Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

VOL. I. THE PEARL OF LOVE.

VOL. II. THE PEARL OF CHARITY.

VOL. III. THE PEARL OF OBEDIENCE.

VOL. IV. THE PEARL OF PENITENCE.

VOL. V. THE PEARL OF HOPE.

VOL. VI. THE PEARL OF PATIENCE.

VOL. I. THE PEARL OF FAITH.

VOL. II. THE PEARL OF DILIGENCE.

VOL. III. THE PEARL OF MEEKNESS.

VOL. IV. THE PEARL OF FORGIVENESS.

VOL. V. THE PEARL OF CONTENTMENT.

VOL. VI. THE PEARL OF PEACE.

CHAPTER VI. THE TEACHER'S WARNING

CHAPTER VIII. THE CHAIN RESTORED

CHAPTER IX. THE CHARITY CIRCLE

"WHAT are you looking for, Frank?" called out Lionel Trask to his school companion.

"I thought I dropped my slate-pencil," answered Frank, hesitating and growing very red.

"Looking for a slate-pencil in that high grass! That's a good joke! Come on, now; I'm going to the Common for a game of base ball."

"I wish I could," muttered Frank, speaking to himself, "but I can't, no," he added, in a louder voice. "I haven't the time." And away he ran without giving himself opportunity to be tempted.

"Hurrah, boys! That's cool," exclaimed Lionel.

But as there were no boys near to answer, he satisfied himself by a long whistle to the tune of "Dan Tucker."

Frank darted off down the street, and presently leaped a wall without touching it, and hurried across a well-trodden path to a cottage on the opposite corner of the field.

Frank Jocelyn was an active, handsome lad of thirteen summers. He was tall of his age, and expert at all the games that boys love. The side he was on was sure to beat at ball, and his kite always flew higher than that of any of his companions. Though the youngest in the "Orford Boys," the name of the Orford boat-club, yet he was accounted one of their best rowers.

But Frank had a great fault. He was proud, not exactly of his personal appearance, though he received praise enough for that to spoil him; but proud of being Frank Jocelyn, the smartest boy in Orford; proud of being the first scholar in his classes, and always at their head in spelling.

Two years before this time, Frank's father was considered to be in as good circumstances as anybody in town except Squire Rawson, who owned the large farm beyond Cedar Hill. But most unfortunately, he endorsed his name on a note to oblige a neighbor. When the time for payment came, the neighbor was missing, and, of course, Mr. Jocelyn had to foot the bill.

It was a heavy loss, but he could have gone through with it, if he had not taken it so much to heart. The disappointment preyed on his spirits; he took cold, and could not readily throw it off. Fever followed, and in less than three months, he was sleeping his long sleep beneath the sods of his native valley.

When his business came to be examined, it was found to be in a bad condition, and his wife, instead of having a competence for herself and her two children, realized only a thousand dollars besides the house and farm where they lived.

Everybody sympathized with the widow, and was indignant at the fraud of their dishonest neighbor; but sympathy, though very soothing to the feelings, does not fill the mouths of the hungry.

Mrs. Jocelyn, after satisfying herself that the reports of the executor were true, made up her mind that she must earn her own bread. Whether she able to have butter with it remained to be proved.

Beside Frank, she had a daughter May, as sweet and fair a girl as one would wish to see. May was two years older than her brother, and loved him with all her heart.

Mrs. Jocelyn, after making and rejecting a number of plans, at last resolved that if she could take a few boarders to occupy her vacant rooms, and thus continue her children at school, she should be very grateful.

This was happily accomplished. The teacher of the high school, with his wife and one child became inmates of her family, and recommended her to their friends so earnestly that she had as many boarders as she could accommodate.

BUT notwithstanding all her pains, the widow found herself unable to meet her bills. Prices for every kind of groceries were so high, and the cost of fuel so dear, she feared she should be obliged to give up housekeeping. She confided her trouble to Mr. Monks, the teacher, who at once proposed to pay more for his rooms; and this gave her means to keep on for another year.

At the time our story opens, her funds had again become exhausted, and, but for her children, she would have sunk at once.

One day she succeeded in making some root beer so superior a quality that she resolved to offer it for sale at the store. It contained sassafras, yellow dock, and sarsaparilla, and was considered very conducive to health.

She succeeded to well in disposing of it that she used to sit up till a late hour brewing and bottling it, ready for Frank to carry to the store in the morning.

This he insisted on doing before any of his companions were out of bed, for he was ashamed to have it known that he was reduced to such an extremity.

It was Frank's business, also, to dig the roots for his mother, and it was for this purpose he was searching behind the rocks when his companion found him. To be sure, he did think he heard his pencil drop, and felt among the grass to find it, otherwise he would not have told Lionel; but he was a truthful boy, and the thought that he did not tell the whole truth made his face burn like fire.

The next morning, as soon as it was light, he was back by the rocks, and dug a fine basket of roots, enough to supply a week's demand.

Toward the close of the school, in the afternoon, Mr. Monks, the teacher, requested his pupils to give him their attention for a minute.

"I have met with a serious loss," he said. "I speak of it now, that if you hear of a watch chain with seals and key attached, you will claim it for me. I had it in the morning, but probably lost it during a walk I took across the fields by the rocks."

Lionel Trask started and colored violently as he glanced at Frank.

"I see you know something about it," remarked the teacher with a smile.

"No, sir, I,—I mean—I don't know—I only suspect."

"And what do you suspect?"

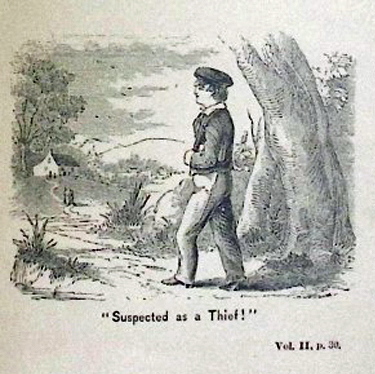

"I—I saw a boy behind the rocks yesterday afternoon. He was bending over as if he had picked up something; and when I asked him what he was looking for, he grew very red."

"Did he not answer?"

"Yes, sir! He said—I lost a slate-pencil.'"

"Is the boy present?"

"Yes, sir."

"I shall take it as a favor if he will rise."

Ever since Lionel began to speak, Frank's mind had been in a tumult. It was his first impulse to get up and indignantly deny that he had seen the chain; but then he must explain why he was in that place and what he had been searching for. This he was too proud to do, and now he sat still, painfully embarrassed.

This, of course, confirmed Lionel in his opinion that he had picked up the chain and concealed it.

Mr. Monks waited a few moments for the boy to rise, then said kindly:

"I do not believe I have one pupil who would willfully keep a chain found under such circumstances. Though the article was very valuable from having been the gift of a friend, now deceased, yet I would far rather lose it, than to suspect one who was not guilty. If any of you have a word to tell me in private, I shall remain in my desk half an hour after school."

When the scholars were dismissed, Lionel, with a hesitating glance at Frank, who stood, cap in hand, in the entry, walked straight up the aisle to the platform.

Frank, who had almost resolved to confide his explanation to his teacher, who was also his mother's and his own best friend, stopped short on seeing this, and saying to himself, "I can tell him better at home," was rushing away, when he heard the words:

"Impossible! I can never believe it!"

He darted a defiant glance toward the spot where his companion stood, and, with his head very erect, walked slowly away.

"A thief!" he exclaimed to himself. "Suspected as a thief! What would my father say if he were alive? What a precious scamp that Lionel must be! Why, I should never imagine such a thing of a companion. O, dear! I'm sick of life! A thief, indeed! But Mr. Monks knows me too well. I've handled hundreds of dollars of his money, for he always sends me to the bank with his checks. Of course, he said, 'Impossible!'"

Still he was rather angry with his teacher for even listening to Lionel's story, and, hearing a hasty step behind him, put on a haughty air of indifference.

"Frank, stop a minute," called out the gentleman.

He turned, and looked Mr. Monks full in the face.

"Did you get the example right at last, my boy?"

This question was asked in so hearty a tone of friendship that Frank's displeasure vanished.

"Yes, sir, I did; I understand the whole principle, now."

"Capital!"

They were entering the gate when the boy stopped short.

"Mr. Monks," he began, "don't you know that I've seen you wear that chain every day for a year?"

"Yes."

"And that if I had found it, as Lionel suspects, and kept it to myself, I should be a thief—the worst kind of thief, stealing from my best friend?"

Mr. Monks answered, "Yes," with a smile.

Frank said no more, but walked off into the house.

"WHAT nonsense!" exclaimed Mrs. Monks, when her husband repeated to her what had passed. "Why, I should as soon suspect Mrs. Jocelyn herself, or Squire Rawson. But I wonder a little that Frank does not explain why he was there."

The gentleman smiled. "I know Frank well enough to guess why he does not. He is a proud fellow, and such a suspicion would cut him like a knife."

Under the window they could hear the boy whistling, and, on looking down, Mrs. Monks saw him sitting on the door-step listlessly breaking a dry stick into pieces.

"Frankey," she called out, "don't you want Ida? she's been calling Ank, Ank, this half hour."

He sprang to his feet, and answered:

"Yes, ma'am, I do," in an eager voice.

"I'll put on her sack, and bring her down to you. She can go to walk if you have a mind."

Mr. Monks smiled archly, as he watched the handsome boy leading little flaxen-haired Ida along the gravelled walk. His merry laugh and bright face proved that, for the time, he had thrown all care to the winds, while the pretty child, clinging so confidingly to his finger was prattling in the sweetest tones.

"That was a happy thought of yours," said her husband, gazing archly in her face; "women always do seem to understand how to manage these matters better than men."

"Unless Frank confessed to me with his own lips, I wouldn't believe such a story of him," she exclaimed, seating herself again at her work.

"Of course not! But there are some who have not your charity."

May Jocelyn, who also attended Mr. Monk's school, repeated to her mother the account of her teacher's loss, and innocently wondered who Lionel Trask meant.

"The scholars all love our teacher so dearly," she went on, "that they would carry him the chain at once. I can't think of a boy so likely to conceal it as Lionel himself."

"Charity thinketh no evil," repeated a manly voice from behind.

"Thank you for reminding me," she said, laughing. "But I do not really suspect him. I happened to catch his eye while you were telling the school of your loss, and could not help observing that he was startled and confused."

"I don't think he looked more so than Frank; and yet we both are sure he is innocent. Indeed, I have known many boys of quick conscience and keen sense of honor, blush painfully with the mere dread of being suspected. I am sorry to lose my chain and seals; but I am glad to say I suspect no one in school or out. I find the ring of my watch is broken, and no doubt, it slipped off during some of my walks."

May was thoughtful for a few moments. "Mr. Monks," she said at last, "do you think anybody can, really and truly, obey the rule about charity?"

"Let me answer your question by asking another. Do you think our Father in Heaven would have commanded us to do anything which he knew we could not do?"

"No, sir; on, no, indeed! I didn't mean that; but it is very hard sometimes to have charity for everybody."

"It certainly is; but that is no reason why we should not strive to 'bear all things, believe all things, endure all things' rather than fail of charity toward our fellow-men."

May looked archly into her teacher's face. "I think, Mr. Monks," she said, "that you do keep the law of charity. With you, I believe, 'charity never faileth.'"

She was astonished at the spasm of pain which passed over his face.

"My dear child," he said, with great emotion, "in that respect I have failed more than in all else. If I do try to bear all things, believe all things, to suffer long and be kind, it is because I have had a fearful lesson to teach me how unjust and cruel one may become who does not aim to obey this inspired rule. Let us be thankful that there is One,—even our divine Saviour, whose charity is not easily provoked, who suffereth long and is kind."

His voice was so serious that her eyes filled with tears.

"I seldom speak of this, my child. It is too painful; but if it might be a warning to you, I should not regret it."

LITTLE did May realize how soon her schoolmates would have occasion for charity toward one dear to her as her own right hand.

On her way to school, she met two or three of the girls of her own class, who were talking, but who stopped as soon as she came within hearing. She spoke to them in her usual pleasant tone, but perceived that they were embarrassed, and, more annoyed than she liked to show, she passed on alone.

Before she reached the Academy, she heard Lionel talking in a loud tone to a group around the steps, and at last heard the words:

"How mean! I despise a thief."

"They have found out the guilty one," she thought, hastening forward.

But again, she was surprised that, on seeing her emerge from the field, their loud tones ceased altogether.

"What can it mean?" she asked herself, her cheeks burning.

Usually her appearance was greeted with a shout of welcome; but now no one ventured near her except little Annie Ross, one of the youngest girls in school.

Annie caught her hand and pulled her into the recitation room, which was quite deserted.

"It's a shame," she began in great excitement, "I shouldn't think they'd treat you so, and for nothing at all."

"Why, Annie, what are you talking about?"

The little girl stared. "Why, don't you know? Lionel Trask says Frank has the chain Mr. Monks lost; he told teacher he saw Frank pick it up: but teacher wouldn't believe it. Lionel has made the scholars think so; and they say he's a thief, and call him all sorts of names. Oh, it's dreadful!"

"Does Frank know of this?" asked May, her lip quivering.

"I don't know; but, oh, dear! There's the first bell. I think Lionel is the ugliest, meanest boy I ever saw. I dare say he found the chain himself."

"Don't—oh, Annie! I'm afraid it's wrong for you to feel so."

May understood now why Mr. Monks had said, "you and I know that Frank is innocent." He had heard this awful charge. "Oh, it is too cruel!" she exclaimed, laying her head on the seat.

"I shouldn't think the big girls would act so," continued Annie. "Sophy, and Maria, and Sarah Ann said, they shouldn't speak to you. They called you sister to a thief; and Maggie said, like as not you knew all about it. Everybody said you were awful poor now."

"Don't, don't, Annie; I can't bear it."

She sobbed as if her heart would break. "I must go home; I can't stay," she cried, holding her aching head.

The sound of many feet taking their places in their seats prevented her rushing through the school-room, anywhere to get to her mother, away from all these cruel eyes.

"Go, go, Annie. I can't; you must take your seat. There's Mr. Monks' bell for devotion. Oh! I wish I could get out of the window. Where is Frank?"

Annie peeped through the crack of the door, and said:

"He's in his seat, sitting up just like this," holding herself very erect. "He looks real solemn, though. There, I can't go now, Mr. Monks has begun."

Poor May! This was her first school trial. She dearly loved and trusted her schoolmates. What had she done that they should treat her so cruelly!

She tried to check her sobs, and devise some way of reaching home without being seen; but crying had brought on a blinding headache, and she had lost self-control. The room seemed to whirl around, growing darker and darker every minute, until, with a groan, she fell to the floor.

The bell for study to commence was just ringing when, with a shriek, Annie rushed into the school-room exclaiming:

"She's dead! Oh come! Do come!"

Motioning the scholars to retain their seats, the teacher lifted the poor, unconscious girl in his arms, and carried her, looking whiter than a lily, to the window, directing Annie to bring some water in a dipper.

A few drops sprinkled in her face restored consciousness, and she opened her eyes in wonder.

Annie then in a breathless manner, began to relate what had passed.

Mr. Monks grew every moment more stern.

"Poor child!" he murmured, caressingly patting her head.

"Call Frank Jocelyn," he said to Annie.

"Your sister has had a fainting fit, and—"

"Who, May? Is that you, May?" And the brave boy, who would not show how deeply his own heart was wounded, shed tears when told of his sister's affliction.

"We must get her home. Look from the window and see whether Squire Rawson's horse and buggy are still standing at the bank."

"Yes, sir."

"Annie, spread a shawl on the settee. Now, May, I will help you to lie down. You'll feel better, presently."

She shook her head mournfully, and then caught hold of Frank's hand.

IN a few moments, Lionel, who had been sent away by the teacher, returned with the Squire's horse; and May, assisted by her brother and Annie, passed through the school-room to the front hall.

"Drive slowly," urged Mr. Monks, "and ask your mother to give her some ammonia. You can return or not, as you please. No marks for absence will be given to either of you."

Lionel started, when he saw May looking so pale and wan. "For the first time," he reflected, "I may be mistaken. Frank certainly does not look nor act like a thief."

Poor May laid her head on her brother's shoulder with a heavy sigh. Their usual path across the field shortened the distance by one half. Now they were obliged to take the road, and for a few minutes, neither of them spoke. At last May murmured:

"Only this morning, I was so happy."

"Sis," exclaimed Frank, as if he could no longer control himself, "if it wasn't for you and mother, I'd never go near that school again. I'd run off and go to sea, or somewhere. I never can live here where they think me a thief."

"Oh, sis! and Lionel too! Why I have helped him to keep his place in the class by going over his lessons with him for a year. He knows I didn't take the chain. He does it out of envy, because; though I'm younger, I'm always above him."

He spoke bitterly, and poor May, who had been silently weeping, said softly:

"Don't, Frank; don't feel so. I'm sure it isn't right. There's mother at the window. She'll feel badly enough."

Mrs. Monks ran to the door to see what brought them home; and Ida held out her arms to Frank begging to be taken to ride.

For almost the first time in his life, he took no notice of her pleading voice. He hardened himself by thinking:

"Perhaps Mrs. Monks thinks I stole the chain."

He merely told his mother that May had fainted in the school, and the teacher sent them home. Then jumping into the buggy, he rode away.

In the mean time, Mr. Monks returned to the recitation room and shut the door.

"Shall I tell them of my own experience?" he asked himself. "Can I open again the wound? They need a warning as to the danger of thinking evil of those about them. A lesson on charity would have double force now. But I cannot; no, such a confession is not required."

"Yet how can I see that noble boy and his tender, loving, pure-hearted sister sacrificed. How bravely he bore up, till he saw her overcome! From the moment he took his seat, I observed the marks of keen suffering on his open countenance. Yes, I will; I will confess my sin, my want of charity. For their sake, and as a warning to all my scholars, I feel that I can do it."

When he returned to the school-room, the scholars started to see what a pallor had taken the place of his usual ruddy color. He made not the slightest allusion to what had passed, but called up one class after another, hearing their recitations, and giving them their marks without a smile. Only when Annie Ross stood by his side, he gazed in her face a moment, put his hand gravely on her head, and repeated, as if to himself:

"'Faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.'"

The moment school was dismissed, the pupils rushed into the yard, where they could discuss the subject which occupied their thoughts.

"What made May faint? Why didn't Frank return to his class? He had never been known to be absent before."

Little Annie was questioned over and over again, until she answered:

"The sobbing made her head ache dreadfully."

"But what was she crying for?"

"You know what made her cry, Sophy Lane. You'd cry yourself, if anybody talked about your brother. I was awfully frightened; I thought she was dead. Frank cried, too, when he saw how she looked."

"Frank cried!" exclaimed one of the large boys. "That's a good joke. I thought he was even stiffer than usual. Ha, ha! He'll have to come down off his high horse, a thief and cry baby."

"Boys!" cried out a loud, authoritative voice. "It is my request that you suspend all comment or judgment on Frank Jocelyn until to-morrow."

THE bell for study to cease, rang a full hour earlier than usual. Mr. Monks requested the school to give him their attention, in a voice so very sad as to awaken the liveliest sympathy.

He opened the large Bible, and turning to the thirteenth chapter of First Corinthians, read to them Paul's exhortation to Charity.

When he came to the words:

"Charity suffereth long, and is kind; charity envieth not, charity vaunteth not itself, is not puffed up," he stopped, and after a moment of painful hesitation said:

"I wish every one of you would ask, 'Have I such charity toward my school-mate as this? Have I suffered long? Have I been really anxious to believe the best? Have my thoughts of him been kind, forbearing, and gentle; or have I been easily provoked, ready to believe the worst? Have I, out of envy of his rich gifts, been pleased with the idea of his falling into temptation? Have I vaunted myself, thinking I could never have so disgraced my character? Have I been puffed up with a belief of my own goodness?"

"Paul here says: 'Charity never faileth.' Has my charity failed? Have I thought and hoped for the best, or the worst, of him whom I have called friend? If it has failed, remember, unless you speedily repent, even though you bestow all your goods to feed the poor, or give your body to be burned, it will avail you nothing, in the solemn day when you will be judged according to your deeds."

He stopped a moment, and covered his eyes with his hand. Presently in a broken voice he went on:

"I am going to give you an account of a few months in my early life. You will condemn me, but not half as much as I do myself. If the recital will teach you to be more forbearing, to think no evil of your neighbors, to hope for the best, to rejoice not in iniquity, but to rejoice in good, then I shall be willing to endure the pain."

"I once had a brother. He was all that a brother could be: noble, brave, generous, loving, faithful; aye, even till death. We loved each other as few boys love; and when I, who was the oldest by eleven months, entered a store as book-keeper, I was not happy until he joined me in learning to be a merchant. I was called grave; and he was mirthful. I heard my employers praise him. I saw them watch his active, pleased endeavors to be useful, and the serpent of suspicion began to steal into my breast. At last one of the clerks left, and Arthur was promoted to a position higher than my own. At least, I thought so at the time."

"Then came all the workings of an uncharitable heart. I was unkind to my brother; I envied him his power of gaining the good will of others; I vaunted myself on my own talents; I said I was older and better fitted than he; I puffed myself up in my own goodness; I was easily provoked; I thought the worst of him; I did not hope for the best."

"When conscience suggested that I was putting a false construction on everything he did, I rejoiced in what I thought his iniquity, because it gave me an excuse for treating him cruelly."

"I knew my conduct grieved him, wounded him to the heart; that he could scarcely believe his ears when I returned a harsh word to his loving caress. I saw his eye fixed mournfully upon me many times; but I would not yield; I believed he was trying to supplant me, to gain a place as partner in the firm; and though he often talked as of old, about the time when we would establish ourselves together, I believed it was all to blind me to his villany."

"At last, I was so given up to envy, jealousy, bitterness and all the scorpions to which uncharitableness leads, that I requested my mother to allow me a separate room for myself. Before this, we had always slept together."

"She then for the first time remonstrated against my unkindness. She said it cut her heart in two. She urged me to explain the change in my manner; but I refused. Even then I knew my suspicions would not bear examining. She turned from me with a look more of sorrow than of anger."

"One night, on leaving the store, I found Arthur had gone before me. On reaching home, our family physician was there. My brother was ill in bed. He had been earnestly calling my name; mother urged me to go to his room at once, but not until I had leisurely eaten my supper, did I go to his side."

"Even then I coolly expressed my regret at finding him ill, and then excused myself, saying I was going to an evening lecture."

MR. MONKS was here so overcome that he groaned aloud, seizing the chair to support himself. It was several minutes before he recovered his voice.

"If I have learned to be careful in judging others, to try and think and hope for the best, instead of the worst," he went on at last, "I acquired the lesson in a fearful school. That night, Arthur, my beloved, my only brother, was seized with delirium. He lived ten days; but the only opportunity to confess my injustice, to plead for his forgiveness, had passed. He raved day and night about my altered looks; he implored me by the love we used to bear each other to forgive him, if he had unintentionally offended; he called me by every endearing name; but not once did he recognise me."

"All this time, I never left him. I could neither eat nor sleep. My love to my pure, noble brother had revived with ten-fold strength; but conscience was aroused at last, and in a voice of thunder set my sins in order before me. I wept, I entreated him by every name that was tender, to live for my sake, to forgive my cruel suspicions. I was answered either by an unmeaning laugh, or a heart-rending cry for me to love him."

"The end came at last; came without one word to ease the anguish that gnawed at my heart. For four months, my reason fled; when I slowly recovered, I was in despair; but through the mercy of a crucified Redeemer, I learned at last to hope that even my sins might be washed away in atoning blood."

Not a sound could be heard except the sobs by which the scholars showed their sympathy with their teacher, and presently, in a broken voice, he asked God to teach them all, both instructors and scholars, to cultivate charity which is the bond of perfectness.

He had intended to speak of Frank and his sister, to express his own conviction of the lad's innocence of the charge laid to him; but his voice failed.

He sat down until they had passed out into the hall, concealing his face behind a book. He started to find a little hand pressed into his.

"Dear Mr. Monks," she said, choking back a sob, "I'm so sorry. I can't help loving Arthur dearly. I know Jesus forgave you."

He caught her in his arms; and blessed tears came to his relief.

"You did not need the lesson," he faltered, at last. "You did have charity for poor Frank."

"Oh, I knew he didn't take the chain! He isn't such a kind of boy. I'm almost sure now the scholars wont treat him unkindly any more. I'm sure they'll remember—"

She interrupted herself quickly as she saw him start, gave his hand a kiss, and darted away.

Child that she was, her words had comforted him.

The school-room was now deserted, and leaning his head on his desk, he poured out a prayer to God for a blessing on his endeavors to cultivate a spirit of love and charity among his pupils. He prayed for Lionel, for Frank and his sister, for the widowed mother, afflicted in her children's affliction; and then he prayed humbly for himself, that the sin of his youth might not rise up in judgment against him.

He was locking his desk, when he thought he heard a noise in the hall, and presently Lionel came in, blushing painfully.

"I forgot my geography," he muttered, going toward his seat, "and oh, Mr. Monks, I believe Frank is innocent! I'm sorry I said what I did. He isn't such a kind of boy as that. He found my rubbers when I thought they were lost; and he might have kept them if he'd been a thief; and oh, Mr. Monks! If it hadn't been for Frank, I never could have kept up with the class. He makes me study my lessons over and over, when a great many times I think I can't do it; and I'd rather play."

"I tried to believe it," he went on, much confused, but resolved now that he had begun, to confess the whole. "I told the boys I knew he'd got it. I asked them what else he could be doing there. I told Sophia Lane how he blushed when I asked him what he was looking for. I was envious of him, Mr. Monks, and when you read that chapter, I thought how it described all I had done."

"I tried to think badly of him, I didn't hope the best, I puffed myself up that I wouldn't steal; but now I do want to have charity, sir."

"You see already its blessed fruits," answered the gentleman, kindly. "First, you begin to think less of yourself, and then more of your neighbor. You recall to mind all his good traits, which previously, you forgot or put out of sight."

"Do you believe he'll forgive me, sir?"

"Go and ask him."

This was said with a smile, and Lionel darted away.

THE next morning, both Frank and May were in their seats.

Frank was paler than usual, and did not join his companions at recess. He sauntered off with May and Annie, though he answered pleasantly when Lionel told him they were getting up a new club for ball.

His sister had a look of meek sadness which cut Lionel to the heart.

Mr. Monks had requested them to attend school; and now he waited with no little anxiety to see how their mates would receive them. He hoped that the example of Lionel would be followed by all.

It was now so many days since the chain was missing that he despaired of ever seeing it again, though he keenly regretted its loss. One of the seals had been the last gift of Arthur, his deeply lamented brother. For Frank's sake, too, he earnestly wished to know where it had so suddenly disappeared. He felt sure nothing else would satisfy the sensitive boy.

Two weeks passed, when one Saturday, Mrs. Jocelyn sent Frank to the store. The merchant owed her quite a sum for root beer; and he called to receive the pay.

While the man made change, he walked listlessly to the counter and took up a paper. The first words on which his eye rested were these:

"FOUND: A valuable gold watch chain with three seals and a medal

of membership to the Phi Beta Kappa Society. Any person claiming

the same, can have his property restored to him by proving it to be his.

Call at — street, number twenty."

"Is this to-day's paper?" enquired the boy, his face all in a blaze.

"Let me see; no, it's an old one."

"May I have it, sir?"

"Certainly."

Frank folded it carefully, clutched the money without a word, and started for home on the run.

"I wonder what he saw in the paper," said the merchant to his clerk.

When about two thirds of the way home, Frank saw Mr. Monks come out of the front door, and take the opposite direction down the street to the depot.

He redoubled his speed, and was soon within hailing distance of the gentleman.

But when he reached him, he was too much out of breath to speak. He could only hold out the paper pointing to the advertisement.

Mr. Monks gazed a moment into the sparkling eyes before him, then turned to the paper, gave a joyful start, and clasped the boy's hands warmly in his own.

"It's all right, you see," he exclaimed. "May I take the paper? I'll go and get it to-day. I'm going to the city, you know."

"Yes, sir; and I was so afraid I should be too late to find you. Oh, I'm so thankful! May will get better right away."

"You must tell Mrs. Monks all about it.'

"I had rather not, sir, till you come home. I had rather tell nobody but May."

"Well, good-bye, then, take care of Ida till I come back."

Notwithstanding, it was the Sabbath, several of the scholars noticed that outside of Mr. Monks' black vest, a chain and seals were exhibited in a most conspicuous manner.

"He has made Frank Jocelyn give it up," whispered Sophia Lane to her companion, Maggie.

"But Frank doesn't look one bit like a thief," was answered in the same tone. "See him now. I never saw him look half so handsome; and how lovingly May glances in his face. I wish I had such a handsome brother. I believe I should be as proud of him as she is."

"I don't see anything to be proud of in a brother who is a thief," murmured Sophia.

The singing had just ceased, and the minister arose to announce his text. There were others beside Sophia who started when he read:

"And above all things have fervent charity among yourselves;

for charity shall cover a multitude of sins."

Mr. Monks' eyes were fixed on the speaker during the whole discourse. He asked God to let his own truth sink deep into the heart; and he prayed that the words might be blessed to those who were so dear to him.

Monday afternoon, when the scholars were out at recess, and the teacher was examining copy books, Annie came timidly toward him. The dear child had regarded him with a kind of awe since the night she saw him weep, and did not speak until he addressed her.

"What is it, Annie? Can I help you?"

"Yes, sir," she answered, clasping her hands, her eyes sparkling. "We're going to do something splendid. May I tell you about it."

"Yes, yes, indeed."

"We're going to have a society; and we'll call it for charity. I mean we're going to try and feel kindly to everybody; and if any boy or girl speaks unkindly of any one, they'll have to be turned right out."

"Capital! I hope they'll admit me."

Annie laughed heartily. "Oh, you're a big man!" she said.

"Not very much taller than Joel Barnes."

"I should like you to belong," she said, "but I'm afraid the girls wouldn't be willing; only they want to know, sir, whether you'll let them meet here once a week."

"Once a day, if they will promise to keep up to their rules."

"And, Mr. Monks," said Annie, lowering her voice and growing very red, "the girls didn't tell me to ask; but if you'd only say where you found this," timidly touching his chain.

"Wait till to-night, my dear."

Once more, just before school closed, the kind teacher requested attention.

"You will see," he said, "that I have recovered my chain and seals. It is now nearly three weeks since a gentleman riding on the main road, near the Academy, saw them lying in his path. He was in haste, and could not stop to inquire for the owner; but he advertised them at once. A copy of the paper was seen, and given me, and I identified them as my property."

Then he dismissed the school, but called out after them to say, "I heartily approve the object of your new society, and will give it all the aid in my power."

"I AM so glad," exclaimed Lionel, overtaking Joel Barnes. "I knew that Frank didn't take the chain; but he never would have felt right about it, if it hadn't been found. Now I can forgive myself. You know, there wouldn't have been any fuss, if I had had charity toward Frank as I ought."

"That was an awful story," said Joel. "I wonder how Mr. Monks could tell us. 'Tisn't every teacher would do so for his scholars."

"I'm sure I never shall forget it," murmured Lionel. "It makes me ashamed every time I remember that little Annie Ross, the youngest girl in school, was the only one who had charity for Frank, or the courage to treat May kindly."

"Is she the little girl Sophy Lane calls a coward?"

"Yes; and she may be afraid to tread on worms, or caterpillars; or even to kill flies; but she isn't afraid to do what she thinks is right."

"There come Frank and May behind us," said Joel. "Let's stop and see what they have to say."

"Shall you join our Charitable Society, as Annie calls it?" asked May.

"I would like to join where they all would promise to think well of me," answered Lionel, laughing, as he put his arm lovingly in Frank's.

"I should think it would be a good plan to have speaking on the subject," remarked Joel.

"Yes," added May, "that is what we want, to have the boys declaim, and the girls write their thoughts, which some one can be appointed to read."

"Mr. Monks would approve of that," said Frank, "because it might be for our benefit in many ways."

"Once in a while we could have a party or picnic, and celebrate our Charity Circle," suggested May.

"That's a capital name," exclaimed a voice from behind; "and if the rules contained in Corinthians are carried out, I prophesy that you will revolutionize our whole town; and be voted the greatest public benefactors that ever lived in it."

"We'll do it, Mr. Monks!" they all exclaimed. "At least we'll try."