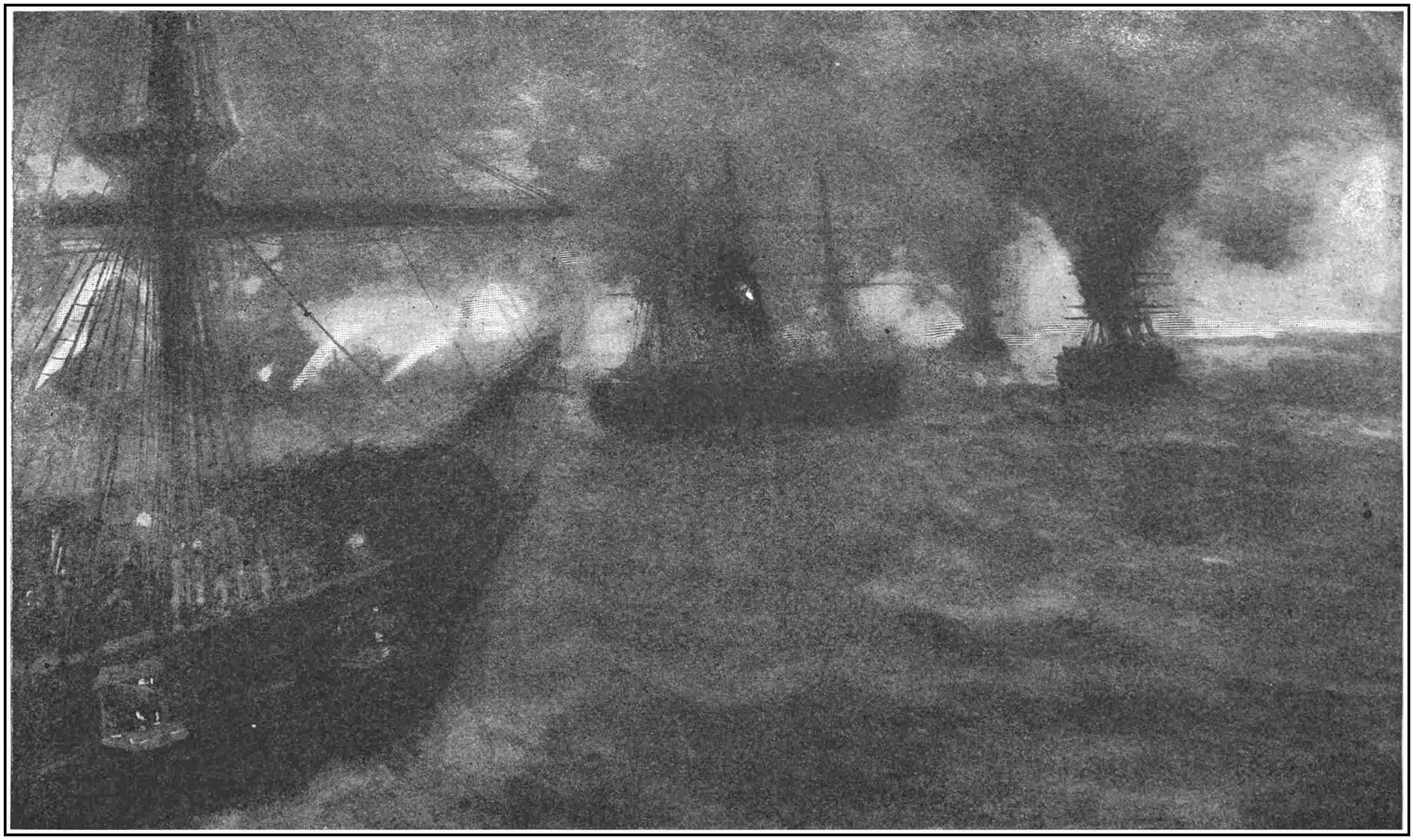

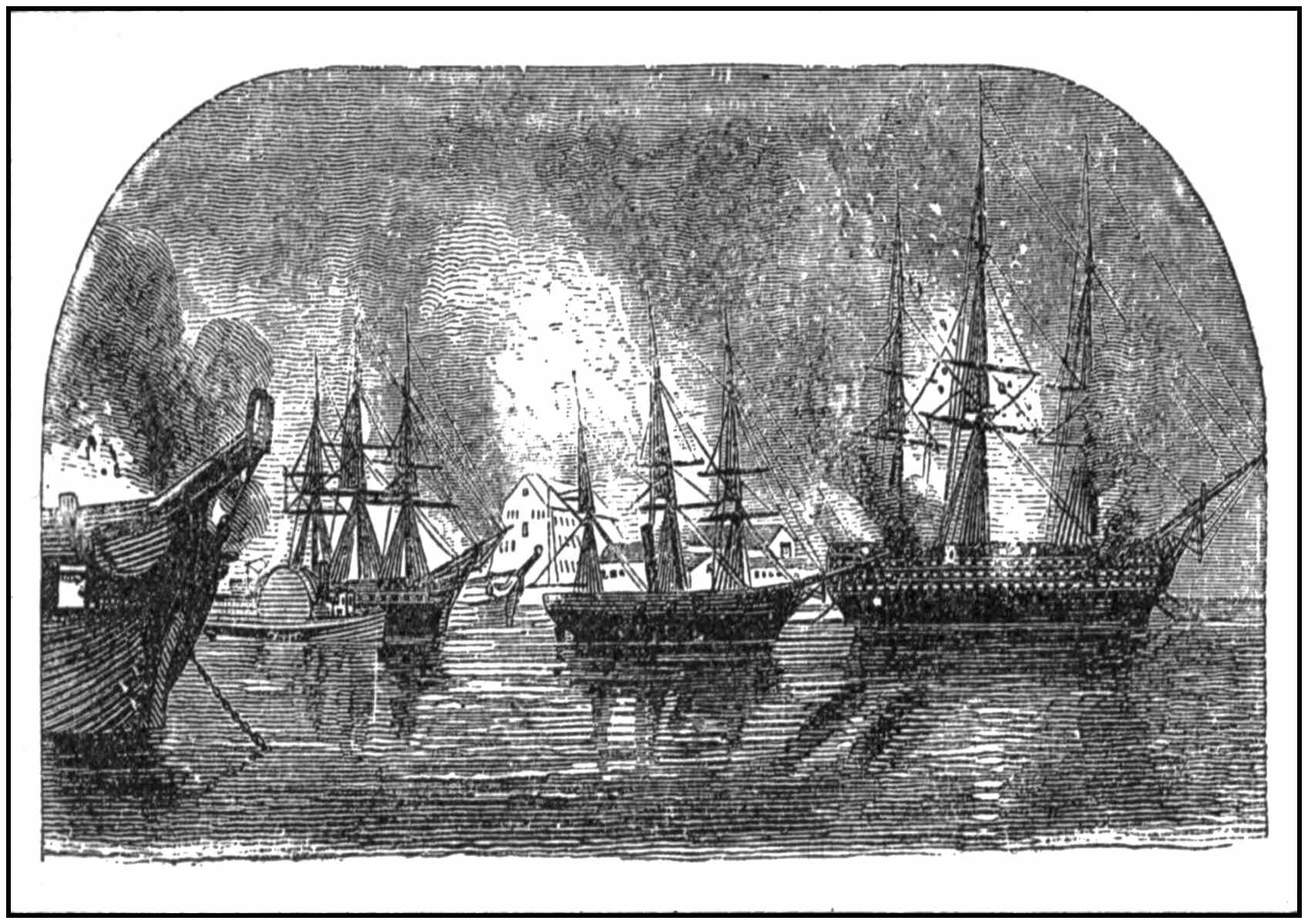

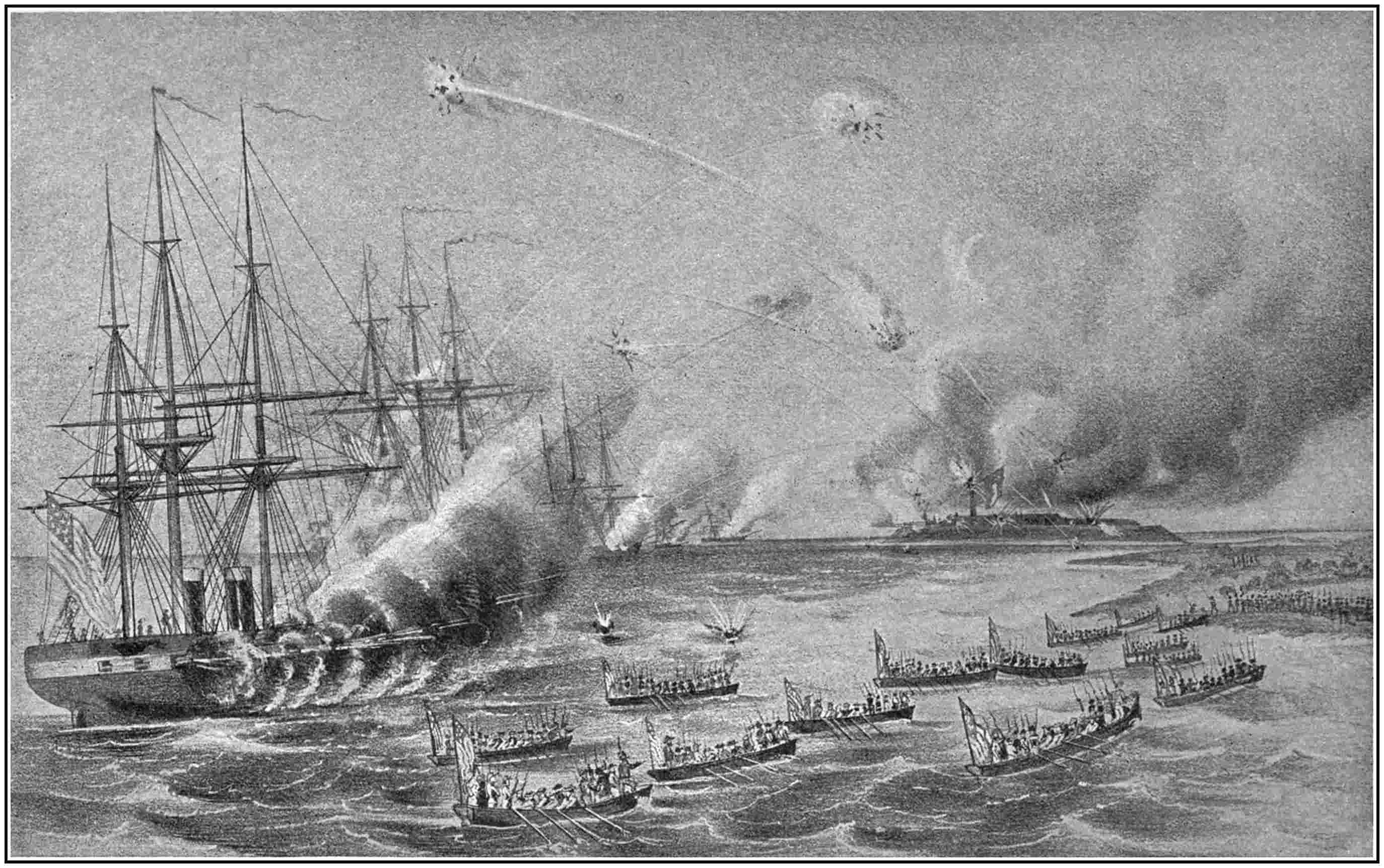

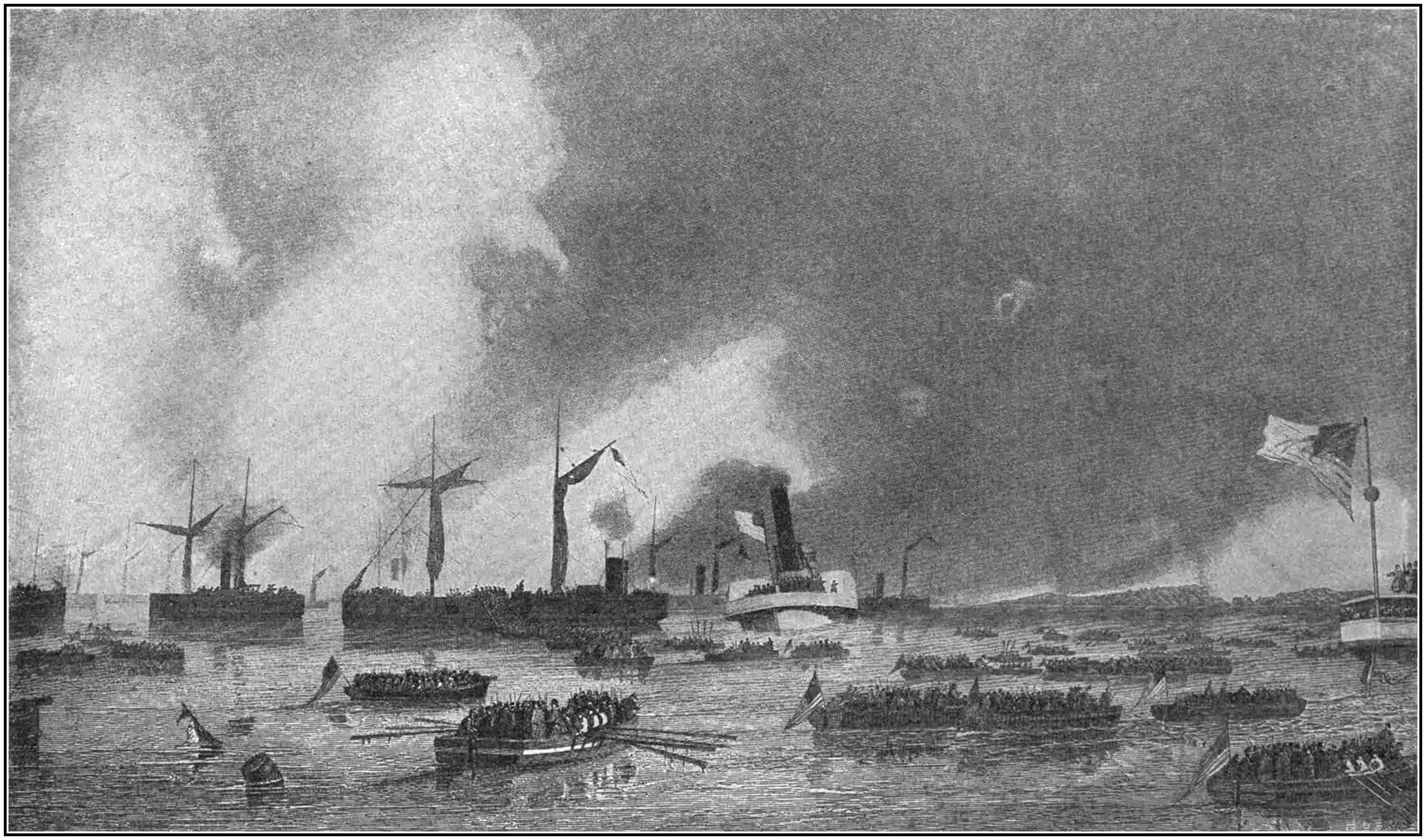

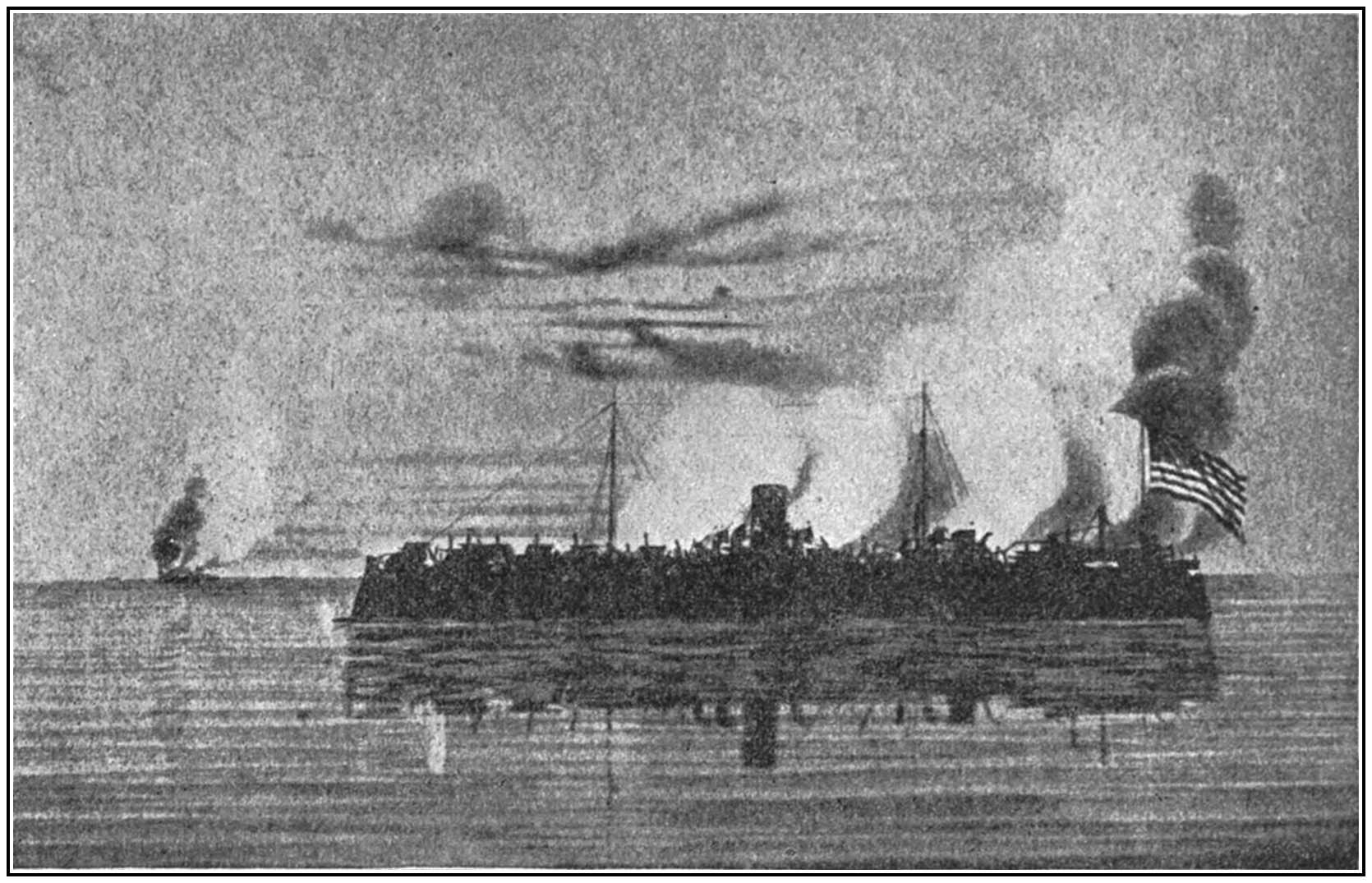

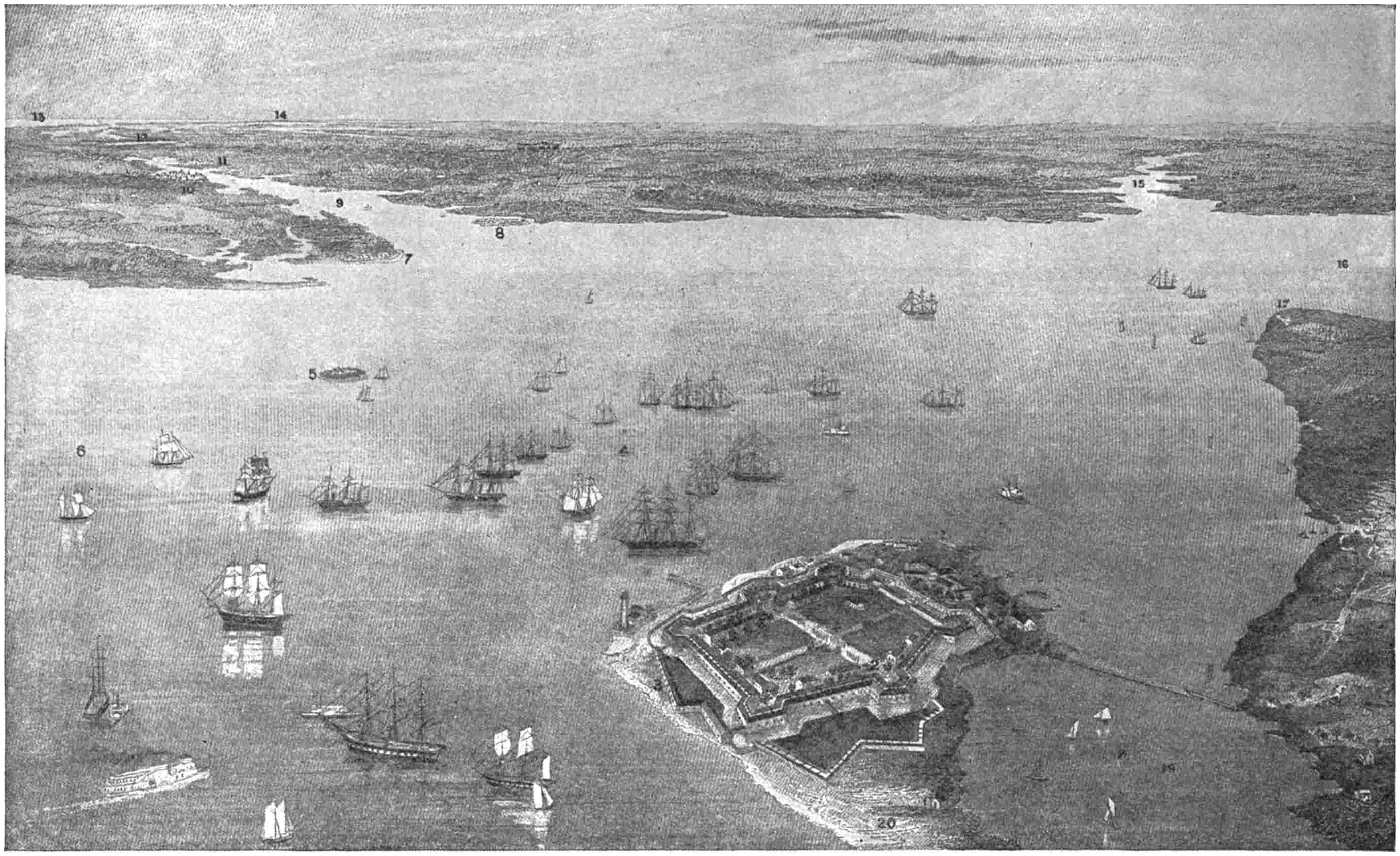

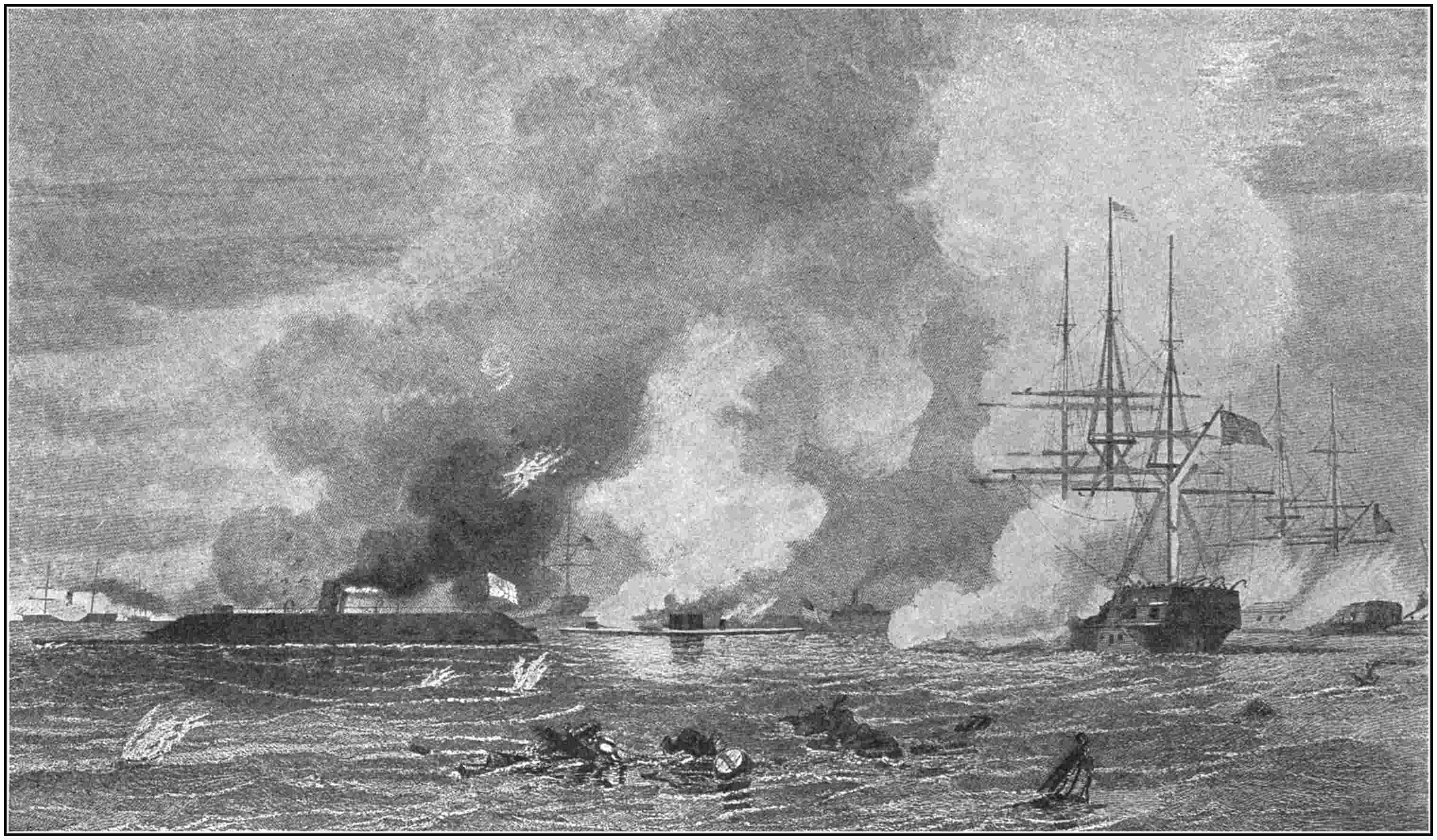

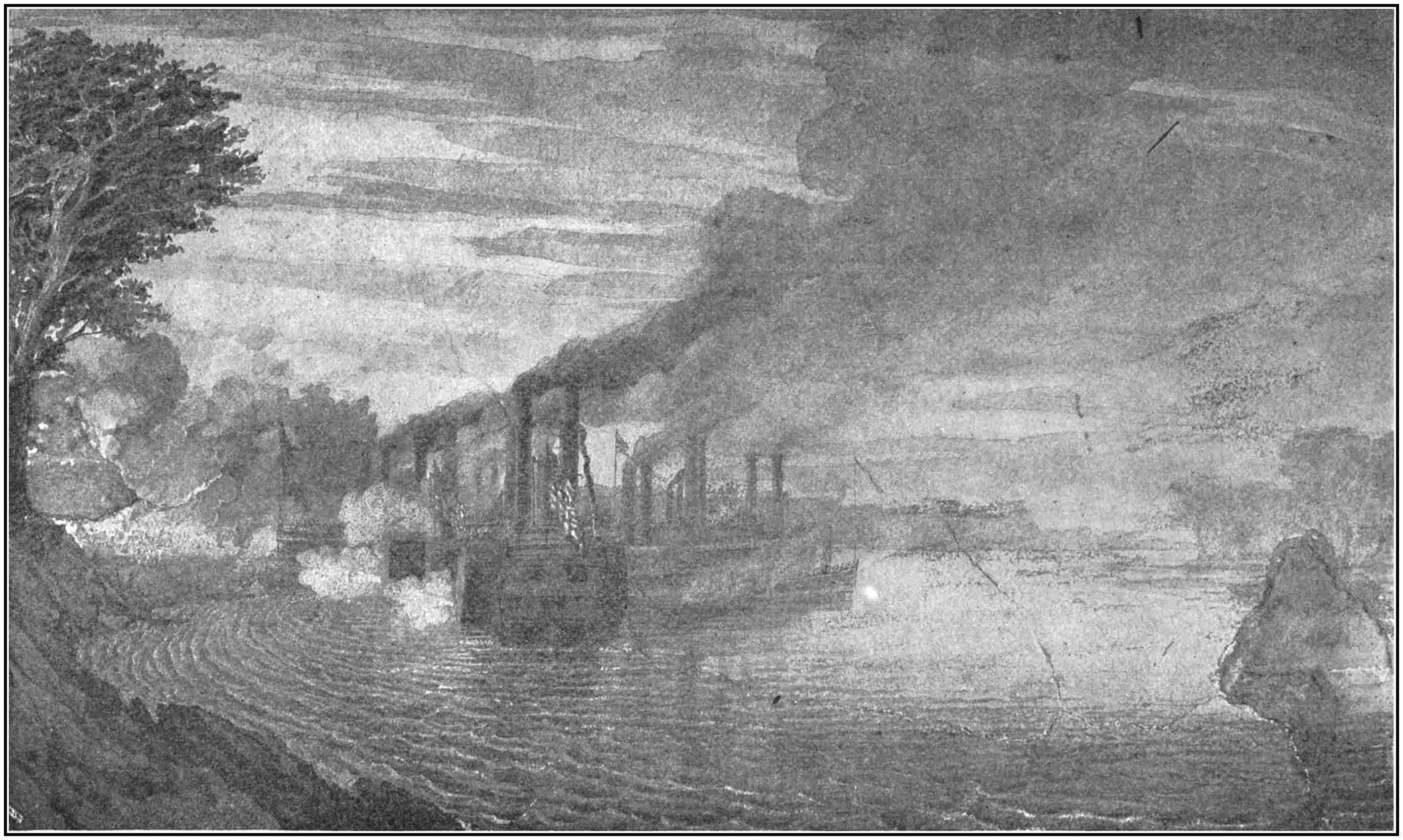

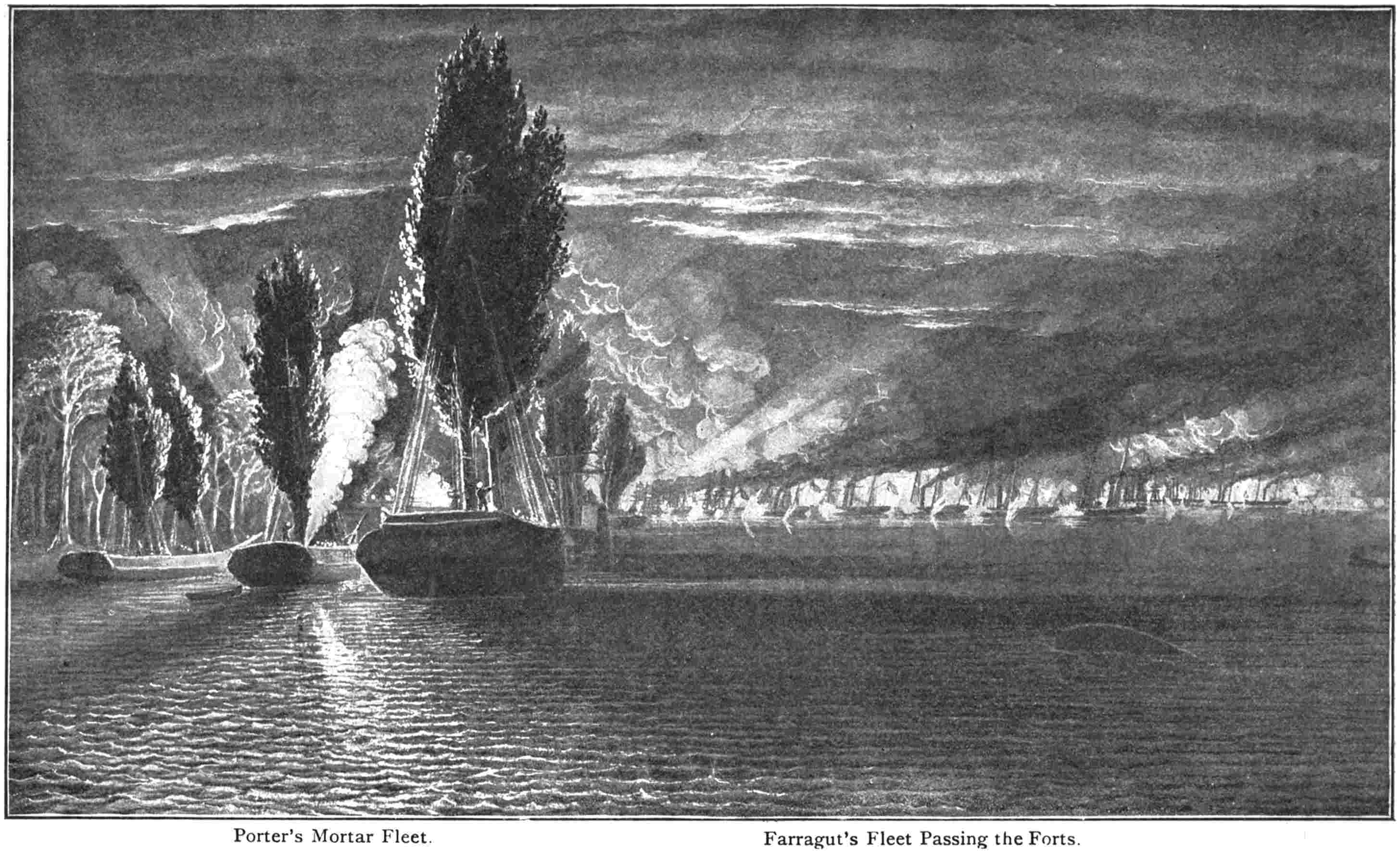

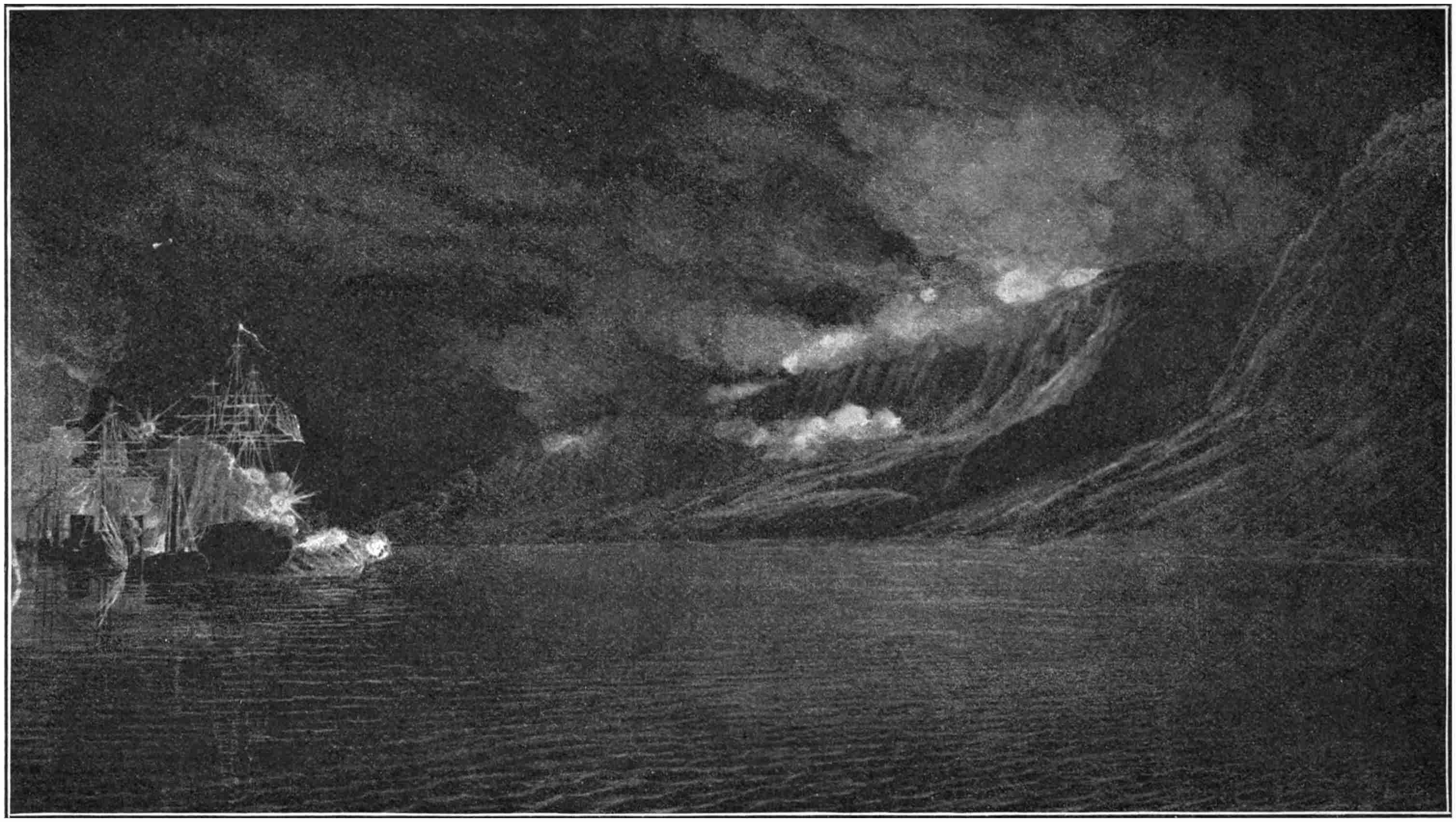

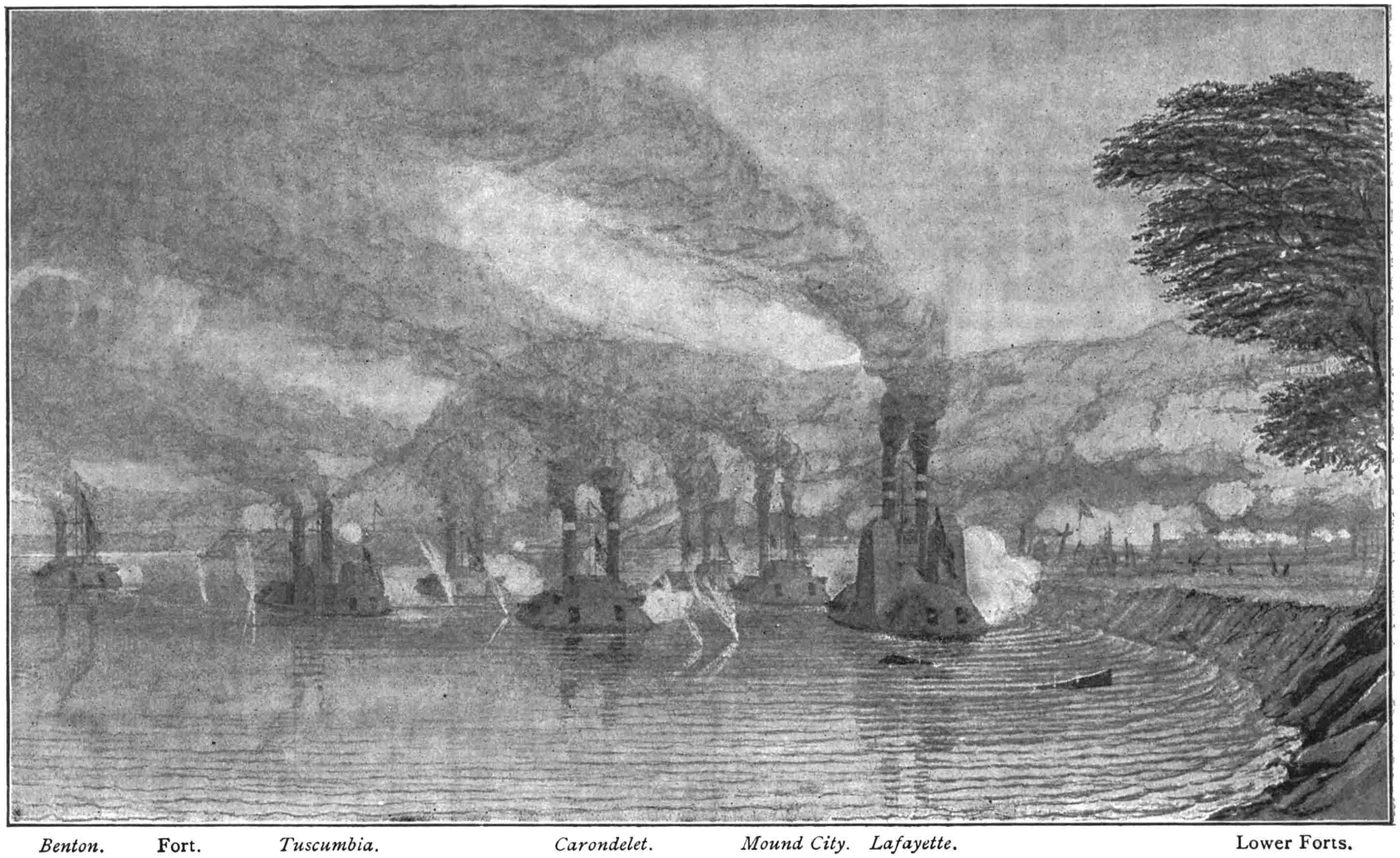

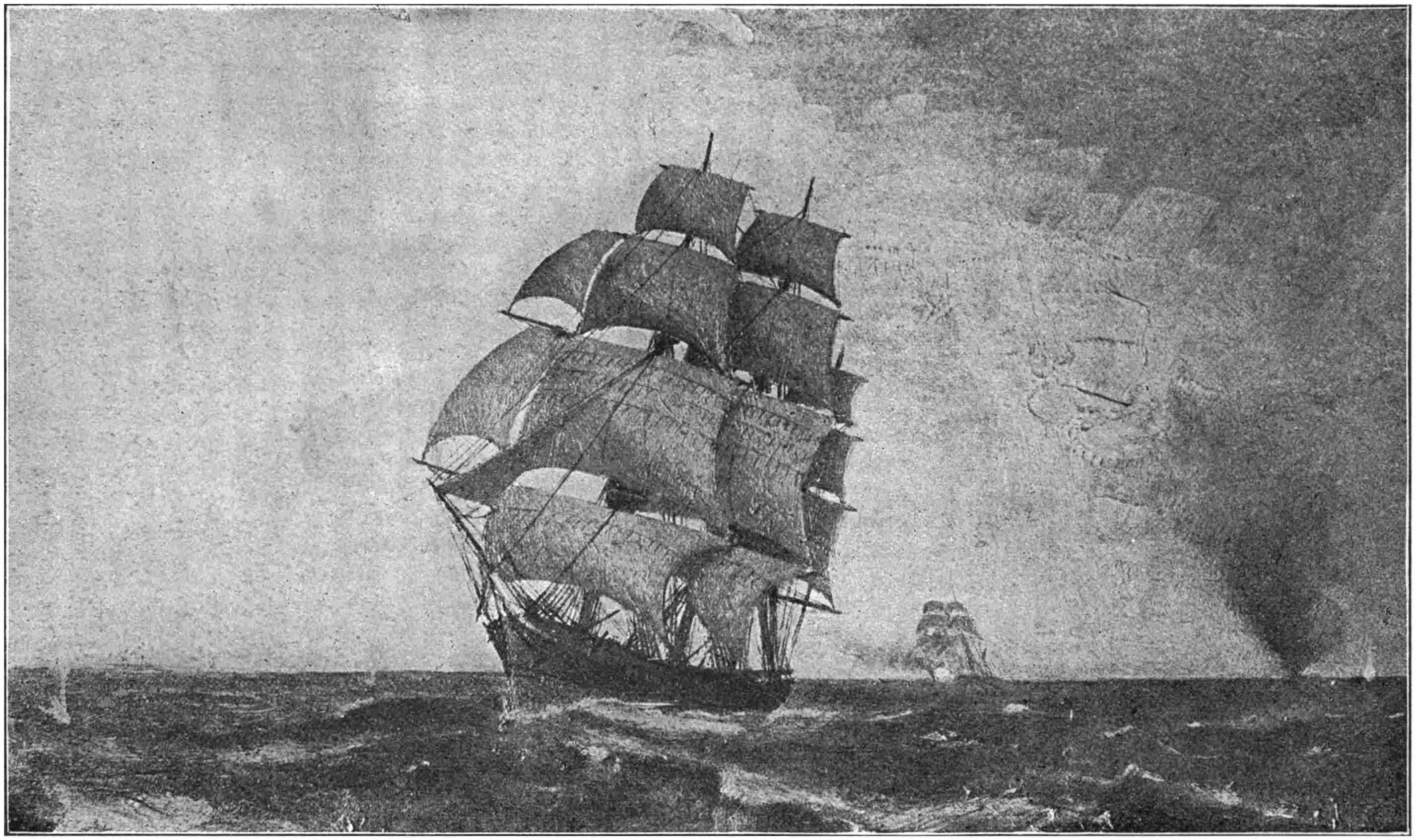

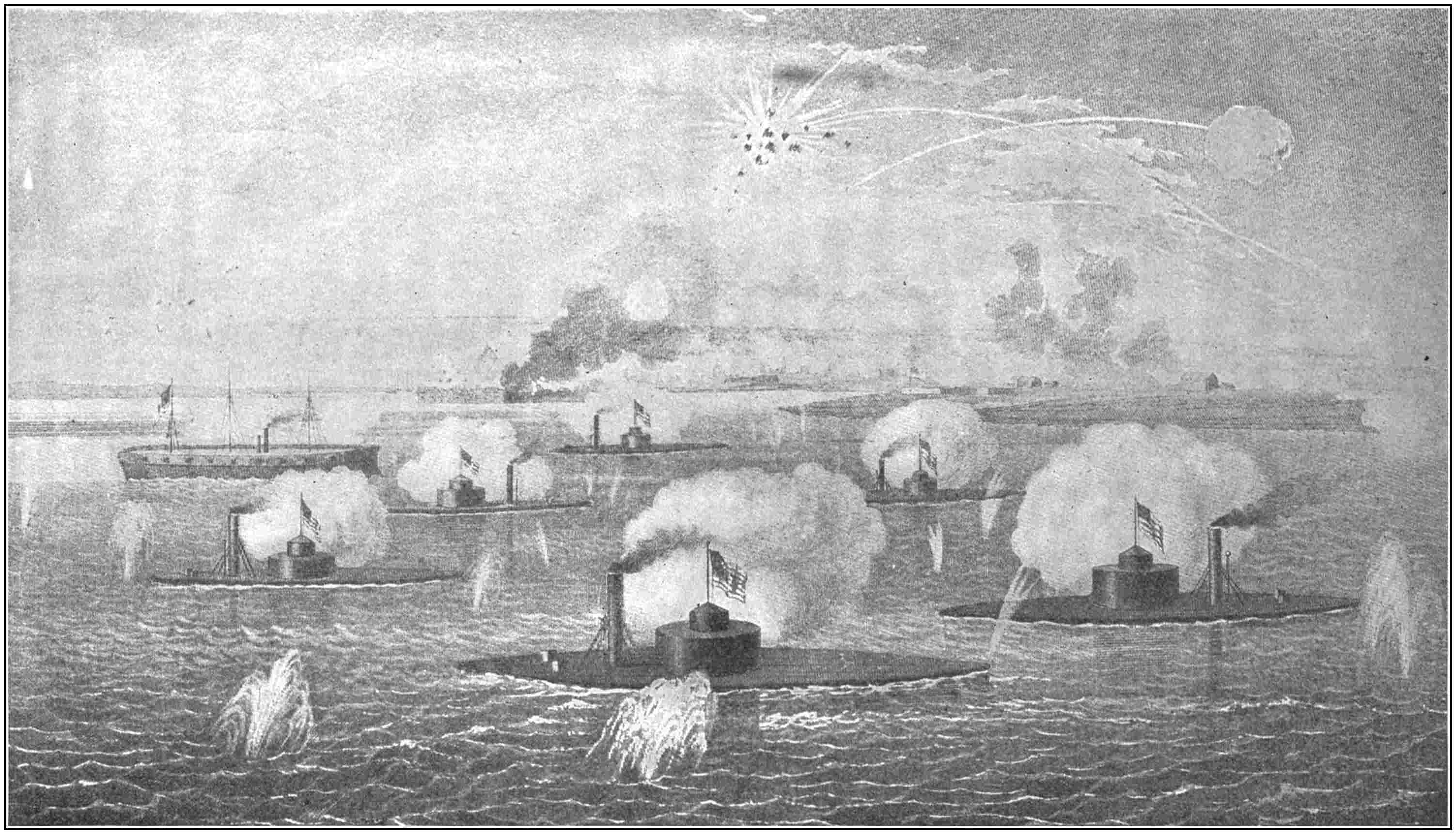

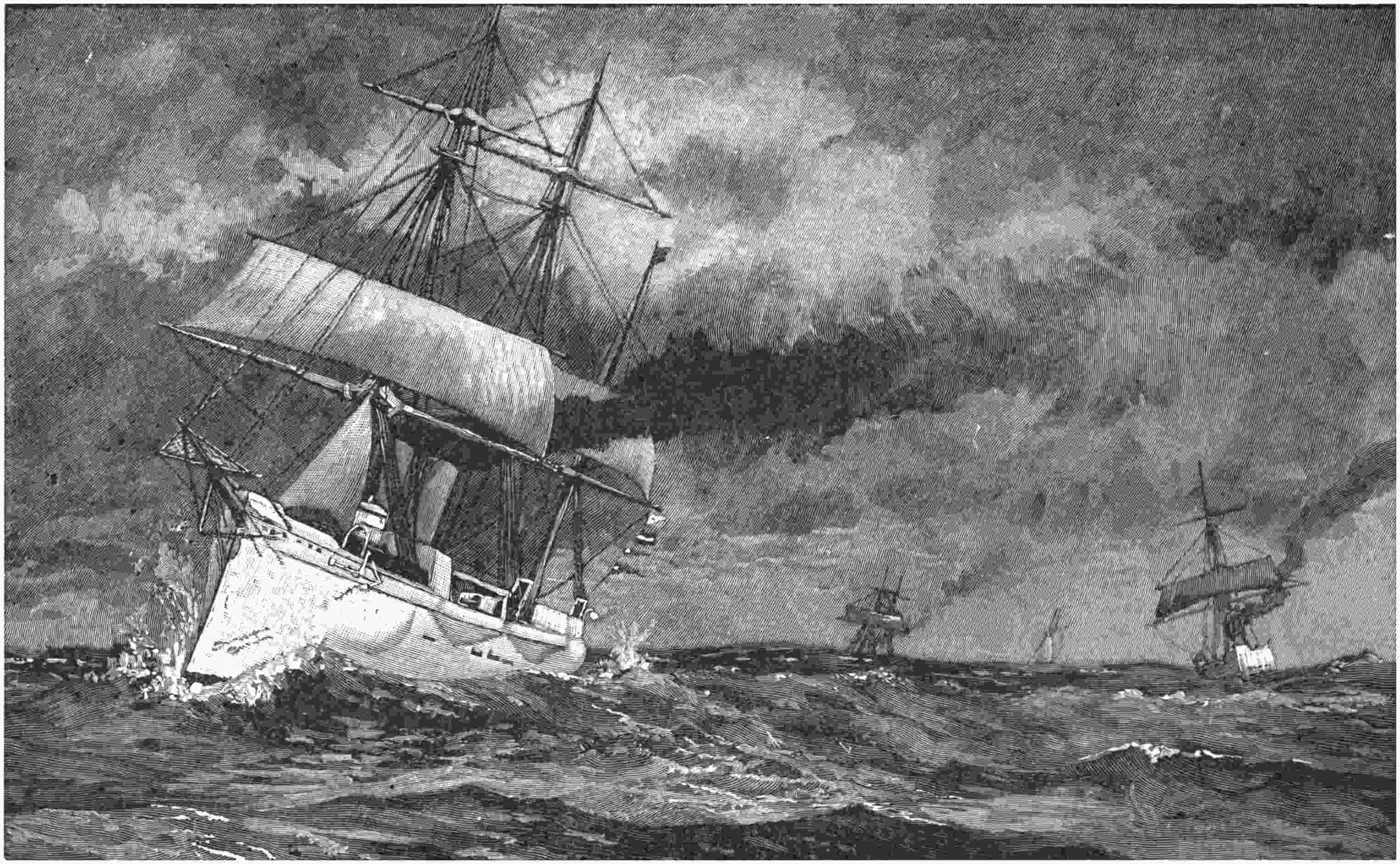

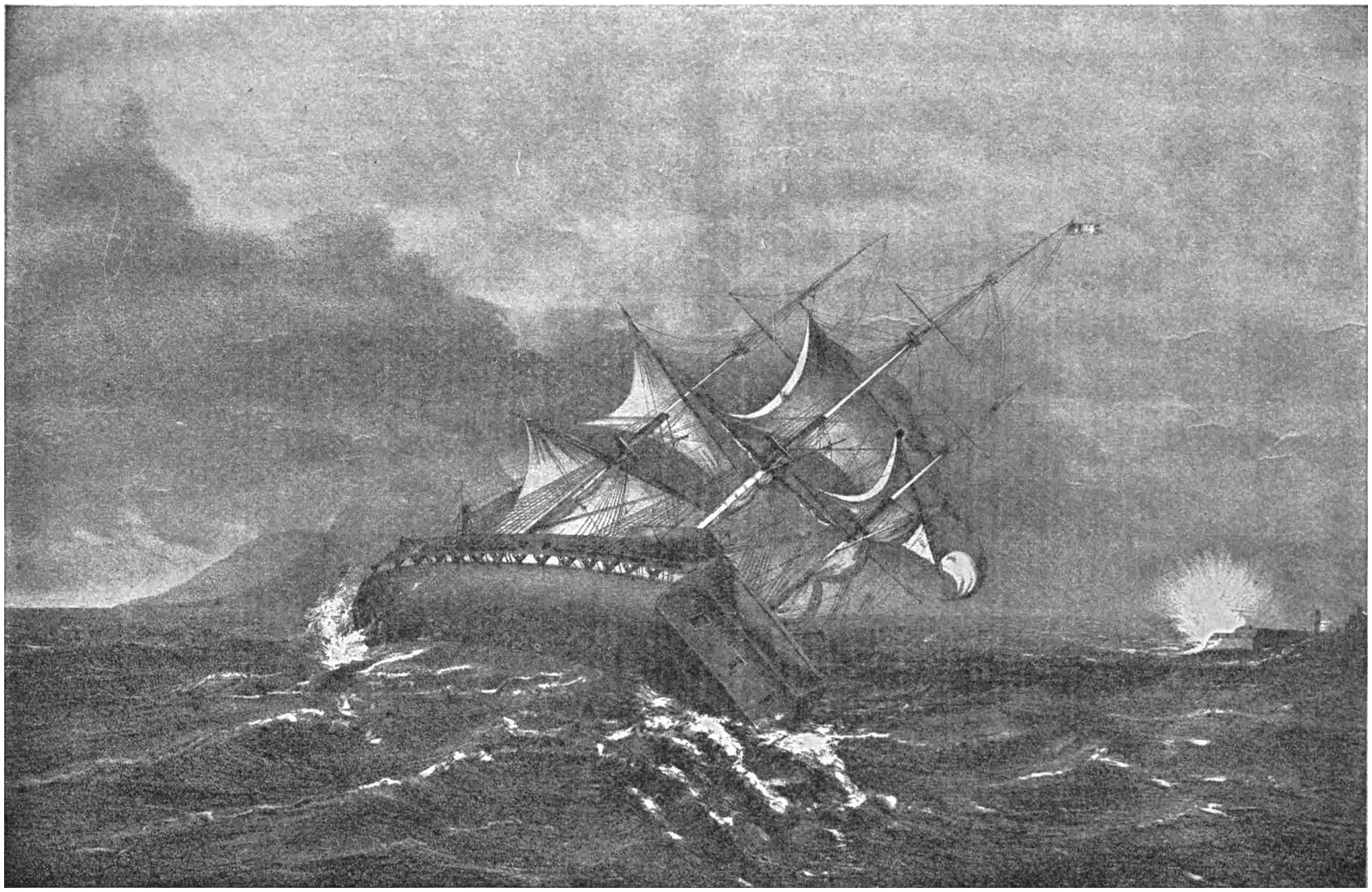

FARRAGUT’S FLEET PASSING FORTS JACKSON AND ST. PHILIP.

From a painting by Carlton T. Chapman.

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

FARRAGUT’S FLEET PASSING FORTS JACKSON AND ST. PHILIP.

From a painting by Carlton T. Chapman.

THE

HISTORY OF OUR NAVY

FROM ITS ORIGIN TO THE PRESENT DAY

1775–1897

BY

JOHN R. SPEARS

AUTHOR OF “THE PORT OF MISSING SHIPS,”

“THE GOLD DIGGINGS

OF CAPE HORN,” ETC.

WITH MORE THAN FOUR HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS AND DIAGRAMS

IN FOUR VOLUMES

VOLUME IV.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

MANHATTAN PRESS

474 W. BROADWAY

NEW YORK

ix

TO ALL WHO WOULD SEEK PEACE

AND PURSUE IT

| PAGE | |

| Chapter I. The State of the Navy in 1859 | 1 |

| A Brief Story of the Development of the Warship that was Propelled by both Sails and Steam—The Remarkable Floating Battery of 1814—Barron’s Idea of a Ram—The Stevens Floating Battery—Ericsson’s Screw Propeller—Stockton and the First Screw Warship—Experiments with Great Guns—Discoveries of Bomford and Rodman—Practical Work by Dahlgren—A Comparison of Yankee Frigates with a Class of British Ships “Avowedly Built to Cope” with them—The Condition of the Personnel. | |

| Chapter II. Blockading the Southern Ports | 28 |

| Lincoln’s Proclamation—It was Something of a Task to Close 185 Inlets and Patrol 11,953 Miles of Sea-beaches, especially with the Force of Ships in Hand—One Merchant’s Notion of the Efficiency of Thirty Sailing Vessels—Gathering and Building Blockaders—Incentives and Favoring Circumstances for Blockade-runners—When Perjury Failed and Uncle Sam was Able to Strike without Waiting for Act of Congress—When Blockade-runners Came to New York and Yankee Smokeless Coal was in Demand. | |

| Chapter III. Loss of the Norfolk Navy Yard | 66 |

| Effective Work Done by Southern Naval Officers who Continued to Wear the National Uniform that they might the more Readily Betray the National Government—The Secretary of the Navy was Deceived and the Commandant at Norfolk Demoralized—William Mahone’s Tricks Added to the Demoralization at the Yard, and it was Abandoned at Last in a Shameful Panic—Property that was Worth Millions of Dollars, and Guns that Took Thousands of Lives, Fell into the Confederates’ Hands—The First Naval Battle of the War—Three Little Wooden Vessels with Seven Small Guns Sent against a Well-built Fort Mounting Thirteen Guns—The Hazardous Work of Patrolling the Potomac.x | |

| Chapter IV. A Story of Confederate Privateers | 84 |

| They Did Plenty of Damage for a Time, but their Career was Brief—Capture of the First of the Class, and Trial of her Crew on a Charge of Piracy—Reasons why they could not be Held as Criminals—Luck of the Jefferson Davis—A Negro who Recaptured a Confederate Prize to Escape the Terrors of Slavery—A Skipper who Thought a Government Frigate was a Merchantman—The “Nest” behind Cape Hatteras. | |

| Chapter V. The Fort of Hatteras Inlet Taken | 99 |

| An Expedition Planned by the Navy Department that Resulted in the First Federal Victory of the Civil War—An Awkward Landing Followed by Ineffectual Fire from Ships under Way—One Fort Taken and Abandoned—Anchored beyond Range of the Fort and Compelled Surrender by Means of the Big Pivot Guns—A Wearisome Race from Chicamicomico to Hatteras Lighthouse Won by the Federals—Capture of Roanoke Island—Origin of the American Medal of Honor. | |

| Chapter VI. Along Shore in the Gulf of Mexico | 112 |

| The Shameful Story of Pensacola and Fort Pickens—When Lieutenant Russell Burned the Judah—A British Consul’s Actions when Confederate Forts were Attacked at Galveston—Extraordinary Panic at the Head of the Passes in the Mississippi when Four Great Warships, Carrying Forty-five of the Best Guns Afloat, Fled from a Disabled Tugboat that was Really Unarmed—Once more in Galveston—Lieutenant Jouett’s Fierce Fight when he Destroyed the Royal Yacht. | |

| Chapter VII. Story of the Trent Affair | 140 |

| Capt. Charles Wilkes, of the American Navy, Took Four Confederate Diplomatic Agents from a British Ship Bound on a Regular Voyage between Neutral Parts, and without any Judicial Proceeding Cast them into a Military Prison—A Case that Created Great Excitement Throughout the Civilized World—A Swift Demand, with a Threat of War Added, Made by the British—Comparing this Case with another of Like Nature—The United States once Went to Warxi to Establish the Principle which Captain Wilkes Ignored—The British Officially Acknowledge that the Americans were Justified in Declaring War in 1812. | |

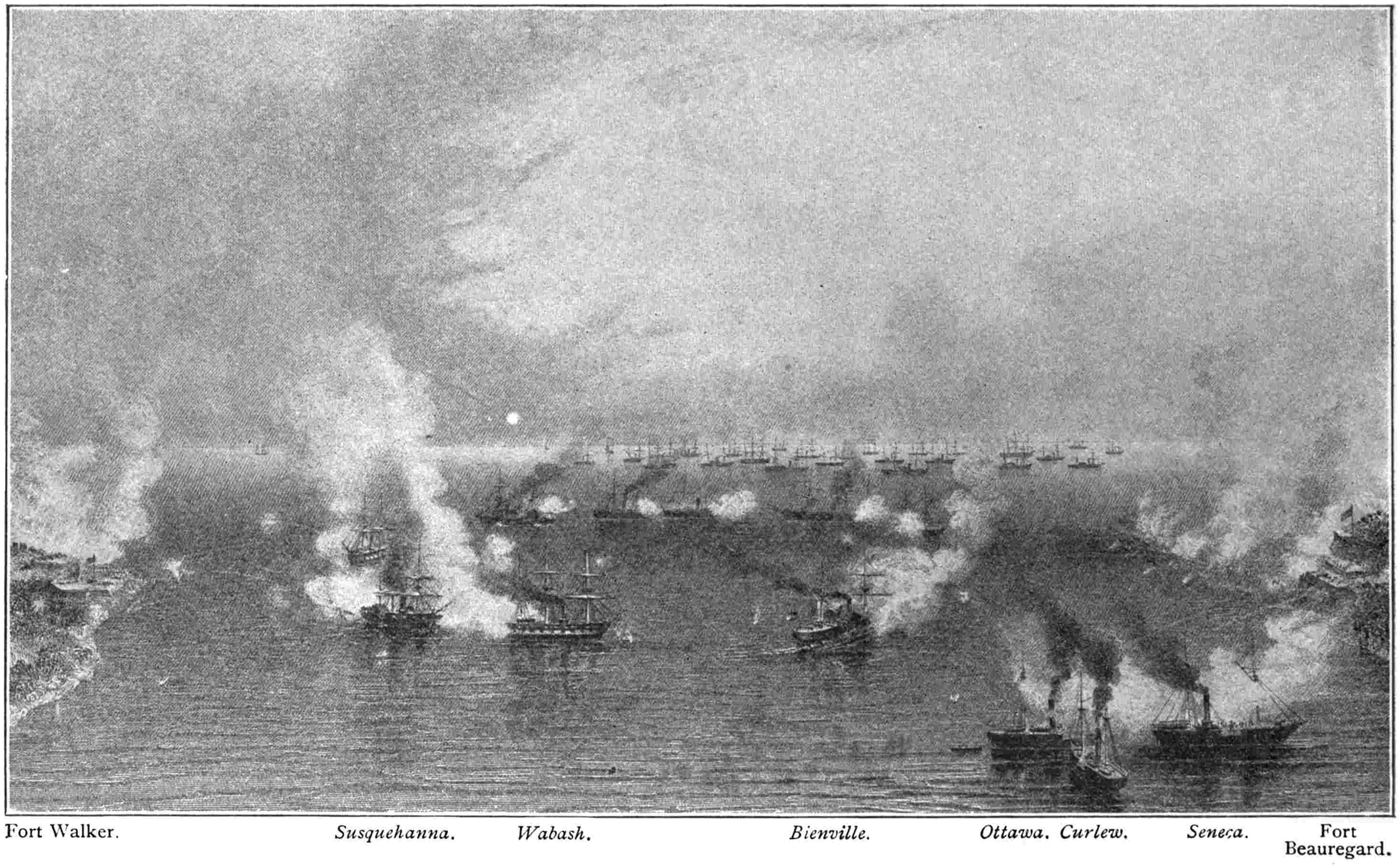

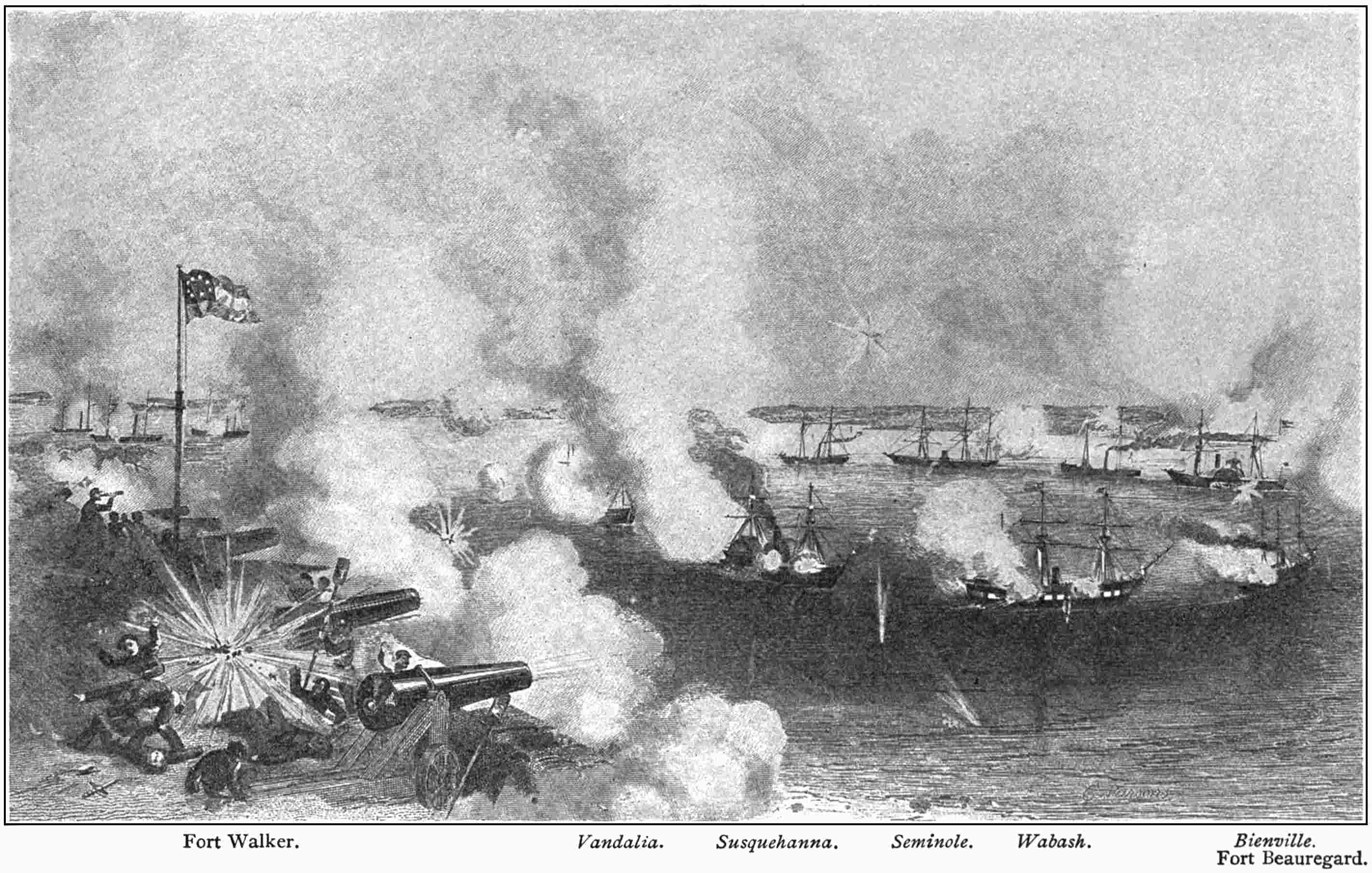

| Chapter VIII. The Capture of Port Royal | 161 |

| A Fleet of Seventeen Ships, Carrying 155 Guns, Sent to Take a Harbor that would Make a Convenient Naval Station for the Atlantic Blockaders—There were Two “Exceedingly Well-built Earthworks” “Rather Heavily Armed” Defending the Channel, but one Part of the Squadron Attacked them in Front, another Enfiladed them, and in Less than Five Hours the Confederates Fled for Life—A Heavy Gale Weathered with Small Loss—Interesting Incidents of the Battle. | |

| Chapter IX. The Monitor and the Merrimac | 184 |

| Superior Activity of the Confederates in Preparing for Ironclad Warfare Afloat—Story of the Building and Arming of the Merrimac—She was a Formidable Ship in Spite of Defects in Detail, but her Design was not the Best Conceivable—Origin and Description of the Ship that Revolutionized the Navies of the World—A Wondrous Trial Trip—For One Day the Merrimac was Irresistibly Triumphant—Two Fine Ships of the Old Style Destroyed while she Herself Suffered but Little—The Magnificent Fight of the Cumberland—A Difference in Opinions. | |

| Chapter X. First Battle between Ironclads | 214 |

| A Comparison between the Monitor and the Merrimac by the English Standard of 1812—It Astonished the Spectators to See the Tiny Monitor’s Temerity—After Half a Day’s Firing it was Plain that the Guns could not Penetrate the Armor—Attempts to Ram that Failed—The Merrimac A-leak—Captain Worden of the Monitor Disabled when the Merrimac’s Fire was Concentrated on the Pilot-house—Where the Monitor’s Gunners Failed—Fair Statement of the Result of the Battle—Worden’s Faithful Crew—The Merrimac Defied the Monitor in May, but when Norfolk was Evacuated she had to be Abandoned and was Burned at Craney Island—Loss of the Monitor. | |

| Chapter XI. With the Mississippi Gunboats | 239 |

| Creating a Fleet for the Opening of the Water Route across the Confederacy—Ironclads that were not Shot-proof, but Fairly Efficient nevertheless—Guns that Burst and Boilers that were Searched byxii Shot from the Enemy—When Grant Retreated and was Covered by a Gunboat—First View of Torpedoes—Capture of Fort Henry—A Disastrous Attack on Fort Donelson—When Walke Braved the Batteries at Island No. 10—The Confederate Defence Squadron at Fort Pillow—The First Battle of Steam Rams—Frightful Effects of Bursted Boilers—In the White River—Farragut Appears. | |

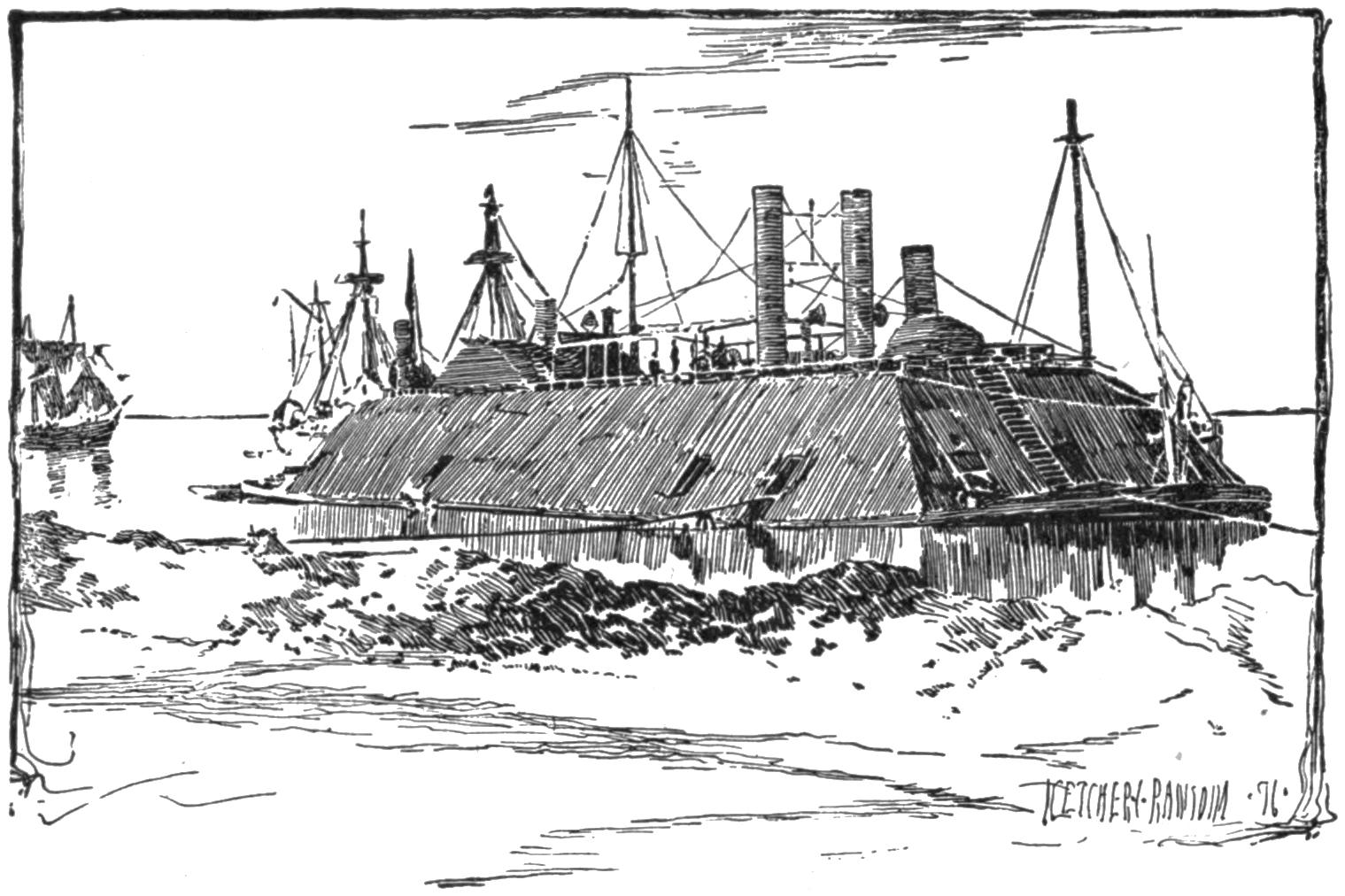

| Chapter XII. Farragut at New Orleans | 311 |

| It was Hard Work Getting the Squadron into the Mississippi—Preparing the Ships to Run by the Forts Guarding the River—Mortar Schooners Hidden by Tree Branches—The Forts were Well Planned, but Poorly Armed—A Barrier Chain that was no Barrier at the Last—The Heterogeneous Confederate Squadron—The Fire-rafts—Work of the Coast Survey—Bravery of Caldwell—Foreigners who Interfered—Work of the Mortar Fleet—When the Squadron Drove past the Forts—Scattering the Confederate Squadron—Nevertheless, at least Three Good Captains were Found among them—Sinking the Varuna—Fate of the Ram Manassas—Surrender of the Forts—End of the Ironclad Louisiana—The Work of the Mississippi Squadron. | |

| Chapter XIII. Farragut at Mobile | 377 |

| The Forts and the Confederate Squadron the Union Forces were Compelled to Face—The Confederate Ironclad just Missed being a most Formidable Ship—Tedious Wait for Monitors—When the Southwest Wind Favored—There was a Fierce Blast from the Forts at First, but the Torpedo was Worse than Many Guns—Fate of the Tecumseh and Captain Craven—The Last Words of the Man for whom “there was no Afterward”—Torpedoes that Failed beneath the Flagship—Captain Stevens on the Deck of his Monitor—When Neilds Unfurled the Old Flag in the midst of the Storm—How Farragut was Lashed to the Mast—Jouett would not be Intimidated by a Leadsman—Mobbing the Tennessee. | |

| Chapter XIV. Tales of the Confederate Cruisers | 407 |

| The most Instructive Chapter in the History of the United States—Work Accomplished by an Energetic Seaman in a Ship his Brother Officers Condemned—Brilliant Work of the Florida under John Newland Maffitt—Bad Marksmanship and a Worse Lookout off Mobile—A Case of Violated Neutrality—Semmes and the Alabama—Thexiii Battle with the Kearsarge—What Kind of a Man is it that Fights his Ship till she Sinks under him?—American Commerce Destroyed—The British without a Rival on the Sea, at Last, and at Very Small Cost. | |

| Chapter XV. The Albemarle and Cushing | 452 |

| A Formidable Warship was Built under Remarkable Conditions to Enable the Confederates to Regain Control of the Inland Waters of North Carolina—Very Successful at First, but she was Laid up to Await the Building of another One, and then came Cushing with his Little Torpedo Boat, and the Confederate Hopes were Destroyed with their Ship. | |

| Chapter XVI. The Navy at Charleston | 465 |

| It was a Well-guarded Harbor, and the Channel was Long and Crooked—The “Stone Fleet” and the Attitude of Foreign Powers—Brief Career of Two Confederate Ironclads—The Blockade was not Raised—A Confederate Cruiser Burned—Utter Failure of the Ironclad Attacks on the Forts—Capture of the Confederate Warship Atlanta—“Boarders Away” at Fort Sumter—Magnificent Bravery of the Men who Manned the Confederate Torpedo Boats. | |

| Chapter XVII. Capture of Fort Fisher | 503 |

| It was One of the Best Works in the South, though not well Located—Butler’s Powder-boat Scheme, and what he Expected to Accomplish by it—Throwing 15,000 Shells at the Fort Disabled Eight Great Guns out of a Total of Thirty-eight—Butler Thought the Fort still too Strong and would not Try—He did not even Make Intrenchments According to Orders—Gen. A. H. Terry, with 6,000 Soldiers and 2,000 from the Ships, Easily Took the Fort Three Weeks Later—The Navy’s Last Fight in the Civil War. | |

| Chapter XVIII. Story of the New Navy | 523 |

| The Folly of Allowing other Nations to Experiment for us—In Spite of what we Learned from their Mistakes, we were Unable, when we First Began for ourselves, to Build even a First-class Cruiser—The Result of Ten Years of Earnest Work—Battle-ships whose Power is Conceded by Foreign Writers—Cruisers that Awakened the Pride of the Nation—Three “Newfangled Notions”—A Yankee Admiral at Rio Janeiro and a Yankee Lieutenant on the Coast of Mexico—The One Important Fact about the New Navy. | |

xiv

xv

| PAGE | |

| Farragut’s Fleet Passing Forts Jackson and St. Philip. (From a painting by Carlton T. Chapman), Frontispiece | |

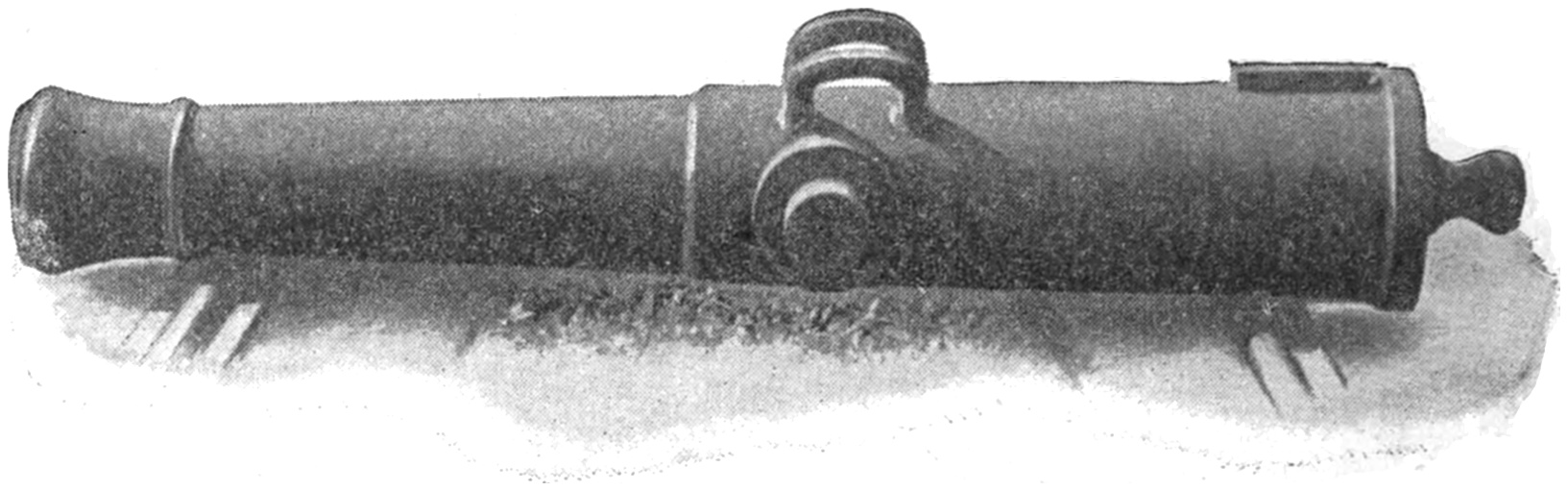

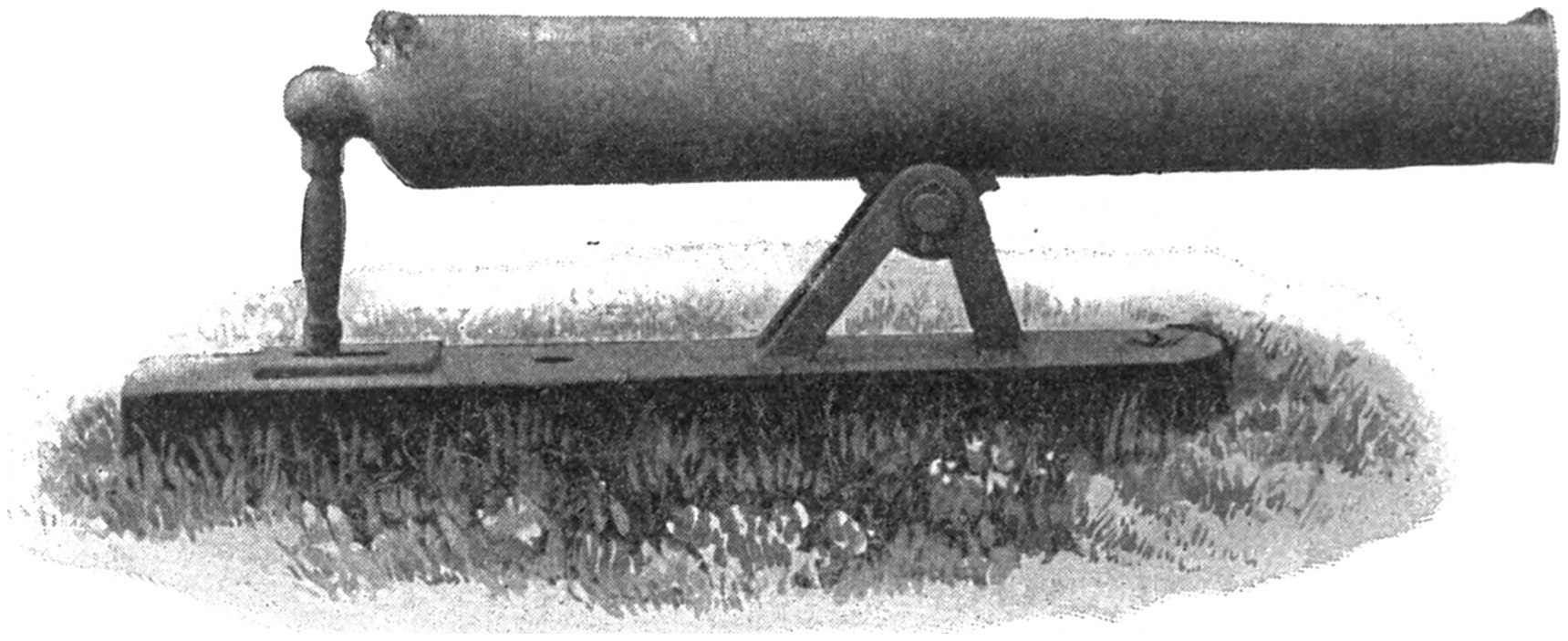

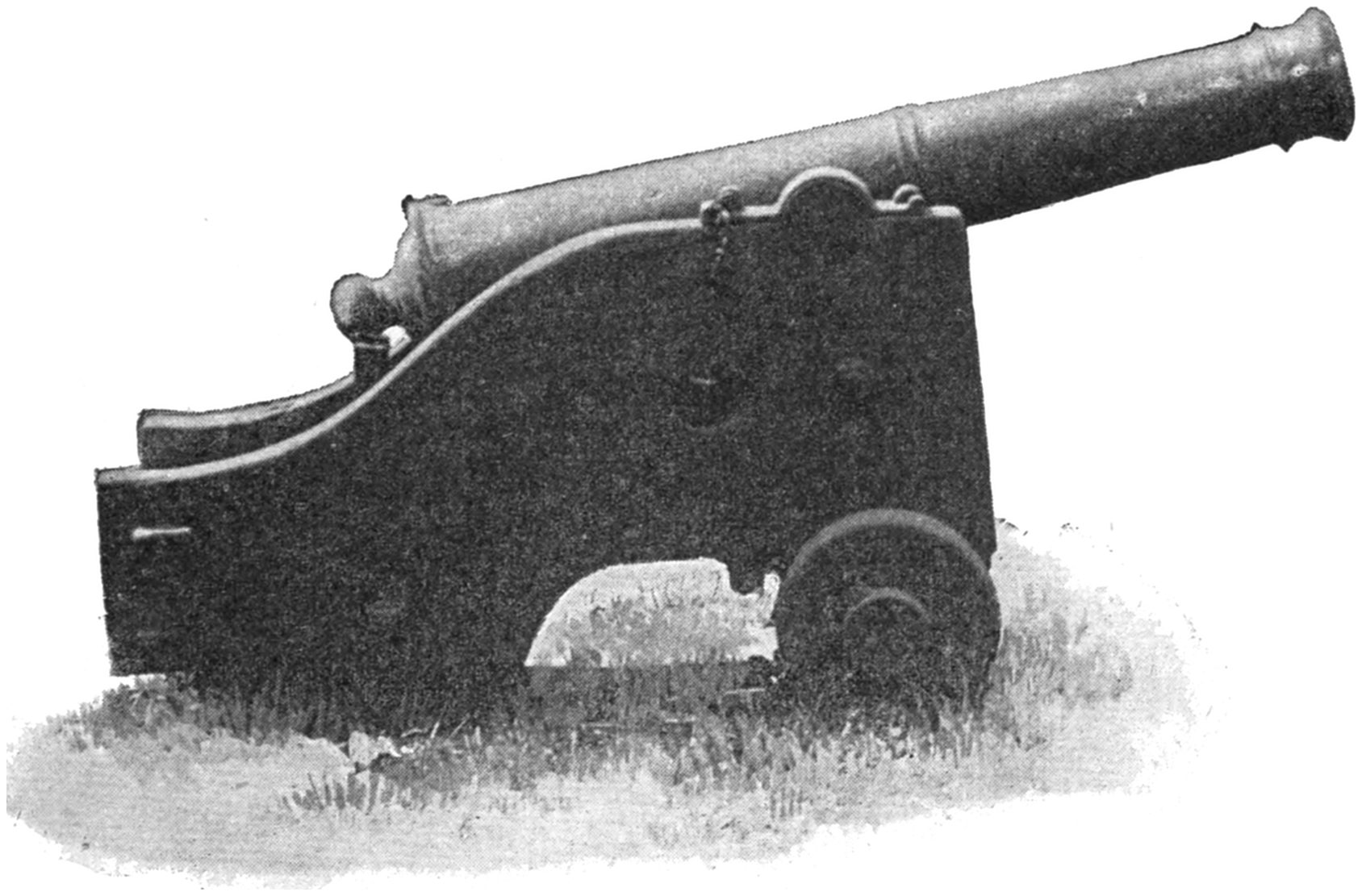

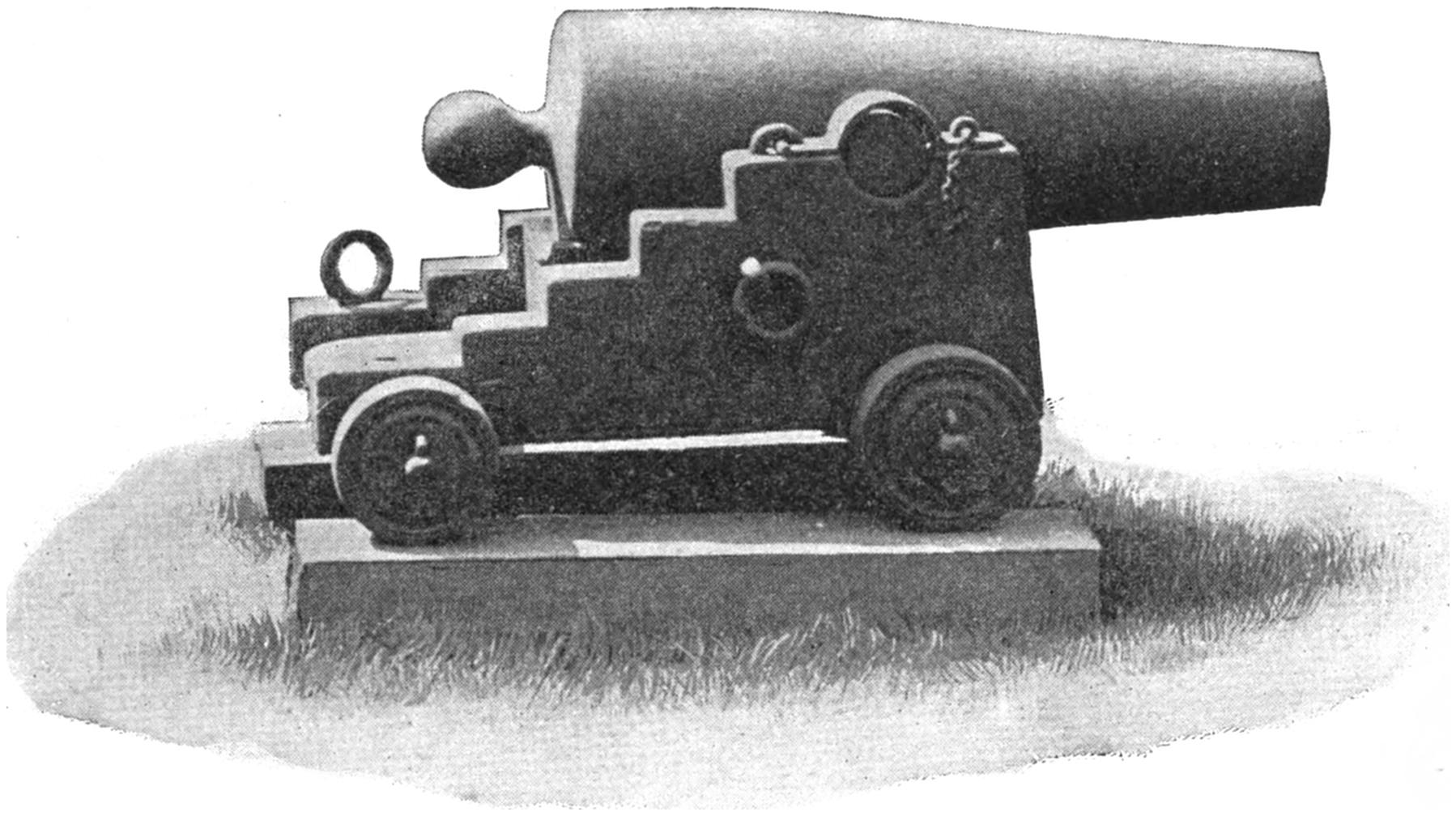

| A Thirty-two-pound Carronade from the Constitution. | 1 |

| The Minnesota as a Receiving Ship. (From a photograph by Rau), | 3 |

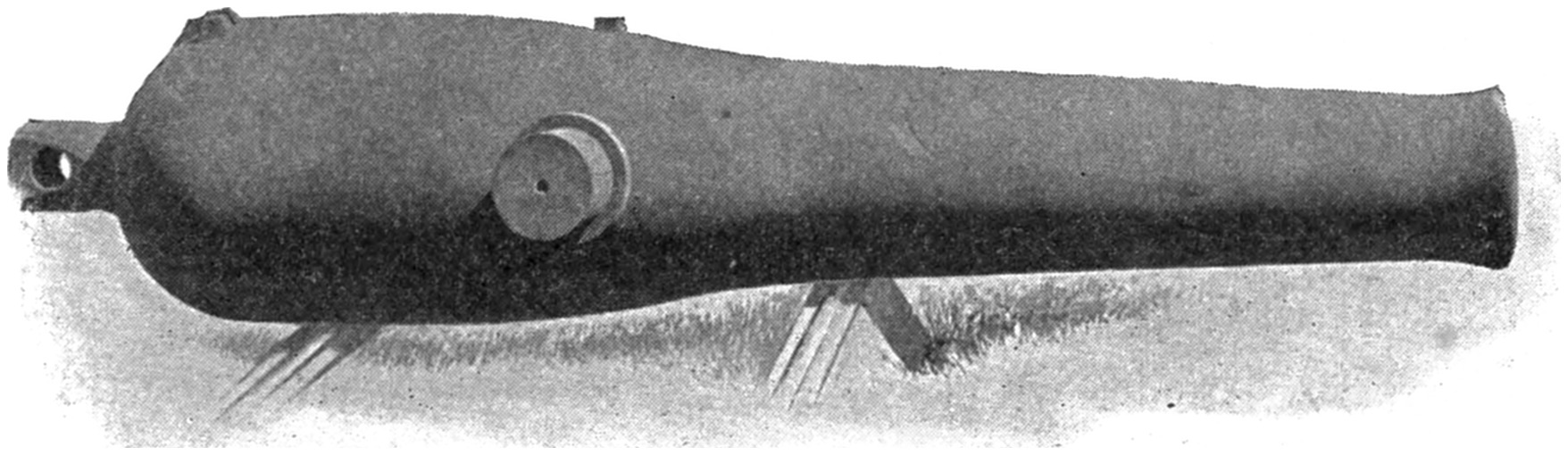

| A Loop-pattern Gun of 1836—a Type which Runs back over 100 Years, | 4 |

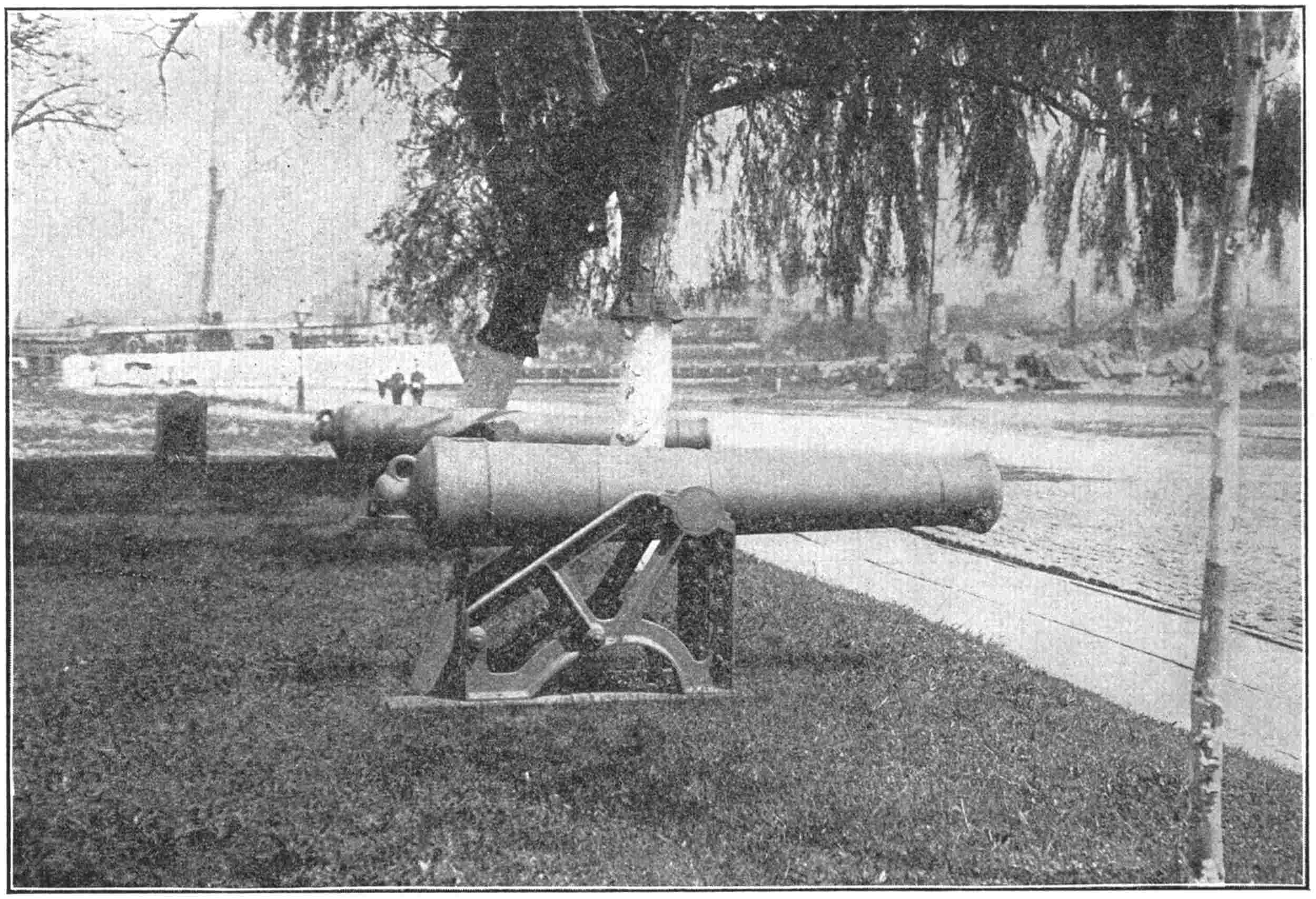

| A Thirty-two-pounder from the Captured Macedonian—now at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. (From a photograph), | 5 |

| A Thirty-two-pounder from the Captured Macedonian. | 7 |

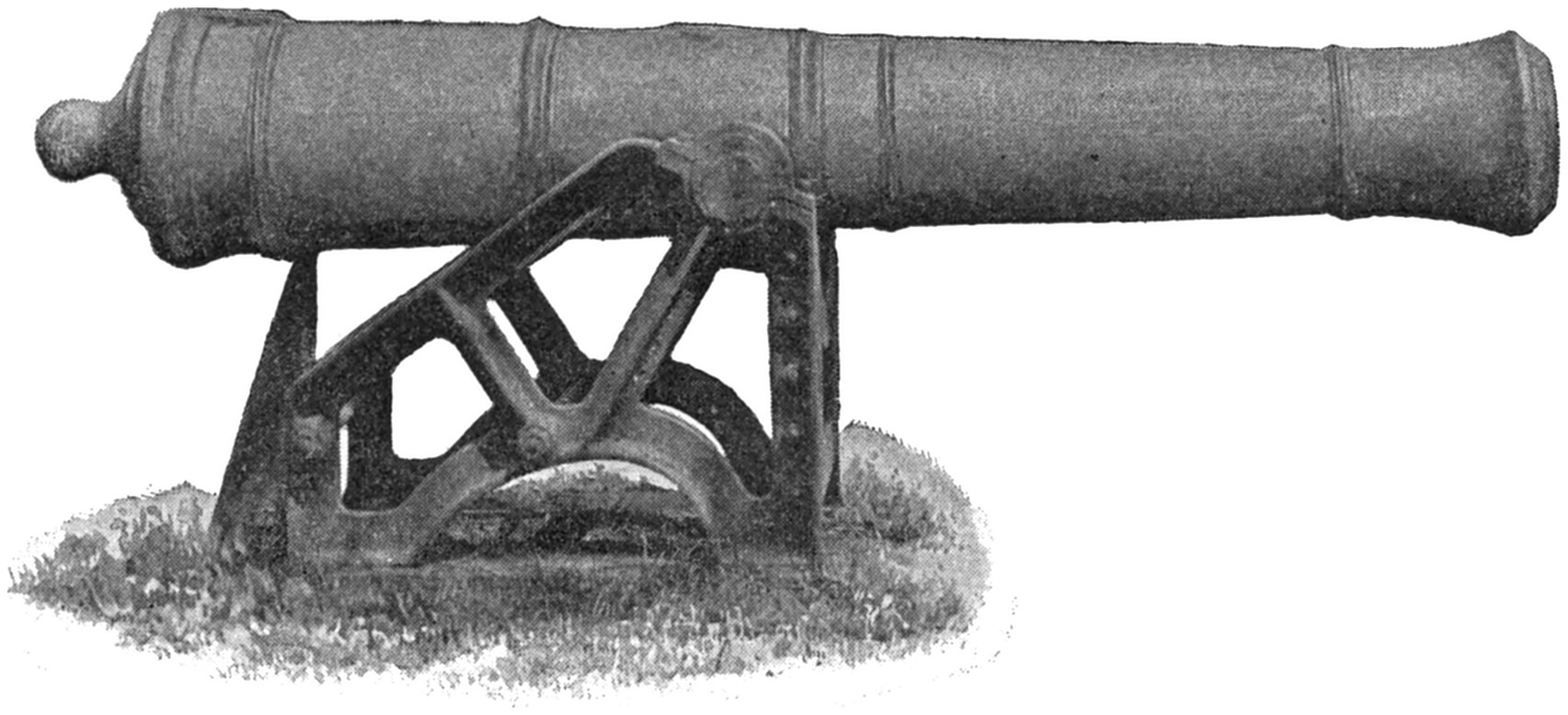

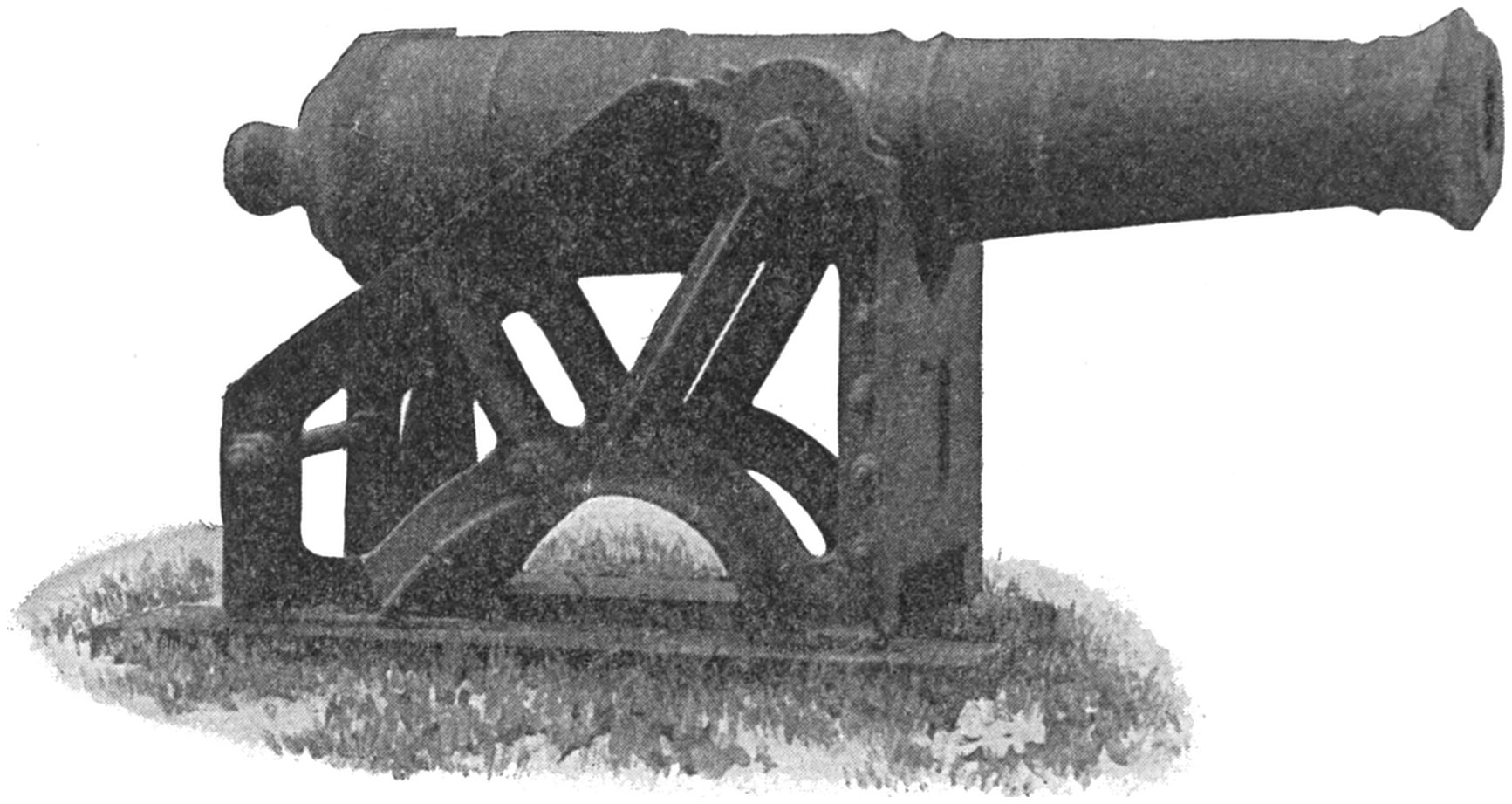

| Old Cast-iron Thirty-two-pounder (Believed to be Spanish), | 8 |

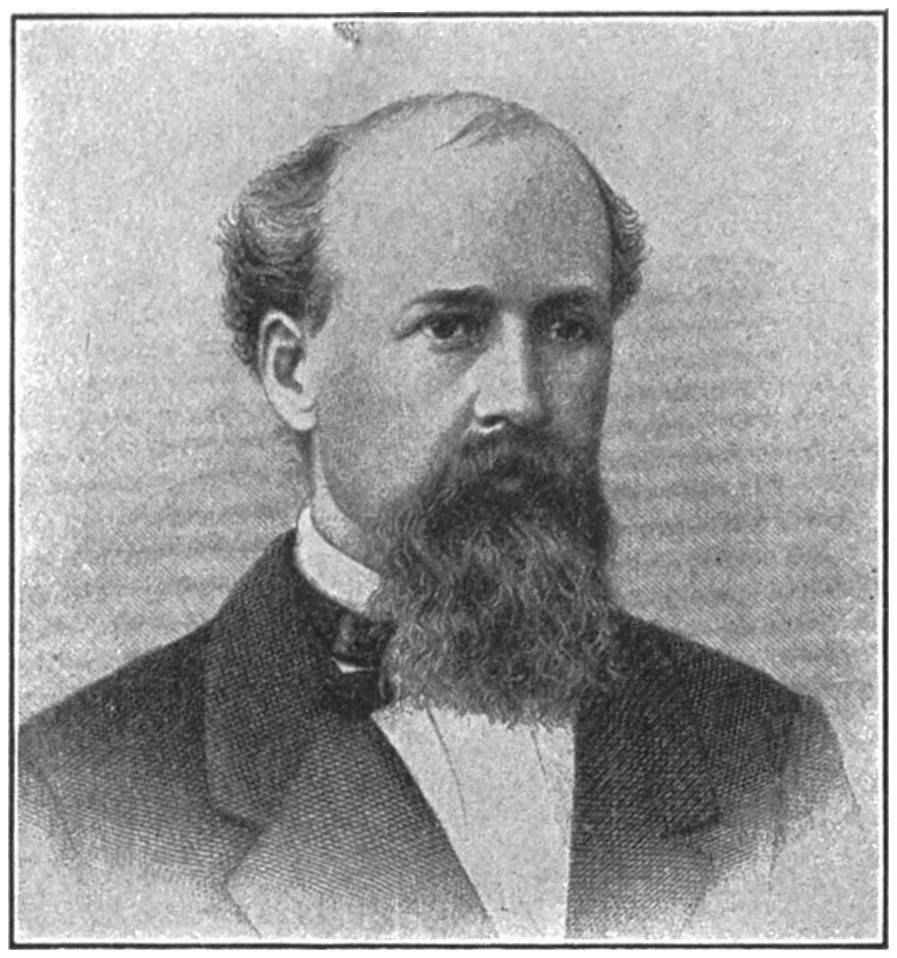

| John Ericsson, | 10 |

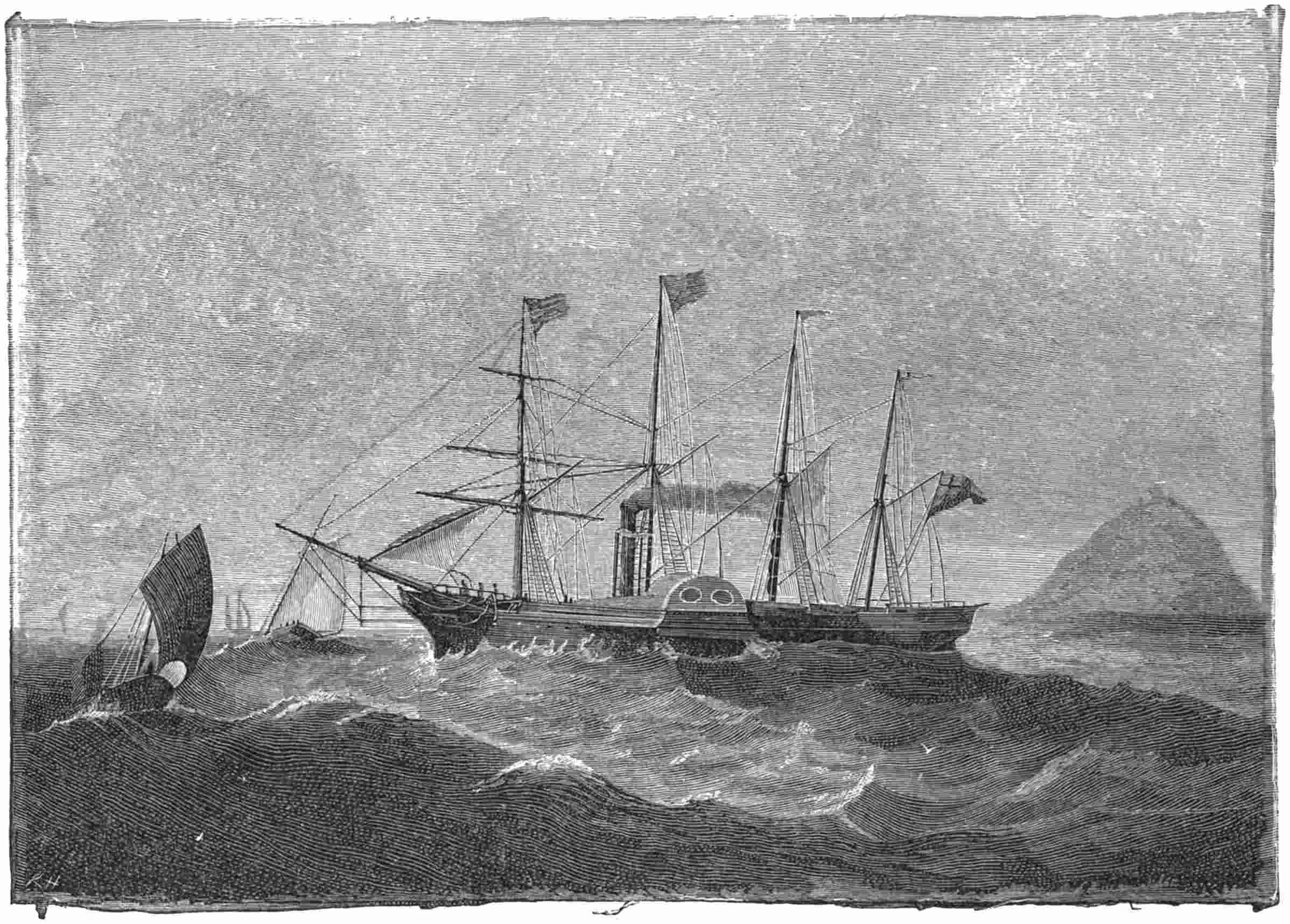

| The Great Western—One of the First Steamships to Cross the Atlantic Ocean. (After an old painting), | 13 |

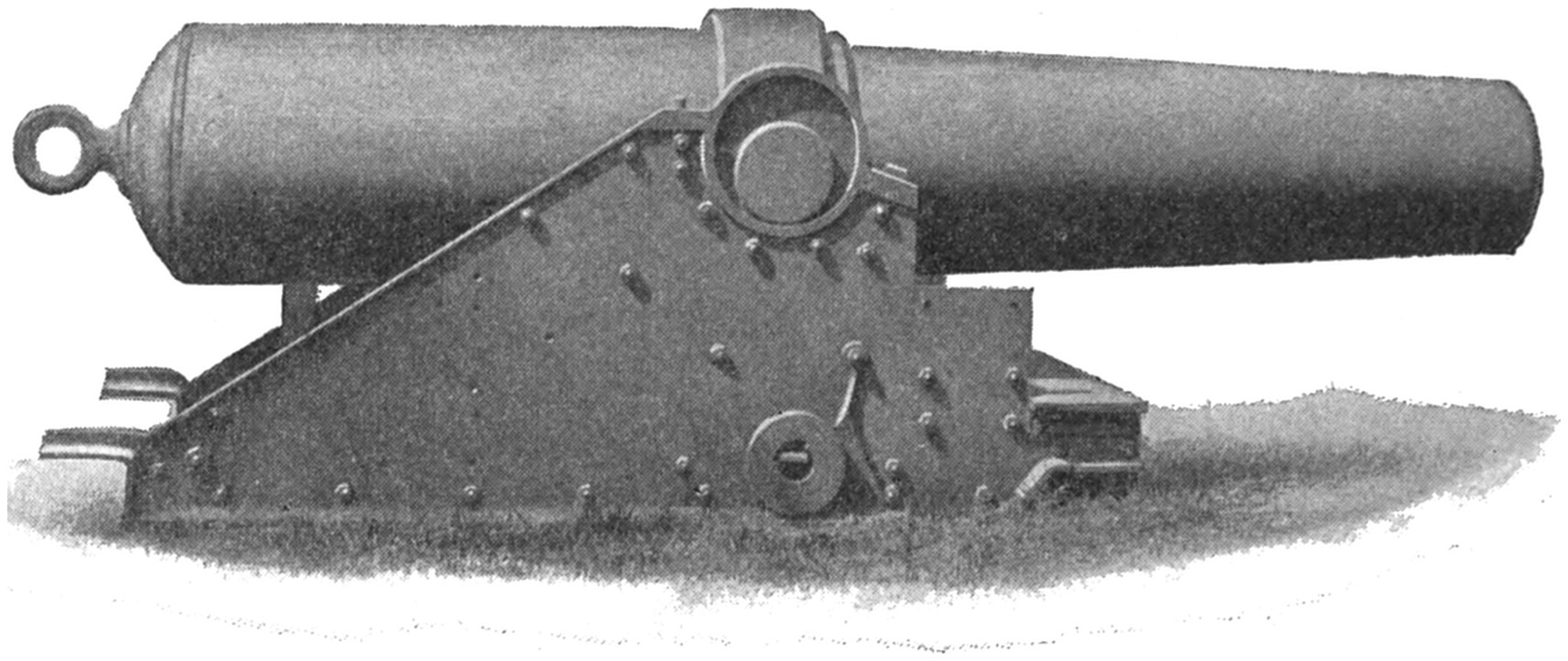

| Twelve-inch Wrought-iron Gun—the Mate to the “Peacemaker,” which Burst on the Princeton. (From a photograph of the original at the Brooklyn Navy Yard), | 14 |

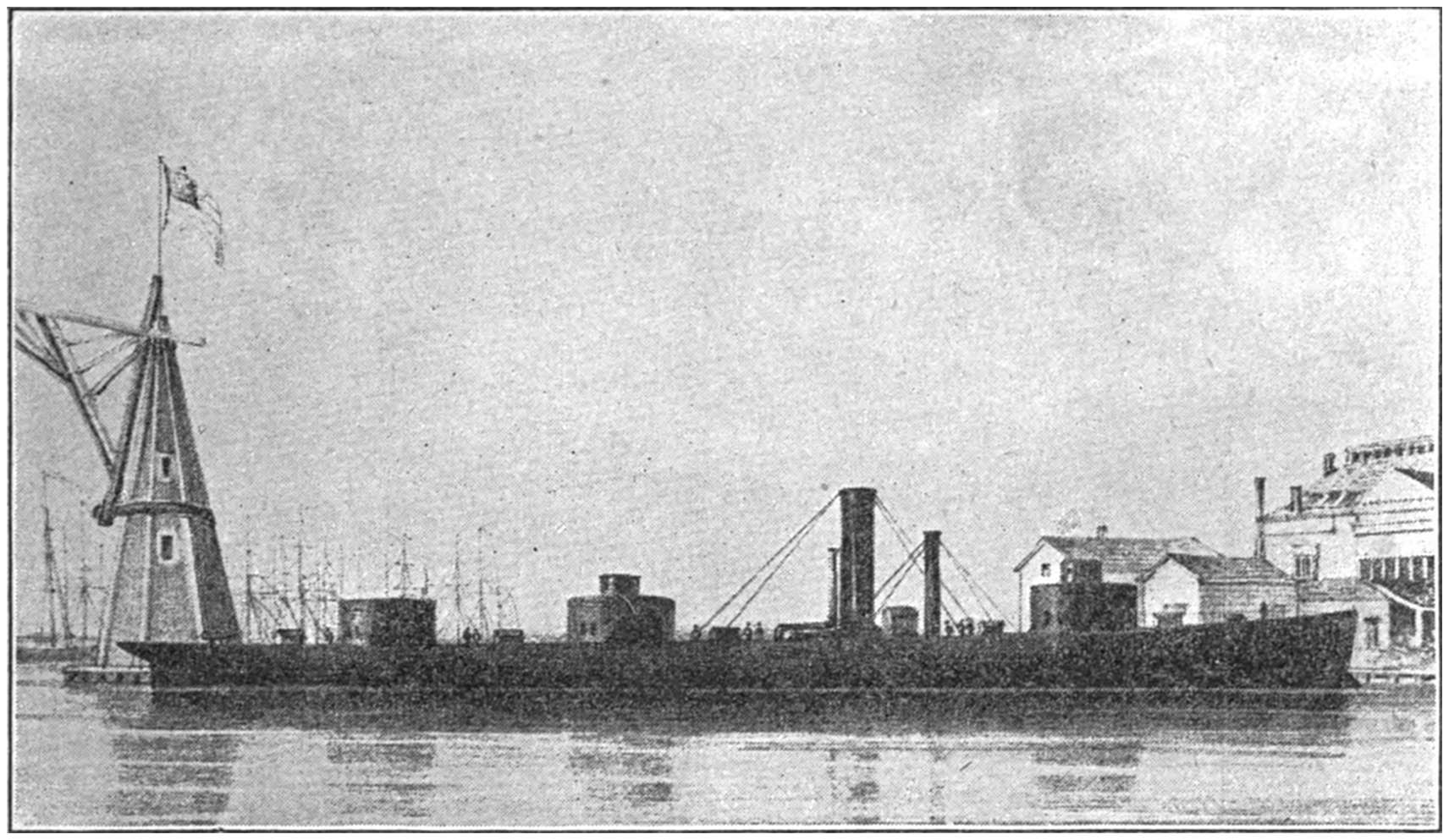

| U. S. Ironclad Steamship Roanoke. (From an old lithograph), | 15 |

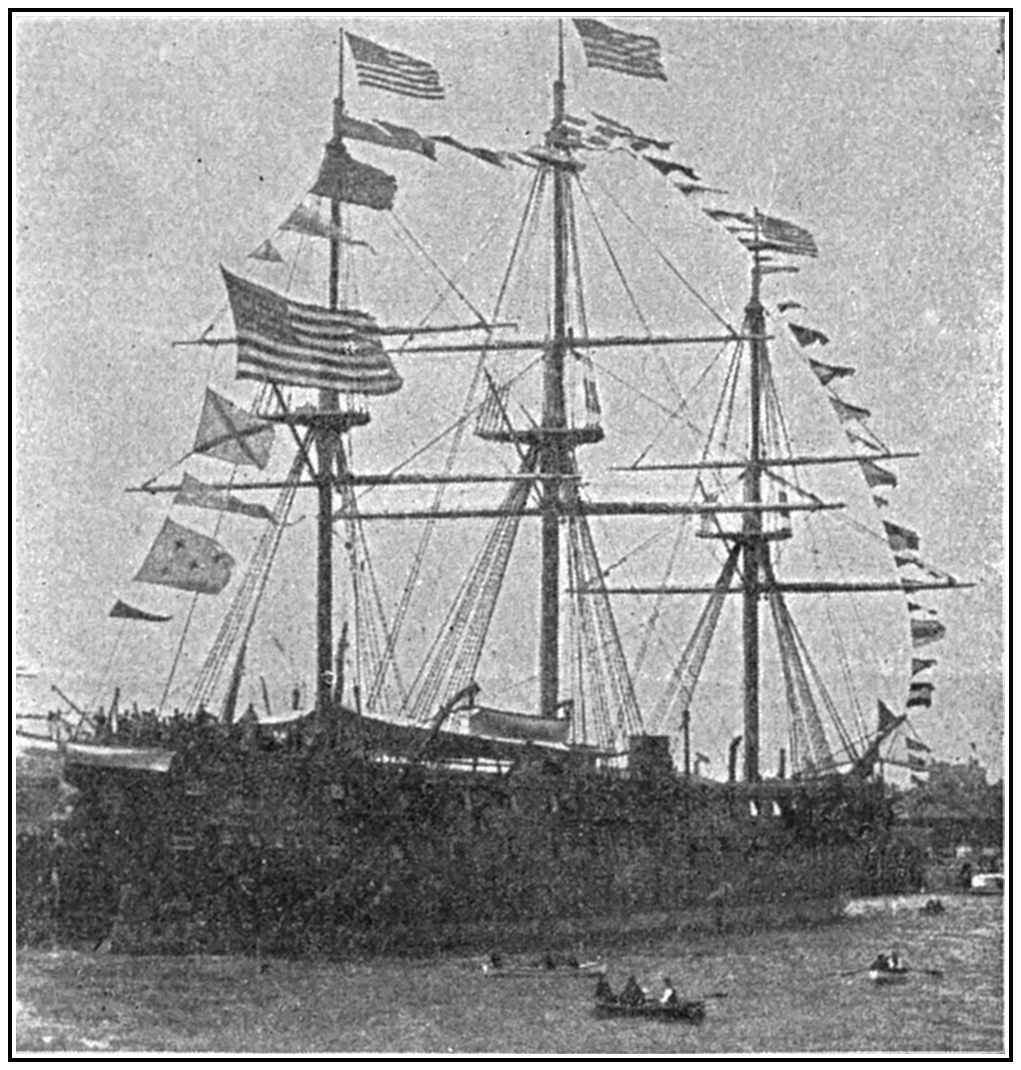

| U. S. Frigate Pensacola off Alexandria. (From a photograph taken in 1865), | 16 |

| A Twelve-pound Bronze Howitzer—the First One Made in the United States. (From a photograph of the original at the Brooklyn Navy Yard), | 18 |

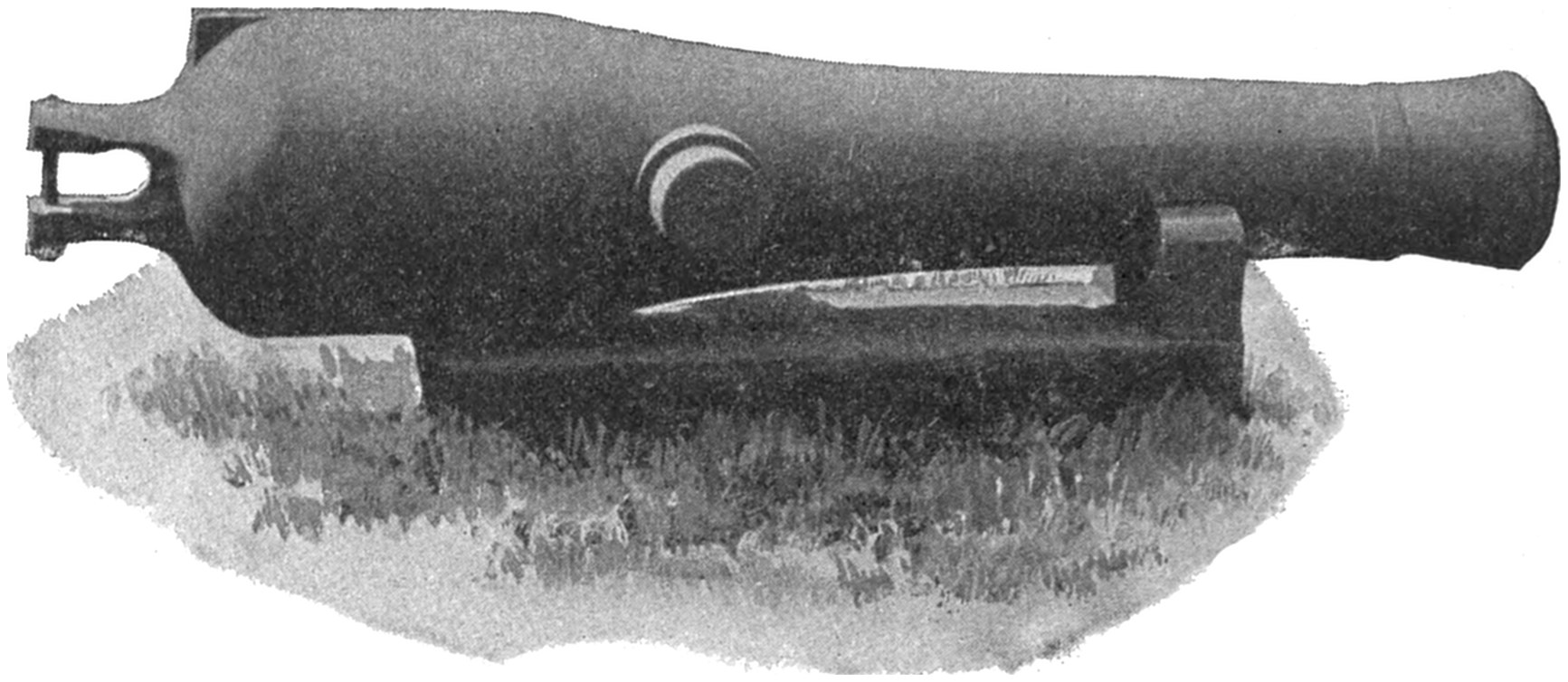

| A Dahlgren Gun, | 19 |

| Two Blakely Guns at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, | 22 |

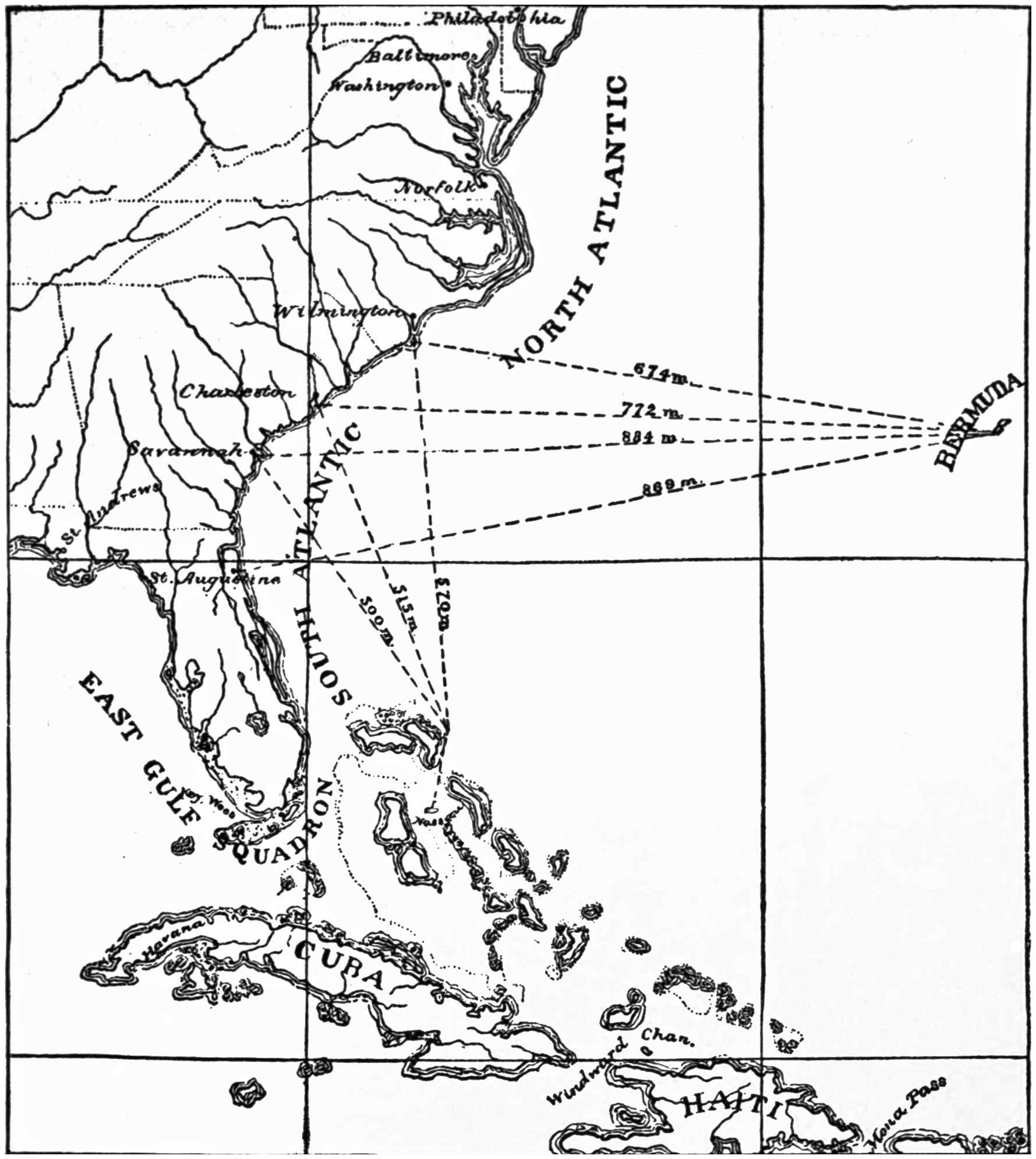

| The Blockaded Coast. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 29 |

| Map Showing Position of United States Ships of War in Commission March 4, 1861, | 33xvi |

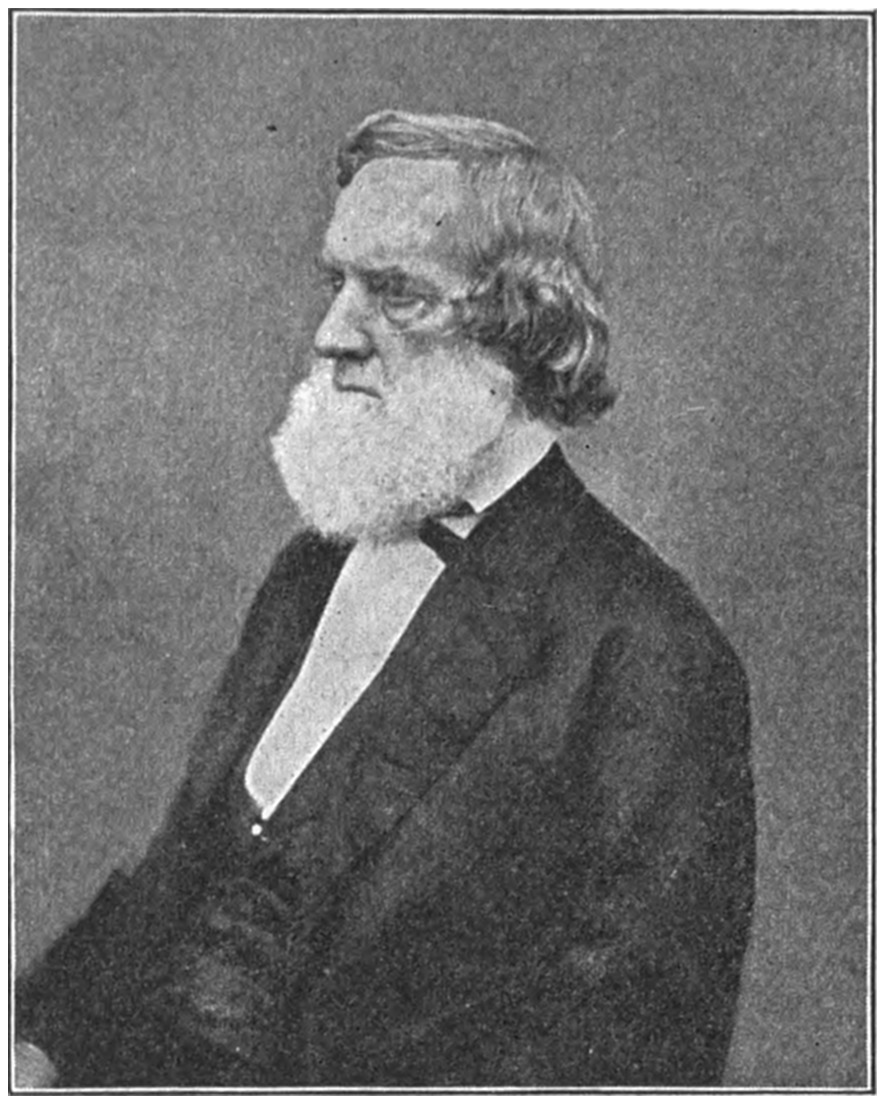

| Gideon Welles. (From a photograph), | 34 |

| Gustavus V. Fox. (From an engraving), | 36 |

| Garrett J. Pendergrast, | 39 |

| A Four-pound Cast-iron Gun Captured from a Blockade-runner, | 49 |

| An Eighteen-pound Rifle Captured from a Blockade-runner, | 52 |

| A Six-pound Gun Captured from a Blockade-runner, | 53 |

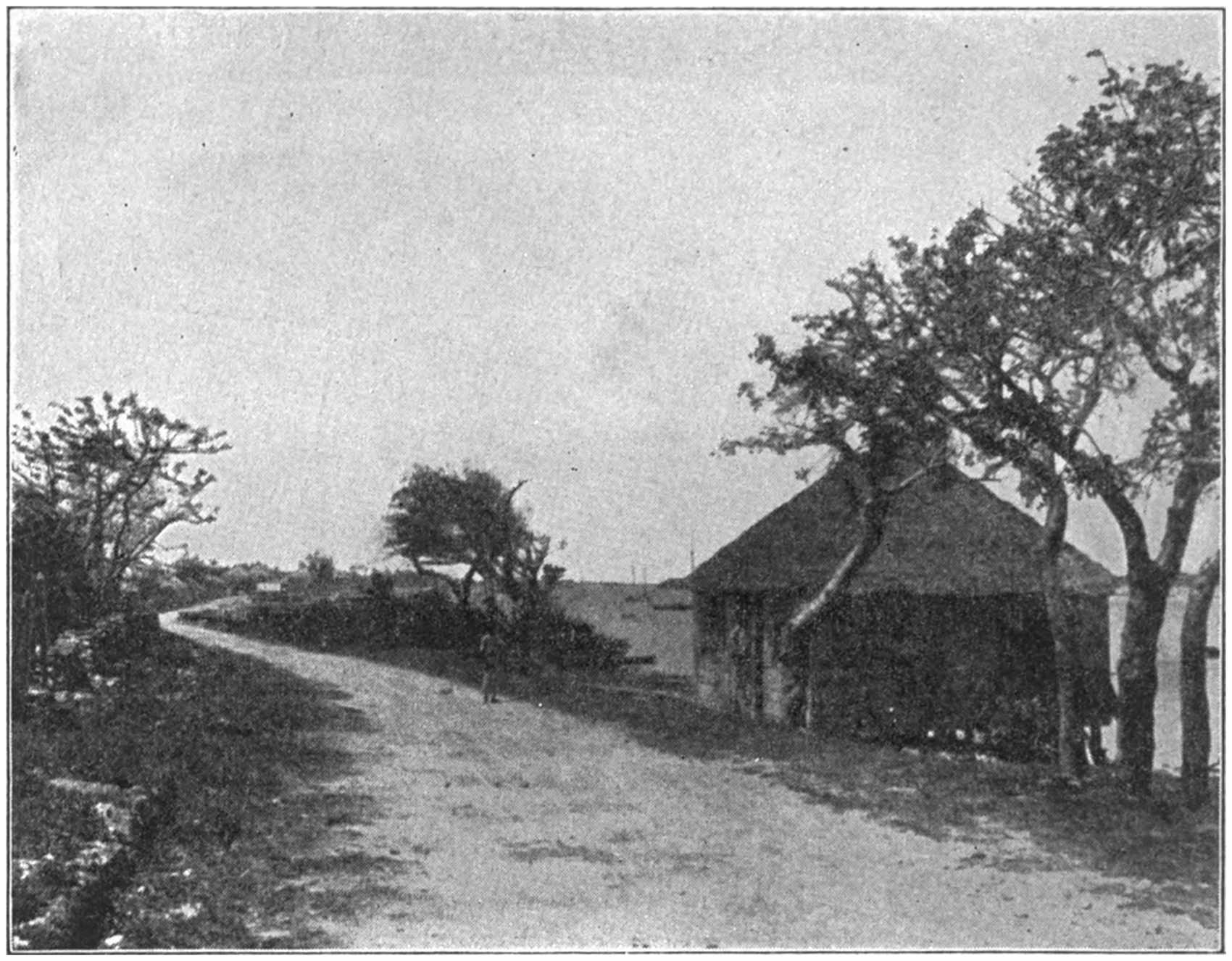

| A Nassau View—Along the Shore East of the Town. (From a photograph by Rau), | 54 |

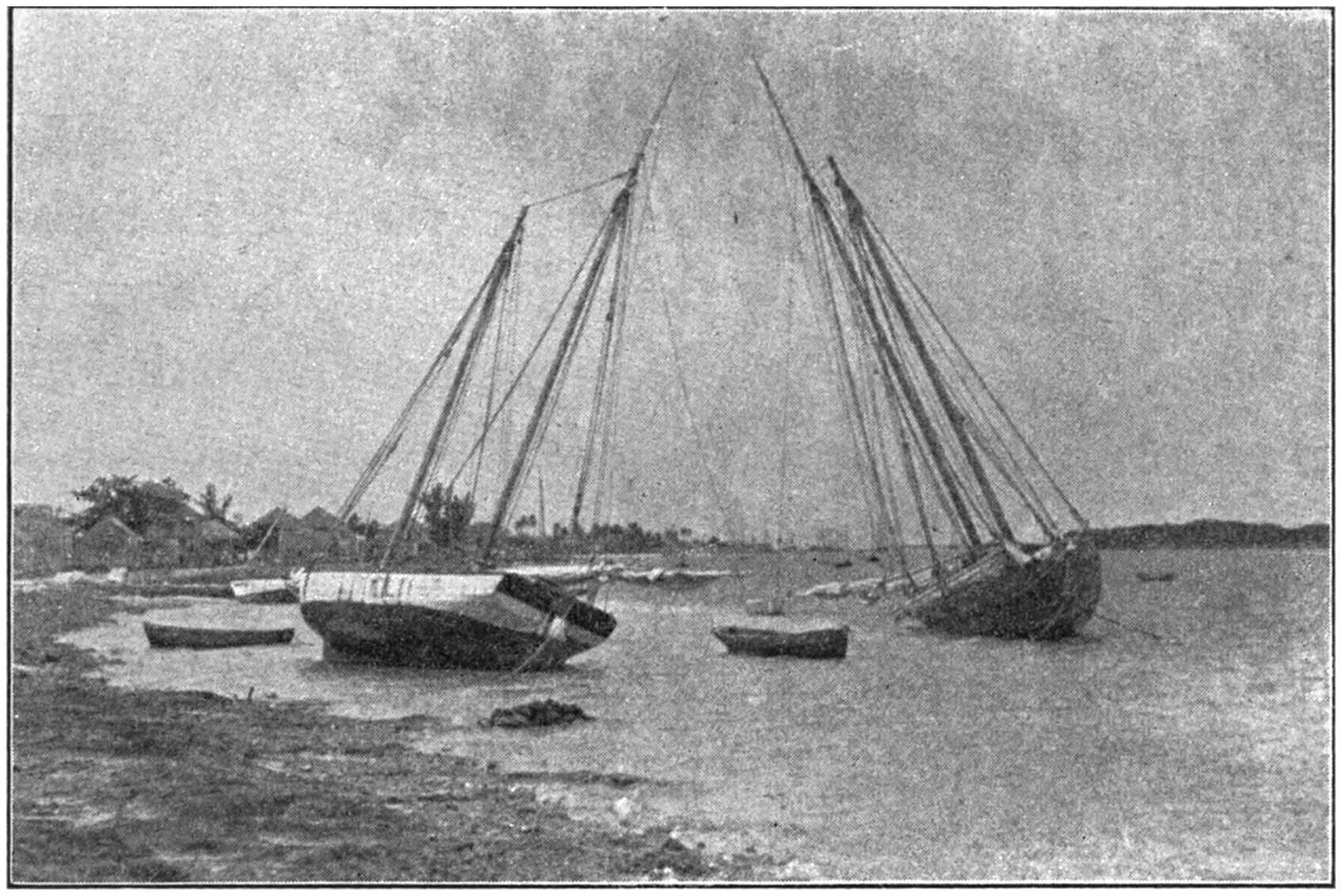

| Nassau Schooners. (From a photograph by Rau), | 55 |

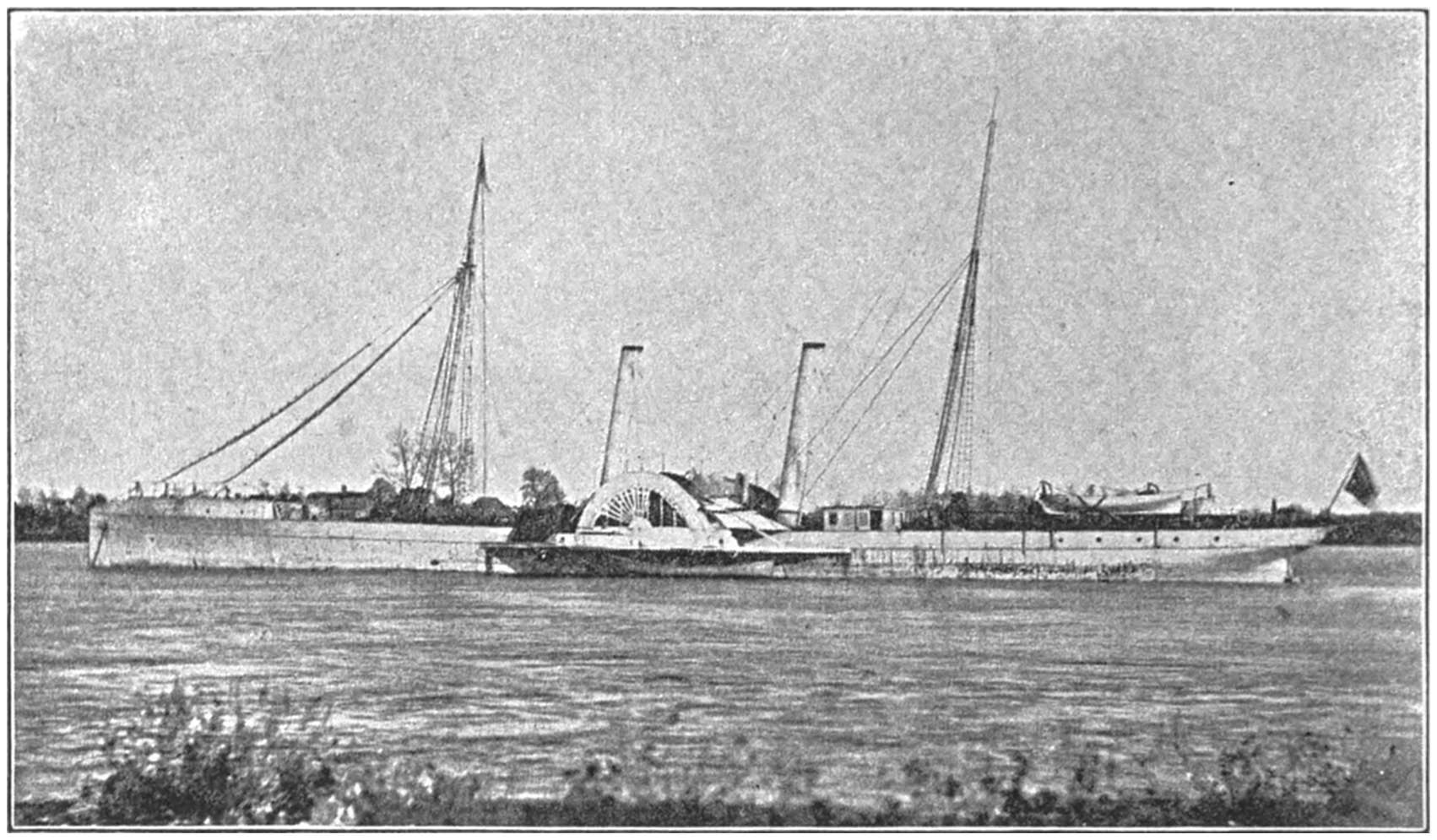

| The Blockade-runner Teaser. (From a photograph made in 1864), | 60 |

| Washington, D. C., and its Vicinity, | 67 |

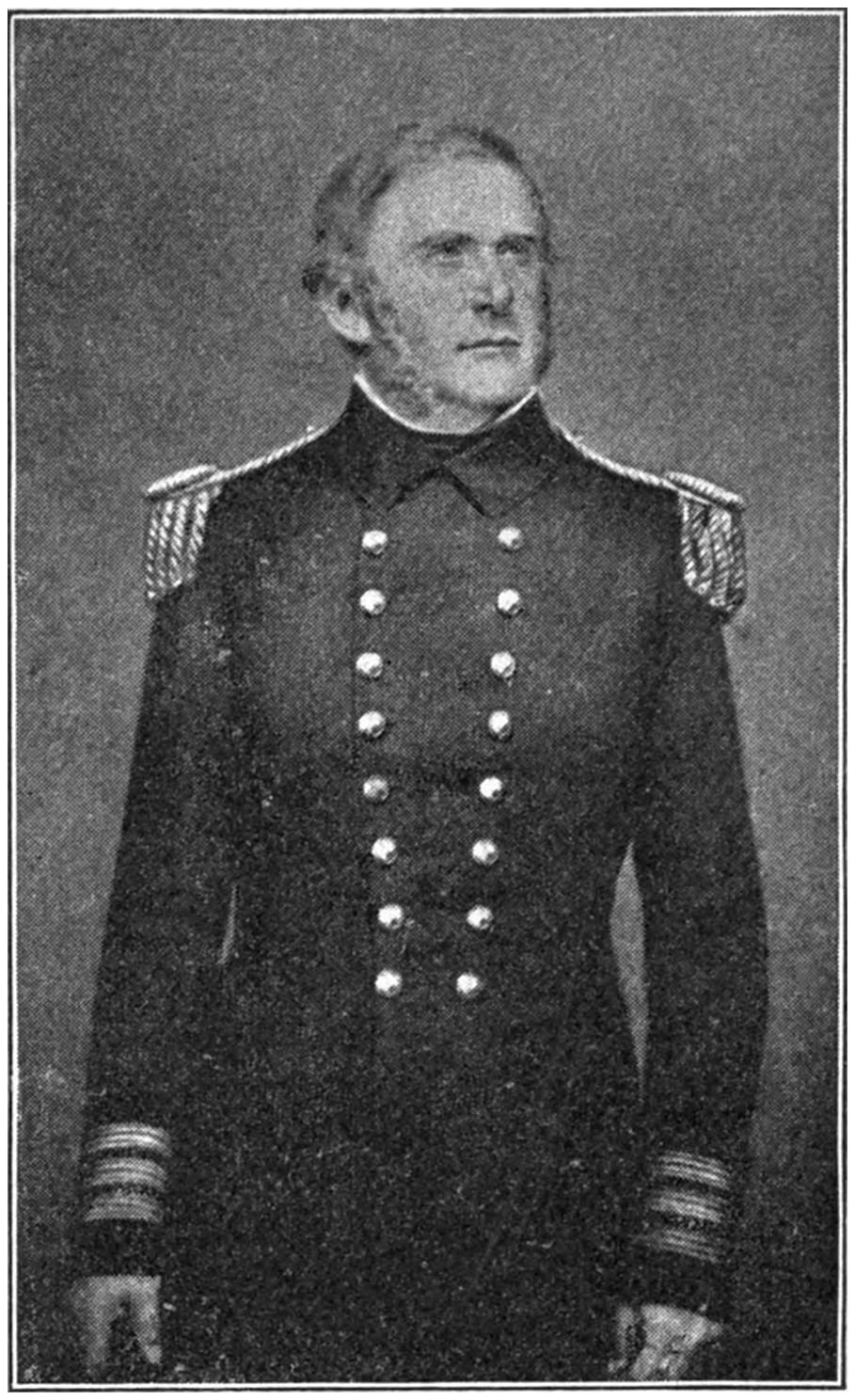

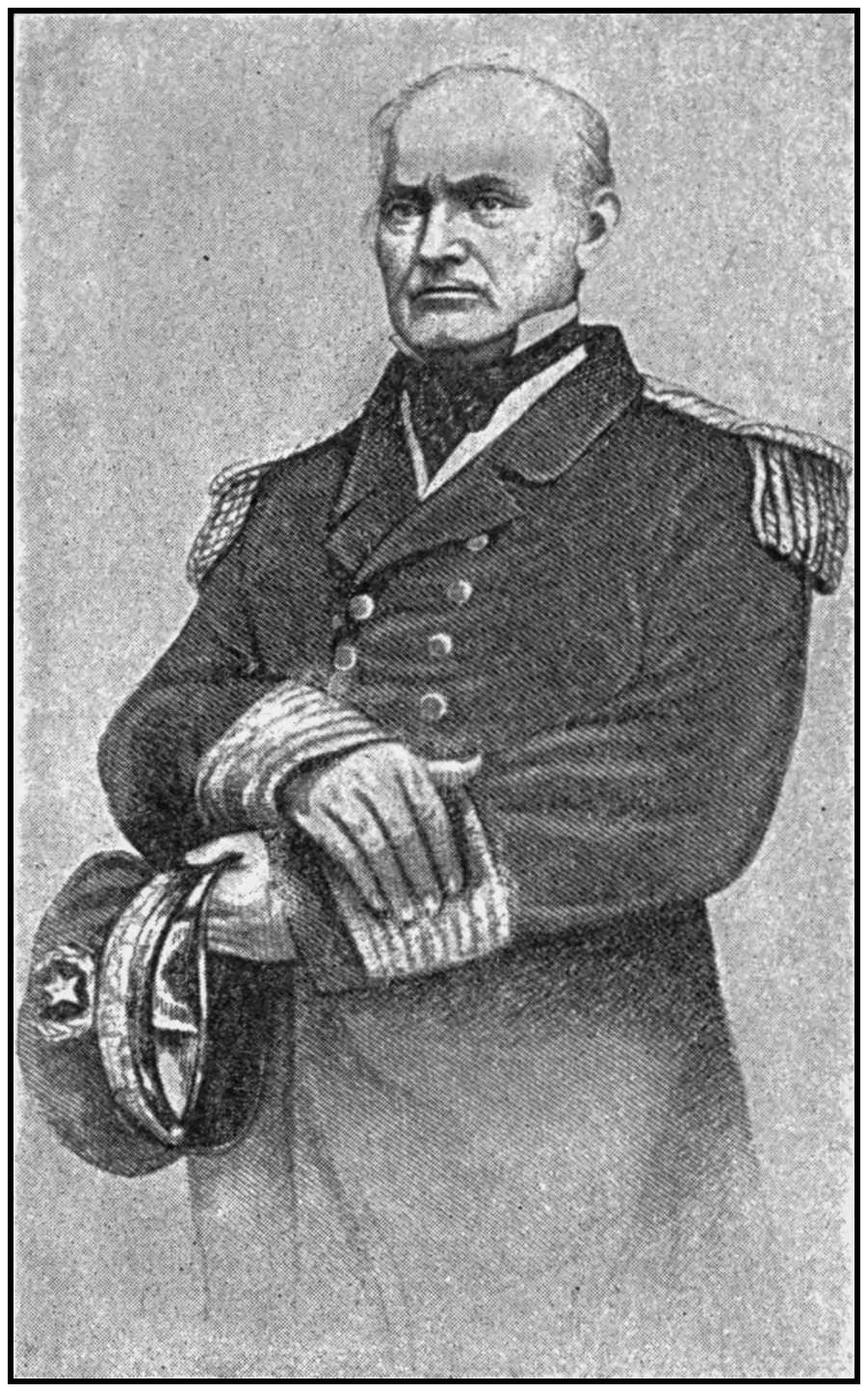

| Hiram Paulding. (From an engraving by Hall), | 71 |

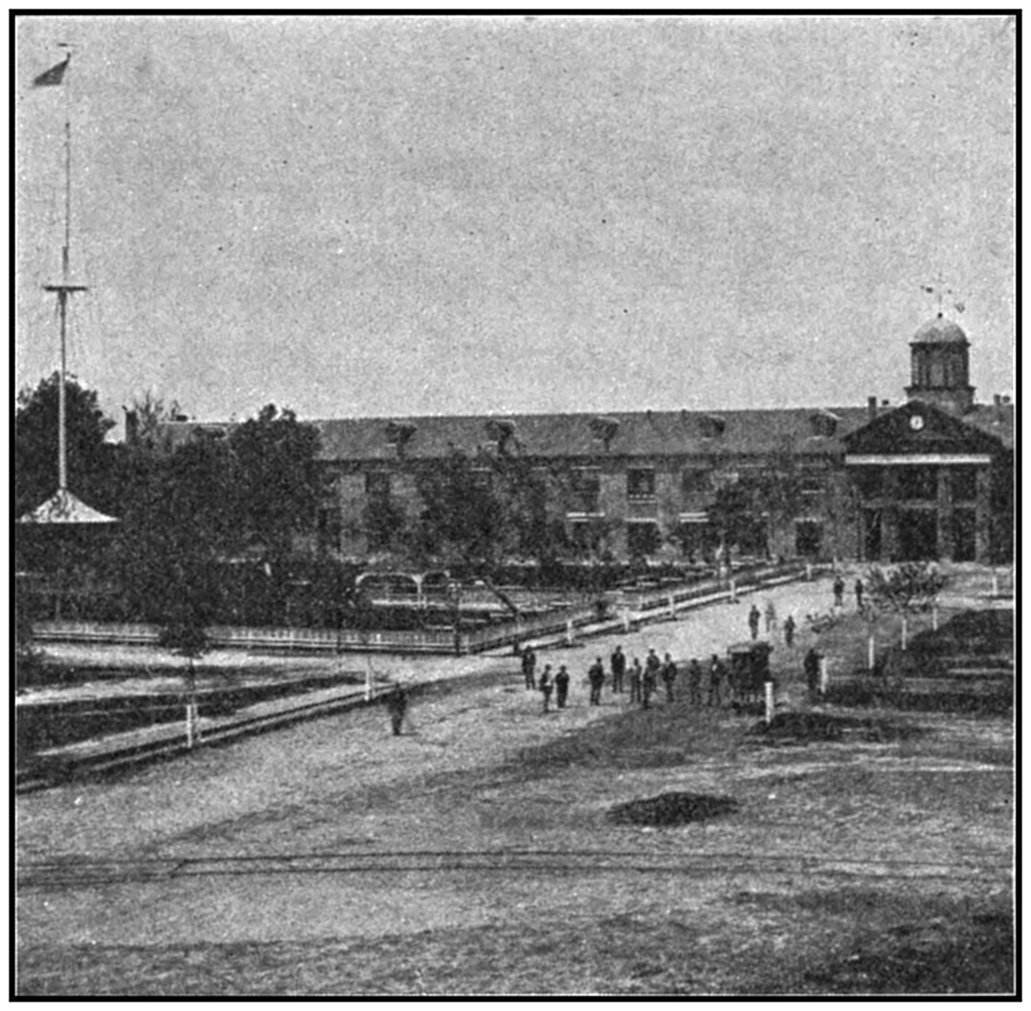

| A View of the Norfolk Navy Yard. (From a photograph by Cook), | 73 |

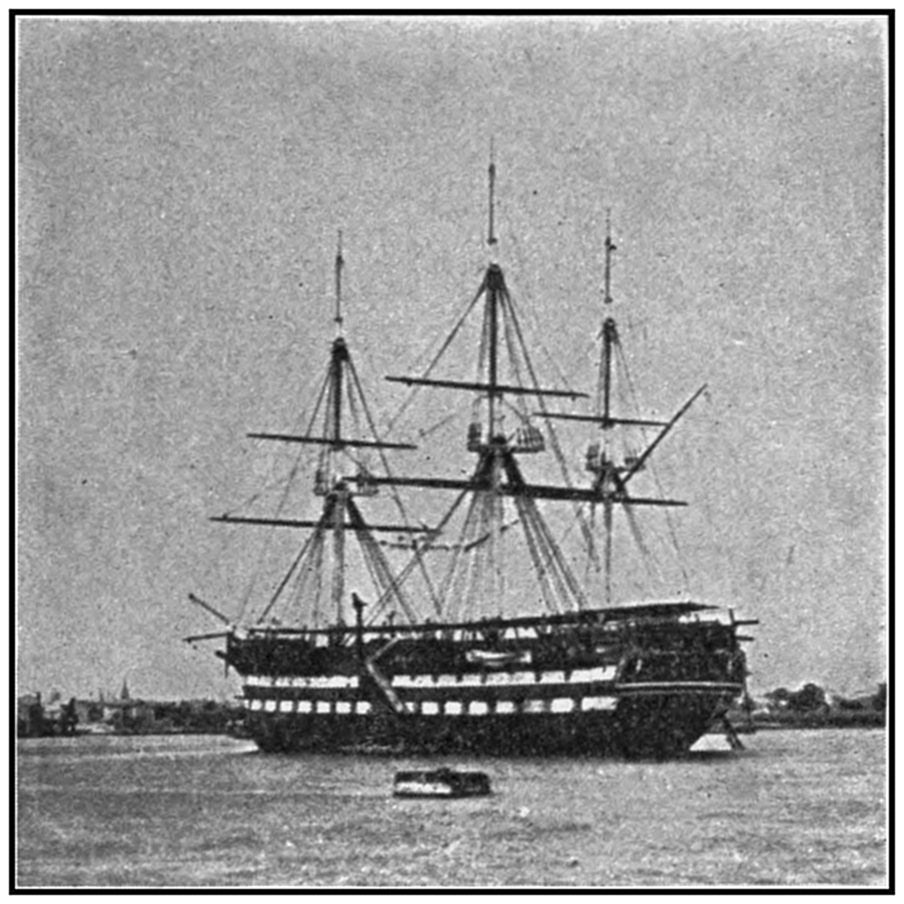

| The Old New Hampshire at the Norfolk Navy Yard. (From a photograph by Cook), | 77 |

| Burning of the Vessels at the Norfolk Navy Yard, | 79 |

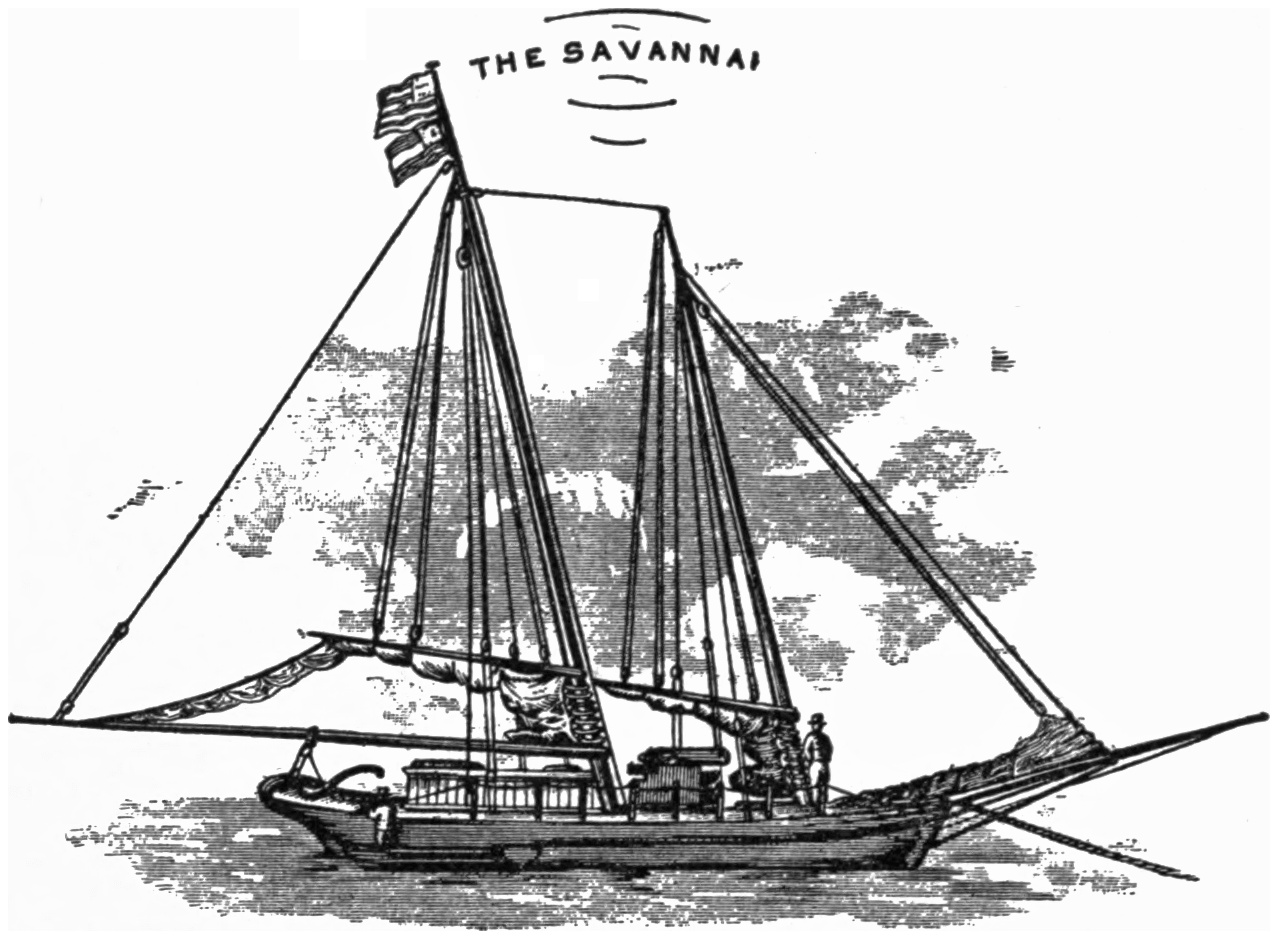

| The Confederate States Privateer Savannah, Letter of Marque No. 1, Captured off Charleston by the U. S. Brig Perry, Lieutenant Parrott, | 88 |

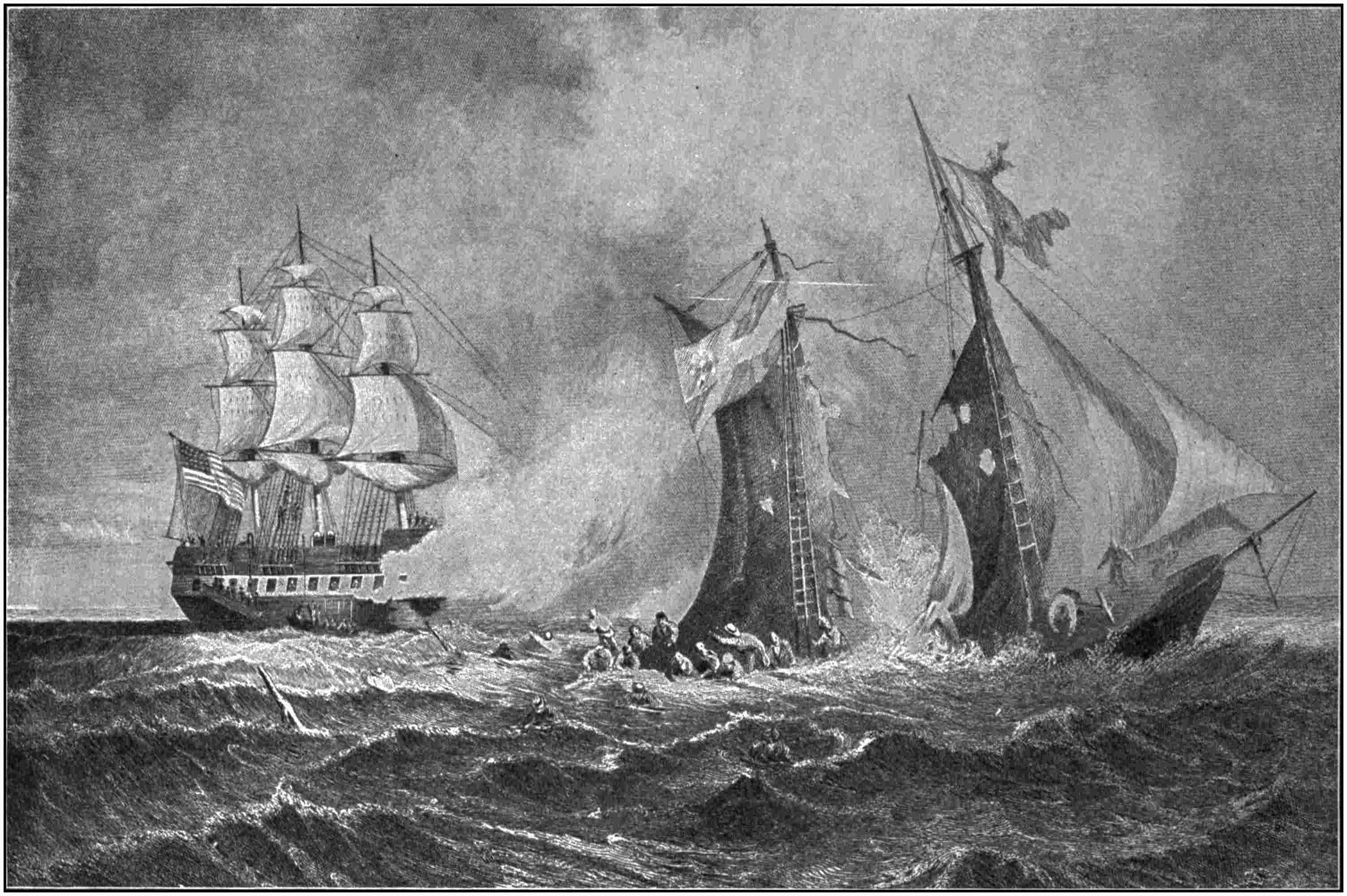

| Destruction of the Privateer Petrel by the St. Lawrence. (From an engraving by Hinshelwood of the painting by Manzoni), | 95 |

| S. H. Stringham. (From an engraving by Buttre), | 100 |

| B. F. Butler. (From a photograph), | 101 |

| Bombardment and Capture of the Forts at Hatteras Inlet, N. C. (From a lithograph published by Currier & Ives), | 103 |

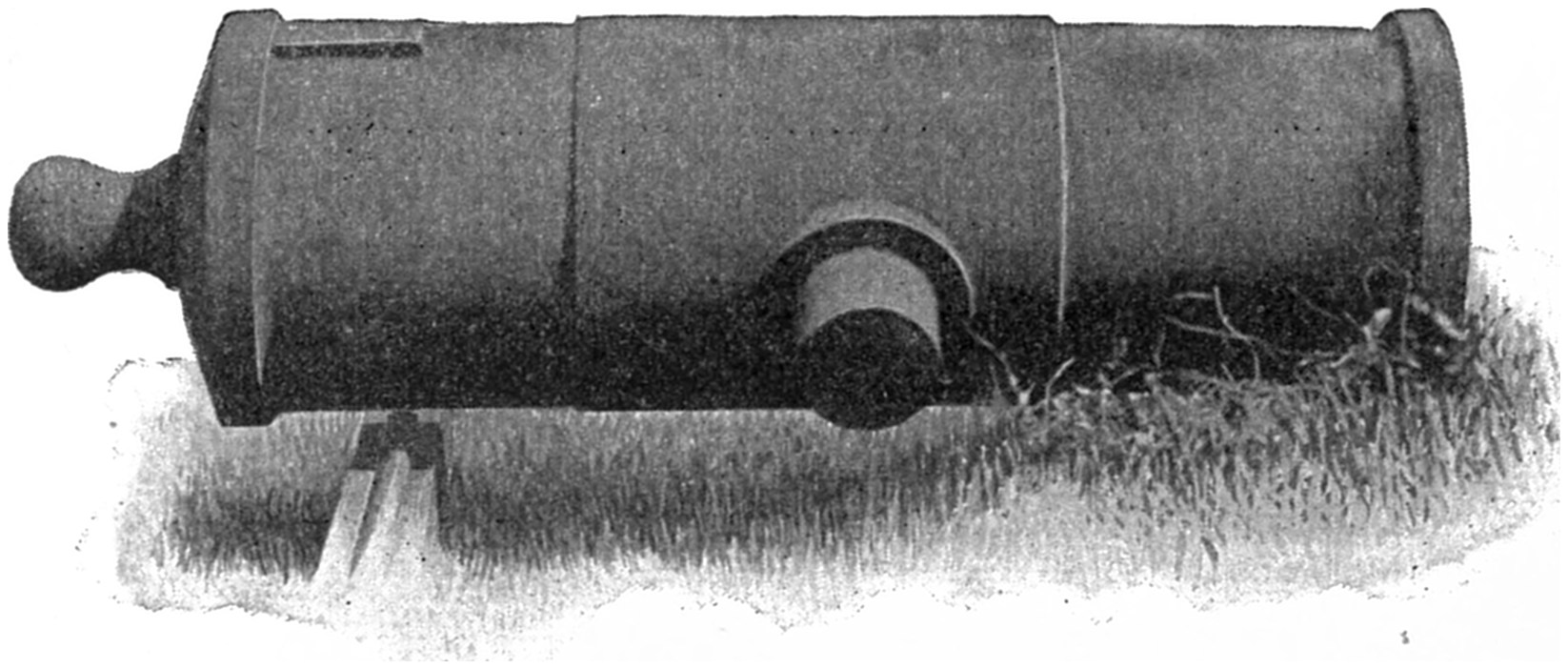

| Eight-inch Mortar Captured at Hatteras, | 107 |

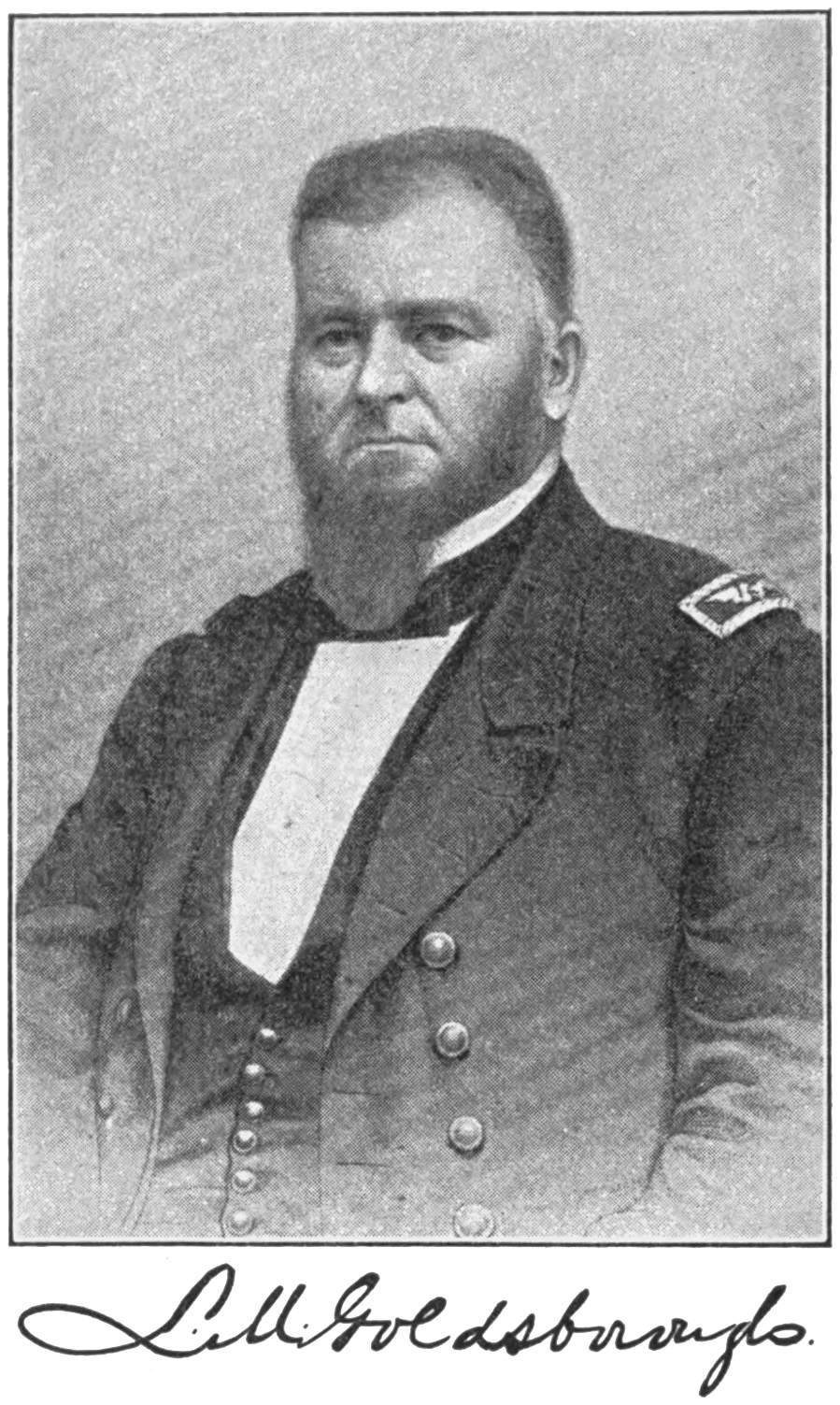

| L. M. Goldsborough. (From an engraving by Buttre), | 108 |

| Stephen C. Rowan. (From a photograph), | 109 |

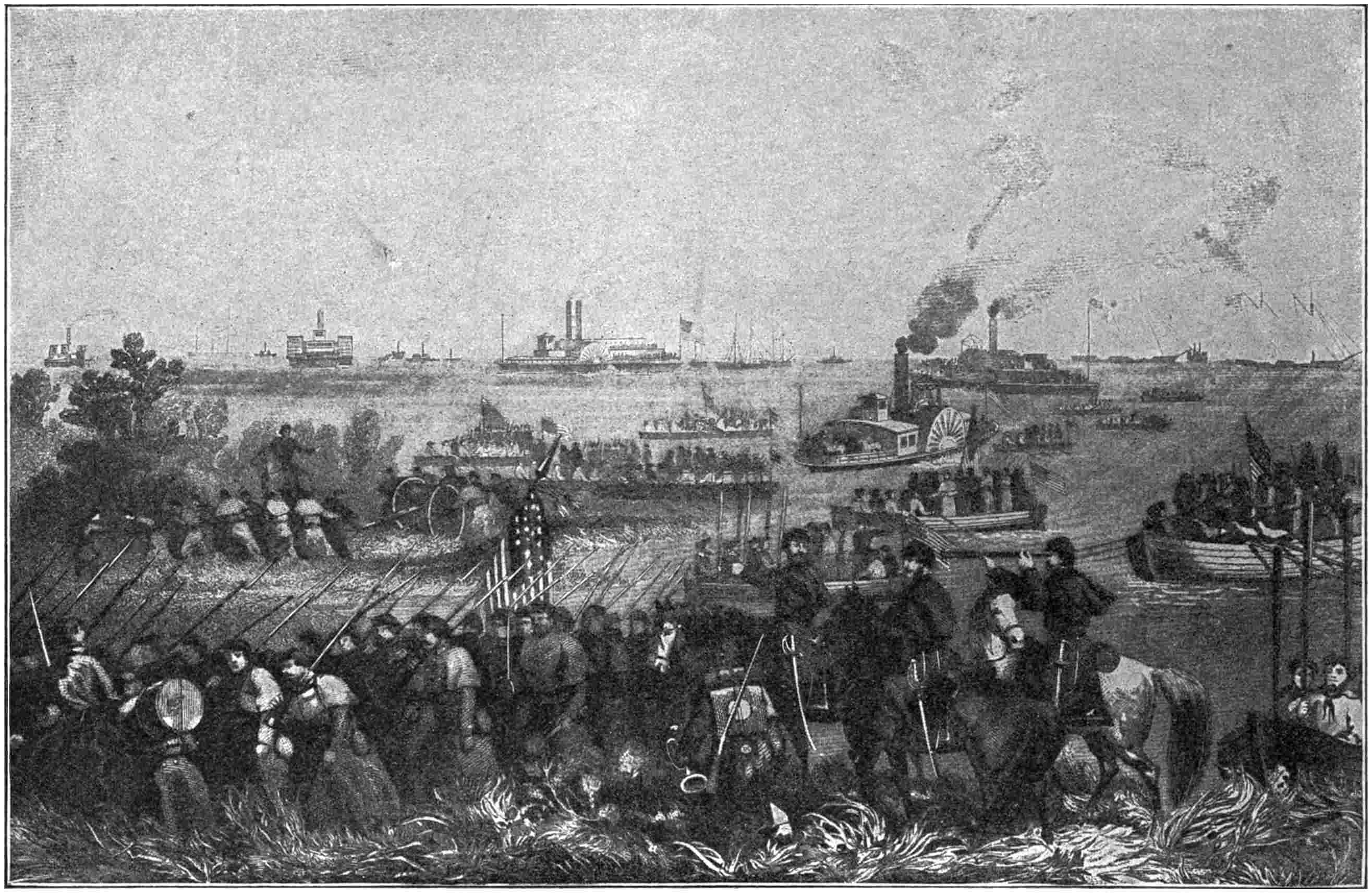

| Attack on Roanoke Island—Landing of the Troops. (From an engraving of the painting by Chappel), | 110 |

| Landing of Troops on Roanoke Island. (From an engraving by Perine of a drawing by Momberger), | 110 |

| Surrender of the Navy Yard at Pensacola. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 113 |

| Henry Walke. (From a photograph), | 114xvii |

| John G. Sproston. (From a photograph at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 120 |

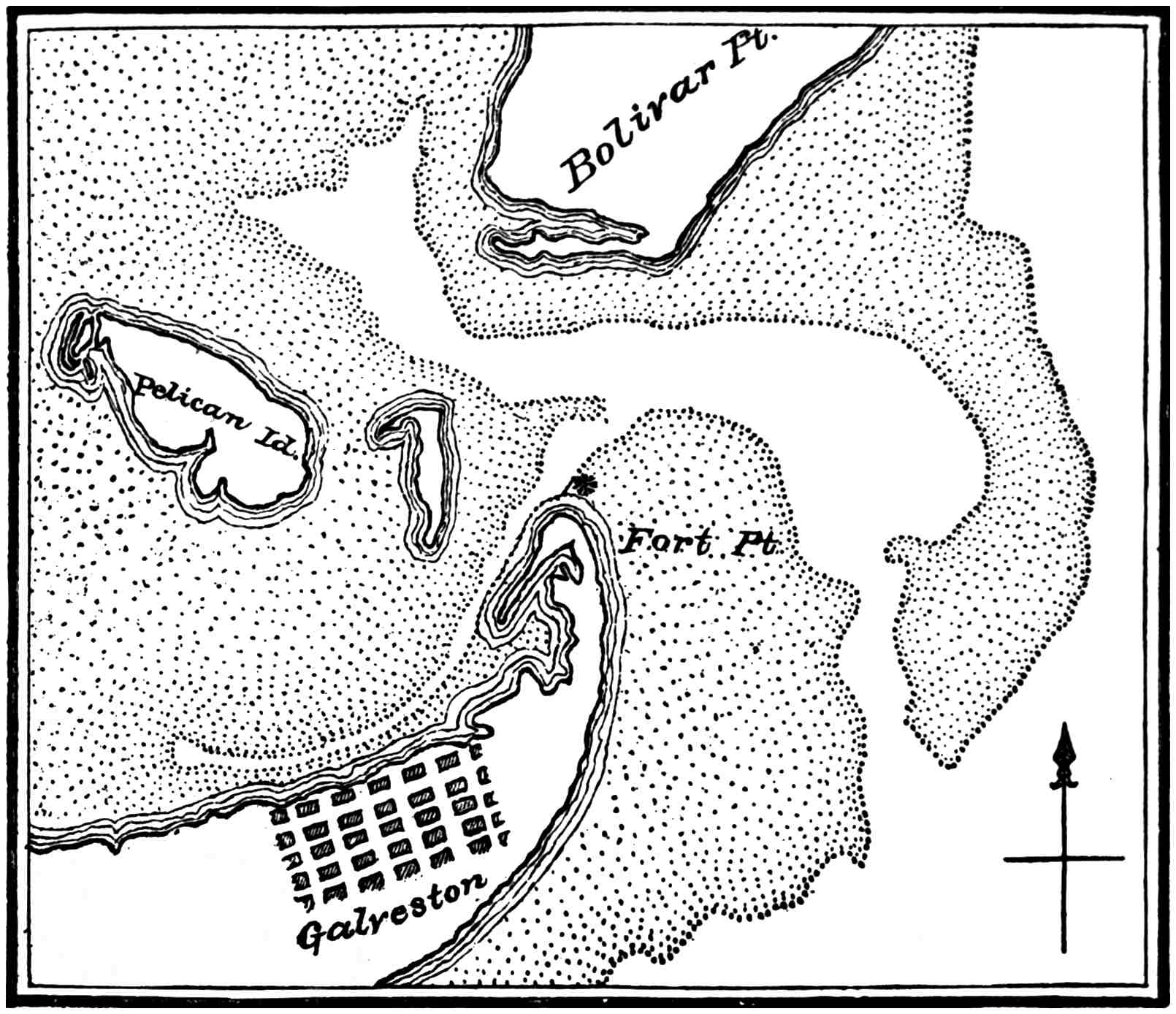

| Galveston Harbor. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 122 |

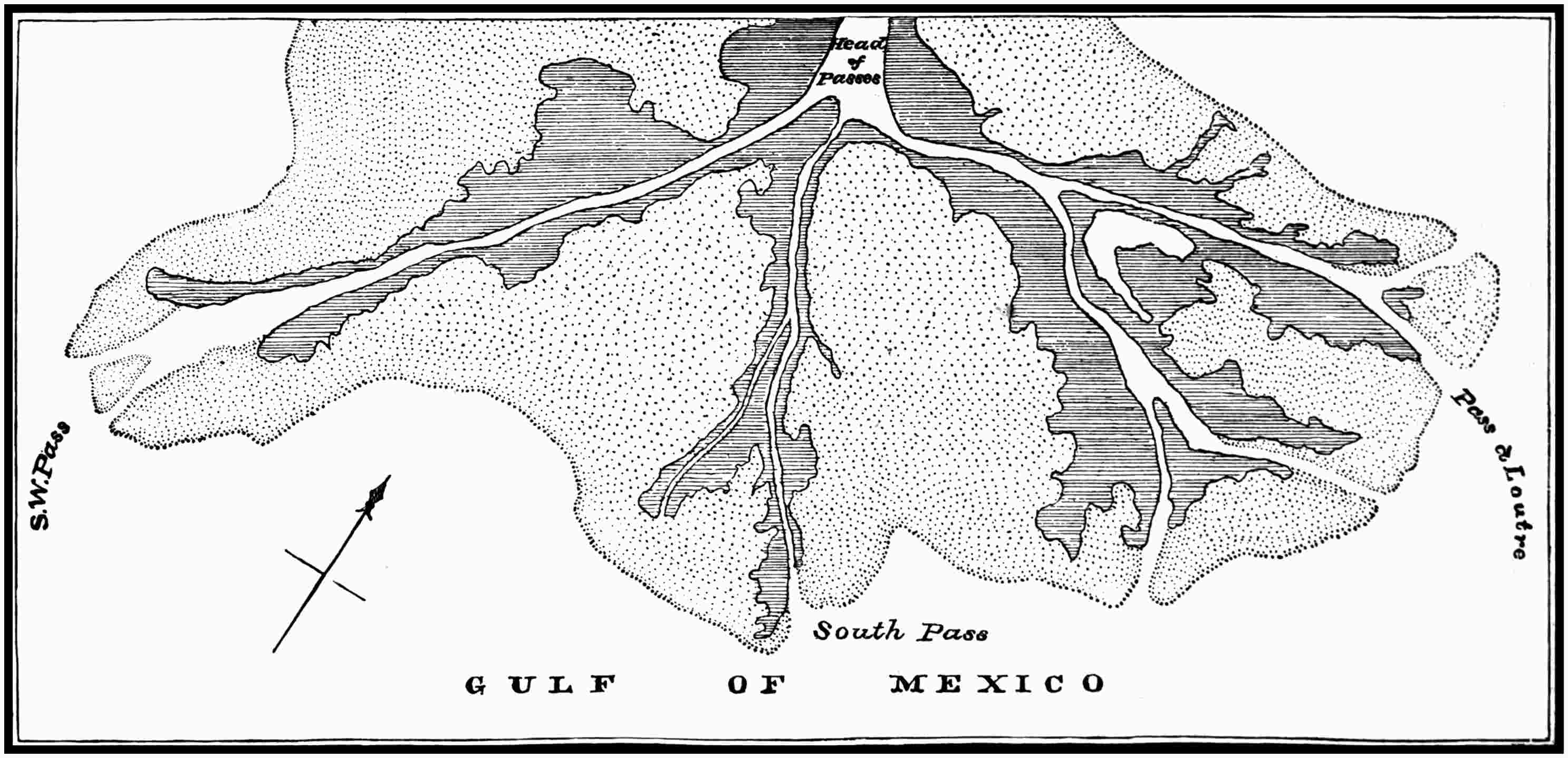

| Passes of the Mississippi. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 126 |

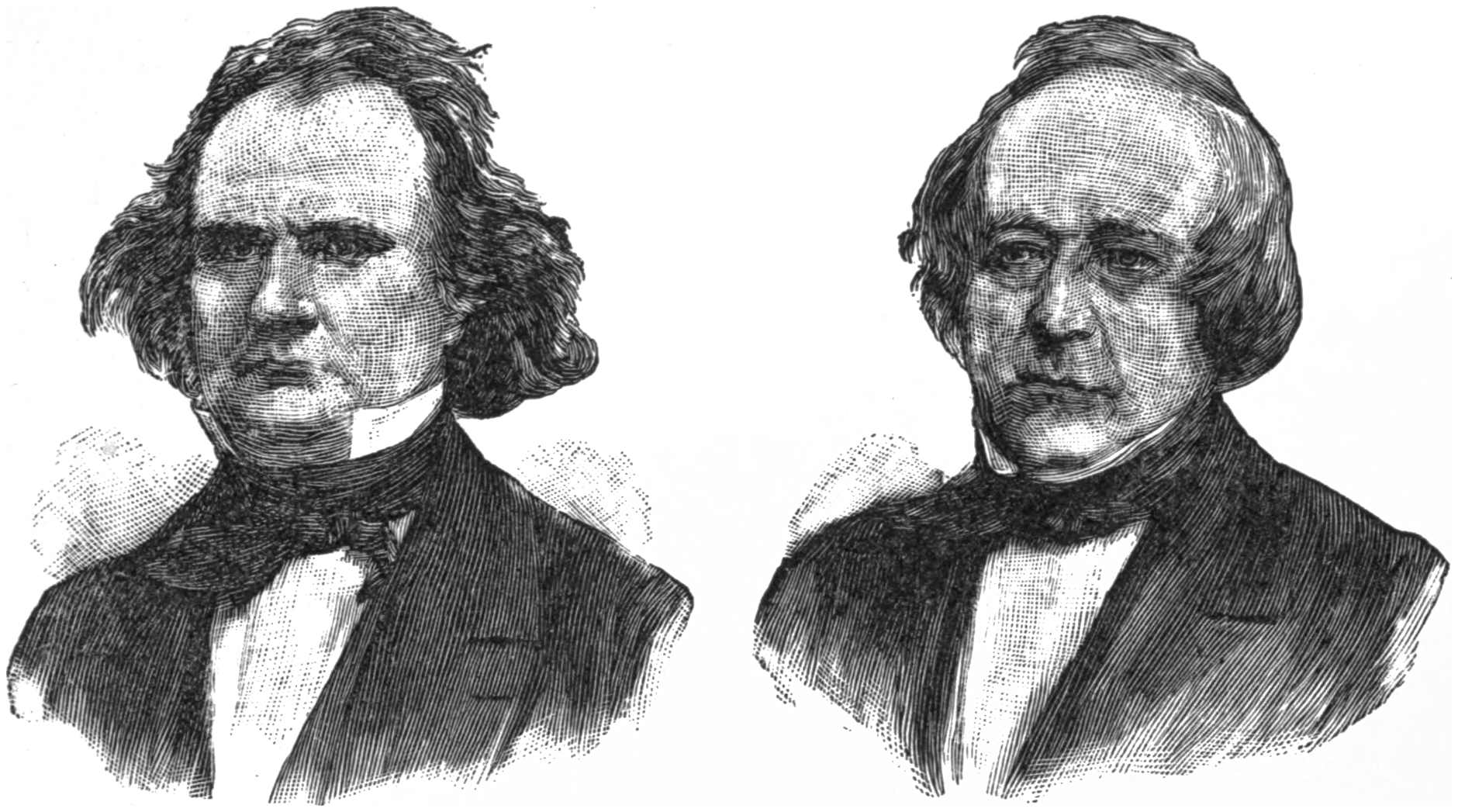

| James Murray Mason and John Slidell. (The two captured commissioners), | 141 |

| Charles Wilkes. (From an engraving by Dodson of the portrait by Sully), | 143 |

| William H. Seward. (From a photograph), | 155 |

| S. F. Dupont. (From a photograph), | 163 |

| C. R. P. Rodgers. (From a photograph), | 164 |

| S. W. Godon. (From a painting at the Naval Academy, Annapolis), | 165 |

| Josiah Tattnall. (From an engraving by Hall), | 168 |

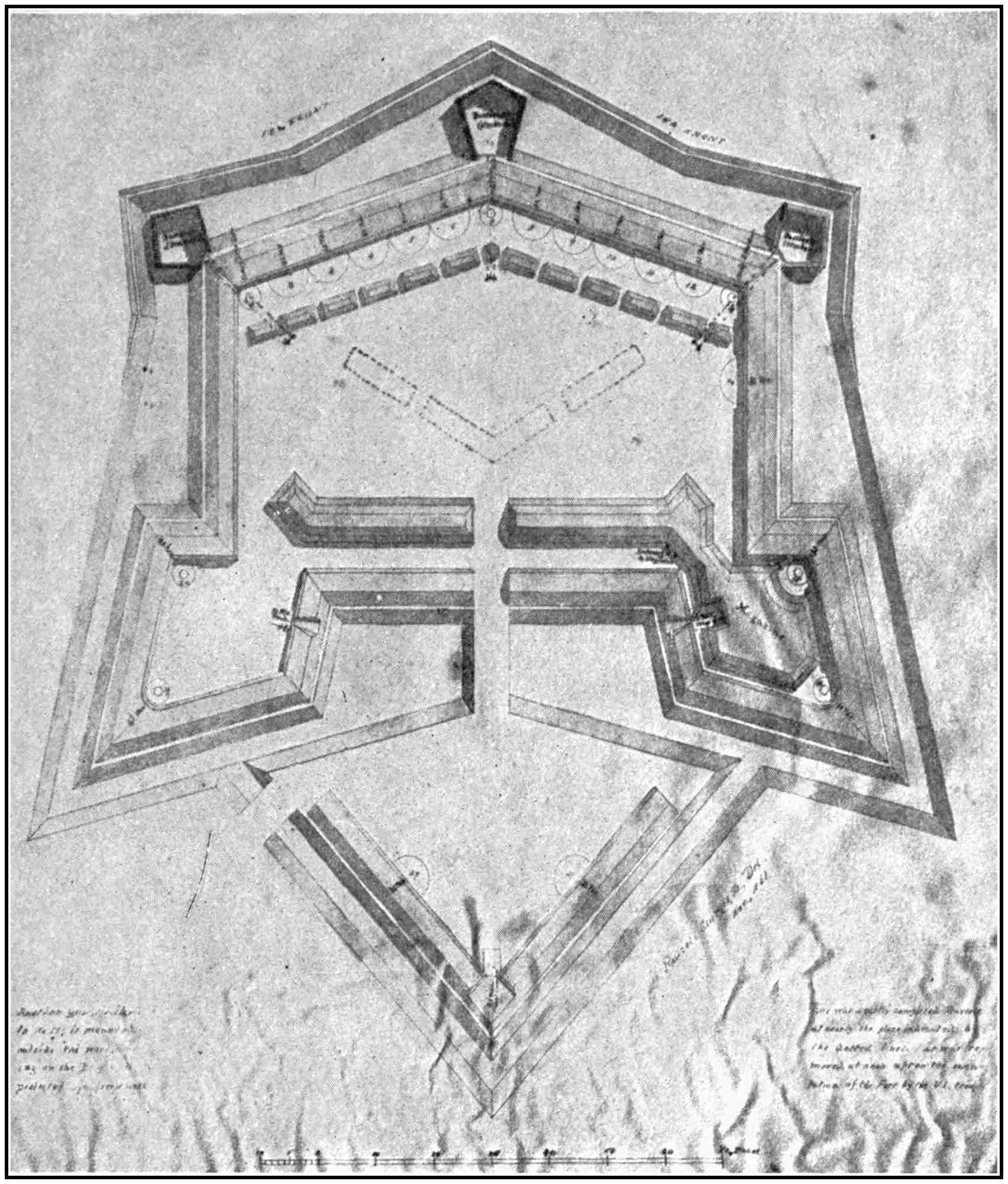

| Plan of Fort Walker on Hilton Head. (From a drawing by R. Sturgis, Jr., in 1861), | 169 |

| Bombardment of Port Royal, S. C. (From an engraving by Ridgeway of a drawing by Parsons), | 175 |

| Bombardment and Capture of Forts Walker and Beauregard, November 7, 1861. (From an engraving by Perine), | 179 |

| Franklin Buchanan, | 189 |

| The New Ironsides in Action. (From a photograph, of a drawing, owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 190 |

| The Giant and the Dwarfs; or, John E. and the Little Mariners. (From a Swedish caricature, February 10, 1867), | 191 |

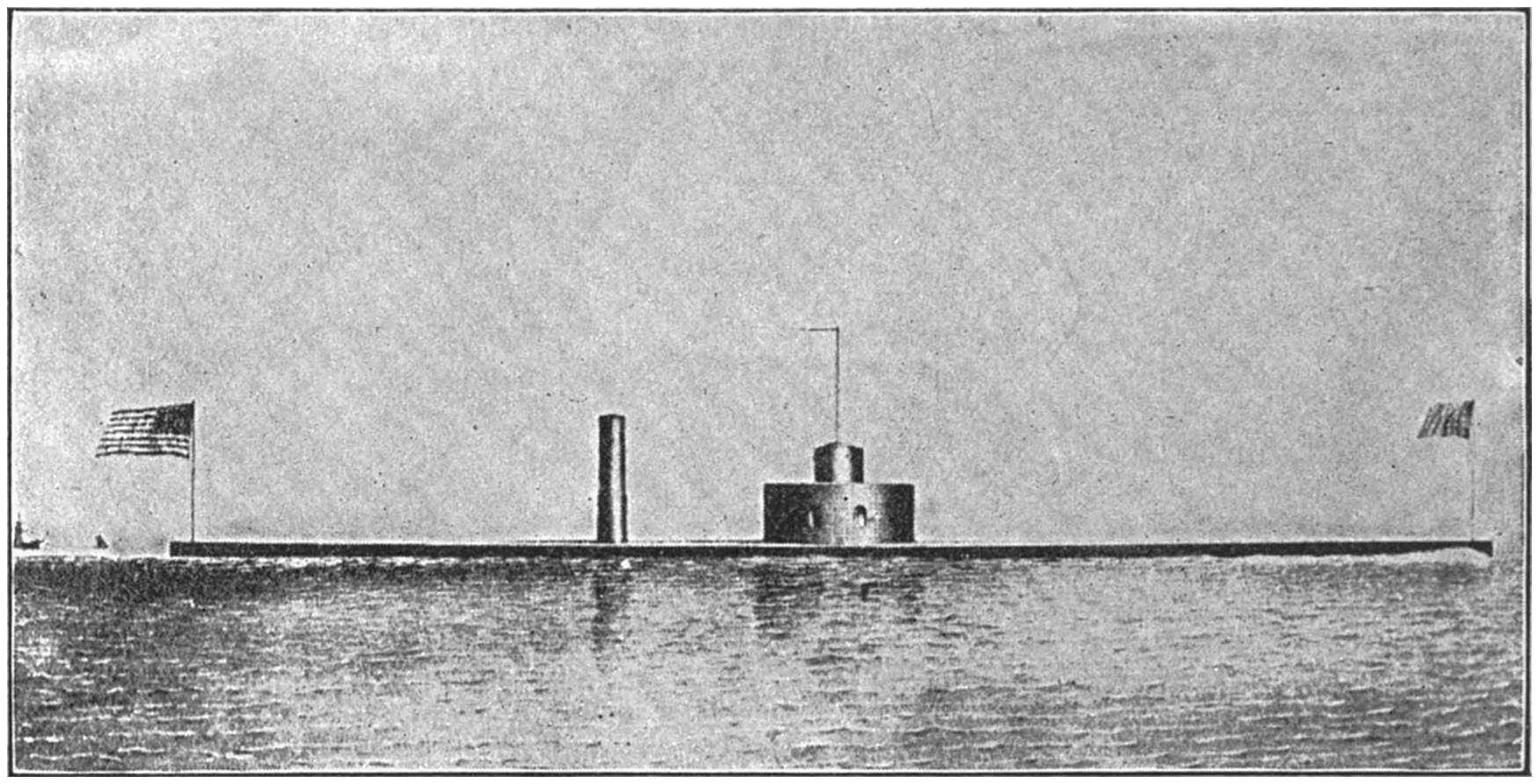

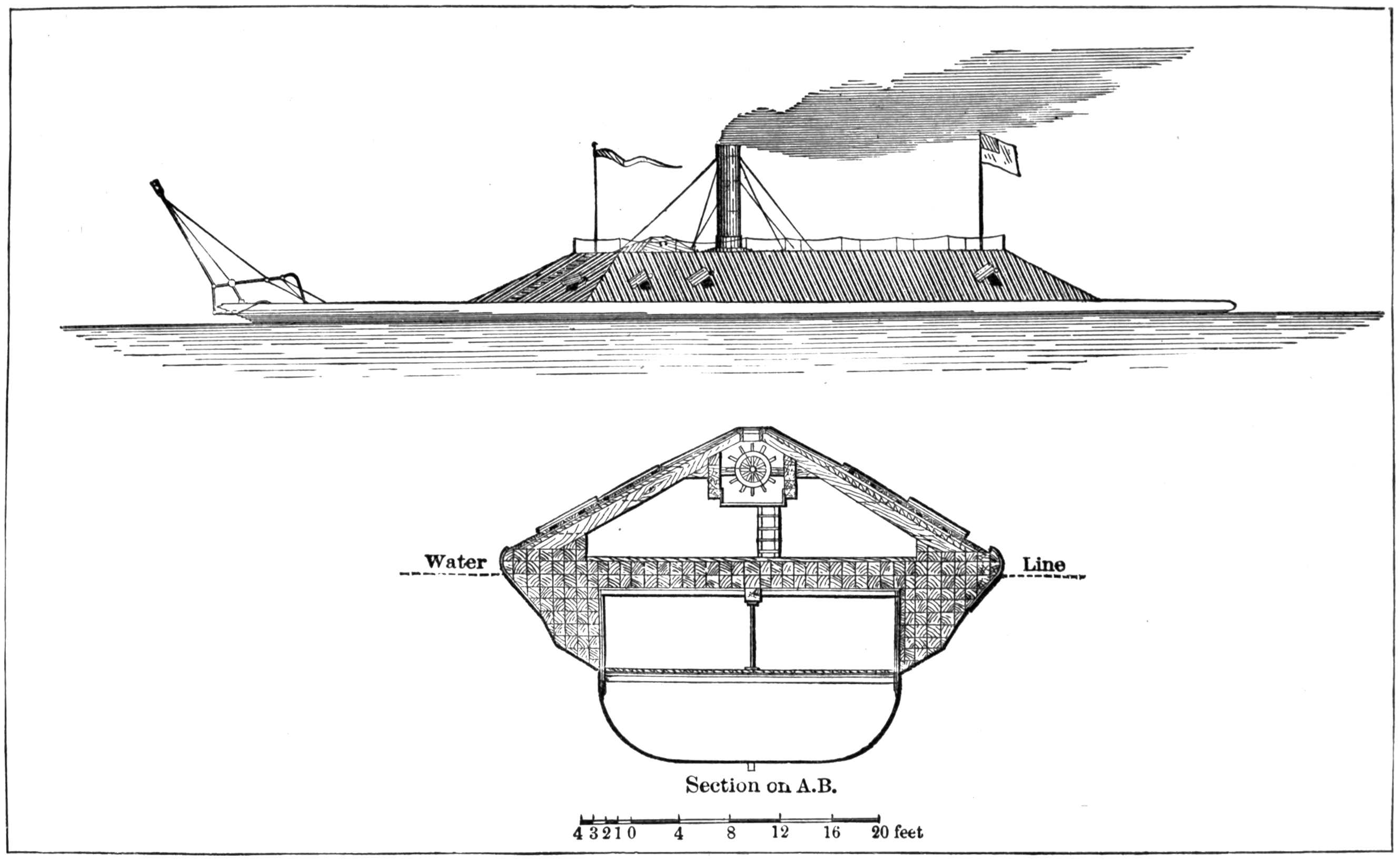

| The Monitor, | 192 |

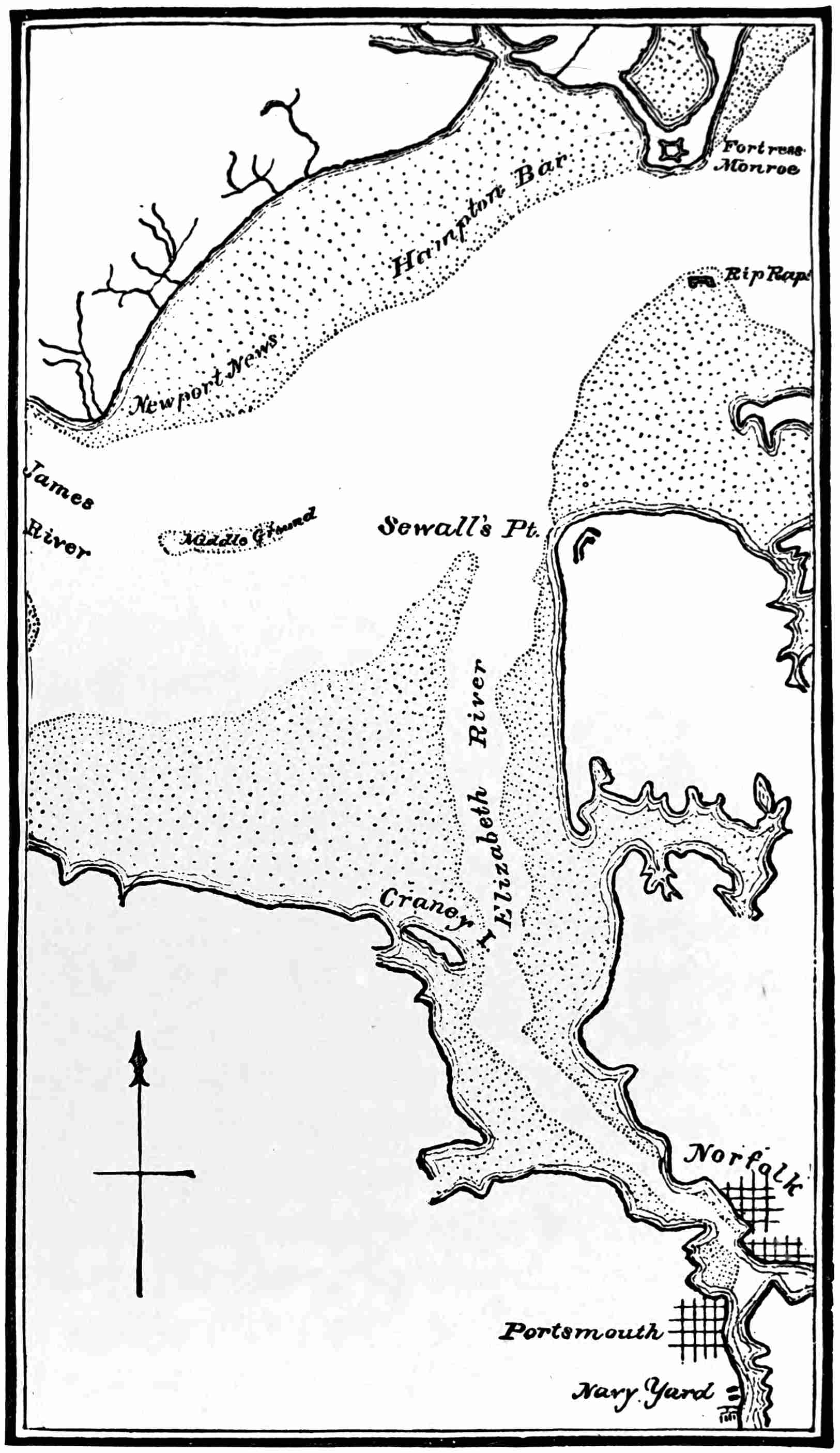

| Hampton Roads. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 196 |

| Fortress Monroe and its Vicinity, | 199 |

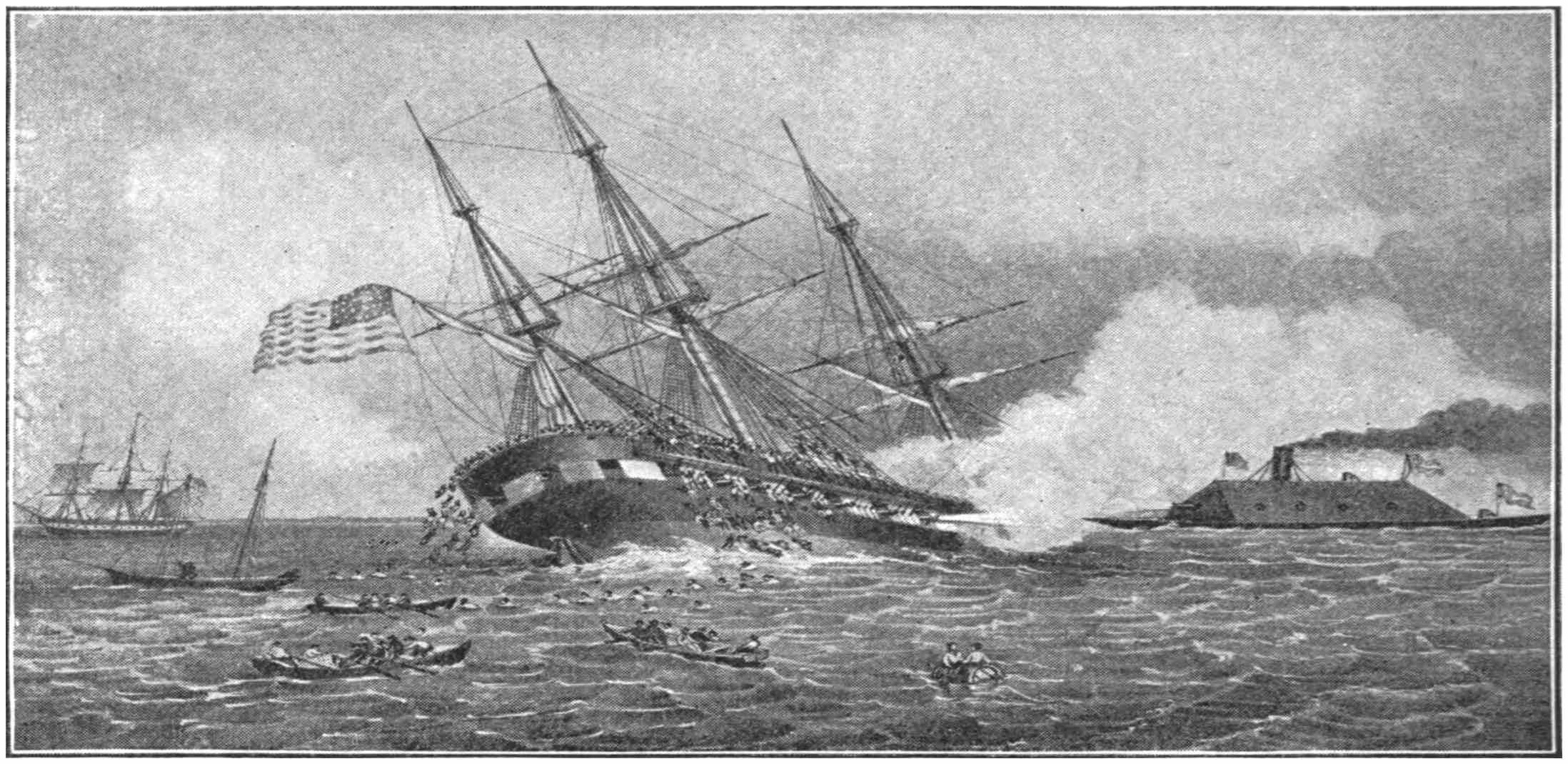

| The Sinking of the Cumberland by the Ironclad Merrimac. (From a lithograph published by Currier & Ives), | 202 |

| The Merrimac Ramming the Cumberland. (From a drawing by M. J. Burns), | 205 |

| George U. Morris. (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 207 |

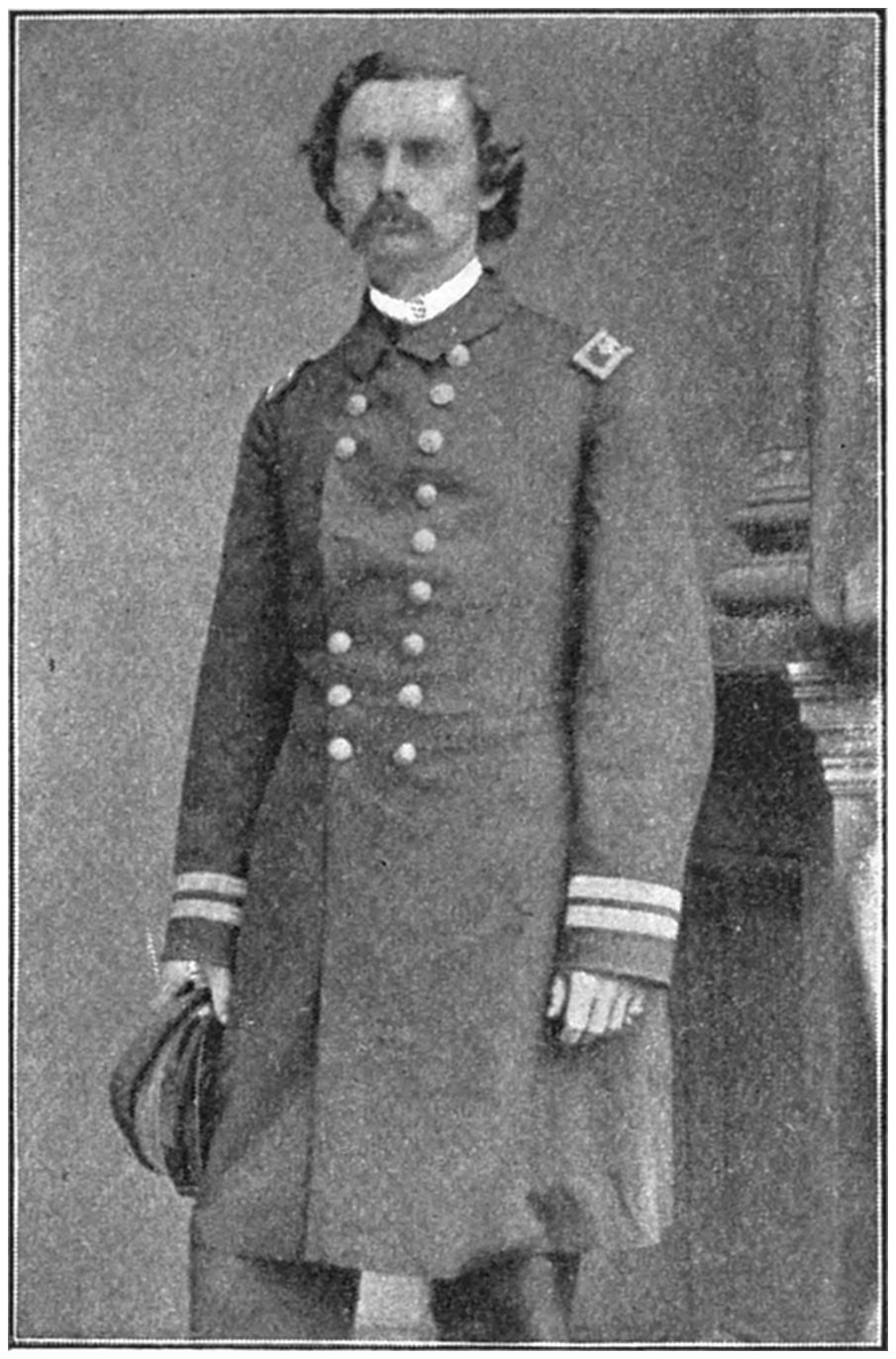

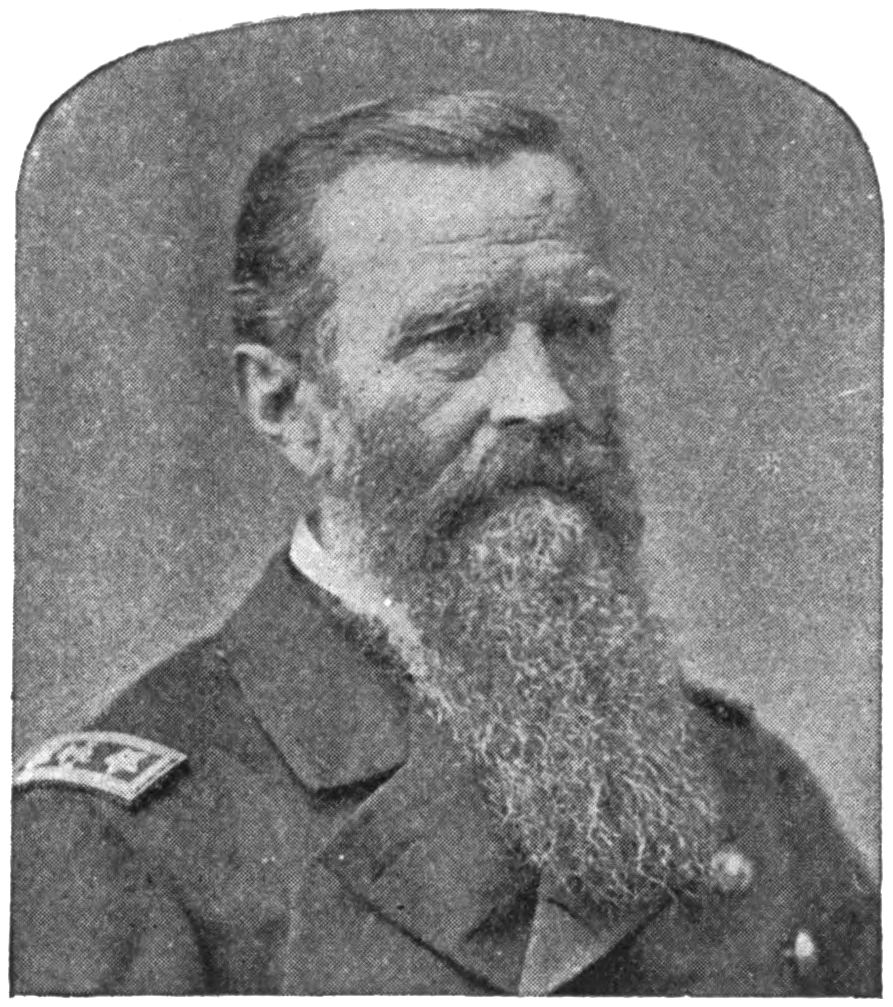

| J. L. Worden. (From a photograph), | 216 |

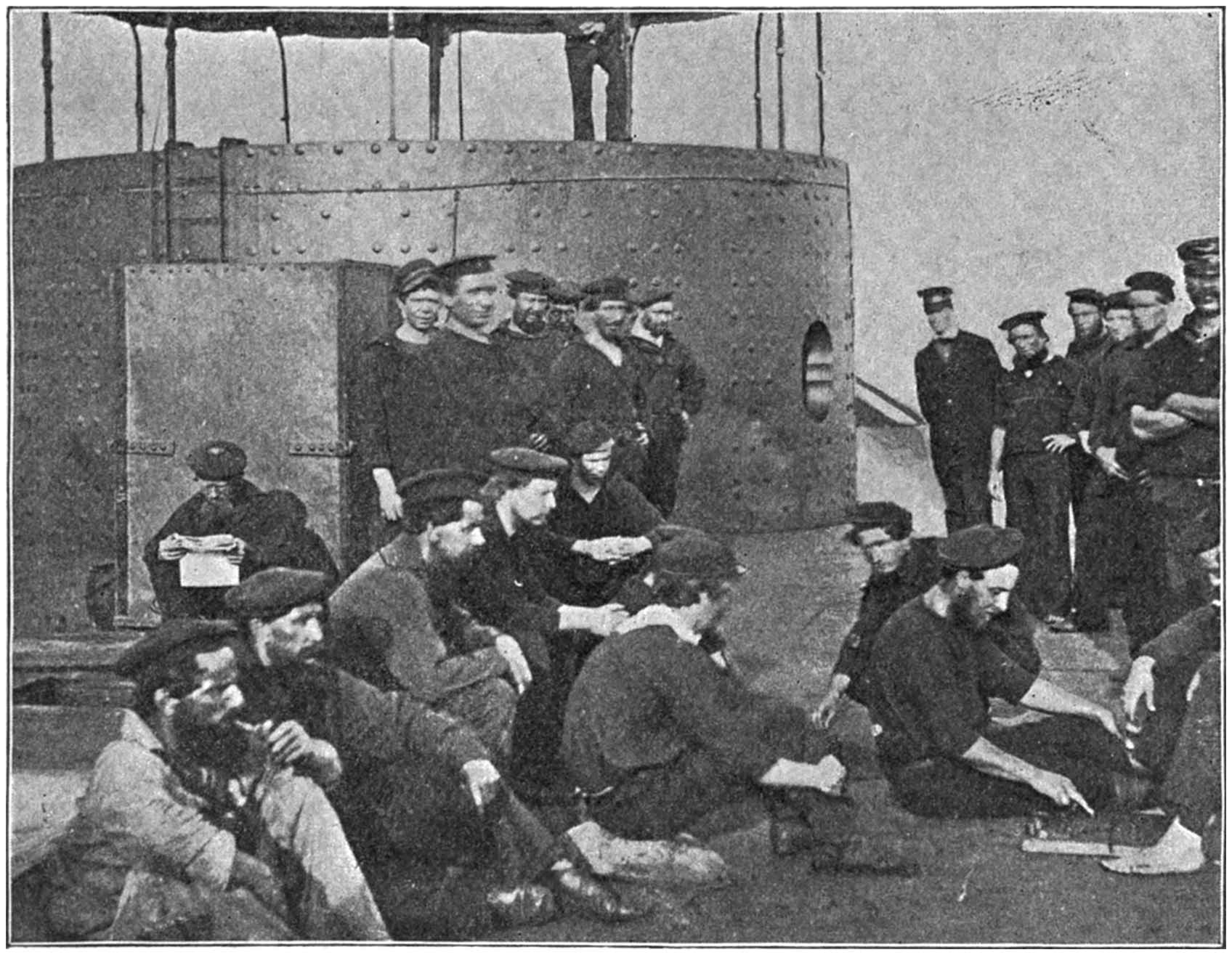

| Deck View of the Monitor and her Crew. (From a photograph), | 219xviii |

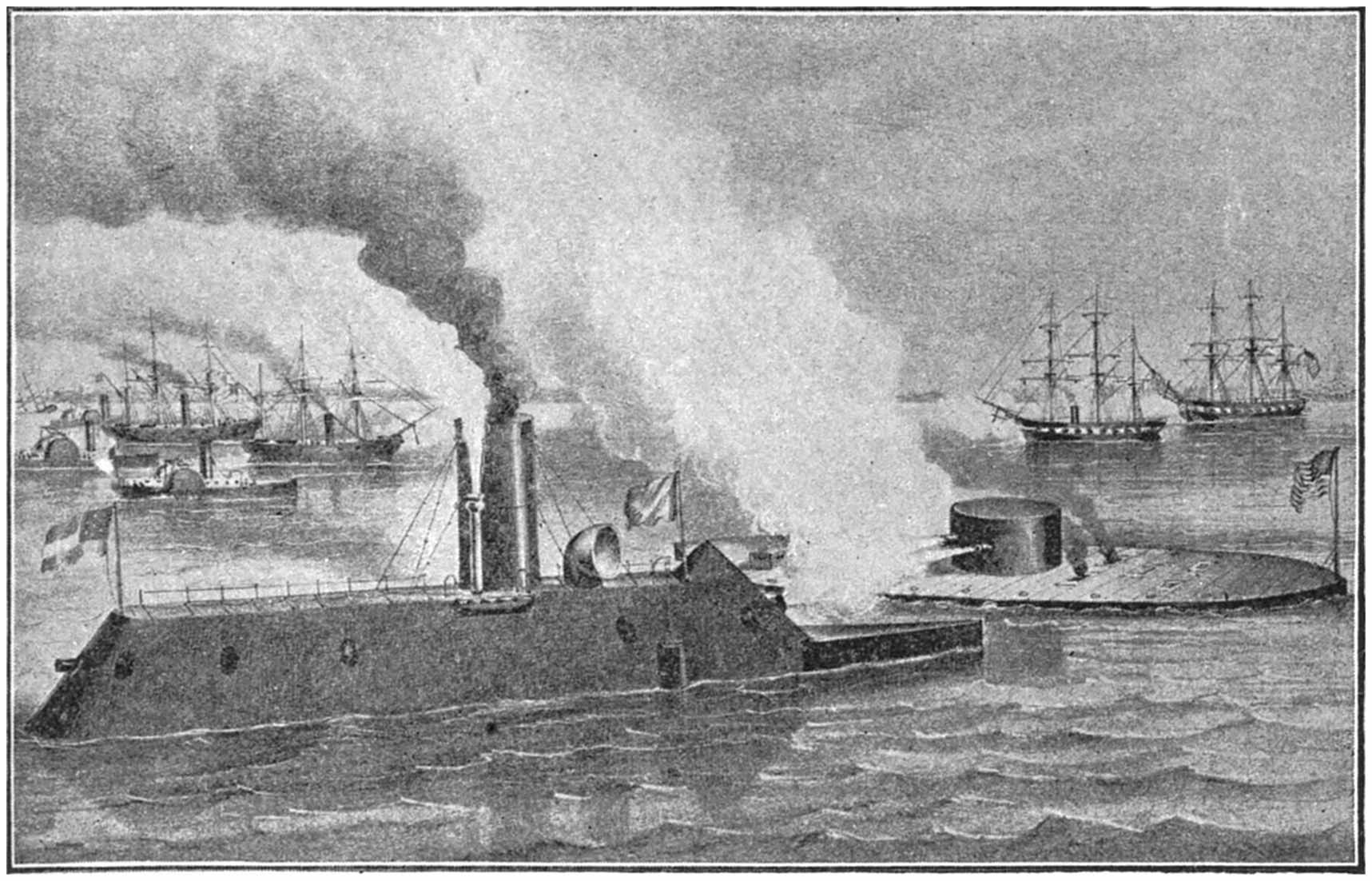

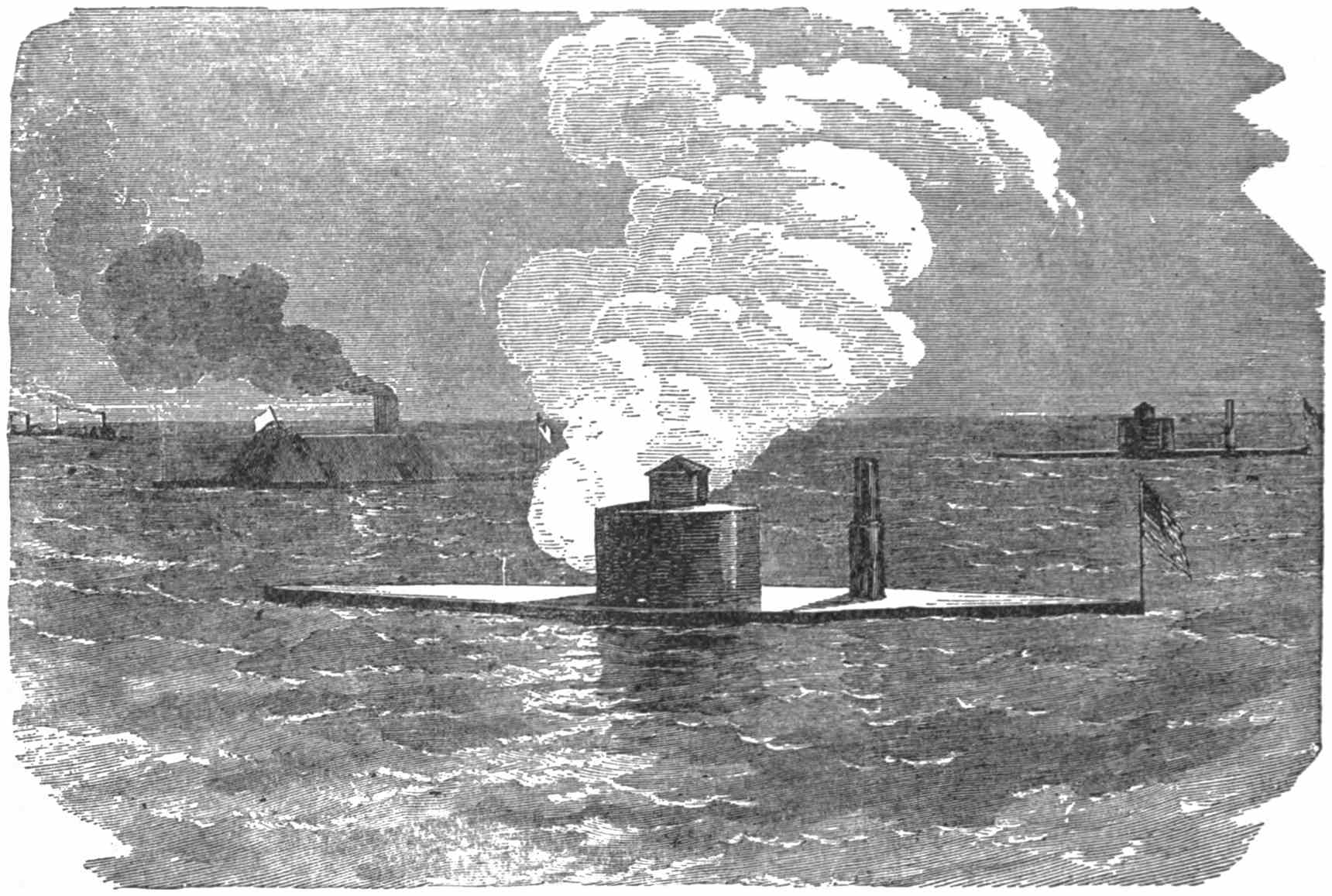

| The Fight between the Merrimac and the Monitor. (From a lithograph published by Currier & Ives), | 221 |

| In the Monitor’s Turret, | 223 |

| The Action between the Monitor and the Merrimac. (From an engraving of the picture by Chappel), | 227 |

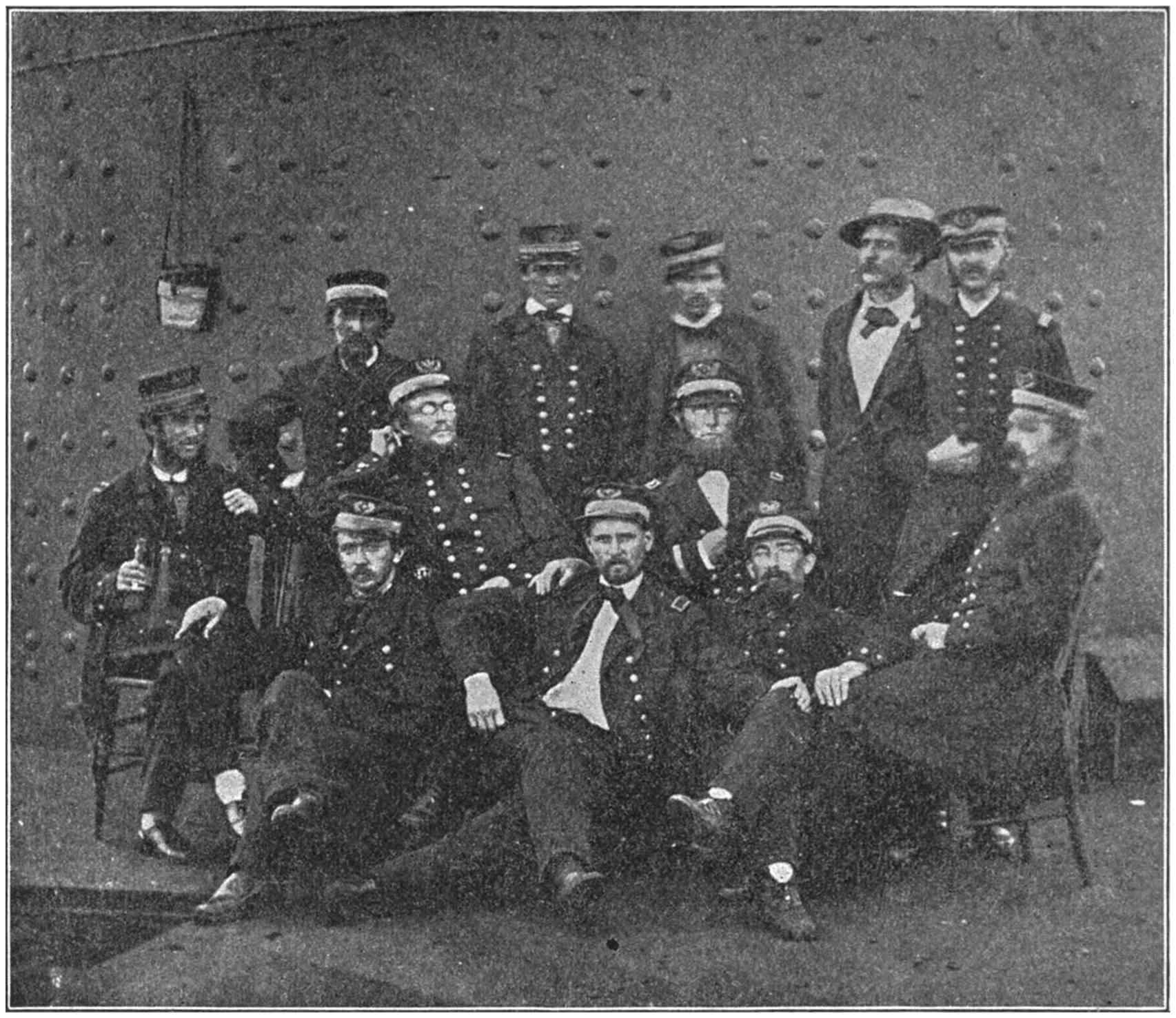

| Group of Officers on Deck of the Monitor. (From a photograph), | 232 |

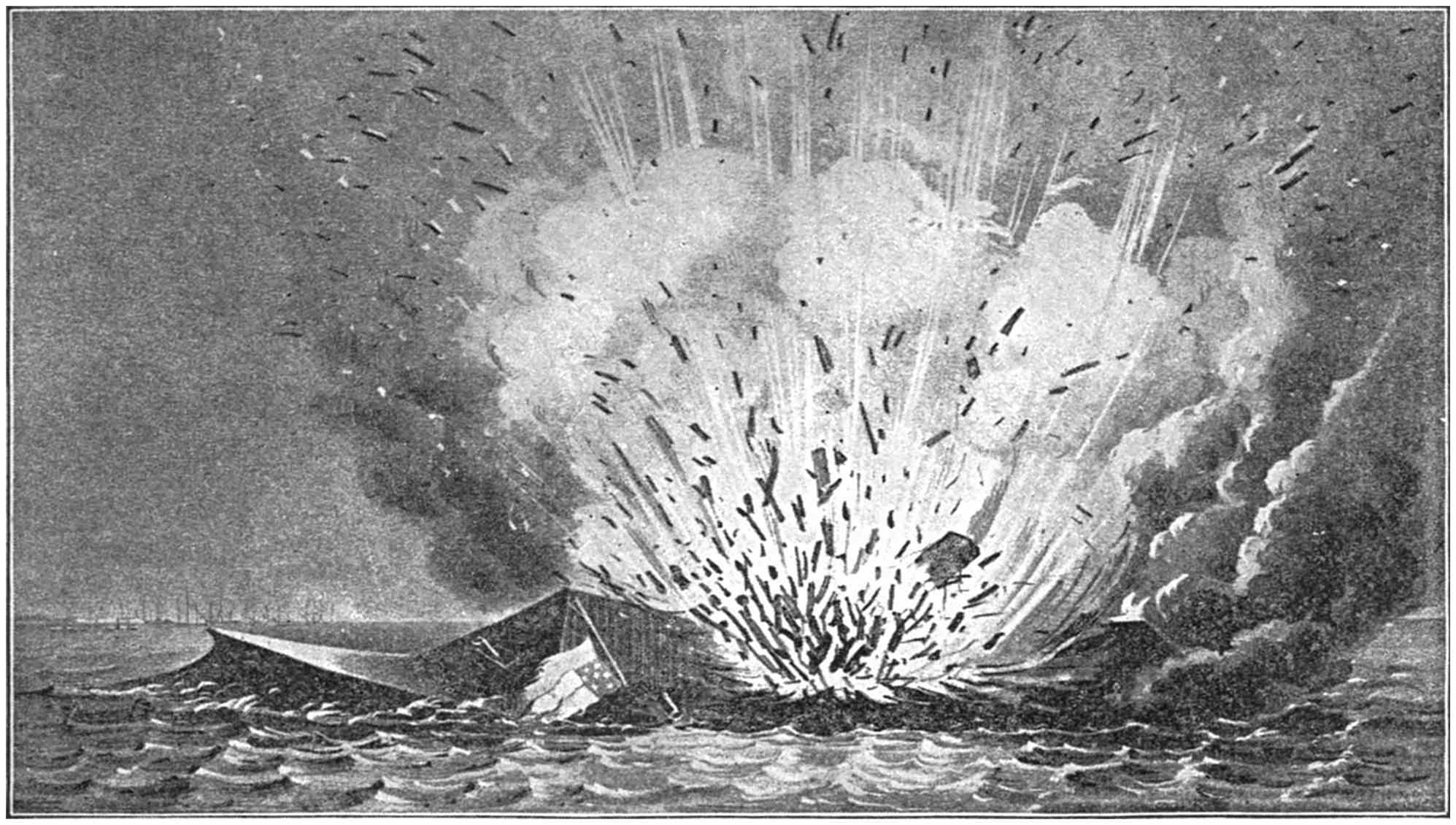

| Destruction of the Merrimac off Craney Island. (From a lithograph published by Currier & Ives), | 237 |

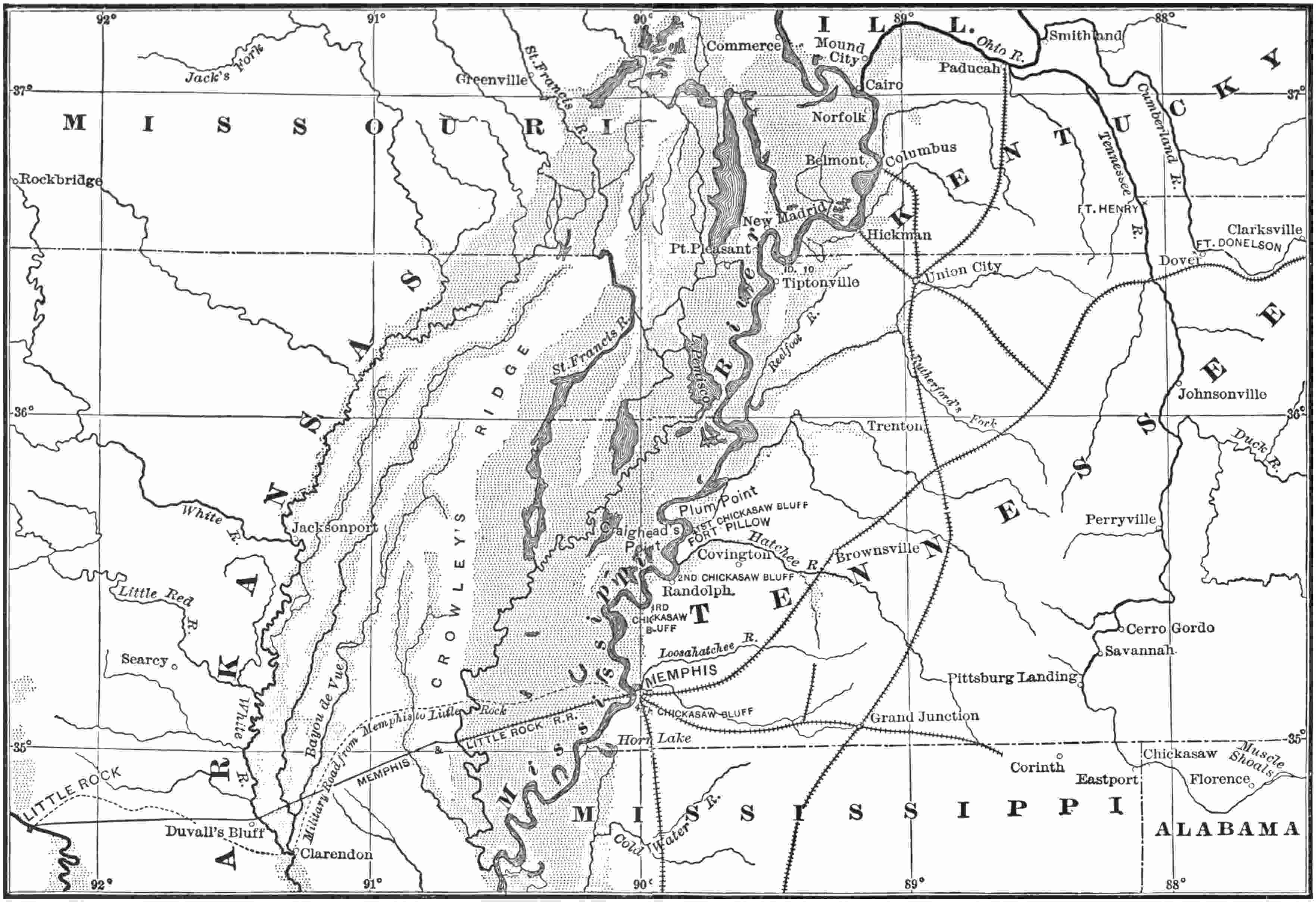

| Mississippi Valley—Cairo to Memphis. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 242–3 |

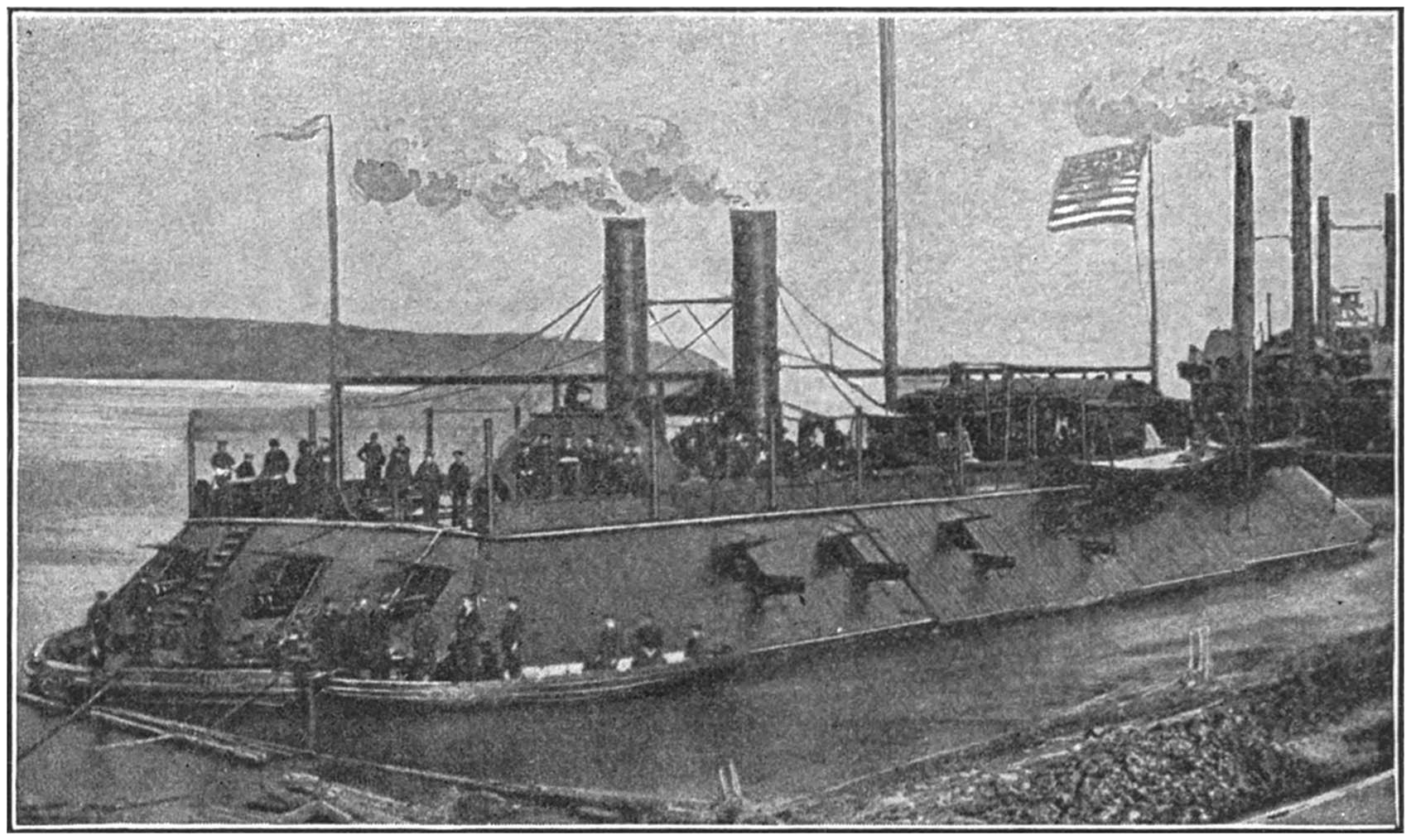

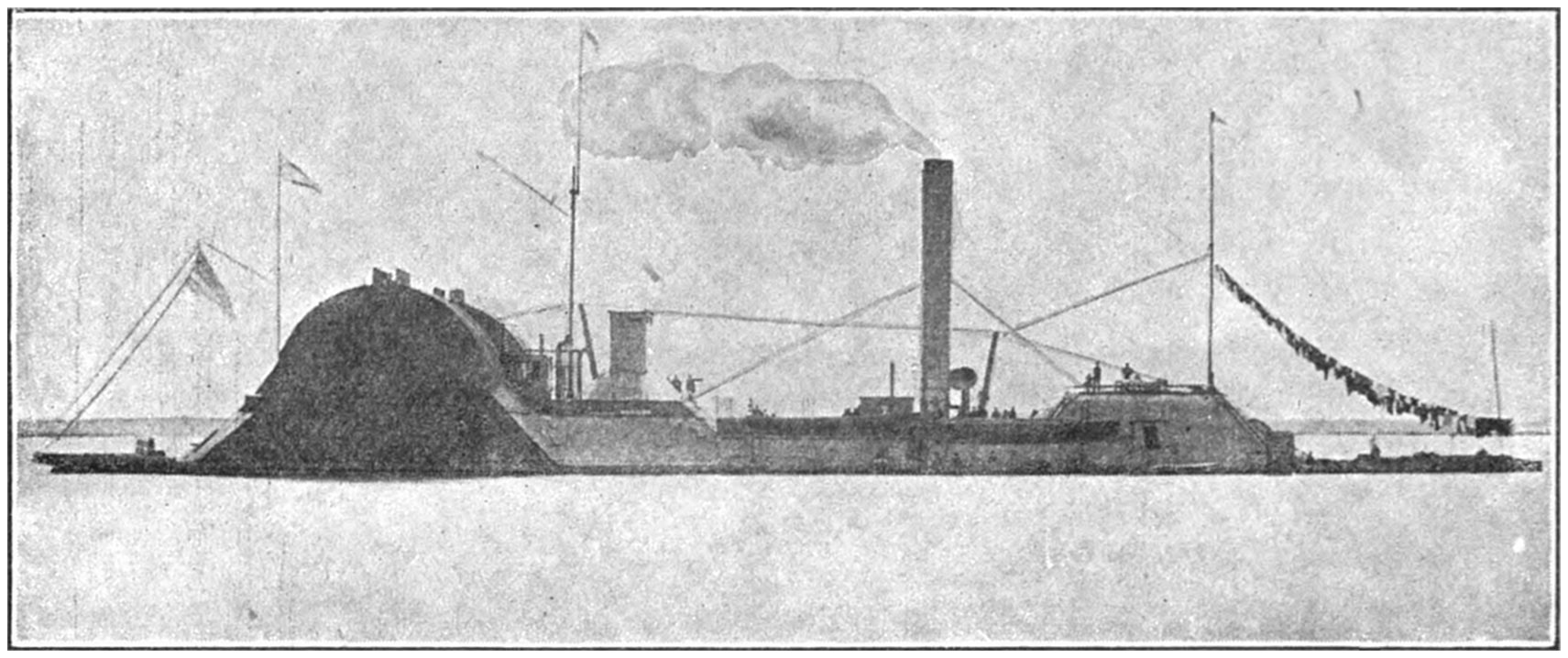

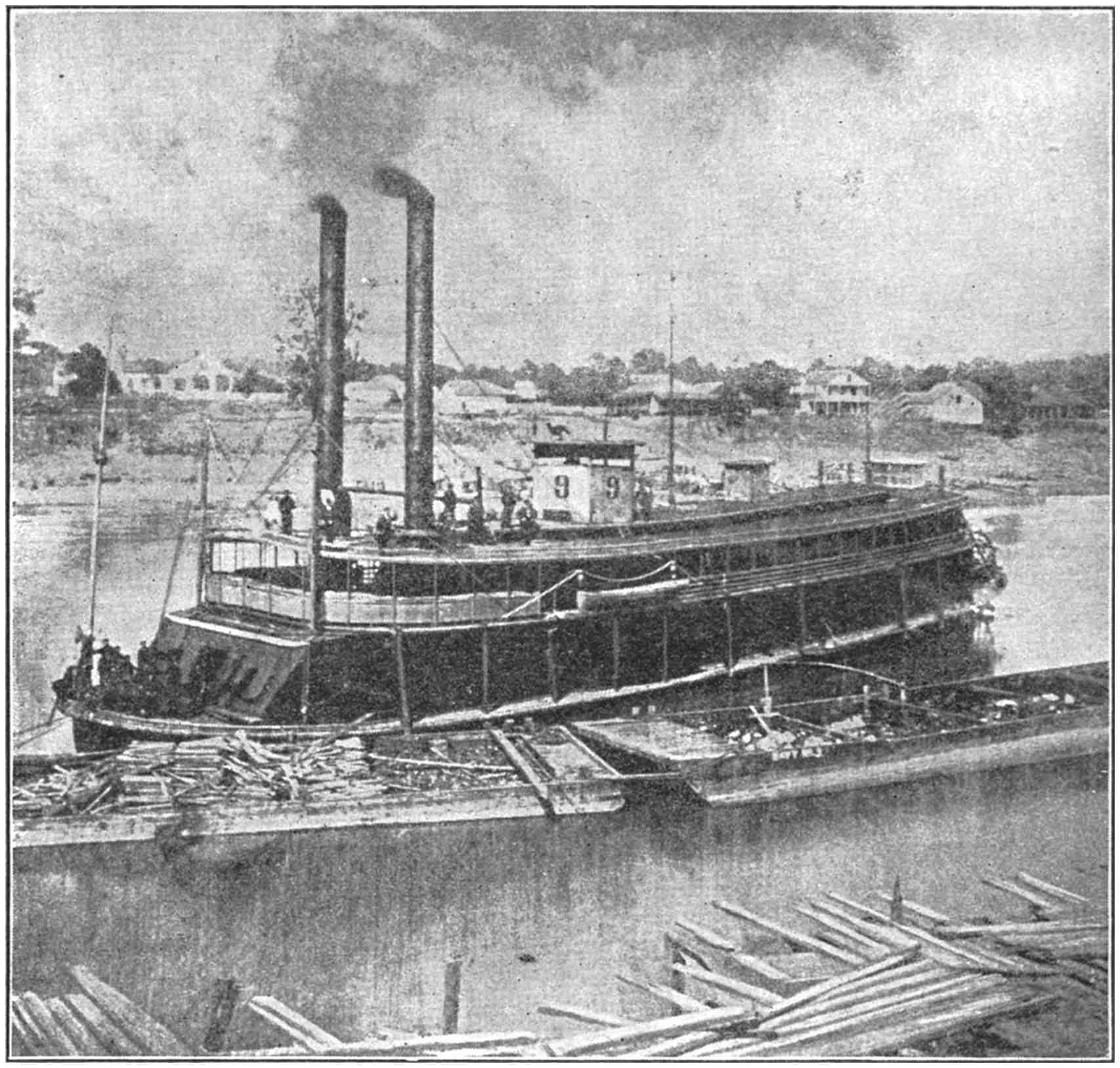

| The Cairo. (From a photograph), | 244 |

| The Pittsburg. (After a photograph), | 245 |

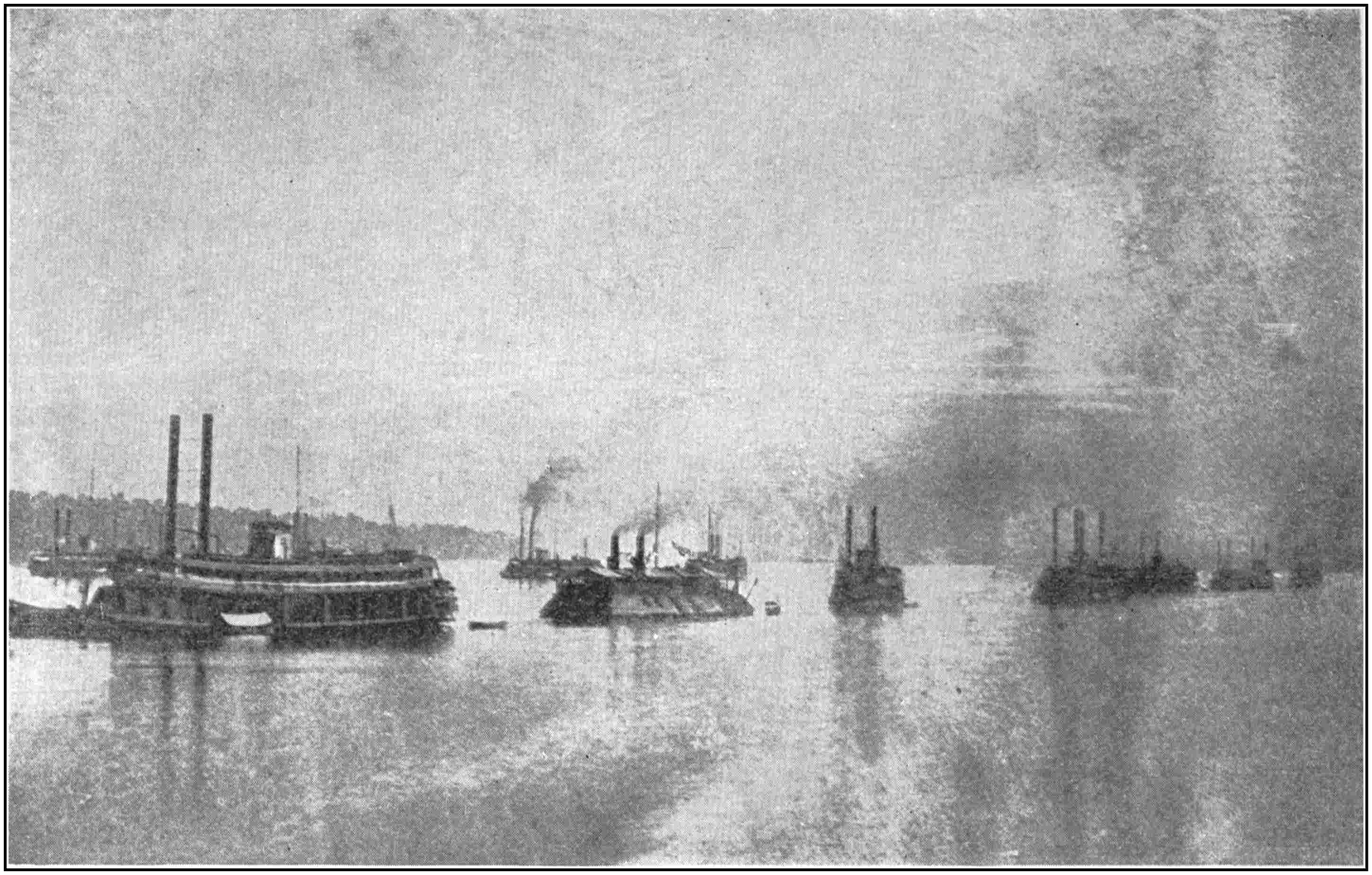

| The Mississippi Fleet off Mound City, Illinois. (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 247 |

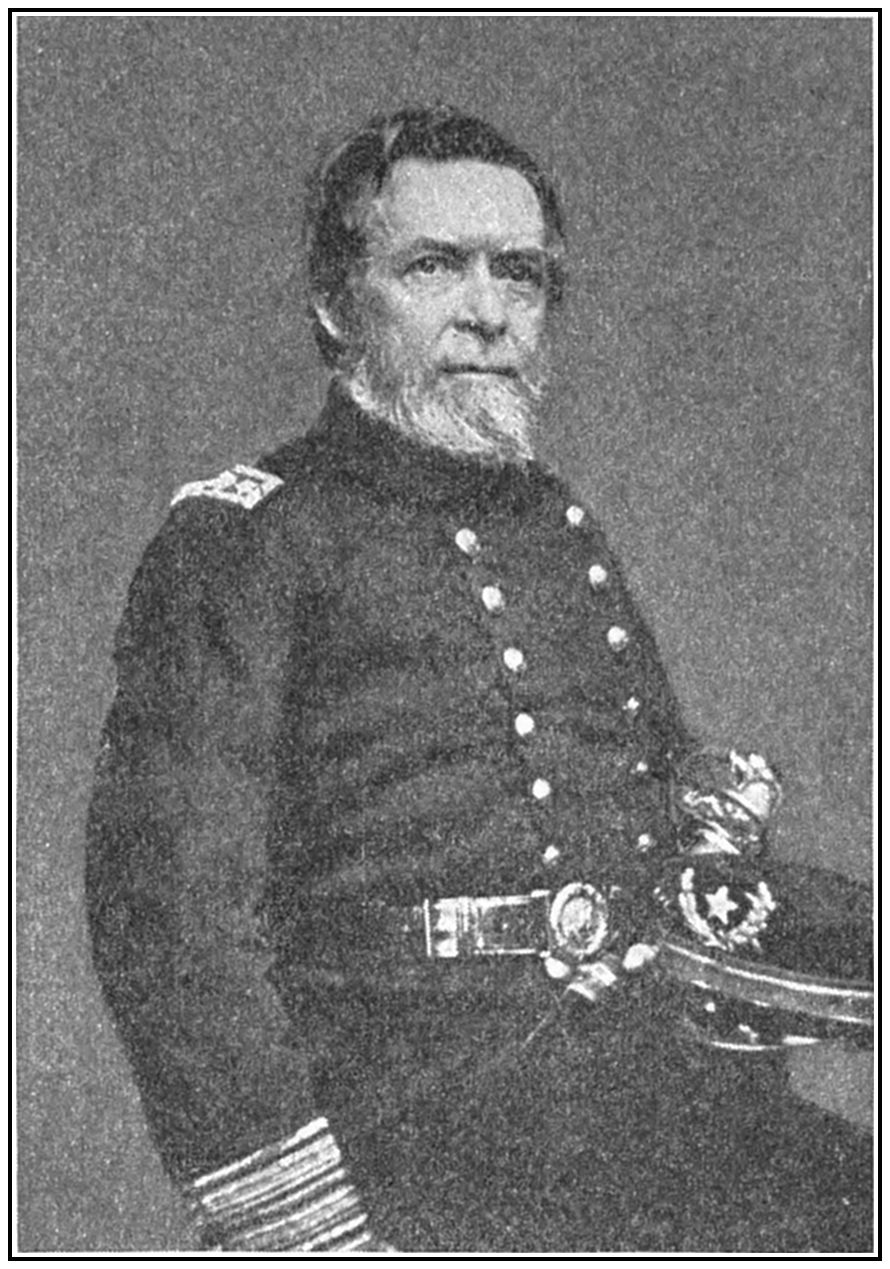

| A. H. Foote. (From a photograph), | 250 |

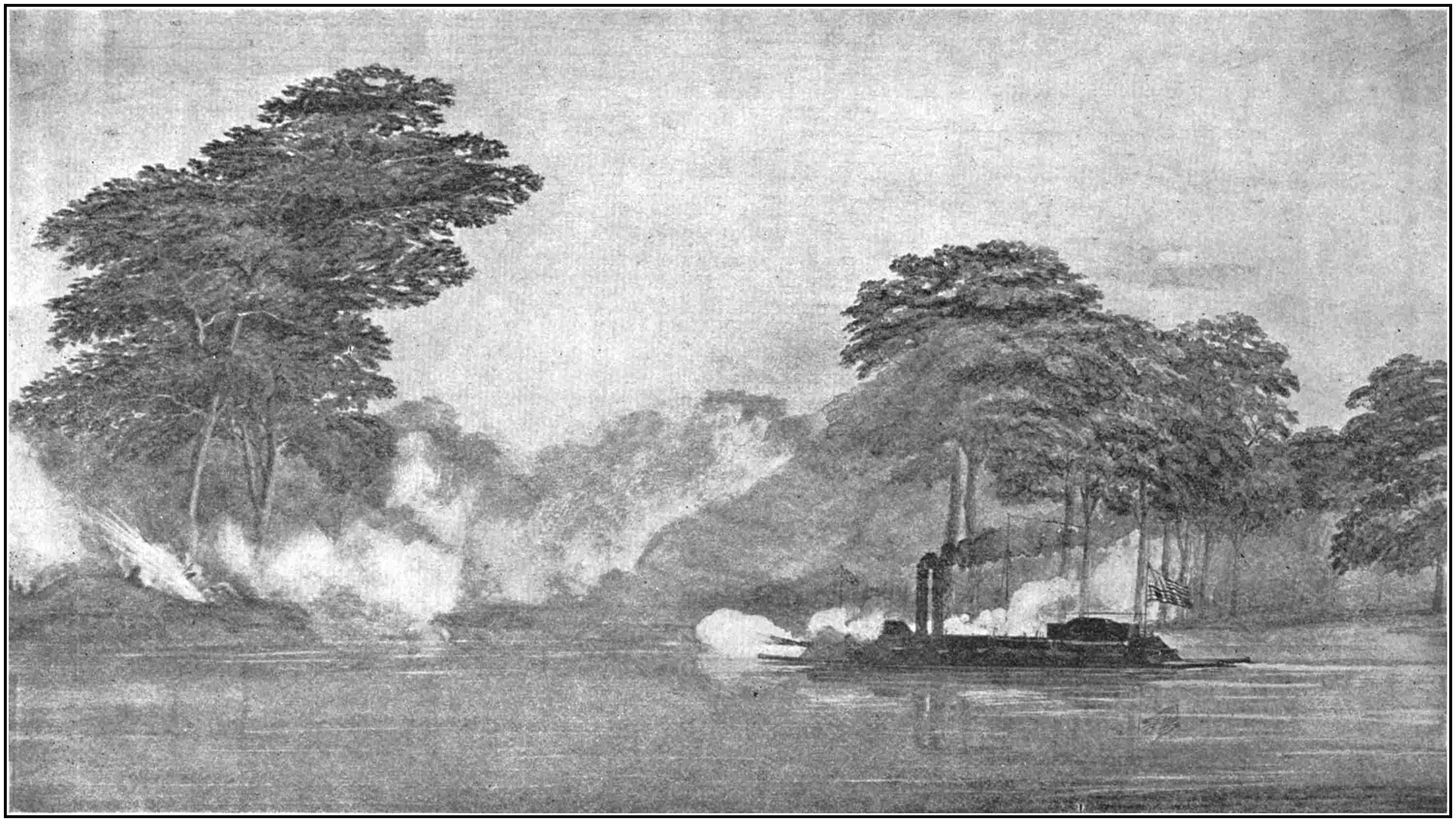

| The Battle of Belmont: First Attack by the Taylor and the Lexington. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 253 |

| Battle of Belmont: U. S. Gunboats Repulsing the Enemy during the Debarkation. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 257 |

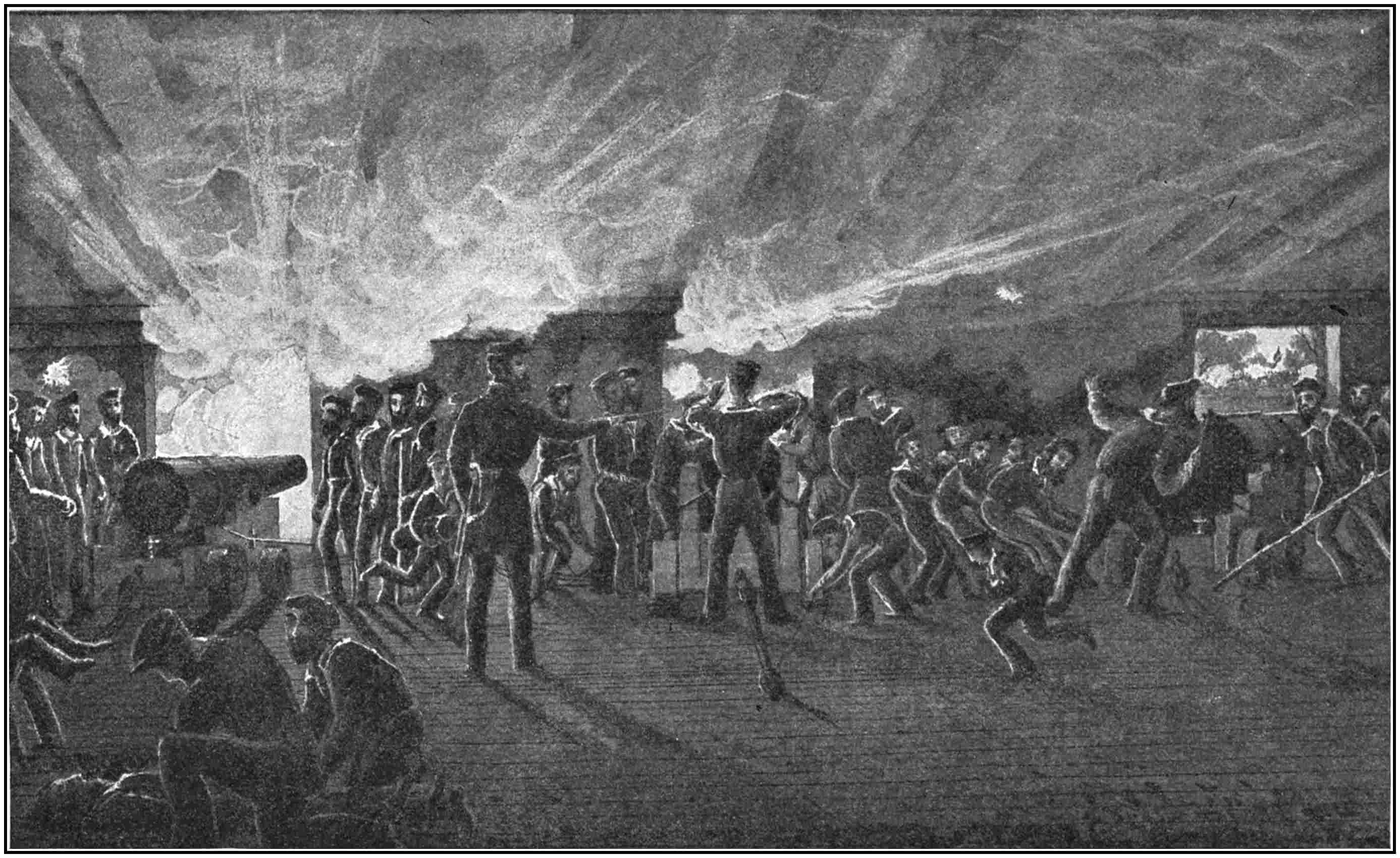

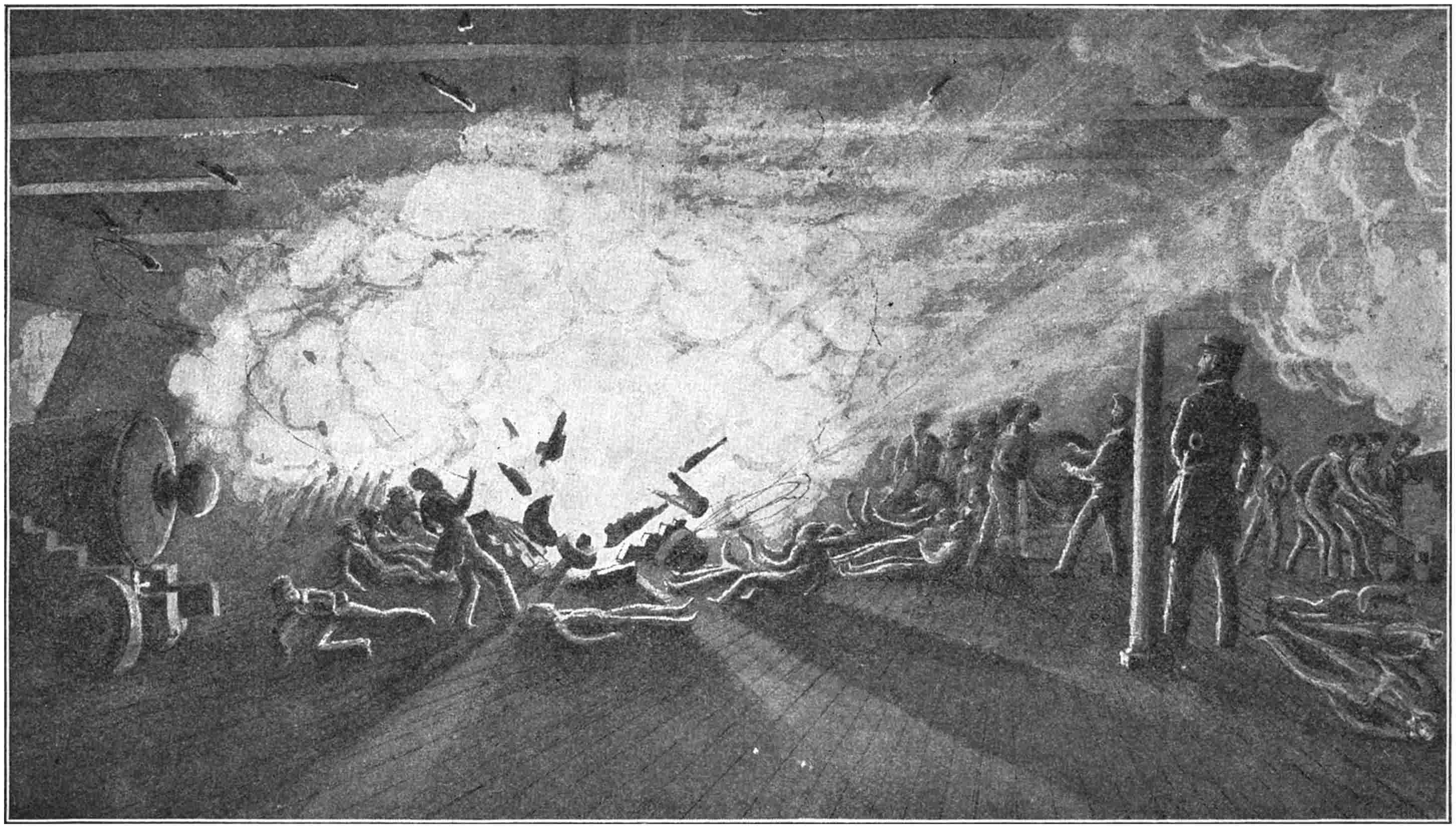

| Interior of the Taylor during the Battle of Belmont. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 259 |

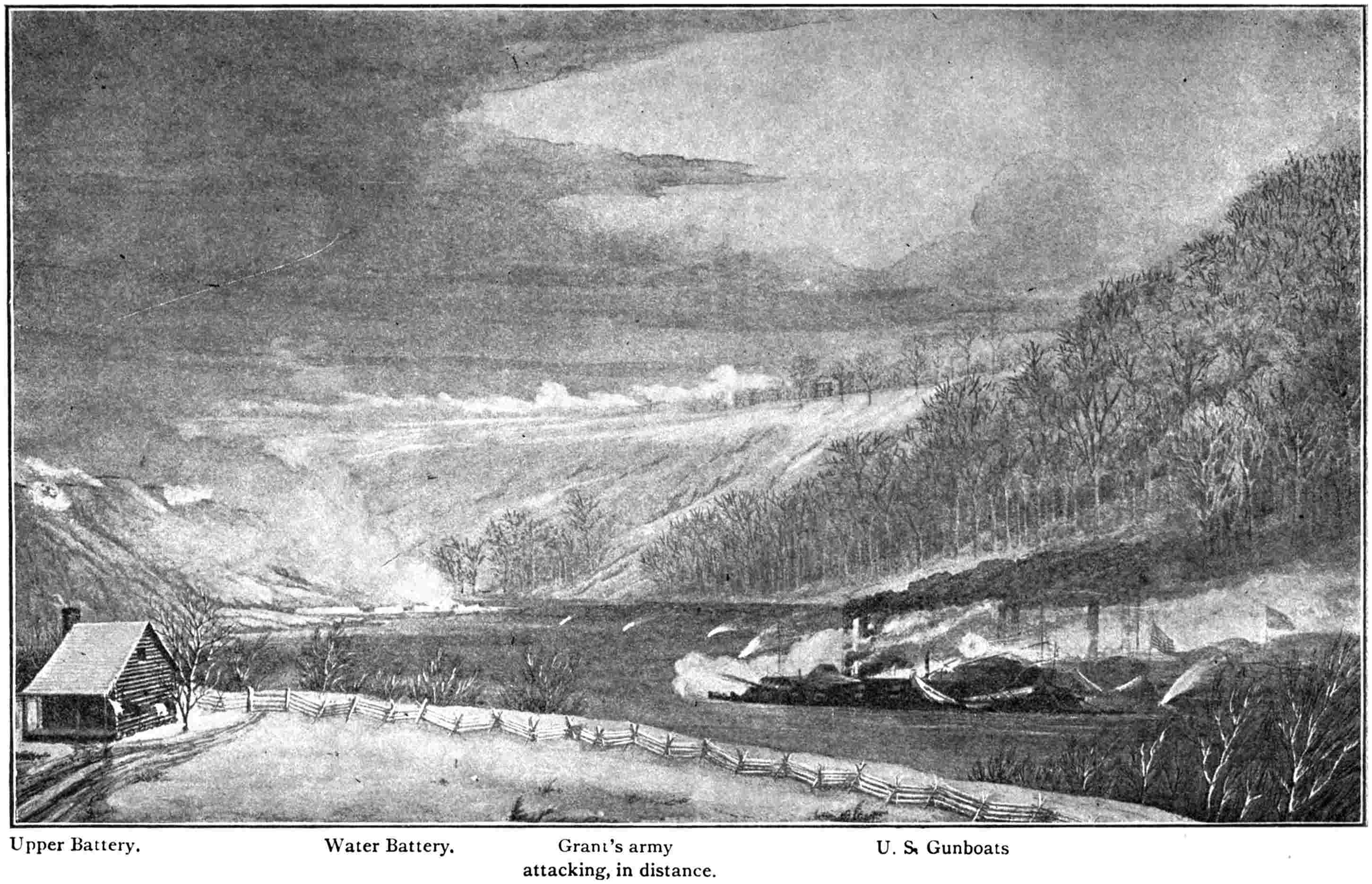

| Battle of Fort Henry. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 263 |

| Battle of Fort Donelson. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 269 |

| Explosion on Board the Carondelet at the Battle of Fort Donelson. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 273 |

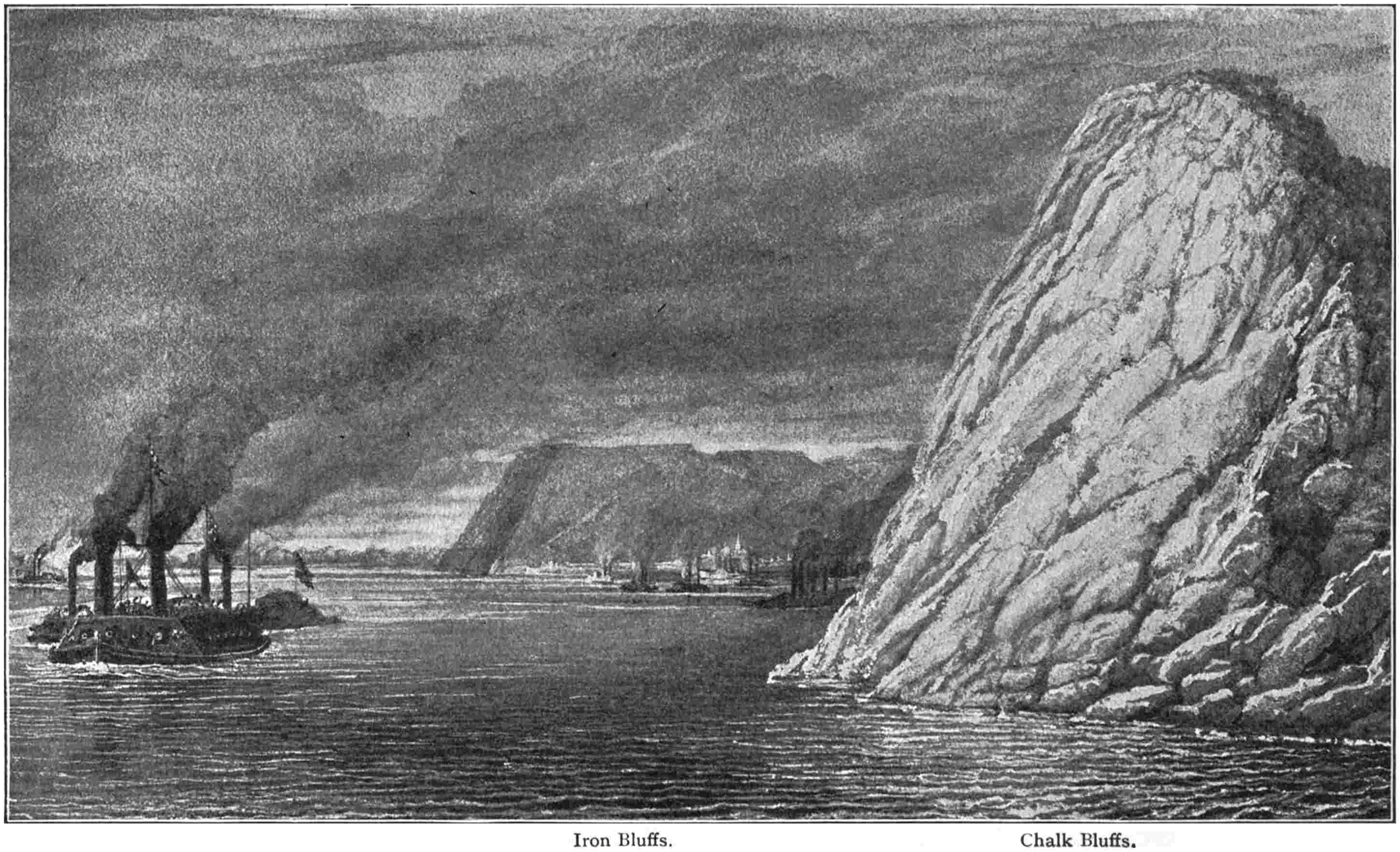

| U. S. Flotilla Descending the Mississippi River. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 277 |

| Battle with Fort No. 1 above Island No. 10. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 279 |

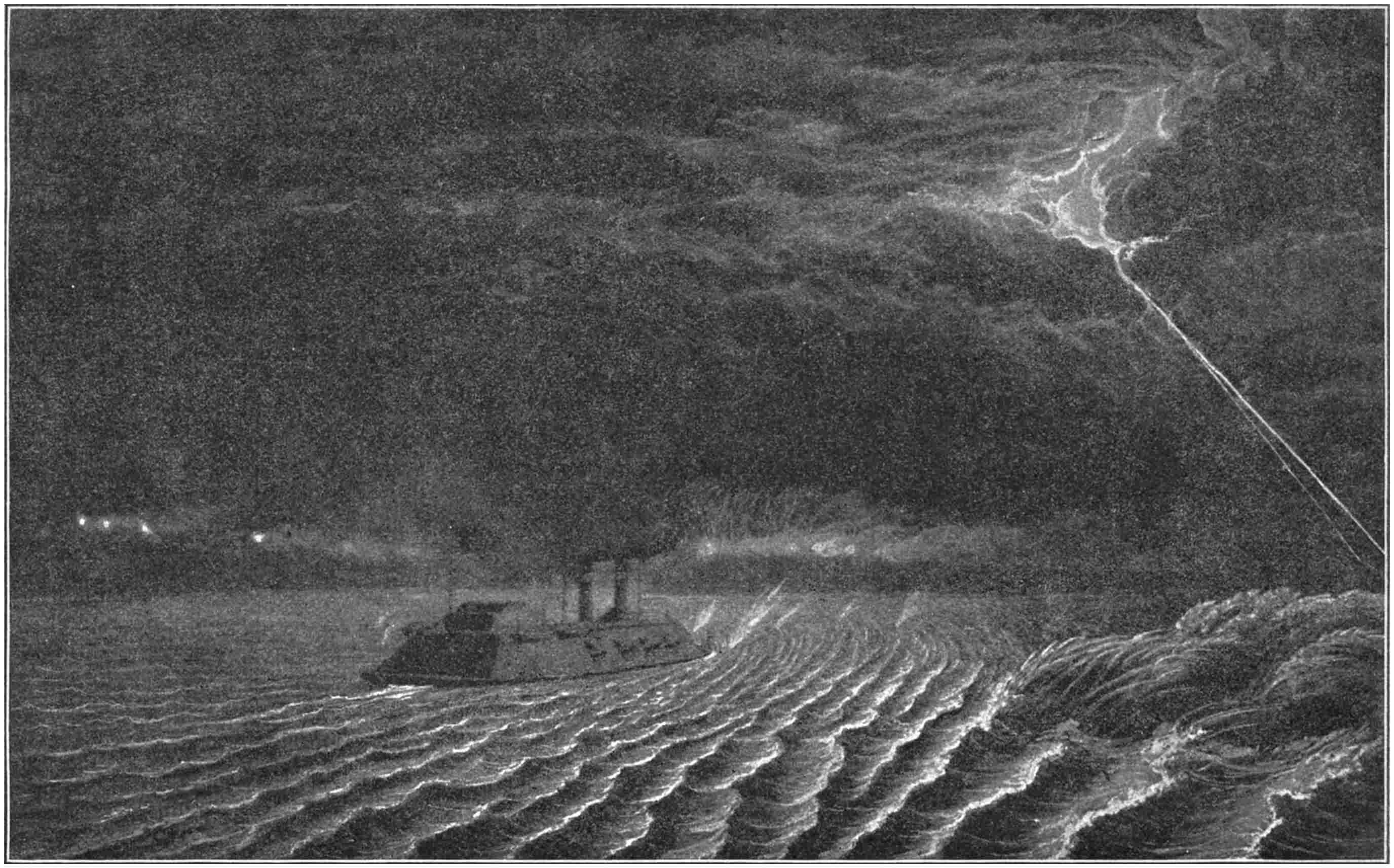

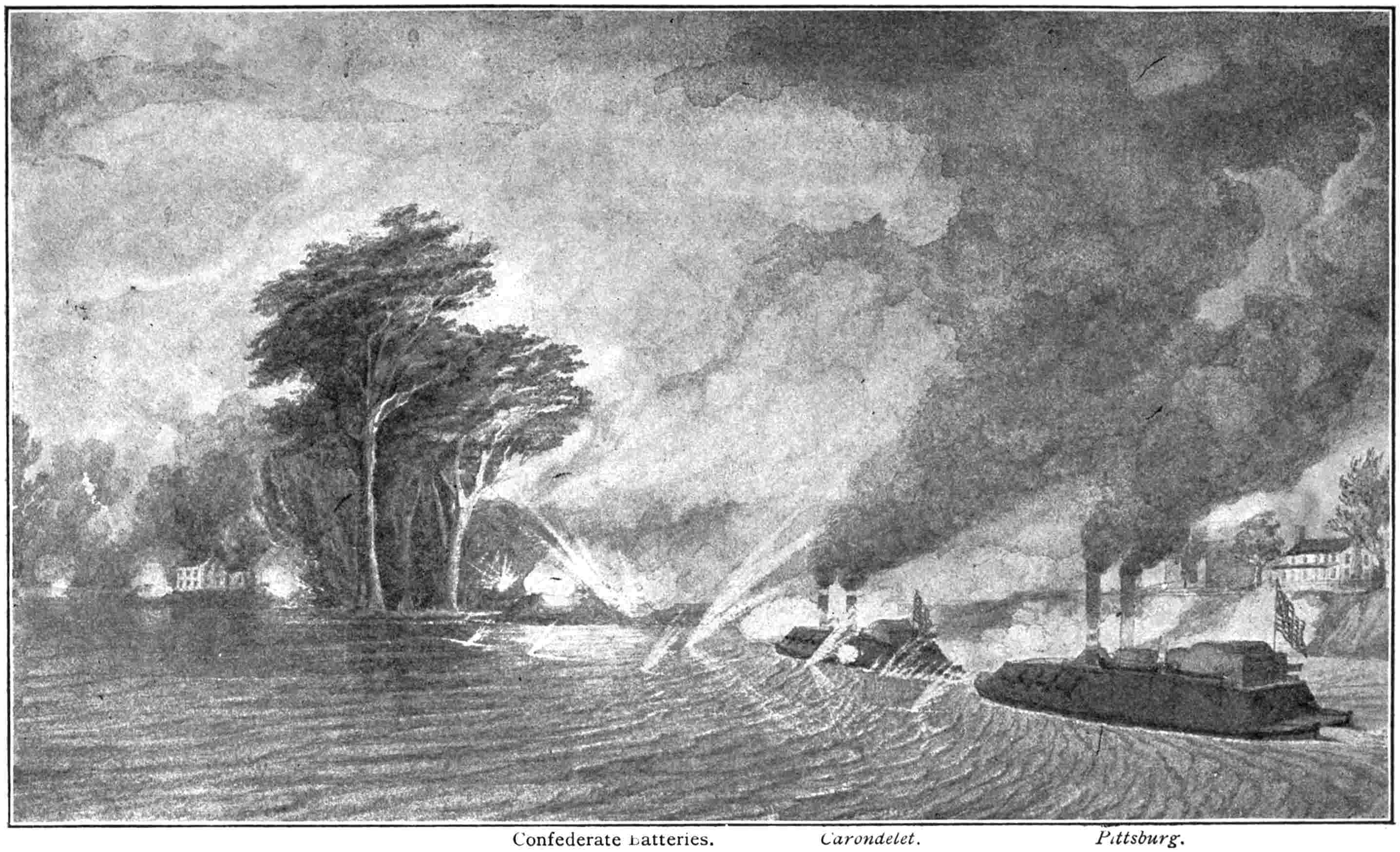

| The Carondelet Running the Gauntlet at Island No. 10. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 285 |

| The Carondelet Attacking the Forts below Island No. 10. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 287 |

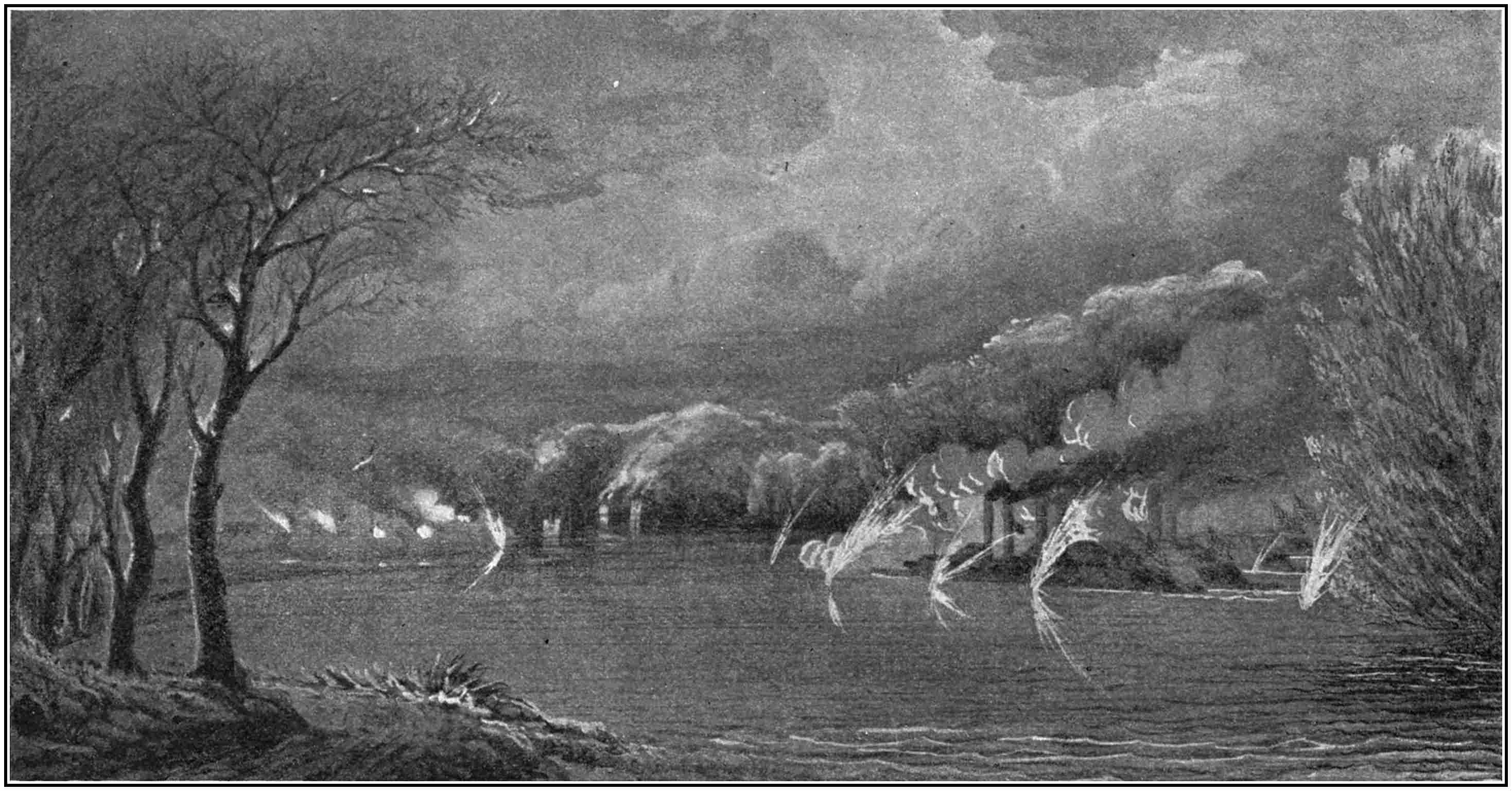

| U. S. Gunboats Capturing the Confederate Forts below Island No. 10, April 7th. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 291 |

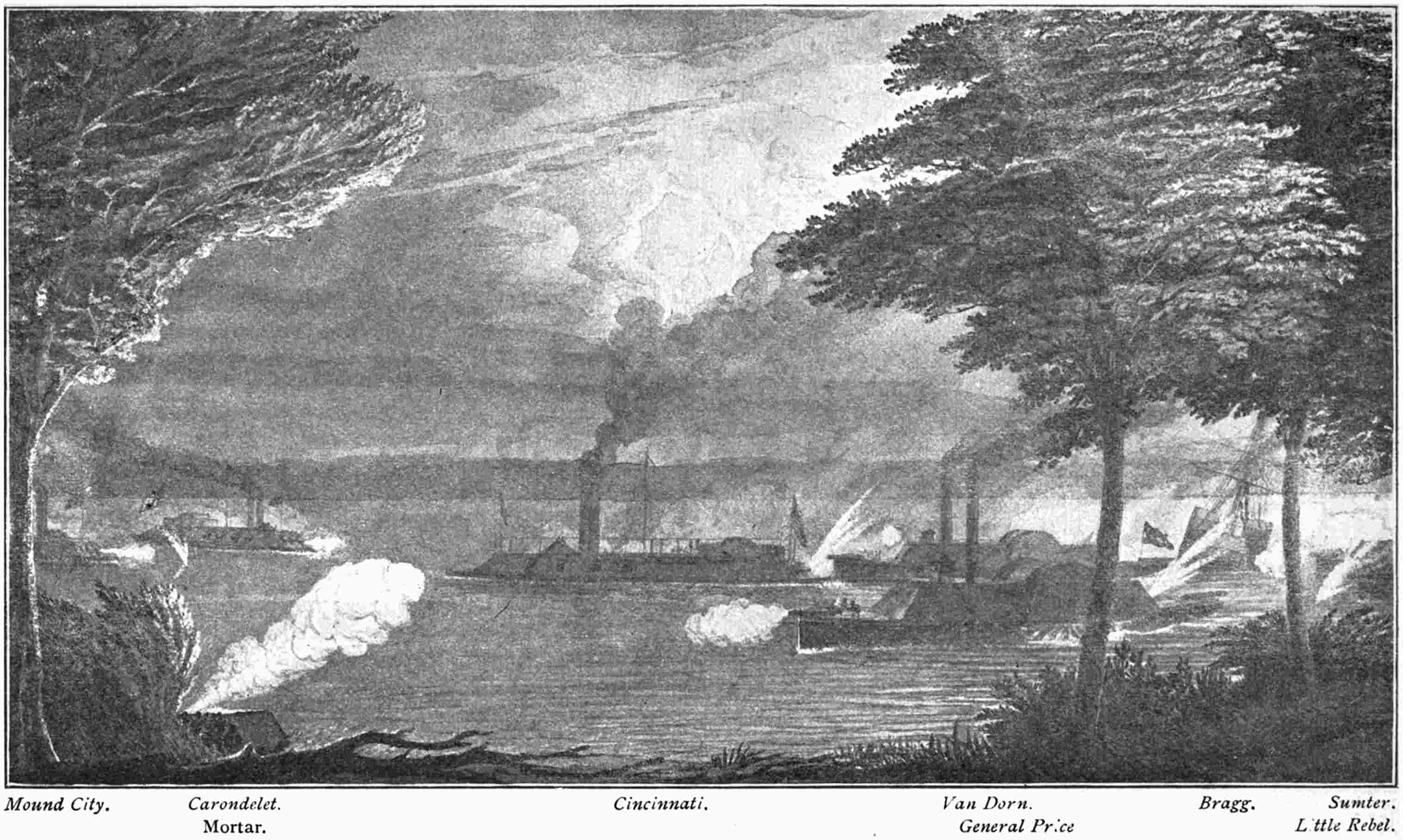

| Battle of Fort Pillow. (From a painting by Admiral Walke) | 295xix |

| The Battle of Fort Pillow. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 299 |

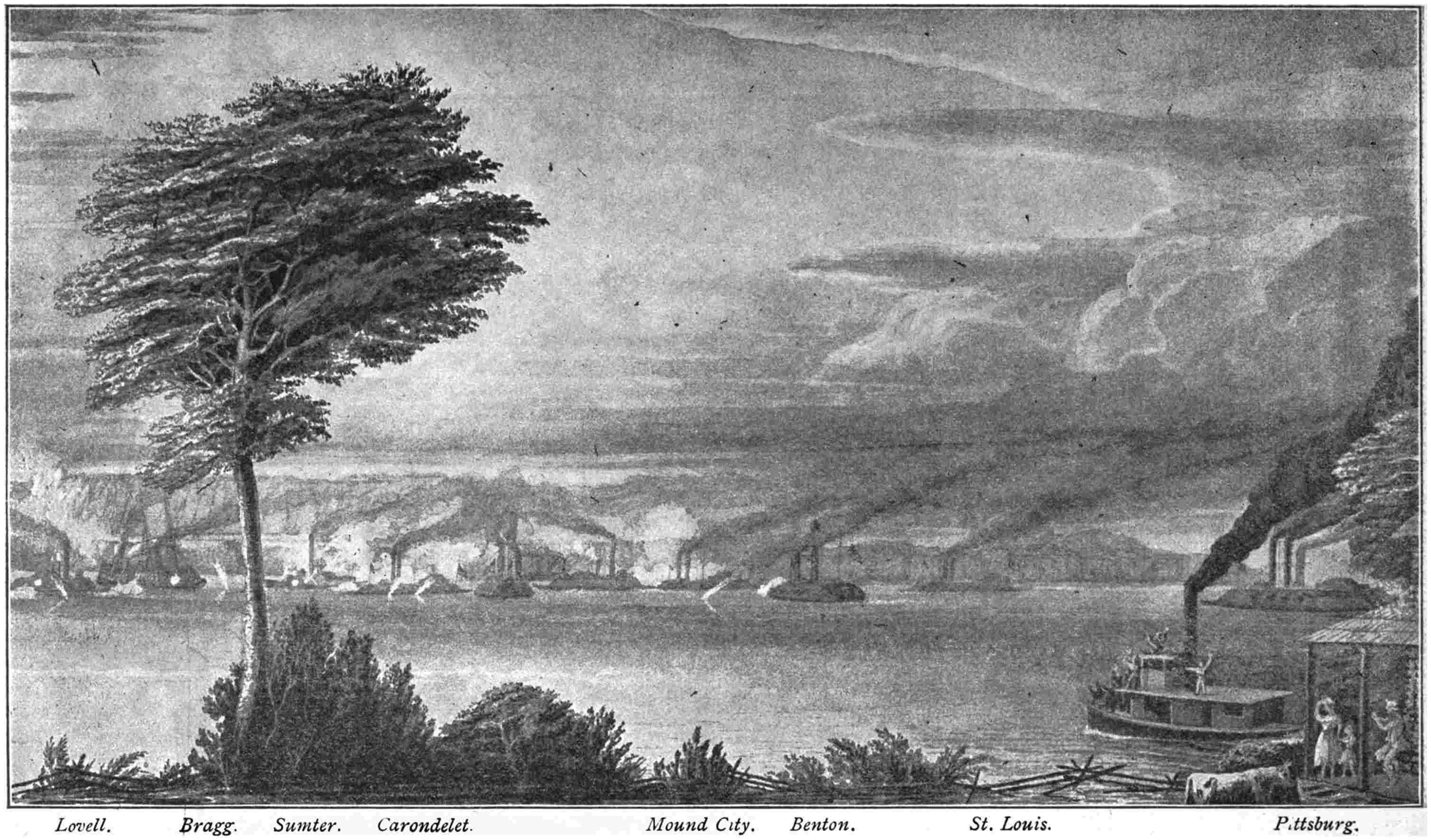

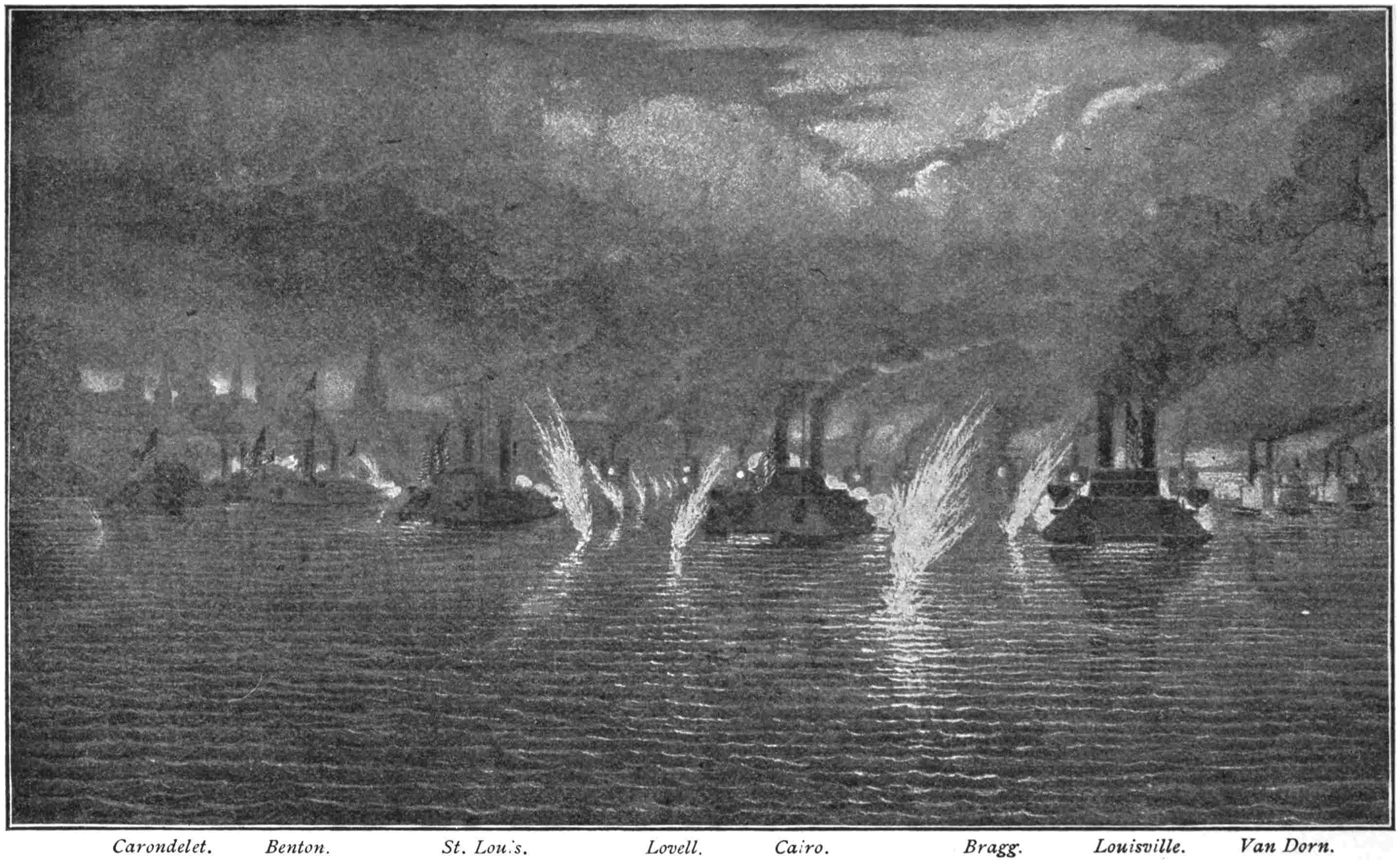

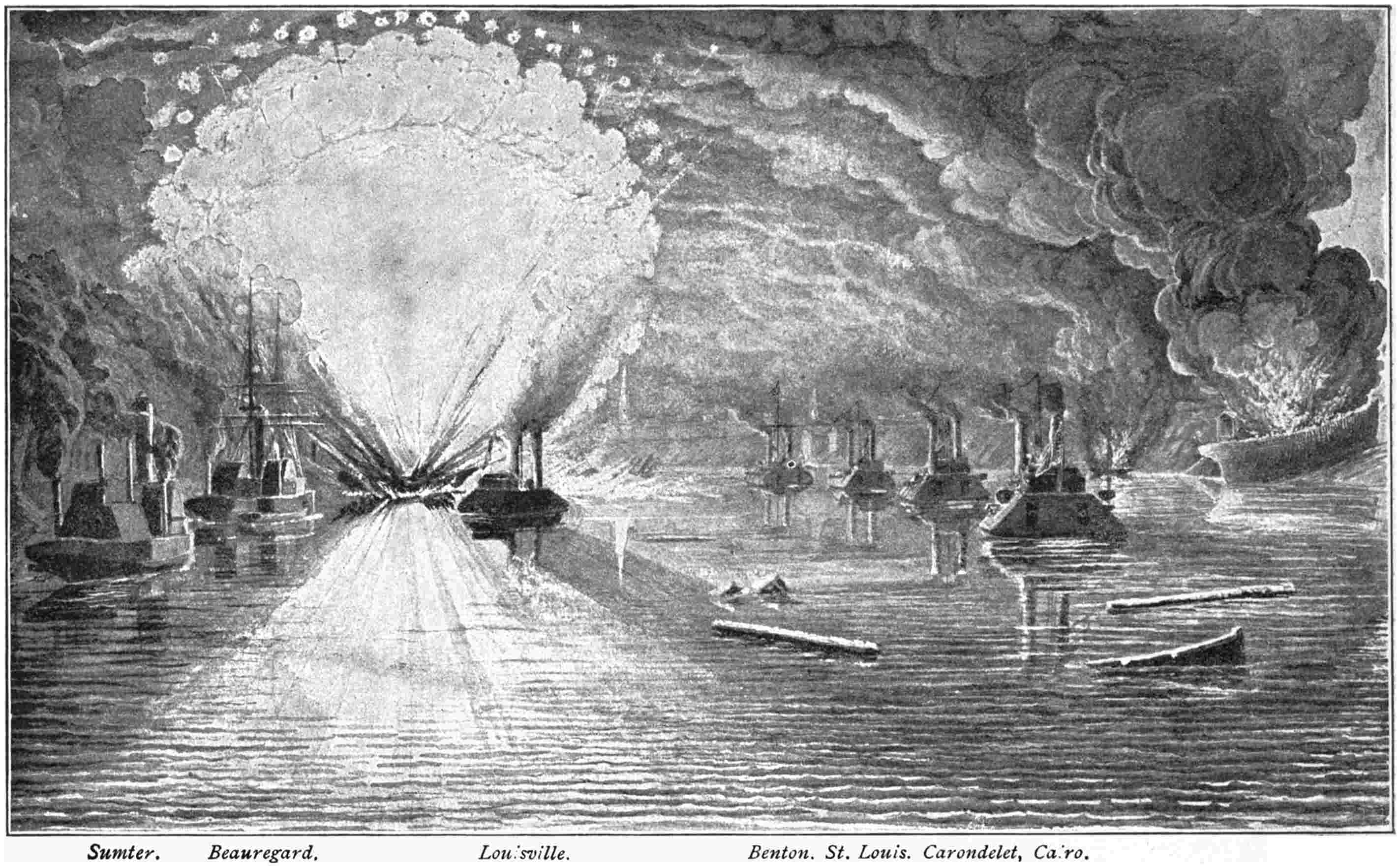

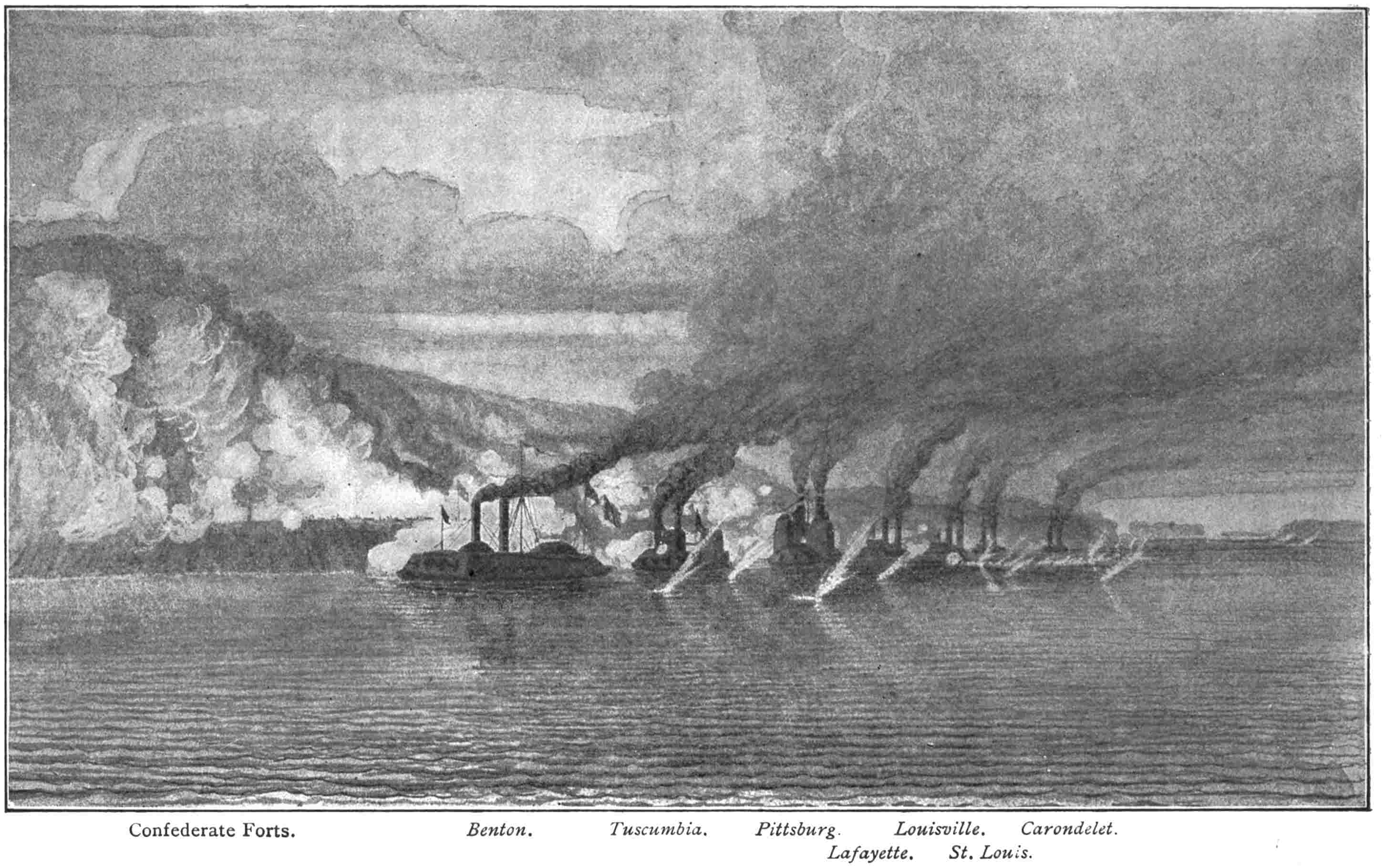

| The Battle of Memphis—First Position. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 303 |

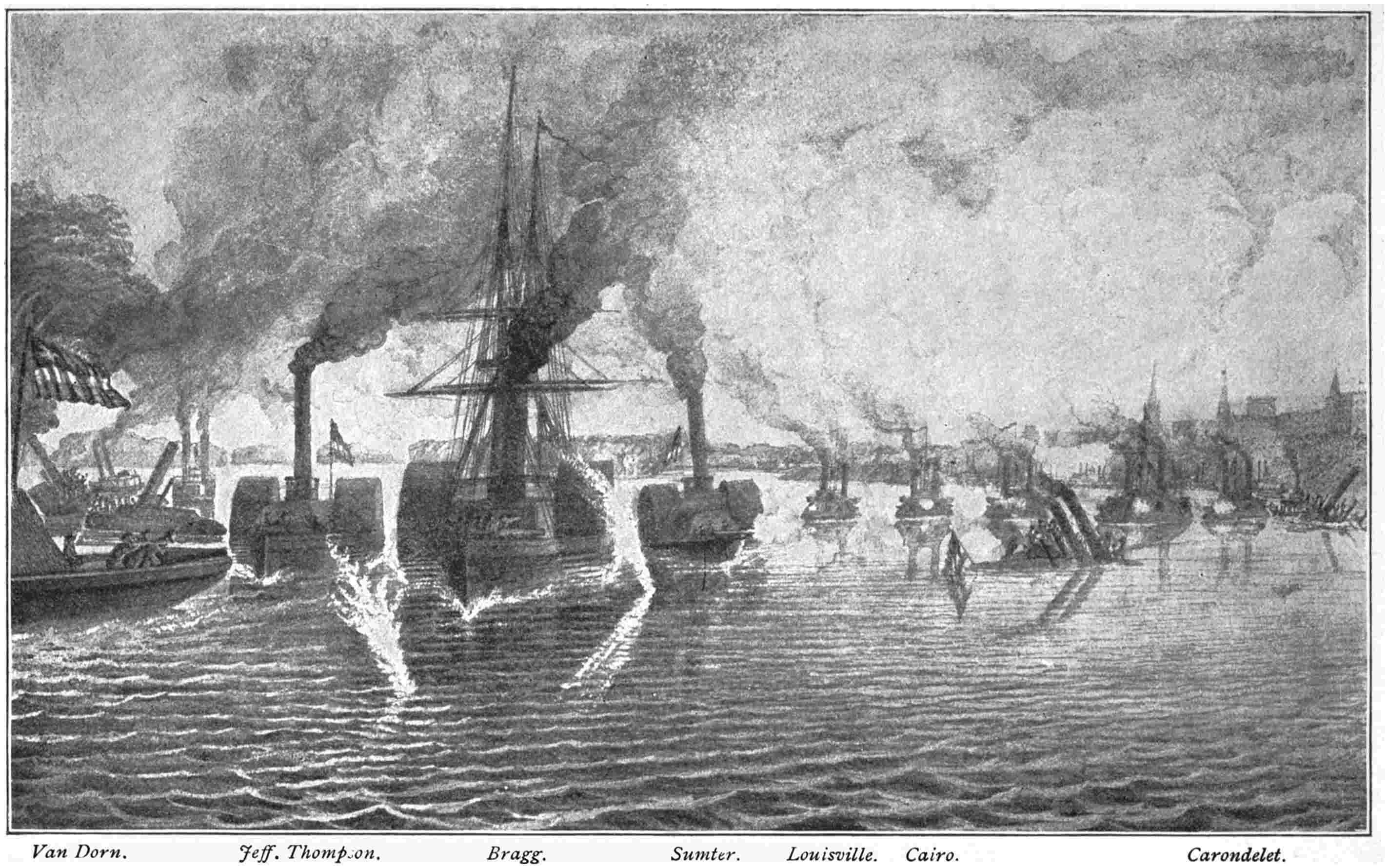

| After the Battle of Memphis. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 305 |

| Battle of Memphis—The Confederates Retreating. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 309 |

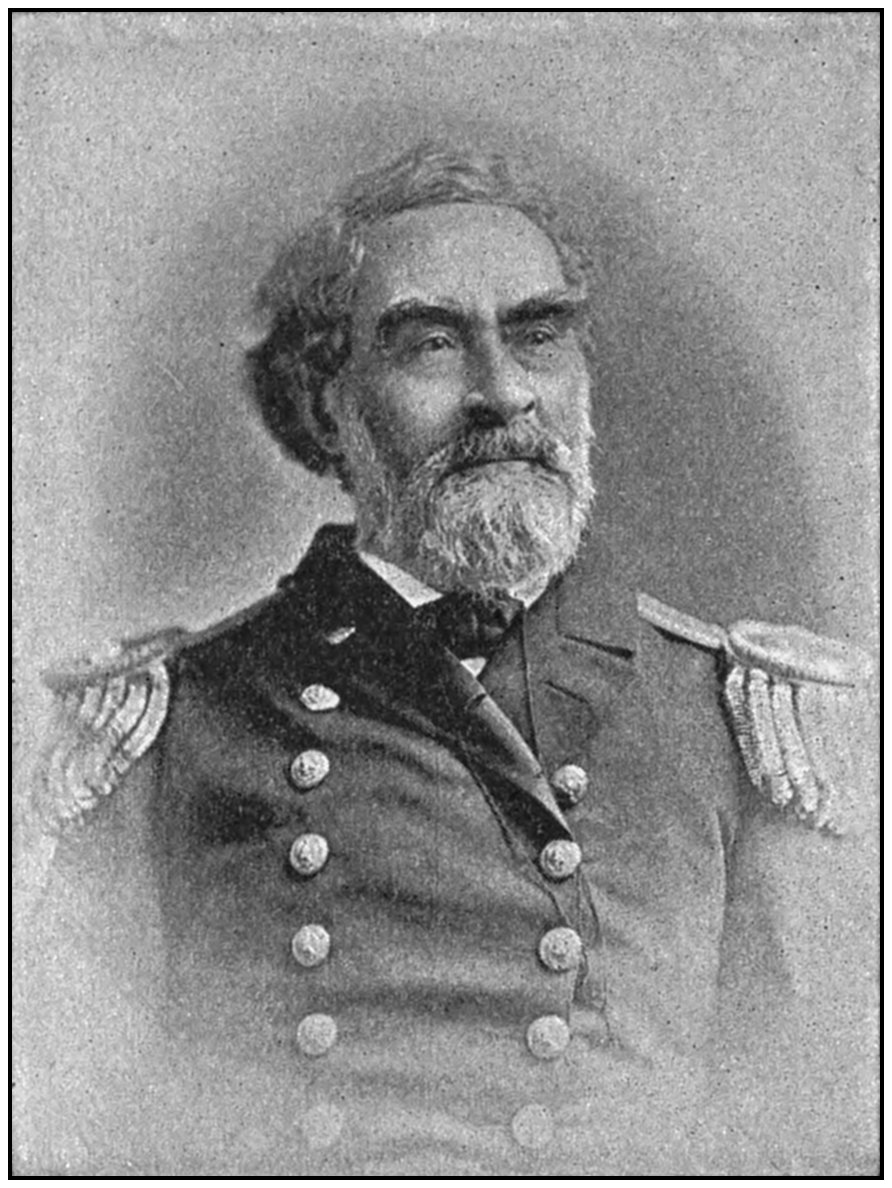

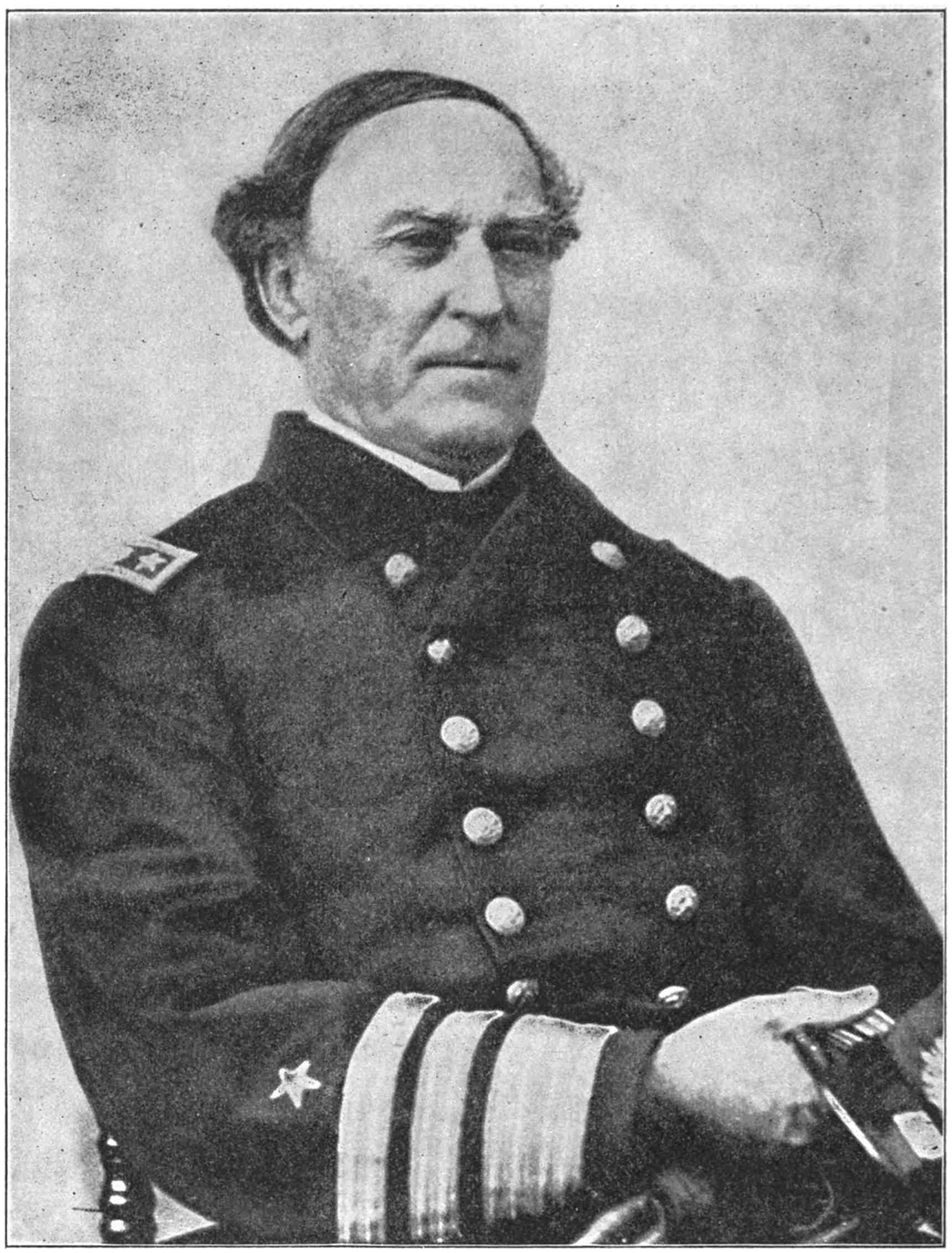

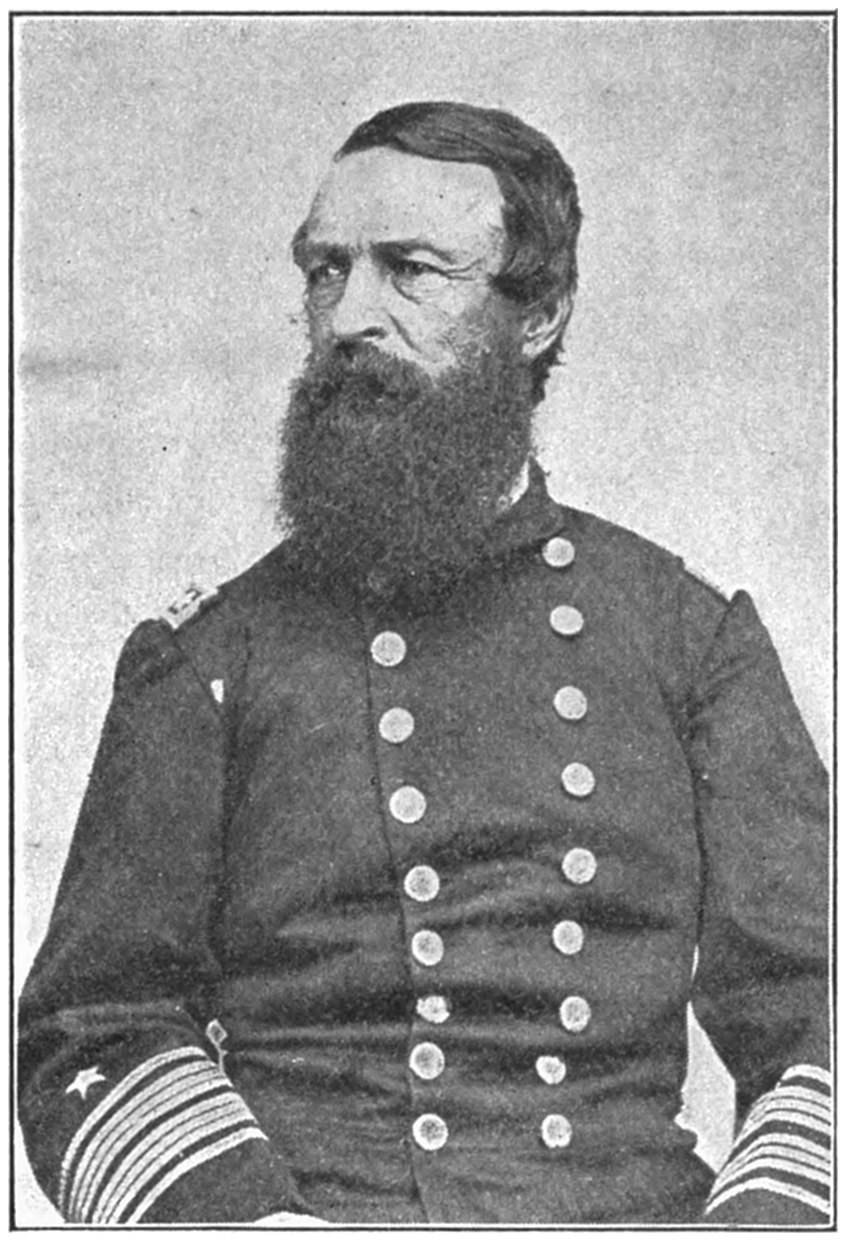

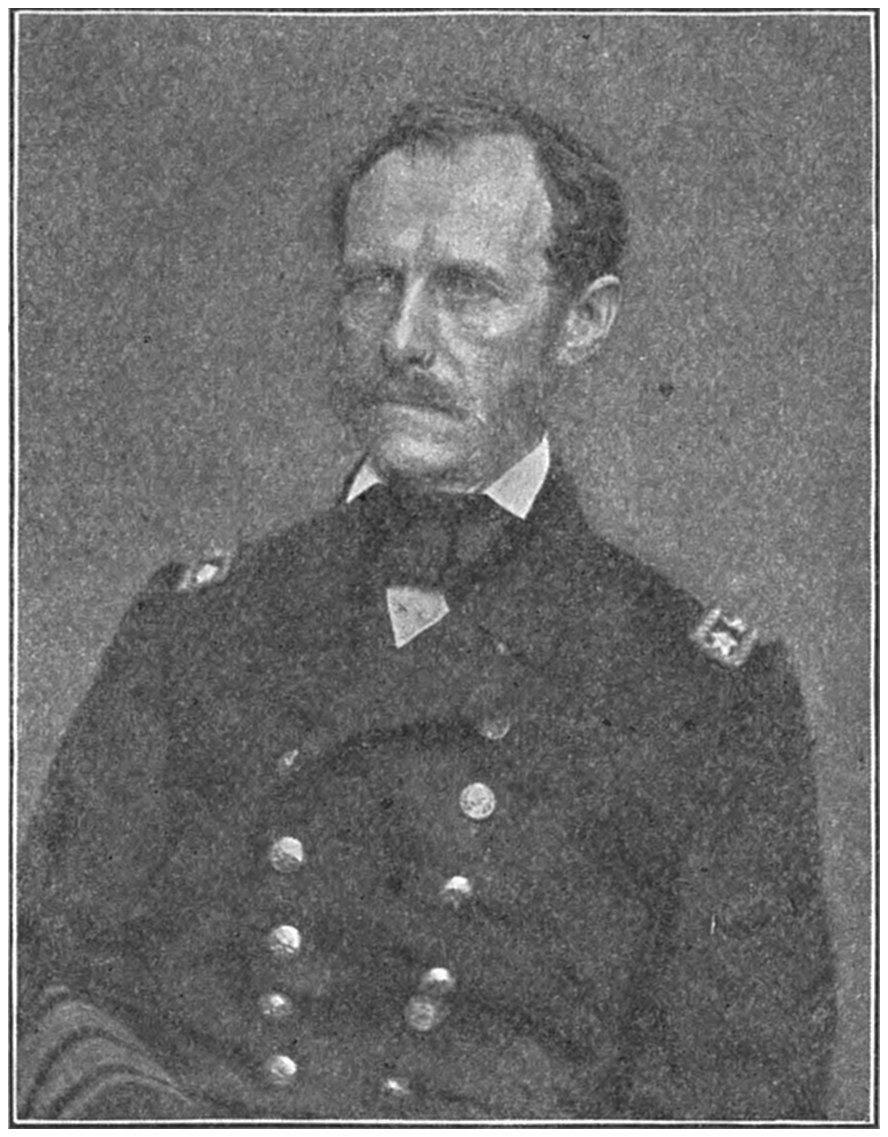

| David Glasgow Farragut. (From a photograph), | 312 |

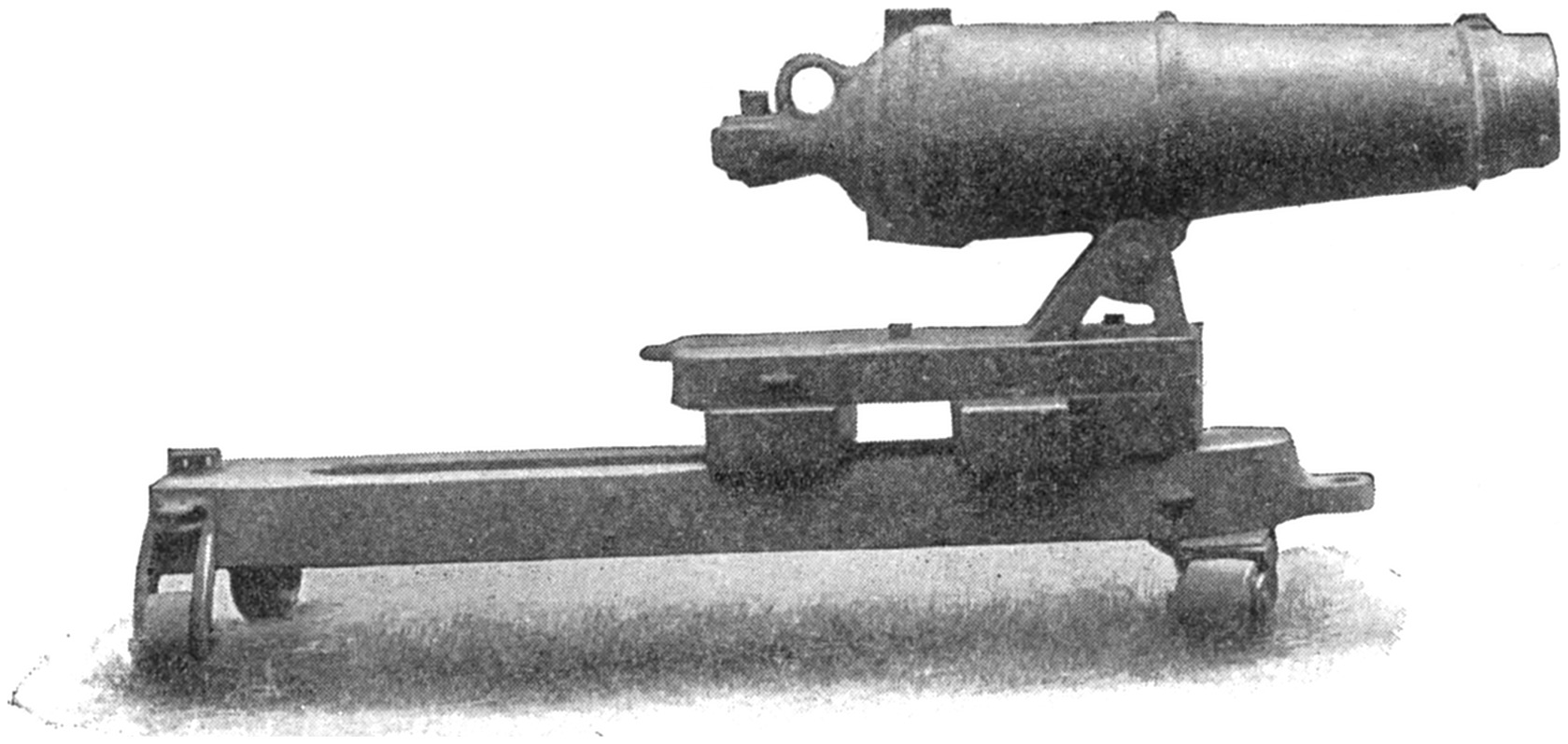

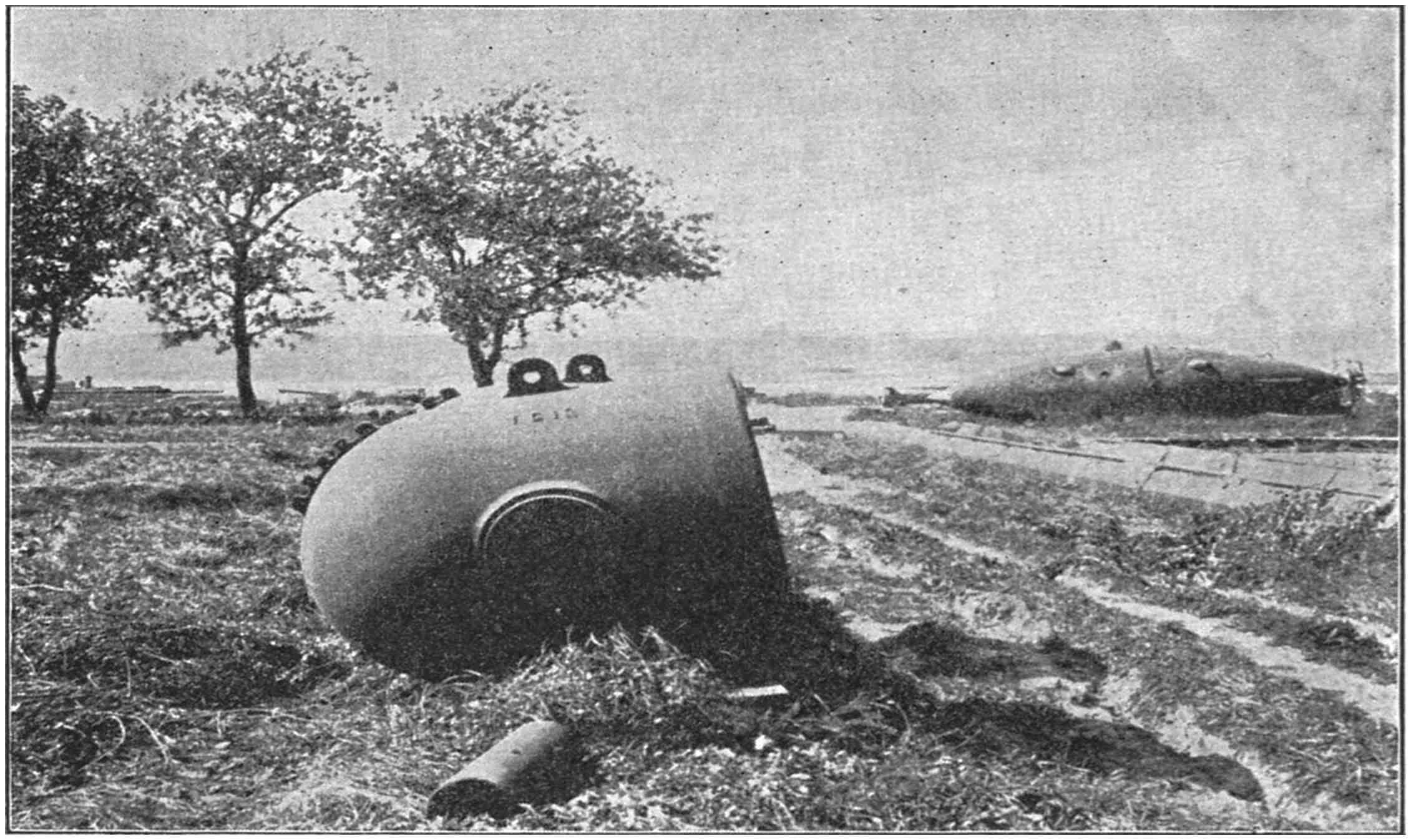

| Thirteen-inch Mortar from Farragut’s Fleet. (From a photograph made at the Brooklyn Navy Yard), | 316 |

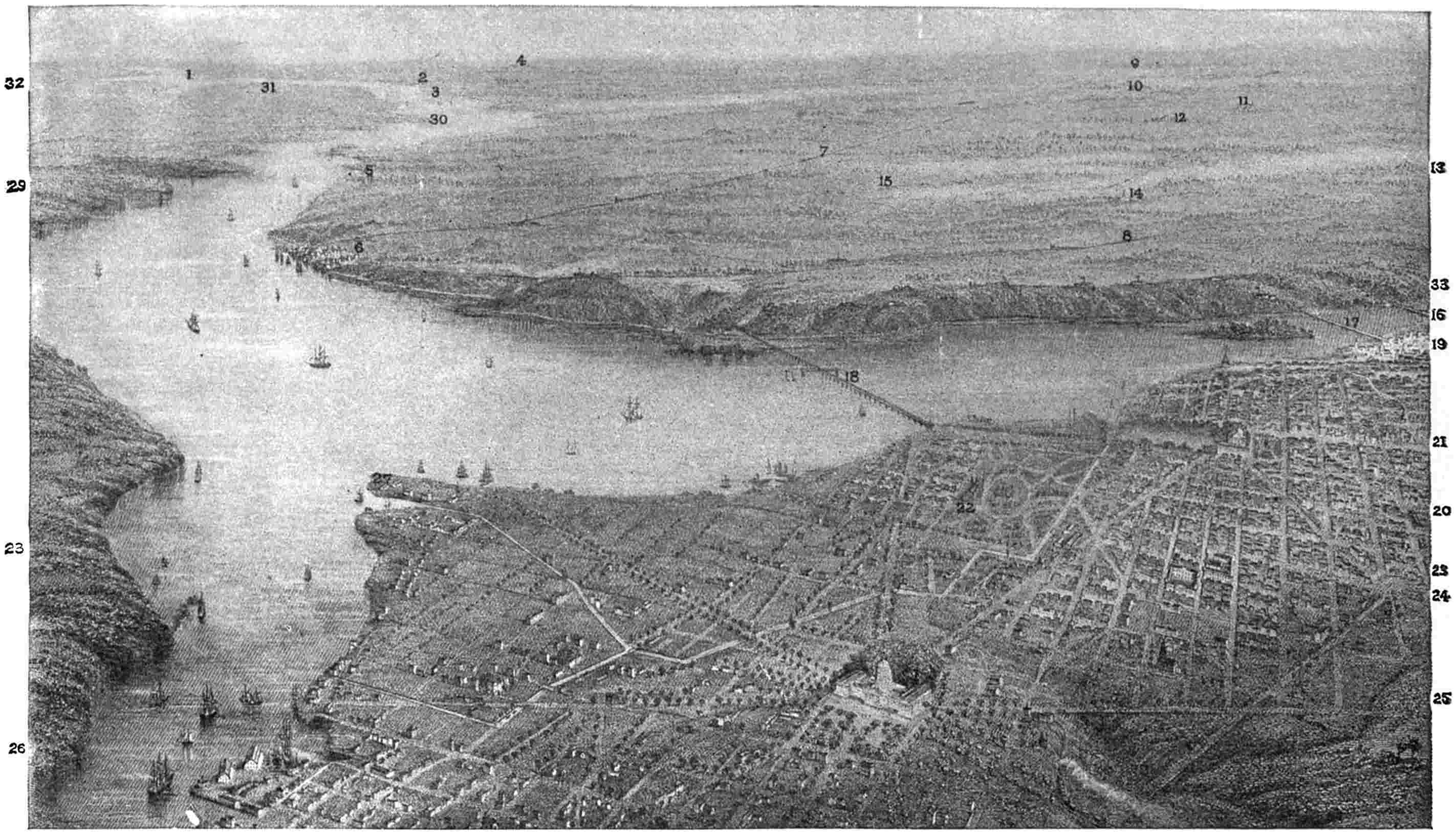

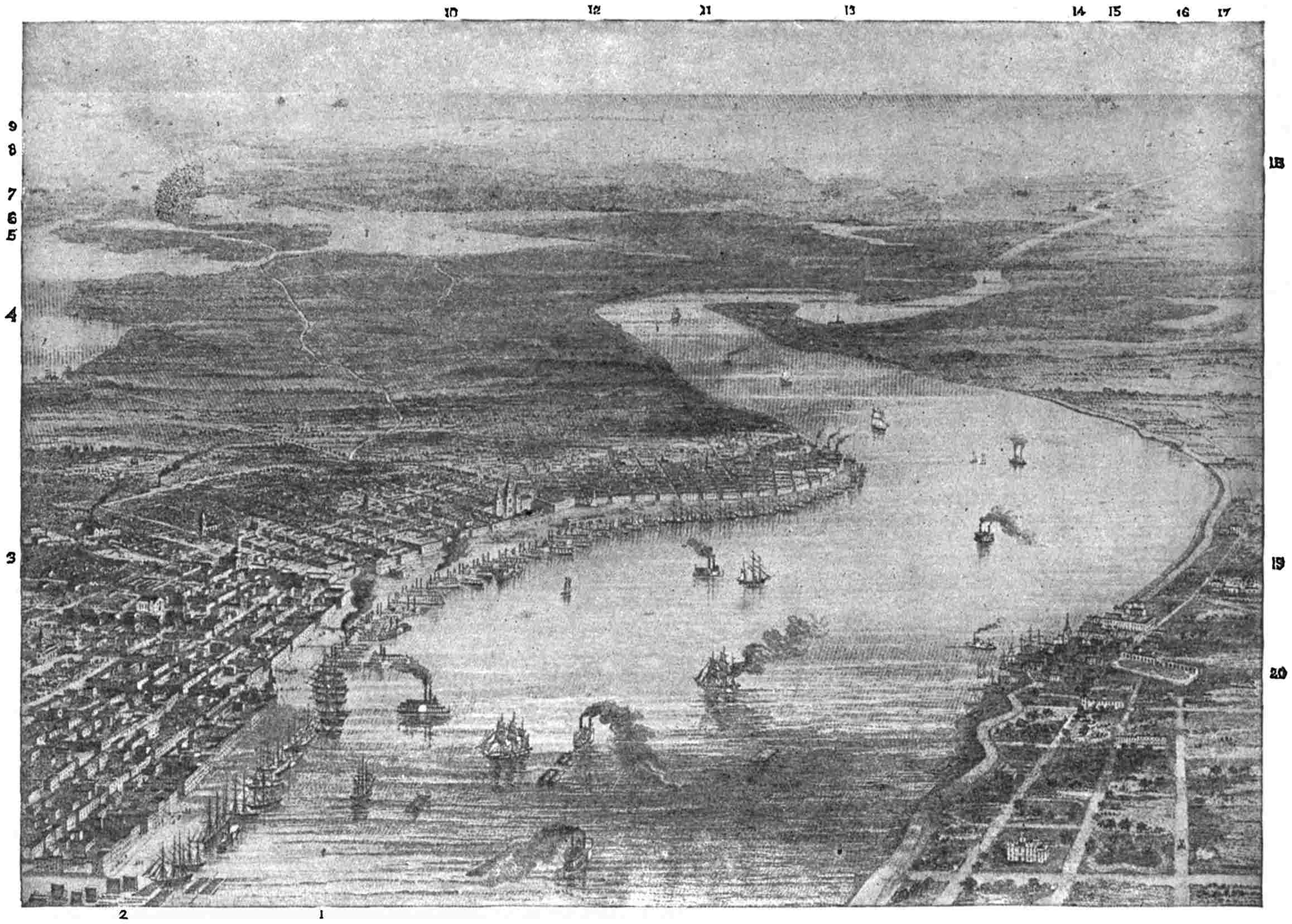

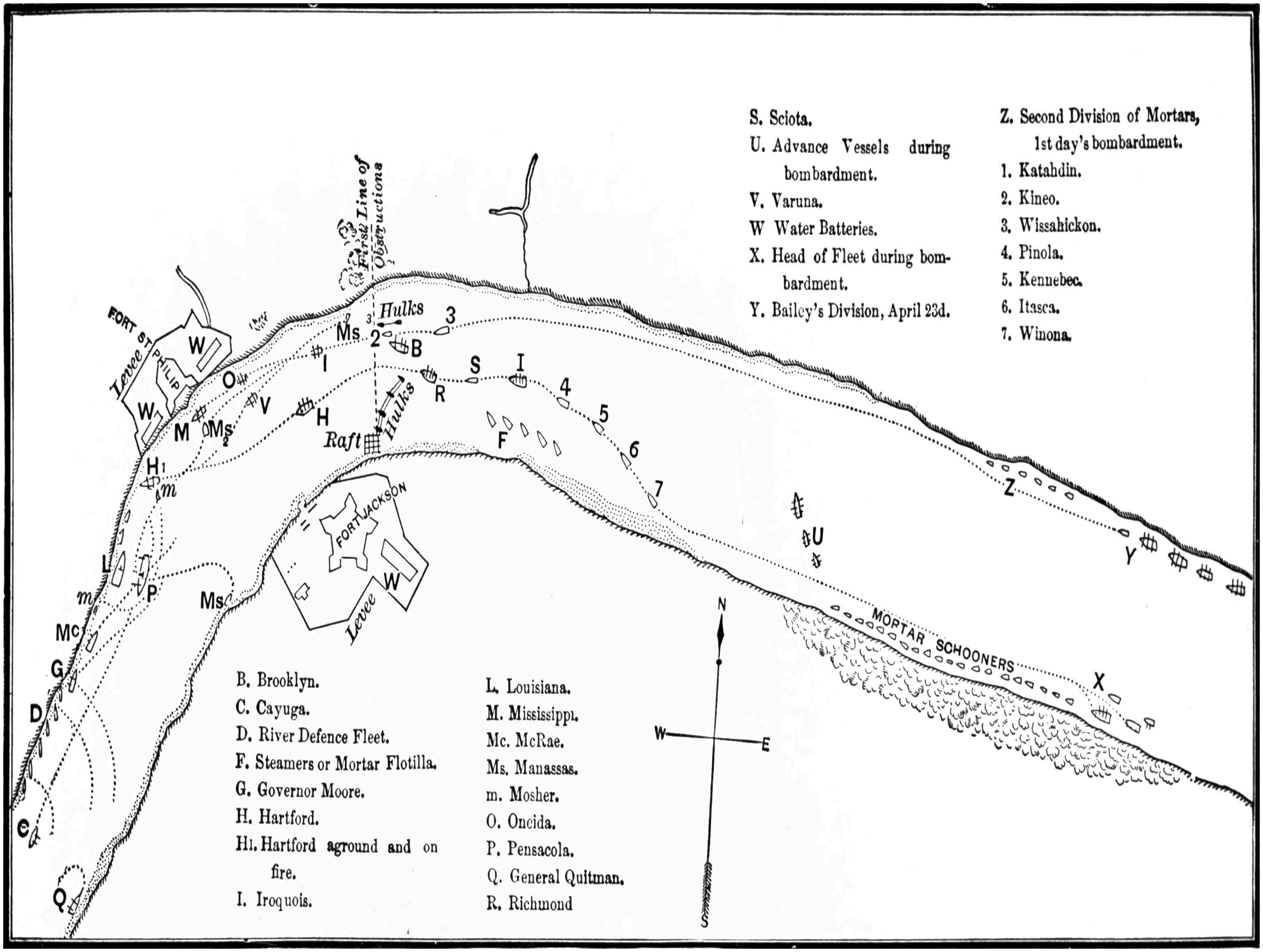

| New Orleans, La., and its Vicinity, | 319 |

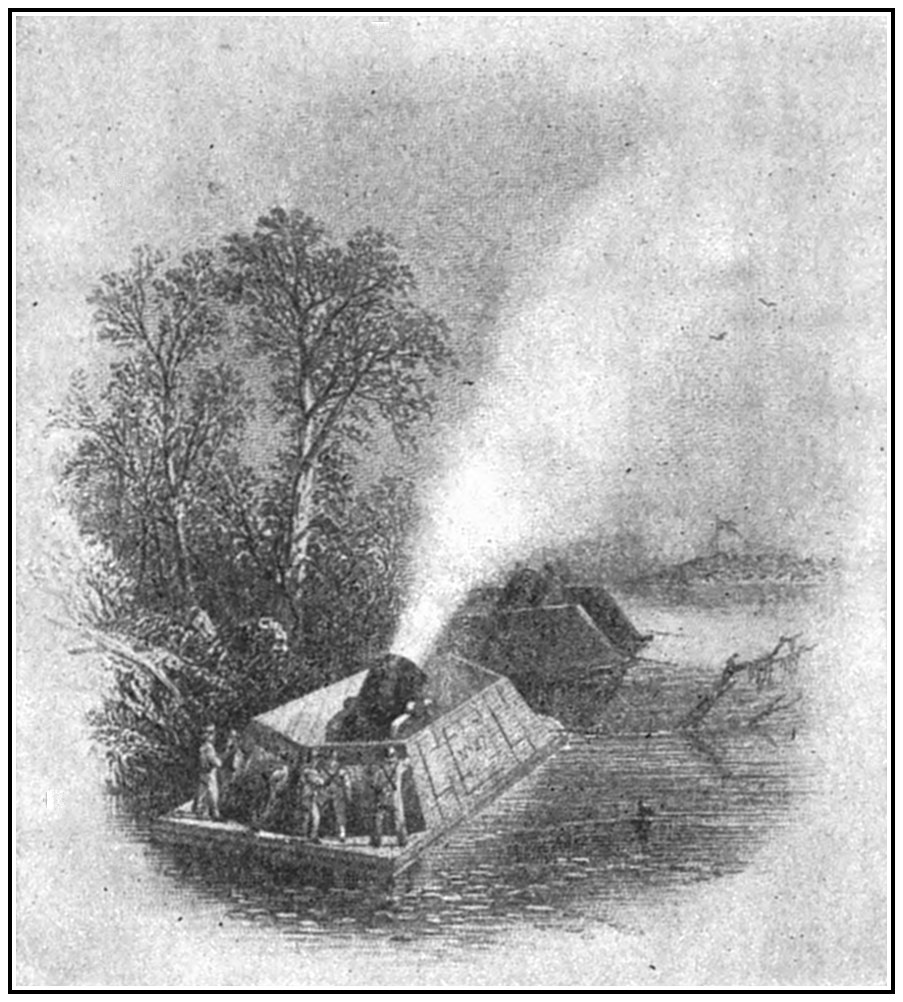

| Mortar Boats. (From an engraving), | 322 |

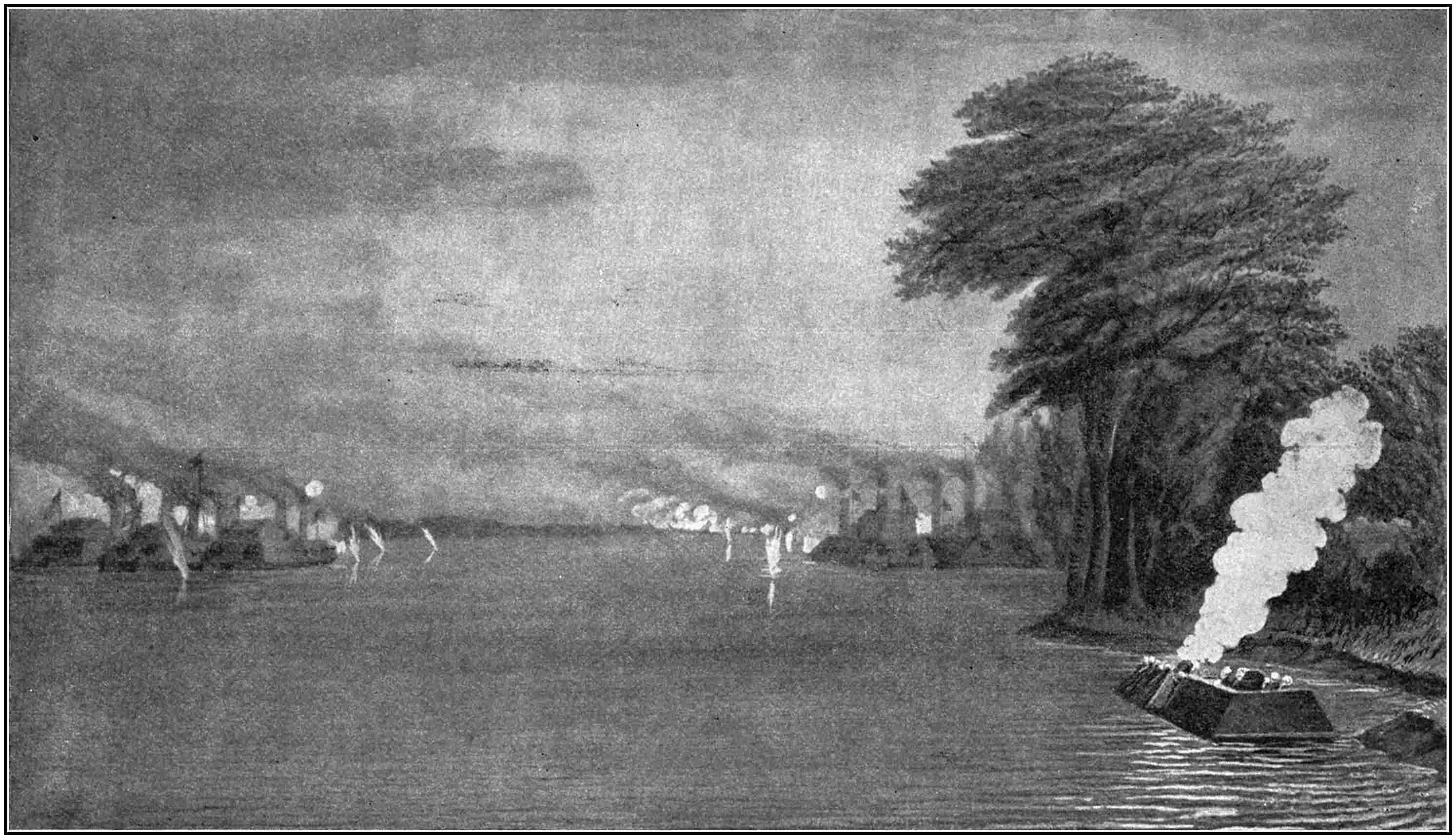

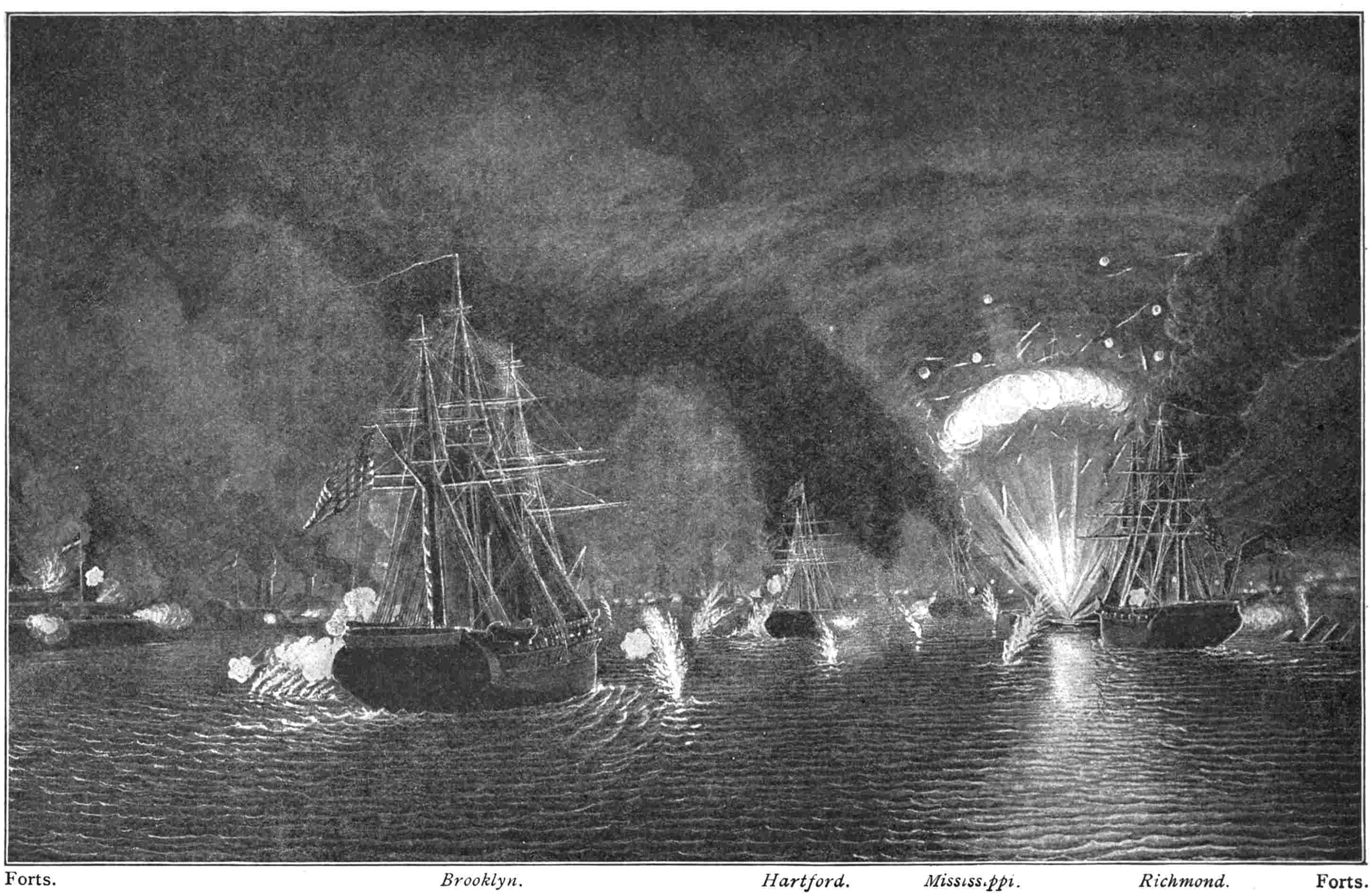

| Beginning of the Battle of New Orleans. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 327 |

| Battle of New Orleans. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 331 |

| The Battle of New Orleans. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 335 |

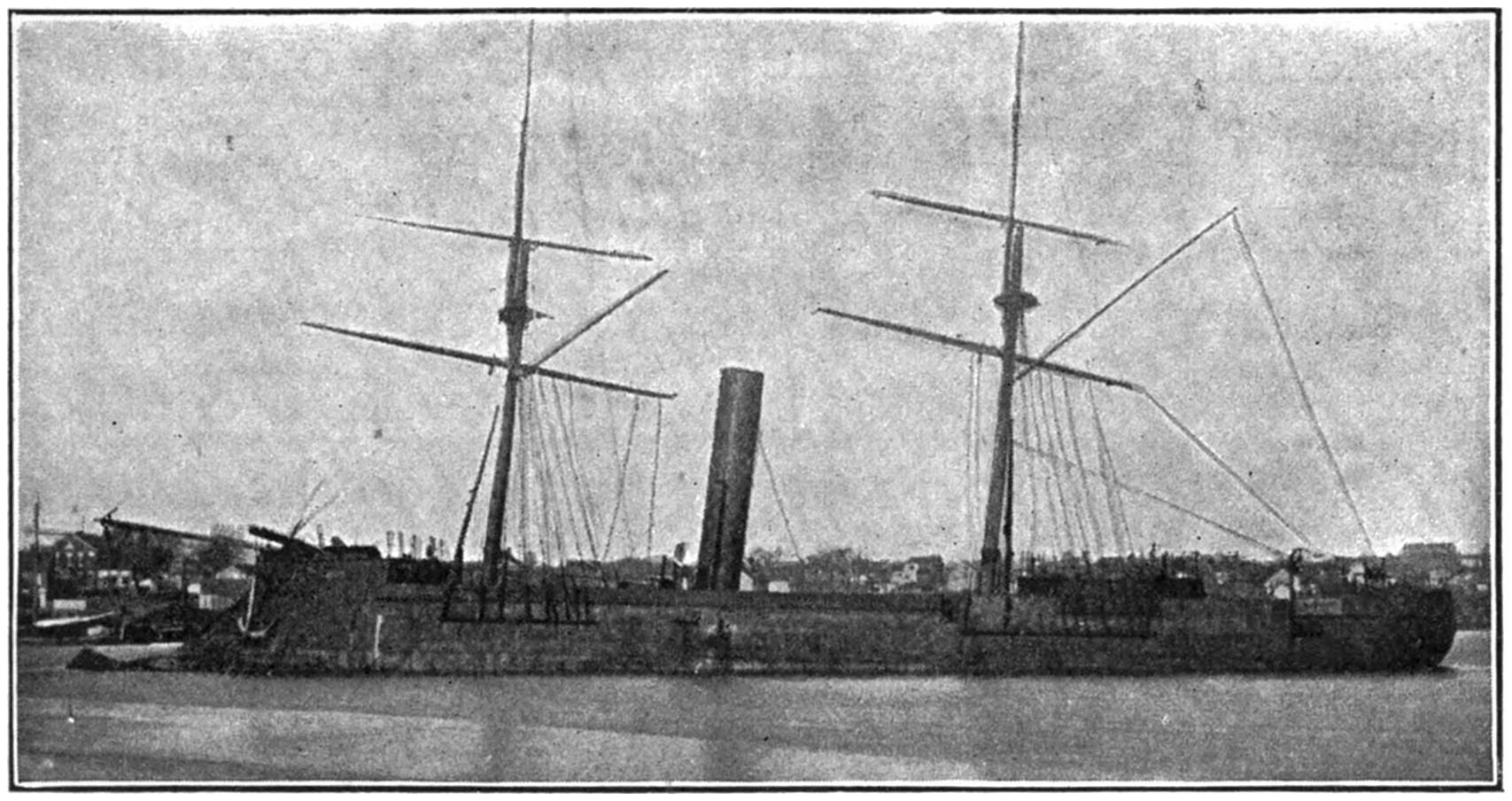

| Confederate Ironclad Ram Stonewall Jackson. (From a photograph), | 337 |

| The Essex after Running the Batteries at Vicksburg and Port Hudson. (After a photograph), | 341 |

| The Carondelet after Passing Vicksburg. (From a photograph), | 342 |

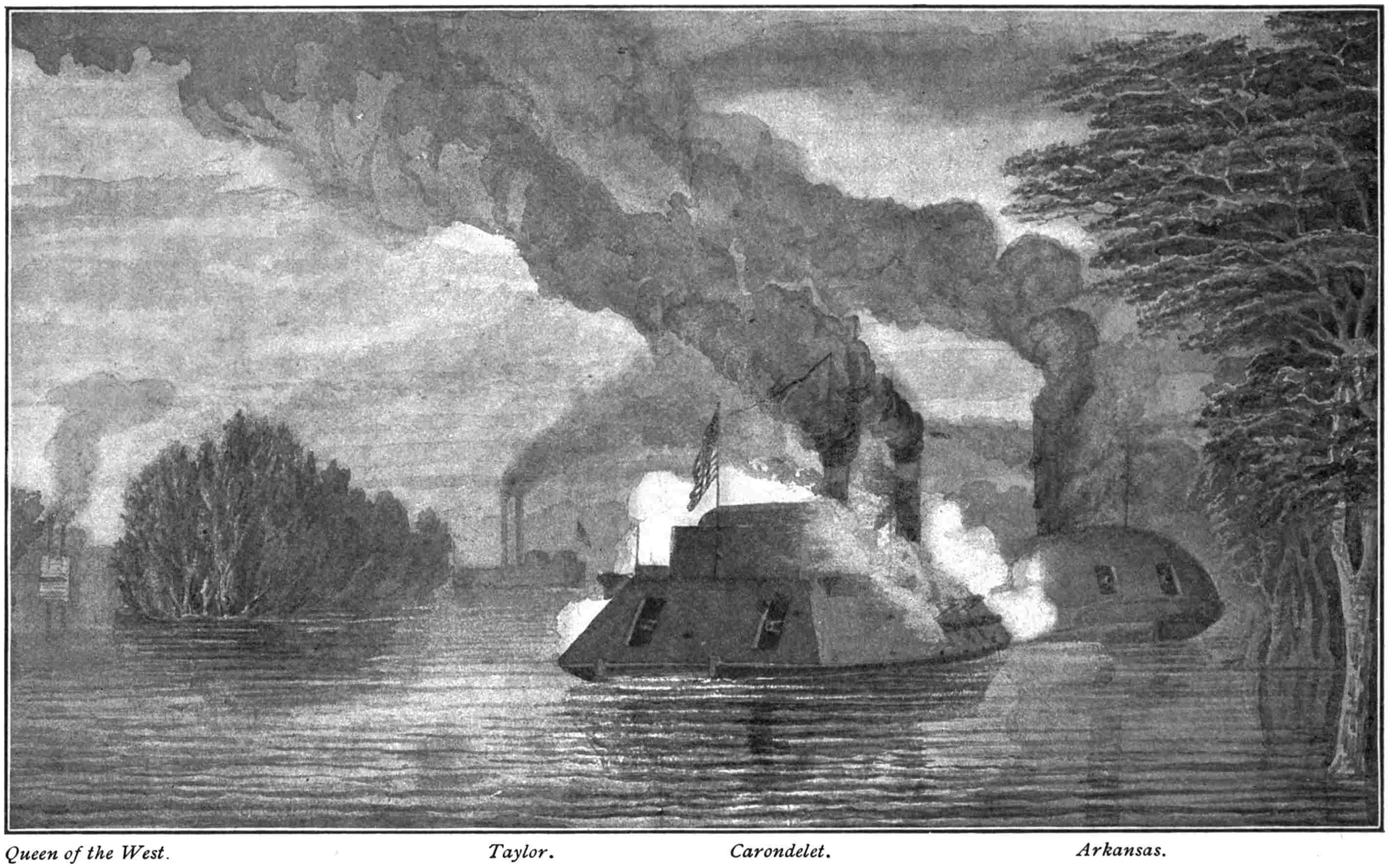

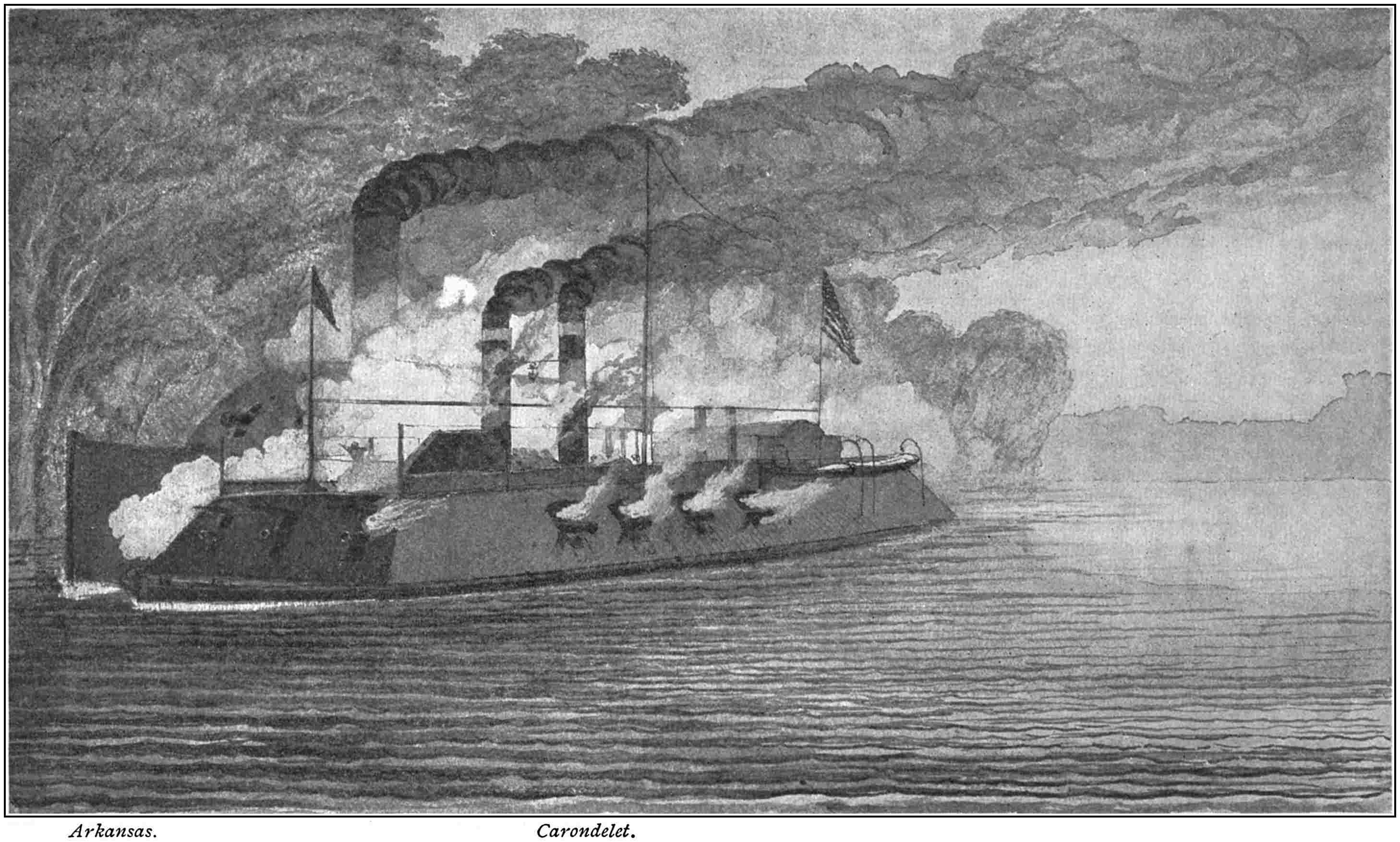

| Battle between the Carondelet and the Arkansas. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 346 |

| Battle between the Arkansas and the Carondelet. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 347 |

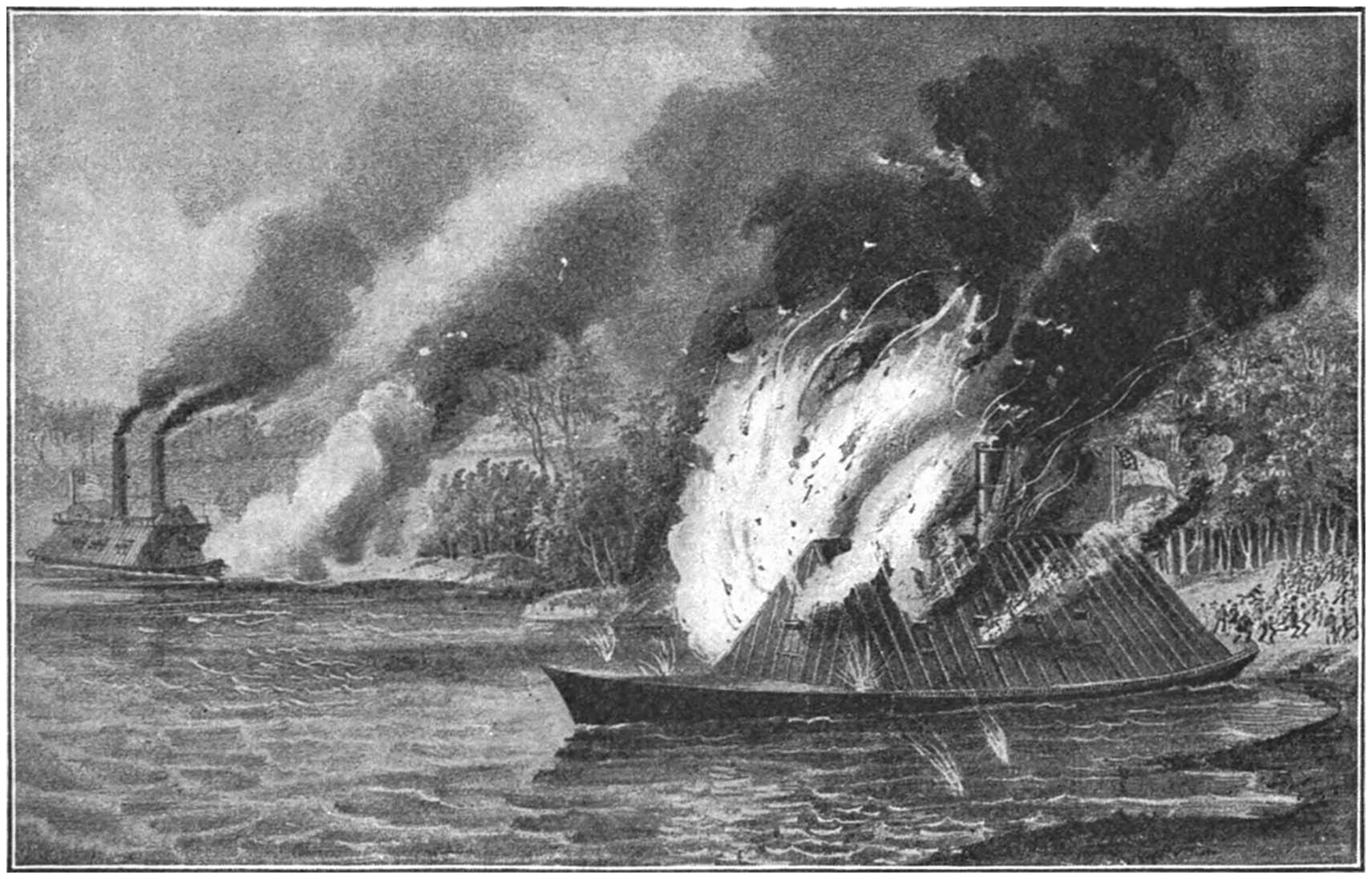

| Destruction of the Arkansas near Baton Rouge, August 4, 1862. (From a lithograph published by Currier & Ives), | 349 |

| David D. Porter. (From a photograph), | 350 |

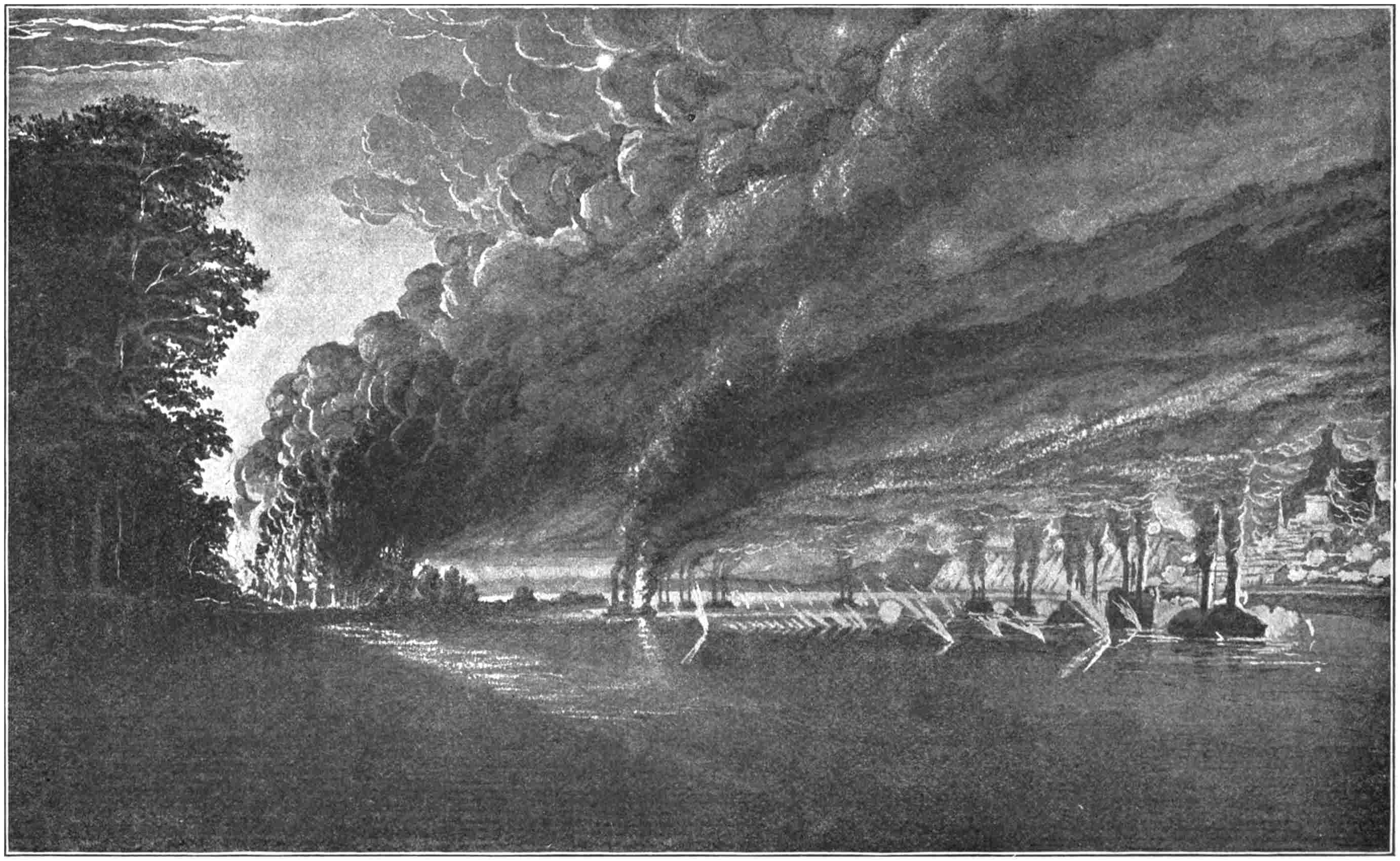

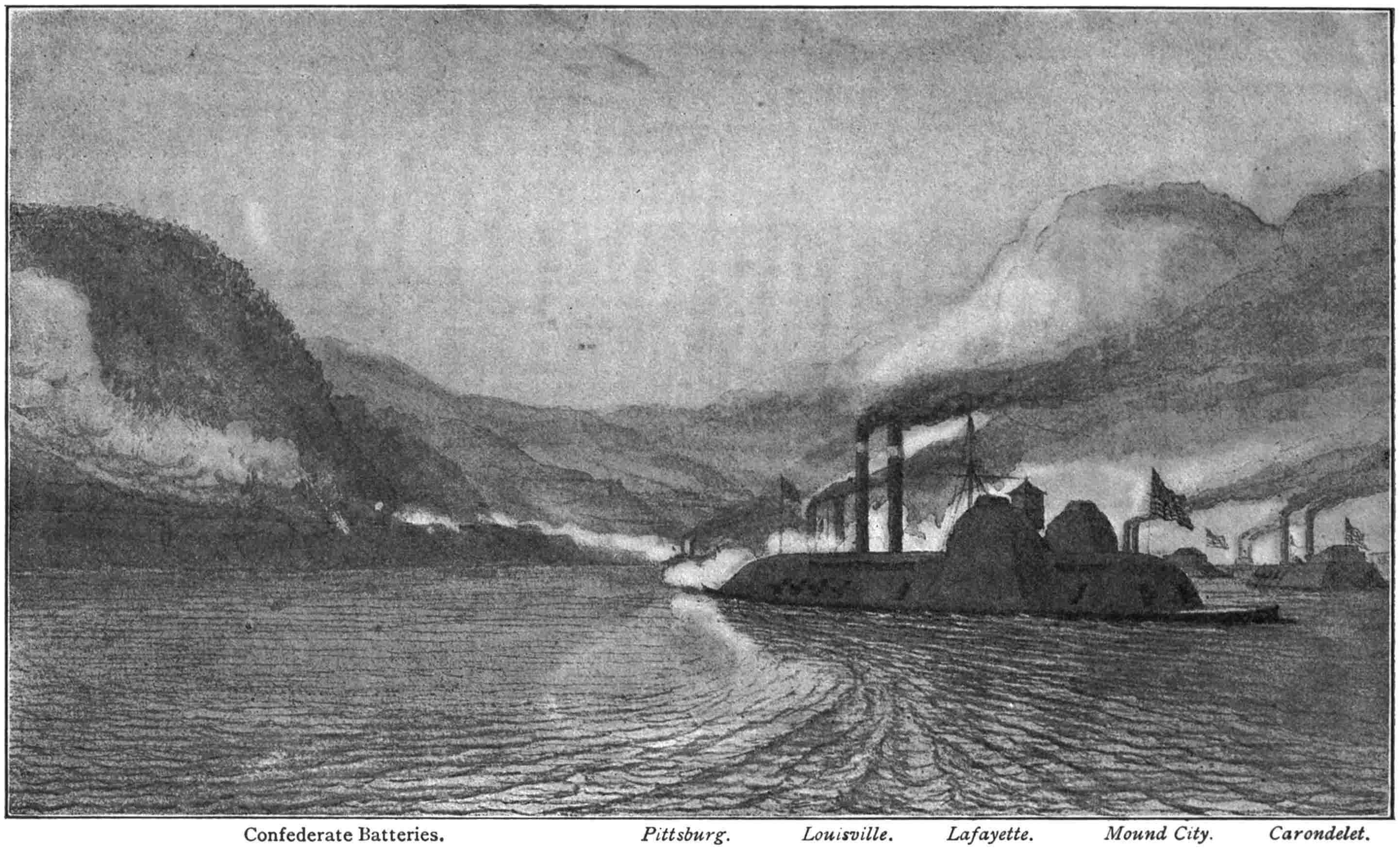

| Admiral Farragut Passing Port Hudson. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 353 |

| The U. S. Flotilla Passing the Vicksburg Batteries. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 355 |

| Battle of Grand Gulf—First Position. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 359 |

| Battle of Grand Gulf—Second Position. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 363xx |

| Battle of Grand Gulf—Third Position. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 365 |

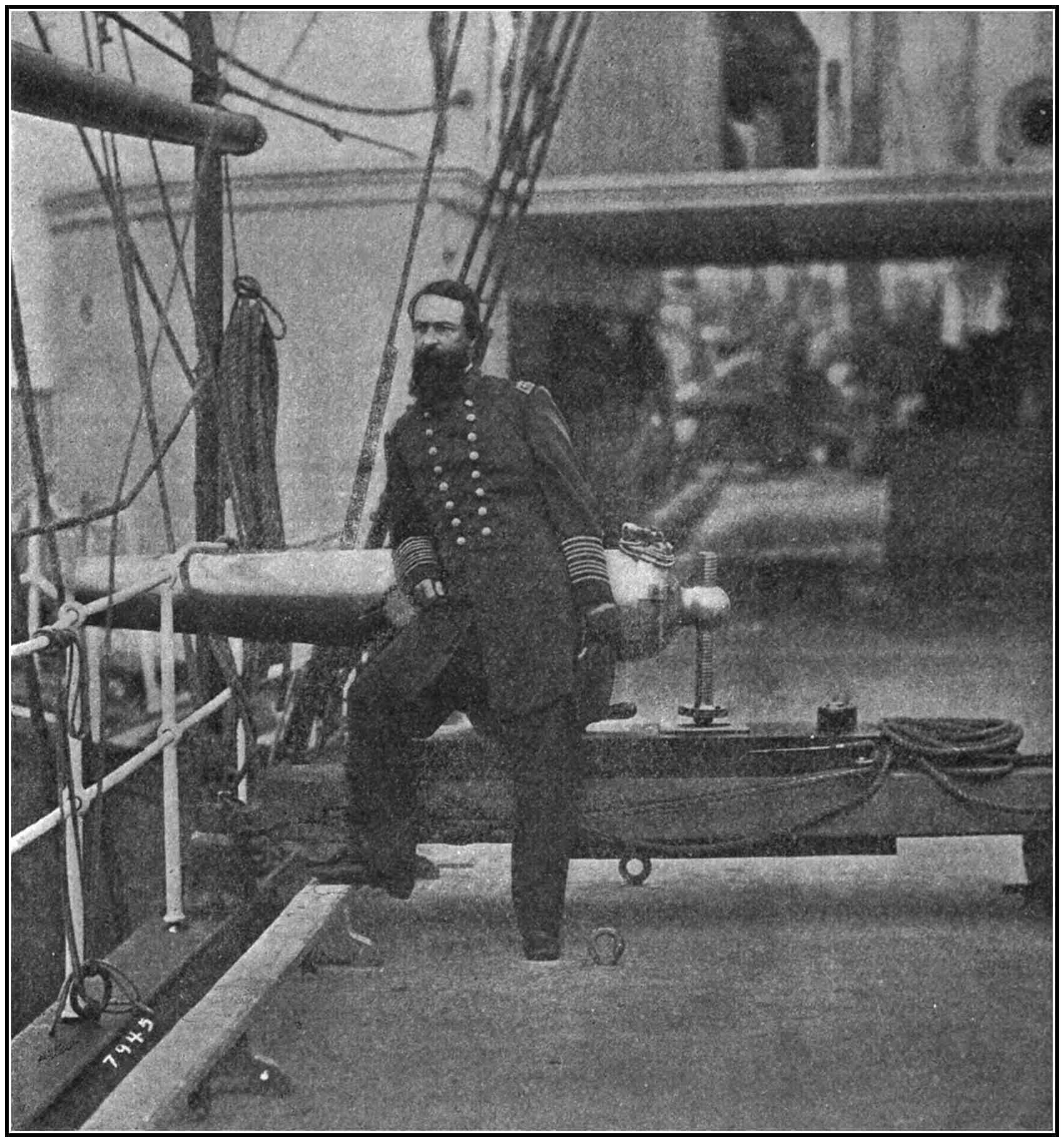

| Admiral Porter on Deck of Flagship at Grand Écore, La. (From a photograph), | 368 |

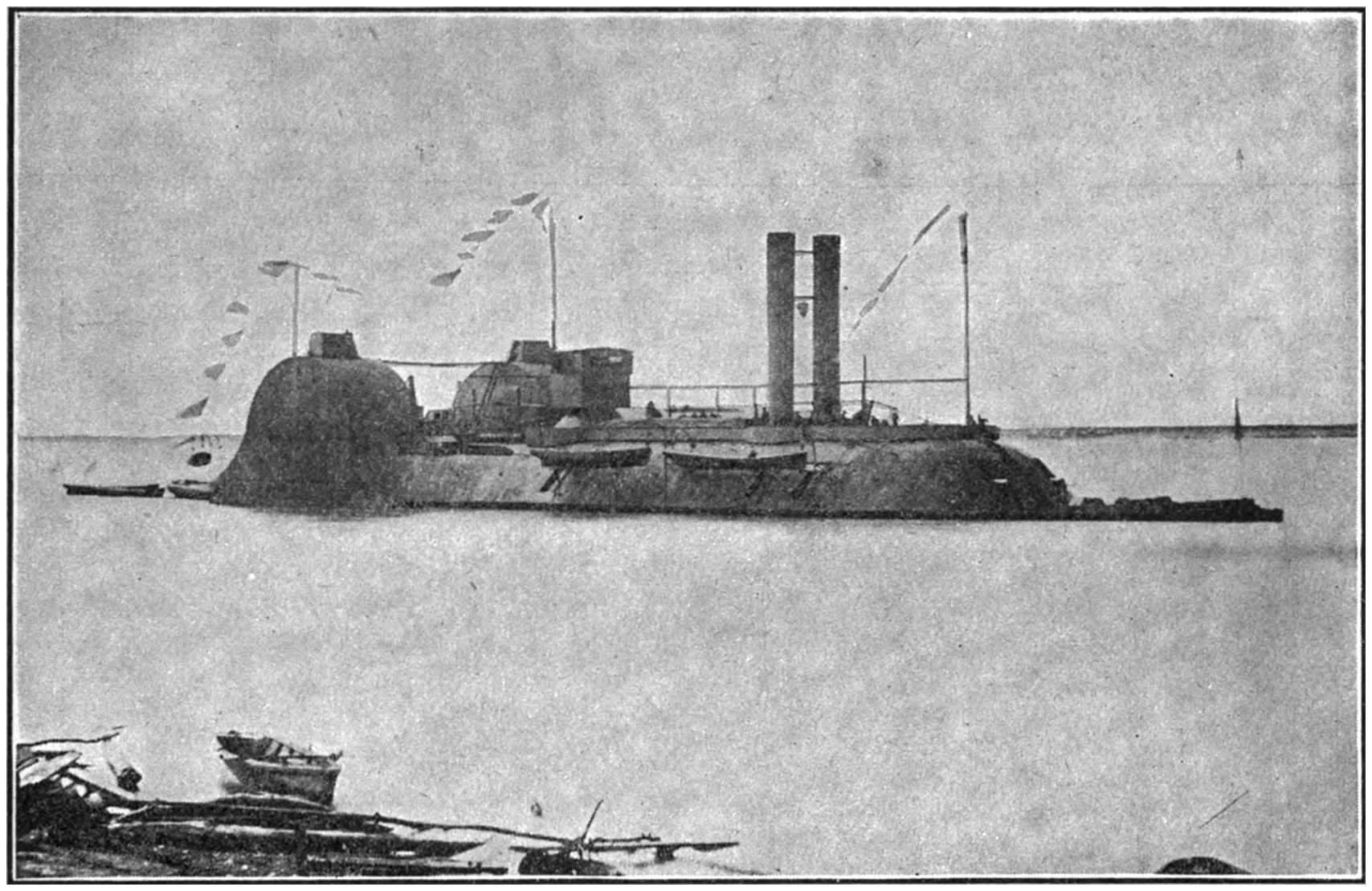

| U. S. Ram Lafayette. (From a photograph), | 369 |

| U. S. Gunboat Fort Hindman. (From a photograph), | 370 |

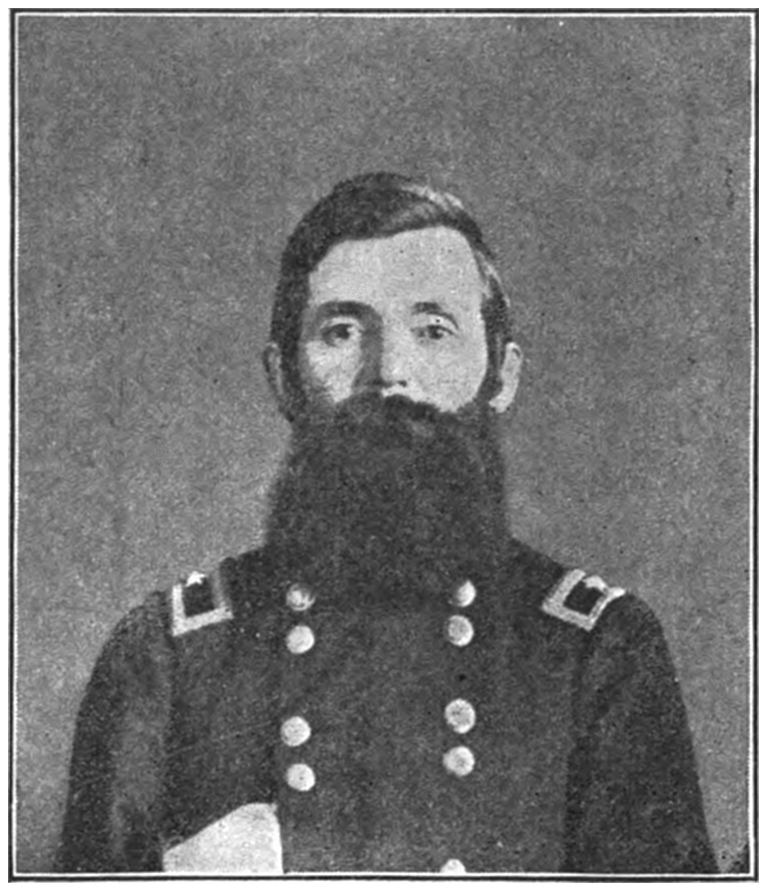

| Joseph Bailey. (From a photograph), | 371 |

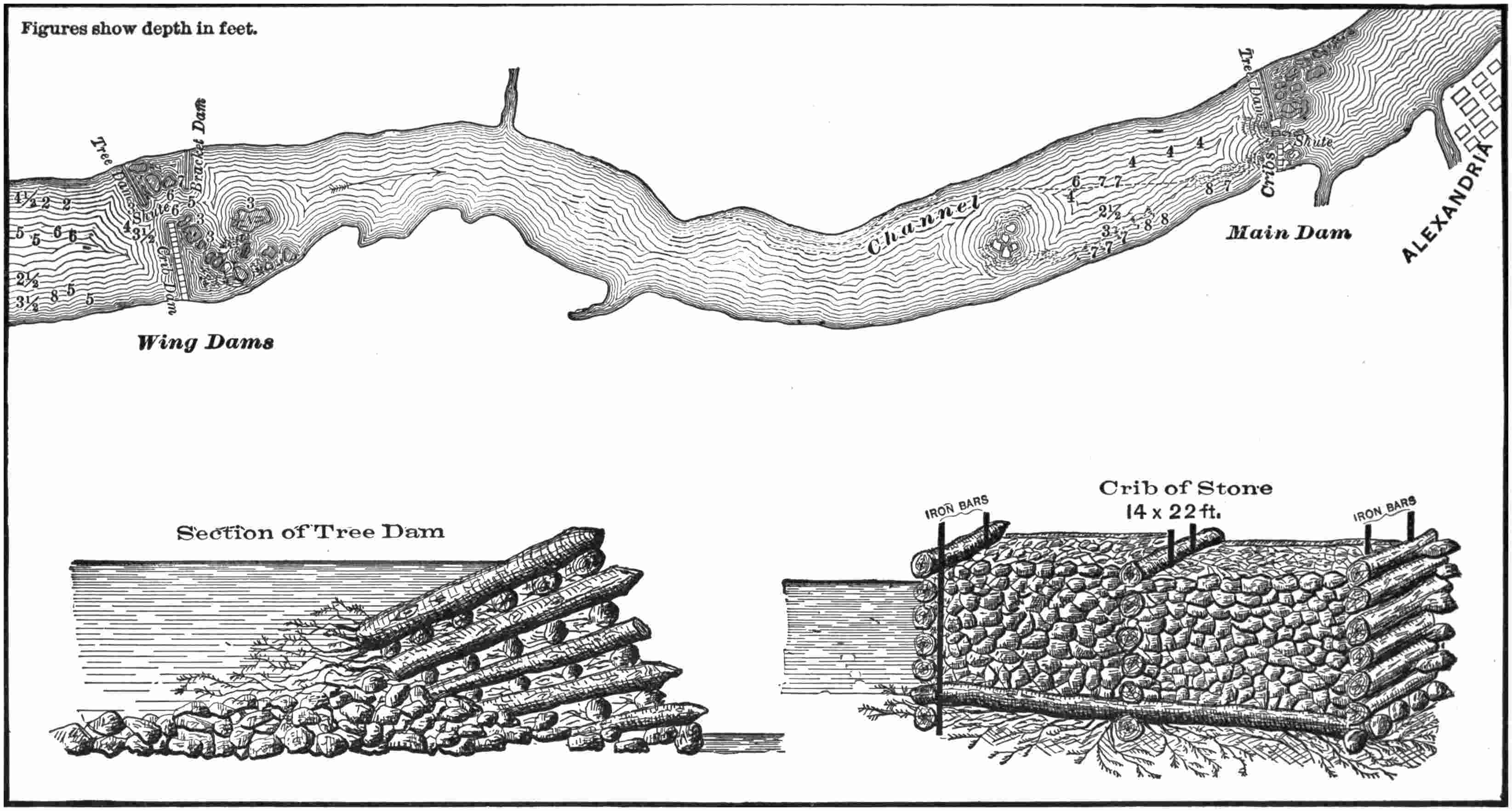

| Red River Dam. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 373 |

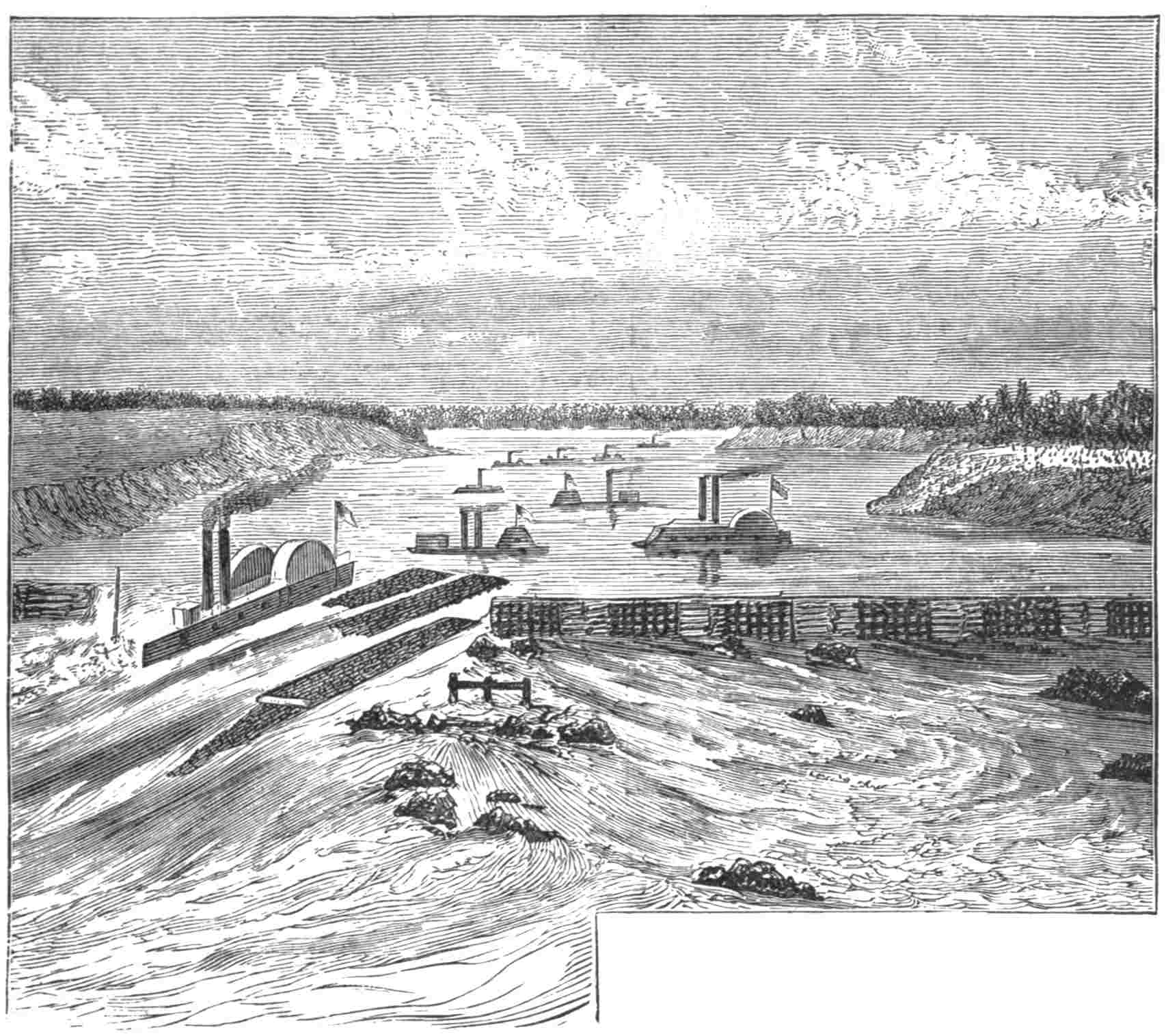

| The Fleet Passing the Dam. (From an engraving), | 375 |

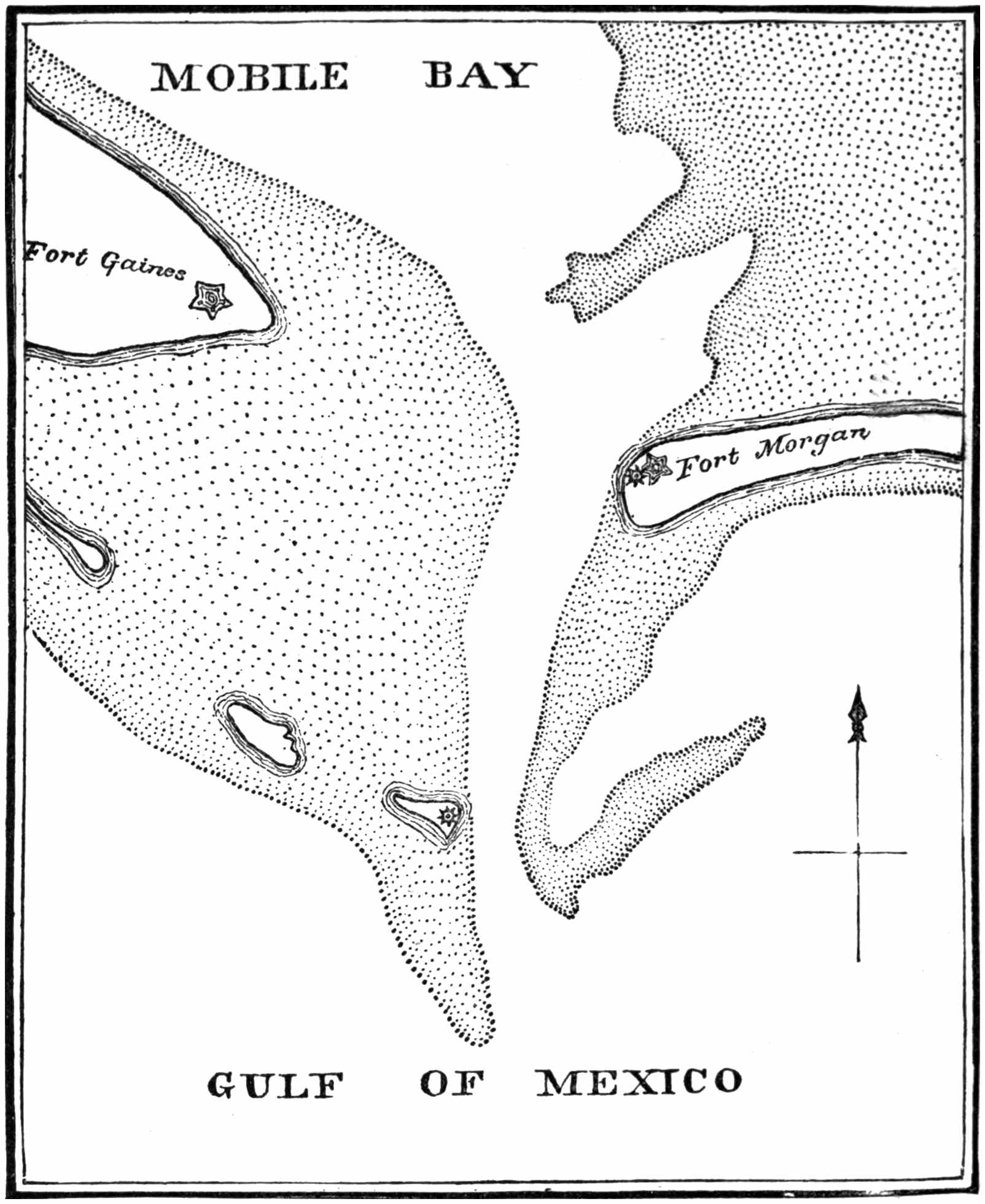

| Entrance to Mobile Bay. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 378 |

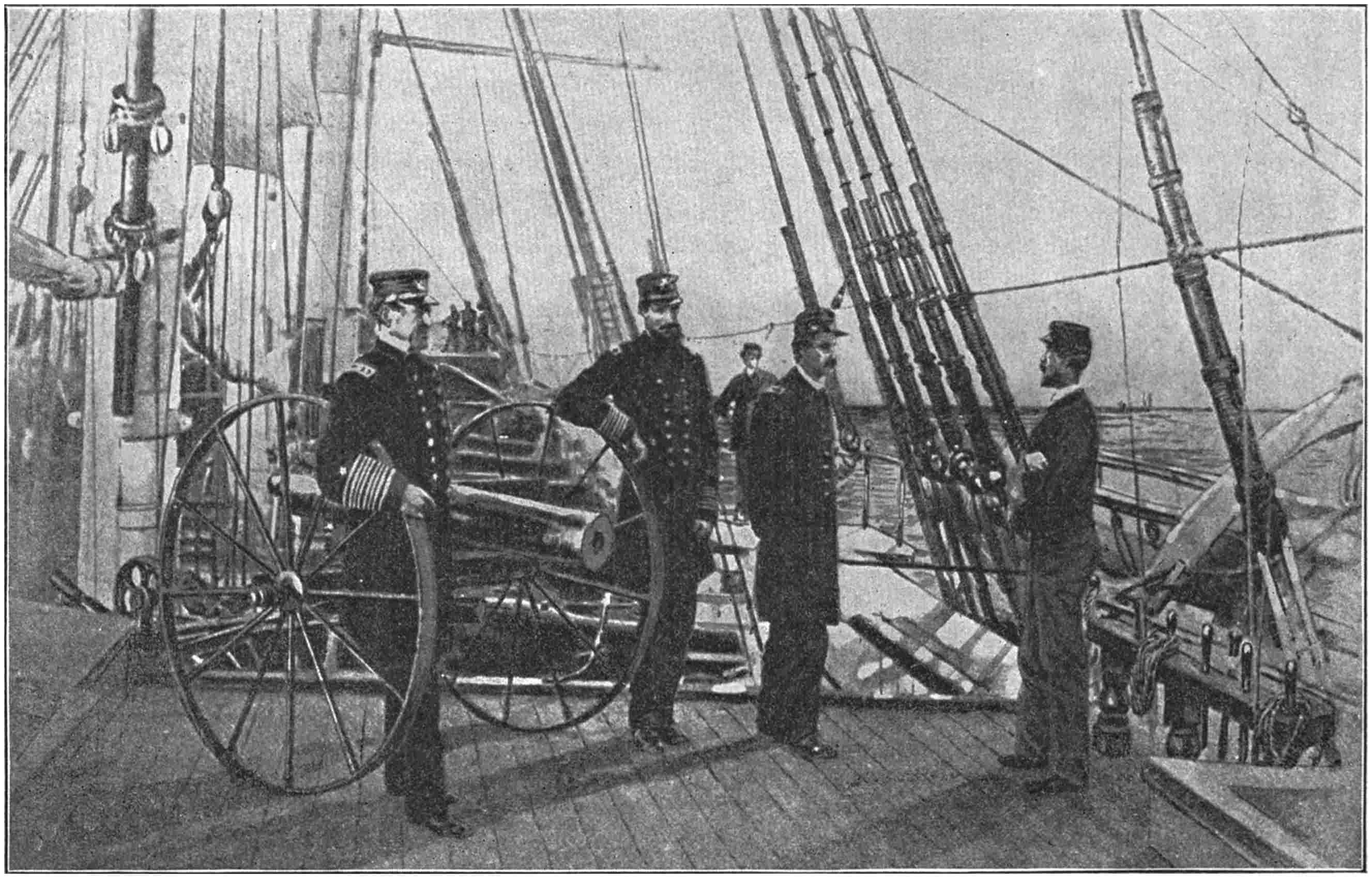

| Farragut and Drayton on Board the Hartford at Mobile Bay. (Drawn by I. W. Taber from a photograph), | 387 |

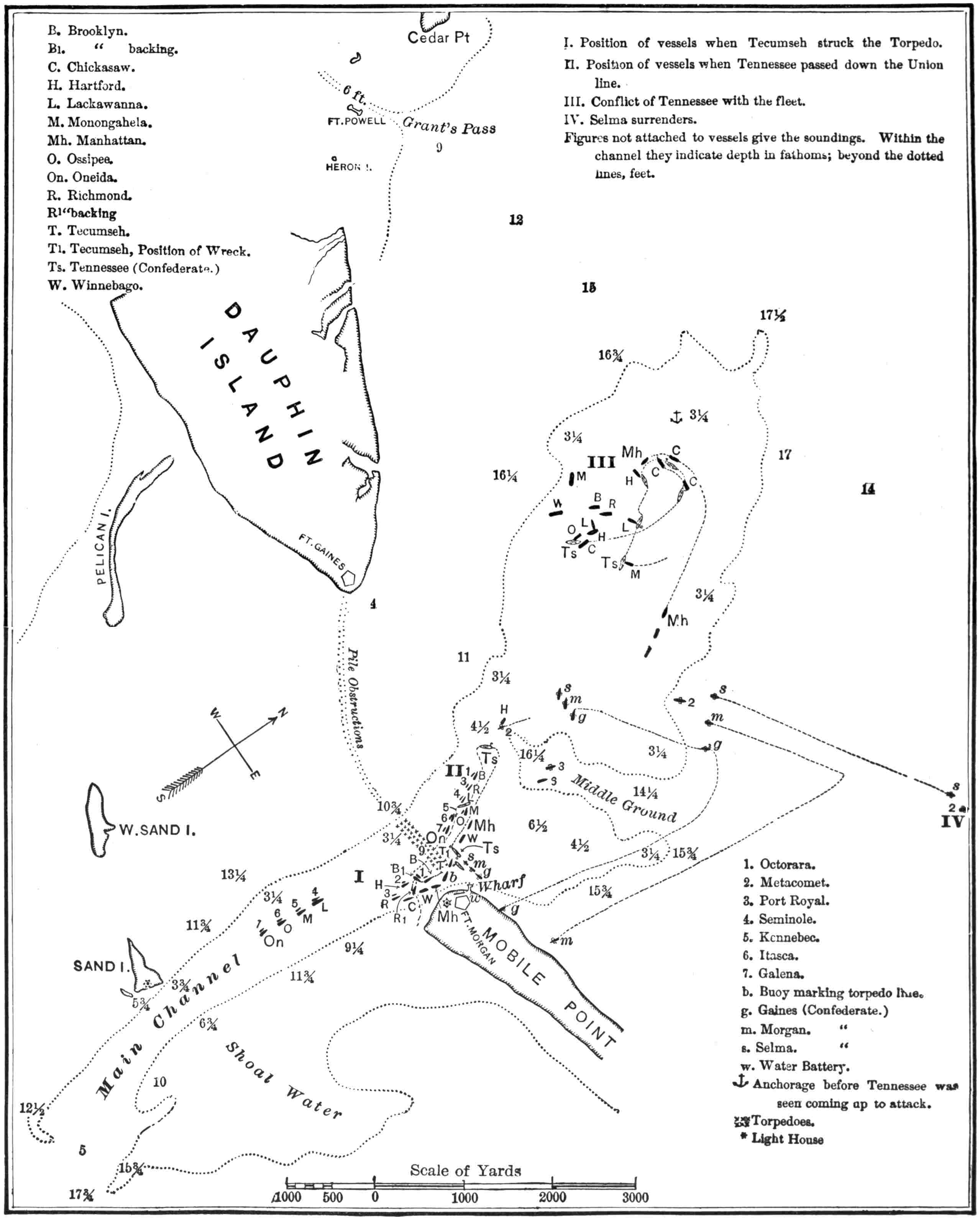

| Battle of Mobile Bay. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 390–91 |

| T. A. M. Craven (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 393 |

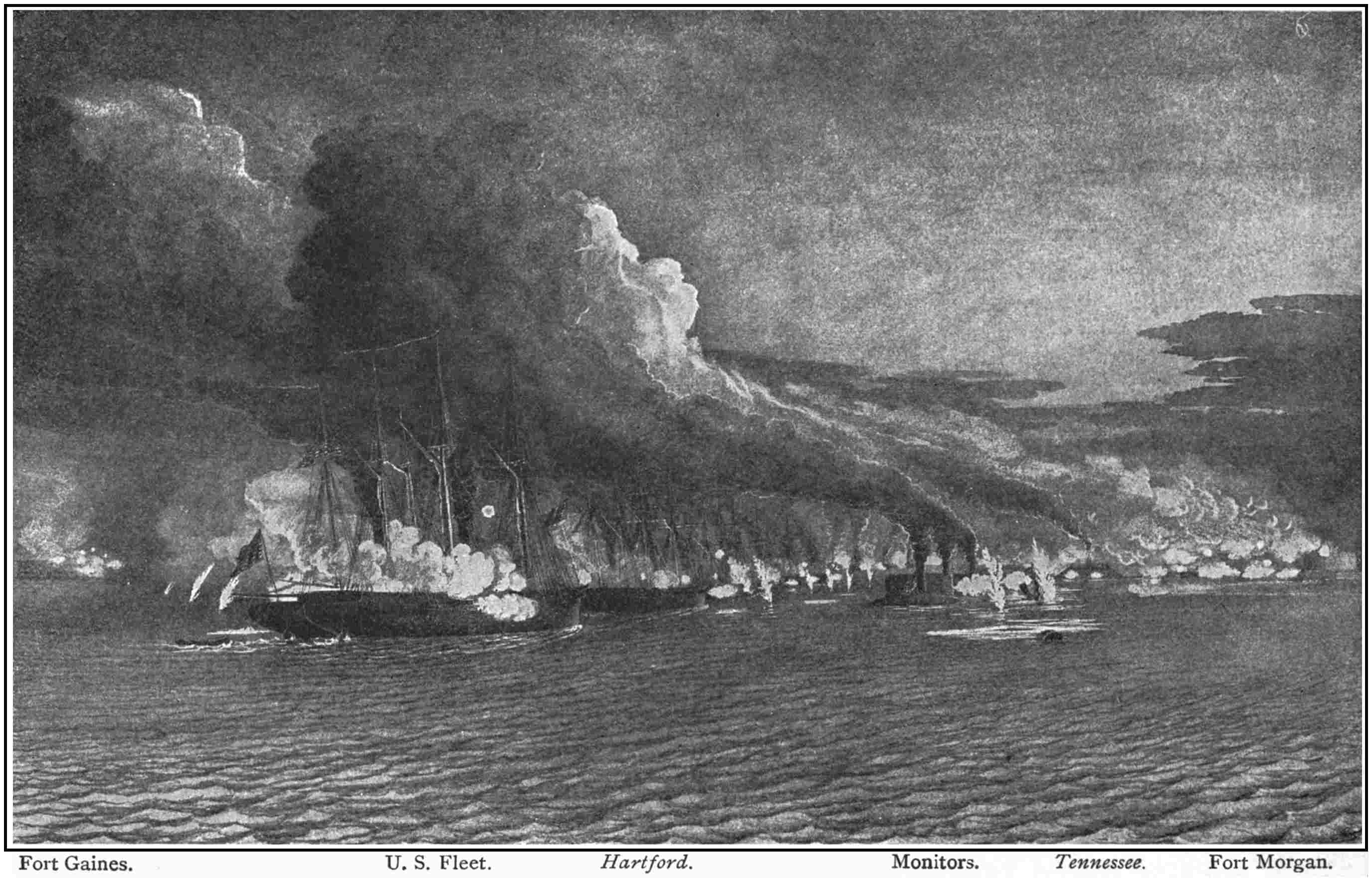

| Battle of Mobile Bay. (From a painting by Admiral Walke), | 397 |

| The Confederate Ram Tennessee, Captured at Mobile. (From a photograph), | 404 |

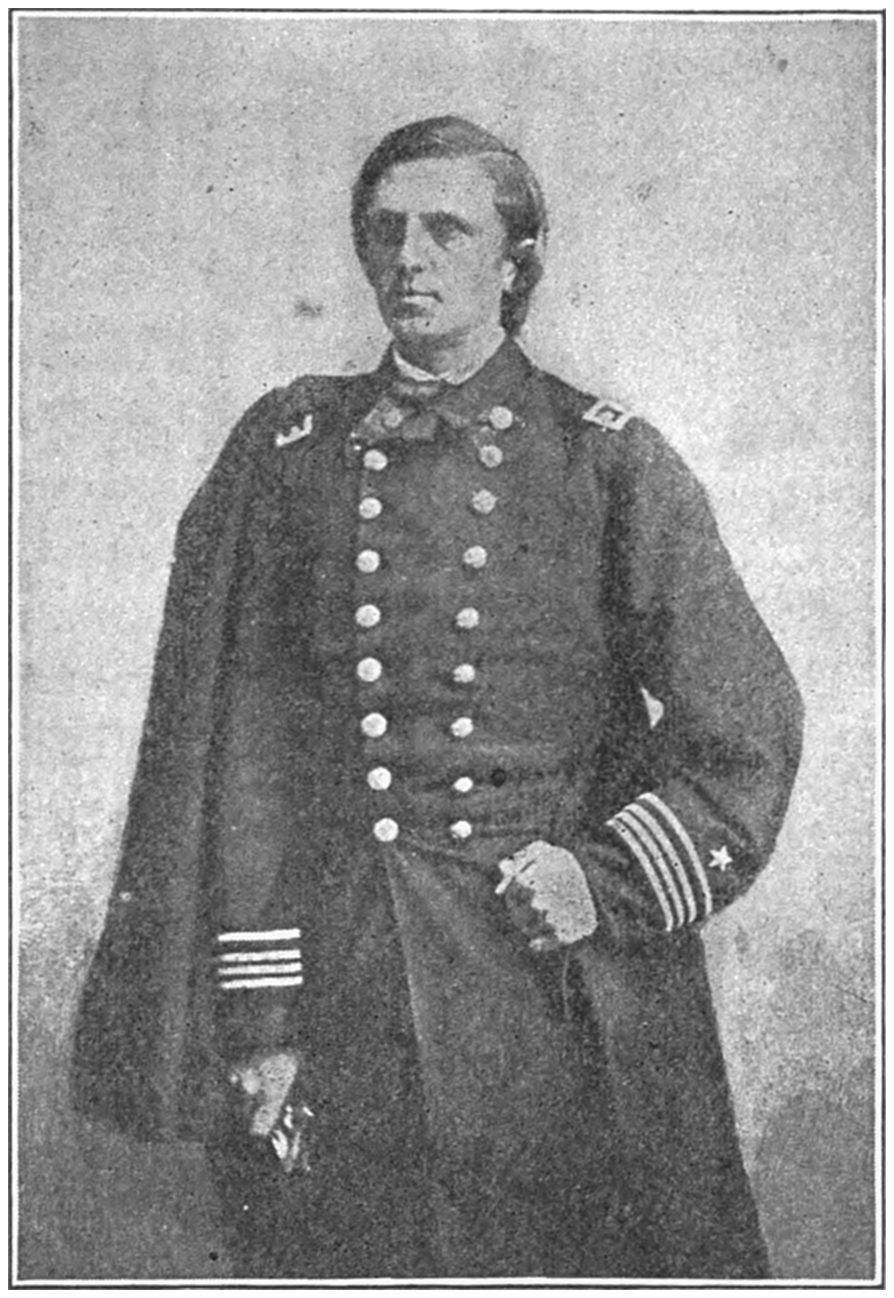

| Raphael Semmes. (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 408 |

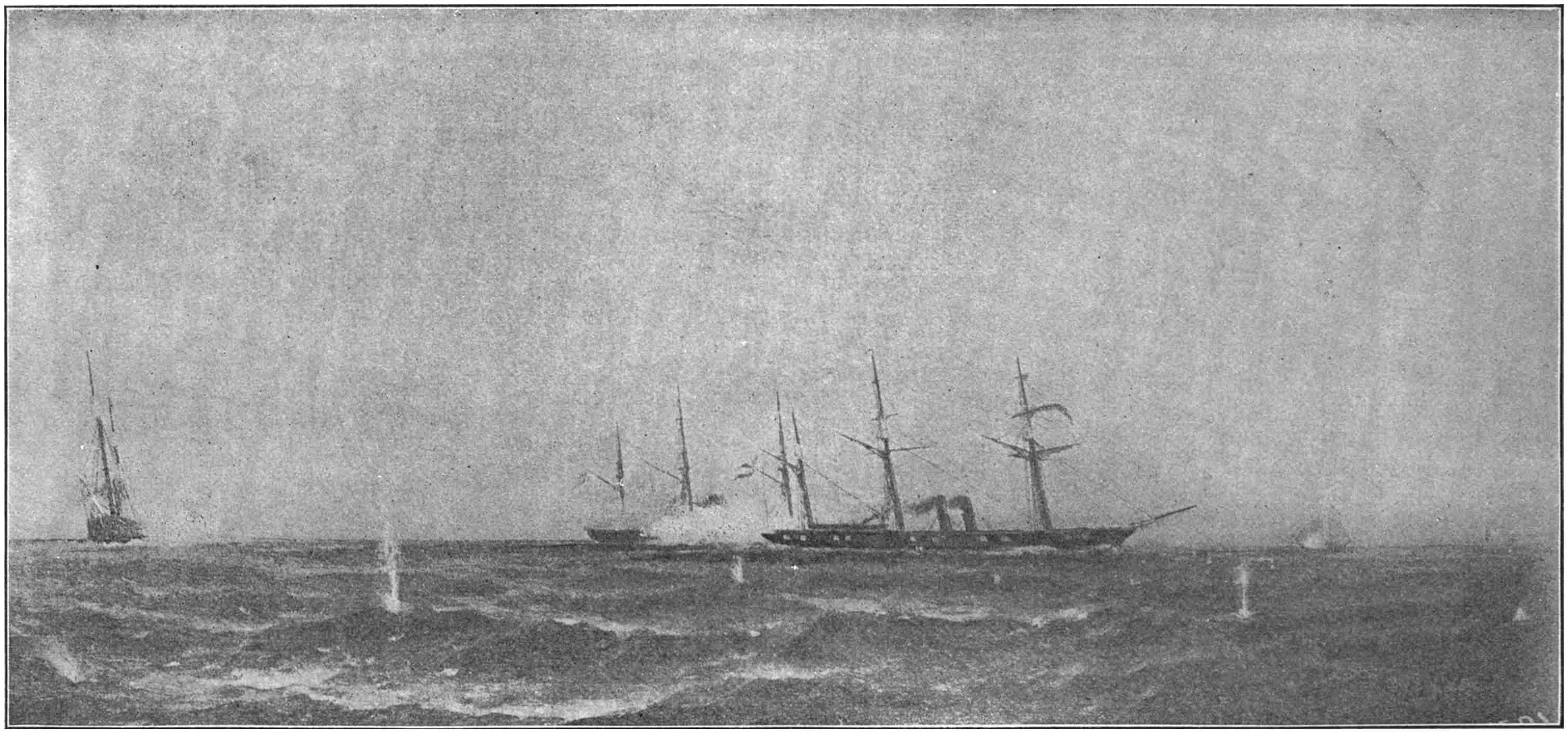

| The Florida Running the Blockade at Mobile. (After a painting by R. S. Floyd), | 421 |

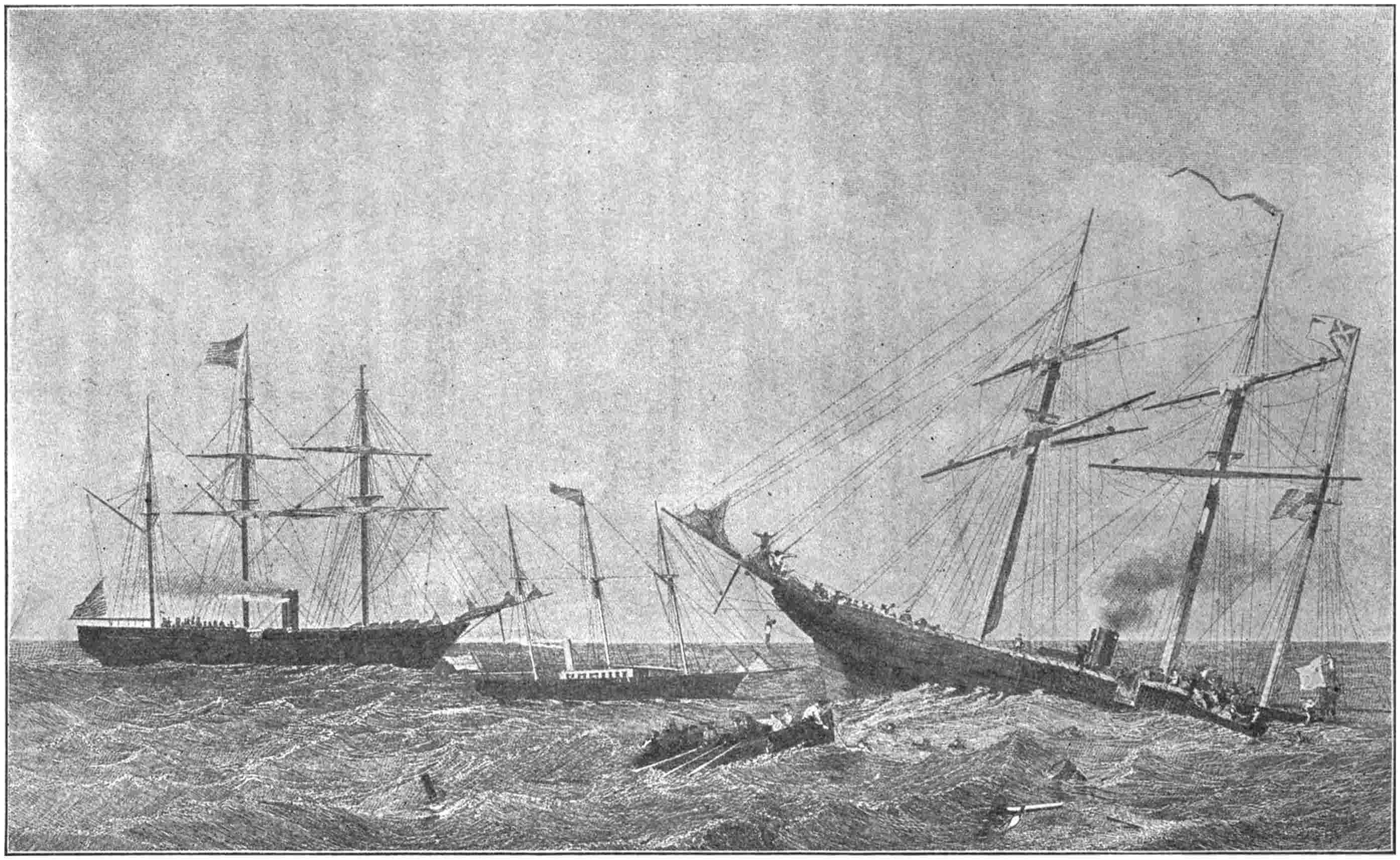

| “A Prize Disposed and One Proposed.” (After a painting by R. S. Floyd), | 425 |

| Raphael Semmes and his Alabama Officers. (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 433 |

| John A. Winslow. (From a photograph), | 436 |

| Engagement between the U. S. S. Kearsarge and the Alabama off Cherbourg, on Sunday, June 19, 1864. (From a French lithograph), | 439 |

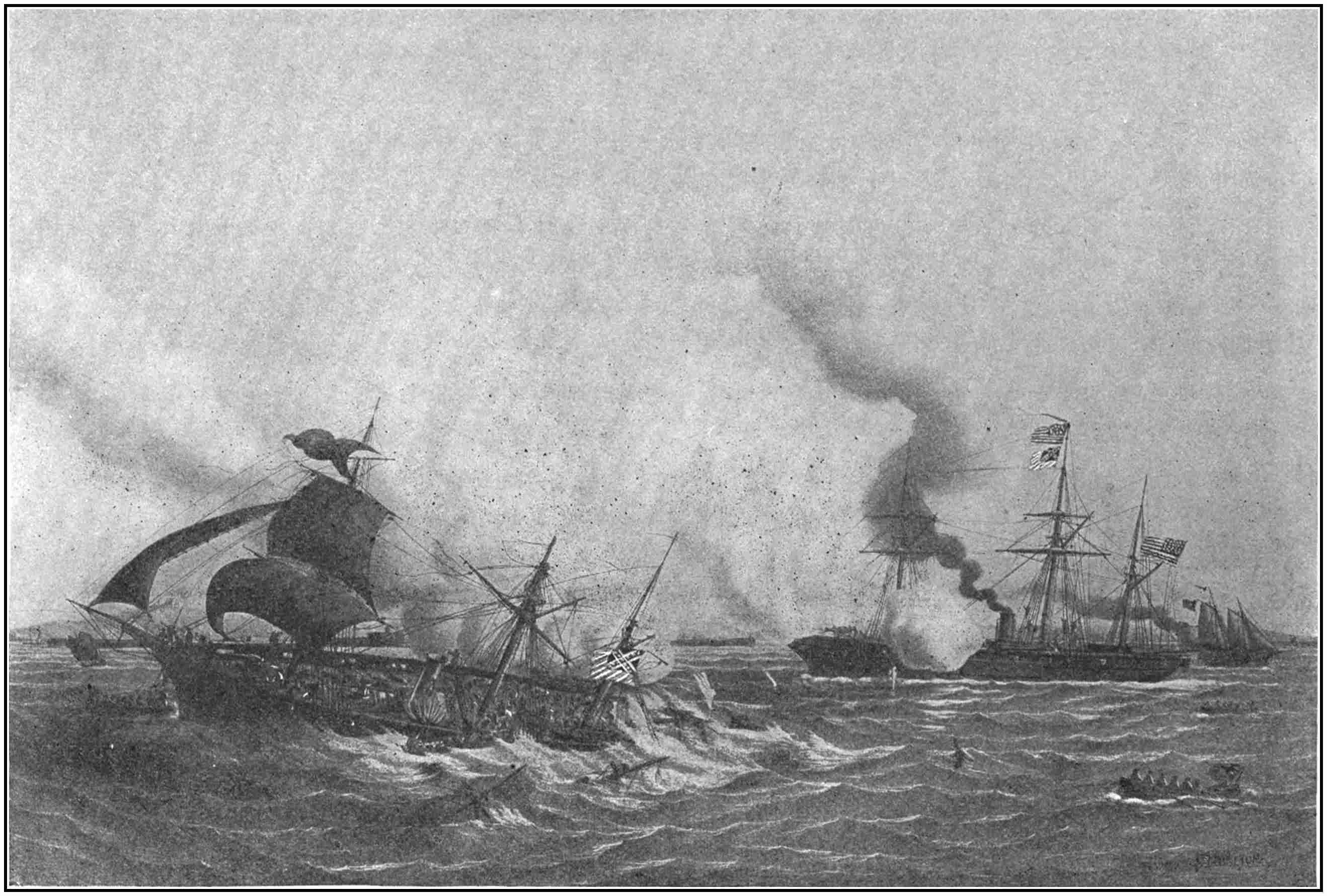

| The Kearsarge Sinking the Alabama. (From an engraving), | 443 |

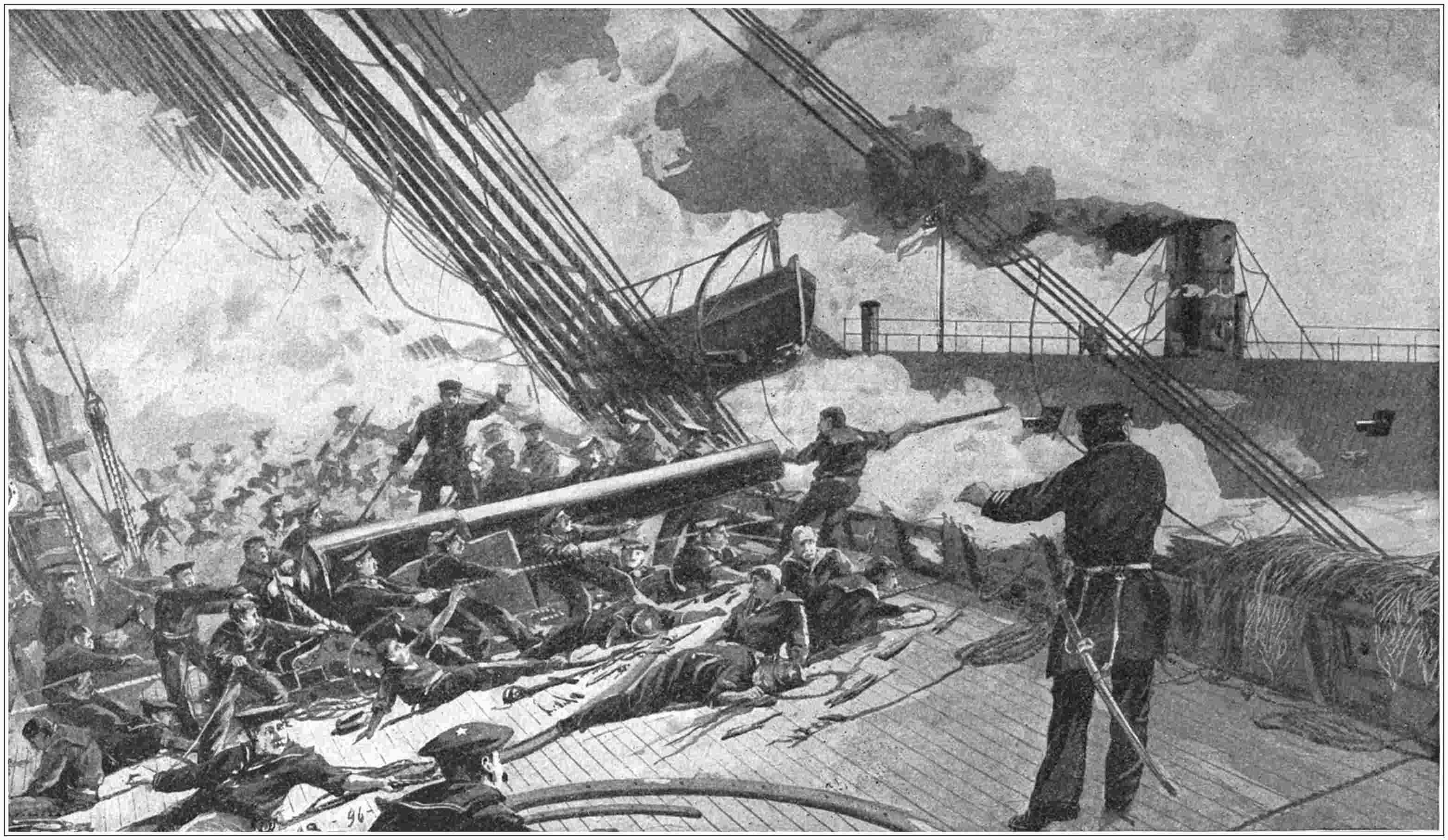

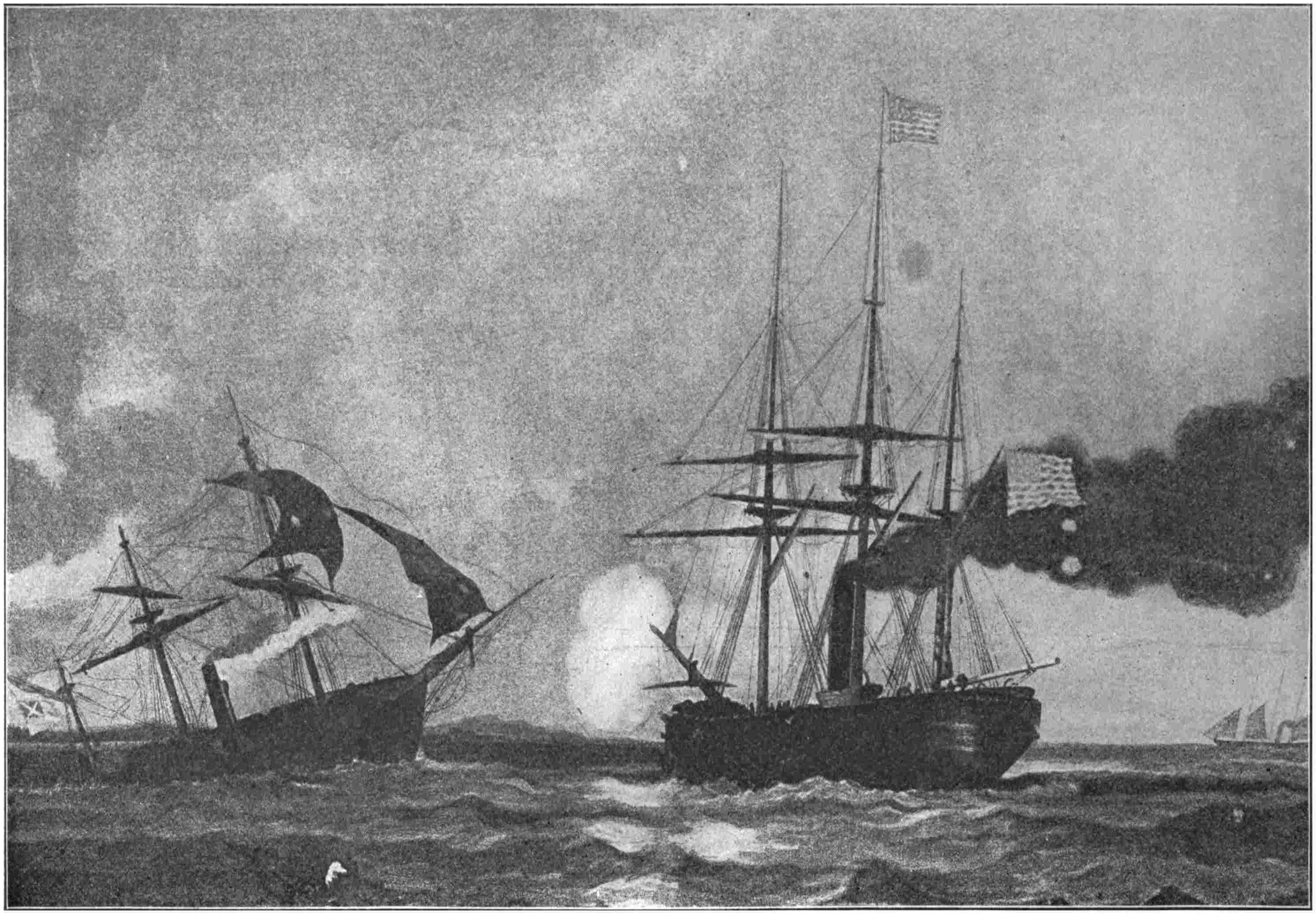

| Action between the Kearsarge and the Alabama. (From an engraving of the painting by Chappel), | 445 |

| Whitworth Rifle Captured from the Shenandoah, | 448 |

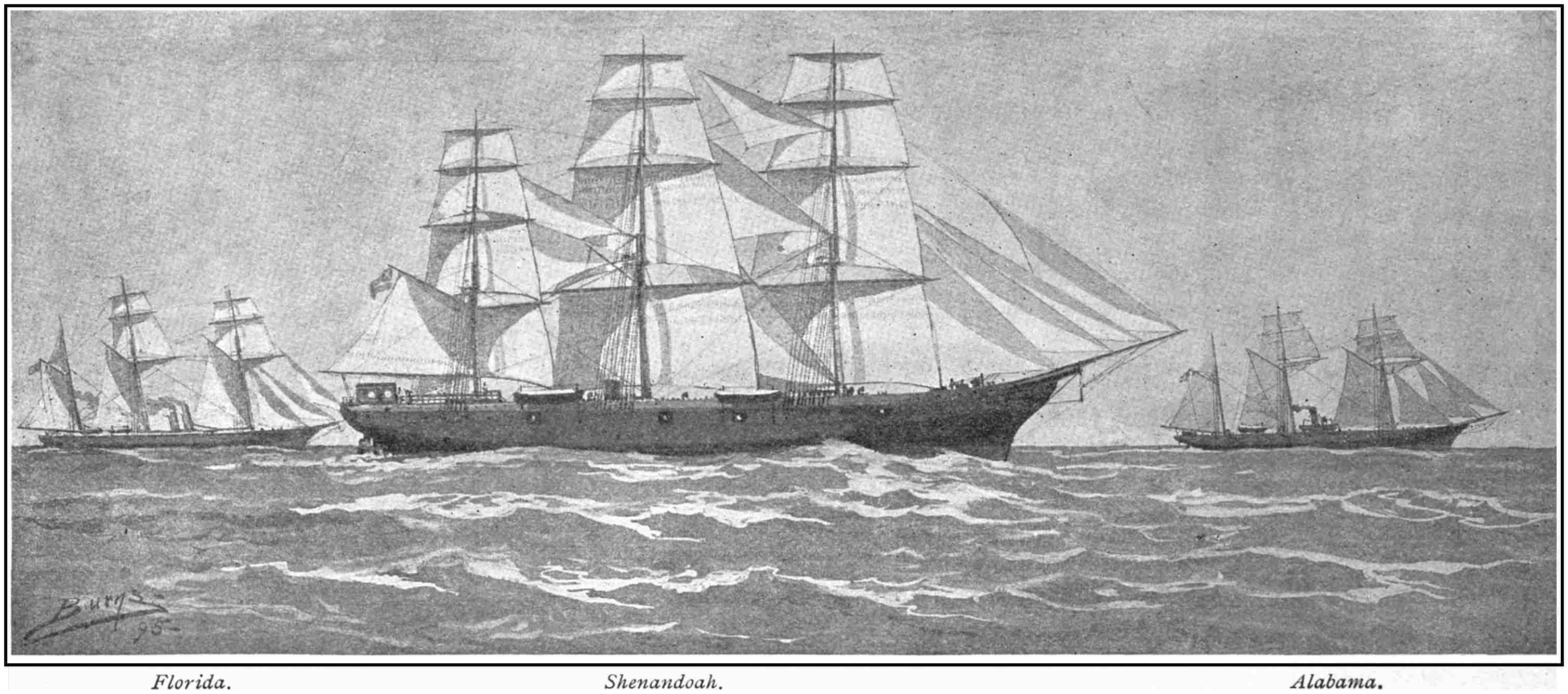

| Three Famous Confederate Cruisers. (From a painting by M. J. Burns), | 449xxi |

| William B. Cushing. (From a photograph), | 457 |

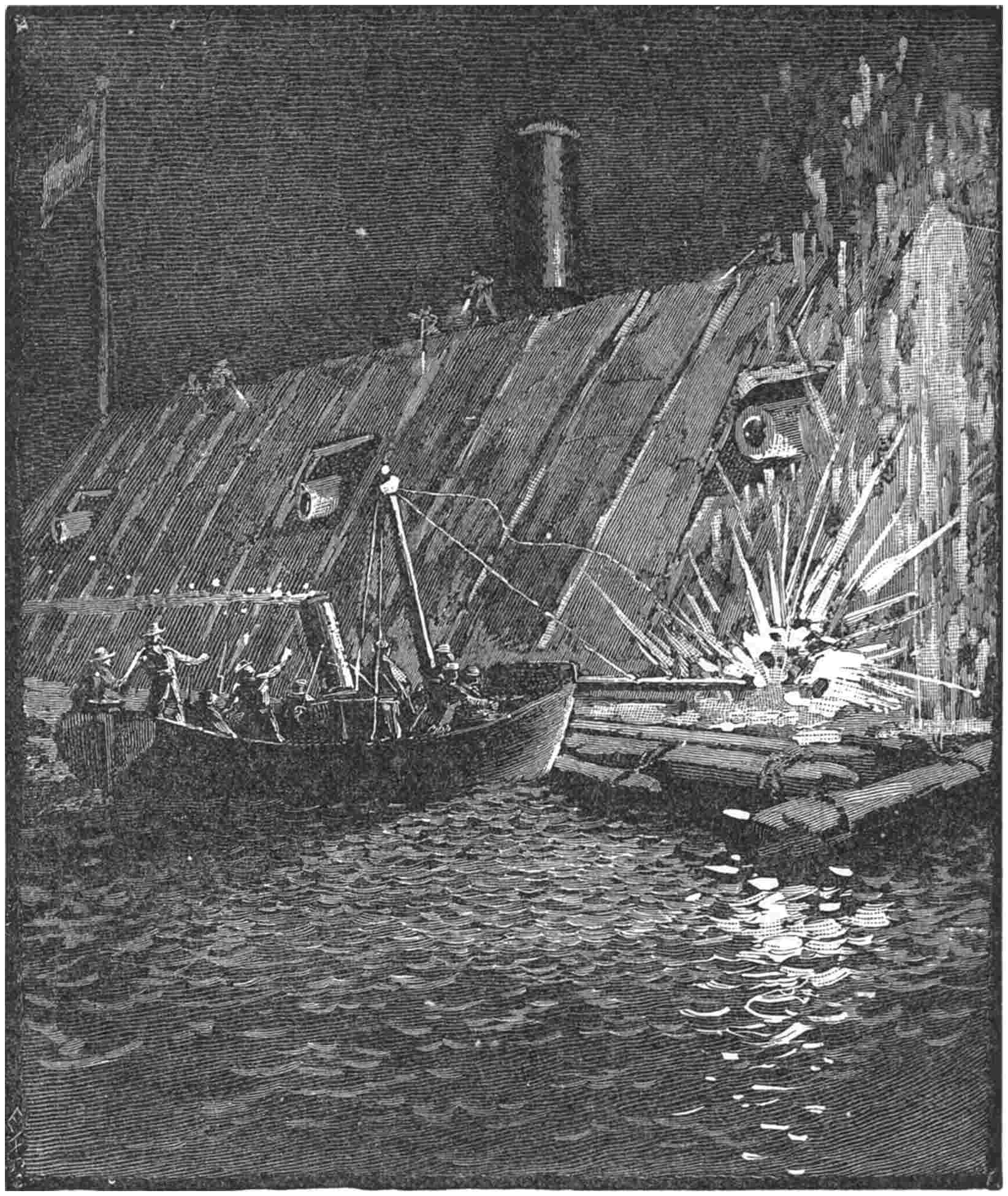

| Cushing Blowing up the Albemarle, | 462 |

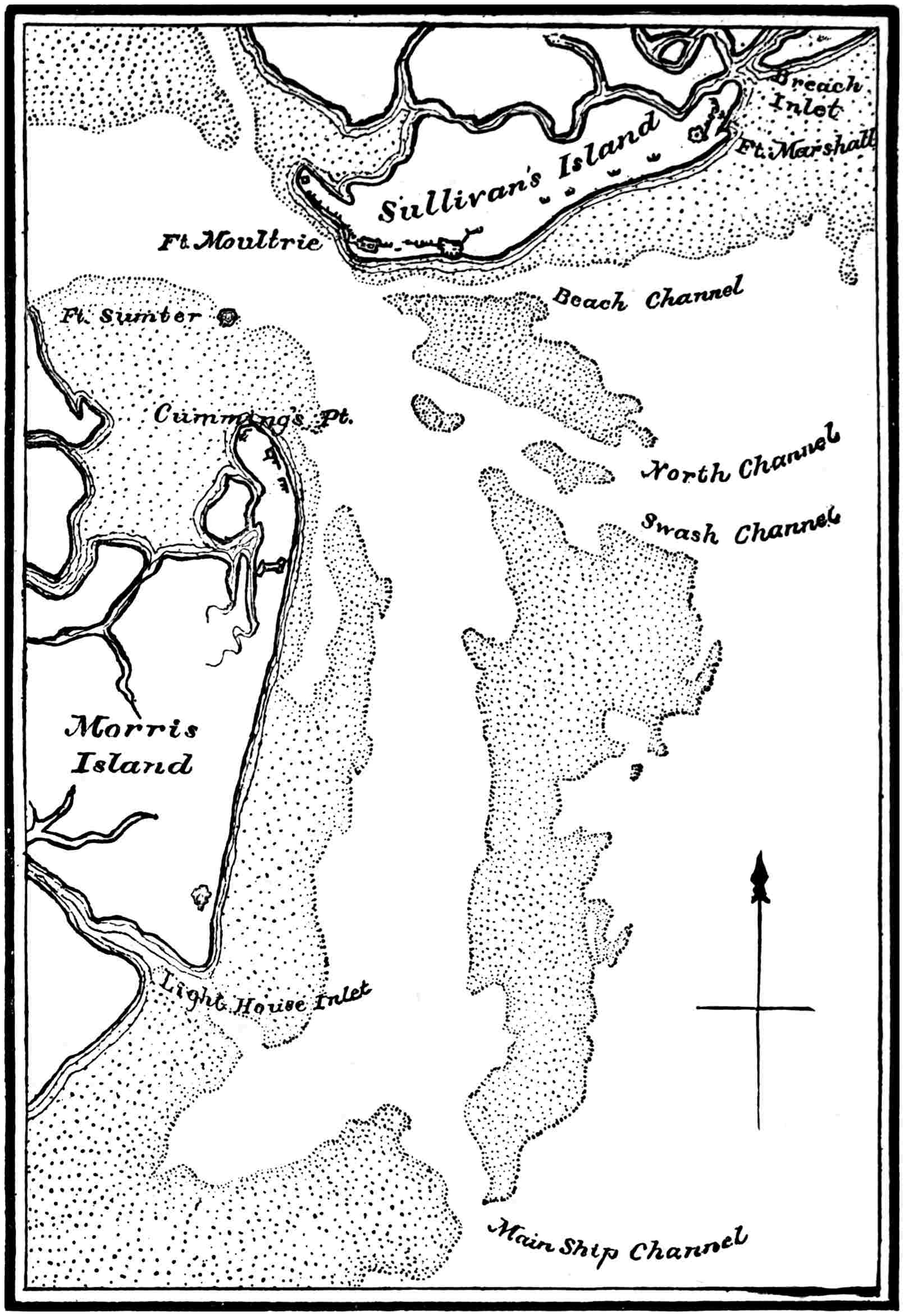

| Charleston Harbor. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 466 |

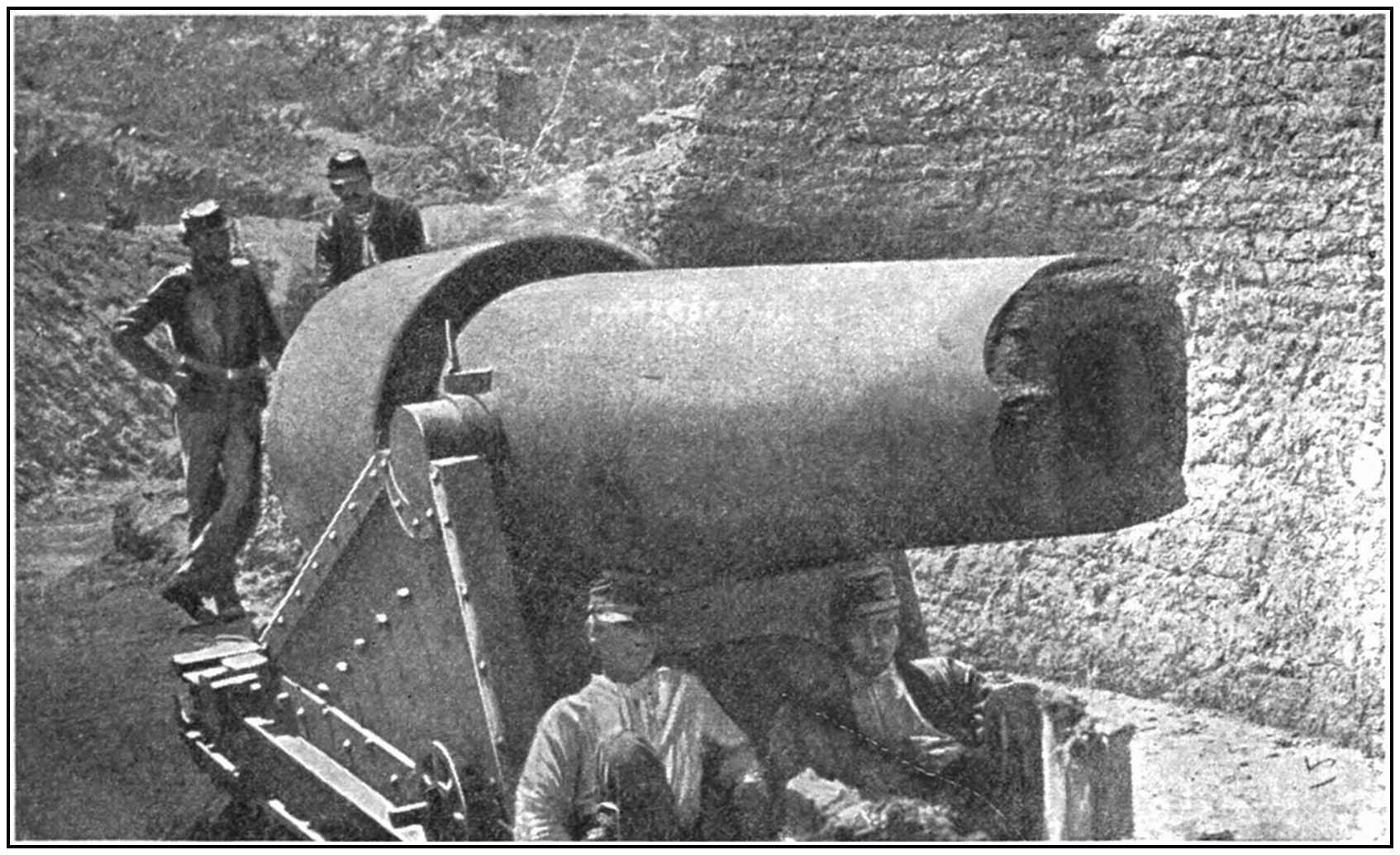

| Battery Brown: Twenty-eight-inch Parrott Rifle. (From a photograph by Haas & Peale), | 468 |

| In the Charleston Batteries: 300-pounder Parrott Rifle after Bursting of Nozzle. (From a photograph by Haas & Peale), | 469 |

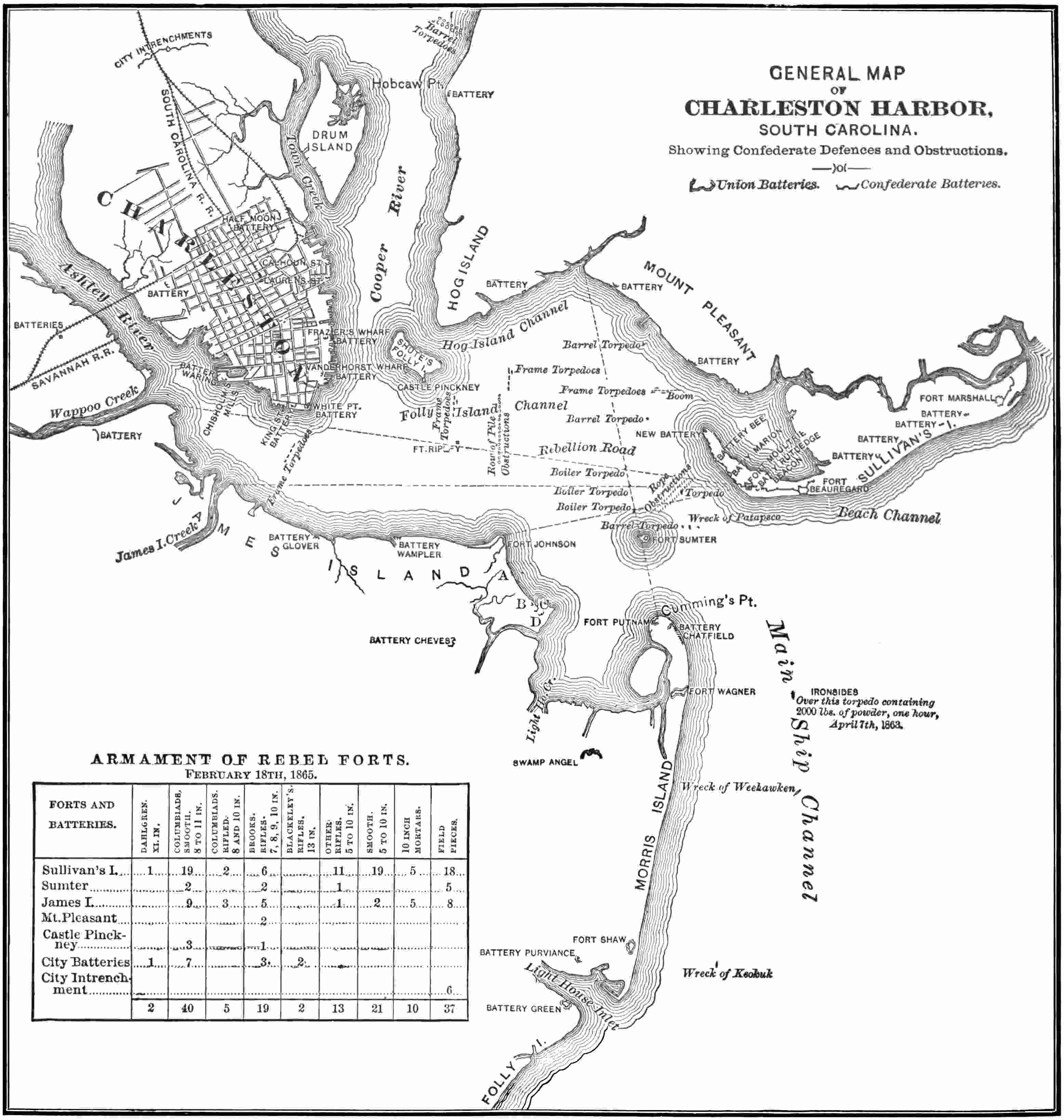

| General Map of Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, Showing Confederate Defences and Obstructions, | 476–7 |

| Ironclads and Monitors Bombarding the Defences at Charleston. (From an engraving), | 481 |

| Confederate Ironclad Atlanta, Captured at Wassaw Sound, June 17, 1863. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 487 |

| The Weehawken and the Atlanta. (From a wood-cut), | 488 |

| John A. B. Dahlgren. (From a photograph), | 489 |

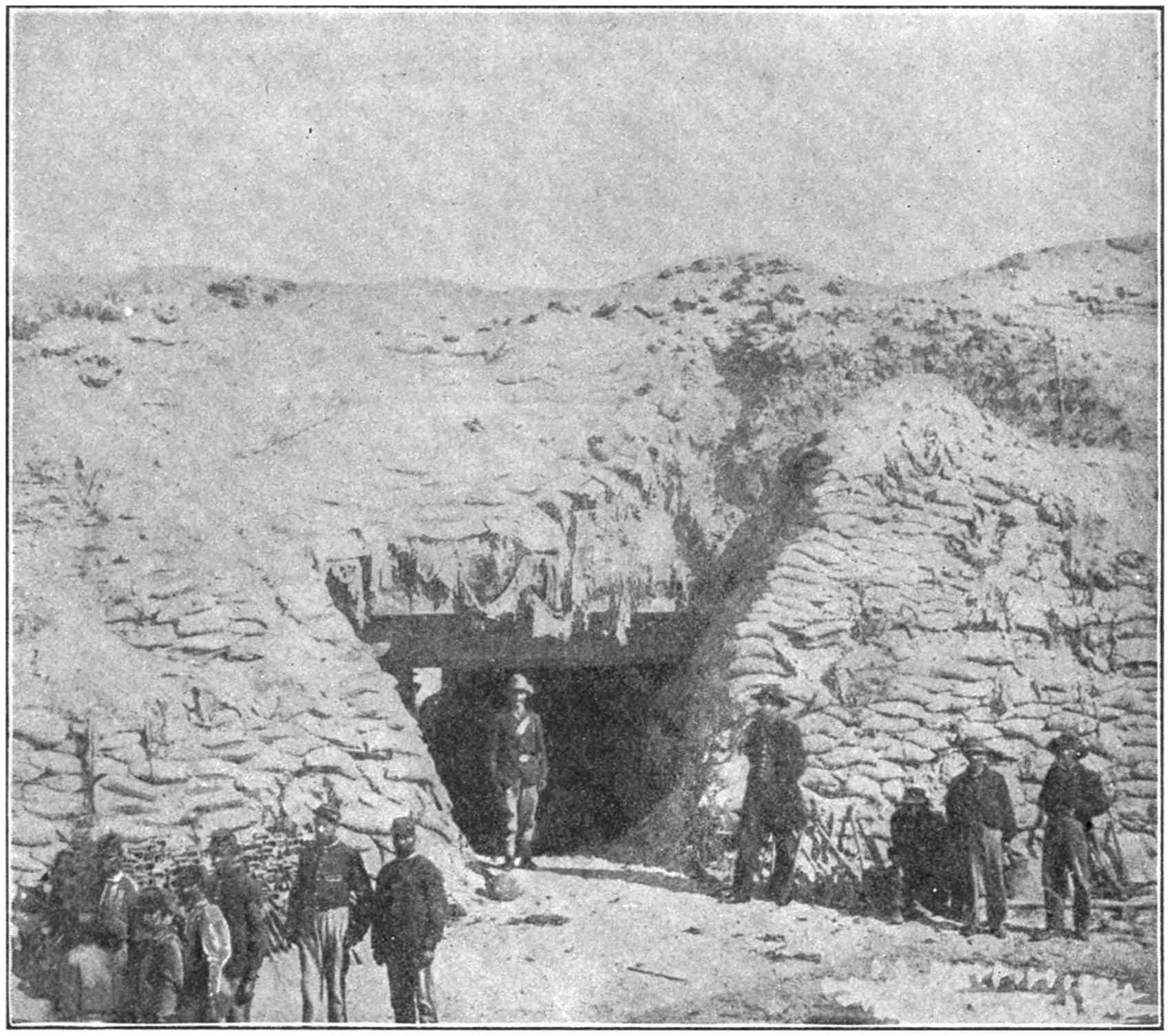

| Bomb-proof of Fort Wagner. (From a photograph by Haas & Peale), | 491 |

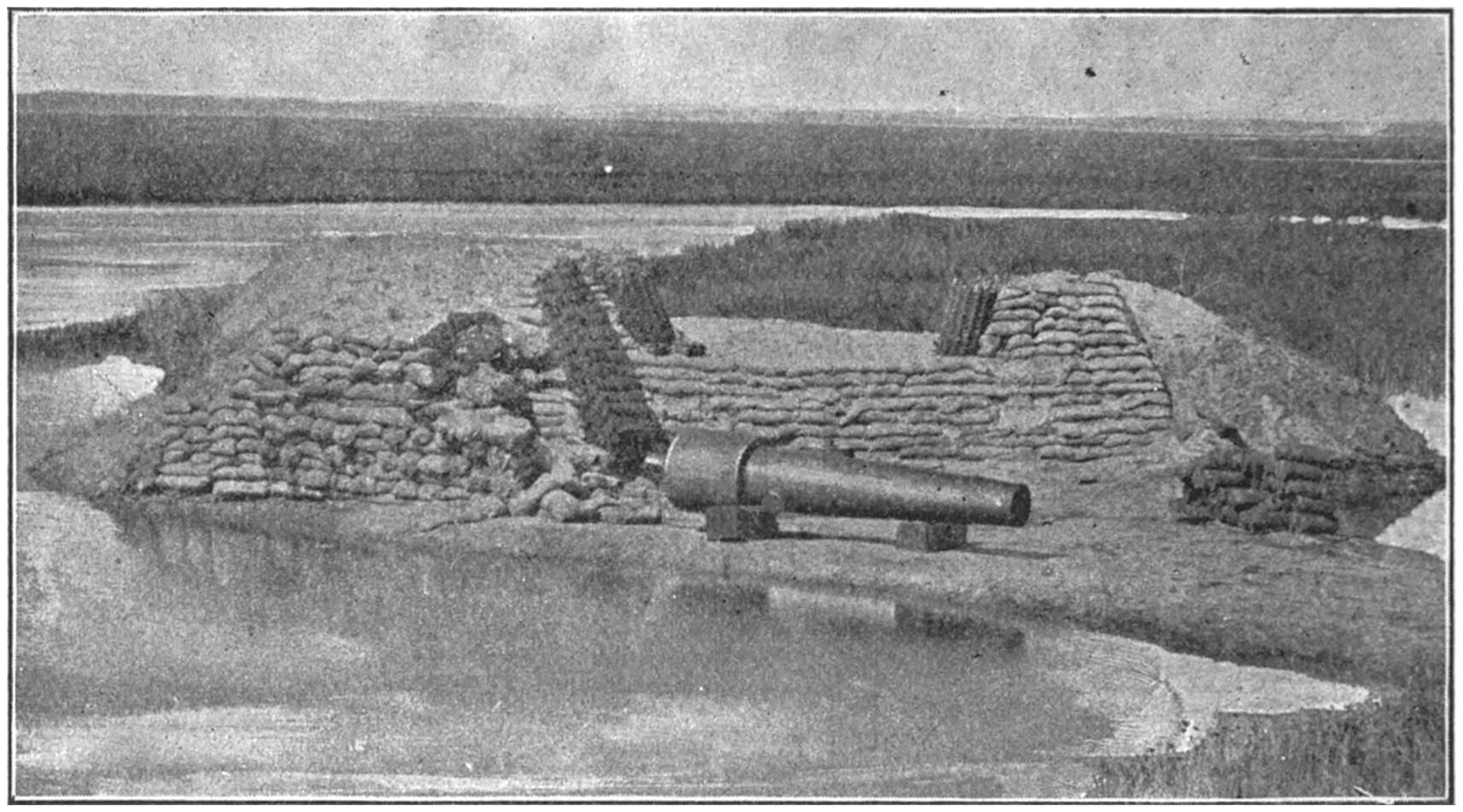

| Battery Hayes: Eighteen-inch Parrott Rifle—Dismounted Breaching Battery against Sumter. (From a photograph by Haas & Peale), | 492 |

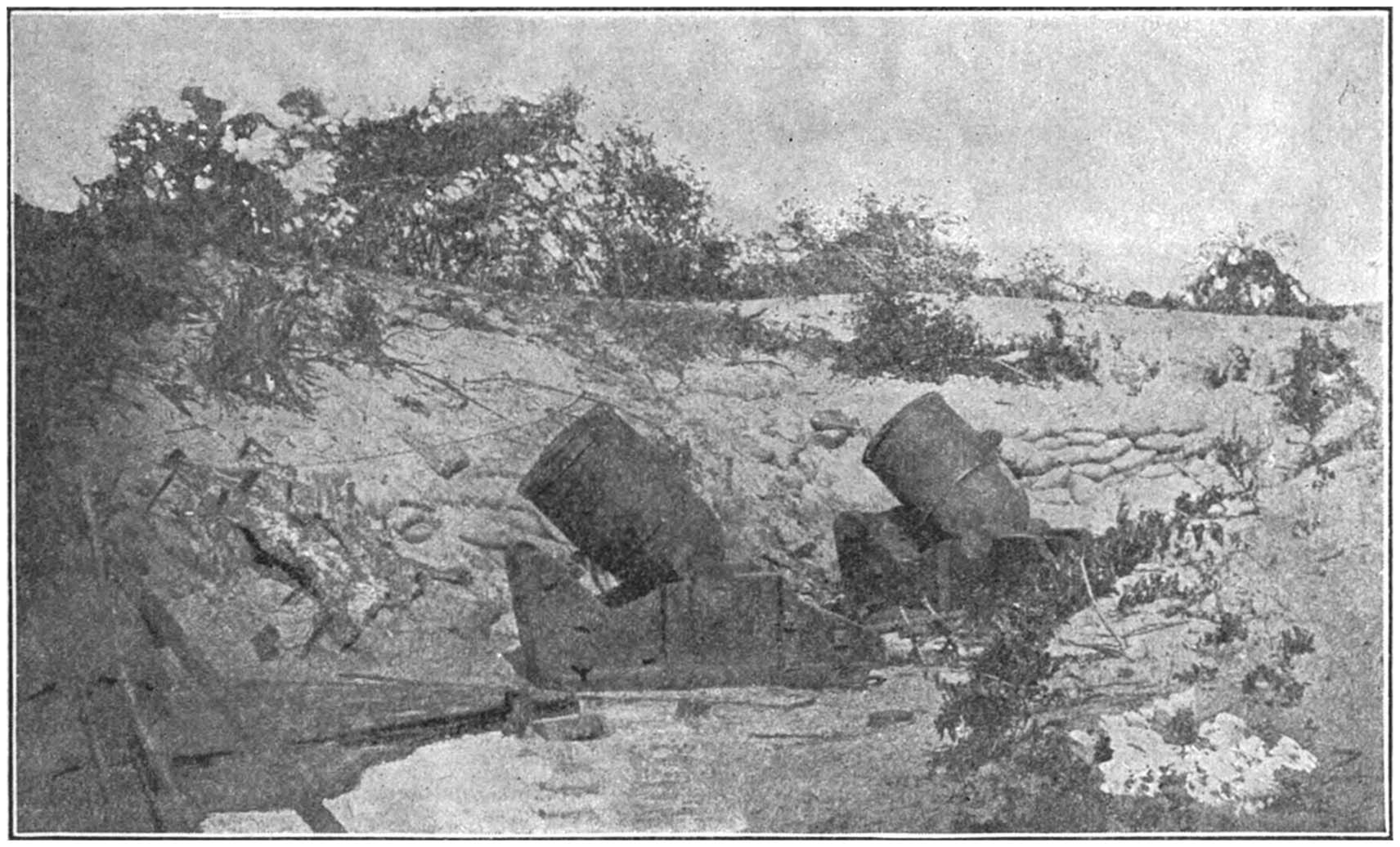

| Battery Kirby: Twenty-eight-inch Seacoast Mortars against Sumter. (From a photograph by Haas & Peale), | 493 |

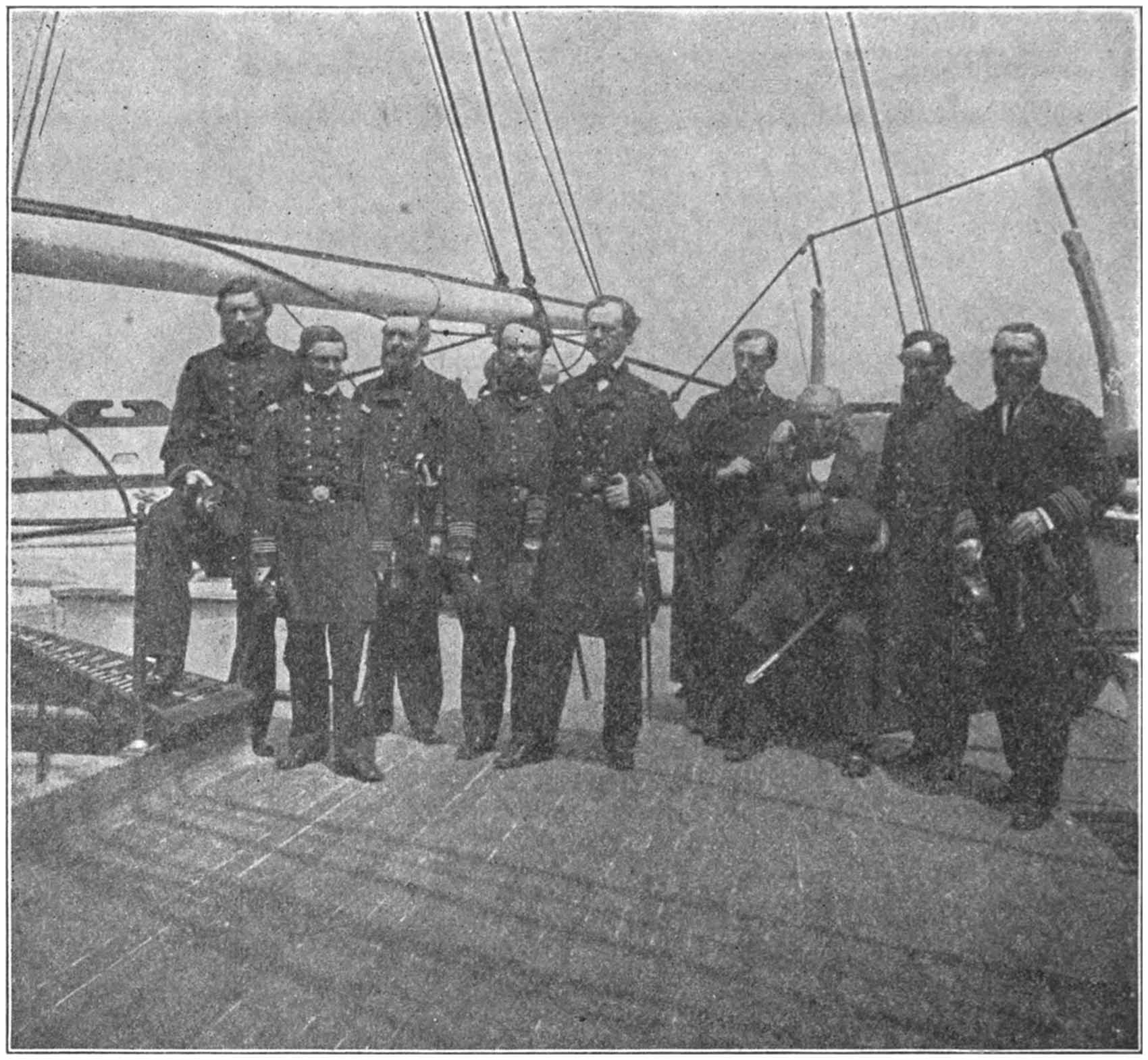

| Admiral Dahlgren and Staff on the Pawnee at Charleston. (From a photograph), | 496 |

| Sketch Showing Torpedo Boats as Constructed at Charleston, S. C. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 498 |

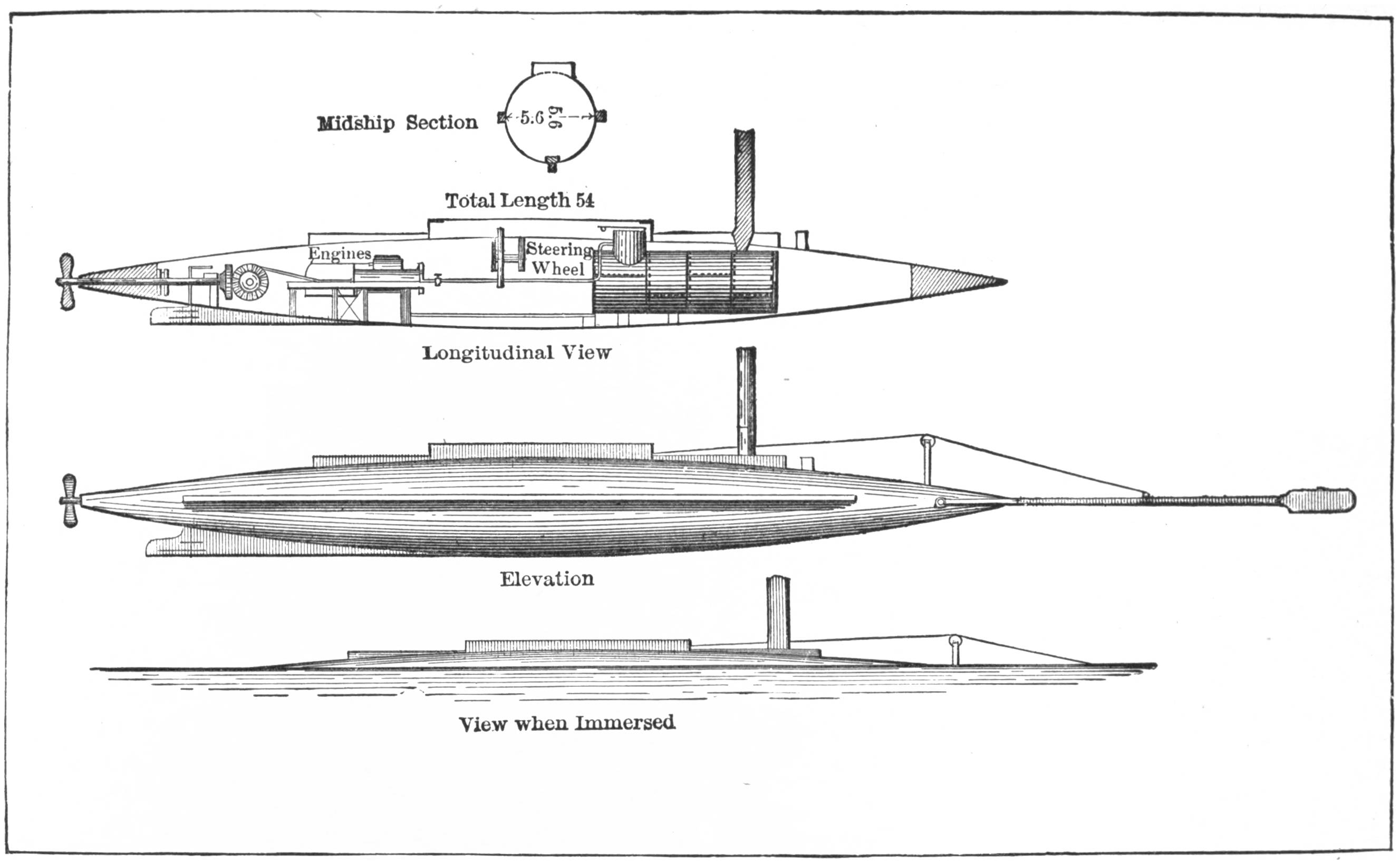

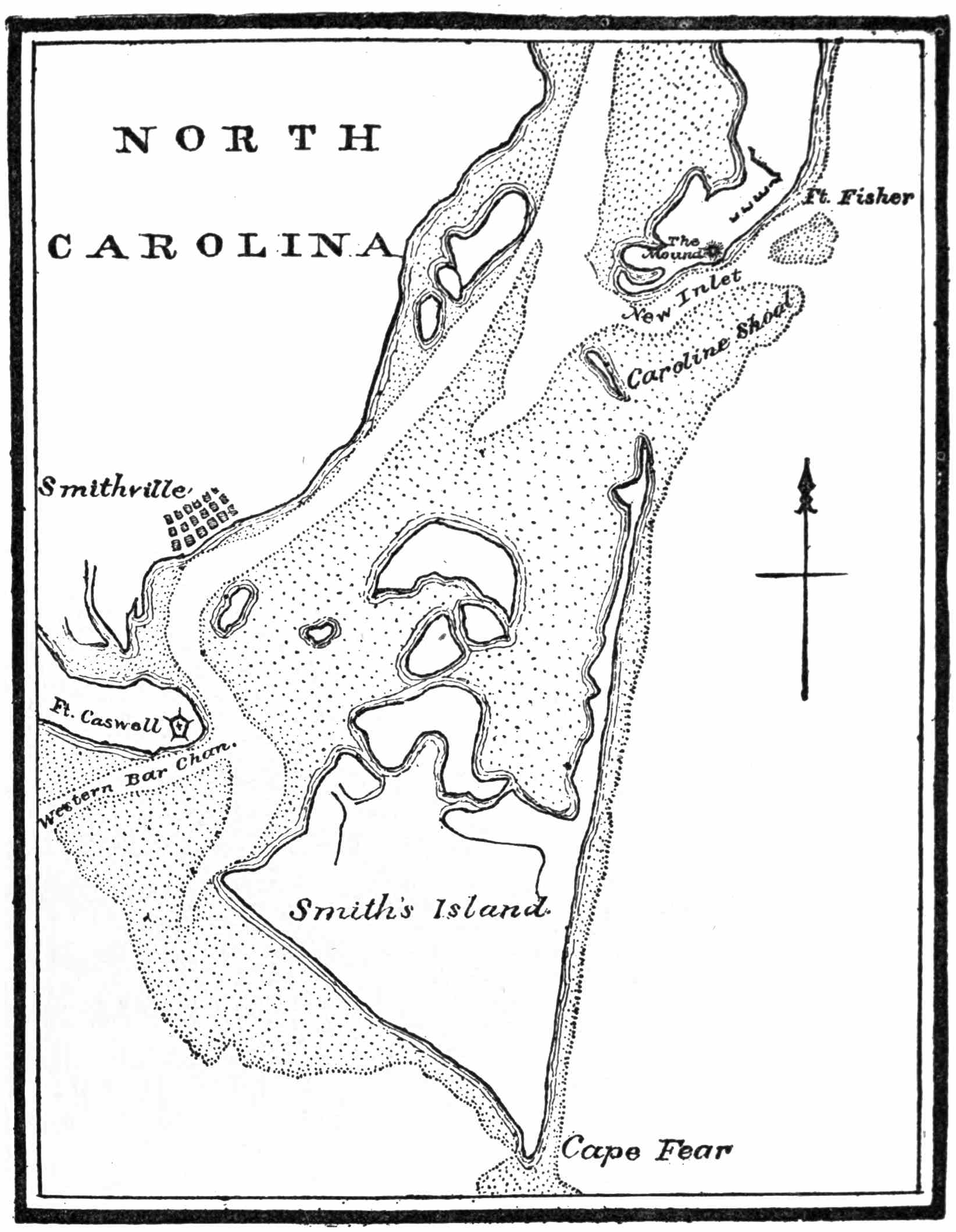

| The Entrance to Cape Fear River, Showing Fort Fisher. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 504 |

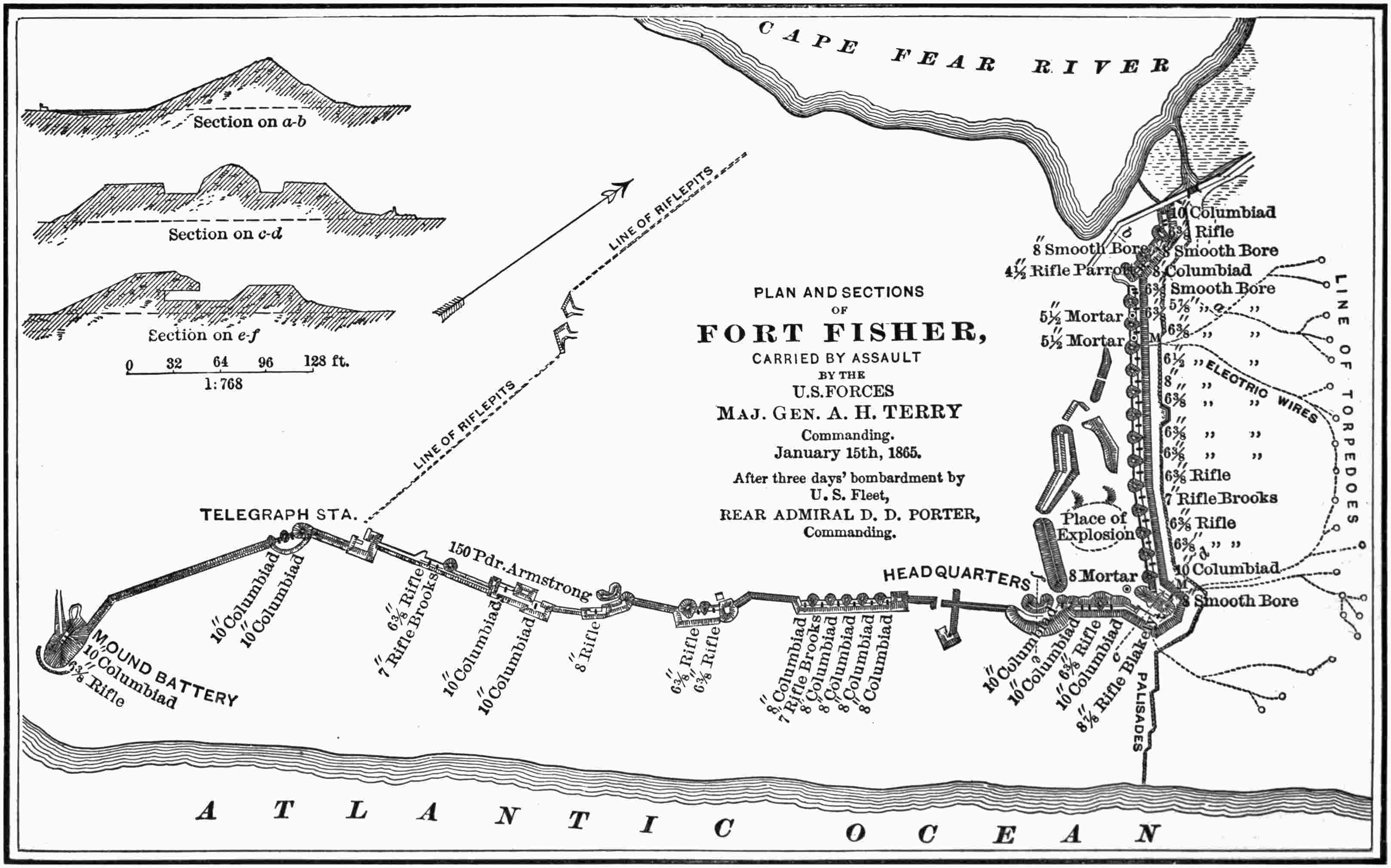

| Plan and Sections of Fort Fisher. (From “The Navy in the Civil War”), | 506 |

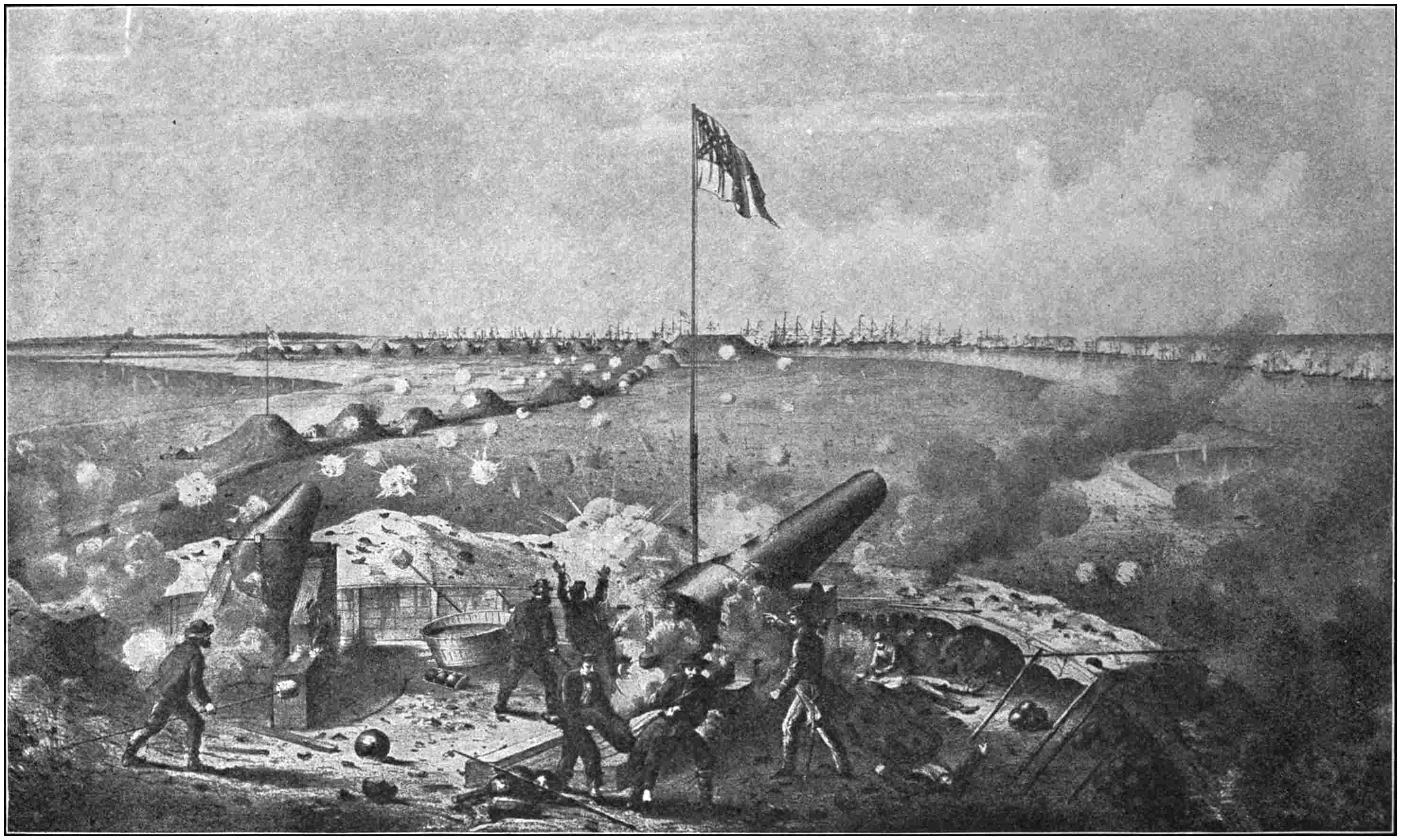

| The Bombardment of Fort Fisher. (From a lithograph), | 517 |

| T. O. Selfredge. (From a photograph owned by Mr. C. B. Hall), | 519 |

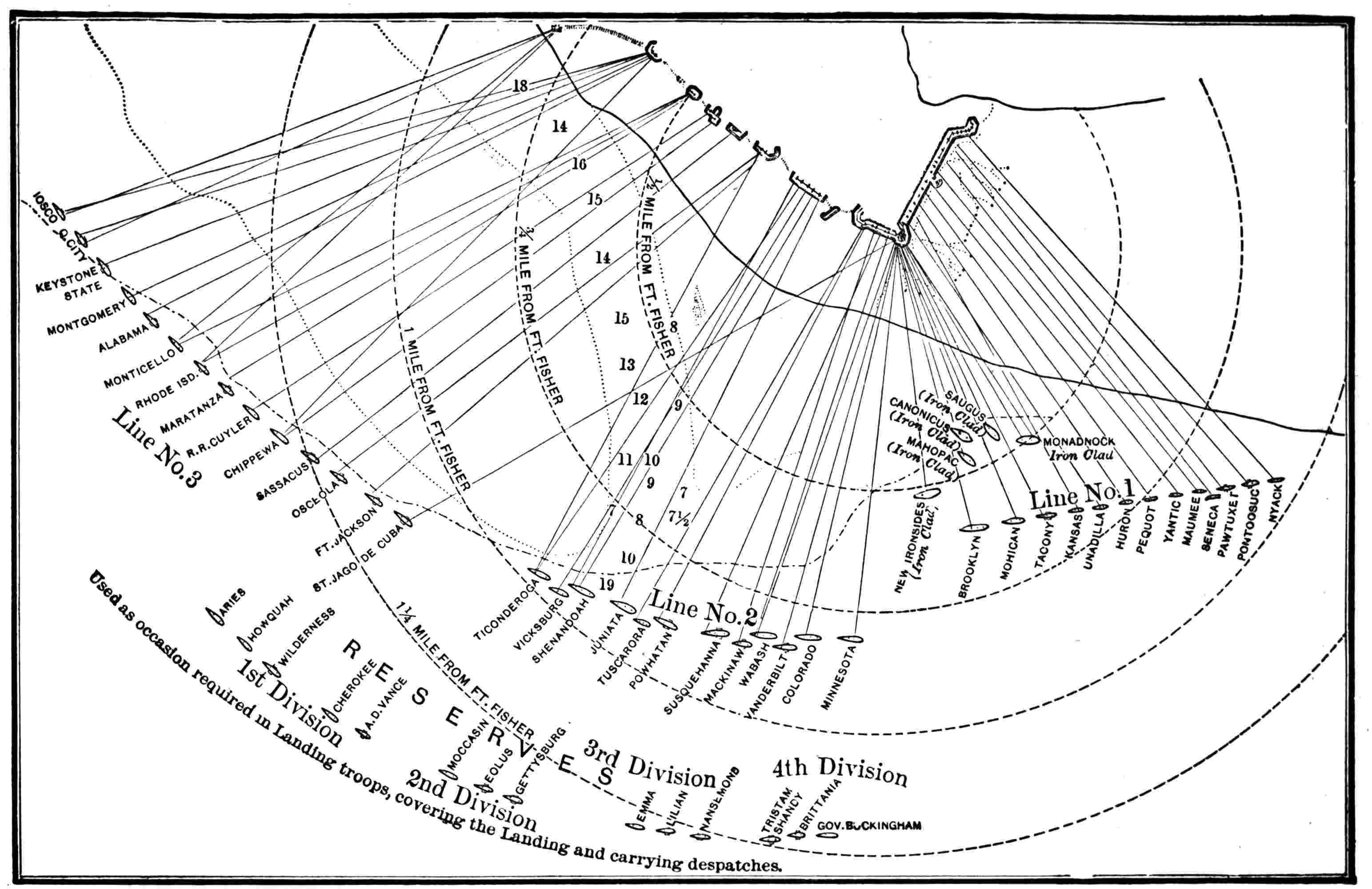

| Second Attack upon Fort Fisher by the U. S. Navy, under Rear-admiral D. D. Porter, January 13, 14, 15, 1865, | 521 |

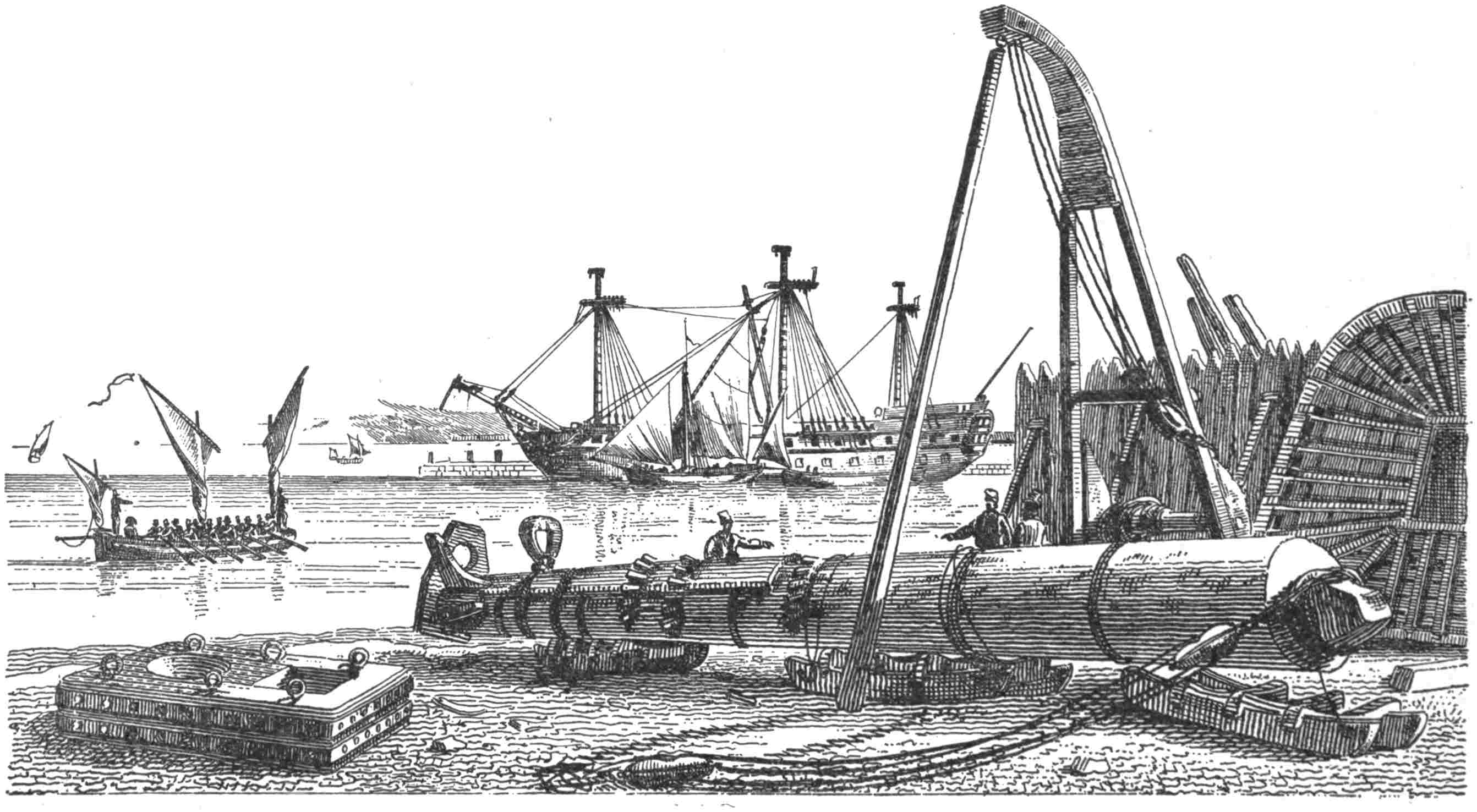

| The Old Method of Handling a Ship’s Bowsprit. (From an old engraving), | 524xxii |

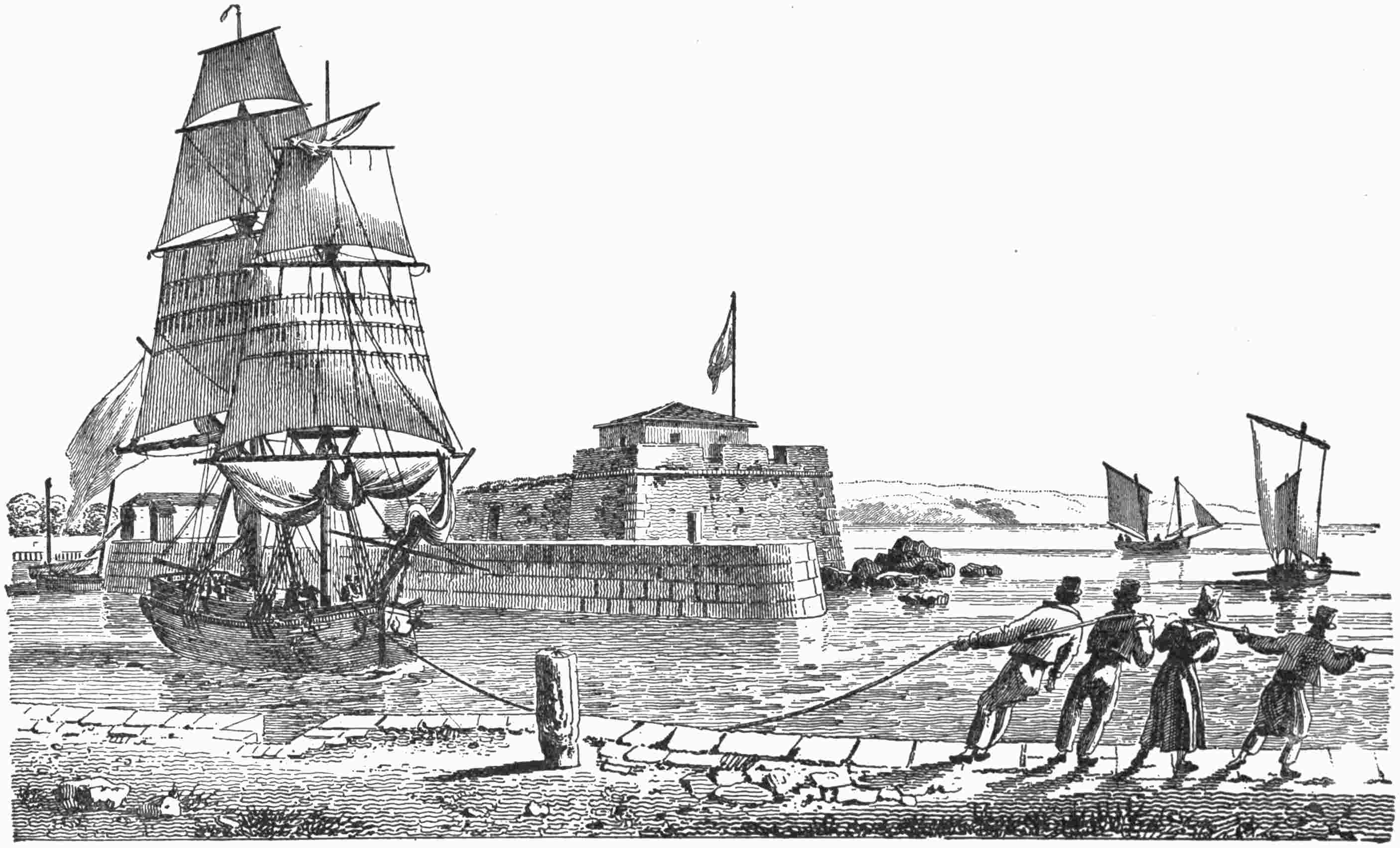

| Hauling a Vessel into Port a Hundred Years Ago. (From an old engraving), | 525 |

| The White Squadron in Mid-ocean. (From a drawing by R. F. Zogbaum), | 529 |

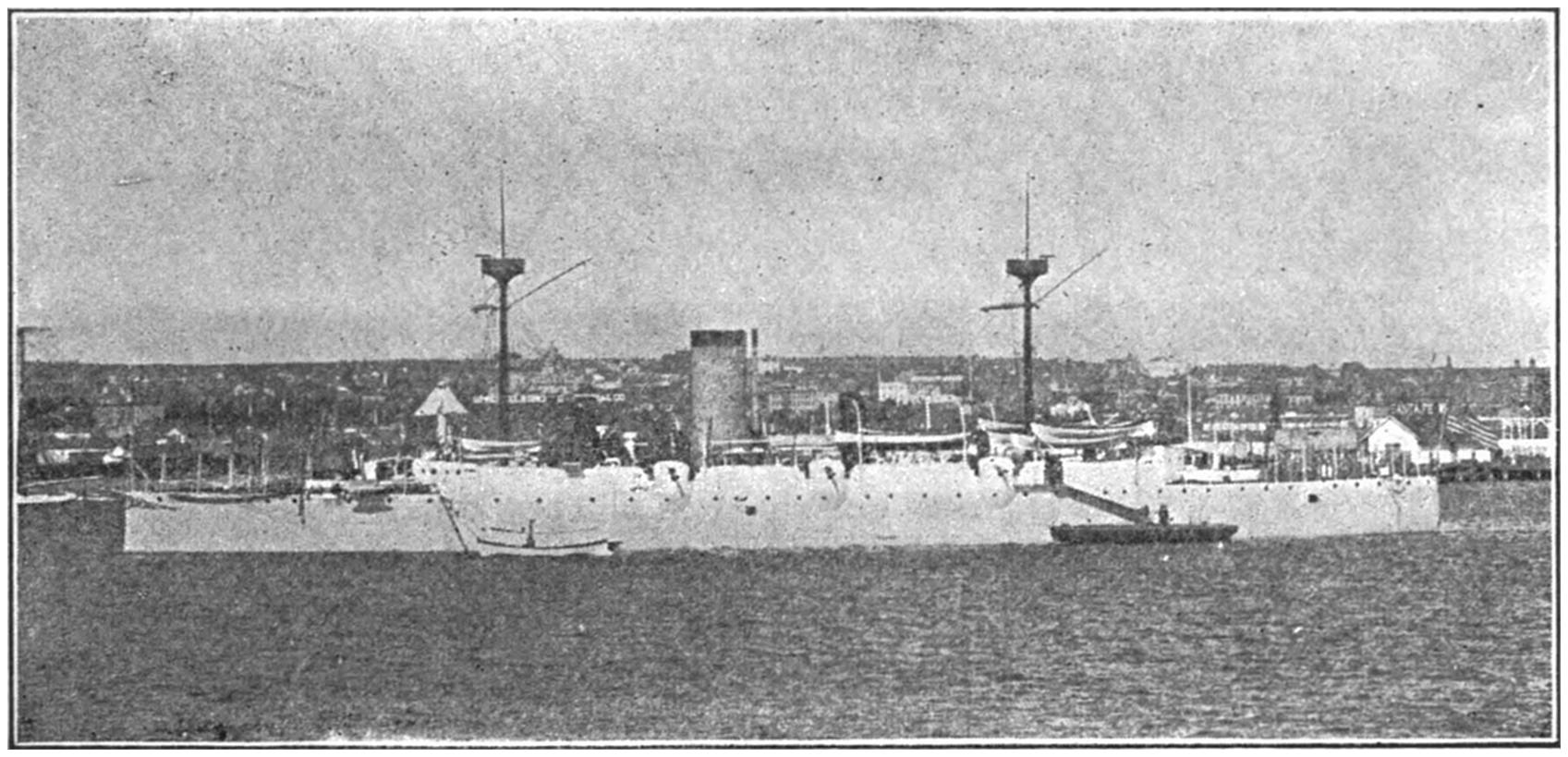

| U. S. S. Charleston, San Diego Harbor. (From a photograph), | 531 |

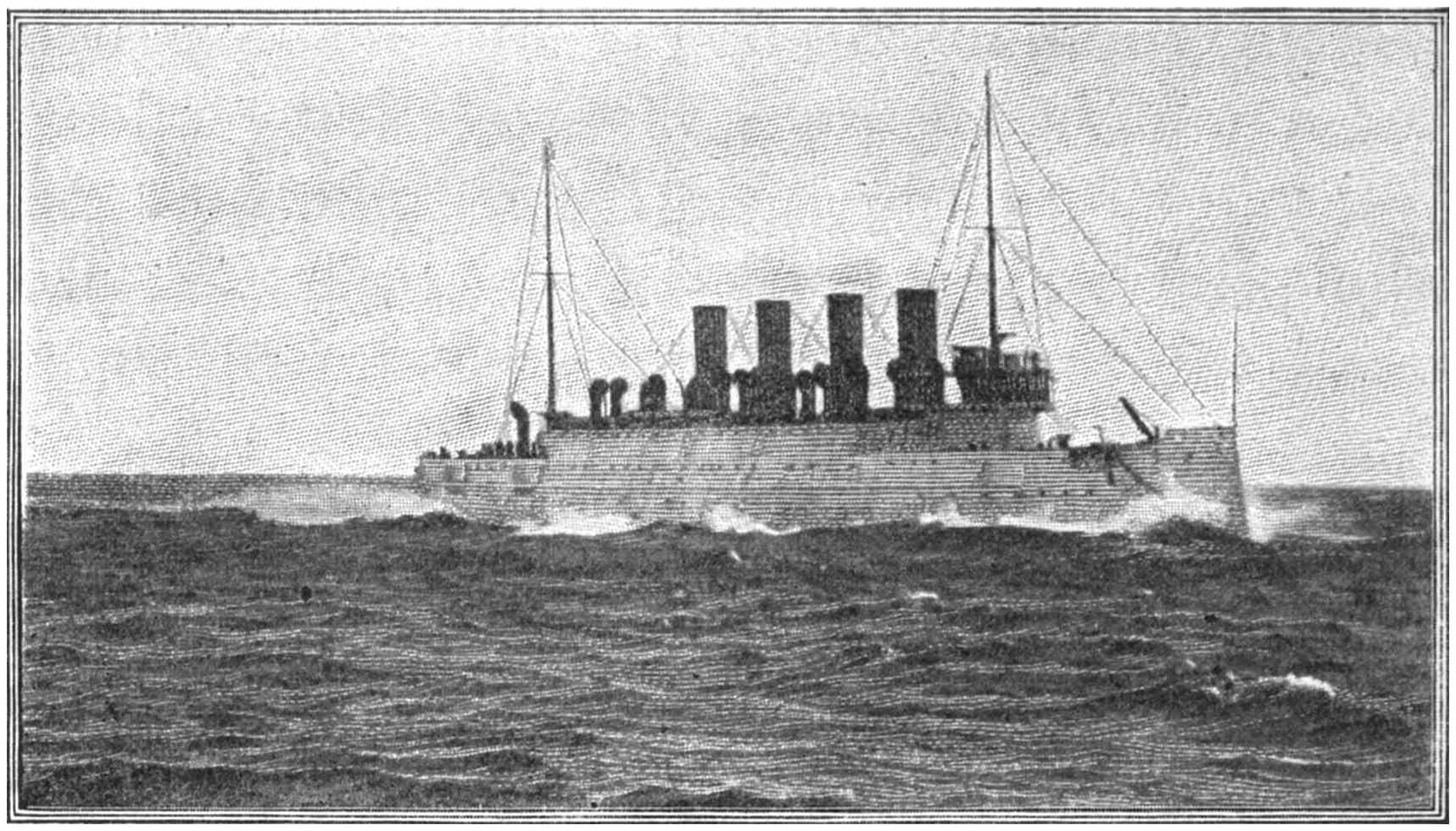

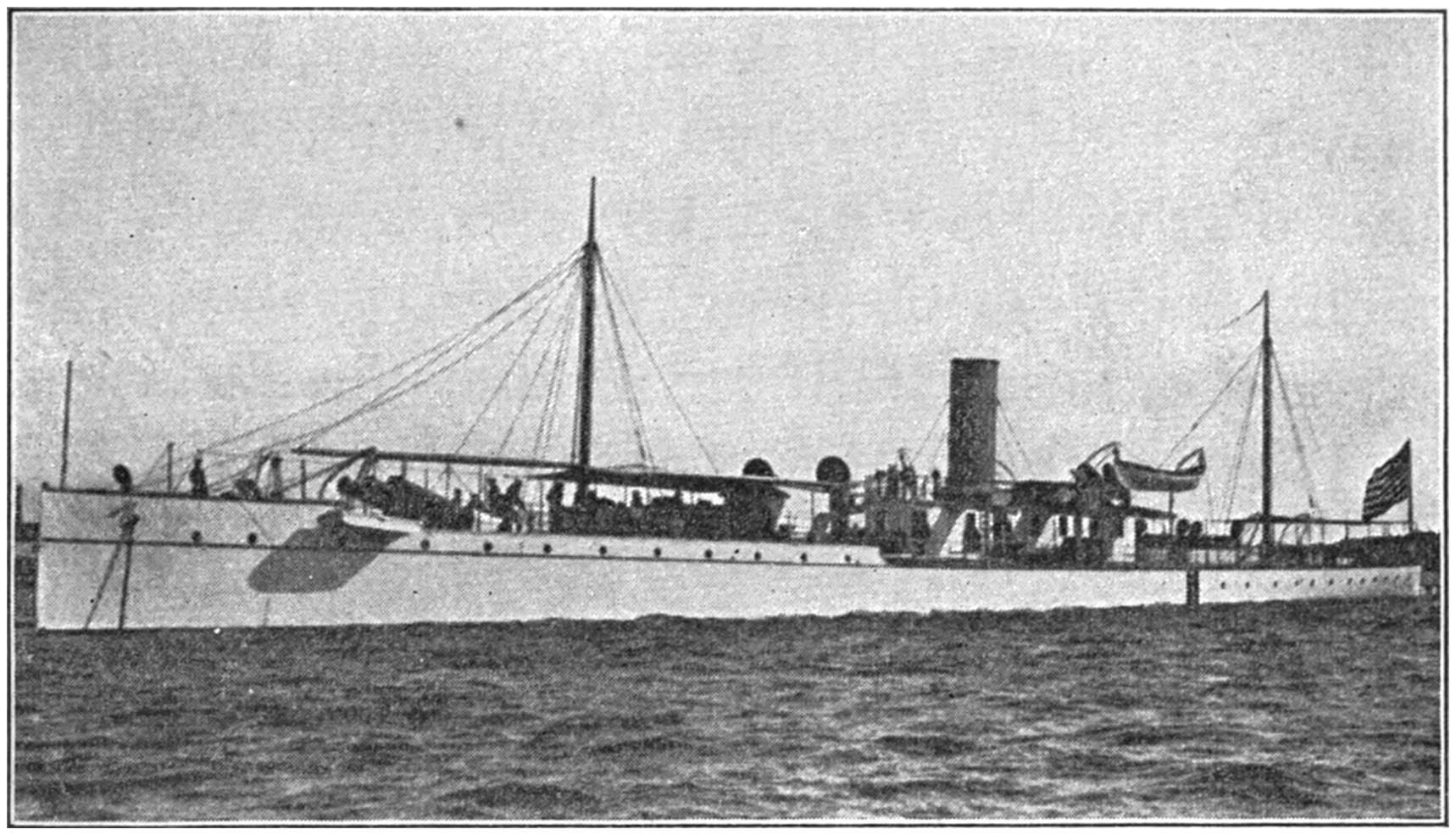

| The Columbia on her Government Speed Trial. (From a photograph by Rau), | 534 |

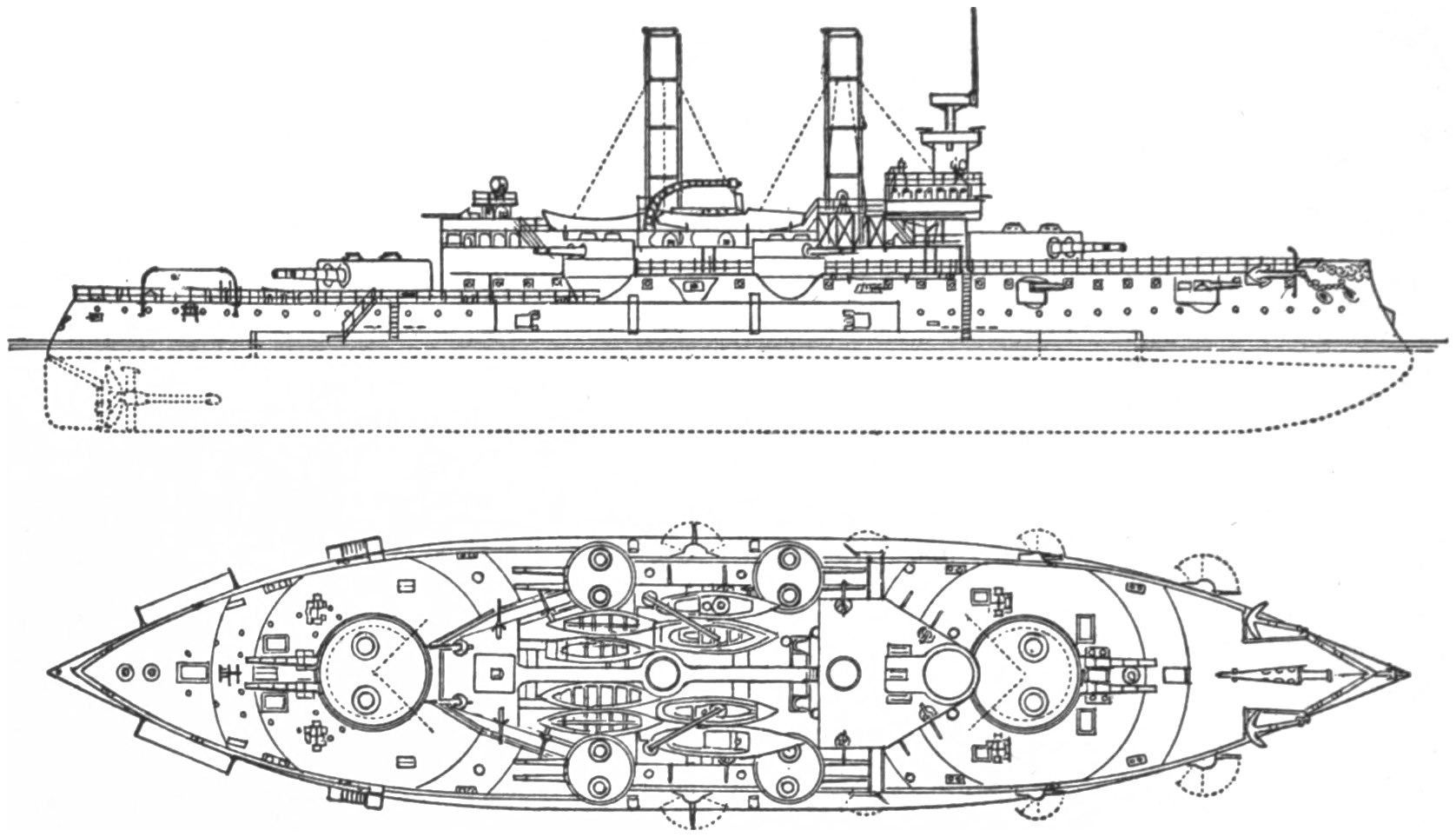

| Plan of the Iowa, | 536 |

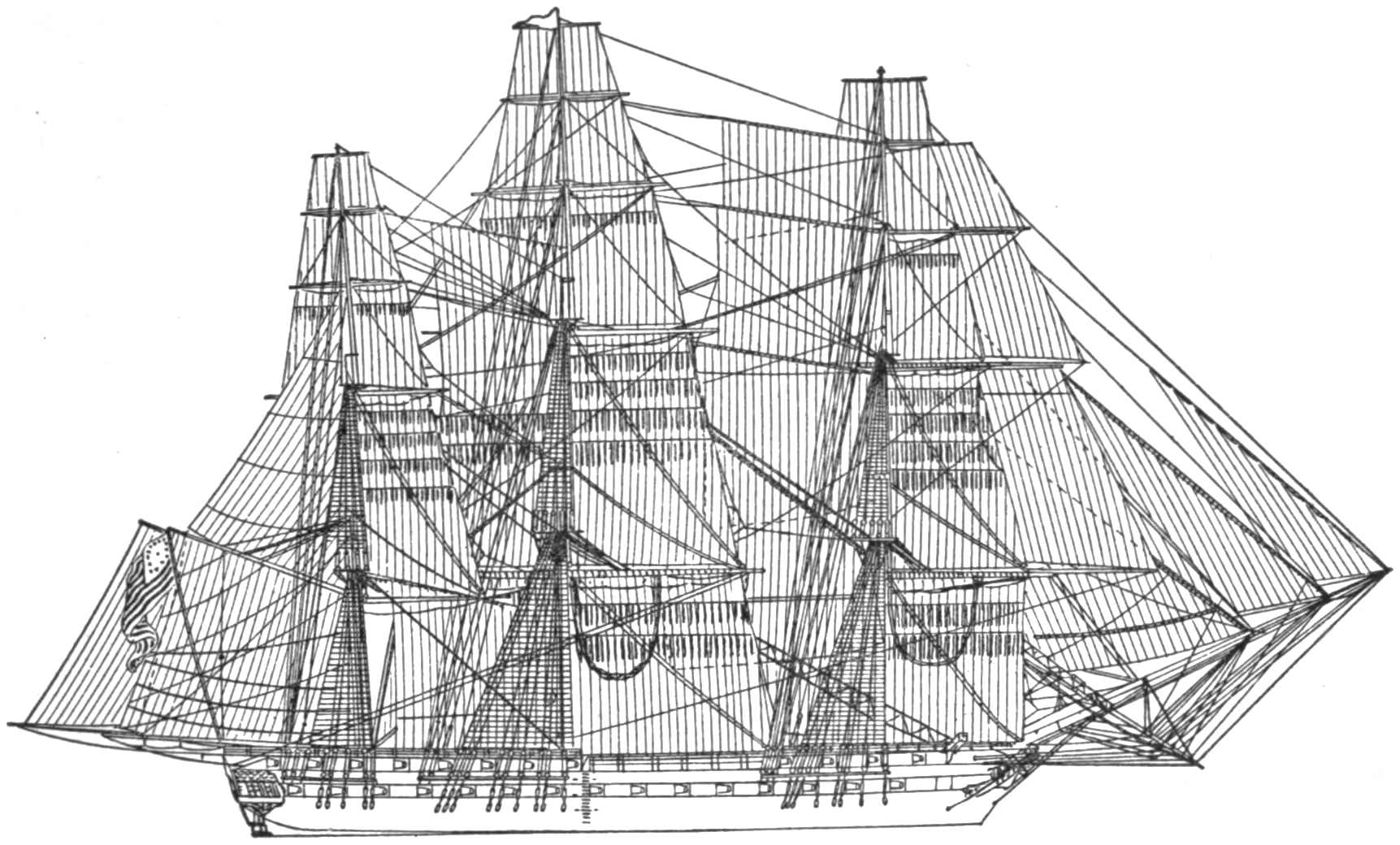

| Plan of the Constitution, | 537 |

| The Vesuvius. (From a photograph by Rau), | 541 |

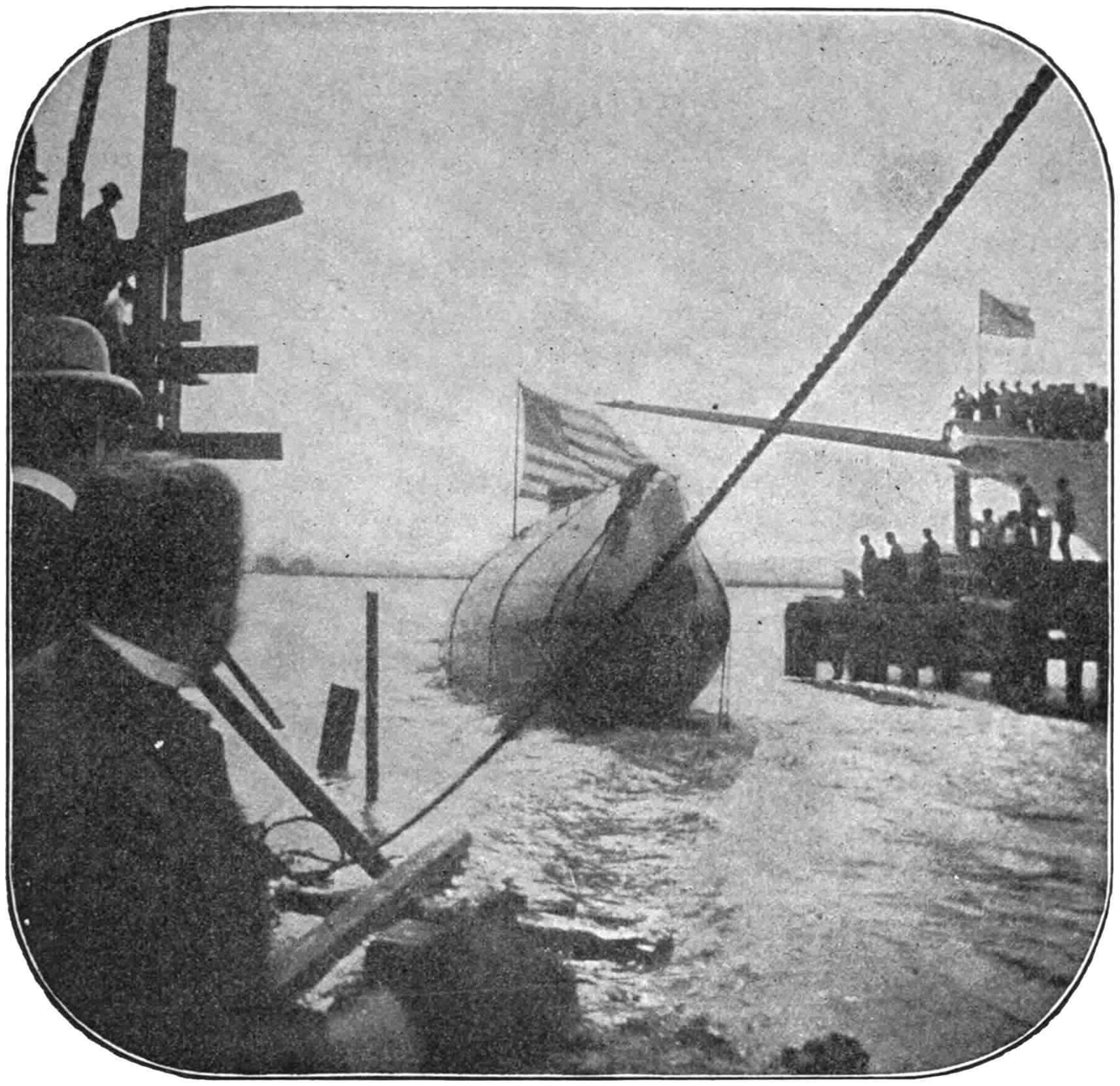

| Launching of one of the Holland Boats, the Holland, at Elizabethport, N. J., 1897. (From a photograph belonging to the John P. Holland Co.), | 543 |

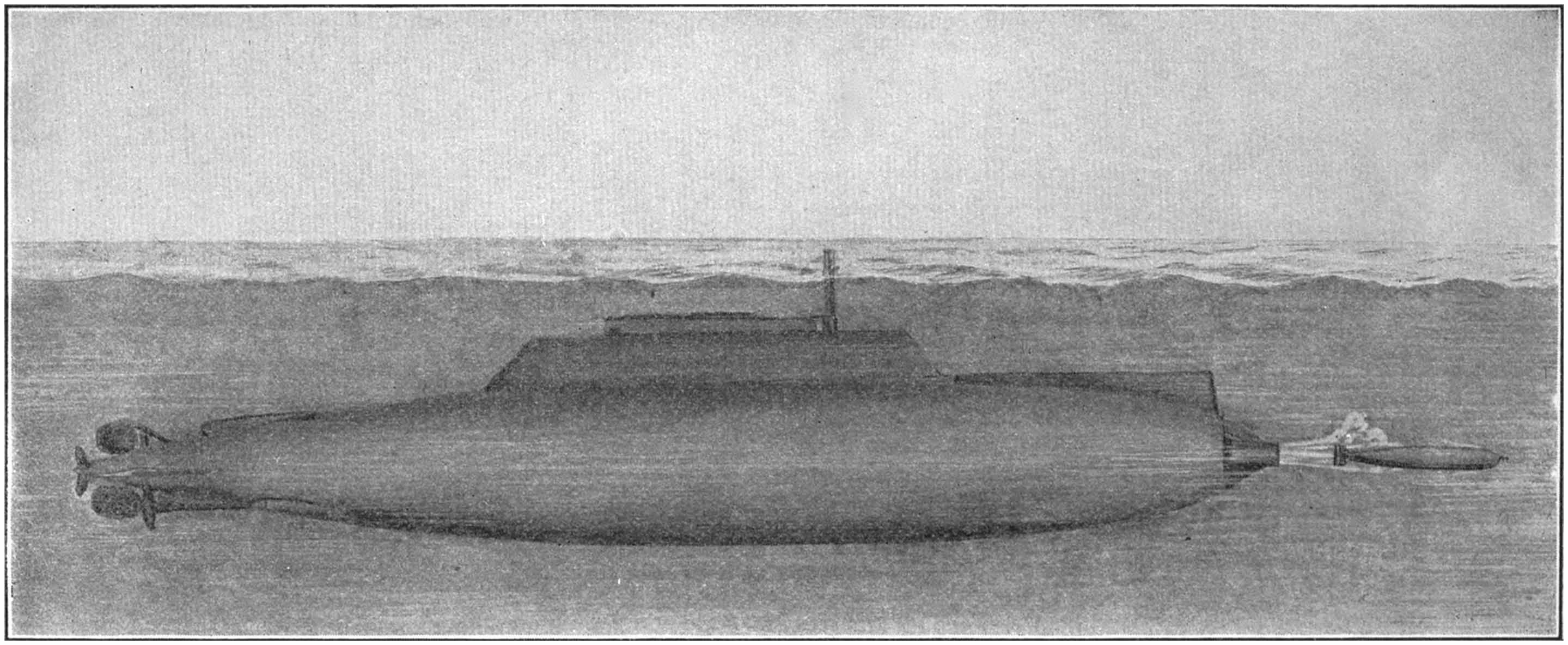

| Another of the Holland Submarine Boats: the Plunger. (From a photograph of a drawing belonging to the John P. Holland Co.), | 545 |

| The Harbor of Rio Janeiro, Showing the Frigate Savannah Struck by a Squall, July 5, 1856. (From a lithograph), | 549 |

| The Stern and Propeller of the Nipsic after the Samoan Hurricane. (From a photograph), | 551 |

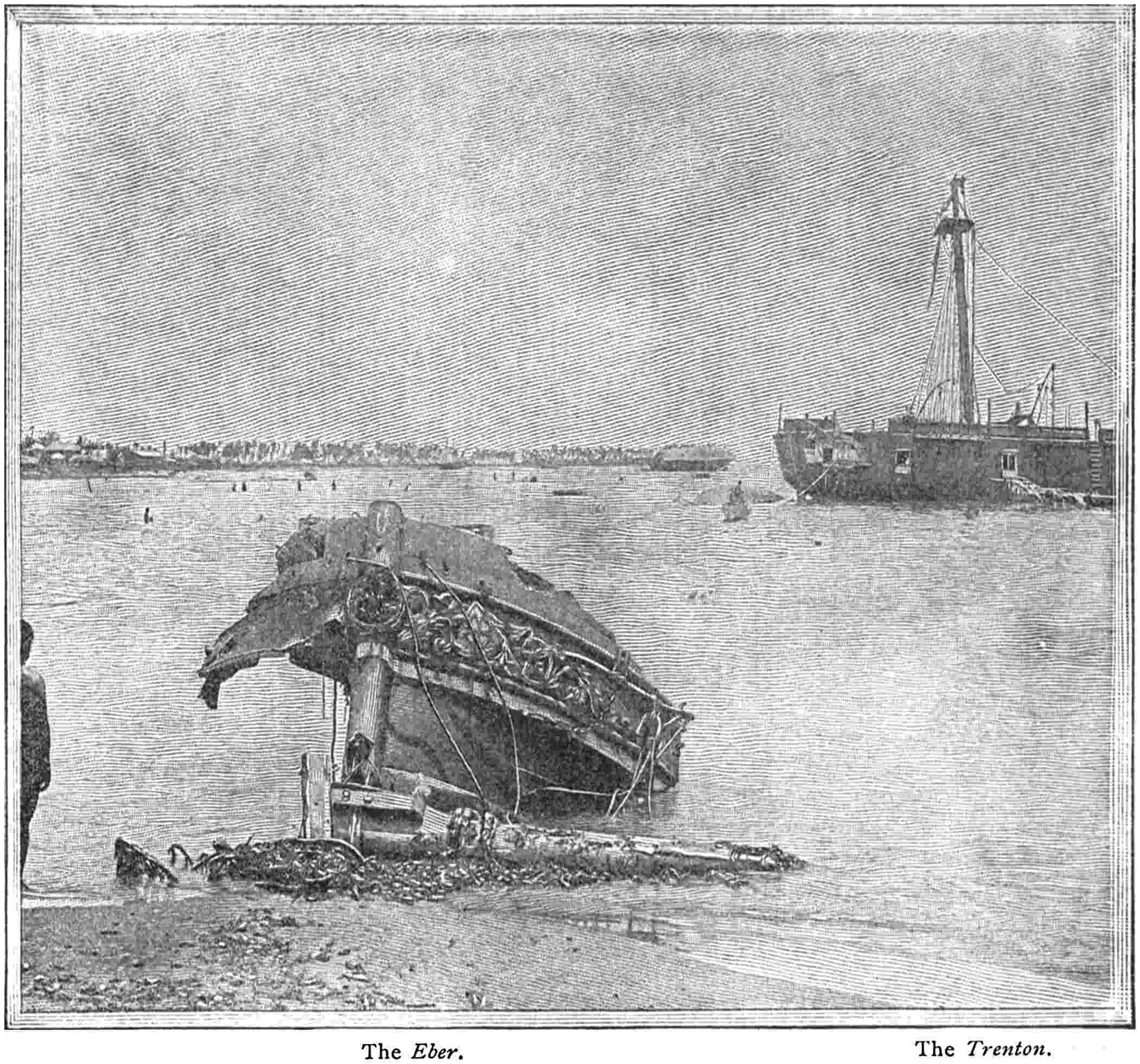

| The Harbor after the Samoan Hurricane. (From a photograph), | 553 |

1

A BRIEF STORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE WARSHIP THAT WAS PROPELLED BY BOTH SAILS AND STEAM—THE REMARKABLE FLOATING BATTERY OF 1814—BARRON’S IDEA OF A RAM—THE STEVENS FLOATING BATTERY—ERICSSON’S SCREW PROPELLER—STOCKTON AND THE FIRST SCREW WARSHIP—EXPERIMENTS WITH GREAT GUNS—DISCOVERIES OF BOMFORD AND RODMAN—PRACTICAL WORK BY DAHLGREN—A COMPARISON OF YANKEE FRIGATES WITH A CLASS OF BRITISH SHIPS “AVOWEDLY BUILT TO COPE” WITH THEM—THE CONDITION OF THE PERSONNEL.

From the point of view of a naval seaman it was a far cry from the first war in defence of the nation’s life to the last one—so far, indeed, that all the progress made in the construction of ships of war from the time when men first went afloat to fight, down to the war of the Revolution, had not equalled that made2 in the eighty odd years that elapsed between, say, the battle of Lake Champlain, which was the most important battle afloat in the Revolution, and that of Hampton Roads, which was first in the Civil War.

Consider the forces that Arnold mustered against the whelming odds under the ambitious Carleton. Though two of the vessels were dignified with the name of schooner and one was called a sloop, the flagship of the squadron was a galley managed by means of oars, and the fleet as a whole, including the Royal Savage, was inferior to an equal number of the galleys with which the Romans, in the days of Carthage, held sway over the Mediterranean.

And then consider the ships that in 1860 graced the register of the American navy—ships that with the aid of steam could hold their own against wind and tide, and that carried guns of so large a calibre that any but the largest from Arnold’s fleet might have been shoved down their throats after the trunnions were knocked off. Arnold in his flagship, the galley Congress, had eight guns of which the bore was about three and a half inches in diameter, and the shot weighed six pounds. But when the Civil War came, the Minnesota was armed with forty-two guns of a nine-inch calibre and one of eleven inches, besides four3 rifles that threw elongated projectiles weighing 100 pounds and one rifle with a projectile weighing 150. Arnold’s Congress could throw at a broadside twenty-four pounds of metal over an effective range of perhaps 300 yards; the Minnesota could throw 1,861 pounds over an effective range of 1,600 yards.

And a still more wondrous advance was in the minds of men; it was at hand—an advance to a point where steel forts were to be sent afloat in place of the ships that were in 1859 the pride of naval seamen.

The Minnesota as a Receiving Ship.

From a photograph by Rau.

Remarkable as it seems to the present-day student of naval history, the changes in naval ships that produced the Minnesota before the year 1859—even the changes that gave us the steel fort afloat—were foreshadowed in 1813 when the immortal Fulton made plans for a ship of war that should not only be propelled by steam, but should be as impregnable to the4 guns of that day as were the ironclads of 1862 to the guns of their day.

Although this ship was designed in 1813, she was not sent afloat until October 29, 1814, and even then, although swifter and more convenient than Fulton had promised that she should be—although she was the very craft that on a smooth-water day could meet and destroy the insolent blockading squadron then off Sandy Hook—she was not put into commission immediately, and the war came to an end before there was opportunity to show what steam might do for the sea power of a nation.

A Thirty-two-pounder from the Captured Macedonian—now at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

From a photograph.

But because this was the first steam warship the world ever saw, and because, when sent on trial trips, she more than fulfilled every promise of her designer, it is worth while giving a full description of her. Her length was 150 feet; breadth, 56 feet; depth, 20 feet; water-wheel, 16 feet diameter; length of bucket, 14 feet; dip, 4 feet; engine, 48-inch cylinder, 5-feet7 stroke; boiler, length, 22 feet; breadth, 12 feet; and depth, 8 feet; tonnage, 2,475. She was the largest steamer by many hundreds of tons that had been built at the date of her launch. The commissioners appointed to examine her, in their report say:

“She is a structure resting upon two boats, keels separated from end to end by a canal fifteen feet wide and sixty-six feet long. One boat contains the caldrons of copper to prepare her steam. The vast cylinder of iron, with its piston, levers, and wheels, occupies a part of its fellow; the great water-wheel revolves in the space between them; the main or gun-deck supporting her armament is protected by a bulwark four feet ten inches thick, of solid timber. This is pierced by thirty portholes, to enable as many 32-pounders to fire red-hot balls; her upper or spar deck, upon which8 several thousand men might parade, is encompassed by a bulwark which affords safe quarters. She is rigged with two short masts, each of which supports a large lateen yard and sails. She has two bowsprits and jibs and four rudders, two at each extremity of the boat; so that she can be steered with either end foremost. Her machinery is calculated for the addition of an engine which will discharge an immense column of water, which it is intended to throw upon the decks and all through the ports of an enemy. If, in addition to all this, we suppose her to be furnished, according to Mr. Fulton’s intention, with 100-pounder columbiads, two suspended from each bow, so as to discharge a ball of that size into an enemy’s ship ten or twelve feet below the water-line, it must be allowed that she has the appearance9 at least of being the most formidable engine of warfare that human ingenuity has contrived.”

Formidable she certainly was, but no war came to demonstrate her powers, and she lay in the Brooklyn Navy Yard as a receiving-ship until the 4th of June, 1829, when her magazine was fired, presumably by a drunken member of the crew, and she was blown to pieces.

Robert L. Stevens, of Hoboken, in 1832, conceived the idea of an ironclad ship that was to be 250 feet long and twenty-eight wide—something lean and eager in pursuit and yet shot-proof. It was an idea that cost him and his family nearly $2,000,000 before he was done with it; but nothing came of it, save as it kept the restless inventors of the world thinking on the subject of swift, impregnable ships of war. Mr. Clinton Roosevelt, of New York, proposed to build a steamer that should be sharp at both ends, “plating them with polished iron armor, with high bulwarks, and a sharp roof plated in like manner, with the design of glancing the balls. The means of offense are a torpedo, made to lower on nearing an enemy, and driven by a mortar into the enemy’s side under water, where, by a fusee, it will explode.” The idea of polishing the armor to make it slippery seems amusing now; but the fact is that even as late as10 1862 the armor of vessels in the Civil War was greased to make the projectiles glance off. Of course, the grease was of no use.

It is worth noting that it was in 1836 that John Ericsson patented in England his screw propeller. A model boat forty-five feet long, which he named, for the American consul at Liverpool, the Francis B. Ogden, attained in 1837 a speed of ten miles an hour. The Lords of the Admiralty took a trip in this boat, and the opinion of Sir William Symonds, who spoke for the others, is worth giving as showing how thick-skulled prejudice operates to retard naval progress. He said: “Even if the propeller had the power of propelling a vessel, it would be found altogether useless in practice, because the power being applied in the stern, it would be absolutely impossible to make the vessel steer.”

However, Capt. Robert F. Stockton made a trip on the Ogden, and fortunately Stockton was at once a man of wealth and of common11 sense. Being convinced of the value of the invention, he induced Ericsson to leave England for the United States in the year 1839, and that was, in a way, one of the most interesting events in the history of the American republic.

Meantime, however, a steamer to replace the old Demologos, Fulton’s first war steamer, had been launched in 1837. Practically the Fulton 2d, as she was called, was a sloop-of-war—a ship of one deck of guns, propelled by paddle-wheels. She was broad and shallow in model, being 180 feet long by thirty-five wide and thirteen deep. She had horizontal engines lying on her upper deck. Her paddle-wheels were twenty-two feet in diameter, towering high above the deck, and her boilers were made of copper. However, she carried eight long forty-twos and a long twenty-four—a right powerful set of guns for that day, and she behaved so well that Capt. Mathew C. Perry, who was assigned to her, expressed the opinion that a time would come when sails, as a means of propelling a man-of-war, would become obsolete. However, it must be said that this remark made almost every one who heard of it, and especially the other officers of the navy, think that Perry was a “visionary.”

It was in 1839 that Perry risked his reputation by an expression of opinion—about the12 time that Ericsson reached the United States. Backed by Stockton, Ericsson planned a man-of-war that should be driven through the water by a submerged screw at the stern. The idea of a ship being driven by machinery that was placed wholly below the water-line, and so out of danger from an enemy’s shot, was of a kind to appeal even to a backwoods congressman, and an appropriation was obtained. In 1843 the ship was launched under the name of Princeton, and she was in a variety of ways vastly superior to anything built before her. She was 164 feet long by thirty wide and twenty-one deep, and with 200 tons of coal and all supplies on board, she had a draft of nearly twenty feet.

Among other features, it appears that she was the first warship fitted to burn anthracite coal, thus avoiding the dense volumes of black smoke which revealed all foreign war-steamers. She was the first to carry telescopic funnels that could be lowered to the level of the rail out of the way of sails, and the first to use blowers to force the draft in the furnaces. She was also the first to couple the screw directly to the engine instead having cog-wheels intervene.

Her armament was also peculiar, for she was fitted with two long wrought-iron guns that threw balls about a foot in diameter, weighing14 225 pounds—guns that, when fired at a target at a range of 560 yards, pierced fifty-seven inches of solid oak timber.

The Great Western—One of the First Steamships to Cross the Atlantic Ocean.

After an old painting.

And there was one other peculiarity to which Stockton, who commanded her, called attention with pride: “To economise room, and that the ship may be better ventilated, curtains of American manufactured linen are substituted for the usual wooden bulkheads.”

Twelve-inch Wrought-iron Gun—the Mate to the “Peacemaker,” which Burst on the Princeton.

(The carriage is a mortar carriage from Porter’s mortar fleet at New Orleans.)

From a photograph of the original at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

As a steamship the Princeton was a very great success, but the art of forging was not then sufficiently advanced to warrant the manufacture of any but cast-iron guns. On a trial trip made from Washington in 1844, one of the great forged guns burst, killing and wounding a number of gentlemen, including the Secretary of State and the Secretary of15 the Navy, with several ladies who had been invited to go on the trip. Stockton had boasted that “the numerical force of other navies, so long boasted, may be set at naught, and the rights of the smallest as well as the greatest nations may once more be respected.” And the boast would have been almost justified but for the failure of the wrought-iron gun.

U. S. Ironclad Steamship Roanoke.

(The first turreted frigate in the United States, 1863.)

From an old lithograph.

However, the success of the Princeton as a ship was so pronounced that money was appropriated from time to time for others designed much as she was until the navy had six screw frigates—the Niagara, the Roanoke, the Colorado, the Merrimac, the Minnesota, and the16 Wabash; six screw sloops of the first class—the San Jacinto, the Lancaster, the Brooklyn, the Hartford, the Richmond, and the Pensacola, besides eight screw sloops of the second class, of which the Iroquois was a type, and five of the third class, of which the Mohawk was a type. There was also a screw frigate on the stocks at the Portsmouth, New Hampshire, dock-yard. The guns that these ships carried, when compared with those of the war of the Revolution, were quite as interesting as the ships themselves.

U. S. Frigate Pensacola off Alexandria.

From a photograph taken in 1865.

17

The prejudices in the way of improving great guns were not only strong, but they were founded on experiences that were seemingly convincing beyond peradventure. For instance, under Charles V a cannon was cast at Genoa that was fifty-eight calibres long; that is, it was of about six inches diameter of bore and twenty-nine feet long. When fired, its ball of thirty-six pounds weight had less range than an ordinary twelve-pounder. So they cut off four feet of the gun and found that its range increased. Cutting off three feet more still further increased the range, as did another cut of six inches—“which shows,” says Simpson’s text-book on gunnery, printed in 1862, “that there is for each piece a maximum length which should not be exceeded.” So that dictum stood in the way of arriving at the design of a gun like the modern rifle, that would really give the greatest possible range to a projectile. Then, the distribution of the metal in the cannon with which Arnold fought on Lake Champlain seems now ridiculous. One must needs see a picture of the old gun beside one of the guns as developed just previous to the Civil War to realize the difference; but it may be said that, with the bell-shaped muzzle and the “rings” and “reinforces,” the old gun in outline had as many ups and downs as some step-ladders, while the cast-iron weapon of 186018 was as smooth and symmetrical as the hull of a Yankee clipper.

A Twelve-pound Bronze Howitzer—the First One Made in the United States.

From a photograph of the original at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

A curious series of experiments, made by Colonel Bomford of the United States Ordnance Department, told for the first time where the greatest strain was exerted on the bore of a gun, and gave some idea of the relative strain elsewhere along the bore. Taking an old cannon, he drilled a hole from the side near the muzzle directly into the bore and inserted a pistol-barrel. Then he put a bullet into the pistol-barrel, and after loading the cannon in the ordinary way, he fired it. Of course, as the cannon-ball was driven from the big gun the powder gas behind it drove the pistol-ball from the pistol-barrel. The colonel measured the velocity of the pistol-ball and made a note of it. Then he drilled another hole in the cannon some inches farther from the muzzle, and repeated19 the experiment. The force exerted on the pistol-ball was slightly greater there. By drilling other holes he learned approximately the pressure all along the bore. It appeared that the greatest pressure was directly over the shot when it was rammed home against the powder. From there the pressure decreased rapidly, being only about half as much when the ball had travelled four times its own diameter from its original resting place.

Captain Rodman of the Ordnance Department, put a piston in place of Bomford’s pistol-barrel and let the piston punch into a piece of copper, and then determined the pressure on the piston by forcing the same kind of a piston into the same kind of a piece of copper by a known weight. “Although not an accurate process,” it was good enough, and with the figures obtained by it before him, Lieut. John Dahlgren, of the United States navy, designed the gun of smooth outline that by its splendid20 success in the hands of both forces, during the Civil War, made him famous. The greatest thickness of metal was placed around the greatest strain, and a proper thickness at every inch of length of the bore.

It was not alone, however, in putting the metal where it would prove most serviceable that Dahlgren made his gun efficient. He was a metallurgist, and was careful to improve the quality of iron used.

Meantime Captain Rodman had proposed to cast cannon hollow and cool them from the interior, instead of casting a solid log of iron and boring it out on the old plan. Although the first experiments did not show any especial improvement in the strength of a gun so cast, the method was eventually found to be the best.

With Dahlgren’s model a gun of eleven inches of diameter of bore was cast in 1852. It was fired 500 times with shells and 655 times with solid shot that weighed 170 pounds, the service charge of powder being fifteen pounds. The gun was not seriously injured or worn even by the work. That settled the status of the Dahlgren guns, and from that time on they were furnished with reasonable rapidity to the new steam warships of the navy.

Meantime rifled cannon made of cast iron reinforced over the breech by a wrought-iron21 jacket that was shrunk on had been introduced into the American navy. They varied from thirty-pounders up to 100-pounders, and, except for the smaller calibres, were in many cases more dangerous for their crews than for the enemy. It must be told also that a cast-iron rifle known as the Brooke, because designed by Commander John M. Brooke, of the Confederate navy, was produced in Richmond that was better than the Parrott. It was strengthened in its early service days by a series of wrought-iron bands two inches thick and six wide, that were shrunk on over the breech. Later a second series of bands was shrunk on over the first, breaking joints with them, of course, and so a very good 150-pounder was produced.

Meantime one Dahlgren smooth-bore, with a bore fifteen inches in diameter, had been successfully made, and the shells for all the Dahlgren guns were provided with fuzes that could be set to explode just about where and when the gunner wished to have them do so. But whether the damage to be done by a fifteen-inch round shot smashing its way through a ship’s side would be greater or less than that of a rifle projectile boring its way through was a question that had not been decided. It was granted that the rifle had the longer range—with a reasonable elevation a rifle would carry22 three miles, maybe four, and do some damage when the projectile arrived, while the effective range of the smooth-bore was, say, 1,500 or 1,600 yards, though gunners made efforts, when the time came, to run in to a range of 600 yards or less instead. But, on the whole, it was the belief among American naval officers before the Civil War that the big Dahlgren smooth-bore was the best gun afloat.

So it came to pass that the newest and best ships of the navy were armed with the Dahlgren gun. The Merrimac, which was not the23 best of the frigates, carried twenty-four nine-inch guns on her gun deck, with fourteen eight-inch and two ten-inch pivots on her spar deck. She could throw 864 pounds of metal from her gun-deck broadside, 360 pounds from her broadside of eight-inch guns, and 200 from her ten-inch, both of which could be fired over either rail.

Mr. Hans Busk, M.A., of Trinity College, Cambridge, was moved to write on page 104, in his “Navies of the World,” that “the navy of the United States has a tolerably imposing appearance upon paper,” but he concludes that a British frigate of the Diadem class, “avowedly built to cope with those of the description of the Merrimac, etc., would speedily capture her great ungainly enemy.” To fully appreciate this remarkable statement it must be known that the Diadem could fire at a broadside ten ten-inch shells, weighing in the aggregate 820 pounds, five thirty-two-pound solid shot, and two sixty-eight-pound solid shot—in all 1,116 pounds of shot to 1,424 pounds that the Merrimac’s broadside weighed.

The frigate Minnesota carried, soon after the Civil War broke out, no less than forty-two nine-inch Dahlgrens, one of eleven inches, four 100-pounder rifles, and one 150-pounder rifle. She could throw 1,861 pounds of metal at a broadside. Moreover, it was not a mere matter24 of weight of metal. The diameter of the American projectiles was a matter for serious consideration by the enemy, and so was the ability of the gun to stand service. The best English gun could stand a charge of twelve pounds of powder, and the best American fifteen. There was a vast difference in the smashing effect of an eleven-inch shell driven by fifteen pounds of powder and a ten-inch shell driven by twelve.

All this seems worth telling only because it shows that the ideas of armament which prevailed among the English and the Americans before the War of 1812 were still held by the two nations in 1859. Indeed, the disproportion between the Minnesota’s armament and that of the Diadem was very much greater than that between the United States and the Macedonian.

In short, all things considered, the American people had just the fleet they needed for that day to resist foreign aggression.

But while the patriot holds up his head in pride at the thought of the ships of 1859, he hesitates and stammers when he comes to tell of the men—of the personnel of the navy. It was a far cry from the sailing ships of the old days to the steam frigates of the later, but it was a farther one, and a cry over the shoulder at that, from the men who swept the seas25 under the once-despised gridiron flag to those who carried the American naval commissions in 1859. It was not that courage and enterprise were dead, or knowledge and skill were lacking. There were, of course, men a-plenty who were brave and tactful and energetic and learned—plenty who were to become during the war men of the widest fame. But “long years of peace, the unbroken course of seniority promotion, and the absence of any provision for retirement,” had served the officers as lying in ordinary served white oak ships. Nearly all of the captains were more than sixty years old. The commanders at the head of the list were between fifty-eight and sixty years of age. There were lieutenants more than fifty years old, and only a few of the lieutenants had known the responsibility of a separate command.

And then, “as a matter of fact,” as Professor J. R. Soley says in his work on “The Blockade and the Cruisers,” “it was no uncommon thing, in 1861, to find officers in command of steamers who had never served in steamers before, and who were far more anxious about their boilers than about their enemy.”

But that was not all nor the worst that can be said of the personnel of that day, for a sentiment—a faith—had developed and spread to a degree that now seems almost incredible,26 under which men who had made oath that they would always defend the Constitution of the United States came to believe that they were under obligations to draw their swords against the flag they had sworn to defend—the flag which some of them had defended with magnificent courage.

That the politicians should have been secessionists is not at all a matter of wonder. It was entirely natural. But how a Tatnall, the story of whose bravery at Vera Cruz still thrills the heart; how an Ingraham, whose quick defence of the rights of a half-fledged American in the Mediterranean is still an example to all naval officers—how these men could have placed the call of friends and neighbors and a State above the obligation of their oath to support the Constitution, is something that is now incomprehensible.

It must be granted that they were of good conscience. There was not a sordid thought in their minds—not one. Indeed, most of them felt that they were making the greatest of sacrifices for the sake of principle. But, if the writer may express his thoughts without offence, no patriot can now read of the glorious achievements of the men who in other days fought afloat for the honor of the nation, without feeling inexpressibly shocked at the thought that any man of the navy should have27 been found willing under any circumstances to strike at the gridiron flag.

There is not a little interest in considering the actual numbers of the men who left the navy to take part with the Southern States. Before South Carolina passed her ordinance of secession there were 1,563 officers, commissioned and warrant, on the naval register. Of these, 677 were from Southern States; but 350 of these Southern-born men remained true to the flag, while 321 resigned to enter the Confederate navy. Of thirty-eight Southern captains, sixteen resigned; of sixty-four Southern commanders, thirty-four resigned; of 151 Southern lieutenants, seventy-six resigned; of 128 Southern acting midshipmen, 106 resigned.

And that is to say that so demoralized had the navy become under the influence of quarrelling politicians that more than one-fifth of all the officers were ready to forsake their allegiance.

28

LINCOLN’S PROCLAMATION—IT WAS SOMETHING OF A TASK TO CLOSE 185 INLETS AND PATROL 11,953 MILES OF SEA-BEACHES, ESPECIALLY WITH THE FORCE OF SHIPS IN HAND—ONE MERCHANT’S NOTION OF THE EFFICIENCY OF THIRTY SAILING VESSELS—GATHERING AND BUILDING BLOCKADERS—INCENTIVES AND FAVORING CIRCUMSTANCES FOR BLOCKADE-RUNNERS—WHEN PERJURY FAILED AND UNCLE SAM WAS ABLE TO STRIKE WITHOUT WAITING FOR ACT OF CONGRESS—WHEN BLOCKADE-RUNNERS CAME TO NEW YORK AND YANKEE SMOKELESS COAL WAS IN DEMAND.

The story of the actual work done by the navy in this last war for the preservation of the life of the nation begins when a blockade of the ports of the seceded States was ordered. Two proclamations were issued to provide for this measure. The first was issued on April 19, 1861, which, as the reader will remember, was six days after the capture of Fort Sumter, in Charleston harbor, by the secessionists. It covered all the ports of the South except those of Virginia and Texas; but on the 27th of the same month, these two States having also joined the Confederacy, their ports were included by a second proclamation. Because,29 from a naval point of view, that was the most important proclamation issued by a President of the United States since the War of 1812, its words shall be given literally.

The Blockaded Coast.

From “The Navy in the Civil War.”

“Now therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States ... have further deemed it advisable to set on foot a blockade30 of the ports within the States aforesaid, in pursuance of the laws of the United States and of the Law of Nations in such case provided. For this purpose a competent force will be posted so as to prevent entrance and exit of vessels from the ports aforesaid. If, therefore, with a view to violate such blockade, a vessel shall approach or shall attempt to leave any of the said ports, she will be duly warned by the commander of one of the blockading vessels, who will endorse on her register the fact and date of such warning, and if the same vessel shall again attempt to enter or leave the blockaded port, she will be captured, and sent to the nearest convenient port for such proceedings against her, and her cargo as prize, as may be deemed advisable.”

It is worth while considering in advance some of the facts relating to the task that was thus set for the navy. The coast line invested extended from Alexandria, Virginia, to the borders of Mexico on the Rio Grande. The continental line was 3,549 miles long. The coast or shore line, including bays and similar openings, was 6,789 miles long; and if to this be added the shore lines of the islands which were included in the blockade and which were necessarily watched by the blockading fleet, the entire length of beaches under guard was exactly 11,953 miles.

31

The South Carolina islands, as described by Jedidiah Morse, “are surrounded by navigable creeks, between which and the mainland is a large extent of salt marsh fronting the whole State, not less on an average than 4 or 5 miles in breadth, intersected with creeks in various directions, admitting through the whole an inland navigation between the islands and mainland from the northeast to the southeast corners of the State. The east sides of these islands are for the most part clean, hard, sandy beaches, exposed to the wash of the ocean. Between these islands are the entrances of the rivers from the interior country, winding through the low salt marshes and delivering their waters into the sounds, which form capacious harbours of from 3 to 8 miles over, and which communicate with each other by parallel salt creeks.” And that will apply to the whole coast.

More than that, in this length of shore line were found 185 harbor and river openings that might be used for the purposes of commerce with the Confederate States. It is also an important fact that these harbor openings were, in almost every instance, too shoal for the ordinary ocean-going cargo ships of that day. If too shoal for a merchantman, they were so for a man-o’-war, and the more intricate and variable the channels the better adapted they32 were to the purposes of a trade that was to be carried on in spite of the blockade.

To close these 185 harbor openings the government had, on the day the proclamation was issued, twenty-six steamers and sixteen sailing ships in commission. But let not the uninformed reader suppose that such a great fleet as this was at once started off on that duty. There were in the home squadron but five sailing ships and seven steamers, while of these a number were at sea en route from nearby foreign to American ports, and of those actually in the United States harbors but three—the Pawnee, the Mohawk, and the Crusader—were in Northern waters. To close 185 harbor openings the Secretary of the Navy had for the moment just three steamers, the rest of the commissioned fleet being either in the ports of the Southern States or scattered the wide world over. And that is to say, there was for the moment no force adequate to blockade efficiently even the one Southern port of Charleston.

The navy register showed, however, in addition to the forty-two ships in commission, twenty-seven that were lying at the navy yards in ordinary but fit for service. The government had thirty-nine steamers and thirty-four sailing ships that might be brought together in the course of a few months to enforce the34 blockade of the 185 harbors of the South and keep contraband trade clear of the eleven thousand and odd miles of Southern sea-beaches.

Map Showing Position of

UNITED STATES SHIPS OF WAR

In Commission March 4, 1861.

NOTE:—There is no log book for the John Adams (No. 18) for the year 1861, but it is known that this ship was at Manilla, January 14, 1861, and at Hong Kong, May 1, 1861.

It is worth noting here that when the Navy Department was first considering its lack of ships for the purpose of enforcing the blockade, a consultation was had with a number of the most eminent ship-owners of New York. The leader of these eminent ship-owners, after considering the subject carefully, said to Secretary Welles that thirty sailing vessels would have to be purchased before an actual blockade of the ports could be completed. As a matter of fact, over 600 ships were employed at the end, and even then some blockaders got through.

Gideon Welles.

From a photograph.

But it was not alone in a lack of ships that the government was embarrassed. It was necessary to find officers and crews for the ships that were not in commission. Hundreds35 of men were needed to man even one of the five screw frigates, and yet to man the whole twenty-seven ships not in commission there were, on March 4, 1861, “only 207 men in all the ports and receiving ships on the Atlantic coast.” “It is a striking illustration of the improvidence of naval legislation and administration that in a country of thirty millions of people only a couple of hundred were at the disposal of the Navy Department.”

And as for the officers, as has been already shown, when the need of the nation was greatest, a fifth of them drew swords against the flag instead of defending it.

To still further hamper the work of the Navy Department, Congress was very slow to learn that a vast naval force was needed. The fact that the South had no navy and no merchant marine of its own, seemed, in the minds of the Congressmen, to make it wholly unnecessary to spend money on fighting ships. Indeed, a Navy Department has rarely been in a more distressful condition than was that under Mr. Gideon Welles in the first six months or so of the administration of President Lincoln.

However, a beginning was made. Perhaps the first step of importance in fitting the navy for war was the appointment of Mr. Gustavus V. Fox as assistant to Mr. Welles, for Fox36 had been a naval lieutenant and brought a practical knowledge of naval affairs with him when he was placed in charge of the actual war operations of the ships.

First of all, of course, was the work of getting men by a call for volunteers. The call was answered by hosts, but never by as great numbers as were needed. Captains and mates from the Northern ports and the Great Lakes were the more valuable part of this volunteer force, but so great was the need of officers that not a few men who had never been at sea received appointments. The youngsters at the Naval Academy who had had one year’s instruction, or more, were taken at once into the service. They were mere boys, but they had learned something of warships, and some of them made names that will not be easily forgotten.

Gustavus V. Fox.

From an engraving.

The next effort after the call for men was to issue a call for ships. The department strove to buy “everything afloat that could be37 made of service,” and where owners would not sell, to charter the ships. At first the ships were purchased by the department direct or by naval officers. Altogether, twelve steamers had been purchased and nine chartered by July 1, 1861; and it is worth recording that, because greed was a stronger passion than love of country, the prices charged were outrageously high. Afterwards a business man was appointed to the task of buying ships, and somewhat better rates were then obtained, while a board of naval officers inspected the ships to decide on their fitness and the alterations needed to make them serviceable.

It was a heterogeneous collection, a nautical curiosity shop, that they got together—deep-water ships, inland-water steamers, ferryboats, and harbor tugs. The inspecting officers were compelled by stress of need to accept about everything that would float and carry a gun. And, singular as it may seem at first thought to those who in these days ride on them, the double-ended ferryboats made very successful naval ships. It was the Fulton ferryboat Somerset that captured the blockade-runner Circassian off Havana—a prize that yielded $315,371.39 to her captors. Nor was that her only service. Being well built to stand the hard knocks of their ordinary service, the ferryboats were easily fitted with heavy guns and38 served well in battering down alongshore forts.

By the 1st of December, 1861, the government had purchased 137 vessels, of which, however, fifty-eight were sailing vessels; and it may as well be told here as elsewhere that 418 vessels were purchased during the war, of which 313 were steamers.

Meantime the department started the work of building ships. Congress authorized seven sloops-of-war, and the department laid down eight, of which four were built to the lines of the sloops of 1858 in order to save time; and it is worth noting that the Kearsarge was among the four. The eight were begun immediately, and six more were laid down before the end of the year.

Without waiting for an appropriation, the department contracted with private shipyards for the building of twenty-three heavily armed screw gunboats. And this contract is worth more space than the mere statement of the fact, for it draws attention to the importance of the private shipbuilder as a factor in the sea power of a nation. Even in the War of 1812, when wooden sailing ships were the sole evidence of sea power, the private shipbuilder was of essential importance. It was a private shipbuilder from New York, Mr. Noah Brown, who sent Perry’s victorious squadron afloat on39 Lake Erie, and it was the private shipbuilder who gave the Americans the supremacy that they enjoyed from time to time on Lake Ontario. Without private yards amply equipped for the construction of the best warships afloat, no nation can have a sea power adequate for the protection of its honor and the preservation of peace.

These twenty-three gunboats mounted from four to five guns each, of which one was an eleven-inch smooth-bore. They were wooden boats, of course, and they were known as the ninety-day fleet because some of them were in commission within three months from the signing of the contract.

The fact that they were so quickly built is also worth considering in connection with the fact that ships relatively as efficient as they were could not now be built in less than a40 year. The day of a ninety-day fleet passed when steel was substituted for wood.

The first point actually blockaded was Hampton Roads. Flag Officer G. J. Pendergrast established the blockade there, and issued the following proclamation on April 30, 1861:

“To all whom it may concern:

“I hereby call attention to the Proclamation of his Excellency Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, under date of the 27th April, 1861, for an efficient blockade of the ports of Virginia and North Carolina, and warn all persons interested that I have a sufficient naval force there for the purpose of carrying out that Proclamation.

“All vessels passing the Capes of Virginia, coming from a distance and ignorant of the Proclamation, will be warned off, and those passing Fortress Monroe will be required to anchor under the guns of the fort, and subject themselves to an examination.

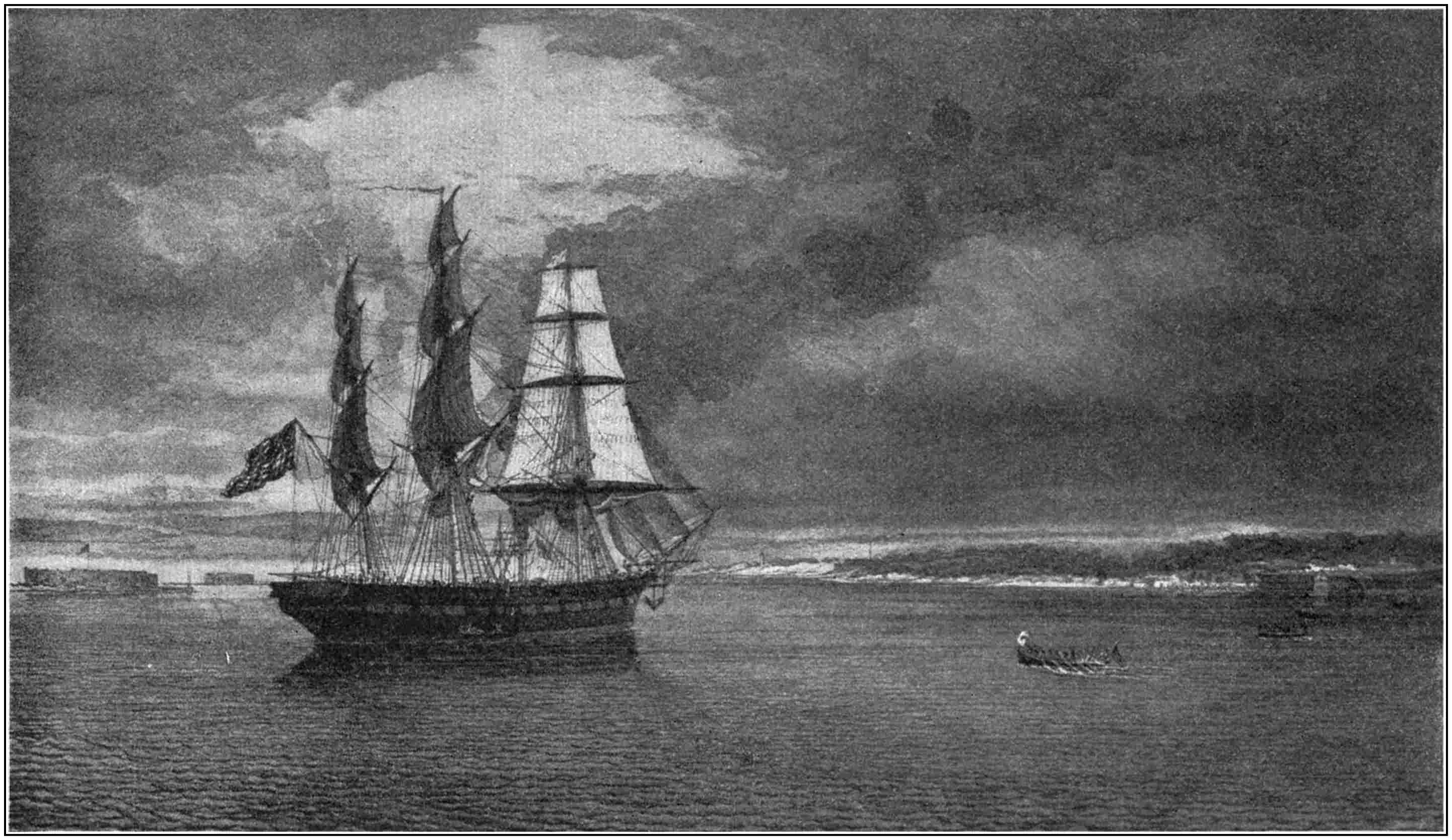

“United States’ Flagship Cumberland, off

“Fortress Monroe, Virginia, April 30, 1861.

(Signed) “G. J. Pendergrast,

“Commanding Home Squadron.”

This proclamation is worth careful perusal for two reasons: The first reason is that it contained an untrue statement. Instead of having “sufficient naval force” “for an efficient blockade of the ports of Virginia and North Carolina,” he had barely enough for41 Virginia alone. Wilmington was a most important harbor of the South; it eventually became the favorite with blockade-runners, but there was not a ship ready to close it for many weeks after this proclamation was issued.

More important still is the second reason for reading the proclamation carefully—the fact that it was issued at the behest of the Navy Department, and illustrates clearly the department’s idea of a blockade at that time. It is necessary to say here that, owing to the excitement of the times, the government was making a very grave error—it was trying to establish a “paper blockade.” That is to say, there was a determined effort made to interdict trade where there was no blockade de facto—not a ship, or a rowboat even, stationed to close the port. And this was a most remarkable undertaking, because the “free trade” for which the War of 1812 was waged was the freedom to trade in any belligerent port not actually closed by the presence of a warship. The government was sacrificing a great principle for the sake of a temporary advantage.

This was not due to the mistake of a naval officer. It was the deliberate action of the administration, and it is not unlikely that it will come back, some time, to plague us when42 we are the neutral nation seeking for trade in a belligerent port.

Proof of the fact that the whole Cabinet was involved is found in the correspondence of Mr. Seward relating to the blockade off Charleston. The Niagara had arrived home from Japan on April 24th, and was sent to blockade Charleston as soon as possible, arriving off the bar on May 11th. She remained there four days only, and then went away in search of a ship that was said to be bringing arms from Belgium to a port further south, and there was no warship off that harbor until May 28th (some accounts say the 29th), when the Minnesota came to take the Niagara’s place. The Harriet Lane, a revenue cutter, used as a warship, did lie off the harbor on the 19th, but for thirteen days Charleston was entirely uncovered.

On May 22, 1861, Lord Lyons, the British minister at Washington, in the interest of British ships at Charleston, called the attention of Mr. Seward to the fact that the Niagara had left Charleston on the 15th and that the harbor was thereby opened. Replying to this, Mr. Seward wrote, along with other things, the following:

“The blockade of the port of Charleston has been neither abandoned, relinquished, nor remitted, as the letter of Her Britannic Majesty’s43 Consul would lead you to infer. We are informed that the Niagara was replaced by the steamer Harriet Lane, but that, owing to some accident, the latter vessel failed to reach the station as ordered until a day or two after the Niagara had left.

“I hasten, however, to express the dissent of this Government from the position which seems to be assumed by your note, that that temporary absence impairs the blockade and renders necessary a new notice of its existence. This Government holds that the blockade took effect at Charleston on the 11th day of this month, and that it will continually be in effect until notice of its relinquishment shall be given by Proclamation of the President of the United States.”

On May 13th the British ship Perthshire appeared off Pensacola, having heard nothing of the blockade there, but she was told that Mobile was open. So she went to Mobile, loaded cotton, and sailed on the 30th, although the port was closed on the 26th by the Powhatan. She was captured at sea on June 9th, by the Massachusetts, but released by the flagship Niagara, whose captain “considered the capture illegal, as, by order of the Department, no neutral vessel not having on board contraband of war was to be detained or captured unless attempting to leave or enter a blockaded port44 after the notification of blockade had been indorsed on her register,” The owner made a claim for £200 compensation on account of the detention of his ship, which had lost twelve days of her voyage; and the claim was allowed and paid by the government of the United States.

The United States had now to abide by the law that its navy had in 1812 established. The ship of a neutral had a right to enter any port left open by the government ships, and for several months after the President’s proclamation nine-tenths of the 185 Southern harbors remained open.

This matter is of importance because of the right of neutrals in case the blockade of a port was actually abandoned or raised even for an hour. The opening of the port made it legally necessary for the blockaders to begin over again as if no blockade had existed. The neutral entering an opened port had a right to remain fifteen days, as the law was applied, after she was officially notified of the blockade, while neutrals approaching a re-blockaded port had the right to go away unmolested if they had not been notified, actually or constructively, that the new blockade existed.

New Orleans was blockaded on May 26, 1861, by the Brooklyn, and Galveston on June 2d by the South Carolina. For celerity of45 movement in carrying out orders to blockade the different ports no man exceeded Lieutenant Woodhull, for within forty-eight hours after receiving orders to charter a steamer he had left Washington, obtained the Keystone State in the Delaware, carried her to Hampton Roads, and reported ready for duty.

On the whole, it may be said that on July 1, 1861, the magnitude of the work of blockading 185 ports and inlets began to be appreciated by the Navy Department. Moreover, the hesitation and vacillation that had characterized the early movements of the government were becoming submerged. The determination of the people of the North to preserve the American nation intact was growing, under the shame of early reverses ashore, into a mighty tide that was to be irresistible at the last. A blockade was established within the time mentioned, in which even the critical eye of British men-o’-warsmen, sent especially to examine it in the interests of British commerce, could find no flaw. When, on the 13th of July, Commodore Pendergrast issued another proclamation saying Virginia and North Carolina were legally closed, he stated the fact, and from that time on the whole coast was, at worst, under guard, if not impassable. It was a blockade that was to starve the hosts fighting against the flag into abandoning their arms and returning46 once more to the ballot-box for a redress of grievances.

This is by no means to say that the blockade was absolutely effectual. Tales of the blockade-runners are to be told further on, but some of the difficulties in the way of effecting a blockade, even when ships a-plenty were on the coast, must be considered here. Mention has already been made of the physical aspects of the coast. No more difficult coast for a blockade can be found in the world. With this in mind, let the reader recall the fact that the South in those days was about the only producer of cotton in the world, and that the sap of the long-leaved pine was converted into tar and turpentine, which were produced there in very great quantities. On the other hand, consider that the South had scarcely anything in the way of factories. The people there were dependent on commerce for their supplies of even the most common necessities of life—for household goods, for clothing, and even for some kinds of food. And as for the arms and supplies needed for a war, there was one small powder mill, but nothing more in all the South, unless, indeed, the existence of the Tredegar iron mills at Richmond might be called a gun and engine factory.

Here, then, were the conditions for commerce: The South was the chief source of47 cotton and naval stores, and it was in desperate need of manufactured articles in a great variety. The blockade stopped all lawful traffic between it and the rest of the world. The cotton for the mills of the world was shut off. The mills of France and England were shut down for want of raw material, and people starved to death in England because the mills were shut down, and there was no way in which the unfortunate operators could get money for food. We can afford to recall this fact when we feel embittered by the attitude of a certain part of the English people toward us during our struggle for national life. In Lancashire, England, no less than ten million dollars had been given away by relief committees to the starving mill hands within two years after the war began. Moreover, the English government was not always one-sided, as will appear further on.

The price of cotton rose to a level that now seems fabulous in the markets of the world. The prices of the goods that the people of the South were accustomed to import rose as rapidly there, while munitions of war commanded any price that might be asked by one who could supply them. Here was a chance for profit such as the world had not seen since the wars of Napoleon, and greed is the steam that turns the wheels of commerce.

48

Just off the Southern coast lay the Bahama Islands, while the Bermudas were but a day’s sail farther away. It is 674 miles from Bermuda to Wilmington, and 515 from Nassau to Charleston—three days’ run, or less, in either case. Here were neutral ports to serve as a basis for the contraband trade, and thither the contraband traders flocked as the pirates of old swarmed about Jamaica.

Nassau was a natural resort for the blockade runners, for its people had been wreckers—had “thanked God for a good wrack”—for time out of mind. Besides that, it was not only near by the Southern coast, but it was surrounded by a host of reefs awash, every one of which was neutral territory, and was surrounded by its marine league of neutral waters, where a blockade-runner was safe.

As the reader will remember, the blockade-running traffic was chiefly in the hands of the British, although Yankees were found not unwilling to turn a contraband dollar with one hand while they flapped the old flag in the air with the other and shouted over Union victories vociferously.

At the beginning of the contraband business the vessels were loaded in England, cleared for Bermuda or Nassau, and sent thence to the Southern destination, Charleston being the chief port. Any vessel, even a condemned49 sailing schooner, was counted good enough; in fact, worthless vessels were preferred because the loss would be less in case of failure.

The touch at the neutral port was, of course, a mere device to deceive the American government officials; but a change was soon made in that game, for the courts held to the doctrine of the continuity of a voyage. If the ultimate destination of the ship and cargo was Charleston, she might be lawfully captured anywhere en route in spite of the fact that she was cleared for a neutral port when the voyage began.

There being no appeal from this decision, the contraband dealers resorted to shipping goods from England to the neutral port off the50 coast, and there unloading the goods. The papers, of course, were made out in proper form, under oath, giving the neutral port as the ultimate destination. They showed, for instance, that a house in Nassau was buying shoes, woollens, guns, gunpowder, swords, etc., sufficient to supply an army, and it was called legitimate trade. Perjury was as common in this contraband business as the drinking of wine. In fact, one cannot help quoting here the words of the favorite “Naval History of Great Britain”—the words of James where he is writing of American traders in the days of the “paper blockades” of 1812. He says:

“Every citizen of every town in the United States, to which a creek leads that can float a canoe, becomes henceforward ‘a merchant’; and the grower of wheat or tobacco sends his son to a counting-house, that he may be initiated in the profitable art of falsifying ship’s papers, and covering belligerent property. Here the young American learns to bolt custom-house oaths by the dozen, and to condemn a lie only when clumsily told, or when timorously or inadequately applied. After a few years of probation, he is sent on board a vessel as mate, or supercargo; and, in due time, besides fabricating fraudulent papers, and swearing to their genuineness, he learns (using a homely phrase) to humbug British officers,51 and to decoy and make American citizens of British seamen.”

What Mr. James says of the American people as a whole, can be truthfully said in substance of the British blockade-runners. They were an infamous lot, without exception, and ever ready to sacrifice honor and risk life so long as the number of pieces of gold was large enough.

But this is not meant to apply to the Confederates engaged in running supplies through the blockaded lines. Their case was entirely different, for they were legally belligerents, and to obtain supplies was, from their point of view, a patriotic duty. So it might—so it usually did happen that a blockade-runner carried one man (the pilot) whose courage and firmness excite the heartiest approbation of every unprejudiced mind, while every other member of the crew was at heart a coward who dared not fight the blockaders in pursuit, and a sneak who would sell his soul for gold.

However, even the trick of transferring cargo at Nassau did not serve them long, for “it was held that the ships carrying on this traffic to neutral ports were confiscable, provided the ultimate destination of the cargo to a blockaded port was known to the owner.”

For this “the United States were accused of sacrificing the rights of neutrals, which they52 had hitherto upheld, to the interests of belligerents, and of disregarding great principles for the sake of momentary advantage.” In fact, however, Lord Stowell had held where a neutral, when trading between two ports of a belligerent, had landed the cargo in a neutral port and re-shipped it on another vessel, the continuity of the voyage was not broken. Cargoes shipped in due form to Nassau and taken before reaching that port having been declared lawful prizes in spite of perjury, the contraband traders then adopted the bold expedient of shipping their goods by regular lines to New York and there re-shipping them to Nassau and Bermuda; but the moment this trade attracted attention the New York customs officials were instructed to refuse clearances to ships “which, whatever their ostensible destination, were believed to be intended for Southern53 ports, or whose cargoes were in imminent danger of falling into the hands of the enemy.”