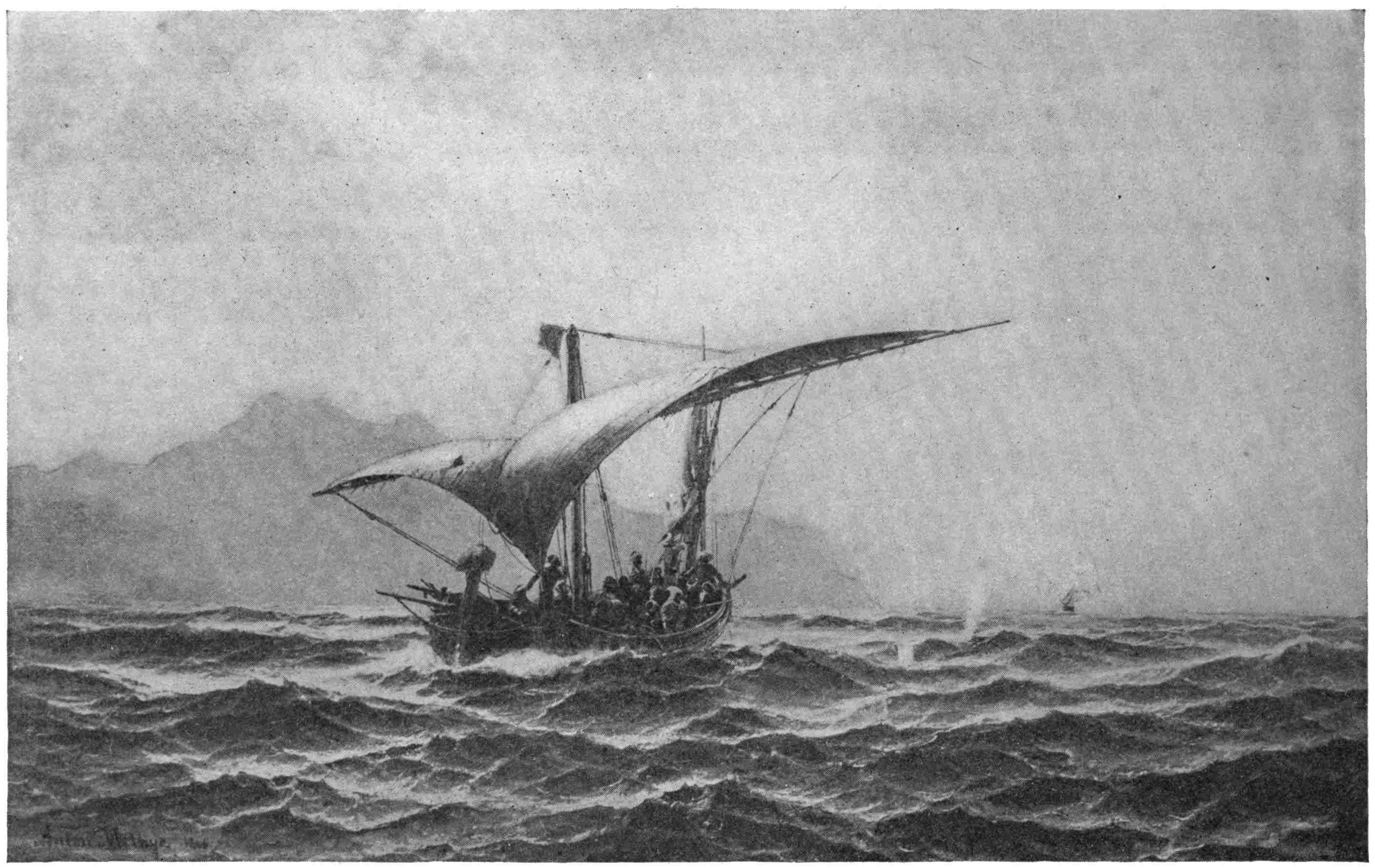

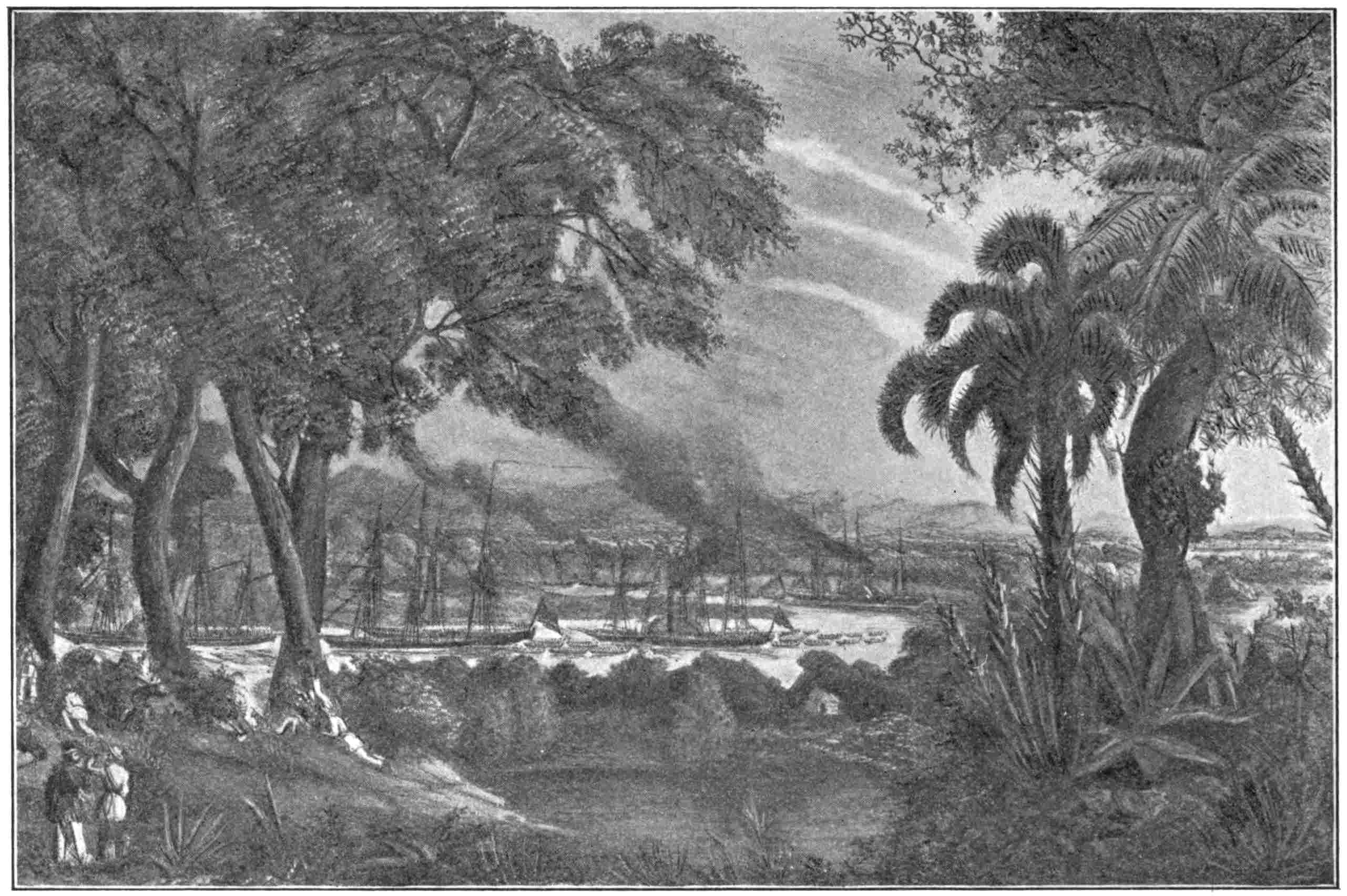

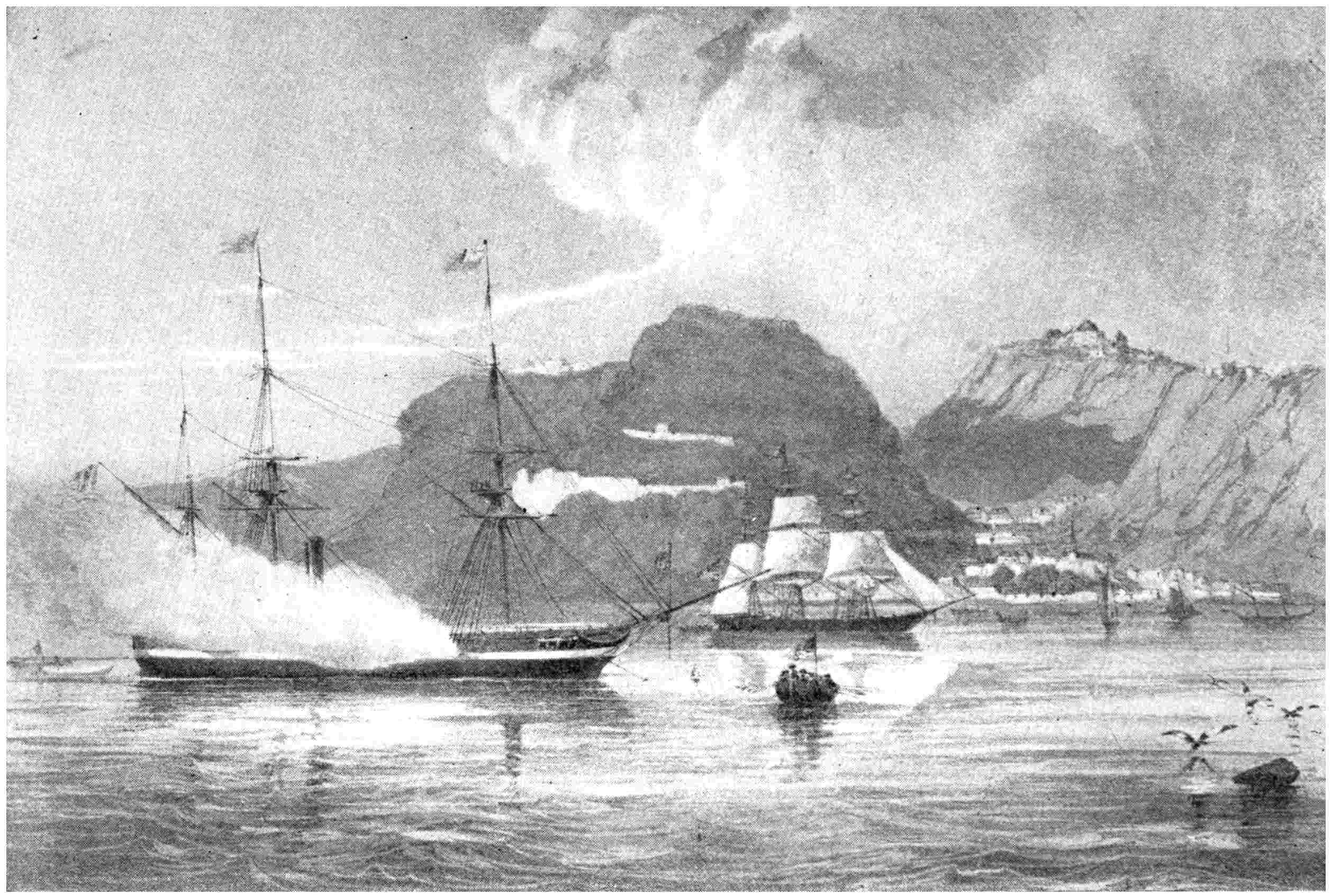

CHASING A SLAVER, OFF THE AFRICAN COAST.

From a photograph, in the possession of Mr. Edward Trenchard, of the painting by Melbye.

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

CHASING A SLAVER, OFF THE AFRICAN COAST.

From a photograph, in the possession of Mr. Edward Trenchard, of the painting by Melbye.

THE

HISTORY OF OUR NAVY

FROM ITS ORIGIN TO THE PRESENT DAY

1775–1897

BY

JOHN R. SPEARS

AUTHOR OF “THE PORT OF MISSING SHIPS,”

“THE GOLD DIGGINGS

OF CAPE HORN,” ETC.

WITH MORE THAN FOUR HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

IN FOUR VOLUMES

VOLUME III.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

MANHATTAN PRESS

474 W. BROADWAY

NEW YORK

v

TO ALL WHO WOULD SEEK PEACE

AND PURSUE IT

| PAGE | |

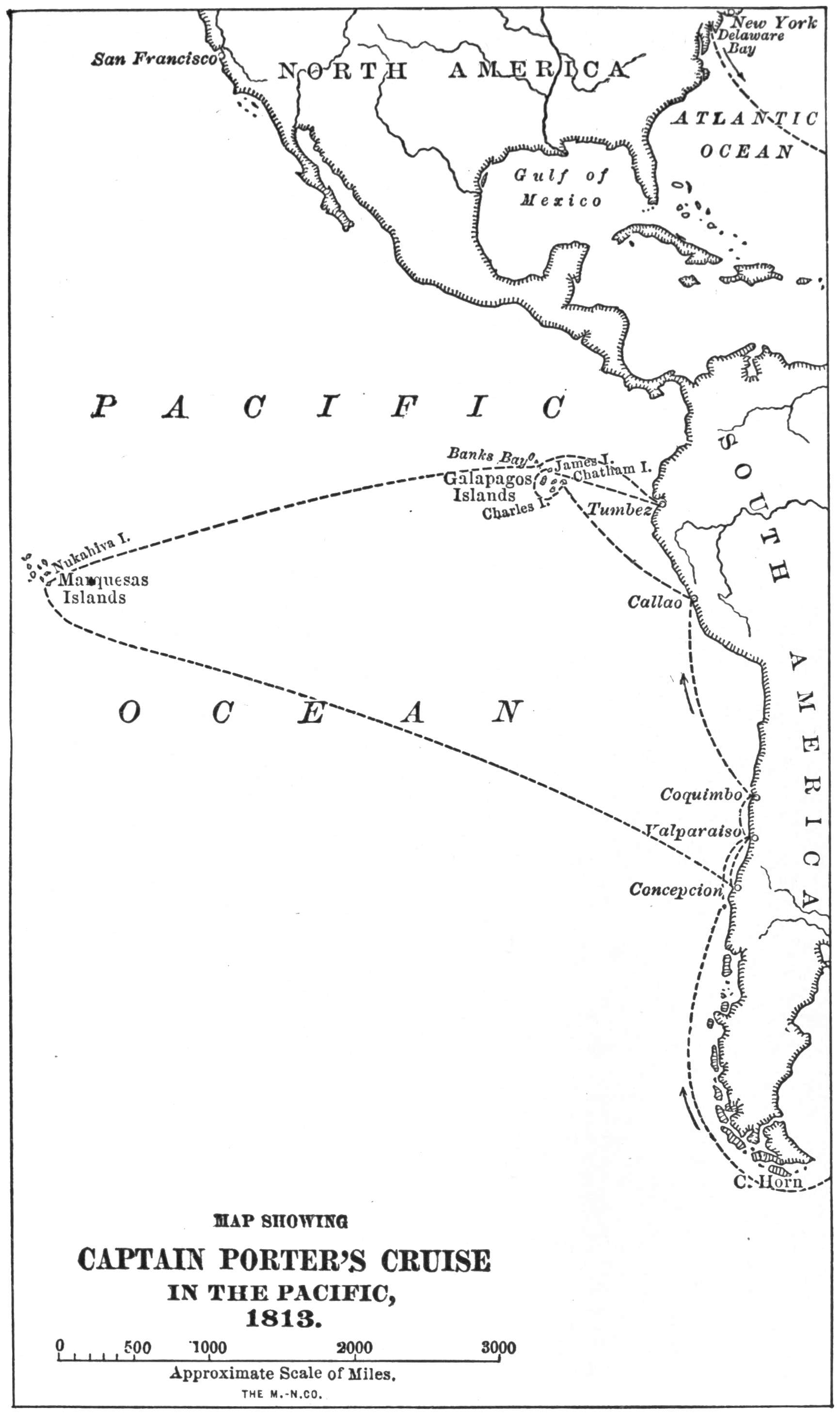

| Chapter I. When Porter Swept the Pacific | 1 |

| The Story of the Second Cruise of the Famous Little Frigate Essex—Around Cape Horn and Alone in the Broad South Sea—Capture of a Peruvian Picaroon—Disguising the Essex—The British Whaling Fleet Taken by Surprise—An Armed Whaler Transformed into a Yankee Cruiser—The Sailorman’s Paradise among the Nukahiva Group—When Farragut was a Midshipman—An Incipient Mutiny among the Sailors who Wanted to Remain among the Islands—Farragut as a Captain at Twelve. | |

| Chapter II. Porter’s Gallant Action At Valparaiso | 24 |

| A Generous Reception for a Predatory British Frigate—Hillyar’s Lucky Escape—Hillyar’s Explicit Orders—When the Essex had Lost her Top-mast the Phœbe and the Cherub Attacked the Yankee in Neutral Water—It was a Two-to-one Fight and the Enemy had Long Guns to our Short—The British had to Get Beyond the Range of the Essex—Magnificent Bravery of the Yankee Crew when under the Fire of the Long Range British Guns—The Essex on Fire—Fought to the Last Gasp—Porter’s Interrupted Voyage Home—The Men who were Left at Nukahiva in Sorry Straits at Last. | |

| Chapter III. Tales of the Yankee Corvettes | 54 |

| A Little Lop-sided Frigate Rebuilt into a Superior Sloop-of-war—Overland (almost) to Escape the Blockade—Her Luck as a Cruiser—A Marvellous Race with a British Frigate over a Course Four Hundred Miles Long—Saved by a Squall—Cornered in the Penobscot—The Gallant Fight of the Yankee Crew against Overwhelming Numbers—Building a New Navy—The Short-lived Portsmouth Corvettevi Frolic—One Broadside was Enough—Captured by the Enemy—Swift and Deadly Work of the Crew of the Yankee Peacock when they Met the Epervier—Distinctly a Lucky Ship—Fate of the Siren After the Coffin Floated. | |

| Chapter IV. Mystery of the Last Wasp | 80 |

| A Typical New England Yankee Crew—Youthful Haymakers and Wood-choppers—Sea-sick for a Week—From Flails to Cutlasses, from Pitchforks to Boarding-pikes, from a Night-watch at a Deer-lick to a Night Battle with the British—After British Commerce in British In-shore Waters—Met by the British Sloop-of-war Reindeer—Magnificent Pluck of the British Captain with a Crew that was “The Pride of Plymouth”—Shot to Pieces in Eighteen Minutes—A Liner that could not Catch her—Wonderful Night Battle with the Avon—Shooting Men from the Enemy’s Tops as Raccoons are Shot from Tree-tops—The Enemy’s Water-line Located by Drifting Foam—Not Captured but Destroyed—The Mystery. | |

| Chapter V. On the Upper Lakes in 1814 | 105 |

| An Expedition into Lake Huron—The British had the Best of it in the End—Gallant Action of a British Commander at the Head of the Niagara River—Cautious Captain Chauncey as a Knight of the Whip-saw, Adze, and Maul—His Equally Prudent Opponent—British Torpedoes that Failed—When a Thousand Men Supported by Seven Ships Armed with One Hundred and Twenty-one Cannon “with Great Gallantry” Routed Three Hundred Yankees at Oswego—Supplies the British did not Get—A Naval Flotilla Caught in Big Sandy Creek—Chauncey Afloat on the Lake—Gallant Young American Officers—Line-of-battle Ships that were Never Launched. | |

| Chapter VI. To Defend the Northern Gateway | 132 |

| Character of the Red-coated Invaders—“Shamed the Most Ferocious Barbarians of Antiquity”—Work of the Youthful Yankee Lieutenant Macdonough to Stay the Tide on Lake Champlain—Ship-building at Otter Creek—A British Attempt against the New Vessels Repulsed—The British Ship-builders at Isle-Aux-Noix—A Comparison of Forces Before the Battle—Macdonough’s Foresight in Choosing the Battle-ground—Macdonough as a Seaman.vii | |

| Chapter VII. Macdonough’s Victory on Lake Champlain | 151 |

| Thousands Gathered on the Hill-tops Overlooking the Scene—The British Chose to Make a Long-range Fight—Influence of the First British Broadside on a Sporting Rooster—Macdonough’s First Shot—A Reeling Blow from the Enemy’s Flagship—Fighting against Tremendous Odds—Too Hot for One Yankee Ship—The Saratoga’s Guns Dismounted—The Swarming British Gun-boats—“Winding Ship” when Defeat Impended—The British Failure when Imitating the Movement—The Stubborn Bravery of a British Captain—When the Firing Ceased and the Smoke Drifted down the Gale—A Measure of the Relative Efficiency of the two Forces—Two Yankee Squadron Victories Compared—A Stirring Tale of Macdonough’s Youth—Reward for the Victors—Results of the Victory. | |

| Chapter VIII. Samuel C. Reid of the General Armstrong | 186 |

| Story of the Desperate Defence of America’s Most Famous Privateer—She was Lying in Neutral Water when Four Hundred Picked British Seamen in Boats that were Armed with Cannon came to Take her by Night—Although she had but Ninety Men, and there was Time to Fire but One Round from her Guns, the Attack was Repelled with Frightful Slaughter—Scuttled when a British Ship came to Attack her—The Cunning Omissions and Deliberate Misstatements of the British Historians Examined in Detail—The Honorable Career of Captain Reid in After Life—A Picked Crew of British Seamen After the Neufchâtel—A Three-to-one Fight where the Yankees Won—Other Brave Militiamen of the Sea. | |

| Chapter IX. A Yankee Frigate Taken by the Enemy | 209 |

| They Completely Mobbed “The Waggon” and so Got her at Last—The First Naval Contest After the Treaty of Peace was Signed—The President, when Running the Blockade at New York, Grounded on the Bar, and, although she Pounded Over, she Fell in with the Squadron—A British Frigate Thoroughly Whipped, but Two more Overtook her—A Point on Naval Architecture—A Treaty that Humiliates the Patriot.viii | |

| Chapter X. The Navy at the Battle of New Orleans | 229 |

| The British Grab at the Valley of the Mississippi—Stopped at Lake Borgne by the Yankee Gun-boats under Lieutenant Thomas Ap Catesby Jones—The British Came Five to One in Numbers and Almost Four to One in Weight of Metal—Defending the Seahorse with Fourteen Men against One Hundred and Seventy-five—The Full British Force Driven upon Two Gun-boats—A Most Heroic Defence that Lasted, in Spite of Overwhelming Odds, more than One Hour—Indomitable Sailing-master George Ulrich—A Fight, the Memory of which still Helps to Preserve the Peace—Work of the Caroline and the Louisiana. | |

| Chapter XI. Once More the Constitution | 241 |

| She was a Long Time Idle in Port—A Touching Tale of Sentiment—Away at Last—Captain Stewart’s Presentiment—Found Two of the Enemy as he had Predicted—A Battle where the Yankee Showed Mastery of the Seaman’s Art—Captain Stewart Settled a Dispute—Caught Napping in Porto Praya—Swift Work Getting to Sea—A Most Remarkable Chase—Three British Frigates in Chase of Two Yankee Chose to Follow the Smaller when the Two Split Tacks—Astounding Exhibit of Bad Marksmanship—A Cause of Suicide—The Poem that Saved Old Ironsides. | |

| Chapter XII. In the Wastes of the South Atlantic | 270 |

| The Story of a Battle—The Hornet and the Penguin in the Shadows of Tristan d’Acunha—As Fair a Match as is Known to Naval Annals—It Took the Yankees Ten Minutes to Dismantle the Enemy and Five more to Riddle his Hull—The British Captain’s Forceful Description of the Yankee Fire—A Marvellous Escape from a Liner—The Peacock in the Straits of Sunda—When the Lonely Situation of this Sloop is Considered did Warrington Show a Lack of Humanity?—If he Did, What did the British Captain Bartholomew Show? | |

| Chapter XIII. In British Prisons | 288 |

| A Typical Story of the Life of an American Seaman who was Impressed in 1810 and Allowed to Become a Prisoner when War wasix Declared—Luck in Escaping a Flogging—Letters to his Father Destroyed—British Regard for the Man’s Rights when the American Government Took up the Case—A Narragansett Indian Impressed—To Dartmoor Prison—Mustered Naked Men in the Snows of Winter and Kept them in Rooms where Buckets of Water Froze Solid—Murder of Prisoners Six Weeks After it was Officially Known that the Treaty of Peace had been Ratified—Notable Self-restraint of the Americans—Smoothed Over with a Disavowal. | |

| Chapter XIV. Stories of the Duellists | 305 |

| Traditions of Personal Combats that Illustrate, in a Way, a Part of the Life Led by the Old Time Naval Officers—When an Englishman did not Get “a Yankee for Breakfast”—They were Offended by the Names of the Yankee Ships—Somers was Able to Prove that he was not Devoid of Courage—The Fate of Decatur, the Most Famous of the Navy’s Duellists. | |

| Chapter XV. Among the West India Pirates | 324 |

| A Breed of Cowardly Cutthroats Legitimately Descended from the Licensed Privateers and Nourished under the Peculiar Conditions of Climate, Geography, and Governmental Anarchy Prevailing Around and in the Caribbean Sea—Commodore Perry Loses his Life Because of them—William Howard Allen Killed—Pirate Caves with the Bones of Dead in them—Porto Rico Treachery—The Unfortunate Foxardo Affair—Making the Coasts of Sumatra and Africa Safe for American Traders. | |

| Chapter XVI. Decatur and the Barbary Pirates | 339 |

| Supposing the British would Sweep the American Navy from the Seas during the War of 1812, the Dey of Algiers went Cruising for Yankee Ships, and Got One, while Tunis and Tripoli Gave up to the British the Prizes that a Yankee Privateer had Made—The Algerian was Humbled After he had Lost Two War-ships, and the others Made Peace on the Yankees’ Terms without the Firing of a Gun—Bravery of the Pirate Admiral and his Crew.x | |

| Chapter XVII. Led a Hard Life and Got Few Thanks | 359 |

| Work that Naval Men have had to Do in Out-of-the-way Parts of the World in Times of Peace—Chasing Slavers on the African Coast when Slave-owners Ruled the Yankee Nation—The American Flag a Shield for an Infamous Traffic—Capture of the Martha and the Chatsworth—Teaching Malayans to Fear the Flag—Stories of Piratical Assaults on Yankee Traders, and the Navy’s Part in the Matter—A Chinese Assault on the American Flag—“Blood is Thicker than Water”—A Medal Well Earned by a Warlike Display in Time of Peace. | |

| Chapter XVIII. In the War with Mexico | 387 |

| Thomas Ap Catesby Jones, the Hero of Lake Borgne, Struck the First Blow of the War—Operations along the Pacific Coast that Insured the Acquisition of California—Stockton and “Pathfinder” Frémont Operate Together—Wild Horses as Weapons of Offence—The Somers Overturned while Chasing a Blockade Runner—Josiah Tattnall Before Vera Cruz—When Santa Anna Landed—The Yankee Sailors in a Shore Battery—The Hard Fate of One of the Bravest American Officers. | |

| Chapter XIX. Expedition in Aid of Commerce | 434 |

| Commodore Matthew C. Perry and the First American Treaty with Japan—An Exhibition of Power and Dignity that Won the Respect of a Nation that had been Justified in its Contempt for Civilized Greed—Services of Naval Officers that are not Well Known and have never been Fully Appreciated by the Nation. | |

xi

| PAGE | |

| Chasing a Slaver off the African Coast. (From a photograph, in the possession of Mr. Edward Trenchard, of the painting by Melbye), Frontispiece. | |

| Map Showing Captain Porter’s Cruise in the Pacific, 1813, | 5 |

| John Downes. (From an oil-painting at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 11 |

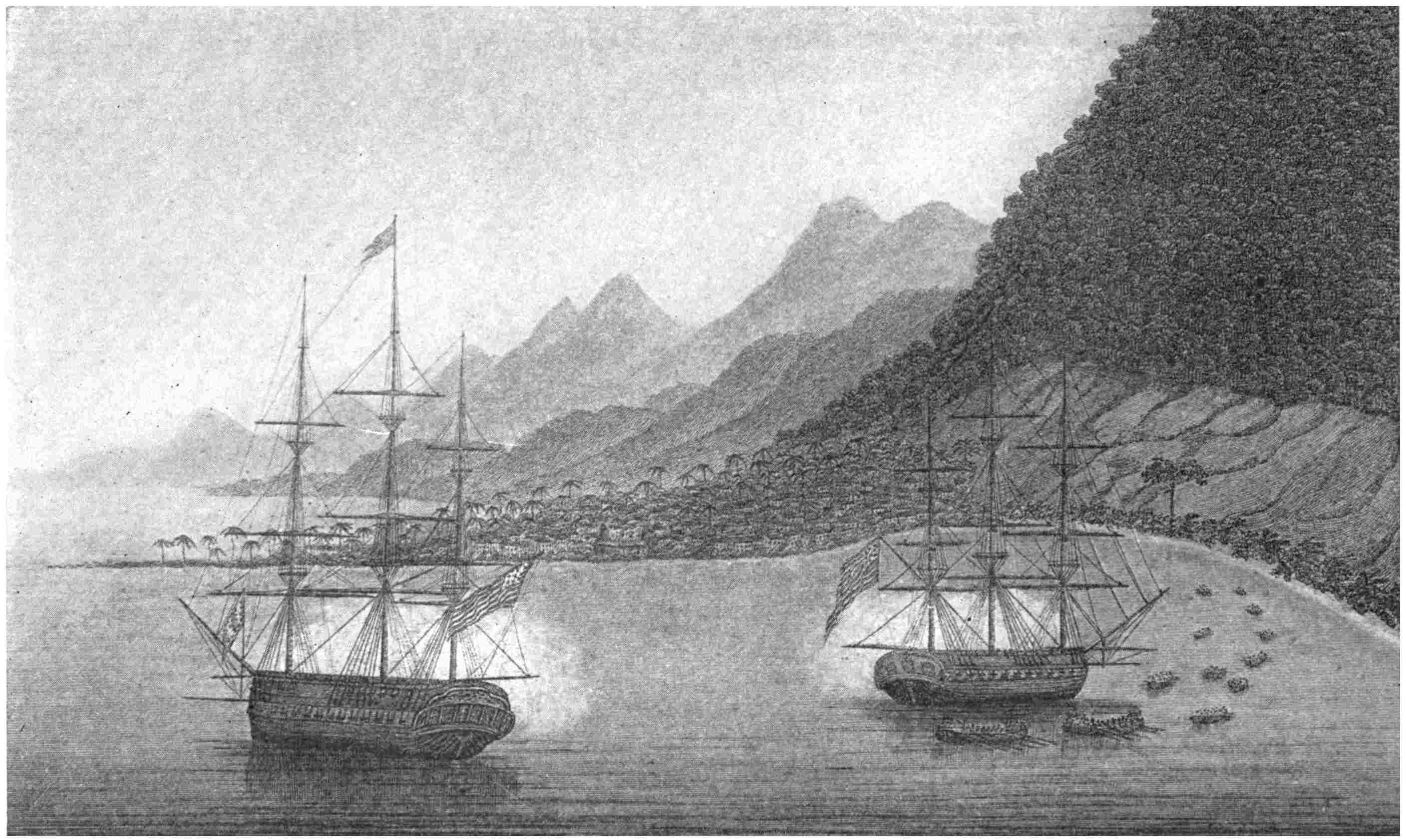

| The Essex and her Prizes at Nukahiva in the Marquesas Islands. (From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter), | 17 |

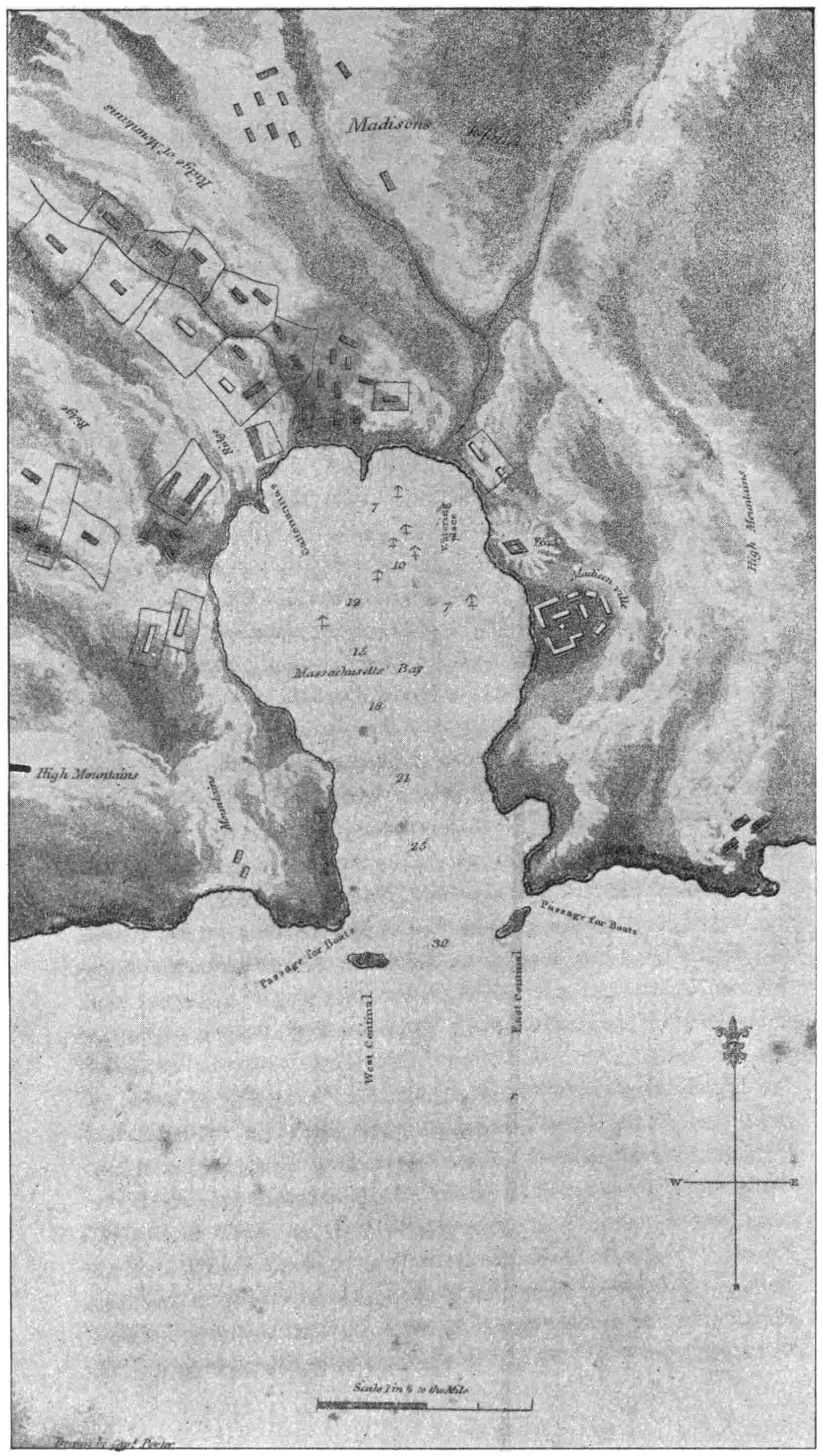

| Map of the Harbor in which the Essex and her Prizes lay. (After a drawing by Captain Porter), | 20 |

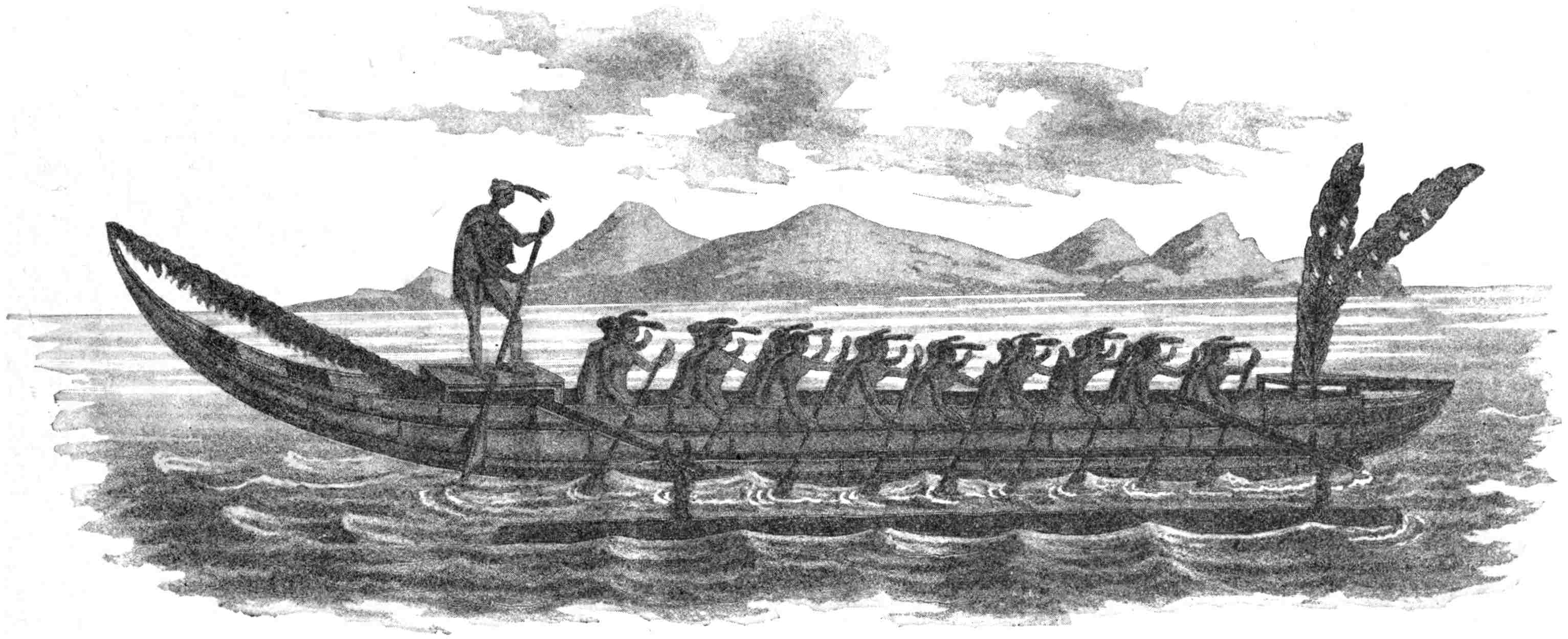

| A Marquesan War-canoe. (From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter), | 22 |

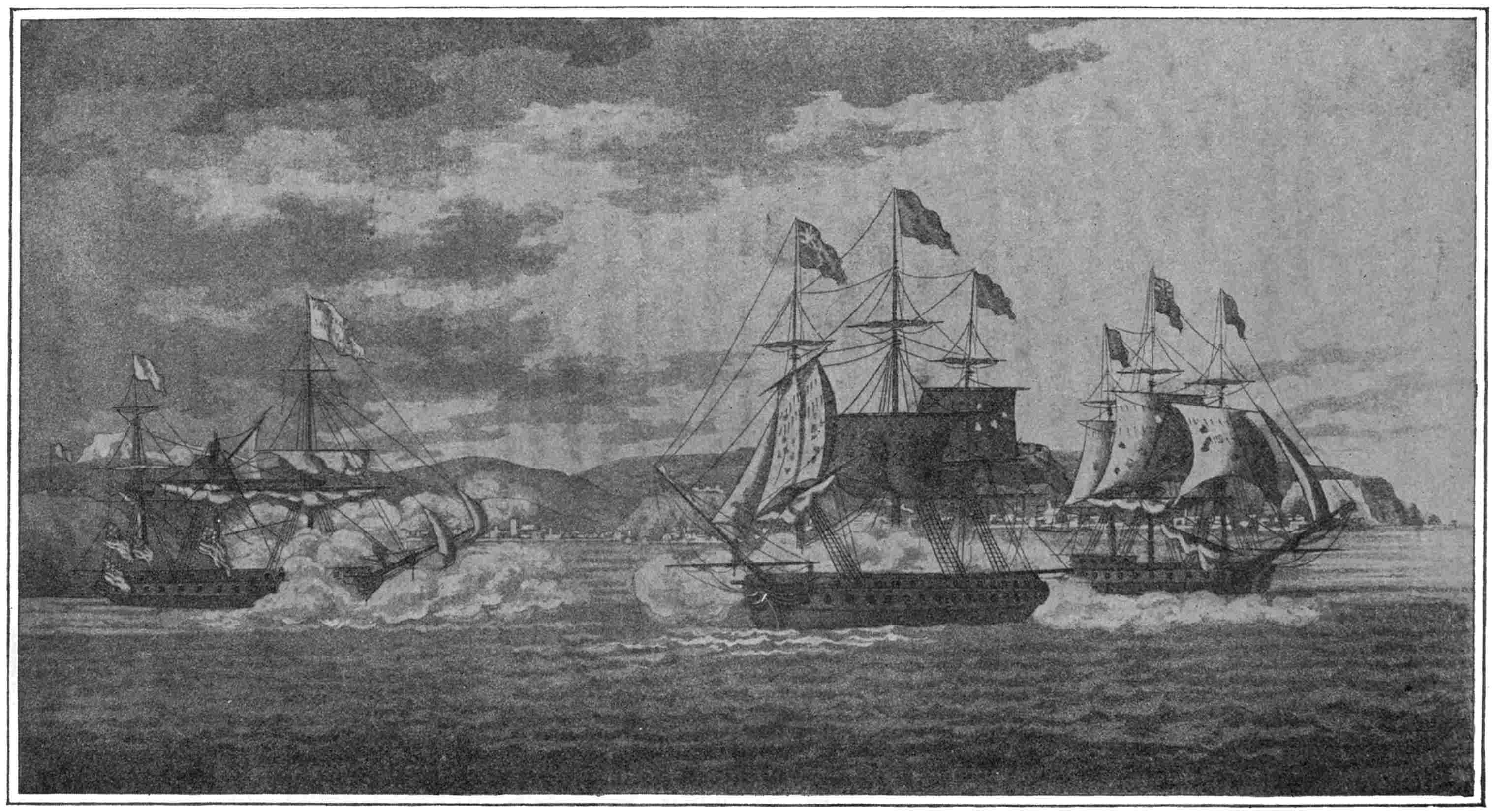

| Fight of the Essex with the Phœbe and Cherub. (From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter), | 37 |

| A Marquesan “Chief Warrior.” (From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter), | 51 |

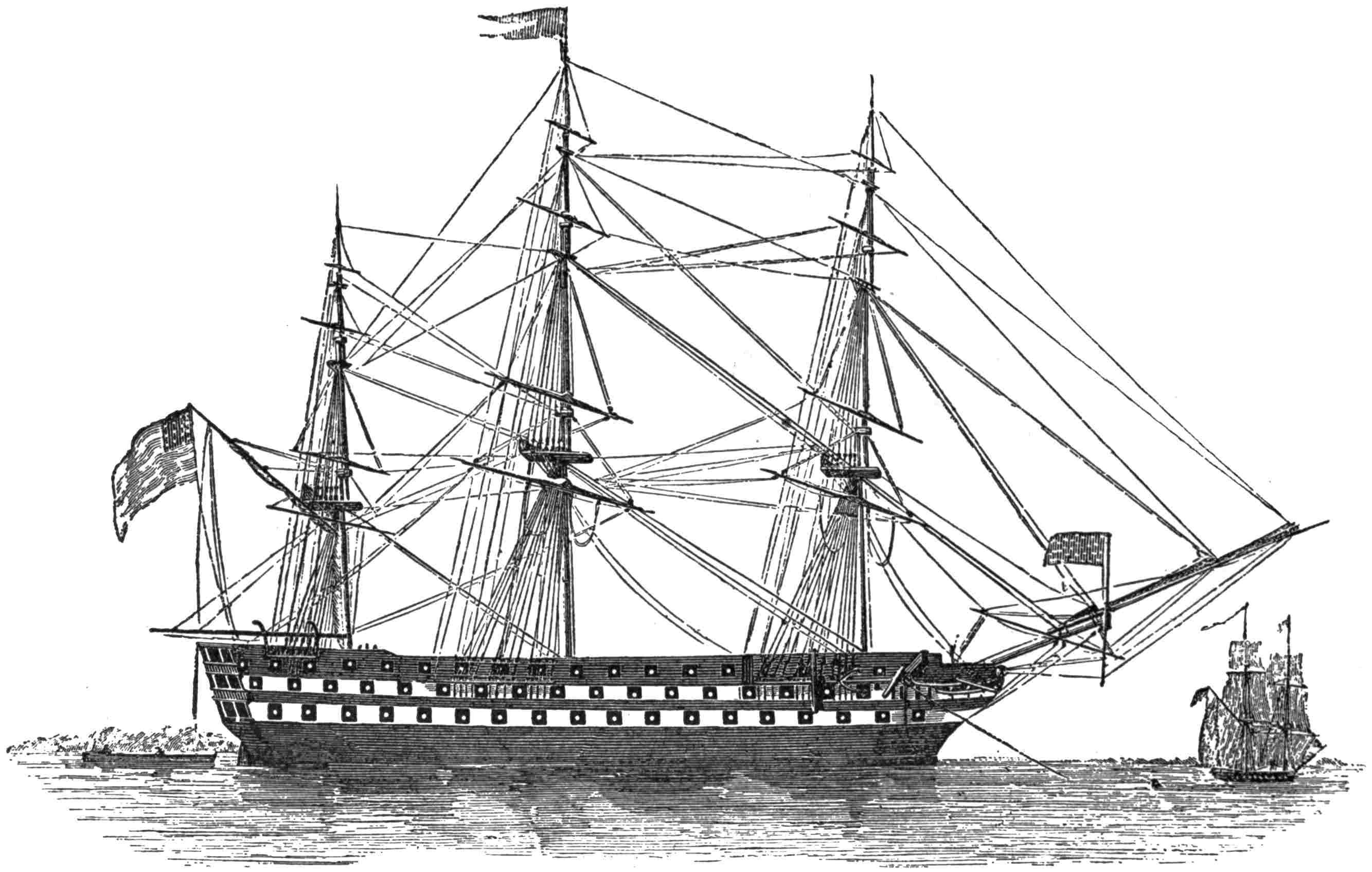

| United States Razee Independence at Anchor. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 56 |

| Charles Morris. (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 57 |

| United States Ship-of-war Columbus at Anchor. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 63 |

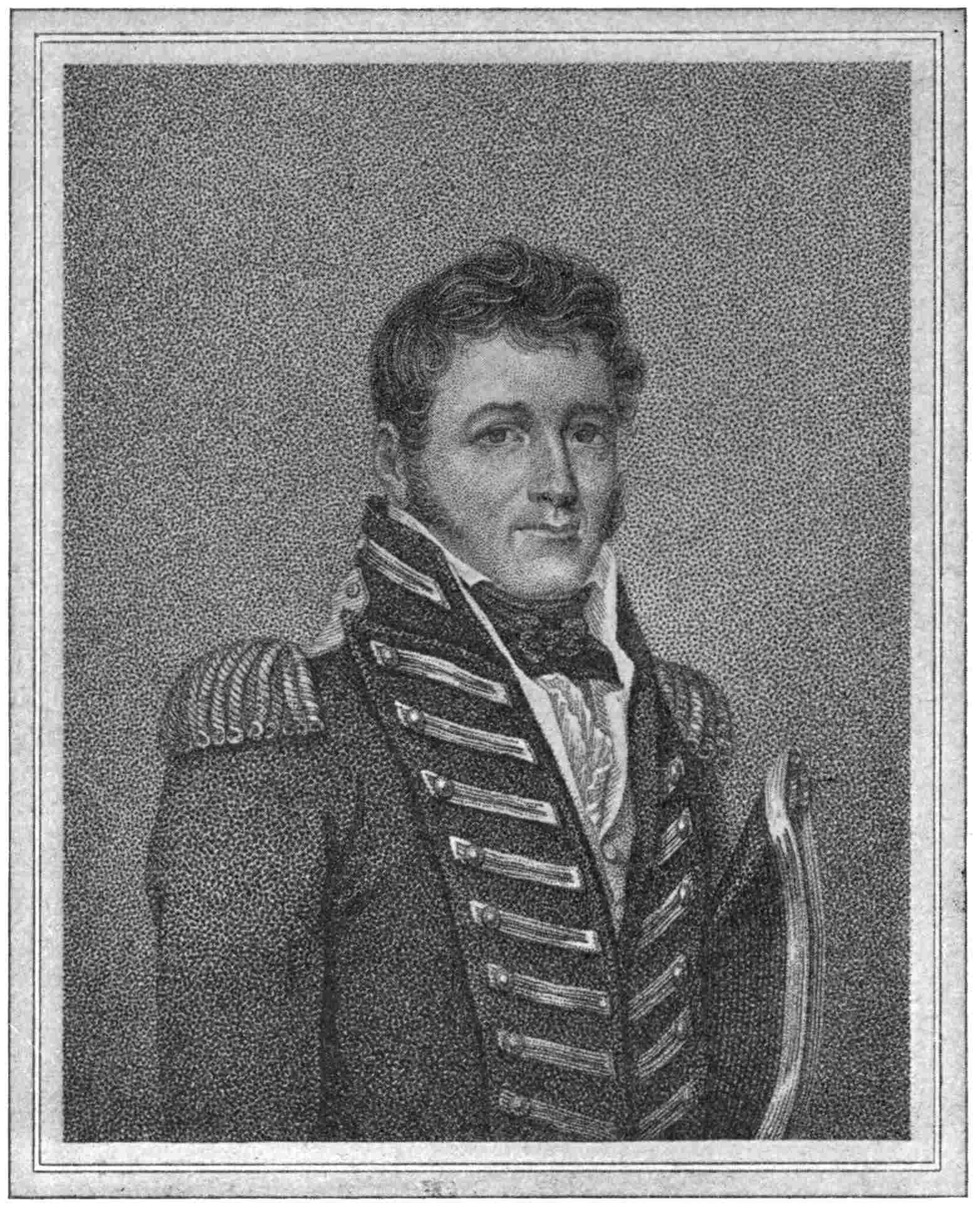

| Lewis Warrington. (From an engraving by Gimbrede of the painting by Jarvis), | 67 |

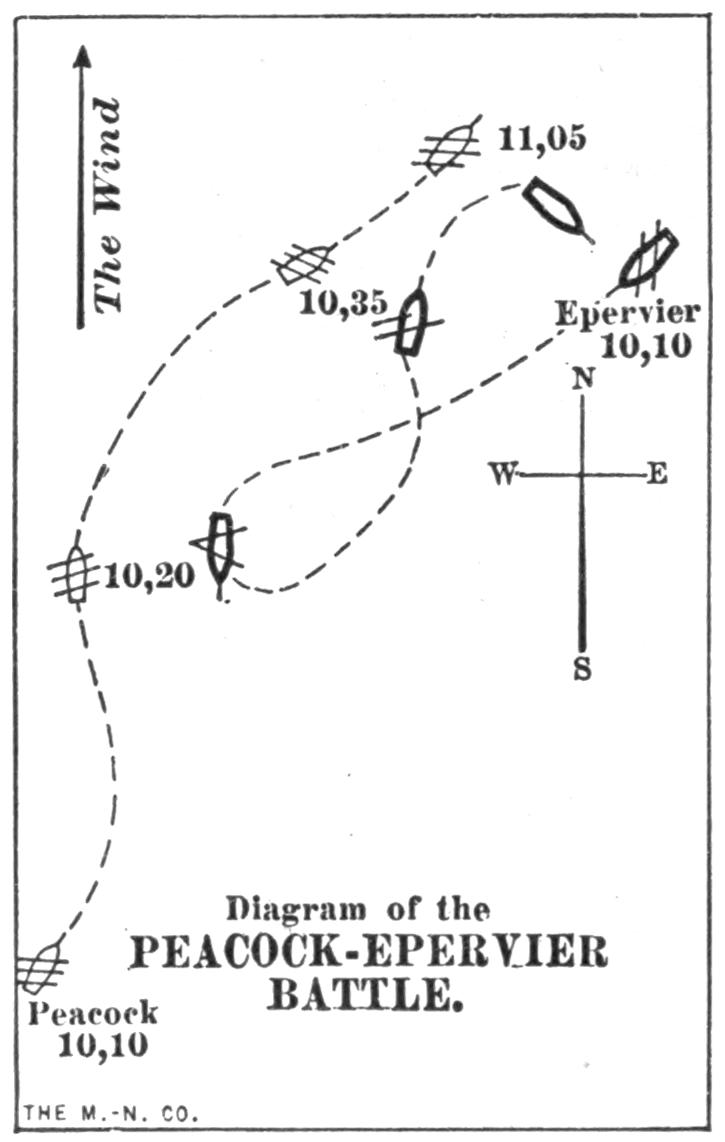

| Diagram of the Peacock-Epervier Battle, | 68 |

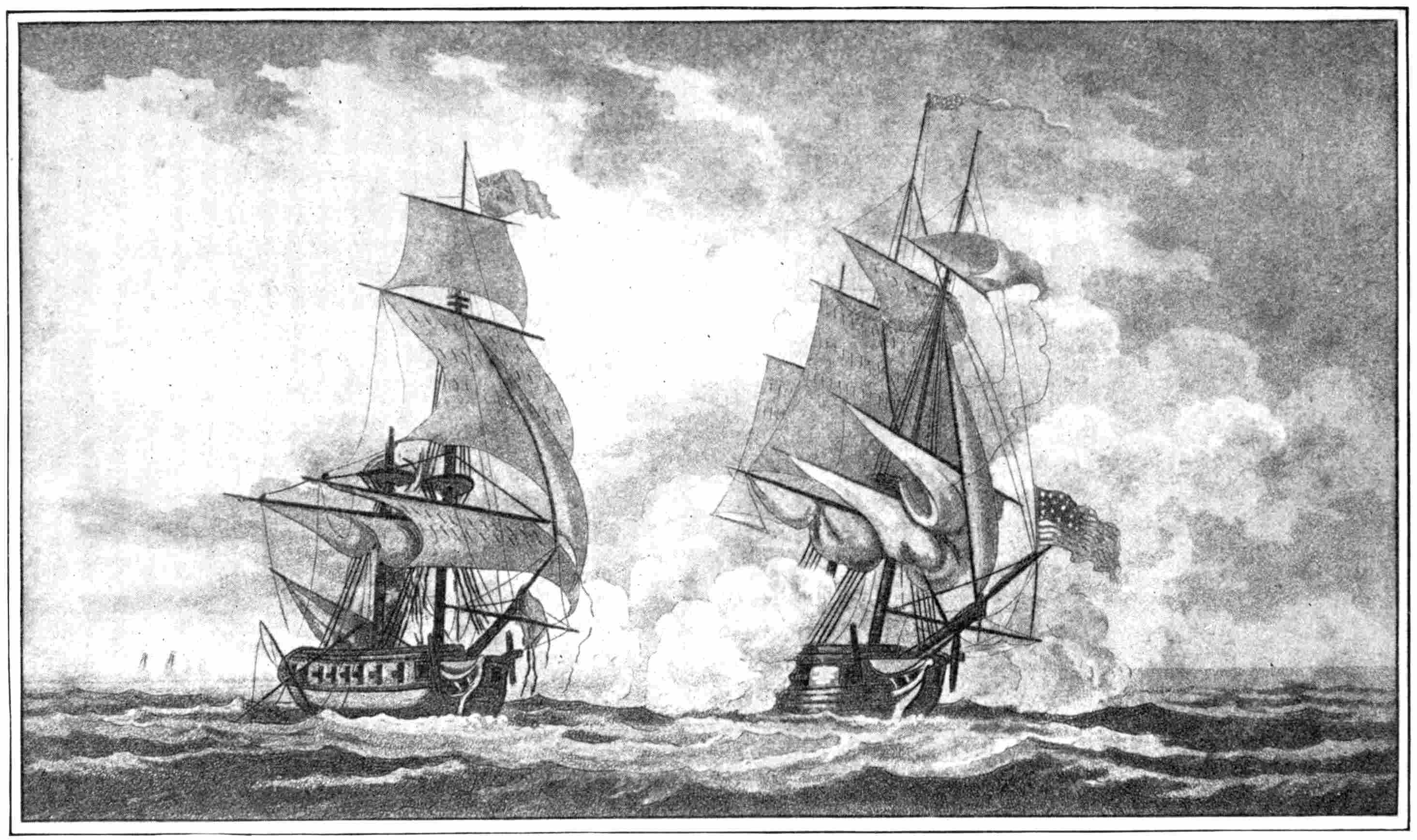

| The Peacock and the Epervier. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 69xii |

| The Peacock and the Epervier. (From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Birch), | 73 |

| Medal Awarded to Lewis Warrington after the Capture of the Epervier by the Peacock, | 77 |

| Johnston Blakeley. (From an engraving by Gimbrede), | 82 |

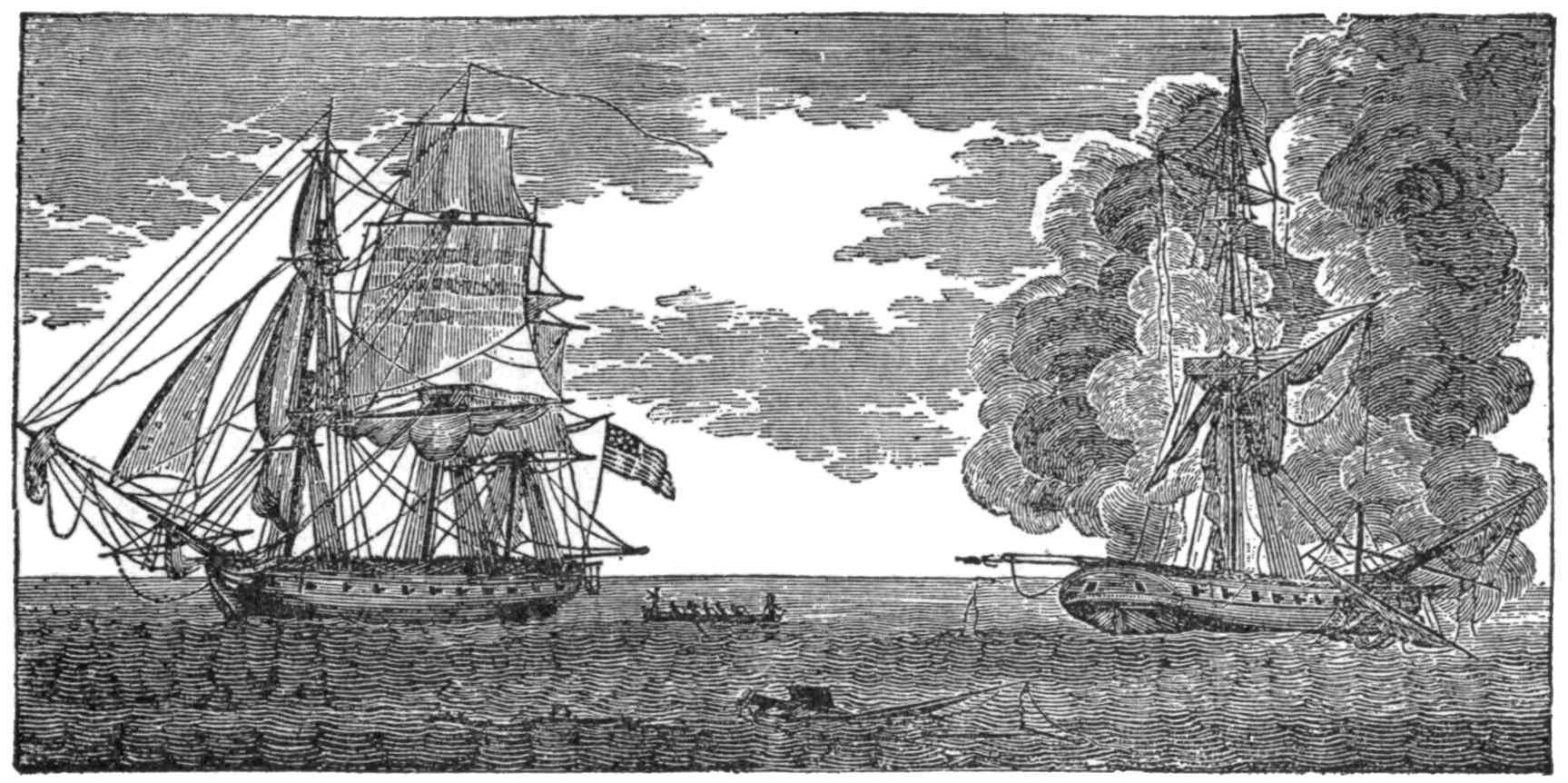

| The Wasp and Reindeer. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 87 |

| Medal Awarded to Johnston Blakeley after the Capture of the Reindeer by the Wasp, | 90 |

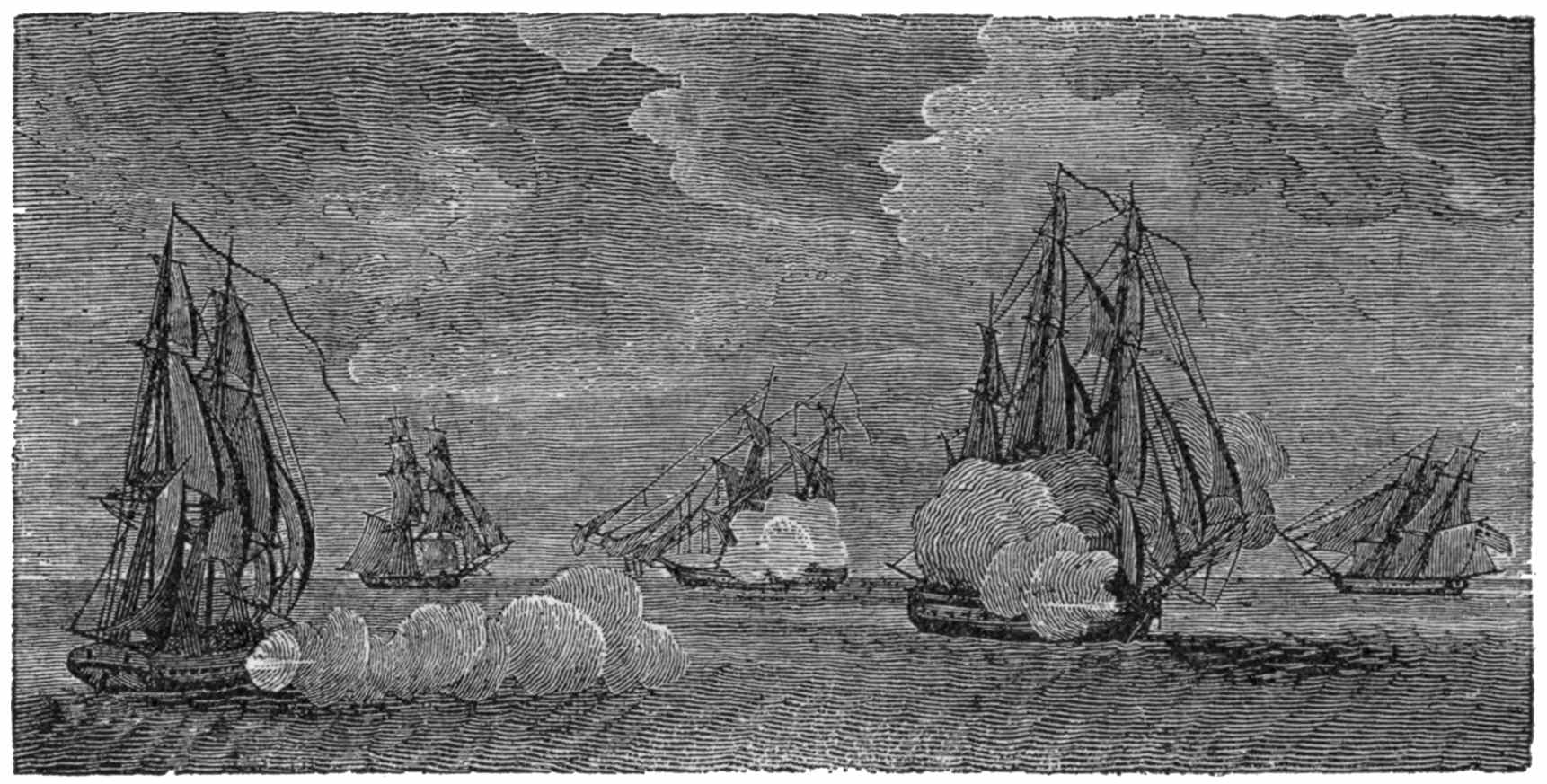

| The Wasp and Avon. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 94 |

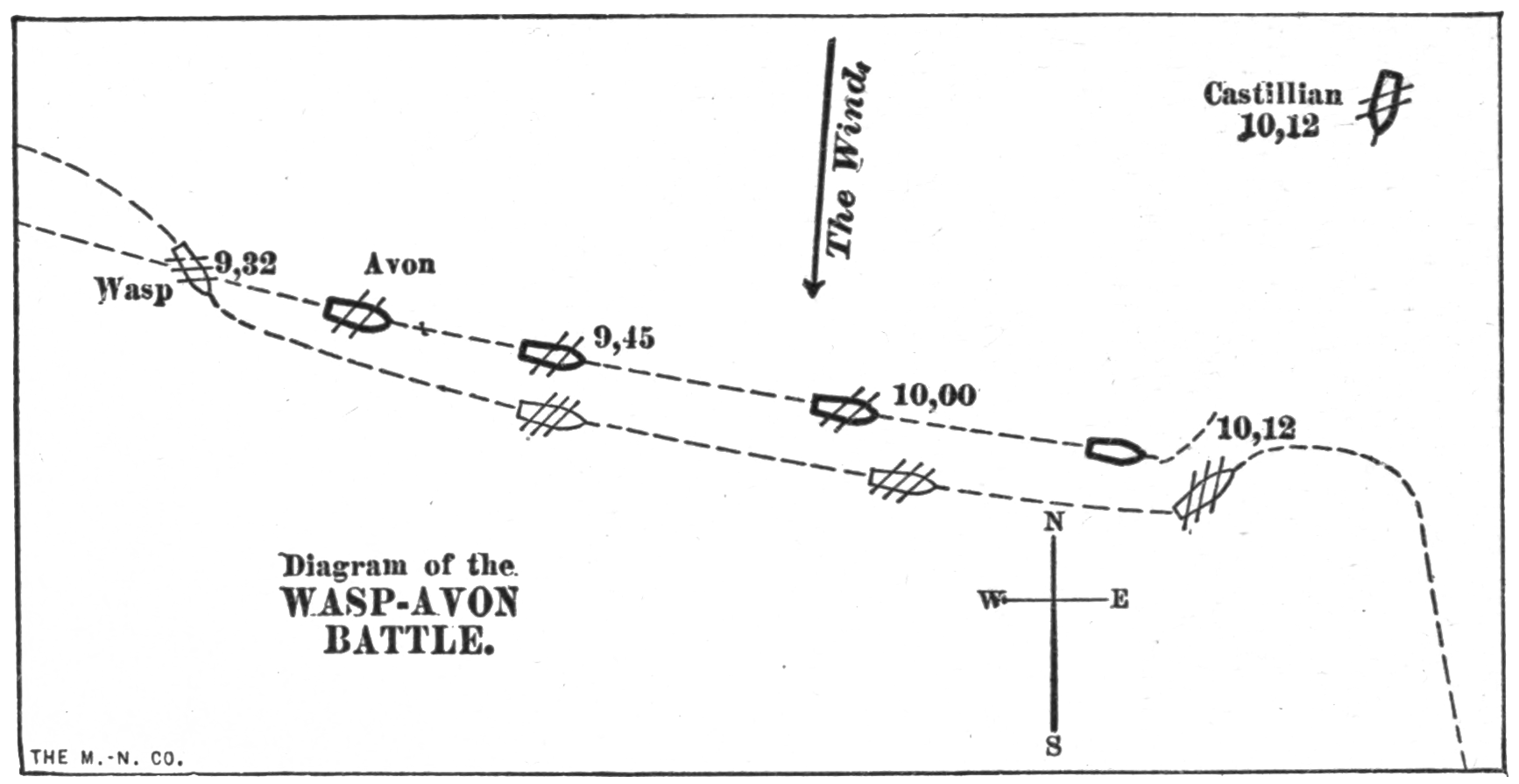

| Diagram of the Wasp-Avon Battle, | 96 |

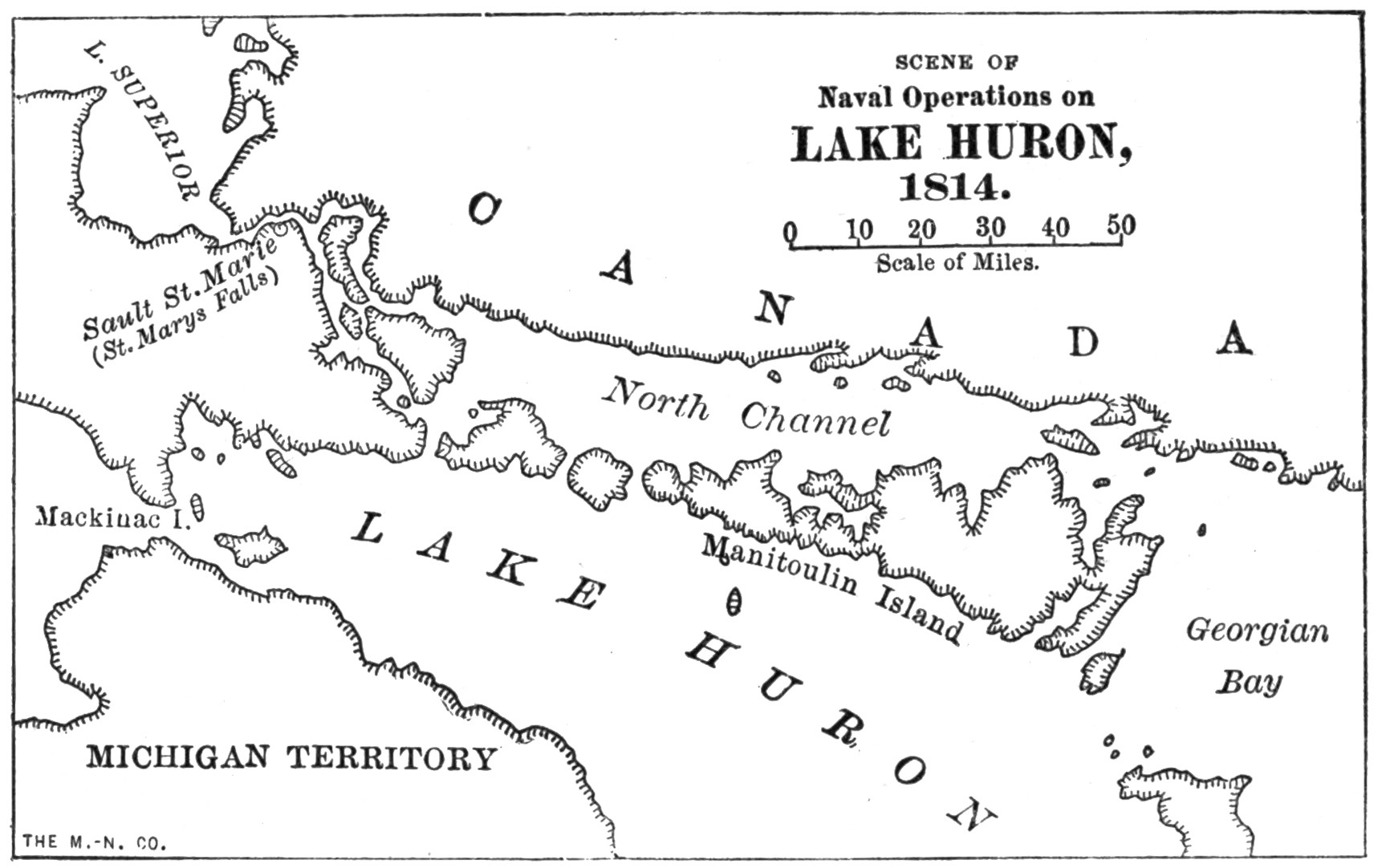

| Scene of Naval Operations on Lake Huron, 1814, | 108 |

| The Attack on Fort Oswego, Lake Ontario, May 6, 1814. (From an engraving, published in 1815, by R. Havel, after a drawing of Lieutenant Hewett, Royal Marines), | 118–119 |

| One of the Unlaunched Lake Vessels. (From a photograph), | 130 |

| Near Skenesborough on Lake Champlain. (From an old engraving in the collection of Mr. W. C. Crane), | 133 |

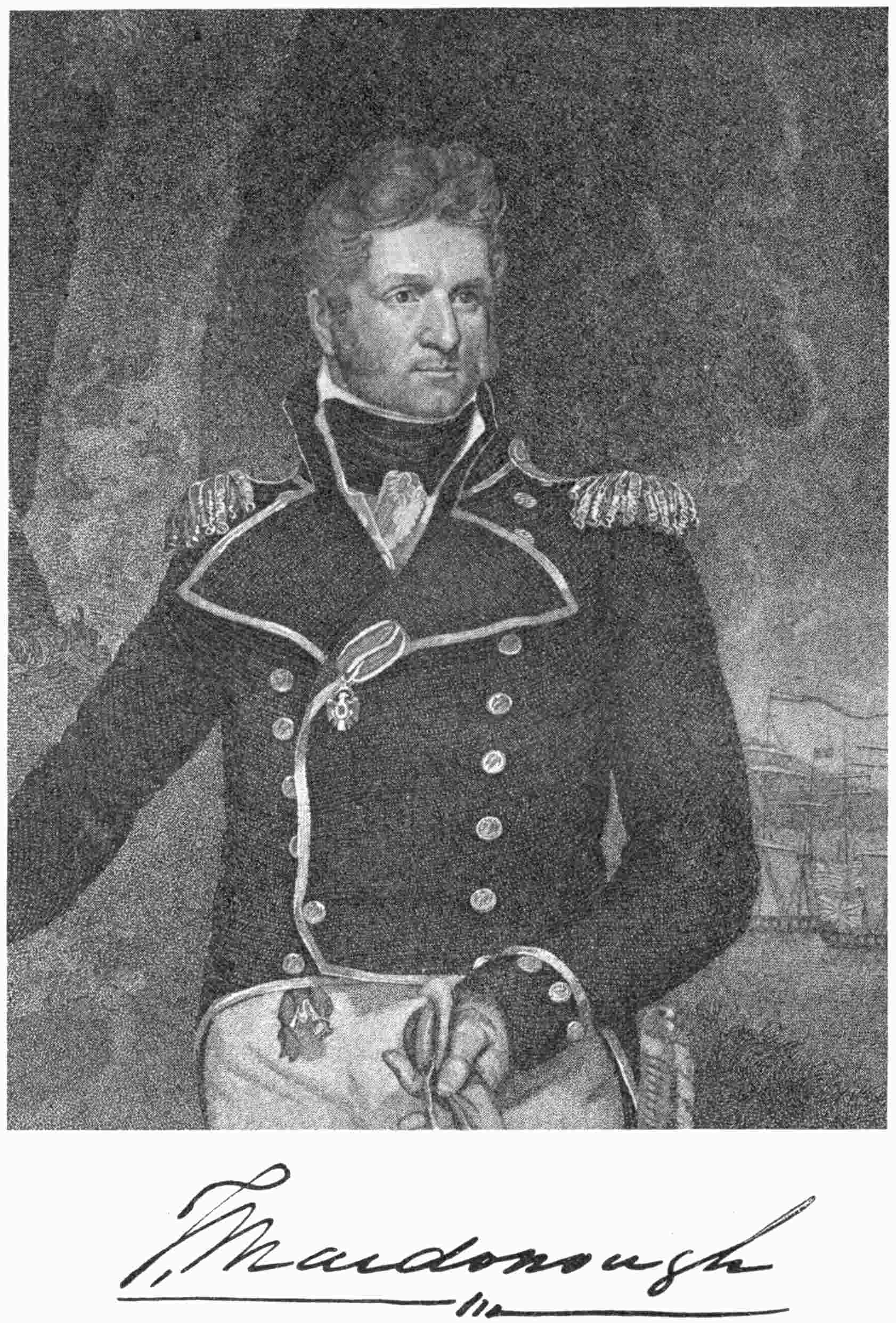

| Thomas Macdonough. (From an engraving by Forrest of the portrait by Jarvis), | 140 |

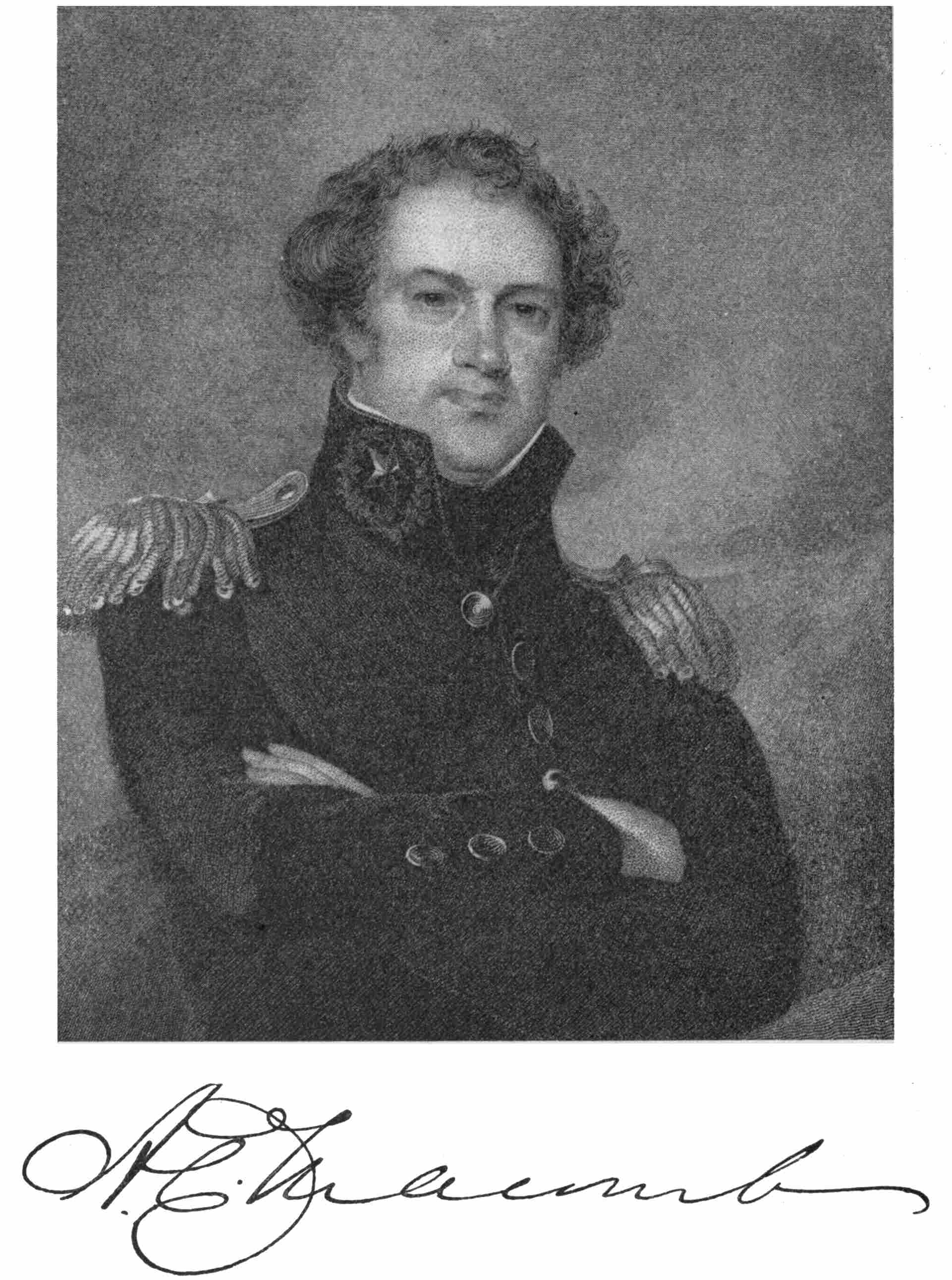

| Major-general Alexander Macomb. (From an engraving by Longacre of the portrait by Sully), | 146 |

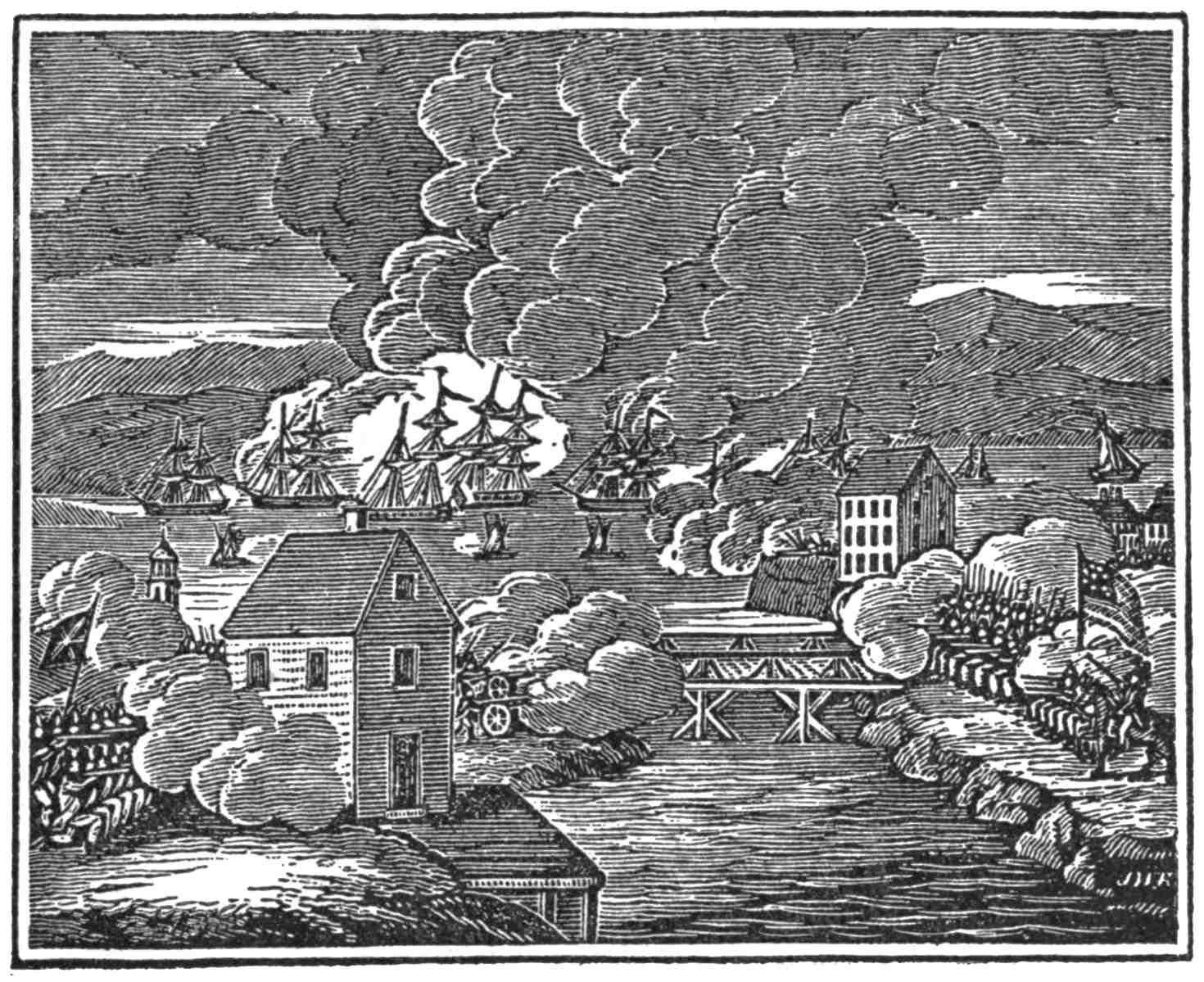

| The Battle of Lake Champlain. (From an old wood-cut), | 155 |

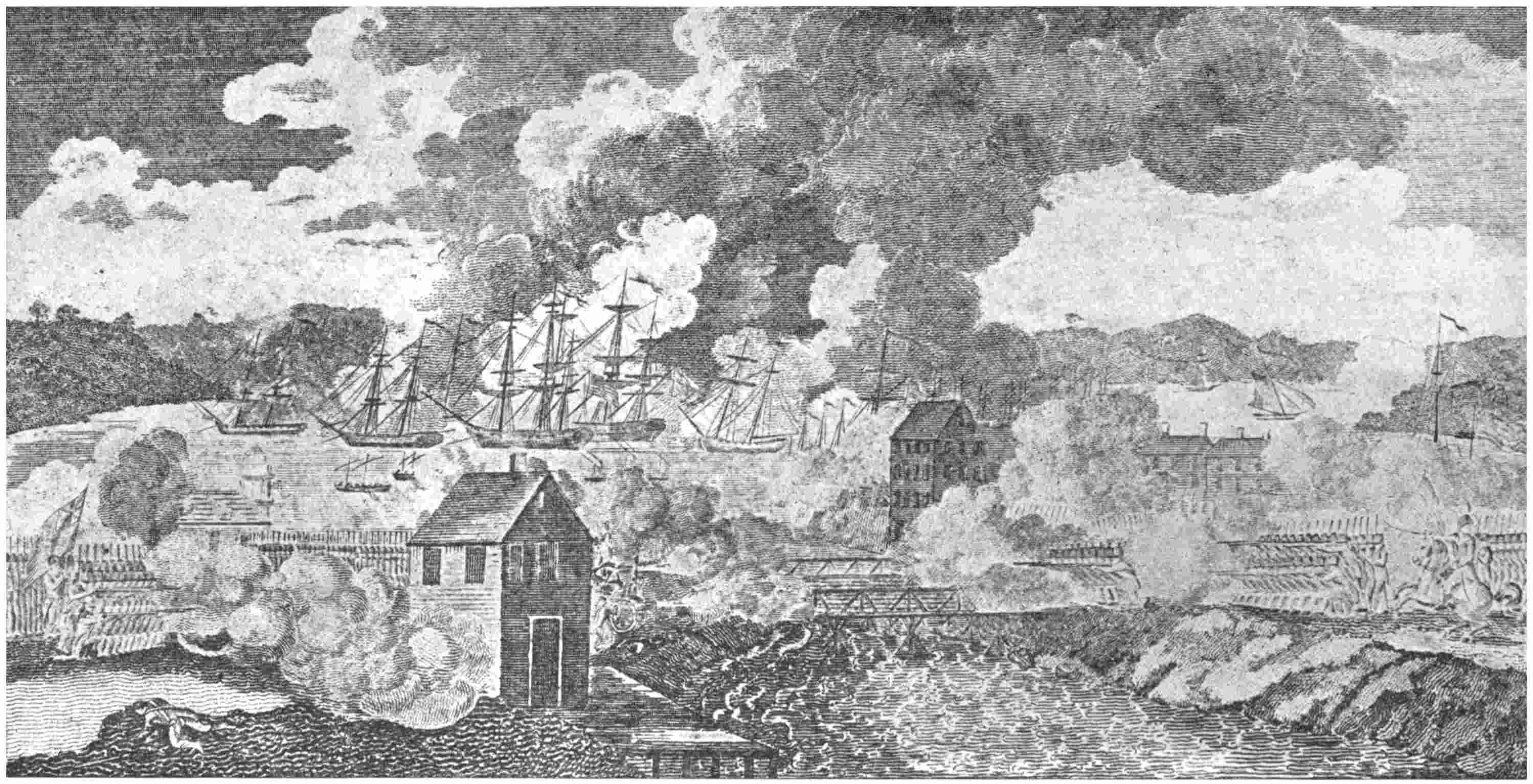

| The Battle of Plattsburg. (From an old wood-cut), | 157 |

| Macdonough’s Victory on Lake Champlain. (From an engraving in the “Naval Monument”), | 159 |

| Battle of Lake Champlain, 1814, | 162 |

| The Battle of Plattsburg. (From an engraving of the picture by Chappel), | 167 |

| Macdonough’s Victory on Lake Champlain. (From an engraving by Tanner of the painting by Reinagle), | 171 |

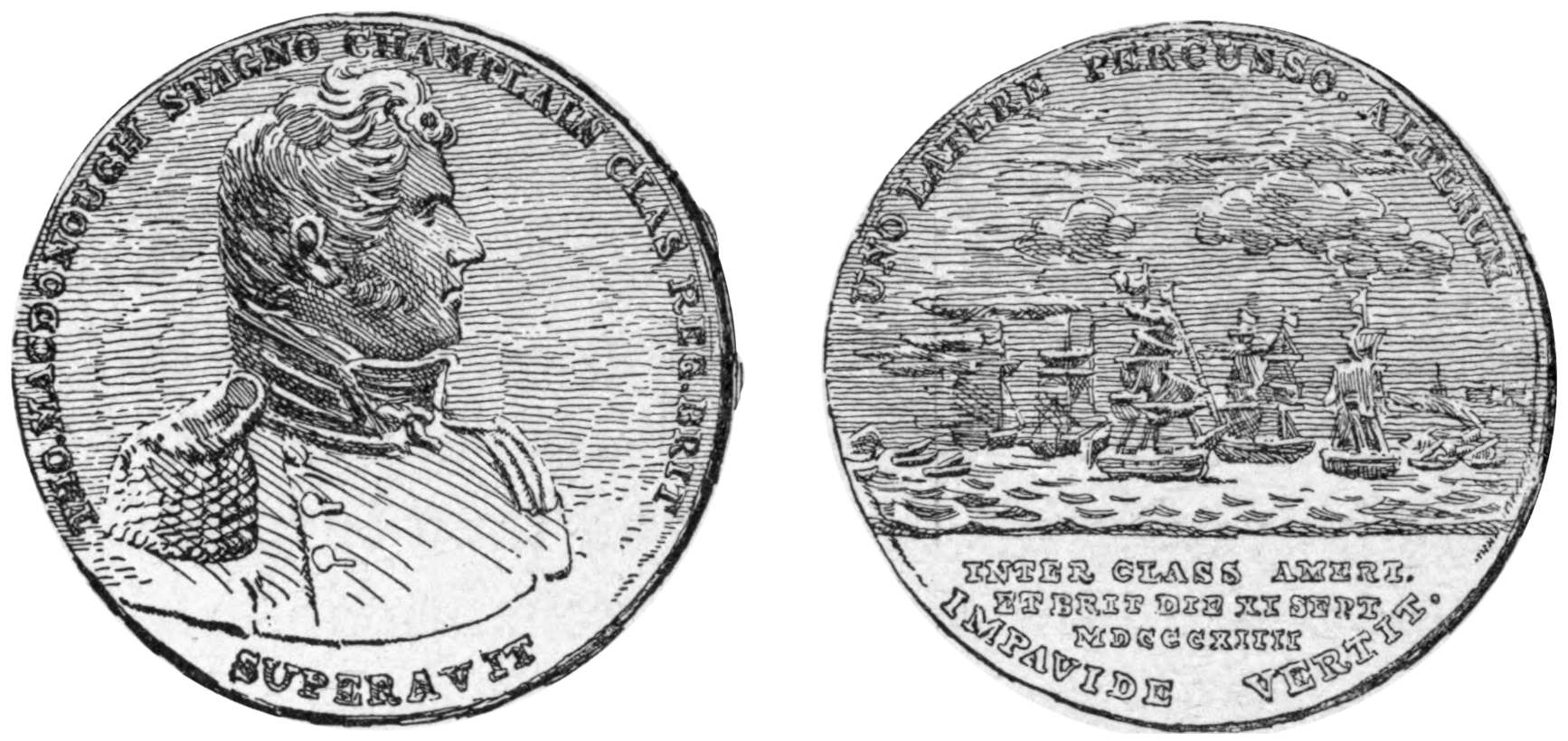

| Medal Awarded to Thomas Macdonough after his Victory on Lake Champlain, | 182 |

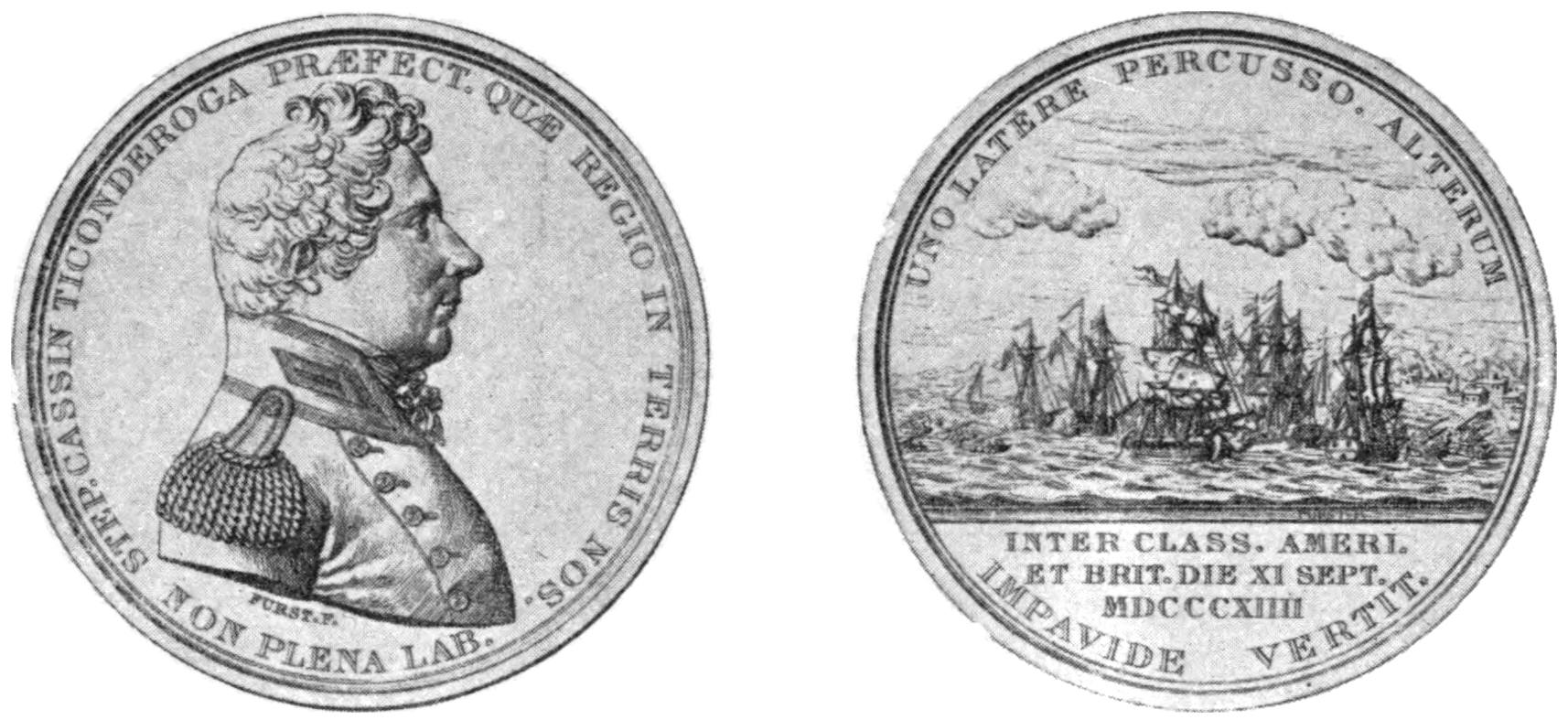

| Stephen Cassin’s Medal, | 183 |

| The General Armstrong at Fayal, | 191 |

| Fight Between the Brig Chasseur and the Schooner St. Lawrence off Havana, February 26, 1815. (From a lithograph in Coggeshall’s “Privateers”), | 205 |

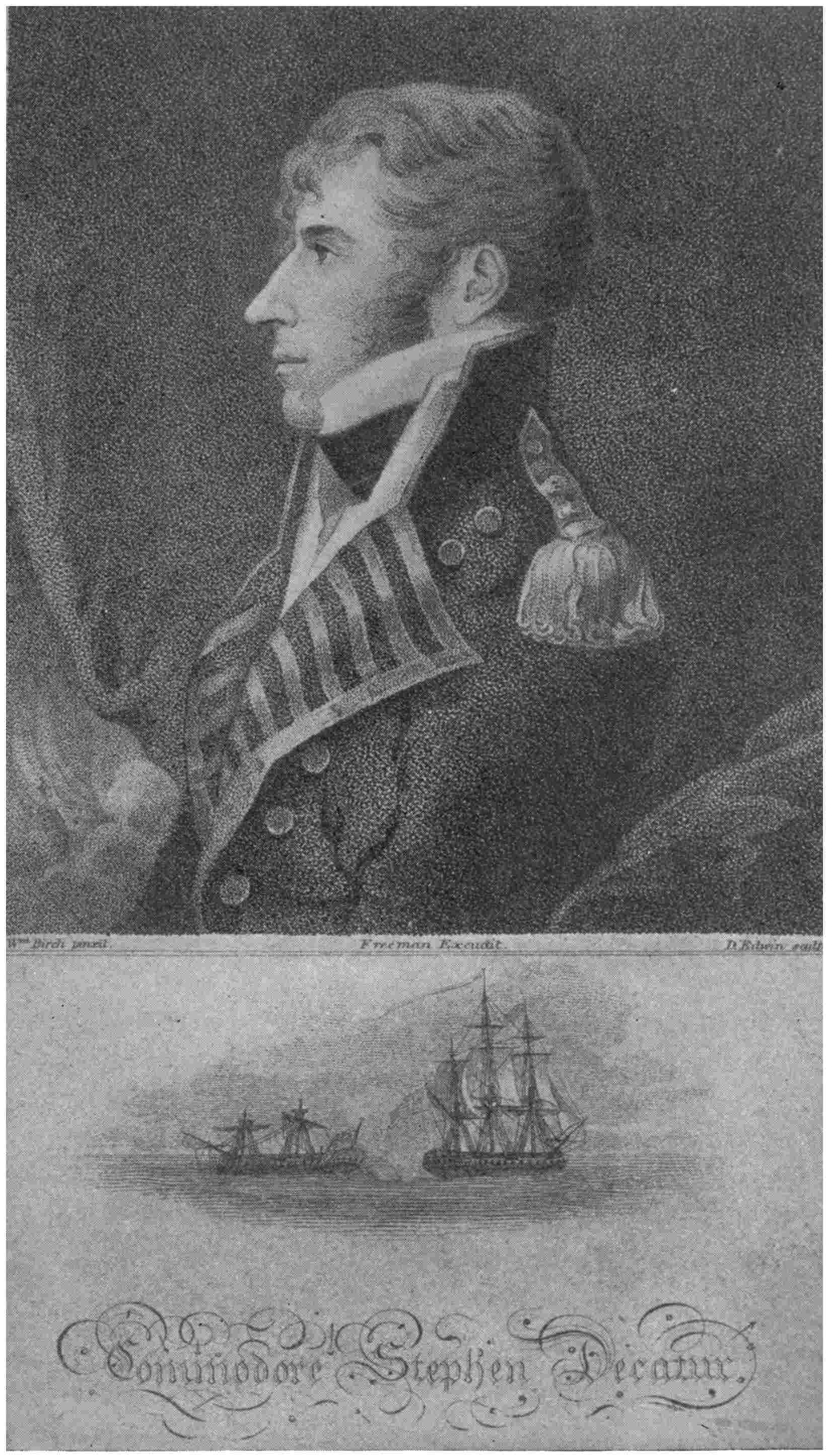

| Commodore Stephen Decatur, | 213xiii |

| The President Engaging the Endymion, while Pursued by the British Squadron. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 219 |

| Capture of the President by a British Squadron. (From a rare lithograph), | 223 |

| Sir Edward Michael Packenham. (From an etching by Rosenthal of a print in the collection of Mr. Clarence S. Bement), | 231 |

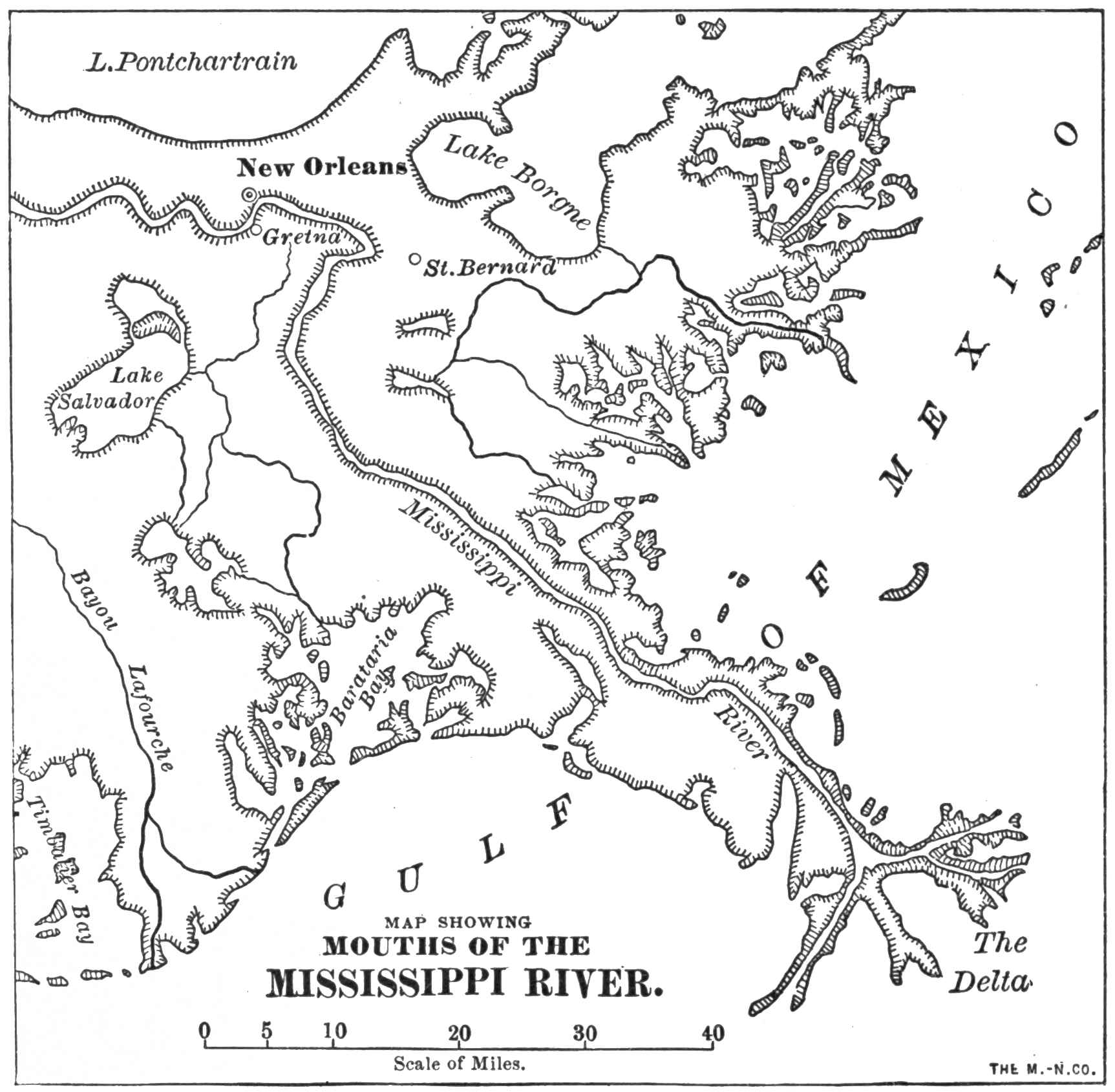

| Map Showing Mouths of the Mississippi River, | 234 |

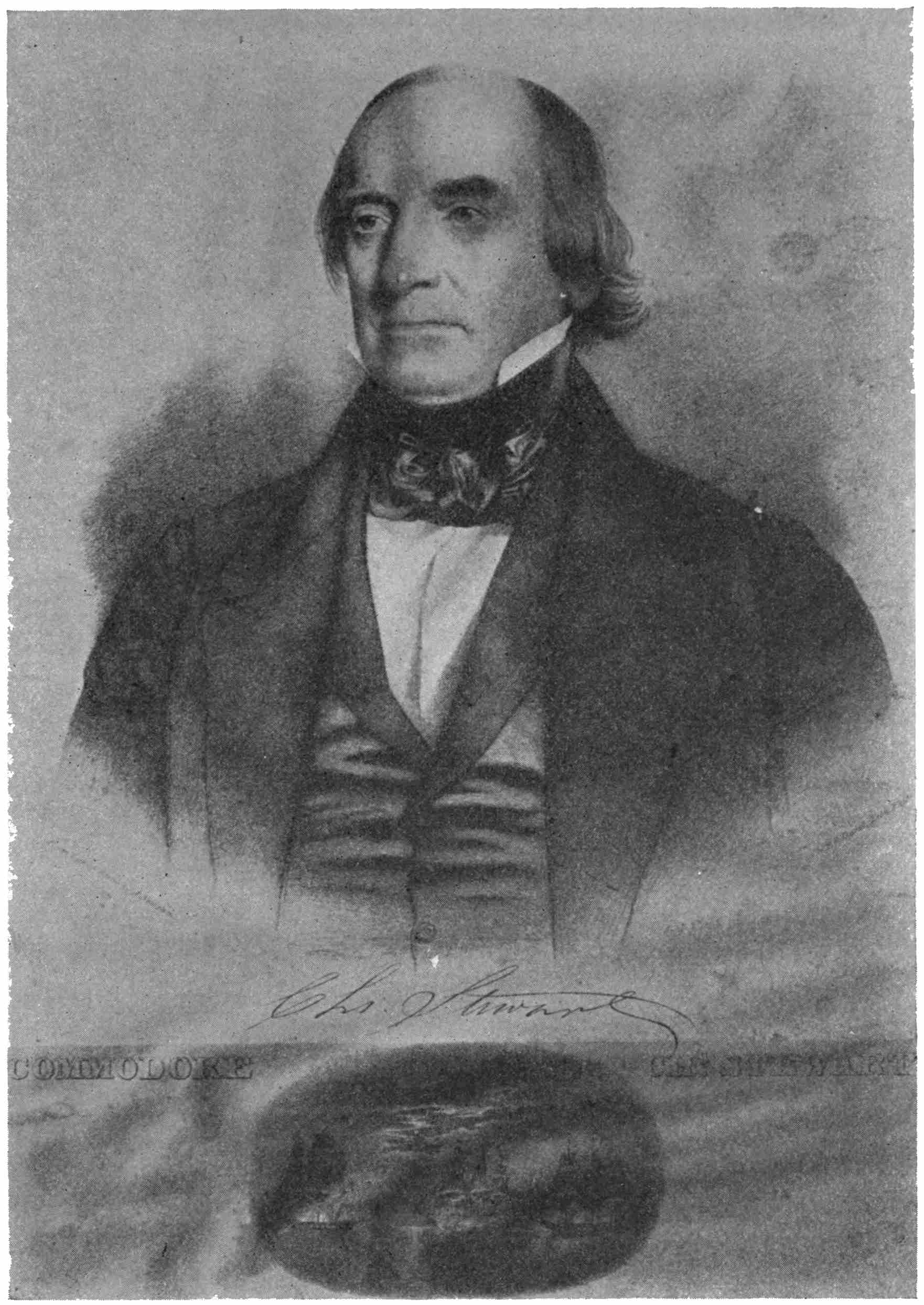

| Charles Stewart. (From a painting by Sully, at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 243 |

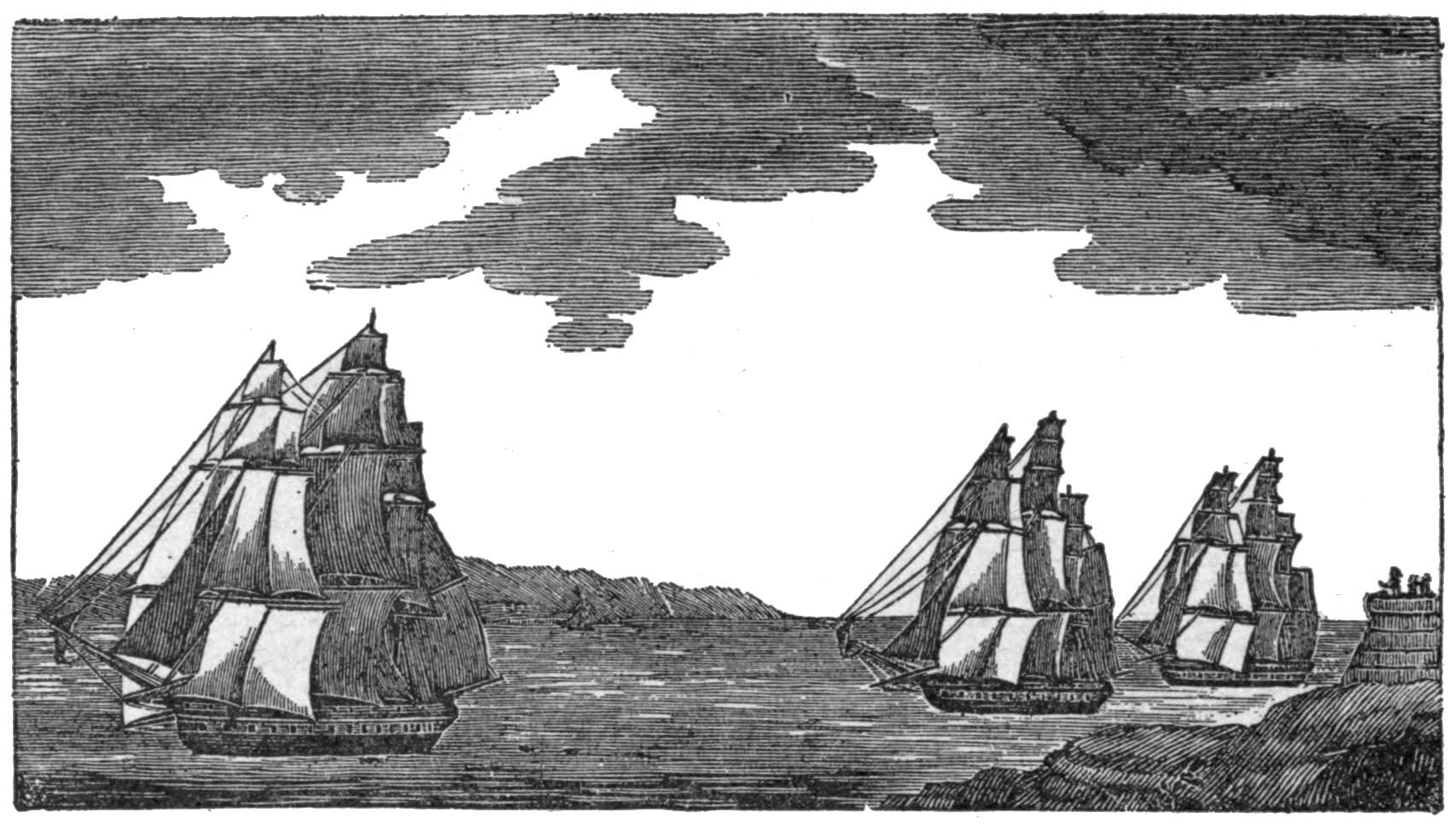

| The Constitution’s Escape from the Tenedos and Junon. (From an old wood-cut), | 244 |

| Diagram of the Battle of the Constitution with the Cyane and Levant, | 249 |

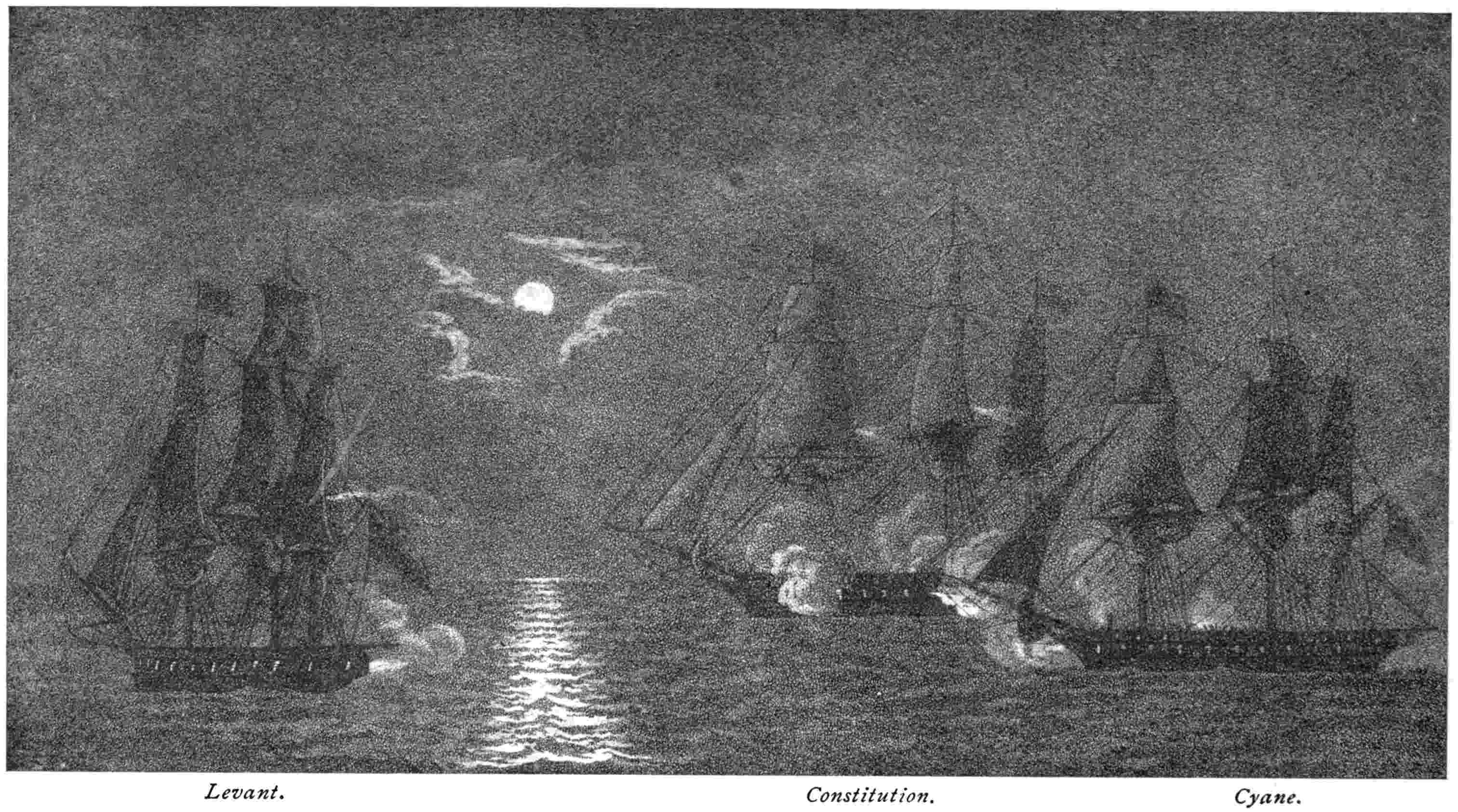

| Action of the Constitution with the Cyane and Levant. (From an aquatint by Strickland), | 253 |

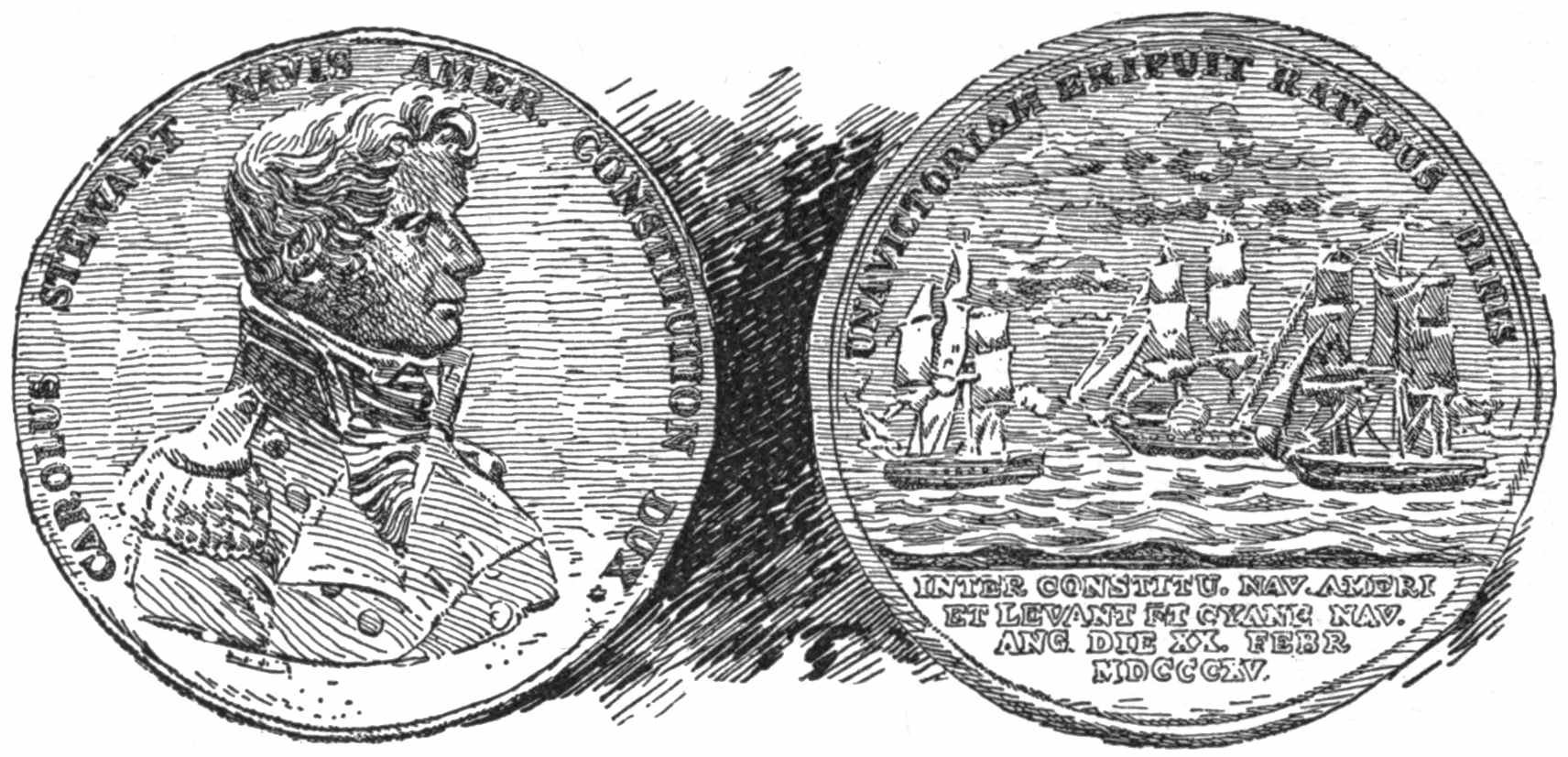

| Medal Awarded to Charles Stewart after the Battle of the Constitution with the Cyane and Levant, | 258 |

| Charles Stewart (and the Battle of the Constitution with the Cyane and Levant). (From a lithograph at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 263 |

| The Hornet and Penguin. (From an old wood-cut), | 274 |

| The Hornet and Penguin. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 277 |

| Medal Awarded to James Biddle for the Capture of the Penguin by the Hornet, | 280 |

| The Hornet’s Escape from the Cornwallis. (From a wood-cut in the “Naval Monument”), | 283 |

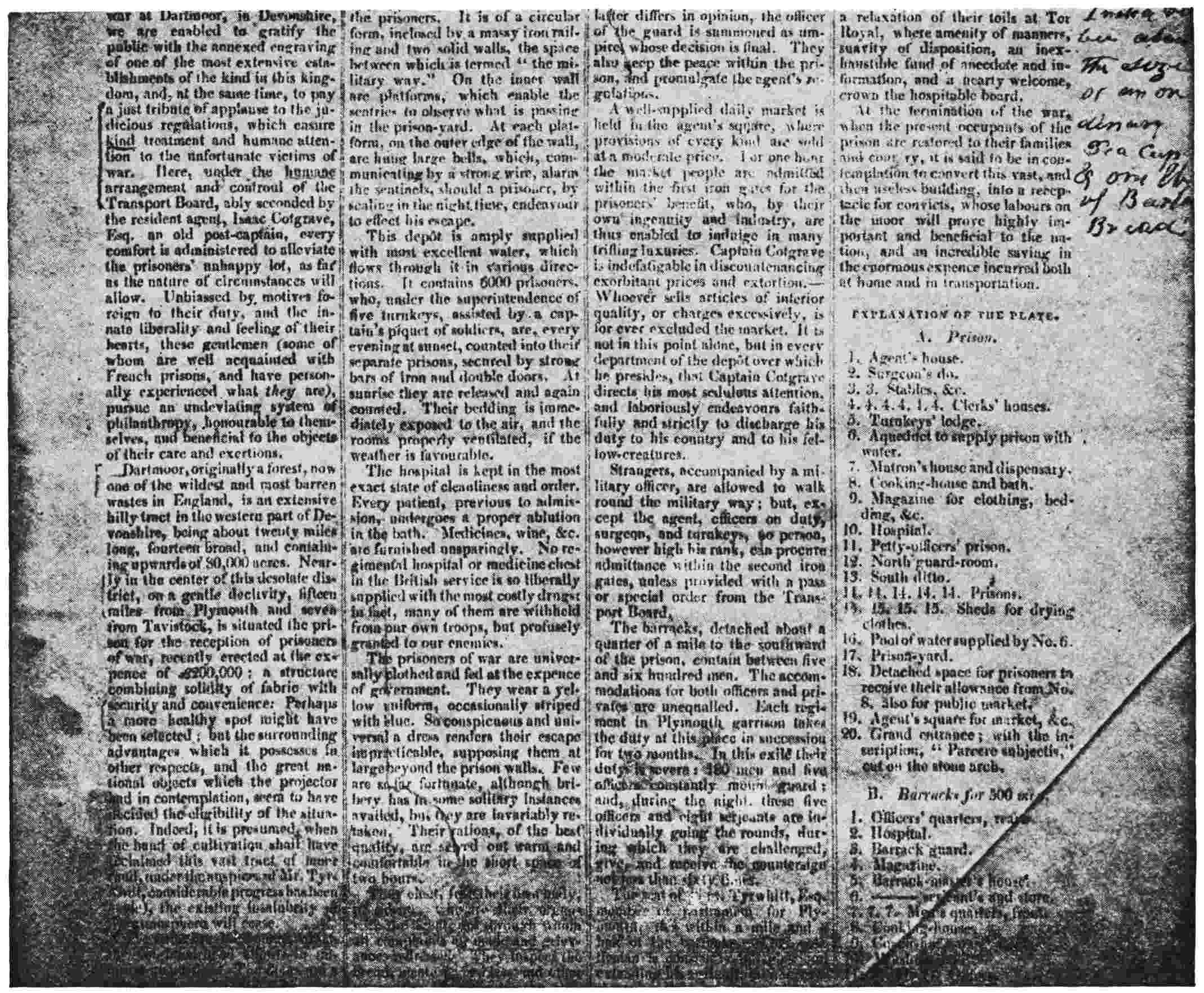

| Dartmoor Prison. (From a wood-cut of a contemporary engraving), | 294 |

| Dartmoor Prison. (From an old broadside, with notes by one of the prisoners), | 297 |

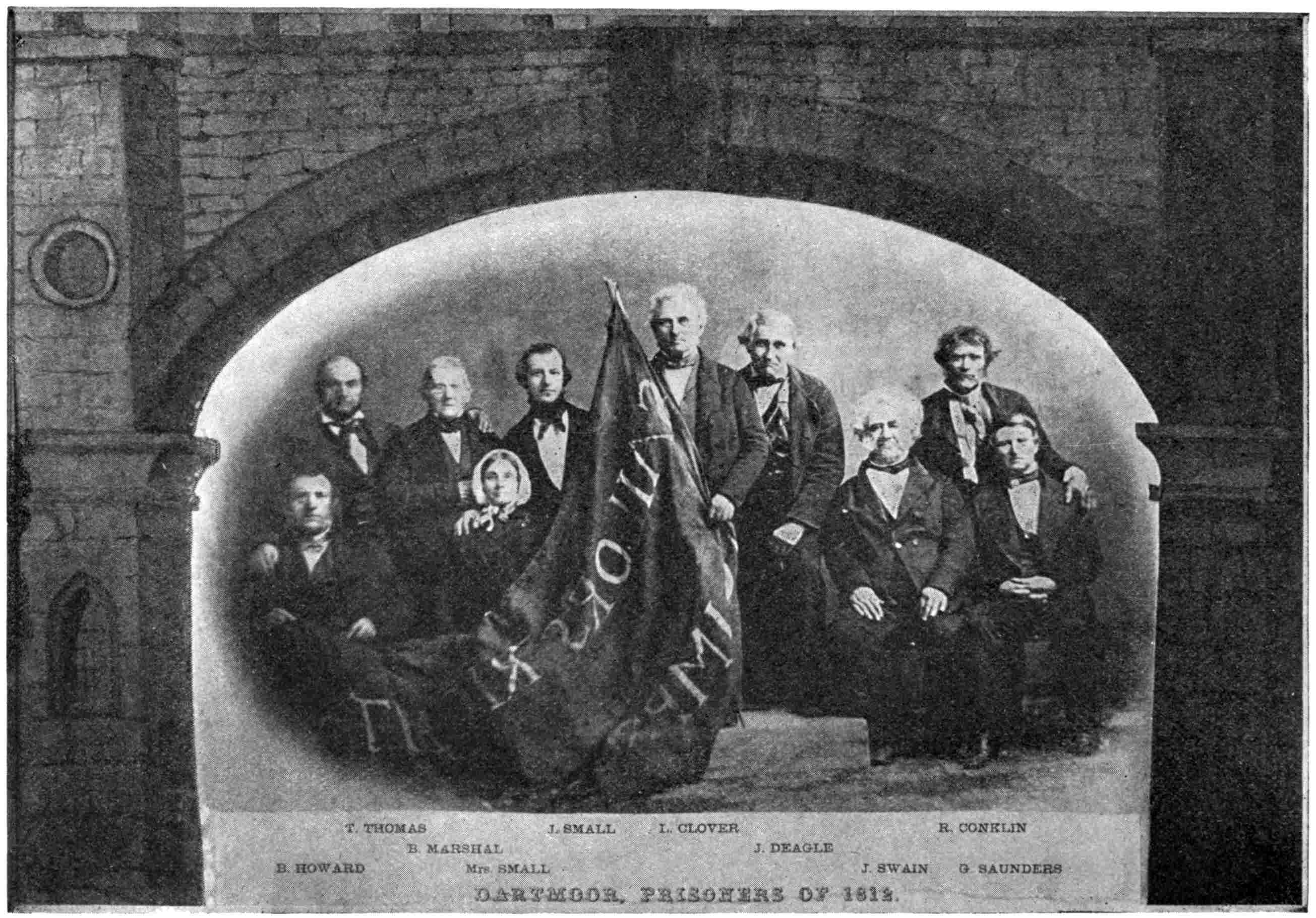

| Dartmoor Prisoners of 1812. (From a copy of a daguerreotype at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 301 |

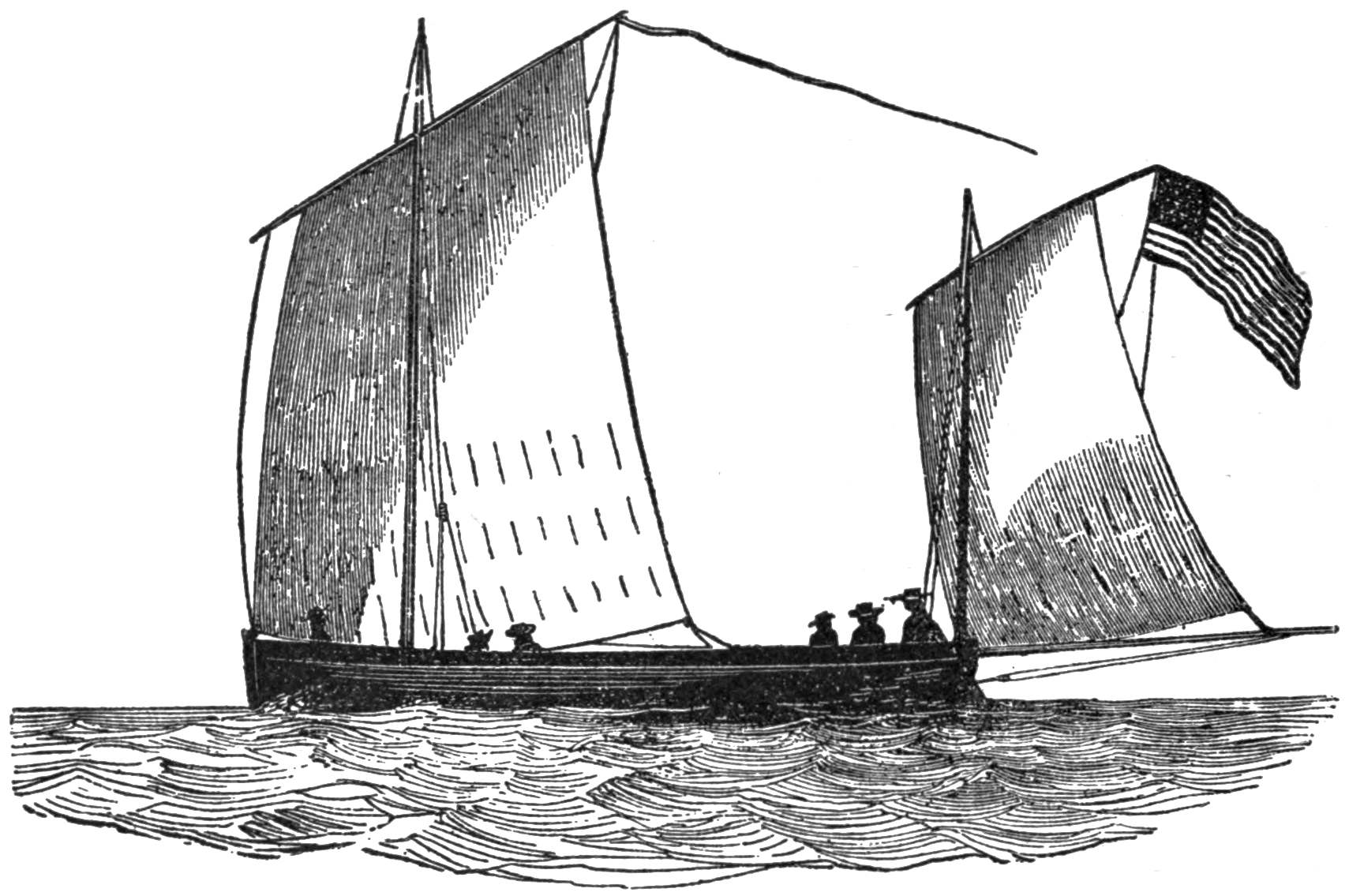

| United States Sloop-of-war Albany Under Sail. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 328 |

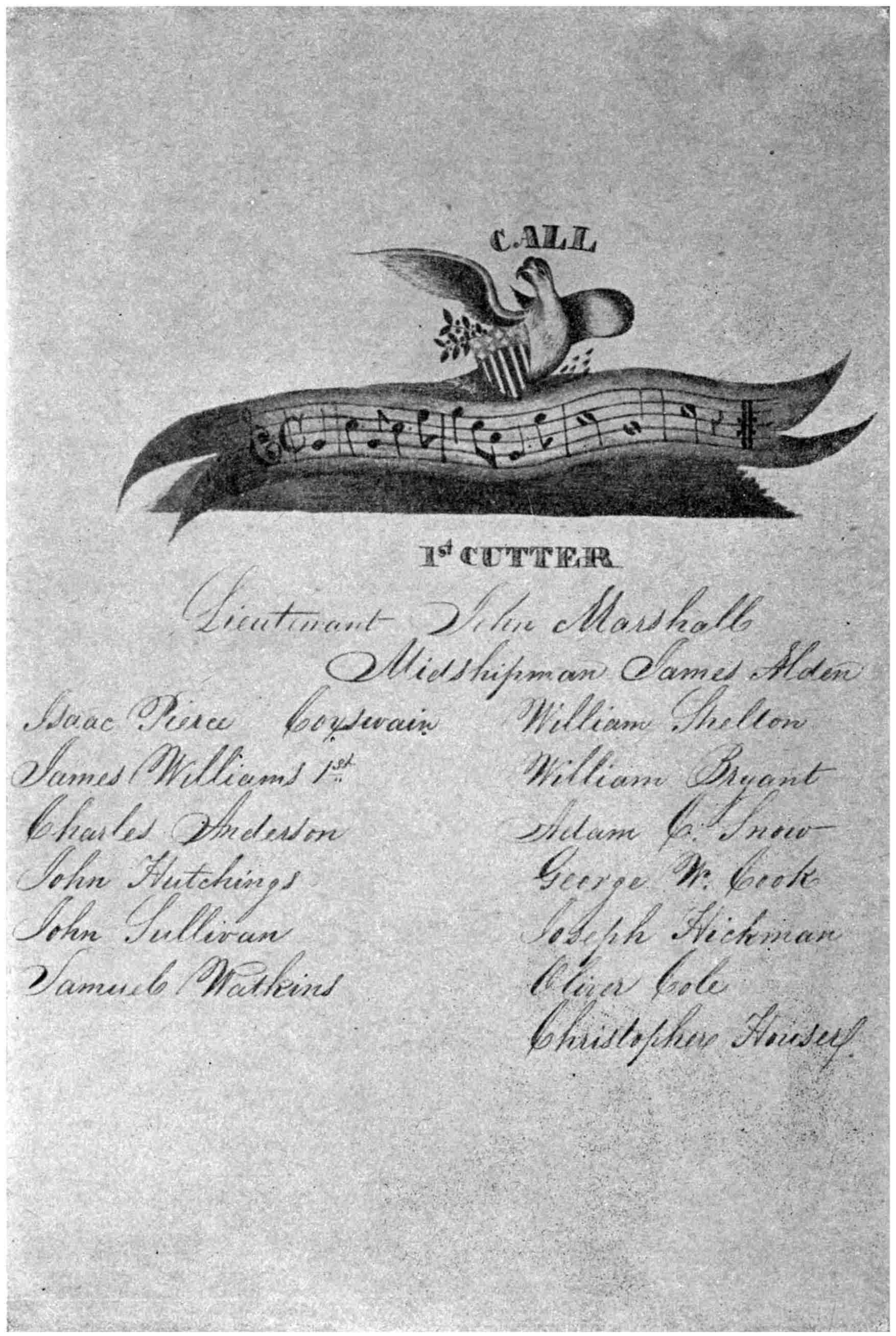

| A Ship-of-war’s Cutter. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 330 |

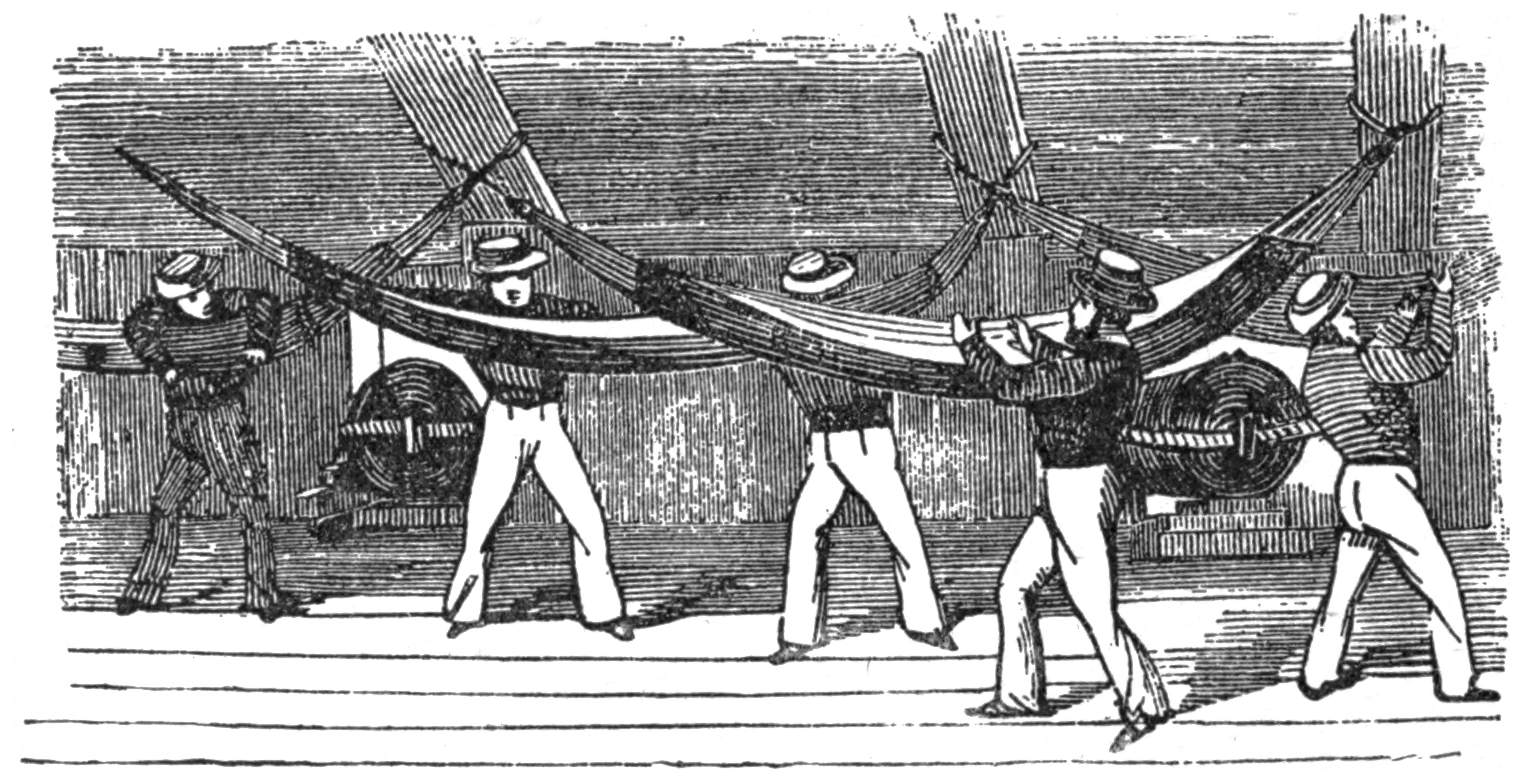

| Lashing up Hammocks. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 332 |

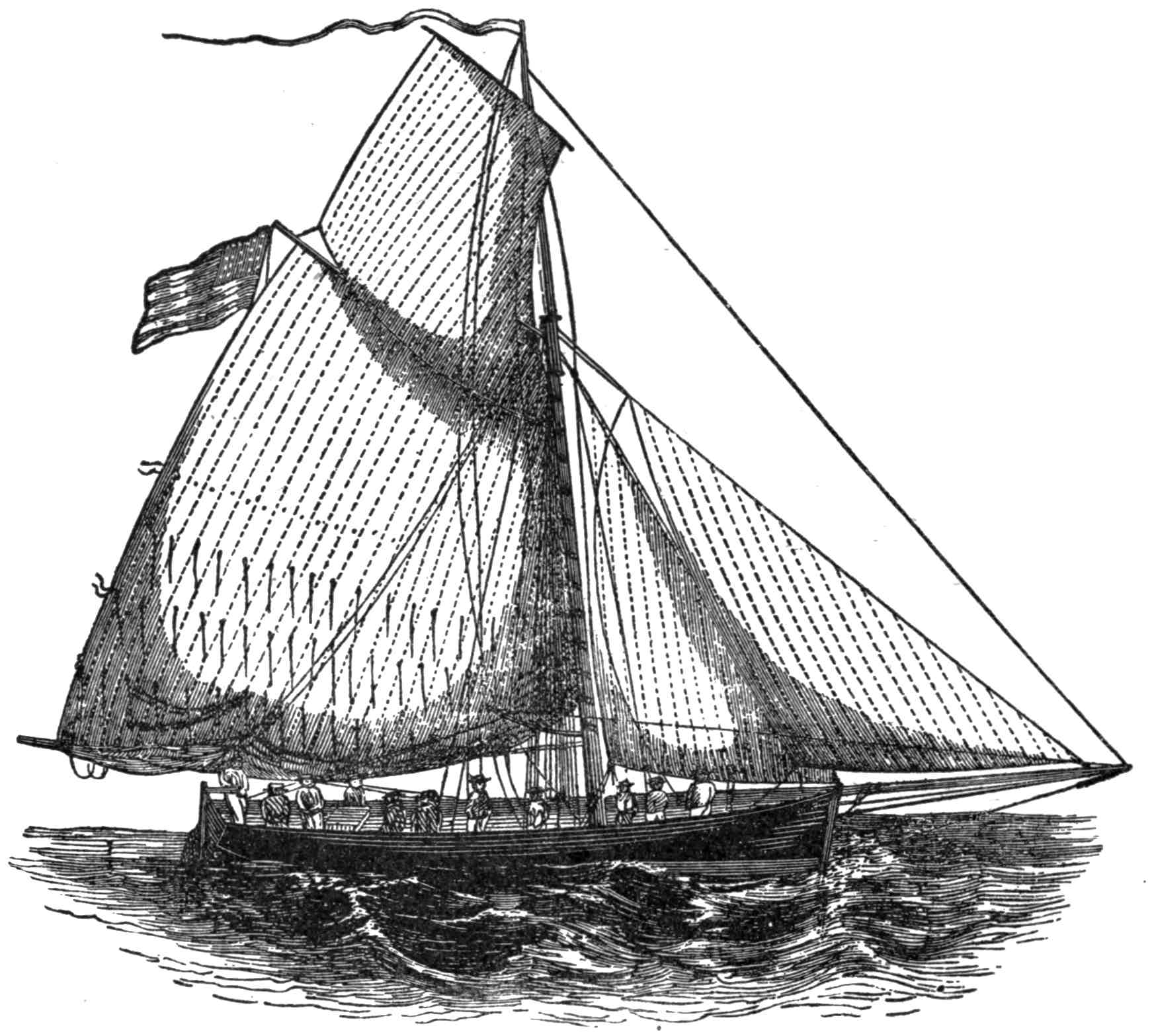

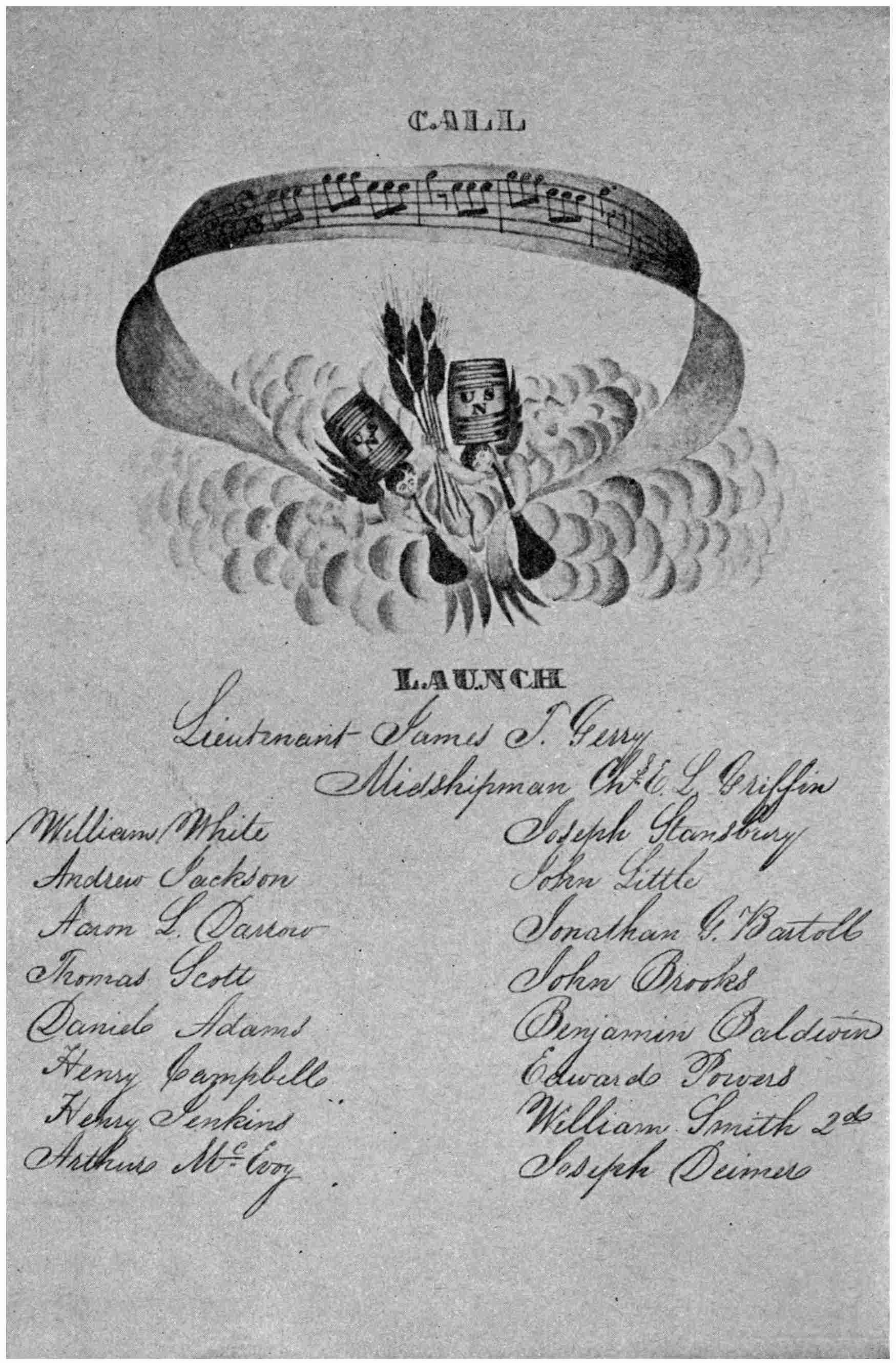

| A Ship-of-war’s Launch. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 334 |

| Sailor’s Mess-table. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 337xiv |

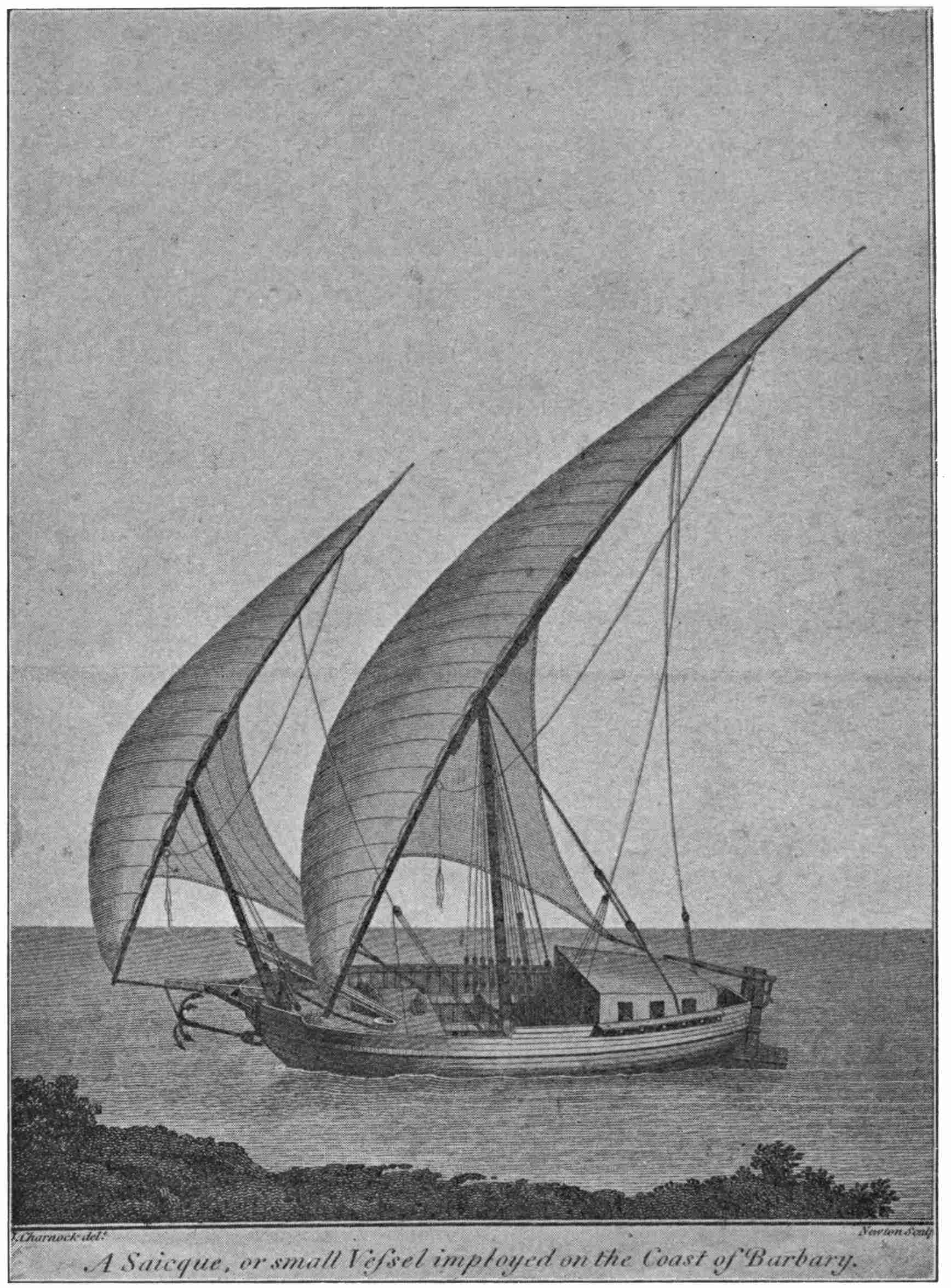

| A Typical Barbary Corsair. (From an engraving by Newton after a drawing by J. Charnock), | 342 |

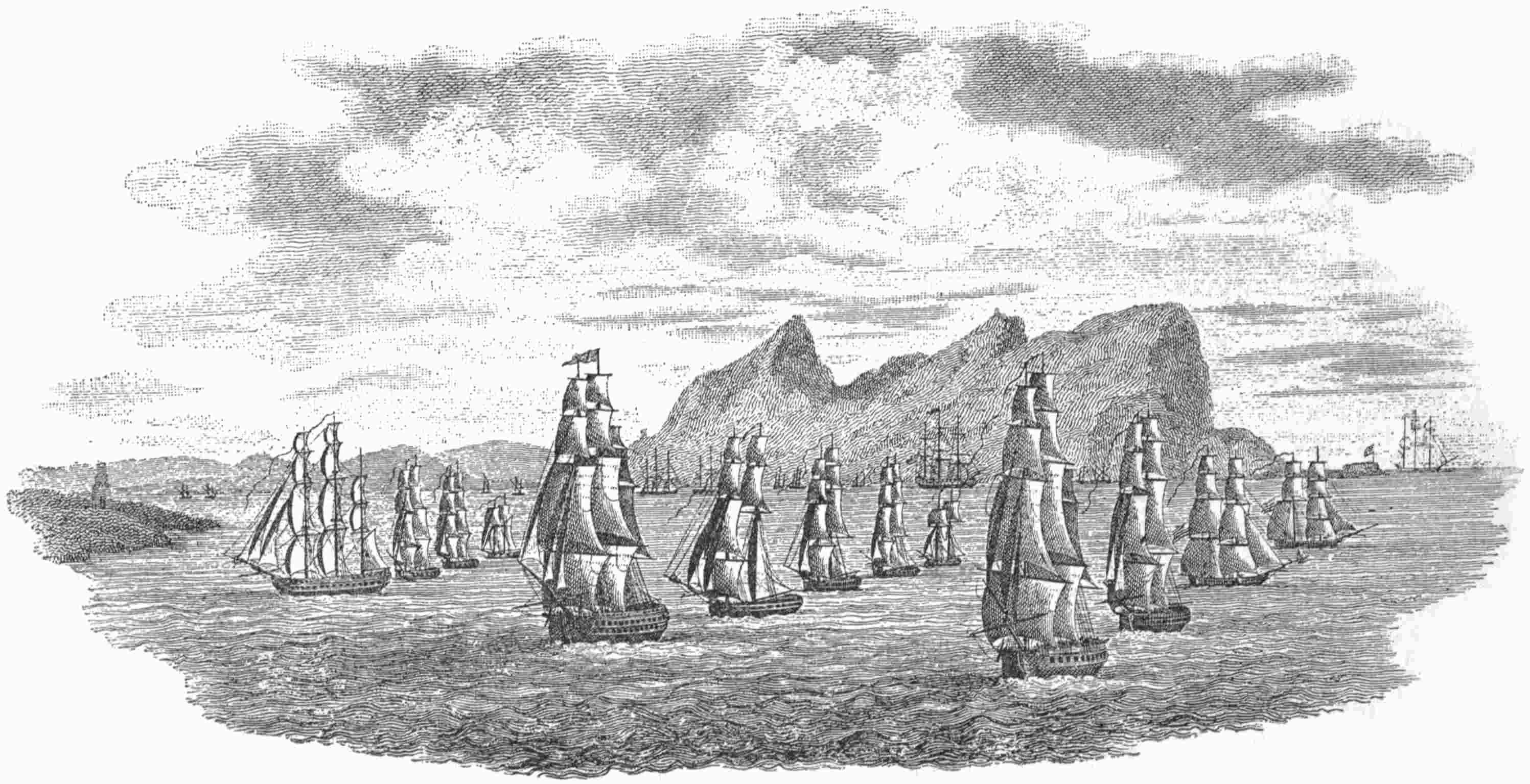

| Decatur’s Squadron at Anchor off the City of Algiers, June 30, 1815. (From an engraving by Monger and Jocelin), | 349 |

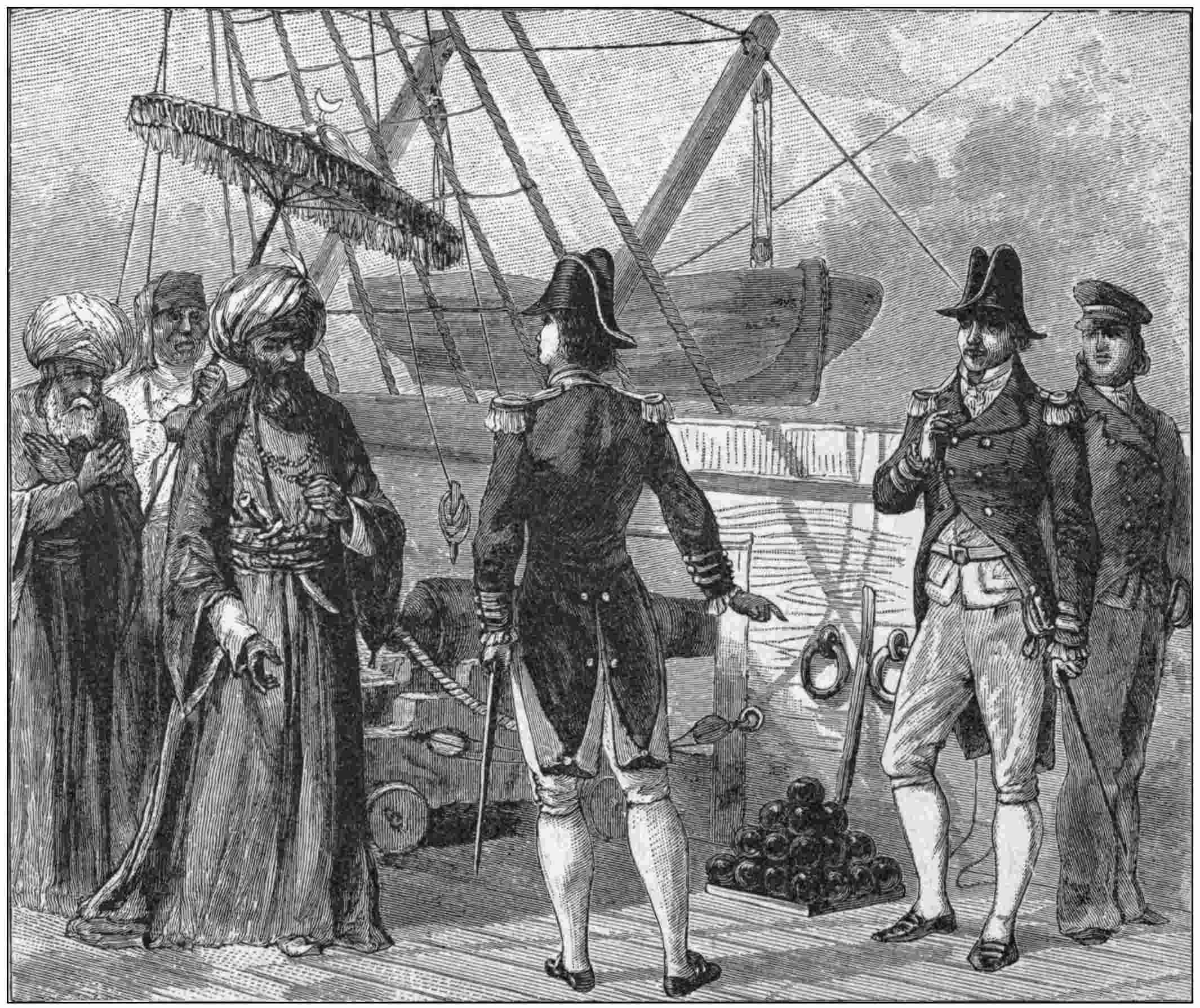

| Decatur and the Algerian, | 352 |

| Return of Bainbridge’s Squadron from the Mediterranean in 1815. (From an engraving by Leney of a drawing by M. Corné), | 356 |

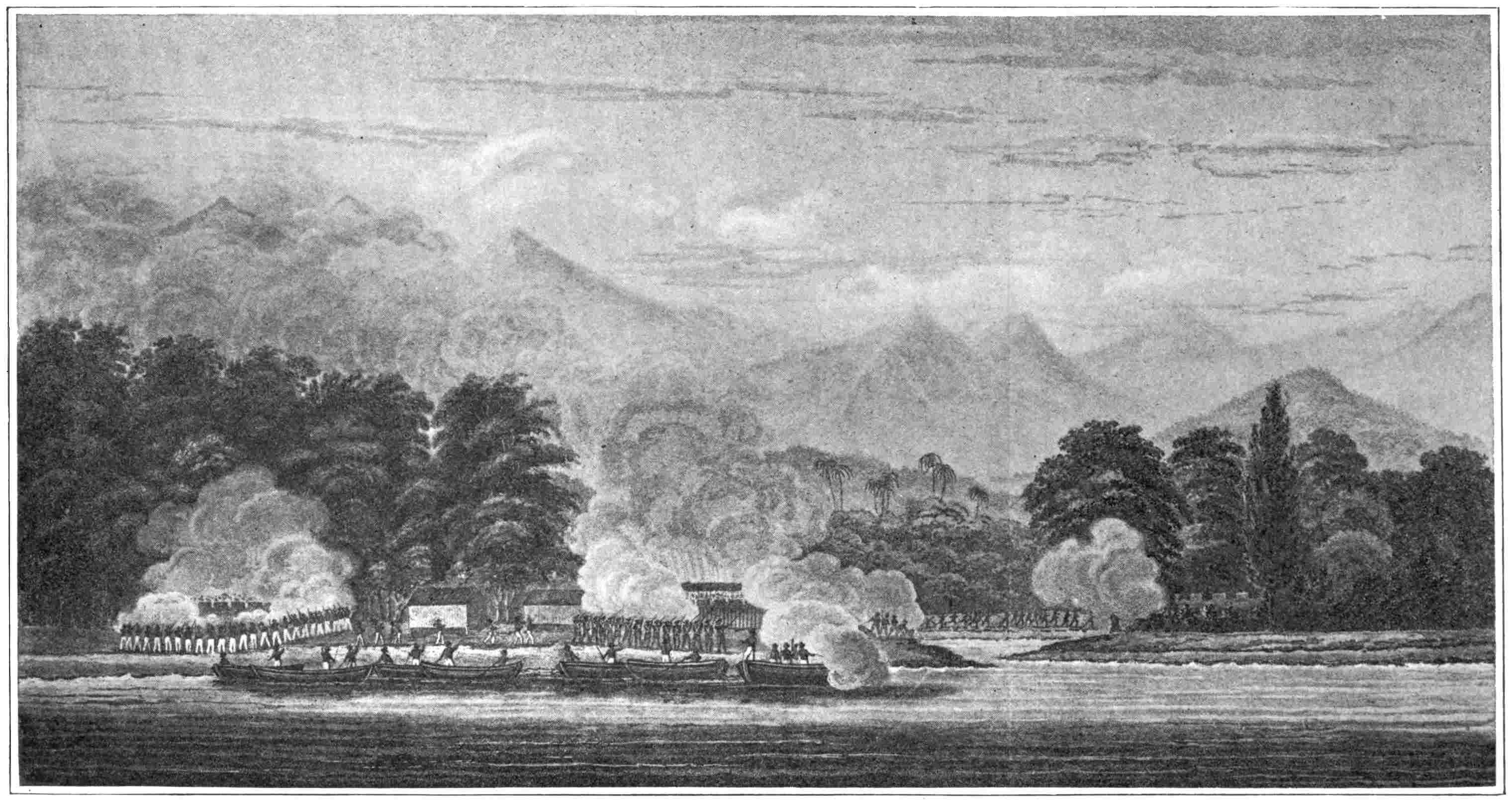

| The Action at Quallah Battoo, February 6, 1832. (From an aquatint by Smith of a drawing made on board the Potomac in the offing), | 371 |

| Bombardment of Muckie and Landing of a Force to Burn the Town. (From an engraving by Osborne in “The Flagship,” published, 1840, by D. Appleton & Co.), | 377 |

| “Blood is Thicker than Water.”—Josiah Tattnall Going to the Assistance of the English Gun-boats at Peiho River. (From a painting, by a Chinese artist, owned by Mr. Edward Trenchard), | 383 |

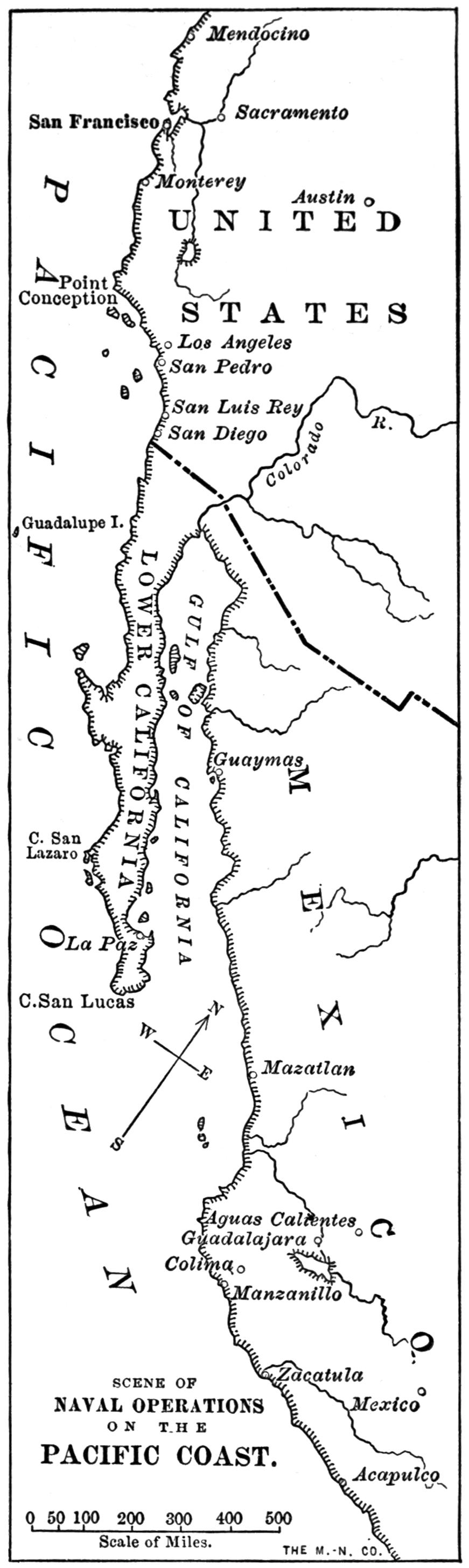

| Scene of Naval Operations on the Pacific Coast, | 389 |

| John B. Montgomery. (From a photograph), | 392 |

| R. F. Stockton. (From an engraving by Hall of a painting on ivory by Newton, 1840), | 393 |

| Perry’s Expedition Crossing the Bar at the Mouth of the Tabasco River. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 395 |

| The Naval Expedition Under Commodore Perry Ascending the Tabasco River at the Devil’s Bend. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 399 |

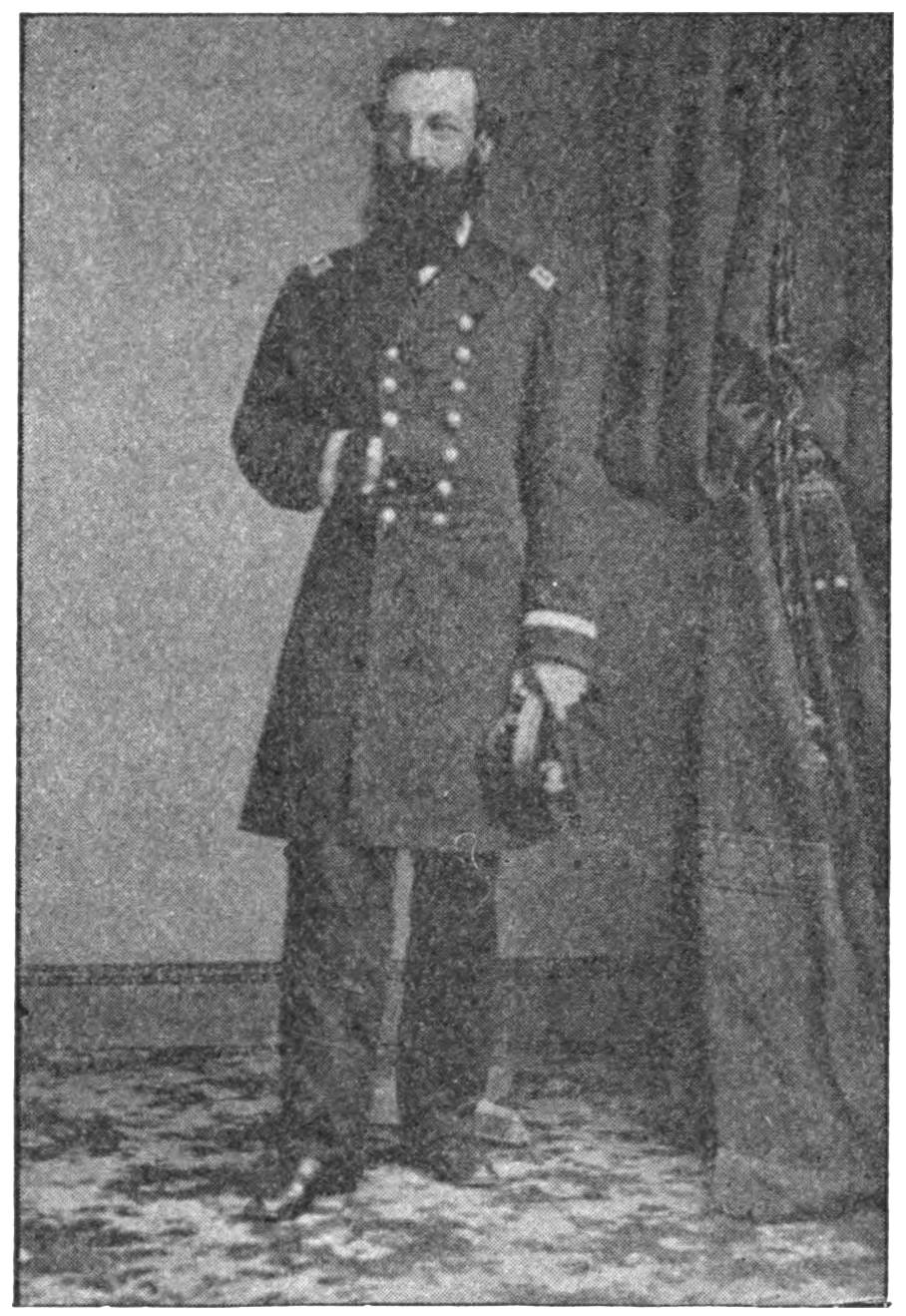

| S. F. Dupont. (From a photograph), | 402 |

| The Tabasco Expedition Attacked by the Mexicans from the Chapparal. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 403 |

| Scene of Naval Operations in Gulf of Mexico, | 406 |

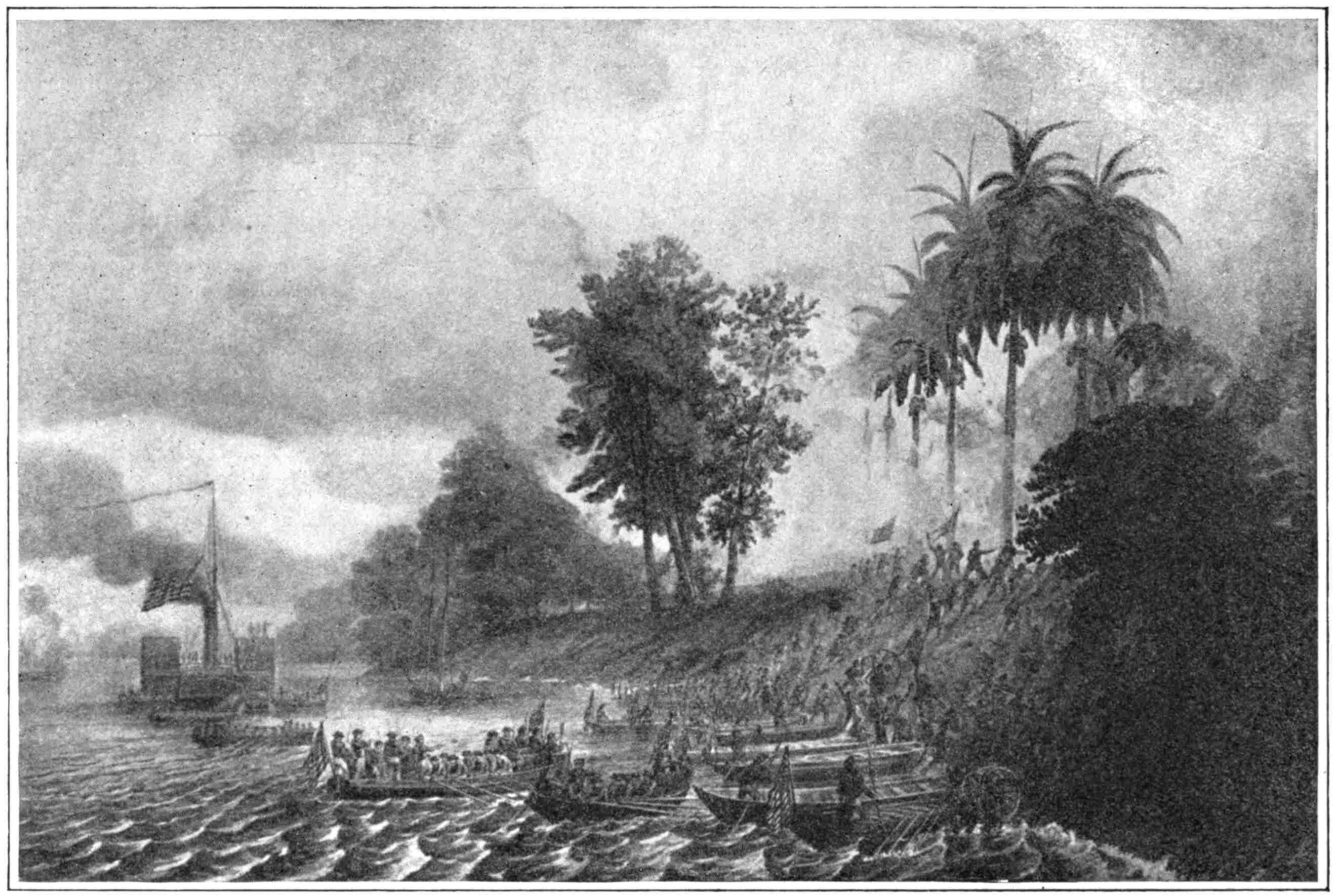

| Landing of Perry’s Expedition Against Tabasco. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 407 |

| Commodore Perry’s Expedition Taking Possession of Tuspan. (From a lithograph of a drawing by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 411xv |

| Matthew Calbraith Perry. (From an oil-painting at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 414 |

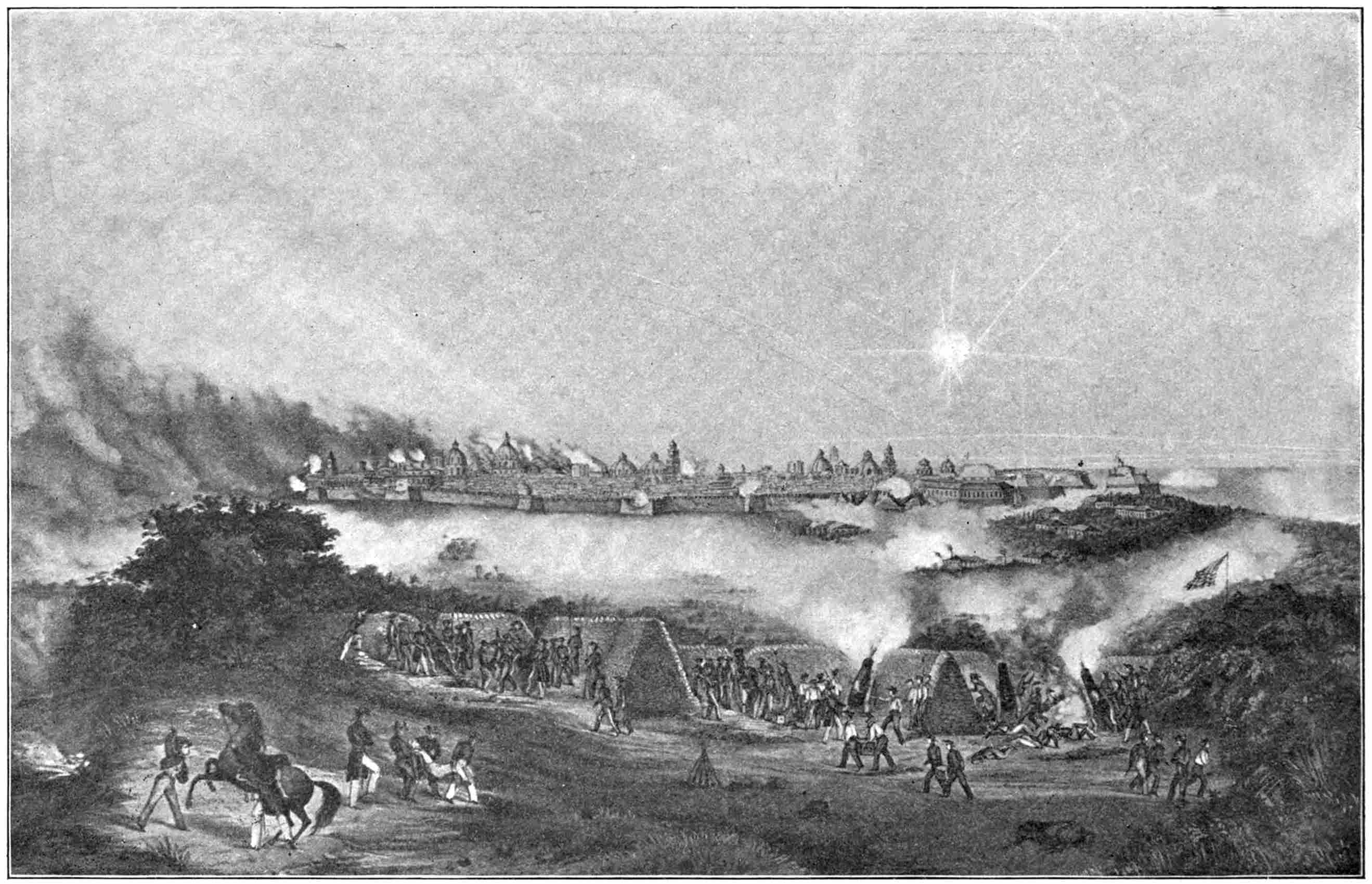

| Capture of Tabasco by Perry’s Expedition. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 415 |

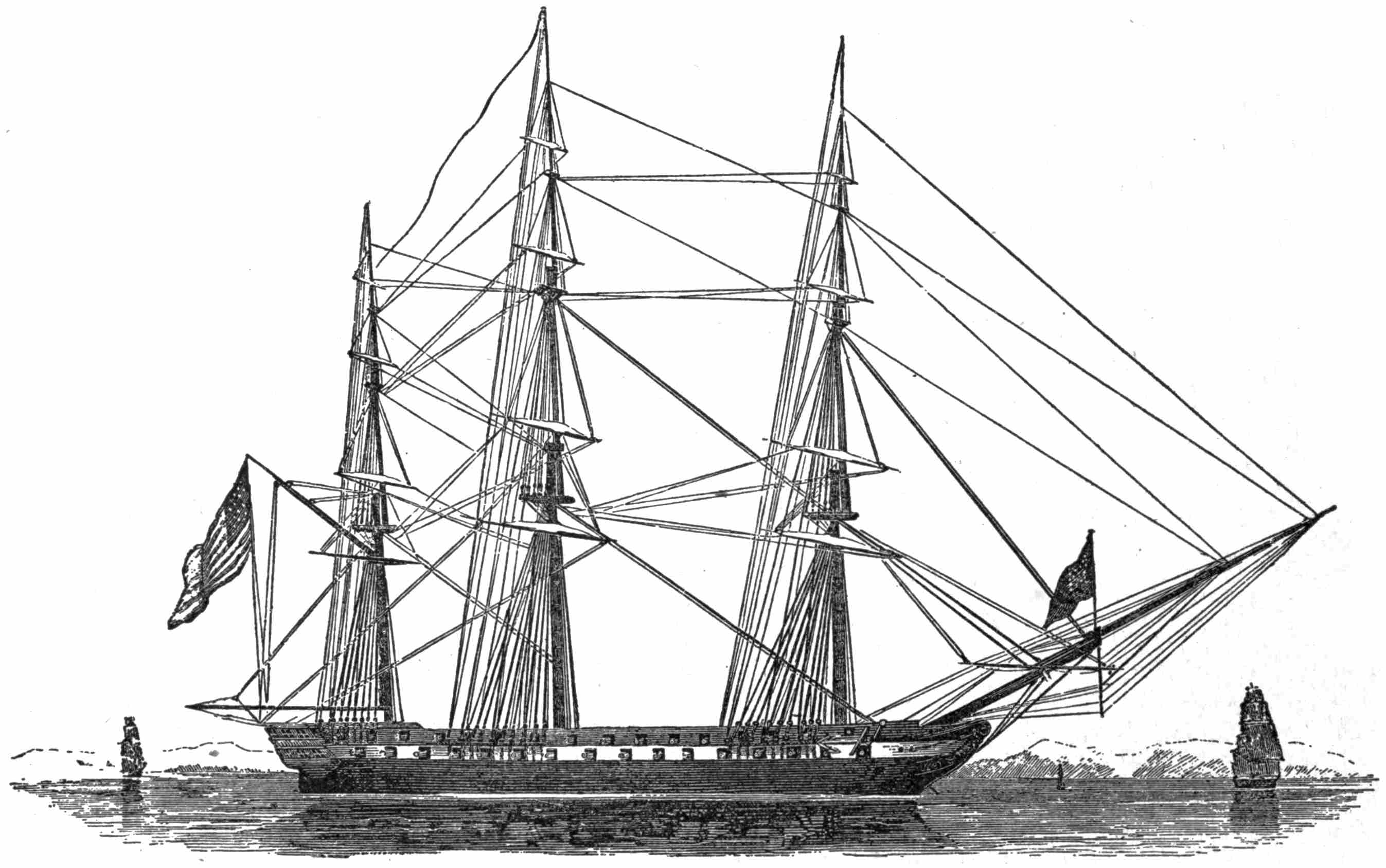

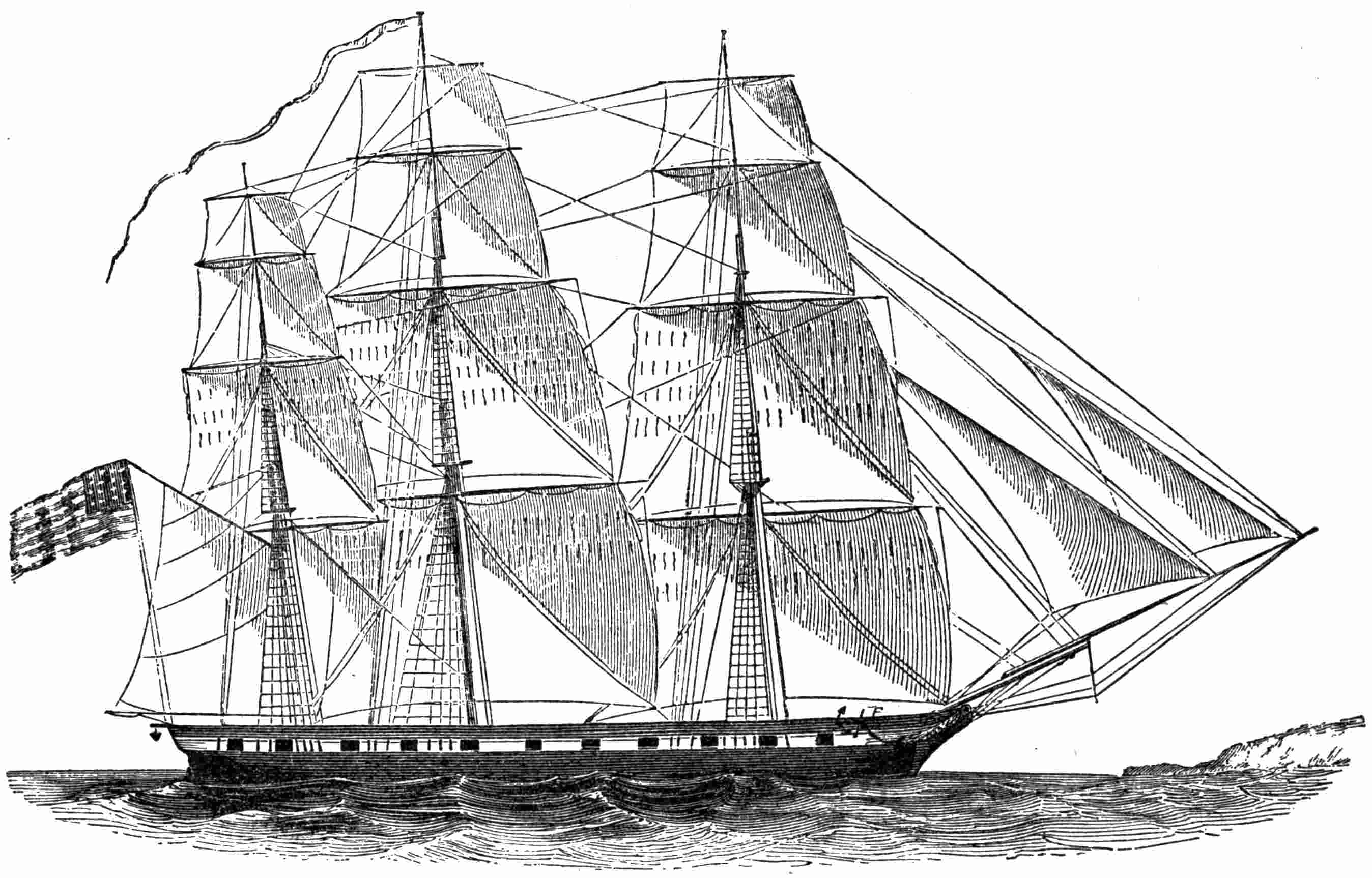

| Brig-of-war Like the Somers Under Full Sail. (From the “Kedge Anchor”), | 419 |

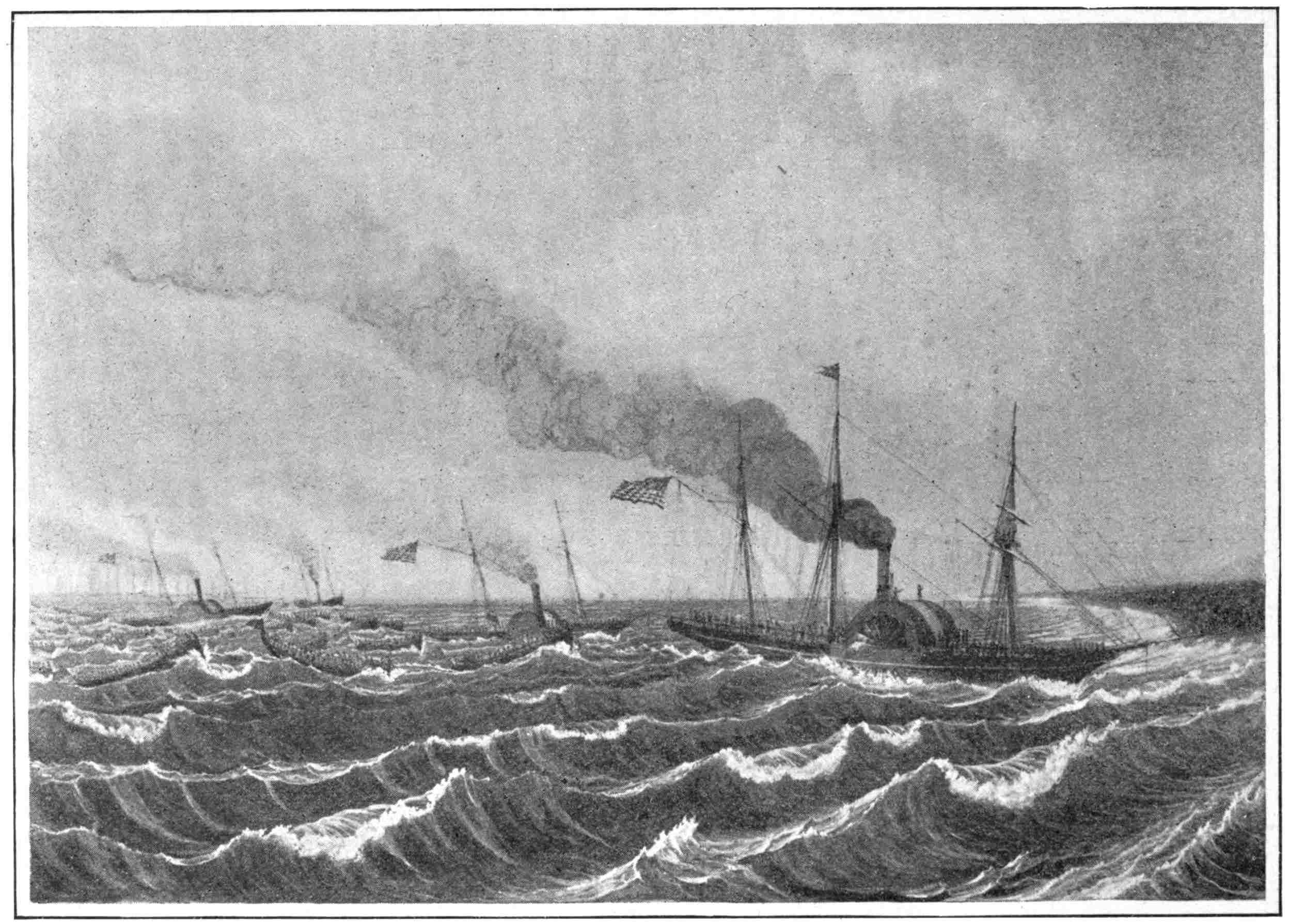

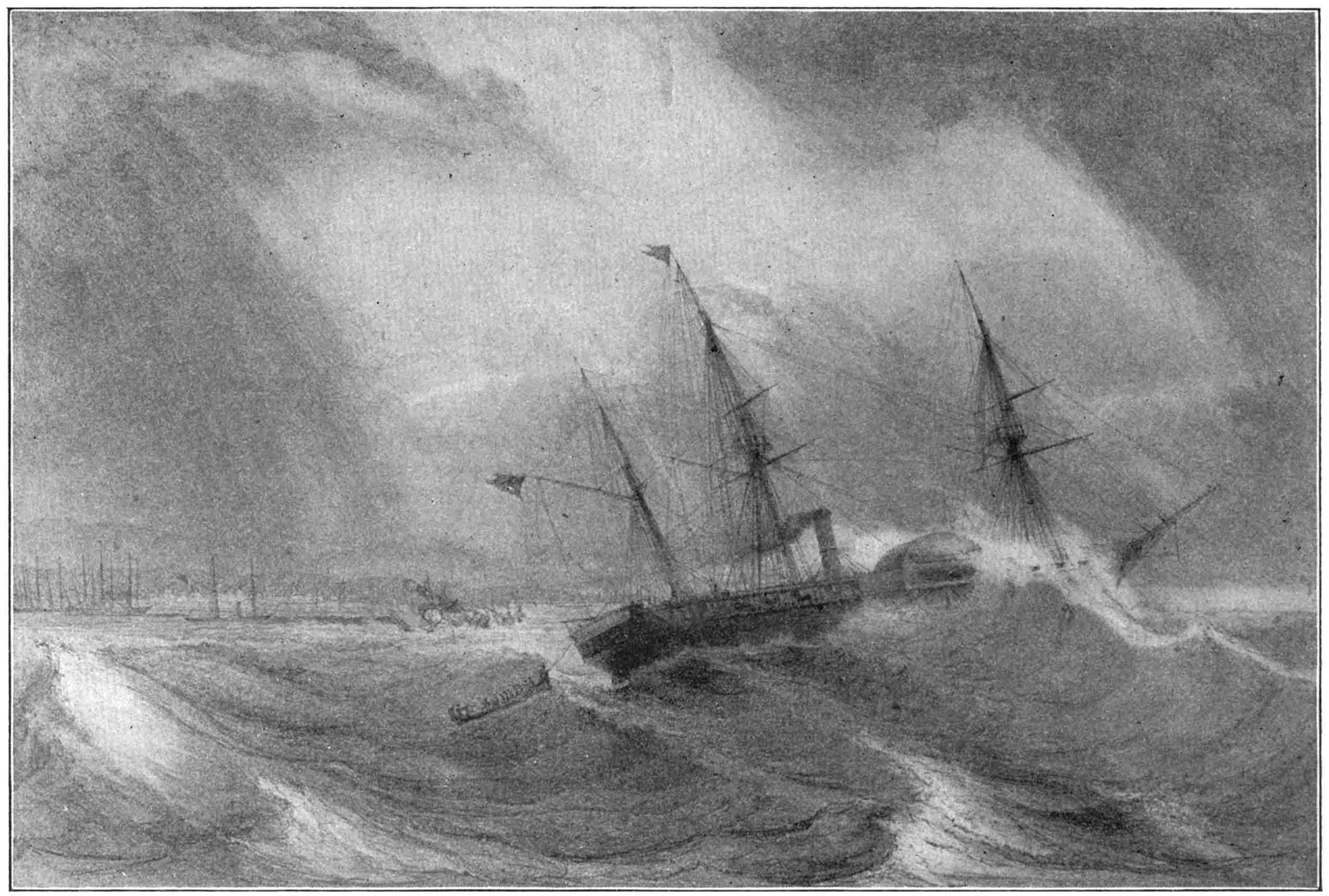

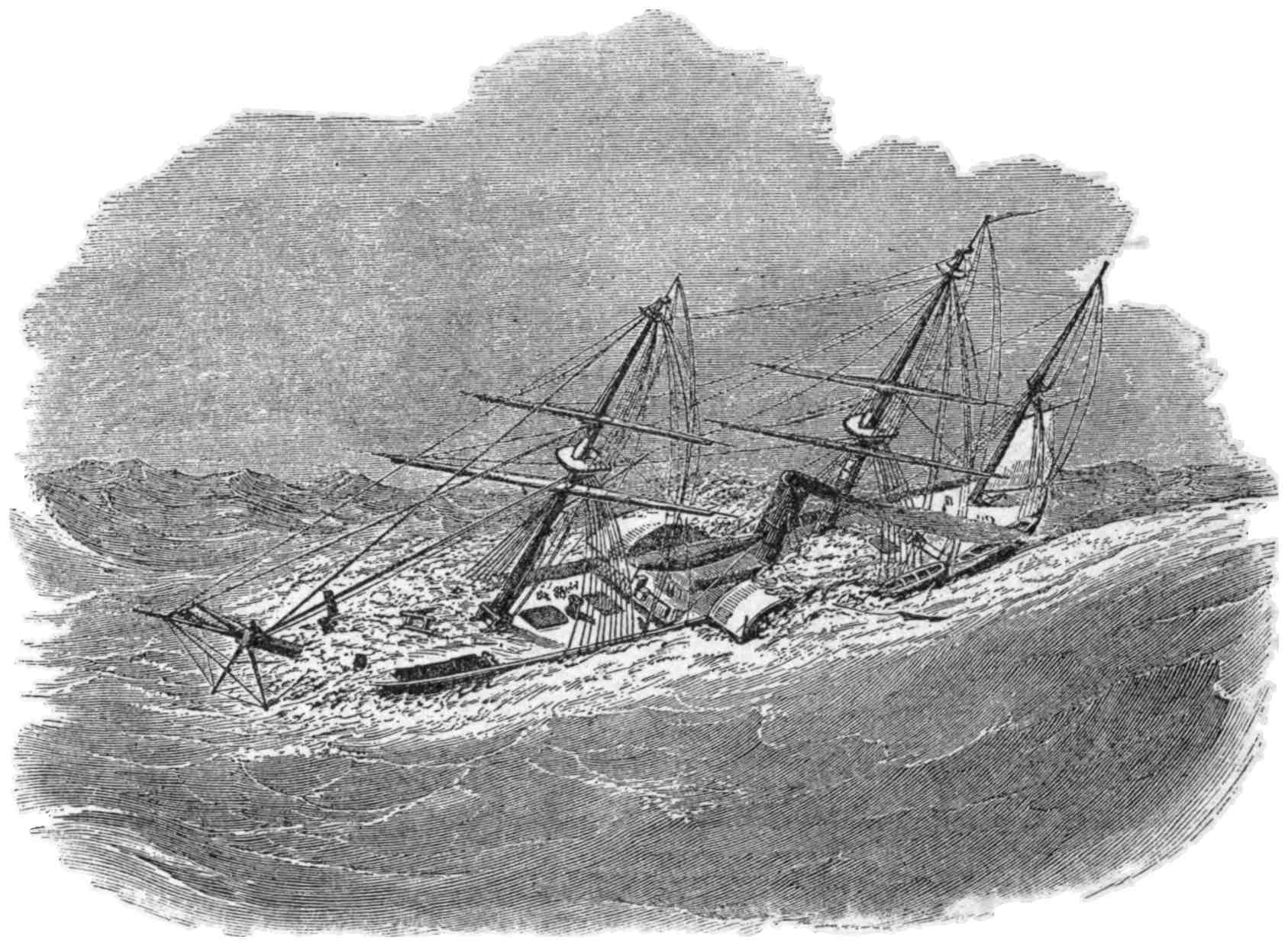

| The Mississippi Going to the Relief of the Hunter in a Storm off Vera Cruz. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 421 |

| Naval Bombardment of Vera Cruz, March, 1847. (From a lithograph published in 1847 by N. Currier), | 425 |

| The United States Naval Battery During the Bombardment of Vera Cruz on the 24th and 25th of March, 1847. (From a lithograph designed and drawn on stone by Lieutenant H. Walke, U. S. N.), | 429 |

| The Battle of Vera Cruz.—Night Scene. (From an engraving by Thompson of a drawing by Billings), | 431 |

| The Mississippi in a Cyclone on her Japan Cruise. (From a wood-cut in Perry’s “Narrative” of this trip), | 440 |

| The Mississippi at Jamestown, St. Helena. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 441 |

| View of Uraga. Yeddo Bay. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 445 |

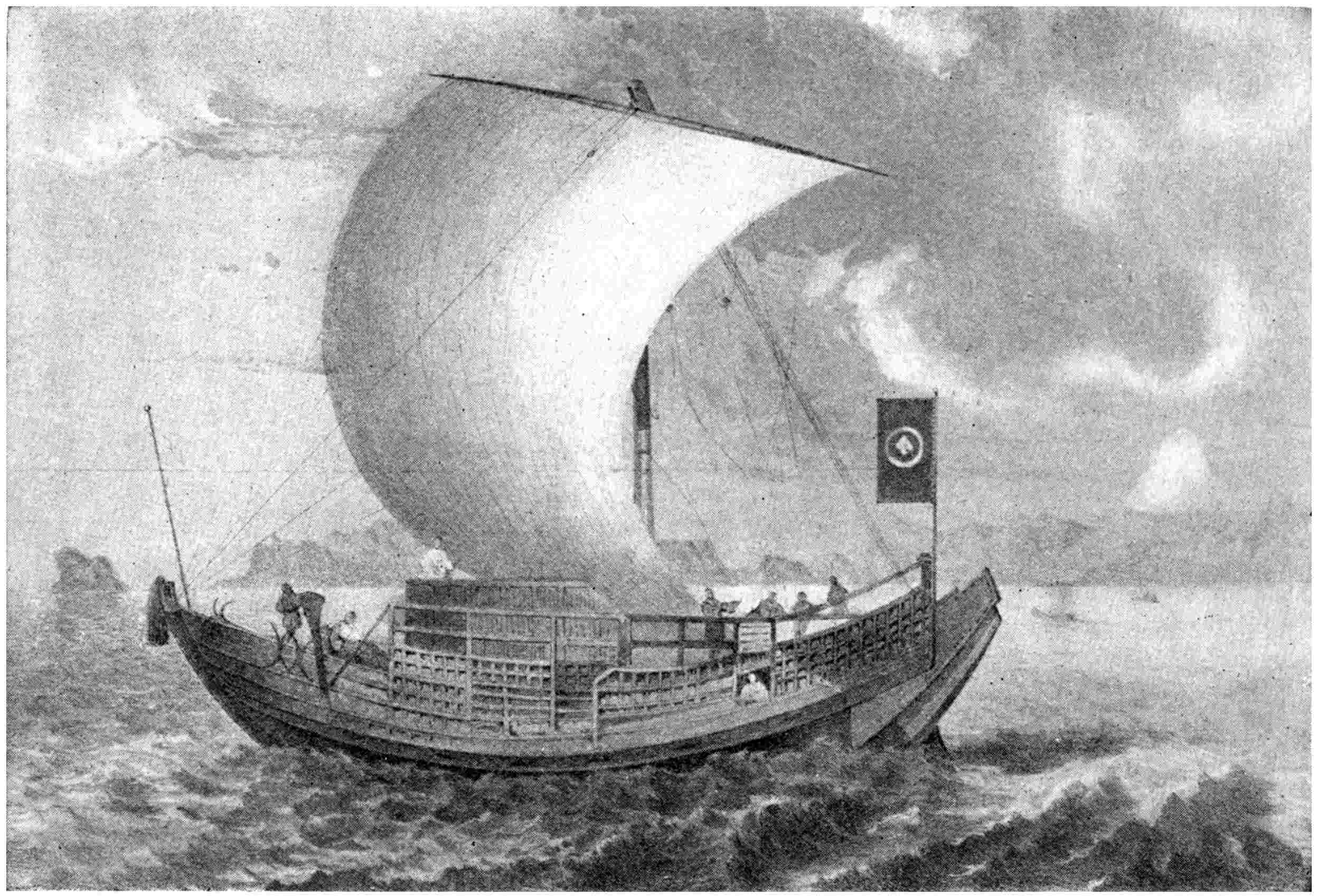

| A Japanese Junk. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 448 |

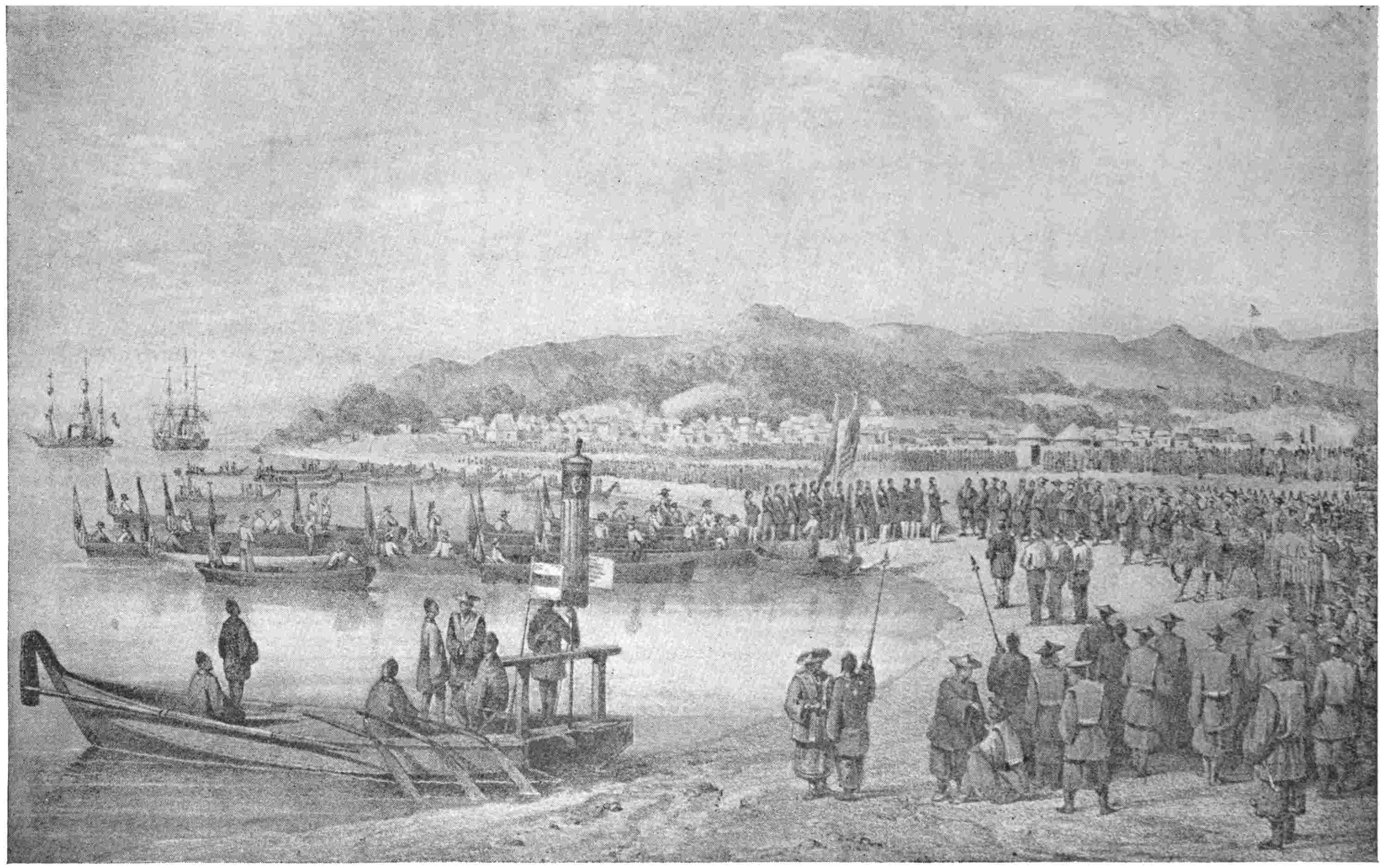

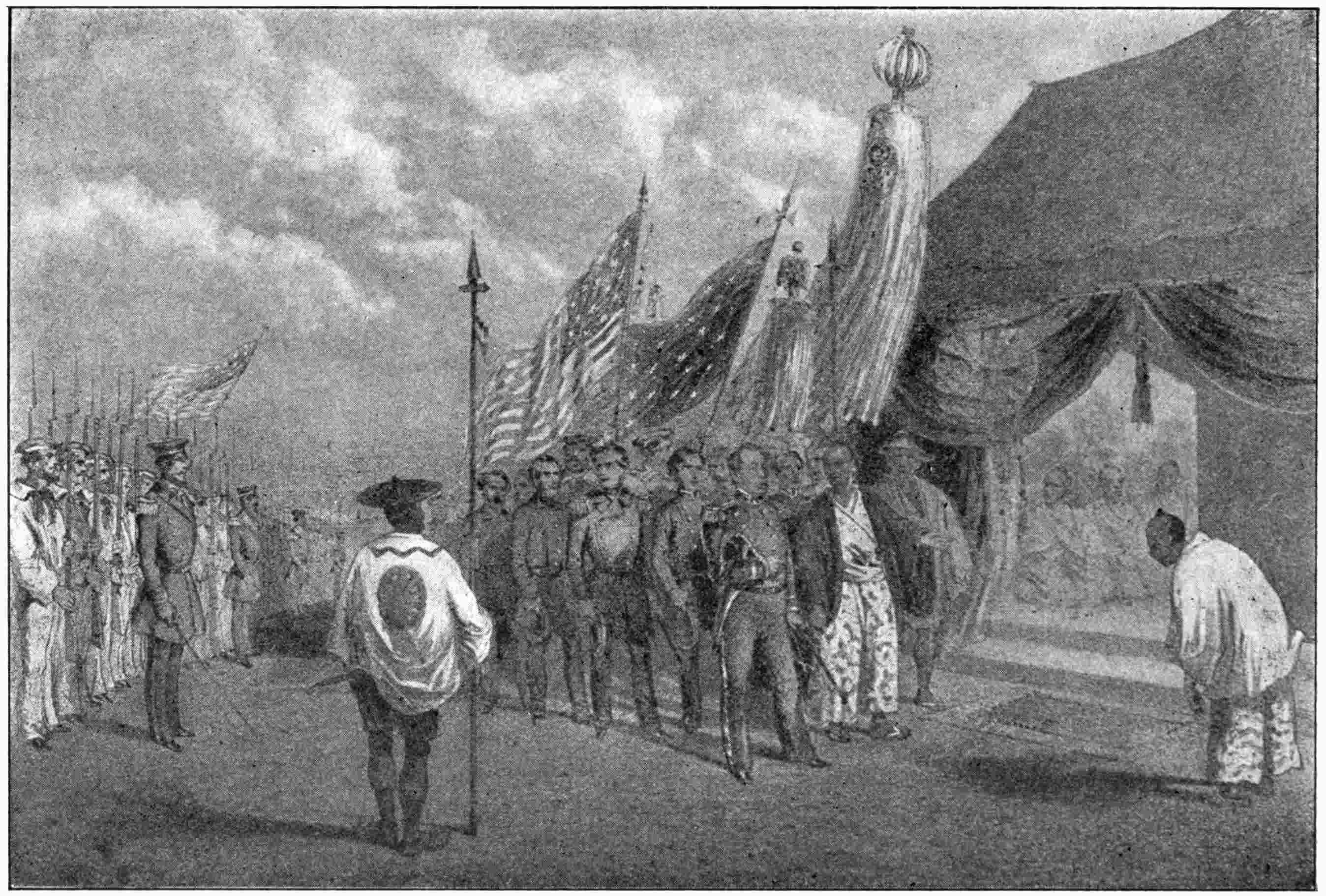

| Commodore Perry’s First Landing at Gorahama. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative ”), | 451 |

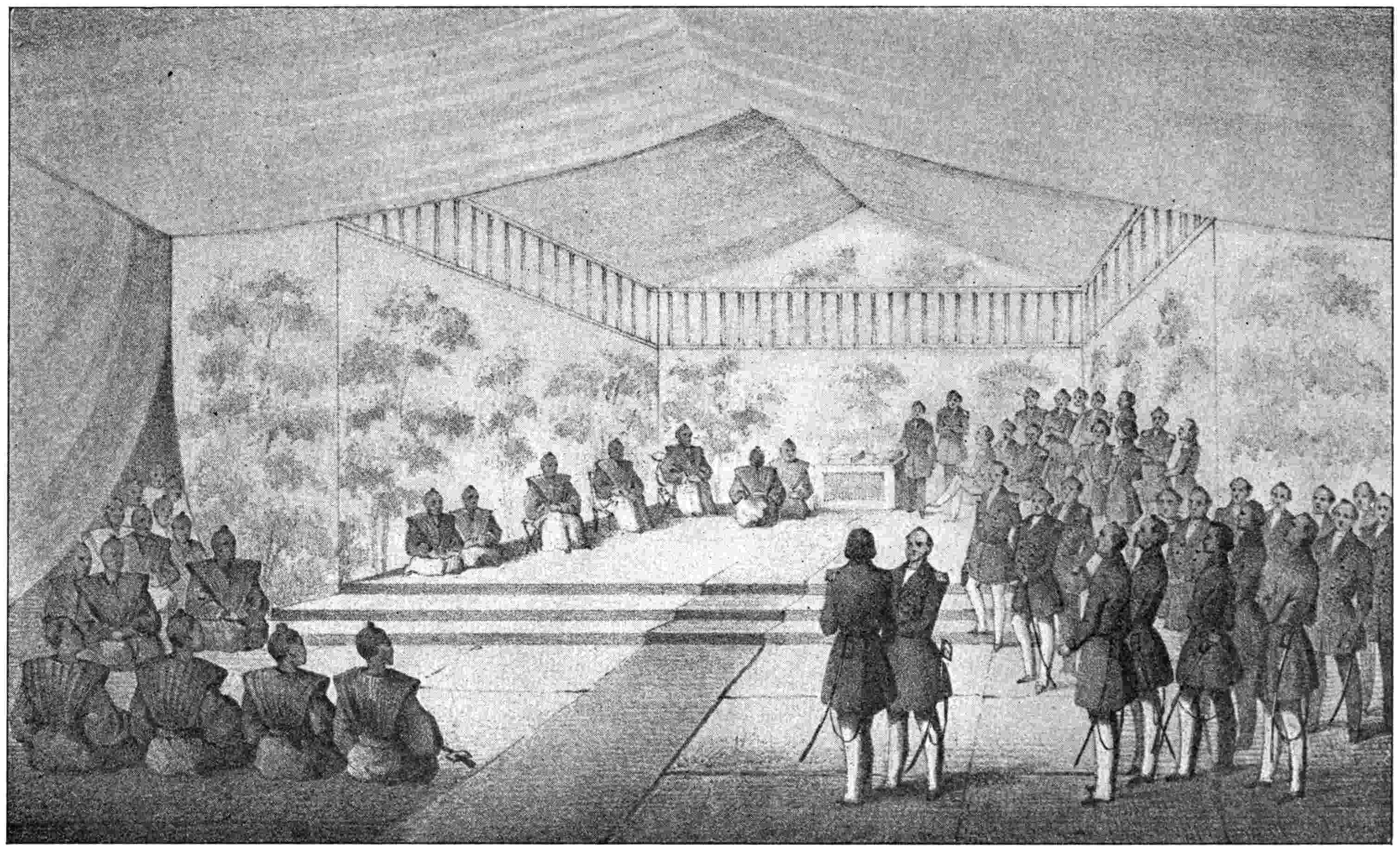

| Commodore Perry Delivering the President’s Letter to the Japanese Representatives. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 453 |

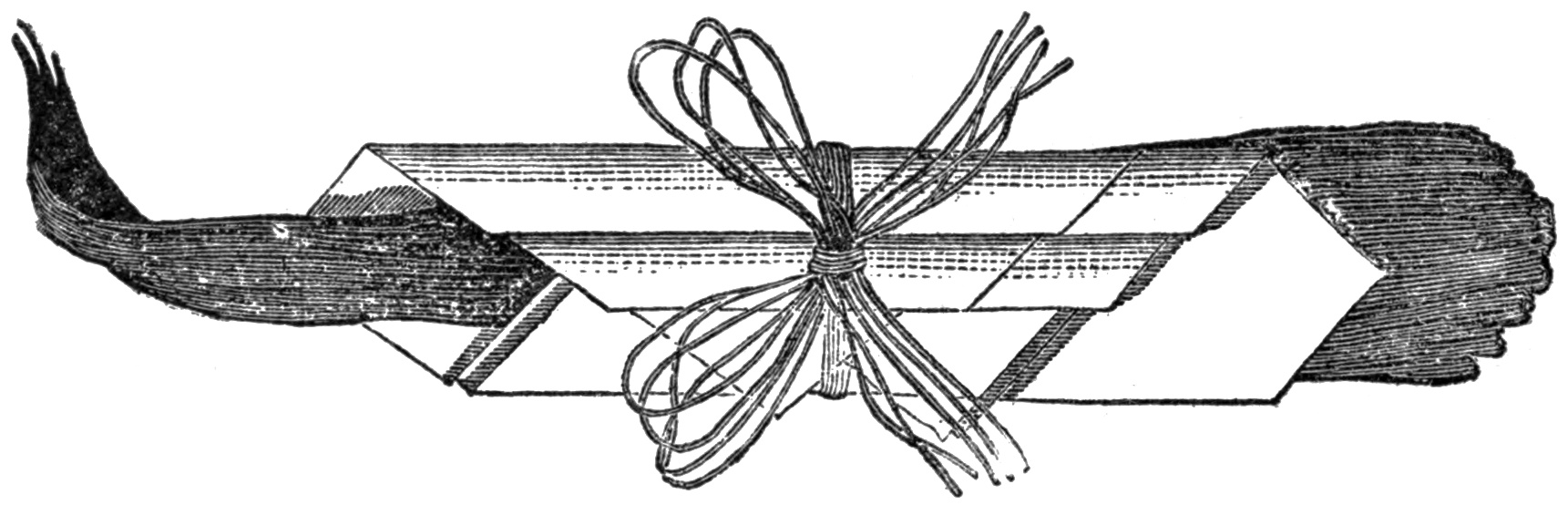

| A Japanese Fish-present. (From a wood-cut in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 456 |

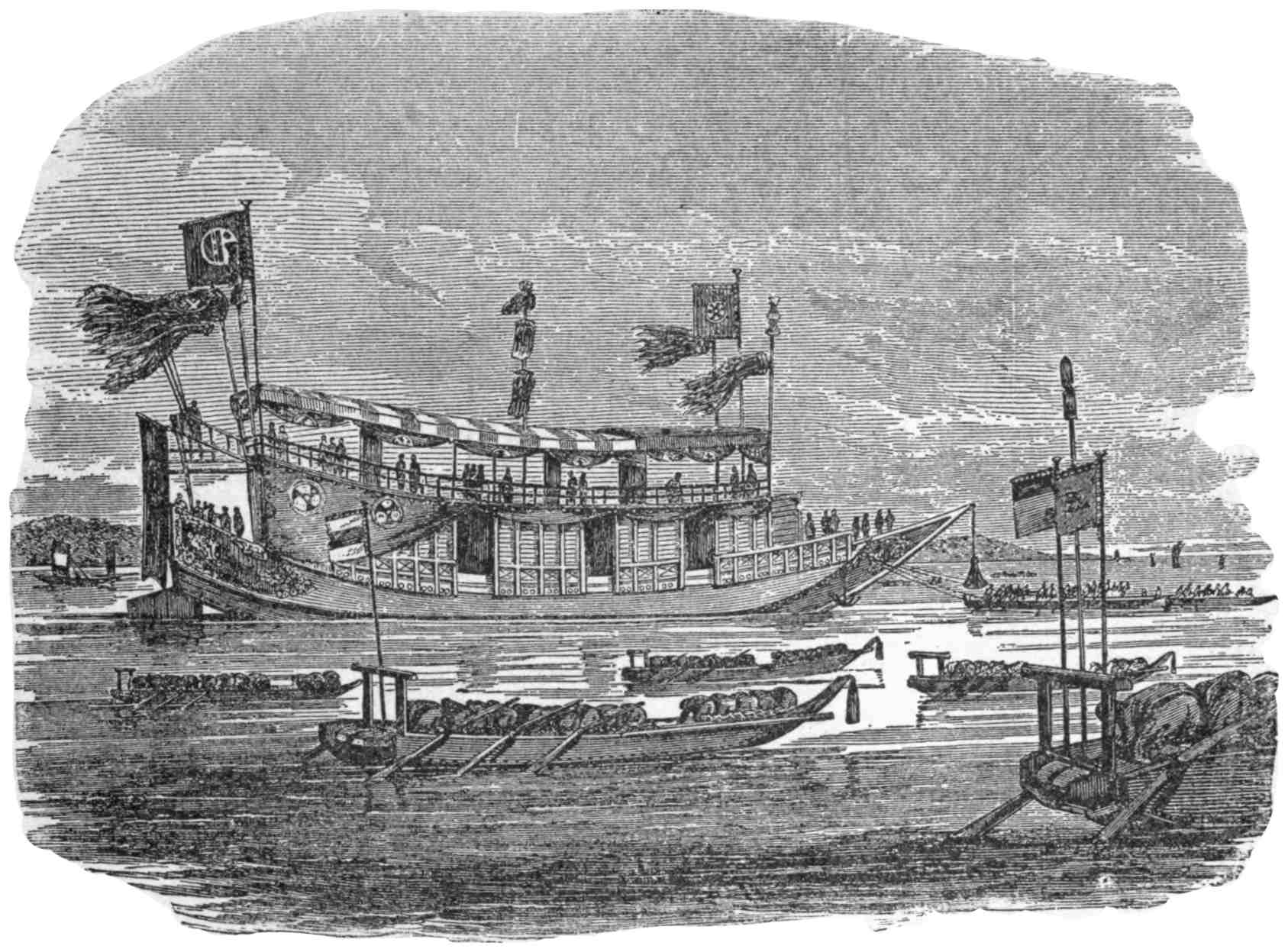

| The Imperial Barge at Yokohama. (From a wood-cut in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 457 |

| The Final Page of the First Treaty with Japan. (From a facsimile of the original), | 458 |

| Commodore Perry Meeting the Imperial Commissioners at Yokohama. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 459xvi |

| Japanese Wrestlers at Yokohama. (From a lithograph in Perry’s “Narrative”), | 461 |

| Commodore’s Pennant, 1812–1860. (From a pennant at the Naval Institute, Annapolis), | 464 |

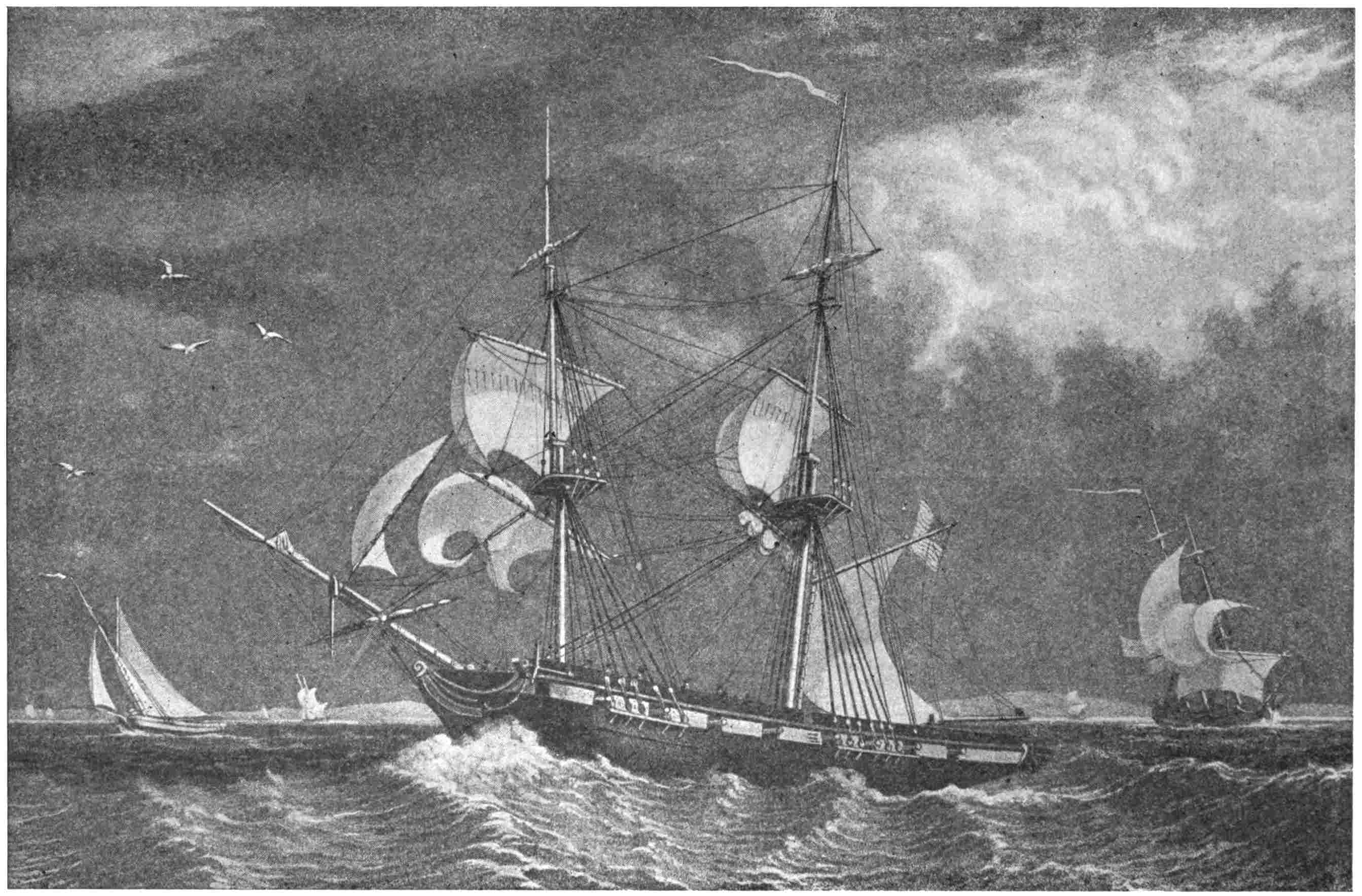

| The United States Brig Porpoise in a Squall. (From a picture drawn and engraved by W. J. Bennett, in 1844), | 465 |

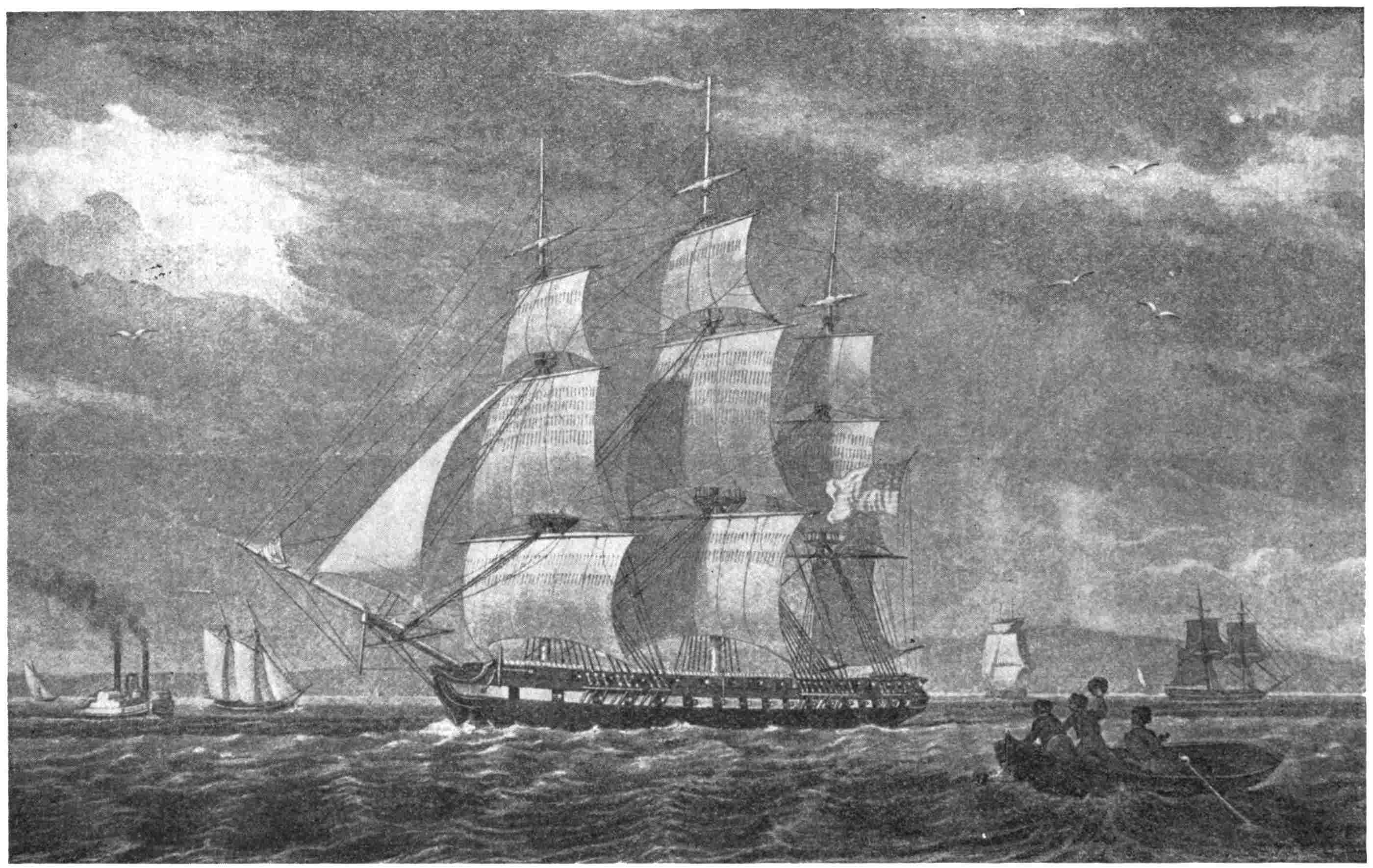

| The United States Frigate Hudson Returning from a Cruise, with a Fair Wind. (From a picture drawn and engraved by W. J. Bennett), | 467 |

1

THE STORY OF THE SECOND CRUISE OF THE FAMOUS LITTLE FRIGATE ESSEX—AROUND CAPE HORN AND ALONE IN THE BROAD SOUTH SEA—CAPTURE OF A PERUVIAN PICAROON—DISGUISING THE ESSEX—THE BRITISH WHALING FLEET TAKEN BY SURPRISE—AN ARMED WHALER TRANSFORMED INTO A YANKEE CRUISER—THE SAILORMAN’S PARADISE AMONG THE NUKAHIVA GROUP—WHEN FARRAGUT WAS A MIDSHIPMAN—AN INCIPIENT MUTINY AMONG THE SAILORS WHO WANTED TO REMAIN AMONG THE ISLANDS—FARRAGUT AS A CAPTAIN AT TWELVE.

Of great renown in the annals of the American Navy is the name of Porter, for the deeds of Captain David Porter with the little frigate Essex fill a large space in the story of the War of 1812; while those of David D. Porter, the son of Captain David Porter, during the Civil War, of which the story will be told farther on, raised him to the highest rank.

The second cruise of the Essex began on October 28, 1812, when she sailed from the2 Delaware bound across the ocean to Port Praya, Cape de Verde, to meet the Constitution and the Hornet and join in a cruise against British commerce in the far East. Her luck in winds having made the passage longer than anticipated, she arrived after the Constitution and Hornet had sailed for Brazil. Having replenished his stores at Port Praya, Captain Porter stood away toward the coast of Africa from Port Praya in order to deceive the people as to his destination, and then ran away toward the island of Fernando de Noronha, where he expected once more to meet his consorts. This passage was without event until December 11, 1812, when at 2 o’clock in the afternoon a sail was seen to windward. Thereat the British signals captured from the Alert in the first cruise were displayed, but they failed to bring the stranger, which was soon seen to be a large brig, toward the Essex. So Porter stood up toward the brig, and by nightfall was near enough to see that she was flying British colors; and a little later she displayed night-signals. When Porter was seen to be unable to answer these, the crew of the brig crowded on all sail and manœuvred with skill to escape, but at 9 o’clock at night the Essex was alongside, and after a volley of musketry from the Yankee, the brig struck. She proved to be the British packet, Nocton, of ten guns and thirty-one men.3 Her cargo included $55,000 in coin. The coin was taken out and the brig sent toward home under a prize-crew of seventeen men, but she was recaptured by the swift-sailing Belvidera when near Bermuda.

The Essex reached Fernando de Noronha on December 14th, and there found a letter from Commodore Bainbridge. As this port was frequented by British men-of-war this letter was signed with the name of the captain of a British ship, the Acasta—Bainbridge having caused the Brazilian authorities of the island to believe that the Constitution and the Hornet were the Acasta and the Morgiana—and directed Porter to pose as Sir James Yeo, of the Southampton, on reaching the island. Because of this diplomacy—because Porter took a letter which Bainbridge had written to him under the name of Sir James Yeo—British writers have said he was guilty of conduct unbecoming to a gentleman and officer!

The letter was double; there was one letter in common ink that meant very little, and on the back of this was another in lime-juice that directed Porter to meet the Constitution and Hornet off Cape Frio.

To Cape Frio, a lofty and most picturesque point on the Brazilian coast, went Porter, and there he lay under short sail, filling and backing, on the day when Bainbridge, with the Constitution,4 won the memorable victory over the British frigate Java. He remained cruising off the Brazilian coast for several days, capturing the British schooner Elizabeth meantime, and eventually put into St. Catharine’s, where he learned what had happened off Bahia, including the fact that the British ship-of-the-line Montagu had driven the Hornet off to the north.

So Porter was left free to choose his own course. It was characteristic of the man that he should have decided, in spite of the fact that the Spaniards, who controlled the west coast of South America, were practically allies of Great Britain, that he would round the Horn and destroy the British shipping in the southern Pacific. He could not hope for a really friendly reception in any port there, but he was confident that he could live off the enemy. Sailing from St. Catharine’s on January 26, 1813, he found an enemy on board his ship next day which we, in this era of the medical science, can scarcely appreciate. A form of dysentery appeared among the crew that was apparently contagious, or was, at least, caused by conditions that threatened the whole crew. It was especially dangerous from the fact that he was bound around the Horn, where the weather would compel the closing of ports, hatches, and companion-ways, and so prevent ventilating the ship. But the commonsense6 of the captain served where the knowledge of medicine failed, for he adopted what would now be called rigorous sanitary measures; he kept the ship and crew absolutely clean and so stopped the epidemic and preserved the health of the crew in a way unheard of, in those days of scurvy and ship fever.

The ship made the Horn in February, the end of the southern summer season—the season of the fiercest gales in that region. The weather became frightful. The seas broke over the little frigate continually, gun-deck ports were broken in fore and aft, extra spars were swept overboard, and boats were knocked to pieces at the davits by the waves. At one time the boatswain was so terrified by the assaults of the sea that he shouted:

“The ship’s side is stove in. We are sinking!” and for a brief time there was a panic among some of the crew.

“This was the only instance in which I ever saw a regular good seaman paralyzed by fear of the perils of the sea,” wrote Midshipman Farragut.

However, early in March the Essex anchored at Mocha Island, where an abundance of hogs and horses were found running wild. The crew had a good time hunting both, and a large quantity of the meat of each was salted down for future use. From here the Essex sailed to7 Valparaiso, where it was learned that Chili had declared herself free of Spain.

Sailing from Valparaiso on March 20, 1813, Porter fell in with the American whaler Charles, of Nantucket, and learned that a Spanish ship of the coast had captured the American whalers Walker and Barclay off Coquimbo, only two days before.

At this, Porter headed for the scene of the trouble, and the next morning (March 26th) saw a sail.

“Immediately, from her appearance and the description I had received of her, I knew her to be one of the picaroons that had been for a long time harassing our commerce,” wrote Porter in his journal. So he hoisted British colors and sailed up beside the stranger and learned that she was the Peruvian cruiser Nereyda, of fifteen guns. Her commander being deceived by the British flag, boasted of having captured the two Yankee whalers. Then Porter got from him a list of the British ships in those waters, with a description of each, so far as the Peruvian could remember. This done, Porter disclosed the character of the Essex to the astonished Peruvian, threw overboard all the guns and arms of his corsairs, and wrote a letter to the Viceroy of Peru telling why this was done, after which the Nereyda was allowed to go.

8

Porter’s next work was in “disguising our ship, which was done by painting in such a manner as to conceal her real force and exhibit in its stead the appearance of painted guns, etc.; also by giving her the appearance of having a poop, and otherwise so altering her as to make her look like a Spanish merchant-vessel.”

The sailormen were still at this work when a sail was seen that, when captured, proved to be the British whaler Barclay. With this vessel in company the Essex sailed to the Galapagos group, where, on April 29th, the British whaler Montezuma, with 1,400 barrels of whale oil on board, was taken. On the same day the whalers Georgiana and Policy were overhauled. The wind having failed, Porter got out his boats to attack these two vessels. When the boats drew near the Georgiana her crew gave three cheers at the sight of the American flag and one of them shouted, “We are all Americans.” And that was very near the truth, for she was a British whaler, licensed as a letter of marque, and had a pressed crew of whom the majority were Americans. The Policy surrendered also without a fight. As the Georgiana was pierced for eighteen guns, and was a smart sailer, Porter transferred the ten guns carried by the Policy to her, which, with the six she already had on board, made her quite a respectable cruiser. She was manned by forty-one men under Lieutenant9 Downes. It was estimated that the three ships taken, with their cargoes, were worth $500,000; but their real value to Porter was in the fact that they carried an abundance of spare canvas, cordage, etc., so that he was able to fit out the Essex with new sails, running gear, and standing rigging wherever needed, and provide liberally for future needs.

On May 28th another sail was seen, but as night came on she was lost to view. Next morning, however, she was sighted from the Montezuma, and after a long chase was taken by the Essex. This prize was the letter-of-marque whaler Atlantic, mounting eight eighteen-pounders, and reputed as the fastest ship in those waters. She was commanded by a man named Weir, “who had the pusillanimity to say that ‘though he was an American-born he was an ‘Englishman at heart,’” so wrote Midshipman Farragut.

That same evening another vessel was seen, and late at night she was captured also. She proved to be the letter-of-marque whaler Greenwich, a ship that had sailed from England under convoy of the ill-fated Java. She was full of ship-stores and provisions of every kind, and had on board, moreover, one hundred tons of water and eight hundred large tortoises, sufficient to furnish all the ships with fresh provisions for a month.

10

“The little squadron now consisted of the Essex, forty-six guns and two hundred and forty-five men; the Georgiana, sixteen guns and forty-two men; the Greenwich, ten guns and fourteen men; the Atlantic, six guns and twelve men; the Montezuma, two guns and ten men; the Policy and the Barclay of ten and seven men, respectively; in all, seven ships carrying eighty guns and three hundred and forty men.” The prisoners numbered eighty. As the number of prizes as well as prisoners proved burdensome, Captain Porter sailed on June 8th for the mainland, and reached Guayaquil Bay on the 19th. Here some provisions were obtained, and while lying here the Georgiana, with her crew of forty men, was sent on a cruise under Lieutenant Downes. The character of Downes was well illustrated on this cruise. Near James Island two British ships were found and secured without a fight. They were the Catherine, of eight guns and twenty-nine men, and the Rose, of eight guns and twenty-one men. Securing his fifty prisoners on the Georgiana, Downes sent ten of his men to each craft taken, and sailed on. That same night another ship was overhauled, and her captain, instead of surrendering when called on to do so, ordered his guns cleared for action.

John Downes.

From an oil-painting at the Naval Academy, Annapolis.

Downes had but twenty men with which to handle his ship, work his guns, and guard his11 prisoners, but he promptly opened fire, and after the fifth broadside the enemy surrendered. She proved to be the British letter-of-marque Hector, of eleven guns and twenty-five men. She had lost in the fight her maintopmast and most of her standing and running rigging, and two12 of her crew were killed and six dangerously wounded.

On manning the Hector with ten men Downes had but ten left with which to guard more than seventy prisoners, care for the wounded, and work the ship. In this emergency he threw overboard the guns of the Rose, destroyed most of her cargo, and made a cartel of her to which to send the prisoners. Then he returned to Guayaquil Bay, from which the Rose sailed for St. Helena.

At Guayaquil a part of the armament and crew of the Georgiana were transferred to the larger and swifter Atlantic, which was rechristened Essex Junior, and the latter was ordered to convoy a part of the fleet of prizes to Valparaiso.

It is worth telling, because of the fame he afterward earned, that Midshipman Farragut was placed on the Barclay as prize-master—was made the captain of the ship. Her original captain had agreed to act as navigator, but he was greatly angered, for some reason, at the order to go to Valparaiso, and when outside he backed the maintopsail and refused to fill away and follow the Essex Junior, declaring “that he would shoot any man who dared to touch a rope without his orders.” Then he went below to get his pistols.

He afterward said he did it merely to scare13 the lad, but if that were so he failed, for Farragut called an able American seaman, and told him to have the main-sails filled away. This was done, and then Farragut told the obdurate captain “not to come on deck unless he wished to be thrown overboard,” and the captain remained below until Farragut made a report of the affair to Lieutenant Downes, of the Essex Junior, and the Britisher agreed to submit quietly to Farragut as captain. Farragut was at this time but twelve years old. Not many boys of twelve would be fit for such a responsible position at that age, and fewer still have had opportunity to show their metal.

The Greenwich was made a store-ship, and the Essex, with her and the Georgiana as consorts, sailed on another cruise, leaving Guayaquil on July 9, 1813. On July 13th, when off Banks Bay, three ships were seen. They separated as soon as the Americans were sighted, whereupon the Essex went in chase, leaving the Georgiana and Greenwich behind. Seeing this, one of the strangers came about and stood for the Greenwich. At that the Greenwich backed her main-yard, brought a number of men from the Georgiana on board, and sailed boldly to meet the stranger.

While these two were approaching each other the Essex overhauled the vessel she was pursuing, and found it was the British whaler Charlton14 of ten guns and twenty-one men. Her captain informed Porter that the stranger approaching the Greenwich was the Seringapatam, a ship of 357 tons, carrying fourteen guns and forty men. She not only outweighed the metal of the Greenwich, but had a larger crew, and was the most dangerous ship in those waters. Nevertheless Porter saw serenely the two ships engage in battle, nor was his confidence in his officers and men misplaced, for, after a brief conflict, the Seringapatam hauled down her flag. A little later, however, she suddenly made sail and strove to escape. The Greenwich at once opened fire on her and kept it up until the British flag was lowered again. It is likely, however, that the Seringapatam would have escaped but for the rapid approach of the Essex, for she could outsail the Greenwich.

Meantime the third ship, the New Zealander, of eight guns and twenty-three men, was taken by the Essex. On overhauling the papers of the Seringapatam it appeared that, although she had no commission either as privateer or letter of marque, she had captured one American whaler, trusting to have the capture legalized by a commission she was expecting to arrive. As his act was really one of piracy the captain was sent to the United States for trial, but he was not convicted.

15

The other prisoners were put on the Charlton and sent under parole to Rio Janeiro. The guns of the New Zealander were transferred to the Seringapatam, giving her a battery of twenty-two, though this was of no great use, save for one broadside, for the reason that she had only men enough to work her sails. Then the Georgiana was loaded with a full cargo of oil, manned with such of the crew of the Essex as had served their full time and also wished to go home (most of those whose time was up re-shipped in the Essex), and on July 25th she sailed for the United States.

The Essex with the other three headed for Albemarle Island, and on July 28th sighted another British whaler. It was a region and a season of light airs and calms, but the Essex rigged a drag that when dropped in the water from the spritsail-yard was hauled aft by a line running through a block on the end of an outrigger aft, and this, although laborious, gave the ship a speed of two knots per hour. As the whaler got out boats to tow his ship, Porter sent a couple of boats of musketeers to drive them on board again. So she was headed off and then other boats were sent to board her. The stranger then hauled down her flag, but before the boats could get alongside a breeze came. At that she hoisted her colors, fired on the Yankee boats and escaped, for the Essex16 did not get the wind until too late. Porter was greatly mortified for the reason that this was the first ship that had escaped him.

However, on September 15th, while cruising among the Galapagos Islands, a whaler was seen cutting in a whale. The Essex was disguised by sending down the small yards, and succeeded in getting within four miles of her before she took alarm, and then by making sail Porter overhauled her. It was now learned that she was the Sir Andrew Hammond, of twelve guns and thirty-one men, and that she was the ship that had run away on July 28th. Luckily for the Essex she had ample stores of excellent beef, pork, bread, wood, and water.

Returning now to Banks Bay, the appointed rendezvous, the Essex was joined by the Essex Junior. Lieutenant Downes brought the news from Valparaiso that several English frigates had been sent to hunt the Essex. At this Porter determined to go to the Marquesas Islands, where he could give the Essex a thorough overhauling in safety. He had cleared those waters of the British whalers and letters of marque, and determined to fit his ship for a battle with equal force before sailing for home. He reached Nukahiva with his squadron on October 23d, built a fort to protect the harbor, and immediately began taking down the masts of the Essex in order to make everything aloft—spars and19 rigging—as sound as possible. In November the New Zealander was sent home with a full cargo of oil, but, unfortunately for the Americans, both she and the Georgiana, sent previously, were recaptured when almost in port by British blockaders. They were very rich prizes for the British tars.

The Essex and her Prizes at Nukahiva in the Marquesas Islands.

From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter.

Nukahiva lies in the tropical climate of the South Pacific—a climate where the sea and the air dance together under an unclouded sun; where the wanton waves tumble and roll invitingly on the beeches; where seemingly the wind-driven light splashes the swaying fronds of the cocoanut-palms; where the air of night is soft and sweet and wooing; where nature asks no labor in return for her bounties; where the thoughts of the people run only to war and love. It was to Jack the ideal country—a paradise on earth.

There were several tribes on Nukahiva. The sailors made friends with those living close at hand, and subdued those, from farther away who came to make trouble. And thereafter they worked upon the ships by day, and at night, by turns, frolicked with the friendly natives.

Says Farragut in his journal:

“During our stay at this island the youngsters—I among the number—were sent on board the vessel commanded by our chaplain21 for the purpose of continuing our studies away from temptation.”

Map of the Harbor in which the Essex and her Prizes lay.

After a drawing by Captain Porter.

The prisoners, having liberty as well as the crews, not only went looking for temptation but they got together and planned to get in a lot of native canoes and carry the Essex Junior by assault, when, the Essex being dismantled, they hoped to capture the entire Yankee force. A traitor revealed the plot, however, and the prisoners were thereafter kept well in hand.

And then came an incipient mutiny. The sailormen had enjoyed life with their friends, the Nukahivas, so much that when, in December, Porter determined to go in search of an enemy worthy of the ship, they first grumbled, and then some of them, under the lead of an Englishman named Robert White, talked of refusing to go at all.

This talk reached flood-tide when on Sunday, December 9, 1813, a lot of the men from the Essex visited the Essex Junior, when White openly boasted that the crew would refuse to get the anchor at the word from Captain Porter. But White was very much mistaken. His words were reported to Porter, who, next morning, mustered the men on the port side of the deck and then, with a drawn sword lying across the capstan before him, said:

22

“All of you who are in favor of weighing23 the anchor when I give the order, pass over to the starboard side.”

A Marquesan War-canoe.

From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter.

They all passed across the deck promptly. Then he called out White, and asked him about his Sunday boasting. White denied having made the boast, but a number of the crew testified to what he had said, and at that Porter turned on the fellow and said in a burst of anger:

“Run, you scoundrel, for your life.”

“And away the fellow went over the starboard gangway.” So Farragut tells the story. He was picked up by one of the ever-present native canoes and carried ashore.

After all it was a lucky affair for him, for the cruise of the Essex was drawing to a close, and had he remained in her he would have been hanged, very likely, by his countrymen as a traitor.

Having addressed the men briefly, praising their good qualities and telling them he “would blow them all to eternity before they should succeed in a conspiracy,” he ordered them to man the capstan, a fiddler began to play “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” the “anchor fairly flew to the bows,” the sails were spread, and the Essex and Essex Junior sailed away, leaving Lieutenant John Gamble with twenty-one men, to look after the Seringapatam, the Sir Andrew Hammond, and the Greenwich until Porter could return for them.

24

A GENEROUS RECEPTION FOR A PREDATORY BRITISH FRIGATE—HILLYAR’S LUCKY ESCAPE—HILLYAR’S EXPLICIT ORDERS—WHEN THE ESSEX HAD LOST HER TOP-MAST THE PHŒBE AND THE CHERUB ATTACKED THE YANKEE IN NEUTRAL WATER—IT WAS A TWO-TO-ONE FIGHT AND THE ENEMY HAD LONG GUNS TO OUR SHORT—THE BRITISH HAD TO GET BEYOND THE RANGE OF THE ESSEX—MAGNIFICENT BRAVERY OF THE YANKEE CREW WHEN UNDER THE FIRE OF THE LONG RANGE BRITISH GUNS—THE ESSEX ON FIRE—FOUGHT TO THE LAST GASP—PORTER’S INTERRUPTED VOYAGE HOME—THE MEN WHO WERE LEFT AT NUKAHIVA IN SORRY STRAITS AT LAST.

The Essex, with her consort, the Essex Junior, got up anchor at Nukahiva on December 12, 1813. For two days they were in the offing and then they sailed for the coast of South America. They sighted the Andes early in January, and after getting water at San Maria and calling at Concepcion, went to Valparaiso, where they arrived on February 3, 1814. There Porter learned that the British frigate Phœbe, Captain James Hillyar, had been on the coast some time looking for the Essex. So Porter determined to await her at Valparaiso.

25

To make the time pass pleasantly a grand reception was given to the officials of the city and their friends on the night of the 7th, the Essex Junior, meantime, having been stationed outside to watch for the enemy. As it happened the enemy was seen next morning while yet the men of the Essex were taking down the bunting with which the ship had been decorated. But when Captain Porter came to read the signals on the guard-ship he found that two ships were in sight instead of the one looked for. After a time the two appeared and displayed British colors, and the Essex Junior was obliged to come into the port. And what made matters still more uncomfortable was the fact that half of the crew of the Essex were on shore enjoying life sailor fashion.

This last fact had not escaped the eye of the patriotic mate of an English merchantman lying in the harbor, and jumping into a small boat he rowed outside to tell his countrymen about the crew of the Essex. As it appeared very soon after this, the two British ships outside were the Phœbe already mentioned and the eighteen-gun war-ship Cherub, Captain Tucker.

Captain Hillyar, of the Phœbe, very naturally assumed that the Yankee sailors on shore were already so full of the excellent native wine of the country that even if got on board they would not be able to make a fight. The wind26 was in just the right direction to enable him to take his two ships into port and handle them there with certainty. It was true that Valparaiso was a neutral port, but that fact was considered unimportant. Captain Hillyar had been sent there expressly to capture the Essex, and the opportunity to do it comfortably seemed to have been made as if to order. So he cleared his ship for action, and, leaving the Cherub outside, steered boldly for the Essex.

But when the Phœbe swept up beside the Yankee ship Captain Hillyar experienced a very great revulsion of feeling. He had approached the Essex under the quarter, where not one of her guns could bear on him, and then slightly shifting his helm he ranged up alongside and within fifteen feet of her. And then to his utter discomfiture he found the Yankee guns fully manned, and every man save one was fit and eager for fight.

The warlike ardor of the Englishman instantly evaporated, and he remembered that he had met Captain Porter some years before on the Mediterranean station, and that they had exchanged friendly visits. Instead of ordering his men to fire he jumped on a gun, where he could get a better view of the deck of the Essex, and said, with marked politeness:

“Captain Hillyar’s compliments to Captain Porter, and hopes he is well.”

27

And Captain Porter, who had never felt better in his life than at that moment, replied:

“Very well, I thank you; but I hope you will not come too near for fear some accident might take place which would be disagreeable to you.” And with that he waved his trumpet toward some of the crew forward who, with ropes in hand, were awaiting the signal, and they instantly triced a couple of kedge anchors out to the weather yard-arms ready for dropping on the enemy to grapple him fast in reach of the well-trained Yankee boarders, armed with sharpened cutlasses and dirks made from old files.

Indeed the Yankee forecastlemen were so eager that they swarmed to the rail as the anchors rose to the yard-arms, while one of them, a quarter-gunner named Adam Roach, with his sleeves rolled up and cutlass in hand, climbed out on the cathead and stood there, in plain view of the British marines, awaiting the moment when the ships should come together.

But they did not come together, yard-arm to yard-arm, either then or afterward. Captain Hillyar hastily braced his yards aback and “exclaimed with great agitation:”

“I had no intention of getting on board of you—I had no intention of coming so near you; I am sorry I came so near you.”

“Well,” said Porter, “you have no business28 where you are. If you touch a rope yarn of this ship, I shall board instantly.” Then he hailed the Essex Junior, that was lying handy by, and ordered Lieutenant Downes to prepare to repel the enemy.

The Phœbe fell off with her jib-boom over the American deck, her bows exposed to the broadside of the American guns, and her stern exposed to the broadside of the Essex Junior.

At that moment the one member of the crew who had come on board the Essex drunk, narrowly escaped precipitating the battle. He was a big boy and served as powder-monkey. While standing beside his gun with a slow-burning match in hand waiting for orders, “he saw, through the port, someone on the Phœbe grinning at him.” He was deeply offended at once.

“My fine fellow, I’ll stop your making faces,” he said, and leaned over to put his match to the gun’s priming. The lieutenant in charge saw the move and knocked the youth to the deck. Had he fired the gun a fight would have followed and the Phœbe would have been taken. As it was she passed free, although some of her yards overlapped those of the Essex, and a little later she came to anchor half a mile away.

“We thus lost an opportunity of taking her, though we had observed the strict neutrality of the port under very aggravating circumstances.”29 So wrote Farragut, but no American at this day regrets the action of Captain Porter. It was, indeed, “over-forbearance, under great provocation,” but it showed the high sense of honor of a typical American officer, and every American reads the story of the Essex with unalloyed pleasure. Such exhibitions as this of the American spirit have done more than cannon-shot to promote and to preserve peace between the nations. Captain Hillyar was so much impressed by it that he promised Porter that he, too, would respect the neutrality of the port, and he would have done so, very likely, only that he was handicapped by his orders from the Admiralty, which compelled him to “capture the Essex with the least possible risk to his vessel and crew.” Hillyar was a cool and calculating man of fifty years. As he said to his first lieutenant, Mr. William Ingram, he had gained his reputation in single-ship encounters and he only expected to “retain it by an explicit obedience to orders.”

That he was going to take “the least possible risk” appeared a few days later when Porter asked him to send the Cherub to the lee side of the harbor and meet the Essex with the Phœbe alone. The Phœbe and the Cherub had by that time replenished their stores and taken a station outside. Hillyar at first agreed to do so, and made preparations for the fight. Among30 other things he had a huge flag painted with a motto in answer to Porter’s burgee containing “Free Trade and Sailor’s Rights.” The British motto read: “God and Country; British Sailors’ Best Rights; Traitors Offend Both.” It was a day when such displays were fashionable among sailors, and Porter at once painted another which he hoisted to the mizzen, where it read: “God, our Country and Liberty; Tyrants Offend them.”

Such things seem rather silly now, but they were inspiring to Jack in those days. With his banners flaunting before the Yankee eyes Captain Hillyar hove his main-yard aback off the weather-side of the harbor, having previously sent the Cherub a fair distance to leeward. Then he fired a gun to invite the Essex out. Captain Porter accepted the invitation and stood out of the harbor. He found he could outsail the Phœbe, and he got near enough to fire several shots from his long twelves that almost reached her, but she squared away for the Cherub, and Porter had to let her go.

Meantime Porter “had received certain information” that the frigate Tagus and two others were coming after him, while the sloop-of-war Raccoon, that had gone to the northwest coast of North America to destroy the fur-gathering establishment of John Jacob Astor, was to be expected at Valparaiso at any time.31 So Porter determined to sail out of the harbor, trusting to the speed of the Essex to carry him clear of the superior force. Should he succeed in drawing the enemy clear of the harbor the Essex Junior was at once to make sail also.

But the day after arriving at this determination a heavy squall came on from the south, the port cable of the Essex broke, and she began dragging the starboard one right out to sea. Without delay Porter made sail, setting his top-gallant sails over reefed top-sails, and stood out of the harbor. As he opened up the sea he saw that he had a chance for sailing between the southwest point of the harbor and the enemy—passing to windward of them, in fact, and so getting clear without trouble. The top-gallant sails were at once clewed up and the yards braced to sail close hauled. The Essex was making a course that was just what Porter wanted, and he was just clearing the point when a sudden squall from around the corner of the land struck the ship, knocking the maintopmast over the lee rail into the sea, and the men who were still aloft furling the top-gallant sail were lost.

At once both of the enemy’s ships gave chase, and Porter, after clearing the wreckage, turned to beat back to his old anchorage. But because he was crippled, and because of a sudden shift of wind, he could not make it, and so he “ran32 close into a small bay about three-quarters of a mile to leeward of the battery on the east side of the harbor,” and there let go his anchor “within pistol-shot of the shore.”

Here he was as much in neutral waters as he would have been at the usual anchorage, but the enemy, with mottoes and banners in abundance flying, came down to attack the cripple. The Cherub came cautiously to the wind off the bow of the Essex, the Phœbe, with equal caution, off her stern, and at 3.54 P.M., on March 28, 1814, in the presence of the whole population of Valparaiso, who thronged to the bluffs, the battle, that was to end the career of the Essex as an American frigate, began. To fully appreciate the fight that followed, the reader should recall the fact that in spite of the protests of Captain Porter the Essex had been compelled to sail with a battery of forty short thirty-twos in place of the long twelves that he wanted. In addition to these she carried six long twelves, three of which, when this fight began, were arranged to fight at the bow and three at the stern. Her crew numbered two hundred and fifty-five when she dragged her anchor, but of these at least four were lost from the top-gallant yard. The exact number is not given.

On the other hand the Phœbe, under the circumstances, was alone in weight of metal superior33 to the Essex. On her main deck were thirty long eighteens, to which were added sixteen short thirty-twos, one howitzer, and in the tops six three-pounders. In all she carried fifty-three guns. She carried more guns than ships of her class usually did, because she had been fitted out especially to catch the Essex with as little risk as possible. Her crew numbered three hundred and twenty, the usual number having been added to, when she was taking in supplies, by gathering sailors from the British ships in port. The Cherub mounted eighteen short thirty-twos, eight short twenty-fours, and two long nines. Her crew, with the additions received in port, numbered one hundred and eighty men.

But this was a battle fought at long range. Captain Hillyar obeyed his instructions to take as little risk as possible, and he held his ships beyond the range of Porter’s short thirty-twos. It was therefore a fight in which five hundred men were pitted against two hundred and fifty-one, and the fifteen long guns in the broadside of the Phœbe and both of the long guns of the Cherub—in short, seventeen long guns, throwing two hundred and eighty-eight pounds of metal, were pitted against six long guns, throwing by actual weight only sixty-six pounds of metal. That was the actual preponderance when the battle began, but even that did not34 satisfy the ideas of the British captains in their desire to obey their orders to take as little risk as possible, for the Cherub, finding her position off the bow of the Essex too hot, wore around and took a station near the Phœbe, where Porter could bring only three guns, throwing together but thirty-three pounds of metal, to bear on the two of them with their seventeen long guns throwing two hundred and eighty-eight pounds of metal. Rarely in the history of the world has a fight been maintained against such odds as these. The Englishmen did, indeed, draw in closer at one time of the battle, but it was for only a brief time. The short guns of the Essex soon made them withdraw to a safer distance.

When the first gun was fired at 3.54 P.M., Porter had not yet been able to get a spring on his cable and could not bring a gun to bear on either ship. For five minutes the Essex lay as an idle target. But as the spring was made fast and the cable veered, the long twelves began to bark and it was then that the Cherub made haste to get clear of the fire from forward, and take a place near the Phœbe. They both delivered a raking fire which “continued about ten minutes, but produced no visible effect,” to quote Hillyar’s report to Commodore Brown of the Jamaica station. But if the British fire produced no “visible effect,” the fire of the guns of the Essex was so well directed that Hillyar35 “increased our distance by wearing,” and he confesses that “appearances were a little inauspicious.” In fact, at the end of half an hour both the British ships sailed out of range to repair damages alow and aloft. The Phœbe alone had seven holes at the water-line to plug and she had lost the use of her mainsail and jib, her fore, main, and mizzen stays were shot away, and her jib-boom was badly wounded. This much the British admit.

But it had been a losing fight on the Essex, nevertheless. The springs on the cable were shot away three times and could be renewed only after delays that prevented working the guns under full speed, and the heavy shot of the enemy’s long guns had been cutting down the crew. And then the enemy returned once more to the fight. Brave Lieutenant William Ingram, of the Phœbe, wanted to close in and carry the Essex by boarding. The two British ships had at this time more than two men to the one of the Essex, but Hillyar refused, quoting the orders he had received from his superiors as a reason, and saying he had “determined not to leave anything to chance.” He would not face Yankee cutlasses wielded in defence of the Essex. So the safest possible positions were chosen, and fire was again opened at 5.35 P.M. It was “a most galling fire, which we were powerless to return.” Even36 the Essex’s “stern guns could not be brought to bear.”

At this juncture, the wind having shifted, Captain Porter ordered his crew to slip the cable and make sail; and it was then found that the running gear had been so badly cut that only the flying jib could be spread.

Did the courage and hope of the brave American falter at this? Not at all. Spreading that one little triangle of canvas by halyard and sheet to the wind, he loosed the square sails, and with their unrestrained and ragged breadths flapping from the yards, the Essex wore around, and while the shot of the enemy filled the air above her deck with splinters, she bore down upon them until her short guns began to reach them, and the Cherub was driven out of range altogether, while Hillyar made haste to obey his orders about taking as little risk as possible—made haste to spread his canvas and sail away to a point where he would be clear of the deadly aim of the Yankee gunners. The Phœbe “was enabled by the better condition of her sails to choose her own distance, suitable for her long guns, and kept up a most destructive fire on our helpless ship.” So says Farragut.

Fight of the Essex with the Phœbe and Cherub.

From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter.

But fearful as was the scene on the doomed Essex, the story of the deeds of her heroic crew stir the blood as few other stories of39 battle can do. “Dying men who had hardly ever attracted notice among the ship’s company, uttered sentiments worthy of a Washington. You might have heard in all directions: ‘Don’t give her up, Logan’—a sobriquet for Porter—‘Hurrah for Liberty!’ and similar expressions.”

A man named Bissley, a young Scotchman by birth, on losing a leg, said: “I hope I have this day proved myself worthy of the country of my adoption. I am no longer of any use to you or to her, so good-by!” And with that he plunged through a port. And John Ripley, who had suffered in like fashion, also went overboard deliberately. John Alvinson, having been struck by an eighteen-pound shot, cried: “Never mind, shipmates; I die in defence of free trade and sailors’ ri——” and so his spirit fled while the last word quivered on his lips. William Call lost his leg and was carried down to the berth-deck. As he lay there weltering in his blood awaiting his turn with the doctor, he saw Quarter-Gunner Roach—he who had so bravely headed the boarders—skulking, and “dragged his shattered stump all around the bag-house, pistol in hand, trying to get a shot at him.”

And there was Lieutenant J. G. Cowell. He had his leg shot off just above the knee and was carried below. The surgeon on seeing40 him at once left a common sailor to attend to him, but Cowell said:

“No, doctor, none of that; fair play is a jewel. One man’s life is as dear as another’s; I would not cheat any poor fellow out of his turn.” And so he bled to death before his turn came.

In the record kept by young Farragut we have a wonderful story of a battle as seen by a lad of twelve. “I performed the duties of captain’s aid, quarter-gunner, powder-boy, and in fact did everything that was required of me,” he wrote.

“I shall never forget the horrid impression made upon me at the sight of the first man I had ever seen killed. He was a boatswain’s mate, and was fearfully mutilated. It staggered and sickened me at first, but they soon began to fall around me so fast that it all appeared like a dream, and produced no effect on my nerves. I can remember well, while I was standing near the captain, just abaft the mainmast, a shot came through the waterways and glanced upwards, killing four men who were standing by the side of the gun, taking the last one in the head and scattering his brains over both of us. But this awful sight did not affect me half as much as the death of the first poor fellow. I neither thought of nor noticed anything but the working of the guns.

41

“On one occasion Midshipman Isaacs came up to the captain and reported that a quarter-gunner named Roach had deserted his post. The only reply of the captain, addressed to me, was, ‘Do your duty, sir.’ I seized a pistol and went in pursuit of the fellow, but did not find him.

“Soon after this, some gun-primers were wanted, and I was sent after them. In going below, while I was on the ward-room ladder, the captain of the gun directly opposite the hatchway was struck full in the face by an eighteen-pound shot, and fell back on me. We tumbled down the hatch together. I struck on my head, and, fortunately, he fell on my hips. I say fortunately, for, as he was a man of at least two hundred pounds’ weight, I would have been crushed to death if he had fallen directly across my body. I lay for some moments stunned by the blow, but soon recovered consciousness enough to rush up on deck. The captain, seeing me covered with blood, asked if I was wounded, to which I replied, ‘I believe not, sir.’ ‘Then,’ said he, ‘where are the primers?’ This first brought me completely to my senses, and I ran below again and carried the primers on deck. When I came up the second time I saw the captain fall, and in my turn ran up and asked if he was wounded. He answered me almost in the same words, ‘I believe42 not, my son; but I felt a blow on the top of my head.’ He must have been knocked down by the windage of a passing shot, as his hat was somewhat damaged.”

With such scenes as these on deck Porter strove to overtake the enemy. The picture of that American ship, with her unsheeted sails flapping in the wind as she struggled to get within range, is among the most heroic known to history. It was a vain struggle. The wind veered once more. The shot from the long guns of the enemy were ripping her hull to pieces, and, in the language of the British first lieutenant, murdering her crew. The brave American commander was baffled but was not yet conquered. Putting up his helm he turned once more toward the shore, determined to beach the ship, broadside on, fight to the last gasp, and then blow her to pieces.

Firing from his stern guns as he ran, he reached out for the sands until they were but half a mile away, and then once more the treacherous wind shifted, and catching the sails aback, wrapped their torn folds as a shroud about the masts. A hawser was bent to the sheet-anchor, which was then let go. That brought her head around where the long guns would bear, but the hawser broke a minute later, and once more the Essex drifted offshore a helpless target.

43

And then came an explosion below. The ship was on fire, and the men came rushing up on deck, “many with their clothes burning.” The men on deck hastened to rip the burning garments from their shipmates, but some whose clothes were flaming were ordered to “jump overboard and quench the flames.” Smoke was rolling up the hatches, and “many of the crew, and even some of the officers, hearing the order to jump overboard, took it for granted that the fire had reached the magazine, and that the ship was about to blow up; so they leaped into the water, and attempted to reach the shore.”

Hope had at last fled from the doomed ship. The decks were strewn with the dead and wounded. There were twenty-one bodies in one pile on the main deck. The long-range shot of the enemy were sinking her. The hold was in flames. The captain called for his lieutenants to ask their opinion of the condition of affairs, and found but one, Lieutenant McKnight, to answer the call. Of the two hundred and fifty-one men who began the fight only seventy-five, including officers and boys, remained on the ship in condition fit for duty. Further effort was useless, “and at 6.20 P.M. the painful order was given to haul down the colors.”

At that, Benjamin Hazen, a Groton seaman44 (who, though painfully wounded, had remained at his post, and at the last had joined in the request to haul down the flag to save the wounded), bade adieu in hearty fashion to those around him, said he had determined never to survive the surrender of the Essex, and jumped overboard. He was drowned.

In what has been said regarding the handling of the Phœbe there was no desire to cast a slur upon the personal character of Captain Hillyar. He had proved his bravery in previous contests. The point to be made clear is that his superiors had so far learned to respect Yankee prowess that he was under definite order to take no unnecessary risks. He conducted the fight in the only way that insured certain victory. Every fair-minded American will grant what Sir Howard Douglas, in his text-book on gunnery (page 108), claims—that “this action displayed all that can reflect honor on the science and admirable conduct of Captain Hillyar and his crew,” save only so far as he broke his word of honor pledged to Captain Porter. And that is to say that it is admitted that a sneer at the “respectful distance the Phœbe kept” is “a fair acknowledgment of the ability with which Captain Hillyar availed himself of the superiority of his arms.”

The losses of the Essex were fifty-eight killed and mortally wounded, thirty-nine severely45 wounded, twenty-seven slightly wounded, and thirty-one missing, the most of whom, if not all, were drowned in trying to swim ashore when the Essex was on fire. These numbers were given by the American officers. Hillyar reported that the Essex lost one hundred and eleven in killed or wounded. The difference in these official reports is unquestionably due to the fact that Hillyar, naturally enough, did not count as wounded those of his prisoners who had received minor scratches and contusions, even though these wounds had temporarily disabled the men during the battle. Nevertheless, the favorite British historian James, although he had read Hillyar’s letter, wrote:

“The Essex, as far as is borne out by proof (the only safe way where an American is concerned), had twenty-four men killed and forty-five wounded. But Captain Porter, thinking by exaggerating his loss to prop up his fame, talks of fifty-eight killed and mortally wounded, thirty-nine severely, twenty-seven slightly.”

And Allen, whose latest edition appeared in 1890, follows the false statement of James.

The British loss was, of course, trifling. They had five killed and ten wounded. But it is not unconsoling to reflect that the Phœbe received in all eight shot at and under the water-line, and that she and the Cherub were not a little cut up aloft—in short the damage inflicted by46 the Essex was greater than the British Java, Macedonian, and Guerrière all together inflicted on the American ships in their battles. Captain Hillyar had good reason for writing to his superior that “the defence of the Essex, taking into consideration our superiority of force and the very discouraging circumstance of her having lost her maintopmast and being twice on fire, did honor to her brave defenders.”

As Roosevelt says, “Porter certainly did everything a man can do to contend successfully with the overwhelming force opposed to him. As an exhibition of dogged courage it has never been surpassed since the time when the Dutch Captain Kaesoon, after fighting two long days, blew up his disabled ship, devoting himself and all his crew to death, rather than surrender to the hereditary foes of his race.”

While no one can justly criticise Captain Hillyar for his handling of his ship during the battle, there is something to be said about his having made an attack on the American ship under the circumstances. And this cannot be better said than in the words of Roosevelt, whose fairness has been acknowledged by the English in the most emphatic manner. He says:

“When Porter decided to anchor near shore, in neutral water, he could not anticipate Hillyar’s deliberate and treacherous breach of faith.47 I do not allude to the mere disregard of neutrality. Whatever international moralists may say, such disregard is a mere question of expediency. If the benefits to be gained by attacking a hostile ship in neutral waters are such as to counterbalance the risk of incurring the enmity of the neutral power, why then the attack ought to be made. Had Hillyar, when he first made his appearance off Valparaiso, sailed in with his two ships, the men at quarters and guns out, and at once attacked Porter, considering the destruction of the Essex as outweighing the insult to Chili, why his behavior would have been perfectly justifiable. In fact, this is unquestionably what he intended to do; but he suddenly found himself in such a position that, in the event of hostilities, his ship would be the captured one, and he owed his escape purely to Porter’s over-forbearance, under great provocation. Then he gave his word to Porter that he would not infringe on the neutrality; and he never dared to break it, until he saw Porter was disabled and almost helpless! This may seem strong language to use about a British officer, but it is justly strong. Exactly as any outsider must consider Warrington’s attack on the British brig Nautilus in 1815 as a piece of needless cruelty, so any outsider must consider Hillyar as having most treacherously broken faith with Porter.”

48

Fair as this statement must seem to candid minds, there is yet a word to be said for Captain Hillyar. A fair interpretation of his orders demanded that he break his faith and attack the ship, and as an officer accustomed to obey all orders from his superiors, he believed his obligation to the Admiralty and his country was greater than his obligation to keep his word. Captain Hillyar believed that his country demanded that he break faith with Porter, and the proof that the British nation has ever since approved of his treachery toward an American is found in the fact that “the naval medal is granted for the capture” of the Essex (see Allen); that the officer who sailed her to England was at once promoted, and that every British writer who has referred to the action has praised Captain Hillyar in the highest terms, and refers to Captain Porter as James did when he said: “Few, even in his own country, will venture to speak well of Captain David Porter.”

After the battle the Essex was repaired and sent to England, where she was added to the British Navy. It is worth noting that she was built in 1779 by the people of Salem, Massachusetts, and the surrounding country, who were enthusiastic in their desire to revenge the injuries done by French cruisers to American commerce. She was the product of the Federalist49 party ardor, and Rear-Admiral George Preble says, “the Federalists considered it a patriotic duty to cut down the finest sticks of their wood lots to help build the ‘noble structure’ that was to chastise French insolence and piracy.” They gave her as a present to the nation, and as armed at that time she was probably the most efficient ship of her size afloat.

The Essex Junior was disarmed and the American prisoners were put into her, and she was sent as a cartel to New York. Off the east coast of Long Island, on July 5, 1814, she was detained by British cruisers so long that the Americans were lawfully released from their parole, when Porter and a boat’s crew escaped ashore aided by a fog, and that was the only occasion during that cruise of this Yankee captain, that weather did aid him. He landed in Long Island, where he had to show his commission before the people would believe his story. He was then carried to New York by enthusiastic admirers, and was there received with every mark of honor. Meantime, the Essex Junior was allowed to come in also.

A few words will tell the fate of Lieutenant Gamble and the men left at Nukahiva with the captured whalers Seringapatam, Greenwich, and Sir Andrew Hammond. Immediately50 after Porter sailed away the natives began to rob the Americans of everything they could carry away, and Gamble had “to land and overpower them.” On February 28, 1814, one man was drowned accidentally. A week later four men deserted in a whale-boat to join their native sweethearts. On April 12th Gamble rigged the Seringapatam and the Hammond for sea, intending to burn the Greenwich, but the men became mutinous. So Gamble removed all the arms, as he supposed, to the Greenwich; but when he boarded the Seringapatam on May 7th, the men there attacked him, shot him in the foot with a pistol, set him adrift in a native canoe, and then sailed away with the Seringapatam, leaving Gamble with but eight men.

Two days later the natives came off to assault the ship. They were repulsed, but Midshipman William W. Feltus was killed, and three men wounded. The fight occurred on the Hammond. The following night the survivors went to sea. They eventually reached the Sandwich Islands, where they were captured by the Cherub, and were detained on her seven months. They finally reached New York in August, 1815.

A Marquesan “Chief Warrior.”

From an engraving by Strickland of a drawing by Captain Porter.

The voyage of the Essex ended in disasters all around, due solely to the misfortune of losing a top-mast in a squall off the Point of Angels at52 Valparaiso. But she had captured twelve British ships, aggregating 3,369 tons, armed with one hundred and seven guns and carrying three hundred and two men. She had maintained herself for more than a year entirely from supplies captured from the enemy—she did not cost the national treasury a cent after her first outfit. A great fleet of British ships were sent at large expense to search for her. On the whole her cruise damaged the enemy millions of dollars—Porter estimated the damage at $6,000,000—and her crew, from master to boy, had “afforded an example of courage in adversity that it would be difficult to match elsewhere.”

Porter was, indeed, defeated, but the victory of the enemy was like those obtained at Bunker Hill and on Lake Champlain during the war of the Revolution. It was a British victory but it strengthened the power of the young republic, and gave renown to the defeated leaders.

Captain Porter aided in the defence of Baltimore after his return home. After the war he served as a commissioner on naval affairs, and in 1826 resigned his commission. He was afterward American Minister to Turkey, and died at Constantinople in 1843. His body was brought to America and was eventually buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, Philadelphia.

54

A LITTLE LOP-SIDED FRIGATE REBUILT INTO A SUPERIOR SLOOP-OF-WAR—OVERLAND (ALMOST) TO ESCAPE THE BLOCKADE—HER LUCK AS A CRUISER—A MARVELLOUS RACE WITH A BRITISH FRIGATE OVER A COURSE FOUR HUNDRED MILES LONG—SAVED BY A SQUALL—CORNERED IN THE PENOBSCOT—THE GALLANT FIGHT OF THE YANKEE CREW AGAINST OVERWHELMING NUMBERS—BUILDING A NEW NAVY—THE SHORT-LIVED PORTSMOUTH CORVETTE FROLIC—ONE BROADSIDE WAS ENOUGH—CAPTURED BY THE ENEMY—SWIFT AND DEADLY WORK OF THE CREW OF THE YANKEE PEACOCK WHEN THEY MET THE EPERVIER—DISTINCTLY A LUCKY SHIP—FATE OF THE SIREN AFTER THE COFFIN FLOATED.