*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY FOR READY REFERENCE, VOLUME 6 ***

[Transcriber's Notes: These modifications are intended to provide

continuity of the text for ease of searching and reading.

1. To avoid breaks in the narrative, page numbers (shown in curly

brackets "{1234}") are usually placed between paragraphs. In this

case the page number is preceded and followed by an empty line.

To remove page numbers use the Regular Expression:

"^{[0-9]+}" to "" (empty string)

2. If a paragraph is exceptionally long, the page number is

placed at the nearest sentence break on its own line, but

without surrounding empty lines.

3. Blocks of unrelated text are moved to a nearby break

between subjects.

5. Use of em dashes and other means of space saving are

replaced with spaces and newlines.

6. Subjects are arranged thusly:

---------------------------------

MAIN SUBJECT TITLE IN UPPER CASE

Subheading one.

Subheading two.

Subject text.

See CROSS REFERENCE ONE.

See Also CROSS REFERENCE TWO.

John Smith,

External Citation Title,

Chapter 3, page 89.

---------------------------------

Main titles are at the left margin, in all upper case

(as in the original) and are preceded by an empty line.

Subheadings (if any) are indented three spaces and

immediately follow the main title.

Text of the article (if any) follows the list of subtitles

(if any) and is preceded with an empty line and indented

three spaces.

References to other articles in this work are in all upper

case (as in the original) and indented six spaces. They

usually begin with "See", "Also" or "Also in".

Citations of works outside this book are indented six spaces

and in italics (as in the original). The bibliography in

Volume 1, APPENDIX F on page xxi provides additional details,

including URLs of available internet versions.

----------Subject: Start--------

----------Subject: End----------

indicates the start/end of a group of subheadings or other

large block.

To search for words separated by an unknown number of other

characters, use this Regular Expression to find the words

"first" and "second" separated by between 1 and 100 characters:

"first.{1,100}second"

A list of all words used in this work is found at the end of

this file as an aid for finding words with unusual spellings

that are archaic, contain non-Latin letters, or are spelled

differently by various authors. Search for:

"Word List: Start".

I use these free search tools:

Notepad++ -- https://notepad-plus-plus.org

Agent Ransack or FileLocator Pro -- https://www.mythicsoft.com

Several tables are best viewed using a fixed spacing font such

Courier New.

End Transcriber's Notes.]

----------------------------------

Spine

|

|

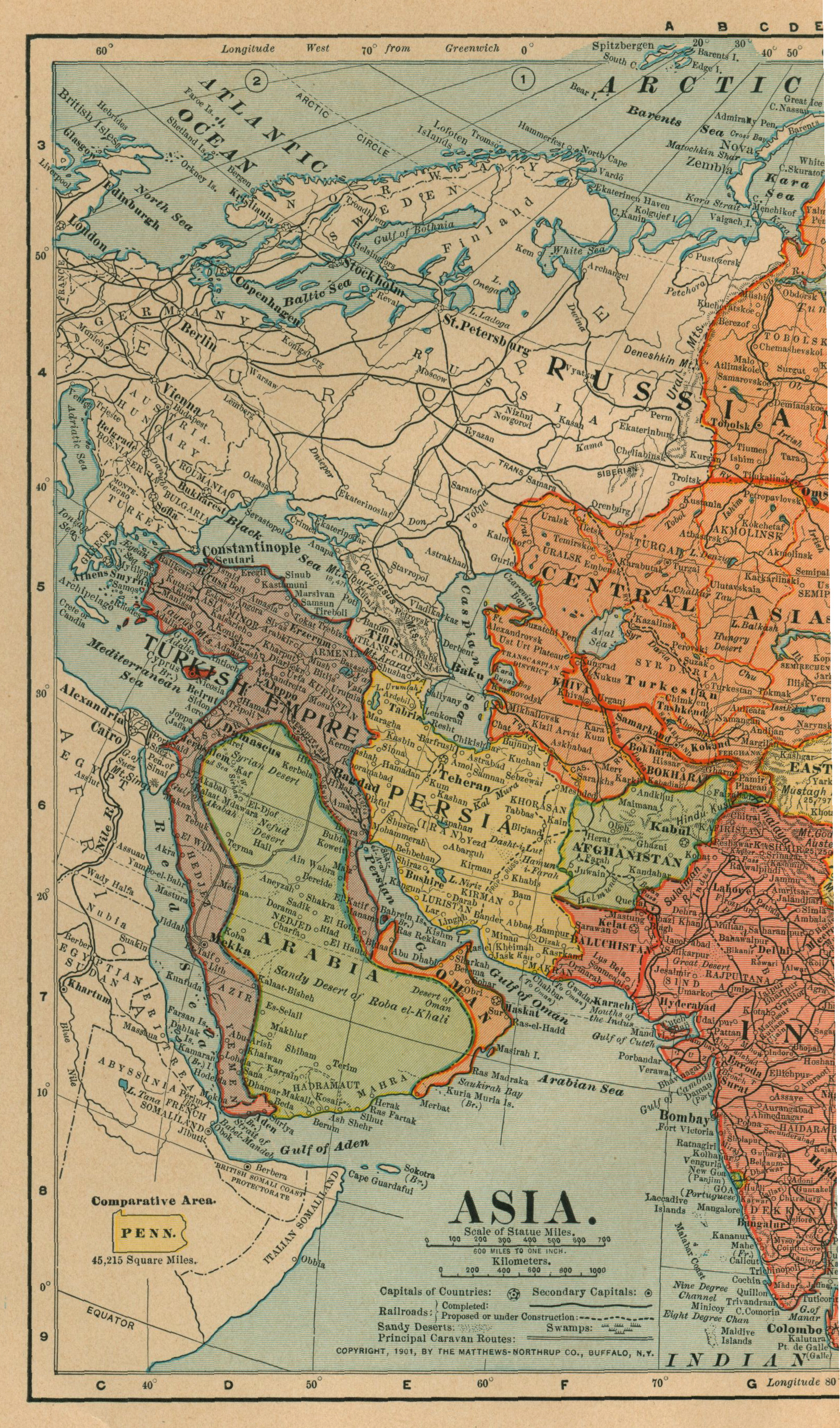

Map of Asia

HISTORY FOR READY REFERENCE.

FROM THE BEST HISTORIANS, BIOGRAPHERS, AND SPECIALISTS

THEIR OWN WORDS IN A COMPLETE SYSTEM OF HISTORY

FOR ALL USES, EXTENDING TO ALL COUNTRIES AND SUBJECTS,

AND REPRESENTING FOR BOTH READERS AND STUDENTS THE BETTER

AND NEWER LITERATURE OF HISTORY IN THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE

BY

J. N. LARNED

WITH NUMEROUS HISTORICAL MAPS FROM ORIGINAL

STUDIES AND DRAWINGS BY

ALAN O. REILEY

REVISED AND ENLARGED EDITION

IN SIX VOLUMES

VOLUME VI—RECENT HISTORY

1894-5 TO 1901

A to Z

SPRINGFIELD, MASS.

THE C. A. NICHOLS CO., PUBLISHERS

COPYRIGHT, 1901,

BY J. N. LARNED.

The Riverside Press,

Cambridge, Massachusetts, U. S. A.

Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

PREFACE TO THE SIXTH VOLUME.

The six years that have passed since the original five volumes

of this compilation were published, in 1894-5, have been

filled with events so remarkable and changes so revolutionary

in political and social conditions that the work has seemed to

need an extension to cover them. The wish for such an

extension, expressed by many people, led to the preparation of

a new volume, in which all the lines of the historical record

are taken from the points at which they were dropped in the

early volumes, and are carried to the end of the Nineteenth

Century, and beyond it, into the opening months of the present

year.

In plan and arrangement this additional volume is uniform with

the preceding ones; but the material used in it is different

from that dealt with before, and a quite different character

is given consequently to the book. The former compilation

represented closet-studies of History—perspective views of a

past more or less remote from those who depicted it. This one,

on the contrary, exhibits History in the making,—the day by

day evolution of events and changes as they passed under the

hands and before the eyes and were recorded by the pens of the

actual makers and witnesses of them. If there is crudeness in the

story thus constructed, there is life in it, to quite make good

the lack of literary finish; and the volume is expected to

prove as interesting and as useful as its predecessors. It

sets forth, with the fulness which their present-day interest

demands, all the circumstances that led to the

Spanish-American war; the unforeseen sequences of that war, in

the Philippine Islands, in Cuba, in Porto Rico, and in

American politics; the whole controversy of Great Britain with

the South African Boers and the resulting war; the shameful

dealings of western nations with China, during late years,

which provoked the outbreak of barbaric hostility to

foreigners, and the dreadful experiences of the siege and

relief of Peking; the strange Dreyfus agitations in France;

the threatening race-conflicts in Austria; the change of

sovereign in England; the Peace Conference at The Hague and

its results; the federation of the Australian colonies; the

development of industrial combinations or trusts in the United

States; the archæological discoveries of late years in the

East, and the more notable triumphs of achievement in the

scientific world. On these and other occurrences of the period

surveyed, the record of fact is quoted from sources the most

responsible and authentic now available, and always with the

endeavor to present both sides of controverted matters with

strict impartiality.

For purposes of reference and study, a large number of

important documents—laws, treaties, new constitutions of

government, and other state papers—are given in full, and, in

most instances, from officially printed texts.

BUFFALO, NEW YORK; May, 1901.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

I am indebted to the following named authors, editors, and

publishers, for permission kindly given me to quote from books

and periodicals, all of which are duly referred to in

connection with the passages severally borrowed from them:

The manager of The American Catholic Quarterly Review;

the editor of The American Journal of Archæology;

the editor of The American Monthly Review of Reviews;

General Thomas F. Anderson;

Messrs. D. Appleton & Company;

Messrs. Wm. Blackwood's Sons (Blackwood's Magazine);

Mr. Andrew Carnegie;

Messrs. Chapman & Hall (The Fortnightly Review);

Mr. Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain);

Hon. W. Bourke Cockran;

the editor of The Contemporary Review;

Prof. John Franklin Crowell;

the G. W. Dillingham Company;

Messrs. Dodd, Mead & Company;

Messrs. Doubleday, Page & Company;

The Ecumenical Conference on Foreign Missions;

Mr. J. Foreman;

The Forum Publishing Company;

Harper & Brothers (Harper's Magazine);

Mr. Howard C. Hillegas;

Prof. H. V. Hilprecht;

Hon. Frederick W. Holls;

Messrs. Houghton, Mifflin & Company (The Atlantic Monthly);

Mr. George Iles;

the editor of The Independent;

Prof. John H. Latané;

Messrs. Longmans, Green & Company (The Edinburgh Review);

Mr. Charles F. Lummis;

Messrs. McClure, Philips & Company (The Popular Science Monthly);

Messrs. MacMillan & Company (London);

The New Amsterdam Book Company;

the editor of The Nineteenth Century Review;

the editor of The North American Review;

the editors of The Outlook;

the managing editor of The Political Science Quarterly;

Mr. Edward Porritt;

Messrs. G. P. Putnam's Sons;

Messrs. Charles Scribner's Sons;

George M. Sternberg, Surgeon-General, U. S. A.;

The Frederick A. Stokes Company;

the managing editor of The Sunday School Times;

Prof. F. W. Taussig;

Prof. Elihu Thomson;

the manager of The Times, London;

The University Press, Cambridge;

Mr. Herbert Welsh; the editors of The Yale Review.

My acknowledgments are likewise due to the Hon. D. S.

Alexander, Representative in Congress, and to many officials

at Washington, for courteous assistance in procuring

publications of the national government for my use.

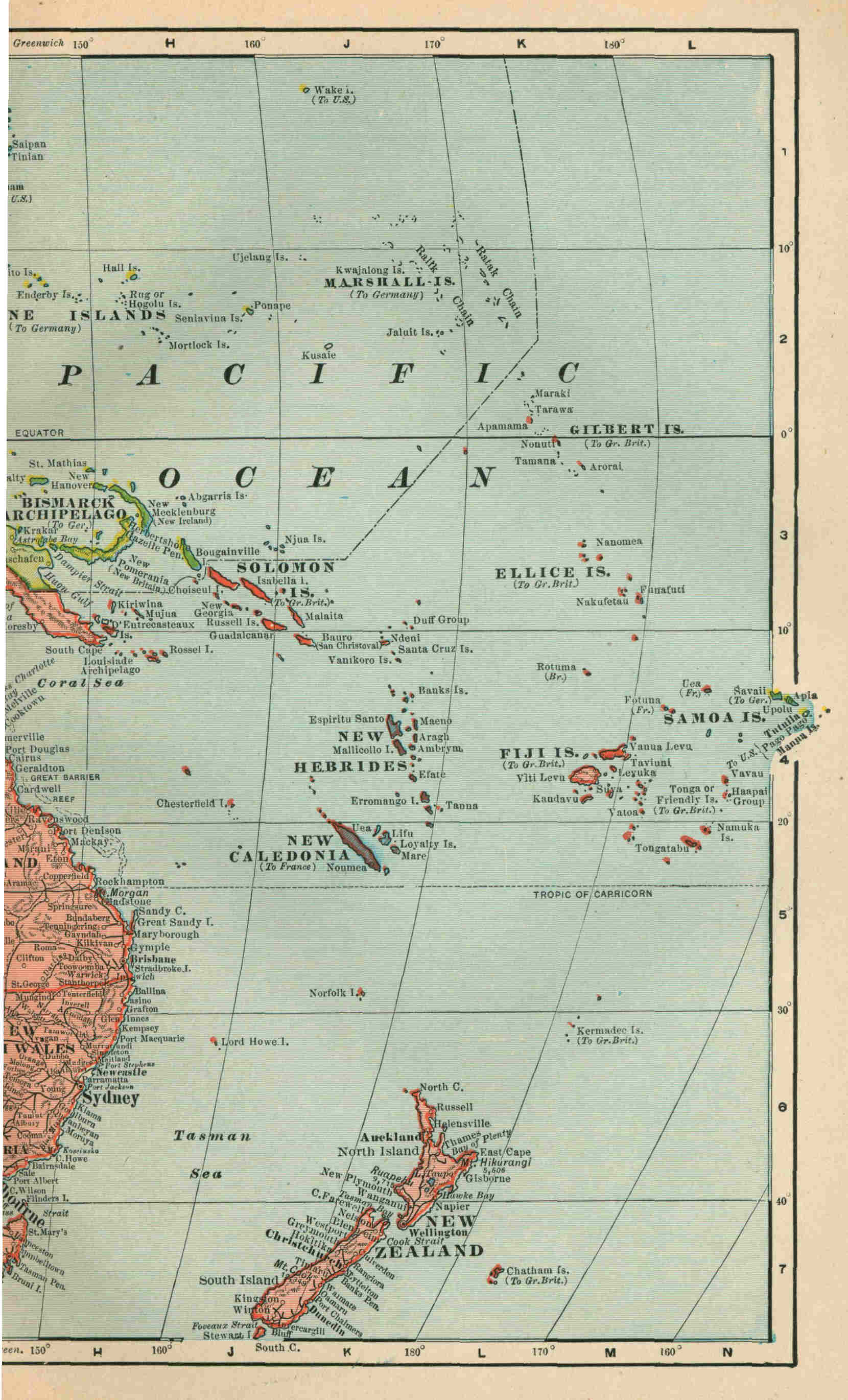

LIST OF MAPS.

Map of Asia, Preceding the title page

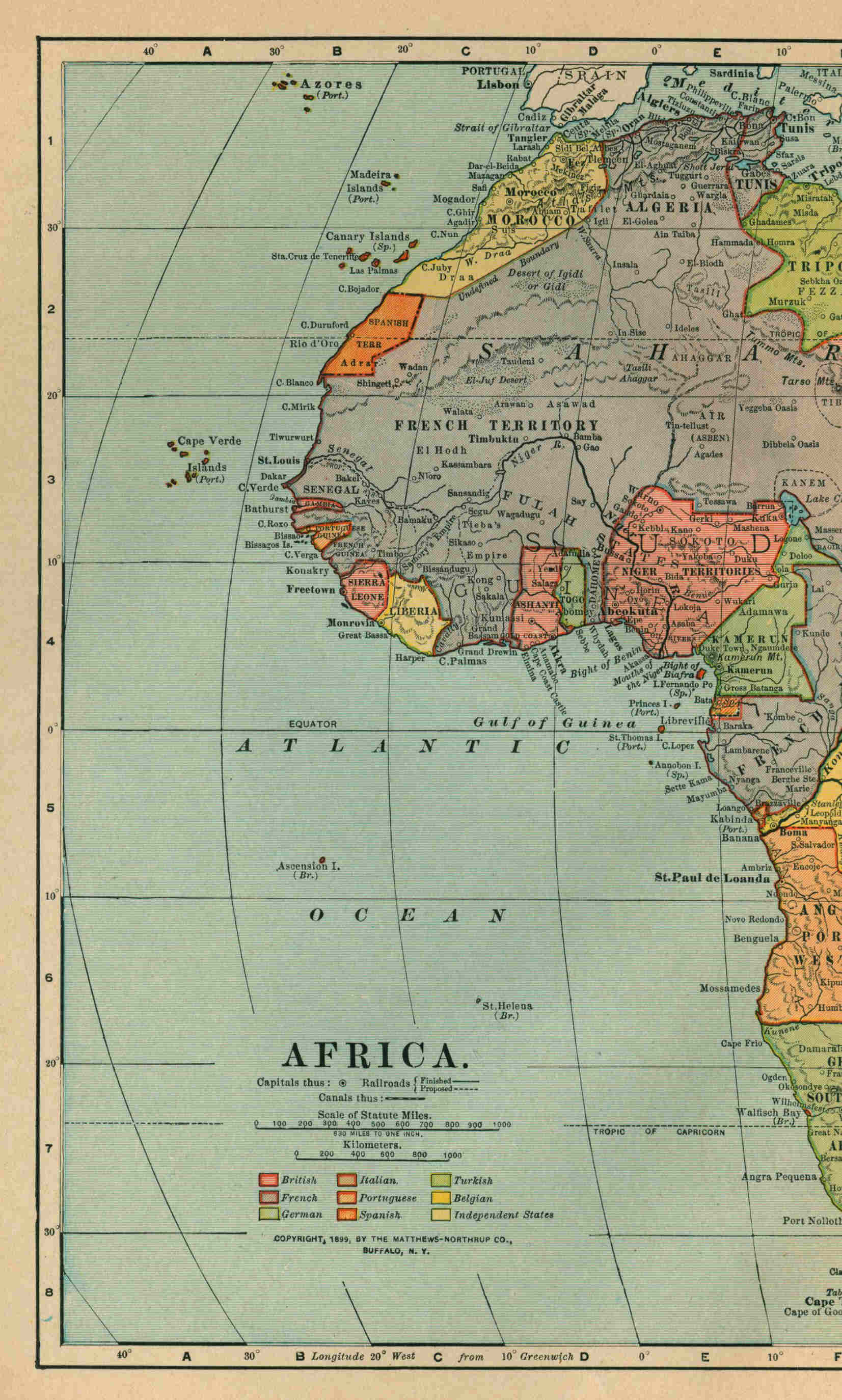

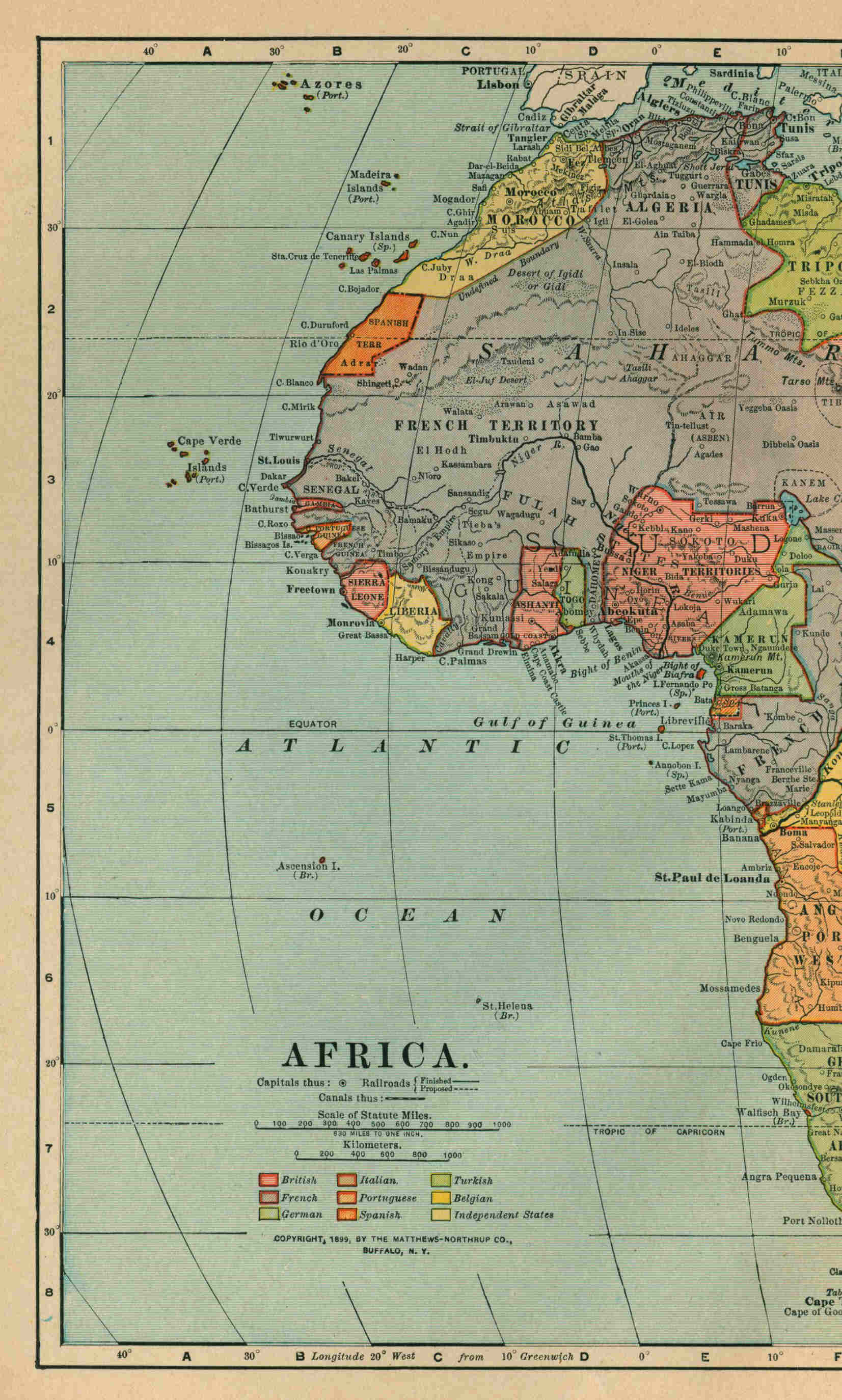

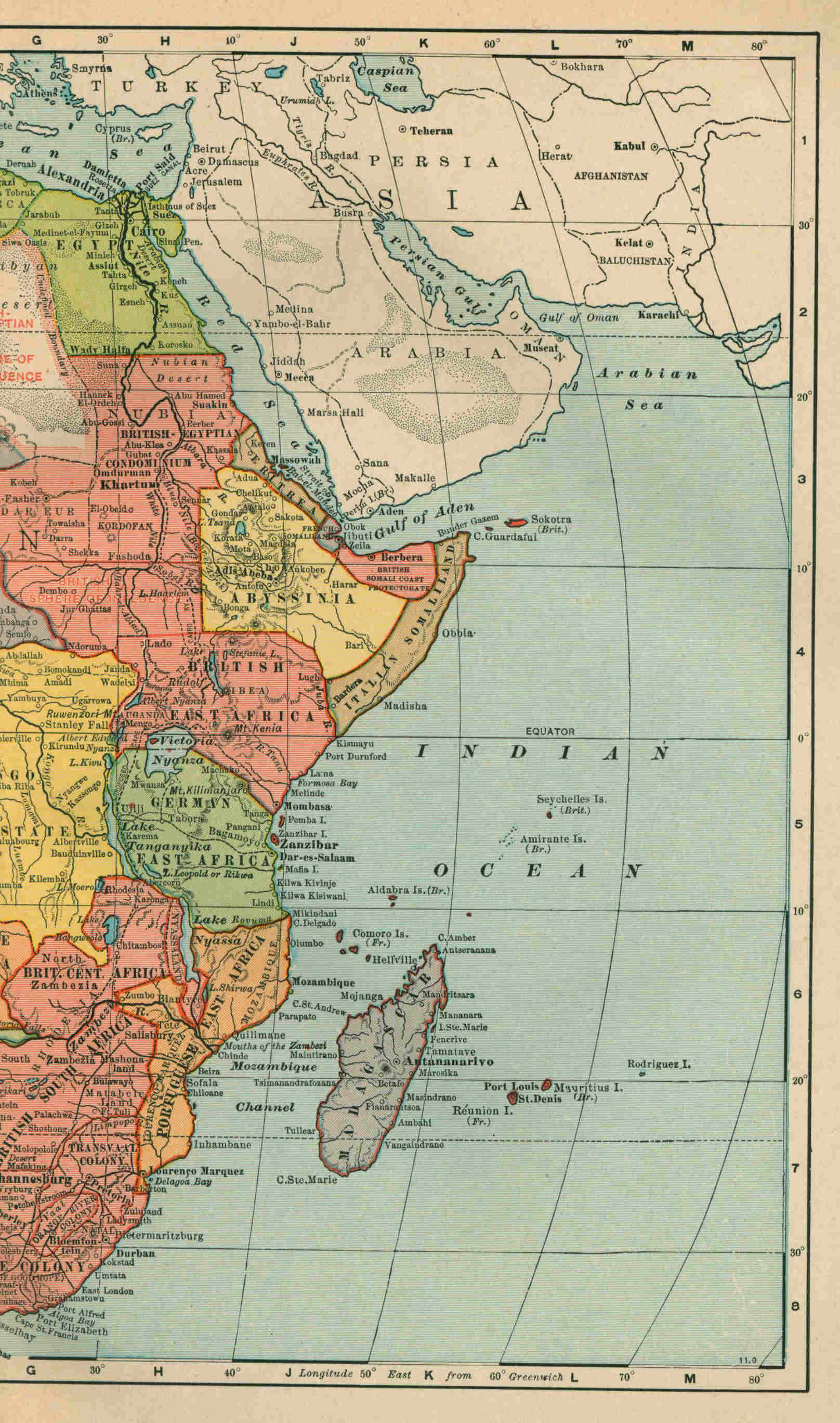

Map of Africa, Following page 2

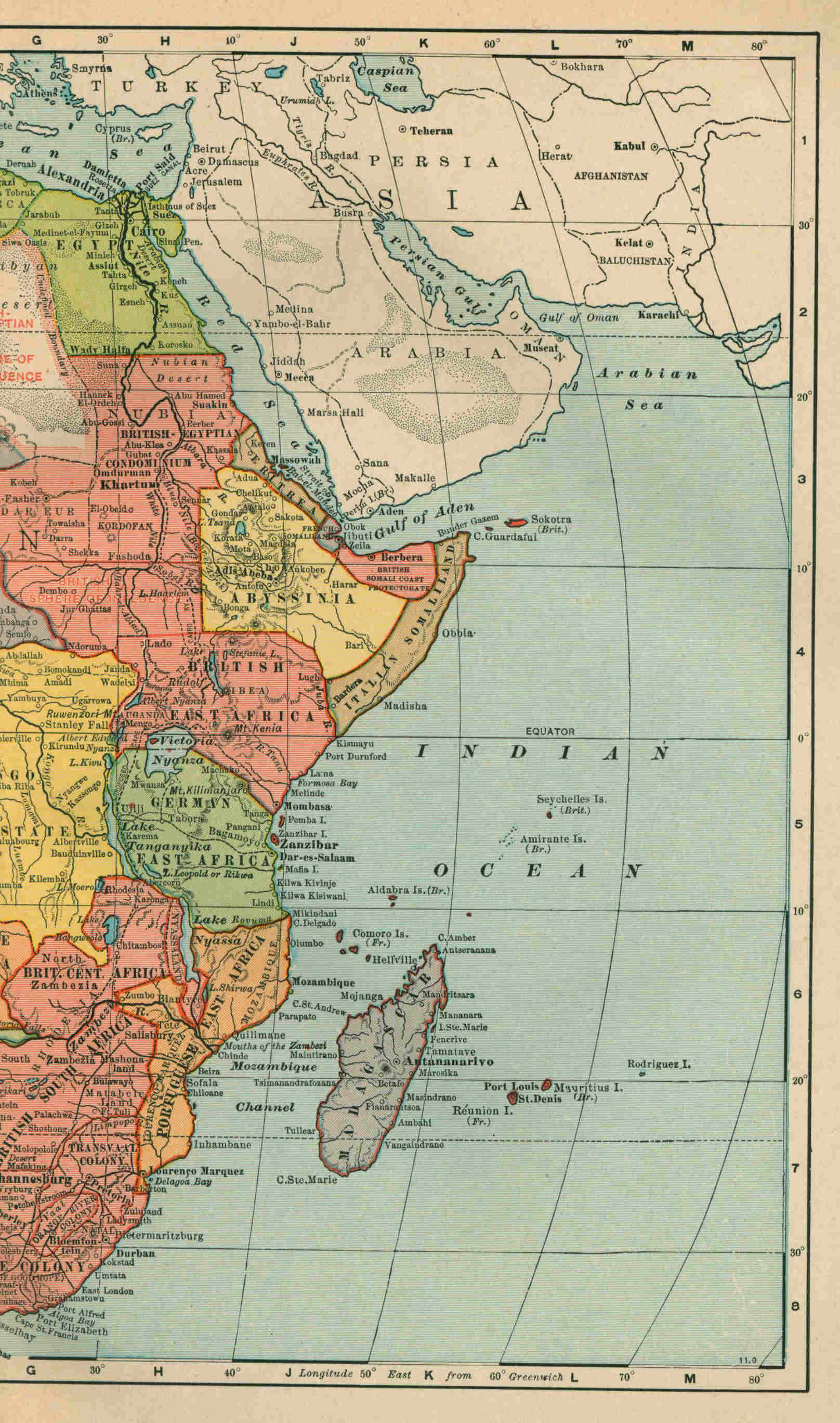

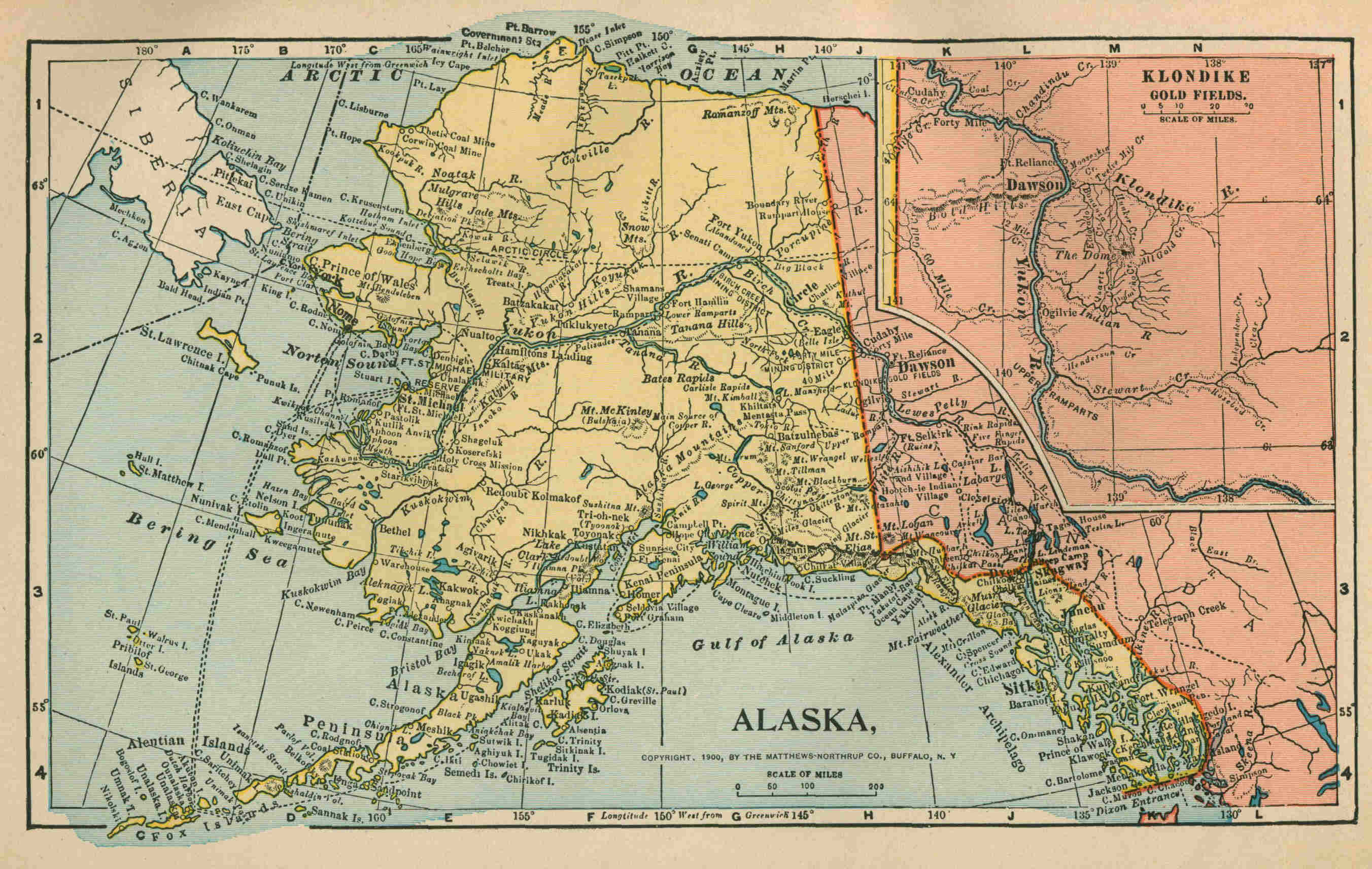

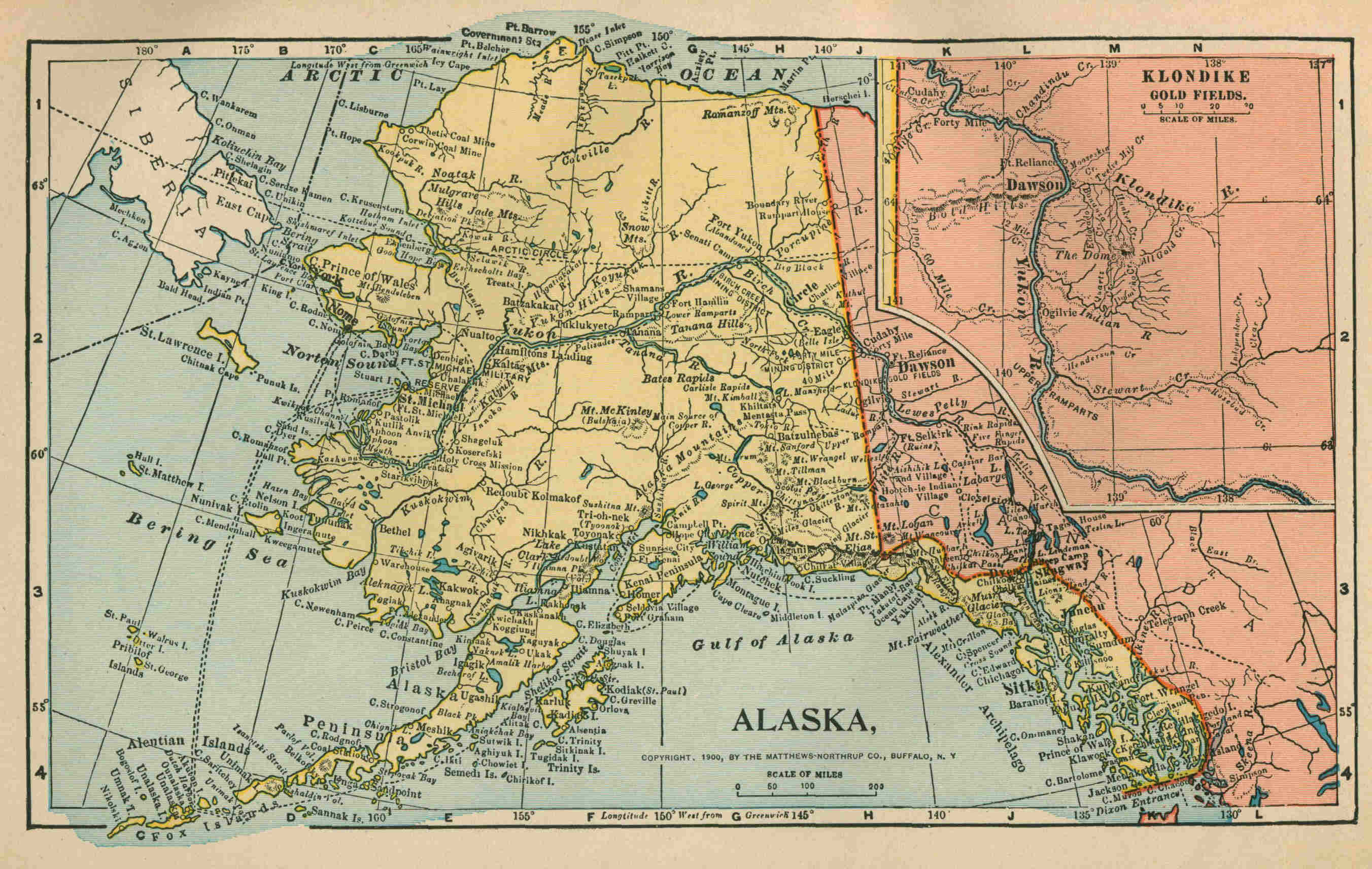

Map of Alaska, Following page 8

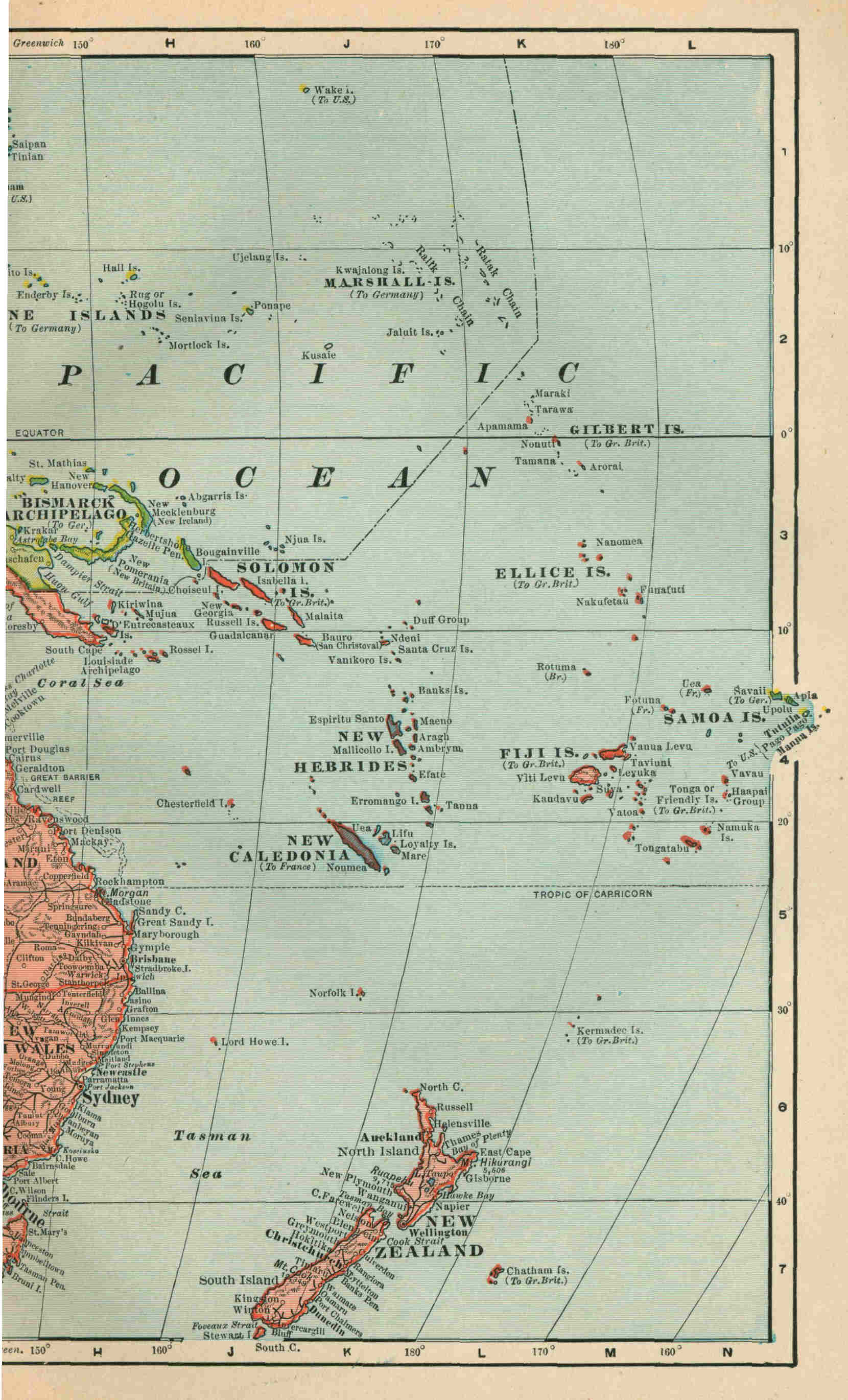

Map of Australia, Following page 30

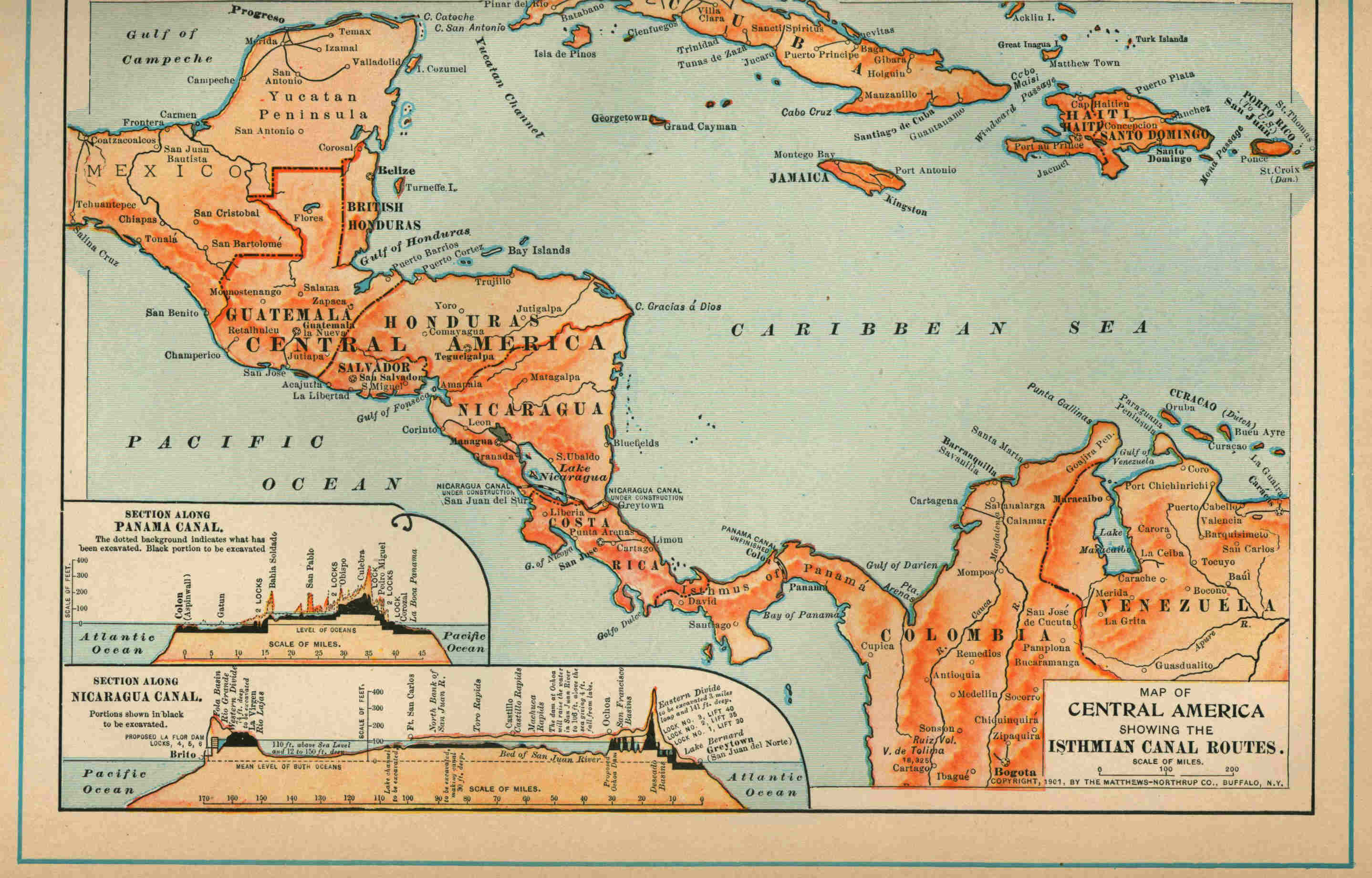

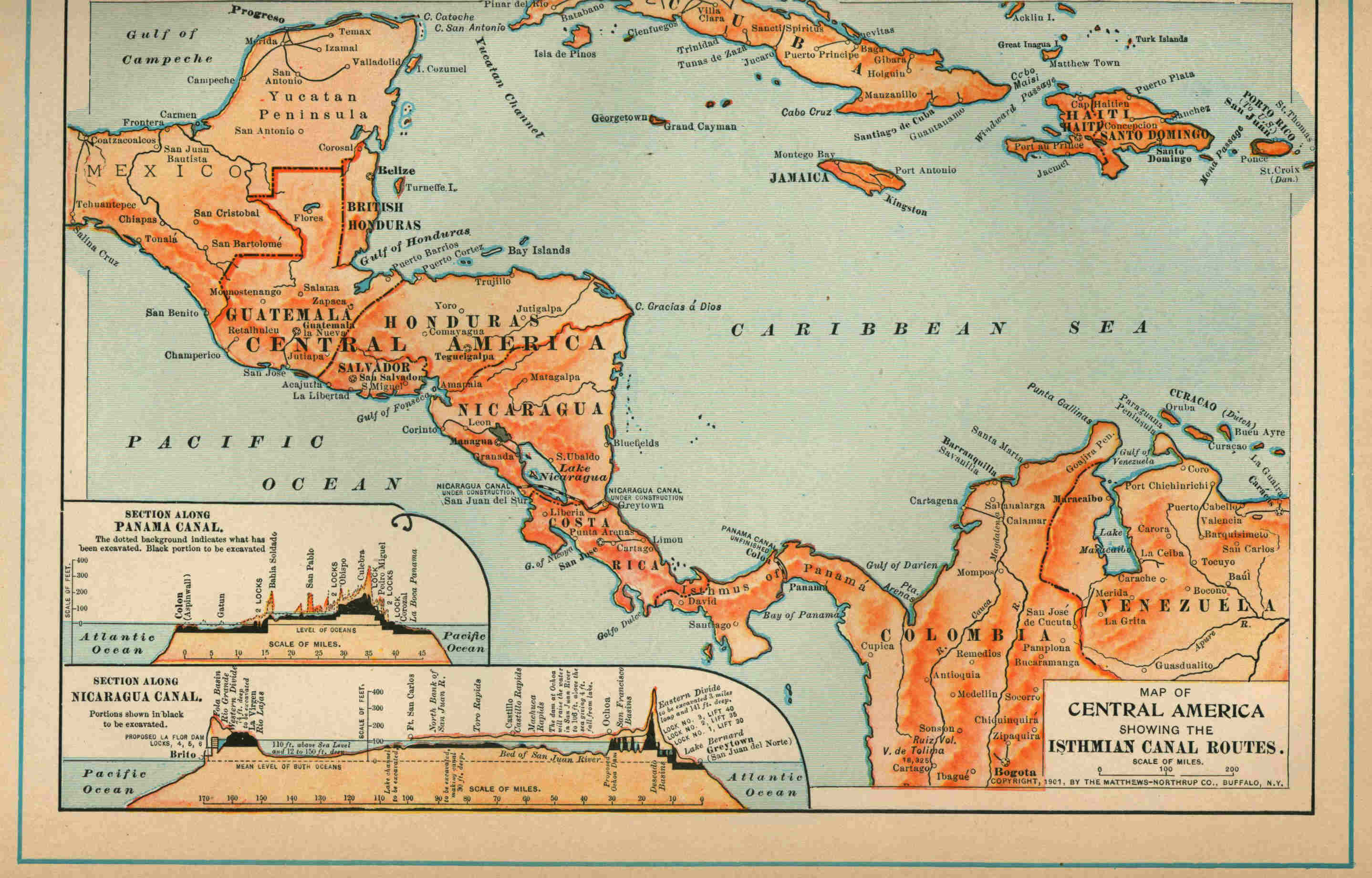

Map of Central America,

showing the Isthmian Canal routes, Following page 66

Map of the East Coast of China, Following page 76

Map of Cuba and the West Indies, Following page 170

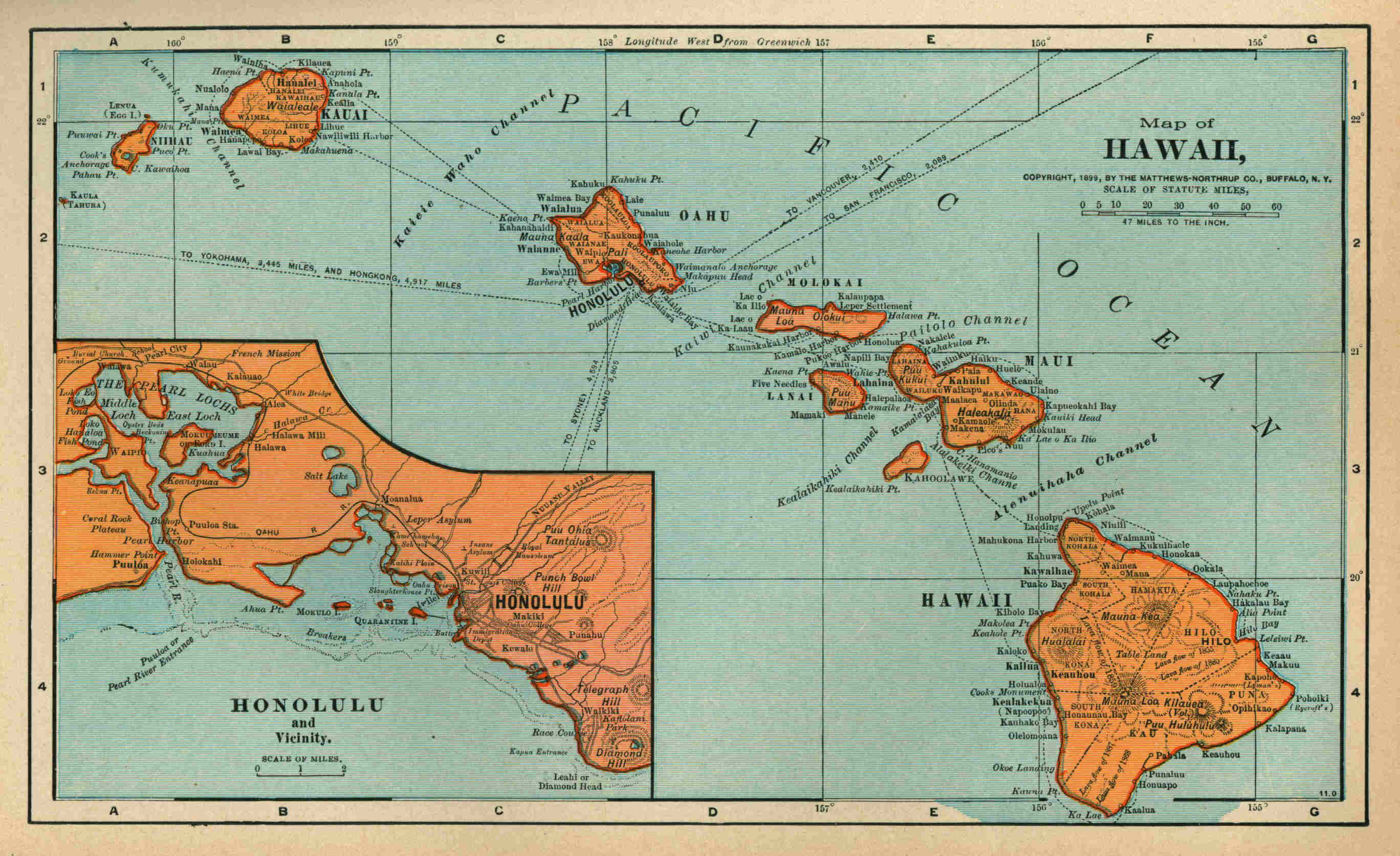

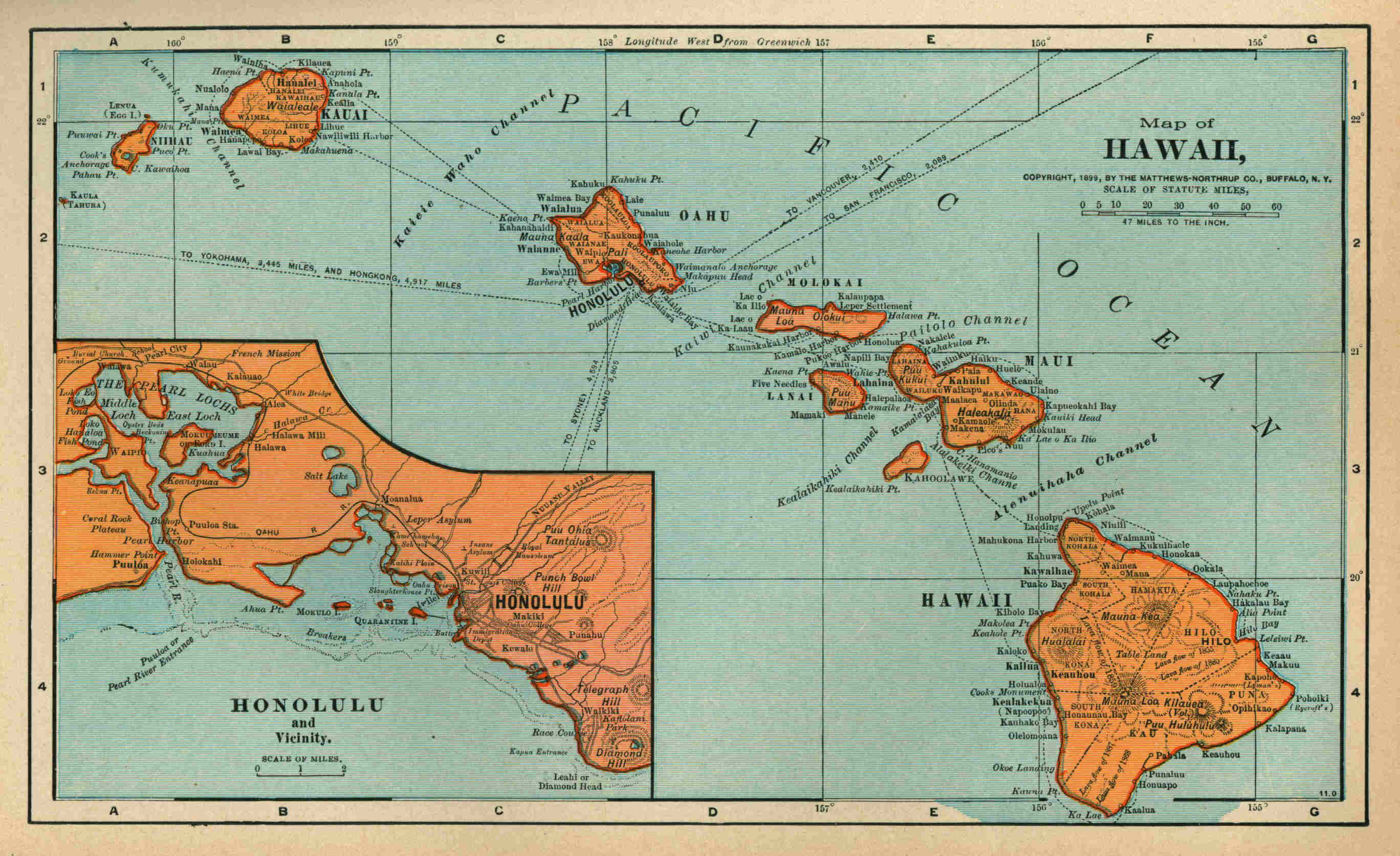

Map of Hawaii, Following page 254

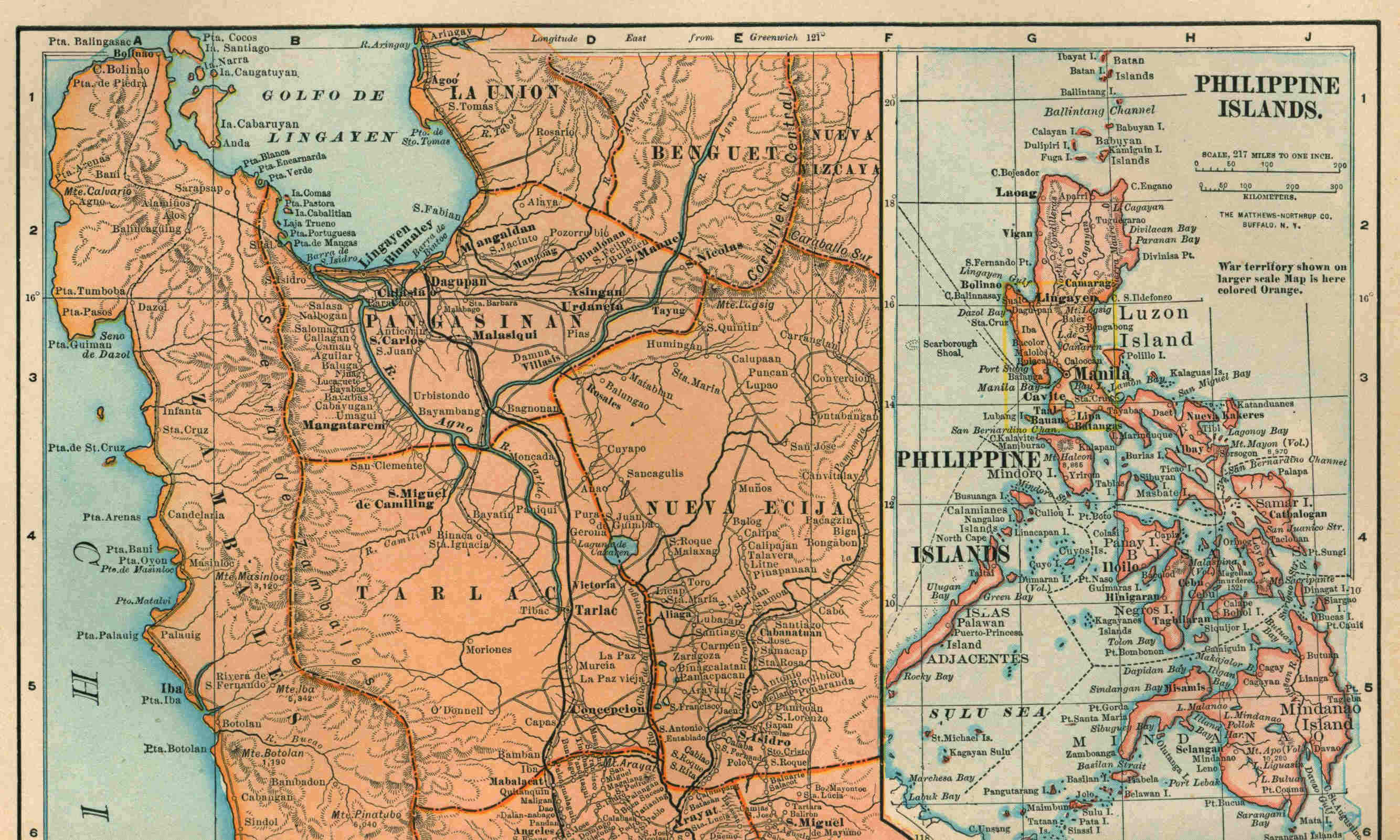

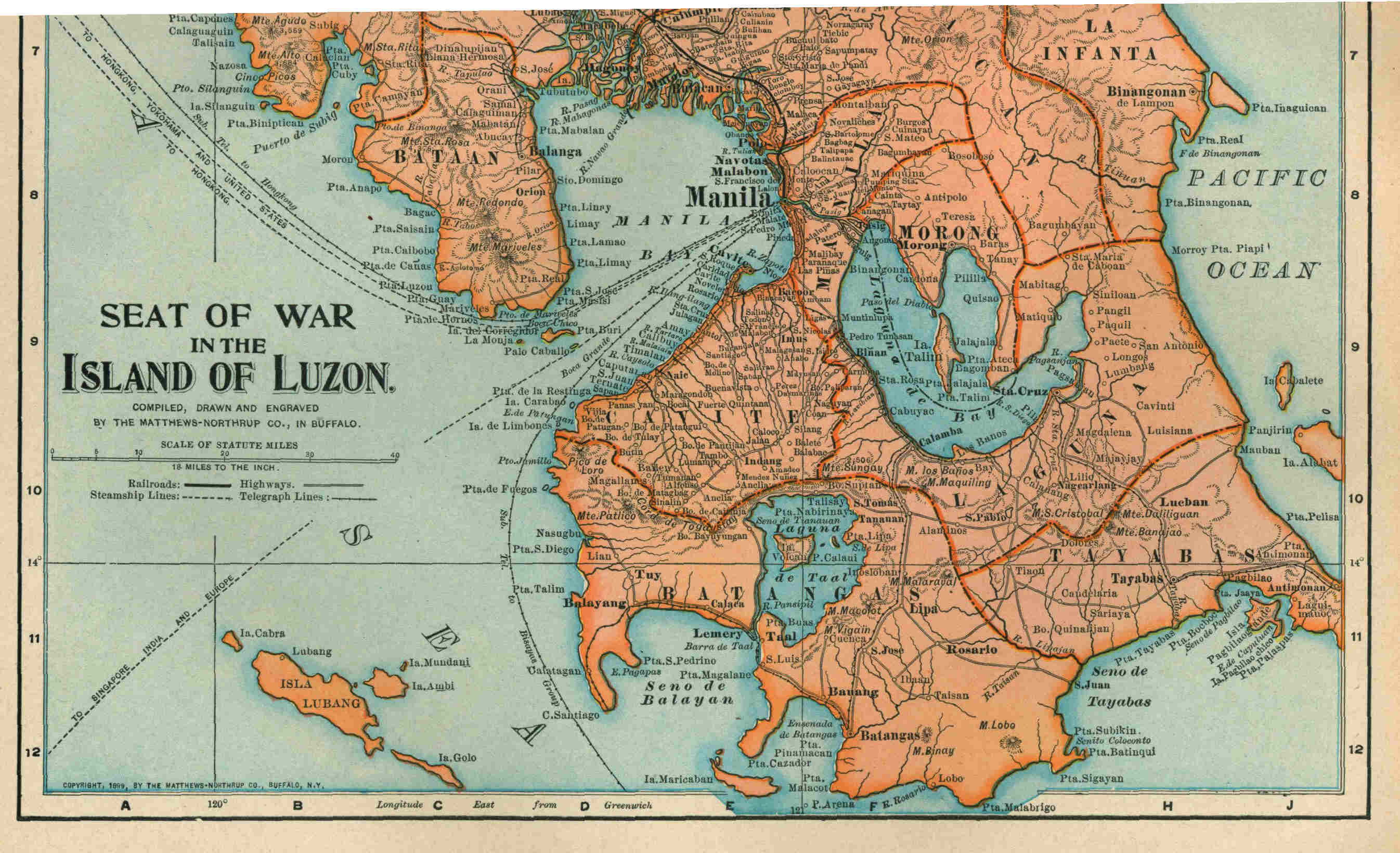

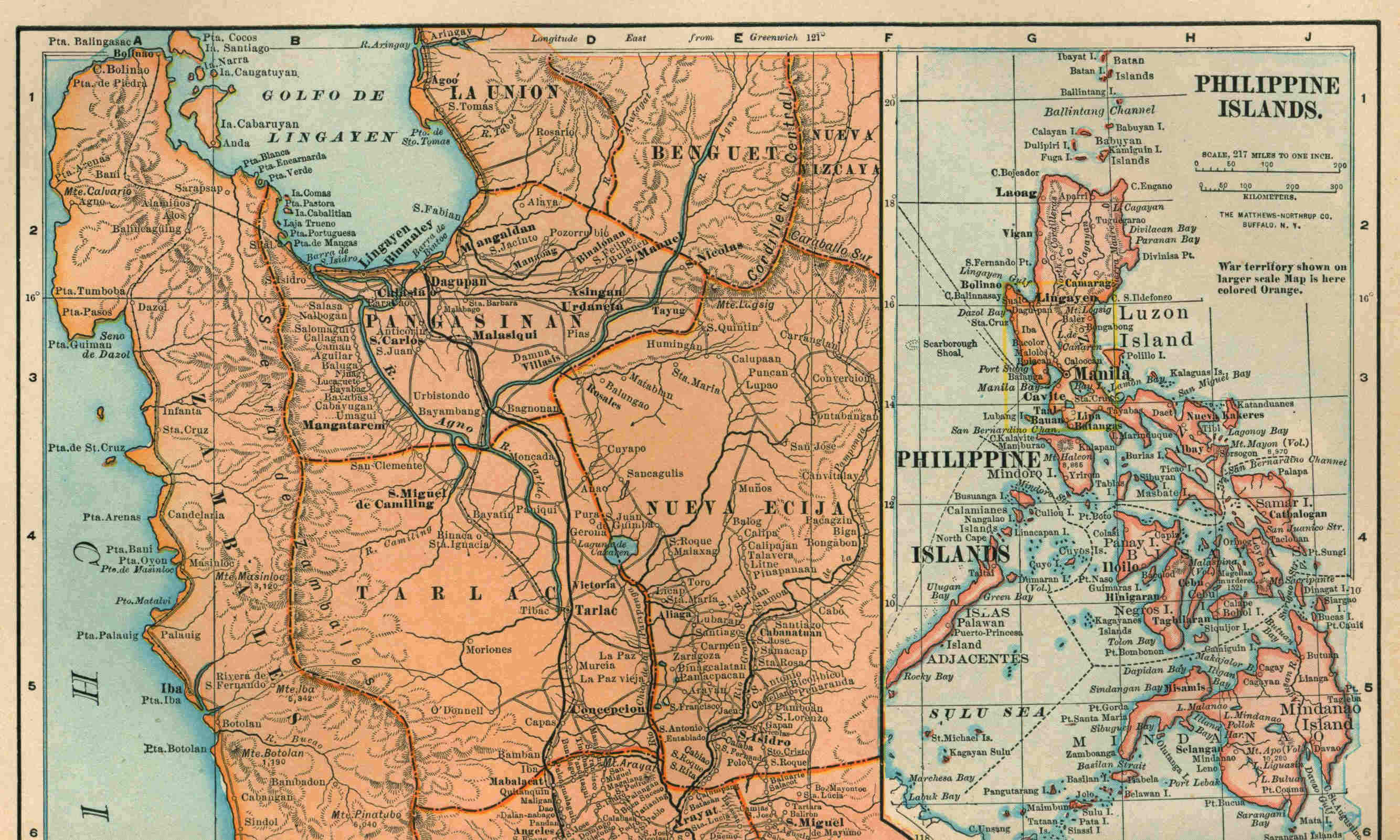

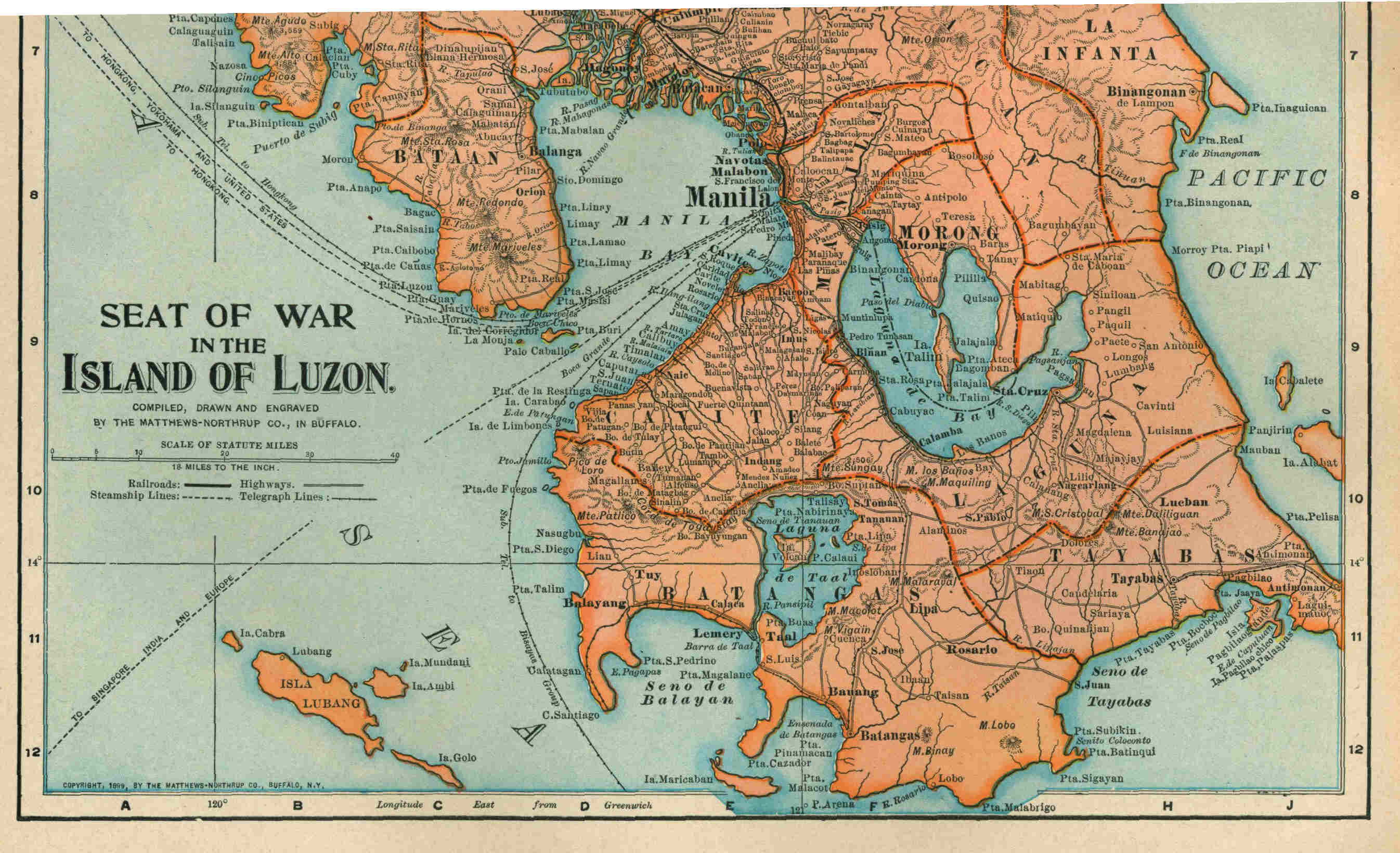

Map of the Philippine Islands,

and of the seat of war in Luzon, Following page 368

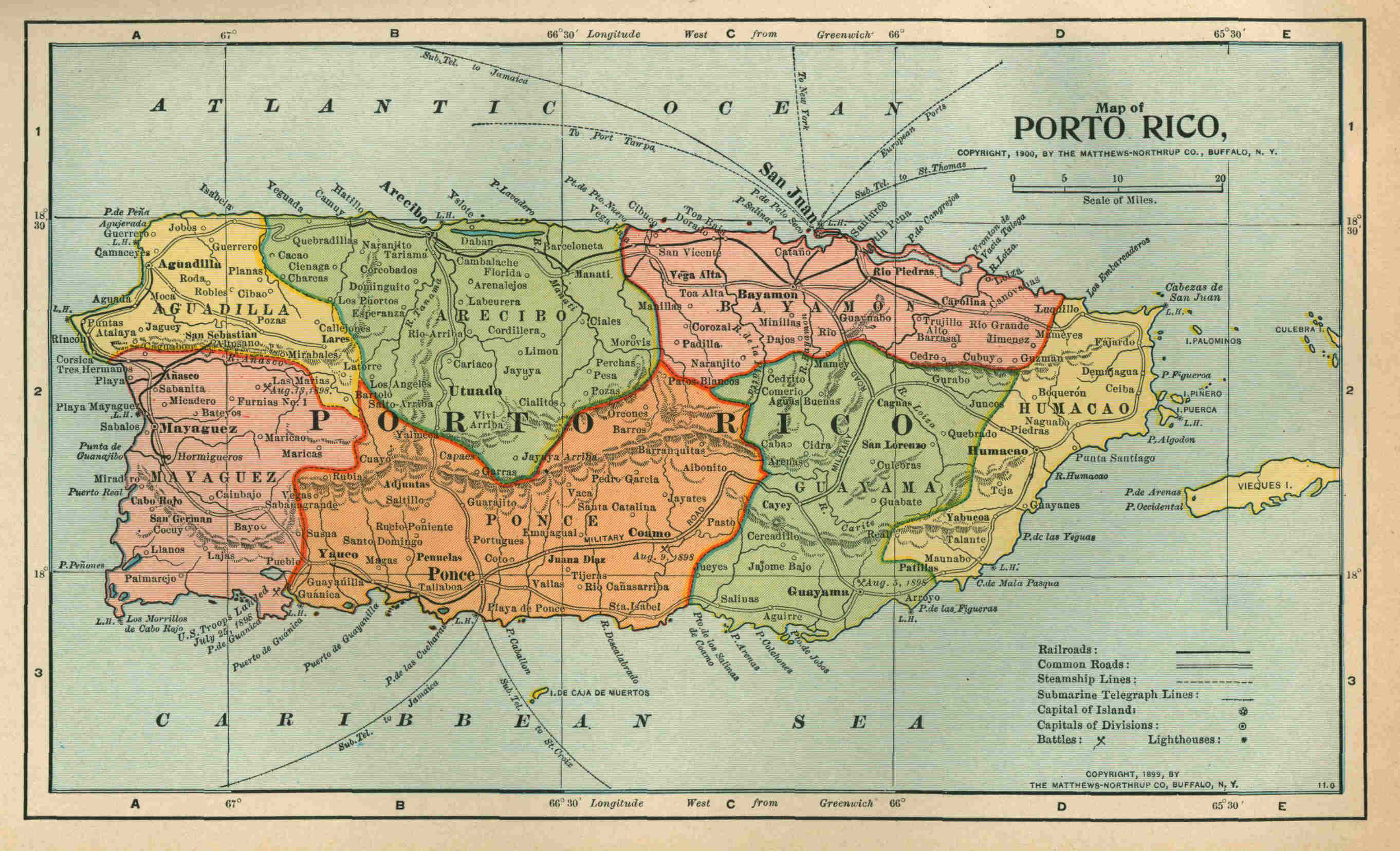

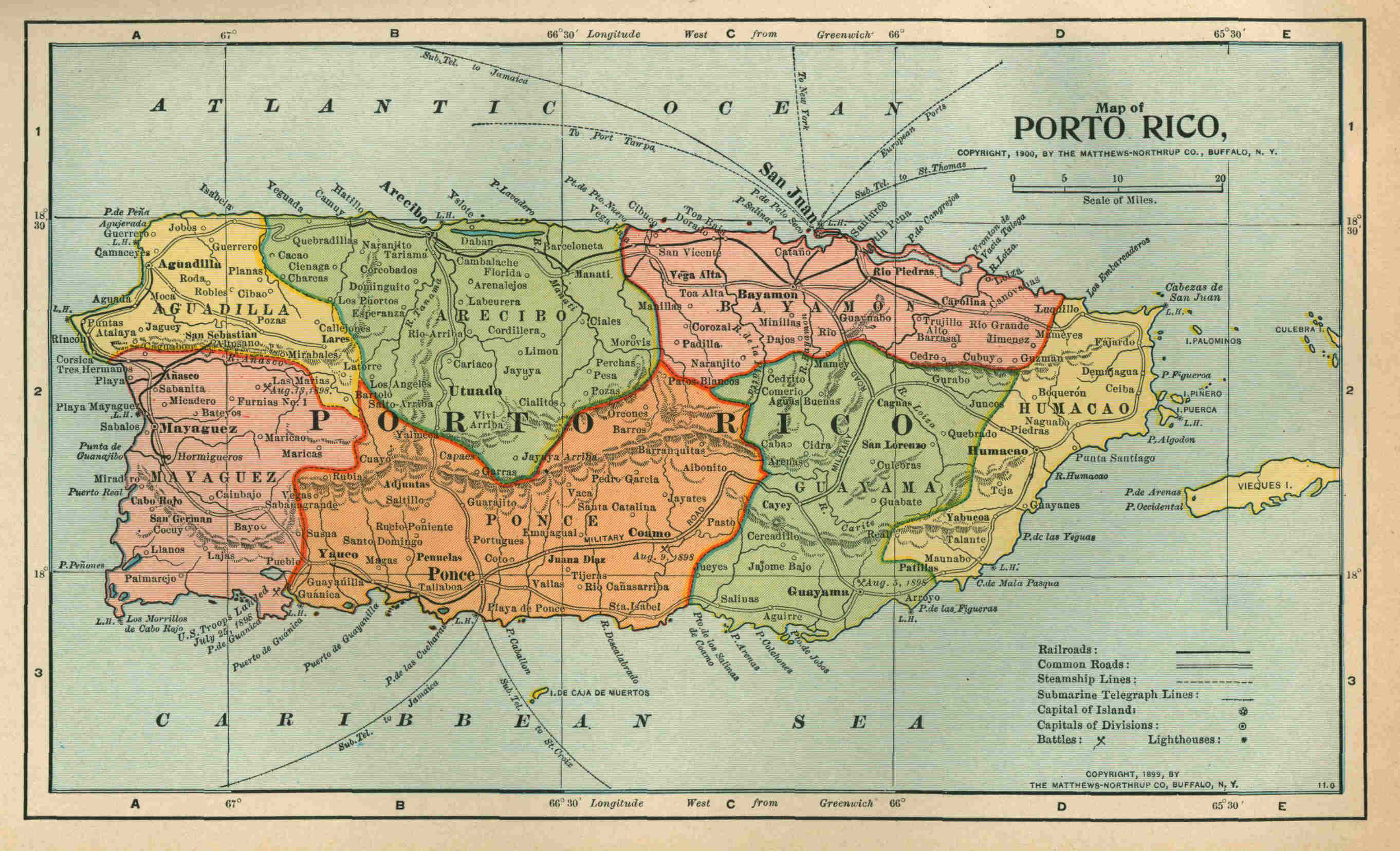

Map of Porto Rico, Following page 410

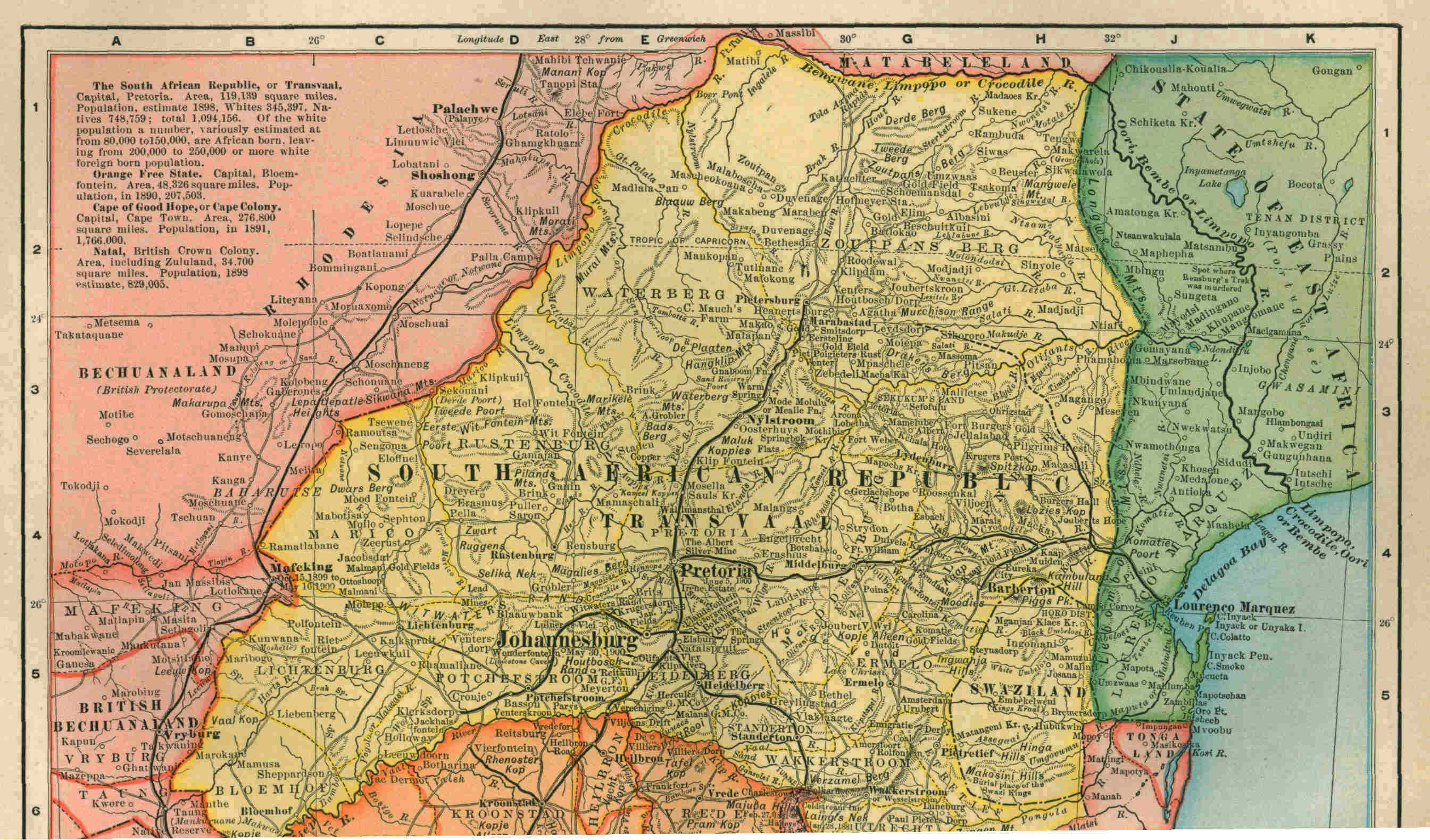

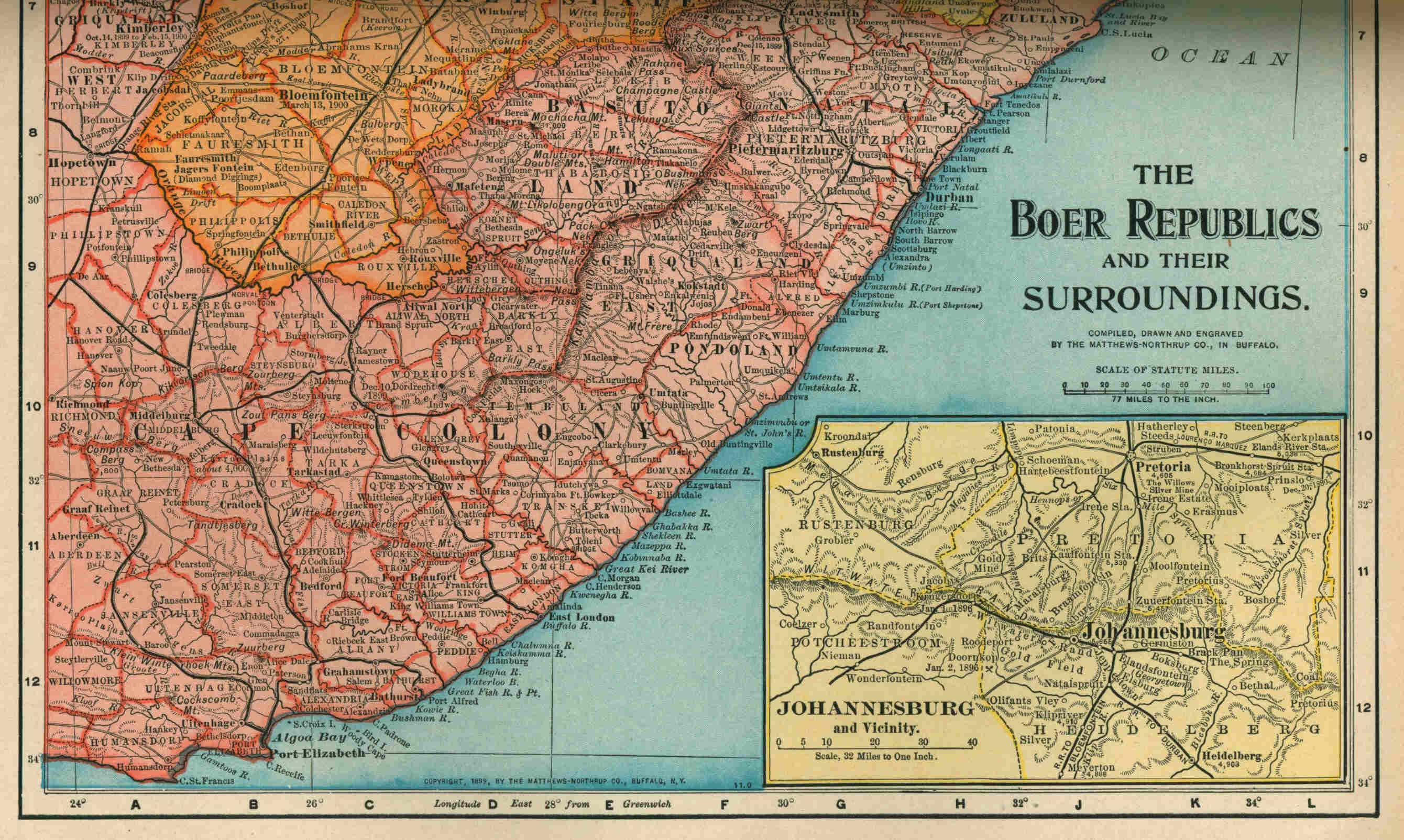

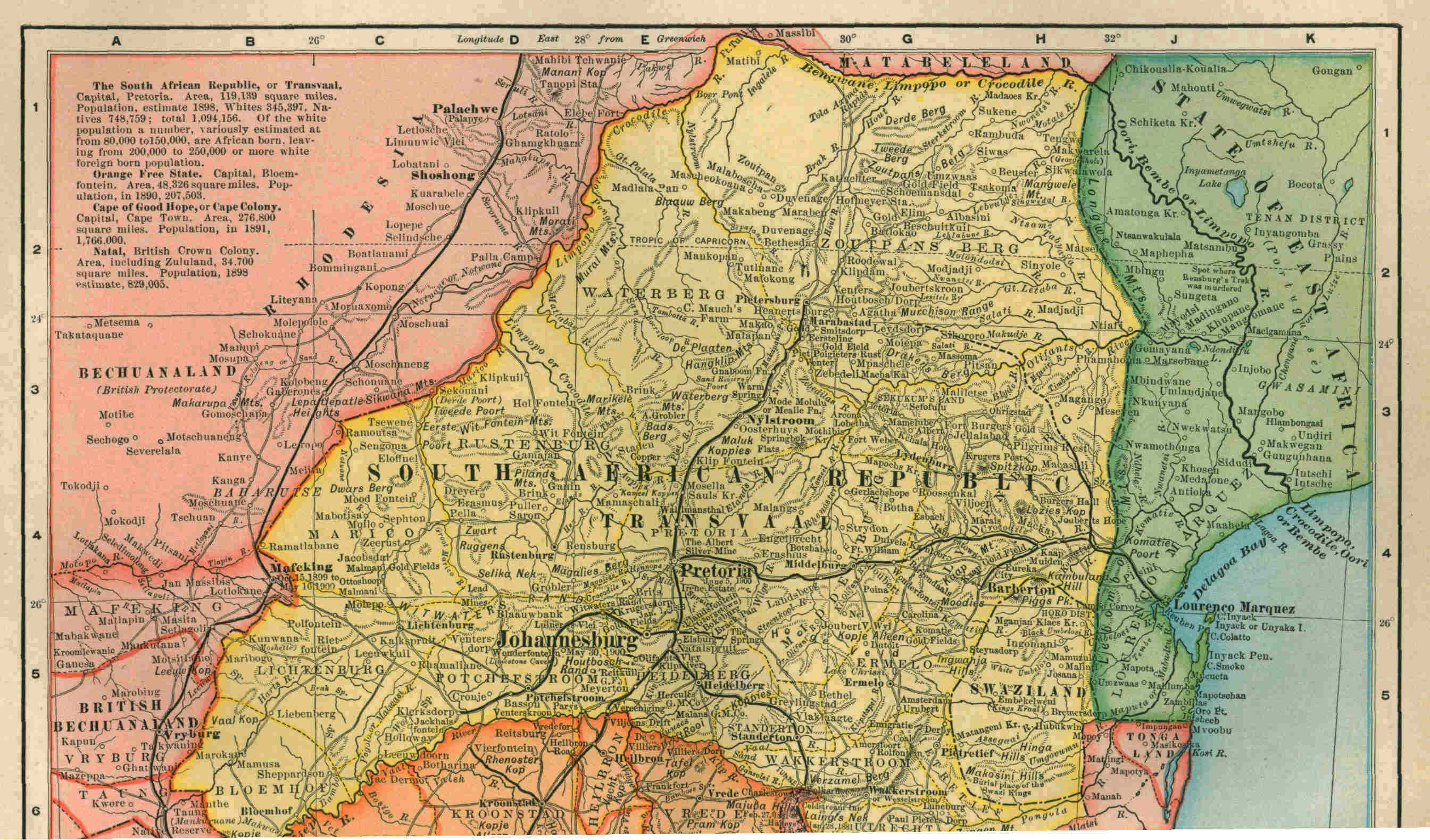

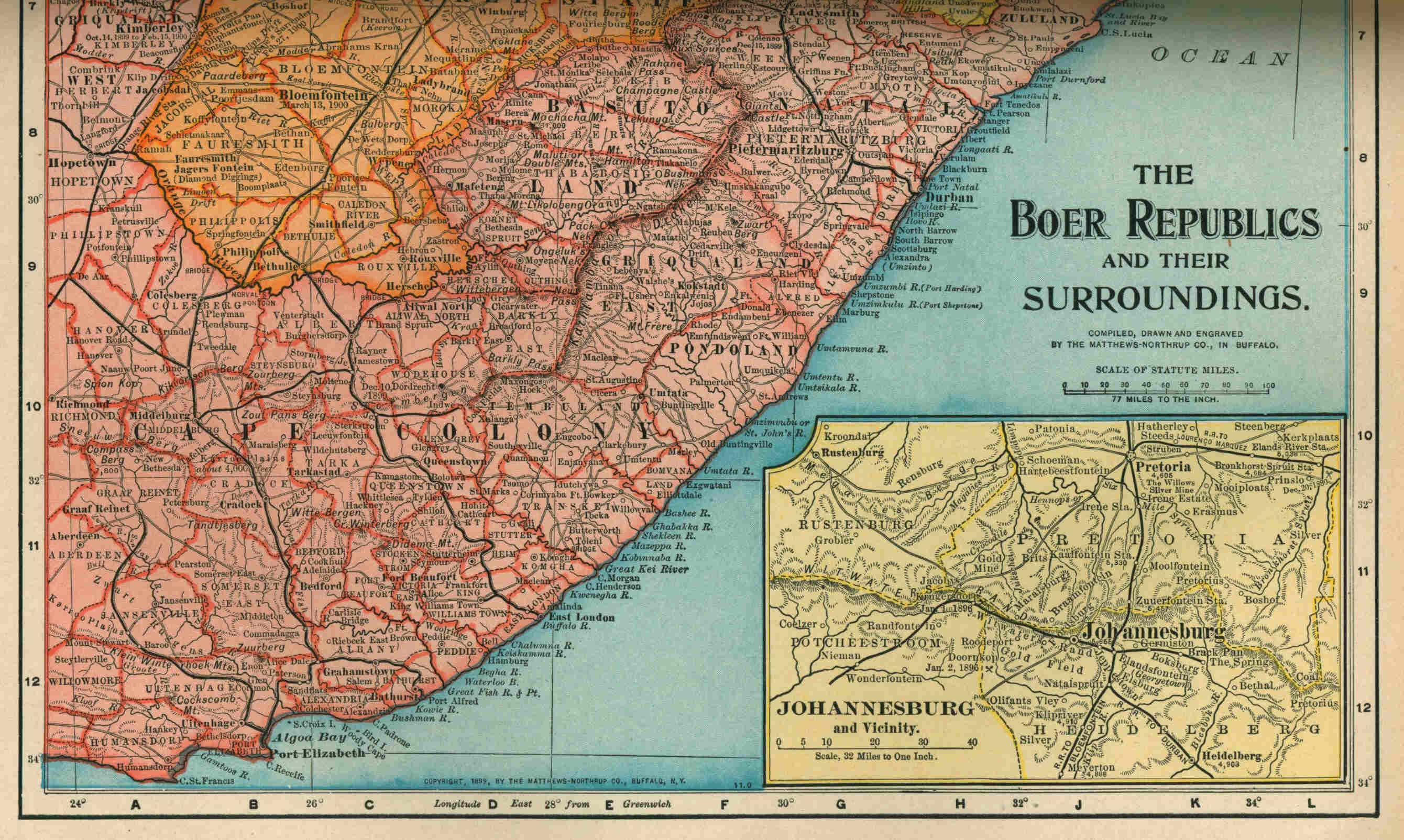

Map of the Boer Republics

and their surroundings, Following page 492

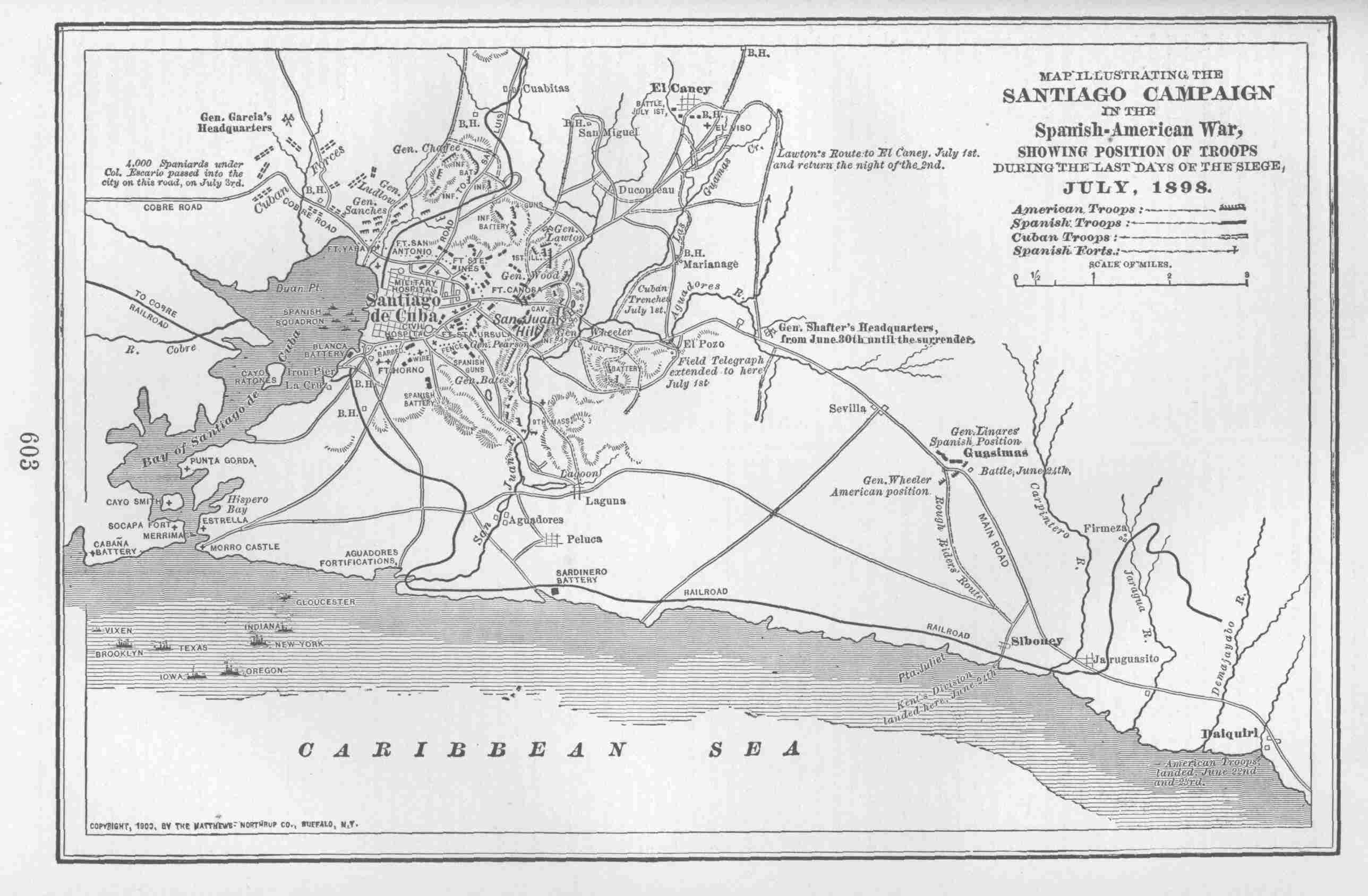

Map illustrating the Santiago campaign

in the Spanish-American war, On page 603

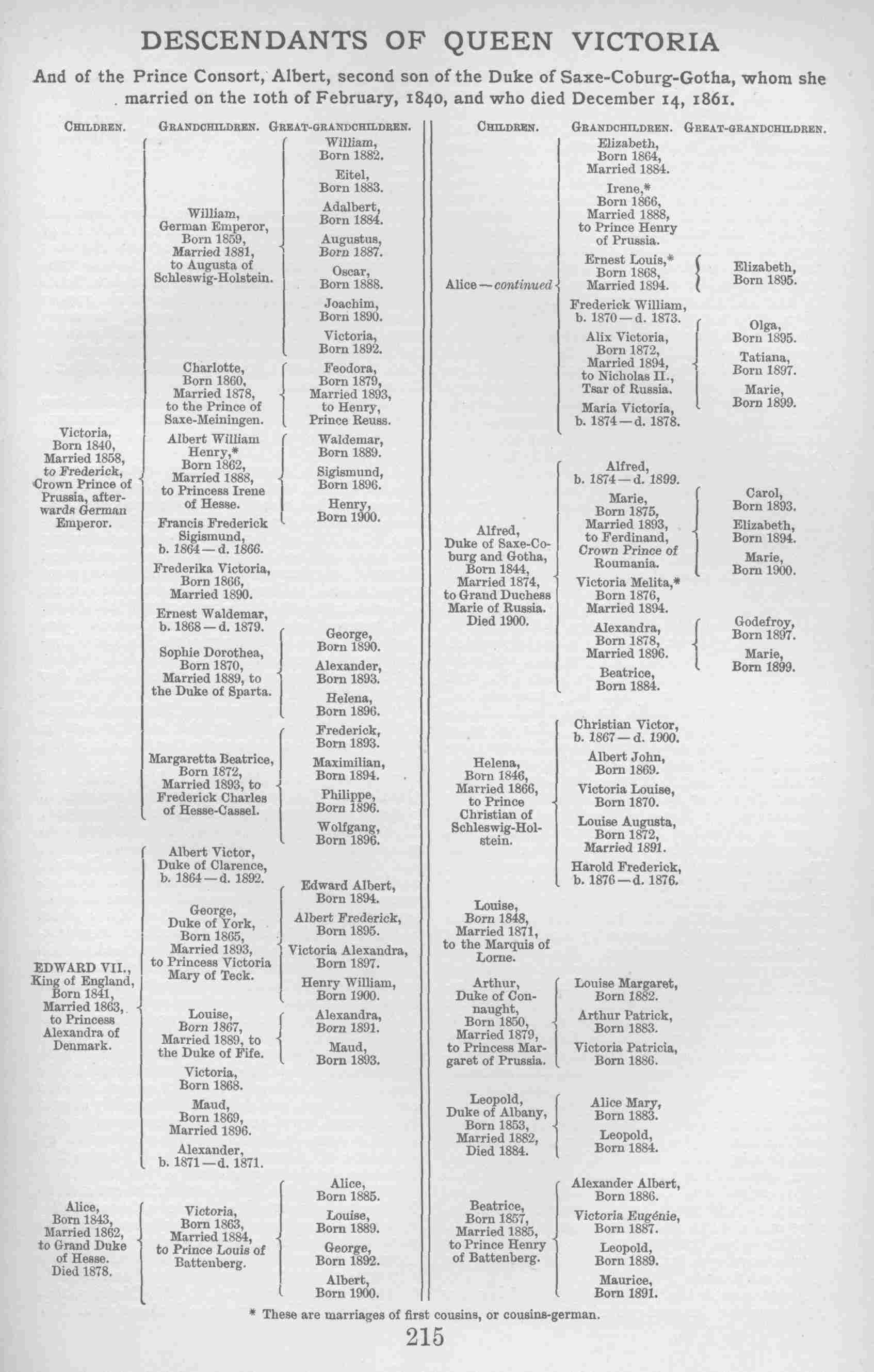

LIST OF TABLES.

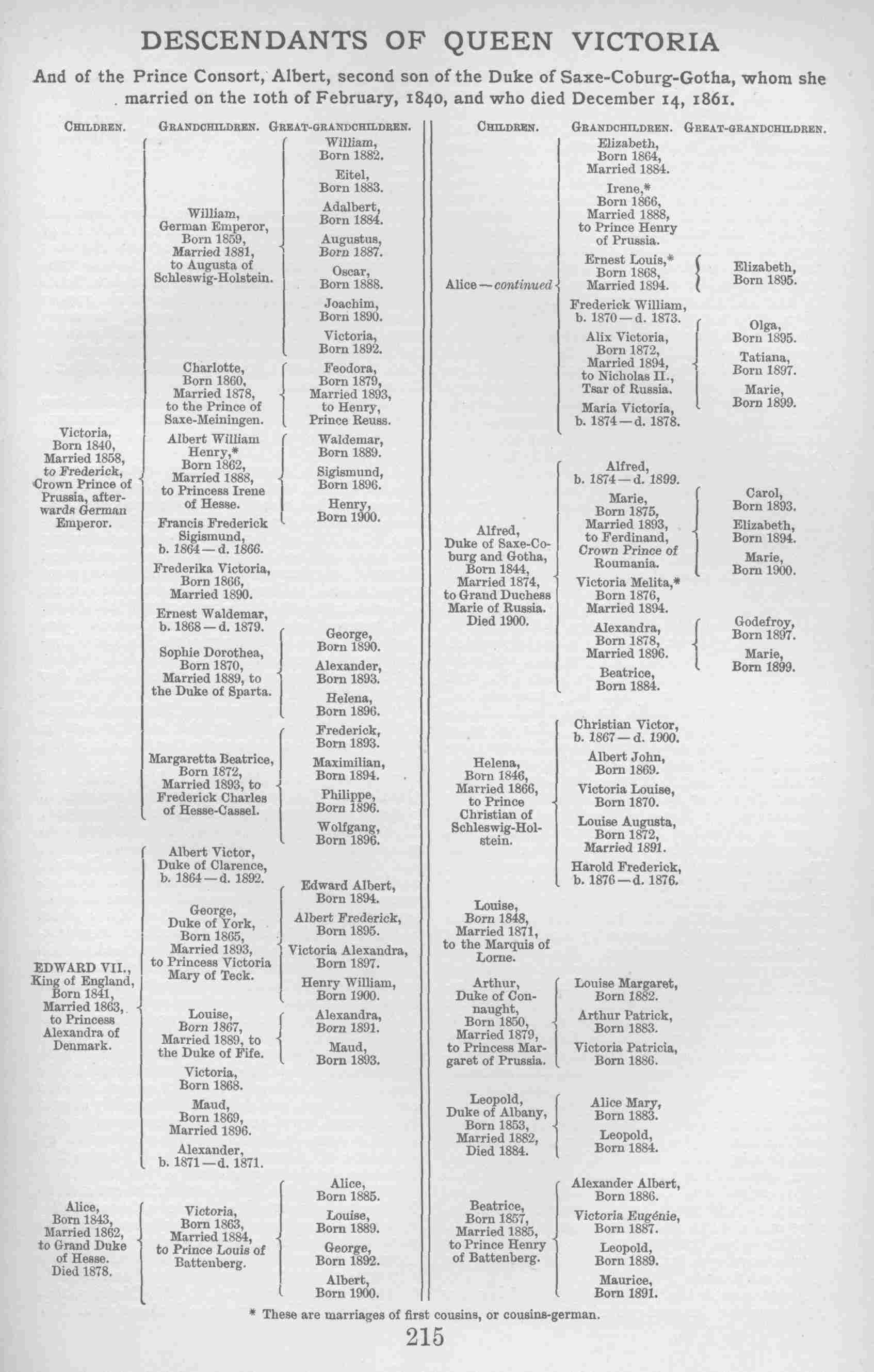

The descendants of Queen Victoria, Page 215

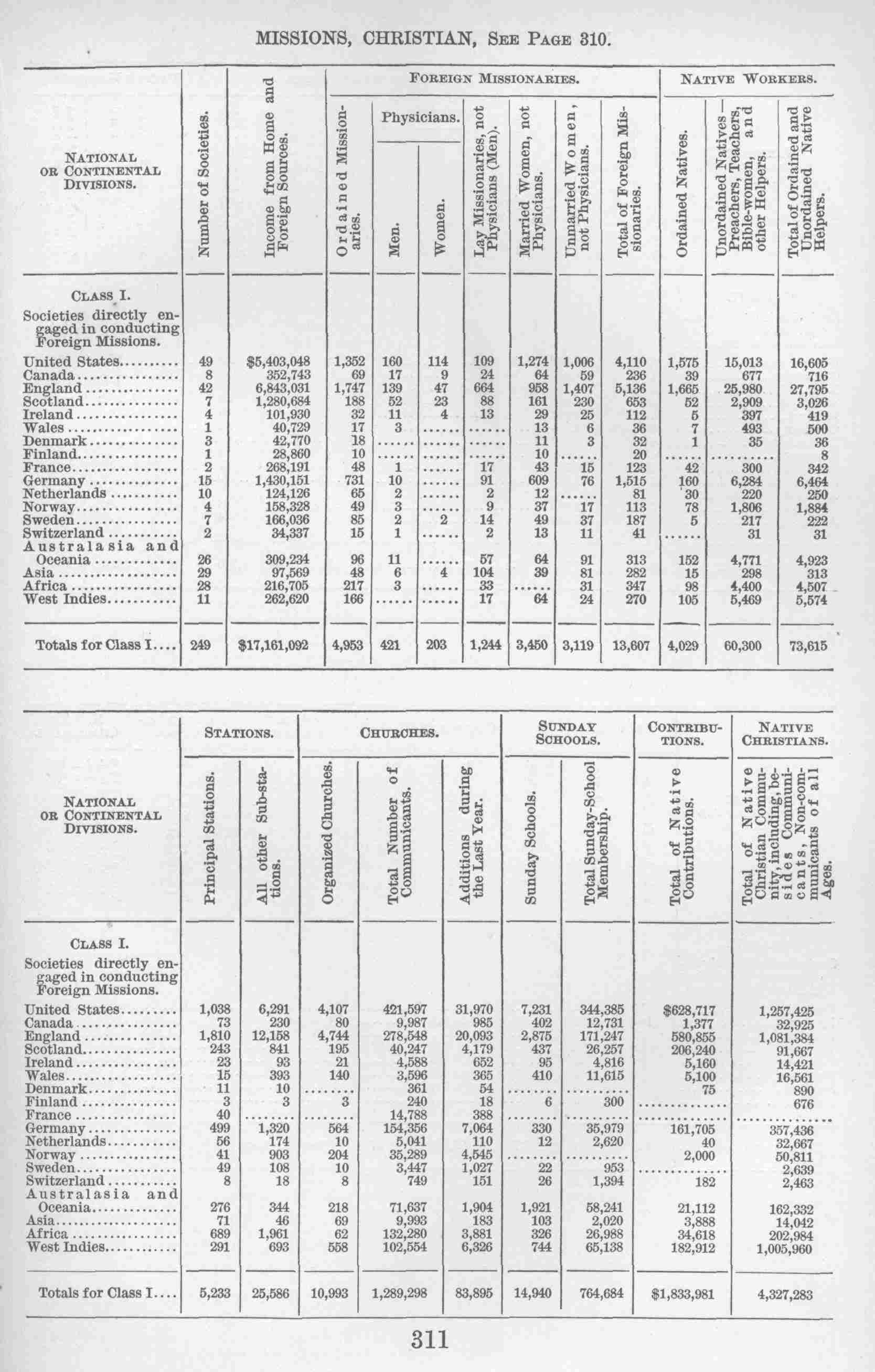

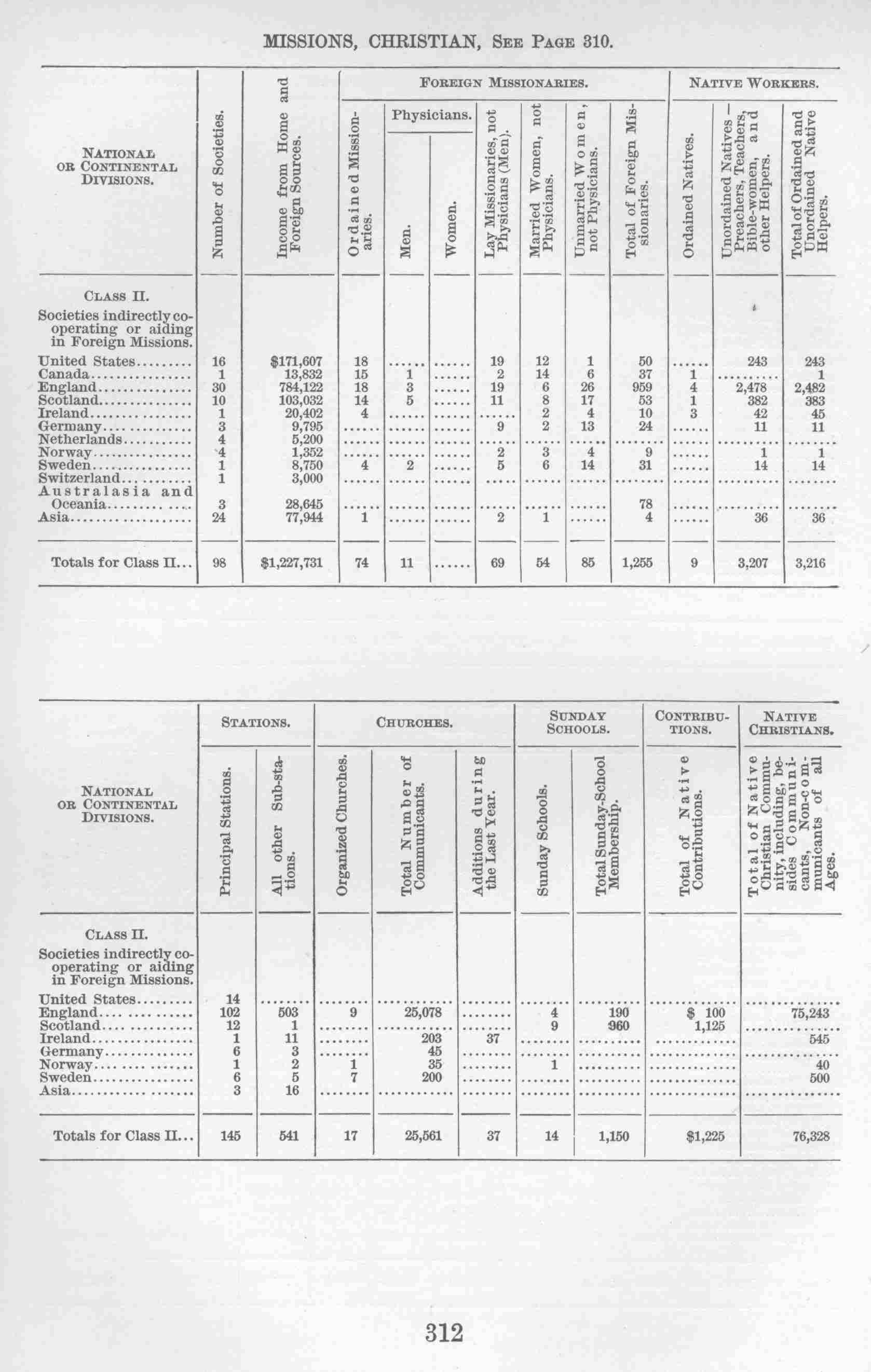

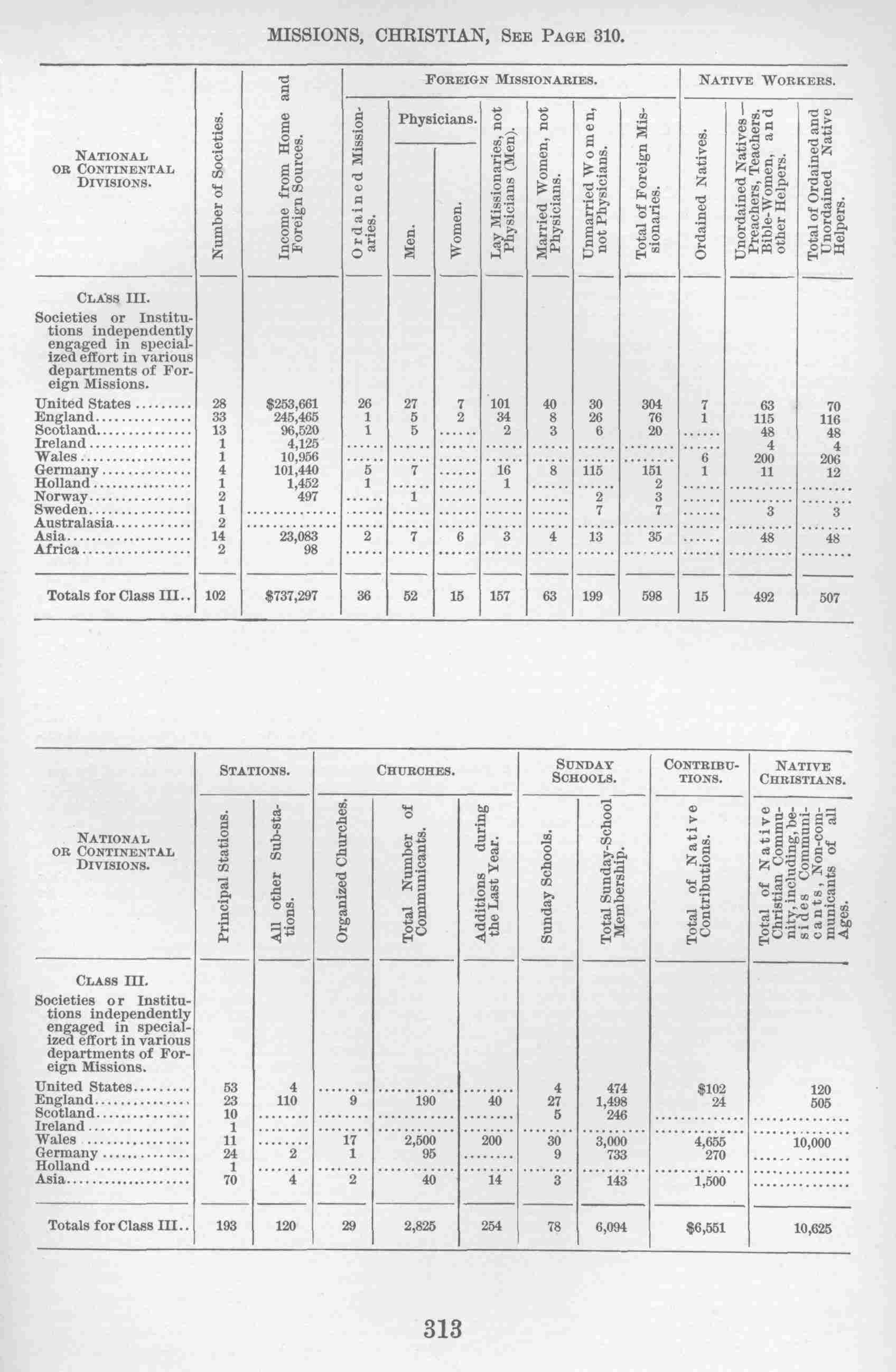

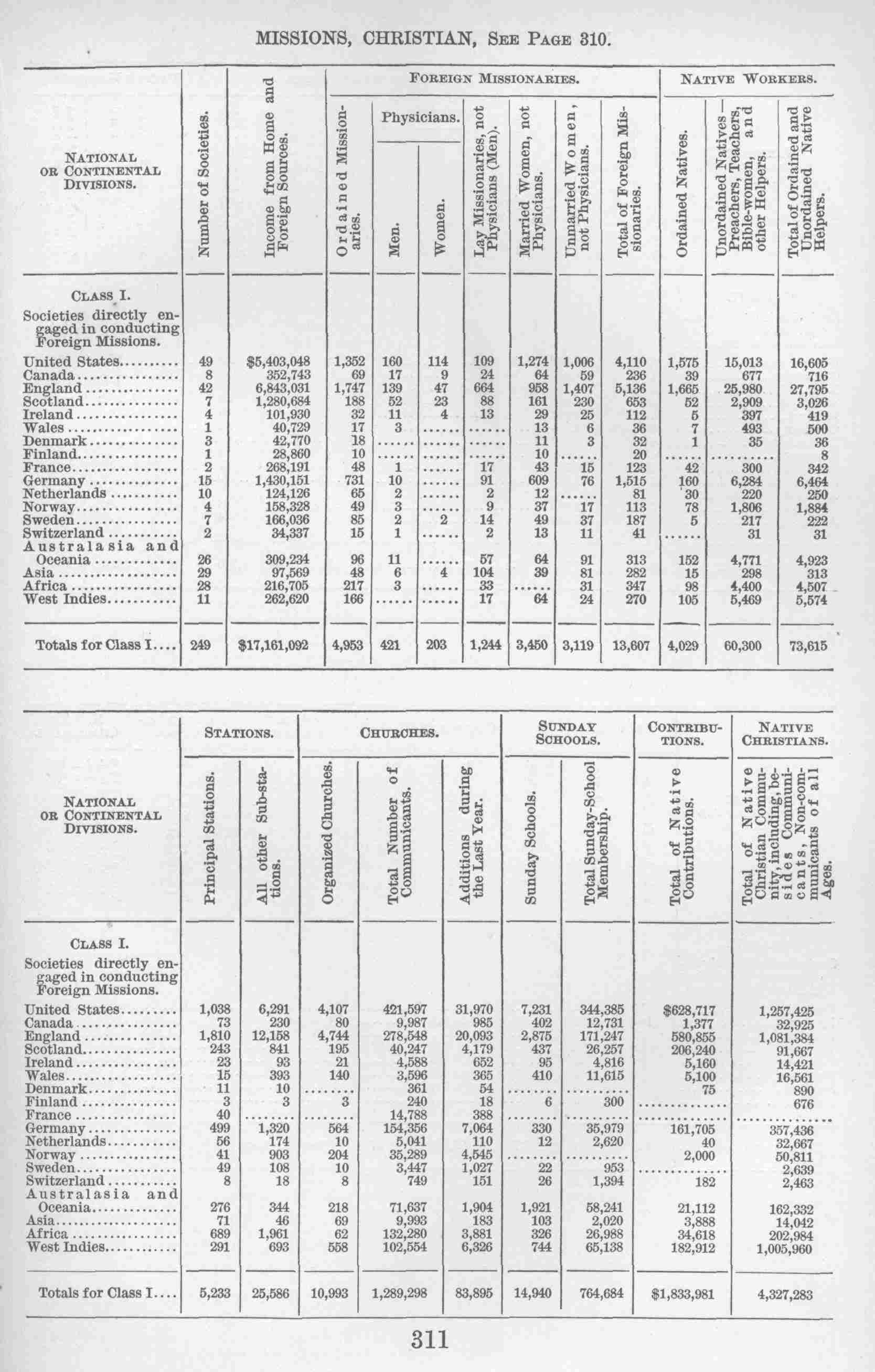

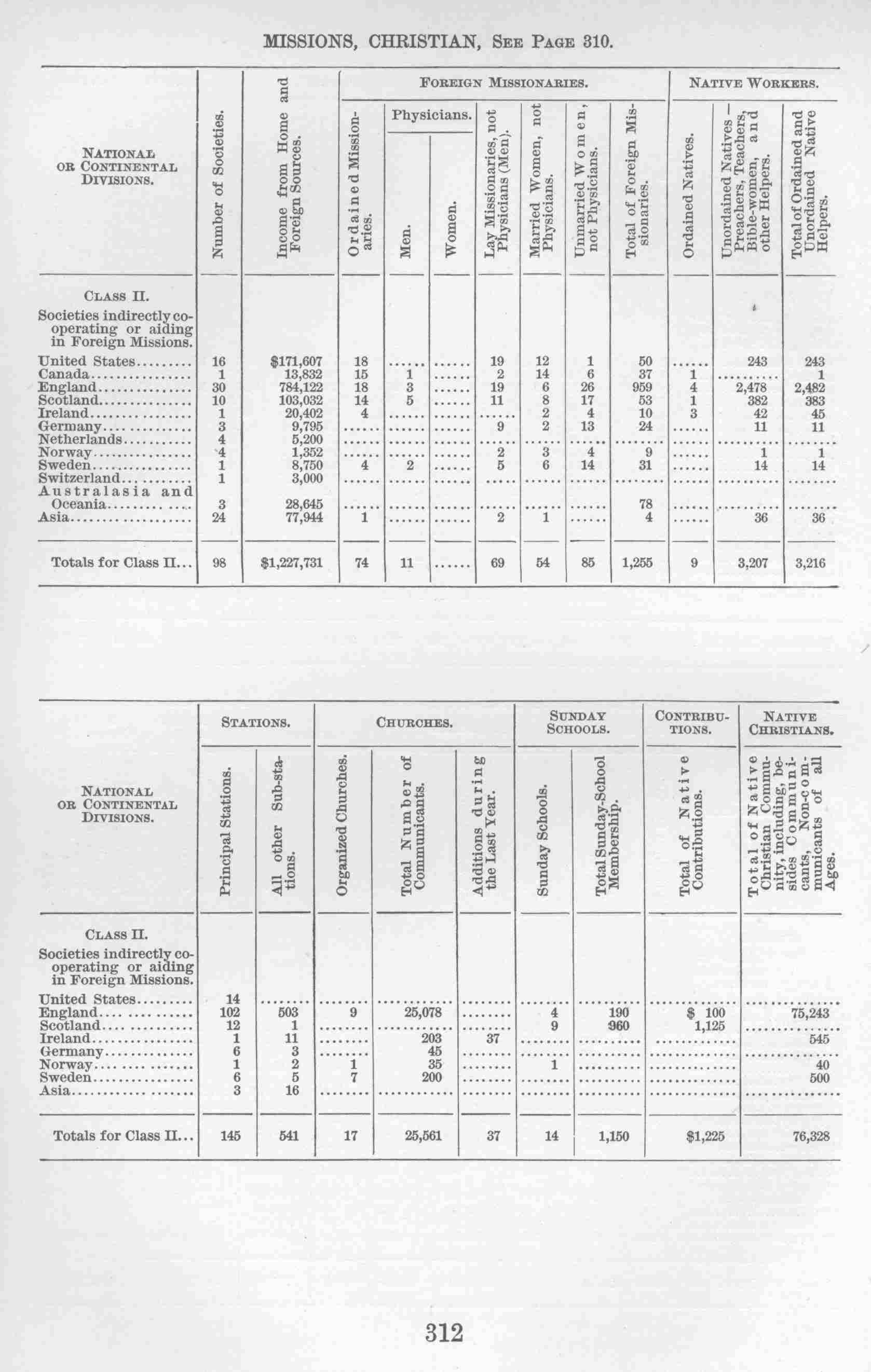

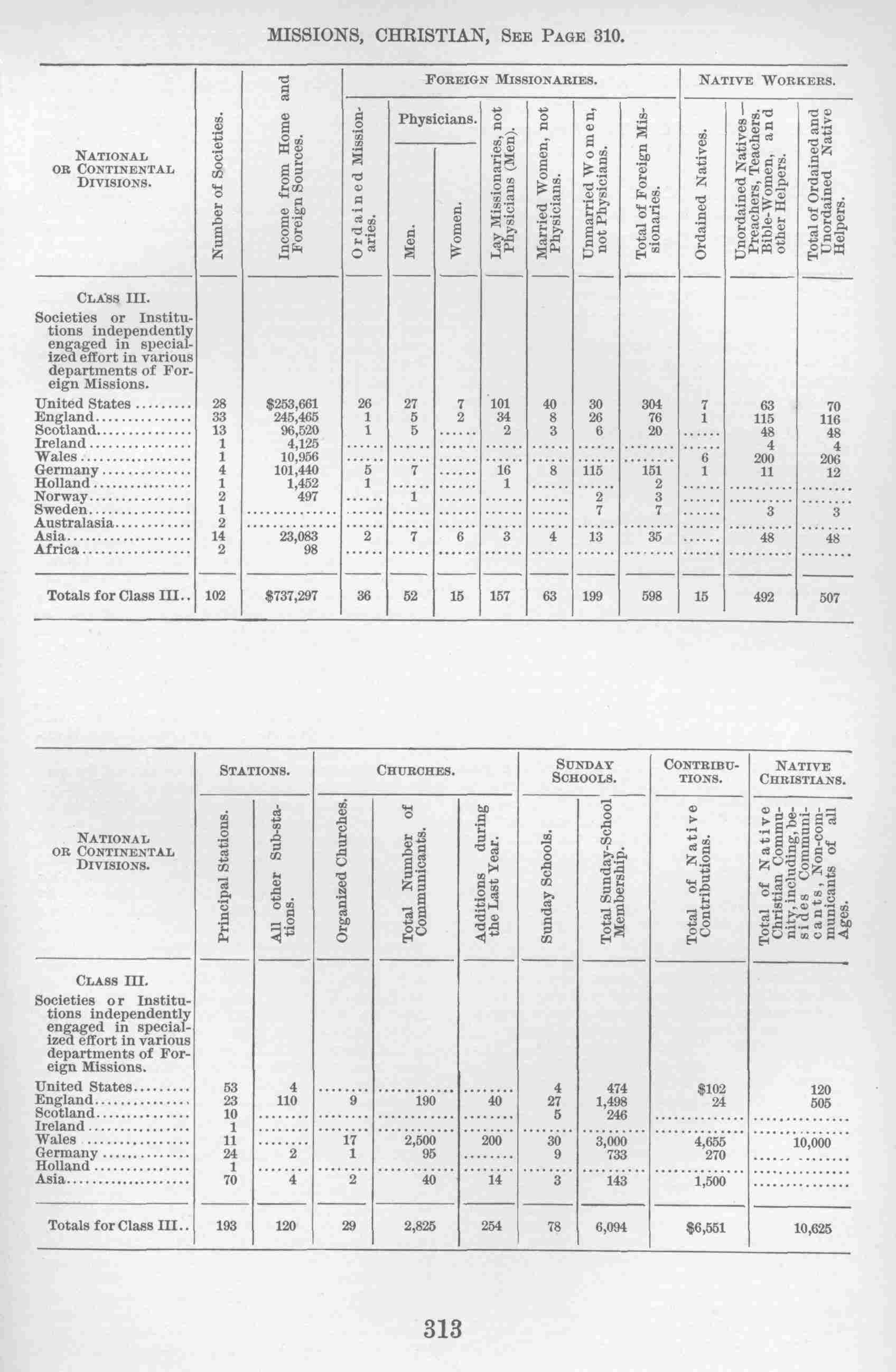

Protestant foreign missions

and missionary societies, Pages 311-313

Navies of the Sea Powers, Page 318

Philippine Islands, area and population, Pages 367-369

The Shipping of the World in 1900, Page 452

British military forces in South African war, Pages 509-510

Statistics of the Spanish-American War, Pages 628-631

Twelfth Census of the United States (1900), Pages 645-646

Revenues and expenditures of the government

of the United States for the fiscal

year ended June 30, 1900, Page 666

Losses from all causes in the armies

of the United States from

May 1, 1898, to May 20, 1900, Pages 666-667

Qualifications of the elective franchise

in the several States of the United States, Pages 676-677

Military and naval expenditures of

the greater Powers, Pages 694-697

Chronological record of events, 1895 to 1901, Pages 702-720

{1}

HISTORY FOR READY REFERENCE.

ABORIGINES, American.

See (in this volume)

INDIANS, AMERICAN.

ABRUZZI, the Duke of: Arctic expedition.

See (in this volume) POLAR EXPLORATION, 1899-1900, 1901.

ABYDOS, Archæological exploration at.

See (in this volume)

ARCHÆOLOGICAL RESEARCH: EGYPT: RESULTS.

ABYSSINIA: A. D. 1895-1896.

Successful war with the Italians.

See (in this volume) ITALY: A. D. 1895-1896.

ABYSSINIA: A. D. 1897.

Treaty with Great Britain.

A treaty between King Menelek of Abyssinia and the British

Government was concluded in May, 1897. It gives to British

subjects the privileges of the most favored nations in trade;

opens the port of Zeyla to Abyssinian importations; defines

the boundary of the British Somali Protectorate, and pledges

Abyssinia to be hostile to the Mahdists.

ACETYLENE GAS, Production of.

See (in this volume)

SCIENCE, RECENT: CHEMISTRY AND PHYSICS.

ADOWA, Battle of.

See (in this volume) ITALY; A. D. 1895-1896.

AFGHANISTAN: A. D. 1893-1895.

Relinquishment of claims over Swat, Bajaur and Chitral.

See (in this volume)

INDIA: A. D. 1895 (MARCH-SEPTEMBER).

AFGHANISTAN: A. D. 1894.

The Waziri War.

See (in this volume) INDIA: A. D. 1894.

AFGHANISTAN: A. D. 1895.

Anglo-Russian Agreement.

Determination of the northern frontier.

The joint Anglo-Russian Commission for fixing the northern

frontier of Afghanistan, from Zulfikar on the Heri-Rud to the

Pamirs, finished its work in July, 1895. This was consequent

upon an Agreement between the governments of Great Britain and

Russia which had been reduced to writing on the previous 11th

of March. In part, that Agreement was as follows:

"Her Britannic Majesty's Government and the Government of His

Majesty the Emperor of Russia engage to abstain from

exercising any political influence or control, the former to

the north, the latter to the south, of the above line of

demarcation. Her Britannic Majesty's Government engage that

the territory lying within the British sphere of influence

between the Hindu Kush and the line running from the east end

of Lake Victoria to the Chinese frontier shall form part of

the territory of the Ameer of Afghanistan, that it shall not

be annexed to Great Britain, and that no military posts or

forts shall be established in it. The execution of this

Agreement is contingent upon the evacuation by the Ameer of

Afghanistan of all the territories now occupied by His

Highness on the right bank of the Panjah, and on the

evacuation by the Ameer of Bokhara of the portion of Darwaz

which lies to the south of the Oxus, in regard to which Her

Britannic Majesty's Government and the Government of His

Majesty the Emperor of Russia have agreed to use their

influence respectively with the two Ameers."

Great Britain, Papers by Command: Treaty Series,

Number 8, 1895.

AFGHANISTAN: A. D. 1896.

Conquest of Kafiristan.

By the agreement of 1893, between the Ameer of Afghanistan and

the government of India (see, in this volume, INDIA. A. D.

1895-MARCH-SEPTEMBER), the mountain district of Kafiristan was

conceded to the former, and he presently set to work to

subjugate its warlike people, who had never acknowledged his

yoke. By the end of 1896 the conquest of these Asiatic Kafirs

was believed to be complete.

AFGHANISTAN: A. D. 1897-1898.

Wars of the British with frontier tribes.

See (in this volume) INDIA: A. D. 1897-1898.

AFGHANISTAN: A. D. 1900.

Russian railway projects.

See (in this volume) RUSSIA-IN-ASIA: A. D. 1900.

----------AFRICA: Start--------

AFRICA: A. D. 1891-1900

(Portuguese East Africa).

Delagoa Bay Railway Arbitration.

See (in this volume)

DELAGOA BAY ARBITRATION.

AFRICA: A. D. 1893 (Niger Coast Protectorate).

Its growth.

See (in this volume)

NIGERIA: A. D. 1882-1899.

AFRICA: A. D. 1894 (The Transvaal).

The Commandeering question.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA: (THE TRANSVAAL): A. D. 1894.

AFRICA: A. D. 1894 (The Transvaal).

Dissatisfaction of the Boers with the

London Convention of 1884.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL): A. D. 1884-1894.

AFRICA: A. D. 1894-1895 (British South Africa Company).

Extension of charter and enlargement of powers.

Influence of Cecil J. Rhodes.

Attitude towards the Transvaal.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA

(BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY): A. D. 1894-1895.

AFRICA: A. D. 1894-1895 (Rhodesia).

Extended territory and enlarged powers of the British

South Africa Company.

Ascendancy of Cecil J. Rhodes.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA

(BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY): A. D. 1894-1895.

AFRICA: A. D. 1894-1898

(British Central Africa Protectorate: Nyassaland).

Administrative separation from British South Africa Company's

territory.

Conflicts with natives.

Resources and prospects.

See (in this volume)

BRITISH CENTRAL AFRICA PROTECTORATE.

{2}

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (Bechuanaland).

Partial conveyance to British South Africa Company.

Several Bechuana chiefs visited England to urge that their

country should not be absorbed by Cape Colony or the British

South Africa Company. An agreement was made with them which

reserved certain territories to each, but yielded the

remainder to the administration of the British South Africa

Company.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (British East Africa).

Transfer of territory to the British Government.

The territories previously administered by the Imperial

British East Africa Company (excepting the Uganda

Protectorate, which had been transferred in 1894) were finally

transferred to the British Government on the 1st of July. At

the same time, the dominion of the Sultan of Zanzibar on the

mainland came under the administrative control of the British

consul-general at Zanzibar.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (Cape Colony).

Annexation of British Bechuanaland.

Proceedings for the annexation of British Bechuanaland to Cape

Colony were adopted by the Cape Parliament in August.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (French West Africa).

Appointment of a Governor-General.

In June, M. Chaudie was appointed Governor-General of French

West Africa, his jurisdiction extending over Senegal, the

Sudan possessions of France, French Guinea, Dahomey, and other

French possessions in the Gulf of Benin.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (Orange Free State).

Proposed federal union of the Free State with the Transvaal.

A resolution making overtures for a federal union with the

Transvaal was passed by the Volksraad of the Orange Free State

in June.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (Sierra Leone).

Establishment of a British Protectorate over the

Hinterland of Sierra Leone.

Anglo-French boundary agreement.

See (in this volume)

SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (Transvaal).

Action in Swaziland.

By a proclamation in February, the Transvaal Government

assumed the administration of Swaziland and installed King

Buna as paramount chief.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (The Transvaal).

Closing of the Vaal River Drifts.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1895 (SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (The Transvaal).

Discontent of the Uitlanders.

The Franchise question.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1895 (NOVEMBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (The Transvaal).

Opening of Delagoa Bay Railway.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1895 (JULY).

AFRICA: A. D. 1895 (Zululand).

Extension of Boundary.

A strip of territory west of Amatongaland, along the Pondoland

River to the Maputa was formally added to Zululand in May, the

South African Republic protesting.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895-1896 (Portuguese East Africa).

War with Gungunhana.

The Portuguese were involved in war with Gungunhana, king of

Gazaland, which lasted from September, 1895, until the

following spring, when Gungunhana was captured and carried a

prisoner, with his wives and son, to Lisbon.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895-1896 (The Transvaal).

Revolutionary conspiracy of Uitlanders at Johannesburg.

The Jameson raid.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1895-1896.

AFRICA: A. D. 1895-1897 (British East Africa Protectorate).

Creation of the Protectorate.

Territories included.

Subjugation of Arab chiefs.

Report of commissioner.

See (in this volume)

BRITISH EAST AFRICA PROTECTORATE:

A. D. 1895-1897.

AFRICA: A. D. 1896 (Ashanti).

British conquest and occupation.

See (in this volume)

ASHANTI.

AFRICA: A. D. 1896 (British South Africa Company).

Resignation of Mr. Rhodes.

Parliamentary movement to investigate.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY):

A. D. 1896 (JUNE); and (JULY).

AFRICA: A. D. 1896 (Cape Colony).

Investigation of the Jameson raid.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (CAPE COLONY): A. D. 1896 (JULY).

AFRICA: A. D. 1896 (Rhodesia).

Matabele revolt.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (RHODESIA):

A. D. 1896 (MARCH-SEPTEMBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1896 (Zanzibar).

Suppression of an usurper by the British.

On the sudden death (supposed to be from poison) of the Sultan

of Zanzibar, August 25, his cousin, Said Khalid, seized the

palace and proclaimed himself sultan. Zanzibar being an

acknowledged protectorate of Great Britain, the usurper was

summoned by the British consul to surrender. He refused, and

the palace was bombarded by war vessels in the harbor, with

such effect that the palace was speedily destroyed and about

500 of its inmates killed. Khalid fled to the German consul,

who protected him and had him conveyed to German territory. A

new sultan, Said Hamud-bin-Mahomed was at once proclaimed.

AFRICA: A. D. 1896-1899 (The Transvaal).

Controversies with the British Government.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1896 (JANUARY-APRIL), to 1899 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Congo Free State).

Mutiny of troops.

The Congo troops of an expedition led by Baron Dhanis mutinied

and murdered a number of Belgian officers. Subsequently they

were attacked in the neighborhood of Lake Albert Edward Nyanza

and mostly destroyed.

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Dahomey and Tongoland).

Definition of boundary.

By a convention concluded in July between Germany and France,

the boundary between German possessions in Tongoland and those

of France in Dahomey and the Sudan was defined.

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Nigeria).

Massacre at Benin.

British expedition.

Capture of the town.

See (in this volume)

NIGERIA: A. D. 1897.

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Nigeria).

Subjugation of Fulah slave-raiders.

In January and February, the forces of the Royal Niger Company

successfully invaded the strong Fulah states of Nupé and

Ilorin, from which slave raiding in the territory under

British protection was carried on. Bida, the Nupé capital, was

entered on the 27th of January, after a battle in which 800

Hausa troops, led by European officers, and using heavy

artillery, drove from the field an army of cavalry and foot

estimated at 30,000 in number. The Emir of Nupé was deposed,

another set up in his place, and a treaty signed which

established British rule. The Emir of Ilorin submitted after

his town had been bombarded, and bowed himself to British

authority in his government. At the same time, a treaty

settled the Lagos frontier. Later in the year, the stronghold

at Kiffi of another slave-raider, Arku, was stormed and

burned.

|

|

Map of Africa

{3}

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Orange Free State and Transvaal).

Treaty defensive between the two republics.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (ORANGE FREE STATE AND TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1897 (APRIL).

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Sudan).

Beginning of the Anglo-Egyptian conquest.

See (in this volume)

EGYPT: A. D. 1885-1896.

A. D. 1897 (Zanzibar).

Abolition of slavery.

Under pressure from the British government, the Sultan of

Zanzibar issued a decree, on the 6th or April, 1897,

terminating the legal status of slavery, with compensation to

be awarded on proof of consequent loss.

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (Zululand).

Annexation to Natal.

By act of the Natal Parliament in December, 1897, Zululand

(with Amatongaland already joined to it) was annexed to Natal

Colony, and Dinizulu, son of the last Zulu king, was brought

from captivity in St. Helena and reinstated.

AFRICA: A. D. 1897-1898 (Sudan).

Completion of the Anglo-Egyptian conquest.

See (in this volume)

EGYPT: A. D. 1897-1898.

AFRICA: A. D. 1897-1898 (Uganda).

Native insurrections and mutiny of Sudanese troops in Uganda.

See (in this volume)

UGANDA: A. D. 1897-1898.

AFRICA: A. D. 1898 (Abyssinia).

Treaty of King Menelek with Great Britain.

See (in this volume)

ABYSSINIA: A. D. 1898.

AFRICA: A. D. 1898 (British South Africa Company).

Reorganization.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (RHODESIA):

A. D. 1898 (FEBRUARY).

AFRICA: A. D. 1898 (Egypt).

The Nile question between England and France.

Marchand's expedition at Fashoda.

See (in this volume)

EGYPT: A. D. 1898 (SEPTEMBER-NOVEMBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1898 (Nigeria and the French Sudan).

Definition of French and English possessions in

West and North Africa.

See (in this volume)

NIGERIA: A. D. 1882-1899.

AFRICA: A. D. 1898 (Rhodesia).

Reorganization of the British South Africa Company and

the administration of its territories.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA

(RHODESIA AND THE BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY):

A. D. 1898 (FEBRUARY).

AFRICA: A. D. 1898 (Tunis).

Results of the French Protectorate.

See (in this volume)

TUNIS: A. D. 1881-1898.

AFRICA: A. D. 1899.

Railway development.

"Railroad development in Africa has been rapid in the past few

years and seems but the beginning of a great system which must

contribute to the rapid development, civilization, and

enlightenment of the Dark Continent. Already railroads run

northwardly from Cape Colony about 1,400 miles, and

southwardly from Cairo about 1,100 miles, thus making 2,500

miles of the 'Cape to Cairo' railroad complete, while the

intermediate distance is about 3,000 miles. Mr. Rhodes, whose

recent visit to England and Germany in the interest of the

proposed through line from the Cape to Cairo is a matter of

record, and whose visit to Germany was made necessary by the

fact that in order to pass from the southern chain of British

territory to the northern chain he must cross German or

Belgian territory, is reported as confident that the through

line will be completed by the year 1910. Certainly it may

reasonably be assumed that a continuous railway line will be

in operation from the southern to the northern end of Africa

in the early years of the twentieth century. Toward this line,

present and prospective, which is to stretch through the

eastern part of the continent, lateral lines from either coast

are beginning to make their way. A line has already been

constructed from Natal on the southeast coast: another from

Lourenço Marquez in Portuguese territory and the gold and

diamond fields: another from Beira, also in Portuguese

territory, but considerably farther north, and destined to

extend to Salisbury in Rhodesia, where it will form a junction

with the 'Cape to Cairo' road; still another is projected from

Zanzibar to Lake Victoria Nyanza, to connect, probably, at

Tabora, with the transcontinental line; another line is under

actual construction westward from Pangani just north of

Zanzibar, both of these being in German East Africa; another

line is being constructed northwestwardly from Mombasa, in

British territory, toward Lake Victoria Nyanza, and is

completed more than half the distance, while at the entrance

to the Red Sea a road is projected westwardly into Abyssinia,

and is expected to pass farther toward the west and connect

with the main line. At Suakim, fronting on the Red Sea, a road

is projected to Berber, the present terminus of the line

running southwardly from Cairo. On the west of Africa lines

have begun to penetrate inward, a short line in the French

Sudan running from the head of navigation on the Senegal

eastwardly toward the head of navigation on the Niger, with

the ultimate purpose of connecting navigation on these two

streams. In the Kongo Free State a railway connects the Upper

Kongo with the Lower Kongo around Livingstone Falls; in

Portuguese Angola a road extends eastwardly from Loanda, the

capital, a considerable distance, and others are projected

from Benguela and Mossamedes with the ultimate purpose of

connecting with the 'Cape to Cairo' road and joining with the

lines from Portuguese East Africa, which also touch that road,

thus making a transcontinental line from east to west, with

Portuguese territory at either terminus. Farther south on the

western coast the Germans have projected a road from Walfisch

Bay to Windhoek, the capital of German Southwest Africa, and

this will probably be extended eastwardly until it connects

with the great transcontinental line from 'Cape to Cairo,'

which is to form the great nerve center of the system, to be

contributed to and supported by these branches connecting it

with either coast. Another magnificent railway project, which

was some years ago suggested by M. Leroy Beaulieu, has been

recently revived, being no less than an east and west

transcontinental line through the Sudan region, connecting the

Senegal and Niger countries on the west with the Nile Valley

and Red Sea on the east and penetrating a densely populated

and extremely productive region of which less is now known,

perhaps, than of any other part of Africa. At the north

numerous lines skirt the Mediterranean coast, especially in

the French territory of Algeria and in Tunis, where the length

of railway is, in round numbers, 2,250 miles, while the

Egyptian railroads are, including those now under

construction, about 1,500 miles in length.

{4}

Those of Cape Colony and Natal are nearly 3,000 miles, and

those of Portuguese East Africa and the South African Republic

another thousand. Taking into consideration all of the roads

now constructed, or under actual construction, their total

length reaches nearly 10,000 miles, while there seems every

reason to believe that the great through system connecting the

rapidly developing mining regions of South Africa with the

north of the continent and with Europe will soon be pushed to

completion. A large proportion of the railways thus far

constructed are owned by the several colonies or States which

they traverse, about 2,000 miles of the Cape Colony system

belonging to the Government, while nearly all that of Egypt is

owned and operated by the State."

United States Bureau of Statistics,

Monthly Summary, August, 1899.

See, also, (in this volume),

RAILWAY, CAPE TO CAIRO.

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (June).

International Convention respecting the liquor traffic.

Representatives of the governments of Great Britain, Germany,

Belgium, Spain, the Congo State, France, Italy, the

Netherlands, Portugal, Russia, Sweden and Norway, and Turkey,

assembled at Brussels, in June, 1899, with due authorization,

and there concluded an international convention respecting the

liquor traffic in Africa. Subsequently the governments of

Austria-Hungary, the United States of America, Liberia and

Persia, gave their adhesion to the Convention, and

ratifications were deposited at Brussels in June, 1900. The

Convention is, in a measure, supplemental to what is known as

"the General Act of Brussels," relative to the African slave

trade, which was framed at a conference of the representatives

of European, American, African, and Asiatic states, at

Brussels. The treaty known as the General Act of Brussels was

signed July 2, 1890, but did not come into force until April

2, 1894. The text of it may be found in (United States) House

Doc. Number 276, 56th Congress, 3d Session. The Convention of

1899 provides:

"Article I.

From the coming into force of the present Convention, the

import duty on spirituous liquors, as that duty is regulated

by the General Act of Brussels, shall be raised throughout the

zone where there does not exist the system of total

prohibition provided by Article XCI, of the said General Act,

to the rate of 70 fr. the hectolitre at 50 degrees centigrade,

for a period of six years. It may, exceptionally, be at the

rate of 60 fr. only the hectolitre at 50 degrees centigrade in

the Colony of Togo and in that of Dahomey. The import duty

shall be augmented proportionally for each degree above 50

degrees centigrade; It may be diminished proportionally for

each degree below 50 degrees centigrade. At the end of the

above-mentioned period of six years, the import duty shall be

submitted to revision, taking as a basis the results produced

by the preceding rate. The Powers retain the right of

maintaining and increasing the duty beyond the minimum fixed

by the present Article in the regions where they now possess

that right.

Article II.

In accordance with Article XCIII of the General Act of

Brussels, distilled drinks made in the regions mentioned in

Article XCII of the said General Act, and intended for

consumption, shall pay an excise duty. This excise duty, the

collection of which the Powers undertake to insure as far as

possible, shall not be lower than the minimum import duty

fixed by Article I. of the present Convention.

Article III.

It is understood that the Powers who signed the General Act of

Brussels, or who have acceded to it, and who are not

represented at the present Conference, preserve the right of

acceding to the present Convention."

Great Britain, Parliamentary Publication.

(Papers by Command: Treaty Series, Number 13, 1900).

AFRICA: A. D. 1899.

Progress of the Telegraph line from the Cape to Cairo.

See (in this volume)

TELEGRAPH, CAPE TO CAIRO.

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (German Colonies).

Cost to Germany, trade, etc.

See (in this volume)

GERMANY: A. D. 1899 (JUNE).

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (Nigeria).

Transfer of territory to the British Crown.

See (in this volume)

NIGERIA: A. D. 1899.

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (Orange Free State).

Treaty of alliance with the Transvaal.

Making common cause.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (ORANGE FREE STATE):

A. D. 1897 (APRIL); and 1899 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (The Sudan).

Anglo-Egyptian Condominium established.

See (in this volume)

EGYPT: A. D. 1899 (JANUARY).

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (Transvaal and Orange Free State).

Outbreak of war with Great Britain.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (TRANSVAAL AND ORANGE FREE STATE):

A. D. 1899 (SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER).

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (West Africa).

Definition of British and German frontiers.

See (in this volume)

SAMOAN ISLANDS.

AFRICA: A. D. 1899 (Zanzibar).

Renunciation of rights of extra-territoriality by Germany.

See (in this volume)

SAMOAN ISLANDS.

AFRICA: A. D. 1899-1900.

Summary of the partition of the Continent.

"Seven European nations, as before remarked, now control

territories in Africa, two of them having areas equal in each

case to about the entire land area of the United States, while

a few small territories remain as independent States.

Beginning at the northeast, Egypt and Tripoli are nominally at

least tributaries of Turkey, though the Egyptian Government,

which was given large latitude by that of Turkey, has of late

years formed such relations with Great Britain that, in

financial matters at least, her guidance is recognized; next

west, Algeria, French; then Morocco on the extreme northwest,

an independent Government and an absolute despotism; next on

the south, Spain's territory of Rio de Oro; then the Senegal

territories, belonging to the French, and connecting through

the desert of Sahara with her Algeria; then a group of small

divisions controlled by England, along the Gulf of Guinea;

then Liberia, the black Republic; Togoland, controlled by the

Germans; Dahomey, a French protectorate; the Niger territory,

one-third the size of the United States, controlled by

England; Kamerun, controlled by Germany; French Kongo; then

the Kongo Free State, under the auspices of the King of

Belgium, and occupying the very heart of equatorial Africa;

then Portuguese Angola; next, German South west Africa; and

finally in the march down the Atlantic side, Cape Colony,

British.

{5}

Following up the eastern side comes the British colony of

Natal; then just inland from this the two Boer Republics, the

Orange Free State and the South African Republic, both of

which are entirely in the interior, without ocean frontage;

next, Portuguese Africa, and west of this the great territory

known as 'Rhodesia'; then German Africa, which extends almost

to the equator; north of these, British East Africa, fronting

on the Indian Ocean, and merging northwardly with the Egyptian

Sudan, which was recently recovered from the Mahdi by the joint

operation of British and Egyptian troops, and the British flag

placed side by side with that of Egypt; next north, upon the

coast, Italian territory and a small tract opposite the

entrance to the Red Sea controlled by England; and a few

hundred miles west of the entrance to the Red Sea, the

independent Kingdom of Abyssinia. This division of African

territory, nearly all of it made within the memory of the

present generation, forms the present political map of Africa.

With England and France controlling an area equal in each case

to that of the United States; Germany, a territory one-third

the size of the United States; Portugal, with an area somewhat

less; the Kongo Free State in the great equatorial basin, but

having a frontage upon the Atlantic with an area nearly

one-third that of the United States; Italy and Spain, each

with a comparatively small area of territory; Egypt, with

relations quite as much British as Turkish; Tripoli, Turkish,

and the five independent States of Morocco, Liberia,

Abyssinia, and the two Boer Republics—nothing remains

unclaimed, even in the desert wastes, while in the high

altitudes and subtropical climate of southeast Africa

civilization and progress are making rapid advancement."

United States Bureau of Statistics,

Monthly Summary, August, 1899.

The following table, given in an article in "The Forum,"

December, 1899, by Mr. O. P. Austin, Chief of the United

States Bureau of Statistics, shows the area, total population,

foreign population, and imports and exports of the territory

in Africa held by each European Government and by the

independent States of that continent, at the time of its

compilation so far as could be ascertained; but the statistics

of area and population, especially the latter, are in many

cases necessarily estimates:

POP.

TOTAL FOREIGN PER SQ.

AREA. POPULATION. POPULATION MILE IMPORTS. EXPORTS.

French Africa. 3,028,000 28,155,000 922,000 9.3 $70,116,000 $69,354,000

British Africa. 2,761,000 35,160,000 455,000 12.8 131,398,000 131,835,000

Turkish Africa. 1,760,000 21,300,000 113,000 12.2 54,091,000 62,548,000

German Africa. 944,000 11,270,000 4,000 12.0 4,993,000 2,349,000

Belgian Africa. 900,000 30,000,000 2,000 33.3 4,522,000 3,309,000

Portuguese Africa. 790,000 8,059,000 3,000 10.2 11,863,000 6,730,000

Spanish Africa. 243,000 36,000 … 0.5 … …

Italian Africa. 188,000 850,000 … 4.5 … …

Independent States.

Morocco. 219,000 5,000,000 … 22.8 6,402,000 6,261,000

Abyssinia. 150,000 3,500,000 … 23.3 … …

South African Republic. 120,000 1,096,000 346,000 9.2 104,703,000 53,532,000

Orange Free State. 48,500 208,000 78,000 4.3 5,994,000 8,712,000

Liberia. 48,000 1,500,000 25,000 31.3 1,217,000 1,034,000

Total. 11,189,500 146,133,000 1,948,000 … $395,299,000 $345,714,000

According to a statistical table in the twentieth volume of

Meyer's Konversations-Lexicon (third annual supplement), based

upon the latest data furnished by the boundary treaties

between the Powers, it would appear that all but about

one-seventh of the African continent is now (A. D. 1900)

included in some "protectorate" or "sphere of influence." The

French sphere is the largest, comprising about 3,700,000

square miles (about the extent of Europe) out of a total area

of 11,600,000. England comes next with 2,400,000 (including

the Boer territories). Then follow in order Germany, Belgium

(Congo Free State), and Portugal, each with somewhat less than

a million square miles. The Egyptian sphere (about 400,000

square miles) may properly be regarded as part of the British.

The extent of the French sphere will appear less imposing on

consulting the map of Africa here given, which shows that it

takes in the greater part of the sands of the Sahara. The

British sphere (including Egypt and her dependencies) is

estimated to contain in round numbers about 50,000,000 souls;

the French, 35,000,000; the Belgian, 17,000,000; the German,

9,000,000; the Portuguese, 8,000,000.

AFRICA: A. D. 1900 (Ashanti).

Revolt of the tribes.

Siege and relief of Kumasai.

See (in this volume)

ASHANTI.

AFRICA: A. D. 1900 (Togoland and Gold Coast).

Demarcation of the Hinterland.

Late in November it was announced from Berlin that conferences

regarding the British and German boundaries in West Africa

were then in progress in the Colonial Department of the German

Foreign Office, their principal object being the demarcation

of the Hinterland of Togoland and of the Gold Coast, and in

particular the partition of the neutral zone of Salaga as

arranged in Article 5 of the Samoa Agreement between Great

Britain and Germany.

See (in this volume)

SAMOAN ISLANDS.

AFRIDIS, British Indian war with the.

See (in this volume)

INDIA: A. D. 1897-1898.

AFRIKANDER BUND, The.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (CAPE, COLONY):

A. D. 1881-1888; 1898; and 1898 (MARCH-OCTOBER).

AFRIKANDER CONGRESS.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (Cape Colony): A. D. 1900 (DECEMBER).

AFRIKANDERS:

Joining the invading Boers.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE FIELD OF WAR):

A. D. 1899 (OCTOBER-NOVEMBER.).

AFRIKANDERS:

Opposition to the annexation of the Boer Republics.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (CAPE COLONY): A. D. 1900 (MAY).

{6}

AGRARIAN PROTECTIONISTS, The German.

See (in this volume)

GERMANY: A. D. 1895-1898; 1899 (AUGUST); and 1901 (FEBRUARY).

AGRICULTURAL LAND BILL, The.

See (in this volume)

ENGLAND: A. D. 1896.

AGUINALDO y FAMY, Emilio.

First appearance in the Filipino insurrection.

His treaty with the Spaniards and departure from the Islands.

See (in this volume)

PHILIPPINE ISLANDS: A. D. 1896-1898.

AGUINALDO y FAMY, Emilio.

Circumstances in which he went to Manila to co-operate with

American forces.

See (in this volume)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1898 (APRIL-MAY: PHILIPPINES).

AGUINALDO y FAMY, Emilio.

Arrival at Manila, May 19, 1898.

His organization of insurgent forces.

His relations with Admiral Dewey.

See (in this volume)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1898 (APRIL-JULY).

AGUINALDO y FAMY, Emilio.

Correspondence with General Anderson.

See (in this volume)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1898 (JULY-AUGUST: PHILIPPINES).

AGUINALDO y FAMY, Emilio.

Relations with American commander at Manila.

Declared President of the Philippine Republic.

See (in this volume)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1898 (JULY-SEPTEMBER).

AGUINALDO y FAMY, Emilio.

Conflict of his army with American forces.

See (in this volume)

PHILIPPINE ISLANDS:

A. D. 1898 (AUGUST-DECEMBER), and after.

ALABAMA: A. D. 1899.

Dispensary Laws.

Acts applying the South Carolina "dispensary" system of

regulation for the liquor traffic to seventeen counties, but

not to the State at large, were passed by the Legislature.

See, in this volume,

SOUTH CAROLINA: A. D. 1892-1899.

ALASKA: A. D. 1898-1899.

Discovery of the Cape Nome gold mining region.

"The Cape Nome mining region lies on the western coast of

Alaska, just beyond the military reservation of St. Michael

and about 120 miles south of the Arctic Circle. It can be

reached by an ocean voyage of ten or twelve days from Seattle.

It has long been known that gold exists in the general vicinity

of Cape Nome, and during the last five or six years a few

adventurous miners have done more or less prospecting and

claim staking throughout the district lying between Norton and

Kotzebue sounds. During the winter of 1898-99, a large number

of miners entered the Kotzebue country, while others spent the

season in the vicinity of Golofnin Bay." On the 15th of

October, 1898, a party of seven men reached Snake River in a

schooner. "Between that date and the 18th a miners' meeting

was held, the boundaries of a district 25 miles square were

established, local mining regulations were formulated, and Dr.

Kittleson was elected recorder for a term of two years. After

organizing the district natives were hired to do the necessary

packing, and a camp was established on Anvil Creek. The

prospecting outfits were quickly brought into service. In one

afternoon $76 was panned out on Snow Creek. Encouraged by this

showing lumber was carried up from the schooner and two

rockers were constructed. … In four or five days over $1,800

was cleaned up with these two rockers. … The weather turned

cold and the water was frozen up. As it was impossible to do

any more work with the rockers the party broke camp on the 3d

of November and returned to the schooner, which they found

frozen solid in 2 feet of ice. They then made their way in a

small boat to an Indian village, near Cape Nome, where they

obtained dogs and sleds, and a little farther on they were met

by reindeer from the Swedish Mission, with which they returned

to Golofnin Bay.

"The lucky miners had agreed among themselves that their

discovery should be held secret, but the news was too good to

keep, and soon leaked out. A general stampede commenced at

once and continued all winter. Every available dog and

reindeer was pressed into the service, and they were soon

racing with each other for the valuable claims which had been

left unstaked in the vicinity of Anvil Creek. As soon as that

creek had been all taken up the stampede extended to the

neighboring streams and gulches, and Glacier and Dexter

creeks, as well as many others which have not proved equally

valuable, were quickly staked and recorded. By the 25th of

December a large party armed with numerous powers of attorney

had entered the district, and as the local regulations allowed

every man to stake on each creek one claim of the full legal

dimensions (660 by 1,320 feet), it was not long until the

whole district had been thoroughly covered, and nearly every

stream had been staked with claims, which in some cases were

'jumped' and the right of possession disputed.

"The news of a rich strike at Nome worked its way up the Yukon

River during the winter, and as soon as the ice broke in June

a large crowd came down from Rampart City, followed by a

larger crowd from Dawson. The 'Yukoners,' as these people were

called, were already disgusted with the hardships,

disappointments, and Canadian misgovernment which they had met

with on the upper river. … Those to whom enough faith had been

given to go over to Cape Nome were disgusted and angered to

find that pretty much the whole district was already staked,

and that the claims taken were two or three times as large as

those commonly allowed on the upper river. Another grievance

was the great abuse of the power of attorney, by means of

which an immense number of claims had been taken up, so that

in many cases (according to common report) single individuals

held or controlled from 50 to 100 claims apiece. …

"A miners' meeting was called by the newcomers to remedy their

grievances. Resolutions were prepared, in which it was

represented that the district had been illegally organized by

men who were not citizens of the United States and who had not

conformed with the law in properly defining the boundaries of

the district with reference to natural objects, in enacting

suitable and sufficient mining regulations, and in complying

with any of the details of organization required by law. It

was intended by the promoters of this meeting to reorganize

the district in such a way as would enable them to share the

benefits of the discovery of a new gold field with the men who

had entered it the previous winter, and, as they expressed it,

'gobbled up the whole country.' It is, of course, impossible

to say what would have been the result if their attempt had

not been interfered with. … On the 28th of June Lieutenant

Spaulding and a detachment of 10 men from the Third Artillery

had been ordered to the vicinity of Snake River, and on the

7th of July their numbers were increased by the addition of 15

more.

{7}

As soon as it was proposed to throw open for restaking a large

amount of land already staked and recorded an appeal was made

to the United States troops to prevent this action by

prohibiting the intended meeting, which was called to assemble

July 10. It was represented to them that if the newcomers

should attempt, under the quasi-legal guise of a miners'

meeting, to take forcible possession of lands already claimed

by others, the inevitable consequence would be a reign of

disorder and violence, with the possibility of considerable

bloodshed. On the strength of this representation and appeal

the army officers decided to prevent the adoption of the

proposed resolutions. The miners were allowed to call their

meeting to order, but as soon as the resolutions were read

Lieutenant Spaulding requested that they be withdrawn. He

allowed two minutes for compliance with his request, the

alternative being that he would clear the hall. The

resolutions were not withdrawn, the troops were ordered to fix

bayonets, and the hall was cleared quietly, without a

conflict. Such meetings as were subsequently attempted were

quickly broken up by virtue of the same authority. The light

in which this action is regarded by the people at Nome

depends, of course, upon the way in which their personal

interests were affected. …

"The great discontent which actually did exist at this time

found sudden and unexpected relief in the discovery of the

beach diggings. It had long been known that there was more or

less gold on the seashore, and before the middle of July it

was discovered that good wages could be taken out of the sand

with a rocker. Even those who were on the ground could hardly

believe the story at first, but its truth was quickly and

easily demonstrated. Before the month was over a great army of

the unemployed was engaged in throwing up irregular

intrenchments along the edge of the sea, and those who had

just been driven nearly to the point of desperation by the

exhaustion of all their resources were soon contentedly

rocking out from $10 to $50 each per day and even more than

that. This discovery came like a godsend to many destitute

men, and was a most fortunate development in the history of

the camp.

"Meantime the men who were in possession of claims on Anvil

and Snow creeks were beginning to sluice their ground and

getting good returns for their work, while others were

actively making preparations to take out the gold which they

knew they had discovered. More sluice boxes were constructed

and put into operation as rapidly as possible. A town site was

laid off at the mouth of Snake River, and on the 4th of July a

post-office was established. The town which has sprung so

suddenly into existence is called 'Nome' by the Post-Office

Department, but at a miners' meeting held February 28, it was

decided to call it 'Anvil City,' and this is generally done by

the residents of the district, as well as in all official

records. At a meeting held in September, however, the name was

again changed to 'Nome.'"

United States, 56th Congress, 1st session,

Senate Document Number 357, pages. 1-4.

"A year ago [that is, in the winter of 1898-1899] a few Eskimo

huts and one or two sod houses of white men were the only

human habitations along 60 miles of the present Nome coast.

Last June [1899] a dozen or score of tents contained the whole

population. By October a town of 5,000 inhabitants fronting

the ocean was crowded for a mile or more along the beach.

Hundreds of galvanized-iron and wooden buildings were

irregularly scattered along two or three thoroughfares,

running parallel with the coast line. There is every

description of building, from the dens of the poor

prospectors, built of driftwood, canvas, and sod, to the large

companies' warehouses, stores, and the army barracks—a city,

as it were, sprung up in the night, built under the most

adverse circumstances on the barren seacoast, a coast without

harbor, all the supplies being landed through the surf. … The

country contributes nothing toward the support of the

population except a few fish and a limited supply of

driftwood.

"The city is of the most cosmopolitan type and contains

representatives of almost every nationality on the globe:

Germans, Canadians, Frenchmen, Englishmen, Russians, Swedes,

Norwegians, Poles, Chinese, negroes, Italians, Spaniards,

Greeks, Jews, and Americans. The dominant type is the

American, through whose efforts, with that inherent talent of

the Anglo-Saxon race for self-government, this isolated

community at once organized a city government. Before the

close of the summer Nome had a mayor, councilmen, a police

force, a deputy United States marshal, a United States

post-office, a fire department with town well, a board of

health, a hospital corps, and charitable organizations. A

majority of the people consists of the shifting population of

the Yukon country, which, upon hearing the news of the

discovery of gold, poured itself into Nome. … Along with the

shifting population of the Yukon from Dawson and other camps

came also many would-be explorers, adventurers, and especially

gamblers, but good order prevails throughout. Drunkenness,

disorderly conduct, and theft are promptly tried before the

police justice and punished by fine and imprisonment. Copies

of the official rules and regulations are kept posted before

the city hall and in other conspicuous places, as a warning to

all: 'Ignorance of the law is no excuse.' Some of the well-known

'toughs' and most undesirable characters are reported to have

been rounded up by the authorities late in the fall and

exported to the States. … There are several printing presses

and three newspapers—the Nome News, Nome Herald, and Nome Gold

Digger. … There are at least 2,500 people now [February, 1900]

wintering at Nome, and, by estimate, at least several thousand

are on their way there by winter routes. …

"Since, according to the conservative estimate of those who

are best situated to judge, it is believed that the Nome

region will have a population of at least 30,000 or 40,000

people this year (1900), some public improvements there seem

not only commendable but urgently necessary. Among these the

most important are: Some municipal form of government, water

supply, land-office service, and harbor facilities. As the

General Government had never made provision for any form of

municipal government in Alaska, the people of Nome, in

response to the urgency of the hour, called a mass meeting,

and organized the present government of Nome, with a complete

corps of city officers, as aforesaid, though they were

conscious at the time that it was without authority from the

United States Government."

F. C. Schrader and A. H. Brooks,

Preliminary Report on the Cape Nome Gold Region, Alaska

(United States Geological Survey), pages 45-47.

{8}

ALASKA: A. D. 1900.

Civil Government.

Better provision for the civil government of Alaska was made

by an Act which passed Congress after much debate and was

approved by the President on the 6th of June, 1900. It

constitutes Alaska a civil and judicial district, with a

governor who has the duties and powers that pertain to the

governor of a Territory, and a district court of general

jurisdiction, civil and criminal, and in equity and admiralty,

the court being in three divisions, each with a district

judge. The act provides a civil code for the district.

ALASKA: A. D. 1900.

Exploration of Seward peninsula.

See (in this volume)

POLAR EXPLORATION, 1900.

ALASKA BOUNDARY QUESTION, The.

The boundary between Alaska, when it was Russian territory,

and the British possessions on the western side of the

American continent, was settled by an Anglo-Russian treaty in

1825. The treaty which ceded the Russian territory to the

United States, in 1867, incorporated the definition of

boundary given in Articles III. and IV. of the above-mentioned

convention, which (translated from French to English) read as

follows:

"III.

The line of demarcation between the possessions of the High

Contracting Parties upon the Coasts of the Continent and the

Islands of America to the North-West, shall be drawn in the

following manner: Commencing from the southernmost point of

the Island called Prince of Wales Island, which point lies in

the parallel of 54 degrees 40 minutes, North Latitude, and

between the 131st and 133d Degree of West Longitude (Meridian

of Greenwich), the said line shall ascend to the North along

the Channel called Portland Channel, as far as the Point of

the Continent where it strikes the 56th Degree of North

Latitude; from this last mentioned Point the line of

demarcation shall follow the summit of the mountains situated

parallel to the coast, as far as the point of intersection of

the 141st Degree of West Longitude (of the same meridian),

and, finally, from the said point of intersection, the said

Meridian Line of the 141st Degree, in its prolongation as far

as the Frozen Ocean, shall form the limit between the Russian

and British Possessions on the Continent of America to the

North West.

"IV.

With reference to the line of demarcation laid down in the

preceding Article, it is understood:

1st.

That the Island called Prince of Wales Island shall belong

wholly to Russia.

2d.

That wherever the summit of the mountains which extend in a

direction parallel to the Coast, from the 56th Degree of North

Latitude to the point of intersection of the 141st Degree of

West Longitude, shall prove to be at the distance of more than

ten marine leagues from the Ocean, the limit between the

British Possessions and the line of Coast which is to belong

to Russia, as above mentioned, shall be formed by a line

parallel to the windings of the Coast, and which shall never

exceed the distance of ten marine leagues therefrom."

When attempts to reduce this description in the treaty to an

actually determined boundary-line were begun, disagreements

arose between Canada and the United States, which became

exceedingly troublesome after the Klondike gold discoveries

had given a new importance to that region and to its

communications with the outside world. The Alaska boundary

question proved, in fact, to be considerably the most

difficult of settlement among all the many subjects of

disagreement between the United States and Canada which a

Joint High Commission was created in 1898 (see—in this

volume—CANADA: A. D. 1898-1900) to adjust. It was the one

question on which no ground of compromise could then be found,

and which compelled the Commission to adjourn in February,

1899, with its labors incomplete. The disputable points in the

definition of the boundary by the Anglo-Russian treaty of 1825

are explained as follows by Professor J. B. Moore,

ex-Assistant Secretary of State, in an article contributed to

the "North American Review" of October, 1899: "An examination

of the boundary defined in Articles III. and IV. of the

convention of 1825 shows," says Professor Moore, "that it is

scientifically divisible into two distinct sections, first,

the line from the southernmost point of Prince of Wales

Island, through Portland Channel and along the summit of the

mountains parallel to the coast, to the point of intersection

of the 141st meridian of longitude; and, second, the line from

this point to the Arctic Ocean. With the latter section, which

is merely a meridian line, and as to which the United States

and Canadian surveys exhibit no considerable difference, we

are not now concerned. The section as to which material

differences have arisen is the first. The principal

differences in this quarter are two in number, first, as to

what channel is meant by Portland Channel (sometimes called

Portland Canal); and, second, as to what is the extent of the

line or strip of coast (la lisière de côte) which was assigned

to Russia."

Map of Alaska.

Map of Alaska.

The following is an English statement of the situation of the

controversy at the time the Joint High Commission adjourned:

"The adjournment of the Commission with nothing accomplished

is fresh in all our memories. Nor is it easy to determine on

whose shoulders lies the blame of this unfortunate break down.

America has been blamed for her stubbornness in refusing to

submit to an arbitration which should take into consideration

the possession of the towns and settlements under the

authority of the United States and at present under their

jurisdiction; while they have also been charged with having

made no concessions at all to Canada in the direction of

allowing her free access to her Yukon possessions. I am

enabled to say, however, in this latter respect the Americans

have not been so stiff-necked as has been made to appear.

Although it was not placed formally before the Commission, it

was allowed clearly to be understood by the other side, that

in regard to Skagway, America was prepared to make a very

liberal concession. They were ready, that is, to allow of the

joint administration of Skagway, the two flags flying side by

side, and to allow of the denationalisation, or

internationalisation as it might otherwise be termed, of the

White Pass and the Yukon Railroad, now completed to Lake

Bennett, and the only railroad which gives access to the

Yukon. They were even prepared to admit of the passage of

troops and munitions of war over this road, thus doing away

with the Canadian contention that, should a disturbance occur

in the Yukon, they are at present debarred from taking

efficient measures to quell it.

{9}

This proposition, however, does not commend itself to the

Canadians, whose main object, I think I am justified in

saying, is to have a railroad route of their own from

beginning to end, in their own territory, as far north as

Dawson City. At one time, owing to insufficient information

and ignorance of the natural obstacles in the way, they

thought they could accomplish this by what was known as the

Stikine route. They even went so far as to make a contract

with Messrs. McKenzie and Mann to construct this road, the

contractors receiving, as part of their payment, concessions

and grants of territory in the Yukon, which would practically

have given them the absolute and sole control of that

district. The value of this to the contractors can hardly be

overestimated. However, not only did the natural obstacles I

have referred to lead to the abandonment of the scheme, but

the Senate at Ottawa threw out the Bill which had passed

through the Lower House, affording a striking proof that there

are times when an Upper House has its distinct value in

legislation. It has been suggested (though I am the last to

confirm it) that it was the influence of the firm of railroad

contractors, to whose lot it would probably fall to construct

any new line of subsidised railway, which caused the Canadian

Commission to reject the tentative American proposal regarding

Skagway, and to put forward the counter claim to the

possession of Pyramid Harbour (which lies lower down upon the

west coast of the Lynn Canal), together with a two mile wide

strip of territory reaching inland, containing the Chilcat

Pass, and through it easy passage through the coast ranges,

and so by a long line of railroad to Fort Selkirk, which lies

on the Yukon River, to the south and east of Dawson City. It

is said also, though of this I have no direct evidence, that

the Canadians included the right to fortify Pyramid Harbour.

It is not surprising that the Americans rejected this

proposal, for they entered into the discussion convinced of

the impossibility of accepting any arrangement which would

involve the surrender of American settlements, and though it

is not so large or important as Skagway or Dyea, Pyramid

Harbour is nevertheless as much an American settlement as the

two latter. I am bound to point out that just as the Dominion

of Canada, as a whole, has a keener interest in this dispute

than has the Home Government, so the Government of British

Columbia is more closely affected by any possible settlement

than is the rest of the Dominion. And British Columbia is as

adverse to the Pyramid Harbour scheme as the United States

themselves. This is due to the fact that when finished the

Pyramid Harbour and Fort Selkirk railroad would afford no

access to the British Columbia gold fields on Atlin Lake,

which would still be reached only by way of Skagway and the

White Pass, or by Dyea and the Chilcat Pass. But quite apart

from this view of the matter, we may take it for granted that

the United States will never voluntarily surrender any of

their tide-water settlements, while the Canadian Government,

on the other hand, are no more disposed to accept any

settlement based on the internationalisation of Skagway, their

argument probably being that, save as a temporary 'modus

vivendi,' this would be giving away their whole case to their

opponents."

H. Townsend,

The Alaskan Boundary Question

(Fortnightly Review, September, 1899).

Pending further negotiations on the subject, a "modus vivendi"

between the United States and Great Britain, "fixing a

provisional boundary line between the Territory of Alaska and

the Dominion of Canada about the head of Lynn Canal," was

concluded October 20, 1899, in the following terms:

"It is hereby agreed between the Governments of the United

States and of Great Britain that the boundary line between

Canada and the territory of Alaska in the region about the

head of Lynn Canal shall be provisionally fixed as follows

without prejudice to the claims of either party in the

permanent adjustment of the international boundary: In the

region of the Dalton Trail, a line beginning at the peak West

of Porcupine Creek, marked on the map No. 10 of the United

States Commission, December 31, 1895, and on Sheet No. 18 of

the British Commission, December 31, 1895, with the number

6500; thence running to the Klehini (or Klaheela) River in the

direction of the Peak north of that river, marked 5020 on the

aforesaid United States map and 5025 on the aforesaid British

map; thence following the high or right bank of the said

Klehini river to the junction thereof with the Chilkat River,

a mile and a half, more or less, north of Klukwan,—provided

that persons proceeding to or from Porcupine Creek shall be

freely permitted to follow the trail between the said creek

and the said junction of the rivers, into and across the

territory on the Canadian side of the temporary line wherever

the trail crosses to such side, and, subject to such

reasonable regulations for the protection of the Revenue as

the Canadian Government may prescribe, to carry with them over

such part or parts of the trail between the said points as may

lie on the Canadian side of the temporary line, such goods and

articles as they desire, without being required to pay any

customs duties on such goods and articles; and from said

junction to the summit of the peak East of the Chilkat river,

marked on the aforesaid map No. 10 of the United States

Commission with the number 5410 and on the map No. 17 of the

aforesaid British Commission with the number 5490. On the Dyea

and Skagway Trails, the summits of the Chilcoot and White

Passes. It is understood, as formerly set forth in

communications of the Department of State of the United

States, that the citizens or subjects of either Power, found

by this arrangement within the temporary jurisdiction of the

other, shall suffer no diminution of the rights and privileges

which they now enjoy. The Government of the United States will

at once appoint an officer or officers in conjunction with an

officer or officers to be named by the Government of Her

Britannic Majesty, to mark the temporary line agreed upon by

the erection of posts, stakes, or other appropriate temporary

marks."

In his Annual Message to Congress, December 3, 1900, the

President of the United States stated the situation as

follows:

"The work of marking certain provisional boundary points, for

convenience of administration, around the head of Lynn Canal,

in accordance with the temporary arrangement of October, 1899,

was completed by a joint survey in July last.

{10}

The modus vivendi has so far worked without friction, and the

Dominion Government has provided rules and regulations for

securing to our citizens the benefit of the reciprocal

stipulation that the citizens or subjects of either Power

found by that arrangement within the temporary jurisdiction of

the other shall suffer no diminution of the rights and

privileges they have hitherto enjoyed. But however necessary

such an expedient may have been to tide over the grave

emergencies of the situation, it is at best but an

unsatisfactory makeshift, which should not be suffered to

delay the speedy and complete establishment of the frontier

line to which we are entitled under the Russo-American treaty

for the cession of Alaska. In this relation I may refer again

to the need of definitely marking the Alaskan boundary where

it follows the 141st meridian. A convention to that end has

been before the Senate for some two years, but as no action

has been taken I contemplate negotiating a new convention for

a joint determination of the meridian by telegraphic

observations. These, it is believed, will give more accurate

and unquestionable results than the sidereal methods

heretofore independently followed, which, as is known, proved

discrepant at several points on the line, although not varying

at any place more than seven hundred feet."

ALEXANDRIA:

Discovery of the Serapeion.

See (in this volume)

ARCHÆOLOGICAL RESEARCH:

EGYPT: DISCOVERY OF THE SERAPEION.

ALEXANDRIA:

Patriarchate re-established.

See (in this volume)

PAPACY: A. D. 1896 (MARCH).

ALIENS IMMIGRATION LAW, The Transvaal.

See (in this volume)

SOUTH AFRICA (THE TRANSVAAL):

A. D. 1896-1897 (MAY-APRIL).

ALPHABET, Light on the origin of the.

See (in this volume)

ARCHÆOLOGICAL RESEARCH: CRETE.

AMATONGALAND:

Annexed, with Zululand, to Natal.

See (in this volume)

AFRICA: A. D. 1897 (ZULULAND).

AMERICA:

The Projected Intercontinental Railway.

See (in this volume)

RAILWAY, THE INTERCONTINENTAL.

AMERICA, Central.

See (in this volume)

CENTRAL AMERICA.

AMERICAN ABORIGINES.

See (in this volume)

INDIANS, AMERICAN.

AMERICAN REPUBLICS, The Bureau of the.

"The idea of the creation of an international bureau, or

agency, representing the Republics of the Western Hemisphere,

was suggested to the delegates accredited to the International

American Conference held in Washington in 1889-90, by the

conference held at Brussels in May, 1888, which planned for an

international union for the publication of customs tariffs,

etc. … On March 29, 1890, the International American

Conference, by a unanimous vote of the delegates of the

eighteen countries there represented, namely: The Argentine

Republic, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica,

Ecuador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua,

Paraguay, Peru, Salvador, United States, Uruguay, and

Venezuela, provided for the establishment of an association to

be known as 'The International Union of American Republics for

the Prompt Collection and Distribution of Commercial

Information,' which should be represented at the capital of

the United States by a Bureau, under the title of 'The Bureau

of the American Republics.' This organ, so to speak, of the

independent governments of the New World was placed under the

supervision of the Secretary of State of the United States,

and was to continue in existence for a period of ten years,

and, if found profitable to the nations participating in its

advantages, it was to be maintained for successive periods of

ten years indefinitely. At the first session of the

Fifty-first Congress of the United States, that body, in an

'Act making appropriations for the support of the Diplomatic

and Consular Service, etc.,' approved July 14, 1890, gave the

President authority to carry into effect the recommendations

of the Conference so far as he should deem them expedient, and

appropriated $36,000 for the organization and establishment of

the Bureau, which amount it had been stipulated by the

delegates in the Conference assembled should not be exceeded,

and should be annually advanced by the United States and

shared by the several Republics in proportion to their

population. … The Conference had defined the purpose of the

Bureau to be the preparation and publication of bulletins

concerning the commerce and resources of the American

Republics, and to furnish information of interest to

manufacturers, merchants, and shippers, which should be at all

times available to persons desirous of obtaining particulars

regarding their customs tariffs and regulations, as well as

commerce and navigation."

Bulletin of the Bureau of American Republics,

June, 1898.

A plan of government for the International Union, by an

executive committee composed of representatives of the

American nations constituting the Union, was adopted in 1896,