By LEE GREGOR

It's easy to get away with murder: just prove insanity.

But make sure you hide the method in your madness!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Infinity November 1957.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

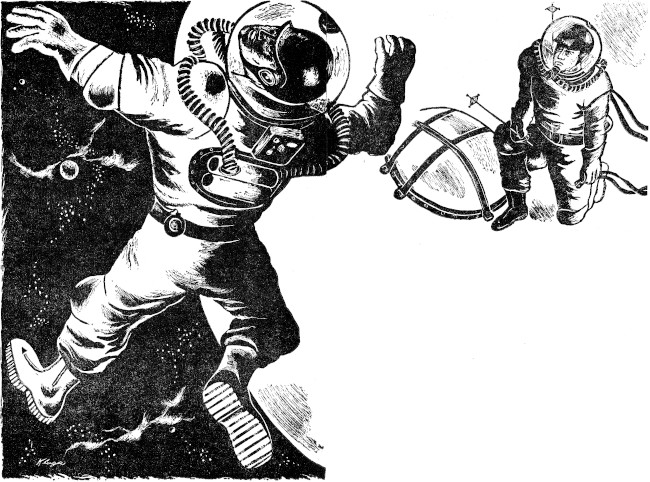

The figure of Professor Glover slipped from the surface of the space station and twinkled away among the stars. Jim Britten stared at it as though he could call it back by the ferocity of his gaze. He stood paralyzed by helplessness while the spacesuited body plummeted off into the void, until he could no longer follow its motion towards the dazzling sun. Seized by an uncontrollable shaking, he dropped the radiophone antenna which he had ripped from Glover's back and flung himself down flat upon the surface of the station, where he clung while catching his breath.

A vast doughnut, twenty-five miles in diameter, the space station stood with no apparent motion a thousand miles above the surface of the earth. It floated in a sea of scintillating stars like diamonds scattered upon the blackest velvet.

"Jim, what's the matter?" John Callahan's voice grated in Britten's headpiece.

"Glover's line broke loose," Britten gasped. "He's gone."

"What!"

"I'm coming back in. Give me a hand."

Britten began the long crawl back to the entrance port, his nerves too shattered to attempt it standing up. He was several yards away when another spacesuited figure emerged from the port and helped him stagger the rest of the way. Inside the airlock he collapsed.

In a small room within a large hospital the two men sat talking. It was a featureless room with pale green walls, containing a desk, two soft chairs, and a leather couch. The doctor, middle-aged, inconspicuous, wearing glasses, a small moustache, and a gray suit, sat in one chair. Facing him in the other chair, Jim Britten, young, lean, and visibly depressed, wore pajamas and a hospital robe.

"You've been a sick boy," Morris Wolf told Jim Britten in a conversational tone.

"I guess so." Britten scratched at the arm of his chair and fingered the sleeve of his gown.

"You're coming along, though. When you arrived at the hospital a week ago, you had to be wheeled in and fed like a baby. Now you've pulled out of the hole and we're ready to do some real talking."

"But, doc, I don't know what happened. Honestly. One minute Glover was starting to climb down into the ion-source chamber and the next minute his magnet line came loose, and when I grabbed after him I caught his phone antenna and ripped it off. Then I got the shakes and the next thing I knew I was back on Earth in the hospital."

The psychiatrist reached for his pipe and began to fill it from a large can on the desk.

"It's a great shock to have the person next to you snuffed out like that," he said. "Some people can take it standing up. When you fall apart like that we want to know the reason, so that it won't happen again."

Britten shrugged. "What's the difference? I'll never work in a laboratory again, let alone the Lunatron. I'll never finish my research and I'll never get my degree."

His voice trailed off in a discouraged whisper.

Wolf watched him for a moment.

"That kind of talk is the reason you are still here. You'll work in a laboratory again and you'll get your degree. You're still not quite well. I'm here to help you get well."

Britten shrugged again. "Okay. Bring on the dancing girls," he said, in a resigned tone.

There were no dancing girls, however, only a tall, blonde, squarish doctor in a white dress, who waited for them in the therapy room. Her cigarette made a cocky angle with the firm line of her mouth as she made final adjustments on the bank of electronic equipment that lined one whole wall.

"Jim, this is Dr. Heller," Wolf told him as they walked into the room. "She will work with us in here. Now suppose you get up on this table."

The two husky attendants who were always in the background helped Britten onto the table and strapped him down. As Wolf fastened the electrodes to Britten's head, he said, conversationally, "In the old days we would have just sat and talked to each other. It would have taken months to get to first base. Now we have ways of aiding the memory, of triggering associations, of lowering resistances to thoughts. It makes psychotherapy a much less tedious process than it used to be."

As he spoke, he slipped a hypodermic needle into Britten's arm.

"Now, suppose we see how much we can remember. Let's begin the day before Glover was killed. I want you to think back to that day and remember everything that happened, how you felt, what you thought about. We want to go through this traumatic experience of yours, and relate it to the elements in your life which caused such a profound shock."

And in addition—Wolf thought bleakly to himself—a good many people were anxious to know other things. For example: was Glover's demise at this particular time a coincidence? The Atomic Energy Commission, though cagy about their reasons, had given top priority to the answers to their questions.

The strength of official interest in this case was further evidenced by the assignment of Bill Grady and Calvin Jones as attendants to Jim Britten. For some time Morris Wolf had wondered vaguely why two such clean-cut and alert young men should follow the low-paid calling of hospital attendant, until recently he had become aware that their pay checks actually came from the U. S. Treasury by way of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

"Now," Wolf said, as Alma Heller switched on the tape recorder, "tell us what you remember."

After a year of being stationed on the Lunatron, Jim Britten had the feeling of being fed up. Lunatics they call us, he thought. Real crazy.

Looking out of the ports, he saw a black, starry space in which the only thing that ever changed was the view of the earth, a thousand miles below, and the moon which was sometimes on one side and sometimes on the other. The stars were incredible jewels, and the sun was something that one never looked at with mortal eyes.

There was bitterness in his heart as he thought of his initial thrill at being chosen to do his thesis research on the Lunatron. He had been an envied boy, but now, after a year, he would have given the chance to the first bidder. But there was no way to back out, short of breaking his contract or breaking his neck. Passage to and from Earth was too costly to be used on weekend vacations.

Many people on Earth would have been excited by the chance to work for two years with Professor Glover on the ten-thousand-billion-volt proton synchrotron which they called the Lunatron. Most physicists thought they were lucky if they could spend a few months with the fifty-billion-volt antique at Brookhaven.

But at Brookhaven you are only a few minutes from New York. Up on the space laboratory Britten was a year from any place, and every day that went by made it a day less.

"Johnny, what's the first thing you're going to do when you get back to Rhodesia?" he asked his roommate.

Britten sat, twanging half-heartedly at his guitar, while Johnny lay undressed on his bunk, his body hard and black against the white sheet.

"Oh, I have a good job lined up in a brand new research institute in Salisbury."

"I don't mean that," Britten said, impatiently. Johnny was such a serious boy. "I mean don't you think of all the fun you're going to have when you get back to Earth? Don't you think of getting a girl friend and living like everybody else lives?"

But Johnny's deep brown eyes remained serious, and he said, "Coming up here has been a great opportunity to learn something so that I will be able to do good work when I get back. Everybody down there does not get such a chance."

Well, Britten thought, that's how it had been with him at first. Now he could think of nothing but walking arm in arm with a pretty girl—his girl—down the street of a big city at night, drinking in the excitement, the feeling of being with other people among the bright lights, under a sky that would be dark blue instead of black, that might have clouds in it, that might even send down rain, instead of being the stark changeless interstellar space that existed up above.

Scientists aren't supposed to have thoughts like these. But Britten was young, he was homesick, and he was bored. A young, homesick scientist cannot remain a solemn, dedicated, single-minded scientist.

The next day at work he absentmindedly switched on some pieces of apparatus in the wrong order and burned out a minor piece of electronics.

"Damn it, Britten," Professor Glover shouted at him. "Where are your brains? Replacements are expensive up here. Time is expensive!"

Britten began shaking with rage. Words rushed to his tongue which he choked down unsaid because Glover had the power of life or death over his degree and these two years must not be torn out of his life for nothing.

"I'm sorry," he said, in an unsteady voice. "I guess I'm not all here today. It won't take long to repair the damage."

"Never mind," Glover said. "You're coming off the project, anyway."

Britten stood still. The anger roared back into his head.

"I'm coming off the project? What happens to the year I've just spent?"

Glover suddenly seemed more embarrassed than angry.

"I'm sorry, Britten," he said, "but it's for your own good. This project has just become classified and you'd never get a publishable thesis out of it."

Britten stood there looking at Glover. "This is a hell of a time to tell me," he exploded, finally. "What's become so secret about this experiment?"

"Obviously, I can't tell you. I'm sorry, but we'll make it up to you somehow. We'll think of something you can do while you're here, and if necessary you can stay a little longer."

Stay longer! Outraged, Britten fled to his room. It was all he could do to stick out the remainder of his two years.

He could not sleep that night. Little teeth of anger nibbled into his mind, while the basic question repeated itself in endless circles. Why had his experiment been pulled out from under him?

Fundamental experiments in high-energy particle physics were not generally classified secret. What were they doing which had suddenly become so important?

The general purpose of the space laboratory was to gather basic information about the laws of nature. The optical telescopes studied the planets as well as the farthest nebulae, unimpeded by atmospheric disturbances. The tremendous twenty-five-mile-diameter radiotelescope pinpointed short-wave radio vibrations from all parts of space. The solid-state group could study the properties of matter in a vacuum chamber of rarity unattainable anywhere on Earth.

In Jim Britten's group, known variously as the Elementary Particle Division, the Lunatron group, or simply as the Lunatics, the topic of investigation was the meson. A long time ago people had considered atoms the most elementary particles. Then they found out about protons and neutrons, which were the bricks that made up the atomic nuclei. A little later, when scientists learned how to build atom smashers such as the two-billion-volt proton synchrotron, they found that they could knock mesons out of the nucleus, and they decided that the protons and neutrons were not so simple after all.

Year after year the atom smashers had become bigger and bigger. There came a time when they could not be built on the surface of the Earth any longer, so a space laboratory was conceived, built around the doughnut of the ten-thousand-billion-volt proton synchrotron. Protons, whirling around for thousands of cycles in this vast doughnut, eighty miles in circumference, could acquire energies equal to those of the most powerful cosmic rays. Even mesons shattered at this energy.

By inspecting the remnants of these broken mesons, scientists could begin to get some idea as to the ultimate structure of matter and energy.

Now, Jim Britten thought, what was there about this work that should suddenly become too secret to be published? Peace had reigned on Earth for many years, and it was once more fashionable to think of science as being free and unbound by security regulations.

But not, apparently, here in Glover's private domain. Rephrase the question, Britten thought. What was there about this work which had suddenly made it desirable for Professor Glover to take Britten off the project? Was there more to this experiment than Britten had seen up to the present?

Sitting through the night, Britten thought and calculated, filling his desk top with paper, feeling the frustration of a scientist who spends day after day with the details of an experiment, pushing buttons, reading meters, soldering wires, until he begins to lose sight of the ultimate aim of the project.

As he fell asleep, long towards morning, his anger was still at a furious temperature, filling his mind with dreams of a tormented, violent nature, which he forgot promptly upon awakening.

Professor Glover stopped by to see him as he ate a late breakfast.

"We have a job to do today," Glover said, his voice tinged with an impersonal annoyance that was not directed at Britten.

Britten stared up at Glover with a hostility that made no impression upon the scientist.

"The ion source has gone bad and has to be replaced," Glover continued. "The spacesuits are being readied in the airlock."

"Why us?" Britten complained. "What's the matter with the maintenance crew?"

Glover's frown deepened. "They're busy with other things. You're free for the moment, and so am I."

Then his face cleared, and he slapped Britten on the back.

"Come on, fella, snap out of it. It'll do us both good to put on the suits and get out in free space."

Britten uttered grumbling noises about "a guy can't even finish a cup of coffee," and followed Glover out to the maintenance lock nearest the ion source.

As he climbed out of the airlock, there again came the sensation of vertigo which he felt every time he stood on this island suspended in nothingness. The circumference of the doughnut stretched its great arc away from him in both directions, while twelve miles away, at the center of the circle, was the spherical shape of the radiotelescope receiver. The long, slender girders which bound the station together had a fragile, spidery appearance.

Britten and Glover walked clumsily to the linear accelerator which projected one-billion-volt protons into the initial lap of their long journey around the doughnut. At the far end of the hundred-foot tube, within a shielded chamber, was the glass bottle of the ion source. Normally, a brilliant crimson flame glowed within this bottle as numberless protons were stripped from their electrons, to be hurled down the accelerator tube. Now there was nothing but the blackened, dead glass.

As they approached the chamber that surrounded the ion source, Britten found that the resentment left over from the previous night had a new object upon which to fasten. Why should he be doing the work that belonged to the technicians? In his anger he lost sight of the fact that Professor Glover was out there doing the same thing.

Damned slave labor, he thought. A PhD candidate was at the bottom of the heap, the lowest form of existence, pushed around by everybody else. Glover thought he was being clever, pushing him off the project, making excuses about security, when probably his aim was to keep for himself the Nobel Prize that the experiment was going to receive some day. Thought he could keep his poor stupid student in the dark about the outcome of the experiment—but the poor student wasn't as stupid as he thought.

Glover reached the hatch that opened into the ion-source chamber and started undoing the fastenings. Suddenly he turned and stared at Britten.

"Where's the new ion source?" he snapped. "Don't tell me you left it in the airlock!"

Britten stammered wordlessly, shocked out of his reverie.

"Well, of all the stupid—Go back and get it! I'll remove the old source."

Glover turned his back and continued to unfasten the hatch.

Rage came into full bloom instantly. Without an instant's thought, Britten reached out both hands, wrenched the antenna rod from Glover's back, tore his anchoring lines from their snaps, and pushed the struggling body out into space, where it soon dwindled away into a tiny speck.

CHAPTER II

Dr. Morris Wolf leaned back in his chair after Jim Britten was wheeled, asleep, from the therapy room. In a random fashion he let his mind wander over the story he had just heard, savoring not only the facts, but the feelings behind them and the intuitions which they built up in his own mind.

"Well, Alma, what do you think?" he said, swiveling his chair to look at the other doctor across his desk.

She hesitated. "The story seems satisfactory, up to a point. That is, we've broken through the memory block and have determined that Glover's death was not really an accident—which of course we suspected all along. And we have a motive—of a sort."

Wolf sighed. "Yes—the motive. The boy feels that Glover is cutting him out of the credit for an important experiment, so in a burst of anger he disposes of the professor. There are just two things that bother me about that. Look."

He switched on his desk projector and ran through the microfilm card of Britten's record until he came to the examinations which Britten had taken to get the post on the space station.

"Here we have the standard Jameson test for paranoid personality. Obviously an important item in an examination of this sort. You wouldn't send even an incipient paranoid into close quarters with a group of people for two years. And so in the case of Jim Britten the Jameson test gives a negative result—no evidence of any paranoia, and in fact no evidence of any neurosis except the drive to do research."

Alma Heller lit a cigarette thoughtfully. "I see. No paranoia predicted, yet the story he tells us now is a typical textbook example of persecution psychosis. Of course...." She paused for a moment. "He might be making up this story to hide his real motive."

Wolf shook his head vigorously. "No dice. Not under deep therapy. He has to tell us the truth."

"So we have a paradox." Dr. Heller's methodical mind ticked off the possibilities systematically. "Either the early exam was wrong, in which case he was paranoid all the time, or the exam was right and he turned paranoid later. Neither of which things are supposed to happen."

"Or," Wolf presented the third possibility, "he is withholding information while in deep therapy. Also something that is not supposed to happen. So this leads us to the second point that bothers me. Britten talks about sitting up all night trying to figure out what his experiment was leading to. Yet he never mentioned what conclusion he came to. Apparently this is a crucial point which is buried in his mind so deeply that we didn't touch it with our first try."

"Could be." Alma Heller seemed skeptical. "There are a lot of very iffy questions running around in my head which could be settled simply if we could get some concrete information. Do you think you could buzz the AEC and ask them why Britten's project became classified? That would settle a number of obscure points and at the same time give us a handle with which to pry Jim open a little more."

Wolf shrugged. "We might get our heads chopped off, but we can try. My contact at the AEC is Charles Wilford. He's the one who was so anxious to know what Britten did the night of the 15th. Maybe he can trade us some information."

Wolf pushed the button for an outside line and asked for the Atomic Energy Commission, extension 5972. Wilford's image appeared on the phone screen, the picture of a large, powerful face with a great mass of gray hair. Wolf knew him only as someone high up in the personnel department of the AEC.

"Good morning, Dr. Wolf," he said. "Find anything out?"

Wolf shrugged. "Britten killed Glover, if that's what you want to know. But why? That's what really interests us. You can tell us one thing that will help us find out. And that is—did Glover really take Britten off his project for security reasons? If so, what were those reasons?"

Wilford's face froze slightly. "Obviously, Dr. Wolf, if security were involved, it is a matter I cannot discuss with you, especially over the phone. You may write me a full, confidential report, and we will consider what is to be done."

Wolf cut the connection in exasperation and pushed his chair away from the desk.

"Well, there's a bureaucratic mind for you!" he exclaimed. "He wants a problem solved and then refuses to give you the information necessary to solve the problem."

Slowly he filled his thinking pipe and lit it. "The hell with them," he said, finally. "We'll see this thing through ourselves. We'll have another session with Britten tomorrow and get to the bottom of his story."

"I hope," Alma Heller added, "that there is a bottom to be found."

As the attendants strapped Jim Britten on the table, the next morning, Dr. Wolf thought how often the formula for murder repeated itself in this psychiatric age. Knock off the victim, prepare a real sick motive, and be sure you'll go to a hospital for treatment, to be released after a "cure." Under these circumstances the psychiatrist must become a detective—required to dig deep for the real motive, which generally resolved itself into the classical ones to love-hate-money.

From his point of view as a doctor, any murder was a sick act, but the authorities were interested only in the legal question of whether the murderer knew what he was doing, and why.

In this case, the question of the motive had a fascination to Wolf even from a purely academic point of view.

"Let's face it," he told Britten. "We both know you killed Glover. You've heard the play-back of yesterday's session, so you can no longer fall back on the old excuse of 'everything went black and when I came to he was dead.' Nobody gets away with that any more."

Britten maintained a sullen silence.

"Just for the record," Wolf continued, "I want to fill in an important gap in the story. You told us that you sat up half the night figuring out what discovery your experiment was aiming at, but you glossed over what you actually decided at that time. Suppose we return to that night and go over the story once more in a little more detail."

Britten continued his silence, and beyond a single hostile glare from beneath half-lidded eyes, gave no expression of emotion. Wolf, as he checked the connections and slipped Britten the hypodermic, was thankful that his technique did not depend upon a friendly rapport between doctor and patient.

Presently Britten began to talk.

"You're being taken off the project because it has become classified secret," Glover had said, and at a blow an entire year of work had been struck out from beneath Jim Britten's feet. As he sat in his room, he picked raucous chords on his guitar and allowed the anger to wash deliciously through his consciousness.

Not for a minute did he believe the security classification story. He knew that the project was beginning to strike gold in an unexpected direction, and he knew what that direction was.

There was a discovery in the making. A discovery so precious that for every diamondlike star out there beyond the porthole there could be a bucket of diamonds accruing to the discoverer.

And Glover was after the profit himself, pushing Britten out of the way. This was the thought that clawed little furrows in his mind. Then, pushing their way into those little furrows came other thoughts such as: "Suppose Glover should have an accident. I'd have his notebooks, and...."

Then he began thinking of returning to Earth, and the vision of spending a life dedicated to research in a laboratory became clouded over; instead there arose a picture of himself riding in an expensive car, with beautiful, expensive women.

He ripped a full chord out of his guitar and began to sing.

In the morning, Glover stopped at Britten's breakfast table, annoyed with word of the ion-source burnout.

"Now how are we going to get it fixed?" he demanded, in exasperation. "Gamp cut his hand yesterday, Williams had his appendix out a week ago, Langsdorf is busy with the kicksorter, and—"

"Why don't we do it ourselves?" Britten interrupted, eagerly. "It'll do us good to get into spacesuits again."

It would do Jim Britten some good, he thought to himself. If genius was measured by the ability to spot an opportunity, then his success was assured. The plan of action was in his mind, completely formed in that instant.

On the outer skin of the satellite, the two of them alone, any one of a number of accidents could occur. Holding them down against the pull of centrifugal force would be only the magnetic shoes and a thin line. From that beginning, his mind went precisely to its conclusion.

"Alma," Morris Wolf said, "I'm beginning to feel very uneasy. What do we have here?"

He poured coffee into the cups on his desk.

Alma Heller looked at him shrewdly, and stirred sugar into her cup.

"I think we have a bear by the tail," she said. "We seem to peel off layers of Jim Britten's mind, and each time there's something different underneath. Every time he tells his story there is something new and contradictory in it. And there is no clue as to whether he is getting nearer or farther from the truth."

Wolf swivelled his chair around and stared out of the window onto the hospital lawn. "We thought that the deep therapy method was something perfect. Something that would make a patient tell the absolute truth as he saw it. But our patient is making hash out of it."

He lifted his coffee cup and tasted the black liquid tentatively.

"Follow it through. The first story he gave us was conscious. He said he couldn't remember exactly what happened to him. Okay. This could be a fabrication. The next story he gave under therapy conditions. He said that he killed Glover in a fit of rage because of an argument. Okay again. We could have accepted that at face value, and he would have gotten away with it, except that we got curious about a couple of things. We wondered how the paranoid tinge got into his thoughts, and we wondered exactly what it was that he and Glover were on the verge of discovering. So we tried again. Now we find that he deliberately plotted to kill Glover, and the paranoid symptoms are now so intense that he gives us a completely phony story about making millions of dollars out of the discovery, when everybody knows that you can't patent anything for personal profit when you invent it in a government laboratory."

Alma Heller lifted her hand, making a one with her forefinger. "So, our friend Jim Britten is doing two things—both of which we did not believe him capable of doing. First, he is lying and inventing stories under deep therapy. Second, he is withholding information. For notice that he is still avoiding specific mention of the result which his experiment was aiming at."

Her voice became flat, precise, and probing.

"Now, could our young physicist, Jim Britten, do this thing? No. Not unless he is an unsuspected superman type. Or—unless he has had special training and conditioning for resistance against deep therapy. How does a young physics student obtain such training? And where?"

She looked across the desk at Morris Wolf, who chewed savagely on his pipe bit.

"If I had any sense," he growled, "I'd call up the AEC and throw Jim Britten right back in their faces. If they give me a problem to solve they should at least tell me how hot they think it is. And my viscera are beginning to tell me that this is going to be a very, very warm baby. Maybe I should holler for help. I have a wife and two kids at home. I don't want to get hurt."

"Who you kidding?" Alma wanted to know. "You wouldn't let a juicy problem like this escape you just when you have it clutched about the middle. Besides, our two undercover friends from the FBI will be keeping their eyes on things. Let them earn their pay."

"Okay." Wolf came to a decision. "We'll give it one more try, and then we'll call for help. First thing tomorrow morning. In the meantime, there are two things I want. First I want Britten to have a complete physical examination. The works. Inside and outside. Blood tests, electro-encephalograph, tissue specimens, complete x-rays—everything they can think of. Then I'll spend tonight keeping company with Britten while the technicians pull down some overtime pay analyzing the examination results."

"You have an idea?"

He nodded. "At least one idea. But it needs feeding."

That evening Morris Wolf walked down the hospital corridor past the door of Britten's room. He entered the next door and found himself in a tiny chamber already occupied by Bill Grady. This was no surprise, for he knew that Grady and Jones kept Britten under constant surveillance. He motioned for Grady to keep his seat, and made himself comfortable in another chair, which he placed so that he could watch Britten through the one-way window set in the wall. Through this window he could see every move which Britten made, and through a loudspeaker he could hear every sound.

It was not clear in Wolf's mind precisely what he expected to find by watching Britten, but he knew that if he was to unravel his puzzle, he must know everything about the boy, including the way he walked and talked and combed his hair.

For a time Britten sat and read, then paced the floor restlessly, as if waiting for something. Finally he picked his guitar up from the bed and sat down on his chair, tuning the instrument. When he began to sing, it was quietly, as though to himself. Wolf had heard him sing before, generally folk songs from the Southern and Midwestern states.

Now there intruded into Wolf's mind a thought which had previously been on the edge of consciousness, and simultaneously his hand reached out to touch the start button on his tape recorder. The manner in which a person sings should reveal a great deal about his early life—about the kind of language he grew up with, down to the very vocal structure which has developed in his body since childhood.

As a result there are many types of voices: French voices, Tennessee voices, Italian voices, Texas voices, each with its own flavor caused by the way in which the vocal muscles have been trained by the native language, and also by the way in which people are accustomed to singing in those places.

When Wolf went home that night he carried a tape of Britten's song with him. It was convenient that he did not have to go far for an expert opinion to corroborate what he had already decided as an amateur.

He entered his house, the pleasant place with the warm colors, the rows of books, the grand piano, and of course his wife.

"Sorry I had to stay late, dear, but there's something important going on. Something really important. And you can be a big help to me right now."

"Me?" asked Lynne. "You're going back to musical therapy?"

"Not exactly," he said, dryly. "More like musical detection. I'm going to play a tape recording of a song or two, and I want your professional opinion as to what part of the world the singer came from."

He walked over to the recorder and began threading the tape. "Now pay no attention to the song itself," he instructed. "I'm interested only in the voice quality."

The tape spool unrolled slowly, and Britten's voice filled the room.

"Not bad for an amateur," Lynne commented, listening closely. For several minutes she remained silent, until finally the tape was completed.

"Well," she said, finally, "I don't think it's an American. A bit too rich. It doesn't have the French quality, nor the Italian. More chesty, kind of ripe and fruity. Central European. Hungarian, Russian, or something of that order."

Wolf kissed her solemnly. "You win first prize, girl. That's the answer I wanted, and that's the answer that fits."

CHAPTER III

In the morning, the act of going to the hospital produced within him a sensation as of marching to the front line of battle.

Whitehead, the laboratory chief, was prowling about his office when he arrived.

"Morning," Wolf greeted him. "Got something for me?"

"I have a strangeness," Whitehead said. "A very great strangeness."

"We all do," Wolf replied. "What's yours?"

"This Britten of yours. How old is he?"

"By appearance, and according to the records, about twenty-one."

"Uh-huh. And by cellular structure and metabolism he is at least forty!"

"So."

Wolf sank down in his chair and cocked an eye at Alma Heller, who came into the room at that moment.

"Did you hear that, Alma? In more ways than one our boy isn't what he seems to be. By last night I was certain that he is not a native of Louisville, Kentucky. Now we are told that he is twice as old as we thought he was."

Alma stared for a moment.

"We do seem to get in deeper and deeper. Have any ideas?"

Wolf ran his hand worriedly through his hair. "One. But I'm afraid of it. At any rate, we're in too far to back out. This morning we're going to dig for more information, and we're not going to stop until we have Britten squeezed dry."

He reached onto his desk for his tobacco can and began filling a pipe, meanwhile organizing his thoughts.

"Somehow or other," he resumed, "Britten has received conditioning to resist giving information under deep therapy."

"And not only that," Alma interposed, "but he has the ability to retain consciousness under deep therapy and fabricate a story to replace the true facts."

"Correct. So, since the ordinary deep therapy method is useless, we have to get tough. We have to eliminate his present set of conditioned reactions and replace them by a new set. In other words, we must reset the controls so that he responds to a new set of orders."

Alma pursed her lips for a soundless whistle. "Fisher's method! Do you know how much of that a nervous system can take?"

Wolf shrugged. "Who knows? This is very new stuff. I've played around with a little of it, but ... who knows? At any rate, we're going to assume that Britten has a fairly tough mind in order to get as far as he has. We'll assume this not only for his own sake, but for ours, because we are going to shake him loose from his present set of memories, and we want enough of his original memories left for us to assemble. Now suppose we begin."

Whitehead excused himself. There was work waiting in his laboratory, he said, and watched wistfully as the two disappeared into the therapy room.

Alma began switching on the apparatus, while Wolf called for Jim Britten to be brought in.

"Still going digging in my mind?" Britten wisecracked as he walked in, flanked by the ubiquitous Grady and Jones.

"With a steam shovel," Wolf replied, and motioned that Britten be strapped onto the table.

This time Wolf wasted no explanations. Without pausing he slipped Britten a preliminary shot and began fitting electrodes onto his head and arms.

"We're going back a long time, now," he said, quietly. "Remember back to the days before you started college. How old are you?"

Britten began dreaming off. "Sixteen years old. It was a hot summer. Kentucky in summer. Hot. Hot as a solar cycle ... hot as a bicycle down the road ... a tricycle down the toad ... doctor you look like a big pimply warty green-eyed toad...."

Morris Wolf waited until the drug-induced schizophrenic symptoms were well under way, then motioned for Alma Heller to send a sequence of high-frequency pulses through Britten's nervous system, breaking down synapses and destroying memory patterns. This, in combination with the drug, was intended to clear the mind of memories involving the period of time to which Britten's attention had been directed. In this period, Wolf guessed, the conditioning had taken place. If not, then he must try another period.

Britten's body stiffened under the onslaught and perspiration rolled out on his brow. His mouth twisted and his eyebrows writhed. Morris Wolf himself felt perspiration starting out on his face, while in the back of the room the two "attendants" stared in amazement.

After enough time of this, Wolf switched the controls so that a rhythmic pattern of pulses went through Britten's system in such a manner as to aid the triggering of synapses and the formation of memory patterns. The slate having been wiped clean, new writing had to be placed on it.

"Now," he said, tensely, leaning over the patient and speaking close to his ears. "Cooperation means obey. Cooperation means obey. Cooperation means you do what I say. Cooperation means you do what I tell you to do, say what I tell you to say, remember what I tell you to remember. Cooperation is the key word."

The words went from Wolf's mouth to Britten's ears in the form of sound waves, were converted into neuro-electrical impulses, and under the influence of the rhythmically repeating pulses, from the machine, circulated around and around through Britten's system, tracing a deeply etched path.

Finally Wolf ceased the talking, and Alma handed him the needle with the antidote to the first drug.

"Now we see how successful we are," he said.

He gave the shot and several minutes went by while they waited for it to take effect. They remained silent, as though to say a word would break the spell.

Then: "Cooperation," Wolf said.

Britten lay still.

"Open your eyes."

Britten's eyelids struggled open, but the eyes stared blankly.

Wolf thought: what question is most basic?

Then he asked: "What is your name?"

The mouth writhed, and then whispered, "Pyotr Fermineyev."

There was a small roaring in Morris Wolf's ears, and beside him he heard the intake of Alma Heller's breath. The FBI agents, Grady and Jones, had moved up until they were leaning over Wolf's shoulder.

Then: "Where were you born?"

Again the whisper from the blank face: "In Leningrad."

Then: "Who sent you to America?"

"The Society for the Restoration of the Revolution."

"What is the nature of this organization?"

"It is an underground group pledged to return the Soviet Union to its status as the leader of the world revolution and to overthrow the present appeasers of the capitalist governments."

Wolf glowed with triumph. "Get that, Alma?" he gloated, and he turned around half way and winked at the two men behind him.

Alma Heller shook a strand of hair back from her eyes. "The fanatical revolutionaries—now they're trying to overthrow their own government because the Soviet is too friendly to the Western governments!"

"This is no comic underground group," Wolf said. "There are some big people in it who know how to do things that we're just barely starting to learn about."

He paused, and considered his next questions. The time had come to dig in.

He phrased his query: "What was your task on the satellite?"

Britten's face writhed. Perspiration rolled down his cheeks in a steady stream. Obviously some of the original conditioning remained, causing interference with Wolf's orders.

Alma Heller's knuckles showed white and her clenched hands trembled. The FBI agents inched forward, their bodies stiff with impatience.

Between hard breaths the words came: "... was on the satellite to watch ... new developments in nuclear power ... complete conversion ... matter to energy...."

Understanding grew in Wolf's mind with a brilliant glare. Glover had been on the verge of taming the ultimate source of energy—the total and complete conversion of matter—a source of power over 130 times more potent than the hydrogen-helium reaction. No wonder the project had been put under wraps!

"So you killed Glover to prevent him from continuing his work. What did you intend to gain by that? Somebody else will take it over. How are you going to develop this power source yourself?"

Britten groaned audibly. His back arched and his arms strained against the table straps.

Through clenched teeth: "Ruppert ... next man in line for Glover's job ... one of us."

Wolf's eyes opened wide, and he whirled to the telephone.

"I'm calling Washington—" he began, then stopped in horror.

Behind him, Britten's voice said, in a strangely firm tone: "Now is the time."

Wolf whirled again. He saw Britten, still strapped to the table, his eyes unglazed, and his facial expression commanding.

The FBI men had stiffened, and were standing in place, motionless.

"Cover them, and untie me," Britten rapped out, in a voice that was greatly different from the youthful, uncertain tone he had previously used.

Grady pulled his gun, backed Wolf and Alma Heller against the wall, while Jones loosened Britten's straps.

"So you're one of them, too, Grady," Wolf growled. "And you, Jones. May you burn in hell."

"Don't malign them," said Britten, sitting up and rubbing his arms. "They are good, loyal G-men. But they sat outside my door too long, and now they do what I tell them to do."

Wolf narrowed his eyes and stared at Britten. "Just what are you?" he demanded.

Britten met his gaze, bleakly, and ignored the question.

"We have a rendezvous to make. The two of you will escort me to a helicopter that Grady will order. I need not repeat that we are prepared to blast our way out of this place. You'll save lives all around by being as inconspicuous as possible."

He indicated that Wolf and Alma Heller would go ahead, while the two agents took up the rear. Out in the main corridor they merged into the confused traffic of the busy hospital, two doctors and two attendants conducting a patient out.

Grady took the controls of the helicopter that waited for them out on the parking lot. As they climbed to a high traffic lane, Jones took care of tying the hands of the two doctors behind their seats.

Britten sat beside the pilot, staring through the windshield. "Head due west one hundred miles," he said. "Then I'll give you further directions."

Wolf looked down through the port next to him and felt his heart constrict as he saw the houses below grow smaller and smaller. One of those houses was his; there was a small figure beside it that could have been his little boy. That was the thought that set his heart beating violently and the adrenalin pumping swiftly through his veins. For himself he didn't care so much, but his son needed a father to come home.

He looked at Alma sitting beside him, her face pale and frightened. He wondered how much time there was before the rendezvous. For this was all the time he had. Beyond that were too many unknown factors to consider.

He leaned over sideways.

"Alma," he said, in a voice not loud enough to carry forward over the roar of the motor. "Tell me exactly what happened when Britten said, 'Now is the time.' My back was turned then. Just what did he look like?"

Alma swallowed. She composed her face and turned her thoughts inward, remembering.

"There was a sudden change," she said. "One moment he was in the trance state, the next moment he was fully aware of his surroundings and in charge of the situation. As though he received a signal at that instant."

A signal, Wolf thought. From where? The implication was shocking.

Look at what we have, he continued to himself. Britten comes to me, under conditioning, ready to act out his part to the hilt. We question him under deep hypnotherapy and he comes forth with a plausible story. We might have stopped right there, but we got curious and began to ask more questions. He brings out another story. Why? Obviously, red herrings to confuse the issue. To stall for time. We apply more pressure, blank out his original conditioning so that he gives us straight answers to questions, and we are getting along fine. Then, suddenly he snaps out of it and into his original, pre-Britten character, all forty years of him. Therefore there must have been another, deeper level to the control over his mind which we did not even touch. A level activated by a new signal which we did not even detect, a signal which came at a crucial time.

"Now is the time" meant that the stalling was over, that the preparations for Britten's escape were completed.

There were still questions to be answered, many blank spaces to be filled in, but at the present instant there was only one question that mattered. The treatment which Wolf had given Britten—had it been at all effective?

Was it still effective?

There was one way to find out.

Morris Wolf leaned forward and called in a loud voice: "Pyotr Fermineyev!"

The man's head snapped around.

"Cooperation is the key word!" Wolf shouted.

Confusion passed over Britten's face as conflict once more knotted his nervous system.

Wolf threw his second punch immediately. "Tell Jones to cut me loose," he demanded.

"Cut him loose," Britten echoed, in bewilderment.

After an interminable interval, Jones laid down his gun, found his knife, opened it, and slashed the cords from Wolf's arms. Wolf's muscles were already tensed. He snatched Jones' gun, lurched forward, and even as Britten's mouth opened to countermand his order, he slugged Britten with the butt of the pistol, hitting him viciously and hard until he lay unconscious on the floor.

Then he said to Grady, "You'd better get us back to the hospital," keeping the gun in his hand.

But Grady and Jones made no trouble. With Britten out of the picture they obeyed the one obviously in command. Poor boys, Wolf thought. Now they were in need of therapy.

As the hospital hove into view, he said to Alma Heller, "We have just seen the real beginning of psychological warfare. Where it took us a whole roomful of equipment to condition Britten's responses to a trigger word, he was able to do it to Jones and Brady single-handed. His method is something we'd like to know. But more than that, Britten himself was conditioned to respond to a signal unknown to us and undetected by us. My God, it could only have been telepathic!"

Alma Heller's eyes closed for a moment.

"I think," she said, "that psychiatrists are going to reach the same position that physicists did during World War II."

Morris Wolf looked dourly out of the window, watching the hospital balloon up under the helicopter.

"That's the most unpleasant thing anybody has said all day," he replied.