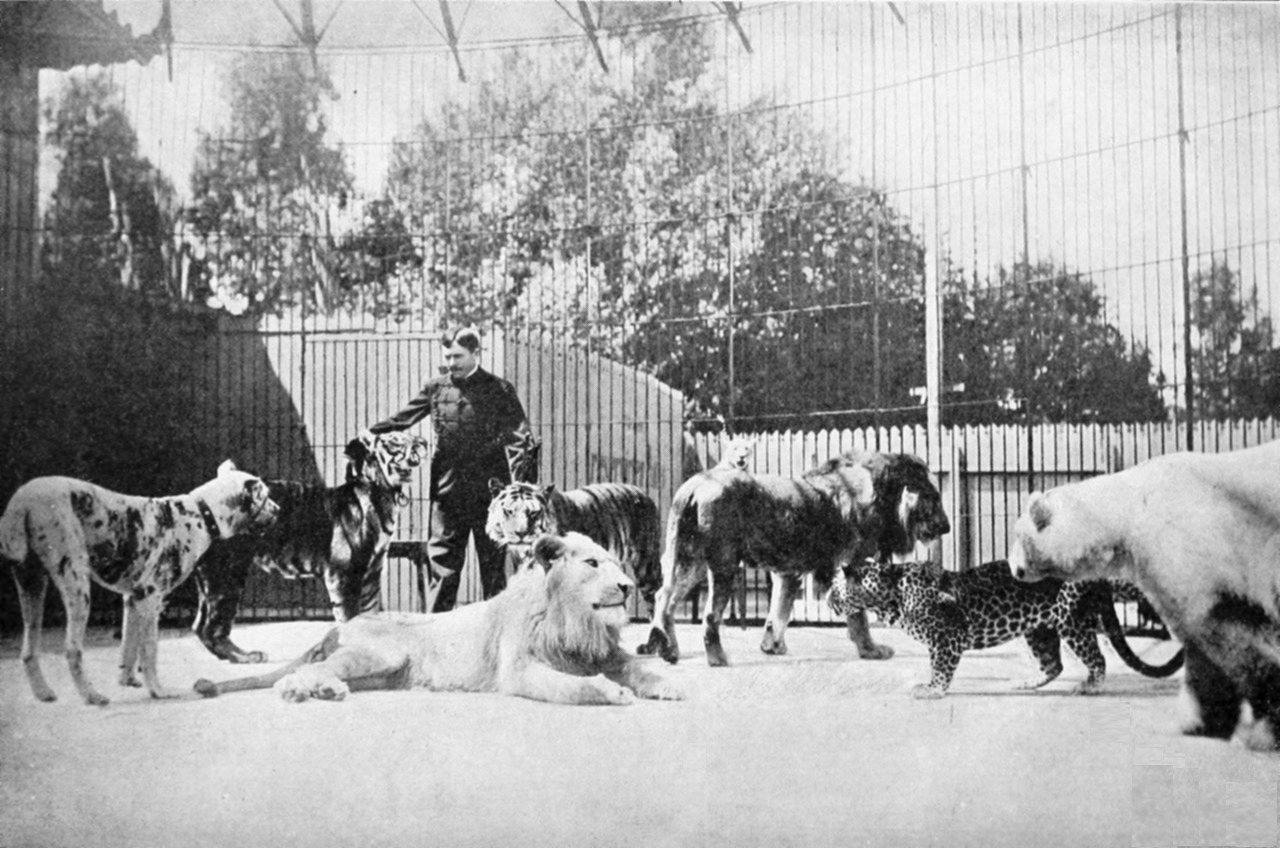

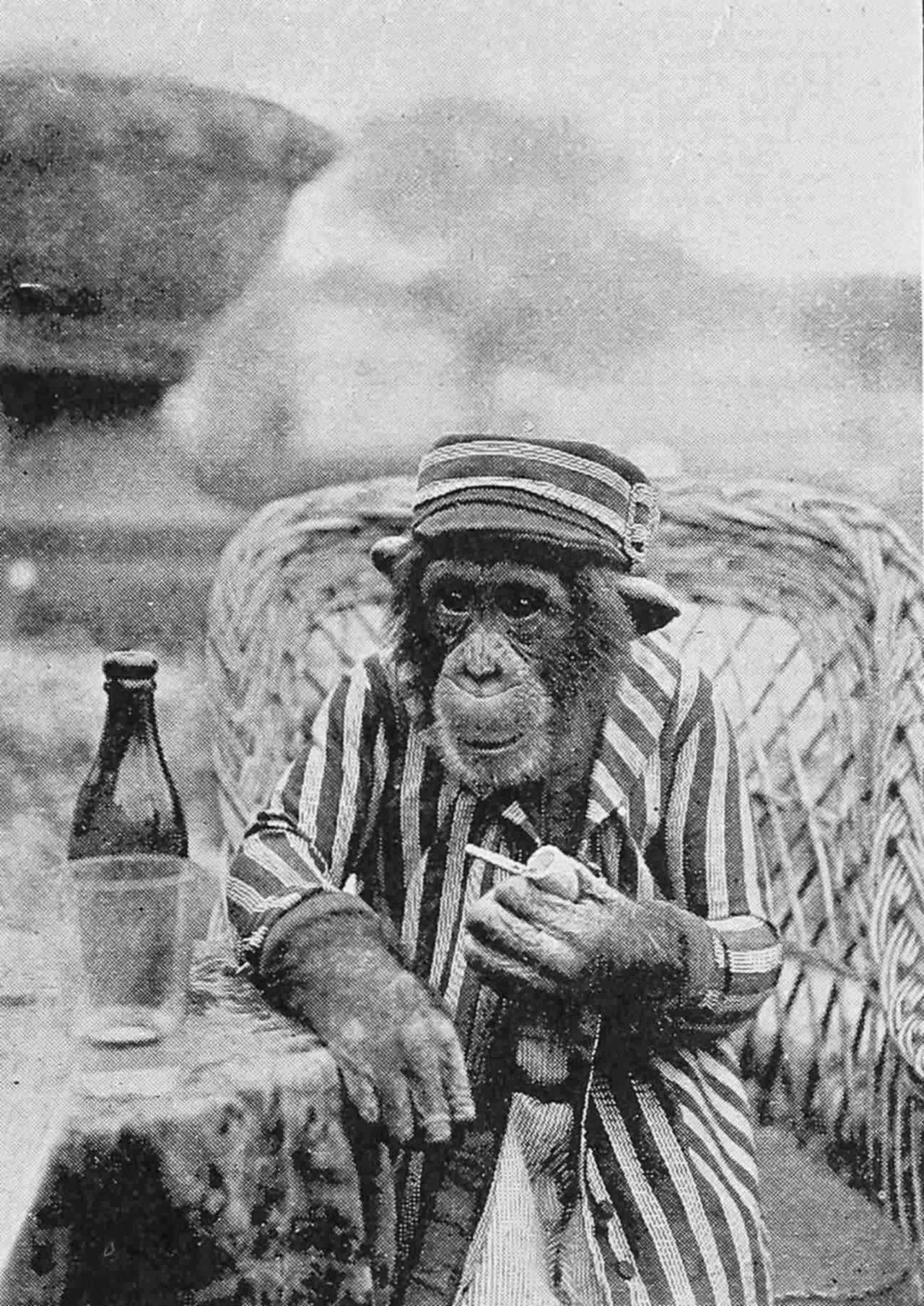

GROUP OF PERFORMING ANIMALS AT CARL HAGENBECK’S.

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

SOMALILAND.

Royal 8vo., cloth extra, gilt top, 18s. net.

A thrilling story of sport and adventure met with in the course of two expeditions into the interior of the country. Profusely illustrated from photographs by the author and with original full-page drawings by that great portrayer of wild animal life, Edmund Caldwell.

This standard work on Somaliland, which has taken upwards of four years to compile, concludes with descriptive lists of every animal and bird known to inhabit the country. The book contains an original map, drawn by the author, showing the heart of the Marehan and Haweea countries previously untrodden by white man’s foot.

Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News.—‘Readers will find this a capital book of sport and travel, in which the life of the hunter in Africa is depicted in graphic and straightforward fashion. Mr. Caldwell’s illustrations are excellent.’

Spectator.—‘Mr. Peel’s two hunting trips in “Somaliland” will make many a man’s mouth water, though the trying experiences of the desert journey will as probably parch their throats in anticipation.’

Saturday Review.—‘This is a pleasant book of sport, natural history, and adventure, rendered additionally interesting by an excellent list of the fauna of the country.’

WILD SPORT IN THE OUTER HEBRIDES.

Demy 8vo., cloth gilt, gilt top, 7s. 6d. net.

The experiences of a sportsman who has made a close study of the habits of all the animals and birds which are to be found in the Outer Hebrides. The illustrations consist of a photogravure frontispiece from an original drawing by Mr. G. E. Lodge, and reproductions of numerous photographs taken by the Author. In an Appendix is given a list of all the animals and birds which have been actually observed by the Author in these islands.

Daily News.—‘A breezy, sportsmanlike book, well illustrated.’

Dundee Advertiser.—‘His book gives a clear insight to the country and the sport it provides. He writes in a graphic, straightforward style, and his experiences leave the reader impressed that he has read the truth and nothing but the truth. The illustrations are very fine.’

Glasgow Herald.—‘Will be found exceedingly useful both by the sportsman and the naturalist who may visit the Western Isles.’

Scotsman.—‘A book which every lover of sport will peruse with interest and profit.’

Times.—‘An exciting book.’

Pall Mall Gazette.—‘Snap-shooting with the camera is Mr. Peel’s last word. He finds it so attractive that he threatens to discard his gun altogether. We hope he will neither discard his gun nor his pen. He has the right way with both.’

F. E. ROBINSON & CO.,

THE RUSSELL PRESS, 20, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON.

GROUP OF PERFORMING ANIMALS AT CARL HAGENBECK’S.

Their History and Chief Features

BY

C. V. A. PEEL, F.Z.S., F.R.G.S.

Author of ‘Somaliland,’ ‘Wild Sport in the Outer Hebrides,’ etc.

LONDON

F. E. ROBINSON & CO.

20, GREAT RUSSELL STREET, BLOOMSBURY

1903

[Pg vii]

This book is intended chiefly as a work of reference. As most Zoological Gardens are much alike, it is impossible to avoid a certain monotony in describing them. And yet each Garden has generally its own distinctive features. These I had the opportunity of observing in a tour which I made early this year, and I have tried to recount them in the following pages, after first giving the main facts connected with the foundation and development of the respective Gardens. In my descriptive walks round I invariably turned to the left on entering, and made my way round the Gardens back to the entrance again.

The chief thought that has occurred to me as the result of my tour is that we in England take little interest in the breeding and acclimatization of wild animals as compared with the Germans, or even Americans. Almost every large town in Germany has its Zoological Garden, and, as it usually contains a[Pg viii] concert-hall and other similar attractions, people flock to it, and are insensibly led to take an interest in the wild animals which they see around them. It seems to me a pity that we do not make our few English Gardens equally attractive. The result would be, I feel sure, that more people would become interested in wild animals, and probably many of our large towns would start Gardens of their own.

It is not generally known that most wild animals can be easily acclimatized, and, if properly treated, will breed well in captivity. The great secret is fresh air: animals which come from the equator do not require heat when once acclimatized. Just as human beings die of consumption through the want of fresh air, so do our anthropoid apes and other animals often die in captivity through being shut up, winter and summer, in hot-houses devoid of fresh air. We are far behind Germany and America in our knowledge of the breeding and cross-breeding of wild animals, and yet there must be many influential men in England who would assist in the formation of a National Park for such a purpose, thereby furthering the cause of science and conferring a great benefit on the nation. Our cousins in America have the Yellowstone National Park; we ought to have a similar place.

[Pg ix]

My thanks are due to many gentlemen who have kindly favoured me with histories, guide-books, photographs, and general information about the Zoological Gardens of Europe. And especially do I owe a debt of gratitude to Dr. P. L. Sclater, the learned Secretary of our own Zoological Society in London; to Herr Carl Hagenbeck of Hamburg, Dr. C. Kerbert of Amsterdam, Dr. H. Bolau of Hamburg, Dr. Seitz of Frankfort-on-Main, Mr. E. W. B. Villiers of Clifton, Professor D. Cunningham of Dublin, Herr Schöff of Dresden, Herr Meissner of Berlin, Dr. Hagman of Basle, Dr. Wünderlich of Cologne, and to Messrs. J. Jennison and Co. of Manchester. The photographs of Berlin are published by kind permission of the Berlin Zoological Society.

In some few cases it has been found impossible to give historical details, through my appeals to the Directors eliciting no reply. The sketch of the London Gardens is a concise summary, with additions, of the history written by Dr. P. L. Sclater, that of Dublin is taken from a pamphlet written by Professor D. Cunningham, whilst the history of the Manchester Gardens is based on materials furnished by Messrs. J. Jennison and Co.

In conclusion, my best thanks are due to my sister,[Pg x] Mrs. Harry Duff, whose knowledge of foreign languages has enabled her to give me much valuable help in the translation of letters, guide-books, and catalogues of animals. Indeed, without her kind assistance I could scarcely have attempted this work.

Oxford,

October, 1902.

[Pg xi]

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS IN FRANCE. | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | JARDIN DES PLANTES, PARIS | 1 |

| II. | JARDIN D’ACCLIMATATION, PARIS | 8 |

| III. | JARDIN ZOOLOGIQUE, MARSEILLES | 26 |

| IV. | JARDIN ZOOLOGIQUE, NICE-CIMIEZ | 32 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS IN HOLLAND. | ||

| V. | KONINKLIJK ZOOLOGISCH GENOOTSCHAP, AMSTERDAM | 36 |

| VI. | THE GARDENS OF THE ROYAL ZOOLOGICAL AND BOTANICAL SOCIETY, THE HAGUE | 45 |

| VII. | ROTTERDAMSCHE DIERGAARDE, ROTTERDAM | 48 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN IN DENMARK. | ||

| VIII. | ZOOLOGISK HAVE, COPENHAGEN | 55 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS IN BELGIUM. | ||

| IX. | THE GARDENS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF ZOOLOGY, ANTWERP | 58 |

| X. | JARDIN ZOOLOGIQUE, GHENT | 63 |

| XI. | JARDIN ZOOLOGIQUE, LIÈGE | 66 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS IN GERMANY. | ||

| XII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, AIX-LA-CHAPELLE | 67 |

| XIII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, COLOGNE | 68 |

| XIV. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, ELBERFELD | 80 |

| XV. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, DÜSSELDORF | 82[Pg xii] |

| XVI. | THE WESTPHALIAN ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, MÜNSTER | 86 |

| XVII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, HANOVER | 90 |

| XVIII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, HAMBURG | 96 |

| XIX. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, BERLIN | 104 |

| XX. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, HALLE | 117 |

| XXI. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, LEIPZIG | 119 |

| XXII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, DRESDEN | 125 |

| XXIII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, BRESLAU | 131 |

| XXIV. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, POSEN | 139 |

| XXV. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, KÖNIGSBERG | 141 |

| XXVI. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, STUTTGART | 146 |

| XXVII. | ZOOLOGISCHER GARTEN, FRANKFORT-ON-MAIN | 151 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS IN RUSSIA. | ||

| XXVIII. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, ST. PETERSBURG | 161 |

| XXIX. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, MOSCOW | 164 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN IN HUNGARY. | ||

| XXX. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, BUDA-PESTH | 168 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN IN AUSTRIA. | ||

| XXXI. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, VIENNA | 172 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN IN SWITZERLAND. | ||

| XXXII. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, BASLE | 175 |

| ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS IN THE BRITISH ISLES. | ||

| XXXIII. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, LONDON | 179 |

| XXXIV. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, CLIFTON | 196 |

| XXXV. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, MANCHESTER | 201 |

| XXXVI. | ZOOLOGICAL GARDEN, DUBLIN | 212 |

| XXXVII. | CARL HAGENBECK, THE KING OF ANIMAL IMPORTERS | 232 |

[Pg xiii]

| PAGE | |

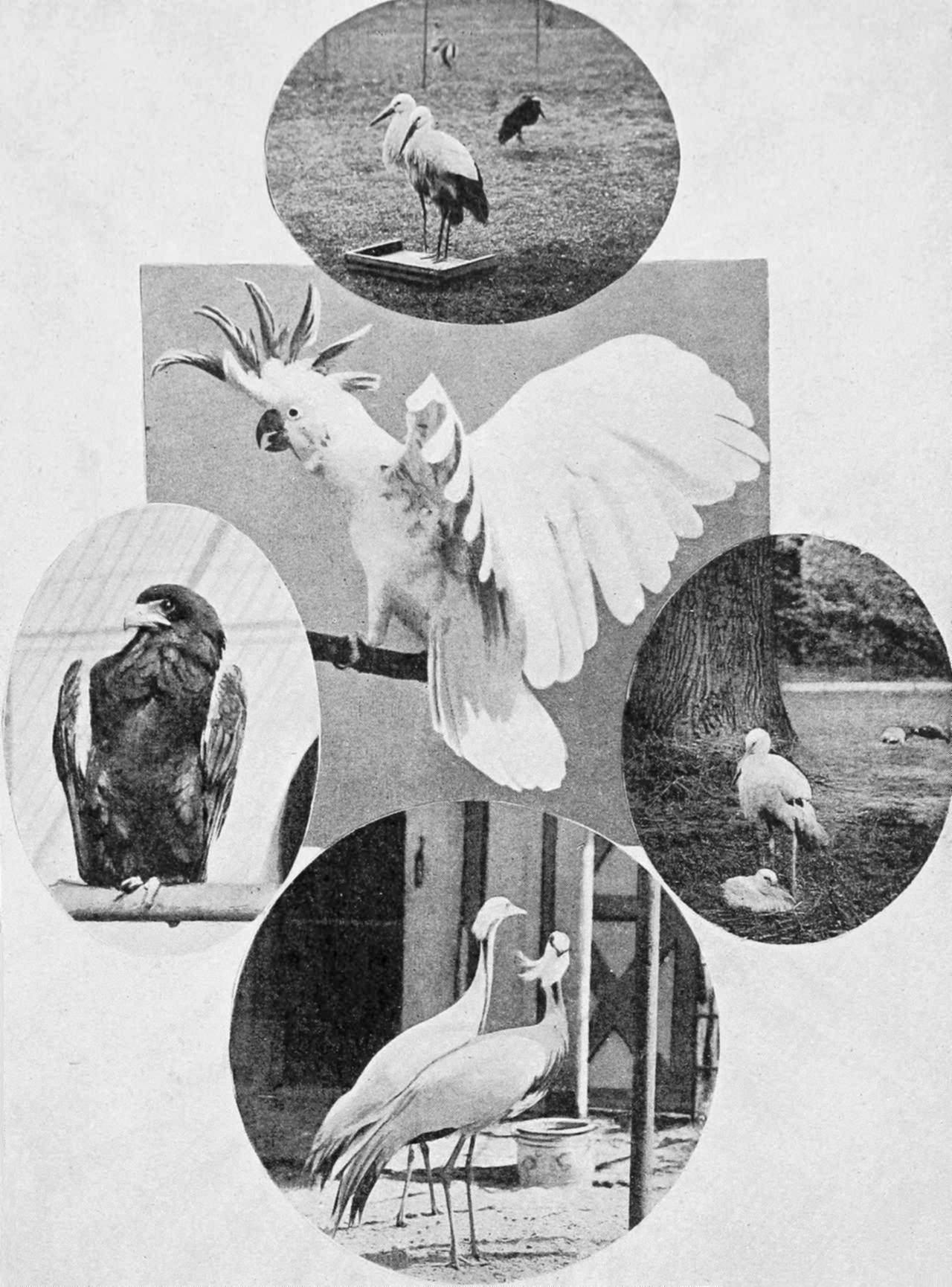

| GROUP OF PERFORMING ANIMALS AT CARL HAGENBECK’S | Frontispiece |

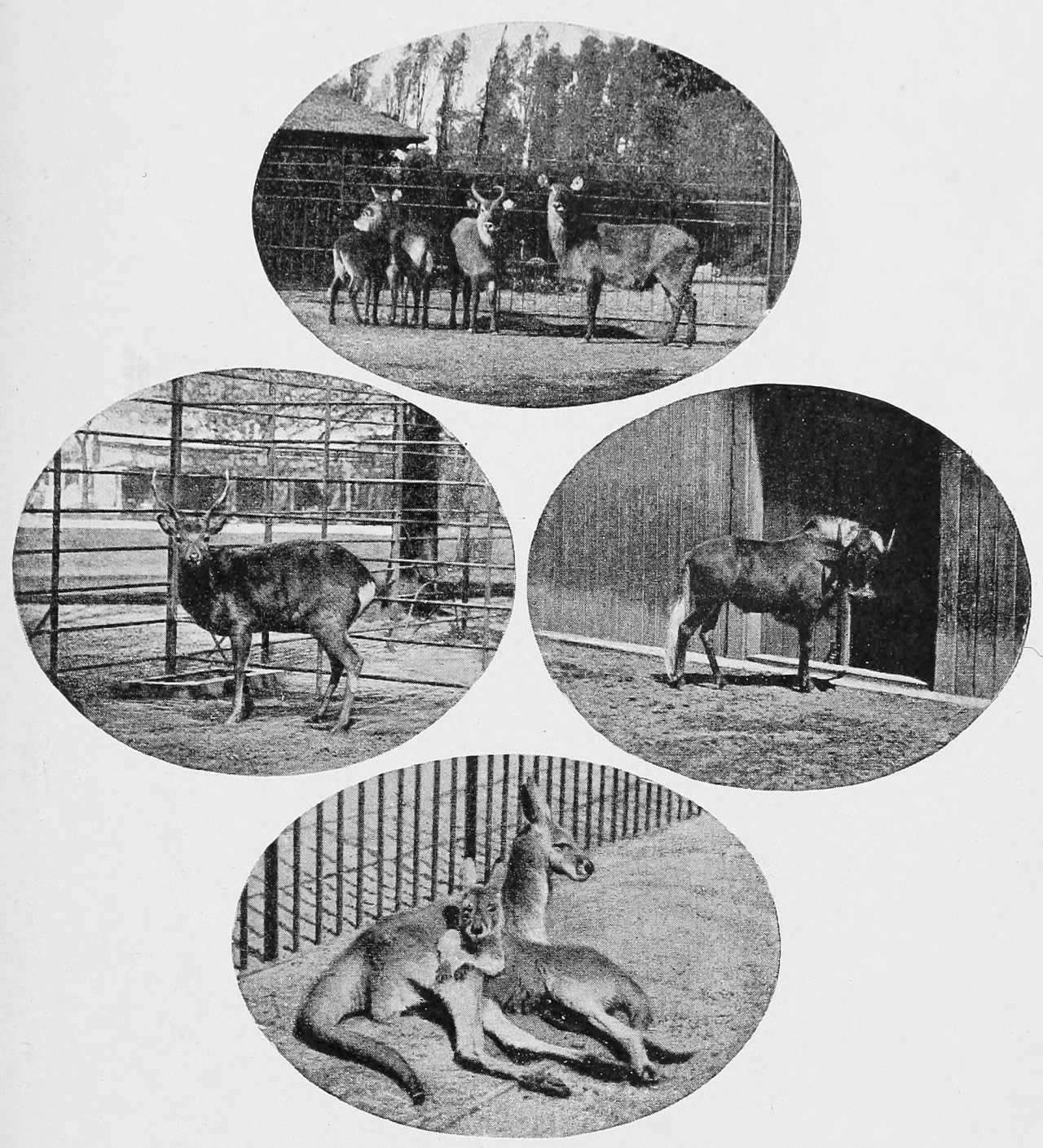

| MARKHOR, JARDIN DES PLANTES, PARIS | 6 |

| SEA-LION SUCKLING ITS YOUNG, JARDIN D’ACCLIMATATION, PARIS | 13 |

| HERD OF BLACKBUCK, JARDIN D’ACCLIMATATION, PARIS | 23 |

| LE PALAIS LONGCHAMP, MARSEILLES | 27 |

| CONCERT-HOUSE AND LAKE, AMSTERDAM | 37 |

| YAK, AMSTERDAM | 43 |

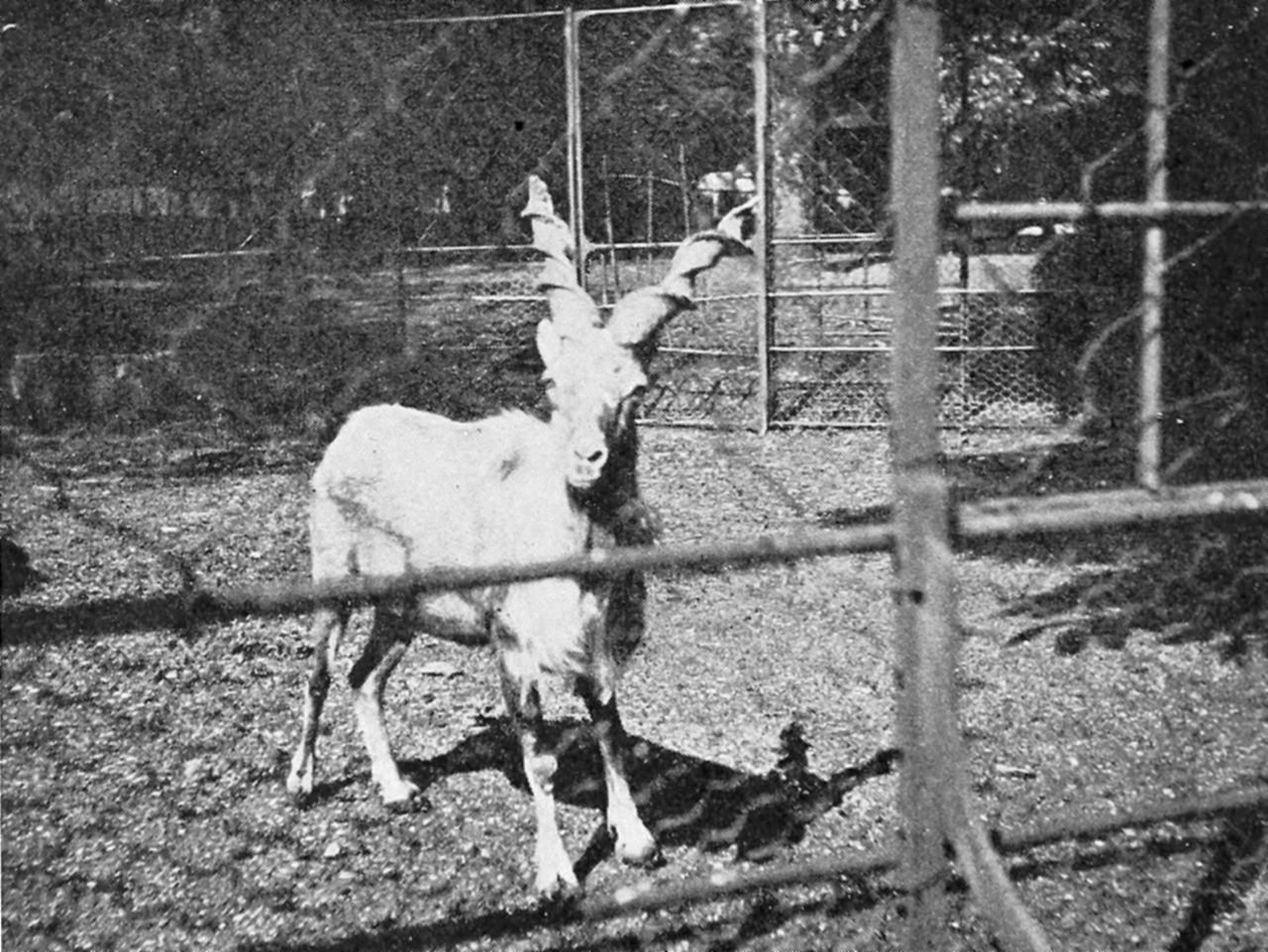

| HERD OF WATERBUCK, JAPANESE DEER, BRINDLED GNU, AND KANGAROOS | 51 |

| KANGAROO | 60 |

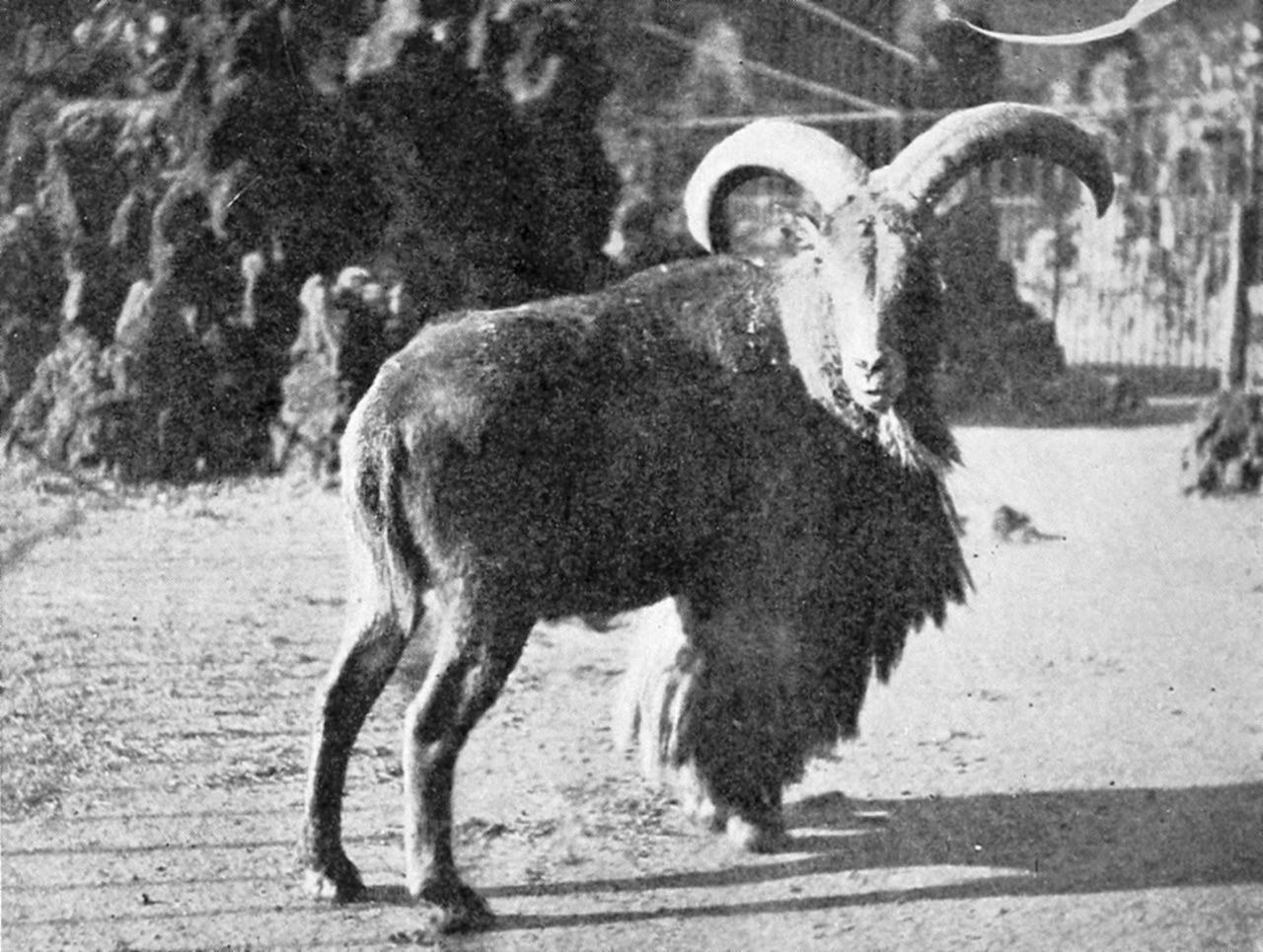

| BARBARY SHEEP, GHENT | 64 |

| STORKS, BATELEUR EAGLE, COCKATOO, STORK NESTING ON THE GROUND, AND CRANES | 73 |

| PELICANS, COLOGNE | 79 |

| BARBARY RAM, DÜSSELDORF | 84 |

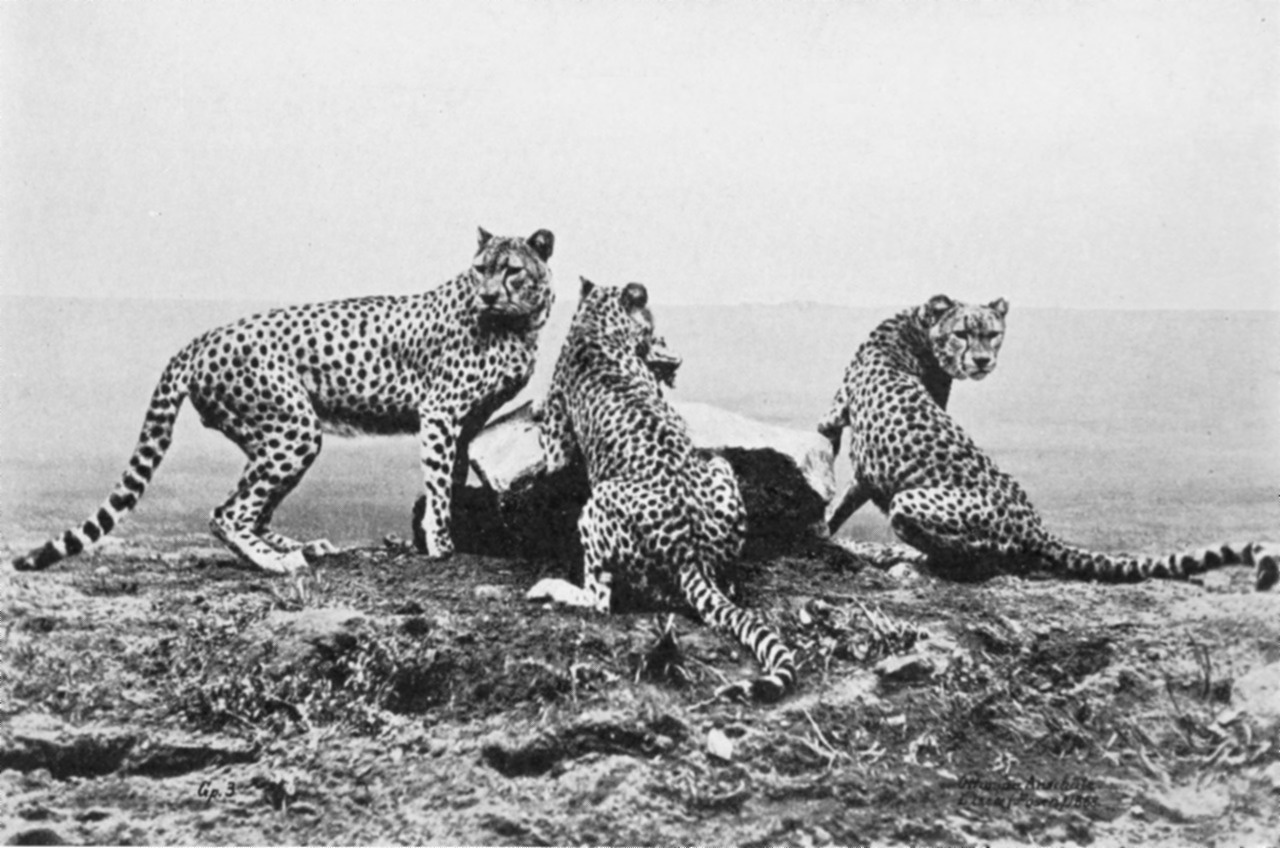

| CHEETAHS OR HUNTING LEOPARDS | 93 |

| MONKEY HOUSE, HAMBURG | 99 |

| STORK AND CRANE ENCLOSURES, HAMBURG | 101 |

| LLAMA AND MOUFFLON ROCKERY, BERLIN | 106 |

| ELEPHANT HOUSE, BERLIN | 107 |

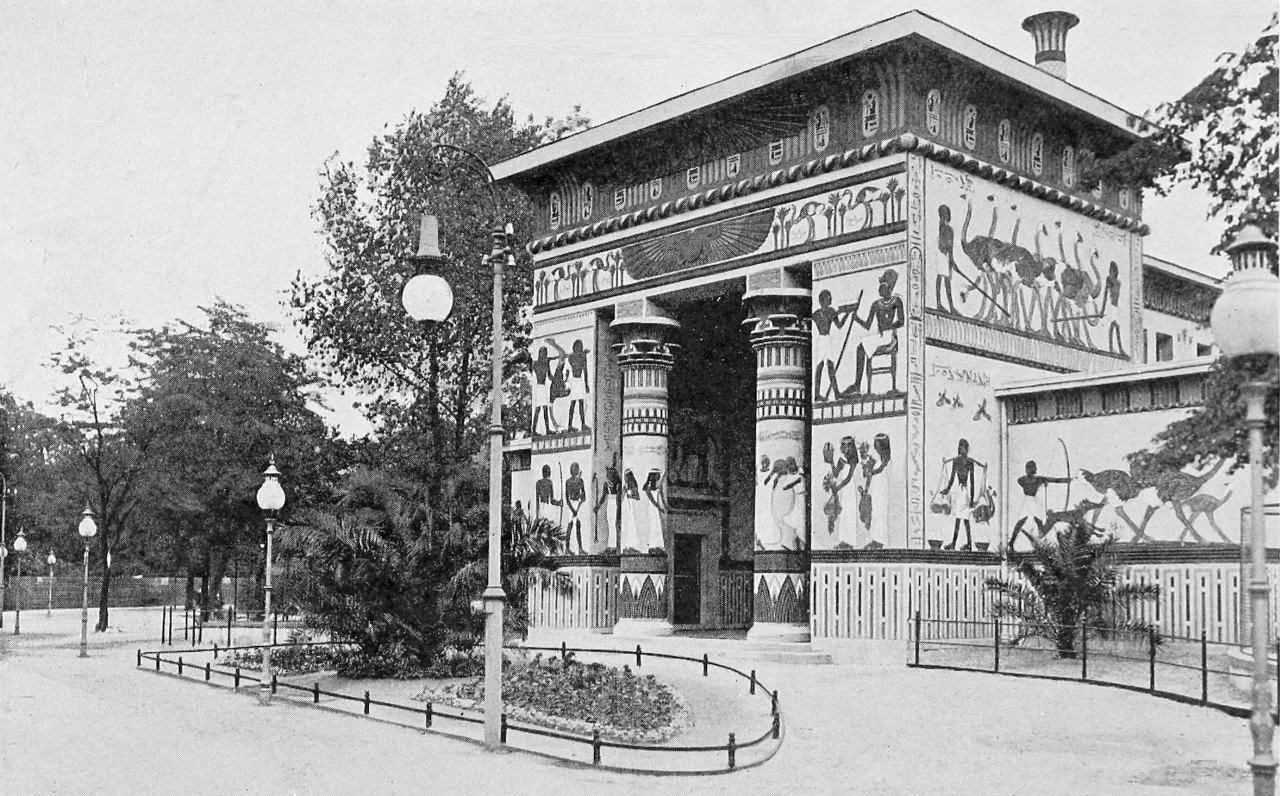

| OSTRICH HOUSE, BERLIN | 111 |

| DEER SHED, BERLIN | 113 |

| KANGAROO, HALLE | 118 |

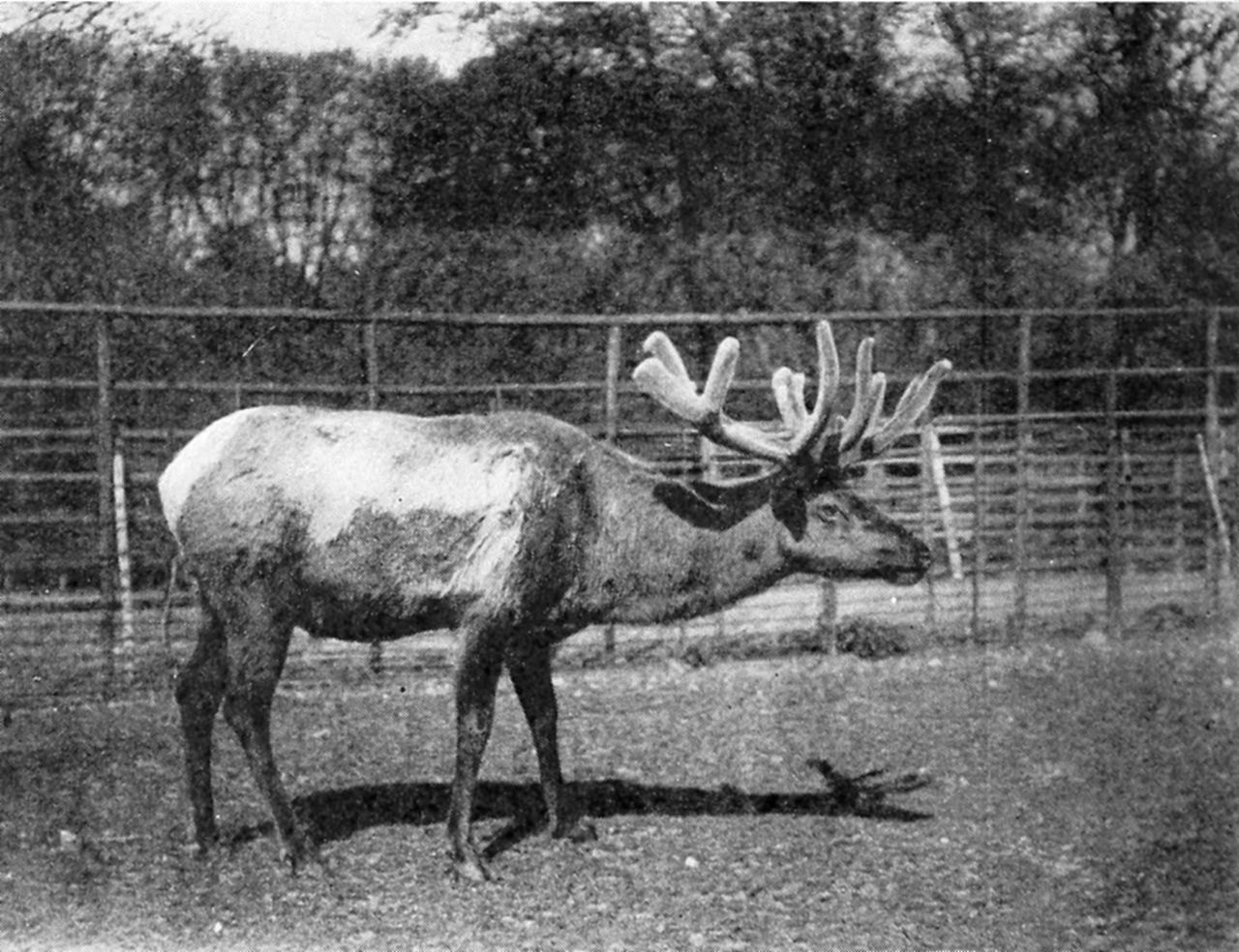

| WAPITI BULL, DRESDEN | 126 |

| OUTSIDE THE LION HOUSE, DRESDEN | 128 |

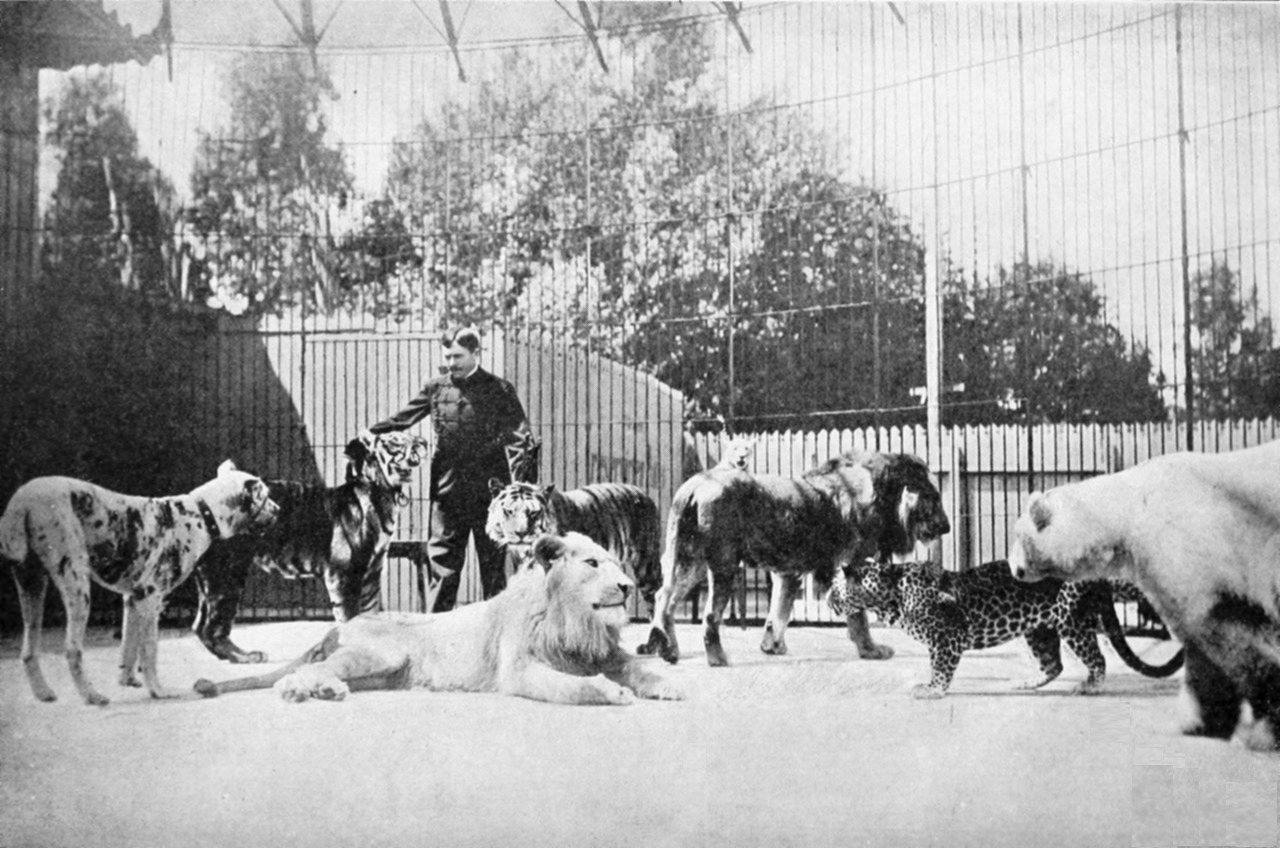

| FOUR-HORNED GOAT, DRESDEN | 129 |

| MONKEY HOUSE, BRESLAU | 133[Pg xiv] |

| DUCK-POND, BRESLAU | 137 |

| OSTRICH SHED, KÖNIGSBERG | 143 |

| PELICANS, STUTTGART | 147 |

| BRINDLED GNU, STUTTGART | 149 |

| TOWER AND LAKE, FRANKFORT-ON-MAIN | 153 |

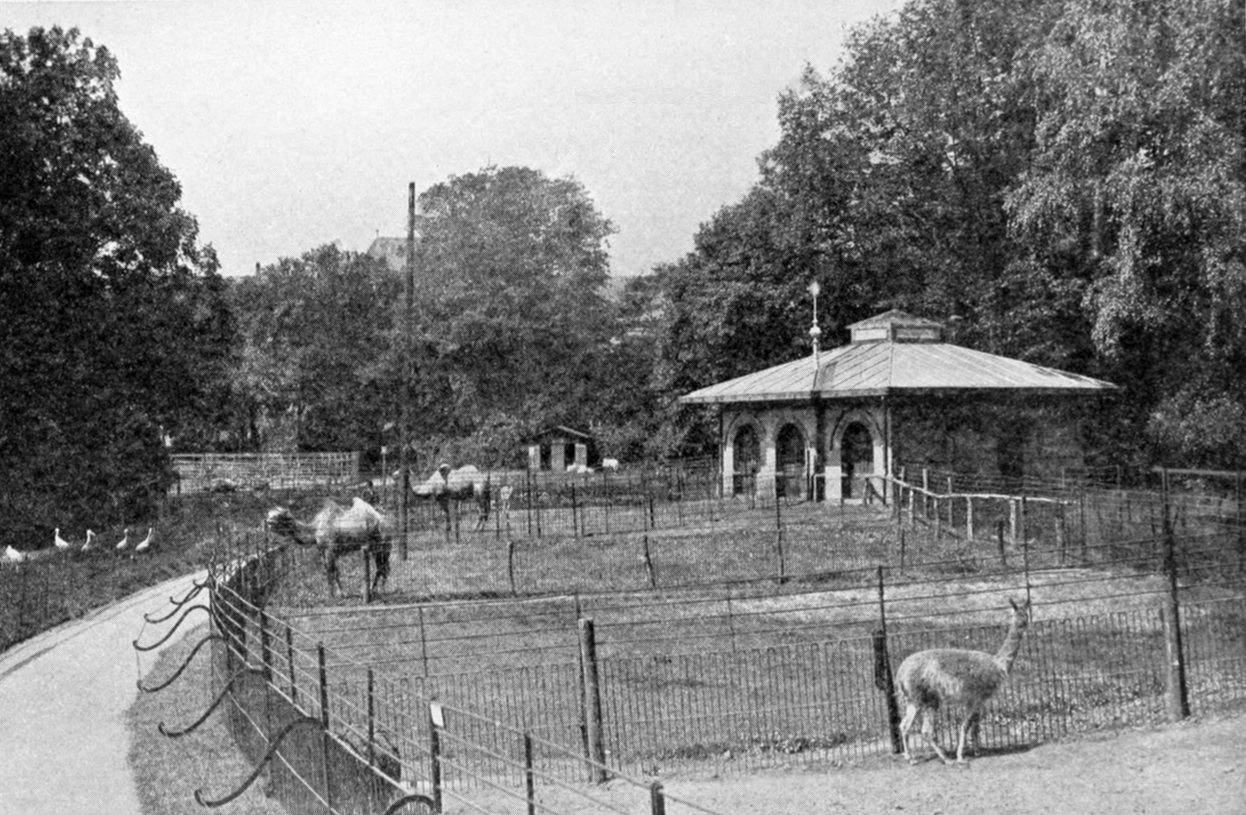

| CAMEL AND LLAMA PENS, FRANKFORT-ON-MAIN | 157 |

| AMERICAN BISON, ST. PETERSBURG | 162 |

| MOOSE YARD, MOSCOW | 165 |

| TOWER, MOSCOW | 167 |

| AVIARY, BASLE | 176 |

| CARIBOU, BASLE | 177 |

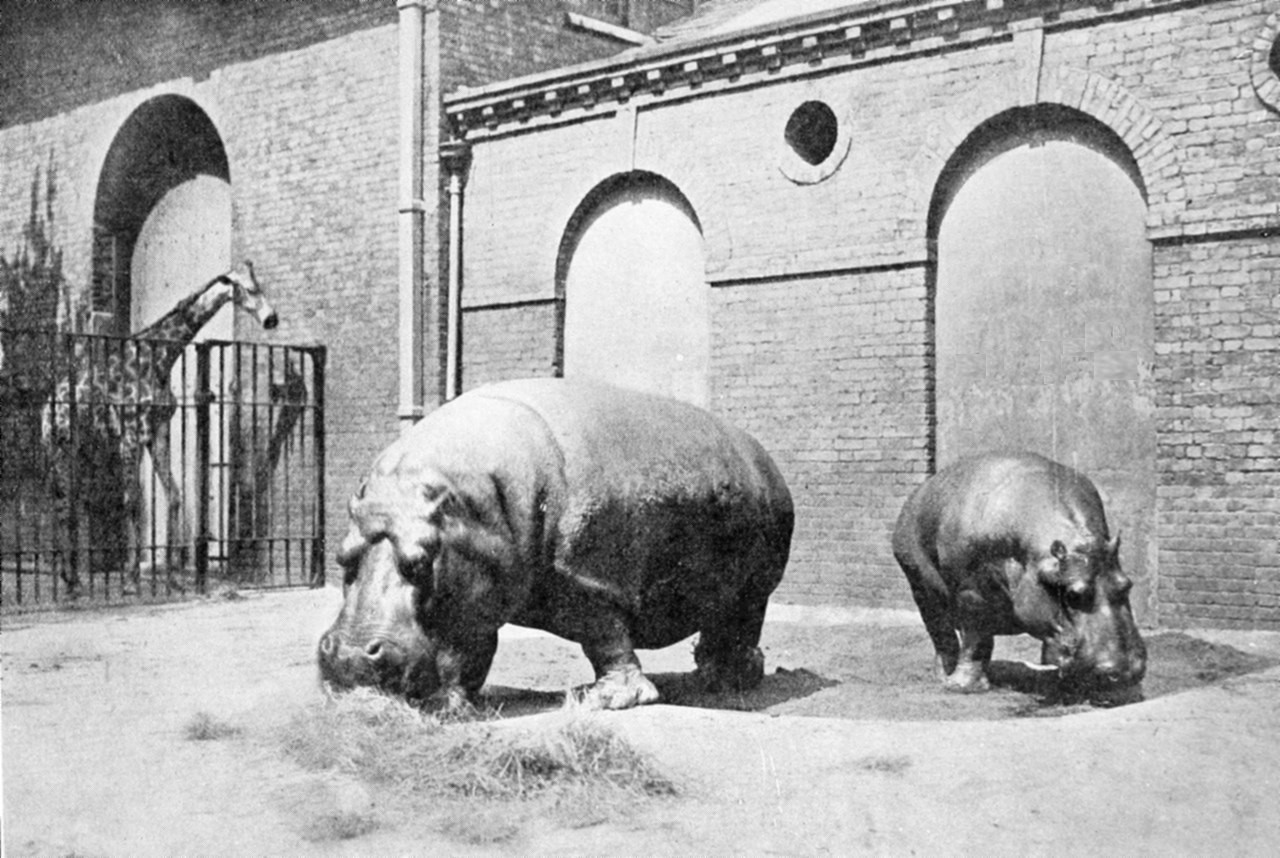

| HIPPOPOTAMI, LONDON | 183 |

| LION, LONDON | 185 |

| GRÉVY’S ZEBRA, LONDON | 189 |

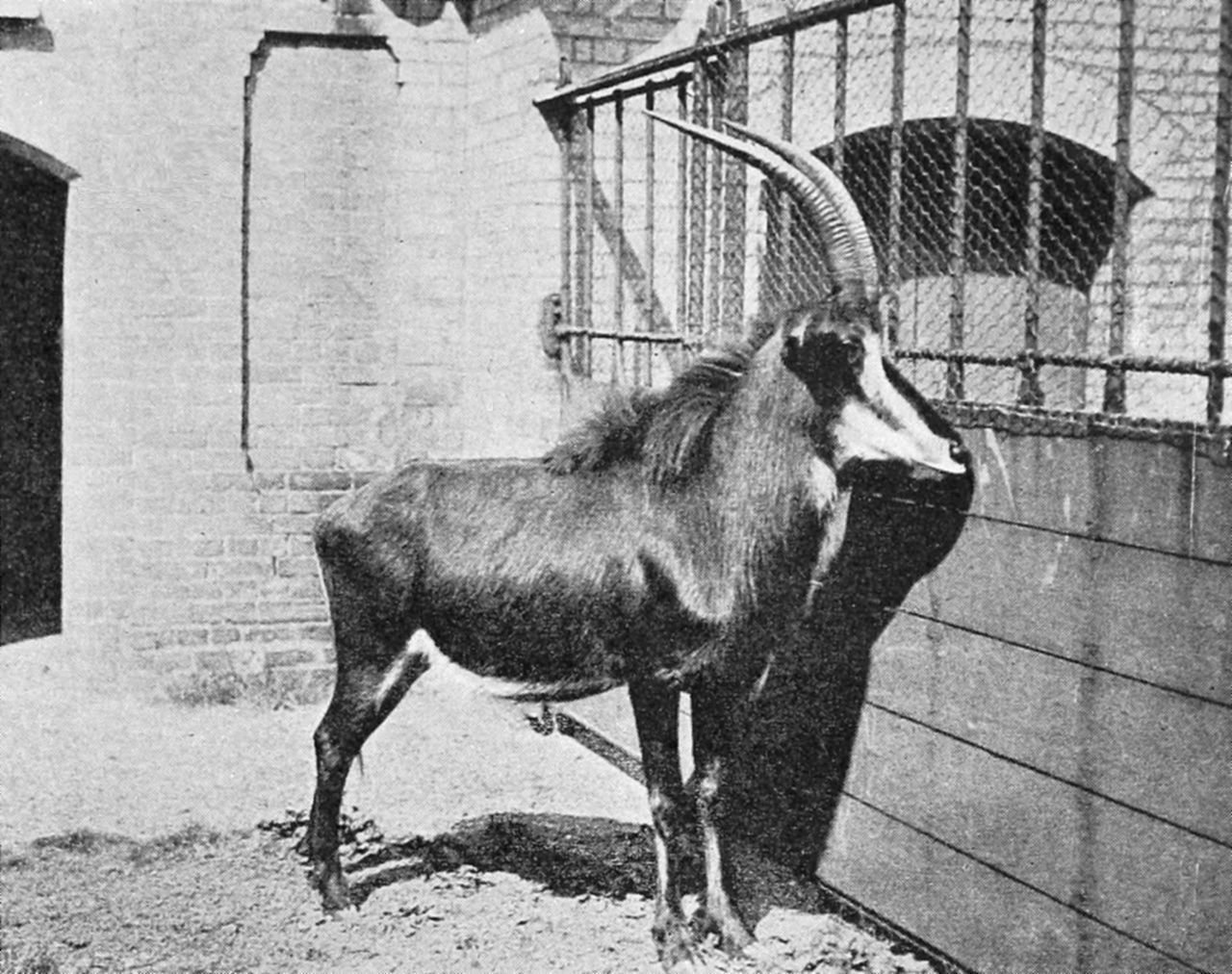

| SABLE ANTELOPE, LONDON | 193 |

| STRIPED HYÆNA, LONDON | 194 |

| GARDEN AND LAKE, CLIFTON | 199 |

| THE BEAR PITS, MANCHESTER | 203 |

| CHIMPANZEE, CONSUL I., MANCHESTER | 207 |

| PHŒNIX PARK, DUBLIN | 215 |

| THE LAKE, DUBLIN | 225 |

| LION CUBS FROM SOMALILAND, DUBLIN | 230 |

| CARL HAGENBECK | 233 |

THE

ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS OF EUROPE

[Pg 1]

JARDIN DES PLANTES, PARIS: DIRECTOR, PROFESSOR MILNE EDWARDS

This Garden, the father of Zoological Gardens, is the oldest of the Zoological Gardens of Europe.

Many of the greatest naturalists have been connected with the Jardin des Plantes, and have studied within its gates.

The botanical portion is more than one hundred years older than the zoological. It was founded in 1626 by Louis XIII., who bought a plot of uncultivated ground in Saint-Victor, twenty-four acres in extent, and laid out a flower-garden and built a little greenhouse upon it. Fagon, the King’s doctor, Gaston of Orleans, Colbert, and Tournefort all helped it along, and caused the Garden to grow in extent and popularity.

A museum of natural history was established, and eleven professors appointed in mineralogy, botany, two courses of zoology, human and animal anatomy, geology, chemistry, etc. A library was formed in[Pg 2] the museum. On the death of the Duc d’Orleans in 1660, Colbert bought for the library the celebrated paintings of flowers on vellum by Robert.

In 1730 the Garden became neglected, but in 1732 M. Buffon became Director, and from that moment success was assured for them. He was well backed by M. Daubenton. Every year the Garden was improved, the old houses were demolished and new ones built. The whole of the ground was put under cultivation. Trees were planted, and the Garden extended to the bank of the Seine. Valuable gifts of plants, minerals and zoological specimens were received from the Academy of Sciences, Comte d’Angevilliers, Chinese missionaries, the King of Poland and M. Bougainville, who brought back from his voyage round the world a magnificent collection of animals and birds. Whilst Director of the Garden, Buffon wrote his chef-d’œuvre—a natural history—and after a splendid career he died in 1788.

Bernardin de Saint-Pierre was the next Director. In 1794 the large and valuable collection of the Palais de Versailles was offered to the Jardin des Plantes, and accepted on its behalf by Bernardin de Saint-Pierre. This collection contained five specimens which had never been seen in Paris before—namely, a quagga, now unhappily extinct, a hartebeest, a crested pigeon from the Isle of Banga, an Indian rhinoceros and a lion from Senegal, which latter had as a companion a dog, with which it lived on terms of the greatest friendship. The remainder of the collection at Versailles had been pillaged by the mob in the French Revolution.

[Pg 3]

In 1796 the Jardin des Plantes received a letter from Captain Baudin asking for a ship and men to convey to France a rich collection of animals and plants which he had gathered together in the island of Trinidad. A vessel was sent out, and, after being shipwrecked on the Canaries, the collection was finally brought home the next year. It was augmented by a collection of birds made by M. le Vaillant in Africa, and a collection brought back from La Guiana by M. Bragton. The Emperor Napoleon added several animals which he bought in England, and among which were a pair of tigers, two lynx, a mandril, a leopard, a hyæna, and a handsome panther, or hunting leopard, besides several birds and plants.

M. Fourcroi, who now made his appearance, collected for the institution animals, birds, precious stones, plants and books from all parts of the world. The collection of minerals of M. Warisse was bought, and 150,000 books were added to the library. The Emperor Napoleon during his wanderings never forgot the museum, and sent back to it fossil-fish from Verona and specimens of rock from the island of Corsica. M. Lesneeur, the painter and historian, and M. Peron brought back from the South 100,000 specimens of animals, large and small, representing many species. They brought home a zebra and a monkey for the Empress Joséphine and plants without number. About this time M. Cuvier, the celebrated naturalist, made his appearance; M. Geoffroy arrived from Lisbon with new animals; M. Michamx brought specimens from the forests of America; and M. Marcel de Serres brought from Italy and Germany all sorts of minerals.

[Pg 4]

Great progress was made in the Jardin des Plantes until 1815, when there came a climax in France. Then commenced a series of miseries and an almost incredible history of disaster. Cossacks, Russians, Germans, and Italians filled Paris, and brought ruin and devastation with them; but, happily, of all the monuments of Paris, the only one which was not insulted was the Jardin des Plantes. The Garden was respected; it was neutral territory, where all sides came to seek rest from war.

In 1820 M. Milbert made large collections of natural history specimens and minerals in America for the Jardin des Plantes. In 1829 M. Victor Jacquemont appeared, and made a name for himself in natural history, but died when quite a young man in the island of Salsette.

In 1841 the Garden contained a zoological museum, a museum of comparative anatomy, a botanical museum, a geological museum and a museum of minerals. Besides a library containing 28,000 books devoted to travel and to physical and natural sciences, such as natural history, botany, physics, chemistry, mineralogy, comparative anatomy, human anatomy and zoology, there were memoirs of learned societies and a collection of paintings on vellum. This library was founded in June, 1793.

In 1841 M. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire was Professor of Zoology, M. Brouguiart Professor of Botany, M. Serres Professor of Anatomy and Physiology, and M. de Mirbel Professor of Agriculture.

During the Siege of Paris in 1870 the Garden suffered terribly. Nearly a hundred shells fell within[Pg 5] its boundaries; most of the glass-houses were battered to ruins, and a great number of the animals were, by the direction of the authorities, handed over to the butchers, killed and sold at fabulous prices. Lion, bear, giraffe and hippopotamus flesh realized 25 francs per pound during the last few months, and was very difficult to obtain even at that price.

This Garden, which runs close by the side of the Seine bank, is open free to the public. It is somewhat of a bewildering place to find one’s way about in. Its collection of animals is very fine, and contains two or three especially good things. There are some pretty spots in it, and plenty of trees and shade. A fine lion house of no less than twenty-two cages contains a good collection of the big cats and bears, a number of the latter coming from Tonquin. Besides these bears, there are others in old but well-built bear-pits in another part of the Garden. Again, we find a pair of hartebeests, so seldom seen in captivity.[A] Deer and antelopes, sheep and goats, are very well represented in the Jardin des Plantes.

I was busily engaged in taking photographs, when I was pounced upon by the inevitable gendarme, and was obliged to ‘box up’ in front of a large and sympathizing crowd. The elephant house contained three Indian elephants and one African, which is the largest to be found in captivity. Unfortunately, he has only stumps of tusks, and is, in consequence, not half such an imposing animal as the magnificent African elephant at Berlin. There was quite a number of zebras, including[Pg 6] a mountain zebra with a foal, born in the Gardens, and a hybrid between a zebra and a kiang (Equus hemionus). There was a good collection of swine, including a Red River hog and an enormous European boar.

There were crowds of people in the Garden, and no wonder, for seldom is such a fine collection of animals to be seen without paying anything.

MARKHOR, JARDIN DES PLANTES, PARIS.

According to the Matin, palatial accommodation is to be provided for the animals in the Jardin des Plantes. The new premises will consist of a series of rotundas, or gigantic cages, 15 metres high, which will be reserved for the pachyderms. A laboratory of animal psychology for the study of character among[Pg 7] the brute beasts is shortly to be opened under the direction of M. Hachet Souplet, assisted by M. Oustallet. It has also been arranged by M. Perrier, a Director of the Gardens, to give popular lectures in the amphitheatre every Sunday afternoon.

[A] A hartebeest has lately been added to the London Zoo.

[Pg 8]

JARDIN D’ACCLIMATATION, PARIS: DIRECTOR, M. A. PORTE

In 1858 a concession of about forty acres was made in the Bois de Boulogne by the city of Paris to five members of the bureau of the Société d’Acclimatation. The Emperor Napoleon III. enlarged upon this concession by a gift of a further ten acres. A subscription was then opened, with a capital of a million francs divided into 4,000 shares, most of which were taken up by the members of the Société d’Acclimatation, who, after having conceived the idea of the Garden, wished to endow it handsomely.

After the preparatory plans had been made by M. Davioud, the resident architect of the city, and approved of by the council of thirty-four of the principal shareholders, the work was begun in July, 1859. The arrangement of the work, under the surveillance of a committee chosen by the members of the council of administration, was entrusted to Mr. D. W. Mitchell, the Secretary of the Zoological Society, London, who had come to offer his services for the creation of the new undertaking. On the sudden death of Mr. Mitchell in November, 1859, the committee took upon themselves the management of the work.

[Pg 9]

In fifteen months the work was finished. On August 1, 1860, Dr. Rufz de Lavison, late President of the General Council of the Martinique, was appointed Director of the Garden, whilst M. Albert Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, the joint Director, busied himself with the hygiene and propagation of the animals. On October 6, 1860, the Emperor inaugurated the new institution in person, and a few days later the public were admitted.

In 1865 Dr. Rufz de Lavison died, and M. Albert Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire was made Director of the Garden.

When the Siege of Paris became imminent, the majority of the animals were deposited in the Zoological Gardens at Brussels; others were confined at Antwerp. The rare birds were sent to Tours; some to M. Barnsby, Director of the Botanical Garden in that city; others to M. Cornély van Heemstra, owner of the Château de Beaujardin. During this sad time an enormous amount of work was done, the animals being transported as quickly as possible. On September 4, 1870, this evacuation began, but it was brought to a stop five days later, as the trains then ceased to run. On the other hand, M. Milne Edwards graciously offered to take into the Jardin des Plantes part of the collection of animals, on condition that they were provided with sufficient food. From that moment, and during the whole of the siege, the Garden, situated as it was outside the fortifications, went well through the sad and sudden changes of fortune.

The famine which ere long besieged the city then[Pg 10] demanded the sacrifice of all the animals. One can imagine what it cost the keepers, who were so attached to the animals they fed, to have to kill the two elephants, Castor and Pollux, the beautiful antelopes, the camels, etc. Nevertheless, when peace came, the animals which returned from the places where they had been deposited were still numerous enough to restock the Garden and put a little life into the place so long deserted.

The collection had scarcely been reinstalled in the Garden when the insurrection of the Commonwealth broke out. This time the Jardin d’Acclimatation was in the very middle of the tempest, and for nearly two months bullets and shells fell night and day in its very midst. The officials remained faithful to their posts, and hid themselves in cellars, from which they emerged when they were able during moments of calm—too short, alas!—to attend to the wants of the animals and plants. In this way, from time to time, they ran the greatest danger. The gate-keeper, Decker, was killed by a bursting shell; the gardener, Loubrieam, succumbed to wounds which he had received; Lemoire, one of the keepers of the animals, and Lombard, the carpenter, were wounded. Troops of regulars and bands of insurgents frequently met in the very heart of the Garden, which was furrowed by trenches and defensive works. The volunteers of the Seine and Oise and the federates fought two serious engagements in it. A number of animals were struck by the bullets, the fences and battlements being pierced by them.

The Jardin d’Acclimatation was very greatly disturbed[Pg 11] by this terrible crisis, and people doubted whether it would ever recover itself.

The Municipal Council and the Ville de Paris happily understood what an interest the Garden had been, and would not allow such an establishment to disappear. They came to the succour of the shareholders by generously voting an annual subscription of 60,000 francs for three years; moreover, the Société d’Acclimatation gave a sum of 35,000 francs and all the animals which it possessed. M. Saint-Hilaire, whose activity and energy had increased in spite of obstacles, received anxious inquiries and marks of sympathy from numerous donors, which hastened the reconstruction of the devastated collections. His Majesty the King of Italy offered two African elephants to replace the two killed during the siege; the venerable M. Westerman, the Director of the Garden at Amsterdam, M. Jacques Vekemans, the learned and sympathetic Director of the Garden at Antwerp, and all the zoological gardens in England and in Belgium added their generous gifts, and contributed largely towards the reinstallation of this beautiful Garden, which had been so cruelly tried. Numerous improvements were voted by the council to suit the requirements of the animals and to please the public. New sheds were built for the goats and sheep, enclosures made for breeding ducks, and a new stable and large dog-kennels were constructed, which were opened shortly afterwards; the dairy service was organized both in the Garden and in the centre of Paris. Depots, where pure milk could be bought, were established at Chevet’s and at the Palais Royal. A building for the[Pg 12] fattening of poultry for the table was given over to a clever breeder of the department of Allier, who brought the whole of his stock-in-trade to the Garden. Animals were lent by several members of the society. In one of the outbuildings of the conservatory a library was opened, where visitors could find natural history works to interest them. Discussions began again, on two days a week—Thursdays and Sundays; concerts, under the direction of M. Mayeur, were held in the afternoons on one of the lawns in the Garden.

At last a new era of prosperity had opened in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne. From the time it was opened to the year 1873 more than 200,000 people had signified by their presence the just popularity which the Garden had acquired.

Besides the Garden in the Bois de Boulogne, the Société d’Acclimatation has other establishments under its control—one at Hyères, one at Chilly-Mazarin, near Paris, one at Pré Catalan, and another at Marseilles, in the South of France.

The Succursale at Hyères is set apart for the cultivation of plants, palms, and trees from hot climates, and these always command a ready sale in Paris for the ornamentation of parks and houses. At Pré Catalan, in well-kept houses, are to be found sixty dairy cows, which are to be seen in summer grazing in the paddocks and fields of the Bois de Boulogne.

At Chilly-Mazarin, on a plot of ground some acres in extent, an overflow establishment was instituted in 1891. Here are to be found dog-kennels, cow-houses, stables, pheasantries, poultry-houses and agricultural products. At Marseilles the Society has[Pg 13] another Zoological Garden, in which imported animals rest and get acclimatized before being sent up to Paris.

SEA-LION SUCKLING ITS YOUNG, JARDIN D’ACCLIMATATION, PARIS.

The Jardin d’Acclimatation is situated in that part of the Bois de Boulogne which extends between the Porte des Sablons and the Porte de Madrid, and runs along the Boulevard Maillot. The principal entrance is in the east, near the Porte des Sablons; a second entrance is to be found in the extreme west, near the Porte de Madrid. You can reach it either by the Central Railway, getting out at Neuilly Station or at the Avenue de l’Imperatrice, or by the Courbevoie and[Pg 14] Suresnes omnibuses, or, of course, by cab. On concert days there is a special service of omnibuses.

Two prominent stone-and-brick buildings will direct the visitor. After having passed the turnstile, you find in front of you a large carriage-drive, which goes right round the Garden, and from this principal artery the whole network of walks and paths runs through the Garden leading to the different sheds and houses. The visitor finds on his immediate left a large conservatory or winter garden, which shelters from the rigour of winter a beautiful and important collection of plants and trees, which would not live in a low temperature.

Almost in front of this large conservatory you see a building, which is intended for the mechanical fattening of fowls (a system not to be encouraged). Here is to be seen on a big scale M. Martin’s system. The fowls are placed in a huge circular cylinder, three metres high and turning on a pivot, which allows the man to cram all the fowls (which are placed in the boxes ranged in tiers one above another) in this fattening apparatus without changing his position. A car on an elevating rail allows the man easily to reach those birds placed on the highest part of the apparatus, for, by turning a handle, the car rises or descends in front of the boxes. Holding them by the head, he introduces an indiarubber tube into their beaks, and forces the food down their throats by pressing with his foot a pedal, which starts a machine worked by a piston. The play of this pedal is regulated by a dial-plate, which shows the operator the amount of food introduced. This varies according to the strength of the bird to be fattened, and also to its state of fatness.[Pg 15] In eighteen days a fowl will go up to more than double its weight, and will be perhaps a pound more at the finish. M. Martin, the inventor of this ingenious system, which allows a man by himself to cram 400 fowls in an hour, had already used it in the department of Allier, at Cusset, near Vichy, and his products, under the name of ‘Phœnix fowls,’ have acquired notoriety. He then asked the Society of the Jardin d’Acclimatation to allow him to construct at his own expense in the Garden a model of his fattening establishment, which he started at his own risk. Visitors can now procure at this establishment fat fowls all ready for the table.

Following on the right a large circular walk, you find, after the fattening establishment, sheds where all kinds of rural and agricultural objects are shown. Here the public can see buildings of every sort applicable to the farm: Swiss cottages made of cut wood, tents, wire-lattices, aviaries, chairs, tables, and garden-seats, elevators, garden-tools, guns and fishing tackle, porcelain and terra-cotta vases—in short, everything which tends to ornament parks and gardens, or to the culture of plants, or the raising of stock. On leaving the exhibition sheds, the first building which catches the eye is the monkey house, in front of the enclosure for storks and river-birds; then you come on the right to the pheasantry, the parrot aviary being attached to a little pheasantry, and on the other side of the way are the ostrich and large-bird enclosures. The large pheasantry follows these, then the upper pheasantry, and next the poultry house, an immense circular monolith building in Coignet mortar, in which there[Pg 16] are also enclosures for different sorts of pigeons. On the left are the enclosures of the sheep and goats. After passing the duck-ponds you reach the kangaroo house, and on the left the cattle enclosures. Here the broad road round the Garden divides itself into two; to the right it leads to the Neuilly Gate and Saint James, to the left to the big stable, before which stands a spacious lawn, where the large ruminants graze during the day. Round this lawn the elephants and horses, with various carriages, carry visitors and children. Continuing to follow the big circular road, you find on the right, a little behind the stables, a collection of vines (the most beautiful and most complete in the world), the bee-house, the dairy, and the refreshment-room; to the left, the huts of the llamas and alpacas, the moufflon rock and the antelope house. Next, you visit the aquarium, situated on the right of the large circular road, and then the experimenting garden and the dog-kennels, which face the deer enclosures. Having returned to the big conservatory close by, you find another conservatory full of paroquets and small cage-birds from hot countries.

The middle of the Garden is cut by an artificial river, upon the banks of which are placed enclosures for geese, ducks, and water-birds. It forms in front of the lawn of the big conservatories a large lake covered with swans, flocks of ducks, some cormorants and seals.

The monkey house is an oblong building 15 metres long and 9 metres broad. The walls are covered with earthenware slabs. In front of the building is an immense cage, where the strongest of the monkeys can[Pg 17] take the air and enjoy themselves on the beams and ropes, which take the place of the trees in their native forests, during the warmest hours of the day. On entering by doors which are arranged to keep out draughts, the interior of the monkey house is found to be a large hall, in which are placed four huge cages reaching almost to the ceiling, and which communicate with the exterior pleasure cage by means of large doors. Against the walls are placed little wooden cages, in which are put those delicate specimens which require special care.

Besides the quarters of the keeper, there is an infirmary for sick monkeys. Heat is supplied in winter by hot-water pipes running under the floor, which keep an even temperature without drying up the air.

Attached to the large conservatories is a spacious hall, the grande salle, measuring 40 metres in length, and being able to accommodate 8,000 people, half of whom can sit down. On the ground-floor, opposite to the entrance-door, is a large stage, upon which lecturers entertain the public several times a week with a magic-lantern, the subjects being Zoology, Ethnology, Travel, Botany, etc. On Sundays and Thursdays a first-class band gives popular concerts, which attract a great number of people to the Garden.

On the west of the hall is an aquarium and a bird-gallery, which were opened to the public at the end of 1892.

To the right of the principal entrance is a room, built in 1887, for the sale of a great variety of vegetables and plants.

Continuing to the right, and passing the exhibition[Pg 18] hall and the shooting and fishing museum, which have been described, we come to the new sale gallery, a large hall 30 metres long, in which are displayed more agricultural implements, carriages, harness, carts, iron rails, wooden fencing, and everything appertaining to the care of animals and plants—all to be sold at very reasonable prices. A catalogue can be obtained free of charge.

Communicating with the new sale hall is a parrot and small bird gallery. Passing the monkey house, we find large wooden constructions, holding the peacocks, the turkeys and fowls of many kinds, such as Houdans, Dorkings, etc. In this part of the Garden are to be found pretty little rustic buildings containing various birds. In one of them are to be seen the great horned owls which belonged to Gustav Doré, the celebrated artist. In another little pavilion is a Norwegian hawk. In an enclosure bordering on the main walk is to be seen a beautiful collection of cranes from all parts of the world. In the same enclosure are the cassowaries, ostriches and the South American rheas, which latter frequently breed in the Garden.

The pheasantries, which contain more than twenty pens, are occupied by such varieties as the Amherst pheasant from Thibet, Elliot’s pheasant from China, the Versicolor from Japan.

We now come to the great aviary, part of which holds the scarlet ibis and the rare stilts, and the other half contains peacocks and large game-birds. In front of the large aviary are the pens of the doves and partridges. Facing the pheasantries is a statue of Daubenton, by Jules Godin Daubenton, who died in[Pg 19] Paris in 1880. It was to the efforts of this scientist that France owes the introduction of merino sheep. This beautiful statue is placed opposite the sheep pens, so that the gentleman can still have his eye on the Ty-ang or Chinese sheep, the grey sheep of Russia, and the Astrakan sheep, which furnishes such a beautiful fur. Not far from here is some rock work executed by M. Teiton, through which runs a little river. Every day at a fixed hour the cormorants are made to fish. The throat of this bird is encircled by a collar, which prevents it from swallowing the fish which it has caught at the bottom of the water. In China these birds are used extensively for fishing.

On the right, following the pheasantries, we come to the poultry house, a monolith building in mortar in a semicircular shape. Here are to be found the following among many other varieties: La Flèche, Mans, Houdan, Bresse, Campine, Dorking, Cochin China, Langshan, Brahma, etc. The eggs form an important article of commerce in the Garden. The pens of the poultry house also contain the largest collection of pigeons ever brought together. Mention must be made of the carrier pigeons, the descendants of those birds which during the Siege of Paris carried no less than 115,000 messages microscopically photographed on bits of collodion which weighed next to nothing.

On the edge of the lake is a large and elegant pigeon tower, made of brick and iron, 30 metres high and 6 metres in diameter, and divided into four stages. The interior is divided into coops for 400 couples of pigeons. The top is reserved for those pigeons which, born in the place, are allowed their liberty, and are[Pg 20] employed in summer to carry messages. The top of the tower is furnished with a meteorological apparatus, which records on registering cylinders (placed at the bottom of the tower) the state of the atmosphere. This apparatus constitutes a veritable observatory in itself. In it there is a barometer, a thermometer, a rain-gauge, a wind-gauge, a hygrometer, and several other instruments.

The kangaroo house next engages our attention, where are to be found examples of the red kangaroo, Bennet’s Wallaby, etc. Many breed here. The enclosures which surround the kangaroos contain many species of deer. There is the deer from the Moluccas, sika deer from Japan, the axis deer from India, etc. Close by are coach-houses and stables capable of holding ninety horses. These recently erected buildings, together with the old stables, can now hold 250 horses, which form a very complete collection. Here are to be seen also an interesting series of ponies from Java, Siam, Cochin China, Shetland, Ireland, Russia, Corsica, Navarre, Finland, etc. There are also many mules.

At the end of the stables is a riding-school for the breaking-in of horses and the teaching of riding. In 1874 a special riding-school was inaugurated for children, their mounts being all little ponies. Close to the stables is a gymnasium, with horizontal bars, trapeze, ropes, etc., which is for the free use of children, who amuse themselves in it whilst they wait their turn to ride the elephants and camels. The charge for a camel or dromedary ride is 50 centimes; elephant ride, 25 centimes; ostrich-cart, 50 centimes; donkey-cart,[Pg 21] trotting zebu-cart, goat-cart, and llama-cart, 25 centimes; saddle-horse, 50 centimes. Tickets are obtained at a kiosk close by.

The African elephant Juliette was a present from Victor Emmanuel, the late King of Italy, together with Romeo, who died in 1886. It will be remembered that these elephants replaced Castor and Pollux, which were sold to the butchers for 27,000 francs during the Siege of Paris in 1870. Close to the large stable is a house containing the yaks from Thibet. The cross between a yak and a zebu is called a ‘dzo.’ In the large stables are to be seen the South American tapirs and the wart hogs from Africa. Burchell’s zebra and a pretty ‘mountain’ zebra are found in the same building. By the side of the zebras are the kiangs from High Asia and Mongolia. There are also many hybrid animals and 100 guinea-pigs in one loose-box. The right side of the big stables is inhabited by a large giraffe; this is the last survivor of a herd received from Abyssinia in 1872, which has bred several times in the Garden.

On the other side of the main road is a large lawn, which serves during the day to pasture the large ruminants. Here are held the yearly exhibitions.

The following exhibitions have been held: In 1877, the Eskimos and Nubians; in 1878, the Laps and Russians; in 1879, the Nubians; in 1883, the Cingalese and Red Indians; in 1886, the Cingalese; in 1887, the Ashantis; in 1888, the Hottentots, Cossacks, and Circassians; in 1889, the Laps and Norwegians; in 1890, the Somalis; in 1891, the Dahomeans.

We next come to the llama house, which includes[Pg 22] specimens of guanaco and vicuna, the llama and alpaca. The reindeer enclosure follows. Behind this, again, are the moufflon and chamois rocks; a grotto cut out of the rock shelters the goats from Chili. Below the rock are lodged the graceful Indian antelopes. Between the rock and the aquarium is a construction with a deep basin, in which live the otters and seals. The otters, which were presented in 1891, are very tame. At the word of command they hop up to the top of a rock and take headers into the water. Opposite the otters’ tank is the cow house, holding forty cows, the little dairy at the side being much frequented during summer, when as many as a thousand glasses of milk are sold in a day. Close by the dairy is a picturesque enclosure of lawn and rockwork, inhabited by a herd of over twenty black buck of all ages. It was an amusing sight to watch them frisking and scampering about after the manner of the springbock of Africa.

The aquarium, situated on the right beyond the dairy, contains ten large tanks of sea-water and four tanks of fresh-water. These basins are made of slate, with one side of glass. They receive light only from above, and in them are to be seen the octopus, shrimps, anemones, soles and plaice. Many of the fish grow tame to a remarkable degree, and know their keeper well.

At the end of the aquarium is the fish-culture pavilion, in which one sees in transparent tanks a very complete collection of fresh-water fish and the most perfect apparatus in connection with fish culture. Every year the establishment incubates a considerable number of salmon spawn. Visitors can follow the operations of artificial fertilization of several species[Pg 23] of trout, including the American rainbow trout. After the aquarium, in front of the concert kiosk, we find the restaurant, where we can have refreshments at fixed prices under large trees.

HERD OF BLACKBUCK, JARDIN D’ACCLIMATATION, PARIS.

Facing the aquarium is a large glass enclosure surrounding the antelope house, in which can be seen the Indian nylgai, which breeds well; the eland, looking amongst the trees as if it was in its native haunts; the gnu, which looks half ox, half horse; the Oryx beisa from Kordofan; a gazelle from the Soudan. And then comes a surprise, for in the same pen with several Patagonian cavies are no less than four hartebeests, one of which was born in the Gardens, August 15, 1901. Next we come to the deer house,[Pg 24] with the wapiti from America, the axis deer from Siam, Père David’s deer, and others.

On the other side of the main drive, and opposite the deer, is a large dog-kennel, containing dogs of every description. Here a large exhibition has been held every year since 1863, and dogs can be bought at fixed prices.

Facing the dog-kennels is a special library, given to the Garden by Dr. W. Evans, of Philadelphia, where are to be found all the papers and publications on agriculture, zoology, travel, domestic economy, etc. In one of the rooms in this building all the Parisian newspapers and magazines are on view.

The pond, which divides the Garden into two nearly equal parts, contains ducks of all kinds, swans, and pelicans. On the left bank of the pond is the concert kiosk, where good concerts are given from April till the end of September by an orchestra of twenty-four performers under M. Mayeur, of the Opéra, who has conducted it since 1872.

Many of the puppies and birds in the Garden are for sale at fixed prices. I quote the following from the catalogue:

| Puppies | |||

| Stud Fee. | (Average). | ||

| Francs. | Francs. | ||

| Great Danes | 50 | 100 | |

| Pomeranians | 10 | 40 | |

| Bull-terriers | 20 | 40 | |

| Basset hounds | 25 | 50 | |

| English setters | 50 | 120 | |

| Red Irish setters | 50 | 100 | |

| Cocker spaniels | 50 | 50 | |

| English greyhounds | 30 | 75 | |

| Bloodhounds | 30 | 60 |

[Pg 25]

Hares (white) old ones: Male, 25 francs; female, 35 francs; young, 15 and 25 francs each.

Rabbits: Adults, 15 francs; young, 10 francs.

Paroquets, from 40 francs to 150 francs.

Parrots, from 10 francs to 75 francs.

Canaries, 17.50 francs.

Toucans, 150 francs.

Ordinary crow (white variety), 20 francs.

Pigeons, from 3 francs to 100 francs.

Wild poultry, from 8.50 to 20 francs.

Turkeys, 30 francs.

Pheasants, from 20 to 150 francs.

Red partridge, 12.50 francs.

Domestic poultry: Bantams, 20 francs; Brahmapootras, 30 francs; Cochins, 30 francs; English gamecocks, 50 francs; Dorkings, 30 francs; Houdans, 15 francs.

Rose-coloured flamingoes, 125 francs.

Ducks, from 15 francs to 75 francs.

Cormorants, 75 francs.

Swans, from 25 francs to 275 francs.

Pelicans, 125 francs.

Domestic ducks: Aylesbury, 17.50 francs; Labrador, 12.50 francs; Rouen, 20 francs; Yeddo, 30 francs.

Loch Leven trout, rainbow trout, salmon, etc., are for sale.

This is a very large and beautifully laid out Garden, and I was allowed to photograph in peace, though, oddly enough, I had no sooner got outside the wood than I was pounced upon by a gendarme and asked to explain the contents of ‘that box.’

[Pg 26]

THE ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS, MARSEILLES

These Gardens, which are worked under the control and direction of the Jardin d’Acclimatation at Paris, contain a collection of both useful and wild animals, many of which are bought and sold here. The Gardens also serve as a resting-place for the animals which the Jardin d’Acclimatation imports from the far East and exports to the hot regions by the Mediterranean. The animals remain and get acclimatized before they are sent on further north to Paris.

Shrubs and plants are also grown, and by their situation behind the Palais de Longchamp the Gardens constitute one of the most attractive promenades in Marseilles.

One of the entrances to the Gardens is through a most magnificent set of buildings, having a large cascade of water in front. This imposing building is called the Palais de Longchamp, and contains an art museum and picture-gallery. On passing through the gate, and going up two flights of steps, you come into a large garden above, and, keeping to the right, you fall in with the pay-gate to the Zoological Gardens.

It must, however, be borne in mind that the quickest[Pg 27] way to reach the Zoological Gardens is by an ever-ascending electric tram-car, which finally lands you right in front of the ordinary entrance-gate. On arrival there, you put a franc into a sort of missionary-box made of tin, and are ushered through into the Gardens by the gate-keeper. You are at once confronted with a pretty little grotto arrangement, down the rockwork of which trickles a waterfall. In the basin at the foot of the fall are a number of flamingoes wading about and feeding.

LE PALAIS LONGCHAMP, MUSÉE DES BEAUX-ARTS, MARSEILLES.

The Gardens will be found to lie upon a steep hillside, upon which walks and terraces are cut one above another. On the second terrace you find a grotto, with another waterfall higher than the one below. This grotto is extremely picturesque, the situation of the Garden on the hillside lending itself well to this form of garden decoration. Here, at the foot of the[Pg 28] second grotto, are to be seen some white swans with black necks, and some pretty black ducks with dark-green heads. It was a cold February day when I visited the Gardens, but, to show how early is the breeding season in the South of France, I may say that the ducks were already beginning to pair.

On the right the visitor will come upon three cleverly-constructed cages of a circular shape, backed with rockwork. In this rockwork are the sleeping apartments of the animals in the cages. These sleeping apartments have doors communicating with the outer cages, so that when rain or wind comes the animals can find shelter. The cages have been cleverly thought out, and are extremely picturesque.

The inmates of the first cage were two lionesses. I wished to get close to the bars in order to obtain a photograph of these big cats without showing the iron bars, but as a man was intently watching my proceedings, I thought it best not to venture over the barrier. I was unable to make out whether he was one of the keepers or perchance a French officer, and could not make up my mind whether I would offer him a franc to let me go closer or not.

In the next circular cage was a most amusing polar bear. His keeper happened to come along, and he dropped some large pieces of bread into the water-tank for him, but, strange to say, the bear would not go in after them. However, after vainly endeavouring to reach them with his outstretched paw, he made a spring, and stood crossways over the tank, with his fore-paws on one side and his hind-paws on the other, where he stood like a white stone bridge stretched[Pg 29] over a river, and, bending down his head between his fore-paws, he seized each bit of bread in his mouth and tossed it on to dry land; then, springing back, he devoured it greedily. When he had finished every bit, he came to the front of the cage within a few feet of me, and obligingly sat up to be photographed.

Next to the bear were a pair of extremely handsome leopards in very good coat. They growled and snarled and showed their teeth at one another, and pretended to fight, but in reality this was only their rough-and-tumble way of flirting with each other. After all, are not some human beings just the same?

Further to the left you find a picturesque little pagoda for the elephant, with a space railed off in front in which he can take air and exercise and have a cooling bath in the deep water-tank.

Crossing a bridge over the street below, we come to a long viaduct, under each arch of which is an enclosure for birds or animals. On the extreme right was a moufflon, which also obligingly stood up with its fore-legs on the rail in front of it in order to have its picture taken. This animal’s legs were somewhat deformed, and stretched outwards from the knee, giving it the appearance of being knock-kneed. Next to the moufflon, under the second arch of the viaduct, were a camel and a zebu housed together. On the left of them was a pair of nylgai (Indian antelopes), male and female, which appeared to be in the very best of health and condition; but I should say they could not have been long in the Gardens, as they were so wild, and whenever I moved the male raced about its enclosure, whilst the female retired into its shelter-shed,[Pg 30] unlike the very docile pair in the London Zoological Gardens, which will feed from your hand. By the side of the nylgai, but separated by a wire fence, raced up and down a fine Barbary sheep, whilst his wife and child lay down close by taking things easily.

The next enclosure contained a very pretty sight—a red-deer stag, hind, and calf making a very picturesque group when standing up together. Under the remaining arches were enclosed some large birds of prey. Just opposite the arches on a bank is an enclosure where was to be found a pure white llama, with its baby, a youngster about six days old. Another Eastern pagoda and railed-off enclosure contained a very fine Bactrian camel. There were many smaller mammals, such as coatis, lemurs from Madagascar, wolves, jackals, a European wild-boar, etc., besides many enclosures of birds, including a pheasantry, tenanted for the most part by domestic fowls, peacocks, French partridges and an occasional golden and Lady Amherst pheasant. In one pen you will notice French partridges running with a Lady Amherst pheasant.

There is a small monkey house with outdoor cages, furnished with wooden railings for the amusement of the inmates. These outdoor cages are connected with the interior cages by little square doors.

I must not forget to mention a large brown bear in a very picturesque bear pit made of rockwork, with a front of stout iron bars.

One of the inmates of a row of sheds devoted to small animals was a caracul, or African lynx, in very good coat and condition. When in Somaliland, North-east[Pg 31] Africa, in 1897, I captured one of these beautiful cats in the mountains, but unfortunately it escaped two days afterwards. The face of this animal is very like that of the American puma, whilst its ears are long and very pointed, and are furnished with tufts of black hair at the tips.

The second day I visited these Gardens it snowed, and the light was so bad that I did not attempt to take any photographs. As on my approach I found nobody at the entrance-gate, I walked in. Apparently there is no fixed charge, but a man usually jingles a tin box before you, and you can put what you like into it. I saw the Marseilles Gardens under the most unfavourable circumstances; still, on the finest day I do not think anyone would be very much impressed by them. The laying out of the Gardens on a bank is pretty, and the rockwork and the waterfalls very picturesque, but the show of animals and birds, on the whole, is small and somewhat poor.

I had a short talk with one of the keepers, a stern man with a gloomy countenance and few words. I did not gather much information concerning the Gardens, but I raised one laugh out of him when, wishing to know when the animals were fed, I asked: ‘A quelle heure est la table d’hôte des animaux?’

[Pg 32]

THE ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS, NICE-CIMIEZ: DIRECTRESS, THE COMTESSE DE LAGRANGE

These prettily situated Gardens are well worth a visit, if only for the magnificent views obtainable from them. They can be reached from Nice by excellent electric tram-cars having first and second class compartments. (Why are tram-cars so very much better abroad than in England?) Close by the Gardens is the fine Excelsior Regina Hotel, where our late Queen Victoria used to stay. The rooms in the hotel should be visited on the way back from the Gardens; an excellent lunch can be had there, for the cooking is truly first-rate.

The Zoological Gardens were founded by the late Comte de Lagrange, a great traveller and naturalist, who died in 1893 at Singapore, at the early age of thirty-six. His widow, the Comtesse de Lagrange, is now sole proprietress and directress.

The entrance fee is one franc, and one franc for a carriage; the latter fee can be saved by alighting at the entrance and simply walking in on foot.

The Gardens are of small extent, and the whole of the animals and birds can be seen in a very short time.

[Pg 33]

As at Marseilles, I experienced the most shocking weather at Cimiez, and the first day not a ray of sun shone, whilst a shower of rain almost gutted my camera. There is a nice collection of lions at this Zoo, and they form quite the greatest attraction of the place. The old mother, which is to be seen in a cage close by a large tiger, has produced three litters of young, all of which are now to be seen in the Gardens. The father of these lions died at the age of seventeen. The children of this pair comprise two lions three and a half years old, three lions two and a half years old, and three lions fourteen months old. All these eight animals are extraordinarily tame and healthy-looking. I was enabled to stand right up against the cages, without the slightest fear of getting mauled, in order to photograph them. One of the oldest lions allowed me to stroke him; and when I put my face up against the bars, he at once licked it with his rough tongue—a perfect feline kiss. I was perfectly charmed with these lions, and was quite loth to leave them. In another set of cages was a common leopard, and the invariably savage black variety, with its beautiful yellow eyes and snarling jaws. It is a curious fact that these black leopards are nearly always savage. There were two brown bears and a polar bear in pits opposite the young lions, and a poor old brown bear, totally blind, in a pit by himself. There was a very handsome old ‘black buck’ from India, with a younger one much lighter in colour. It was comical to watch them at play, butting at each other with their horns. It is often extremely difficult to photograph these creatures in confinement, because they are so tame. This sounds[Pg 34] odd, but the difficulty lies in the fact that the animals, expecting to be fed, will insist on coming close up to you to the bars, and utterly refuse to go away, in spite of shouts, hisses, showers of stones, and prods with umbrellas. One cannot go back one’s self with the camera, or the bars or wire-netting will show in the photograph, and look unsightly. Oddly enough, the bars or wire-netting do not show in the photograph when the camera is held close up against them.

An ostrich and its baby could be seen near a rather mangy duck-pond. There were also some monkeys, animals I am not fond of; they are too much like human beings. But one of them was amusing. When a man said ‘Salût’ to him, he saluted in proper military fashion; but if a woman asked him to do so, he would do nothing of the sort, but would snarl and show every symptom of anger and annoyance. He was, like some really good military men, a true woman-hater and despiser.

On the second day I visited the Cimiez Zoo I was more lucky in the weather, for it was a lovely sunny day. On the way there I was obliged to run the gauntlet of scores of masqueraders, as the Nice carnival was on. They threw hard pellets of clay with great force into my face, and I can assure the reader they hurt considerably. Nearly every other person I met wore a wire mask to protect himself from these attacks. At length the very excellent electric tram was reached, which soon brings one up to the Zoo. The head keeper, Andruetto François, is a very genial and chatty man, and helped me a great deal in taking photographs of all the lions, of which he seemed[Pg 35] immensely fond and proud. I took him in the lion’s den, and a very pretty picture of a fine lion in the act of kissing him was unfortunately spoilt in the developing.

At the back of the lion-cages was a side-show, given by Richard List from Hamburg, who performed twice daily with a ‘happy family’ of lions, tigers, leopards, bears, monkeys, dogs, etc. Close by were a pair of extremely pretty white goats, a rather mangy camel, a bull zebu or Indian sacred bull, some eagles, and a picturesque duck-pond.

The Gardens certainly looked better bathed in sunshine, and the view of the Alpes Maritimes seen from them was superb.

[Pg 36]

ROYAL ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS OF THE SOCIETY OF ZOOLOGY, ‘NATURA ARTIS MAGISTRA,’ AMSTERDAM: DIRECTOR, DR. C. KERBERT

The Zoological Gardens at Amsterdam are the third oldest institution of their kind in Europe, the Jardin des Plantes coming first, and the London Zoological Gardens second. Besides the Gardens of the Society of Zoology, ‘Natura artis magistra,’ Amsterdam possesses a large Aquarium, a Zoological Museum, and a Scientific Library of Natural History.

Encouraged by the success of the Zoological Gardens in London, M. G. F. Westerman of Amsterdam conceived the idea of founding a similar institution in his native town. However, his initial efforts in 1836 failed. At length an opportunity presented itself. M. R. Draak, a great student of natural history, who possessed an important private collection of stuffed birds, fishes, etc., valued at 8,000 francs at least, wished to transfer them into more spacious quarters. In order to achieve this, he sought the assistance of M. Westerman, known throughout Europe for his interest in natural history. He, on his part, always ready to assist anyone fond of natural history, succeeded in obtaining a site in 1837, and built and[Pg 37] arranged a natural history museum upon it. It was opened to the public for a small entrance fee the same year. In spite of great efforts, the enterprise flourished but little; but, aided by two friends, M. Westerman bought other large buildings, and laid out some beautiful gardens, which he thought would be more attractive to the visitors. When in possession of these gardens, the proprietors tried to give more force to their enterprise by addressing the following circular to the inhabitants of Amsterdam:

CONCERT-HOUSE AND LAKE, AMSTERDAM.

‘Natura Artis Magistra

‘A society has been formed under this title, having for its object the study of natural history in an agreeable[Pg 38] and attractive form, not only by exhibiting stuffed animals, but also by a collection of living animals and birds.’

In a very short time 120 persons, whose numbers quickly rose to 400, gave their services and help to the enterprise, and were inscribed as members of the Society, paying an annual subscription.

Encouraged by this first success, the Council decided to negotiate for a loan, with part of which a convenient site was arranged to receive the collections of M. R. Draak. Gradually the number of members of the Society rose, and in 1839, with the authority of the general assembly, the menagerie of C. van Ascen, at that time well known, was bought. Bitter disappointment was, however, caused when the Council, who had asked permission of the municipal authorities to build further houses on their grounds for the animals of the above-mentioned menagerie, were given permission, but on such bad terms that their request was to all intents and purposes met by a refusal. With much regret, the Society was therefore obliged to lodge the animals provisionally in some barrack-stables.

However, little by little other buildings were acquired, with large gardens, and the collection of living animals and objects for the museum was enriched both by generous gifts and by purchases.

In 1840 the Society numbered 700 members, and in 1841 the number rose to 1,000. The members then agreed to pay double the former subscription—i.e., twenty francs. The grounds had now increased to the extent of three and a quarter acres. In 1843 M. Westerman,[Pg 39] at the request of the Council of Administration, was put at the head of the Society, and accepted the entire control of it, which, in spite of his age, he continued to hold until his death.

In May, 1850, the Gardens occupied nearly five acres, and in the same year the Council instituted attractive concerts twice a week. In April, 1852, His Majesty the King paid a visit to the Gardens, with which he was much pleased. He presented them with his portrait, and gave the Society the name of ‘The Royal Zoological Society.’ In 1877 the last enlargement of the premises was completed. The Society, after many futile efforts, succeeded in obtaining from the Municipal Council a piece of land, on condition that the Society should erect on the site a large building, to be utilized as an aquarium, and that superior instruction in Zoology should be given to the University of the town, partly at the Society’s expense. In all, the extent of the Gardens was increased to more than twenty-five acres, for which 463,369 francs were paid.

In 1888, the year in which the Society held its fiftieth anniversary, there were in the Gardens 378 animals of 141 different kinds, 2,009 birds of 462 different kinds, and 77 reptiles of 28 kinds.

The aquarium, opened in 1882, consists of a large and small hall, in which are three big reservoirs containing sea water and fresh, pumped in by machinery after having been well filtered. In the large hall will be found sea-water tanks, the two fresh-water tanks being in the small hall. There is a very rich collection of fish in them from all parts of the world,[Pg 40] and many others have been bred there. Besides contributing to the enjoyment of the public, this aquarium is greatly used for research work and the study of anatomy. Here Dr. Kerbert discovered the hitherto unknown fish parasite, Chromatophagus parasiticus. This aquarium is justly considered one of the most important institutions of its kind in Europe. For the study of ethnography a large museum has been built, in which is housed a fine collection of objects appertaining to that subject. Another spacious room was built during recent years for the rich collection of skeletons which the Society possessed, containing the celebrated collections of G. and E. Vrolik and the skeletons of animals which have died in the Gardens. The total number of skulls and skeletons reaches 1,500, and they are exhibited on long shelves.

After the aquarium had been opened, three rooms were reserved for the collection of Crustacea, Molluscs, Echinides, Zoophytes, and Polyparies, with the famous collection of sponges, which is unsurpassed in any other museum. The total number of objects kept in these three rooms is 5,976. In this part of the museum is to be found a valuable collection of marine animals, brought from the Arctic regions by M. Barents and M. Varna. During the last three years a collection of local animals has been commenced. In the second room of the museum you find not only a collection of stuffed animals and birds, with their eggs and nests, but also a collection of indigenous shells, fish, reptiles and the lower animals. The insects are lodged in three cabinets—one for the indigenous butterflies and moths, one for the exotic lepidoptera,[Pg 41] and one for the coleoptera or beetles, arranged in 920 drawers.

The scientific library is very rich in works on natural history; amongst other volumes is to be seen a complete edition of the works of Gould, the celebrated ornithologist. The library contains 5,131 books. There are in the museum upwards of 975 stuffed animals and 3,478 birds. The collection of shells is the most beautiful and most important which exists.

After the death of M. Westerman in 1890, the directorship of the Society was conferred upon Dr. C. Kerbert, who was formerly conservator of the aquarium.

The fee for admission to these large Gardens is one gulden. There are no less than fifty different houses or pens, besides the aquarium (one of the finest in Europe), and four museums.

Turning to the left after paying at the turnstile, one sees the llama pens, containing specimens of the huanaco, the vicuna and the alpaca; near them are two camels of different kinds. Close by is a pretty little deer shed, one of the inmates of which is a very fine example of Père David’s deer from Manchuria. The insect house is next encountered, with a good collection of living caterpillars and chrysalides in glass-cases. Some specimens of the atlas moth and common swallow-tail butterfly had just emerged (May 2). Passing through a door, the visitor comes to a reptile house, well lighted and heated. Here are to be seen some very fine examples of pythons from Java, boa-constrictors and other large snakes, tortoises, lizards, alligators and a Temminck’s snapper. In the centre[Pg 42] of this room are three specimens of the curious Surinam sloth (Cholopus didactylus), hanging from horizontal bars by large curved claws. Passing through a door, you find yourself in the parrot house, which is well filled with the brilliant-coloured noisy birds. Here, also, was the magnificent bird of paradise from New Guinea, and the curious wingless kiwi from New Zealand. A monkey house, well stocked, is next passed, and we then come to the large duck-pond, simply teeming with mute swans, wild swans, black swans, bernacle and Canadian geese, gannets, gadwalls, sheldrake, mallard, wigeon, teal, pintail and flamingoes. We next see a very fine pair of American bison, and two young ones born in the Gardens. The crane and wading-bird pens are close at hand, one large pen containing an extraordinary number of coots, rails and oyster-catchers, all looking the picture of health. There is a long, well-lighted lion house, built in 1859, containing twelve cages inhabited by a pair of lions from Somaliland, a pair of tigers from Delhi, some leopards and jaguars, and a pair of pumas, with their young born in the Gardens.

We now come to the elephant house, built in 1897, in which are housed four Indian elephants and a tapir. In the antelope house, which stands near, are a fine pair of elands in a large roomy paddock, water-buck, a harnessed antelope and its baby, a brindled gnu, an oryx, and the rare inyala. Next, we find a very fine collection of birds of prey, including a beautiful specimen of the Bateleur eagle from Africa.

We now come to the ethnological or anthropological museum, built in 1888, containing native armour,[Pg 43] weapons, dress, etc., from all parts of the world, and many draped waxen figures (life-size) of Chinese and Japanese. Behind this museum are some black-and-white yaks from Thibet, and several zebras from India. Further on is the skeleton museum, and after that we come to a hippopotamus house, containing two specimens of this huge pachyderm. They are very well housed, having, besides their large bathing-tanks inside, an outdoor playground and water-tank. Passing through a large conservatory, full of trees and plants, we come to an extremely picturesque seal grotto, and close by a deer shed.

YAK, AMSTERDAM.

The aquarium is reached next, for admission to which an extra charge of fifty cents is made. This[Pg 44] building, erected in 1882, is well worth a visit. Its tanks contain, amongst many others, specimens of coal-fish, sea-anemones, huge cod, conger-eel, crabs, lobsters, plaice, lump-sucker, skate, dog-fish, cat-fish, stickleback, king-crab (very curious), barnacles, newts, gold-fish, pike, barbel, roach, some magnificent trout, carp, perch, American trout and a salamander. In the aquarium is a large museum of preserved natural history objects, mostly fish, shells and reptiles.

After leaving the aquarium, we encounter large pheasantries and peacock houses, wild-sheep pens, ibis pens and a pigeon house, from which the birds have free exit. A third museum is found to be full of stuffed birds, eggs, and nests; some of the birds stuffed in their natural surroundings are very beautifully done. The zoological library adjoins. A fourth museum, built in 1894, contains a large collection of stuffed animals and a collection of shells. Here is a huge skeleton of an African elephant, with good tusks, and a stuffed giraffe; a whole unmounted hippopotamus skin, and a stuffed quagga, now extinct.

Close by this museum are some pens containing zebras and wild asses. The new bear house, built in 1897, contains a fine collection. A large house, built like a fortress, containing wolves, hyænas and jackals, is close at hand.

Dr. C. Kerbert very kindly sent me a volume of many hundred pages, containing the names of all the specimens in the gardens, aquarium, and museums; but in a work of this size it would be utterly impossible to give the names of even one-quarter of the treasures that are contained in these most remarkable Gardens.

[Pg 45]

THE GARDENS OF THE ROYAL ZOOLOGICAL AND BOTANICAL SOCIETY, THE HAGUE (S’GRAVENAGE): DIRECTOR, DR. DIETZ

These Gardens were opened in 1863.

In 1902 many alterations and repairs were done to the concert-house, the stage, and the aquarium. The museum and the library were enlarged. Important restorations were made in one of the old pheasant houses and in the crane house.

In 1902 the following creatures were in the Gardens: 126 animals of 36 species; 767 birds of 220 species. The income of 1900 was £4,751; of 1901, £4,184.

The Zoological Gardens at ‘den Haag’ are very different from those at Amsterdam. On paying half a gulden at the entrance, we first come upon a pen occupied by a pair of peacocks. Close by is a guinea-pig and Dutch rabbit house, and then we reach an extremely rude Indian elephant, which throws sand at us. This animal is found in a house built in the Eastern style, with minarets, and has an open-air paddock. There is rather a nice aviary, containing parrots (some of which speak English as well as[Pg 46] Dutch), jays and many other birds. Above the aviary is a museum.

Next we come to a funny little Himalayan bear, and a monkey house, with large open-air cages for summer use. After passing through some greenhouses full of plants and ferns, we find a nice collection of pheasants from Germany, China, New Guinea, the Himalayas, and Japan. These birds are housed in two long lines of pens, separated from each other by a greenhouse. In the centre of the Gardens, near a pond, is to be found a deer pen. On the back of one of the deer a jackdaw was perched, but unluckily he flew off before I could obtain a photograph of this somewhat unusual sight. Crows and jackdaws are often to be seen upon the backs of cows and sheep, but one would have imagined that a deer was too timid an animal to allow a large bird to perch upon it.

In the Gardens is a fine concert-hall; and here I may remark that in nearly all foreign Zoological Gardens there is such a music-hall, which on concert nights is packed to overflowing, adding largely to the revenue of the Gardens. It has always been a puzzle to me why our Council in London do not try to attract more people by the erection of such a hall and the engagement of the best artistes. An outdoor band appears to be the only attraction of the kind in our Gardens at home, such a thing as an evening concert being almost unheard of.

Close by the concert-hall is a reindeer shed, a llama paddock, a bear pit, and a very tame collie dog kept in a cage as a rarity. Close to a duck-pond containing[Pg 47] sheldrake, wigeon, pochard and swans, there is a pen containing a kangaroo and young, some more llamas, and some zebus.

Taken as a whole, these Gardens are neither pretty nor rich in animals, and are, in consequence, perhaps scarcely worth a visit.

[Pg 48]

THE ZOOLOGICAL GARDENS, ROTTERDAM DIRECTOR, DR. BÜTTIKOFER

The idea of having a Zoological Garden in Rotterdam owes its origin to three amateur zoologists. One of these enthusiasts, a station-master on the Holland Railway, took a small plot of land on lease, and started a collection of animals and birds. Some years after a number of wealthy citizens subscribed 300,000 guilders, with which they bought thirty-four acres of land, half of which they laid out as a garden, where they built several houses for animals and birds. May 1, 1857, is to be considered the date of the foundation of these Gardens.

In 1863 the remaining ground was laid out and added to the Gardens. The director, Mr. P. H. Martin, originally a renowned lion-tamer, who had been in office since the foundation of the Gardens, resigned, and Mr. A. A. van Bemmelen succeeded him.

At frequent intervals additions were made to the number of buildings, including a large plant house 170 feet long, costing 45,000 guilders.

In 1874 a 5 per cent. loan of 500,000 guilders was contracted, and about twenty-five acres of land bought at a cost of 230,000 guilders. A splendid[Pg 49] casino was built on the newly acquired land, containing a restaurant, reading-rooms and a museum, at a cost of 325,000 guilders. In 1878 an officials’ dwelling-house and a house for succulent plants were erected.

In 1882 the loan alluded to above was converted into a 4 per cent. one of 600,000 guilders. Large aviaries were erected in 1883 and 1885, and the ‘Victoria’ house for stove-plants in 1886. Other houses followed in 1889 and 1891. The year 1893 brought the conversion of the former loan into a 3½ per cent. mortgage loan of 1,000,000 guilders, the issue of new shares to the amount of 700,000 guilders, and the paying-off of the old shares.

In 1895 a handsome new house for the carnivores was completed at a cost of 82,000 guilders. This house measures about 200 feet in length. In January, 1897, Mr. van Bemmelen died suddenly, after having been in office thirty-four years; and in May of the same year Dr. J. Büttikofer was appointed his successor. The fortieth anniversary of the founding of the Gardens was celebrated by a grand fête.

During the following years many more new buildings were erected, and the borders of some of the ponds were lined with an edging of concrete reaching for some feet down into the water, which proved successful in putting a stop to the devastations by rats.

The Gardens are planted chiefly with elms, but besides these trees there are numerous poplars, chestnuts, planes, limes, ashes, maples, oaks, willows, birches, alders, thorns, etc. Conifers are few in number, as the soil does not suit them, but holly and box grow well enough.

[Pg 50]

A good amount of bedding-out is done; for summer planting alone more than 4,500 plants are used annually. The houses contain collections of orchids, palms, tree and other ferns (the tallest Balantium antarcticum in Europe is said to be there), agaves, azaleas, and various other stove and greenhouse plants. One house has been set apart chiefly for tropical economic plants.

The collection of animals numbers actually 394 mammals of 127 species, of which there are no less than 91 apes of 29 species, and 154 ungulates of 46 species.

There are 1,406 birds of 360 species, 94 reptiles of 24 species, and 39 amphibia of 3 species.

The management of the affairs of the Society is entrusted to a board of twenty-five shareholders, with president, vice-president, hon. secretary, and hon. treasurer included.

Out of these twenty-five members different committees are formed, who have the supervision respectively of: (1) The collection of animals; (2) the garden and plants; (3) the buildings; (4) the clubhouse, concerts, etc.; (5) the library and the museum. All these gentlemen render their services gratuitously.

Holders of original tickets have the right of free admission to the Gardens. Members who are residents of Rotterdam pay thirty guilders a year, with an entrance fee of ten guilders. They have free access with their families to the Gardens. There are in all 5,837 members at the present day. The admission for visitors is one-half guilder, children half-price.

[Pg 51]

HERD OF WATERBUCK.

JAPANESE DEER.

KANGAROOS.

BRINDLED GNU.[Pg 52]

During the summer season about thirty-five evening[Pg 53] and thirteen morning concerts are given. On the Queen’s birthday there is an additional display of fireworks.