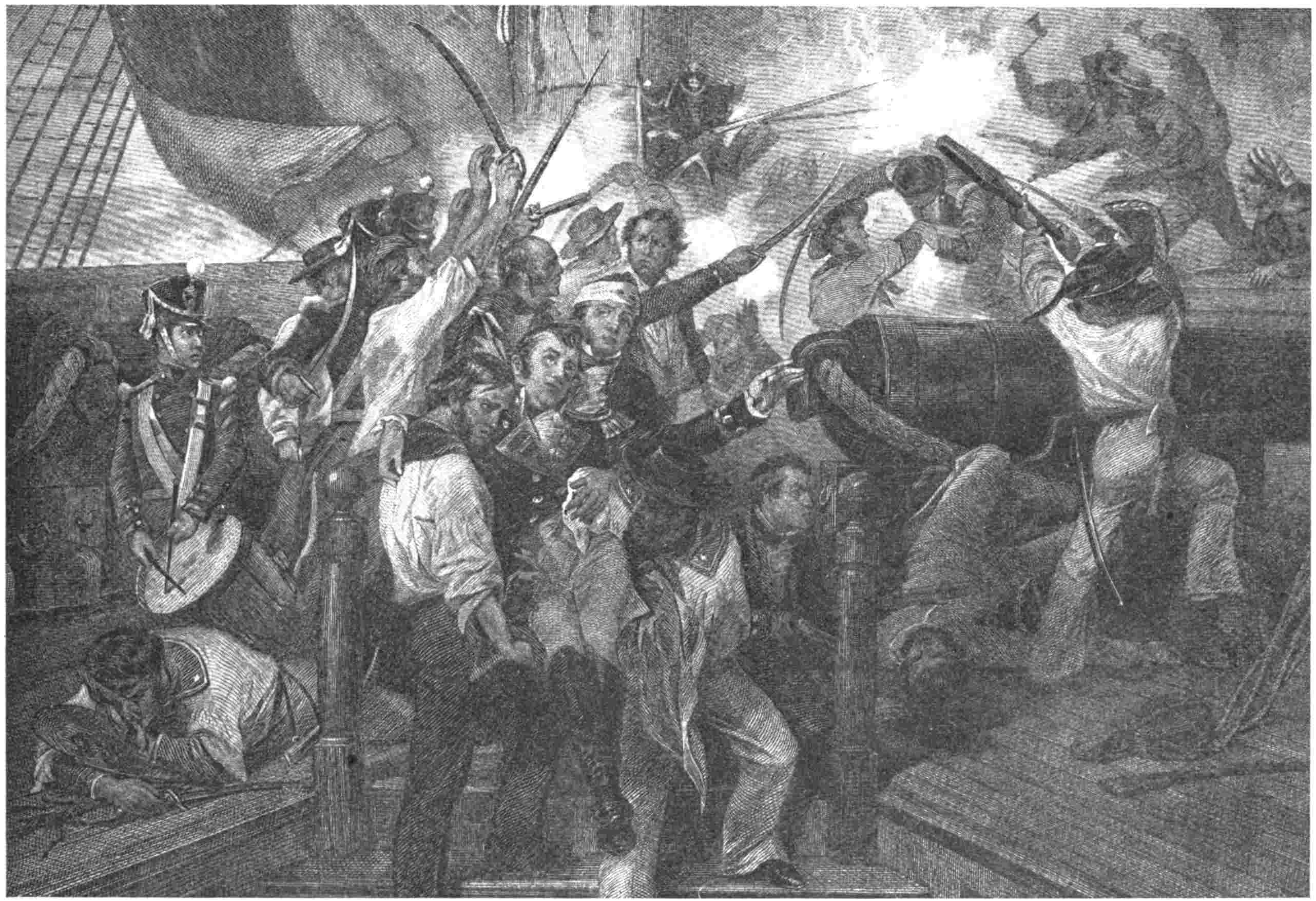

| The Fight on the Chesapeake’s Forecastle. (From a lithograph in the “Memoir of Admiral Broke”), | 223 |

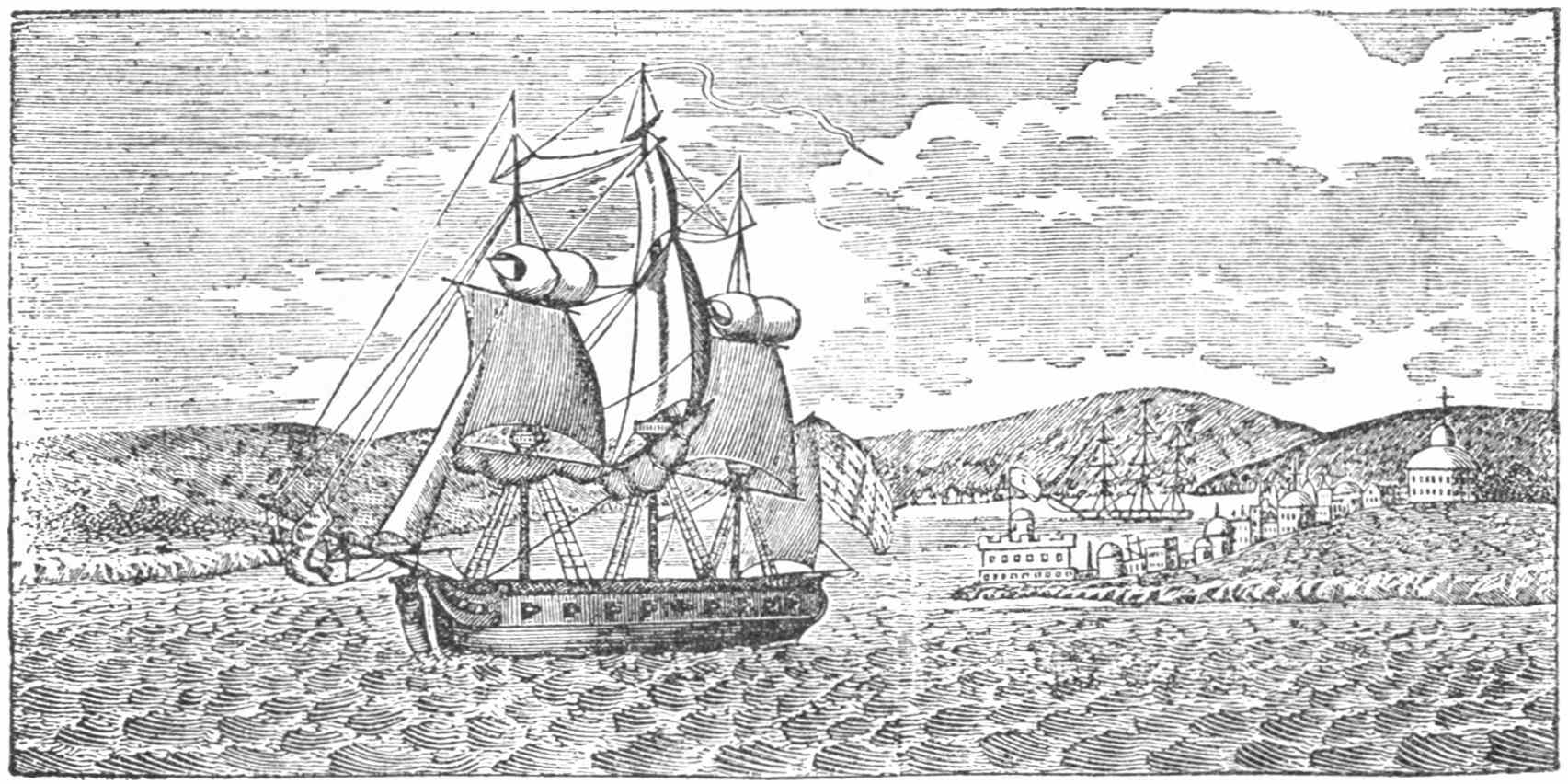

| The Shannon taking the Chesapeake into Halifax Harbor. (From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington), | 227 |

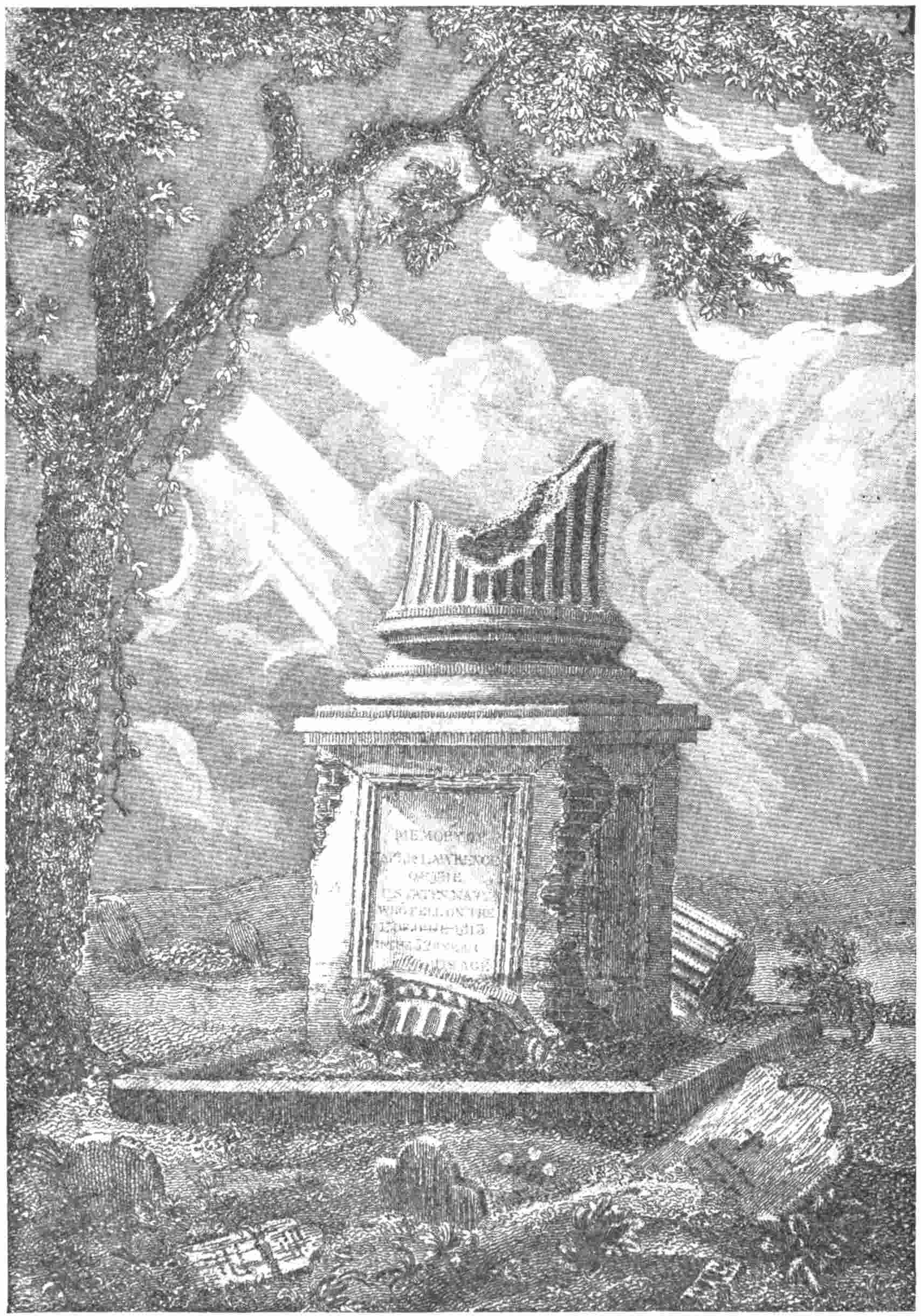

| “In Memory of Captain James Lawrence.” (From an old engraving), | 231 |

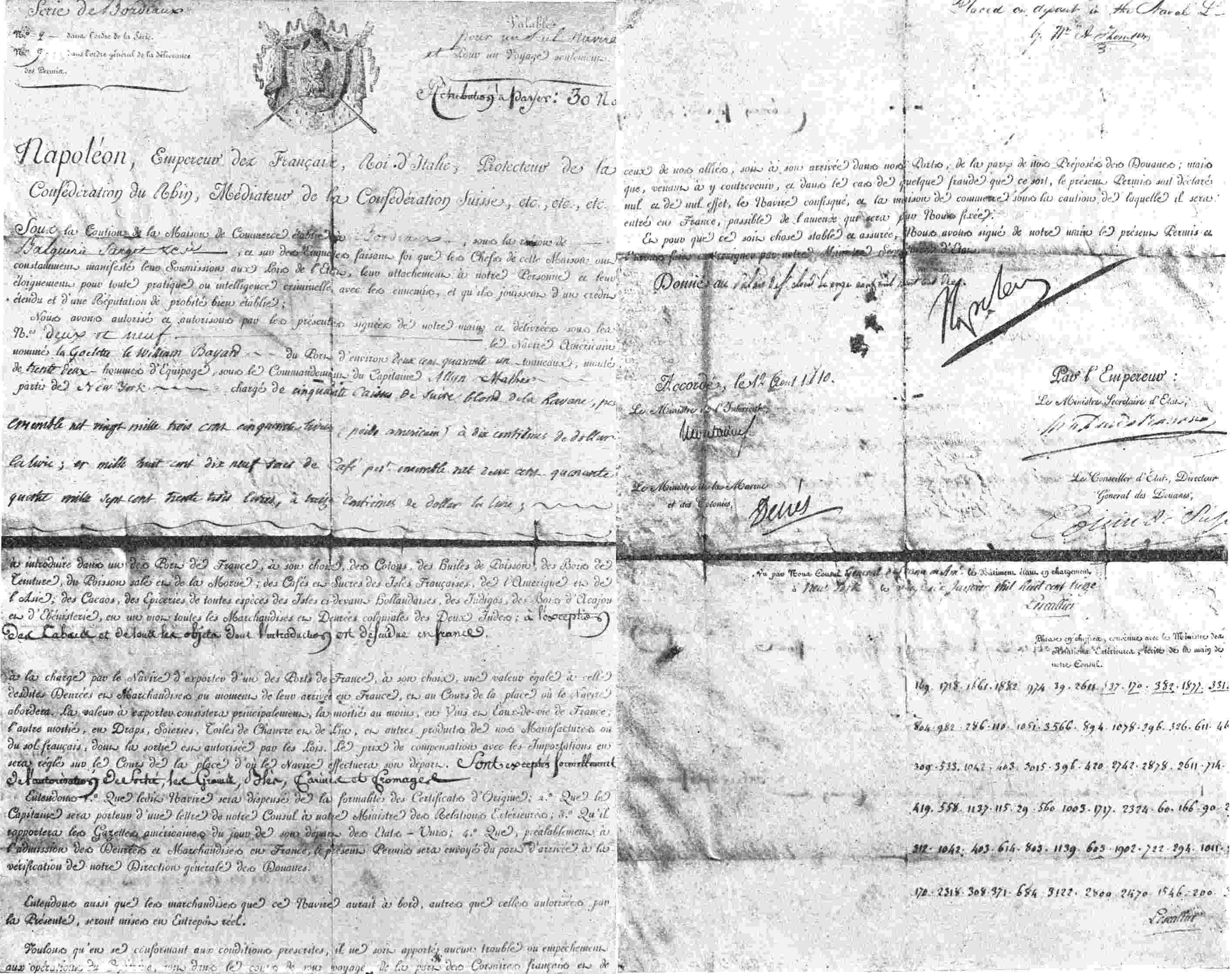

| Ship’s Papers of the William Bayard in 1810, signed by Napoleon. (From the original at the Naval Institute, Annapolis), | 236–7 |

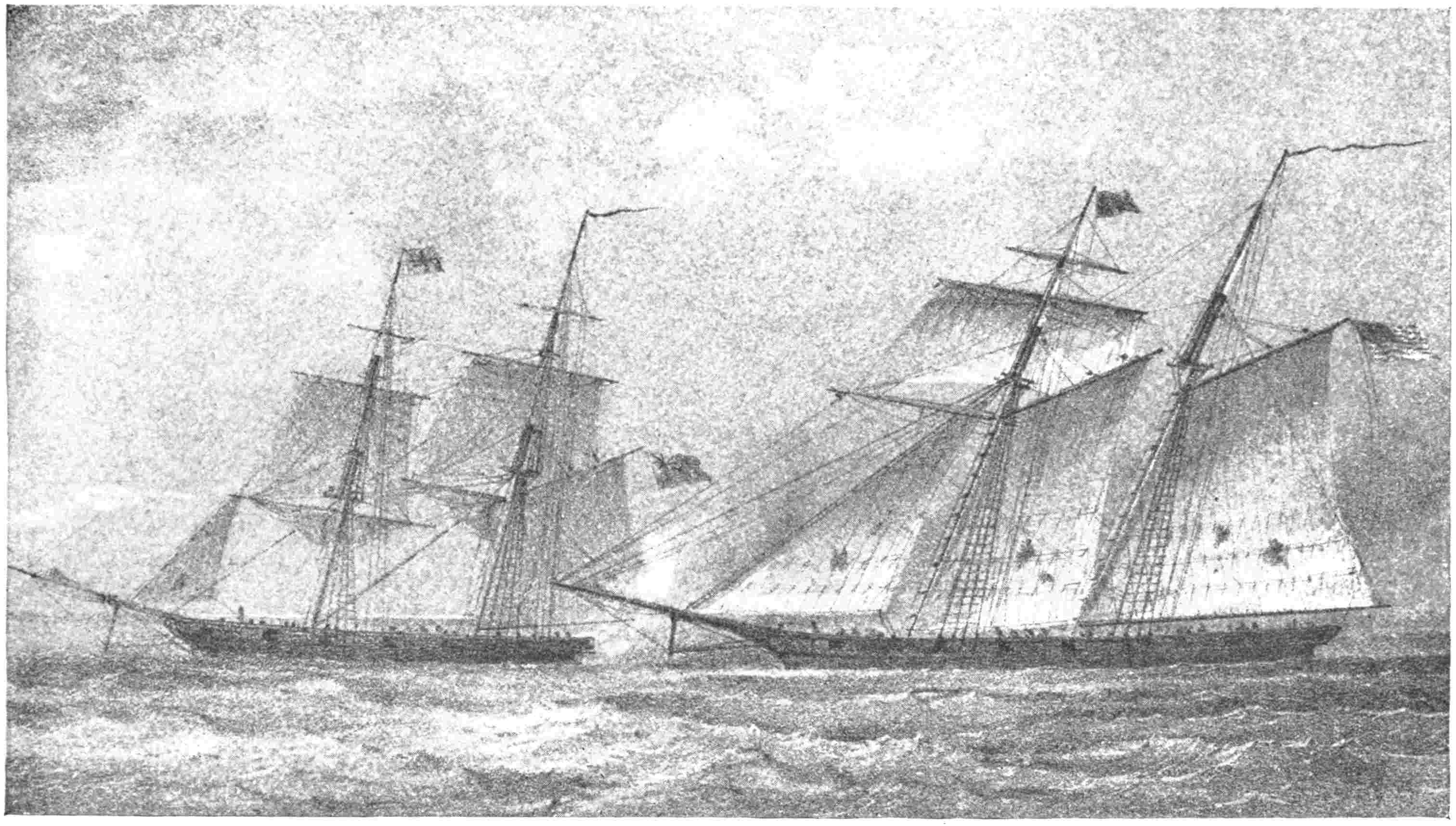

| Battle between the Schooner Atlas and two British Ships, August 5, 1812. (From a lithograph in Coggeshall’s “Privateers”), | 243 |

| The Rossie and the Princess Amelia. (From a lithograph in Coggeshall’s “Privateers”), | 249 |

| Battle between the Schooner Saratoga and the Brig Rachel. (From a lithograph in Coggeshall’s “Privateers”), | 255 |

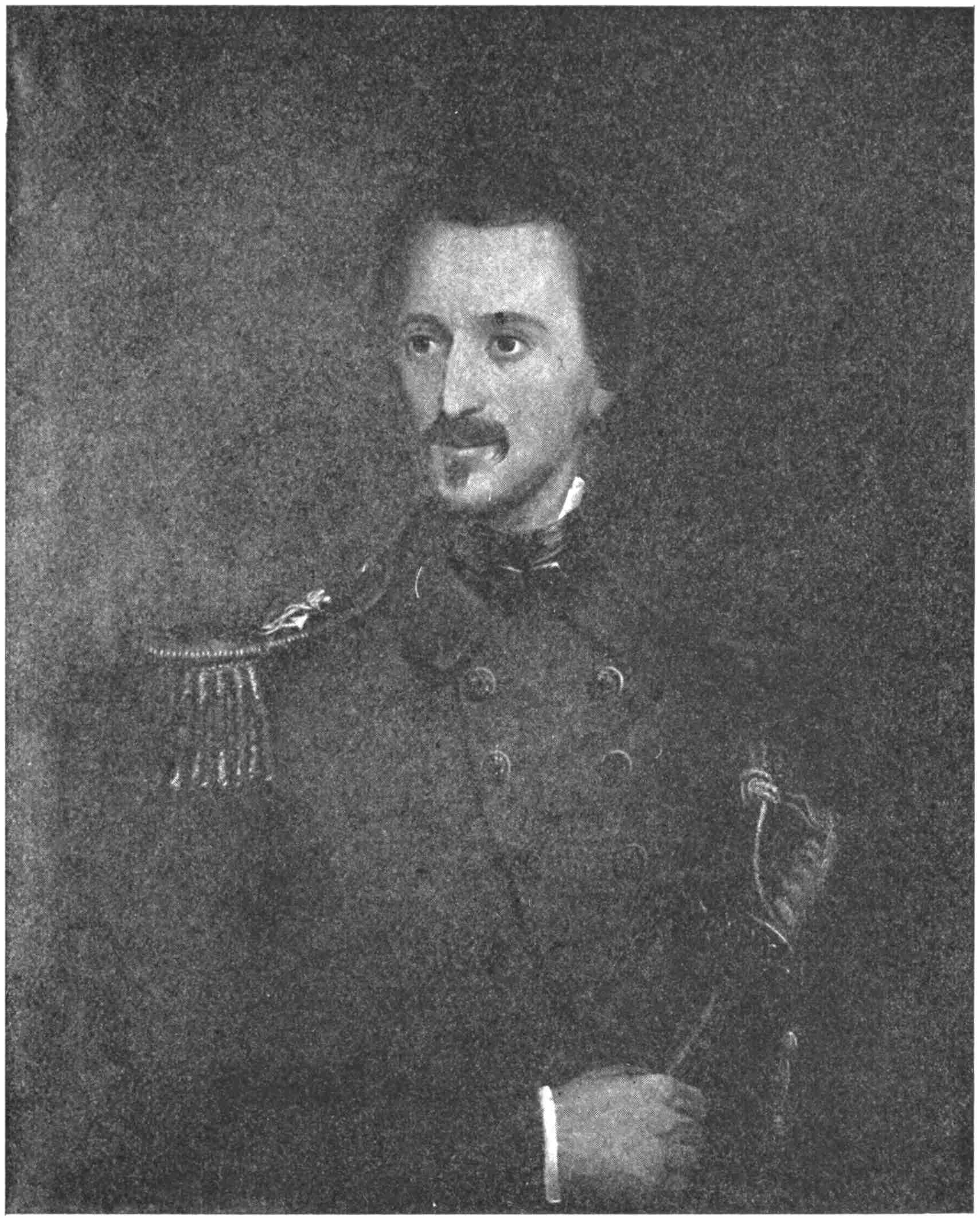

| Jesse D. Elliott. (From a lithograph at the Navy Department, Washington), | 260 |

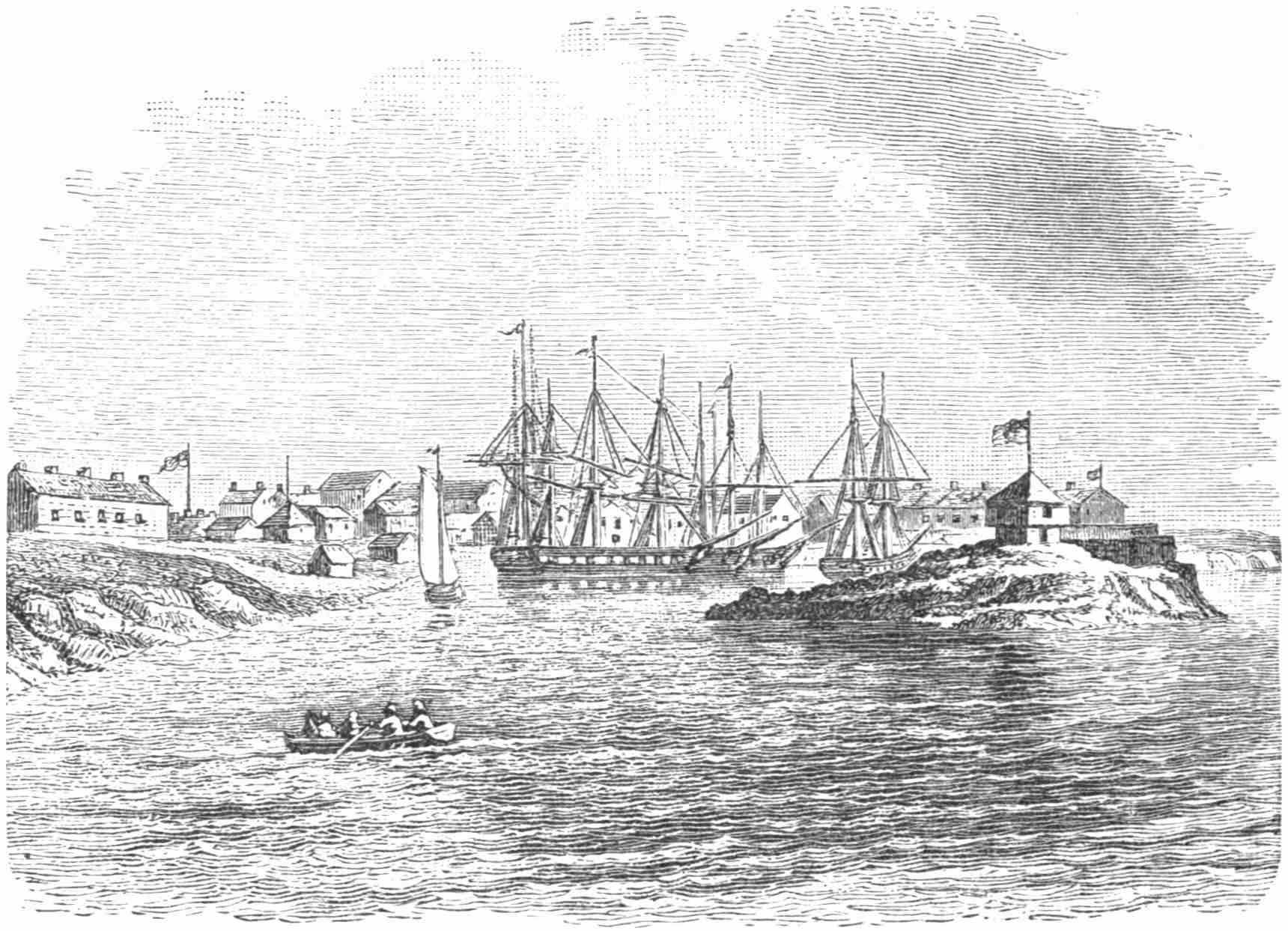

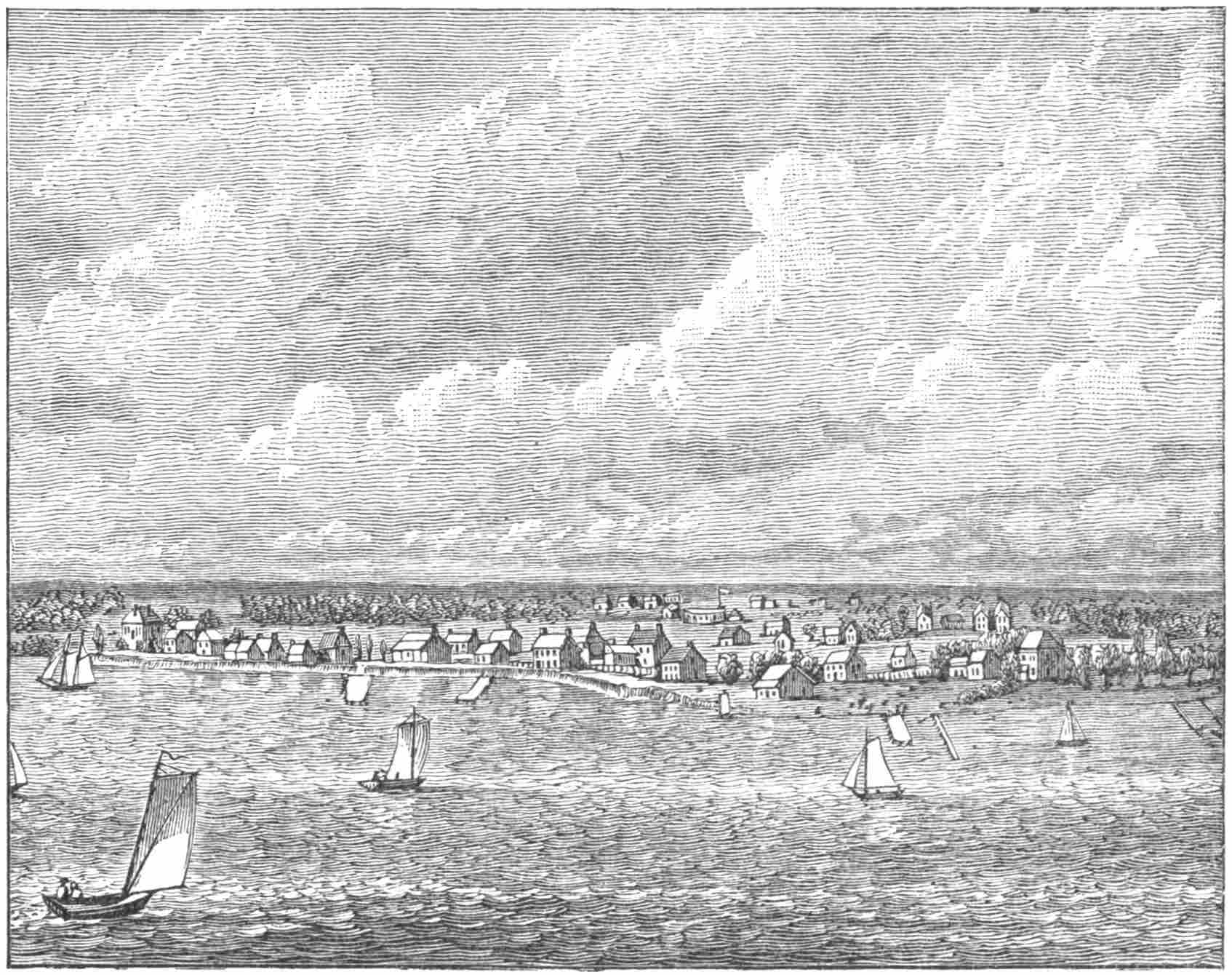

| Sackett’s Harbor, 1814. (After an old engraving), | 264 |

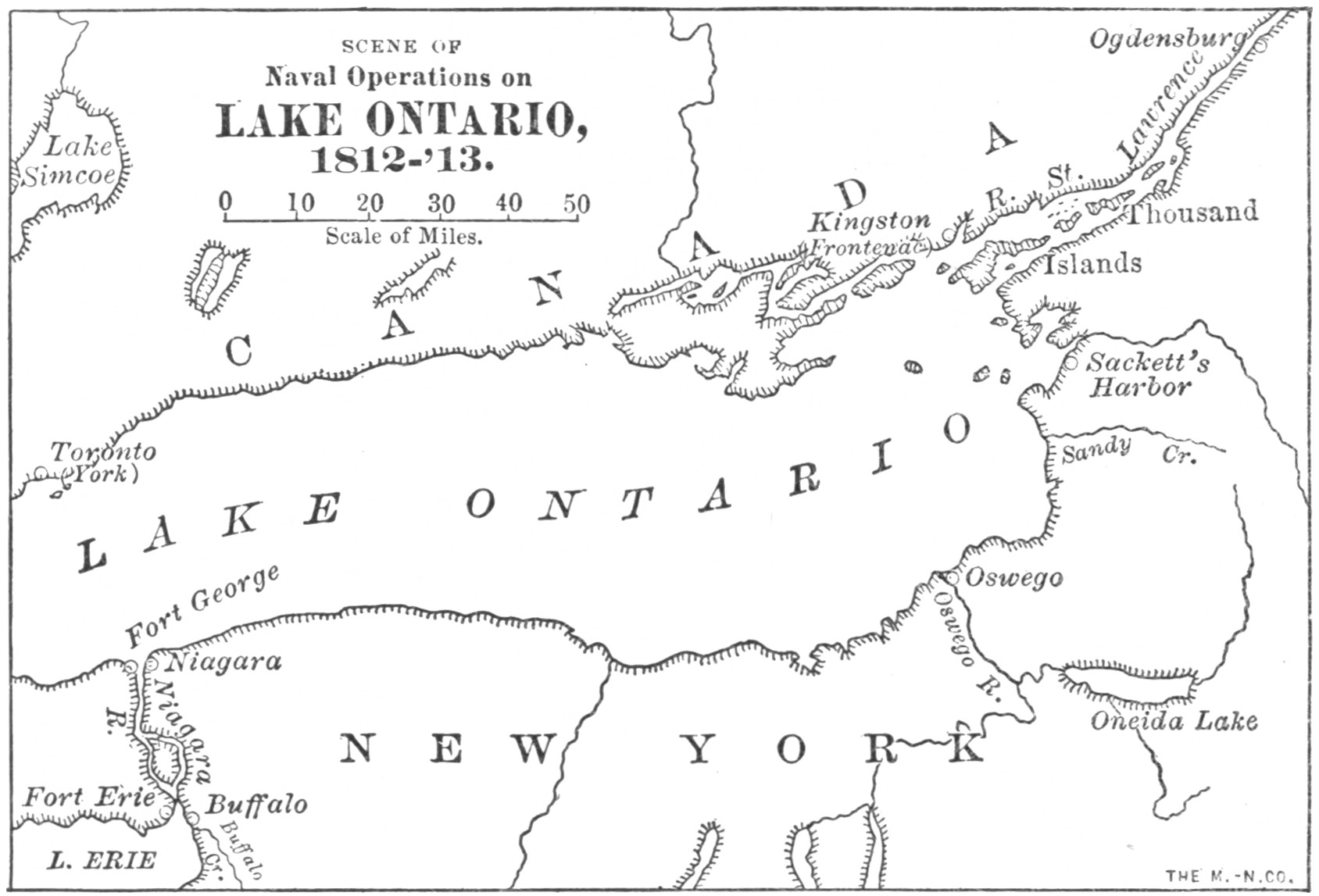

| Map, Scene of Naval Operations on Lake Ontario, 1812–1813, | 266 |

| Captain Woolsey. (From a painting at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 269 |

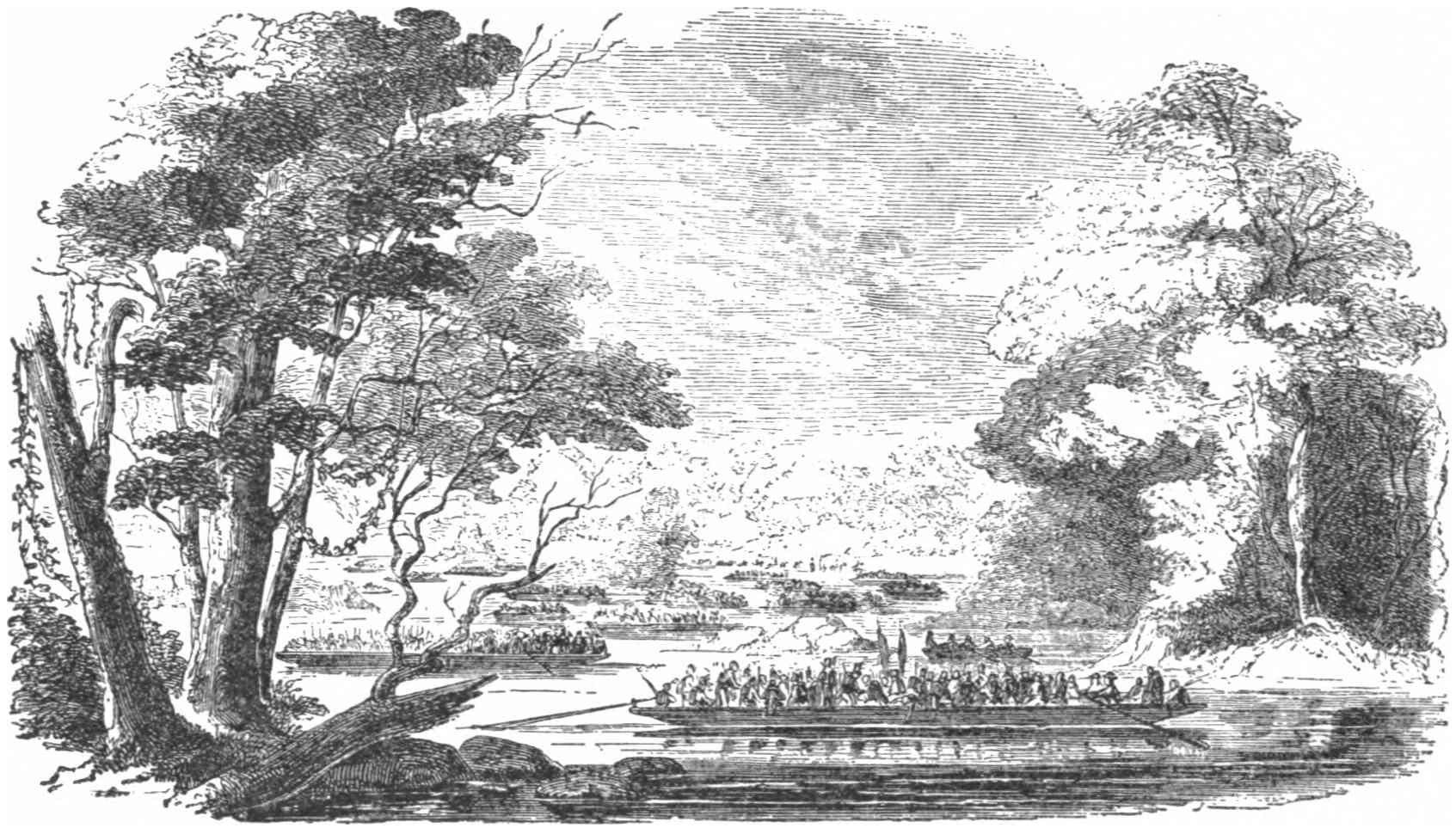

| Wilkinson’s Flotilla. (From an old wood-cut), | 272 |

| Detroit in 1815. (After an old engraving), | 274xix |

| Capture of the British Brigs Detroit and Caledonia, October 12, 1812. (From a wood-cut prepared under the supervision of Lieutenant Jesse D. Elliott himself), | 277 |

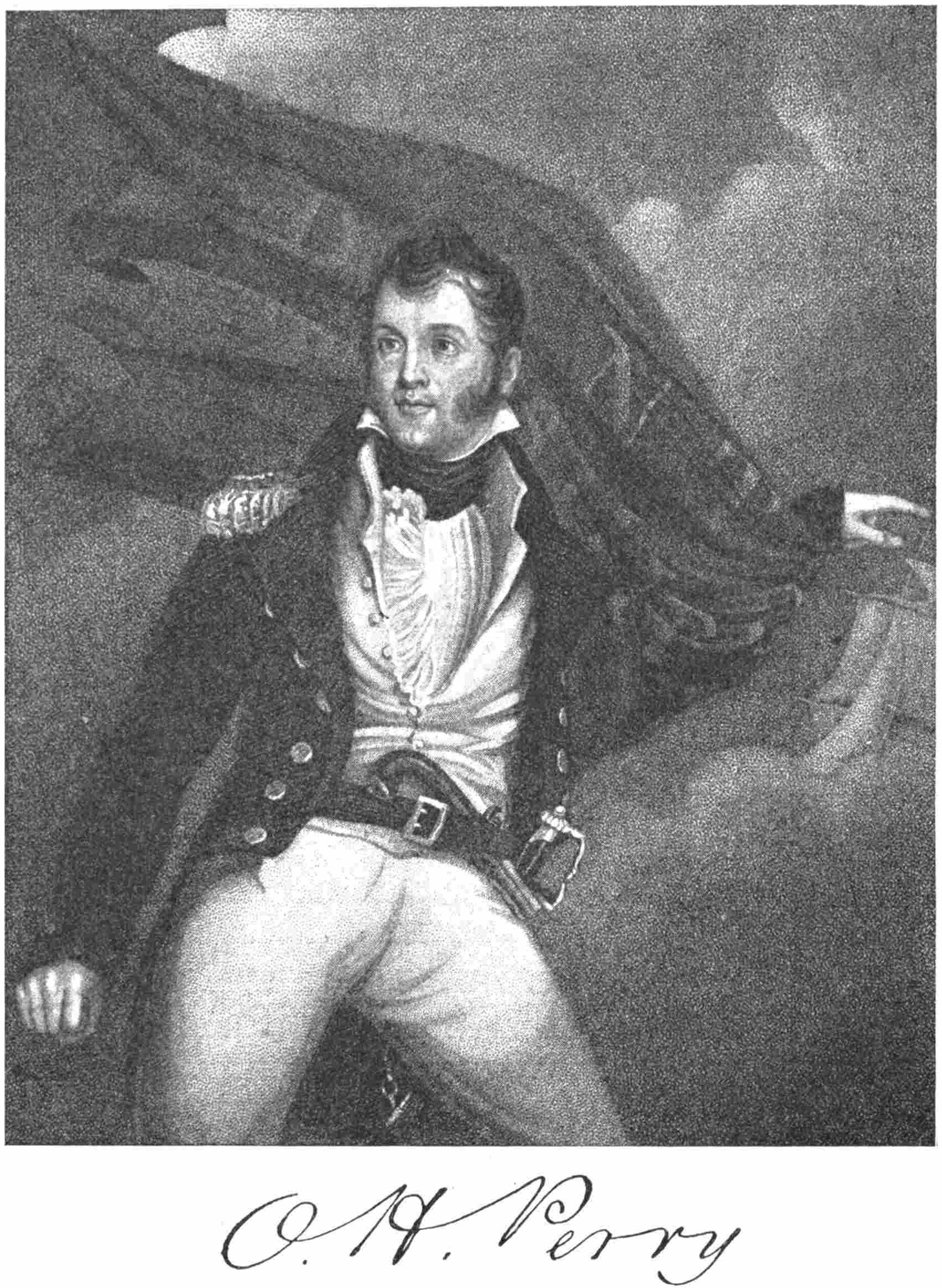

| O. H. Perry. (From an engraving by Forrest of the portrait by Jarvis), | 281 |

| Port of Buffalo in 1815. (After a contemporary engraving), | 284–5 |

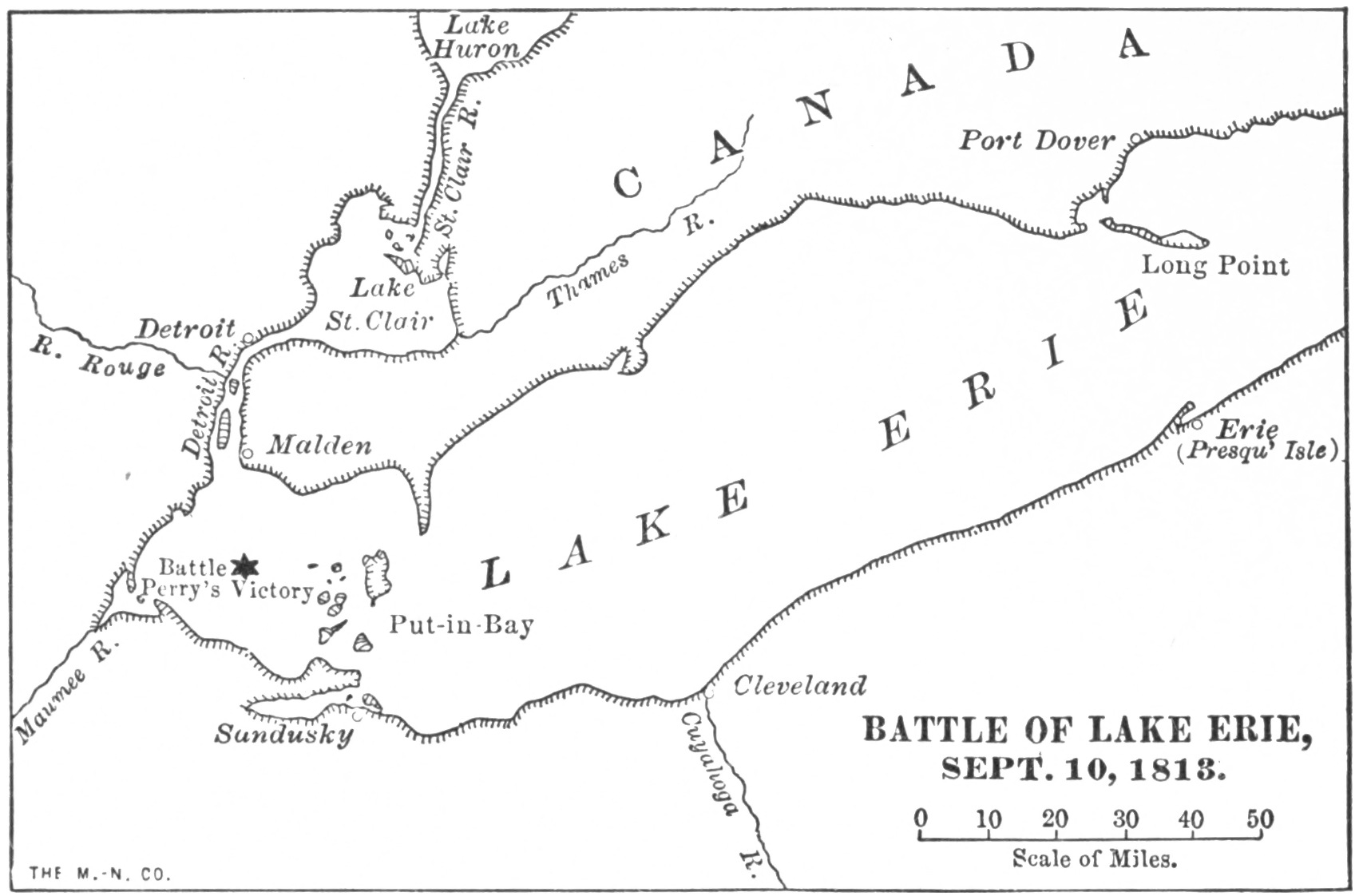

| Map of the Battle of Lake Erie, | 293 |

| Perry and his Officers on Board the Flag-ship Lawrence, Preparing for the Engagement. (From an old wood-cut), | 303 |

| Diagram of Perry’s Victory—the Approach. (After Ward’s “Naval Tactics”), | 304 |

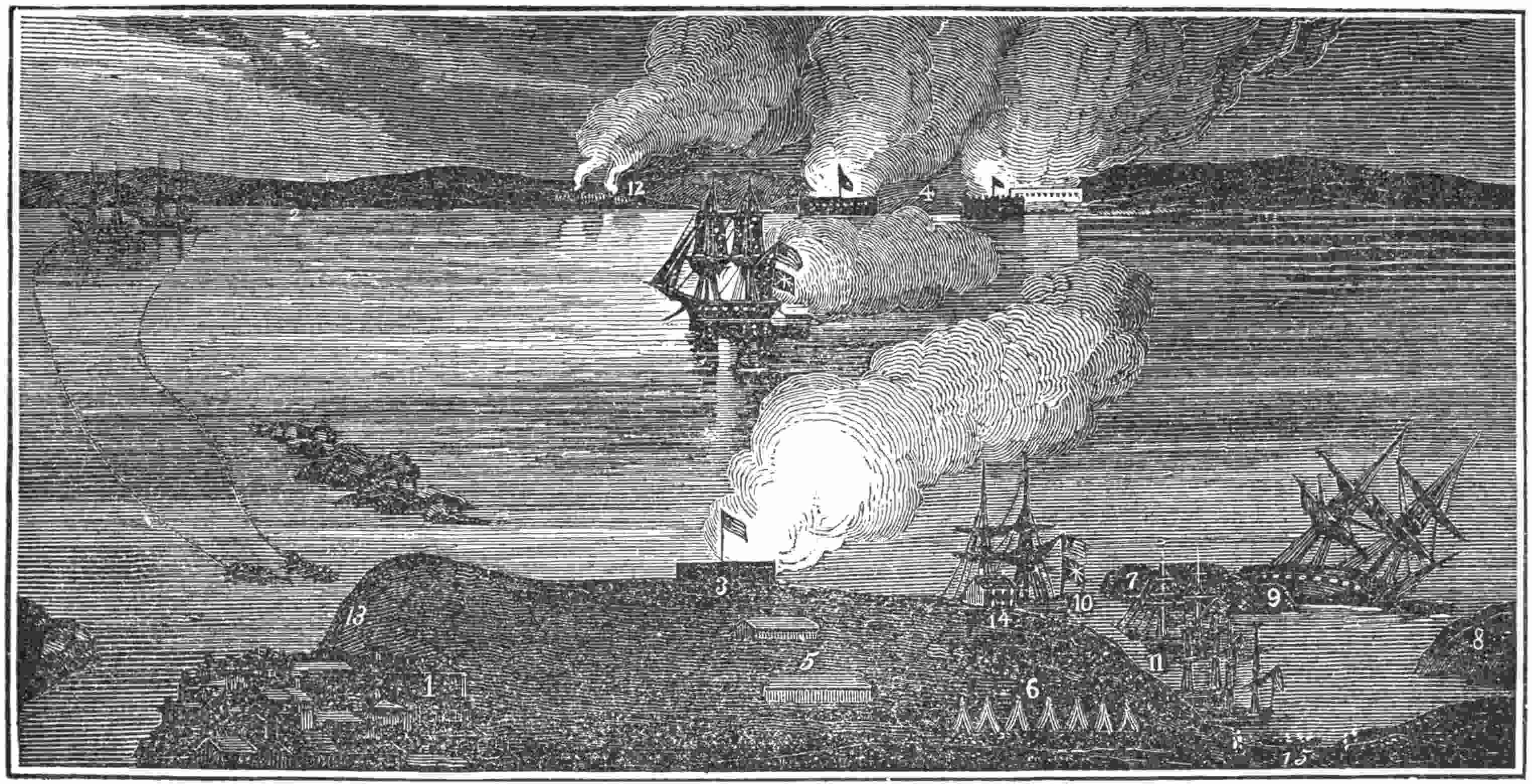

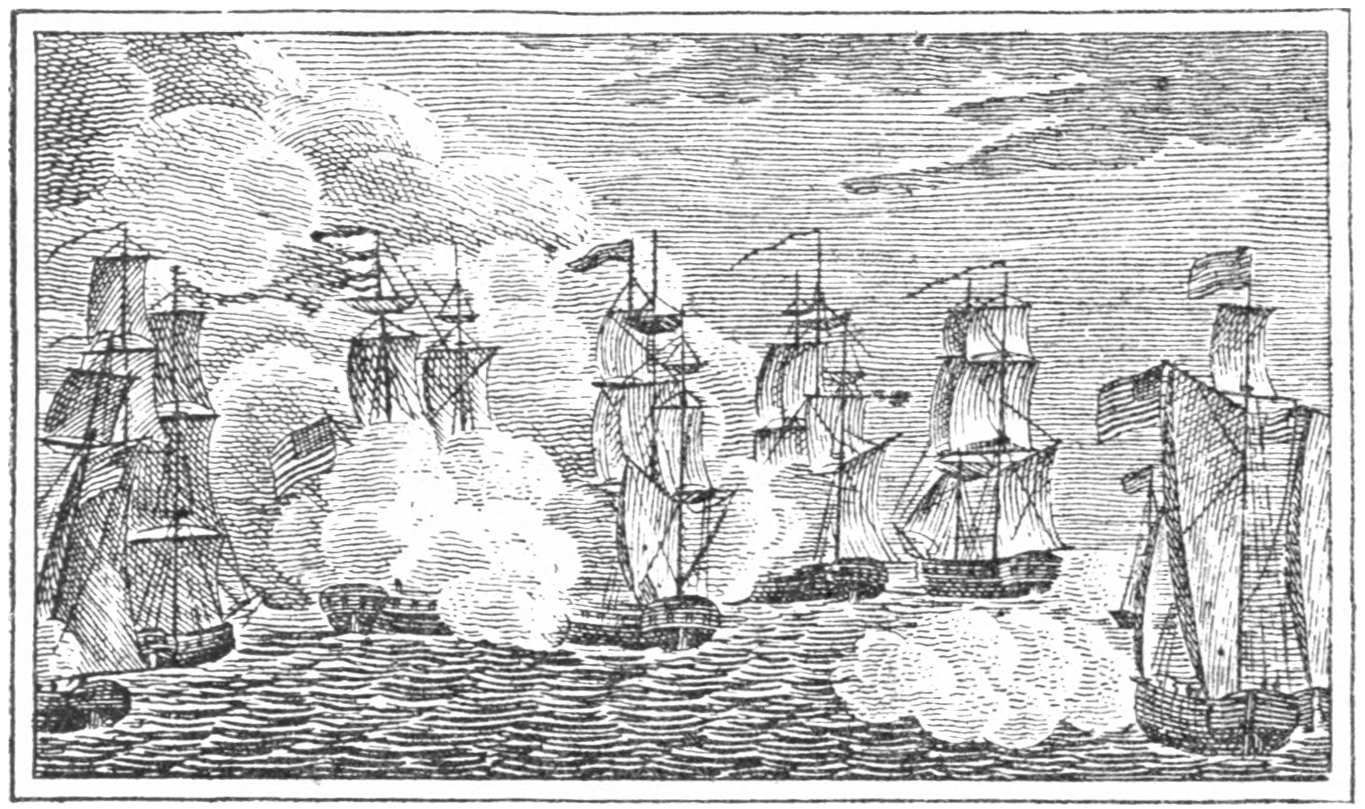

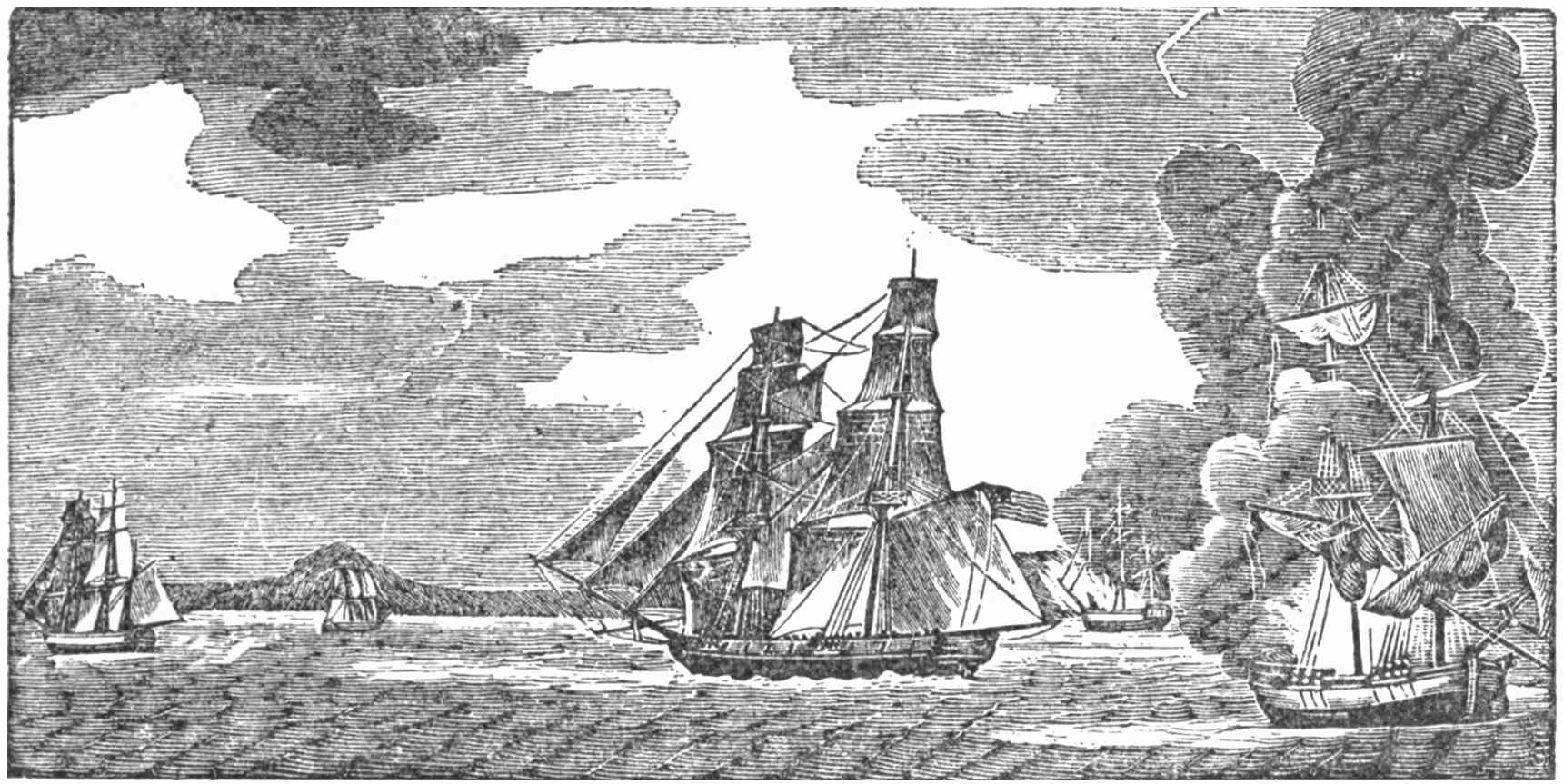

| The Battle of Lake Erie. (From an old engraving), | 308 |

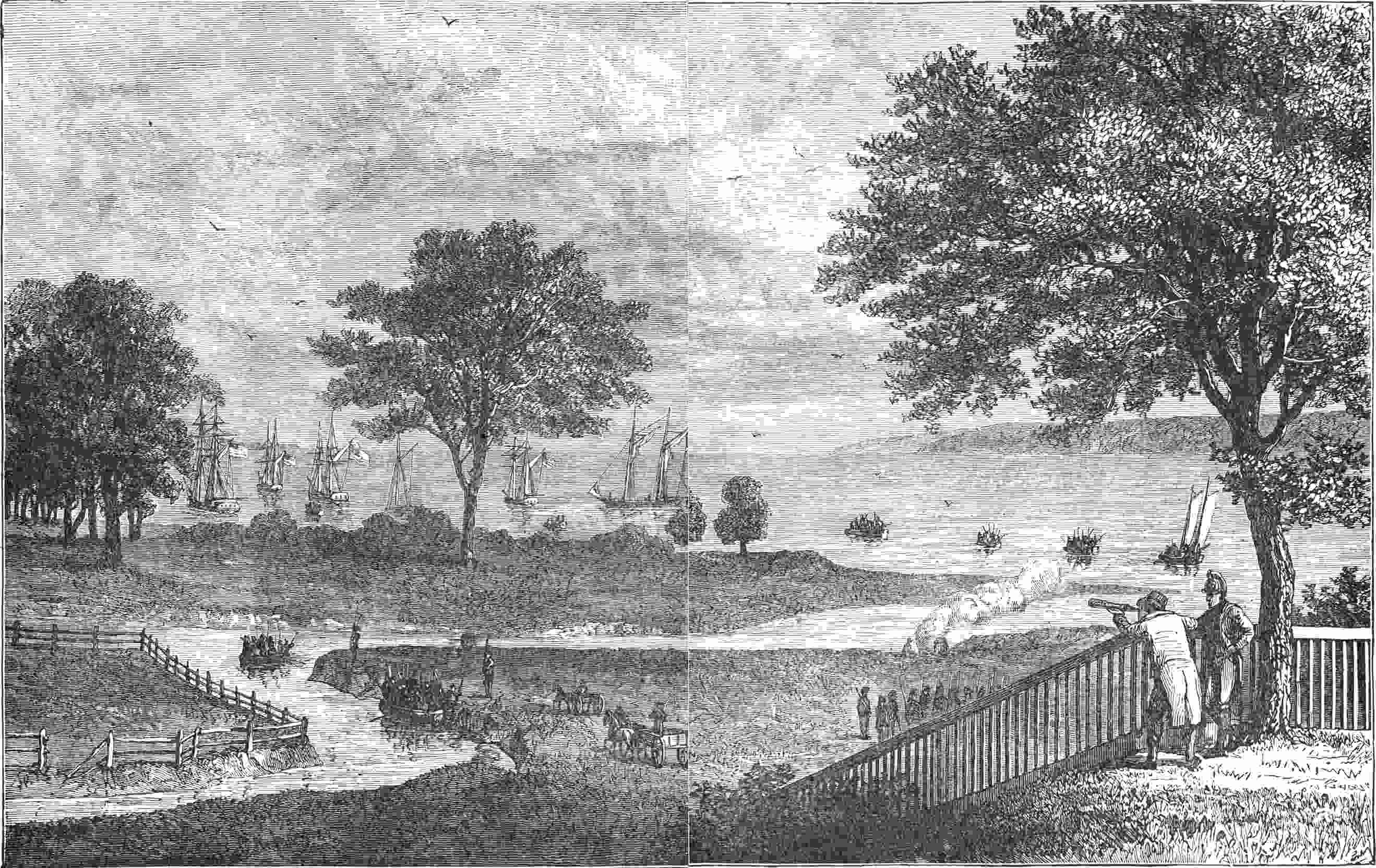

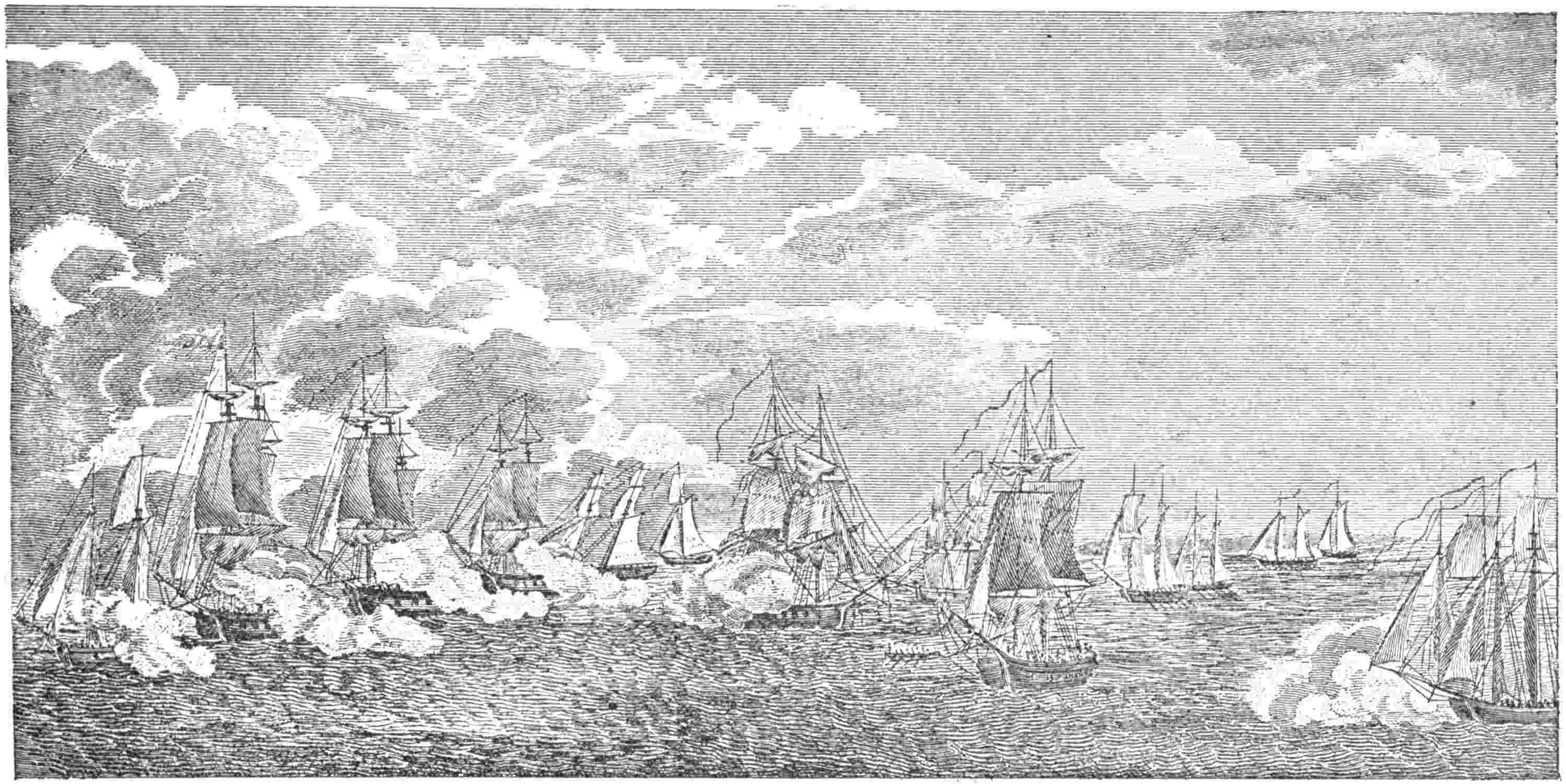

| First View of Perry’s Victory. (From an engraving of a drawing by Corné), | 310 |

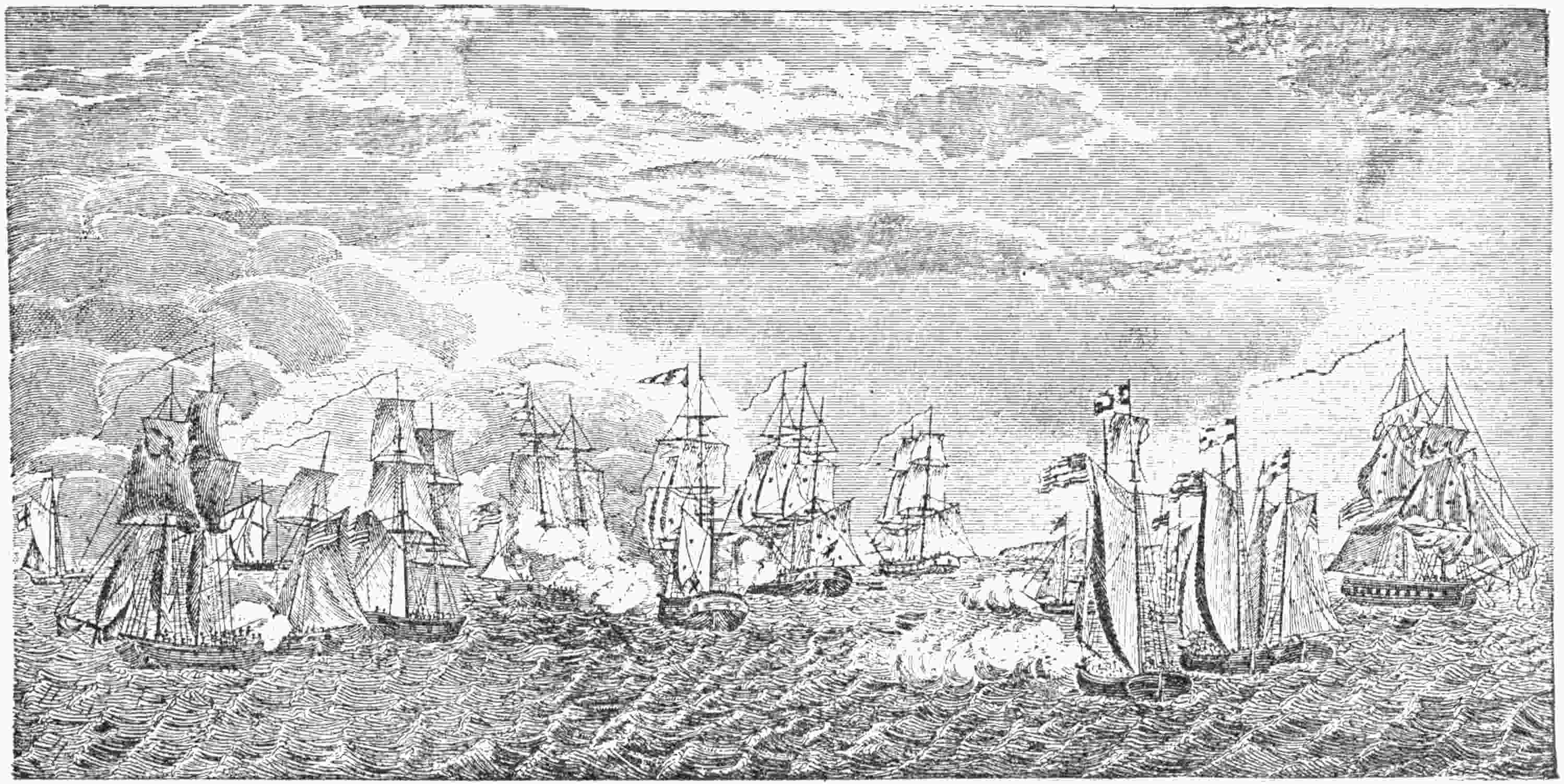

| “Perry’s Sieg.”—A German View of the Victory on Lake Erie. (From an old engraving), | 312 |

| Diagram of Perry’s Victory.—Positions at Height of Battle, | 314 |

| Second View of Perry’s Victory. (From an engraving of a drawing by Corné), | 316 |

| Perry Transferring his Colors. (After the painting by Powell), | 319 |

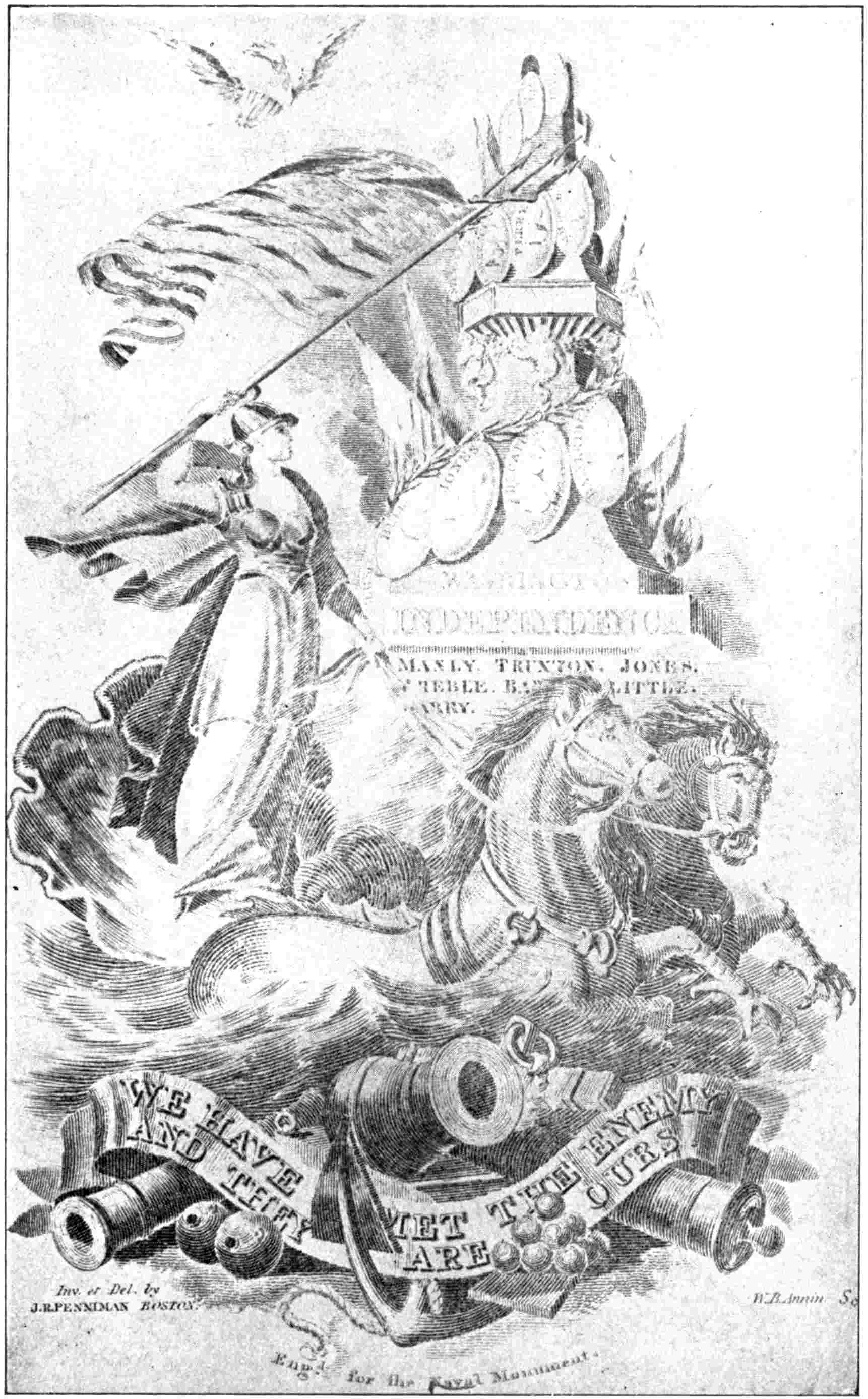

| “We have met the Enemy and they are Ours.” (From the “Naval Monument”), | 324 |

| Stephen Champlin. (From a painting at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 327 |

| The Medal Awarded to Oliver H. Perry after his Victory on Lake Erie, | 334 |

| Medal Awarded to Jesse D. Elliott, | 335 |

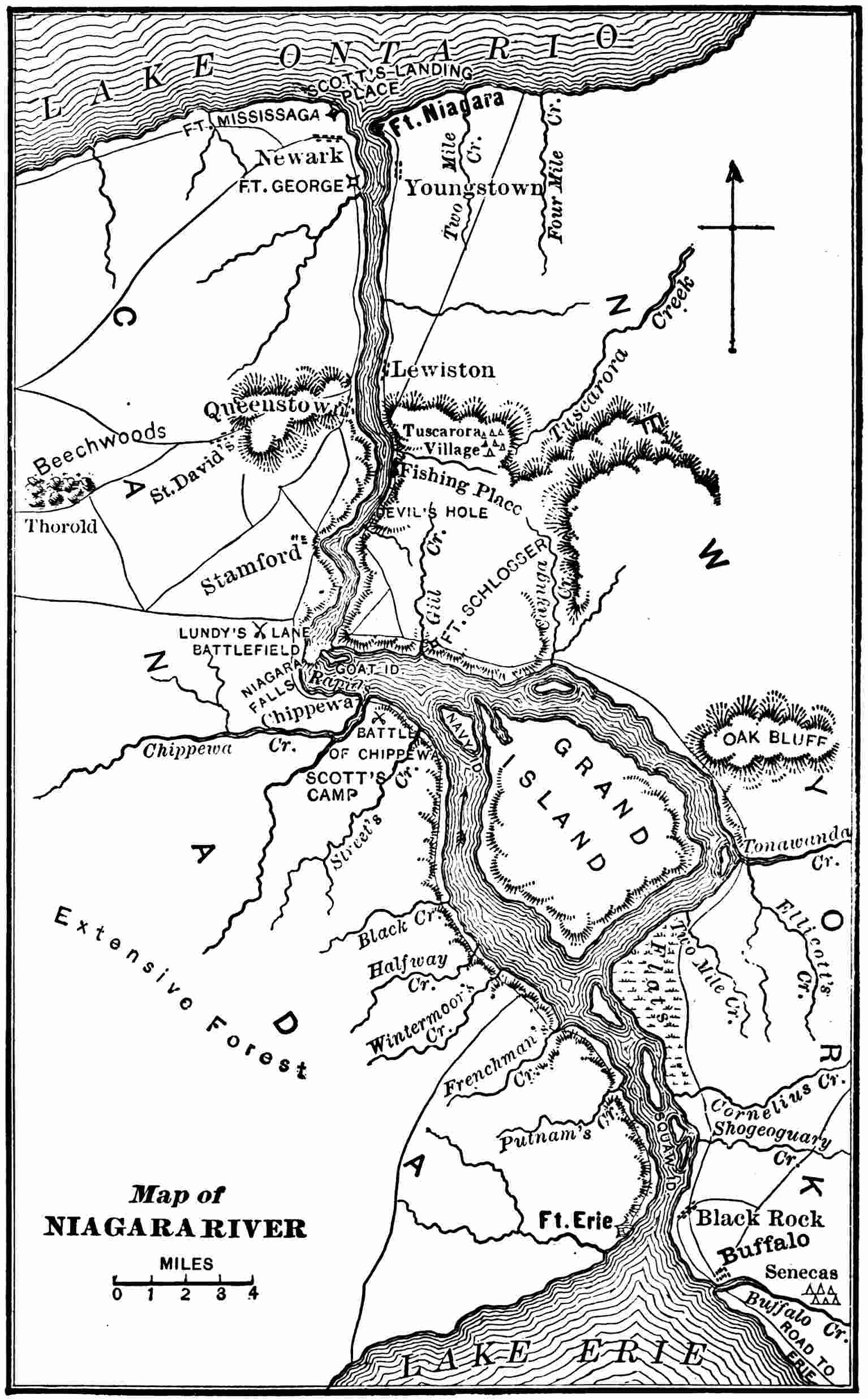

| Map of Niagara River, | 340 |

| The Death of General Pike. (From an old wood-cut), | 342 |

| The Niagara River and Scenes from the War of 1812. (From an engraving in Hinton’s “History of the United States”), | 343 |

| Isaac Chauncey. (From an engraving by Edwin of the portrait by Wood), | 345 |

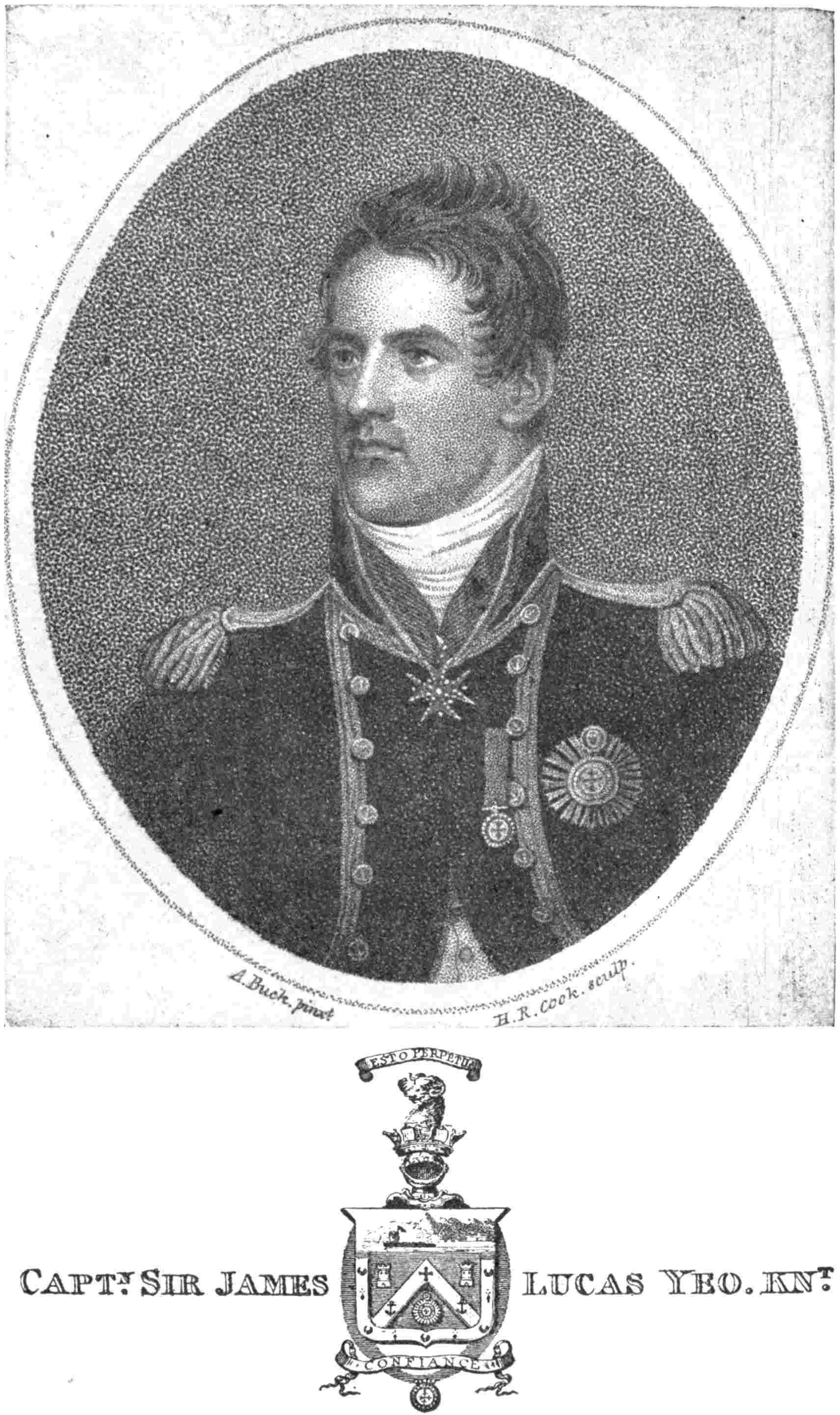

| Captain Sir James Lucas Yeo. (From an engraving by Cook of the portrait by Buck), | 347 |

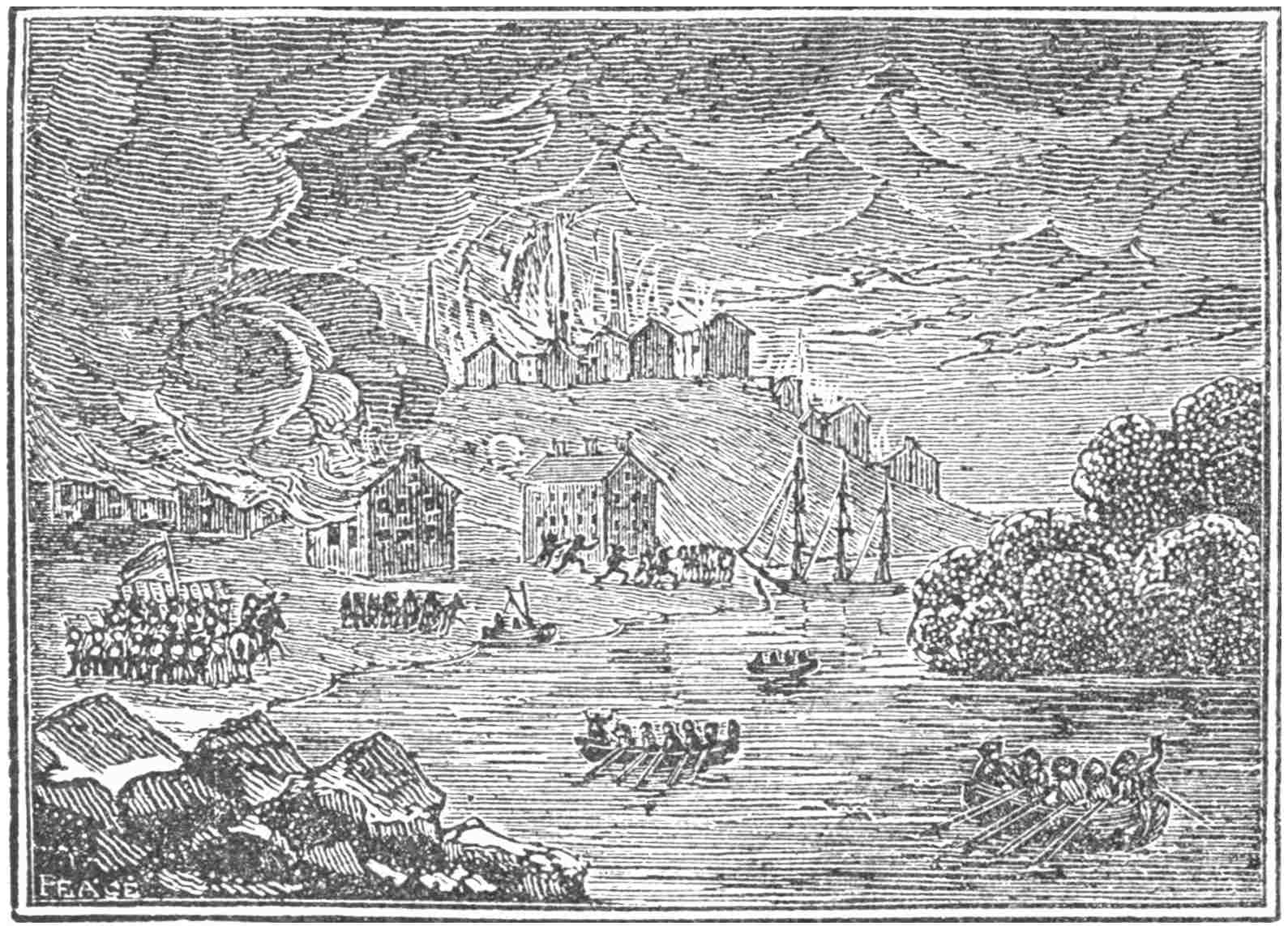

| Buffalo, N. Y., Burned by the British, December 30, 1813. (From an old wood-cut), | 354xx |

| The Argus Burning British Vessels. (From an old wood-cut), | 361 |

| The Argus Captured by the Pelican, August 14, 1813. (From an engraving by Sutherland of the painting by Whitcombe), | 365 |

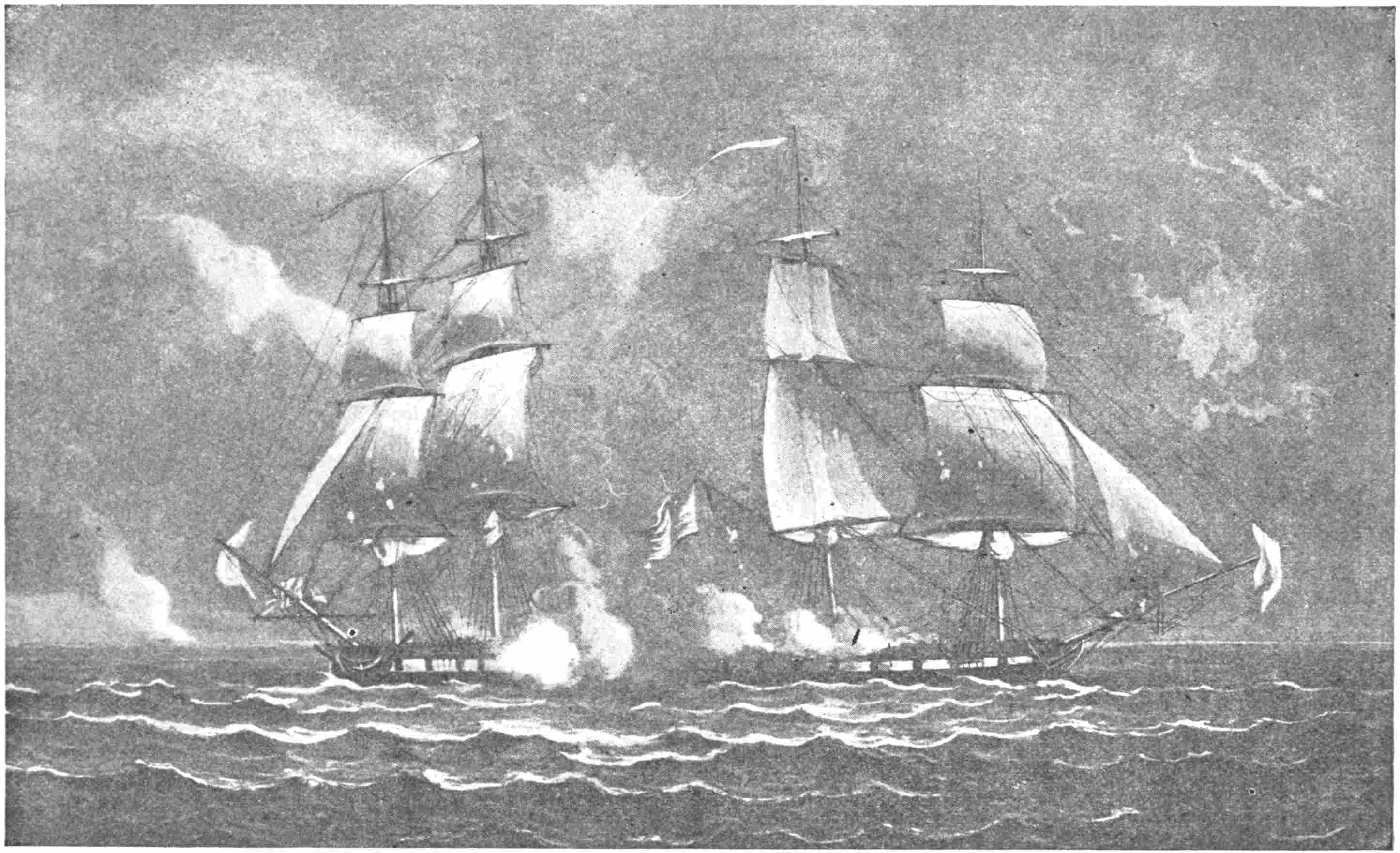

| The Enterprise and Boxer. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 377 |

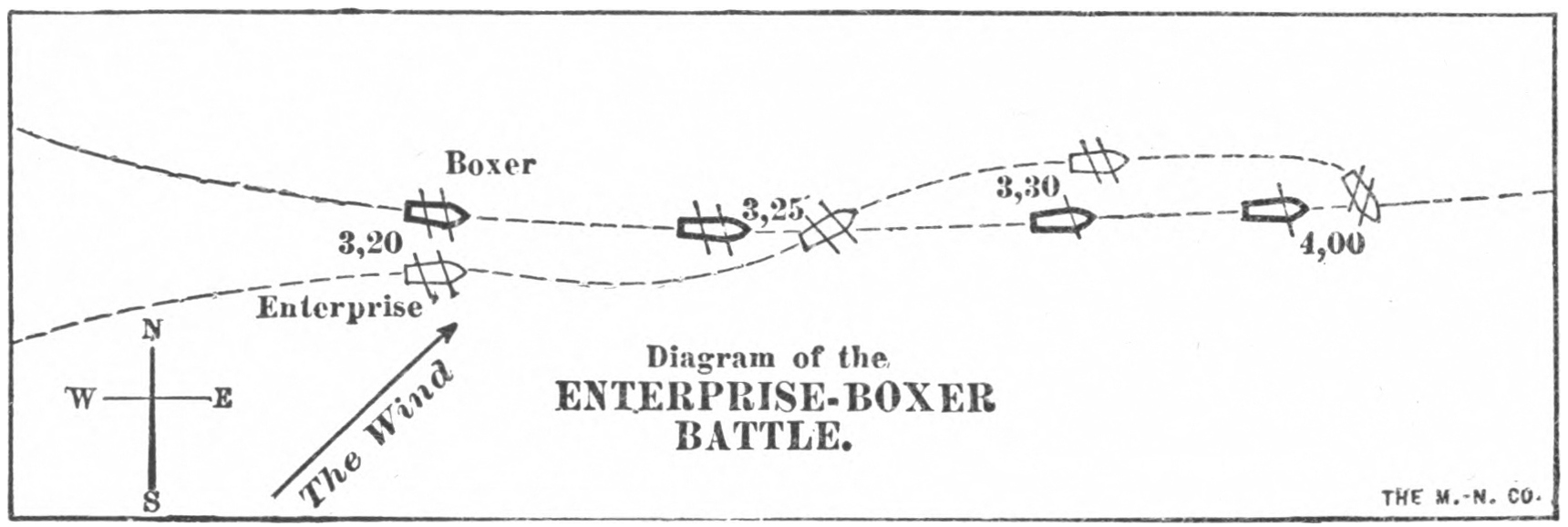

| Diagram of the Enterprise-Boxer Battle, | 378 |

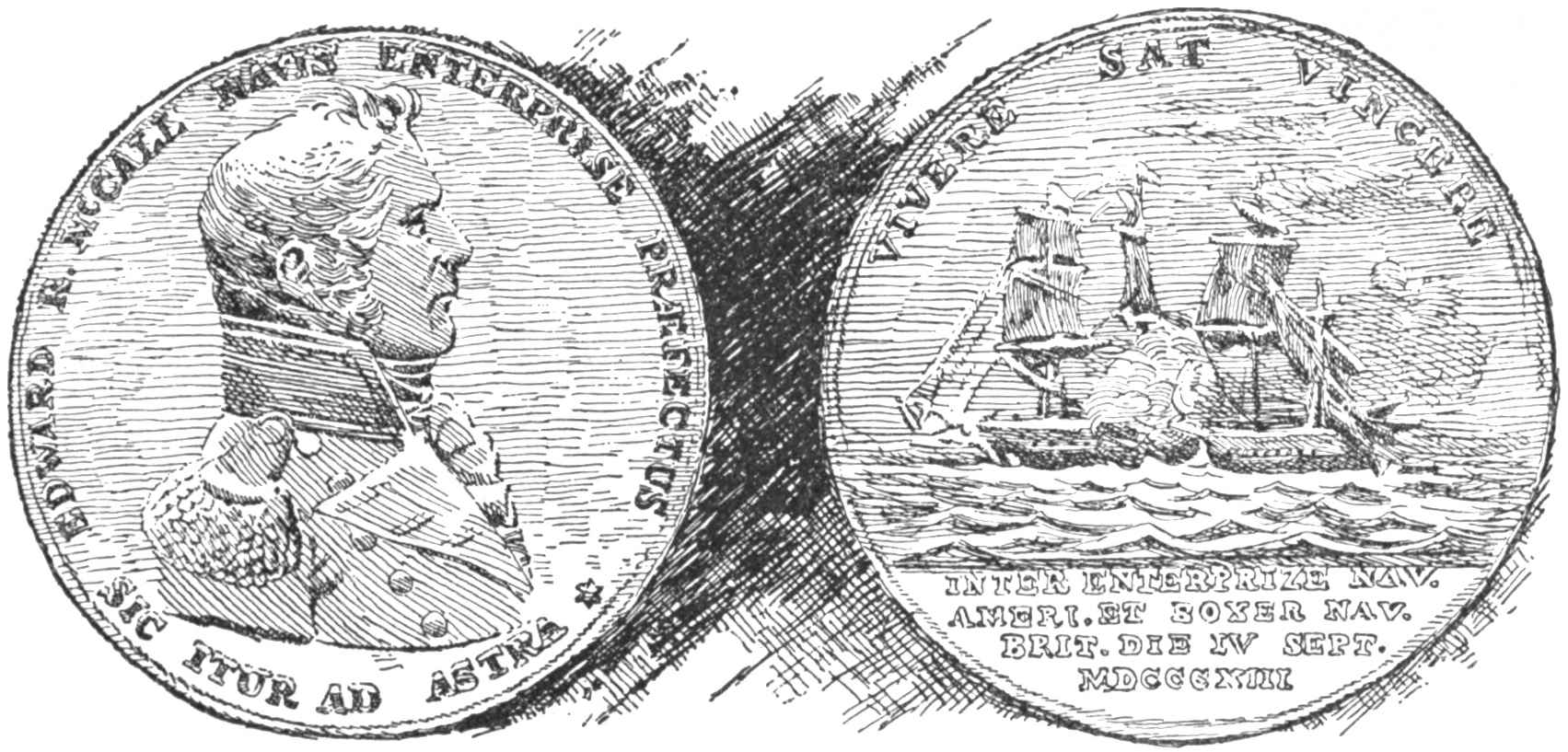

| Medal Awarded to Edward R. McCall after the Battle between the Enterprise and the Boxer, | 385 |

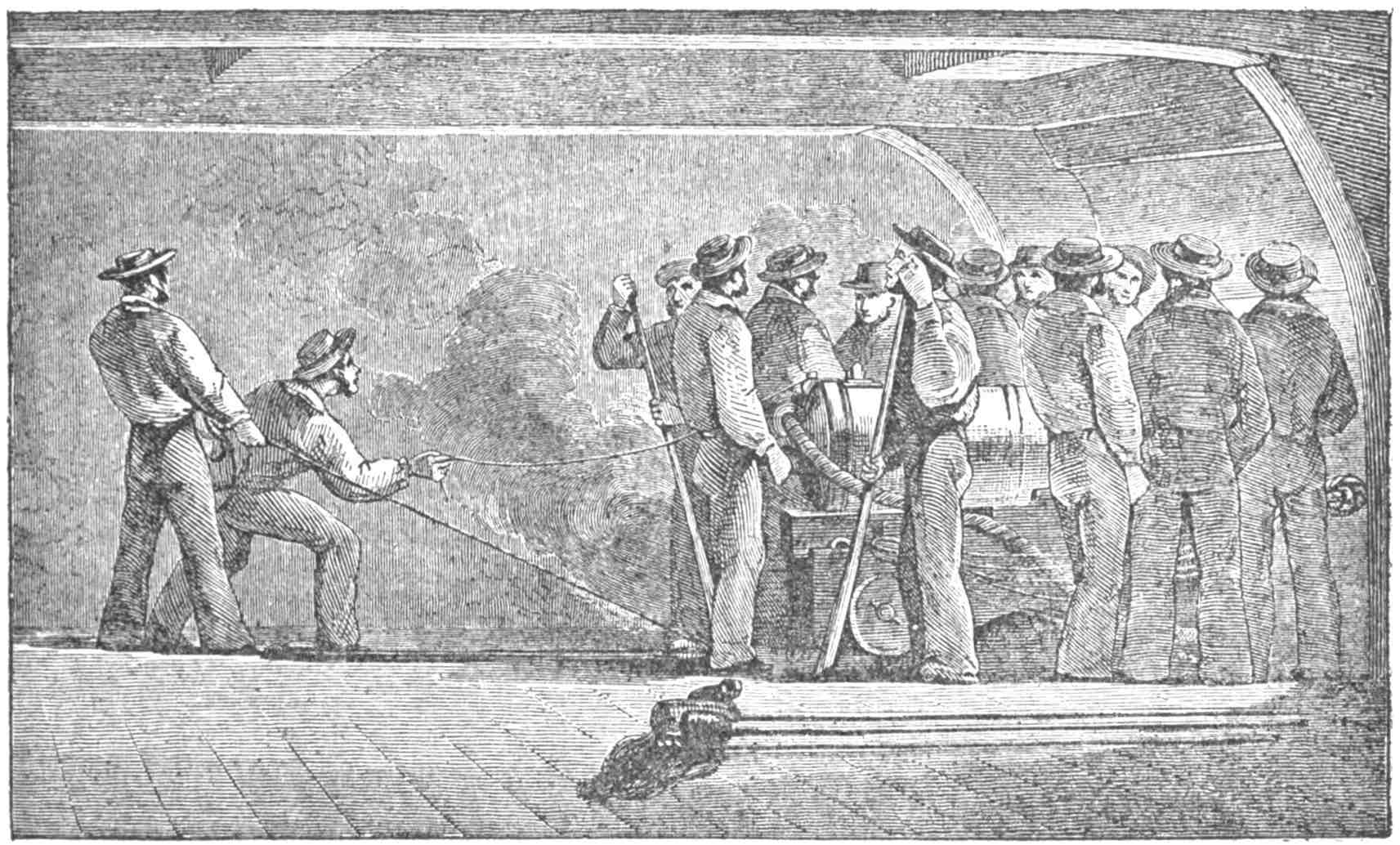

| Old-time Naval Gunnery. (From a wood-cut), | 391 |

| John Cassin. (From a lithograph at the Navy Department, Washington), | 399 |

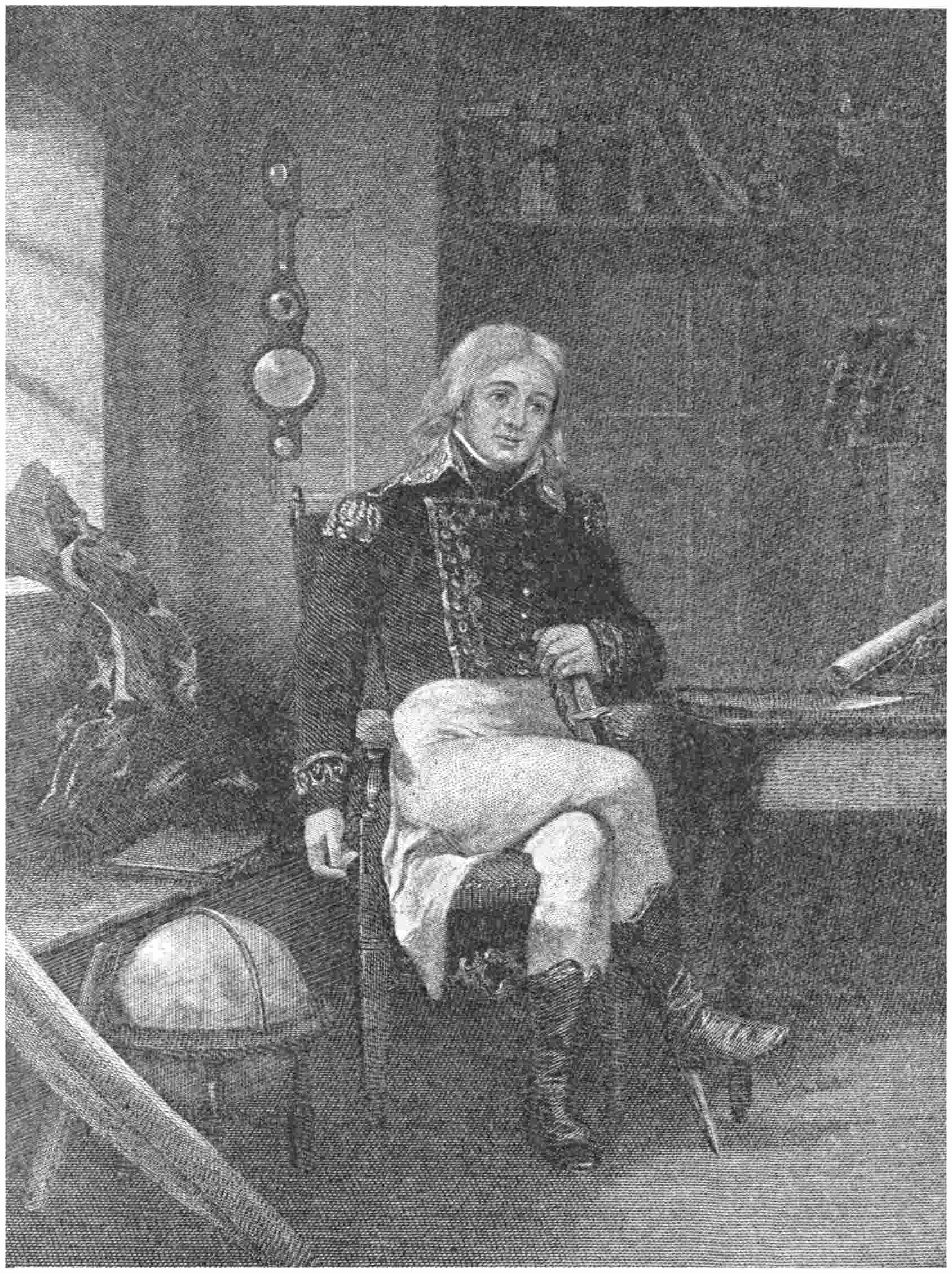

| Joshua Barney. (From an engraving of the painting by Chappel), | 404 |

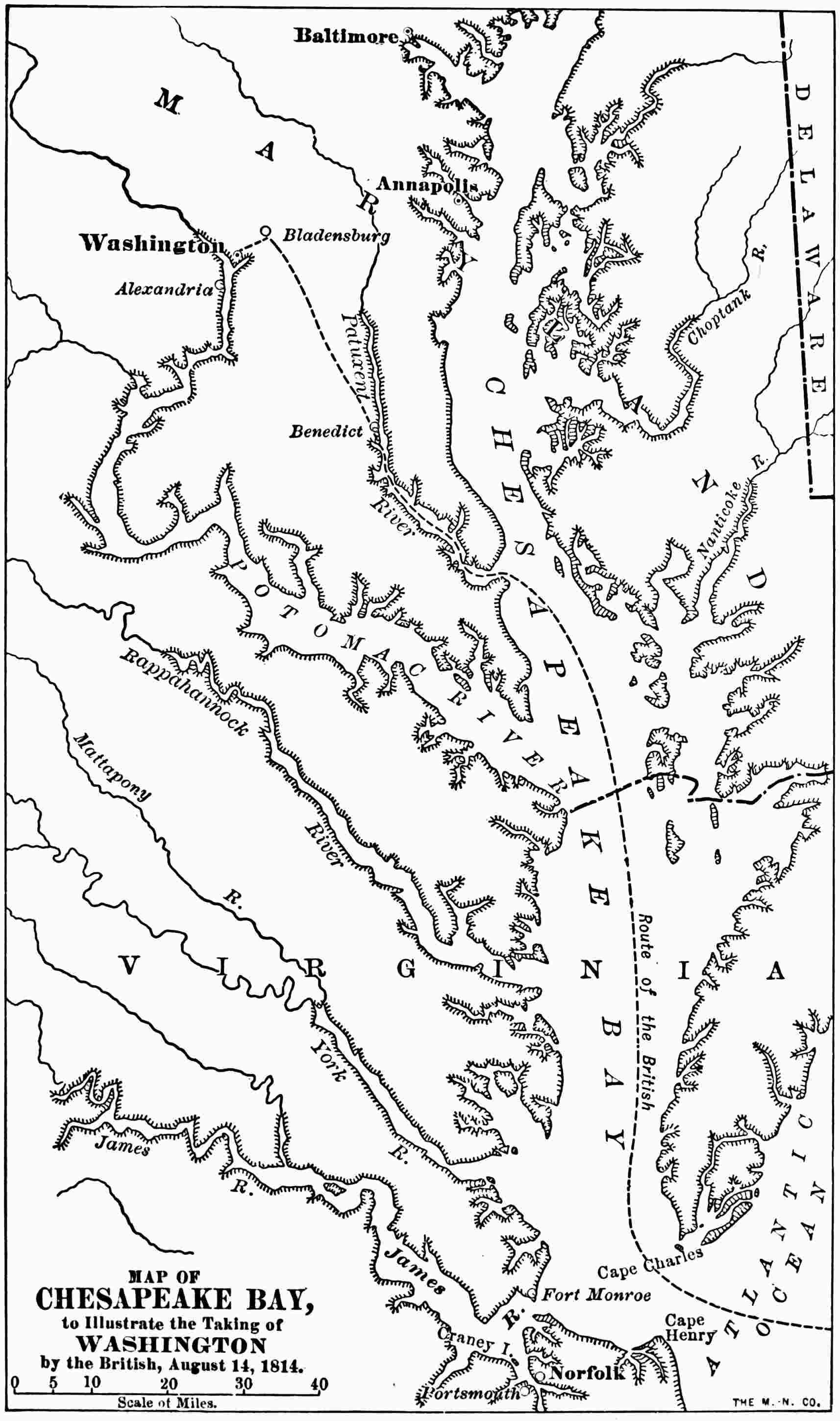

| Map of Chesapeake Bay, | 411 |

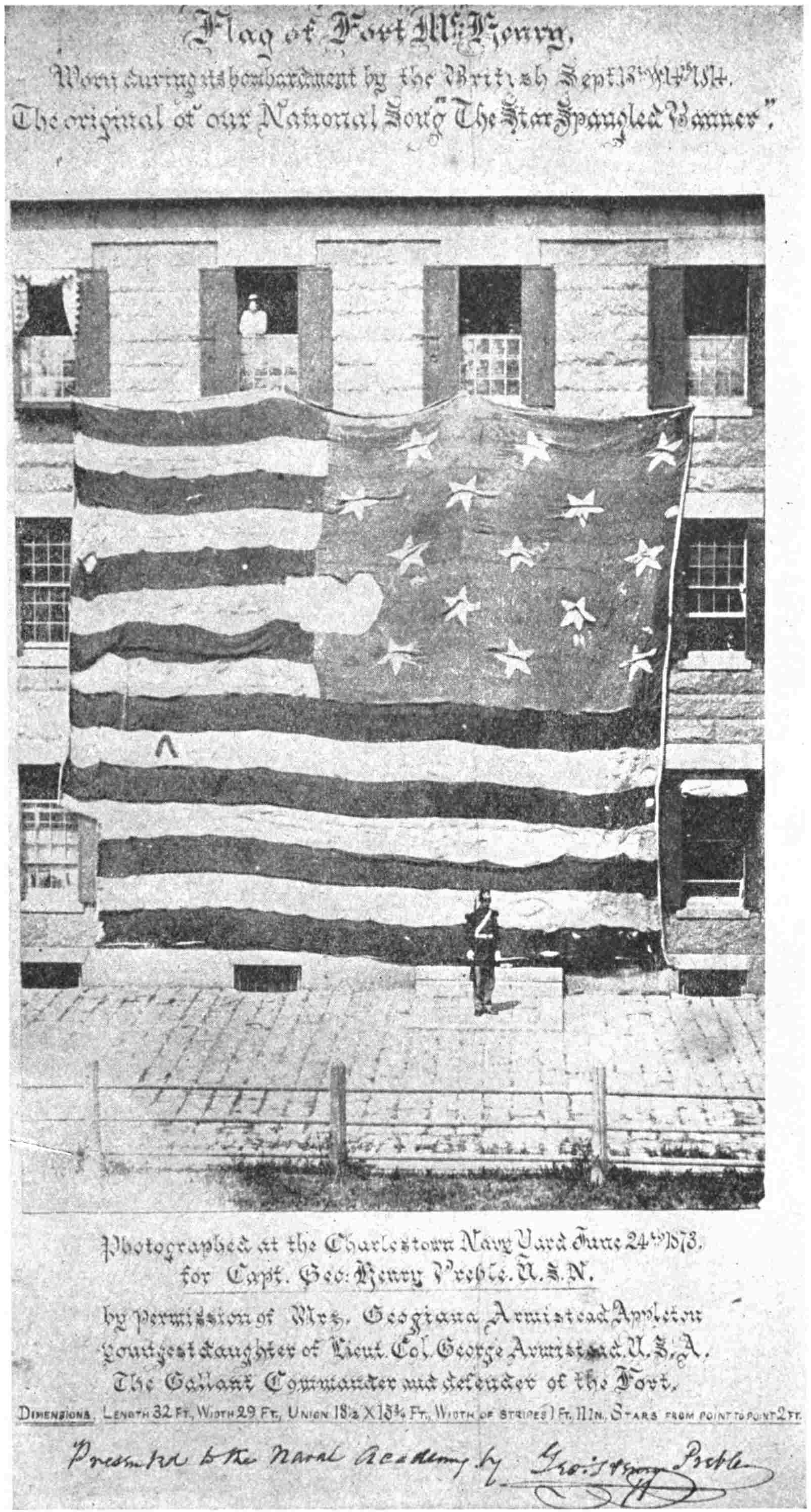

| The Flag of Fort McHenry—After the British Attack in 1814. (From a photograph at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 415 |

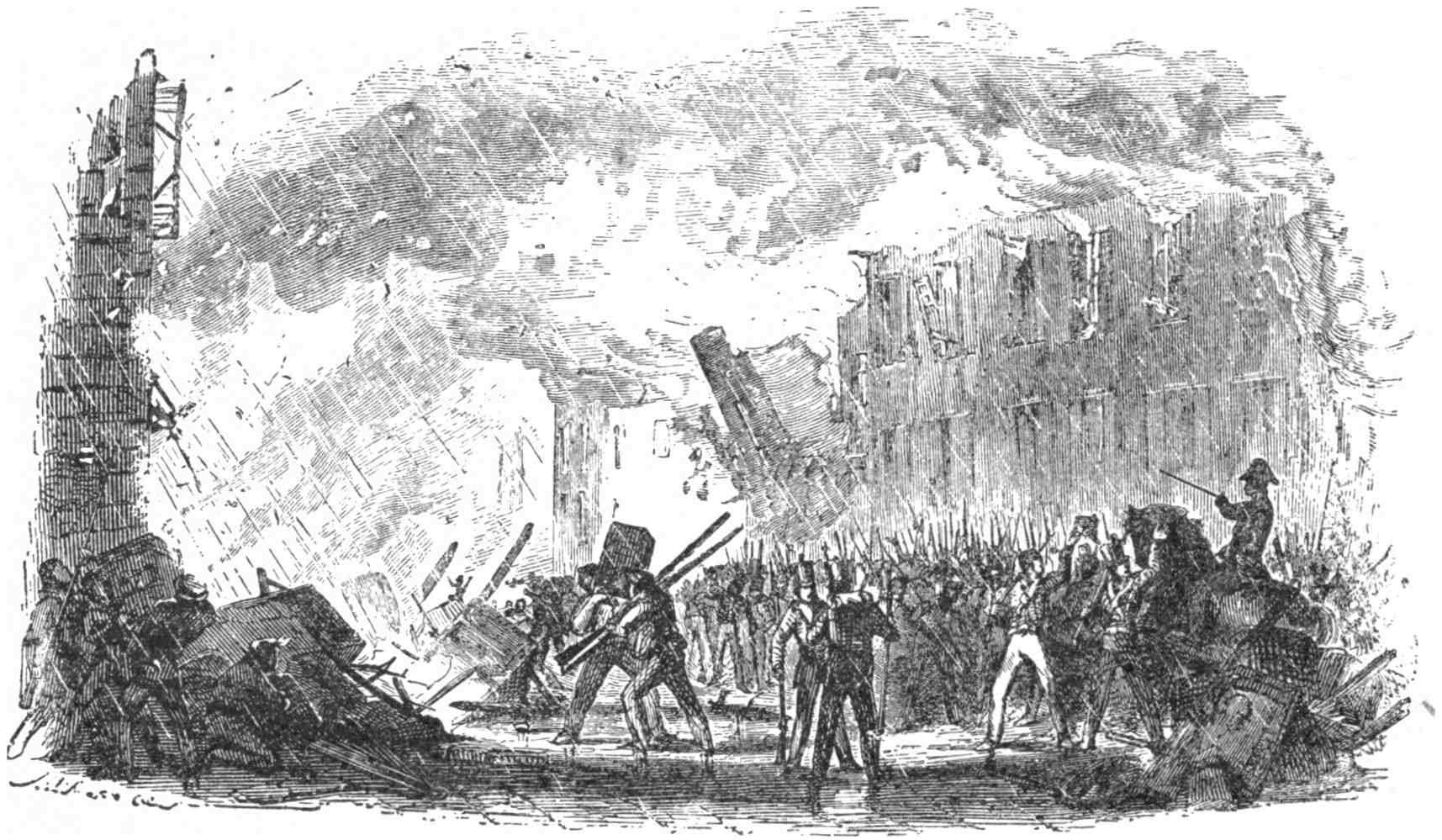

| The Capture of Washington. (From an old wood-cut), | 416 |

1

A FAIR ESTIMATE OF THE NUMBER OF AMERICANS ENSLAVED BY THE PRESS GANGS—A BRAGGART BRITISH CAPTAIN’S WORK AT SANDY HOOK—A SEARCH FOR THE GUERRIÈRE—ATTACK ON THE BRITISH SHIP LITTLE BELT—A FEATURE OF THE BATTLE THAT WAS OVERLOOKED—WHEN THE CONSTITUTION SHOWED HER TEETH THE BRITISH SHIP BRAILED ITS SPANKER AND HEADED FOR SAFER WATERS—AN EAGER YANKEE SAILOR WHO COULDN’T WAIT FOR AN ORDER TO FIRE—WAR UNAVOIDABLE.

By base arts and promises intended to be broken—by sending, for instance, one George Rose as a commissioner to Washington, ostensibly to adjust the whole matter amicably, but in reality to gain time, the British Prime Minister (the “impetuous Canning”) succeeded in getting the Chesapeake affair “put out to nurse.” The three American seamen were “reprieved on condition of re-entering the British service; not, however, without a grave2 lecture from Berkeley on the enormity of their offence, and its tendency to provoke a war.” Berkeley himself was called home. The British Minister told the American Government this was done by way of reproval for Berkeley’s act in ordering the assault on the Chesapeake. As a matter of fact, he was at once rewarded with a more important command than that he had held—just as the commander of the Leander was promoted after having shot to death the man at the tiller of an American coaster.

Not only was the Chesapeake affair “put out to nurse,” it was actually nursed to sleep. The people waited for the politicians to adjust it, but waited in vain, waited and watched while the brutal press-gangs continued their work. The results of these press-gang assaults upon American seamen seem—as seems the patience of the American people—almost incredible. But the figures are a matter of undisputed record. The American Minister in London, during one period of nine months, presented two hundred and seventy one petitions, begging the release of that number of American impressed seamen.

The British Admiralty at one time reported 2,548 seamen in the service who had refused to do duty on the ground that they were enslaved American citizens.

Lord Castlereagh admitted in a speech before43 Parliament on February 18, 1811, that “out of 145,000 seamen employed in the British service the whole number of American subjects amounts to more than 3,300.” And when the papers of the State Department at Washington were searched it was found that the friends of the enormous number of 6,257 different American citizens, impressed into the British service, had filed protests there.

That more than two men would be so impressed without having a protest filed, to every one for whom such a protest was filed, is a matter of course. And what is the moderate conclusion drawn from these facts? It is that more than twenty thousand free American men were forced into the service of the British navy by the press-gangs. Their fate, save in a few cases, is unrecorded, but we know that some met the perils of the deep and were lost. Many were sent to the fever coasts of Africa and there died. Some were flogged to death at the order of officers who laughed at their tortures. And of the rest—the few—we shall read farther on. For their cries to righteous heaven for help, and the wails of mothers and wives and children left helpless by these aggressions, were to be heard at last.

A Frigate with her Sails Loose to Dry.

From a wood-cut in the “Kedge Anchor.”

A body of Massachusetts Tory merchants strove wickedly and falsely to make the world believe that Massachusetts homes had not been6 invaded by the press-gangs; a member of Congress stood in his place to say that in spite of restrictions the nation had “profitably exported” goods worth forty-five millions of dollars during one year, and asked if all that trade was to be sacrificed in order to strike a blow for mere sentiment; the faint-hearted pointed to the exhausted condition of the national treasury, to the utter lack of trained soldiers, and to the feebleness of the navy when it was compared with that of the nation whose “naval supremacy was become a part of the law of nations.” But all these were at last brushed aside by the indignant host that arose to strike another blow for liberty—they were brushed aside so rudely, that, in one place, at least, a mob violently assaulted the toady element as represented by a Tory newspaper.

It happened that actual fighting occurred before war was declared, and most significant was one feature of the first battle of the war of 1812. The British frigate Guerrière, of thirty-eight guns, commanded then by Captain Samuel John Pechell, was one of the great host of war-ships that hovered about the American coast in 1811, picking able-bodied sailors from American ships, and in other ways annoying American commerce. Captain Pechell’s contempt for the young republic and his personal vanity were so great that he caused the name7 of his ship to be painted in huge letters across his foretopsail. Like a mine-camp bad man, he wanted every one to know who it was that tore open the water and split the air off the American coast. He was looking for trouble and his ship found enough of it, later on, although under another commander. Pechell himself found it, also, but he did not stay long to face it. In fact he fled from a very inferior force the moment he smelled the burning powder.

On May 1, 1811, the American merchant brig, Spitfire, while en route from Portland (formerly Falmouth), Maine, to New York, passed the Guerrière, that was lying-to at Sandy Hook, and but eighteen miles from New York City. The Guerrière, finding the brig bound in, deliberately stopped her there within the waters of New York and took off John Deguyo, an American citizen, who was a passenger.

At the time of this outrage the United States frigate President, of forty-four guns, commanded by Captain John Rodgers, was lying off Fort Severn, at Annapolis, Maryland. Captain Rodgers was at Havre de Grace, her chaplain and purser were at Washington, and her sailing-master was at Baltimore. That was in the days of stage coaches, as the reader will recall, but in spite of the slowness with which mails travelled—especially official mails—the8 President tripped her anchor at dawn on the morning of May 12th, and headed away for the ocean, with her name painted on each of her three topsails. As a poker-player might say, Captain Rodgers was holding three of a kind to Captain Pechell’s ace high. That he had been sent to sea to look for the Guerrière and get John Deguyo from her does not admit of a doubt, although he had not been specifically ordered to do so. He had been ordered to cruise up and down the coast to “protect American commerce,” and the facts of the Guerrière’s assault upon the liberty of John Deguyo had been communicated to him. The proper proceedings in the matter should he fall in with the Guerrière were left to his discretion. That he assumed the responsibility gladly may be inferred from what he said before sailing. He said that if he fell in with the Guerrière “he hoped he might prevail upon her commander to release the impressed young man.”

Four days after leaving Annapolis (on May 16, 1811) the look-out saw a man-of-war approaching, and the looked-for Guerrière was supposed to be at hand. But while yet too far away for her name to be distinguished, the stranger wore around and headed away south. Still supposing it was the Guerrière, Captain Rodgers made sail after her. This was soon after the noonday meal. The President steadily9 gained on the stranger, but the wind was light, and a stern chase is a long one. As night came on the stranger hauled to the wind and tacked, and did various things, manifestly10 in the hope of evading the Yankee, but all in vain, even though night and thick weather came on to help.

John Rodgers.

From the portrait by Jarvis at the Naval Academy.

Finally, at 8.20 o’clock the President, with her crew at quarters, drew up close on the weather bow of the stranger, and Captain Rodgers hailed from the lee rail:

“What ship is that?”

Instead of an answer, the stranger replied by hailing in turn:

“What ship is that?”

Captain Rodgers repeated his question, and to his intense surprise he got for an answer a shot from the stranger that struck the President’s mainmast. Like an echo to this shot was one, fired without orders, from the President. To this the stranger replied with three shots in quick succession, and then with a broadside. At that the impatient gunner who had fired from the President without orders had opportunity to try again under orders, and the rest of the crew joined in. For ten minutes they loaded the guns with a rapidity well worth noting, and fired with a deliberation and precision never to be forgotten. And then the stranger almost ceased firing. Because she was manifestly much inferior to the President in armament, Captain Rodgers ordered his men to cease firing, but no sooner had this order been obeyed than the stranger opened once11 more, and his fire had to be returned. The order was obeyed with such increasing good-will that, in spite of darkness and growing wind and sea, one broadside knocked the stranger helpless, so that she wore around stern on, where another broadside might rake her fore and aft.

Now when Rodgers once more hailed he received a reply, but owing to his position to windward he could not understand it, but it is recorded that the captain pluckily said “no” when asked if he had struck. However, Rodgers ran down under the stranger’s lee and hove to, where he might be of service in case she should sink, and there he waited for daylight.

During the night the two vessels drifted apart, but at 8 o’clock the next morning the President ranged up and sent Lieutenant Creighton on board the stranger, to “regret the necessity which had led to such an unhappy result,” and offer assistance, if any were needed.

It was then learned that she was the “twenty-gun corvette Little Belt, Commander Arthur B. Bingham.” She had carried a crew of one hundred and twenty-one all told, and of these no less than eleven were killed, and twenty-one wounded—a list of casualties amounting to more than one-fourth of all she carried, although, even by the British account (see Allen)12 the time that elapsed between the first hail and the last was but half an hour, while the time passed in actual combat did not exceed fifteen minutes. On the President one boy was slightly hurt by a splinter.

The Little Belt Breaking up at Battersea.

From an engraving by Cooke of a drawing by Francia.

In the controversy that followed this conflict the significance of the figures—significance of13 the deadly fire of the Americans—was wholly lost to sight. The whole affair was, of course, carefully investigated by both Governments. The officers on each ship swore that the other fired the first gun. The British captain’s statement, however, was greatly weakened by his assertion that he had kept up the fight for three-quarters of an hour and that he had really beaten off his bigger opponent. So Allen, already quoted, says that “a gun was fired from each ship, but whether by accident or design, or from which ship first, remains involved in doubt.”

This fight occurred, as the reader remembers, when the two nations were nominally at peace, but it was a blow—the first blow struck at the press-gangs.

Another incident of similar import, though bloodless, occurred before the end of the year 1811. The Constitution, Captain Isaac Hull, had gone to Texel to carry specie for the payment of interest on the American bonds held there, and when returning had called at Portsmouth to enable Captain Hull to communicate with the American legation in London. One night, while the captain was in London, a British officer came on board the Constitution to say that an American deserter was on the British war-ship Havana, lying near by, and the Constitution could have him by sending for14 him. So the executive officer, Lieutenant Morris, sent a boat next morning, but it came back with a notice that an order for the man must first be obtained from Admiral Sir Roger Curtis. To this official then went Lieutenant Morris, when the admiral calmly informed him that the man claimed to be a British subject, and therefore he should not be returned.

It was fairly manifest that the British officials had for some reason been playing with the temporary commander of the Constitution, but Lieutenant Morris had his revenge within a day, for on the next night a British sailor boarded the Constitution, admitted that he was a deserter from the Havana, and said, when asked his nationality, that he was “An American, sor.”

At that, word was sent the commander of the Havana that a deserter from his ship was on the Constitution, but when an officer from the Havana came after the man, Lieutenant Morris blandly informed him that the man claimed to be an American and therefore he could not be given up.

This threw the British naval people into a turmoil, and a little later two British frigates shifted their berths and anchored where it was probable that the Constitution would, on getting under way, foul one or the other.

Seeing they were laying a trap for him, Lieutenant15 Morris got up anchor, and by the skill in handling a ship common among American officers, dropped clear to a new berth.

Hardly was he at anchor again, however, before the two frigates once more drew near and again anchored to trap the Yankee frigate.

The three ships were lying so when Captain Hull returned from London that evening. That the Englishmen were intending to make trouble about the sailor with a brogue seemed plain, but Captain Hull, remembering the trick played on the Chesapeake, was not to be caught napping. He cleared the ship for action, and, with battle-lanterns burning, guns loaded, and extra ammunition at each gun, he made sail, got up his anchor, and, slipping clear of the British frigates, put to sea. There were two Britishers to the one Yankee, but the Yankee was ready to fight.

As the Constitution stood away down the roads the British frigates made sail in chase. For a time the Constitution carried a press of canvas, but when it was seen that one of the enemy was dropping out of sight Captain Hull backed his main-yard and waited for the other.

“If that fellow wants to fight we won’t disappoint him,” said the captain.

As the enemy ranged up within hail Lieutenant Morris walked forward along the gun-deck to encourage the men, and found that16 never did a crew need encouragement less. Gun-captains were bringing their guns to bear on the enemy, and their men, stripped to the waist in many cases, were hauling on the side-tackles with a vigor that made the carriages jump.

But they were to be disappointed. The Englishman came yapping up till he saw the teeth of the silent Yankee turned upon him, when he hesitated, turned, brailed in his spanker as a dog tucks its tail between its legs, and ran back to his own enclosure.

And then there was the occasion when the United States, commanded by Captain Stephen Decatur, of Tripoli fame, fell in with the British ships Eurydice and Atalanta while cruising off Sandy Hook. Decatur had his men at their guns, of course, though he had no reason for trying either to force or to avoid a fight. But while he was exchanging hails with one of the other ships an impatient gunner on the United States pulled his lanyard and sent a ball into one of the British ships. It was unquestionably done by the man to force a fight, though when he saw that it did not bring a single return shot he said he did it accidentally, and the shot was so explained to the British captains.

The Section of a First-rate Ship.

Being cut or divided by the middle from the stem to the stern, at one view discovering the decks, guns, cabins, etc.

This incident, like that of the Constitution at Plymouth, is worth mentioning to show the18 feeling of the American seamen regarding the British theory and practice of impressment. And this feeling was becoming well known to all informed and thinking persons in both countries. It could now no longer be doubted that the American people would fight to gain freedom for their countrymen enslaved in British warships.

It is admitted that the politicians at Washington still talked as loudly of free trade on the high seas as ever they had done; it is admitted that “free trade” stood before “sailors’ rights” in the motto of the day—but it is declared, nevertheless, that the sentiment of the people, which alone can declare a war in this republic, was roused by the outrages upon man, and not upon property.

Had the British been animated by any other feeling than “the spirit of animosity and unconciliating contempt,” they could have averted further trouble by definitely abandoning their hostile attitude toward the young republic. They had opportunity to do this gracefully, for, yielding to the sentiment of the humane element of their nation, the Ministry had decided to once more disavow the Chesapeake affair and to return the men to the deck of the ship from which they had been taken. Two only remained alive, one having been hanged and the other having succumbed to the hardships19 to which he was subjected, but these were in fact put on the Chesapeake in Boston Harbor. Nevertheless, instead of abandoning the practice which led to the outrage, the right to continue it was reaffirmed. Indeed, every proposition made by the portion of the nation that loved justice more than conquest excited only derision among the nation’s rulers, and among the masses, too, for that matter. War was inevitable, and on June 18, 1812, it was declared to exist.

20

THE SILLY CRY OF “ON TO CANADA!”—THE NAVAL FORCES OF THE UNITED STATES COMPARED WITH THOSE OF GREAT BRITAIN—THE FORESIGHT AND QUICK WORK OF CAPTAIN RODGERS IN GETTING A SQUADRON TO SEA—BUT HE MISSED THE JAMAICA FLEET HE WAS AFTER, AND WHEN HE FELL IN WITH A BRITISH FRIGATE, THE RESULTS OF THE AFFAIR WERE LAMENTABLE.

Although “vast multitudes” of the American people had “passionately wished for” a declaration of war against Great Britain, that declaration was, indeed, “a solemn and serious fact” to those who stopped to consider what odds must be met. What those odds were will be told further on, but in view of the fact that the naval supremacy of England is about as pronounced at the end of the nineteenth century as it was at the beginning, it is well worth while giving a glance at the plans of the Americans in 1812. For the cry was “on to Canada!” Canada was very likely to welcome an opportunity to join the republic, but even if she did not do that she was but feeble, and21 the spirited Yankee militia would overrun the whole region and take revenge for the wrongs received at the hands of the English by annexing the whole fair domain. The sea-power of Great Britain was overwhelming, of course, but we had coast-defence vessels by the hundred—nearly three hundred schooners carrying a big gun each, and these should defend the principal American forts while the valiant militia slaughtered the Canadians! The majority of the American people seriously believed that the way to defend American citizens from the aggressions of the only nation likely to abuse them was by building a navy for coast defence only and marching to Canada when ready for offensive operations. But if that must seem astonishing to every one who has rightly studied the war of 1812, what can be said of the fact that this same theory of protecting the United States from British aggression is still held by as great a majority as ever? For it must not be forgotten that the American assaults on Canada were as futile as the American militia were worthless. There was but one fight made by the land forces alone of which Americans are proud—that at New Orleans.

A Brigantine of a Hundred Years Ago at Anchor.

From a picture drawn and engraved by Baugean.

On a casual glance at the American sea-power in 1812 the lack of confidence in it was merited. For of sea-going craft we had only22 17, carrying all told 442 guns and 5,025 men. Even of these ships two were condemned as unfit for service as soon as they were inspected. And as for the gun-boats, they were simply brushed aside the moment actual hostilities began. But Great Britain had 1,048 ships to our 17; these ships carried 27,800 guns to our 442 and 151,572 men to our 5,025. Of course the majority of these ships were employed elsewhere than on the American coast. But by the London Times of December 28, 1812, the British had, “from Halifax to the West Indies, seven times the force of the whole American navy.” By a pennant sheet taken23 from the British schooner Highflyer in 1813 there were on the American coast on March 13th, 107 British ships rated as carrying 3,055 guns, among which were 12 ships of the line rated as seventy-fours. As a matter of fact these ships actually carried at least ten per cent. more guns than their rating indicated. That this preponderance was increased as time passed, and that there was good reason for increasing it, will appear farther on.

The faint-hearted, indeed, were not without reason when they spoke of the declaration of war as “the dreaded and alarming intelligence.” But if the reader wishes for a correct idea of the quality of the men who in that day stood erect, facing the quarter-deck, and uncovered their heads whenever the brawny quartermaster hoisted the old flag, he will find it in the fact that they—the men of the American navy—were the foremost among those who “passionately wished for” a war with this power—a power that outnumbered them and out-weighed them on their own coast as seven to one.

An English Admiral of 1809.

From an engraving at the Navy Department, Washington.

Nor was the power of the British navy found only in the number and size of her ships and the number and size of the guns. “Since the year 1792 each European nation in turn had learned to feel bitter dread of the weight of England’s hand. In the Baltic Sir Samuel Hood had taught the Russians that they must25 needs keep in port when the English cruisers were in the offing. The descendants of the Vikings had seen their whole navy destroyed at Copenhagen. No Dutch fleet ever put out after the day when, off Camperdown, Lord Duncan took possession of De Winter’s shattered ships. But a few years before 1812 the greatest sea-fighter of all time had died in Trafalgar Bay, and in dying had crumbled to pieces the navies of France and Spain.” In spite of the infamous system under which the British ships were manned, the personnel of the British navy was—one is tempted to say it was beyond comparison better than that of any other European nation. For the others felt “the lack of habit—may it not even be said without injustice, of aptitude for the sea.” The officers and men who gathered to crush the navy of the young republic came from Aboukir and Copenhagen and Trafalgar Bay. They were veterans in naval warfare—men who preferred short weapons as the Romans did, men who preferred to fight with yard-arm interlocking yard-arm, where short carronades were better than long guns of smaller bore, and where even these might be made more effective through loading with double shot. Luckily for us their long experience had engendered prejudiced conservatism, their many victories had cultivated an overweening confidence, and their bull-dog courage26 had made them careless of the arts of seamanship.

As to the ability of the American crews who were to meet these tar-stained, smoke-begrimed, cicatrice-marked veterans, enough will be told in the descriptions of their battles, for they astounded the whole world.

Nevertheless, the war at sea began in a fashion to discourage the nation and humiliate the whole navy.

On the day (June 18, 1812) that war was declared, the effective part of the American navy—the only American naval ships ready for a fight—lay in New York Harbor, or else were at sea where they could not hear the news. The ships in New York were the flag-ship President, rated forty-four, Captain Rodgers; the United States, forty-four, Captain Decatur; the Congress, thirty-eight, Captain Smith; the Hornet, eighteen, Captain Lawrence, and the Argus, sixteen, Lieutenant Sinclair. Nothing more discreditable to the administration of President Madison than this fact can be told. He had seen for months that war was inevitable and yet he had done nothing to gather in the ships and prepare them for the fight. And Monroe was Secretary of State. But for the earnest remonstrances of Captains Bainbridge and Stewart, who repeatedly addressed the Department, every American warship2827 would have been kept in port for harbor defence.

Representation of a Ship-of-war, dressed with flags, and yards manned.

1. American Ensign.

2. Ottoman-Greek

3. Norden.

4. Stralsund.

5. Greek.

6. Brandenburg.

7. Hanover.

8. Prussia.

9. Saxony.

10. Morocco.

11. Maltese.

12. Arabia.

13. Columbia.

14. Mexican.

15. Brazil.

16. Hayti.

17. Japan.

18. Mogul.

19. Buenos Ayres.

20. Spanish.

21. Tunis.

22. St. Domingo.

23. Old Sardinia.

24. Majorca.

25. Peru.

26. English (blue).

27. Venezuela.

28. Chili.

29. Normandy.

30. English (white).

31. French.

32. Tripoli.

33. Salee.

34. Old Portugal.

35. Algiers.

36. Senegal.

37. Oporto.

38. Central America.

39. English (red).

40. E. Russia.

41. Sandwich Islands.

42. American Jack.

o. Commodore’s Broad Pendant.

Note.—Those which have no numbers affixed are the ship’s signals, or, rather, the telegraphic numbers.

From the “Kedge Anchor.”

1. Paint-room.

2. General store-room.

3. Bread-room.

4. Coal-locker.

5. Tanks.

6. Casks.

7. Chain-locker.

8. Tier gratings.

9. Shot-locker.

10. Shell-room.

11. Spirit-room.

12. Bread-room.

13. Slop-room.

14. Marine stores.

15. Magazine.

16. Light-room.

The Internal Arrangements and Stowage of an American Sloop-of-War.

From the “Kedge Anchor.”

But if the Administration had done nothing, Captain Rodgers, as commodore of the squadron in New York, had done everything—he had done so well that within one hour from the time that a messenger from Washington arrived on board the President with the declaration of war and instructions to put to sea, the whole squadron except the Essex was under sail, heading down New York Bay toward Sandy Hook.

This was on June 21, 1812. Commodore Rodgers was bound out to intercept a big fleet of British merchantmen sailing home from Jamaica, convoyed only by the thirty-six-gun frigate29 Thalia and the eighteen-gun corvette Reindeer. This fleet had left Jamaica, it was said, on the 20th, and it was sure to follow the Gulf Stream under very easy sail. But when Rodgers was a short way out to sea an American brig reported the fleet well down the stream (about due east of Boston and well off shore) on June 17th. The fleet had sailed some days earlier than the Americans had supposed. So the squadron hauled to the northeast in pursuit.

At 6 o’clock on the morning of June 23d, when the squadron was thirty-five miles southwest of Nantucket shoals, a sail was seen. It was the thirty-three-gun frigate Belvidera, Captain Byron, that was then lying in wait for a French privateer expected from New London, Connecticut. At once the Belvidera headed toward the American squadron to examine them, but when at 6.30 A.M. she discovered their character she wore around and headed away to the northeast with a smacking breeze over the port quarter and studding-sails set.

At once the Yankees made sail in chase, with the President, the swiftest of the squadron when sailing free, well in the lead. By 11 o’clock the President was near enough to warrant clearing for action, but a shift of wind helped the Belvidera and she held her own until 2 P.M., when another shift favored the President,30 so that at 4.20 P.M. the Britisher with her colors flying was within range.

Getting behind one of the long bow-chasers on the forecastle of the President, Commodore Rodgers carefully sighted it, and pulling the lanyard, fired the first shot of the war of 1812. It knocked the splinters out of the stern of the flying enemy. The second shot was fired from a bow-chaser on the deck below, and a third was fired on the forecastle. Each of these reached its target. One passed through the rudder-coat, and another, striking the muzzle of a stern-chaser, broke into pieces, which killed two men, severely wounded two more, and slightly wounded three others, including a lieutenant who was aiming the gun.

Guns Secured for a Gale.

From the “Kedge Anchor.”

Greatly elated at the accuracy of their fire, the men working the President’s bow-chaser31 on the lower deck aimed a fourth shot. A boy with his leather box full of powder-cartridges arrived just as the gunner was pulling his lanyard, and then when the hammer fell the gun exploded and the flames from the splitting breech darted into the open box of powder, setting it off as well.

The explosion knocked the men in all directions, disabled for the moment every one of the bow-chasers, and bursting up the deck above, it threw Commodore Rodgers so violently into the air that when he fell his leg was broken. Of the men standing about the gun two were killed and thirteen wounded.

At that moment the Belvidera opened an effective fire with her stern-chasers, and one of her projectiles came crashing into the President’s bows, and went bounding along the gun-deck, killing a midshipman and wounding a number of seamen. For a time there was not a little confusion on the President, but her crew soon got to work again and began to make it warm on the Belvidera once more. But the mistake of yawing to fire broadsides was made. That “a whole broadside battery will be much less likely to ‘disable a flying enemy’ than the cool and careful use of one well-served gun,” has been amply proven. The yawing gave the Belvidera a gain in the race. That she would have waited for a fight with32 the President but for the presence of the other ships is not doubted, but, as it was, Captain Byron saw that something desperate must be done to escape, so he threw over his spare anchors and boats and fourteen tons of water in casks. So lightened, he was able to outsail the Yankee squadron and escape.

The President lost three killed and nineteen wounded, and was considerably cut up aloft. The Belvidera lost two killed and twenty-two wounded, Captain Byron being among the number. His rigging was also cut up somewhat, but he made such a good running fight of it that a painting, by a British artist, was made of the scene, that, according to Allen’s history, is preserved to this day.

As for the American squadron, it vainly followed the Jamaica fleet to within less than a day’s sail of the English Channel, and returned home by the way of the Madeiras and Azores, reaching Boston after a cruise of sixty-nine days, in which nothing had been accomplished, save only that seven merchantmen were taken and an American ship recaptured.

33

CAPTAIN DAVID PORTER’S IDEAS ABOUT TRAINING SEAMEN—THE GUNS OF THE ESSEX—TAKING A TRANSPORT OUT OF A CONVOY AT NIGHT—A BRITISH FRIGATE CAPTAIN WHO WAS CALLED A COWARD BY HIS COUNTRYMEN—CAPTAIN LAUGHARNE’S MISTAKE—A FIGHT THAT BEGAN WITH CHEERS AND ENDED IN DISMAY FOR WHICH THERE WAS GOOD CAUSE—WORK THAT WAS DONE BY YANKEE GUNNERS IN EIGHT MINUTES—WHEN FARRAGUT SAVED THE SHIP—AN ATTACK ON A FIFTY-GUN SHIP PLANNED.

During the time that Commodore Rodgers was making what was practically a fruitless cruise with his squadron, Captain David Porter was doing somewhat better with the little frigate Essex. Rarely has a naval man had the benefit of such experiences as those through which Captain Porter had passed. At the age of sixteen (1796), while in the West Indies on the merchant-schooner Eliza, of which his father was commander, he had stood at the rail with the rest of the crew and fought off a British press-gang in such a determined assault that several men were killed and wounded on both sides. A year later he was twice impressed34 into the British navy, but escaped both times. Then he joined the American navy as a midshipman, and, as already told, showed himself a hero in helping to hold the prisoners on a captured French frigate for three days, although they were in overwhelming numbers, and he had to watch them during all the time without a moment’s sleep. In a pilot-boat called the Amphitrite, that mounted but five one-pounder swivels and carried fifteen men, he attacked a French privateer armed with a long twelve-pounder and a number of swivels, and carrying forty men. Moreover, the Frenchman was supported by a barge armed with swivels and carrying thirty men. Such odds had rarely been taken, but the impetuous onslaught of the Yankees carried the privateer after a bloody resistance. She had lost seven killed and fifteen wounded, more than half her crew, when she surrendered. Porter did not lose a man. The barge escaped, but a merchant-prize they had captured was retaken. After a variety of exploits only less daring than this, he was sent to the Mediterranean Sea, and there continued to gain knowledge, skill, and reputation until, by the grounding of the Philadelphia, he became a prisoner to the Tripolitans.

When war was declared in 1812 he was in the Essex. She was undergoing repairs in New York Harbor. It was fortunate for Porter that35 she was not ready to sail with Rodgers, for the delay enabled him to make a cruise alone. And this cruise, because of what it shows about the American armament and American seamen, is worth describing in detail.

David Porter.

From an engraving by Edwin of the portrait by Wood.

The Essex was rated as a thirty-two-gun frigate, but she carried forty-six carriage-guns all told. As to her numbers of guns she was36 greatly underrated, but as to the effectiveness of her armament she was the most overrated ship in the little navy. She had originally mounted twenty-six long twelve-pounders on her main deck, while her forecastle and poop carried sixteen twenty-four-pounder carronades, “but official wisdom changed all this.” The Navy Department took out twenty-four of her main deck long twelves and put thirty-two-pounder carronades there instead. Then the poop and forecastle were swept clear of the twenty-four-pounder carronades and four long twelves and sixteen thirty-two-pounder carronades were mounted there. Porter protested over and again, but in vain.

To fully understand why Porter should have protested against this armament one must know the character of the guns. This is a matter that has been discussed at very great length by almost every one who has written on the navy of any nation. But, for the aid of the uninformed reader, it may be said that an average long thirty-two-pounder was eight and a half feet long, and weighed 4,500 pounds, while a thirty-two-pounder carronade was four feet long and weighed but 1,700 pounds. Being thick at the breech and long, the long gun had a long range. That is, a heavy powder charge would act on the ball throughout the length of the long bore and so hurl the ball over a long37 range. The short gun being short, and thin at the breech, could stand only about one-third of the charge of powder used in the long gun. Where the long thirty-two burned seven pounds of powder and had a range, when elevated one degree, of six hundred and forty yards (not counting the ricochet leaps), the short thirty-two burned two and a half pounds of powder and had a range of three hundred and eighty yards.

A short range means a small power to penetrate, not fully expressed by the above figures. To make a carronade really effective the ship had to be placed within two hundred yards of the enemy, and even at twenty yards it was known that a thirty-two-pounder ball stuck in a ship’s mast instead of crashing through it, and the long twelves could do effective work when entirely beyond the range of the short thirty-two, for they were made heavier in proportion to the size of the ball than the long thirty-two, and had a range quite equal to that of the larger calibre. But the long gun in that day was exceedingly heavy. It needed a big carriage and big tackles, and a big crew. It was a hard job to load and aim one of these long guns. The short gun, throwing a ball of the same size, weighed, as shown, comparatively little and could, therefore, be loaded and fired much more rapidly. When within pistol-shot38 of the enemy this was an advantage, of course. Another advantage of the short gun was in the fact that a battery of them did not strain a ship as a battery of long guns would do. But when all was said in favor of a short gun of big bore, the fact remained that in a combat, a handy ship having long guns could remain out of range of the ship having short guns and shoot it to pieces. The short-gun ship had to close in on the other or suffer defeat. Had Porter’s petition for his long twelves been granted he would have had a different story to tell when he reached the Pacific.

But this chapter is to tell of his first cruise in the Essex. On July 2, 1812, he was off to sea in search of the British thirty-six-gun frigate Thetis, which was bound to South America with specie. The Thetis escaped, but a few merchantmen were captured, and then on the night of the 10th a fleet of seven merchantmen in convoy was discovered. As it happened the moon was shining, but the sky was so well overcast with clouds that the alternating shadows and lights made it easy for Porter to pose the Essex as a merchant-ship. Her top-gallant masts were dropped part way down to conceal their height, the lee braces and other running rigging were left slack, and the guns were run in and ports closed. In39 this fashion Porter jogged with the fleet, where in casual conversation he learned that a thousand soldiers were there en route from Barbadoes to Quebec, and that the thirty-two-gun frigate Minerva was the sole guard.

After a time a ship-captain to whom Porter was talking became suspicious, and started to signal the presence of a stranger to the Minerva, but Porter threw open his ports and compelled the merchantman to follow the Essex out of the fleet. This manœuvre was done without alarming any other one in the fleet. On boarding her, one hundred and ninety-seven soldiers were found.

The merchantman was captured at 3 o’clock in the morning. Before another could be overhauled daylight came. At that, Porter took in the slack of his loose rigging, set up his masts and invited the Minerva to come and try for victory. Captain Richard Hawkins, who commanded her, thought best to tack and sail into the midst of his fleet, where, in case he was attacked, the eight hundred and odd soldiers who were on the transports could render him effective service by sweeping the decks of the Essex with their muskets, and by firing such cannon as the transports carried. James, who is the standard naval historian in the British navy, says of this affair:

“Had Captain Porter really endeavored to40 bring the Minerva to action we do not see what could have prevented the Essex, with her superiority of sailing, from coming alongside of her. But no such thought, we are sure, entered into Captain Porter’s head.”

David G. Farragut, of lasting fame, was a midshipman on the Essex, and was keeping a journal. He wrote:

“The captured British officers were very anxious for us to have a fight with the Minerva, as they considered her a good match for the Essex, and Captain Porter replied that he should gratify them with pleasure if his Majesty’s commander was of their taste. So we stood toward the convoy, and when within gunshot hove to, and awaited the Minerva; but she tacked and stood in among the convoy, to the utter amazement of our prisoners, who denounced the commander as a base coward, and expressed their determination to report him to the Admiralty.”

But to further explain the difference between long and short guns, it should be mentioned that the Minerva carried on her main deck the long twelves which Porter had wanted, and in a fight she would have been able to riddle the Essex while still far beyond the range of the short thirty-twos with which the American was armed. At pistol range the Essex was much more powerful, and she carried, moreover, fifty men more than the Minerva, though Captain41 Hawkins could not know that, and, doubtless, would have been ashamed to offer that as a reason for declining to fight.

Fight of the Essex and the Alert.

From an old wood-cut.

Until August 13th the Essex had no adventure. On that day, while cruising along under reefed top-sails, a ship was seen to windward that appeared to be a man-of-war. At this, drags were put over the stern of the Essex to hold her back, and then a few men were sent aloft to shake out the reefs, and the sails were then spread to the breeze exactly as a merchant-crew would have done it. The stranger was entirely deceived by this, and she came bowling down toward the Essex, which was now flying the British flag. The stranger having fired a gun, the Essex hove to until she had passed under her stern to leeward. Having now the weather-gage, the Essex suddenly filled away42 her main-sails, cut away the drags, hauled down the British flag, ran up the Stars and Stripes, and, throwing open her ports, ran out the muzzles of her guns.

At the sight of these doings the Englishmen gave three cheers, and, without waiting to get where their guns would bear effectively, they blazed away with grape and canister.

The Essex waited for a minute or two until her guns would bear, and then gave the stranger a broadside, “tompions and all,” as Midshipman Farragut wrote at the time. The effect on the stranger was stunning. Her crew were actually stunned into inaction, and all of them but three officers were severely reprimanded at the court-martial of the captain, and several of the lower officers were dishonorably dismissed from the service on a charge of cowardice. They tried to veer off and run away, but “she was in the lion’s reach,” to again quote the youngster, and within eight minutes the Essex was alongside, when the stranger fired a musket and then struck her flag.

The American officer who boarded her found that she was the corvette Alert, Captain Thomas L. P. Laugharne, carrying eighteen short thirty-twos and two long twelves, a very inferior force to that of the Essex. And yet the result of this brief contest was of the greatest significance. The British histories say the fight lasted43 fifteen minutes. Doubtless this means from the time the Alert’s crew cheered so vigorously until they hauled down their flag. Farragut says that it was eight minutes from the first broadside of the Essex until the flag came down, and this is not disputed. In eight minutes the Essex had shot the Alert so full of holes that when the American boat’s crew reached the beaten ship the water was seven feet deep in her hold in spite of the utmost efforts of her crew to check the leaks! Not a man was killed on the Alert, and only three were wounded. The gunners of the Essex aimed low—they shot to sink the enemy, and they wellnigh succeeded. No one was hurt on the Essex.

For several days after this the Essex, having repaired the Alert, cruised with her in tow, and then an incident occurred, the story of which brings out very clearly another characteristic of the American crews; that is to say, the care with which the green crews were trained from the day they came on board.

The number of prisoners on the Essex very greatly exceeded her crew after the capture of the Alert, for the Alert’s crew were added to the soldiers and men from the transport, while the Essex had put out two prize crews. Knowing this, the prisoners formed a plan to take the ship, the coxswain of the Alert’s gig being the44 leader in the conspiracy. Young Farragut happened to discover the plot on the night it was to be executed. He was lying in his hammock and saw the coxswain with a pistol in hand on the deck where the hammock was swinging. The coxswain was looking around to see if all was in order for his men to rise, and going to Farragut’s hammock, looked earnestly at the boy, who had the wit to feign sleep. But the moment the coxswain was gone, Farragut ran into the cabin and told Captain Porter, who sprang from his berth, and running out of his cabin began to shout:

“Fire! Fire!”

A more distressful cry than that is never heard at sea. To the prisoners it brought utter confusion. To the crew of the Essex it meant only that they were to hasten to fire-quarters for a night-drill—something to which they had been trained ever since leaving New York. Captain Porter had even built fires that sent up volumes of smoke through the hatches in order to make the crew face what seemed to be a real fire, and so had steadied their nerves. Now they promptly but coolly went to their quarters. It was then a simple matter to turn them on the mutineers.

An English Thirty-gun Corvette.

From an engraving by Merlo in 1794.

Afterwards the prisoners were sent to St. John’s, Newfoundland, in the Alert as a cartel. She was not by the letter of the law a proper47 cartel, for she was still at sea and quite likely to be captured, but it is pleasant to observe that Admiral Sir John T. Duckworth “generously sustained the agreement” made by Captain Laugharne. He wrote:

“It is utterly inconsistent with the laws of war to recognize the principle upon which this arrangement has been made. Nevertheless I am willing to give a proof at once of my respect for the liberality with which the captain of the Essex has acted in more than one instance toward the British subjects who had fallen into his hands; of the sacred obligation that is always felt to fulfil the engagements of a British officer, and of my confidence in the disposition of his Highness, the Prince Regent, to allay the violence of war by encouraging a reciprocation of that courtesy by which its pressure upon individuals may be so essentially diminished.”

SIR JOHN THOMAS DUCKWORTH, K.B.

Vice Admiral of the White Squadron.

There is still one more incident of this cruise worth describing. The Essex was chased by the British frigate Shannon and another ship when off St. George’s Bank. Captain Porter supposed that the speedier ship of the two was the fifty-gun Acasta, a much more powerful ship than the Shannon, and that a third ship he had seen with the two was also in chase. As the largest ship was gaining, and a splendid breeze for working the ship was blowing, Captain4948 Porter planned a most daring defence. Running until night was fully come, he called his crew together and told them that he was going to tack ship, run alongside the enemy, and board her while under full sail. According to Farragut, Porter believed that the enemy would be sailing at the rate of eight knots an hour, at least, while his ship would foul her while going at not less than four knots. Nevertheless, the proposition was greeted with enthusiastic cheers.

The cause of the enthusiasm may be found readily in Farragut’s account of the crew. He says:

“Every day the crew were exercised at the great guns, small-arms, and single-stick. And I may here mention the fact that I have never been on a ship where the crew of the old Essex was represented, but that I found them to be the best swordsmen on board. They had been so thoroughly trained as boarders that every man was prepared for such an emergency, with his cutlass as sharp as a razor, a dirk made by the ship’s armorer out of a file, and a pistol.” They had been drilled until they had confidence in themselves as well as their leaders, and it was not an overweening confidence, either.

So a kedge anchor with a cable attached was hoisted to the end of the main-yard, where it could be readily dropped on the passing enemy50 as the two crashed together and so hold her fast. At the proper hour the Essex tacked in search of the enemy, but failed to find her.

At the end of sixty days from the time he sailed, Porter was back in port. He had captured nine prizes, with more than five hundred prisoners, and retaken five American privateers and merchantmen.

The little American navy was beginning in a small way to do something for the nation.

51

STORY OF THE CONSTITUTION’S ESCAPE FROM A BRITISH SQUADRON OFF THE JERSEY BEACH—FOUR FRIGATES AND A LINER WERE AFTER HER—FOR MORE THAN TWO DAYS THE BRAVE OLD CAPTAIN STOOD AT HIS POST WHILE THE SHIP TACKED AND WORE AND REACHED AND RAN, AND THE TIRELESS SAILORS TOWED AND KEDGED AND WET THE SAILS TO CATCH THE SHIFTING AIR—THOUGH ONCE HALF-SURROUNDED AND ONCE WITHIN RANGE, OLD IRONSIDES ELUDED THE WHOLE SQUADRON TILL A FRIENDLY SQUALL CAME TO WRAP HER IN ITS BLACK FOLDS AND CARRY HER FAR FROM DANGER.

As the story of the first cruise of the Essex shows how thoroughly the American seamen were drilled in that day, and, after a fashion, somewhat of their skill in the use of weapons, so the story of an adventure of another American war-ship—an adventure that occurred soon after the Minerva refused to fight the Essex—shows in a splendid light their skill and unwearied strength as seamen. This adventure was the escape of the Constitution, Captain Isaac Hull, from a British squadron off the Jersey coast—somewhat to the south, indeed,52 of the modern racing ground between English and American crack yachts, but near enough to be worth mentioning.

The Constitution, after the Portsmouth incident, returned to Chesapeake Bay and was there cleaned and coppered. Before this work was done war was declared, but as soon as possible she was floated and a new crew shipped. This crew numbered, including officers, etc., four hundred and fifty. Of them Captain Hull wrote, at the time, to the Secretary of the Navy:

“The crew are as yet unacquainted with a ship-of-war, as many have but lately joined and have never been on an armed ship before.... We are doing all that we can to make them acquainted with their duty, and in a few days we shall have nothing to fear from any single-deck ship.”

That is to say, the crew contained many green hands instead of experienced sailors like those on the British war-ships. But though inexperienced they were intelligent—they could learn readily, and they were to a man willing. A most important fact about the American crews at that time was that even the landsmen were willing and able workers. The experienced members of the crews, of course, fought with a will in very many cases because of their hatred of the British press-gang. But that does not account for all the excellent qualities of the53 American crews. The Yankee was willing and able because he was the best-fed naval seaman in the world. The humane system of treatment, made imperative when the fathers of the nation were careful to provide that canvas for pudding-bags be served out at proper intervals, had been continued wherever American warships were found.

And it is worth noting in connection with this subject that when American and English ship-captains met socially during the interval between the Tripoli war and that of 1812 the English habitually sneered at the American system that gave the men plenty of good food and good pay, and prohibited an officer from striking a forecastleman, and limited the punishment by the lash to a dozen strokes, which could only be inflicted after a court-martial at that.

Leaving the capes of the Chesapeake on July 12, 1812, the Constitution beat her way slowly through light airs up the coast for five days. Then on Friday, the 17th, at 2 P.M., “being in twenty-two fathoms of water off Egg Harbor” (from twelve to fourteen miles offshore) “four sail of ships were discovered from the mast-head, to the northward and inshore—apparently ships-of-war.” Captain Hull thought they were the American squadron under Commodore Rodgers, and so held on his drifting course. Two hours later the lookout saw another54 sail. The others were northwesterly from the Constitution, but this one was in the northeast, and she was heading for the Constitution under full sail. But the fact that she was under full sail must not be taken as indicating that she was making any great headway. In fact, at sundown she was still so far off that her signals could not be made out.

However, this ship in the northeast was manifestly alone, and so Captain Hull stood for her. She might be a friend, but if she and the others were of the enemy it would be safer to attack the single one.

At about this time the breeze shifted to the south, and, wearing around, Captain Hull set studding-sails to starboard to help him along, and then as the light was fading in the west he beat to quarters. And thereafter with the men at their guns and peering through the ports for glimpses of the stranger the two ships drew slowly toward each other.

But they did not get together. At 10 o’clock Captain Hull hoisted his secret night-signal, by which American ships were to know each other, and kept it up for an hour. The stranger being unable to answer, it was plainly an enemy. Captain Hull had correctly concluded that the ships inshore were also of the enemy. So he “hauled off to the southward and eastward and made all sail.”

Isaac Hull.

From an engraving, at the Navy Department, Washington, of the painting by Stuart.

55

As the event proved, the lone ship for which the Constitution had been heading was the Guerrière, Captain Dacres, while the squadron in the northwest included the ship-of-the-line Africa, the frigates Shannon, Belvidera, and Eolus, and the United States brig Nautilus that the squadron had captured a short time before. The squadron was under Captain Philip Vere Broke, of the Shannon, and it had been sent out from Halifax immediately after the squadron of Commodore Rodgers had vainly chased the Belvidera.

Now, although Captain Hull headed the Constitution offshore, he did not by any means try to avoid the Guerrière. He held a course enough to the eastward to enable her to draw near. What he wanted was to draw her clear of the rest before he fought her. But in this he was not successful. At 3.30 o’clock the next morning (July 18th) the Guerrière was but half a mile from the Constitution, and the two were nearing each other hopefully, when the Guerrière saw for the first time the other ships spread out inshore in chase. At that Captain Dacres made the private British signal, but it was not answered because the captains inshore assumed that Dacres knew who they were—and that misunderstanding led these captains to say unpleasant things to each other afterwards.

56

Supposing that the failure to answer his signals was due to the ships inshore being Yankees, Captain Dacres wore the Guerrière around and ran away from the Constitution for some time before he discovered his mistake. Meantime the ships inshore had had the benefit of enough wind to bring them within dangerous distance of the Constitution, so that when the wind failed the Constitution, as it did at 5.30 in the morning, her condition was desperate. The Guerrière having once more entered the chase, there were four frigates and a ship of the line all spread out in such fashion as would enable them to take advantage of the slightest change in the direction of the wind, and three of them were less than five miles away. It was then that the most famous race between warships known to the annals of the American navy really began, for up to that time Captain Hull had not tried to avoid the Guerrière.

Seeing now that he must fly from all, Captain Hull called away all his boats, and running a line to them, sent them ahead, towing the Constitution away to southward. Although some little air was still wafting on the enemy they very promptly imitated the example of the Constitution. In fact, they did better, for the boats of the squadron were concentrated on two ships, and what with their aid and the faint zephyr blowing they gained rapidly on the57 Constitution. In fact, at 6 o’clock the Shannon, which was in the lead, opened fire on the Constitution, her captain being of the opinion that she was within reach of the long guns.

The shot failed to reach, but the captain of the Constitution “being determined they should not get her without resistance on our part, notwithstanding their force,” ordered one of the long twenty-four pounders brought from the gun-deck up to the poop where it would bear over the stern at the enemy. A long eighteen was brought from the forecastle to do similar service, while two long twenty-fours were run out of the cabin windows below.

The Constitution’s Escape from the British Squadron after a Chase of Sixty Hours.

From an engraving by Hoogland of the picture by Corné.

At 7 o’clock one of these long twenty-fours was tried on the Shannon, but the ball fell short. It did some good, however, for it58 showed the enemy that their boats were in danger, and so prevented their towing fairly within gunshot.

But this by no means freed the Constitution. If they did not dare tow up within range astern, they could with their superior forces tow their vessels out on each side of her, and so far surround her as to absolutely prevent her escape when a wind did come, and the situation was apparently more nearly hopeless for the Constitution than at any time since the chase began.

In this emergency the wit of the “smart Yankee” executive officer of the Constitution—Lieutenant Charles Morris—gave the ship a new lease of life. Morris had had experience in towing a ship through crooked channels by means of a light anchor carried ahead with a line attached to haul on. This method of towing is called kedging. Dropping a lead-line over the rail, Morris found that the water was but one hundred and fifty-six feet deep, and suggested at once that they kedge her along.

A few minutes later the Constitution’s largest boat was rowing away ahead with a small anchor on board, and stretching out a half mile of lines and cables knotted together. When that anchor was dropped to the bottom the men on the ship began to haul in on the line—to walk away with it at a smart pace, and the59 speed of the Constitution, which at best had been no more than a mile an hour, was at once trebled. She was literally clawing her way out of trouble, clear of the enemy.