ANTHROPOLOGY

By

A. L. KROEBER

NEW YORK

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY

COPYRIGHT, 1923, BY

HARCOURT, BRACE AND COMPANY, INC.

PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. BY

THE QUINN & BODEN COMPANY

RAHWAY, N. J.

In the preparation of Chapters II, III, and VI of this book I have drawn on a University of California syllabus, “Three Essays on the Antiquity and Races of Man”; for Chapter VII, on an article “Heredity, Environment, and Civilization” in the American Museum Journal for 1918; and Chapter V makes use of some passages of “The Languages of the American Indians” from the Popular Science Monthly of 1911. In each case there has been revision and for the most part rewriting.

Whatever quality of lucidity the volume may have is due to several thousand young men and women with whom I have been associated during many years at the University of California. Without their unwitting but real co-authorship the book might never have been written, or would certainly have been written less simply.

A. L. K.

Berkeley, California, January 22, 1923.

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

| I. Scope and Character of Anthropology | 1 |

| 1. Anthropology, biology, history.—2. Organic and social elements.—3. Physical anthropology.—4. Cultural anthropology.—5. Evolutionary processes and evolutionistic fancies.—6. Age of anthropological science. | |

| II. Fossil Man | 11 |

| 7. The “Missing Link.”—8. Family tree of the Primates.—9. Geological and glacial time.—10. Place of man’s origin and development.—11. Pithecanthropus.—12. Heidelberg man.—13. The Piltdown form.—14. Neandertal man.—15. Rhodesian man.—16. The Cro-Magnon race.—17. The Brünn race.—18. The Grimaldi race: Neolithic races.—19. The metric expression of human evolution. | |

| III. Living Races | 34 |

| 20. Race origins.—21. Race classification.—22. Traits on which classification rests.—23. The grand divisions or primary stocks.—24. Caucasian races.—25. Mongoloid races.—26. Negroid races.—27. Peoples of doubtful position.—28. Continents and oceans.—29. The history of race classifications.—30. Emergence of the three-fold classification.—31. Other classifications.—32. Principles and conclusions common to all classifications.—33. Race, nationality, and language. | |

| IV. Problems of Race | 58 |

| 34. Questions of endowment and their validity.—35. Plan of inquiry.—36. Anatomical evidence on evolutionary rank.—37. Comparative physiological data.—38. Disease.—39. Causes of cancer incidence.—40. Mental achievement and social environment.—41. Psychological tests on the sense faculties.—42. Intelligence tests.—43. Status of hybrids.—44. Evidence from the cultural record of races.—45. Emotional bias.—46. Summary. | |

| V. Language | 87 |

| 47. Linguistic relationship: the speech family.—48. Criteria of relationship.—49. Sound equivalences and phonetic laws.—50. The principal speech families.—51. Classification of language by types.—52. Permanence of language and race.—53. The biological and historical nature of language.—54. Problems of the relation of language and[vi] culture.—55. Period of the origin of language.—56. Culture, speech, and nationality.—57. Relative worth of languages.—58. Size of vocabulary.—59. Quality of speech sounds.—60. Diffusion and parallelism in language and culture.—61. Convergent languages.—62. Unconscious factors in language and culture.—63. Linguistic and cultural standards.—64. Rapidity of linguistic change. | |

| VI. The Beginnings of Human Civilization | 137 |

| 65. Fossils of the body and of the mind.—66. Stone and metals.—67. The old and the new stone ages.—68. The Eolithic Age.—69. The Palæolithic Age: duration, climate, animals.—70. Subdivisions of the Palæolithic.—71. Human racial types in the Palæolithic.—72. Palæolithic flint implements.—73. Other materials: bone and horn.—74. Dress.—75. Harpoons and weapons.—76. Wooden implements.—77. Fire.—78. Houses.—79. Religion.—80. Palæolithic art.—81. Summary of advance in the Palæolithic. | |

| VII. Heredity, Climate, and Civilization | 180 |

| 82. Heredity.—83. Geographical environment.—84. Diet.—85. Agriculture.—86. Cultural factors.—87. Cultural distribution.—88. Historical induction. | |

| VIII. Diffusion | 194 |

| 89. The couvade.—90. Proverbs.—91. Geographic distribution.—92. The magic flight.—93. Flood legends.—94. The double-headed eagle.—95. The Zodiac.—96. Measures.—97. Divination.—98. Tobacco.—99. Migrations. | |

| IX. Parallels | 216 |

| 100. General observations.—101. Cultural context.—102. Universal elements.—103. Secondary parallelism in the Indo-European languages.—104. Textile patterns and processes.—105. Primary parallelism: the beginnings of writing.—106. Time reckoning.—107. Scale and pitch of Pan’s pipes.—108. Bronze.—109. Zero.—110. Exogamic institutions.—111. Parallels and psychology.—112. Limitations on the parallelistic principle. | |

| X. The Arch and the Week | 241 |

| 113. House building and architecture.—114. The problem of spanning.—115. The column and beam.—116. The corbelled arch.—117. The true arch.—118. Babylonian and Etruscan beginnings.—119. The Roman arch and dome.—120. Mediæval cathedrals.—121. The Arabs: India: modern architecture.—122. The week: holy numbers.—123. Babylonian discovery of the planets.—124. Greek and Egyptian contributions: the astrological combination.—125. The names of the days and the Sabbath.—126. The week in Christianity, Islam, and eastern Asia.—127. Summary of the diffusion.—128. Month-thirds and market weeks.—129. Leap days as parallels.[vii] | |

| XI. The Spread of the Alphabet | 263 |

| 130. Kinds of writing: pictographic and mixed phonetic.—131. Deficiencies of transitional systems.—132. Abbreviation and conventionalization.—133. Presumptive origins of transitional systems.—134. Phonetic writing: the primitive Semitic alphabet.—135. The Greek alphabet: invention of the vowels.—136. Slowness of the invention.—137. The Roman alphabet.—138. Letters as numeral signs.—139. Reform in institutions.—140. The sixth and seventh letters.—141. The tail of the alphabet.—142. Capitals and minuscules.—143. Conservatism and rationalization.—144. Gothic.—145. Hebrew and Arabic.—146. The spread eastward: the writing of India.—147. Syllabic tendencies.—148. The East Indies: Philippine alphabets.—149. Northern Asia: the conflict of systems in Korea. | |

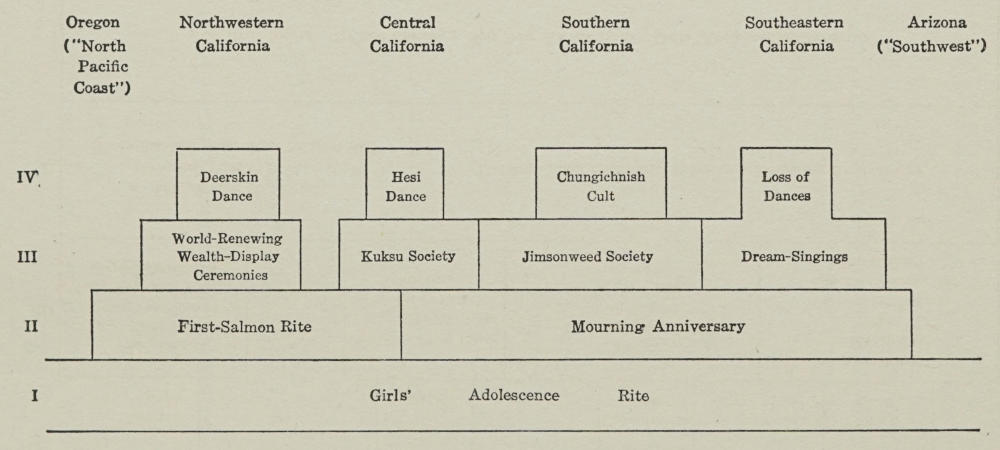

| XII. The Growth of a Primitive Religion | 293 |

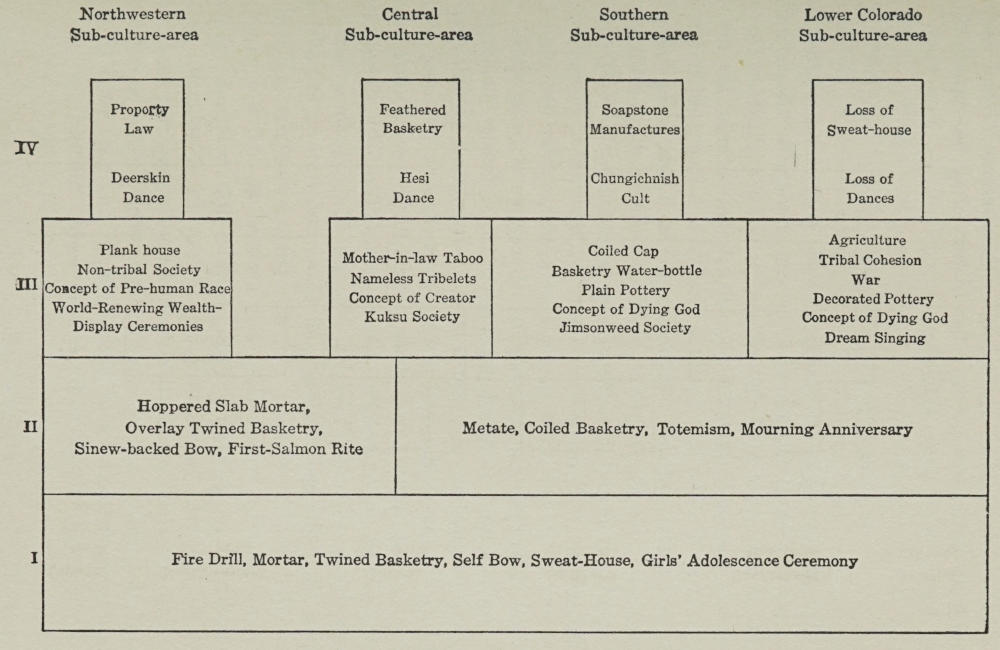

| 150. Regional variation of culture.—151. Plains, Southwest, Northwest areas.—152. California and its sub-areas.—153. The shaping of a problem.—154. Girls’ Adolescence Rite.—155. The First Period.—156. The Second Period: Mourning Anniversary and First-salmon rite.—157. Era of regional differentiation.—158. Third and Fourth Periods in Central California: Kuksu and Hesi.—159. Third and Fourth Periods in Southern California: Jimsonweed and Chungichnish.—160. Third and Fourth Periods on the Lower Colorado: Dream Singing.—161. Northwestern California: world-renewal and wealth display.—162. Summary of religious development.—163. Other phases of culture.—164. Outline of the culture history of California.—165. The question of dating.—166. The evidence of archæology.—167. Age of the shell mounds.—168. General serviceability of the method. | |

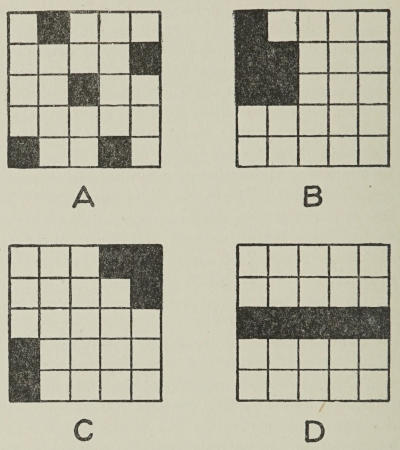

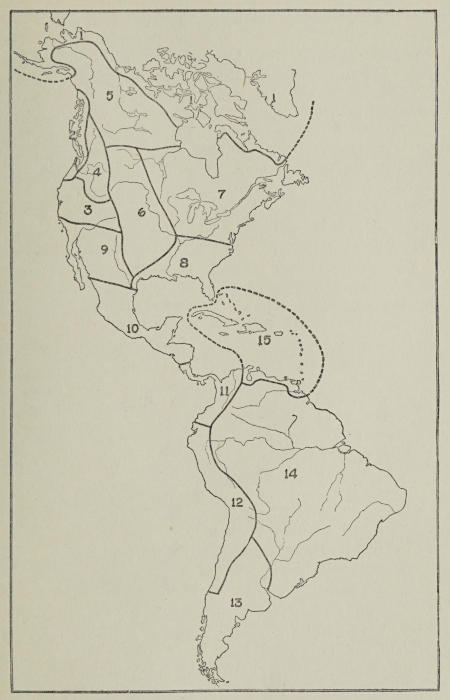

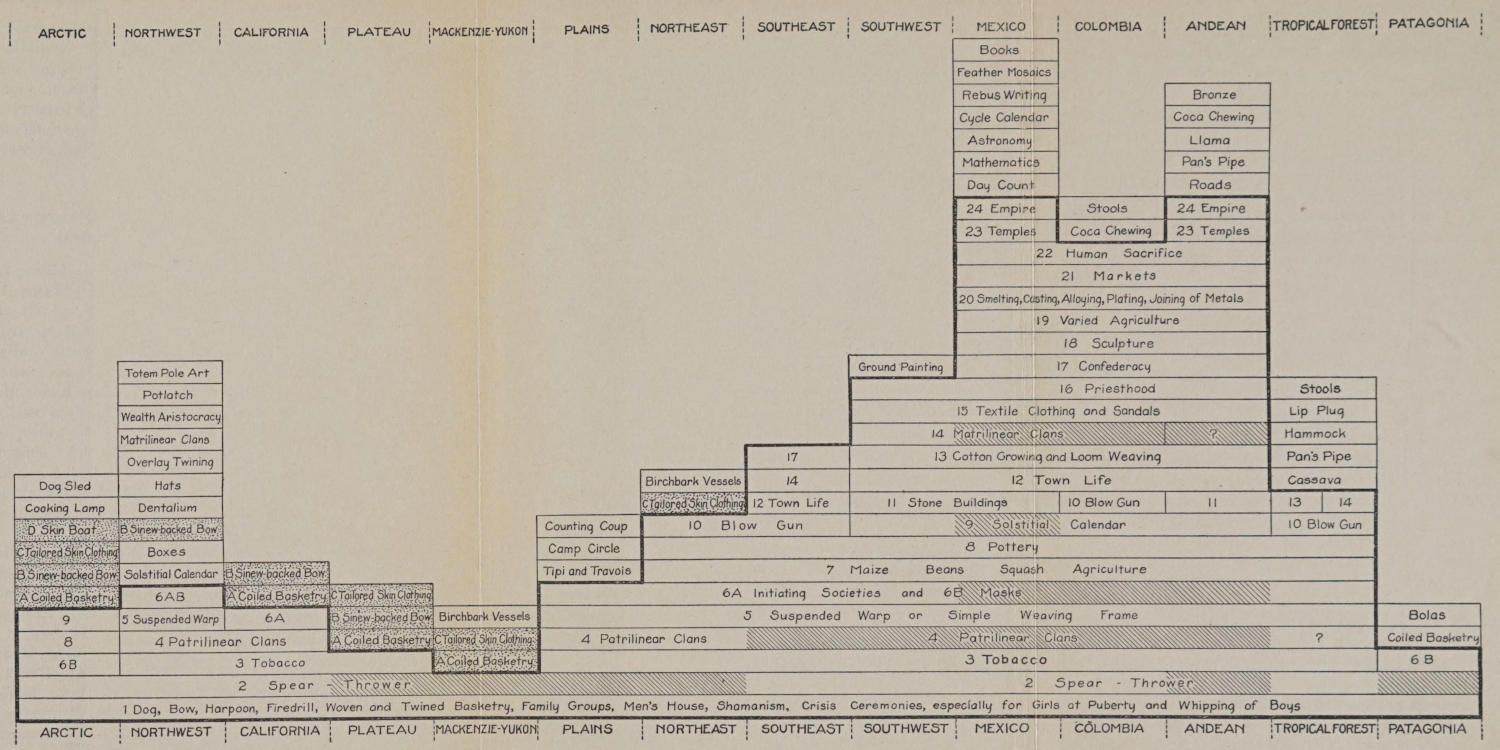

| XIII. The History of Civilization in Native America | 326 |

| 169. Review of the method of culture examination.—170. Limitations on the diffusion principle.—171. Cultural ranking.—172. Cultural abnormalities.—173. Environmental considerations.—174. Culture areas.—175. Diagrammatic representation of accumulation and diffusion of culture traits.—176. Representation showing contemporaneity and narrative representation.—177. Racial origin of the American Indians.—178. The time of the peopling of America.—179. Linguistic diversification.—180. The primitive culture of the immigrants.—181. The route of entry into the western hemisphere.—182. The spread over two continents.—183. Emergence of middle American culture: maize.—184. Tobacco.—185. The sequence of social institutions.—186. Rise of political institutions: confederacy and empire.—187. Developments in weaving.—188. Progress in spinning: cotton.—189. Textile clothing.—190. Cults: Shamanism.—191. Crisis rites and initiations.—192. Secret societies and masks.—193. Priesthood.—194. Temples and sacrifice.—195. Architecture, sculpture, towns.—196. Metallurgy.—197. Calendars[viii] and astronomy.—198. Writing.—199. The several provincial developments: Mexico.—200. The Andean area.—201. Colombia.—202. The Tropical Forest.—203. Patagonia.—204. North America: the Southwest.—205. The Southeast.—206. The Northern Woodland.—207. Plains area.—208. The Northwest Coast.—209. Northern marginal areas.—210. Later Asiatic influences. | |

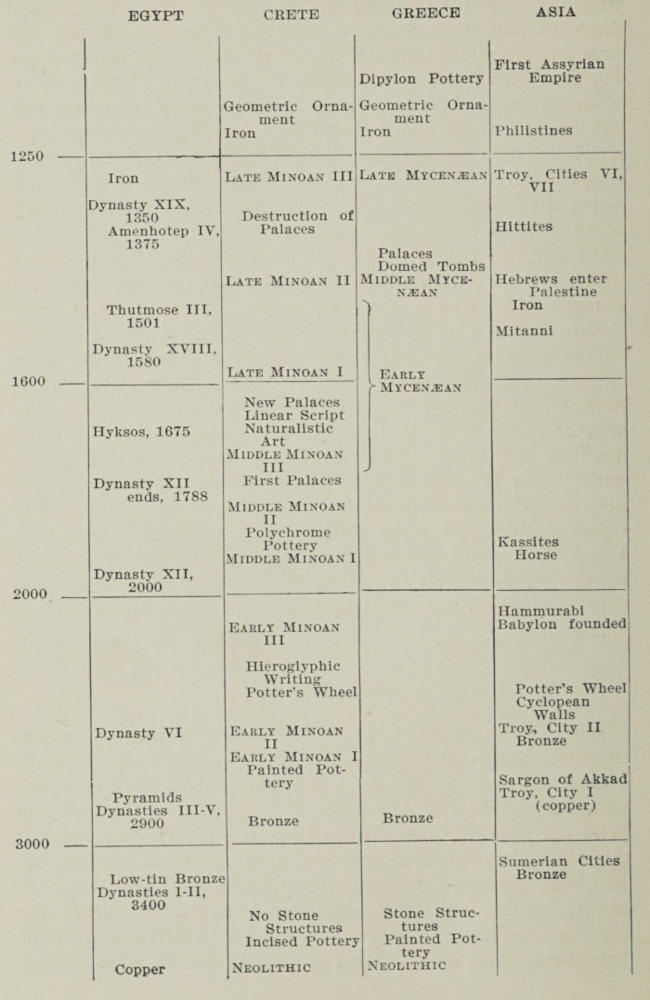

| XIV. The Growth of Civilization: Old World Prehistory and Archæology | 393 |

| 211. Sources of knowledge.—212. Chronology of the grand divisions of culture history.—213. The Lower and Upper Palæolithic.—214. Race influence and regional differentiation in the Lower Palæolithic.—215. Upper Palæolithic culture growths and races.—216. The Palæolithic aftermath: Azilian.—217. The Neolithic: its early phase.—218. Pottery and the bow.—219. Bone tools.—220. The dog.—221. The hewn ax.—222. The Full Neolithic.—223. Origin of domesticated animals and plants.—224. Other traits of the Full Neolithic.—225. The Bronze Age: Copper and Bronze phases.—226. Traits associated with bronze.—227. Iron.—228. First use and spread of iron.—229. The Hallstadt and La Tène Periods.—230. Summary of Development: Regional differentiation.—231. The Scandinavian area as an example.—232. The late Palæolithic Ancylus or Maglemose Period.—233. The Early Neolithic Litorina or Kitchenmidden Period.—234. The Full Neolithic and its subdivisions in Scandinavia.—235. The Bronze Age and its periods in Scandinavia.—236. Problems of chronology.—237. Principles of the prehistoric spread of culture. | |

| XV. The Growth of Civilization: Old World History and Ethnology | 440 |

| 238. The early focal area.—239. Egypt and Sumer and their background.—240. Predynastic Egypt.—241. Culture growth in dynastic Egypt.—242. The Sumerian development.—243. The Sumerian hinterland.—244. Entry of Semites and Indo-Europeans.—245. Iranian peoples and cultures.—246. The composite culture of the Near East.—247. Phœnicians, Aramæans, Hebrews.—248. Other contributing nationalities.—249. Ægean civilization.—250. Europe.—251. China.—252. Growth and spread of Chinese civilization.—253. The Lolos.—254. Korea.—255. Japan.—256. Central and northern Asia.—257. India.—258. Indian caste and religion.—259. Relations between India and the outer world.—260. Indo-China.—261. Oceania.—262. The East Indies.—263. Melanesia and Polynesia.—264. Australia.—265. Tasmania.—266. Africa.—267. Egyptian radiations.—268. The influence of other cultures.—269. The Bushmen.—270. The West African culture-area and its meaning.—271. Civilization, race, and the future. | |

| Index | 507 |

| FIGURE | PAGE | |

| 1. | The descent of man: diagram | 12 |

| 2. | The descent of man, elaborated | 14 |

| 3. | The descent of man in detail, according to Gregory | 16 |

| 4. | The descent of man in detail, according to Keith | 17 |

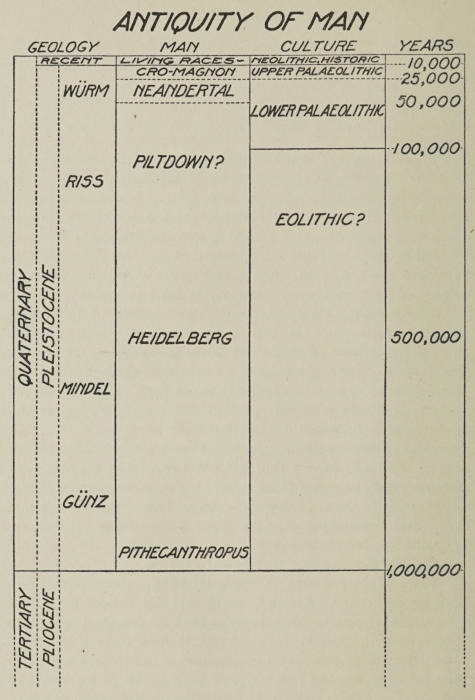

| 5. | Antiquity of man: diagram | 20 |

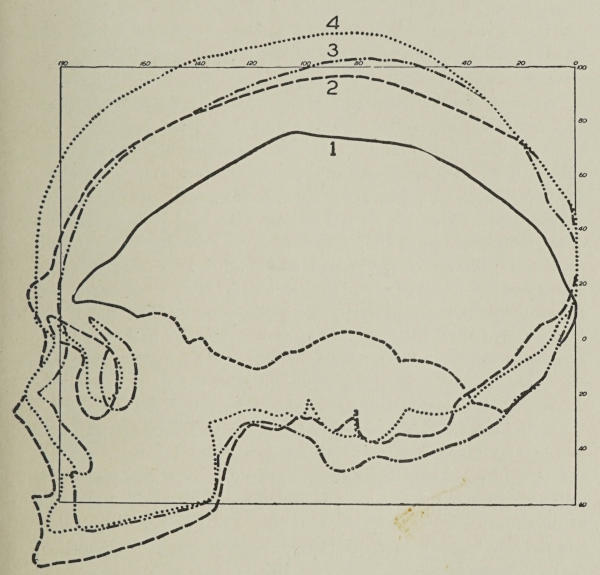

| 6. | Fossil and modern skull outlines superposed | 25 |

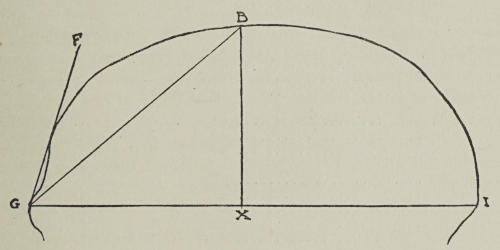

| 7. | Measurements made on fossil skulls | 31 |

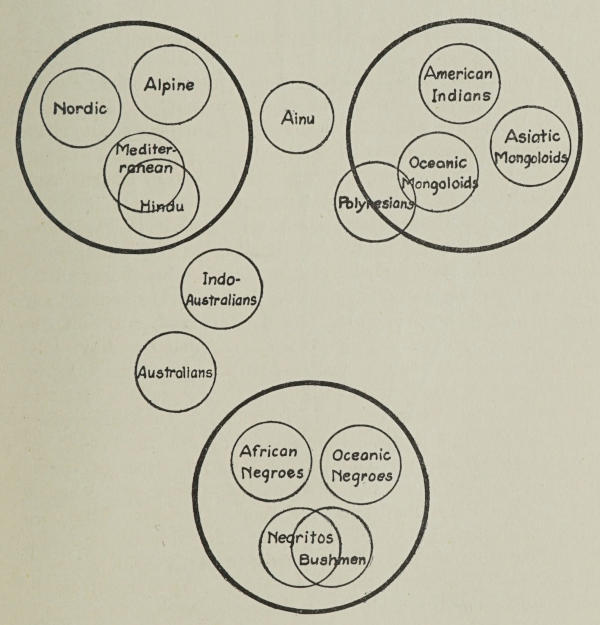

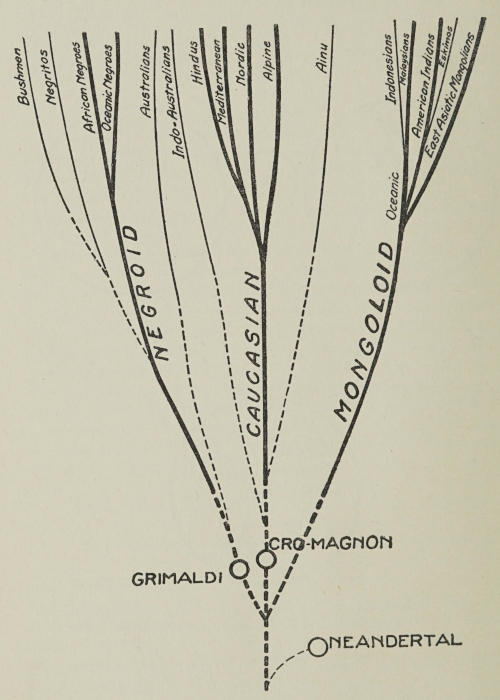

| 8. | Relationship of the races: diagram | 47 |

| 9. | Family tree of the human races | 48 |

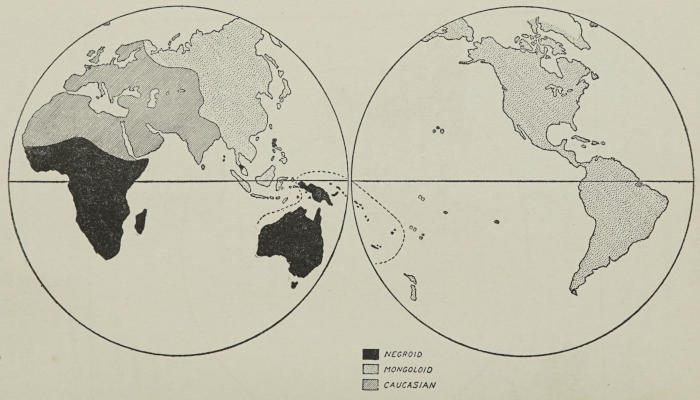

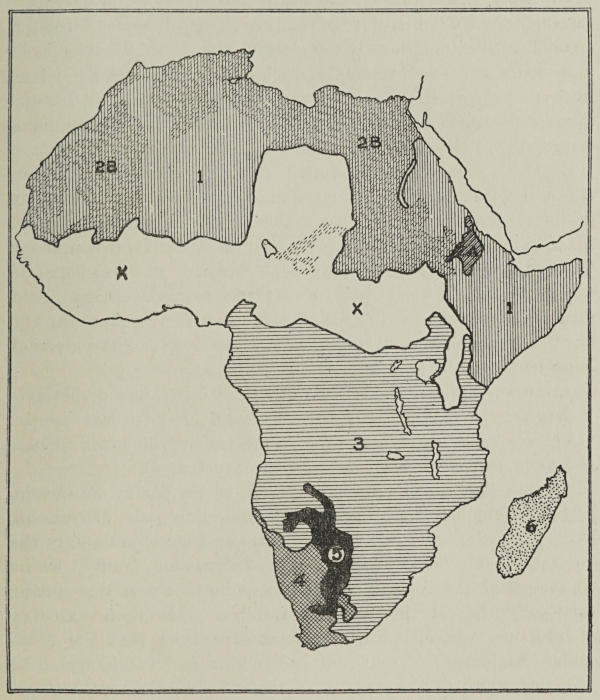

| 10. | Map: distribution of primary racial stocks | 50 |

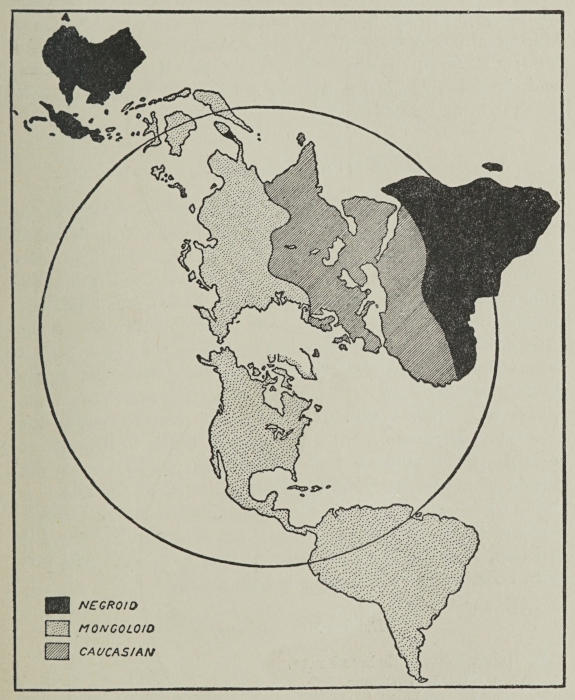

| 11. | Map: circumpolar distribution of the races | 51 |

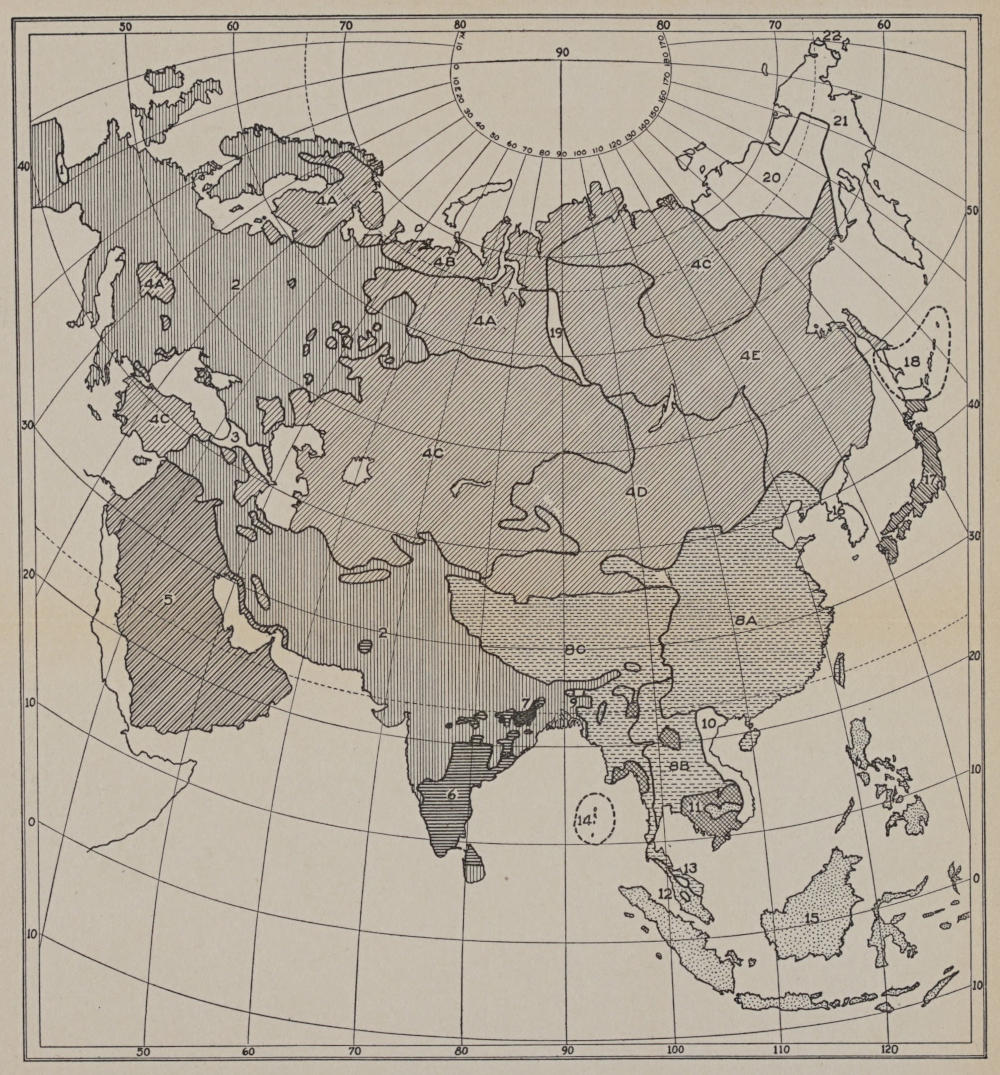

| 12. | Map: linguistic families of Asia and Europe | (facing) 94 |

| 13. | Map: linguistic families of Africa | 97 |

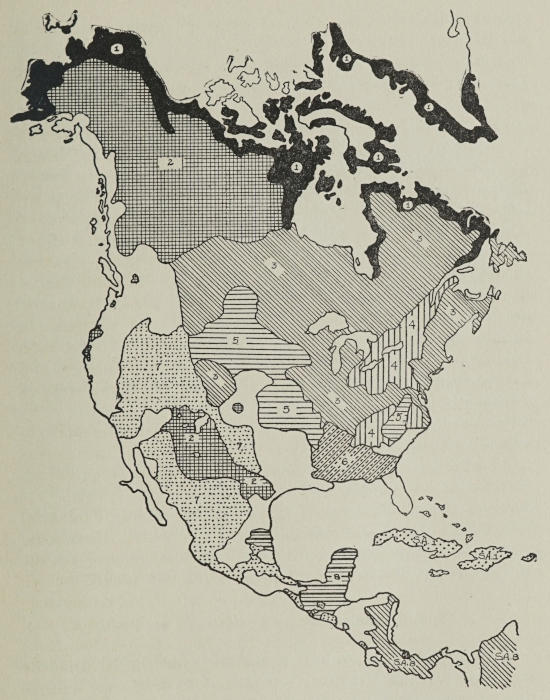

| 14. | Map: principal linguistic families of North America | 99 |

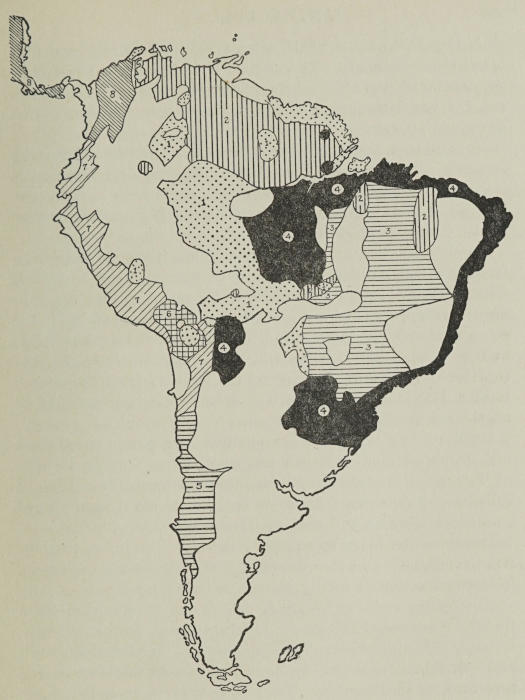

| 15. | Map: principal linguistic families of South America | 101 |

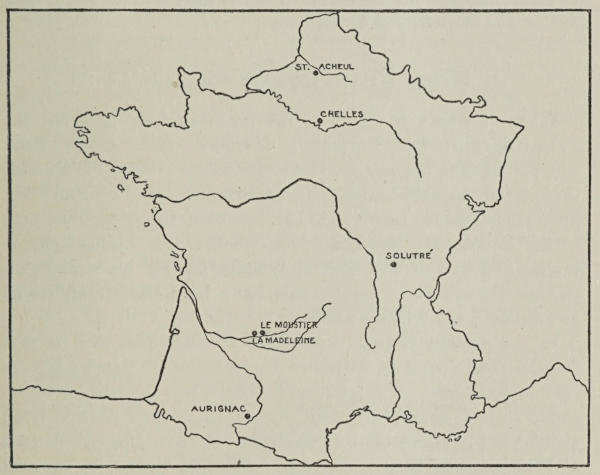

| 16. | Map: type stations of the Palæolithic periods | 153 |

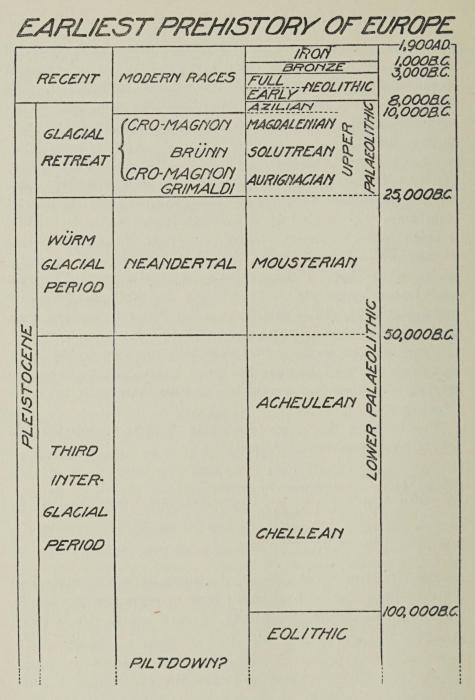

| 17. | Earliest prehistory of Europe: diagram | 156 |

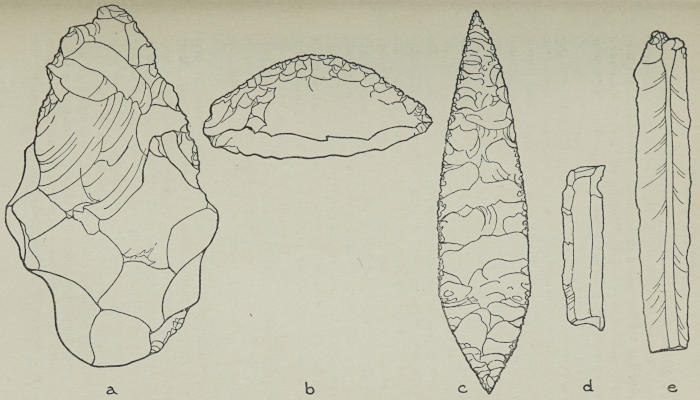

| 18. | Palæolithic flint implements, illustrating the principal techniques | 159 |

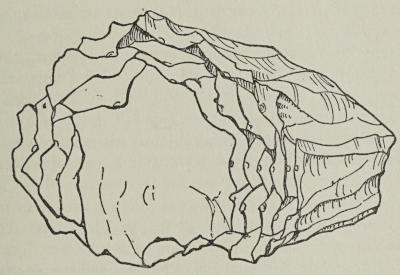

| 19. | Flint core with reassembled flakes | 163 |

| 20. | Aurignacian sculpture: human figure | 173 |

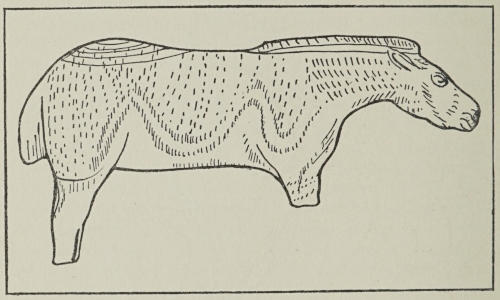

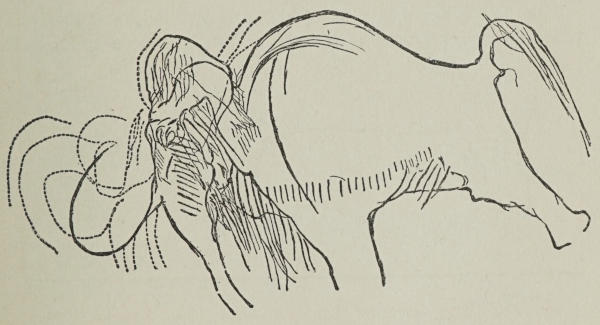

| 21. | Magdalenian sculpture: horse | 174 |

| 22. | Magdalenian engraving of a mammoth | 175 |

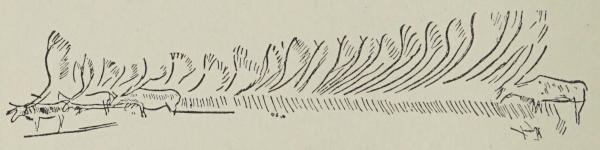

| 23. | Magdalenian engraving of a herd | 176 |

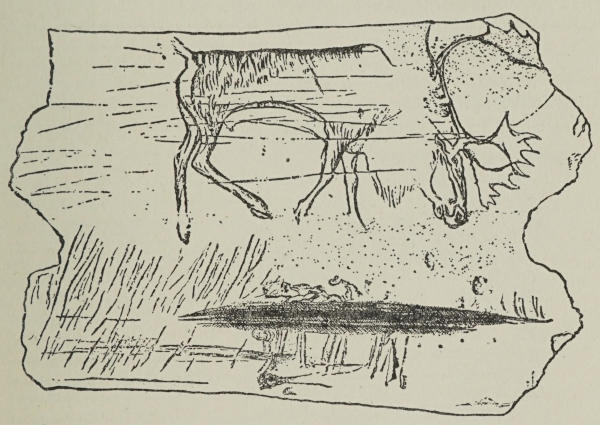

| 24. | Magdalenian engraving of a browsing reindeer | 177 |

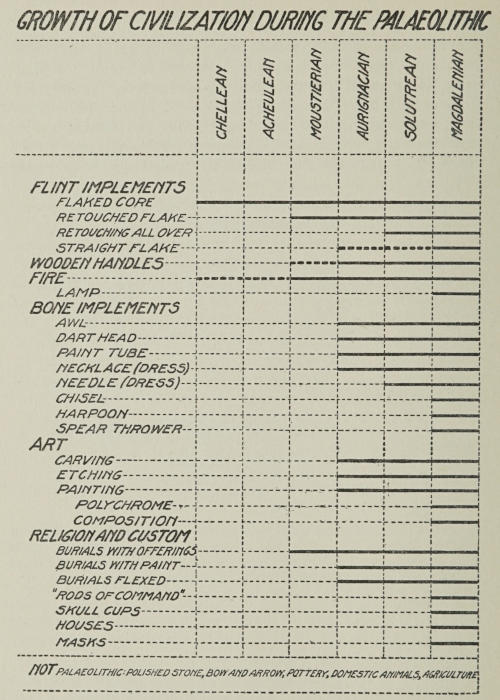

| 25. | Growth of civilization during the Palæolithic: diagram | 178 |

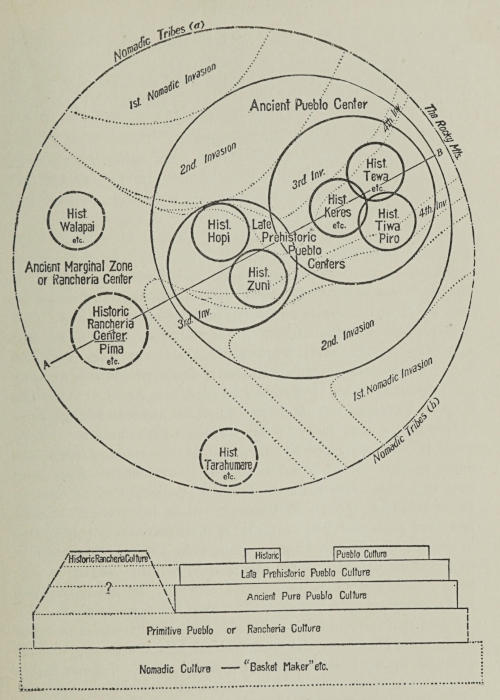

| 26. | Culture distribution and history in the Southwest: diagram | 191 |

| 27. | Map: diffusion of the Magic Flight tale | 201 |

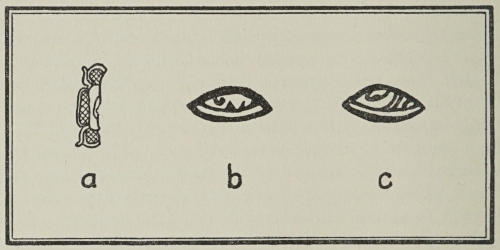

| 28. | Maya symbols for zero | 230 |

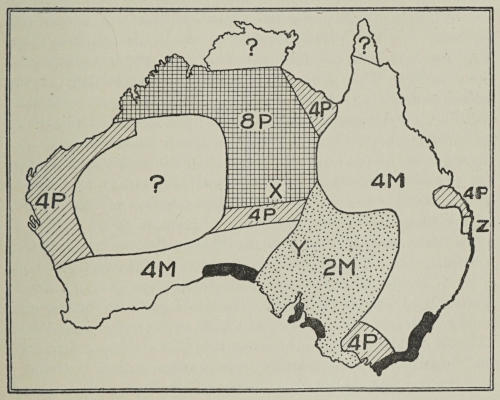

| 29. | Map: types of exogamic institutions in Australia | 233 |

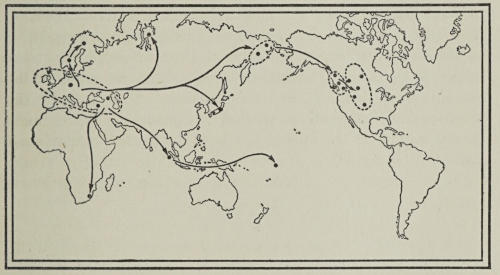

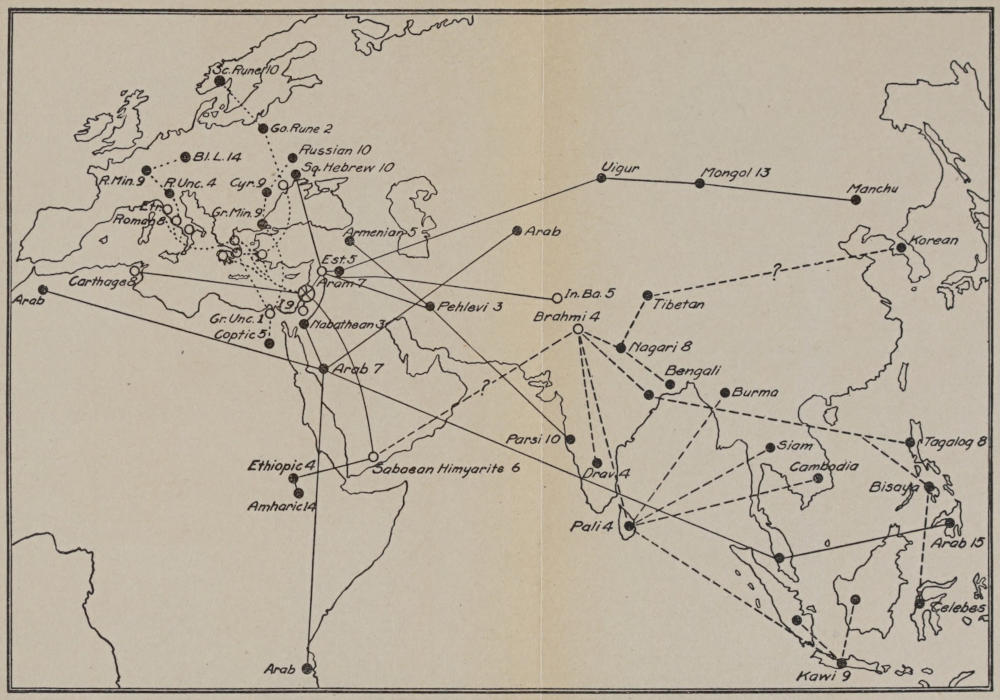

| 30. | Map: the spread of alphabetic writing | (facing) 284 |

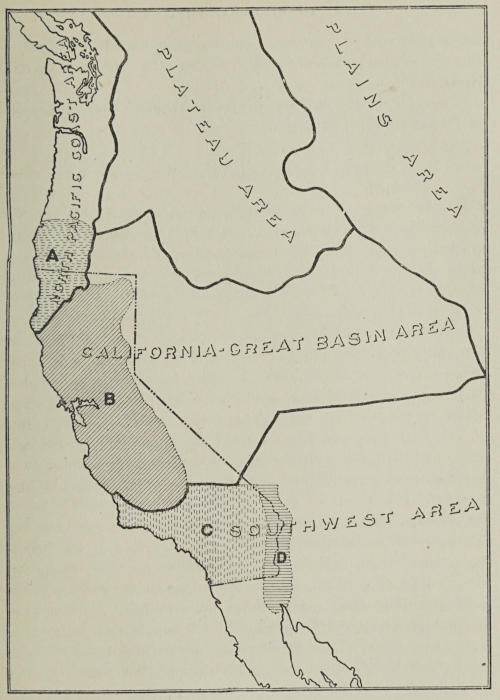

| 31. | Map: culture-areas of native California | 297 |

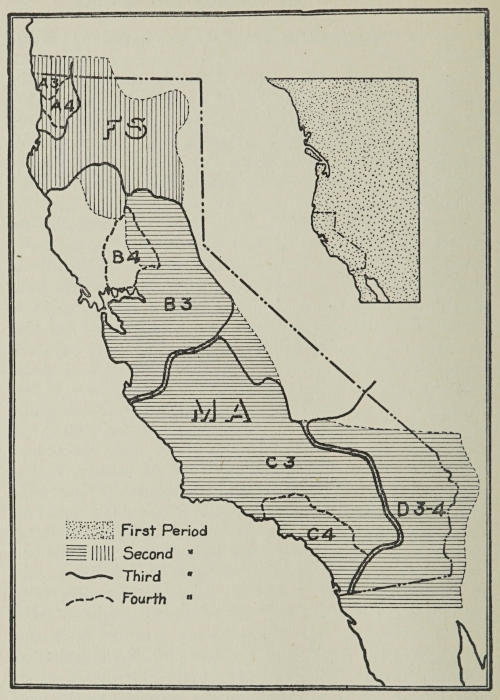

| 32. | Map: the growth of rituals in native California | 308[x] |

| 33. | Distribution of culture elements indicative of their history: diagram | 328 |

| 34. | Map: culture-areas of America | 337 |

| 35. | Occurrence of elements in the culture-areas of America: diagram | (facing) 340 |

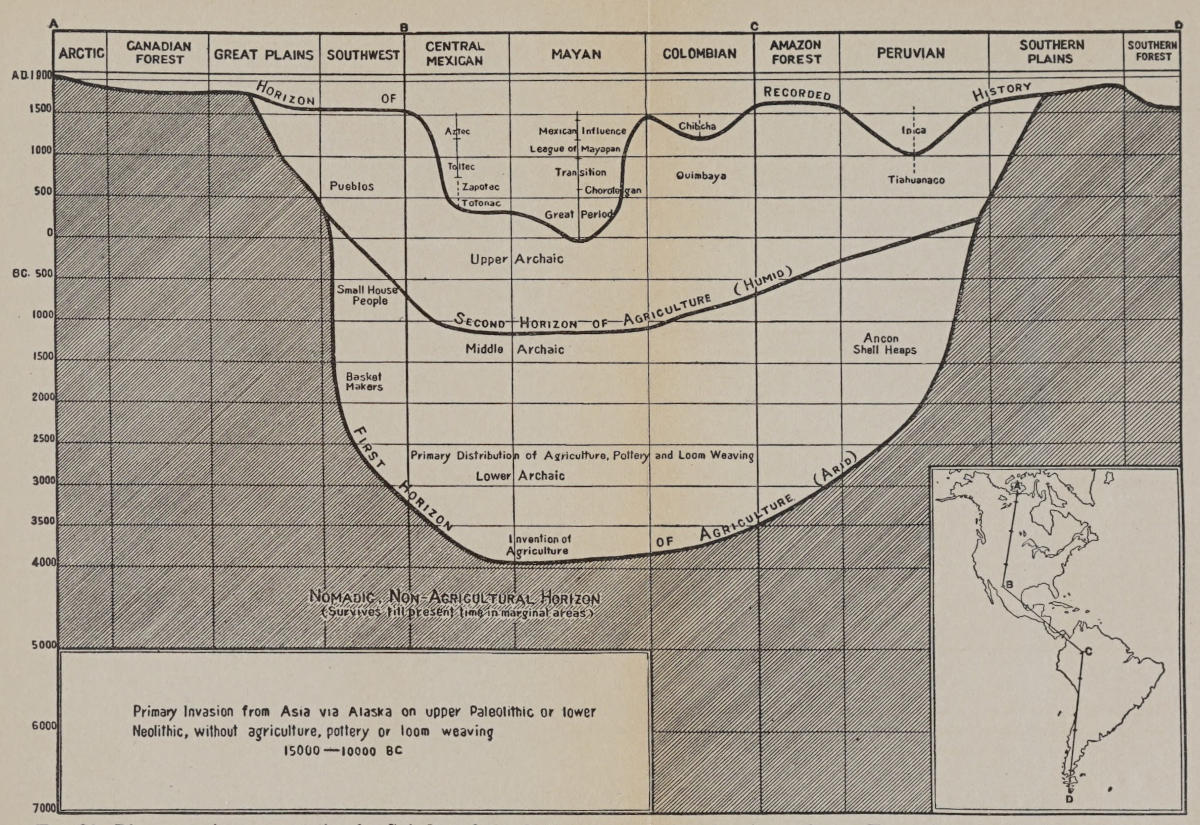

| 36. | Development of American civilization in time, according to Spinden: diagram | (facing) 342 |

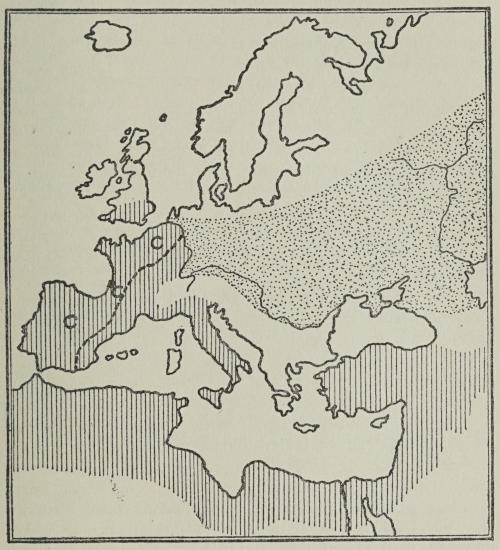

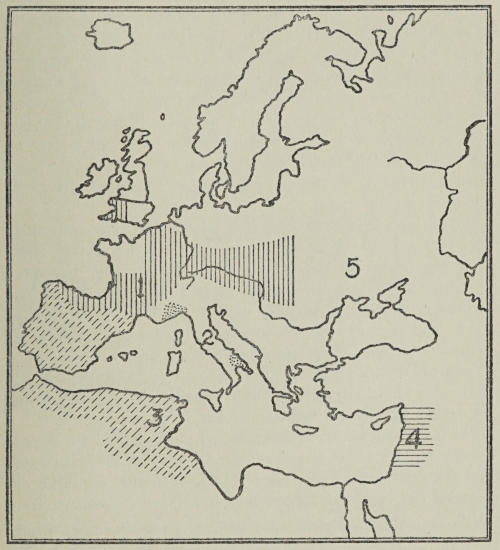

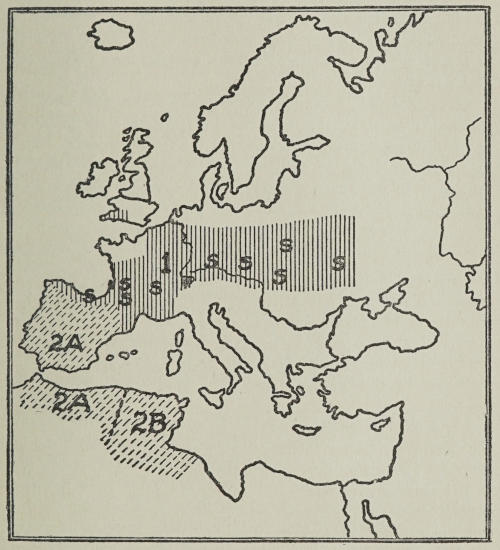

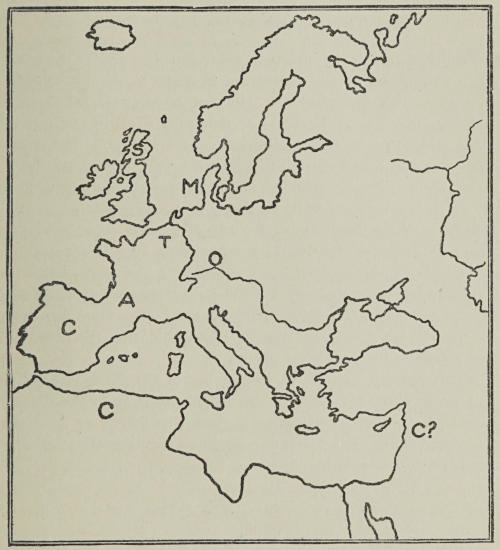

| 37. | Map: Europe in the early Lower Palæolithic | 399 |

| 38. | Map: Europe in the Aurignacian and Lower Capsian | 401 |

| 39. | Map: Europe in the Solutrean, Magdalenian, and Upper Capsian | 403 |

| 40. | Map: Europe in the Azilian and Terminal Capsian | 409 |

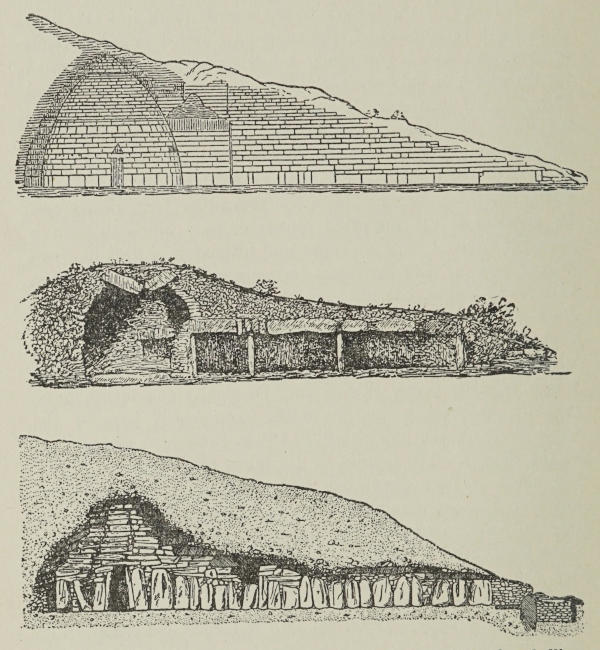

| 41. | Prehistoric corbelled domes in Greece, Portugal, and Ireland | 420 |

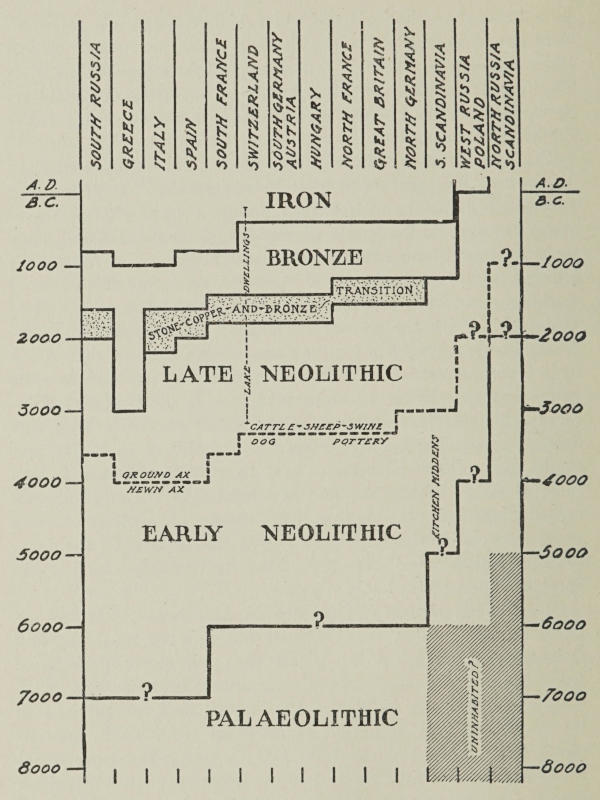

| 42. | Growth and spread of prehistoric civilization in Europe, according to Müller: diagram | 436 |

1. Anthropology, biology, history.—2. Organic and social elements.—3. Physical anthropology.—4. Cultural anthropology.—5. Evolutionary processes and evolutionistic fancies.—6. Age of anthropological science.

Anthropology is the science of man. This broad and literal definition takes on more meaning when it is expanded to “the science of man and his works.” Even then it may seem heterogeneous and too inclusive. The products of the human mind are something different from the body. And these products, as well as the human body, are the subjects of firmly established sciences, which would seem to leave little room for anthropology except as a less organized duplication. Ordinary political history, economics, literary criticism, and the history of art all deal with the works and doings of man; biology and medicine study his body. It is evident that these various branches of learning cannot be relegated to the position of mere subdivisions of anthropology and this be exalted to the rank of a sort of holding corporation for them. There must be some definite and workable relation.

One way in which this relation can be pictured follows to some extent the course of anthropology as it grew into self-consciousness and recognition. Biology, medicine, history, economies were all tilling their fields of knowledge in the nineteenth century, some with long occupancy, when anthropology shyly entered the scene and began to cultivate a corner here and a patch there. It examined some of the most special and[2] non-utilitarian aspects of the human body: the shape of the head, the complexion, the texture of the hair, the differences between one variety of man and another, points of negligible import in medicine and of quite narrow interest as against the broad principles which biology was trying to found and fortify as the science of all life. So too the historical sciences had preëmpted the most convenient and fruitful subjects within reach. Anthropology modestly turned its attention to nations without records, to histories without notable events, to institutions strange in flavor and inventions hanging in their infancy, to languages that had never been written.

Yet obviously the heterogeneous leavings of several sciences will never weld into an organized and useful body of knowledge. The dilettante, the collector of oddities who loves incoherence, may be content to observe to-day the flare of the negro’s nostrils, to-morrow the intricacy of prefixes that bind his words into sentences, the day after, his attempts to destroy a foe by driving nails into a wooden idol. A science becomes such only when it learns to discover relations and a meaning in facts. If anthropology were to remain content with an interest in the Mongolian eye, the dwarfishness of the Negrito, the former home of the Polynesian race, taboos against speaking to one’s mother-in-law, rituals to make rain, and other such exotic and superseded superstitions, it would earn no more dignity than an antiquarian’s attic. As a co-laborer on the edifice of fuller understanding, anthropology must find more of a task than filling with rubble the temporarily vacant spaces in the masonry that the sciences are rearing.

The other manner in which the subject of anthropology can be conceived is that this is neither so vast as to include everything human, nor is it the unappropriated odds and ends of other sciences, but rather some particular aspect of human phenomena. If such an aspect exists, anthropology vindicates its unity and attains to integrity of aim.

To the question why a Louisiana negro is black and thick lipped, the answer is ready. He was born so. As dogs produce[3] pups, and lions cubs, so negro springs from negro and Caucasian from Caucasian. We call the force at work, heredity. The same negro is lazy by repute, easy going at his labor. Is this too an innate quality? Off-hand, most of us would reply: Yes. He sings at his corn-hoeing more frequently than the white man across the fence. Is this also because of his heredity? “Of course: he is made so,” might be a common answer; “Probably: why not?” a more cautious one. But now our negro is singing Suwanee River, which his great-grandfather in Africa assuredly did not sing. As regards the specific song, heredity is obviously no longer the cause. Our negro may have learned it from an uncle, perhaps from his schoolmates; he can have acquired it from human beings not his ancestors, acquired it as part of his customs, like being a member of the Baptist church and wearing overalls, and the thousand other things that come to him from without instead of from within. At these points heredity is displaced by tradition, nature by nurture, to use a familiar jingle. The efficient forces now are quite different from those that made his skin black and his lips thick. They are causes of another order.

The particular song of the negro and his complexion represent the clear-cut extremes of the matter. Between them lie the sloth and the inclination to melody. Obviously these traits may also be the result of human example, of social environment, of contemporary tradition. There are those that so believe, as well as those who see in them only the effects of inborn biological impulse. Perhaps these intermediate dubious traits are the results of a blending of nature and nurture, the strength of each factor varying according to each trait or individual examined. Clearly, at any rate, there is room here for debate and evidence. A genuine problem exists. This problem cannot be solved by the historical sciences alone because they do not concern themselves with heredity. Nor can it be solved by biology which deals with heredity and allied factors but does not go on to operate with the non-biological principle of tradition.

Here, then, is a specific task and place in the sun for anthropology: the interpretation of those phenomena into which both organic and social causes enter. The untangling and determination and reconciling of these two sets of forces are anthropology’s[4] own. They constitute, whatever else it may undertake, the focus of its attention and an ultimate goal. No other science has grappled with this set of problems as its primary end. Nor has anthropology as yet much of a solution to offer. It may be said to have cleared the ground of brush, rather than begun the felling of its tree. But, in the terminology of science, it has at least defined its problem.

To deal with this interplay of what is natural and nurtural, organic and social, anthropology must know something of the organic, as such, and of the social, as such. It must be able to recognize them with surety before it endeavors to analyze and resynthesize them. It must therefore effect close contact with the organic and the social sciences respectively, with “biology” and “history,” and derive all possible aid from their contributions to knowledge. Up to the present time, a large part of the work of anthropology has consisted in acquiring the fruits of the activity of these sister sciences and applying them for its own ends; or, where the needed biological and historical data were not available, securing them.

The organic sciences underlie the social ones. They are more directly “natural.” Anthropology has therefore found valuable general principles in biology: laws of heredity, the doctrines of cell development and evolution, for instance, based on facts from the whole range of life. Its business has been to ascertain how far these principles apply to man, what forms they take in his particular case. This has meant a concentration of attention, the devising of special methods of inquiry. Many biological problems, including most physiological and hereditary ones, can be most profitably attacked in the laboratory, or at least under experimental conditions. This method, however, is but rarely open as regards human beings, who must ordinarily be observed as they are. The phenomena concerning man have to be taken as they come and laboriously sifted and re-sifted afterward, instead of being artificially simplified in advance, as by the experimental method. Then, too, since anthropology was operating within the narrow limits of one species, it was driven to[5] concern itself with minute traits, such as the zoölogist is rarely troubled with: the proportions of the length and breadth of the skull—the famous cephalic index—for instance; the number of degrees the arm bones are twisted, and the like. Also, as these data had to be used in the gross, unmodifiable by artificially varied conditions, it has been necessary to secure them from all possible varieties of men, different races, sexes, ages, and their nearest brute analogues. The result is that biological or physical anthropology—“Somatology” it is sometimes called in Anglo-Saxon countries, and simply “anthropology” in continental Europe—has in part constituted a sort of specialization or sharpening of general biology, and has become absorbed to a considerable degree in certain particular phenomena and methods of studying them about which general biologists, physiologists, palæontologists, and students of medicine are usually but vaguely informed.

The historical or social sciences overlie the organic ones. Men’s bodies and natural equipment are back of their deeds and accomplishments as transmitted by tradition, primary to their culture or civilization. The relation of anthropology to historical science has therefore been in a sense the opposite of its relation to biological science. Instead of specializing, anthropology has been occupied with trying to generalize the findings of history. Historians cannot experiment. They deal with the concrete, with the unique; for in a degree every historical event has something unparalleled about it. They may paint with a broad sweep, but they do not lay down exact laws.

Moreover, history inevitably begins with an interest in the present and in ourselves. In proportion as it reaches back in time and to wholly foreign peoples, its interest tends to flag and its materials become scant and unreliable. It is commonly considered useful for a man to know that Napoleon was a Corsican and was defeated at Waterloo in 1815, but a rather pedantic piece of knowledge that Shi Hwang-ti was born in northwestern China and unified the rule of China in 221 B.C. From a theoretical or general point of view, however, one of these facts is[6] presumably as important as the other, for if we wish to know the principles that go into the shaping of human social life or civilization, China counts for as much as France, and the ancient past for as much as the nearby present. In fact, the foreign and the old are likely to be inquired into with even more assiduity by the theoretically minded, since they may furnish wholly new clues to insight, whereas the subjects of conventional history have been so familiarized as to hold out less hope of novel conclusions still to be extricated from them.

Here, then, is the cause of the seeming preoccupation of social or cultural anthropology with ancient and savage and exotic and extinct peoples: the desire to understand better all civilizations, irrespective of time and place, in the abstract or in form of generalized principle if possible. It is not that cave men are more illuminating than Romans, or flint knives more interesting than fine porcelains or the art of printing, that has led anthropology to bear so heavily on the former, but the fact that it wanted to know about cave men and flint knives as well as about Romans and printing presses. It would be irrational to prefer the former to the latter, and anthropology has never accepted the adjudication sometimes tacitly rendered that its proper field is the primitive, as such. As well might zoölogy confine its interest to eggs or protozoans. It is probably true that many researches into early and savage history have sprung from an emotional predilection for the forgotten or neglected, the obscure and strange, the unwonted and mysterious. But such occasional personal æsthetic trends can not delimit the range of a science or determine its aims and methods. Innumerable historians have been inveterate gossips. One does not therefore insist that the only proper subject of history is backstairs intimacies.

This, then, is the reason for the special development of those subdivisions of anthropology known as Archæology, “the science of what is old” in the career of humanity, especially as revealed by excavations of the sites of prehistoric occupation; and Ethnology, “the science of peoples,” irrespective of their degree of advancement.[1]

In their more elementary aspects the two strands of the organic and the social, or the hereditary and environmental, as they are generally called with reference to individuals, run through all human life and are distinguishable as mechanisms, as well as in their results. Thus a comparison of the acquisition of the power of flight respectively by birds in their organic development out of the ancestral reptile stem some millions of years ago, and by men as a result of cultural progress in the field of invention during the past generation, reveals at once the profound differences of process that inhere in the ambiguous concept of “evolution.” The bird gave up a pair of walking limbs to acquire wings. He added a new faculty by transforming part of an old one. The sum total of his parts or organs was not greater than before. The change was transmitted only to the blood descendants of the altered individuals. The reptile line went on as it had been before, or if it altered, did so for causes unconnected with the evolution of the birds. The aeroplane, on the contrary, gave men a new faculty without impairing any of those they had previously possessed. It led to no visible bodily changes, nor alterations of mental capacity. The invention has been transmitted to individuals and groups not derived by descent from the inventors; in fact, has already influenced their careers. Theoretically, it is transmissible to ancestors if they happen to be still living. In sum, it represents an accretion to the stock of existing culture rather than a transformation.

Once the broad implications of the distinction which this example illustrates have been grasped, many common errors are guarded against. The program of eugenics, for instance, loses much of its force. There is certainly much to be said in favor of intelligence and discrimination in mating, as in everything else. There is need for the acquisition of exacter knowledge on human heredity. But, in the main, the claims sometimes made that eugenics is necessary to preserve civilization from dissolution, or to maintain the flourishing of this or that nationality, rest on the fallacy of recognizing only organic causes as operative, when social as well as organic ones are active—when[8] indeed the social factors may be much the more powerful ones. So, in what are miscalled race problems, the average thought of the day still reasons largely from social effects to organic causes and perhaps vice versa. Anthropology is by no means yet in a position to state just where the boundary between the contributing organic and social causes of such phenomena lies. But it does hold to their fundamental distinctness and to the importance of this distinctness, if true understanding is the aim. Without sure grasp of this principle, many of the arguments and conclusions in the present volume will lose their significance.

Accordingly, the designation of anthropology as “the child of Darwin” is most misleading. Darwin’s essential achievement was that he imagined, and substantiated by much indirect evidence, a mechanism through which organic evolution appeared to be taking place. The whole history of man however being much more than an organic matter, a pure Darwinian anthropology would be largely misapplied biology. One might almost as justly speak of a Copernican or Newtonian anthropology.

What has greatly influenced anthropology, mainly to its damage, has been not Darwinism, but the vague idea of evolution, to the organic aspect of which Darwin gave such substance that the whole group of evolutionistic ideas has luxuriated rankly ever since. It became common practice in social anthropology to “explain” any part of human civilization by arranging its several forms in an evolutionary sequence from lowest to highest and allowing each successive stage to flow spontaneously from the preceding—in other words, without specific cause. At bottom this logical procedure was astonishingly naïve. We of our land and day stood at the summit of the ascent, in these schemes. Whatever seemed most different from our customs was therefore reckoned as earliest, and other phenomena disposed wherever they would best contribute to the straight evenness of the climb upward. The relative occurrence of phenomena in time and space was disregarded in favor of their logical fitting into a plan. It was argued that since we hold to definitely monogamous marriage, the beginnings of human sexual union probably lay in indiscriminate promiscuity. Since we accord precedence to descent from the father, and generally[9] know him, early society must have reckoned descent from the mother and no one knew his father. We abhor incest; therefore the most primitive men normally married their sisters. These are fair samples of the conclusions or assumptions of the classic evolutionistic school of anthropology, whose roster was graced by some of the most illustrious names in the science. Needless to say, these men tempered the basic crudity of their opinions by wide knowledge, acuity or charm of presentation, and frequent insight and sound sense in concrete particulars. In their day, a generation or two ago, under the spell of the concept of evolution in its first flush, such methods of reasoning were almost inevitable. To-day they are long threadbare, descended to material for newspaper science or idle speculation, and evidence of a tendency toward the easy smugness of feeling oneself superior to all the past. These ways of thought are mentioned here only as an example of the beclouding that results from baldly transferring biologically legitimate concepts into the realm of history, or viewing this as unfolding according to a simple plan of progress.

The foregoing exposition will make clear why anthropology is generally regarded as one of the newer sciences—why its chairs are few, its places in curricula of education scattered. As an organized science, with a program and a method of its own, it is necessarily recent because it could not arise until the biological and social sciences had both attained enough organized development to come into serious contact.

On the other hand, as an unmethodical body of knowledge, as an interest, anthropology is plainly one of the oldest of the sisterhood of sciences. How could it well be otherwise than that men were at least as much interested in each other as in the stars and mountains and plants and animals? Every savage is a bit of an ethnologist about neighboring tribes and knows a legend of the origin of mankind. Herodotus, the “father of history,” devoted half of his nine books to pure ethnology, and Lucretius, a few centuries later, tried to solve by philosophical deduction and poetical imagination many of the same problems[10] that modern anthropology is more cautiously attacking with the methods of science. In neither chemistry nor geology nor biology was so serious an interest developed as in anthropology, until nearly two thousand years after these ancients.

In the pages that follow, the central anthropological problems that concern the relations of the organic and cultural factors in man will be defined and solutions offered to the degree that they seem to have been validly determined. On each side of this goal, however, stretches an array of more or less authenticated formulations, of which some of the more important will be reviewed. On the side of the organic, consideration will tend largely to matters of fact; in the sphere of culture, processes can here and there be illustrated; in accord with the fact that anthropology rests upon biological and underlies purely historical science.

7. The “Missing Link.”—8. Family tree of the Primates.—9. Geological and glacial time.—10. Place of man’s origin and development.—11. Pithecanthropus.—12. Heidelberg man.—13. The Piltdown form.—14. Neandertal man.—15. Rhodesian man.—16. The Cro-Magnon race.—17. The Brünn race.—18. The Grimaldi race: Neolithic races.—19. The metric expression of human evolution.

No modern zoölogist has the least doubt as to the general fact of organic evolution. Consequently anthropologists take as their starting point the belief in the derivation of man from some other animal form. There is also no question as to where in a general way man’s ancestry is to be sought. He is a mammal closely allied to the other mammals, and therefore has sprung from some mammalian type. His origin can be specified even more accurately. The mammals fall into a number of fairly distinct groups, such as the Carnivores or flesh-eating animals, the Ungulates or hoofed animals, the Rodents or gnawing animals, the Cetaceans or whales, and several others. The highest of these mammalian groups, as usually reckoned, is the Primate or “first” order of the animal kingdom. This Primate group includes the various monkeys and apes and man. The ancestors of the human race are therefore to be sought somewhere in the order of Primates, past or present.

The popular but inaccurate expression of this scientific conviction is that “man is descended from the monkeys,” but that a link has been lost in the chain of descent: the famous “missing link.” In a loose way this statement reflects modern scientific opinion; but it certainly is partly erroneous. Probably not a single authority maintains to-day that man is descended from any species of monkey now living. What students during the past sixty years have more and more come to be convinced of, was already foreshadowed by Darwin: namely that man and the[12] apes are both descended from a common ancestor. This common ancestor may be described as a primitive Primate, who differed in a good many details both from the monkeys and from man, and who has probably long since become extinct.

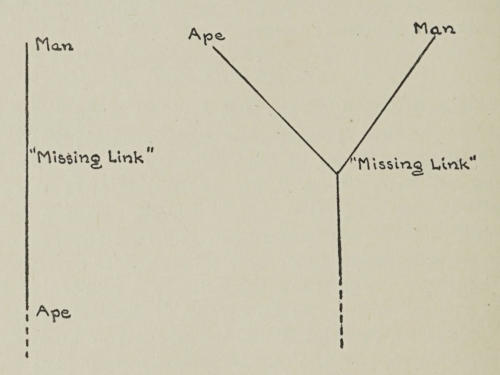

Fig. 1. Erroneous (left) and more valid (right) representation of the descent of man.

The situation may be clarified by two diagrams (Fig. 1). The first diagram represents the inaccurate view which puts the monkey at the bottom of the line of descent, man at the top, and the missing link in the middle of the straight line. The illogicality of believing that our origin occurred in this manner is apparent as soon as one reflects that according to this scheme the monkey at the beginning and man at the end of the line still survive, whereas the “missing link,” which is supposed to have connected them, has become extinct.

Clearly the relation must be different. Whatever the missing link may have been, the mere fact that he is not now alive on earth means that we must construct our diagram so that it will indicate his past existence as compared with the survival of man and the apes. This means that the missing link must be put lower in the figure than man and the apes, and our illustration therefore takes on the form shown in the right half of figure 1, which may be described as Y-shaped. The stem of the Y denotes[13] the pre-ancestral forms leading back into other mammalian groups and through them—if carried far enough down—to the amphibians and invertebrates. The missing link comes at the fork of the Y. He represents the last point at which man and the monkeys were still one, and beyond which they separated and became different. It is just because the missing link represented the last common form that he was the link between man and the monkeys. From him onwards, the monkeys followed their own course, as indicated by the left-hand branch of the Y, and man went his separate way along the right-hand branch.

While this second diagram illustrates the most essential elements in modern belief as to man’s origin, it does not of course pretend to give the details. To make the diagram at all precise, the left fork of the Y, which here stands for the monkeys as a group—in other words, represents all the living Primates other than man—would have to be denoted by a number of branching and subdividing lines. Each of the main branches would represent one of the four or five subdivisions or “families” of the Primates, such as the Anthropoid or manlike apes, and the Cebidæ or South American monkeys. The finer branches would stand for the several genera and species in each of these families. For instance, the Anthropoid line would split into four, standing respectively for the Gibbon, Orang-utan, Chimpanzee, and Gorilla.

The fork of the Y representing man would not branch and rebranch so intricately as the fork representing the monkeys. Many zoölogists regard all the living varieties of man as constituting a single species, while even those who are inclined to recognize several species limit the number of these species to three or four. Then too the known extinct varieties of man are comparatively few. There is some doubt whether these human fossil types are to be reckoned as direct ancestors of modern man, and therefore as mere points in the main human line of our diagram; or whether they are to be considered as having been ancient collateral relatives who split off from the main line of human development. In the latter event, their designation[14] in the diagram would have to be by shorter lines branching out of the human fork of the Y.

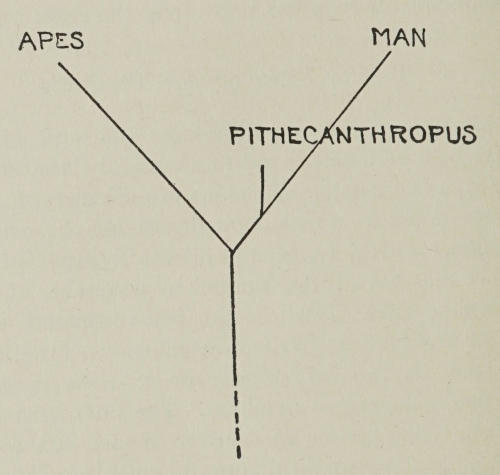

Fig. 2. The descent of man, elaborated over Figure 1. For further ramifications, see Figures 3, 4, 9.

This subject quickly becomes a technical problem requiring rather refined evidence to answer. In general, prevailing opinion looks upon the later fossil ancestors of man as probably direct or true ancestors, but tends to regard the earlier of these extinct forms as more likely to have been collateral ones. This verdict applies with particular force to the earliest of all, the very one which comes nearest to fulfilling the popular idea of the missing link: the so-called Pithecanthropus erectus. If the Pithecanthropus were truly the missing link, he would have to be put at the exact crotch of the Y. Since he is recognized, however, as a form more or less ancestral to man, and somewhat less ancestral to the apes, he should probably be placed a short distance up on the human stem of the Y, or close alongside it. On the other hand, inasmuch as most palæontologists and comparative anatomists believe that Pithecanthropus was not directly ancestral to us, in the sense that no living men have Pithecanthropus blood flowing in their veins, he would therefore be an ancient collateral relative of humanity—a sort of great-great-granduncle—and[15] would be best represented by a short stub coming out of the human line a little above its beginning (Fig. 2).

Even this figure is not complete, since it is possible that some of the fossil types which succeeded Pithecanthropus in point of time, such as the Heidelberg and Piltdown men, were also collateral rather than direct ancestors. Some place even the later Neandertal man in the collateral class. It is only when the last of the fossil types, the Cro-Magnon race, is reached, that opinion becomes comparatively unanimous that this is a form directly ancestral to us. For accuracy, therefore, figure 2 might be revised by the addition of other short lines to represent the several earlier fossil types: these would successively spring from the main human line at higher and higher levels.

In order not to complicate unnecessarily the fundamental facts of the case—especially since many data are still interpreted somewhat variously—no attempt will be made here to construct such a complete diagram as authoritative. Instead, there are added reproductions of the family tree of man and the apes as the lineages have been worked out independently by two authorities (Figs. 3, 4). It is clear that these two family trees are in substantial accord as regards their main conclusions, but that they show some variability in details. This condition reflects the present state of knowledge. All experts are in accord as to certain basic principles; but it is impossible to find two authors who agree exactly in their understanding of the less important data.

A remark should be made here as to the age of these ancestral forms. The record of life on earth, as known from the fossils in stratified rocks, is divided into four great periods. The earliest, the Primary or Palæozoic, comprises about two-thirds of the total lapse of geologic time. During the Palæozoic all the principal divisions of invertebrate animals came into existence, but of the vertebrates only the fishes. In the Secondary or Mesozoic period, evolution progressed to the point where reptiles were the highest and dominant type, and the first feeble bird and mammal forms appeared. The Mesozoic embraces most of the remaining third or so of the duration of life on the earth, leaving only something like five million years for the last two periods combined, as against thirty, fifty, ninety, or four hundred million years that the Palæozoic and Mesozoic are variously estimated to have lasted.

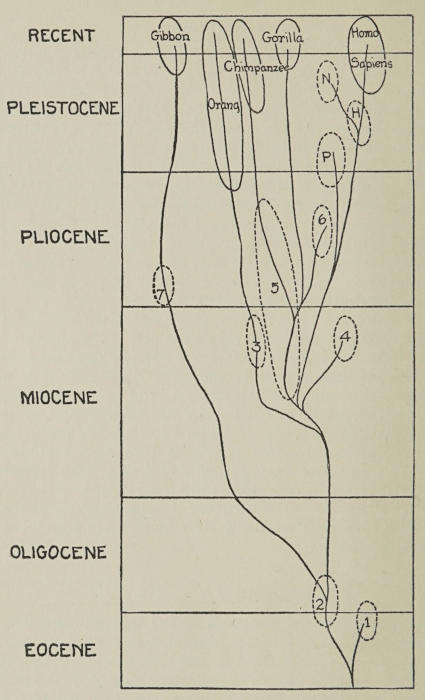

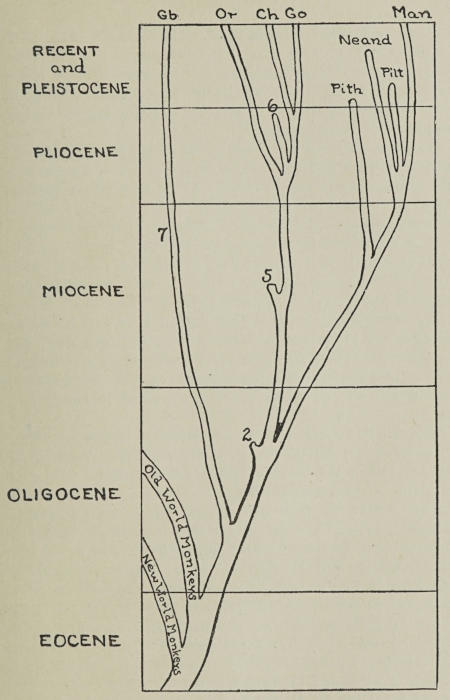

Fig. 3. The descent of man in detail, according to Gregory (somewhat simplified). Extinct forms: 1, Parapithecus; 2, Propliopithecus; 3, Palæosimia; 4, Sivapithecus; 5, Dryopithecus; 6, Palæopithecus; 7, Pliopithecus; P, Pithecanthropus erectus; H, Homo Heidelbergensis; N, Homo Neandertalensis.

Fig. 4. The descent of man in detail, according to Keith (somewhat simplified). Extinct forms: 2, 5, 6, 7 as in Figure 3; Pith(ecanthropus), Pilt(down), Neand(ertal). Living forms: Gb, Or, Ch, Go, the anthropoid apes as in Figure 3.

These last five million years or so of the earth’s history are divided unequally between the Tertiary or Age of Mammals, and the Quaternary or Age of Man. About four million years are usually assigned to the Tertiary with its subdivisions, the Eocene, Oligocene, Miocene, and Pliocene. The Quaternary was formerly reckoned by geologists to have lasted only about a hundred thousand years. Later this estimate was raised to four or five hundred thousand, and at present the prevailing opinion tends to put it at about a million years. There are to be recognized, then, a four million year Age of Mammals before man, or even any definitely pre-human form, had appeared; and a final period of about a million years during which man gradually assumed his present bodily and mental type. In this Quaternary period fall all the forms which are treated in the following pages.

The Quaternary is usually subdivided into two periods, the Pleistocene and the Recent. The Recent is very short, perhaps not more than ten thousand years. It represents, geologically speaking, the mere instant which has elapsed since the final disappearance of the great glaciers. It is but little longer than historic time; and throughout the Recent there are encountered only modern forms of man. Back of it, the much longer Pleistocene is often described as the Ice Age or Glacial Epoch; and both in Europe and North America careful research has succeeded in demonstrating four successive periods of increase of the ice. In Europe these are generally known as the Günz, Mindel, Riss, and Würm glaciations. The probable American equivalents are the Nebraskan, Kansan, Illinoian, and Wisconsin periods of ice spread. Between each of these four came a warmer period when the ice melted and its sheets receded. These are the “interglacial periods” and are designated as the first, second, and third. These glacial and interglacial periods are of importance because they offer a natural chronology or time scale[19] for the Pleistocene, and usually provide the best means of dating the fossil human types that have been or may hereafter be discovered (Fig. 5).

Before we proceed to the fossil finds themselves, we must note that the greater part of the surface of the earth has been very imperfectly explored. Africa, Asia, and Australia may quite conceivably contain untold scientific treasures which have not yet been excavated. One cannot assert that they are lying in the soil or rocks of these continents; but one also cannot affirm that they are not there. North and South America have been somewhat more carefully examined, at least in certain of their areas, but with such regularly negative results that the prevailing opinion now is that these two continents—possibly through being shut off by oceans or ice masses from the eastern hemisphere—were not inhabited by man during the Pleistocene. The origin of the human species cannot then be sought in the western hemisphere. This substantially leaves Europe as the one continent in which excavations have been carried on with prospects of success; and it is in the more thoroughly explored western half of Europe that all but two of the unquestioned discoveries of ancient man have been made. One of these exceptional finds is from Africa. The other happens to be the one that dates earliest of all—the same Pithecanthropus already mentioned as being the closest known approach to the “missing link.” Pithecanthropus was found in Java.

Now it might conceivably prove true that man originated in Europe and that this is the reason that the discoveries of his most ancient remains have to date been so largely confined to that continent. On the other hand, it does seem much more reasonable to believe that this smallest of the continents, with its temperate or cold climate, and its poverty of ancient and modern species of monkeys, is likely not to have been the true home, or at any rate not the only home, of the human family. The safest statement of the case would be that it is not known in what part of the earth man originated; that next to nothing is known of the history of his development on most of the continents; and that that portion of his history which chiefly is known is the fragment which happened to take place in Europe.

Fig. 5. Antiquity of man. This diagram is drawn to scale, proportionate to the number of years estimated to have elapsed, as far down as 100,000. Beyond, the scale is one-half, to bring the diagram within the limits of the page.

Pithecanthropus erectus, the “erect ape-man,” was determined from the top part of a skull, a thigh bone, and two molar teeth found in 1891 under fifty feet of strata by Dubois, a Dutch surgeon, near Trinil, in the East Indian island of Java. The skull and the thigh lay some distance apart but at the same level and probably are from the same individual. The period of the stratum is generally considered early Pleistocene, possibly approximately contemporary with the first or Günz glaciation of Europe—nearly a million years ago, by the time scale here followed. Java was then a part of the mainland of Asia.

The skull is low, with narrow receding forehead and heavy ridges of bone above the eye sockets—“supraorbital ridges.” The capacity is estimated at 850 or 900 cubic centimeters—half as much again as that of a large gorilla, but nearly one-half less than the average for modern man. The skull is dolichocephalic—long for its breadth—like the skulls of all early fossil men; whereas the anthropoid apes are more broad-headed. The jaws are believed to have projected almost like a snout; but as they remain undiscovered, this part of the reconstruction is conjectural. The thigh bone is remarkably straight, indicating habitual upright posture; its length suggests that the total body stature was about 5 feet 7 inches, or as much as the height of most Europeans.

Pithecanthropus was a terrestrial and not an arboreal form. He seems to have been slightly more similar to modern man than to any ape, and is the most primitive manlike type yet discovered. But he is very different from both man and the apes, as his name indicates: Pithecanthropus is a distinct genus, not included in Homo, or man.

Knowledge of Heidelberg man rests on a single piece of bone—a lower jaw found in 1907 by Schoetensack at a depth of[22] nearly eighty feet in the Mauer sands not far from Heidelberg, Germany. Like the Pithecanthropus remains, the Heidelberg specimen lay in association with fossils of extinct mammals, a fact which makes possible its dating. It probably belongs to the second interglacial period, so that its antiquity is only about half as great as that of Pithecanthropus (Fig. 5).

The jaw is larger and heavier than any modern human jaw. The ramus, or upright part toward the socket, is enormously broad, as in the anthropoid apes. The chin is completely lacking; but this area does not recede so much as in the apes. Heidelberg man’s mouth region must have projected considerably more than that of modern man, but much less than that of a gorilla or a chimpanzee. The contour of the jaw as seen from above is human (oval), not simian (narrow and oblong).

The teeth, although large, are essentially human. They are set close together, with their tops flush, as in man; the canines lack the tusk-like character which they retain in the apes.

Since the skull and the limb bones of this form are wholly unknown, it is somewhat difficult to picture the type as it appeared in life. But the jaw being as manlike as it is apelike, and the teeth distinctly human, the Heidelberg type is to be regarded as very much nearer to modern man than to the ape, or as farther along the line of evolutionary development than Pithecanthropus; as might be expected from its greater recency. This relationship is expressed by the name, Homo Heidelbergensis, which recognizes the type as belonging to the genus man.

This form is reconstructed from several fragments of a female brain case, some small portions of the face, nearly half the lower jaw, and a number of teeth, found in 1911-13 by Dawson and Woodward in a gravel layer at Piltdown in Sussex, England. Great importance has been ascribed to this skull, but too many of its features remain uncertain to render it safe to build large conclusions upon the discovery. The age cannot be fixed with positiveness; the deposit is only a few feet below the surface, and in the open; the associated fossils have been washed or rolled into the layer; some of them are certainly much older[23] than the skull, belonging to animals characteristic of the Pliocene, that is, the Tertiary. If the age of the skull was the third interglacial period, as on the whole seems most likely, its antiquity might be less than a fourth that of Pithecanthropus and half that of Heidelberg man.

The skull capacity has been variously estimated at 1,170, nearly 1,300, and nearly 1,500 c.c.; the pieces do not join, so that no certain proof can be given for any figure. Except for unusual thickness of the bone, the skull is not particularly primitive. The jaw and the teeth, on the other hand, are scarcely distinguishable from those of a chimpanzee. They are certainly far less human than the Heidelberg jaw and teeth, which are presumably earlier. This human skull and simian jaw are an almost incompatible combination. More than one expert has got over the difficulty by assuming that the skull of a contemporary human being and the jaw of a chimpanzee happened to be deposited in the same gravel.

In view of these doubts and discrepancies, the claim that the Piltdown form belongs to a genus Eoanthropus distinct from that of man is to be viewed with reserve. This interpretation would make the Piltdown type more primitive than the probably antecedent Heidelberg man. Some authorities do regard it as both more primitive and earlier.

The preceding forms are each known only from partial fragments of the bones of a single individual. The Neandertal race is substantiated by some dozens of different finds, including half a dozen nearly complete skulls, and several skeletons of which the greater portions have been preserved. These fossils come from Spain, France, Belgium, Germany, and what was Austro-Hungary, or, roughly, from the whole western half of Europe. They are all of similar type and from the Mousterian period of the Palæolithic or Old Stone Age (§ 70-72, Fig. 17); whereas Pithecanthropus, Heidelberg, and perhaps Piltdown are earlier than the Stone Age. The Mousterian period may be dated as coincident with the peak of the last or Würm glaciation, that is, about 50,000 to 25,000 years ago. Its race—the Neandertal type—was[24] clearly though primitively human; which fact is reflected in the various systematic names that have been given it: Homo Neandertalensis, Homo Mousteriensis, or Homo primigenius.

The Most Important Neandertal Discoveries

| 1856 | Neandertal | Near Düsseldorf, Germany | Skull cap and parts of skeleton |

| 1848 | Gibraltar | Spain | Greater part of skull |

| 1887 | Spy I | Belgium | Skull and parts of skeleton |

| 1887 | Spy II | Belgium | Skull and parts of skeleton |

| 1889-1905 | Krapina | Moravia | Parts of ten or more skulls and skeletons |

| 1908 | La-Chapelle-aux-Saints | Corrèze, France | Skeleton including skull |

| 1908 | Le Moustier | Dordogne, France | Skeleton, including skull, of youth |

| 1909 | La Ferrassie I | Dordogne, France | Partial skeleton |

| 1910 | La Ferrassie II | Dordogne, France | Skeleton |

| 1911 | La Quina | Charente, France | Skull and parts of skeleton |

| 1911 | Jersey | Island in English Channel | Teeth |

Neandertal man was short: around 5 feet 3 inches for men, 4 feet 10 inches for women, or about the same as the modern Japanese. A definite curvature of his thigh bone indicates a knee habitually somewhat bent, and probably a slightly stooping or slouching attitude. All his bones are thickset: his musculature must have been powerful. The chest was large, the neck bull-like, the head hung forward upon it. This head was massive: its capacity averaged around 1,550 c.c., or equal to that of European whites and greater than the mean of all living races of mankind (Fig. 6). The head was rather low and the forehead sloped back. The supraorbital ridges were heavy: the eyes peered out from under beetling brows. The jaws were prognathous, though not more than in many Australians and Negroes; the chin receded but existed.

Some Neandertal Measurements

| Fossil | Skull Capacity | Stature |

|---|---|---|

| Neandertal | 1400 c.c. | 5 ft. 4 (or 1) in. |

| Spy I | 1550 c.c. | 5 ft. 4 in. |

| Spy II | 1700 c.c. | |

| La Chapelle-aux-Saints | 1600 c.c. | 5 ft. 3 (or 2) in. |

| La Ferrassie I | 5 ft. 5 in. | |

| Average of male Neandertals | 1550 c.c. | 5 ft. 4 (or 3) in. |

| Average of modern European males | 1550 c.c. | 5 ft. 5 to 8 in. |

| Average—modern mankind | 1450 c.c. | 5 ft. 5 in. |

| Gibraltar | 1300 c.c. | |

| La Quina | 1350 c.c. | |

| La Ferrassie II | 4 ft. 10 in. | |

| Average of modern European females | 1400 c.c. | 5 ft. 1 to 3 in. |

The artifacts found in Mousterian deposits show that Neandertal man chipped flint tools in several ways, knew fire, and buried his dead. It may be assumed as almost certain that he spoke some sort of language.

Fig. 6. Skulls of 1, Pithecanthropus; 2, Neandertal man (Chapelle-aux-Saints); 3, Sixth Dynasty Egyptian; 4, Old Man of Cro-Magnon. Combined from Keith. The relatively close approximation of Neandertal man to recent man, and the full frontal development of the Cro-Magnon race, are evident.

Quite recent is the discovery of an African fossil man. This occurred in 1921 at Broken Hill Bone Cave in northern Rhodesia. A nearly complete skull was found, though without[26] lower jaw; a small piece of the upper jaw of a second individual; and several other bones, including a tibia. The remains were ninety feet deep in a cave, associated with vast quantities of mineralized animal bones. Their age however is unknown. The associated fauna is one of living species only; but this does not imply the same recency as in Europe, since the animal life of Africa has altered relatively little since well back in the Pleistocene.

Measurements of Rhodesian man have not yet been published. The available descriptions point to a small brain case with low vault in the frontal region; more extremely developed eyebrow ridges than in any living or fossil race of man, including Pithecanthropus; a large gorilla-like face, with marked prognathism and a long stretch between nose and teeth—the area covered by the upper lip; a flaring but probably fairly prominent nose; an enormous palate and dental arch—too large to accommodate even the massive Heidelberg jaw; large teeth, but without the projecting canines of the apes and of the lower jaw attributed to Piltdown man; and a forward position of the foramen magnum—the aperture by which the spinal cord enters the brain—which suggests a fully upright position. The same inference is derivable from the long, straight shin-bone.

On the whole, this seems to be a form most closely allied to Neandertal man, though differing from him in numerous respects, and especially in the more primitive type of face. It is well to remember, however, that of none of the forms anterior to Neandertal man—Pithecanthropus, Heidelberg, Piltdown—has the face been recovered. If these were known, the Rhodesian face might seem less impressively ape-like. It is also important to observe that relatively primitive and advanced features exist side by side in Rhodesian man; the face and eyebrow ridges are somewhat off-set by the prominent nose, erect posture, and long clean limb bones. It is therefore likely that this form was a collateral relative of Neandertal man rather than his ancestor or descendant. Its place in the history of the human species can probably be fixed only after the age of the bones is determined. Yet it is already clear that the discovery is important in at least three respects. It reveals the most ape-like face yet found in a human variety; it extends the record of fossil man[27] to a new continent; and that continent is the home of the two living apes—the gorilla and chimpanzee—recognized as most similar to man.

The Cro-Magnon race is not only within the human species, but possibly among the ancestors of modern Europeans. While Neandertal man is still Homo Neandertalensis—the genus of living man, but a different species—the Cro-Magnon type is Homo sapiens—that is, a variety of ourselves. The age is that of the gradual, fluctuating retreat of the glaciers—the later Cave period of the Old Stone Age: the Upper Palæolithic, in technical language, comprising the Aurignacian, the Solutrean, and the Magdalenian (§ 70). In years, this was the time from 25,000 to 10,000 B.C.

Some Important Remains of Cro-Magnon Type

| Aurignacian | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1868 | Cro-Magnon | Dordogne, France | 5 incomplete skeletons |

| 1872-74 | Grimaldi | Mentone, N.W. Italy | 12 skeletons |

| 1909 | Laugerie Haute | Dordogne, France | Skeleton |

| 1909 | Combe-Capelle | Périgord, France | Skeleton |

| Magdalenian | |||

| 1872 | Laugerie Basse | Dordogne, France | Skeleton |

| 1888 | Chancelade | Dordogne, France | Skeleton, nearly complete |

| 1914 | Obercassel | Near Bonn, Germany | 2 skeletons |

The Cro-Magnon race of Aurignacian times, as represented by the finds at Cro-Magnon and Grimaldi,[2] was excessively tall and large-brained, surpassing any living race of man in both respects.

The adult male buried at Cro-Magnon measured 5 feet 11 inches in life; five men at Grimaldi measured from 5 feet 10½ inches to 6 feet 4½ inches, averaging 6 feet 1½ inches. The[28] tallest men now on earth, certain Scots and Negroes, average less than 5 feet 11 inches. A girl at Grimaldi measured 5 feet 5 inches. This race was not only tall, but clean-limbed, lithe, and swift.

Their brains were equally large. Those of the five male skulls from Grimaldi contain from over 1,700 to nearly 1,900 c.c.—an average of 1,800 c.c.; that of the old man of Cro-Magnon, nearly 1,600 c.c.; of a woman there, 1,550 c.c. If these individuals were not exceptional, the figures mean that the size and weight of the brain of the early Cro-Magnon people was some fifteen or twenty per cent greater than that of modern Europeans.

The cephalic index is low—that is, the skull was long and narrow, as in all the types here considered; but the face was particularly broad. The forehead rose well domed; the supraorbital development was moderate, as in recent men; the features must have been attractive even by our standards.

Three of the best preserved skeletons of the Magdalenian period are those of women. Their statures run 4 feet 7 inches, 5 feet 1 inch, 5 feet 1 inch, which would indicate a corresponding normal height for men not far from that of the average European of to-day. The male from Obercassel attained a stature of about 5 feet 3 inches, a cranial capacity of 1,500 c.c., and combined a long skull with a wide face. The general type of the Magdalenian period might be described as a reduced Cro-Magnon one.

The Cro-Magnon peoples used skilfully made harpoons, originated a remarkable art, and in general attained a development of industries parallel to their high degree of bodily progress.

Several remains have been found in central Europe which have sometimes been considered as belonging to the Neandertal race and sometimes to the subsequent Cro-Magnon race, but do not belong clearly with either, and may perhaps be regarded as distinct from both and possibly bridging them. The type is generally known as the Brünn race. Its habitat was Czecho-Slovakia and perhaps adjacent districts; its epoch, postglacial,[29] in the Solutrean period of the Upper Palæolithic (§ 70). The Brünn race, so far as present knowledge of it goes, was therefore both preceded and succeeded by Cro-Magnon man.

| 1871 | Brüx | Bohemia | Skull cap |

| 1880 | Predmost | Moravia | Parts of 20 skeletons |

| 1891 | Brünn | Moravia | Skeleton, 2 skulls |

The Brünn race belongs with modern man: its species is no longer Homo Neandertalensis, but Homo sapiens, to which we also belong. The heavy supraorbital ridges of the earlier type are now divided by a depression over the nose instead of stretching continuously across the forehead; the chin is becoming pronounced, the jaws protrude less than in Neandertal man. The skull is somewhat higher and better vaulted. In all these respects there is an approach to the Cro-Magnon race. But the distinctively broad face of the Cro-Magnon people is not in evidence.

A skull of uncertain geologic age, found in 1888 at Galley Hill, near London, is by some linked with the Brünn race. The same is true of an unusually well preserved skeleton found in 1909 at Combe-Capelle, in Périgord, southern France. The period of the Combe-Capelle skeleton is Upper Palæolithic Aurignacian. This was part of the era of the Cro-Magnon race in western Europe; and as the Combe-Capelle remains do not differ much from the Cro-Magnon type, they are best considered as belonging to it.

The Grimaldi race is to date represented by only two skeletons, those of a woman and a youth—possibly mother and son—found in 1906 in a grotto at Grimaldi near Mentone, in Italy, close to the French border. They reposed in lower layers, above which subsequent Cro-Magnon burials of Aurignacian date had been made. Their age is therefore early Aurignacian: the beginning of the Upper Palæolithic or later Cave period of the Old Stone Age. The statures are 5 feet 2 inches and 5 feet 1 inch—the youth was not fully grown; the skull capacities 1,375 and nearly 1,600 c.c.

The outstanding feature of both skeletons is that they bear a number of Negroid characteristics. The forearm and lower leg are long as compared with the upper arm and thigh; the pelvis high and small; the jaws prognathous, the nose flat, the eye orbits narrow. All these are Negro traits. This is important, in view of the fact that all the other ancient fossils of men are either more primitive than the living races or, like Cro-Magnon, perhaps ancestral to the Caucasian race.

No fossil remains of any ancestral Mongolian type have yet been discovered.

The New Stone Age, beginning about 10,000 or 8,000 B.C., brings the Grenelle and other types of man; but these are so essentially modern that they need not be considered here. In the Neolithic period, broad heads are for the first time encountered, as they occur at present in Europe and other continents, alongside of narrow ones. The virtual fixity of the human type for these last ten thousand years is by no means incredible. Egyptian mummies and skeletons prove that the type of that country has changed little in five thousand years except as the result of invasions and admixture.

The relations of the several fossil types of man and their gradual progression are most accurately expressed by certain skull angles and proportions, or indexes, which have been specially devised for the purpose. The anthropometric criteria that are of most importance in the study of living races, more or less fail in regard to prehistoric man. The hair, complexion, and eye-color are not preserved. The head breadth, as indicated by the cephalic index, is substantially the same from Pithecanthropus to the last Cro-Magnons. Stature on the other hand varies from one to another ancient race without evincing much tendency to grow or to diminish consistently. Often, too, there is only part of a skull preserved. The following proportions of the top or vault of the skull—the calvarium—are therefore useful for expressing quantitatively the gradual physical progress of humanity from its beginning.

Three anatomical points on the surface of the skull are the[31] pivots on which these special indexes and angles rest. One is the Glabella (G in figure 7), the slight swelling situated between the eyebrows and above the root of the nose. The second is the Inion (I), the most rearward point on the skull. The third is the Bregma (B) or point of intersection of the sutures which divide the frontal from the parietal bones. The bregma falls at or very near the highest point of the skull.

If now we see a skull lengthwise, or draw a projection of it, and connect the glabella and the inion by a line GI, and the glabella and the bregma by a line GB, an acute angle, BGI, is formed. This is the “bregma angle.” Obviously a high vaulted skull or one that has the superior point B well forward will show a greater angle than a low flat skull or one with its summit lying far back.

Fig. 7. Indices and angles of special significance in the change from fossil to living man. Calvarial height index, BX: GI. Bregma position index, GX: GI. Bregma angle, BGI. Frontal angle, FGI.

Next, let us drop a vertical from the bregma to the line GI, cutting it at X. Obviously the proportion which the vertical line BX bears to the horizontal line GI will be greater or less as the arch or vault of the brain case is higher or lower. This proportion BX: GI, expressed in percentages, is the “calvarial height index.”

The Skull of Modern and Fossil Man

| Calvarial Height Index |

Bregma Angle |

Bregma Position Index |

Frontal Angle |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum for modern man | 68 | 66 | ||

| Average for modern man | 59 | 58 | 30.5 | 90 |

| 90 Central Europeans | 60 | 61 | 31 | |

| 28 Bantu Negroes | 59 | 59 | 31 | |

| 7 Greenland Eskimos | 56 | 58 | 30 | |

| 43 Australian natives | 56 | 57.5 | (33) | |

| 8 Tasmanian natives | 56 | 57 | ||

| Minimum for modern man | 47.5 | 46 | 37 | 72 |

| Chancelade | 57 | 60 | ||

| Combe-Capelle | 54.5 | 58 | ||

| Aurignac | 54.5 | |||

| Cro-Magnon I | 50 | 54 | 33 | |

| Brünn I | 51 | 52 | 75 | |

| Galley Hill | 48 | 52 | 82 | |

| Brüx | 48 | 51? | 75? | |

| Le Moustier | 47 | |||

| Krapina C | 46 | 52 | 70 | |

| Spy II | 44 | 50 | 35 | 67 |

| Krapina D | 42 | 50 | 32 | 66 |

| Chapelle-aux-Saints | 40.5 | 45.5 | 36.5 | 65 |

| Spy I | 41 | 45 | 35 | 57.5 |

| Gibraltar | 40 | 50 | 73? | |

| Neandertal | 40 | 44 | 38 | 62 |

| Pithecanthropus | 34 | 38 | 42 | 52.5 |

| Maximum for any Anthropoid ape | 38 | 39.5 | 63 | |

| Chimpanzee | 32 | 34 | 47 | 56 |

| Gorilla | 20 | 22 | 42 | |

| Orang-utan | 27 | 32 | 45 | |

| Summarized Averages | ||||

| Modern races | 59 | 58 | 31 | 90 |

| Cro-Magnon race | 54 | 57 | 33 | |

| Brünn race | 49 | 52 | 77 | |

| Neandertal man | 42 | 48 | 35 | 66 |

| Pithecanthropus | 34 | 38 | 42 | 52 |

| Anthropoid apes | 26 | 30 | 45 | |

If now we compute the proportion of the GX part of the line GI to the whole of this line, we have the “bregma position index”; that is, a numerical indication of how far forward on the skull the highest point B lies. A sloping or retreating forehead naturally tends to have the bregma rearward; whereas if the frontal bone is nearly vertical, resulting in a high, domed expanse of forehead, the bregma tends to be situated farther forward, the point X shifts in the same direction, the distance GX becomes shorter in comparison to the whole line GI, and the “bregma position index” falls numerically.

The “frontal angle,” finally, is determined by drawing a line GF from the glabella tangent to the most protruding part of the frontal bone and measuring the angle between this and the horizontal GI. A small frontal angle obviously means a receding forehead.

All these data can be obtained from the mere upper fragment of a skull; they relate to that feature which is probably of the greatest importance in the evolution of man from the lower animals—the development of the brain case and therefore of the brain, especially of the cerebrum or fore-brain; and they define this evolution rather convincingly. The table, which compiles some of the most important findings, shows that progress has been fairly steadily continuous in the direction of greater cerebral development.

20. Race origins.—21. Race classification.—22. Traits on which classification rests.—23. The grand divisions or primary stocks.—24. Caucasian races.—25. Mongoloid races.—26. Negroid races.—27. Peoples of doubtful position.—28. Continents and oceans.—29. The history of race classifications.—30. Emergence of the threefold classification.—31. Other classifications.—32. Principles and conclusions common to all classifications.—33. Race, nationality, and language.

Almost every one sooner or later becomes interested in the problem of the origin of the human races and the history of their development. We see mankind divided into a number of varieties that differ strikingly in appearance. If these varieties are modifications of a single ancestral form, what caused them to alter, and what has been the history of the change?

In the present state of science, we cannot wholly answer these important questions. We know very little about the causes that change human types; and we possess only incomplete information as to the history of races. Stray bits of evidence here and there are too scattered to afford many helpful clues. The very earliest men, as we know them from fossils, are too far removed from any of the living varieties, are too primitive, to link very definitely with the existing races, which can all be regarded as intergrading varieties of a single species, Homo sapiens. In the latter half of the Old Stone Age, in the Aurignacian period, at a time estimated to have been from twenty to twenty-five thousand years ago, we commence to encounter fossils which seem to foreshadow the modern races. The so-called Grimaldi type of man from this period possesses Negroid affinities, the contemporary Cro-Magnon and perhaps Brünn types evince Caucasian ones. But we know neither the origin nor the precise[35] descendants of these fossil races.[3] They appear and then vanish from the scene. About all that we can conclude from this fragment of evidence is that the races of man as they are spread over the earth to-day must have been at least some tens of thousands of years in forming. What caused them to differentiate, on which part of the earth’s surface each took on its peculiarities, how they further subdivided, what were the connecting links between them, and what happened to these lost links—on all these points the answer of anthropology is as yet incomplete.

It is no different in other fields of biology. As long as the zoölogist or botanist reviews his grand classifications or the wide sweep of organic evolution for fifty million years back, he seems to obtain striking and simple results. When he turns his attention to a small group, attempting to trace in detail its subvarieties, and the relations and history of these, the task is seen to be intricate and the accumulated knowledge is usually insufficient to solve more than a fraction of the problems that arise.

There is, then, nothing unusual in the situation of partial bafflement in which anthropology still finds itself as regards the human races.

What remains is the possibility of making an accurate survey of the living races in the hope that the relationships which a classification brings out may indicate something as to the former development of the races. If for instance it could be established that the Ainu or aborigines of Japan are closely similar in their bodies to the peoples of Europe, we would then infer that they are a branch of the Caucasian stock, that their origin took place far to the west of their present habitat, and that they have no connection with the Mongolian Japanese among whom they now live. This is working by indirect evidence, it is true; but sooner or later that is the method to which science always finds itself reduced.

The desirability of a trustworthy classification of the human[36] races will therefore be generally accepted without further argument. But the making of such a classification proves to be more difficult than might be imagined. To begin with, a race is only a sort of average of a large number of individuals; and averages differ from one another much less than individuals. Popular impression exaggerates the differences, accurate measurements reduce them. It is true that a Negro and a north European cannot possibly be confused: they happen to represent extreme types. Yet as soon as we operate with less divergent races we find that variations between individuals of the same race are often greater than differences between the races. The tallest individuals of a short race are taller than the shortest individuals of a tall race. This is called overlapping; and it occurs to such an extent as to make it frequently difficult for the physical anthropologist to establish clear-cut types.

In addition, the lines of demarcation between races have time and again been obliterated by interbreeding. Adjacent peoples, even hostile ones, intermarry. The number of marriages in one generation may be small; but the cumulative effect of a thousand years is often quite disconcerting. The half-breeds or hybrids are also as fertile as each of the original types. There is no question but that some populations are nothing but the product of such race crossing. Thus there is a belt extending across the entire breadth of Africa of which it is difficult to say whether the inhabitants belong to the Negro or to the Caucasian type. If we construct a racial map and represent the demarcation between Negro and Caucasian by a line, we are really misrepresenting the situation. The truth could be expressed only by inserting a transition zone of mixed color. Yet as soon as we allow such transitions, the definiteness of our classification begins to crumble.

In spite of these difficulties, some general truths can be discovered from a careful race classification, and certain constant principles of importance emerge from all the diversity.

Since every human being obviously possesses a large number of physical features or traits, the first thing that the prospective[37] classifier of race must do is to determine how much weight he will attach to each of these features.

The most striking of all traits probably is stature or bodily height. Yet this is a trait which experience has shown to be of relatively limited value for classifactory purposes. The imagination is easily impressed by a few inches when they show at the top of a man and make him half a head taller or shorter than oneself. Except for a few groups which numerically are rather insignificant, there is no human race that averages less than 5 feet in height. There is none at all that averages taller than 5 feet 10 inches. This means that practically the whole range of human variability in height, from the race standpoint, falls within less than a foot. The majority of averages of populations do not differ more than 2 inches from the general human average of 5 feet 5 inches.